Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979

哲学と自然の鏡

Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979

池田光穂

『哲学と自然の鏡』は、アメリカの哲学者リチャード・ローティが 1979年に著した書物である。著者はこの中で、現代哲学の問題を解決するのではなく解消しようと試みる。ローティは、分析哲学に集約される認識論的企て の言語ゲームの中にのみ存在する疑似問題としてそれらを提示することでこれを成し遂げる。実用主義的な姿勢で、ロティは哲学が生産的であるためには、こう した疑似問題を乗り越えなければならないと示唆している。

「自然の鏡(Mirror of Nature)」とは、リチャード・ローティ(Richard Rorty, 1931-2007)が、自然を忠実に映し出す心、彼の言葉によると我々に「正しい意見」を与える心的装置につけた比喩・メタファーのことである。そこで 問題化されるのは、デカルト、ロック、カントにはじまる近代哲学が、知識、真理、主客の二元論に正当性を与えるために、自然を忠実に映し出す心の 役割を、その認識論において押し付けてきたのだという。

| Philosophy

and the Mirror of Nature is a 1979 book by the American philosopher

Richard Rorty, in which the author attempts to dissolve modern

philosophical problems instead of solving them. Rorty does this by

presenting them as pseudo-problems that only exist in the language-game

of epistemological projects culminating in analytic philosophy. In a

pragmatist gesture, Rorty suggests that philosophy must get past these

pseudo-problems if it is to be productive. |

『哲学と自然の鏡』は、アメリカの哲学者リチャード・ローティが

1979年に著した書物である。著者はこの中で、現代哲学の問題を解決するのではなく解消しようと試みる。ローティは、分析哲学に集約される認識論的企て

の言語ゲームの中にのみ存在する疑似問題としてそれらを提示することでこれを成し遂げる。実用主義的な姿勢で、ロティは哲学が生産的であるためには、こう

した疑似問題を乗り越えなければならないと示唆している。 |

| Background By the mid-20th century, interest in the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey had significantly waned. He has been described as having been "passé in the minds of a preponderance of philosophers from approximately the 1940s through the 1980s," with the publication of Rorty's book playing a role in the resurgence of interest in Dewey.[1] Rorty was rather interested in the history of philosophy and described the book as "very much the old McKeonite trick of taking the larger historical view."[2] |

背景 20世紀半ばまでに、アメリカのプラグマティスト哲学者ジョン・デューイへの関心は著しく薄れていた。彼は「1940年代から1980年代にかけて、大多 数の哲学者の間で時代遅れと見なされていた」と評され、ロティの著書の出版がデューイへの関心再燃の一因となった。[1] ロティは哲学史に強い関心を持ち、この本を「より大きな歴史的視点を取るという、まさに昔ながらのマッキオン流の手法だ」と評した。[2] |

| Summary In Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, Rorty argues that the history of philosophy is the history of the quest to make sense of the claim that the mind has knowledge of an objective reality, and thus to give philosophy the ability to judge other aspects of culture as being in or out of touch with this reality. He dubs this idea "representationalism" and refers to it using the metaphor of the "mirror of nature," hence the title of the book. In the introduction, Rorty claims that Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and John Dewey are the three most important philosophers of the 20th century; Wittgenstein for his diagnosis of philosophy as a set of linguistic confusions, Heidegger for his historical deconstruction of such confusions, and Dewey for his hopeful prognosis of a post-metaphysical culture. In continuing this quietist and historicist tradition, the book is therapeutic rather than constructive in nature. However, Rorty aims to carry out his therapy by using the arguments of such systematic philosophers as W. V. O. Quine, Wilfrid Sellars, Thomas Kuhn, and Donald Davidson in order to undermine our philosophical intuitions about the mind (mirror), knowledge (mirroring), and philosophy itself (the study of mirroring), and thus to undermine the representationalist picture of the "mirror of nature." In Part One, titled "Our Glassy Essence," Rorty examines the philosophical notion of the mind as an immaterial, non-spatial entity which is somehow able to have knowledge of things. He first sets out to dissolve the intuition that there is a "mark of the mental" which can be used to categorize things a priori as being either mental or physical. After having shown that the traditional candidates for marks of the mental, namely non-spatiality, intentionality, and phenomenality, fail to justify dualistic intuitions, Rorty declares the mind–body problem to have been dissolved. He then examines the history of the mind from Aristotle to Descartes in order to demonstrate its historical contingency, which he hopes will dissuade future generations from attempting to resurrect the mind–body problem, before presenting his social-linguistic account of incorrigibility about the mental through his "Antipodeans" thought experiment. In Part Two, titled "Mirroring," Rorty examines the philosophical notion of knowledge as the possession of accurate representations of an objective reality. He first examines the history of this idea, claiming that philosophy only became concerned with a "theory of knowledge" when Locke and Kant confused psychological processes with normative justification. Rorty then argues that Quine's critique of the analytic–synthetic distinction and Sellars's critique of the Myth of the Given both undermine the idea that philosophy holds a privileged position from which it can judge the progress of inquiry. The rejection of such a privileged position leads to a position which Rorty calls "epistemological behaviorism," which states that knowledge and justification are social-linguistic practices, or what Sellars would call having a place in the "logical space of reasons," rather than a matter of representing reality. Rorty also addresses recent attempts by philosophers such as Quine and Jerry Fodor to replace epistemology with psychology, and by Michael Dummett and Hilary Putnam to replace it with philosophy of language, arguing that these attempts ultimately fail in giving sense to representationalism. In Part Three, titled "Philosophy," Rorty discusses what philosophy could look like after giving up representationalism. Borrowing Kuhn's concept of incommensurability, he claims that philosophy has traditionally sought commensuration, or the grounding of all discourses on a single, ahistorical foundation, but he claims that without a privileged position outside all inquiry, this is impossible, and so different discourses are incommensurable. Rorty instead opts for hermeneutics, which is where instead of seeking commensuration of all discourses, people simply try out different, incommensurable discourses and see which one works best to achieve their goals. This means redefining objectivity as intersubjective consensus rather than as correspondence to the world. Rorty also draws a distinction between systematic and edifying philosophers. Whereas systematic philosophers engage in epistemology and aim to find the "correct" way of speaking, or the one which hooks them up to reality, edifying philosophers engage in hermeneutics and aim to deconstruct all such attempts, instead offering new projects to pursue and new tools to pursue them once inquiry has reached a dead end. |

