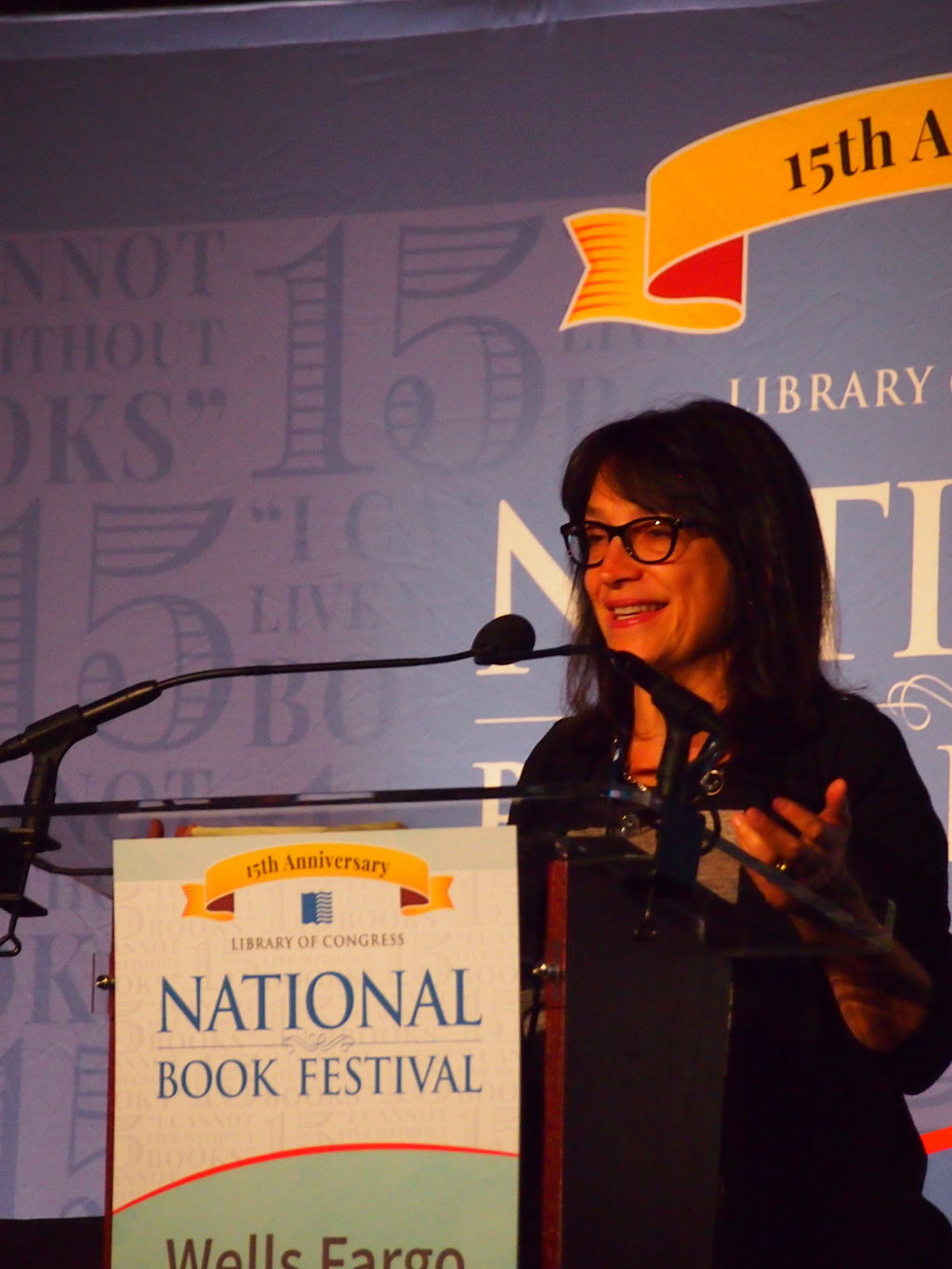

エイミー・ウィレンツ

Amy Wilentz

☆ エイミー・ウィレンツ(Amy Wilentz)はアメリカのジャーナリスト、作家である。カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校の英語教授で、文学ジャーナリズムを教えている[1]。回顧録 『Farewell, Fred Voodoo』で2013年ナショナリズム・サークル賞を受賞: ウィレンツ氏はニューヨーカー誌の元エルサレム特派員で、ザ・ネーションの寄稿編集者でもある[4]。

| Amy Wilentz

is an American journalist and writer. She is a professor of English at

the University of California, Irvine, where she teaches Literary

Journalism.[1] Wilentz received a 2013 National Book Critics Circle

Award for her memoir, Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter from Haiti, as

well as a 2020 Guggenheim Fellowship in General Nonfiction.[2][3]

Wilentz is The New Yorker's former Jerusalem correspondent and is a

contributing editor at The Nation.[4] |

エ

イミー・ウィレンツ(Amy

Wilentz)はアメリカのジャーナリスト、作家である。カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校の英語教授で、文学ジャーナリズムを教えている[1]。回顧録

