アブラハム・マズロー

Abraham Maslow,

1908-1970

☆ア

ブラハム・ハロルド・マズロー(Abraham Harold Maslow、1908年4月1日 -

1970年6月8日)は、人間の心理的健康の理論を提唱したアメリカの心理学者。[1]

マズローは、ブランドイス大学、ブルックリン大学、ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチ、コロンビア大学で心理学の教授を務めた。彼は、人々

を「症状の袋」として扱うのではなく、そのポジティブな特性に焦点を当てる重要性を強調した。[2]

2002年に発表された『一般心理学のレビュー』の調査では、マズローは20世紀で最も引用された心理学者ランキングで10位にランクインした。[3]

| Abraham Harold Maslow

(/ˈmæzloʊ/ MAZ-loh; April 1, 1908 – June 8, 1970) was an American

psychologist who created Maslow's hierarchy of needs, a theory of

psychological health predicated on fulfilling innate human needs in

priority, culminating in self-actualization.[1] Maslow was a psychology

professor at Brandeis University, Brooklyn College, New School for

Social Research, and Columbia University. He stressed the importance of

focusing on the positive qualities in people, as opposed to treating

them as a "bag of symptoms".[2] A Review of General Psychology survey,

published in 2002, ranked Maslow as the tenth most cited psychologist

of the 20th century.[3] |

ア

ブラハム・ハロルド・マズロー(Abraham Harold Maslow、1908年4月1日 -

1970年6月8日)は、人間の心理的健康の理論を提唱したアメリカの心理学者。[1]

マズローは、ブランドイス大学、ブルックリン大学、ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチ、コロンビア大学で心理学の教授を務めた。彼は、人々

を「症状の袋」として扱うのではなく、そのポジティブな特性に焦点を当てる重要性を強調した。[2]

2002年に発表された『一般心理学のレビュー』の調査では、マズローは20世紀で最も引用された心理学者ランキングで10位にランクインした。[3] |

| Biography Youth Born in 1908 and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Maslow was the oldest of seven children. His parents were first-generation Jewish immigrants from Kyiv, then part of the Russian Empire (now Kyiv, Ukraine), who fled from Czarist persecution in the early 20th century.[4][5] They had decided to live in New York City and in a multiethnic, working-class neighborhood.[6] His parents were poor and not intellectually focused, but they valued education. He had various encounters with antisemitic gangs who would chase and throw rocks at him.[7] Maslow and other young people with his background were struggling to overcome such acts of racism and ethnic prejudice in an attempt to establish an idealistic world based on widespread education and economic justice.[editorializing][8] The tension outside his home was also felt within it: he rarely got along with his mother and eventually developed a strong revulsion towards her. He is quoted as saying, "What I had reacted to was not only her physical appearance, but also her values and world view, her stinginess, her total selfishness, her lack of love for anyone else in the world—even her own husband and children—her narcissism, her Negro prejudice, her exploitation of everyone, her assumption that anyone was wrong who disagreed with her, her lack of friends, her sloppiness and dirtiness...". He also grew up with few friends other than his cousin Will, and as a result, he "grew up in libraries and among books".[9] It was here that he developed his love for reading and learning. He went to Boys High School, one of the top high schools in Brooklyn, where his best friend was his cousin Will Maslow.[10][11] Here, he served as the officer to many academic clubs and became editor of the Latin magazine. He also edited Principia, the school's physics paper, for a year.[12] He developed other strengths as well: As a young boy, Maslow believed physical strength to be the single most defining characteristic of a true male; hence, he exercised often and took up weight lifting in hopes of being transformed into a more muscular, tough-looking guy, however, he was unable to achieve this due to his humble-looking and chaste figure as well as his studiousness.[13] |

略歴 青年期 1908年にニューヨークのブルックリンで生まれ、7人兄弟の長男として育った。両親は、20世紀初頭に帝政ロシアの迫害から逃れてきた、キエフ(当時ロ シア帝国、現在はウクライナのキエフ)出身の第一世代のユダヤ人移民だった。[4][5] 彼らはニューヨーク市に移住し、多民族の労働者階級が住む地域で生活することを決めた。[6] 両親は貧しく、知的関心は高くなかったが、教育を重視していた。彼は、彼を追いかけ、石を投げる反ユダヤ主義のギャングたちと何度も遭遇した。[7] マズローと彼と同じような背景を持つ若者たちは、広範な教育と経済的な正義に基づく理想的な世界を構築しようと、このような人種主義や民族的偏見と闘って いた。[編集者注][8] 彼の家の外での緊張は、家の中にも及んでいた。彼は母親とほとんど仲が良くなく、やがて彼女に対して強い嫌悪感を抱くようになった。彼は次のように述べて いる。「私が反応したのは、彼女の外見だけでなく、彼女の価値観や世界観、吝嗇、完全な自己中心性、世界中の誰に対しても愛がないこと——自分の夫や子供 たちさえも——ナルシシズム、ニグロ差別、他人を搾取する態度、自分と意見が異なる者は皆間違っているという前提、友人がいないこと、不潔で乱雑な生活態 度……」 彼は、従兄弟のウィル以外の友人がほとんどいない環境で育ち、その結果、「図書館と本の中で育った」[9]。ここで彼は読書と学習への愛を育んだ。彼はブ ルックリンのトップ高校の一つであるボーイズ・ハイスクールに通い、そこで従兄弟のウィル・マスロウが最良の友人となった。[10][11] ここで彼は多くの学術クラブの役員を務め、ラテン語雑誌の編集長になった。また、学校の物理学誌『Principia』の編集長を1年間務めた。[12] 彼は他の強みも育んだ: 幼少期、マズローは真の男性を定義する最も重要な特徴は肉体的な強さだと信じていた。そのため、彼は頻繁に運動し、筋骨隆々の逞しい体を目指すためにウェ イトトレーニングを始めた。しかし、彼の控えめな外見と清廉な性格、そして勉強熱心な性格のため、この目標を達成することはできなかった。[13] |

| College and university Maslow attended the City College of New York after high school. In 1926, he began taking legal studies classes at night in addition to his undergraduate course load. He hated it and almost immediately dropped out. In 1927, he transferred to Cornell but left after just one semester due to poor grades and high costs.[14] He later graduated from City College and went to graduate school at the University of Wisconsin (UW) to study psychology. In 1928, he married his first cousin, Bertha, who was still in high school. The pair had met in Brooklyn years earlier.[15] Maslow's psychology training at UW was decidedly experimental-behaviorist.[16] At Wisconsin, he pursued a line of research that included investigating primate dominance behavior and sexuality. Maslow's early experience with behaviorism would leave him with a strong positivist mindset.[17] Upon the recommendation of professor Hulsey Cason, Maslow wrote his master's thesis on "learning, retention, and reproduction of verbal material".[18] Maslow regarded the research as embarrassingly trivial, but he completed his thesis in the summer of 1931 and was awarded his master's degree in psychology. He was so ashamed of the thesis that he removed it from the psychology library and tore out its catalog listing.[19] However, Cason admired the research enough to urge Maslow to submit it for publication. Maslow's thesis was published as two articles in 1934.[citation needed] |

大学 マズローは高校卒業後、ニューヨーク市立大学に通った。1926年、彼は学部課程の履修に加え、夜間法律の勉強を始めた。しかし、その勉強が嫌で、すぐに 中退した。1927年にコーネル大学に転入したが、成績不振と学費の高さから1学期で退学した。[14] その後、シティ・カレッジを卒業し、ウィスコンシン大学(UW)の大学院に進学して心理学を学んだ。1928年に、当時まだ高校生の従姉妹であるベルタと 結婚した。二人は数年前にブルックリンで出会っていた。[15] マズローのUWでの心理学の訓練は、明らかに実験的行動主義的だった。[16] ウィスコンシン大学では、霊長類の支配行動や性行動を調査する研究に取り組んだ。マズローの行動主義との初期の経験は、彼に強い実証主義的な思考パターン を残した。[17] 教授のハルシー・カソン氏の推薦で、マズローは修士論文「言語材料の学習、保持、再現」を執筆した。[18] マズローはこの研究を恥ずかしいほど軽薄なものと考えていたが、1931年の夏に修士論文を完成させ、心理学の修士号を取得した。彼はこの論文を非常に恥 じて、心理学図書館から取り除き、目録の記載を破り捨てた。[19] しかし、キャソンは研究を高く評価し、マズローに出版を勧めた。マズローの修士論文は1934年に2つの論文として発表された。[出典が必要] |

| Academic career Maslow continued his research on similar themes at Columbia University. There he found another mentor in Alfred Adler, one of Sigmund Freud's early colleagues. From 1937 to 1951, Maslow was on the faculty of Brooklyn College. His family life and his experiences influenced his psychological ideas. After World War II, Maslow began to question how psychologists had come to their conclusions, and though he did not completely disagree, he had his own ideas on how to understand the human mind.[20] He called his new discipline humanistic psychology. Maslow was already a 33-year-old father and had two children when the United States entered World War II in 1941. He was thus ineligible for the military. However, the horrors of war inspired a vision of peace in him, leading to his groundbreaking psychological studies of self-actualizing.[editorializing] The studies began under the supervision of two mentors, anthropologist Ruth Benedict and Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer, whom he admired both professionally and personally. They accomplished a lot in both realms. Being such "wonderful human beings" also inspired Maslow to take notes about them and their behavior. This would be the basis of his lifelong research and thinking about mental health and human potential.[21] Maslow extended the subject, borrowing ideas from other psychologists and adding new ones, such as the concepts of a hierarchy of needs, metaneeds, metamotivation, self-actualizing persons, and peak experiences. He was a professor at Brandeis University from 1951 to 1969. He became a resident fellow of the Laughlin Institute in California. In 1967, Maslow had a serious heart attack and knew his time was limited. He considered himself to be a psychological pioneer.[fact or opinion?] He pushed future psychologists by bringing to light different paths to ponder.[22] He built the framework that later allowed other psychologists to conduct more comprehensive studies. Maslow believed that leadership should be non-intervening. Consistent with this approach, he rejected a nomination in 1963 to be the Association for Humanistic Psychology president because he felt the organization should develop an intellectual movement without a leader.[23] |

