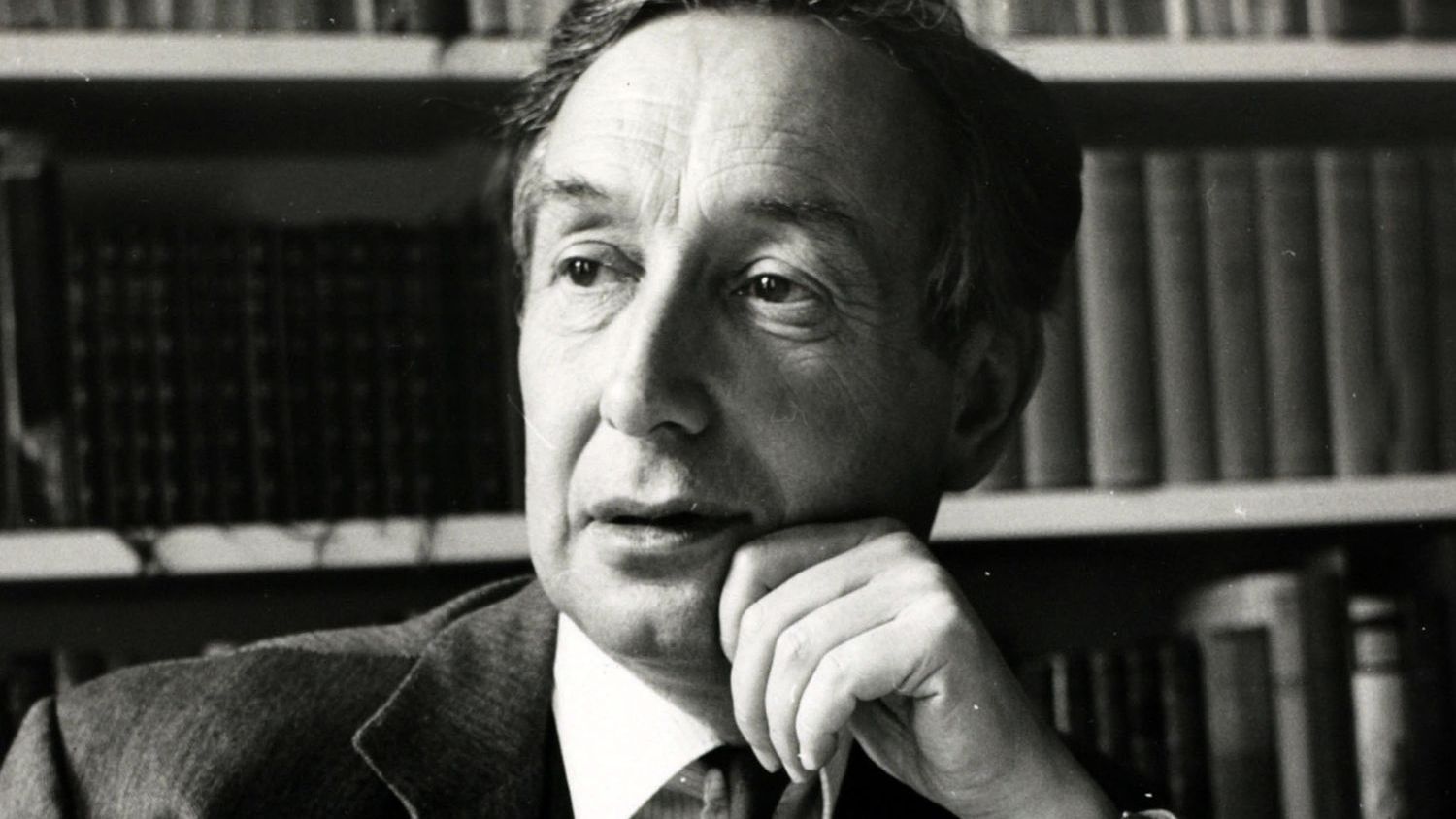

アルフレッド・エイヤー(A. J. エイヤー)

Alfred Jules "Freddie" Ayer, 1910-1989

☆ サー・アルフレッド・ジュールズ・「フレディー」・エア FBA (/ɛər/ AIR;[2] 1910年10月29日 - 1989年6月27日)[3]は、論理実証主義の推進者として知られるイギリスの哲学者であり、特に著書『言語・真理・論理』(1936年)と『知識の問 題』(1956年)で知られる。 エイヤーはイートン・カレッジとオックスフォード大学で教育を受け、その後ウィーン大学で論理実証主義の哲学を学んだ。1933年から1940年にかけ て、オックスフォード大学クライスト・チャーチ・カレッジで哲学の講義を行った。 第二次世界大戦中、エイヤーは特殊作戦執行部およびMI6のエージェントであった。 1946年から1959年まで、ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジで心の哲学と論理学のグロート教授を務め、その後オックスフォードに戻り、ニュー・ カレッジのウィケハム教授(論理学)となった。1951年から1952年までアリストテレス協会の会長を務め、1970年にナイト爵に叙せられた。彼は ヒューマニズムの擁護者として知られ、英国ヒューマニスト協会(現ヒューマニストUK)の2代目会長を務めた。 エイヤーは同性愛法改正協会の会長も務めたことがあり、「悪名高い異性愛者である私は、自分の懐を肥やすために罪に問われることは決してないだろう」と述 べた。

