アレバロ・セペーダ・サムディオ

Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, 1926-1972

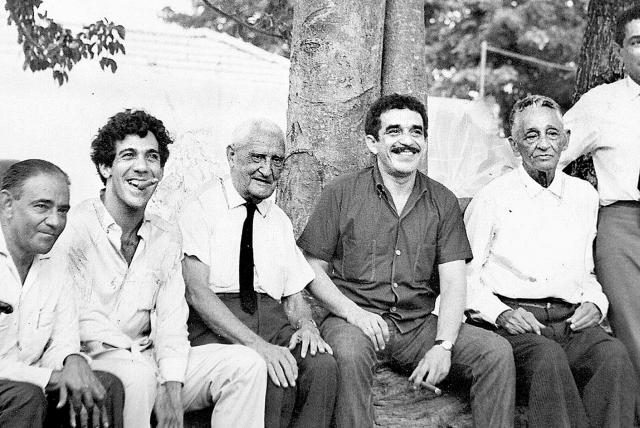

セペーダ・サムディオは左から2番目、一人おいてガルシア・マルケス

アレバロ・セペーダ・サムディオ

Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, 1926-1972

セペーダ・サムディオは左から2番目、一人おいてガルシア・マルケス

★アルバロ・セペダ・サムーディオ(Álvaro Cepeda Samudio、1926年3月30日 - 1972年10月12日)は、コロンビアのジャーナリスト、小説家、短編小説家、映画製作者である。コロンビアをはじめとするラテンアメリカでは、重要か つ革新的な作家、ジャーナリストとして知られ、世紀半ばのコロンビアという特殊な時代と場所で知られるようになった芸術的、知的、政治的に活発な風潮の多 くを、彼自身が刺激した。

| Álvaro

Cepeda Samudio (March 30, 1926 – October 12, 1972) was a Colombian

journalist, novelist, short story writer, and filmmaker. Within

Colombia and the rest of Latin America, he is known in his own right as

an important and innovative writer and journalist, largely inspiring

much of the artistically, intellectually and politically active climate

for which this particular time and place, that of mid-century Colombia,

has become known. His fame is considerably more quaint outside his home

country, where it derives primarily from his standing as having been

part of the influential artistic and intellectual circle in Colombia in

which fellow writer and journalist Gabriel García Márquez—with whom he

was also a member of the more particularized Barranquilla Group—and

painter Alejandro Obregón also played prominent roles. Only one of his

works, La casa grande, has received considerable notice beyond the

Spanish-speaking world, having been translated into several languages,

English and French among them; his fame as a writer has therefore been

significantly curtailed in the greater international readership, as the

breadth of his literary and journalistic output has reached few

audiences beyond those of Latin America and Latin American literary

scholars. |

アルバロ・セペ

ダ・サムーディオ(Álvaro Cepeda Samudio、1926年3月30日 -

1972年10月12日)は、コロンビアのジャーナリスト、小説家、短編小説家、映画製作者である。コロンビアをはじめとするラテンアメリカでは、重要か

つ革新的な作家、ジャーナリストとして知られ、世紀半ばのコロンビアという特殊な時代と場所で知られるようになった芸術的、知的、政治的に活発な風潮の多

くを、彼自身が刺激した。彼の名声は、彼の母国以外ではかなり古風なものであり、それは主に、同じ作家でジャーナリストのガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケス

