美学

Aesthetics

Christiaan

Tonnis ~ William S. Burroughs 3 / Oil on Canvas / 61 x 72.8 inches /

1999 Print

☆

美しさはつねに呪われている(Beauty is always doomed.)——ウィリアム・バロウズ, Ghost of chance

(1991:17)

☆ 美学(びがく、英: esthetics)とは、美の本質と味覚の本質に関わる哲学の一分野であり、芸術の哲学として機能する。美学は、芸術的センスに対する批判的判断によっ て決定される美的価値の哲学を考察するものであり、美学の機能は「芸術、文化、自然に対する批判的考察」である(ウィキペディア英語「美学」)。

★ 美学とは、狭義には「美の理論」、広義には「芸術哲学」とも定義される。美そのものに対する伝統的な関心は、18世紀には崇高なものへと広がり、1950 年以降、文献で論じられる純粋な美的概念の数はさらに増えている。伝統的に、芸術の哲学はその定義に集中していたが、近年はそれが中心ではなく、芸術の側 面を注意深く分析することがそれに大きく取って代わっている。哲学的美学は、このような後進の発展を中心に据えたものと考えられる。そのため、美とそれに 関連する概念についての考えを概観した後、美的経験の価値と美的態度の多様性に関する疑問を取り上げ、芸術と純粋な美学を分ける問題、とりわけ意図の存在 について考察する。そして、これまで提唱されてきた芸術の主な定義のいくつかを、近年の「脱定義」の時代とともに概観する。その後、表現、表象、そして美 術品の本質の概念を取り上げる(インターネット哲学百科事典「美 学」)。

★ 美の概念への関心の隆盛と終焉:「18世紀に哲学の辞書に登場した「美的」という用語は、とりわけ、対象の種類、判断の種類、態度の種類、経験の種類、価 値の種類を指すようになった。芸術 作品は必然的に美的対象であるのか、美的判断の根拠が知覚的であるとされることと、私たちがそれを支持する理由を与えるという事実とをどのように結びつけ るのか、美的態度と実践的態度との間のとらえどころのない対比をどのように捉えるのが最善なのか、美的経験を現象学的な内容か表象的な内容かによって定義 するのか、美的価値と美的経験との関係をどのように理解するのが最善なのか、などである。「美的」のどのような用法も、他の用法に訴えることなく説明でき るのか、どのような用法に関しても同意することが、意味のある理論的な同意や不同意の根拠として十分なのか、この用語が辞書に含まれることを正当化するよ うな、正当な哲学的目的に最終的に答えるものなのか、などである。このような一般的 な疑問によって表明される懐疑論が定着し始めたのは20世紀後半になってからであり、この事実は、(a)美学という概念は本質的に問題があり、それを何と か理解できるようになったのはごく最近のことなのか、(b)概念は問題なく、そうでないと想像できるほど混乱したのはごく最近のことなのか、という問いを 投げかける。これらの可能性の間を裁くには、美学的な事柄に関する初期と後期の理論化を取り入れる視点が必要である。」(スタンフォード哲 学事典「美学/美 的なものの概念」)

★ 美学批判:「実践としての美学の哲学は、社会学者や芸術と社会に関する作家の一部によって批判されてきた。例えば、レイモンド・ウィリアムズは、 芸術の世界から外挿できる唯一無二の、あるいは個別の美的対象は存在せず、むしろ、通常の言論や経験が芸術としてシグナルを発するような、文化的形態や経 験の連続体が存在すると主張している。芸術」によって、私たちはいくつかの芸術的な「作品」や「創作物」をそのように枠にはめることができるが、この参照 はそれを生み出す制度や特別な出来事の中にとどまり、いくつかの作品や他の可能性のある「芸術」は枠外に残され、あるいは「芸術」とはみなされないかもし れない他の現象などの他の解釈が残される。 ピエール・ブルデューはカントの「美学」の考えに同意しない。彼は、 カントの「美的」とは、カントの狭い定義の外側にある他の可能で等しく妥当な「美的」経験とは対照的に、単に高められた階級的ハビトゥスと学問的余暇の産 物である経験を表しているに過ぎないと論じている。 ティモシー・ローリーは、音楽美学の理論が「鑑賞、熟考、内省の観点 から完全に組み立てられたものであることは、彼らを複雑な意図や動機が文化的な対象や実践に対する様々な魅力を生み出す人間として見るのではなく、音楽的 な対象を通してのみ定義される、ありえないほど動機づけのない聴き手を理想化する危険をはらんでいる」と論じている。」

| Die Kritik der

Urteilskraft (KdU) S.243 |

(人工物よりも自然がもつ美的な力をカントは認めざるをえない)——第22節の注記の最後の部分(S.243) |

| Marsden, in his description of

Sumatra. comments that the free beauties of nature there surround

the beholder everywhere, so that there is little left in them to attract

him; whereas, when in the midst of a forest he came upon a pepper

garden, with the stakes that supported the climbing plants forming

paths between them along parallel lines, it charmed him greatly. He

concludes from this that we like wild and apparently ruleless beauty

only as a change, when we have been satiated with the sight of

regular beauty. And yet he need only have made the experiment

of spending one day with his pepper garden to realize that. once

regularity has [prompted] the understanding to put itself into attunement

with order which it requires everywhere, the object ceases

to entertain him and instead inflicts on his imagination an irksome

constraint; whereas nature in those regions. extravagant in

all its diversity to the point of opulence, subject to no constraint

from artificial rules, can nourish his taste permanently. Even bird

song, which we cannot bring under any rule of music. seems to

contain more freedom and hence to offer more to taste than human

song, even when this human song is performed according to all the

rules of the art of music, because we tire much sooner of a human

song if it is repeated often and for long periods. And yet in this

case we probably confuse our participation in the cheerfulness

of a favorite little animal with the beauty of its song, for when

bird song is imitated very precisely by a human being (as is sometimes

done with the nightingale's warble) it strikes our ear as quite

tasteless.

|

マースデンはスマトラの記述の中

で、そこでは自然の自由な美しさが至る所に見る者を包み込むため、もはや人を惹きつける要素がほとんど残されていないと述べている。一方で、森の奥で偶然

見つけた胡椒畑では、つる植物を支える支柱が平行な線を描いて小道を形成しており、これが彼を大いに魅了したという。彼はこのことから、我々が野性的で一

見無秩序な美を好むのは、規則的な美に飽き飽きした時の気分転換に過ぎないと結論づける。しかし彼は、胡椒畑で一日を過ごす実験さえすれば、その真実に気

づけただろう。規則性が理解力を刺激し、あらゆる場所で秩序を求めるようになると、対象はもはや彼を楽しませず、代わりに想像力に煩わしい制約を課す。一

方、自然はそうした領域において、人工的な規則による制約を受けず、豊かさすら感じさせるほどの多様性に富み、彼の趣味を永続的に養うことができるのだ。

鳥のさえずりでさえ、音楽のいかなる規則にも従わせられないが、人間の歌よりも自由を含んでいるように思われ、したがって味覚により多くを提供している。

たとえその人間の歌が音楽の芸術のすべての規則に従って演奏されたとしても、人間の歌は頻繁に、そして長期間繰り返されると、我々ははるかに早く飽きてし

まうからだ。しかしこの場合、我々は愛する小動物の陽気さに共感する気持ちと、その鳴き声の美しさを混同しているのだろう。なぜなら人間の歌声で鳥の鳴き

声を極めて正確に模倣した場合(ナイチンゲールのさえずりを模倣する例がある)、それは我々の耳には全く味気なく響くからだ。 |

★カ ントのÄsthetikをどう訳するのか?

カ

ントのÄsthetikは美学と訳さず「感性論」と訳すべきだという警邏主張はやはり奇矯だ.カントはこの語をあらゆる感覚的経験を指すために用いてい

る.我々の知っている狭量なその概念を超えているので美学よりも美学論/美論(=美しいと感じることの議論)と言えばよい.

| Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics)

is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and the

nature of taste; and functions as the philosophy of art.[1] Aesthetics

examines the philosophy of aesthetic value, which is determined by

critical judgements of artistic taste;[2] thus, the function of

aesthetics is the "critical reflection on art, culture and

nature".[3][4] Aesthetics studies natural and artificial sources of experiences and how people form a judgement about those sources of experience. It considers what happens in our minds when we engage with objects or environments such as viewing visual art, listening to music, reading poetry, experiencing a play, watching a fashion show, movie, sports or exploring various aspects of nature. The philosophy of art specifically studies how artists imagine, create, and perform works of art, as well as how people use, enjoy, and criticize art. Aesthetics considers why people like some works of art and not others, as well as how art can affect our moods and our beliefs.[5] Both aesthetics and the philosophy of art try to find answers to what exactly is art and what makes good art. Etymology The word aesthetic is derived from the Ancient Greek αἰσθητικός (aisthētikós, "perceptive, sensitive, pertaining to sensory perception"), which in turn comes from αἰσθάνομαι (aisthánomai, "I perceive, sense, learn") and is related to αἴσθησις (aísthēsis, "perception, sensation").[6] Aesthetics in this central sense has been said to start with the series of articles on "The Pleasures of the Imagination", which the journalist Joseph Addison wrote in the early issues of the magazine The Spectator in 1712.[7] The term aesthetics was appropriated and coined with new meaning by the German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten in his dissertation Meditationes philosophicae de nonnullis ad poema pertinentibus (English: "Philosophical considerations of some matters pertaining the poem") in 1735;[8] Baumgarten chose "aesthetics" because he wished to emphasize the experience of art as a means of knowing. Baumgarten's definition of aesthetics in the fragment Aesthetica (1750) is occasionally considered the first definition of modern aesthetics.[9] The term was introduced into the English language by Thomas Carlyle in his Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825).[10] The history of the philosophy of art as aesthetics covering the visual arts, the literary arts, the musical arts and other artists forms of expression can be dated back at least to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks. Aristotle writing of the literary arts in his Poetics stated that epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and dance are all fundamentally acts of mimesis ("imitation"), each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[11][12] He applies the term mimesis both as a property of a work of art and also as the product of the artist's intention[11] and contends that the audience's realisation of the mimesis is vital to understanding the work itself.[11] Aristotle states that mimesis is a natural instinct of humanity that separates humans from animals[11][13] and that all human artistry "follows the pattern of nature".[11] Because of this, Aristotle believed that each of the mimetic arts possesses what Stephen Halliwell calls "highly structured procedures for the achievement of their purposes."[14] For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language. The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation – through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[15] Erich Auerbach has extended the discussion of history of aesthetics in his book titled Mimesis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