『Farewell, Fred Voodoo』で2013年ナショナリズム・サークル賞を受賞:

ウィレンツ氏はニューヨーカー誌の元エルサレム特派員で、ザ・ネーションの寄稿編集者でもある[4]。 |

| Early life and education Wilentz is the daughter of Robert Wilentz and Jacqueline Malino Wilentz. Her father was chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court from 1979 to 1996; her mother was a painter. She was raised in Perth Amboy, New Jersey.[5] Wilentz is also the granddaughter of David T. Wilentz, the New Jersey attorney general from 1934 to 1944, best known for prosecuting Bruno Hauptmann in the Lindbergh kidnapping trial.[6] She attended Harvard for undergraduate study in 1976, where she wrote for The Harvard Crimson.[7][8] She spent a year after graduation on a Harvard/Radcliffe fellowship at the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, France.[9] |

幼少期と教育 ロバート・ウィレンツとジャクリーン・マリノ・ウィレンツの娘である。父親は1979年から1996年までニュージャージー州最高裁長官を務め、母親は画 家だった。また、1934年から1944年までニュージャージー州司法長官を務め、リンドバーグ誘拐事件でブルーノ・ハウプトマンを起訴したことで知られ るデビッド・T・ウィレンツの孫娘でもある[6]。1976年にハーバード大学に入学し、『ハーバード・クリムゾン』誌に寄稿した[7][8]。卒業後、 ハーバード大学/ラドクリフ大学のフェローシップでフランス・パリのエコール・ノルマル・シュペリウールで1年間過ごした[9]。 |

| Career Wilentz's first jobs in journalism were for The Nation, Newsday, and Time. She also worked for Ben Sonnenberg's literary periodical Grand Street in its early years. Wilentz has covered events in Haiti for many years, from the fall of Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986 through the 2010 earthquake and Duvalier's death in 2014.[10] Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Time, The New Republic, Mother Jones,[11] Harper's,[12] Vogue, Condé Nast Traveler,[13] Travel & Leisure, San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice,[14] The London Review of Books, The Huffington Post,[15] Democracy: A Journal of Ideas[16], and The Spectator.[17] Wilentz is the author of two books on Haiti, The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier (1989) and Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter from Haiti (2013). She is the translator of In the Parish of the Poor: Writings from Haiti, by Jean-Bertrand Aristide (1991). She continues to write frequently about Haiti, most often for The Nation. Martyrs’ Crossing, Wilentz's novel about the Oslo peace process in Jerusalem in the mid-1990s, was published in 2000. Her memoir, I Feel Earthquakes More Often Than They Happen: Coming to California in the Age of Schwarzenegger was published in 2006. |

経歴 ウィレンツにとってジャーナリズムの最初の仕事は、『ナショナリズム』、『ニューズデイ』、『タイム』だった。また、ベン・ソネンバーグが創刊した文芸定 期刊行物『グランド・ストリート』の初期にも働いていた。1986年のジャン=クロード・デュバリエ政権崩壊から2010年の地震、2014年のデュバリ エの死まで、長年ハイチの出来事を取材してきた[10]。 Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Time, The New Republic, Mother Jones,[11] Harper's,[12] Vogue, Condé Nast Traveler,[13] Travel & Leisure, San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice,[14] The London Review of Books, The Huffington Post,[15] Democracy: A Journal of Ideas』誌[16]、『The Spectator』誌などである[17]。 ウィレンツにはハイチに関する2冊の本『The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier』(1989年)と『Farewell, Fred Voodoo』(2013年)がある: A Letter from Haiti』(2013年)の著者である。ジャン=ベルトラン・アリスティド著『In the Parish of the Poor: Writings from Haiti』(1991年)の翻訳者でもある。『ナショナリズム』誌を中心にハイチに関する執筆活動を続けている。 1990年代半ばのエルサレムにおけるオスロ和平プロセスを描いた小説『Martyrs' Crossing』は2000年に出版された。回顧録『I Feel Earthquakes Moreften Than They Happen(私は地震よりも頻繁に地震を感じる)』がある: 2006年には『シュワルツェネッガー時代のカリフォルニアへ』が出版された。 |

| Personal life Wilentz is married to Nicholas Goldberg, opinion editor of the Los Angeles Times.[18] |

私生活 ウィレンツ氏は、ロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙のオピニオン・エディターであるニコラス・ゴールドバーグ氏と結婚している[18]。 |

| Awards 1990 Whiting Award 1990 PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction for The Rainy Season 2000 Rosenthal Award, American Academy of Arts and Letters for Martyrs' Crossing 1989 National Book Critics Circle Award, General Nonfiction finalist[19] 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award (Autobiography/Memoir), winner for Farewell, Fred Voodoo[20][21][22] 2020 Guggenheim Fellowship in General Nonfiction[23] |

