ラビンドラナート・タゴール

Rabindranath

Tagore, 1861-1941

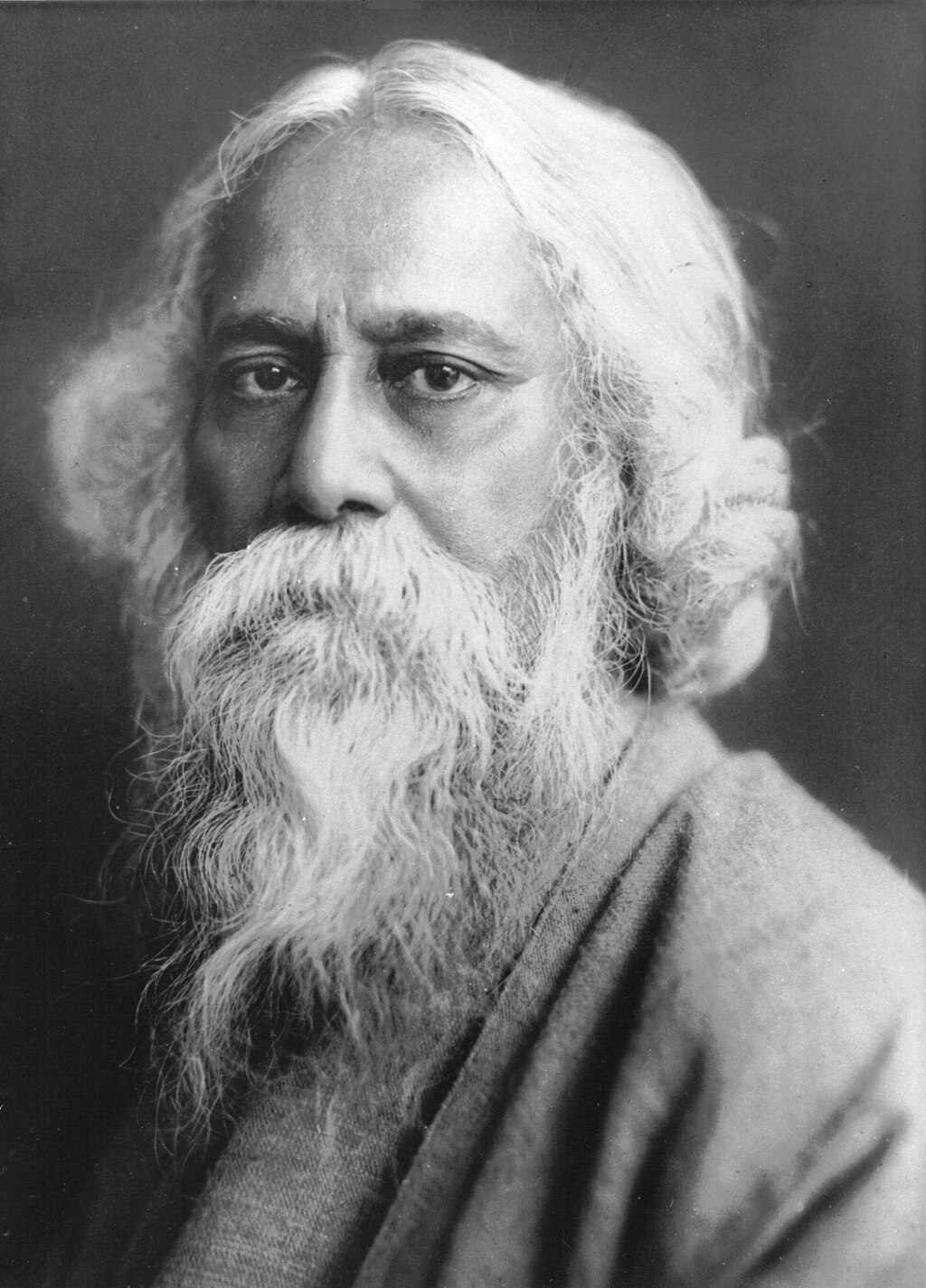

☆ ラビンドラナート・タゴール(Rabindranath Tagore 1861年5月7日[2]- 1941年8月7日[3])は、インドの詩人、作家、劇作家、作曲家、哲学者、社会改革者、ベンガル・ルネッサンスの画家である。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、文脈的モダニズムによって ベンガル文学や 音楽、インド芸術を再構築した。1913年、タゴールは非ヨーロッパ人として初めてノーベル文学賞を受賞し、また作詞家としても初めてノーベル文学賞を受 賞した。タゴールの詩的な歌はスピリチュアルでメルヘンチックなものとされ、彼のエレガントな散文と魔術的な詩はインド亜大陸で広く人気を博した。「ベンガルの吟遊詩人」と呼ばれ、タゴールはグルデブ、コビグル、ビスウォコビという 俗称で知られていた。

| Rabindranath Tagore

FRAS (/rəˈbɪndrənɑːt tæˈɡɔːr/ ⓘ; pronounced [roˈbindɾonatʰ ˈʈʰakuɾ];[1]

7 May 1861[2] – 7 August 1941[3]) was an Indian poet, writer,

playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer, and painter of the

Bengal Renaissance.[4][5][6] He reshaped Bengali literature and music

as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries. Author of the "profoundly sensitive, fresh and

beautiful" poetry of Gitanjali,[7] in 1913 Tagore became the first

non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in

Literature.[8] Tagore's poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and

mercurial; where his elegant prose and magical poetry were widely

popular in the Indian subcontinent.[9] He was a fellow of the Royal

Asiatic Society. Referred to as "the Bard of Bengal",[10][5][6] Tagore

was known by the sobriquets Gurudeb, Kobiguru, and Biswokobi.[a] A Bengali Brahmin from Calcutta with ancestral gentry roots in Burdwan district[12] and Jessore, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old.[13] At the age of sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics.[14] By 1877 he graduated to his first short stories and dramas, published under his real name. As a humanist, universalist, internationalist, and ardent critic of nationalism,[15] he denounced the British Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy also endures in his founding of Visva-Bharati University.[16][17] Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. His novels, stories, songs, dance dramas, and essays spoke to topics political and personal. Gitanjali (Song Offerings), Gora (Fair-Faced) and Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed—or panned—for their lyricism, colloquialism, naturalism, and unnatural contemplation. His compositions were chosen by two nations as national anthems: India's "Jana Gana Mana" and Bangladesh's "Amar Shonar Bangla" .The Sri Lankan national anthem was also inspired by his work.[18] His Song "Banglar Mati Banglar Jol" has been adopted as the state anthem of West Bengal. |

ラビンドラナート・タゴール(Rabindranath

Tagore FRAS,/rəm_2C8↩bɪ /rəːt tæɑˈɡɔːⓘ[roˈbind'ˈʈʰakuɾ] と発音する;

[1]1861年5月7日[2]-

1941年8月7日[3])は、インドの詩人、作家、劇作家、作曲家、哲学者、社会改革者、ベンガル・ルネッサンスの画家である。

[4][5][6]。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、文脈的モダニズムによって ベンガル文学や

音楽、インド芸術を再構築した。1913年、タゴールは非ヨーロッパ人として初めてノーベル文学賞を受賞し、また作詞家としても初めてノーベル文学賞を受

賞した[8]。タゴールの詩的な歌はスピリチュアルでメルヘンチックなものとされ、彼のエレガントな散文と魔術的な詩はインド亜大陸で広く人気を博した

[9]。ベンガルの吟遊詩人」と呼ばれ[10][5][6]、タゴールはグルデブ、コビグル、ビスウォコビという 俗称で知られていた[a]。 16歳のとき、Bhānusiṃha(「太陽のライオン」)というペンネームで初めて本格的な詩を発表し、文学当局に長らく失われていた古典として取り上 げられた[14]。ヒューマニスト、普遍主義者、国際主義者、ナショナリズムの熱心な批判者として、彼はイギリス・ラージを糾弾し、イギリスからの独立を 提唱した[15]。ベンガル・ルネッサンスの提唱者として、絵画、スケッチ、落書き、数百のテキスト、約2,000の歌からなる膨大な規範を発展させ、彼 の遺産はヴィスヴァ=バラティ大学の創設にも受け継がれている[16][17]。 タゴールは、厳格な古典形式を排し、言語的な厳格さに抵抗することで、ベンガル芸術を近代化した。彼の小説、物語、歌、舞踊劇、エッセイは、政治的かつ個 人的なテーマについて語っている。ギタンジャリ(歌の捧げもの)』、『ゴーラ(公正な顔)』、『ガーレ・ベール(家庭と世界)』は彼の最も有名な作品であ り、彼の詩、短編小説、小説は、その抒情性、口語体、自然主義、不自然な思索によって絶賛され、あるいは非難された。彼の曲は2つの国で国歌に選ばれた: インドの"Jana Gana Mana"とバングラデシュの"Amar Shonar Bangla"である。スリランカの国歌も彼の作品にインスパイアされている[18]。 |

| Family Background See also: Tagore family The name Tagore is the anglicised transliteration of Thakur.[19] The original surname of the Tagores was Kushari. They were Pirali Brahmin ('Pirali' historically carried a stigmatized and pejorative connotation)[20][21] who originally belonged to a village named Kush in the district named Burdwan in West Bengal. The biographer of Rabindranath Tagore, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyaya wrote in the first volume of his book Rabindrajibani O Rabindra Sahitya Prabeshak that The Kusharis were the descendants of Deen Kushari, the son of Bhatta Narayana; Deen was granted a village named Kush (in Burdwan zilla) by Maharaja Kshitisura, he became its chief and came to be known as Kushari.[12] |

家族の背景 こちらも参照のこと: タゴール家 タゴールという名前はタークルの音訳である[19]。彼らはピラリ・ブラフミン(「ピラリ」は歴史的に汚名を着せられ、侮蔑的な意味合いを持つ)[20] [21]であり、元々は西ベンガル州バルドワン県のクシュという村に属していた。ラビンドラナート・タゴールの伝記作者であるプラバット・クマール・ムホ パディヤヤは、その著書『ラビンドラジバニ・オー・ラビンドラ・サヒティヤ・プラベシャク』の第1巻で次のように書いている。 クシャリ族はバッタ・ナーラーヤナの息子であるディーン・クシャリの子孫である。ディーンはマハラジャ・クシティスラからクシュ(バードワン・ジラ)とい う名の村を与えられ、彼はその村長となり、クシャリとして知られるようになった[12]。 |

