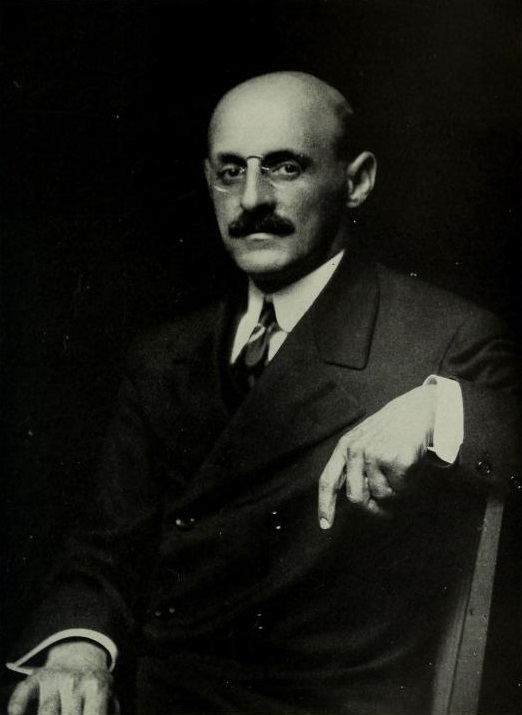

エイブラハム・フレクスナー

Abraham Flexner, 1866-1959

☆ エイブラハム・フレクスナー(Abraham Flexner;1866 年11月13日-1959年9月21日)はアメリカの教育者であり、20世紀におけるアメリカとカナダの医学・高等教育改革に果たした役割で最もよく知ら れている。 故郷のケンタッキー州ルイビルで大学準備学校を設立し、指導した後、フレクスナーは1908年に『アメリカの大学』と題するアメリカの教育制度のあり方に 対する批判的な評価を発表した: A Criticism)と題する批判的な評価を発表した。彼の著作はカーネギー財団の関心を引き、アメリカとカナダの155の医学部に対する詳細な評価を依 頼した。その結果、1910年に発表された自著『フレクスナー・レポート』が、米国とカナダの医学教育改革に火をつけた。フレクスナーはまた、プリンスト ンにある高等研究所の創設者でもあり、歴史上最も偉大な頭脳を集めて知的発見と研究に協力させた。

| Abraham Flexner

(November 13, 1866 – September 21, 1959) was an American educator, best

known for his role in the 20th century reform of medical and higher

education in the United States and Canada.[1] After founding and directing a college-preparatory school in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, Flexner published a critical assessment of the state of the American educational system in 1908 titled The American College: A Criticism. His work attracted the Carnegie Foundation to commission an in-depth evaluation into 155 medical schools in the US and Canada.[2] It was his resultant self-titled Flexner Report, published in 1910, that sparked the reform of medical education in the United States and Canada.[1] Flexner was also a founder of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, which brought together some of the greatest minds in history to collaborate on intellectual discovery and research.[2] |

エイブラハム・フレクスナー(1866年11月13日-1959年9月

21日)はアメリカの教育者であり、20世紀におけるアメリカとカナダの医学・高等教育改革に果たした役割で最もよく知られている。 故郷のケンタッキー州ルイビルで大学準備学校を設立し、指導した後、フレクスナーは1908年に『アメリカの大学』と題するアメリカの教育制度のあり方に 対する批判的な評価を発表した: A Criticism)と題する批判的な評価を発表した。彼の著作はカーネギー財団の関心を引き、アメリカとカナダの155の医学部に対する詳細な評価を依 頼した。その結果、1910年に発表された自著『フレクスナー・レポート』が、米国とカナダの医学教育改革に火をつけた。フレクスナーはまた、プリンスト ンにある高等研究所の創設者でもあり、歴史上最も偉大な頭脳を集めて知的発見と研究に協力させた。 |

| Biography Early life and education Flexner was born in Louisville, Kentucky on November 13, 1866. He was the sixth of nine children born to German Jewish immigrants Ester and Moritz Flexner.[3] He was the first in his family to complete high school and go on to college.[2] In 1886, at age 19, Flexner completed a B.A. in classics at Johns Hopkins University, where he studied for only two years. In 1905, he pursued graduate studies in psychology at Harvard University, and at the University of Berlin.[4] He did not, however, complete work on an advanced degree at either institution. Personal life Flexner had three brothers named Jacob, Bernard and Simon Flexner. He also had a sister named Rachel Flexner.[5] The success of Abraham Flexner's experimental schooling allowed him to help finance Simon Flexner's medical education at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. He proceeded to become a pathologist, bacteriologist and a medical researcher employed by the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research from 1901 to 1935.[5]  Flexner c. 1895 Flexner also financed his sister's undergraduate studies at Bryn Mawr College. Jacob ran a drugstore and used the profits from selling the establishment to attend medical school. He then practiced as a physician in Louisville. Bernard pursued a career in law and later practiced in both Chicago and New York.[5] In 1896, Flexner married a former student of his school, Anne Laziere Crawford. She was a teacher who soon became a successful playwright and children's author. The success of her play Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch (based on the 1901 novel) funded Flexner's studies at Harvard and his year abroad at European universities. The couple supported women's suffrage and had two daughters Jean and Eleanor. Jean went on to become one of the original employees of the United States Division of Labor Standards. Eleanor Flexner became an independent scholar and pioneer of women's studies.[5] Flexner grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family; however, early on he became a religious agnostic.[2] In addition to contributions by his brother Simon, their nephew, Louis Barkhouse Flexner, was founding director of the Mahoney Institute of Neurological Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania and a former editor of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[citation needed] Death Flexner died in Falls Church, Virginia, in 1959 at 92 years of age. He was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.[5] |

略歴 生い立ちと教育 フレクスナーは1866年11月13日にケンタッキー州ルイビルで生まれた。1886年、19歳の時、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学で古典学の学士号を取得した。1905年、ハーバード大学とベルリン大学の大学院で心理学を学ぶ。 私生活 フレクスナーにはジェイコブ、バーナード、シモン・フレクスナーという3人の兄弟がいた。また、レイチェル・フレクスナーという妹もいた[5]。 アブラハム・フレクスナーの実験的な学校教育の成功により、ジョンズ・ホプキンス医科大学でのサイモン・フレクスナーの医学教育の資金を援助することができた。彼(サイモン)は病理学者、細菌学者となり、1901年から1935年までロックフェラー医学研究所に雇われた医学研究者となった[5]。  1895年頃のフレクスナー フレクスナーは、妹がブリンマー大学で学ぶための資金も援助した。ジェイコブはドラッグストアを経営し、その店を売って得た利益で医学部に通った。その後、ルイビルで医師として開業した。バーナードは法律の道に進み、後にシカゴとニューヨークで開業した[5]。 1896年、フレックスナーは自分の学校の元生徒であるアン・ラジエール・クロフォードと結婚した。彼女は教師であったが、すぐに劇作家、児童文学作家と して成功した。彼女の戯曲『キャベツ畑のウィッグス夫人』(1901年の小説が原作)の成功は、フレクスナーのハーバード大学での学業とヨーロッパの大学 での1年間の留学の資金となった。夫妻は女性参政権を支持し、2人の娘ジーンとエレノアをもうけた。ジーンは米国労働基準監督局の創設者の一人となった。 エレノア・フレクスナーは独立した学者となり、女性学の先駆者となった[5]。 フレクスナーは正統派ユダヤ教徒の家庭で育ったが、早くから宗教的不可知論者となった[2]。 兄のサイモンによる貢献に加え、彼らの甥であるルイス・バークハウス・フレクスナーは、ペンシルベニア大学のマホニー神経科学研究所の創設所長であり、米国科学アカデミー紀要の元編集者であった[要出典]。 死去 フレックスナーは1959年、バージニア州フォールズチャーチで92歳で死去した。ケンタッキー州ルイビルのケーブ・ヒル墓地に埋葬された[5]。 |

