アラン・ローマックス

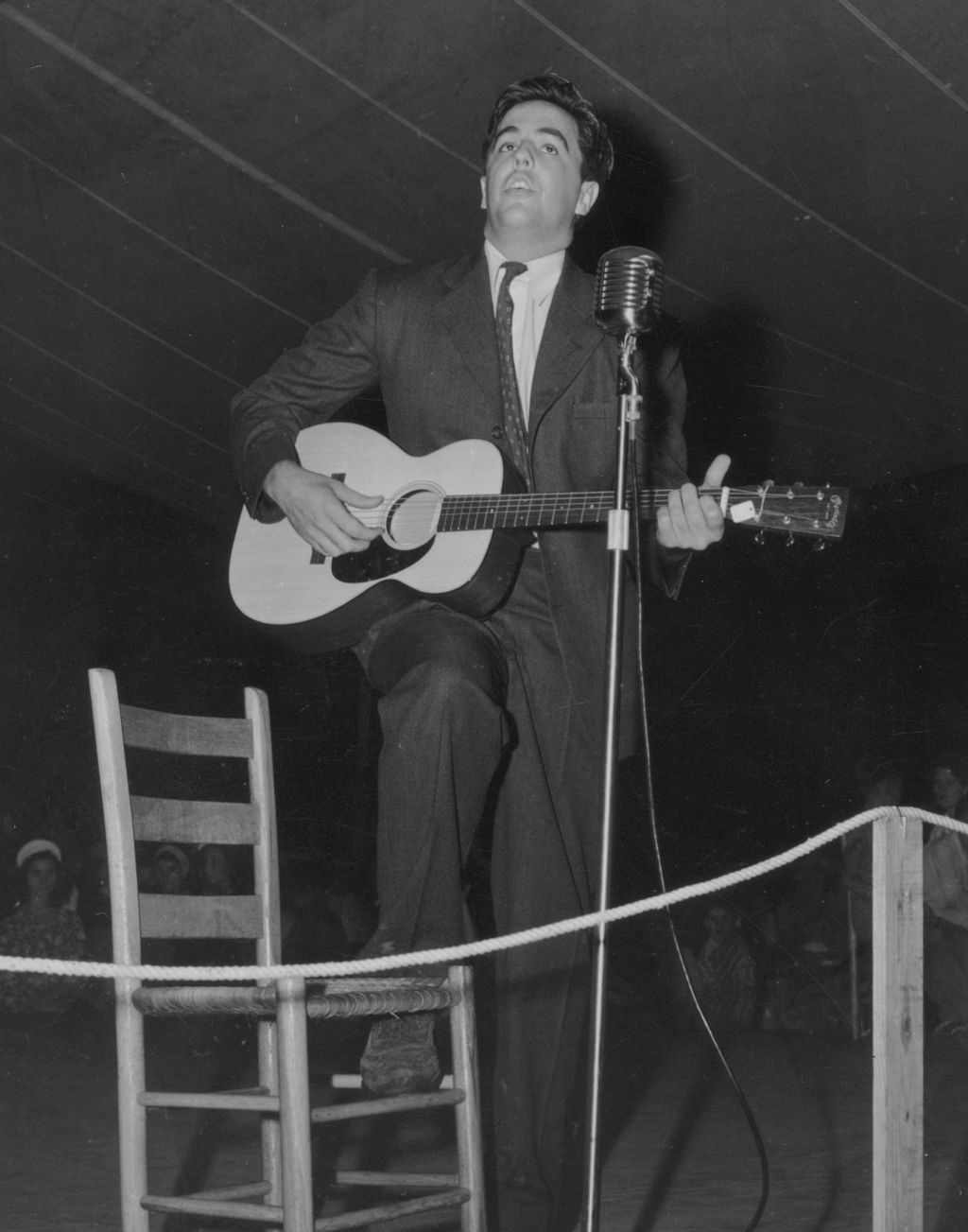

Alan Lomax, 1915-2002

☆アラン・ローマックス(/ˈloʊmæks/、1915年1月31日 - 2002年7月19日)はアメリカの民族音楽学者であり、20世紀の民族音楽を数多くフィールドレコーディングしたことで知られる。音楽家、民俗学者、記 録保管家、作家、学者、政治活動家、口承史家、映画製作者でもあった。ローマックスはアメリカとイギリスで録音、コンサート、ラジオ番組を制作し、両国の フォーク音楽の伝統を守る上で重要な役割を果たすとともに、1940年代、1950年代、1960年代初頭のアメリカとイギリスのフォーク・リヴァイヴァ ルの立ち上げに貢献した。彼はまず父である民俗学者でコレクターのジョン・ローマックスとともに資料を収集し、その後単独で、また他の人々とともに、アメ リカ議会図書館で彼が館長を務めていた『アーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・フォークソング』のために、何千もの歌やインタビューをアルミ盤やアセテート盤に 録音した。

| Alan Lomax

(/ˈloʊmæks/; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American

ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk

music of the 20th century. He was a musician, folklorist, archivist,

writer, scholar, political activist, oral historian, and film-maker.

Lomax produced recordings, concerts, and radio shows in the US and in

England, which played an important role in preserving folk music

traditions in both countries, and helped start both the American and

British folk revivals of the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. He

collected material first with his father, folklorist and collector John

Lomax, and later alone and with others, Lomax recorded thousands of

songs and interviews for the Archive of American Folk Song, of which he

was the director, at the Library of Congress on aluminum and acetate

discs. After 1942, when Congress terminated the Library of Congress's funding for folk song collecting, Lomax continued to collect independently in Britain, Ireland, Caribbean region, Italy, Spain, and United States, using the latest recording technology, assembling an enormous collection of American and international culture. In March 2004, the material captured and produced without Library of Congress funding was acquired by the Library, which "brings the entire seventy years of Alan Lomax's work together under one roof at the Library of Congress, where it has found a permanent home."[1] With the start of the Cold War, Lomax continued to advocate for a public role for folklore,[2] even as academic folklorists turned inward. He devoted much of the latter part of his life to advocating what he called Cultural Equity, which he sought to put on a solid theoretical foundation through to his Cantometrics research (which included a prototype Cantometrics-based educational program, the Global Jukebox). In the 1970s and 1980s, Lomax advised the Smithsonian Institution's Folklife Festival and produced a series of films about folk music, American Patchwork, which aired on PBS in 1991. In his late 70s, Lomax completed the long-deferred memoir The Land Where the Blues Began (1993), linking the birth of the blues to debt peonage, segregation, and forced labor in the American South. Lomax's greatest legacy is in preserving and publishing recordings of musicians in many folk and blues traditions around the US and Europe. Among the artists Lomax is credited with discovering and bringing to a wider audience include blues guitarist Robert Johnson, protest singer Woody Guthrie, folk artist Pete Seeger, country musician Burl Ives, Scottish Gaelic singer Flora MacNeil, and country blues singers Lead Belly and Muddy Waters, among many others. "Alan scraped by the whole time, and left with no money," said Don Fleming, director of Lomax's Association for Culture Equity. "He did it out of the passion he had for it, and found ways to fund projects that were closest to his heart".[3] |

アラン・ロー

マックス(/ˈloʊmæks/、1915年1月31日 -

2002年7月19日)はアメリカの民族音楽学者であり、20世紀の民族音楽を数多くフィールドレコーディングしたことで知られる。音楽家、民俗学者、記

録保管家、作家、学者、政治活動家、口承史家、映画製作者でもあった。ローマックスはアメリカとイギリスで録音、コンサート、ラジオ番組を制作し、両国の

フォーク音楽の伝統を守る上で重要な役割を果たすとともに、1940年代、1950年代、1960年代初頭のアメリカとイギリスのフォーク・リヴァイヴァ

ルの立ち上げに貢献した。彼はまず父である民俗学者でコレクターのジョン・ローマックスとともに資料を収集し、その後単独で、また他の人々とともに、アメ

リカ議会図書館で彼が館長を務めていた『アーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・フォークソング』のために、何千もの歌やインタビューをアルミ盤やアセテート盤に

録音した。 米国議会が民謡収集に対する米国議会図書館の資金援助を打ち切った1942年以降も、ローマックスは英国、アイルランド、カリブ海地域、イタリア、スペイ ン、米国で、最新の録音技術を駆使して独自に収集を続け、アメリカと世界の文化に関する膨大なコレクションを作り上げた。2004年3月、米国議会図書館 の資金援助なしに収集・制作された資料が同図書館に収蔵され、「アラン・ローマックスの70年にわたる仕事全体が米国議会図書館の一つ屋根の下に集めら れ、恒久的な住処が見つかった」[1]。冷戦が始まると、学術的な民俗学者が内向きになる中でも、ローマックスは民俗学の公的な役割を提唱し続けた [2]。彼は人生の後期の大半を、カントメトリックス研究(カントメトリックスに基づく教育プログラム「グローバル・ジュークボックス」のプロトタイプを 含む)を通じて確固たる理論的基礎の上に置こうとした、彼が「文化的公正」と呼ぶものの提唱に費やした。1970年代から1980年代にかけて、ローマッ クスはスミソニアン協会のフォークライフ・フェスティバルのアドバイザーを務め、1991年にPBSで放映されたフォーク・ミュージックに関する一連の映 画『American Patchwork』を制作した。70代後半、ローマックスは長らく延期されていた回顧録『The Land Where the Blues Began』(1993年)を完成させ、ブルースの誕生をアメリカ南部における借金の小作権、隔離、強制労働と関連づけた。 ローマックスの最大の遺産は、アメリカやヨーロッパの多くのフォークやブルースの伝統のミュージシャンの録音を保存し、出版したことである。ローマックス が発見し、より多くの聴衆に知らしめたアーティストとしては、ブルース・ギタリストのロバート・ジョンソン、プロテスト・シンガーのウディ・ガスリー、 フォーク・アーティストのピート・シーガー、カントリー・ミュージシャンのバール・アイヴス、スコットランド・ゲール人シンガーのフローラ・マクニール、 カントリー・ブルース・シンガーのリード・ベリーやマディ・ウォーターズなどが挙げられる。「ローマックスのAssociation for Culture Equityのディレクター、ドン・フレミングは言う。「彼はその情熱からそれを行い、彼の心に最も近いプロジェクトに資金を提供する方法を見つけた」 [3]。 |

