啓蒙の時代

Age of Enlightenment

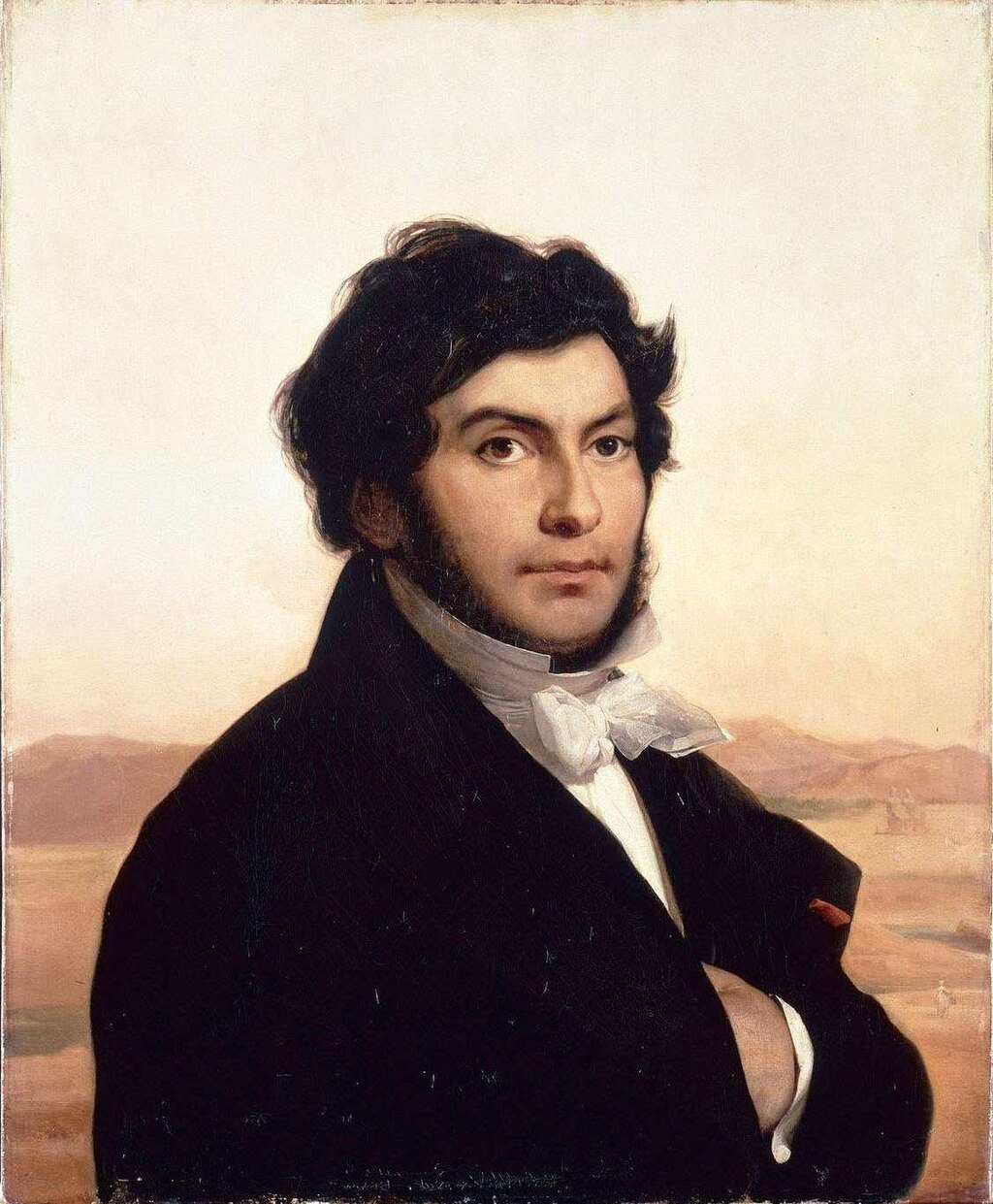

In the Salon of Madame Geoffrin in 1755. Reading of Voltaire's tragedy, The Orphan of China, in the salon of Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin, by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier, c. 1812[a]

1755年、マダム・ジョフルランのサロンにて。マリー・テレーズ・ロデ・ジョフルランのサロンにおけるヴォルテールの悲劇『中国の孤児』の朗読。アニセ・シャルル・ガブリエル・ルモニエ作、約1812年

☆啓蒙時代(Age of

Enlightenment

,理性時代とも呼ばれる)は、ヨーロッパと西洋文明の歴史における一時期である。この時代には、啓蒙主義という [b]

知的[6]かつ文化的[6]な運動が隆盛を極めた。17世紀後半[6]に西ヨーロッパ[7]で始まり、18世紀に頂点を迎えた。その思想はヨーロッパ

[7]全域に広がり、アメリカ大陸やオセアニアの植民地にも及んだ。[8][9][10]

理性、経験的証拠、科学的方法を重視する特徴を持ち、啓蒙主義は個人の自由、宗教的寛容、進歩、自然権の理念を推進した。その思想家たちは立憲政府、政教

分離、社会・政治改革への合理的原則の適用を提唱した。[11][12] [13]

啓蒙思想は、16世紀から17世紀にかけての科学革命を基盤として発展した。ガリレオ・ガリレイ、ヨハネス・ケプラー、フランシス・ベーコン、ピエール・

ガッサンディ、クリスティアン・ホイヘンス、アイザック・ニュートンらによる科学的探究の新手法が確立されたこの革命が、その礎となったのである。哲学的

基盤はルネ・デカルト、トマス・ホッブズ、バルーフ・スピノザ、ジョン・ロックらによって築かれた。彼らの理性、自然権、経験的知識に関する思想は啓蒙思

想の中核となった。啓蒙主義の始まりを特定する時期としては、1637年にデカルトが『方法序説』を出版したことが挙げられる。この著作では、確固たる根

拠がない限りあらゆるものを体系的に疑う方法論が示され、有名な「我思う、故に我あり(Cogito, ergo

sum)」という命題が提示された。また、ニュートンの『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』(1687年)の出版を科学革命の頂点かつ啓蒙主義の始まりとする

見解もある[14][15][16]。ヨーロッパの歴史家たちは伝統的に、その始まりを1715年のフランス国王ルイ14世の死、終わりを1789年のフ

ランス革命勃発と定めてきた。現在では多くの歴史家が啓蒙主義の終焉を19世紀の始まりと位置付け、最も新しい提案では1804年のイマヌエル・カントの

死をその年としている。[17]

| The Age of

Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason) was a period in the history of

Europe and Western civilization[1] during which the Enlightenment,[b]

an intellectual[6] and cultural[6] movement, flourished, emerging in

the late 17th century[6] in Western Europe[7] and reaching its peak in

the 18th century, as its ideas spread more widely across Europe[7] and

into the European colonies, in the Americas and Oceania.[8][9][10]