要約 『哲学と自然の鏡』の中で、ローティは、哲学の歴史とは、精神が客観的現実について知識を持っているという主張を理解しようとする探求の歴史であり、それ によって哲学に、文化の他の側面がこの現実と接触しているかどうかを判断できる能力を与える歴史であると論じている。彼はこの考えを「表象主義」と呼び、 「自然の鏡」という隠喩を用いて言及しており、それがこの本のタイトルになっている。 序文で、ローティは、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン、マーティン・ハイデガー、ジョン・デューイが 20 世紀の 3 大哲学者であると主張している。ウィトゲンシュタインは哲学を一連の言語的混乱と診断したこと、ハイデガーはそのような混乱を歴史的に脱構築したこと、 デューイは形而上学後の文化に対する希望に満ちた予後を提示したことである。この静寂主義的で歴史主義的な伝統を引き継いで、この本は建設的というよりも 治療的な性質を持っている。しかし、ローティは、W. V. O. クワイン、ウィルフリッド・セラーズ、トーマス・クーン、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソンといった体系的な哲学者の議論を用いて、心(鏡)、知識(鏡像)、そ して哲学そのもの(鏡像の研究)に関する私たちの哲学的直感を弱体化させ、それによって「自然の鏡」という表象主義的な見方を弱体化させることを目指して いる。 第一部「我々のガラスの本質」において、ローティは心という哲学的概念を検証する。それは非物質的・非空間的な実体でありながら、何らかの形で事物に関す る知識を持つことができるという概念である。彼はまず、事物をア・プリオリに精神的か物理的かに分類できる「精神性の印」が存在するという直観を解体する ことから着手する。非空間性、意図性、現象性といった伝統的な精神的印の候補が二元論的直観を正当化できないことを示した後、ローティは心身問題を解消し たと宣言する。続いて彼は、心という概念がアリストテレスからデカルトに至るまでの歴史的偶然性に根ざしていることを示すため、その歴史的経緯を検証す る。これにより、後世の人々が心身問題を再燃させようとする試みを思いとどまらせたいと彼は考えている。そして「対蹠地人」という思考実験を通じて、精神 に関する修正不能性についての社会言語学的解釈を提示する。 第二部「ミラーリング」では、ローティが哲学的概念として、客観的現実の正確な表象の所有としての知識を検証する。まずこの思想の歴史を考察し、ロックと カントが心理的過程と規範的正当化を混同したことで初めて哲学が「知識論」に関心を向けたと主張する。次にローティは、クワインによる分析的・総合的区別 の批判と、セラーズによる「与えられたものの神話」批判が、哲学が探究の進捗を判断できる特権的立場にあるという考えをともに弱体化させると論じる。この ような特権的な立場を拒否すると、ローティが「認識論的行動主義」と呼ぶ立場に至る。それは、知識と正当性は、現実を表現することではなく、社会言語学的 実践、あるいはセラーズが「理由の論理的空間」と呼ぶものの中に位置づけられるものであると主張する。ローティはまた、クワインやジェリー・フォドルと いった哲学者による、認識論を心理学に置き換えるという最近の試みや、マイケル・ダメットやヒラリー・パットナムによる、認識論を言語哲学に置き換えると いう試みについても論じ、これらの試みは、結局のところ、表象主義に意味を与えることに失敗していると主張している。 第 3 部「哲学」では、ローティは表象主義を放棄した後の哲学がどのようなものになるかを論じている。クーンの「共約不可能性」の概念を借用し、哲学は伝統的 に、単一の非歴史的な基盤の上にすべての言説を共測化、つまり基礎付けしようとしてきたと主張する。しかし、あらゆる探究の外側に特権的な立場がなけれ ば、それは不可能であり、したがって、異なる言説は共約不可能性であると主張する。ローティは代わりに解釈学を選択する。ここではあらゆる言説の共通基準 を求める代わりに、人々は単に異なる、共約不可能な言説を試してみて、どの言説が目標達成に最も効果的かを見極める。これは客観性を世界との対応ではな く、相互主観的な合意として再定義することを意味する。ローティはまた、体系的な哲学者と啓発的な哲学者の区別を引く。体系的な哲学者は認識論に取り組 み、「正しい」語り方、つまり現実と結びつく語り方を見つけようとする。一方、啓発的な哲学者は解釈学に取り組み、そうした試みをすべて解体することを目 指す。そして、探究が行き詰まった時には、新たな追求すべきプロジェクトと、それを追求するための新たな道具を提供するのである。 |

| Reception Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature was seen to be somewhat controversial upon its publication. It had its greatest success outside analytic philosophy, despite its reliance on arguments by Quine and Sellars, and was widely influential in the humanities. In the decades since its publication, it has seen more appreciation within analytic circles. For example, John McDowell, in the preface to his book Mind and World (1994), states that the initial sketches of the ideas propounded in this work were made "during the winter of 1985–6, in an attempt to get under control my usual excited reaction to a reading—my third or fourth—of Richard Rorty's Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature." He added that it was "obvious that Rorty's work is in any case central for the way I define my stance here".[3] |

レセプション 『哲学と自然の鏡』は、出版当時、やや物議を醸した。クワインやセラーズの議論に依存しているにもかかわらず、分析哲学以外の分野で最大の成功を収め、人 文科学に広く影響を与えた。 出版から数十年が経過し、分析哲学の分野でも評価が高まっている。例えば、ジョン・マクダウェルは、著書『心と世界』(1994年)の序文で、この著作で 提唱された考えの最初の草稿は、「1985年から1986年の冬、リチャード・ローティの『哲学と自然の鏡』を3度目か4度目読んだときに、私がいつも読 書に対して抱く興奮した反応をコントロールしようとしたときに書かれた」と述べている。彼は、「いずれにせよ、ローティの著作が、私がここで自分の立場を 定義する上で中心的な役割を果たしていることは明らかである」と付け加えている。 |

| Direct

and indirect realism Neopragmatism |

直接的・間接的リアリズム 新実用主義(ネオプラグマティズム) |

| Notes and references 1. Fairfield, Paul (2024). Introducing Dewey. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 212–3. 2. Take Care of Freedom and Truth Will Take Care of Itself: Interviews with Richard Rorty. Stanford. 2006. p. 19. 3. Take Care of Freedom and Truth Will Take Care of Itself: Interviews with Richard Rorty. Stanford. 2006. p. 13. |

注釈と参考文献 1. フェアフィールド、ポール(2024)。『デューイ入門』。ブルームズベリー出版。212–3頁。 2. 『自由を守れ、そうすれば真実は自ずと守られる:リチャード・ローティとの対話』。スタンフォード大学出版局。2006年。19頁。 3. 『自由を守れ、真実は自ずと守られる:リチャード・ローティとの対話』. スタンフォード大学出版局. 2006. p. 13. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_and_the_Mirror_of_Nature |

★

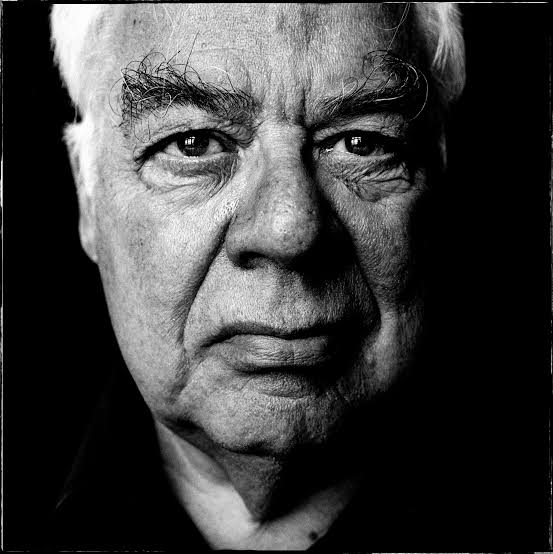

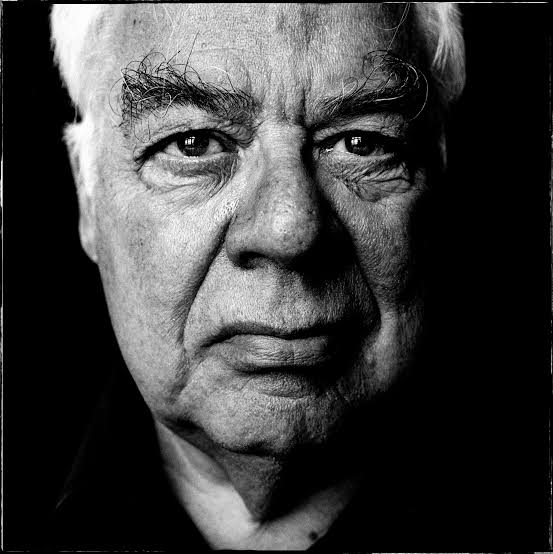

| Richard McKay Rorty | リチャード・マッキー・ローティ(1931年10月4日 - 2007年6月8日) |

| Richard McKay Rorty

(October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher. Educated

at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong

interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in

contemporary analytic philosophy. Rorty's academic career included

appointments as the Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton

University, the Kenan Professor of Humanities at the University of

Virginia, and as a professor of comparative literature at Stanford

University. Among his most influential books are Philosophy and the

Mirror of Nature (1979), Consequences of Pragmatism (1982), and

Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989). Rorty rejected the long-held idea that correct internal representations of objects in the outside world are a necessary prerequisite for knowledge. Rorty argued instead that knowledge is an internal and linguistic affair; knowledge relates only to our own language.[3][4] Rorty argues that language is made up of vocabularies that are temporary and historical,[5] and concludes that "since vocabularies are made by human beings, so are truths."[6] The acceptance of the preceding arguments leads to what Rorty calls "ironism"; a state of mind where people are completely aware that their knowledge is dependent on their time and place in history, and are therefore somewhat detached from their own beliefs.[7] However, Rorty also argues that "a belief can still regulate action, can still be thought worth dying for, among people who are quite aware that this belief is caused by nothing deeper than contingent historical circumstance."[8] |

