アレクサンドル・ボグダーノフ

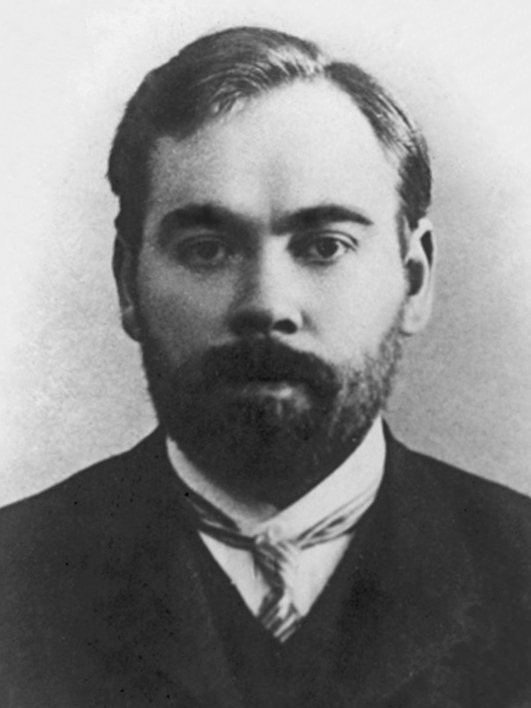

Alexander Bogdanov, 1873-1928

☆ アレクサンドル・アレクサンドロヴィチ・ボグダノフ(ロシア語: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Богда́нов、1873年8月22日[旧暦10日] - 1928年4月7日)は、アレクサンドル・マリノフスキーとして生まれ、ロシアの医師、哲学者、SF作家、ボリシェヴィキの革命家である。彼は、輸血 [1]や一般システム理論[2]のパイオニアであり、サイバネティクスにも重要な貢献をした博識家であった。 彼は、1898年に設立されたロシア社会民主労働党(後のソビエト連邦共産党)およびそのボリシェヴィキ派の初期の歴史において重要な人物であった。ボグ ダノフは1903年、メンシェビキ派と分裂した際にボリシェヴィキを共同で創設した。彼は1909年に追放され、自身の派閥「Vpered」を創設するま で、ボリシェヴィキ内部でウラジーミル・レーニン(1870年~1924年)のライバルであった。1917年のロシア革命後、崩壊しつつあったロシア共和 国でボリシェヴィキが政権を握ると、彼はマルクス主義左派の観点から、1920年代のソビエト連邦の最初の10年間、ボリシェヴィキ政府とレーニンの有力 な反対派となった。 ボグダノフは医学と精神医学の教育を受けた。彼の科学と医学に対する幅広い関心は、普遍的なシステム理論から輸血による若返りの可能性にまで及んだ。彼は 「テクトロジー」と呼ばれる独自の哲学を考案し、現在ではシステム理論の先駆けとみなされている。また、経済学者、文化理論家、SF作家、政治活動家でも あった。レーニンは彼を「ロシア・マチスト」の一人として描いている。

| Alexander

Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (Russian: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович

Богда́нов;

22 August 1873 [O.S. 10 August] – 7 April 1928), born Alexander

Malinovsky, was a Russian and later Soviet physician, philosopher,

science fiction writer and Bolshevik revolutionary. He was a polymath

who pioneered blood transfusion,[1] as well as general systems

theory,[2] and made important contributions to cybernetics.[3] He was a key figure in the early history of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (later the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), originally established 1898, and of its Bolshevik faction. Bogdanov co-founded the Bolsheviks in 1903, when they split with the Menshevik faction. He was a rival within the Bolsheviks to Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), until being expelled in 1909 and founding his own faction Vpered. Following the Russian Revolutions of 1917, when the Bolsheviks came to power in the collapsing Russian Republic, he was an influential opponent of the Bolshevik government and Lenin from a Marxist leftist perspective during the first decade of the subsequent Soviet Union in the 1920s. Bogdanov received training in medicine and psychiatry. His wide scientific and medical interests ranged from the universal systems theory to the possibility of human rejuvenation through blood transfusion. He invented an original philosophy called "tectology", now regarded as a forerunner of systems theory. He was also an economist, culture theorist, science fiction writer, and political activist. Lenin depicted him as one of the "Russian Machists". |

アレクサンドル・アレクサンドロヴィチ・ボグダノフ(ロシア語:

Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Богда́нов、1873年8月22日[旧暦10日] -

1928年4月7日)は、アレクサンドル・マリノフスキーとして生まれ、ロシアの医師、哲学者、SF作家、ボリシェヴィキの革命家である。彼は、輸血

[1]や一般システム理論[2]のパイオニアであり、サイバネティクスにも重要な貢献をした博識家であった。 彼は、1898年に設立されたロシア社会民主労働党(後のソビエト連邦共産党)およびそのボリシェヴィキ派の初期の歴史において重要な人物であった。ボグ ダノフは1903年、メンシェビキ派と分裂した際にボリシェヴィキを共同で創設した。彼は1909年に追放され、自身の派閥「Vpered」を創設するま で、ボリシェヴィキ内部でウラジーミル・レーニン(1870年~1924年)のライバルであった。1917年のロシア革命後、崩壊しつつあったロシア共和 国でボリシェヴィキが政権を握ると、彼はマルクス主義左派の観点から、1920年代のソビエト連邦の最初の10年間、ボリシェヴィキ政府とレーニンの有力 な反対派となった。 ボグダノフは医学と精神医学の教育を受けた。彼の科学と医学に対する幅広い関心は、普遍的なシステム理論から輸血による若返りの可能性にまで及んだ。彼は 「テクトロジー」と呼ばれる独自の哲学を考案し、現在ではシステム理論の先駆けとみなされている。また、経済学者、文化理論家、SF作家、政治活動家でも あった。レーニンは彼を「ロシア・マチスト」の一人として描いている。 |

