Positivism

実証主義

Positivism

解説:池田光穂

西洋哲学において使われる、実証主義(英語: positivism)は経験的データ自体から確証されるあらゆるタイプの[説明や信条の]システムであり、それはア・プリオリ(先験的: a priori)あるいは形而上学的な推論を排除するような考え方にもとづいている。この用語は、フランスの哲学者(実証主義哲学者とも呼ばれる)オーギュ スト・コント(Auguste Comte (1798–1857))の用語に由来する。以下の説明は、ブリタニカ百科事典(英語オンライン版)の「実証主義(positivism)」 説明に対応している。

実証主義の哲学は、コントの著作に最初に 登場する。コントは社会学という述語の考案者でもあるが、体系的な社会学という科学そのものを指す言葉 でもある。その後、経験批判論(empiriocriticism)、論理実証主義(logical positivism)、論理的経験主義(logical empiricism)、分析哲学( analytic philosophy)などの用語で呼ばれるようにさまざまな立場に多様化した。

実証主義の2つのことを肯定的にとらえ る:(1)事実というものを認定するあらゆる知識は経験から得られる「実証」データに基礎づけられる。 (2)事実の領域を超えるものは、純粋論理(学)と純粋数学のそれである。この2つの考え方は、18世紀のスコットランドの経験論者と懐疑主義の(「観念 の連関(relations of ideas)」を説いた)ディビッド・ヒューム(David Hume, 1711-1776)により、すでに指摘されていた。

実証主義に対立する考え方が、形而上学に おける熟慮(repudiation of metaphysics)——どんな実証可能なものをも超える「超越論的」知恵は現実の本質を見抜く力があるとする立場や主張——である。そのため、実証 主義は、世界性を見ようとする態度、世俗的態度、反神学的態度、そして反形而上学的な態度をとるものとされている。実証主義に対する形而上学的立場を擁護 するものとしては、このように実証主義立場が理解できれば、それに反する考え方が可能なのは、我々が「形而上学的な熟慮」をすることが可能だからという論 法が、経験的あるいは思考実験上可能ではないかと反論することである。

他方、実証主義「実践」の特徴は、観察や 経験上における証拠や証言を求める態度である。それはこの主義=信条における命令語法 (imperative)にすらなっている。そのため、この態度により、実証主義者は倫理や道徳哲学を要請するという態度にも反映される。たとえば、道徳 哲学派のひとつの功利主義者(utilitarian)では、「最大の多数者のための最大幸福」ということが彼/彼女らの倫理的格率(ethical maxim)になっている。

コントは、宗教というものを一神教的信仰 の神格を崇拝するものではなく、その人間性を崇拝す べきだと主張した。

"The law is this: that each of

our leading conceptions – each branch of our knowledge – passes

successively through three different theoretical conditions: the

Theological, or fictitious; the Metaphysical, or abstract; and the

Scientific, or positive."— A. Comte, The Positive Philosophy of

Auguste Comte (trans. Harriet Martineau; London, 1853), Vol. I, p. 1.

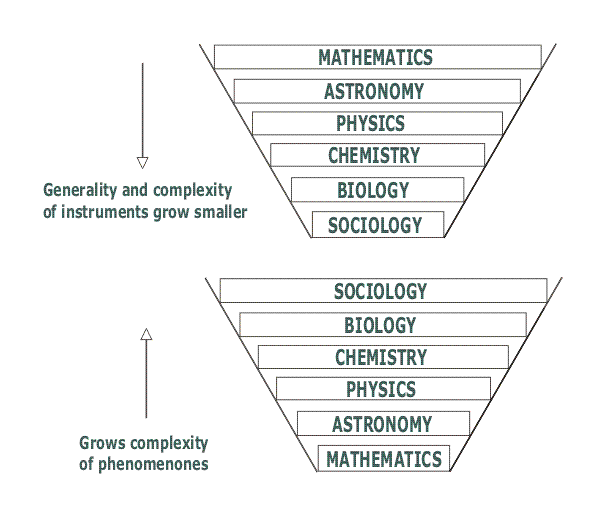

"Comte's Theory of Science – According to him whole of sciences consists of theoretical and applied knowledge. Theoretical knowledge divide on general fields as physics or biology, which are an object of his research and detailed such as botany, zoology or mineralogy. Main fields mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology and sociology it is possible to order according to decrescent range of research and complicatedness of theoretical tools what is connected with growing complexity of investigated phenomenones. Following sciences are based on previous, for example to methodically coll chemistry, we must imply acquaintance of physics, because all chemical phenomena are more complicated than physical phenomena, are also from them dependent and themselves do not have on them an influence. Similarly sciences classified as earlier, are older and more advanced from these which are presented as later." - Auguste Comte.

「コントの科学理論 -

彼によれば、科学全体は理論的知識と応用知識から成る。理論的知識は、物理学や生物学といった一般的な分野に分けられ、これらは彼の研究対象であり、植物

学、動物学、鉱物学など、より詳細な分野に分けられる。主な分野は数学、天文学、物理学、化学、生物学、社会学であり、研究対象の現象の複雑化に伴い、研

究範囲の減少と理論的ツールの複雑さに応じて分類することができる。例えば、系統的なコロイド化学を研究するには、物理の知識が必要である。なぜなら、化

学現象は物理現象よりも複雑であり、また、化学現象は物理現象に依存しているが、物理現象は化学現象に影響を与えないからである。同様に、先に分類された

科学は、後に分類されたものよりも古く、より高度である」。

| Positivism

is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is

either true by definition or positive – meaning a posteriori facts

derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.[1][2] Other ways

of knowing, such as intuition, introspection, or religious faith, are

rejected or considered meaningless. Although the positivist approach has been a recurrent theme in the history of western thought, modern positivism was first articulated in the early 19th century by Auguste Comte.[3][4] His school of sociological positivism holds that society, like the physical world, operates according to scientific laws.[5] After Comte, positivist schools arose in logic, psychology, economics, historiography, and other fields of thought. Generally, positivists attempted to introduce scientific methods to their respective fields. Since the turn of the 20th century, positivism, although still popular, has declined under criticism within the social sciences by antipositivists and critical theorists, among others, for its alleged scientism, reductionism, overgeneralizations, and methodological limitations. Positivism also exerted an unusual influence on Kardecism.[6][7][8] |

実証主義は、すべての真の知識は定義上真であるか、または実証的である

という哲学派である。実証的とは、感覚経験から理性と論理によって導き出されたア・ポステリオリな事実を意味する。[1][2]

直観、内省、または宗教的信仰といった他の認識方法は否定されるか、または無意味であるとみなされる。 実証主義のアプローチは西洋思想の歴史において繰り返し登場するテーマであったが、近代実証主義は19世紀初頭にオーギュスト・コントによって初めて明確 にされた。[3][4] 彼の社会学的実証主義学派は、社会は物理的世界と同様に科学的法則に従って機能していると主張している。[5] コント以降、実証主義学派は論理学、心理学、経済学、歴史学、その他の思想分野で登場した。一般的に、実証主義者はそれぞれの分野に科学的手法を導入しよ うとした。20世紀に入ると、実証主義は依然として人気を博していたものの、反実証主義者や批判理論家などによる社会科学分野での批判を受け、科学主義、 還元主義、一般化のしすぎ、方法論の限界などの理由で衰退した。実証主義は、カルデシズムにも大きな影響を与えた。[6][7][8] |

| Etymology The English noun positivism in this meaning was imported in the 19th century from the French word positivisme, derived from positif in its philosophical sense of 'imposed on the mind by experience'. The corresponding adjective (Latin: positivus) has been used in a similar sense to discuss law (positive law compared to natural law) since the time of Chaucer.[9] |

語源 この意味での英語の名詞「実証主義」は、19世紀にフランス語の「実証主義」から輸入された。これは、哲学的な意味での「経験によって心に植え付けられた もの」という「陽性」に由来する。対応する形容詞(ラテン語:陽性)は、チョーサーの時代から、法律を論じる際に同様の意味で使用されてきた(自然法に対 する「陽法」)。 |

| Background Kieran Egan argues that positivism can be traced to the philosophy side of what Plato described as the quarrel between philosophy and poetry, later reformulated by Wilhelm Dilthey as a quarrel between the natural sciences (German: Naturwissenschaften) and the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften).[10][11][12] In the early nineteenth century, massive advances in the natural sciences encouraged philosophers to apply scientific methods to other fields. Thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Pierre-Simon Laplace and Auguste Comte believed that the scientific method, the circular dependence of theory and observation, must replace metaphysics in the history of thought.[13] |

背景 キエラン・イーガンは、プラトンが「哲学と詩の論争」として描いたものの哲学的な側面を辿ると、実証主義に行き着くとし、後にヴィルヘルム・ディルタイが 自然科学(ドイツ語:Naturwissenschaften)と人文科学(ドイツ語:Geisteswissenschaften)の論争として再定義 したと主張している。[10][11][12] 19世紀初頭、自然科学の著しい進歩は、哲学者たちに科学的手法を他の分野にも応用することを促した。アンリ・ド・サン=シモン、ピエール=シモン・ラプ ラス、オーギュスト・コントなどの思想家たちは、科学的手法、すなわち理論と観察の循環的依存関係が、思想史における形而上学に取って代わるべきだと考え ていた。[13] |