| Career Experimental schooling After graduating from Johns Hopkins University in two years with a degree in classics, Flexner returned to Louisville to teach classics at Louisville Male High School. Four years later, Flexner founded a private school in which he would test his growing ideas about education. Flexner opposed the standard model of education that focused on mental discipline and a rigid structure. Moreover, "Mr. Flexner's School" did not give out traditional grades, used no standard curriculum, refused to impose examinations on students, and kept no academic record of students. Instead, it promoted small learning groups, individual development, and a more hands-on approach to education. Graduates of his school were soon accepted at leading colleges, and his teaching style began to attract considerable attention.[2] The American College In 1908, Flexner published his first book, The American College. Strongly critical of many aspects of American higher education, it denounced, in particular, the university lecture as a method of instruction. According to Flexner, lectures enabled colleges to "handle cheaply by wholesale a large body of students that would be otherwise unmanageable and thus give the lecturer time for research." In addition, Flexner was concerned about the chaotic condition of the undergraduate curriculum and the influence of the research culture of the university. Neither contributed to the mission of the college to address the whole person. He feared that "research had largely appropriated the resources of the college, substituting the methods and interest of highly specialized investigation for the larger objects of college teaching."[6] His book attracted the attention of Henry Pritchett, president of the Carnegie Foundation, who was looking for someone to lead a series of studies of professional education. The book consistently cited Pritchett in discussions of views on educational reform, and the two soon arranged to meet through the then-president of Johns Hopkins University, Ira Remsen. Although Flexner had never set foot inside a medical school, he was Pritchett's first choice to lead a study of American medical education, and soon joined the research staff at the Carnegie Foundation in 1908. Although not a physician himself, Flexner was selected by Pritchett for his writing ability and his disdain for traditional education.[2] Flexner Report Main article: Flexner Report In 1910, Flexner published the Flexner Report, which examined the state of American medical education and led to far-reaching reform in the training of doctors. The Flexner Report led to the closure of most rural medical schools and five out of seven African-American medical colleges in the United States given his adherence to germ theory, in which he argued that if not properly trained and treated, African-Americans and the poor posed a health threat to middle/upper class European-Americans.[7] His position was: The practice of the Negro doctor will be limited to his own race, which in its turn will be cared for better by good Negro physicians than by poor white ones. But the physical well-being of the Negro is not only of moment to the Negro himself. Ten million of them live in close contact with sixty million whites. Not only does the Negro himself suffer from hookworm and tuberculosis; he communicates them to his white neighbors, precisely as the ignorant and unfortunate white contaminates him. Self-protection not less than humanity offers weighty counsel in this matter; self-interest seconds philanthropy. The Negro must be educated not only for his sake, but for ours. He is, as far as the human eye can see, a permanent factor in the nation.[8] Ironically, one of the schools, Louisville National Medical College, was located in Flexner's hometown. In response to the report, some schools fired senior faculty members in a process of reform and renewal.[9] Influence on Europe Flexner soon conducted a related study of medical education in Europe.[10] According to Bonner (2002), Flexner's work came to be "nearly as well known in Europe as in America."[2] With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, Flexner "...exerted a decisive influence on the course of medical training and left an enduring mark on some of the nation's most renowned schools of medicine."[2] Bonner worried that "the imposition of rigid standards by accrediting groups was making the medical curriculum a monstrosity," with medical students moving through it with "little time to stop, read, work or think." Bonner (2002) calls Flexner "the severest critic and the best friend American medicine ever had."[2] New Lincoln School Between 1912 and 1925, Flexner served on the Rockefeller Foundation's General Education Board, and after 1917 was its secretary. With the help of the board, he founded another experimental school, the Lincoln School, which opened in 1917, in cooperation with the faculty at Teachers College of Columbia University.[citation needed] Institute for Advanced Study Main article: Institute for Advanced Study  Left to right: Albert Einstein, Abraham Flexner, John R. Hardin, and Herbert Maass at the Institute for Advanced Study on May 22, 1939 Louis Bamberger and his sister Caroline Bamberger Fuld, founders of Bamberger's department store, which they had sold to Macy's following the death of co-founder and husband Felix Fuld, were set on creating a medical school in Newark, New Jersey. They wanted to give admissions preference to Jewish applicants in an effort to fight the rampant prejudice against Jews in the medical profession at that time. Flexner informed them that a teaching hospital and other faculties required a successful school. A few months later, in June 1930, he had persuaded the Bamberger siblings and their representatives to fund instead the development of an Institute for Advanced Study.[5] The institute was headed by Flexner from 1930 to 1939 and it possessed a renowned faculty including Kurt Gödel and John von Neumann. During his time there, Flexner helped bring over many European scientists who would likely have suffered persecution by the rising Nazi government. This included Albert Einstein, who arrived at the Institute in 1933 under Flexner's directorship.[11] Universities: American, English, German In his 1930 Universities: American, English, German,[12] Flexner returned to his earlier interest in the direction and purpose of the American university, attacking distractions from serious learning, such as intercollegiate athletics, student government, and other student activities. |

キャリア 実験的な学校教育 ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学で古典の学位を取得して2年で卒業したフレクスナーは、ルイビルに戻り、ルイビル男子高校で古典を教えた。4年後、フレクスナー は私立学校を設立し、そこで教育についての考えを深めていった。フレクスナーは、精神的な規律と厳格な構造を重視する標準的な教育モデルに反対した。さら に、「フレクスナー氏の学校」では、伝統的な成績を与えず、標準的なカリキュラムを用いず、生徒に試験を課すことを拒否し、生徒の学業記録を一切残さな かった。その代わりに、少人数の学習グループ、個人の能力開発、より実践的な教育アプローチを推進した。彼の学校の卒業生はすぐに一流大学に合格し、彼の 教育スタイルは大きな注目を集めるようになった[2]。 アメリカのカレッジ 1908年、フレクスナーは最初の著書『アメリカン・カレッジ』を出版した。この本は、アメリカの高等教育の様々な側面を強く批判し、特に大学の講義とい う教育方法を非難した。フレクスナーによれば、講義によって大学は、「そうしなければ管理しきれないような大勢の学生を卸すことによって安く扱い、その結 果、講師に研究のための時間を与えることができる」のだという。さらにフレクスナーは、学士課程カリキュラムの無秩序な状態と大学の研究文化の影響を懸念 していた。どちらも、全人格を扱うという大学の使命に貢献していない。彼は、「研究が大学の資源をほとんど横取りし、高度に専門化された調査の方法と関心 を、大学教育のより大きな目的に置き換えている」ことを懸念していた[6]。 彼の著書は、カーネギー財団のヘンリー・プリチェット会長の目に留まり、カーネギー財団は、専門教育に関する一連の研究を主導する人物を探していた。この 本は、教育改革についての見解の議論の中で常にプリチェットを引き合いに出しており、2人はすぐに、当時のジョンズ・ホプキンス大学学長アイラ・レムゼン を通じて会う約束を取り付けた。フレックスナーは医学部に足を踏み入れたことはなかったが、プリチェットがアメリカの医学教育の研究を主導する第一候補と して選んだ人物であり、すぐに1908年にカーネギー財団の研究スタッフに加わった。フレクスナー自身は医師ではなかったが、プリチェットによって、その 著述能力と伝統的な教育を軽んじている点が評価されて選ばれた[2]。 フレクスナー報告書 主な記事 フレクスナー報告 1910年、フレクスナーはアメリカの医学教育のあり方を検討した「フレクスナー報告」を発表し、医師養成の大幅な改革につながった。フレクスナー・レ ポートは、彼の細菌理論への固執から、アメリカ国内のほとんどの農村部の医学部と、アフリカ系アメリカ人の医学部7校のうち5校を閉鎖するに至ったが、そ の中で彼は、適切な訓練と治療が行われなければ、アフリカ系アメリカ人と貧困層は、中流階級/上流階級のヨーロッパ系アメリカ人に健康上の脅威をもたらす と主張した[7]: 黒人医師の診療は彼自身の人種に限定され、その人種は貧しい白人医師よりも優れた黒人医師の方がより良い治療を受けられるだろう。しかし、黒人の身体的健 康は、黒人自身だけの問題ではない。1,000万人の黒人は、6,000万人の白人と密接に接触して暮らしている。黒人自身が鉤虫症や結核に苦しむだけで なく、無知で不幸な白人が黒人を汚染するのと同じように、黒人も隣人の白人に鉤虫症や結核をうつすのである。この問題では、人道に勝るとも劣らない自己保 護が重要な助言を与えてくれる。黒人を教育しなければならないのは、彼のためだけでなく、私たちのためでもある。彼は、人間の目で見る限り、国家の永続的 な要因なのである[8]。 皮肉なことに、この学校の一つであるルイビル国立医科大学は、フレクスナーの故郷にあった。この報告書を受けて、改革と刷新の過程で上級教員を解雇した学校もあった[9]。 ヨーロッパへの影響 ボナー(2002)によれば、フレクスナーの研究は、「アメリカ国内と同様、ヨーロッパでもほぼよく知られるようになった」[2]。 ボナーは、「認定団体による厳格な基準の押し付けが、医学カリキュラムを怪物的なものにしている」と憂慮していた。ボナー(2002)は、フレクスナーを 「アメリカ医学史上最も厳しい批評家であり、最高の友人」と呼んでいる[2]。 新しいリンカーン学派 1912年から1925年の間、フレクスナーはロックフェラー財団の一般教育委員会の委員を務め、1917年以降はその幹事を務めた。同委員会の協力を得 て、彼はコロンビア大学ティーチャーズ・カレッジの教授陣と共同で、1917年に開校したもう一つの実験校、リンカーン・スクールを設立した[要出典]。 高等研究所 主な記事 高等研究所  左から右へ: アルバート・アインシュタイン、エイブラハム・フレクスナー、ジョン・R・ハーディン、ハーバート・マース(1939年5月22日、高等研究所にて ルイス・バンバーガーと妹のキャロライン・バンバーガー・フルードは、バンバーガー百貨店の創業者であり、共同創業者であった夫のフェリックス・フルード の死後、メイシーズに売却していたが、ニュージャージー州ニューアークに医学部を設立することを決めていた。当時、医学界に蔓延していたユダヤ人に対する 偏見に対抗するため、彼らはユダヤ人志願者を優先的に入学させたいと考えていた。フレクスナーは彼らに、教育病院とその他の学部が必要であることを伝え た。数カ月後の1930年6月、彼はバンベルガー兄妹とその代理人を説得し、代わりに高等研究所の設立に資金を提供した[5]。 この研究所は1930年から1939年までフレクスナーが所長を務め、クルト・ゲーデルやジョン・フォン・ノイマンら著名な教授陣を擁していた。 フレックスナーは、ナチスの台頭により迫害を受けていたであろうヨーロッパの科学者たちを、研究所に呼び寄せる手助けをした。その中には、フレクスナーが所長を務めていた1933年に研究所に到着したアルベルト・アインシュタインも含まれていた[11]。 大学 アメリカ、イギリス、ドイツ 1930年に出版された『大学』には、次のように書かれている: フレクスナーは、アメリカの大学の方向性と目的について以前抱いていた関心に立ち返り、インカレ、学生自治会、その他の学生活動など、真剣な学問を妨げるものを攻撃した[12]。 |

