2666

2666 ,novela, por Roberto Bolaño.

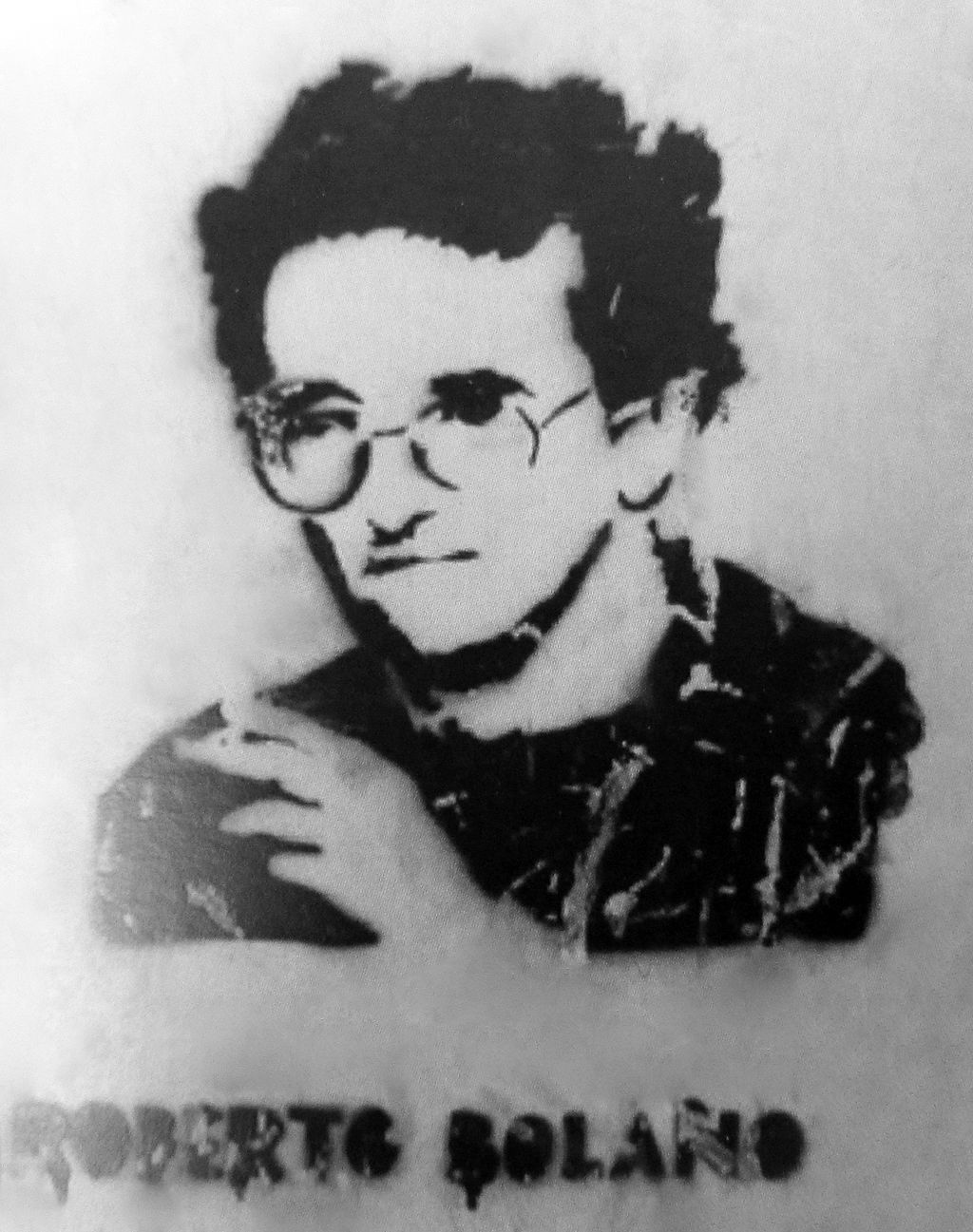

Esténcil de Roberto Bolaño

en Barcelona en 2012. (Barrio de Sant Antoni)

☆『2666』は、チリの作家ロベルト・ボラーニョが2004年に発表した 遺作である。この作品は5つの部分から構成されており、著者は経済的な理由から、自分の死後、子供たちの将来を保証するために5冊の独立した本として出版 することを計画していた。 しかし、彼の死後、相続人はその文学的価値を考慮し、1冊の小説として出版することを決定した。 この小説は、つかみどころのないドイツ人作家(アルチンボルディ)と、シウダー・フアレスに触発された暴力都市サンタ・テレサで未解決のまま続いている女性殺人事件を中心に展 開する。サンタ・テレサ以外にも、第二次世界大戦の東部戦線、学問の世界、精神病、ジャーナリズム、人間関係やキャリアの崩壊などが舞台やテーマとなって いる。『2666』は、さまざまな登場人物、場所、時代、物語の中の物語を通して、20世紀の退廃を探求している。

| 2666

es una novela póstuma del escritor chileno Roberto Bolaño publicada en

el año 2004. Consta de cinco partes que el autor, por razones

económicas, planeó publicar como cinco libros independientes para

asegurar así, en caso de fallecimiento, el futuro de sus hijos.2 No

obstante, tras su muerte, los herederos ponderaron el valor literario y

decidieron editarla como una única novela. La decisión la tomaron junto

con su editor, Jorge Herralde, y el crítico literario Ignacio

Echevarría, que revisó y preparó para su publicación los manuscritos

del autor.2 Gran parte de la acción de las cinco partes transcurre en la ciudad ficticia de Santa Teresa, que se ha identificado con Ciudad Juárez.34 La primera parte se titula La parte de los críticos, y los personajes principales son el francés Jean-Claude Pelletier, el italiano Piero Morini, el español Manuel Espinoza y la inglesa Liz Norton, profesores de literatura que se embarcan en la búsqueda del escritor alemán Benno von Archimboldi.5 En La parte de Amalfitano el personaje principal es Óscar Amalfitano,nota 1 un profesor chileno que se trasladó a Santa Teresa desde Barcelona junto con su hija para dar clases en la universidad de dicha ciudad.78 En La parte de Fate, un periodista estadounidense, Quincy Williams, cuyo apodo es Fate, debido al fallecimiento de un compañero se desplaza a la ciudad mencionada a cubrir la noticia de un combate de boxeo.9 La cuarta parte se titula La parte de los crímenes y describe los asesinatos de mujeres acontecidos en la ciudad de Santa Teresa, junto con las investigaciones que se llevan a cabo y que normalmente no arrojan ningún resultado.10 La novela finaliza con La parte de Archimboldi, donde se narra la vida del escritor Benno von Archimboldi, y los intentos de su hermana para sacar al hijo de esta de la prisión de Santa Teresa.511 El nexo de todas las partes de la novela parece ser los asesinatos de las mujeres en Santa Teresa.4 La novela ha recibido varios premios literarios. En el año 2004 obtuvo el premio Ciudad de Barcelona,12 y al año siguiente fue ganadora casi por unanimidad del Premio Salambó.6 El 12 de marzo de 2009 2666 ganó el National Book Critics Circle Award.13 Otros galardones que ha recibido la novela son el Premio Altazor, el Premio Municipal de Literatura de Santiago y el Premio Fundación José Manuel Lara al libro con mejor acogida por parte de la crítica especializada.14 Ha sido traducida al inglés, francés y al italiano entre otros idiomas.14 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/2666_(novela) |

『2666』は、チリの作家ロベルト・ボラーニョが2004年に発表した

遺作である。この作品は5つの部分から構成されており、著者は経済的な理由から、自分の死後、子供たちの将来を保証するために5冊の独立した本として出版

することを計画していた。

しかし、彼の死後、相続人はその文学的価値を考慮し、1冊の小説として出版することを決定した。この決定は、出版社のホルヘ・エラルデ、文芸評論家のイグ

ナシオ・エチェバリアとともに行われ、彼は著者の原稿を校閲し、出版の準備をした。 第1部のタイトルは『評論家のパート』(La parte de los críticos)で、主な登場人物はフランス人のジャン=クロード・ペレティエ、イタリア人のピエロ・モリーニ、スペイン人のマヌエル・エスピノサ、イ ギリス人のリズ・ノートンで、ドイツ人作家ベンノ・フォン・アルチンボルディを探す旅に出る文学教授たちである。ラ・パルテ・デ・アマルフィターノ』で は、バルセロナからサンタ・テレサに移り住んだチリ人教授オスカル・アマルフィターノが主人公。 ラ・パルテ・デ・フェイト』では、アメリカ人ジャーナリスト、クインシー・ウィリアムズ(ニックネームはフェイト)が、同僚の死後、ボクシングの試合を取 材するためにサンタ・テレサを訪れる。 第4部は『殺人編』と題され、サンタ・テレサの街で起こる女性殺人事件と、通常は何の結果も得られない捜査が描かれる。小説の最後は、作家ベンノ・フォ ン・アルチンボルディの生涯と、彼の姉がサンタ・テレサの刑務所から息子を救い出そうとする姿を描いた『アルチンボルディ・パート』で終わる。 この小説のすべてのパートの結びつきは、サンタ・テレサの女性殺人事件にあるようだ。 この小説はいくつかの文学賞を受賞している。2004年にはバルセロナ市賞を受賞し、翌年にはほぼ満場一致でサランボ賞を受賞した。 2009年3月12日、2666は全米図書批評家協会賞を受賞した13。 その他、アルタゾール賞、サンティアゴ市立文学賞、ホセ・マヌエル・ララ財団賞(最も批評家の評価が高かった本に贈られる)などを受賞している。 英語、フランス語、イタリア語などに翻訳されている。 |

| Premise The novel revolves around an elusive German author and the unsolved and ongoing murders of women in Santa Teresa, a violent city inspired by Ciudad Juárez and its epidemic of female homicides. In addition to Santa Teresa, settings and themes include the Eastern Front in World War II, the academic world, mental illness, journalism, and the breakdown of relationships and careers. 2666 explores 20th-century degeneration through a wide array of characters, locations, time periods, and stories within stories. |