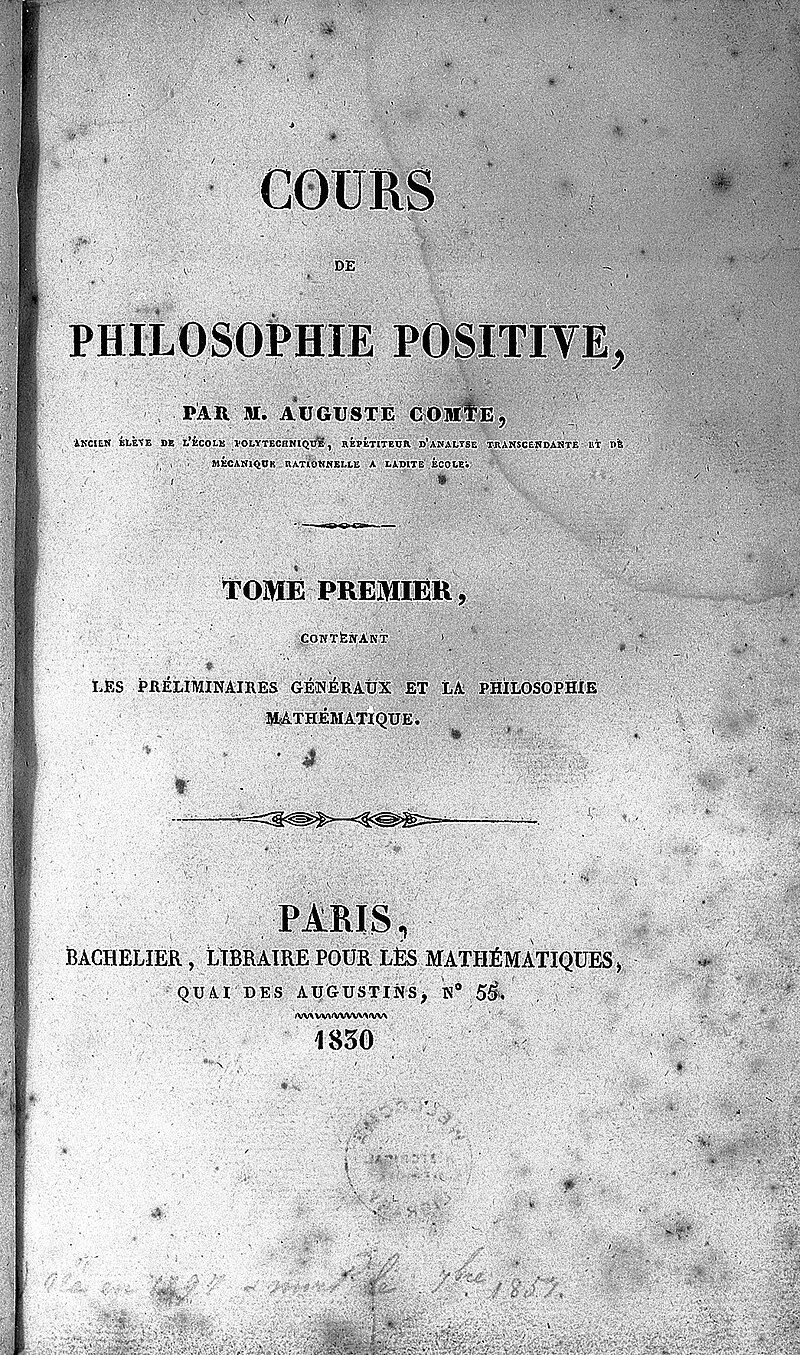

| Positivism in the social sciences Comte's positivism  Comte first laid out his theory of positivism in The Course in Positive Philosophy.  Auguste Comte (1798–1857) first described the epistemological perspective of positivism in The Course in Positive Philosophy, a series of texts published between 1830 and 1842. These texts were followed in 1844 by A General View of Positivism (published in French 1848, English in 1865). The first three volumes of the Course dealt chiefly with the physical sciences already in existence (mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology), whereas the latter two emphasized the inevitable coming of social science. Observing the circular dependence of theory and observation in science, and classifying the sciences in this way, Comte may be regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.[14][15] For him, the physical sciences had necessarily to arrive first, before humanity could adequately channel its efforts into the most challenging and complex "Queen science" of human society itself. His View of Positivism therefore set out to define the empirical goals of sociological method: The most important thing to determine was the natural order in which the sciences stand—not how they can be made to stand, but how they must stand, irrespective of the wishes of any one. ... This Comte accomplished by taking as the criterion of the position of each the degree of what he called "positivity," which is simply the degree to which the phenomena can be exactly determined. This, as may be readily seen, is also a measure of their relative complexity, since the exactness of a science is in inverse proportion to its complexity. The degree of exactness or positivity is, moreover, that to which it can be subjected to mathematical demonstration, and therefore mathematics, which is not itself a concrete science, is the general gauge by which the position of every science is to be determined. Generalizing thus, Comte found that there were five great groups of phenomena of equal classificatory value but of successively decreasing positivity. To these he gave the names astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, and sociology. — Lester F. Ward, The Outlines of Sociology (1898), [16] Comte offered an account of social evolution, proposing that society undergoes three phases in its quest for the truth according to a general "law of three stages". Comte intended to develop a secular-scientific ideology in the wake of European secularisation. Comte's stages were (1) the theological, (2) the metaphysical, and (3) the positive.[17] The theological phase of man was based on whole-hearted belief in all things with reference to God. God, Comte says, had reigned supreme over human existence pre-Enlightenment. Humanity's place in society was governed by its association with the divine presences and with the church. The theological phase deals with humankind's accepting the doctrines of the church (or place of worship) rather than relying on its rational powers to explore basic questions about existence. It dealt with the restrictions put in place by the religious organization at the time and the total acceptance of any "fact" adduced for society to believe.[18] Comte describes the metaphysical phase of humanity as the time since the Enlightenment, a time steeped in logical rationalism, to the time right after the French Revolution. This second phase states that the universal rights of humanity are most important. The central idea is that humanity is invested with certain rights that must be respected. In this phase, democracies and dictators rose and fell in attempts to maintain the innate rights of humanity.[19] The final stage of the trilogy of Comte's universal law is the scientific, or positive, stage. The central idea of this phase is that individual rights are more important than the rule of any one person. Comte stated that the idea of humanity's ability to govern itself makes this stage inherently different from the rest. There is no higher power governing the masses and the intrigue of any one person can achieve anything based on that individual's free will. The third principle is most important in the positive stage.[20] Comte calls these three phases the universal rule in relation to society and its development. Neither the second nor the third phase can be reached without the completion and understanding of the preceding stage. All stages must be completed in progress.[21] Comte believed that the appreciation of the past and the ability to build on it towards the future was key in transitioning from the theological and metaphysical phases. The idea of progress was central to Comte's new science, sociology. Sociology would "lead to the historical consideration of every science" because "the history of one science, including pure political history, would make no sense unless it was attached to the study of the general progress of all of humanity".[22] As Comte would say: "from science comes prediction; from prediction comes action".[23] It is a philosophy of human intellectual development that culminated in science. The irony of this series of phases is that though Comte attempted to prove that human development has to go through these three stages, it seems that the positivist stage is far from becoming a realization. This is due to two truths: The positivist phase requires having a complete understanding of the universe and world around us and requires that society should never know if it is in this positivist phase. Anthony Giddens argues that since humanity constantly uses science to discover and research new things, humanity never progresses beyond the second metaphysical phase.[21] |

社会科学における実証主義 コントの実証主義  コントは、著書『ポジティブ(実証)哲学講座』において、初めて実証主義の理論を提示した。  オーギュスト・コント(1798年~1857年)は、1830年から1842年の間に出版された一連の著作『ポジティブ哲学講座』において、実証主義の認 識論的観点について初めて説明した。これらの著作に続き、1844年に『一般の観念論』(フランス語版1848年、英語版1865年)が出版された。 『コース』の最初の3巻では、すでに存在していた自然科学(数学、天文学、物理学、化学、生物学)が主に扱われていたが、後の2巻では社会科学の到来が不 可避であることが強調された。科学における理論と観察の循環的依存関係を観察し、科学をこのように分類したことで、コントは近代的な意味での科学哲学の最 初の哲学者とみなされるかもしれない。[14][15] 彼にとって、人類がその努力を人類社会そのものにおける最も挑戦的で複雑な「女王科学」に適切に注ぐ前に、必然的に自然科学がまず最初に到達しなければな らなかった。したがって、彼の実証主義の考え方は、社会学的方法の実証的な目標を定義することから始まった。 最も重要なのは、科学がどのような位置づけにあるかという自然の秩序を決定することであり、それをどのように位置づけるかではなく、誰の希望に関係なく、 科学はどのように位置づけられるべきかということである。... このコントは、各々の位置づけの基準として、彼が「実証性」と呼ぶものの度合いを採択することでこれを達成した。これは、単に現象が正確に決定される度合 いである。これは、容易に理解できるとおり、それぞれの相対的な複雑さの尺度でもある。科学の厳密性はその複雑さと反比例するからだ。厳密性または確実性 の度合いは、さらに、数学的証明に耐えうるものである。したがって、数学はそれ自体が具体的な科学ではないが、あらゆる科学の地位を決定する一般的な尺度 となる。このように一般化して、コンテは、等しい分類上の価値を持つが、徐々に正の値が減少する5つの大きな現象群を見出した。これらの現象群に、天文 学、物理学、化学、生物学、社会学という名称を与えた。 — レスター・F・ウォード、『社会学概論』(1898年)、[16] コントは社会進化論を提示し、社会は真理を追求する過程で「三段階の法則」に従って3つの段階を経ると提唱した。コントはヨーロッパの世俗化の流れを受け、世俗的かつ科学的なイデオロギーを展開しようとした。 コントの段階は、(1)神学、(2)形而上学、(3)実証主義の3つである。[17] 人間の神学段階は、神を基準としたあらゆるものへの心からの信仰に基づいている。コントによると、啓蒙主義以前は神が人間の存在を支配していた。社会にお ける人類の地位は、神の存在や教会との関連によって規定されていた。神学の段階では、人間は、存在に関する基本的な疑問を理性的な力で探求するのではな く、教会(または礼拝所)の教義を受け入れる。それは、当時の宗教組織によって定められた制限と、社会が信じるように提示された「事実」を全面的に受け入 れることを扱っている。[18] コントは、啓蒙思想の時代からフランス革命直後の時代までを、人類の形而上学的段階と表現している。この第二段階では、人類の普遍的な権利が最も重要であ るとされている。その中心となる考え方は、人類には尊重されるべき一定の権利が与えられているというものである。この段階では、人類に生まれつき備わって いる権利を維持しようとする試みの中で、民主主義と独裁が興亡を繰り返した。 コンテの普遍的法則三部作の最終段階は、科学的、または実証的な段階である。この段階の中心となる考え方は、個人の権利は特定の人物による支配よりも重要 であるというものである。コンテは、人類が自らを統治する能力を持つという考え方が、この段階を本質的に他の段階と異なるものにしていると述べている。大 衆を統治するより高い権力はなく、特定の人物の陰謀は、その個人の自由意志に基づいて何でも達成できる。第3の原則は、肯定段階において最も重要である。 [20] コントは、社会とその発展に関する普遍的な規則として、これら3つの段階を呼んでいる。第2段階も第3段階も、先行する段階の完成と理解なしには到達でき ない。すべての段階は、進行中に完了しなければならない。[21] コントは、過去を評価し、それを基盤として未来を築く能力が、神学と形而上学の段階から移行する鍵であると考えていた。進歩という考え方は、コントの新し い科学である社会学の中心的なものであった。社会学は「あらゆる科学の歴史的考察につながる」ものであり、なぜなら「純粋な政治史を含む一つの科学の歴史 は、全人類の一般的な進歩の研究と結びついていなければ意味を持たない」からである。[22] コントが言うように、 「科学から予測が生まれ、予測から行動が生まれる」[23]のである。これは、科学に集約される人間の知的発展の哲学である。この一連の段階の皮肉な点 は、コンテが人間の成長はこれらの3つの段階を経なければならないと証明しようとしたにもかかわらず、実証主義の段階が実現されるにはほど遠いということ である。その理由は2つの真実による。すなわち、実証主義の段階では、私たちを取り巻く宇宙と世界の完全な理解が必要であり、社会がこの実証主義の段階に あることを決して知られてはならない。アンソニー・ギデンズは、人類は常に科学を利用して新しいものを発見し研究しているため、人類は第2の形而上学的段 階から決して進歩しないと主張している。[21] |

Positivist temple in Porto Alegre, Brazil Comte's fame today owes in part to Emile Littré, who founded The Positivist Review in 1867. As an approach to the philosophy of history, positivism was appropriated by historians such as Hippolyte Taine. Many of Comte's writings were translated into English by the Whig writer, Harriet Martineau, regarded by some as the first female sociologist. Debates continue to rage as to how much Comte appropriated from the work of his mentor, Saint-Simon.[24] He was nevertheless influential: Brazilian thinkers turned to Comte's ideas about training a scientific elite in order to flourish in the industrialization process. Brazil's national motto, Ordem e Progresso ("Order and Progress") was taken from the positivism motto, "Love as principle, order as the basis, progress as the goal", which was also influential in Poland.[citation needed] In later life, Comte developed a 'religion of humanity' for positivist societies in order to fulfil the cohesive function once held by traditional worship. In 1849, he proposed a calendar reform called the 'positivist calendar'. For close associate John Stuart Mill, it was possible to distinguish between a "good Comte" (the author of the Course in Positive Philosophy) and a "bad Comte" (the author of the secular-religious system).[14] The system was unsuccessful but met with the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species to influence the proliferation of various secular humanist organizations in the 19th century, especially through the work of secularists such as George Holyoake and Richard Congreve. Although Comte's English followers, including George Eliot and Harriet Martineau, for the most part rejected the full gloomy panoply of his system, they liked the idea of a religion of humanity and his injunction to "vivre pour autrui" ("live for others", from which comes the word "altruism").[25] The early sociology of Herbert Spencer came about broadly as a reaction to Comte; writing after various developments in evolutionary biology, Spencer attempted (in vain) to reformulate the discipline in what we might now describe as socially Darwinistic terms.[citation needed] |

