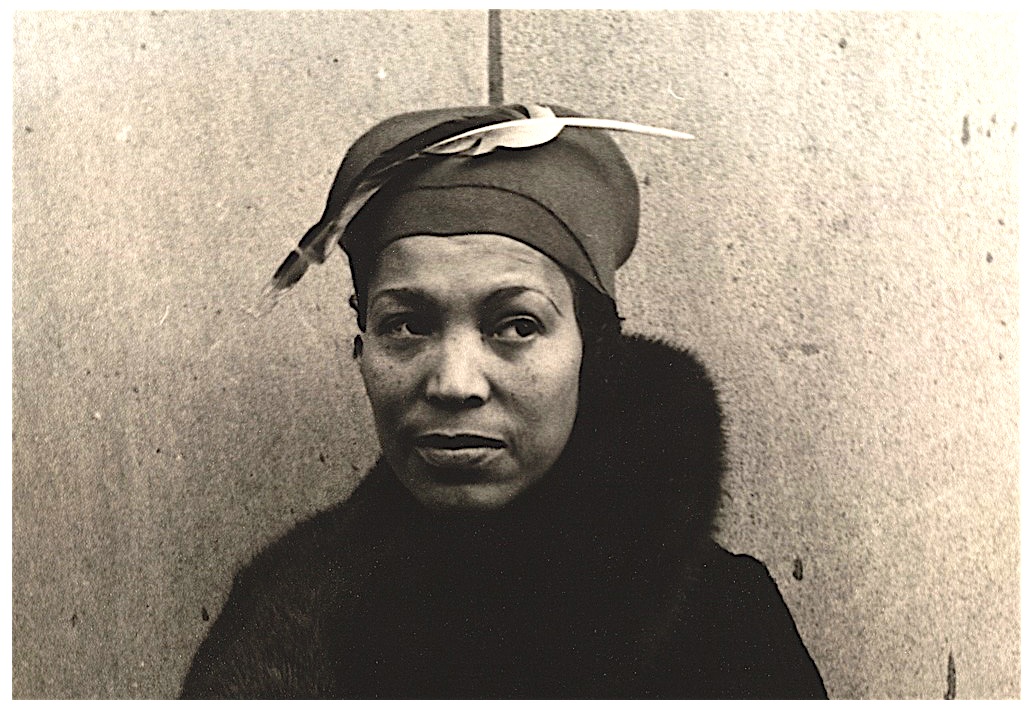

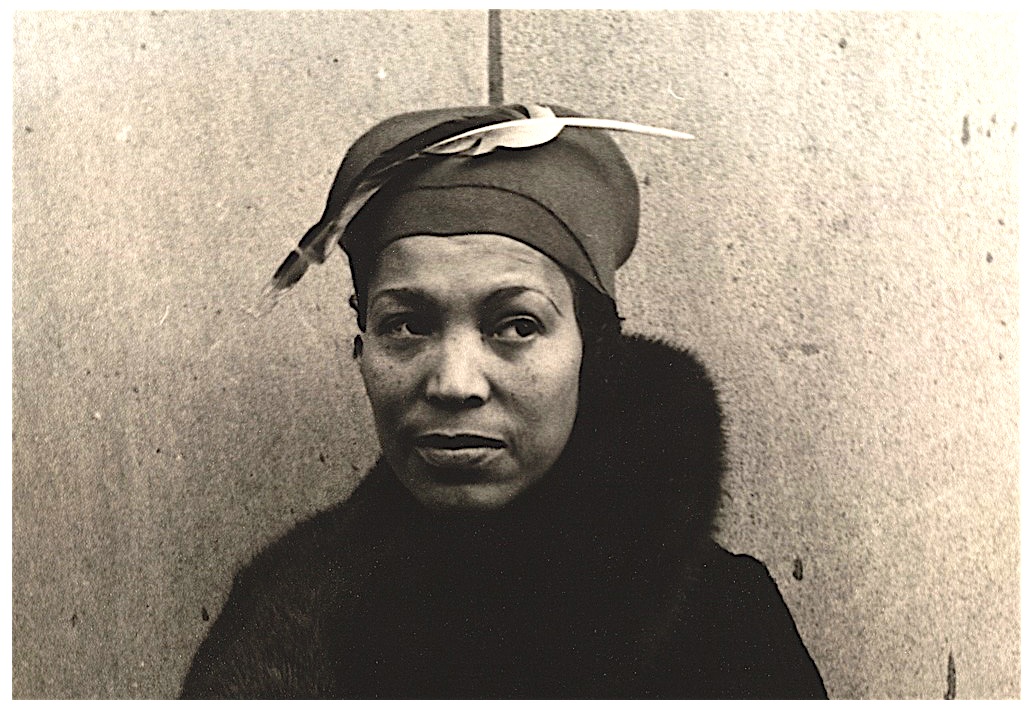

Hurston, Zora Neale: 1891-1960, from "Zora Neale Hurston Collection," by Yale University

ゾラ・ニール・ハーストンは Zora_Neale_Hurston.html に移転しました

My Web-page of Zora

Neale Hurston, 1891-1960 is now moved to Zora_Neale_Hurston.html

Hurston, Zora Neale: 1891-1960, from "Zora Neale Hurston Collection," by Yale University