Introducition to Homo ludens, by J. Huizinga

ホモ・ルーデンス入門

Introducition to Homo ludens, by J. Huizinga

ホモ・ルーデンスは、オランダの歴史家ヨアン・ハイ ジンハ(ドイツ語読みでヨハン・ホイジンガ)の著作の書名である。ホモ・ルーデンスとは「遊ぶ人(Homo ludens)」のラテン語で、ホモ・サピエンス(考える人、知恵ある人)が人間のラテン語の学名のように、人間を定義して、遊ぶ存在が人間であることを 謳った文化史の書物である。

この本は、1938年にオランダのハールレム (Haarlem)でHomo Ludens. Proeve eener bepaling van het spel-element der cultuur, H. D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon.として出版されて、翌1939年にスイス(Basel)でAkademische Verlagsanstalt Pantheonよりドイツ語に出版されている(翻訳=著述はホイジンガ自身による)。世界で翻訳されているホモ・ルーデンスは、ドイツ語版のものを翻訳 したものがほとんどである。英訳は、ホイジンガが亡くなる少し前に彼自身が翻訳したものがあったが、ドイツ語版との異同が多く(英訳版の「翻訳者のノー ト」による)、その照合を経て実際には、R.F.G. Hullが翻訳をして、ルートリッジ・ケーガン・ポール社から出版されたのは1949年である。

1949年の英語版の章立ては以下のようになってい る。

| 序文(1938年6月) | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_Ludens より(下に邦訳あり) |

| 1.文化的現象としての遊びの本質と諸意義 | I. Nature and significance of play as a cultural phenomenon Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.[7] Huizinga begins by making it clear that animals played before humans. One of the most significant (human and cultural) aspects of play is that it is fun.[8] Huizinga identifies 5 characteristics that play must have:[9] Play is free, is in fact freedom. Play is not "ordinary" or "real" life. Play is distinct from "ordinary" life both as to locality and duration. Play creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme. Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it.[10] |

| 2.言語によって表現されたものとしての遊び=概念(play-concept) | II. The play concept as expressed in language Word and idea are not born of scientific or logical thinking but of creative language, which means of innumerable languages—for this act of "conception" has taken place over and over again.[11] Huizinga has much to say about the words for play in different languages. Perhaps the most extraordinary remark concerns the Latin language. "It is remarkable that ludus, as the general term for play, has not only not passed into the Romance languages but has left hardly any traces there, so far as I can see... We must leave to one side the question whether the disappearance of ludus and ludere is due to phonetic or to semantic causes."[12] Of all the possible uses of the word "play" Huizinga specifically mentions the equation of play with, on the one hand, "serious strife", and on the other, "erotic applications".[13] Play-category, play-concept, play-function, play-word in selected languages Huizinga attempts to classify the words used for play in a variety of natural languages. The chapter title uses "play-concept" to describe such words. Other words used with the "play-" prefix are play-function and play-form. The order in which examples are given in natural languages is as follows: Greek[14] (3) παιδιά — pertaining to children's games, ἄθυρμα — associated with the idea of the trifling, the nugatory, ἀγών — for matches and contests. Sanskrit[15] (4) krīdati — denoting the play of animals, children, adults, divyati — gambling, dicing, joking, jesting, ..., vilāsa — shining, sudden appearance, playing and pursuing an occupation, līlayati — light, frivolous insignificant sides of playing. Chinese[16] (3) wan — is the most important word covering children's games and much much more, cheng — denoting anything to do with contests, corresponds exactly to the Greek agon, sai — organized contest for a prize. Blackfoot[17] (2) koani — all children's games and also in the erotic sense of "dallying", kachtsi — organized play. Japanese[18] (1) asobu — is a single, very definite word, for the play function. Semitic languages la’ab (a root, cognate with la’at) — play, laughing, mocking, la’iba (Arabic) — playing in general, making mock of, teasing,[19] la’ab (Aramaic) — laughing and mocking, sahaq (Hebrew) — laughing and playing. Latin (1) ludus — from ludere, covers the whole field of play[20] |

| 3.文明化の機能としての遊びと競争(コンテスト) | III. Play and contest as civilizing functions The view we take in the following pages is that culture arises in the form of play, that it is played from the very beginning... Social life is endued with supra-biological forms, in the shape of play, which enhances its value.[21] Huizinga does not mean that "play turns into culture". Rather, he sets play and culture side by side, talks about their "twin union", but insists that "play is primary".[21] |

| 4.遊びと法 | IV. Play and law The judge's wig, however, is more than a mere relic of antiquated professional dress. Functionally it has close connections with the dancing masks of savages. It transforms the wearer into another "being". And it is by no means the only very ancient feature which the strong sense of tradition so peculiar to the British has preserved in law. The sporting element and the humour so much in evidence in British legal practice is one of the basic features of law in archaic society.[22] Three play-forms in the lawsuit Huizinga puts forward the idea that there are "three play-forms in the lawsuit" and that these forms can be deduced by comparing practice today with "legal proceedings in archaic society":[23] the game of chance, the contest, the verbal battle. |

| 5.遊びと戦争 | V. Play and war Until recently the "law of nations" was generally held to constitute such a system of limitation, recognizing as it did the ideal of a community with rights and claims for all, and expressly separating the state of war—by declaring it—from peace on the one hand and criminal violence on the other. It remained for the theory of "total war" to banish war's cultural function and extinguish the last vestige of the play-element.[24] This chapter occupies a certain unique position not only in the book but more obviously in Huizinga's own life. The first Dutch version was published in 1938 (before the official outbreak of World War II). The Beacon Press book is based on the combination of Huizinga's English text and the German text, published in Switzerland 1944. Huizinga died in 1945 (the year the Second World War ended). One wages war to obtain a decision of holy validity.[25] An armed conflict is as much a mode of justice as divination or a legal proceeding.[25] War itself might be regarded as a form of divination.[26] The chapter contains some pleasantly surprising remarks: One might call society a game in the formal sense, if one bears in mind that such a game is the living principle of all civilization.[27] In the absence of the play-spirit civilization is impossible.[28] |

| 6.遊ぶことと知ること | VI. Playing and knowing For archaic man, doing and daring are power, but knowing is magical power. For him all particular knowledge is sacred knowledge—esoteric and wonder-working wisdom, because any knowing is directly related to the cosmic order itself.[29] The riddle-solving and death-penalty motif features strongly in the chapter. Greek tradition: the story of the seers Chalcas and Mopsos.[30] |

| 7.遊びと詩(作) | VII. Play and poetry Poiesis, in fact, is a play-function. It proceeds within the play-ground of the mind, in a world of its own which the mind creates for it. There things have a different physiognomy from the one they wear in "ordinary life", and are bound by ties other than those of logic and causality.[31] For Huizinga, the "true appellation of the archaic poet is vates, the possessed, the God-smitten, the raving one".[32] Of the many examples he gives, one might choose Unferd who appears in Beowulf.[33] |

| 8.神話形成の諸要素(The elements of Mythpoiesis) | VIII. The elements of mythopoiesis As soon as the effect of a metaphor consists in describing things or events in terms of life and movement, we are on the road to personification. To represent the incorporeal and the inanimate as a person is the soul of all myth-making and nearly all poetry.[34] Mythopoiesis is literally myth-making (see Mythopoeia and Mythopoeic thought). |

| 9.哲学における遊び=諸形態(play-forms) | IX. Play-forms in philosophy At the centre of the circle we are trying to describe with our idea of play there stands the figure of the Greek sophist. He may be regarded as an extension of the central figure in archaic cultural life who appeared before us successively as the prophet, medicine-man, seer, thaumaturge and poet and whose best designation is vates. |

| 10.芸術における遊び=諸形態 | X. Play-forms in art Wherever there is a catch-word ending in -ism we are hot on the tracks of a play-community.[35] Huizinga has already established an indissoluble bond between play and poetry. Now he recognizes that "the same is true, and in even higher degree, of the bond between play and music"[36] However, when he turns away from "poetry, music and dancing to the plastic arts" he "finds the connections with play becoming less obvious".[37] But here Huizinga is in the past. He cites the examples of the "architect, the sculptor, the painter, draughtsman, ceramist, and decorative artist" who in spite of her/his "creative impulse" is ruled by the discipline, "always subjected to the skill and proficiency of the forming hand".[38] On the other hand, if one turns away from the "making of works of art to the manner in which they are received in the social milieu",[39] then the picture changes completely. It is this social reception, the struggle of the new "-ism" against the old "-ism", which characterises the play. |

| 11.Sub specie ludi (遊びの諸相のもとでの)西洋文明 | XI. Western civilization sub specie ludi We have to conclude, therefore, that civilization is, in its earliest phases, played. It does not come from play like a baby detaching itself from the womb: it arises in and as play, and never leaves it.[40] |

| 12.現代文明における遊び=要素(play-element) | XII. Play-element in contemporary civilization In American politics it [the play-factor present in the whole apparatus of elections] is even more evident. Long before the two-party system had reduced itself to two gigantic teams whose political differences were hardly discernible to an outsider, electioneering in America had developed into a kind of national sport.[41] |

| 索引 |

★ヨハン・ホイジンガ(オランダ語: [ˈjoːɦɑn ˈɦœyzɪŋɣaː]、1872年12月7日 - 1945年2月1日)は、オランダの歴史家であり、現代の文化史の創始者の一人である。