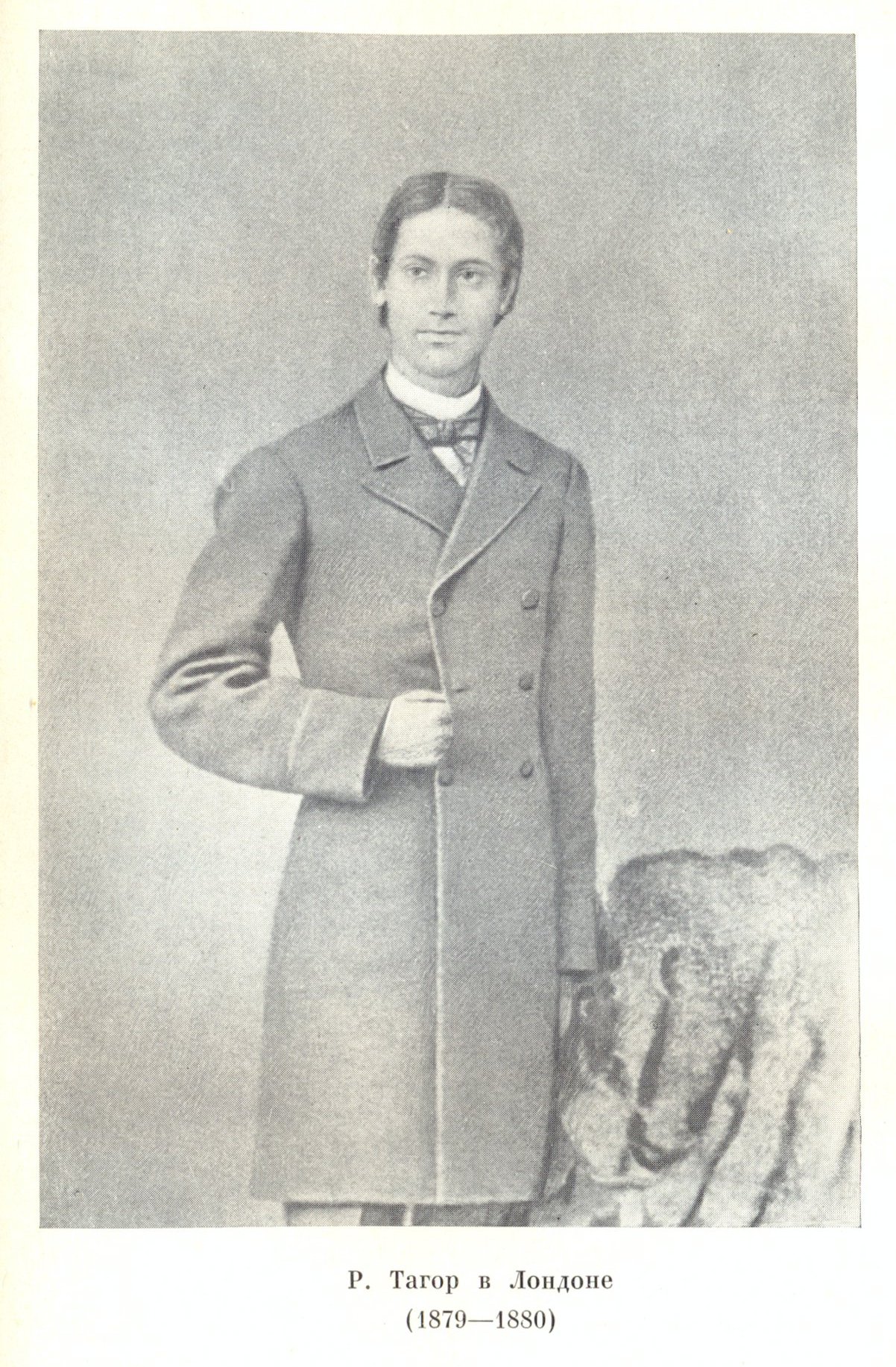

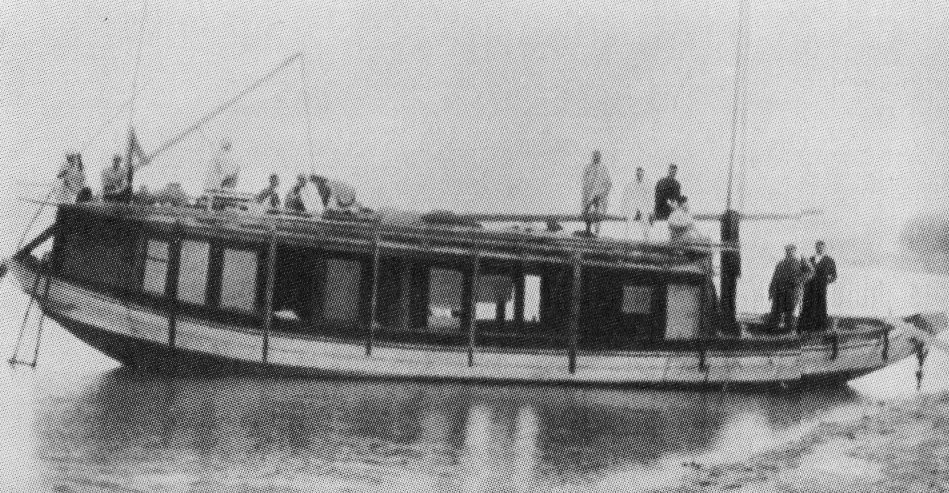

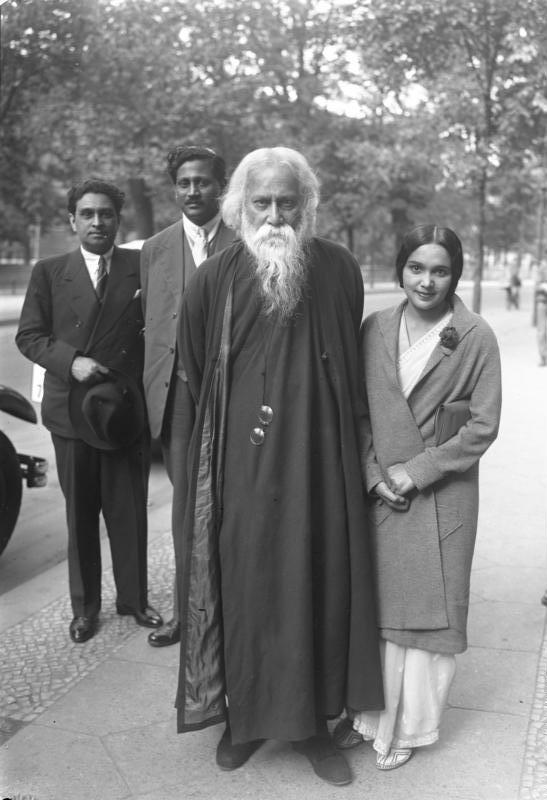

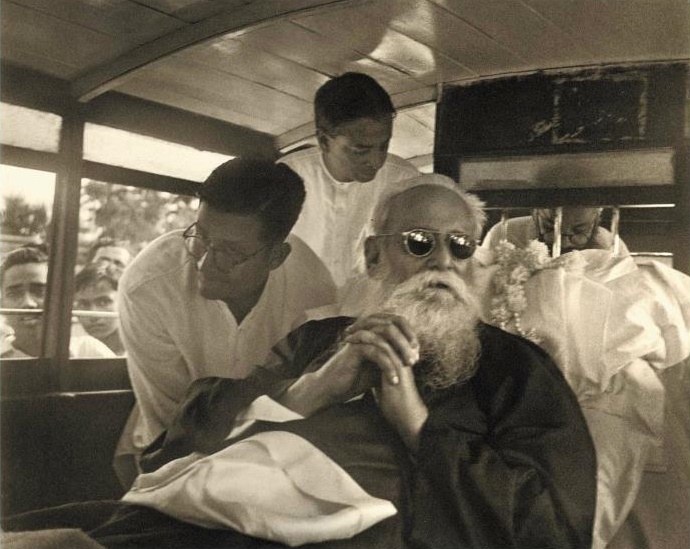

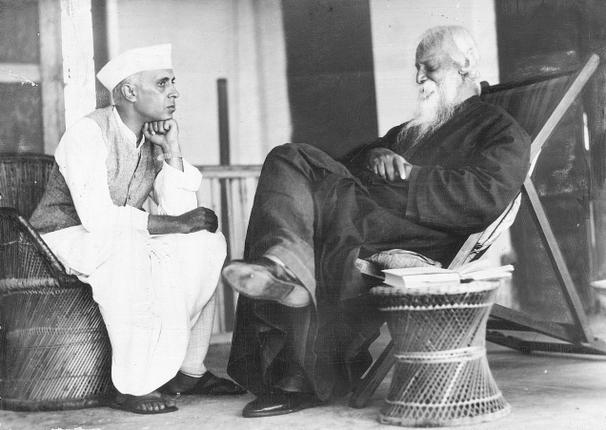

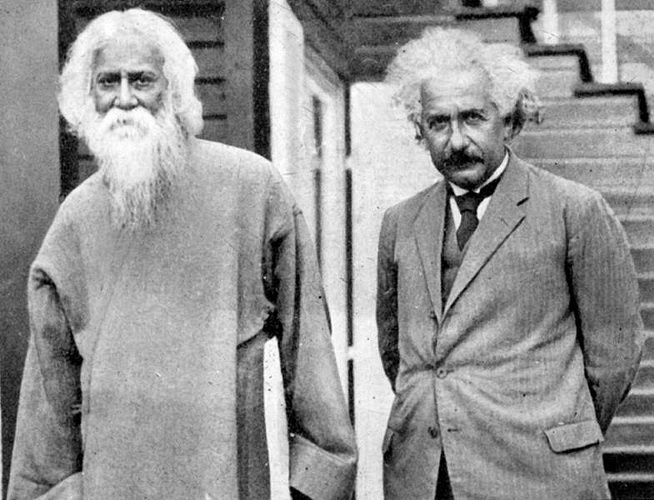

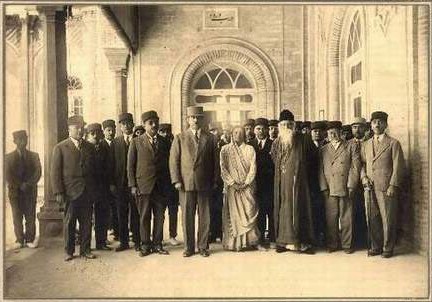

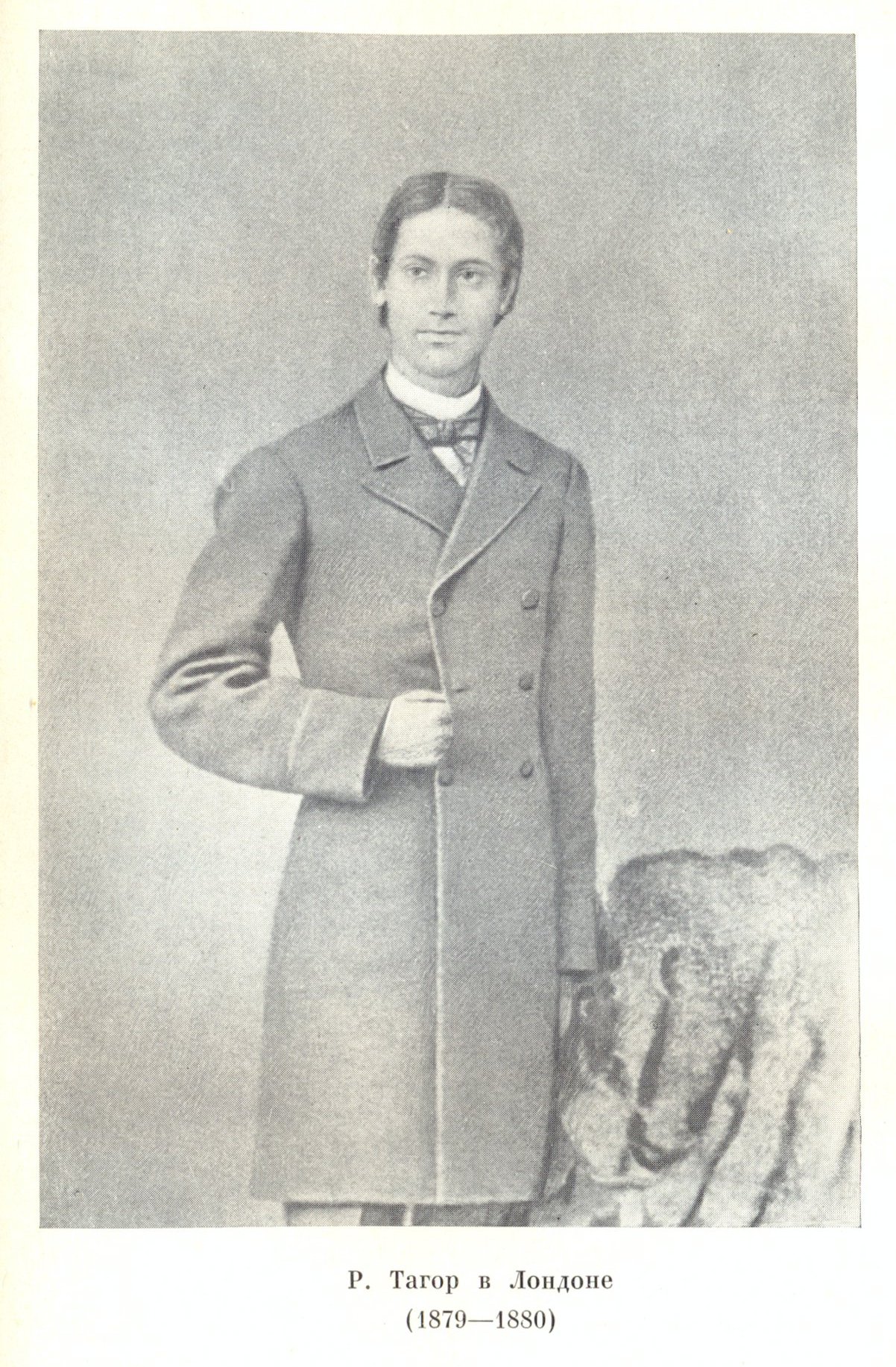

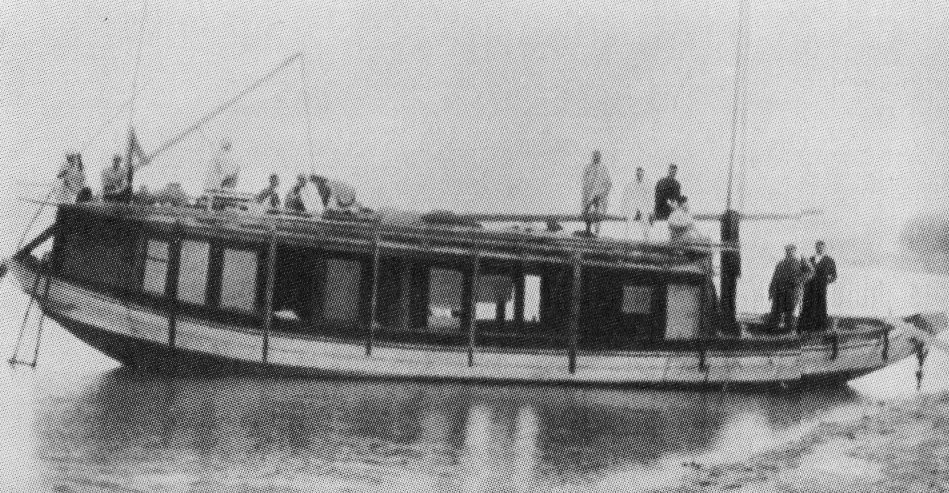

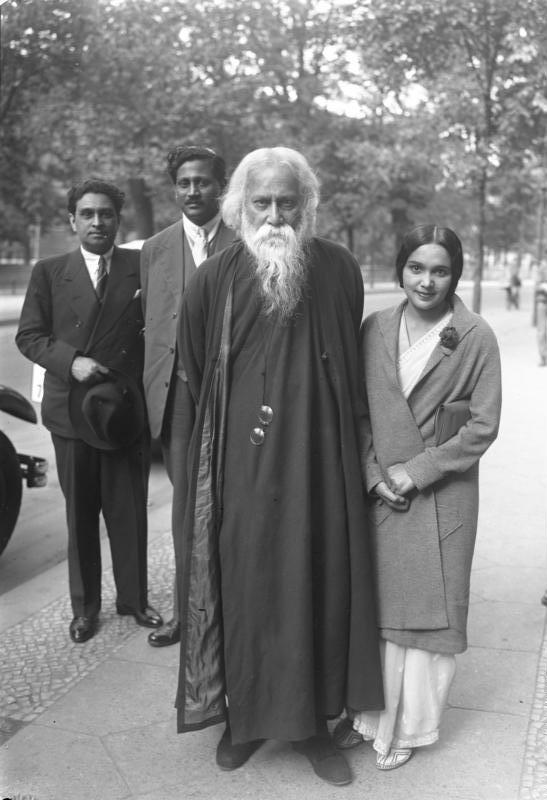

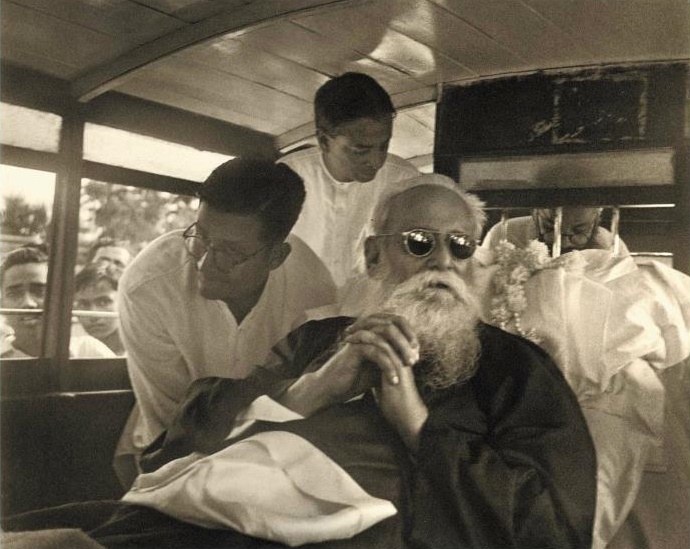

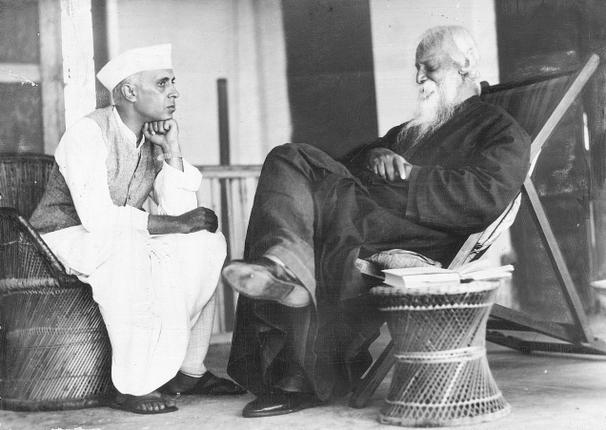

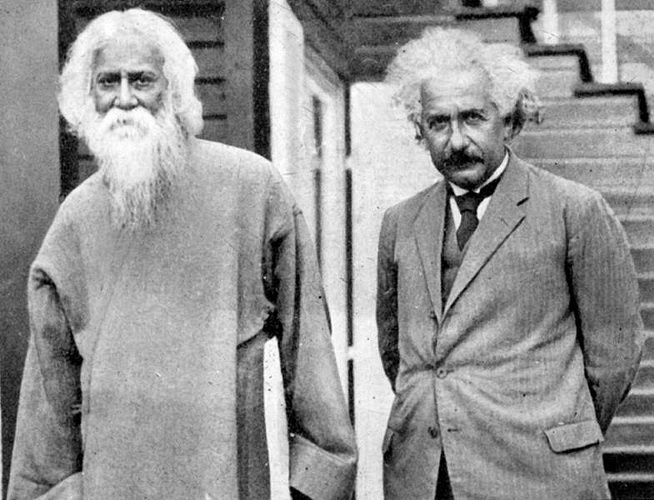

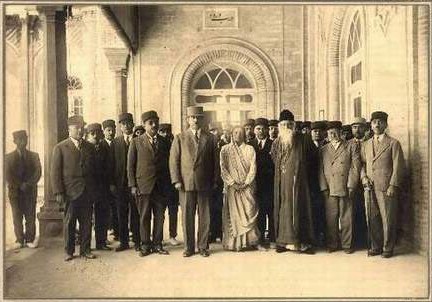

| Life and events Early life: 1861–1878 Main article: Early life of Rabindranath Tagore  Young Tagore in London, 1879 The last two days a storm has been raging, similar to the description in my song—Jhauro jhauro borishe baridhara [... amidst it] a hapless, homeless man drenched from top to toe standing on the roof of his steamer [...] the last two days I have been singing this song over and over [...] as a result the pelting sound of the intense rain, the wail of the wind, the sound of the heaving Gorai River, [...] have assumed a fresh life and found a new language and I have felt like a major actor in this new musical drama unfolding before me. — Letter to Indira Devi.[22] The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta,[23] the son of Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).[b] Black-and-white photograph of a finely dressed man and woman: the man, smiling, stands with the hand on the hip and elbow turned outward with a shawl draped over his shoulders and in Bengali formal wear. In front of him, the woman, seated, is in an elaborate dress and shawl; she leans against a carved table supporting a vase and flowing leaves.  Tagore and his wife Mrinalini Devi, 1883 Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely.[29] The Tagore family was at the forefront of the Bengal renaissance. They hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly. Tagore's father invited several professional Dhrupad musicians to stay in the house and teach Indian classical music to the children.[30] Tagore's oldest brother Dwijendranath was a philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright.[31] His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist.[32] Jyotirindranath's wife Kadambari Devi, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884, soon after he married, left him profoundly distraught for years.[33] Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur and Panihati, which the family visited.[34][35] His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him—by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, by gymnastics, and by practising judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favourite subject.[36] Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity.[37] After his upanayan (coming-of-age rite) at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta in February 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father's Santiniketan estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of Kālidāsa.[38][39] During his 1-month stay at Amritsar in 1873 he was greatly influenced by melodious gurbani and Nanak bani being sung at Golden Temple for which both father and son were regular visitors. He writes in his My Reminiscences (1912): The golden temple of Amritsar comes back to me like a dream. Many a morning have I accompanied my father to this Gurudarbar of the Sikhs in the middle of the lake. There the sacred chanting resounds continually. My father, seated amidst the throng of worshippers, would sometimes add his voice to the hymn of praise, and finding a stranger joining in their devotions they would wax enthusiastically cordial, and we would return loaded with the sanctified offerings of sugar crystals and other sweets.[40] He wrote 6 poems relating to Sikhism and several articles in Bengali children's magazine about Sikhism.[41] Poems on Guru Gobind Singh: নিষ্ফল উপহার Nishfal-upahaar (1888, translated as "Futile Gift"), গুরু গোবিন্দ Guru Gobinda (1899) and শেষ শিক্ষা Shesh Shiksha (1899, translated as "Last Teachings")[41] Poem on Banda Bahadur: বন্দী বীর Bandi-bir (The Prisoner Warrior written in 1888 or 1898)[41] Poem on Bhai Torusingh: প্রার্থনাতীত দান (prarthonatit dan – Unsolicited gift) written in 1888 or 1898[41] Poem on Nehal Singh: নীহাল সিংহ (Nihal Singh) written in 1935.[41] Tagore returned to Jorosanko and completed a set of major works by 1877, one of them a long poem in the Maithili style of Vidyapati. As a joke, he claimed that these were the lost works of newly discovered 17th-century Vaiṣṇava poet Bhānusiṃha.[42] Regional experts accepted them as the lost works of the fictitious poet.[43] He debuted in the short-story genre in Bengali with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[44][45] Published in the same year, Sandhya Sangit (1882) includes the poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall"). Shilaidaha: 1878–1901  Tagore's house in Shilaidaha, Bangladesh Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878.[22] He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton and Hove, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi, the children of Tagore's brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore's sister-in-law, to live with him.[46] He briefly read law at University College London, but again left, opting instead for independent study of Shakespeare's plays Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra and the Religio Medici of Thomas Browne. Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored kirtans and tappas and Brahmo hymnody was subdued.[22][47] In 1880 he returned to Bengal degree-less, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each.[48] After returning to Bengal, Tagore regularly published poems, stories, and novels. These had a profound impact within Bengal itself but received little national attention.[49] In 1883 he married 10-year-old[50] Mrinalini Devi, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902 (this was a common practice at the time). They had five children, two of whom died in childhood.[51]  Tagore family boat (bajra or budgerow), the "Padma". In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his Manasi poems (1890), among his best-known work.[52] As Zamindar Babu, Tagore criss-crossed the Padma River in command of the Padma, the luxurious family barge (also known as "budgerow"). He collected mostly token rents and blessed villagers who in turn honoured him with banquets—occasionally of dried rice and sour milk.[53] He met Gagan Harkara, through whom he became familiar with Baul Lalon Shah, whose folk songs greatly influenced Tagore.[54] Tagore worked to popularise Lalon's songs. The period 1891–1895, Tagore's Sadhana period, named after one of his magazines, was his most productive;[29] in these years he wrote more than half the stories of the three-volume, 84-story Galpaguchchha.[44] Its ironic and grave tales examined the voluptuous poverty of an idealised rural Bengal.[55] Santiniketan: 1901–1932 Main article: Middle years of Rabindranath Tagore Posed group black-and-white photograph of seven Chinese men, possibly academics, in formal wear: two wear European-style suits, the five others wear Chinese traditional dress; four of the seven sit on the floor in the foreground; another sits on a chair behind them at centre-left; two others stand in the background. They surround an eighth man who is robed, bearded, and sitting in a chair placed at centre-left. Four elegant windows are behind them in a line.  Tsinghua University, 1924 In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—The Mandir—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, a library.[56] There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewellery, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties.[57] He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) and translated poems into free verse. In 1912, Tagore translated his 1910 work Gitanjali into English. While on a trip to London, he shared these poems with admirers including William Butler Yeats and Ezra Pound. London's India Society published the work in a limited edition, and the American magazine Poetry published a selection from Gitanjali.