1954年のグアテマラのクーデター

1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

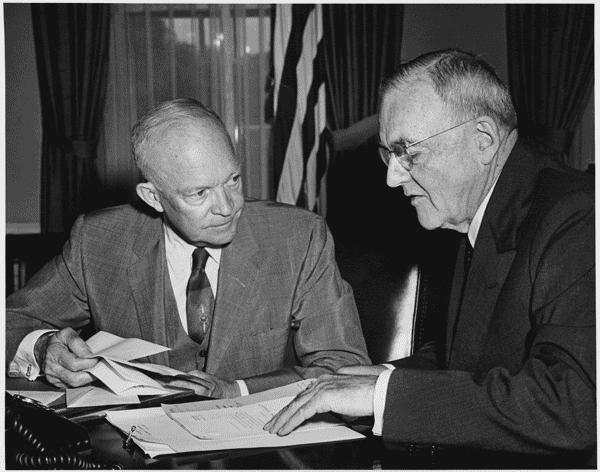

Photograph

of Dwight D. Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles Meeting, 08/14/1956

☆1954年のグアテマラクーデター(Golpe de Estado en Guatemala de 1954, The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état)は、民主的に選出されたグアテマラ大統領ハコボ・アルベンスを退陣させ、グアテマラ革命の終焉を告げた。このクーデターにより、カルロス・カス ティーヨ・アルマスによる軍事独裁政権が樹立された。これは米国が支援するグアテマラの権威主義的支配者たちの最初の例である。クーデターはCIAの秘密 作戦「PBSuccess」によって引き起こされた。

| The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

(Golpe de Estado en Guatemala de 1954) deposed the democratically

elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz and marked the end of the

Guatemalan Revolution. The coup installed the military dictatorship of

Carlos Castillo Armas, the first in a series of U.S.-backed

authoritarian rulers in Guatemala. The coup was precipitated by a CIA

covert operation code-named PBSuccess. The Guatemalan Revolution began in 1944, after a popular uprising toppled the military dictatorship of Jorge Ubico. Juan José Arévalo was elected president in Guatemala's first democratic election. He introduced a minimum wage and near-universal suffrage. Arévalo was succeeded in 1951 by Árbenz, who instituted land reforms which granted property to landless peasants.[1] The Guatemalan Revolution was disliked by the U.S. federal government, which was predisposed during the Cold War to see it as communist. This perception grew after Árbenz had been elected and formally legalized the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour. The U.S. government feared that Guatemala's example could inspire nationalists wanting social reform throughout Latin America.[2] The United Fruit Company (UFC), whose highly profitable business had been affected by the softening of exploitative labor practices in Guatemala, engaged in an influential lobbying campaign to persuade the U.S. to overthrow the Guatemalan government. U.S. President Harry Truman authorized Operation PBFortune to topple Árbenz in 1952, which was a precursor to PBSuccess. Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected U.S. president in 1952, promising to take a harder line against communism, and his staff members John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles had significant links to the United Fruit Company. The U.S. federal government drew exaggerated conclusions about the extent of communist influence among Árbenz's advisers, and Eisenhower authorized the CIA to carry out Operation PBSuccess in August 1953. The CIA armed, funded, and trained a force of 480 men led by Carlos Castillo Armas. After U.S. efforts to criticize and isolate Guatemala internationally, Armas' force invaded Guatemala on 18 June 1954, backed by a heavy campaign of psychological warfare, as well as air bombings of Guatemala City and a naval blockade. The invasion force fared poorly militarily, and most of its offensives were defeated. However, psychological warfare and the fear of a U.S. invasion intimidated the Guatemalan Army, which eventually refused to fight. Árbenz unsuccessfully attempted to arm civilians to resist the invasion, before resigning on 27 June. Castillo Armas became president ten days later, following negotiations in San Salvador. Described as the definitive deathblow to democracy in Guatemala, the coup was widely criticized internationally, and strengthened the long-lasting anti-U.S. sentiment in Latin America. Attempting to justify the coup, the CIA launched Operation PBHistory, which sought evidence of Soviet influence in Guatemala among documents from the Árbenz era, but found none. Castillo Armas quickly assumed dictatorial powers, banning opposition parties, executing, imprisoning and torturing political opponents, and reversing the social reforms of the revolution. In the first few months of his government, Castillo Armas rounded up and executed between three thousand and five thousand supporters of Árbenz.[3] Nearly four decades of civil war followed, as leftist guerrillas fought the series of U.S.-backed authoritarian regimes whose brutalities include a genocide of the Maya peoples. |

1954年のグアテマラクーデター

(Golpe de Estado en Guatemala de

1954)は、民主的に選出されたグアテマラ大統領ハコボ・アルベンスを退陣させ、グアテマラ革命の終焉を告げた。このクーデターにより、カルロス・カス

ティーヨ・アルマスによる軍事独裁政権が樹立された。これは米国が支援するグアテマラの権威主義的支配者たちの最初の例である。クーデターはCIAの秘密

作戦「PBSuccess」によって引き起こされた。 グアテマラ革命は1944年、民衆蜂起によってホルヘ・ウビコ軍事独裁政権が倒された後に始まった。グアテマラ初の民主的選挙でフアン・ホセ・アレバロが 大統領に選出された。彼は最低賃金とほぼ完全な普通選挙を導入した。アレバロの後継として1951年にアルベンスが就任し、土地のない農民に土地を分配す る土地改革を実施した。[1] グアテマラ革命は米国連邦政府の嫌悪を買った。冷戦下において、米国政府はこれを共産主義と見なす傾向にあった。この認識は、アルベンスが選出されグアテ マラ労働党(共産党)を正式に合法化した後に強まった。米国政府は、グアテマラの事例がラテンアメリカ全域で社会改革を求めるナショナリストたちに影響を 与えることを恐れたのである。[2] グアテマラにおける搾取的な労働慣行の緩和によって高収益事業が影響を受けたユナイテッド・フルーツ社(UFC)は、米国にグアテマラ政府転覆を促す影響 力のあるロビー活動を行った。ハリー・トルーマン米大統領は1952年、アルベンス打倒のための「PBFortune作戦」を承認した。これは 「PBSuccess作戦」の前身である。 ドワイト・D・アイゼンハワーは1952年に米国大統領に選出され、共産主義に対してより強硬な姿勢を取ることを約束した。彼のスタッフであるジョン・ フォスター・ダレスとアレン・ダレスはユナイテッド・フルーツ社と深い繋がりを持っていた。米国連邦政府はアルベンスの顧問団における共産主義の影響力の 程度について誇張した結論を導き出し、アイゼンハワーは1953年8月にCIAにPBSuccess作戦の実行を承認した。CIAはカルロス・カスティー ヨ・アルマス率いる480名の部隊に武器・資金・訓練を提供した。米国が国際的にグアテマラを非難・孤立化させる動きの後、アルマスの部隊は1954年6 月18日にグアテマラへ侵攻した。この侵攻は、大規模な心理戦、グアテマラシティへの空爆、海上封鎖によって支援されていた。 侵攻部隊は軍事的には不振で、ほとんどの攻勢は撃退された。しかし心理戦と米国侵攻への恐怖がグアテマラ軍を萎縮させ、最終的に戦闘を拒否した。アルベン スは民間人に武器を与えて抵抗させようとしたが失敗し、6月27日に辞任した。サンサルバドルでの交渉を経て、10日後にカスティーヨ・アルマスが大統領 に就任した。グアテマラの民主主義に対する決定的な致命傷と評されたこのクーデターは国際的に広く非難され、ラテンアメリカにおける長きにわたる反米感情 を強めた。クーデターを正当化しようと、CIAは「PB歴史作戦」を開始し、アルベンス政権時代の文書からグアテマラにおけるソ連の影響力の証拠を探した が、何も見つからなかった。カスティージョ・アルマスは即座に独裁権力を掌握し、野党を禁止、政治的反対派を処刑・投獄・拷問し、革命による社会改革を覆 した。政権発足後数ヶ月で、カスティージョ・アルマスはアルベンス支持者3000人から5000人を一斉に逮捕し処刑した[3]。その後ほぼ40年にわた る内戦が続き、左翼ゲリラは米国が支援する一連の権威主義政権と戦った。これらの政権の残虐行為にはマヤ人民に対するジェノサイドも含まれる。 |

| Historical background Monroe Doctrine Further information: Monroe Doctrine  The Monroe Doctrine stated that the Western Hemisphere, including the Republic of Guatemala, was within the U.S. sphere of influence. U.S. President James Monroe's foreign policy doctrine of 1823 warned the European powers against further colonization in Latin America. The stated aim of the Monroe Doctrine was to maintain order and stability, and to ensure that U.S. access to resources and markets was not limited. Historian Mark Gilderhus states that the doctrine also contained racially condescending language, which likened Latin American countries to squabbling children. While the U.S. did not initially have the power to enforce the doctrine, during the 19th century many European powers withdrew from Latin America, allowing the U.S. to expand its sphere of influence.[4][5] In 1895, President Grover Cleveland laid out a more militant version of the doctrine, stating that the U.S. was "practically sovereign" on the continent.[6] Following the Spanish–American War in 1898, this aggressive interpretation was used to create a U.S. economic empire across the Caribbean, such as with the 1903 treaty with Cuba that was heavily tilted in the U.S.' favor.[6] U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt believed that the U.S. should be the main beneficiary of production in Central America.[7] The U.S. enforced this hegemony with armed interventions in Nicaragua (1912–33), and Haiti (1915–34). The U.S. did not need to use its military might in Guatemala, where a series of dictators were willing to accommodate the economic interests of the U.S. in return for its support for their regimes.[8] Guatemala was among the Central American countries of the period known as a banana republic.[9][10] From 1890 to 1920, control of Guatemala's resources and its economy shifted away from Britain and Germany to the U.S., which became Guatemala's dominant trade partner.[8] The Monroe Doctrine continued to be seen as relevant to Guatemala, and was used to justify the coup in 1954.[11] |

歴史的背景 モンロー主義 詳細情報:モンロー主義  モンロー主義は、グアテマラ共和国を含む西半球が米国の影響圏内にあると宣言した。 1823年にアメリカ合衆国大統領ジェームズ・モンローが打ち出した外交政策の原則であり、ヨーロッパ列強に対しラテンアメリカでのさらなる植民地化を警 告した。モンロー主義の表明された目的は秩序と安定を維持し、アメリカ合衆国の資源と市場へのアクセスが制限されないことを確保することだった。歴史家 マーク・ギルダーハスは、この主義には人種的に見下した表現も含まれており、ラテンアメリカ諸国を言い争う子供たちに例えたと述べている。当初アメリカに はこの教義を強制する力はないが、19世紀を通じて多くの欧州列強がラテンアメリカから撤退したため、アメリカは勢力圏を拡大できた[4][5]。 1895年にはグローバー・クリーブランド大統領がより強硬な教義を提示し、アメリカが大陸において「実質的に主権を有する」と宣言した。[6] 1898年の米西戦争後、この攻撃的な解釈はカリブ海全域に及ぶ米国の経済帝国を構築するために利用された。例えば1903年のキューバとの条約は米国に 大きく有利な内容だった。[6] セオドア・ルーズベルト大統領は、中米の生産物から最大の利益を得るべきは米国だと考えていた。[7] 米国はこのヘゲモニーを、ニカラグア(1912-33年)やハイチ(1915-34年)への武力介入によって強行した。グアテマラでは、一連の独裁政権が 自政権への支援と引き換えに米国の経済的利益を受け入れる意思を示したため、米国は軍事力を行使する必要がなかった。[8] 当時グアテマラは、バナナ共和国として知られる中米諸国の一つであった。[9][10] 1890年から1920年にかけ、グアテマラの資源と経済の支配権は英国やドイツから米国へ移行し、米国はグアテマラの主要貿易相手国となった。[8] モンロー主義はグアテマラに関しても依然として有効と見なされ、1954年のクーデターを正当化する根拠として用いられた。[11] |