前提 この小説は、つかみどころのないドイツ人作家と、シウダー・フアレスに触発された暴力都市サンタ・テレサで未解決のまま続いている女性殺人事件を中心に展 開する。サンタ・テレサ以外にも、第二次世界大戦の東部戦線、学問の世界、精神病、ジャーナリズム、人間関係やキャリアの崩壊などが舞台やテーマとなって いる。『2666』は、さまざまな登場人物、場所、時代、物語の中の物語を通して、20世紀の退廃を探求している。 |

| Background While Bolaño was writing 2666, he was already sick and on the waiting list for a liver transplant.[1][2] He had never visited Ciudad Juárez but received information and support from friends and colleagues such as the Mexican journalist Sergio González Rodríguez, author of the 2002 book of essays and journalistic chronicles Huesos en el desierto (Spanish: "Bones in the Desert"), concerning the place and its femicides.[3] He discussed the novel with his friend Jorge Herralde, director of Barcelona-based publisher Anagrama, but he never showed the actual manuscript to anyone until he died: the manuscript is a first copy.[citation needed] Originally planning it as a single book, Bolaño then considered publishing 2666 as five volumes to provide more income for his children; however, the heirs decided otherwise and the book was published in one lengthy volume. Bolaño had been well aware of the book's unfinished status, and said a month before his death that over a thousand pages still had to be revised.[2] |

背景 ボラーニョが2666を執筆していた頃、彼はすでに病気で肝臓移植の待機リストに載っていた[1][2]。彼はシウダー・フアレスを訪れたことはなかった が、2002年に出版されたエッセイ集『Huesos en el desierto』(スペイン語:『砂漠の骨』)の著者であるメキシコ人ジャーナリストのセルヒオ・ゴンサレス・ロドリゲスなど、友人や同僚から、シウ ダー・フアレスとその女性殺害者に関する情報やサポートを得た。 [3]彼はバルセロナを拠点とする出版社アナグラマのディレクターである友人ホルヘ・ヘラルデと小説について話し合ったが、彼が亡くなるまで実際の原稿を 誰かに見せることはなかった。 当初は単行本として出版する予定だったボラーニョは、子供たちにより多くの収入を与えるため、『2666』を全5巻で出版することを考えたが、相続人たち の決定により、長大な1巻で出版されることになった。ボラーニョはこの本が未完成であることを十分承知しており、死の1ヶ月前には、まだ1000ページ以 上の改稿が必要だと語っていた[2]。 |

| Title The meaning of the title, 2666, is typically elusive; even Bolaño's friends did not know the reasons for it. Larry Rohter, writing for The New York Times, notes that Bolaño apparently ascribed an apocalyptic quality to the number.[4] Henry Hitchings noted that "the novel's cryptic title is one of its many grim jokes" and may be a reference to the biblical Exodus from Egypt, supposedly 2,666 years after God created the earth.[5] The number does not appear in the book, though it does in some of Bolaño's other books—in Amulet, a Mexico City road looks like "a cemetery in the year 2666",[5] and The Savage Detectives contains another, approximate reference: "And Cesárea said something about days to come... and the teacher, to change the subject, asked her what times she meant and when they would be. And Cesárea named a date, sometime around the year 2600. Two thousand six hundred and something".[6] |

タイトル ボラーニョの友人でさえその理由を知らなかった。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に寄稿したラリー・ローターは、ボラーニョがこの数字に黙示録的な性質を見出し たらしいと指摘している[4]。ヘンリー・ヒッチングスは、「この小説の暗号めいたタイトルは、その多くの重苦しいジョークのひとつである」と指摘し、神 が地球を創造してから2666年後に起こったとされる聖書のエジプト出エジプトにちなんでいるのかもしれないと述べている[5]。 [アミュレット』ではメキシコ・シティの道路が「2666年の墓地」のように見える[5]: 「そしてセサレアは、来るべき日々について何か言った。するとセサレアは、2600年ごろのある日のことを言った。2,600と何か」[6]。 |

| Plot summary The novel is substantially concerned with violence and death. According to Levi Stahl, it "is another iteration of Bolaño's increasingly baroque, cryptic, and mystical personal vision of the world, revealed obliquely by his recurrent symbols, images, and tropes". Within the novel, "There is something secret, horrible, and cosmic afoot, centered around Santa Teresa (and possibly culminating in the mystical year of the book's title, a date that is referred to in passing in Amulet as well). We can at most glimpse it, in those uncanny moments when the world seems wrong."[7] The novel's five parts are linked by varying degrees of concern with unsolved murders of upwards of 300 young, poor, mostly uneducated Mexican women in the fictional border town of Santa Teresa (based on Ciudad Juárez but located in Sonora rather than Chihuahua) though it is the fourth part which focuses specifically on the murders. The Part about the Critics This part describes a group of four European literary critics, the French Jean-Claude Pelletier, the Italian Piero Morini, the Spaniard Manuel Espinoza and the English woman Liz Norton, who have forged their careers around the reclusive German novelist Benno von Archimboldi. Their search for Archimboldi himself and details of his life causes them to get to know his aging publisher Mrs. Bubis. Then in a seminary in Toulouse the four academics meet up with Rodolfo Alatorre, a Mexican who says a friend knew him in Mexico City a short while back and that from there the elusive German was said to be going to the Mexican border town of Santa Teresa in Sonora. Three of the academics go there in search of him but fail to find him. A major element of this part centers around romantic entanglements between the critics. The Part about Amalfitano This part concentrates on Óscar Amalfitano, a Chilean professor of philosophy who arrives at the University of Santa Teresa from Barcelona with his young adult daughter Rosa. As a single parent (since her mother Lola abandoned them both when Rosa was two) Amalfitano fears Rosa will become another victim of the femicides plaguing the city. The Part about Fate This part follows Oscar Fate, an American journalist from New York City who works for an African-American interest magazine in Harlem, New York City. He is sent to Santa Teresa to cover a boxing match despite not being a sports correspondent and knowing very little about boxing. A Mexican journalist, Chucho Flores, who is also covering the fight, tells him about the murders. He asks his newspaper if he can write an article about the murders but his proposal is rejected. He meets up with a female journalist, Guadalupe, who is covering the murders and who promises to get him an interview with one of the main suspects, Klaus Haas, a German who had become a citizen of the United States before moving to Santa Teresa. The day of the fight Chucho presents Oscar to Rosa Amalfitano. After a violent incident they end up at Óscar Amalfitano's house where the father pays Fate to take Rosa with him back to the United States by car. Before leaving, however, Rosa and Fate go to the prison with Guadalupe to interview the femicide suspect, Klaus Haas. The Part about the Crimes This part chronicles the murders of 112 women in Santa Teresa from 1993 to 1997 and the lives they lived. It also depicts the police force in their mostly fruitless attempts to solve the crimes, as well as giving clinical descriptions of the circumstances and probable causes of the various homicides. One of the policemen focused on is Juan de Dios Martínez, who is having a relationship with the older Elvira Campo (the head of a sanitarium) and who also has to investigate the case of a man, aptly nicknamed "The Penitent," who keeps urinating and defecating in churches. Klaus Haas (the German femicide suspect Fate was to interview in "the part about Fate") is another of the characters this part focuses on. Haas calls a press conference where he claims that Daniel Uribe, son of a rich local family, is responsible for the murders. The Part about Archimboldi This part reveals that the mysterious writer Archimboldi is really Hans Reiter, born in 1920 in Prussia. This section describes how a provincial German soldier on the Eastern Front became an author in contention for the Nobel Prize. Mrs. Bubis, who was introduced in the first part, turns out to have been Baroness von Zumpe; her family were a major part of Archimboldi's childhood, since his mother cleaned their country home and young Hans spent a lot of time with the Baroness's cousin, Hugo Halder, from whom he learned about the artistic life. Reiter meets the Baroness again during the war while in Romania, and has an affair with her after the war (she is then married to Bubis, the publisher). At the end of this part Bolaño's narrator describes the life of Lotte, Archimboldi's sister, and it is revealed that the femicide suspect Klaus Haas is her son and thus Archimboldi's nephew. |