| Early years A Russian born in Belarus,[4][5] Alexander Malinovsky was born in Sokółka, Russian Empire (now Poland),[6] into a rural teacher's family, the second of six children.[7] He attended the Gymnasium at Tula,[8] which he compared to a barracks or prison. He was awarded a gold medal when he graduated.[9] Upon completion of the gymnasium, Bogdanov was admitted to the Natural Science Department of Imperial Moscow University.[10] In his autobiography, Bogdanov reported that, while studying at Moscow University, he joined the Union Council of Regional Societies and was arrested and exiled to Tula because of it.[11] The head of the Moscow Okhrana had used an informant to acquire the names of members of the Union Council of Regional Societies, which included Bogdanov's name. On October 30, 1894, students rowdily demonstrated against a lecture by the history Professor Vasily Klyuchevsky who, despite being a well-known liberal, had written a favourable eulogy for the recently deceased Tsar Alexander III of Russia. Punishment of a few of the students was seen as so arbitrary and unfair that the Union Council requested a fair reexamination of the issue. That very night, the Okhrana arrested all the students on the list mentioned above – including Bogdanov – all of whom were expelled from the university and banished to their hometowns.[12] Expelled from Moscow State University, he enrolled as an external student at the University of Kharkov, from which he graduated as a physician in 1899. Bogdanov remained in Tula from 1894 to 1899, where – since his own family was living in Sokółka – he lodged with Alexander Rudnev, the father of Vladimir Bazarov, who became a close friend and collaborator in future years. Here he met and married Natalya Bogdanovna Korsak, who, as a woman, had been refused entrance to the university. She was eight years older than he was[13] and worked as a nurse for Rudnev. Malinovsky adopted the pen name that he used when he wrote his major theoretical works and his novels from her patronym.[14] Alongside Bazarov and Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov he became a tutor in a workers' study circle. This was organised in the Tula Armament Factory by Ivan Saveliev, whom Bogdanov credited with founding Social Democracy in Tula. During this period, he wrote his Brief course of economic science, which was published – "subject to many modifications made for the benefit of the censor" – only in 1897. He later said that this experience of student-led education gave him his first lesson in proletarian culture. In autumn 1895, he resumed his medical studies at the university of Kharkiv (Ukraine) but still spent much time in Tula. He came across the works of Lenin in 1896, particularly the latter's critique of Peter Berngardovich Struve. In 1899, he graduated as a medical doctor and published his next work, "Basic elements of the historical perspective on nature". However, because of his political views, he was also arrested by the Tsar's police, spent six months in prison, and was exiled to Vologda. |

初期 ロシアで生まれたベラルーシ人[4][5]のアレクサンドル・マリノフスキーは、ロシア帝国(現ポーランド)のソコウカで、教師の家庭に6人兄弟の2番目 として生まれた[7]。彼はトゥーラのギムナジウムに通っていたが、そこを兵舎や刑務所に例えていた。卒業時には金メダルを授与された[9]。 ギムナジウムを卒業すると、ボグダノフはモスクワ帝国大学の自然科学部に進学した。[10] 自伝の中で、ボグダノフはモスクワ大学在学中に地域社会連合評議会に参加し、そのために逮捕されトゥーラに追放されたと報告している。[11] モスクワ・オークラーナのトップは、密告者を使って連合評議会のメンバーの名前を入手し、その中にはボグダノフの名前も含まれていた。1894年10月 30日、自由主義者として知られていたにもかかわらず、最近亡くなったロシア皇帝アレクサンドル3世を称賛する賛辞を書いた歴史学教授ワシーリー・クリュ チェフスキーの講義に対して、学生たちが騒々しく抗議した。一部の学生に対する処罰はあまりにも恣意的かつ不公平であるとみなされ、連合評議会は公正な再 調査を要請した。その夜のうちに、オークラーナは、ボグダノフを含む上記のリストに載っていたすべての学生を逮捕し、全員が大学から追放され、故郷に追放 された。[12] モスクワ大学を退学した彼は、ハルキウ大学に外部学生として入学し、1899年に医師として卒業した。ボグダノフは1894年から1899年までトゥーラ に滞在し、自身の家族がソコルカに住んでいたため、ウラジーミル・バザロフの父親であるアレクサンドル・ルドネフの家に下宿した。ルドネフは、後に親しい 友人となり協力者となる人物であった。ここで、女性であるために大学入学を拒否されていたナターリヤ・ボグダノヴナ・コルサコフと出会い、結婚した。彼女 は彼より8歳年上で[13]、ルドネフの看護婦として働いていた。マリノフスキーは、主要な理論作品や小説を書く際に、彼女の父称から取ったペンネームを 使用した[14]。 バザロフやイワン・スクヴォルツォフ=ステパノフらとともに、労働者たちの学習サークルの講師となった。これはイワン・サヴェリエフがトゥーラ造兵工場で 組織したもので、ボグダノフは彼をトゥーラ社会民主主義の創設者とみなしている。この時期に彼は『経済学の概論』を執筆したが、検閲官の都合による多くの 修正が加えられ、1897年にようやく出版された。後に彼は、学生主導の教育というこの経験が、彼にとってプロレタリア文化の最初のレッスンとなったと 語っている。 1895年秋、彼はハリコフ(ウクライナ)の大学で医学の勉強を再開したが、依然として多くの時間をトゥーラで過ごしていた。1896年、彼はレーニンの 著作に出会い、特に後者のペテル・ベルンガルドヴィッチ・ストルーヴェ批判に注目した。1899年、彼は医師として卒業し、次の著作『自然に対する歴史的 観点の基本要素』を出版した。しかし、政治的見解により、彼は皇帝の警察に逮捕され、6か月間刑務所に収監された後、ヴォログダに追放された。 |