| Legacy This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Flexner Report and his work in education has had a lasting impact on medical and higher education. The specific impacts of the Flexner Report on American and Canadian medicine include: Average physician quality has increased significantly[13] Medicine has become a lucrative and well-respected profession A physician must receive at minimum six years, preferably eight years of post-secondary education, typically in a university setting Medical education is based on research, specifically in the fields of human physiology and biochemistry Medical research follows the same protocols as scientific research[7] The state government must approve the founding of any medical school and medical schools are subject to state regulation The state branches of the American Medical Association oversee all the conventional medical schools in each state The Institute for Advanced Study, which Flexner co-founded, has been conducting valuable research for over 80 years in attempt to understand the complexities of the physical world and humanity The Flexner Report damaged and marginalized historically Black medical schools, which today produce more than their fair share of Black medical graduates. Honors The Association of American Medical Colleges created the Abraham Flexner Award for Distinguished Service to Medical Education to annually recognize individuals who have made a notable contribution to American medical education.[14] In 2020, "in light of racist and sexist writings" the AAMC renamed the award, removing Flexner's name.[15] The University of Kentucky College of Medicine has the Academy of Medical Educator Excellence in Medical Education Award, which was formerly named the Abraham Flexner Master Educator Award, to recognize achievement in six categories: Educational Leadership and Administration Outstanding Teaching Contribution or Mentorship Educational Innovation and Curriculum Development Educational Evaluation and Research Faculty Development in Education[16] Abraham Flexner Way in downtown Louisville's hospital district was named by the Louisville Board of Aldermen in November 1978 to honor Flexner. Bibliography 1908. The American College: A Criticism Archived November 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine 1910. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. 1910. Medical Education in the United States and Canada (at Google Books). 1912. Medical education in Europe; a report to the Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching. 1915. "Is Social Work a Profession?" Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction at the Forty-second annual session held in Baltimore, Maryland, May 12–19, 1915. 1916. A Modern School. 1916 (with Frank P. Bachman). Public Education in Maryland: A Report to the Maryland Educational Survey Commission. 1918 (with F.B. Bachman). The Gary Schools. 1927 "Do Americans Really Value Education?" The Inglis Lecture 1927(Harvard University Press) 1928. The Burden of Humanism. The Taylorian Lecture at Oxford University. 1930. Universities: American, English, German. 1939. Flexner Abraham (1939 June/November). The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge. Harpers, Issue 179, pp. 544–552. [1]. 1940. I Remember: The Autobiography of Abraham Flexner. Simon and Schuster. Fulltext Archived July 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine 1943. A biography of H.S. Pritchett. |

レガシー このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2024年1月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) フレクスナー報告と彼の教育における仕事は、医学教育と高等教育に永続的な影響を与えた。フレクスナー・レポートがアメリカやカナダの医学に与えた具体的な影響には、以下のようなものがある: 医師の平均的な質は著しく向上した[13]。 医学は有利で評価の高い職業となった。 医師は最低6年間、できれば8年間の中等後教育を受けなければならない。 医学教育は、特に人体生理学と生化学の分野における研究に基づいている。 医学研究は、科学研究と同じプロトコルに従う[7]。 医学部の設立には州政府の承認が必要であり、医学部は州の規制を受ける。 アメリカ医師会の各州支部が、各州の従来の医学部すべてを監督している。 フレクスナーが共同設立した高等研究所は、物理的世界と人類の複雑さを理解しようと、80年以上にわたって貴重な研究を行ってきた。 フレックスナー報告書は、歴史的に黒人の医学部にダメージを与え、疎外した。 名誉 アメリカ医科大学協会は、毎年アメリカの医学教育に顕著な貢献をした個人を表彰するため、医学教育への特別功労賞としてエイブラハム・フレクスナー賞を創 設した[14]。2020年、AAMCは「人種差別的で性差別的な著作を考慮して」賞の名称を変更し、フレクスナーの名前を削除した[15]。 ケンタッキー大学医学部には、以前はエイブラハム・フレクスナー・マスター・エデュケーター賞と呼ばれていた、医学教育における卓越した医学教育者アカデミー賞があり、6つのカテゴリーにおける功績を称えている: 教育指導と管理 卓越した教育貢献またはメンターシップ 教育革新とカリキュラム開発 教育評価と研究 教育における教員養成[16] ルイビル・ダウンタウンの病院街にあるエイブラハム・フレクスナー・ウェイは、1978年11月にルイビル市会によりフレクスナーを称えるために命名された。 文献 1908. アメリカン・カレッジ A Criticism Archived November 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. 1910. アメリカとカナダの医学教育。 1910. アメリカとカナダの医学教育(Google Booksにて)。 1912. ヨーロッパの医学教育;カーネギー教育振興財団への報告書。 1915. 「ソーシャルワークは職業か?1915年5月12日~19日、メリーランド州ボルチモアで開催された第40回年次会議における慈善・矯正全国会議の議事録。 1916. 現代の学校 1916年(フランク・P・バックマンと共著)。メリーランド州の公教育: メリーランド州教育調査委員会への報告。 1918年(F.B.バックマンと共著)。ゲーリー・スクール 1927 "アメリカ人は本当に教育を重視するか?". イングリス講義1927(ハーバード大学出版局) 1928. ヒューマニズムの重荷 オックスフォード大学でのテイラー講義 1930. 大学: アメリカ、イギリス、ドイツ 1939. フレクスナー・エイブラハム(1939年6月/11月)。役に立たない知識の有用性. Harpers, Issue 179, pp. [1]. 1940. 私は覚えている: アブラハム・フレクスナー自伝. サイモン・アンド・シュスター Fulltext Archived July 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. 1943. H.S.プリチェットの伝記。 |

| Charles Flexner (born 1956), American physician, clinical pharmaceutical scientist, academic, author and researcher James Thomas Flexner (1908–2003), American historian and biographer Simon Flexner (1863–1946), physician, scientist, administrator, and professor |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Flexner |

