それが、どうした?

so what?

1917 Billie Holiday, age two

それが、どうした?

so what?

1917 Billie Holiday, age two

それが、どうした?——(承前:pdf)

だけど自虐的に腐るのはやめておこう。スローガンのように叫ばれるが、事実として水俣病事件は終わったわけではない。まだまだ未解決の課題は

山積みされている。われわれには忘却という公共的病魔に徐々に苛まれようとしているし、また過去を解決済みの問題として社会的に封印する動きもある。これ

らに抗して生きるのは、しんどい面もあるが、楽しいこともある。また、われわれの可能性を救済してくれる幸運というものもどこかにあるはずだ。

1938年末当時のビリー・ホリディは無名であり、ニューヨークのナイト・クラブで毎夜ステージに立っていた。「奇妙な果実(Strange Fruit)」の 編曲を担当した ダニー・ メンデルスゾーンはビリーが納得いくまで練習につき合ってくれた。安っぽい女心を歌うムーディな音楽がほとんどのレパートリーのなかで「奇妙な果実」とい う名曲は船出することになった。ハーレムで開かれたあるパーティが公衆の前での「奇妙な果実」のデビューであった。当然、ビリーは自分がたぶん場違いな歌 を披露することに心配でたまらなかった。彼女の回想によれば、歌をうたい終わった時には、パーティの会場は沈黙が支配していたという。ビリーは自分の計画 が失敗に終わったと思った時——少なくとも彼女の心理的時間の中では暫くたってから、観客の一人が狂ったように拍手をし始めた。やがて次々と拍手が連鎖的 におこって、彼女の心配が杞憂に終わったことがわかったという(9)。

→(9)これらのエピソードは彼女の自伝『奇妙な果実』によって今日まで語り継がれていることだが、この歴史的事実を子細に検討したマーゴ リック[2003]によると、後の人たちのプロテスト・ソングの創始としての読みとりたい人たちによって集合的に形成された一種の「神話」ともいえる潤色 がさまざまなところに入っていることがわかる。だからと言ってビリーの「奇妙な果実」が蒔いた反人種主義の情念とそのアウラ性の社会的価値が下がるわけで はない。同じことは、石牟礼道子『苦海浄土』や宮本常一「土佐源氏」といった偉大な作品と、それらが生まれてきた経緯に関する事実とフィクションの境界を 神経質に警邏する議論との関係にも言えるかもしれない。

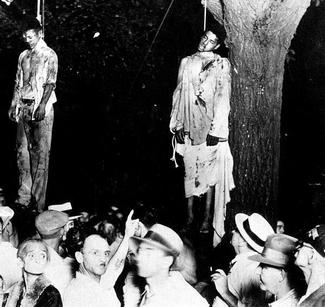

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

Source:

http://www.lyricsfreak.com/b/billie+holiday/strange+fruit_20017859.html

Billie Holiday, Strange fruit

水俣に関わり、水俣のことを歌うビリー・ホリディ級の心のうたの歌い手はこれまでにも幾人もいることを誰しもが知っている。しかし、水俣病事 件に終わりがない限り、水俣病事件をうたう次なる新人は必ず現れるだろう。ちょうどビリーの「奇妙な果実」がその内容とはかなり場違いなハーレムのパー ティでデビューしたのと同じように、水俣病事件を歌う未来の新人は、その誕生の日々を期待しつつきっとどこかで研鑽を積んでいるに違いない。未来とは永遠 に続く時間のことをさす言葉なのだから、水俣病事件研究にも未来が到来しないわけがない。

(完)

| "Strange Fruit"

is a

song written and composed by Abel Meeropol

(under his pseudonym Lewis Allan) and recorded by Billie Holiday in

1939. The lyrics were drawn from a poem by Meeropol published in 1937.

The song protests the lynching of Black Americans with lyrics that

compare the victims to the fruit of trees. Such lynchings had reached a

peak in the Southern United States at the turn of the 20th century and

the great majority of victims were black.[2] The song has been called

"a declaration" and "the beginning of the civil rights movement".[3] Meeropol set his lyrics to music with his wife and the singer Laura Duncan and performed it as a protest song in New York City venues in the late 1930s, including Madison Square Garden. Holiday's version was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1978.[4] It was also included in the "Songs of the Century" list of the Recording Industry of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.[5] In 2002, "Strange Fruit" was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress[6] as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant". |