ブラジルのポルト・アレグレにある実証主義の寺院 今日、コントの名声は、1867年に『実証主義評論』を創刊したエミール・リトレに負うところもある。歴史哲学へのアプローチとして、実証主義は、例え ば、テーヌなどの歴史家によって採用された。コンテの著作の多くは、ホイッグ党の作家で、一部では初の女性社会学者とされるハリエット・マーティノーに よって英語に翻訳された。コンテが師であるサン=シモンの著作からどの程度影響を受けたかについては、現在も激しい論争が続いている。[24] しかし、コンテは大きな影響力を持ち、ブラジルの思想家たちは、工業化プロセスで繁栄するために科学エリートを育成するというコンテの考えに注目した。ブ ラジルの国民的標語「秩序と進歩(Ordem e Progresso)」は、実証主義の標語「愛を原則とし、秩序を基礎とし、進歩を目的とする」から取られたもので、この標語はポーランドでも影響力を 持っていた。 晩年、コントは伝統的な崇拝がかつて担っていた結束の機能を果たすべく、実証主義社会のための「人道の宗教」を打ち立てた。1849年には「実証主義暦」 と呼ばれる暦の改革を提案した。親しい協力者ジョン・スチュアート・ミルにとって、「善良なコント」(『ポジティブ哲学講座』の著者)と「邪悪なコント」 ( (世俗宗教体系の著者)であった。[14] この体系は成功しなかったが、19世紀にダーウィンの『種の起源』が出版されたことにより、特にジョージ・ホリオークやリチャード・コングリーヴといった 世俗主義者の活動を通じて、さまざまな世俗ヒューマニズム団体の拡大に影響を与えた。ジョージ・エリオットやハリエット・マーティノーを含む、コンテのイ ギリス人信奉者の多くは、彼の体系の陰鬱な要素のすべてを拒絶したが、彼らは「他者のために生きよ」(「利他主義」の語源となった言葉)という、人間性の 宗教という考えと彼の教えを好んだ。 ハーバート・スペンサーの初期の社会学は、概ねコントへの反動として生まれた。進化生物学におけるさまざまな発展を経て執筆されたスペンサーの著作は、今で言うところの社会ダーウィニズムの用語で学問を再定義しようとしたが(残念ながら)失敗に終わった。[要出典] |

| Early followers of Comte Within a few years, other scientific and philosophical thinkers began creating their own definitions for positivism. These included Émile Zola, Emile Hennequin, Wilhelm Scherer, and Dimitri Pisarev. Fabien Magnin was the first working-class adherent to Comte's ideas, and became the leader of a movement known as "Proletarian Positivism". Comte appointed Magnin as his successor as president of the Positive Society in the event of Comte's death. Magnin filled this role from 1857 to 1880, when he resigned.[26] Magnin was in touch with the English positivists Richard Congreve and Edward Spencer Beesly. He established the Cercle des prolétaires positivistes in 1863 which was affiliated to the First International. Eugène Sémérie was a psychiatrist who was also involved in the Positivist movement, setting up a positivist club in Paris after the foundation of the French Third Republic in 1870. He wrote: "Positivism is not only a philosophical doctrine, it is also a political party which claims to reconcile order—the necessary basis for all social activity—with Progress, which is its goal."[27] |

コントの初期の信奉者 数年以内に、他の科学者や哲学者たちも、それぞれ独自の定義で実証主義を打ち立て始めた。その中には、エミール・ゾラ、エミール・アンネケン、ヴィルヘル ム・シェラー、ディミトリ・ピサレフなどがいた。ファビアン・マグナンは、コントの思想を支持した最初の労働者階級の信奉者であり、「プロレタリア実証主 義」として知られる運動の指導者となった。コントは、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表か ら10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表か ら10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表か ら10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力の法則の発表から10年後に、万有引力 ウジェーヌ・セミエは、1870年のフランス第三共和制樹立後にパリで実証主義クラブを設立した精神科医であり、実証主義運動にも関与していた。彼は「実 証主義は単なる哲学上の教義ではなく、社会活動のすべての必要条件である秩序と進歩を調和させることを主張する政党でもある。それがその目標である」と書 いている。[27] |

| Durkheim's positivism Émile Durkheim The modern academic discipline of sociology began with the work of Émile Durkheim (1858–1917). While Durkheim rejected much of the details of Comte's philosophy, he retained and refined its method, maintaining that the social sciences are a logical continuation of the natural ones into the realm of human activity, and insisting that they may retain the same objectivity, rationalism, and approach to causality.[28] Durkheim set up the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method (1895).[29] In this text he argued: "[o]ur main goal is to extend scientific rationalism to human conduct... What has been called our positivism is but a consequence of this rationalism."[16] Durkheim's seminal monograph, Suicide (1897), a case study of suicide rates amongst Catholic and Protestant populations, distinguished sociological analysis from psychology or philosophy.[30] By carefully examining suicide statistics in different police districts, he attempted to demonstrate that Catholic communities have a lower suicide rate than Protestants, something he attributed to social (as opposed to individual or psychological) causes. He developed the notion of objective sui generis "social facts" to delineate a unique empirical object for the science of sociology to study.[28] Through such studies, he posited, sociology would be able to determine whether a given society is 'healthy' or 'pathological', and seek social reform to negate organic breakdown or "social anomie". Durkheim described sociology as the "science of institutions, their genesis and their functioning".[31] David Ashley and David M. Orenstein have alleged, in a consumer textbook published by Pearson Education, that accounts of Durkheim's positivism are possibly exaggerated and oversimplified; Comte was the only major sociological thinker to postulate that the social realm may be subject to scientific analysis in exactly the same way as natural science, whereas Durkheim saw a far greater need for a distinctly sociological scientific methodology. His lifework was fundamental in the establishment of practical social research as we know it today—techniques which continue beyond sociology and form the methodological basis of other social sciences, such as political science, as well of market research and other fields.[32] |

デュルケムのポシティブ主義 エミール・デュルケム 社会学という近代的な学問分野は、エミール・デュルケム(1858年~1917年)の研究から始まった。デュルケムは、コンテの哲学の細部の多くを否定し たが、その方法論は維持し、改良を加えた。デュルケムは、社会科学は自然界の論理的延長として人間の活動領域に存在するものであり、自然科学と同じ客観 性、合理主義、因果関係へのアプローチを維持できると主張した。 [28] デュルケムは1895年にボルドー大学にヨーロッパ初の社会学講座を開設し、『社会学的方法の規準』(1895年)を出版した。[29] この著作で彼は次のように論じている。「私たちの主な目標は、人間の行動に科学的合理主義を適用することである。私たちの実証主義と呼ばれるものは、この 合理主義の結果にすぎない。」[16] デュルケムの画期的な単行本『自殺論』(1897年)は、カトリック教徒とプロテスタント教徒の自殺率に関する事例研究であり、心理学や哲学とは一線を画 する社会学的な分析を行っている。[30] 彼は、異なる警察管区における自殺統計を慎重に調査することで、カトリック教徒のコミュニティはプロテスタント教徒よりも自殺率が低いことを証明しようと した。彼は、その原因を社会的(個人や心理とは対照的な)要因に帰した。彼は、社会学という科学が研究する独自の経験的対象を明確にするために、客観的な 独自の「社会的事実」という概念を展開した。[28] このような研究を通じて、社会学は、ある社会が「健全」であるか「病理的」であるかを判断し、有機的な機能不全や「社会的アノミー」を否定するための社会 改革を求めることができると、彼は主張した。デュルケムは社会学を「制度、その起源、その機能に関する科学」と表現した。[31] デビッド・アシュレイとデビッド・M・オレンスタインは、ピアソン・エデュケーションが出版した消費者向け教科書の中で、デュルケムの実証主義に関する記 述は誇張され、単純化されすぎている可能性があると主張している。コンテは、社会領域が自然科学とまったく同じ方法で科学的分析の対象となりうることを仮 定した唯一の主要な社会学者であったが、デュルケムは、はるかに明確な社会科学的科学的手法の必要性を認識していた。彼のライフワークは、今日私たちが知 るような実用的な社会調査の確立に不可欠であった。その手法は社会学の領域を超えて、政治学などの他の社会科学の方法論的基礎を形成し、市場調査やその他 の分野にも影響を与えている。[32] |

| Historical positivism In historiography, historical or documentary positivism is the belief that historians should pursue the objective truth of the past by allowing historical sources to "speak for themselves", without additional interpretation.[33][34] In the words of the French historian Fustel de Coulanges, as a positivist, "It is not I who am speaking, but history itself". The heavy emphasis placed by historical positivists on documentary sources led to the development of methods of source criticism, which seek to expunge bias and uncover original sources in their pristine state.[33] The origin of the historical positivist school is particularly associated with the 19th-century German historian Leopold von Ranke, who argued that the historian should seek to describe historical truth "wie es eigentlich gewesen ist" ("as it actually was")—though subsequent historians of the concept, such as Georg Iggers, have argued that its development owed more to Ranke's followers than Ranke himself.[35] Historical positivism was critiqued in the 20th century by historians and philosophers of history from various schools of thought, including Ernst Kantorowicz in Weimar Germany—who argued that "positivism ... faces the danger of becoming Romantic when it maintains that it is possible to find the Blue Flower of truth without preconceptions"—and Raymond Aron and Michel Foucault in postwar France, who both posited that interpretations are always ultimately multiple and there is no final objective truth to recover.[36][34][37] In his posthumously published 1946 The Idea of History, the English historian R. G. Collingwood criticized historical positivism for conflating scientific facts with historical facts, which are always inferred and cannot be confirmed by repetition, and argued that its focus on the "collection of facts" had given historians "unprecedented mastery over small-scale problems", but "unprecedented weakness in dealing with large-scale problems".[38] Historicist arguments against positivist approaches in historiography include that history differs from sciences like physics and ethology in subject matter and method;[39][40][41] that much of what history studies is nonquantifiable, and therefore to quantify is to lose in precision; and that experimental methods and mathematical models do not generally apply to history, so that it is not possible to formulate general (quasi-absolute) laws in history.[41] |

