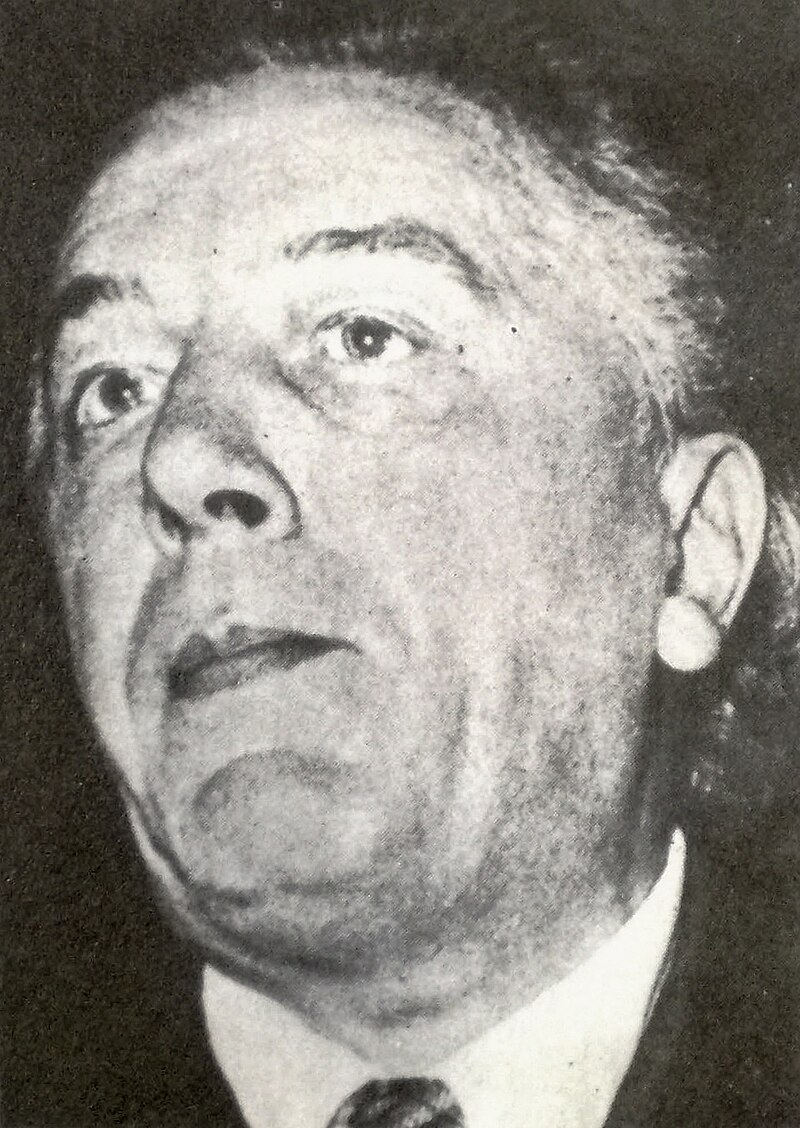

アンドレ・ブルトン

André Breton, 1896-1966

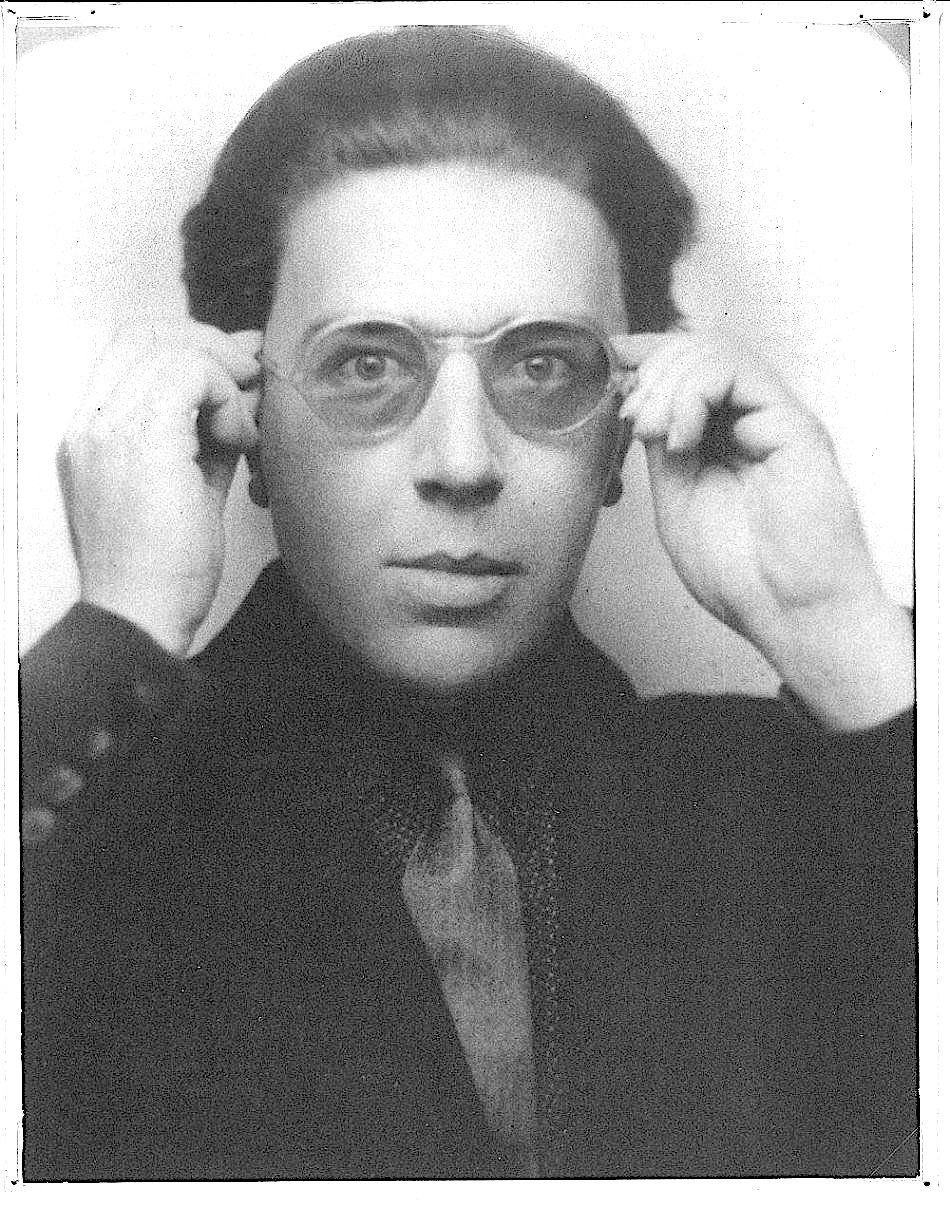

Breton

in 1924

☆ アンドレ・ロベール・ブルトン(André Robert Breton、1896年2月19日 - 1966年9月28日)は、フランスの作家、詩人、シュルレアリスムの共同創設者、指導者、そして主要理論家である。[2] 彼の著作には、1924年に発表した最初のシュルレアリスム宣言(Manifeste du surréalisme)があり、この中で彼はシュルレアリスムを「純粋な精神の自動表現」と定義している。[3] シュルレアリスム運動の指導者としての役割に加え、彼は『ナジャ』や『狂愛』などの著名な著作の著者でもある。これらの活動と、文学と造形芸術に関する批 判的・理論的な研究を組み合わせたことで、アンドレ・ブルトンは20世紀のフランス芸術と文学における主要な人物となった。

| André Robert Breton

(/brəˈtɔːn/;[1] French: [ɑ̃dʁe ʁɔbɛʁ bʁətɔ̃]; 19 February 1896 – 28

September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader,

and principal theorist of surrealism.[2] His writings include the first

Surrealist Manifesto (Manifeste du surréalisme) of 1924, in which he

defined surrealism as "pure psychic automatism".[3] Along with his role as leader of the surrealist movement he is the author of celebrated books such as Nadja and L'Amour fou. Those activities, combined with his critical and theoretical work on writing and the plastic arts, made André Breton a major figure in twentieth-century French art and literature. |

