class, social class

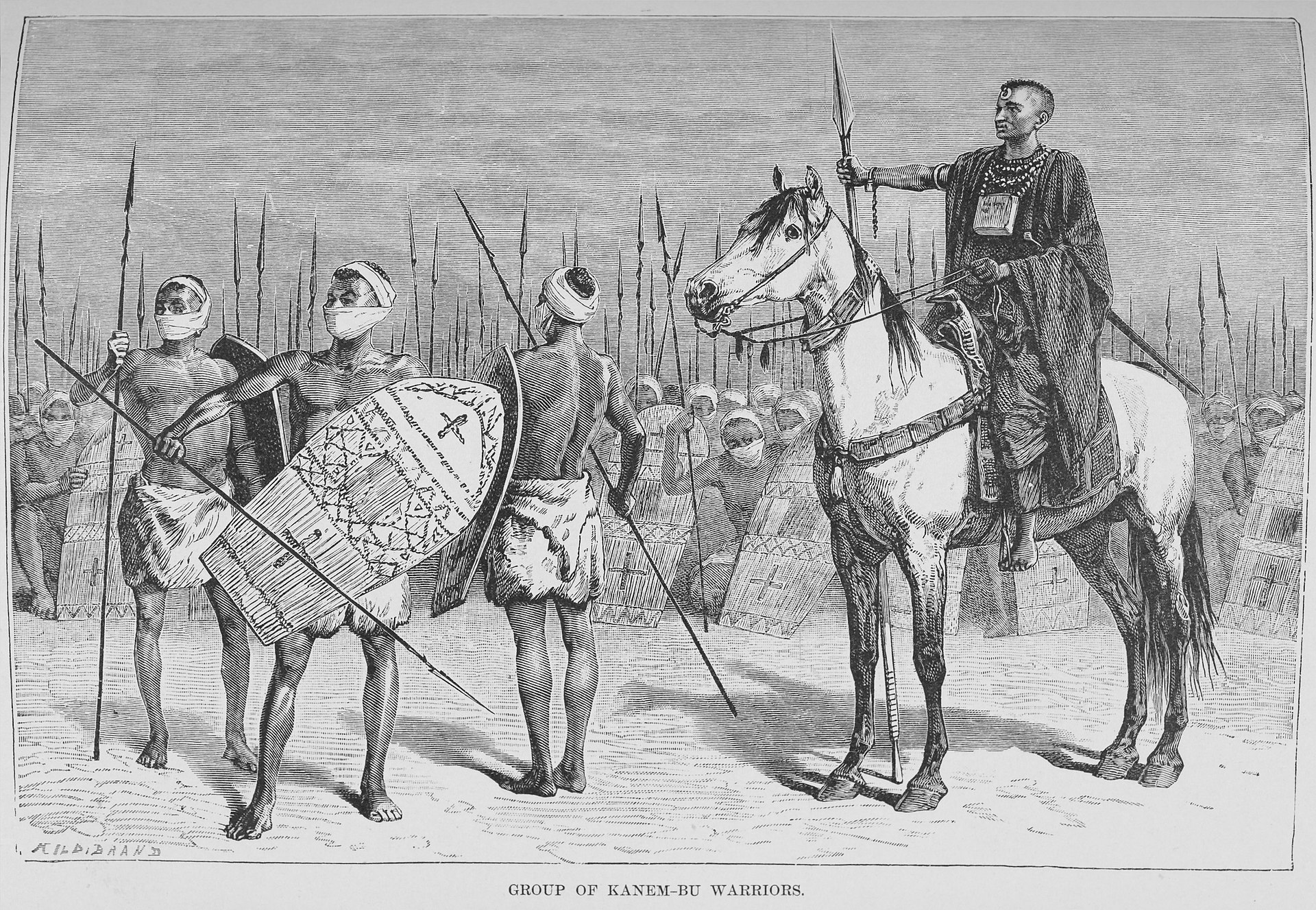

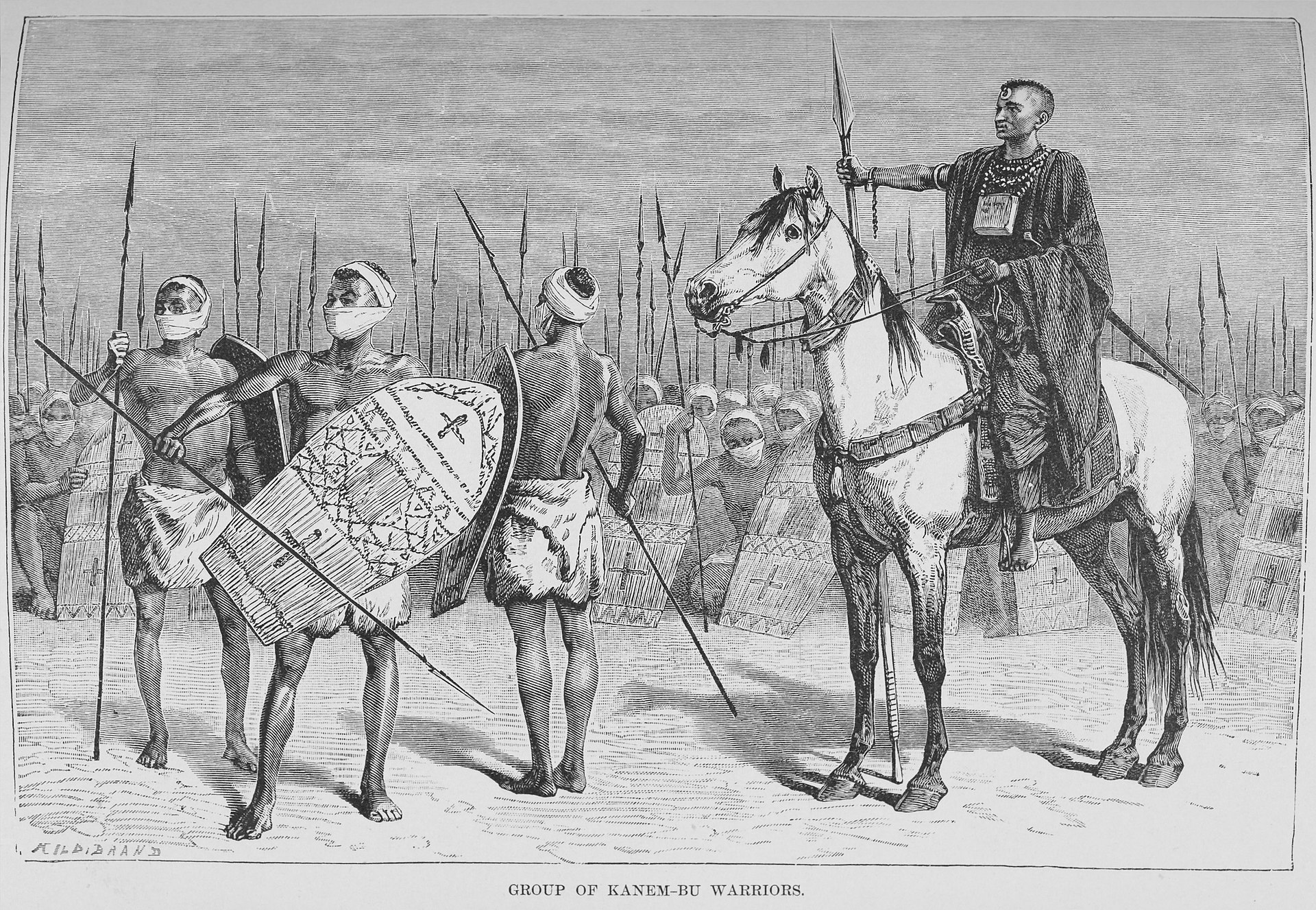

Nigerian warriors armed with spears in the retinue of a mounted war chief. The Earth and Its Inhabitants, 1892

階級・社会階級

class, social class

Nigerian warriors armed with spears in the retinue of a mounted war chief. The Earth and Its Inhabitants, 1892

| A social class or

social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical

social categories,[1] the most common being the working class, middle

class, and upper class. Membership of a social class can for example be

dependent on education, wealth, occupation, income, and belonging to a

particular subculture or social network.[2] Class is a subject of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists and social historians. The term has a wide range of sometimes conflicting meanings, and there is no broad consensus on a definition of class. Some people argue that due to social mobility, class boundaries do not exist. In common parlance, the term social class is usually synonymous with socioeconomic class, defined as "people having the same social, economic, cultural, political or educational status", e.g. the working class, "an emerging professional class" etc.[3] However, academics distinguish social class from socioeconomic status, using the former to refer to one's relatively stable cultural background and the latter to refer to one's current social and economic situation which is consequently more changeable over time.[4] The precise measurements of what determines social class in society have varied over time. Karl Marx defined class by one's relationship to the means of production (their relations of production). His understanding of classes in modern capitalist society is that the proletariat work but do not own the means of production, and the bourgeoisie, those who invest and live off the surplus generated by the proletariat's operation of the means of production, do not work at all. This contrasts with the view of the sociologist Max Weber, who contrasted class as determined by economic position, with social status (Stand) which is determined by social prestige rather than simply just relations of production.[5] The term class is etymologically derived from the Latin classis, which was used by census takers to categorize citizens by wealth in order to determine military service obligations.[6] In the late 18th century, the term class began to replace classifications such as estates, rank and orders as the primary means of organizing society into hierarchical divisions.[fact or opinion?] This corresponded to a general decrease in significance ascribed to hereditary characteristics and increase in the significance of wealth and income as indicators of position in the social hierarchy.[7][8] The existence of social classes is considered normal in many societies, both historic and modern, to varying degrees.[citation needed] |