| Biography Early life Lomax was born in Austin, Texas in 1915,[4][5][6] the third of four children born to Bess Brown and pioneering folklorist and author John A. Lomax. Two of his siblings also developed significant careers studying folklore: Bess Lomax Hawes and John Lomax Jr. The elder Lomax, a former professor of English at Texas A&M University and a celebrated authority on Texas folklore and cowboy songs, had worked as an administrator, and later Secretary of the Alumni Society, of the University of Texas.[7] Due to childhood asthma, chronic ear infections, and generally frail health, Lomax had mostly been home schooled in elementary school. In Dallas, he entered the Terrill School for Boys (a tiny prep school that later became St. Mark's School of Texas). Lomax excelled at Terrill and then transferred to the Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Connecticut for a year, graduating eighth in his class at age 15 in 1930.[8] Owing to his mother's declining health, however, rather than going to Harvard University as his father had wished, Lomax matriculated at the University of Texas at Austin. A roommate, future anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt, recalled Lomax as "frighteningly smart, probably classifiable as a genius", though Goldschmidt remembers Lomax exploding one night while studying: "Damn it! The hardest thing I've had to learn is that I'm not a genius."[9] At the University of Texas Lomax read Nietzsche and developed an interest in philosophy. He joined and wrote a few columns for the school paper, The Daily Texan but resigned when it refused to publish an editorial he had written on birth control.[9] At this time he also he began collecting "race" records and taking his dates to black-owned night clubs, at the risk of expulsion. During the spring term his mother died, and his youngest sister Bess, age 10, was sent to live with an aunt. Although the Great Depression was rapidly causing his family's resources to plummet, Harvard came up with enough financial aid for the 16-year-old Lomax to spend his second year there. He enrolled in philosophy and physics and also pursued a long-distance informal reading course in Plato and the Pre-Socratics with University of Texas professor Albert P. Brogan.[10] He also became involved in radical politics and came down with pneumonia. His grades suffered, diminishing his financial aid prospects.[11] Lomax, now 17, therefore took a break from studying to join his father's folk song collecting field trips for the Library of Congress, co-authoring American Ballads and Folk Songs (1934) and Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly (1936).[6] His first field collecting without his father was done with Zora Neale Hurston and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in the summer of 1935. He returned to the University of Texas that fall and was awarded a BA in Philosophy,[6] summa cum laude, and membership in Phi Beta Kappa in May 1936.[12] Lack of money prevented him from immediately attending graduate school at the University of Chicago, as he desired, but he later corresponded with and pursued graduate studies with Melville J. Herskovits at Columbia University and with Ray Birdwhistell at the University of Pennsylvania. Alan Lomax married Elizabeth Harold Goodman, then a student at the University of Texas, in February 1937.[13] They were married for 12 years and had a daughter, Anne (later known as Anna). Elizabeth assisted him in recording in Haiti, Alabama, Appalachia, and Mississippi. Elizabeth also wrote radio scripts of folk operas featuring American music that were broadcast over the BBC Home Service as part of the war effort. During the 1950s, after she and Lomax divorced, she conducted lengthy interviews for Lomax with folk music personalities, including Vera Ward Hall and the Reverend Gary Davis. Lomax also did important field work with Elizabeth Barnicle and Zora Neale Hurston in Florida and the Bahamas (1935);[14] with John Wesley Work III and Lewis Jones in Mississippi (1941 and 42); with folksingers Robin Roberts[15] and Jean Ritchie in Ireland (1950); with his second wife Antoinette Marchand in the Caribbean (1961); with Shirley Collins in Great Britain and the Southeastern U.S. (1959); with Joan Halifax in Morocco; and with his daughter.[16] All those who assisted and worked with him were accurately credited on the resultant Library of Congress and other recordings, as well as in his many books, films, and publications.[14] |

略歴 生い立ち ローマックスは1915年にテキサス州オースティンで、ベス・ブラウンと先駆的な民俗学者で作家のジョン・A・ローマックスの間に生まれた4人兄弟の3番 目として生まれた[4][5][6]。兄弟のうち2人も民俗学を研究する重要なキャリアを築いた: ベス・ローマックス・ホーズとジョン・ローマックス・ジュニアである。 長男のローマックスはテキサスA&M大学の元英語教授で、テキサス民俗学とカウボーイ・ソングの権威として知られ、テキサス大学の管理者、後に同窓会幹事を務めた[7]。 小児喘息、慢性的な耳の感染症、そして全体的に虚弱体質であったため、ローマックスは小学校の頃はほとんど家庭教育を受けていた。ダラスでは、テリル少年 学校(後にセント・マーク・スクール・オブ・テキサスとなる小さな予備校)に入学した。テリルで優秀な成績を収めたローマックスは、コネチカット州の チョート・スクール(現チョート・ローズマリー・ホール)に1年間転校し、1930年に15歳でクラス8位で卒業した[8]。 しかし、母親の健康状態が悪化していたため、父の希望通りハーバード大学には進学せず、テキサス大学オースティン校に入学した。ルームメイトで後に人類学 者となるウォルター・ゴールドシュミットは、ローマックスを「恐ろしく頭がよく、おそらく天才に分類されるだろう」と回想しているが、ゴールドシュミット はある晩、勉強中にローマックスが爆発したことを覚えている: 「ちくしょう!テキサス大学でローマックスはニーチェを読み、哲学に興味を持った。彼は学内紙『The Daily Texan』に加わり、いくつかのコラムを書いたが、避妊について書いた社説の掲載を拒否されたため、辞職した[9]。 この頃、彼はまた「人種」記録を集め始め、退学の危険を冒して黒人が経営するナイトクラブにデートに連れて行った。春の学期中に母親が亡くなり、10歳の 末の妹ベスは叔母の家に預けられた。世界大恐慌の影響で家計は急速に苦しくなったが、ハーバード大学は16歳のローマックスが2年目を過ごすのに十分な資 金援助を用意した。彼は哲学と物理学を専攻し、テキサス大学のアルバート・P・ブローガン教授のもとで、プラトンとソクラテス以前の古典を遠距離で読むイ ンフォーマルなコースにも通った[10]。成績は悪化し、学資援助の見込みは薄れた[11]。 そのため17歳になったローマックスは勉強を中断し、議会図書館のために父親が行っていたフォークソング収集のフィールドトリップに参加し、共著として 『American Ballads and Folk Songs』(1934年)と『Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly』(1936年)を出版した[6]。父親抜きで初めて行ったフィールド収集は、1935年の夏にゾラ・ニール・ハーストンとメアリー・エリザベ ス・バーニクルと行ったものであった。同年秋にテキサス大学に戻り、1936年5月に哲学の学士号[6]を首席で授与され、ファイ・ベータ・カッパの会員 となった[12]。資金不足のため、すぐに希望していたシカゴ大学の大学院に進学することはできなかったが、後にコロンビア大学のメルヴィル・J・ハース コヴィッツやペンシルベニア大学のレイ・バードウィステルと文通し、大学院での研究を進めた。 アラン・ローマックスは1937年2月、当時テキサス大学の学生だったエリザベス・ハロルド・グッドマンと結婚した[13]。2人は12年間結婚生活を送 り、娘のアン(後のアンナ)をもうけた。エリザベスはハイチ、アラバマ、アパラチア、ミシシッピでのレコーディングを手伝った。エリザベスはまた、アメリ カの音楽をフィーチャーしたフォーク・オペラのラジオ台本を書き、戦争努力の一環としてBBCホーム・サービスで放送された。 ローマックスと離婚した後の1950年代、彼女はローマックスのために、ヴェラ・ウォード・ホールやゲーリー・デイヴィス牧師をはじめとするフォーク・ ミュージックの著名人に長時間のインタビューを行った。また、エリザベス・バーニクルやゾラ・ニール・ハーストンとフロリダとバハマで(1935年)、 ジョン・ウェズリー・ワーク3世やルイス・ジョーンズとミシシッピで(1941年と42年)、フォークシンガーのロビン・ロバーツ[15]やジーン・リッ チーとアイルランドで(1950年)、2番目の妻アントワネット・マーシャンとカリブ海で(1961年)、シャーリー・コリンズとイギリスとアメリカ南東 部で(1959年)、シャーリー・コリンズとイギリスとアメリカ南東部で(1959年)、シャーリー・コリンズとアメリカ南東部で(1959年)、それぞ れ重要なフィールドワークを行った。 彼を援助し、共に活動したすべての人々は、結果として米国議会図書館やその他のレコーディング、また彼の多くの著書、映画、出版物に正確にクレジットされ ている[14]。 |

| Assistant in charge as well as commercial records and radio broadcasts From 1937 to 1942, Lomax was Assistant in Charge of the Archive of Folk Song of the Library of Congress to which he and his father and numerous collaborators contributed more than ten thousand field recordings.[17] A pioneering oral historian, Lomax recorded substantial interviews with many folk and jazz musicians, including Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Jelly Roll Morton and other jazz pioneers, and Big Bill Broonzy. On one of his trips in 1941, he went to Clarksdale, Mississippi, hoping to record the music of Robert Johnson. When he arrived, he was told by locals that Johnson had died but that another local man, Muddy Waters, might be willing to record his music for Lomax. Using recording equipment that filled the trunk of his car, Lomax recorded Waters' music; it is said that hearing Lomax's recording was the motivation that Waters needed to leave his farm job in Mississippi to pursue a career as a blues musician, first in Memphis and later in Chicago.[18] As part of this work, Lomax traveled through Michigan and Wisconsin in 1938 to record and document the traditional music of that region. Over four hundred recordings from this collection are now available at the Library of Congress. "He traveled in a 1935 Plymouth sedan, toting a Presto instantaneous disc recorder and a movie camera. And when he returned nearly three months later, having driven thousands of miles on barely paved roads, it was with a cache of 250 discs and 8 reels of film, documents of the incredible range of ethnic diversity, expressive traditions, and occupational folklife in Michigan."[19] In late 1939, Lomax hosted two series on CBS's nationally broadcast American School of the Air, called American Folk Song and Wellsprings of Music, both music appreciation courses that aired daily in the schools and were supposed to highlight links between American folk and classical orchestral music. As host, Lomax sang and presented other performers, including Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Josh White, and the Golden Gate Quartet. The individual programs reached ten million students in 200,000 U.S. classrooms and were also broadcast in Canada, Hawaii, and Alaska, but both Lomax and his father felt that the concept of the shows, which portrayed folk music as mere raw material for orchestral music, was deeply flawed and failed to do justice to vernacular culture. In 1940, under Lomax's supervision, RCA made two groundbreaking suites of commercial folk music recordings: Woody Guthrie's Dust Bowl Ballads and Lead Belly's The Midnight Special and Other Southern Prison Songs.[20] Though they did not sell especially well when released, Lomax's biographer John Szwed calls these "some of the first concept albums".[21] In 1940, Lomax and his close friend Nicholas Ray wrote and produced the 15-minute program Back Where I Came From, which aired three nights per week on CBS and featured folk tales, proverbs, prose, and sermons, as well as songs, organized thematically. Its racially integrated cast included Burl Ives, Lead Belly, Josh White, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee. In February 1941, Lomax spoke and gave a demonstration of his program along with talks by Nelson A. Rockefeller from the Pan American Union, and the president of the American Museum of Natural History, at a global conference in Mexico of a thousand broadcasters CBS had sponsored to launch its worldwide programming initiative. Mrs. Roosevelt invited Lomax to Hyde Park.[22] Despite its success and high visibility, Back Where I Come From never picked up a commercial sponsor. The show ran for only twenty-one weeks before it was suddenly canceled in February 1941.[23] On hearing the news, Woody Guthrie wrote Lomax from California, "Too honest again, I suppose? Maybe not purty enough. O well, this country's a getting to where it can't hear its own voice. Someday the deal will change."[24] Lomax himself wrote that in all his work he had tried to capture "the seemingly incoherent diversity of American folk song as an expression of its democratic, inter-racial, international character, as a function of its inchoate and turbulent many-sided development."[25] On December 8, 1941, as "Assistant in Charge at the Library of Congress", he sent telegrams to fieldworkers in ten different localities across the United States, asking them to collect reactions of ordinary Americans to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declaration of war by the United States. A second series of interviews, called "Dear Mr. President", was recorded in January and February 1942.[26] While serving in the United States Army in World War II, Lomax produced and hosted numerous radio programs in connection with the war effort. The 1944 "ballad opera", The Martins and the Coys, broadcast in Britain (but not the USA) by the BBC, featuring Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Will Geer, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger, and Fiddlin' Arthur Smith, among others, was released on Rounder Records in 2000.[27] In the late 1940s, Lomax produced a series of commercial folk music albums for Decca Records and organized a series of concerts at New York's Town Hall and Carnegie Hall, featuring blues, calypso, and flamenco music. He also hosted a radio show, Your Ballad Man, in 1949 that was broadcast nationwide on the Mutual Radio Network and featured a highly eclectic program, such as gamelan music; Django Reinhardt; klezmer music; Sidney Bechet; Wild Bill Davison; jazzy pop songs by Maxine Sullivan and Jo Stafford; readings of the poetry of Carl Sandburg; hillbilly music with electric guitars; and Finnish brass bands.[28] He also was a key participant in the V.D. Radio Project in 1949, creating a number of "ballad dramas" featuring country and gospel superstars, including Roy Acuff, Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe (among others), that aimed to convince men and women suffering from syphilis to seek treatment.[29] |