|

The Flexner Report[

1]is a book-length landmark report of medical education in the United

States and Canada, written by Abraham Flexner and published in 1910

under the aegis of the Carnegie Foundation. Flexner not only described

the state of medical education in North America, but he also gave

detailed descriptions of the medical schools that were operating at the

time. He provided both criticisms and recommendations for improvements

of medical education in the United States. The Flexner Report[

1]is a book-length landmark report of medical education in the United

States and Canada, written by Abraham Flexner and published in 1910

under the aegis of the Carnegie Foundation. Flexner not only described

the state of medical education in North America, but he also gave

detailed descriptions of the medical schools that were operating at the

time. He provided both criticisms and recommendations for improvements

of medical education in the United States.Many aspects of the present-day American medical profession stem from the Flexner Report and its aftermath. While it had many positive impacts on American medical education, the Flexner report has been criticized for introducing policies that encouraged systemic racism and sexism.[2][3][4] The Report, also called Carnegie Foundation Bulletin Number Four, called on American medical schools to enact higher admission and graduation standards, and to adhere strictly to the protocols of mainstream science principles in their teaching and research. The report talked about the need for revamping and centralizing medical institutions. Many American medical schools fell short of the standard advocated in the Flexner Report and, subsequent to its publication, nearly half of such schools merged or were closed outright. Colleges for the education of the various forms of alternative medicine, such as electrotherapy, were closed. Homeopathy, traditional osteopathy, eclectic medicine, and physiomedicalism (botanical therapies that had not been tested scientifically) were derided.[5] The Report also concluded that there were too many medical schools in the United States, and that too many doctors were being trained. A repercussion of the Flexner Report, resulting from the closure or consolidation of university training, was the closure of all but two black medical schools and the reversion of American universities to male-only admittance programs to accommodate a smaller admission pool. |

フ

レクスナー報告書[1]は、アブラハム・フレクスナーによって書かれ、カーネギー財団の庇護のもと1910年に出版された、米国とカナダの医学教育に関す

る画期的な報告書である。フレクスナーは北米における医学教育の現状を述べただけでなく、当時運営されていた医学部についても詳細に記述した。彼は、アメ

リカの医学教育に対する批判と改善のための提言の両方を行った。 フ

レクスナー報告書[1]は、アブラハム・フレクスナーによって書かれ、カーネギー財団の庇護のもと1910年に出版された、米国とカナダの医学教育に関す

る画期的な報告書である。フレクスナーは北米における医学教育の現状を述べただけでなく、当時運営されていた医学部についても詳細に記述した。彼は、アメ

リカの医学教育に対する批判と改善のための提言の両方を行った。現在のアメリカの医学界の多くの側面は、フレクスナー報告とその余波に由来している。アメリカの医学教育に多くの肯定的な影響を与えた一方で、フレクスナー報告は体系的な人種差別や性差別を助長する政策を導入したとして批判されている[2][3][4]。 カーネギー財団会報第4号とも呼ばれるこの報告書は、アメリカの医学部に対し、より高い入学・卒業基準を制定し、教育と研究において主流科学の原則のプロ トコルを厳守するよう求めた。この報告書は、医療機関の改革と一元化の必要性について述べている。アメリカの多くの医学部は、フレクスナー報告書で提唱さ れた水準に達しておらず、報告書の発表後、そのような医学部の半数近くが合併したり、そのまま閉鎖されたりした。 電気療法など、さまざまな代替医療を教育する大学も閉鎖された。ホメオパシー、伝統的なオステオパシー、折衷医学、フィジオメディカリズム(科学的に検証されていない植物療法)は嘲笑された[5]。 報告書はまた、アメリカには医学部が多すぎ、医師が養成されすぎていると結論づけた。フレクスナー報告の反動として、大学教育の閉鎖や統合が行われた結 果、2校を除くすべての黒人医学部が閉鎖され、アメリカの大学は、より少ない入学者数に対応するため、男子のみの入学プログラムに逆戻りした。 |

Background Abraham Flexner During the nineteenth century, American medicine was neither economically supported nor regulated by the government.[6] Few state licensing laws existed,[7] and when they did exist, they were weakly enforced. There were numerous medical schools, all varying in the type and quality of the education they provided. In 1904, the American Medical Association (AMA) created the Council on Medical Education (CME),[8] whose objective was to restructure American medical education. At its first annual meeting, the CME adopted two standards: one laid down the minimum prior education required for admission to a medical school; the other defined a medical education as consisting of two years training in human anatomy and physiology followed by two years of clinical work in a teaching hospital. Generally speaking, the council strove to improve the quality of medical students, looking to draw from the society of upper-class, educated students.[9] In 1908, seeking to advance its reformist agenda and hasten the elimination of schools that failed to meet its standards, the CME contracted with the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to survey American medical education. Henry Pritchett, president of the Carnegie Foundation and a staunch advocate of medical school reform, chose Abraham Flexner to conduct the survey. Neither a physician, a scientist, nor a medical educator, Flexner held a Bachelor of Arts degree and operated a for-profit school in Louisville, Kentucky.[10] He visited every one of the 155 North American medical schools that were in operation at the time, all of which differed greatly in their curricula, methods of assessment, and requirements for admission and graduation. Summarizing his findings, he wrote:[11] "Each day students were subjected to interminable lectures and recitations. After a long morning of dissection or a series of quiz sections, they might sit wearily in the afternoon through three or four or even five lectures delivered in methodical fashion by part-time teachers. Evenings were given over to reading and preparation for recitations. If fortunate enough to gain entrance to a hospital, they observed more than participated." The Report became notorious for its harsh description of certain establishments. For example, Flexner described Chicago's fourteen medical schools as "a disgrace to the State whose laws permit its existence . . . indescribably foul . . . the plague spot of the nation."[1] Nevertheless, several schools received praise for excellent performance, including Western Reserve (now Case Western Reserve), Michigan, Wake Forest, McGill, Toronto, and particularly Johns Hopkins, which was described as the 'model for medical education'.[12] The Report ultimately produced many unintended consequences, and many of the repercussions of the Report are still seen in American medicine today. Minority groups, such as African Americans and women, faced fewer opportunities as a result of the publishing of the Flexner Report.[4] Additionally, many medical schools for alternative medicine and osteopathic medicine eventually closed as a result of the Report.[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flexner_Report |

背景 エイブラハム・フレクスナー 19世紀、アメリカの医学は、経済的な支援も政府による規制もなかった[6]。医学部は数多く存在し、その教育の種類や質はさまざまであった。 1904年、アメリカ医師会(AMA)は、アメリカの医学教育を再構築することを目的とした医学教育審議会(CME)を設立した[8]。1つは、医学部入 学に必要な最低限の事前教育を定めたもので、もう1つは、医学教育を、人体解剖学と生理学の2年間のトレーニングと、教育病院での2年間の臨床業務から構 成されるものと定義したものであった。一般的に言って、評議会は医学生の質の向上に努め、上流階級で教育を受けた学生の社会から引き抜こうと考えていた [9]。 1908年、改革主義的なアジェンダを推進し、基準を満たさない学校の排除を急ごうとしたCMEは、カーネギー教育振興財団と契約し、アメリカの医学教育 を調査した。カーネギー財団の会長であり、医学部改革の熱心な提唱者であったヘンリー・プリチェットは、エイブラハム・フレクスナーを調査の実施者に選ん だ。フレクスナーは、医師でも科学者でも医学教育者でもなく、文学士号を持ち、ケンタッキー州ルイビルで営利目的の学校を経営していた[10]。彼は、当 時運営されていた北米の医学部155校をすべて訪問したが、どの学校もカリキュラム、評価方法、入学と卒業の条件が大きく異なっていた。その結果を要約し て、彼は次のように書いている[11]。 「学生は毎日、延々と講義と暗唱を聞かされた。午前中の長い解剖や小テストが終わると、午後はパートタイムの教師による3つか4つ、あるいは5つの講義が 理路整然と行われる。夜は読書と暗唱の準備にあてられた。幸運にも病院に入ることができれば、参加するよりも見学する方が多かった」。 この報告書は、特定の施設に対する厳しい記述で悪名高いものとなった。例えば、フレクスナーはシカゴの14の医学部について、「その存在を法律が許可して いる州の恥......筆舌に尽くしがたいほど汚らわしい......国の疫病スポットである」と評した[1]。それにもかかわらず、ウェスタン・リザー ブ(現在のケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ)、ミシガン、ウェイク・フォレスト、マギル、トロント、そして特に「医学教育の模範」と評されたジョンズ・ホプ キンスなど、いくつかの学校は優れた業績を上げていると賞賛された[12]。 この報告書は、最終的に多くの予期せぬ結果をもたらし、その反動の多くは、今日でもアメリカの医学界に見られる。アフリカ系アメリカ人や女性などのマイノ リティ・グループは、フレクスナー報告の発表の結果、より少ない機会に直面した[4]。さらに、代替医療やオステオパシー医学のための多くの医学部は、最 終的に報告の結果として閉鎖された[13]。 |