Huizinga (right) with the ethnographer A.W. Nieuwenhuis, Leiden (1917); ホイジンガ(右)と民族学者A.W. ニューエンハウスのライデンでの写真(1917年)

| Johan Huizinga

(Dutch: [ˈjoːɦɑn ˈɦœyzɪŋɣaː]; 7 December 1872 – 1 February 1945) was a

Dutch historian and one of the founders of modern cultural history. |

ヨハン・ホイジンガ(オランダ語: [ˈjoːɦɑn ˈɦœyzɪŋɣaː]、1872年12月7日 - 1945年2月1日)は、オランダの歴史家であり、現代の文化史の創始者の一人である。 |

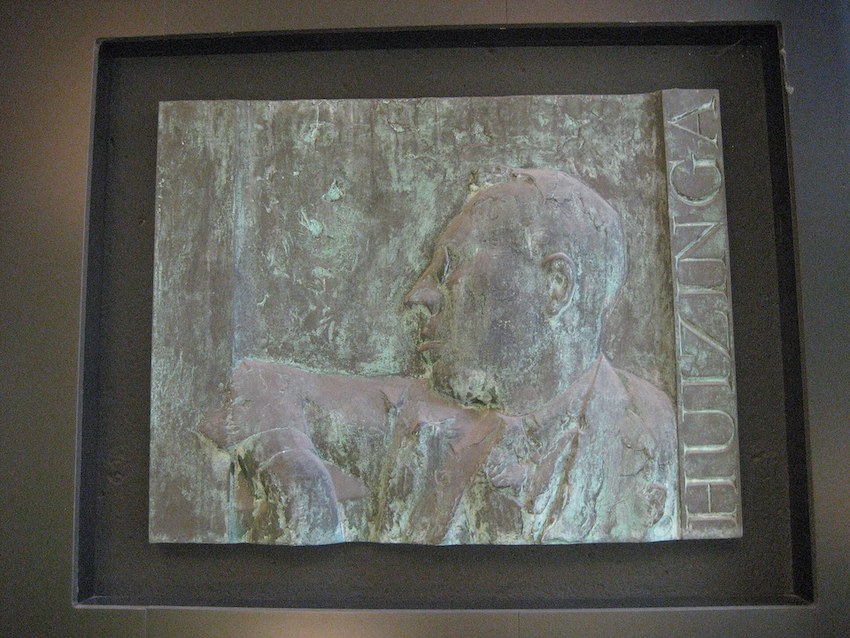

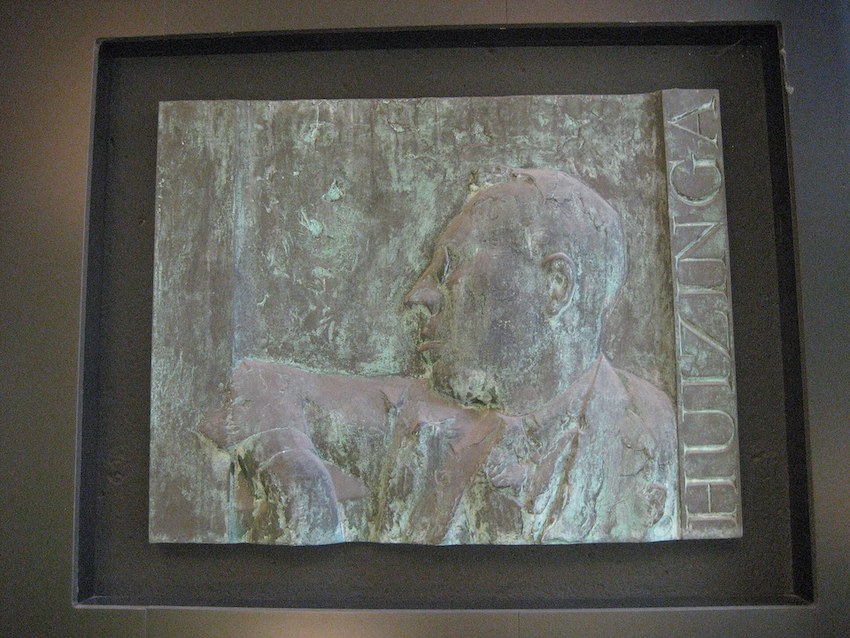

Life Huizinga plaque at Leiden University Born in Groningen as the son of Dirk Huizinga, a professor of physiology, and Jacoba Tonkens, who died two years after his birth,[1] he started out as a student of Indo-European languages, earning his degree in 1895. He then studied comparative linguistics, gaining a good command of Sanskrit. He wrote his doctoral thesis on the role of the jester in Indian drama in 1897. In 1902 his interest turned towards medieval and Renaissance history. He continued teaching as an Orientalist until he became a Professor of General and Dutch History at Groningen University in 1905. In 1915, he was made Professor of General History at Leiden University, a post he held until 1942. In 1916 he became member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[2] In 1942, he spoke critically of his country's German occupiers, comments that were consistent with his writings about Fascism in the 1930s. He was held in detention by the Nazis between August and October 1942. Upon his release, he was banned from returning to Leiden. He subsequently lived at the house of his colleague Rudolph Cleveringa in De Steeg in Gelderland, near Arnhem, where he died just a few weeks before Nazi rule ended.[3] He lies buried in the graveyard of the Reformed Church at 6 Haarlemmerstraatweg in Oegstgeest.[4] |

ライフ ライデン大学にあるフーイジンガの銘板 フローニンゲンで、生理学教授のディルク・フージンガとヤコバ・トンケンスの息子として生まれた彼は、生後2年で母親が死去した。[1] 彼はインド・ヨーロッパ語学の学生としてスタートし、1895年に学位を取得した。その後、比較言語学を学び、サンスクリット語を習得した。1897年に は、インドの喜劇における道化の役割について博士論文を執筆した。 1902年には、中世とルネサンスの歴史に興味の対象が移った。 1905年にフローニンゲン大学のオランダおよび一般史の教授になるまで、東洋学者として教鞭をとり続けた。 1915年にはライデン大学の一般史の教授となり、1942年までその職にあった。 1916年にはオランダ王立芸術科学アカデミーの会員となった。 1942年、彼は自国のドイツ占領者について批判的な発言をし、そのコメントは1930年代のファシズムに関する彼の著作と一致していた。彼は1942年 8月から10月にかけてナチスに拘留された。釈放後、ライデンへの帰郷を禁じられた。その後、同僚のルドルフ・クレフェリンガの家(オランダ、ヘルダーラ ント州デ・ステーグ、アーネム近郊)で暮らしたが、ナチス支配が終結する数週間前に亡くなった。[3] 彼は、オークストヘストの6 Haarlemmerstraatwegにある改革派教会の墓地に埋葬されている。[4] |