[58] In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year's Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focused on the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings.[59] He was awarded a knighthood by King George V in the 1915 Birthday Honours, but Tagore renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre.[60] Renouncing the knighthood, Tagore wrote in a letter addressed to Lord Chelmsford, the then British Viceroy of India, "The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments...The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my countrymen."[61][62] In 1919, he was invited by the president and chairman of Anjuman-e-Islamia, Syed Abdul Majid to visit Sylhet for the first time. The event attracted over 5000 people.[63] In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the "Institute for Rural Reconstruction", later renamed Shriniketan or "Abode of Welfare", in Surul, a village near the ashram. With it, Tagore sought to moderate Gandhi's Swaraj protests, which he occasionally blamed for British India's perceived mental – and thus ultimately colonial – decline.[64] He sought aid from donors, officials, and scholars worldwide to "free village[s] from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis[ing] knowledge".[65][66] In the early 1930s he targeted ambient "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability. He lectured against these, he penned Dalit heroes for his poems and his dramas, and he campaigned—successfully—to open Guruvayoor Temple to Dalits.[67][68] Twilight years: 1932–1941  In Germany, 1931  Last picture of Rabindranath, 1941 Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic litterateur". It affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that "Our Prophet has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm ..." Tagore confided in his diary: "I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity."[69] To the end Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic karma, as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious implications.[70] He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal and detailed this newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar.[71][72] Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them prose-poem works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose-songs and dance-dramas— Chitra (1914), Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938)— and in his novels— Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934).[73] Clouds come floating into my life, no longer to carry rain or usher storm, but to add color to my sunset sky. —Verse 292, Stray Birds, 1916. Tagore's remit expanded to science in his last years, as hinted in Visva-Parichay, a 1937 collection of essays. His respect for scientific laws and his exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy informed his poetry, which exhibited extensive naturalism and verisimilitude.[74] He wove the process of science, the narratives of scientists, into stories in Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941). His last five years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for a time. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. Poetry from these valetudinary years is among his finest.[75][76] A period of prolonged agony ended with Tagore's death on 7 August 1941, aged 80.[23] He was in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he grew up.[77][78] The date is still mourned.[79] A. K. Sen, brother of the first chief election commissioner, received dictation from Tagore on 30 July 1941, a day before a scheduled operation: his last poem.[80] I'm lost in the middle of my birthday. I want my friends, their touch, with the earth's last love. I will take life's final offering, I will take the human's last blessing. Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return, if I receive anything—some love, some forgiveness—then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end. Travels  Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore, February 1940 Our passions and desires are unruly, but our character subdues these elements into a harmonious whole. Does something similar to this happen in the physical world? Are the elements rebellious, dynamic with individual impulse? And is there a principle in the physical world that dominates them and puts them into an orderly organization? — Interviewed by Einstein, 14 April 1930.[81]  Rabindranath with Einstein in 1930 Group shot of dozens of people assembled at the entrance of an imposing building; two columns in view. All subjects face the camera. All but two are dressed in lounge suits: a woman at front-center wears light-coloured Persian garb; the man to her left, first row, wears a white beard and dark-coloured oriental cap and robes.  At the Iranian Majlis (parliament) in Tehran, Iran, 1932 Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents.[82] In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others.[83] Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States[84] and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews's clergymen friends.[85] From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan[86] and the United States.[87] He denounced nationalism.[88] His essay "Nationalism in India" was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland and other pacifists.[89] Shortly after returning home, the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged US$100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits.[90] A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires,[91] an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini in Rome.[92] Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon Il Duce's fascist finesse.[93] He had earlier enthused: "[w]without any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigor in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo's chisel." A "fire-bath" of fascism was to have educed "the immortal soul of Italy ... clothed in quenchless light".[94] On 1 November 1926 Tagore arrived in Hungary and spent some time on the shore of Lake Balaton in the city of Balatonfüred, recovering from heart problems at a sanitarium. He planted a tree, and a bust statue was placed there in 1956 (a gift from the Indian government, the work of Rasithan Kashar, replaced by a newly gifted statue in 2005) and the lakeside promenade still bears his name since 1957.[95] On 14 July 1927, Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia. They visited Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The resultant travelogues compose Jatri (1929).[96] In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Upon returning to Britain—and as his paintings were exhibited in Paris and London—he lodged at a Birmingham Quaker settlement. He wrote his Oxford Hibbert Lectures[c] and spoke at the annual London Quaker meet.[97] There, addressing relations between the British and the Indians – a topic he would tackle repeatedly over the next two years – Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness".[98] He visited Aga Khan III, stayed at Dartington Hall, toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then went on into the Soviet Union.[99] In April 1932 Tagore, intrigued by the Persian mystic Hafez, was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi.[100][101] In his other travels, Tagore interacted with Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Romain Rolland.[102][103] Visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Sri Lanka (in 1933) composed Tagore's final foreign tour, and his dislike of communalism and nationalism only deepened.[69] Vice-president of India M. Hamid Ansari has said that Rabindranath Tagore heralded the cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations much before it became the liberal norm of conduct. Tagore was a man ahead of his time. He wrote in 1932, while on a visit to Iran, that "each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and needs, but the lamp they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge."[104] |