| Recommended changes To help with the transition and change the minds of other doctors and scientists, John D. Rockefeller gave many millions to colleges, hospitals and founded a philanthropic group called "General Education Board" (GEB).[14] In the nineteenth century, it was relatively easy to not only receive a medical education, but also to start a medical school. When Flexner researched his report, many American medical schools were small "proprietary" trade schools owned by one or more doctors, unaffiliated with a college or university, and run to make a profit. A degree was typically awarded after only two years of study with laboratory work and dissection optional. Many of the instructors were local doctors teaching part-time. There were very few full-time professors, dedicated to medical education. Medical schools did not receive funding, and their only money came from the students' tuitions. Regulation of the medical profession by state governments was minimal or nonexistent. American doctors varied enormously in their scientific understanding of human physiology, and the word "quack" was in common use. Flexner carefully examined the situation. Using the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine as the ideal medical school,[15] he issued the following recommendations:[16] 1. Reduce both the number of medical schools (from 155 to 31) and the number of poorly trained physicians; 2. Increase the prerequisites to enter medical training; 3. Train physicians to practice in a scientific manner and engage medical faculty in research; 4. Give medical schools control of clinical instruction in hospitals; 5. Hire trained, full-time staff for medical education; 6. Grant medical schools increased funding; 7. Strengthen state regulation of medical licensure Flexner expressed that he found Hopkins to be a "small but ideal medical school, embodying in a novel way, adapted to American conditions, the best features of medical education in England, France, and Germany." To Flexner, Hopkins incorporated the high standards of German medical education, while keeping the American standard of high respect for patients by physicians.[17] In his efforts to ensure that Hopkins was the standard to which all other medical schools in the United States were compared, Flexner went on to claim that all the other medical schools were subordinate in relation to this "one bright spot."[18] In addition to Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Flexner also considered the medical schools at Harvard, University of Michigan, and the University of Pennsylvania to be strong schools. He said that medical schools that did not meet these high standards must change their approach to medical education or close their doors. Flexner also believed that admission to a medical school should require, at minimum, a high school diploma and at least two years of college or university study, primarily devoted to basic science. When Flexner researched his report, in the nineteenth century, only 16 out of 155 medical schools in the United States and Canada required applicants to have completed two or more years of university education.[19] By 1920, 92 percent of U.S. medical schools required this prerequisite of applicants. Flexner also argued that the length of medical education should be four years, and its content should be what the CME agreed to in 1905. Flexner recommended that the proprietary medical schools should either close or be incorporated into existing universities. Furthermore, he stated that medical schools needed to be part of a larger university since a proper stand-alone medical school would have to charge too much in order to break even financially. Less known is Flexner's recommendation that medical schools appoint full-time clinical professors. During the research of his report, Flexner noted a lack of dedicated, full-time professors. American medical education needed committed professors to teach the next generations of physicians. Holders of these appointments would become "true university teachers, barred from all but charity practice, in the interest of teaching."[1] Flexner pursued this objective for years, despite widespread opposition from existing medical faculty. Flexner was the child of German immigrants, and he had studied and traveled in Europe extensively. He was well aware that one could not practice medicine in continental Europe without having undergone an extensive specialized university education. There were many aspects of German medical education that Flexner, along with other medical educators and physicians who had traveled to Germany, admired, such as their national standards for students and universities, academic freedom, and the expectation of postgraduate training.[17][20] Furthermore, many physicians who traveled to Europe to receive postgraduate training were impressed with the German dedication to research, innovation, and teaching.[17] In effect, Flexner demanded that American medical education conform to prevailing practice in continental Europe. By and large, medical schools in Canada and the United States followed many of Flexner's recommendations. However, schools have increased their emphasis on matters of public health.[citation needed] |

推奨される変化 移行を助け、他の医師や科学者の意識を変えるために、ジョン・D・ロックフェラーは大学や病院に何百万ドルもの寄付をし、「一般教育委員会」(GEB)と呼ばれる慈善団体を設立した[14]。 19世紀には、医学教育を受けるだけでなく、医学部を設立することも比較的容易であった。フレクスナーが報告書を調査した当時、アメリカの医学部の多く は、1人または複数の医師が所有し、大学やカレッジとは無関係で、利益を上げるために運営されていた小規模な「私立」商科学校であった。通常、わずか2年 間の就学で学位が授与され、実験室での実習や解剖は任意であった。講師の多くは地元の医師で、非常勤で教えていた。医学教育に専念する常勤の教授はほとん どいなかった。医学部は資金援助を受けておらず、唯一の財源は学生の授業料だった。州政府による医療専門職の規制は最小限か存在しなかった。アメリカの医 師は、人体生理学に対する科学的理解に大きな差があり、「ヤブ医者」という言葉が普通に使われていた。 フレクスナーはこの状況を慎重に検討した。ジョンズ・ホプキンス医科大学を理想的な医学部とし[15]、次のような提言を発表した[16]。 1. 医学部の数を減らし(155校から31校へ)、不十分な訓練を受けた医師の数を減らす; 2. 医学部入学の前提条件を増やす; 3. 科学的な診療を行う医師を養成し、医学部教員を研究に従事させる; 4. 病院での臨床指導を医学部に管理させる; 5. 医学教育のために訓練を受けた常勤スタッフを雇用する; 6. 医学部への助成金を増額する; 7. 医師免許に関する州の規制を強化する。 フレクスナーは、ホプキンスは「小規模だが理想的な医学部であり、イギリス、フランス、ドイツの医学教育の最良の特徴を斬新な方法で体現し、アメリカの状 況に適応している」と評価した。フレクスナーにとって、ホプキンスはドイツの医学教育の高い水準を取り入れながら、医師が患者を尊重するというアメリカの 基準を保っていた[17]。ホプキンスがアメリカの他のすべての医学部と比較される基準であることを保証するために、フレクスナーは、他のすべての医学部 は、この「1つの光明」[18]に対して従属的であると主張し続けた。ジョンズ・ホプキンス医科大学に加えて、フレクスナーはハーバード大学、ミシガン大 学、ペンシルベニア大学の医学部も強力な学校であると考えていた。彼は、これらの高い基準を満たさない医学部は、医学教育へのアプローチを変えるか、門戸 を閉じなければならないと述べた。 フレクスナーはまた、医学部への入学には、最低でも高校卒業資格と、大学または短大で少なくとも2年間、主に基礎科学に専念することが必要だと考えてい た。フレクスナーが報告書を調査した19世紀には、米国とカナダの医学部155校のうち、志願者に2年以上の大学教育を修了していることを要求したのは 16校だけであった。フレクスナーはまた、医学教育の期間は4年であるべきであり、その内容は1905年にCMEが合意したものであるべきだと主張した。 フレクスナーは、私立の医学部は閉鎖するか、既存の大学に組み込むべきであると提言した。さらにフレクスナーは、医学部はより大きな大学の一部である必要 があると述べた。 あまり知られていないが、フレックスナーは医学部に常勤の臨床教授を任命するよう勧告している。フレクスナーは報告書の調査中、専任の常勤教授が不足して いることを指摘した。アメリカの医学教育には、次世代の医師を指導する熱心な教授が必要であった。フレクスナーは、既存の医学部教授陣の広範な反対にもか かわらず、何年にもわたってこの目標を追求した。 フレクスナーはドイツ移民の子であり、ヨーロッパで広く学び、旅をしていた。彼は、ヨーロッパ大陸では広範な専門的大学教育を受けなければ医学を実践でき ないことをよく知っていた。フレックスナーは、他の医学教育者やドイツを旅行した医師とともに、ドイツの医学教育には、学生や大学に対する国家的基準、学 問の自由、卒後研修への期待など、称賛すべき多くの側面があった[17][20]。さらに、卒後研修を受けるためにヨーロッパを旅行した多くの医師は、研 究、革新、教育に対するドイツの献身に感銘を受けた[17]。事実上、フレックスナーは、アメリカの医学教育をヨーロッパ大陸の一般的な慣習に合わせるこ とを要求した。 概して、カナダと米国の医学部は、フレクスナーの提言の多くに従った。しかし、学校は公衆衛生の問題に重点を置くようになった[要出典]。 |