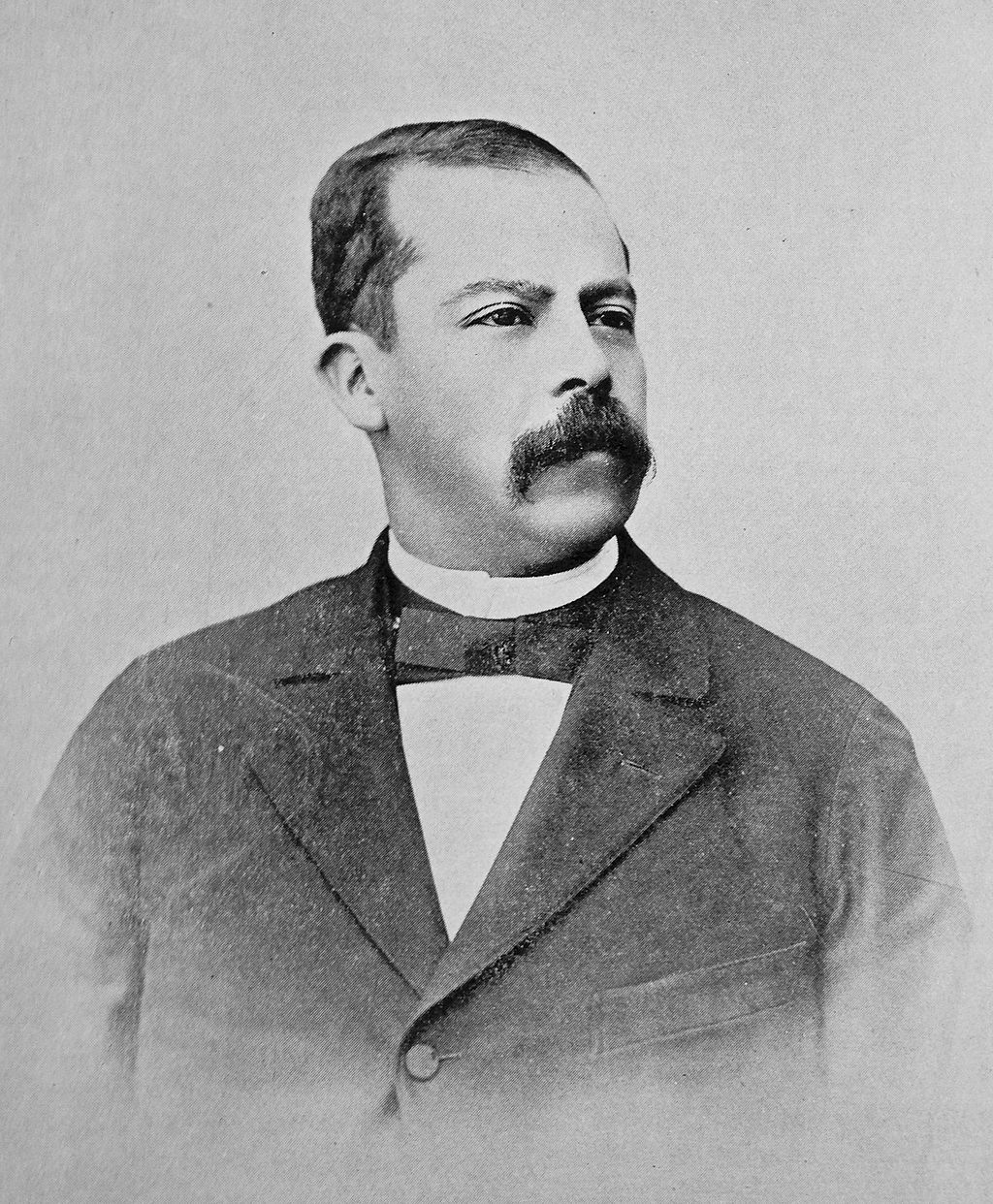

| Authoritarian governments and the United Fruit Company Further information: Manuel Estrada Cabrera and Jorge Ubico  Manuel Estrada Cabrera, President of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920, granted several concessions to the United Fruit Company. Following a surge in global coffee demand in the late 19th century, the Guatemalan government made several concessions to plantation owners. It passed legislation that dispossessed the communal landholdings of the Indigenous population and allowed coffee growers to purchase it.[12][13] Manuel Estrada Cabrera, President of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920, was one of several rulers who made large concessions to foreign companies, including the United Fruit Company (UFC).[14] Formed in 1899 by the merger of two large U.S. corporations,[15] the new entity owned large tracts of land across Central America, and in Guatemala controlled the railroads, the docks, and the communication systems.[16][17] By 1900 it had become the largest exporter of bananas in the world,[18] and had a monopoly over the Guatemalan banana trade.[17] Journalist and writer William Blum describes UFC's role in Guatemala as a "state within a state".[19] The U.S. government was closely involved with the Guatemalan state under Cabrera, frequently dictating financial policies and ensuring that American companies were granted several exclusive rights.[20] When Cabrera was overthrown in 1920, the U.S. sent an armed force to make certain that the new president remained friendly to it.[21] Fearing a popular revolt following the unrest created by the Great Depression, wealthy Guatemalan landowners lent their support to Jorge Ubico, who won an uncontested election in 1931.[12][13][21] Ubico's regime became one of the most repressive in the region. He abolished debt peonage, replacing it with a vagrancy law which stipulated that all landless men of working age needed to perform a minimum of 100 days of forced labor annually. He authorized landowners to take any actions they wished against their workers, including executions.[22][23][24] Ubico was an admirer of European fascist leaders such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, but had to ally with the U.S. for geopolitical reasons,[25] and received substantial support from this country throughout his reign.[24] A staunch anti-communist, Ubico reacted to several peasant rebellions with incarcerations and massacres.[24][26][27] By 1930 the UFC had built an operating capital of 215 million U.S. dollars,[a] and had been the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala for several years.[28] Ubico granted it a new contract, which was immensely favorable to the company. This included 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land,[29] an exemption from taxes,[30] and a guarantee that no other company would receive any competing contract.[18] Ubico requested the UFC cap the daily salary of its workers at 50 U.S. cents, so that workers in other companies would be less able to demand higher wages.[28] |

権威主義政府とユナイテッド・フルーツ社 詳細情報:マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラとホルヘ・ウビコ  1898年から1920年までグアテマラ大統領を務めたマヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に複数の特権を認めた。 19世紀末の世界的なコーヒー需要の急増を受け、グアテマラ政府は農園所有者に複数の特権を与えた。先住民の共有地を没収し、コーヒー栽培者が購入できる ようにする法律を可決した[12][13]。1898年から1920年までグアテマラ大統領を務めたマヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは、ユナイテッド・ フルーツ・カンパニー(UFC)を含む外国企業に大規模な特権を与えた数人の統治者の一人であった。[14] 1899年に2つの米国大企業が合併して設立された[15]この新企業は、中央アメリカ全域に広大な土地を所有し、グアテマラでは鉄道、埠頭、通信システ ムを支配していた[16][17]。1900年までに世界最大のバナナ輸出業者となり[18]、グアテマラのバナナ貿易を独占した。[17] ジャーナリスト兼作家のウィリアム・ブルームは、UFCのグアテマラにおける役割を「国家の中の国家」と表現している[19]。米国政府はカブレラ政権下 のグアテマラ国家と密接に関与し、頻繁に金融政策を指示し、米国企業に複数の独占的権利が与えられるよう保証した。[20] 1920年にカブレラ政権が倒れた際、米国は新大統領が親米姿勢を維持するよう軍隊を派遣した。[21] 大恐慌による混乱後の民衆蜂起を恐れたグアテマラの富裕地主層は、ホルヘ・ウビコを支援した。彼は1931年の選挙で無投票当選を果たした。[12] [13][21] ウビコ政権は地域で最も抑圧的な体制の一つとなった。彼は債務奴隷制を廃止したが、代わりに浮浪者法を制定し、土地を持たない労働年齢の男性は全員、年間 最低100日の強制労働を義務付けた。また地主に対し、労働者に対する処刑を含むあらゆる措置を許可した。[22][23][24] ウビコはベニート・ムッソリーニやアドルフ・ヒトラーといった欧州のファシスト指導者を崇拝していたが、地政学的な理由から米国と同盟を結ばざるを得な かった[25]。そして彼の統治期間を通じて、米国から多大な支援を受けた[24]。強硬な反共主義者であったウビコは、幾度かの農民反乱に対し投獄や虐 殺で対応した[24][26]。[27] 1930年までに、UFCは2億1500万米ドルの運転資金を築き上げ[a]、数年にわたりグアテマラ最大の土地所有者かつ雇用主となっていた[28]。 ウビコは同社に新たな契約を認めたが、これは企業にとって非常に有利な内容であった。これには公有地20万ヘクタール(49万エーカー)の付与[29]、 税金の免除[30]、他社が競合契約を獲得しない保証が含まれていた[18]。ウビコはUFCに対し、労働者の日給を50米セントに制限するよう要求し た。これにより他社労働者が賃上げを要求しにくくなるためである[28]。 |

| Guatemalan Revolution and presidency of Arévalo Main article: Guatemalan Revolution The repressive policies of the Ubico government resulted in a popular uprising led by university students and middle-class citizens in 1944.[31] Ubico fled, handing over power to a three-person junta which continued Ubico's policies until it was toppled by the October Revolution that aimed to transform Guatemala into a liberal democracy.[31] The largely free election that followed installed a philosophically conservative university professor, Juan José Arévalo, as the President of Guatemala. Arévalo's administration drafted a more liberal labor code, built health centers, and increased funding to education.[32][33] Arévalo enacted a minimum wage, and created state-run farms to employ landless laborers. He cracked down on the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour (Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo, PGT) and in 1945 criminalized labor unions in workplaces with fewer than 500 workers.[34] By 1947, the remaining unions had grown strong enough to pressure him into drafting a new labor code, which made workplace discrimination illegal and created health and safety standards.[35] However, Arévalo refused to advocate land reform of any kind, and stopped short of drastically changing labor relations in the countryside.[32] Despite Arévalo's anti-communism, the U.S. was suspicious of him, and worried that he was under Soviet influence.[36] The communist movement did grow stronger during Arévalo's presidency, partly because he released its imprisoned leaders, and also through the strength of its teachers' union.[34] However, the communists were still oppressed by the state, as they were harassed by Arévalo's police at any opportunity.[37]Another cause for U.S. worry was Arévalo's support of the Caribbean Legion. The Legion was a group of progressive exiles and revolutionaries, whose members included Fidel Castro, that aimed to overthrow U.S.-backed dictatorships across Central America.[38] The government also faced opposition from within the country; Arévalo survived at least 25 coup attempts.[39][40] A notable example was an attempt in 1949 led by Francisco Arana, which was foiled in an armed shootout between Arana's supporters and a force led by Arévalo's defense minister Jacobo Árbenz. Arana was among those killed, but details of the coup attempt were never made public.[41] Other sources of opposition to Arévalo's government were the right-wing politicians and conservatives within the military who had grown powerful during Ubico's dictatorship, as well as the clergy of the Catholic Church.[42] |

グアテマラ革命とアレバロ大統領 詳細記事: グアテマラ革命 ウビコ政権の抑圧的な政策は、1944年に大学生と中産階級市民が主導する民衆蜂起を引き起こした。[31] ウビコは逃亡し、権力を3人格による軍事政権に引き継いだ。この政権はウビコの政策を継続したが、グアテマラを自由民主主義国家に変革することを目指した 10月革命によって打倒された。[31] その後実施されたほぼ自由な選挙により、哲学的に保守的な大学教授フアン・ホセ・アレバロがグアテマラ大統領に就任した。アレバロ政権はより自由主義的な 労働法を制定し、健康センターを建設し、教育予算を増額した。[32][33] アレバロは最低賃金を導入し、土地を持たない労働者を雇用するための国営農場を創設した。彼は共産主義のグアテマラ労働党(PGT)を弾圧し、1945年 には従業員500人未満の職場における労働組合を非合法化した。[34] 1947年までに残存する組合は勢力を拡大し、職場での差別を違法化し健康と安全の基準を設ける新たな労働法の制定を迫るに至った。[35] しかしアレバロはあらゆる土地改革を拒否し、農村部の労使関係に抜本的な変化をもたらすには至らなかった[32]。 アレバロの反共姿勢にもかかわらず、米国は彼を疑わしく思い、ソ連の影響下にあるのではないかと懸念した[36]。アレバロ政権下で共産主義運動は確かに 勢力を拡大した。その一因は彼が投獄されていた指導者たちを釈放したこと、また教師組合の力強さによるものであった。[34] とはいえ、共産主義者は依然として国家による弾圧下にあり、アレバロ政権の警察があらゆる機会を利用して迫害を加えた。[37] 米国が懸念したもう一つの要因は、アレバロがカリブ海連隊を支援したことだ。この連隊は進歩的な亡命者や革命家から成る集団で、フィデル・カストロもメン バーに含まれ、中米全域で米国が支援する独裁政権の打倒を目指していた。[38] 政府は国内からの反対にも直面した。アレバロは少なくとも25回のクーデター未遂を生き延びた。[39][40] 顕著な例は1949年のフランシスコ・アラナ主導のクーデター未遂で、アラナ支持派とアレバロの国防相ヤコボ・アルベンス率いる部隊との銃撃戦で阻止され た。アラナは死亡者の中に含まれていたが、クーデター未遂の詳細は公表されなかった。[41] アレバロ政権に対するその他の反対勢力としては、ウビコ独裁政権下で勢力を拡大した軍内の右派政治家や保守派、そしてカトリック教会の聖職者たちがいた。 [42] |

| Presidency of Árbenz and land reform Further information: Decree 900 The largely free 1950 elections were won by the popular Árbenz,[43] and represented the first transfer of power between democratically elected leaders in Guatemala.[44] Árbenz had personal ties to some members of the communist PGT, which was legalized during his government,[43] and a couple of members played a role in drafting the new president's policies.[45][46] Nonetheless, Árbenz did not try to turn Guatemala into a communist state, instead choosing a moderate capitalist approach.[47][48] The PGT too committed itself to working within the existing legal framework to achieve its immediate objectives of emancipating peasants from feudalism and improving workers' rights.[49] The most prominent component of Árbenz's policy was his agrarian reform bill.[50] Árbenz drafted the bill himself,[51] having sought advice from economists across Latin America.[50] The focus of the law was on transferring uncultivated land from large landowners to poor laborers, who would then be able to begin viable farms of their own.[50] The official title of the agrarian reform bill was Decree 900. It expropriated all uncultivated land from landholdings that were larger than 673 acres (272 ha). If the estates were between 224 acres (91 ha) and 672 acres (272 ha), uncultivated land was to be expropriated only if less than two-thirds of it was in use. The owners were compensated with government bonds, the value of which was equal to that of the land expropriated. The value of the land itself was what the owners had declared it to be in their tax returns in 1952. Of the nearly 350,000 private landholdings, only 1,710 were affected by expropriation. The law was implemented with great speed, which resulted in some arbitrary land seizures. There was violence directed at landowners.[52]  Farmland in the Quetzaltenango Department, in western Guatemala By June 1954, 1,400,000 acres (570,000 ha) of land had been expropriated and distributed. Approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this point. Contrary to the predictions made by detractors, the law resulted in a slight increase in Guatemalan agricultural productivity, cultivated area, and purchases of farm machinery. Overall, the law resulted in a significant improvement in living standards for thousands of peasant families, the majority of whom were Indigenous.[52] Historian Greg Grandin sees the law as representing a fundamental power shift in favor of the hitherto marginalized.[53] |