| Sir Alfred Jules

"Freddie" Ayer FBA (/ɛər/ AIR;[2] 29 October 1910 – 27 June 1989)[3]

was an English philosopher known for his promotion of logical

positivism, particularly in his books Language, Truth, and Logic (1936)

and The Problem of Knowledge (1956). Ayer was educated at Eton College and the University of Oxford, after which he studied the philosophy of logical positivism at the University of Vienna. From 1933 to 1940 he lectured on philosophy at Christ Church, Oxford.[4] During the Second World War Ayer was a Special Operations Executive and MI6 agent.[5] Ayer was Grote Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College London from 1946 until 1959, after which he returned to Oxford to become Wykeham Professor of Logic at New College.[1] He was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1951 to 1952 and knighted in 1970. He was known for his advocacy of humanism, and was the second president of the British Humanist Association (now known as Humanists UK). Ayer was president of the Homosexual Law Reform Society for a time; he remarked, "as a notorious heterosexual I could never be accused of feathering my own nest." |

サー・アルフレッド・ジュールズ・「フレディー」・エア FBA

(/ɛər/ AIR;[2] 1910年10月29日 -

1989年6月27日)[3]は、論理実証主義の推進者として知られるイギリスの哲学者であり、特に著書『言語・真理・論理』(1936年)と『知識の問

題』(1956年)で知られる。 エイヤーはイートン・カレッジとオックスフォード大学で教育を受け、その後ウィーン大学で論理実証主義の哲学を学んだ。1933年から1940年にかけ て、オックスフォード大学クライスト・チャーチ・カレッジで哲学の講義を行った。 第二次世界大戦中、エイヤーは特殊作戦執行部およびMI6のエージェントであった。 1946年から1959年まで、ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジで心の哲学と論理学のグロート教授を務め、その後オックスフォードに戻り、ニュー・ カレッジのウィケハム教授(論理学)となった。1951年から1952年までアリストテレス協会の会長を務め、1970年にナイト爵に叙せられた。彼は ヒューマニズムの擁護者として知られ、英国ヒューマニスト協会(現ヒューマニストUK)の2代目会長を務めた。 エイヤーは同性愛法改正協会の会長も務めたことがあり、「悪名高い異性愛者である私は、自分の懐を肥やすために罪に問われることは決してないだろう」と述 べた。 |