受賞歴 1990年 ホワイティング賞 1990年 PEN/マーサ・アルブランド賞(初のノンフィクション部門) 『雨の季節』で受賞 2000年 ローゼンタール賞(『殉教者の交差点』でアメリカ芸術文学アカデミー賞 1989年 国民図書批評家協会賞一般ノンフィクション部門最終候補[19]。 2013年 ナショナル・ブック・クリティックス・サークル賞(自伝/回想録)、『さらば、フレッド・ブードゥー』で受賞[20][21][22]。 2020年グッゲンハイム・フェローシップ(一般ノンフィクション部門)受賞[23]。 |

| Works Books Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter From Haiti. Simon & Schuster. January 8, 2013. ISBN 978-1-451-64397-8.[24] I Feel Earthquakes More Often Than They Happen: Coming to California in the Age of Schwarzenegger. Simon and Schuster. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7432-6439-6. Martyrs' Crossing. Simon & Schuster. 2001. ISBN 978-0-684-85436-6. The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier. Simon and Schuster. 1989. ISBN 978-0-671-64186-3. Anthologies Robert Maguire and Scott Freeman, ed. (2017). Who Owns Haiti?: People, Power, and Sovereignty. Contributor Amy Wilentz. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813062266. The Nation's 150th Anniversary Special Issue (2015). Contributor Amy Wilentz: "The Future of a Failed State". Jeff Sharlet, ed. (2014). Radiant Truths: Essential Dispatches, Reports, Confessions, and Other Essays on American Belief. Contributor Amy Wilentz. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300169218. Richard Stengel, ed. (2010). Haiti: Tragedy and Hope. Contributor Amy Wilentz. Time Books. ISBN 978-1-60320-163-6. Susan Morrison, ed. (2008). Thirty Ways of Looking at Hillary: Reflections by Women Writers. Contributor Amy Wilentz. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-145593-3. Jean-Bertrand Aristide (1990). In the parish of the poor: writings from Haiti. Translator Amy Wilentz. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-0-88344-682-9. Anne Fuller; Amy Wilentz (1991). Return to the Darkest Days: Human Rights in Haiti Since the Coup. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-054-4. |

作品紹介 書籍 さらば、フレッド・ブードゥー: ハイチからの手紙 サイモン&シュスター 2013年1月8日。ISBN 978-1-451-64397-8.[24]. I Feel Earthquakes Moreften Than They Happen: I Feel Earthquakes Moreften Than They Happen: Coming to California in the Age of Schwarzenegger. Simon and Schuster. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7432-6439-6. Martyrs' Crossing. サイモン&シュスター。2001. ISBN 978-0-684-85436-6. 雨季:デュヴァリエ以来のハイチ. サイモン&シュスター。1989. ISBN 978-0-671-64186-3. アンソロジー ロバート・マグワイア、スコット・フリーマン編 (2017). ハイチは誰のものか?People, Power, and Sovereignty. 寄稿 エイミー・ウィレンツ。フロリダ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0813062266. ナショナリズム創刊150周年記念特集号(2015年)。寄稿者 Amy Wilentz: 「The Future of a Failed State」. ジェフ・シャーレット編 (2014). Radiant Truths: エッセンシャル・ディスパッチ、レポート、告白、その他アメリカの信念に関するエッセイ。寄稿者 Amy Wilentz. エール大学出版。ISBN 978-0300169218. リチャード・ステンゲル編 (2010). ハイチ: 悲劇と希望. 寄稿者 Amy Wilentz. タイムブックス。ISBN 978-1-60320-163-6. スーザン・モリソン編 (2008). Thirty Ways of Looking at Hillary: Thirty ways of Looking at Hillary: Reflections by Women Writers. 寄稿者 Amy Wilentz. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-145593-3. Jean-Bertrand Aristide (1990). In the parish of the poor: writings from Haiti. エイミー・ウィレンツ訳。オルビス・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-88344-682-9. Anne Fuller; Amy Wilentz (1991). 暗い日々への回帰:クーデター以降のハイチの人権. ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチ。ISBN 978-1-56432-054-4. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Wilentz |

|

| “Farewell,

Fred Voodoo showcases all [Wilentz’s] formidable gifts as a reporter:

her love of, and intimate familiarity with, Haiti; her sense of

historical perspective; and her eye for the revealing detail. Like Joan

Didion and V. S. Naipaul, she has an ability not only to provide a

visceral, physical feel for a place, but also to communicate an

existential sense of what it’s like to be there as a journalist with a

very specific and sometimes highly subjective relationship with her

subject.” -- Michiko Kakutani ― The New York Times “Excellent and illuminating….a love letter to—and a lament for—Haiti, a country with an already strange and tortured history that became even more tragic, interesting and convoluted in the months after the earthquake…. [Wilentz] brings to Haiti empathy and her great skills as a narrator….it's Wilentz's honesty about her own role in Haiti and that of so many other American visitors to that country that ultimately distinguishes her book most from other works that cover similar terrain.” ― Los Angeles Times "A veteran journalist captures the functioning chaos of Haiti. ... An extraordinarily frank cultural study/memoir that eschews platitudes of both tragedy and hope." ― Kirkus Reviews, starred review “Farewell, Fred Voodoo is engrossing and gorgeous and funny, a meticulously reported story of love for a maddening place. Wilentz’s writing is so lyrical it’s like hearing a song – in this case, the magical, confounding, sad song of Haiti.” -- Susan Orlean, author of The Orchid Thief and Rin Tin Tin “Farewell, Fred Voodoo is written with authority and great affection for Haiti and Haitians and for those who are trying to help them. An informative and wonderful piece of writing, it is a work of considerable artistry, immensely evocative. I read it with pleasure and with mounting gratitude.” -- Tracy Kidder, author of Mountains Beyond Mountains “Amy Wilentz is a brilliant writer, an ace journalist and, perhaps most important, she is not an outsider. She's the perfect guide through the heartbreak and beauty of post-earthquake Haiti. I was gripped by her respectful and first-hand reporting on Voodoo, and impressed by her enormous sensitivity to the crushing deprivation most Haitians endure.” -- Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Nickel and Dimed “Amy Wilentz knows Haiti deeply: its language, its tragic history, the foibles of her fellow Americans who often miss the story there. This makes her a wise, wry, indispensable guide to a country whose fate has long been so interwoven with our own.” -- Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold’s Ghost “I can't imagine there's a better book about Haiti—a smarter, more thoughtful, tough-minded, romantic, plainspoken, intimate, well-reported book. Amy Wilentz has paid exceptionally close attention to this dreamy, nightmarish place for a quarter century, and with Farewell, Fred Voodoo she turns all that careful watching and thinking into a riveting work of nonfiction literature.” -- Kurt Andersen, author of Heyday and True Believers |

『さ

らば、フレッド・ブードゥー』には、ハイチへの愛と親しみ、歴史的な視点、細部を見抜く目など、ウィレンツ氏の記者としての才能が遺憾なく発揮されてい

る。ジョーン・ディディオンやV.S.ナイポールのように、彼女には、その土地に対する直感的で身体的な感覚を提供するだけでなく、非常に具体的で、時に

は非常に主観的な対象との関係を持つジャーナリストとして、そこにいることがどのようなことなのかという実存的な感覚を伝える能力がある。--

角谷美智子 -ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙 「すでに奇妙で苛烈な歴史を持ち、地震後の数ヶ月でさらに悲劇的で、興味深く、複雑なものとなったハイチへのラブレターであり、ハイチへの嘆きでもある。 [ウィレンツはハイチへの共感と語り手としての素晴らしい才能をハイチにもたらしている......ハイチでの自分自身の役割と、ハイチを訪れた他の多く のアメリカ人の役割に対するウィレンツの正直さが、最終的に彼女の本を、同じような地形を扱った他の作品から最も際立たせている。」 - ロサンゼルス・タイムズ 「ベテラン・ジャーナリストがハイチの機能的な混乱を捉えている。... 悲劇と希望の両方の平凡な表現を排した、極めて率直な文化研究/回想録である。」 - カーカス・レビュー、星付きレビュー 「『さらば、フレッド・ブードゥー』は夢中にさせられ、ゴージャスで面白い。ウィレンツ氏の文章はとても叙情的で、まるで歌を聴いているようである。-- スーザン・オーリアン(『蘭泥棒』『リン・ティン・ティン』の著者 『さらば、フレッド・ブードゥー』は、ハイチとハイチ人、そして彼らを助けようとする人々に対して、権威と大きな愛情を持って書かれている。有益で素晴ら しい文章であり、非常に芸術的な作品であり、計り知れないほど喚起的である。喜びと感謝の念を抱きながら読んだ。-- トレーシー・キダー(『マウンテン・ビヨンド・マウンテンズ』著者 「エイミー・ウィレンツ氏は素晴らしい作家であり、エース・ジャーナリストであり、そしておそらく最も重要なことだが、彼女は部外者ではない。彼女は地震 後のハイチの傷心と美しさを伝える完璧なガイドだ。ブードゥー教に関する彼女の敬意に満ちた直接取材に心をつかまれ、ほとんどのハイチ人が耐え忍んでいる 屈辱的な困窮に対する彼女の大きな感受性に感銘を受けた」。-- バーバラ・エーレンライク(『ニッケル・アンド・ディメッド』の著者 「エイミー・ウィレンツ氏はハイチを深く知っている。その言語、悲劇的な歴史、そしてしばしばハイチの物語を見逃しがちな同胞アメリカ人の弱点。そのた め、彼女は賢明で、辛辣で、私たち自身の運命と長い間織り成されてきたこの国への欠くことのできないガイドとなる。-- アダム・ホックチャイルド(『レオポルド王の亡霊』著者 「ハイチについて、これほど賢く、思慮深く、したたかで、ロマンチックで、率直で、親密で、よく取材された本はないだろう。エイミー・ウィレンツ氏は四半 世紀にわたり、この夢のようで悪夢のような場所に特別な注意を払ってきた。そして『さらば、フレッド・ブードゥー』で、彼女はその注意深い観察と思考のす べてを、ノンフィクション文学の魅力的な作品へと昇華させた。-- クルト・アンダーセン(『ヘイデイ』『トゥルー・ビリーバーズ』の著者 |