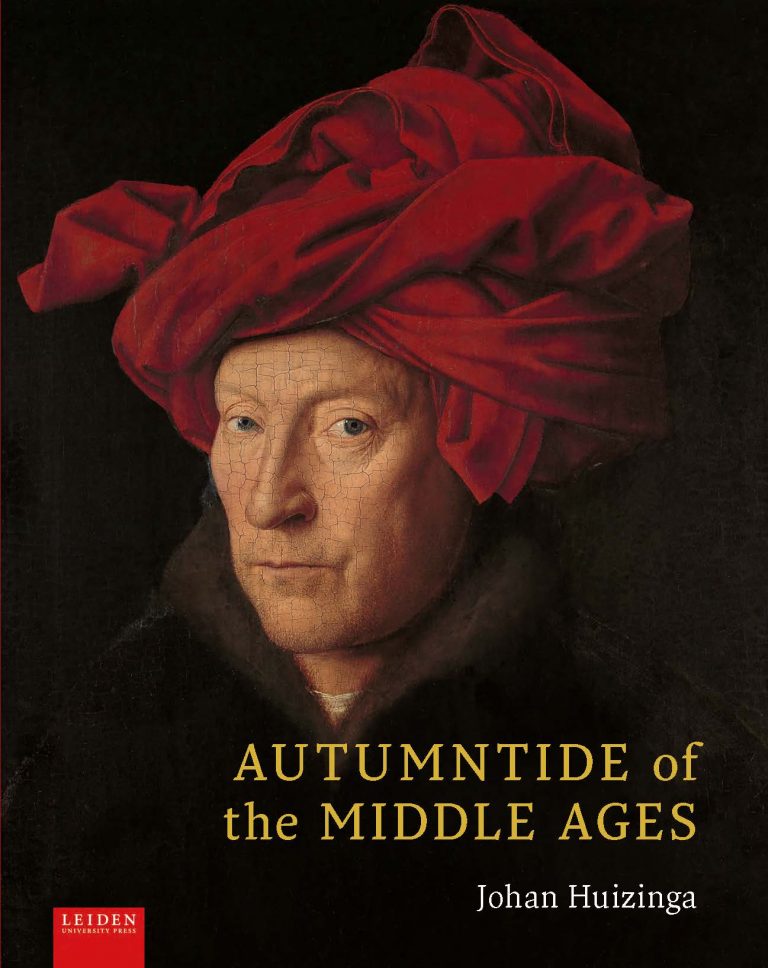

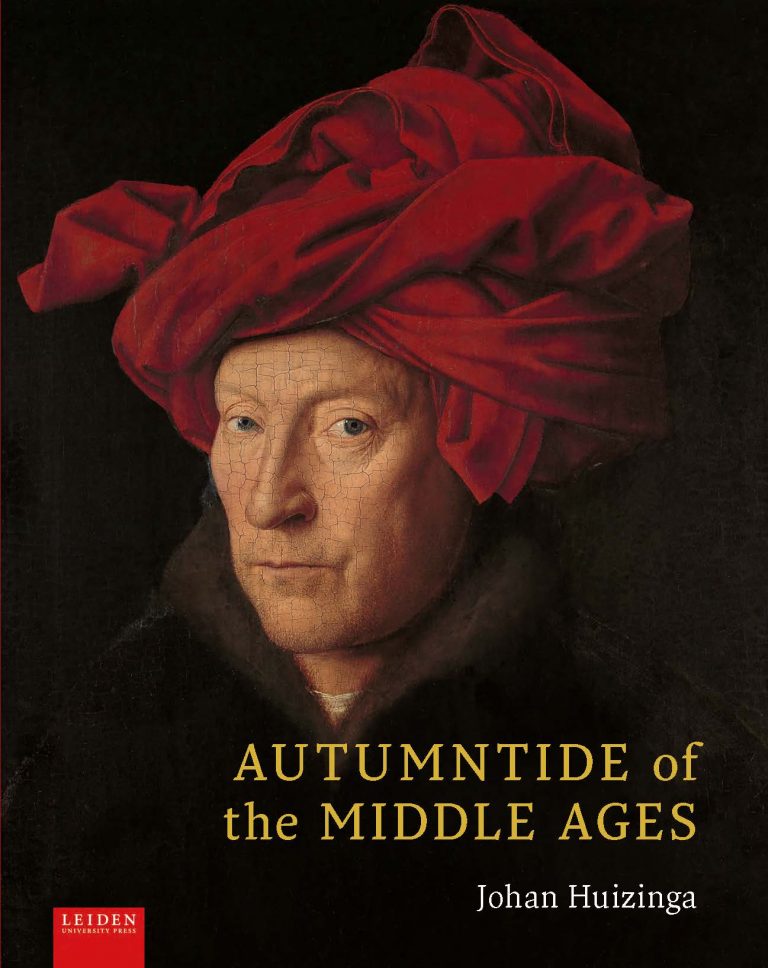

| Works Huizinga had an aesthetic approach to history, where art and spectacle played an important part. His most famous work is The Autumn of the Middle Ages (also released as The Waning of the Middle Ages or Autumntide of the Middle Ages) (1919). Other works include Erasmus (1924) and Homo Ludens (1938). In the latter book he discussed the possibility that play is the primary formative element in human culture. Huizinga also published books on American history and Dutch history in the 17th century. Alarmed by the rise of National Socialism in Germany, Huizinga wrote several works of cultural criticism. Many similarities can be noted between his analysis and that of contemporary critics such as Ortega y Gasset and Oswald Spengler. Huizinga argued that the spirit of technical and mechanical organisation had replaced spontaneous and organic order in cultural as well as political life. (Citation needed) The Huizinga Lecture (Dutch: Huizingalezing) is a prestigious annual lecture in the Netherlands about a subject in the domains of cultural history or philosophy in honour of Johan Huizinga.[5] Johan Huizinga’s archive and papers are held by Leiden University Libraries’ Special Collections and also available in its Digital Collections.[6] A complete inventory has been published.[7] Family Huizinga's son Leonhard Huizinga became a writer, including his series of tongue-in-cheek novels on the Dutch aristocratic twins Adrian and Oliver [nl] ("Adriaan en Olivier"). |

作品 ホイジンガは歴史に対する審美的なアプローチをとり、芸術とスペクタクルが重要な役割を果たした。彼の最も有名な作品は『中世の秋』(『中世の衰退』、『中世の秋分』とも)である(1919年)。 その他の作品には『エラスムス』(1924年)や『ホモ・ルーデンス』(1938年)などがある。後者の著書では、遊びが人間文化の主要な形成要素である可能性について論じている。ホイジンガは17世紀のアメリカ史やオランダ史に関する著書も出版している。 ドイツにおける国家社会主義の台頭に危機感を抱いたホイジンガは、文化批評の著作をいくつか著した。彼の分析とオルテガ・イ・ガセットやオズヴァルト・ シュペングラーといった同時代の批評家の分析には、多くの類似点が見られる。ホイジンガは、技術的・機械的な組織化の精神が、文化面でも政治面でも、自発 的で有機的な秩序に取って代わったと主張した。(要出典) ホイジンガ講演会(オランダ語:Huizingalezing)は、オランダで毎年開催される由緒ある講演会で、ヨハン・ホイジンガを記念して文化史や哲学の分野におけるテーマを取り上げている。 ヨハン・ホイジンガのアーカイブおよび論文はライデン大学図書館の特別コレクションに保管されており、デジタルコレクションでも閲覧可能である。[6] 完全な目録が出版されている。[7] 家族 ホイジンガの息子レオンハルト・ホイジンガは作家となり、オランダの貴族の双子エイドリアンとオリバーを皮肉った小説シリーズ[nl](「アドリアーンとオリヴィエ」)を執筆した。 |

| Bibliography Mensch en menigte in America (1918), translated by Herbert H. Rowen as America; A Dutch historian's vision, from afar and near (Part 1) (Harper & Row, 1972) Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen (1919), translated as Herbst des Mittelalters by Mathilde Wolff-Mönckeberg (1924), The Waning of the Middle Ages (1924), as The Autumn of the Middle Ages (1996) and as Autumntide of the Middle Ages by Diane Webb (2020) Erasmus of Rotterdam (1924), translated by Frederik Hopman as Erasmus and the Age of Reformation (1924) Amerika Levend en Denkend (1926), translated by Herbert H. Rowen as America: A Dutch Historian's Vision, from Afar and Near (Part 2) (Harper & Row, 1972) Leven en werk van Jan Veth (1927) Cultuurhistorische verkenningen (1929) In de schaduwen van morgen (1935), translated by his son Jacob Herman Huizinga In the Shadow of Tomorrow De wetenschap der geschiedenis (1937) Geschonden wereld (1946, published posthumously) Homo Ludens. Proeve eener bepaling van het spel-element der cultuur (1938), translated as Homo Ludens, a study of the play element in culture (1955) Nederland's beschaving in de zeventiende eeuw (1941). Translated by Arnold Pomerans as Dutch civilisation in the seventeenth century (1968) “Patriotism and Nationalism in European History”. In: Men and Ideas. History, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance. Transl. by James S. Holmes and Hans van Marle. New York: Meridian Books, 1959. Men and ideas. History, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance. Essays (1959). Translations by James S. Holmes and Hans van Marle of parts of Huizinga's Collected Works |

参考文献 『アメリカにおける人間と群衆』(1918年)、ハーバート・H・ローウェン訳『アメリカ:オランダ人歴史家の遠くからの、そして近くからの展望(第1部)』(Harper & Row、1972年) 中世の秋(1919年)は、マティルデ・ウォルフ=メンケベリ(1924年)によって『中世の秋』、1924年)は『中世の衰退』(1996年)として、またダイアン・ウェッブ(2020年)によって『中世の秋』として翻訳された。 ロッテルダムのエラスムス(1924年)、フレデリック・ホプマンによる翻訳『エラスムスと宗教改革の時代』(1924年) アメリカ、生きているもの、考えているもの(1926年)、ハーバート・H・ローウェンによる翻訳『アメリカ:オランダ人歴史家の遠近両方の視点(第2部)』(Harper & Row、1972年) ヤン・フェスの生涯と作品(1927年) 文化史的探求(1929年) 明日の影の中で(1935年)は、息子のヤコブ・ハーマン・ホイジンガによって翻訳された。明日の影の中で 歴史学の科学(1937年) 傷ついた世界(1946年、死後出版) 『ホモ・ルーデンス。文化における遊びの要素の定義の試み』(1938年)は、『ホモ・ルーデンス。文化における遊びの要素の研究』(1955年)として翻訳された 『オランダの17世紀における文明』(1941年)は、アーノルド・ポメランズによって『17世紀のオランダ文明』(1968年)として翻訳された 「ヨーロッパ史における愛国心とナショナリズム」。『人間と思想。歴史、中世、ルネサンス』ジェームズ・S・ホームズ、ハンス・ヴァン・マール共訳。ニューヨーク:メリディアンブックス、1959年。 人間と思想。歴史、中世、ルネサンス。エッセイ(1959年)。ホイジンガ全集の一部をジェームズ・S・ホームズ、ハンス・ヴァン・マールが翻訳。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johan_Huizinga |

|

| The Autumn of the Middle Ages,

The Waning of the Middle Ages, or Autumntide of the Middle Ages

(published in 1919 as Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen and translated into