| Life Ayer was born in St John's Wood, in north west London, to Jules Louis Cyprien Ayer and Reine (née Citroen), wealthy parents from continental Europe. His mother was from the Dutch-Jewish family that founded the Citroën car company in France; his father was a Swiss Calvinist financier who worked for the Rothschild family, including for their bank and as secretary to Alfred Rothschild.[6][7][8] Ayer was educated at Ascham St Vincent's School, a former boarding preparatory school for boys in the seaside town of Eastbourne in Sussex, where he started boarding at the relatively early age of seven for reasons to do with the First World War, and at Eton College, where he was a King's Scholar. At Eton Ayer first became known for his characteristic bravado and precocity. Though primarily interested in his intellectual pursuits, he was very keen on sports, particularly rugby, and reputedly played the Eton Wall Game very well.[9] In the final examinations at Eton, Ayer came second in his year, and first in classics. In his final year, as a member of Eton's senior council, he unsuccessfully campaigned for the abolition of corporal punishment at the school. He won a classics scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford. He graduated with a BA with first-class honours. After graduating from Oxford, Ayer spent a year in Vienna, returned to England and published his first book, Language, Truth and Logic, in 1936. This first exposition in English of logical positivism as newly developed by the Vienna Circle, made Ayer at age 26 the enfant terrible of British philosophy. As a newly famous intellectual, he played a prominent role in the Oxford by-election campaign of 1938.[10] Ayer campaigned first for the Labour candidate Patrick Gordon Walker, and then for the joint Labour-Liberal "Independent Progressive" candidate Sandie Lindsay, who ran on an anti-appeasement platform against the Conservative candidate, Quintin Hogg, who ran as the appeasement candidate.[10] The by-election, held on 27 October 1938, was quite close, with Hogg winning narrowly.[10] In the Second World War, Ayer served as an officer in the Welsh Guards, chiefly in intelligence (Special Operations Executive (SOE) and MI6[11]). He was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Welsh Guards from the Officer Cadet Training Unit on 21 September 1940.[12] After the war, Ayer briefly returned to the University of Oxford where he became a fellow and Dean of Wadham College. He then taught philosophy at University College London from 1946 until 1959, during which time he started to appear on radio and television. He was an extrovert and social mixer who liked dancing and attending clubs in London and New York. He was also obsessed with sport: he had played rugby for Eton, and was a noted cricketer and a keen supporter of Tottenham Hotspur football team, where he was for many years a season ticket holder.[13] For an academic, Ayer was an unusually well-connected figure in his time, with close links to 'high society' and the establishment. Presiding over Oxford high-tables, he is often described as charming, but could also be intimidating.[14] Ayer was married four times to three women.[15] His first marriage was from 1932 to 1941, to (Grace Isabel) Renée, with whom he had a son—allegedly the son of Ayer's friend and colleague Stuart Hampshire[16]—and a daughter.[8] Renée subsequently married Hampshire.[15] In 1960, Ayer married Alberta Constance (Dee) Wells, with whom he had one son.[15] That marriage was dissolved in 1983, and the same year, Ayer married Vanessa Salmon, the former wife of politician Nigel Lawson. She died in 1985, and in 1989 Ayer remarried Wells, who survived him.[15] He also had a daughter with Hollywood columnist Sheilah Graham Westbrook.[15] In 1950, Ayer attended the founding meeting of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in West Berlin, though he later said he went only because of the offer of a "free trip".[17] He gave a speech on why John Stuart Mill's conceptions of liberty and freedom were still valid in the 20th century.[17] Together with the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, Ayer fought against Arthur Koestler and Franz Borkenau, arguing that they were far too dogmatic and extreme in their anti-communism, in fact proposing illiberal measures in the defence of liberty.[18] Adding to the tension was the location of the congress in West Berlin, together with the fact that the Korean War began on 25 June 1950, the fourth day of the congress, giving a feeling that the world was on the brink of war.[18] From 1959 to his retirement in 1978, Ayer held the Wykeham Chair, Professor of Logic at Oxford. He was knighted in 1970. After his retirement, Ayer taught or lectured several times in the United States, including as a visiting professor at Bard College in 1987. At a party that same year held by fashion designer Fernando Sanchez, Ayer confronted Mike Tyson, who was forcing himself upon the then little-known model Naomi Campbell. When Ayer demanded that Tyson stop, Tyson reportedly asked, "Do you know who the fuck I am? I'm the heavyweight champion of the world", to which Ayer replied, "And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic. We are both pre-eminent in our field. I suggest that we talk about this like rational men". Ayer and Tyson then began to talk, allowing Campbell to slip out.[19] Ayer was also involved in politics, including anti-Vietnam War activism, supporting the Labour Party (and later the Social Democratic Party), chairing the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination in Sport, and serving as president of the Homosexual Law Reform Society.[1] In 1988, a year before his death, Ayer wrote an article titled "What I saw when I was dead", describing an unusual near-death experience after his heart stopped for four minutes as he choked on smoked salmon.[20] Of the experience, he first said that it "slightly weakened my conviction that my genuine death ... will be the end of me, though I continue to hope that it will be."[21] A few weeks later, he revised this, saying, "what I should have said is that my experiences have weakened, not my belief that there is no life after death, but my inflexible attitude towards that belief".[22] Ayer died on 27 June 1989. From 1980 to 1989 he lived at 51 York Street, Marylebone, where a memorial plaque was unveiled on 19 November 1995.[23] |