美

学(びがく、英:

esthetics)とは、美の本質と味覚の本質に関わる哲学の一分野であり、芸術の哲学として機能する。美学は、芸術的センスに対する批判的判断によっ

て決定される美的価値の哲学を考察するものであり、美学の機能は「芸術、文化、自然に対する批判的考察」である。 美学は、自然および人為的な経験の源と、それらの経験の源について人々がどのように判断を下すかを研究する。例えば、視覚芸術を鑑賞したり、音楽を聴いた り、詩を読んだり、演劇を体験したり、ファッションショーや映画を観たり、スポーツをしたり、自然の様々な側面を探検したりするなど、対象や環境と関わる ときに私たちの心に何が起こるのかを考える。芸術哲学は特に、芸術家がどのように芸術作品を想像し、創造し、実行するのか、また人々がどのように芸術を利 用し、楽しみ、批評するのかを研究する。美学は、ある芸術作品が好まれ、他の芸術作品が好まれないのはなぜか、また芸術が私たちの気分や信念にどのような 影響を与えるかを考察する。 語源 美学という言葉は、古代ギリシア語のαἰσθητικός(aisthētikós、「知覚する、敏感な、感覚的知覚に関係する」)に由来し、さらに αἰσθάνομαι(aisthánomai、「知覚する、感じる、学ぶ」)に由来し、αἴσθησις(aísthēsis、=アイステーシス「知覚、感覚」)に関連 している。 [6] この中心的な意味での美学は、ジャーナリストであるジョセフ・アディソンが1712年に雑誌『スペクテイター』の初期の号に書いた「想像力の快楽」に関す る一連の記事から始まったと言われている[7]。 美学という用語は、ドイツの哲学者アレクサンダー・バウムガルテンが1735年に発表した論文『Meditationes philosophicae de nonnullis ad poema pertinentibus』(英語: "Philosophical considerations of some matters pertaining the poem")において、新しい意味を持つ造語として使用された[8]。バウムガルテンの『Aesthetica』(1750)における美学の定義は、近代 美学の最初の定義と見なされることもある[9]。 この言葉はトーマス・カーライルによって『フリードリヒ・シラーの生涯』(1825年)の中で英語に導入された[10]。 視覚芸術、文学芸術、音楽芸術、その他の芸術家の表現形式を網羅する美学としての芸術哲学の歴史は、少なくともアリストテレスと古代ギリシャまで遡ること ができる。アリストテレスは『詩学』の中で文芸について、叙事詩、悲劇、喜劇、ディトラム詩、絵画、彫刻、音楽、舞踊はすべて基本的にミメーシス(「模 倣」)の行為であり、それぞれ媒体、対象、方法によって模倣の仕方が異なると述べている。彼はミメーシスという言葉を、芸術作品の特性として、また芸術家 の意図の産物として適用し、作品そのものを理解するためには、観客がミメーシスを理解することが不可欠であると主張する。アリストテレスは、ミメーシスは 人間と動物を隔てる人間の自然な本能であり、人間の芸術性はすべて「自然の型に従う」と述べている。このことから、アリストテレスは、模倣芸術のそれぞれ が、スティーブン・ハリウェルが言うところの "目的を達成するための高度に構造化された手順 "を持っていると考えた。例えば、音楽はリズムとハーモニーを媒介として模倣するのに対し、舞踊はリズムだけで模倣し、詩は言語を媒介として模倣する。形 式はまた、模倣の対象においても異なる。たとえば喜劇は、平均より悪い人間を劇的に模倣するのに対し、悲劇は平均より少し良い人間を模倣する。最後に、形 式はその模倣の仕方にも違いがある。物語かキャラクターか、変化か変化でないか、ドラマかドラマでないか。エーリッヒ・アウエルバッハは、『ミメーシス』 という著書で美学史の議論を拡張している。 |

| Aesthetics

may be defined narrowly as the theory of beauty, or more broadly as

that together with the philosophy of art. The traditional interest in

beauty itself broadened, in the eighteenth century, to include the

sublime, and since 1950 or so the number of pure aesthetic concepts

discussed in the literature has expanded even more. Traditionally, the

philosophy of art concentrated on its definition, but recently this has

not been the focus, with careful analyses of aspects of art largely

replacing it. Philosophical aesthetics is here considered to center on

these latter-day developments. Thus, after a survey of ideas about

beauty and related concepts, questions about the value of aesthetic

experience and the variety of aesthetic attitudes will be addressed,

before turning to matters which separate art from pure aesthetics,

notably the presence of intention. That will lead to a survey of some

of the main definitions of art which have been proposed, together with

an account of the recent “de-definition” period. The concepts of

expression, representation, and the nature of art objects will then be

covered. Table of Contents Introduction Aesthetic Concepts Aesthetic Value Aesthetic Attitudes Intentions Definitions of Art Expression Representation Art Objects References and Further Reading https://iep.utm.edu/aesthetics/ |

美

学とは、狭義には「美の理論」、広義には「芸術哲学」とも定義される。美そのものに対する伝統的な関心は、18世紀には崇高なものへと広がり、1950年

以降、文献で論じられる純粋な美的概念の数はさらに増えている。伝統的に、芸術の哲学はその定義に集中していたが、近年はそれが中心ではなく、芸術の側面

を注意深く分析することがそれに大きく取って代わっている。哲学的美学は、このような後進の発展を中心に据えたものと考えられる。そのため、美とそれに関

連する概念についての考えを概観した後、美的経験の価値と美的態度の多様性に関する疑問を取り上げ、芸術と純粋な美学を分ける問題、とりわけ意図の存在に

ついて考察する。そして、これまで提唱されてきた芸術の主な定義のいくつかを、近年の「脱定義」の時代とともに概観する。その後、表現、表象、そして美術

品の本質の概念を取り上げる。 目次 はじめに 美的概念 美的価値 美的態度 意図 芸術の定義 表現 表現 美術品 参考文献 |

| Introduced into the

philosophical lexicon during the Eighteenth Century, the term

‘aesthetic’ has come to designate, among other things, a kind of

object, a kind of judgment, a kind of attitude, a kind of experience,

and a kind of value. For the most part, aesthetic theories have divided

over questions particular to one or another of these designations:

whether artworks are necessarily aesthetic objects; how to square the

allegedly perceptual basis of aesthetic judgments with the fact that we

give reasons in support of them; how best to capture the elusive

contrast between an aesthetic attitude and a practical one; whether to

define aesthetic experience according to its phenomenological or

representational content; how best to understand the relation between

aesthetic value and aesthetic experience. But questions of more general

nature have lately arisen, and these have tended to have a skeptical

cast: whether any use of ‘aesthetic’ may be explicated without appeal

to some other; whether agreement respecting any use is sufficient to

ground meaningful theoretical agreement or disagreement; whether the

term ultimately answers to any legitimate philosophical purpose that

justifies its inclusion in the lexicon. The skepticism expressed by

such general questions did not begin to take hold until the later part

of the 20th century, and this fact prompts the question whether (a) the

concept of the aesthetic is inherently problematic and it is only

recently that we have managed to see that it is, or (b) the concept is

fine and it is only recently that we have become muddled enough to

imagine otherwise. Adjudicating between these possibilities requires a

vantage from which to take in both early and late theorizing on

aesthetic matters. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetic-concept/ |

18世紀に哲学の辞書に登場した「美的」という用語は、とりわけ、対象

の種類、判断の種類、態度の種類、経験の種類、価値の種類を指すようになった。芸術作品は必然的に美的対象であるのか、美的判断の根拠が知覚的であるとさ

れることと、私たちがそれを支持する理由を与えるという事実とをどのように結びつけるのか、美的態度と実践的態度との間のとらえどころのない対比をどのよ

うに捉えるのが最善なのか、美的経験を現象学的な内容か表象的な内容かによって定義するのか、美的価値と美的経験との関係をどのように理解するのが最善な

のか、などである。「美的」のどのような用法も、他の用法に訴えることなく説明できるのか、どのような用法に関しても同意することが、意味のある理論的な

同意や不同意の根拠として十分なのか、この用語が辞書に含まれることを正当化するような、正当な哲学的目的に最終的に答えるものなのか、などである。こ

のような一般的な疑問によって表明される懐疑論が定着し始めたのは20世紀後半になってからであり、この事実は、(a)美学という概念は本質的に問題があ

り、それを何とか理解できるようになったのはごく最近のことなのか、(b)概念は問題なく、そうでないと想像できるほど混乱したのはごく最近のことなの

か、という問いを投げかける。これらの可能性の間を裁くには、美学的な事柄に関する初期と後期の理論化を取り入れる視点が必要である。 |

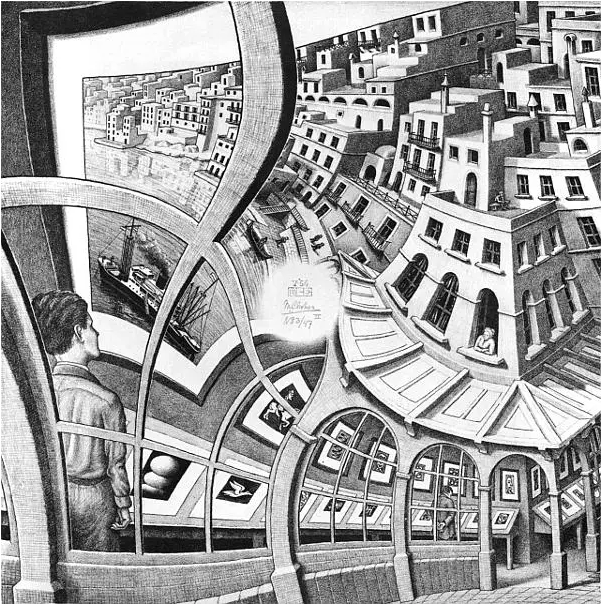

Aesthetics and the philosophy of

art A man admiring a painting A man enjoying a painting of a landscape. The nature of such experience is studied by aesthetics. Some distinguish aesthetics from the philosophy of art, claiming that the former is the study of beauty and taste while the latter is the study of works of art. But aesthetics typically considers questions of beauty as well as of art. It examines topics such as art works, aesthetic experience, and aesthetic judgment.[16] Aesthetic experience refers to the sensory contemplation or appreciation of an object (not necessarily a work of art), while artistic judgment refers to the recognition, appreciation or criticism of art in general or a specific work of art. In the words of one philosopher, "Philosophy of art is about art. Aesthetics is about many things—including art. But it is also about our experience of breathtaking landscapes or the pattern of shadows on the wall opposite your office.[17] Philosophers of art weigh a culturally contingent conception of art versus one that is purely theoretical. They study the varieties of art in relation to their physical, social, and cultural environments. Aesthetic philosophers sometimes also refer to psychological studies to help understand how people see, hear, imagine, think, learn, and act in relation to the materials and problems of art. Aesthetic psychology studies the creative process and the aesthetic experience.[18] |

美学と芸術哲学 絵画を鑑賞する男 風景画を楽しむ男。このような体験の本質を研究するのが美学である。 美学を芸術哲学と区別し、前者は美と趣味の研究であり、後者は芸術作品の研究であると主張する人もいる。しかし、美学は通常、美と芸術の問題を考察する。 美学は、芸術作品、美的経験、美的判断などのトピックを検討する[16]。 美的経験とは、対象物(必ずしも芸術作品とは限らない)に対する感覚的な観想や鑑賞を指し、芸術的判断とは、芸術全般や特定の芸術作品に対する認識、鑑 賞、批評を指す。ある哲学者の言葉を借りれば、「芸術哲学とは芸術に関するものである。美学とは、芸術を含む多くの事柄に関するものである。しかしそれ は、息を呑むような風景や、オフィスの向かいの壁に映る影のパターンなど、私たちが経験することに関するものでもある」[17]。 芸術の哲学者は、文化的に偶発的な芸術の概念と、純粋に理論的な概念とを比較検討する。彼らは物理的、社会的、文化的環境との関係において芸術の多様性を 研究する。美学的哲学者は、芸術の素材や問題に関連して、人がどのように見、聞き、想像し、考え、学び、行動するかを理解するために、心理学的研究を参照 することもある。美学心理学は創造的プロセスと美的経験を研究する[18]。 |

