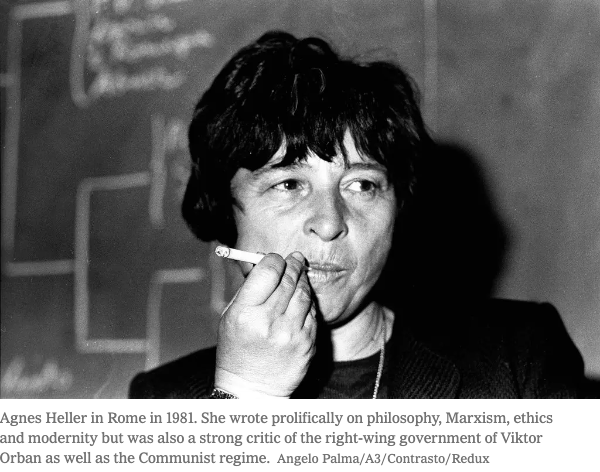

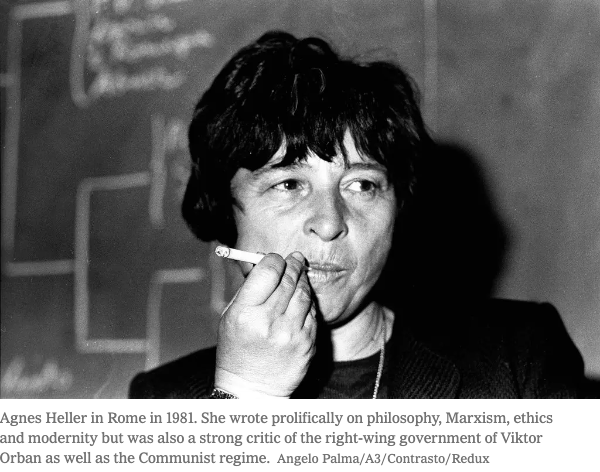

アグネス・ヘラー

Ágnes Heller, 1929-2019

☆ ア グネス・ヘラー(Ágnes Heller、1929年5月12日 - 2019年7月19日)は、ハンガリーの哲学者、講演家。1960年代にブダペスト学派の哲学フォーラムの中心メンバーとして活躍し、後にニューヨークの ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチで25年間にわたり政治理論を教えた。ブダペストで生活、執筆、講義を行った。

| Ágnes Heller (12

May 1929 – 19 July 2019) was a Hungarian philosopher and lecturer. She

was a core member of the Budapest School philosophical forum in the

1960s and later taught political theory for 25 years at the New School

for Social Research in New York City. She lived, wrote and lectured in

Budapest.[1] |

ア

グネス・ヘラー(Ágnes Heller、1929年5月12日 -

2019年7月19日)は、ハンガリーの哲学者、講演家。1960年代にブダペスト学派の哲学フォーラムの中心メンバーとして活躍し、後にニューヨークの

ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチで25年間にわたり政治理論を教えた。ブダペストで生活、執筆、講義を行った。 |

| Ágnes

Heller was born on May 12, 1929 to Pál Heller and Angéla "Angyalka"

Ligeti.[2] They were a middle-class Jewish family.[3] During World War

II her father used his legal training and knowledge of German to help

people get the necessary paperwork to emigrate from Nazi Europe. In

1944, Heller's father was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp

where he died before the war ended.[2] Heller and her mother managed to

avoid deportation. |

ア

グネス・ヘラーは、1929年5月12日、パル・ヘラーとアンゲ ラ・"アンギャルカ"・リゲティの間に生まれた。 ユダヤ人の中流家庭で育った。

第二次世界大戦中、彼女の父親は、法律家としての訓練を受け、ドイツ語の知識を生かして、ナチス・ヨーロッパからの移住に必要な書類の作成を手伝ってい

た。1944年、父親はアウシュビッツ強制収容所に送還され、戦争終結前に死亡した。 |

| With

regard to the influence of the Holocaust on her work, Heller said: I

was always interested in the question: How could this possibly happen?

