書簡体小説・書簡体記述

Epistolary

novel, or Epistolographic genre

Young

Werther writes a letter after deciding upon his suicide, the climax of

Goethe's Sorrows of Young Werther

☆ 書簡体小説(epistolary novel)あるいは書簡小説とは、物語の架空の登場人物間の一連の手紙として書かれた小説のことである。この用語はしばしば、手紙に他の種類の 文書、最も一般的なのは 日記や新聞の切り抜きなどを織り交ぜた小説にまで拡張され、手紙をまったく含まない場合でも文書で構成された小説を含むと見なされることがある。最近では、書簡には録音やラジオなどの電子文書、ブログの投稿、電子メールが含まれることもあ る。エピストーリーの語源はギリシャ語で手紙を意味 するepistolē(Đπιστοήλ)に由来するラテン語である(epistleを参照)。このタイプのフィクションは、ドイツ語でブリーフロマン (Briefroman)とも呼ばれる。書簡体という形式は、登場人物の生活の中にテキストが直接的に存在するため、物語に大きなリアリズムを加えると考 えられる。特に、全知全能の語り手(omniscient narrator)という 装置に頼ることなく、異なる視点を示すことができる。書簡小説において、書簡の信憑性を印象づけるための重要な戦略的装置は、架空の編集者である。

★

書簡記述・書簡術(Epistolography)は、ビザンチン時代の知的エリートに人気があった修辞学に似たビザンチン文学のジャンルである。

書簡は紀元4世紀には一般的な文学形式となり、キリスト教と古典ギリシアの伝統が組み合わされた。ユリアヌス帝、リバニオス帝、シネシウス帝の書簡集や

カッパドキア教父の著作が特に注目され、アリストテレス、プラトン、新約聖書のパウロ書簡がこのジャンルの発展に影響を与えた[1]。

より多作な実践者たちの書簡が大量に残っている場合もある。Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

(345-402)の900通が現存し、Libanius (c. 314-392 or

393)は1500通以上のギリシャ語の書簡を残している。研究者たちは書簡の内容に失望することもあった。事実的な事柄を排除して修辞的な慣習を盛り込

んだり、リバニウスの場合はローマ官僚機構への申請者に代わって一般的な勧告を多く盛り込む傾向があった[2]。

その後、このジャンルは11世紀と12世紀に復活する前に消滅した。https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistolography

| ★An epistolary

novel is a novel written as a series of letters between the

fictional characters of a narrative.[1] The term is often extended to

cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the

letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and

sometimes considered to include novels composed of documents even if

they do not include letters at all.[2][3] More recently, epistolaries

may include electronic documents such as recordings and radio, blog

posts, and e-mails. The word epistolary is derived from Latin from the

Greek word epistolē (ἐπιστολή), meaning a letter (see epistle). This

type of fiction is also sometimes known by the German term Briefroman

or more generally as epistolary fiction. The epistolary form can be seen as adding greater realism to a story, due to the text existing diegetically within the lives of the characters. It is in particular able to demonstrate differing points of view without recourse to the device of an omniscient narrator. An important strategic device in the epistolary novel for creating the impression of authenticity of the letters is the fictional editor.[4] |

書

簡小説とは、物語の架空の登場人物間の一連の手紙として書かれた小説のことである[1]。この用語はしばしば、手紙に他の種類の文書、最も一般的なのは日

記や新聞の切り抜きなどを織り交ぜた小説にまで拡張され、手紙をまったく含まない場合でも文書で構成された小説を含むと見なされることがある[2]

[3]。最近では、書簡には録音やラジオなどの電子文書、ブログの投稿、電子メールが含まれることもある。エピストーリーの語源はギリシャ語で手紙を意味

するepistolē(Đπιστοήλ)に由来するラテン語である(epistleを参照)。このタイプのフィクションは、ドイツ語でブリーフロマン

(Briefroman)とも呼ばれる。 書簡体という形式は、登場人物の生活の中にテキストが直接的に存在するため、物語に大きなリアリズムを加えると考えられる。特に、全知全能の語り手という 装置に頼ることなく、異なる視点を示すことができる。書簡小説において、書簡の信憑性を印象づけるための重要な戦略的装置は、架空の編集者である[4]。 |

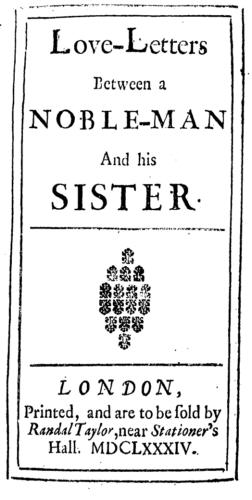

Early works Love-Letters between a Nobleman and His Sister. London, Printed, and to be sold by Randal Taylor, near Stationers' Hall. MDCLXXXIV. Title page of Aphra Behn's early epistolary novel, Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684) There are two theories on the genesis of the epistolary novel: The first claims that the genre is originated from novels with inserted letters, in which the portion containing the third-person narrative in between the letters was gradually reduced.[5] The other theory claims that the epistolary novel arose from miscellanies of letters and poetry: some of the letters were tied together into a (mostly amorous) plot.[6] There is evidence to support both claims. The first truly epistolary novel, the Spanish "Prison of Love" (Cárcel de amor) (c. 1485) by Diego de San Pedro, belongs to a tradition of novels in which a large number of inserted letters already dominated the narrative. Other well-known examples of early epistolary novels are closely related to the tradition of letter-books and miscellanies of letters. Within the successive editions of Edmé Boursault's Letters of Respect, Gratitude and Love (Lettres de respect, d'obligation et d'amour) (1669), a group of letters written to a girl named Babet were expanded and became more and more distinct from the other letters, until it formed a small epistolary novel entitled Letters to Babet (Lettres à Babet). The immensely famous Letters of a Portuguese Nun (Lettres portugaises) (1669) generally attributed to Gabriel-Joseph de La Vergne, comte de Guilleragues, though a small minority still regard Marianna Alcoforado as the author, is claimed to be intended to be part of a miscellany of Guilleragues prose and poetry.[7] The founder of the epistolary novel in English is said by many to be James Howell (1594–1666) with "Familiar Letters" (1645–50), who writes of prison, foreign adventure, and the love of women. Perhaps first work to fully utilize the potential of an epistolary novel was Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister. This work was published anonymously in three volumes (1684, 1685, and 1687), and has been attributed to Aphra Behn though its authorship remains disputed in the 21st century.[8] The novel shows the genre's results of changing perspectives: individual points were presented by the individual characters, and the central voice of the author and moral evaluation disappeared (at least in the first volume; further volumes introduced a narrator). The author furthermore explored a realm of intrigue with complex scenarios such as letters that fall into the wrong hands, faked letters, or letters withheld by protagonists. The epistolary novel as a genre became popular in the 18th century in the works of such authors as Samuel Richardson, with his immensely successful novels Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1749). John Cleland's early erotic novel Fanny Hill (1748) is written as a series of letters from the titular character to an unnamed recipient. In France, there was Lettres persanes (1721) by Montesquieu, followed by Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Choderlos de Laclos' Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782), which used the epistolary form to great dramatic effect, because the sequence of events was not always related directly or explicitly. In Germany, there was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) (1774) and Friedrich Hölderlin's Hyperion. The first Canadian novel, The History of Emily Montague (1769) by Frances Brooke,[9] and twenty years later the first American novel, The Power of Sympathy (1789) by William Hill Brown,[10] were both written in epistolary form. Starting in the 18th century, the epistolary form was subject to much ridicule, resulting in a number of savage burlesques. The most notable example of these was Henry Fielding's Shamela (1741), written as a parody of Pamela. In it, the female narrator can be found wielding a pen and scribbling her diary entries under the most dramatic and unlikely of circumstances. Oliver Goldsmith used the form to satirical effect in The Citizen of the World, subtitled "Letters from a Chinese Philosopher Residing in London to his Friends in the East" (1760–61). So did the diarist Fanny Burney in a successful comic first novel, Evelina (1788). The epistolary novel slowly became less popular after 18th century. Although Jane Austen tried the epistolary in juvenile writings and her novella Lady Susan (1794), she abandoned this structure for her later work. It is thought that her lost novel First Impressions, which was redrafted to become Pride and Prejudice, may have been epistolary: Pride and Prejudice contains an unusual number of letters quoted in full and some play a critical role in the plot. The epistolary form nonetheless saw continued use, surviving in exceptions or in fragments in nineteenth-century novels. In Honoré de Balzac's novel Letters of Two Brides, two women who became friends during their education at a convent correspond over a 17-year period, exchanging letters describing their lives. Mary Shelley employs the epistolary form in her novel Frankenstein (1818). Shelley uses the letters as one of a variety of framing devices, as the story is presented through the letters of a sea captain and scientific explorer attempting to reach the north pole who encounters Victor Frankenstein and records the dying man's narrative and confessions. Published in 1848, Anne Brontë's novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is framed as a retrospective letter from one of the main heroes to his friend and brother-in-law with the diary of the eponymous tenant inside it. In the late 19th century, Bram Stoker released one of the most widely recognized and successful novels in the epistolary form to date, Dracula. Printed in 1897, the novel is compiled entirely of letters, diary entries, newspaper clippings, telegrams, doctor's notes, ship's logs, and the like. |