学歴 マズローはコロンビア大学で同様のテーマの研究を続けた。そこで、彼はジークムント・フロイトの初期の同僚の一人であるアルフレッド・アドラーというもう 一人の師匠に出会った。1937年から1951年まで、マズローはブルックリン大学の教員を務めた。彼の家庭生活や経験は、彼の心理学の考え方に影響を与 えた。第二次世界大戦後、マズローは心理学者たちが結論に至った過程に疑問を抱き始め、完全に反対するわけではなかったものの、人間の心を理解する独自の 考えを持っていた。[20] 彼はこの新しい学問分野を「人間[主義]的な心理学(humanistic psychology)」 と名付けた。マズローは1941年にアメリカが第二次世界大戦に参戦した際、33歳で2人の子供を持つ父親だったため、軍務に就く資格がなかった。しか し、戦争の残虐さは彼に平和のビジョンを植え付け、自己実現に関する画期的な心理学的研究へとつながった。[編集者注] これらの研究は、人類学者のルース・ベネディクトとゲシュタルト心理学者のマックス・ヴェルツハイマーという、彼らが職業的にも人格的にも尊敬する2人の 指導者の下で始まった。彼らは両分野で多くの成果を上げた。このような「素晴らしい人間たち」は、マズローにも彼らや彼らの行動についてメモを取るよう促 した。これが、彼の生涯にわたる精神保健と人間の可能性に関する研究と思考の基礎となった。[21] マズローは、他の心理学者からアイデアを借用し、ニーズの階層、メタニーズ、メタモチベーション、自己実現者、ピーク体験などの新しい概念を追加して、こ のテーマをさらに発展させた。彼は1951年から1969年までブランダイス大学で教授を務めた。カリフォルニアのラフリン研究所の常任研究員にも就任し た。1967年、マズローは深刻な心臓発作を起こし、自分の余命が限られていることを悟った。彼は自分を心理学的先駆者だと考えていた。[事実か意見 か?] 彼は、異なる道を示唆することで、未来の心理学者たちに刺激を与えた。[22] 彼は、後に他の心理学者たちがより包括的な研究を行うための枠組みを構築した。マズローは、リーダーシップは非介入的であるべきだと考えていた。このアプ ローチに沿って、彼は1963年に人間主義心理学協会会長の指名を受けましたが、組織はリーダーなしの知的運動を発展させるべきだと考え、これを拒否し た。[23] |

| Death While jogging, Maslow had a severe heart attack and died on June 8, 1970, at the age of 62 in Menlo Park, California.[24][25] He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. |

死 ジョギング中に、マズローは重度の心臓発作を起こし、1970年6月8日、62歳でカリフォルニア州メンロパークで死去した。[24][25] 彼はマウント・オーバーン墓地に埋葬されている。 |

| Maslow's contributions Humanistic psychology Most psychologists before him had been concerned with the abnormal and the ill. He urged people to acknowledge their basic needs before addressing higher needs and ultimately self-actualization. He wanted to know what constituted positive mental health. Humanistic psychology gave rise to several different therapies, all guided by the idea that people possess the inner resources for growth and healing and that the point of therapy is to help remove obstacles to individuals' achieving them. The most famous of these was client-centered therapy developed by Carl Rogers. The basic principles behind humanistic psychology are simple: Someone's present functioning is their most significant aspect. As a result, humanists emphasize the here and now instead of examining the past or attempting to predict the future. To be mentally healthy, individuals must take personal responsibility for their actions, regardless of whether the actions are positive or negative. Each person, simply by being, is inherently worthy. While any given action may be negative, these actions do not cancel out the value of a person. The ultimate goal of living is to attain personal growth and understanding. Only through constant self-improvement and self-understanding can an individual ever be truly happy.[26] Humanistic psychology theory suits people who see the positive side of humanity and believe in free will. This theory clearly contrasts with Freud's theory of biological determinism. Another significant strength is that humanistic psychology theory is compatible with other schools of thought. Maslow's hierarchy is also applicable to other topics, such as finance, economics, or even in history or criminology. Humanist psychology, also coined positive psychology, is criticized for its lack of empirical validation and therefore its lack of usefulness in treating specific problems. It may also fail to help or diagnose people who have severe mental disorders.[26] Humanistic psychologists believe that every person has a strong desire to realize their full potential, to reach a level of "self-actualization". The main point of that new movement, that reached its peak in the 1960s, was to emphasize the positive potential of human beings.[27] Maslow positioned his work as a vital complement to that of Freud: It is as if Freud supplied us the sick half of psychology and we must now fill it out with the healthy half.[28] However, Maslow was highly critical of Freud, since humanistic psychologists did not recognize spirituality as a navigation for our behaviors.[29] To prove that humans are not blindly reacting to situations, but trying to accomplish something greater, Maslow studied mentally healthy individuals instead of people with serious psychological issues. He focused on self-actualizing people. Self-actualizing people indicate a coherent personality syndrome and represent optimal psychological health and functioning.[30] This informed his theory that a person enjoys "peak experiences", high points in life when the individual is in harmony with themself and their surroundings. In Maslow's view, self-actualized people can have many peak experiences throughout a day while others have those experiences less frequently.[31] He believed that psychedelic drugs like LSD and psilocybin can produce peak experiences in the right people under the right circumstances.[32] |

マズローの貢献 人間主義(ヒューマニスト)心理学 彼以前のほとんどの心理学者は、異常や病気に関心を持っていました。彼は、より高いニーズや最終的には自己実現に取り組む前に、人民は自分の基本的なニー ズを認識すべきだと主張しました。彼は、ポジティブな保健とは何なのかを知りたかったのです。人間主義心理学は、人間には成長と癒しの内なる資源があり、 セラピーの目的は、個人がそれを達成するための障害を取り除くことにあるという考え方に基づいて、いくつかの異なるセラピーを生み出しました。その最も有 名なものが、カール・ロジャースによって開発されたクライアント中心療法だ。 人間性心理学の基本原則は単純だ。 人の現在の機能は、その人にとって最も重要な側面だ。その結果、人間主義者は、過去を考察したり、未来を予測したりするのではなく、今この瞬間を重視する。 精神的に健康であるためには、人格が自分の行動に対して責任を負う必要がある。その行動がポジティブかネガティブかに関わらずだ。 各人格は、単に存在しているだけで、本質的に価値がある。特定の行動がネガティブであっても、その行動は人格の価値を否定するものではない。 人生の最終的な目標は、個人的な成長と理解を達成することだ。個人が真に幸せになるためには、継続的な自己改善と自己理解を通じてのみ可能だ。[26] 人間主義心理学の理論は、人間性のポジティブな側面を見出し、自由意志を信じる人民に適している。この理論は、フロイトの生物学的決定論とは明らかに対照 的だ。もう一つの大きな強みは、人間主義心理学の理論が他の学派とも相容れることだ。マズローの階層理論は、金融、経済学、さらには歴史や犯罪学などの他 の分野にも適用できる。人間中心心理学(ポジティブ心理学とも呼ばれる)は、経験的検証の欠如を理由に、特定の問題の治療における有用性がないと批判され ている。また、重度の精神障害を抱える人民を助けることや診断することに失敗する可能性もある。[26] 人間中心の心理学者たちは、誰もが「自己実現」の段階に達し、潜在能力を最大限に発揮したいという強い欲求を持っていると信じている。1960年代に最盛 期を迎えたこの新しい運動の主なポイントは、人間のポジティブな可能性を強調することだった[27]。マズローは、自分の研究をフロイトの研究の重要な補 完物として位置付けた。 それは、フロイトが心理学の病んだ半分を私たちに提供し、私たちは今、その半分を健康な半分で埋める必要があるようなものだ[28]。 しかし、マズローはフロイトに対して非常に批判的だった。なぜなら、人間中心の心理学者たちは、精神性が私たちの行動の指針となることを認めなかったからだ。[29] 人間が状況に盲目的に反応しているのではなく、より大きな目標を達成しようとしていることを証明するため、マズローは深刻な心理的問題を抱える人民ではな く、精神的に健康な個人を研究した。彼は自己実現を目指す人民に焦点を当てた。自己実現を目指す人民は、一貫した人格症候群を示し、最適な心理的な保健と 機能を表している。[30] この考えは、人格が自分自身と周囲と調和している人生の最高点である「ピーク体験」を楽しむという彼の理論の基盤となった。マズローの視点では、自己実現 した人民は1日に多くのピーク体験を経験できるが、他の人民はそれらを経験する頻度が低い。[31] 彼は、LSDやシロシビンなどの幻覚剤が、適切な人民に適切な状況下でピーク体験を引き起こす可能性があると信じていた。[32] |

| Peak and plateau experiences Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as "peak experiences", which are profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient and yet a part of the world, more aware of truth, justice, harmony, goodness, and so on. Self-actualizing people are more likely to have peak experiences. In other words, these "peak experiences" or states of flow are the reflections of the realization of one's human potential and represent the height of personality development.[33] In later writings, Maslow moved to a more inclusive model that allowed for, in addition to intense peak experiences, longer-lasting periods of serene being-cognition that he termed plateau experiences.[34][35] He borrowed this term from the Indian scientist and yoga practitioner, U. A. Asrani, with whom he corresponded.[36] Maslow stated that the shift from the peak to the plateau experience is related to the natural aging process, in which an individual has a shift in life values about what is actually important in one's life and what is not important. In spite of the personal significance with the plateau experience, Maslow was not able to conduct a comprehensive study of this phenomenon due to health problems that developed toward the end of his life.[35] |

