The "Origin of Japanese" Theory : Cultural Nationalism or Scientific Racism?

The "Origin of Japanese" Theory : Cultural Nationalism or Scientific Racism?

Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij

The Theory of "Origin of Japanese": Cultural Nationalism or Scientific Racism? [Stampa_presen_241121.pdf]

Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij as Mitsuho IKEDA, Osaka University, Japan, tiocaima7n_gmail.com

Poster session Presented at the Annual

Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Tampa,

Florida, Novenmber 21, 2024.

1. Introduction

In Japan, the book genre of “Origin of the Japanese”

is popular among both specialists and general readers. Since the

imperial rule of Japan under Emperor Meiji in 1868, the Japanese people

have emphasized their “national” uniqueness to other countries. The

interest in emphasizing one's uniqueness has not changed much over

time. The Japanese emphasis on uniqueness has been strongly influenced

by nationalism, culminating in the era of imperialist expansion.

Nationalism generally arouses strong ethnocentrism, and Japan is no

exception. Ethnocentrism and ideas of racism (especially the idea of

racial superiority) in Japan, as in other modern nations, have a

complex and intertwined history. This presentation will take as its

source material recent (since the new millennium) popular writings on

the “origin of the Japanese.” We examine whether the discourses found

in the form of (a) cultural nationalism or (b) scientific racism.

2. Literature Review

4.1 Historical Evolution of the Research Paradigm on the Origin of the Japanese.

The theory of the origin of

Japanese has been an important topic in Japanese anthropological

research since 1893 when Shogoro Tsuboi(坪井正五郎) was appointed professor

in the Department of Anthropology at the Tokyo Imperial University

College of Science. In the same year, Koganei Yoshikiyo(小金井良精), an

anatomist at the Tokyo Imperial University Medical College, was

appointed professor of the Second Department of Anatomy. Through

comparative anatomical research, Koganei participated in the debate on

the Ainu, which was [can be possible of the] stone-age proto-Japanese.

Before the 1940s, the theory

of the migration of the Japanese was standard. Still, with the

intensification of World War II and the imperialization policy,

ideological claims of the Japanese as a “pure race” with the emperor at

the top increased. However, no researcher had ever “certified” it from

a physical anthropological point of view. In the late 1940s, Kotondo

Hasebe(長谷部言人) and others began to argue that there was no

“miscegenation” ( to maintain "the pure-bloodedness of the Japanese

race"). In “The Formation of the Japanese Nation” (1949), Dr. Hasebe

examined the transformation of the inhabitants of the Japanese

archipelago since the Early Pleistocene from both physical and cultural

perspectives. He concluded that the physical differences between the

Jomon and Kofun people were the variations within the same race,

Japanese. There was a shift from a Stone Age based on a hunting

and gathering economy to a Metal Age on paddy field farming, which

weakened masticatory and lower limb muscles as anatomical

evidence.

In the 1950s and 1960s,

anatomist Dr. Hisashi Suzuki(鈴木尚), based on a detailed study of human

remains from the transition period from the Jomon to the Yayoi period,

proposed the “deformation theory” that the Jomon people changed into

the Yayoi people through a so-called minor evolution due to changes in

the living environment caused by the influx of the Yayoi culture. This

theory holds that the Jomon were a native race and that the Jomon were

transformed by immigrants, the Torai-jin (i.e., people who came to

Japan through the Korean Peninsula) who brought agriculture with them.

This was the dominant paradigm until the 1970s. On the other hand, from

the 1950s to the 1970s, physical anthropologists and ethnologists

supported Takeo Kanaseki(金関丈夫)’s mixed-race migratory theory. In their

view, the Japanese were a heterogeneous “race.”