歴史的実証主義 歴史学において、歴史的または文書的実証主義とは、歴史家は過去の客観的な真実を追求すべきであり、歴史資料を「それ自身で語らせる」ことで、追加の解釈 をせずに済むという信念である。[33][34] フランスの歴史家フュステル・ド・クーランジュの言葉によれば、実証主義者として、「語るのは私ではなく、歴史そのものである」という。歴史実証主義者が 史料に重きを置いたことにより、史料批判の方法が発展し、偏見を排除し、原初の状態で原典を明らかにしようとするようになった。 歴史的実証主義学派の起源は、特に19世紀のドイツの歴史家レオポルト・フォン・ランケと関連付けられている。ランケは、歴史家は「実際のありのままの姿 (wie es eigentlich gewesen ist)」としての歴史的真実を記述すべきであると主張した。しかし、その後の歴史家、例えばゲオルク・イッガースなどは、この概念の発展はランケ自身と いうよりも、むしろランケの信奉者たちによるものだと主張している。 歴史的実証主義は、20世紀には、ワイマール・ドイツのエルンスト・カントロヴィッツをはじめとするさまざまな学派の歴史家や歴史哲学者たちによって批判 された。カントロヴィッツは、「実証主義は... 先入観なしに真実の青い花を見つけることが可能であると主張する」ロマン主義の危険性があると論じた。また、戦後のフランスでは、レイモン・アロンとミ シェル・フーコーの両者が、解釈は常に最終的には複数であり、回復すべき最終的な客観的真理は存在しないと主張した。[36][34][37] 1946年に死後出版された『歴史の理念』において、イギリスの歴史家R. G. コリングウッドは、科学的事実と歴史的事実を混同しているとして歴史的実証主義を批判し、歴史的事実の「収集」に重点を置くことで、歴史家は「小規模な問 題に対してはかつてないほどの精通度を得た」が、「大規模な問題に対処する上ではかつてないほどの弱点を抱える」ようになったと論じた。[38] 歴史学における実証主義的アプローチに対する歴史主義者の主張には、歴史学は物理学や動物行動学のような科学とは主題や方法において異なるというもの [39][40][41]、歴史学が研究するものの多くは非数量化可能であり、したがって数量化することは正確性を失うことであるというもの、実験的手法 や数学的モデルは一般的に歴史には適用できないため、歴史において一般的な(準絶対的な)法則を定式化することは不可能であるというものがある[41]。 |

| Other subfields In psychology the positivist movement was influential in the development of operationalism. The 1927 philosophy of science book The Logic of Modern Physics in particular, which was originally intended for physicists, coined the term operational definition, which went on to dominate psychological method for the whole century.[42] In economics, practicing researchers tend to emulate the methodological assumptions of classical positivism, but only in a de facto fashion: the majority of economists do not explicitly concern themselves with matters of epistemology.[43] Economic thinker Friedrich Hayek (see "Law, Legislation and Liberty") rejected positivism in the social sciences as hopelessly limited in comparison to evolved and divided knowledge. For example, much (positivist) legislation falls short in contrast to pre-literate or incompletely defined common or evolved law. In jurisprudence, "legal positivism" essentially refers to the rejection of natural law; thus its common meaning with philosophical positivism is somewhat attenuated and in recent generations generally emphasizes the authority of human political structures as opposed to a "scientific" view of law. |

その他のサブフィールド 心理学では、実証主義運動は操作主義の発展に影響を与えた。特に、もともとは物理学者を対象として書かれた1927年の科学哲学書『近代物理学の論理』では、操作上の定義という用語が作られ、それが20世紀を通じて心理学的手法を支配することとなった。 経済学では、実務家の研究者は古典的実証主義の方法論的仮定を模倣する傾向にあるが、それはあくまで事実上の方法論である。大多数の経済学者は、認識論の 問題を明確に意識することはない。経済学者フリードリヒ・ハイエク(「法、立法と自由」を参照)は、社会科学における実証主義は、発展し、細分化された知 識と比較すると、絶望的に限定的であるとして否定した。例えば、多くの(実証主義の)立法は、文字が発明される以前の慣習法や不完全に定義された一般法や 発展法と比較すると見劣りする。 法学において、「法実証主義」は本質的には自然法の拒絶を意味する。したがって、哲学における実証主義との共通の意味合いはやや薄れ、最近の世代では一般的に「科学的」な法観とは対照的に、人間の政治構造の権威を強調する傾向にある。 |

| Logical positivism Main article: Logical positivism  Moritz Schlick, the founding father of logical positivism and the Vienna Circle Logical positivism (later and more accurately called logical empiricism) is a school of philosophy that combines empiricism, the idea that observational evidence is indispensable for knowledge of the world, with a version of rationalism, the idea that our knowledge includes a component that is not derived from observation. Logical positivism grew from the discussions of a group called the "First Vienna Circle", which gathered at the Café Central before World War I. After the war Hans Hahn, a member of that early group, helped bring Moritz Schlick to Vienna. Schlick's Vienna Circle, along with Hans Reichenbach's Berlin Circle, propagated the new doctrines more widely in the 1920s and early 1930s. It was Otto Neurath's advocacy that made the movement self-conscious and more widely known. A 1929 pamphlet written by Neurath, Hahn, and Rudolf Carnap summarized the doctrines of the Vienna Circle at that time. These included the opposition to all metaphysics, especially ontology and synthetic a priori propositions; the rejection of metaphysics not as wrong but as meaningless (i.e., not empirically verifiable); a criterion of meaning based on Ludwig Wittgenstein's early work (which he himself later set out to refute); the idea that all knowledge should be codifiable in a single standard language of science; and above all the project of "rational reconstruction," in which ordinary-language concepts were gradually to be replaced by more precise equivalents in that standard language. However, the project is widely considered to have failed.[44][45] After moving to the United States, Carnap proposed a replacement for the earlier doctrines in his Logical Syntax of Language. This change of direction, and the somewhat differing beliefs of Reichenbach and others, led to a consensus that the English name for the shared doctrinal platform, in its American exile from the late 1930s, should be "logical empiricism."[citation needed] While the logical positivist movement is now considered dead, it has continued to influence philosophical development.[46] |

論理実証主義 詳細は「論理実証主義」を参照  論理実証主義の創始者でありウィーン学団の中心人物であったモーリッツ・シュリック 論理実証主義(のちにより正確には論理経験主義と呼ばれる)は、経験論(観察による証拠は世界の知識に不可欠であるという考え)と合理主義(我々の知識には観察から得られない要素が含まれるという考え)を組み合わせた哲学の一派である。 論理実証主義は、第一次世界大戦前にウィーンのカフェ・セントラルに集まった「ウィーン学団」と呼ばれるグループの議論から発展した。大戦後、初期のグ ループのメンバーであったハンス・ハーンがモリッツ・シュリックをウィーンに招いた。シュリックのウィーン学団は、ハンス・ライヘンバッハのベルリン学団 とともに、1920年代から1930年代初頭にかけて、この新しい学説を広めた。 この運動を意識的にし、より広く知らしめたのはオットー・ノイラートの提唱であった。1929年にノイラート、ハーン、ルドルフ・カルナップが執筆したパ ンフレットは、当時のウィーン学派の教義を要約したものである。これには、形而上学全般、特に存在論や総合的ア・プリオリ命題への反対、形而上学を誤りと してではなく無意味(すなわち、経験的に検証できない)として否定すること、ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの初期の研究(後に彼自身が反論しようと したもの)に基づく意味の基準、すべての知識は科学の単一の標準言語でコード化できるという考え、そして何よりも「合理的再構成」というプロジェクトが含 まれていた。そのプロジェクトでは、日常言語の概念を徐々にその標準言語におけるより精密な同義語に置き換えることを目指していた。しかし、このプロジェ クトは広く失敗したと考えられている。[44][45] アメリカ合衆国に移住した後、カーナップは『言語の論理統語論』において、それ以前の学説に代わるものを提案した。この方向転換と、ライヘンバッハやその 他の人々の信念がやや異なっていたことが、1930年代後半にアメリカに亡命した後の共通の教義的プラットフォームの英語名を「論理経験論」とすべきだと いうコンセンサスにつながった。論理実証主義運動は現在では死んだと考えられているが、哲学の発展に影響を与え続けている。 |

| Criticism Historically, positivism has been criticized for its reductionism, i.e., for contending that all "processes are reducible to physiological, physical or chemical events," "social processes are reducible to relationships between and actions of individuals," and that "biological organisms are reducible to physical systems."[47] The consideration that laws in physics may not be absolute but relative, and, if so, this might be even more true of social sciences, was stated, in different terms, by G. B. Vico in 1725.[40][48] Vico, in contrast to the positivist movement, asserted the superiority of the science of the human mind (the humanities, in other words), on the grounds that natural sciences tell us nothing about the inward aspects of things.[49] Wilhelm Dilthey fought strenuously against the assumption that only explanations derived from science are valid.[12] He reprised Vico's argument that scientific explanations do not reach the inner nature of phenomena[12] and it is humanistic knowledge that gives us insight into thoughts, feelings and desires.[12] Dilthey was in part influenced by the historism of Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886).[12] The contesting views over positivism are reflected both in older debates (see the Positivism dispute) and current ones over the proper role of science in the public sphere. Public sociology—especially as described by Michael Burawoy—argues that sociologists should use empirical evidence to display the problems of society so they might be changed.[50] |

批判 歴史的に、実証主義は還元主義であると批判されてきた。すなわち、「すべてのプロセスは生理学的、物理学的、あるいは化学的現象に還元できる」、「社会的 プロセスは個人間の関係や個人の行動に還元できる」、「生物学的有機体は物理システムに還元できる」と主張していることに対してである。[47] 物理学における法則は絶対的なものではなく相対的なものであり、もしそうであるならば、社会科学においてはさらにその傾向が強いという考え方は、異なる表 現ではあるが、1725年にG. B. ヴィーコは1725年に、異なる表現を用いて同じことを述べている。[40][48] ヴィーコは実証主義の動きとは対照的に、自然科学は物事の内面的側面について何も語らないという理由から、人間の精神の科学(言い換えれば人文科学)の優 位性を主張した。[49] ヴィルヘルム・ディルタイは、科学から導き出された説明のみが有効であるという前提に強く反対した。[12] 彼は、ヴィーコの主張を再び取り上げ、科学的な説明は現象の内なる本質には到達しない[12]とし、思考、感情、欲望に対する洞察力を与えるのは人文科学 的な知識であると主張した。[12] ディルタイは、レオポルト・フォン・ランケ(1795年~1886年)の歴史主義に影響を受けた部分もある。[12] 実証主義に対する見解の相違は、過去の論争(実証主義論争を参照)と公共の場における科学の適切な役割に関する現在の論争の両方に反映されている。公共社 会学(特にマイケル・ブラヴォイによるもの)は、社会学者は経験的証拠を用いて社会の問題を明らかにし、それらを変化させるべきであると主張している。 [50] |

| Antipositivism Main article: Antipositivism At the turn of the 20th century, the first wave of German sociologists formally introduced methodological antipositivism, proposing that research should concentrate on human cultural norms, values, symbols, and social processes viewed from a subjective perspective. Max Weber, one such thinker, argued that while sociology may be loosely described as a 'science' because it is able to identify causal relationships (especially among ideal types), sociologists should seek relationships that are not as "ahistorical, invariant, or generalizable" as those pursued by natural scientists.[51][52] Weber regarded sociology as the study of social action, using critical analysis and verstehen techniques. The sociologists Georg Simmel, Ferdinand Tönnies, George Herbert Mead, and Charles Cooley were also influential in the development of sociological antipositivism, whilst neo-Kantian philosophy, hermeneutics, and phenomenology facilitated the movement in general. |