| Bolshevism Bogdanov dated his support for Bolshevism from autumn of 1903. Early in 1904, Martyn Liadov was sent by the Bolsheviks in Geneva to seek out supporters in Russia. He found a sympathetic group of revolutionaries, including Bogdanov, in Tver. Bogdanov was then sent by the Tver Committee to Geneva, where he was greatly impressed by Lenin's One Step Forward, Two Steps Back. Back in Russia during the 1905 Revolution, Bogdanov was arrested on 3 December 1905 and held in prison until 27 May 1906. Upon release, he was exiled to Bezhetsk for three years. However, he obtained permission to spend his exile abroad, and joined Lenin in Kokkola, Finland. For the next six years, Bogdanov was a major figure among the early Bolsheviks, second only to Lenin in influence. In 1904–1906, he published three volumes of the philosophic treatise Empiriomonizm (Empiriomonism), in which he tried to merge Marxism with the philosophy of Ernst Mach, Wilhelm Ostwald, and Richard Avenarius. His work later affected a number of Russian Marxist theoreticians, including Nikolai Bukharin.[15] In 1907, he helped organize the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery with both Lenin and Leonid Krasin. For four years after the collapse of the Russian Revolution of 1905, Bogdanov led a group within the Bolsheviks ("ultimatists" and "otzovists" or "recallists"), who demanded a recall of Social Democratic deputies from the State Duma, and he vied with Lenin for the leadership of the Bolshevik faction. In 1908 he joined Bazarov, Lunacharsky, Berman, Helfond, Yushkevich and Suvorov in a symposium Studies in the Philosophy of Marxism which espoused the views of the Russian Marxists. By mid-1908, the factionalism within the Bolsheviks had become irreconcilable. A majority of Bolshevik leaders either supported Bogdanov or were undecided between him and Lenin. Lenin concentrated on undermining Bogdanov's reputation as a philosopher. In 1909 he published a scathing book of criticism entitled Materialism and Empiriocriticism, assaulting Bogdanov's position and accusing him of philosophical idealism.[16] In June 1909, Bogdanov was defeated by Lenin at a Bolshevik mini-conference in Paris organized by the editorial board of the Bolshevik magazine Proletary and was expelled from the Bolsheviks. He joined his brother-in-law Anatoly Lunacharsky, Maxim Gorky, and other Vperedists on the island of Capri, where they started the Capri Party School for Russian factory workers. In 1910, Bogdanov, Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky, and their supporters moved the school to Bologna, where they continued teaching classes through 1911, while Lenin and his allies soon started the Longjumeau Party School just outside of Paris. Bogdanov broke with the Vpered in 1912 and abandoned revolutionary activities. After six years of his political exile in Europe, Bogdanov returned to Russia in 1914, following the political amnesty declared by Tsar Nicholas II as part of the festivities connected with the tercentenary of the Romanov Dynasty. |

ボリシェヴィズム ボグダノフは、1903年の秋からボリシェヴィズムを支持していた。1904年初頭、マルティン・リャードフはジュネーブのボリシェヴィキからロシア国内 の支持者を探し出すよう派遣された。彼はトヴェリでボグダノフを含む革命家たちの共感を得るグループを見つけた。その後、ボグダノフはトヴェリ委員会から ジュネーブに派遣され、そこでレーニンの著書『一歩前進、二歩後退』に感銘を受けた。1905年のロシア革命の際、ボグダノフは1905年12月3日に逮 捕され、1906年5月27日まで投獄された。釈放後、3年間ベジェツクに追放された。しかし、国外追放を許可され、フィンランドのコッコラでレーニンと 合流した。 その後6年間、ボグダノフは初期のボリシェヴィキの主要人物であり、影響力はレーニンに次ぐものだった。1904年から1906年にかけて、彼は3巻から なる哲学論文『経験一元論』(Empiriomonizm)を出版し、その中でマルクス主義をエルンスト・マッハ、ヴィルヘルム・オストヴァルト、リヒャ ルト・アヴェナリウスの哲学と融合させようとした。彼の著作は後に、ニコライ・ブハーリンを含む多くのロシアのマルクス主義理論家に影響を与えた。 1907年、彼はレーニンとレオニード・クラシンとともに1907年のトビリシ銀行強盗を組織した。 1905年のロシア革命の崩壊後、4年間にわたり、ボグダノフはボルシェビキ内のグループ(「最終主義者」および「オッツォフ派」または「リコール派」) を率いて、国家評議会から社会民主主義代議員の解任を要求し、ボルシェビキ派閥の指導権をめぐってレーニンと争った。1908年、彼はバザロフ、ルナチャ ルスキー、ベルマン、ヘルフォンド、ユシケーヴィチ、スヴォーロフらとともに、ロシア・マルクス主義者の見解を支持するシンポジウム「マルクス主義哲学研 究」に参加した。1908年半ばには、ボリシェヴィキ内の派閥主義は和解不可能な状態となっていた。ボリシェヴィキ指導者の大半はボグダノフを支持する か、あるいはボグダノフとレーニンのどちらを支持するか決めかねていた。 レーニンは、哲学者としてのボグダノフの評判を落とすことに集中した。1909年には『唯物論と経験批判主義』という痛烈な批判書を出版し、ボグダノフの 立場を攻撃し、彼を哲学上の観念論者であると非難した。[16] 1909年6月、ボグダノフはパリでボリシェヴィキ機関誌『プロレタリー』の編集委員会が主催したボリシェヴィキの小会議でレーニンに敗れ、ボリシェヴィ キから除名された。 義理の兄弟のアナトリー・ルナチャルスキー、マクシム・ゴーリキー、その他の「前進派」のメンバーとともにカプリ島に渡り、ロシアの工場労働者のためのカ プリ党学校を創設した。1910年、ボグダノフ、ルナチャルスキー、ミハイル・ポクロフスキー、および彼らの支持者たちは、この学校をボローニャに移し、 1911年まで授業を続けた。一方、レーニンとその仲間たちは、まもなくパリ郊外で「ロンジュモー党学校」を立ち上げた。 ボグダノフは1912年に「前進」を離れ、革命活動から手を引いた。ヨーロッパでの6年間の亡命生活を経て、ボグダノフはロマノフ王朝300周年記念の一 環としてニコライ2世が宣言した政治的恩赦を受けて、1914年にロシアに戻った。 |