| Aesthetic judgment, universals,

and ethics Aesthetics is for the artist as ornithology is for the birds. — Barnett Newman[19][20] Aesthetic judgment See also: Value judgment Oil painting of Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant believed that aesthetics arises from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Aesthetics examines affective domain response to an object or phenomenon. Judgements of aesthetic value rely on the ability to discriminate at a sensory level. However, aesthetic judgments usually go beyond sensory discrimination. For David Hume, delicacy of taste is not merely "the ability to detect all the ingredients in a composition", but also the sensitivity "to pains as well as pleasures, which escape the rest of mankind."[21] Thus, sensory discrimination is linked to capacity for pleasure. For Immanuel Kant (Critique of Judgment, 1790), "enjoyment" is the result when pleasure arises from sensation, but judging something to be "beautiful" has a third requirement: sensation must give rise to pleasure by engaging reflective contemplation. Judgements of beauty are sensory, emotional and intellectual all at once. Kant observed of a man "if he says that 'Canary wine is pleasant,' he is quite content if someone else corrects his expression and remind him that he ought to say instead: 'It is pleasant to me,'" because "every one has his own [sense of] taste". The case of "beauty" is different from mere "pleasantness" because "if he gives out anything as beautiful, he supposes in others the same satisfaction—he judges not merely for himself, but for every one, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things."[22] Viewer interpretations of beauty may on occasion be observed to possess two concepts of value: aesthetics and taste. Aesthetics is the philosophical notion of beauty. Taste is a result of an education process and awareness of elite cultural values learned through exposure to mass culture. Bourdieu examined how the elite in society define the aesthetic values like taste and how varying levels of exposure to these values can result in variations by class, cultural background, and education.[23] According to Kant, beauty is subjective and universal; thus certain things are beautiful to everyone.[24] In the opinion of Władysław Tatarkiewicz, there are six conditions for the presentation of art: beauty, form, representation, reproduction of reality, artistic expression and innovation. However, one may not be able to pin down these qualities in a work of art.[25] The question of whether there are facts about aesthetic judgments belongs to the branch of metaphilosophy known as meta-aesthetics.[26] Factors involved in aesthetic judgment Rainbows often have aesthetic appeal Aesthetic judgment is closely tied to disgust.[citation needed] Responses like disgust show that sensory detection is linked in instinctual ways to facial expressions including physiological responses like the gag reflex. Disgust is triggered largely by dissonance; as Darwin pointed out, seeing a stripe of soup in a man's beard is disgusting even though neither soup nor beards are themselves disgusting. Aesthetic judgments may be linked to emotions or, like emotions, partially embodied in physical reactions. For example, the awe inspired by a sublime landscape might physically manifest with an increased heart-rate or pupil dilation. As seen, emotions are conformed to 'cultural' reactions, therefore aesthetics is always characterized by 'regional responses', as Francis Grose was the first to affirm in his Rules for Drawing Caricaturas: With an Essay on Comic Painting (1788), published in W. Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, Bagster, London s.d. (1791? [1753]), pp. 1–24. Francis Grose can therefore be claimed to be the first critical 'aesthetic regionalist' in proclaiming the anti-universality of aesthetics in contrast to the perilous and always resurgent dictatorship of beauty.[27] 'Aesthetic Regionalism' can thus be seen as a political statement and stance which vies against any universal notion of beauty to safeguard the counter-tradition of aesthetics related to what has been considered and dubbed un-beautiful just because one's culture does not contemplate it, e.g. Edmund Burke's sublime, what is usually defined as 'primitive' art, or un-harmonious, non-cathartic art, camp art, which 'beauty' posits and creates, dichotomously, as its opposite, without even the need of formal statements, but which will be 'perceived' as ugly.[28] Likewise, aesthetic judgments may be culturally conditioned to some extent. Victorians in Britain often saw African sculpture as ugly, but just a few decades later, Edwardian audiences saw the same sculptures as beautiful. Evaluations of beauty may well be linked to desirability, perhaps even to sexual desirability. Thus, judgments of aesthetic value can become linked to judgments of economic, political, or moral value.[29] In a current context, a Lamborghini might be judged to be beautiful partly because it is desirable as a status symbol, or it may be judged to be repulsive partly because it signifies over-consumption and offends political or moral values.[30] The context of its presentation also affects the perception of artwork; artworks presented in a classical museum context are liked more and rated more interesting than when presented in a sterile laboratory context. While specific results depend heavily on the style of the presented artwork, overall, the effect of context proved to be more important for the perception of artwork than the effect of genuineness (whether the artwork was being presented as original or as a facsimile/copy).[31] Aesthetic judgments can often be very fine-grained and internally contradictory. Likewise aesthetic judgments seem often to be at least partly intellectual and interpretative. What a thing means or symbolizes is often what is being judged. Modern aestheticians have asserted that will and desire were almost dormant in aesthetic experience, yet preference and choice have seemed important aesthetics to some 20th-century thinkers. The point is already made by Hume, but see Mary Mothersill, "Beauty and the Critic's Judgment", in The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics, 2004. Thus aesthetic judgments might be seen to be based on the senses, emotions, intellectual opinions, will, desires, culture, preferences, values, subconscious behaviour, conscious decision, training, instinct, sociological institutions, or some complex combination of these, depending on exactly which theory is employed.[citation needed] A third major topic in the study of aesthetic judgments is how they are unified across art forms. For instance, the source of a painting's beauty has a different character to that of beautiful music, suggesting their aesthetics differ in kind.[32] The distinct inability of language to express aesthetic judgment and the role of social construction further cloud this issue. Aesthetic universals The philosopher Denis Dutton identified six universal signatures in human aesthetics:[33] 1. Expertise or virtuosity. Humans cultivate, recognize, and admire technical artistic skills. 2. Nonutilitarian pleasure. People enjoy art for art's sake, and do not demand that it keep them warm or put food on the table. 3. Style. Artistic objects and performances satisfy rules of composition that place them in a recognizable style. 4. Criticism. People make a point of judging, appreciating, and interpreting works of art. 5. Imitation. With a few important exceptions like abstract painting, works of art simulate experiences of the world. 6. Special focus. Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience. Artists such as Thomas Hirschhorn have indicated that there are too many exceptions to Dutton's categories. For example, Hirschhorn's installations deliberately eschew technical virtuosity. People can appreciate a Renaissance Madonna for aesthetic reasons, but such objects often had (and sometimes still have) specific devotional functions. "Rules of composition" that might be read into Duchamp's Fountain or John Cage's 4′33″ do not locate the works in a recognizable style (or certainly not a style recognizable at the time of the works' realization). Moreover, some of Dutton's categories seem too broad: a physicist might entertain hypothetical worlds in his/her imagination in the course of formulating a theory. Another problem is that Dutton's categories seek to universalize traditional European notions of aesthetics and art forgetting that, as André Malraux and others have pointed out, there have been large numbers of cultures in which such ideas (including the idea "art" itself) were non-existent.[34] Aesthetic ethics Aesthetic ethics refers to the idea that human conduct and behaviour ought to be governed by that which is beautiful and attractive. John Dewey[35] has pointed out that the unity of aesthetics and ethics is in fact reflected in our understanding of behaviour being "fair"—the word having a double meaning of attractive and morally acceptable. More recently, James Page[36] has suggested that aesthetic ethics might be taken to form a philosophical rationale for peace education. |

美的判断、普遍、倫理 鳥類学が鳥のためにあるように、美学は芸術家のためにある。 - バーネット・ニューマン[19][20]。 美的判断 こちらも参照のこと: 価値判断 イマヌエル・カントの油絵 イマヌエル・カントは、美学は無関心な判断力から生じると考えた。 美学は、ある対象や現象に対する情緒的な領域の反応を検討する。美的価値の判断は、感覚レベルでの識別能力に依存している。しかし、美的判断は通常、感覚 的な識別を超えている。 デイヴィッド・ヒュームにとって、味覚の繊細さとは単に「ある組成物に含まれるすべての成分を検出する能力」ではなく、「他の人間から逃れる苦痛や快楽に 対する感受性」でもある[21]。したがって、感覚的識別は快楽の能力と結びついている。 イマヌエル・カント(『判断力批判』1790年)にとって、「快楽」とは感覚から快楽が生じるときの結果であるが、何かを「美しい」と判断するには第三の 要件がある。美の判断は、感覚的、感情的、そして知的なものである。カントは人間について、「もし彼が『カナリアワインは心地よい』と言ったとしても、他 の誰かが彼の表現を訂正し、代わりにこう言うべきだと思い起こさせても、彼は満足する: なぜなら「味覚は人それぞれ」だからである。美しさ」の場合は、単なる「心地よさ」とは異なる。なぜなら、「もし彼が何かを美しいと言うならば、彼は他の 人にも同じような満足を与えるだろう。 美に対する鑑賞者の解釈には、美学と味覚という2つの価値概念が存在することがある。美学とは美の哲学的概念である。嗜好とは、大衆文化に触れることで学 んだエリート文化的価値観の教育過程と自覚の結果である。ブルデューは、社会のエリート層がどのように味覚のような美的価値を定義しているのか、また、こ れらの価値観への曝露のレベルの違いが、どのように階級、文化的背景、教育による差異をもたらすのかを考察している[23]。カントによれば、美は主観的 かつ普遍的なものであり、したがって特定のものは誰にとっても美しい。しかし、芸術作品においてこれらの特質を突き止めることはできないかもしれない [25]。 美的判断に関する事実が存在するかどうかという問題は、メタ美学として知られる形而上学の一分野に属する[26]。 美的判断に関わる要因 虹はしばしば美的魅力を持つ 美的判断は嫌悪と密接に結びついている[要出典]。嫌悪のような反応は、感覚検出が咽頭反射のような生理的反応を含む表情と本能的な方法で結びついている ことを示している。嫌悪は主に不協和によって引き起こされる。ダーウィンが指摘したように、スープもひげもそれ自体嫌悪するものではないにもかかわらず、 男性のひげにスープの縞模様が見えると嫌悪感を抱く。美的判断は感情と結びついている場合もあれば、感情と同様、部分的に身体的反応として具現化されてい る場合もある。例えば、崇高な風景に触発された畏敬の念は、心拍数の上昇や瞳孔の散大という形で身体的に現れるかもしれない。 このように、感情は「文化的」反応に適合するものであり、したがって美学は常に「地域的反応」によって特徴づけられる: コミカルな絵画に関するエッセイを添えて』(1788年)(W. Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, Bagster, London s.d. (1791? [1753]), pp. したがって、フランシス・グロースは、危うく常に復活する美の独裁と対照的に、美学の反普遍性を宣言した最初の批評的な「美的地域主義者」であると主張す ることができる[27]。「美的地域主義」はこのように、自分の文化がそれを観念していないというだけで、美しくないものとみなされ、美しくないものとさ れてきたものに関連する美学の反伝統を守るために、美のあらゆる普遍的概念に対抗する政治的声明であり、姿勢であるとみなすことができる。 例えば、エドモンド・バークの崇高さ、通常「原始的な」芸術と定義されるもの、調和的でない、非カタルシス的な芸術、キャンプ・アートなどは、「美」がそ の対極にあるものとして、形式的な記述すら必要とせずに、二項対立的に仮定し、創造するものであるが、醜いものとして「知覚」されるものである[28]。 同様に、美的判断は文化的にある程度条件づけられているのかもしれない。イギリスのヴィクトリア朝では、アフリカの彫刻を醜いと見ることが多かったが、 そのわずか数十年後、エドワード朝では同じ彫刻を美しいと見るようになった。美に対する評価は、おそらく性的な欲望とさえも結びついたものであろう。した がって、美的価値の判断は、経済的、政治的、あるいは道徳的価値の判断と連動する可能性がある[29]。現在の文脈でいえば、ランボルギーニは、ステータ スシンボルとして望ましいという理由もあって美しいと判断されるかもしれないし、過剰消費を意味し、政治的あるいは道徳的価値観を害するという理由もあっ て嫌悪的と判断されるかもしれない[30]。 古典的な美術館で展示された作品は、無菌状態の実験室で展示された作品よりも好まれ、面白いと評価される。具体的な結果は、提示された作品のスタイルに大 きく依存するが、全体として、コンテクストの効果は、真正性(作品がオリジナルとして提示されているか、ファクシミリ/コピーとして提示されているか)の 効果よりも作品の知覚にとって重要であることが証明された[31]。 美的判断はしばしば非常にきめ細かく、内部的に矛盾することがある。同様に美的判断は、少なくとも部分的には知的で解釈的であることが多いようだ。あるも のが何を意味するのか、何を象徴しているのかが、しばしば判断の対象となる。近代の美学者たちは、美的経験において意志や欲望はほとんど休眠状態であると 主張してきたが、20世紀の一部の思想家にとっては、嗜好や選択が重要な美学であったようだ。この指摘はすでにヒュームによってなされているが、Mary Mothersill, 「Beauty and the Critic's Judgment」, in The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics, 2004を参照されたい。このように美的判断は、感覚、感情、知的意見、意志、欲望、文化、嗜好、価値観、潜在意識的行動、意識的決定、訓練、本能、社会 学的制度、あるいはこれらの複雑な組み合わせに基づくと見なされるかもしれないが、厳密にどの理論を採用するかによって異なる[要出典]。 美的判断の研究における3つ目の主要なトピックは、美的判断が芸術形式を超えてどのように統一されるかということである。例えば、絵画の美しさの源泉は、 美しい音楽のそれとは異なる性格を持っており、両者の美学が種類において異なることを示唆している[32]。美的判断を表現するための言語の明確な不能性 と、社会的構築の役割は、この問題をさらに曇らせている。 美的普遍性 哲学者のデニス・ダットンは、人間の美学における6つの普遍的な特徴を特定した。 1. 専門性または名人芸。人間は技術的な芸術的技能を培い、認識し、賞賛する。 2. 非実用的な喜び。人々は芸術のために芸術を楽しみ、芸術によって暖をとったり、食卓に食べ物を並べたりすることを要求しない。 3. 様式。芸術的なオブジェやパフォーマティビティは、それらを認識可能なスタイルに位置づける構成上のルールを満たしている。 4. 批評。人々は芸術作品を判断し、評価し、解釈する。 5. 模倣。抽象絵画のようないくつかの重要な例外を除いて、芸術作品は世界の経験をシミュレートする。 6. 特別な焦点。芸術は普通の生活から切り離され、経験の劇的な焦点となる。 トーマス・ヒルシュホーンのような芸術家は、ダットンのカテゴリーには例外が多すぎると指摘している。例えば、ヒルシュホーンのインスタレーションは、技 術的な妙技を意図的に排除している。ルネサンスのマドンナを美的な理由で評価することは可能だが、そのようなオブジェにはしばしば特定の信仰的な機能が あった(そして時には今もある)。デュシャンの「泉」やジョン・ケージの「4′33″」に読み取れるかもしれない「作曲の規則」は、作品を認識可能な様式 に位置づけるものではない(あるいは、作品が実現した時点で認識可能な様式ではないことは確かだ)。さらに、ダットンのカテゴリーは広すぎるように思われ るものもある。物理学者が理論を構築する過程で、想像の中で仮定の世界を楽しむかもしれない。もう一つの問題は、アンドレ・マルローなどが指摘しているよ うに、そのような考え方(「芸術」という考え方自体を含む)が存在しない文化が数多くあったことを忘れて、ダットンのカテゴリーがヨーロッパの伝統的な美 学や芸術の概念を普遍化しようとしていることである[34]。 美的倫理 美的倫理とは、人間の行動や振る舞いは美しく魅力的なものに支配されるべきだという考え方を指す。ジョン・デューイ[35]は、美学と倫理の一体性は、行 動が「公正」であるという我々の理解に実際に反映されていると指摘している。より最近では、ジェームズ・ペイジ[36]が、美学的倫理が平和教育の哲学的 根拠を形成する可能性を示唆している(→Ethik und Ästhetik sind Eins)。 |