担当補佐、市販のレコードやラジオ放送も手がける 1937年から1942年まで、ローマックスは米国議会図書館のフォークソング・アーカイブの担当補佐を務め、父や多くの協力者たちとともに1万件以上の フィールド・レコーディングに貢献した[17]。オーラル・ヒストリアンの先駆者であるローマックスは、ウディ・ガスリー、リード・ベリー、ジェリー・ ロール・モートンらジャズの先駆者たち、ビッグ・ビル・ブルーンジーなど、多くのフォークやジャズのミュージシャンとの膨大なインタビューを録音した。 1941年のある旅で、彼はロバート・ジョンソンの音楽を録音しようとミシシッピ州クラークスデールに向かった。ジョンソンは亡くなったが、地元のマ ディ・ウォーターズがローマックスのために彼の音楽を録音してくれるかもしれないと、彼は地元の人々から聞かされた。ローマックスは車のトランクを埋め尽 くすほどの録音機材を使い、ウォーターズの音楽を録音した。ウォーターズがミシシッピでの農場の仕事を辞め、ブルース・ミュージシャンとしてのキャリアを 追求するために必要だった動機は、ローマックスの録音を聴くことだったと言われており、最初はメンフィスで、後にシカゴで活躍するようになった[18]。 この仕事の一環として、ローマックスは1938年にミシガン州とウィスコンシン州を旅し、その地域の伝統音楽を録音・記録した。このコレクションからの 400以上の録音は、現在、米国議会図書館で入手可能である。「彼は1935年のプリムスのセダンで、プレストの瞬間ディスクレコーダーとムービーカメラ を携えて旅をした。かろうじて舗装された道路を何千マイルも走った彼が約3ヵ月後に戻ってきたとき、それは250枚のディスクと8リールのフィルムの隠し 場所であり、ミシガン州の驚くほど幅広い民族的多様性、表現的伝統、職業的フォークライフの記録だった」[19]。 1939年後半、ローマックスはCBSの国民放送『American School of the Air』で、『American Folk Song(アメリカ民謡)』と『Wellsprings of Music(音楽の源泉)』という2つのシリーズを司会した。司会者としてローマックスが歌い、バール・アイヴス、ウディ・ガスリー、リード・ベリー、 ピート・シーガー、ジョシュ・ホワイト、ゴールデン・ゲート・カルテットなどの演奏家を紹介した。個々の番組は、全米20万教室の1千万人の生徒に届けら れ、カナダ、ハワイ、アラスカでも放送されたが、ローマックスも彼の父も、民族音楽を単なるオーケストラ音楽の素材としか描いていない番組のコンセプトに は深い欠陥があり、地方文化を正当に評価していないと感じていた。 1940年、ローマックスの監督の下、RCAは2つの画期的な商業用フォーク音楽録音スイートを制作した: ウディ・ガスリーの『Dust Bowl Ballads』とリード・ベリーの『The Midnight Special and Other Southern Prison Songs』である[20]。発売当時は特に売れなかったが、ローマックスの伝記作家ジョン・スウェドはこれらを「最初のコンセプト・アルバムのいくつ か」と呼んでいる[21]。 1940年、ローマックスは親友のニコラス・レイとともに15分の番組『Back Where I Came From』を脚本・制作し、CBSで週に3晩放送した。人種的に統合された出演者には、バール・アイヴス、リード・ベリー、ジョシュ・ホワイト、ソニー・ テリー、ブラウニー・マクギーらがいた。1941年2月、ローマックスは、CBSが世界的な番組制作イニシアチブを立ち上げるために主催した1000人の 放送局によるメキシコでの世界会議で、パン・アメリカン・ユニオンのネルソン・A・ロックフェラーやアメリカ自然史博物館館長の講演とともに、自分のプロ グラムの実演を行った。ルーズベルト夫人はローマックスをハイドパークに招待した[22]。 その成功と知名度の高さにもかかわらず、『Back Where I Come From』に商業スポンサーがつくことはなかった。その知らせを聞いたウディ・ガスリーは、カリフォルニアからローマックスに手紙を書いた。また正直すぎ たかな?そうか、この国は自分の声が聞こえなくなってきているんだ。いつか取引は変わるだろう」[24] ローマックス自身は、すべての仕事において「アメリカ民謡の一見支離滅裂な多様性を、その民主的、人種間的、国際的性格の表現として、その未熟で激動的な 多面的発展の機能として」捉えようとしてきたと書いている[25]。 1941年12月8日、彼は「議会図書館の担当補佐官」として、全米10か所の異なる地域のフィールドワーカーに電報を打ち、真珠湾爆撃とそれに続くアメ リカの宣戦布告に対する一般アメリカ人の反応を収集するよう依頼した。親愛なる大統領へ」と呼ばれる2回目の一連のインタビューは、1942年1月と2月 に収録された[26]。 第二次世界大戦でアメリカ陸軍に従軍していたとき、ローマックスは戦争に関連したラジオ番組を数多く制作し、司会も務めた。1944年にBBCによってイ ギリスで放送された(アメリカでは放送されなかった)、バール・アイヴス、ウディ・ガスリー、ウィル・ギア、ソニー・テリー、ピート・シーガー、フィドリ ン・アーサー・スミスなどが出演した 「バラード・オペラ」『The Martins and the Coys』は、2000年にラウンダー・レコードからリリースされた[27]。 1940年代後半、ローマックスはデッカ・レコードのために一連の商業用フォーク・ミュージック・アルバムを制作し、ニューヨークのタウン・ホールとカー ネギー・ホールでブルース、カリプソ、フラメンコ音楽をフィーチャーした一連のコンサートを企画した。また、1949年にはラジオ番組『Your Ballad Man』の司会を務め、Mutual Radio Networkで全国放送され、ガムラン音楽、ジャンゴ・ラインハルト、クレズマー音楽、シドニー・ベシェ、ワイルド・ビル・デイヴィソン、マキシン・サ リヴァンとジョー・スタッフォードによるジャジーなポップ・ソング、カール・サンドバーグの詩の朗読、エレキギターによるヒルビリー・ミュージック、フィ ンランドのブラスバンドなど、非常に折衷的なプログラムを特集した。 [また、1949年にはV.D.ラジオ・プロジェクトに参加し、ロイ・エイカフ、ウディ・ガスリー、ハンク・ウィリアムス、シスター・ロゼッタ・サーペな ど、カントリーやゴスペルのスーパースターをフィーチャーした「バラード・ドラマ」を数多く制作し、梅毒に苦しむ男女に治療を受けるよう説得することを目 的としていた[29]。 |

| Move to Europe and later life In December 1949 a newspaper printed a story, "Red Convictions Scare 'Travelers'", that mentioned a dinner given by the Civil Rights Association to honor five lawyers who had defended people accused of being Communists. The article mentioned Alan Lomax as one of the sponsors of the dinner, along with C. B. Baldwin, campaign manager for Henry A. Wallace in 1948; music critic Olin Downes of The New York Times; and W.E.B. Du Bois, all of whom it accused of being members of Communist front groups.[30] The following June, Red Channels, a pamphlet edited by former F.B.I. agents which became the basis for the entertainment industry blacklist of the 1950s, listed Lomax as an artist or broadcast journalist sympathetic to Communism. (Others listed included Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Yip Harburg, Lena Horne, Langston Hughes, Burl Ives, Dorothy Parker, Pete Seeger, and Josh White.) That summer, Congress was debating the McCarran Act, which required the registration and fingerprinting of all "subversives" in the United States, restrictions of their right to travel, and detention in case of "emergencies",[31] while the House Un-American Activities Committee was broadening its hearings. Feeling sure that the Act would pass and realizing that his career in broadcasting was in jeopardy, Lomax, who was newly divorced and already had an agreement with Goddard Lieberson of Columbia Records to record in Europe,[32] hastened to renew his passport, cancel his speaking engagements, and plan for his departure, telling his agent he hoped to return in January "if things cleared up". He set sail on September 24, 1950, on board the steamer RMS Mauretania. Sure enough, in October, FBI agents were interviewing Lomax's friends and acquaintances. Lomax never told his family exactly why he went to Europe, only that he was developing a library of world folk music for Columbia. Nor did he allow anyone to say he was forced to leave. In a letter to the editor of a British newspaper, Lomax took a writer to task for describing him as a "victim of witch-hunting," insisting that he was in the UK only to work on his Columbia Project.[33] Lomax spent the 1950s based in London, from where he edited the 18-volume Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, an anthology issued on newly invented LP records. He spent seven months in Spain, where, in addition to recording three thousand items from most of the regions of Spain, he made copious notes and took hundreds of photos of "not only singers and musicians but anything that interested him – empty streets, old buildings, and country roads", bringing to these photos, "a concern for form and composition that went beyond the ethnographic to the artistic".[34] He drew a parallel between photography and field recording: Recording folk songs works like a candid cameraman. I hold the mike, use my hand for shading volume. It's a big problem in Spain because there is so much emotional excitement, noise all around. Empathy is most important in field work. It's necessary to put your hand on the artist while he sings. They have to react to you. Even if they're mad at you, it's better than nothing.[34] When Columbia Records producer George Avakian gave jazz arranger Gil Evans a copy of the Spanish World Library LP, Miles Davis and Evans were "struck by the beauty of pieces such as the 'Saeta', recorded in Seville, and a panpiper's tune ('Alborada de Vigo') from Galicia, and worked them into the 1960 album Sketches of Spain."[35] For the Scottish, English, and Irish volumes, he worked with the BBC and folklorists Peter Douglas Kennedy, Scots poet Hamish Henderson, and with the Irish folklorist Séamus Ennis,[36] recording among others, Margaret Barry and the songs in Irish of Elizabeth Cronin; Scots ballad singer Jeannie Robertson; and Harry Cox of Norfolk, England, and interviewing some of these performers at length about their lives. In 1953 a young David Attenborough commissioned Lomax to host six 20-minute episodes of the BBC TV series The Song Hunter, which featured performances by a wide range of traditional musicians from all over Britain and Ireland, as well as Lomax himself.[37] In 1957, Lomax hosted a folk music show on BBC's Home Service titled A Ballad Hunter and organized a skiffle group, Alan Lomax and the Ramblers (who included Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, and Shirley Collins), which appeared on British television. His ballad opera Big Rock Candy Mountain premiered December 1955 at Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop and featured Ramblin' Jack Elliot. In Scotland, Lomax is credited with being an inspiration for the School of Scottish Studies, founded in 1951, the year of his first visit there.[38][39] Lomax and Diego Carpitella's survey of Italian folk music for the Columbia World Library, conducted in 1953 and 1954, with the cooperation of the BBC and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, helped capture a snapshot of a multitude of important traditional folk styles shortly before they disappeared. The pair amassed one of the most representative folk song collections of any culture. From Lomax's Spanish and Italian recordings emerged one of the first theories explaining the types of folk singing that predominate in particular areas, a theory that incorporates work style, the environment, and the degrees of social and sexual freedom. |