How can I understand this? And this experience of the holocaust was

joined with my experience in the totalitarian regime. This brought up

very similar questions in my soul-search and world investigation: how

could this happen? How could people do things like this? So I had to

find out what morality is all about, what is the nature of good and

evil, what can I do about crime, what can I figure out about the

sources of morality and evil? That was the first inquiry. The other

inquiry was a social question: what kind of world can produce this?

What kind of world allows such things to happen? What is modernity all

about? Can we expect redemption?[4] |

ホ

ロコーストが彼女の作品に与えた影響について、ヘラーはこう語っ

ている;「私はいつも疑問に興味を持っていました。どうしてこんなことが起こるのだろう?どうすればこれを理解できるのか?そして、このホロコーストの経

験は、全体主義体制での経験と結びついていた。このことは、私の魂の探求と世界の調査において、非常によく似た疑問をもたらしました:どうしてこんなこと

が起こるのか?どうしてこのようなことが起こるのか?そこで私は、道徳とは何か、善と悪の本質とは何か、犯罪に対してどうすればいいのか、道徳や悪の源は

何か、といったことを調べなければなりませんでした。これが第一の問題です。もう1つの問いは社会的な問いであり、どのような世界がこのようなものを生み

出すことができるのか?どのような世界がこのようなことを可能にするのか?近代とはいったい何なのか?贖罪を期待していいのか」ということなのです。 |

| In

1947, Heller began to study physics and chemistry at the University of

Budapest. She changed her focus to philosophy, however, when her

boyfriend at the time urged her to listen to the lecture of the

philosopher György Lukács, on the intersections of philosophy and

culture. She was immediately taken by how much his lecture addressed

her concerns and interests in how to live in the modern world,

especially after the experience of World War II and the Holocaust. |

1947

年、ヘラーはブダペスト大学で物理学と化学を学び始めた。

しかし、当時付き合っていたボーイフレンドに誘われて、哲学者のジェルジ・ルカーチの「哲学と文化の接点」についての講義を聴き、哲学に目を向けるように

なった。ルカーチの講義は、第二次世界大戦とホロコーストを経験した後の、現代社会をどう生きるかという彼女の関心事と一致しており、すぐに魅了された。 |

| Heller

joined the Communist Party that year, 1947, while at a Zionist work

camp and began to develop her interest in Marxism. However, she felt

that the Party was stifling the ability of its adherents to think

freely due to its adherence to democratic centralism . She was expelled

from it for the first time in 1949, the year that Mátyás Rákosi came

into power and ushered in the years of Stalinist rule. |

1947

年、シオニストのワークキャンプで共産党に入党したヘラー

は、マルクス主義に興味を持ち始めた。しかし彼女は、共産党が民主的中央集権主義に固執するあまり、党員の自由な発想を阻害していると感じていた。

1949年、マーチャーシュ・ラーコーシが政権を握り、スターリン体制に突入した年に、初めて党から追放される。 |

| Early

career in Hungary; After 1953 and the installation of Imre Nagy as

Prime Minister, Heller was able to safely undertake her doctoral

studies under the supervision of Lukács, and in 1955 she began to teach

at the University of Budapest. |

ハンガリーでの初期のキャリア;1953年にイムレ・ナギーが首相 に就任した後、ヘラーはルカーチの指導の下で博士課程の研究を無事に行うことができ、1955年にはブダペスト大学で教え始めた。 |

| From

the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 to the Prague Spring of 1968; The 1956