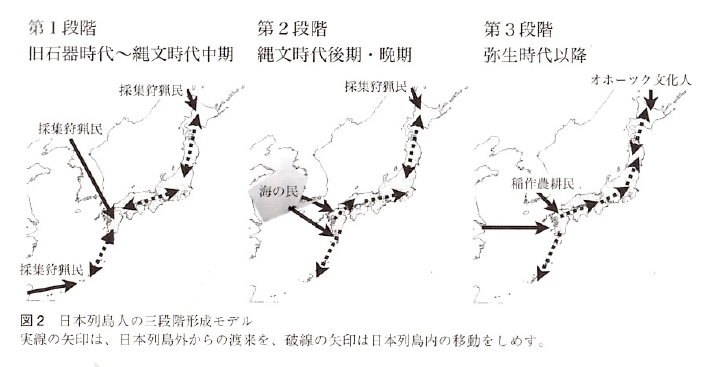

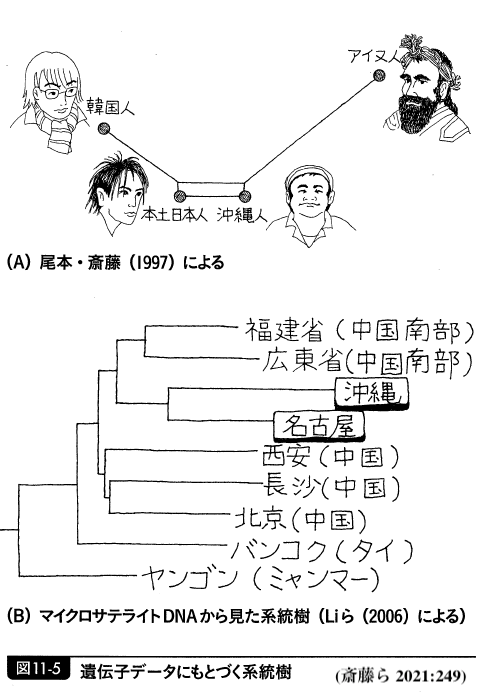

From the 1980s to the 1990s, genetic studies were added to the previous physical anthropological research that had focused on measurement studies. It was discovered that there were similarities and diversities in genetic traits, which led to the “Dual Structure Model” by Kazuro Haniwara(埴原和郎) in 1991. In the “Dual Structure Model,” the Jomon people of Southeast Asian origin were overlaid by a group of Northeast Asian descent from the Yayoi period onward, resulting in the formation of the modern Japanese people through interbreeding.

4.2 Research Trends Since Emerging Genomics

In the genre of Japanese origins theory, genome scientist Professor Naruya Saito(斎藤成也) has been awarded a huge grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) from 2018 to 2024, the Research on New Areas of Science, “Origin and formation of Yaponesians based on genome sequences”. The advent of next-generation sequencing machines is thought to best serve medical research, which is more tailor-made than the previous research. The introduction of new sequencers in research settings has raised the bar for genomic research and has also been a major inducement for innovation in the industry.