ヨーロッパへの移住とその後の人生 1949年12月、ある新聞に「赤の有罪判決に怯える 「旅行者」」という記事が掲載され、公民権協会が共産主義者として告発された人々を弁護した5人の弁護士を称える晩餐会を開いたことが紹介された。記事 は、1948年のヘンリー・A・ウォレスの選挙運動マネージャーであったC・B・ボールドウィン、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の音楽評論家オリン・ダウネ ス、W・E・B・デュボアとともに、晩餐会のスポンサーの一人としてアラン・ローマックスを挙げ、その全員が共産主義者のフロントグループのメンバーであ ると非難した。 [30] 翌年6月、元F.B.I.捜査官によって編集され、1950年代のエンターテインメント業界のブラックリストの基礎となった小冊子『Red Channels』は、共産主義に共鳴する芸術家または放送ジャーナリストとして、ローマックスをリストアップした。(他にも、アーロン・コープランド、 レナード・バーンスタイン、イップ・ハーバーグ、レナ・ホーン、ラングストン・ヒューズ、バール・アイヴス、ドロシー・パーカー、ピート・シーガー、ジョ シュ・ホワイトらがリストアップされていた)。その夏、議会はマッカラン法について議論していた。マッカラン法は、米国内のすべての「破壊活動家」の登録 と指紋押捺、渡航権の制限、「緊急事態」の場合の拘留を義務付けるものであり[31]、一方で下院非米活動委員会は公聴会を拡大していた。この法律が可決 されることを確信し、放送界でのキャリアが危うくなることを悟ったローマックスは、離婚したばかりで、すでにコロンビア・レコードのゴダード・リーバーソ ンとヨーロッパでレコーディングする契約を結んでいた[32]が、急いでパスポートを更新し、講演の仕事をキャンセルし、出発の計画を立て、代理人に「事 態が好転すれば」1月に帰国したいと伝えた。彼は1950年9月24日、蒸気船RMSマウレタニア号で出航した。案の定、10月にはFBI捜査官がロー マックスの友人や知人に事情聴取を行っていた。ローマックスは家族に、ヨーロッパに行った理由を正確に話すことはなかったが、コロムビアのために世界の民 族音楽のライブラリーを開発することだけは話していた。また、強制連行されたとは誰にも言わせなかった。イギリスの新聞の編集者に宛てた手紙の中で、自分 を「魔女狩りの犠牲者」と表現した作家を非難し、自分はコロンビア・プロジェクトに取り組むためだけにイギリスにいたのだと主張した[33]。 ローマックスは1950年代をロンドンを拠点に過ごし、そこで18巻からなる『Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music』(新しく発明されたLPレコードで発行されたアンソロジー)を編集した。彼はスペインに7ヶ月間滞在し、スペインのほとんどの地方から 3,000曲を録音したほか、膨大な量のメモを作成し、「歌手やミュージシャンだけでなく、誰もいない道、古い建物、田舎道など、彼が興味を持ったものな ら何でも」何百枚もの写真を撮影した: 民謡を録音するのは、率直なカメラマンのようなものだ。マイクを持ち、手で音量を調節する。スペインでは感情的な興奮やノイズが多いので、それは大きな問 題だ。フィールドワークでは共感が最も重要だ。アーティストが歌っている間、手を添えることが必要だ。彼らはあなたに反応しなければならない。たとえ彼ら があなたに腹を立てていたとしても、何もしないよりはましだ[34]」。 コロンビア・レコードのプロデューサー、ジョージ・アヴァキアンがジャズ・アレンジャーのギル・エヴァンスに『スパニッシュ・ワールド・ライブラリー』の LPを渡したとき、マイルス・デイヴィスとエヴァンスは「セビリアで録音された『サエタ』やガリシア地方のパンパイの曲(『アルボラーダ・デ・ヴィー ゴ』)といった曲の美しさに心を打たれ、1960年のアルバム『スケッチ・オブ・スペイン』に取り入れた」[35]。 スコットランド、イギリス、アイルランドの各巻のために、彼はBBCや民俗学者のピーター・ダグラス・ケネディ、スコッツの詩人ヘイミッシュ・ヘンダーソ ン、アイルランドの民俗学者セーマス・エニス[36]と協力し、とりわけマーガレット・バリーとエリザベス・クローニンのアイルランド語による歌、スコッ ツのバラッド歌手ジーニー・ロバートソン、イギリス・ノーフォークのハリー・コックスを録音し、これらのパフォーマーの何人かに彼らの人生について詳しく インタビューした。1953年、若き日のデイヴィッド・アッテンボローがローマックスに依頼し、BBCのテレビシリーズ『ザ・ソング・ハンター』(The Song Hunter)の20分6エピソードの司会を務めた。1957年、ローマックスはBBCのホームサービスで『ア・バラッド・ハンター』(A Ballad Hunter)と題したフォーク音楽番組の司会を務め、イギリスのテレビに出演したスキッフル・グループ、アラン・ローマックス&ザ・ランブラーズ (Alan Lomax and the Ramblers)(ユアン・マッコール、ペギー・シーガー、シャーリー・コリンズらが参加)を組織した。彼のバラード・オペラ『ビッグ・ロック・キャン ディ・マウンテン』は、1955年12月にジョーン・リトルウッドのシアター・ワークショップで初演され、ランブリン・ジャック・エリオットが出演した。 スコットランドでは、ローマックスが初めてスコットランドを訪れた1951年に設立されたスコットランド研究学校にインスピレーションを与えたとされてい る[38][39]。 1953年と1954年にBBCとローマのサンタ・チェチーリア国立アカデミーの協力を得て行われた、ローマックスとディエゴ・カルピテッラによるコロン ビア世界図書館のためのイタリア民俗音楽の調査は、多数の重要な伝統的民俗様式が消滅する直前のスナップショットを捉えるのに役立った。二人は、あらゆる 文化の中で最も代表的な民謡コレクションのひとつを集めた。ローマックスが録音したスペイン語とイタリア語から、特定の地域で優勢な民謡のタイプを説明す る最初の理論のひとつが生まれた。 |

| Return to the United States Upon his return to New York in 1959, Lomax produced a concert, Folksong '59, in Carnegie Hall, featuring Arkansas singer Jimmy Driftwood; the Selah Jubilee Singers and Drexel Singers (gospel groups); Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim (blues); Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys (bluegrass); Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger (urban folk revival); and The Cadillacs (a rock and roll group). The occasion marked the first time rock and roll and bluegrass were performed on the Carnegie Hall Stage. "The time has come for Americans not to be ashamed of what we go for, musically, from primitive ballads to rock 'n' roll songs", Lomax told the audience. According to Izzy Young, the audience booed when he told them to lay down their prejudices and listen to rock 'n' roll. In Young's opinion, "Lomax put on what is probably the turning point in American folk music...At that concert, the point he was trying to make was that Negro and white music were mixing, and rock and roll was that thing."[40] Alan Lomax had met 20-year-old English folk singer Shirley Collins while living in London. The two were romantically involved and lived together for some years. When Lomax obtained a contract from Atlantic Records to re-record some of the American musicians first recorded in the 1940s, using improved equipment, Collins accompanied him. Their folk song collecting trip to the Southern states, known colloquially as the Southern Journey, lasted from July to November 1959 and resulted in many hours of recordings, featuring performers such as Almeda Riddle, Hobart Smith, Wade Ward, Charlie Higgins and Bessie Jones and culminated in the discovery of Fred McDowell. Recordings from this trip were issued under the title Sounds of the South and some were also featured in the Coen brothers' 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou?. Lomax wished to marry Collins but when the recording trip was over, she returned to England and married Austin John Marshall. In an interview in The Guardian newspaper, Collins expressed irritation that The Land Where The Blues Began, Lomax's 1993 account of the journey, barely mentioned her. "All it said was, 'Shirley Collins was along for the trip'. It made me hopping mad. I wasn't just 'along for the trip'. I was part of the recording process, I made notes, I drafted contracts, I was involved in every part".[41] Collins addressed the perceived omission in her memoir, America Over the Water, published in 2004.[42][43] Lomax married Antoinette Marchand on August 26, 1961. They separated the following year and divorced in 1967.[44] In 1962, Lomax and singer and Civil Rights Activist Guy Carawan, music director at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, produced the album, Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia, 1961–62, on Vanguard Records for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Lomax was a consultant to Carl Sagan for the Voyager Golden Record sent into space on the 1977 Voyager Spacecraft to represent the music of the earth. Music he helped choose included the blues, jazz, and rock 'n' roll of Blind Willie Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and Chuck Berry; Andean panpipes and Navajo chants; Azerbaijani mugham performed by two balaban players,[45] a Sicilian sulfur miner's lament; polyphonic vocal music from the Mbuti Pygmies of Zaire, and the Georgians of the Caucasus; and a shepherdess song from Bulgaria by Valya Balkanska;[46] in addition to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and more. Sagan later wrote that it was Lomax "who was a persistent and vigorous advocate for including ethnic music even at the expense of Western classical music. He brought pieces so compelling and beautiful that we gave in to his suggestions more often than I would have thought possible. There was, for example, no room for Debussy among our selections because Azerbaijanis play bagpipe-sounding instruments [balaban] and Peruvians play panpipes and such exquisite pieces had been recorded by ethnomusicologists known to Lomax."[47] |

アメリカへの帰国 1959年にニューヨークに戻ったローマックスは、カーネギー・ホールでのコンサート『Folksong '59』をプロデュースし、アーカンソー州のシンガー、ジミー・ドリフトウッド、セラ・ジュビリー・シンガーズとドレクセル・シンガーズ(ゴスペル・グ ループ)、マディ・ウォーターズとメンフィス・スリム(ブルース)、アール・テイラーとストーニー・マウンテン・ボーイズ(ブルーグラス)、ピート・シー ガー、マイク・シーガー(アーバン・フォーク・リバイバル)、ザ・キャデラックス(ロックンロール・グループ)が出演した。ロックンロールとブルーグラス がカーネギーホールのステージで演奏されたのは、この日が初めてだった。「アメリカ人は、プリミティブなバラードからロックンロールまで、音楽的に何を目 指すかを恥じない時が来た」とローマックスは聴衆に語った。イジー・ヤングによれば、彼が偏見を捨ててロックンロールを聴けと言ったとき、聴衆はブーイン グしたという。ヤングの意見によれば、「ローマックスは、おそらくアメリカン・フォーク・ミュージックのターニングポイントとなるようなコンサートを開い た......そのコンサートで彼が言いたかったのは、黒人と白人の音楽が混ざり合っていることであり、ロックンロールはそのことだった」[40]。 アラン・ローマックスはロンドンに住んでいたとき、20歳のイギリス人フォークシンガー、シャーリー・コリンズと出会っていた。2人は恋愛関係になり、何 年か同棲していた。ローマックスがアトランティック・レコードと契約を結び、1940年代に初めて録音されたアメリカのミュージシャンたちを、改良された 機材を使って再録音することになったとき、コリンズも同行した。俗にサザン・ジャーニーと呼ばれる南部の州へのフォークソング収集の旅は1959年7月か ら11月まで続き、アルメダ・リドル、ホバート・スミス、ウェイド・ウォード、チャーリー・ヒギンズ、ベッシー・ジョーンズといった演奏家をフィーチャー し、フレッド・マクダウェルの発見で最高潮に達した。この旅の録音は『Sounds of the South』というタイトルで出版され、一部はコーエン兄弟の2000年の映画『O Brother, Where Art Thou? ローマックスはコリンズとの結婚を望んでいたが、録音旅行が終わるとイギリスに戻り、オースティン・ジョン・マーシャルと結婚した。ガーディアン』紙のイ ンタビューでコリンズは、ローマックスが1993年に出版した旅の記録『The Land Where The Blues Began(ブルースが始まった土地)』がほとんど彼女のことに触れていないことに苛立ちを示した。「シャーリー・コリンズは旅に同行した 」としか書かれていなかった。私は頭にきたよ。私はただ 「旅に同行した 」だけではなかった。私はレコーディングのプロセスの一部であり、メモをとり、契約書を作成し、あらゆる部分に関与していた」[41]。コリンズは 2004年に出版された回顧録『America Over the Water』の中で、この脱落について言及している[42][43]。 1961年8月26日、ローマックスはアントワネット・マーシャンと結婚した。翌年に別居し、1967年に離婚した[44]。 1962年、テネシー州モンテーグルのハイランダー・フォーク・スクールの音楽監督であったローマックスとシンガーで公民権運動家のガイ・キャラワンは、 アルバム『Freedom in the Air』を制作した: アルバム『Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia, 1961-62』は、学生非暴力調整委員会(Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee)のためにヴァンガード・レコードからリリースされた。 1977年にボイジャー宇宙船で宇宙に送られたボイジャー・ゴールデン・レコードでは、カール・セーガンのコンサルタントを務め、地球の音楽を表現した。 彼が選曲に携わった音楽には、ブラインド・ウィリー・ジョンソン、ルイ・アームストロング、チャック・ベリーのブルース、ジャズ、ロックンロール、アンデ スのパンパイプ、ナバホ族の聖歌、2人のバラバン奏者によるアゼルバイジャンのムガム[45]、シチリアの硫黄鉱夫の嘆きなどがある; ザイールのムブティ・ピグミーやコーカサスのグルジア人によるポリフォニックな声楽曲、ヴァリヤ・バルカンスカによるブルガリアの羊飼いの歌[46]、さ らにバッハ、モーツァルト、ベートーヴェンなどがある。セーガンは後に、「西洋のクラシック音楽を犠牲にしてでも、民族音楽を取り入れることを粘り強く精 力的に提唱したのがローマックスだった」と書いている。彼はとても魅力的で美しい曲を持ってきたので、私たちは彼の提案に可能な限り従った。例えば、アゼ ルバイジャン人はバグパイプのような楽器(バラバン)を演奏し、ペルー人はパンパイプを演奏し、そのような絶妙な曲はローマックスが知っている民族音楽学 者によって録音されていたからだ」[47]。 |

| Death Alan Lomax died in Safety Harbor, Florida on July 19, 2002 at the age of 87.[48] |