| From Chapter 14 I’m stirred and moved by things I see here, but I’m not sure why, and I wonder: Would you be moved? Here are the things that touch me, but a warning: they are not entirely normal. ... [One is a] bone in a burned foot. The man sits in a broken wheelchair—he’s young, maybe twenty-two. He’s a friend of Jerry and Samuel’s. He was riding on his motorbike in the middle of a post-quake, pre-election demonstration when a government thug, so he says, took a potshot at him. The bullet went through his abdomen, and he was in such shock that his foot got caught in the bike’s muffler and burned. They took him to the general hospital, where doctors repaired the bullet’s damage and left a big scar along his abdomen, which he matter-of-factly shows to anyone who asks, but the foot was left to heal on its own with no skin graft, and now, three months after the injury, you can still see the entirely exposed three inches of metatarsal bone through a blood-red hole in the top of his foot, like a peek at the guy’s skeleton, as he sits there in his unwheeled wheelchair in a stony fury over his situation. Another item in my list of what moves me here: the death of the woman who hated me. Just after the earthquake, I had a spaghetti dinner—this was the one made by the New York Times’s Haiti reporting team—in the kitchen of the half-destroyed Park Hotel. You had to walk under hanging cement and over broken floors to get to the lobby, and then tiptoe through the perilous lobby to the kitchen. One of the Haitians staying there, behind the rubble of the front rooms, was a Madame Coupet, an older, very light-skinned Haitian lady, wouj, actually, who was wearing a housedress. Her son was in America. She had heard of the book I had published on Haiti many years earlier. How she had hated me then, she told me now—well, I had supported Aristide, she had gathered, and he was the man she held responsible for everything bad that had happened in the past twenty-five years. For this earthquake, even, it seemed. I bowed my head. What could I tell her? She wouldn’t have wanted to hear what I wanted to say. But we talked about other things—her children, her family, Haiti—and in the end, we got along. She decided that I was not a demon, and that we both loved Haiti. She was surprised that I seemed nice. Polite. Well-broughtup, is how the Haitians say it. After I left the country, I thought of Madame Coupet often, and longed to see her again. I wanted to talk to her, because I needed to hear more about old Haiti, the lost country, the country she said she loved. I thought of her mottled skin, its fairness ruined by age and the Haitian sun, of her gracious diction, and of her generosity in forgiving me for Aristide—and of mine in forgiving her for forgiving me for Aristide. When I came back to Port-au-Prince, five months after the earthquake, the middle-aged men sitting in metal chairs on the still rubble-strewn terrace of the Park Hotel, smoking cigarettes and gossiping with one another, told me the old lady had died. They wanted to tell me gently but didn’t know how. So they told me bluntly: she died. Therefore, no interview. But I can still tell you what she might have said, or at any rate, what someone like her might have said. Here it is: When I was a girl, there were lace curtains. The wind was sweet. I had a pet cat and she would chase the guinea fowl in the courtyard. I had a blue dress with a sash that only my mother knew how to tie properly. The frangipani tree in the corner of the garden smelled like my mother’s perfume. There was Duvalier, sure: Papa Doc. But we children, me and my brothers, we paid very little attention. My parents tried to keep out of his way, I suppose. My father was a professor at the university, an engineer. My brothers and I, we read poetry, Durand, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Morisseau-Leroy, Roumer, and meanwhile the bougainvillea tumbled over the front wall and there were plants in pots in the gardens and two servants, and one poor distant girl cousin who helped with chores. She was from the deep country, and did marry, finally. In summers we went to my aunt’s house in the mountains and picked flowers and rode donkeys and helped make the morning coffee. I went to school in a checkered uniform that I loved. I read French literature until I met my husband, who was in the import-export business. I was beautiful, and he loved me until I grew old. We had two children, and a third who died in childbirth. Now one is dead and the other lives in New Jersey. I prefer to be here where I understand things. Here’s something that got to me: the last time I saw Filibert Waldeck. The last time I saw Filibert, I was standing in front of the ruined cathedral downtown. It was January 12, 2011, the first anniversary of the earthquake. People were praying under the statue of Jesus that still stands outside the rubble. A man rushed up and exhibited his little daughter to me. She had, to put it nicely, failure to thrive. She must have been five but she looked two, with huge eyes, reddish hair, bone-thin limbs. The man told me they’d been homeless since the earthquake. A person nearby told me, while the man was standing there in front of me with his silent child balanced in his arms, that that fellow came to the cathedral ruins with the kid every day looking for