生涯と出来事 初期:1861-1878年 主な記事 ラビンドラナート・タゴールの生い立ち  1879年、ロンドンでの若きタゴール この2日間、嵐が吹き荒れていた。私の歌「Jhaurojhauro borishe baridhara」の描写と同じような嵐が吹き荒れていた......その中、汽船の屋根の上に立っている、上からつま先までずぶ濡れになった哀れな ホームレスの男がいた......この2日間、私は何度も何度もこの歌を歌っていた......。 ...)その結果、激しい雨の音、風の慟哭、波打つゴライ川の音、[...]が新鮮な生命を宿し、新しい言葉を見つけ、私は目の前で繰り広げられるこの新 しい音楽劇の主役になったような気がした。 - インディラ・デヴィへの手紙 [22]。 現存する13人の子供の末っ子であるタゴール(愛称「ラビ」)は、デベンドラナート・タゴール(1817-1905)とサラダ・デヴィ(1830- 1875)の息子として、1861年5月7日にカルカッタの ジョラサンコ邸で生まれた[23]。  タゴールと妻のムリナリニ・デヴィ、1883年 タゴールは幼少期に母を亡くし、父は広く旅をしていた[29]。タゴール家は ベンガル・ルネッサンスの最前線にいた。タゴール一家はベンガル・ルネッサンスの最前線にいた。文学雑誌の出版を主催し、演劇やベンガル音楽と西洋古典音 楽のリサイタルが定期的に催された。タゴールの父は、何人かのプロのドラパド音楽家を家に招き、子供たちにインド古典音楽を教えた[30]。もう一人の 兄、サティ ンドラナートは、エリートであり、かつてはヨーロッパ人ばかりであったインド民 族公務員に任命された最初のインド人であった。妹のスワルナクマリは小説家になった[32]。ジョティリンドラナートの妻カダンバリ・デヴィはタゴールよ り少し年上で、親しい友人であり、強い影響力を持った。結婚直後の1884年に彼女が突然自殺したことで、タゴールは何年にもわたり深く取り乱すことにな る[33]。 兄のヘーメンドラナートは、タゴールにガンジス川を泳がせたり、丘陵をトレッキングさせたり、体操をさせたり、柔道やレスリングの練習をさせたりして、家 庭教師をし、体を鍛えさせた。タゴールは正式な教育を嫌っており、地元のプレスティデンシー・カレッジで学問に励んだのは1日だけであった[36]。数年 後、彼は適切な教育は物事を説明するものではなく、適切な教育は好奇心をかき立てるものだと考えていた[37]。 11歳でウパナヤン(成人の儀式)を受けた後、タゴールは1873年2月に父とともにカルカッタを出発し、数ヶ月間インドを巡り、父の所有するサンティニ ケタンの地所やアムリトサルを訪れた後、ヒマラヤの 丘陵地 ダルハウジーに到着した。そこでタゴールは伝記を読み、歴史、天文学、近代科学、サンスクリット語を学び、カーリダーサの古典詩を研究した[38] [39]。1873年にアムリトサールに1ヶ月滞在した際、父子ともに定期的に訪れていたゴールデン・テンプルで歌われていたメロディアスなグルバニとナ ナーク・バニに大きな影響を受けた。彼は『私の回想』(1912年)の中でこう書いている: アムリトサルの黄金寺院が夢のように蘇ってくる。湖の真ん中にあるこのシーク教徒のグルダルバールには、何度も父と一緒に朝を迎えた。そこでは聖なる聖歌 が絶え間なく響き渡っている。父は参拝者の群れの中に座り、賛美の讃美歌に自分の声を加えることもあった。見知らぬ人が彼らの献身に加わっているのを見つ けると、彼らは熱狂的に親しみを示し、私たちは砂糖の結晶やその他のお菓子という神聖な供え物を積んで帰ってきた[40]。 彼はシク教に関連する6編の詩を書き、ベンガル語の子供向け雑誌にシク教に関する記事をいくつか書いた[41]。 バイ・トルシンゲに関する詩:1888年または1898年に書かれた『prarthonatit dan - Unsolicited gift』[41]。 ネハール・シンについての詩:1935年に書かれた『ニハール・シン(Nihal Singh)』[41]。 ジョロサンコに戻ったタゴールは、1877年までに一連の大作を完成させた。地域の専門家たちは、それらを架空の詩人の失われた作品として認めた [42]。 [同年出版されたSandhya Sangit(1882)には詩 "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga"(「滝の轟き」)が収められている[43]。 シライダハ:1878-1901  バングラデシュ、シライダハのタゴールの家 デベンドラナートは息子に法廷弁護士になってほしかったため、タゴールは1878年にイギリスのイースト・サセックス州ブライトンのパブリック・スクール に入学した[22]。1877年には、タゴールの兄サティンドラナートの子供である甥と姪のシュレンとインディラ・デヴィが、母親(タゴールの義理の姉) と一緒にタゴールの家に住むことになった。 [46] ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンで短期間法律を学んだが、再び退学し、代わりにシェイクスピアの戯曲 『コリオレイナス』、『アントニーとクレオパトラ』 、 トマス・ブラウンの『レリジオ・メディチ』を独習した。1880年、タゴールは学位なしでベンガルに戻り、ヨーロッパの斬新さとブラフモの伝統を調和さ せ、それぞれの長所を取り入れることを決意した[48]。1883年、タゴールは1873-1902年生まれの10歳[50]のムリナリニ・デヴィと結婚 する(当時はこれが一般的であった)。2人の間には5人の子供がいたが、そのうち2人は幼少期に亡くなっている[51]。  タゴール家のボート(バジュラまたはブッジェロー)、「パドマ号」。 1890年、タゴールはシェライダハ(現在のバングラデシュの一地域)にある広大な先祖伝来の土地を管理し始めた。1898年には妻と子供たちがそこに加 わった。ザミンダル・バブとして、タゴールはパドマ川を横断し、パドマ号という豪華な家船(「バッジャーロー」とも呼ばれる)を操った。タゴールはガガ ン・ハルカラと出会い、彼を通じてバウル・ラロン・シャーと知り合う。1891年から1895年にかけてのタゴールのサダナ期(彼の雑誌のひとつにちなん で名付けられた)は、彼にとって最も生産的な時期であった[29]。この時期に彼は3巻84話からなる『ガルパグチャ』の半分以上の物語を書いた [44]。 サンティニケタン:1901年-1932年 主な記事 ラビンドラナート・タゴールの中年期  清華大学、1924年 1901年、タゴールはサンティニケタンに移り住み、大理石の床の礼拝堂 、マンディール、実験学校、木立、庭園、図書館を備えたアシュラムを設立した[56]。父親は1905年に亡くなった。トリプラのマハラジャからの遺産と 収入、家族の宝飾品の販売、プリの海辺のバンガロー、そして本の印税2,000ルピーを毎月受け取っていた[57]。 1912年、タゴールは1910年の作品『ギタンジャリ』を英訳した。ロンドンへの旅行中、ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツや エズラ・パウンドをはじめとする崇拝者たちとこれらの詩を分かち合った。1913年11月、タゴールはその年のノーベル文学賞を受賞したことを知る。ス ウェーデン・アカデミーは、1912年の『ギタンジャリ:歌の捧げもの』を中心とした、彼の翻訳した小品群の理想主義的で、西洋人にとって親しみやすい性 質を高く評価した。 [1915年の誕生日に国王ジョージ5世から爵位を授与されたが、1919年のジャリアンワラ・バグの虐殺事件の後、タゴールは爵位を返上した。 [爵位を放棄したタゴールは、当時の英国インド総督であったチェルムスフォード卿に宛てた書簡の中で、「不幸な人々に加えられた刑罰の不釣り合いな厳しさ と、それを実行する方法は、文明政府の歴史において並ぶものがないと確信している。 名誉のバッジが、屈辱という不釣り合いな文脈の中でわれわれの恥をまざまざと見せつけるときが来た。 1919年、彼はAnjuman-e-Islamiaの会長であるSyed Abdul Majidに招かれ、初めてシレットを訪れた。このイベントには5000人以上が集まった[63]。 1921年、タゴールは農業経済学者レナード・エルムハーストとともに、後にシュリニケタン(福祉の住処)と改名される「農村復興研究所」をアシュラム近 くの村スルールに設立した。この研究所によって、タゴールはガンディーの スワラージ抗議を和らげようと努めた。ガンディーは時折、英領インドの精神的、ひいては植民地的な衰退の原因であると非難していた[64]。彼は「知識を 活性化する」ことによって「無力と無知の束縛から村を解放する」ために、世界中の篤志家、役人、学者に援助を求めた[65][66]。彼はこれらに反対す る講義を行い、詩や戯曲にダリットの英雄を登場させ、グルヴァユール寺院をダリットに開放するキャンペーンを行い、成功を収めた[67][68]。 黄昏の時代: 1932-1941  1931年、ドイツにて  ラビンドラナート最後の写真、1941年 ダッタとロビンソンは、この時期のタゴールを「放浪の文学者」と表現している。それは、人間の区分は浅はかであるという彼の意見を裏付けるものであった。 1932年5月、イラクの砂漠にあるベドウィンの野営地を訪れたとき、部族の長が彼に言った。「預言者は、真のムスリムとは、その言動によって、自分の兄 弟である男たちのうち、誰一人として危害を加えることのない者のことであると言われました」。タゴールは日記にこう打ち明けた: 「私は彼の言葉の中に、本質的な人間性の声を認めて驚かされた」[69] 。その年、ビハール州で地震が発生し、何千人もの死者が出た。ガンジーはこれを地震的カルマ、ダリットへの抑圧に復讐する神の報いとして歓迎した。彼はカ ルカッタの恒常的な貧困とベンガルの社会経済的衰退を嘆き、サタジット・レイの映画『Apur Sansar』を予感させるような二重視覚の技法を用いた韻を踏まない百行詩で、この新しく平民的な美学を詳述した[70]。 [散文詩の『Punashcha』(1932年)、『Shes Saptak』(1935年)、『Patraput』(1936年)などがある。散文詩や舞踊劇(Chitra(1914)、Shyama(1939)、 Chandalika(1938))、小説(Dui Bon(1933)、Malancha(1934)、Char Adhyay(1934))でも実験が続けられた[73]。 雲はもはや雨を運ぶためでも嵐を告げるためでもなく、私の夕焼け空に色を添えるために、私の人生に浮かんでくる。 -292節、 『迷い鳥』、1916年。 1937年に出版されたエッセイ集『Visva-Parichay』に示唆されているように、タゴールは晩年、その領域を科学にまで広げた。科学の法則を 尊重し、生物学、物理学、天文学を探求していた彼の詩は、広範な自然主義と臨場感を示していた[74]。科学の過程、科学者たちの物語を『セ』(1937 年)、『ティン・サンギ』(1940年)、『ガルパサルパ』(1941年)の物語に織り込んだ。晩年の5年間は、慢性的な痛みと2度にわたる長い闘病生活 が続いた。1937年末にタゴールが意識を失ったことから始まり、昏睡状態が続き、一時は死に瀕した。1940年末にも同じような状態が続き、そこから回 復することはなかった。1941年8月7日、タゴールは80歳で死去した[23]。彼が育ったジョラサンコ邸の2階の部屋で息を引き取った。 [初代選挙管理委員長の弟であるA・K・センは、予定されていた手術の前日、1941年7月30日にタゴールから口述を受け取った。 私は誕生日の真ん中で道に迷っている。私は友を求め、彼らの触れ合いを求め、地球最後の愛を求める。私は人生の最後の捧げ物を手にする、私は人間の最後の 祝福を手にする。今日、私の袋は空っぽだ。与えるべきものはすべて与えてしまった。その見返りとして、もし私が何かを受け取るなら--何らかの愛、何らか の赦し--言葉のない終わりの祭りへと渡る船に乗るとき、私はそれを持っていくだろう。 旅行記  ネルーとラビンドラナート・タゴール、1940年2月 私たちの情熱や欲望は手に負えないものだが、私たちの性格は、これらの要素を調和ある全体へと鎮める。これと似たようなことが物理的世界でも起こるのだろ うか?元素は反抗的で、個人の衝動によって躍動しているのだろうか?そして物理世界には、それらを支配し、秩序だった組織にする原理があるのだろうか? - 1930年4月14日、アインシュタインによるインタビュー[81]。  1930年、ラビンドラナートとアインシュタイン  1932年、イラン、テヘランの イラン・マジュリス(国会)にて。 1878年から1932年の間に、タゴールは五大陸の30カ国以上に足を踏み入れた[82]。1912年、彼は翻訳作品の束を携えてイギリスに渡り、宣教 師でありガンジーの弟子であったチャールズ・F・アンドリュース、アイルランドの詩人ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ、エズラ・パウンド、ロバート・ブ リッジス、アーネスト・リース、トーマス・スタージ・ムーア等から注目を集めた[83]。1912年11月、タゴールはアメリカ[84]とイギリスのツ アーを開始し、アンドリュースの聖職者の友人とともにスタフォードシャーのバタートンに滞在した[85]。 帰国後まもなく、63歳のタゴールはペルー政府からの招待を受ける。彼はメキシコに旅行した。1924年11月6日にブエノスアイレスに到着してから1週 間後[91]、病気のタゴールはビクトリア・オカンポの要請でミラリオ荘に移った。1925年1月に帰国の途についた。1926年5月、タゴールはナポリ に到着し、その翌日、ローマでムッソリーニに会う: 「間違いなく、彼は偉大な人格者だ。その頭には、ミヒャエル・アンジェロのノミを思わせるような巨大な活力がある」。ファシズムの「火の湯」は「イタリア の不滅の魂......消えない光をまとった」[94]を教育した。 1926年11月1日、タゴールはハンガリーに到着し、バラトンフュレド市のバラトン湖畔で療養生活を送った。彼は木を植え、1956年にはそこに胸像が 置かれ(インド政府からの寄贈、ラシタン・カシャールの作品、2005年に新たに寄贈された像に置き換えられた)、湖畔の遊歩道には1957年以来、彼の 名前が今も刻まれている[95]。 1927年7月14日、タゴールは2人の仲間と4ヶ月間の東南アジアのツアーを開始した。彼らはバリ、ジャワ、クアラルンプール、マラッカ、ペナン、シャ ム、シンガポールを訪れた。その旅行記が『Jatri』(1929年)を構成している[96]。1930年初頭、彼はベンガルを離れ、ヨーロッパとアメリ カを1年近くかけて巡った。イギリスに戻ると、パリとロンドンで彼の絵画が展示されたため、バーミンガムのクエーカー教徒の集落に下宿した。そこでタゴー ルは、イギリス人とインド人の関係--その後2年間に渡って繰り返し取り組むことになるテーマである--を取り上げ、「飄々とした暗い溝」について語った [98]。 [1932年4月、ペルシアの神秘主義者ハーフェズに興味を持ったタゴールは、レザー・シャー・パーラヴィーの接待を受ける。 [1932年4月、ペルシャの神秘主義者ハーフェズに興味を抱いたタゴールは、レザ・シャー・パフラヴィーに謁見する[99]。 [インドのM.ハミド・アンサリ副大統領は、ラビンドラナート・タゴールは、コミュニティ、社会、国家間の文化的和解がリベラルな行動規範となるはるか以 前に、その先駆けであったと述べている。タゴールは時代を先取りした人物だった。彼は1932年、イランを訪問した際に、「アジアのそれぞれの国は、その 強さ、性質、必要性に応じて、それぞれの歴史的問題を解決していくだろうが、それぞれが進歩への道を歩む際に携える灯火は、知識という共通の光線を照らす ために収束していくだろう」と書いている[104]。 |