アルベンス政権と土地改革 詳細情報:法令900号 1950年のほぼ自由な選挙で、人気のあるアルベンスが勝利した[43]。これはグアテマラにおいて、民主的に選出された指導者間の初めての政権移譲を意 味した。[44] アルベンスは、彼の政権下で合法化された共産主義政党PGTの一部のメンバーと個人的な繋がりを持っていた[43]。また、数名のメンバーが新大統領の政 策立案に関与した[45][46]。しかしながら、アルベンスはグアテマラを共産主義国家に変えようとはせず、代わりに穏健な資本主義的アプローチを選択 した。[47][48] PGTもまた、既存の法的枠組み内で活動することを約束し、農民を封建制から解放し労働者の権利を改善するという当面の目標達成を目指した。[49] アルベンス政策の最も顕著な要素は、彼の農地改革法案であった。[50] アルベンスは自ら法案を起草し、[51] ラテンアメリカ全域の経済学者から助言を求めていた。[50] この法律の焦点は、未耕作地を大地主から貧しい労働者へ移転させることにあった。これにより労働者は自ら持続可能な農場を始められるようになるはずだっ た。[50] 農地改革法案の正式名称は法令900号であった。これは673エーカー(272ヘクタール)を超える土地所有地から、全ての未耕作地を収用する内容だっ た。224エーカー(91ヘクタール)から672エーカー(272ヘクタール)の土地所有地については、耕作地の割合が3分の2未満の場合に限り未耕作地 を収用した。所有者には収用地の価値に相当する国債が補償として支払われた。土地の価値は、所有者が1952年の納税申告書で申告した金額を基準とした。 約35万件の私有地のうち、収用対象となったのはわずか1,710件だった。法律は急速に施行されたため、恣意的な土地接収も発生した。地主に対する暴力 行為も見られた。[52]  グアテマラ西部ケツァルテナンゴ県の農地 1954年6月までに、140万エーカー(57万ヘクタール)の土地が収用・分配された。この時点で約50万人の個人、すなわち人口の6分の1が土地を受 け取っていた。批判派の予測に反し、この法律はグアテマラの農業生産性、耕作面積、農業機械の購入をわずかに増加させた。全体として、この法律は数千の農 民世帯(その大半が先住民)の生活水準を大幅に改善した。[52] 歴史家グレッグ・グランディンは、この法律をこれまで疎外されてきた者たちにとっての根本的な権力移行を表すものと見なしている。[53] |

| Genesis and prelude United Fruit Company lobbying  The former headquarters of the United Fruit Company, in New Orleans. The company played a key role in instigating the 1954 coup d'état. By 1950, the United Fruit Company's (now Chiquita) annual profits were 65 million U.S. dollars,[b] twice as large as the revenue of the government of Guatemala.[54] The company was the largest landowner in Guatemala,[55] and virtually owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic, allowing it to profit from the flow of goods through the port.[28] Because of its long association with Ubico's government, Guatemalan revolutionaries saw the UFC as an impediment to progress after 1944. This image was reinforced by the company's discriminatory policies against the native population.[54][56] Owing to its size, the reforms of Arévalo's government affected the UFC more than other companies. Among other things, the new labor code allowed UFC workers to strike when their demands for higher wages and job security were not met. The company saw itself as being targeted by the reforms, and refused to negotiate with strikers, despite frequently being in violation of the new laws.[57] The company's troubles were compounded with the passage of Decree 900 in 1952. Of the 550,000 acres (220,000 ha) that the company owned, only 15 percent was being cultivated; the rest was idle, and thus came under the scope of the agrarian reform law.[57] The UFC responded by intensively lobbying the U.S. government. Several Congressmen criticized the Guatemalan government for not protecting the interests of the company. The Guatemalan government replied that the company was the main obstacle to progress in the country. American historians observed that "[to] the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare".[58] In 1953, 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of uncultivated land was expropriated by the government, which paid 2.99 U.S. dollars per acre (7.39 U.S. dollars per hectare),[c] twice what the company had paid when it bought the property.[58] More expropriation occurred soon after, bringing the total to over 400,000 acres (160,000 ha), at the rate which UFC had valued its property for tax purposes.[57] The company was unhappy with losing the land, and the level of profit resulting from the sale, resulting in further lobbying in Washington, particularly through U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had close ties to the company.[58] The UFC also began a public relations campaign to discredit the Guatemalan government, hiring Edward Bernays, who mounted a concerted misinformation campaign for several years which portrayed the company as the victim of a "communist" Guatemalan government.[59] The company stepped up its efforts after Dwight Eisenhower was elected U.S. president in 1952. These included commissioning a research study from a firm known to be hostile to social reform, which produced a 235-page report that was highly critical of the Guatemalan government. Historians have stated that the report was full of "exaggerations, scurrilous descriptions and bizarre historical theories" but it nonetheless had a significant impact on the members of Congress who read it.[60] Overall, the company spent over half a million dollars to convince lawmakers and the American public that the Guatemalan government needed to be overthrown.[60] |

起源と序章 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社のロビー活動  ニューオーリンズにあるユナイテッド・フルーツ社の旧本社。同社は1954年のクーデターを扇動する上で重要な役割を果たした。 1950年までに、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(現チキータ)の年間利益は6500万米ドル[b]に達し、グアテマラ政府の歳入の2倍の規模であった。 [54] 同社はグアテマラ最大の土地所有者であり[55]、同国唯一の大西洋港であるプエルト・バリオスを実質的に支配していたため、港を通る物資の流れから利益 を得ていた[28]。ウビコ政権との長年の関係から、グアテマラ革命家たちは1944年以降の進歩の妨げとしてUFCを認識していた。このイメージは、先 住民に対する同社の差別的政策によってさらに強化された。[54][56] その規模ゆえに、アレバロ政権の改革はUFCを他社以上に強く影響した。特に新労働法は、賃上げや雇用保障の要求が受け入れられない場合、UFC労働者が ストライキを行うことを認めた。同社は自らを改革の標的と見なし、新法を頻繁に違反しながらも、ストライキ参加者との交渉を拒否した。[57] 1952年の法令900号の成立により、同社の問題はさらに深刻化した。同社が所有する55万エーカー(22万ヘクタール)のうち、耕作されていたのはわ ずか15%で、残りは遊休地であったため、農地改革法の適用対象となった。[57] これに対しUFCは米国政府への強力なロビー活動を展開した。複数の議員がグアテマラ政府を「企業の利益を守らない」と批判。グアテマラ政府は「同社が国 家発展の主要な障害である」と反論した。米国史家は「グアテマラ国民には、自国が外国資本に容赦なく搾取され、巨額の利益を得ながら国家の福祉には何ら貢 献していないように映った」と指摘している。[58] 1953年、政府は20万エーカー(81,000ヘクタール)の未耕作地を収用した。支払額は1エーカーあたり2.99米ドル(1ヘクタールあたり 7.39米ドル)[c]で、同社が土地購入時に支払った額の2倍であった。[58] その後も収用は続き、総面積は40万エーカー(16万ヘクタール)を超えた。この価格は、UFCが税務目的で評価した額に基づいていた。[57] 会社は土地喪失と売却益の水準に不満を抱き、ワシントンでのロビー活動を強化した。特に同社と密接な関係にあったジョン・フォスター・ダレス米国務長官を 通じての働きかけが活発化した。[58] UFCはまた、グアテマラ政府の信用を傷つけるための広報キャンペーンを開始した。エドワード・バーネイズを雇い、数年にわたり組織的な誤報キャンペーン を展開し、同社を「共産主義」グアテマラ政府の犠牲者として描いたのである。[59] 同社は1952年にドワイト・アイゼンハワーが米国大統領に選出された後、活動を強化した。これには社会改革に敵対的と知られる企業に委託した調査研究が 含まれ、グアテマラ政府を厳しく批判する235ページの報告書が作成された。歴史家たちは、この報告書が「誇張、中傷的な描写、奇妙な歴史理論」に満ちて いたと指摘しているが、それにもかかわらず、それを読んだ国会議員たちに大きな影響を与えた。[60] 全体として、同社はグアテマラ政府を打倒する必要があると議員やアメリカ国民を説得するために、50万ドル以上を費やした。[60] |