初期の作品 貴族とその妹の恋文。ロンドン、印刷、販売:ランダル・テイラー、ステーショナーズ・ホール近

く。MDCLXXXIV. 貴族とその妹の恋文。ロンドン、印刷、販売:ランダル・テイラー、ステーショナーズ・ホール近

く。MDCLXXXIV.アフラ・ベーンの初期の書簡小説『貴族とその妹の恋文』(1684年) のタイトルページ。 書簡小説の起源については2つの説がある: ひとつは、書簡が挿入された小説がこのジャンルの起源で、書簡と書簡の間の三人称の物語を含む部分が徐々に減少していったという説[5]。もうひとつは、 書簡小説は書簡と詩の雑文から生まれたという説で、書簡の一部が結びつけられて(主に情事的な)筋書きになったというものである。最初の本格的な書簡小説 である、ディエゴ・デ・サンペドロによるスペインの『愛の牢獄』(Cárcel de amor)(1485年頃)は、挿入された多数の書簡がすでに物語を支配していた小説の伝統に属する。初期の書簡小説の他の有名な例は、書簡集や書簡雑記 の伝統と密接な関係がある。エドメ・ブルソー(Edmé Boursault)の『尊敬、感謝、愛の手紙』(Lettres de respect, d'obligation et d'amour)(1669)の版を重ねるうちに、バベト(Babet)という名の少女に宛てた手紙の一群が拡張され、他の手紙とますます区別されるよう になり、『バベトへの手紙』(Lettres à Babet)と題された小さな書簡小説を形成するに至った。非常に有名な『ポルトガルの修道女の手紙』(Lettres portugaises)(1669年)は、一般的にはギエラーゲス伯爵ガブリエル=ジョゼフ・ド・ラ・ヴェルニュの作とされているが、マリアンナ・アル コフォラードが作者であるとする少数派もおり、ギエラーゲスの散文と詩の寄せ書きの一部であると主張されている。 [7] 英語における書簡小説の創始者は、牢獄、外国での冒険、女性への愛について書いた "Familiar Letters"(1645-50)を書いたジェームズ・ハウエル(1594-1666)であると多くの人が言っている。 書簡小説の可能性を十分に活用した最初の作品は、おそらく『貴族と妹の恋文』であろう。この作品は匿名で3巻(1684年、1685年、1687年)にわ たって出版され、アフラ・ベーンの作とされているが、21世紀になってもその作者については論争が続いている[8]。この小説は、視点を変えるというこの ジャンルの成果を示している。個々の論点は個々の登場人物によって提示され、作者の中心的な声や道徳的評価は姿を消した(少なくとも第1巻では。) 作者はさらに、悪人の手に落ちる手紙、偽造された手紙、主人公が隠した手紙など、複雑なシナリオで陰謀の領域を探求した。 18世紀には、サミュエル・リチャードソンが『パメラ』(1740年)や『クラリッサ』(1749年)で大成功を収め、書簡小説というジャンルが流行し た。ジョン・クレランドの初期のエロティック小説『ファニー・ヒル』(1748年)は、主人公が無名の受取人に宛てた一連の手紙として書かれている。フラ ンスでは、モンテスキューの『Lettres persanes』(1721年)、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの『Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse』(1761年)、ショデルロ・ド・ラクロの『Les Liaisons dangereuses』(1782年)などがある。ドイツでは、ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテの『若きウェルテルの悩み』(Die Leiden des jungen Werther)(1774)やフリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンの『ハイペリオン』(Hyperion)があった。フランシス・ブルックによるカナダ初の小説 『エミリー・モンタギューの歴史』(1769年)[9]と、その20年後のウィリアム・ヒル・ブラウンによるアメリカ初の小説『同情の力』(1789年) [10]は、いずれも書簡形式で書かれた。 18世紀から、書簡形式は多くの嘲笑の対象となり、その結果、野蛮なバーレスクが数多く生まれた。その最も顕著な例が、『パメラ』のパロディとして書かれ たヘンリー・フィールディングの『シャメラ』(1741年)である。この作品では、女性の語り手がペンを振り回し、最も劇的でありそうもない状況下で日記 を書き綴っている。オリヴァー・ゴールドスミスは、"Letters from a Chinese Philosopher Residing in London to his Friends in the East"(1760-61)という副題のついた『世界の市民』で、この形式を風刺的な効果に使っている。日記作家のファニー・バーニーも、コミカルな処 女作『エヴェリナ』(1788年)で成功を収めた。 18世紀以降、書簡小説は徐々に人気を失っていった。ジェーン・オースティンは、少年時代や小説『レディ・スーザン』(1794年)で書簡体小説を試みた が、その後の作品ではこの構成を放棄した。彼女の失われた小説『第一印象』(『高慢と偏見』へと改稿された)は、書簡体であった可能性があると考えられて いる: 高慢と偏見』には、全文が引用された珍しい数の手紙が含まれており、プロットで重要な役割を果たすものもある。 高慢と偏見』には、全文が引用された珍しい数の手紙があり、その一部はプロットで重要な役割を果たしている。それでも、書簡形式は使われ続け、19世紀の 小説には例外的に、あるいは断片的に残っている。オノレ・ド・バルザックの小説『二人の花嫁の手紙』では、修道院で教育を受けている間に友人となった二人 の女性が、17年間にわたって、それぞれの人生を綴った手紙をやりとりする。メアリー・シェリーは小説『フランケンシュタイン』(1818年)で書簡形式 を採用している。シェリーは、北極を目指そうとする船長と科学探検家がヴィクター・フランケンシュタインに出会い、瀕死の男の語りと告白を記録した手紙を 通して物語を表現するため、さまざまなフレーミングの仕掛けのひとつとして手紙を用いている。1848年に出版されたアン・ブロントの小説『The Tenant of Wildfell Hall』は、主人公の一人が友人と義弟に宛てた回顧的な手紙と、その中に記された同名の借家人の日記という枠組みで描かれている。19世紀後半、ブラ ム・ストーカーは、書簡体小説として今日まで最も広く知られ、成功を収めた作品のひとつ『ドラキュラ』を発表した。1897年に印刷されたこの小説は、手 紙、日記、新聞の切り抜き、電報、医者のメモ、船の日誌などで構成されている。 |

| Types Epistolary novels can be categorized based on the number of people whose letters are included. This gives three types of epistolary novels: monophonic (giving the letters of only one character, like Letters of a Portuguese Nun and The Sorrows of Young Werther), dialogic (giving the letters of two characters, like Mme Marie Jeanne Riccoboni's Letters of Fanni Butler (1757), and polyphonic (with three or more letter-writing characters, such as in Bram Stoker's Dracula). A crucial element in polyphonic epistolary novels like Clarissa and Dangerous Liaisons is the dramatic device of 'discrepant awareness': the simultaneous but separate correspondences of the heroines and the villains creating dramatic tension. They can also be classified according to their type and quantity of use of non-letter documents, though this has obvious correlations with the number of voices – for example, newspaper clippings are unlikely to feature heavily in a monophonic epistolary and considerably more likely in a polyphonic one.[11] |