プロットの概要 この小説は暴力と死に大きく関わっている。レヴィ・スタールによれば、「ボラーニョのバロック的、暗号的、神秘的な個人的世界観の新たな反復であり、繰り 返し登場するシンボル、イメージ、主題によって斜めに明らかにされる」。この小説の中では、「サンタ・テレサを中心に、何か秘密めいた、恐ろしい、宇宙的 なことが進行中である(そしておそらく、この本のタイトルにもなっている神秘的な年、この日付は『アミュレット』でもちらっと言及されている)。私たちが それを垣間見ることができるのは、世界が間違っているように見える不気味な瞬間だけだ」[7]。 この小説の5つのパートは、架空の国境の町サンタ・テレサ(シウダー・フアレスをモデルにしているが、チワワではなくソノラに位置する)で起きた、若く、 貧しく、ほとんど無学なメキシコ人女性300人以上の未解決殺人事件と、さまざまな度合いで関連しているが、特に殺人事件に焦点を当てているのは第4パー トである。 批評家について このパートでは、フランス人のジャン=クロード・ペレティエ、イタリア人のピエロ・モリーニ、スペイン人のマヌエル・エスピノサ、イギリス人のリズ・ノー トンという4人のヨーロッパ人文芸批評家グループが、ドイツの隠遁小説家ベンノ・フォン・アルチンボルディを中心にキャリアを築いていく様子が描かれる。 アルチンボルディ自身と彼の生涯の詳細を探る彼らは、老齢の出版社ミセス・ブビスと知り合う。そしてトゥールーズの神学校で、4人の学者たちはロドル フォ・アラトーレというメキシコ人と出会う。ロドルフォは、少し前に友人がメキシコ・シティでアルチンボルディを知り、そこからアルチンボルディがメキシ コ国境の町ソノラのサンタ・テレサに行くと言われていると言う。学者の3人は彼を探しにそこに行くが、見つけることはできなかった。このパートでは、批評 家たちの恋愛のもつれが大きな要素となっている。 アマルフィターノ編 このパートは、バルセロナからサンタ・テレサ大学にやってきたチリ人の哲学教授オスカル・アマルフィターノに焦点を当てる。片親であるアマルフィターノ は、ロサが2歳のときに母親のロラに捨てられて以来、ロサがこの街を悩ます女性殺人の犠牲者になることを恐れている。 運命 このパートは、ニューヨークのハーレムにあるアフリカ系アメリカ人向け雑誌に勤めるニューヨーク出身のアメリカ人ジャーナリスト、オスカー・フェイトを描 く。彼はスポーツ特派員でもなく、ボクシングのこともほとんど知らないにもかかわらず、ボクシングの試合を取材するためにサンタ・テレサに派遣される。同 じく試合を取材していたメキシコ人ジャーナリスト、チュチョ・フローレスから殺人事件の話を聞く。彼は新聞社に殺人事件についての記事を書けないかと持ち かけるが、却下される。彼は、この殺人事件を取材している女性ジャーナリスト、グアダルーペに会い、主要容疑者の一人で、サンタ・テレサに移り住む前にア メリカ国籍を取得していたドイツ人、クラウス・ハースへのインタビューを約束する。その日、チュチョはオスカーをロサ・アマルフィターノに紹介する。暴力 沙汰の後、二人はオスカル・アマルフィターノの家に辿り着き、父親はフェイトに金を払ってロサを車でアメリカに連れ帰らせる。しかし、ロサとフェイトは出 発する前に、グアダルーペとともに刑務所に行き、女性殺人の容疑者クラウス・ハースと面会する。 犯罪パート このパートでは、1993年から1997年にかけてサンタ・テレサで112人の女性が殺害された事件と、彼女たちの人生が描かれる。また、事件解決のため にほとんど徒労に終わった警察の姿や、さまざまな殺人の状況や原因について臨床的な描写もある。年上のエルビラ・カンポ(療養所の院長)と関係を持ちなが ら、教会で排尿と排便を繰り返す "懺悔者 "というニックネームを持つ男の事件を捜査しなければならない。クラウス・ハース(「フェイトに関するパート」でフェイトが事情聴取するはずだったドイツ 人女性殺人容疑者)も、このパートで注目される人物の一人である。ハースは記者会見を開き、地元の金持ち一家の息子ダニエル・ウリベが殺人事件の犯人だと 主張する。 アルチンボルディ このパートで、謎の作家アルチンボルディの正体が、1920年プロイセン生まれのハンス・ライターであることが明らかになる。東部戦線の地方ドイツ兵が、 いかにしてノーベル賞候補の作家となったかが描かれる。第一部で登場したブビス夫人は、フォン・ツンペ男爵夫人であったことが判明する。アルチンボルディ の幼少期にとって、彼女の家族は大きな存在であり、彼の母親は彼らの田舎の家を掃除し、幼いハンスは男爵夫人の従兄弟であるフーゴ・ハルダーと多くの時間 を過ごし、彼から芸術家としての生き方を学んだ。ライターは戦時中、ルーマニアで男爵夫人と再会し、戦後は彼女と関係を持つ(彼女は出版社のブビスと結婚 している)。このパートの最後に、ボラーニョの語り手はアルチンボルディの妹ロッテの生涯を描き、女性殺人の容疑者クラウス・ハースは彼女の息子であり、 したがってアルチンボルディの甥であることが明らかになる。 |

| Critical reception The critical reception has been almost unanimously positive. 2666 was considered the best novel of 2005 within the literary world of both Spain and Latin America. Before the English-language edition was published in 2008, 2666 was praised by Oprah Winfrey in her O, The Oprah Magazine after she was given a copy of the translation before it was officially published.[8] The book was listed in The New York Times Book Review "10 Best Books of 2008" by the paper's editors.[9] with Jonathan Lethem writing: "2666 is as consummate a performance as any 900-page novel dare hope to be: Bolaño won the race to the finish line in writing what he plainly intended as a master statement. Indeed, he produced not only a supreme capstone to his own vaulting ambition, but a landmark in what's possible for the novel as a form in our increasingly, and terrifyingly, post-national world. The Savage Detectives looks positively hermetic beside it. (...) As in Arcimboldo's paintings, the individual elements of 2666 are easily catalogued, while the composite result, though unmistakable, remains ominously implicit, conveying a power unattainable by more direct strategies. (...) "[10] Amaia Gabantxo in the Times Literary Supplement wrote: "(A)n exceptionally exciting literary labyrinth.... What strikes one first about it is the stylistic richness: rich, elegant yet slangy language that is immediately recognizable as Bolaño's own mixture of Chilean, Mexican and European Spanish. Then there is 2666's resistance to categorization. At times it is reminiscent of James Ellroy: gritty and scurrilous. At other moments it seems as though the Alexandria Quartet had been transposed to Mexico and populated by ragged versions of Durrell's characters. There's also a similarity with W. G. Sebald's work.... There are no defining moments in 2666. Mysteries are never resolved. Anecdotes are all there is. Freak or banal events happen simultaneously, inform each other and poignantly keep the wheel turning. There is no logical end to a Bolano book."[11] Ben Ehrenreich in the Los Angeles Times: "This is no ordinary whodunit, but it is a murder mystery. Santa Teresa is not just a hell. It's a mirror also—"the sad American mirror of wealth and poverty and constant, useless metamorphosis."... He wrote 2666 in a race against death. His ambitions were appropriately outsized: to make some final reckoning, to take life's measure, to wrestle to the limits of the void. So his reach extends beyond northern Mexico in the 1990s to Weimar Berlin and Stalin's Moscow, to Dracula's castle and the bottom of the sea."[12] Adam Kirsch in Slate: "2666 is an epic of whispers and details, full of buried structures and intuitions that seem too evanescent, or too terrible, to put into words. It demands from the reader a kind of abject submission—to its willful strangeness, its insistent grimness, even its occasional tedium—that only the greatest books dare to ask for or deserve."[13] Francisco Goldman in New York Review of Books: "The multiple story lines of 2666 are borne along by narrators who seem also to represent various of its literary influences, from European avant-garde to critical theory to pulp fiction, and who converge on the [fictional] city of Santa Teresa as if propelled toward some final unifying epiphany. It seems appropriate that 2666's abrupt end leaves us just short of whatever that epiphany might have been.."[14] Online book review site The Complete Review gave it an "A+", a rating reserved for a small handful of books, saying: "Forty years after García Márquez shifted the foundations with One Hundred Years of Solitude, Bolaño has moved them again. 2666 is, simply put, epochal. No question, the first great book of the twenty-first century."[15] Henry Hitchings in Financial Times: "2666... is a summative work – a grand recapitulation of the author's main concerns and motifs. As before, Bolaño is preoccupied with parallel lives and secret histories. Largely written after 9/11, the novel manifests a new emphasis on the dangerousness of the modern world.... 2666 is an excruciatingly challenging novel, in which Bolaño redraws the boundaries of fiction. It is not unique in blurring the margins between realism and fantasy, between documentary and invention. But it is bold in a way that few works really are – it kicks away the divide between playfulness and seriousness. And it reminds us that literature at its best inhabits what Bolaño, with a customary wink at his own pomposity, called "the territory of risk" – it takes us to places we might not wish to go."[5] Stephen King in Entertainment Weekly: "This surreal novel can't be described; it has to be experienced in all its crazed glory. Suffice it to say it concerns what may be the most horrifying real-life mass-murder spree of all time: as many as 400 women killed in the vicinity of Juarez, Mexico. Given this as a backdrop, the late Bolaño paints a mural of a poverty-stricken society that appears to be eating itself alive. And who cares? Nobody, it seems."[16] In 2018, Fiction Advocate published a book-length analysis of 2666 entitled An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom by author and critic Jonathan Russell Clark. An excerpt of the book was published in The Believer in March 2018.[17] Awards and honors It won the Chilean Altazor Award in 2005. The 2008 National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction was posthumously awarded to Roberto Bolaño for 2666.[18] It was short-listed for the Best Translated Book Award. Time also awarded it the honour of Best Fiction Book of 2008.[18][19] Adaptation In 2007, the novel was adapted as a stage play by Spanish director Àlex Rigola, and it premiered in Bolaño's adopted hometown of Blanes. The play was the main attraction of Barcelona's Festival Grec that year. In 2016, it was adapted into a five-hour stage play at Chicago's Goodman Theater.[20] The stage adaptation was praised for its ambition, but according to The New York Times, it fell "short as a work of dramatic art."[21] In 2016, it was adapted into an 11-hour play by Julien Gosselin and his troupe "Si vous pouviez lécher mon cœur". It was presented at the Festival d'Avignon and then in Paris at the Odéon theatre as part of Festival d'Automne. |