"Strange Fruit

"は、アベル・ミーロポール(ルイス・アランのペンネーム)が作詞・作曲し、1939年にビリー・ホリデイが録音した曲である。歌詞は、1937年に出版

されたミーロポールの詩から引用されたものである。この歌は、アメリカ黒人のリンチに抗議するもので、犠牲者を木の実に例えた歌詞になっている。このよう

なリンチは20世紀初頭のアメリカ南部でピークに達しており、被害者の大多数は黒人だった[2]。この曲は「宣言」、「公民権運動の始まり」と呼ばれてい

る[3]。 ミーロポールは妻で歌手のローラ・ダンカンとともに歌詞を音楽化し、1930年代後半にマディソン・スクエア・ガーデンなどニューヨークの会場でプロテス トソングとして演奏した。ホリデー版は1978年にグラミー賞の殿堂入りを果たし[4]、アメリカレコード協会と全米芸術基金による「ソングス・オブ・ ザ・センチュリー」にも選出された[5]。 2002年、「奇妙な果実」は「文化的、歴史的、美学的に重要」であるとして、米国議会図書館のナショナル・レコーディング・レジストリに保存されること が決定した[6]。 |

| Poem and song "Strange Fruit" originated as a poem written by the Jewish-American writer, teacher and songwriter Abel Meeropol, under his pseudonym Lewis Allan, as a protest against lynchings.[8][9][10] In the poem, Meeropol expressed his horror at lynchings, inspired by Lawrence Beitler's photograph of the 1930 lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana.[9] Meeropol published the poem under the title "Bitter Fruit" in January 1937 in The New York Teacher, a union magazine of the Teachers Union.[11][12] Though Meeropol had asked others (notably Earl Robinson) to set his poems to music, he set "Strange Fruit" to music himself. First performed by Meeropol's wife and their friends in social contexts,[12] his protest song gained a certain success in and around New York. Meeropol, his wife, and the Black vocalist Laura Duncan performed it at Madison Square Garden.[13] |

詩と歌 "Strange Fruit "は、ユダヤ系アメリカ人の作家、教師、ソングライターのアベル・ミーロポールが、リンチに対する抗議としてルイス・アランというペンネームで書いた詩と して生まれた[8][9][10]。 この詩でミーロポールは、ローレンス・ベイトラーによる、インディアナ州マリオンでのトーマス・シップとアブラム・スミスのリンチの写真からインスピレー ションを受けてリンチに対する恐怖を表現した[9]。 ミーロポールは1937年1月、教師組合の組合誌『ニューヨーク・ティーチャー』に「苦い果実」というタイトルでこの詩を発表した[11][12]。ミー ロポールは自分の詩を音楽にするよう他の人(特にアール・ロビンソン)に頼んでいたが、「奇妙な果実」は自分で音楽にしたものであった。ミーロポルの妻と その友人たちによって社交の場で最初に演奏され[12]、彼のプロテスト・ソングはニューヨークとその周辺で一定の成功を収めた。ミーロポール、妻、そし て黒人ヴォーカリストのローラ・ダンカンは、マディソン・スクエア・ガーデンでこの曲を演奏した[13]。 |