ピークとプラトーの経験 マズローは、ニーズの充足という日常を超えた、愛、理解、幸福、または恍惚といった深い感情に満たされる「ピーク体験」という特別な瞬間を想定していまし た。この瞬間、人格はより完全で、生き生きと、自立し、かつ世界の一部であると感じ、真実、正義、調和、善などに対する意識が高まります。自己実現を遂げ た人民は、ピーク体験を経験する可能性が高い。つまり、これらの「ピーク体験」やフロー状態は、人間の潜在能力の実現の反映であり、人格の発達の高みを表 している。[33] その後の著作では、マズローは、強烈なピーク体験に加えて、より長く続く穏やかな存在認識の期間、すなわち「プラトー体験」を認める、より包括的なモデル に移行した。[34][35] この用語は、彼が文通していたインディアンの科学者でありヨガ実践者である U. A. アスラニから借用したものだ。[36] マズローは、ピーク体験からプレートオ体験への移行は、人生において何が重要で何が重要でないかという人生の価値観の変化を伴う自然な老化プロセスと関連 していると述べた。プレートオ体験の人格的意義にもかかわらず、マズローは生涯の終わりに健康問題が発生したため、この現象に関する包括的な研究を行うこ とができなかった。[35] |

| B-values In studying accounts of peak experiences, Maslow identified a manner of thought he called "being-cognition" (or "B-cognition"), which is holistic and accepting, as opposed to the evaluative "deficiency-cognition" (or "D-cognition"), and values he called "Being-values".[37] He listed the B-values as: Truth: honesty; reality; simplicity; richness; oughtness; beauty; pure, clean and unadulterated; completeness; essentiality Goodness: rightness; desirability; oughtness; justice; benevolence; honesty Beauty: rightness; form; aliveness; simplicity; richness; wholeness; perfection; completion; uniqueness; honesty Wholeness: unity; integration; tendency to one-ness; interconnectedness; simplicity; organization; structure; dichotomy-transcendence; order Aliveness: process; non-deadness; spontaneity; self-regulation; full-functioning Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy; individuality; non-comparability; novelty Perfection: necessity; just-right-ness; just-so-ness; inevitability; suitability; justice; completeness; "oughtness" Completion: ending; finality; justice; "it's finished"; fulfillment; finis and telos; destiny; fate Justice: fairness; orderliness; lawfulness; "oughtness" Simplicity: honesty; essentiality; abstract, essential, skeletal structure Richness: differentiation, complexity; intricacy Effortlessness: ease; lack of strain, striving or difficulty; grace; perfect, beautiful functioning Playfulness: fun; joy; amusement; gaiety; humor; exuberance; effortlessness Self-sufficiency: autonomy; independence; not-needing-other-than-itself-in-order-to-be-itself; self-determining; environment-transcendence; separateness; living by its own laws |

B-値 ピーク体験の報告を研究する中で、マズローは「存在認知」(または「Being-認知」)と呼ばれる、全体的で受容的な思考様式を、評価的な「欠乏認知」 (または「D-認知」)と対比して特定し、その価値を「存在価値」と呼んだ。[37] 彼は B 値を次のように挙げた。 真実:誠実さ、現実性、単純さ、豊かさ、当然性、美しさ、純粋、清潔、混じりけのない、完全性、本質性 善:正しさ、望ましさ、当然性、正義、慈悲、誠実さ 美:正しさ;形;生命力;単純さ;豊かさ;全体性;完璧さ;完成;独自性;正直さ 全体性:統一性;統合性;一体性への傾向;相互接続性;単純さ;組織;構造;二元性の超越;秩序 生命力:プロセス;非死;自発性;自己調節;完全機能 独自性:特異性;個性;比較不能性;新しさ 完全性:必要性;適切さ;必然性;適合性;正義;完全性;「あるべき」 完成:終わり;最終性;正義;「終わった」;充足;フィニスとテロス;運命;宿命 正義:公平性;秩序;法遵守;「べき」 シンプルさ:正直さ;本質性;抽象的、本質的、骨格的な構造 豊かさ:差別化;複雑さ;精巧さ 努力のなさ:容易さ;緊張や努力、困難の欠如;優雅さ;完璧で美しい機能 遊び心:楽しさ;喜び;娯楽;明るさ;ユーモア;活気;努力のなさ 自立性:自律性;独立性;自分自身であるために他を必要としないこと;自己決定性;環境超越性;分離性;独自の法則に従って生きる |