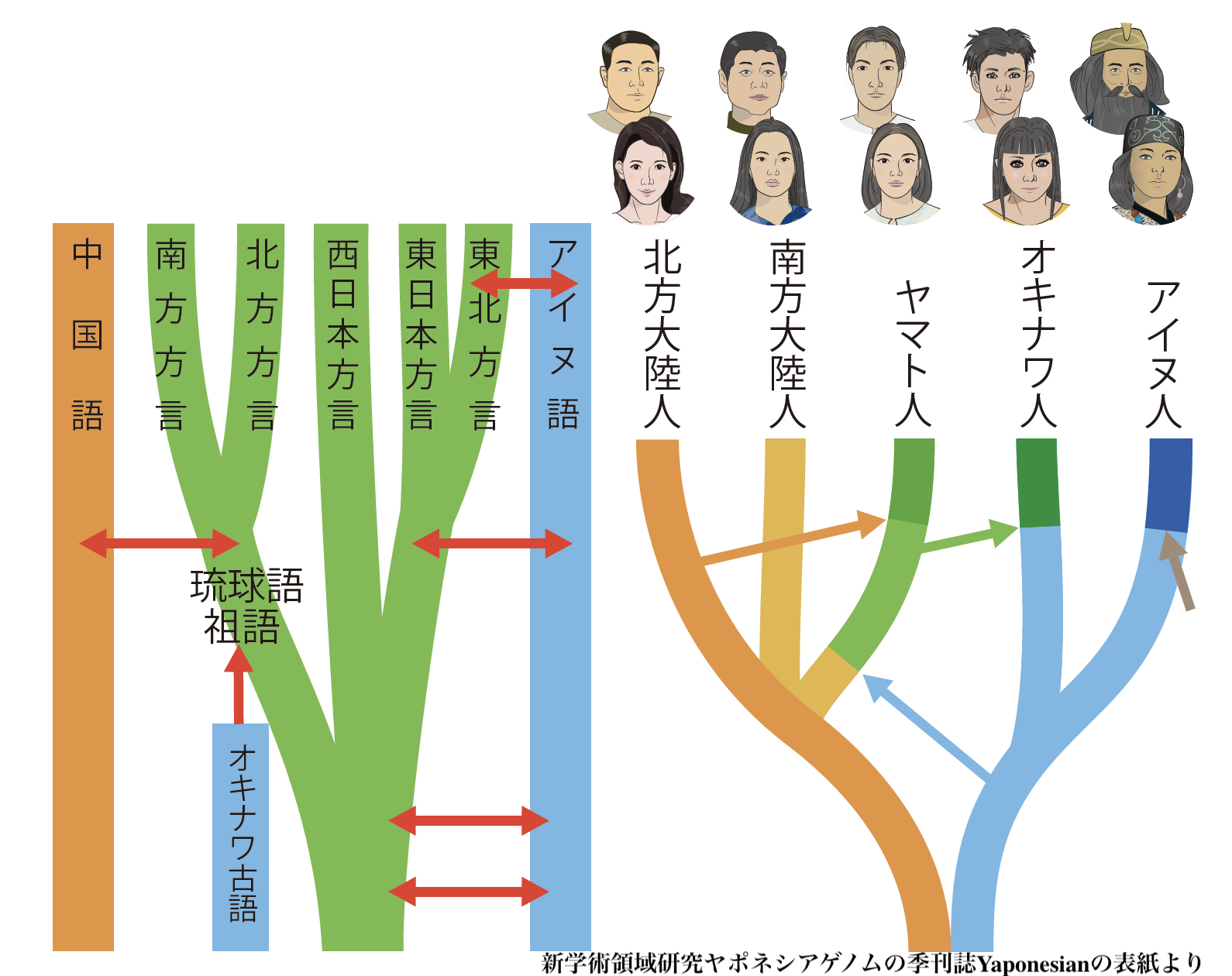

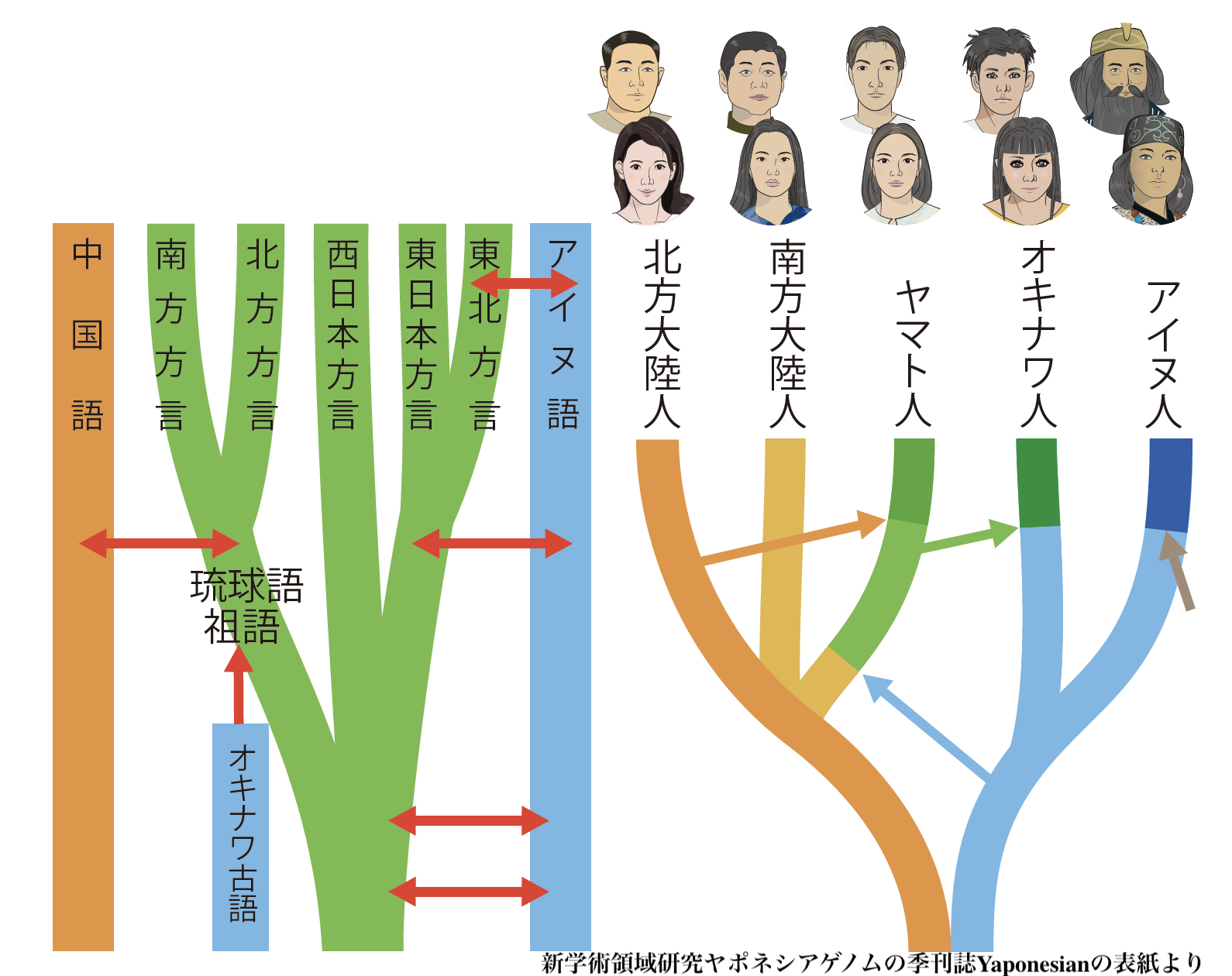

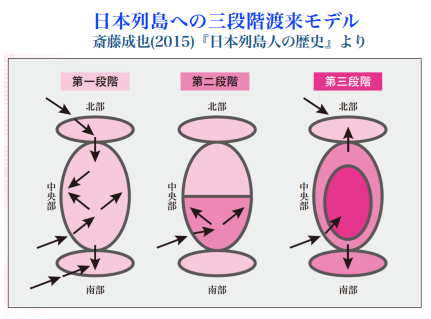

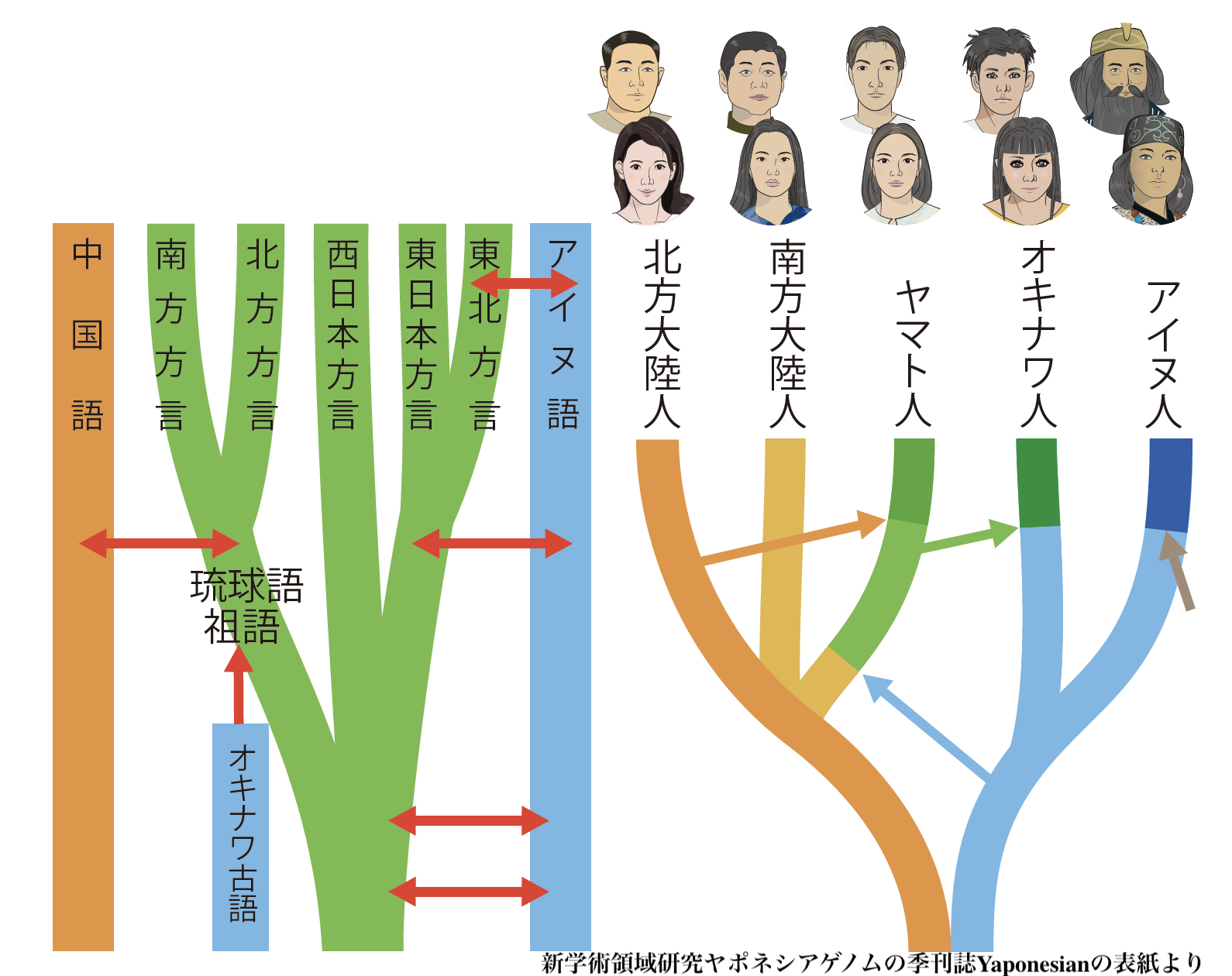

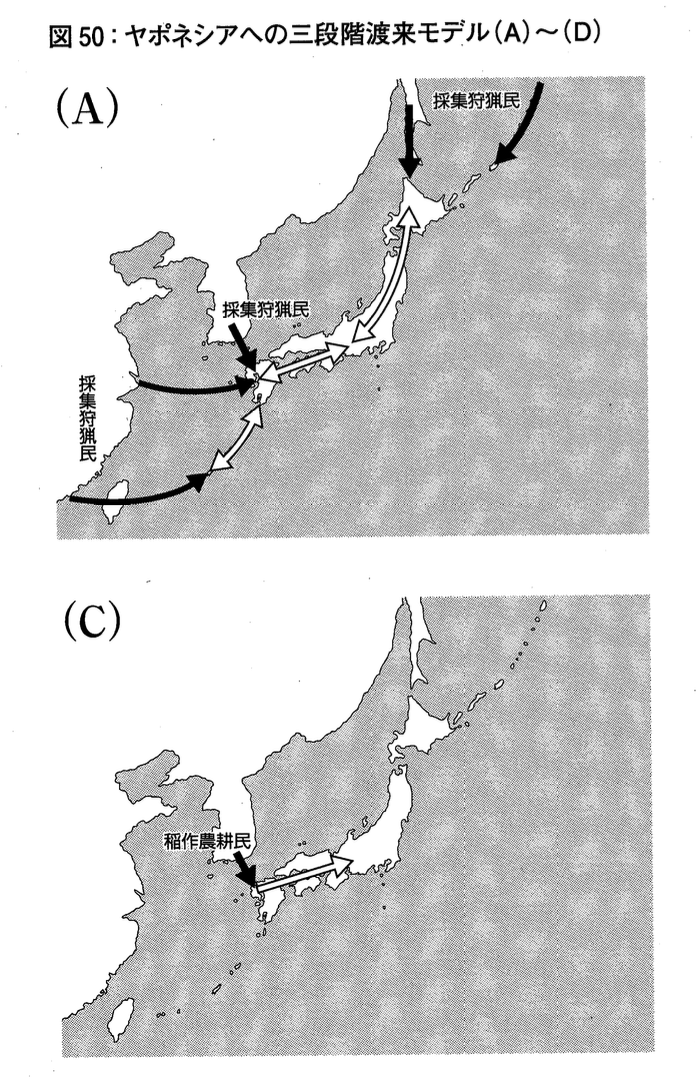

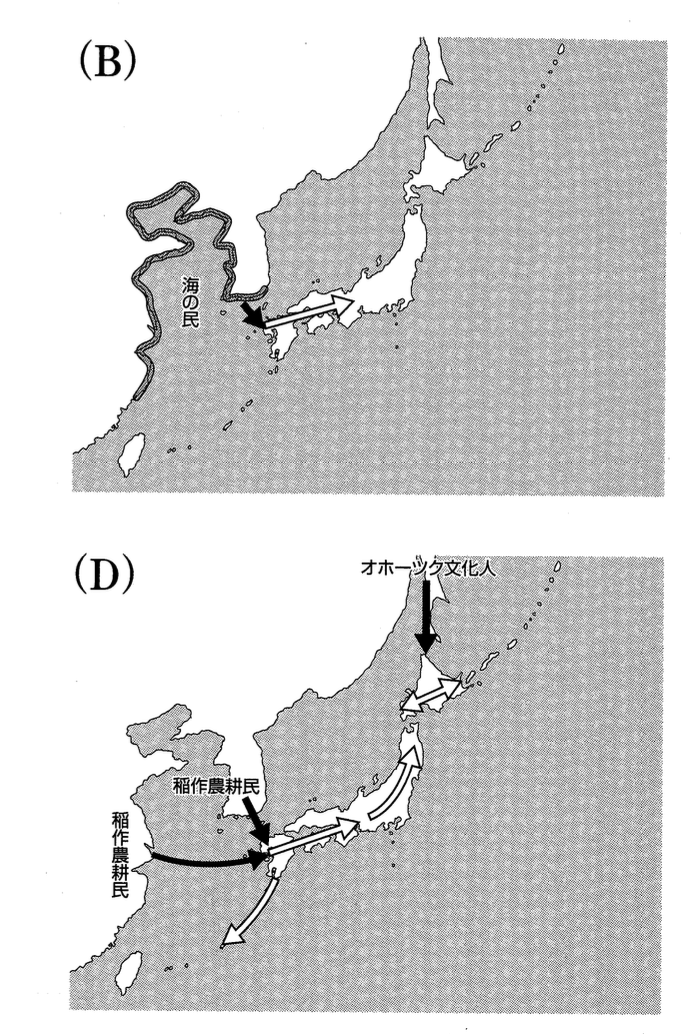

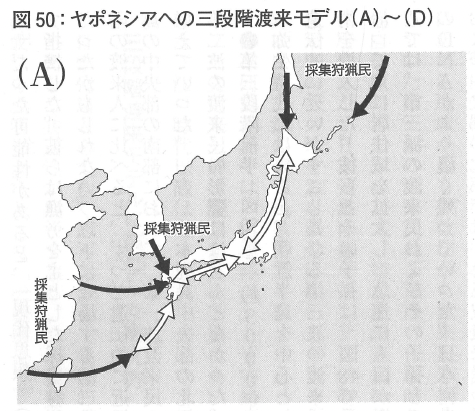

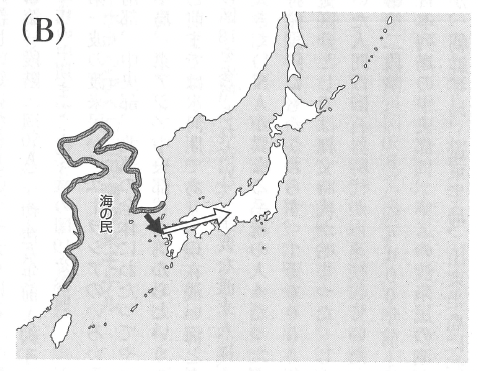

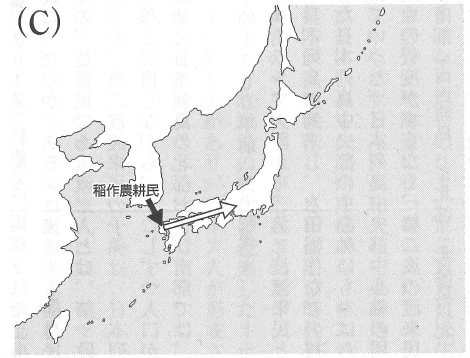

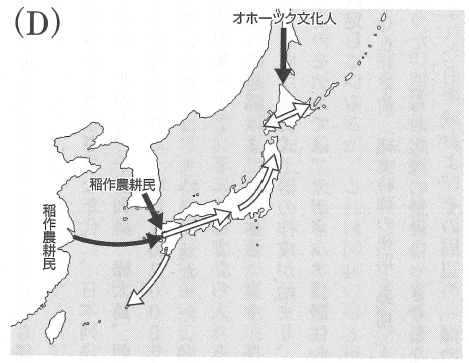

The overused term “Japanese” has led to create alternative terms that connotate the same race and ethnic group. In this context, Dr. Saito created the term Yaponesian in place of the designation of the Japanese race or biological human sub-grupe. The Yaponesian is as close as possible to the concept of