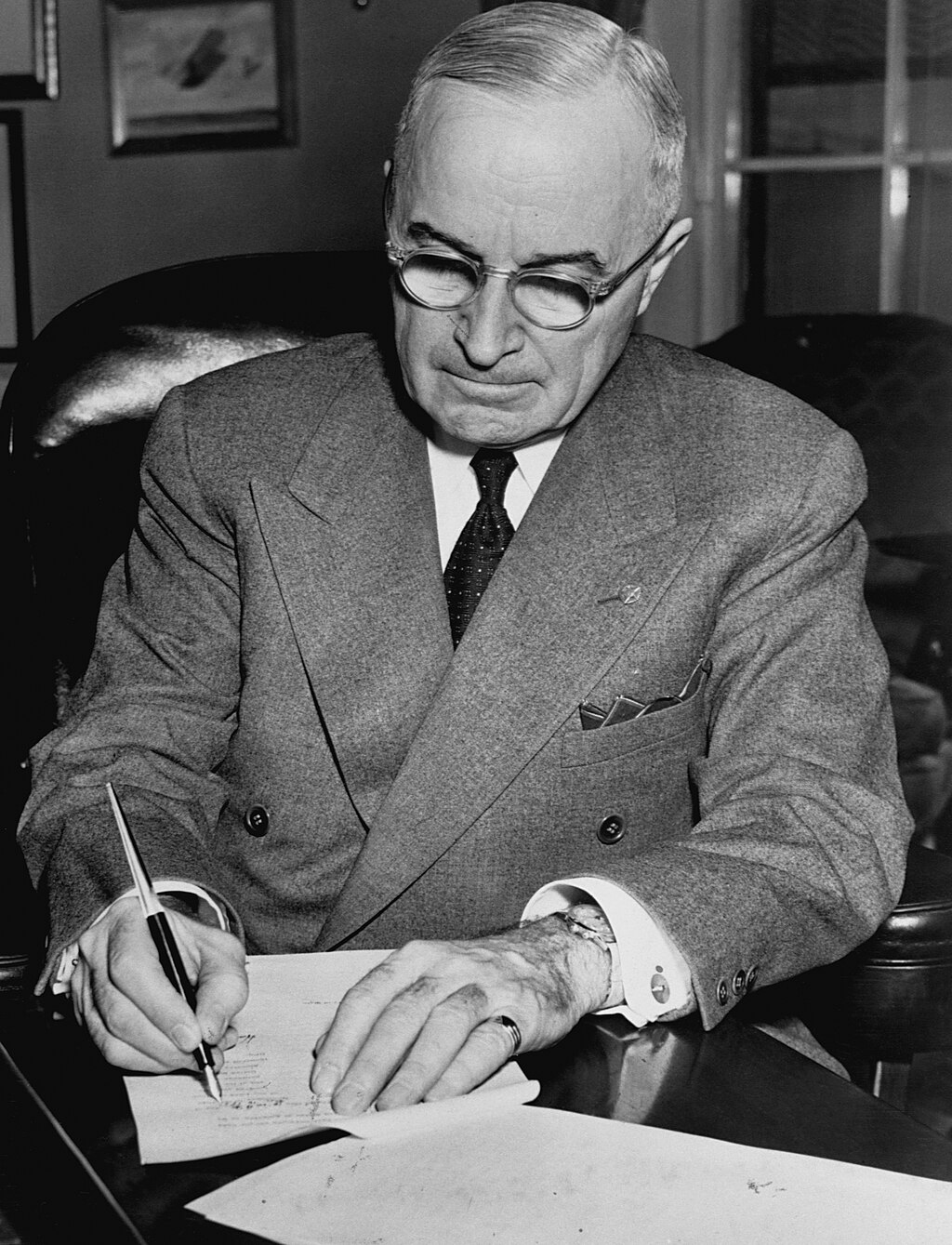

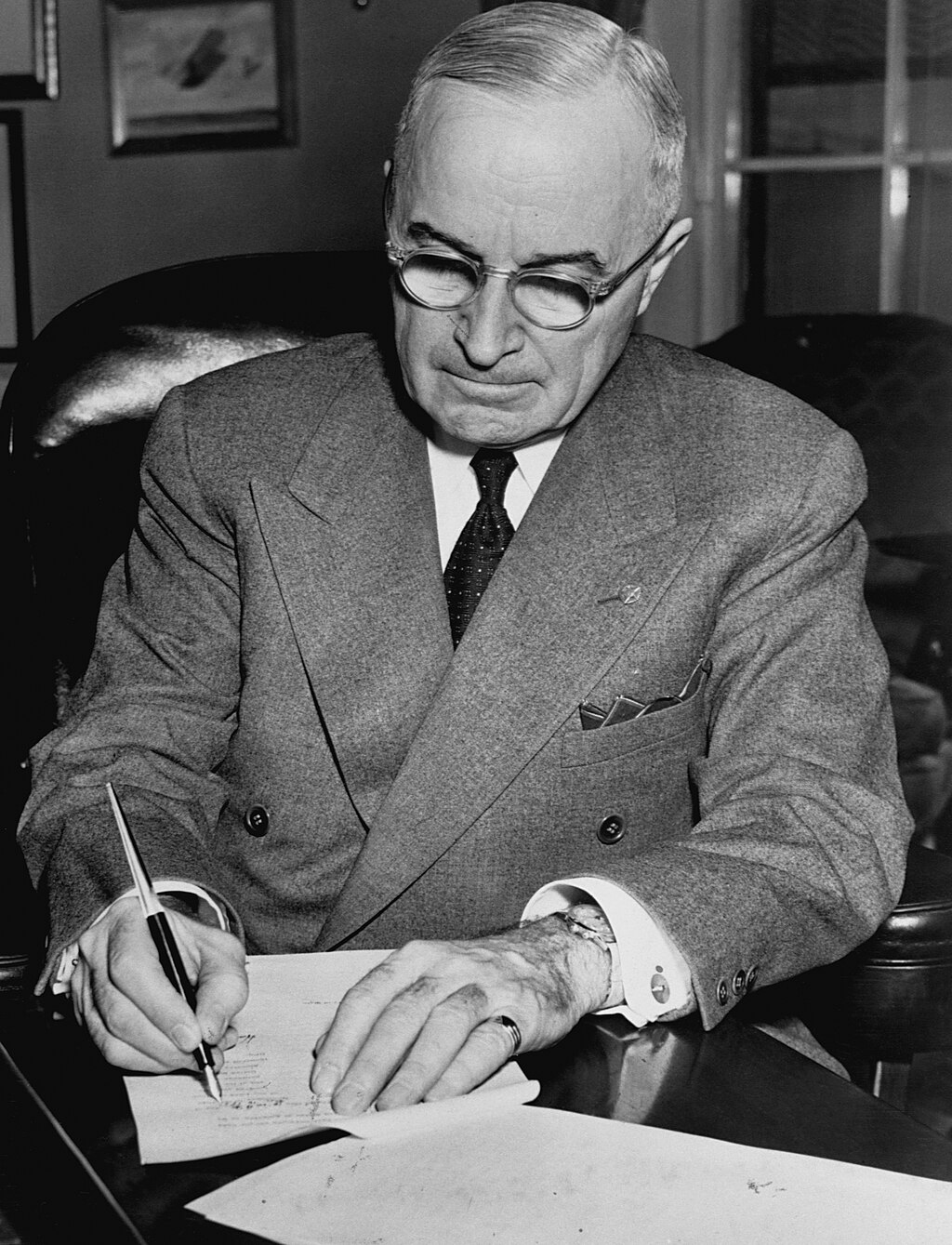

| Operation PBFortune Main article: Operation PBFortune  U.S. President Harry Truman (pictured here in 1950) authorized the CIA to effect a Guatemalan coup d'état in 1952. As the Cold War developed and the Guatemalan government clashed with U.S. corporations on an increasing number of issues, the U.S. government grew increasingly suspicious of the Guatemalan Revolution.[61][62] In addition, the Cold War predisposed the Truman administration to see the Guatemalan government as communist.[61] Arévalo's support for the Caribbean Legion also worried the Truman administration, which saw it as a vehicle for communism, rather than as the anti-dictatorial force it was conceived as.[63] Until the end of its term, the Truman administration had relied on purely diplomatic and economic means to try to reduce the perceived communist influence.[64] The U.S. had refused to sell arms to the Guatemalan government after 1944; in 1951 it began to block all weapons purchases by Guatemala.[65] The U.S.'s worries over communist influence increased after the election of Árbenz in 1951 and his enactment of Decree 900 in 1952.[62][66] In April 1952 Anastasio Somoza García, the dictator of Nicaragua, made his first state visit to the U.S.[67] He made several public speeches praising the U.S., and was awarded a medal by the New York City government. During a meeting with Truman and his senior staff, Somoza said that if the U.S. gave him the arms, he would "clean up Guatemala".[68] The proposal did not receive much immediate support, but Truman instructed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to follow up on it. The CIA contacted Carlos Castillo Armas, a Guatemalan army officer who had been exiled from the country in 1949 following a failed coup attempt against President Arévalo.[69] Believing that Castillo Armas would lead a coup with or without their assistance, the CIA decided to supply him with weapons and 225,000 U.S. dollars.[d][67] The CIA considered Castillo Armas sufficiently corrupt and authoritarian to be well suited to lead the coup.[70]  Gloriosa victoria, mural by Diego Rivera which satirizes the role of the US, UFC, Catholic Church and the military in the Guatemalan coup. The individuals giving the handshake are John Foster Dulles and general Castillo Armas. The coup was planned in detail over the next few weeks by the CIA, the UFC, and Somoza. The CIA also contacted Marcos Pérez Jiménez of Venezuela and Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic; the two U.S.-backed dictators were supportive of the plan, and agreed to contribute some funding.[71] Although PBFortune was officially approved on 9 September 1952, various planning steps had been taken earlier in the year. In January 1952, officers in the CIA's Directorate of Plans compiled a list of "top flight Communists whom the new government would desire to eliminate immediately in the event of a successful anti-Communist coup".[72] The CIA plan called for the assassination of over 58 Guatemalans, as well as the arrest of many others.[72] The CIA put the plan into motion in late 1952. A freighter that had been borrowed from the UFC was specially refitted in New Orleans and loaded with weapons under the guise of agricultural machinery, and set sail for Nicaragua.[73] However, the plan was terminated soon after: accounts of its termination vary. Some sources state that the State Department discovered the plan when a senior official was asked to sign a certain document, while others suggest that Somoza was indiscreet. The eventual outcome was that Secretary of State Dean Acheson called off the operation. The CIA continued to support Castillo Armas; it paid him a monthly retainer of 3000 U.S. dollars,[e] and gave him the resources to maintain his rebel force.[67][71] |

PBFortune作戦(オペレーション PBフォーチュン) 詳細記事: PBFortune作戦  ハリー・トルーマン米大統領(写真は1950年)は1952年、CIAにグアテマラでのクーデター実行を許可した。 冷戦が進行し、グアテマラ政府が米国企業と対立する問題が増えるにつれ、米国政府はグアテマラ革命への疑念を強めた。[61] [62] さらに冷戦構造は、トルーマン政権がグアテマラ政府を共産主義と見なす傾向を強めた。[61] アレバロがカリブ海連隊を支援したことも、トルーマン政権を不安にさせた。同政権はこれを反独裁勢力としてではなく、共産主義の手段と見なしていたのであ る。[63] トルーマン政権は任期終了まで、共産主義の影響力削減を試みる手段として純粋に外交的・経済的手段に依存していた。[64] 米国は1944年以降グアテマラ政府への武器売却を拒否し、1951年にはグアテマラのあらゆる武器購入を阻止し始めた。[65] 1951年のアルベンス当選と1952年の法令900号発布後、米国の共産主義勢力への懸念は増大した。[62][66] 1952年4月、ニカラグアの独裁者アナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシアが初の米国公式訪問を行った。[67] 彼は米国を称賛する数回の公的演説を行い、ニューヨーク市政府から勲章を授与された。トルーマン大統領及び上級スタッフとの会談で、ソモサは「米国が武器 を提供すればグアテマラを一掃する」と述べた。[68] この提案は直ちに大きな支持を得られなかったが、トルーマンは中央情報局(CIA)に追跡調査を指示した。CIAはカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスに接 触した。彼は1949 年、アレバロ大統領に対するクーデター未遂事件で国外追放されたグアテマラ軍将校だった。[69] CIAは、支援の有無にかかわらずアルマスがクーデターを主導すると判断し、武器と22万5千ドルの資金提供を決断した。[d][67] CIAはカスティージョ・アルマスを十分に腐敗し権威主義的であると見なし、クーデター指導者に適任と判断した。[70]  「栄光の勝利」:ディエゴ・リベラ作。グアテマラクーデターにおける米国、UFC、カトリック教会、軍部の役割を風刺した壁画。握手を交わす人物はジョン・フォスター・ダレスとカスティージョ・アルマス将軍である。 クーデターはその後数週間、CIA、UFC、ソモサによって詳細に計画された。CIAはベネズエラのマルコス・ペレス・ヒメネスとドミニカ共和国のラファ エル・トルヒーヨにも接触した。両独裁者は米国の支援を受けており、計画を支持し資金提供に同意した。[71] PBFortune作戦は1952年9月9日に正式承認されたが、計画の様々な段階は同年より早くから進められていた。1952年1月、CIA計画局の職 員らは「反共クーデター成功時に新政府が即時排除を望む共産主義者上位リスト」を作成した[72]。CIA計画では58名以上のグアテマラ人暗殺と多数の 逮捕が想定されていた。[72] CIAは1952年末に計画を実行に移した。UFCから借り受けた貨物船がニューオーリンズで特別に改造され、農業機械を装って武器を積載し、ニカラグア に向けて出航した。[73] しかし計画は間もなく中止された。中止の経緯については諸説ある。ある情報源によれば、国務省の高官が特定の文書への署名を求められた際に計画が発覚した という。また別の説では、ソモサが軽率な行動を取ったためだとされる。結局、ディーン・アチソン国務長官が作戦の中止を命じた。CIAはカスティージョ・ アルマスへの支援を継続し、月額3000米ドルの報酬を支払い[e]、反乱軍を維持するための資源を提供した。[67][71] |

Eisenhower administration The memorandum which describes the CIA's organisation of the paramilitary deposition of President Jacobo Árbenz in June 1954 During his successful campaign for the U.S. presidency, Dwight Eisenhower pledged to pursue a more proactive anti-communist policy, promising to roll back communism, rather than contain it. Working in an atmosphere of increasing McCarthyism in government circles, Eisenhower was more willing than Truman to use the CIA to depose governments the U.S. disliked.[74][75] Although PBFortune had been quickly aborted, tension between the U.S. and Guatemala continued to rise, especially with the legalization of the communist PGT, and its inclusion in the government coalition for the elections of January 1953.[76] Articles published in the U.S. press often reflected this predisposition to see communist influence; for example, a New York Times article about the visit to Guatemala by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda highlighted his communist beliefs, but neglected to mention his reputation as the greatest living poet in Latin America.[77] Several figures in Eisenhower's administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother CIA Director Allen Dulles, had close ties to the United Fruit Company. The Dulles brothers had been partners of the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, and in that capacity had arranged several deals for the UFC. Undersecretary of State Walter Bedell Smith would later become a director of the company, while Eisenhower's personal assistant Ann C. Whitman was the wife of UFC public relations director Edmund S. Whitman. These personal connections meant that the Eisenhower administration tended to conflate the interests of the UFC with that of U.S. national security interests, and made it more willing to overthrow the Guatemalan government.[78][79] The success of the 1953 CIA operation to overthrow the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran also strengthened Eisenhower's belief in using the agency to effect political change overseas.[74] Historians and authors writing about the 1954 coup have debated the relative importance of the role of the United Fruit Company and the worries about communist influence (whether or not these were grounded in reality) in the U.S.'s decision to instigate the coup in 1954.[80][81][82] Several historians have maintained that the lobbying of the UFC, and the expropriation of its lands, were the chief motivation for the U.S., strengthened by the financial ties of individuals within the Eisenhower administration to the UFC.[82][83][84][85] Others have argued that the overthrow was motivated primarily by U.S. strategic interest; the knowledge of the presence of a small number of communists close to Árbenz led the U.S. to reach incorrect conclusions about the extent of communist influence.[80][81][82] Yet others have argued that the overthrow was part of a larger tendency within the U.S. to oppose nationalist movements in the Third World.[86] Some assert that Washington didn't believe Guatemala to be an immediate communist threat, citing declassified documents from the U.S. Policy Planning Staff, which state the real risk was the example of independence of the U.S. that Guatemala might offer to nationalists wanting social reform throughout Latin America.[2] Both the role of the UFC and that of the perception of communist influence continue to be cited as motivations for the U.S.'s actions today.[80][81][83][84][87] |