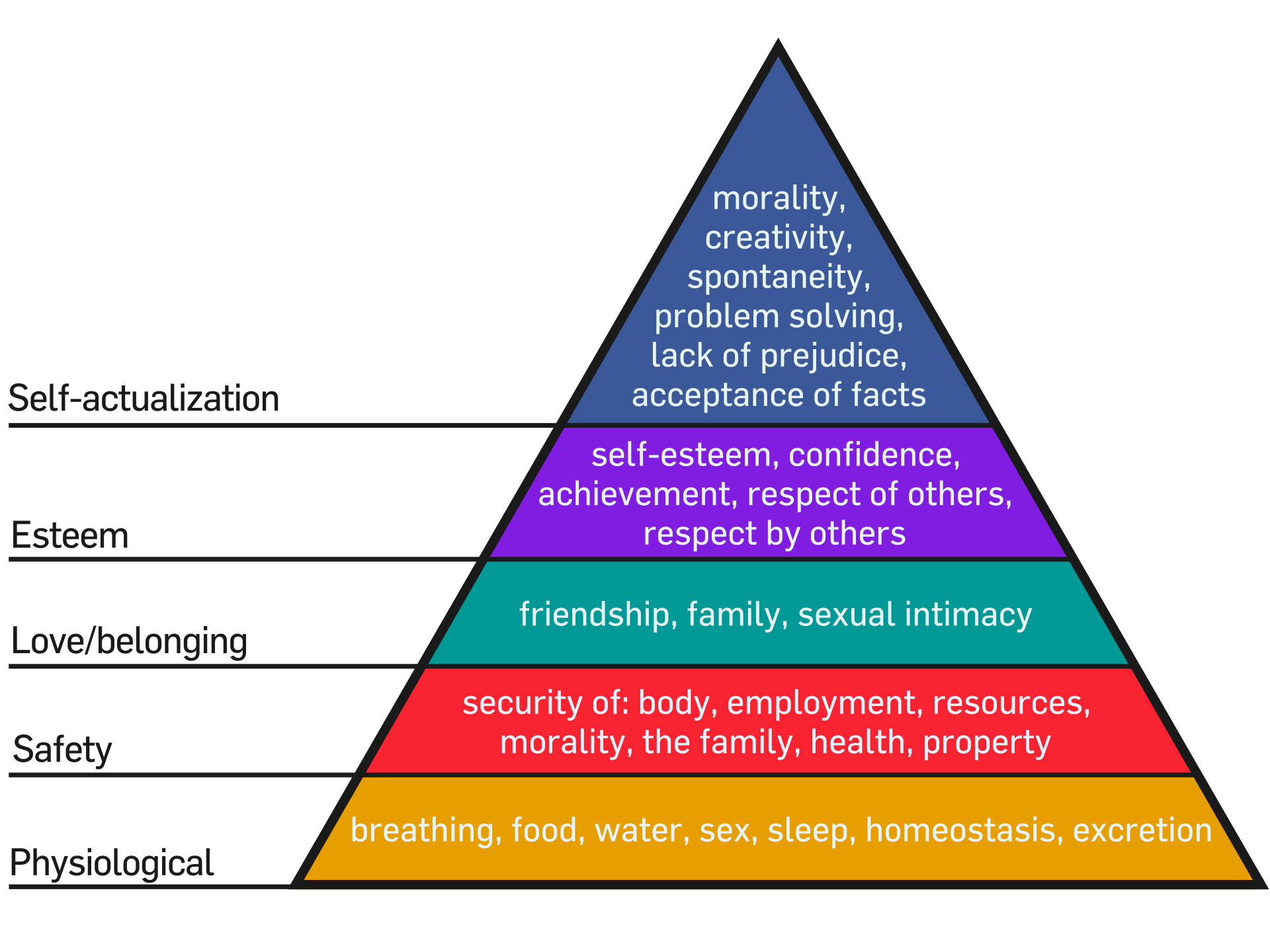

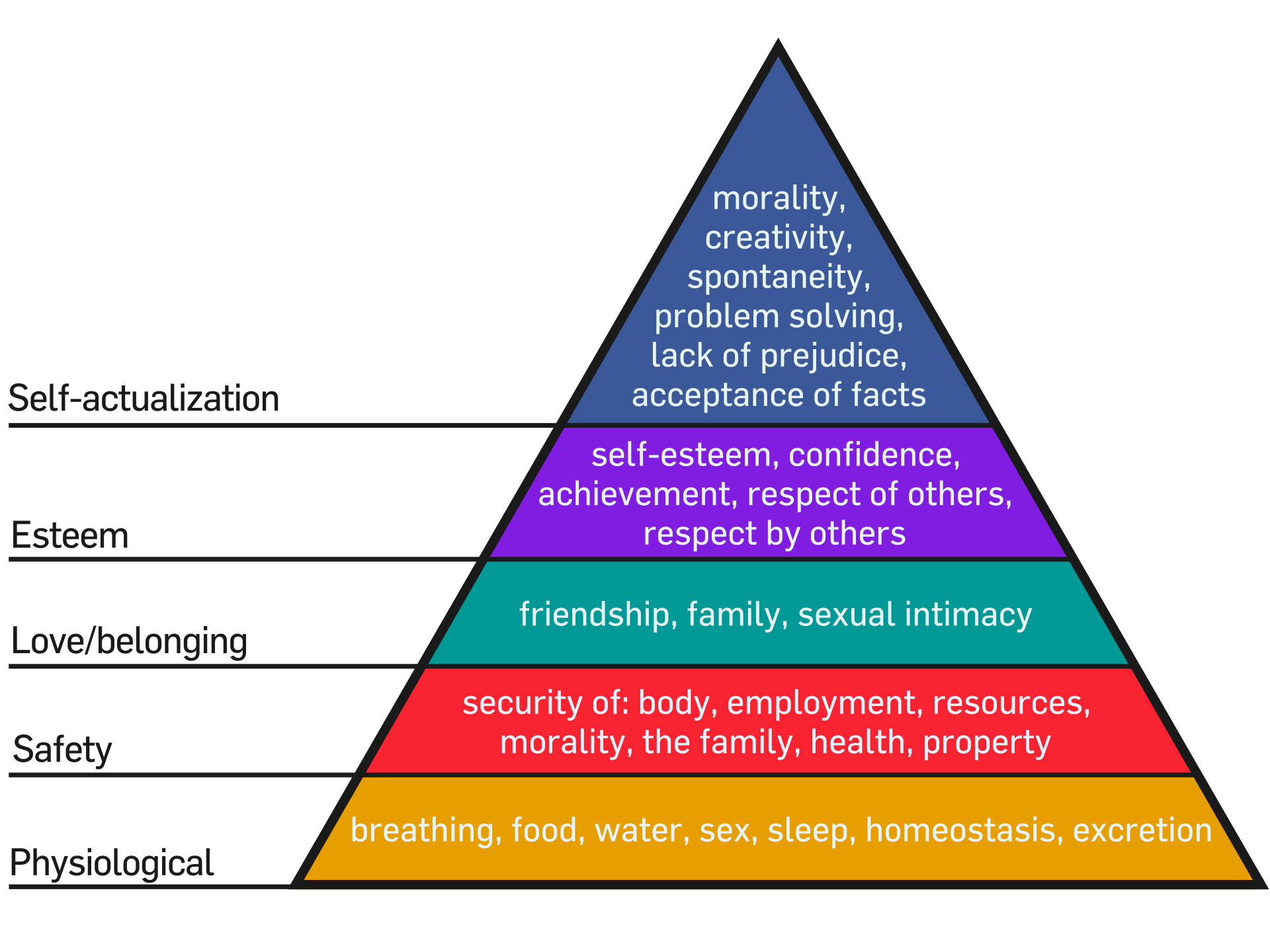

| Hierarchy of needs Main article: Maslow's hierarchy of needs  An interpretation of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, represented as a pyramid, with the more basic needs at the bottom[38] Maslow described human needs as ordered in a prepotent hierarchy—a pressing need would need to be mostly satisfied before someone would give their attention to the next highest need. None of his published works included a visual representation of the hierarchy. The pyramidal diagram illustrating the Maslow needs hierarchy may have been created by a psychology textbook publisher as an illustrative device. This now iconic pyramid frequently depicts the spectrum of human needs, both physical and psychological, as accompaniment to articles describing Maslow's needs theory and may give the impression that the hierarchy of needs is a fixed and rigid sequence of progression. Yet, starting with the first publication of his theory in 1943, Maslow described human needs as being relatively fluid—with many needs being present in a person simultaneously.[39] The hierarchy of human needs model suggests that human needs will only be fulfilled one level at a time.[40] According to Maslow's theory, when a human being ascends the levels of the hierarchy having fulfilled the needs in the hierarchy, one may eventually achieve self-actualization. Late in life, Maslow came to conclude that self-actualization was not an automatic outcome of satisfying the other human needs.[41][42] Human needs as identified by Maslow: At the bottom of the hierarchy are the "basic needs or physiological needs" of a human being: food, water, sleep, sex, homeostasis, and excretion. The next level is "safety needs: security, order, and stability". These two steps are important to the physical survival of the person. Once individuals have basic nutrition, shelter and safety, they attempt to accomplish more. The third level of need is "love and belonging", which are psychological needs; when individuals have taken care of themselves physically, they are ready to share themselves with others, such as with family and friends. The fourth level is achieved when individuals feel comfortable with what they have accomplished. This is the "esteem" level, the need to be competent and recognized, such as through status and level of success. Then there is the "cognitive" level, where individuals intellectually stimulate themselves and explore. After that is the "aesthetic" level, which is the need for harmony, order and beauty.[43] At the top of the pyramid, "need for self-actualization" occurs when individuals reach a state of harmony and understanding because they are engaged in achieving their full potential.[44] Once a person has reached the self-actualization state they focus on themselves and try to build their own image. They may look at this in terms of feelings such as self-confidence or by accomplishing a set goal.[4] The first four levels are known as deficit needs or D-needs. This means that if there are not enough of one of those four needs, there will be a need to get it. Getting them brings a feeling of contentment. These needs alone are not motivating.[4] Maslow wrote that there are certain conditions that must be fulfilled in order for the basic needs to be satisfied. For example, freedom of speech, freedom to express oneself, and freedom to seek new information[45] are a few of the prerequisites. Any blockages of these freedoms could prevent the satisfaction of the basic needs. Maslow's hierarchy is used in higher education for advising students and for student retention[46] as well as a key concept in student development.[47] Maslow's hierarchy has been subject to internet memes over the past few years, specifically looking at the modern integration of technology in people's lives and humorously suggesting that Wi-Fi was among the most basic of human needs. |

欲求の階層 主な記事:マズローの欲求階層説  マズローの欲求階層説をピラミッドで表現したもの。下層にはより基本的な欲求が位置している[38] マズローは、人間の欲求は優先順位の高い階層構造に整列していると説明した。つまり、ある欲求がほぼ満たされるまで、人はその次のより高い欲求に注意を向 けることはできない。彼の出版物には、この階層構造を視覚的に表現したものは一切含まれていない。マズローの欲求階層を説明するピラミッド図は、心理学の 教科書出版社によって説明用の図として作成された可能性がある。この現在では象徴的なピラミッドは、マズローの欲求理論を説明する記事の付随図として、人 間の物理的・心理的な欲求のスペクトルを頻繁に表現しており、欲求の階層が固定的で rigid な進行順序であるという印象を与える可能性があります。しかし、1943年に理論を初めて発表した際から、マズローは人間の欲求を比較的流動的なものとし て説明しており、多くの欲求が同時に存在すると述べています[39] 人間の欲求の階層モデルは、人間の欲求は1段階ずつ満たされていくと示唆している。[40] マズローの理論によると、人間が階層の欲求を満たしながら階層を上昇していくと、最終的に自己実現を達成することができる。晩年、マズローは、自己実現は他の欲求を満たすことで自動的に達成されるものではないと結論付けた。[41][42] マズローが特定した人間の欲求: 階層の底辺には、人間の「基本的欲求または生理的欲求」がある:食料、水、睡眠、性、恒常性、排泄。 次の段階は「安全欲求:安全、秩序、安定」だ。これらの2つの段階は、個人の物理的な生存に重要だ。個人が基本的な栄養、住居、安全を確保すると、より多くのことを達成しようとする。 3番目のレベルは「愛と所属」で、心理的欲求です。個人が物理的に自分をケアすると、家族や友人など他者と自分を共有する準備が整います。 4番目のレベルは、個人が達成したことに満足感を感じる段階です。これは「自尊心」のレベルで、能力や成功の程度を通じて認められる欲求です。 次に「認知的」レベルがあり、個人が知的に刺激を受け、探求する段階です。 その次は「美的」レベルで、調和、秩序、美への欲求です。[43] ピラミッドの頂点にある「自己実現の欲求」は、個人が潜在能力を最大限に発揮する過程で、調和と理解の状態に達した際に生じます。[44] 自己実現の状態に達した人格は、自分自身に焦点を当て、自分のイメージを築こうとする。これは、自己信頼感のような感情や、設定した目標を達成することで 捉えることができる。[4] 最初の4つのレベルは、欠乏欲求またはD-ニーズと呼ばれている。これは、これらの4つの欲求のうち1つでも不足していると、それを満たす必要が生じることを意味する。これらの欲求が満たされると、満足感が生まれる。これらの欲求だけでは、動機付けにはならない。[4] マズローは、基本的な欲求が満たされるためには、一定の条件が満たされなければならないと書いた。例えば、言論の自由、自己表現の自由、新しい情報を求め る自由[45] は、その前提条件の一部だ。これらの自由が妨げられると、基本的な欲求の満足が妨げられる可能性がある。 マズローの階層理論は、高等教育において学生の指導や学生の留任[46]、および学生の発達における重要な概念として用いられている[47]。マズローの 階層理論は、過去数年間、インターネットのミームの対象となり、特に現代のテクノロジーが人民の生活に統合されたことをユーモアを交えて指摘し、Wi- Fiが人間の最も基本的なニーズの一つであるとの提案がなされている。 |

| Self-actualization Maslow defined self-actualization as achieving the fullest use of one's talents and interests—the need "to become everything that one is capable of becoming".[48] As implied by its name, self-actualization is highly individualistic and reflects Maslow's premise that the self is "sovereign and inviolable" and entitled to "his or her own tastes, opinions, values, etc."[49] Indeed, some have characterized self-actualization as "healthy narcissism".[50] |