死去 アラン・ローマックスは2002年7月19日、フロリダ州セーフティハーバーで87歳で死去した[48]。 |

| Cultural equity The dimension of cultural equity needs to be added to the humane continuum of liberty, freedom of speech and religion, and social justice.[49] Folklore can show us that this dream is age-old and common to all mankind. It asks that we recognize the cultural rights of weaker peoples in sharing this dream. And it can make their adjustment to a world society an easier and more creative process. The stuff of folklore—the orally transmitted wisdom, art and music of the people can provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, "You are my brother."[50] As a member of the Popular Front and People's Songs in the 1940s, Alan Lomax promoted what was then known as "One World" and today is called multiculturalism.[51] In the late forties he produced a series of concerts at Town Hall and Carnegie Hall that presented flamenco guitar and calypso, along with country blues, Appalachian music, Andean music, and jazz. His radio shows of the 1940s and 1950s explored musics of all the world's peoples. Lomax recognized that folklore (like all forms of creativity) occurs at the local and not the national level and flourishes not in isolation but in fruitful interplay with other cultures. He was dismayed that mass communications appeared to be crushing local cultural expressions and languages. In 1950 he echoed anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942), who believed the role of the ethnologist should be that of advocate for primitive man (as indigenous people were then called), when he urged folklorists to similarly advocate for the folk. Some, such as Richard Dorson, objected that scholars shouldn't act as cultural arbiters, but Lomax believed it was unethical to stand idly by as the magnificent variety of the world's cultures and languages was "grayed out" by centralized commercial entertainment and educational systems. Although he acknowledged potential problems with intervention, he urged that folklorists with their special training actively assist communities in safeguarding and revitalizing their own local traditions. Similar ideas had been put into practice by Benjamin Botkin, Harold W. Thompson, and Louis C. Jones, who believed that folklore studied by folklorists should be returned to its home communities to enable it to thrive anew. They have been realized in the annual (since 1967) Smithsonian Folk Festival on the Mall in Washington, D.C. (for which Lomax served as a consultant), in national and regional initiatives by public folklorists and local activists in helping communities gain recognition for their oral traditions and lifeways both in their home communities and in the world at large; and in the National Heritage Awards, concerts, and fellowships given by the NEA and various State governments to master folk and traditional artists.[52] In 1983, Lomax founded The Association for Cultural Equity (ACE). It is housed at the Fine Arts Campus of Hunter College in New York City and is the custodian of the Alan Lomax Archive. The Association's mission is to "facilitate cultural equity" and practice "cultural feedback" and "preserve, publish, repatriate and freely disseminate" its collections.[53] Though Alan Lomax's appeals to anthropology conferences and repeated letters to UNESCO fell on deaf ears, the modern world seems to have caught up to his vision. In an article first published in the 2009 Louisiana Folklore Miscellany, Barry Jean Ancelet, folklorist and chair of the Modern Languages Department at University of Louisiana at Lafayette, wrote: Every time [Lomax] called me over a span of about ten years, he never failed to ask if we were teaching Cajun French in the schools yet. His notions about the importance of cultural and linguistic diversity have been affirmed by many contemporary scholars, including Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann who concluded his recent book, The Quark and the Jaguar, with a discussion of these very same issues, insisting on the importance of "cultural DNA" (1994: 338–343). His cautions about "universal popular culture" (1994: 342) sound remarkably like Alan's warning in his "Appeal for Cultural Equity" that the "cultural grey-out" must be checked or there would soon be "no place worth visiting and no place worth staying" (1972). Compare Gell-Mann: Just as it is crazy to squander in a few decades much of the rich biological diversity that has evolved over billions of years, so is it equally crazy to permit the disappearance of much of human cultural diversity, which has evolved in a somewhat analogous way over many tens of thousands of years...The erosion of local cultural patterns around the world is not, however, entirely or even principally the result of contact with the universalizing effect of scientific enlightenment. Popular culture is in most cases far more effective at erasing distinctions between one place or society and another. Blue jeans, fast food, rock music, and American television serials have been sweeping the world for years. (1994: 338–343) and Lomax: carcasses of dead or dying cultures on the human landscape, that we have learned to dismiss this pollution of the human environment as inevitable, and even sensible, since it is wrongly assumed that the weak and unfit among musics and cultures are eliminated in this way...Not only is such a doctrine anti-human; it is very bad science. It is false Darwinism applied to culture – especially to its expressive systems, such as music language, and art. Scientific study of cultures, notably of their languages and their musics, shows that all are equally expressive and equally communicative, even though they may symbolize technologies of different levels...With the disappearance of each of these systems, the human species not only loses a way of viewing, thinking, and feeling but also a way of adjusting to some zone on the planet which fits it and makes it livable; not only that, but we throw away a system of interaction, of fantasy and symbolizing which, in the future, the human race may sorely need. The only way to halt this degradation of man's culture is to commit ourselves to the principles of political, social, and economic justice. (2003 [1972]: 286)[54] In 2001, in the wake of the attacks in New York and Washington of September 11, UNESCO's Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity declared the safeguarding of languages and intangible culture on a par with protection of individual human rights and as essential for human survival as biodiversity is for nature,[55] ideas remarkably similar to those forcefully articulated by Alan Lomax many years before. |

文化的公平性 自由、言論と宗教の自由、社会正義といった人道的な連続体に、文化的公正という次元を加える必要がある[49]。 民俗学は、この夢が古くからのものであり、全人類に共通するものであることを示してくれる。民俗学は、この夢を共有する上で、弱い立場の人々の文化的権利 を認めるよう求めている。そして、世界社会への適応をより容易で創造的なプロセスにすることができる。民俗学、すなわち口承で伝えられる知恵、芸術、音楽 は、あらゆる国民が「あなたは私の兄弟です」と言えるような万本の架け橋となりうる[50]。 1940年代、人民戦線と人民の歌のメンバーとして、アラン・ローマックスは当時「ワン・ワールド」と呼ばれ、今日では多文化主義と呼ばれるものを推進し た[51]。40年代後半、彼はタウンホールとカーネギーホールで一連のコンサートをプロデュースし、カントリーブルース、アパラチア音楽、アンデス音 楽、ジャズとともにフラメンコギターとカリプソを紹介した。1940年代から1950年代にかけてのラジオ番組では、世界のあらゆる民族の音楽を探求し た。 ローマックスは、フォークロアは(あらゆる形態の創造性と同様に)国民レベルではなく地域レベルで発生し、孤立することなく他の文化との実りある相互作用 の中で花開くものだと認識していた。彼は、マスコミュニケーションが地域の文化表現や言語を押しつぶそうとしているように見えることに落胆していた。 1950年、彼は人類学者ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキ(Bronisław Malinowski、1884~1942年)の意見に共鳴し、民族学者の役割は原始人(当時は先住民族と呼ばれていた)の擁護者であるべきだと考えた。 リチャード・ドーソンのように、学者が文化の裁定者として行動すべきではないと異議を唱える者もいたが、ローマックスは、世界の文化や言語の壮大な多様性 が中央集権的な商業的娯楽や教育システムによって「灰色化」されるのを傍観するのは倫理に反すると考えていた。介入に潜在的な問題があることは認めつつ も、特殊な訓練を受けた民俗学者が、自分たちの地域の伝統を守り、活性化させるために地域社会を積極的に支援することを強く求めた。 同様の考え方は、ベンジャミン・ボトキン、ハロルド・W・トンプソン、ルイス・C・ジョーンズらによって実践されていた。彼らは、民俗学者が研究した民俗 学は、それが新たに繁栄することができるように、故郷の地域社会に還元されるべきであると考えていた。それらは、(ローマックスがコンサルタントを務め た)ワシントンD.C.のスミソニアン・モールで毎年開催されるスミソニアン・フォーク・フェスティバル(1967年以来)、地域社会が口承による伝統と 生活様式を地元地域社会と世界全体の両方で認められるようにするための公的な民俗学者と地元の活動家による全国的・地域的な取り組み、NEAとさまざまな 州政府が優れた民俗・伝統芸術家に授与するナショナリズム賞、コンサート、フェローシップにおいて実現されている[52]。 1983年、ローマックスはAssociation for Cultural Equity(ACE)を設立した。同協会はニューヨークのハンター・カレッジのファイン・アーツ・キャンパスにあり、アラン・ローマックス・アーカイブ を管理している。同協会の使命は「文化的公平性の促進」と「文化的フィードバック」の実践、そしてコレクションの「保存、出版、送還、自由な普及」である [53]。人類学会議でのアラン・ローマックスの訴えやユネスコへの度重なる手紙は耳に届かなかったが、現代世界は彼のビジョンに追いついたようだ。 2009年の『Louisiana Folklore Miscellany』に初めて掲載された記事で、民俗学者でルイジアナ大学ラファイエット校現代語学部の学科長であるバリー・ジーン・アンスレットはこ う書いている: ローマックスは)10年以上にわたって私に電話をかけてくるたびに、ケイジャンフランス語を学校で教えているのかと聞いてきた。ノーベル賞を受賞した物理 学者マレー・ゲルマンは、近著『クォークとジャガー』の最後に、まさにこの同じ問題を取り上げ、「文化的DNA」の重要性を主張している(1994: 338-343)。普遍的な大衆文化」(1994: 342)についての彼の警告は、「文化的グレーアウト」を抑制しなければ、やがて「訪れる価値のある場所も、滞在する価値のある場所も」なくなってしまう という、アランの「文化的公平性の訴え」(1972)での警告に酷似している。ゲルマンと比較してみよう: 何十億年もかけて進化してきた豊かな生物学的多様性の多くを数十年で浪費してしまうことが狂気の沙汰であるように、何万年もかけて同じように進化してきた 人間の文化的多様性の多くを消滅させてしまうことを許すことも、同様に狂気の沙汰である。大衆文化は、ほとんどの場合、ある場所や社会と別の場所や社会と の区別を消し去るのにはるかに効果的である。ブルージーンズ、ファーストフード、ロックミュージック、アメリカの連続テレビドラマは、何年にもわたって世 界を席巻してきた。(1994: 338-343) とローマックスは言う: 音楽と文化の中で弱く不適格なものは、このようにして排除されると誤って想定されているのだから......このような教義は反人間的であるだけでなく、 非常に悪い科学である。このような教義は反人間的であるだけでなく、非常に悪い科学なのである。それは誤ったダーウィニズムを文化、特に音楽や言語、芸術 などの表現システムに適用したものである。文化、特に言語や音楽を科学的に研究すると、たとえそれらが異なるレベルの技術を象徴していたとしても、すべて が等しく表現的であり、等しくコミュニケーション的であることがわかる......これらのシステムがそれぞれ消滅することで、人類はものの見方、考え 方、感じ方を失うだけでなく、地球上のある地域に適応する方法をも失う。人間文化の劣化を食い止める唯一の方法は、政治的、社会的、経済的正義の原則に身 を投じることである。(2003 [1972]: 286)[54] 2001年、9月11日にニューヨークとワシントンで起きた同時多発テロを受け、ユネスコの文化多様性世界宣言は、言語と無形文化の保護を個人の人権保護と同等に、生物多様性が自然にとって不可欠であるのと同様に、人類の生存にとっても不可欠であると宣言した[55]。 |