(より特殊なバランキージャ・グループのメンバーでもあった)や画家のアレハンドロ・オブレゴンも大きな役割を果たした、コロンビアで影響力のある芸術

的・知的サークルの一員だったという立場に由来している。彼の作品は、スペイン語圏以外では『ラ・カサ・グランデ』の1冊だけが注目され、英語とフランス

語に翻訳されている。したがって、彼の作家としての名声は、国際的な読者にはかなり低く、彼の文学やジャーナリストの幅広い活動は、ラテンアメリカやラテ

ンアメリカ文学者以外の読者にはほとんど届いていない。 |

| Early life and education Álvaro Cepeda Samudio was born in Barranquilla (although his birthplace is commonly mistaken for the town of Ciénaga, where his family was from[1]), Colombia, two years before striking United Fruit Company workers at Ciénaga's railroad station were massacred by the Colombian army, an event that with age became pivotal to the writer's social- and political-consciousness, as evidenced in its central role in his only novel, La casa grande. Known as the Santa Marta Massacre, the incident is also depicted in Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) (1967), the seminal novel of his close friend Gabriel García Márquez, and served a similar motivating principle in his dedication to social and political awareness through journalism and literature, among other means. He enrolled at the Colegio Americano, an English-language school in Barranquilla, for elementary and high school. In the spring of 1949, he traveled to Ann Arbor, MI, United States and attended the University of Michigan English Language Institute for the summer term. For the fall term in the 1949-50 school year he attended Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York City. For the winter term, he attended what is now Michigan State University (then Michigan State College) in Lansing, MI before returning home to Barranquilla. |

幼少期と教育 アルバロ・セペダ・サムーディオはコロンビアのバランキージャ(ただし、彼の生家はシエナガという町とよく間違えられる[1])で生まれた。シエナガの鉄 道駅でストライキに参加したユナイテッド・フルーツ社の労働者がコロンビア軍によって虐殺される2年前に、この事件は彼の社会・政治意識にとって極めて重 要で、それは彼の唯一の小説La casa grandeの中心をなすものとして年齢とともに証明されることになった。サンタマルタの虐殺」として知られるこの事件は、親友ガブリエル・ガルシア・マ ルケスの代表作『百年の孤独』(1967年)にも描かれており、ジャーナリズムや文学などを通じて社会的・政治的意識を高めるための、同様の原動力となっ た。バランキヤにある英語学校、コレヒオ・アメリカーノで小学校と高校に入学する。1949年春、米国ミシガン州アナーバーに渡り、夏学期はミシガン大学 英語学院に通った。1949-50年の秋学期は、ニューヨークのコロンビア大学ジャーナリズム大学院に通った。冬学期には、ミシガン州ランシングにある現 在のミシガン州立大学(当時はミシガン州立カレッジ)で学び、バランキージャに帰国した。 |

| Journalistic career As with many of the core members of the Barranquilla Group, Cepeda Samudio began his career as a journalist, writing first, in August 1947, for El Nacional, where his first short stories were also published. Along with García Márquez and fellow journalists and Barranquilla Group members Alfonso Fuenmayor and Germán Vargas, he founded the weekly newspaper Crónica in April 1950, dedicating its pages primarily to literature and sports reporting. Cepeda Samudio made the point to include, for the first eight months of its publication, a foreign short story in each issue.[2] He also spent time writing columns for the Barranquilla daily newspaper El Heraldo, for which his wife, Tita Cepeda, currently contributes cultural columns. In 1953, he was offered the general management position of this paper, which he accepted with great enthusiasm, telling García Márquez that he wanted to transform it "into the modern newspaper he had learned how to make in the United States",[3] at Columbia University. However, it was "a fatal adventure," owing, García Márquez suggests, to the fact that "some aging veterans could not tolerate the renovatory regime and conspired with their soulmates until they succeeded in destroying their empire."[3] Cepeda Samudio left the paper shortly thereafter. He was also the Colombian bureau chief for Sporting News, based out of St. Louis, and ultimately secured his position as one of his country's preeminent journalists and editors by becoming the editor-in-chief first of El Nacional and later of the Diario del Caribe.[2] |

