ニコマコス倫理学(第6巻)翻訳:W. D. Ross

Ēthika Nikomacheia,

vol.6 translated by W.D. Ross

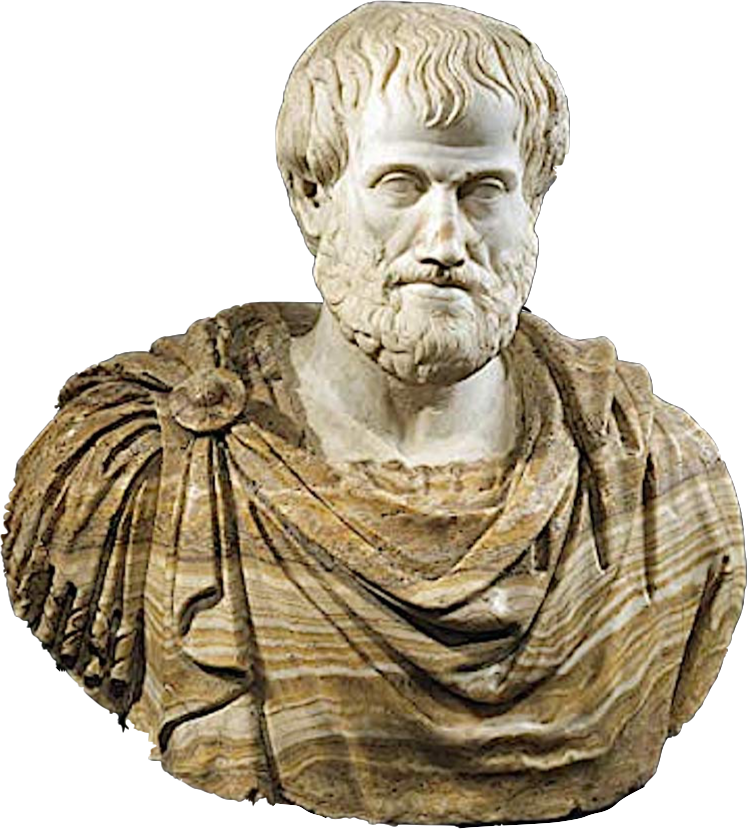

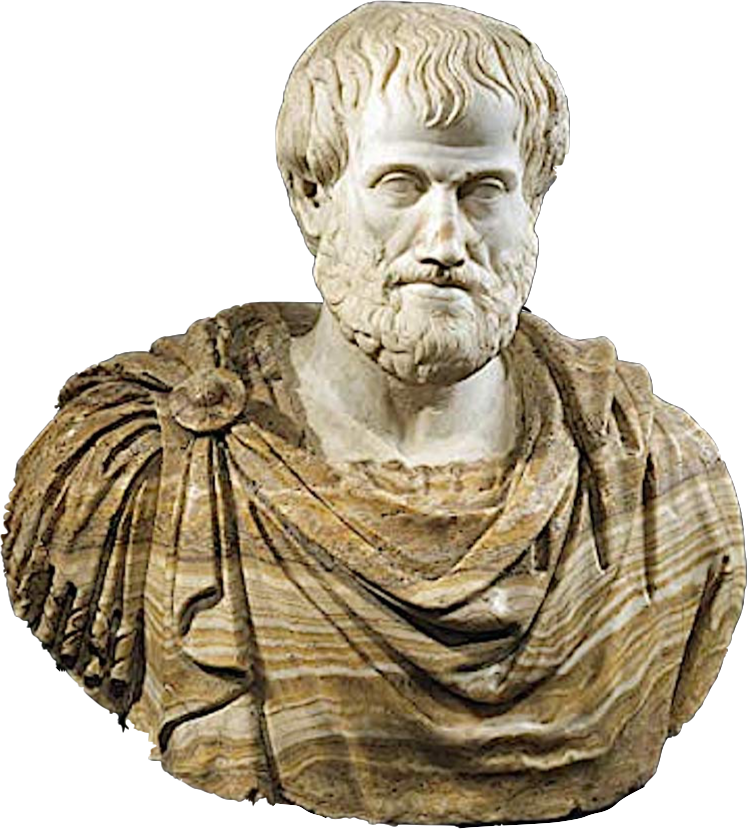

★『ニコマコ ス倫理学』はアリストテレスの倫理学に関 する著作群を、息子のニコマコス(Nicomachus) らが編纂しまとめた書物といわれる。

☆ニコマコス倫理学(第6巻)翻訳:W. D. Ross

| 1章 |

|

| Since

we have previously said that one ought to choose that which is

intermediate, not the excess nor the defect, and that the intermediate

is determined by the dictates of the right rule, let us discuss the

nature of these dictates. In all the states of character we have

mentioned, as in all other matters, there is a mark to which the man

who has the rule looks, and heightens or relaxes his activity

accordingly, and there is a standard which determines the mean states

which we say are intermediate between excess and defect, being in

accordance with the right rule. But such a statement, though true, is

by no means clear; for not only here but in all other pursuits which

are objects of knowledge it is indeed true to say that we must not

exert ourselves nor relax our efforts too much nor too little, but to

an intermediate extent and as the right rule dictates; but if a man had

only this knowledge he would be none the wiser e.g. we should not know

what sort of medicines to apply to our body if some one were to say

'all those which the medical art prescribes, and which agree with the

practice of one who possesses the art'. Hence it is necessary with

regard to the states of the soul also not only that this true statement

should be made, but also that it should be determined what is the right

rule and what is the standard that fixes it. |

以

前、人は過不足なく中庸を選ぶべきであり、その中庸は正しい規範によって定められると述べた。では、この規範の本質について論じよう。我々が述べたあらゆ

る性格状態において、他のあらゆる事柄と同様に、規範を持つ者はある基準を目印とし、それに応じて自らの活動を強めたり緩めたりする。そして、過剰と欠乏

の中間にあり、正しい規範に合致する中庸の状態を決定する基準が存在するのだ。しかし、この主張は真実ではあるが、決して明快ではない。なぜなら、ここに

限らず、知識の対象となるあらゆる追求において、努力を過度に傾けたり怠ったりせず、中庸の度合いで正しい規範が示す通りに振る舞わねばならないというの

は確かに真実だが、

しかし、もし人がこの知識だけを持っていたとしても、何の知恵にもならない。例えば、もし誰かが「医学が処方するすべての薬、そしてその技術を所有する者

の実践に合致する薬」と言うだけでは、我々は自分の体にどんな薬を適用すべきかを知ることができないのだ。したがって、魂の状態に関しても、この真実の主

張がなされるだけでなく、正しい規範とは何か、それを定める基準とは何かを明らかにすることが必要である。 |

| We

divided the virtues of the soul and a said that some are virtues of

character and others of intellect. Now we have discussed in detail the

moral virtues; with regard to the others let us express our view as

follows, beginning with some remarks about the soul. We said before

that there are two parts of the soul-that which grasps a rule or

rational principle, and the irrational; let us now draw a similar

distinction within the part which grasps a rational principle. And let

it be assumed that there are two parts which grasp a rational

principle-one by which we contemplate the kind of things whose

originative causes are invariable, and one by which we contemplate

variable things; for where objects differ in kind the part of the soul

answering to each of the two is different in kind, since it is in

virtue of a certain likeness and kinship with their objects that they

have the knowledge they have. Let one of these parts be called the

scientific and the other the calculative; for to deliberate and to

calculate are the same thing, but no one deliberates about the

invariable. Therefore the calculative is one part of the faculty which

grasps a rational principle. We must, then, learn what is the best

state of each of these two parts; for this is the virtue of each. |

我

々は魂の徳を二分し、あるものは性格の徳であり、あるものは知性の徳であると述べた。さて道徳的徳については詳細に論じたが、他の徳については次のように

見解を述べよう。まず魂についての考察から始めよう。以前、魂には二つの部分があると述べた――規則や理性的原理を把握する部分と、非理性的部分である。

今度は理性的原理を把握する部分の中で、同様の区別を設けよう。理性原理を把握する部分には二つあると仮定しよう。一つは不変的な起源原因を持つ事物の種

類を考察する部分、もう一つは変動する事物を考察する部分である。なぜなら、対象が種類において異なる場合、それぞれの部分に対応する魂の部分も種類が異

なるからだ。それらは対象とのある種の類似性や親和性によって、その知識を得ているのである。この二つの部分の片方を科学的と呼び、もう片方を計算的と呼

ぼう。なぜなら、熟議することと計算することは同じことだが、不変のものについて熟議する者はいないからだ。したがって、計算的というものは、理性的な原

理を把握する能力の一部である。では、この二つの部分それぞれにとって最善の状態が何かを学ばねばならない。それがそれぞれの徳だからである。 |

| 2章 |

|

| The

virtue of a thing is relative to its proper work. Now there are three

things in the soul which control action and truth-sensation, reason,

desire. Of these sensation originates no action; this is plain from the fact that the lower animals have sensation but no share in action. What affirmation and negation are in thinking, pursuit and avoidance are in desire; so that since moral virtue is a state of character concerned with choice, and choice is deliberate desire, therefore both the reasoning must be true and the desire right, if the choice is to be good, and the latter must pursue just what the former asserts. Now this kind of intellect and of truth is practical; of the intellect which is contemplative, not practical nor productive, the good and the bad state are truth and falsity respectively (for this is the work of everything intellectual); while of the part which is practical and intellectual the good state is truth in agreement with right desire. The origin of action-its efficient, not its final cause-is choice, and that of choice is desire and reasoning with a view to an end. This is why choice cannot exist either without reason and intellect or without a moral state; for good action and its opposite cannot exist without a combination of intellect and character. Intellect itself, however, moves nothing, but only the intellect