アイゼンハワー政権 1954年6月、CIAが組織したヤコボ・アルベンス大統領の準軍事的追放に関する覚書 ドワイト・アイゼンハワーは大統領選勝利へのキャンペーン中、より積極的な反共政策を推進すると公約した。共産主義を封じ込めるのではなく、後退させるこ とを約束したのである。政府内でマッカーシズムが高まる中、アイゼンハワーはトルーマンよりも積極的にCIAを利用して米国が好まぬ政権を転覆させる姿勢 を示した[74][75]。PBFortune作戦は早期に中止されたものの、米国とグアテマラの緊張は高まり続けた。特に共産党PGTの合法化と、 1953年1月の選挙に向けた連立政権への参加が契機となった。[76] 米国の報道機関に掲載された記事は、共産主義の影響を過度に強調する傾向を反映していた。例えば、チリの詩人パブロ・ネルーダのグアテマラ訪問に関する ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事は、彼の共産主義的信念を強調する一方で、ラテンアメリカ最高の現存詩人としての評価には触れていなかった。[77] アイゼンハワー政権内には、国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスやその弟でCIA長官のアレン・ダレスなど、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(UFC)と密接な 関係を持つ人物が複数いた。ダレス兄弟は法律事務所サリバン・アンド・クロムウェルのパートナーであり、その立場でUFCの取引を幾度も取り持っていた。 国務次官ウォルター・ベデル・スミスは後に同社の取締役となり、アイゼンハワーの個人秘書アン・C・ホイットマンはUFC広報部長エドマンド・S・ホイッ トマンの妻であった。こうした個人的な繋がりにより、アイゼンハワー政権はUFCの利益と米国の国家安全保障上の利益を混同する傾向にあり、グアテマラ政 府の転覆をより積極的に推進する姿勢を示した。[78] [79] 1953年にCIAが民主的に選出されたイラン首相を転覆させた作戦の成功も、海外で政治的変革を起こすためにCIAを利用するというアイゼンハワーの信 念を強めた。[74] 1954年のクーデターについて論じる歴史家や著者は、米国がクーデターを画策した決定において、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の役割と共産主義勢力への懸念 (それが現実に基づいていたか否か)の相対的な重要性を議論してきた。[80][81][82] 複数の歴史家は、UFCのロビー活動と土地収用が米国の主たる動機であり、アイゼンハワー政権内の個人とUFCの金銭的結びつきがこれを強化したと主張し ている。[82][83][84] [85] 他方、クーデターは主に米国の戦略的利益が動機だったとする見解もある。アルベンス政権周辺に少数ながら共産主義者が存在した事実が、米国に共産主義の影 響力について誤った結論を導かせたとされる。[80][81][82] また別の見解では、このクーデターは第三世界のナショナリスト運動に反対する米国全体の傾向の一部だったと主張されている。[86] ワシントンはグアテマラを差し迫った共産主義の脅威とは見なしていなかったと主張する者もいる。米国政策企画局の機密解除文書を引用し、真のリスクはグア テマラがラテンアメリカ全域で社会改革を求めるナショナリストたちに提示しうる米国の独立の模範であったと述べている。[2] UFCの役割と共産主義影響力の認識は、今日でも米国の行動の動機として引用され続けている。[80][81][83][84][87] |

| Operation PBSuccess Planning  File photo of Allen Dulles Allen Dulles, director of the CIA during the 1954 coup, and brother of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles Eisenhower authorized the CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSuccess, in August 1953. The operation was granted a budget of 2.7 million U.S. dollars[f] for "psychological warfare and political action".[88] The total budget has been estimated at between 5 and 7 million dollars, and the planning employed over 100 CIA agents.[89] In addition, the operation recruited scores of individuals from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of the surrounding countries.[89] The plans included drawing up lists of people within Árbenz's government to be assassinated if the coup were to be carried out. Manuals of assassination techniques were compiled, and lists were also made of people whom the junta would dispose of.[88] These were the CIA's first known assassination manuals, and were reused in subsequent CIA actions.[90] The State Department created a team of diplomats who would support PBSuccess. It was led by John Peurifoy, who took over as Ambassador to Guatemala in October 1953.[91][92] Another member of the team was William D. Pawley, a wealthy businessman and diplomat with extensive knowledge of the aviation industry.[93] Peurifoy was a militant anti-communist, and had proven his willingness to work with the CIA during his time as United States Ambassador to Greece.[94] Under Peurifoy's tenure, relations with the Guatemalan government soured further, although those with the Guatemalan military improved. In a report to John Dulles, Peurifoy stated that he was "definitely convinced that if [Árbenz] is not a communist, then he will certainly do until one comes along".[95] Within the CIA, the operation was headed by Deputy Director of Plans Frank Wisner. The field commander selected by Wisner was former U.S. Army Colonel Albert Haney, then chief of the CIA station in South Korea. Haney reported directly to Wisner, thereby separating PBSuccess from the CIA's Latin American division, a decision which created some tension within the agency.[96] Haney decided to establish headquarters in a concealed office complex in Opa-locka, Florida.[97] Codenamed "Lincoln", it became the nerve center of Operation PBSuccess.[98] The CIA operation was complicated by a premature coup on 29 March 1953, with a futile raid against the army garrison at Salamá, in the central Guatemalan department of Baja Verapaz. The rebellion was swiftly crushed, and a number of participants were arrested. Several CIA agents and allies were imprisoned, weakening the coup effort. Thus the CIA came to rely more heavily on the Guatemalan exile groups and their anti-democratic allies in Guatemala.[99] The CIA considered several candidates to lead the coup. Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the conservative candidate who had lost the 1950 election to Árbenz, held favor with the Guatemalan opposition but was rejected for his role in the Ubico regime, as well as his European appearance, which was unlikely to appeal to the majority mixed-race mestizo population.[100] Another popular candidate was the coffee planter Juan Córdova Cerna, who had briefly served in Arévalo's cabinet before becoming the legal adviser to the UFC. The death of his son in an anti-government uprising in 1950 turned him against the government, and he had planned the unsuccessful Salamá coup in 1953 before fleeing to join Castillo Armas in exile. Although his status as a civilian gave him an advantage over Castillo Armas, he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1954, taking him out of the reckoning.[101] Thus it was Castillo Armas, in exile since the failed 1949 coup and on the CIA's payroll since the aborted PBFortune in 1951, who was to lead the coming coup.[67] Castillo Armas was given enough money to recruit a small force of mercenaries from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of nearby countries. This band was called the Army of Liberation. The CIA established training camps in Nicaragua and Honduras and supplied them with weapons as well as several bombers. The U.S. signed military agreements with both those countries prior to the invasion of Guatemala, allowing it to move heavier arms freely.[102] The CIA trained at least 1,725 foreign guerillas plus thousands of additional militants as reserves.[103] These preparations were only superficially covert: the CIA intended Árbenz to find out about them, as a part of its plan to convince the Guatemalan people that the overthrow of Árbenz was a fait accompli. Additionally, the CIA made covert contact with a number of church leaders throughout the Guatemalan countryside, and persuaded them to incorporate anti-government messages into their sermons.[102] |

オペレーション・ピービーサクセス 計画  アレン・ダレスのファイル写真 1954年のクーデター当時CIA長官であり、米国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスの弟であるアレン・ダレス アイゼンハワーは1953年8月、コードネーム「オペレーション・ピービーサクセス」によるハコボ・アルベンス打倒作戦をCIAに許可した。作戦には「心 理戦と政治工作」のために270万米ドル[f]の予算が割り当てられた[88]。総予算は500万~700万ドルと推定され、計画には100人以上の CIA工作員が動員された[89]。さらに、グアテマラ亡命者や周辺国の人々から多数の協力者を募った。[89] 計画には、クーデター実行時に暗殺対象とするアルベンス政権関係者のリスト作成が含まれていた。暗殺技術マニュアルが編纂され、軍事政権が排除すべき人物 リストも作成された[88]。これらはCIA初の暗殺マニュアルとして知られ、後のCIA作戦で再利用された。[90] 国務省はPBSuccessを支援する外交官チームを編成した。チームはジョン・ピュリフォイが率い、彼は1953年10月にグアテマラ大使に就任した。 [91] [92] チームのもう一人のメンバーは、航空産業に精通した富裕な実業家兼外交官ウィリアム・D・ポーリーであった。[93] ピュリフォイは過激な反共主義者であり、在ギリシャ米国大使時代にはCIAとの協力姿勢を既に示していた。[94] ピュリフォイの在任中、グアテマラ政府との関係はさらに悪化したものの、グアテマラ軍との関係は改善した。ピュリフォイはジョン・ダレスへの報告書で「ア ルベンスが共産主義者でなくとも、共産主義者が現れるまでは確実にその役割を果たすだろう」と断言した。[95] CIA内部では、作戦は計画部副部長フランク・ウィズナーが指揮した。ウィズナーが選んだ現地指揮官は、当時韓国駐在CIA支局長だった元米陸軍大佐アル バート・ヘイニーであった。ヘイニーはウィズナーに直接報告したため、PBSuccess作戦はCIAのラテンアメリカ部門から分離された。この決定は機 関内に若干の緊張を生んだ[96]。ヘイニーはフロリダ州オパロッカの隠蔽されたオフィス複合施設に司令部を設置することを決定した[97]。コードネー ム「リンカーン」と名付けられたこの施設は、PBSuccess作戦の中枢となった[98]。 CIAの作戦は、1953年3月29日に起きた時期尚早なクーデターによって複雑化した。グアテマラ中部バハ・ベラパス県のサラマにある陸軍駐屯地への襲 撃は失敗に終わり、反乱は迅速に鎮圧された。多数の参加者が逮捕され、複数のCIA工作員や協力者が投獄されたことでクーデター勢力は弱体化した。こうし てCIAは、グアテマラ亡命グループと国内の反民主主義勢力への依存度を高めていった。[99] CIAはクーデター指導者として複数の候補を検討した。1950年の選挙でアルベンスに敗れた保守派候補ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスはグアテマラ野 党の支持を得ていたが、ウビコ政権での役割と、混血メスティソが多数を占める国民に受け入れられにくいヨーロッパ風の風貌が理由で却下された。[100] もう一人の有力候補はコーヒー農園主フアン・コルドバ・セルナであった。彼はアレバロ内閣に短期間在籍した後、UFCの法律顧問となった。1950年の反 政府蜂起で息子を失ったことで政府に反旗を翻し、1953年にはサラマクーデターを計画したが失敗に終わり、亡命中のカスティーヨ・アルマスに合流するた め国外へ逃亡した。民間人という立場はカスティージョ・アルマスより有利だったが、1954年に喉頭癌と診断され、候補から外れた[101]。こうして、 1949年のクーデター失敗以来亡命中で、1951年のPBFortune作戦中止以降CIAの給与を受けていたカスティージョ・アルマスが、次のクーデ ターを主導することになった。[67] カスティージョ・アルマスは、グアテマラ亡命者や近隣諸国の住民から少数の傭兵部隊を募集するのに十分な資金を与えられた。この部隊は解放軍と呼ばれた。 CIAはニカラグアとホンジュラスに訓練キャンプを設置し、武器と爆撃機数機を供給した。米国はグアテマラ侵攻前に両国と軍事協定を結び、重火器の自由な 移動を可能にした[102]。CIAは少なくとも1,725人の外国人ゲリラに加え、予備兵として数千人の戦闘員を訓練した。[103] これらの準備は表向きは秘密裏に行われたが、CIAはアルベンスがそれを知ることを意図していた。これはアルベンス政権打倒が既成事実であるとグアテマラ の人民に納得させる計画の一環だった。さらにCIAはグアテマラ全土の教会指導者らと密かに接触し、説教に反政府メッセージを盛り込むよう説得した。 [102] |

| Caracas conference and U.S. propaganda While preparations for Operation PBSuccess were underway, Washington issued a series of statements denouncing the Guatemalan government, alleging that it had been infiltrated by communists.[104] The State Department also asked the Organization of American States to modify the agenda of the Inter-American Conference, which was scheduled to be held in Caracas in March 1954, requesting the addition of an item titled "Intervention of International Communism in the American Republics", which was widely seen as a move targeting Guatemala.[104] On 29 and 30 January 1954, the Guatemalan government published documents containing information leaked to it by a member of Castillo Armas' team who had turned against him. Lacking in original documents, the government had engaged in poor forgery to enhance the information it possessed, undermining the credibility of its charges.[105] A spate of arrests followed of allies of Castillo Armas within Guatemala, and the government issued statements implicating a "Government of the North" in a plot to overthrow Árbenz. Washington denied these allegations, and the U.S. media uniformly took the side of their government; even publications which had until then provided relatively balanced coverage of Guatemala, such as The Christian Science Monitor, suggested that Árbenz had succumbed to communist propaganda.[106] Several Congressmen also pointed to the allegations from the Guatemalan government as proof that it had become communist.[107] At the conference in Caracas, the various Latin American governments sought economic aid from the U.S., as well as its continuing non-intervention in their internal affairs.[108] The U.S. government's aim was to pass a resolution condemning the supposed spread of communism in the Western Hemisphere. The Guatemalan foreign minister Guillermo Toriello argued strongly against the resolution, stating that it represented the "internationalization of McCarthyism". Despite support among the delegates for Toriello's views, the anti-communist resolution passed with only Guatemala voting against, because of the votes of dictatorships dependent on the U.S. and the threat of economic pressure applied by John Dulles.[109] Although support among the delegates for Dulles' strident anti-communism was less strong than he and Eisenhower had hoped for,[108] the conference marked a victory for the U.S., which was able to make concrete Latin American views on communism.[109] The U.S. had stopped selling arms to Guatemala in 1951 while signing bilateral defense agreements and increasing arms shipments to neighboring Honduras and Nicaragua. The U.S. promised the Guatemalan military that it too could obtain arms—if Árbenz were deposed. In 1953, the State Department aggravated the U.S. arms embargo by thwarting the Árbenz government's arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia.[110][111] By 1954 Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, which would have been the first time that a Soviet bloc country shipped weapons to the Americas, an action seen as establishing a communist beachhead in the Americas.[112][113][114] The weapons were delivered to Guatemala at the Atlantic port of Puerto Barrios by the Swedish freight ship MS Alfhem, which sailed from Szczecin in Poland.[113] The U.S. failed to intercept the shipment despite imposing an illegal naval quarantine on Guatemala.[115] However "Guatemalan army officers" quoted in The New York Times said that "some of the arms ... were duds, worn out, or entirely wrong for use there".[116] The CIA portrayed the shipment of these weapons as Soviet interference in the United States' backyard; it was the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[113] U.S. rhetoric abroad also had an effect on the Guatemalan military. The military had always been anti-communist, and Ambassador Peurifoy had applied pressure on senior officers since his arrival in Guatemala in October 1953.[117] Árbenz had intended the secret shipment of weapons from the Alfhem to be used to bolster peasant militias, in the event of army disloyalty, but the U.S. informed army chiefs of the shipment, forcing Árbenz to hand them over to the military, and deepening the rift between him and his top generals.[117] |