リチャード・マッキー・ローティ(1931年10月4日 -

2007年6月8日)は、アメリカの哲学者である。シカゴ大学とイェール大学で教育を受け、哲学史と現代分析哲学の両方に強い関心と研鑽を積んだ。ロー

ティはプリンストン大学スチュアート哲学教授、バージニア大学キーン人文科学教授、スタンフォード大学比較文学教授などを歴任した。

彼の最も影響力のある著書には、『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)、『プラグマティズムの帰結』(1982年)、『偶然性・皮肉・連帯』(1989年)な

どがある。 ローティは、外界にある物体の正確な内部表現が知識の必要条件であるという長年信じられてきた考えを否定した。代わりに、知識とは内的かつ言語的なもので あり、知識はあくまでも我々の言語に関連するものであると論じた。[3][4] ローティは、言語は一時的かつ歴史的な語彙から成り立っていると論じ[5]、「語彙は人間によって作られるものであるから、真理もまた人間によって作られ るものである」と結論づけている。[6] これらの主張を受け入れることは、ローティが「アイロニズム」と呼ぶものにつながる。 アイロニズム」と呼ぶ心理状態である。人々は、自らの知識が歴史における時代や場所に依存していることを完全に認識しており、それゆえに自らの信念からや や離れた状態にある。[7] しかし、ローティはまた、「信念は依然として行動を規制し、この信念が偶発的な歴史的状況によって引き起こされたものにすぎないことを十分に認識している 人々にとって、死ぬ価値があると思われることもある」とも主張している。[8] |

| Biography Richard Rorty was born on October 4, 1931, in New York City.[9] His parents, James and Winifred Rorty, were activists, writers and social democrats. His maternal grandfather, Walter Rauschenbusch, was a central figure in the Social Gospel movement of the early 20th century.[10] His father experienced two nervous breakdowns in his later life. The second breakdown, which he had in the early 1960s, was more serious and "included claims to divine prescience."[11] Consequently, Richard Rorty fell into depression as a teenager and in 1962 began a six-year psychiatric analysis for obsessional neurosis.[11] Rorty wrote about the beauty of rural New Jersey orchids in his short autobiography, "Trotsky and the Wild Orchids," and his desire to combine aesthetic beauty and social justice.[12] His colleague Jürgen Habermas's obituary for Rorty points out that Rorty's childhood experiences led him to a vision of philosophy as the reconciliation of "the celestial beauty of orchids with Trotsky's dream of justice on earth."[13] Habermas describes Rorty as an ironist: Nothing is sacred to Rorty the ironist. Asked at the end of his life about the "holy", the strict atheist answered with words reminiscent of the young Hegel: "My sense of the holy is bound up with the hope that some day my remote descendants will live in a global civilization in which love is pretty much the only law."[13] Rorty enrolled at the University of Chicago shortly before turning 15, where he received a bachelor's and a master's degree in philosophy (studying under Richard McKeon),[14][15] continuing at Yale University for a PhD in philosophy (1952–1956).[16] He married another academic, Amélie Oksenberg (Harvard University professor), with whom he had a son, Jay Rorty, in 1954. After two years in the United States Army, he taught at Wellesley College for three years until 1961.[17] Rorty divorced his wife and then married Stanford University bioethicist Mary Varney in 1972. They had two children, Kevin and Patricia, now Max. While Richard Rorty was a "strict atheist" (Habermas),[13] Mary Varney Rorty was a practicing Mormon.[11] Rorty was a professor of philosophy at Princeton University for 21 years.[17] In 1981, he was a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, commonly known as the "Genius Award", in its first year of awarding, and in 1982 he became Kenan Professor of the Humanities at the University of Virginia, working closely with colleagues and students in multiple departments, especially in English.[18] In 1998 Rorty became professor of comparative literature (and philosophy, by courtesy), at Stanford University, where he spent the remainder of his academic career.[18] During this period he was especially popular, and once quipped that he had been assigned to the position of "transitory professor of trendy studies."[19] Rorty's doctoral dissertation, The Concept of Potentiality was a historical study of the concept, completed under the supervision of Paul Weiss, but his first book (as editor), The Linguistic Turn (1967), was firmly in the prevailing analytic mode, collecting classic essays on the linguistic turn in analytic philosophy. However, he gradually became acquainted with the American philosophical movement known as pragmatism, particularly the writings of John Dewey. The noteworthy work being done by analytic philosophers such as Willard Van Orman Quine and Wilfrid Sellars caused significant shifts in his thinking, which were reflected in his next book, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979). Pragmatists generally hold that the meaning of a proposition is determined by its use in linguistic practice. Rorty combined pragmatism about truth and other matters with a later Wittgensteinian philosophy of language which declares that meaning is a social-linguistic product, and sentences do not "link up" with the world in a correspondence relation. Rorty wrote in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989): Truth cannot be out there—cannot exist independently of the human mind—because sentences cannot so exist, or be out there. The world is out there, but descriptions of the world are not. Only descriptions of the world can be true or false. The world on its own unaided by the describing activities of humans cannot. (p. 5) Views like this led Rorty to question many of philosophy's most basic assumptions—and have also led to his being apprehended as a postmodern/deconstructionist philosopher. Indeed, from the late 1980s through the 1990s, Rorty focused on the continental philosophical tradition, examining the works of Friederich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard and Jacques Derrida. His work from this period included: Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989); Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers II (1991); and Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers III (1998). The latter two works attempt to bridge the dichotomy between analytic and continental philosophy by claiming that the two traditions complement rather than oppose each other. According to Rorty, analytic philosophy may not have lived up to its pretensions and may not have solved the puzzles it thought it had. Yet such philosophy, in the process of finding reasons for putting those pretensions and puzzles aside, helped earn itself an important place in the history of ideas. By giving up on the quest for apodicticity and finality that Edmund Husserl shared with Rudolf Carnap and Bertrand Russell, and by finding new reasons for thinking that such quest will never succeed, analytic philosophy cleared a path that leads past scientism, just as the German idealists cleared a path that led around empiricism. In the last fifteen years of his life, Rorty continued to publish his writings, including Philosophy as Cultural Politics (Philosophical Papers IV), and Achieving Our Country (1998), a political manifesto partly based on readings of Dewey and Walt Whitman in which he defended the idea of a progressive, pragmatic left against what he felt were defeatist, anti-liberal, anti-humanist positions espoused by the critical left and continental school. Rorty felt these anti-humanist positions were personified by figures like Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Foucault. Such theorists were also guilty of an "inverted Platonism" in which they attempted to craft overarching, metaphysical, "sublime" philosophies—which in fact contradicted their core claims to be ironist and contingent. According to Eduardo Mendieta "Rorty described himself as a 'postmodern bourgeois liberal', even if he also attacked the academic left, though not for being anti-truth, but for being unpatriotic. Rorty’s Zen attitude about truth could easily be confused for a form of political relativism—a Machiavellian type of politics."[20] Rorty's last works, after his move to Stanford University concerned the place of religion in contemporary life, liberal communities, comparative literature and philosophy as "cultural politics." Shortly before his death, he wrote a piece called "The Fire of Life" (published in the November 2007 issue of Poetry magazine)[21] in which he meditates on his diagnosis and the comfort of poetry. He concludes: I now wish that I had spent somewhat more of my life with verse. This is not because I fear having missed out on truths that are incapable of statement in prose. There are no such truths; there is nothing about death that Swinburne and Landor knew but Epicurus and Heidegger failed to grasp. Rather, it is because I would have lived more fully if I had been able to rattle off more old chestnuts—just as I would have if I had made more close friends. Cultures with richer vocabularies are more fully human—farther removed from the beasts—than those with poorer ones; individual men and women are more fully human when their memories are amply stocked with verses. On June 8, 2007, Rorty died in his home from pancreatic cancer.[16][18][22] |