生涯 Ayerは、ジュール・ルイ・シプリアン・エイヤーとレーヌ(旧姓シトロエン)の間にロンドン北西部のセントジョンズ・ウッドで生まれた。両親はヨーロッ パ大陸出身の富裕層であった。母親はオランダ系ユダヤ人の家系で、フランスでシトロエン自動車を創業した一族の出身である。父親はスイス・カルヴァン派の 金融家で、ロスチャイルド家のために働いており、銀行業務やアルフレッド・ロスチャイルドの秘書も務めていた。 エイヤーは、サセックス州イーストボーンの海辺の町にある元男子寄宿制予備校のアシャム・セント・ヴィンセント・スクールで教育を受け、第一次世界大戦の 影響で7歳という比較的早い年齢で寄宿生活を始めた。また、イートン・カレッジではキングス・スカラーであった。エイヤーはイートンで、その特徴的な虚勢 と早熟ぶりで初めて知られるようになった。主に知的な探求に興味を持っていたが、スポーツ、特にラグビーに熱中し、イートン・ウォールゲームの名手であっ たと言われている。[9] イートンでの最終試験では、彼は学年で2位、古典では1位であった。最終学年では、イートン上級評議会のメンバーとして、学校での体罰廃止を訴える運動を 行ったが、成功しなかった。彼は古典の奨学生としてオックスフォード大学クライスト・チャーチ・カレッジに入学した。彼は優等で学士号を取得して卒業し た。 オックスフォード大学を卒業後、アイヤーは1年間ウィーンに滞在し、その後イギリスに戻り、1936年に最初の著書『言語・真理・論理』を出版した。 ウィーン学団によって新たに展開された論理実証主義を英語で初めて論じたこの著書により、26歳だったエイヤーは英国哲学界の異端児となった。新たに著名 な知識人となったエイヤーは、1938年のオックスフォード補欠選挙のキャンペーンで重要な役割を果たした。[10] エイヤーはまず労働党候補のパトリック・ゴードン・ウォーカーを、次に労働党と自由党の合同候補である「独立進歩党」のサンディー・リンゼイを支援した。 リンゼイは 宥和政策を掲げて出馬した保守党候補のクイントン・ホッグ氏に対して、宥和政策に反対する姿勢を掲げて出馬した。[10] 1938年10月27日に行われた補欠選挙は接戦となり、ホッグ氏が僅差で勝利した。[10] 第二次世界大戦中、エアはウェールズ近衛連隊の主に諜報部(特別作戦執行部(SOE)およびMI6)の将校として勤務した。1940年9月21日、士官候補生訓練部隊からウェールズ近衛連隊に少尉として任官した。 戦後、エイヤーは短期間オックスフォード大学に戻り、ワドナム・カレッジの研究員および学部長となった。その後、1946年から1959年までロンドン大 学ユニバーシティ・カレッジで哲学を教え、その間、ラジオやテレビにも出演するようになった。社交的で社交好きだった彼は、ロンドンやニューヨークのダン スクラブやクラブに好んで出かけていた。また、スポーツにも熱中しており、イートン校ではラグビーをプレーし、クリケットの名選手として知られ、トッテナ ム・ホットスパー・フットボールチームの熱心なサポーターでもあった。長年シーズンチケットの所有者でもあった。学者としては、エイヤーは当時の時代にお いて、上流社会やエスタブリッシュメントと緊密なつながりを持つ、異例の社交的な人物であった。オックスフォード大学の有力者たちを統括する彼は、魅力的 な人物であると評されることが多いが、威圧的であるとも評されることがある。 エイヤーは3人の女性と4度結婚した。最初の結婚は1932年から1941年までで、グレース・イザベル・レネーとであった。彼女との間には息子が一人お り、エイヤーの友人であり同僚であったスチュアート・ハンプシャーの息子であると噂されている[16]。また、娘も一人いた。 8] レネはその後、ハンプシャーと再婚した。[15] 1960年、エイヤーはアルバータ・コンスタンス(ディー)・ウェルズと結婚し、1人の息子をもうけた。[15] その結婚は1983年に解消され、同じ年にエイヤーは、政治家ナイジェル・ローソンの元妻であるヴァネッサ・サーモンと再婚した。彼女は1985年に死去 し、1989年にエイヤーはウェルズと再婚した。彼女はエイヤーより先に亡くなった。[15] また、ハリウッドのコラムニスト、シーラ・グラハム・ウェストブルックとの間に娘がいる。[15] 1950年、アイヤーは西ベルリンで開催された「文化の自由のための会議」の創立総会に出席したが、後に「ただただ『無料旅行』というオファーがあったか ら行っただけだ」と語っている。[17] 彼は、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの自由と解放に関する概念が20世紀においても依然として有効である理由についてスピーチを行った。[17] 歴史家のヒュー・トレヴァー=ローパーとともに、アイヤーはアーサー・ケストラーとフランツ・ボルカーヌに対して戦いを挑んだ。 彼らの反共産主義はあまりにも独断的かつ極端であり、実際には自由を守るための不自由な手段を提案していると論じた。[18] 緊張を高めた要因として、この会議が西ベルリンで開催されたこと、そして会議の4日目にあたる1950年6月25日に朝鮮戦争が始まり、世界が戦争の瀬戸 際に立たされているという感覚を人々に与えたことが挙げられる。[18] 1959年から1978年に引退するまで、エアはオックスフォード大学のワイカム教授職(論理学教授)に就いていた。1970年にナイト爵位を授けられ た。引退後は、1987年にバードカレッジの客員教授として教鞭をとるなど、米国で何度か教鞭をとったり講演を行ったりした。同年、ファッションデザイ ナーのフェルナンド・サンチェスが主催したパーティーで、当時ほとんど無名だったモデルのナオミ・キャンベルに暴行を加えていたマイク・タイソンと対峙し た。エイヤーがタイソンに止めるよう要求すると、タイソンは「俺が誰だか知ってるのか?俺はヘビー級チャンピオンだ」と尋ねた。それに対してエイヤーは 「私は元ワイカム教授の論理学の教授だ。我々はどちらもそれぞれの分野で卓越している。理性的な人間らしく話し合おうじゃないか」と提案した。その後、ア イヤーとタイソンは話し合いを始め、キャンベルは抜け出すことができた。[19] アイヤーは政治にも関与しており、反ベトナム戦争運動、労働党(後に社会民主党)の支援、スポーツにおける人種差別撤廃キャンペーンの議長、同性愛法改革 協会の会長などを務めた。[1] 1988年、エイヤーは死の前年、自身の心臓が4分間停止し、スモークサーモンを喉に詰まらせた後に経験した、珍しい臨死体験について「死んだときに見た もの」と題する記事を書いた。[20] その体験について、彼はまず「私の真の死が 。しかし、私は今でもそうなることを願っている」と述べた。[21] 数週間後、彼はこれを修正し、「私が言うべきだったのは、私の経験は、死後の世界はないという信念を弱めたのではなく、その信念に対する私の柔軟性のない 態度を弱めたということだ」と述べた。[22] エイヤーは1989年6月27日に死去した。1980年から1989年にかけてはメリルボーンのヨーク・ストリート51番地に住んでおり、1995年11月19日にはその家屋に記念プレートが設置された。[23] |