アンドレ・ロベール・ブルトン(André Robert

Breton、1896年2月19日 -

1966年9月28日)は、フランスの作家、詩人、シュルレアリスムの共同創設者、指導者、そして主要理論家である。[2]

彼の著作には、1924年に発表した最初のシュルレアリスム宣言(Manifeste du

surréalisme)があり、この中で彼はシュルレアリスムを「純粋な精神の自動表現」と定義している。[3] シュルレアリスム運動の指導者としての役割に加え、彼は『ナジャ』や『狂愛』などの著名な著作の著者でもある。これらの活動と、文学と造形芸術に関する批 判的・理論的な研究を組み合わせたことで、アンドレ・ブルトンは20世紀のフランス芸術と文学における主要な人物となった。 |

| Biography André Breton was the only son born to a family of modest means in Tinchebray (Orne) in Normandy, France. His father, Louis-Justin Breton, was a policeman and atheist, and his mother, Marguerite-Marie-Eugénie Le Gouguès, was a former seamstress. Breton attended medical school, where he developed a particular interest in mental illness.[4] His education was interrupted when he was conscripted for World War I.[4] During World War I, he worked in a neurological ward in Nantes, where he met the Alfred Jarry devotee Jacques Vaché, whose anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition influenced Breton considerably.[5] Vaché committed suicide when aged 23, and his war-time letters to Breton and others were published in a volume entitled Lettres de guerre (1919), for which Breton wrote four introductory essays.[6] Breton married his first wife, Simone Kahn, on 15 September 1921. The couple relocated to rue Fontaine No. 42 in Paris on 1 January 1922. The apartment on rue Fontaine (in the Pigalle district) became home to Breton's collection of more than 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art. Like his father, he was an atheist.[7][8][9][10] |

略歴 アンドレ・ブルトンは、フランス、ノルマンディー地方のティンシュブレ(オルヌ県)の貧しい家庭に生まれた一人息子だった。父親のルイ・ジャスティン・ブ ルトンは警察官で無神論者、母親のマルグリット・マリー・ウジェニー・ル・ググは元裁縫師だった。ブルトンは医学部に進学し、そこで精神疾患に特別な関心 を抱くようになった[4]。第一次世界大戦に徴兵され、学業は中断された[4]。 第一次世界大戦中、彼はナントの神経科病棟で働き、アルフレッド・ジャリ(Alfred Jarry)の熱烈な信奉者であるジャック・ヴァシェ(Jacques Vaché)と出会った。ヴァシェの反社会的態度と既成の芸術伝統への軽蔑は、ブルトンに大きな影響を与えた。[5] ヴァシェは23歳で自殺し、戦争中にブルトンや他の人物に送った手紙は『戦争の手紙』(Lettres de guerre、1919年)という書籍にまとめられ、ブルトンが4つの序文を執筆した。[6] ブルトンは1921年9月15日に最初の妻シモーヌ・カンと結婚した。夫婦は1922年1月1日にパリのフォンテーヌ通り42番地に引っ越した。フォン テーヌ通り(ピガール地区)のアパートは、ブレットンのコレクション(現代絵画、ドローイング、彫刻、写真、書籍、美術カタログ、雑誌、原稿、大衆芸術と オセアニア芸術の作品など、5,300点以上)の収蔵庫となった。父同様、彼は無神論者だった。[7][8][9][10] |