経歴 リチャード・ローティは1931年10月4日、ニューヨーク市で生まれた。[9] 彼の両親、ジェームズとウィニフレッド・ローティは活動家であり、作家であり、社会民主党員であった。彼の母方の祖父、ウォルター・ラウシェンブッシュは 20世紀初頭の社会福音主義運動の中心人物であった。[10] 父親は晩年、2度神経衰弱を経験した。1960年代初頭に経験した2度目の発作はより深刻で、「神の予知能力を主張するもの」も含まれていた。[11] その結果、リチャード・ローティは10代の時にうつ病となり、1962年には強迫神経症の治療として6年間にわたる精神分析治療を受けた。[11] ローティは、ニュージャージー州の田舎に自生するランの美しさを、短い自伝『トロツキーと野性のラン』で書き記し、 そして、美的な美と社会的正義を結びつけたいという願いを綴っている。[12] 彼の同僚ユルゲン・ハーバーマスによるロティの追悼文では、ロティの幼少期の経験が「ランの天上の美とトロツキーの地上における正義の夢」の調和という哲 学のビジョンにつながったと指摘している。[13] ハーバーマスはロティをアイロニストとして次のように描写している。 皮肉屋のローティにとって、神聖なものなど何もない。晩年、「神聖なもの」について尋ねられた厳格な無神論者は、若い頃のヘーゲルを思わせる言葉で答え た。「私の考える神聖なものは、いつの日か私の遠い子孫たちが、愛が唯一の法であるような地球規模の文明社会で暮らすという希望と結びついている」 [13] ローティは15歳になる直前にシカゴ大学に入学し、リチャード・マキオンに師事して哲学の学士号と修士号を取得した。その後、 哲学博士号取得のため(1952年から1956年)にイエール大学に在籍した。[16] 彼は別の学者であるアメリー・オクセンバーグ(ハーバード大学教授)と結婚し、1954年に息子ジェイ・ロルティが生まれた。2年間のアメリカ陸軍勤務を 経て、1961年まで3年間ウェルズリー・カレッジで教鞭をとった。[17] ロティは妻と離婚し、1972年にスタンフォード大学の生命倫理学者メアリー・バーニーと再婚した。2人の子供、ケビンとパトリシア(現在はマックス)が 生まれた。リチャード・ローティは「厳格な無神論者」であったが(ハーバーマス)、[13] メアリー・バーニー・ローティはモルモン教徒であった。[11] ローティはプリンストン大学で21年間哲学の教授を務めた。[17] 1981年、彼は「天才賞」として一般に知られるマッカーサー・フェローシップの最初の受賞者となり、1982年にはバージニア大学の人文科学のケナン教 授となり、複数の学科の同僚や学生と緊密に協力しながら働いた。1998年、ロルティはスタンフォード大学の比較文学(および哲学)教授となり、そこで残 りの学術キャリアを過ごした。[18] この期間、彼は特に人気があり、かつて「流行の学問の臨時教授」に任命されたと冗談を言ったことがある。[19] ローティの博士論文『潜在性の概念』は、ポール・ワイス(Paul Weiss)の指導の下で完成した、潜在性の概念に関する歴史的研究であったが、彼の最初の著書(編集者として)である『言語学的転回』(1967年) は、分析哲学における言語学的転回に関する古典的な論文を集めたもので、当時の主流であった分析的な傾向を色濃く反映したものだった。しかし、彼は徐々に プラグマティズムとして知られるアメリカ哲学運動、特にジョン・デューイ(John Dewey)の著作に精通するようになった。ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインやウィルフリッド・セラーズといった分析哲学の哲学者たちの注目すべ き業績が、彼の考え方に大きな変化をもたらし、それは次の著書『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)に反映されている。 一般的にプラグマティストは、命題の意味は言語上の実践におけるその使用によって決定されると考える。 ロルティは、意味は社会言語学的な産物であり、文は世界と対応関係で「結びつく」ものではないと宣言するウィトゲンシュタインの言語哲学と、真理に関する プラグマティズムを組み合わせた。 ロルティは『偶然性・皮肉・連帯』(1989年)で次のように書いている。 文はそうして存在することはできないし、また「そこにある」こともできない。世界は「そこにある」が、世界の記述は「そこにある」わけではない。世界の記 述のみが真実たり得るか、あるいは偽りである。人間による記述活動の助けを借りずに、世界が「そこにある」ことはありえない。(p. 5) このような見解から、ローティは哲学の最も基本的な仮定の多くに疑問を投げかけた。そして、ポストモダン/脱構築主義の哲学者として捉えられるようになっ た。実際、1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、ローティは大陸哲学の伝統に焦点を当て、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、マルティン・ハイデッガー、ミ シェル・フーコー、ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール、ジャック・デリダの作品を検証した。この時期の彼の著作には、『偶然性・皮肉・連帯』(1989 年)、『ハイデガーとその他:哲学論文II』(1991年)、『真理と進歩:哲学論文III』(1998年)などがある。後者の2作品では、分析哲学と大 陸哲学の二分法を埋めようと試み、この2つの伝統は互いに相反するものではなく、むしろ補い合うものであると主張している。 ローティによれば、分析哲学は自らの主張に見合うものではなく、また、自ら考えた謎を解決できていない可能性がある。しかし、そのような哲学は、その見せ かけや謎を脇に置く理由を見つける過程において、思想史上において重要な地位を獲得することに貢献した。エドムンド・フッサールがルドルフ・カナルプや バートランド・ラッセルと共有していた、証明可能性や最終性への探求を諦め、そのような探求が決して成功しないという新たな理由を見出すことで、分析哲学 は、ドイツ観念論者が経験論を回避する道筋を切り開いたように、科学主義を回避する道筋を切り開いた。 ローティは晩年の15年間も、『哲学としての文化政治』(Philosophical Papers IV)や、デューイとウォルト・ホイットマンの研究を基に、進歩的で実用的な左派の考えを擁護した政治的マニフェスト『われらが祖国』(1998年)など の著作を発表し続けた。ロルティは、こうした反ヒューマニズムの立場を、ニーチェ、ハイデッガー、フーコーといった人物に体現されていると感じていた。こ うした理論家たちは、包括的で形而上学的、そして「崇高」な哲学を構築しようとする「逆プラトン主義」の罪にも問われるべきである。実際、皮肉屋で偶発的 であるという彼らの主張の核心部分と矛盾している。 エドゥアルド・メンディエタによると、「ローティは、たとえアカデミックな左派を攻撃していたとしても、反真実主義ではなく非愛国主義を理由としていたた め、自らを『ポストモダン的ブルジョワ自由主義者』と称していた。ロルティの真理に対する禅的な態度は、政治的相対主義、すなわちマキャベリズム的な政治 の一形態と混同されやすい」[20]。 スタンフォード大学に移ってからのローティの最後の作品は、現代生活における宗教のあり方、リベラルなコミュニティ、比較文学や哲学を「文化政治」として 扱ったものだった。 死の直前に、彼は「The Fire of Life(生命の炎)」という作品を書き、詩誌『Poetry』2007年11月号に掲載された。[21] その作品の中で、彼は自身の診断と詩の慰めについて瞑想している。彼は次のように結んでいる。 私は今、人生のもう少しの時間を詩とともに過ごしたかったと願っている。これは、散文では表現できない真実を見逃したことを恐れているからではない。その ような真実など存在しない。スウィンバーンやランドーが知っていた死に関する真実で、エピクロスやハイデッガーが理解できなかったものなどないのだ。むし ろ、古い馴染みの詩をもっと口ずさめていれば、もっと充実した人生を送れただろうと思うからだ。親しい友人をもっと多く作っていれば、そうだっただろう。 語彙が豊かな文化は、そうでない文化よりも人間味に溢れ、獣からかけ離れている。個々の男性や女性も、詩を十分に記憶しているときにより人間味に溢れる。 2007年6月8日、ロートリは膵臓癌のため自宅で死去した。[16][18][22] |