批評家の評価 批評家の評価はほぼ一致して肯定的である。2666』は、スペインとラテンアメリカの文学界で2005年最高の小説とされた。2008年に英語版が出版さ れる前、『O, The Oprah Magazine』でオプラ・ウィンフリーが公式出版前に翻訳版を手にしたことをきっかけに『2666』を賞賛した[8]: 2666』は、900ページの小説が望むのと同じくらい完璧な出来栄えだ: ボラーニョは、明らかにマスター・ステートメントとして意図したものを書くことで、ゴールまでの競争に勝利した。実際、ボラーニョは、彼自身の高みにある 野心への至高の石碑を作り上げただけでなく、ますます、そして恐るべきことに、ポスト・ナショナルな世界において、小説という形式が可能であることを示す 画期的な作品を生み出したのだ。野蛮な探偵たち』は、その傍らで、まさに密閉されたように見える。(...)アルチンボルドの絵画のように、『2666』 の個々の要素は簡単に分類できるが、複合的な結果は、紛れもないにもかかわらず、不吉なほど暗示的であり、より直接的な戦略では到達できない力を伝えてい る。(...) "[10] タイムズ・リテラリー・サプリメントのアマイア・ガバンチョはこう書いている: 「極めて刺激的な文学的迷宮......。チリ、メキシコ、ヨーロッパのスペイン語を混ぜ合わせたボラーニョ独自のものだとすぐにわかる。そして、 2666のカテゴリー化への抵抗である。ある時はジェームズ・エルロイを彷彿とさせ、硬質で陰険。また、アレクサンドリア四重奏団がメキシコに移され、ダ レルの登場人物のボロが出てきたかのような場面もある。W・G・セバルトの作品にも似ている......。2666』には決定的な瞬間はない。謎は決して 解決されない。あるのは逸話だけ。奇想天外な出来事やありふれた出来事が同時に起こり、互いに情報を与え合い、痛烈に歯車を回し続ける。ボラーノの本に論 理的な終わりはない」[11]。 ロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙のベン・エーレンライク: 「これは普通の殺人ミステリーではない。サンタ・テレサは単なる地獄ではない。サンタ・テレサは単なる地獄ではなく、「富と貧困、絶え間ない無駄な変身と いう悲しいアメリカの鏡」でもある。彼は死との戦いの中で『2666』を書いた。最後の清算をすること、人生の尺度を知ること、虚空の限界に挑むこと。だ から彼の到達点は、1990年代のメキシコ北部にとどまらず、ワイマール・ベルリンやスターリンのモスクワ、ドラキュラの城や海の底にまで及んでいる」 [12]。 Slate』誌のアダム・カーシュ: 「2666は囁きと細部の叙事詩であり、埋もれた構造と直感に満ちている。それは読者に対して、その意志的な奇妙さ、執拗な重苦しさ、時折の退屈ささえ も、偉大な本だけがあえて求め、あるいはそれに値するような、ある種の禁欲的な服従を要求する」[13]。 フランシスコ・ゴールドマン(『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』誌 2666』の複数のストーリーラインは、ヨーロッパの前衛から批評理論、パルプ・フィクションまで、さまざまな文学的影響を受けた語り手たちによって運ば れ、最終的な統一的啓示に向かって突き進むかのように、サンタ・テレサという[架空の]都市に収束していく。2666の唐突な結末が、その啓示が何であっ たかもしれないにせよ、私たちをあと一歩のところまで追い詰めているのは、適切なことのように思える......」[14]。 オンライン書評サイト『コンプリート・レビュー』は、ほんの一握りの本にしか与えられない評価である「A+」を与え、こう述べている: ガルシア・マルケスが『百年の孤独』でその土台を変えてから40年、ボラーニョは再びその土台を動かした。2666』は端的に言ってエポックである。間違 いなく、21世紀最初の名著だ」[15]。 フィナンシャル・タイムズ紙のヘンリー・ヒッチングス 2666』は...総括的な作品であり、著者の主要な関心事とモチーフの壮大な再集編である。以前と同様、ボラーニョはパラレルライフと秘密の歴史に夢中 になっている。主に9.11の後に書かれたこの小説は、現代世界の危険性を新たに強調している。2666』は、ボラーニョがフィクションの境界線を引き直 した、耐え難いほど挑戦的な小説である。リアリズムとファンタジー、ドキュメンタリーと創作の境界を曖昧にするという点で、この作品が特別なわけではな い。遊び心と真剣さの間の隔たりを一蹴してしまうのだ。そしてこの作品は、ボラーニョが彼自身の尊大さに対するお決まりのウィンクを交えながら「リスクの 領域」と呼んだものに、最高の文学が宿っていることを思い出させてくれる。 エンターテインメント・ウィークリー誌のスティーブン・キング 「このシュールな小説は説明できない。メキシコのフアレス近郊で400人もの女性が殺害されたのだ。この事件を背景に、故ボラーニョは貧困にあえぐ社会の 壁画を描く。そして誰が気にかけるのか?誰も気にしていないようだ」[16]。 2018年、フィクション・アドヴォケイト誌は、作家で批評家のジョナサン・ラッセル・クラークによる『退屈の砂漠の中の恐怖のオアシス』と題した 『2666』の長編分析を掲載した。本書の抜粋は2018年3月に『The Believer』に掲載された[17]。 受賞と栄誉 2005年にチリのアルタゾール賞を受賞。2008年の全米図書批評家協会賞フィクション部門は、『2666』でロベルト・ボラーニョに死後授与された [18]。また、タイム誌は2008年の最優秀フィクション作品賞を受賞した[18][19]。 映画化 2007年、この小説はスペインの演出家アレックス・リゴラによって舞台化され、ボラーニョの故郷であるブラネスで初演された。その年のバルセロナのフェ スティバル・グレックの目玉となった。 2016年、シカゴのグッドマン・シアターで5時間の舞台劇に脚色された[20]。この舞台化はその野心的な作品として賞賛されたが、ニューヨーク・タイ ムズ紙によれば、「劇的芸術作品としては物足りなかった」[21]。 2016年、ジュリアン・ゴセランと彼の劇団 "Si vous pouviez lécher mon cœur "によって11時間の劇に脚色された。この作品はアヴィニョン演劇祭で上演された後、パリのオデオン座でオートンヌ演劇祭の一環として上演された。 |

Roberto

Bolaño Ávalos (Spanish: [roˈβeɾto βoˈlaɲo ˈaβalos] ⓘ; 28 April 1953 –

15 July 2003) was a Chilean novelist, short-story writer, poet and

essayist. In 1999, Bolaño won the Rómulo Gallegos Prize for his novel

Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives), and in 2008 he was

posthumously awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction

for his novel 2666, which was described by board member Marcela Valdes

as a "work so rich and dazzling that it will surely draw readers and

scholars for ages".[1] The New York Times described him as "the most

significant Latin American literary voice of his generation".[2] Roberto

Bolaño Ávalos (Spanish: [roˈβeɾto βoˈlaɲo ˈaβalos] ⓘ; 28 April 1953 –

15 July 2003) was a Chilean novelist, short-story writer, poet and

essayist. In 1999, Bolaño won the Rómulo Gallegos Prize for his novel

Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives), and in 2008 he was

posthumously awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction

for his novel 2666, which was described by board member Marcela Valdes

as a "work so rich and dazzling that it will surely draw readers and

scholars for ages".[1] The New York Times described him as "the most

significant Latin American literary voice of his generation".[2]His work has been translated into numerous languages, including English, French, German, Italian,[3] Lithuanian, and Dutch. At the time of his death he had 37 publishing contracts in ten countries. Posthumously, the list grew to include more countries, including the United States, and amounted to 50 contracts and 49 translations in twelve countries, all of them prior to the publication of 2666, his most ambitious novel. In addition, the author enjoys excellent reviews from both writers and contemporary literary critics and is considered one of the great Latin American authors of the 20th century, along with other writers of the stature of Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, with whom he is usually compared.[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Bola%C3%B1o |

ロ

ベルト・ボラーニョ・アバロス(スペイン語: [roˈβe' [roˈβo ˈaβalos] ⓘ; 1953年4月28日 -

2003年7月15日)はチリの小説家、短編作家、詩人、エッセイスト。1999年、ボラーニョは小説『Los detectives

salvajes(野蛮な刑事たち)』でロムロ・ガジェゴス賞を受賞し、2008年には小説『2666』で全米図書批評家協会賞フィクション部門を死後受

賞した。 ロ

ベルト・ボラーニョ・アバロス(スペイン語: [roˈβe' [roˈβo ˈaβalos] ⓘ; 1953年4月28日 -

2003年7月15日)はチリの小説家、短編作家、詩人、エッセイスト。1999年、ボラーニョは小説『Los detectives

salvajes(野蛮な刑事たち)』でロムロ・ガジェゴス賞を受賞し、2008年には小説『2666』で全米図書批評家協会賞フィクション部門を死後受

賞した。彼の作品は、英語、フランス語、ドイツ語、イタリア語、リトアニア語、オランダ語など数多くの言語に翻訳されている[3]。死の直前には、10カ国で37 の出版契約を結んでいた。死後、そのリストは米国を含むさらに多くの国を含むようになり、12カ国で50の契約と49の翻訳に達したが、それらはすべて彼 の最も野心的な小説である『2666』の出版前であった。 また、作家と現代文学批評家の双方から高い評価を得ており、通常比較されるホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスやフリオ・コルタサールと並ぶ20世紀の偉大なラテンアメリカ作家の一人とみなされている[4]。 |