| Beauty Main article: Beauty Beauty is one of the main subjects of aesthetics, together with art and taste.[37][38] Many of its definitions include the idea that an object is beautiful if perceiving it is accompanied by aesthetic pleasure. Among the examples of beautiful objects are landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty is a positive aesthetic value that contrasts with ugliness as its negative counterpart.[39] Different intuitions commonly associated with beauty and its nature are in conflict with each other, which poses certain difficulties for understanding it.[40][41][42] On the one hand, beauty is ascribed to things as an objective, public feature. On the other hand, it seems to depend on the subjective, emotional response of the observer. It is said, for example, that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".[43][37] It may be possible to reconcile these intuitions by affirming that it depends both on the objective features of the beautiful thing and the subjective response of the observer. One way to achieve this is to hold that an object is beautiful if it has the power to bring about certain aesthetic experiences in the perceiving subject. This is often combined with the view that the subject needs to have the ability to correctly perceive and judge beauty, sometimes referred to as "sense of taste".[37][41][42] Various conceptions of how to define and understand beauty have been suggested. Classical conceptions emphasize the objective side of beauty by defining it in terms of the relation between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts should stand in the right proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole.[37][39][42] Hedonist conceptions, on the other hand, focus more on the subjective side by drawing a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, e.g. that for an object to be beautiful is for it to cause disinterested pleasure.[44] Other conceptions include defining beautiful objects in terms of their value, of a loving attitude towards them or of their function.[45][39][37] |

美しさ 主な記事 美 美は、芸術や味覚とともに美学の主要な主題のひとつである[37][38]。その定義の多くには、対象を知覚することが美的快楽を伴うならば、その対象は 美しいという考え方が含まれている。美しいものの例としては、風景、夕日、人間、芸術作品などが挙げられる。美は肯定的な美的価値であり、否定的な対極に ある醜さとは対照的である[39]。 一方では、美は客観的で公的な特徴として物事に帰属する。他方で、それは観察者の主観的で感情的な反応に依存しているように思われる。例えば、「美は見る 者の眼に宿る」と言われるように[43][37]、美は美しいものの客観的特徴と観察者の主観的反応の両方に依存すると断言することで、これらの直観を調 和させることができるかもしれない。これを実現する一つの方法は、知覚する主体に特定の美的経験をもたらす力があれば、その対象は美しいとすることであ る。これはしばしば、対象が美を正しく知覚し判断する能力を持つ必要があるという見解と組み合わされ、「センス・オブ・センス」と呼ばれることもある [37][41][42]。美をどのように定義し理解するかについては、様々な概念が提案されている。古典的な概念では、美の客観的側面を強調し、全体と しての美しい対象とその部分との間の関係という観点から美を定義している。 [37][39][42]他方、ヘドニスト的な概念は、快楽と美との間に必要な関係を描くことによって、主観的な側面に重点を置く。 |

| New Criticism and "The

Intentional Fallacy" During the first half of the twentieth century, a significant shift to general aesthetic theory took place which attempted to apply aesthetic theory between various forms of art, including the literary arts and the visual arts, to each other. This resulted in the rise of the New Criticism school and debate concerning the intentional fallacy. At issue was the question of whether the aesthetic intentions of the artist in creating the work of art, whatever its specific form, should be associated with the criticism and evaluation of the final product of the work of art, or, if the work of art should be evaluated on its own merits independent of the intentions of the artist.[citation needed] In 1946, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published a classic and controversial New Critical essay entitled "The Intentional Fallacy", in which they argued strongly against the relevance of an author's intention, or "intended meaning" in the analysis of a literary work. For Wimsatt and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation of meanings from outside the text was considered irrelevant, and potentially distracting.[citation needed] In another essay, "The Affective Fallacy," which served as a kind of sister essay to "The Intentional Fallacy", Wimsatt and Beardsley also discounted the reader's personal/emotional reaction to a literary work as a valid means of analyzing a text. This fallacy would later be repudiated by theorists from the reader-response school of literary theory. One of the leading theorists from this school, Stanley Fish, was himself trained by New Critics. Fish criticizes Wimsatt and Beardsley in his essay "Literature in the Reader" (1970).[46] As summarized by Berys Gaut and Livingston in their essay "The Creation of Art": "Structuralist and post-structuralists theorists and critics were sharply critical of many aspects of New Criticism, beginning with the emphasis on aesthetic appreciation and the so-called autonomy of art, but they reiterated the attack on biographical criticisms' assumption that the artist's activities and experience were a privileged critical topic."[47] These authors contend that: "Anti-intentionalists, such as formalists, hold that the intentions involved in the making of art are irrelevant or peripheral to correctly interpreting art. So details of the act of creating a work, though possibly of interest in themselves, have no bearing on the correct interpretation of the work."[48] Gaut and Livingston define the intentionalists as distinct from formalists stating that: "Intentionalists, unlike formalists, hold that reference to intentions is essential in fixing the correct interpretation of works." They quote Richard Wollheim as stating that, "The task of criticism is the reconstruction of the creative process, where the creative process must in turn be thought of as something not stopping short of, but terminating on, the work of art itself."[48] |

新批評と 「意図的誤謬」 20世紀前半、一般的な美学理論に大きな転換が起こり、文芸と視覚芸術を含む様々な芸術の間に美学理論を適用しようとした。その結果、新批評学派が台頭 し、意図的誤謬に関する議論が起こった。具体的な形式が何であれ、芸術作品を創作する際の芸術家の美的意図が、最終的な芸術作品の批評や評価と関連づけら れるべきなのか、それとも芸術作品は芸術家の意図とは無関係にそれ自体の長所で評価されるべきなのかという問題が争点となった[要出典]。 1946年、ウィリアム・K・ウィムサットとモンロー・ビアズリーは、「意図の誤謬」と題する古典的かつ論争的なニュークリティカル論考を発表し、文学作 品の分析における作者の意図、つまり「意図された意味」の関連性に強く異議を唱えた。ウィムサットとビアズリーにとって、重要なのはページ上の言葉だけで あり、テキストの外から意味を輸入することは無関係であり、注意をそらす可能性があると考えられていた[要出典]。 ウィムサットとビアズリーは、「意図的誤謬」の姉妹編のような別のエッセイ「感情的誤謬」においても、文学作品に対する読者の個人的/感情的反応を、テキ ストを分析する有効な手段として割り引いていた。この誤謬は後に、文学理論の読者反応学派の理論家によって否定されることになる。この学派の代表的な理論 家の一人であるスタンリー・フィッシュは、自らも新批評派の薫陶を受けている。フィッシュは「読者における文学」(1970年)というエッセイの中でウィ ムサットとビアズリーを批判している[46]。 ベリス・ガウトとリヴィングストンは「芸術の創造」というエッセイの中で次のように要約している: 「構造主義者やポスト構造主義者の理論家や批評家たちは、美的鑑賞やいわゆる芸術の自律性の強調に始まる新批評の多くの側面を鋭く批判したが、彼らは芸術 家の活動や経験が特権的な批評テーマであるという伝記的批評の前提に対する攻撃を繰り返した」[47]: 「形式主義者のような反意図主義者は、芸術の制作に関わる意図は、芸術を正しく解釈するためには無関係であるか、周辺的なものであると主張する。そのた め、作品を創作する行為の詳細は、それ自体には関心があるかもしれないが、作品の正しい解釈には関係しない」[48]。 ゴートとリヴィングストンは、形式主義者とは異なるものとして意図主義者を次のように定義している: 「意図論者は形式論者とは異なり、作品の正しい解釈を確定するためには意図への言及が不可欠であるとする。彼らはリチャード・ウォルハイムの言葉を引用 し、「批評の仕事は創造的なプロセスの再構築であり、創造的なプロセスは芸術作品そのものに止まらず、芸術作品そのものに終着するものとして考えなければ ならない」と述べている[48]。 |