| Major works Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature Main article: Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature In Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) Rorty argues that the central problems of modern epistemology depend upon a picture of the mind as trying to faithfully represent (or "mirror") a mind-independent, external reality. When we give up this metaphor, the entire enterprise of foundationalist epistemology simply dissolves. An epistemological foundationalist believes that in order to avoid the regress inherent in claiming that all beliefs are justified by other beliefs, some beliefs must be self-justifying and form the foundations to all knowledge. Rorty however criticized both the idea that arguments can be based upon self-evident premises (within language) and the idea that arguments can be based upon noninferential sensations (outside language). The first critique draws on Quine's work on sentences thought to be analytically true – that is, sentences thought to be true solely by virtue of what they mean and independently of fact.[23] Quine argues that the problem with analytically true sentences is the attempt to convert identity-based but empty analytical truths like "no unmarried man is married" to synonymity-based analytical truths like "no bachelor is married."[24] When trying to do so, one must first prove that "unmarried man" and "bachelor" means exactly the same, and that is not possible without considering facts – that is, looking towards the domain of synthetic truths. When doing so, one will notice that the two concepts actually differ; "bachelor" sometimes mean "bachelor of arts" for instance.[25] Quine therefore argues that "a boundary between analytic and synthetic statements simply has not been drawn", and concludes that this boundary or distinction "[...] is an unempirical dogma of empiricists, a metaphysical article of faith."[26] The second critique draws on Sellars's work on the empiricist idea that there is a non-linguistic but epistemologically relevant "given" available in sensory perception. Sellars argue that only language can work as a foundation for arguments; non-linguistic sensory perceptions are incompatible with language and are therefore irrelevant. In Sellars' view, the claim that there is an epistemologically relevant "given" in sensory perception is a myth; a fact is not something that is given to us, it is something that we as language-users actively take. Only after we have learned a language is it possible for us to construe as "empirical data" the particulars and arrays of particulars we have come to be able to observe.[27] Each critique, taken alone, provides a problem for a conception of how philosophy ought to proceed but leaves enough of the tradition intact to proceed with its former aspirations. Combined, Rorty claimed, the two critiques are devastating. With no privileged realm of truth or meaning that can work as a self-evident foundation for our arguments, we have instead only truth defined as beliefs that pay their way: in other words, beliefs that are useful to us somehow. The only worthwhile description of the actual process of inquiry, Rorty claimed, was a Kuhnian account of the standard phases of the progress of disciplines, oscillating through normal and abnormal periods, between routine problem-solving and intellectual crises. After rejecting foundationalism, Rorty argues that one of the few roles left for a philosopher is to act as an intellectual gadfly, attempting to induce a revolutionary break with previous practice, a role that Rorty was happy to take on himself. Rorty suggests that each generation tries to subject all disciplines to the model that the most successful discipline of the day employs. In Rorty's view, the success of modern science has led academics in philosophy and the humanities to mistakenly imitate scientific methods. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity Main article: Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989), Rorty argues that there is no worthwhile theory of truth, aside from the non-epistemic semantic theory Donald Davidson developed (based on the work of Alfred Tarski).[28] Rorty also suggests that there are two kinds of philosophers; philosophers occupied with private or public matters. Private philosophers, who provide one with greater abilities to (re)create oneself (a view adapted from Nietzsche[29] and which Rorty also identifies with the novels of Marcel Proust and Vladimir Nabokov) should not be expected to help with public problems. For a public philosophy, one might instead turn to philosophers like Rawls or Habermas,[30] even though, according to Rorty, the latter is a "liberal who doesn't want to be an ironist".[31] While Habermas believes that his theory of communicative rationality constitutes an update of rationalism, Rorty thinks that the latter and any "universal" pretensions should be totally abandoned.[32] This book also marks his first attempt to specifically articulate a political vision consistent with his philosophy, the vision of a diverse community bound together by opposition to cruelty, and not by abstract ideas such as "justice" or "common humanity." Consistent with his anti-foundationalism, Rorty states that there is "[...] no noncircular theoretical backup for the belief that cruelty is horrible."[33] Rorty also introduces the terminology of ironism, which he uses to describe his mindset and his philosophy. Rorty describes the ironist as a person who "[...] worries that the process of socialization which turned her into a human being by giving her a language may have given her the wrong language, and so turned her into the wrong kind of human being. But she cannot give a criterion of wrongness."[34] Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth Rorty describes the project of this essay collection as trying to "offer an antirepresentationalist account of the relation between natural science and the rest of culture."[35] Amongst the essays in Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth: Philosophical Papers, Volume 1 (1990), is "The Priority of Democracy to Philosophy," in which Rorty defends Rawls against communitarian critics. Rorty argues that liberalism can "get along without philosophical presuppositions," while at the same time conceding to communitarians that "a conception of the self that makes the community constitutive of the self does comport well with liberal democracy."[36] Moreover, for Rorty Rawls could be compared to Habermas, a sort of United States' Habermas, with E. Mendieta's words: "An Enlightenment figure who thought that all we have is communicative reason and the use of public reason, two different names for the same thing—the use of reason by a public for the purpose of deciding how to live collectively and what aims should be the goal of the public good".[20] For Rorty, social institutions ought to be thought of as "experiments in cooperation rather than as attempts to embody a universal and ahistorical order."[37] Essays on Heidegger and Others In this text, Rorty focuses primarily on the continental philosophers Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida. He argues that these European "post-Nietzscheans" share much with American pragmatists, in that they critique metaphysics and reject the correspondence theory of truth.[38] Taking up and developing what he had argued in previous works,[39] Rorty claims that Derrida is most useful when viewed as a funny writer who attempted to circumvent the Western philosophical tradition, rather than the inventor of a philosophical (or literary) "method". In this vein, Rorty criticizes Derrida's followers like Paul de Man for taking deconstructive literary theory too seriously. Achieving Our Country Main article: Achieving Our Country In Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America (1998), Rorty differentiates between what he sees as the two sides of the Left, a cultural Left and a progressive Left. He criticizes the cultural Left, which is exemplified by post-structuralists such as Foucault and postmodernists such as Lyotard, for offering critiques of society, but no alternatives (or alternatives that are so vague and general as to be abdications). Although these intellectuals make insightful claims about the ills of society, Rorty suggests that they provide no alternatives and even occasionally deny the possibility of progress. On the other hand, the progressive Left, exemplified for Rorty by the pragmatist John Dewey, Whitman and James Baldwin, makes hope for a better future its priority. Without hope, Rorty argues, change is spiritually inconceivable and the cultural Left has begun to breed cynicism. Rorty sees the progressive Left as acting in the philosophical spirit of pragmatism. |