| Impact of the report Many aspects of the medical profession in North America changed following the Flexner Report. Medical training adhered more closely to the scientific method and became grounded in human physiology and biochemistry. Medical research aligned more fully with the protocols of scientific research.[21] Average physician quality significantly increased.[16] Medical school closings Flexner wanted to improve both the admissions standards of medical school and the quality of medical education itself. He recognized that many of the medical schools had inadequate admissions requirements and a lack of adequate education. Consequently, Flexner sought to reduce the number of medical schools in the United States.[22] A majority of American institutions granting MD or DO degrees as of the date of the Report (1910) closed within two to three decades. (In Canada, only the medical school at Western University was deemed inadequate, but none was closed or merged subsequent to the Report.) In 1904, before the Report, there were 160 MD-granting institutions with more than 28,000 students. By 1920, after the Report, there were only 85 MD-granting institutions, educating only 13,800 students. By 1935, there were only 66 medical schools operating in the United States. Between 1910 and 1935, more than half of all American medical schools merged or closed. The dramatic decline was in some part due to the implementation of the Report's recommendation that all "proprietary" schools be closed and that medical schools should henceforth all be connected to universities. Of the 66 surviving MD-granting institutions in 1935, 57 were part of a university. An important factor driving the mergers and closures of medical schools was the national regulation and enforcement of medical school criteria: All state medical boards gradually adopted and enforced the Report 's recommendations. In response to the Flexner Report, some schools fired senior faculty members as part of a process of reform and renewal.[23] Impact on the role of physician The vision for medical education described in the Flexner Report narrowed medical schools' interests to disease, moving away from an interest on the system of health care or society's health beyond disease. Preventive medicine and population health were not considered a responsibility of physicians, bifurcating "health" into two separate fields: scientific medicine and public health.[24] Impact on African-American doctors and patients The Flexner Report has been criticized for introducing policies that encouraged systemic racism .[2][3][4][25][26] Flexner advocated for the closing of all but two of the historically black medical schools. As a result, only Howard University College of Medicine and Meharry Medical College were left open, while five other schools were closed. Flexner emphasized his view that black doctors should treat only black patients and should play roles subservient to those of white physicians. Flexner promoted the idea that African American medical students should be trained in "hygiene rather than surgery" and be employed as "sanitarians," with a primary role to protect white Americans from disease.[27] Flexner stated in the Report:[1] "A well-taught negro sanitarian will be immensely useful; an essentially untrained negro wearing an M.D. degree is dangerous." Furthermore, along with his adherence to germ theory, Flexner argued that, if not properly trained and treated, African-Americans posed a health threat to middle and upper-class whites.[28] Flexner argued that African American physicians should be educated in order to stop the transmission of diseases among African Americans and to prevent the contamination of white people from those same diseases.[1] "The practice of the Negro doctor will be limited to his own race, which in its turn will be cared for better by good Negro physicians than by poor white ones. But the physical well-being of the Negro is not only of moment to the Negro himself. Ten million of them live in close contact with sixty million whites. Not only does the Negro himself suffer from hookworm and tuberculosis; he communicates them to his white neighbors, precisely as the ignorant and unfortunate white contaminates him. Self-protection not less than humanity offers weighty counsel in this matter; self- interest seconds philanthropy. The Negro must be educated not only for his sake, but for ours. He is, as far as the human eye can see, a permanent factor in the nation."[28] Flexner's findings also restricted opportunities for African-American physicians in the medical sphere. Even the Howard and Meharry schools struggled to stay open following the Flexner Report, having to meet the institutional requirements of white medical schools, reflecting a divide in access to health care between white and African-Americans. Following the Flexner Report, African-American students sued universities, challenging the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson. However, those students were met by opposition from schools that remained committed to segregated medical education. It was not until 15 years after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that the AAMC ensured access to medical education for African-Americans and minorities by supporting the diversification of medical schools.[29] The closure of the five schools, and the fact that black students were not admitted to many U.S. medical schools for the 50 years following the Flexner Report, has contributed to the low numbers of American-born physicians of color as the ramifications are still felt, more than a century later.[30] Tens of thousands of African American physicians disappeared as a result of the Flexner Report.[27] In relation to the national Census, physicians belonging to minority groups, including African Americans, remain underrepresented in medicine.[31] In response to the racist writings of the Flexner Report, the AAMC decided to rename the prestigious Abraham Flexner award in 2020.[4] David Acosta, M.D., the chief diversity and inclusion officer of AAMC, stated, "We must not ignore medicine's racist history and make every effort toward reparation when this history is identified."[4] However, the view that Flexner and the Report were detrimental to black medical schools is largely refuted by Thomas N. Bonner, a scholar referred to as a “distinguished historian” by the AAMC. Bonner contended that Flexner worked to save the two black medical schools that were graduating most of the black physicians at that time.[32] The preceding sentence is inaccurate because one of the schools that was shut down Leonard Medical School Shaw University graduated more students than Meharry and Howard combined See Table 1 Black Medical Schools Evaluated by Flexner, 1908–1910 Source The State of Diversity in the Health Professions a Century After Flexner Academic Medicine85(2):246-253, February 2010. Impact on women The Flexner Report has also been criticized for introducing policies that encouraged sexism.[4] Before the publication of the Flexner Report, in the mid-to-latter part of the nineteenth century, universities had just begun opening and expanding female admissions as part of both women's and co-educational facilities with the founding of co-educational Oberlin College in 1833 and private all-women's colleges such as Vassar College and Pembroke College. Furthermore, many women opened their own medical schools for women as a response to other medical schools refusing to admit them. In the Report, Flexner noted that there were few women in medical education.[1] Flexner believed that the small numbers of female medical students and female physicians was not due to a lack of opportunity because, as he saw it, there were ample opportunities for women to be educated in medicine. Thus, he believed that the low numbers were due to a decreased desire and tendency to enter medical school.[1] “Now that women are freely admitted to the medical profession, it is clear that they show a decreasing inclination to enter it. More schools in all sections are open to them; fewer attend and fewer graduate.” Flexner also emphasized women's particular role in medicine throughout the Report: "Woman has so apparent a function in certain medical specialties…". [1] While some people thought that women were intellectual equals of men, more people thought that women were naturally nurturing and loving, so they should pursue a medical career in child health, occupational health, and maternal health.[33] Today, these consequences of the Report are still seen as many female physicians specialize in pediatrics and obstetrician and gynecologist.[33] Impact on alternative medicine When Flexner researched his report, "modern" medicine faced vigorous competition from several quarters, including osteopathic medicine, chiropractic medicine, electrotherapy, eclectic medicine, naturopathy, and homeopathy.[34] Flexner clearly doubted the scientific validity of all forms of medicine other than that based on scientific research, deeming any approach to medicine that did not advocate the use of treatments such as vaccines to prevent and cure illness as tantamount to quackery and charlatanism. Medical schools that offered training in various disciplines including electromagnetic field therapy, phototherapy, eclectic medicine, physiomedicalism, naturopathy, and homeopathy, were told either to drop these courses from their curriculum or lose their accreditation and underwriting support. A few schools resisted for a time, but eventually most schools for alternative medicine complied with the Report or shut their doors.[13] Impact on osteopathic medicine While almost all the alternative medical schools listed in the Flexner Report were closed, the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) brought a number of osteopathic medical schools into compliance with Flexner's recommendations to produce an evidence-based approach and practice.[35] Today, the curricula of DO- and MD-awarding medical schools are now nearly identical, the chief difference being the additional instruction in osteopathic schools of osteopathic manipulative medicine.[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flexner_Report |