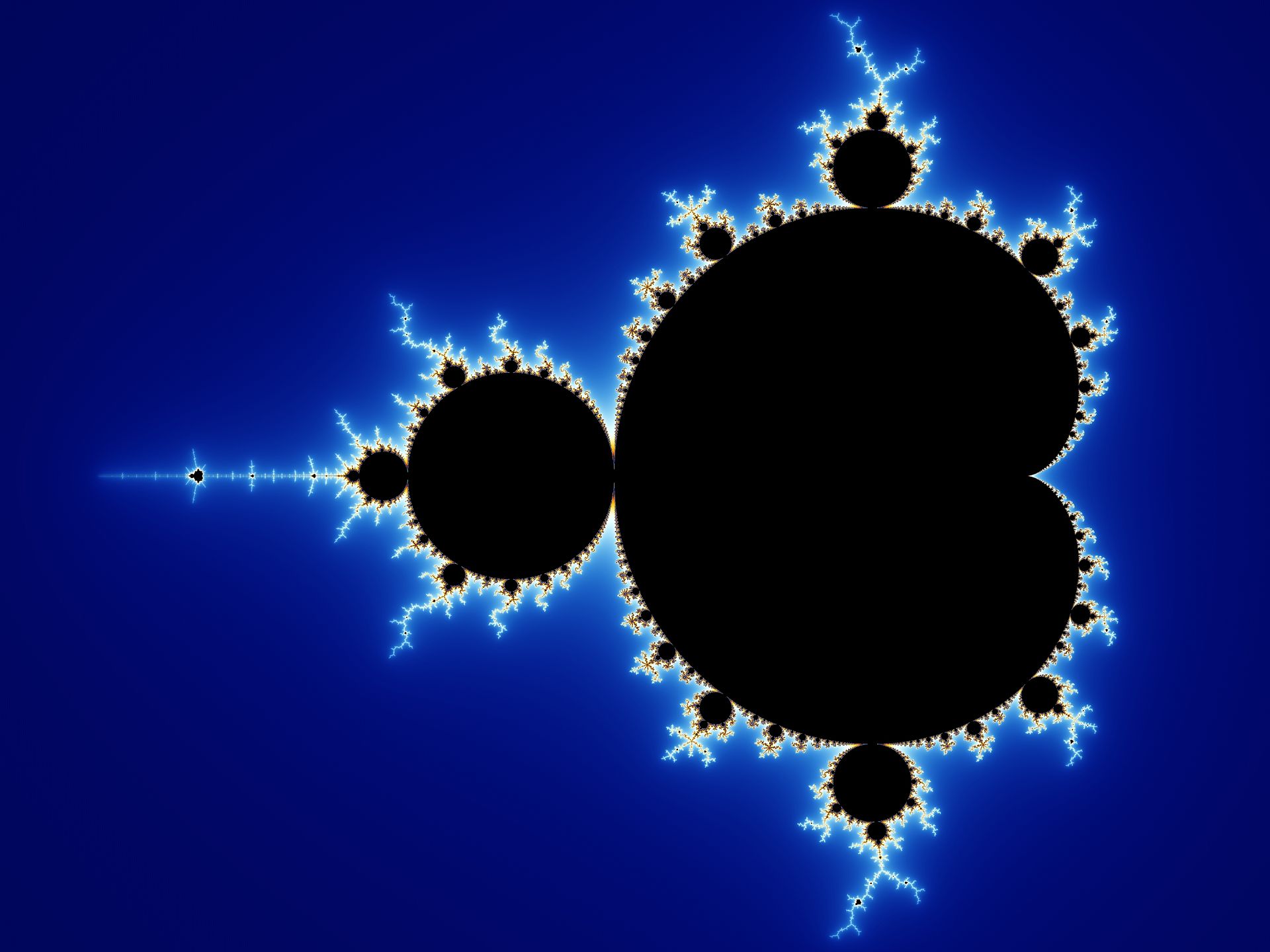

| Derivative forms of aesthetics A large number of derivative forms of aesthetics have developed as contemporary and transitory forms of inquiry associated with the field of aesthetics which include the post-modern, psychoanalytic, scientific, and mathematical among others.[citation needed] Post-modern aesthetics and psychoanalysis Early-twentieth-century artists, poets and composers challenged existing notions of beauty, broadening the scope of art and aesthetics. In 1941, Eli Siegel, American philosopher and poet, founded Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy that reality itself is aesthetic, and that "The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites."[49][50] Various attempts have been made to define Post-Modern Aesthetics. The challenge to the assumption that beauty was central to art and aesthetics, thought to be original, is actually continuous with older aesthetic theory; Aristotle was the first in the Western tradition to classify "beauty" into types as in his theory of drama, and Kant made a distinction between beauty and the sublime. What was new was a refusal to credit the higher status of certain types, where the taxonomy implied a preference for tragedy and the sublime to comedy and the Rococo. Croce suggested that "expression" is central in the way that beauty was once thought to be central. George Dickie suggested that the sociological institutions of the art world were the glue binding art and sensibility into unities.[51] Marshall McLuhan suggested that art always functions as a "counter-environment" designed to make visible what is usually invisible about a society.[52] Theodor Adorno felt that aesthetics could not proceed without confronting the role of the culture industry in the commodification of art and aesthetic experience. Hal Foster attempted to portray the reaction against beauty and Modernist art in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Arthur Danto has described this reaction as "kalliphobia" (after the Greek word for beauty, κάλλος kallos).[53] André Malraux explains that the notion of beauty was connected to a particular conception of art that arose with the Renaissance and was still dominant in the eighteenth century (but was supplanted later). The discipline of aesthetics, which originated in the eighteenth century, mistook this transient state of affairs for a revelation of the permanent nature of art.[54] Brian Massumi suggests to reconsider beauty following the aesthetical thought in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari.[55] Walter Benjamin echoed Malraux in believing aesthetics was a comparatively recent invention, a view proven wrong in the late 1970s, when Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty, information processing, and information theory. Denis Dutton in "The Art Instinct" also proposed that an aesthetic sense was a vital evolutionary factor. Jean-François Lyotard re-invokes the Kantian distinction between taste and the sublime. Sublime painting, unlike kitsch realism, "... will enable us to see only by making it impossible to see; it will please only by causing pain."[56][57] Sigmund Freud inaugurated aesthetical thinking in Psychoanalysis mainly via the "Uncanny" as aesthetical affect.[58] Following Freud and Merleau-Ponty,[59] Jacques Lacan theorized aesthetics in terms of sublimation and the Thing.[60] The relation of Marxist aesthetics to post-modern aesthetics is still a contentious area of debate. Aesthetics and science The field of experimental aesthetics was founded by Gustav Theodor Fechner in the 19th century. Experimental aesthetics in these times had been characterized by a subject-based, inductive approach. The analysis of individual experience and behaviour based on experimental methods is a central part of experimental aesthetics. In particular, the perception of works of art,[61] music, sound,[62] or modern items such as websites[63] or other IT products[64] is studied. Experimental aesthetics is strongly oriented towards the natural sciences. Modern approaches mostly come from the fields of cognitive psychology (aesthetic cognitivism) or neuroscience (neuroaesthetics[65]). Truth in beauty and mathematics Mathematical considerations, such as symmetry and complexity, are used for analysis in theoretical aesthetics. This is different from the aesthetic considerations of applied aesthetics used in the study of mathematical beauty. Aesthetic considerations such as symmetry and simplicity are used in areas of philosophy, such as ethics and theoretical physics and cosmology to define truth, outside of empirical considerations. Beauty and Truth have been argued to be nearly synonymous,[66] as reflected in the statement "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" in the poem "Ode on a Grecian Urn" by John Keats, or by the Hindu motto "Satyam Shivam Sundaram" (Satya (Truth) is Shiva (God), and Shiva is Sundaram (Beautiful)). The fact that judgments of beauty and judgments of truth both are influenced by processing fluency, which is the ease with which information can be processed, has been presented as an explanation for why beauty is sometimes equated with truth.[67] Recent research found that people use beauty as an indication for truth in mathematical pattern tasks.[68] However, scientists including the mathematician David Orrell[69] and physicist Marcelo Gleiser[70] have argued that the emphasis on aesthetic criteria such as symmetry is equally capable of leading scientists astray. Computational approaches  The Mandelbrot set with continuously colored environment Computational approaches to aesthetics emerged amid efforts to use computer science methods "to predict, convey, and evoke emotional response to a piece of art.[71] In this field, aesthetics is not considered to be dependent on taste but is a matter of cognition, and, consequently, learning.[72] In 1928, the mathematician George David Birkhoff created an aesthetic measure  {\displaystyle M=O/C} as the ratio of order to complexity.[73] In the 1960s and 1970s, Max Bense, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake were among the first to analyze links between aesthetics, information processing, and information theory.[74][75][76] Max Bense, for example, built on Birkhoff's aesthetic measure and proposed a similar information theoretic measure {\displaystyle H} the entropy, which assigns higher value to simpler artworks. In the 1990s, Jürgen Schmidhuber described an algorithmic theory of beauty. This theory takes the subjectivity of the observer into account and postulates that among several observations classified as comparable by a given subjective observer, the most aesthetically pleasing is the one that is encoded by the shortest description, following the direction of previous approaches.[77][78] Schmidhuber's theory explicitly distinguishes between that which is beautiful and that which is interesting, stating that interestingness corresponds to the first derivative of subjectively perceived beauty. He supposes that every observer continually tries to improve the predictability and compressibility of their observations by identifying regularities like repetition, symmetry, and fractal self-similarity.[79][80][81][82] Since about 2005, computer scientists have attempted to develop automated methods to infer aesthetic quality of images.[83][84][85][86] Typically, these approaches follow a machine learning approach, where large numbers of manually rated photographs are used to "teach" a computer about what visual properties are of relevance to aesthetic quality. A study by Y. Li and C.J. Hu employed Birkhoff's measurement in their statistical learning approach where order and complexity of an image determined aesthetic value.[87] The image complexity was computed using information theory while the order was determined using fractal compression.[87] There is also the case of the Acquine engine, developed at Penn State University, that rates natural photographs uploaded by users.[88] There have also been relatively successful attempts with regard to chess[further explanation needed] and music.[89] Computational approaches have also been attempted in film making as demonstrated by a software model developed by Chitra Dorai and a group of researchers at the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center.[90] The tool predicted aesthetics based on the values of narrative elements.[90] A relation between Max Bense's mathematical formulation of aesthetics in terms of "redundancy" and "complexity" and theories of musical anticipation was offered using the notion of Information Rate.[91] Evolutionary aesthetics Main article: Evolutionary aesthetics Evolutionary aesthetics refers to evolutionary psychology theories in which the basic aesthetic preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success.[92] One example being that humans are argued to find beautiful and prefer landscapes which were good habitats in the ancestral environment. Another example is that body symmetry and proportion are important aspects of physical attractiveness which may be due to this indicating good health during body growth. Evolutionary explanations for aesthetical preferences are important parts of evolutionary musicology, Darwinian literary studies, and the study of the evolution of emotion. Applied aesthetics Main article: Applied aesthetics As well as being applied to art, aesthetics can also be applied to cultural objects, such as crosses or tools. For example, aesthetic coupling between art-objects and medical topics was made by speakers working for the US Information Agency. Art slides were linked to slides of pharmacological data, which improved attention and retention by simultaneous activation of intuitive right brain with rational left.[93] It can also be used in topics as diverse as cartography, mathematics, gastronomy, fashion and website design.[94][95][96][97][98] Other approaches Guy Sircello has pioneered efforts in analytic philosophy to develop a rigorous theory of aesthetics, focusing on the concepts of beauty,[99] love[100] and sublimity.[101] In contrast to romantic theorists, Sircello argued for the objectivity of beauty and formulated a theory of love on that basis. British philosopher and theorist of conceptual art aesthetics, Peter Osborne, makes the point that "'post-conceptual art' aesthetic does not concern a particular type of contemporary art so much as the historical-ontological condition for the production of contemporary art in general ...".[102] Osborne noted that contemporary art is 'post-conceptual' in a public lecture delivered in 2010. Gary Tedman has put forward a theory of a subjectless aesthetics derived from Karl Marx's concept of alienation, and Louis Althusser's antihumanism, using elements of Freud's group psychology, defining a concept of the 'aesthetic level of practice'.[103] Gregory Loewen has suggested that the subject is key in the interaction with the aesthetic object. The work of art serves as a vehicle for the projection of the individual's identity into the world of objects, as well as being the irruptive source of much of what is uncanny in modern life. As well, art is used to memorialize individuated biographies in a manner that allows persons to imagine that they are part of something greater than themselves.[104] |