Characterized by an emphasis on reason, empirical evidence, and

scientific method, the Enlightenment promoted ideals of individual

liberty, religious tolerance, progress, and natural rights. Its

thinkers advocated for constitutional government, the separation of

church and state, and the application of rational principles to social

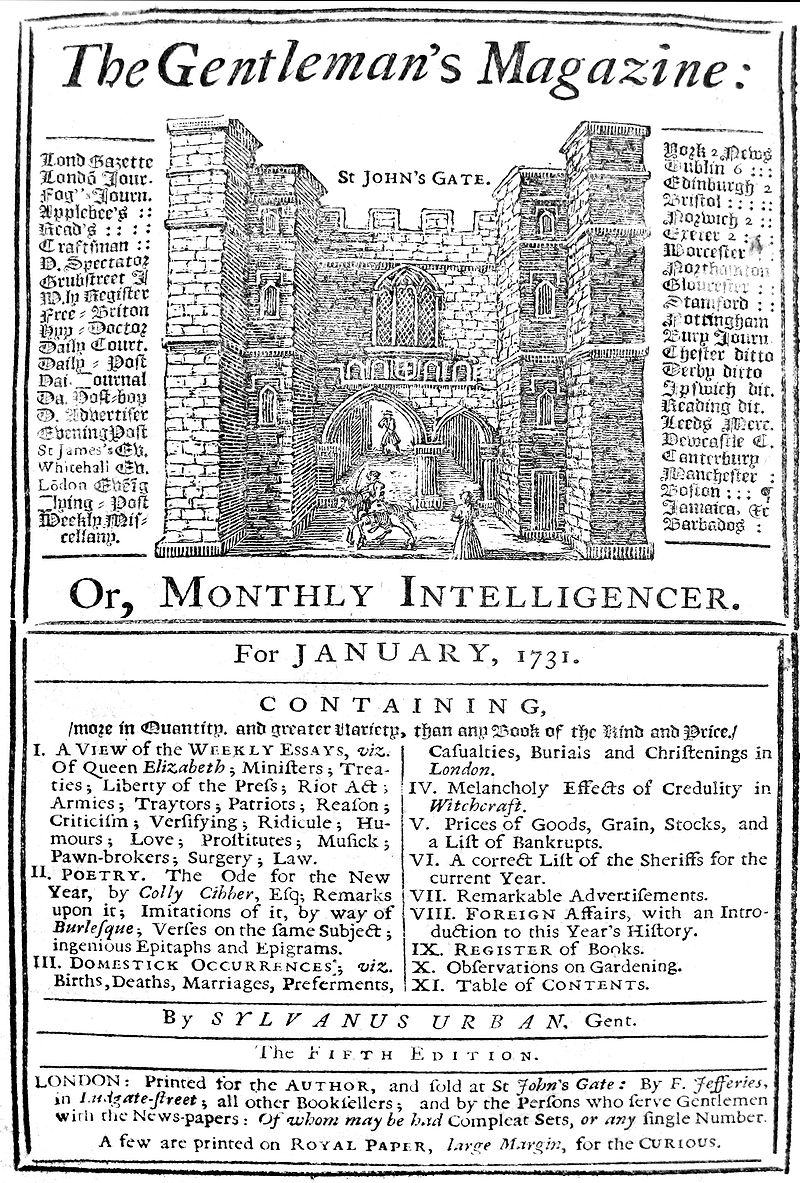

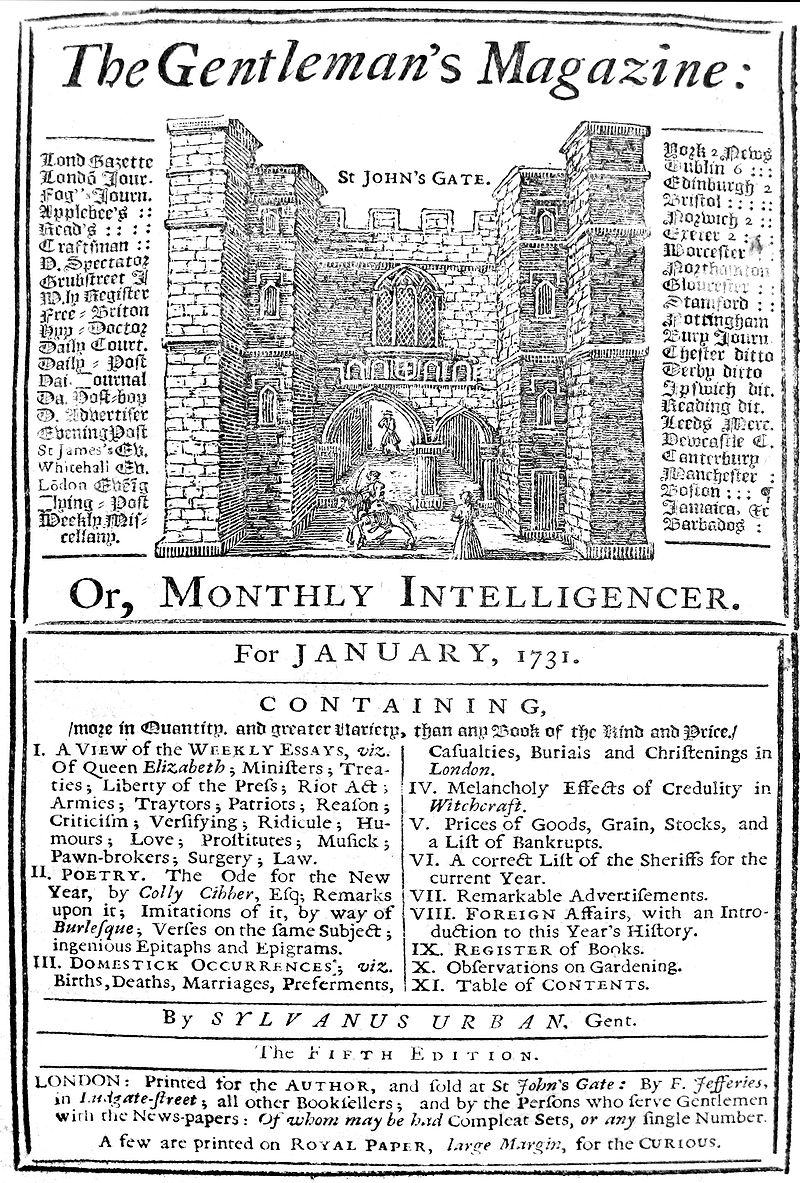

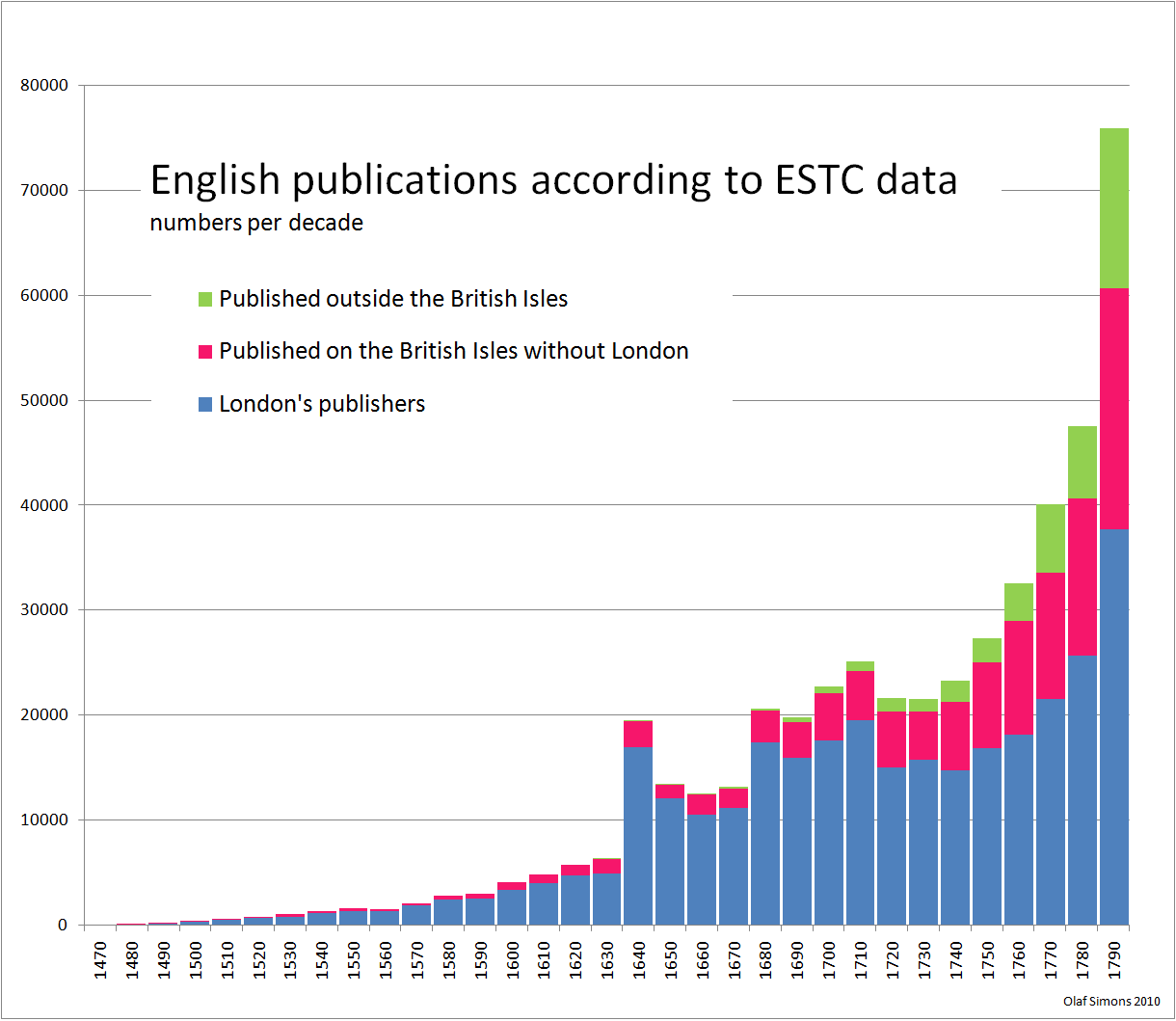

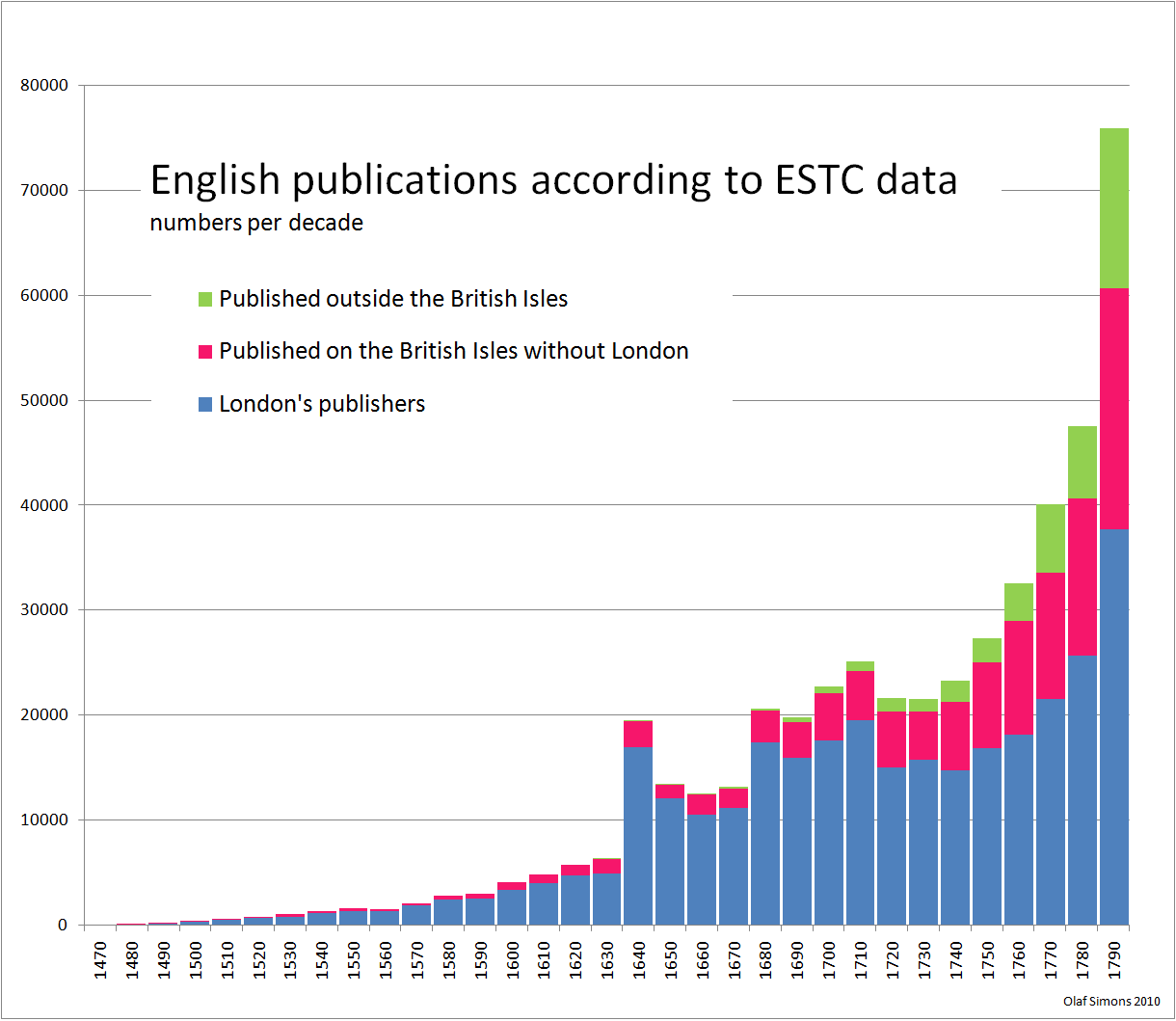

and political reform.[11][12][13] The Enlightenment emerged from and built upon the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, which had established new methods of empirical inquiry through the work of figures such as Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Francis Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. Philosophical foundations were laid by thinkers including René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, and John Locke, whose ideas about reason, natural rights, and empirical knowledge became central to Enlightenment thought. The dating of the period of the beginning of the Enlightenment can be attributed to the publication of Descartes' Discourse on the Method in 1637, with his method of systematically disbelieving everything unless there was a well-founded reason for accepting it, and featuring his famous dictum, Cogito, ergo sum ('I think, therefore I am'). Others cite the publication of Newton's Principia Mathematica (1687) as the culmination of the Scientific Revolution and the beginning of the Enlightenment.[14][15][16] European historians traditionally dated its beginning with the death of Louis XIV of France in 1715 and its end with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. Many historians now date the end of the Enlightenment as the start of the 19th century, with the latest proposed year being the death of Immanuel Kant in 1804.[17] The movement was characterized by the widespread circulation of ideas through new institutions: scientific academies, literary salons, coffeehouses, Masonic lodges, and an expanding print culture of books, journals, and pamphlets. The ideas of the Enlightenment undermined the authority of the monarchy and religious officials and paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries. A variety of 19th-century movements, including liberalism, socialism,[18] and neoclassicism, trace their intellectual heritage to the Enlightenment.[19] The Enlightenment was marked by an increasing awareness of the relationship between the mind and the everyday media of the world,[20] and by an emphasis on the scientific method and reductionism, along with increased questioning of religious dogma—an attitude captured by Kant's essay Answering the Question: What Is Enlightenment?, where the phrase sapere aude ('dare to know') can be found.[21] The central doctrines of the Enlightenment were individual liberty, representative government, the rule of law, and religious freedom, in contrast to an absolute monarchy or single party state and the religious persecution of faiths other than those formally established and often controlled outright by the State. By contrast, other intellectual currents included arguments in favour of anti-Christianity, Deism and Atheism, accompanied by demands for secular states, bans on religious education, suppression of monasteries, the suppression of the Jesuits, and the expulsion of religious orders. The Enlightenment also faced contemporary criticism, later termed the "Counter-Enlightenment" by Sir Isaiah Berlin, which defended traditional religious and political authorities against rationalist critique. |

啓蒙時代(理性時代とも呼ばれる)は、ヨーロッパと西洋文明の歴史にお

ける一時期である。この時代には、啓蒙主義という [b]

知的[6]かつ文化的[6]な運動が隆盛を極めた。17世紀後半[6]に西ヨーロッパ[7]で始まり、18世紀に頂点を迎えた。その思想はヨーロッパ

[7]全域に広がり、アメリカ大陸やオセアニアの植民地にも及んだ。[8][9][10]

理性、経験的証拠、科学的方法を重視する特徴を持ち、啓蒙主義は個人の自由、宗教的寛容、進歩、自然権の理念を推進した。その思想家たちは立憲政府、政教

分離、社会・政治改革への合理的原則の適用を提唱した。[11][12] [13] 啓蒙思想は、16世紀から17世紀にかけての科学革命を基盤として発展した。ガリレオ・ガリレイ、ヨハネス・ケプラー、フランシス・ベーコン、ピエール・ ガッサンディ、クリスティアン・ホイヘンス、アイザック・ニュートンらによる科学的探究の新手法が確立されたこの革命が、その礎となったのである。哲学的 基盤はルネ・デカルト、トマス・ホッブズ、バルーフ・スピノザ、ジョン・ロックらによって築かれた。彼らの理性、自然権、経験的知識に関する思想は啓蒙思 想の中核となった。啓蒙主義の始まりを特定する時期としては、1637年にデカルトが『方法序説』を出版したことが挙げられる。この著作では、確固たる根 拠がない限りあらゆるものを体系的に疑う方法論が示され、有名な「我思う、故に我あり(Cogito, ergo sum)」という命題が提示された。また、ニュートンの『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』(1687年)の出版を科学革命の頂点かつ啓蒙主義の始まりとする 見解もある[14][15][16]。ヨーロッパの歴史家たちは伝統的に、その始まりを1715年のフランス国王ルイ14世の死、終わりを1789年のフ ランス革命勃発と定めてきた。現在では多くの歴史家が啓蒙主義の終焉を19世紀の始まりと位置付け、最も新しい提案では1804年のイマヌエル・カントの 死をその年としている。[17] この運動は、新たな機関——科学アカデミー、文芸サロン、喫茶店、フリーメイソンロッジ、そして書籍・雑誌・パンフレットといった拡大する印刷文化——を 通じた思想の広範な流通によって特徴づけられた。啓蒙思想は君主制や宗教指導者の権威を揺るがし、18世紀から19世紀にかけての政治革命への道を開い た。自由主義、社会主義[18]、新古典主義など19世紀の様々な運動は、その知的源流を啓蒙思想に求める。[19] 啓蒙主義は、精神と世界の日常的媒体[20]との関係に対する認識の高まり、科学的メソッドと還元主義の重視、そして宗教的教義への疑問の増大によって特 徴づけられた。この姿勢はカントの論文『啓蒙とは何か』に表れており、そこには「知れと敢えて言え(sapere aude)」というフレーズが見られる。[21] 啓蒙主義の中核的教義は、個人の自由、代議制政府、法の支配、宗教的自由であった。これらは絶対君主制や一党独裁国家、国家が公式に確立ししばしば直接支 配する宗教以外の信仰に対する迫害と対比される。一方、他の知的潮流には反キリスト教、自然神論、無神論を支持する主張も含まれ、世俗国家の要求、宗教教 育の禁止、修道院の廃止、イエズス会の弾圧、修道会の追放などが伴った。啓蒙主義はまた、後にアイザイア・バーリン卿によって「反啓蒙主義」と称されるよ うになった当時の批判にも直面した。これは合理主義的批判に対して伝統的な宗教的・政治的権威を擁護する立場であった。 |