| FBI investigations From 1942 to 1979, Lomax repeatedly was investigated and interviewed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), but nothing incriminating was discovered, and the investigation was abandoned. Scholar and jazz pianist Ted Gioia uncovered and published extracts from Alan Lomax's 800-page FBI files.[56] The investigation appears to have started when an anonymous informant reported overhearing Lomax's father telling guests in 1941 about what he considered his son's communist sympathies. Looking for leads, the FBI seized on the fact that, at the age of 17 in 1932 while attending Harvard University for a year, Lomax had been arrested in Boston, Massachusetts in connection with a political demonstration. In 1942 the FBI sent agents to interview students at Harvard's freshman dormitory about Lomax's participation in a demonstration that had occurred at Harvard ten years earlier in support of the immigration rights of one Edith Berkman, a Jewish woman, dubbed the "red flame" for her labor organizing activities among the textile workers of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and threatened with deportation as an alleged "Communist agitator".[57] Lomax had been charged with disturbing the peace and fined $25. Berkman, however, had been cleared of all accusations against her and was not deported. Nor had Lomax's Harvard academic record been affected in any way by his activities in her defense. Nevertheless, the bureau continued trying vainly to show that in 1932 Lomax had either distributed communist literature or made public speeches in support of the Communist Party. According to Ted Gioia: Lomax must have felt it necessary to address the suspicions. He gave a sworn statement to an FBI agent on April 3, 1942, denying both of these charges. He also explained his arrest while at Harvard as the result of police overreaction. He was, he claimed, 15 at the time – he was actually 17 and a college student – and he said he had intended to participate in a peaceful demonstration. Lomax said he and his colleagues agreed to stop their protest when police asked them to, but that he was grabbed by a couple of policemen as he was walking away. "That is pretty much the story there, except that it distressed my father very, very much", Lomax told the FBI. "I had to defend my righteous position, and he couldn't understand me and I couldn't understand him. It has made a lot of unhappiness for the two of us because he loved Harvard and wanted me to be a great success there." Lomax transferred to the University of Texas the following year.[56] Lomax left Harvard, after having spent his sophomore year there, to join John A. Lomax and John Lomax, Jr. in collecting folk songs for the Library of Congress and to assist his father in writing his books. In withdrawing him (in addition to not being able to afford the tuition), the elder Lomax had probably wanted to separate his son from new political associates that he considered undesirable. But Alan had also not been happy there and probably also wanted to be nearer his bereaved[citation needed] father and young sister, Bess, and to return to the close friends he had made during his first year at the University of Texas. In June 1942 the FBI approached the Librarian of Congress, Archibald McLeish, in an attempt to have Lomax fired as Assistant in Charge of the Library's Archive of American Folk Song. At the time, Lomax was preparing for a field trip to the Mississippi Delta on behalf of the Library, where he made landmark recordings of Muddy Waters, Son House, and David "Honeyboy" Edwards, among others. McLeish wrote to Hoover, defending Lomax: "I have studied the findings of these reports very carefully. I do not find positive evidence that Mr. Lomax has been engaged in subversive activities and I am therefore taking no disciplinary action toward him." Nevertheless, according to Gioia: Yet what the probe failed to find in terms of prosecutable evidence, it made up for in speculation about his character. An FBI report dated July 23, 1943, describes Lomax as possessing "an erratic, artistic temperament" and a "bohemian attitude". It says: "He has a tendency to neglect his work over a period of time and then just before a deadline he produces excellent results." The file quotes one informant who said that "Lomax was a very peculiar individual, that he seemed to be very absent-minded and that he paid practically no attention to his personal appearance." This same source adds that he suspected Lomax's peculiarity and poor grooming habits came from associating with the "hillbillies" who provided him with folk tunes. Lomax, who was a founding member of People's Songs, was in charge of campaign music for Henry A. Wallace's 1948 Presidential run on the Progressive Party ticket on a platform opposing the arms race and supporting civil rights for Jews and African Americans. Subsequently, Lomax was one of the performers listed in the publication Red Channels as a possible Communist sympathizer and was consequently blacklisted from working in US entertainment industries. A 2007 BBC news article revealed that in the early 1950s, the British MI5 placed Alan Lomax under surveillance as a suspected Communist. Its report concluded that although Lomax undoubtedly held "left wing" views, there was no evidence he was a Communist. Released September 4, 2007 (File ref KV 2/2701), a summary of his MI5 file reads as follows: Noted American folk music archivist and collector Alan Lomax first attracted the attention of the Security Service when it was noted that he had made contact with the Romanian press attaché in London while he was working on a series of folk music broadcasts for the BBC in 1952. Correspondence ensued with the American authorities as to Lomax' suspected membership of the Communist Party, though no positive proof is found on this file. The Service took the view that Lomax' work compiling his collections of world folk music gave him a legitimate reason to contact the attaché, and that while his views (as demonstrated by his choice of songs and singers) were undoubtedly left wing, there was no need for any specific action against him. The file contains a partial record of Lomax' movements, contacts and activities while in Britain, and includes for example a police report of the "Songs of the Iron Road" concert at St Pancras in December 1953. His association with [blacklisted American] film director Joseph Losey is also mentioned (serial 30a).[58] The FBI again investigated Lomax in 1956 and sent a 68-page report to the CIA and the Attorney General's office. However, William Tompkins, assistant attorney general, wrote to Hoover that the investigation had failed to disclose sufficient evidence to warrant prosecution or the suspension of Lomax's passport. Then, as late as 1979, an FBI report suggested that Lomax had recently impersonated an FBI agent. The report appears to have been based on mistaken identity. The person who reported the incident to the FBI said that the man in question was around 43, about 5 feet 9 inches and 190 pounds. The FBI file notes that Lomax stood 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, weighed 240 pounds and was 64 at the time: Lomax resisted the FBI's attempts to interview him about the impersonation charges, but he finally met with agents at his home in November 1979. He denied that he'd been involved in the matter but did note that he'd been in New Hampshire in July 1979, visiting a film editor about a documentary. The FBI's report concluded that "Lomax made no secret of the fact that he disliked the FBI and disliked being interviewed by the FBI. Lomax was extremely nervous throughout the interview."[56] The FBI investigation was concluded the following year, shortly after Lomax's 65th birthday. |

FBIの調査 1942年から1979年まで、ローマックスは連邦捜査局(FBI)の調査や事情聴取を繰り返し受けたが、犯罪につながるものは発見されず、捜査は放棄さ れた。学者でジャズピアニストのテッド・ジョイアは、800ページに及ぶアラン・ローマックスのFBIファイルの抜粋を発見し、公表した[56]。捜査 は、1941年に匿名の情報提供者が、ローマックスの父親が息子の共産主義シンパと思われることを客に話しているのを耳にしたと報告したことから始まった ようだ。手がかりを探していたFBIは、ハーバード大学に1年間通っていた1932年、17歳のときにマサチューセッツ州ボストンで政治的デモに関連して 逮捕されたという事実をつかんだ。1942年、FBIは捜査官を送り込み、ハーバードの新入生寮で、10年前にハーバードで起こった、マサチューセッツ州 ローレンスの織物労働者の労働組織化活動で「赤い炎」と呼ばれ、「共産主義扇動者」の嫌疑で国外追放の危機にさらされたユダヤ人女性エディス・バークマン の移民権を支持するデモにローマックスが参加していたことについて、学生たちに事情聴取を行った[57]。しかし、バークマンは彼女に対するすべての嫌疑 が晴れ、国外追放にはならなかった。また、ローマックスのハーバード大学での学業成績も、彼女の弁護活動によって影響を受けることはなかった。それにもか かわらず、1932年にローマックスが共産主義的な文献を配布したり、共産党を支持する公の場で演説したりしたことを示そうと、局は無駄な努力を続けた。 テッド・ジョイアによれば ローマックスはこの疑惑に対処する必要があると感じたに違いない。彼は1942年4月3日、FBI捜査官に宣誓供述書を提出し、これら2つの容疑を否定し た。彼はまた、ハーバード大学在学中に逮捕されたのは警察の過剰反応の結果だと説明した。彼は当時15歳で、実際は17歳の大学生だったと主張し、平和的 なデモに参加するつもりだったと語った。ローマックスは、警察から抗議活動を止めるように言われたので、仲間とともに抗議活動を止めることに同意したが、 その場を立ち去ろうとしたときに数人の警官につかまったと語った。「それが私の父をとてもとても苦しめたということを除けば、ほとんどそのような話です」 と、ローマックスはFBIに語った。「私は自分の正当な立場を守らなければならなかったが、父は私を理解できず、私も父を理解できなかった。彼はハーバー ドを愛し、私がそこで大成功することを望んでいたのだから」。ローマックスは翌年テキサス大学に転校した[56]。 ハーバードの2年生を過ごした後、ローマックスはジョン・A・ローマックスとジョン・ローマックス・ジュニアとともに議会図書館のためにフォークソングを 収集し、父の著作を手伝うためにハーバードを去った。学費が払えなかったことに加えて)息子を引き離すにあたって、長男のローマックスはおそらく、好まし くないと考える新たな政治的仲間から引き離したかったのだろう。しかし、アランもまたそこでは満足できず、おそらくは死別した[citation needed]父と幼い妹ベスの近くにいたかったのだろう。そして、テキサス大学での最初の年にできた親しい友人たちのもとに戻りたかったのだろう。 1942年6月、FBIは議会司書のアーチボルド・マクリーシュに働きかけ、図書館のアメリカ民謡アーカイブ担当補佐官を解任させようとした。当時、ロー マックスは図書館の代表としてミシシッピ・デルタへのフィールド・トリップの準備をしており、そこでマディ・ウォーターズ、ソン・ハウス、デヴィッド・ 「ハニーボーイ」・エドワーズらの画期的な録音を行った。マクリーシュはフーバーに手紙を書き、ローマックスを擁護した: 「私はこれらの報告書の調査結果を注意深く調べた。私はこれらの報告書の調査結果を非常に注意深く調べたが、ローマックス氏が破壊活動に従事していたとい う積極的な証拠は見つからなかった。とはいえ、ジョイアによれば しかし、この調査は起訴可能な証拠を見つけられなかった分、彼の性格に関する憶測で補ったのである。1943年7月23日付のFBIの報告書には、ロー マックスは「不安定で芸術的な気質」と「ボヘミアン的な態度」を持っていると書かれている。彼は一定期間仕事をおろそかにする傾向があり、締め切りの直前 になると素晴らしい結果を出す」と書かれている。このファイルでは、ある情報提供者の言葉を引用している。「ローマックスは非常に特異な人物で、非常に無 頓着で、身だしなみにはほとんど気を配っていないようだった」。この同じ情報源は、ローマックスの特異性と身だしなみの悪さは、彼にフォークソングを提供 した 「ヒルビリー 」たちとの付き合いからきているのではないかと付け加えている。 ピープル・ソングスの創設メンバーであったローマックスは、軍拡競争に反対し、ユダヤ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の公民権を支持することを掲げた進歩党から 1948年の大統領選に出馬したヘンリー・A・ウォレスのキャンペーン音楽を担当した。その後、ローマックスは共産主義シンパの可能性があるとして 『Red Channels』誌に掲載されたパフォーマティのひとりとなり、結果的にアメリカのエンターテイメント業界で働くことを禁じられるブラックリストに載っ た。 2007年のBBCのニュース記事によると、1950年代初頭、英国MI5はアラン・ローマックスを共産主義者の疑いがあるとして監視下に置いた。その報 告書は、ローマックスが 「左翼的 」見解を持っていたことは間違いないが、彼が共産主義者である証拠はないと結論づけた。2007年9月4日に発表された(File ref KV 2/2701)彼のMI5ファイルの要約は以下の通りである: アメリカの著名な民族音楽記録家であり収集家であったアラン・ローマックスが最初に保安庁の注意を引いたのは、彼が1952年にBBCのために一連の民族 音楽放送に携わっていたときに、ロンドンのルーマニア報道官と接触したことが指摘されたときであった。このファイルには確証はないが、共産党員の疑いがあ るとしてアメリカ当局とやりとりが続いた。同局は、ローマックスが世界の民俗音楽のコレクションを編纂していることは、アタッシェと連絡を取る正当な理由 であり、彼の見解(彼の選曲や歌手によって実証されている)が左翼的であることは間違いないが、彼に対して特別な行動を取る必要はないという見解を示し た。 このファイルには、イギリス滞在中のローマックスの動向、連絡先、活動の記録の一部が含まれており、例えば、1953年12月にセント・パンクラスで行わ れた「鉄路の歌」コンサートに関する警察の報告書も含まれている。ブラックリストに載ったアメリカの)映画監督ジョセフ・ロージーとの関係も言及されてい る(連載30a)[58]。 FBIは1956年に再びローマックスを調査し、68ページの報告書をCIAと司法長官に送った。しかし、ウィリアム・トンプキンス検事総長補佐はフーバーに対し、この調査は起訴やローマックスのパスポート停止を正当化する十分な証拠を開示できなかったと書いた。 その後、1979年の時点で、FBIの報告書は、ローマックスが最近FBI捜査官になりすましたことを示唆していた。この報告書は、人違いによるものだっ たようだ。この事件をFBIに報告した人物は、問題の男は43歳前後、身長約170センチ、体重約190キロだったという。FBIのファイルには、ロー マックスは身長6フィート(1.8メートル)、体重240ポンド、当時64歳だったと記されている: ローマックスは、なりすまし容疑についてのFBIの事情聴取に抵抗したが、1979年11月にようやく自宅で捜査官と面会した。彼はこの件に関与していな いことを否定したが、1979年7月にニューハンプシャーに滞在し、ドキュメンタリーの件で映画編集者を訪ねていたことを明かした。FBIの報告書の結論 は、「ローマックスはFBIを嫌っており、FBIの事情聴取を嫌っていることを隠していなかった。ローマックスはインタビューの間中、非常に緊張してい た」[56]。 FBIの調査は翌年、ローマックスの65歳の誕生日の直後に終了した。 |