the Japanese race. Dr. Saito now proposes a three-layer hypothesis instead of the Dual Structure Model. He explains that the three subpopulations of Yaponesians were formed by overlapping layers (ref. Figure, page 3.).

4.3 The Relationship between the Historical Theory of the Japanese Races and Eugenics, etc.

Let us talk about the definition of the Japanese. The Japanese are defined, as (1) Nationality(Kokuseki), (2) Ethnicity(Minzoku), and (3) Identity(Dooitsu-sei). However, when referring to “the Japanese,” many people consider a person to be “Japanese” if he or she possesses the two elements of Minzoku (which can be seen as race) and legal nationality.

4.3 The Relationship between the Historical Theory of the Japanese Races and Eugenics, etc.(contin.)

The English name of the

(formerly) Japanese Society of Race Hygiene(“Nippon Minzoku-Eisei

Gakkai”) was founded by Hisomu Nagai (永井潜,1876-1957) in November 1930.

They published the first issue of the Journal of Race Hygiene

(“Minzoku-Eisei” ). Dr. Nagai was the first president of the society.

He introduced the most advanced eugenics research and contributed to

the legislation of the National Eugenics Law (1940) under the influence

of the Nazi-German Sterilisation Law, the predecessor of the National

Eugenics Protection Law (1948-1996) in Japan.

3. Methods and Object

Through a bibliographic critical survey, this presentation will answer the following questions.

Why is the theory of the origin of the Japanese such continuing interest and popularity in Japanese society?

(2) Why is the “Japanese” as a nationality replaced by the essentialist race in the context of questioning the origin of the Japanese?

(3) Can the Japanese anthropologists avoid

using the concept of essential entity when they invent the neologism

instead of “race”?

4. Results

A review of the history of the research paradigm on the origin of the

Japanese shows that it is still a popular research genre among both

specialists and the general public. This is due in part to the ease of

obtaining public funding. The scientists have good skills in public

relations, which has led to its long-term popularity.