| Life Childhood in Chile Bolaño was born in 1953 in Santiago, the son of a truck driver (who was also a boxer) and a teacher.[5] He and his sister spent their early years in southern and coastal Chile. By his own account, he was skinny, nearsighted, and bookish: an unpromising child. He was dyslexic and was often bullied at school, where he felt like an outsider. He came from a lower-middle-class family,[6] and while his mother was a fan of best-sellers, they were not an intellectual family.[7] He had one younger sister.[8] He was ten when he started his first job, selling bus tickets on the Quilpué-Valparaiso route.[9] He spent the greater part of his childhood living in Los Ángeles, Bío Bío.[10] Youth in Mexico In 1968 he moved with his family to Mexico City, dropped out of school, worked as a journalist, and became active in left-wing political causes.[11] Brief return to Chile A key episode in Bolaño's life, mentioned in different forms in several of his works, occurred in 1973, when he left Mexico for Chile to "help build the revolution" by supporting the democratic socialist government of Salvador Allende. After Augusto Pinochet's right-wing military coup against Allende, Bolaño was arrested on suspicion of being a "terrorist" and spent eight days in custody.[12] He was rescued by two former classmates who had become prison guards. Bolaño describes this experience in the story "Dance Card". According to the version of events he provides in this story, he was not tortured as he had expected, but "in the small hours I could hear them torturing others; I couldn't sleep and there was nothing to read except a magazine in English that someone had left behind. The only interesting article in it was about a house that had once belonged to Dylan Thomas... I got out of that hole thanks to a pair of detectives who had been at high school with me."[13] The episode is also recounted, from the point of view of Bolaño's former classmates, in the story "Detectives". Nevertheless, since 2009 Bolaño's Mexican friends from that era have cast doubts on whether he was even in Chile in 1973 at all.[14] Bolaño had conflicted feelings about his native country. He was notorious in Chile for his fierce attacks on Isabel Allende and other members of the literary establishment.[15][16] "He didn't fit into Chile, and the rejection that he experienced left him free to say whatever he wanted, which can be a good thing for a writer," commented Chilean-Argentinian novelist and playwright Ariel Dorfman.[11] Return to Mexico On his overland return from Chile to Mexico in 1974, Bolaño allegedly passed an interlude in El Salvador, spent in the company of the poet Roque Dalton and the guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, though the veracity of this episode has been cast into doubt.[17] In the 1960s, Bolaño, an atheist since his youth,[18] became a Trotskyist[19] and in 1975 a founding member of Infrarrealismo (Infrarealism), a minor poetic movement. He affectionately parodied aspects of the movement in The Savage Detectives.[20] On his return to Mexico he lived as a literary enfant terrible and bohemian poet, "a professional provocateur feared at all the publishing houses even though he was a nobody, bursting into literary presentations and readings", as recalled by his editor Jorge Herralde.[11] Move to Spain Bolaño moved to Europe in 1977, and finally made his way to Spain, where he married and settled on the Mediterranean coast near Barcelona, on the Costa Brava, working as a dishwasher, campground custodian, bellhop, and garbage collector.[11] He used his spare time to write. From the 80's to his death, he lived in the small Catalan beach town of Blanes.[21][22][23][24] He continued with poetry, before shifting to fiction in his early forties. In an interview Bolaño said that he began writing fiction because he felt responsible for the future financial well-being of his family, which he knew he could never secure from the earnings of a poet. This was confirmed by Jorge Herralde, who explained that Bolaño "abandoned his parsimonious beatnik existence" because the birth of his son in 1990 made him "decide that he was responsible for his family's future and that it would be easier to earn a living by writing fiction." However, he continued to think of himself primarily as a poet, and a collection of his verse, spanning 20 years, was published in 2000 under the title Los perros románticos (The Romantic Dogs).[citation needed] Declining health and death Bolaño's death in 2003 came after a long period of declining health. He experienced liver failure and had been on a liver transplant waiting list while working on 2666;[25][26] he was third on the list at the time of his death.[27] Six weeks before he died, Bolaño's fellow Latin American novelists hailed him as the most important figure of his generation at an international conference he attended in Seville. Among his closest friends were the novelists Rodrigo Fresán and Enrique Vila-Matas; Fresán's tribute included the statement that "Roberto emerged as a writer at a time when Latin America no longer believed in utopias, when paradise had become hell, and that sense of monstrousness and waking nightmares and constant flight from something horrid permeates 2666 and all his work." "His books are political," Fresán also observed, "but in a way that is more personal than militant or demagogic, that is closer to the mystique of the beatniks than the Boom." In Fresán's view, he "was one of a kind, a writer who worked without a net, who went all out, with no brakes, and in doing so, created a new way to be a great Latin American writer."[28] Larry Rohter of the New York Times wrote, "Bolaño joked about the 'posthumous', saying the word 'sounds like the name of a Roman gladiator, one who is undefeated,' and he would no doubt be amused to see how his stock has risen now that he is dead."[11] He died of liver failure in the Vall d'Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona on 15 July 2003.[24] Bolaño was survived by his Spanish wife and their two children, whom he once called "my only motherland". In his last interview, published by the Mexican edition of Playboy magazine, Bolaño said he regarded himself as a Latin American, adding that "my only country is my two children and wife and perhaps, though in second place, some moments, streets, faces or books that are in me, and which one day I will forget..."[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Bola%C3%B1o |

生活 チリでの幼少期 ボラーニョは1953年、トラック運転手(ボクサーでもあった)と教師の息子としてサンティアゴに生まれる。彼自身の証言によると、彼は痩せていて、近視 で、本好きだった。彼は失読症で、学校ではしばしばいじめられ、部外者のように感じていた。母親はベストセラーを愛読していたが、知的な家庭ではなかった [7]。 10歳のとき、キルプエとバルパライソを結ぶ路線バスの切符を売る仕事を始める。 メキシコでの少年時代 1968年、家族とともにメキシコ・シティに移り住み、学校を中退してジャーナリストとして働き、左翼政治活動に参加するようになる[11]。 チリへの一時帰国 1973年、サルバドール・アジェンデの民主的社会主義政権を支持し、「革命の手助けをする」ためにメキシコからチリに渡った。アウグスト・ピノチェトに よるアジェンデに対する右派の軍事クーデターの後、ボラーニョは「テロリスト」の疑いで逮捕され、8日間拘留された[12]。ボラーニョはこの体験を「ダ ンス・カード」という物語の中で描いている。この物語で彼が語っている出来事のバージョンによると、彼は予想していたような拷問は受けなかったが、「小さ な時間になると、彼らが他の人を拷問しているのが聞こえた。その中で唯一興味深い記事は、ディラン・トマスがかつて所有していた家についてのものだっ た...。このエピソードは、ボラーニョのかつての同級生の視点からも、「刑事たち」という物語の中で語られている[13]。とはいえ、2009年以降、 ボラーニョの当時のメキシコ人の友人たちは、彼が1973年にチリにいたのかどうかさえ疑問視している[14]。 ボラーニョは母国に対して葛藤を抱えていた。彼はチリではイサベル・アジェンデや他の文壇のメンバーに対する激しい攻撃で悪名高かった[15][16]。「彼はチリに馴染めず、彼が経験した拒絶は、彼が好きなことを何でも自由に言えるようにした。 メキシコへの帰還 1974年にチリからメキシコに陸路で戻る際、ボラーニョはエルサルバドルで詩人のロケ・ダルトンやファラブンド・マルティ民族解放戦線のゲリラと過ごしたとされるが、このエピソードの信憑性は疑問視されている[17]。 1960年代、若い頃から無神論者であったボラーニョはトロツキストとなり[18]、1975年にはマイナーな詩的運動であるインフラレアリスモ(インフ ラリアリズム)の創設メンバーとなる。彼は『野蛮な探偵たち』の中で、この運動の側面を愛情を込めてパロディにしている[20]。 メキシコに戻ると、編集者のホルヘ・ヘラルデが回想するように、「無名であったにもかかわらず、あらゆる出版社から恐れられ、文学的な発表や朗読会に飛び入り参加するプロの挑発者」であり、文学界のアンファン・テリブル、ボヘミアン詩人として生きた[11]。 スペインへの移住 1977年、ボラーニョはヨーロッパに移り住み、最終的にスペインに辿り着き、結婚してバルセロナ近郊の地中海沿岸、コスタ・ブラバに居を構え、皿洗い、 キャンプ場の管理人、ベルボーイ、ゴミ収集員として働いた[11]。80年代から亡くなるまで、カタルーニャの小さなビーチタウン、ブラネスに住んでいた [21][22][23][24]。 彼は詩を書き続け、40代前半で小説に移行した。インタビューの中でボラーニョは、小説を書き始めたのは、詩人の収入では決して確保できないとわかってい た家族の将来の経済的な幸福に責任を感じたからだと語っている。このことはホルヘ・ヘラルデも認めており、ボラーニョは1990年に息子が生まれたこと で、「家族の将来に責任があり、小説を書いて生計を立てる方が簡単だと考えた」ため、「質素なビートニクの生活を捨てた」と説明している。しかし、彼は自 分自身を主に詩人として考え続け、20年にわたる詩集が2000年に『Los perros románticos(ロマンティックな犬たち)』というタイトルで出版された[要出典]。 健康状態の悪化と死 2003年、ボラーニョは長期にわたる健康状態の悪化を経て死去した。彼は肝不全を経験し、『2666』の執筆中に肝臓移植の待機リストに載っていた[25][26]。 亡くなる6週間前、ボラーニョがセビリアで出席した国際会議で、ラテンアメリカの小説家仲間は彼を同世代で最も重要な人物と称えた。彼の最も親しい友人の 中には、小説家のロドリゴ・フレサンとエンリケ・ビラ=マタスがいた。フレサンの賛辞には、「ロベルトは、ラテンアメリカがもはやユートピアを信じなくな り、楽園が地獄と化した時代に作家として登場した。「彼の本は政治的である」ともフレサンは言う。フレサンの見解では、彼は「ネットなしで仕事をし、ブ レーキなしで全力を尽くした作家であり、そうすることで偉大なラテンアメリカ人作家としての新しい道を切り開いた」。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のラリー・ローターは「ボラーニョは "死後 "という言葉について冗談を言い、"ローマの剣闘士の名前のようだ、無敗の者のようだ "と言った。 ボラーニョにはスペイン人の妻と二人の子供がおり、スペイン人の妻はボラーニョを「私の唯一の祖国」と呼んだ。『プレイボーイ』誌のメキシコ版が掲載した 最後のインタビューで、ボラーニョは自分をラテンアメリカ人だと考えていると語り、「私の唯一の祖国は二人の子供と妻、そしておそらくは二番手ではある が、私の中にあり、いつか忘れてしまうであろういくつかの瞬間、通り、顔、本...」と付け加えた[29]。 |