which aims at an end and is practical; for this rules the productive intellect, as well, since every one who makes makes for an end, and that which is made is not an end in the unqualified sense (but only an end in a particular relation, and the end of a particular operation)-only that which is done is that; for good action is an end, and desire aims at this. Hence choice is either desiderative reason or ratiocinative desire, and such an origin of action is a man. (It is to be noted that nothing that is past is an object of choice, e.g. no one chooses to have sacked Troy; for no one deliberates about the past, but about what is future and capable of being otherwise, while what is past is not capable of not having taken place; hence Agathon is right in saying. For this alone is lacking even to God, To make undone things thathave once been done.) The work of both the intellectual parts, then, is truth. Therefore the states that are most strictly those in respect of which each of these parts will reach truth are the virtues of the two parts. |

物の徳は、その本来の働きに対して相対的なものである。さて、魂の中には三つのものがあり、それらが行動と真実を支配する。感覚、理性、欲望である。 このうち感覚からは何の行動も生じない。これは、下等動物が感覚を持ちながらも行動には関与しないという事実から明らかである。 思考における肯定と否定が、欲望においては追求と回避にあたる。したがって、道徳的徳性が選択に関わる性格状態であり、選択が熟議された欲望である以上、 選択が善であるためには、推論が真実であり、欲望が正しいものでなければならない。そして後者は、前者が主張するものをまさに追求しなければならない。さ て、この種の知性と真理は実践的である。観照的で実践的でも生産的でもない知性においては、善悪の状態はそれぞれ真偽である(これはあらゆる知的なものの 働きだからだ)。一方、実践的で知的な部分においては、善の状態とは正しい欲望と一致する真理である。 行為の起源―その効率的原因であって最終原因ではない―は選択であり、選択の起源は目的を視野に入れた欲望と推論である。ゆえに選択は、理性と知性なくし て、あるいは道徳的状態なくして存在しえない。善き行為とその反対は、知性と性格の結合なくして存在しえないからである。しかし知性そのものは何も動かさ ない。目的を志向する実践的知性だけが動かすのである。なぜなら、この知性は生産的知性も支配するからだ。作る者は皆目的のために作り、作られたものは無 条件の意味での目的ではない(特定の関係における目的、特定の操作の目的である)。成し遂げられたものだけが目的である。善い行為は目的であり、欲望はこ の目的を志向する。ゆえに選択とは、願望的理性あるいは推論的欲望であり、このような行為の起源こそが人間である。(なお、過去事象は選択の対象とならな い。例えばトロイア陥落を選択する者はいない。過去について熟議する者はおらず、未来かつ変更可能な事柄についてのみ熟議するからである。過去は起こらな かった状態にはなり得ない。故にアガトンが言う通りである。神でさえも、一度成し遂げたことを無に帰することはできないのだから。) したがって、知的な二つの部分の働きは真実である。ゆえに、これらの各部分が真実へと至る状態こそが、二つの部分の徳である。 |

| 3章 |

|

| Let

us begin, then, from the beginning, and discuss these states once more.

Let it be assumed that the states by virtue of which the soul possesses

truth by way of affirmation or denial are five in number, i.e. art,

scientific knowledge, practical wisdom, philosophic wisdom, intuitive

reason; we do not include judgement and opinion because in these we may

be mistaken. Now what scientific knowledge is, if we are to speak exactly and not follow mere similarities, is plain from what follows. We all suppose that what we know is not even capable of being otherwise; of things capable of being otherwise we do not know, when they have passed outside our observation, whether they exist or not. Therefore the object of scientific knowledge is of necessity. Therefore it is eternal; for things that are of necessity in the unqualified sense are all eternal; and things that are eternal are ungenerated and imperishable. Again, every science is thought to be capable of being taught, and its object of being learned. And all teaching starts from what is already known, as we maintain in the Analytics also; for it proceeds sometimes through induction and sometimes by syllogism. Now induction is the starting-point which knowledge even of the universal presupposes, while syllogism proceeds from universals. There are therefore starting-points from which syllogism proceeds, which are not reached by syllogism; it is therefore by induction that they are acquired. Scientific knowledge is, then, a state of capacity to demonstrate, and has the other limiting characteristics which we specify in the Analytics, for it is when a man believes in a certain way and the starting-points are known to him that he has scientific knowledge, since if they are not better known to him than the conclusion, he will have his knowledge only incidentally. Let this, then, be taken as our account of scientific knowledge. |

では、初めから始めよう。これらの状態について改めて論じよう。魂が肯定または否定によって真理を所有する状態は五つあると仮定しよう。すなわち、技術、科学的知識、実践的知恵、哲学的知恵、直観的理性である。判断と意見は含めない。これらは誤り得るからだ。 さて、科学的知識とは何か。厳密に語って類似点に流されないならば、以下から明らかである。我々は皆、知っているものは他のありえ方すらありえないと考え る。他のありえ方を持つものについては、観察の範囲外に去った後、それが存在するかどうかすら知らないのだ。ゆえに科学的認識の対象は必然的なものであ る。したがってそれは永遠である。なぜなら無条件の意味で必然的なものは全て永遠であり、永遠なるものは無生で不滅だからだ。またあらゆる科学は教えられ る可能性があり、その対象は学ばれるべきものと見なされる。そしてあらゆる教育は既に知られているものから始まる。我々が『分析論』でも主張するように、 それは時に帰納によって、時に三段論法によって進むのである。帰納法は普遍的概念の知識さえも前提とする出発点である。一方、三段論法は普遍的概念から出 発する。したがって三段論法が到達しない出発点が存在する。それらは帰納法によって獲得されるのである。科学的知識とは、証明する能力の状態であり、『分 析篇』で規定した他の限定的特徴も備えている。なぜなら、ある方法で信じ、出発点が知られている時にのみ科学的知識を持つからである。もし結論よりも出発 点がよく知られていなければ、その知識は偶然のものでしかないからだ。 以上を科学的知識に関する我々の説明とせよ。 |

| 4章 |

|

| In

the variable are included both things made and things done; making and

acting are different (for their nature we treat even the discussions

outside our school as reliable); so that the reasoned state of capacity

to act is different from the reasoned state of capacity to make. Hence

too they are not included one in the other; for neither is acting

making nor is making acting. Now since architecture is an art and is

essentially a reasoned state of capacity to make, and there is neither

any art that is not such a state nor any such state that is not an art,

art is identical with a state of capacity to make, involving a true

course of reasoning. All art is concerned with coming into being, i.e.

