Affaire Dreyfus

Affaire Dreyfus

ドレフュス事件

★【梗概】

ドレフュス事件(仏: affaire

Dreyfus、発音: [afɛ

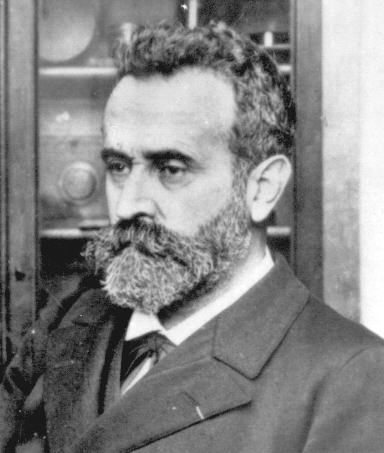

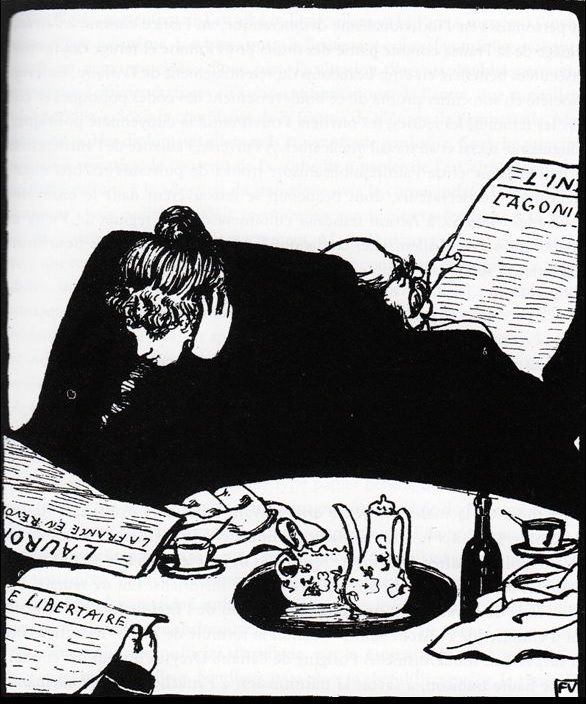

dʁʁ])は、1894年から1906年の解決まで、フランス第三共和政を二分した政治スキャンダルである。このスキャンダルは1894年12月、ユダヤ

系アルザス人のフランス人砲兵将校アルフレッド・ドレフュス大尉(35歳)が、パリのドイツ大使館にフランスの軍事機密を伝えたとして国家反逆罪で不当に

有罪判決を受けたことから始まった。彼は終身刑を宣告され、海外にあるフランス領ギアナの悪魔の島の流刑地に送られ、その後5年間、非常に過酷な環境で投

獄生活を送った。

1896年、主にスパイ対策責任者ジョルジュ・ピカール中佐の調査によって、真犯人がフェルディナン・ワルサン・エステルハージというフランス陸軍少佐で

あることが判明した。軍高官たちはこの新証拠を封じ込め、軍法会議はわずか2日間の裁判の後、満場一致でエステルハージを無罪とした。陸軍は偽造文書に基

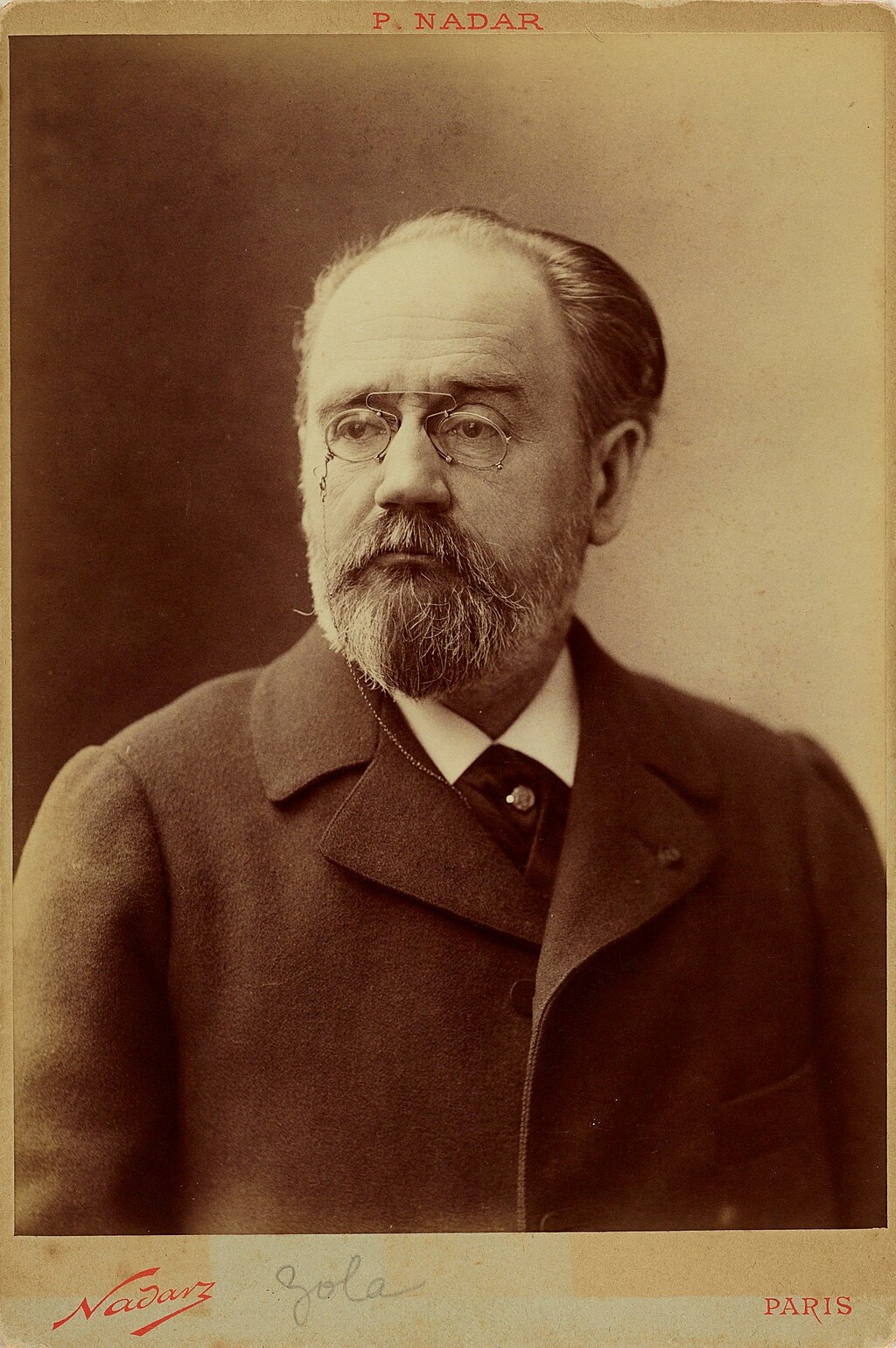

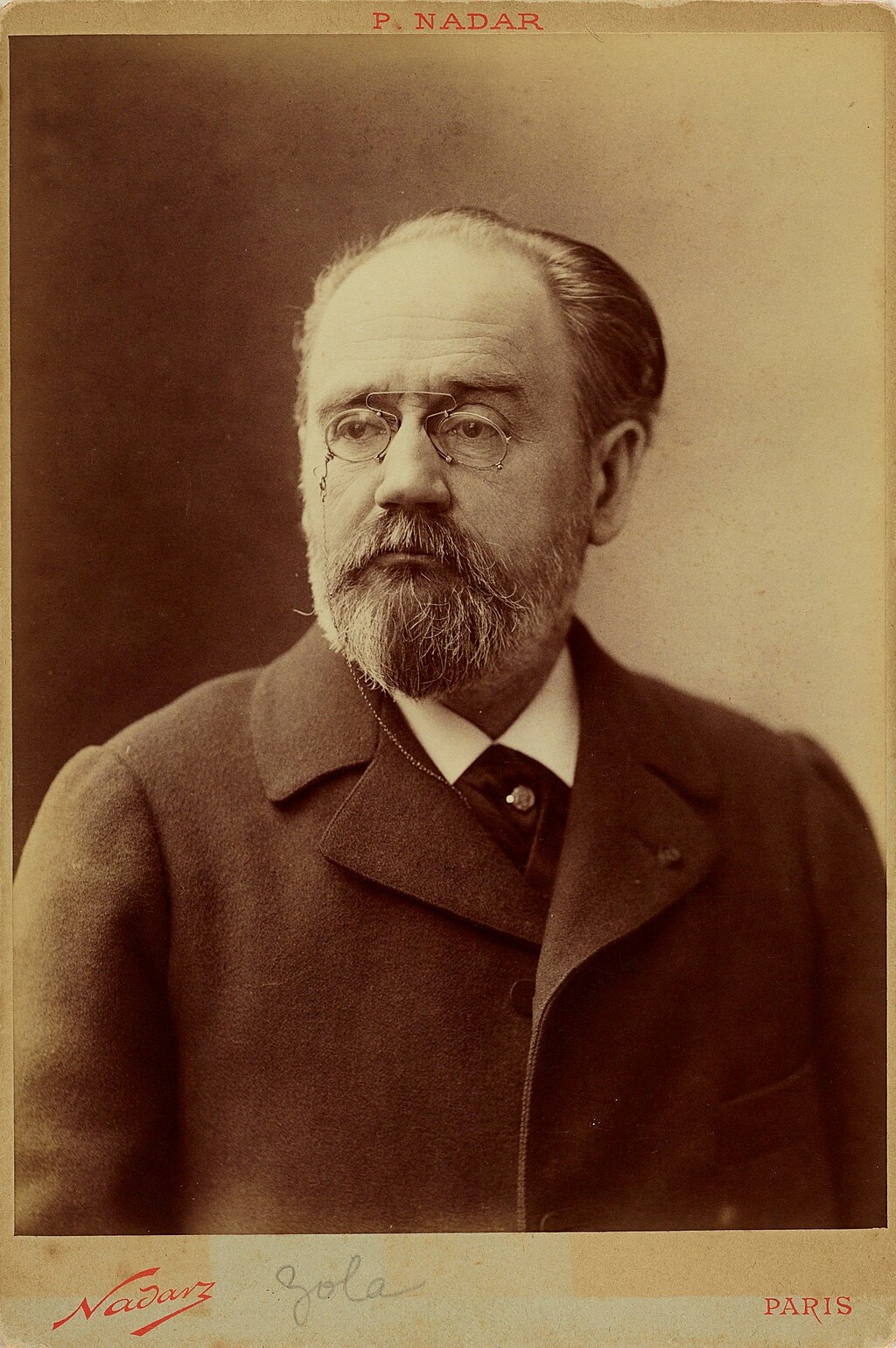

づき、ドレフュスに対してさらなる告発を行った。その後、作家エミール・ゾラが『オーロール』紙に発表した公開書簡「私は告発する...!」が、ドレフュ

スを支持する政治的な動きを煽り、ドレフュスの裁判を再開するよう政府に圧力をかけた。

1899年、ドレフュスは再び裁判を受けるためにフランスに戻された。ドレフュスを支持するサラ・ベルナール、アナトール・フランス、シャルル・ペギー、

アンリ・ポアンカレ、ジョルジュ・クレマンソーなどの「ドレフュス派」と、ドレフュスを非難する、反ユダヤ主義的な新聞『ラ・リーブル・パロール』の発行

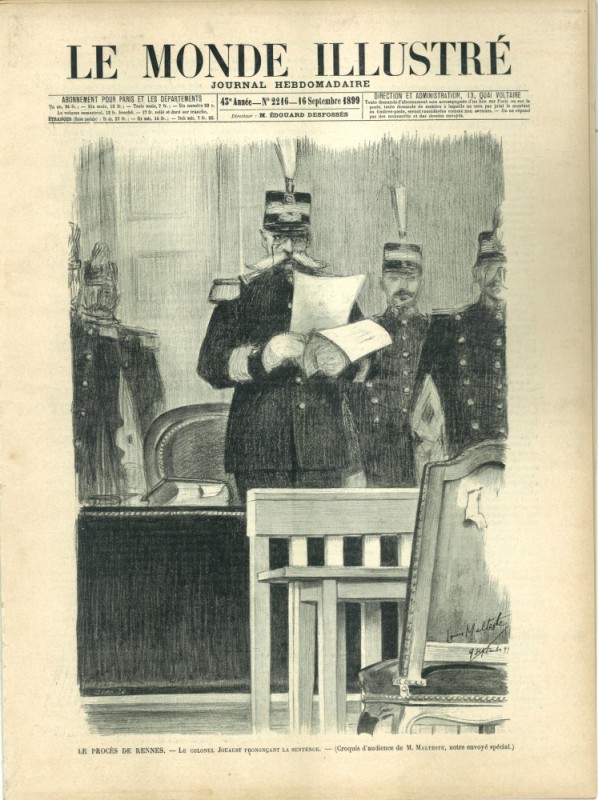

人であったエドゥアール・ドラモンなどの「反ドレフュス派」にフランス社会は二分された。新たな裁判の結果、ドレフュスは再び有罪判決を受け、10年の刑

期を言い渡されたが、赦免され釈放された。1906年、ドレフュスは釈放された。フランス陸軍少佐に復職したドレフュスは、第一次世界大戦の全期間に従軍

し、中佐の地位でその任務を終えた。1935年に死去した。

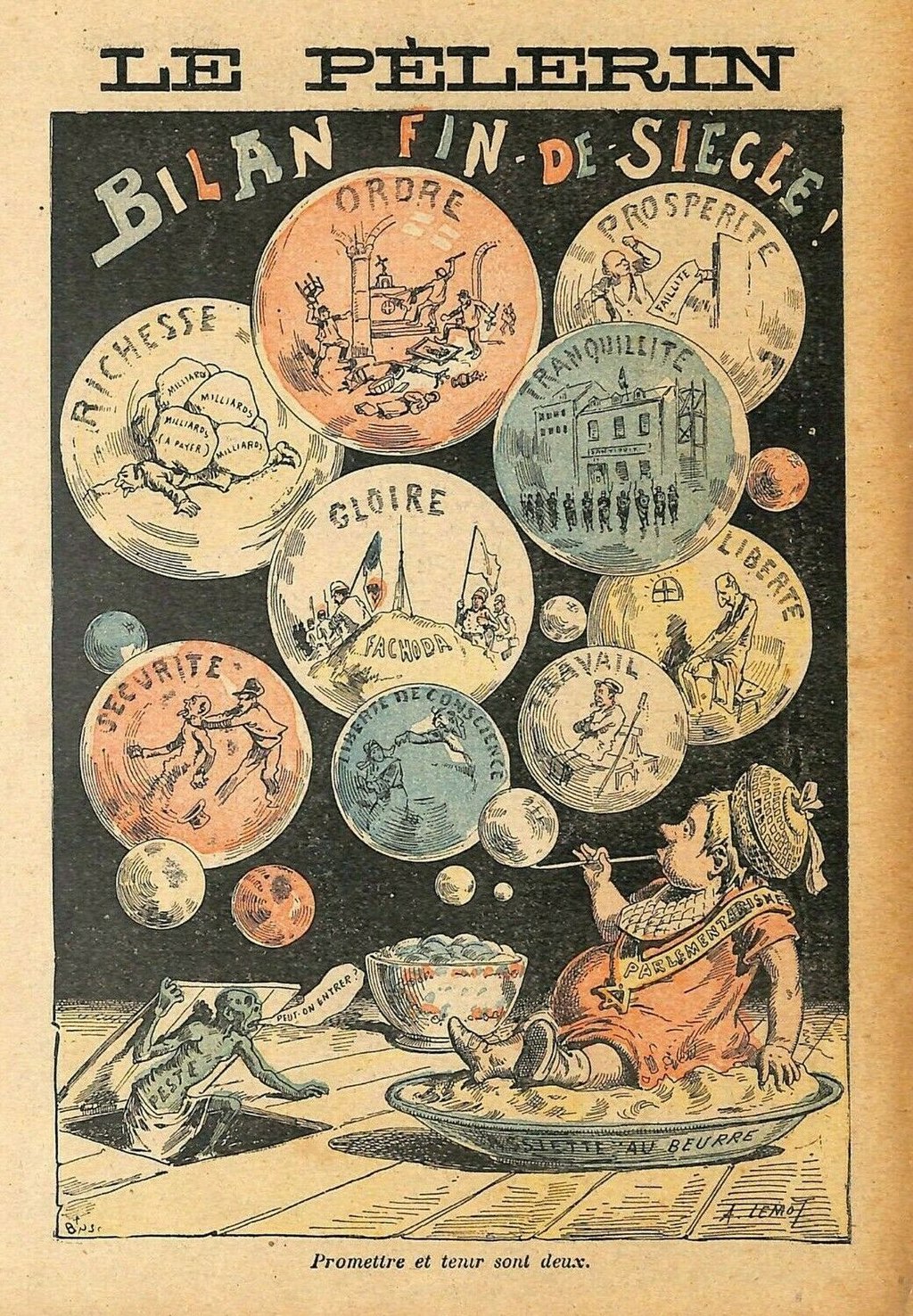

ドレフュス事件は、フランス語圏における現代の不公正を象徴する事件となった[1]。ドレフュス事件は、フランスを親共和主義的で反神権的なドレフュス派

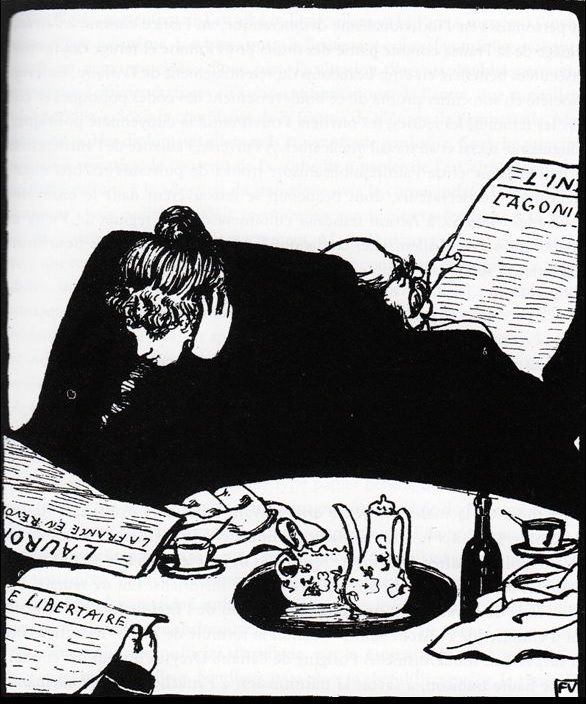

と親陸軍的でほとんどがカトリックの反ドレフュス派に分裂させ、フランスの政治を混乱させ、急進化を促した[2]。報道機関は、情報を暴露し、対立する双

方の世論を形成し表現する上で重要な役割を果たした。

★【時系列】

1)1894年7月20日 マリー=シャ ルル=フェルディナン・ワルシン・エ ステラージ少佐は、パリ駐在ドイツ大使館附武官マクシミリアン・フォン・シュヴァルツコッペンに面会を申し入れ、フランス陸軍に関わる機密 情報の売却を持ちかける。

2)エステラージ少佐とシュヴァルツコッ ペンの間で、複数回の面会と書面の交換がおこなわれる。

3)120ミリ砲制動機使用法等「数日中 に入手見込み」軍事情報が書かれたエステラージ作成の1通の手紙が、6片に破られて・シュヴァルツコッ ペンの屑篭に捨て置かれる。

4)ドイツ大使館の掃除婦を装ったフラン ス側のスパイであるバスティアン夫人が、焼却処分を装いその屑篭の中味を、拾い出す。

5)同年9月26日バスティアン夫人は、 フランス陸軍参謀本部統計局に中味を委ねる。

6)統計局内でスパイの実務を引き受けて いたユベール=ジョゼフ・アンリ少佐は、この文書を「明細書」と名付けて、翌9月27日、局長ジャン・ サンデール大佐に実物を示し報告する。

7)その場にいたマトン大尉は、明細書の 中味から、明細書の書き手は、参謀本部内の砲兵士官である可能性を示唆する。

8)サンデールは、9月27日のうちに、 参謀次長ルヌアールを通じて、陸軍大臣メルシェに事実関係を報告する。メルシェは真相究明を指示。

9)9月28日以降の数日間に、ルヌアー ル、サンデール、アンリによる内偵がすすむ。

10)明細書の筆跡を調べ、写真版を作成 し、部署の局長級に配布し、同様の、類似書類がないかの作業を依頼する。

11)10月5日までは、なんの進展もな かった。

12)10月6日。同日に着任した参謀本 部第4局次長ダボヴィル中佐は、 局長ファーブル大佐に対して、容疑者の可能性について独自の自説を披 露する(同日昇進の勇みがあったのではないか言われる)。それは、「明細書」の内容が、ひろく局内の情報に分散していたために、自由に局内(第1〜4局ま である)に出入りできるのは、参謀本部付きの研修生であると。

13)ファーブル局長は、過去4,5名の 研修生を受け入れており、個別に評価を認めている。

14)ファーブル局長の予見は、前年 1893年の下半期で第4局で研修を受けて、当時大尉であったアルフレッド・ドレフュス大尉を焦点があてら れた。

15)その理由は、ファーブルの評価がド レフュスに対して低いものであることにつきた(後に裁判に証拠として文書が提出される)。評価書の記述 「士官として欠陥あり。知力、才気ともに申し分なきも、矜持に満ち、性格、良心、勤務態度の面で参謀本部に配属されるための条件を満たしておらず」(菅野 2002:9)。

16)しかし、このファーブルの評価書 は、部下で研修生の指導に関わるロジェ中佐とベルタン=ムロー少佐の報告をそのまま鵜呑みにしたもので あった(破毀院, 2:41)。また、ベルタン=ムロー少佐は、自らのユダヤ系出自(母方)を気に病みそれを忘れ去るかのように反ユダヤ言説を標榜す。

17)ファーブル局長に取り入ったダボ ヴィル中佐は、「明細書」の筆跡と、ドレフュスの筆跡が類似であることを多数の文書から「確信」するに至 る。

18)ファーブル大佐は、参謀総長ボワ デッフル将軍、参謀次長ゴンス将軍に、ダボヴィル中佐の調査結果を報告する。

19)同時に、ドレフュスの名と履歴は、 陸軍大臣メルシェ、統計局長サンデールにも報告される。サンデールは額を叩き「そんなことだと思ってい た」と叫んだ(レンヌ再審 1:578)。メルシェ将軍は、ドレフュスと自分がアルザス(Alsace, Elsàss, Elsäß, Elsass)出身であることに「身の毛のよだつ思い」をしたという。

20)サンデールの口からはこの件に関し て「ユダヤ人」という言葉が頻出する。

21)ダボヴィル中佐とファーヴル (ファーブル)大佐の筆跡鑑定だけでは説得力に欠けると判断したメルシェ将軍は、参謀本部内に筆跡分析に心得 ある部下を探し、参謀本部第3局のアルマン=オーギュスト=シャルル=フェルディナン=マリー・メルシェ・デュ・パティ・ド・クラム少佐を指名する。

22)1894年10月6日夕刻、デュ・パティ少佐は、ゴ ンス将軍のもとに呼ばれ、「明細書」と名前を付したドレフュスの筆跡をみせられ、その間に「一致」があると証言した。ゴンス将軍は直後に、デュ・パティ少 佐にその筆跡はドレフュスのものだと告げられる。

23)翌10月7日は日曜だったが1日が かりで鑑定作業をおこない、完全な一致はないものの、司法鑑定として一致を結論づけるだけの類似性はあ ると、報告書を作成する。

24)10月8日から11日までの4日間 は、政界工作に費やされる。メルシェ将軍が会談を重ねたのは、パリ軍事総監ソーシエ将軍、共和国大統領 カジミール=ペリエ、首相デュピュイ、法務大臣ゲランら。とくに、外相アノトーは、ドイツ帝国との一大外交事件にならぬように「明細書」以外の確実な情報 のさらなる提出を求めたという。

25)10月12日、メルシェ将軍は、法 務大臣から推薦されたフランス銀行専属筆跡鑑定士アフレッド・ゴベールを 陸軍に召喚するよう依頼。拡大写真等を手渡される。ボワデッフル参謀 総長に呼び出されたデュ・パティ少佐は、司法警察史として事件にあたるよう命令される。

26)10月13日(土)午前、ゴベール は鑑定の結果「明細書の筆跡とドレフュスの筆跡は一致せず」と結論づける。同時に、同じ鑑定依頼をうけ たパリ警察司法人体測定課アルフォンス・ベルティヨンは「偽造の形跡はあるが、ふたつの筆跡は完全一致」の結論を出す。

27)10月13日(土)午前の同時期 に、ドレフュスの自宅には、週明けの10月15日平服にてボワデッフル将軍の執務室に出頭せよとの命令が くだる。

28)10月14日(日)ダボヴィル中佐 は、重罪被告人の準備をせよと陸軍監獄司令に書き送り、デュ・パティ少佐は、警察庁と協議して逮捕と尋 問のシナリオを準備する。

29)10月14日(日)夕方、メルシェ 将軍を囲んで最終打ち合わせがおこなわれる。デュ・パティ少佐は口実をつけてドレフュスに「明細書」に 似た文面を書かせて、心理的動揺を与えて逮捕するというシナリオを開陳した。また、ドレフュス当人の自決を想定し提案したデュ・パティ少佐は、メルシェ将 軍の無言の頷きにより、弾1発を込めた回転拳銃(リヴォルバー)をさりげに被疑者の近くに置く、という段取りまで整えた。

30)ドレフュスは、平服にて、10月 15日午前9時に出頭。種々のやりとりがあり、逮捕の宣言があり、ドレフュスは無罪を主張する。

31)1894年10月15日ドレフュス

大尉は、シェルシュ=ミディ陸軍監獄に収監される。ただし、この事件はすぐには報道されなかった。

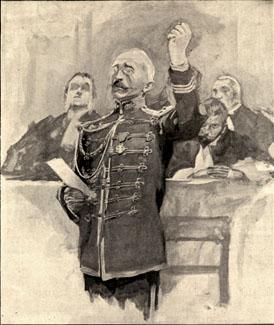

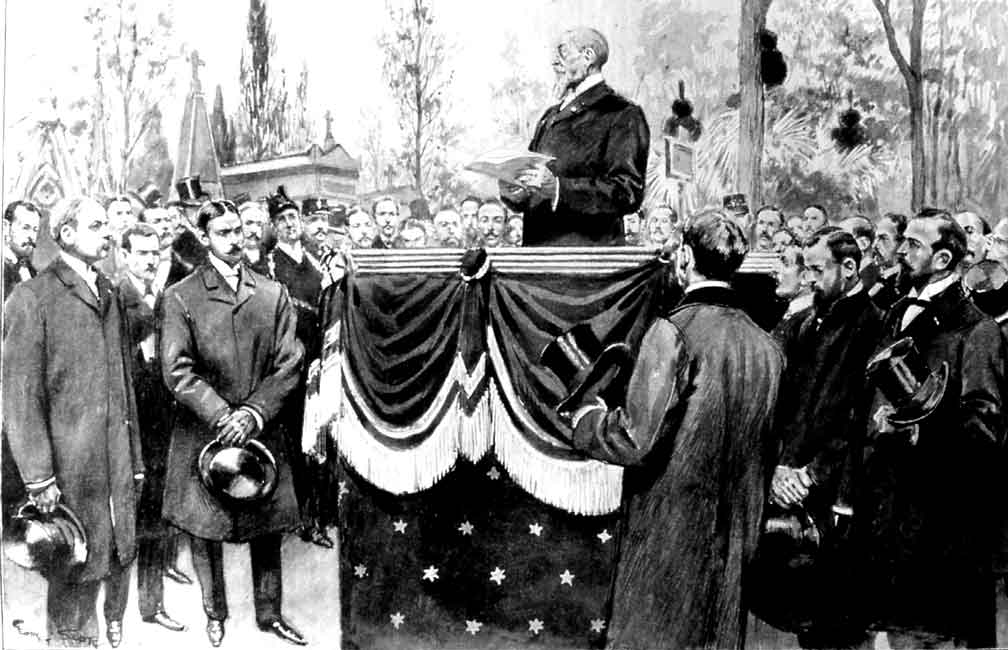

ドレフュス大尉の不名誉な除隊を描いた挿 絵(官位剥奪式で剣を折られるドレフュス=左側)"The traitor: Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, degradation in the Morland Court of the military school in Paris"