社会階級または社会層とは、人々を階層的な社会カテゴリーに分類したも

のであり、最も一般的なものは労働者階級、中流階級、上流階級である。社会階級の構成員は、例えば教育、富、職業、収入、特定のサブカルチャーや社会ネッ

トワークへの帰属などに依存している場合がある。 階級は、社会学者、政治学者、人類学者、社会史家にとって分析の対象である。この用語は、幅広い意味を持ち、時には相反する意味を持つこともあり、階級の 定義について幅広い合意は存在しない。社会の流動性により、階級の境界は存在しないという意見もある。一般的に、「社会階級」という用語は「社会経済階 級」と同義語として使用され、「社会、経済、文化、政治、教育などの面で同等の地位にある人々」と定義される。例えば、労働者階級、「新興の専門職階級」 などである。[3] しかし、学者たちは「社会階級」と「社会経済的地位」を区別しており、前者は比較的安定した文化的背景を指し、後者は現在の社会的・経済的状況を指し、こ れは時間とともに変化しやすいものである。[4] 社会における社会階級を決定する要因の正確な測定方法は、時代とともに変化してきた。 カール・マルクスは、階級を生産手段との関係(生産関係)によって定義した。 彼が考える近代資本主義社会における階級とは、プロレタリアートは労働するが生産手段を所有せず、ブルジョワはプロレタリアートの生産手段の運用によって 生み出された余剰から投資し利益を得るが、労働は一切しないというものである。これは、経済的地位によって決定される階級と、生産関係よりもむしろ社会的 威信によって決定される社会的地位(Stand)とを対比させた社会学者マックス・ウェーバーの見解とは対照的である。[5] 階級という用語は語源的にはラテン語のclassisに由来し、これは国勢調査員が市民を富によって分類し、兵役義務を決定するために使用されていた。 [6] 18世紀後半には、階級という用語が、不動産、地位、勲位などの分類に取って代わり、社会を階層的に区分する主な手段となった。これは、世襲的特徴に帰属 する意義の一般的な低下と、社会階層における地位の指標としての富や収入の意義の増加に対応するものである。 社会階級の存在は、程度の差こそあれ、歴史的にも現代においても、多くの社会で普通のことと考えられている。[要出典] |

| History Ancient Egypt The existence of a class system dates back to times of Ancient Egypt, where the position of elite was also characterized by literacy.[9] The wealthier people were at the top in the social order and common people and slaves being at the bottom.[10] However, the class was not rigid; a man of humble origins could ascend to a high post.[11]: 38– The ancient Egyptians viewed men and women, including people from all social classes, as essentially equal under the law, and even the lowliest peasant was entitled to petition the vizier and his court for redress.[12] Farmers made up the bulk of the population, but agricultural produce was owned directly by the state, temple, or noble family that owned the land.[13]: 383 Farmers were also subject to a labor tax and were required to work on irrigation or construction projects in a corvée system.[14]: 136 Artists and craftsmen were of higher status than farmers, but they were also under state control, working in the shops attached to the temples and paid directly from the state treasury. Scribes and officials formed the upper class in ancient Egypt, known as the "white kilt class" in reference to the bleached linen garments that served as a mark of their rank.[15]: 109 The upper class prominently displayed their social status in art and literature. Below the nobility were the priests, physicians, and engineers with specialized training in their field. It is unclear whether slavery as understood today existed in ancient Egypt; there is difference of opinions among authors.[16]  Slave beating in ancient Egypt Not a single Egyptian was, in our sense of the word, free. No individual could call in question a hierarchy of authority which culminated in a living god. — Emile Durkheim[11] Although slaves were mostly used as indentured servants, they were able to buy and sell their servitude, work their way to freedom or nobility, and were usually treated by doctors in the workplace.[17] |

歴史 古代エジプト 階級制度の存在は古代エジプトの時代まで遡り、エリートの地位は読み書き能力によって特徴づけられていた。[9] 社会秩序では富裕層が上位に位置し、庶民と奴隷が下位に位置していた。[10] しかし、階級は固定されておらず、謙虚な出自の人物が高位に昇進することも可能であった。[11]:38– 古代エジプト人は、あらゆる社会階級の人々を含め、男性も女性も基本的に法の下では平等であると見なしていた。最も身分の低い農民でさえも、宰相とその裁 判所に救済を求める権利を有していた。 農民が人口の大半を占めていたが、農作物は土地を所有する国家、神殿、貴族が直接所有していた。農民は労働税の対象でもあり、 。農民は労働税の対象でもあり、コルヴェー制度に従って灌漑や建設プロジェクトに従事することが義務付けられていた。[14]: 136 芸術家や職人は農民よりも高い地位にあったが、彼らもまた国家の管理下にあり、寺院に付属する店舗で働き、国家の金庫から直接給与が支払われていた。古代 エジプトでは、書記や役人が上流階級を形成しており、その地位の象徴として漂白されたリネンの衣服を身にまとっていたことから、「白いキルト階級」と呼ば れていた。[15]:109 上流階級は、芸術や文学において、その社会的地位を顕著に示していた。貴族の下には、その分野での専門教育を受けた聖職者、医師、技術者がいた。古代エジ プトに現代でいうところの奴隷制が存在したかどうかは不明である。学者の間でも意見が分かれている。  古代エジプトにおける奴隷の殴打 エジプト人には、我々の感覚で言えば、自由な人間は一人もいなかった。生ける神に象徴される権威のヒエラルキーを疑うことなど、誰にもできなかった。 — エミール・デュルケーム[11] 奴隷はほとんどが年季奉公人として使役されていたが、奴隷身分を売買したり、自由の身になるために働いたり、貴族になるために働くこともでき、また、職場 では医師の治療を受けることもできた。[17] |