with contriving and considering how something may come into being which

is capable of either being or not being, and whose origin is in the

maker and not in the thing made; for art is concerned neither with

things that are, or come into being, by necessity, nor with things that

do so in accordance with nature (since these have their origin in

themselves). Making and acting being different, art must be a matter of

making, not of acting. And in a sense chance and art are concerned with

the same objects; as Agathon says, 'art loves chance and chance loves

art'. Art, then, as has been is a state concerned with making,

involving a true course of reasoning, and lack of art on the contrary

is a state concerned with making, involving a false course of

reasoning; both are concerned with the variable. |

変

数には、作られたものとなされたものの両方が含まれる。作る行為と行う行為は異なる(その本質については、我々の学派外の議論さえも信頼できるものとして

扱う)。したがって、行う能力の理性的な状態は、作る能力の理性的な状態とは異なる。ゆえに、それらは互いに包含されない。行うことが作ることでなく、作

ることも行うことではないからである。さて、建築は芸術であり、本質的に理性的であるものを作る能力の状態である。そして、そのような状態でない芸術もな

ければ、芸術でないそのような状態もない。したがって、芸術とは、真の推論の過程を伴うものを作る能力の状態と同一である。あらゆる芸術は生成に関わる。

すなわち、存在し得るか否かの可能性を持ち、その起源が作り手にあるものであって、作られたもの自体にないものの、いかにして生成し得るかを考案し考察す

ることに関わる。なぜなら芸術は、必然的に存在するものや生成するもの、あるいは自然に従ってそうするものを扱わないからである(これらは自らに起源を持

つ)。作る行為と行動は異なるため、芸術は行動ではなく作ることに関わる。ある意味で偶然と芸術は同じ対象に関わる。アガトンが言うように「芸術は偶然を

愛し、偶然は芸術を愛する」。したがって芸術とは、前述の通り、真の推論過程を伴う作ることに関わる状態であり、逆に芸術の欠如とは、偽りの推論過程を伴

う作ることに関わる状態である。両者とも変動するものに関わる。 |

| 5章 |

|

| Regarding practical wisdom we

shall get at the truth by considering who are the persons we credit

with it. Now it is thought to be the mark of a man of practical wisdom

to be able to deliberate well about what is good and expedient for

himself, not in some particular respect, e.g. about what sorts of thing

conduce to health or to strength, but about what sorts of thing conduce

to the good life in general. This is shown by the fact that we credit

men with practical wisdom in some particular respect when they have

calculated well with a view to some good end which is one of those that

are not the object of any art. It follows that in the general sense

also the man who is capable of deliberating has practical wisdom. Now

no one deliberates about things that are invariable, nor about things

that it is impossible for him to do. Therefore, since scientific

knowledge involves demonstration, but there is no demonstration of

things whose first principles are variable (for all such things might

actually be otherwise), and since it is impossible to deliberate about

things that are of necessity, practical wisdom cannot be scientific

knowledge nor art; not science because that which can be done is

capable of being otherwise, not art because action and making are

different kinds of thing. The remaining alternative, then, is that it

is a true and reasoned state of capacity to act with regard to the

things that are good or bad for man. For while making has an end other

than itself, action cannot; for good action itself is its end. It is

for this reason that we think Pericles and men like him have practical

wisdom, viz. because they can see what is good for themselves and what

is good for men in general; we consider that those can do this who are

good at managing households or states. (This is why we call temperance

(sophrosune) by this name; we imply that it preserves one's practical

wisdom (sozousa tan phronsin). Now what it preserves is a judgement of

the kind we have described. For it is not any and every judgement that

pleasant and painful objects destroy and pervert, e.g. the judgement

that the triangle has or has not its angles equal to two right angles,

but only judgements about what is to be done. For the originating

causes of the things that are done consist in the end at which they are

aimed; but the man who has been ruined by pleasure or pain forthwith

fails to see any such originating cause-to see that for the sake of

this or because of this he ought to choose and do whatever he chooses

and does; for vice is destructive of the originating cause of action.)

Practical wisdom, then, must be a reasoned and true state of capacity

to act with regard to human goods. But further, while there is such a

thing as excellence in art, there is no such thing as excellence in

practical wisdom; and in art he who errs willingly is preferable, but

in practical wisdom, as in the virtues, he is the reverse. Plainly,

then, practical wisdom is a virtue and not an art. There being two

parts of the soul that can follow a course of reasoning, it must be the

virtue of one of the two, i.e. of that part which forms opinions; for

opinion is about the variable and so is practical wisdom. But yet it is

not only a reasoned state; this is shown by the fact that a state of

that sort may forgotten but practical wisdom cannot. |

実践的知恵について、我々は誰をその人格と見なすかを考察することで真

理に迫る。実践的知恵を持つ者の特徴は、特定の点――例えば健康や体力増進に資する事柄――ではなく、人生全般における善い生活に資する事柄について、自

らにとって何が善く、何が有益かをよく熟議できることにあると考えられている。このことは、ある特定の点において実践的知恵を持つと認められる人々が、技

術の対象とならない善き目的のためにうまく計算した事実によって示されている。したがって、一般的な意味においても、熟議できる人間は実践的知恵を持つと

言える。さて、誰も不変の事柄について熟議したり、自分には不可能な事柄について熟議したりはしない。したがって、科学的知識は証明を伴うが、第一原理が

変動する事柄(そのような事柄は実際にもっとも異なる可能性がある)には証明が存在しない。また必然的な事柄について熟議することは不可能である。ゆえに

実践的知恵は科学的知識でも技術でもない。科学的でないのは、実行可能な事柄は別のありうる状態を持つからであり、技術でないのは、行動と製作は異なる種

類の事柄だからである。残る選択肢は、人間にとって善悪となる事柄に関して、真に理性的で能力を備えた行動状態である。なぜなら、製作はそれ自体以外の目

的を持つが、行動は持たない。善い行動そのものが目的だからだ。この理由から、我々はペリクレスや彼のような人物が実践的知恵を持つと考える。すなわち、

彼らは自己にとって善なるものと、人間一般にとって善なるものを見極められるからだ。家政や国家運営に長けた者こそ、これを為し得ると我々は考える。(こ

れが我々が節制(ソフロスネ)をこの名で呼ぶ所以である。我々は、それが実践的知恵(ソゾウサ・タン・フロシン)を保つことを意味しているのだ。)

さて、それが守るものは、我々が述べた種類の判断である。なぜなら、快楽や苦痛の対象が破壊し歪めるのは、あらゆる判断ではないからだ。例えば、三角形の

角度が二つの直角に等しいか否かという判断ではなく、何をなすべきかについての判断だけである。なぜなら、行われる事柄の根源的な原因は、それらが目指す

目的にあるからだ。しかし快楽や苦痛に破れた者は、即座にそのような根源的原因を見失う——すなわち、この目的のために、あるいはこの理由によって、自分

が選択し実行するべきことを選択し実行すべきだという見失うのだ。なぜなら悪徳は、行動の根源的原因を破壊するからである。したがって、実践的知恵とは、

人間の善に関して行動する能力の、理性的かつ真実な状態でなければならない。さらに言えば、技術には卓越性というものが存在するが、実践的知恵にはそのよ

うなものは存在しない。技術においては、進んで誤る者がむしろ好ましいが、実践的知恵においては、徳性と同様に、その逆が好ましいのである。明らかに、実

践的知恵は技術ではなく徳である。魂には二つの部分があり、それぞれが推論の過程をたどることができる。したがって、実践的知恵は二つのうち一方の徳、す

なわち意見を形成する部分の徳でなければならない。なぜなら、意見は変動する事柄に関するものであり、実践的知恵もまた同様だからだ。しかし、それは単な

る理性的状態ではない。そのような状態は忘れ去られることがあるが、実践的知恵は忘れ去られることがないという事実がそれを示している。 |

| 6章 |

|

| Scientific knowledge is

judgement about things that are universal and necessary, and the

conclusions of demonstration, and all scientific knowledge, follow from

first principles (for scientific knowledge involves apprehension of a

rational ground). This being so, the first principle from which what is

scientifically known follows cannot be an object of scientific

knowledge, of art, or of practical wisdom; for that which can be

scientifically known can be demonstrated, and art and practical wisdom

deal with things that are variable. Nor are these first principles the

objects of philosophic wisdom, for it is a mark of the philosopher to

have demonstration about some things. If, then, the states of mind by

which we have truth and are never deceived about things invariable or

even variable are scientific knowlededge, practical wisdom, philosophic

wisdom, and intuitive reason, and it cannot be any of the three (i.e.