1894 「反ユダヤ系の新聞「自由言 論」がすっぱ抜きで大々的に報じ、ユダヤ人は祖国を裏切る売国奴であり、その売国奴を軍部が庇っていると 論じて、軍部の優柔不断を糾弾」(ウィキ、以下同様)

1895? 「軍上層部は、証拠不十分の まま非公開の軍法会議においてドレフュスに「有罪」の判決を下し、南米の仏領ギアナ沖のディアブル島 (デヴィルズ島)に終身城塞禁錮とした」(ウィキ)

---- 「ドレフュスは初めから無罪を 主張しており、彼の誠実な人柄から無実を確信した妻のリュシーと兄のマテューらは、再審を強く求めると ともに、真犯人の発見に執念を燃や」す。

1896 情報部長に着任したピカール中 佐は、真犯人はハンガリー生まれのフェルディナン・ヴァルザン・エステラージ少 佐であることを突き止めた。しかし、軍上層部はフランス陸軍大臣 のシャルル・シャノワーヌが再審に反対[2]したように軍の権威失墜を恐れてもみ消しを図り、ピカールを脅して左遷、形式的な裁判でエステラージを「無罪」とし釈放した(エステルアジはイギリスに逃亡し、そこで 平穏な生涯を終えた)

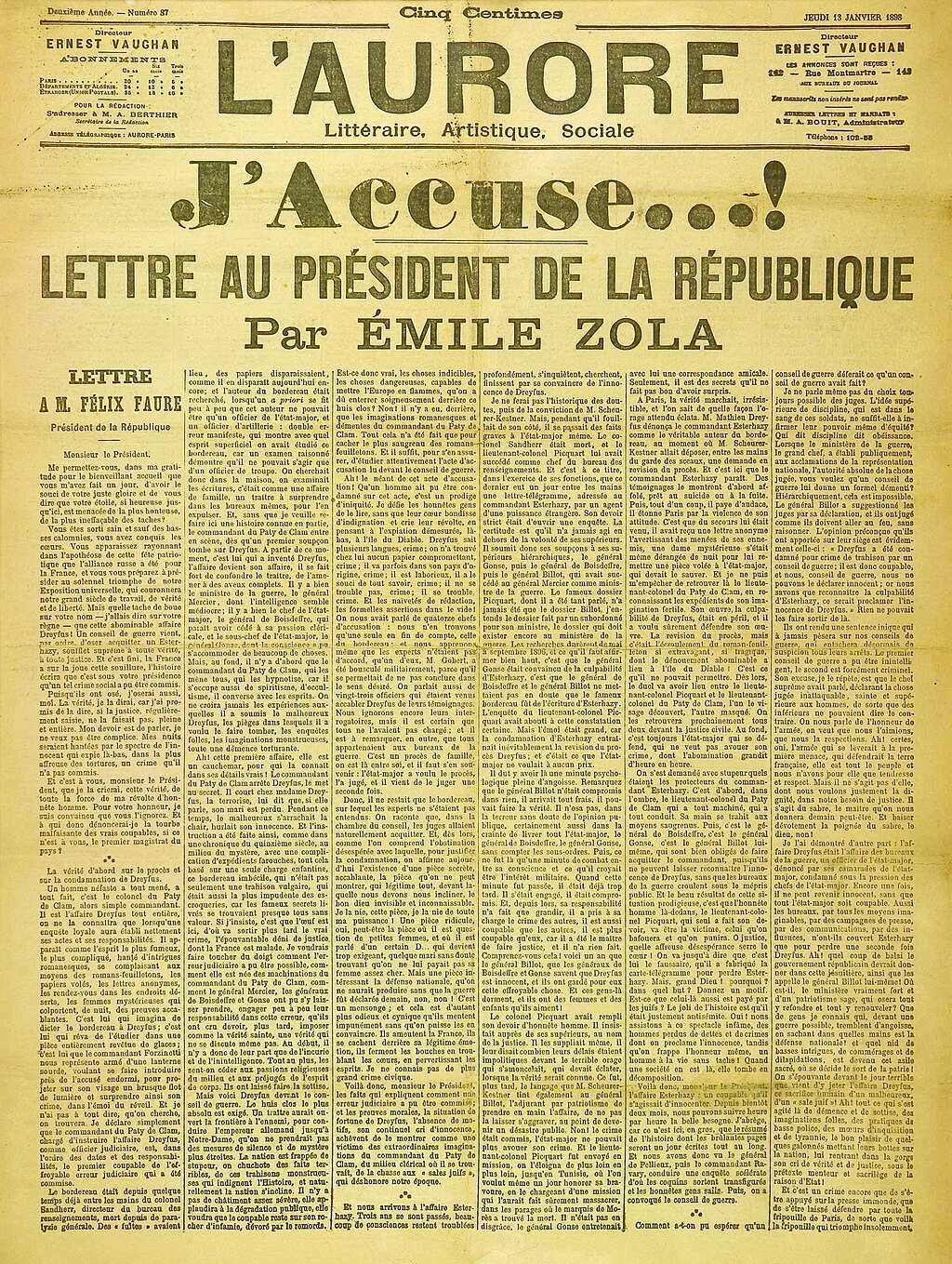

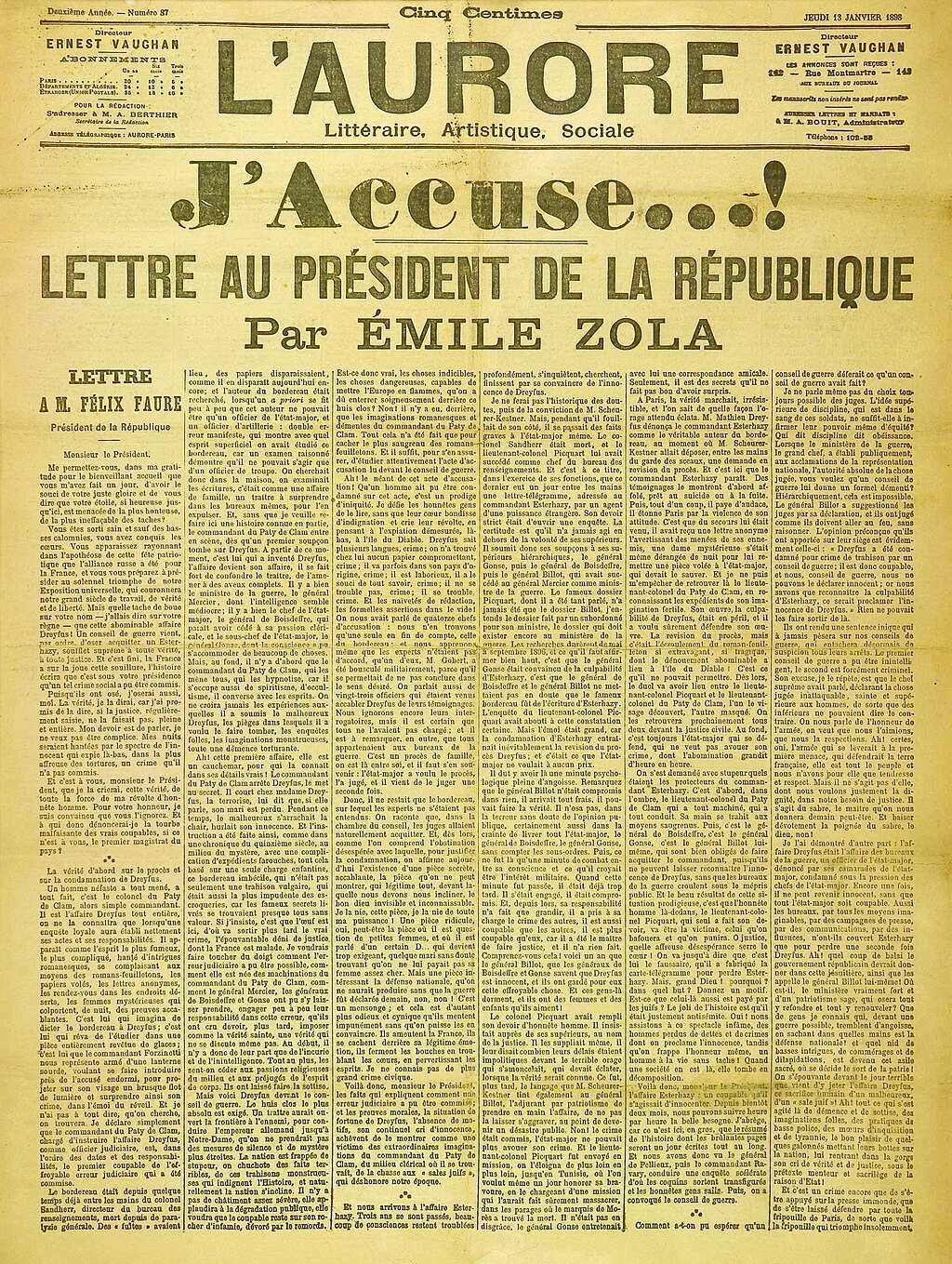

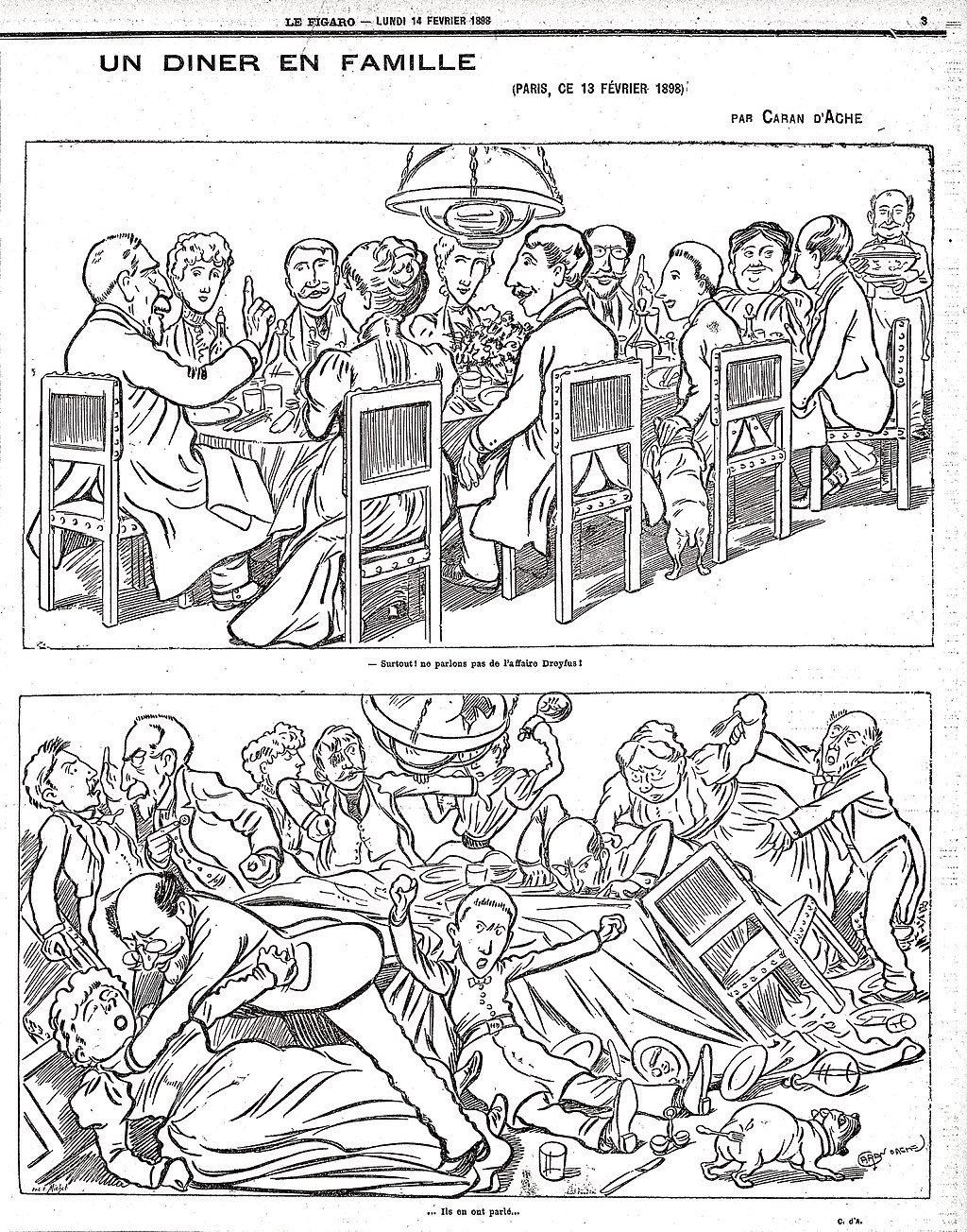

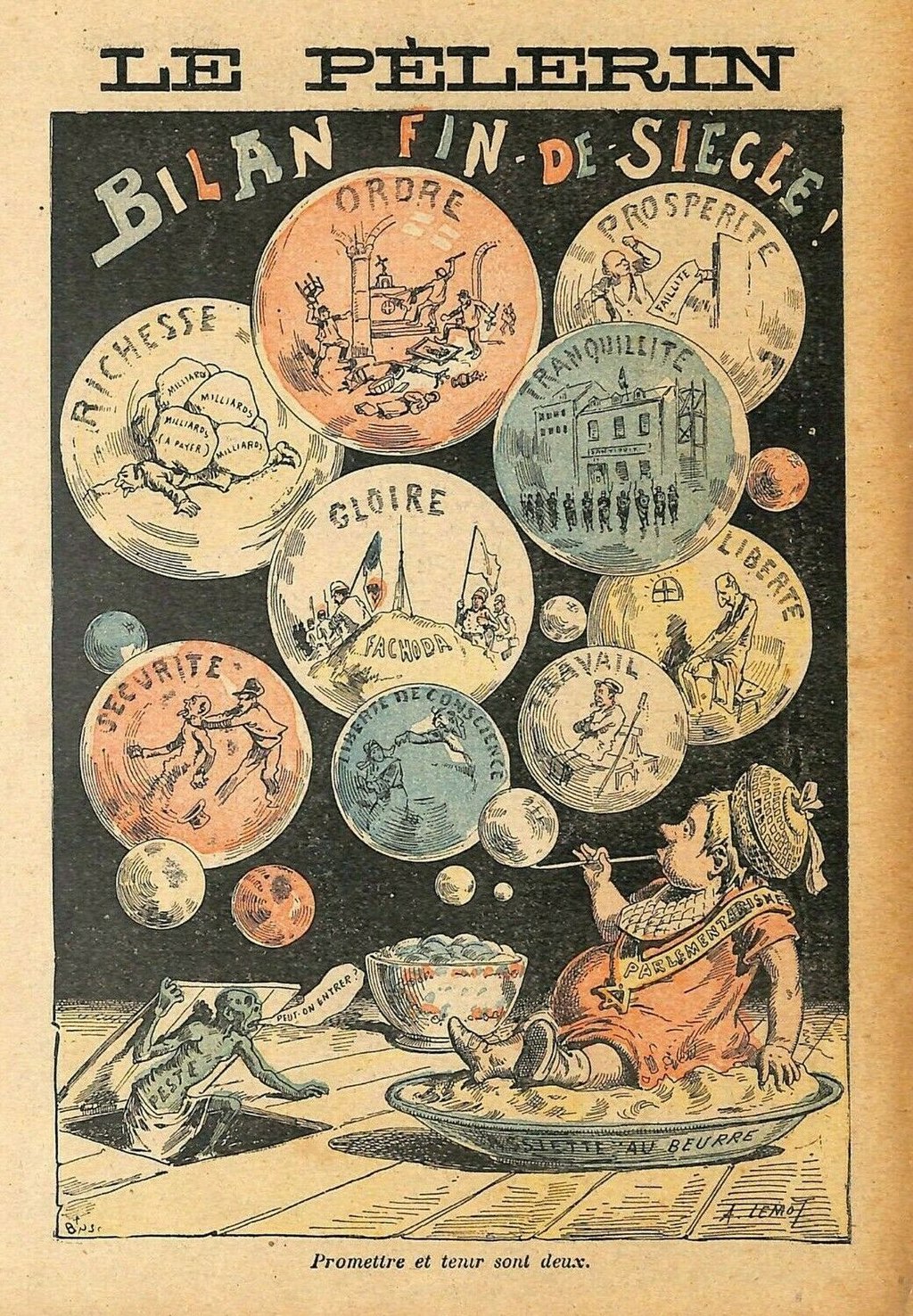

1898 「1月13日号の新聞「オー ロール(フランス語版、英語版)」紙は、一面に「私は弾劾する」(フランス語: J'accuse)という大見出しで、作家のエミール・ゾラによる大統領フェリックス・フォール宛ての公開質問状を掲載した。その中でゾラは、軍部を中心 とする不正と虚偽の数々を徹底的に糾弾した。」

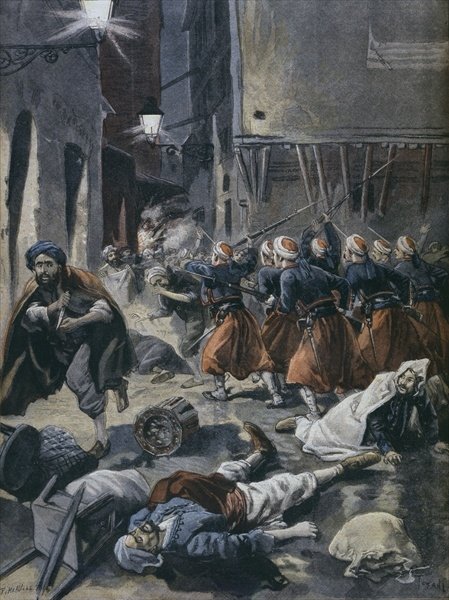

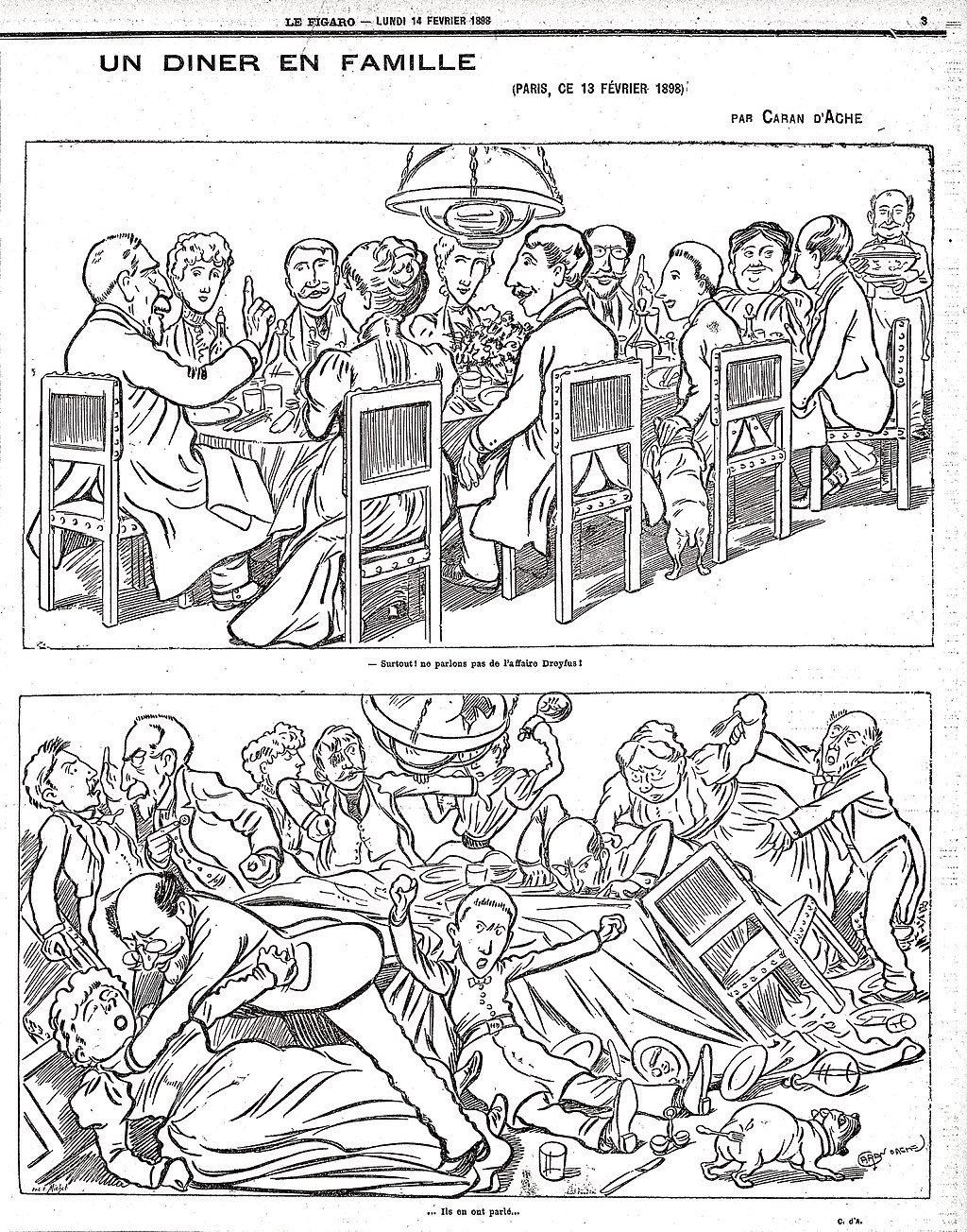

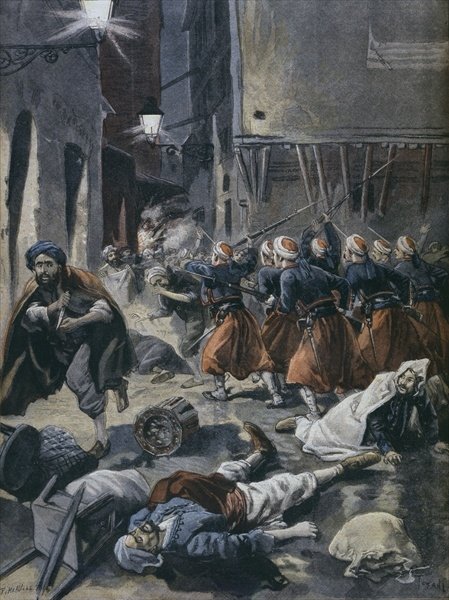

---- 「世論は沸騰し、それまで細々 と続けられてきたドレフュス支持の運動が一挙に盛り上る一方、各地でユダヤ人迫害事件が頻発した。ゾラ も名誉毀損で告発されて有罪判決を受け、一時はイギリスへ亡命を余儀なくされた。ドレフュスらの再審を求める勢力はフランス人権同盟[3]を結成して、正 義と真理、自由と平等を唱え、軍国主義批判を展開した。反対派、反ドレフェス派はフランス祖国同盟を結成して国家の尊厳を力説」

---- 「こうして事態はドレフュス個 人の事件から、自由と民主主義・共和制擁護か否かの一大政治闘争の色彩を帯び始め、フランス世論を二分 して展開された。その後、ドレフュスの無実を明らかにする事件(彼の有罪の証拠となったものが、偽造されたものであることが判明)が続いたため、軍部は世 論に押されてやむなく再審軍法会議を開いた。しかし、ドレフュスの有罪は覆されなかった」

1906 「ドレフュスは時の首相により

特赦で釈放されたが、その後も無罪を主張し続け、1906年、ようやく無罪判決を勝ち取って名誉を回復

することとなった。ドレフュスを擁護した民主主義・共和制擁護派が、その後のフランス政治の主導権を握り、第三共和政はようやく相対的安定を確保すること

ができた。」

| The Dreyfus affair

(French: affaire Dreyfus, pronounced [afɛːʁ dʁɛfys]) was a political

scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its

resolution in 1906. The scandal began in December 1894 when Captain

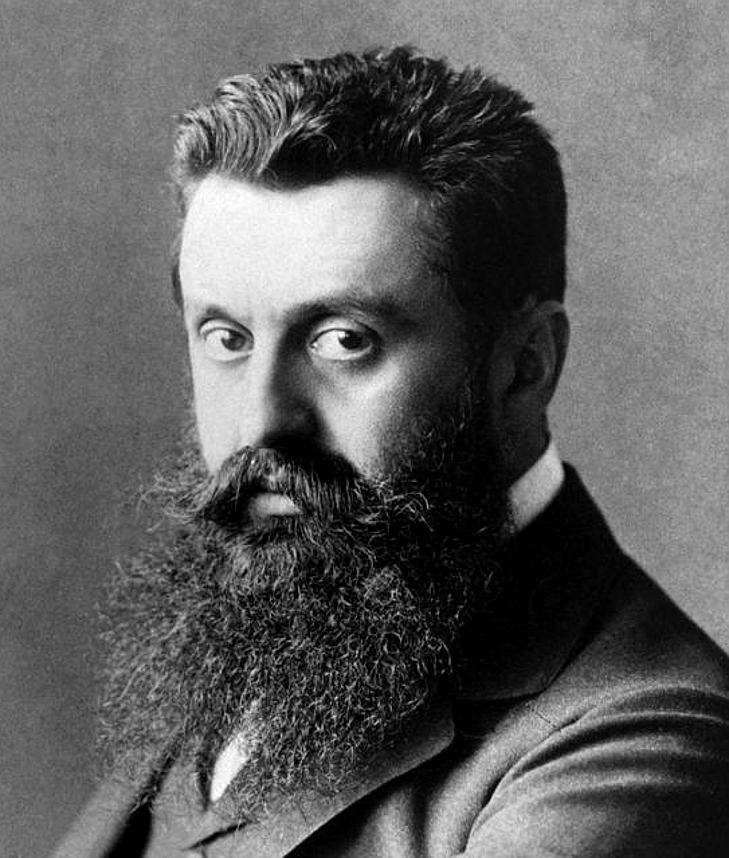

Alfred Dreyfus, a 35-year-old Alsatian French artillery officer of

Jewish descent, was wrongfully convicted of treason for communicating

French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris. He was

sentenced to life imprisonment and sent overseas to the penal colony on

Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent the following five

years imprisoned in very harsh conditions. In 1896, evidence came to light—primarily through the investigations of Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart, head of counter-espionage—which identified the real culprit as a French Army Major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. High-ranking military officials suppressed the new evidence, and a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy after a trial lasting only two days. The Army laid additional charges against Dreyfus, based on forged documents. Subsequently, writer Émile Zola's open letter J'Accuse...! in the newspaper L'Aurore stoked a growing movement of political support for Dreyfus, putting pressure on the government to reopen the case. In 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France for another trial. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus, the "Dreyfusards" such as Sarah Bernhardt, Anatole France, Charles Péguy, Henri Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau; and those who condemned him, the "anti-Dreyfusards" such as Édouard Drumont, the director and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence, but Dreyfus was pardoned and released. In 1906, Dreyfus was exonerated. After being reinstated as a major in the French Army, he served during the whole of World War I, ending his service with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He died in 1935. The Dreyfus affair came to symbolise modern injustice in the Francophone world;[1] it remains one of the most notable examples of a miscarriage of justice and of antisemitism. The affair divided France into pro-republican, anticlerical Dreyfusards and pro-Army, mostly Catholic anti-Dreyfusards, embittering French politics and encouraging radicalisation.[2] The press played a crucial role in exposing information and in shaping and expressing public opinion on both sides of the conflict. |