| Works Although known for his novels and short stories, Bolaño was a prolific poet of free verse and prose poems.[30] Bolaño, who saw himself primarily as a poet, said, "Poetry is more than enough for me," a character says in The Savage Detectives, "although sooner or later I'm bound to commit the vulgarity of writing stories."[31] In rapid succession, he published a series of critically acclaimed works, the most important of which are the novel Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives), the novella Nocturno de Chile (By Night in Chile), and, posthumously, the novel 2666. His two collections of short stories Llamadas telefónicas and Putas asesinas were awarded literary prizes. In 2009 a number of unpublished novels were discovered among the author's papers. Novels and novellas The Skating Rink The Skating Rink (La pista de hielo in Spanish) is set in the seaside town of Z, on the Costa Brava, north of Barcelona and is told by three male narrators while revolving around a beautiful figure-skating champion, Nuria Martí. When she is suddenly dropped from the Olympic team, a pompous but besotted civil servant secretly builds a skating rink in a local ruin of a mansion, using public funds. But Nuria has affairs, provokes jealousy, and the skating rink becomes a crime scene. Nazi Literature in the Americas Nazi Literature in the Americas (La literatura Nazi en América in Spanish) is an entirely fictitious, ironic encyclopedia of fascist Latin American and American writers and critics, blinded to their own mediocrity and sparse readership by passionate self-mythification. While this is a risk that literature generally runs in Bolaño's works, these characters stand out by force of the heinousness of their political philosophy.[32] Published in 1996, the events of the book take place from the late 19th century up to 2029. The last portrait was expanded into a novel in Distant Star. Distant Star Distant Star (Estrella distante in Spanish) is a novella nested in the politics of the Pinochet regime, concerned with murder, photography and even poetry blazed across the sky by the smoke of air force planes. This dark satirical work deals with the history of Chilean politics in a morbid and sometimes humorous fashion. The Savage Detectives The Savage Detectives (Los detectives salvajes in Spanish) has been compared by Jorge Edwards to Julio Cortázar's Rayuela and José Lezama Lima's Paradiso. In a review in El País, the Spanish critic and former literary editor of said newspaper Ignacio Echevarría declared it "the novel that Borges would have written." (Bolaño often expressed his love for Borges and Cortázar's work, and once concluded an overview of contemporary Argentinian literature by saying that "one should read Borges more.") "Bolaño's genius is not just the extraordinary quality of his writing, but also that he does not conform to the paradigm of the Latin American writer", said Echeverria. "His writing is neither magical realism, nor baroque nor localist, but an imaginary, extraterritorial mirror of Latin America, more as a kind of state of mind than a specific place." The central section of The Savage Detectives presents a long, fragmentary series of reports about the trips and adventures of Arturo Belano, an alliteratively named alter-ego, who also appears in other stories & novels, and Ulises Lima, between 1976 and 1996. These trips and adventures, narrated by 52 characters, take them from Mexico DF to Israel, Paris, Barcelona, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vienna and finally to Liberia during its civil war in the mid-nineties.[33] The reports are sandwiched at the beginning and end of the novel by the story of their quest to find Cesárea Tinajero, the founder of "real visceralismo", a Mexican avant-garde literary movement of the twenties, set in late 1975 and early 1976, and narrated by the aspiring 17-year-old poet García Madero, who tells us first about the poetic and social scene around the new "visceral realists" and later closes the novel with his account of their escape from Mexico City to the state of Sonora. Bolaño called The Savage Detectives "a love letter to my generation." Amulet Amulet (Amuleto in Spanish) focuses on the Uruguayan poet Auxilio Lacouture, who also appears in The Savage Detectives as a minor character trapped in a bathroom at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) in Mexico City for two weeks while the army storms the school.[34] In this short novel, she runs across a host of Latin American artists and writers, among them Arturo Belano, Bolaño's alter ego. Unlike The Savage Detectives, Amulet stays in Auxilio's first-person voice, while still allowing for the frenetic scattering of personalities Bolaño is so famous for. By Night in Chile By Night in Chile (Nocturno de Chile in Spanish), is a narrative constructed as the loose, uneditorialised deathbed rantings of a Chilean Opus Dei priest and failed poet, Sebastian Urrutia Lacroix. At a crucial point in his career, Father Urrutia is approached by two agents of Opus Dei, who inform him that he has been chosen to visit Europe to study the preservation of old churches – the perfect job for a cleric with artistic sensitivities. On his arrival, he is told that the major threat to European cathedrals is pigeon droppings, and that his Old World counterparts have devised a clever solution to the problem. They have become falconers, and in town after town he watches as the priests' hawks viciously dispatch flocks of harmless birds. Chillingly, the Jesuit's failure to protest against this bloody means of architectural preservation signals to his employers that he will serve as a passive accomplice to the predatory and brutal methods of the Pinochet regime. This is the beginning of Bolano's indictment of "l'homme intellectuel" who retreats into art, using aestheticism as a cloak and shield while the world lies around him, nauseatingly unchanged, perennially unjust and cruel. This book represents Bolaño's views upon returning to Chile and finding a haven for the consolidation of power structures and human rights violations. It is important to note that this book was originally going to be called Tormenta de Mierda (Shit Storm in English) but was convinced by Jorge Herralde and Juan Villoro to change the name.[35] Antwerp Antwerp is considered by his literary executor Ignacio Echevarría[2] to be the big bang of the Bolaño universe, the loose prose-poem novel was written in 1980 when Bolaño was 27. The book remained unpublished until 2002, when it was published in Spanish as Amberes, a year before the author's death. It contains a loose narrative structured less around a story arc and more around motifs, reappearing characters and anecdotes, many of which went on to become common material for Bolaño: crimes and campgrounds, drifters and poetry, sex and love, corrupt cops and misfits.[36] The back of the first New Directions edition of the book contains a quote from Bolaño about Antwerp: "The only novel that doesn't embarrass me is Antwerp." 2666 2666 was published in 2004, reportedly as a first draft submitted to his publisher after his death. The text of 2666 was the major preoccupation of the last five years of his life when he was facing death from liver problems. At more than 1,100 pages (898 pages in the English-language edition), the novel is divided into five "parts". Focused on the mostly unsolved and still ongoing serial murders of the fictional Santa Teresa (based on Ciudad Juárez), 2666 depicts the horror of the 20th century through a wide cast of characters, including police officers, journalists, criminals, and four academics on a quest to find the secretive, Pynchonesque German writer Benno von Archimboldi—who also resembles Bolaño himself. In 2008, the book won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. The award was accepted by Natasha Wimmer, the book's translator. In March 2009, The Guardian newspaper reported that an additional Part 6 of 2666 was among papers found by researchers going through Bolaño's literary estate.[37] The Third Reich The Third Reich (El Tercer Reich in Spanish) was written in 1989 but only discovered among Bolaño's papers after he died. It was published in Spanish in 2010 and in English in 2011. The protagonist is Udo Berger, a German war-game champion. With his girlfriend Ingeborg he goes back to the small town on the Costa Brava where he spent his childhood summers. He plays a game of Rise and Decline of the Third Reich with a stranger.[38] Woes of the True Policeman Woes of the True Policeman (Los sinsabores del verdadero policía in Spanish) was first published in Spanish in 2011 and in English in 2012. The novel has been described as offering readers plot lines and characters that supplement or propose variations on Bolaño's novel 2666.[2] It was begun in the 1980s but remained a work-in-progress until his death. The Spirit of Science Fiction The Spirit of Science Fiction (El espíritu de la ciencia-ficción in Spanish) was completed by Bolaño in approximately 1984. It was published posthumously in Spanish in 2016 and in English in 2019. The novel is seen by many as an ur-text to The Savage Detectives, "populated with precursory character sketches and situations" and centering on the activities of young poets and writers living in Mexico City.[39] Short story collections Last Evenings on Earth Last Evenings on Earth (Llamadas Telefónicas in Spanish) is a collection of fourteen short stories narrated by a host of different voices primarily in the first person. A number are narrated by an author, "B.", who is – in a move typical of the author – a stand-in for the author himself. The Return The Return is a collection of twelve short stories, first published in English in 2010, and translated by Chris Andrews. The Insufferable Gaucho The Insufferable Gaucho (El Gaucho Insufrible in Spanish) collects a disparate variety of work.[40] It contains five short stories and two essays, with the title story inspired by Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges's short story The South, said story being mentioned in Bolaño's work. The Secret of Evil The Secret of Evil (El Secreto del Mal in Spanish) is a collection of short stories and recollections or essays. The Spanish version was published in 2007 and contains 21 pieces, 19 of which appear in the English edition, published in 2010. Several of the stories in the collection feature characters that have appeared in previous works by Bolaño, including his alter ego Arturo Belano and characters that first appeared in Nazi Literature in the Americas. Poems The Romantic Dogs The Romantic Dogs (Los perros románticos in Spanish), published in 2006, is his first collection of poetry to be translated into English, appearing in a bilingual edition in 2008 under New Directions and translated by Laura Healy. Bolaño has stated that he considered himself first and foremost a poet and took up fiction writing primarily later in life in order to support his children. The Unknown University A deluxe edition of Bolaño's complete poetry, The Unknown University, was translated from the Spanish by Laura Healy (Chile, New Directions, 2013). It was shortlisted for the 2014 Best Translated Book Award.[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Bola%C3%B1o |