自己実現 マズローは、自己実現を「自分の才能や興味を最大限に発揮すること、つまり「自分ができるすべてになる」という欲求」と定義した。[48] その名称が示すように、自己実現は極めて個人主義的であり、マズローの「自己は主権的で不可侵であり、自分の好み、意見、価値観などを持つ権利がある」と いう前提を反映している。[49] 実際、自己実現を「健全なナルシシズム」と表現する者もいる。[50] |

| Qualities of self-actualizing people Maslow realized that the self-actualizing individuals he studied had similar personality traits. Maslow selected individuals based on his subjective view of them as self-actualized people. Some of the people he studied included Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Eleanor Roosevelt.[51] In his daily journal (1961–63) Maslow wrote: "Eupsychia club, heroes that I write for, my judges, the ones I want to please: Jefferson, Spinoza, Socrates, Aristotle, James, Bergson, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair (both heroes of my youth)."[52] All were "reality centered", able to differentiate what was fraudulent from what was genuine. They were also "problem centered", meaning that they treated life's difficulties as problems that demanded solutions. These individuals also were comfortable being alone and had healthy personal relationships. They had only a few close friends and family rather than a large number of shallow relationships.[53] Self-actualizing people tend to focus on problems outside themselves; have a clear sense of what is true and what is false; are spontaneous and creative; and are not bound too strictly by social conventions. Maslow noticed that self-actualized individuals had a better insight of reality, deeply accepted themselves, others and the world, and also had faced many problems and were known to be impulsive people. These self-actualized individuals were very independent and private when it came to their environment and culture, especially their very own individual development on "potentialities and inner resources".[54] According to Maslow, self-actualizing people share the following qualities: Truth: honest, reality, beauty, pure, clean and unadulterated completeness Goodness: rightness, desirability, uprightness, benevolence, honesty Beauty: rightness, form, aliveness, simplicity, richness, wholeness, perfection, completion, Wholeness: unity, integration, tendency to oneness, interconnectedness, simplicity, organization, structure, order, not dissociated, synergy Dichotomy-transcendence: acceptance, resolution, integration, polarities, opposites, contradictions Aliveness: process, not-deadness, spontaneity, self-regulation, full-functioning Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy, individuality, non comparability, novelty Perfection: nothing superfluous, nothing lacking, everything in its right place, just-rightness, suitability, justice Necessity: inevitability: it must be just that way, not changed in any slightest way Completion: ending, justice, fulfillment Justice: fairness, suitability, disinterestedness, non partiality, Order: lawfulness, rightness, perfectly arranged Simplicity: abstract, essential skeletal, bluntness Richness: differentiation, complexity, intricacy, totality Effortlessness: ease; lack of strain, striving, or difficulty Playfulness: fun, joy, amusement Self-sufficiency: autonomy, independence, self-determining.[55] Maslow based his theory partially on his own assumptions about human potential and partially on his case studies of historical figures whom he believed to be self-actualized, including Albert Einstein and Henry David Thoreau.[56] Consequently, Maslow argued, the way in which essential needs are fulfilled is just as important as the needs themselves. Together, these define the human experience. To the extent a person finds cooperative social fulfillment, he establishes meaningful relationships with other people and the larger world. In other words, he establishes meaningful connections to an external reality—an essential component of self-actualization. In contrast, to the extent that vital needs find selfish and competitive fulfillment, a person acquires hostile emotions and limited external relationships—his awareness remains internal and limited. |

自己実現する人民の特徴 マズローは、彼が研究した自己実現した個人には、類似した性格特性があることに気づいた。マズローは、自己実現した人格として彼自身の主観的な見解に基づ いて人格を選定した。彼が研究した人民には、トーマス・ジェファーソン、エイブラハム・リンカーン、エレノア・ルーズベルトなどがいる[51]。マズロー は、1961年から1963年にかけての毎日の日記に、「ユーサイキア・クラブ、私が書くヒーローたち、私の判断者たち、私が喜ばせたい人たち:ジェ ファーソン、スピノザ、ソクラテス、アリストテレス、ジェームズ、ベルクソン、ノーマン・トーマス、アップトン・シンクレア(どちらも私の青春のヒーロー たち)」と記している。[52] 彼らは皆、「現実中心」であり、偽りと真実を区別することができた。また、「問題中心」であり、人生の困難を解決すべき問題として捉えていた。これらの個 人は、一人でいることを苦にせず、健全な人格関係を築いていた。彼らは、多くの表面的な人格関係を築くのではなく、少数の親しい友人や家族しか持っていな かった。[53] 自己実現型の人々は、自分以外の問題に関心を向け、何が真実で何が虚偽であるかを明確に認識し、自発的で創造的であり、社会的慣習にあまり縛られない傾向がある。 マズローは、自己実現した個人は現実をよりよく理解し、自分自身、他者、そして世界を受け入れ、多くの問題にも直面し、衝動的な人物として知られているこ とを発見した。これらの自己実現した個人は、自分の環境や文化、特に「可能性と内なる資源」に関する自分の成長に関しては、非常に独立心があり、プライ ベートを大切にする傾向があった。[54] マズローによると、自己実現した人民は、以下の特徴を共有している。 真実:誠実、現実、美、純粋、清らか、純粋で完全 善:正しさ、望ましさ、正直さ、慈愛、誠実さ 美:正しさ、形、生命力、シンプルさ、豊かさ、完全性、完成度 完全性:統一性、統合性、一体性への傾向、相互接続性、シンプルさ、組織化、構造、秩序、分離していない、シナジー 二元性の超越:受容、解決、統合、対立、相反、矛盾 生命力:プロセス、死の欠如、自発性、自己調節、完全な機能 独自性:個性、独自性、比較不能性、新しさ 完璧さ:余分なものがなく、欠けるものがなく、すべてが適切な場所にあり、ちょうどよさ、適性、正義 必然性:不可避性:その通りでなければならない、少しでも変えてはならない 完成:終わり、正義、充足 正義:公平性、適切性、利害関係のないこと、偏りのなさ 秩序:法遵守、正しさ、完璧な配置 単純さ:抽象的、本質的な骨格、率直さ 豊かさ:多様性、複雑さ、精巧さ、全体性 努力のなさ:容易さ;緊張や努力、困難の欠如 遊び心:楽しさ、喜び、娯楽 自立性:自律性、独立性、自己決定性。[55] マズローは、この理論を、人間の可能性に関する自身の仮定と、アルバート・アインシュタインやヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローなど、自己実現を達成したと 彼が考える歴史上の人物の事例研究に部分的に基づいて構築した[56]。その結果、マズローは、基本的なニーズが満たされる方法は、ニーズそのものと同じ くらい重要であると主張した。これらが一体となって、人間の経験を定義する。人は、協力的な社会的充実感を見出せば見出すほど、他の人々やより大きな世界 と有意義な関係を築くことができる。つまり、自己実現に欠かせない要素である、外部の現実との有意義なつながりを確立するのです。対照的に、生存のニーズ が利己的で競争的な方法で満たされるほど、人格は敵意に満ちた感情を抱き、外部との関係が制限され、意識は内面にとどまり、限定的なものになります。 |

| Metamotivation Maslow used the term metamotivation to describe self-actualized people who are driven by innate forces beyond their basic needs, so that they may explore and reach their full human potential.[57] Maslow's theory of motivation gave insight on individuals having the ability to be motivated by a calling, mission or life purpose. It is noted that metamotivation may also be connected to what Maslow called B-(being) creativity, which is a creativity that comes from being motivated by a higher stage of growth. Another type of creativity that was described by Maslow is known as D-(deficiency) creativity, which suggests that creativity results from an individual's need to fill a gap that is left by an unsatisfied primary need or the need for assurance and acceptance.[58] |

メタモチベーション マズローは、基本的なニーズを超えた生来の力によって駆り立てられ、人間の潜在能力を最大限に探求し、発揮する自己実現した人々を「メタモチベーション」 と表現した[57]。マズローの動機付け理論は、天職、使命、人生の目的によって動機付けられる個人の能力について洞察を与えた。メタモチベーションは、 マズローが「B(存在)の創造性」と呼んだものとも関連していると考えられています。これは、より高い成長段階からの動機付けによって生じる創造性です。 マズローが説明したもう一つの創造性のタイプは「D(欠如)の創造性」と呼ばれ、これは、満たされていない基本的な欲求や、安心や承認の欲求によって生じ るギャップを埋めるために、個人が創造性を発揮する現象を指します。[58] |

| Methodology Maslow based his study on the writings of other psychologists, Albert Einstein, and people he knew who [he felt] clearly met the standard of self-actualization.[59] Maslow used Einstein's writings and accomplishments to exemplify the characteristics of the self-actualized person. Ruth Benedict and Max Wertheimer work was also very influential to Maslow's models of self-actualization.[60] In this case, from a quantitative-sciences perspective there are numerous problems with this particular approach, which has caused much criticism. First, it could be argued that biographical analysis as a method is extremely subjective as it is based entirely on the opinion of the researcher. Personal opinion is always prone to bias, which reduces the validity of any data obtained. Therefore, Maslow's operational definition of Self-actualization must not be uncritically accepted as quantitative fact.[61] |