ドレフュス事件(仏: affaire Dreyfus、発音:

[afɛ

dʁʁ])は、1894年から1906年の解決まで、フランス第三共和政を二分した政治スキャンダルである。このスキャンダルは1894年12月、ユダヤ

系アルザス人のフランス人砲兵将校アルフレッド・ドレフュス大尉(35歳)が、パリのドイツ大使館にフランスの軍事機密を伝えたとして国家反逆罪で不当に

有罪判決を受けたことから始まった。彼は終身刑を宣告され、海外にあるフランス領ギアナの悪魔の島の流刑地に送られ、その後5年間、非常に過酷な環境で投

獄生活を送った。 1896年、主にスパイ対策責任者ジョルジュ・ピカール中佐の調査によって、真犯人がフェルディナン・ワルサン・エステルハージというフランス陸軍少佐で あることが判明した。軍高官たちはこの新証拠を封じ込め、軍法会議はわずか2日間の裁判の後、満場一致でエステルハージを無罪とした。陸軍は偽造文書に基 づき、ドレフュスに対してさらなる告発を行った。その後、作家エミール・ゾラが『オーロール』紙に発表した公開書簡「告発する...!」が、ドレフュスを 支持する政治的な動きを煽り、ドレフュスの裁判を再開するよう政府に圧力をかけた。 1899年、ドレフュスは再び裁判を受けるためにフランスに戻された。ドレフュスを支持するサラ・ベルナール、アナトール・フランス、シャルル・ペギー、 アンリ・ポアンカレ、ジョルジュ・クレマンソーなどの「ドレフュス派」と、ドレフュスを非難する、反ユダヤ主義的な新聞『ラ・リーブル・パロール』の発行 人であったエドゥアール・ドラモンなどの「反ドレフュス派」にフランス社会は二分された。新たな裁判の結果、ドレフュスは再び有罪判決を受け、10年の刑 期を言い渡されたが、赦免され釈放された。1906年、ドレフュスは釈放された。フランス陸軍少佐に復職したドレフュスは、第一次世界大戦の全期間に従軍 し、中佐の地位でその任務を終えた。1935年に死去した。 ドレフュス事件は、フランス語圏における現代の不公正を象徴する事件となった[1]。ドレフュス事件は、フランスを親共和主義的で反神権的なドレフュス派 と親陸軍的でほとんどがカトリックの反ドレフュス派に分裂させ、フランスの政治を混乱させ、急進化を促した[2]。報道機関は、情報を暴露し、対立する双 方の世論を形成し表現する上で重要な役割を果たした。 |

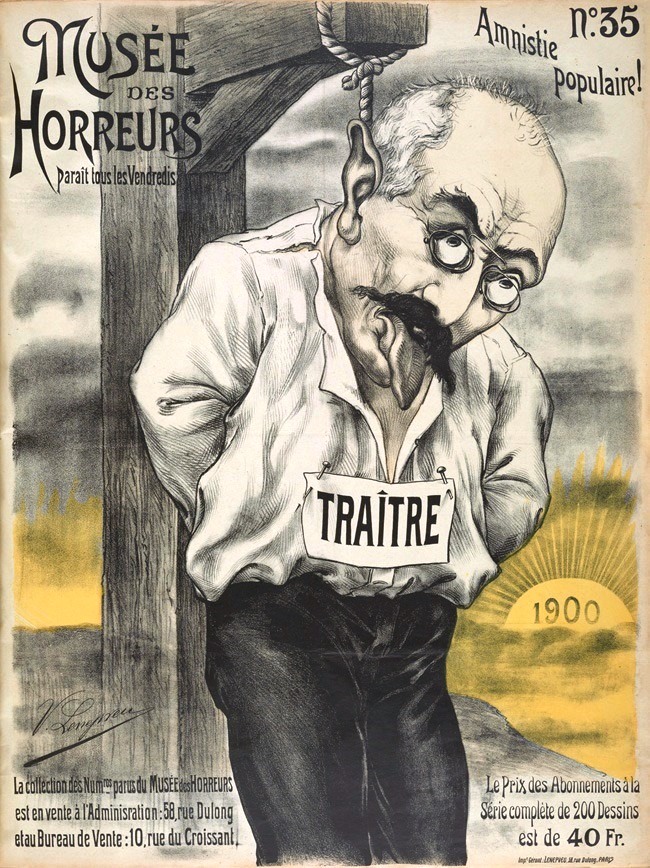

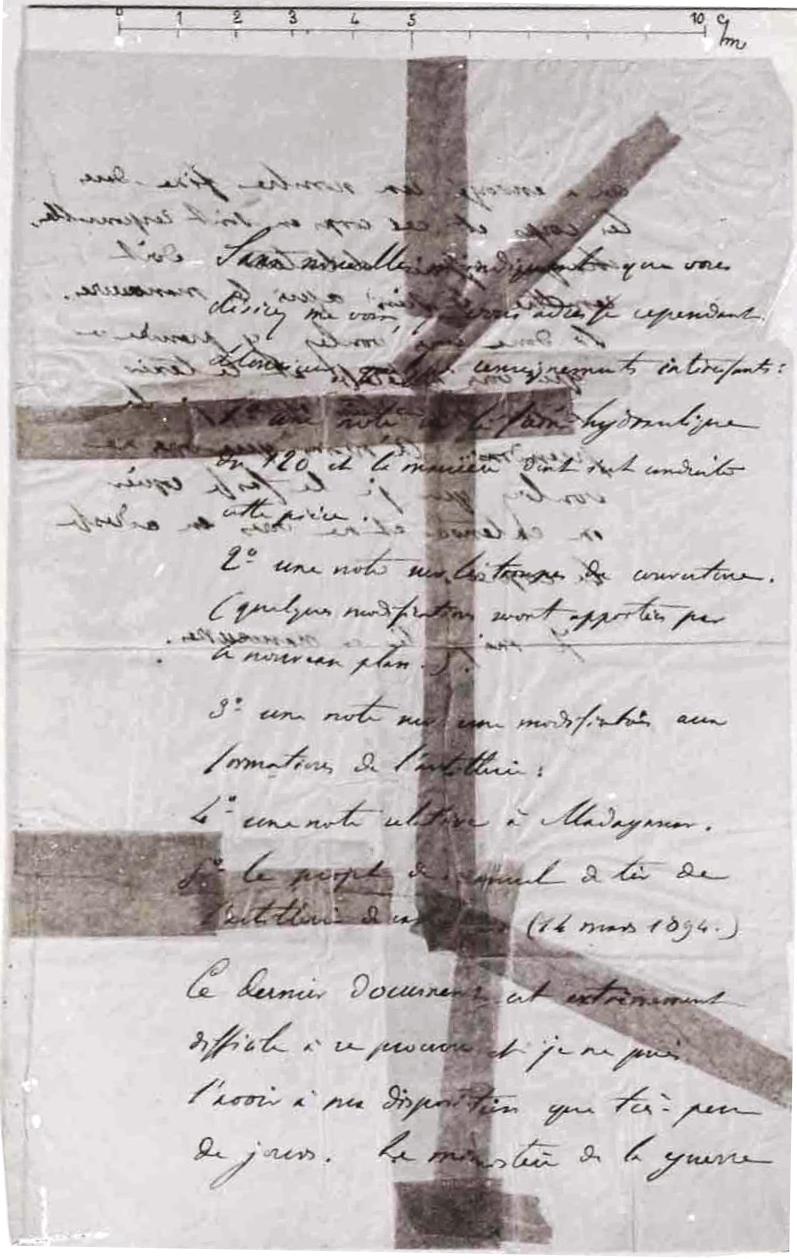

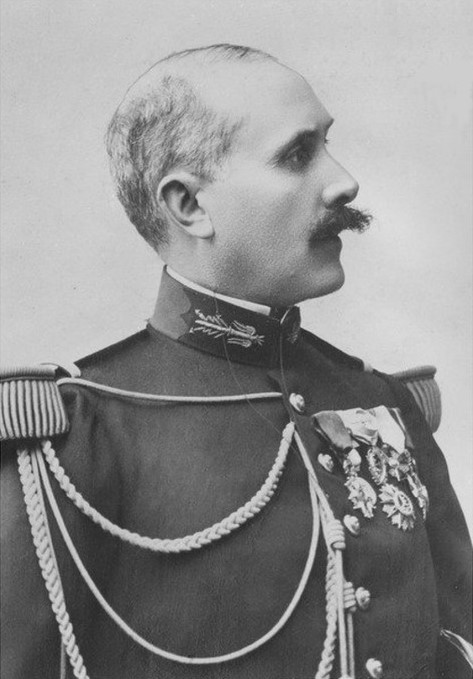

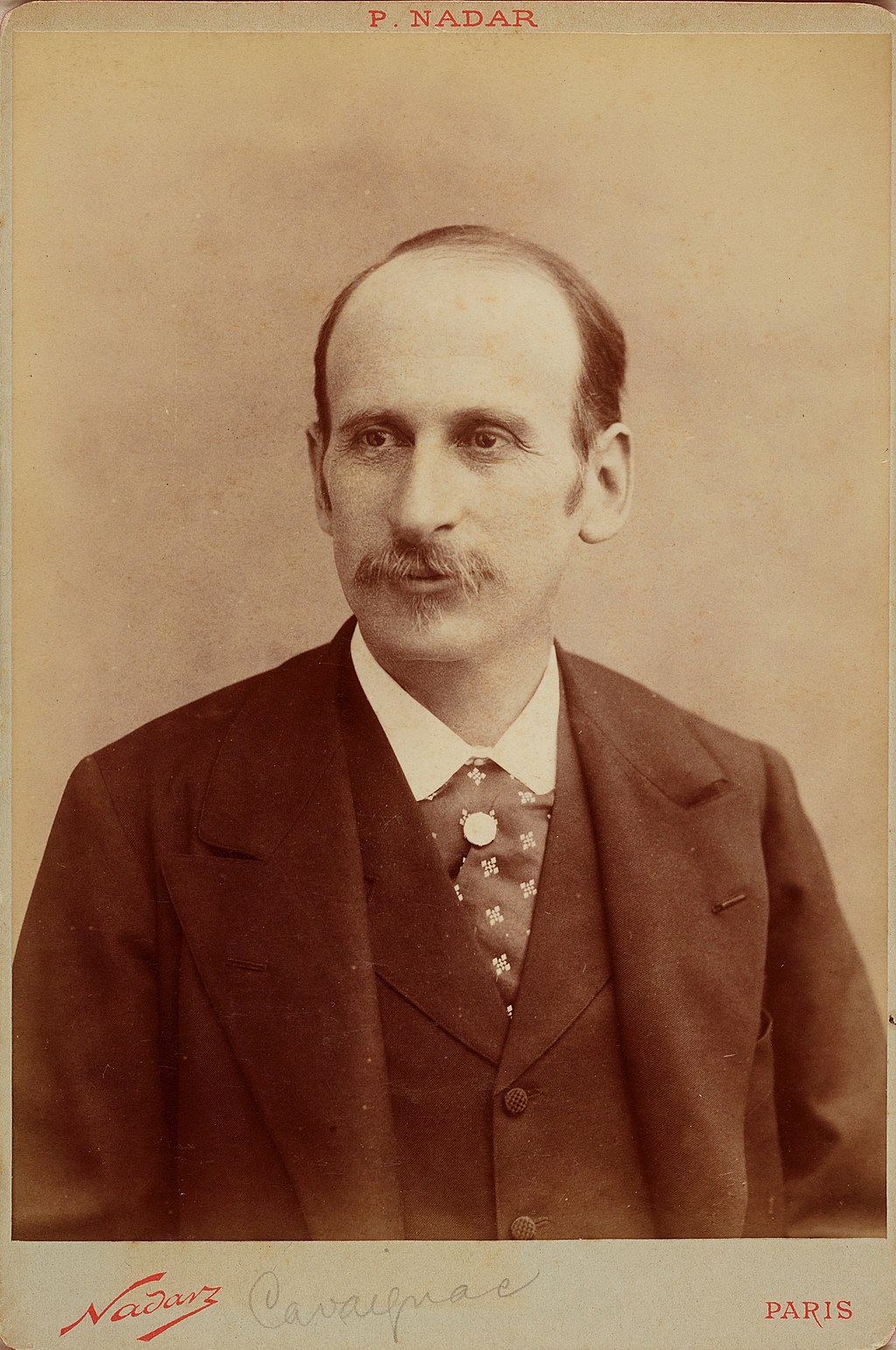

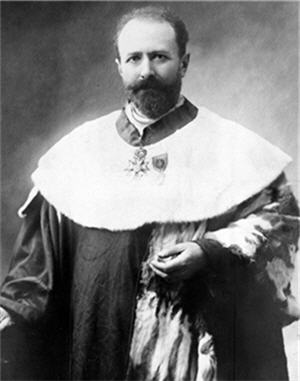

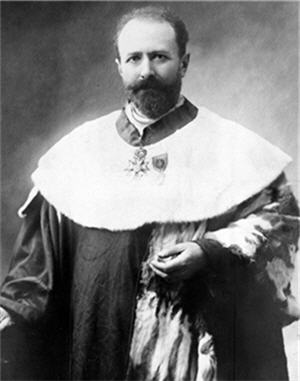

| Contexts Political In 1894, the Third Republic was twenty-four years old. Although the 16 May Crisis in 1877 had crippled the political influence of both the Bourbon and Orléanist royalists, its ministries continued to be short-lived as the country lurched from crisis to crisis: three years immediately preceding the Dreyfus affair were the near-coup of Georges Boulanger in 1889, the Panama scandals in 1892, and the anarchist threat (reduced by the "villainous laws" of July 1894). The elections of 1893 were focused on the "social question" and resulted in a Republican victory (just under half the seats) against the conservative right, and the reinforcement of the Radicals (about 150 seats) and Socialists (about 50 seats). The opposition of the Radicals and Socialists resulted in a centrist government with policies oriented towards economic protectionism, a certain indifference to social issues, a willingness to break international isolation, the Russian alliance, and development of the colonial empire. These centrist policies resulted in cabinet instability, with some Republican members of the government sometimes aligning with the radicals and some Orléanists aligning with the Legitimists in five successive governments from 1893 to 1896. This instability coincided with an equally unstable presidency: President Sadi Carnot was assassinated on 24 June 1894; his moderate successor Jean Casimir-Perier resigned several months later on 15 January 1895 and was replaced by Félix Faure. Following the failure of the radical government of Léon Bourgeois in 1896, the president appointed Jules Méline as prime minister. His government faced the opposition of the left and of some Republicans (including the Progressive Union) and made sure to keep the support of the right. He sought to appease religious, social, and economic tensions and conducted a fairly conservative policy. He succeeded in improving stability, and it was under this stable government that the Dreyfus affair occurred.[3] Military  General Raoul Le Mouton de Boisdeffre, architect of the military alliance with Russia The Dreyfus affair occurred in the context of German annexation of Alsace and Moselle, an event that fed the most extreme nationalism. The traumatic defeat of France in 1870 seemed far away, but a vengeful spirit remained. The military required considerable resources to prepare for the next conflict, and it was in this spirit that the Franco-Russian Alliance of 27 August 1892 was signed, although some opponents thought it "against nature".[Note 1] The army had recovered from the defeat, but many of its officers were aristocrats and monarchists. Cult of the flag and contempt for the parliamentary republic prevailed in the army.[4] The Republic celebrated its army; the army ignored the Republic. Over the previous ten years the army had undergone a significant shift resulting from its twofold aim to democratize and modernize. The graduates of the École Polytechnique now competed effectively with officers from the main career path of Saint-Cyr, which caused strife, bitterness, and jealousy among junior officers expecting promotions. The period was also marked by an arms race that primarily affected artillery. There were improvements in heavy artillery (guns of 120 mm and 155 mm, Models 1890 Baquet, new hydropneumatic brakes), but also, and especially, development of the ultra-secret 75mm gun.[5] The operation of military counterintelligence, alias the "Statistics Section" (SR), should be noted. Spying as a tool for secret war was a novelty as an organised activity by governments in the late 19th century. The Statistics Section was created in 1871 but consisted of only a handful of officers and civilians. Its head in 1894 was Lieutenant-Colonel Jean Sandherr, a graduate of Saint-Cyr, an Alsatian from Mulhouse, and a convinced antisemite. Its military mission was clear: to retrieve information about potential enemies of France and to feed them false information. The Statistics Section was supported by the "Secret Affairs" of the Quai d'Orsay at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was headed by a young diplomat, Maurice Paléologue. The arms race created an acute atmosphere of intrigue from 1890 in French counter-espionage. One of the missions of the section was to spy on the German Embassy at Rue de Lille in Paris to thwart any attempt by the French to transmit important information to the Germans. This was especially critical since several cases of espionage had already been featured in the headlines of newspapers, which were fond of sensationalism. In 1890, the archivist Boutonnet was convicted for selling plans of shells that used melinite.[6] The German military attaché in Paris in 1894 was Count Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, who developed a policy of infiltration that appears to have been effective. In the 1880s Schwartzkoppen had begun an affair with an Italian military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Count Alessandro Panizzardi.[7] While neither had anything to do with Dreyfus, their intimate and erotic correspondence (e.g. "Don't exhaust yourself with too much buggery."),[8] which was obtained by the authorities, lent an air of truth to other documents that were forged by prosecutors to lend retroactive credibility to Dreyfus's conviction as a spy. Some of these forgeries referred to the real affair between the two officers; in one, Alessandro supposedly informed his lover that if "Dreyfus is brought in for questioning", they must both claim that they "never had any dealings with that Jew. ... Clearly, no one can ever know what happened with him."[9] The letters, real and fake, provided a convenient excuse for placing the entire Dreyfus dossier under seal, given that exposure of the liaison would have 'dishonoured' Germany and Italy's military and compromised diplomatic relations. As homosexuality was, like Judaism, then often perceived as a sign of national degeneration, recent historians have suggested that combining them to inflate the scandal may have shaped the prosecution strategy.[10][11] Since early 1894, the Statistics Section had investigated traffic in master plans for Nice and the Meuse conducted by an officer whom the Germans and Italians nicknamed Dubois. This is what led to the origins of the Dreyfus affair. Social  No. 35 Amnistie populaire of the Musée des Horreurs depicts the hanged corpse of an antisemitic caricature of Alfred Dreyfus.[12] The social context was marked by the rise of nationalism and antisemitism. The growth of antisemitism, virulent since the publication of Jewish France by Édouard Drumont in 1886 (150,000 copies in the first year), went hand in hand with the rise of clericalism. Tensions were high in all strata of society, fueled by an influential press, which was virtually free to write and disseminate any information even if offensive or defamatory. Legal risks were limited if the target was a private person. Antisemitism did not spare the military, which practised hidden discrimination with the "cote d'amour" (a subjective assessment of personal acceptability) system of irrational grading, encountered by Dreyfus in his application to the Bourges School.[13] However, while prejudices of this nature undoubtedly existed within the confines of the General Staff, the French Army as a whole was relatively open to individual talent. At the time of the Dreyfus affair there were an estimated 300 Jewish officers in the army (about 3 per cent of the total), of whom ten were generals.[14] The popularity of the duel using sword or small pistol, sometimes causing death, bore witness to the tensions of the period. When a series of press articles in La Libre Parole[15] accused Jewish officers of "betraying their birth", the officers challenged the editors. Captain Crémieu-Foa, a Jewish Alsatian graduated from the Ecole Polytechnique, fought unsuccessfully against Drumont[16] and against M. de Lamase, who was the author of the articles. Captain Mayer, another Jewish officer, was killed by the Marquis de Morès, a friend of Drumont, in another duel. Hatred of Jews was now public and violent, driven by a firebrand (Drumont) who demonized the Jewish presence in France. Jews in metropolitan France in 1895 numbered about 80,000 (40,000 in Paris alone), who were highly integrated into society; an additional 45,000 Jews lived in Algeria. The launch of La Libre Parole with a circulation estimated at 200,000 copies in 1892,[17] allowed Drumont to expand his audience to a popular readership already enticed by the boulangiste adventure in the past. The antisemitism circulated by La Libre Parole, as well as by L'Éclair, Le Petit Journal, La Patrie, L'Intransigeant and La Croix, drew on antisemitic roots in certain Catholic circles.[18] Publications remarking on the Dreyfus affair often reinforced antisemitic sentiments, language and imagery. The Musée des Horreurs was a collection of anti-Dreyfus posters illustrated by Victor Lenepveu during the Dreyfus affair. Lenepveu caricatured "prominent Jews, Dreyfus supporters, and Republican statesman".[19] No. 35 Amnistie populaire depicts the corpse of Dreyfus himself as it dangles from a noose. Large noses, money, and Lenepveu's general tendency to illustrate subjects with bodies of animals likely contributed to the dissemination of antisemitism in French popular culture.[12] |

コンテクスト 政治 1894年、第三共和政は24歳になっていた。ドレフュス事件の直前の3年間は、1889年のジョルジュ・ブーランジェのクーデター寸前、1892年のパ ナマ疑獄、無政府主義の脅威(1894年7月の「悪法」によって減少)であった。1893年の選挙は「社会問題」に焦点が当てられ、保守右派に対する共和 党の勝利(半数弱の議席)、急進派(約150議席)と社会党(約50議席)の強化という結果となった。 急進派と社会党の反対により、経済保護主義、社会問題へのある種の無関心、国際的孤立の解消への意欲、ロシア同盟、植民地帝国の発展などを志向する中道派 政権が誕生した。こうした中道主義的な政策は内閣の不安定化を招き、1893年から1896年までの5回の連続政権では、共和党議員の一部が急進派と、オ ルレアン派の一部が正統派と手を組むこともあった。この不安定さは、同様に不安定な大統領職と重なった: サディ・カルノ大統領は1894年6月24日に暗殺され、穏健派の後継者ジャン・カシミール=ペリエは数ヵ月後の1895年1月15日に辞任し、フェリッ クス・フォールが後任となった。 1896年に急進派のレオン・ブルジョワ政権が失敗すると、大統領はジュール・メリーヌを首相に任命した。彼の政権は、左派と一部の共和党(進歩同盟を含 む)の反対に直面し、右派の支持を維持することに努めた。彼は宗教的、社会的、経済的緊張を和らげようと努め、かなり保守的な政策をとった。彼は安定を高 めることに成功し、この安定した政権の下でドレフュス事件が起こった[3]。 軍事  ロシアとの軍事同盟の立役者、ラウル・ル・ムートン・ド・ボワデフル将軍 ドレフュス事件は、ドイツによるアルザスとモーゼルの併合という、極端な国民主義を煽る出来事の中で起こった。1870年のフランス敗戦のトラウマははるか彼方にあるように思えたが、復讐心は残っていた。 軍部は次の紛争に備えるために多大な資源を必要とし、1892年8月27日の日露同盟はこの精神に基づいて調印されたが、「自然に反する」と考える反対派 もいた[注釈 1]。軍は敗戦から回復していたが、将校の多くは貴族や君主主義者だった。共和国は軍隊を称え、軍隊は共和国を無視した。 それまでの10年間で、軍隊は民主化と近代化という2つの目的から大きな変化を遂げた。エコール・ポリテクニークの卒業生たちは、サン・シルの主要なキャ リアパスから来た将校と効果的に競争するようになり、昇進を期待する下級将校たちの間に争い、恨み、嫉妬を引き起こした。この時期は、主に砲兵に影響を与 えた軍拡競争も顕著であった。重砲の改良(120ミリ砲と155ミリ砲、1890年型バケ、新型水空圧式ブレーキ)だけでなく、特に超極秘の75ミリ砲の 開発も行われた[5]。 軍事防諜、別名「統計課」(SR)の活動にも注目すべきである。秘密戦争の道具としてのスパイ活動は、19世紀後半には政府による組織的な活動としては目 新しいものであった。統計課は1871年に創設されたが、ほんの一握りの将校と民間人で構成されていた。1894年当時の責任者はジャン・サンヘル中佐 で、サン・シールを卒業し、ミュルーズ出身のアルザス人で、確信犯的な反ユダヤ主義者であった。その軍事的使命は明確であった。フランスの潜在的な敵に関 する情報を入手し、彼らに偽の情報を流すことであった。統計課は、若い外交官モーリス・パレオログが責任者を務める外務省オルセー研究所の「秘密部」に支 えられていた。 軍拡競争は、1890年以降、フランスの対スパイ活動における熾烈な陰謀の雰囲気を生み出した。この課の任務のひとつは、パリのリール通りにあるドイツ大 使館をスパイして、フランスがドイツに重要な情報を伝えようとする企てを阻止することだった。センセーショナリズムを好む新聞の見出しには、すでにいくつ かのスパイ事件が取り上げられていたため、これは特に重要な任務であった。1890年には、メリナイトを使用した砲弾の設計図を販売した罪で、記録係のブ トネが有罪判決を受けた[6]。 1894年にパリに駐在したドイツ軍のアタッシェはマクシミリアン・フォン・シュバルツコッペン伯爵であり、彼は効果的であったと思われる潜入政策を展開 した。1880年代、シュバルツコッペンはイタリア軍アタッシェのアレッサンドロ・パニツァルディ伯爵中佐と関係を持ち始めていた[7]。どちらもドレ フュスとは何の関係もなかったが、当局が入手した二人の親密でエロティックな書簡(例えば、「あまり盗撮で疲弊するなよ」[8])は、ドレフュスのスパイ としての有罪判決に遡及的な信憑性を持たせるために検察が偽造した他の文書に真実味を与えていた。アレッサンドロは恋人に、「ドレフュスが尋問のために連 行されたら」、二人とも「あのユダヤ人とは何の関係もない」と主張しなければならないと告げたとされる。明らかに、彼と何があったのか、誰も知ることはで きない」[9]。 この手紙は本物であろうと偽物であろうと、ドレフュスとの関係を暴露すればドイツとイタリアの軍部の「名誉を傷つけ」、外交関係を危うくすることになるた め、ドレフュス文書全体を封印するための都合のよい口実となった。当時、同性愛はユダヤ教と同様、しばしば国民的堕落の兆候として認識されていたため、最 近の歴史家は、スキャンダルを煽るために両者を組み合わせたことが起訴戦略を形成した可能性があると指摘している[10][11]。 1894年初頭から、統計課は、ドイツ人とイタリア人がデュボワとあだ名した将校が行ったニースとムーズ川のマスタープランの交通量を調査していた。これがドレフュス事件の発端となった。 社会  ホレール美術館のNo.35 Amnistie populaireには、反ユダヤ風刺画のアルフレッド・ドレフュスの絞首刑死体が描かれている[12]。 社会的背景には、ナショナリズムと反ユダヤ主義の台頭があった。1886年にエドゥアール・ドリュモンが『ユダヤ人のフランス』を出版して以来、反ユダヤ 主義は猛威を振るい(最初の年に15万部)、聖職者主義の台頭と密接に関係していた。社会のあらゆる階層で緊張が高まり、影響力のある報道機関がそれに拍 車をかけ、たとえ攻撃的で中傷的であっても、どんな情報でも事実上自由に書き、広めることができた。標的が個人であれば、法的リスクは限られていた。 ドレフュスがブールジュ学校を受験した際に遭遇した「コート・ダムール」(個人的な可否の主観的評価)という不合理な等級制度によって、隠れた差別が行わ れていたのである。ドレフュス事件当時、陸軍には推定300人(全体の約3パーセント)のユダヤ人将校がおり、そのうち10人が将官であった[14]。 剣や小型のピストルを使った決闘の人気は、時には死を招くこともあり、当時の緊張を物語っていた。La Libre Parole』[15]に掲載された一連の記事がユダヤ人将校を「自分たちの出生を裏切っている」と非難したとき、将校たちは編集者に異議を申し立てた。 エコール・ポリテクニークを卒業したユダヤ系アルザス人のクレミュー=フォア大尉は、ドラモン[16]および記事の著者であるド・ラマセM.と争って失敗 した。もう一人のユダヤ人将校メイヤー大尉は、ドラモンの友人であったモレス侯爵に決闘で殺された。 フランスにおけるユダヤ人の存在を悪者扱いする火付け役(ドラモン)によって、ユダヤ人に対する憎悪は今や公然かつ暴力的になっていた。1895年当時、 フランス首都圏のユダヤ人は約8万人(パリだけで4万人)で、高度に社会に溶け込んでおり、さらに4万5千人のユダヤ人がアルジェリアに住んでいた。 1892年に発行部数20万部と推定される『La Libre Parole』[17]が創刊されたことで、ドラモンは、過去にすでにブーランジェの冒険に魅了されていた大衆読者に読者を広げることができた。ラ・リー ブル・パロール』や『レクレール』、『ル・プティ・ジャーナル』、『ラ・パトリエ』、『ラントランシジャン』、『ラ・クロワ』によって流布された反ユダヤ 主義は、ある種のカトリック界における反ユダヤ主義の根源を引くものであった[18]。 ドレフュス事件に言及した出版物は、しばしば反ユダヤ的な感情、言葉、イメージを強化した。Musée des Horreurs』は、ドレフュス事件の最中にヴィクトール・ルヌプーヴーが描いた反ドレフュスポスターのコレクションであった。ルネプーヴーは「著名な ユダヤ人、ドレフュス支持者、共和党の政治家」を風刺画で描いた[19]。No.35 Amnistie populaireには、ドレフュス自身の死体が縄で吊るされている様子が描かれている。大きな鼻、金銭、動物の死体を題材にしたルネプヴーの一般的な傾 向は、フランスの大衆文化における反ユダヤ主義の普及に貢献したと思われる[12]。 |