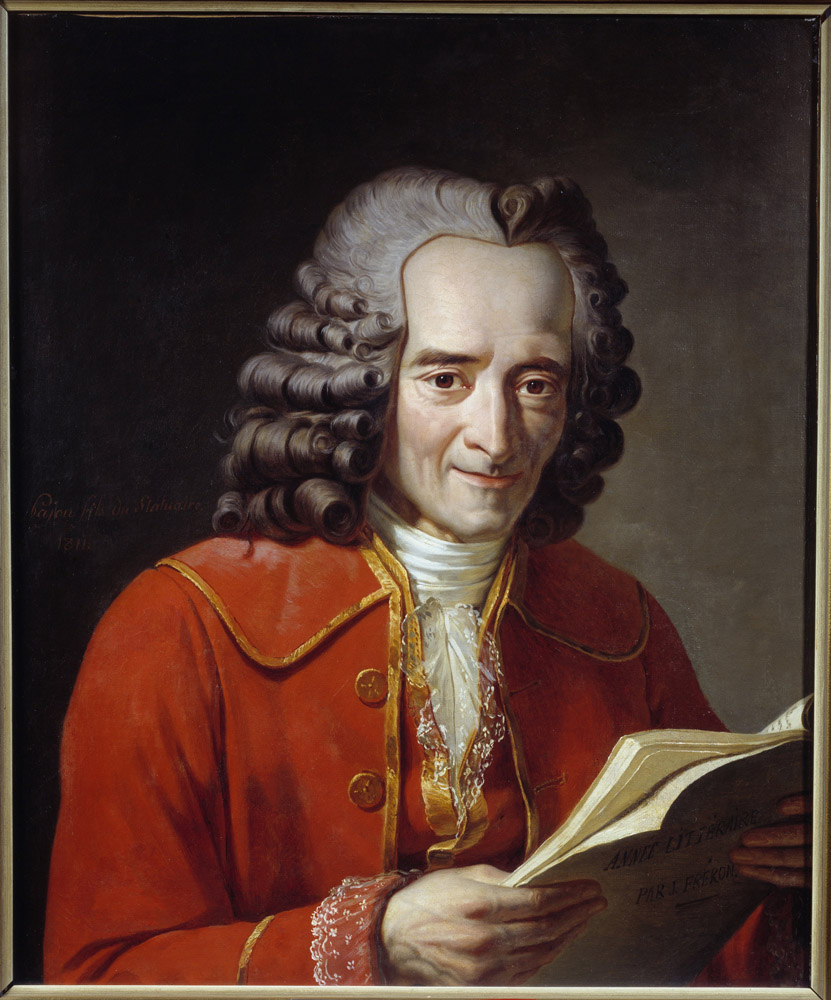

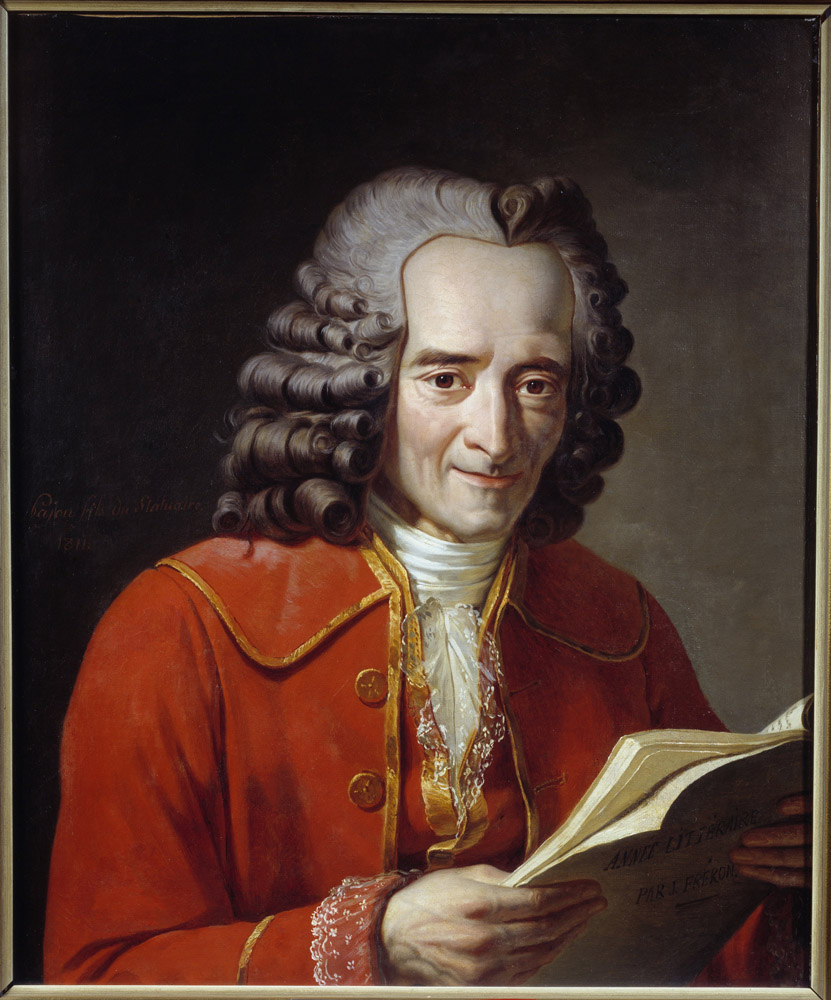

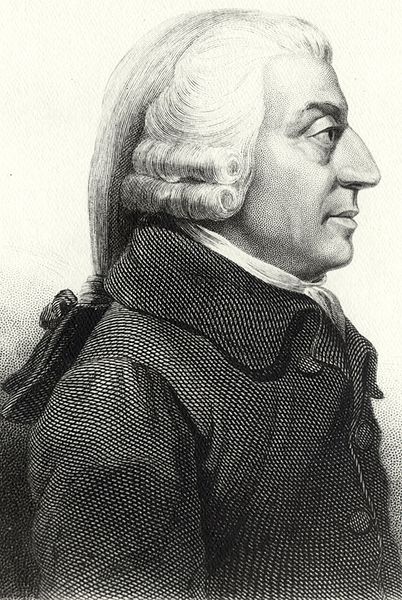

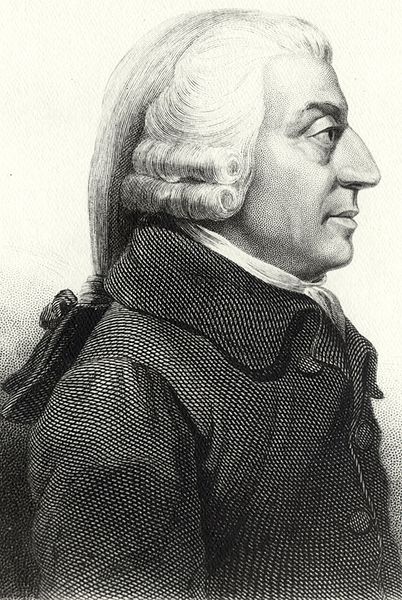

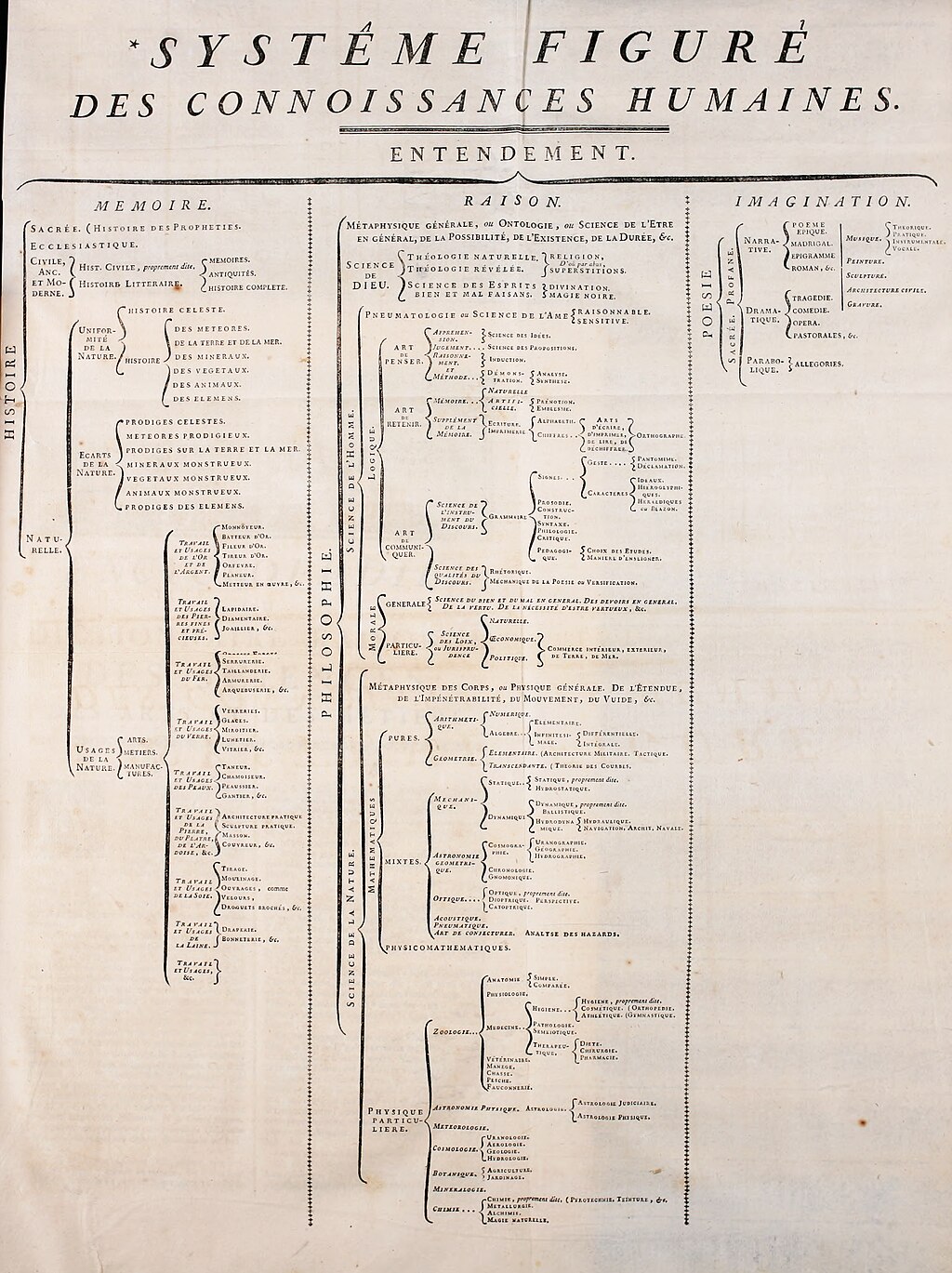

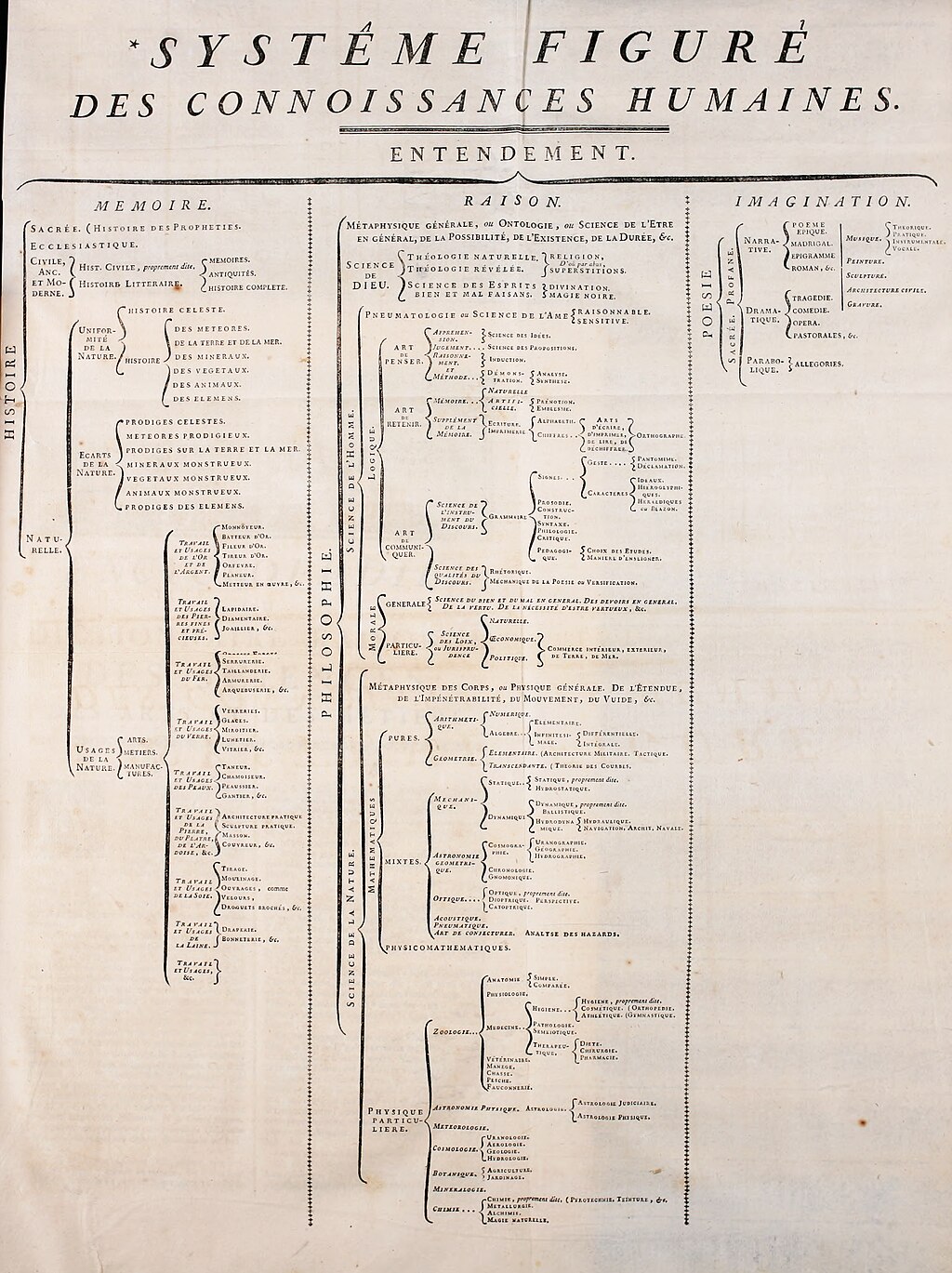

| Influential intellectuals For a more comprehensive list, see List of intellectuals of the Enlightenment. The Age of Enlightenment was preceded by and closely associated with the Scientific Revolution.[22] Earlier philosophers whose work influenced the Enlightenment included Francis Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, Pierre Bayle, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.[23][24] Some of the figures of the Enlightenment included Cesare Beccaria, George Berkeley, Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Lord Monboddo, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Hugo Grotius, and Voltaire.[25] One of the most influential Enlightenment publications was the Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia). Published between 1751 and 1772 in 35 volumes, it was compiled by Diderot, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and a team of 150 others. The Encyclopédie helped spread the ideas of the Enlightenment across Europe and beyond.[26] Other publications of the Enlightenment included Locke's A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) and Two Treatises of Government (1689); Berkeley's A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710), Voltaire's Letters on the English (1733) and Philosophical Dictionary (1764); Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature (1740); Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws (1748); Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality (1754) and The Social Contract (1762); Cesare Beccaria's On Crimes and Punishments (1764); Adam Smith's The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and The Wealth of Nations (1776); and Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781).[citation needed] |

影響力のある知識人 より包括的なリストについては、啓蒙思想家のリストを参照のこと。 啓蒙時代は科学革命に先行し、密接に関連していた。[22] 啓蒙思想に影響を与えた初期の哲学者には、フランシス・ベーコン、ピエール・ガッサンディ、ルネ・デカルト、トマス・ホッブズ、バルーフ・スピノザ、ジョ ン・ロック、ピエール・ベイル、ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツらが含まれる。[23] [24] 啓蒙主義の代表的な人物には、チェーザレ・ベッカリア、ジョージ・バークリー、ドニ・ディドロ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、イマヌエル・カント、モンボド 卿、モンテスキュー、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー、アダム・スミス、ウーゴ・グロティウス、ヴォルテールらがいる。[25] 啓蒙思想で最も影響力のある出版物の一つが『百科全書』(Encyclopédie)だ。1751年から1772年にかけて全35巻で刊行され、ディド ロ、ジャン・ル・ロン・ダルランベール、そして150人以上のチームによって編纂された。『百科全書』は啓蒙思想の理念をヨーロッパ全土およびその外へ広 めるのに貢献した。[26] 啓蒙思想のその他の著作には、ロックの『寛容に関する書簡』(1689年)と『二つの政府論』(1689年)、バークリーの『人間の知識の原理に関する論 考』(1710年)、ヴォルテールの『英国論』(1733年)と『哲学辞典』(1764年)、 ヒュームの『人間本性論』(1740年)、モンテスキューの『法の精神』(1748年)、ルソーの『不平等起源言説』(1754年)と『社会契約論』 (1762年)、 チェーザレ・ベッカリアの『犯罪と刑罰について』(1764年);アダム・スミスの『道徳感情論』(1759年)と『国富論』(1776年);そしてカン トの『純粋理性批判』(1781年)。[出典が必要] |

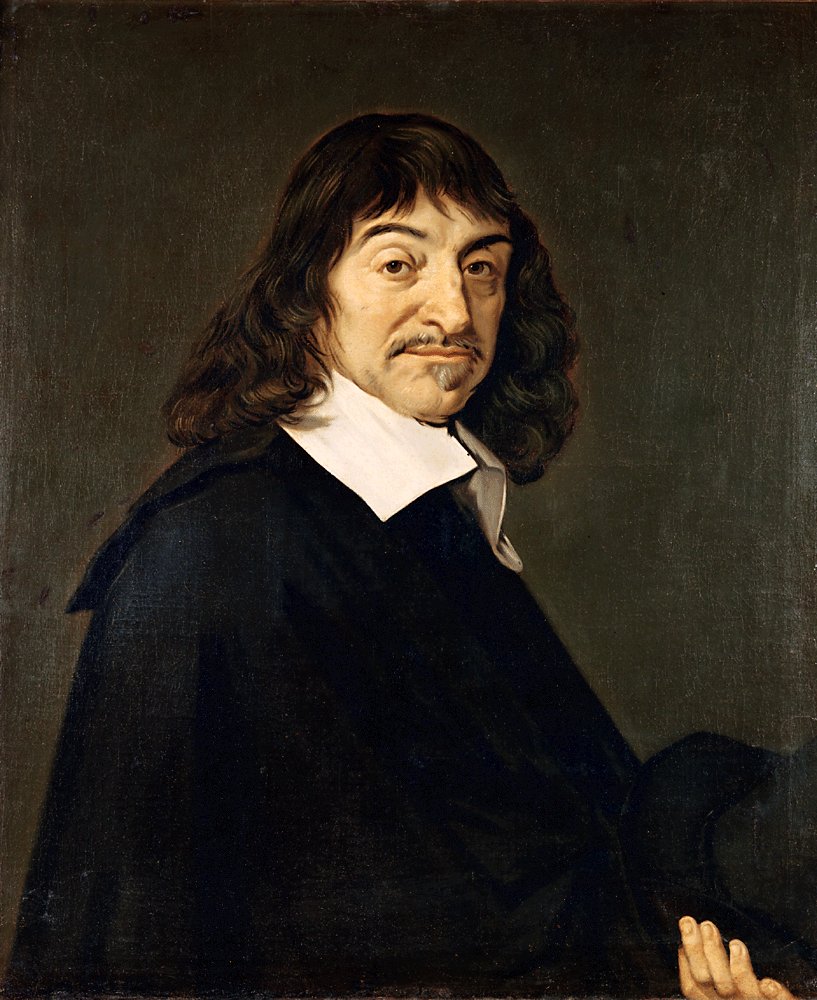

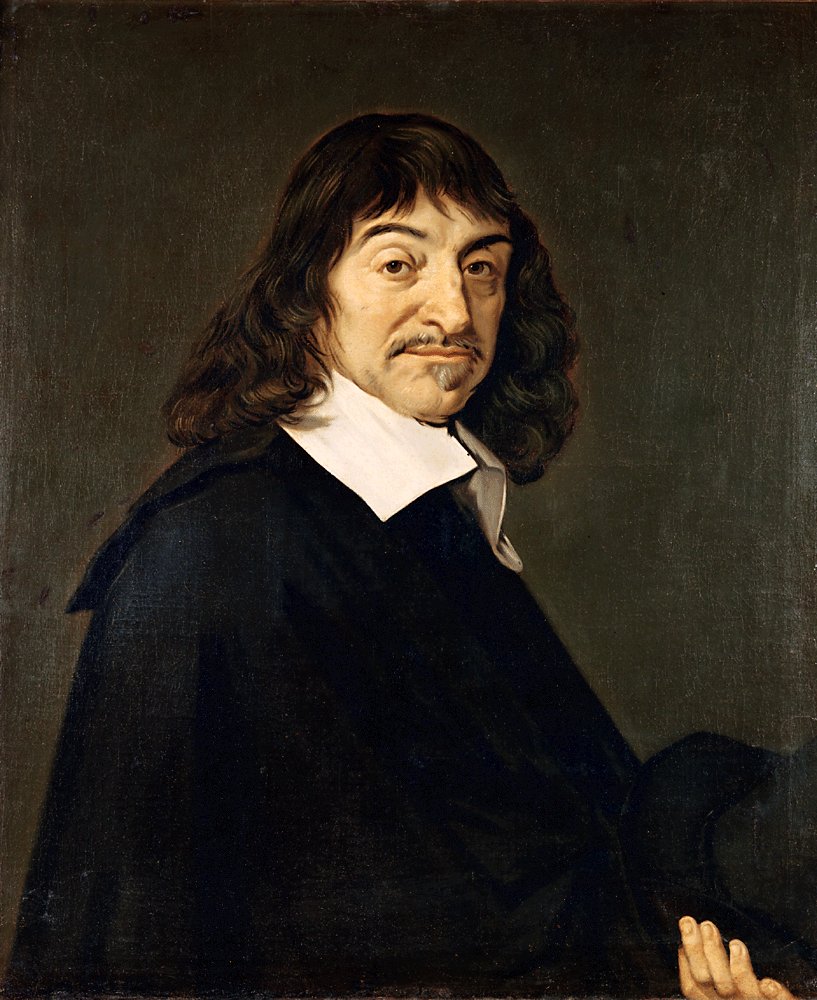

| Topics Philosophy Main article: Enlightenment philosophy  English philosopher Francis Bacon's work is considered foundational to the age of enlightenment  René Descartes, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science Bacon's empiricism and Descartes' rationalist philosophy laid the foundation for enlightenment thinking.[27] Descartes' attempt to construct the sciences on a secure metaphysical foundation was not as successful as his method of doubt applied to philosophy, which led to a dualistic doctrine of mind and matter. His skepticism was refined by Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) and Hume's writings in the 1740s. Descartes' dualism was challenged by Spinoza's uncompromising assertion of the unity of matter in his Tractatus (1670) and Ethics (1677).[28] According to Jonathan Israel, these laid down two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought: first, the moderate variety, following Descartes, Locke, and Christian Wolff, which sought accommodation between reform and the traditional systems of power and faith, and, second, the Radical Enlightenment, inspired by the philosophy of Spinoza, advocating democracy, individual liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority.[29][30] The moderate variety tended to be deistic whereas the radical tendency separated the basis of morality entirely from theology. Both lines of thought were eventually opposed by a conservative Counter-Enlightenment which sought a return to faith.[31] In the mid-18th century, Paris became the center of philosophic and scientific activity challenging traditional doctrines and dogmas. After the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685, the relationship between church and the absolutist government was very strong. The early enlightenment emerged in protest to these circumstances, gaining ground under the support of Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV.[32] Called the Siècle des Lumières, the philosophical movement of the Enlightenment had already started by the early 18th century, when Pierre Bayle launched the popular and scholarly Enlightenment critique of religion. As a skeptic Bayle only partially accepted the philosophy and principles of rationality. He did draw a strict boundary between morality and religion. The rigor of his Dictionnaire Historique et Critique influenced many of the Enlightenment Encyclopédistes.[33] By the mid-18th century the French Enlightenment had found a focus in the project of the Encyclopédie.[32] The philosophical movement was led by Voltaire and Rousseau, who argued for a society based upon reason rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiments and observation. The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution. While the philosophes of the French Enlightenment were not revolutionaries and many were members of the nobility, their ideas played an important part in undermining the legitimacy of the Old Regime and shaping the French Revolution.[34] Francis Hutcheson, a moral philosopher and founding figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, described the utilitarian and consequentialist principle that virtue is that which provides, in his words, "the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers." Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by Hutcheson's protégés in Edinburgh: David Hume and Adam Smith.[35][36] Hume became a major figure in the skeptical philosophical and empiricist traditions of philosophy.  German philosopher Immanuel Kant, one of the most influential figures of Enlightenment and modern philosophy Kant tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom and political authority, as well as map out a view of the public sphere through private and public reason.[37] Kant's work continued to influence German intellectual life and European philosophy more broadly well into the 20th century.[38] Mary Wollstonecraft was one of England's earliest feminist philosophers.[39] She argued for a society based on reason and that women as well as men should be treated as rational beings. She is best known for her work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).[40] |

トピック 哲学 主な記事: 啓蒙主義哲学  英国の哲学者フランシス・ベーコンの著作は、啓蒙主義時代の基礎を築いたとされる  ルネ・デカルトは、近代哲学と科学の誕生における先駆的な人物として広く認められている ベーコンの経験論とデカルトの合理主義哲学は啓蒙思想の基盤を築いた[27]。デカルトが確固たる形而上学的基盤の上に科学を構築しようとした試みは、哲 学に応用された彼の懐疑法ほど成功しなかった。この懐疑法は心と物質の二元論的教義へと導いた。彼の懐疑主義はロックの『人間知性論』(1690年)と ヒュームの1740年代の著作によって洗練された。デカルトの二元論は、スピノザが『論考』(1670年)と『倫理学』(1677年)で示した物質の統一 性に関する断固たる主張によって挑戦を受けた。[28] ジョナサン・イスラエルによれば、これらは啓蒙思想の二つの異なる流れを確立した。第一に、デカルト、ロック、クリスティアン・ヴォルフに続く穏健派は、 改革と権力・信仰の伝統的体系との調和を模索した。第二に、スピノザの哲学に触発された急進的啓蒙主義は、民主主義、個人の自由、表現の自由、宗教的権威 の排除を主張した。[29] [30] 穏健派はデイズム的傾向が強かったのに対し、急進派は道徳の基盤を神学から完全に分離させた。いずれの思想潮流も、信仰回帰を求める保守的な反啓蒙主義に よって最終的に対抗された。[31] 18世紀半ば、パリは伝統的な教義やドグマに挑む哲学・科学活動の中心地となった。1685年のフォンテーヌブロー勅令以降、教会と絶対主義政府の関係は 極めて強固だった。初期啓蒙主義はこうした状況への抗議として台頭し、ルイ15世の愛人ポンパドゥール夫人の支援を得て勢力を拡大した。[32] 「啓蒙の世紀」と呼ばれるこの哲学運動は、18世紀初頭には既に始まっていた。ピエール・ベイルが、大衆的かつ学術的な啓蒙主義的宗教批判を展開したのが その端緒である。懐疑主義者であったベイルは、合理性の哲学と原理を部分的にしか受け入れなかった。彼は道徳と宗教の間に厳格な境界線を引いた。彼の『歴 史的批判辞典』の厳密さは、多くの啓蒙主義的百科事典編纂者たちに影響を与えた。[33] 18世紀半ばまでに、フランス啓蒙主義は『百科全書』プロジェクトに焦点を定めた。[32] この哲学的運動はヴォルテールとルソーが主導し、信仰やカトリック教義ではなく理性に基づく社会、自然法に基づく新たな市民秩序、実験と観察に基づく科学 を主張した。政治哲学者モンテスキューは政府における三権分立の概念を導入し、この考えはアメリカ合衆国憲法の起草者たちに熱狂的に採用された。フランス 啓蒙思想家たちは革命家ではなく、多くが貴族階級に属していたが、彼らの思想は旧体制の正当性を揺るがしフランス革命を形作る上で重要な役割を果たした。 道徳哲学者でありスコットランド啓蒙思想の創始者であるフランシス・ハッチェソンは、功利主義的・結果主義的原理を「最大の多数に最大の幸福をもたらすも のこそが徳である」と表現した。科学的メソッド(知識・証拠・経験・因果関係の本質)の多くと、科学と宗教の関係に対する現代的見解の幾つかは、ハッチェ ソンのエディンバラにおける弟子たちによって発展させた。デイヴィッド・ヒュームとアダム・スミスである。[35][36] ヒュームは懐疑主義的哲学と経験主義的哲学の伝統における主要人物となった。  啓蒙思想および近代哲学において最も影響力のある人物の一人であるドイツの哲学者イマヌエル・カント カントは、合理主義と宗教的信念、個人の自由と政治的権威の調和を図るとともに、私的理性と公的理性を介した公共圏の構想を提示しようとした。[37] カントの思想は20世紀に至るまで、ドイツの知的生活やより広範なヨーロッパ哲学に影響を与え続けた。[38] メアリー・ウルストンクラフトはイングランド初期のフェミニスト哲学者の一人であった。[39] 彼女は理性に基づく社会を主張し、女性も男性と同様に理性的な存在として扱われるべきだと論じた。彼女の代表作『女性の権利の擁護』(1792年)で最も よく知られている。[40] |

| Science Main article: Science in the Age of Enlightenment Science played an important role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favour of the development of free speech and thought.[41] There were immediate practical results. The experiments of Antoine Lavoisier were used to create the first modern chemical plants in Paris, and the experiments of the Montgolfier brothers enabled them to launch the first manned flight in a hot air balloon in 1783.[42] Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism and rational thought and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress. The study of science, under the heading of natural philosophy, was divided into physics and a conglomerate grouping of chemistry and natural history, which included anatomy, biology, geology, mineralogy, and zoology.[43] As with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were not seen universally: Rousseau criticized the sciences for distancing man from nature and not operating to make people happier.[44] Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Scientific academies and societies grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific knowledge, in contrast to the scholasticism of the university.[45] Some societies created or retained links to universities, but contemporary sources distinguished universities from scientific societies by claiming that the university's utility was in the transmission of knowledge while societies functioned to create knowledge.[46] As the role of universities in institutionalized science began to diminish, learned societies became the cornerstone of organized science. Official scientific societies were chartered by the state to provide technical expertise.[47] Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members and the administration of the society.[48] In the 18th century, a very large number of official academies and societies were founded in Europe; by 1789 there were over 70 official scientific societies. In reference to this growth, Bernard de Fontenelle coined the term "the Age of Academies" to describe the 18th century.[49] Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population. Philosophes introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the Encyclopédie and the popularization of Newtonianism by Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet. Some historians have marked the 18th century as a drab period in the history of science.[50] The century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine, mathematics, and physics; the development of biological taxonomy; a new understanding of magnetism and electricity; and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.[citation needed] The influence of science began appearing more commonly in poetry and literature. While some societies were established with ties to universities or maintained existing ones contemporary sources often distinguished between the two, asserting that universities primarily served to transmit knowledge, whereas scientific societies were oriented toward the creation of new knowledge.[51] James Thomson penned his "Poem to the Memory of Newton," which mourned the loss of Newton and praised his science and legacy.[52] |