主要作品 哲学と自然の鏡 詳細は「哲学と自然の鏡」を参照 『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)において、ローティは、近代の認識論における中心的な問題は、心から独立した外部の現実を忠実に表現しようとする(すな わち「映し出す」)心の姿に依存していると論じている。この比喩を放棄すると、基礎づけ主義の認識論の事業全体が単純に消滅してしまう。 認識論的基礎主義者は、すべての信念が他の信念によって正当化されるという主張に内在する後退を避けるためには、いくつかの信念が自己正当化され、すべて の知識の基礎を形成しなければならないと考える。しかし、ローティは、議論が自明の前提(言語内)に基づいているという考え方と、議論が非推論的な感覚 (言語外)に基づいているという考え方の両方を批判した。 最初の批判は、クワインの分析的に真であると考えられる文に関する研究に基づいている。つまり、事実とは無関係に、意味する内容のみによって真であると考 えられる文である。[23] クワインは、分析的に真である文の問題は、「未婚の男性は結婚していない」のような同一性に基づくが中身のない分析的真理を、「独身男性は結婚していな い」のような同義性に基づく分析的真理に変換しようとすることであると主張している。「という同義語に基づく分析的真理に変換しようとすることであると主 張している。[24] これを試みる場合、まず「未婚の男性」と「独身男性」がまったく同じ意味であることを証明しなければならないが、これは事実を考慮せずに、つまり総合的真 理の領域に目を向けずに実行することは不可能である。そうすると、2つの概念は実際には異なることに気づく。例えば、「独身者」は「文学士」を意味するこ ともある。[25] したがってクワインは、「分析的命題と総合的命題の境界は、単純に引かれていない」と主張し、この境界または区別は「...経験論者の非経験的な教義であ り、形而上学的な信仰の条項である」と結論づけている。[26] 第二の批判は、感覚知覚において言語ではないが認識論的に関連する「与えられたもの」が存在するという経験論的な考え方に関するセラーズの研究に基づいて いる。セラーズは、論証の基礎として機能できるのは言語のみであり、言語ではない感覚知覚は言語と両立しないため、関連性がないと主張している。セラーズ の見解では、感覚知覚に認識論的に関連する「与件」があるという主張は神話であり、事実とは私たちに与えられるものではなく、言語を使用する私たちが能動 的に獲得するものである。言語を習得した後で初めて、私たちは観察可能となった特定の事柄や特定の事柄の集合を「経験データ」として解釈することが可能に なるのである。 各々の批判は、それだけを取り出せば、哲学がどのように進むべきかという考え方に対して問題を提起するが、それまでの理想を継続させるのに十分な伝統はそ のまま残される。 ローティは、この2つの批判を組み合わせると、それは破壊的であると主張した。 議論の自明な基礎として機能するような、真実や意味の特権的な領域が存在しないため、代わりに、信念がその道を切り開くように定義された真実だけが存在す る。つまり、何らかの形で私たちにとって有益な信念である。実際の探究のプロセスを唯一価値あるものとして説明できるのは、クーンの学問の進歩の標準的な 段階に関する説明であり、それは通常の期間と異常な期間の間を揺れ動き、日常的な問題解決と知的危機の間を行き来するものである、とローティは主張した。 基礎主義を否定したロルティは、哲学者に残された数少ない役割のひとつは、知的あぶらむしとして、これまでの慣行を根本的に変えることを試みることである と主張し、自らその役割を引き受けることを喜んだ。ロルティは、各世代が、その時代で最も成功している学問分野が採用しているモデルを、あらゆる学問分野 に適用しようとする、と示唆している。ロートリィの見解では、近代科学の成功により、哲学や人文科学の学者たちは科学的手法を誤って模倣するようになっ た。 偶然性・皮肉・連帯 詳細は「偶然性・皮肉・連帯」を参照 『偶有性・皮肉・連帯』(1989年)において、ローティは、ドナルド・デヴィッドソンが(アルフレッド・タルスキの研究を基に)展開した非認識論的意味 論を除いて、真実の価値ある理論は存在しないと主張している。[28] また、ロルティは哲学者には2つの種類があり、私的な問題や公共の問題に関わる哲学者がいると示唆している。私的な哲学者は、自己を(再)創造する能力を 人々に与える(ニーチェの見解を引用したもの[29]であり、ローティはこれをマルセル・プルーストやウラジーミル・ナボコフの小説と関連付けている)。 しかし、彼らに公共の問題の解決を期待すべきではない。公共哲学については、ロールズやハーバーマスといった哲学者に頼るべきかもしれない。[30] ただし、ハーバーマスは、自身のコミュニケーション的理性の理論が合理主義のアップデートであると考えているが、ロールズは、合理主義や「普遍的」な主張 はすべて完全に放棄されるべきだと考えている。[32] 本書はまた、彼の哲学と一致する政治的ビジョンを明確に表現しようとした彼の最初の試みでもあり、そのビジョンは、残酷さへの反対によって結びついた多様 なコミュニティのビジョンであり、「正義」や「共通の人間性」といった抽象的な概念によって結びついたものではない。反基礎主義に一致するロティは、「残 酷さは恐ろしいという信念を裏付ける、循環しない理論的根拠は存在しない」と述べている。 また、ロルティはアイロニーの用語も紹介しており、自身の考え方や哲学を表現する際に用いている。ロルティはアイロニストを「...社会化の過程で言語を 与えられ人間となったが、間違った言語を与えられ、間違った人間になってしまったのではないかと心配する人」と表現している。しかし、彼女は間違っている ことの基準を示すことはできない。」[34] 客観性、相対主義、そして真理 ローティは、このエッセイ集のプロジェクトを「自然科学とその他の文化の関係について反表象主義的な説明を提示する」試みであると説明している。[35] 『客観性、相対主義、そして真理:哲学論文集』第1巻(1990年)に収録された論文のひとつ「哲学に対する民主主義の優先」では、ロルティは共同体主義 の批判者に対してジョン・ロールズを擁護している。ローティはリベラリズムは「哲学的仮定なしでもやっていける」と主張する一方で、コミュニタリアンに対 しては「共同体が自己の構成要素となるような自己の概念は、リベラルな民主主義と調和する」と認める。[36] さらにローティにとって、ロールズは米国のハーバーマスともいえる存在であり、E. メンディエタの言葉によれば、 「我々にあるのはコミュニケーション能力と公共理性の行使のみであり、この2つは同じものを指す別名である。すなわち、公共による理性の行使であり、集団 としてどのように生き、公共の利益の目標としてどのような目的を掲げるべきかを決定することを目的とする」と述べている。[20] ロルティにとって、社会制度は「普遍的かつ歴史を超越した秩序を体現する試みというよりも、むしろ協力の試み」として考えられるべきである。[37] ハイデガーとその他に関するエッセイ この論文で、ローティは主に大陸哲学のマルティン・ハイデガーとジャック・デリダに焦点を当てている。彼は、これらのヨーロッパの「ポスト・ニーチェ派」 は、形而上学を批判し、真理の対応説を否定するという点で、アメリカのプラグマティストと多くの共通点がある、と主張している。[38] これまでの著作で主張してきたことを引き継ぎ、さらに発展させた上で、[39] ロルティは、デリダは、哲学(あるいは文学)の「方法」を発明した人物というよりも、西洋の哲学の伝統を回避しようとした滑稽な作家として捉えるのが最も 有益であると主張している。この観点から、ロルティは、脱構築的な文学理論を真剣に受け止めすぎているポール・ド・マンなどのデリダの追随者たちを批判し ている。 『われらの国を達成する 詳細は「われらの国を達成する」を参照 『われらの国を達成する:20世紀アメリカにおける左派思想』(1998年)において、ローティは左派の2つの側面、すなわち文化左派と進歩左派を区別し ている。彼は、フーコーなどのポスト構造主義者やリオタールなどのポストモダニストに代表される文化左派を批判している。彼らは社会に対する批判は行う が、代案(あるいは、放棄に等しいほど曖昧で一般的な代案)は提示しない。これらの知識人は社会の悪弊について洞察力に富んだ主張を行うが、ロティは彼ら が代案を提供しておらず、時には進歩の可能性さえ否定していると指摘している。一方、進歩的な左派は、プラグマティストのジョン・デューイ、ホイットマ ン、ジェイムズ・ボールドウィンを例に挙げたロートリィによれば、より良い未来への希望を最優先事項としている。ロートリィは、希望がなければ変化は精神 的に考えられないとし、文化左派はシニシズムを助長し始めていると主張する。ロートリィは、進歩的な左派はプラグマティズムの哲学的精神に基づいて行動し ていると見ている。 |