作品 小説や短編小説で知られるボラーニョだが、自由詩や散文詩の詩人としても多作であった[30]。自分を主に詩人として見ていたボラーニョは、『野蛮な刑事たち』の中で登場人物が「詩は私にとって十分すぎるほどだ。 小説『野蛮な刑事たち』(Los detectives salvajes)、小説『チリの夜』(Nocturno de Chile)、そして死後に発表された小説『2666』などがその代表作である。2冊の短編集『Llamadas telefónicas』と『Putas asesinas』は文学賞を受賞。2009年、遺品の中から未発表の小説が発見された。 小説 スケートリンク The Skating Rink(スペイン語でLa pista de hielo)は、バルセロナの北、コスタ・ブラバの海辺の町Zを舞台に、フィギュアスケートの美しいチャンピオン、ヌリア・マルティを軸に、3人の男性の 語り手によって描かれる。彼女が突然オリンピック代表から外されると、偉そうだが惚れっぽい公務員は、公金を使って地元の廃墟のような邸宅にスケートリン クを密かに建設する。しかしヌリアは浮気をし、嫉妬を買い、スケートリンクは犯罪現場と化す。 アメリカ大陸のナチ文学 『アメリカ大陸のナチ文学』(スペイン語でLa literatura Nazi en América)は、情熱的な自己神話化によって自らの凡庸さとまばらな読者層に目を奪われているファシズムのラテンアメリカとアメリカの作家と批評家た ちの、まったく架空の皮肉な百科事典である。これはボラーニョの作品では一般的に文学が冒すリスクであるが、これらの登場人物は、その政治思想の凶悪さに よって力強く際立っている[32]。1996年に出版された本書の出来事は、19世紀後半から2029年までの出来事である。最後の肖像画は『遠い星』で 小説化された。 遠い星 『遠い星』(スペイン語ではEstrella distante)は、ピノチェト政権の政治に絡む小説で、殺人、写真、空軍機の煙が空に放つ詩さえも題材にしている。この暗い風刺作品は、病的で時にユーモラスな手法でチリの政治の歴史を扱っている。 野蛮な探偵たち 野蛮な刑事たち(スペイン語でLos detectives salvajes)は、ホルヘ・エドワーズによってフリオ・コルタサルの『Rayuela』やホセ・レサマ・リマの『Paradiso』と比較されている。 スペインの批評家で同紙の元文芸編集長イグナシオ・エチェバリアは、エル・パイス紙の批評でこの作品を「ボルヘスが書いたであろう小説」と断言した。(ボ ラーニョはしばしばボルヘスとコルタサルの作品への愛情を表明し、「ボルヘスをもっと読むべきだ」と現代アルゼンチン文学の概説を締めくくったこともあ る)。「ボラーニョの天才的なところは、その文章の並外れた質だけでなく、ラテンアメリカの作家のパラダイムに準拠していないことだ」とエチェベリアは言 う。「彼の文章は、魔術的リアリズムでも、バロックでも、ローカリズムでもなく、ラテンアメリカの想像上の、治外法権的な鏡である。 『The Savage Detectives』の中心部は、1976年から1996年にかけての、他の物語や小説にも登場するアルトゥーロ・ベラーノとウリセス・リマの旅と冒険 についての、断片的で長い報告のシリーズである。これらの旅と冒険は、52人の登場人物によって語られ、メキシコDFからイスラエル、パリ、バルセロナ、 ロサンゼルス、サンフランシスコ、ウィーン、そして最後に90年代半ばの内戦中のリベリアへと至る。 [1975年末から1976年初頭にかけて、20年代のメキシコの前衛文学運動である「本物の臓器リアリズム」の創始者、セサレイア・ティナヘロを探す物 語が小説の最初と最後に挟まれ、17歳の詩人ガルシア・マデロの語りによって、新しい「臓器リアリスト」たちを取り巻く詩的・社会的情景が語られる。ボ ラーニョは『野蛮な刑事たち』を "私の世代へのラブレター "と呼んだ。 アミュレット 『アミュレット(スペイン語でAmuleto)は、ウルグアイの詩人アウクシリオ・ラクチュールに焦点を当てた作品。彼女は『未開の探偵たち』にも登場 し、軍隊が学校を襲撃している間、メキシコ・シティのメキシコ自治大学(UNAM)のトイレに2週間閉じ込められる。The Savage Detectives』とは異なり、『Amulet』はオクシリオの一人称のままであるが、ボラーニョが得意とする個性的な人物の熱狂的な散在は健在であ る。 チリの夜に 『チリの夜によって』(スペイン語では『Nocturno de Chile』)は、チリのオプス・デイ司祭で落ち目の詩人、セバスチャン・ウルティア・ラクロワの死に際の戯言として、編集なしで構成された物語である。 ウルシア神父は、そのキャリアの重要な時期に、オプス・デイの2人のエージェントから、古い教会の保存を研究するためにヨーロッパを訪問することになった と告げられる。 到着した彼は、ヨーロッパの聖堂にとって大きな脅威はハトの糞であり、旧世界の聖職者たちがこの問題に対する巧妙な解決策を考案したことを聞かされる。彼 らは鷹匠となり、町々で神父たちの鷹が害のない鳥の群れを獰猛に退治するのを彼は見ている。冷ややかなことに、イエズス会がこの血なまぐさい建築物保護手 段に抗議しなかったことは、彼がピノチェト政権の略奪的で残忍な手法の受動的な共犯者としての役割を果たすことを雇い主に知らせることになる。これがボ ラーノの「知性ある人間」に対する告発の始まりである。ボラーノは芸術の中に引きこもり、美学を隠れ蓑や盾にしながら、周囲には吐き気を催すほど変わり映 えのしない、いつまでも不正で残酷な世界が横たわっている。本書は、チリに戻り、権力構造の強化と人権侵害の隠れ家を見つけたボラーニョの見解を表してい る。なお、本書は当初『Tormenta de Mierda』(英語では『Shit Storm』)と呼ばれる予定だったが、ホルヘ・ヘラルデとフアン・ビジョーロの説得により改名された[35]。 アントワープ 『アントワープ』は、ボラーニョの文学的エグゼキューターであるイグナシオ・エチェバリア[2]によって、ボラーニョの世界のビッグバンとみなされてい る。2002年にスペイン語で『アンベレス』として出版されるまで未発表のままであった。本書は、ストーリー・アークというよりは、モチーフや再登場する 人物、逸話を中心に構成された緩やかな物語を含み、その多くはボラーニョにとって共通の題材となった:犯罪とキャンプ場、流れ者と詩、セックスと愛、汚職 警官と不良たち[36]。 2666 『2666』は2004年に出版されたが、ボラーニョの死後、出版社に提出された初稿だったと伝えられている。2666の文章は、肝臓の病気で死に直面し ていた彼の人生の最後の5年間における主要な関心事だった。1,100ページを超える(英語版では898ページ)この小説は、5つの「部分」に分かれてい る。架空の町サンタ・テレサ(シウダー・フアレスがモデル)で起きた、ほとんどが未解決で現在も進行中の連続殺人事件を中心に、警察官、ジャーナリスト、 犯罪者、そしてボラーニョ自身にも似た、秘密主義でピンチョネスクなドイツ人作家ベンノ・フォン・アルチンボルディを探し求める4人の学者など、幅広い登 場人物を通して20世紀の恐怖を描く。2008年、本書は全米図書批評家協会賞フィクション部門を受賞。同賞を受賞したのは、同書の翻訳者であるナター シャ・ウィマーである。2009年3月、ガーディアン紙は、ボラーニョの文学遺産を調査していた研究者が発見した書類の中に、『2666』の第6部が追加 されていたと報じた[37]。 第三帝国 『第三帝国』(スペイン語ではEl Tercer Reich)は1989年に執筆されたが、ボラーニョの死後、ボラーニョの書類の中から発見された。2010年にスペイン語で、2011年に英語で出版さ れた。主人公はドイツの戦争ゲームチャンピオン、ウド・ベルガー。ガールフレンドのインゲボルグとともに、彼は幼少期に夏を過ごしたコスタ・ブラバの小さ な町に帰る。彼は見知らぬ男と『第三帝国の興亡』をプレイする[38]。 真の警察官の苦悩 真の警察官の苦悩』(スペイン語ではLos sinsabores del verdadero policía)は2011年にスペイン語で、2012年に英語で出版された。この小説は、ボラーニョの小説『2666』を補完する、あるいはそのバリ エーションを提案するような筋書きと登場人物を読者に提供すると評されている[2]。 SFの精神 The Spirit of Science Fiction(スペイン語でEl espíritu de la ciencia-ficción)は、ボラーニョによって1984年頃に完成された。死後、2016年にスペイン語で、2019年に英語で出版された。こ の小説は『野蛮な探偵たち』の原典であり、「前兆的な人物スケッチや状況が盛り込まれ」、メキシコシティに住む若い詩人や作家の活動を中心に描かれている と多くの人が見ている[39]。 短編集 地球の夕べ 地球の夕べ』(Llamadas Telefónicas、スペイン語)は14の短編から成る短編集。B.」と呼ばれる作者が語り手となっており、B.は作者自身の代役を務めている。 ザ・リターン クリス・アンドリュースが翻訳し、2010年に初めて英語で出版された12編からなる短編集。 むかつくガウチョ 5つの短編と2つのエッセイが収録されており、表題作はアルゼンチンの作家ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスの短編集『南』にインスパイアされたもの。 悪の秘密 悪の秘密』(スペイン語:El Secreto del Mal)は、短編小説と回想やエッセイから成る作品集である。スペイン語版は2007年に出版され、21編が収録されているが、そのうち19編は2010 年に出版された英語版に収録されている。ボラーニョの分身であるアルトゥーロ・ベラーノや、『アメリカ大陸のナチス文学』に登場した人物など、ボラーニョ の過去の作品に登場した人物が登場する。 詩集 ロマンティックな犬たち 2006年に出版された『The Romantic Dogs』(スペイン語では『Los perros románticos』)は、ボラーニョが初めて英訳した詩集であり、2008年にニュー・ディレクションズ社からローラ・ヒーリー訳の対訳版が出版され た。ボラーニョは、自分は何よりもまず詩人であり、子供たちを養うために後年主に小説を書くようになったと述べている。 未知の大学 ボラーニョの全詩集『The Unknown University』のデラックス版がローラ・ヒーリーによってスペイン語から翻訳された(チリ、ニューディレクションズ、2013年)。2014年最優秀翻訳図書賞の最終候補になった[41]。 |