種類 書簡小説は、手紙に登場する人物の数によって分類することができる。単旋律小説(『ポルトガル人修道女の手紙』や『若きウェルテルの悩み』のように、一人 の登場人物の手紙だけが登場する)、対話小説(マリー・ジャンヌ・リッコボーニ女史の『ファンニ・バトラーの手紙』(1757年)のように、二人の登場人 物の手紙が登場する)、多旋律小説(ブラム・ストーカーの『ドラキュラ』のように、三人以上の手紙を書く人物が登場する)である。 『クラリッサ』や『危険な関係』のような多声的書簡小説の重要な要素は、「意識の不一致」という劇的な仕掛けである。また、手紙以外の文書の種類や使用量 によって分類することもできるが、これは声の数と明らかに相関関係がある。例えば、新聞の切り抜きが単旋律の書簡で大きく取り上げられることはまずなく、 多旋律の書簡ではかなり多く取り上げられる[11]。 |

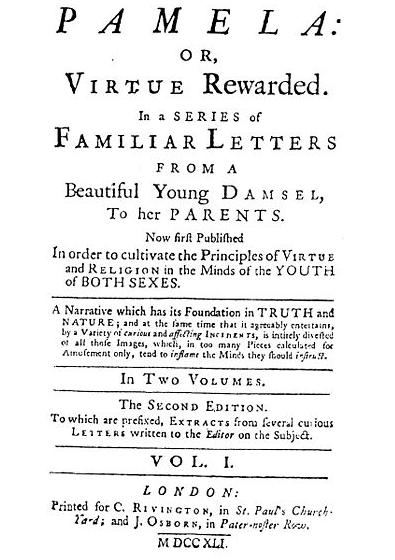

| Notable works See also: List of fictional diaries  Pamela: Or, Virtue

Rewarded. In a Series of Familiar Letters from a Beautiful Young

Damsel, to her Parents. Pamela: Or, Virtue

Rewarded. In a Series of Familiar Letters from a Beautiful Young

Damsel, to her Parents.Title page of the second edition of Samuel Richardson's epistolary novel Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), a bestselling early epistolary novel The epistolary novel form has continued to be used after the eighteenth century. Eighteenth century Lettres persanes, a 1721 novel by Montesquieu. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, by Samuel Richardson 1740, a bestselling early epistolary novel which prompted artistic interest in the epistolary form. Julie; or, The New Heloise, an epistolary novel by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, published in 1761. The Sorrows of Young Werther is a 1774 novel by Johann Wolfgang Goethe. Les Liaisons dangereuses is a 1782 French novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, about the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, two narcissistic rivals (and ex-lovers) who use seduction as a weapon to socially control and exploit others, all the while enjoying their cruel games and boasting about their talent for manipulation (also seen as depicting the corruption and depravity of the French nobility shortly before the French Revolution). The book is composed entirely of letters written by the various characters to each other. Cartas marruecas (Moroccan Letters), a 1789 novel by José Cadalso, Spanish author, poet, playwright and essayist. Marquis de Sade's Aline and Valcour (1795). Nineteenth century Fyodor Dostoevsky used the epistolary format for his first novel, Poor Folk (1846), as a series of letters between two friends, struggling to cope with their impoverished circumstances and life in Imperial-era Russia. The Moonstone (1868) by Wilkie Collins uses a collection of various documents to construct a detective novel in English. In the second piece, a character explains that he is writing his portion because another had observed to him that the events surrounding the disappearance of the eponymous diamond might reflect poorly on the family, if misunderstood, and therefore he was collecting the true story. This is an unusual element, as most epistolary novels present the documents without questions about how they were gathered. He also used the form previously in The Woman in White (1859). Spanish foreign minister Juan Valera's Pepita Jiménez (1874) is written in three sections, the first and third being a series of letters, the middle part narrated by an unknown observer. Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897) uses not only letters and diaries, but also dictation cylinders and newspaper accounts.[1] Twentieth century Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace's The Documents in the Case (1930). E.M. Delafield's Diary of a Provincial Lady (1930). Kathrine Taylor's Address Unknown (1938) is an anti-Nazi novel in which the final letter is returned marked "Address Unknown", indicating the disappearance of the German character. C. S. Lewis used the epistolary form for The Screwtape Letters (1942), and considered writing a companion novel from an angel's point of view – though he never did so. It is less generally realized that his Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (1964) is a similar exercise, exploring theological questions through correspondence addressed to a fictional recipient, "Malcolm", though this work may be considered a "novel" only loosely in that developments in Malcolm's personal life gradually come to light and impact the discussion. Thornton Wilder's fifth novel Ides of March (1948) consists of letters and documents illuminating the last days of the Roman Republic. Saul Bellow's novel Herzog (1964) is largely written in letter format. These are both real and imagined letters, written by the protagonist Moses Herzog to family members, friends, and celebrities. Shūsaku Endō's novel Silence (1966) is an example of the epistolary form, half of which consists of letters from Rodrigues, the other half either in the third person or in letters from other persons. Daniel Keyes's short story and novel Flowers for Algernon (1959, 1966) takes the form of a series of lab progress reports written by the main character as his treatment progresses, with his writing style changing correspondingly. The Anderson Tapes (1969, 1970) by Lawrence Sanders is a novel primarily consisting of transcripts of tape recordings. Stephen King's novel Carrie (1974) is written in an epistolary structure through newspaper clippings, magazine articles, letters, and book excerpts. Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, 1985, ends with an epilogue consisting of the minutes from the meeting of a historical society in the future discussing the text of the novel, revealed to have been recently transcribed from a series of cassette tape recordings made by the protagonist Offred. Alice Walker employed the epistolary form in The Color Purple (1982).[12] The 1985 film adaptation echoes the form by incorporating into the script some of the novel's letters, which the actors deliver as monologues. John Updike's S. (1988) is an epistolary novel consisting of the heroine's letters and transcribed audio recordings. Patricia Wrede and Caroline Stevermer's Sorcery and Cecelia (1988) is an epistolary fantasy novel in a Regency setting from the first-person perspectives of cousins Kate and Cecelia, who recount their adventures in magic and polite society. Unusually for modern fiction, it is written using the style of the letter game. Avi's young-adult novel Nothing but the Truth (1991) uses only documents, letters, and conversation transcripts. Last Words from Montmartre (1995) by Qiu Miaojin is a novel written in the form of twenty letters that can be read in any order. Last Days of Summer (1998) by Steve Kluger is written in a series of letters, telegrams, therapy transcripts, newspaper clippings, and baseball box scores. The Perks of Being a Wallflower (1999) was written by Stephen Chbosky in the form of letters from an anonymous character to a secret role model of sorts.[1] House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski (2000) is written as a series of found footage film transcripts, essays, fictitious footnotes, and letters spread over several layers of metafiction. Twenty-first century Main article: List of contemporary epistolary novels Between Friends by Debbie Macomber (2001) tells the story of a lifelong friendship between Jillian Lawton and Lesley Adamski from the 1950s to the early 2000s, using a combination of letters (later becoming emails) and daily paraphernalia like a gas station receipt. Mark Dunn's Ella Minnow Pea (2001) is a progressively lipogrammatic epistolary novel – the letters become increasingly more difficult to read as the lipogrammatic constraints are brought in, and this requires the reader to attempt to interpret what is being written. La silla del águila ("The Eagle's Throne") by Carlos Fuentes (2003) is a political satire written as a series of letters between persons in high levels of the Mexican government in 2020. The epistolary format is treated by the author as a consequence of necessity: the United States impedes all telecommunications in Mexico as a retaliatory measure, leaving letters and smoke signals as the only possible methods of communication, particularly ironic given one character's observation that "Mexican politicians put nothing in writing." We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver (2003) is a monologic epistolary novel written as a series of letters from Eva, Kevin's mother, to her husband Franklin.[12] The Sluts (2004) by Dennis Cooper is composed of online posts, reviews and email correspondence. Each contributes to a central mystery, fuelled by competing narratives about an escort. The 2004 novel Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell tells a story in several time periods in a nested format, with some sections told in epistolary style, including an interview, journal entries and a series of letters. March (2005), by Geraldine Brooks, is a novel depicting the events of the protagonist's experiences during the American Civil War in 1862 through letters. World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (2006), by Max Brooks, is a series of interviews from various survivors of a zombie apocalypse. Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (2007) by Paul Torday, is a series of letters, e-mails, interview transcripts, newspaper articles and other non-narrative media. The White Tiger (2008) by Aravind Adiga, winner of the 40th Man Booker Prize in 2008, is a novel in the form of letters written by an Indian villager to the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008), by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, is written as a series of letters and telegraphs sent and received by the protagonist. A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010) by Jennifer Egan has parts which are epistolary in nature. One chapter is written as a report of a celebrity interview, and another as a PowerPoint presentation. The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 3⁄4 is one of a series of books written by Adrian Plass, this one consisting entirely of diary entries. Another consists of transcripts of tapes, yet another consists of letters.[13] Illuminae, by Jay Kristoff and Amie Kaufmann, is told exclusively through a series of classified documents, censored emails, interviews, and others. |