| Philosophical ideas In Language, Truth and Logic (1936), Ayer presents the verification principle as the only valid basis for philosophy. Unless logical or empirical verification is possible, statements like "God exists" or "charity is good" are not true or untrue but meaningless, and may thus be excluded or ignored. Religious language in particular is unverifiable and as such literally nonsense. He also criticises C. A. Mace's opinion[24] that metaphysics is a form of intellectual poetry.[25] The stance that a belief in God denotes no verifiable hypothesis is sometimes referred to as igtheism (for example, by Paul Kurtz).[26] In later years, Ayer reiterated that he did not believe in God[27] and began to call himself an atheist.[28] He followed in the footsteps of Bertrand Russell by debating religion with the Jesuit scholar Frederick Copleston. Ayer's version of emotivism divides "the ordinary system of ethics" into four classes: "Propositions that express definitions of ethical terms, or judgements about the legitimacy or possibility of certain definitions" "Propositions describing the phenomena of moral experience, and their causes" "Exhortations to moral virtue" "Actual ethical judgements"[29] He focuses on propositions of the first class—moral judgements—saying that those of the second class belong to science, those of the third are mere commands, and those of the fourth (which are considered normative ethics as opposed to meta-ethics) are too concrete for ethical philosophy. Ayer argues that moral judgements cannot be translated into non-ethical, empirical terms and thus cannot be verified; in this he agrees with ethical intuitionists. But he differs from intuitionists by discarding appeals to intuition of non-empirical moral truths as "worthless"[29] since the intuition of one person often contradicts that of another. Instead, Ayer concludes that ethical concepts are "mere pseudo-concepts": The presence of an ethical symbol in a proposition adds nothing to its factual content. Thus if I say to someone, "You acted wrongly in stealing that money," I am not stating anything more than if I had simply said, "You stole that money." In adding that this action is wrong I am not making any further statement about it. I am simply evincing my moral disapproval of it. It is as if I had said, "You stole that money," in a peculiar tone of horror, or written it with the addition of some special exclamation marks. … If now I generalise my previous statement and say, "Stealing money is wrong," I produce a sentence that has no factual meaning—that is, expresses no proposition that can be either true or false. … I am merely expressing certain moral sentiments. — A. J. Ayer, Language Truth and Logic, Ch. VI. Critique of Ethics and Theology Between 1945 and 1947, together with Russell and George Orwell, Ayer contributed a series of articles to Polemic, a short-lived British "Magazine of Philosophy, Psychology, and Aesthetics" edited by the ex-Communist Humphrey Slater.[30][31] Ayer was closely associated with the British humanist movement. He was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association from 1947 until his death. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1963.[32] In 1965, he became the first president of the Agnostics' Adoption Society and in the same year succeeded Julian Huxley as president of the British Humanist Association, a post he held until 1970. In 1968 he edited The Humanist Outlook, a collection of essays on the meaning of humanism. He was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.[33] |

哲学的考え 『言語・真理・論理』(1936年)において、エイヤーは検証主義を哲学の唯一の妥当な基礎として提示している。論理的または経験的な検証が不可能である 限り、「神は存在する」や「慈善は善である」といった主張は真実でも偽でもないが、無意味であり、したがって排除または無視されるべきである。特に宗教的 な言語は検証不可能であり、文字通りナンセンスである。また、C. A. Maceの「形而上学は知的な詩の一形態である」という意見[24]を批判している。神への信仰は検証可能な仮説ではないとする立場は、時に「イグゼイス ム(igtheism)」と呼ばれる(例えばポール・クルーツによる)[ [26] 晩年、エイヤーは神を信じていないことを繰り返し[27]、自らを無神論者と呼ぶようになった[28]。彼はイエズス会の学者フレデリック・コープストン と宗教について討論し、バートランド・ラッセルの足跡を追った。 エイヤーの感情主義の定義では、「通常の倫理体系」を4つのカテゴリーに分類している。 「倫理用語の定義、または特定の定義の正当性や可能性に関する判断を表現する命題」 「道徳的経験の現象とその原因を説明する命題」 「道徳的美徳への勧告」 「実際の倫理的判断」[29] 彼は第一種の命題、すなわち道徳的判断に焦点を当て、第二種の命題は科学に属し、第三種の命題は単なる命令であり、第四種(これはメタ倫理学に対する規範倫理学とみなされる)は倫理哲学としては具体的すぎると述べている。 エイヤーは、道徳的判断は非倫理的な経験的用語に翻訳することはできず、したがって検証もできないと主張している。 この点において、彼は倫理直観主義者たちと同意見である。しかし、彼は直観主義者たちとは異なり、非経験的な道徳的真理の直観を「価値のないもの」として 退けている[29]。なぜなら、ある人物の直観は、別の人物の直観と矛盾することが多いからである。その代わりに、エイヤーは倫理的概念は「単なる疑似概 念」であると結論づけている。 命題に倫理的なシンボルが存在しても、その事実的内容に何も付け加えることはない。したがって、私が誰かに「君はあの金を盗むという行動を誤っていた」と 言う場合、私が単に「君はあの金を盗んだ」と言う場合と比べて、何も付け加えているわけではない。この行動が誤りであると付け加えることで、それについて さらに何かを述べているわけではない。私は単に、それに対する私の道徳的な非難を表明しているだけである。それはあたかも私が「あなたがお金を盗んだ」 と、恐怖に満ちた独特の口調で言ったか、あるいは特別な感嘆符を付け加えて書いたかのようだ。…もし私が今、先の主張を一般化して「お金を盗むことは悪い ことだ」と言った場合、それは事実上の意味を持たない文章を生み出すことになる。つまり、真実か偽りかどちらかである命題を表現しない文章だ。…私は単に 特定の道徳的感傷を表現しているだけだ。 — A. J. Ayer, 『言語・真理・論理』第6章 倫理と神学の批判 1945年から1947年の間、ラッセルとジョージ・オーウェルとともに、エイヤーは元共産党員のハンフリー・スレイターが編集する短命に終わったイギリスの「哲学、心理学、美学の雑誌」『Polemic』に一連の記事を寄稿した。 エイヤーはイギリスのヒューマニズム運動と密接な関係にあった。1947年から死去するまで、彼はラショナリスト・プレス・アソシエーションの名誉会員で あった。1963年には、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選出された。1965年には不可知論者養子協会の初代会長となり、同年ジュリア ン・ハックスリーの後任として英国ヒューマニスト協会の会長に就任し、1970年までその職を務めた。1968年には、ヒューマニズムの意味に関するエッ セイ集『ヒューマニストの展望』を編集した。彼はヒューマニスト宣言の署名者の一人である。[33] |