English in 1924, German in 1924, and French in 1932), is the best-known

work by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga. In the book, Huizinga presents the idea that the exaggerated formality and romanticism of late medieval court society was a defense mechanism against the constantly increasing violence and brutality of general society. He saw the period as one of pessimism, cultural exhaustion, and nostalgia, rather than of rebirth and optimism. His main conclusion is that the combination of required modernization of statehood governance, stuck in traditionalism, in combination with the exhausting inclusion of an ever-growing corpus of Catholic rites and popular beliefs in daily life, led to the implosion of late medieval society. This provided light to the rise of (religious) individualism, humanism and scientific progress: the renaissance. The book was nominated for the 1939 Nobel Prize for Literature, but lost to the Finnish writer Frans Eemil Sillanpää. Huizinga's work later came under some criticism, especially for relying too heavily on evidence from the rather exceptional case of the Burgundian court. Other criticisms include the writing of the book being "old-fashioned" and "too literary".[1] A new English translation of the book was published in 1996 because of perceived deficiencies in the original translation. The new translation, by Rodney Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch, was based on the second edition of the Dutch publication in 1921 and compared with the German translation published in 1924.  Johan Huizinga: Autumntide of the Middle Ages. Book cover of 2020 edition. To mark the centenary of Herfsttij, a new translation by Diane Webb appeared in 2020, published by Leiden University Press: Autumntide of the Middle Ages. According to Benjamin Kaplan, this translation "captures Huizinga's original voice better than either of the two previous English editions".[2] This new English edition also includes for the first time 300 full-colour illustrations of all the works of art Huizinga mentions in his text. In the 1970s, Radio Netherlands produced an audio series about the book, entitled "Autumn of the Middle Ages: A Six-part History in Words and Music from the Low Countries".[3] |

中世の秋、中世の衰退、または中世の秋分(1919年に『中世の秋分』として出版され、1924年に英語、1924年にドイツ語、1932年にフランス語に翻訳された)は、オランダの歴史家ヨハン・ホイジンガによる最も有名な著作である。 この著書の中で、フイジンガは、後期中世の宮廷社会における誇張された形式主義とロマン主義は、一般社会における絶え間なく増加する暴力と残虐性に対する 防衛メカニズムであったという考えを提示している。彼は、この時代を再生と楽観主義の時代というよりも、むしろ悲観主義、文化の疲弊、郷愁の時代と捉えて いた。 彼の主な結論は、国家統治の近代化が伝統主義に阻まれ、日常生活におけるカトリックの儀式や民間信仰の膨大な数の慣習の取り込みに疲れ果てたことが、中世後期の社会崩壊につながったというものである。これが(宗教的)個人主義、ヒューマニズム、科学の進歩、すなわちルネサンスの台頭に光を当てた。 この著書は1939年のノーベル文学賞にノミネートされたが、フィンランドの作家フランシス・エミール・シルッカに敗れた。 フイジンガの研究は後に、特にブルゴーニュ宮廷というかなり例外的な事例の証拠に過度に依存しているという理由で批判を受けることとなった。その他の批判としては、この著書が「時代遅れ」で「文学的過ぎる」というものもある。 元の翻訳の欠点が指摘されたため、1996年にこの本の新しい英語訳が出版された。ロドニー・ペイトンとウルリッヒ・マンミッチによる新しい翻訳は、1921年のオランダ語版第2版を基にしており、1924年に出版されたドイツ語訳と比較されている。  ヨハン・ホイジンガ著『中世の秋』。2020年版の表紙。 ハーフティデの100周年を記念して、2020年にダイアン・ウェッブによる新訳『中世の秋』がライデン大学出版から出版された。ベンジャミン・カプラン によると、この翻訳は「これまでの2つの英語版よりも、ホイジンガの本来の声をよりよく捉えている」という。[2] この新しい英語版には、ホイジンガが本文中で言及しているすべての芸術作品の300点のフルカラーのイラストが初めて収録されている。 1970年代には、オランダ放送協会がこの本に関するオーディオシリーズを制作し、「中世の秋:低地諸国からの言葉と音楽による6部構成の歴史」というタイトルが付けられた。[3] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Autumn_of_the_Middle_Ages |

|

| Homo Ludens

is a book originally published in Dutch in 1938[2] by Dutch historian

and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga.[3] It discusses the importance of