practical wisdom, scientific knowledge, or philosophic wisdom), the

remaining alternative is that it is intuitive reason that grasps the

first principles. |

科学的知識とは、普遍的かつ必然的な事物についての判断であり、証明の

結論である。そしてあらゆる科学的知識は、第一原理から導かれる(科学的知識は合理的な根拠の把握を伴うからである)。そうである以上、科学的知識が導か

れる第一原理は、科学的知識や技術、実践的知恵の対象とはなりえない。なぜなら科学的知識の対象は証明可能であるが、技術と実践的知恵は変動する事物を扱

うからだ。またこれらの第一原理は哲学的知恵の対象でもない。哲学者とは何事かについて証明を持つ者を指すからである。したがって、不変あるいは変動する

事物について真実を把握し、決して誤らない精神状態が科学的知識、実践的知恵、哲学的知恵、直観的理性であるならば、それがこれら三者(すなわち実践的知

恵、科学的知識、哲学的知恵)のいずれでもない場合、残る選択肢は第一原理を把握する直観的理性である。 |

| 7章 |

|

| Wisdom (1) in the arts we

ascribe to their most finished exponents, e.g. to Phidias as a sculptor

and to Polyclitus as a maker of portrait-statues, and here we mean

nothing by wisdom except excellence in art; but (2) we think that some

people are wise in general, not in some particular field or in any

other limited respect, as Homer says in the Margites, Him did the gods make neither a digger nor yet a ploughman Nor wise in anything else. Therefore wisdom must plainly be the most finished of the forms of knowledge. It follows that the wise man must not only know what follows from the first principles, but must also possess truth about the first principles. Therefore wisdom must be intuitive reason combined with scientific knowledge-scientific knowledge of the highest objects which has received as it were its proper completion. Of the highest objects, we say; for it would be strange to think that the art of politics, or practical wisdom, is the best knowledge, since man is not the best thing in the world. Now if what is healthy or good is different for men and for fishes, but what is white or straight is always the same, any one would say that what is wise is the same but what is practically wise is different; for it is to that which observes well the various matters concerning itself that one ascribes practical wisdom, and it is to this that one will entrust such matters. This is why we say that some even of the lower animals have practical wisdom, viz. those which are found to have a power of foresight with regard to their own life. It is evident also that philosophic wisdom and the art of politics cannot be the same; for if the state of mind concerned with a man's own interests is to be called philosophic wisdom, there will be many philosophic wisdoms; there will not be one concerned with the good of all animals (any more than there is one art of medicine for all existing things), but a different philosophic wisdom about the good of each species. |

芸術における知恵(1)とは、その最も完成された表現者に帰せられる。

例えば彫刻家としてのフィディアスや肖像彫像の作者としてのポリュクレイトスに当てはまる。ここで言う知恵とは、単に芸術における卓越性を指すに過ぎな

い。しかし(2)我々は、特定分野や限定された点においてではなく、全般的に賢明な人々がいると考える。ホメロスが『マルギテス』で言うように、 神々は彼を掘る者にも耕す者にもせず 他の何事にも賢くは造らなかった。したがって、知恵とは明らかに知識の形態の中で最も完成されたものであるに違いない。これに従えば、賢者は第一原理から 導かれることを知るだけでなく、第一原理そのものについての真理をも有していなければならない。ゆえに知恵とは、科学的知識と直観的理性を組み合わせたも のであり、最高対象に関する科学的知識が、いわばその適切な完成を得た状態である。 最高位の対象についてと言うのは、政治術や実践的知恵が最高の知識だとは考えにくいからだ。人間は世界最高の存在ではないのだから。さて、健康や善が人間 と魚で異なるのに対し、白や直線は常に同じであるならば、賢明であることは同じでも、実践的賢明さは異なる、と誰もが言うだろう。なぜなら、実践的知恵と は、自らに関わる様々な事柄をよく観察する能力を指し、そうした事柄を委ねるに値するのは、この能力を持つ者だからである。だからこそ我々は、下等動物の 中にも実践的知恵を持つ者がいると言うのだ。つまり、自らの生命に関して予見する力を持つことが確認されている動物たちである。また、哲学的知恵と政治術 が同一であるはずがないことも明らかだ。なぜなら、もし個人の利益に関わる心の状態を哲学的知恵と呼ぶなら、哲学的知恵は複数存在する。すべての動物の善 に関わる哲学的知恵は一つではない(すべての存在物に共通する医学が一つでないのと同じだ)。各種の善について、それぞれ異なる哲学的知恵が存在するの だ。 |

| But if the argument be that man

is the best of the animals, this makes no difference; for there are

other things much more divine in their nature even than man, e.g., most

conspicuously, the bodies of which the heavens are framed. From what

has been said it is plain, then, that philosophic wisdom is scientific

knowledge, combined with intuitive reason, of the things that are

highest by nature. This is why we say Anaxagoras, Thales, and men like

them have philosophic but not practical wisdom, when we see them

ignorant of what is to their own advantage, and why we say that they

know things that are remarkable, admirable, difficult, and divine, but

useless; viz. because it is not human goods that they seek. Practical wisdom on the other hand is concerned with things human and things about which it is possible to deliberate; for we say this is above all the work of the man of practical wisdom, to deliberate well, but no one deliberates about things invariable, nor about things which have not an end, and that a good that can be brought about by action. The man who is without qualification good at deliberating is the man who is capable of aiming in accordance with calculation at the best for man of things attainable by action. Nor is practical wisdom concerned with universals only-it must also recognize the particulars; for it is practical, and practice is concerned with particulars. This is why some who do not know, and especially those who have experience, are more practical than others who know; for if a man knew that light meats are digestible and wholesome, but did not know which sorts of meat are light, he would not produce health, but the man who knows that chicken is wholesome is more likely to produce health. Now practical wisdom is concerned with action; therefore one should have both forms of it, or the latter in preference to the former. But of practical as of philosophic wisdom there must be a controlling kind. |

しかし、人間が動物の中で最も優れているという主張があっても、それは

何の違いもない。なぜなら、人間よりもはるかに神聖な性質を持つものが他にも存在するからだ。例えば、最も顕著なのは、天体を構成する物質である。以上か

ら明らかなように、哲学的知恵とは、自然界において最も高貴な事物に関する科学的知識と直観的理性を組み合わせたものである。だからこそ我々は、アナクサ

ゴラスやタレスらのような者たちが、自らの利益となることを知らないのを見ると、彼らには哲学的知恵はあるが実践的知恵はないと言うのだ。また彼らが驚く

べき、称賛に値する、困難で神聖な事柄を知っているが役に立たないと言うのも、彼らが求めるのは人間の幸福ではないからだ。 一方、実践的知恵は人間的な事柄、そして熟議が可能な事柄に関わる。なぜなら我々は、よく熟議することが何よりも実践的知恵を持つ者の仕事だと言うが、誰 も不変の事柄や目的を持たない事柄、そして行動によって実現可能な善について熟議することはないからだ。熟議に長けた者は、行動によって達成可能な事柄の 中で、計算に基づいて人間にとって最善のものを目指す能力を持つ者である。また実践的知恵は普遍的なものだけに関わるのではない。個別的なものも認識しな ければならない。なぜならそれは実践的であり、実践は個別的なものに関わるからである。だからこそ、知識のない者、特に経験のある者は、知識のある者より 実践的である。例えば、軽い肉が消化しやすく健康に良いと知っていても、どの肉が軽いのかを知らなければ、健康をもたらすことはできない。しかし、鶏肉が 健康に良いと知っている者は、健康をもたらす可能性が高い。 さて、実践的知恵は行動に関わる。ゆえに人は両方の形態を持つべきであり、あるいは後者を前者より優先すべきだ。しかし実践的知恵も哲学的知恵も、統制する種類がなければならない。 |

| 8章 | |

| Political wisdom and practical

wisdom are the same state of mind, but their essence is not the same.

Of the wisdom concerned with the city, the practical wisdom which plays

a controlling part is legislative wisdom, while that which is related

to this as particulars to their universal is known by the general name

'political wisdom'; this has to do with action and deliberation, for a

decree is a thing to be carried out in the form of an individual act.