| During World War I Bogdanov was drafted soon after the outbreak of World War I and was assigned as a junior regimental doctor with the 221st Smolensk infantry division in the Second Army commanded by General Alexander Samsonov. In the Battle of Tannenberg, August 26–30, the Second Army was surrounded and almost completely destroyed, but Bogdanov survived because he had been sent to accompany a seriously wounded officer to Moscow.[17] However following the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes, he succumbed to a nervous disorder and subsequently became junior house surgeon at an evacuation hospital.[18] In 1916 he wrote four articles for Vpered which provided an analysis of the World War I and the dynamics of war economies. He attributed a central role to the armed forces in the economic restructuring of the belligerent powers. He saw the army as creating a "consumers' communism" with the state taking over ever-increasing parts of the economy. At the same time military authoritarianism had also spread to civil society. This created the conditions for two consequences: consumption-led war communism and the destruction of the means of production. He thus predicted that even after the war, the new system of state capitalism would replace that of finance capitalism even though the destruction of the forces of production would cease.[19] |

第一次世界大戦 ボグダノフは第一次世界大戦勃発直後に徴兵され、アレクサンドル・サモソノフ将軍が指揮する第2軍の第221スモレンスク歩兵師団に少尉軍医として配属さ れた。8月26日から30日にかけて行われたタンネンベルクの戦いにおいて、第2軍は包囲され、ほぼ壊滅状態となったが、ボグダノフは重傷を負った士官を モスクワまで護送する任務に就いていたため、生き残った。[17] しかし、マズールィ湖の戦いの後、神経障害を患い、その後は避難病院の年少外科医となった。[18] 1916年には、Vpered誌に第一次世界大戦と戦争経済の力学を分析した4つの記事を寄稿した。彼は、交戦国の経済再編における軍の中心的役割を指摘 した。彼は、軍が国家が経済のますます大きな部分を担う「消費者の共産主義」を作り出していると捉えていた。 同時に、軍事的権威主義も市民社会に広がった。これにより、2つの結果が生じる条件が整った。すなわち、消費主導の戦争共産主義と生産手段の破壊である。 彼は、生産力の破壊が止むことがあっても、戦争後には国家資本主義という新たな体制が金融資本主義に取って代わるだろうと予測した。[19] |

| During the Russian Revolution Bogdanov had no party-political involvement in the Russian Revolution of 1917, although he did publish a number of articles and books about the events that unfurled around him. He supported the Zimmerwaldist programme of "peace without annexations or indemnities". He deplored the Provisional Government's continued prosecution of the war. After the July Days, he advocated "revolutionary democracy" as he now considered the socialists capable of forming a government. However, he viewed this as a broad-based socialist provisional government that would convene a Constituent Assembly. In May 1917, he published Chto my svergli in Novaya Zhizn. Here he argued that between 1904 and 1907, the Bolsheviks had been "decidedly democratic" and that there was no pronounced cult of leadership. However, following the decision of Lenin and the émigré group around him to break with Vpered in order to unify with the Mensheviks, the principle of leadership became more pronounced. After 1912, when Lenin insisted on splitting the Duma group of the RSDLP, the leadership principle became entrenched. However, he saw this problem as not being confined to the Bolsheviks, noting that similar authoritarian ways of thinking were shown in the Menshevik attitude to Plekhanov, or the cult of heroic individuals and leaders amongst the Narodniks. Every organisation, on achieving a position of decisive influence in the life and ordering of society, quite inevitably, irrespective of the formal tenets of its programme, attempts to impose on society its own type of structure, the one with which it is most familiar and to which it is most accustomed. Every collective re-creates, as far as it can, the whole social environment after its own image and in its own likeness.[20] |