反実証主義 詳細は「反実証主義」を参照 20世紀の変わり目に、ドイツの社会学者たちが方法論としての反実証主義を初めて正式に導入し、研究は主観的な視点から見た人間の文化的規範、価値、象 徴、社会的プロセスに集中すべきであると提唱した。マックス・ウェーバーもそうした思想家の一人であり、社会学は因果関係(特に理想型間の因果関係)を特 定できるため、大まかに「科学」と表現できるかもしれないが、自然科学研究者が追求するような「非歴史的、不変的、一般化可能」な関係ではないものを、社 会学者は追求すべきであると主張した。[51][52] ウェーバーは社会学を社会行動の研究と見なし、批判的分析と理解の技法を用いた。社会学者のゲオルク・ジンメル、フェルディナント・トニース、ジョージ・ ハーバート・ミード、チャールズ・クーリーも、反実証主義的社会学の発展に影響を与えた。一方で、新カント哲学、解釈学、現象学は、社会学の反実証主義の 動きを促進した。 |

| Critical rationalism and postpositivism Main articles: Postpositivism and Critical rationalism In the mid-twentieth century, several important philosophers and philosophers of science began to critique the foundations of logical positivism. In his 1934 work The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Karl Popper argued against verificationism. A statement such as "all swans are white" cannot actually be empirically verified, because it is impossible to know empirically whether all swans have been observed. Instead, Popper argued that at best an observation can falsify a statement (for example, observing a black swan would prove that not all swans are white).[53] Popper also held that scientific theories talk about how the world really is (not about phenomena or observations experienced by scientists), and critiqued the Vienna Circle in his Conjectures and Refutations.[54][55] W. V. O. Quine and Pierre Duhem went even further. The Duhem–Quine thesis states that it is impossible to experimentally test a scientific hypothesis in isolation, because an empirical test of the hypothesis requires one or more background assumptions (also called auxiliary assumptions or auxiliary hypotheses); thus, unambiguous scientific falsifications are also impossible.[56] Thomas Kuhn, in his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, put forward his theory of paradigm shifts. He argued that it is not simply individual theories but whole worldviews that must occasionally shift in response to evidence.[57][53] Together, these ideas led to the development of critical rationalism and postpositivism.[58] Postpositivism is not a rejection of the scientific method, but rather a reformation of positivism to meet these critiques. It reintroduces the basic assumptions of positivism: the possibility and desirability of objective truth, and the use of experimental methodology. Postpositivism of this type is described in social science guides to research methods.[59] Postpositivists argue that theories, hypotheses, background knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed.[60] Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases.[60][53][61] While positivists emphasize quantitative methods, postpositivists consider both quantitative and qualitative methods to be valid approaches.[61] In the early 1960s, the positivism dispute arose between the critical theorists (see below) and the critical rationalists over the correct solution to the value judgment dispute (Werturteilsstreit). While both sides accepted that sociology cannot avoid a value judgement that inevitably influences subsequent conclusions, the critical theorists accused the critical rationalists of being positivists; specifically, of asserting that empirical questions can be severed from their metaphysical heritage and refusing to ask questions that cannot be answered with scientific methods. This contributed to what Karl Popper termed the "Popper Legend", a misconception among critics and admirers of Popper that he was, or identified himself as, a positivist.[62] |

批判的合理主義とポスト実証主義 主な記事:ポスト実証主義と批判的合理主義 20世紀半ば、いくつかの重要な哲学および科学哲学の分野において、論理実証主義の基礎を批判する動きが始まった。カール・ポパーは1934年の著書『科 学発見の論理』において、検証主義に反対する主張を行った。「すべての白鳥は白い」というような主張は、実際には経験的に検証することはできない。なぜな ら、すべての白鳥が観察されたかどうかを経験的に知ることは不可能だからである。その代わり、ポパーは、観察によってせいぜいその命題を反証できる(例え ば、黒い白鳥を観察すれば、白鳥がすべて白いわけではないことが証明できる)と主張した。[53] ポパーはまた、科学理論は世界のありのままの姿について語るものであり(科学者が経験する現象や観察について語るものではない)、『推測と反証』の中で ウィーン学団を批判した。[54][55] W. V. O. クワインとピエール・ドゥエムはさらに踏み込んだ。ドゥエム=クワインのテーゼは、科学的仮説を単独で実験的に検証することは不可能であると主張する。な ぜなら、仮説の実証には1つ以上の背景仮定(補助仮説または補助仮説とも呼ばれる)が必要だからである。したがって、明確な科学的反証も不可能である。 トーマス・クーンは、1962年の著書『科学革命の構造』で、パラダイムシフトの理論を提唱した。彼は、証拠に応じて時折シフトしなければならないのは、 単に個々の理論ではなく、世界観全体であると主張した。[57][53] これらの考えは、批判的合理主義とポスト実証主義の発展につながった。ポスト実証主義は科学的方法の否定ではなく、むしろこれらの批判に応えるための実証 主義の改革である。ポスト実証主義は、客観的真理の可能性と望ましさ、実験的手法の使用という実証主義の基本的な前提を再び導入する。この種のポスト実証 主義は、社会科学の研究方法に関するガイドで説明されている。[59] ポスト実証主義者は、研究者の理論、仮説、背景知識、価値観が観察結果に影響を与える可能性があると主張している。[60] ポスト実証主義者は、バイアスの影響を認識することで客観性を追求している。[60][53][61] 実証主義者は量的手法を重視するが、ポスト実証主義者は量的手法と質的手法の両方を有効なアプローチとみなしている。[61] 1960年代初頭、価値判断論争(Werturteilsstreit)の正しい解決策をめぐって、批判理論家(下記参照)と批判的合理主義者との間で実 証主義論争が起こった。両者とも、社会学が価値判断を避けることはできず、その価値判断が必然的にその後の結論に影響を与えることを認めていたが、批判理 論家たちは批判的合理主義者たちを実証主義者であると非難した。具体的には、経験的な問いは形而上学的な遺産から切り離すことができると主張し、科学的手 法では答えられない問いを拒否していると非難した。これは、カール・ポパーが「ポパー伝説」と呼んだものに寄与した。ポパーの批判者や支持者たちの間で、 ポパーが実証主義者であった、あるいは自らを実証主義者とみなしていたという誤解である。[62] |

| Critical theory Main article: Critical theory Although Karl Marx's theory of historical materialism drew upon positivism, the Marxist tradition would also go on to influence the development of antipositivist critical theory.[63] Critical theorist Jürgen Habermas critiqued pure instrumental rationality (in its relation to the cultural "rationalisation" of the modern West) as a form of scientism, or science "as ideology".[64] He argued that positivism may be espoused by "technocrats" who believe in the inevitability of social progress through science and technology.[65][66] New movements, such as critical realism, have emerged in order to reconcile postpositivist aims with various so-called 'postmodern' perspectives on the social acquisition of knowledge. Max Horkheimer criticized the classic formulation of positivism on two grounds. First, he claimed that it falsely represented human social action.[67] The first criticism argued that positivism systematically failed to appreciate the extent to which the so-called social facts it yielded did not exist 'out there', in the objective world, but were themselves a product of socially and historically mediated human consciousness.[67] Positivism ignored the role of the 'observer' in the constitution of social reality and thereby failed to consider the historical and social conditions affecting the representation of social ideas.[67] Positivism falsely represented the object of study by reifying social reality as existing objectively and independently of the labour that actually produced those conditions.[67] Secondly, he argued, representation of social reality produced by positivism was inherently and artificially conservative, helping to support the status quo, rather than challenging it.[67] This character may also explain the popularity of positivism in certain political circles. Horkheimer argued, in contrast, that critical theory possessed a reflexive element lacking in the positivistic traditional theory.[67] Some scholars today hold the beliefs critiqued in Horkheimer's work, but since the time of his writing critiques of positivism, especially from philosophy of science, have led to the development of postpositivism. This philosophy greatly relaxes the epistemological commitments of logical positivism and no longer claims a separation between the knower and the known. Rather than dismissing the scientific project outright, postpositivists seek to transform and amend it, though the exact extent of their affinity for science varies vastly. For example, some postpositivists accept the critique that observation is always value-laden, but argue that the best values to adopt for sociological observation are those of science: skepticism, rigor, and modesty. Just as some critical theorists see their position as a moral commitment to egalitarian values, these postpositivists see their methods as driven by a moral commitment to these scientific values. Such scholars may see themselves as either positivists or antipositivists.[68] |

批判理論 詳細は「批判理論」を参照 カール・マルクスの唯物史観は実証主義の影響を受けていたが、マルクス主義の伝統は実証主義に反対する批判理論の発展にも影響を与え続けた。[63] 批判理論家のユルゲン・ハーバーマスは、純粋な道具的合理性(近代西欧の文化的「合理化」との関係において)を科学主義の一形態、すなわち「イデオロギー としての科学」として批判した。 [64] 彼は、科学技術による社会進歩の必然性を信じる「テクノクラート」が実証主義を支持している可能性があると主張した。[65][66] 批判的リアリズムなどの新たな運動が、ポスト実証主義の目標と、知識の社会的獲得に関するいわゆる「ポストモダン」のさまざまな視点とを調和させるために 登場した。 マックス・ホルクハイマーは、実証主義の古典的な定式化を2つの理由から批判した。まず、彼は、実証主義が人間の社会的行動を誤って表現していると主張し た。[67] 最初の批判は、実証主義は、いわゆる「社会的事実」が客観的世界に「そこにある」のではなく、それ自体が社会的・歴史的に媒介された人間の意識の産物であ ることを体系的に評価できていないと論じた。 [67] 実証主義は、社会的事実の構成における「観察者」の役割を無視し、それによって社会的な考えの表現に影響を与える歴史的および社会的条件を考慮できなかっ た。[67] 実証主義は、社会的事実を客観的に、かつそれらの条件を実際に生み出した労働とは無関係に存在するものとして物象化することで、研究対象を誤って表現し た。 [67] 第二に、彼が主張するように、実証主義によって生み出された社会現実の表現は、本質的に人為的に保守的であり、現状に挑戦するのではなく、現状を維持する のに役立つ。[67] この性格は、特定の政治的サークルにおける実証主義の人気を説明するものでもある。これに対し、ホロコーイマーは批判理論には実証主義の伝統理論には欠け ている反省的要素がある、と主張した。[67] 今日では、ホルクハイマーの著作で批判された考えを持つ学者もいるが、彼が批判主義を批判した当時以来、特に科学哲学の分野では、ポスト・ポスチュイヴィ ズムが発展している。この哲学は論理実証主義の認識論的立場を大幅に緩和し、もはや知る者と知られる者の分離を主張していない。ポスト実証主義者は、科学 プロジェクトを全面的に否定するのではなく、それを変革し修正しようとしているが、科学との親和性の正確な範囲は大きく異なる。例えば、ポスト実証主義者 の一部は、観察には常に価値判断が伴うという批判を受け入れているが、社会学的な観察に採用する価値観として最もふさわしいのは、科学の価値観であると主 張している。すなわち、懐疑主義、厳格さ、謙虚さである。批判理論家の一部が、自らの立場を平等主義的価値への道徳的コミットメントと捉えるように、こう したポスト実証主義者は、自らの手法をこうした科学的価値への道徳的コミットメントによって推進されるものと捉えている。こうした学者は、自らを実証主義 者または反実証主義者のいずれかとみなしている可能性がある。[68] |

| Other criticisms During the later twentieth century, positivism began to fall out of favor with scientists as well. Later in his career, German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, Nobel laureate for his pioneering work in quantum mechanics, distanced himself from positivism: The positivists have a simple solution: the world must be divided into that which we can say clearly and the rest, which we had better pass over in silence. But can any one conceive of a more pointless philosophy, seeing that what we can say clearly amounts to next to nothing? If we omitted all that is unclear we would probably be left with completely uninteresting and trivial tautologies.[69] In the early 1970s, urbanists of the quantitative school like David Harvey started to question the positivist approach itself, saying that the arsenal of scientific theories and methods developed so far in their camp were "incapable of saying anything of depth and profundity" on the real problems of contemporary cities.[70] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Positivism has also come under fire on religious and philosophical grounds, whose proponents state that truth begins in sense experience, but does not end there. Positivism fails to prove that there are not abstract ideas, laws, and principles, beyond particular observable facts and relationships and necessary principles, or that we cannot know them. Nor does it prove that material and corporeal things constitute the whole order of existing beings, and that our knowledge is limited to them. According to positivism, our abstract concepts or general ideas are mere collective representations of the experimental order—for example; the idea of "man" is a kind of blended image of all the men observed in our experience.[71] This runs contrary to a Platonic or Christian ideal, where an idea can be abstracted from any concrete determination, and may be applied identically to an indefinite number of objects of the same class.[citation needed] From the idea's perspective, Platonism is more precise. Defining an idea as a sum of collective images is imprecise and more or less confused, and becomes more so as the collection represented increases. An idea defined explicitly always remains clear. Other new movements, such as critical realism, have emerged in opposition to positivism. Critical realism seeks to reconcile the overarching aims of social science with postmodern critiques. Experientialism, which arose with second generation cognitive science, asserts that knowledge begins and ends with experience itself.[72][73] In other words, it rejects the positivist assertion that a portion of human knowledge is a priori. |