報告書の影響 フレクスナー報告を受けて、北米の医療界の多くの側面が変化した。医療訓練は科学的手法により忠実になり、人間の生理学と生化学に基礎を置くようになっ た。医学研究は、科学研究のプロトコルにより完全に沿ったものとなった[21]。 医師の平均的な質は著しく向上した[16]。 医学部の閉鎖 フレクスナーは、医学部の入学基準と医学教育そのものの質の両方を改善したいと考えていた。彼は、多くの医学部は入学条件が不十分で、十分な教育が行われ ていないことを認識していた。その結果、フレクスナーは米国の医学部の数を減らそうとした[22]。報告書の日付(1910年)時点で、医学博士号または 医学博士号を授与していた米国の教育機関の大半は、20年から30年のうちに閉鎖された。(カナダでは、ウェスタン大学の医学部のみが不適切とされたが、 報告書の後に閉鎖や合併されたものはなかった)。報告以前の1904年には、160の医学部授与機関があり、28,000人以上の学生が学んでいた。報告 書後の1920年には、医学博士号を授与する教育機関は85しかなく、13,800人の学生を教育しているに過ぎなかった。1935年には、米国で運営さ れている医学部はわずか66校であった。 1910年から1935年の間に、アメリカの医学部の半分以上が合併または閉鎖された。この劇的な衰退は、すべての「プロプライエタリ」スクールを閉鎖 し、医学部は今後すべて大学に接続されるべきであるという報告書の勧告が実施されたことが原因の一部であった。1935年当時、現存する66の医学部設置 校のうち、57校が大学の一部であった。医学部の合併と閉鎖を促した重要な要因は、医学部基準の全国的な規制と施行であった: 各州の医学委員会は、この報告書の勧告を徐々に採用し、実施するようになった。フレクスナー報告書を受けて、改革と再生のプロセスの一環として、上級教員 を解雇した学校もあった[23]。 医師の役割への影響 フレクスナー報告に記載された医学教育のビジョンは、医学部の関心を疾病に絞り込み、医療システムや疾病を超えた社会の健康への関心から遠ざけた。予防医 学と住民の健康は医師の責任とはみなされず、「健康」は科学的医学と公衆衛生という2つの別々の分野に二分された[24]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の医師と患者への影響 フレクスナー・レポートは、体系的な人種差別を助長する政策を導入したとして批判されている[2][3][4][25][26]。 フレクスナーは、歴史的に黒人の多い医学部のうち2校を除くすべての閉鎖を提唱した。その結果、ハワード大学医学部とメハリー医科大学だけが残され、他の 5校は閉鎖された。フレクスナーは、黒人医師は黒人患者だけを診療し、白人医師に従属する役割を果たすべきだという考えを強調した。フレクスナーは、アフ リカ系アメリカ人の医学生は「外科よりもむしろ衛生」の訓練を受け、「衛生士」として採用されるべきであり、白人アメリカ人を病気から守ることを主な役割 とすべきだという考えを推進した[27]。 フレクスナーは報告書の中で次のように述べている[1]。 「よく教育された黒人の衛生兵は非常に役に立つだろうが、本質的に訓練を受けていない黒人が医学博士の学位を取得するのは危険である」。 さらにフレクスナーは、細菌理論への固執とともに、適切に訓練され治療されなければ、アフリカ系アメリカ人は中流階級や上流階級の白人にとって健康上の脅 威となると主張した[28]。 フレクスナーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の間での病気の感染を阻止し、同じ病気による白人の汚染を防ぐために、アフリカ系アメリカ人の医師は教育を受けるべ きだと主張した[1]。 「黒人医師の診療は彼自身の人種に限定され、その人種は貧しい白人医師よりも優れた黒人医師によってよりよく治療されるだろう。しかし、黒人の身体的健康 は、黒人自身だけの問題ではない。1,000万人の黒人は、6,000万人の白人と密接に接触して暮らしている。黒人自身が鉤虫症や結核に苦しむだけでな く、無知で不幸な白人が黒人を汚染するのと同じように、黒人も隣人の白人に鉤虫症や結核をうつすのである。この問題では、人道に勝るとも劣らない自己保護 が重要な助言を与えてくれる。黒人は彼のためだけでなく、我々のためにも教育されなければならない。彼は、人間の目で見る限り、国家の永続的な要因なので ある」[28]。 フレクスナーの発見は、アフリカ系アメリカ人医師の医学界での活躍の機会をも制限した。フレクスナー報告の後、ハワード校とメハリー校でさえ、白人医学部 の制度的要件を満たさなければならず、開校を維持するのに苦労し、白人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の間の医療へのアクセスの格差を反映した。フレクスナー報告 の後、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学生たちは、プレッシー対ファーガソンの判例に異議を唱え、大学を訴えた。しかし、こうした学生たちは、隔離された医学教育 に固執する学校からの反対に遭った。AAMCが医学部の多様化を支援することで、アフリカ系アメリカ人やマイノリティの医学教育へのアクセスを確保したの は、1954年のブラウン対教育委員会事件から15年後のことであった[29]。 5校の閉鎖、そしてフレクスナー報告書後の50年間、黒人の学生がアメリカの多くの医学部に入学できなかったという事実は、その影響が100年以上経った 今でも感じられるように、アメリカ生まれの有色人種の医師数の少なさの一因となっている[30]。 フレクスナー報告書の結果、何万人ものアフリカ系アメリカ人の医師が姿を消した[27]。国勢調査との関連では、アフリカ系アメリカ人を含むマイノリ ティ・グループに属する医師は、医学界において依然として存在感が薄い[31]。 フレクスナー報告の人種差別的な記述を受けて、AAMCは2020年に権威あるアブラハム・フレクスナー賞の名称を変更することを決定した[4]、 しかし、フレクスナーと報告書が黒人医学部にとって有害であったという見解については、AAMCが「著名な歴史家」と呼ぶ学者、トーマス・N・ボナー (Thomas N. Bonner)が大きく反論している。ボナーは、フレックスナーは当時黒人医師のほとんどを卒業させていた2つの黒人医学部を救うために働いたと主張して いる[32] 閉鎖された学校の1つであるレナード医科大学ショー大学は、メハリーとハワードの合計よりも多くの学生を卒業させたので、前出の文章は不正確である。 表1 フレックスナーが評価した黒人医学部(1908-1910年) 出典 The State of Diversity in the Health Professions a Century After Flexner Academic Medicine85(2):246-253, February 2010. 女性への影響 フレクスナー報告書は、性差別を助長する政策を導入したとの批判もある[4]。 フレクスナー報告書が発表される前、19世紀半ばから後半にかけて、大学は、1833年に男女共学のオバーリン・カレッジや、ヴァッサー・カレッジやペン ブローク・カレッジのような私立の女子大学が設立され、女子大学や男女共学の施設の一部として女性の入学許可を開設し、拡大し始めたばかりであった。さら に、他の医学部が女性の入学を拒否したことに対抗して、多くの女性が女性のための独自の医学部を開設した。 報告の中でフレクスナーは、医学教育に携わる女性の数が少ないことを指摘している[1]。フレクスナーは、女子医学生や女性医師の数が少ないのは機会の不 足によるものではないと考えた。したがって、その数の少なさは、医学部への進学意欲や傾向の低下によるものだと考えていた[1]。 「女性が自由に医学職に就けるようになった今、女性が医学職に就こうとする傾向が弱まっていることは明らかである。すべてのセクションで、より多くの学校が彼女たちに開かれているが、通う者も卒業する者も少ない。" フレクスナーはまた、報告書全体を通して、医学における女性の特別な役割を強調している: 「女性は特定の医学の専門分野において、非常に明白な働きをしている。[1] 女性は男性と知的には対等であると考える人もいたが、女性は生まれながらにして養育能力があり、愛情深いので、小児保健、産業保健、妊産婦保健の分野で医 学的キャリアを積むべきだと考える人の方が多かった[33]。今日でも、多くの女性医師が小児科や産婦人科を専門としていることから、この報告書のこうし た結果が見られる[33]。 代替医療への影響 フレクスナーが報告書を調査した当時、「近代」医学は、オステオパシー医学、カイロプラクティック医学、電気療法、折衷医学、自然療法、ホメオパシーな ど、いくつかの方面からの活発な競争に直面していた[34]。フレクスナーは、科学的研究に基づく医学以外のあらゆる形態の医学の科学的妥当性を明確に疑 い、病気の予防や治癒のためにワクチンなどの治療法の使用を提唱しない医学へのアプローチは、ヤブ医者やシャルラタニズムに等しいとみなした。電磁場療 法、光線療法、折衷医学、フィジオメディカリズム、自然療法、ホメオパシーなど、さまざまな分野のトレーニングを提供していた医学部は、これらのコースを カリキュラムから外すか、認定と引き受けのサポートを失うかのどちらかを言い渡された。一時は抵抗した学校もあったが、最終的にはほとんどの代替医療の学 校が報告書に従うか、門戸を閉じた[13]。 オステオパシー医学への影響 フレクスナー・レポートに記載された代替医療学校はほとんどすべて閉鎖されたが、米国オステオパシー協会(AOA)は、多くのオステオパシー医学部を、エ ビデンスに基づいたアプローチと実践を生み出すフレクスナーの勧告に準拠させた[35]。 今日では、DOを授与する医学部とMDを授与する医学部のカリキュラムはほぼ同じであるが、主な違いは、オステオパシー学校におけるオステオパシー操作医 学の追加教育である[36]。 |