ロシア革命の間、 ボグダノフは1917年のロシア革命に党派的な関与はしなかったが、彼を取り巻く出来事について多くの記事や書籍を出版した。彼は「併合や賠償金なしの平 和」を求めるジメルヴァルト主義のプログラムを支持した。彼は臨時政府が戦争を継続したことを嘆いた。七月革命の後、彼は「革命的民主主義」を提唱し、社 会主義者が政府を樹立できると考えるようになった。しかし、彼はこれを幅広い社会主義者の暫定政府と捉え、憲法制定議会を召集するものと考えた。 1917年5月、彼は『われわれに何ができようか』を『新しい生活』誌に発表した。ここで彼は、1904年から1907年の間、ボリシェヴィキは「明らか に民主的」であり、指導者崇拝の傾向は顕著ではなかったと主張した。しかし、レーニンと彼を取り巻く亡命グループがメンシェヴィキと統一するために「前 進」との決別を決めた後、指導者原理がより顕著になった。1912年以降、レーニンがロシア社会民主労働党のドゥーマ(国会)グループの分裂を主張したこ とで、指導者原理が定着した。しかし、彼はこの問題はボリシェヴィキに限ったことではないと見ており、メンシェヴィキのプレハーノフに対する態度や、ナ ロードニキの英雄的人物や指導者崇拝にも同様の権威主義的な考え方が見られると指摘している。 あらゆる組織は、社会の生活や秩序に決定的な影響力を及ぼす立場を獲得すると、そのプログラムの正式な信条とは関係なく、必然的に、最も慣れ親しんだ、最 も慣れ親しんだ構造を社会に押し付けようとする。あらゆる集団は、可能な限り、自分たちのイメージと似た形で、社会環境全体を再創造する。[20] |

| After the October Revolution At the beginning of February 1918, Bogdanov denied that the Bolsheviks' October seizure to power had constituted a conspiracy. Rather, he explained that an explosive situation had arisen through the prolongation of the war. He pointed to a lack of cultural development in that all strata of society, whether the bourgeoisie, the intelligentsia, or the workers, had shown a failure to resolve conflicts through negotiation. He described the revolution as being a combination of a peasant revolution in the countryside and a soldier-worker revolution in the cities. He regarded it as paradoxical that the peasantry expressed itself through the Bolshevik party rather than through the Socialist Revolutionaries. He analysed the effect of the First World War as creating 'War Communism', which he defined as a form of 'consumer communism', which created the circumstances for the development of state capitalism. He saw military state capitalism as a temporary phenomenon in the West, lasting only as long as the war. However, thanks to the predominance of the soldiers in the Bolshevik Party, he regarded it as inevitable that their backwardness should predominate in the re-organisation of society. Instead of proceeding in a methodical fashion, the pre-existing state was simply uprooted. The military-consumerist approach of simply requisitioning what was required had predominated and could not cope with the more complex social relations necessitated by the market: There is a War Communist party which is mobilising the working class, and there are groups of socialist intelligentsia. The war has made the army the end and the working class the means.[21] He refused multiple offers to rejoin the party and denounced the new regime as similar to Aleksey Arakcheyev's arbitrary and despotic rule in the early 1820s.[22] In 1918, Bogdanov became a professor of economics at the University of Moscow and director of the newly established Socialist Academy of Social Sciences.[23] |

十月革命の後 1918年2月初頭、ボグダノフは、ボリシェヴィキが10月に権力を掌握したことは陰謀などではなかったと否定した。むしろ、戦争の長期化によって爆発的 な状況が生じたと説明した。彼は、ブルジョワ、知識階級、労働者など社会のあらゆる階層が、交渉による紛争解決に失敗していることを指摘し、文化的な発展 の欠如を指摘した。彼は、革命は農村における農民革命と都市における兵士労働者革命の組み合わせであると説明した。彼は、農民が社会革命党ではなくボリ シェヴィキ党を通じて自己表現したことを逆説的だと考えた。 彼は、第一次世界大戦の影響として「戦時共産主義」が生み出されたと分析し、それを「消費共産主義」の一形態と定義した。消費共産主義は国家資本主義の発 展の条件を作り出した。彼は軍事国家資本主義を西側諸国における一時的な現象であり、戦争が続く限り続くものだと考えていた。しかし、ボリシェヴィキ党に おける兵士の優勢のおかげで、社会の再編成において彼らの後進性が優勢になることは避けられないと彼は考えていた。整然と進むのではなく、既存の国家は単 に根こそぎにされた。必要なものを徴発するだけの軍事的消費主義的アプローチが優勢となり、市場によって必要とされるより複雑な社会関係に対処することは できなかった。 労働者階級を動員する戦争共産党があり、社会主義知識人のグループもある。戦争によって軍隊が目的となり、労働者階級が手段となったのだ。[21] 彼は何度も党への復党を求められたが拒否し、新体制を1820年代初頭のアレクセイ・アラクチェーエフの専制的な支配と似ていると非難した。 1918年、ボグダノフはモスクワ大学の経済学教授となり、新設された社会科学院の所長に就任した。 |

| Proletkult Between 1918 and 1920, Bogdanov co-founded the proletarian art movement Proletkult and was its leading theoretician. In his lectures and articles, he called for the total destruction of the "old bourgeois culture" in favour of a "pure proletarian culture" of the future. It was also through Proletkult that Bogdanov's educational theories were given form with the establishment of the Moscow Proletarian University. At first Proletkult, like other radical cultural movements of the era, received financial support from the Bolshevik government, but by 1920, the Bolshevik leadership grew hostile, and on December 1, 1920, Pravda published a decree denouncing Proletkult as a "petit bourgeois" organization operating outside of Soviet institutions and a haven for "socially alien elements". Later in that month, the president of Proletkult was removed, and Bogdanov lost his seat on its Central Committee. He withdrew from the organization completely in 1921–1922.[24] |