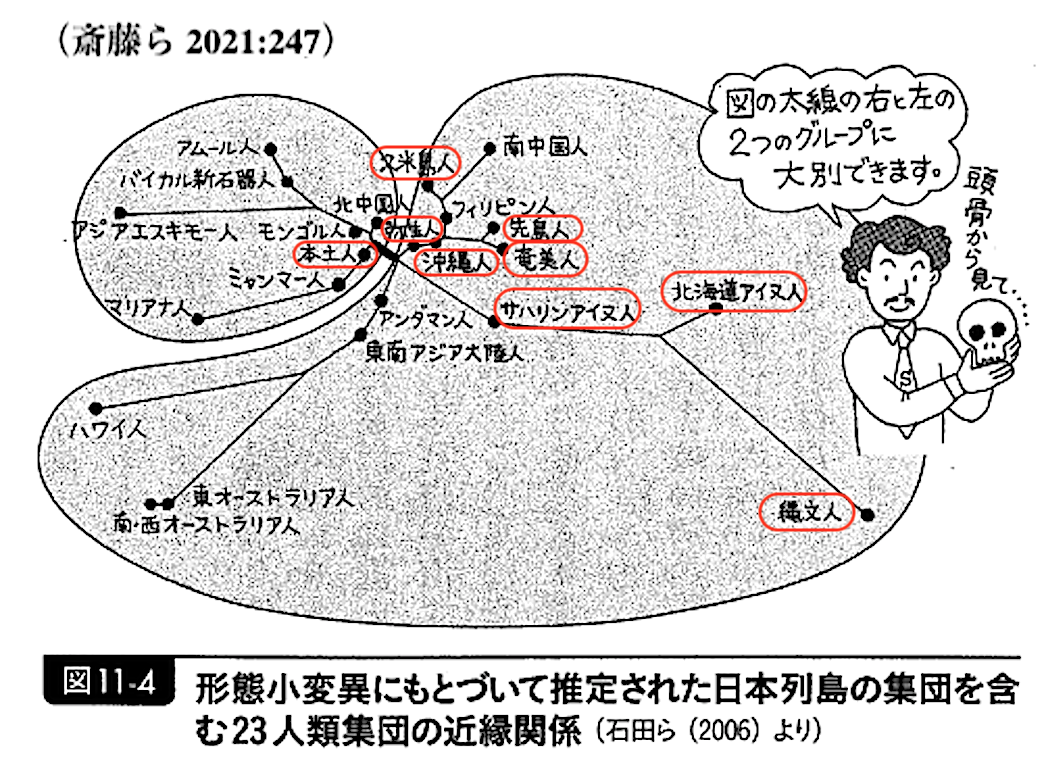

The research approach to exploring the origin of the Japanese requires

a “racial concept” as an essential entity. However, the researchers

tend to avoid using racial terms even though it is necessary to use

essential entities representing genomics terminologies. The theory of

the origin of the Japanese is currently explained by the admixture or

replacement of four subpopulations or “races.”: (1) Jomon, (2)

Torai-jin or immigrants, (3) Ainu, and (3) Ryukyuans or Okinawans. The

latter two are now regarded as indigenous peoples living in Japan. The

Trai-jin are given the ethnic label of “Kika-jin(assimilated person)”

and are understood to have been “Japanized.” Scientists can easily

confuse ethnic and racial terminologies.

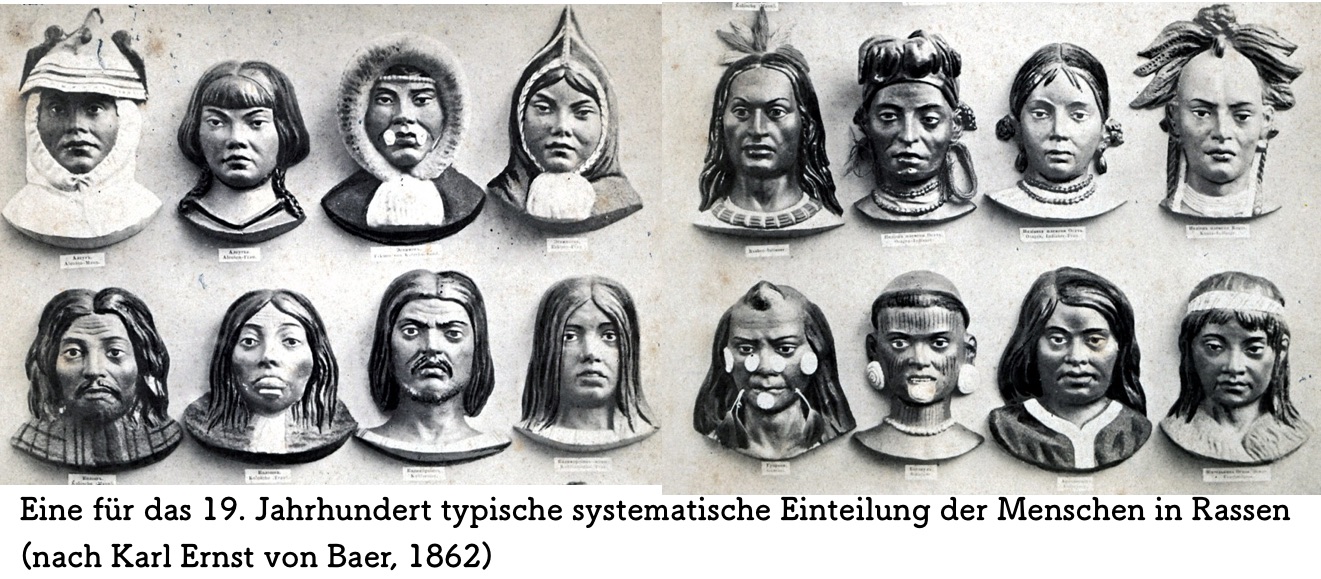

(2) The vocabulary of race, ethnicity, ethnic group, and people in

Japanese is often used interchangeably, and although the use of the

term race has tended to disappear (or to hide) in Japan since the

UNESCO declaration on race in 1950. However, some researchers use

racial concepts in their research, especially on genomics medicine.