代表作 こちらも参照: 架空の日記のリスト  パメラ:あるいは、報われる美徳。美貌の乙女が両親に

宛てた親しみやすい手紙のシリーズ。 パメラ:あるいは、報われる美徳。美貌の乙女が両親に

宛てた親しみやすい手紙のシリーズ。サミュエル・リチャードソンの書簡小説Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740)の第2版のタイトルページ。 書簡小説の形式は18世紀以降も使われ続けている。 18世紀 モンテスキューによる1721年の小説『Lettres persanes』。 Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, by Samuel Richardson 1740, ベストセラーとなった初期の書簡小説。 1761年に出版されたジャン=ジャック・ルソーの書簡小説『ジュリー、あるいは新しいヘロワーズ』。 若きウェルテルの悩み』はヨハン・ヴォルフガング・ゲーテによる1774年の小説。 メルトゥイユ侯爵夫人とヴァルモン子爵夫人は、誘惑を武器に他人を社会的に支配・搾取するナルシストなライバル(そして元恋人)であり、残酷な駆け引きを 楽しみ、人を操る才能を自慢している(フランス革命直前のフランス貴族の腐敗と堕落を描いた作品とも見られる)。この本は、さまざまな登場人物が互いに書 いた手紙だけで構成されている。 スペインの作家、詩人、劇作家、エッセイスト、ホセ・カダルソによる1789年の小説。 マルキ・ド・サドの『アリーヌとヴァルクール』(1795年)。 19世紀 フョードル・ドストエフスキーは、彼の処女作『貧しき人々』(1846年)で、帝政ロシア時代の貧しい境遇と生活に対処しようと奮闘する2人の友人の間の 一連の手紙として、書簡形式を用いた。 ウィルキー・コリンズの『月の石』(1868年)は、さまざまな文書を集めて英語で探偵小説を構成している。2つ目の作品では、登場人物が、同名のダイヤ モンドの失踪にまつわる出来事が誤解されると一家の評判を落とすかもしれないと別の人物から指摘されたので、本当のことを書いているのだと説明している。 ほとんどの書簡小説は、どのように収集されたかを問うことなく文書を提示するので、これは珍しい要素である。彼は以前、『白衣の女』(1859年)でもこ の形式を使っている。 スペインの外相フアン・ヴァレラの『ペピタ・ヒメネス』(1874年)は3部構成で、第1部と第3部は手紙の連なり、中間部は見知らぬ観察者によって語ら れる。 ブラム・ストーカーの『ドラキュラ』(1897年)には、手紙や日記だけでなく、口述筆記用のシリンダーや新聞記事も使われている[1]。 20世紀 ドロシー・L・セイヤーズとロバート・ユースタスの『事件の文書』(1930年)。 E.M.デラフィールドの『地方婦人の日記』(1930年)。 カトリーヌ・テイラーの『宛先不明』(1938年)は反ナチス小説で、最後の手紙には「宛先不明」と書かれて返送され、ドイツ人登場人物の消息を示してい る。 C. S.ルイスは『ねじまき鳥の手紙』(1942年)で書簡形式を使い、天使の視点から書かれた関連小説を書くことも考えたが、結局書かなかった。一般にはあ まり知られていないが、彼の『マルコムへの手紙』(Letters to Malcolm: 主に祈りについて』(1964年)も同様の作品で、架空の受取人「マルコム」に宛てた手紙を通して神学的な問題を探求しているが、マルコムの個人的な生活 の進展が徐々に明るみに出て議論に影響を与えるという点で、この作品は緩やかにしか「小説」と見なされないかもしれない。 ソーントン・ワイルダーの5作目『Ides of March』(1948年)は、ローマ共和国末期を照らし出す手紙と文書で構成されている。 ソール・ベローの小説『ヘルツォーク』(1964年)は、大部分が手紙形式で書かれている。これらは、主人公モーゼス・ヘルツォークが家族や友人、有名人 に宛てて書いた、現実の手紙と想像上の手紙の両方である。 遠藤周作の小説『沈黙』(1966年)は書簡形式の一例であり、その半分はロドリゲスからの手紙、残りの半分は三人称または他の人物からの手紙で構成され ている。 ダニエル・キーズの短編小説『アルジャーノンに花束を』(1959年、1966年)は、主人公が治療の経過とともに書く一連の実験経過報告書の形式をとっ ており、それに応じて文体も変化する。 ローレンス・サンダースの『アンダーソン・テープ』(1969年、1970年)は、主にテープ録音の記録で構成された小説である。 スティーヴン・キングの小説『キャリー』(1974年)は、新聞の切り抜き、雑誌記事、手紙、本の抜粋などを通して、書簡体で書かれている。 マーガレット・アトウッドの『人魚物語』(1985年)は、主人公オフレッドによって録音された一連のカセットテープから最近書き起こされたことが明らか になった、小説の本文を議論する未来の歴史学会の議事録からなるエピローグで終わる。 アリス・ウォーカーは『カラー・パープル』(1982年)で書簡形式を採用した[12]。1985年の映画化では、小説の書簡の一部を脚本に組み込み、俳 優がモノローグとして語ることで、この形式を反響させている。 ジョン・アップダイクの『S』(1988年)は、ヒロインの手紙と書き起こされた音声記録からなる書簡小説である。 Patricia WredeとCaroline Stevermerの『Sorcery and Cecelia』(1988年)は、リージェンシーを舞台に、従姉妹のケイトとセセリアの一人称の視点から、魔法と礼儀正しい社交界での冒険を語る書簡 ファンタジー小説である。現代の小説としては珍しく、手紙ゲームのスタイルで書かれている。 アヴィのヤングアダルト小説『Nothing but the Truth』(1991年)は、文書、手紙、会話の記録のみを使用している。 邱妙仁の『モンマルトルからの最後の言葉』(1995年)は、20通の手紙の形式で書かれた小説で、どの順番でも読むことができる。 ラスト・デイズ・オブ・サマー』(1998年、スティーブ・クルーガー著)は、手紙、電報、セラピー記録、新聞の切り抜き、野球のボックススコアで書かれ ている。 The Perks of Being a Wallflower』(1999年)は、スティーヴン・チョボスキーによって、匿名の登場人物から秘密のロールモデルのような人物への手紙の形で書かれ ている[1]。 マーク・Z・ダニエレフスキの『House of Leaves』(2000年)は、ファウンド・フッテージ映画の記録、エッセイ、架空の脚注、メタフィクションの何層にも広がる手紙のシリーズとして書か れている。 21世紀 主な記事 現代の書簡小説リスト デビー・マコンバー著『Between Friends』(2001年)は、1950年代から2000年代初頭までのジリアン・ロートンとレスリー・アダムスキーの生涯の友情を、手紙(後にE メールになる)とガソリンスタンドのレシートのような日常の道具を組み合わせて描いている。 マーク・ダンの『Ella Minnow Pea』(2001年)は、次第にリポグラマティックな書簡小説になっていく。リポグラマティックな制約が加わると、書簡はますます読みづらくなり、読者 は何が書かれているのかを解釈しなければならなくなる。 カルロス・フエンテス(2003)のLa silla del águila(「鷲の玉座」)は、2020年のメキシコ政府高官間の一連の手紙として書かれた政治風刺である。アメリカは報復措置としてメキシコのすべて の通信を妨害し、可能な通信手段は手紙と発煙筒のみとなった。 ライオネル・シュライヴァー著『ケヴィンについて話そう』(2003年)は、ケヴィンの母エヴァから夫フランクリンへの一連の手紙として書かれた一話完結 型の書簡小説である[12]。 デニス・クーパーの『The Sluts』(2004年)は、オンライン上の投稿、レビュー、電子メールのやり取りで構成されている。それぞれが中心的なミステリーに貢献し、エスコー トに関する競合する物語によって煽られる。 デイヴィッド・ミッチェルによる2004年の小説『クラウド・アトラス』は、いくつかの時代の物語を入れ子形式で描いており、インタビュー、日記、一連の 手紙など、書簡体で語られる部分もある。 ジェラルディン・ブルックス著『March』(2005年)は、1862年のアメリカ南北戦争中に主人公が体験した出来事を手紙を通して描いた小説であ る。 マックス・ブルックス著『World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War』(2006年)は、ゾンビの黙示録を生き延びた人々のインタビューをまとめたシリーズ。 Paul Torday著『Salmon Fishing in the Yemen』(2007年)は、手紙、Eメール、インタビュー記録、新聞記事、その他非物語的メディアのシリーズ。 2008年に第40回マン・ブッカー賞を受賞したアラヴィンド・アディガ作『The White Tiger』(2008年)は、インドの村人が中国の温家宝首相に宛てた手紙という形式の小説である。 メアリー・アン・シェイファーとアニー・バローズによる『ガーンジー文学ポテトパイ協会』(2008年)は、主人公が送受信する一連の手紙や電信として書 かれている。 ジェニファー・イーガンの『A Visit from the Goon Squad』(2010年)には、手紙文的な部分がある。ある章は有名人のインタビューのレポートとして書かれ、別の章はパワーポイントのプレゼンテー ションとして書かれている。 The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 3⁄4』は、エイドリアン・プラスが書いた一連の本のひとつで、この本はすべて日記の記録で構成されている。もう1冊はテープの書き写しで、さらにもう1 冊は手紙で構成されている[13]。 ジェイ・クリストフとアミー・カウフマンによる『イルミナエ』は、一連の機密文書、検閲された電子メール、インタビュー等によってのみ語られている。 |