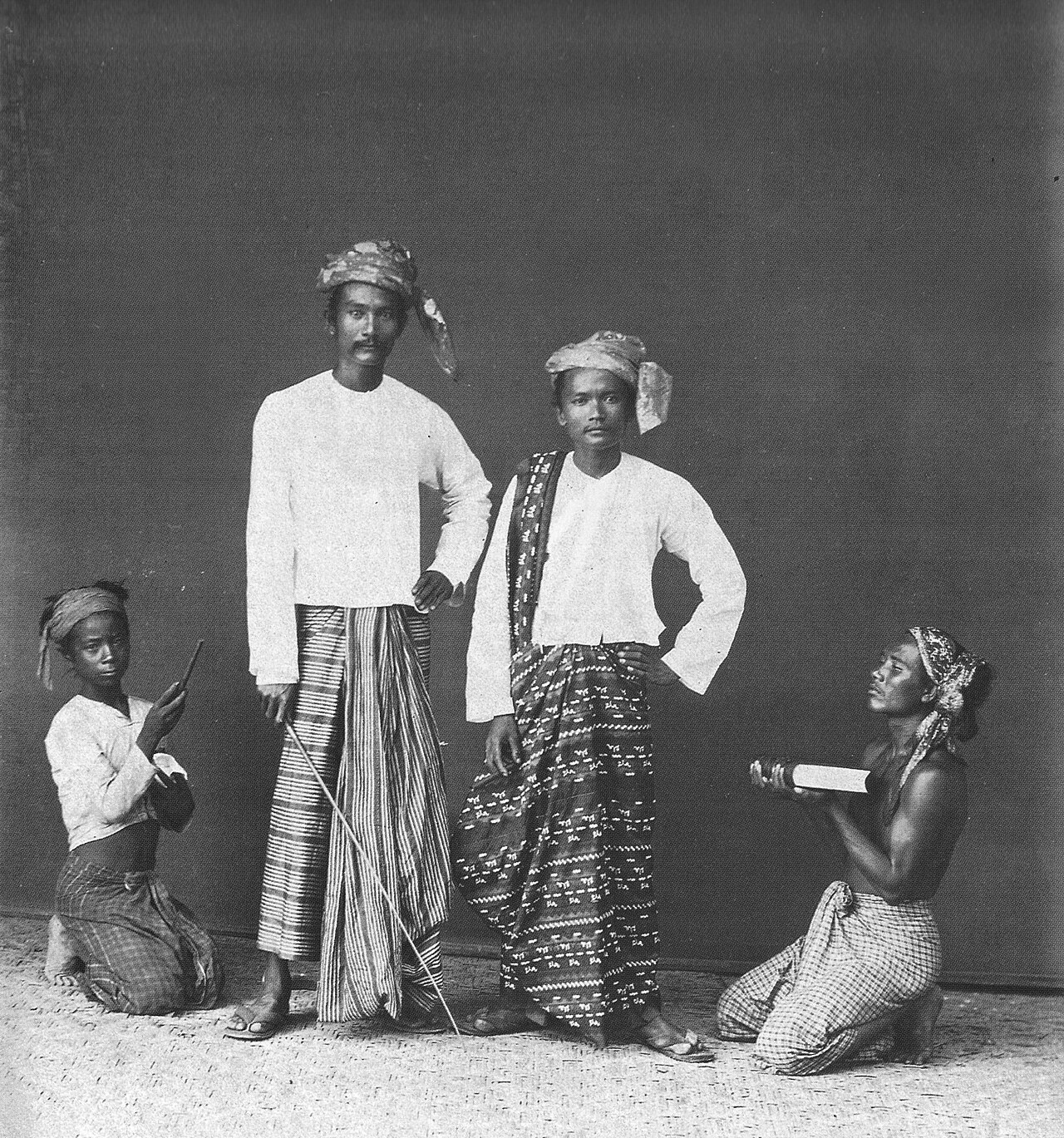

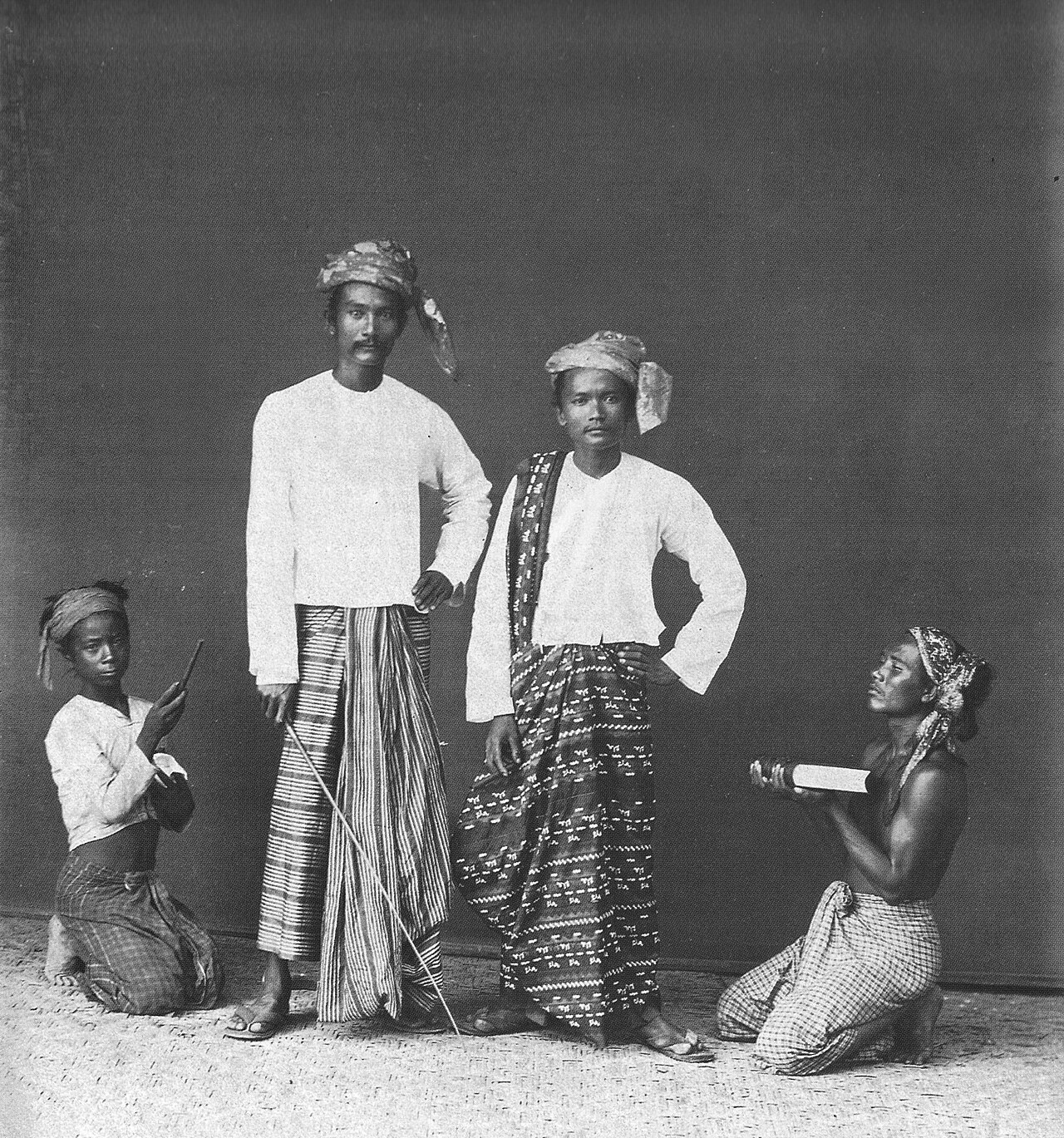

| Elsewhere In Ancient Greece when the clan system[a] was declining. The classes[b] replaced the clan society when it became too small to sustain the needs of increasing population. The division of labor is also essential for the growth of classes.[11]: 39  Burmese nobles and servants  Nigerian warriors armed with spears in the retinue of a mounted war chief. The Earth and Its Inhabitants, 1892 Historically, social class and behavior were laid down in law. For example, permitted mode of dress in some times and places was strictly regulated, with sumptuous dressing only for the high ranks of society and aristocracy, whereas sumptuary laws stipulated the dress and jewelry appropriate for a person's social rank and station. In Europe, these laws became increasingly commonplace during the Middle Ages. However, these laws were prone to change due to societal changes, and in many cases, these distinctions may either almost disappear, such as the distinction between a patrician and a plebeian being almost erased during the late Roman Republic. Jean-Jacques Rousseau had a large influence over political ideals of the French Revolution because of his views of inequality and classes. Rousseau saw humans as "naturally pure and good," meaning that humans from birth were seen as innocent and any evilness was learned. He believed that social problems arise through the development of society and suppress the innate pureness of humankind. He also believed that private property is the main reason for social issues in society because private property creates inequality through the property's value. Even though his theory predicted if there were no private property then there would be wide spread equality, Rousseau accepted that there will always be social inequality because of how society is viewed and run.[18] Later Enlightenment thinkers viewed inequality as valuable and crucial to society's development and prosperity. They also acknowledged that private property will ultimately cause inequality because specific resources that are privately owned can be stored and the owners profit off of the deficit of the resource. This can create competition between the classes that was seen as necessary by these thinkers.[18] This also creates stratification between the classes keeping a distinct difference between lower, poorer classes and the higher, wealthier classes. India (↑), Nepal, North Korea (↑), Sri Lanka (↑) and some Indigenous peoples maintain social classes today. In class societies, class conflict has tended to recur or is ongoing, depending on the sociological and anthropolitical perspective.[19][20] Class societies have not always existed; there have been widely different types of class communities.[21][22][23] For example, societies based on age rather than capital.[24] During colonialism, social relations were dismantled by force, which gave rise to societies based on the social categories of waged labor, private property, and capital.[24][25] |

他の場所では 古代ギリシャでは、氏族制[a]が衰退していた。人口増加に伴うニーズを維持することが難しくなったため、氏族社会は階級[b]に取って代わられた。階級 の成長には、労働の分業も不可欠である。[11]: 39  ビルマの貴族と使用人  騎乗した戦士長の随行員として槍で武装したナイジェリアの戦士。『地球とその住民』、1892年 歴史的に、社会階級と行動は法律で規定されていた。例えば、ある時代や場所で許容される服装は厳格に規制されており、社会の上層部や貴族階級のみが豪華な 服装を許されていた。一方、倹約令では、個人の社会的地位や立場にふさわしい服装や装飾品が規定されていた。ヨーロッパでは、中世の時代にこうした法律が ますます一般的になっていった。しかし、こうした法律は社会の変化によって変わりやすかったため、多くの場合、こうした区別はほとんど消滅することもあ り、例えば、ローマ共和国末期には貴族と平民の区別がほとんどなくなっていた。 ジャン・ジャック・ルソーは、不平等と階級に関する見解により、フランス革命の政治的理念に大きな影響を与えた。ルソーは人間を「生まれながらにして純粋 で善良」と捉え、人間は生まれながらにして無垢であり、悪は学習によって身に付くものだと考えた。彼は、社会が発展するにつれて社会問題が生じ、人間が生 まれながらにして持つ純粋さが抑圧されると信じていた。また、私有財産が財産の価値を通じて不平等を生み出すため、私有財産こそが社会問題の主な原因であ ると信じていた。私有財産がなければ平等が広まるだろうという彼の理論にもかかわらず、ルソーは社会のあり方や運営方法によって社会的不平等が常に存在す ることを認めていた。 後の啓蒙思想家たちは、不平等を社会の発展と繁栄にとって価値があり、不可欠なものとみなした。また、私有財産は最終的に不平等を引き起こすということも 認めていた。私有財産は、私有されている特定の資源を蓄えることができ、所有者はその資源の不足から利益を得ることができるからである。これは、階級間の 競争を生み出すが、この競争はこれらの思想家たちにとって必要不可欠なものとみなされていた。また、これは、下層階級と上層階級の間に明確な違いを維持す る階層化を生み出す。 インド(↑)、ネパール、北朝鮮(↑)、スリランカ(↑)、および一部の先住民社会では、今日でも社会階級が維持されている。 階級社会では、階級間の対立が繰り返される傾向にあるか、社会学や政治学の見解によって継続している。[19][20] 階級社会は常に存在してきたわけではなく、階級社会にはさまざまな形態があった。[21][22][2 例えば、資本ではなく年齢に基づく社会などである。[24] 植民地主義時代には、社会関係は力によって解体され、賃金労働、私有財産、資本といった社会カテゴリーに基づく社会が誕生した。[24][25] |

| Class society Class society or class-based society is an organizing principle society in which ownership of property, means of production, and wealth is the determining factor of the distribution of power, in which those with more property and wealth are stratified higher in the society and those without access to the means of production and without wealth are stratified lower in the society. In a class society, at least implicitly, people are divided into distinct social strata, commonly referred to as social classes or castes. The nature of class society is a matter of sociological research.[26][27][28] Class societies exist all over the globe in both industrialized and developing nations.[29] Class stratification is theorized to come directly from capitalism.[30] In terms of public opinion, nine out of ten people in a Swedish survey considered it correct that they are living in a class society.[31] Comparative sociological research One may use comparative methods to study class societies, using, for example, comparison of Gini coefficients, de facto educational opportunities, unemployment, and culture.[32][33] Effect on the population Societies with large class differences have a greater proportion of people who suffer from mental health issues such as anxiety and depression symptoms.[34][35][36] A series of scientific studies have demonstrated this relationship.[37] Statistics support this assertion and results are found in life expectancy and overall health; for example, in the case of high differences in life expectancy between two Stockholm suburbs. The differences between life expectancy of the poor and less-well-educated inhabitants who live in proximity to the station Vårby gård, and the highly educated and more affluent inhabitants living near Danderyd differ by 18 years.[38][39] Similar data about New York is also available for life expectancy, average income per capita, income distribution, median income mobility for people who grew up poor, share with a bachelor's degree or higher.[40] In class societies, the lower classes systematically receive lower-quality education and care.[41][42][43] There are more explicit effects where those within the higher class actively demonize parts of the lower-class population.[33][44] |