カラカス会議と米国のプロパガンダ オペレーションPBSuccessの準備が進む中、ワシントンはグアテマラ政府を非難する一連の声明を発表した。共産主義者に浸透されていると主張したの である。[104] 国務省はまた、1954年3月にカラカスで開催予定だった米州会議の議題変更を米州機構に要請し、「米州諸国における国際共産主義の介入」と題する項目の 追加を求めた。これは広くグアテマラを標的とした動きと見なされた。[104] 1954年1月29日と30日、グアテマラ政府は、カスティージョ・アルマス陣営から離反した人物から漏洩された情報を含む文書を公表した。原本を欠いて いた政府は、所持情報を補強するため拙劣な偽造を行い、告発内容の信憑性を損なった。[105] その後、グアテマラ国内でカスティージョ・アルマス派の支持者に対する一連の逮捕が行われ、政府は「北の政府」がアルベンス政権転覆の陰謀に関与している と示唆する声明を発表した。ワシントンはこれらの主張を否定し、米メディアは一様に政府の立場を支持した。それまでグアテマラ情勢を比較的公平に報じてき た『クリスチャン・サイエンス・モニター』紙でさえ、アルベンスが共産主義プロパガンダに屈したとの見解を示した[106]。複数の米国議会議員も、グア テマラ政府の主張を同国が共産化した証拠として指摘した[107]。 カラカスでの会議で、ラテンアメリカ諸国政府は米国に対し、経済援助と内政不干渉の継続を求めた[108]。米国政府の目的は、西半球における共産主義の 拡散を非難する決議を可決させることだった。グアテマラの外相ギジェルモ・トリエロは、この決議が「マッカーシズムの国際化」を意味すると強く反論した。 トリエロの見解に賛同する代表者もいたにもかかわらず、反共決議は米国に依存する独裁政権の票とジョン・ダレスによる経済的圧力の脅威により、グアテマラ だけが反対票を投じる中で可決された。[109] 代表団の間でダレスの過激な反共主義への支持は、彼とアイゼンハワーが期待したほど強くなかったが[108]、この会議は米国にとって勝利を意味した。米 国はラテンアメリカ諸国の共産主義に対する見解を具体化することに成功したのである[109]。 米国は1951年、グアテマラへの武器販売を停止すると同時に、近隣のホンジュラスとニカラグアとの二国間防衛協定を締結し、これらへの武器供与を拡大し た。米国はグアテマラ軍に対し、アルベンス政権が打倒されれば武器を入手できると約束した。1953年には国務省が、アルベンス政権のカナダ、ドイツ、 ローデシアからの武器購入を妨害し、米国の武器禁輸措置を強化した。[110][111] 1954年までにアルベンスは武器を必死に求めており、チェコスロバキアから密かに調達することを決めた。これはソ連圏の国が初めてアメリカ大陸に武器を 輸送する事例となり、アメリカ大陸における共産主義の前哨基地を確立する行動と見なされた。[112][113] [114] これらの武器は、ポーランドのシュチェチンから出航したスウェーデンの貨物船MSアルフェム号によって、大西洋岸の港湾都市プエルトバリオスに運ばれた。 [113] 米国はグアテマラに対して違法な海上封鎖を課していたにもかかわらず、この輸送を阻止できなかった。[115] しかしニューヨーク・タイムズ紙が引用した「グアテマラ軍将校」によれば、「武器の一部は…不発弾、消耗品、あるいは現地での使用に全く不適切なものだっ た」という。[116] CIAはこの武器輸送を、米国の裏庭におけるソ連の干渉と位置付け、これがCIAによるクーデター実行の最終的な引き金となった。[113] 米国の対外的な言説はグアテマラ軍にも影響を与えた。軍は常に反共主義であり、ピュリフォイ大使は1953年10月にグアテマラ着任以来、上級将校らに圧 力をかけていた。アルフェム号からの武器の秘密輸送は、軍が反旗を翻した場合に備え、農民民兵を強化するためにアルベンスが意図したものだった。しかし米 国は軍首脳部にこの輸送を通知し、アルベンスに武器を軍に引き渡すよう強要した。これにより彼と最高将軍たちの間の亀裂は深まった。 |

| Psychological warfare Castillo Armas' army of 480 men was not large enough to defeat the Guatemalan military, even with U.S.-supplied aircraft. Therefore, the plans for Operation PBSuccess called for a campaign of psychological warfare, which would present Castillo Armas' victory as a fait accompli to the Guatemalan people, and would force Árbenz to resign.[88][118][119] The propaganda campaign had begun well before the invasion, with the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) writing hundreds of articles on Guatemala based on CIA reports, and distributing tens of thousands of leaflets throughout Latin America. The CIA persuaded friendly governments to screen video footage of Guatemala that supported the U.S. version of events.[120] As part of the psychological warfare, the U.S. Psychological Strategy Board authorized a "Nerve War Against Individuals" to instill fear and paranoia in potential loyalists and other potential opponents of the coup. This campaign included death threats against political leaders deemed loyal or deemed to be communist, and the sending of small wooden coffins, non-functioning bombs, and hangman's nooses to such people.[121] The US bombing was also intended to have psychological consequences with E. Howard Hunt of the CIA saying "What we wanted to do was to have a terror campaign, to terrify Arbenz particularly, to terrify his troops, much as the German Stuka bombers terrified the population of Holland, Belgium and Poland".[122][123] Alfhem's success in evading the quarantine led to Washington escalating its intimidation of Guatemala through its navy. On 24 May, the U.S. launched Operation Hardrock Baker, a naval blockade of Guatemala. Ships and submarines patrolled the Guatemalan coasts, and all approaching ships were stopped and searched; these included ships from Britain and France, violating international law.[124] However Britain and France did not protest very strongly, hoping that in return the U.S. would not interfere with their efforts to subdue rebellious colonies in the Middle East. The intimidation was not solely naval; on 26 May one of Castillo Armas' planes flew over the capital, dropping leaflets that exhorted people to struggle against communism and support Castillo Armas.[124] The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station Voice of Liberation, La Voz de la Liberación. E. Howard Hunt's deputy, David Atlee Phillips, directed the radio station.[125] It began broadcasting on 1 May 1954, carrying anti-communist propaganda, telling its listeners to resist the Árbenz government and support the liberating forces of Castillo Armas. The station claimed to be broadcasting from deep within the jungles of the Guatemalan hinterland, a message which many listeners believed. This belief extended outside of Guatemala itself, with foreign correspondents from publications such as The New York Times believing it to be the most authentic source of information.[126] In actuality, the broadcasts were concocted in Miami by Guatemalan exiles, flown to Central America, and broadcast through a mobile transmitter. The Voice of Liberation made an initial broadcast that was repeated four times, after which it took to transmitting two-hour bulletins twice a day. The transmissions were initially only heard intermittently in Guatemala City; a week later, the CIA significantly increased their transmitting power, allowing clear reception in the Guatemalan capital. The radio broadcasts have been given a lot of credit by historians for the success of the coup, owing to the unrest they created throughout the country. They were unexpectedly assisted by the outage of the government-run radio station, which stopped transmitting for three weeks while a new antenna was being fitted.[127] The Voice of Liberation transmissions continued throughout the conflict, broadcasting exaggerated news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributing to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[128] |

心理戦 カスティージョ・アルマス率いる480名の軍隊は、米国から提供された航空機があってもグアテマラ軍を打ち破るには十分ではなかった。そのため、作戦 「PBSuccess」の計画では、心理戦を展開し、カスティージョ・アルマスの勝利をグアテマラの人民に既成事実として提示し、アルベンスを辞任に追い 込むことが求められた。[88][118] [119] このプロパガンダ作戦は侵攻よりずっと前から始まっていた。米国情報局(USIA)はCIAの報告書に基づきグアテマラに関する数百本の記事を執筆し、ラ テンアメリカ全域に数万枚のビラを配布した。CIAは友好国政府に対し、米国の主張を支持するグアテマラの映像を放映するよう働きかけた。[120] 心理戦の一環として、米国心理戦略委員会は「個人に対する神経戦」を承認した。これはクーデターに反対する可能性のある忠誠派やその他の潜在的な敵対者に 恐怖と妄想を植え付けるためだった。この作戦には、忠誠派と見なされた政治指導者や共産主義者と見なされた者に対する殺害予告、そしてそのような人民への 小さな木製の棺、不発弾、絞首刑用の縄の送付が含まれていた。[121] 米軍の爆撃は心理的効果も意図しており、CIAのE・ハワード・ハントは「我々が望んだのは恐怖作戦であり、特にアルベンツを恐怖に陥れ、その部隊を恐怖 に陥れることだった。ドイツのストゥーカ爆撃機がオランダ、ベルギー、ポーランドの住民を恐怖に陥れたのと同様だ」と述べている。[122] [123] アルフェムが検疫を回避した成功は、ワシントンが海軍を通じてグアテマラへの威嚇をエスカレートさせる結果となった。5月24日、米国はグアテマラに対す る海上封鎖作戦「ハードロック・ベイカー作戦」を発動した。艦船と潜水艦がグアテマラ沿岸を哨戒し、接近する全ての船舶は停止・検査を受けた。これには英 国やフランスの船舶も含まれ、国際法違反であった。[124] しかし英国とフランスは強く抗議しなかった。中東の反乱植民地鎮圧への米国の干渉を避けるためである。威嚇は海軍だけにとどまらなかった。5月26日、カ スティーヨ・アルマス派の航空機が首都上空を飛行し、共産主義との闘争とアルマス支持を呼びかけるビラを投下した。[124] 最も広範な心理的兵器は、ラジオ局「解放の声(La Voz de la Liberación)」であった。E・ハワード・ハントの副官デイヴィッド・アトリー・フィリップスが同局を指揮した[125]。1954年5月1日に 放送を開始し、反共産主義プロパガンダを流して、リスナーにアルベンス政権への抵抗とカスティージョ・アルマス率いる解放勢力の支持を訴えた。同局はグア テマラ奥地の密林深くから放送していると主張し、多くの聴取者がこれを信じた。この認識はグアテマラ国外にも広がり、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』などの外 国特派員も最も信頼できる情報源とみなした。[126] 実際には放送内容はマイアミのグアテマラ亡命者によって捏造され、中米に空輸された移動式送信機を通じて放送されていた。解放の声は初回放送を4回繰り返 し、その後は1日2回・2時間のニュースを放送した。当初グアテマラシティでは断続的にしか受信できなかったが、1週間後にCIAが送信出力を大幅に増強 したため、首都でも明瞭に受信可能となった。このラジオ放送は国内に動乱を引き起こしたことで、クーデター成功の要因として歴史家から高く評価されてい る。政府系ラジオ局が新アンテナ設置のため3週間放送を停止したことも、予想外の追い風となった[127]。「解放の声」は紛争中も放送を継続し、反乱軍 が首都に集結しているという誇張された情報を流した。これにより軍と民間人の双方に深刻な士気低下をもたらした[128]。 |