| Billie Holiday's performances

and recordings One version of events claims that Barney Josephson, the founder of Café Society in Greenwich Village, New York's first integrated nightclub, heard the song and introduced it to Billie Holiday. Other reports say that Robert Gordon, who was directing Holiday's show at Café Society, heard the song at Madison Square Garden and introduced it to her.[11] Holiday first performed the song at Café Society in 1939. She said that singing it made her fearful of retaliation but, because its imagery reminded her of her father, she continued to sing the piece, making it a regular part of her live performances.[14] Because of the power of the song, Josephson drew up some rules: Holiday would close with it; the waiters would stop all service in advance; the room would be in darkness except for a spotlight on Holiday's face; and there would be no encore.[11] During the musical introduction to the song, Holiday stood with her eyes closed, as if she were evoking a prayer. Holiday approached her recording label, Columbia, about the song, but the company feared reaction by record retailers in the South, as well as negative reaction from affiliates of its co-owned radio network, CBS.[15] When Holiday's producer John Hammond also refused to record it, she turned to her friend Milt Gabler, owner of the Commodore label.[16] Holiday sang "Strange Fruit" for him a cappella, and moved him to tears. Columbia gave Holiday a one-session release from her contract so she could record it; Frankie Newton's eight-piece Café Society Band was used for the session. Because Gabler worried the song was too short, he asked pianist Sonny White to improvise an introduction. On the recording, Holiday starts singing after 70 seconds.[11] It was recorded on April 20, 1939.[17] Gabler worked out a special arrangement with Vocalion Records to record and distribute the song.[18] Holiday recorded two major sessions of the song at Commodore, one in 1939 and one in 1944. The song was highly regarded; the 1939 recording eventually sold a million copies,[9] in time becoming Holiday's biggest-selling recording. In her 1956 autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, Holiday suggested that she, together with Meeropol, her accompanist Sonny White, and arranger Danny Mendelsohn, set the poem to music. The writers David Margolick and Hilton Als dismissed that claim in their work Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song, writing that hers was "an account that may set a record for most misinformation per column inch". When challenged, Holiday—whose autobiography had been ghostwritten by William Dufty—claimed, "I ain't never read that book."[19] Holiday was so well known for her rendition of "Strange Fruit" that "she crafted a relationship to the song that would make them inseparable".[20] Holiday's 1939 version of the song was included in the National Recording Registry on January 27, 2003. In October 1939, Samuel Grafton of the New York Post said of "Strange Fruit", "If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its Marseillaise."[21] In an attempt to have a two-thirds majority in the Senate that would break the filibusters by southern senators, anti-racism activists were encouraged to mail copies of "Strange Fruit" to their senators.[22] |

ビリー・ホリデイの演奏と録音 ある説では、ニューヨーク初の統合ナイトクラブであるグリニッチビレッジのカフェ・ソサエティの創設者バーニー・ジョセフソンがこの曲を聴いて、ビリー・ ホリデイに紹介したとされている。また、カフェ・ソサエティでホリデイのショーを演出していたロバート・ゴードンが、マディソン・スクエア・ガーデンでこ の曲を聴いて紹介したという話もある[11] ホリデイは1939年にカフェ・ソサエティでこの曲を初披露した。彼女はこの曲を歌うことで報復を恐れていたというが、そのイメージから父親を思い出した ため、歌い続け、ライブの定番曲となった[14]。 この曲の持つ力から、ジョセフソンはいくつかのルールを設けた。ホリデーはこの曲で幕を閉じること、ウェイターは事前にすべてのサービスを停止すること、 会場はホリデーの顔にスポットライトが当たる以外は暗闇にすること、アンコールはないこと[11]。 曲の導入部では、まるで祈りを捧げるかのように目を閉じて立っていた。 ホリデーは所属レコード会社のコロンビアにこの曲の録音を打診したが、同社は南部のレコード店からの反発や、共同出資していたラジオ局CBSの系列局から の反発を恐れた[15]。ホリデーのプロデューサーのジョン・ハモンドも録音を拒否すると、彼女は友人のコモドールレーベルのオーナー、ミルト・ガブラー に頼み、アカペラで「Strange Fruit」を歌って感動して涙を見せた[16]。コロンビアはホリデーに1セッションだけ契約を解除し、この曲を録音できるようにした。セッションには フランキー・ニュートンの8人編成のカフェ・ソサエティ・バンドが使われた。ガブラーは、この曲が短すぎることを心配して、ピアニストのソニー・ホワイト にイントロを即興で作ってもらった。録音では、ホリデーは70秒後に歌い始めている[11] 1939年4月20日に録音された[17] ガブラーはボーカリオン・レコードと特別な契約を結び、この曲を録音・配給した[18]。 ホリデーはこの曲をコモドール社で1939年と1944年の2回にわたって大規模なセッションを録音した。この曲は高く評価され、1939年の録音は最終 的に100万枚を売り上げ、ホリデーにとって最も売れた録音となった[9]。 1956年の自伝『レディ・シングス・ザ・ブルース』の中で、ホリデー はミーロポール、伴奏者のソニー・ホワイト、編曲者のダニー・メンデルゾーンとともに、この詩を音楽にすることを提案している。しかし、作家のデビッド・ マルゴリックとヒルトン・アルスは、『ストレンジ・フルーツ』という著作の中で、この主張を退けている。作家のデビッド・マルゴリックとヒルトン・アルス は、『Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song』という本の中で、ホリデーの話は「コラムインチあたりの誤報の最多記録を打ち立てるかもしれない」と書いて、この主張を否定している。自伝は、ゴーストライターのウィリアム・デュフティが書いた当該の著者のホリデーは、「そんな本は読んだことがない」と反 論している[19]。 ホリデーは「奇妙な果実」の演奏があまりにも有名だったため、「彼女はこの曲と切っても切れない関係を作り上げた」[20]。ホリデーの1939年版は 2003年1月27日にナショナル・レコーディング・レジストリに収録された。 1939年10月、ニューヨーク・ポスト紙のサミュエル・グラフトンは「奇妙な果実」について、「もし被搾取者の怒りが南部で十分に高まったとしたら、そ れは今やマルセイエーズを持っている」と述べている[21]。南部の上院議員によるフィリバスターを破るために上院の3分の2の多数を確保しようと、反人 種差別活動家は上院議員に「奇妙な果実」のコピーを郵送するように奨励されていた[22]。 |