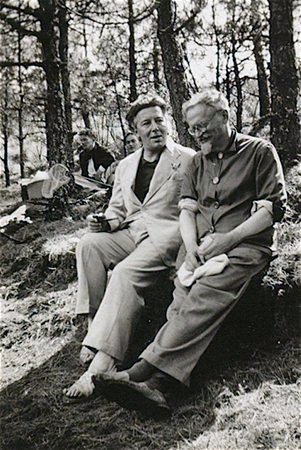

| From Dada to Surrealism Breton launched the review Littérature in 1919, with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault.[11] He also associated with Dadaist Tristan Tzara.[12] In Les Champs Magnétiques[13] (The Magnetic Fields), a collaboration with Soupault, he implemented the principle of automatic writing. With the publication of his Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 came the founding of the magazine La Révolution surréaliste and the Bureau of Surrealist Research.[14] A group of writers became associated with him: Soupault, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, René Crevel, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret, Antonin Artaud, and Robert Desnos. Eager to combine the themes of personal transformation found in the works of Arthur Rimbaud with the politics of Karl Marx, Breton and others joined the French Communist Party in 1927, from which he was expelled in 1933. Nadja, a novel about his imaginative encounter with a woman who later becomes mentally ill, was published in 1928. Due to the economic depression, he had to sell his art collection and rebuilt it later.[15][16] In December 1929, Breton published the Second manifeste du surréalisme (Second manifesto of surrealism), which contained an oft-quoted declaration for which many, including Albert Camus, reproached Breton: "The simplest surrealist act consists, with revolvers in hand, of descending into the street and shooting at random, as much as possible, into the crowd".[17][18] In reaction to the Second manifesto, writers and artists published in 1930 a collective collection of pamphlets against Breton, entitled (in allusion to an earlier title by Breton) Un Cadavre. The authors were members of the surrealist movement who were insulted by Breton or had otherwise opposed his leadership.[19]: 299–302 The pamphlet criticized Breton's oversight and influence over the movement. It marked a divide amidst the early surrealists. Georges Limbour and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes commented on the sentence where shooting at random in the crowd is described as the simplest surrealist act. Limbour saw in it an example of buffoonery and shamelessness and Ribemont-Dessaignes called Breton a hypocrite, a cop and a priest.[20] After the publication of this pamphlet against Breton, the Manifesto had a second edition, where Breton added in a note: "While I say that this act is the simplest, it is clear that my intention is not to recommend it to all merely by virtue of its simplicity; to quarrel with me on this subject is much like a bourgeois asking any non-conformist why he does not commit suicide, or asking a revolutionary why he hasn't moved to the USSR".[21] In 1935, there was a conflict between Breton and the Soviet writer and journalist Ilya Ehrenburg during the first International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, which opened in Paris in June. Breton had been insulted by Ehrenburg—along with all fellow surrealists—in a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists shunned work, favouring parasitism, and that they endorsed "onanism, pederasty, fetishism, exhibitionism, and even sodomy". Breton slapped Ehrenburg several times on the street, which resulted in surrealists being expelled from the Congress.[22] René Crevel, who according to Salvador Dalí was "the only serious communist among surrealists",[23] was isolated from Breton and other surrealists, who were unhappy with Crevel because of his bisexuality and annoyed with communists in general.[15] In 1938, Breton accepted a cultural commission from the French government to travel to Mexico. After a conference at the National Autonomous University of Mexico about surrealism, Breton stated after getting lost in Mexico City (as no one was waiting for him at the airport) "I don't know why I came here. Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world."  Trotsky and Breton in Mexico 1938 However, visiting Mexico provided the opportunity to meet Leon Trotsky. Breton and other surrealists traveled via a long boat ride from Patzcuaro to the town of Erongarícuaro. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were among the visitors to the hidden community of intellectuals and artists. Together, Breton and Trotsky wrote the Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art (published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera) calling for "complete freedom of art", which was becoming increasingly difficult with the world situation of the time. |