階級社会 階級社会または階級に基づく社会とは、財産、生産手段、富の所有が権力の配分の決定要因となる社会の組織化原理である。財産や富を多く持つ者は社会的に高 い階層に属し、生産手段へのアクセスや富を持たない者は社会的に低い階層に属する。階級社会では、少なくとも暗黙のうちに、人々は明確な社会階層に分けら れ、一般的に社会階級またはカーストと呼ばれる。階級社会の性質は社会学の研究対象である。[26][27][28] 階級社会は先進国と発展途上国を問わず、世界中に存在している。[29] 階級分化は資本主義から直接的に生じると理論化されている。[30] 世論調査によると、スウェーデン人の10人中9人が、自国は階級社会であると答えている。[31] 比較社会学的研究 たとえばジニ係数、事実上の教育機会、失業率、文化などの比較を行う比較方法を用いて、階級社会を研究することができる。 人口への影響 階級格差が大きい社会では、不安やうつ症状などの精神衛生上の問題を抱える人の割合が大きい。[34][35][36] 科学的研究のシリーズがこの関係を示している。[37] この主張は統計によって裏付けられており、その成果は平均余命や健康全般に見られる。例えば、ストックホルムの2つの郊外の平均余命の差が大きい場合など である。ヴァールビー・ゴーズ駅に近い場所に住む貧困層や低学歴層の住民と、ダーネリッド駅に近い場所に住む高学歴層や富裕層の住民の平均余命の差は18 歳にもなる。 ニューヨークに関する同様のデータも、平均余命、一人当たりの平均収入、所得分布、貧困層で育った人々の平均収入の変動、学士号以上の学位保有率などにつ いて入手可能である。 階級社会では、下層階級は組織的に質が低い教育やケアしか受けられない。[41][42][43] 上層階級に属する人々が下層階級の一部を積極的に悪者にしている場合、より明白な影響がある。[33][44] |

| Theoretical models Definitions of social classes reflect a number of sociological perspectives, informed by anthropology, economics, psychology and sociology. The major perspectives historically have been Marxism and structural functionalism. The common stratum model of class divides society into a simple hierarchy of working class, middle class and upper class. Within academia, two broad schools of definitions emerge: those aligned with 20th-century sociological stratum models of class society and those aligned with the 19th-century historical materialist economic models of the Marxists and anarchists.[45][46][47] Another distinction can be drawn between analytical concepts of social class, such as the Marxist and Weberian traditions, as well as the more empirical traditions such as socioeconomic status approach, which notes the correlation of income, education and wealth with social outcomes without necessarily implying a particular theory of social structure.[48] Further information: People accounting hypothesis Marxist Main articles: Class in Marxist theory and Communist society "[Classes are] large groups of people differing from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organization of labor, and, consequently, by the dimensions of the share of social wealth of which they dispose and the mode of acquiring it." —Vladimir Lenin, A Great Beginning in June 1919 For Marx, class is a combination of objective and subjective factors. Objectively, a class shares a common relationship to the means of production. The class society itself is understood as the aggregated phenomenon to the "interlinked movement", which generates the quasi-objective concept of capital.[49] Subjectively, the members will necessarily have some perception ("class consciousness") of their similarity and common interest. Class consciousness is not simply an awareness of one's own class interest but is also a set of shared views regarding how society should be organized legally, culturally, socially and politically. These class relations are reproduced through time. In Marxist theory, the class structure of the capitalist mode of production is characterized by the conflict between two main classes: the bourgeoisie, the capitalists who own the means of production and the much larger proletariat (or "working class") who must sell their own labour power (wage labour). This is the fundamental economic structure of work and property, a state of inequality that is normalized and reproduced through cultural ideology. For Marxists, every person in the process of production has separate social relationships and issues. Along with this, every person is placed into different groups that have similar interests and values that can differ drastically from group to group. Class is special in that does not relate to specifically to a singular person, but to a specific role.[18] Marxists explain the history of "civilized" societies in terms of a war of classes between those who control production and those who produce the goods or services in society. In the Marxist view of capitalism, this is a conflict between capitalists (bourgeoisie) and wage-workers (the proletariat). For Marxists, class antagonism is rooted in the situation that control over social production necessarily entails control over the class which produces goods—in capitalism this is the exploitation of workers by the bourgeoisie.[50] Furthermore, "in countries where modern civilisation has become fully developed, a new class of petty bourgeois has been formed".[50] "An industrial army of workmen, under the command of a capitalist, requires, like a real army, officers (managers) and sergeants (foremen, over-lookers) who, while the work is being done, command in the name of the capitalist".[51] Marx makes the argument that, as the bourgeoisie reach a point of wealth accumulation, they hold enough power as the dominant class to shape political institutions and society according to their own interests. Marx then goes on to claim that the non-elite class, owing to their large numbers, have the power to overthrow the elite and create an equal society.[52] In The Communist Manifesto, Marx himself argued that it was the goal of the proletariat itself to displace the capitalist system with socialism, changing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a future communist society in which: "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all". This would mark the beginning of a classless society in which human needs rather than profit would be motive for production. In a society with democratic control and production for use, there would be no class, no state and no need for financial and banking institutions and money.[53][54] These theorists have taken this binary class system and expanded it to include contradictory class locations, the idea that a person can be employed in many different class locations that fall between the two classes of proletariat and bourgeoisie. Erik Olin Wright stated that class definitions are more diverse and elaborate through identifying with multiple classes, having familial ties with people in different a class, or having a temporary leadership role.[18] |

理論モデル 社会階級の定義は、人類学、経済学、心理学、社会学などの知見に基づく、多くの社会学的な視点が反映されている。歴史的に主要な視点は、マルクス主義と構 造機能主義であった。一般的な階層モデルでは、社会を労働者階級、中流階級、上流階級という単純な階層に分ける。学術界では、2つの大きな定義の流派が現 れた。20世紀の階級社会の社会学的層モデルに一致するものと、マルクス主義者やアナーキストの19世紀の唯物史観経済モデルに一致するものである。 また、マルクス主義やウェーバー学派の伝統といった社会階級の分析的概念と、社会構造の特定の理論を必ずしも暗示することなく、所得、教育、富と社会的成 果との相関関係を指摘する社会経済的地位アプローチのようなより経験的な伝統との間にも区別することができる。 詳細情報:ピープル・アカウンティング仮説 マルクス主義 詳細は「マルクス主義における階級」および「共産主義社会」を参照 「階級とは、歴史的に決定された社会生産の体系における占める位置、生産手段との関係(ほとんどの場合、固定され、法律で規定されている)、労働の社会的 組織における役割、そしてその結果として、彼らが管理する社会の富の分配の規模と、それを獲得する方法によって、互いに異なる人々の大きな集団である。 —ウラジーミル・レーニン、1919年6月の「偉大な始まり」 マルクスにとって、階級とは客観的および主観的要因の組み合わせである。客観的には、階級は生産手段に対する共通の関係を共有している。階級社会そのもの は、「相互に結びついた運動」の集合現象として理解され、それは資本という準客観的概念を生み出す。主観的には、その構成員は必然的に自分たちの類似性と 共通の利害について何らかの認識(「階級意識」)を持つことになる。階級意識とは、単に自分自身の階級的利益を認識するだけではなく、社会が法的に、文化 的に、社会的に、政治的にどのように組織されるべきかに関する共有された見解の集合でもある。こうした階級関係は、時を経ても再生産される。 マルクス主義理論では、資本主義的生産様式の階級構造は、主に2つの階級間の対立によって特徴づけられる。すなわち、生産手段を所有する資本家であるブル ジョワジーと、自身の労働力(賃金労働)を販売しなければならないはるかに大きなプロレタリアート(または「労働者階級」)である。これは労働と財産の基 本的経済構造であり、文化的なイデオロギーによって正常化され、再生産される不平等な状態である。 マルクス主義者にとって、生産過程におけるあらゆる人々は、それぞれ異なる社会的関係や問題を抱えている。これに伴い、あらゆる人は、グループによって大 きく異なる可能性がある、類似した利害や価値観を持つさまざまなグループに分けられる。階級は、特定の個人ではなく、特定の役割に関連している点で特殊で ある。 マルクス主義者は、「文明化」された社会の歴史を、生産を支配する者と社会で商品やサービスを生産する者との階級間の戦いとして説明する。マルクス主義の 資本主義観では、これは資本家(ブルジョワジー)と賃金労働者(プロレタリアート)の間の対立である。マルクス主義者にとって、階級間の対立は、社会生産 の管理が必然的に生産物を作り出す階級の管理を伴うという状況に根ざしている。資本主義では、これはブルジョワジーによる労働者の搾取である。 さらに、「近代文明が完全に発達した国々では、小市民階級という新たな階級が形成された」[50]。「資本家の指揮下にある労働者の軍隊は、本物の軍隊の ように、資本家の名のもとに指揮を執る士官(マネージャー)と軍曹(現場監督、監督者)を必要とする」[51]。 マルクスは、ブルジョワジーが富を蓄積する段階に達すると、支配階級として政治制度や社会を自らの利益に合わせて形作るのに十分な力を握るという主張をし ている。そして、マルクスは、エリート層ではない階級が多数派であるがゆえに、エリート層を打倒し、平等な社会を創り出す力を持っていると主張している。 『共産党宣言』の中で、マルクス自身は、資本主義制度を社会主義に置き換え、階級制度を支える社会関係を変化させ、最終的には「各人の自由な発展が万人の 自由な発展の条件である」未来の共産主義社会へと発展させることがプロレタリアートの目標であると主張した。これは、利益よりも人間のニーズが生産の動機 となる階級のない社会の始まりを意味する。民主的な管理と使用のための生産が行われる社会では、階級も国家も存在せず、金融機関や銀行、貨幣も必要ない。 [53][54] これらの理論家たちは、この二元的な階級制度を拡大し、プロレタリアートとブルジョワジーの2つの階級の中間に位置する、矛盾した階級の位置付けを含める ようにした。エリック・オリン・ライトは、複数の階級に属すること、異なる階級の人々と家族的なつながりを持つこと、一時的に指導的な役割を担うことなど を通じて、階級の定義はより多様かつ複雑になるとしている。[18] |

| Weberian Main article: Three-component theory of stratification Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification that saw social class as emerging from an interplay between "class", "status" and "power". Weber believed that class position was determined by a person's relationship to the means of production, while status or "Stand" emerged from estimations of honor or prestige.[55] Weber views class as a group of people who have common goals and opportunities that are available to them. This means that what separates each class from each other is their value in the marketplace through their own goods and services. This creates a divide between the classes through the assets that they have such as property and expertise.[18] Weber derived many of his key concepts on social stratification by examining the social structure of many countries. He noted that contrary to Marx's theories, stratification was based on more than simply ownership of capital. Weber pointed out that some members of the aristocracy lack economic wealth yet might nevertheless have political power. Likewise in Europe, many wealthy Jewish families lacked prestige and honor because they were considered members of a "pariah group". Class: A person's economic position in a society. Weber differs from Marx in that he does not see this as the supreme factor in stratification. Weber noted how managers of corporations or industries control firms they do not own. Status: A person's prestige, social honour or popularity in a society. Weber noted that political power was not rooted in capital value solely, but also in one's status. Poets and saints, for example, can possess immense influence on society with often little economic worth. Power: A person's ability to get their way despite the resistance of others. For example, individuals in state jobs, such as an employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or a member of the United States Congress, may hold little property or status, but they still hold immense power. |