科学 主な記事: 啓蒙時代の科学 科学は啓蒙主義の言説と思想において重要な役割を果たした。多くの啓蒙主義の作家や思想家は科学の背景を持ち、科学の進歩を宗教や伝統的権威の打倒と結び つけ、言論と思想の自由の発展を支持した。[41] これには即時の実践的成果があった。アントワーヌ・ラヴォアジエの実験はパリに最初の近代的化学工場を設立する基盤となり、モンゴルフィエ兄弟の実験は 1783年に熱気球による初の有人飛行を実現させた。[42] 大まかに言えば、啓蒙主義の科学は経験主義と合理的な思考を高く評価し、啓蒙主義の進歩と発展という理想に深く根ざしていた。自然哲学の枠組みにおける科 学研究は、物理学と、解剖学・生物学・地質学・鉱物学・動物学を含む化学と自然史の複合分野に分けられていた[43]。啓蒙思想の多くの見解と同様、科学 の恩恵は普遍的に認識されていなかった。ルソーは科学が人間を自然から遠ざけ、人民の幸福を増進しないとして批判した。[44] 啓蒙時代の科学は、大学に代わって科学研究開発の中心地となった科学協会やアカデミーが主導した。これらの組織は科学専門職の成熟を支える基盤でもあっ た。科学アカデミーや協会は、大学の学究主義とは対照的に、科学的知識の創造者として科学革命から発展した。[45] 一部の学会は大学との連携を創出または維持したが、当時の資料は大学と科学学会を区別し、大学の有用性は知識の伝達にあるのに対し、学会は知識を創造する 機能を持つと主張した。[46] 制度化された科学における大学の役割が減少し始めると、学術団体が組織化された科学の礎となった。公式の科学学会は国家から認可を受け、技術的専門知識を 提供した。[47] ほとんどの学会は、自らの出版物の監督、新会員の選出、運営管理を許可された。[48] 18世紀には、ヨーロッパで非常に多くの公認アカデミーや学会が設立された。1789年までに70以上の公認科学学会が存在した。この成長を指して、ベル ナール・ド・フォンテネルは18世紀を「アカデミーの時代」と称した。[49] もう一つの重要な進展は、識字率の向上に伴い科学が一般大衆に普及したことだ。哲学者たちは『百科全書』やヴォルテール、エミリー・デュ・シャトレによる ニュートン力学の普及を通じて、多くの科学的理論を大衆に紹介した。一部の歴史家は18世紀を科学史における停滞期と位置づけている。[50] この世紀には医学・数学・物理学の実践が著しく進歩し、生物分類学が発展し、磁気と電気の新たな理解が生まれ、化学が学問として成熟して現代化学の基礎が 築かれた。[出典必要] 科学の影響は詩や文学にもより頻繁に現れ始めた。大学と結びついた学会が設立されたり既存のものが維持されたりした一方で、当時の資料はしばしば両者を区 別し、大学は主に知識の伝達に役立つのに対し、科学学会は新たな知識の創造に向けられていると主張していた。[51] ジェームズ・トムソンは「ニュートンの追悼の詩」を執筆し、ニュートンの死を悼み、その科学と遺産を称賛した。[52] |

Sociology, economics, and law Cesare Beccaria, father of classical criminal theory Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a "science of man,"[53] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Modern sociology largely originated from this movement,[54] and Hume's philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison (and thus the U.S. Constitution), and as popularised by Dugald Stewart was the basis of classical liberalism.[55] In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, often considered the first work on modern economics as it had an immediate impact on British economic policy that continues into the 21st century.[56] It was immediately preceded and influenced by Anne Robert Jacques Turgot's drafts of Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766). Smith acknowledged indebtedness and possibly was the original English translator.[57] Beccaria, a jurist, criminologist, philosopher, and politician and one of the great Enlightenment writers, became famous for his masterpiece Dei delitti e delle pene (Of Crimes and Punishments, 1764). His treatise, translated into 22 languages,[58] condemned torture and the death penalty and was a founding work in the field of penology and the classical school of criminology by promoting criminal justice. Francesco Mario Pagano wrote important studies such as Saggi politici (Political Essays, 1783); and Considerazioni sul processo criminale (Considerations on the Criminal Trial, 1787), which established him as an international authority on criminal law.[59] |

社会学、経済学、法学 古典的犯罪理論の父、チェーザレ・ベッカリア ヒュームやその他のスコットランド啓蒙思想家たちは「人間科学」を発展させた[53]。これは、ジェームズ・バーネット、アダム・ファーガソン、ジョン・ ミラー、ウィリアム・ロバートソンなどの著作に歴史的に表現されており、彼らは皆、古代や原始文化における人間の行動に関する科学的研究と、近代化の決定 的な力に対する強い認識とを融合させた。現代社会学は、この運動に大きく起因している[54]。また、ジェームズ・マディソン(ひいてはアメリカ合衆国憲 法)に直接影響を与えたヒュームの哲学的概念は、ダガルド・スチュワートによって普及し、古典的自由主義の基礎となった[55]。 1776年、アダム・スミスは『国富論』を出版した。この著作は、21世紀に至るまで英国の経済政策に直接的な影響を与えたことから、現代経済学の最初の 著作とよく考えられている[56]。この著作は、アン・ロベール・ジャック・トゥルゴの『富の形成と分配に関する考察』(1766年)の草稿に先行し、そ の影響を受けた。スミスは、その恩義を認め、おそらくは最初の英語翻訳者であった。[57] ベッカリアは、法学者、犯罪学者、哲学者、政治家であり、啓蒙思想の偉大な作家の一人である。彼の傑作『犯罪と刑罰』(1764年)で有名になった。この 論文は22の言語に翻訳され[58]、拷問と死刑を非難し、刑事司法を推進することで、刑罰学と古典派犯罪学の分野における基礎的な著作となった。フラン チェスコ・マリオ・パガーノは『政治論集』(1783年)や『刑事裁判に関する考察』(1787年)といった重要な研究を著し、刑法学における国際的権威 としての地位を確立した[59]。 |

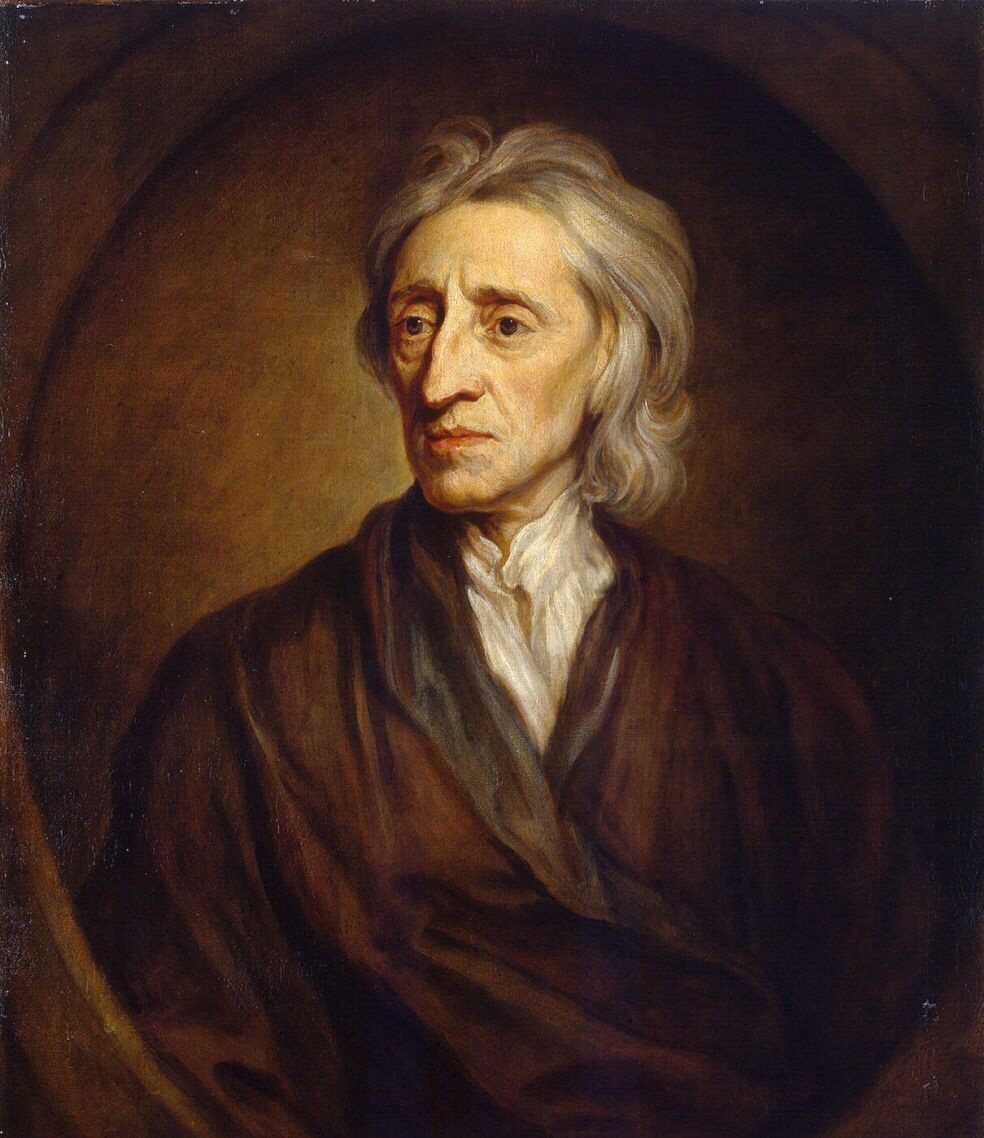

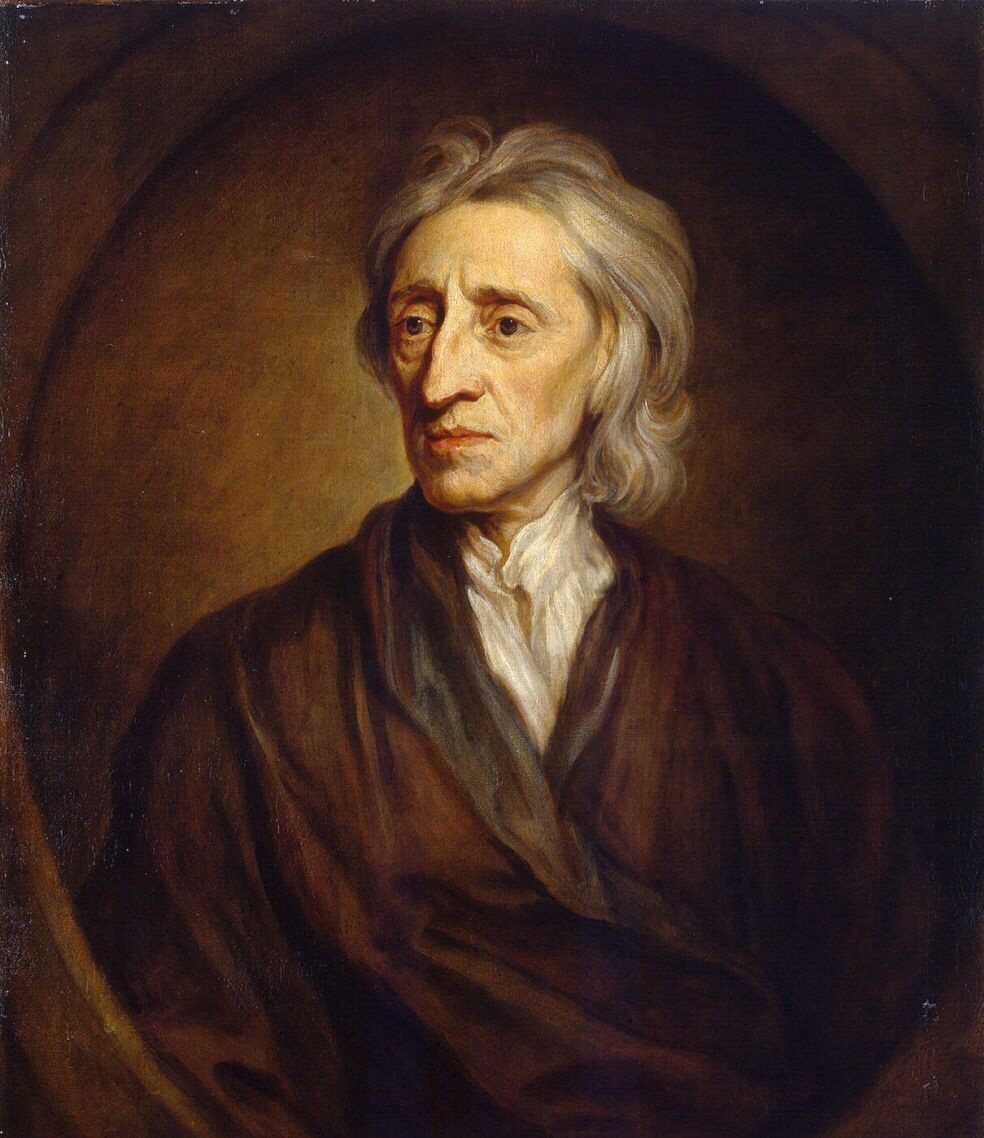

| Politics The Enlightenment has long been seen as the foundation of modern Western political and intellectual culture.[60] The Enlightenment brought political modernization to the West, in terms of introducing democratic values and institutions and the creation of modern, liberal democracies. This thesis has been widely accepted by scholars and has been reinforced by the large-scale studies by Robert Darnton, Roy Porter, and, most recently, by Jonathan Israel.[61][62] Enlightenment thought was deeply influential in the political realm. European rulers such as Catherine II of Russia, Joseph II of Austria, and Frederick II of Prussia tried to apply Enlightenment thought on religious and political tolerance, which became known as enlightened absolutism.[25] Many of the major political and intellectual figures behind the American Revolution associated themselves closely with the Enlightenment: Benjamin Franklin visited Europe repeatedly and contributed actively to the scientific and political debates there and brought the newest ideas back to Philadelphia; Thomas Jefferson closely followed European ideas and later incorporated some of the ideals of the Enlightenment into the Declaration of Independence; and Madison incorporated these ideals into the U.S. Constitution during its framing in 1787.[63] Theories of government  Philosopher John Locke argued that the authority of government stems from a social contract based on natural rights. According to Locke, the authority of government was limited and required the consent of the governed. Locke, one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers,[64] based his governance philosophy on social contract theory, a subject that permeated Enlightenment political thought. English philosopher Thomas Hobbes ushered in this new debate with his work Leviathan in 1651. Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual, the natural equality of all men, the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state), the view that all legitimate political power must be "representative" and based on the consent of the people, and a liberal interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.[65] Both Locke and Rousseau developed social contract theories in Two Treatises of Government and Discourse on Inequality, respectively. While quite different works, Locke, Hobbes, and Rousseau agreed that a social contract, in which the government's authority lies in the consent of the governed,[66] is necessary for man to live in civil society. Locke defines the state of nature as a condition in which humans are rational and follow natural law, in which all men are born equal and with the right to life, liberty, and property. However, when one citizen breaks the law of nature both the transgressor and the victim enter into a state of war, from which it is virtually impossible to break free. Therefore, Locke said that individuals enter into civil society to protect their natural rights via an "unbiased judge" or common authority, such as courts. In contrast, Rousseau's conception relies on the supposition that "civil man" is corrupted, while "natural man" has no want he cannot fulfill himself. Natural man is only taken out of the state of nature when the inequality associated with private property is established.[67] Rousseau said that people join into civil society via the social contract to achieve unity while preserving individual freedom. This is embodied in the sovereignty of the general will, the moral and collective legislative body constituted by citizens.[citation needed] Locke is known for his statement that individuals have a right to "Life, Liberty, and Property," and his belief that the natural right to property is derived from labor. Tutored by Locke, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, wrote in 1706: "There is a mighty Light which spreads its self over the world especially in those two free Nations of England and Holland; on whom the Affairs of Europe now turn."[68] Locke's theory of natural rights has influenced many political documents, including the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the French National Constituent Assembly's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Some philosophes argued that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to apply rationality to every problem is considered the essential change.[69] Although much of Enlightenment political thought was dominated by social contract theorists, Hume and Ferguson criticized this camp. Hume's essay Of the Original Contract argues that governments derived from consent are rarely seen and civil government is grounded in a ruler's habitual authority and force. It is precisely because of the ruler's authority over-and-against the subject that the subject tacitly consents, and Hume says that the subjects would "never imagine that their consent made him sovereign," rather the authority did so.[70] Similarly, Ferguson did not believe citizens built the state, rather polities grew out of social development. In his 1767 An Essay on the History of Civil Society, Ferguson uses the four stages of progress, a theory that was popular in Scotland at the time, to explain how humans advance from a hunting and gathering society to a commercial and civil society without agreeing to a social contract. Both Rousseau's and Locke's social contract theories rest on the presupposition of natural rights, which are not a result of law or custom but are things that all men have in pre-political societies and are therefore universal and inalienable. The most famous natural right formulation comes from Locke's Second Treatise, when he introduces the state of nature. For Locke, the law of nature is grounded on mutual security or the idea that one cannot infringe on another's natural rights, as every man is equal and has the same inalienable rights. These natural rights include perfect equality and freedom, as well as the right to preserve life and property. Locke argues against indentured servitude on the basis that enslaving oneself goes against the law of nature because a person cannot surrender their own rights: freedom is absolute, and no one can take it away. Locke argues that one person cannot enslave another because it is morally reprehensible, although he introduces a caveat by saying that enslavement of a lawful captive in time of war would not go against one's natural rights. |