| Epistolary poem Epistolography Found footage (film technique) Letter collection |

書簡体詩 エピストログラフィー ファウンド・フッテージ 書簡集 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistolary_novel |

|

| An epistolary poem,

also called a verse letter or letter poem,[1] is a poem in the form of

an epistle or letter. History Epistolary poems date at least as early as the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17 or 18 AD), who wrote the Heroides (The Heroines) or Epistulae Heroidum (Letters of Heroines), a collection of fifteen epistolary poems presented as though written by a selection of aggrieved heroines of Greek and Roman mythology, addressing their heroic lovers who have in some way mistreated, neglected, or abandoned them. Ovid extended this with the Double Heroides consisting of three separate exchanges of paired epistles, one each from a heroic lover to his absent beloved and from the heroine in return. A number of epistolary poems were published as separate works in England during the so-called "Long Eighteenth Century", i.e., about 1688 – 1815. Examples of epistolary poems include: Fridugisus (8th century) Baldric of Dol (c. 1050 – 1130) William Pittis & Nahum Tate, An epistolary poem to N. Tate, Esquire, and poet laureat to His Majesty, occasioned by the taking of Namur, London, R. Baldwin, 1696 William Pittis, An epistolary poem to John Dryden, Esq: occasion'd by the much lamented death of the Right Honourable James Earl of Abingdon, London, H. Walwyn, 1699. Ricard Butler, A.M., British Michael: an epistolary poem, to a friend in the country, London, J. Matthews, 1710. James Belcher, A cat may look upon a king: An epistolary poem, on the loss of the ears of a favourite female cat, Dublin, 1732. T R; Charles Cathcart, Lord, An epistolary poem to a lady on the present expedition of Lord Cathcart, London, Olive Payne, 1740. George Canning, An epistolary poem: supposed to be written by Lord William Russell, to Lord William Cavendish; from the prison of Newgate, ... the 20th of July, 1683, in the evening before the execution of that virtuous and patriotic nobleman, ... under the false pretext of his being concerned in the pretended ..., London, R. H. Westley, 1793. The conduct of man. A didactic epistolary poem, London, C. Chapple, 1811. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistolary_poem |

書簡詩(しょかんし)は、詩文詩、書簡詩とも呼ばれ[1]、書簡や手紙

の形をした詩である。 歴史 叙事詩の歴史は少なくともローマ時代の詩人オヴィッド(紀元前43年 - 紀元後17、18年)に遡る。オヴィッドは、ギリシャ・ローマ神話に登場するヒロインたちの中から、自分を虐待したり、無視したり、見捨てたりした英雄的 な恋人に宛てて、まるで悲嘆に暮れたヒロインたちが書いたかのような15の叙事詩を集めた『英雄たち』(The Herooides)または『ヒロインたちの手紙』(Epistulae Heroidum)を書いた。オヴィッドは、英雄的な恋人から不在の最愛の人への手紙と、それに対するヒロインからの手紙という、3つの対になった手紙の やり取りからなる『二重の英雄たち』でこれを拡張した。 いわゆる「長い18世紀」、すなわち1688年から1815年ごろのイギリスでは、多くの書簡詩が別々の作品として出版された。 |