Weberian Main article: Three-component theory of stratification Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification that saw social class as emerging from an interplay between "class", "status" and "power". Weber believed that class position was determined by a person's relationship to the means of production, while status or "Stand" emerged from estimations of honor or prestige.[55] Weber views class as a group of people who have common goals and opportunities that are available to them. This means that what separates each class from each other is their value in the marketplace through their own goods and services. This creates a divide between the classes through the assets that they have such as property and expertise.[18] Weber derived many of his key concepts on social stratification by examining the social structure of many countries. He noted that contrary to Marx's theories, stratification was based on more than simply ownership of capital. Weber pointed out that some members of the aristocracy lack economic wealth yet might nevertheless have political power. Likewise in Europe, many wealthy Jewish families lacked prestige and honor because they were considered members of a "pariah group". Class: A person's economic position in a society. Weber differs from Marx in that he does not see this as the supreme factor in stratification. Weber noted how managers of corporations or industries control firms they do not own. Status: A person's prestige, social honour or popularity in a society. Weber noted that political power was not rooted in capital value solely, but also in one's status. Poets and saints, for example, can possess immense influence on society with often little economic worth. Power: A person's ability to get their way despite the resistance of others. For example, individuals in state jobs, such as an employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or a member of the United States Congress, may hold little property or status, but they still hold immense power. |

| Bourdieu Main article: Bourdieu § Theory of capital and class distinction For Bourdieu, the place in the social strata for any person is vaguer than the equivalent in Weberian sociology. Bourdieu introduced an array of concepts of what he refers to as types of capital. These types were economic capital, in the form assets convertible to money and secured as private property. This type of capital is separated from the other types of culturally constituted types of capital, which Bourdieu introduces, which are: personal cultural capital (formal education, knowledge); objective cultural capital (books, art); and institutionalized cultural capital (honours and titles). |

ブルデュー 詳細は「ブルデュー § 資本と階級区分の理論」を参照 ブルデューにとって、社会階層における個人の位置づけは、ヴェーバーの社会学におけるそれよりも曖昧である。ブルデューは、彼が資本のタイプと呼ぶ概念の 体系を導入した。これらのタイプは、私有財産として確保され、金銭に変換可能な資産の形態である経済資本であった。このタイプの資本は、ブルデューが紹介 するその他のタイプの文化的に構成された資本、すなわち、個人的文化資本(正規の教育、知識)、客観的文化資本(書籍、芸術)、制度化された文化資本(名 誉、称号)とは区別される。 |

| Great British Class Survey Main article: Great British Class Survey On 2 April 2013, the results of a survey[56] conducted by BBC Lab UK developed in collaboration with academic experts and slated to be published in the journal Sociology were published online.[57][58][59][60][61] The results released were based on a survey of 160,000 residents of the United Kingdom most of whom lived in England and described themselves as "white". Class was defined and measured according to the amount and kind of economic, cultural and social resources reported. Economic capital was defined as income and assets; cultural capital as amount and type of cultural interests and activities; and social capital as the quantity and social status of their friends, family and personal and business contacts.[60] This theoretical framework was developed by Pierre Bourdieu who first published his theory of social distinction in 1979. |

英国の偉大なクラス調査 詳細は「英国の偉大なクラス調査」を参照 2013年4月2日、学識経験者との共同作業でBBC Lab UKが実施し、学術誌『Sociology』で発表予定の調査[56]の結果がオンラインで発表された。[57][58][59][60][61] 発表された結果は、イングランド在住で自身を「白人」と表現する英国在住者16万人を対象とした調査に基づいている。階級は、報告された経済的、文化的、 社会的資源の量と種類に基づいて定義され、測定された。経済的資本は収入と資産、文化的資本は文化的関心と活動の量と種類、そして社会的資本は友人、家 族、個人およびビジネス上の人脈の量と社会的地位として定義された。[60] この理論的枠組みは、1979年に社会的区別の理論を初めて発表したピエール・ブルデューによって開発された。 |

| Three-level economic class model Today, concepts of social class often assume three general economic categories: a very wealthy and powerful upper class that owns and controls the means of production; a middle class of professional workers, small business owners and low-level managers; and a lower class, who rely on low-paying jobs for their livelihood and experience poverty. Upper class Main article: Upper class See also: Elite, Aristocracy, Oligarchy, Business magnate, and Ruling class  A symbolic image of three orders of feudal society in Europe prior to the French Revolution, which shows the rural third estate carrying the clergy and the nobility The upper class[62] is the social class composed of those who are rich, well-born, powerful, or a combination of those. They usually wield the greatest political power. In some countries, wealth alone is sufficient to allow entry into the upper class. In others, only people who are born or marry into certain aristocratic bloodlines are considered members of the upper class and those who gain great wealth through commercial activity are looked down upon by the aristocracy as nouveau riche.[63] In the United Kingdom, for example, the upper classes are the aristocracy and royalty, with wealth playing a less important role in class status. Many aristocratic peerages or titles have seats attached to them, with the holder of the title (e.g. Earl of Bristol) and his family being the custodians of the house, but not the owners. Many of these require high expenditures, so wealth is typically needed. Many aristocratic peerages and their homes are parts of estates, owned and run by the title holder with moneys generated by the land, rents or other sources of wealth. However, in the United States where there is no aristocracy or royalty, the upper class status exclusive of Americans of ancestral wealth or patricians of European ancestry is referred to in the media as the extremely wealthy, the so-called "super-rich", though there is some tendency even in the United States for those with old family wealth to look down on those who have accrued their money through business, the struggle between new money and old money. The upper class is generally contained within the richest one or two percent of the population. Members of the upper class are often born into it and are distinguished by immense wealth which is passed from generation to generation in the form of estates.[64] Based on some new social and political theories upper class consists of the most wealthy decile group in society which holds nearly 87% of the whole society's wealth.[65] Middle class Main articles: Middle class, Upper middle class, Lower middle class, and Bourgeoisie See also: Middle-class squeeze The middle class is the most contested of the three categories, the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the lower and upper classes.[66] One example of the contest of this term is that in the United States "middle class" is applied very broadly and includes people who would elsewhere be considered working class. Middle-class workers are sometimes called "white-collar workers". Theorists such as Ralf Dahrendorf have noted the tendency toward an enlarged middle class in modern Western societies, particularly in relation to the necessity of an educated work force in technological economies.[67] Perspectives concerning globalization and neocolonialism, such as dependency theory, suggest this is due to the shift of low-level labour to developing nations and the Third World.[68] Middle class is the group of people with jobs that pay significantly more than the poverty line. Examples of these types of jobs are factory workers, salesperson, teacher, cooks and nurses. There is a new trend by some scholars which assumes that the size of the middle class in every society is the same. For example, in paradox of interest theory, middle class are those who are in 6th–9th decile groups which hold nearly 12% of the whole society's wealth.[69] Lower class  In many countries, the lowest stratum of the working class, the underclass, often lives in urban areas with low-quality civil services Main articles: Working class and Proletariat See also: Precarity Lower class (occasionally described as working class) are those employed in low-paying wage jobs with very little economic security. The term "lower class" also refers to persons with low income. The working class is sometimes separated into those who are employed but lacking financial security (the "working poor") and an underclass—those who are long-term unemployed and/or homeless, especially those receiving welfare from the state. The latter is today considered analogous to the Marxist term "lumpenproletariat". However, during the time of Marx's writing the lumpenproletariat referred to those in dire poverty; such as the homeless.[62] Members of the working class are sometimes called blue-collar workers. |

3段階の経済的階級モデル 今日、社会階級の概念は、一般的に3つの経済的カテゴリーを想定している。すなわち、生産手段を所有し管理する非常に裕福で強力な富裕層、専門職従事者、 小規模事業主、低レベルの管理職からなる中流階級、そして低賃金の仕事に頼って生活し、貧困を経験する下層階級である。 上流階級 詳細は「上流階級」を参照 エリート、貴族政治、寡頭制、実業家、支配階級も参照  フランス革命以前のヨーロッパにおける封建社会の3つの身分階級を象徴的に表した図。農村部の第三身分の身分の者が聖職者と貴族を担いでいる 上流階級[62]とは、富裕、高貴な生まれ、権力、またはそれらの組み合わせを持つ人々から構成される社会階級である。彼らは通常、最大の政治的権力を 握っている。国によっては、富のみで上流階級に属することが認められる。また、特定の貴族の血筋に生まれ、または結婚した人だけが上流階級と見なされ、商 業活動によって巨額の富を築いた人は、貴族階級から成り上がり者として見下される国もある。例えば、イギリスでは上流階級は貴族と王族であり、階級の地位 において富はそれほど重要な役割を果たさない。多くの貴族の爵位や称号には、それに付随する土地があり、称号の保有者(例えばブリストル伯爵)とその家族 がその家の管理責任者となるが、所有者ではない。これらの多くは多額の出費を必要とするため、通常は財産が必要となる。多くの貴族の爵位とその家屋敷は、 土地や家賃、その他の財産から生み出される資金によって保有者によって所有・運営される不動産の一部である。しかし、貴族や王族が存在しないアメリカで は、先祖代々からの財産を持つアメリカ人やヨーロッパの貴族を除く上流階級の地位は、メディアでは「超富裕層」、いわゆる「スーパーリッチ」と呼ばれてい る。ただし、アメリカでも旧家の財産を持つ人々が、事業で財を成した人々を見下す傾向があることは事実であり、ニューマネーとオールドマネーの闘争が存在 する。 一般的に、富裕層は人口の1パーセントから2パーセントの富裕層を指す。富裕層は生まれながらの階級であることが多く、代々受け継がれてきた莫大な財産に よって区別される。[64] いくつかの新しい社会・政治理論によると、富裕層は社会の富裕層の上位10パーセントのグループで構成され、社会全体の富の87パーセント近くを保有して いる。[65] 中流階級 詳細は「中流階級」、「上流中流階級」、「下流中流階級」、および「ブルジョワジー」を参照 関連項目:中流階級の圧迫 中流階級は、3つのカテゴリーの中で最も論争の的となっている。現代社会における幅広い人々の集団であり、社会経済的には下層階級と上層階級の間に位置す る。[66] この用語の論争の例としては、アメリカ合衆国では「中流階級」が非常に広く適用され、他の国では労働者階級と見なされる人々も含むということがある。中流 階級の労働者は「ホワイトカラー労働者」と呼ばれることもある。 ラルフ・ダレンドルフなどの理論家は、特に技術経済における教育を受けた労働力の必要性との関連において、現代の西洋社会における中流階級の拡大傾向を指 摘している。[67] グローバル化と新植民地主義に関する視点、例えば従属理論などは、これは低レベル労働が発展途上国や第三世界に移転したことによるものだと示唆している。 [68] 中流階級とは、貧困ラインを大幅に上回る賃金を得る仕事に就く人々のグループである。この種の仕事の例としては、工場労働者、販売員、教師、調理師、看護 師などが挙げられる。一部の学者の間では、あらゆる社会における中流階級の規模は同じであるという新たな傾向が見られる。例えば、利害のパラドックス理論 では、中流階級とは、社会全体の富の約12%を保有する第6~第9百分位数のグループに属する人々であるとされる。 下層階級  多くの国々では、労働者階級の最下層であるアンダークラスは、都市部に居住し、質が低い公共サービスを受けていることが多い。 詳細は「労働者階級」および「プロレタリアート」を参照。 不安定労働も参照。 低所得者層(労働者階級と表現されることもある)は、経済的な安定性がほとんどない低賃金の仕事に就いている人々である。 「低所得者層」という用語は、低所得者にも用いられる。 労働者階級は、雇用されているが経済的な安定を欠く人々(ワーキングプア)と、長期失業者やホームレス(特に生活保護受給者)であるアンダークラスに分け られることもある。後者は今日では、マルクス主義の用語である「ルンペンプロレタリアート」に類似していると考えられている。しかし、マルクスが著述して いた時代には、ルンペンプロレタリアートは極貧層、例えばホームレスなどを指していた。[62] 労働者階級のメンバーは、ブルーカラー労働者と呼ばれることもある。 |