その他の批判 20世紀後半には、科学者たちからも実証主義は支持されなくなった。 量子力学の分野における先駆的な研究でノーベル賞を受賞したドイツの理論物理学者ヴェルナー・ハイゼンベルクは、キャリアの後期に実証主義から距離を置いた。 実証主義者たちは単純な解決策を持っている。世界は、明確に言えることと、黙って見過ごした方が良い残りの部分とに分けるべきだというのだ。しかし、明確 に言えることなどほとんどないというのに、これ以上に無意味な哲学が考えられるだろうか?不明瞭なものをすべて省いてしまえば、おそらくは完全に興味のな い、ありふれた同語反復だけが残るだろう。 1970年代初頭、デイヴィッド・ハーヴェイのような数量化を志向する都市研究者は、実証主義のアプローチそのものを疑問視し始め、自分たちの陣営でこれ まで開発されてきた科学理論や方法の武器庫は、現代都市の現実的な問題について「深みや奥深さを語ることはできない」と主張した。 カトリック百科事典によると、実証主義は宗教的および哲学的根拠からも批判の対象となっており、その支持者たちは、真実は感覚経験から始まるが、そこで終 わるわけではないと主張している。実証主義は、特定の観察可能な事実や関係性、必要な原則を超えた抽象的な概念、法則、原則が存在しないこと、あるいは、 それらを知ることができないことを証明できていない。また、物質的および肉体的なものが存在する生物の秩序全体を構成しており、我々の知識はそれらに限ら れていることを証明できていない。実証主義によれば、我々の抽象概念や一般概念は、単に実験的な秩序の集合的表現にすぎない。例えば、「人間」という概念 は、我々の経験の中で観察されたすべての人間のイメージを混ぜ合わせたものの一種である。 [71] これは、あらゆる具体的な決定から抽象化された概念が、同じクラスの無数の対象に同一に適用できるという、プラトン主義やキリスト教の理想とは対立するも のである。[要出典] 概念の観点から見ると、プラトン主義の方がより正確である。概念を集合的なイメージの総体と定義することは不正確であり、多かれ少なかれ混乱を招く。ま た、表現される集合が増えるほど、その傾向は強くなる。明確に定義された観念は常に明確なままである。 批判的リアリズムなどの他の新しい運動は、実証主義に反対して登場した。批判的リアリズムは、社会科学の包括的な目的とポストモダンの批判を調和させよう としている。経験論は、第二世代の認知科学とともに登場し、知識は経験そのものに始まり、経験そのものに終わる、と主張している。[72][73] 言い換えれば、人間の知識の一部はア・プリオリに存在するという実証主義の主張を否定している。 |

| Positivism today Echoes of the "positivist" and "antipositivist" debate persist today, though this conflict is hard to define. Authors writing in different epistemological perspectives do not phrase their disagreements in the same terms and rarely actually speak directly to each other.[74] To complicate the issues further, few practising scholars explicitly state their epistemological commitments, and their epistemological position thus has to be guessed from other sources such as choice of methodology or theory. However, no perfect correspondence between these categories exists, and many scholars critiqued as "positivists" are actually postpositivists.[75] One scholar has described this debate in terms of the social construction of the "other", with each side defining the other by what it is not rather than what it is, and then proceeding to attribute far greater homogeneity to their opponents than actually exists.[74] Thus, it is better to understand this not as a debate but as two different arguments: the "antipositivist" articulation of a social meta-theory which includes a philosophical critique of scientism, and "positivist" development of a scientific research methodology for sociology with accompanying critiques of the reliability and validity of work that they see as violating such standards. Strategic positivism aims to bridge these two arguments. |

今日の実証主義 「実証主義者」と「反実証主義者」の論争の余韻は今日も残っているが、この対立を定義するのは難しい。異なる認識論的観点から執筆する著者は、意見の相違 を同じ言葉で表現するわけではないし、実際に互いに直接語り合うことはほとんどない。[74] 問題をさらに複雑にしているのは、実務に携わる研究者の多くが、自身の認識論的立場を明確に表明していないことである。そのため、その認識論的立場は、方 法論や理論の選択といった他の情報源から推測するしかない。しかし、これらのカテゴリーの間には完全な一致は存在せず、多くの学者は「実証主義者」として 批判されているが、実際にはポスト実証主義者である。ある学者は、この論争を「他者」の社会的構築という観点から説明しており、各派は他派を「何である か」ではなく「何ではないか」によって定義し、そして、実際よりもはるかに大きな均質性を相手に帰属させている。 [74] したがって、これは議論ではなく、2つの異なる主張として理解する方が良い。すなわち、科学主義に対する哲学的な批判を含む社会的なメタ理論の「反実証主 義」的な解釈と、社会学のための科学的研究方法論の「実証主義」的な発展であり、その基準に違反しているとみなされる研究の信頼性と妥当性に対する批判を 伴うものである。戦略的実証主義は、この2つの主張を橋渡しすることを目的としている。 |

| Social Science While most social scientists today are not explicit about their epistemological commitments, articles in top American sociology and political science journals generally follow a positivist logic of argument.[76][77] It can be thus argued that "natural science and social science [research articles] can therefore be regarded with a good deal of confidence as members of the same genre".[76][clarification needed] In contemporary social science, strong accounts of positivism have long since fallen out of favour. Practitioners of positivism today acknowledge in far greater detail observer bias and structural limitations. Modern positivists generally eschew metaphysical concerns in favour of methodological debates concerning clarity, replicability, reliability and validity.[78] This positivism is generally equated with "quantitative research" and thus carries no explicit theoretical or philosophical commitments. The institutionalization of this kind of sociology is often credited to Paul Lazarsfeld,[28] who pioneered large-scale survey studies and developed statistical techniques for analyzing them. This approach lends itself to what Robert K. Merton called middle-range theory: abstract statements that generalize from segregated hypotheses and empirical regularities rather than starting with an abstract idea of a social whole.[79] In the original Comtean usage, the term "positivism" roughly meant the use of scientific methods to uncover the laws according to which both physical and human events occur, while "sociology" was the overarching science that would synthesize all such knowledge for the betterment of society. "Positivism is a way of understanding based on science"; people don't rely on the faith in God but instead on the science behind humanity. "Antipositivism" formally dates back to the start of the twentieth century, and is based on the belief that natural and human sciences are ontologically and epistemologically distinct. Neither of these terms is used any longer in this sense.[28] There are no fewer than twelve distinct epistemologies that are referred to as positivism.[80] Many of these approaches do not self-identify as "positivist", some because they themselves arose in opposition to older forms of positivism, and some because the label has over time become a term of abuse[28] by being mistakenly linked with a theoretical empiricism. The extent of antipositivist criticism has also become broad, with many philosophies broadly rejecting the scientifically based social epistemology and other ones only seeking to amend it to reflect 20th century developments in the philosophy of science. However, positivism (understood as the use of scientific methods for studying society) remains the dominant approach to both the research and the theory construction in contemporary sociology, especially in the United States.[28] The majority of articles published in leading American sociology and political science journals today are positivist (at least to the extent of being quantitative rather than qualitative).[76][77] This popularity may be because research utilizing positivist quantitative methodologies holds a greater prestige[clarification needed] in the social sciences than qualitative work; quantitative work is easier to justify, as data can be manipulated to answer any question.[81][need quotation to verify] Such research is generally perceived as being more scientific and more trustworthy, and thus has a greater impact on policy and public opinion (though such judgments are frequently contested by scholars doing non-positivist work).[81][need quotation to verify] |

社会科学 今日、ほとんどの社会科学者は自らの認識論的立場を明確にしていないが、米国の社会学および政治学の一流学術誌に掲載される論文は一般的に実証主義の論理 に従っている。[76][77] したがって、「自然科学と社会科学の研究論文は、同じジャンルのものとして、かなりの信頼性をもって見なすことができる」と主張できる。[76][要説 明] 現代の社会科学では、実証主義の強力な主張は長い間支持されなくなっている。今日の実証主義の実践者は、観察者のバイアスや構造的な限界をはるかに詳細に 認める。現代の実証主義者は一般的に、明瞭性、再現性、信頼性、妥当性に関する方法論的議論を支持し、形而上学的関心は避ける。この実証主義は一般的に 「量的研究」と同一視され、明示的な理論的または哲学的コミットメントは持たない。この種の社会学の制度化は、しばしばポール・ラザーズフェルドに帰され るが[28]、彼は大規模な調査研究の先駆者であり、それを分析するための統計的手法を開発した。このアプローチは、ロバート・K・マートンがミドルレン ジ・セオリーと呼んだものに適している。すなわち、社会全体についての抽象的な考えから出発するのではなく、分離された仮説と経験則から一般化する抽象的 なステートメントである[79]。 コンテの当初の用法では、「実証主義」という用語は、物理的および人間的な出来事が起こる法則を解明するための科学的手法の使用を意味し、一方「社会学」 は、社会の向上のためにそうした知識をすべて総合する包括的な科学であった。「実証主義は科学に基づく理解の方法である。人々は神への信仰ではなく、人間 性を支える科学に頼るのである。「反実証主義」は、20世紀初頭に正式に始まったもので、自然科学と人文科学は存在論的にも認識論的にも異なるという信念 に基づいている。これらの用語は、現在ではこの意味では使用されていない。[28] 実証主義と呼ばれる認識論は12種類以上ある。[80] これらのアプローチの多くは「実証主義者」と自らを規定していない。その理由のいくつかは、それ自体が古い実証主義への反対として生まれたためであり、ま た、そのラベルが、理論的経験論と誤って関連付けられたことで、時代とともに罵倒の言葉となったためである。反実証主義の批判も広範囲にわたっており、科 学に基づく社会認識論を広く拒絶する哲学もあれば、20世紀の科学哲学の発展を反映させるために修正を求めるだけのものもある。しかし、実証主義(社会研 究における科学的方法の使用と理解される)は、現代の社会学、特に米国における研究と理論構築の両方において、依然として支配的なアプローチである。 今日、米国の社会学や政治学の主要ジャーナルで発表される論文の大半は実証主義的である(少なくとも量的なものであり、質的なものではない)。[76] [77] この人気は、実証主義的な量的方法論を用いた研究が質的な研究よりも社会科学において高い評価を得ているためかもしれない。[要出典] 量的な研究は、あらゆる質問に答えるためにデータを操作できるため、正当化しやすい。 [81][検証が必要] このような研究は一般的に、より科学的で信頼性が高いと認識されており、政策や世論に大きな影響を与える(ただし、このような判断は、非実証主義的な研究 を行う学者たちから頻繁に異議が唱えられている)。[81][検証が必要] |