美学の派生形態 美学の派生形態は、ポストモダン、精神分析、科学的、数学的など、美学の分野に関連する現代的かつ一過性の探究形態として数多く発展してきた[要出典]。 ポストモダンの美学と精神分析 20世紀初頭の芸術家、詩人、作曲家たちは、既存の美の概念に挑戦し、芸術と美学の範囲を広げた。1941年、アメリカの哲学者であり詩人であったイーラ イ・シーゲルは、現実そのものが美的であり、「世界、芸術、自己は互いに説明しあう:それぞれが相反するものの美的一体性である」という哲学である美的リ アリズムを創始した[49][50]。 ポスト・モダン美学を定義するために様々な試みがなされてきた。アリストテレスは西洋の伝統の中で初めて、戯曲論のように「美」をタイプに分類したし、カ ントは美と崇高さを区別した。新しいのは、特定のタイプの地位の高さを認めないことであり、その分類は喜劇やロココよりも悲劇や崇高さを好むことを意味し ていた。 クローチェは、かつて美が中心であると考えられていたように、「表現」が中心であることを示唆した。ジョージ・ディッキーは、芸術界の社会学的制度が芸術 と感性を一体化させる接着剤であることを示唆した[51]。マーシャル・マクルーハンは、芸術は常に「対抗環境」として機能し、社会について通常目に見え ないものを可視化するように設計されていることを示唆した[52]。テオドール・アドルノは、芸術と美的経験の商品化における文化産業の役割に直面するこ となしに美学を進めることはできないと考えた。ハル・フォスターは『反美学』の中で、美とモダニズム芸術に対する反動を描こうとした: Essays on Postmodern Culture)の中で、美とモダニズム芸術に対する反動を描こうとしている。アーサー・ダントはこの反応を「カリフォビア」(ギリシャ語で美を意味する κάλλος kallosにちなむ)と表現している[53]。アンドレ・マルローは、美の概念はルネサンスとともに生まれ、18世紀にも支配的であった(しかし、後に 取って代わられた)芸術の特定の概念と結びついていたと説明している。ブライアン・マスミは、ドゥルーズとガタリの哲学における美学的思考に従って、美を 再考することを提案している[55]。ヴァルター・ベンヤミンもマルローと同様に、美学は比較的最近の発明であると考えていたが、1970年代後半にアブ ラハム・モールズとフリーダー・ネイクが美と情報処理、そして情報理論との関連性を分析したことで、この見解が間違っていることが証明された。デニス・ ダットンも『芸術の本能』の中で、美的感覚は進化に不可欠な要素であると提唱している。 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールは、味覚と崇高さの間のカント的な区別を再び呼び起こした。崇高な絵画は、キッチュな写実主義とは異なり、「...... 見ることを不可能にすることによってのみ見ることを可能にし、苦痛を与えることによってのみ喜ばせる」[56][57]。 ジークムント・フロイトは主に美的情動としての「不気味さ」を介して精神分析における美学的思考を創始した[58]。フロイトとメルロ=ポンティに続き [59]、ジャック・ラカンは美学を昇華と「もの」の観点から理論化した[60]。 マルクス主義の美学とポスト・モダンの美学との関係は、いまだに論争の的となっている。 美学と科学 実験美学の分野は19世紀にグスタフ・テオドール・フェヒナーによって創設された。この時代の実験美学は、主体的で帰納的なアプローチを特徴としていた。 実験的手法に基づく個人の経験や行動の分析は、実験美学の中心的な部分である。特に、芸術作品[61]、音楽、音響[62]、あるいはウェブサイト [63]やその他のIT製品[64]のような現代的なアイテムの知覚が研究されている。実験美学は自然科学を強く志向している。現代的なアプローチは、認 知心理学(美的認知主義)や神経科学(神経美学[65])の分野からもたらされることがほとんどである。 美と数学における真理 理論的美学では、対称性や複雑性といった数学的考察が分析に用いられる。これは、数学的美の研究に用いられる応用美学の美学的考察とは異なる。対称性や単 純性といった美学的考察は、倫理学や理論物理学・宇宙論といった哲学の分野では、経験的考察とは別に、真理を定義するために用いられる。美と真理はほぼ同 義であると主張されており[66]、ジョン・キーツの詩「グレシアの壷の歌」にある「美は真理であり、真理は美である」という言葉や、ヒンドゥー教のモッ トーである「Satyam Shivam Sundaram」(サティヤ(真理)はシヴァ(神)であり、シヴァはスンダラム(美しい)である)に反映されている。美しさの判断と真実の判断がとも に、情報を処理することの容易さである処理の流暢さに影響されるという事実は、美しさが時として真実と同一視される理由の説明として提示されている [67]。最近の研究では、数学的パターンの課題において、人は美しさを真実の指標として用いることが発見されている[68]。しかしながら、数学者のデ イヴィッド・オレル[69]や物理学者のマルセロ・グライザー[70]を含む科学者たちは、対称性のような美的基準の強調は科学者たちを迷わせる可能性が あると主張している。 計算論的アプローチ  連続的に着色された環境を持つマンデルブロ集合 美学への計算論的アプローチは、「芸術作品に対する感情的反応を予測し、伝え、喚起する」コンピュータ科学の手法を使おうとする取り組みの中で生まれた [71]。この分野では、美学は嗜好に依存するものではなく、認知の問題であり、結果として学習の問題であると考えられている[72]。  {M=O/C}を秩序と複雑性の比としている[73]。 1960年代から1970年代にかけて、マックス・ベンゼ、アブラハム・モールズ、フリーダー・ネイクは、美学、情報処理、情報理論との関連を分析した最 初の人物の一人であった[74][75][76]。 ここで、� {displaystyle R}は冗長度、� {displaystyle H}はエントロピーであり、単純な作品ほど高い価値を与える。 1990年代、ユルゲン・シュミッドフーバーは美のアルゴリズム理論について述べた。この理論は観察者の主観を考慮に入れ、与えられた主観的観察者によっ て同等のものとして分類されたいくつかの観察の中で、最も美的に好ましいものは、以前のアプローチの方向性に従って、最も短い記述によって符号化されたも のであると仮定している[77][78]。シュミッドフーバーの理論は、美しいものと興味深いものを明確に区別し、面白さは主観的に知覚された美しさの一 次導関数に対応すると述べている。彼は、すべての観察者は、繰り返し、対称性、フラクタル自己相似性のような規則性を識別することによって、その観察の予 測可能性と圧縮性を絶えず改善しようとすると仮定している[79][80][81][82]。 2005年頃から、コンピュータ科学者は画像の美的品質を推論する自動化された方法を開発しようと試みている[83][84][85][86]。一般的 に、これらのアプローチは機械学習アプローチに従っており、大量の手動で評価された写真が、どのような視覚的特性が美的品質に関連するかについてコン ピュータに「教える」ために使用される。Y.LiとC.J.Huによる研究では、画像の順序と複雑さが美的価値を決定する統計的学習アプローチにおいて、 バーコフの測定法を採用している[87]。 また、チェス[さらに説明が必要]や音楽に関しても比較的成功した試みがある[89]。このツールは物語要素の価値に基づいて美学を予測した[90]。 マックス・ベンゼの「冗長性」と「複雑性」という観点からの美学の数学的定式化と音楽的先読みの理論との関係は、情報率という概念を用いて提示された [91]。 進化論的美学 主な記事 進化美学 進化美学とは、ホモ・サピエンスの基本的な美的嗜好が、生存と繁殖の成功を高めるために進化したと主張する進化心理学理論のことである。もう一つの例とし て、身体の対称性とプロポーションは身体的魅力の重要な側面であるが、これは身体の成長過程において健康であることを示すためかもしれない。美的嗜好の進 化論的説明は、進化音楽学、ダーウィン文学研究、感情の進化研究の重要な部分である。 応用美学 主な記事 応用美学 美学は芸術に応用されるだけでなく、十字架や道具などの文化的対象にも応用できる。例えば、米国の情報局で働く講演者たちによって、美術品と医療トピック の美学的結合が行われた。アートのスライドを薬理学的データのスライドにリンクさせたところ、直感的な右脳と理性的な左脳が同時に活性化され、注意力と記 憶力が向上した[93]。また、地図製作、数学、美食、ファッション、ウェブサイト・デザインなど、多様なトピックにも利用できる[94][95] [96][97][98]。 その他のアプローチ ガイ・シルセロは分析哲学において、美、[99]愛、[100]崇高さの概念に焦点を当て、美学の厳密な理論を発展させる取り組みの先駆者である [101]。ロマン主義の理論家たちとは対照的に、シルセロは美の客観性を主張し、それに基づいて愛の理論を定式化した。 イギリスの哲学者でありコンセプチュアル・アートの美学の理論家であるピーター・オズボーンは、「『ポスト・コンセプチュアル・アート』の美学は、現代 アートの特定のタイプに関わるものではなく、現代アート全般の制作における歴史的=存在論的な条件に関わるものである」と指摘している[102]。 ゲイリー・テッドマンは、カール・マルクスの疎外の概念とルイ・アルチュセールの反人間主義に由来する主体なき美学の理論を提唱し、フロイトの集団心理学 の要素を用いて、「実践の美的レベル」の概念を定義している[103]。 グレゴリー・ローウェンは、美的対象との相互作用において主体が鍵となることを示唆している。芸術作品は、個人のアイデンティティをオブジェの世界に投影 するための手段としての役割を果たすだけでなく、現代生活における不気味なものの多くを生み出している。また、芸術は、自分が自分自身よりも偉大なものの 一部であると想像させるようなやり方で、個人化された伝記を記念するために用いられる[104]。 |

| Criticism The philosophy of aesthetics as a practice has been criticized by some sociologists and writers of art and society. Raymond Williams, for example, argues that there is no unique and or individual aesthetic object which can be extrapolated from the art world, but rather that there is a continuum of cultural forms and experience of which ordinary speech and experiences may signal as art. By "art" we may frame several artistic "works" or "creations" as so though this reference remains within the institution or special event which creates it and this leaves some works or other possible "art" outside of the frame work, or other interpretations such as other phenomenon which may not be considered as "art".[105] Pierre Bourdieu disagrees with Kant's idea of the "aesthetic". He argues that Kant's "aesthetic" merely represents an experience that is the product of an elevated class habitus and scholarly leisure as opposed to other possible and equally valid "aesthetic" experiences which lay outside Kant's narrow definition.[106] Timothy Laurie argues that theories of musical aesthetics "framed entirely in terms of appreciation, contemplation or reflection risk idealizing an implausibly unmotivated listener defined solely through musical objects, rather than seeing them as a person for whom complex intentions and motivations produce variable attractions to cultural objects and practices".[107] 107. Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149 [pdf] |

批判 実践としての美学の哲学は、社会学者や芸術と社会に関する作家の一部によって批判されてきた。例えば、レイモンド・ウィリアムズは、芸術の世界から外挿できる唯一無二の、あるいは個別の美的対象は 存在せず、むしろ、通常の言論や経験が芸術としてシグナルを発するような、文化的形態や経験の連続体が存在すると主張している。芸術」によって、私たちは いくつかの芸術的な「作品」や「創作物」をそのように枠にはめることができるが、この参照はそれを生み出す制度や特別な出来事の中にとどまり、いくつかの 作品や他の可能性のある「芸術」は枠外に残され、あるいは「芸術」とはみなされないかもしれない他の現象などの他の解釈が残される[105]。 ピエール・ブルデューはカントの「美学」の考えに同意しない。彼は、カ ントの「美的」とは、カントの狭い定義の外側にある他の可能で等しく妥当な「美的」経験とは対照的に、単に高められた階級的ハビトゥスと学問的余暇の産物 である経験を表しているに過ぎないと論じている[106]。 ティモシー・ローリーは、音楽美学の理論が「鑑賞、熟考、内省の 観点から完全に組み立てられたものであることは、彼らを複雑な意図や 動機が文化的な対象や実践に対する様々な魅力を生み出す人間として見るので はなく、音楽的な対象を通してのみ定義される、ありえないほど動機づけのない聴き手を理想化する危険をはらんでいる」と論じている [107]。 107. Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review. 20 (2). doi:10.5130/csr.v20i2.4149 |

| Further information: Outline of

aesthetics Philosophy portal Aestheticism Aesthetics of science Art and Theosophy Art periods Esthesic and poietic Everyday Aesthetics History of aesthetics before the 20th century Japanese aesthetics Medieval aesthetics Mise en scène Theological aesthetics Theory of art |

さらに詳しい情報 美学の概要 哲学ポータル 美学主義 科学の美学 芸術と神智学 芸術の時代 エステティックとポエティック 日常美学 20世紀以前の美学史 日本の美学 中世の美学 ミザンセーヌ 神学的美学 芸術理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aesthetics |