方法論 マズローは、他の心理学者、アルバート・アインシュタイン、そして彼が「自己実現の基準を明確に満たしている」と感じた人々(人民)の著作を研究の基礎とした[59]。 マズローは、自己実現した人格の特徴を例示するために、アインシュタインの著作や業績を用いた。ルース・ベネディクトとマックス・ヴェルツハイマーの研究 も、マズローの自己実現のモデルに大きな影響を与えた[60]。この場合、定量科学の観点からは、この特定のアプローチには多くの問題があり、多くの批判 を受けています。まず、伝記分析という方法は、研究者の意見に完全に依存しているため、極めて主観的であるとの指摘が可能です。人格の意見は常に偏見に陥 りやすく、これにより得られたデータの信頼性が低下します。したがって、マズローの自己実現の操作的定義は、定量的事実として無批判に受け入れるべきでは ありません。[61] |

| Transpersonal psychology During the 1960s Maslow founded with Stanislav Grof, Viktor Frankl, James Fadiman, Anthony Sutich, Miles Vich and Michael Murphy, the school of transpersonal psychology. Maslow had concluded that humanistic psychology was incapable of explaining all aspects of human experience. He identified various mystical, ecstatic, or spiritual states known as "peak experiences" as experiences beyond self-actualization. Maslow called these experiences "a fourth force in psychology", which he named transpersonal psychology. Transpersonal psychology was concerned with the "empirical, scientific study of, and responsible implementation of the finding relevant to, becoming, mystical, ecstatic, and spiritual states" (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011).[62] In 1962 Maslow published a collection of papers on this theme,[63] which developed into his 1968 book Toward a Psychology of Being.[62][64] In this book Maslow stresses the importance of transpersonal psychology to human beings, writing: "without the transpersonal, we get sick, violent, and nihilistic, or else hopeless and apathetic" (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011).[62] Human beings, he came to believe, need something bigger than themselves that they are connected to in a naturalistic sense, but not in a religious sense: Maslow himself was an atheist[65] and found it difficult to accept religious experience as valid unless placed in a positivistic framework.[66] In fact, Maslow's position on God and religion was quite complex. While he rejected organized religion and its beliefs, he wrote extensively on the human being's need for the sacred and spoke of God in more philosophical terms, as beauty, truth and goodness, or as a force or a principle.[67][68] Awareness of transpersonal psychology became widespread within psychology, and the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology was founded in 1969, a year after Abraham Maslow became the president of the American Psychological Association. In the United States, transpersonal psychology encouraged recognition for non-western psychologies, philosophies, and religions, and promoted understanding of "higher states of consciousness", for instance through intense meditation.[69] Transpersonal psychology has been applied in many areas, including transpersonal business studies. |

トランスパーソナル心理学 1960年代、マズローはスタニスラフ・グロフ、ヴィクトール・フランクル、ジェームズ・ファディマン、アンソニー・スティッチ、マイルズ・ヴィッチ、マ イケル・マーフィーとともに、トランスパーソナル心理学の学派を設立した。マズローは、人間主義心理学では人間の経験のあらゆる側面を説明することはでき ないと結論づけた。彼は、「ピーク体験」として知られる、さまざまな神秘的、恍惚的、あるいは霊的な状態を、自己実現を超えた体験として特定した。マズ ローは、これらの経験を「心理学の第四の力」と呼び、トランスパーソナル心理学と名付けた。トランスパーソナル心理学は、「神秘的、恍惚的、そして霊的な 状態になること、およびそれに関連する発見の「経験的、科学的研究と責任ある実施」に関心を持っていた(Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011)。[62] 1962年、マズローはこのテーマに関する論文集を出版し[63]、これが1968年の著書『存在の心理学へ』に発展した[62]。[64] この本でマズローは、トランスパーソナル心理学が人間にとって重要であることを強調し、次のように書いている:「トランスパーソナルが欠如すると、私たち は病気になり、暴力的になり、虚無的になるか、あるいは絶望的で無気力になる」(オルソン&ヘルゲンハーン、2011)。[62] マズローは、人間は自分よりも大きな存在と自然的な意味でつながっている必要があると考えるようになった。ただし、それは宗教的な意味ではなく、マズロー 自身は無神論者であり[65]、宗教体験をポジティヴィスト的な枠組みに置かない限り、その有効性を認めることが困難だった[66]。実際、マズローの神 と宗教に関する立場は極めて複雑だった。彼は組織化された宗教とその信条を拒否したが、人間にとって神聖なものへの必要性を広く論じ、神を美、真実、善、 あるいは力や原理といったより哲学的な用語で表現した[67][68]。 トランスパーソナル心理学は心理学の分野で広く知られるようになり、アブラハム・マズローがアメリカ心理学会の会長に就任した翌年の1969年に『トラン スパーソナル心理学ジャーナル』が創刊された。アメリカ合衆国では、トランスパーソナル心理学は非西洋の心理学、哲学、宗教の認識を促進し、「より高い意 識状態」の理解を推進した。例えば、集中的な瞑想を通じてだ。[69] トランスパーソナル心理学は、トランスパーソナルビジネス研究を含む多くの分野に応用されている。 |

| Positive psychology Maslow called his work positive psychology.[70] Since 1968 his work has influenced the development of positive psychotherapy, a transcultural, humanistic based psychodynamic psychotherapy method used in mental health and psychosomatic treatment founded by Nossrat Peseschkian.[71] Since 1999 Maslow's work enjoyed a revival of interest and influence among leaders of the positive psychology movement such as Martin Seligman. This movement focuses only on a higher human nature.[72][73] Positive psychology spends its research looking at the positive side of things and how they go right rather than the pessimistic side.[74] |

ポジティブ心理学 マズローは、自分の研究を「ポジティブ心理学」と呼んだ[70]。1968年以来、彼の研究は、ノスラット・ペセスキアンによって創設された、メンタルヘ ルスや心身治療に使用される、文化を超えた人間主義的な心理力学療法である「ポジティブ心理療法」の発展に影響を与えている。[71] 1999 年以降、マーティンの研究は、マーティン・セリグマンなどのポジティブ心理学運動の指導者たちの間で、再び関心と影響力を高めている。この運動は、より高 い人間性にのみ焦点を当てている。[72][73] ポジティブ心理学は、物事の悲観的な側面ではなく、そのポジティブな側面や、物事がうまくいく仕組みを研究している。[74] |

| Psychology of science In 1966, Maslow published a pioneering work in the psychology of science, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, the first book ever actually titled 'psychology of science'. In this book Maslow proposed a model of 'characterologically relative' science, which he characterized as an ardent opposition to the historically, philosophically, sociologically and psychologically naıve positivistic reluctance to see science relative to time, place, and local culture.[75] Maslow acknowledged that the book was greatly inspired by Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), and it offers a psychological reading of Kuhn's famous distinction between "normal" and "revolutionary" science in the context of his own distinction between "safety" and "growth" science, put forward as part of a larger program for the psychology of science, outlined already in his 1954 magnum opus Motivation and Personality. Not only that Maslow offered a psychological reading of Kuhn's categories of "normal" and "revolutionary" science as an aftermath of Kuhn's Structure, but he also offered a strikingly similar dichotomous structure of science 16 years before the first edition of Structure, in his nowadays little known 1946 paper "Means-Centering Versus Problem-Centering in Science" published in the journal Philosophy of Science.[76][77] |

科学心理学 1966年、マズローは科学心理学の先駆的な著作『科学の心理学:偵察』を出版した。これは「科学心理学」というタイトルが実際に付けられた最初の書籍で ある。この本の中で、マズローは「性格的に相対的な」科学のモデルを提案し、それを、歴史的、哲学的、社会学的、心理学的観点から、科学を時間、場所、地 域文化と相対的に捉えることを拒否する、素朴な実証主義に対する熱烈な反対として特徴づけた。[75] マズローは、この本がトーマス・クーン『科学革命の構造』(1962年)から大きな影響を受けたことを認め、 クーンの有名な「正常な科学」と「革命的な科学」の区別を、自身の「安全」と「成長」の科学の区別という文脈で心理学的解釈を加えた。これは、1954年 の大著『動機と人格』で既に概説された、科学心理学のより広範なプログラムの一部として提示されたものだ。マズローは、クーンの『科学の構造』の後に、 クーンの「通常の」科学と「革命的な」科学のカテゴリーを心理学的解釈で読み解いただけでなく、クーンの『科学の構造』の初版が刊行される16年前、現在 ではほとんど知られていない1946年の論文「科学における手段中心と問題中心」で、驚くほど類似した二分法的な科学の構造を提唱していた。[76] [77] |

| Maslow's hammer Abraham Maslow is also known for Maslow's hammer, popularly phrased as "if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail" from his book The Psychology of Science, published in 1966.[78] |