| Notable covers Notable cover versions of this song include Nina Simone,[23] René Marie,[23] Jeff Buckley,[23] Siouxsie and the Banshees,[24] Dee Dee Bridgewater,[24] Josh White,[25] UB40,[24] Bettye LaVette[26] and Edward W. Hardy.[27] Nina Simone recorded the song in 1965,[28] a recording described by journalist David Margolick in The New York Times as featuring a "plain and unsentimental voice".[23] René Marie's rendition was coupled with the Confederate anthem "Dixie", making for an "uncomfortable juxtaposition".[23] Journalist Lara Pellegrinelli wrote that Jeff Buckley while singing it "seems to meditate on the meaning of humanity the way Walt Whitman did, considering all of its glorious and horrifying possibilities".[23] LA Times noted that Siouxsie and the Banshees's version contained "a solemn string section behind the vocals" and "a bridge of New Orleans funeral-march jazz" which enhanced the singer's "evocative interpretation".[29] The group's rendition was selected by the Mojo staff to be included on the compilation Music Is Love: 15 Tracks That Changed The World .[30][31] |

(カバーを歌った人たち) |

| Awards and honors 1999: Time magazine named "Strange Fruit" as "Best Song of the Century" in its issue dated December 31, 1999.[32][33] 2002: The Library of Congress honored the song as one of 50 recordings chosen that year to add to the National Recording Registry.[34] 2010: The New Statesman listed it as one of the "Top 20 Political Songs".[35] 2011: The Atlanta Journal-Constitution listed the song as Number One on "100 Songs of the South".[36] 2021: Rolling Stone listed as the 21st best song on their "Top 500 Best Songs of All Time".[37] |

|

| Bibliography Margolick, David (2001). Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060959562. Clarke, Donald (1995). Billie Holiday: Wishing on the Moon. München: Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-03756-3. Davis, Angela (1999). Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-77126-5. Holiday, Billie; Dufty, William (1992). Lady Sings the Blues. Edition Nautilus. ISBN 978-3-89401-110-9. Autobiography. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Commodore Records

78 label for "Strange Fruit" by Billie Holiday and Her Orchestra

(526A), published by Commodore Music Shop, 136 East 42nd Street, New

York City// Meeropol cited this photograph of the lynching of Thomas

Shipp and Abram Smith, August 7, 1930, as inspiring his poem.[-> "Strange

Fruit: Anniversary Of A Lynching". NPR. August 6, 2010]

文献

◆オンライン文献

熊本日日新聞「『智子を休ませてあげた い』故ユージン・スミス氏撮影『入浴する母子像』封印」(二〇〇〇年二月二八日朝刊)(http: //www.kumanichi.co.jp/minamata/nenpyou/m-kiji20000228.html)2005年1月11日[最終 確認日]

【ご注意】

この論文の出典は、池田光穂、『水俣から の想像力:問い続ける水俣病』丸山定巳・田口宏昭・田中雄次編、熊本出版文化会館(担当箇所:「水俣が 私に出会ったとき:社会的関与と視覚表象」Pp.123-146 )、2005年3月です。引用される場合は原著に当たって確認されることをお勧めします(→朗読版pdf「水俣が私に出会ったとき:悲劇の視覚表象 ̶」)。

●附論、細川周平『レコードの美学』勁草 書房、1990年

「レコードの悪しき聴取者とは、そこに機

械論的な因果関係しか見ず……必然的な循環しか聴かない人間である。……良き聴取者にとってレコードをかけ直すことはまさに遊び直す(re-play)で

ある」——細川周平(1990).

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