| Awards Alan Lomax received the National Medal of Arts from President Ronald Reagan in 1986; a Library of Congress Living Legend Award[59] in 2000; and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Philosophy from Tulane University in 2001. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award in 1993 for his book The Land Where the Blues Began, connecting the story of the origins of blues music with the prevalence of forced labor in the pre-World War II South (especially on the Mississippi levees). Lomax also received a posthumous Grammy Trustees Award for his lifetime achievements in 2003. Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax (Rounder Records, 8 CDs boxed set) won in two categories at the 48th annual Grammy Awards ceremony held on February 8, 2006[60] Alan Lomax in Haiti: Recordings For The Library Of Congress, 1936–1937, issued by Harte Records and made with the support and major funding from Kimberley Green and the Green foundation, and featuring 10 CDs of recorded music and film footage (shot by Elizabeth Lomax, then nineteen), a bound book of Lomax's selected letters and field journals, and notes by musicologist Gage Averill, was nominated for two Grammy Awards in 2011.[61] |

受賞歴 アラン・ローマックスは1986年にロナルド・レーガン大統領からナショナリズム賞を、2000年には米国議会図書館リビング・レジェンド賞[59]を、 2001年にはチューレーン大学から名誉哲学博士号を授与された。1993年には、ブルース音楽の起源と第二次世界大戦前の南部(特にミシシッピ州の堤 防)における強制労働の蔓延を結びつけた著書『The Land Where the Blues Began』でナショナリズム・サークル賞とラルフ・J・グリーソン音楽図書賞を受賞した。また、ローマックスは2003年にその生涯の功績を称えられ、 死後グラミー・トラスティーズ賞を受賞している。ジェリー・ロール・モートン The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax』(Rounder Records、8枚組ボックスセット)は、2006年2月8日に開催された第48回グラミー賞授賞式で2部門を受賞した[60]: ハルト・レコードから発売され、キンバリー・グリーンとグリーン財団の支援と主要な資金提供を受けて制作された『Recording For The Library Of Congress, 1936-1937』は、録音された音楽とフィルム映像(当時19歳だったエリザベス・ローマックスが撮影)、ローマックスが選んだ手紙と現地日誌の綴じ 込み本、音楽学者ゲイジ・アヴリルによるメモを収録したCD10枚組で、2011年のグラミー賞で2部門にノミネートされた[61]。 |

| World music and digital legacy Brian Eno wrote of Lomax's later recording career in his notes to accompany an anthology of Lomax's world recordings: [He later] turned his intelligent attentions to music from many other parts of the world, securing for them a dignity and status they had not previously been accorded. The "World Music" phenomenon arose partly from those efforts, as did his great book, Folk Song Style and Culture. I believe this is one of the most important books ever written about music, in my all time top ten. It is one of the very rare attempts to put cultural criticism onto a serious, comprehensible, and rational footing by someone who had the experience and breadth of vision to be able to do it.[62] In January 2012, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, with the Association for Cultural Equity, announced that it would release Lomax's vast archive in digital form. Lomax spent the last 20 years of his life working on an interactive multimedia educational computer project he called the Global Jukebox, which included 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of film, 3,000 videotapes, and 5,000 photographs.[63] By February 2012, 17,000 music tracks from his archived collection were expected to be made available for free streaming, and later some of that music may be for sale as CDs or digital downloads.[64] As of March 2012 this has been accomplished. Approximately 17,400 of Lomax's recordings from 1946 and later have been made available free online.[65][66] This is material from Alan Lomax's independent archive, begun in 1946, which has been digitized and offered by the Association for Cultural Equity. This is "distinct from the thousands of earlier recordings on acetate and aluminum discs he made from 1933 to 1942 under the auspices of the Library of Congress. This earlier collection – which includes the famous Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Muddy Waters sessions, as well as Lomax's prodigious collections made in Haiti and Eastern Kentucky (1937) – is the provenance of the American Folklife Center"[65] at the Library of Congress. This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (October 2021) On August 24, 1997, at a concert at Wolf Trap in Vienna, Virginia, Bob Dylan said about Lomax, who had helped introduce him to folk music and whom he had known as a young man in Greenwich Village: There is a distinguished gentlemen here who came...I want to introduce him – named Alan Lomax. I don't know if many of you have heard of him [Audience applause.] Yes, he's here, he's made a trip out to see me. I used to know him years ago. I learned a lot there and Alan...Alan was one of those who unlocked the secrets of this kind of music. So if we've got anybody to thank, it's Alan. Thanks, Alan.[67] In 1999 electronica musician Moby released his fifth album Play. It extensively used samples from field recordings collected by Lomax on the 1993 box set Sounds of the South: A Musical Journey from the Georgia Sea Islands to the Mississippi Delta.[68] The album went on to be certified platinum in more than 20 countries.[69] In his autobiography Chronicles, Part One, Bob Dylan recollects a 1961 scene: "There was an art movie house in the Village on 12th Street that showed foreign movies—French, Italian, German. This made sense, because even Alan Lomax himself, the great folk archivist, had said somewhere that if you want to go to America, go to Greenwich Village."[70] Lomax is portrayed by actor Norbert Leo Butz in the 2024 feature film about Bob Dylan's early career entitled A Complete Unknown.[71] |

ワールドミュージックとデジタル遺産 ブライアン・イーノは、ローマックスの世界録音のアンソロジーに添えたメモの中で、ローマックスのその後の録音活動についてこう書いている: [彼は後に)世界の他の多くの地域の音楽に知的な関心を向け、それまで与えられていなかった威厳と地位を確保した。ワールド・ミュージック」現象は、彼の 偉大な著書『フォークソングの様式と文化』と同様に、こうした努力から部分的に生まれた。この本は、音楽について書かれた本の中で最も重要なもののひとつ であり、私の中でベスト10に入る。文化批評を、それをなしうるだけの経験と視野の広さを持った人物によって、まじめで理解しやすく、合理的な足場に置こ うとした非常に稀な試みのひとつである[62]。 2012年1月、米国議会図書館のアメリカン・フォークライフ・センターは、Association for Cultural Equityとともに、ローマックスの膨大なアーカイブをデジタル形式で公開すると発表した。ローマックスは人生の最後の20年間を、彼が「グローバル・ ジュークボックス」と呼ぶ双方向マルチメディア教育コンピュータ・プロジェクトに費やしており、そのプロジェクトには5,000時間の録音、 400,000フィートのフィルム、3,000本のビデオテープ、5,000枚の写真が含まれていた[63]。2012年2月までに、彼のアーカイブ・コ レクションから17,000曲の音楽が無料ストリーミングで利用できるようになり、後にその音楽の一部がCDやデジタル・ダウンロードで販売される予定 だった[64]。 2012年3月現在、これは達成されている。1946年以降に録音されたローマックスの音源のうち、約17,400枚がオンラインで無料公開されている [65][66]。これは、1946年に始まったアラン・ローマックスの独立したアーカイブの音源で、Association for Cultural Equityによってデジタル化され、提供されている。これは、「1933年から1942年にかけて、米国議会図書館の後援のもとで彼が行った、アセテー トとアルミニウム・ディスクによる何千もの以前の録音とは異なるもの」である。この初期のコレクションには、有名なジェリー・ロール・モートン、ウディ・ ガスリー、リード・ベリー、マディ・ウォーターズのセッションや、ハイチと東ケンタッキー(1937年)で行われたローマックスの膨大なコレクションが含 まれており、米国議会図書館のアメリカン・フォークライフ・センターが所蔵している」[65]。 この記事は更新が必要である。最近の出来事や新たに入手した情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力いただきたい。(2021年10月) 1997年8月24日、ヴァージニア州ウィーンのウルフ・トラップでのコンサートで、ボブ・ディランは、彼にフォーク・ミュージックを紹介する手助けをし、グリニッジ・ヴィレッジで若者として知り合ったローマックスについてこう語った: ここにアラン・ローマックスという著名な紳士が来ている。アラン・ローマックスという人だ。彼のことを聞いたことがある人はあまりいないだろう。私は何年 も前に彼を知っていた。そこで多くのことを学んだし、アランは......アランはこの種の音楽の秘密を解き明かした一人だ。だから誰かに感謝するとした ら、それはアランだ。ありがとう、アラン」[67]。 1999年、エレクトロニカ・ミュージシャンのモービーは5枚目のアルバム『プレイ』をリリースした。このアルバムには、1993年のボックスセット 『Sounds of the South』でローマックスが収集したフィールド・レコーディングのサンプルが多用されている: このアルバムは20カ国以上でプラチナ認定を受けた[69]。 ボブ・ディランは自伝『Chronicles, Part One』の中で、1961年のあるシーンを回想している: 「ヴィレッジの12番街に、フランス、イタリア、ドイツなどの外国映画を上映するアート映画館があった。偉大なフォーク・アーカイヴァーであるアラン・ ローマックス自身も、アメリカに行きたければグリニッジ・ヴィレッジに行けとどこかで言っていたからだ」[70]。 ボブ・ディランの初期のキャリアを描いた2024年の長編映画『A Complete Unknown』では、俳優のノーバート・レオ・ブッツがローマックスを演じている[71]。 |