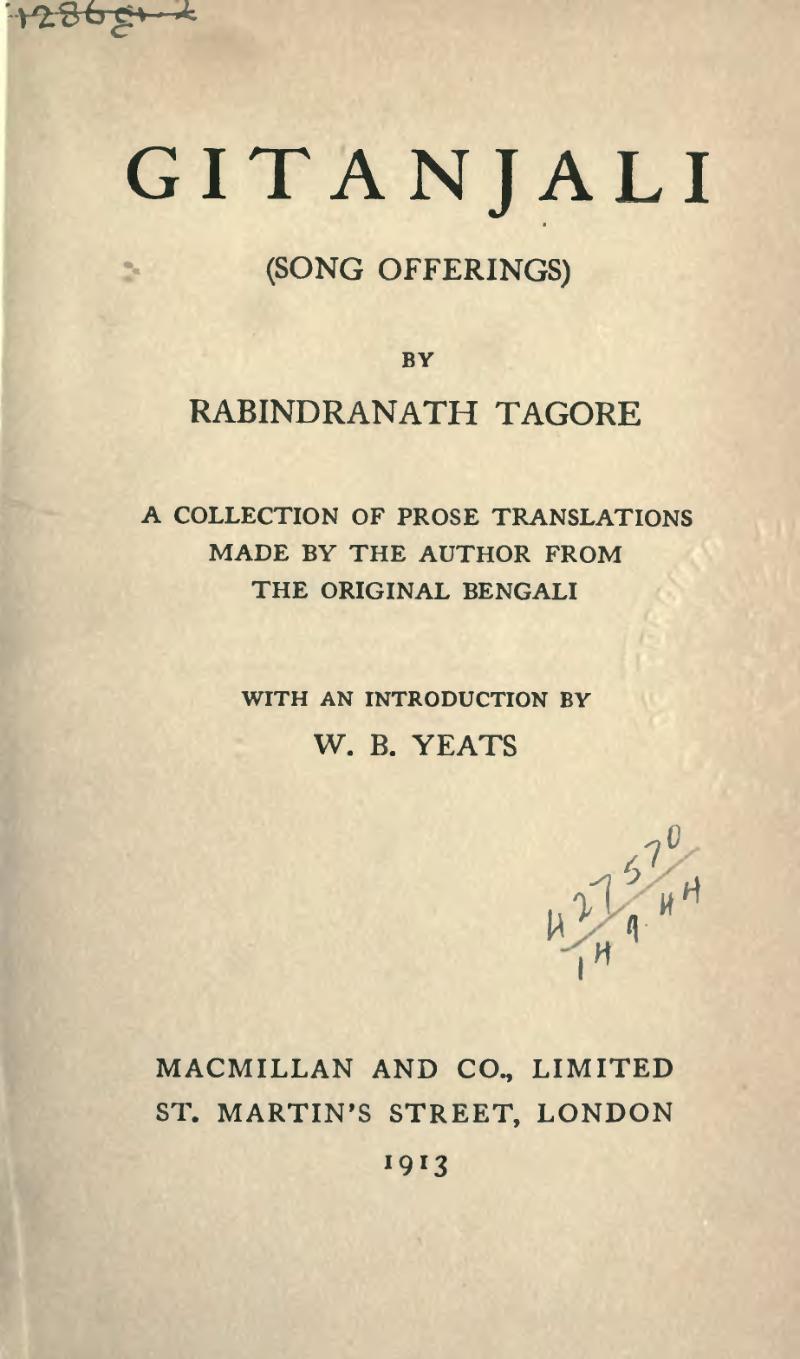

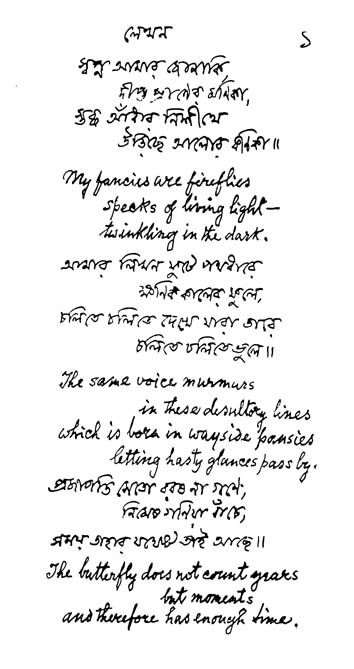

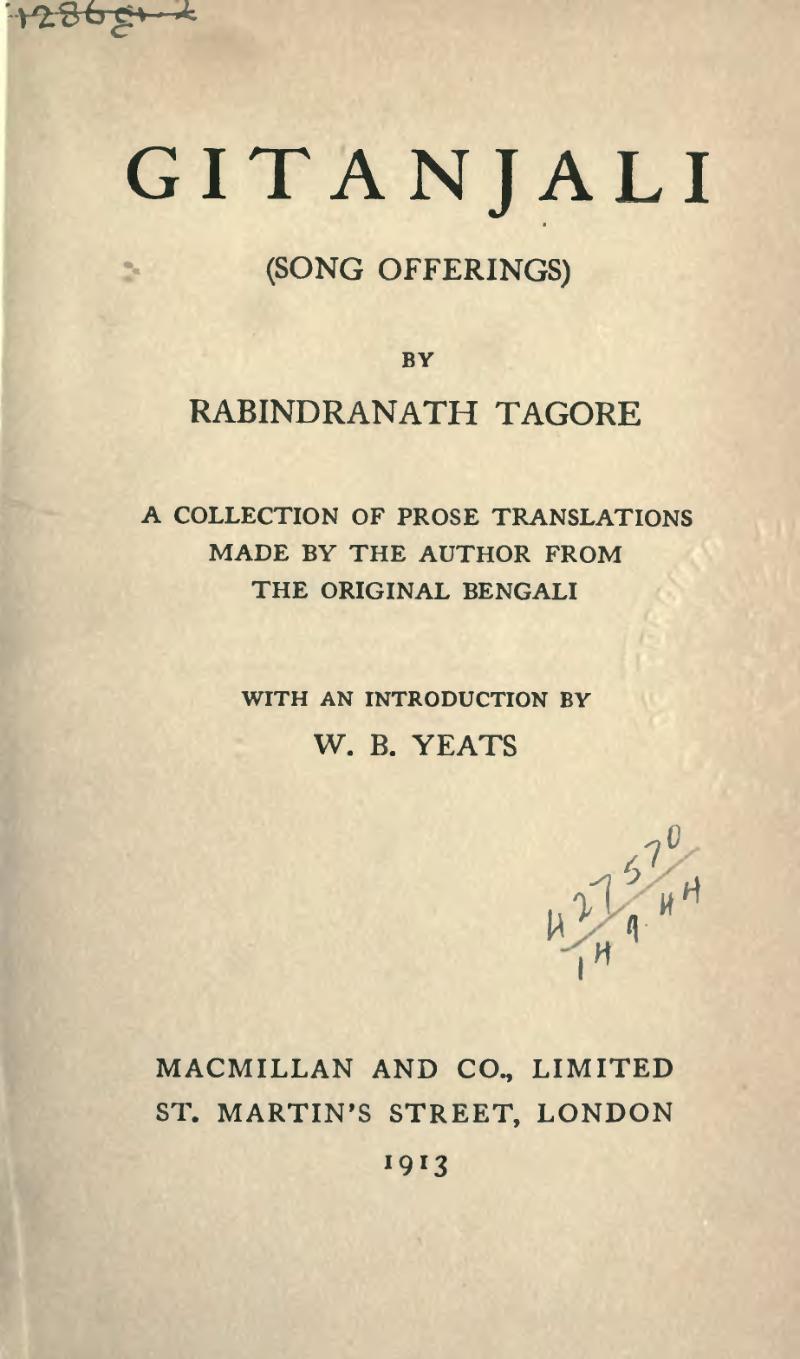

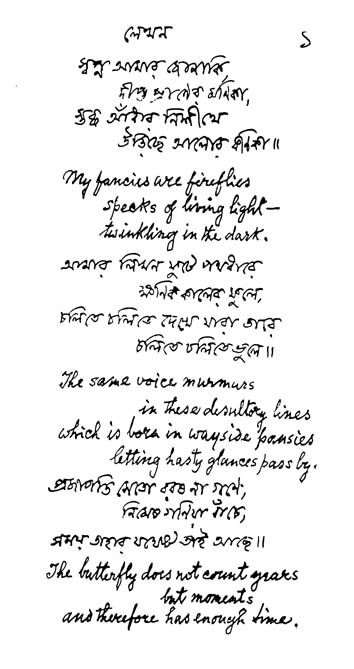

| Works Main article: Works of Rabindranath Tagore Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps the most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from the lives of common people. Tagore's non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Patro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, "Note on the Nature of Reality", is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore's 150th birthday, an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes.[105] In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore's works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore's birth.[106] Drama  Tagore performing the title role in Valmiki Pratibha (1881) with his niece Indira Devi as the goddess Lakshmi Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty – Valmiki Pratibha which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote Visarjan (an adaptation of his novella Rajarshi), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play Dak Ghar (The Post Office; 1912), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall[ing] asleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds".[107][108] Another is Tagore's Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha's disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.[109] In Raktakarabi ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders") is an allegorical struggle against a kleptocrat king who rules over the residents of Yaksha puri.[110] Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya. Short stories  Cover of the Sabuj Patra magazine, edited by Pramatha Chaudhuri Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[111] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[112] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[111] Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "Sadhana" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings.[111] There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[113] In particular, such stories as "Kabuliwala" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atithi" ("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[114] Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.[111] Novels Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)—through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil's—likely mortal—wounding.[115] Gora raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle.[116] In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora—"whitey". Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a "true dialectic" advancing "arguments for and against strict traditionalism", it tackles the colonial conundrum by "portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame [...] not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy but the extremist reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share." Among these Tagore highlights "identity [...] conceived of as dharma."[117] In Jogajog (Relationships), the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of Śiva-Sati, exemplified by Dākshāyani—is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roué of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; pathos depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honor; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal's putrescent landed gentry.[118] The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families—the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas' sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations. Others were uplifting: Shesher Kobita—translated twice as Last Poem and Farewell Song—is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: "Rabindranath Tagore". Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by Ray and others: Chokher Bali and Ghare Baire are exemplary. In the first, Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness. Tagore wrote of it: "I have always regretted the ending".[citation needed] Poetry  Title page of the 1913 Macmillan edition of Tagore's Gitanjali Three-verse handwritten composition; each verse has original Bengali with English-language translation below: "My fancies are fireflies: specks of living light twinkling in the dark. The same voice murmurs in these desultory lines, which is born in wayside pansies letting hasty glances pass by. The butterfly does not count years but moments, and therefore has enough time."  Part of a poem written by Tagore in Hungary, 1926 Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and the second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after Theodore Roosevelt.[119] Besides Gitanjali, other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori ("Golden Boat"), Balaka ("Wild Geese" – the title being a metaphor for migrating souls)[120] Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen.[121] Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon.[122][123] These, rediscovered and re-popularized by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy.[124][125] During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the jeevan devata—the demiurge or the "living God within".[22] This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which was repeatedly revised over seventy years.[126][127] Later, with the development of new poetic ideas in Bengal – many originating from younger poets seeking to break with Tagore's style – Tagore absorbed new poetic concepts, which allowed him to further develop a unique identity. Examples of this include Africa and Camalia, which are among the better-known of his latter poems. Songs (Rabindra Sangeet) Tagore was a prolific composer with around 2,230 songs to his credit.[128] His songs are known as rabindrasangit ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricized. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.[129] They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully, others newly blended elements of different ragas.[130] Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavors "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.[22] Rabindranath Tagore reciting Jana Gana Mana In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written – ironically – to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised form of Bengali,[131] and is the first of five stanzas of the Brahmo hymn Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress[132] and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem. Sri Lanka's National Anthem was inspired by his work.[18] For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs".[133] Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.[130] Art works Black-and-white photograph of a stylised sketch depicting a tribal funerary mask.  Primitivism: a pastel-coloured rendition of a Malagan mask from northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea Black-and-white close-up photograph of a piece of wood boldly painted in unmixed solid strokes of black and white in a stylised semblance to "ro" and "tho" from the Bengali syllabary.  Tagore's Bengali-language initials, the letters র and ঠ, are worked into this "Ro-Tho" (of RAbindranath THAkur) wooden seal, stylistically similar to designs used in traditional Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Tagore often embellished his manuscripts with such art.