★ 美学の歴史(History of aesthetics)

| Ancient Greek

aesthetics The first important contributions to aesthetic theory are usually considered to stem from philosophers in Ancient Greece, among which the most noticeable are Plato, Aristotle and Plotinus. When interpreting writings from this time, it is worth noticing that it is debatable whether an exact equivalent to the term beauty existed in classical Greek.[1] Xenophon regarded the beautiful as coincident with the good, while both of these concepts are resolvable into the useful. Every beautiful object is so called because it serves some rational end: either the security or the gratification of man. Socrates rather emphasized the power of beauty to further the more necessary ends of life than the immediate gratification which a beautiful object affords to perception and contemplation. His doctrine puts forward the relativity of beauty. Plato, in contrast, recognized that beauty exists as an abstract Form. It is therefore absolute and does not necessarily stand in relation to a percipient mind.[2] Plato Of the views of Plato on the subject, it is hardly less difficult to gain a clear conception from the Dialogues, than it is in the case of ethical good. In some of these, various definitions of the beautiful are rejected as inadequate by the Platonic Socrates. At the same time we may conclude that Plato's mind leaned decidedly to the conception of an absolute beauty, which took its place in his scheme of ideas or self-existing forms. This true beauty is nothing discoverable as an attribute in another thing, for these are only beautiful things, not the beautiful itself. Love (Eros) produces aspiration towards this pure idea. Elsewhere the soul's intuition of the self-beautiful is said to be a reminiscence of its prenatal existence. As to the precise forms in which the idea of beauty reveals itself, Plato is not very decided. His theory of an absolute beauty does not easily adjust itself to the notion of its contributing merely a variety of sensuous pleasure, to which he appears to lean in some dialogues. He tends to identify the self-beautiful with the conceptions of the true and the good, and thus there arose the Platonic formula kalokagathia. So far as his writings embody the notion of any common element in beautiful objects, it is proportion, harmony or unity among their parts. He emphasizes unity in its simplest aspect as seen in evenness of line and purity of color. He recognizes in places the beauty of the mind, and seems to think that the highest beauty of proportion is to be found in the union of a beautiful mind with a beautiful body. He had but a poor opinion of art, regarding it as a trick of imitation (mimesis) which takes us another step further from the luminous sphere of rational intuition into the shadowy region of the semblances of sense. Accordingly, in his scheme for an ideal republic, he provided for the most inexorable censorship of poets, etc., so as to make art as far as possible an instrument of moral and political training.[2] An example of Plato's considerations about poetry is: "For the authors of those great poems which we admire, do not attain to excellence through the rules of any art; but they utter their beautiful melodies of verse in a state of inspiration, and, as it were, possessed by a spirit not their own."[3] Aristotle Aristotle, in contrast to Plato, developed certain principles of beauty and art, most clearly so in his treatises on poetry and rhetoric. He saw the absence of all lust or desire in the pleasure it bestows as another characteristic of the beautiful. Aristotle finds (in the Metaphysics) the universal elements of beauty to be order (taxis), symmetry and definiteness or determinateness (to orismenon). In the Poetics he adds another essential, namely, a certain magnitude; the object should not be too large, while clearness of perception requires that it should not be too small.[4] Aristotle was passionate about goodness in men as he valued "taking [its] virtues to be central to a well-lived life."[5] In Politics, he writes, "Again, men in general desire the good, and not merely what their fathers had."[6] To thoroughly comprehend goodness, Aristotle also studied Beauty. As noted in the Encyclopædia Britannica (1902), moreover, Aristotle, "ignores all conceptions of an absolute Beauty, and at the same time seeks to distinguish the Beautiful from the Good." Aristotle explains that men "will be better able to achieve [their] good if [they] develop a fuller understanding of what it is to flourish."[5] He nonetheless seeks (in the Metaphysics) to distinguish the good and the beautiful by saying that the former is always in action (`en praxei) whereas the latter may exist in motionless things as well (`en akinetois). At the same time he allowed that the good might under certain conditions be called beautiful. He further distinguished the beautiful from the fit, and in a passage of the Politics set beauty above the useful and necessary.[2] Aristotle's views on fine art distinctly recognized (in the Politics and elsewhere) that the aim of art is immediate pleasure, as distinct from utility, which is the end of the mechanical arts. He took a higher view of artistic imitation than Plato, holding that it implied knowledge and discovery, that its objects not only comprised particular things which happen to exist, but contemplated what is probable and what necessarily exists. In the Poetics he declares poetry to be more philosophical and serious a matter (spoudaiteron) than History. He gives us no complete classification of the fine arts, and it is doubtful how far his principles, e.g. his idea of a purification of the passions by tragedy, are to be taken as applicable to other than the poetic art.[7] Plotinus Of the later Greek and Roman writers the Neo-Platonist Plotinus deserves to be mentioned. According to him, objective reason (nous) as self-moving, becomes the formative influence which reduces dead matter to form. Matter when thus formed becomes a notion (logos), and its form is beauty. Objects are ugly so far as they are unacted upon by reason, and therefore formless. The creative reason is absolute beauty, and is called the more than beautiful. There are three degrees or stages of manifested beauty: that of human reason, which is the highest; of the human soul, which is less perfect through its connexion with a material body; and of real objects, which is the lowest manifestation of all. As to the precise forms of beauty, he supposed, in opposition to Aristotle, that a single thing not divisible into parts might be beautiful through its unity and simplicity. He gives a high place to the beauty of colours in which material darkness is overpowered by light and warmth. In reference to artistic beauty he said that when the artist has notions as models for his creations, these may become more beautiful than natural objects. This is clearly a step away from Plato's doctrine towards our modern conception of artistic idealization.[7] |

古代ギリシャの美学 美学理論への最初の重要な貢献は、通常、古代ギリシアの哲学者たちからもたらされたと考えられており、中でもプラトン、アリストテレス、プロティノスが顕 著である。この時代の著作を解釈する際、古典ギリシア語において美という用語に正確に相当するものが存在したかどうか議論の余地があることは注目に値する [1]。 クセノフォンは美しいものを善と同一視していたが、これらの概念はどちらも有用なものに分解可能である。あらゆる美しいものがそう呼ばれるのは、それが何 らかの合理的な目的、すなわち人間の安全や満足に役立っているからである。ソクラテスはむしろ、美しい対象が知覚や観照に与える目先の満足よりも、人生の より必要な目的を促進する美の力を強調した。彼の教義は、美の相対性を打ち出している。対照的に、プラトンは美が抽象的な形として存在することを認めた。 それゆえ、美は絶対的なものであり、必ずしも知覚者の心との関係には立たない[2]。 プラトン この主題に関するプラトンの見解について、対話篇から明確な概念を得ることは、倫理的善の場合ほど困難ではない。対話篇のいくつかでは、プラトン的なソク ラテスによって、美しいもののさまざまな定義が不適切なものとして否定されている。同時に、プラトンの心は、絶対的な美の概念にはっきりと傾いていたと結 論づけることができる。この真の美は、他のものの属性として発見できるものではない。愛(エロス)は、この純粋なイデアへの願望を生み出す。別のところで は、魂が自己の美を直観するのは、生前の存在を思い出すためであると言われている。美のイデアがどのような形で現れるかについては、プラトンはあまり明確 にしていない。絶対的な美というプラトンの理論は、いくつかの対話においてプラトンが傾倒しているように見える、美が単に感覚的な快楽の多様性に寄与して いるという概念に容易に馴染まない。彼は自己の美を真と善の概念と同一視する傾向があり、こうしてプラトン的な公式カロカガティアが生まれたのである。彼 の著作が美しいものに共通する要素の概念を具体化している限り、それは比例、調和、部分間の統一である。彼は、線の均整や色の純粋さに見られるような、最 も単純な面での統一性を強調している。彼は、ところどころに心の美を認め、最高の均整の美は、美しい心と美しい身体との結合の中に見出されると考えている ようだ。彼は芸術を、理性的直観の光り輝く領域から、感覚の似姿の影の領域へともう一歩踏み込む模倣のトリック(ミメーシス)とみなして、あまり評価して いなかった。それゆえ、プラトンは理想共和制の構想の中で、芸術を可能な限り道徳的・政治的訓練の道具とするために、詩人などに対する最も容赦のない検閲 を規定した[2]。 詩に関するプラトンの考察の一例を挙げよう: 「われわれが賞賛する偉大な詩の作者たちは、いかなる芸術の規則によっても卓越性を獲得することはできない。 アリストテレス アリストテレスはプラトンとは対照的に、美と芸術に関する一定の原則を打ち立てた。アリストテレスは、美のもう一つの特徴として、美が与える快楽に欲望が ないことを挙げている。アリストテレスは(『形而上学』において)美の普遍的な要素として、秩序(taxis)、対称性、明確性(orismenon)を 挙げている。詩学』において、彼はもう一つの本質、すなわち一定の大きさを加えている。対象は大きすぎてはならず、知覚の明瞭さは小さすぎてはならないこ とを要求している[4]。 アリストテレスは「(その)徳がよく生きる人生の中心であるとする」ことを重んじ、人の善について熱く語っていた[5]。『政治学』では、「繰り返すが、 人は一般に善を欲するのであって、単に先祖が持っていたものを欲するのではない。ブリタニカ百科事典』(1902年)に記されているように、アリストテレ スは「絶対的な美の概念をすべて無視し、同時に美を善から区別しようとする」のである。それにもかかわらず、アリストテレスは(『形而上学』において)、 善と美を区別するために、前者がつねに作用している(プラクセイ)のに対して、後者は動かないものにも存在する(アキネトイス)と述べている。同時に、あ る条件下では善を美と呼ぶことも認めた。アリストテレスはさらに、美しいものとふさわしいものを区別し、『政治学』の一節において、美を有用で必要なもの よりも上位に置いた[2]。 芸術に関するアリストテレスの見解は、(『政治学』やその他の箇所において)芸術の目的は即物的な快楽であり、機械的芸術の目的である有用性とは異なるこ とを明確に認識していた。彼はプラトンよりも芸術的模倣を高く評価し、芸術的模倣は知識と発見を意味し、その対象は偶然に存在する特定の事物だけでなく、 可能性のあるもの、必然的に存在するものを熟考するとした。詩学』の中で彼は、詩は歴史よりも哲学的で深刻な問題(spoudaiteron)であると宣 言している。彼は芸術の完全な分類を与えておらず、彼の原理、例えば悲劇による情念の浄化という考え方が、詩的芸術以外にどこまで当てはまるかは疑問であ る[7]。 プロティノス 後期ギリシア・ローマの作家の中では、新プラトン主義のプロティノスを挙げるに値する。彼によれば、自己運動する客観的理性(ヌース)は、死んだ物質を形 に還元する形成的影響力となる。こうして形成された物質は観念(ロゴス)となり、その形は美となる。物体は、理性によって作用されない限り醜いものであ り、それゆえ形がない。創造的な理性は絶対的な美であり、「美以上のもの」と呼ばれる。人間の理性は最高のものであり、人間の魂は物質的な身体と結びつい ているために完全ではなく、現実の物体は最も低いものである。美の正確な形については、アリストテレスに対抗して、部分に分割できない単一のものは、その 統一性と単純さによって美しいかもしれないと考えた。彼は、物質的な闇が光と暖かさによって圧倒されるような色彩の美を高く評価している。芸術的な美につ いては、芸術家が自分の創造物のモデルとして観念を持つとき、それらは自然物よりも美しくなる可能性があると述べている。これは明らかに、プラトンの教義 から、芸術的理想化という現代の概念へと一歩踏み出したものである[7]。 |

Western medieval aesthetics Lorsch Gospels 778–820. Charlemagne's Court School. Surviving medieval art is primarily religious in focus and funded largely by the State, Roman Catholic or Orthodox church, powerful ecclesiastical individuals, or wealthy secular patrons. These art pieces often served a liturgical function, whether as chalices or even as church buildings themselves. Objects of fine art from this period were frequently made from rare and valuable materials, such as gold and lapis, the cost of which commonly exceeded the wages of the artist. Medieval aesthetics in the realm of philosophy built upon Classical thought, continuing the practice of Plotinus by employing theological terminology in its explications. St. Bonaventure's "Retracing the Arts to Theology", a primary example of this method, discusses the skills of the artisan as gifts given by God for the purpose of disclosing God to mankind, which purpose is achieved through four lights: the light of skill in mechanical arts which discloses the world of artifacts; which light is guided by the light of sense perception which discloses the world of natural forms; which light, consequently, is guided by the light of philosophy which discloses the world of intellectual truth; finally, this light is guided by the light of divine wisdom which discloses the world of saving truth. Saint Thomas Aquinas's aesthetic is probably the most famous and influential theory among medieval authors, having been the subject of much scrutiny in the wake of the neo-Scholastic revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and even having received the approbation of the celebrated Modernist writer, James Joyce. Thomas, like many other medievals, never gives a systematic account of beauty itself, but several scholars have conventionally arranged his thought—though not always with uniform conclusions—using relevant observations spanning the entire corpus of his work. While Aquinas's theory follows generally the model of Aristotle, he develops a singular aesthetics which incorporates elements unique to his thought. Umberto Eco's The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas identifies the three main characteristics of beauty in Aquinas's philosophy: integritas sive perfectio (integrity or perfection), consonantia sive debita proportio (consonance or proportion), and claritas sive splendor formae (brightness or form). While Aristotle likewise identifies the first two characteristics, St. Thomas conceives of the third as an appropriation from principles developed by neo-Platonic and Augustinian thinkers. With the shift from the Middle Ages to the [Renaissance], art likewise changed its focus, as much in its content as in its mode of expression. |