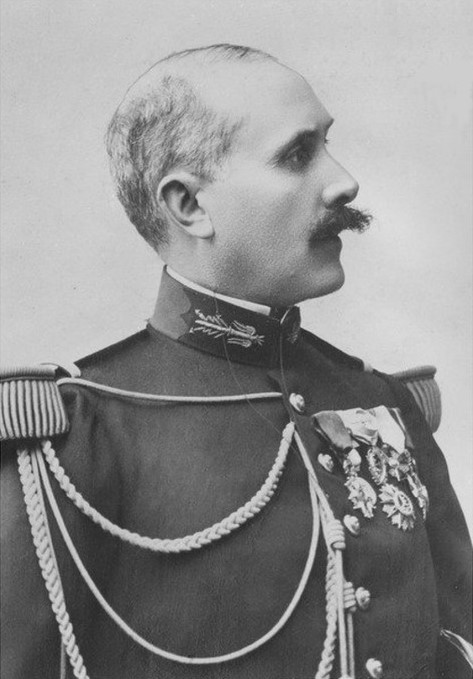

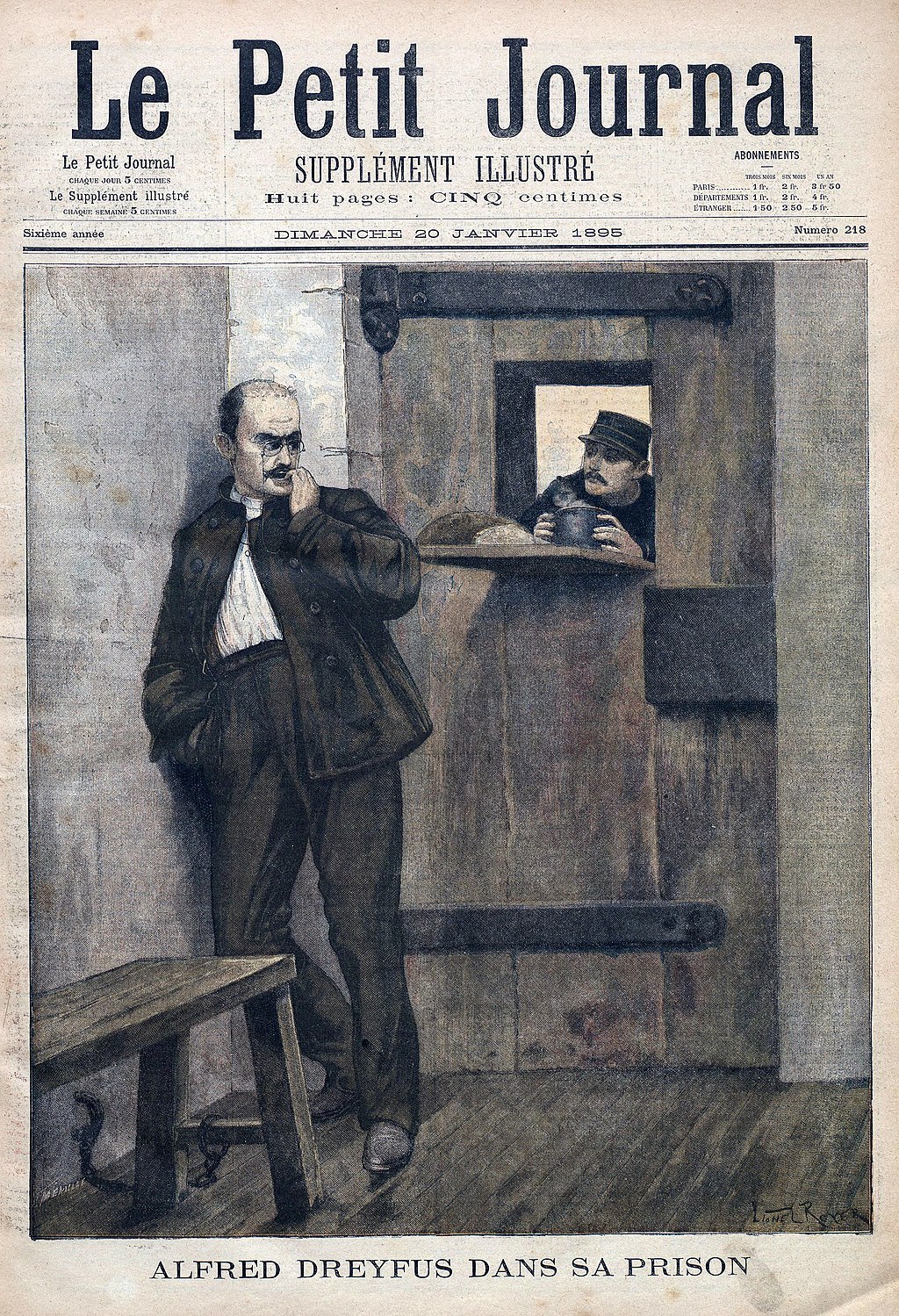

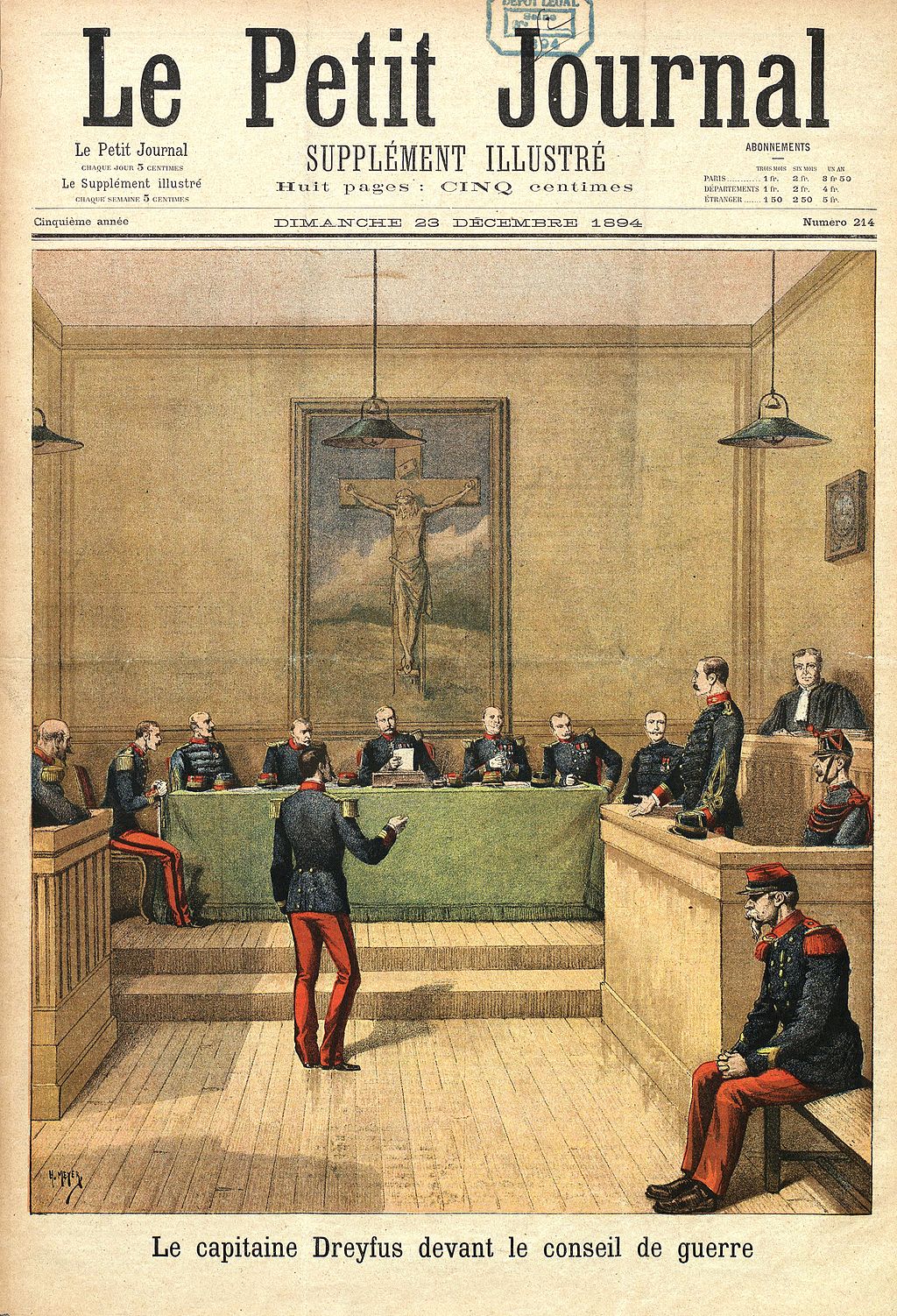

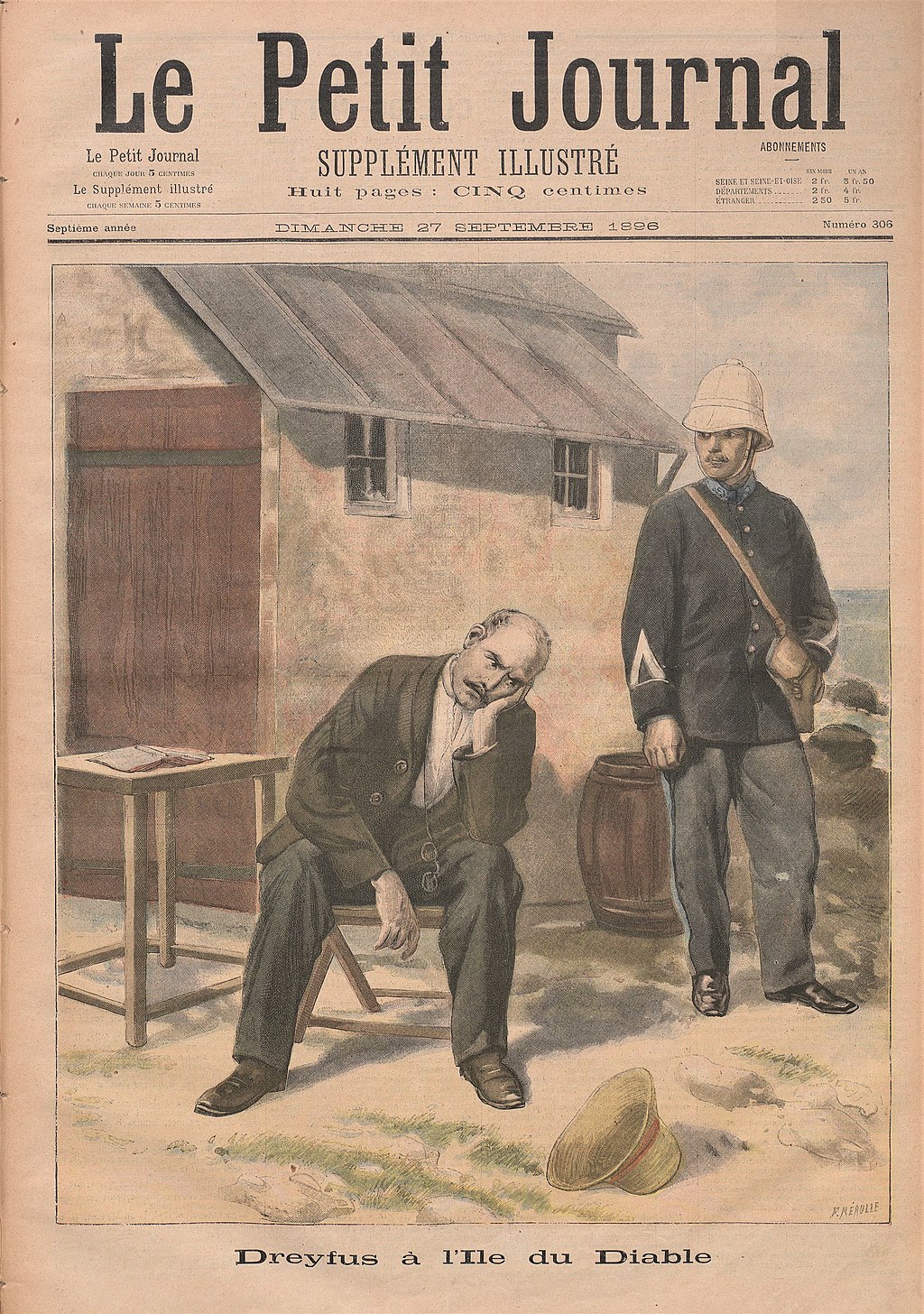

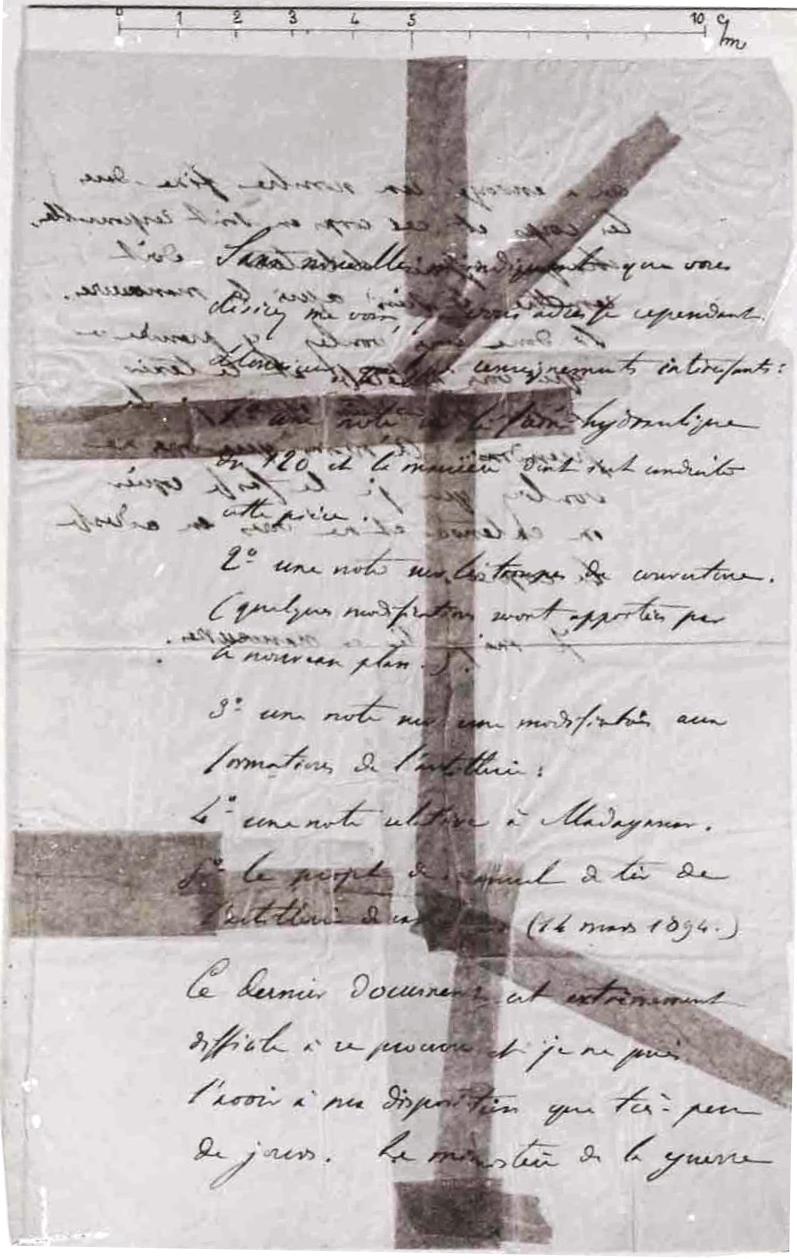

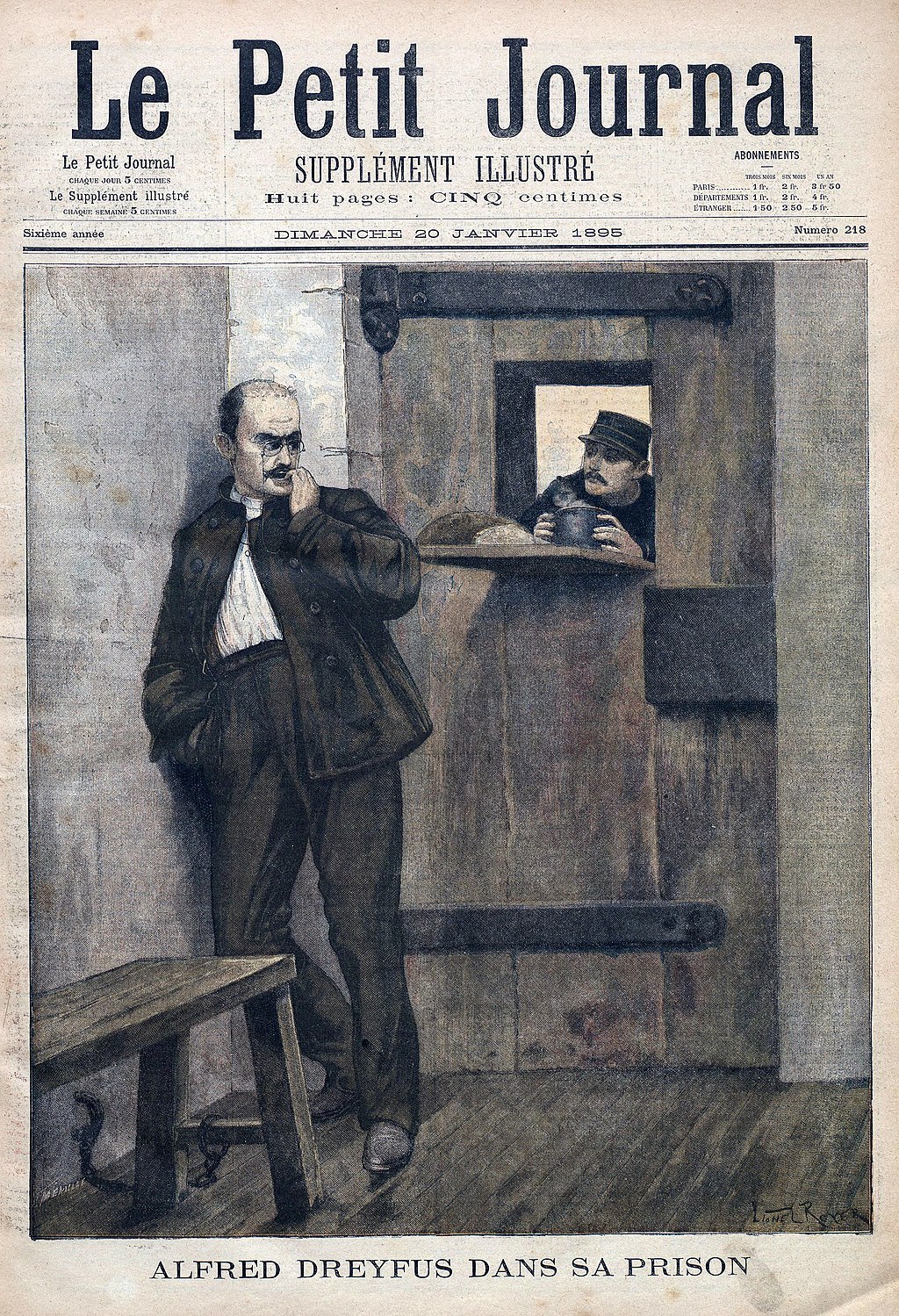

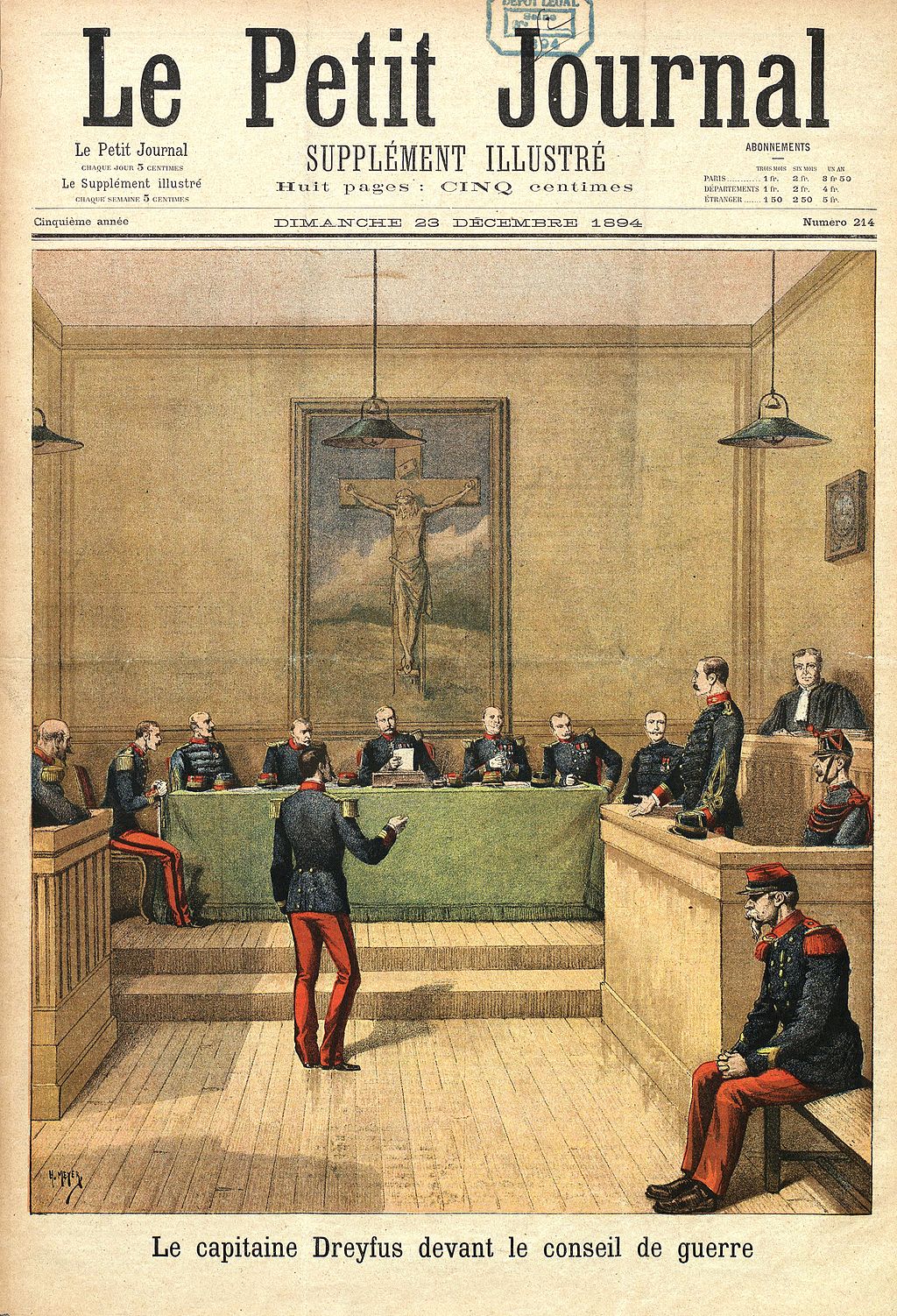

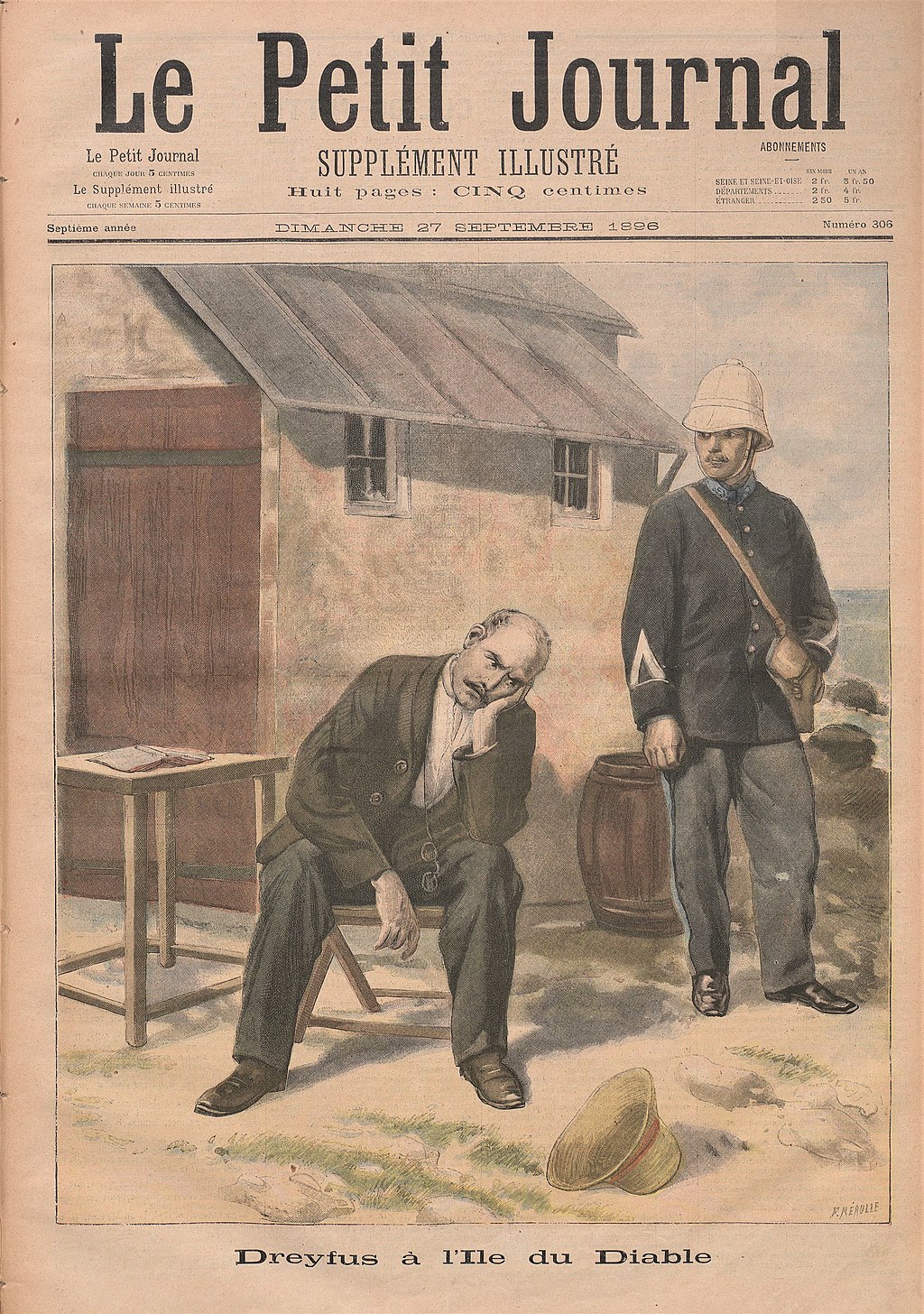

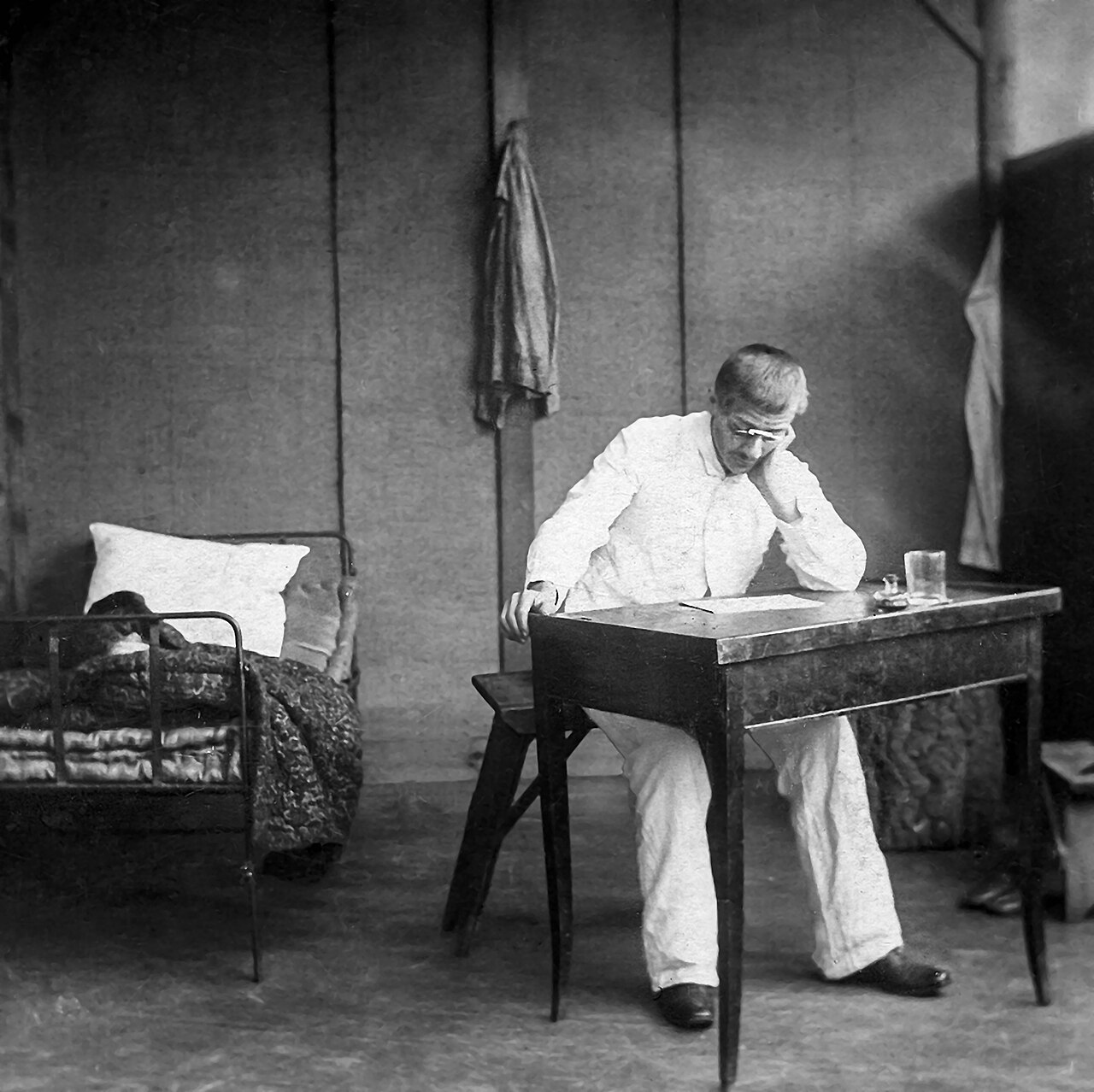

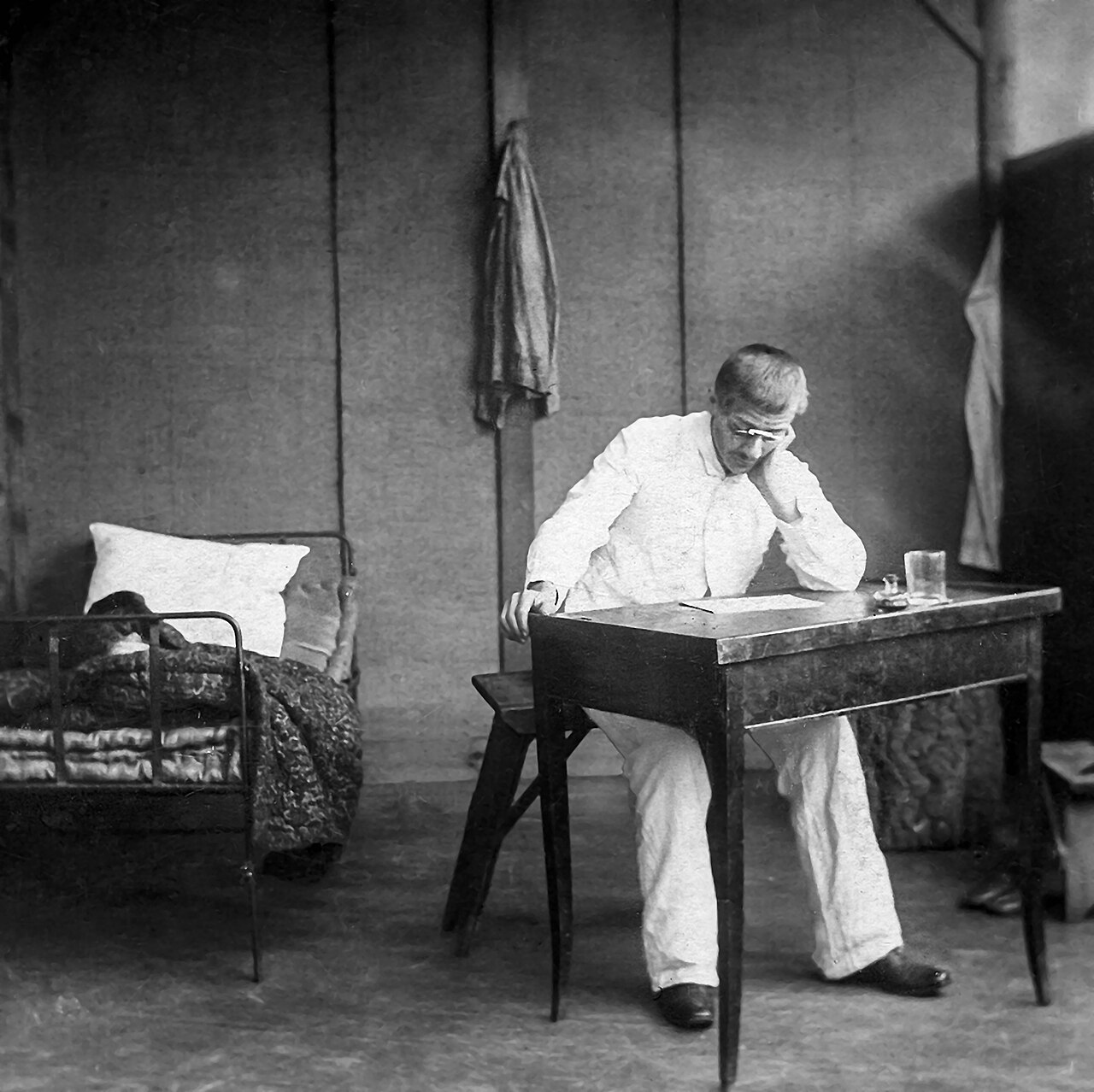

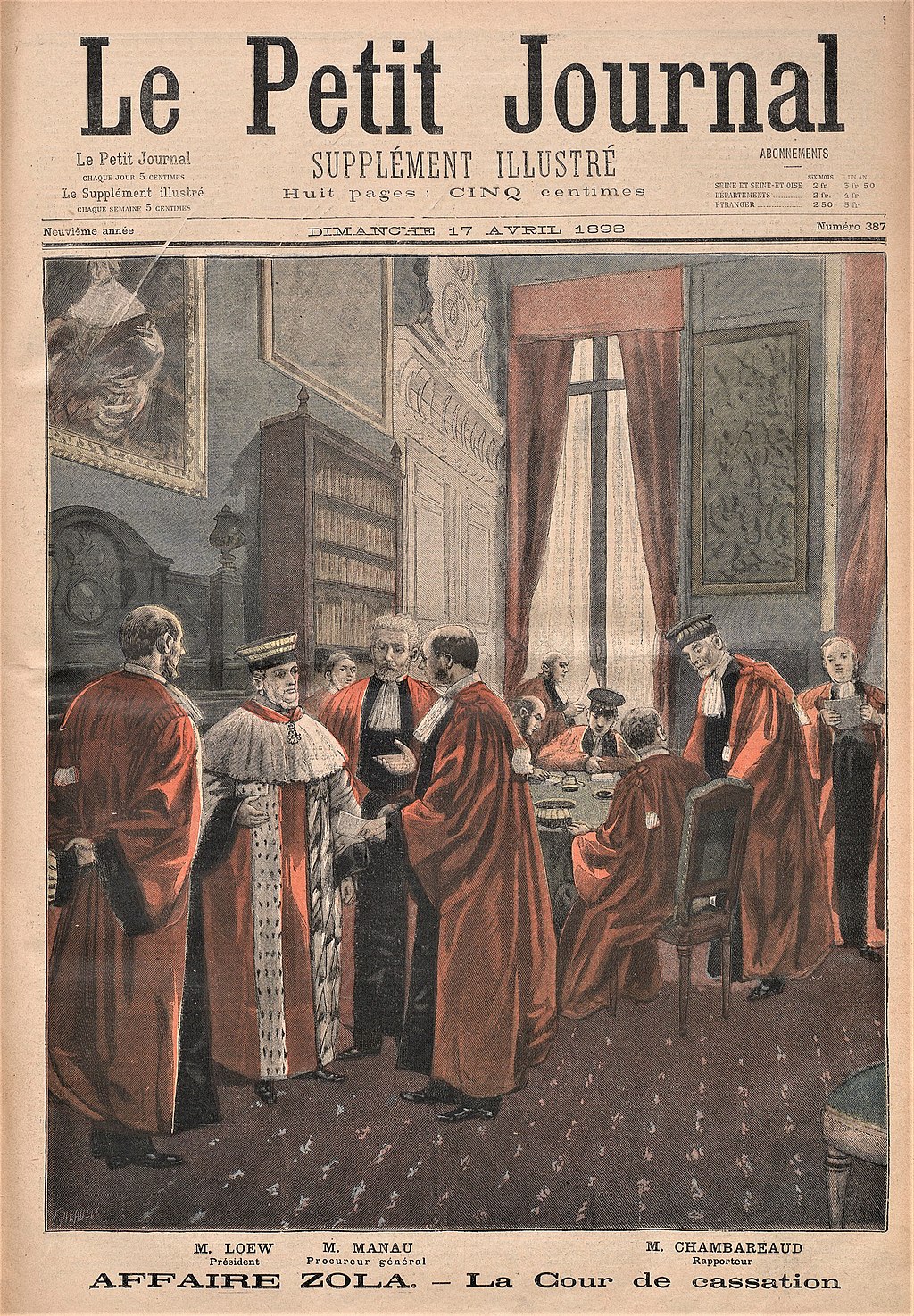

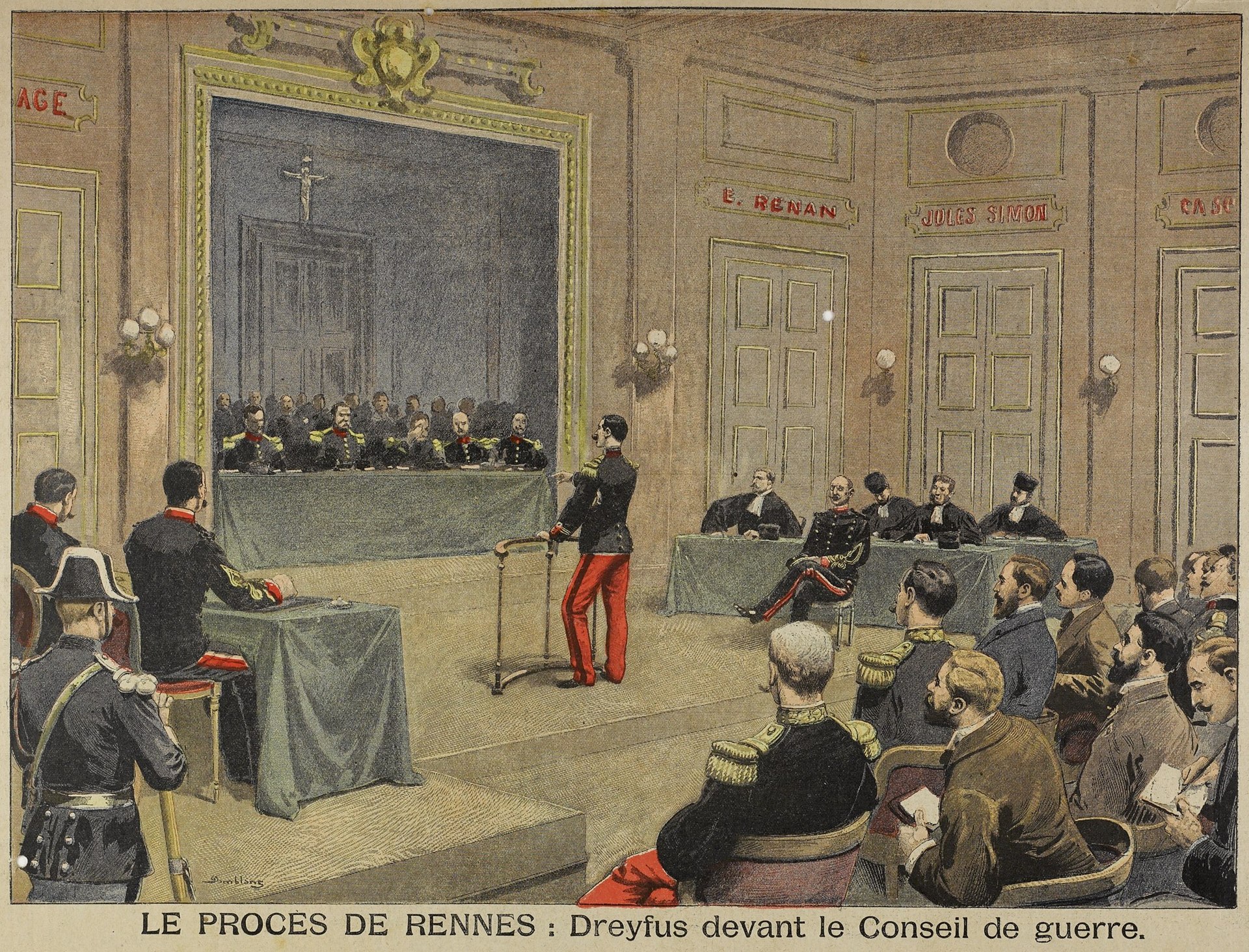

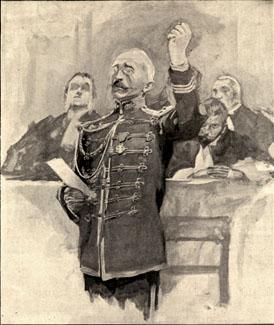

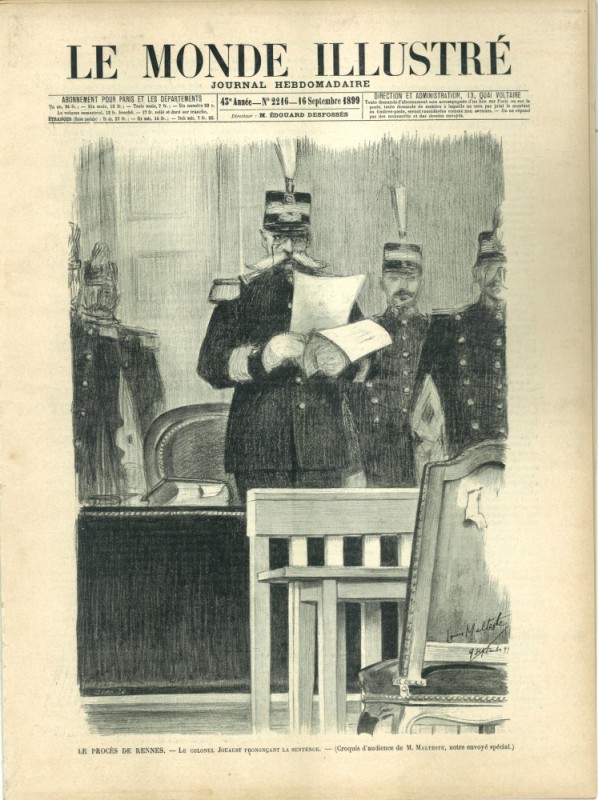

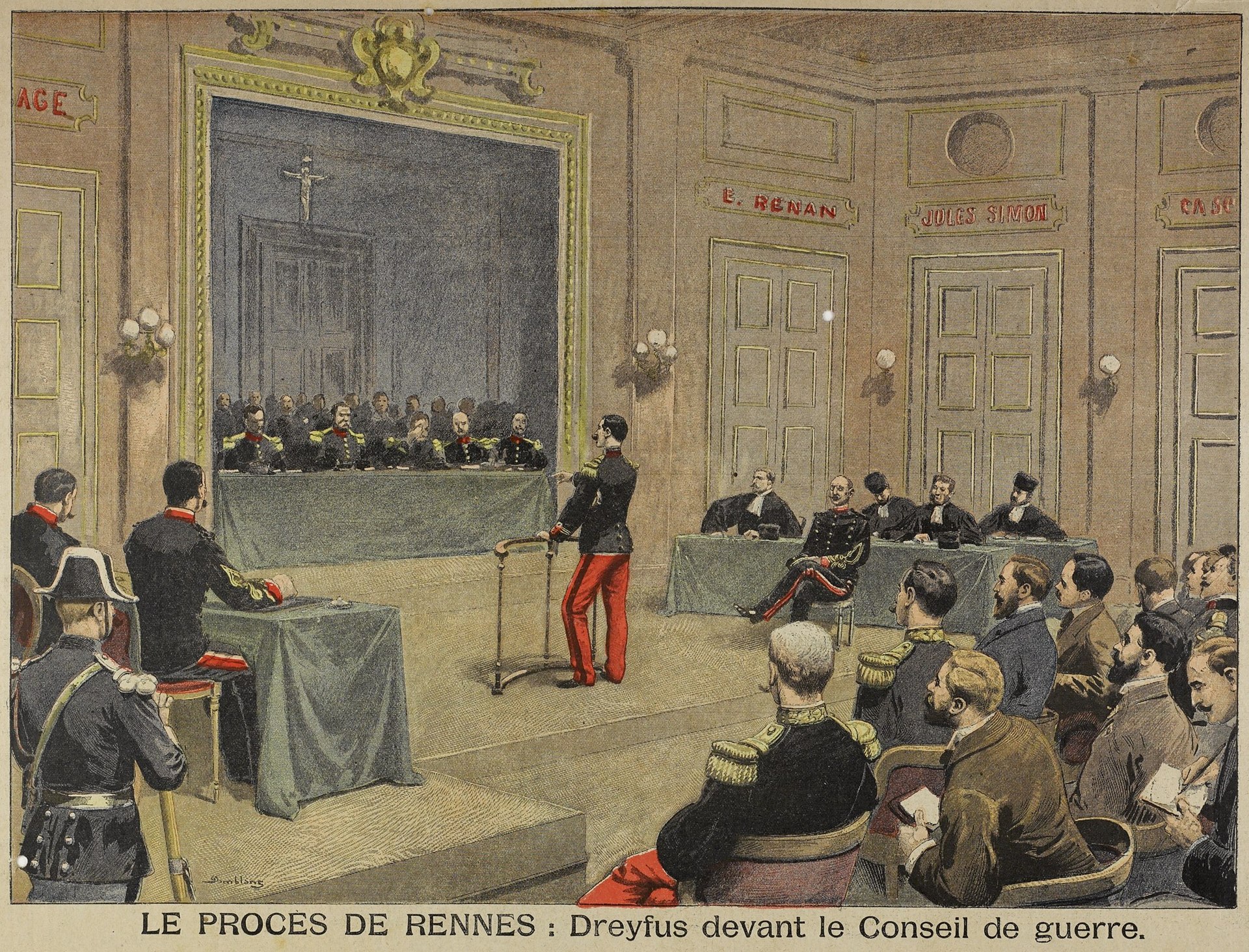

| Origins of the case and the trial of 1894 Main article: Investigation and arrest of Alfred Dreyfus  Photograph of the bordereau dated 13 October 1894. The original disappeared in 1940. Discovery of the "bordereau" The staff of the Military Intelligence Service (SR) worked around the clock[20] to spy on the German Embassy in Paris. They had managed to get a French housekeeper named "Madame Bastian" hired to work in the building and spy on the Germans. In September 1894, she found a torn-up note[21] which she handed over to her employers at the Military Intelligence Service. This note later became known as "the bordereau".[Note 2] This piece of paper, torn into six large pieces,[22] unsigned and undated, was addressed to the German military attaché stationed at the German Embassy, Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen. It stated that confidential French military documents regarding the newly developed "hydraulic brake of 120, and the way this gun has worked"[23][24] were about to be sent to a foreign power. The search for the author of the bordereau  General Auguste Mercier, Minister of War in 1894 This catch seemed of sufficient importance for the head of the "Statistical Section",[25] the Mulhousian[26] Jean Sandherr, to inform the Minister of War, General Auguste Mercier. In fact the SR suspected that there had been leaks since the beginning of 1894 and had been trying to find the perpetrator. The minister had been harshly attacked in the press for his actions, which were deemed incompetent,[27] and appears to have sought an opportunity to enhance his image.[28][29] He immediately initiated two secret investigations, one administrative and one judicial. To find the culprit, using simple though crude reasoning,[30] the circle of the search was arbitrarily restricted to suspects posted to, or former employees of, the General Staff – necessarily a trainee artillery[Note 3] officer.[Note 4] The ideal culprit was identified: Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a graduate of the École polytechnique and an artillery officer, of the Jewish faith and of Alsatian origin, coming from the republican meritocracy.[31] At the beginning of the case, the emphasis was rather on the Alsatian origins of Dreyfus than on his religion. These origins were not, however, exceptional because these officers were favoured by France for their knowledge of the German language and culture.[32][33] There was also antisemitism in the offices of the General Staff,[34] and it fast became central to the affair by filling in the credibility gaps in the preliminary enquiry.[30] In particular, Dreyfus was at that time the only Jewish officer to be recently passed by the General Staff. In fact, the reputation[35] of Dreyfus as a cold and withdrawn or even haughty character, as well as his "curiosity", worked strongly against him. These traits of character, some false, others natural, made the charges plausible by turning the most ordinary acts of everyday life in the ministry into proof of espionage. From the beginning a biased and one-sided multiplication of errors led the State to a false position. This was present throughout the affair, where irrationality prevailed over the positivism in vogue in that period:[36] From this first hour the phenomenon occurred that will dominate the whole affair. It is no longer controlled by facts and circumstances carefully examined which will constitute a belief; it is the irresistible cavalier conviction which distorts the facts and beliefs. — Joseph Reinach Expertise in writing  Major du Paty de Clam, head of investigation, arrested Captain Dreyfus. To condemn Dreyfus, the writing on the bordereau had to be compared to that of the Captain. There was nobody competent to analyse the writing on the General Staff.[37] Then Major du Paty de Clam[38][39] entered the scene: an eccentric man who prided himself on being an expert in graphology. On being shown some letters by Dreyfus and the bordereau on 5 October, du Paty concluded immediately who had written the two writings. After a day of additional work he provided a report that, despite some differences, the similarities were sufficient to warrant an investigation. Dreyfus was therefore "the probable author" of the bordereau in the eyes of the General Staff.[40]  Alphonse Bertillon was not a handwriting expert, but he invented the theory of "autoforgery". General Mercier believed he had the guilty party, but he exaggerated the value of the affair, which took on the status of an affair of state during the week preceding the arrest of Dreyfus. The Minister did consult and inform all the authorities of the State,[41] yet despite prudent counsel and courageous objections expressed by Gabriel Hanotaux in the Council of Ministers[42] he decided to pursue it.[43] Du Paty de Clam was appointed Judicial Police Officer to lead an official investigation. Meanwhile, several parallel sources of information were opening up, some on the personality of Dreyfus, others to ensure the truth of the identity of the author of the bordereau. The expert[Note 5] Gobert was not convinced and found many differences. He even wrote that "the nature of the writing on the bordereau excludes disguised handwriting".[44] Disappointed, Mercier then called in Alphonse Bertillon, the inventor of forensic anthropometry but no handwriting expert. He was initially no more positive than Gobert but he did not exclude the possibility of its being the writing of Dreyfus.[45] Later, under pressure from the military,[46] he argued that Dreyfus had autocopied it and developed his theory of "autoforgery". The arrest On 13 October 1894, without any tangible evidence and with an empty file, General Mercier summoned Captain Dreyfus for a general inspection in "bourgeois clothing", i.e. in civilian clothes. The purpose of the General Staff was to obtain the perfect proof under French law: a confession. That confession was to be obtained by surprise – by dictating a letter based on the bordereau[47][48] to reveal his guilt. On the morning of 15 October 1894, Captain Dreyfus underwent this ordeal but admitted nothing. Du Paty even tried to suggest suicide by placing a revolver in front of Dreyfus, but he refused to take his life, saying he "wanted to live to establish his innocence". The hopes of the military were crushed. Nevertheless Du Paty de Clam still arrested the captain,[49] accused him of conspiring with the enemy, and told him that he would be brought before a court-martial. Dreyfus was imprisoned at the Cherche-Midi prison in Paris.[50] The enquiry and the first military court  Cover of Le Petit Journal, 20 January 1895 (illustration by Fortuné Méaulle after Lionel Royer) Mrs. Dreyfus was informed of the arrest the same day by a police raid to search their apartment. She was terrorized by Du Paty, who ordered her to keep the arrest of her husband secret and even said, "One word, one single word and it will be a European war!"[51] Illegally,[52] Dreyfus was placed in solitary confinement in prison, where Du Paty interrogated him day and night in order to obtain a confession, which failed. The captain was morally supported by the first Dreyfusard, Major Forzinetti, commandant of the military prisons of Paris. On 29 October 1894, the affair was revealed in an article in La Libre Parole, the antisemitic newspaper owned by Édouard Drumont. This marked the beginning of a very brutal press campaign until the trial. This event put the affair in the field of antisemitism where it remained until its conclusion.[53] On 1 November 1894, Alfred's brother, Mathieu Dreyfus, became aware of the arrest after being called urgently to Paris. He became the architect of the arduous fight for the liberation of his brother.[54] Without hesitation, he began looking for a lawyer, and retained the distinguished criminal lawyer Edgar Demange.[55] The enquiry On 3 November 1894, General Saussier, the Military governor of Paris, reluctantly[56] gave the order for an enquiry. He had the power to stop the process but did not, perhaps because of an exaggerated confidence in military justice.[57] Major Besson d'Ormescheville, the recorder for the Military Court, wrote an indictment in which "moral elements" of the charge (which gossiped about the habits of Dreyfus and his alleged attendance at "gambling circles", his knowledge of German, and his "remarkable memory") were developed more extensively than the "material elements",[Note 6] which are rarely seen in the charge: "This is a proof of guilt because Dreyfus made everything disappear". The complete lack of neutrality of the indictment led to Émile Zola calling it a "monument of bias".[58] After the news broke on Dreyfus' arrest, many journalists flocked to the story and flooded the story with speculations and accusations. The renowned journalist and antisemitic agitator Edouard Drumont wrote in his publication on November 3, 1894, "What a terrible lesson, this disgraceful treason of the Jew Dreyfus." On 4 December 1894, Dreyfus was referred to the first Military Court with this dossier. The secrecy was lifted and Demange could access the file for the first time. After reading it the lawyer had absolute confidence, as he saw the emptiness of the prosecution's case.