| Committee of Ten |

|

| The National Education Association of the United States Committee on Secondary School Studies known as the NEA Committee of Ten

was a working group of educators that convened in 1892. They were

charged with taking stock of current practices in American high schools

and making recommendations for future practice. They collected data via

surveys and interviews with educators across the United States, met in

a series of multi-day committee meetings, and developed consensus and

dissenting reports. Background Education is a matter left up to individual states and territories in the United States. This meant that each state developed its own system, including its own structure for secondary education, or high school. These disparate systems often led to a disconnect between high schools in the same state or large gaps between the skills students had when they left high school and what colleges were looking for. The rise of the common school helped even out differences in different states grammar schools but by the late 1800s, a desire for educational standardization had manifested across the country.[1] Across the nation and within communities, there were competing academic philosophies which the Committee of Ten aimed to resolve. One philosophy favored rote memorization, whereas another favored critical thinking. One philosophy designated American high schools as institutions that would divide students into college-bound and working-trades groups from the start; these institutions sometimes further divided students based on race or ethnic background. Another philosophy attempted to provide standardized courses for all students. Somewhat similarly, another philosophy promoted classic Latin/Greek studies, whereas other philosophies stressed practical studies. Membership of the Committee of Ten To resolve these issues, the National Education Association formed The 1892 Committee of Ten. The committee was largely composed of representatives of higher education. Its subgroups, consisting of eight to ten members each, were convened by the following individuals: Charles William Eliot, President of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts Chairman William T. Harris, Commissioner of Education, Washington, D.C. James B. Angell, President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan John Tetlow, Head Master of the Girls’ High School, Boston, Massachusetts James Monroe Taylor, President of Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York Oscar D. Robinson, Principal of the High School, Albany, New York James H. Baker, President of the University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado Richard Henry Jesse, President of the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri James C. Mackenzie, Head Master of the Lawrenceville School, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Henry Churchill King, Professor in Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio Recommendations External videos video icon You can view Coursera's summary on the Committee of Ten on YouTube The committee provided its recommendations in a report published in 1894 that answered an initial set of eleven questions, and outlined important curricular knowledge within each major instructional specialty including Latin, Greek, English, "Other Modern Languages", mathematics, and the sciences (physics, chemistry, and astronomy).[2] Twelve years of education were recommended, with eight years of elementary education followed by four years of high school. The committee was explicitly asked to address tracking, or course differentiation based upon postsecondary pursuit. The committee responded unanimously that "...every subject which is taught at all in a secondary school should be taught in the same way and to the same extent to every pupil so long as he pursues it, no matter what the probable destination of the pupil may be, or at what point his education is to cease."[3] In addition to promoting equality in instruction, they stated that by unifying courses of study, school instruction and the training of new teachers could be greatly simplified. These recommendations were generally interpreted as a call to teach English, mathematics, and history or civics to every student every academic year in high school. The recommendations also formed the basis of the practice of teaching chemistry, and physics, respectively, in ascending high school academic years. The Committee identified the need for more highly qualified educators, and proposed that universities could enhance training by offering subject-education courses, lowering tuition and paying travel fees for classroom teachers and that superintendents, principals or other "leading teachers" could show other teachers, "... by precept and example, how to [teach] better".[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Committee_of_Ten |

NEAの10人委員会として知られる全米教育協会の中等学校研究委員会

は、1892年に招集された教育者の作業部会であった。彼らは、アメリカの高校における実践の現状を把握し、将来の実践に向けた提言を行うことを任務とし

ていた。彼らは、全米の教育者へのアンケートやインタビューを通じてデータを収集し、数日間にわたる一連の委員会を開き、コンセンサスと反対意見をまとめ

た報告書を作成した。 背景 米国では、教育は各州と準州に委ねられている。そのため、各州は、中等教育(高校)の仕組みを含め、独自のシステムを構築していた。このように制度がバラ バラであるため、同じ州内の高校間で断絶が生じたり、生徒が高校を卒業するときに持っているスキルと大学が求めるスキルとの間に大きな隔たりが生じたりす ることがしばしばあった。コモン・スクールの台頭は、各州の文法学校の違いを均等にするのに役立ったが、1800年代後半になると、教育の標準化を望む声 が全米に現れた[1]。全米で、また地域社会で、10人委員会が解決を目指した学問哲学が競合していた。ある哲学は暗記を支持し、別の哲学は批判的思考を 支持した。ある哲学は、アメリカの高校を、生徒を最初から大学進学組と社会人組に分ける教育機関と位置づけ、こうした教育機関は、人種や民族的背景によっ て生徒をさらに分けることもあった。別の哲学は、すべての生徒に標準化されたコースを提供しようとした。同様に、古典的なラテン語やギリシャ語の勉強を奨 励する哲学もあれば、実践的な勉強を重視する哲学もあった。 10人委員会のメンバー これらの問題を解決するために、全米教育協会は1892年10人委員会を結成した。この委員会は、主に高等教育の代表者で構成された。それぞれ8名から10名で構成されたサブグループは、以下の人物によって招集された: チャールズ・ウィリアム・エリオット(ハーバード大学学長、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ 会長 ウィリアム・T・ハリス(ワシントンD.C.教育庁長官 ジェームズ・B・アンゲル ミシガン大学学長(ミシガン州アナーバー ジョン・テトロー マサチューセッツ州ボストン女子高校校長 ジェームズ・モンロー・テイラー(ニューヨーク州ポキプシー、ヴァッサー・カレッジ学長 オスカー・D・ロビンソン(ニューヨーク州オルバニー高校校長 ジェームズ・H・ベイカー、コロラド大学学長(コロラド州ボルダー リチャード・ヘンリー・ジェシー ミズーリ大学学長(ミズーリ州コロンビア ジェームズ・C・マッケンジー、ローレンスヴィル・スクール校長(ニュージャージー州ローレンスヴィル ヘンリー・チャーチル・キング、オハイオ州オベリン、オベリン・カレッジ教授 推薦 外部ビデオ ビデオアイコン YouTubeでCourseraの10人委員会に関する要約を見ることができる。 同委員会は、1894年に発表した報告書で勧告を行った。この報告書では、当初の11の質問に答え、ラテン語、ギリシア語、英語、「その他の現代語」、数学、科学(物理学、化学、天文学)を含む各主要教育分野における重要なカリキュラムの知識を概説している[2]。 12年間の教育が推奨され、8年間の初等教育に続いて4年間の高等教育が行われた。委員会は、追跡調査、つまり中等教育修了後の進路に基づくコースの差別 化について明確に求められた。委員会は満場一致で、「中等学校で全く教えられていないすべての科目は、生徒がそれを追求する限り、どの生徒にも同じ方法 で、同じ程度に教えられるべきである。 これらの勧告は、一般に、高校では各学年で英語、数学、歴史または公民を全生徒に教えるよう求めていると解釈された。また、この勧告は、化学と物理をそれぞれ高校の学年が上がるごとに教えるという慣行の基礎にもなった。 委員会は、より多くの優秀な教育者の必要性を指摘し、大学が教科教育コースを提供し、授業料を引き下げ、クラス担任のための旅費を負担することによって研 修を強化し、教育長、校長、その他の「指導的教師」が、「......教訓と模範によって、どのようにすれば(よりよく)教えることができるか」を他の教 師に示すことができると提案した[4]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