Hungarian Revolution was the most important political event of her

life, for at this time she saw the effect of the academic freedoms of

Marxist critical theory as dangerous to the entire political and social

structure of Hungary. Heller saw the uprising as confirming her ideas

that what Marx really means for the people is to have political

autonomy and collective determination of social life. Lukács, Heller

and other critical theorists emerged from the Revolution with the

belief that Marxism and socialism needed to be applied to different

nations in individual ways, effectively questioning the role of the

Soviet Union in Hungary's future. These ideas set Heller on an

ideological collision course with the new Moscow-supported government

of János Kádár: Heller was again expelled from the Communist Party and

she was dismissed from the University in 1958 for refusing to indict

Lukács as a collaborator in the Revolution. She was not able to resume

her research until 1963, when she was invited to join the Sociological

Institute at the Hungarian Academy as a researcher. From 1963 can be

seen the emergence of what would later be called the "Budapest School",

a philosophical forum that was formed by Lukács to promote the renewal

of Marxist criticism in the face of practiced and theoretical

socialism. Other participants in the Budapest School included together

with Heller her second husband Ferenc Fehér, György Márkus, Mihály

Vajda and some other scholars with the looser connection to the school

(such as András Hegedüs, István Eörsi, János Kis and György Bence).

Heller's work from this period, concentrated on themes such as what

Marx means to be the character of modern societies; liberation theory

as applied to the individual; the work of changing society and

government from "the bottom up," and affecting change through the level

of the values, beliefs and customs of "everyday life". |

1956

年のハンガリー革命から1968年のプラハの春まで。

1956年のハンガリー革命は、彼女の人生で最も重要な政治的出来事であった。このとき彼女は、マルクス主義批判理論の学問的自由の影響が、ハンガリーの

政治的・社会的構造全体にとって危険なものであると考えていたからである。ヘラーはこの蜂起を、マルクスが人民にとって本当に意味するのは、政治的自律性

と社会生活の集団的決定であるという彼女の考えを裏付けるものと考えた。ルカーチやヘラーをはじめとする批判的理論家たちは、マルクス主義や社会主義はそ

れぞれの国にそれぞれの方法で適用される必要があると考え、ハンガリーの将来におけるソビエト連邦の役割を事実上疑問視して、革命から生まれた。このよう

な考えから、ヘラーはモスクワが支援するヤーノシュ・カダール新政権とイデオロギー的に衝突することになった。ヘラーは再び共産党から追放され、1958

年にはルカーチを革命の協力者として起訴することを拒否したため、大学から解雇された。彼女が研究を再開できたのは、1963年にハンガリー・アカデミー

の社会学研究所に研究員として招かれてからであった。1963年からは、後に「ブダペスト学派」と呼ばれる哲学フォーラムが始まり、ルカーチは実践的・理

論的な社会主義に直面してマルクス主義批判の刷新を促進するために結成された。ブダペスト学派には、ヘラーのほかに、彼女の2番目の夫であるフェヘル、

ギョルギー・マルクス、ミハーイ・ヴァイダや、アンドラーシュ・ヘゲデュス、イシュトヴァン・エオルシ、ヤーノシュ・キス、ギョルギー・ベンスなど、学派

とは関係の薄い学者たちが参加していた。この時期のヘラーは、マルクスの言う現代社会の性格とは何か、個人に適用される解放論、社会や政府を「ボトムアッ

プ」で変えていく作業、「日常生活」の価値観や信念、習慣のレベルで変化をもたらすことなどをテーマにしていた。 |

| Career

in Hungary after the Prague Spring; Until the events of the 1968 Prague

Spring, the Budapest School remained supportive of reformist attitudes

towards socialism. After the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact

forces and the crushing of dissent, however, the School and Heller came

to believe that the Eastern European regimes were entirely corrupted

and that reformist theory was apologist. Heller explains in her

interview with Polony that: "the regime just could not tolerate any

other opinion; that is what a totalitarian regime is. But a

totalitarian regime cannot totalize entirely, it cannot dismiss

pluralism; pluralism exists in the modern world, but it can outlaw

pluralism. To outlaw pluralism means that the Party decided which kind

of dissenting opinion was allowed. That is, you could not write

something without it being allowed by the Party. But we had started to

write and think independently and that was such a tremendous challenge

against the way the whole system worked. They could not possibly

tolerate not playing by the rules of the game. And we did not play by

the rules of the game." This view was completely incompatible

with Kadar's view of Hungary's political future after the Revolution of

1956.[citation needed] According to an interview with Heller in 2010 in

the German newspaper Jungle World, she thought that political and

criminal processes after 1956 were antisemitic.After Lukács died in

1971, the School's members were victims of political persecution, were

made unemployed through their dismissal from their university jobs, and

were subjected to official surveillance and general

harassment.[citation needed] Rather than remain as dissidents, Heller

and her husband the philosopher Ferenc Fehér, along with many other

members of the core group of the School, chose exile in Australia in

1977. |

プ

ラハの春」後のハンガリーでのキャリア;