[59] The prosecution rested completely on the writing on a single piece of paper, the bordereau, on which experts disagreed, and on vague indirect testimonies. The trial: "Closed Court or War!"  From Le Petit Journal (23 December 1894) During the two months before the trial, the press went wild. La Libre Parole, L'Autorité, Le Journal, and Le Temps described the supposed life of Dreyfus through lies and bad fiction.[60] This was also an opportunity for extreme headlines from La Libre Parole and La Croix to justify their previous campaigns against the presence of Jews in the army on the theme "You have been told!"[61] This long delay above all enabled the General Staff to prepare public opinion and to put indirect pressure on the judges.[62] On 8 November 1894, General Mercier declared Dreyfus guilty in an interview with Le Figaro.[63] He repeated himself on 29 November 1894 in an article by Arthur Meyer in Le Gaulois, which in fact condemned the indictment against Dreyfus and asked, "How much freedom will the military court have to judge the defendant?"[64] The jousting of the columnists took place within a broader debate about the issue of a closed court. For Ranc and Cassagnac, who represented the majority of the press, the closed court was a low manoeuvre to enable the acquittal of Dreyfus, "because the minister is a coward". The proof was "that he grovels before the Prussians" by agreeing to publish the denials of the German ambassador in Paris.[65] In other newspapers, such as L'Éclair on 13 December 1894: "the closed court is necessary to avoid a casus belli"; while for Judet in Le Petit Journal of 18 December: "the closed court is our impregnable refuge against Germany"; or in La Croix the same day: it must be "the most absolute closed court".[66] The trial opened on 19 December 1894 at one o'clock[67] and a closed court was immediately pronounced. This closed court was not legally consistent since Major Picquart and Prefect Louis Lépine were present at certain proceedings in violation of the law. The closed court allowed the military to avoid disclosing the emptiness of their evidence to the public and to stifle debate.[68][69] As expected, the emptiness of their case appeared clearly during the hearings. Detailed discussions on the bordereau showed that Captain Dreyfus could not be the author.[70][71] At the same time the accused himself protested his innocence and defended himself point by point with energy and logic.[72] Moreover, his statements were supported by a dozen defense witnesses. Finally, the absence of motive for the crime was a serious thorn in the prosecution case. Dreyfus was indeed a very patriotic officer highly rated by his superiors, very rich and with no tangible reason to betray France.[73] The fact of Dreyfus's Jewishness, which was used extensively by the right-wing press, was not openly presented in court. Alphonse Bertillon, an eccentric criminologist who was not an expert in handwriting, was presented as a scholar of the first importance. He advanced the theory of "autoforgery" during the trial and accused Dreyfus of imitating his own handwriting, explaining the differences in writing by using extracts of writing from his brother Matthieu and his wife Lucie. This theory, although later regarded as bizarre and astonishing, seems to have had some effect on the judges.[74] In addition, Major Hubert-Joseph Henry, deputy head of the SR and discoverer of the bordereau, made a theatrical statement in open court.[75] He argued that leaks betraying the General Staff had been suspected to exist since February 1894 and that "a respectable person" accused Captain Dreyfus. He swore on oath that the traitor was Dreyfus, pointing to the crucifix hanging on the wall of the court.[76] Dreyfus was apoplectic with rage and demanded to be confronted with his anonymous accuser, which was rejected by the General Staff. The incident had an undeniable effect on the court, which was composed of seven officers who were both judges and jury. However, the outcome of the trial remained uncertain. The conviction of the judges had been shaken by the firm and logical answers of the accused.[77] The judges took leave to deliberate, but the General Staff still had a card in hand to tip the balance decisively against Dreyfus. Transmission of a secret dossier to the judges  Max von Schwartzkoppen always claimed never to have known Dreyfus. Military witnesses at the trial alerted high command about the risk of acquittal. For this eventuality the Statistics Section had prepared a file containing, in principle, four "absolute" proofs of the guilt of Captain Dreyfus accompanied by an explanatory note. The contents of this secret file remained uncertain until 2013, when they were released by the French Ministry of Defence.[78][79] Recent research indicates the existence of numbering which suggests the presence of a dozen documents. Among these letters were some of an erotic homosexual nature (the Davignon letter among others) raising the question of the tainted methods of the Statistics Section and the objective of their choice of documents.[80] The secret file was illegally submitted at the beginning of the deliberations by the President of the Military Court, Colonel Émilien Maurel, by order of the Minister of War, General Mercier.[81] Later at the Rennes trial of 1899, General Mercier explained (falsely) the nature of the prohibited disclosure of the documents submitted in the courtroom. This file contained, in addition to letters without much interest, some of which were falsified, a piece known as the "Scoundrel D ...".[82] It was a letter from the German military attaché, Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, to the Italian military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Alessandro Panizzardi, intercepted by the SR. The letter was supposed to accuse Dreyfus definitively since, according to his accusers, it was signed with the initial of his name.[83] In reality, the Statistics Section knew that the letter could not be attributed to Dreyfus and if it was, it was with criminal intent.[84] Colonel Maurel confirmed in the second Dreyfus trial that the secret documents were not used to win the support of the judges of the Military Court. He contradicted himself, however, by saying that he read only one document, "which was enough".[85] Conviction, degradation, and deportation  Dreyfus's officer stripes, ripped off as a symbol of treason – Museum of Jewish Art and History On 22 December 1894, after several hours of deliberation, the verdict was reached. Seven judges unanimously convicted Alfred Dreyfus of collusion with a foreign power, to the maximum penalty under section 76 of the Criminal Code: permanent exile in a walled fortification (prison), the cancellation of his army rank and military degradation, also known as cashiering. Dreyfus was not sentenced to death, as it had been abolished for political crimes since 1848. For the authorities, the press and the public, doubts had been dispelled by the trial and his guilt was certain. Right and left regretted the abolition of the death penalty for such a crime. Antisemitism peaked in the press and occurred in areas so far spared.[86] Socialist leader Jean Jaurès regretted the lightness of the sentence in an address to the Chamber of Deputies and wrote, "A soldier has been sentenced to death and executed for throwing a button in the face of his corporal. So why leave this miserable traitor alive?" Radical Republican Georges Clemenceau in La Justice made a similar comment.[87] On 5 January 1895, the ceremony of degradation took place in the Morlan Court of the Military School in Paris. While the drums rolled, Dreyfus was accompanied by four artillery officers, who brought him before an officer of the state who read the judgment. A Republican Guard adjutant tore off his badges, thin strips of gold, his stripes, cuffs and sleeves of his jacket. As he was paraded throughout the streets, the crowd chanted "Death to Judas, death to the Jew." Witnesses report the dignity of Dreyfus, who continued to maintain his innocence while raising his arms: "Innocent, Innocent! Vive la France! Long live the Army". The Adjutant broke his sword on his knee and then the condemned Dreyfus marched at a slow pace in front of his former companions.[88] An event known as "the legend of the confession" took place before the degradation. In the van that brought him to the military school, Dreyfus is said to have confided his treachery to Captain Lebrun-Renault.[89][90] It appears that this was merely self-promotion by the captain of the Republican Guard, and that in reality Dreyfus had made no admission. Due to the affair's being related to national security, the prisoner was then held in solitary confinement in a cell awaiting transfer. On 17 January 1895, he was transferred to the prison on Île de Ré where he was held for over a month. He had the right to see his wife twice a week in a long room, each of them at one end, with the director of the prison in the middle.[91]  Dreyfus's Hut on Devil's Island in French Guiana At the last minute, at the initiative of General Mercier, a law was passed on 9 February 1895, restoring the Îles du Salut in French Guiana, as a place of fortified deportation so that Dreyfus was not sent to Ducos, New Caledonia.