| On human rights Rorty's notion of human rights is grounded on the notion of sentimentality. He contended that throughout history humans have devised various means of construing certain groups of individuals as inhuman or subhuman. Thinking in rationalist (foundationalist) terms will not solve this problem, he claimed. Rorty advocated the creation of a culture of global human rights in order to stop violations from happening through a sentimental education. He argued that we should create a sense of empathy or teach empathy to others so as to understand others' suffering.[40] On hope Rorty advocates for what philosopher Nick Gall characterizes as a "boundless hope" or type of "melancholic meliorism." According to this view, Rorty replaces foundationalist hopes for certainty with those of perpetual growth and constant change, which he believes enables us to send conversation and hopes in new directions we currently can't imagine.[41] Rorty articulates this boundless hope in his 1982 book Consequences of Pragmatism,[42] where he applies his framework of wholesale hope versus retail hope. Herein he says, "Let me sum up by offering a third and final characterization of pragmatism: It is the doctrine that there are no constraints on inquiry save conversational ones-no wholesale constraints derived from the nature of the objects, or of the mind, or of language, but only those retail constraints provided by the remarks of our fellow inquirers." Reception and criticism Rorty is among the most widely discussed and controversial contemporary philosophers,[17] and his works have provoked thoughtful responses from many other well-respected figures in the field. In Robert Brandom's anthology Rorty and His Critics, for example, Rorty's philosophy is discussed by Donald Davidson, Jürgen Habermas, Hilary Putnam, John McDowell, Jacques Bouveresse, and Daniel Dennett, among others.[43] In 2007, Roger Scruton wrote, "Rorty was paramount among those thinkers who advance their own opinion as immune to criticism, by pretending that it is not truth but consensus that counts, while defining the consensus in terms of people like themselves."[44] Ralph Marvin Tumaob concludes that Rorty was influenced by Jean-François Lyotard's metanarratives, and added that "postmodernism was influenced further by the works of Rorty".[45] McDowell is strongly influenced by Rorty, particularly Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979).[46] In continental philosophy, authors such as Jürgen Habermas, Gianni Vattimo, Jacques Derrida, Albrecht Wellmer, Hans Joas, Chantal Mouffe, Simon Critchley, Esa Saarinen, and Mike Sandbothe are influenced in different ways by Rorty's thinking. American novelist David Foster Wallace titled a short story in his collection Oblivion: Stories "Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature," and critics have identified Rorty's influence in some of Wallace's writings on irony.[47] Susan Haack has been a fierce critic of Rorty's neopragmatism. Haack criticises Rorty's claim to be a pragmatist at all and wrote a short play called We Pragmatists, where Rorty and Charles Sanders Peirce have a fictional conversation using only accurate quotes from their own writing. For Haack, the only link between Rorty's neopragmatism and Peirce's pragmatism is the name. Haack believes Rorty's neopragmatism is anti-philosophical and anti-intellectual, and exposes people further to rhetorical manipulation.[17][48][49] Although Rorty was an avowed liberal, his political and moral philosophies have been attacked by commentators from the Left, some of whom believe them to be insufficient frameworks for social justice.[50] Rorty was also criticized for his rejection of the idea that science can depict the world.[51] One criticism, especially of Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, is that Rorty's philosophical hero, the ironist, is an elitist figure.[52] Rorty argues that most people would be "commonsensically nominalist and historicist" but not ironist. They would combine an ongoing attention to the particular as opposed to the transcendent (nominalism) with an awareness of their place in a continuum of contingent lived experience alongside other individuals (historicist), without necessarily having continual doubts about the resulting worldview as the ironist does. An ironist is someone who "has radical and continuing doubts about their final vocabulary", that is "a set of words which they [humans] employ to justify their actions, their beliefs, and their lives"; "realizes that argument phrased in their vocabulary can neither underwrite nor dissolve these doubts"; and "does not think their vocabulary is closer to reality than others".[53] On the other hand, the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo and the Spanish philosopher Santiago Zabala in their 2011 book Hermeneutic Communism: from Heidegger to Marx affirm that together with Richard Rorty we also consider it a flaw that "the main thing contemporary academic Marxists inherit from Marx and Engels is the conviction that the quest for the cooperative commonwealth should be scientific rather than utopian, knowing rather than romantic." As we will show hermeneutics contains all the utopian and romantic features that Rorty refers to because, contrary to the knowledge of science, it does not claim modern universality but rather postmodern particularism.[54] Rorty often draws on a broad range of other philosophers to support his views, and his interpretation of their work has been contested.[17] Since he is working from a tradition of reinterpretation, he is not interested in "accurately" portraying other thinkers, but rather in using it in the same way a literary critic might use a novel. His essay "The Historiography of Philosophy: Four Genres" is a thorough description of how he treats the greats in the history of philosophy. In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Rorty attempts to disarm those who criticize his writings by arguing that their philosophical criticisms are made using axioms that are explicitly rejected within Rorty's own philosophy.[55] For instance, he defines allegations of irrationality as affirmations of vernacular "otherness", and so—Rorty argues—accusations of irrationality can be expected during any argument and must simply be brushed aside.[56] |

人権について ローティの人権に関する考え方は感傷的な考えに基づいている。彼は、歴史を通じて人間は特定の個人グループを非人間的または亜人間的とみなすさまざまな手 段を考案してきたと主張した。合理主義(基礎主義)の観点から考えてもこの問題は解決しないと彼は主張した。ローティは、感傷的な教育を通じて侵害を未然 に防ぐために、グローバルな人権文化の創造を提唱した。彼は、他者の苦しみを理解するために、共感の感覚を創り出すか、他者に共感を教えるべきだと主張し た。 希望について ローティは、哲学者ニック・ガルが「限りない希望」あるいは「メランコリック改良主義」と表現するものを提唱している。この見解によると、ロルティは確実 性への基礎主義的な希望を永遠の成長と絶え間ない変化への希望に置き換える。これにより、現在では想像もつかない新たな方向へと会話と希望を向けることが できると彼は考えている。 ローティは、1982年の著書『プラグマティズムの帰結』で、この無限の希望を明確に表現しており、そこでは「全体的な希望」と「部分的な希望」という自 身の枠組みが適用されている。 ここで彼は次のように述べている。「プラグマティズムの3つ目で最後の特徴を提示して、まとめよう。それは、会話上の制約を除いて、探究に対する制約はな いという教義である。つまり、対象の性質、心、言語から派生する全体的な制約はなく、探究仲間による発言によって提供される小規模な制約のみである」と述 べている。 評価と批判 ローティは最も広く議論され、物議を醸す現代の哲学者の一人であり、[17] 彼の作品は、その分野で尊敬を集める多くの著名人から思慮深い反応を引き起こしている。例えば、ロバート・ブランドン(Robert Brandom)のアンソロジー『Rorty and His Critics』では、ロバート・ローティの哲学について、ドナルド・デヴィッドソン(Donald Davidson)、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス(Jürgen Habermas)、ヒラリー・パトナム(Hilary Putnam)、ジョン・マクダウェル(John McDowell)、ジャック・ブーヴェレス(Jacques Bouveresse)、ダニエル・デネット(Daniel Dennett)など、多くの著名な人物が論じている。[43] 2007年には、ロジャー・スクルートン(Roger Scruton)が「ローティは、 真実ではなくコンセンサスこそが重要であるかのように装いながら、自分たちのような人々によるコンセンサスを定義することで、批判に晒されることのない自 らの意見を主張する思想家たちの中で、ローティは最も重要な存在であった」と述べている。[44]ラルフ・マーヴィン・トゥマオブは、ロートリはジャン= フランソワ・リオタールのメタ物語の影響を受けており、「ポストモダニズムはロートリの著作からさらに影響を受けた」と結論づけている。[45] マクダウェルはローティ、特に『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)から強い影響を受けている。[46] 大陸哲学では、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス、ジャンニ・ヴァッティモ、ジャック・デリダ、アルブレヒト・ウェルマー、ハンス・ヨアス、シャンタル・ムッフ、サ イモン・クリッチリー、エサ・サーリネン、マイク・サンドボースといった著者が、ロティの考え方にさまざまな形で影響を受けている。アメリカの小説家デ ヴィッド・フォスター・ウォレスは、自身の短編集『忘却:物語』に収録された短編のひとつに『哲学と自然の鏡』というタイトルを付けた。批評家たちは、 ウォレスの皮肉に関するいくつかの文章にロティの影響が見られると指摘している。 スーザン・ハックはローティのネオプラグマティズムを激しく批判している。ハックはロティがプラグマティストであるという主張を一切批判しており、戯曲 『われらプラグマティスト』を執筆している。この戯曲では、ロティとチャールズ・サンダース・ピアースが、彼らの著作からの正確な引用のみを使用して架空 の会話をしている。ハックにとって、ロートの新プラグマティズムとピアスのプラグマティズムの唯一の接点は名称だけである。ハックは、ロートの新プラグマ ティズムは反哲学、反知性であり、人々をさらに修辞学的な操作に晒すものだと考えている。[17][48][49] ローティはリベラリズムを公言していたが、彼の政治的・道徳的哲学は左派の論者たちから攻撃されており、その中には、それらの哲学が社会正義の枠組みとし ては不十分であると考える者もいる。[50] ロルティはまた、科学が世界を描写できるという考えを拒絶したことについても批判されている。[51] 特に『偶然性・皮肉・連帯』に対する批判として、ロートの哲学的ヒーローである皮肉屋はエリート主義的な人物であるというものがある。[52] ロートは、ほとんどの人は「常識的には唯名論者であり歴史主義者」であるが、皮肉屋ではないと主張している。彼らは、超越的なもの(汎名論)に対する特定 のものへの継続的な関心を、他の個人とともに偶発的な生活体験の連続体における自分の位置を認識すること(歴史主義)と組み合わせるが、アイロニストのよ うに、その結果生じる世界観について常に疑いを抱いているわけではない。アイロニストとは、「最終的な語彙について、根本的かつ継続的な疑いを抱いてい る」人であり、それは「人間が自らの行動、信念、人生を正当化するために用いる言葉の集合」である。また、「その語彙で表現された論拠は、これらの疑念を 裏付けることも解消することもできない」ことを理解しており、 そして、「自分たちの語彙が他の人々よりも現実により近いとは思わない」人である。[53] 一方、イタリアの哲学者ジャンニ・ヴァッティモとスペインの哲学者サンティアゴ・サバラは、2011年の著書『解釈学的共産主義:ハイデガーからマルクス へ』の中で、 リチャード・ローティとともに、我々も「現代の学術的なマルクス主義者がマルクスとエンゲルスから受け継いだ主なものは、協力的な共同体を求める探求は、 ユートピア的ではなく科学的であるべきであり、ロマン主義的ではなく知的なものであるべきだという信念である」ことを欠点であると考えている。我々が示す ように、解釈学はローティが言及するようなユートピア的およびロマン主義的な特徴をすべて含んでいる。なぜなら、科学の知識とは逆に、それは近代的な普遍 性を主張するのではなく、むしろポストモダンの特殊主義を主張しているからである。 ローティは自身の意見を裏付けるために、幅広い他の哲学者の考えを引用することが多いが、その解釈については異論もある。[17] 彼は再解釈の伝統に基づいて研究しているため、他の思想家を「正確に」描写することには関心がなく、むしろ文学評論家が小説を扱うのと同じ方法でそれを利 用することに関心がある。彼のエッセイ「哲学史の叙述:4つのジャンル」は、彼が哲学史上の偉人たちをどのように扱っているかを詳細に記述したものであ る。『偶有性・皮肉・連帯』において、ローティは、自身の哲学において明確に否定されている公理を用いて哲学的な批判がなされていると主張することで、自 身の著作を批判する人々を論駁しようとしている。[55] 例えば、彼は非合理性の主張を、日常的な「他者性」の肯定として定義している。したがって、ロルティは、非合理性の告発はあらゆる議論において予想される ものであり、単に無視されるべきであると主張している。[56] |