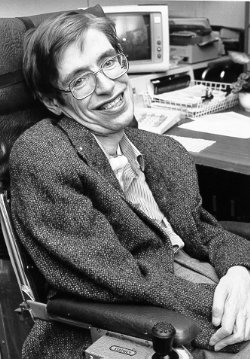

| Natural sciences See also: Constructive empiricism The key features of positivism as of the 1950s, as defined in the "received view",[82] are: A focus on science as a product, a linguistic or numerical set of statements; A concern with axiomatization, that is, with demonstrating the logical structure and coherence of these statements; An insistence on at least some of these statements being testable; that is, amenable to being verified, confirmed, or shown to be false by the empirical observation of reality. Statements that would, by their nature, be regarded as untestable included the teleological; thus positivism rejects much of classical metaphysics. The belief that science is markedly cumulative; The belief that science is predominantly transcultural; The belief that science rests on specific results that are dissociated from the personality and social position of the investigator; The belief that science contains theories or research traditions that are largely commensurable; The belief that science sometimes incorporates new ideas that are discontinuous from old ones; The belief that science involves the idea of the unity of science, that there is, underlying the various scientific disciplines, basically one science about one real world. The belief that science is nature and nature is science; and out of this duality, all theories and postulates are created, interpreted, evolve, and are applied.  Stephen Hawking Stephen Hawking was a recent high-profile advocate of positivism in the physical sciences. In The Universe in a Nutshell (p. 31) he wrote: Any sound scientific theory, whether of time or of any other concept, should in my opinion be based on the most workable philosophy of science: the positivist approach put forward by Karl Popper and others. According to this way of thinking, a scientific theory is a mathematical model that describes and codifies the observations we make. A good theory will describe a large range of phenomena on the basis of a few simple postulates and will make definite predictions that can be tested. ... If one takes the positivist position, as I do, one cannot say what time actually is. All one can do is describe what has been found to be a very good mathematical model for time and say what predictions it makes. |

自然科学 関連項目: 構成論的経験論 1950年代における実証主義の主な特徴は、「定説」として定義されているように、以下の通りである。 科学を、言語的または数値的な一連のステートメント(製品)として重視すること。 公理化、すなわち、これらのステートメントの論理構造と一貫性を実証することに重点を置くこと。 これらの主張の少なくとも一部は検証可能であるべきであるという主張、すなわち、現実の実証的観察によって、検証、確認、あるいは誤りであることを示すこ とができるという主張。その性質上、検証不能とみなされる主張には目的論が含まれる。したがって、実証主義は古典的な形而上学の多くを否定する。 科学は著しく累積的であるという信念、 科学は主として文化を超越するものであるという信念、 科学は研究者の人格や社会的地位とは切り離された特定の結果に基づいているという信念、 科学には、ほぼ同等に比較できる理論や研究の伝統が含まれているという信念、 科学は時に、古いものとは不連続な新しいアイデアを取り入れるという信念、 科学には科学の統一という考え方が含まれており、様々な科学分野の根底には、基本的に1つの現実世界に関する1つの科学があるという信念、 科学は自然であり、自然は科学であるという信念、そして、この二元性から、すべての理論や仮説が生み出され、解釈され、進化し、応用される。  スティーブン・ホーキング スティーブン・ホーキングは、近年、物理科学における実証主義の著名な擁護者であった。『宇宙を語る』(p. 31)の中で、彼は次のように書いている。 時間に関するものであれ、その他の概念に関するものであれ、あらゆる健全な科学理論は、私の意見では、最も実用的な科学哲学、すなわちカール・ポパーやそ の他の人々が提唱した実証主義的アプローチに基づくべきである。この考え方によると、科学理論とは、私たちが観察したものを記述し、体系化する数学モデル である。優れた理論は、少数の単純な仮定に基づいて広範な現象を説明し、検証可能な明確な予測を行う。... もし私が実証主義の立場をとるのであれば、時間とは実際何なのかを述べることはできない。できることは、時間について非常に優れた数学モデルであることが 判明しているものを説明し、それがどのような予測を行うかを述べるだけである。 |

| Cliodynamics Científico Charvaka Determinism Gödel's incompleteness theorems London Positivist Society Nature versus nurture Physics envy Scientific politics Sociological naturalism The New Paul and Virginia Vladimir Solovyov |

クリオダイナミクス 科学者 チャールヴァカ 決定論 ゲーデルの不完全性定理 ロンドン実証主義協会 生得説対環境説 物理学の羨望 科学的政治 社会学的自然主義 新しいポールとバージニア ウラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフ |

| References Amory, Frederic. "Euclides da Cunha and Brazilian Positivism". Luso-Brazilian Review. 36 (1 (Summer 1999)): 87–94. Armenteros, Carolina. 2017. "The Counterrevolutionary Comte: Theorist of the Two Powers and Enthusiastic Medievalist." In The Anthem Companion to Auguste Comte, edited by Andrew Wernick, 91–116. London: Anthem. Annan, Noel. 1959. The Curious Strength of Positivism in English Political Thought. London: Oxford University Press. Ardao, Arturo. 1963. "Assimilation and Transformation of Positivism in Latin America." Journal of the History of Ideas 24 (4):515–22. Bevir, Mark (1993). "Ernest Belfort Bax: Marxist, Idealist, Positivist". Journal of the History of Ideas. 54 (1): 119–35. doi:10.2307/2709863. JSTOR 2709863. Bevir, Mark. 2002. "Sidney Webb: Utilitarianism, Positivism, and Social Democracy." The Journal of Modern History 74 (2):217–252. Bevir, Mark. 2011. The Making of British Socialism. Princeton. PA: Princeton University Press. Bourdeau, Michel. 2006. Les trois états: Science, théologie et métaphysique chez Auguste Comte. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. Bourdeau, Michel, Mary Pickering, and Warren Schmaus, eds. 2018. Love, Order and Progress. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. Bryant, Christopher G. A. 1985. Positivism in Social Theory and Research. New York: St. Martin's Press. Claeys, Gregory. 2010. Imperial Sceptics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Claeys, Gregory. 2018. "Professor Beesly, Positivism and the International: the Patriotism Issue." In "Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth": The First International in a Global Perspective, edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quinton Deluermoz and Jeanne Moisand. Leiden: Brill. De Boni, Carlo. 2013. Storia di un'utopia. La religione dell'Umanità di Comte e la sua circolazione nel mondo. Milano: Mimesis. Dixon, Thomas. 2008. The Invention of Altruism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Feichtinger, Johannes, Franz L. Fillafer, and Jan Surman, eds. 2018. The Worlds of Positivism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Forbes, Geraldine Handcock. 2003. "The English Positivists and India." In Essays on Indian Renaissance, edited by Raj Kumar, 151–63. Discovery: New Delhi. Gane, Mike. 2006. Auguste Comte. London: Routledge. Giddens, Anthony. Positivism and Sociology. Heinemann. London. 1974. Gilson, Gregory D. and Irving W. Levinson, eds. Latin American Positivism: New Historical and Philosophic Essays (Lexington Books; 2012) 197 pages; Essays on positivism in the intellectual and political life of Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. Harp, Gillis J. 1995. Positivist Republic: Auguste Comte and the Reconstruction of American Liberalism, 1865–1920. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. Harrison, Royden. 1965. Before the Socialists. London: Routledge. Hoecker-Drysdale, Susan. 2001. "Harriet Martineau and the Positivism of Auguste Comte." In Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives, edited by Michael R. Hill and Susan Hoecker-Drysdale, 169–90. London: Routledge. Kremer-Marietti, Angèle. L'Anthropologie positiviste d'Auguste Comte, Librairie Honoré Champion, Paris, 1980. Kremer-Marietti, Angèle. Le positivisme, Collection "Que sais-je?", Paris, PUF, 1982. LeGouis, Catherine. Positivism and Imagination: Scientism and Its Limits in Emile Hennequin, Wilhelm Scherer and Dmitril Pisarev. Bucknell University Press. London: 1997. Lenzer, Gertrud, ed. 2009. The Essential Writings of Auguste Comte and Positivism. London: Transaction. "Positivism." Marxists Internet Archive. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. McGee, John Edwin. 1931. A Crusade for Humanity. London: Watts. Mill, John Stuart. Auguste Comte and Positivism. Mises, Richard von. Positivism: A Study In Human Understanding. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1951. Petit, Annie. Le Système d'Auguste Comte. De la science à la religion par la philosophie. Vrin, Paris (2016). Pickering, Mary. Auguste Comte: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England; 1993. Quin, Malcolm. 1924. Memoirs of a Positivist. London: George Allen & Unwin. Richard Rorty (1982). Consequences of Pragmatism. Scharff, Robert C. 1995. Comte After Positivism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schunk, Dale H. Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective, 5th. Pearson, Merrill Prentice Hall. 1991, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008. Simon, W. M. 1963. European Positivism in the Nineteenth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Sutton, Michael. 1982. Nationalism, Positivism and Catholicism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Trindade, Helgio. 2003. "La république positiviste chex Comte." In Auguste Comte: Trajectoires positivistes 1798–1998, edited by Annie Petit, 363–400. Paris: L'Harmattan. Turner, Mark. 2000. "Defining Discourses: The "Westminster Review", "Fortnightly Review", and Comte's Positivism." Victorian Periodicals Review 33 (3):273–282. Wernick, Andrew. 2001. Auguste Comte and the Religion of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Whatmore, Richard. 2005. "Comte, Auguste (1798–1857)." In Encyclopaedia of Nineteenth-Century Thought, edited by Gregory Claeys, 123–8. London: Routledge. Whetsell, Travis and Patricia M. Shields. "The Dynamics of Positivism in the Study of Public Administration: A Brief Intellectual History and Reappraisal", Administration & Society. doi:10.1177/0095399713490157. Wils, Kaat. 2005. De omweg van de wetenschap: het positivisme en de Belgische en Nederlandse intellectuele cultuur, 1845–1914. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Wilson, Matthew. 2018. "British Comtism and Modernist Design." Modern Intellectual History x (xx):1–32. Wilson, Matthew. 2018. Moralising Space: the Utopian Urbanism of the British Positivists, 1855–1920. London: Routledge. Wilson, Matthew. 2020. "Rendering sociology: on the utopian positivism of Harriet Martineau and the ‘Mumbo Jumbo club." Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas 8 (16):1–42. Woll, Allen L. 1976. "Positivism and History in Nineteenth-Century Chile." Journal of the History of Ideas 37 (3):493–506. Woodward, Ralph Lee, ed. 1971. Positivism in Latin America, 1850–1900. Lexington: Heath. Wright, T. R. 1986. The Religion of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wright, T. R. 1981. "George Eliot and Positivism: A Reassessment." The Modern Language Review 76 (2):257–72. Wunderlich, Roger. 1992. Low Living and High Thinking at Modern Times, New York. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Zea, Leopoldo. 1974. Positivism in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press. |