[134] At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[135]—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red, green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by numerous styles, including scrimshaw by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein.[134] His artist's eye for handwriting was revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore's lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.[22] Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, playwriting and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadish Chandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily." He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[136]  Face of a woman, inspired by Kadambari Devi.[137] Ink on paper. National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi India's National Gallery of Modern Art lists 102 works by Tagore in its collections.[138][139] In 1937, Tagore's paintings were removed from Berlin's baroque Crown Prince Palace by the Nazi regime and five were included in the inventory of "degenerate art" compiled by the Nazis in 1941–1942.[140] |

作品 主な記事 ラビンドラナート・タゴールの作品 タゴールは主に詩で知られるが、小説、エッセイ、短編小説、旅行記、ドラマ、そして何千もの歌を書いた。タゴールの散文の中で、おそらく最も高く評価され ているのは短編小説であり、ベンガル語版の短編小説を創始したと言われている。彼の作品は、リズミカルで、楽観的で、叙情的であることがよく指摘される。 このような物語は、ほとんどが庶民の生活を借用している。タゴールのノンフィクションは歴史、言語学、精神性に取り組んでいる。自伝も書いた。旅行記、 エッセイ、講演は、『ヨーロッパからの手紙 』(Europe Jatrir Patro)、『人間の宗教』(Manusher Dhormo)など数冊にまとめられている。アインシュタインとの短い会話「現実の本質についてのノート」は、後者の付録として収録されている。現在、タ ゴールの生誕150周年を記念して、彼の全著作を年代順にベンガル語でまとめたアンソロジー(『Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali』)が出版されている。2011年、ハーヴァード大学出版局はヴィスヴァ・バーラティ大学と共同で、タゴール作品の英語版としては 最大規模のアンソロジーであるThe Essential Tagoreを出版した。 ドラマ  ヴァルミキ・プラティバ』(1881年)でタイトルロールを演じるタゴール。 タゴールの演劇経験は、16歳のときに兄のジョティリンドラナートと始めた。20歳の時に初めてオリジナルの戯曲を書き、ヴァルミキ・プラティバとしてタ ゴールの邸宅で上演された。タゴールは、自分の作品は「行動ではなく、感情の戯れ」を表現するものだと述べている。1890年に書いた 『Visarjan』(小説『Rajarshi』の翻案)は、彼の最高傑作とされている。原語のベンガル語では、このような作品には複雑なサブプロットや 長大なモノローグが含まれていた。その後、タゴールの戯曲はより哲学的で寓話的なテーマを用いるようになった。Dak Ghar(郵便局、1912年)という戯曲では、子供のアマルが窮屈で幼稚な窮屈さに逆らい、最終的に「眠りに落ちる」様子が描かれているが、これは彼の 肉体的な死を暗示している。ボーダーレスな魅力を持つ物語で、ヨーロッパで絶賛された。ダク・ガールは、タゴールの言葉を借りれば、「ため込まれた富と認 証された信条の世界」からの「精神的自由」として死を扱った。 [107][108]もうひとつはタゴールの『チャンダリカ(不可触民の少女)』で、ゴータマ・ブッダの弟子であるアーナンダが 部族の少女に水を求める様子を描いた古代仏教の伝説をモデルにしている[109]。『ラクタカラビ(「赤」または「血の夾竹桃」)』は、ヤクシャ プリの住民を支配するクレプトクラットの王に対する寓話的な闘争である[110]。 Chitrangada』、『Chandalika』、『Shyama』は、ダンス・ドラマ化された他の重要な戯曲であり、これらは合わせて Rabindra Nritya Natyaとして知られている。 短編集  プラマータ・チャウドゥリー編集のSabuj Patra誌の表紙 1891年から1895年までの4年間は、タゴールの「サダナ」期(タゴールの雑誌のひとつにちなんで名付けられた)として知られている。この時期はタ ゴールにとって最も豊饒な時期のひとつであり、3巻からなる『ガルパグチャ』に収録されている物語の半分以上を生み出した。これらの特徴は、タゴール家の 広大な土地を管理する傍ら、パティサール、シャジャドプル、シライダなどの庶民的な村でのタゴールの生活と密接に結びついていた。 [そこで彼はインドの貧しい庶民の生活を目の当たりにし、タゴールはそれまでのインド文学にはない深い洞察と感覚で彼らの生活を考察するようになった。 [特に、「カブリワラ」(「カブールの果物屋」、1892年出版)、「クシュディタ・パシャン」(「飢えた石」、1895年8月)、「アティティ」(「逃 亡者」、1895年)などの物語は、このような虐げられた人々への分析的な焦点を代表するものであった。 [他のガルパグチャの物語の多くは、1914年から1917年までのタゴールのサブジ・パトラ時代に書かれた。 小説 タゴールは8つの小説と4つのノヴェラを書いており、その中にはChaturanga、Shesher Kobita、Char Odhay、Noukadubiなどがある。理想主義的なザミンダールの主人公ニヒルを通して、台頭するインド・ナショナリズム、テロリズム、スワデシ運 動における宗教的熱意を糾弾した『家と世界』は、タゴールの葛藤する心情を率直に表現したもので、1914年の鬱病の発作から生まれた。この小説は、ヒン ドゥー教徒とイスラム教徒の暴力とニキルの致命傷で終わる[115]。 ゴーラ』は、インド人のアイデンティティに関する論争的な問題を提起している。Ghare Baire』と同様に、自己同一性(jāti)、個人の自由、宗教の問題が、家族の物語と三角関係の中で展開される[116]。この小説では、セポイの反 乱で孤児となったアイルランド人の少年が、ヒンドゥー教徒にゴーラ(「白人」)として育てられる。自分の出自が外国であることを知らない彼は、先住民であ るインド人への愛と、覇権主義者である同胞に対する彼らとの連帯感から、ヒンドゥー教の宗教的背信者を懲らしめる。彼はブラフモ教徒の少女と恋に落ち、心 配する養父に自分の失われた過去を明かし、土着主義への熱意を止めさせる。厳格な伝統主義に対する賛否両論」を展開する「真の弁証法」として、この作品は 「特定の枠の中のあらゆる立場の価値を描く」ことによって、植民地時代の難問に取り組んでいる。これらの中でタゴールは「ダルマとして考えられたアイデン ティティ[...]」を強調している[117]。 ジョガジョグ』(『人間関係』)では、ヒロインのクムディニーは、ダークシャイヤニーに代表されるシヴァ=サティの理想に縛られ、進歩的で慈悲深い兄の沈 みゆく運命を憐れむ気持ちと、その仇である夫との間で揺れ動く。タゴールはフェミニズムへの傾倒を誇示し、妊娠、義務、家族の名誉に囚われた女性の苦境と 最終的な終焉をペーソスで描き、同時にベンガルの腐敗した地主階級をトラックで描いている。ビプロダスの妹であるクムディニは、マドゥスダンに嫁ぐことに なり、両者の板挟みになる。ビプロダスの妹クムディニは、マドゥスダンに嫁ぐことになるのだが、クムディニは伝統的な家庭で育った。 他の女性たちも高揚していた: Shesher Kobita』(『最後の詩』『別れの歌』と二度訳されている)は、詩人である主人公の詩とリズミカルな文章で構成された、彼の最も叙情的な小説である。 風刺とポストモダニズムの要素を含み、古く、時代遅れで、抑圧的に有名な詩人の評判を嬉々として攻撃する登場人物がいる。彼の小説は、彼の作品の中でも最 も評価の低いもののひとつに数えられているが、レイらによる映画化によって再び注目されている: Chokher Bali』と『Ghare Baire』はその典型である。最初の作品では、タゴールはベンガル社会を、自分ひとりのために生きようとする反抗的な未亡人というヒロインを通して描き 出している。再婚を許されず、隠遁と孤独に追いやられた未亡人の側に、永久に喪に服す風習を説いている。タゴールはそれについてこう書いている: 「私はいつもその結末を後悔している」[要出典]。 詩  タゴールの『ギタンジャリ』1913年マクミラン版のタイトルページ  1926年、タゴールがハンガリーで書いた詩の一部 国際的には、『ギタンジャリ』(ベンガル語: গীাঞ্লি)はタゴールの詩集の中で最もよく知られており、1913年にノーベル文学賞を受賞している。ヨーロッパ人以外でノーベル文学賞を受賞した のはタゴールが初めてであり、ヨーロッパ人以外ではセオドア・ルーズベルトに次いで2人目である[119]。 ギタンジャリ以外の代表作には、マナシー、ソナール・トリ(「黄金の舟」)、バラカ(「雁」-タイトルは移動する魂の比喩)などがある[120]。 15~16世紀のヴァイシュナヴァ派の詩人たちによって確立された系譜を受け継ぐタゴールの詩風は、古典的な形式主義から滑稽、幻視、恍惚まで幅広い。タ ゴールの最も革新的で成熟した詩は、吟遊詩人ラロンのような神秘的なバウル・バラッドを含むベンガルの農村民謡に触れたことを体現している[122] [123]。 [タゴールによって再発見され再人気となったこれらのバラッドは、19世紀のカルターバジャーの賛美歌に似ており、内面的な神性を強調し、ブルジョア的な バドラロックの宗教的・社会的正統性への反抗を強調している。 [124][125]シェライダハ時代には、彼の詩はモナー・マヌーシュ(バウルスの「心の中の人間」、タゴールの「深い奥底の生命力」)の抒情的な声、 あるいはジーヴァン・デーヴァタ(デミウルゲ、「内なる生ける神」)の瞑想の声を帯びていた[22]。このようなツールは、70年以上にわたって繰り返し 改訂されたラーダ =クリシュナのロマンスを綴った彼の詩『Bhānusiṃha』において使用された[126][127]。 その後、ベンガルでは新しい詩的思想が発展し、その多くはタゴールの作風を打破しようとする若い詩人たちから生まれたものであったが、タゴールは新しい詩 的概念を吸収し、独自のアイデンティティをさらに発展させることができた。その例として、彼の後期の詩の中でも特によく知られている『アフリカ』や『カマ リア』などが挙げられる。 歌曲(ラビンドラ・サンゲート) タゴールは多作な作曲家であり、およそ2,230曲の歌曲を残している[128]。彼の歌曲はラビンドラサンギット(「タゴールの歌」)として知られ、そ のほとんどが小説、物語、戯曲の詩や一部であり、彼の文学と流動的に融合している。ヒンドゥスターニー音楽のトゥムリ・スタイルの影響を受け、初期の悲歌 のようなブラフモの献身的な賛美歌から、擬似エロティックな曲まで、人間の感情のあらゆる領域に及んでいる[129]。ある曲は与えられたラーガのメロ ディとリズムを忠実に模倣し、またある曲は異なるラーガの要素を新たに融合させた[130]。しかし、彼の作品の約9/10はバンガ・ガーンではなく、西 洋、ヒンドゥスターニー、ベンガルの民謡、その他タゴール自身の祖先文化に「外在する」地域の特色を厳選して「新鮮な価値」をもって刷新された楽曲群で あった[22]。 ジャナ・ガナ・マナを朗読するラビンドラナート・タゴール 1971年、アマール・ショナー・バングラは バングラデシュの国歌となった。この歌は、皮肉なことに、1905年のベンガル分割に抗議するために作られた。ヒンドゥー教徒が支配する西ベンガルから、 イスラム教徒が支配する東ベンガルを切り離すことで、地域の血の惨禍を避けるためだった。タゴールは、この分割を独立運動を阻止するための狡猾な計画とみ なし、ベンガルの団結とタール共産主義を再燃させることを目指した。ジャナ・ガナ・マナは、ベンガル語のサンスクリット化された形式であるシャドゥ・バ シャで書かれ[131]、タゴールが作曲したブラフモ讃歌バロット・バギョ・ビダータの5つのスタンザのうちの最初のものである。1911年にインド国民 会議のカルカッタ会議で初めて歌われ[132]、1950年にインド共和国の制憲議会で国歌として採択された。 スリランカの国歌は彼の作品に触発されたものである[18]。 ベンガル人にとって、タゴールの詩さえも凌ぐと評される情感の強さと美しさの組み合わせに由来するこの歌の魅力は、モダン・レビュー誌が「ラビンドラナー トの歌が歌われない、あるいは少なくとも歌おうとしない文化的な家はベンガルにはない。タゴールはシタールの巨匠ヴィラヤト・カーンや サロディヤのブッダデヴ・ダスグプタやアムジャド・アリー・カーンに影響を与えた[130]。 芸術作品  原始主義:パプアニューギニア、ニューアイルランド北部のマラガンの仮面をパステルカラーで表現したもの。  タゴールのベンガル語の頭文字である「ঠ」と「ঠ」は、この「Ro-Tho」(RAbindranath THAkurの)木製の印章に彫られている。タゴールはしばしばこのようなアートで原稿を飾った[134]。 南仏で出会った芸術家たち[135]の勧めでパリでデビューした彼の多くの作品の展覧会は、ヨーロッパ全土で開催され成功を収めた。彼はおそらく赤と緑の 色盲であったため、奇妙な配色と奇抜な美学を示す作品が生まれた。タゴールは、パプアニューギニア、ニューアイルランド北部のマランガン族によるスクリム ショウ、北米太平洋岸北西部のハイダ族の彫刻、ドイツ人マックス・ペヒシュタインによる木版画など、数多くの様式から影響を受けている[134]。彼の手 書き文字に対する芸術家の目は、彼の原稿の走り書き、クロスアウト、単語レイアウトを飾るシンプルで芸術的かつリズミカルなライトモチーフに現れている。 タゴールの歌詞のいくつかは、共感覚的な意味で特定の絵画と呼応していた[22]。 何人かの画家に囲まれていたラビンドラナートは、いつも絵を描きたいと思っていた。文章を書いたり、音楽を演奏したり、劇を書いたり、演技をしたりするこ とは、家族の他の何人かがそうであったように、ほとんど訓練することなく、自然に、そしてさらに大きな規模で、彼にもたらされた。しかし、絵を描くことは できなかった。しかし、彼は何度もこの芸術を習得しようと試みた。例えば1900年、40歳を間近に控え、すでに著名な作家となっていた彼は、ジャガ ディッシュ・チャンドラ・ボースにこう書いている。言うまでもないが、この絵はパリのサロンに飾るためのものではなく、どこかの国のナショナル・ギャラ リーが突然、この絵を手に入れるために増税を決定するのではないかという疑念を抱かせるものでもない。しかし、母親が最も醜い息子に惜しみない愛情を注ぐ ように、私は自分に最も馴染みにくい技術に密かに惹かれているのだ」。彼はまた、自分が鉛筆よりも消しゴムを使っていることに気づき、その結果に不満を抱 いて、画家になるのは自分には向いていないと判断し、ついに撤退した[136]。  カダンバリ・デヴィに触発された女性の顔[137]紙にインク。ニューデリー国立近代美術館 インドの国立近代美術館は、タゴールの102点の作品を所蔵している[138][139]。 1937年、タゴールの絵画はナチス政権によってベルリンのバロック様式の皇太子宮殿から撤去され、5点が1941年から1942年にかけてナチスによっ て編纂された「退廃芸術」の目録に含まれている[140]。 |