some visitor to beg from. Did that make his story less true? I asked myself. The crowd pressed on us and the man and his daughter were shoved away. There was a band playing, and there were priests and nuns seated, waiting for the service to begin. I was standing off to the side near a white man I’d never seen before, an older man with thinning hair. As usual with any big Haitian event, huge numbers of people were all shoved together in a giant bubbling human mass. The white man near me was at least five people away. Although we were outside, there was barely room to inhale where we stood, but uncannily, up in front of my face popped someone I recognized. At first I wasn’t sure who he was, exactly. Then he spoke in his familiar growl of a voice, the same rasp he’d had as a child, only deeper. It was Filibert, wearing some kind of satanic red and silver T-shirt and old dirty jeans. He was too thin. I said, “Filibert, what’s wrong with you?” He wasn’t making sense. The white man standing near me was watching. He pushed his way forward and took Filibert by the arm and rattled him, shook him up a bit. I was astonished. Filibert looked astonished, too, if you can look astonished while looking sullen. The white man, whose self-assured demeanor I now recognized as that of a lay Christian brother of some kind, was interrogating Filibert. He called him by his full name: “Filibert Waldeck, what’s wrong with you?” Filibert just shook his head, looked down at the ground. The man looked at me and back at Filibert. “You’re on crack or something, aren’t you?” he asked him. “I know it. I know it.” The man shook his head and tried to peer into Filibert’s eyes, but Filibert looked away. “You stop that stuff, do you hear me?” The man was speaking fluent Creole. I took Filibert aside and he began that same long rant I’d already heard about his sons and their mother and about how he had to keep them inside so she wouldn’t get them, and how his motorbike had broken down and he didn’t have money to get it fixed. Throughout the whole long saga, which was much more detailed and a lot less comprehensible than what I am putting down here, he would look at me sideways, slantwise, assessing my potential. Half the time he had the demeanor of a person on drugs or in the throes of mental illness of some kind, which I’ve always suspected with him. And the rest of the time, he looked like a smart old market lady sizing up her client. Finally, I asked him if I could help him in any way, and he just looked at me. “Amy, you ahr my mozzer,” he said to me, in English. So I gave him some money. And then he disappeared into the crowd. I saw a splotch of red fading away down toward Grande Rue. My child, I thought. I tried to imagine it. I wondered if there had really ever been any connection between us, other than monetary. Because of where I was from, I had always had the power in our relationship. Because of where he was from, Filibert was always the weak one, poor, needy, desperate. Of course we each bore some responsibility for who we were and how we had ended up, but we were also prisoners of our fates, each of us locked in our individual history and geography. I was from the U.S. and he was from Haiti. That was it. I always had and gave money; he always did not have it and needed it. It was always my choice: would I give him something? How much, this time? It was easy, even pleasurable, for me to give it to him; but it was all cruel for him. The crowd around me was singing a spindly soprano hymn as the memorial service began. But where was Filibert going now? Why didn’t he have a cell phone? Why didn’t he have my number? And now that speck of red had vanished. I squinted into the sun, trying to find him again, but he had slipped back away into the heat and darkness, and was lost to me. As I am writing this, at around five in the morning, I hear gunfire and screaming outside my window. Two shots. Ridiculous, it cannot be, but it is. Freelance fire, I figure—meaningless gang shit. In the old days violence had political meaning in Haiti, but, as elsewhere in the world, now it’s often pretty pointless. More gunfire now. Definitely gunfire. And screaming and a rumble of low shouting, as if a whole crowd is yelling far away. Carnival is coming, I remember; that can be a violent time. And elections are coming: that also means violence. First I get up to go to the window to look: when I peek out from a sharp sideways angle, I see a crowd down on the street below, pushing and shoving, and screaming. It’s violent, and that’s definitely where the shooting has been coming from. Maybe it is some kind of political protest, I think now. I retract my head as another round of shooting begins, and return to my desk. Later, when I interviewed some acquaintances in the neighborhood, I discovered that the reason for the shooting and screaming and the angry nub of a crowd in the street was that the pharmacy down below my window had announced the previous day that it would be offering to fill children’s prescriptions for free today, in a one-day trial program. The crowd was composed of mothers, all fighting to get in before the place stopped serving. The shooter was the pharmacy owner, trying to protect his place from the poverty-maddened consumers. I’d mistaken the mothers for a politically motivated riot. And, in a way, they were. |