Castillo Armas' invasion The CIA-trained and funded army of Carlos Castillo Armas invaded the Republic of Guatemala from Honduras and from El Salvador. The invasion force was split into four teams, targeting the towns of Puerto Barrios, Zacapa, Esquipulas and Jutiapa. Castillo Armas' force of 480 men had been split into four teams, ranging in size from 60 to 198. On 15 June 1954 these four forces left their bases in Honduras and El Salvador, and assembled in various towns just outside the Guatemalan border. The largest force was supposed to attack the Atlantic harbor town of Puerto Barrios, while the others attacked the smaller towns of Esquipulas, Jutiapa, and Zacapa, the Guatemalan army's largest frontier post.[129] Zapaca was of great significance to controlling Guatemala as it handled the majority of commerce along key rail routes.[130] The invasion plan quickly faced difficulties; the 60-man force was intercepted and jailed by Salvadoran policemen before it got to the border.[129] At 8:20 am on 18 June 1954, Castillo Armas led his invading troops over the border. Ten trained saboteurs preceded the invasion, with the aim of blowing up railways and cutting telegraph lines. At about the same time, Castillo Armas' planes flew over a pro-government rally in the capital.[129] The U.S. Psychological Strategy Board ordered the bombing of the Matamoros Fortress in downtown Guatemala City, and a U.S. P-47 warplane flown by a mercenary pilot bombed the city of Chiquimula.[131] Castillo Armas demanded Árbenz's immediate surrender.[132] The invasion provoked a brief panic in the capital, which quickly decreased as the rebels failed to make any striking moves. Bogged down by supplies and a lack of transportation, Castillo Armas' forces took several days to reach their targets, although their planes blew up a bridge on 19 June.[129] When the rebels did reach their targets, they met with further setbacks. The force of 122 men targeting Zacapa were intercepted and decisively beaten by a garrison of 30 Guatemalan soldiers, with only 30 men escaping death or capture.[133] The force that attacked Puerto Barrios was dispatched by policemen and armed dockworkers, with many of the rebels fleeing back to Honduras. In an effort to regain momentum, the rebel planes tried air attacks on the capital.[133] These attacks caused little material damage, but they had a significant psychological impact, leading many citizens to believe that the invasion force was more powerful than it actually was. The rebel bombers needed to fly out of the Nicaraguan capital of Managua; as a result, they had a limited payload. A large number of them substituted dynamite or Molotov cocktails for bombs, in an effort to create loud bangs with a lower payload.[134] The planes targeted ammunition depots, parade grounds, and other visible targets. On 22 June, another plane bombed the Honduran town of San Pedro de Copán; John Dulles claimed the attack had been conducted by the Guatemalan air force, thus avoiding diplomatic consequences.[135] However, by 22 June 1954, Armas' forces were down to one P-47 which made an ineffective air strike on the capital. The CIA sponsors of Armas began to worry Operation PBSuccess may fail. Col. Al Haney, heading the CIA's operation, informed Allen Dulles that more aircraft was needed or else the Armas invasion would surely fail. Dulles made arrangements for the sale of three additional P-47s from the military to the Nicaraguan government, to be paid for by William Pawley, a successful businessman, Eisenhower supporter, and CIA consultant. In an Oval Office meeting, Dulles and others briefed President Eisenhower on the need for additional aircraft in the Armas invasion. Upon Eisenhower's approval, the planes were purchased by Pawley on behalf of the Nicaraguan government. The P-47s flew from Puerto Rico to Panama and went into action on 23 June, hitting Guatemalan army forces and other targets in the capital.[136] Early in the morning on 27 June 1954, a plane attacked Puerto San José and bombed the British cargo ship, SS Springfjord, which was on charter to the U.S. company W.R. Grace and Company Line, and was being loaded with Guatemalan cotton and coffee.[137] This incident cost the CIA one million U.S. dollars in compensation.[g][134] |

カスティーヨ・アルマスによる侵攻 CIAが訓練し資金を提供したカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスの軍隊は、ホンジュラスとエルサルバドルからグアテマラ共和国に侵攻した。侵攻部隊は四つのチームに分かれ、プエルト・バリオス、サカパ、エスキプラス、フティアパの各町を標的とした。 480名のカスティージョ・アルマス部隊は、60名から198名規模の4つのチームに分かれていた。1954年6月15日、これら4つの部隊はホンジュラ スとエルサルバドルの基地を出発し、グアテマラ国境直近の様々な町に集結した。最大規模の部隊は大西洋岸の港湾都市プエルト・バリオスを攻撃する予定だっ た。他の部隊はエスキプラス、フティアパ、ザカパといった小規模な町を攻撃対象とした。ザカパはグアテマラ軍最大の国境警備拠点であった[129]。ザカ パは主要鉄道路線沿いの商業の大半を扱うため、グアテマラ支配において極めて重要な位置を占めていた。[130] 侵攻計画は早々に困難に直面した。60名の部隊は国境到達前にエルサルバドル警察に阻止され投獄された。[129] 1954年6月18日午前8時20分、カスティーヨ・アルマスは侵攻部隊を率いて国境を越えた。10名の訓練を受けた破壊工作員が先行し、鉄道の爆破と電 信線の切断を目的としていた。ほぼ同時刻、カスティージョ・アルマス軍の航空機が首都で開催中の親政府集会上空を飛行した[129]。米国心理作戦委員会 はグアテマラシティ中心部のマタモロス要塞爆撃を命じ、傭兵パイロット操縦の米軍P-47戦闘機がチキムラ市を爆撃した[131]。カスティージョ・アル マスはアルベンスの即時降伏を要求した。[132] この侵攻は首都に一時的なパニックを引き起こしたが、反乱軍が目立った動きを見せなかったため、その動揺はすぐに収まった。補給品と輸送手段の不足に足止 めされたカスティージョ・アルマス軍は、目標地点に到達するまでに数日を要した。ただし、彼らの航空機は6月19日に橋を爆破している。[129] 反乱軍がようやく目標地点に到達した時、さらなる挫折に見舞われた。ザカパを標的とした122名の部隊は、30名のグアテマラ兵の守備隊に迎撃され、決定 的な敗北を喫した。死や捕虜を免れたのはわずか30名であった。[133] プエルト・バリオスを攻撃した部隊は警察官と武装した港湾労働者によって撃退され、多くの反乱軍兵士はホンジュラスへ逃亡した。勢いを取り戻そうと、反乱 軍の航空機は首都への空襲を試みた。[133] これらの攻撃は物的損害はほとんど与えなかったが、心理的衝撃は大きく、多くの市民に侵攻部隊が実際以上に強力だと信じ込ませた。反乱軍の爆撃機はニカラ グアの首都マナグアから離陸する必要があったため、爆弾搭載量は限られていた。多くの機体が爆弾の代わりにダイナマイトや火炎瓶を使用し、少ない搭載量で 大きな爆発音を生み出そうとしたのである[134]。航空機は弾薬庫、練兵場、その他の目立つ標的を狙った。6月22日には別の機体がホンジュラスのサ ン・ペドロ・デ・コパンを爆撃した。ジョン・ダレスはこの攻撃をグアテマラ空軍によるものと主張し、外交的結果を回避した。[135] しかし1954年6月22日までに、アルマス軍の戦力はP-47戦闘機1機にまで減少し、首都への空襲は効果を挙げられなかった。アルマスを支援する CIAは、作戦「PBSuccess」の失敗を懸念し始めた。作戦責任者のアル・ヘイニー大佐はアレン・ダレスに、追加航空機がなければアルマスの侵攻は 確実に失敗すると報告した。ダレスは軍からニカラグア政府へP-47戦闘機3機の追加売却を手配し、その代金は実業家でアイゼンハワー支持者、CIA顧問 のウィリアム・ポーリーが負担することとなった。大統領執務室での会議で、ダレスらはアーマス侵攻に追加航空機が必要だとアイゼンハワー大統領に説明し た。大統領の承認を得て、ポーリーがニカラグア政府の代理として機体を購入。P-47はプエルトリコからパナマへ飛行し、6月23日に実戦投入された。グ アテマラ軍部隊や首都内のその他の目標を攻撃したのである。[136] 1954年6月27日未明、航空機がプエルト・サンホセを攻撃し、英国の貨物船SSスプリングフィヨルド号を爆撃した。同船は米国企業W.R.グレイス・ アンド・カンパニー・ラインにチャーターされ、グアテマラ産綿花とコーヒーを積載中だった。[137] この事件でCIAは100万米ドルの賠償金を支払う羽目になった。[g][134] |

| Guatemalan response The Árbenz government originally meant to repel the invasion by arming the military-age populace, workers' militias, and the Guatemalan Army. Resistance from the armed forces, as well as public knowledge of the secret arms purchase, compelled the President to supply arms only to the Army.[137] From the beginning of the invasion, Árbenz was confident that Castillo Armas could be defeated militarily and expressed this confidence in public. But he was worried that a defeat for Castillo Armas would provoke a direct invasion by the U.S. military. This also contributed to his decision not to arm civilians initially; lacking a military reason to do so, this could have cost him the support of the army. Carlos Enrique Díaz, the chief of the Guatemalan armed forces, told Árbenz that arming civilians would be unpopular with his soldiers, and that "the army [would] do its duty".[138] Árbenz instead told Díaz to select officers to lead a counter-attack. Díaz chose a corps of officers who were all regarded to be men of personal integrity, and who were loyal to Árbenz.[138] On the night of 19 June, most of the Guatemalan troops in the capital region left for Zacapa, joined by smaller detachments from other garrisons. Árbenz stated that "the invasion was a farce", but worried that if it was defeated on the Honduran border, Honduras would use it as an excuse to declare war on Guatemala, which would lead to a U.S. invasion. Because of the rumours spread by the Voice of Liberation, there were worries throughout the countryside that a fifth column attack was imminent; large numbers of peasants went to the government and asked for weapons to defend their country. They were repeatedly told that the army was "successfully defending our country".[139] Nonetheless, peasant volunteers assisted the government war effort, manning roadblocks and donating supplies to the army. Weapons shipments dropped by rebel planes were intercepted and turned over to the government.[139] The Árbenz government also pursued diplomatic means to try to end the invasion. It sought support from El Salvador and Mexico; Mexico declined to get involved, and the Salvadoran government merely reported the Guatemalan effort to Peurifoy. Árbenz's largest diplomatic initiative was in taking the issue to the United Nations Security Council. On 18 June the Guatemalan foreign minister petitioned the council to "take measures necessary ... to put a stop to the aggression", which he said Nicaragua and Honduras were responsible for, along with "certain foreign monopolies which have been affected by the progressive policy of my government".[140] The Security Council looked at Guatemala's complaint at an emergency session on 20 June. The debate was lengthy and heated, with Nicaragua and Honduras denying any wrongdoing, and the U.S. stating that Eisenhower's role as a general in World War II demonstrated that he was against imperialism. The Soviet Union was the only country to support Guatemala. When the U.S. and its allies proposed referring the matter to the Organization of American States, the Soviet Union vetoed the proposal. Guatemala continued to press for a Security Council investigation; the proposal received the support of Britain and France, but on 24 June it was vetoed by the U.S., the first time it did so against its allies. The U.S. accompanied this with threats to the foreign offices of both countries that the U.S. would stop supporting their other initiatives.[141] UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld called the U.S. position "the most serious blow so far aimed at the [United Nations]".[142] A fact-finding mission was set up by the Inter-American Peace Committee; Washington used its influence to delay the entry of the committee until the coup was complete and a military dictatorship installed.[141] |

Respuesta guatemalteca El gobierno de Árbenz tenía inicialmente la intención de repeler la invasión armando a la población en edad militar, a las milicias obreras y al Ejército guatemalteco. La resistencia de las fuerzas armadas, así como el conocimiento público de la compra secreta de armas, obligaron al presidente a suministrar armas solo al Ejército. [137] Desde el comienzo de la invasión, Árbenz estaba convencido de que Castillo Armas podía ser derrotado militarmente y expresó esta confianza en público. Pero le preocupaba que una derrota de Castillo Armas provocara una invasión directa por parte del ejército estadounidense. Esto también contribuyó a su decisión de no armar a los civiles inicialmente; al carecer de una razón militar para hacerlo, esto podría haberle costado el apoyo del ejército. Carlos Enrique Díaz, jefe de las fuerzas armadas guatemaltecas, le dijo a Árbenz que armar a los civiles sería impopular entre tus soldados y que «el ejército cumpliría con su deber».[138] Árbenz, en cambio, le dijo a Díaz que seleccionara a los oficiales que liderarían el contraataque. Díaz eligió a un grupo de oficiales que eran considerados hombres íntegros y leales a Árbenz. [138] La noche del 19 de junio, la mayoría de las tropas guatemaltecas de la región de la capital partieron hacia Zacapa, acompañadas por pequeños destacamentos de otras guarniciones. Árbenz declaró que «la invasión era una farsa», pero le preocupaba que, si era derrotada en la frontera con Honduras, este país la utilizara como excusa para declarar la guerra a Guatemala, lo que daría lugar a una invasión estadounidense. Debido a los rumores difundidos por la Voz de la Liberación, en todo el campo se temía que fuera inminente un ataque de la quinta columna; un gran número de campesinos acudieron al gobierno y pidieron armas para defender su país. Se les dijo repetidamente que el ejército estaba «defendiendo con éxito nuestro país».[139] No obstante, los campesinos voluntarios ayudaron al gobierno en su esfuerzo bélico, montando barricadas y donando suministros al ejército. Los envíos de armas lanzados por aviones rebeldes fueron interceptados y entregados al gobierno. [139] El gobierno de Árbenz también recurrió a medios diplomáticos para intentar poner fin a la invasión. Buscó el apoyo de El Salvador y México; México se negó a involucrarse y el gobierno salvadoreño se limitó a informar a Peurifoy de los esfuerzos guatemaltecos. La mayor iniciativa diplomática de Árbenz fue llevar el asunto al Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas. El 18 de junio, el ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Guatemala solicitó al Consejo que «tomara las medidas necesarias... para poner fin a la agresión», de la que, según él, eran responsables Nicaragua y Honduras, junto con «ciertos monopolios extranjeros que se han visto afectados por la política progresista de mi gobierno».[140] El Consejo de Seguridad examinó la denuncia de Guatemala en una sesión de emergencia celebrada el 20 de junio. El debate fue largo y acalorado, con Nicaragua y Honduras negando cualquier irregularidad y Estados Unidos afirmando que el papel de Eisenhower como general en la Segunda Guerra Mundial demostraba que estaba en contra del imperialismo. La Unión Soviética fue el único país que apoyó a Guatemala. Cuando Estados Unidos y sus aliados propusieron remitir el asunto a la Organización de Estados Americanos, la Unión Soviética vetó la propuesta. Guatemala siguió presionando para que el Consejo de Seguridad investigara el asunto; la propuesta recibió el apoyo de Gran Bretaña y Francia, pero el 24 de junio fue vetada por Estados Unidos, la primera vez que lo hacía contra sus aliados. Estados Unidos acompañó esta medida con amenazas a las oficinas de relaciones exteriores de ambos países de que dejaría de apoyar sus otras iniciativas. [141] El secretario general de la ONU, Dag Hammarskjöld, calificó la postura de Estados Unidos como «el golpe más grave asestado hasta la fecha a las Naciones Unidas».[142] La Comisión Interamericana de Paz estableció una misión de investigación; Washington utilizó su influencia para retrasar la entrada de la comisión hasta que se completó el golpe y se instauró una dictadura militar.[141] |