政治 啓蒙主義は、長い間、近代西洋の政治的・知的文化の基盤と見なされてきた。[60] 啓蒙主義は、民主主義的価値観や制度の導入、そして近代的自由民主主義国家の創出という点で、西洋に政治的近代化をもたらした。この説は学者たちに広く受 け入れられており、ロバート・ダントン、ロイ・ポーター、そして最近ではジョナサン・イスラエルによる大規模な研究によってさらに補強されている[61] [62]。啓蒙思想は政治の分野にも深い影響を与えた。ロシアのエカチェリーナ2世、オーストリアのヨーゼフ2世、プロイセンのフリードリヒ2世などの ヨーロッパの支配者たちは、宗教的・政治的寛容に関する啓蒙思想を適用しようとし、それは啓蒙絶対主義として知られるようになった。[25] アメリカ独立革命の背後にいた主要な政治家や知識人の多くは、啓蒙思想と密接な関係があった。ベンジャミン・フランクリンはヨーロッパを繰り返し訪問し、 その科学や政治に関する議論に積極的に貢献し、最新の思想をフィラデルフィアに持ち帰った。トーマス・ジェファーソンはヨーロッパの思想を注視し、後に啓 蒙思想の理想の一部を独立宣言に盛り込んだ。また、ジェームズ・マディソンは、1787年の憲法制定の際に、これらの理想を合衆国憲法に盛り込んだ。 [63] 政府の理論  哲学者ジョン・ロックは、政府の権威は自然権に基づく社会契約に由来すると主張した。ロックによれば、政府の権威は限定的であり、被統治者の同意を必要とした。 啓蒙思想家の中でも最も影響力のある一人であるロック[64]は、その統治哲学を社会契約論に基盤を置いた。この主題は啓蒙主義の政治思想全体に浸透して いた。英国の哲学者トマス・ホッブズは1651年の著作『リヴァイアサン』でこの新たな議論を導いた。ホッブズはまた、ヨーロッパ自由主義思想の基礎とな るいくつかの概念を発展させた。個人の権利、全人類の自然的平等、政治秩序の人為的性格(後に市民社会と国家の区別へと発展)、全ての正当な政治権力は 「代表制」であり人民の同意に基づくべきという見解、そして法律が明示的に禁止していない限り人々を自由に行動させるという自由主義的法解釈である。 [65] ロックとルソーはそれぞれ『二論』と『不平等言説』において社会契約論を展開した。両者の著作は大きく異なるが、ロック、ホッブズ、ルソーは、政府の権威 が被統治者の同意に由来する社会契約[66]が、人間が市民社会で生きるために必要である点で一致していた。ロックは自然状態を、人間が理性的に自然法に 従う状態と定義する。そこでは全ての人が平等に生まれ、生命・自由・財産の権利を有する。しかし一人の市民が自然法を破ると、違反者と被害者の双方が戦争 状態に陥り、そこから脱することは事実上不可能となる。したがってロックは、個人が自然権を守るために「公平な裁判官」や裁判所のような共通の権威を通じ て市民社会に入るのだと述べた。これに対しルソーの構想は、「市民的人間」は堕落しているが、「自然的人間」は自ら満たせない欲求を持たないという前提に 依拠する。自然的人間は、私有財産に伴う不平等が確立された時にのみ自然状態から引き離されるのだ。[67] ルソーは、人民は個人の自由を保ちながら団結を達成するために、社会契約を通じて市民社会に参加すると述べた。これは、市民によって構成される道徳的かつ 集団的な立法機関である、一般意志の主権に体現されている。 ロックは、個人には「生命、自由、財産」に対する権利があるとの主張、および財産に対する自然権は労働から派生するとの信念で知られている。ロックの指導 を受けた、第3代シャフトズベリー伯爵アンソニー・アシュリー・クーパーは、1706年に次のように記している。「世界、特にヨーロッパの情勢が今、その 行方を左右している、イングランドとオランダという二つの自由な国民の上に、強大な光が降り注いでいる」 [68] ロックの自然権理論は、アメリカ独立宣言やフランス国民憲法制定議会による「人権宣言」など、多くの政治文書に影響を与えた。 一部の哲学者たちは、権利の契約的基盤の確立が、市場メカニズムと資本主義、科学的方法、宗教的寛容、そして民主的な手段による自治共和国としての国民の 組織化につながるだろうと主張した。この見解では、特に哲学者たちがあらゆる問題に合理性を適用する傾向が、本質的な変化と考えられている。 啓蒙主義の政治思想の多くは社会契約論者によって支配されていたが、ヒュームとファーガソンはこの陣営を批判した。ヒュームの論文『原契約について』は、 同意に基づいて成立した政府はめったに見られず、市民政府は支配者の慣習的な権威と力に基づいて成立していると論じている。支配者が被支配者に対して持つ 権威があるからこそ、被支配者は暗黙のうちに同意するのだ。ヒュームは、被支配者は「自分たちの同意が支配者を君主にしたとは決して考えない」と述べ、む しろ権威がそうさせたのだと主張している[70]。同様に、ファーガソンも、市民が国家を構築したとは考えておらず、むしろ政治体制は社会の発展から生ま れたと主張した。1767年の『市民社会の歴史に関するエッセイ』の中で、ファーガソンは、当時スコットランドで流行していた進歩の4段階説を用いて、人 間が社会契約に合意することなく、狩猟採集社会から商業社会、市民社会へとどのように進歩したかを説明している。 ルソーとロックの社会契約論は、いずれも自然権という前提に基づいている。自然権とは、法律や慣習の結果ではなく、政治社会以前のすべての人が持つもので あり、したがって普遍的かつ不可侵のものである。最も有名な自然権の定式化は、ロックが自然状態を紹介した『第二論考』にある。ロックにとって自然法は相 互安全、すなわち全ての人が平等で同じ不可譲の権利を持つ以上、他者の自然権を侵害してはならないという考えに根ざしている。これらの自然権には完全な平 等と自由、そして生命と財産の保持権が含まれる。 ロックは、契約奴隷制に反対する論拠として、自らを奴隷化することは自然法に反すると主張する。なぜなら、人格は自らの権利を放棄することはできず、自由 は絶対的であり、誰もそれを奪うことはできないからだ。ロックは、一人の人格が別の人格を奴隷化することは道徳的に許されない行為だと論じる。ただし、戦 争時に合法的に捕虜とした者を奴隷化することは、自然権に反しないという留保条件を付している。 |

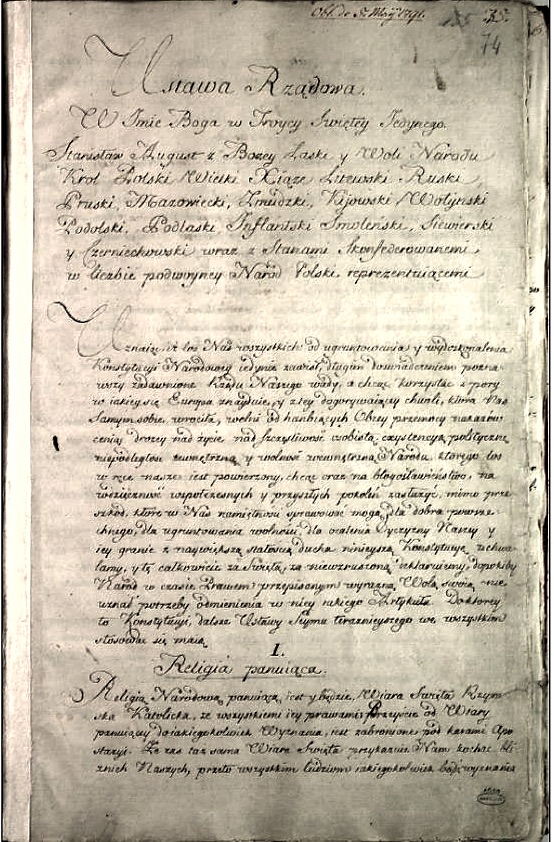

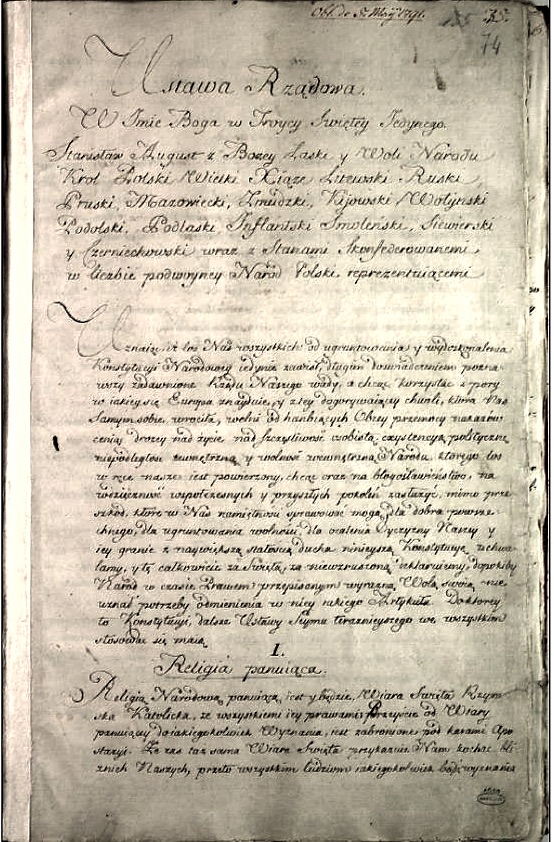

| Enlightened absolutism Main article: Enlightened absolutism  The Marquis of Pombal, as the head of the government of Portugal, implemented sweeping socio-economic reforms. The leaders of the Enlightenment were not especially democratic, as they more often look to absolute monarchs as the key to imposing reforms designed by the intellectuals. Voltaire despised democracy and said the absolute monarch must be enlightened and must act as dictated by reason and justice—in other words, be a "philosopher-king."[71] In several nations, rulers welcomed leaders of the Enlightenment at court and asked them to help design laws and programs to reform the system, typically to build stronger states. These rulers are called "enlightened despots" by historians.[72] They included Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine the Great of Russia, Leopold II of Tuscany and Joseph II of Austria. Joseph was over-enthusiastic, announcing many reforms that had little support so that revolts broke out and his regime became a comedy of errors, and nearly all his programs were reversed.[73] Senior ministers Pombal in Portugal and Johann Friedrich Struensee in Denmark also governed according to Enlightenment ideals. In Poland, the model constitution of 1791 expressed Enlightenment ideals, but was in effect for only one year before the nation was partitioned among its neighbors. More enduring were the cultural achievements, which created a nationalist spirit in Poland.[74]  Denmark's minister Johann Struensee, a social reformer, was publicly executed in 1772 for usurping royal authority. Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, saw himself as a leader of the Enlightenment and patronized philosophers and scientists at his court in Berlin. Voltaire, who had been imprisoned and maltreated by the French government, was eager to accept Frederick's invitation to live at his palace. Frederick explained: "My principal occupation is to combat ignorance and prejudice... to enlighten minds, cultivate morality, and to make people as happy as it suits human nature, and as the means at my disposal permit."[75] American Revolution and French Revolution The Enlightenment has been frequently linked to the American Revolution of 1776[76] and the French Revolution of 1789—both had some intellectual influence from Thomas Jefferson.[77][78] A key aspect of this era was a profound shift from the absolute monarchies of Europe, which asserted the "divine right" to rule. John Locke rejected this view in his writings on the Two Treatises of Government (1689). He asserted that citizens were seen to possess natural rights, including life, liberty, and property. Therefore governments exist to protect these rights through the "consent of the governed." The clash between these competing ethos often resulted in violent upheaval in differing ways. In France, Ancien régime, with its rigid social hierarchy and absolute monarchical power, was systematically dismantled during the French Revolution. While the American Revolution focused more on breaking free from a government - represented by King George III and Parliament - that colonists felt did not adequately represent their interests. Alexis de Tocqueville proposed the French Revolution as the inevitable result of the radical opposition created in the 18th century between the monarchy and the men of letters of the Enlightenment. These men of letters constituted a sort of "substitute aristocracy that was both all-powerful and without real power." This illusory power came from the rise of "public opinion," born when absolutist centralization removed the nobility and the bourgeoisie from the political sphere. The "literary politics" that resulted promoted a discourse of equality and was hence in fundamental opposition to the monarchical regime.[79] De Tocqueville "clearly designates... the cultural effects of transformation in the forms of the exercise of power."[80] |

啓蒙絶対主義 メイン記事: 啓蒙絶対主義  ポンバル侯爵はポルトガル政府の長として、抜本的な社会経済改革を実施した。 啓蒙思想の指導者たちは特に民主的ではなかった。彼らはむしろ、知識人が設計した改革を押し付ける鍵として絶対君主を仰ぐことが多かった。ヴォルテールは 民主主義を軽蔑し、絶対君主は啓蒙され、理性と正義に基づいて行動すべきだと述べた。つまり「哲人王」であるべきだというのである[71]。 いくつかの国民では、統治者が啓蒙思想の指導者を宮廷に迎え、制度改革のための法律や計画の立案を依頼した。その目的は通常、国家の強化にあった。歴史家 たちはこうした統治者を「啓蒙専制君主」と呼んでいる。[72] その中にはプロイセンのフリードリヒ大王、ロシアのエカテリーナ2世、トスカーナ大公レオポルド2世、オーストリア皇帝ヨーゼフ2世が含まれる。ヨーゼフ は熱意が過剰で、支持の薄い改革を多数発表し、反乱が勃発して政権は失態の連続となり、ほぼ全ての政策が撤回された。[73] ポルトガルのポンバルやデンマークのヨハン・フリードリヒ・シュトゥルーンゼーといった上級大臣も啓蒙思想に基づいて統治した。ポーランドでは、1791 年の模範憲法が啓蒙思想の理想を体現したが、隣国による国民の分割統治が始まるまでわずか1年間しか施行されなかった。より永続的だったのは文化的成果で あり、これらがポーランドにナショナリストの精神を育んだ。[74]  デンマークの社会改革者ヨハン・シュトゥルーンゼーは、1772年に王権を簒奪した罪で公開処刑された。 1740年から1786年までプロイセン王であったフリードリヒ大王は、自らを啓蒙主義の指導者と見なし、ベルリンの宮廷で哲学者や科学者を後援した。フ ランス政府によって投獄され虐待されたヴォルテールは、フリードリヒの宮殿に住むよう招かれたことを喜んで受け入れた。フリードリヒはこう説明している: 「私の主な仕事は無知と偏見と戦うことだ…人々の心を啓発し、道徳を育み、人間の本性にかなう限り、そして私の手にある手段が許す限り、人民を幸せにする ことである」[75] アメリカ独立戦争とフランス革命 啓蒙思想は1776年のアメリカ独立戦争[76]と1789年のフランス革命と頻繁に結びつけられてきた。両者ともトマス・ジェファーソンの思想的影響を 受けていた。[77][78] この時代の重要な側面は、統治の「神権」を主張したヨーロッパの絶対君主制からの根本的な転換であった。ジョン・ロックは『二つの政府論』(1689年) においてこの見解を否定した。彼は、市民には生命、自由、財産を含む自然権が備わっていると主張した。したがって政府は「被統治者の同意」を通じてこれら の権利を保護するために存在する。こうした対立する倫理観の衝突は、しばしば異なる形で暴力的な動乱を引き起こした。フランスでは、硬直した社会階層と絶 対的君主権力を特徴とするアンシャン・レジームが、フランス革命によって体系的に解体された。一方、アメリカ独立戦争は、植民地住民が自らの利益を十分に 代表していないと感じた政府——ジョージ3世と議会に象徴される——からの脱却に重点を置いた。 アレクシス・ド・トクヴィルは、フランス革命を18世紀に王政と啓蒙思想家たちの間に生じた急進的な対立の必然的帰結と位置付けた。これらの知識人層は 「実権を持たないが全権を掌握する」一種の「代替貴族階級」を形成していた。この幻想的な権力は「世論」の台頭から生まれた。絶対主義的な中央集権化が貴 族とブルジョワジーを政治圏から排除した時に生まれたものだ。その結果生まれた「文芸政治」は平等を主張する言説を促進し、したがって君主制体制と根本的 に対立した[79]。ド・トクヴィルは「権力行使の形態における変革の文化的影響を明確に指摘している」[80]。 |

| Religion It does not require great art or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God? -- Voltaire (1763)[81]  French philosopher Voltaire argued for religious tolerance. Enlightenment era religious commentary was a response to the preceding century of religious conflict in Europe, especially the Thirty Years' War.[82] Theologians of the Enlightenment wanted to reform their faith to its generally non-confrontational roots and to limit the capacity for religious controversy to spill over into politics and warfare while still maintaining a true faith in God. For moderate Christians, this meant a return to simple Scripture. Locke abandoned the corpus of theological commentary in favor of an "unprejudiced examination" of the Word of God alone. He determined the essence of Christianity to be a belief in Christ the redeemer and recommended avoiding more detailed debate.[83] Anthony Collins, one of the English freethinkers, published his "Essay concerning the Use of Reason in Propositions the Evidence whereof depends on Human Testimony" (1707), in which he rejects the distinction between "above reason" and "contrary to reason," and demands that revelation should conform to man's natural ideas of God. In the Jefferson Bible, Thomas Jefferson went further and dropped any passages dealing with miracles, visitations of angels, and the resurrection of Jesus after his death, as he tried to extract the practical Christian moral code of the New Testament.[84] Enlightenment scholars sought to curtail the political power of organized religion and thereby prevent another age of intolerant religious war.[85] Spinoza determined to remove politics from contemporary and historical theology (e.g., disregarding Judaic law).[86] Moses Mendelssohn advised affording no political weight to any organized religion but instead recommended that each person follow what they found most convincing.[87] They believed a good religion based in instinctive morals and a belief in God should not theoretically need force to maintain order in its believers, and both Mendelssohn and Spinoza judged religion on its moral fruits, not the logic of its theology.[88] Several novel ideas about religion developed with the Enlightenment, including deism and talk of atheism. According to Thomas Paine, deism is the simple belief in God the Creator with no reference to the Bible or any other miraculous source. Instead, the deist relies solely on personal reason to guide his creed,[89] which was eminently agreeable to many thinkers of the time.[90] Atheism was much discussed, but there were few proponents. Wilson and Reill note: "In fact, very few enlightened intellectuals, even when they were vocal critics of Christianity, were true atheists. Rather, they were critics of orthodox belief, wedded rather to skepticism, deism, vitalism, or perhaps pantheism."[91] Some followed Pierre Bayle and argued that atheists could indeed be moral men.[92] Many others like Voltaire held that without belief in a God who punishes evil, the moral order of society was undermined; that is, since atheists gave themselves to no supreme authority and no law and had no fear of eternal consequences, they were far more likely to disrupt society.[93] Bayle observed that, in his day, "prudent persons will always maintain an appearance of [religion]," and he believed that even atheists could hold concepts of honor and go beyond their own self-interest to create and interact in society.[94] Locke said that if there were no God and no divine law, the result would be moral anarchy: every individual "could have no law but his own will, no end but himself. He would be a god to himself, and the satisfaction of his own will the sole measure and end of all his actions."[95] Separation of church and state Main articles: Separation of church and state and Separation of church and state in the United States The "Radical Enlightenment"[96][97] promoted the concept of separating church and state,[98] an idea that is often credited to Locke.[99] According to his principle of the social contract, Locke said that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he said must therefore remain protected from any government authority. These views on religious tolerance and the importance of individual conscience, along with the social contract, became particularly influential in the American colonies and the drafting of the United States Constitution.[100] In a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, Thomas Jefferson calls for a "wall of separation between church and state" at the federal level. He previously had supported successful efforts to disestablish the Church of England in Virginia[101] and authored the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.[102] Jefferson's political ideals were greatly influenced by the writings of Locke, Bacon, and Newton,[103] whom he considered the three greatest men that ever lived.[104] |