| Works Ayer is best known for popularising the verification principle, in particular through his presentation of it in Language, Truth, and Logic. The principle was at the time at the heart of the debates of the so-called Vienna Circle, which Ayer had visited as a young guest. Others, including the circle's leading light, Moritz Schlick, were already writing papers on the issue.[34] Ayer's formulation was that a sentence can be meaningful only if it has verifiable empirical import; otherwise, it is either "analytical" if tautologous or "metaphysical" (i.e. meaningless, or "literally senseless"). He started to work on the book at the age of 23[35] and it was published when he was 26. Ayer's philosophical ideas were deeply influenced by those of the Vienna Circle and David Hume. His clear, vibrant and polemical exposition of them makes Language, Truth and Logic essential reading on the tenets of logical empiricism; the book is regarded as a classic of 20th-century analytic philosophy and is widely read in philosophy courses around the world. In it, Ayer also proposes that the distinction between a conscious man and an unconscious machine resolves itself into a distinction between "different types of perceptible behaviour",[36] an argument that anticipates the Turing test published in 1950 to test a machine's capability to demonstrate intelligence. Ayer wrote two books on the philosopher Bertrand Russell, Russell and Moore: The Analytic Heritage (1971)[37] and Russell (1972). He also wrote an introductory book on the philosophy of David Hume and a short biography of Voltaire. Ayer was a strong critic of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. As a logical positivist, Ayer was in conflict with Heidegger's vast, overarching theories of existence. Ayer considered them completely unverifiable through empirical demonstration and logical analysis, and this sort of philosophy an unfortunate strain in modern thought. He considered Heidegger the worst example of such philosophy, which Ayer believed entirely useless. In Philosophy in the Twentieth Century, Ayer accuses Heidegger of "surprising ignorance" or "unscrupulous distortion" and "what can fairly be described as charlatanism."[38] In 1972–73, Ayer gave the Gifford Lectures at the University of St Andrews, later published as The Central Questions of Philosophy. In the book's preface, he defends his selection to hold the lectureship on the basis that Lord Gifford wished to promote "natural theology, in the widest sense of that term", and that non-believers are allowed to give the lectures if they are "able reverent men, true thinkers, sincere lovers of and earnest inquirers after truth".[39] He still believed in the viewpoint he shared with the logical positivists: that large parts of what was traditionally called philosophy—including metaphysics, theology and aesthetics—were not matters that could be judged true or false, and that it was thus meaningless to discuss them. In The Concept of a Person and Other Essays (1963), Ayer heavily criticised Wittgenstein's private language argument. Ayer's sense-data theory in Foundations of Empirical Knowledge was famously criticised by fellow Oxonian J. L. Austin in Sense and Sensibilia, a landmark 1950s work of ordinary language philosophy. Ayer responded in the essay "Has Austin Refuted the Sense-datum Theory?",[40] which can be found in his Metaphysics and Common Sense (1969). Awards Ayer was awarded a knighthood as Knight Bachelor in the London Gazette on 1 January 1970.[41] Collections Ayer's biographer, Ben Rogers, deposited 7 boxes of research material accumulated through the writing process at University College London in 2007.[42] The material was donated in collaboration with Ayer's family.[42] |