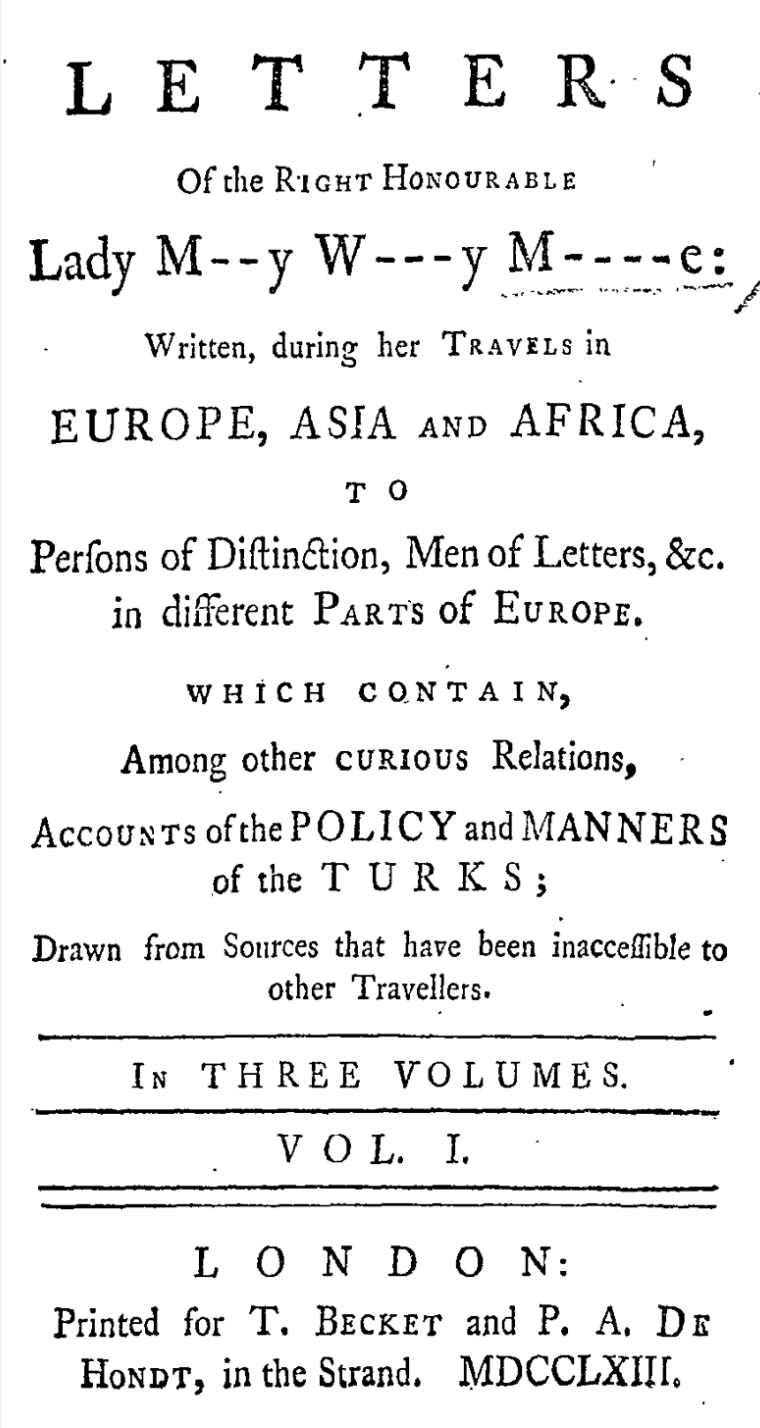

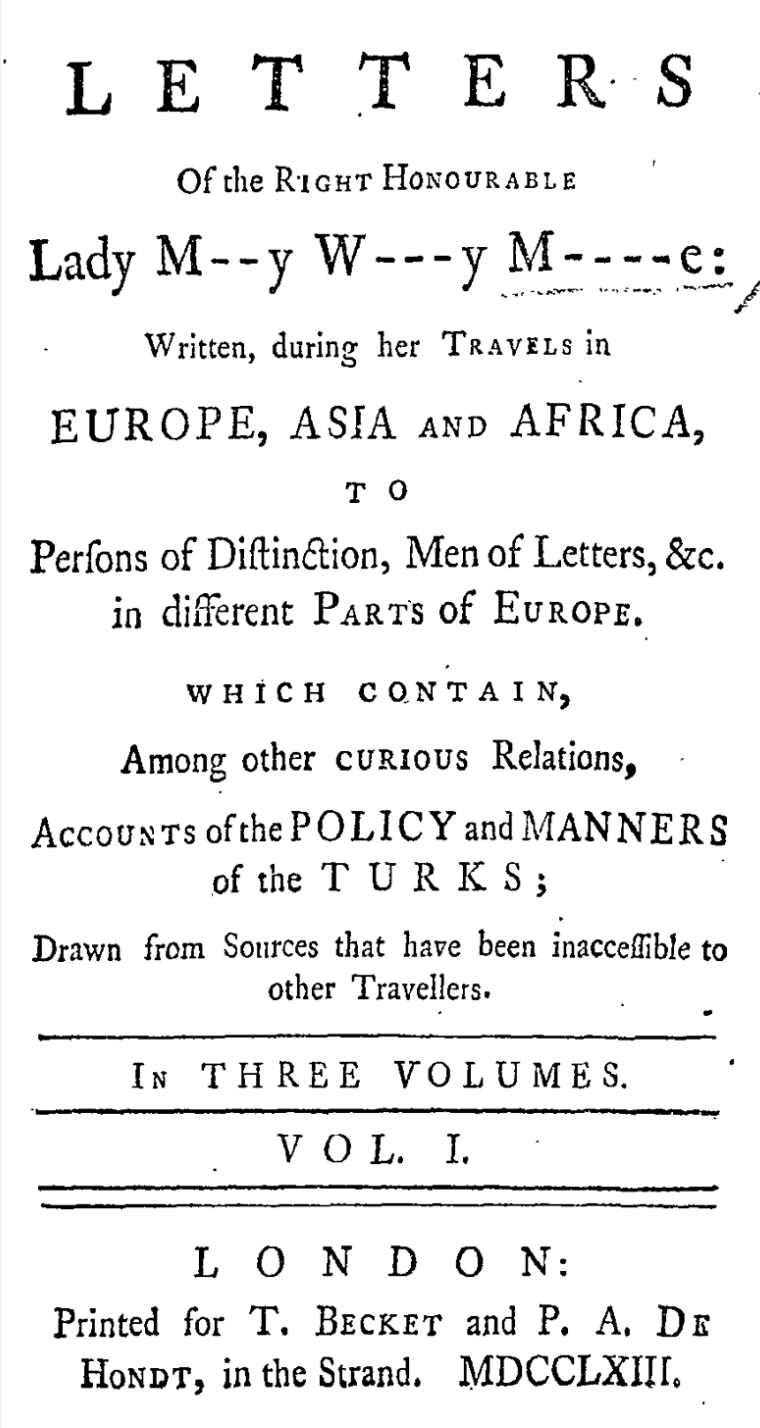

| A letter collection consists of a publication,

usually a book, containing a compilation of letters written by a real

person. Unlike an epistolary novel, a letter collection belongs to

non-fiction literature. As a publication, a letter collection is

distinct from an archive, which is a repository of original documents. Usually, the original letters are written over the course of the lifetime of an important individual, noted either for their social position or their intellectual influence, and consist of messages to specific recipients. They might also be open letters intended for a broad audience. After these letters have served their original purpose, a letter collection gathers them to be republished as a group.[1] Letter collections, as a form of life writing, serve a biographical purpose.[2] They also typically select and organize the letters to serve an aesthetic or didactic aim, as in literary belles-lettres and religious epistles.[3] The editor who chooses, organizes, and sometimes alters the letters plays a major role in the interpretation of the published collection.[4] Letter collections have existed as a form of literature in most times and places where letter-writing played a prominent part of public life. Before the invention of printing, letter collections were recopied and circulated as manuscripts, like all literature.[1]  Title page of Mary Wortley Montagu's Turkish Embassy Letters (1763) |

書簡集(letter collection)とは、実在の人物が書いた書簡をまとめた出版物、通常は書籍のこと

である。書簡小説とは異なり、書簡集はノンフィクション文学に属する。出版物としての書簡集は、オリジナル文書の保管庫であるアーカイブとは異なる。 通常、書簡の原本は、社会的地位や知的影響力を持つ重要な個人の生涯にわたって書かれたもので、特定の受取人に宛てたメッセージで構成されている。また、 幅広い読者を対象とした公開書簡の場合もある。これらの書簡が本来の目的を果たした後、書簡集はそれらを集めてグループとして再出版される[1]。書簡集 は、ライフ・ライティングの一形態として、伝記的な目的を果たす[2]。 また、一般的には、文学のベル・レトルや宗教的書簡のように、美学的または教訓的な目的を果たすために書簡を選択し、整理する。 [3]書簡を選び、整理し、時には手を加える編集者は、出版された書簡集の解釈において大きな役割を果たす。 4]書簡集は、手紙のやり取りが公的生活の中で重要な役割を果たしていたほとんどの時代や場所で、文学の一形態として存在していた。印刷が発明される以前 は、書簡集は他の文学と同様に写本として複写され、流通していた[1]。  メアリー・ウォートリー・モンタグ著『トルコ大使館書簡集』(1763年)のタイトルページ |