ダダからシュルレアリスムへ ブルトンは、1919年にルイ・アラゴン、フィリップ・スーポーとともに雑誌『リテラトゥール』を創刊した[11]。また、ダダイストのトリスタン・ツァラとも交流があった[12]。 スーポーとの共著『磁気畑』[13] では、自動筆記の原則を採用した。 1924年に『シュルレアリスム宣言』を発表すると、雑誌『シュルレアリスム革命』とシュルレアリスム研究局が設立された。スーポー、ルイ・アラゴン、 ポール・エリュアール、ルネ・クレヴェル、ミシェル・レイリス、ベンジャミン・ペレ、アントナン・アルトー、ロベール・デノスといった作家たちが、彼と関 わることになった。 アルチュール・ランボーの作品に見られる個人的な変容のテーマとカール・マルクスの政治思想を融合させたいと願ったブルトンたちは、1927年にフランス 共産党に入党したが、1933年に除名された。後に精神疾患を患う女性との想像上の出会いを描いた小説『ナジャ』は、1928年に出版された。経済不況の ため、彼は自分の美術コレクションを売却し、後にそれを再構築した。[15][16] 1929年12月、ブルトンは『シュルレアリスム第二宣言』を発表し、その中に、アルベール・カミュをはじめとする多くの人々がブルトンを非難した、よく 引用される宣言が掲載された。「最も単純なシュルレアリスムの行為とは、拳銃を手に、街頭に出て、できるだけ多く、無作為に群衆に向かって発砲すること だ」[17][18]。 第 2 のマニフェストに対して、作家や芸術家たちは 1930 年に、ブルトンに対する反対のパンフレット集『Un Cadavre(死体)』(ブルトンの以前の作品のタイトルを引用)を出版した。このパンフレットは、ブルトンに侮辱された、あるいは彼の指導力に反対し ていたシュルレアリスム運動のメンバーたちによって執筆された[19]: 299–302 。このパンフレットは、ブルトンの監督能力と運動に対する影響 力を批判した。これは、初期のシュルレアリスム運動の分裂を象徴する出来事だった。ジョルジュ・リンブールとジョルジュ・リベモン・デセーンは、群衆を無 差別に撃つことを最も単純なシュルレアリスム行為と表現した文章についてコメントした。リンブールは、この文章を道化師のような恥知らずな行為だと考え、 リベモン・デサニュはブルトンを偽善者、警官、司祭だと非難した[20]。 ブルトンを批判するこのパンフレットが発行された後、マニフェストは第 2 版が発行され、ブルトンは次のような注釈を追加した。「この行為が最も単純だと言うが、その単純さだけでそれをすべての人に推奨するつもりはないことは明 らかだ。この件について私と論争するのは、非順応者に「なぜ自殺しないのか」と尋ねるブルジョアや、革命家に「なぜソ連に移住しないのか」と尋ねるブル ジョアとほとんど同じだ」[21]。 1935年、6月にパリで開幕した第1回文化防衛国際作家会議で、ブルトンとソ連の作家・ジャーナリスト、イリヤ・エレンブルグとの間で対立が起こった。 ブルトンは、シュルレアリストたちが仕事を避け、寄生生活を好み、「自慰、小児性愛、フェティシズム、露出狂、さらにはソドミー」を容認していると述べた パンフレットで、エレンバーグから、他のシュルレアリストたちとともに侮辱されていた。ブルトンは街頭でエーレンブルグを何度も平手打ちし、その結果、 シュルレアリストたちは会議から追放された[22]。サルバドール・ダリによると「シュルレアリストの中で唯一の真剣な共産主義者」[23] であったルネ・クレヴェルは、そのバイセクシュアルであることからブルトンや他のシュルレアリストたちから孤立し、共産主義者全般に嫌悪感を抱いていた [15]。 1938年、ブルトンはフランス政府からの文化使節団としてメキシコへの旅を受け入れた。メキシコ国立自治大学でシュルレアリスムに関する会議を行った 後、メキシコシティで迷子になったブルトン(空港には誰も迎えに来ていなかった)は、「なぜここに来たのかわからない。メキシコは、世界で最もシュルレア リスム的な国だ」と述べた。  1938年、メキシコでのトロツキーとブルトン しかし、メキシコ訪問は、レオン・トロツキーと出会う機会をもたらした。ブルトンと他のシュルレアリストたちは、パツクアロからエロンガリクアロの町まで 長い船旅をした。ディエゴ・リベラやフリーダ・カーロも、この知的な芸術家たちが集まる隠れたコミュニティを訪れていた。ブルトンとトロツキーは、当時の 世界情勢の中でますます困難になっていた「芸術の完全な自由」を求める「独立革命芸術宣言」(ブルトンとディエゴ・リベラの名前で発表)を共同で執筆し た。 |