プロレタール文化 1918年から1920年にかけて、ボグダノフはプロレタリアート芸術運動「プロレカルト」を共同創設し、その理論の第一人者となった。 彼は講演や論文で、未来の「純粋なプロレタリア文化」を支持し、「古いブルジョワ文化」の完全な破壊を呼びかけた。 また、プロレカルトを通じて、ボグダノフの教育理論は「モスクワ・プロレタリア大学」の設立という形で具体化された。 当初プロレカルトは、当時の他の急進的文化運動と同様に、ボリシェヴィキ政府から財政的支援を受けていたが、1920年にはボリシェヴィキ指導部の反感を 買い、1920年12月1日付のプラウダ紙が、プロレカルトをソビエト機関の外で活動する「小ブルジョワ」組織であり、「社会的に疎外された要素」の温床 であると非難する法令を掲載した。その月の後半にはプロレタールクートの議長が解任され、ボグダノフは中央委員の座を失った。彼は1921年から1922 年にかけて完全に組織から身を引いた。[24] |

| rrest Bogdanov gave a lecture to a club at Moscow University, which, according to Yakov Yakovlev, included an account of the formation of Vpered and reiterated some of the criticisms Bogdanov had made at the time of the individualism of certain leaders. Yakovlev further claimed that Bogdanov discussed the development of the concept of proletarian culture up to the present day and discussed to what extent the Communist Party saw Proletkult as a rival. Bogdanov hinted at the prospect of a new International that might emerge if there were a revival of the socialist movement in the West. He said he envisaged such an International as merging political, trade union, and cultural activities into a single organisation. Yakovlev characterised these ideas as Menshevik, pointing to the refusal of Vpered to acknowledge the authority of the 1912 Prague Conference. He cited Bogdanov's characterization of the October Revolution as "soldiers'-peasants' revolt", his criticisms of the New Economic Policy, and his description of the new regime as expressing the interests of a new class of technocratic and bureaucratic intelligentsia, as evidence that Bogdanov was involved in forming a new party.[25] Meanwhile, Workers' Truth had received publicity in the Berlin-based Menshevik journal Sotsialisticheskii Vestnik, and they also distributed a manifesto at the 12th Bolshevik Congress and were active in the industrial unrest which swept Moscow and Petrograd in July and August 1923. On 8 September 1923, Bogdanov was among a number of people arrested by the GPU (the Soviet secret police) on suspicion of being involved in them. He demanded to be interviewed by Felix Dzerzhinsky, to whom he explained that while he shared a range of views with Workers' Truth, he had no formal association with them. He was released after five weeks on 13 October; however, his file was not closed until a decree passed by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 16 January 1989. He wrote about his experiences under arrest in Five weeks with the GPU.[26] |

逮捕 ボグダノフはモスクワ大学のクラブで講演を行い、ヤコフ・ヤコブレフによると、その講演では「前進」結成の経緯が説明され、一部の指導者の個人主義を批判 した当時のボグダノフの主張が繰り返された。ヤコブレフはさらに、ボグダノフがプロレタリア文化の概念が今日に至るまでの発展について論じ、共産党がプロ レクウルトをどの程度ライバル視していたかについても論じたと主張した。ボグダノフは、もし西欧で社会主義運動が復活すれば、新たなインターナショナルが 誕生する可能性を示唆した。彼は、政治、労働組合、文化活動をひとつの組織に統合するようなインターナショナルを構想していると述べた。ヤコブレフは、こ れらの考え方をメンシェビキ的であると特徴づけ、1912年のプラハ会議の権威をボグダノフが認めようとしなかったことを指摘した。彼は、ボグダノフが十 月革命を「兵士と農民の反乱」と表現したこと、新経済政策に対する批判、新しい政権をテクノクラートや官僚のインテリ層という新しい階級の利益を体現する ものとして表現したことを挙げ、ボグダノフが新党結成に関与していた証拠であると主張した。[25] 一方、『労働者の真実』はベルリンを拠点とするメンシェヴィキの機関誌『ソツィアリステチスキイ・ヴェストニク』で広く知られるようになり、第12回ボル シェビキ大会ではマニフェストを配布し、1923年7月と8月にモスクワとペトログラードを襲った労働争議にも積極的に関与した。1923年9月8日、ボ グダノフはこれらの活動に関与した容疑でGPU(ソビエト秘密警察)に多数逮捕された者のうちの一人となった。彼はフェリックス・ジェルジンスキーとの面 会を要求し、そこで『労働者真理』のさまざまな見解には同意するものの、彼らとは公式なつながりはないと説明した。彼は5週間後に10月13日に釈放され たが、彼のファイルは1989年1月16日にソビエト連邦最高会議が制定した法令によって閉じられるまで、閉じられることはなかった。彼は『GPUとの5 週間』で、逮捕時の経験について書いている。[26] |