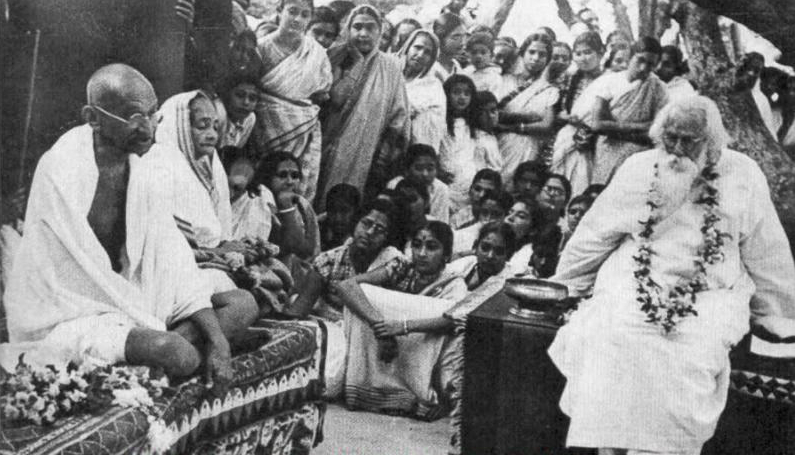

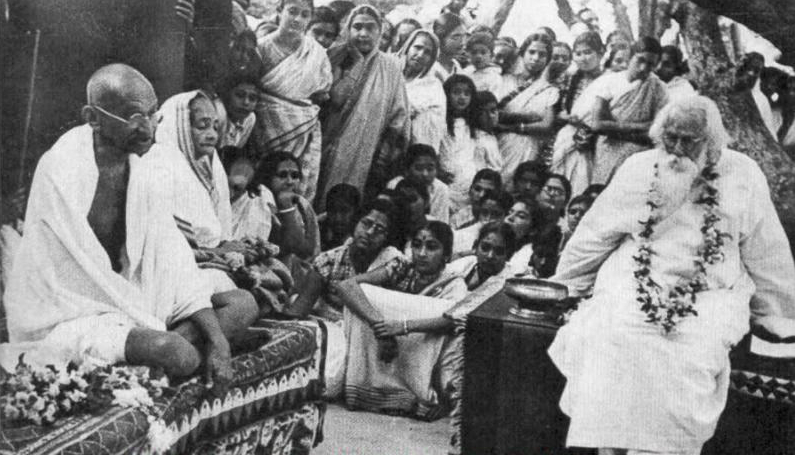

| Politics Main article: Political views of Rabindranath Tagore  Photo of a formal function, an aged bald man and old woman in simple white robes are seated side-by-side with legs folded on a rug-strewn dais; the man looks at a bearded and garlanded old man seated on another dais at left. In the foreground, various ceremonial objects are arrayed; in the background, dozens of other people observe. Tagore hosts Gandhi and wife Kasturba at Santiniketan in 1940. Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists,[141][142][143] and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties.[52] Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu.[144] Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in The Cult of the Charkha, an acrid 1925 essay.[145] According to Amartya Sen, Tagore rebelled against strongly nationalist forms of the independence movement, and he wanted to assert India's right to be independent without denying the importance of what India could learn from abroad.[146] He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a "political symptom of our social disease". He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, "there can be no question of blind revolution"; preferable to it was a "steady and purposeful education".[147][148] So I repeat we never can have a true view of man unless we have a love for him. Civilisation must be judged and prized, not by the amount of power it has developed, but by how much it has evolved and given expression to, by its laws and institutions, the love of humanity. — Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, 1916.[149] Such views enraged many. He escaped assassination—and only narrowly—by Indian expatriates during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916; the plot failed when his would-be assassins fell into an argument.[150] Tagore wrote songs lionizing the Indian independence movement.[151] Two of Tagore's more politically charged compositions, "Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo" ("Where the Mind is Without Fear") and "Ekla Chalo Re" ("If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone"), gained mass appeal, with the latter favored by Gandhi.[152] Though somewhat critical of Gandhian activism,[153] Tagore was key in resolving a Gandhi–Ambedkar dispute involving separate electorates for untouchables, thereby mooting at least one of Gandhi's fasts "unto death".[154][155] Repudiation of knighthood See also: List of people who have declined a British honour § Renouncing an honour Tagore renounced his knighthood in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote[156] The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings. |

政治 主な記事 ラビンドラナート・タゴールの政治的見解  1940年、サンティニケタンでガンジーと妻のカスターナを迎えるタゴール。 タゴールは帝国主義に反対し、インドの民族主義者を支持しており[141][142][143]、これらの見解は、ほとんどが20代に作曲された『マナス ト』で初めて明らかにされた[52]。 [ヒンドゥー=ドイツ共謀罪裁判で提出された証拠や後世の証言によれば、彼はガーダル派を意識しており、日本の寺内正毅首相や大隈重信元首相の支援を求め ていたと述べている[144]。しかし彼はスワデシ運動を軽蔑しており、1925年に発表された辛辣なエッセイ『The Cult of the Charkha』ではスワデシ運動を非難している。 [アマルティア・センによれば、タゴールは独立運動の強いナショナリズムの形態に反発しており、インドが海外から学ぶことの重要性を否定することなく、イ ンドの独立の権利を主張したかったのである。彼は、貧困の極みにいる人々にとってさえ、「盲目的な革命の問題はありえない」と主張し、革命よりも望ましい のは「着実で目的にかなった教育」であるとした[147][148]。 だから繰り返すが、人間に対する愛がなければ、人間に対する真の見解を持つことはできない。文明は、それが発展させた力の大きさによってではなく、その法律や制度によって、人間愛をどれだけ進化させ、表現させたかによって判断され、評価されなければならない。 - サーダナー 生命の実現』1916年[149]。 こうした見解は多くの人々を激怒させた。タゴールは、1916年後半にサンフランシスコのホテルに滞在していた際、インド人駐在員による暗殺を間一髪で逃 れたが、暗殺を企てた者たちが口論になり、計画は失敗に終わった[150]。 [151]タゴールのより政治色の強い2曲、"Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo"("Where the Mind is Without Fear")と"Ekla Chalo Re"("If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone")は大衆にアピールし、後者はガンディーに好まれた。 [152]ガンジーの活動主義にはやや批判的であったが[153]、タゴールは不可触民のための別個の選挙区をめぐるガンジー-アンベードカルの論争を解 決する上で重要な役割を果たし、それによってガンジーの「死に至るまで」の断食のうち少なくとも1つが決行された[154][155]。 爵位の否認 以下も参照のこと: イギリスの名誉を辞退した人物のリスト § 名誉の放棄 タゴールは1919年のジャリアンワラ・バグの虐殺事件を受けて爵位を返上した。総督チェルムスフォード卿に宛てた否認の手紙の中で、彼はこう書いている[156]。 名誉のバッジが、屈辱という不釣り合いな文脈の中で、われわれの恥をまざまざと見せつけるときが来たのである。私としては、いわゆる取るに足らない存在で あるがゆえに、人間にはふさわしくない劣悪な境遇に置かれがちな同胞の側に、あらゆる特別な区別をそぎ落として立ちたいと思う。 |

Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati Kala Bhavan (Institute of Fine Arts), Santiniketan, India Tagore despised rote classroom schooling, as shown in his short story, "The Parrot's Training", wherein a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death.[157][158] Visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, Tagore conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography."[150] The school, which he named Visva-Bharati,[d] had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later.[159] Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance—emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies,[160] and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: mornings he taught classes; afternoons and evenings he wrote the students' textbooks.[161] He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.[162] Theft of Nobel Prize On 25 March 2004, Tagore's Nobel Prize was stolen from the safety vault of the Visva-Bharati University, along with several other of his belongings.[163] On 7 December 2004, the Swedish Academy decided to present two replicas of Tagore's Nobel Prize, one made of gold and the other made of bronze, to the Visva-Bharati University.[164] It inspired the fictional film Nobel Chor. In 2016, a baul singer named Pradip Bauri, accused of sheltering the thieves, was arrested.[165][166] |