[citation needed] Indeed, during the deportation of Adjutant Lucien Châtelain, sentenced for conspiring with the enemy in 1888, the facilities did not provide the required conditions of confinement and detention conditions were considered too soft. On 21 February 1895, Dreyfus embarked on the ship Ville de Saint-Nazaire. The next day the ship sailed for French Guiana.  Le Petit Journal (27 September 1896) On 12 March 1895, after a difficult voyage of fifteen days, the ship anchored off the Îles du Salut. Dreyfus stayed one month in prison on Île Royale and was transferred to Devil's Island on 14 April 1895. Apart from his guards, he was the only inhabitant of the island and he stayed in a stone hut 4 by 4 metres (13 ft × 13 ft).[92] Haunted by the risk of escape, the commandant of the prison sentenced him to a hellish life, even though living conditions were already very painful. The temperature reached 45 °C, he was underfed or fed contaminated food and hardly had any treatment for his many tropical diseases. Dreyfus became sick and shaken by fevers that got worse every year.[93] Dreyfus was allowed to write on paper numbered and signed. He underwent censorship by the commandant even when he received mail from his wife Lucie, whereby they encouraged each other. On 6 September 1896, the conditions of life for Dreyfus worsened again; he was chained double looped, forcing him to stay in bed motionless with his ankles shackled. This measure was the result of false information of his escape revealed by a British newspaper. For two long months, Dreyfus was plunged into deep despair, convinced that his life would end on this remote island.[94][tone] |

事件の起源と1894年の裁判 主な記事 アルフレッド・ドレフュスの捜査と逮捕  1894年10月13日付のボルドローの写真。原本は1940年に紛失した。 ボルドロー」の発見 軍事情報部(SR)のスタッフは、24時間体制でパリのドイツ大使館をスパイしていた[20]。彼らは「マダム・バスティアン」というフランス人の家政婦 を雇い、この建物で働いてドイツ人をスパイするように仕向けた。1894年9月、彼女は破られたメモ[21]を見つけ、軍事情報部の雇い主に渡した。この メモは後に「ボルドロー」として知られるようになった[注 2]。この紙切れは大きく6つに破れ[22]、署名も日付もなく、ドイツ大使館駐在のドイツ軍アタッシェ、マクシミリアン・フォン・シュバルツコッペン宛 だった。そこには、新しく開発された「120式油圧ブレーキとこの銃の作動方法」[23][24]に関するフランス軍の機密文書が外国に送られようとして いることが記されていた。 ボルドローの作者探し  1894年、陸軍大臣オーギュスト・メルシエ将軍 統計課」[25]の責任者であるミュルホーズ派[26]のジャン・サンヘルが陸軍大臣オーギュスト・メルシエ将軍に報告するほど、この捕獲は重要であった ようだ。実際、SRは1894年の初めから情報漏洩があったことを疑っており、犯人を突き止めようとしていた。メルシエ陸軍大臣は、その行動が無能であっ たとしてマスコミから厳しく非難されており[27]、自分のイメージを高める機会を狙っていたようである[28][29]。犯人を見つけるために、単純だ が粗雑な推論[30]を用いて、捜査の対象は参謀本部に配属された、あるいは配属されたことのある容疑者に恣意的に限定され、必然的に砲兵[注釈 3]将校の訓練生となった[注釈 4]。 理想的な犯人が特定された: アルフレッド・ドレフュス大尉である。ドレフュスはエコール・ポリテクニックを卒業した砲兵将校で、ユダヤ教を信仰し、アルザス出身で、共和制功労者階級 の出身であった[31]。事件の当初は、ドレフュスの宗教よりもむしろアルザス出身であることが強調されていた。しかし、これらの将校はドイツ語やドイツ 文化に精通しているという理由でフランスから好意を持たれていたため、これらの出自は例外的なものではなかった[32][33]。参謀本部のオフィスにも 反ユダヤ主義が存在し[34]、予備調査における信憑性のギャップを埋めることで、それは急速に事件の中心的存在となった。 実際、ドレフュスは冷淡で引っ込み思案、あるいは高慢な性格であるという評判[35]や、彼の「好奇心」が強く不利に働いた。こうした性格の特徴は、ある ものは偽りであり、あるものは生まれつきのものであったが、省内の日常生活のごく普通の行為をスパイの証拠に変えることによって、告発をもっともらしくし た。当初から、偏った一方的な誤りの積み重ねが、国家を誤った立場に導いた。これはこの事件全体を通じて見られ、当時流行していた実証主義よりも非合理性 が勝っていた[36]。 この最初の時間から、事件全体を支配することになる現象が起こった。信念を構成するのは、注意深く吟味された事実や状況によって支配されるのではなく、事実や信念を歪める抗いがたい軽率な確信なのである。 - ジョセフ・ライナッハ 執筆の専門家  捜査責任者のデュ・パティ・ド・クラム少佐はドレフュス大尉を逮捕した。 ドレフュスを断罪するためには、ボルドローに書かれた文字を大尉のものと比較しなければならなかった。参謀本部には筆跡を分析できる者は誰もいなかった [37]。 そこでデュ・パティ・ド・クラム少佐[38][39]が登場する。彼は筆跡学の専門家であると自負する風変わりな人物であった。10月5日、ドレフュスと ボルドローの手紙を見せられたデュ・パティは、誰がこの2通の手紙を書いたのかを即座に結論づけた。一日がかりの追加作業の後、彼は、いくつかの相違点は あるものの、類似点は調査を正当化するに十分であるとの報告書を提出した。従って、参謀本部の目には、ドレフュスはボルドローの「作者と思われる人物」で あった[40]。  アルフォンス・ベルティヨンは筆跡の専門家ではなかったが、「自書偽造」の理論を考案した。 メルシエ将軍は犯人を捕まえたと信じていたが、彼はこの事件の価値を誇張し、ドレフュス逮捕の前週には国家的な事件となった。同大臣は国家のあらゆる当局 に相談し、知らせたが[41]、閣僚会議でガブリエル・ハノトーが慎重な助言と勇気ある反対を表明したにもかかわらず[42]、追及することを決定した。 その一方で、ドレフュスの人物像に関するものや、ボルドローの作者の正体を確かめるためのものなど、並行していくつかの情報源が開かれていた。専門家[注 釈 5]のゴベールは納得せず、多くの相違点を発見した。さらにゴベールは「ボルドローに書かれた文字の性質から、筆跡が偽装されている可能性はない」とまで 書いている[44]。失望したメルシエは、その後、法医人体計測の発明者でありながら筆跡の専門家ではなかったアルフォンス・ベルティヨンを呼び寄せた。 ベルティヨンは当初、ゴベールほど肯定的ではなかったが、ドレフュスの筆跡である可能性を否定しなかった[45]。後に軍部からの圧力を受け[46]、ベ ルティヨンはドレフュスが自作自演したものだと主張し、「自作自演」説を展開した。 逮捕 1894年10月13日、具体的な証拠もなく、ファイルも空っぽのまま、メルシエ将軍はドレフュス大尉を「ブルジョワの服装」、つまり私服で一般検査のた めに呼び出した。参謀本部の目的は、フランス法の下で完璧な証拠、すなわち自白を得ることであった。その自白は不意打ちによって、つまりボルドロー [47][48]に基づいた手紙を口述筆記することによって、彼の罪を明らかにすることで得られるはずだった。 1894年10月15日の朝、ドレフュス大尉はこの試練を受けたが、何も認めなかった。デュ・パティはドレフュスの前にリボルバーを突きつけて自殺を仄め かそうとさえしたが、ドレフュスは「自分の無実を立証するために生きたい」と言って命を絶つことを拒否した。軍の望みは潰えた。それでもデュ・パティ・ ド・クラムはドレフュス大尉を逮捕し[49]、敵との共謀の罪で告発し、軍法会議にかけると告げた。ドレフュスはパリのシェルシュ=ミディ刑務所に収監さ れた[50]。 尋問と最初の軍事法廷  1895年1月20日付『プチ・ジャーナル』紙の表紙(リオネル・ロワイエにちなんでフォルテュヌ・メーユが描いたイラスト)。 ドレフュス夫人は同日、警察の家宅捜索によって逮捕を知らされた。夫人はデュ・パティに脅迫され、夫の逮捕を秘密にするよう命じられ、「一言、一言言え ば、ヨーロッパ戦争になる!」とまで言われた[51]。違法に[52]ドレフュスは刑務所に独房に入れられ、デュ・パティは自白を得るために昼夜を問わず 尋問したが、失敗に終わった。ドレフュスは、最初のドレフュサールであり、パリの軍刑務所の司令官であったフォルジネッティ少佐に道徳的に支持されてい た。 1894年10月29日、エドゥアール・ドリュモンが所有する反ユダヤ主義新聞『La Libre Parole』の記事で、この事件が明らかになった。これを皮切りに、裁判に至るまで非常に残酷な報道キャンペーンが展開された。この出来事によって、こ の事件は反ユダヤ主義の分野に入り込み、その終結までそのまま残った[53]。 1894年11月1日、アルフレッドの弟であるマチュー・ドレフュスは、パリに緊急に呼び出され、逮捕を知った。彼は迷うことなく弁護士を探し始め、著名な刑事弁護士エドガー・ドゥマンジュに依頼した[55]。 尋問 1894年11月3日、パリ軍総督ソシエ将軍は不本意ながら[56]、査問の命令を下した。軍事法廷の記録官であったベッソン・ドルメシュヴィル少佐は起 訴状を書き、その中で、罪状の「道徳的要素」(ドレフュスの習慣や「賭博場」への出席疑惑、ドイツ語の知識、「驚くべき記憶力」についての噂話)が、罪状 にはほとんど見られない「物質的要素」[注 6]よりも広範囲に展開されていた: 「ドレフュスはすべてを消し去ったのだから、これは有罪の証拠である」。 起訴状が完全に中立性を欠いていたことから、エミール・ゾラはこれを「偏見の記念碑」と呼んだ[58]。 ドレフュス逮捕のニュースが流れると、多くのジャーナリストがこの記事に群がり、憶測と非難で溢れかえった。著名なジャーナリストで反ユダヤ主義運動家の エドゥアール・ドリュモンは、1894年11月3日付の自身の出版物に、「ユダヤ人ドレフュスの不名誉な反逆、なんと恐ろしい教訓であろうか 」と記している。 1894年12月4日、ドレフュスはこの書類とともに第一軍事法廷に召喚された。秘密は解かれ、ドゥマンジュは初めてこの書類にアクセスすることができ た。ドレフュスは、検察側の立証の空虚さを目の当たりにし、絶対的な自信を得た[59]。検察側は、専門家の意見が分かれた一枚の紙、ボルドローに書かれ た文章と、曖昧な間接的証言に完全に依拠していた。 裁判は 「閉廷か戦争か!」  ル・プティ・ジャーナル紙(1894年12月23日)より 裁判前の2ヶ月間、マスコミは大騒ぎした。ラ・リーブル・パロル』、『ル・オートリテ』、『ル・ジュルナル』、『ル・タン』は、ドレフュスの生涯を嘘と下 手な作り話で描写した[60]。 また、『ラ・リーブル・パロル』や『ラ・クロワ』の過激な見出しは、「あなた方は聞かされている!」[61]というテーマで、軍隊におけるユダヤ人の存在 に反対する以前のキャンペーンを正当化する機会でもあった。 [1894 年 11 月 8 日、メルシエ将軍は『フィガロ』紙のインタビューでドレフュスが有罪であると宣言した[63]。 1894 年 11 月 29 日、メルシエ将軍は『ゴロワ』紙に掲載されたアルチュール・マイヤーの記事で、ドレフュスに対する起訴を非難し、「軍事裁判所は被告人を裁く自由をどれほ ど持つだろうか」と問いかけた[64]。 コラムニストたちの争いは、非公開法廷の問題についてのより広範な議論の中で行われた。大多数のマスコミを代表するランとカサニャックにとって、非公開法 廷はドレフュスを無罪にするための卑怯な作戦であった。その証拠に、パリのドイツ大使の否認を公表することに同意したことで、「プロイセンの前にひれ伏し た」のである[65]。1894年12月13日付のレクレールのような他の新聞では、次のように述べている: 「一方、ジュデは12月18日付のル・プティ・ジャーナル紙で「閉廷はドイツに対する我々の難攻不落の避難所である」と述べ、同日付のラ・クロワ紙では 「最も絶対的な閉廷」でなければならないと述べている[66]。 裁判は1894年12月19日1時に開始され[67]、直ちに非公開法廷が宣言された。この非公開法廷は、ピッカート少佐とルイ・レピーヌ県知事が法律に 違反して特定の手続きに出席していたため、法的には整合性がなかった。非公開法廷によって、軍部は自分たちの証拠の空虚さを国民に公表することを避け、議 論を抑圧することができた[68][69]。予想通り、公聴会の間、彼らの主張の空虚さは明らかになった。ボルドローに関する詳細な議論は、ドレフュス大 尉が作者であるはずがないことを示した[70][71]。同時に、被告人自身は無実を訴え、エネルギーと論理性をもって一点一点弁明した[72]。最後 に、犯罪の動機がなかったことは、検察側にとって重大なとげとなった。ドレフュスは確かに上官から高く評価された非常に愛国的な将校であり、非常に裕福 で、フランスを裏切る具体的な理由もなかった[73]。右翼マスコミが盛んに利用したドレフュスのユダヤ人であるという事実は、法廷では公然と提示されな かった。 アルフォンス・ベルティヨンは、筆跡の専門家ではない風変わりな犯罪学者であったが、第一級の学者として紹介された。彼は裁判中に「自筆偽造」説を唱え、 ドレフュスが自分の筆跡を真似ていると非難し、弟マチューとその妻リュシーの筆跡の抜粋を使って筆跡の違いを説明した。この説は、後に奇妙で驚くべきもの とみなされたものの、裁判官には一定の効果があったようである[74]。 さらに、SRの副責任者でボルドローの発見者であるユベール=ジョゼフ・アンリ少佐は、公開の法廷で芝居じみた陳述を行った[75]。 彼は、参謀本部を裏切るリークの存在が1894年2月から疑われており、「立派な人物」がドレフュス大尉を告発したと主張した。ドレフュスは激怒し、匿名 の告発者と面会することを要求したが、参謀本部はこれを拒否した[76]。この事件は、裁判官であり陪審員でもある7人の将校で構成された法廷に紛れもな い影響を与えた。しかし、裁判の結果は不透明なままだった。裁判官たちは審議のために休暇を取ったが、参謀本部はまだドレフュスに不利になるようなカード を手にしていた。 裁判官への秘密文書の送信  マックス・フォン・シュバルツコッペンは、ドレフュスとは面識がないと常に主張していた。 裁判での軍証人は、無罪になる危険性を上層部に警告した。このような事態に備えて、統計課は、原則として、ドレフュス大尉の有罪を証明する4つの「絶対 的」証拠と説明書きを含むファイルを用意していた。この秘密ファイルの内容は、2013年にフランス国防省によって公開されるまで不明のままであった [78][79]。最近の調査で、12通の文書の存在を示唆するナンバリングの存在が判明した。これらの書簡の中には、エロティックな同性愛の性質を持つ ものもあり(ダヴィニョンの書簡など)、統計課の汚染された手法と、彼らの文書選択の目的に疑問を投げかけている[80]。 この秘密ファイルは、陸軍大臣メルシエ将軍の命令により、軍事裁判所長官エミリアン・モーレル大佐によって審議の冒頭に違法に提出された[81]。後に 1899年のレンヌ裁判において、メルシエ将軍は法廷に提出された文書の開示禁止の性質について(偽って)説明した。このファイルには、あまり興味のない 書簡のほかに、「悪党D...」として知られるものが含まれていた[82]。 それは、ドイツ軍アタッシェのマクシミリアン・フォン・シュバルツコッペンがイタリア軍アタッシェのアレッサンドロ・パニッツァルディ中佐にあてた書簡 で、SRが傍受したものであった。この書簡は、ドレフュスを告発する者たちによれば、ドレフュスの名前の頭文字で 署名されていたことから、ドレフュスを決定的に告発するものと思われていた[83]。実際には、統計課は、この書簡がドレフュスのものであるはずがないこ と、もしそうであったとしても、それは犯罪的意図に基づくものであることを知っていた[84]。しかし彼は、自分が読んだのはたった一つの文書だけであ り、「それで十分であった」と述べ、自分自身と矛盾していた[85]。 有罪判決、劣化、国外追放  反逆のシンボルとして剥がされたドレフュスの将校ストライプ - ユダヤ美術歴史博物館 1894年12月22日、数時間の審議の後、判決は下された。7人の裁判官は全員一致で、アルフレッド・ドレフュスを外国勢力との共謀の罪で有罪判決を下 し、刑法第76条に基づく最高刑である、城壁に囲まれた要塞(刑務所)への永久追放、陸軍の階級取り消し、出頭とも呼ばれる軍紀粛正を言い渡した。 1848年以降、政治犯に対する死刑は廃止されていたため、ドレフュスは死刑を宣告されなかった。 当局、マスコミ、国民にとって、裁判によって疑惑は払拭され、彼の有罪は確実となった。右派も左派も、このような犯罪に対する死刑廃止を惜しんだ。社会党 の指導者ジャン・ジョレスは、下院での演説で刑の軽さを悔やみ、「一人の兵士が伍長の顔にボタンを投げつけた罪で死刑を宣告され、処刑された。それなの に、なぜこの惨めな裏切り者を生かしておくのか?" と書いた。急進派の共和主義者ジョルジュ・クレマンソーも『ラ・ジャスティス』で同様のコメントを寄せている[87]。 1895年1月5日、パリの陸軍士官学校のモルラン宮廷で除隊式が行われた。太鼓が鳴り響く中、ドレフュスは4人の砲兵将校に付き添われ、判決を読み上げ る国家将校の前に連れて行かれた。共和国軍の副官が、彼のバッジ、金の細い帯、ストライプ、袖口、上着の袖を引き裂いた。彼が通りをパレードすると、群衆 は 「ユダに死を、ユダヤ人に死を 」と唱えた。目撃者によれば、腕を上げながら無実を主張し続けたドレフュスの威厳が伝えられている: 「無実だ、無実だ!フランス万歳!軍隊万歳」。准尉は膝の上で剣を折ると、死刑囚ドレフュスはかつての仲間の前をゆっくりとした足取りで行進した [88]。「自白の伝説」として知られる出来事が、堕落の前に起こった。ドレフュスは軍学校に運ばれる車の中で、ルブラン=ルノー大尉に自分の裏切りを打 ち明けたと言われている[89][90]。これは共和国軍の大尉による自己宣伝に過ぎず、実際にはドレフュスは告白していなかったようである。この事件は 国民安全保障に関わるものであったため、ドレフュスは独房に収容され、移送を待つことになった。1895年1月17日、ドレフュスはイル・ド・レの刑務所 に移送され、1ヵ月以上収容された。ドレフュスは週に2回、長い部屋で妻と面会する権利を与えられた。  フランス領ギアナの悪魔の島にあるドレフュスの小屋 ドレフュスがニューカレドニアのデュコスに送られないように、メルシエ将軍の発案で、1895年2月9日、フランス領ギアナのイル・デュ・サルーを要塞化 された強制送還地として復活させる法律が成立した[要出典]。実際、1888年に敵国との共謀の罪で判決を受けたルシアン・シャトラン准尉の強制送還の 際、施設は必要な監禁条件を提供しておらず、拘禁条件は甘すぎると考えられていた。1895年2月21日、ドレフュスはヴィル・ド・サン・ナゼール号に乗 船した。翌日、船はフランス領ギアナに向けて出航した。  ル・プティ・ジャーナル紙(1896年9月27日) 1895年3月12日、15日間の困難な航海の後、船はサリュ島沖に停泊した。ドレフュスはイル・ロワイヤルの牢獄に1ヶ月滞在し、1895年4月14日 に悪魔の島に移送された。看守を除けば、この島の住人はドレフュスただ一人であり、彼は4メートル×4メートルの石造りの小屋に寝泊まりした[92]。脱 獄の危険性に取り憑かれた牢獄の指揮官は、生活環境がすでに非常に苦しいものであったにもかかわらず、彼に地獄のような生活を宣告した。気温は45℃に達 し、栄養不足か汚染された食べ物を与えられ、多くの熱帯病の治療もほとんど受けられなかった。ドレフュスは毎年悪化する熱にうなされ、病気になった [93]。 ドレフュスは番号と署名の入った紙に書くことを許された。ドレフュスは、妻のリュシーからの手紙を受け取ったときでさえ、司令官による検閲を受けた。 1896年9月6日、ドレフュスの生活環境は再び悪化した。彼は二重の輪で鎖につながれ、足首に足かせをはめられたままベッドで動かないことを強いられ た。この措置は、イギリスの新聞が暴露したドレフュス逃亡の虚偽情報の結果であった。ドレフュスは2ヶ月という長い間、深い絶望の淵に立たされ、自分の人 生はこの離島で終わるのだと確信した[94][論調]。 |