マズローのハンマー アブラハム・マズローは、1966年に出版された著書『The Psychology of Science』の中で、「ハンマーしか持っていないと、すべてが釘に見える」と表現した「マズローのハンマー」でも知られています。[78] |

| Maslow and Eugenics Although articulating his beliefs in a more positive manner than many of his contemporaries, Abraham Maslow was a eugenicist for his entire career.[79][80] Abraham Maslow began his career as a protege of Edward Thorndike, a leading eugenicist.[81] Under the influence of his mentor and financial backer Thorndike, Maslow expressed the belief that IQ tests were an accurate measure of one's genetic superiority or inferiority and that intelligence was a genetic, rather than acquired, trait.[81] Maslow expressed particular disdain for the nation of India, believing that the entire nation should be euthanized.[79][citation needed] Maslow also expressed critical views of Jonas Salk, believing mass vaccination to be interfering with natural selection by allowing "cripples" and "genetically inferior" people to live longer lives and reproduce.[81] Maslow's private journals in the late 1960s indicate that he took immense pleasure in seeing drug addicts die from overdoses, believing their deaths to be doing a public service to genetically superior individuals such as himself. He also criticized advances in agriculture for developing the ability to grow more food, believing that famine and starvation were beneficial to society and that those who died of hunger were doing a great service to superior humans.[79] Like Thorndike, Maslow expressed his belief that eugenics could be a religion of the future. To this end, he blended his earlier work with Thorndike with influences from Aldous Huxley and Alan Watts in order to found what he referred to as his own religion based upon "peak experiences" and the use of psychedelic drugs. Maslow referred to his religion as Eupsychianism.[82][83] He also expressed a belief in Transhumanism and that psychedelic drugs could help elite humans evolve, not just intellectually or spiritually, but into a new biological species, again showing his lifelong belief that acquired traits could be passed on genetically.[82] Maslow's definition of "human" is key to understanding the contradiction between his more traditional psychological theories and his ardent support for eugenics. According to Maslow, not all people are humans. Drug addicts, mentally ill persons, people with low intelligence and those deemed "surplus" were not, according to Maslow, humans but rather "less-than-humans" or "cripple humans" whose material and intellectual needs were an impediment to the advancement of superior "aggridant humans".[81] Throughout his life, Maslow also expressed a fondness for Nietzsche and his theory of the Übermensch, and Maslow often quoted and paraphrased Nietzsche in relation to his theories of "aggridant humans" and "less-than-humans". |

マズローと優生学 同時代の多くの人々よりもより前向きな形で自分の信念を表明していたものの、アブラハム・マズローは、そのキャリア全体を通じて優生学者だった。[79] [80] アブラハム・マズローは、優生学者の第一人者であったエドワード・ソーンダイクの弟子としてキャリアをスタートさせた。[81] メンターであり財政的支援者でもあったソーンダイクの影響を受けて、マズローはIQテストが個人の遺伝的優劣を正確に測る指標であり、知能は後天的なもの ではなく遺伝的な特性であると主張した。[81] マズローは特にインドの国民に対して強い嫌悪感を示し、その国民全体を安楽死させるべきだと主張した。[79][出典必要] マズローはまた、ジョナス・サルクに対して批判的な見解を表明し、集団接種が「障害のある人々」や「遺伝的に劣った人々」がより長く生き、繁殖するのを許 すことで、自然選択を妨げていると信じていた。[81] 1960年代後半のマズローの私的な日記には、薬物依存者が過剰摂取で死亡するのを目撃し、その死が自分を含む遺伝的に優越した個人への公共の利益になる と信じて、大きな喜びを感じていたことが記されている。彼はまた、農業の進歩が食料の生産量を増加させたことを批判し、飢饉と飢餓が社会に有益であり、飢 餓で死亡した人々は優越した人類への大きな奉仕をしたと信じていた。[79] ソーンダイクと同様に、マズローは優生学が未来の宗教になる可能性があると信じていた。この目的のために、彼はソーンダイクとの以前の研究に、アルドウ ス・ハクスリーやアラン・ワッツの影響を取り入れ、 「ピーク体験」とサイケデリック薬の使用に基づく、彼自身の宗教を創設した。マズローは、この宗教を「ユーサイキアニズム」と呼んだ。[82][83] 彼はまた、トランスヒューマニズムを信じ、サイケデリック薬がエリート人類の進化を助けることができると主張した。これは、知的・精神的な進化だけでな く、新たな生物種への進化を意味し、獲得した特性は遺伝的に伝達可能であるという彼の生涯にわたる信念を再び示している。[82] マズローの「人間」の定義は、彼の伝統的な心理学理論と優生学への熱烈な支持との矛盾を理解する上で鍵となる。マズローによると、すべての人間が人民では ない。薬物依存者、精神疾患の人民、知能の低い人民、そして「余剰」とみなされる人民は、マズローによると人民ではなく、「人民未満」または「障害のある 人民」であり、彼らの物質的・知的ニーズは、より優れた「アグリダント・ヒューマン」の進歩の障害となる。[81] マズローは生涯を通じて、ニーチェと彼の「超人」理論への愛着を表明し、自身の「アグリダント・ヒューマン」と「ヒューマン未満」の理論に関連して、ニー チェの言葉を引用したり要約したりすることが多かった。 |

| Criticism Maslow's ideas have been criticized for their lack of scientific rigor. He was criticized as too soft scientifically by American empiricists.[66] In 2006, author and former philosophy professor Christina Hoff Sommers and practicing psychiatrist Sally Satel asserted that, due to lack of empirical support, Maslow's ideas have fallen out of fashion and are "no longer taken seriously in the world of academic psychology".[84] Positive psychology spends much of its research looking for how things go right rather than the more pessimistic view point, how things go wrong.[85][further explanation needed] The hierarchy of needs has furthermore been accused of having a cultural bias—mainly reflecting Western values and ideologies. From the perspective of many cultural psychologists, this concept is considered relative to each culture and society and cannot be universally applied.[86] However, according to the University of Illinois researchers Ed Diener and Louis Tay,[87] who put Maslow's ideas to the test with data collected from 60,865 participants in 123 countries around the world over the period of five years (2005-2010), Maslow was essentially right in that there are universal human needs regardless of cultural differences, although the authors claim to have found certain departures from the order of their fulfillment Maslow described. In particular, while they found—clearly in accordance with Maslow—that people tend to achieve basic and safety needs before other needs, as well as that other "higher needs" tend to be fulfilled in a certain order, the order in which they are fulfilled apparently does not strongly influence their subjective well-being (SWB). As put by the authors of the study, humans thus can derive 'happiness' from simultaneously working on a number of needs regardless of the fulfillment of other needs. This might be why people in impoverished nations, with only modest control over whether their basic needs are fulfilled, can nevertheless find a measure of well-being through social relationships and other psychological needs over which they have more control. — Diener & Tay (2011), p. 364 Maslow, however, would probably not be surprised by these findings, since he clearly and repeatedly emphasized that the need hierarchy is not a rigid fixed order as it is often presented: We have spoken so far as if this hierarchy were a fixed order, but actually it is not nearly so rigid as we may have implied. It is true that most of the people with whom we have worked have seemed to have these basic needs in about the order that has been indicated. However, there have been a number of exceptions. — Maslow, 'Motivation and Personality' (1970), p. 51 Maslow also regarded that the relationship between different human needs and behavior, being in fact often motivated simultaneously by multiple needs, is not a one-to-one correspondence, i.e., that "these needs must be understood not to be exclusive or single determiners of certain kinds of behavior".[88] Maslow's concept of self-actualizing people was united with Piaget's developmental theory to the process of initiation in 1993.[89] Maslow's theory of self-actualization has been met with significant resistance. The theory itself is crucial to the humanistic branch of psychology and yet it is widely misunderstood. The concept behind self-actualization is widely misunderstood and subject to frequent scrutiny.[90] Maslow was criticized for noting too many exceptions to his theory. As he acknowledged these exceptions, he did not do much to account for them. Shortly prior to his death, one problem he tried to resolve was that there are people who have satisfied their deficiency needs but still do not become self-actualized. He never resolved this inconsistency within his theory.[91] |

批判 マズローの考えは、その科学的厳密さの欠如について批判されている。彼は、アメリカの経験主義者たちから、科学的に甘すぎると批判された。[66] 2006年、作家で元哲学教授のクリスティーナ・ホフ・ソマーズと、現役精神科医のサリー・サテルは、経験的裏付けの欠如から、マズローの考えは時代遅れ となり、「学術的な心理学の世界ではもはや真剣に受け止められていない」と主張した。[84] ポジティブ心理学は、物事がうまくいかないという悲観的な視点ではなく、物事がうまくいく方法を探る研究に多くの時間を費やしている。[85][さらに説 明が必要] さらに、欲求の階層は、主に西洋の価値観やイデオロギーを反映した文化的な偏見があるとの批判も受けている。多くの文化心理学者の立場から、この概念は各 文化や社会に相対的なものであり、普遍的に適用できないと考えられている。[86] しかし、イリノイ大学の研究者エド・ダイナーとルイ・テイは、2005年から2010年の5年間に世界123カ国で60,865人の参加者を対象に収集し たデータを用いてマズローの理論を検証した結果、 マズローは、文化の違いに関わらず普遍的な人間のニーズが存在するという点では本質的に正しかったと結論付けています。ただし、著者たちは、マズローが説 明した充足の順序から一定の乖離を発見したと主張しています。特に、マズローの主張と一致して、人民は基本的なニーズと安全のニーズを他のニーズよりも先 に満たす傾向があり、他の「より高いニーズ」も一定の順序で満たされる傾向があることが確認されたが、その順序が主観的幸福感(SWB)に強く影響を与え るわけではないことが明らかになった。研究の著者たちが指摘するように、人間は thus 他の欲求の充足に関わらず、複数の欲求を同時に追求することで『幸福』を得ることができる。これが、基本的な欲求の充足にほとんどコントロールできない貧困の国民が、それでも社会関係やよりコントロール可能な心理的欲求を通じて一定の幸福感を見出せる理由かもしれない。 — Diener & Tay (2011), p. 364 しかし、マズローはこれらの結果に驚かないだろう。彼は、欲求の階層がしばしば提示されるような rigid fixed order(厳格な固定順序)ではないことを明確かつ繰り返し強調していたからだ: 私たちはこれまで、この階層が固定された順序であるかのように話してきたが、実際には、私たちが示唆したほど rigid ではない。私たちが研究対象とした人民のほとんどは、示された順序に近い形でこれらの基本的な欲求を持っているように見えたのは事実だ。しかし、例外もい くつかあった。 — マズロー、『動機と人格』(1970年)、51ページ マズローはまた、異なる人間のニーズと行動の関係は、実際には複数のニーズによって同時に動機付けられることが多く、一対一の対応関係ではないと考えた。 つまり、「これらのニーズは、特定の種類の行動の排他的または唯一の決定要因として理解されるべきではない」と述べた。[88] マズローの自己実現の人の概念は、1993年にピアジェの発達理論と統合され、開始のプロセスに組み込まれた。[89] マズローの自己実現の理論は、大きな抵抗に直面してきた。この理論自体は、人間主義心理学の分野において極めて重要であるが、広く誤解されている。自己実 現の背後にある概念は、広く誤解されており、頻繁に精査の対象となっている。[90] マズローは、自分の理論に例外が多すぎることを指摘して批判された。彼はこれらの例外を認めたものの、それらを説明するための努力はあまりしなかった。死 の直前に、彼は、欠乏欲求を満たしても自己実現に至らない人民がいるという問題を解決しようとした。しかし、彼はこの理論の矛盾を解決することはなかっ た。[91] |