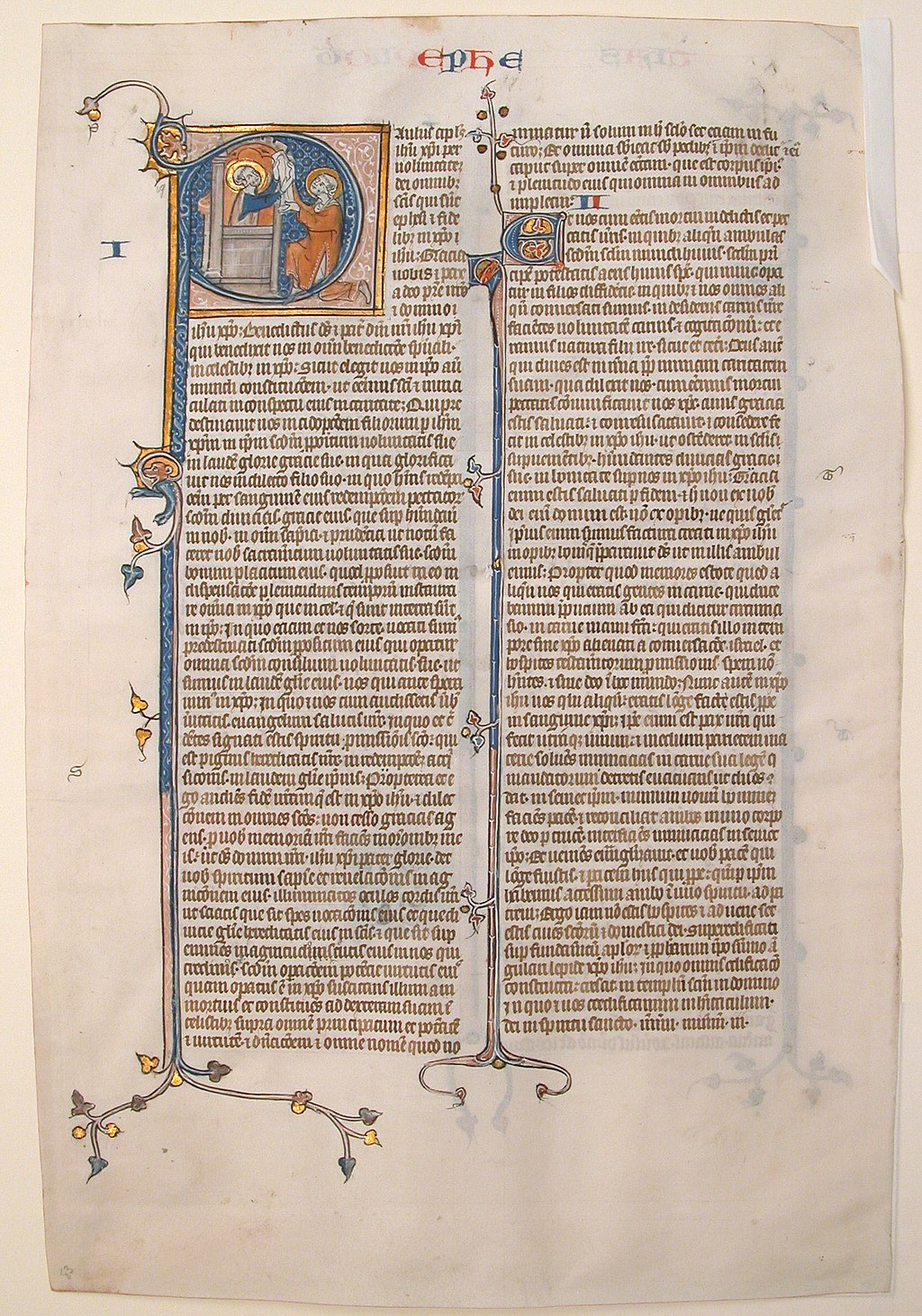

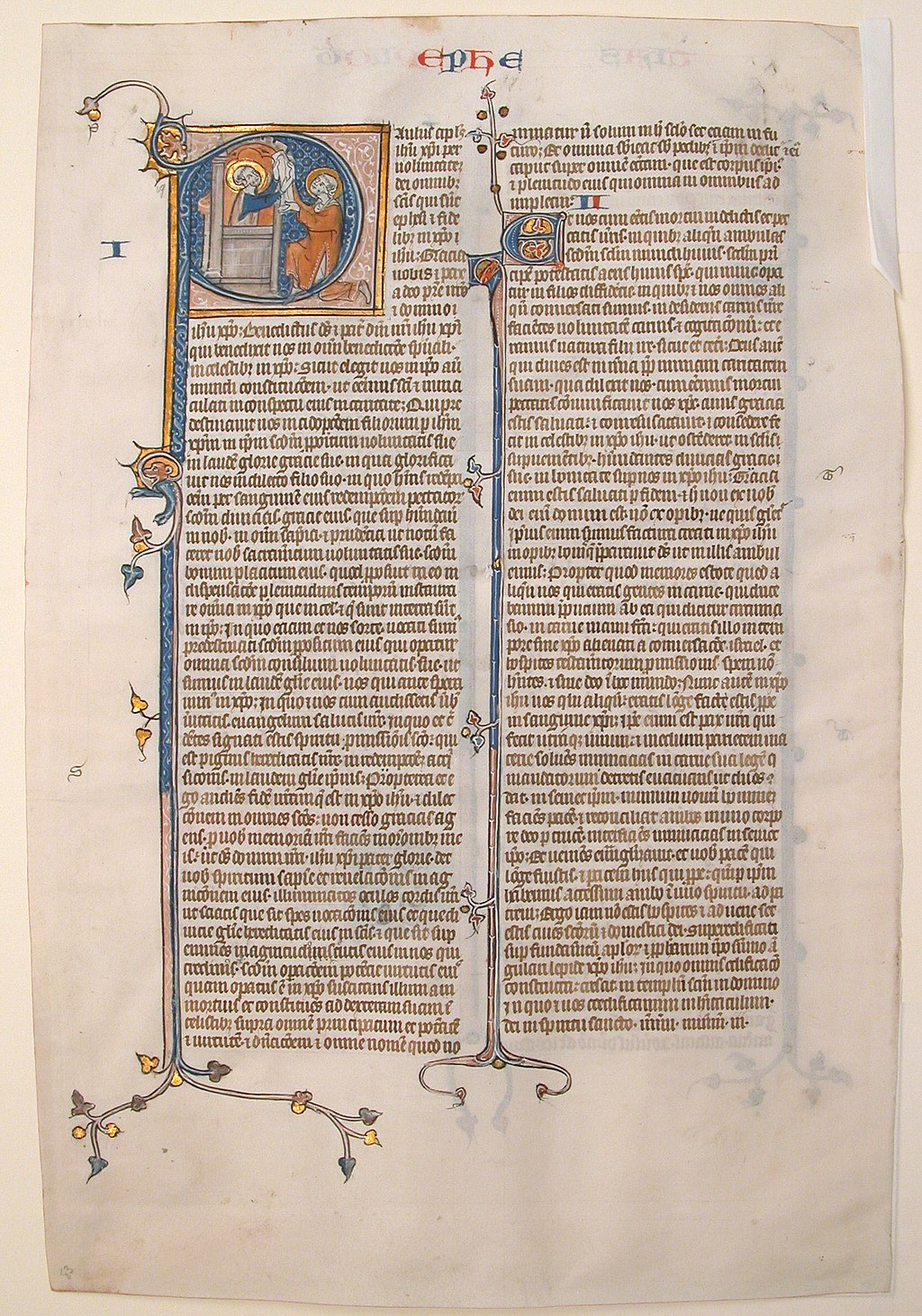

| Letter collections in history Antiquity In ancient Rome, Cicero (106 – 43 BC) is known for his Letters to Atticus, to Brutus, to friends, and to his brother.[3] Seneca the Younger (c. 5 – 65 CE) and Pliny the Younger (c. 61 – c. 112 CE) both published their own letters. Seneca's Letters to Lucilius are strongly moralizing. Pliny's Epistulae have a self-consciously literary style.[2] Ancient letter collections typically did not organize the letters chronologically.[3]  Page of a French medieval manuscript copy of the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Ephesians (c. 1300 AD) Early Christianity is also associated with collected and published letters, typically referred to as epistles for their didactic focus. Paul the Apostle (c. 5 – c. 64/67 CE) is known for the Pauline epistles which make up thirteen books of the New Testament.[3] In late antiquity (340 – 600 CE), letter collections became particularly popular and widespread.[5] Saint Augustine (354 – 430 CE) and Saint Jerome (c. 342-347 – 420 CE) are noted in this period for their prolific and influential theological letters.[1] Medieval and Renaissance Europe Medieval European letter-writers were heavily influenced by Cicero in the development of rhetorical conventions (ars dictaminis) for letter-writing.[2] Petrarch (1304 – 1374 CE) added a greater level of personal autobiographical detail in his Epistolae familiares. Erasmus (1466 –1536 CE) and Justus Lipsius (1547 – 1606 CE) also promoted flexibility and enjoyable reading in letter-writing, rather than a rule-focused formula.[2] Eighteenth-century Europe Published letters and diaries were particularly prominent in eighteenth-century British print, sometimes called "the defining genres of the period."[6] Particularly popular were letter collections focused on the private lives of their writers, which would garner praise based on how well they could demonstrate the personal character of the author.[7] Stylistically, eighteenth-century familiar letters were influenced more by the amusing Vincent Voiture (1597 – 1648) than the formal classics of Cicero, Pliny, and Seneca.[7] The letters of Marie de Rabutin-Chantal (1626 – 1696) and her daughter were published beginning in 1725, and widely regarded across Europe as the model for witty, enjoyable letters.[2] Many eighteenth-century figures gained their reputations as eloquent writers primarily through their letters, such as the bluestockings Elizabeth Montagu and Mary Delany.[8] Twentieth-century letters Letter collections were less prominent as literary publications in the twentieth century. Instead of being published during the writer's lifetime in order to build their reputation, the letters of twentieth-century artists were typically collected and published posthumously in order to cement their legacy. Some nineteenth-century authors, such as Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Edith Wharton, first had their letters published in the twentieth century as scholarly editions. Major collections by twentieth-century authors include those of Joseph Conrad, George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf.[8] Other artists' letters in the twentieth century include The Letters of Vincent van Gogh (first published in 1914), Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke (first published in 1929), and Letters to Milena by Franz Kafka (first published in 1952). |