| Consequences of class position A person's socioeconomic class has wide-ranging effects. It can determine the schools they are able to attend,[70][71][72] their health,[73] the jobs open to them,[70] when they exit the labour market,[74] whom they may marry[75] and their treatment by police and the courts.[76] Angus Deaton and Anne Case have analyzed the mortality rates related to the group of white, middle-aged Americans between the ages of 45 and 54 and its relation to class. There has been a growing number of suicides and deaths by substance abuse in this particular group of middle-class Americans. This group also has been recorded to have an increase in reports of chronic pain and poor general health. Deaton and Case came to the conclusion from these observations that because of the constant stress that these white, middle aged Americans feel fighting poverty and wavering between the middle and lower classes, these strains have taken a toll on these people and affected their whole bodies.[73] Social classifications can also determine the sporting activities that such classes take part in. It is suggested that those of an upper social class are more likely to take part in sporting activities, whereas those of a lower social background are less likely to participate in sport. However, upper-class people tend to not take part in certain sports that have been commonly known to be linked with the lower class.[77] Social privilege Main article: Social privilege Education  A physician consulted on the street by a farmer (Italy, 1938) A person's social class has a significant effect on their educational opportunities. Not only are upper-class parents able to send their children to exclusive schools that are perceived to be better, but in many places, state-supported schools for children of the upper class are of a much higher quality than those the state provides for children of the lower classes.[78][79][80] This lack of good schools is one factor that perpetuates the class divide across generations. In the UK, the educational consequences of class position have been discussed by scholars inspired by the cultural studies framework of the CCCS and/or, especially regarding working-class girls, feminist theory. On working-class boys, Paul Willis' 1977 book Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs is seen within the British Cultural Studies field as a classic discussion of their antipathy to the acquisition of knowledge.[81] Beverley Skeggs described Learning to Labour as a study on the "irony" of "how the process of cultural and economic reproduction is made possible by 'the lads' ' celebration of the hard, macho world of work."[82] |

階級の位置づけがもたらす影響 個人の社会経済的階級は、広範囲にわたる影響を及ぼす。 その人が通える学校[70][71][72]、健康状態[73]、就ける仕事[70]、労働市場から退出する時期[74]、結婚相手[75]、警察や裁判 所による処遇[76]などが、その人の階級によって決定される可能性がある。 アンガス・デイトンとアン・ケースは、45歳から54歳の中年白人アメリカ人グループの死亡率と階級との関係を分析した。この中流アメリカ人グループで は、自殺や薬物乱用による死亡が増加している。また、このグループでは慢性的な痛みの訴えや健康状態の悪化も増加していることが記録されている。 デイトンとケースは、これらの観察結果から、貧困と戦い、中流階級と下流階級の間で揺れ動くことで絶え間なくストレスを感じているため、これらの白人の中 年アメリカ人はその負担に耐えられず、全身に影響が出ているという結論に達した。 社会階級は、そうした階級が参加するスポーツ活動も決定づける。 上流階級の人々はスポーツ活動に参加する可能性が高いが、社会的な背景が低い人々はスポーツに参加する可能性が低い。 しかし、上流階級の人々は、一般的に下層階級と結びついていると認識されている特定のスポーツには参加しない傾向にある。[77] 社会的特権 詳細は「社会的特権」を参照 教育  農民に道端で相談する医師(イタリア、1938年) 個人の社会階級は、その個人の教育機会に大きな影響を与える。富裕層の親は、より良いとされる私立学校に子供を通わせることができるだけでなく、多くの地 域では、富裕層の子供のための国公立学校は、国公立の下層階級の子供のための学校よりもはるかに質が高い。[78][79][80] このような質の高い学校の不足は、世代を超えた階級間の格差を永続させる要因の一つである。 イギリスでは、階級の位置づけによる教育への影響は、CCCSのカルチュラル・スタディーズの枠組みや、特に労働者階級の少女についてはフェミニズム理論 に触発された学者たちによって議論されてきた。労働者階級の少年については、ポール・ウィリス(Paul Willis)の1977年の著書『Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs』が、知識の習得に対する彼らの反感についての古典的な議論として、イギリスのカルチュラル・スタディーズの分野で評価されている。 Learning to Labourを「労働者階級の若者たちが、いかにして労働の世界というタフでマッチョな世界を祝うことで、文化と経済の再生産のプロセスを可能にしている か」という「皮肉」についての研究であると評している。[82] |

| Health and nutrition Main article: Social determinants of health A person's social class often affects their physical health, their ability to receive adequate medical care and nutrition and their life expectancy.[83][84][85] Lower-class people experience a wide array of health problems as a result of their economic status. They are unable to use health care as often and when they do it is of lower quality, even though they generally tend to experience a much higher rate of health issues. Lower-class families have higher rates of infant mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease and disabling physical injuries. Additionally, poor people tend to work in much more hazardous conditions, yet generally have much less (if any) health insurance provided for them, as compared to middle- and upper-class workers.[86] |

健康と栄養 詳細は「健康の社会的決定要因」を参照 個人の社会階級は、しばしばその個人の身体的健康、適切な医療や栄養を受けられる能力、平均余命に影響を与える。 低所得者層の人々は、経済状態の結果として、さまざまな健康問題に直面している。彼らは、経済状態が原因で、より頻繁に医療サービスを利用できず、利用で きたとしてもその質は低い。低所得層では、乳児死亡率、癌、心臓血管疾患、身体障害の発生率が高い。さらに、貧困層の人々は、中流階級や上流階級の労働者 に比べて、はるかに危険な環境で働く傾向にあるが、一般的に提供される医療保険はほとんどない(あるいはまったくない)。[86] |

| Employment The conditions at a person's job vary greatly depending on class. Those in the upper-middle class and middle class enjoy greater freedoms in their occupations. They are usually more respected, enjoy more diversity and are able to exhibit some authority.[87] Those in lower classes tend to feel more alienated and have lower work satisfaction overall. The physical conditions of the workplace differ greatly between classes. While middle-class workers may "suffer alienating conditions" or "lack of job satisfaction", blue-collar workers are more apt to suffer alienating, often routine, work with obvious physical health hazards, injury and even death.[88][89] In the UK, a 2015 government study by the Social Mobility Commission suggested the existence of a "glass floor" in British society preventing those who are less able, but who come from wealthier backgrounds, from slipping down the social ladder. The report proposed a 35% greater likelihood of less able, better-off children becoming high earners than bright poor children.[90] |

雇用 階級によって、個人の職場の状況は大きく異なる。アッパーミドルクラスとミドルクラスの人々は、職業においてより大きな自由を享受している。彼らは通常、 より尊敬され、より多様性を享受し、ある程度の権限を行使することができる。[87] 下層階級の人々は、より疎外感を感じやすく、全体的な仕事の満足度が低い傾向にある。職場の物理的条件は、階級によって大きく異なる。中流階級の労働者は 「疎外的な状況」や「仕事への満足感の欠如」に苦しむことがあるが、肉体労働者は、明白な健康被害や負傷、さらには死亡につながることも多い、疎外的な、 しばしば単調な仕事を強いられる傾向にある。 英国では、2015年の社会流動性委員会による政府調査が、能力は低いが裕福な家庭に育った人々が社会的な地位を失うことを防ぐ、英国社会における「ガラ スの床」の存在を示唆した。この報告書では、能力は低いが裕福な家庭に育った子供たちが高収入を得る可能性は、貧しい家庭に育った聡明な子供たちよりも 35%高いと提案している。[90] |

| Class conflict Main article: Class conflict Class conflict, frequently referred to as class struggle, is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to competing socioeconomic interests and desires between people of different classes. For Marx, the history of class society was a history of class conflict. He pointed to the successful rise of the bourgeoisie and the necessity of revolutionary violence—a heightened form of class conflict—in securing the bourgeois rights that supported the capitalist economy. Marx believed that the exploitation and poverty inherent in capitalism were a pre-existing form of class conflict. Marx believed that wage labourers would need to revolt to bring about a more equitable distribution of wealth and political power.[91][92] |