宗教 キリスト教徒が互いに寛容であるべきことを証明するのに、大した芸術や見事な修練を経た雄弁さは必要ない。しかし俺はさらに踏み込む。全ての人間を兄弟と 見なすべきだと言うのだ。何だと?トルコ人が俺の兄弟だと?中国人が俺の兄弟だと?ユダヤ人が?シャム人が?そうだ、疑いなく。我々は皆同じ父の子であ り、同じ神の被造物ではないか? ——ヴォルテール(1763年)[81]  フランスの哲学者ヴォルテールは宗教的寛容を主張した。 啓蒙時代の宗教論評は、前世紀のヨーロッパにおける宗教紛争、特に三十年戦争への反応であった[82]。啓蒙時代の神学者たちは、自らの信仰を、一般的に 非対立的な根源へと改革し、宗教論争が政治や戦争へと波及する余地を制限しつつ、なお神への真の信仰を維持することを望んだ。穏健なキリスト教徒にとっ て、これは単純な聖書への回帰を意味した。ロックは、神学上の解説の体系を放棄し、神の言葉のみに対する「偏見のない検証」を支持した。彼は、キリスト教 の本質は救い主キリストへの信仰であると決定し、より詳細な議論は避けるよう勧めた。[83] 英国の自由思想家の一人であるアンソニー・コリンズは、「人間の証言に依存する証拠に関する命題における理性の使用に関するエッセイ」(1707年)を発 表し、その中で「理性を超えたもの」と「理性に反するもの」の区別を否定し、啓示は人間の神に対する自然な考えに合致すべきであると主張した。ジェファー ソン聖書では、トーマス・ジェファーソンはさらに踏み込んで、奇跡、天使の訪問、死後のイエスの復活に関する箇所をすべて削除し、新約聖書から実用的なキ リスト教の道徳規範を抽出しようとした。[84] 啓蒙主義の学者たちは、組織化された宗教の政治的権力を制限し、それによって不寛容な宗教戦争の時代が再び訪れるのを防ごうとした。[85] スピノザは、現代および歴史的な神学から政治を排除することを決意した(例えば、ユダヤ教の律法を無視すること)。[86] モーゼス・メンデルスゾーンは、いかなる組織化された宗教にも政治的な重みを認めず、代わりに各人格が最も説得力があると感じるものを追うべきだと助言し た。[87] 彼らは、本能的な道徳と神への信仰に基づく良き宗教は、理論上、信者の秩序維持に強制力を必要とすべきでないと考えた。メンデルスゾーンもスピノザも、宗 教をその神学の論理ではなく、道徳的な成果によって評価した。[88] 啓蒙主義とともに、自然神論や無神論の議論など、宗教に関するいくつかの斬新な考え方が発展した。トーマス・ペインによれば、自然神論とは、聖書やその他 の奇跡的な情報源に言及することなく、創造主である神を単純に信じる考えである。その代わりに、自然神論者は、自分の信条を導くために、個人的な理性のみ に頼る[89]。これは、当時の多くの思想家に非常に受け入れられた考えであった。[90] 無神論は多くの議論を呼んだが、その支持者はほとんどいなかった。ウィルソンとレイルは次のように述べている。「実際、キリスト教を声高に批判していた啓 蒙知識人でさえ、真の無神論者はごくわずかだった。むしろ彼らは、懐疑論、自然神論、生命力論、あるいは汎神論に傾倒した、正統的な信仰の批判者たちだっ た」[91]。ピエール・ベールに従う者もいて、無神論者も確かに道徳的な人間であり得る、と主張した[92]。ヴォルテールのような他の多くの人々は、 悪を罰する神を信じなければ、社会の道徳的秩序は損なわれる、と主張した。つまり、無神論者は、いかなる最高権威や法律にも従わず、永遠の結果を恐れるこ ともないので、社会を混乱させる可能性がはるかに高い、と主張したのである。[93] ベールは当時について「賢明な者は常に(宗教の)見せかけを保つ」と観察し、無神論者でさえ名誉の概念を持ち、自己利益を超えて社会を創造し交流できると 信じていた。[94] ロックは、神も神の法も存在しなければ、道徳的無秩序が生じると述べた。あらゆる個人は「自らの意志以外に法を持たず、自己以外に目的を持たない。彼は自 らを神とし、自らの意志の満足を全ての行動の唯一の尺度かつ目的とするだろう」[95]。 政教分離 関連項目: 政教分離、アメリカ合衆国における政教分離 「急進的啓蒙主義」[96][97]は政教分離の概念を推進した[98]。この思想はしばしばロックに帰せられる。[99] ロックは社会契約論の原則に基づき、個人の良心の領域において政府には権威がないと述べた。これは理性ある人民が政府や他者に支配させるために譲渡できな いものだからだ。ロックにとって、これは良心の自由における自然権を生み出し、したがっていかなる政府の権威からも保護され続けなければならないと彼は主 張した。 こうした宗教的寛容と個人の良心の重要性に関する見解は、社会契約論と共に、アメリカ植民地やアメリカ合衆国憲法の起草において特に大きな影響力を持った [100]。トーマス・ジェファーソンはコネチカット州のダンベリー・バプテスト協会への書簡で、連邦レベルにおける「教会と国家の分離の壁」を求めてい る。彼は以前、バージニア州における英国国教会の廃止運動を成功裏に支援し[101]、『バージニア宗教自由法』を起草した[102]。ジェファーソンの 政治的理想は、ロック、ベーコン、ニュートンの著作に大きく影響を受けており[103]、彼はこれら3人を史上最高の偉人と考えていた[104]。 |

National variations Europe at the beginning of the War of the Spanish Succession, 1700 The Enlightenment took hold in most European countries and influenced nations globally, often with a specific local emphasis. For example, in France it became associated with anti-government and anti-Church radicalism, while in Germany it reached deep into the middle classes, where it expressed a spiritualistic and nationalistic tone without threatening governments or established churches.[105] Government responses varied widely. In France, the government was hostile, and the philosophes fought against its censorship, sometimes being imprisoned or hounded into exile. The British government, for the most part, ignored the Enlightenment's leaders in England and Scotland, although it did give Newton a knighthood and a very lucrative government office. A common theme among most countries which derived Enlightenment ideas from Europe was the intentional non-inclusion of Enlightenment philosophies pertaining to slavery. Originally during the French Revolution, a revolution deeply inspired by Enlightenment philosophy, "France's revolutionary government had denounced slavery, but the property-holding 'revolutionaries' then remembered their bank accounts."[106] Slavery frequently showed the limitations of the Enlightenment ideology as it pertained to European colonialism, since many colonies of Europe operated on a plantation economy fueled by slave labor. In 1791, the Haitian Revolution, a slave rebellion by emancipated slaves against French colonial rule in the colony of Saint-Domingue, broke out. European nations and the United States, despite the strong support for Enlightenment ideals, refused to "[give support] to Saint-Domingue's anti-colonial struggle."[106] |

国家ごとの差異 スペイン継承戦争開始時のヨーロッパ、1700年 啓蒙思想はほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国で根付き、世界中の国民に影響を与えた。その影響はしばしば特定の地域的特徴を帯びていた。例えばフランスでは反政 府・反教会の急進主義と結びつき、ドイツでは中産階級に深く浸透し、政府や既存の教会を脅かすことなく、精神主義的かつナショナリスト的な色合いを帯び た。[105] 政府の対応は大きく異なった。フランスでは政府が敵対的であり、哲学者たちは検閲と戦い、投獄されたり国外追放に追い込まれたりした。イギリス政府は、 ニュートンに騎士号と非常に有利な政府職を与えたものの、イングランドとスコットランドの啓蒙思想の指導者たちをほぼ無視した。 ヨーロッパから啓蒙思想を受け入れたほとんどの国に共通する特徴は、奴隷制に関する啓蒙哲学を意図的に排除したことだ。啓蒙思想に深く影響されたフランス 革命の初期には、「革命政府は奴隷制を非難したが、財産を持つ『革命家』たちはその後、自らの銀行口座を思い出した」のである。[106] 奴隷制は、ヨーロッパの植民地主義に関わる啓蒙イデオロギーの限界を頻繁に露呈した。多くのヨーロッパ植民地が奴隷労働に支えられたプランテーション経済 で運営されていたからだ。1791年、サン・ドミンゴ植民地で解放奴隷によるフランス植民地支配への反乱、ハイチ革命が勃発した。啓蒙主義の理想を強く支 持していたにもかかわらず、ヨーロッパの国民とアメリカ合衆国は「サン・ドミンゴの反植民地闘争への支援」を拒否した。[106] |

| Great Britain England Further information: Georgian era § English Enlightenment The very existence of an English Enlightenment has been hotly debated by scholars. The majority of textbooks on British history make little or no mention of an English Enlightenment. Some surveys of the entire Enlightenment include England and others ignore it, although they do include coverage of such major intellectuals as Joseph Addison, Edward Gibbon, John Locke, Isaac Newton, Alexander Pope, Joshua Reynolds, and Jonathan Swift.[107] Freethinking, a term describing those who stood in opposition to the institution of the Church, and the literal belief in the Bible, can be said to have begun in England no later than 1713, when Anthony Collins wrote his "Discourse of Free-thinking," which gained substantial popularity. This essay attacked the clergy of all churches and was a plea for deism. Roy Porter argues that the reasons for this neglect were the assumptions that the movement was primarily French-inspired, that it was largely a-religious or anti-clerical, and that it stood in outspoken defiance to the established order.[108] Porter admits that after the 1720s England could claim thinkers to equal Diderot, Voltaire, or Rousseau. However, its leading intellectuals such as Gibbon,[109] Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson were all quite conservative and supportive of the standing order. Porter says the reason was that Enlightenment had come early to England and had succeeded such that the culture had accepted political liberalism, philosophical empiricism, and religious toleration, positions which intellectuals on the continent had to fight against powerful odds. Furthermore, England rejected the collectivism of the continent and emphasized the improvement of individuals as the main goal of enlightenment.[110] According to Derek Hirst, the 1640s and 1650s saw a revived economy characterised by growth in manufacturing, the elaboration of financial and credit instruments, and the commercialisation of communication. The gentry found time for leisure activities, such as horse racing and bowling. In the high culture important innovations included the development of a mass market for music, increased scientific research, and an expansion of publishing. All the trends were discussed in depth at the newly established coffee houses.[111][112]  One leader of the Scottish Enlightenment was Adam Smith, the father of modern economic science. Scotland In the Scottish Enlightenment, the principles of sociability, equality, and utility were disseminated in schools and universities, many of which used sophisticated teaching methods which blended philosophy with daily life.[20] Scotland's major cities created an intellectual infrastructure of mutually supporting institutions such as schools, universities, reading societies, libraries, periodicals, museums, and masonic lodges.[113] The Scottish network was "predominantly liberal Calvinist, Newtonian, and 'design' oriented in character which played a major role in the further development of the transatlantic Enlightenment."[114] In France, Voltaire said "we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization."[115] The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen, physician and chemist; James Anderson, agronomist; Joseph Black, physicist and chemist; and James Hutton, the first modern geologist.[35][116] Anglo-American colonies Further information: American Enlightenment  John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence imagines the drafting committee presenting its work to the Congress. Several Americans, especially Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, played a major role in bringing Enlightenment ideas to the New World and in influencing British and French thinkers.[117] Franklin was influential for his political activism and for his advances in physics.[118][119] The cultural exchange during the Age of Enlightenment ran in both directions across the Atlantic. Thinkers such as Paine, Locke, and Rousseau all take Native American cultural practices as examples of natural freedom.[120] The Americans closely followed English and Scottish political ideas, as well as some French thinkers such as Montesquieu.[121] As deists, they were influenced by ideas of John Toland and Matthew Tindal. There was a great emphasis upon liberty, republicanism, and religious tolerance. There was no respect for monarchy or inherited political power. Deists reconciled science and religion by rejecting prophecies, miracles, and biblical theology. Leading deists included Thomas Paine in The Age of Reason and Thomas Jefferson in his short Jefferson Bible, from which he removed all supernatural aspects.[122] |

イギリス イングランド 詳細情報:ジョージ王朝時代 § 英国啓蒙主義 英国啓蒙主義の存在そのものは、学者たちの間で熱く議論されている。英国史に関する教科書の大半は、英国啓蒙主義についてほとんど、あるいはまったく触れ ていない。啓蒙主義全体に関する調査の中には、イングランドを取り上げるものもあれば、無視するものもある。ただし、ジョセフ・アディソン、エドワード・ ギボン、ジョン・ロック、アイザック・ニュートン、アレクサンダー・ポープ、ジョシュア・レイノルズ、ジョナサン・スウィフトといった主要な知識人は取り 上げられている。[107] 教会という制度や聖書を文字通り信じることに反対した人々を表す「自由思想」という用語は、1713年までにイギリスで始まったと言える。この年、アンソ ニー・コリンズが「自由思想の言説」を書き、それが大きな人気を博した。この言説は、あらゆる教会の聖職者を攻撃し、自然神論を擁護するものであった。 ロイ・ポーターは、この軽視の理由は、この運動が主にフランスに端を発したものであり、大部分が非宗教的あるいは反聖職的であり、既存の秩序に率直に反抗 する立場にあるという仮定があったためだと主張している。[108] ポーターは、1720年代以降、イングランドはディドロ、ヴォルテール、ルソーに匹敵する思想家を擁していたことを認めている。しかし、ギボン、 [109] エドマンド・バーク、サミュエル・ジョンソンといった英国の主要知識人は皆、極めて保守的で既存秩序を支持していた。ポーターによれば、その理由は啓蒙思 想が英国に早く到来し、政治的自由主義・哲学的経験論・宗教的寛容といった立場を文化が受け入れ、大陸の知識人が強大な逆風と戦わねばならなかった立場を 英国は既に達成していたからだという。さらに英国は大陸の集団主義を拒絶し、啓蒙の主目的を個人の向上に置いた。[110] デレク・ハーストによれば、1640年代から1650年代にかけて経済は回復し、製造業の成長、金融・信用手段の高度化、通信の商業化が特徴だった。紳士 階級は競馬やボウリングといった余暇活動に時間を割くようになった。高尚な文化分野では、音楽の大衆市場の発展、科学研究の増加、出版の拡大といった重要 な革新があった。こうした潮流はすべて、新たに設立された喫茶店で深く議論された。[111][112]  スコットランド啓蒙主義の指導者の一人が、現代経済学の父アダム・スミスである。 スコットランド スコットランド啓蒙主義では、社交性・平等・実用性の原則が学校や大学で広められた。その多くは哲学と日常生活を融合させた洗練された教授法を採用してい た。[20] スコットランドの主要都市では、学校、大学、読書会、図書館、定期刊行物、博物館、フリーメイソンロッジといった相互に支え合う機関からなる知的基盤が形 成された。[113] スコットランドのネットワークは「主にリベラルなカルヴァン主義、ニュートン主義、そして『デザイン』志向の性格を持ち、大西洋を跨ぐ啓蒙思想のさらなる 発展に重要な役割を果たした」[114]。フランスでは、ヴォルテールが「文明に関するあらゆる考えはスコットランドに求める」と述べた。[115] スコットランド啓蒙主義の焦点は、知的・経済的問題から、医師であり化学者であるウィリアム・カレン、農学者であるジェームズ・アンダーソン、物理学者で あり化学者であるジョセフ・ブラック、そして最初の近代的な地質学者であるジェームズ・ハットンの研究のように、特に科学的な問題にまで及んだ。[35] [116] 英米植民地 詳細情報:アメリカ啓蒙主義  ジョン・トランブルの『独立宣言』は、起草委員会が議会にその成果を提示する様子を描いている。 ベンジャミン・フランクリンやトーマス・ジェファーソンをはじめとする数人のアメリカ人が、啓蒙思想を新大陸にもたらし、イギリスやフランスの思想家に影 響を与える上で大きな役割を果たした。[117] フランクリンは、その政治活動と物理学における進歩で影響力があった。[118][119] 啓蒙時代における文化交流は、大西洋を挟んで双方向で進んだ。ペイン、ロック、ルソーといった思想家たちは皆、ネイティブアメリカン文化の慣習を自然の自 由の例として挙げている。[120] アメリカ人たちは、イギリスやスコットランドの政治思想、そしてモンテスキューなどのフランス人思想家たちの思想を熱心に追った。[121] 自然神論者として、彼らはジョン・トーランドやマシュー・ティンダルの思想に影響を受けた。自由、共和主義、宗教的寛容が強く強調された。君主制や世襲的 政治権力への敬意は皆無だった。デイストたちは予言、奇跡、聖書神学を否定することで科学と宗教を調和させた。代表的なデイストには『理性時代』のトマ ス・ペインや、超自然的要素を全て削除した『ジェファーソン聖書』のトマス・ジェファーソンがいた。[122] |