This is why the exponents of this art are alone said to 'take part in

politics'; for these alone 'do things' as manual labourers 'do things'. Practical wisdom also is identified especially with that form of it which is concerned with a man himself-with the individual; and this is known by the general name 'practical wisdom'; of the other kinds one is called household management, another legislation, the third politics, and of the latter one part is called deliberative and the other judicial. Now knowing what is good for oneself will be one kind of knowledge, but it is very different from the other kinds; and the man who knows and concerns himself with his own interests is thought to have practical wisdom, while politicians are thought to be busybodies; hence the word of Euripides, But how could I be wise, who might at ease, Numbered among the army's multitude, Have had an equal share? For those who aim too high and do too much. Those who think thus seek their own good, and consider that one ought to do so. From this opinion, then, has come the view that such men have practical wisdom; yet perhaps one's own good cannot exist without household management, nor without a form of government. Further, how one should order one's own affairs is not clear and needs inquiry. |

政治的知恵と実践的知恵は同じ心境だが、その本質は異なる。都市に関わ

る知恵のうち、支配的役割を果たす実践的知恵は立法的知恵であり、これに関連して個別的事項が普遍的事項に結びつくものは総称して「政治的知恵」と呼ばれ

る。これは行動と熟議に関わるもので、法令とは個々の行為として実行されるべきものだからだ。だからこそ、この術を体得した者だけが「政治に参加する」と

言われる。彼らだけが、肉体労働者が「物事を成す」ように「物事を成す」からだ。 実践的知恵は特に、個人、すなわち人間自身に関わる形態と同一視される。これが「実践的知恵」という総称で知られる。他の種類では、一つは家政、もう一つ は立法、三つ目は政治と呼ばれ、後者のうち一つは審議的、もう一つは司法的と呼ばれる。さて、己にとって何が善いかを知ることは一種の知識ではあるが、他 の種類の知識とは大きく異なる。己の利益を知り、それに心を配る者は実践的知恵を持つと見なされる一方、政治家たちは余計なお世話をする者たちと見なされ る。故にエウリピデスの言葉にあるように、 しかし、どうして私が賢明でいられようか。 軍勢のマルチチュードの中に数えられ、 等しい分け前を得られたかもしれないのに。 高望みし過ぎ、やり過ぎる者たちのために。このように考える者たちは自らの利益を求め、そうすべきだと考える。この見解から、そうした者たちは実践的知恵 を持つという見方が生まれた。しかしおそらく、家政なくして、また何らかの統治形態なくして、自らの利益は存在し得ない。さらに、いかにして自らの事柄を 秩序立てるべきかは明らかではなく、探究を要する。 |

| What has been said is confirmed

by the fact that while young men become geometricians and

mathematicians and wise in matters like these, it is thought that a

young man of practical wisdom cannot be found. The cause is that such

wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars,

which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no

experience, for it is length of time that gives experience; indeed one

might ask this question too, why a boy may become a mathematician, but

not a philosopher or a physicist. It is because the objects of

mathematics exist by abstraction, while the first principles of these

other subjects come from experience, and because young men have no

conviction about the latter but merely use the proper language, while

the essence of mathematical objects is plain enough to them? Further, error in deliberation may be either about the universal or about the particular; we may fall to know either that all water that weighs heavy is bad, or that this particular water weighs heavy. That practical wisdom is not scientific knowledge is evident; for it is, as has been said, concerned with the ultimate particular fact, since the thing to be done is of this nature. It is opposed, then, to intuitive reason; for intuitive reason is of the limiting premisses, for which no reason can be given, while practical wisdom is concerned with the ultimate particular, which is the object not of scientific knowledge but of perception-not the perception of qualities peculiar to one sense but a perception akin to that by which we perceive that the particular figure before us is a triangle; for in that direction as well as in that of the major premiss there will be a limit. But this is rather perception than practical wisdom, though it is another kind of perception than that of the qualities peculiar to each sense. |

若者が幾何学者や数学者となり、こうした事柄に精通する一方で、実践的

な知恵を持つ若者は見当たらないと言われる事実が、この主張を裏付けている。その原因は、この種の知恵が普遍的なものだけでなく、経験によって親しむべき

個別的なものにも関わるからである。しかし若者は経験を持たない。経験は長い時間によって得られるものだからだ。実際、少年が数学者にはなれるのに、哲学

者や物理学者にはなれないのはなぜか、という疑問も抱くかもしれない。数学の対象は抽象によって存在するが、他の学問の第一原理は経験から来るからだ。若

者は後者について確信を持たず単に適切な言葉を使うだけだが、数学的対象の本質は彼らには十分に明白だからだ。 さらに、熟議における誤りは普遍的なものについてでも、個別のものについてでも起こりうる。すなわち「重い水は全て悪い」という普遍的な誤りに陥ることもあれば、「この特定の水が重い」という個別的な誤りに陥ることもあるのだ。 実践的知恵が科学的知識ではないことは明らかである。なぜなら、それは前述の通り、究極的な個別的事実に関わるものだからだ。なすべきことはこの性質のも のだからである。したがって実践的知恵は直観的理性と対立する。直観的理性は限定的前提に関わるが、これには理由を説明できない。一方実践的知恵は究極的 な個別的事実に関わる。これは科学的知識の対象ではなく知覚の対象である。特定の感覚に特有の性質の知覚ではなく、眼前の特定の図形が三角形であると知覚 するのと類似した知覚である。大前提の方向と同様に、この方向にも限界が存在するからだ。しかしこれは実践的知恵というよりは知覚であり、各感覚特有の性 質の知覚とは別の種類の知覚である。 |

| 9章 |

|

| There is a difference between

inquiry and deliberation; for deliberation is inquiry into a particular

kind of thing. We must grasp the nature of excellence in deliberation

as well whether it is a form of scientific knowledge, or opinion, or

skill in conjecture, or some other kind of thing. Scientific knowledge

it is not; for men do not inquire about the things they know about, but

good deliberation is a kind of deliberation, and he who deliberates

inquires and calculates. Nor is it skill in conjecture; for this both

involves no reasoning and is something that is quick in its operation,

while men deliberate a long time, and they say that one should carry

out quickly the conclusions of one's deliberation, but should

deliberate slowly. Again, readiness of mind is different from

excellence in deliberation; it is a sort of skill in conjecture. Nor

again is excellence in deliberation opinion of any sort. But since the

man who deliberates badly makes a mistake, while he who deliberates

well does so correctly, excellence in deliberation is clearly a kind of

correctness, but neither of knowledge nor of opinion; for there is no

such thing as correctness of knowledge (since there is no such thing as

error of knowledge), and correctness of opinion is truth; and at the

same time everything that is an object of opinion is already

determined. But again excellence in deliberation involves reasoning.

The remaining alternative, then, is that it is correctness of thinking;

for this is not yet assertion, since, while even opinion is not inquiry

but has reached the stage of assertion, the man who is deliberating,

whether he does so well or ill, is searching for something and

calculating. |

探究と熟議には違いがある。熟議とは特定の事柄に対する探究だからだ。

我々は熟議における卓越性の本質を把握しなければならない。それが科学的知識の一形態なのか、意見なのか、推測の技なのか、あるいは他の何かなのかを。科

学的知識ではない。人は知っている事柄について探究しないからだ。しかし良き熟議は一種の熟議であり、熟議する者は探究し計算する。また推論の技でもな

い。推論には推論が伴わず、その作用は迅速である。一方、人は長く熟議し、熟議の結論は迅速に実行すべきだが、熟議自体はゆっくり行うべきだと言う。さら

に、心の機敏さは熟議の卓越性とは異なる。それは一種の推論の技である。また熟議の卓越性は、いかなる種類の意見でもない。しかし、熟議を誤る者は過ちを

犯し、熟議を正しく行う者は正しく行う。ゆえに熟議の卓越性は明らかに一種の正しさである。ただし知識の正しさでも意見の正しさでもない。知識の正しさな

ど存在しない(知識の誤りなど存在しないからである)。意見の正しさは真実である。同時に、意見の対象となるものはすべて既に決定されている。しかし熟議

の卓越性は推論を伴う。残る選択肢は、思考の正しさである。これはまだ断言ではない。なぜなら、意見でさえ探求ではなく断言の段階に達しているのに対し、

熟議する者は、それが良くあれ悪くあれ、何かを探し求め、計算しているからだ。 |

| But excellence in deliberation

is a certain correctness of deliberation; hence we must first inquire

what deliberation is and what it is about. And, there being more than

one kind of correctness, plainly excellence in deliberation is not any

and every kind; for (1) the incontinent man and the bad man, if he is

clever, will reach as a result of his calculation what he sets before

himself, so that he will have deliberated correctly, but he will have

got for himself a great evil. Now to have deliberated well is thought

to be a good thing; for it is this kind of correctness of deliberation

that is excellence in deliberation, viz. that which tends to attain

what is good. But (2) it is possible to attain even good by a false

syllogism, and to attain what one ought to do but not by the right

means, the middle term being false; so that this too is not yet

excellence in deliberation this state in virtue of which one attains

what one ought but not by the right means. Again (3) it is possible to

attain it by long deliberation while another man attains it quickly.