階級闘争 詳細は「階級闘争」を参照 階級闘争(class struggle)とは、異なる階級の人々の間の社会経済的利益や願望の対立から生じる緊張や対立を指す。 マルクスにとって、階級社会の歴史とは階級闘争の歴史であった。彼は、ブルジョワ階級の成功と、資本主義経済を支えるブルジョワの権利を確保するための革 命的暴力(階級闘争の激化形態)の必要性を指摘した。 マルクスは、資本主義に内在する搾取と貧困は、階級闘争の既成の形態であると考えていた。マルクスは、賃金労働者が富と政治的権力のより公平な分配を実現 するために反乱を起こす必要があると信じていた。[91][92] |

| Classless society Main article: Classless society A "classless" society is one in which no one is born into a social class. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement in such a society. Since these distinctions are difficult to avoid, advocates of a classless society (such as anarchists and communists) propose various means to achieve and maintain it and attach varying degrees of importance to it as an end in their overall programs/philosophy. |

階級なき社会 詳細は「階級なき社会」を参照 「階級なき」社会とは、誰もが生まれながらにして社会階級に属さない社会である。そのような社会では、富、収入、教育、文化、あるいは社会的なネットワー クなどによる区別が生じる可能性はあるが、それは個々人の経験や功績によってのみ決定される。 こうした区別は避けがたいものであるため、階級なき社会の支持者(無政府主義者や共産主義者など)は、それを達成し維持するためのさまざまな手段を提案 し、また、その実現を最終目標として、さまざまな程度の重要性を付与している。 |

| Relationship between ethnicity

and class Further information: Racial inequality  Equestrian portrait of Empress Elizabeth of Russia with a Moor servant Race and other large-scale groupings can also influence class standing. The association of particular ethnic groups with class statuses is common in many societies, and is linked with race as well.[93] Class and ethnicity can impact a person's or community's socioeconomic standing, which in turn influences everything including job availability and the quality of available health and education.[93] The labels ascribed to an individual change the way others perceive them, with multiple labels associated with stigma combining to worsen the social consequences of being labelled.[94] As a result of conquest or internal ethnic differentiation, a ruling class is often ethnically homogenous and particular races or ethnic groups in some societies are legally or customarily restricted to occupying particular class positions.[citation needed] Which ethnicities are considered as belonging to high or low classes varies from society to society. In modern societies, strict legal links between ethnicity and class have been drawn, such as the caste system in Africa, apartheid, the position of the Burakumin in Japanese society and the casta system in Latin America.[citation needed][95] |

民族と階級の関係 さらに詳しい情報:人種的不平等  ロシア女帝エリザベスの乗馬姿の肖像画とムーア人の召使い 人種やその他の大規模な集団も、階級に影響を与えることがある。特定の民族集団と階級的地位の関連は多くの社会で一般的であり、人種とも関連している。 [93] 階級と民族性は個人やコミュニティの社会経済的地位に影響を与え、ひいては仕事や利用可能な医療・教育の質など、あらゆるものに影響を与える。[93] 個人に付与されたラベルは、他の人々によるその人に対する認識の仕方を変える。複数のラベルが汚名と結びつき、ラベル付けされたことによる社会的影響を悪 化させる。[94] 征服や内部での民族分化の結果、支配階級はしばしば民族的に均質であり、一部の社会では特定の民族や人種が法律上または慣習上、特定の階級に属することが 制限されている。どの民族が上流階級または下流階級に属するとみなされるかは、社会によって異なる。 現代社会では、民族と階級の間に厳格な法的つながりが存在する。例えば、アフリカのカースト制度、アパルトヘイト、日本社会における部落民の地位、ラテン アメリカにおけるカースト制度などである。[要出典][95] |

| Caste Class stratification Drift hypothesis Elite theory Elitism Four occupations Health equity Hostile architecture Inca society Mass society National Statistics Socio-economic Classification Passing (sociology) Post-industrial society Ranked society Raznochintsy Psychology of social class Welfare state |

カースト 階級社会の階層化 ドリフト仮説 エリート理論 エリート主義 四つの職業 健康の公平性 敵対的アーキテクチャ インカ社会 マス・ソサイエティ 国民統計 社会経済的分類 合格(社会学 ポスト工業化社会 ランク社会 Raznochintsy 社会階級の心理学 福祉国家 |

| Archer, Louise et al. Higher

Education and Social Class: Issues of Exclusion and Inclusion

(RoutledgeFalmer, 2003) (ISBN 0-415-27644-6) Aronowitz, Stanley, How Class Works: Power and Social Movement Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-10504-5 Barbrook, Richard (2006). The Class of the New (paperback ed.). London: OpenMute. ISBN 978-0-9550664-7-4. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2022. Beckert, Sven, and Julia B. Rosenbaum, eds. The American Bourgeoisie: Distinction and Identity in the Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 284 pages; Scholarly studies on the habits, manners, networks, institutions, and public roles of the American middle class with a focus on cities in the North. Benschop, Albert. Classes – Transformational Class Analysis Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Amsterdam: Spinhuis; 1993/2012). Bertaux, Daniel & Thomson, Paul; Pathways to Social Class: A Qualitative Approach to Social Mobility (Clarendon Press, 1997) Bisson, Thomas N.; Cultures of Power: Lordship, Status, and Process in Twelfth-Century Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995) Blackledge, Paul (2011). "Why workers can change the world". Socialist Review. Vol. 364. London. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Blau, Peter & Duncan Otis D.; The American Occupational Structure (1967) classic study of structure and mobility Brady, David "Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty" Social Forces Vol. 81 No. 3, (March 2003), pp. 715–751 (abstract online Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Project Muse). Broom, Leonard & Jones, F. Lancaster; Opportunity and Attainment in Australia (1977) Cohen, Lizabeth; Consumer's Republic, (Knopf, 2003) (ISBN 0-375-40750-2). (Historical analysis of the working out of class in the United States). Connell, R.W and Irving, T.H., 1992. Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress. Longman Cheshire. de Ste. Croix, Geoffrey (July–August 1984). "Class in Marx's conception of history, ancient and modern". New Left Review. I (146): 94–111. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016. (Good study of Marx's concept.) Dargin, Justin The Birth of Russia's Energy Class, Asia Times (2007) (good study of contemporary class formation in Russia, post communism) Day, Gary; Class, (Routledge, 2001) (ISBN 0-415-18222-0) Domhoff, G. William, Who Rules America? Power, Politics, and Social Change, Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice-Hall, 1967. (Domhoff's companion site to the book Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the University of California, Santa Cruz) Eichar, Douglas M.; Occupation and Class Consciousness in America (Greenwood Press, 1989) Fantasia, Rick; Levine, Rhonda F.; McNall, Scott G., eds.; Bringing Class Back in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives (Westview Press, 1991) Featherman, David L. & Hauser Robert M.; Opportunity and Change (1978). Fotopoulos, Takis, Class Divisions Today: The Inclusive Democracy approach Archived 1 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Democracy & Nature, Vol. 6, No. 2, (July 2000) Fussell, Paul; Class (a painfully accurate guide through the American status system), (1983) (ISBN 0-345-31816-1) Giddens, Anthony; The Class Structure of the Advanced Societies, (London: Hutchinson, 1981). Giddens, Anthony & Mackenzie, Gavin (Eds.), Social Class and the Division of Labour. Essays in Honour of Ilya Neustadt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982). Goldthorpe, John H. & Erikson Robert; The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Society (1992) Grusky, David B. ed.; Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective (2001) scholarly articles Hazelrigg, Lawrence E. & Lopreato, Joseph; Class, Conflict, and Mobility: Theories and Studies of Class Structure (1972). Hymowitz, Kay; Marriage and Caste in America: Separate and Unequal Families in a Post-Marital Age (2006) ISBN 1-56663-709-0 Kaeble, Helmut; Social Mobility in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Europe and America in Comparative Perspective (1985) Jakopovich, Daniel, The Concept of Class Archived 24 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge Studies in Social Research, No. 14, Social Science Research Group, University of Cambridge, 2014 Jens Hoff, "The Concept of Class and Public Employees". Acta Sociologica, vol. 28, no. 3, July 1985, pp. 207–226. Mahalingam, Ramaswami; "Essentialism, Culture, and Power: Representations of Social Class" Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 59, (2003), pp. 733+ on India Mahony, Pat & Zmroczek, Christine; Class Matters: 'Working-Class' Women's Perspectives on Social Class (Taylor & Francis, 1997) Manza, Jeff & Brooks, Clem; Social Cleavages and Political Change: Voter Alignments and U.S. Party Coalitions (Oxford University Press, 1999). Manza, Jeff; "Political Sociological Models of the U.S. New Deal" Annual Review of Sociology, (2000) pp. 297+ Manza, Jeff; Hout, Michael; Clem, Brooks (1995). "Class Voting in Capitalist Democracies since World War II: Dealignment, Realignment, or Trendless Fluctuation?". Annual Review of Sociology. 21: 137–162. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.21.1.137. Marmot, Michael; The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity (2004) Marx, Karl & Engels, Frederick; The Communist Manifesto, (1848). (The key statement of class conflict as the driver of historical change). Merriman, John M.; Consciousness and Class Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1979) Ostrander, Susan A.; Women of the Upper Class (Temple University Press, 1984). Owensby, Brian P.; Intimate Ironies: Modernity and the Making of Middle-Class Lives in Brazil (Stanford University, 1999). Pakulski, Jan & Waters, Malcolm; The Death of Class (Sage, 1996). (rejection of the relevance of class for modern societies) Payne, Geoff; The Social Mobility of Women: Beyond Male Mobility Models (1990) Savage, Mike; Class Analysis and Social Transformation (London: Open University Press, 2000). Stahl, Garth; "Identity, Neoliberalism and Aspiration: Educating White Working-Class Boys" (London, Routledge, 2015). Sennett, Richard & Cobb, Jonathan; The Hidden Injuries of Class, (Vintage, 1972) (classic study of the subjective experience of class). Siegelbaum, Lewis H., Suny, Ronald; eds.; Making Workers Soviet: Power, Class, and Identity. (Cornell University Press, 1994). Russia 1870–1940 Wlkowitz, Daniel J.; Working with Class: Social Workers and the Politics of Middle-Class Identity (University of North Carolina Press, 1999). Weber, Max. "Class, Status and Party", in e.g. Gerth, Hans and C. Wright Mills, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, (Oxford University Press, 1958). (Weber's key statement of the multiple nature of stratification). Weinburg, Mark; "The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th century French liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer" Archived 24 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 45–63, (1978). Wood, Ellen Meiksins; The Retreat from Class: A New 'True' Socialism, (Schocken Books, 1986) (ISBN 0-8052-7280-1) and (Verso Classics, January 1999) reprint with new introduction (ISBN 1-85984-270-4). Wood, Ellen Meiksins; "Labor, the State, and Class Struggle", Monthly Review, Vol. 49, No. 3, (1997). Wouters, Cas.; "The Integration of Social Classes". Journal of Social History. Volume 29, Issue 1, (1995). pp 107+. (on social manners) Wright, Erik Olin; The Debate on Classes (Verso, 1990). (neo-Marxist) Wright, Erik Olin; Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 1997) Wright, Erik Olin ed. Approaches to Class Analysis (2005). (scholarly articles) Zmroczek, Christine & Mahony, Pat (Eds.), Women and Social Class: International Feminist Perspectives. (London: UCL Press 1999) The lower your social class, the 'wiser' you are, suggests new study Archived 22 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Science. 20 December 2017. |

Archer, Louise et al.