| World War II and exile Breton was again in the medical corps of the French Army at the start of World War II. The Vichy government banned his writings as "the very negation of the national revolution"[24] and Breton escaped, with the help of the American Varian Fry and Hiram "Harry" Bingham IV, to the United States and the Caribbean during 1941.[25][26] He emigrated to New York City and lived there for a few years.[4] In 1942, Breton organized a groundbreaking surrealist exhibition at Yale University.[4] In 1942,[27] Breton collaborated with artist Wifredo Lam on the publication of Breton's poem "Fata Morgana", which was illustrated by Lam. Breton got to know Martinican writers Suzanne Césaire and Aimé Césaire, and later composed the introduction to the 1947 edition of Aimé Césaire's Cahier d'un retour au pays natal. During his exile in New York City he met Elisa Bindhoff, the Chilean woman who would become his third wife.[15] In 1944, he and Elisa traveled to the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec, where he wrote Arcane 17, a book which expresses his fears of World War II, describes the marvels of the Percé Rock and the extreme northeastern part of North America, and celebrates his new romance with Elisa.[15] During his visit to Haiti in 1945–46, he sought to connect surrealist politics and automatist practices with the legacies of the Haitian Revolution and the ritual practices of Vodou possession. Recent developments in Haitian painting were central to his efforts, as can be seen from a comment that Breton left in the visitors' book at the Centre d'Art in Port-au-Prince: "Haitian painting will drink the blood of the phoenix. And, with the epaulets of [Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, it will ventilate the world." Breton was specifically referring to the work of painter and Vodou priest Hector Hyppolite, whom he identified as the first artist to directly depict Vodou scenes and the lwa (Vodou deities), as opposed to hiding them in chromolithographs of Catholic saints or invoking them through impermanent vevé (abstracted forms drawn with powder during rituals). Breton's writings on Hyppolite were undeniably central to the artist's international status from the late 1940s on, but the surrealist readily admitted that his understanding of Hyppolite's art was inhibited by their lack of a common language. Returning to France with multiple paintings by Hyppolite, Breton integrated this artwork into the increased surrealist focus on the occult, myth, and magic.[28] Breton's sojourn in Haiti coincided with the overthrow of the country's president, Élie Lescot, by a radical protest movement. Breton's visit was warmly received by La Ruche, a youth journal of revolutionary art and politics, which in January 1946 published a talk given by Breton alongside a commentary which Breton described as having "an insurrectional tone". The issue concerned was suppressed by the government, sparking a student strike, and two days later, a general strike: Lescot was toppled a few days later. Among the figures associated with both La Ruche and the instigation of the revolt were the painter and photographer Gérald Bloncourt and the writers René Depestre and Jacques Stephen Alexis. In subsequent interviews Breton downplayed his personal role in the unrest, stressing that "the misery, and thus, the patience of the Haitian people, were at the breaking point" at the time and stating that "it would be absurd to say that I alone incited the fall of the government". Michael Löwy has argued that the lectures that Breton gave during his time in Haiti resonated with the youth associated with La Ruche and the student movement, resulting in them "plac(ing) them as a banner on their journal" and "t(aking) hold of them as they would a weapon". Löwy has identified three themes in Breton's talks which he believes would have struck a particular chord with the audience, namely surrealism's faith in youth, Haiti's revolutionary heritage, and a quote from Jacques Roumain extolling the revolutionary potential of the Haitian masses.[29] |