サンティニケタンとヴィスヴァ・バーラティ インド、サンティニケタン、カラバヴァン(美術研究所) 1917年にサンタバーバラを訪れたタゴールは、新しいタイプの大学を構想する。彼は「サンティニケタンをインドと世界を結ぶ糸とし、国家や地理的な限界 を超えて、どこかで人類を研究する世界の中心とする」ことを目指した。 「彼がヴィスヴァ・バーラティと名づけたこの学校は、1918年12月24日に礎石が据えられ、そのちょうど3年後に開校した[159]。指導はしばしば 木の下で行われた。1919年から1921年にかけて、タゴールはヨーロッパとアメリカで学校のために広く資金調達を行った[162]。 ノーベル賞の窃盗 2004年3月25日、タゴールのノーベル賞がヴィスヴァ=バラティ大学の金庫から、他のいくつかの遺品とともに盗まれた[163]。2016年、窃盗団を匿ったとして告発されたプラディップ・バウリというバウル歌手が逮捕された[165][166]。 |

| Impact and legacy See also: List of things named after Rabindranath Tagore  Bust of Rabindranath in Tagore promenade, Balatonfüred, Hungary  Rabindranath Tagore statue in Dublin, Ireland Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (US); Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries.[84][167][168] Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker".[168][146] Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 Rabīndra Rachanāvalī—is canonized as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".[169] Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution;[170] in Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata.[171] In colonial Vietnam Tagore was a guide for the restless spirit of the radical writer and publicist Nguyen An Ninh[172] Tagore's works were widely translated into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and other European languages by Czech Indologist Vincenc Lesný,[173] French Nobel laureate André Gide, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova,[174] former Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit,[175] and others. In the United States, Tagore's lecturing circuits, particularly those of 1916–1917, were widely attended and wildly acclaimed. Some controversies[e] involving Tagore, possibly fictive, trashed his popularity and sales in Japan and North America after the late 1920s, concluding with his "near total eclipse" outside Bengal.[9] Yet a latent reverence of Tagore was discovered by an astonished Salman Rushdie during a trip to Nicaragua.[181] By way of translations, Tagore influenced Chileans Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral; Mexican writer Octavio Paz; and Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset, Zenobia Camprubí, and Juan Ramón Jiménez. In the period 1914–1922, the Jiménez-Camprubí pair produced twenty-two Spanish translations of Tagore's English corpus; they heavily revised The Crescent Moon and other key titles. In these years, Jiménez developed "naked poetry".[182] Ortega y Gasset wrote that "Tagore's wide appeal [owes to how] he speaks of longings for perfection that we all have [...] Tagore awakens a dormant sense of childish wonder, and he saturates the air with all kinds of enchanting promises for the reader, who [...] pays little attention to the deeper import of Oriental mysticism". Tagore's works circulated in free editions around 1920—alongside those of Plato, Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, and Tolstoy. Tagore was deemed over-rated by some. Graham Greene doubted that "anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously." Several prominent Western admirers—including Pound and, to a lesser extent, even Yeats—criticized Tagore's work. Yeats, unimpressed with his English translations, railed against that "Damn Tagore [...] We got out three good books, Sturge Moore and I, and then, because he thought it more important to see and know English than to be a great poet, he brought out sentimental rubbish and wrecked his reputation. Tagore does not know English, no Indian knows English."[9][183] William Radice, who "English[ed]" his poems, asked: "What is their place in world literature?"[184] He saw him as "kind of counter-cultur[al]", bearing "a new kind of classicism" that would heal the "collapsed romantic confusion and chaos of the 20th century."[183][185] The translated Tagore was "almost nonsensical",[186] and subpar English offerings reduced his trans-national appeal: Anyone who knows Tagore's poems in their original Bengali cannot feel satisfied with any of the translations (made with or without Yeats's help). Even the translations of his prose works suffer, to some extent, from distortion. E.M. Forster noted [of] The Home and the World [that] '[t]he theme is so beautiful,' but the charms have 'vanished in translation,' or perhaps 'in an experiment that has not quite come off.' — Amartya Sen, "Tagore and His India".[9] |

影響と遺産 こちらも参照のこと: ラビンドラナート・タゴールの名を冠したもののリスト  ハンガリー、バラトンフュレッドのタゴール遊歩道にあるラビンドラナートの胸像  アイルランド、ダブリンのラビンドラナート・タゴール像 毎年、多くのイベントがタゴールに敬意を表している: タゴールの生誕記念日であるカビプラナムは世界中に散らばるグループによって祝われ、イリノイ州アーバナ(米国)で毎年開催されるタゴール・フェスティバ ル、コルカタからサンティニケタンまでのラビンドラ・パス・パリクラマ(Rabindra Path Parikrama)徒歩巡礼、重要な記念日に開催されるタゴールの詩の朗読会などがある[84][167][168]。アマルティア・センはタゴールを 「そびえ立つ人物」であり、「深く関連し、多面的な現代思想家」であるとみなした[168][146]。タゴールのベンガル語の原典である1939年のラ ビンドラ・ラチャナーヴァリーは、彼の国の最も偉大な文化的宝物のひとつとして聖典化されており、彼は「インドが生んだ最も偉大な詩人」という、それなり に謙虚な役割を担っている[169]。 タゴールはヨーロッパ、北アメリカ、東アジアの多くの地域で有名であった。日本では、ノーベル賞受賞者の川端康成などに影響を与えた。 [タゴールの作品は、チェコのインド学者ヴィンセント・レスニー、[173]フランスのノーベル賞受賞者アンドレ・ギド、ロシアの詩人アンナ・アフマート ワ、[174]トルコの元首相ビュレント・エチェヴィトらによって、英語、オランダ語、ドイツ語、スペイン語、その他のヨーロッパの言語に広く翻訳された [175]。米国では、タゴールの講演会、特に1916年から1917年にかけての講演会は広く聴衆を集め、大絶賛された。1920年代後半以降、タゴー ルにまつわるいくつかの論争[e](おそらく架空のもの)は、日本と北米におけるタゴールの人気と売上を壊滅させ、ベンガル国外では「ほぼ完全に消滅」し た[9]。 翻訳によって、タゴールはチリ人のパブロ・ネルーダと ガブリエラ・ミストラル、メキシコ人作家のオクタビオ・パス、スペイン人のホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセット、ゼノビア・カンプルビ、フアン・ラモン・ヒメネ スに影響を与えた。1914年から1922年にかけて、ヒメネスとカンプルビのペアは、タゴールの英語詩集のスペイン語訳を22編も手がけた。オルテガ・ イ・ガセットは、「タゴールの幅広い魅力は、私たち誰もが持っている完全性への憧れをどのように語っているかにある」と書いている[182]。タゴールの 作品は、プラトン、ダンテ、セルバンテス、ゲーテ、トルストイの作品と並んで、1920年頃にフリー版で出回った。 タゴールは一部の人々から過大評価されていた。グレアム・グリーンは、「イェーツ氏以外、いまだに彼の詩をまじめに読んでいる人はいない」と述べている。 パウンドを含む何人かの著名な西洋の崇拝者たち、そしてそれほどでもなかったが、イェーツでさえもタゴールの作品を批判した。イェイツは彼の英訳に感心せ ず、「くそタゴールめ......スタージ・ムーアと私で3冊もいい本を出したのに、彼は偉大な詩人であることよりも英語を見たり知ったりすることのほう が重要だと考えたから、感傷的なゴミを持ち出して評判を台無しにしたんだ」と憤慨した。タゴールは英語を知らないし、インド人で英語を知っている者はいな い」[9][183] ウィリアム・ラディスは彼の詩を「英語化」し、こう問いかけた: 「彼はタゴールを「一種のカウンターカルチャー」であり、「20世紀の崩壊したロマン主義的混乱と混沌」を癒すであろう「新しい種類の古典主義」を担って いると考えていた[183][185]。翻訳されたタゴールは「ほとんど無意味」であり[186]、劣悪な英語の提供は彼の国を超えた魅力を減少させた: タゴールの詩を原語のベンガル語で知っている者であれば、(イェイツの助けの有無にかかわらず)どの翻訳にも満足感を覚えることはできない。彼の散文作品 の翻訳でさえ、ある程度は歪曲に苦しんでいる。E.M.フォースターは、『家庭と世界』について、「テーマはとても美しい」のだが、その魅力は「翻訳に よって消えてしまった」、あるいは「実験がうまくいかなかったのだろう」と述べている。 - アマルティア・セン『タゴールと彼のインド』[9]。 |

Museums Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Kolkata; the room in which Tagore died in 1941. There are eight Tagore museums, three in India and five in Bangladesh: Rabindra Bharati Museum, at Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Kolkata, India Tagore Memorial Museum, at Shilaidaha Kuthibadi, Shilaidaha, Bangladesh Rabindra Memorial Museum at Shahzadpur Kachharibari, Shahzadpur, Bangladesh Rabindra Bhavan Museum, in Santiniketan, India Rabindra Museum, in Mungpoo, near Kalimpong, India Patisar Rabindra Kacharibari, Patisar, Atrai, Naogaon, Bangladesh Pithavoge Rabindra Memorial Complex, Pithavoge, Rupsha, Khulna, Bangladesh Rabindra Complex, Dakkhindihi village, Phultala Upazila, Khulna, Bangladesh Jorasanko Thakur Bari (Bengali: House of the Thakurs; anglicised to Tagore) in Jorasanko, north of Kolkata, is the ancestral home of the Tagore family. It is currently located on the Rabindra Bharati University campus at 6/4 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane[187] Jorasanko, Kolkata 700007.[188] It is the house in which Tagore was born, and also the place where he spent most of his childhood and where he died on 7 August 1941. |

博物館 コルカタのジョラサンコ・タクール・バリ。1941年にタゴールが亡くなった部屋である。 インドに3つ、バングラデシュに5つ、合計8つのタゴール博物館がある: ラビンドラ・バーラティ博物館(インド、コルカタのジョラサンコ・タクール・バリにある バングラデシュ、シライダハの シライダハ・クティバディにあるタゴール記念博物館 ラビンドラ記念博物館(バングラデシュ、シャーザドプル、 シャーザドプル・カチャリバリ インド、サンティニケタンのラビンドラ・バヴァン博物館 インド、カリンポン近郊のムンプーにあるラビンドラ博物館 Patisar Rabindra Kacharibari(バングラデシュ、ナオガオン、アットライ、パティサール Pithavoge Rabindra Memorial Complex, Pithavoge,Rupsha, Khulna, Bangladesh Rabindra Complex, Dakkhindihi village,Phultala Upazila,Khulna, Bangladesh コルカタの北、ジョラサンコにあるジョラサンコ・タクール・バリ(ベンガル語:タクール人の家 、英語ではタゴール)は、タゴール家の先祖代々の家である。現在はラビンドラ・バーラティ大学のキャンパス内にあり、6/4 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane[187]Jorasanko, Kolkata 700007にある[188]。タゴールが生まれた家であり、幼少期のほとんどを過ごした場所でもあり、1941年8月7日に亡くなった場所でもある。 |

| ist of works Main articles: List of works by Rabindranath Tagore and Adaptations of works of Rabindranath Tagore in film and television Further information: Rabindranath Tagore filmography Who are you, reader, reading my poems a hundred years hence? I cannot send you one single flower from this wealth of the spring, one single streak of gold from yonder clouds. Open your doors and look abroad. From your blossoming garden gather fragrant memories of the vanished flowers of an hundred years before. In the joy of your heart may you feel the living joy that sang one spring morning, sending its glad voice across an hundred years. The Gardener, 1915[189] The SNLTR hosts the 1415 BE edition of Tagore's complete Bengali works. Tagore Web also hosts an edition of Tagore's works, including annotated songs. Translations are found at Project Gutenberg and Wikisource. More sources are below. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabindranath_Tagore |

作品リスト 主な記事 ラビンドラナート・タゴールの作品リスト、ラビンドラナート・タゴールの作品の映画化・テレビ化 さらに詳しい情報 ラビンドラナート・タゴールのフィルモグラフィ 読者よ、100年後に私の詩を読んでいるあなたは誰だろう? この豊かな春から一輪の花も、彼方の雲から一筋の黄金も、あなたに送ることはできない。 戸を開けて外国を見よ。 あなたの花咲く庭から、百年前の消え去った花々の香り高い思い出を集めなさい。 ある春の朝に歌い、百年の時を越えてその喜びの声を送った、生きている喜びを、心の喜びの中で感じることができるように。 庭師』1915年[189]。 SNLTRはタゴールのベンガル語全集の1415年BE版を所蔵している。また、タゴール・ウェブでも、注釈付きの歌を含むタゴールの作品のエディション を公開している。翻訳はProject GutenbergとWikisourceにある。その他の情報源は以下の通り。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabindranath_Tagore |

| In popular culture Rabindranath Tagore is a 1961 Indian documentary film written and directed by Satyajit Ray, released during the birth centenary of Tagore. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division. Serbian composer Darinka Simic-Mitrovic used Tagore's text for her song cycle Gradinar in 1962.[191] In 1969, American composer E. Anne Schwerdtfeger was commissioned to compose Two Pieces, a work for women's chorus based on text by Tagore.[192] In Sukanta Roy's Bengali film Chhelebela (2002) Jisshu Sengupta portrayed Tagore.[193] In Bandana Mukhopadhyay's Bengali film Chirosakha He (2007) Sayandip Bhattacharya played Tagore.[194] In Rituparno Ghosh's Bengali documentary film Jeevan Smriti (2011) Samadarshi Dutta played Tagore.[195] In Suman Ghosh's Bengali film Kadambari (2015) Parambrata Chatterjee portrayed Tagore.[196] |

大衆文化において ラビンドラナート・タゴールは、サタジット・レイが脚本と監督を手がけた1961年のインドのドキュメンタリー映画で、タゴールの生誕100周年に公開された。インド政府 映画局が製作した。 セルビアの作曲家ダリンカ・シミッチ=ミトロヴィッチは、1962年にタゴールのテキストを歌曲集『Gradinar』に使用した[191]。 1969年、アメリカの作曲家E.アン・シュヴェルトフェーガーは、タゴールのテキストに基づく女声合唱のための作品『Two Pieces』の作曲を依頼された[192]。 スカンタ・ロイ監督のベンガル映画『Chhelebela』(2002年)では、ジシュ・セングプタがタゴールを演じた[193]。 バンダナ・ムコパディヤイのベンガル映画『Chirosakha He』(2007年)では、サヤンディプ・バッタチャリヤがタゴールを演じた[194]。 リトゥパルノ・ゴーシュ監督のベンガル・ドキュメンタリー映画『Jeevan Smriti』(2011年)では、サマダルシ・ダッタがタゴールを演じた[195]。 スマン・ゴーシュ監督のベンガル映画『Kadambari』(2015年)では、パラムブラタ・チャタルジーがタゴールを演じた[196]。 |

| List of Indian writers Kazi Nazrul Islam Rabindra Jayanti Rabindra Puraskar Tagore family An Artist in Life – biography by Niharranjan Ray Taptapadi Timeline of Rabindranath Tagore Music of Bengal |

インド人作家一覧 カジ・ナズル・イスラム ラビンドラ・ジャヤンティ ラビンドラ・プラスカール タゴール家 ニハランジャン・レイによる伝記「人生の中の芸術家 タプタパディ ラビンドラナート・タゴールの年表 ベンガルの音楽 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabindranath_Tagore |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099