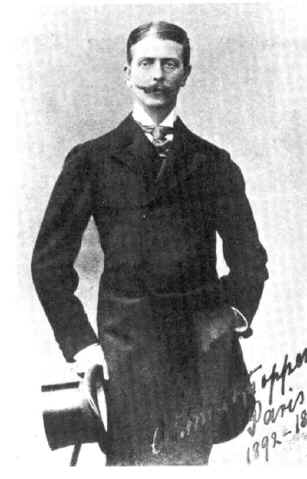

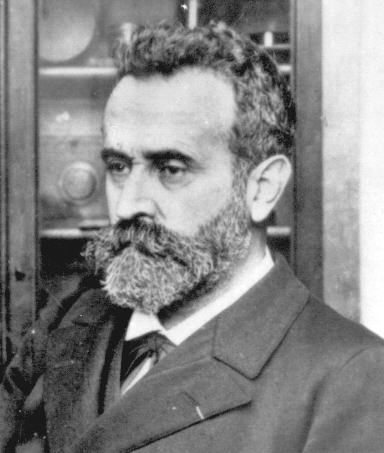

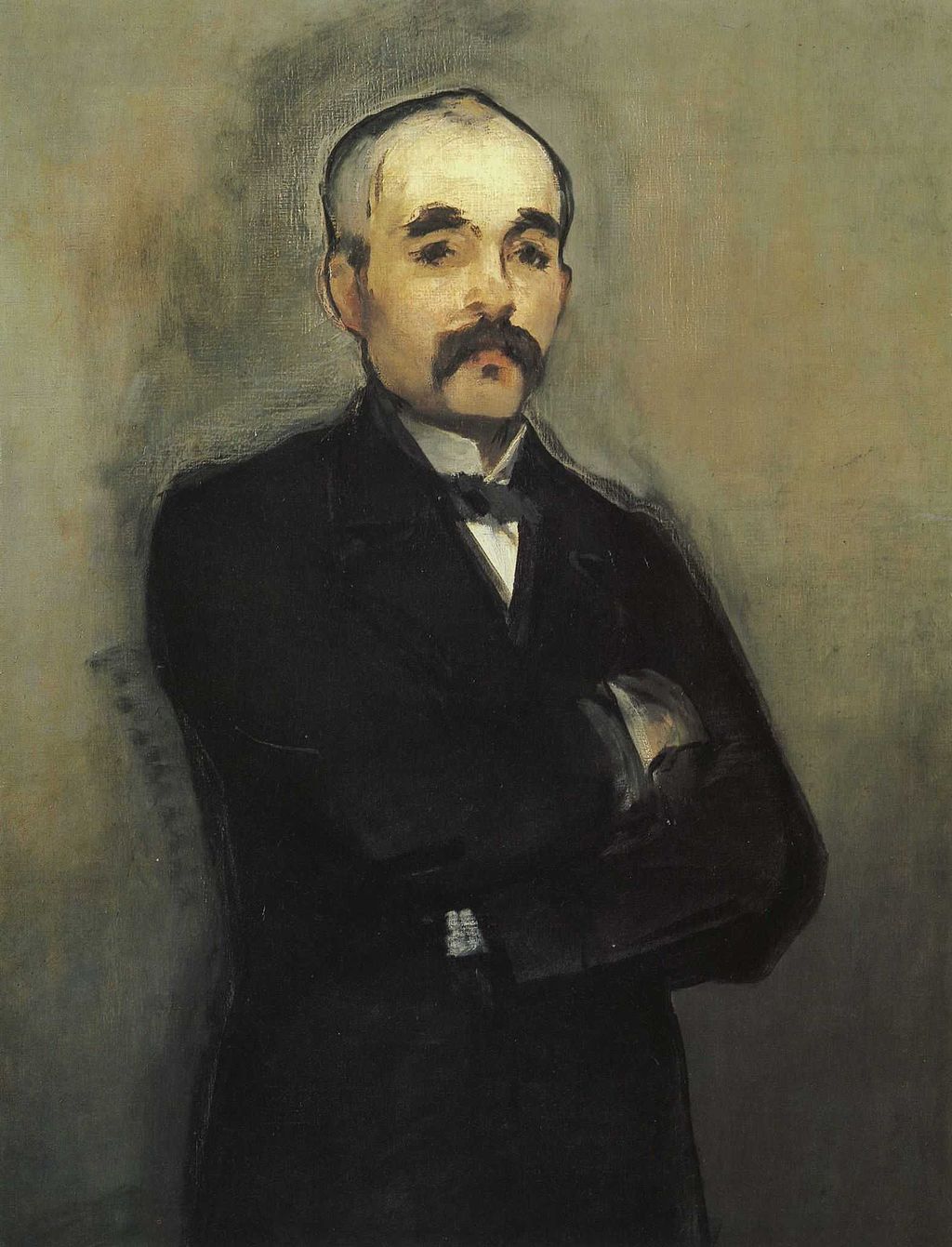

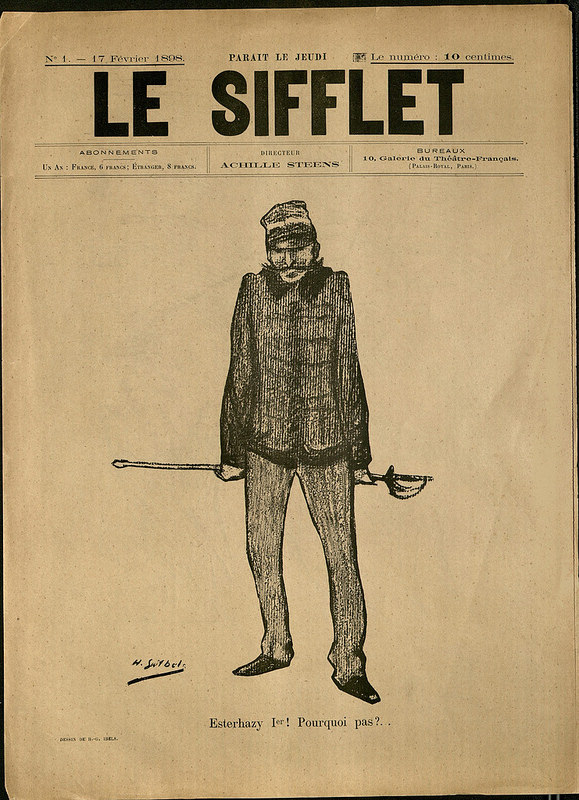

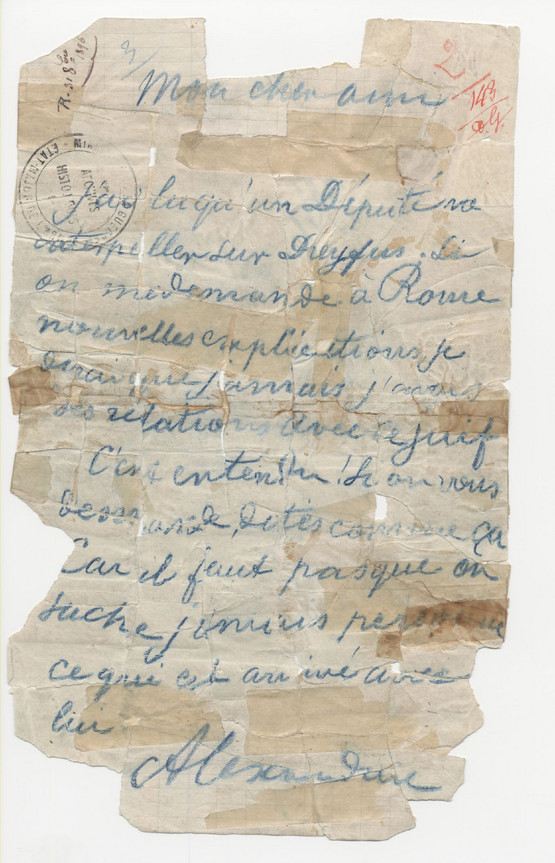

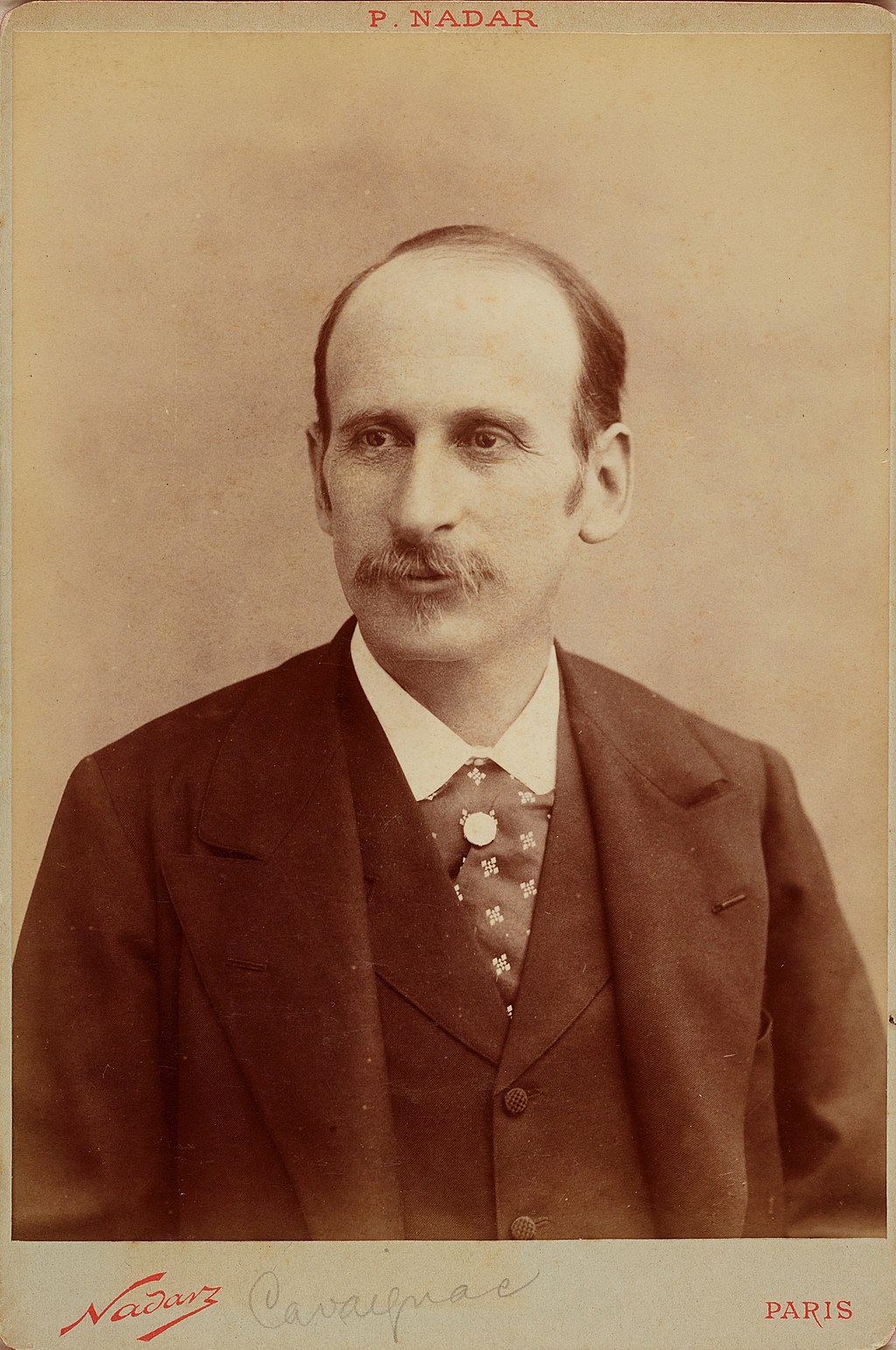

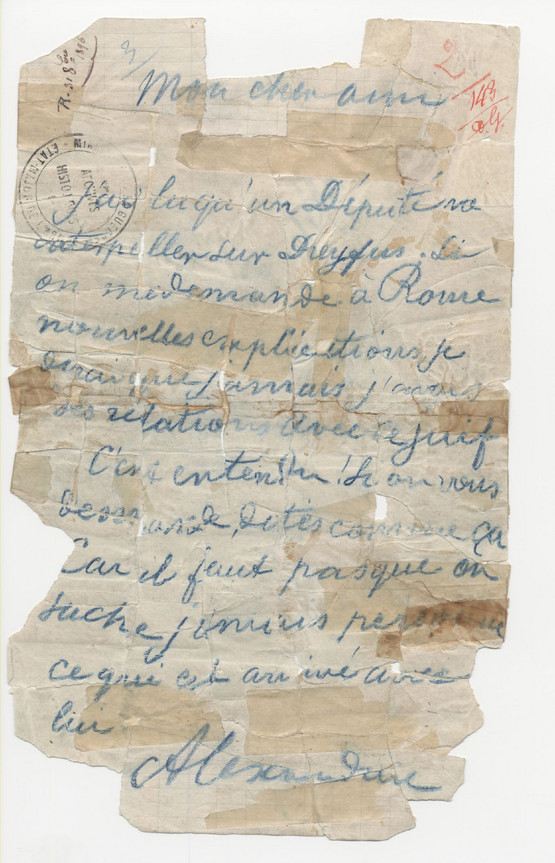

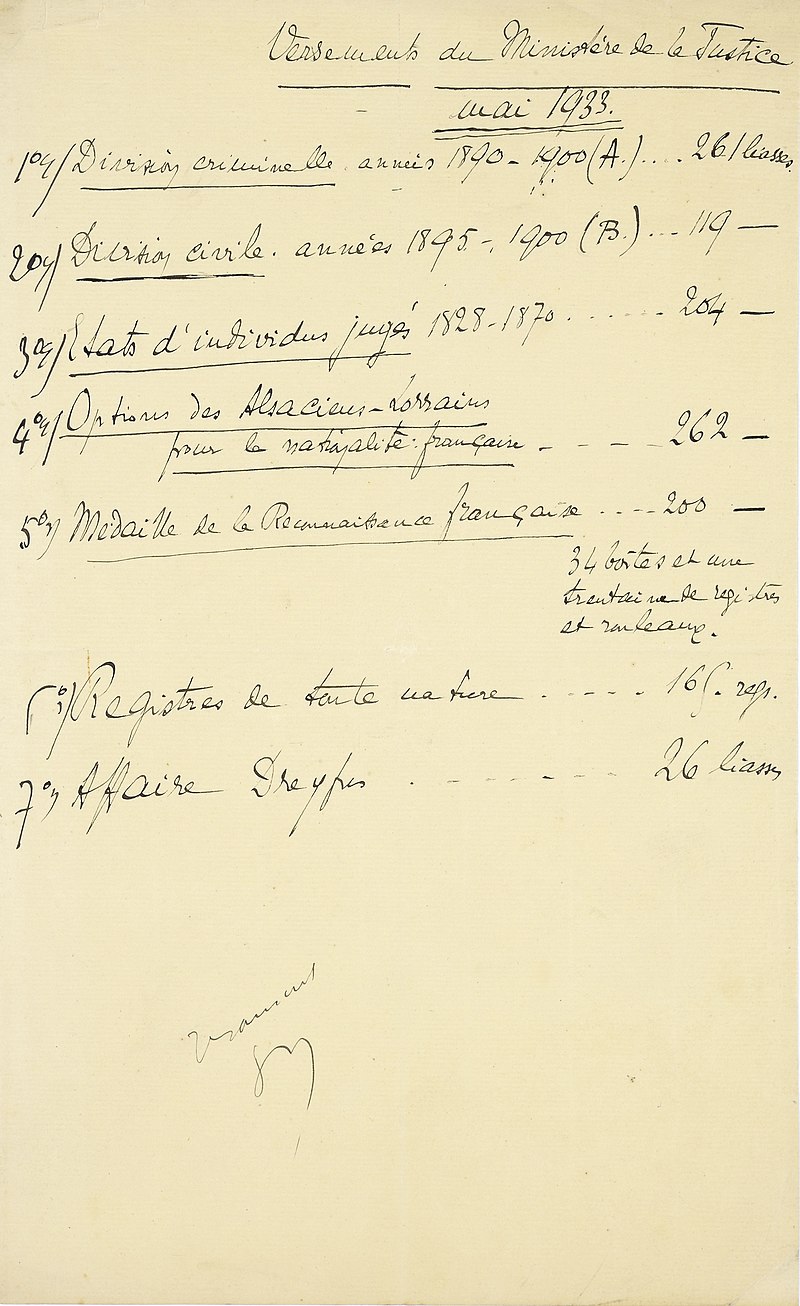

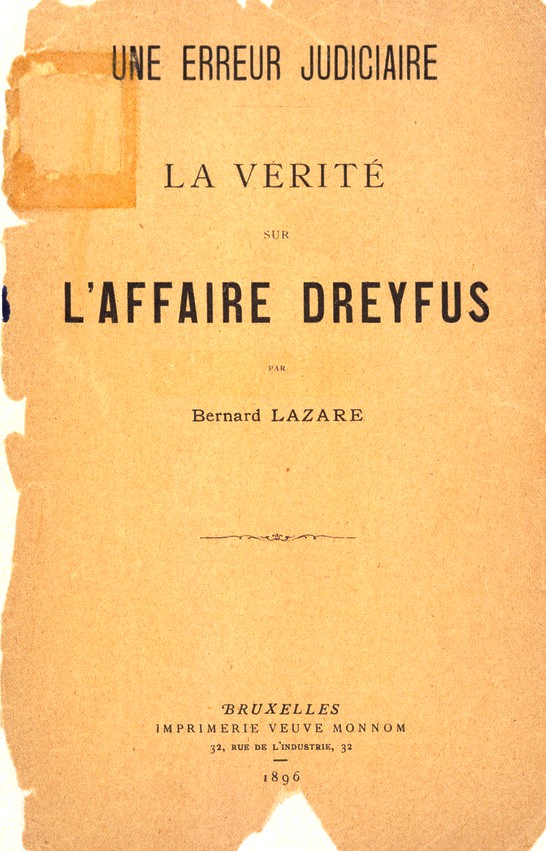

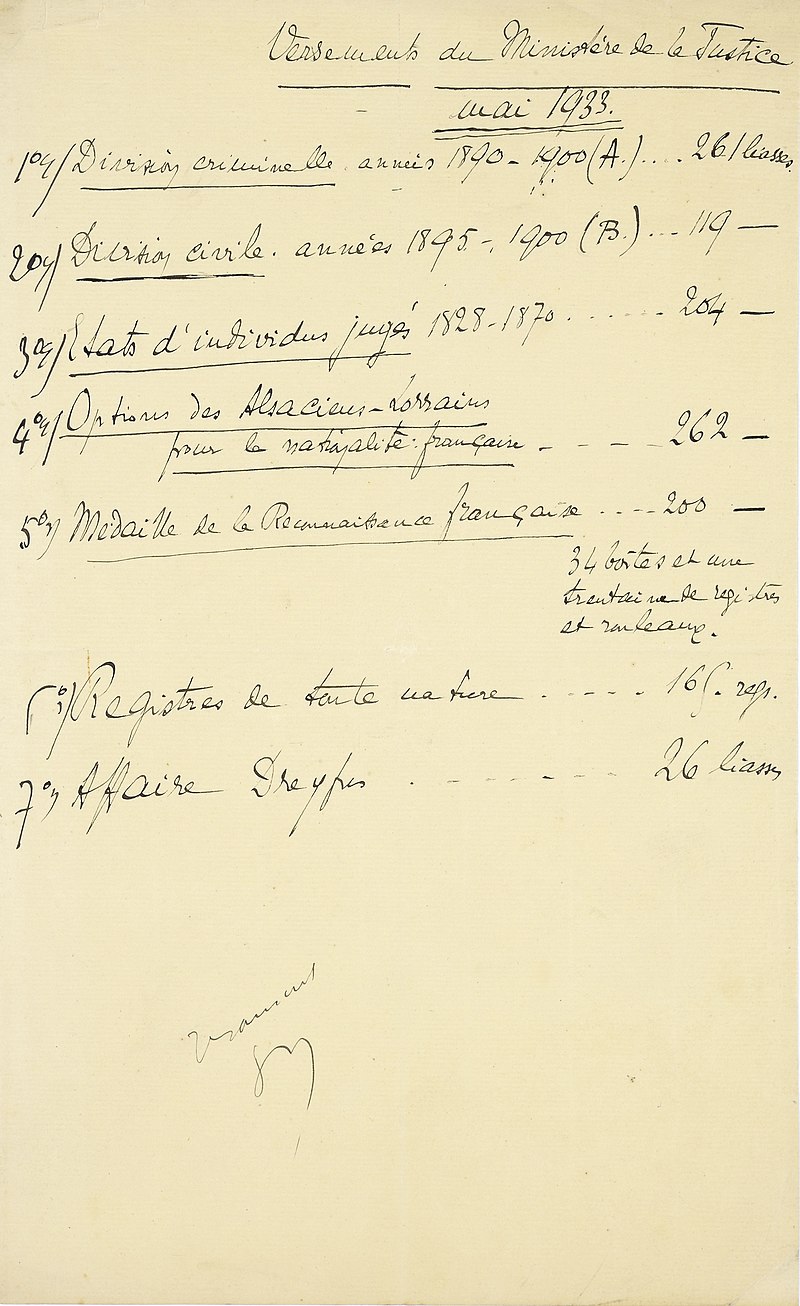

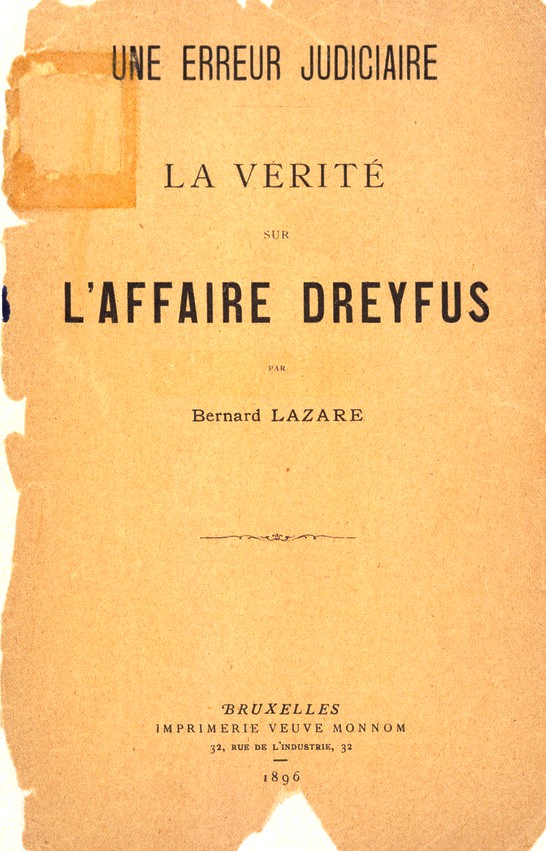

| The truth emerges (1895–1897) The Dreyfus family exposes the affair and takes action Mathieu Dreyfus, the elder brother of Alfred, was convinced of his innocence. He was the chief architect of the rehabilitation of his brother and spent his time, energy and fortune to gather an increasingly powerful movement for a retrial in December 1894, despite the difficulties of the task:[95] After the degradation emptiness was around us. It seemed to us that we were no longer human beings like others, we were cut off from the world of the living.[96] Mathieu tried all paths, even the most fantastic. Thanks to Dr. Gibert, a friend of President Félix Faure, he met at Le Havre a woman who spoke for the first time under hypnosis of a "secret file".[97][98] This fact was confirmed by the President of the Republic to Dr. Gibert in a private conversation. Little by little, despite threats of arrest for complicity, machinations and entrapment by the military, he managed to convince various moderates.[99] Thus the anarchist journalist Bernard Lazare looked into the proceedings. In 1896, Lazare published the first Dreyfusard booklet in Brussels.[100] This publication had little influence on the political and intellectual world, but it contained so much detail that the General Staff suspected that Picquart, the new head of SR, was responsible. The campaign for the review, relayed little by little into the leftist anti-military press, triggered a return of a violent yet vague antisemitism.[101] France was overwhelmingly anti-Dreyfusard; Major Henry from the Statistics Section in turn was aware of the thinness of the prosecution case. At the request of his superiors, General Boisdeffre, Chief of the General Staff and Major-General Gonse, he was charged with the task of enlarging the file to prevent any attempt at a review. Unable to find any evidence, he decided to build some after the fact. [citation needed] The discovery of the real culprit: Picquart "going to the enemy" Main article: Georges Picquart's investigations of the Dreyfus affair  Lieutenant Colonel Georges Picquart dressed in the uniform of the 4th Algerian Tirailleurs Major Georges Picquart was assigned to be head of the staff of the Military Intelligence Service (SR) in July 1895, following the illness of Colonel Sandherr. In March 1896, Picquart, who had followed the Dreyfus affair from the outset, now required to receive the documents stolen from the German Embassy directly without any intermediary.[97] He discovered a document called the "petit bleu": a telegram that was never sent, written by von Schwarzkoppen and intercepted at the German Embassy at the beginning of March 1896.[102] It was addressed to a French officer, Major Walsin-Esterhazy, 27 rue de la Bienfaisance – Paris.[103] In another letter in black pencil, von Schwarzkoppen revealed the same clandestine relationship with Esterhazy.[104] On seeing letters from Esterhazy, Picquart realized with amazement that his writing was exactly the same as that on the "bordereau", which had been used to incriminate Dreyfus. He procured the "secret file" given to the judges in 1894 and was astonished by the lack of evidence against Dreyfus, and became convinced of his innocence. Moved by his discovery, Picquart diligently conducted an enquiry in secret without the consent of his superiors.[105] The enquiry demonstrated that Esterhazy had knowledge of the elements described by the "bordereau" and that he was in contact with the German Embassy.[106] It was established that the officer sold the Germans many secret documents, whose value was quite low.[107] Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was a former member of French counterespionage where he had served after the war of 1870.[108] He had worked in the same office as Major Henry from 1877 to 1880.[109] A man with a personality disorder, a sulphurous reputation and crippled by debt, he was considered by Picquart to be a traitor driven by monetary reasons to betray his country.[110] Picquart communicated the results of his investigation to the General Staff, which opposed him under "the authority of the principle of res judicata". After this, everything was done to oust him from his position, with the help of his own deputy, Major Henry. It was primarily the upper echelons of the Army that did not want to admit that Dreyfus's conviction could be a grave miscarriage of justice. For Mercier, then Zurlinden and the General Staff, what was done was done and should never be returned to.[111] They found it convenient to separate the Dreyfus and Esterhazy affairs. The denunciation of Esterhazy and the progress of Dreyfusism The nationalist press launched a violent campaign against the burgeoning Dreyfusards. In counter-attack, the General Staff discovered and revealed the information hitherto ignored in the "secret file".[112] Doubt began to surface, and figures in the artistic and political spheres asked questions.[Note 7] Picquart tried to convince his seniors to react in favour of Dreyfus, but the General Staff seemed deaf. An investigation was started against him, he was monitored when he was in the east, then transferred to Tunisia "in the interest of the service".[113] At this moment Major Henry chose to take action. On 1 November 1896, he created a false document, subsequently called the "faux Henry" [Henry forgery],[Note 8] keeping the header and signature of an ordinary letter from Panizzardi, and wrote the central text himself: I read that a deputy will call on Dreyfus. If you ask further explanations from Rome, I would say that I never had relations with the Jew. That is understood. If asked, speak like that, because that person should never know what happened with him. This was a rather crude forgery. Generals Gonse and Boisdeffre, however, without asking questions, brought the letter to their minister, General Jean-Baptiste Billot. The doubts of the General Staff regarding the innocence of Dreyfus flew out the window.[114] With this discovery the General Staff decided to protect Esterhazy and persecute Colonel Picquart, "who did not understand anything".[114] Picquart, who knew nothing of the "faux Henry", quickly felt isolated from his fellow soldiers. Major Henry accused Picquart of embezzlement and sent him a letter full of innuendo.[115] He protested in writing and returned to Paris. Picquart confided in his friend, lawyer Louis Leblois, who promised secrecy. Leblois, however, spoke to the vice president of the Senate, the Alsatian Auguste Scheurer-Kestner (born in Mulhouse, like Dreyfus), who was in turn infected by doubts. Without citing Picquart, the senator revealed the affair to the highest people in the country. The General Staff, however, still suspected Picquart of causing leaks. This was the beginning of the Picquart affair, a new conspiracy by the General Staff against an officer.[116] Major Henry, although deputy to Picquart, was jealous and fostered his own malicious operation to compromise his superior.[117] He engaged in various malpractices (making a letter and designating it as an instrument of a "Jewish syndicate", wanting to help Dreyfus to escape, rigging the "petit bleu" to create a belief that Picquart erased the name of the real recipient, drafting a letter naming Dreyfus in full). Parallel to the investigations of Picquart, the defenders of Dreyfus were informed in November 1897 that the identity of the writer of the "bordereau" was Esterhazy. Mathieu Dreyfus had a reproduction of the bordereau published by Le Figaro. A banker, Castro, formally identified the writing as that of Esterhazy, who was his debtor, and told Mathieu. On 11 November 1897, the two paths of investigation met during a meeting between Scheurer-Kestner and Mathieu Dreyfus. The latter finally received confirmation that Esterhazy was the author of the note. Based on this, on 15 November 1897 Mathieu Dreyfus made a complaint to the minister of war against Esterhazy.[118] The controversy was now public and the army had no choice but to open an investigation. At the end of 1897, Picquart returned to Paris and made public his doubts about the guilt of Dreyfus because of his discoveries. Collusion to eliminate Picquart seemed to have failed.[119] The challenge was very strong and turned to confrontation. To discredit Picquart, Esterhazy sent, without effect, letters of complaint to the president of the republic.[120]  Émile Zola in 1898 The Dreyfusard movement, led by Bernard Lazare, Mathieu Dreyfus, Joseph Reinach and Auguste Scheurer-Kestner gained momentum.[121] Émile Zola, informed in mid-November 1897 by Scheurer-Kestner with documents, was convinced of the innocence of Dreyfus and undertook to engage himself officially.[Note 9] On 25 November 1897 the novelist published Mr. Scheurer-Kestner in Le Figaro, which was the first article in a series of three.[Note 10] Faced with threats of massive cancellations from its readers, the paper's editor stopped supporting Zola.[122] Gradually, from late-November through early-December 1897, a number of prominent people got involved in the fight for retrial. These included the authors Octave Mirbeau (his first article was published three days after Zola)[123] and Anatole France, academic Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, the librarian of the École normale supérieure Lucien Herr (who convinced Léon Blum and Jean Jaurès), the authors of La Revue Blanche,[Note 11] (where Lazare knew the director Thadee Natanson), and the Clemenceau brothers Albert and Georges. Blum tried in late November 1897 to sign, with his friend Maurice Barrès, a petition calling for a retrial, but Barrès refused, broke with Zola and Blum in early-December, and began to popularize the term "intellectuals".[124] This first break was the prelude to a division among the educated elite after 13 January 1898. The Dreyfus affair occupied more and more discussions, something the political world did not always recognize. Jules Méline declared in the opening session of the National Assembly on 7 December 1897, "There is no Dreyfus affair. There is not now and there can be no Dreyfus affair."