| Select bibliography As author Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979. Consequences of Pragmatism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0816610631 Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521353816 Philosophical Papers vols. I–IV: Objectivity, Relativism and Truth: Philosophical Papers I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521353694 Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Truth and Progress: Philosophical Papers III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Philosophy as Cultural Politics: Philosophical Papers IV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Mind, Language, and Metaphilosophy: Early Philosophical Papers Eds. S. Leach and J. Tartaglia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1107612297. Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0674003118 Philosophy and Social Hope. New York: Penguin, 2000. Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies: A Conversation with Richard Rorty. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2002. The Future of Religion with Gianni Vattimo Ed. Santiago Zabala. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231134941 An Ethics for Today: Finding Common Ground Between Philosophy and Religion. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231150569 What's the Use of Truth? with Pascal Engel, transl. by William McCuaig, New York: Columbia University Press, 2007 ISBN 9780231140140 On Philosophy and Philosophers: Unpublished papers 1960-2000, Ed. by W. P. Małecki and Chris Vopa, CUPress 2020 ISBN 9781108488457 Pragmatism as Anti-Authoritarianism, Ed. E. Mendieta, foreword by Robert B. Brandom, Harvard UP 2021, ISBN 9780674248915 As editor The Linguistic Turn, Essays in Philosophical Method, (1967), edited by Richard M. Rorty, University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0226725697 (an introduction and two retrospective essays) Philosophy in History. edited by Richard M. Rorty, J. B. Schneewind, and Quentin Skinner, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985 (an essay by Richard M. Rorty, "Historiography of Philosophy", pp. 29–76) |

参考文献 著者として 『哲学と自然の鏡』プリンストン大学出版、1979年 『プラグマティズムの帰結』ミネアポリス大学出版、1982年 ISBN 978-0816610631 偶然性・皮肉・連帯。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1989年。ISBN 978-0521353816 哲学的論文集 第1巻~第4巻: 客観性・相対主義・真理:哲学的論文集 第1巻。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1991年。ISBN 978-0521353694 『ハイデガーとその他に関するエッセイ:哲学的論文集 II』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1991年 『真理と進歩:哲学的論文集 III』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1998年 『文化政治としての哲学:哲学的論文集 IV』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2007年 『心と言語、そしてメタ哲学:初期の哲学論文』編者:S. Leach、J. Tartaglia。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2014年。ISBN 978-1107612297。 『われらが祖国の実現:20世紀アメリカにおける左派思想』ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ:ハーバード大学出版局、1998年。ISBN 978-0674003118 哲学と社会への希望。ニューヨーク:ペンギン、2000年。 ボスや寡頭制に反対する:リチャード・ローティとの対話。シカゴ:プリックリー・パラダイム・プレス、2002年。 ジャンニ・ヴァッティモとの宗教の未来。サンティアゴ・サバラ編。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版、2005年。ISBN 978-0231134941 現代のための倫理:哲学と宗教の共通項を見出す。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版、2005年。ISBN 978-0231150569 真実の価値とは?パスカル・エンゲルとの共著、ウィリアム・マックエッグ訳、ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版、2007年。ISBN 9780231140140 『哲学と哲学者について:未発表論文 1960-2000』W. P. Małecki、Chris Vopa 編、CUPress 2020 ISBN 9781108488457 反権威主義としてのプラグマティズム、E. メンドエタ編、ロバート・B・ブランドンによる序文、ハーバード大学出版局、2021年、ISBN 9780674248915 編集者として 『言語学的転回:哲学的メソッドの試み』(1967年)リチャード・ローティ編、シカゴ大学出版、1992年、ISBN 978-0226725697(序文と2つの回顧的エッセイ) 『歴史の中の哲学』リチャード・ローティ、J. B. シュニーウィンド、クエンティン・スナイダー編、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1985年(リチャード・ローティ著「哲学史」29~76ページ) |

| Instrumentalism List of American philosophers List of liberal theorists List of thinkers influenced by deconstruction |

道具主義 アメリカの哲学者の一覧 リベラリズム理論家の一覧 脱構築に影響を受けた思想家の一覧 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Rorty |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

文献

ローティ、リチャード『哲学と自然の鏡』野家啓一監訳 、産業図書, 1993年(Richard Rorty, 1979. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton University Press.)

グレイディのプライマリー・メタファー論(レイコフ+ジョンソン『肉中の哲学』計見一雄訳、

Pp.67-71、哲学書房、2004年[Lakoff,George and Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in

the flesh : the embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. New

York: Basic Books.]による)

1. 親愛は暖かさ

2. 重要は大

3. 幸福であることは上にあること

4. 親密は接近

5. 悪いは臭い

6. 困難性は重荷

7. 沢山は上方

8. カテゴリーは容器

9. 類似性は接近

10. 線形尺度は経路(訳語は変えました)

11. 組織することは物理的な構造

12. 助けは支え

13. 時間は運動

14. 状態は位置

15. 変化は運動

16. 行動は自己推進的運動

17. 目標は目的地

18. 目標は欲せられた対象

19. 原因は物理的力

20. 関係性は囲まれていること

21. 制御は上方

22. 見ることは知ること

23. 理解は把握

24. 見ることとは触れること

身体経験と、メタファーとの関係としては、他に……

* 記憶の問題

* ジョージ・レイコフ

* マーク・ジョンソン

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099