| Netherlands The Dutch Enlightenment began in 1640.[123] During the Early Dutch Enlightenment (1640–1720), many books were translated from Latin, French or English to Dutch, often at the risk of their translators and publishers.[123] By the 1720s, the Dutch Republic had also become a major center for printing and exporting banned books to France.[124] The most famous figure of the Dutch Enlightenment was Baruch Spinoza. France Main article: French Enlightenment The French Enlightenment was influenced by England[125] and in turn influenced other national enlightenments. As worded by Sharon A. Stanley, "the French Enlightenment stands out from other national enlightenments for its unrelenting assault on church leadership and theology."[126] German states Main article: German Enlightenment See also: Hymnody of continental Europe § Rationalism Prussia took the lead among the German states in sponsoring the political reforms that Enlightenment thinkers urged absolute rulers to adopt. There were important movements as well in the smaller states of Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, and the Palatinate. In each case, Enlightenment values became accepted and led to significant political and administrative reforms that laid the groundwork for the creation of modern states.[127] The princes of Saxony, for example, carried out an impressive series of fundamental fiscal, administrative, judicial, educational, cultural, and general economic reforms. The reforms were aided by the country's strong urban structure and influential commercial groups and modernized pre-1789 Saxony along the lines of classic Enlightenment principles.[128][129]  Weimar's Courtyard of the Muses by Theobald von Oer, a tribute to The Enlightenment and the Weimar Classicism depicting German poets Schiller, Wieland, Herder, and Goethe Before 1750, the German upper classes looked to France for intellectual, cultural, and architectural leadership, as French was the language of high society. By the mid-18th century, the Aufklärung (The Enlightenment) had transformed German high culture in music, philosophy, science, and literature. Christian Wolff was the pioneer as a writer who expounded the Enlightenment to German readers and legitimized German as a philosophic language.[130] Johann Gottfried von Herder broke new ground in philosophy and poetry, as a leader of the Sturm und Drang movement of proto-Romanticism. Weimar Classicism (Weimarer Klassik) was a cultural and literary movement based in Weimar that sought to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical, and Enlightenment ideas. The movement (from 1772 until 1805) involved Herder as well as polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, a poet and historian. The theatre principal Abel Seyler greatly influenced the development of German theatre and promoted serious German opera, new works and experimental productions, and the concept of a national theatre.[131] Herder argued that every group of people had its own particular identity, which was expressed in its language and culture. This legitimized the promotion of German language and culture and helped shape the development of German nationalism. Schiller's plays expressed the restless spirit of his generation, depicting the hero's struggle against social pressures and the force of destiny.[132] German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under composers Johann Sebastian Bach, Joseph Haydn, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[133] In remote Königsberg, Kant tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom, and political authority. Kant's work contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought—and indeed all of European philosophy—well into the 20th century.[134] German Enlightenment won the support of princes, aristocrats, and the middle classes, and it permanently reshaped the culture.[135] However, there was a conservatism among the elites that warned against going too far.[136] In 1788, Prussia issued an "Edict on Religion" that forbade preaching any sermon that undermined popular belief in the Holy Trinity or the Bible. The goal was to avoid theological disputes that might impinge on domestic tranquility. Men who doubted the value of Enlightenment favoured the measure, but so too did many supporters. German universities had created a closed elite that could debate controversial issues among themselves, but spreading them to the public was seen as too risky. This intellectual elite was favoured by the state, but that might be reversed if the process of the Enlightenment proved politically or socially destabilizing.[137] Austria Main article: Austrian Enlightenment During the 18th century, Austria was under Habsburg rule. The reign of Maria Theresa, the first Habsburg monarch to be considered influenced by the Enlightenment in some areas, was marked by a mix of enlightenment and conservatism. Her son Joseph II's brief reign was marked by this conflict, with his ideology of Josephinism facing opposition. Joseph II carried out numerous reforms in the spirit of the Enlightenment, which affected, for example, the school system, monasteries and the legal system. Emperor Leopold II, who was an early opponent of capital punishment, had a brief and contentious rule that was mostly marked by relations with France. Similarly, Emperor Francis II's rule was primarily marked by relations with France. The ideas of the Enlightenment also appeared in literature and theater works. Joseph von Sonnenfels was an important representative. In music, Austrian musicians such as Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart were associated with the Enlightenment. Hungary The Hungarian Enlightenment[138] emerged during the 18th century, while Hungary was part of the Habsburg Empire. The Hungarian Enlightenment is usually said to have begun in 1772 and was greatly influenced by French Enlightenment (through Vienna).[138] Romania The Romanian Enlightenment[139] emerged during the 18th century across the three major historical regions inhabited by Romanians: Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia. At that time, Transylvania was in the Habsburg Empire while Wallachia and Moldavia were vassals of the Ottoman Empire. The Transylvanian Enlightenment was represented by the Transylvanian School, a group of thinkers who promoted a cultural revival and rights for Romanians (who were marginalized by the Habsburgs). The Wallachian Enlightenment was represented by such figures as Dinicu Golescu (1777–1830), while the Moldavian Englightenment was headed by prince Dimitrie Cantemir (1673-1723). Switzerland Main article: Swiss Enlightenment The Enlightenment arrived relatively late in Switzerland, spreading from England, the Netherlands, and France toward the end of the 17th century. The movement initially took hold in Protestant regions, where it gradually replaced orthodox religious thinking. The 1712 victory of the reformed cantons of Zurich and Bern over the five Catholic cantons of central Switzerland in the Second War of Villmergen marked both a Protestant triumph and a victory for Enlightenment ideas in the economically more developed regions.[140] In Switzerland, which lacked a central court or academy, the Enlightenment spread through the intellectual elite of reformed cities, particularly pastors educated in academies and colleges with strong humanist traditions. The theological "Helvetic triumvirate" of Jean-Alphonse Turrettini (Geneva), Jean-Frédéric Ostervald (Neuchâtel), and Samuel Werenfels (Basel) led their churches toward a humanistic Christianity beginning in 1697, creating what Paul Wernle termed "reasoned orthodoxy" that balanced rational thought with Christian ethics.[140] Swiss Enlightenment thinkers made significant contributions across multiple fields. The Romand school developed influential theories of natural law, with scholars like Jean Barbeyrac (Lausanne), Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (Geneva), and Emer de Vattel (Neuchâtel) promoting concepts of inalienable rights and justified resistance to tyranny that influenced the American independence movement. In literature, Johann Jakob Bodmer and Johann Jakob Breitinger made Zurich a center of German literary innovation, while Albert von Haller's poetry represented the peak of Swiss Enlightenment literature. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, considering himself both a Genevan and Swiss citizen, developed democratic republican theories that extended Genevan models to broader European federalist principles.[140] The movement was characterized by what scholars term "Helvetism" – specifically Swiss aspects including a Christian conception of natural law, patriotic ethics, and philosophical approaches grounded in practical pedagogy and economics. Most distinctively, Swiss Enlightenment thought celebrated Alpine nature, viewing Switzerland as the "land of shepherds" whose republican and federalist traditions were shaped by its mountain environment. The movement organized through numerous societies and publications, including the Encyclopédie d'Yverdon (1770-1780), which offered a moderate alternative to the French Encyclopédie. Swiss intellectuals gained international prominence, with many serving in foreign academies, particularly in Berlin under Frederick II and in St. Petersburg under Catherine II.[140] |

オランダ オランダ啓蒙主義は1640年に始まった[123]。初期オランダ啓蒙主義期(1640年~1720年)には、多くの書籍がラテン語、フランス語、英語か らオランダ語へ翻訳された。翻訳者や出版者はしばしば危険を冒してこれを行った[123]。1720年代までに、オランダ共和国は禁書印刷とフランスへの 輸出の主要拠点ともなった。[124] オランダ啓蒙主義で最も著名な人物はバルーフ・スピノザである。 フランス 主な記事: フランス啓蒙主義 フランス啓蒙主義はイングランドの影響を受け[125]、逆に他の国民の啓蒙主義に影響を与えた。シャロン・A・スタンレーが述べたように、「フランス啓蒙主義は、教会指導層と神学に対する容赦ない攻撃において、他の国民の啓蒙主義と一線を画している」[126]。 ドイツ諸邦 メイン記事: ドイツ啓蒙主義 関連項目: ヨーロッパ大陸の賛美歌 § 理性主義 プロイセンは、啓蒙思想家が絶対君主に採用を促した政治改革を後押しする点で、ドイツ諸邦の中で主導的役割を果たした。バイエルン、ザクセン、ハノー ファー、プファルツといった小国でも重要な運動が起こった。いずれの場合も、啓蒙主義の価値観が受け入れられ、近代国家創設の基盤となる重要な政治・行政 改革につながった[127]。例えばザクセンの諸侯は、財政・行政・司法・教育・文化・経済全般にわたる一連の抜本的改革を成し遂げた。これらの改革は、 同国の強固な都市構造と影響力ある商業集団に支えられ、1789年以前のザクセンを古典的啓蒙主義の原則に沿って近代化したのである。[128] [129]  テオバルト・フォン・オーア作「ワイマールのミューズの中庭」。啓蒙主義とワイマール古典主義への賛辞として、ドイツの詩人シラー、ヴィーラント、ヘルダー、ゲーテを描いた作品 1750年以前、ドイツの上流階級は知的・文化的・建築的指導力をフランスに求めていた。当時の上流社会の共通語はフランス語だったからだ。18世紀半ば までに、啓蒙主義(アウフクレルクンング)は音楽・哲学・科学・文学におけるドイツの高尚な文化を変容させた。クリスティアン・ヴォルフは啓蒙思想をドイ ツ読者に解説し、哲学言語としてのドイツ語を正当化した先駆的著述家である。[130] ヨハン・ゴットフリート・フォン・ヘルダーは、前ロマン主義のストルム・ウント・ドラング運動の指導者として、哲学と詩の分野で新たな地平を切り開いた。 ワイマール古典主義(Weimarer Klassik)はワイマールを拠点とした文化的・文学的運動であり、ロマン主義、古典主義、啓蒙思想を統合することで新たなヒューマニズムを確立しよう とした。この運動(1772年から1805年まで)にはヘルダーに加え、博学者ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテ、詩人かつ歴史家のフリードリヒ・ シラーが関わった。劇場支配人アベル・ザイラーはドイツ演劇の発展に大きく影響し、本格的なドイツオペラ、新作・実験的演出、国民劇場の概念を推進した。 [131] ヘルダーは、あらゆる集団が独自の個別主義を持ち、それが言語と文化に表れると主張した。これはドイツ語とドイツ文化の振興を正当化し、ドイツナショナリ ズムの発展を形作る一助となった。シラーの戯曲は、社会的な圧力や運命の力に対する英雄の闘いを描き、彼の世代の落ち着きのない精神を表現した。 上流階級に支援されたドイツ音楽は、ヨハン・ゼバスティアン・バッハ、ヨーゼフ・ハイドン、ヴォルフガング・アマデウス・モーツァルトといった作曲家たちのもとで成熟期を迎えた。[133] 辺境のケーニヒスベルクで、カントは合理主義と宗教的信念、個人の自由と政治的権威の調和を試みた。カントの著作には、20世紀に至るまでドイツ思想―そ して実際はヨーロッパ哲学全体―を形作り続ける根本的な緊張関係が含まれていた。[134]ドイツ啓蒙主義は諸侯、貴族、中産階級の支持を得て、文化を恒 久的に再構築した。[135] しかし、エリート層には行き過ぎを戒める保守的な姿勢もあった。[136] 1788年、プロイセンは「宗教に関する勅令」を発布し、聖三位一体や聖書に対する民衆の信仰を損なう説教を禁じた。その目的は、国内の平穏を損なう恐れ のある神学論争を避けることにあった。啓蒙主義の価値を疑う者たちはこの措置を支持したが、多くの支持者も同様であった。ドイツの大学は閉鎖的なエリート 層を生み出し、彼らは論争的な問題を内部で議論できたが、それを公衆に広めることは危険すぎると見なされた。この知的エリート層は国家に寵愛されていた が、啓蒙主義の過程が政治的・社会的に不安定化をもたらすと判明すれば、その立場は逆転する可能性があった。[137] オーストリア 詳細記事: オーストリア啓蒙主義 18世紀、オーストリアはハプスブルク家の支配下にあった。マリア・テレジアの治世は、啓蒙主義の影響を一部受けたとされる最初のハプスブルク君主とし て、啓蒙主義と保守主義が混在する特徴を示した。その息子ヨーゼフ2世の短い治世はこの対立に特徴づけられ、彼のイデオロギーであるヨーゼフィニズムは反 対に直面した。ヨーゼフ2世は啓蒙主義の精神に基づき、学校制度、修道院、法制度など多岐にわたる改革を実施した。死刑制度の早期廃止を主張した皇帝レオ ポルト2世の治世は短く、主にフランスとの関係に特徴づけられた。同様に、皇帝フランツ2世の治世もフランスとの関係が主な特徴であった。 啓蒙思想は文学や演劇作品にも現れた。ヨーゼフ・フォン・ゾンネンフェルスは重要な代表者である。音楽分野では、ヨーゼフ・ハイドンやヴォルフガング・アマデウス・モーツァルトといったオーストリアの音楽家が啓蒙思想と結びついている。 ハンガリー ハンガリー啓蒙主義[138]は18世紀、ハンガリーがハプスブルク帝国の一部であった時期に現れた。ハンガリー啓蒙主義は通常1772年に始まり、ウィーン経由でフランス啓蒙主義の影響を強く受けたとされる[138]。 ルーマニア ルーマニア啓蒙主義[139]は18世紀、ルーマニア人が居住する三つの主要歴史地域(トランシルヴァニア、ワラキア、モルダヴィア)で現れた。当時、トランシルヴァニアはハプスブルク帝国に属していたが、ワラキアとモルダヴィアはオスマン帝国の属国であった。 トランシルヴァニア啓蒙主義は、トランシルヴァニア学派によって代表された。この思想家集団は、文化復興と(ハプスブルク家によって境界に置かれていた)ルーマニア人の権利を推進した。 ワラキア啓蒙主義はディニク・ゴレスク(1777-1830)らによって代表され、モルダヴィア啓蒙主義はディミトリエ・カンテミル公(1673-1723)が主導した。 スイス 主な記事:スイス啓蒙主義 啓蒙主義はスイスには比較的遅く到来し、17世紀末にイギリス、オランダ、フランスから広がった。この運動は当初プロテスタント地域で根付き、次第に正統 的な宗教思想に取って代わった。1712年のヴィルメルゲン第二次戦争で、チューリッヒとベルンの改革派カントンがスイス中央部の5つのカトリックカント ンに勝利したことは、プロテスタントの勝利であると同時に、経済的に発展した地域における啓蒙思想の勝利でもあった[140]。 中央裁判所やアカデミーを欠いていたスイスでは、啓蒙思想は改革派都市の知識人エリート、特に強い人文主義的伝統を持つアカデミーやカレッジで教育を受け た牧師たちを通じて広まった。ジャン=アルフォンス・トゥレッティーニ(ジュネーブ)、ジャン=フレデリック・オステルヴァルト(ヌーシャテル)、サミュ エル・ヴェレンフェルス(バーゼル)からなる神学上の「ヘルヴェティア三頭政治」は、1697年から各教会を人文主義的キリスト教へと導き、ポール・ヴェ ルンレが「理性的な正統主義」と呼んだ、合理的な思考とキリスト教倫理の均衡を成す思想を創出した。[140] スイス啓蒙思想家は多分野で顕著な貢献を果たした。ロマン派学派は自然法の有力な理論を発展させ、ジャン・バルベラック(ローザンヌ)、ジャン=ジャッ ク・ブルラマキ(ジュネーブ)、エメール・ド・ヴァテル(ヌーシャテル)ら学者が、不可侵の権利や専制への正当な抵抗といった概念を提唱し、アメリカ独立 運動に影響を与えた。文学分野では、ヨハン・ヤコブ・ボドマーとヨハン・ヤコブ・ブライティンガーがチューリッヒをドイツ文学革新の中心地とし、アルベル ト・フォン・ハラーの詩はスイス啓蒙文学の頂点を示した。ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは自らをジュネーブ市民かつスイス市民と位置づけ、ジュネーブのモデル を欧州全体の連邦主義原理へと拡張する民主的共和主義理論を展開した。[140] この運動は、学者らが「ヘルヴェティズム」と呼ぶ特徴を備えていた。具体的には、キリスト教的自然法観念、愛国的倫理観、実践的教育学と経済学に基づく哲 学的アプローチといったスイス特有の側面である。最も顕著なのは、アルプスの自然を称賛し、スイスを「牧人の国」と位置づけた点だ。その共和主義的・連邦 主義的伝統は、山岳環境に形作られていた。この運動は数多くの学会や出版物を通じて組織化され、フランス版『百科全書』に対する穏健な代替案を提示した 『イヴェルドン百科全書』(1770-1780)もその一つである。スイスの知識人は国際的な名声を獲得し、多くの者が外国の学士院、特にフリードリヒ2 世治下のベルリンやエカテリーナ2世治下のサンクトペテルブルクで活動した。[140] |

| Italy Main article: Italian Enlightenment  Statue of Cesare Beccaria, considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment In Italy the main centers of diffusion of the Enlightenment were Naples and Milan:[141] in both cities the intellectuals took public office and collaborated with the Bourbon and Habsburg administrations. In Naples, Antonio Genovesi, Ferdinando Galiani, and Gaetano Filangieri were active under the tolerant King Charles of Bourbon. However, the Neapolitan Enlightenment, like Vico's philosophy, remained almost always in the theoretical field.[142] Only later, many Enlighteners animated the unfortunate experience of the Parthenopean Republic. In Milan, however, the movement strove to find concrete solutions to problems. The center of discussions was the magazine Il Caffè (1762–1766), founded by brothers Pietro and Alessandro Verri (famous philosophers and writers, as well as their brother Giovanni), who also gave life to the Accademia dei Pugni, founded in 1761. Minor centers were Tuscany, Veneto, and Piedmont, where among others, Pompeo Neri worked. From Naples, Genovesi influenced a generation of southern Italian intellectuals and university students. His textbook Della diceosina, o sia della Filosofia del Giusto e dell'Onesto (1766) was a controversial attempt to mediate between the history of moral philosophy on the one hand and the specific problems encountered by 18th-century commercial society on the other. It contained the greater part of Genovesi's political, philosophical, and economic thought, which became a guidebook for Neapolitan economic and social development.[143] Science flourished as Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani made break-through discoveries in electricity. Pietro Verri was a leading economist in Lombardy. Historian Joseph Schumpeter states he was "the most important pre-Smithian authority on Cheapness-and-Plenty."[144] The most influential scholar on the Italian Enlightenment has been Franco Venturi.[145][146] Italy also produced some of the Enlightenment's greatest legal theorists, including Cesare Beccaria, Giambattista Vico, and Francesco Mario Pagano. |