| Themes In the final decade of his life Bolaño produced a significant body of work, consisting of short stories and novels. In his fiction the characters are often novelists or poets, some of them aspiring and others famous, and writers appear ubiquitous in Bolaño's world, variously cast as heroes, villains, detectives and iconoclasts. Other significant themes of his work include quests, "the myth of poetry", the "interrelationship of poetry and crime", the inescapable violence of modern life in Latin America, and the essential human business of youth, love and death.[42] In one of his stories, Dentist, Bolaño appears to set out his basic aesthetic principles. The narrator pays a visit to an old friend, a dentist. The friend introduces him to a poor Indian boy who turns out to be a literary genius. At one point during a long evening of inebriated conversation, the dentist expresses what he believes to be the essence of art: That's what art is, he said, the story of a life in all its particularity. It's the only thing that really is particular and personal. It's the expression and, at the same time, the fabric of the particular. And what do you mean by the fabric of the particular? I asked, supposing he would answer: Art. I was also thinking, indulgently, that we were pretty drunk already and that it was time to go home. But my friend said: What I mean is the secret story.... The secret story is the one we'll never know, although we're living it from day to day, thinking we're alive, thinking we've got it all under control and the stuff we overlook doesn't matter. But every damn thing matters! It's just that we don't realize. We tell ourselves that art runs on one track and life, our lives, on another, we don't even realize that's a lie. Like large parts of Bolaño's work, this conception of fiction manages to be at once elusive and powerfully suggestive. As Jonathan Lethem has commented, "Reading Roberto Bolaño is like hearing the secret story, being shown the fabric of the particular, watching the tracks of art and life merge at the horizon and linger there like a dream from which we awake inspired to look more attentively at the world."[43] When discussing the nature of literature, including his own, Bolaño emphasized its inherent political qualities. He wrote, "All literature, in a certain sense, is political. I mean, first, it's a reflection on politics, and second, it's also a political program. The former alludes to reality—to the nightmare or benevolent dream that we call reality—which ends, in both cases, with death and the obliteration not only of literature, but of time. The latter refers to the small bits and pieces that survive, that persist; and to reason."[44] Bolaño's writings repeatedly manifest a concern with the nature and purpose of literature and its relationship to life. One recent assessment of his works discusses his idea of literary culture as a "whore": Among the many acid pleasures of the work of Roberto Bolaño, who died at 50 in 2003, is his idea that culture, in particular literary culture, is a whore. In the face of political repression, upheaval and danger, writers continue to swoon over the written word, and this, for Bolaño, is the source both of nobility and of pitch-black humor. In his novel "The Savage Detectives," two avid young Latino poets never lose faith in their rarefied art no matter the vicissitudes of life, age and politics. If they are sometimes ridiculous, they are always heroic. But what can it mean, he asks us and himself, in his dark, extraordinary, stinging novella "By Night in Chile," that the intellectual elite can write poetry, paint and discuss the finer points of avant-garde theater as the junta tortures people in basements? The word has no national loyalty, no fundamental political bent; it's a genie that can be summoned by any would-be master. Part of Bolaño's genius is to ask, via ironies so sharp you can cut your hands on his pages, if we perhaps find a too-easy comfort in art, if we use it as anesthetic, excuse and hide-out in a world that is very busy doing very real things to very real human beings. Is it courageous to read Plato during a military coup or is it something else? —Stacey D'Erasmo, The New York Times Book Review, 24 February 2008[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Bola%C3%B1o |

テーマ ボラーニョは晩年の10年間に、短編と小説からなる重要な作品を発表した。ボラーニョの小説の登場人物は、小説家や詩人であることが多く、志望する者もいれば有名な者もいる。 彼の作品のその他の重要なテーマには、探求、「詩の神話」、「詩と犯罪の相互関係」、ラテンアメリカにおける現代生活の逃れられない暴力、若さ、愛、死という人間の本質的なビジネスなどがある[42]。 彼の物語のひとつである『歯医者』では、ボラーニョは基本的な美学的原則を打ち出しているように見える。語り手は旧友の歯科医を訪ねる。その友人から、文 学の天才であることが判明した貧しいインド人の少年を紹介される。ある時、長い晩の酩酊した会話の中で、歯科医は芸術の本質が何であるかを語る: それこそが芸術なんだ。それこそが芸術であり、人生の物語なんだ。それは表現であり、同時に特別なものである。"特別なもの "とはどういう意味ですか?と私は尋ねた: アートだ。私はまた、私たちはもうかなり酔っ払っていて、そろそろ家に帰ろうかと甘えたことを考えていた。しかし友人は言った: 私が言いたいのは、秘密の話なんだ......。秘密の物語とは、私たちが決して知ることのできない物語のことだ。私たちは日々それを生きていて、生きて いると思っていて、すべてをコントロールしていると思っていて、私たちが見過ごしていることは重要ではないと思っている。しかし、あらゆることが重要なの だ!ただ、私たちが気づいていないだけなのだ。私たちは、芸術はある軌道を走り、人生、私たちの人生は別の軌道を走ると自分に言い聞かせている。 ボラーニョの作品の大部分がそうであるように、このフィクションの概念もまた、捉えどころがなく、力強い示唆に富んでいる。ジョナサン・レテムがコメント しているように、「ロベルト・ボラーニョを読むことは、秘密の物語を聞くようなものであり、特別なものの布地を見せられるようなものであり、芸術と人生の 軌跡が地平線で合流するのを見るようなものであり、そこから目を覚ますと、世界をより注意深く見るように促される夢のように、そこに留まるものである」 [43]。 彼自身を含め、文学の本質について論じるとき、ボラーニョは文学に内在する政治的特質を強調した。すべての文学は、ある意味で政治的である。つまり、第一 に、政治に対する考察であり、第二に、政治的プログラムでもある。前者は現実、つまり私たちが現実と呼んでいる悪夢や慈悲深い夢を暗示し、それはどちらの 場合も、死と文学のみならず時間の抹殺によって終わる。後者は、生き残り、存続する小さな断片、そして理性に言及している」[44]。 ボラーニョの著作は、文学の本質と目的、そして人生との関係への関心を繰り返し明らかにしている。彼の作品に対する最近の評価のひとつに、文学文化を「娼婦」と見なす彼の考えがある: 2003年に50歳で亡くなったロベルト・ボラーニョの作品の多くの酸っぱい喜びの中に、文化、特に文学文化は娼婦であるという彼の考えがある。政治的抑 圧、激動、危険に直面しながらも、作家たちは書かれた言葉にうっとりし続ける。ボラーニョにとって、このことは気高さであると同時に、漆黒のユーモアの源 泉でもある。ボラーニョの小説『野蛮な探偵たち』では、2人の熱心な若いラテン系詩人が、人生、年齢、政治がどう変わろうとも、自分たちの稀有な芸術への 信頼を失うことはない。彼らは時に滑稽であっても、常に英雄的である。しかし、知的エリートが詩を書き、絵を描き、アバンギャルドな演劇の精巧さを論じる ことができる一方で、政権が地下室で人々を拷問しているというのはどういうことなのか、と彼は暗く、非凡で、刺々しい小説『チリの夜に』で私たちに、そし て彼自身に問いかける。この言葉には国家的忠誠心もなければ、根本的な政治的傾向もない。ボラーニョの天才の一端は、彼のページで手を切ることができるほ ど鋭い皮肉を通して、私たちが芸術にあまりにも安易な安らぎを見いだし、現実の人間に現実的なことをするのに忙しい世界で、芸術を麻酔薬、言い訳、隠れ家 として使っているのではないかと問うことだ。軍事クーデターの最中にプラトンを読むのは勇気あることなのだろうか? -ステイシー・デラスモ、ニューヨーク・タイムズ・ブックレビュー、2008年2月24日[45]号 |

| English translation and publication Bolaño's first American publisher, Barbara Epler of New Directions, read a galley proof of By Night in Chile and decided to acquire it, along with Distant Star and Last Evenings on Earth, all translated by Chris Andrews. By Night in Chile came out in 2003 and received an endorsement by Susan Sontag; at the same time Bolaño's work also began appearing in various magazines, which gained him broader recognition among English readers. The New Yorker first published a Bolaño short story, Gómez Palacio, in its 8 August 2005 issue.[46] By 2006 Bolaño's rights were represented by Carmen Balcells, who decided to place his two bigger books at a larger publishing house; both were eventually published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux (The Savage Detectives in 2007 and 2666 in 2008) in a translation by Natasha Wimmer. At the same time New Directions took on the publication of the rest of Bolaño's work (to the extent that it was known at the time) for a total of 13 books, translated by Laura Healy (two poetry collections), Natasha Wimmer (Antwerp and Between Parentheses) and Chris Andrews (6 novels and 3 short story collections).[47] The posthumous discovery of additional works by Bolaño has thus far led to the publication of the novel The Third Reich (El Tercer Reich in Spanish), (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011, translated by Wimmer) and The Secret of Evil (El Secreto del Mal), (New Directions, 2012, translated by Wimmer and Andrews), a collection of short stories. A translation of the novel Woes of the True Policeman (Los sinsabores del verdadero policía in Spanish), (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, translated by Wimmer) was released on 13 November 2012. A collection of three novellas, Cowboy Graves (Sepulcros de vaqueros in Spanish), (Penguin Press, translated by Wimmer), was released on 16 February 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberto_Bola%C3%B1o |

英訳と出版 ボラーニョの最初のアメリカ人出版社であるニューディレクションズのバーバラ・エプラーは、『チリの夜』のゲラ刷りを読み、クリス・アンドリュースが翻訳 した『遠い星』『地球最後の夕べ』とともに入手することを決めた。チリの夜』は2003年に出版され、スーザン・ソンタグの推薦を受けた。同時に、ボラー ニョの作品はさまざまな雑誌に掲載されるようになり、英語の読者にも広く知られるようになった。ニューヨーカー』誌は2005年8月8日号でボラーニョの 短編小説『Gómez Palacio』を初めて掲載した[46]。 2006年までにボラーニョの権利はカルメン・バルセルズによって代表され、ボラーニョはより大きな出版社に2冊の大きな本を置くことを決めた。同時に、 ニューディレクションズはボラーニョの残りの作品(当時知られていた範囲)の出版を引き受け、ローラ・ヒーリー(詩集2冊)、ナターシャ・ウィマー(『ア ントワープ』と『括弧の間』)、クリス・アンドリュース(小説6冊、短編集3冊)の翻訳で合計13冊を出版した[47]。 死後にボラーニョの作品が追加発見され、これまでに小説『第三帝国』(El Tercer Reich、スペイン語)(Farrar, Straus and Giroux、2011年、ウィマー訳)、短編小説集『悪の秘密』(El Secreto del Mal、New Directions、2012年、ウィマー、アンドリュース訳)が出版されている。2012年11月13日には、小説『Woes of the True Policeman』(Los sinsabores del verdadero policía、スペイン語)の翻訳版(Farrar, Straus and Giroux、ウィマー訳)が発売された。2021年2月16日には、3つの小説からなる小説集『Cowboy Graves』(スペイン語でSepulcros de vaqueros、ペンギン・プレス、ウィマー訳)が発売された。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