These four categories function as racial “elements” and have the

potential to invent Japanese “scientific racism.” The trend over the

past half-century has been to suppress the use of the term race in

physical anthropology in this study, many researchers have restrained

the word in their terminology. But there is always the possibility that

this kind of research genre could lead to scientific racism that does

not use the term race (“racism without using racial term”).

(3) The establishment of the genre of Yaponesian genome research led to

the birth of the pseudo-racial designation avoiding the term “Japanese

race.”

The scientists cannot use the term “Japanese” instead of any kind of

connotating race anymore because the term is in both national and

ethnic categories. That is the reason why they invented the term

“Yaponesian.” If scientists use Yaponesian, can they avoid the

terminological contradiction between cultural category and racial one?

The answer is “No” because they only maintain the racial nuance in this

terminology. This is the resort for avoiding cultural and ethnic

nuances from “Japanese.” However, the original terminology “Japanese”

has cultural and ethnic nuance, not racial one.

5. Discussion

We found no evidence that the research genre of “Origin of

the Japanese” directly leads to cultural nationalism or scientific

racism. However, there is a group of researchers who have named

“Yaponesians” because “Japanese” as a nationality or ethnic category

cannot be used as a biological essentialist concept. Such a neologism

could functionally guarantee that it refers to the Japanese as a

pseudo-racial concept. Étienne Balibar (1991:23)called the existence of

“racism without race” as “cultural racism.” The rhetoric of

highlighting differences of race is mobilized to ethnic discrimination

within the EU for exclusion of migrants from outside Europe.

The neologism Yaponesian has no anti-immigrant or xenophobic

meaning among scientists. However, it is conceivable that the use of

the term to explain popularly the “origin of the Japanese” could

contribute to making nationalism through scientific research (that

suggests “scientific nationalism”). When the Yaponesians are considered

in the genomic continuum as a genetic regional group, they cannot be

equated with the “Japanese” as a nationality or ethnicity. This is

because the Yaponesian’s genetic component is also shared by the Ainu

of the Kuril Islands and Okhotsk, as well as by the peoples of

Northeast Asian and Southeast Asian origin on the Korean Peninsula. In

another example, the genetic components of the Ryukuan from the Medival

time have increased the mainlanders’ ones. This hybridization

phenomenon implies military campaigns by the mainlanders. Genetic

diversity within Yaponesia is continuous with populations outside

Yaponesia. In other words, Yaponesians cannot have clear genetic

boundaries with the outlandes of the Yaponesians.

6. Conclusion

(1) Why is the theory of the origin of the Japanese such continuing interest and popularity in Japanese society?

One of the reasons behind the popularity

of the theory of the origin of the Japanese is the larger genre of the

“Nipponjin-Ron” (Japanese National Character). The Nipponjin-Ron

flourished during the publishing boom that followed World War II, with

books and articles published to analyze, explain, and explore Japanese

culture and cultural identities. The Nipponjin-Ron is one of

exceptionalism, emphasizing “the fundamental difference of the Japanese

from other peoples,” Peter N. Dale (1986:42) notes that the Japanese

concept of race, as opposed to that of Westerners, is not “a mixture of

races (miscegenation of race),” whereas the Japanese maintain the same

“pure blood”. Eiji Oguma (2002) explained that the Japanese have shared

the myth of a mono-ethnic and mono-racial nation for a long time. And

this ideology can be a source of their xenophobic exceptionalism.

(2) Why is the “Japanese” as a nationality replaced by the essentialist

race in the context of questioning the origin of the Japanese?

The Japanese are commonly defined by

nationality. However, scientists always think that the Japanese must be

a biological entity as a race because of a physical anthropological

point of view. The reason is that the vocabulary of race, ethnicity,

ethnic group, and people are often used interchangeably in Japanese.

Since the UNESCO declaration on race in 1950, the term “race” has

tended to fade out of use in academic contexts. However, some

researchers still use racial terms in their genomic medical research.

(3) Can the Japanese anthropologists avoid using the concept of

essential entity when they invent the neologism Yaposesian instead of

“race”?

The term “Japanese” was originally a concept of nationality, but when discussing the origins of the Japanese, one must assume the biological essence of the Japanese. As a way around this dilemma, a group of researchers has invented a pseudo-racial category called “Yaponesian.” However, once Yaponesian is defined as a purely biological essence, the “origin of the Japanese” is subsumed within the genetic diversity of East Asians, and the boundaries of the Japanese cannot be contained within the political boundaries defined by the borders of reality. The Yaponesian becomes an ideotype within the genetic diversity with certain tendencies that have nothing to do with the actual and variously definable “Japanese.” The term "Yaponesian" is extrapolated with a pseudo-racial concept not using racial terminology.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Link

Bibliography

other information