1968年の「プラハの春」の出来事まで、ブダペスト学校は社会主義に対する改革派の姿勢を支持していた。しかし、ワルシャワ条約機構によるチェコスロバ

キア侵攻と反体制派の鎮圧を経て、学校とヘラーは、東欧の政権は完全に腐敗しており、改革派の理論は謝罪すべきものだと考えるようになった。ヘラーは、ポ

ロニーとのインタビューで次のように説明している。「政権は他の意見を許しませんで

した。それが全体主義体制というものなのです。しかし、全体主義体制は完全に全体化することはできません。多元主義を否定することはできません。現代世界

には多元主義が存在しますが、多元主義を違法化することはできます。多元主義を非合法化するということは、どのような反対意見が許されるかを党が決めたと

いうことです。つまり、党が許可しないと何も書けないということです。しかし、私たちは独立して文章を書き、考え始めていました。それは、全体のシステム

が機能する方法に対して、非常に大きな挑戦でした。党は、ゲームのルールに従わないことを容認することはできませんでした。そして、私たちはゲームのルー

ルに従わなかったのです」。

この見解は、1956年の革命後のハンガリーの政治的未来についてのカダールの見解とは全く相容れないものであった[要出典]。2010年にドイツの新聞

「ジャングル・ワールド」に掲載されたヘラーのインタビューによると、彼女は1956年以降の政治的・犯罪的プロセスは反ユダヤ的であると考えていたとい

う。

1971年にルカーチが死去した後、学派のメンバーは政治的な迫害を受け、大学を解雇されて失業者となり、公的な監視や嫌がらせを受けた[要出典]。 |

| Career

abroad; Heller and Fehér encountered what they regarded as the

sterility of local culture and lived in relative suburban obscurity

close to La Trobe University in Melbourne. They assisted in the

founding of Thesis Eleven in 1980, and its development into a leading

Australian journal of social theory and forum for "politically

independent" left wing thought. As described by Tormey, Heller's mature

thought during this time period was based on the tenets that can be

attributed to her personal history and experience as a member of the

Budapest School, focusing on the stress on the individual as agent; the

hostility to the justification of the state of affairs by reference to

non-moral or non-ethical criteria; the belief in "human substance" as

the origin of everything that is good or worthwhile; and the hostility

to forms of theorizing and political practice that deny equality,

rationality and self-determination in the name of "our" interests and

needs, however defined. Heller and Fehér left Australia in 1986 to take

up positions in The New School in New York City, where Heller held the

position of Hannah Arendt Professor of Philosophy in the Graduate

Studies Program. Her contribution to the field of philosophy was

recognized by the many awards that she received (such as the Hannah

Arendt Prize for Political Philosophy, Bremen, 1995) and the Szechenyi

National Prize in Hungary, 1995[citation needed] and the various

academic societies that she served on, including the Hungarian Academy

of Sciences. In 2006 she visited China for a week for the first time.