西洋中世の美学 ローシュ福音書 778-820年 カール大帝の宮廷学派 現存する中世美術は、主に宗教色が強く、国家、ローマ・カトリック教会、正教会、有力な教会関係者、あるいは裕福な世俗のパトロンから資金提供を受けてい る。これらの美術品は、聖杯として、あるいは教会建築そのものとして、典礼的な機能を果たすことが多かった。この時代の美術品は、金やラピスといった希少 価値の高い素材で作られることが多く、その費用は芸術家の賃金を上回ることが一般的だった。 哲学の領域における中世の美学は、古典的な思想を基礎とし、神学的な用語を用いて説明することで、プロティノスの実践を引き継いだ。聖 Bonaventureの 「Retracing the Arts to Theology 」は、この方法の主要な例であり、職人の技術を、神を人間に開示する目的で神から与えられた賜物として論じている: その目的は、人工物の世界を開示する機械芸術の技能の光、その光は自然形態の世界を開示する感覚知覚の光によって導かれ、その結果、その光は知的真理の世 界を開示する哲学の光によって導かれ、最後に、その光は救いの真理の世界を開示する神の知恵の光によって導かれる。 聖トマス・アクィナスの美学は、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのネオ・スコラリスティック・リヴァイヴァルの後、多くの精査の対象となり、著名なモ ダニズム作家ジェイムズ・ジョイスの承認さえ受けた、中世の作家の中ではおそらく最も有名で影響力のある理論である。トマスは、他の多くの中世人と同様、 美そのものについて体系的な説明をすることはなかったが、何人かの学者が、彼の著作全体にわたる関連する観察を用いて、必ずしも一様な結論ではないもの の、彼の思想を慣習的に整理してきた。アクィナスの理論は概ねアリストテレスを手本としながらも、彼の思想独自の要素を取り入れた特異な美学を展開してい る。ウンベルト・エーコの『トマス・アクィナスの美学』は、アクィナス哲学における美の三大特徴として、「完全性(integritas sive perfectio)」、「調和(consonptia sive debita proportio)」、「輝き(clarritas sive splendor formae)」を挙げている。アリストテレスも同様に最初の2つの特徴を挙げているが、聖トマスは3つ目の特徴を、新プラトン主義やアウグスティヌス主 義の思想家たちが発展させた原理からの転用として考えている。中世から[ルネサンス]への移行に伴い、芸術も同様に、その表現方法と同様にその内容におい て、その焦点を変えた。 |

| Baroque and Neoclassicism Tesauro In the seventeenth-century aesthetic concepts from classical antiquity in Western art, including proportion, harmony, unity, decorum, were challenged by new styles, such as Baroque, that adopted new styles and technique to distinguish itself from previous forms of art.[8] The key concepts of the Baroque aesthetic, such as "conceit" (concetto), "wit" (acutezza, ingegno), and "wonder" (meraviglia), were not fully developed in literary theory until the publication of Emanuele Tesauro's Il Cannocchiale aristotelico (The Aristotelian Telescope) in 1654. This seminal treatise - inspired by Giambattista Marino's epic Adone and the work of the Spanish Jesuit philosopher Baltasar Gracián - developed a theory of metaphor as a universal language of images and as a supreme intellectual act, at once an artifice and an epistemologically privileged mode of access to truth. Bellori In 1664, Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Roman art theorist and close friend of Poussin, gave a lecture at the Roman Accademia di San Luca entitled "L'idea del pittore, dello scultore e dell'architetto". The Idea was published in 1672 as the preface to Bellori's Le vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni. Since then it has acquired almost canonical status as one of the earliest declarations of the principles of Classicism.[9] For Bellori, under the influence of the Neoplatonic aesthetic of Plotinus, the 'highest and eternal intellect' had fashioned the supreme archetypes of multifarious nature, the 'Ideas', out of his own being, as the 'perfection of natural beauty', and the artists of antiquity had looked beyond nature to the superior 'Idea' itself.[10] Bellori was hugely influential in the development of the concept of 'ideal beauty'. According to Erwin Panofsky, Bellori is the predecessor of Winckelmann as an art theorist.[11] Winckelmann's theory of the "ideally beautiful" as he expounds it in Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums, thoroughly agrees with the content of Bellori's Idea (to which Winckelmann also owes his acquaintance with the letters of Raphael and Guido Reni). Winckelmann himself frankly recognizes this indebtedness.[12] In the essay "A Parallel of Poetry and Painting," which prefaces his translation of Du Fresnoy Latin poem De arte graphica, Dryden includes a lengthy excerpt from Bellori's Idea.[13] It is through Bellori's formulation, that the notion of ideal beauty was introduced in France, Germany and England, in art criticism generally, and survived throughout the 19th century. |

バロックと新古典主義 テサウロ 17世紀、西洋美術における比例、調和、統一性、礼儀正しさといった古典古代からの美的概念は、バロックのような新しい様式によって挑戦された。 [8] 「驕り」(concentetto)、「機知」(acutezza, ingegno)、「驚き」(meraviglia)といったバロック美学の重要な概念は、1654年にエマヌエーレ・テサウロの『アリストテレスの望遠 鏡』(Il Cannocchiale aristotelico)が出版されるまで、文学理論において十分に発展しなかった。ジャンバッティスタ・マリーノの叙事詩『アドーネ』とスペインのイ エズス会哲学者バルタサル・グラシアンの研究に触発されたこの重要な論考は、普遍的なイメージの言語として、また最高の知的行為としての比喩の理論を展開 した。 ベローリ 1664年、ローマの芸術理論家でプッサンの親友であったジョヴァンニ・ピエトロ・ベッローリは、ローマ・アカデミア・ディ・サン・ルカで「L'idea del pittore, dello scultore e dell'architetto (芸術家、彫刻家、建築家の思想)」と題する講義を行った。このアイデアは、1672年にベローリの『Le vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni』の序文として出版された。それ以来、古典主義の原則を最も早く宣言したものとして、ほぼ正典的な地位を獲得している[9]。 ベッローリにとって、プロティノスの新プラトン主義的美学の影響のもと、「最高にして永遠の知性」は、「自然の美の完成」として、自らの存在から、多様な 自然の最高の原型である「イデア」を作り出し、古代の芸術家たちは、自然を超えて、優れた「イデア」そのものに目を向けていた[10]。 ベローリは「理想的な美」という概念の発展に大きな影響を与えた。エルヴィン・パノフスキーによれば、ベローリは芸術理論家としてのヴィンケルマンの前任 者である[11]。ヴィンケルマンが『アルターの芸術史』(Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums)の中で展開している「理想的な美」の理論は、ベローリのイデア(ヴィンケルマンがラファエロやグイド・レーニの書簡に親しんだのもこ のためである)の内容と完全に一致している。ドライデンは、デュ・フレノワのラテン語詩『De arte graphica』の翻訳に先立ち、「詩と絵画の並列」というエッセイの中で、ベローリの『イデア』からの長い抜粋を掲載している[13]。ベローリの定 式化によって、理想的な美の概念は、フランス、ドイツ、イギリス、そして一般的な美術批評に導入され、19世紀を通じて存続した。 |

| Age of Enlightenment Addison Joseph Addison's "Essays on the Imagination" contributed to the Spectator, though they belong to popular literature, contain the germ of scientific analysis in the statement that the pleasures of imagination (which arise originally from sight) fall into two classes — (1) primary pleasures, which entirely proceed from objects before our eyes; and (2) secondary pleasures, flowing from the ideas of visible objects. The latter are greatly extended by the addition of the proper enjoyment of resemblance, which is at the basis of all mimicry and wit. Addison recognizes, too, to some extent, the influence of association upon our aesthetic preferences.[14] Shaftesbury Shaftesbury is the first of the intuitional writers on beauty. In his Characteristicks the beautiful and the good are combined in one ideal conception, much as with Plato. Matter in itself is ugly. The order of the world, wherein all beauty really resides, is a spiritual principle, all motion and life being the product of spirit. The principle of beauty is perceived not with the outer sense, but with an internal or moral sense which apprehends the good as well. This perception yields the only true delight, namely, spiritual enjoyment.[15] Hutcheson Francis Hutcheson, in his System of Moral Philosophy, though he adopts many of Shaftesbury's ideas, distinctly disclaims any independent self-existing beauty in objects. "All beauty", he says, "is relative to the sense of some mind perceiving it." One cause of beauty is to be found not in a simple sensation such as colour or tone, but in a certain order among the parts, or "uniformity amidst variety". The faculty by which this principle is discerned is an internal sense which is defined as "a passive power of receiving ideas of beauty from all objects in which there is uniformity in variety". This inner sense resembles the external senses in the immediateness of the pleasure which its activity brings, and further in the necessity of its impressions: a beautiful thing being always, whether we will or no, beautiful. He distinguishes two kinds of beauty, absolute or original, and relative or comparative. The latter is discerned in an object which is regarded as an imitation or semblance of another. He distinctly states that "an exact imitation may still be beautiful though the original were entirely devoid of it." He seeks to prove the universality of this sense of beauty, by showing that all men, in proportion to the enlargement of their intellectual capacity, are more delighted with uniformity than the opposite.[15] Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten Perhaps the first German philosopher who developed an independent aesthetic theory was Baumgarten. In his best-known work Aesthetica, he complemented the Leibniz-Wolffian theory of knowledge by adding to the clear scientific or "logical" knowledge of the understanding the knowledge of the senses, to which he gave the name "aesthetic". It is for this reason that Baumgarten is said to have "coined" the term aesthetics. Beauty to him corresponds to perfect sense-knowledge. Baumgarten reduces taste to an intellectual act and ignores the element of feeling. To him, nature is the highest embodiment of beauty, and thus art must seek its supreme function in the strictest possible imitation of nature.[7] Burke Burke's speculations, in his Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, illustrate the tendency of English writers to treat the problem as a psychological one and to introduce physiological considerations. He finds the elements of beauty to be:-- (1) smallness; (2) smoothness; (3) gradual variation of direction in gentle curves; (4) delicacy, or the appearance of fragility; (5) brightness, purity and softness of colour. The sublime is rather crudely resolved into astonishment, which he thinks always retains an element of terror. Thus "infinity has a tendency to fill the mind with a delightful horror." Burke seeks what he calls "efficient causes" for these aesthetic impressions in certain affections of the nerves of sight analogous to those of other senses, namely, the soothing effect of a relaxation of the nerve fibres. The arbitrariness and narrowness of this theory cannot well escape the reader's attention.[14] Kant Immanuel Kant's theory of aesthetic judgments remains a highly debated aesthetic theory until today. It is important to note that Kant uses the term "aesthetics" ("Ästhetik") to refer to any sensual experience.[16] The work most crucial to aesthetics as a strand of philosophy is the first half of his Critique of the Power of Judgment, the Critique of the Aesthetic Power of Judgment. It is subdivided in two main parts - the Analytic of the Beautiful and the Analytic of the Sublime, but also deals with the experience of fine art. For Kant, beauty does not reside inside an object, but is defined as the pleasure that stems from the ″free play″ of imagination and understanding inspired by the object — which as a result we will call beautiful. Such pleasure is more than mere agreeableness, since it must be disinterested and free — that is to say independent from the object's ability to serve as a means to an end. Even though the feeling of beauty is subjective, Kant goes beyond the notion of ″beauty is in the eye of the beholder″: If something is beautiful to me, I also think that it should be so for everybody else, even though I cannot prove beauty to anyone. Kant also insists that the aesthetic judgment is always, an "individual" i.e. a singular one, of the form "This object (e.g. rose) is beautiful." He denies that we can reach a valid universal aesthetic judgment of the form "All objects possessing such and such qualities are beautiful." (A judgment of this form would be logical, not aesthetic.) Nature, in Kant's aesthetics, is the primary example for beauty, ranking as a source of aesthetic pleasure above art, which he only considers in the last parts of the third Critique of the Aesthetic Judgment. It is in these last paragraphs where he connects to his earlier works when he argues that the highest significance of beauty is to symbolize moral good; going in this regard even further than Ruskin.[7] |