ジャーナリストとしてのキャリア セペダ・サムーディオは、バランキージャ・グループの中心メンバーの多くと同様、ジャーナリストとしてのキャリアをスタートさせ、1947年8月にエル・ ナシオナル紙に初めて執筆し、そこで最初の短編小説も出版されました。1950年4月、ガルシア・マルケス、バランキージャ・グループのメンバーであるア ルフォンソ・フエンマヨール、ゲルマン・バルガスとともに週刊新聞『クロニカ』を創刊し、主に文学とスポーツの報道にページを割く。また、バランキージャ の日刊紙『エル・ヘラルド』にもコラムを書き、現在は妻のティタ・セペダが文化コラムを担当している[2]。1953年、この新聞の総経理職のオファーを 受け、ガルシア・マルケスに、コロンビア大学で「アメリカで作り方を学んだ近代的な新聞に変えたい」[3]と熱意をもって引き受けた。しかし、それは「致 命的な冒険」であり、「一部の老齢の退役軍人が刷新的な体制に耐えられず、彼らの帝国を破壊することに成功するまで、魂の友と共謀した」ことに起因すると ガルシア・マルケスは示唆する[3] セペダ・サムディオはその後まもなく紙面を離れることになる。彼はセントルイスを拠点とするSporting News誌のコロンビア支局長でもあり、最終的にはEl Nacional紙の編集長、後にDiario del Caribe紙の編集長となり、自国の優れたジャーナリスト、編集者の1人としてその地位を確保した[2]。 |

| Literary career and outlook Cepeda Samudio's desire for a "renovatory regime" extended, however, far beyond his influence over La Nacional. Writing for his column Brújula de la cultura (Cultural Compass) in El Heraldo, he consistently decried a need for "a renovation of Colombian prose fiction".[2] He avidly sought out and championed what would have been, particularly at the time and in the considerably culturally conservative Colombia, considered "unorthodox" literature to many of his friends, notably García Márquez and other members of the Barranquilla Group, by introducing many to Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner. In his column in El Heraldo acclaimed the innovations of Bestiario (1951), the first volume of short stories by Julio Cortázar.[2] His promotion of the need for innovative literary styles and means, particularly within Colombia, is found in more than simply his essayistic criticism and columns, however, and he went on to write two short story collections and a novel in which his ideals found themselves manifested. His first published short story collection, Todos estábamos a la espera (We Were All Waiting) (1954), bears the markings of his interest in Hemingway, and created a considerable publishing event among academic critics of the time. Seymour Menton, who translated La Casa Grande into English, states that the first story in the collection "is narrated in the first person by the protagonist without any intervention by the traditional moralizing and artistic omniscient narrator."[2] This full embrace of a greater psychological impulse within the stories, as well as a rejection of any mediating contextualizations, was among the many claims Cepeda Samudio made for the necessary "modernization" of literature. García Márquez would later state that Todos estábamos a la espera "was the best book of stories that had been published in Colombia".[3] His first novel, La casa grande (1962) further explores this narrative reliance on a singular, unmediated narrator, and experiments, in a manner he hadn't displayed before, with structure, breaking the narrative up into ten distinct sections. His adoration of the works of Faulkner can perhaps be most fully seen in this work. In addressing the events of the Santa Marta Massacre through disjointed narratives which circumnavigate the violence without fully delving into the actualities of it, the central actions and content of the novel are presented as the inner reactions to them on the part of those associated with the event, not as an expository account of the event itself; García Márquez states that "everything in this book is a magnificent example of how a writer can honestly filter out the immense quantity of rhetorical and demagogic garbage that stands in the way of indignation and nostalgia."[4] Menton suggests that, in this way, it "is one of the important forerunners of One Hundred Years of Solitude,"[2] and García Márquez elaborates, "it represents a new and formidable contribution to the most important literary phenomenon in today's world: the Latin American novel."[3] Cepeda Samudio's final publication of fiction was the short story collection Los Cuentos de Juana (1972), with illustrations by his good friend Alejandro Obregón. One of the short stories was developed into a film, Juana Tenía el Pelo de Oro, which was released in Colombia in 2006. |