歴史上の手紙コレクション 古代 古代ローマでは、キケロ(紀元前106~43年)がアッティカス宛、ブルータス宛、友人宛、弟宛の書簡で知られている[3]。セネカの『ルキリウスへの手 紙』は強く道徳的である。プリニウスの『エピストゥラエ』は、自意識過剰なまでに文学的な文体である[2]。古代の書簡集は通常、年代順に書簡を整理して いなかった[3]。  フランス中世写本『エフェソの信徒への聖パウロの手紙』のページ(西暦1300年頃) 初期キリスト教は、その教訓的な焦点から一般的に書簡と呼ばれる、収集・出版された書簡とも関連している。使徒パウロ(紀元5年頃~紀元64/67年頃) は、新約聖書の13の書物を構成するパウロ書簡で知られている[3]。 古代後期(340年~600年)には、書簡集が特に流行し広まった[5]。この時代には、聖アウグスティヌス(354年~430年)と聖ジェローム (342年~347年~420年)が、多作で影響力のある神学書簡で知られている[1]。 中世・ルネサンス期のヨーロッパ 中世ヨーロッパの手紙の書き手たちは、手紙の書き方に関する修辞学的規則(ars dictaminis)の発展において、キケロの大きな影響を受けていた[2]。 ペトラルカ(Epistolae familiares, 1304 - 1374 CE)は、『家族への手紙』(Epistolae familiares)において、個人的な自伝的内容をより詳細に記している。エラスムス(1466年 - 1536年)やユストゥス・リプシウス(1547年 - 1606年)もまた、手紙の書き方において、規則を重視した定型ではなく、柔軟で楽しい読み物を推奨していた[2]。 18世紀のヨーロッパ 出版された書簡と日記は18世紀のイギリスの印刷物において特に顕著であり、「この時代を定義するジャンル」と呼ばれることもあった[6]。特に人気が あったのは、書き手の私生活に焦点を当てた書簡集であり、それらは、書き手の個人的な性格をいかにうまく示すことができたかによって賞賛を集めた。 [7] 文体的には、18世紀の親しみやすい手紙は、キケロ、プリニウス、セネカといった形式的な古典よりも、愉快なヴァンサン・ヴォワチュール(1597年 - 1648年)の影響を受けていた[7]。マリー・ド・ラブタン=シャンタル(1626年 - 1696年)とその娘の手紙は1725年から出版され、機知に富んだ楽しい手紙の手本としてヨーロッパ中で広く評価された[2]。 18世紀の多くの人物は、青鞜派のエリザベス・モンタグやメアリー・デラニーなど、主に手紙を通じて雄弁な作家としての評判を得た[8]。 20世紀の手紙 20世紀の書簡集は、文学出版物としてはあまり目立たなかった。20世紀の芸術家の書簡は、その作家の名声を高めるために存命中に出版されるのではなく、 その遺産を確固たるものにするために死後に収集され、出版されるのが一般的であった。チャールズ・ディケンズ、マーク・トウェイン、イーディス・ウォート ンなど、19世紀の作家の中には、20世紀になって初めて書簡を学術的な版として出版した者もいる。20世紀の作家の主な書簡集には、ジョセフ・コンラッ ド、ジョージ・バーナード・ショー、ジェイムズ・ジョイス、ヴァージニア・ウルフのものがある[8]。20世紀の他の芸術家の書簡集には、フィンセント・ ファン・ゴッホの『ゴッホの手紙』(1914年初版)、ライナー・マリア・リルケの『若き詩人への手紙』(1929年初版)、フランツ・カフカの『ミレー ナへの手紙』(1952年初版)などがある。 |

| Relationship to authentic letters Letter collections have not always been considered "literary" texts. In the nineteenth century, scholars like Adolf Deissmann promoted a distinction between a "real missive" and a "literary letter": a "real missive" was a private document focusing solely on a functional communication purpose, whereas a "literary letter" was written with the expectation of a wide audience and carried artistic value. In this distinction, real missives could be used as evidence of factual events, while literary letters required interpretation as works of art. Contemporary scholars, however, see all letters as having both historical information and artistic merit, both of which require careful contextualization.[5] In eighteenth century Europe, many works were written an epistolary style without having been mailed as real letters: these included scholarly research and travel narratives, as well as epistolary novels.[7] The term "familiar letters" was used to designate letter collections consisting of authentic correspondence which had been written for a private audience prior to publication.[7] Role of the collector It was more common for authors to collect their own letters in Latin antiquity than in Greek antiquity. In Latin antiquity, Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BCE) published a self-organized letter collection, which does not survive today. Cicero also mentioned plans to collect his own letters, though he did not do so before his death. Pliny the Younger's letters are the oldest extant letter collection in which the letters were collected by the author himself.[5] |

本物の書簡との関係 書簡集は常に「文学的」テキストとみなされてきたわけではない。19世紀、アドルフ・ダイスマン(Adolf Deissmann)のような学者は、「本物の手紙」と「文学的な手紙」を区別することを提唱した。「本物の手紙」は機能的なコミュニケーション目的のみ に焦点を当てた私的な文書であるのに対し、「文学的な手紙」は多くの読者を想定して書かれ、芸術的な価値を持つ。この区別の中で、「本物の手紙」は事実の 出来事の証拠として用いることができ、「文学的な手紙」は芸術作品としての解釈を必要とした。しかし、現代の学者たちは、すべての書簡は歴史的情報と芸術 的価値の両方を持っているとみなしており、そのどちらにも慎重な文脈の整理が必要であるとしている[5]。 18世紀のヨーロッパでは、多くの作品が本物の書簡として郵送されることなく書簡体として書かれていた。これらの作品には、書簡体小説だけでなく、学術研 究や旅行物語も含まれていた[7]。 収集家の役割 ギリシャ古代よりもラテン古代の方が、作家が自らの書簡を収集することは一般的であった。ラテン古代では、ユリウス・カエサル(前100年 - 前44年)が自ら組織した書簡集を出版しているが、これは現在では残っていない。キケロも自らの書簡を収集する計画について言及しているが、生前には実現 しなかった。プリニウスの書簡集は、現存する最古の書簡集であり、著者自身が書簡を収集したものである[5]。 |

| Letter Autobiography Biography Epistle Epistolography Epistolary novel Epistolary poem Belles-lettres List of fictional diaries |

手紙 自伝 伝記 書簡 書簡記述 書簡体小説 書簡詩 手紙 架空の日記のリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_collection |

|

| Epistolography,

or the art of writing letters, is a genre of Byzantine literature

similar to rhetoric that was popular with the intellectual elite of the

Byzantine age.[1] The letter became a popular literary form in the fourth century AD and combined Christian and classical Greek traditions. The collections of the emperors Julian, Libanios, and Synesius, and the work of the Cappadocian Fathers were particularly notable, while letters of Aristotle, Plato and the Pauline Epistles of the New Testament were influential in the development of the genre.[1] In some cases, large numbers of letters have survived from the more prolific practitioners. Nine hundred from Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (345–402) survive, and Libanius (c. 314–392 or 393) left over 1500 letters in Greek. Scholars have sometimes been disappointed with the content of the letters, which have tended to include rhetorical conventions to the exclusion of factual matters, or, in the case of Libanius, to include many generic recommendations on behalf of applicants to the Roman bureaucracy.[2] A.H.M. Jones described the writing of letters in the later Roman Empire as a social convention of elegant compositions which contained no information and solicited none.[3] The genre later died out before being revived in the 11th and 12th centuries.[1] |

書簡記述・書簡術(Epistolography)は、ビザンチン時代

の知的エリートに人気があった修辞学に似たビザンチン文学のジャンルである[1]。 書簡は紀元4世紀には一般的な文学形式となり、キリスト教と古典ギリシアの伝統が組み合わされた。ユリアヌス帝、リバニオス帝、シネシウス帝の書簡集や カッパドキア教父の著作が特に注目され、アリストテレス、プラトン、新約聖書のパウロ書簡がこのジャンルの発展に影響を与えた[1]。 より多作な実践者たちの書簡が大量に残っている場合もある。Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (345-402)の900通が現存し、Libanius (c. 314-392 or 393)は1500通以上のギリシャ語の書簡を残している。研究者たちは書簡の内容に失望することもあった。事実的な事柄を排除して修辞的な慣習を盛り込 んだり、リバニウスの場合はローマ官僚機構への申請者に代わって一般的な勧告を多く盛り込む傾向があった[2]。 その後、このジャンルは11世紀と12世紀に復活する前に消滅した[1]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistolography |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099