| Árbenz's resignation Árbenz was initially confident that his army would quickly dispatch the rebel force. The victory of a small garrison of 30 soldiers over the 180 strong rebel force outside Zacapa strengthened his belief. By 21 June, Guatemalan soldiers had gathered at Zacapa under the command of Colonel Víctor M. León, who was believed to be loyal to Árbenz. León told Árbenz that the counter-attack would be delayed for logistical reasons, but assured him not to worry, as Castillo Armas would be defeated very soon. Other members of the government were not so certain. Army Chief of Staff Parinello inspected the troops at Zacapa on 23 June, and returned to the capital believing that the army would not fight. Afraid of a U.S. intervention in Castillo Armas' favor, he did not tell Árbenz of his suspicions.[140] PGT leaders also began to have their suspicions; acting secretary general Alvarado Monzón sent a member of the central committee to Zacapa to investigate. He returned on 25 June, reporting that the army was highly demoralized, and would not fight. Monzón reported this to Árbenz, who quickly sent another investigator. He too returned the same report, carrying an additional message for Árbenz from the officers at Zacapa—asking the President to resign. The officers believed that given U.S. support for the rebels, defeat was inevitable, and Árbenz was to blame for it. He stated that if Árbenz did not resign, the army was likely to strike a deal with Castillo Armas, and march on the capital with him.[143][144] During this period, Castillo Armas had begun to intensify his aerial attacks with the extra planes that Eisenhower had approved. They had limited material success; many of their bombs were surplus material from World War II, and failed to explode. Nonetheless, they had a significant psychological impact.[145] On 25 June, the same day that he received the army's ultimatum, Árbenz learned that Castillo Armas had scored what later proved to be his only military victory, defeating the Guatemalan garrison at Chiquimula.[143] Historian Piero Gleijeses has stated that if it were not for U.S. support for the rebellion, the officer corps of the Guatemalan army would have remained loyal to Árbenz because, although they were not uniformly his supporters, they were more wary of Castillo Armas, and also had strong nationalist views. As it was, they believed that the U.S. would intervene militarily, leading to a battle they could not win.[143] On the night of 25 June, Árbenz called a meeting of the senior leaders of the government, the political parties, and the labor unions. Colonel Díaz was also present. The President told them that the army at Zacapa had abandoned the government, and that the civilian population needed to be armed to defend the country. Díaz raised no objections, and the unions pledged several thousand troops. When the troops were mustered the next day, only a few hundred showed up. The civilian population of the capital had fought alongside the Guatemalan Revolution twice before—during the popular uprising of 1944, and during the attempted coup of 1949—but on this occasion the army, intimidated by the U.S., refused to fight. The union members were reluctant to fight both the invasion and their own military.[128][146] Seeing this, Díaz reneged on his support of the President, and began plotting to overthrow Árbenz with the assistance of other senior army officers. They informed Peurifoy of this plan, asking him to stop the hostilities in return for Árbenz's resignation. Peurifoy promised to arrange a truce, and the plotters went to Árbenz and informed him of their decision. Árbenz, utterly exhausted and seeking to preserve at least a measure of the democratic reforms that he had brought, agreed without demur. After informing his cabinet of his decision, he left the presidential palace at 8 pm on 27 June 1954, having taped a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later. In it, he stated that he was resigning to eliminate the "pretext for the invasion", and that he wished to preserve the gains of the October Revolution of 1944.[147] He walked to the nearby Mexican Embassy, seeking political asylum.[148] Two months later he was granted safe passage out of the country, and flew to exile in Mexico.[149] Some 120 Árbenz loyalists or communists were also allowed to leave, and the CIA stated that none of the assassination plans contemplated by the CIA were actually implemented.[150] On June 30, 1954, the CIA began a comprehensive destruction process of documents related to Operation PBSuccess. When an oversight committee of the United States Senate in 1975 investigated the history of the CIA's assassinations program and requested information about the CIA's assassination program as part of Operation PBSuccess, the CIA stated it had lost all such records.[151] Journalist Annie Jacobsen states that the CIA claim of no assassinations having taken place is doubtful. In May 1997, the CIA stated it had rediscovered some of its documents that it had said were lost. The names of assassination targets had all been redacted, which made it impossible to verify whether any of the people on the CIA assassination list were actually killed as part of the operation.[151] |

アルベンスの辞任 アルベンスは当初、自軍が反乱軍を迅速に撃破できると確信していた。ザカパ郊外で30名の小規模守備隊が180名の反乱軍を撃破した勝利が、その信念を強 めた。6月21日までに、アルベンスに忠実とされるビクトル・M・レオン大佐の指揮下でグアテマラ兵がザカパに集結した。レオンはアルベンスに対し、兵站 上の理由で反撃が遅れると伝えたが、カスティージョ・アルマスは間もなく敗北するから心配するなと保証した。政府の他のメンバーはそれほど確信を持ってい なかった。陸軍参謀総長パリネッロは6月23日にザカパの部隊を視察し、軍は戦わないだろうと確信して首都に戻った。カスティージョ・アルマスを支持する 米国の介入を恐れた彼は、その疑念をアルベンスに伝えなかった[140]。PGT指導部も疑念を抱き始め、アルバラド・モンソン事務総長代行は中央委員会 のメンバーをザカパに調査に派遣した。彼は6月25日に戻り、軍は士気が著しく低下しており、戦わないだろうと報告した。モンソンはこの報告をアルベンス に伝えた。アルベンスは直ちに別の調査員を派遣した。この調査員も同様の報告を持ち帰るとともに、ザカパの将校たちからアルベンスへの追加メッセージを携 えていた。それは大統領の辞任を求めるものだった。将校たちは、反乱軍への米国の支援を考慮すれば敗北は避けられず、その責任はアルベンスにあると考えて いた。アルベンスが辞任しなければ、軍はカスティーヨ・アルマスと取引し、彼と共に首都へ進軍する可能性が高いと述べた。[143][144] この時期、カスティーヨ・アルマスはアイゼンハワーが承認した追加航空機を用いて空爆を強化し始めていた。物的成果は限定的だった。爆弾の多くは第二次世 界大戦の余剰物資で、不発が多かった。それでも、心理的な影響は大きかった[145]。6月25日、軍からの最後通告を受けたその日、アルベンスはカス ティージョ・アルマスがチキムラのグアテマラ守備隊を撃破し、後に彼の唯一の軍事的勝利となる戦果を挙げたことを知った。[143] 歴史家ピエロ・グレイヘセスは、もし米国が反乱を支援していなければ、グアテマラ軍将校団はアルベンスに忠誠を保っただろうと述べている。彼らは一様にア ルベンス支持者ではなかったが、カスティージョ・アルマスを警戒し、強いナショナリストを持っていたからだ。実際、彼らは米国が軍事介入すると確信し、勝 てない戦いを強いられると考えたのである。[143] 6月25日の夜、アルベンスは政府、政党、労働組合の上級指導者たちを集めて会議を開いた。ディアス大佐も同席していた。大統領はザカパの軍隊が政府を見 捨てたこと、そして国を守るために民間人に武器を持たせる必要があると伝えた。ディアスは異議を唱えず、組合は数千の兵力を提供すると約束した。しかし翌 日兵士を集結させると、現れたのはわずか数百名だった。首都の市民は過去に二度、グアテマラ革命と共に戦ったことがある——1944年の民衆蜂起と 1949年のクーデター未遂の時だ——しかし今回は、米国に脅された軍が戦闘を拒否したのである。組合員たちは、侵略軍と自国軍の両方と戦うことに消極的 だった[128][146]。これを見たディアスは大統領支持を撤回し、他の上級将校らと協力してアルベンス打倒を画策し始めた。彼らはこの計画をピュリ フォイに伝え、アルベンスの辞任と引き換えに戦闘停止を要求した。ピュリフォイは休戦の手配を約束し、謀議者たちはアルベンスのもとへ赴き決定を伝えた。 アルベンスは完全に疲弊し、自らが成し遂げた民主的改革の少なくとも一部を保存しようと望み、異議なく同意した。閣僚に決定を伝えた後、彼は1954年6 月27日午後8時に大統領宮殿を去り、1時間後に放送される辞任演説を録音した。辞任演説で彼は「侵略の口実をなくすため」辞任すると述べ、1944年 10月革命の成果を守りたいと語った[147]。その後、政治亡命を求めて近くのメキシコ大使館へ歩いて向かった[148]。2か月後、国外退去の安全な 通行が認められ、メキシコへ亡命した。[149] アルベンス派の支持者や共産主義者約120名も出国を許可され、CIAは自らが計画した暗殺案はいずれも実行されなかったと表明した。[150] 1954年6月30日、CIAは「オペレーション・ピービーサクセス」関連文書の包括的破棄作業を開始した。1975年、米国上院の監視委員会がCIA暗 殺計画の歴史を調査し、オペレーションPBSuccessの一環としてのCIA暗殺計画に関する情報を要求した際、CIAはそうした記録を全て紛失したと 主張した。[151] ジャーナリストのアニ・ジェイコブセンは、CIAの「暗殺は行われなかった」という主張は疑わしいと述べている。1997年5月、CIAは以前紛失したと していた文書の一部を再発見したと発表した。暗殺対象者の名前は全て黒塗りされており、CIAの暗殺リストに載っていた人々を実際に作戦の一環として殺害 されたかどうかを検証することは不可能であった。[151] |

| Military governments Immediately after the President announced his resignation, Díaz announced on the radio that he was taking over the presidency, and that the army would continue to fight against the invasion of Castillo Armas.[152][153] He headed a military junta which also consisted of Colonels Elfego Hernán Monzón Aguirre and Jose Angel Sánchez.[153][154][155][156] Two days later Ambassador Peurifoy told Díaz that he had to resign because, in the words of a CIA officer who spoke to Díaz, he was "not convenient for American foreign policy".[156][157] Peurifoy castigated Díaz for allowing Árbenz to criticize the United States in his resignation speech; meanwhile, a U.S.-trained pilot dropped a bomb on the army's main powder magazine to intimidate the colonel.[153][158] Soon after, Díaz was overthrown by a rapid bloodless coup led by Colonel Monzón, who was more pliable to U.S. interests.[156] Díaz later stated that Peurifoy had presented him with a list of names of communists, and demanded that all of them be shot by the next day; Díaz had refused, turning Peurifoy further against him.[159] On 17 June, the army leaders at Zacapa had begun to negotiate with Castillo Armas. They signed a pact, the Pacto de Las Tunas, three days later, which placed the army at Zacapa under Castillo Armas, in return for a general amnesty. The army returned to its barracks a few days later, "despondent, with a terrible sense of defeat".[156] Although Monzón was staunchly anti-communist and repeatedly spoke of his loyalty to the U.S., he was unwilling to hand over power to Castillo Armas. The fall of Díaz led Peurifoy to believe that the CIA should let the State Department play the lead role in negotiating with the new government.[160] The State Department asked Óscar Osorio, the dictator of El Salvador, to invite all players for talks in San Salvador. Osorio agreed, and Monzón and Castillo Armas arrived in the Salvadoran capital on 30 June.[156] Peurifoy initially remained in Guatemala City, to avoid the appearance of a heavy U.S. role but was forced to travel to San Salvador when the negotiations came close to breaking down on the first day.[156][161] In the words of John Dulles, Peurifoy's role was to "crack some heads together".[161] Neither Monzón nor Castillo Armas could have remained in power without U.S. support, so Peurifoy was able to force an agreement, which was announced at 4:45 am on 2 July. Castillo Armas and his subordinate Major Enrique Trinidad Oliva joined the three-person junta headed by Monzón, who remained president.[42][156] On 7 July Colonels Dubois and Cruz Salazar, Monzón's supporters on the junta, resigned, according to the secret agreement they had made without Monzón's knowledge. Outnumbered, Monzón also resigned, allowing Castillo Armas to be unanimously elected president of the junta.[156] The two colonels were paid 100,000 U.S. dollars apiece for their cooperation.[h][156] The U.S. promptly recognized the new government on 13 July.[162] Soon after taking office, Castillo Armas faced a coup from young army cadets, who were unhappy with the army's surrender. The coup was crushed, leaving 29 dead and 91 wounded.[163] Elections were held in early October, from which all political parties were barred. Castillo Armas was the only candidate; he won the election with 99% of the vote.[164][165] |