the play element of culture and society.[4] Huizinga suggests that play

is primary to and a necessary (though not sufficient) condition of the

generation of culture. The Latin word ludens is the present active

participle of the verb ludere, which itself is cognate with the noun

ludus. Ludus has no direct equivalent in English, as it simultaneously

refers to sport, play, school, and practice.[5] Contents I. Nature and significance of play as a cultural phenomenon Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.[6] Huizinga begins by making it clear that animals played before humans. One of the most significant (human and cultural) aspects of play is that it is fun.[7] Huizinga identifies 5 characteristics that play must have:[8] Play is free, is in fact freedom. Play is not "ordinary" or "real" life. Play is distinct from "ordinary" life both as to locality and duration. Play creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme. Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it.[9] Huizinga shows that in ritual dances a person 'becomes' a kangaroo. There is a difference in how western thought expresses this concept and how "primitive" religions view this. Scholars of religion use western terminology to describe non western concepts. "He has taken on the "essence" of the kangaroo, says the savage; he is playing the kangaroo, say we. The savage, however, knows nothing of the conceptual distinctions between "being" and "playing"; he knows nothing of "identity'\ "image" or "symbol"." [10] In this way Huizinga suggests the universally understood concept of play is more fitting to both societies to describe this phenomenon. II. The play concept as expressed in language Word and idea are not born of scientific or logical thinking but of creative language, which means of innumerable languages—for this act of "conception" has taken place over and over again.[11] Huizinga has much to say about the words for play in different languages. Perhaps the most extraordinary remark concerns the Latin language. "It is remarkable that ludus, as the general term for play, has not only not passed into the Romance languages but has left hardly any traces there, so far as I can see... We must leave to one side the question whether the disappearance of ludus and ludere is due to phonetic or to semantic causes."[12] Of all the possible uses of the word "play" Huizinga specifically mentions the equation of play with, on the one hand, "serious strife", and on the other, "erotic applications".[13] Play-category, play-concept, play-function, play-word in selected languages Huizinga attempts to classify the words used for play in a variety of natural languages. The chapter title uses "play-concept" to describe such words. Other words used with the "play-" prefix are play-function and play-form. The order in which examples are given in natural languages is as follows: Greek[14] (3) παιδιά — pertaining to children's games, ἄθυρμα — associated with the idea of the trifling, the nugatory, ἀγών — for matches and contests. Sanskrit[15] (4) krīdati — denoting the play of animals, children, adults, divyati — gambling, dicing, joking, jesting, ..., vilāsa — shining, sudden appearance, playing and pursuing an occupation, līlayati — light, frivolous insignificant sides of playing. Chinese[16] (3) 玩 (wán) — is the most important word covering children's games and much much more, 爭 (zhēng) — denoting anything to do with contests, corresponds exactly to the Greek agon, 賽 (sài) — organized contest for a prize. Blackfoot[17] (2) koani — all children's games and also in the erotic sense of "dallying", kachtsi — organized play. Japanese[18] (1) 遊ぶ (asobu) — is a single, very definite word, for the play function. Semitic languages la’ab (a root, cognate with la’at) — play, laughing, mocking, la’iba (Arabic) — playing in general, making mock of, teasing,[19] la’ab (Aramaic) — laughing and mocking, sahaq (Hebrew) — laughing and playing. Latin (1) ludus — from ludere, covers the whole field of play[20] III. Play and contest as civilizing functions The view we take in the following pages is that culture arises in the form of play, that it is played from the very beginning... Social life is endued with supra-biological forms, in the shape of play, which enhances its value.[21] Huizinga does not mean that "play turns into culture". Rather, he sets play and culture side by side, talks about their "twin union", but insists that "play is primary".[21] In this chapter, Huizinga highlights the antagonistic aspect of play and its "civilizing function". Using the research of Marcel Granet, Huizinga describes the festal practices of ancient Chinese clans, who incorporated various contests in their celebrations and rituals. These contests, in essence, divided the clan internally into what are known by anthropologists as phratriai, and these internal divisions become a social hierarchy, laying the groundwork for more "complex" civilizations.[22] When describing antagonistic relationships between clans (as opposed to internally), Huizinga mentions the practice of potlatch. He writes, In its most typical form as found among the Kwakiutl tribe the potlatch is a great solemn feast, during which one of two groups, with much pomp and ceremony, makes gifts on a large scale to the other group for the express purpose of showing its [the gift-giving group's] superiority.[23] The potlatch is meant to be a frivolous, wasteful, even destruction display of superiority, and accounts are given of rival clans ruining their estates, killing their livestock and slaves, and even -- in one instance -- a spouse. Instances of this practice can be traced all over the world and throughout history, even in sacred texts; for example, Marcel Mauss claimed that "the Mahabharata is the story of a gigantic potlach" (quoted by Huizinga).[24] Tying his reflections on the potlach to his underlying thesis regarding play, Huizinga claims that the potlatch is, in my view, the agonistic "instinct" pure and simple. [All instances of the potlatch] must be regarded first and foremost as a violent expression of the human need to fight. Once this is admitted we may call them, strictly speaking, "play" -- serious play, fateful and fatal play, bloody play, sacred play, but nonetheless that playing which, in archaic society, raises the individual or the collective personality to a higher power.[25] The remainder of this chapter is devoted to an analysis of the idea of virtue (άρετή) as it relates to αγων and play. Competition affords members of a community to win accolades, esteem, and honor, and honor, according to Aristotle, is what allows people "to persuade themselves of their own worth, their virtue." From this, Huizinga concludes that "virtue, honor, nobility, and glory fall at the outset within the field of competition, which is that of play." This connection between virtue (άρετή) and play affords Huizinga the connection he needs to link play with civilization: Training for aristocratic living leads to training for life in the State and for the State. Here too άρετή is not as yet entirely ethical. It still means above all the fitness of the citizen for his tasks in the polis, and the idea it originally contained of exercise by means of contests still retains much of its old weight.[26] The remainder of the chapter is devoted to providing literary and mythological examples of contests that have served the civilizing function, with reference being made to Beowulf, Old Norse sagas, and many others. IV. Play and law The judge's wig, however, is more than a mere relic of antiquated professional dress. Functionally it has close connections with the dancing masks of savages. It transforms the wearer into another "being". And it is by no means the only very ancient feature which the strong sense of tradition so peculiar to the British has preserved in law. The sporting element and the humour so much in evidence in British legal practice is one of the basic features of law in archaic society. [27] Three play-forms in the lawsuit Huizinga puts forward the idea that there are "three play-forms in the lawsuit" and that these forms can be deduced by comparing practice today with "legal proceedings in archaic society":[28] the game of chance, the contest, the verbal battle. V. Play and war Until recently the "law of nations" was generally held to constitute such a system of limitation, recognizing as it did the ideal of a community with rights and claims for all, and expressly separating the state of war—by declaring it—from peace on the one hand and criminal violence on the other. It remained for the theory of "total war" to banish war's cultural function and extinguish the last vestige of the play-element.[29] This chapter occupies a certain unique position not only in the book but more obviously in Huizinga's own life. The first Dutch version was published in 1938 (before the official outbreak of World War II). The Beacon Press book is based on the combination of Huizinga's English text and the German text, published in Switzerland 1944. Huizinga died in 1945 (the year the Second World War ended). One wages war to obtain a decision of holy validity.[30] An armed conflict is as much a mode of justice as divination or a legal proceeding.[30] War itself might be regarded as a form of divination.[31] The chapter contains some pleasantly surprising remarks: One might call society a game in the formal sense, if one bears in mind that such a game is the living principle of all civilization.[32] In the absence of the play-spirit civilization is impossible.[33] VI. Playing and knowing For archaic man, doing and daring are power, but knowing is magical power. For him all particular knowledge is sacred knowledge—esoteric and wonder-working wisdom, because any knowing is directly related to the cosmic order itself.[34] The riddle-solving and death-penalty motif features strongly in the chapter. Greek tradition: the story of the seers Chalcas and Mopsos.[35] VII. Play and poetry Poiesis, in fact, is a play-function. It proceeds within the play-ground of the mind, in a world of its own which the mind creates for it. There things have a different physiognomy from the one they wear in "ordinary life", and are bound by ties other than those of logic and causality.[36] For Huizinga, the "true appellation of the archaic poet is vates, the possessed, the God-smitten, the raving one".[37] Of the many examples he gives, one might choose Unferd who appears in Beowulf.[38] VIII. The elements of mythopoiesis As soon as the effect of a metaphor consists in describing things or events in terms of life and movement, we are on the road to personification. To represent the incorporeal and the inanimate as a person is the soul of all myth-making and nearly all poetry.[39] Mythopoiesis is literally myth-making (see Mythopoeia and Mythopoeic thought). IX. Play-forms in philosophy At the centre of the circle we are trying to describe with our idea of play there stands the figure of the Greek sophist. He may be regarded as an extension of the central figure in archaic cultural life who appeared before us successively as the prophet, medicine-man, seer, thaumaturge and poet and whose best designation is vates. X. Play-forms in art Wherever there is a catch-word ending in -ism we are hot on the tracks of a play-community.[40] Huizinga has already established an indissoluble bond between play and poetry. Now he recognizes that "the same is true, and in even higher degree, of the bond between play and music"[41] However, when he turns away from "poetry, music and dancing to the plastic arts" he "finds the connections with play becoming less obvious".[42] But here Huizinga is in the past. He cites the examples of the "architect, the sculptor, the painter, draughtsman, ceramist, and decorative artist" who in spite of her/his "creative impulse" is ruled by the discipline, "always subjected to the skill and proficiency of the forming hand".[43] On the other hand, if one turns away from the "making of works of art to the manner in which they are received in the social milieu",[44] then the picture changes completely. It is this social reception, the struggle of the new "-ism" against the old "-ism", which characterises the play. XI. Western civilization sub specie ludi We have to conclude, therefore, that civilization is, in its earliest phases, played. It does not come from play like a baby detaching itself from the womb: it arises in and as play, and never leaves it.[45] XII. Play-element in contemporary civilization In American politics it [the play-factor present in the whole apparatus of elections] is even more evident. Long before the two-party system had reduced itself to two gigantic teams whose political differences were hardly discernible to an outsider, electioneering in America had developed into a kind of national sport.[46] Quotations "Man only plays when in the full meaning of the word he is a man, and he is only completely a man when he plays." (On the Aesthetic Education of Man — Friedrich Schiller)[page needed] "It is ancient wisdom, but it is also a little cheap, to call all human activity 'play'. Those who are willing to content themselves with a metaphysical conclusion of this kind should not read this book." (from the Foreword, unnumbered page) Reception Homo Ludens is an important part of the history of game studies. It influenced later scholars of play, like Roger Caillois. The concept of the magic circle was inspired by Homo Ludens. Foreword controversy Huizinga makes it clear in the foreword of his book that he means the play element of culture, and not the play element in culture. He writes that he titled the initial lecture on which the book is based, "The Play Element of Culture". This title was repeatedly corrected to "in" Culture, a revision he objected to. The English version modified the subtitle of the book to "A Study of the Play-Element in Culture", contradicting Huizinga's stated intention. The translator explains in a footnote in the Foreword, "Logically, of course, Huizinga is correct; but as English prepositions are not governed by logic I have retained the more euphonious ablative in this sub-title."[47] |

ホモ・ルーデンス(Homo

Ludens)は、1938年にオランダの歴史家であり文化理論家であるヨハン・ホイジンガ(Johan

Huizinga)によってオランダ語で出版された書籍である。[2][3]

この本では、文化と社会における遊びの要素の重要性について論じている。[4]