イタリア 主な記事: イタリア啓蒙主義  啓蒙主義の偉大な思想家の一人とされるチェザーレ・ベッカリアの像 イタリアにおいて啓蒙主義が広まった主な中心地はナポリとミラノであった[141]。両都市の知識人は公職に就き、ブルボン家とハプスブルク家の政権と協 力した。ナポリでは、アントニオ・ジェノヴェージ、フェルディナンド・ガリアーニ、ガエターノ・フィランジェーリが寛容なブルボン家のカルロ王のもとで活 動した。しかしナポリ啓蒙主義は、ヴィーコの哲学と同様、ほとんど常に理論の領域にとどまった[142]。後に多くの啓蒙思想家がパルテノペ共和国という 不幸な経験に活気を与えたのは、そのことである。一方ミラノでは、この運動は問題に対する具体的な解決策を見出そうと努めた。議論の中心となったのは、ピ エトロとアレッサンドロ・ヴェッリ兄弟(著名な哲学者・作家であり、弟ジョヴァンニも同様)が創刊した雑誌『イル・カッフェ』(1762-1766年)で あった。彼らは1761年に設立された「拳のアカデミー」にも命を吹き込んだ。小規模な中心地としてはトスカーナ、ヴェネト、ピエモンテがあり、ポンペ オ・ネリらが活動した。 ナポリから、ジェノヴェージは南イタリアの知識人や大学生の世代に影響を与えた。彼の教科書『道徳論、すなわち正義と誠実の哲学について』(1766年) は、道徳哲学の歴史と18世紀商業社会が直面した具体的な問題との間を仲介しようとする論争的な試みであった。この著作にはジェノヴェーゼの政治思想、哲 学思想、経済思想の大部分が収められており、ナポリの経済・社会発展の指針となった[143]。 科学はアレッサンドロ・ボルタとルイージ・ガルヴァーニが電気分野で画期的な発見をしたことで発展した。ピエトロ・ヴェッリはロンバルディアを代表する経 済学者であった。歴史家ヨーゼフ・シュンペーターは彼を「スミス以前の『安価と豊富』に関する最も重要な権威」と評している[144]。イタリア啓蒙主義 研究で最も影響力のある学者はフランコ・ヴェントゥーリである[145][146]。イタリアはまた、チェザーレ・ベッカリア、ジャンバッティスタ・ ヴィーコ、フランチェスコ・マリオ・パガーノら啓蒙主義を代表する法理論家も輩出した。 |

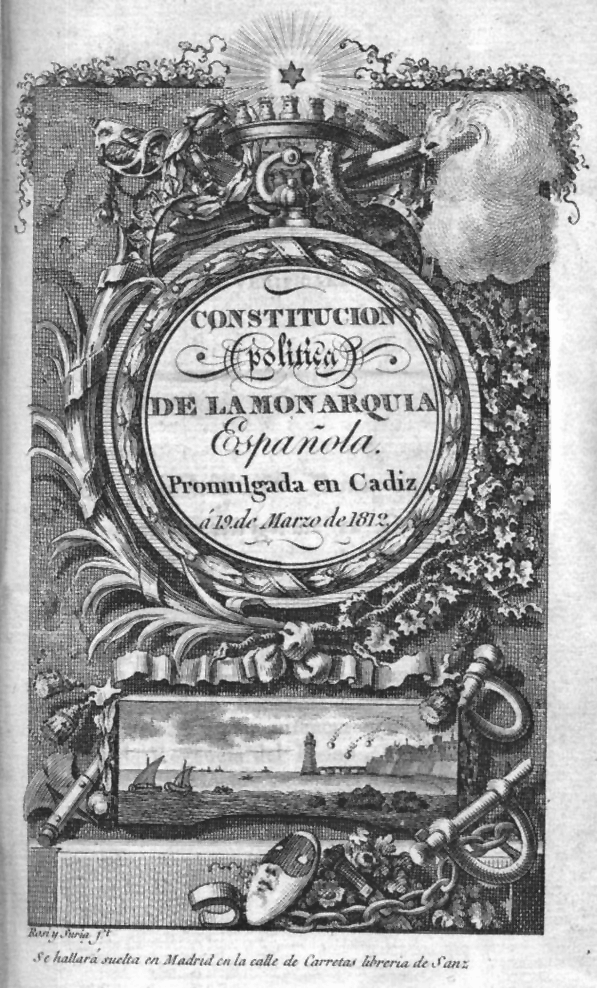

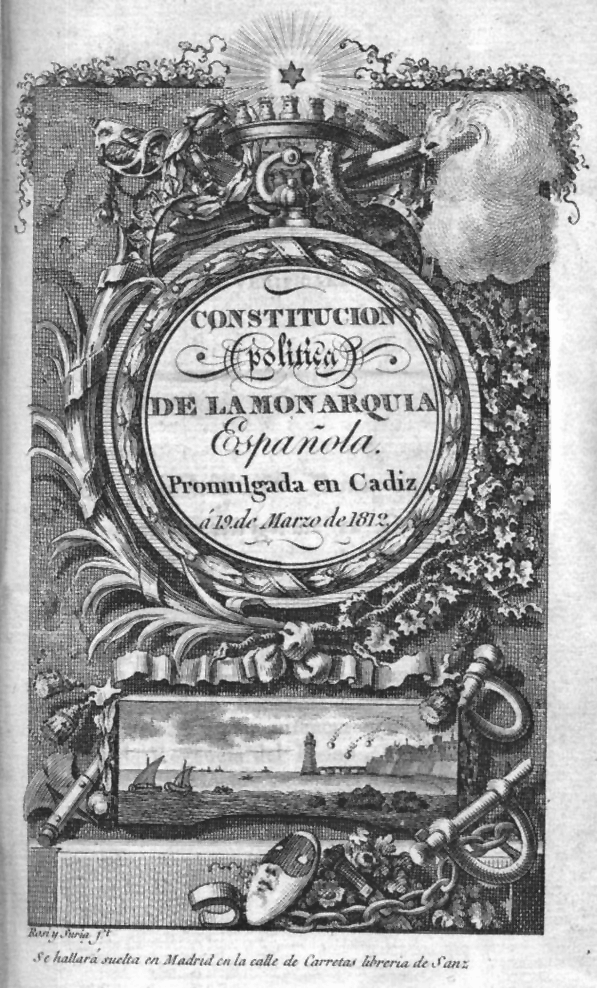

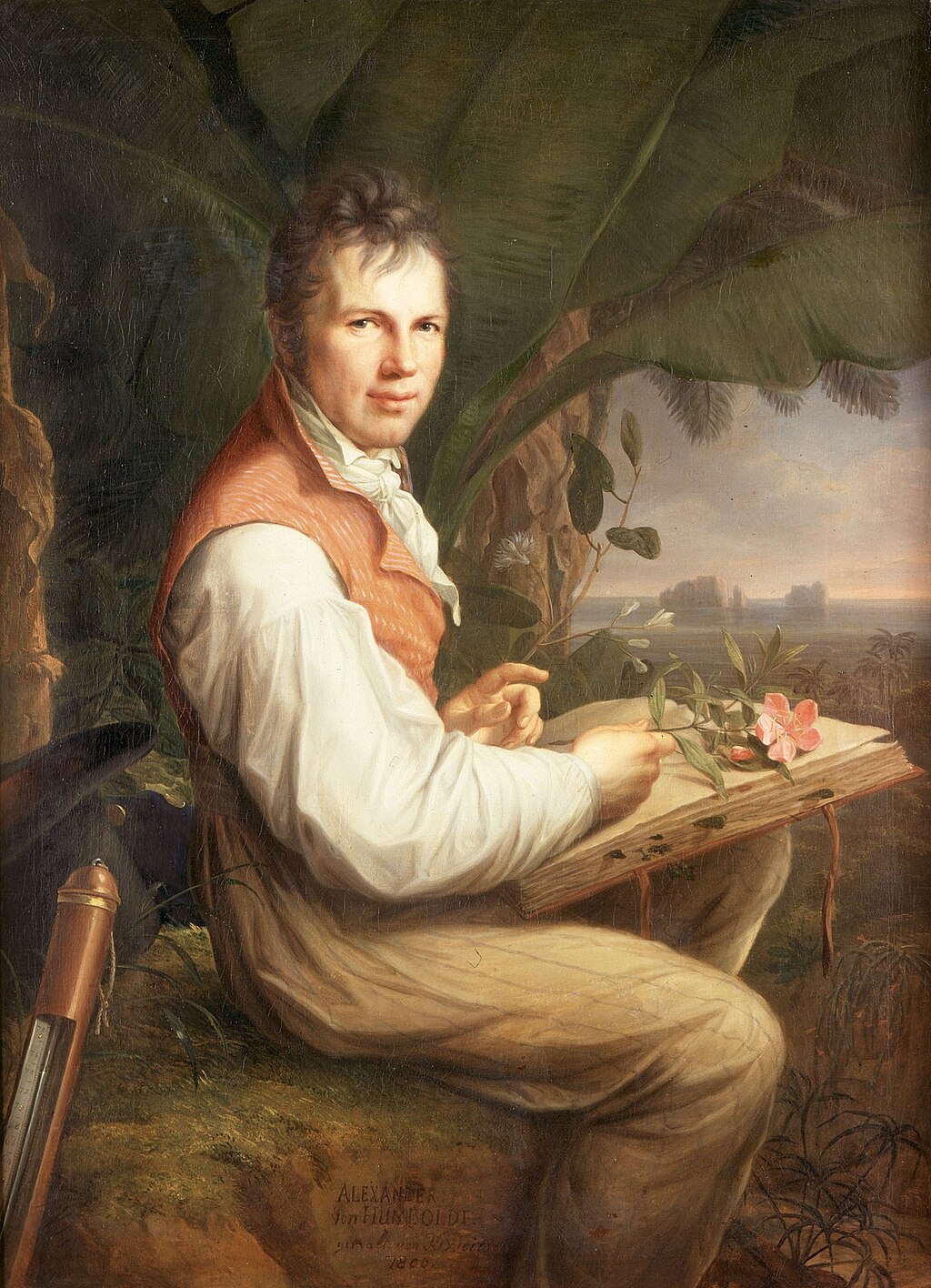

| Bourbon Spain and Spanish America Main articles: Spanish Enlightenment and Spanish American Enlightenment  Spanish Constitution of 1812 When Charles II, the last Spanish Habsburg monarch, died his successor was from the French House of Bourbon, initiating a period of French Enlightenment influence in Spain and the Spanish Empire.[147][148] In the 18th Century, the Spanish continued to expand their empire in the Americas with the Spanish missions in California and established missions deeper inland in South America. Under Charles III, the crown began to implement serious structural changes. The monarchy curtailed the power of the Catholic Church, and established a standing military in Spanish America. Freer trade was promoted under comercio libre in which regions could trade with companies sailing from any other Spanish port, rather than the restrictive mercantile system. The crown sent out scientific expeditions to assert Spanish sovereignty over territories it claimed but did not control, but also importantly to discover the economic potential of its far-flung empire. Botanical expeditions sought plants that could be of use to the empire.[149] Charles IV gave Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt free rein to travel in Spanish America, usually closed to foreigners, and more importantly, access to crown officials to aid the success of his scientific expedition.[150] When Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, Ferdinand VII abdicated and Napoleon placed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. To add legitimacy to this move, the Bayonne Constitution was promulgated, which included representation from Spain's overseas components, but most Spaniards rejected the whole Napoleonic project. A war of national resistance erupted. The Cortes de Cádiz (parliament) was convened to rule Spain in the absence of the legitimate monarch, Ferdinand. It created a new governing document, the Constitution of 1812, which laid out three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial; put limits on the king by creating a constitutional monarchy; defined citizens as those in the Spanish Empire without African ancestry; established universal manhood suffrage; and established public education starting with primary school through university as well as freedom of expression. The constitution was in effect from 1812 until 1814, when Napoleon was defeated and Ferdinand was restored to the throne of Spain. Upon his return, Ferdinand repudiated the constitution and reestablished absolutist rule.[151] |

ブルボン朝スペインとスペイン領アメリカ 主な記事: スペイン啓蒙主義とスペイン領アメリカ啓蒙主義  1812年スペイン憲法 スペイン最後のハプスブルク君主カルロス2世が死去した際、後継者はフランスのブルボン家出身であった。これによりスペインとスペイン帝国においてフランス啓蒙主義の影響が及ぶ時代が始まった。[147][148] 18世紀、スペインはカリフォルニアのスペイン伝道所や南米内陸部への伝道所設立により、アメリカ大陸での帝国拡大を続けた。カルロス3世の治世下で、王 室は本格的な構造改革を実施し始めた。王政はカトリック教会の権力を制限し、スペイン領アメリカに常備軍を配置した。自由貿易(コメルシオ・リブレ)が推 進され、地域は制限的な重商主義体制ではなく、他のスペイン港から出航する会社と自由に取引できるようになった。王室は、自国が領有権を主張しているが支 配権は持っていない領土に対するスペインの主権を主張するため、また、その広大な帝国の経済的可能性を発見するという重要な目的のために、科学探検隊を派 遣した。植物探検隊は、帝国に有用な植物を探した。[149] カルロス4世は、プロイセンの科学者アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトに、通常は外国人に閉鎖されているスペイン領アメリカを自由に旅行する許可を与 え、さらに重要なことに、彼の科学探検の成功を支援するために王室当局者にアクセスする許可を与えた。[150] 1808年にナポレオンがスペインに侵攻すると、フェルディナンド7世は退位し、ナポレオンは弟のジョセフ・ボナパルトを王位に就けた。この動きに正当性 を加えるため、スペインの海外領土からの代表も含むバイヨンヌ憲法が公布されたが、ほとんどのスペイン国民はナポレオンの計画全体を拒否した。国民抵抗戦 争が勃発した。合法的な君主であるフェルディナンドが不在の中、スペインを統治するためにカディス議会(コルテス・デ・カディス)が召集された。これによ り新たな統治文書である1812年憲法が制定された。この憲法は三権分立(行政・立法・司法)を定め、立憲君主制を創設して国王の権限を制限した。市民権 をスペイン帝国内のアフリカ系祖先を持たない者に限定し、男子普通選挙権を確立した。さらに初等教育から大学までの公教育制度と表現の自由を定めた。この 憲法は1812年から1814年まで施行されたが、ナポレオンが敗北しフェルディナンドがスペイン王位に復帰すると、フェルディナンドは憲法を無効化し絶 対主義統治を再確立した。 |

| Haiti The Haitian Revolution began in 1791 and ended in 1804 and shows how Enlightenment ideas "were part of complex transcultural flows."[10] Radical ideas in Paris during and after the French Revolution were mobilized in Haiti, such as by Toussaint Louverture.[10] Toussaint had read the critique of European colonialism in Guillaume Thomas François Raynal's book Histoire des deux Indes and "was particularly impressed by Raynal's prediction of the coming of a 'Black Spartacus.'"[10] The revolution combined Enlightenment ideas with the experiences of the slaves in Haiti, two-thirds of whom had been born in Africa and could "draw on specific notions of kingdom and just government from West and Central Africa, and to employ religious practices such as voodoo for the formation of revolutionary communities."[10] The revolution also affected France and "forced the French National Convention to abolish slavery in 1794."[10] |

ハイチ ハイチ革命は1791年に始まり1804年に終結したが、この革命は啓蒙思想が「複雑な越境的な流れの一部であった」ことを示している。[10] フランス革命期およびその後のパリで生まれた急進的思想は、トゥーサン・ルヴェルチュールらによってハイチで活用された。[10] トゥーサンはギヨーム・トマ・フランソワ・レイナルの著書『二つのインド諸島の歴史』でヨーロッパ植民地主義への批判を読み、「特に『黒人のスパルタク ス』の到来を予言したレイナルの言葉に強く感銘を受けた」のである。[10] この革命は啓蒙思想とハイチの奴隷たちの経験を融合させた。奴隷の3分の2はアフリカ生まれであり、彼らは「西・中央アフリカ特有の王国観や正義の統治概 念を援用し、革命共同体の形成にヴードゥー教などの宗教的実践を活用できた」[10]. 革命はフランスにも影響を与え、「フランス国民公会に1794年の奴隷制廃止を強いた」[10]. |

| Portugal and Brazil See also: History of Portugal (1640–1777) The Portuguese Enlightenment was heavily marked by the rule of Prime Minister Marquis of Pombal under King Joseph I from 1756 to 1777. Following the 1755 Lisbon earthquake which destroyed a large part of Lisbon, the Marquis of Pombal implemented important economic policies to regulate commercial activity (in particular with Brazil and England), and to standardise quality throughout the country (for example by introducing the first integrated industries in Portugal). His reconstruction of Lisbon's riverside district in straight and perpendicular streets (the Lisbon Baixa), methodically organized to facilitate commerce and exchange (for example by assigning to each street a different product or service), can be seen as a direct application of the Enlightenment ideas to governance and urbanism. His urbanistic ideas, also being the first large-scale example of earthquake engineering, became collectively known as Pombaline style, and were implemented throughout the kingdom during his stay in office. His governance was as enlightened as ruthless, see for example the Távora affair. In literature, the first Enlightenment ideas in Portugal can be traced back to the diplomat, philosopher, and writer António Vieira[152] who spent a considerable amount of his life in colonial Brazil denouncing discriminations against New Christians and the indigenous peoples in Brazil. During the 18th century, enlightened literary movements such as the Arcádia Lusitana (lasting from 1756 until 1776, then replaced by the Nova Arcádia in 1790 until 1794) surfaced in the academic medium, in particular involving former students of the University of Coimbra. A distinct member of this group was the poet Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage. The physician António Nunes Ribeiro Sanches was also an important Enlightenment figure, contributing to the Encyclopédie and being part of the Russian court. The ideas of the Enlightenment influenced various economists and anti-colonial intellectuals throughout the Portuguese Empire, such as José de Azeredo Coutinho, José da Silva Lisboa, Cláudio Manoel da Costa, and Tomás Antônio Gonzaga. The Napoleonic invasion of Portugal had consequences for the Portuguese monarchy. With the aid of the British navy, the Portuguese royal family was evacuated to Brazil, its most important colony. Even though Napoleon had been defeated, the royal court remained in Brazil. The Liberal Revolution of 1820 forced the return of the royal family to Portugal. The terms by which the restored king was to rule was a constitutional monarchy under the Constitution of Portugal. Brazil declared its independence from Portugal in 1822 and became a monarchy. |