第14章より 私はここで目にしたものに心を揺さぶられ、心を動かされる: あなたは感動するだろうか?以下が私の心を揺さぶるものだが、警告:それらは完全に正常なものではない。[ひとつは)火傷した足の骨だ。その男は壊れた車 椅子に座っている。ジェリーとサミュエルの友人だ。彼は地震後、選挙前のデモの真っ最中にバイクに乗っていたが、政府のチンピラに銃撃されたという。銃弾 は腹部を貫通し、彼はショックでバイクのマフラーに足を取られて火傷を負った。総合病院に連れて行かれ、医師が銃弾の損傷を修復し、腹部に大きな傷跡を残 した。 私の心を揺さぶるもののリストにもうひとつ、「私を憎んでいた女の死」という項目がある。地震の直後、私はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のハイチ取材チームが 作ったスパゲッティ・ディナーを、半壊したパークホテルのキッチンで食べた。ロビーに行くには、垂れ下がったセメントの下をくぐり、壊れた床の上を歩かな ければならなかった。そこに泊まっていたハイチ人の一人、マダム・クーペは、前室の瓦礫の向こうにいた。年配の、とても肌の白いハイチ人女性で、実はハウ スドレスを着ていた。彼女の息子はアメリカにいた。 彼女は、私が何年も前にハイチについて出版した本のことを聞いていた。私がアリスティドを支持し、過去25年間に起きたすべての悪いことの責任を彼に押し 付けていたからだ。今回の地震でさえもそうだった。私は頭を下げた。何を話せばいいのだろう?彼女は私の言いたいことなど聞きたくなかっただろう。しか し、私たちは他のこと、つまり彼女の子供たち、家族、ハイチのことを話し、最後には仲良くなった。彼女は私が悪魔ではないと判断した。彼女は私がいい人そ うだと驚いた。礼儀正しい。育ちがいい、とはハイチ人の言い方だ。 国を離れてからも、私はマダム・クーペのことをよく思い出し、また会いたいと思った。彼女と話したかった。失われた国、彼女が愛したという昔のハイチのこ とをもっと聞きたかったからだ。私は彼女の斑点のある肌、年齢とハイチの太陽によって台無しにされた色白の肌、優雅な口調、そしてアリスティドのことで私 を許してくれた彼女の寛大さ、そしてアリスティドのことで私を許してくれた彼女を許した私の寛大さを思った。地震から5ヵ月後、私がポルトープランスに 戻ったとき、パークホテルのまだ瓦礫の残るテラスで金属製の椅子に座り、タバコを吸いながら互いに噂話をしていた中年男性たちは、老婦人が亡くなったこと を私に告げた。彼らは優しく私に伝えたかったが、どう伝えたらいいのかわからなかった。だから、「彼女は死にました」と単刀直入に告げた。だからインタ ビューはなしだ。でも、彼女が言ったかもしれないこと、少なくとも彼女のような人が言ったかもしれないことは、まだ言える。それはこうだ: 私が少女の頃、レースのカーテンがあった。風は甘かった。私はペットの猫を飼っていて、中庭でモルモットを追いかけていた。母だけが正しい結び方を知って いた帯のついた青いドレスを着ていた。庭の隅のフランジパニの木は母の香水の匂いがした。確かにデュヴァリエはいた: パパ・ドクだ。しかし、私たち子供、私と弟たちは、ほとんど関心を持たなかった。両親は彼の邪魔をしないようにしていたのだろう。父は大学の教授で、エン ジニアだった。兄たちと私は、デュラン、ランボー、ボードレール、モリソー・ルロワ、ルメールなどの詩を読んだ。ブーゲンビリアが正面の壁に倒れ、庭には 鉢植えの植物が植えられていた。彼女は奥地の出身で、ついに結婚した。夏には山の中の叔母の家に行き、花を摘んだり、ロバに乗ったり、朝のコーヒーを入れ るのを手伝ったりした。私は大好きだったチェックの制服を着て学校に通った。輸出入業を営む夫に出会うまで、フランス文学を読んだ。私は美しく、彼は私が 年をとるまで愛してくれた。私たちには2人の子供がいたが、3人目は出産で亡くなった。今は1人は亡くなり、もう1人はニュージャージーに住んでいる。私 はここで物事を理解するのが好きなんだ。 最後に会ったときのことだ。フィルベルトを最後に見たのは、ダウンタウンの廃墟と化した大聖堂の前だった。2011年1月12日、地震から1周年だった。 人々は瓦礫の外に立つイエス像の下で祈りを捧げていた。一人の男性が駆け寄ってきて、小さな娘を私に見せた。彼女は、よく言えば、発育不全だった。大きな 目、赤みがかった髪、骨のように細い手足。その男性は、地震以来ホームレスになったと言った。近くにいた人が、その男が黙っている子供を両腕にバランスよ く抱えて私の前に立っている間に、あの男は毎日子供を連れて大聖堂の廃墟に物乞いに来る客を探しに来ていた、と言った。だからといって、彼の話が真実でな くなるのだろうか?私は自問した。群衆は私たちに押し寄せ、その男と娘は追い払われた。バンドが演奏し、司祭と尼僧が座って礼拝が始まるのを待っていた。 私は、見たこともない白人男性、髪の薄くなった年配の男性のそばに立っていた。 