作品 エイヤーは、特に著書『言語・真理・論理』における検証原理の提示により、その普及に貢献したことで知られている。この原理は当時、いわゆるウィーン学団 の議論の中心であった。エイヤーは若い頃、その学団を訪問していた。ウィーン学派の中心人物であったモリッツ・シュリックをはじめとする他の人々は、すで にこの問題に関する論文を書いていた。[34] エイヤーの定式化は、文は検証可能な経験的な含意を持つ場合にのみ意味を持つことができるというものであり、そうでない場合は、同語反復であれば「分析 的」であり、そうでなければ「形而上学的」(すなわち、無意味、または「文字通りに無意味」)であるというものであった。彼は23歳のときにこの本の執筆 に取りかかり[35]、26歳のときに出版された。エイヤーの哲学思想は、ウィーン学団やデイヴィッド・ヒュームの思想に強く影響を受けていた。それらを 明晰かつ活気のある論争的な形で展開した『言語・真理・論理』は、論理実証主義の信条に関する必読書であり、20世紀の分析哲学の古典とみなされ、世界中 の哲学コースで広く読まれている。また、アイヤーは、意識を持つ人間と無意識の機械の区別は、「知覚可能な行動の異なるタイプ」の区別に帰着するという主 張も提示している。これは、1950年に発表され、機械が知性を示す能力をテストするチューリングテストの先駆けとなった議論である。 エイヤーは哲学者バートランド・ラッセルに関する2冊の本、『ラッセルとムーア:分析的遺産』(1971年)[37]と『ラッセル』(1972年)を著した。また、デイヴィッド・ヒュームの哲学に関する入門書とヴォルテールの短い伝記も著している。 エイヤーはドイツの哲学者マルティン・ハイデッガーの強力な批判者であった。論理実証主義者であったエイヤーは、ハイデッガーの広大で包括的な存在論と対立していた。エ イヤーは、経験的な実証や論理的分析によってそれらを完全に検証できないと考え、このような哲学を現代思想における不幸な流れであるとした。彼はハイデ ガーをそのような哲学の最悪の例と考え、エイヤーはそれを全くの無益であると信じていた。『20世紀の哲学』において、エイヤーはハイデガーを「驚くべき 無知」や「不誠実な歪曲」、そして「詐欺的と表現するのが妥当な」人物であると非難している[38]。 1972年から73年にかけて、エイヤーはセント・アンドルーズ大学でギフォード講義を行い、後に『哲学の中心問題』として出版された。この本の序文で、 彼はギフォード卿が「広義での自然神学」を推進することを望んでいたこと、そして「敬虔な人物であり、真の思想家であり、誠実な愛好家であり、 真実を求める誠実な探究者」であれば、と。[39] 彼は依然として、論理実証主義者たちと共有していた見解を信じていた。すなわち、伝統的に哲学と呼ばれてきたものの大部分、すなわち形而上学、神学、美学 などは、真実か偽りかを判断できるような問題ではないため、それらについて議論することは無意味であるという見解である。 『The Concept of a Person and Other Essays』(1963年)において、エイヤーはウィトゲンシュタインのプライベート・ランゲージ論を厳しく批判した。 『経験的知識の基礎』におけるエイヤーの感覚データ理論は、同じオックスフォード大学のJ.L.オースティンによって、日常言語哲学の画期的な1950年 代の著作『感覚と感性』で有名に批判された。エイヤーは論文「オースティンは感覚データ理論を論駁したか?」でこれに反論した。この論文は『形而上学と常 識』(1969年)に掲載されている。 受賞 エイヤーは1970年1月1日付のロンドン・ガゼットでナイト・バチェラーの称号を授与された。[41] コレクション エイヤーの伝記作家であるベン・ロジャースは、執筆過程で集めた7箱分の研究資料を2007年にロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジに寄託した。[42] 資料はエイヤーの家族と協力して寄贈された。[42] |