Heller researched and wrote prolifically on ethics, Shakespeare,

aesthetics, political theory, modernity, and the role of Central Europe

in historical events. From 1990, Heller was more interested in the

issues of aesthetics in The Concept of The Beautiful (1998), Time Is

Out of Joint (2002), and Immortal Comedy (2005). In 2006, she was the

recipient of the Sonning Prize, in 2010 she received the Goethe

Medal.[citation needed] In 2010, Heller, with 26 other well known and

successful Hungarian women, joined the campaign for a referendum for a

female quota in the Hungarian legislature. Heller published

internationally renowned works, including republications of her

previous works in English, all of which are internationally revered by

scholars such as Lydia Goehr (on Heller's The Concept of the

Beautiful), Richard Wolin (on Heller's republication of A Theory of

Feelings), Dmitri Nikulin (on comedy and ethics), John Grumley (whose

own work focuses on Heller in Agnes Heller: A Moralist in the Vortex of

History), John Rundell (on Heller's aesthetics and theory of

modernity), Preben Kaarsholm (on Heller's A Short History of My

Philosophy), among others. Heller was Professor Emeritus at the New

School for Social Research in New York. She worked actively both

academically and politically around the globe. She spoke at the Imre

Kertész College in Jena, Germany together with Polish sociologist,

Zygmunt Bauman, at the Tübingen Book Fair in Germany speaking together

with Former German Justice Minister, Herta Däubler-Gmelin, and other

venues worldwide. |

海

外でのキャリア:ヘラーとフェールは、地元の文化が不毛であると考え、メルボルンのラ・トローブ大学の近くの郊外で比較的無名の生活を送っていた。二人

は、1980年に『テーゼ・イレブン』の創刊を支援し、オーストラリアを代表する社会理論の雑誌であり、「政治的に独立した」左翼思想のフォーラムへと発

展させたのである。トーミーが述べているように、この時期のヘラーの成熟した思想は、ブダペスト学派のメンバーとしての彼女の個人的な歴史と経験に起因す

る教義に基づいており、エージェントとしての個人への強調、非道徳的あるいは非倫理的な基準を参照して状況を正当化することへの敵意などに焦点を当ててい

た。善いことや価値のあることの起源として「人間の本質」を信じること、そして、定義された「我々」の利益やニーズの名の下に、平等、合理性、自己決定を

否定する理論化や政治的実践の形態に敵意を抱くことです。ヘラーとフェールは1986年にオーストラリアを離れ、ニューヨークのニュースクールに赴任し、

ヘラーはハンナ・アーレント哲学教授として大学院に在籍した。彼女の哲学分野への貢献は、ハンナ・アーレント賞(政治哲学部門、ブレーメン、1995年)

やシェチェーニ国民賞(ハンガリー、1995年)などの多くの賞の受賞[要出典]や、ハンガリー科学アカデミーをはじめとする様々な学会での活動によって

認められている。2006年には、初めて中国を1週間訪問した。ヘラーは、倫理、シェイクスピア、美学、政治理論、近代性、歴史的出来事における中欧の役

割などについて研究し、多くの著作を残している。1990年以降は、"The Concept of The

Beautiful"(1998年)、"Time Is Out of Joint"(2002年)、"Immortal

Comedy#(2005年)など、美学の問題に関心を寄せている。2006年にはソニング賞、2010年にはゲーテ・メダルを受賞[要出典]。2010

年、ヘラーは他の26人の著名な成功したハンガリー人女性とともに、ハンガリー議会に女性枠を設けるための国民投票のキャンペーンに参加した。ヘラーは、

彼女の過去の著作を英語で再出版するなど、国際的に有名な作品を出版しており、そのすべてが、リディア・ゲーア(ヘラーの『美しいものの概念』につい

て)、リチャード・ウォーリン(ヘラーの再出版『感情の理論』について)、ドミトリー・ニクリン(喜劇と倫理について)、ジョン・グラムリー(彼自身の研

究では、ヘラーに焦点を当てた『アグネス・ヘラー(A Moralist in the Vortex of History)』)、John

Rundell(ヘラーの美学と現代性の理論について)、Preben Kaarsholm(ヘラーの『A Short History of My

Philosophy』について)などがある。ヘラーは、ニューヨークのニュースクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチの名誉教授を務めた。

また、学術的にも政治的にも世界各地で精力的に活動した。ポーランドの社会学者ジグムント・バウマンと共にドイツ・イエナのイムレ・ケルテス大学で講演し

たり、ドイツのチュービンゲンブックフェアで元ドイツ法務大臣ヘルタ・デゥブラー・グメリンと共に講演するなど、世界各地で活躍した。 |

| Personal

Life; Heller married fellow philosopher István Hermann in 1949. Their

only daughter, Zsuzsanna "Zsuzsa" Hermann, was born on 1 October 1952.