ホイジンガは、遊びは文化の生成にとって最も重要であり、必要(ただし十分ではない)な条件であると示唆している。ラテン語のludensは、

ludereという動詞の現在能動分詞であり、ludere自体はludusという名詞と語源を同じくする。ルドゥスには、スポーツ、遊び、学校、練習と

いう意味があり、英語には直接的な訳語がない。[5] 目次 I. 文化現象としての遊びの本質と意義 文化がどのように定義されるかにかかわらず、文化は常に人間社会を前提としている。動物は人間が遊び方を教えるのを待つことはなかった。[6] ホイジンガはまず、人間よりも前に動物たちが遊んでいたことを明らかにしている。遊びの最も重要な(人間的、文化的)側面のひとつは、それが楽しいということである。 ホイジンガは、遊びが持つべき5つの特徴を特定している。 遊びは自由であり、実際には自由そのものである。 遊びは「日常」でも「現実」でもない。 遊びは「日常」の生活とは場所的にも時間的にも異なる。 遊びは秩序を生み出し、秩序そのものである。遊びは絶対的かつ至高の秩序を要求する。 遊びは物質的利益とは無関係であり、そこから利益を得ることはできない。 フイジンガは、儀式の踊りにおいて人は「カンガルーになる」ことを示している。西洋の思想がこの概念を表現する方法と、「原始的」宗教がこの概念を捉える方法には違いがある。宗教学者は西洋の概念を表現するために西洋の用語を使用する。 「野蛮人は、彼がカンガルーの『本質』を身につけたと言う。我々は、彼がカンガルーの真似をしていると言う。しかし、野蛮人は『本質』と『真似』の概念上 の区別を知らない。彼は『同一性』、『イメージ』、『象徴』について何も知らないのだ。」[10] このように、フイジンガは、この現象を説明するのに、普遍的に理解されている「遊び」という概念が両方の社会によりふさわしいと示唆している。 II. 言語で表現される「遊び」の概念 言葉や概念は、科学的あるいは論理的な思考から生まれるのではなく、創造的な言語から生まれる。つまり、無数の言語から生まれるのである。なぜなら、この「概念化」という行為は、繰り返し行われてきたからだ。 ホイジンガは、さまざまな言語における「遊び」を表す言葉について、多くのことを述べている。おそらく最も驚くべき指摘は、ラテン語に関するものである。 「遊び」の一般的な用語である「ルドゥス」がロマンス諸語に伝わらなかったばかりか、私が知る限り、ほとんど痕跡も残していないのは注目に値する。ルドゥ スとルデレが消滅した原因が音声学的なものか意味論的なものかという問題はさておき、私たちはそれを考慮に入れなければならない。」[12] 「遊び」という言葉のあらゆる使用法について、フイジンガは特に、遊びと「深刻な争い」の同一視、そしてもう一方では「エロティックな用途」の同一視について言及している。[13] 遊びのカテゴリー、遊びの概念、遊びの機能、遊びの言葉(一部の言語 フイジンガは、さまざまな自然言語における「遊び」を表す語を分類しようとしている。この章のタイトルでは、そうした語を「遊びの概念」と表現している。 「遊び-」という接頭辞を持つ他の語には、「遊びの機能」や「遊びの形態」がある。自然言語における例の順序は以下の通りである。 ギリシャ語[14] (3) παιδιά — 子供の遊びに関する ἄθυρμα — 取るに足らない、無益なという考えに関連する ἀγών — 試合や競技に関する。 サンスクリット語[15] (4) krīdati — 動物、子供、大人の遊び、 divyati — 賭け事、サイコロ遊び、冗談、冗談を言う、...、 vilāsa — 輝く、突然の登場、職業に従事する、 līlayati — 軽い、遊びの軽薄で取るに足らない側面。 中国語[16] (3) 玩 (wán) — 子供たちの遊びや、その他多くのことを意味する最も重要な言葉である。 争う (zhēng) — コンテストに関わることを示す。ギリシャ語の agon に正確に対応する。 賽 (sài) — 賞品を賭けた組織的なコンテスト。 ブラックフット族[17] (2) koani — すべての子供の遊び、また「たわむれる」というエロティックな意味でも。 kachtsi — 組織的な遊び。 日本語[18] (1) 遊ぶ (asobu) — 遊びの機能を表す、非常に明確な単語である。 セム語族 la'ab (語幹、la'atと同族) — 遊ぶ、笑う、あざける、 la'iba (アラビア語) — 遊ぶこと一般、あざける、からかう、[19] la'ab (アラム語) — 笑う、あざける、 sahaq (ヘブライ語) — 笑う、遊ぶ。 ラテン語 (1) ludus — ludere から派生した語で、遊びの全領域をカバーする[20] III. 文明化機能としての遊びと競争 以下で述べる見解は、文化は遊びの形態で生じ、それは最初から行われていたというものである。社会生活は、遊びという生物学的形態を超えた形を備えており、その価値を高めている。 ホイジンガは「遊びが文化に変わる」という意味で言っているのではない。むしろ、遊びと文化を並列に置き、その「双子の結合」について語っているが、「遊びが第一である」と主張している。 この章でフイジンガは、遊びの敵対的な側面と「文明化機能」を強調している。マルセル・グラネの研究を引用しながら、フイジンガは古代中国の氏族の祝祭慣 習について述べている。祝祭ではさまざまな競技が行われていた。これらの競技は、本質的には氏族を内部的に、人類学者がフラトリと呼ぶものに分割し、これ らの内部的な区分が社会的な階層となり、より「複雑な」文明の基盤となったのである。 氏族間の敵対関係(内部の対立とは対照的)について述べるとき、ホイジンガはポトラッチの慣習について言及している。彼は次のように書いている。 クワキウト族に見られる最も典型的な形のポトラッチは、厳粛な祝宴であり、その間、2つのグループのうちの1つが、贈り物を贈る側の優位性を示すことを明確な目的として、大規模な贈り物を、多くの儀式とともに、もう一方のグループに対して行うのである。 ポトラッチは、優越性を軽薄に、浪費的に、時には破壊的に誇示するものであり、ライバル一族が財産を破棄し、家畜や奴隷を殺し、さらには配偶者まで殺す例 さえあったと伝えられている。この慣習の例は、世界中の歴史を通じて、聖典の中にも見出すことができる。例えば、マルセル・モースは「『マハーバーラタ』 は巨大なポトラッチの物語である」と主張している(ホイジンガによる引用)[24]。ポトラッチに関する考察を遊びに関する基本的な主張と結びつけ、ホイ ジンガは次のように主張している。 ポトラッチは、私の考えでは、純粋かつ単純な闘争本能である。ポトラッチのすべての事例は、何よりもまず、戦うという人間の欲求の暴力的な表現と見なさな ければならない。このことが認められれば、厳密に言えば、それらを「遊び」と呼ぶことができる。深刻な遊び、運命的な遊び、致命的な遊び、血なまぐさい遊 び、神聖な遊び、しかし、それにもかかわらず、それらの遊びは、古代社会において、個人または集団の個性をより高い力へと高めるものである。 本章の残りの部分では、アゴーンと遊戯に関連する美徳(άρετή)の概念の分析に焦点を当てる。競争は、共同体に属する人々が称賛、尊敬、名誉を勝ち取 る機会を与える。アリストテレスによれば、名誉とは、人々が「自らの価値、美徳を自らに納得させる」ことを可能にするものである。このことから、ホイジン ガは「美徳、名誉、高潔さ、栄光は、そもそも遊びという競争の分野に属するものである」と結論づけている。美徳(άρετή)と遊びの間のこのつながり が、ホイジンガに遊びと文明を結びつけるために必要なつながりをもたらした。 貴族的な生活のための訓練は、国家における生活、そして国家のための訓練につながる。この場合も、まだ「アレテー」は完全に倫理的な意味合いを持っている わけではない。それは依然として、ポリスにおける市民の任務遂行能力を意味しており、もともと「アレテー」が含んでいた競技による鍛錬という概念は、依然 としてその昔の重みを保っている。[26] 本章の残りの部分では、ベオウルフや古ノルド語のサガなど、多くの文献や神話に登場する競技の例を挙げ、文明化の機能について論じている。 IV. 遊びと法 しかし、裁判官の被り物は、単なる時代遅れの職業的服装の遺物以上のものだ。機能的には、それは野蛮人の踊る仮面と密接な関係がある。それは着用者を別の 「存在」へと変身させる。そして、英国人に特有の強い伝統意識が法律の中に保存している非常に古い特徴は、それだけにとどまらない。英国の法実務において 顕著なスポーツ的要素やユーモアは、古代社会の法律の基本的な特徴のひとつである。[27] 訴訟における3つの遊びの形態 ホイジンガは、「訴訟における3つの遊びの形態」という考えを提示し、これらの形態は今日の慣行を「古代社会における法的手続き」と比較することで推論できると主張している。[28] 偶然のゲーム、 競技、 言葉による戦い。 V. 遊びと戦争 つい最近まで、「国際法」は一般的に制限の体系を構成するものと考えられていた。それは、万人の権利と主張を認める共同体という理想を掲げ、戦争状態を宣 言することで平和と犯罪的な暴力から明確に区別していた。戦争の文化的機能を排除し、遊びの要素の最後の痕跡を消し去るには、「総力戦」理論が残されてい た。 この章は、この本の中でも、またフイジンガ自身の生涯においても、独特な位置を占めている。 最初のオランダ語版は1938年に出版された(第二次世界大戦の公式勃発前)。 ビーコン・プレス社から出版された本は、フイジンガの英語版と1944年にスイスで出版されたドイツ語版を組み合わせたものである。 フイジンガは1945年に死去した(第二次世界大戦が終結した年)。 人は神聖な正当性を求めるために戦争を行う。[30] 武力紛争は占いや法的手続きと同様に、正義の手段である。[30] 戦争そのものが占いの一形態であるとみなすこともできる。[31] この章には、いくつかの驚くべき指摘がある。 社会を形式的な意味でのゲームと呼ぶこともできる。そのようなゲームがすべての文明の生きた原則であることを念頭に置くならば。 遊びの精神がなければ、文明は不可能である。[33] VI. 遊びと知識 原始人にとって、行動と挑戦こそが力であるが、知識こそが魔法の力である。彼にとって、あらゆる特定の知識は神聖な知識であり、秘教的なものであり、驚異的な知恵である。なぜなら、あらゆる知識は宇宙の秩序そのものに直接関係しているからである。[34] この章では、謎解きと死刑のモチーフが強く特徴づけられている。 ギリシアの伝統:予言者カルカスとモプソスの物語。[35] VII. 演劇と詩 実際、ポイエーシスは演劇的な機能である。それは心の遊び場の中で進行する。心はそれ自身のために、心が生み出した独自の領域の中で。そこでは、物事は「日常」で身にまとうものとは異なる外観を持ち、論理や因果関係以外の絆によって結びつけられている。[36] ホイジンガにとって、「古代の詩人の真の呼称は、神に憑かれた、神に選ばれた、狂気じみた、神託者である」[37]。彼が挙げた多くの例のうち、ベオウルフに登場するアンフェルドを選ぶことができるだろう。[38] VIII. 神話生成の要素 比喩の効果が、物事や出来事を生命や動きの観点から描写することにあるとすれば、私たちは擬人化への道を歩み始めている。無形のものや生命のないものを人として表現することは、神話の創造や詩作の魂である。[39] 神話生成とは文字通り神話の創造を意味する(「神話生成」および「神話生成思想」を参照)。 IX. 哲学における遊びの形態 円の中心に、私たちが「遊び」という概念で説明しようとしているものがある。そこにはギリシアのソフィストの姿が立ちはだかっている。彼は、預言者、呪術 師、予言者、奇術師、詩人として次々と現れた、初期の文化的生活における中心人物の延長と見なすことができる。その人物を最もよく表す言葉は「神託者」で ある。 X. 芸術における遊びの形態 -ismで終わるキャッチフレーズがあるところでは、私たちは遊びの共同体の足跡を追っているのだ。[40] ホイジンガはすでに、遊びと詩歌の間に切っても切れない絆があることを証明している。そして今、彼は「遊びと音楽の絆についても同じことが言え、さらにそ の度合いは高い」と認識している。[41] しかし、彼が「詩歌、音楽、舞踏から造形芸術へと目を向けると、遊びとのつながりは明白ではなくなる」と気づく。[42] しかし、ここでホイジンガは過去に遡っている。彼は「建築家、彫刻家、画家、製図者、陶芸家、装飾芸術家」の例を挙げているが、彼らは「創造的な衝動」を 抱えながらも、規律に支配され、「常に形成する手の技術と熟練に左右される」のである。[43] 一方、「芸術作品の制作から、それが社会環境の中で受容される方法」へと目を向けると[44]、状況は一変する。この社会的受容、新しい「-イズム」と古い「-イズム」の闘争こそが、この劇の特徴である。 XI. ゲームとしての西洋文明 したがって、文明は、その初期段階においては「遊戯」であると結論せざるを得ない。 それは、赤ん坊が子宮から自らを切り離すように、遊びから生まれるものではない。 遊びの中で、遊びとして生まれ、決してそこから離れることはない。[45] XII. 現代文明における遊びの要素 アメリカ政治においては、[選挙という仕組み全体に存在する遊びの要素は]さらに明白である。二大政党制が、政治的な違いが外部の人間にはほとんど見分け がつかないほど巨大な2つのチームに縮小されるはるか以前から、アメリカでは選挙運動が国民的スポーツのようなものへと発展していた。[46] 引用 「人間は、その言葉の完全な意味において人間であるときにのみ遊び、そして、人間は遊ぶときにのみ完全に人間となる。」(『人間美育論』フリードリヒ・シラー)[要ページ番号] 「それは古代の知恵であるが、人間のあらゆる活動を『遊び』と呼ぶのは、少し安直でもある。このような形而上学的な結論に満足する人は、この本を読んではならない。」(序文、ノンブルなしページより) 受容 『ホモ・ルーデンス』はゲーム研究の歴史において重要な位置を占めている。この本は、ロジェ・カイヨスのような、後の遊びの研究者に影響を与えた。魔法円の概念は『ホモ・ルーデンス』から着想を得たものである。 序文の論争 ホイジンガは、自著の序文で、文化における遊びの要素ではなく、文化の遊びの要素を意味していることを明確にしている。彼は、この本のもととなった最初の 講義のタイトルを「文化の遊びの要素」としたと書いている。このタイトルは「文化における」に何度も修正され、彼はそれに異議を唱えた。英語版では、この 本の副題が「文化における遊びの要素の研究」と修正され、フイジンガの意図に反するものとなった。訳者は序文の脚注で、「論理的にはもちろんフイジンガが 正しい。しかし、英語の前置詞は論理に従わないため、私はこの副題ではより耳触りの良いablativeを残した」と説明している。[47] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_Ludens |