参考文献 Amory, Frederic. 「エウクリデス・ダ・クーニャとブラジル・ポシヴィズム」『ルソ=ブラジル・レビュー』36 (1 (1999年夏)): 87–94. Armenteros, Carolina. 2017. 「反革命家コンテ:二つの権力の理論家にして熱狂的な中世主義者」 『オーギュスト・コント研究』アンドリュー・ワーニック編、91-116ページ。ロンドン:アンセム。 アナン、ノエル。1959年。『英語政治思想におけるポストイヴィズムの奇妙な強さ』ロンドン:オックスフォード大学出版。 アルダオ、アルトゥーロ。1963年。「ラテンアメリカにおけるポストイヴィズムの同化と変容」。『思想史ジャーナル』24 (4):515–22. Bevir, Mark (1993). 「Ernest Belfort Bax: Marxist, Idealist, Positivist」. 『思想史ジャーナル』. 54 (1): 119–35. doi:10.2307/2709863. JSTOR 2709863. Bevir, Mark. 2002. 「シドニー・ウェブ:功利主義、実証主義、社会民主主義」『The Journal of Modern History』74 (2):217–252. Bevir, Mark. 2011. 『The Making of British Socialism』プリンストン大学出版、プリンストン、ペンシルベニア州。 Bourdeau, Michel. 2006. Les trois états: Science, théologie et métaphysique chez Auguste Comte. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. Bourdeau, Michel, Mary Pickering, and Warren Schmaus, eds. 2018. Love, Order and Progress. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. Bryant, Christopher G. A. 1985. Positivism in Social Theory and Research. New York: St. Martin's Press. グレゴリー・クレイス著、2010年。『帝国の懐疑論者たち』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 グレゴリー・クレイス著、2018年。「ビーズリー教授、実証主義、そしてインターナショナル:愛国心の問題」ファブリス・ベンシモン、クイントン・デル ルモズ、ジャンヌ・モワサン編『「大地の呪われし者たちよ、立ち上がれ」:グローバルな視点から見た第一インターナショナル』ブリュッセル:ブリュッセル 大学出版局。 デ・ボニ、カルロ。2013年。『ユートピアの歴史。コンテの「人類の宗教」とその世界への普及。ミラノ:Mimesis。 ディクソン、トーマス。2008年。『利他主義の発明。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ファイヒティンガー、ヨハネス、フランツ・L・フィラファー、ヤン・サーマン編。2018年。『ポストイズムの世界』ロンドン:パルグレーブ・マクミラン。 フォーブス、ジェラルディン・ハンドコック。2003年。「英国のポストイストとインド」ラジ・クマール編『インディアン・ルネサンスに関する論文集』151-63ページ。ディスカバリー:ニューデリー。 ゲイン、マイク。2006年。『オーギュスト・コント』ロンドン:ルートレッジ。 ギデンズ、アンソニー。『実証主義と社会学』。ハインマン。ロンドン。1974年。 ジルソン、グレゴリー・D.およびアーヴィング・W・レヴィンソン編。『ラテンアメリカ実証主義:新しい歴史的および哲学的エッセイ』(レキシントン・ ブックス、2012年)197ページ。ブラジル、コロンビア、メキシコの知的および政治的生活における実証主義に関するエッセイ。 ハープ、ギリス J. 1995. 『実証主義共和国:オーギュスト・コントとアメリカ自由主義の再構築、1865年~1920年』ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティ・パーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版。 ハリソン、ロイデン。1965. 『社会主義以前』ロンドン:ルートレッジ。 ホーカー=ドライスデール、スーザン。2001. 「ハリエット・マーティノーとオーギュスト・コントのポストイズム」マイケル・R・ヒル、スーザン・ヘッカー=ドライスデール編『ハリエット・マーティ ノー:理論的および方法論的視点』169-90ページ。ロンドン:ルートレッジ。 クレメール=マリエッティ、アンジェル『オーギュスト・コントのポストイズム的人類学』リブラリー・オノレ・チャンピオン、パリ、1980年。 クレメール=マリエッティ、アンジェル。『実証主義』、コレクション「Que sais-je?」、パリ、PUF、1982年。 ルグイス、キャサリン。『実証主義と想像力:エミール・ヘネクアン、ヴィルヘルム・シェラー、ドミトリル・ピサレフにおける科学主義とその限界』。バックネル大学出版。ロンドン:1997年。 Lenzer, Gertrud, ed. 2009. The Essential Writings of Auguste Comte and Positivism. London: Transaction. 「実証主義」Marxists Internet Archive. ウェブ。2012年2月23日。 McGee, John Edwin. 1931. A Crusade for Humanity. London: Watts. Mill, John Stuart. Auguste Comte and Positivism. ミース、リヒャルト・フォン著。『実証主義:人間理解の研究』ハーバード大学出版局。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:1951年。 プティ、アニー著。『オーギュスト・コントの体系。科学から哲学を経て宗教へ』ヴィリン、パリ(2016年)。 ピカリング、メアリー著。『オーギュスト・コント:知の伝記』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。イングランド、ケンブリッジ:1993年。 クイン、マルコム。1924年。『実証主義者の回想録』。ロンドン:ジョージ・アレン・アンド・ユニウィン。 リチャード・ローティ(1982年)。『プラグマティズムの帰結』。 シャーフ、ロバート・C。1995年。『ポスト実証主義のコンテ』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 シュンク、デール H. 学習理論:教育の視点、第5版。ピアソン、メリル・プレンティス・ホール。1991年、1996年、2000年、2004年、2008年。 サイモン、W. M. 1963年。19世紀のヨーロッパにおける実証主義。ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版。 Sutton, Michael. 1982. Nationalism, Positivism and Catholicism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Trindade, Helgio. 2003. 「La république positiviste chex Comte.」 In Auguste Comte: Trajectoires positivistes 1798–1998, edited by Annie Petit, 363–400. Paris: L'Harmattan. ターナー、マーク。2000年。「言説の定義:『ウェストミンスター・レビュー』、『フォーティウィークリー・レビュー』、そしてコントのポジティヴィズム」『ヴィクトリア朝の定期刊行物レビュー』33(3):273-282。 ウェルニック、アンドリュー。2001年。『オーギュスト・コントと人類の宗教』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 リチャード・ワットモア著、2005年。「コンテ、オーギュスト(1798~1857年)」『19世紀の思想百科事典』グレゴリー・クレイス編、123~8ページ。ロンドン:ルートレッジ。 Whetsell, Travis and Patricia M. Shields. 「行政学における実証主義の力学:簡潔な知的歴史と再評価」『Administration & Society』。doi:10.1177/0095399713490157. ウィルス、カト。2005年。『科学の迂回路:実証主義とベルギーおよびオランダの知的風土、1845年~1914年』アムステルダム:アムステルダム大学出版。 ウィルソン、マシュー。2018年。「英国のコンティズムとモダニズム・デザイン」『近代思想史』x(xx):1~32。 ウィルソン、マシュー。2018年。『道徳化する空間:1855年~1920年の英国実証主義者のユートピア的都市計画』ロンドン:Routledge。 ウィルソン、マシュー。2020年。「社会学の描写:ハリエット・マーティノーのユートピア的実証主義と「マンボ・ジャンボ・クラブ」について」『学際的アイデア史ジャーナル』8(16):1~42。 ウォール、アレン・L. 1976. 「19世紀チリの歴史における実証主義」『思想史ジャーナル』37 (3):493–506. ウッドワード、ラルフ・リー編。1971. 『ラテンアメリカにおける実証主義、1850–1900』レキシントン:ヒース。 ライト、T. R. 1986. 『人類の宗教』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ライト、T. R. 1981. 「ジョージ・エリオットと実証主義:再評価」『The Modern Language Review』76 (2):257–72。 Wunderlich, Roger. 1992. Low Living and High Thinking at Modern Times, New York. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Zea, Leopoldo. 1974. Positivism in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Positivism |

●ちなみに数学研究のビッグスリーは「論理主義」「形式主義」「直観主義」

| 「直観主義」 | 直観主義(ちょっかんしゅぎ、英:

Intuitionism)とは、数学の基礎を数学者の直観におく立場のことを指す。これに類する主張は、カントールの集合論に対抗する形で、クロネッ

カーやポアンカレによってもなされていたが、最も明確に表明したのは、オランダの位相幾何学者、ブラウワーである。ブラウワーの立場に対してポアンカレら

の立場は前直観主義と言われることがある。ブラウワーは、数学的概念とは数学者の精神の産物であり、その存在はその構成によって示されるべきだという立場

から、無限集合において、背理法によって、非存在の矛盾から存在を示す証明を認めなかった。それ故、無限集合において「排中律」、すなわち、ある命題は真

であるか偽であるかのどちらかであるという推論法則を捨てるべきだと主張し、ヒルベルトとの間に有名な論争を引き起こした。 |

| 「形式主義」 | 形式主義(英:

formalism)とは、数学における命題を少数の記号によって表し、証明において使われる推論を純粋に記号の操作と捉える考え方のことを指す。形式主

義の最も原理的な見方では、数学は決められたルール(公理と推論法則)に従って行われるゲームであり、ルールを取り替えることによってできる異なるゲーム

は、それぞれ同等である。形式主義によると、数学的命題は確実な文字列処理ルールを必要とする命題と考えられる。例として、(「公理」と呼ばれる文字列

と、与えられた公理から新しい文字列を生成する「推論規則」からなるものとして見られる)ユークリッド幾何学の「ゲーム」では、ピタゴラスの定理が有効で

あることを証明できる(それは、あなたが、ピタゴラスの定理に対応する文字列を生成できることである)。数学的真理は、数や集合や三角形やそのようなもの

についてのものではない。実際、それは何に「ついて(about)」のものでもない。 |

| 「論理主義」 | 論理主義(ろんりしゅぎ、英:

Logicism、仏: Logicism、独:

Logizismus)は、数学全体を論理学の一部とみなし、数学を基礎付け、数学を論理学への還元することができるとする立場である。方法的には、論理

学の諸規則から数学のそれを演繹することが出来ると主張する。ゴットロープ・フレーゲの先駆的な論理主義の仕事を受けて、特にバートランド・ラッセルやア

ルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドによって唱えられた。彼らはその主張を3巻に及ぶ大部の書物『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』(Principia

Mathematica, 1910年 -

1913年)のうちである程度実現してみせた。フレーゲの『算術の基本法則』第2巻が刊行直前に控えていた1903年に、ラッセルから後にラッセルのパラ

ドックスと呼ばれるパラドックスの指摘が来たため、フレーゲはパラドックス解消を目指すが、最終的には数学的な方法の徹底を放棄した。ラッセルはフレーゲ

とは独立に、型の理論(タイプ理論)と呼ばれる方法で、彼自身が発見したパラドックスを避けることに成功したが、その無矛盾性および完全性が証明されてい

なかった。 |

●背理法(矛盾による証明)

| In logic, proof by

contradiction is a form of proof that establishes the truth or the

validity of a proposition, by showing that assuming the proposition to

be false leads to a contradiction. Although it is quite freely used in

mathematical proofs, not every school of mathematical thought accepts

this kind of nonconstructive proof as universally valid.[1] More broadly, proof by contradiction is any form of argument that establishes a statement by arriving at a contradiction, even when the initial assumption is not the negation of the statement to be proved. In this general sense, proof by contradiction is also known as indirect proof, proof by assuming the opposite,[2] and reductio ad impossibile.[3] |

論理学において、矛盾による証明(背理法)とは、命題を偽と仮定すると

矛盾が生じることを示すことによって、命題の真理または妥当性を立証する証明の形式である。数学の証明ではかなり自由に使われているが、すべての数学思想

の学派がこの種の非構築的証明を普遍的に有効なものとして認めているわけではない[1]。 より広義には、矛盾による証明とは、最初の仮定が証明される文の否定でない場合でも、矛盾に到達することによって文を立証するあらゆる形式の論証である。 この一般的な意味において、矛盾による証明は、間接証明、反対を仮定することによる証明、[2]および不可説による証明としても知られている[3]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proof_by_contradiction |

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

The humanist motto Ordem e Progresso is derived from Auguste Comte's motto of positivism: "L'amour pour principe et l'ordre pour base; le progrès pour but" ("Love as a principle and order as the basis; progress as the goal"). - Wiki.

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