文学者としてのキャリアと展望 しかし、セペダ・サムーディオの「刷新的な体制」への願望は、ラ・ナシオナル紙への影響力をはるかに超えたものであった。エル・ヘラルド』誌のコラム Brújula de la cultura(文化の羅針盤)に寄稿し、一貫して「コロンビア散文小説の刷新」の必要性を説いた[2]。 彼は、特にガルシア・マルケスや他のバランキージャ・グループのメンバーなど多くの友人にとって「異端」文学と見なされるものを熱心に探し出し支持し、 アーネスト・ヘミングウェイやウィリアム・フォークナーを多くの友人に紹介した。エル・ヘラルド』誌のコラムでは、フリオ・コルタサルの短編集第1巻『ベ スティアリオ』(1951年)の革新性を絶賛している[2]。 しかし、特にコロンビア国内において革新的な文学スタイルや手段の必要性を説いたことは、単にエッセイ的な評論やコラムにとどまらず、その後、2冊の短編 集と1冊の小説を書き、その中で彼の理想が実現されることになった。最初に出版された短編集Todos estábamos a la espera (We Were All Waiting) (1954)には、ヘミングウェイへの関心が見られ、当時の学術評論家の間で大きな出版イベントとなった。ラ・カサ・グランデ』を英訳したセイモア・メン トンは、この作品集の最初の物語が「伝統的な道徳的・芸術的な全知全能の語り手の介入なしに、主人公の一人称で語られている」と述べている[2]。物語の 中に大きな心理衝動を完全に受け入れると同時に、あらゆる媒介的文脈を拒否したことは、セペダ・サムディオが文学に必要な「近代化」について主張した多く の事柄の一つであった。ガルシア・マルケスは後に、『Todos estábamos a la espera』は「コロンビアで出版された最高の物語集だった」と述べている[3]。 彼の処女作である『ラ・カサ・グランデ』(1962年)は、一人の無媒介の語り手に依存した物語をさらに追求し、それまで見せたことのない方法で、物語を 10の異なるセクションに分割して構造を実験している。フォークナー作品に対する彼の敬愛は、おそらくこの作品に最もよく表れている。サンタマルタの大虐 殺を、その実態を十分に掘り下げることなく、暴力を回避するバラバラの物語で扱うことで、この小説の中心となる行動と内容は、事件そのものを説明するもの ではなく、事件に関わった人々のそれに対する内なる反応として提示されているのである。ガルシア・マルケスは、「本書のすべてが、作家がいかにして憤りや 郷愁の邪魔をする膨大な量の修辞やデマゴーグのゴミを正直にろ過できるかを示す見事な例である」と述べている[4]。 このように、「『百年の孤独』の重要な前身の一つである」とメントンは示唆し[2]、ガルシア・マルケスは「今日の世界で最も重要な文学現象であるラテン アメリカ小説に新しく手ごわい貢献をしている」と詳しく述べている[3]。 セペダ・サムーディオの最後の小説の出版は、親友のアレハンドロ・オブレゴンが挿絵を描いた短編集『Los Cuentos de Juana』(1972年)であった。短編の1つは映画『Juana Tenía el Pelo de Oro』になり、2006年にコロンビアで封切られた。 |

| Film career Cepeda Samudio harbored an intense love and knowledge of films, and often wrote in his columns criticisms on the subject. García Márquez writes that his sustenance as a film critic would not have been possible had he not partaken in "the traveling school of Álvaro Cepeda".[3] The two eventually made a short black and white feature together called La langosta azul (The Blue Lobster) (1954), which they co-wrote and directed based on an idea by Cepeda Samudio; García Márquez states that he conceded to take part in its creation as "it had a large dose of lunacy to make it seem like ours."[3] The film still occasionally makes appearances at "daring festivals" around the world, with the help of Cepeda Samudio's wife, Tita Cepeda.[3] |