| Later years and death In 1922 whilst visiting London to negotiate the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, Bogdanov acquired a copy of the British surgeon Geoffrey Keynes's book Blood Transfusion. Returning to Moscow, he founded the Institute for Haematology and Blood Transfusions in 1924-25[23] and started blood transfusion experiments, apparently hoping to achieve eternal youth or at least partial rejuvenation. Lenin's sister Maria Ulyanova was among many who volunteered to take part in Bogdanov's experiments. After undergoing 11 blood transfusions, he remarked with satisfaction the improvement of his eyesight, suspension of balding, and other positive symptoms. His fellow revolutionary Leonid Krasin wrote to his wife that "Bogdanov seems to have become 7, no, 10 years younger after the operation". In 1925–1926, Bogdanov founded the Institute for Haematology and Blood Transfusions, which was later named after him. A later transfusion in 1928 cost him his life, when he took the blood of a student suffering from malaria and tuberculosis. The student injected with his blood made a complete recovery. Some scholars (e.g. Loren Graham) have speculated that his death may have been a suicide, because Bogdanov wrote a highly nervous political letter shortly beforehand. However, his death could be attributed to the adverse effects of blood transfusion, which were poorly understood at the time.[27][13][28] |

晩年と死 1922年、英ソ通商協定の交渉のためにロンドンを訪れた際、ボグダノフはイギリスの外科医ジェフリー・ケインズの著書『輸血』を手に入れた。モスクワに 戻った彼は、1924年から1925年にかけて血液学・輸血研究所を設立し[23]、輸血実験を開始した。永遠の若さ、あるいは少なくとも部分的な若返り を達成することを期待していたようである。レーニンの妹マリア・ウリヤノワも、ボグダノフの実験に参加した志願者の一人であった。11回にわたる輸血の 後、視力の改善、脱毛の停止、その他の好ましい兆候を満足げに述べた。彼の同志であった革命家レオニード・クラシンは妻に宛てた手紙の中で、「手術後、ボ グダノフは7歳、いや10歳は若返ったようだ」と書いている。1925年から1926年にかけて、ボグダノフは後に自身の名を冠することになる血液学・輸 血研究所を設立した。 1928年にマラリアと結核を患う学生の血液を輸血されたことで、彼の命は奪われた。彼の血液を輸血された学生は完治した。一部の学者(例えばLoren Graham)は、ボグダノフが直前に非常に神経質な政治的な手紙を書いていたことから、彼の死は自殺だったのではないかという推測をしている。しかし、 彼の死は、当時まだ十分に理解されていなかった輸血の副作用によるものだった可能性もある。[27][13][28] |

| Legacy Both Bogdanov's fiction and his political writings imply that he expected the coming revolution against capitalism to lead to a technocratic society.[29] This was because the workers lacked the knowledge and initiative to seize control of social affairs for themselves as a result of the hierarchical and authoritarian nature of the capitalist production process. However, Bogdanov also considered that the hierarchical and authoritarian mode of organization of the Bolshevik party was also partly to blame, although Bogdanov considered at least some such organization necessary and inevitable. In the 1920s and 1930s, Bogdanov's theorizing, being the product of a non-Leninist Bolshevik, became an important, though "underground", influence on certain dissident factions in the Soviet Union who turned against Bolshevik autocracy while accepting the necessity of the Revolution and wishing to preserve its achievements.[30] |

レガシー ボグダノフのフィクションと政治的な著作の両方において、資本主義に対する革命がテクノクラート社会につながることを期待していたことが暗示されている。 [29] これは、資本主義的生産プロセスの階層的かつ権威的な性質の結果として、労働者が社会問題を自分たちのために管理する知識とイニシアチブを欠いていたため である。しかし、ボグダノフは、ボルシェビキ党の階層的かつ権威主義的な組織形態もまた、一部は非難されるべきであると考えた。ただし、ボグダノフは、少 なくともそのような組織形態が一部必要であり、不可避であると考えていた。 1920年代と1930年代には、レーニン主義者ではないボルシェビキの理論家であるボグダノフの理論は、革命の必要性は認めながらもボルシェビキの専制 政治に反対し、その成果を維持することを望むソビエト連邦内の特定の反対派に、重要な影響を与えた。[30] |

| In popular culture Bogdanov served as an inspiration for the character Arkady Bogdanov in Kim Stanley Robinson's science-fiction novels the Mars Trilogy. It is revealed in 'Blue Mars' that Arkady is a descendant of Alexander Bogdanov.[31] Bogdanov is also the protagonist of the novel Proletkult (2018) by Italian collective Wu Ming. |

大衆文化において、 ボグダノフはキム・スタンリー・ロビンスンのSF小説『火星三部作』に登場するアルカディ・ボグダノフのモデルとなった。『ブルー・マーズ』では、アルカ ディがアレクサンドル・ボグダノフの子孫であることが明らかになっている。 また、ボグダノフはイタリアの作家ウー・ミンによる小説『プロレカルト』(2018年)の主人公でもある。 |