ハイチの大きなイベントの常として、大勢の人々が巨大な泡のような人間の塊の中に押し込まれていた。私の近くにいた白人は、少なくとも5人は離れていた。 外とはいえ、私たちが立っている場所には息を吸い込むスペースがほとんどなかった。しかし、不意に私の顔の前に、見覚えのある人物が飛び込んできた。最初 は誰なのかよくわからなかった。そして、子供の頃と同じような、ただ深いだけの唸り声で話しかけてきた。悪魔のような赤と銀のTシャツを着て、古く汚れた ジーンズをはいていた。痩せぎすだった。 私は言った。「フィリベール、どうしたんだ?彼は意味不明だった。私の近くに立っていた白人が見ていた。フィリベールの腕をつかみ、少し揺さぶった。私は 驚いた。フィリベールも驚いているように見えた。その白人は、自信に満ちた態度で、ある種のキリスト教信者の兄弟であることがわかったが、フィリベールを 尋問していた。フィリベルト・ワルデック、どうしたんだ」。 フィリベルトはただ首を振り、地面に目を落とした。男は私を見て、フィリベールを見返した。「クラックか何かをやっているんだろう?「そうだ。わかってるんだ」 男は首を振り、フィリベールの目を覗き込もうとしたが、フィリベールは目をそらした。 「そういうことはやめろ、聞いてるのか?" 男は流暢なクレオール語を話していた。男は流暢なクレオール語を話していた。 私はフィリベールを脇に連れて行くと、彼はすでに聞いたのと同じように、息子たちとその母親について、そして母親に取られないように息子たちを家の中に閉 じ込めておかなければならないこと、バイクが故障して修理に出すお金がないこと、など長いわだかまりを話し始めた。私がここに書いていることよりもずっと 詳しく、理解しがたい長い武勇伝の間中、彼は横目で、斜めに、私の可能性を評価するような目で私を見ていた。その半分の時間は、薬物をやっているか、ある 種の精神病に罹患しているかのような態度だった。そして残りの時間は、賢い老マーケットレディが顧客を見極めるような態度だった。最後に、彼に何か手伝え ることはないかと尋ねると、彼はただ私を見た。 「エイミー、君は僕のモッツァーだ」と彼は英語で言った。それで私は彼にいくらかのお金を渡した。そして彼は人ごみの中に消えていった。私はグランド・ リュウの方に赤い斑点が消えていくのを見た。私の子供だ。想像してみた。私たちの間に、金銭以外のつながりが本当にあったのだろうかと。私の出身地のせい で、私たちの関係は常に私が力を持っていた。フィリベールは、貧しく、困窮し、自暴自棄になっていた。もちろん、私たちはそれぞれ、自分が何者であり、ど のような結末を迎えたかについて、何らかの責任を負っていたが、同時に私たちは、それぞれの歴史と地理に縛られた運命の囚人でもあった。私はアメリカ出身 で、彼はハイチ出身だった。それだけだった。私はいつもお金を持っていて、与えていた。彼はいつもお金を持っていなくて、必要としていた。彼に何かを与え るかどうかは、いつも私の選択だった。今回はいくら渡そうか?彼にお金を渡すのは簡単で、快感でさえあった。 追悼式が始まると、私の周りの群衆はのびやかなソプラノ賛美歌を歌っていた。しかし、フィリベールはこれからどこへ行くのだろう?なぜ携帯電話を持ってい なかったのだろう?なぜ私の電話番号を知らなかったのだろう?そして今、あの赤い斑点は消えていた。私は太陽に向かって目を細め、再び彼を見つけようとし たが、彼は暑さと暗闇の中にそそくさと戻ってしまい、私の前から姿を消した。 これを書いている午前5時頃、窓の外で銃声と叫び声が聞こえた。発の銃声だ。ばかばかしい、そんなはずはない。フリーランスの銃撃だ。意味のないギャング のたわごとだ。昔はハイチでも暴力が政治的な意味を持っていたが、世界の他の地域と同様、今は無意味なことが多い。今は銃声が多い。確かに銃声だ。そして 叫び声と、群衆全体が遠くで叫んでいるような低い声が響く。カーニバルが近づいている。選挙も近い。横からの鋭い角度で外を覗くと、下の通りに群衆が押し 合いへし合いしているのが見えた。暴力的で、銃撃戦は間違いなくそこから起こっている。政治的な抗議活動の一種なのかもしれない。別の銃撃戦が始まったの で、私は頭を引っ込め、自分のデスクに戻った。 後日、近所の知人に話を聞いてみると、発砲事件と叫び声、そして怒りに満ちた人だかりの原因は、私の窓の下にある薬局が前日、1日限定で子供の処方箋を無 料にすると発表したからだった。人だかりは母親たちで構成され、その店がサービスを停止する前に入ろうと争っていた。犯人は薬局のオーナーで、貧困に苦し む消費者から自分の店を守ろうとしていた。私は母親たちを政治的な動機による暴動と勘違いしていた。そして、ある意味そうだった。 |

| https://www.amazon.co.jp/Farewell-Fred-Voodoo-Letter-Haiti/dp/1451644078 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