|

| Der Homo ludens [ˈhɔmoː

ˈluːdeːns] (lateinisch homō lūdēns, deutsch „der spielende Mensch“) ist

ein Erklärungsmodell, wonach der Mensch seine kulturellen Fähigkeiten

vor allem über das Spiel entwickelt[1]: Der Mensch entdeckt im Spiel

seine individuellen Eigenschaften und wird über die dabei gemachten

Erfahrungen zu der in ihm angelegten Persönlichkeit. Das Spiel

ermöglicht es, die Zwänge der äußeren Welt zu erfahren und gleichzeitig

zu überschreiten. Phantasievolles Spielen dient schon im frühkindlichen

Alter der Darstellung des inneren Erlebens. Auch Märchen sind eine Form

des gedanklichen Spiels. Im erzählerischen „Spiel“ ergänzt der Mensch

seine pragmatischen Erfahrungen um die Dimension einer phantasievollen

Sinnfindung.[2] Insofern ist Homo ludens ein anthropologischer

Gegenbegriff zu Homo faber. |

ホモ・ルーデンス(ラテン語:homō lūdēns、「遊戯する人」)は、人間が遊びを通して文化的能力を主に発達させることを説明するモデルである。[1]

人間は遊びを通して、個々の特性を発見し、経験を通して本来あるべき人格となる。遊びは、外の世界の制約を経験し、同時にそれを乗り越えることを可能にす

る。幼児期においても、想像力に富んだ遊びは内面の経験を表現するのに役立つ。おとぎ話もまた、精神的な遊びの一形態である。物語という「ゲーム」におい

て、人間は実用的な経験に想像力に富んだ意味の探求という次元を加える。2] この点において、ホモ・ルーデンスはホモ・ファベルの対義語である。 |

| Begriffsherkunft Johan Huizinga: Homo ludens, erschienen als Band 21 in rowohlts deutsche enzyklopädie Der Begriff Homo ludens, zur Kennzeichnung des Spiels als Grundkategorie menschlichen Verhaltens, ist in der ersten Hälfte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts vor allem durch den Titel des gleichnamigen Buches von Johan Huizinga (1938/39) bekannt geworden, in dem dieser die Funktion des Spiels als kulturbildenden Faktor hervorhebt und aufgezeigt hat, dass sich unsere kulturellen Systeme wie Politik, Wissenschaft, Religion, Recht usw. ursprünglich aus spielerischen Verhaltensweisen entwickelt (Selbstorganisation) und über Ritualisierungen im Laufe der Zeit institutionell verfestigt haben. Aus Spiel werde „heiliger Ernst“, und wenn sich die Regeln erst richtig „eingespielt“ hätten, seien sie nicht mehr ohne weiteres zu ändern und begännen ihrerseits Zwangscharakter anzunehmen.[3] Huizinga wählte mit seiner Bezeichnung einen Kontrastbegriff zu der in der philosophischen Anthropologie seit 1928 von Max Scheler verwendeten Typisierung des Homo faber (Anthropologie), die Max Frisch 1957 als Titel für seinen gleichnamigen Erfolgsroman Homo faber übernahm. Im Gegensatz zum „Spielenden Menschen“ kennzeichnete diese den „arbeitenden, handwerklich tätigen Menschen“. Die eher wirtschaftliche Orientierung menschlichen Handelns betont dagegen der Begriff des Homo oeconomicus, der erstmals in der lateinischen Form 1906 von Vilfredo Pareto benutzt worden ist. Homo ludens und Homo faber Für die Spielwissenschaftler Siegbert A. Warwitz und Anita Rudolf betonen die Begriffe Homo ludens und Homo faber zwei unterschiedliche Dimensionen der Weltaneignung.[4] Kinder wie Erwachsene finden über die Zufälle und Möglichkeiten des selbstgenügsamen, zweckfreien und phantasievollen Spiels zu einem Verständnis ihrer Identität. Der Pädagoge Johannes Merkel begreift insbesondere auch das frühkindliche Spielen als eine „Sprache der inneren Welt“ – ähnlich wie Erzählen, Phantasieren und Träumen: Im Spielen verarbeiten Kinder wie Erwachsene die Erfahrung, dass individuelle psychische Innenwelt und soziale Außenwelt auseinanderklaffen. Der Begriff des Homo faber unterstreicht dagegen die kulturelle Praxis, ein zweckgerichtetes, systematisch aufgebautes Spiel für das Lernen und für Erfahrungsgewinn zu nutzen. Dazu dienen dem Homo faber ausdrückliche Lernspiele (siehe dazu auch Spielwissenschaft, Kinderspiel). Weitere Vertreter des Konzepts Friedrich Schiller hob in seinen Briefen Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen die Bedeutung des Spielens hervor und sprach sich gegen die Spezialisierung und Mechanisierung der Lebensabläufe aus. Nach Schiller ist das Spiel eine menschliche Leistung, die allein in der Lage ist, die Ganzheitlichkeit der menschlichen Fähigkeiten hervorzubringen. Schiller prägte auch die berühmt gewordene Sentenz: „Der Mensch spielt nur, wo er in voller Bedeutung des Worts Mensch ist, und er ist nur da ganz Mensch, wo er spielt.“ Eine der schillerschen ähnliche Kritik an der Reduzierung der Lebensweise übte auch Herbert Marcuse. In seinem 1967 erschienenen Werk Der eindimensionale Mensch, in dem er die mit der Vorherrschaft der „instrumentellen Vernunft“ in den Industriegesellschaften einhergehende Beschränkung der Lebensweise und Kultur kritisierte, die keinen Platz mehr für Ganzheit, Persönlichkeitsentfaltung und autonome Selbstwerdung lasse. Ähnlich wie Friedrich Schiller hält Herbert Marcuse daher eine Rückbesinnung auf das Ästhetische und Spielerische für erstrebenswert, um entgegen den allgegenwärtigen Zwängen einen Freiraum für eine menschliche Betätigung nach selbst gewählten Regeln und um ihrer selbst willen zu schaffen. Die Überlegungen von Marcuse gehen auf dessen früheres Werk Eros and Civilisation (deutsch Triebstruktur und Gesellschaft) aus dem Jahr 1955 zurück. Er entwickelt darin den Spielbegriff ausgehend von Kants Kritik der Urteilskraft, Schiller (und im Rahmen seiner Auseinandersetzung mit Freuds Psychoanalyse) im Kapitel „Die ästhetische Dimension“[5]. Entsprechend heißt es darin: „Da nur die Triebe jene überdauernde Kraft besitzen, die das menschliche Dasein in seinen Grundlagen berührt, muß die Versöhnung der beiden Triebe [sinnlicher Trieb und Formtrieb] das Werk eines dritten Impulses sein. Schiller definiert diesen dritten, vermittelnden Trieb als den Spieltrieb, dessen Gegenstand die Schönheit, dessen Endziel die Freiheit ist.“[6] Dies interpretiert Marcuse politisch. Es gehe um das „Spiel des Lebens selbst, jenseits von Bedürfnis und äußerem Zwang – die Manifestation eines Daseins ohne Furcht und Angst, und somit die Manifestation der Freiheit.“[7] Marcuse fasst diese politische Dimension wie folgt zusammen, wenn er schreibt: „Die Umformung von Arbeit (Mühe) in Spiel und von repressiver Produktivität in ‚Schein‘ – eine Umformung, der die Überwindung des Mangels (der Lebensnot) als determinierender Faktor der Kultur und Zivilisation vorangehen müßte.“[8] Auch Künstler wie Asger Jorn (1914–1973) und die Situationistische Internationale vertraten solche Ansätze. Potenzial des Spiels Zusammenfassend lässt sich festhalten, dass das Spiel eine grundlegende menschliche Aktivität ist, die Kreativität und – im Wettkampf – Energie und Kraft freisetzt. Damit enthält das Spiel das Potenzial, verfestigte Strukturen zu durchbrechen und Innovation hervorzubringen. Deshalb sind spielerische Elemente auch in vielen Kreativitätstechniken und modernen Managementschulungen enthalten, die darauf zielen, neue, kreative und innovative Ergebnisse zu erzeugen. So spricht man auch von einer ludischen Wende in der Medientheorie, die durch die Dominanz von Spielanwendungen auf dem Computer gekennzeichnet ist, und von ludischem Innovationsverhalten.[9] Das Spiel scheint eine menschliche Aktivität zu sein, die in der Lage ist, die Elemente einer Situation so zu verändern, dass Neues und Unbekanntes entsteht und Lösungen für scheinbar nicht mehr lösbare Probleme gefunden werden können. Nach Huizinga dient das Spiel auch zur Abfuhr von Affekten. Damit steht er in der Tradition der Aristotelischen Lehre von der Katharsis. Umstritten ist der Ursprung des Sports im Spiel als etwas ursprünglich Menschliches[10] und dem Sport als einer eher neueren Erfindung, die sich nicht aus alten Spielen entwickelt hat.[11] |