| Published works Russian Non-fiction Poznanie s Istoricheskoi Tochki Zreniya (Knowledge from a Historical Viewpoint) (St. Petersburg, 1901) Empiriomonizm: Stat'i po Filosofii (Empiriomonism: Articles on Philosophy) 3 volumes (Moscow, 1904–1906) Kul'turnye zadachi nashego vremeni (The Cultural Tasks of Our Time) (Moscow: Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1911) Filosofiya Zhivogo Opyta: Populiarnye Ocherki (Philosophy of Living Experience: Popular Essays) (St. Petersburg, 1913) Tektologiya: Vseobschaya Organizatsionnaya Nauka 3 volumes (Berlin and Petrograd-Moscow, 1922) "Avtobiografia" in Entsiklopedicheskii slovar, XLI, pp. 29–34 (1926) God raboty Instituta perelivanya krovi (Annals of the Institute of Blood Transfusion) (Moscow 1926–1927) Fiction Krasnaya zvezda (Red Star) (St. Petersburg, 1908) Inzhener Menni (Engineer Menni) (Moscow: Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1912) The title page carries the date 1913[32] English translation Non-fiction Art and the working class, translated by Taylor R Genovese (Iskra Books, 2022) Essays in Organisation Science (1919) Очерки организационной науки (Ocherki organizatsionnoi nauki) Proletarskaya kul'tura, No. 7/8 (April–May) 'Proletarian Poetry' (1918), Labour Monthly, Vol IV, No. 5–6, May–June 1923 'The Criticism of Proletarian Art' (from Kritika proletarskogo iskusstva, 1918) Labour Monthly, Vol V, No. 6, December 1923 'Religion, Art and Marxism', Labour Monthly, Vol VI, No. 8, August 1924 Essays in Tektology: The General Science of Organization, translated by George Gorelik (Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications, 1980) A Short Course of Economics Science, (London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 1923) Bogdanov's Tektology. Book 1, edited by Peter Dudley (Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies Press, 1996). The Philosophy of Living Experience (1913/2015). Translated, edited and introduced by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2015) Empiriomonism: Essays in Philosophy, Books 1–3. Edited and translated by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2019) Fiction Red Star: The First Bolshevik Utopia, edited by Loren Graham and Richard Stites; trans. Charles Rougle (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984): Red Star (1908). Novel. In English Engineer Menni (1913). Novel. "A Martian Stranded on Earth" (1924). Poem. |

出版作品 ロシア語 ノンフィクション Poznanie s Istoricheskoi Tochki Zreniya (Knowledge from a Historical Viewpoint) (サンクトペテルブルク、1901年) Empiriomonizm: Stat'i po Filosofii (Empiriomonism: Articles on Philosophy) 3巻 (モスクワ、1904年~1906年) Kul'turnye zadachi nashego vremeni (The Cultural Tasks of Our Time) (モスクワ:Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1911) Filosofiya Zhivogo Opyta: Populiarnye Ocherki (Philosophy of Living Experience: Popular Essays) (サンクトペテルブルク、1913) 組織学:組織学の一般科学 3巻(ベルリンおよびペトログラード・モスクワ、1922年) 「自伝」『百科事典』第41巻、29~34ページ(1926年) 「血液輸送研究所の研究業績」(『血液輸送研究所紀要』)(モスクワ、1926年~1927年) フィクション 『赤い星』(『赤い星』)(サンクトペテルブルク、1908年) 『エンジニア・メニー』(Engineer Menni)(モスクワ:Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1912) タイトルページの日付は1913年となっている[32]。 英訳 ノンフィクション 『芸術と労働者階級』、テイラー・R・ジェノヴェーゼ訳(Iskra Books、2022年) 組織科学のエッセイ(1919年) 組織科学の概説(Ocherki organizatsionnoi nauki) プロレタリア文化、第7/8号(4月~5月) 「プロレタリア詩」(1918年)『労働月報』第4巻第5~6号、1923年5月~6月 『プロレタリア芸術の批判』(『プロレタリア芸術批判』より、1918年)『労働月報』第5巻第6号、1923年12月 『宗教、芸術、マルクス主義』『労働月報』第6巻第8号、1924年8月 『テクトロジーの試論:組織の一般科学』ジョージ・ゴレリク訳(カリフォルニア州シーサイド:インターシステムズ出版、1980年) 『経済科学の短期コース』(ロンドン:英国共産党、1923年) ボグダノフのテクトロジー。第1巻、ピーター・ダドリー編(英国ハル:システム研究センター出版、1996年)。 『生の哲学』(1913/2015)。 デイヴィッド・G・ローリー訳、編、序文、ライデン&ボストン:ブリル(2015年) 『経験論的唯物論:哲学論集第1巻~第3巻』。 デイヴィッド・G・ローリー編、訳、ライデン&ボストン:ブリル(2019年) フィクション 『赤い星:最初のボリシェヴィキのユートピア』、編集:ローレン・グラハム、リチャード・ステイツ、翻訳:チャールズ・ラグル(インディアナ州ブルーミン トン:インディアナ大学出版、1984年): 『赤い星』(1908年)。小説。英語 『エンジニア・メニー』(1913年)。小説。 「地球に取り残された火星人」(1924年)。詩。 |

| Two Events Celebrating the Life

and Contribution of Alexander Bogdanov, hosted by the Centre for

Systems Studies on 2–3 June 2021 List of dystopian literature 1908 in literature Arkady Bogdanov, a character in K.S. Robinson's Mars Trilogy, inspired by Aleksandr Bogdanov |

アレクサンドル・ボグダノフの生涯と貢献を祝う2つのイベントが、シス

テム研究センター主催で2021年6月2日~3日に開催 ディストピア文学の一覧 文学における1908年 アレクサンドル・ボグダノフにインスピレーションを得たK.S.ロビンソンの火星三部作の登場人物、アルカージー・ボグダノフ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Bogdanov |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