Therefore in the former case we have not yet got excellence in

deliberation, which is rightness with regard to the expedient-rightness

in respect both of the end, the manner, and the time. (4) Further it is

possible to have deliberated well either in the unqualified sense or

with reference to a particular end. Excellence in deliberation in the

unqualified sense, then, is that which succeeds with reference to what

is the end in the unqualified sense, and excellence in deliberation in

a particular sense is that which succeeds relatively to a particular

end. If, then, it is characteristic of men of practical wisdom to have

deliberated well, excellence in deliberation will be correctness with

regard to what conduces to the end of which practical wisdom is the

true apprehension. |

しかし、熟議における卓越性とは、ある種の正しい熟議である。したがっ

て我々はまず、熟議とは何か、そしてそれが何について行われるものかを問わねばならない。そして、正しさには複数の種類があるから、明らかに熟議の卓越性

はあらゆる種類の正しさではない。なぜなら、(1)

自制心のない者や悪人であっても、もし賢明であれば、自らの計算の結果として自らに定めた目的を達成するだろう。つまり彼は正しく熟議したことになるが、

自らに大きな災いをもたらすことになる。さて、よく熟議することは良いことと考えられている。なぜなら、熟議の正しさのうち、善なるものを達成する傾向に

あるものこそが、熟議の卓越性だからだ。しかし(2)誤った三段論法によってさえ善は達成可能であり、また、中項が誤っているために、行うべきことを達成

するものの正しい手段ではない場合もある。したがって、これまた、行うべきことを達成するものの正しい手段ではないという状態において、まだ熟議の卓越性

とは言えない。さらに(3)長い熟議によって達成する一方で、別の者は素早く達成する可能性もある。したがって前者の場合、我々はまだ熟議の卓越性を得て

いない。熟議の卓越性とは、手段に関しての正しさ、すなわち目的・方法・時期の三点における正しさである。さらに(4)熟議が良く行われる場合、それは無

条件の意味での熟議、あるいは特定の目的に関する熟議のいずれかである。したがって、無条件の意味での熟議の卓越性は、無条件の意味での目的に関して成功

するものであり、特定の意味での熟議の卓越性は、特定の目的に対して相対的に成功するものである。もし熟議を良く行うことが実践的知恵を持つ者の特徴であ

るならば、熟議の卓越性とは、実践的知恵が真に把握する目的に寄与するものに関しての正しさである。 |

| 10章 | |

| Understanding, also, and

goodness of understanding, in virtue of which men are said to be men of

understanding or of good understanding, are neither entirely the same

as opinion or scientific knowledge (for at that rate all men would have

been men of understanding), nor are they one of the particular

sciences, such as medicine, the science of things connected with

health, or geometry, the science of spatial magnitudes. For

understanding is neither about things that are always and are

unchangeable, nor about any and every one of the things that come into

being, but about things which may become subjects of questioning and

deliberation. Hence it is about the same objects as practical wisdom;

but understanding and practical wisdom are not the same. For practical

wisdom issues commands, since its end is what ought to be done or not

to be done; but understanding only judges. (Understanding is identical

with goodness of understanding, men of understanding with men of good

understanding.) Now understanding is neither the having nor the

acquiring of practical wisdom; but as learning is called understanding

when it means the exercise of the faculty of knowledge, so

'understanding' is applicable to the exercise of the faculty of opinion

for the purpose of judging of what some one else says about matters

with which practical wisdom is concerned-and of judging soundly; for

'well' and 'soundly' are the same thing. And from this has come the use

of the name 'understanding' in virtue of which men are said to be 'of

good understanding', viz. from the application of the word to the

grasping of scientific truth; for we often call such grasping

understanding. |

理解、そして理解の良さは、人間が「理解力のある者」あるいは「良識あ

る者」と呼ばれる所以であるが、それは意見や科学的知識とは全く同じものでもない(そうでなければ、すべての人間が理解力のある者となってしまう)。ま

た、医学(健康に関わる事物の科学)や幾何学(空間的大きさの科学)といった特定の科学の一種でもない。なぜなら、理解は常に存在し不変のものについてで

もなければ、生じるあらゆるものについてでもなく、問いや熟議の対象となり得るものについてだからだ。したがって、それは実践的知恵と同じ対象についてで

ある。しかし理解と実践的知恵は同一ではない。実践的知恵は命令を下す。その目的は、なすべきこと、あるいはなすべきでないことにあるからだ。しかし知性

は判断するだけである。(知性は良識と同義であり、知性ある者は良識ある者と同一視される。)

さて、理解とは実践的知恵の保有でも獲得でもない。しかし、知識の能力の行使を意味する時に学問が理解と呼ばれるのと同様に、「理解」という言葉は、実践

的知恵に関わる事柄について他者が語ることを判断する目的で、意見の能力を行使すること、そして正しく判断することに対して適用される。なぜなら「良く」

と「正しく」は同じものだからだ。このことから「良識ある」という表現が生まれたのである。すなわち、科学的真理の把握に対してこの言葉が用いられること

から、我々はしばしばそのような把握を「良識」と呼ぶのである。 |

| 11章 |

|

| What is called judgement, in

virtue of which men are said to 'be sympathetic judges' and to 'have

judgement', is the right discrimination of the equitable. This is shown

by the fact that we say the equitable man is above all others a man of

sympathetic judgement, and identify equity with sympathetic judgement

about certain facts. And sympathetic judgement is judgement which

discriminates what is equitable and does so correctly; and correct

judgement is that which judges what is true. Now all the states we have considered converge, as might be expected, to the same point; for when we speak of judgement and understanding and practical wisdom and intuitive reason we credit the same people with possessing judgement and having reached years of reason and with having practical wisdom and understanding. For all these faculties deal with ultimates, i.e. with particulars; and being a man of understanding and of good or sympathetic judgement consists in being able judge about the things with which practical wisdom is concerned; for the equities are common to all good men in relation to other men. Now all things which have to be done are included among particulars or ultimates; for not only must the man of practical wisdom know particular facts, but understanding and judgement are also concerned with things to be done, and these are ultimates. And intuitive reason is concerned with the ultimates in both directions; for both the first terms and the last are objects of intuitive reason and not of argument, and the intuitive reason which is presupposed by demonstrations grasps the unchangeable and first terms, while the intuitive reason involved in practical reasonings grasps the last and variable fact, i.e. the minor premiss. For these variable facts are the starting-points for the apprehension of the end, since the universals are reached from the particulars; of these therefore we must have perception, and this perception is intuitive reason. This is why these states are thought to be natural endowments-why, while no one is thought to be a philosopher by nature, people are thought to have by nature judgement, understanding, and intuitive reason. This is shown by the fact that we think our powers correspond to our time of life, and that a particular age brings with it intuitive reason and judgement; this implies that nature is the cause. (Hence intuitive reason is both beginning and end; for demonstrations are from these and about these.) Therefore we ought to attend to the undemonstrated sayings and opinions of experienced and older people or of people of practical wisdom not less than to demonstrations; for because experience has given them an eye they see aright. We have stated, then, what practical and philosophic wisdom are, and with what each of them is concerned, and we have said that each is the virtue of a different part of the soul. |