用語の起源 ヨハン・ホイジンガ著『ホモ・ルーデンス』は、ローベルト・ロルフス編『ドイツ百科全書』第21巻として出版された 遊びを人間行動の基本カテゴリーとして特徴づける「ホモ・ルーデンス」という用語は、20世紀前半に主にヨハン・ホイジンガ(1938/39年)の同名の 著書のタイトルを通じて知られるようになった。ホイジンガは、 遊びが文化形成の要因として果たす機能を強調し、政治、科学、宗教、法律などの文化的システムは、もともとは遊びの行動(自己組織化)から発展し、儀式化 を通じて時間をかけて制度的に固定化されてきたことを示している。遊びは「神聖な真剣さ」となり、いったんルールが本当に「定着」すると、もはや簡単に変 更することはできなくなり、それ自体が強制的な性格を帯び始める。 ホイジンガの用語は、1928年以降、マックス・シェーラーが哲学的人間学で用いた「ホモ・ファベル(労働者人)」の類型論(人類学)とは対照的なもので あった。この類型論は、マックス・フリッシュが1957年に同名のベストセラー小説『ホモ・ファベル』のタイトルとして採用したものである。「遊ぶ人」と は対照的に、この類型論は「働く職人」を特徴づけるものである。一方、人間の経済活動への志向は、ホモ・エコノミクス(homo oeconomicus)という概念によって強調される。ホモ・エコノミクスという概念は、1906年にヴィルフレード・パレートがラテン語で初めて使用 したものである。 ホモ・ルーデンスとホモ・ファーベル ゲーム科学者であるジークベルト・A・ワーヴィッツとアニタ・ルドルフにとって、ホモ・ルーデンスとホモ・ファーベルという用語は、世界を適応させる2つ の異なる次元を強調するものである。4] 子どもも大人も、自給自足的で目的を持たない想像力豊かな遊びの偶然性や可能性を通じて、自己のアイデンティティに対する理解を深めていく。教育学者ヨハ ネス・メルケルは、特に幼児期の遊びを「内なる世界の言語」として理解している。これは、物語を語ったり空想したり夢を見たりすることに似ている。遊びを 通して、子どもも大人も、個々の内なる心理世界と外側の社会世界とのギャップを経験する。一方、「ホモ・ファベル」の概念は、目的を持って体系的に構築さ れたゲームを学習や経験の獲得に利用するという文化的な慣習を強調している。ホモ・ファベルは、この目的のために明示的な教育的なゲームを利用する(ゲー ム研究、子供のゲームも参照)。 この概念の他の代表者としては フリードリヒ・シラーが挙げられ、著書『人間美的教育について』の中で遊びの重要性を強調し、人生の過程における専門化と機械化に反対を唱えた。シラーに よれば、遊びとは人間に特有の活動であり、人間の能力の総体を引き出すことができる。シラーはまた、有名な格言を創作した。「人間は、言葉の完全な意味で 人間であるところでのみ遊び、遊びにおいてのみ完全に人間である」と。 ヘルベルト・マルクーゼもまた、シラーと同様の観点からライフスタイルの単純化を批判した。1967年の著書『一次元的人間』において、彼は、全体性や個 人の成長、自律的な自己実現の余地を残さない、産業社会における「道具的理性」の優位性と表裏一体のライフスタイルや文化の制限を批判した。フリードリ ヒ・シラーと同様に、ハーバート・マルクーゼは、いたるところに存在する制約とは対照的に、自ら選択したルールに従って、またそのルール自体のために、人 間の活動のための空間を創出するためには、美的かつ遊び心のあるものへの回帰が望ましいと考える。マルクーゼの考察は、1955年の著書『エロスと文明』 (ドイツ語:Triebstruktur und Gesellschaft)にまで遡る。その中で彼は、カントの『判断力批判』、そして「美的次元」の章におけるシラー(およびフロイトの精神分析の検討 の文脈)を基に、遊びの概念を展開している。5] それによれば、「人間の存在の基盤に触れるような永続的な力を有しているのは衝動だけであるため、2つの衝動(感覚的衝動と形式衝動)の和解は、第三の衝 動の働きによるものでなければならない。シラーは、この第三の調停的な衝動を「遊びの本能」と定義し、その対象は美であり、究極の目標は自由であると述べ ている。[6] マルクーゼはこれを政治的に解釈している。「それは、必要や外部からの強制を超えた、人生そのもののゲームであり、恐怖や不安のない存在の顕在化であり、 したがって自由の顕在化である。」[7] マルクーゼは、次のように記述し、この政治的側面を要約している。「労働(努力)を遊びに、抑圧的な生産性を『外見』に変えること。つまり、文化や文明の 決定要因としての不足(生活の欠如)を克服する変革である。」[8] 労働(努力)を遊びに、抑圧的な生産性を「外観」に変えること。この変革は、文化や文明を決定づける要因としての欠乏(生活必需品の不足)を克服すること に先行すべきである。」[8] アスガー・ヨーン(1914-1973)やシチュエーショニスト・インターナショナルなどの芸術家も、同様のアプローチを提唱していた。 遊びの潜在能力 まとめると、遊びとは創造性を解き放ち、競争の中でエネルギーと強さを引き出す人間の基本的な活動であると言える。遊びには、硬直した構造を打ち破り、革 新をもたらす潜在能力がある。だからこそ、遊びの要素は、新しい創造的で革新的な成果を生み出すことを目的とした多くの創造性技法や現代的な経営研修コー スに盛り込まれているのだ。また、コンピュータ上のゲームアプリケーションの優勢を特徴とするメディア理論における「遊び的転回」や「遊び的革新行動」と いう概念も存在する。9] 遊びとは、状況の要素を変化させ、新しいものや未知のものを作り出し、一見解決不可能な問題に対する解決策を見出すことのできる人間の活動であるようだ。 フイジンガによれば、遊びは感情を発散させる役割も果たす。この点において、彼はカタルシス説のアリストテレスの伝統に従っている。スポーツの起源は、も ともと人間的なものであり[10]、古代のゲームから発展したものではないという新しい考え方については議論の余地がある[11]。 |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

-----------

For all undergraduate

students!!!, you do not copy & paste but [re]think my message.

Remind Wittgenstein's phrase,

"I should not like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking. But, if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own," - Ludwig Wittgenstein

(c) Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j. Copyright 2016