『高等教育と社会階級:排除と包含の問題』(RoutledgeFalmer、2003年)(ISBN 0-415-27644-6) Aronowitz, Stanley, 『How Class Works: Power and Social Movement』(2023年4月8日アーカイブ分)Yale University Press、2003年。ISBN 0-300-10504-5 Barbrook, Richard (2006). The Class of the New (paperback ed.). London: OpenMute. ISBN 978-0-9550664-7-4. オリジナルの2018年8月1日時点によるアーカイブ。2022年3月15日取得。 ベッカート、スヴェン、ジュリア・B・ローゼンバウム編著『アメリカの中流階級:19世紀における区別とアイデンティティ』(パルグレーブ・マクミラン、 2011年)284ページ。北アメリカの都市に焦点を当てた、アメリカの中流階級の習慣、マナー、ネットワーク、制度、公共的役割に関する学術的研究。 Benschop, Albert. Classes – Transformational Class Analysis Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Amsterdam: Spinhuis; 1993/2012). Bertaux, Daniel & Thomson, Paul; Pathways to Social Class: A Qualitative Approach to Social Mobility (Clarendon Press, 1997) Bisson, Thomas N.; Cultures of Power: Lordship, Status, and Process in Twelfth-Century Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995) Blackledge, Paul (2011). 「Why workers can change the world」. Socialist Review. Vol. 364. London. 2011年12月10日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Blau, Peter & Duncan Otis D.; 『The American Occupational Structure』(1967年)構造と流動性に関する古典的研究 Brady, David 「Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty」 Social Forces Vol. 81 No. 3, (March 2003), pp. 715–751 (abstract online Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Project Muse). Broom, Leonard & Jones, F. Lancaster; Opportunity and Attainment in Australia (1977) Cohen, Lizabeth; Consumer's Republic, (Knopf, 2003) (ISBN 0-375-40750-2). (米国における階級の形成に関する歴史的分析)。 Connell, R.W and Irving, T.H., 1992. 『オーストラリア史における階級構造:貧困と進歩』Longman Cheshire. デ・ステ・クロワ、ジェフリー(1984年7月~8月)。「マルクスの歴史観における階級、古代と近代」。『ニューレフトレビュー』第1巻第146号、 94~111ページ。2016年3月4日アーカイブ分。2016年1月7日取得。(マルクスの概念に関する優れた研究) Dargin, Justin 『ロシアのエネルギー階級の誕生』、アジアタイムズ(2007年)(ポスト共産主義後のロシアにおける現代の階級形成に関する優れた研究) デイ、ゲイリー、『階級』(ラウトレッジ、2001年)(ISBN 0-415-18222-0) ドムホフ、G. ウィリアム著『アメリカを支配するのは誰か?権力、政治、社会変動』、ニュージャージー州イングルウッド・クリフス:プレンティス・ホール、1967年。 (ドムホフ著書の関連サイト カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校にてアーカイブ 2009年1月26日 - ウェブアーカイブ) Eichar, Douglas M.; Occupation and Class Consciousness in America (Greenwood Press, 1989) Fantasia, Rick; Levine, Rhonda F.; McNall, Scott G., eds.; Bringing Class Back in Contemporary and Historical Perspectives (Westview Press, 1991) Featherman, David L. & Hauser Robert M.; Opportunity and Change (1978). Fotopoulos, Takis, Class Divisions Today: The Inclusive Democracy approach Archived 1 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Democracy & Nature, Vol. 6, No. 2, (July 2000) Fussell, Paul; Class (a painfully accurate guide through the American status system), (1983) (ISBN 0-345-31816-1) ギデンズ、アンソニー著『先進社会の階級構造』(ロンドン:ハッチンソン、1981年)。 ギデンズ、アンソニーおよびマッケンジー、ギャビン編『社会階級と労働の分業。イリヤ・ノイバウートの功績をたたえて』(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学 出版、1982年)。 Goldthorpe, John H. & Erikson Robert; 『The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Society』(1992年) Grusky, David B. 編; 『Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective』(2001年)学術論文 ヘーゼルリッグ、ローレンス・E. & ロプレアト、ジョセフ; 『階級、対立、流動性:階級構造の理論と研究』(1972年)。 ハイモウィッツ、ケイ; 『アメリカにおける結婚とカースト:ポスト結婚時代の別居不平等家族』(2006年) ISBN 1-56663-709-0 ヘルムート・ケーブル著『19世紀と20世紀における社会移動:ヨーロッパとアメリカを比較する視点』(1985年) ダニエル・ヤコポビッチ著『階級の概念』2021年9月24日アーカイブ、ウェイバックマシン、ケンブリッジ大学社会研究シリーズ第14号、ケンブリッジ 大学社会科学研究グループ、2014年 イェンス・ホフ、「階級の概念と公務員」『Acta Sociologica』第28巻第3号、1985年7月、207-226ページ。 マハリンガム、ラマスワミ、「本質主義、文化、権力:社会階級の表現」『社会問題ジャーナル』第59巻、2003年、インドに関する733ページ以降 マホニー、パット & ズモチェク、クリスティーン著、『階級の問題:労働者階級の女性による社会階級の視点』(テイラー・アンド・フランシス、1997年) マンザ、ジェフ & ブルックス、クレム著、『社会分裂と政治的変化:有権者の支持基盤と米国の政党連合』(オックスフォード大学出版、1999年) マンザ、ジェフ、「米国ニューディールの政治社会学モデル」『Annual Review of Sociology』2000年、297ページ以降 Manza, Jeff; Hout, Michael; Clem, Brooks (1995). 「Class Voting in Capitalist Democracies since World War II: Dealignment, Realignment, or Trendless Fluctuation?」. Annual Review of Sociology. 21: 137–162. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.21.1.137. マーモット、マイケル著『ステータス症候群:社会的地位が健康と長寿に及ぼす影響』(2004年) カール・マルクス、フレデリック・エンゲルス著『共産党宣言』(1848年)。(階級闘争が歴史的変化の推進力であるという重要な主張)。 ジョン・M・メリマン著『19世紀ヨーロッパにおける意識と階級体験』(ホームズ&マイヤー出版社、1979年) オストランダー、スーザン・A.; 『アッパー・クラスの女性たち』(テンプル大学出版、1984年)。 オーエンスビー、ブライアン・P.; 『親密な皮肉:モダニティとブラジルにおける中流階級の生活の形成』(スタンフォード大学、1999年)。 パクルスキー、ヤン & ウォーターズ、マルコム; 『階級の死』(セイジ、1996年)。(現代社会における階級の関連性の否定) ペイン、ジェフ著『女性の社会移動:男性の移動モデルを超えて』(1990年) サベージ、マイク著『階級分析と社会変容』(ロンドン:オープン大学出版、2000年) スタール、ガース著『アイデンティティ、新自由主義、そして向上心:白人労働者階級の少年の教育』(ロンドン、ルートレッジ、2015年) Sennett, Richard & Cobb, Jonathan; The Hidden Injuries of Class, (Vintage, 1972) (階級の主観的経験に関する古典的研究)。 Siegelbaum, Lewis H., Suny, Ronald; eds.; Making Workers Soviet: Power, Class, and Identity. (Cornell University Press, 1994). ロシア 1870–1940 Wlkowitz, Daniel J.; Working with Class: Social Workers and the Politics of Middle-Class Identity (University of North Carolina Press, 1999). Weber, Max. 「Class, Status and Party」, in e.g. Gerth, Hans and C. Wright Mills, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, (Oxford University Press, 1958). (Weberによる階層化の多様性に関する主要な主張)。 ワインバーグ、マーク、「19世紀初頭の3人のフランス自由主義者の社会分析:セイ、コント、デュノワイエ」『リバタリアン研究ジャーナル』第2巻第1 号、45-63ページ、1978年。 ウッド、エレン・マイキンズ著『階級からの撤退:新しい「真の」社会主義』(Schocken Books、1986年)(ISBN 0-8052-7280-1)および(Verso Classics、1999年1月)再版(ISBN 1-85984-270-4)に新しい序文を追加。 ウッド、エレン・マイクシンス著、「労働、国家、階級闘争」、月刊レビュー、第49巻、第3号、1997年。 ウータス、カス著、「社会階級の統合」。社会史ジャーナル。第29巻、第1号、1995年。107ページ以上。(社会的なマナーについて) ライト、エリック・オリエン著『The Debate on Classes』(Verso、1990年)。(ネオ・マルクス主義) ライト、エリック・オリエン著『Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis』(ケンブリッジ大学出版、1997年) ライト、エリック・オリエン編著『Approaches to Class Analysis』(2005年)。(学術論文) Zmroczek, Christine & Mahony, Pat (Eds.), Women and Social Class: International Feminist Perspectives. (London: UCL Press 1999) 社会的階級が低いほど「賢い」ことが、新たな研究で示唆される 2022年7月22日アーカイブ分 科学。2017年12月20日。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_class |

【医療人類学辞典】

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