| Bias Social psychologist David Myers has pointed out Maslow's selection bias, rooted in the choice to study individuals who lived out his own values. If he had studied other historical heroes, such as Napoleon, Alexander the Great, and John D. Rockefeller, his descriptions of self-actualization might have been significantly different.[51] |

偏見 社会心理学者デビッド・マイヤーズは、マズローが自分の価値観に合致する個人を研究対象としたことに根ざす、マズローの選択の偏見を指摘している。もし彼 が、ナポレオン、アレクサンダー大王、ジョン・D・ロックフェラーなどの他の歴史上の英雄を研究していたなら、自己実現に関する彼の記述は大きく異なって いただろう[51]。 |

| Legacy Later in life, Maslow was concerned with questions such as, "Why don't more people self-actualize if their basic needs are met? How can we humanistically understand the problem of evil?"[70] In the spring of 1961, Maslow and Tony Sutich founded the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, with Miles Vich as editor until 1971.[92] The journal printed its first issue in early 1961 and continues to publish academic papers.[92] Maslow attended the Association for Humanistic Psychology's founding meeting in 1963 where he declined nomination as its president, arguing that the new organization should develop an intellectual movement without a leader which resulted in useful strategy during the field's early years.[92] In 1967, Maslow was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association.[93] |

遺産 晩年、マズローは「基本的なニーズが満たされているにもかかわらず、なぜより多くの人々が自己実現できないのか?人間主義的な観点から悪の問題をどのように理解することができるのか?」といった問題に関心を抱くようになった[70]。 1961年の春、マズローとトニー・スティッチは『人間主義心理学ジャーナル』を創刊し、1971年までマイルズ・ヴィッチが編集長を務めた。[92] この雑誌は1961年初めに創刊号を発行し、現在も学術論文を掲載している。[92] マズローは1963年に人間主義心理学協会の設立総会に出席したが、新組織はリーダーのない知的運動を展開すべきだと主張して会長の指名を辞退した。この決定は、この分野がまだ揺籔期にあった当時、有用な戦略となった。[92] 1967年、マズローはアメリカヒューマニスト協会から「ヒューマニスト・オブ・ザ・イヤー」に選ばれた。[93] |

| Writings Maslow, A. H. (July 1943). "A theory of human motivation". Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346. S2CID 53326433. Motivation and Personality (1st edition: 1954, 2nd edition: 1970, 3rd edition 1987) Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences, Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1964. Eupsychian Management, 1965; republished as Maslow on Management, 1998 The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance, New York: Harper & Row, 1966; Chapel Hill: Maurice Bassett, 2002. Toward a Psychology of Being, (1st edition, 1962; 2nd edition, 1968; 3rd edition, 1999) The Farther Reaches of Human Nature, 1971 Future Visions: The Unpublished Papers of Abraham Maslow by E. L. Hoffman (editor) 1996 Personality and Growth: A Humanistic Psychologist in the Classroom, Anna Maria, FL: Maurice Bassett, 2019. |

著作 マズロー、A. H. (1943年7月). 「人間の動機付けの理論」. 心理レビュー. 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346. S2CID 53326433. 『動機と人格』(第1版:1954年、第2版:1970年、第3版:1987年) 『宗教、価値観、そしてピーク体験』、オハイオ州コロンバス:オハイオ州立大学出版局、1964年。 『ユーサイキアン・マネジメント』、1965年;『マズローのマネジメント』として再版、1998年 科学の心理学:探求、ニューヨーク:ハーパー&ロウ、1966年;チャペルヒル:モーリス・バセット、2002年。 存在の心理学に向けて、(第1版、1962年;第2版、1968年;第3版、1999年) 『人間の本質の最深部』1971年 『未来のビジョン:アブラハム・マズローの未発表論文集』E. L. ホフマン(編)1996年 『人格と成長:教室における人間主義的心理学者』フロリダ州アンナ・マリア:モーリス・バセット、2019年。 |

| Clayton Alderfer Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi Erich Fromm Frederick Herzberg Human Potential Movement Humanistic psychology Law of the instrument Manfred Max-Neef Rollo May Organismic theory Organizational behavior Positive disintegration Post-materialism Reverence Self-esteem Victor Vroom |

クレイトン・アルダーファー ミハイ・チクセントミハイ エリック・フロム フレデリック・ヘルツバーグ 人間の可能性運動 人間主義心理学 道具の法則 マンフレッド・マックス・ニーフ ロロ・メイ 有機体理論 組織行動 ポジティブな崩壊 ポスト物質主義 敬虔 自尊心 ヴィクター・ヴルーム |

| Sources Berger, Kathleen Stassen (1983). The Developing Person through the Life Span. Goble, F. (1970). The Third Force: The Psychology of Abraham Maslow. Richmond, CA: Maurice Bassett Publishing. Goud, Nelson (October 2008). "Abraham Maslow: A Personal Statement". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 48 (4): 448–451. doi:10.1177/0022167808320535. S2CID 143617210. Hoffman, Edward (1988). The Right to be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-87477-461-0. Hoffman, E. (1999), Abraham Maslow: A Brief Reminiscence. In: Journal of Humanistic Psychology Fall 2008 vol. 48 no. 4 443-444, New York: McGraw-Hill Sommers, Christina Hoff; Satel, Sally (2006). One Nation Under Therapy: How the Helping Culture is Eroding Self-reliance. MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-312-30444-7. |

出典 Berger, Kathleen Stassen (1983). 発達する人格 through the 生命 span. Goble, F. (1970). The Third Force: 人格の心理学 of Abraham Maslow. Richmond, CA: Maurice Bassett Publishing. Goud, Nelson (October 2008). 「Abraham Maslow: A Personal Statement」. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 48 (4): 448–451. doi:10.1177/0022167808320535. S2CID 143617210. ホフマン、エドワード (1988)。人間である権利:アブラハム・マズローの伝記。ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス。ISBN 978-0-87477-461-0。 ホフマン、E. (1999)、アブラハム・マズロー:短い回想。掲載:Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2008年秋号 vol. 48 no. 4 443-444、ニューヨーク:McGraw-Hill ソマーズ、クリスティーナ・ホフ、サテル、サリー (2006)。セラピーに覆われた国民:援助文化が自立心を蝕む。マクミラン。ISBN 978-0-312-30444-7。 |

| Cooke, B; Mills, A; Kelley, E

(2005). "Situating Maslow in Cold War America". Group and Organization

Management. 30 (2): 129–152. doi:10.1177/1059601104273062. S2CID

146365008. DeCarvalho, Roy Jose (1991) The Founders of Humanistic Psychology. Praeger Publishers[ISBN missing] Grogan, Jessica (2012) Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self. Harper Perennial [ISBN missing] Hoffman, Edward (1999) The Right to Be Human. McGraw-Hill ISBN 0-07-134267-2 Wahba, M.A.; Bridwell, L. G. (1976). "Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory". Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 15 (2): 212–240. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6. Wilson, Colin (1972) New Pathways in Psychology: Maslow and the post-Freudian revolution. London: Victor Gollancz ISBN 0-575-01355-9 |

クック、B;ミルズ、A;ケリー、E(2005)。「冷戦時代のアメリカにおけるマズローの位置付け」。グループと組織の管理。30 (2): 129–152. doi:10.1177/1059601104273062. S2CID 146365008. デカルヴァリョ、ロイ・ホセ (1991) 人文主義心理学の創始者たち. Praeger Publishers[ISBN 欠落] グローガン、ジェシカ (2012) アメリカとの出会い:人文主義心理学、60年代文化、そして現代的自己の形成. Harper Perennial [ISBN 欠落] ホフマン、エドワード (1999) 人間である権利。McGraw-Hill ISBN 0-07-134267-2 Wahba, M.A.; Bridwell, L. G. (1976). 「マズローの再考:欲求階層理論に関する研究レビュー」。組織行動と人間能力。15 (2): 212–240. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6. ウィルソン、コリン (1972) 心理学の新しい道:マズローとフロイト後の革命。ロンドン:ヴィクター・ゴランツ ISBN 0-575-01355-9 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Maslow |

An interpretation of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, represented as a pyramid, with the more basic needs at the bottom[38] - "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs"

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099