| Selected publications 1936, Language, Truth, and Logic, London: Gollancz., 2nd ed., with new introduction (1946) OCLC 416788667 ISBN 978-0-14-118604-7 1936, "Causation and free will",[43] The Aryan Path. 1940, The Foundations of Empirical Knowledge, London: Macmillan. OCLC 2028651 1954, Philosophical Essays, London: Macmillan. (Essays on freedom, phenomenalism, basic propositions, utilitarianism, other minds, the past, ontology.) OCLC 186636305 1957, "The conception of probability as a logical relation", in S. Korner, ed., Observation and Interpretation in the Philosophy of Physics, New York, N.Y.: Dover Publications. 1956, The Problem of Knowledge, London: Macmillan. OCLC 557578816 1957, "Logical Positivism - A Debate" (with F. C. Copleston) in: Edwards, Paul, Pap, Arthur (eds.), A Modern Introduction to Philosophy; readings from classical and contemporary sources[44] 1963, The Concept of a Person and Other Essays, London: Macmillan. (Essays on truth, privacy and private languages, laws of nature, the concept of a person, probability.) OCLC 3573935 1967, "Has Austin Refuted the Sense-Datum Theory?"[40] Synthese vol. XVIII, pp. 117–140. (Reprinted in Ayer 1969). 1968, The Origins of Pragmatism, London: Macmillan. OCLC 641463982 1969, Metaphysics and Common Sense, London: Macmillan. (Essays on knowledge, man as a subject for science, chance, philosophy and politics, existentialism, metaphysics, and a reply to Austin on sense-data theory [Ayer 1967].) ISBN 978-0-333-10517-7 1971, Russell and Moore: The Analytical Heritage, London: Macmillan. OCLC 464766212 1972, Probability and Evidence, London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-12756-8 1972, Russell, London: Fontana Modern Masters. OCLC 186128708 1973, The Central Questions of Philosophy, London: Weidenfeld. ISBN 978-0-297-76634-6 1977, Part of My Life, London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-216017-9[45] 1979, "Replies", in G. F. Macdonald, ed., Perception and Identity: Essays Presented to A. J. Ayer, With His Replies, London: Macmillan; Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.[46] 1980, Hume, Oxford: Oxford University Press 1982, Philosophy in the Twentieth Century, London: Weidenfeld. 1984, Freedom and Morality and Other Essays, Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1984, More of My Life, London: Collins. 1986, Ludwig Wittgenstein, London: Penguin. 1986, Voltaire, New York: Random House. 1988, Thomas Paine, London: Secker & Warburg. 1990, The Meaning of Life and Other Essays, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.[47] 1991, "A Defense of Empiricism" in: Griffiths, A. Phillips (ed.), A. J. Ayer: Memorial Essays (Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements). Cambridge University Press.[48] 1992, "Intellectual Autobiography" and Replies in: Lewis Edwin Hahn (ed.), The Philosophy of A.J. Ayer (The Library of Living Philosophers Volume XXI), Open Court Publishing Co.[49] *For more complete publication details see "The Philosophical Works of A. J. Ayer" (1979) and "Bibliography of the writings of A.J. Ayer" (1992). |

主な著書 1936年、『言語・真理・論理』ロンドン:Gollancz.、第2版、序文を新たに追加(1946年)OCLC 416788667 ISBN 978-0-14-118604-7 1936年、「因果関係と自由意志」、『アーリア人の道』。 1940年、『経験的知識の基礎』、ロンドン:マクミラン。OCLC 2028651 1954年、『哲学エッセイ』、ロンドン:マクミラン。(自由、現象論、基本命題、功利主義、他者の心、過去、存在論に関するエッセイ)OCLC 186636305 1957年、「論理関係としての確率の概念」、S. Korner編、『物理学哲学における観察と解釈』、ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク:ドーヴァー・パブリケーションズ。 1956年、『知識の問題』、ロンドン:マクミラン。OCLC 557578816 1957年、「論理実証主義 - 討論」(F. C. コープストンとの共著)ポール・エドワーズ、アーサー・パップ編『現代哲学入門;古典および現代の資料からの抜粋』[44] 1963年、『The Concept of a Person and Other Essays』ロンドン:マクミラン。(真理、プライバシーと私的言語、自然法則、人格の概念、確率に関する論文。)OCLC 3573935 1967年、「オースティンは感覚データ理論を反駁したか?」[40] 『シンセーゼ』第18巻、117-140ページ。(『エイヤー1969』に再録)。 1968年、『プラグマティズムの起源』、ロンドン:マクミラン。OCLC 641463982 1969年、『形而上学と常識』ロンドン:マクミラン。(知識、科学の対象としての人間、偶然、哲学と政治、実存主義、形而上学、および感覚データ理論に関するオースティンへの返答についての論文集。ISBN 978-0-333-10517-7 1971年、ラッセルとムーア:分析的遺産、ロンドン:マクミラン。OCLC 464766212 1972年、確率と証拠、ロンドン:マクミラン。ISBN 978-0-333-12756-8 1972年、ラッセル、ロンドン:フォンタナ・モダン・マスターズ。OCLC 186128708 1973年、『哲学の中心問題』、ロンドン:ウィーデンフェルド。ISBN 978-0-297-76634-6 1977年、『私の人生の一部』、ロンドン:コリンズ。ISBN 978-0-00-216017-9[45] 1979年、「返信」、G. F. マクドナルド編、『知覚とアイデンティティ:A. J. エイヤーへの寄稿論文と彼の返信』、ロンドン:マクミラン、ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版局。[46] 1980年、『ヒューム』、オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局 1982年、『20世紀の哲学』、ロンドン:ウィーデンフェルド 1984年、『自由と道徳およびその他のエッセイ』オックスフォード:Clarendon Press。 1984年、『私の人生の続き』ロンドン:Collins。 1986年、『ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン』ロンドン:ペンギン。 1986年、『ヴォルテール』ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス。 1988年、トマス・ペイン、ロンドン:Secker & Warburg。 1990年、『人生の意味とその他のエッセイ』、Weidenfeld & Nicolson。[47] 1991年、「経験論の擁護」:Griffiths, A. Phillips (編)、A. J. Ayer: Memorial Essays (Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements)。ケンブリッジ大学出版。[48] 1992年、「知的自伝」および返答:Lewis Edwin Hahn(編)、『A.J.エイヤーの哲学』(『生ける哲学者文庫』第21巻)、Open Court Publishing Co. *より完全な出版情報については、『A. J. エイヤーの哲学著作集』(1979年)および『A.J.エイヤー著作目録』(1992年)を参照のこと。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._J._Ayer |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