After their divorce in 1962, Heller married Ferenc Fehér in 1963, also

a member of Lukács' circle. Heller and Fehér had a son, György Fehér

(1964). Ferenc Fehér died in 1994. Ágnes Heller mentions that prominent

Hungarian violinist Leopold Auer was related to her family on her

mother's side. Heller is second-cousin of 20th century contemporary

composer György Ligeti. While going for a swim in Lake Balaton on 19

July 2019, Heller drowned at Balatonalmádi. |

私

生活;ヘラーは1949年に同じ哲学者のイシュトヴァン・ヘルマ ンと結婚した。1952年10月1日には、二人の間に一人娘のズズサンナ "ズサ

"ヘルマンが誕生した。1962年に離婚した後、ヘラーは1963年に同じくルカーチのサークルのメンバーであるフェヘルと結婚した。ヘラーとフェヘルの

間には、1964年に息子のギョルギー・フェヘルが生まれた。フェヘルは1994年に亡くなった。ハンガリーの著名なヴァイオリニスト、レオポルド・アウ

アーが母方の家系にいたことをアグネス・ヘラーが語っている。

20世紀の現代作曲家、ジェルジ・リゲティの二親等にあたる。2019年7月19日にバラトン湖に泳ぎに行った際、ヘラーはバラトナルマーディで溺死し

た。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81gnes_Heller |

|

| Books Towards a Marxist Theory of Value. Carbondale: University of Southern Illinois, Telos Books, 1972. (contributor) Individuum and Praxis: Positionen der Budapester Schule (ed. György Lukács; collected essays translated from Hungarian). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1975. (contributor) The Humanisation of Socialism: Writings of the Budapest School (ed. András Hegedűs; collected essays translated from Hungarian). London: Allison and Busby, 1976. The Theory of Need in Marx. London: Allison and Busby, 1976. Renaissance Man (English translation of Hungarian original). London, Boston, Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978. On Instincts (English translation of Hungarian original). Assen: Van Gorcum, 1979. A Theory of History. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982. Dictatorship Over Needs (with Ferenc Fehér and G. Markus). Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983. Hungary, 1956 Revisited: The Message of a Revolution – a Quarter of a Century After (with F. Fehér). London, Boston, Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1983. (ed.) Lukács Revalued. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983 (paperback, 1984). Everyday Life (English translation of Hungarian 1970 original). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984. A Radical Philosophy B. Blackwell; First edition. (1 January 1984) The Power of Shame: A Rationalist Perspective. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985. Doomsday or Deterrence (with F. Fehér). White Plains: M. E. Sharpe, 1986. (ed. with F. Fehér) Reconstructing Aesthetics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986. Eastern Left – Western Left. Freedom, Totalitarianism, Democracy (with F. Fehér). Cambridge, New York: Polity Press, Humanities Press, 1987. Beyond Justice, Oxford, Boston: Basil Blackwell, 1988. General Ethics. Oxford, Boston: Basil Blackwell, 1989. The Postmodern Political Condition (with F. Fehér). Cambridge, New York: Polity Press Columbia University Press, 1989. Can Modernity Survive? Cambridge, Berkeley, Los Angeles: Polity Press and University of California Press, 1990. From Yalta to Glasnost: The Dismantling of Stalin's Empire (with F. Fehér). Oxford, Boston: Basil Blackwell, 1990. The Grandeur and Twilight of Radical Universalism (with F. Fehér). New Brunswick: Transaction, 1990. A Philosophy of Morals. Oxford, Boston: Basil Blackwell, 1990. An Ethics of Personality. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell, 1996. A Theory of Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999. The Time is Out of Joint: Shakespeare as Philosopher of History. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000. The insolubility of the "Jewish question", or Why was I born Hebrew, and why not negro? Budapest: Múlt és Jövő Kiadó, 2004. Immortal Comedy: The Comic Phenomenon in Art, Literature, and Life. Lanham et al.: Lexington Books, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc, 2005. A mai történelmi regény ("The historical novel today", in Hungarian). Budapest: Múlt és Jövő Kiadó, 2011. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