| Bibliography A partial list of books by Alan Lomax includes: L'Anno piu' felice della mia vita (The Happiest Year of My Life), a book of ethnographic photos by Alan Lomax from his 1954–55 fieldwork in Italy, edited by Goffredo Plastino, preface by Martin Scorsese. Milano: Il Saggiatore, M2008. Alan Lomax: Mirades Miradas Glances. Photos by Alan Lomax, ed. by Antoni Pizà (Barcelona: Lunwerg / Fundacio Sa Nostra, 2006) ISBN 84-9785-271-0 Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934–1997. Ronald D. Cohen, Editor (includes a chapter defining all the categories of cantometrics). New York: Routledge: 2003. Brown Girl in the Ring: An Anthology of Song Games from the Eastern Caribbean Compiler, with J. D. Elder and Bess Lomax Hawes. New York: Pantheon Books, 1997 (Cloth, ISBN 0-679-40453-8); New York: Random House, 1998 (Cloth). The Land Where The Blues Began. New York: Pantheon, 1993. Cantometrics: An Approach to the Anthropology of Music: Audiocassettes and a Handbook. Berkeley: University of California Media Extension Center, 1976. Folk Song Style and Culture. With contributions by Conrad Arensberg, Edwin E. Erickson, Victor Grauer, Norman Berkowitz, Irmgard Bartenieff, Forrestine Paulay, Joan Halifax, Barbara Ayres, Norman N. Markel, Roswell Rudd, Monika Vizedom, Fred Peng, Roger Wescott, David Brown. Washington, D.C.: Colonial Press Inc, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Publication no. 88, 1968. Penguin Book of American Folk Songs (1968) 3000 Years of Black Poetry. Alan Lomax and Raoul Abdul, Editors. New York: Dodd Mead Company, 1969. Paperback edition, Fawcett Publications, 1971. The Leadbelly Songbook. Moses Asch and Alan Lomax, Editors. Musical transcriptions by Jerry Silverman. Foreword by Moses Asch. New York: Oak Publications, 1962. Folk Songs of North America. Melodies and guitar chords transcribed by Peggy Seeger. New York: Doubleday, 1960. The Rainbow Sign. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1959. Leadbelly: A Collection of World Famous Songs by Huddie Ledbetter. Edited with John A. Lomax. Hally Wood, Music Editor. Special note on Lead Belly's 12-string guitar by Pete Seeger. New York: Folkways Music Publishers Company, 1959. Harriet and Her Harmonium: An American adventure with thirteen folk songs from the Lomax collection. Illustrated by Pearl Binder. Music arranged by Robert Gill. London: Faber and Faber, 1955. Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and "Inventor of Jazz". Drawings by David Stone Martin. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1950. Folk Song: USA. With John A. Lomax. Piano accompaniment by Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, c.1947. Republished as Best Loved American Folk Songs, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947 (Cloth). Freedom Songs of the United Nations. With Svatava Jakobson. Washington, D.C.: Office of War Information, 1943. Our Singing Country: Folk Songs and Ballads. With John A. Lomax and Ruth Crawford Seeger. New York: MacMillan, 1941. Check-list of Recorded Songs in the English Language in the Archive of American Folk Song in July 1940. Washington, D.C.: Music Division, Library of Congress, 1942. Three volumes. American Folksong and Folklore: A Regional Bibliography. With Sidney Robertson Cowell. New York, Progressive Education Association, 1942. Reprint, Temecula, California: Reprint Services Corp., 1988 (62 pp. ISBN 0-7812-0767-3). Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly. With John A. Lomax. New York: Macmillan, 1936. American ballads and folk songs. With John Avery Lomax. Macmillan, 1934. |

書誌 アラン・ローマックスの著書の一部を紹介する: L'Anno piu' felice della mia vita (The Happiest Year of My Life), アラン・ローマックスが1954年から55年にかけてイタリアで行ったフィールドワークのエスノグラファー写真集。Milano: Il Saggiatore, M2008. アラン・ローマックス Mirades Miradas Glances. 写真:アラン・ローマックス、編:アントニ・ピザ(バルセロナ:ルンヴェルグ/サ・ノストラ財団、2006年)ISBN 84-9785-271-0 アラン・ローマックス 選集 1934-1997. Ronald D. Cohen, Editor (カントメトリクスの全カテゴリーを定義した章を含む). ニューヨーク: Routledge: 2003. Brown Girl in the Ring: An Anthology of Song Games from the Eastern Caribbean Compiler, with J. D. Elder and Bess Lomax Hawes. ニューヨーク: Pantheon Books, 1997 (Cloth, ISBN 0-679-40453-8); New York: Random House, 1998(布)。 ブルースが始まった土地 ニューヨーク: Pantheon, 1993. カントメトリックス: 音楽の人類学へのアプローチ: オーディオカセットとハンドブック。バークレー: カリフォルニア大学メディア・エクステンション・センター, 1976. フォークソングのスタイルと文化。Conrad Arensberg, Edwin E. Erickson, Victor Grauer, Norman Berkowitz, Irmgard Bartenieff, Forrestine Paulay, Joan Halifax, Barbara Ayres, Norman N. Markel, Roswell Rudd, Monika Vizedom, Fred Peng, Roger Wescott, David Brownによる寄稿。ワシントンD.C.:コロニアル・プレス社、アメリカ科学振興協会、出版番号88、1968年。 ペンギン・ブック・オブ・アメリカ民謡 (1968) 黒人詩の3000年 Alan Lomax and Raoul Abdul, Editors. ニューヨーク: ドッド・ミード社、1969年。ペーパーバック版、フォーセット出版、1971年。 The Leadbelly Songbook. モーゼス・アッシュ、アラン・ローマックス編。ジェリー・シルバーマンによるトランスクリプション。モーゼズ・アッシュによる序文。ニューヨーク: Oak Publications, 1962. 北アメリカの民謡。ペギー・シーガーによるメロディーとギターコードの書き起こし。ニューヨーク: Doubleday, 1960. The Rainbow Sign. ニューヨーク: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1959. リードベリー: ハディ・レッドベターの世界的名曲集。ジョン・A・ローマックスと編集。Hally Wood, Music Editor. ピート・シーガーによるリードベリーの12弦ギターについての特別注。ニューヨーク: Folkways Music Publishers Company, 1959. ハリエットとハーモニウム: ローマックス・コレクションからの13のフォークソングによるアメリカの冒険。パール・バインダー絵。ロバート・ギル編曲。ロンドン: Faber and Faber, 1955. Mister Jelly Roll: ジェリー・ロール・モートン、ニューオリンズ・クレオール、「ジャズの発明者」の幸運。デビッド・ストーン・マーティン画。ニューヨーク: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1950. フォークソング: アメリカ。ジョン・A・ローマックスと。チャールズ&ルース・クロフォード・シーガーによるピアノ伴奏。ニューヨーク: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1947年頃。Best Loved American Folk Songsとして再出版された: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947 (Cloth). フリーダム・ソングス・オブ・ザ・ユニオンズ(Freedom Songs of the United Nations)。スヴァタヴァ・ヤコブソンと。ワシントンD.C.:戦争情報局、1943年。 Our Singing Country: フォークソングとバラッド。ジョン・A・ローマックス、ルース・クロフォード・シーガーと。New York: MacMillan, 1941. Check-list of Recorded Songs in the English Language in the Archive of American Folk Song in July 1940. ワシントン D.C.: 米国議会図書館音楽課、1942年。全3巻。 アメリカ民謡とフォークロア: 地域別文献目録。シドニー・ロバートソン・コーウェルと。New York, Progressive Education Association, 1942. リプリント、カリフォルニア州テメキュラ: Reprint Services Corp., 1988 (62 pp. ISBN 0-7812-0767-3). リード・ベリーが歌う黒人民謡。ジョン・A・ローマックスと。ニューヨーク: マクミラン, 1936. アメリカのバラッドとフォークソング。ジョン・エイブリー・ローマックスと。マクミラン、1934年。 |

| Film Lomax the Songhunter, documentary directed by Rogier Kappers, 2004 (issued on DVD 2007). American Patchwork television series, 1990 (five DVDs). Oss Oss Wee Oss 1951 (on a DVD with other films related to the Padstow May Day). Rhythms of Earth. Four films (Dance & Human History, Step Style, Palm Play, and The Longest Trail) made by Lomax (1974–1984) about his Choreometric cross-cultural analysis of dance and movement style. Two-and-a-half hours, plus one-and-a-half hours of interviews and 177 pages of text. The Land Where The Blues Began, expanded, thirtieth-anniversary edition of the 1979 documentary by Alan Lomax, filmmaker John Melville Bishop, and ethnomusicologist and civil rights activist Worth Long, with 3.5 hours of additional music and video. Ballads, Blues and Bluegrass, an Alan Lomax documentary released in 2012. His assistant Carla Rotolo was seen in the film. Southern Journey (Revisited), this 2020 documentary retraces the route of an iconic song-collecting trip from the late 1950s - Alan Lomax's so-called "Southern Journey". |

フィルム ロジャー・カッパーズ監督によるドキュメンタリー『Lomax the Songhunter』2004年(2007年DVD化)。 American Patchwork テレビシリーズ 1990年(DVD5枚組)。 Oss Oss Wee Oss 1951年(パドストウのメーデーに関連した他の作品と一緒にDVD化されている)。 地球のリズム。ローマックス(1974-1984)がダンスとムーブメントスタイルの異文化分析「コレオメトリック」について制作した4本のフィルム (Dance & Human History、Step Style、Palm Play、The Longest Trail)。時間半、インタビュー1時間半、テキスト177ページ。 アラン・ローマックス、映画監督ジョン・メルヴィル・ビショップ、民族音楽学者で公民権運動家のワース・ロングによる1979年のドキュメンタリーの30周年記念増補版。 2012年に公開されたアラン・ローマックスのドキュメンタリー『Ballads, Blues and Bluegrass』。助手のカーラ・ロトロが出演している。 Southern Journey (Revisited)』この2020年のドキュメンタリーは、1950年代後半の象徴的な楽曲収集の旅、アラン・ローマックスのいわゆる 「南部の旅 」のルートを辿っている。 |

| Notable alumni of St. Mark's School of Texas Ian Brennan (music producer) Cantometrics The Singing Street |

セント・マーク・スクール・オブ・テキサスの著名な卒業生 イアン・ブレナン(音楽プロデューサー) カントメトリクス シンギング・ストリート |

| Barton, Matthew. "The Lomaxes",

pp. 151–169, in Spenser, Scott B. The Ballad Collectors of North

America: How Gathering Folksongs Transformed Academic Thought and

American Identity (American Folk Music and Musicians Series). Plymouth,

UK: Scarecrow Press. 2011. The American song collecting of John A. and

Alan Lomax in historical perspective. Salsburg, Nathan (2019) Southern Journeys: Alan Lomax's Steel-String Discoveries. Acoustic Guitar magazine, March/April 2019. Sorce Keller, Marcello. "Kulturkreise, Culture Areas, and Chronotopes: Old Concepts Reconsidered for the Mapping of Music Cultures Today", in Britta Sweers and Sarah H. Ross (eds.) Cultural Mapping and Musical Diversity. Sheffield UK/Bristol CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd. 2020, 19–34. Szwed, John. Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World . New York: Viking Press, 2010 (438 pp.: ISBN 978-0-670-02199-4) / London: William Heinemann, 2010 (438 pp.;ISBN 978-0-434-01232-9). Comprehensive biography. Wood, Anna Lomax. Songs of Earth: Aesthetic and Social Codes in Music. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2021. 480 pages. ISBN: 1496840356. |

Barton, Matthew. 「The Lomaxes」,

pp. 151-169, in Spenser, Scott B. The Ballad Collectors of North

America: How Gathering Folksongs Transformed Academic Thought and

American Identity (American Folk Music and Musicians Series). Plymouth,

UK: Scarecrow Press. 2011. ジョン・A・ローマックスとアラン・ローマックスのアメリカ歌曲収集の歴史的展望。 Salsburg, Nathan (2019) Southern Journeys: Alan Lomax's Steel-String Discoveries. Acoustic Guitar誌、2019年3月/4月号。 Sorce Keller, Marcello. 「Kulturkreise, Culture Areas, and Chronotopes: Kulturkreise, Culture Areas, and Chronotopes: Old Concepts Reconsidered for the Mapping of Music Cultures Today」, in Britta Sweers and Sarah H. Ross. Ross (eds.) Cultural Mapping and Musical Diversity. Sheffield UK/Bristol CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2020, 19-34. 2020, 19-34. Szwed, John. Alan Lomax: 世界を記録した男. ニューヨーク: Viking Press, 2010 (438 pp.: ISBN 978-0-670-02199-4) / London: William Heinemann, 2010 (438 pp.; ISBN 978-0-434-01232-9). 総合的な伝記。 ウッド、アンナ・ローマックス Songs of Earth: 音楽における美的および社会的規範。ジャクソン: University Press of Mississippi, 2021. 480ページ。ISBN: 1496840356。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Lomax |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099