[125] Trial and acquittal of Esterhazy  Portrait of Georges Clemenceau by the painter Édouard Manet General Georges-Gabriel de Pellieux was responsible for conducting an investigation. It was brief, thanks to the General Staff's skillful manipulation of the investigator. The real culprit, they said, was Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart.[126] The investigation was moving towards a predictable conclusion until Esterhazy's former mistress, Madame de Boulancy, published letters in Le Figaro in which ten years earlier Esterhazy had expressed violently his hatred for France and his contempt for the French army. The militarist press rushed to the rescue of Esterhazy with an unprecedented antisemitic campaign. The Dreyfusard press replied with strong new evidence in its possession. Georges Clemenceau, in the newspaper L'Aurore, asked, "Who protects Major Esterhazy? The law must stop sucking up to this ineffectual Prussian disguised as a French officer. Why? Who trembles before Esterhazy? What occult power, why shamefully oppose the action of justice? What stands in the way? Why is Esterhazy, a character of depravity and more than doubtful morals, protected while the accused is not? Why is an honest soldier such as Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart discredited, overwhelmed, dishonoured? If this is the case we must speak out!"  Newspaper showing Esterhazy Although protected by the General Staff and therefore by the government, Esterhazy was obliged to admit authorship of the Francophobe letters published by Le Figaro. This convinced the Office of the General Staff to find a way to stop the questions, doubts, and the beginnings of demands for justice. The idea was to require Esterhazy to demand a trial and be acquitted, to stop the noise and allow a return to order. Thus, to finally exonerate him, according to the old rule Res judicata pro veritate habetur,[Note 12] Esterhazy was set to appear before a military court on 10 January 1898. A "delayed" closed court[Note 13] trial was pronounced. Esterhazy was notified of the matter on the following day, along with guidance on the defensive line to take. The trial was not normal: the civil trial Mathieu and Lucy Dreyfus[Note 14] requested was denied, and the three handwriting experts decided the writing in the bordereau was not Esterhazy's.[127] The accused was applauded and the witnesses booed and jeered. Pellieux intervened to defend the General Staff without legal substance.[128] The real accused was Picquart, who was dishonoured by all the military protagonists of the affair.[129] Esterhazy was acquitted unanimously the next day after just three minutes of deliberation.[130] With all the cheering, it was difficult for Esterhazy to make his way toward the exit, where some 1,500 people were waiting. By error an innocent person was convicted, but on order the guilty party was acquitted. For many moderate Republicans it was an intolerable infringement of the fundamental values they defended. The acquittal of Esterhazy therefore brought about a change of strategy for the Dreyfusards. Liberalism-friendly Scheurer-Kestner and Reinach, took more combative and rebellious action.[131] In response to the acquittal, large and violent riots by anti-Dreyfusards and antisemites broke out across France. Flush with victory, the General Staff arrested Picquart on charges of violation of professional secrecy following the disclosure of his investigation through his lawyer, who revealed it to Senator Scheurer-Kestner. The colonel, although placed under arrest at Fort Mont-Valérien, did not give up and involved himself further in the affair. When Mathieu thanked him, he replied curtly that he was "doing his duty".[130] Esterhazy benefited from special treatment by the upper echelons of the army, which was inexplicable except for the General Staff's desire to stifle any inclination to challenge the verdict of the court martial that had convicted Dreyfus in 1894. The army declared Esterhazy unfit for service. Esterhazy's flight to England and confession To avoid personal risk Esterhazy shaved off his prominent moustache and went into exile in England.[132] Rachel Beer, editor of The Observer and the Sunday Times, interviewed him twice. He confessed to writing the bordereau under orders from Sandherr in an attempt to frame Dreyfus. She wrote about her interviews in September 1898,[133] reporting his confession and writing a leader column accusing the French military of antisemitism and calling for a retrial for Dreyfus.[134] Esterhazy lived comfortably in England until his death in 1923.[132] |

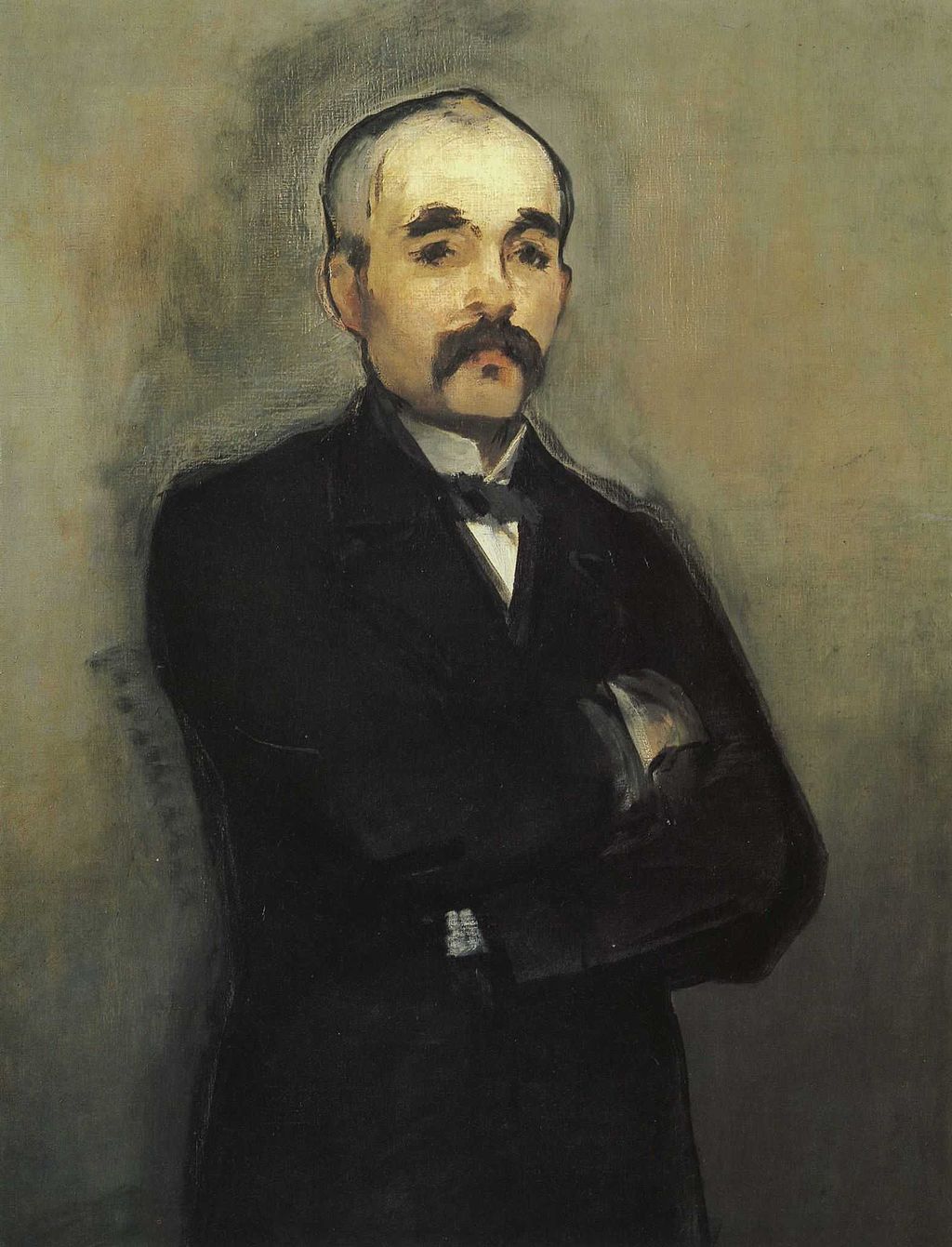

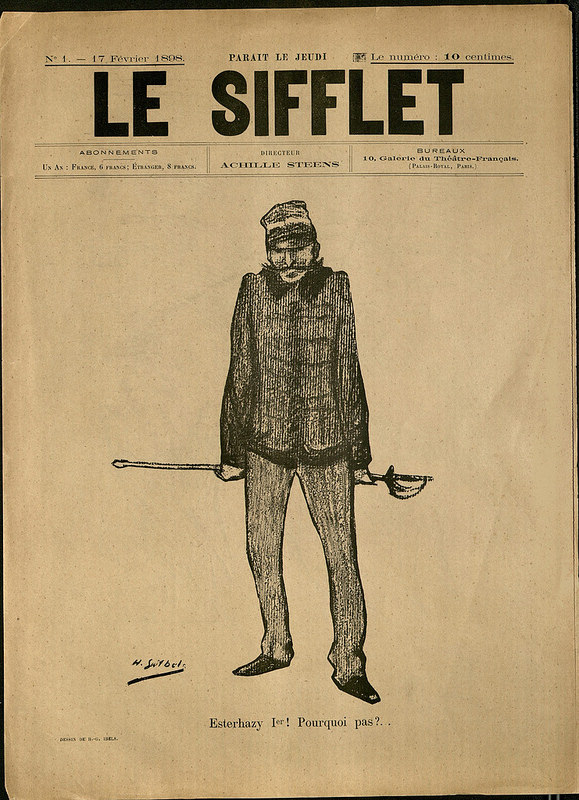

真実が明らかになる(1895年-1897年) ドレフュス一家が事件を暴露し、行動を起こす アルフレッドの兄であるマチュー・ドレフュスは、アルフレッドの無実を確信していた。彼は兄の更生の立役者であり、1894年12月、困難な任務にもかかわらず、時間とエネルギーと財産を費やして、ますます強力な再審請求運動を起こした[95]。 堕落の後、私たちの周りは虚無に包まれた。私たちはもはや他の人たちのような人間ではなく、生者の世界から切り離されているように思えた[96]。 マチューはあらゆる道を試した。フェリックス・フォール大統領の友人であったジベール博士のおかげで、彼はル・アーブルで、催眠術のもとで初めて「秘密の ファイル」について話した女性に出会った[97][98]。この事実は、共和国大統領がジベール博士に私的な会話の中で確認した。 軍部による共謀、策略、囮捜査による逮捕の脅迫にもかかわらず、彼は少しずつ、さまざまな穏健派を説得することに成功した。1896年、ラザールはブ リュッセルで最初のドレフュサールの小冊子を出版した[100]。この出版物は政界や知識人にはほとんど影響を与えなかったが、参謀本部がSRの新しい責 任者であったピッカールの仕業ではないかと疑うほど詳細な内容を含んでいた。 左派の反軍報道機関に少しずつ伝えられる閲兵運動は、暴力的でありながら漠然とした反ユダヤ主義の再来を引き起こした[101]。フランスは圧倒的に反ド レフサードであり、統計課のアンリ少佐は検察側の立件の薄弱さを認識していた。上司である参謀総長のボワデフル将軍とゴンス少将の要請で、彼は再審査の試 みを防ぐためにファイルを拡大する任務を負った。証拠を見つけることができなかったため、彼は事後的に証拠を作ることにした。[要出典]。 真犯人の発見 ピッカートの "敵前逃亡」 主な記事 ジョルジュ・ピカールによるドレフュス事件の調査  アルジェリア第4ティライユールの軍服を着たジョルジュ・ピカール中佐 ジョルジュ・ピカール少佐は1895年7月、サンヘル大佐の病気療養に伴い、軍事情報部(SR)の幕僚長に任命された。1896年3月、ドレフュス事件を 当初から追っていたピッカールは、ドイツ大使館から盗まれた文書を仲介者なしに直接受け取ることを要求した[97]。 [フォン・シュヴァルツコッペンは、黒い鉛筆で書かれた別の手紙の中で、エステルハージとの同じ秘密の関係を明らかにしている[104]。 エステルハージからの手紙を見て、ピッカールは、彼の筆跡がドレフュスを有罪にするために使われた「ボルドロー」の筆跡とまったく同じであることに驚きな がら気づいた。彼は1894年に裁判官たちに渡された「秘密のファイル」を入手し、ドレフュスに不利な証拠がないことに驚き、彼の無実を確信した。その発 見に心を動かされたピッカールは、上官の同意を得ることなく、秘密裏に熱心に調査を行った[105]。 調査の結果、エステルハージが「ボルドロー」に記載された要素を知っていたこと、ドイツ大使館と接触していたことが判明した[106]。 同将校がドイツ人に多くの秘密文書を売っていたことが立証されたが、その価値はかなり低かった[107]。 フェルディナンド・ヴァルサン・エステルハージは、1870年の戦争後に勤務していた元フランス情報局員であった[108]。彼は1877年から1880 年までアンリ少佐と同じ職場で働いていた[109]。人格障害で、硫黄のような評判を持ち、借金で不自由な生活を送っていた彼は、ピッカールに金銭的な理 由で祖国を裏切るように仕向けられた裏切り者であると見なされていた[110]。ピッカールは調査結果を参謀本部に伝えたが、参謀本部は「裁判外の原則の 権威」のもとで彼に反対した。この後、彼自身の副官であったヘンリー少佐の協力を得て、彼をその地位から追い落とすためにあらゆることが行われた。ドレ フュスの有罪判決が重大な誤審である可能性を認めたくなかったのは、主に陸軍上層部であった。メルシエ、ズルリンデン、参謀本部にとって、ドレフュスとエ ステルハージの問題を切り離して考えることは好都合であった[111]。 エステルハージの糾弾とドレフュス主義の進展 ナショナリストのマスコミは、急成長するドレフュス派に対して激しいキャンペーンを展開した。ピッカールはドレフュスを支持するよう先輩たちを説得しよう としたが、参謀本部は聞く耳を持たなかった[注釈 7]。ドレフュスに対する調査が開始され、彼は東部にいるときに監視され、その後「兵役のために」チュニジアに移送された[113]。 このとき、ヘンリー少佐は行動を起こすことを選択した。1896年11月1日、彼は後に「偽ヘンリー」[ヘンリー偽書]と呼ばれる偽の文書を作成し[注 8]、パニツァルディからの普通の手紙のヘッダーと署名を残し、中心的な文章を自分で書いた: 副官がドレフュスを呼び出すと読んだ。ローマからさらに説明を求めるなら、私はユダヤ人と関係を持ったことはないと言うだろう。その通りだ。もし尋ねられたら、そのように答えればよい。 これはかなり粗雑な偽造であった。しかし、ゴンス将軍とボワデフル将軍は、質問することなく、この書簡を大臣のジャン=バティスト・ビヨー将軍に渡した。 ドレフュスの潔白に関する参謀本部の疑念は窓から飛び出した[114]。この発見により、参謀本部はエステルハージを保護し、「何も理解していなかった」 ピッカル大佐を迫害することを決定した[114]。偽アンリ」のことを何も知らなかったピッカルは、すぐに仲間の兵士たちから孤立することになった。アン リ少佐はピッカールの横領を非難し、陰口に満ちた手紙を送った[115]。 ピッカールは書面で抗議し、パリに戻った。 ピッカールは友人の弁護士ルイ・ルブロワに打ち明け、秘密を守ると約束した。しかし、ルブロワは元老院の副議長であるアルザス人のオーギュスト・シェウ ラー=ケストナー(ドレフュスと同じミュルーズ生まれ)に話した。元老院議長はピッカールを引き合いに出すことなく、この件を国の最高権力者に暴露した。 しかし、参謀本部は依然としてピッカールがリークを引き起こしたのではないかと疑っていた。これがピッカート事件の始まりであり、将校に対する参謀本部の 新たな陰謀であった[116]。 アンリ少佐はピッカールの副官であったが、嫉妬にかられ、上司を陥れるために独自の悪意ある作戦を展開した[117]。 彼はさまざまな不正行為(書簡を作成し、それを「ユダヤ人シンジケート」の道具と指定する、ドレフュスの逃亡を手助けしようとする、ピッカールが本当の受 取人の名前を消したと思わせるために「プチ・ブルー」を不正に操作する、ドレフュスを全面的に名指しする書簡を作成する)を行った。 ピッカールの調査と並行して、ドレフュス擁護派は1897年11月、「ボルドロー」の筆者がエステルハージであることを知らされた。マチュー・ドレフュス は、ル・フィガロにボルドローの複製を出版させた。銀行家のカストロは、その文章が自分の債務者であるエステルハージのものであることを正式に確認し、マ チューに伝えた。1897年11月11日、ショイエール=ケストナーとマチュー・ドレフュスが会談した際、二つの捜査方針が一致した。ドレフュスは最終的 にエステルハージが手形の作者であることを確認した。これに基づき、1897年11月15日、マチュー・ドレフュスは陸軍大臣にエステルハージに対する苦 情を申し立てた。1897年末、ピッカールはパリに戻り、ドレフュスの有罪に対する疑念を公表した。ピッカールを排除するための共謀は失敗に終わったよう に思われた[119]。ピッカールの信用を失墜させるために、エステルハージは共和国大統領に苦情の手紙を送ったが、効果はなかった[120]。  1898年、エミール・ゾラ ベルナール・ラザール、マチュー・ドレフュス、ジョゼフ・ライナッハ、オーギュスト・ショイエール=ケストナーらによって率いられたドレフュサール運動は 勢いを増した[121]。 1897年11月中旬にショイエール=ケストナーから資料を知らされたエミール・ゾラは、ドレフュスの無実を確信し、公式に関与することを約束した[注 9] 。この記事は3回シリーズの最初の記事であった[注釈 10]。読者からの大量解約の脅迫に直面した同紙の編集者は、ゾラへの支援を中止した[122]。1897年11月下旬から12月上旬にかけて、徐々に多 くの著名人が再審闘争に参加するようになった。その中には、作家のオクターヴ・ミルボー(彼の最初の記事はゾラの3日後に掲載された)[123]とアナ トール・フランス、学者のルシアン・レヴィ=ブリュール、高等師範学校の司書ルシアン・ヘル(レオン・ブルムとジャン・ジョレスを説得した)、『ラ・ル ヴュ・ブランシュ』[注釈 11]の著者たち(ラザールはタデ・ナタンソン監督を知っていた)、クレマンソー兄弟のアルベールとジョルジュが含まれていた。ブルムは1897年11月 下旬、友人のモーリス・バレスとともに再審を求める嘆願書に署名しようとしたが、バレスはこれを拒否し、12月初旬にはゾラやブルムと決裂し、「知識人」 という言葉を普及させ始めた[124]。この最初の決裂は、1898年1月13日以降の教養あるエリートたちの分裂への序曲であった。 ドレフュス事件はますます多くの議論を占めるようになったが、政界はこのことを必ずしも認識していなかった。ジュール・メリーヌは1897年12月7日の国民議会開会式で、「ドレフュス事件は存在しない。ドレフュス事件は存在しないし、存在しえない」[125]。 エステルハージの裁判と無罪判決  画家エドゥアール・マネによるジョルジュ・クレマンソーの肖像画 ジョルジュ=ガブリエル・ド・ペリュー将軍が捜査を担当した。参謀本部が調査官を巧みに操ったおかげで、調査は短時間で終わった。エステルハージのかつて の愛人であったブーランシー夫人が、10年前にエステルハージがフランスへの憎悪とフランス軍への軽蔑を激しく表明した手紙を『フィガロ』紙に発表するま で、調査は予想通りの結末に向かっていた[126]。軍国主義マスコミは、前例のない反ユダヤ主義キャンペーンを展開し、エステルハージの救援に駆けつけ た。ドレフュサールのマスコミは、強力な新証拠を手にしてこれに反論した。ジョルジュ・クレマンソーは『オロール』紙で、「誰がエステルハージ少佐を守る のか?このフランス軍将校を装った無能なプロイセンを法律で保護するのはやめるべきだ。なぜだ?誰がエステルハージの前で震え上がるのか?どんなオカルト 的な権力が、なぜ恥ずかしげもなく正義の行動に反対するのか?何が邪魔をするのか?なぜエステルハージは、堕落し、モラルも疑わしいにもほどがある人物な のに、被告人は保護され、被告人は保護されないのか?ピッカート中佐のような誠実な兵士が、なぜ信用を失い、圧倒され、不名誉な扱いを受けるのか。もしそ うなら、我々は声を上げなければならない。  エステルハージーを映した新聞 エステルハージは、参謀本部、つまり政府の保護を受けながらも、ル・フィガロ紙に掲載されたフランコフォビア書簡の著者であることを認めざるを得なかっ た。このため参謀本部は、疑問や疑念、正義を求める声の高まりを食い止める方法を考えなければならなくなった。それは、エステルハージに裁判を要求し、無 罪にすることで、騒ぎを収め、秩序を取り戻すことだった。こうして、Res judicata pro veritate habetur[注釈 12]という古いルールに従って、最終的に彼の容疑を晴らすために、エステルハージは1898年1月10日に軍事法廷に出廷することになった。遅延され た」非公開裁判[注釈 13]が宣告された。エステルハージは翌日、取るべき防衛線についての指導とともに、この件について通告を受けた。マチューとルーシー・ドレフュス[注釈 14]が要求した民事裁判は却下され、3人の筆跡鑑定人はボルドローに書かれた文字はエステルハージのものではないと判断した[127]。ペリューは法的 根拠なく参謀本部を擁護するために介入した[128]。 本当の被告人はピッカートであり、彼はこの事件のすべての軍部の主人公たちから不名誉な扱いを受けた[129]。 エステルハージは翌日、わずか3分間の審議の後、満場一致で無罪となった[130]。 歓声の中、エステルハージが1,500人ほどの人々が待つ出口に向かうのは困難だった。 誤って無実の者が有罪になったが、命令により有罪の者は無罪になった。多くの穏健派共和党員にとって、それは彼らが擁護してきた基本的価値観に対する耐え 難い侵害であった。エステルハージの無罪判決は、ドレフュサール派に戦略の変更をもたらした。リベラリズムに親和的なシェウラー=ケストナーとライナッハ は、より闘争的で反抗的な行動をとった[131]。無罪判決に呼応して、反ドレフュサール派と反ユダヤ主義者による大規模で暴力的な暴動がフランス全土で 発生した。 勝利に浮かれていた参謀本部は、弁護士を通じてピッカールの調査を暴露し、ピッカールがそれをショイラー=ケストナー上院議員に暴露したため、職務上の秘 密侵害の容疑でピッカールを逮捕した。大佐はモン・ヴァレリアン要塞で逮捕されたものの、あきらめずにさらに事件に関与した。1894年にドレフュスに有 罪判決を下した軍法会議の評決に異議を唱えようとする気持ちを封じ込めようとする参謀本部の思惑を除けば、エステルハージは陸軍上層部による特別待遇の恩 恵を受けていた。陸軍はエステルハージの軍務不適格を宣言した。 エステルハージのイギリスへの逃亡と自白 身の危険を避けるため、エステルハージは目立つ口髭を剃り落とし、イギリスに亡命した[132]。 オブザーバー』紙と『サンデー・タイムズ』紙の編集者レイチェル・ビアは彼に2度インタビューした。彼はドレフュスに濡れ衣を着せようとして、サンヘルの 命令でボルドローを書いたことを告白した。彼女は1898年9月にインタビューについて書き、彼の告白を報じ、フランス軍の反ユダヤ主義を非難し、ドレ フュスの再審を求めるリーダーコラムを書いた[134]。 |