いわゆる判断力とは、人間が「共感的な判断者」であり「判断力を持つ」

と言われる根拠であり、公平なものを正しく見分ける能力である。これは、公平な人間が何よりも共感的な判断力を持つ人間だと我々が言い、公平さを特定の事

実に対する共感的な判断と同一視する事実によって示される。そして共感的な判断とは、公平なものを正しく見分ける判断であり、正しい判断とは真実を判断す

るものである。 さて、これまで検討してきた諸状態は、予想通り同一の点に収束する。なぜなら、我々が判断力や理解力、実践的知恵、直観的理性について語る時、同じ人々が 判断力を持ち、理性の年齢に達し、実践的知恵と理解力を備えていると認めるからだ。これらの能力は全て究極的なもの、すなわち個別的事柄を扱う。そして理 解力と良きあるいは共感的な判断力を持つとは、実践的知恵が関わる事柄について判断できることを意味する。なぜなら公平性は、他者との関係において全ての 善き人に共通するからだ。さて、なすべきすべての事柄は個別的事項、すなわち究極的事項に含まれる。なぜなら、実践的知恵を持つ者は個別的事実を知る必要 があるだけでなく、理解と判断もなすべき事柄に関わるからであり、これらは究極的事項である。直観的理性は両方向において究極的事柄に関わる。第一項と最 終項はどちらも直観的理性の対象であり、論証の対象ではない。証明が前提とする直観的理性は不変の第一項を把握し、実践的推論に伴う直観的理性は最終的か つ変動する事実、すなわち小前提を把握する。なぜなら、これらの変動する事実は目的を把握する出発点だからだ。普遍は個別から到達される。ゆえに我々はこ れらを認識しなければならず、この認識こそが直観的理性である。 これが、これらの状態が自然の賜物と考えられる理由である。つまり、生まれながらの哲学者などいないと考えられる一方で、人民は生まれながらに判断力、理 解力、直観的理性を備えていると考えられるのだ。これは、我々が自らの能力が人生の段階に対応していると考え、特定の年齢が直観的理性と判断力を伴って訪 れるという事実によって示される。これは自然が原因であることを意味する。(したがって直観的理性は始まりであり終わりでもある。なぜなら証明はこれらか ら生じ、これらについて行われるからである。) したがって我々は、証明されたものと同じくらい、経験豊富で年長の人々や実践的知恵を持つ人々の証明されていない言葉や意見にも注意を払うべきだ。なぜな ら経験が彼らに正しい見方をする目を授けているからだ。 以上、実践的知恵と哲学的知恵とは何か、それぞれが何を扱うものか、そしてそれぞれが魂の異なる部分の徳であることを述べた。 |

| 12章 |

|

| Difficulties might be raised as

to the utility of these qualities of mind. For (1) philosophic wisdom

will contemplate none of the things that will make a man happy (for it

is not concerned with any coming into being), and though practical

wisdom has this merit, for what purpose do we need it? Practical wisdom

is the quality of mind concerned with things just and noble and good

for man, but these are the things which it is the mark of a good man to

do, and we are none the more able to act for knowing them if the

virtues are states of character, just as we are none the better able to

act for knowing the things that are healthy and sound, in the sense not

of producing but of issuing from the state of health; for we are none

the more able to act for having the art of medicine or of gymnastics.

But (2) if we are to say that a man should have practical wisdom not

for the sake of knowing moral truths but for the sake of becoming good,

practical wisdom will be of no use to those who are good; again it is

of no use to those who have not virtue; for it will make no difference

whether they have practical wisdom themselves or obey others who have

it, and it would be enough for us to do what we do in the case of

health; though we wish to become healthy, yet we do not learn the art

of medicine. (3) Besides this, it would be thought strange if practical

wisdom, being inferior to philosophic wisdom, is to be put in authority

over it, as seems to be implied by the fact that the art which produces

anything rules and issues commands about that thing. These, then, are the questions we must discuss; so far we have only stated the difficulties. |

これらの心の資質の有用性については疑問が呈されるかもしれない。なぜ

なら(1)哲学的知恵は人間を幸福にする事柄を一切考察しない(それは生じるものに関心を持たないからである)。また実践的知恵にはこの長所があるとはい

え、我々はそれを何のために必要とするのか?実践的知恵とは、正義と高貴さと人間にとって善なる事柄に関わる心の性質である。しかしこれらは善き人間が為

すべき事柄の証であり、もし徳が性格の状態であるならば、我々はそれらを知ったからといって行動能力が増すわけではない。健康で健全な事柄を知ったからと

いって行動能力が増さないのと同じである。ここで言う健全とは、健康状態を生み出す意味ではなく、健康状態から生じる意味である。医学や体操の技術を学ん

でも、それだけで行動能力が向上するわけではない。しかし(2)もし実践的知恵が道徳的真理を知るためではなく、善人となるために必要だとするなら、実践

的知恵は善人にとっては無用である。また徳を持たない者にも役立たない。なぜなら、彼ら自身が実践的知恵を持つか、あるいはそれを有する者に従うかは問題

にならないからだ。健康の場合と同じことをすれば十分である。我々は健康になりたいと願うが、医学の技術を学ぶことはない。(3)

さらに言えば、実践的知恵が哲学的知恵より劣るのに、それを支配下に置くのは奇妙に思われる。なぜなら、何かを生み出す技術がそのものについて支配し命令

を下すという事実が、それを示唆しているように見えるからだ。 以上が我々が議論すべき問題である。ここまでで我々は困難を述べたに過ぎない。 |

| (1) Now first let us say that in

themselves these states must be worthy of choice because they are the

virtues of the two parts of the soul respectively, even if neither of

them produce anything. (2) Secondly, they do produce something, not as the art of medicine produces health, however, but as health produces health; so does philosophic wisdom produce happiness; for, being a part of virtue entire, by being possessed and by actualizing itself it makes a man happy. (3) Again, the work of man is achieved only in accordance with practical wisdom as well as with moral virtue; for virtue makes us aim at the right mark, and practical wisdom makes us take the right means. (Of the fourth part of the soul-the nutritive-there is no such virtue; for there is nothing which it is in its power to do or not to do.) (4) With regard to our being none the more able to do because of our practical wisdom what is noble and just, let us begin a little further back, starting with the following principle. As we say that some people who do just acts are not necessarily just, i.e. those who do the acts ordained by the laws either unwillingly or owing to ignorance or for some other reason and not for the sake of the acts themselves (though, to be sure, they do what they should and all the things that the good man ought), so is it, it seems, that in order to be good one must be in a certain state when one does the several acts, i.e. one must do them as a result of choice and for the sake of the acts themselves. Now virtue makes the choice right, but the question of the things which should naturally be done to carry out our choice belongs not to virtue but to another faculty. We must devote our attention to these matters and give a clearer statement about them. There is a faculty which is called cleverness; and this is such as to be able to do the things that tend towards the mark we have set before ourselves, and to hit it. Now if the mark be noble, the cleverness is laudable, but if the mark be bad, the cleverness is mere smartness; hence we call even men of practical wisdom clever or smart. Practical wisdom is not the faculty, but it does not exist without this faculty. And this eye of the soul acquires its formed state not without the aid of virtue, as has been said and is plain; for the syllogisms which deal with acts to be done are things which involve a starting-point, viz. 'since the end, i.e. what is best, is of such and such a nature', whatever it may be (let it for the sake of argument be what we please); and this is not evident except to the good man; for wickedness perverts us and causes us to be deceived about the starting-points of action. Therefore it is evident that it is impossible to be practically wise without being good. |