映画人としてのキャリア セペダ・サムーディオは、映画に対する強い愛と知識を持ち、しばしばコラムに批評を書きました。ガルシア・マルケスは、「アルヴァロ・セペダの旅行学校」 に参加しなければ、映画評論家として生きていくことはできなかっただろうと書いている[3]。 2人は最終的に、セペダ・サムーディオのアイデアを基に共同で脚本・監督した『青いロブスター』(La langosta azul)(1954)というモノクロ短編を一緒に作った。ガルシア・マルケスは、「我々のものだと思わせるために大量の狂気があった」としてその制作に 参加することを譲ったと述べている[3]。 「3] この映画は、セペダ・サムディオの妻ティタ・セペダの協力のもと、現在でも時々、世界中の「大胆な映画祭」に登場する[3]。 |

| Late life Cepeda Samudio died in 1972, the year that his final collection of short stories, Los cuentos de Juana, was released, of lymphatic cancer, the same condition which his lifelong friend García Márquez was diagnosed with in 1999. In his memoir, Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell the Tale) (2002), García Márquez writes that his friend was "more than anything a dazzling driver—of automobiles as well as letters."[5] The influence of Cepeda Samudio, not solely on the works of later Colombian and Latin American writers, but also on García Márquez, is evident not only in the latter writer's confessions in his autobiography of "imitating"[3] his friend, but also in his clear admiration for his literary abilities. In his short story, La increible y triste historia de la cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada (The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and her Heartless Grandmother) (1978), written in the year of Cepeda Samudio's death and published six years later in a collection of the same name, the third-person narrative takes a brief and sudden digression into the first-person, informing the reader that "Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, who was also traveling in the region, selling beer-cooling equipment, took me through the desert towns" of which the story, and most of the stories in the collection, take place, suggesting the sharedness of the lands traversed in his stories with his polymath "driver" friend.[6] In the final chapter of Cien años de soledad, the fictionalized Barranquilla Group referred to as the "four friends" leave Macondo, "Álvaro" being the first among them.[7] In preparation for his departure, the narrator states that Álvaro bought an eternal ticket on a train that never stopped traveling. In the postcards that he sent from the way stations he would describe with shouts the instantaneous images that he had seen from the window of his coach, and it was as if he were tearing up and throwing into oblivion some long, evanescent poem.[7] |

晩年 セペダ・サムーディオは、最後の短編集『フアナの言葉』が出版された1972年に、生涯の友であるガルシア・マルケスが1999年に診断されたのと同じリ ンパ系癌で死去した。ガルシア・マルケスは回顧録『Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell the Tale)』(2002年)の中で、彼の友人について「何よりもまばゆいばかりの、自動車と手紙の運転手だった」と書いている[5]。 「セペダ・サムーディオの影響は、後のコロンビアやラテンアメリカの作家だけでなく、ガルシア・マルケスにも及んでおり、後者の作家が自伝で友人の「真 似」をしたと告白しているだけでなく、彼の文才を明確に賞賛していることからも明らかである[3]。セペダ・サムディオが亡くなった年に書かれ、6年後に 同名の短編集として出版された『La increible y triste historia de la cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada(無実のエレンジラと心なき祖母の信じられないほど悲しい物語)』(1978)では、三人称の物語が短く突然一人称に脱線している。ア ルヴァロ・セペダ・サムーディオもまた、この地方を旅して、ビールを冷やす装置を売っていたが、私を砂漠の町に連れて行ってくれた」と読者に伝え、物語の 中で横断される土地が、彼の多才な「運転手」の友人と共有されることを示唆している[6]。 [Cien años de soledad』の最終章では、「4人の友人」と呼ばれる架空のバランキージャ集団がマコンドを出発し、「アルヴァロ」がその一人目となる[7]...。 アルヴァーロは旅立ちの準備のために、旅をやめない汽車の永遠の切符を買ったと語り手は言う。途中の駅から送る絵葉書には、車窓から見た瞬間の映像を叫びながら描写し、それはまるで、長く儚い詩を引き裂いて忘却の彼方へと投げ捨てるかのようだった[7]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81lvaro_Cepeda_Samudio |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報