(1) まず第一に、これらの状態はそれ自体、魂の二つの部分の徳であるゆえに、たとえどちらも何ものも生み出さなくとも、選択に値するものであると言おう。 (2) 第二に、それらは確かに何かを生み出す。ただし医学の技が健康を生み出すようにではなく、健康が健康を生み出すようにである。同様に、哲学的知恵は幸福を 生み出す。なぜなら、それは徳全体の一部であり、それを持ち、それを実現することによって、人を幸福にするからである。 (3) さらに、人間の営みは道徳的徳性だけでなく実践的知恵によってのみ達成される。徳性が正しい目標を定めさせ、実践的知恵が正しい手段を取らせるからであ る。(魂の第四の部分である栄養的徳性には、このような徳性はない。なぜなら、それが為し得ることも為さぬことも何もないからである。) (4) 実践的知恵によって高貴で正義ある行為をより良く行えるわけではない点については、次の原理から少し遡って始めよう。正義ある行為を行う人民の中には必ず しも正義の人ではない人民もいると言うように――つまり法律で定められた行為を、行為そのもののためにではなく、不本意に、あるいは無知ゆえに、あるいは 他の理由で行っている人民である(もっとも彼らは 善人はなすべきことをすべて行っている)のと同じように、善人であるためには、様々な行為を行う際に特定の状態にある必要がある。つまり、選択の結果とし て、行為そのもののためにそれらを行わなければならない。さて、徳は選択を正しくするが、その選択を実行するために自然に為すべき事柄の問題は、徳ではな く別の能力に属する。我々はこれらの事柄に注意を向け、より明確に述べる必要がある。「巧みさ」と呼ばれる能力がある。これは自ら定めた目標に向かって行 動し、それを達成する能力である。目標が高貴であれば、この巧みさは称賛に値するが、目標が卑劣であれば、それは単なる小賢しさとなる。ゆえに我々は実践 的知恵を持つ者さえも「巧み」あるいは「小賢しい」と呼ぶのである。実践的知恵そのものはこの能力ではないが、この能力なしには存在し得ない。そしてこの 魂の眼は、前述の通り明らかなように、徳の助けなしには形成されない。なぜなら、なすべき行為を扱う三段論法は出発点を伴うものだからだ。すなわち「目 的、すなわち最善なるものはこうこうたる性質である」という前提から始まる(その目的が何であれ、仮に我々が望むものだとしよう)。これは善人以外には明 らかではない。悪は我々を歪め、行動の出発点について我々を欺くからである。したがって、善人でない者が実践的知恵を持つことは不可能であることは明らか だ。 |

| 13章 |

|

| We must therefore consider

virtue also once more; for virtue too is similarly related; as

practical wisdom is to cleverness-not the same, but like it-so is

natural virtue to virtue in the strict sense. For all men think that

each type of character belongs to its possessors in some sense by

nature; for from the very moment of birth we are just or fitted for

selfcontrol or brave or have the other moral qualities; but yet we seek

something else as that which is good in the strict sense-we seek for

the presence of such qualities in another way. For both children and

brutes have the natural dispositions to these qualities, but without

reason these are evidently hurtful. Only we seem to see this much,

that, while one may be led astray by them, as a strong body which moves

without sight may stumble badly because of its lack of sight, still, if

a man once acquires reason, that makes a difference in action; and his

state, while still like what it was, will then be virtue in the strict

sense. Therefore, as in the part of us which forms opinions there are

two types, cleverness and practical wisdom, so too in the moral part

there are two types, natural virtue and virtue in the strict sense, and

of these the latter involves practical wisdom. This is why some say

that all the virtues are forms of practical wisdom, and why Socrates in

one respect was on the right track while in another he went astray; in

thinking that all the virtues were forms of practical wisdom he was

wrong, but in saying they implied practical wisdom he was right. This

is confirmed by the fact that even now all men, when they define

virtue, after naming the state of character and its objects add 'that

(state) which is in accordance with the right rule'; now the right rule

is that which is in accordance with practical wisdom. All men, then,

seem somehow to divine that this kind of state is virtue, viz. that

which is in accordance with practical wisdom. But we must go a little

further. For it is not merely the state in accordance with the right

rule, but the state that implies the presence of the right rule, that

is virtue; and practical wisdom is a right rule about such matters.

Socrates, then, thought the virtues were rules or rational principles

(for he thought they were, all of them, forms of scientific knowledge),

while we think they involve a rational principle. |

したがって我々は徳についても改めて考察せねばならない。というのも徳 もまた同様の関係にあるからだ。実践的知恵が才覚に対してそうであるように―同一ではないが類似している―自然徳は厳密な意味での徳に対してそうである。 なぜなら、あらゆる人間は、あらゆる種類の性格が、ある意味で生まれつきその持ち主に備わっていると考えているからだ。つまり、生まれた瞬間から、我々は 正義であるとか、自制心があるとか、勇敢であるとか、その他の道徳的資質を持っているとか考えられている。しかし、我々は厳密な意味での善として、別の何 かを求めている。つまり、そのような資質が別の形で備わっていることを求めているのだ。子供も獣もこれらの資質の自然的素質は持っているが、理性を伴わな ければ明らかに有害である。ただ我々がこれだけは理解しているのは、それらが人を誤った方向に導く可能性があることだ。例えば視力のない強靭な身体が、視 力不足ゆえにひどく躓くように。しかし人間が一度理性を獲得すれば、それは行動に違いをもたらす。その状態は以前と似ているが、厳密な意味での徳となるの だ。したがって、我々の中に意見を形成する部分には、知性と実践的知恵という二種類があるように、道徳的部分にも自然徳と厳密な意味での徳という二種類が あり、後者は実践的知恵を伴うのである。これが、あらゆる徳は実践的知恵の形態であると言う者もいる所以であり、またソクラテスが一点では正しい道を歩 み、別の点では誤った道を歩んだ所以である。あらゆる徳が実践的知恵の形態であるという彼の考えは誤りだったが、徳が実践的知恵を包含すると言う点では正 しかった。このことは、今でも人々が徳を定義する際に、性格の状態とその対象を挙げた後で「正しい規範に合致する(状態)」と付け加える事実によって裏付 けられる。さて、正しい規範とは実践的知恵に合致するものである。したがって、人々は皆、この種の状態、すなわち実践的知恵に合致する状態こそが徳である と、何らかの形で直感しているようだ。しかし我々はもう少し踏み込まねばならない。なぜなら、単に正しい規則に合致する状態ではなく、正しい規則の存在を 内包する状態こそが徳だからだ。そして実践的知恵は、そうした事柄に関する正しい規則である。ソクラテスは徳を規則や理性的原理と考えていた(彼は徳をす べて科学的知識の形態と見なしていた)。一方、我々は徳が理性的原理を含むと考えている。 |

| It is clear, then, from what has

been said, that it is not possible to be good in the strict sense

without practical wisdom, nor practically wise without moral virtue.

But in this way we may also refute the dialectical argument whereby it

might be contended that the virtues exist in separation from each

other; the same man, it might be said, is not best equipped by nature

for all the virtues, so that he will have already acquired one when he

has not yet acquired another. This is possible in respect of the

natural virtues, but not in respect of those in respect of which a man

is called without qualification good; for with the presence of the one

quality, practical wisdom, will be given all the virtues. And it is

plain that, even if it were of no practical value, we should have

needed it because it is the virtue of the part of us in question; plain

too that the choice will not be right without practical wisdom any more

than without virtue; for the one deter, mines the end and the other

makes us do the things that lead to the end. But again it is not supreme over philosophic wisdom, i.e. over the superior part of us, any more than the art of medicine is over health; for it does not use it but provides for its coming into being; it issues orders, then, for its sake, but not to it. Further, to maintain its supremacy would be like saying that the art of politics rules the gods because it issues orders about all the affairs of the state. |

以上から明らかなように、厳密な意味での善は実践的知恵なしにはありえ

ず、また実践的知恵は道徳的徳なしにはありえない。しかしこの考え方は、徳が互いに分離して存在するという弁証法的議論に対しても反論となり得る。つま

り、同じ人間が全ての徳に対して生まれつき最も適しているわけではないため、ある徳を既に獲得している間に別の徳をまだ獲得していない、という主張に対し

て反論できるのだ。これは自然徳に関してはあり得るが、人が無条件に善いと呼ばれる徳に関してはあり得ない。なぜなら、実践的知恵という一つの徳があれ

ば、他のすべての徳も与えられるからだ。そして、たとえ実践的価値がなかったとしても、それが我々の人間性における当該部分の徳である以上、我々はそれを

必要としていたはずだ。また、実践的知恵なしに選択が正しくなるはずがないことも明らかである。それは、一方(実践的知恵)が目的を決定し、他方(徳)が

目的へと導く行為を行わせるからである。 しかし、それは哲学的知恵、すなわち我々の中の優れた部分に対して、医学が健康に対して優位にあるのと同じように、絶対的な優位性を持つわけではない。な ぜなら、それは哲学的知恵を利用するのでなく、その誕生を促すからだ。つまり、それは哲学的知恵のために命令を下すが、哲学的知恵に対して命令を下すので はない。さらに、その優位性を主張することは、政治術が国家のあらゆる事柄について命令を下すからといって、神々を支配すると言うようなものだ。 |

| http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099