第二次世界大戦と亡命 第二次世界大戦開始時、ブルトンは再びフランス陸軍医療隊に所属していた。ヴィシー政権は、彼の著作を「国民革命の否定そのものである」として禁止 [24]、ブルトンはアメリカ人のヴァリアン・フライとハイラム・「ハリー」・ビンガム 4 世の助けを借りて、1941 年にアメリカとカリブ海諸国に逃亡した。[25][26] 彼はニューヨークに移住し、数年間過ごした[4]。1942年、ブルトンはイェール大学で画期的なシュルレアリスム展を開催した[4]。 1942年[27]、ブルトンは芸術家ウィフレド・ラムと協力して、ラムがイラストを描いたブルトンの詩「ファタ・モルガーナ」を出版した。 ブルトンは、マルティニーク島の作家スザンヌ・セゼールとエイメ・セゼールと知り合い、後にエイメ・セゼールの『故郷への帰還』の1947年版の序文を執筆した。ニューヨークに亡命中、彼は3番目の妻となるチリの女性、エリサ・ビンドホフと出会った。 1944年、エリザと共にケベック州のガスペ半島を訪れ、第二次世界大戦への恐怖を表現し、ペルセ岩と北米最北東部の驚異を描き、エリザとの新しい恋愛を謳歌した『アルカン17』を執筆した。[15] 1945年から46年にかけてハイチを訪れた際、彼はシュルレアリスムの政治とオートマティズムの実践を、ハイチ革命の遺産やヴードゥーの憑依の儀式と結 びつけようとした。彼の取り組みの中心となったのは、ハイチの絵画の最近の動向だった。これは、ブルトンがポルトープランスのセンター・ダール (Centre d'Art)の訪問者名簿に残したコメントからもわかる。「ハイチの絵画は、フェニックスの血を飲むだろう。そして、[ジャン・ジャック]・デッサライン ズの肩章を身につけて、世界中に風を吹き込むだろう」。ブルトンは、この言葉で、画家でありヴードゥーの司祭でもあるヘクトル・イポリットの作品を具体的 に指していた。ブルトンは、イポリットを、ヴードゥーの場面やルワ(ヴードゥーの神々)を、カトリックの聖人のリトグラフに隠したり、一時的なヴェヴェ (儀式で粉を使って描く抽象的な形)で呼び出したりすることなく、直接描いた最初の芸術家だと評価していた。イポリットに関するブルトンの著作は、 1940年代後半以降のこの芸術家の国際的な地位確立に間違いなく重要な役割を果たしたが、シュルレアリストであるブルトンは、イポリットの芸術に対する 理解は、両者に共通言語がないために制限されていることを率直に認めていた。イポリットの絵画を多数持ち帰ったブルトンは、この作品を、オカルト、神話、 呪術に焦点を当てたシュルレアリスムの流れに組み込んだ[28]。 ブルトンのハイチ滞在は、過激な抗議運動によるエリ・レスコット大統領の追放と重なった。ブルトンの訪問は、革命的な芸術と政治を扱う青年誌「ラ・ルッ シュ」によって温かく迎えられ、1946年1月には、ブルトンによる講演が、ブルトンが「反乱的な口調」と表現した解説とともに掲載された。この号は政府 によって抑圧され、学生ストライキを引き起こし、2日後には一般ストライキが発生。レスコットは数日後に打倒された。ラ・ルッシュと反乱の扇動に関わった 人物には、画家・写真家のジェラルド・ブロンクール、作家ルネ・デペストレ、ジャック・ステファン・アレクシスなどがいた。その後のインタビューで、ブル トンは、この騒乱における自分の役割を軽視し、「当時、ハイチの人々の貧困、そしてそれによる忍耐は限界に達していた」と強調し、「私だけが政府の転覆を 扇動したと言うのは不条理だ」と述べた。マイケル・ローウィは、ブルトンがハイチ滞在中に開催した講演は、ラ・ルシュや学生運動に関わった若者たちに共感 を呼び、「彼らの雑誌の旗印とし、武器のように手にした」と主張している。ローウィは、ブルトンの講演には、聴衆の共感を特に呼んだ3つのテーマがあった と分析している。それは、シュルレアリスムが信奉する「若者への信頼」、ハイチの革命の伝統、そしてハイチの大衆の革命の可能性を称賛したジャック・ルメ インの引用だ[29]。 |

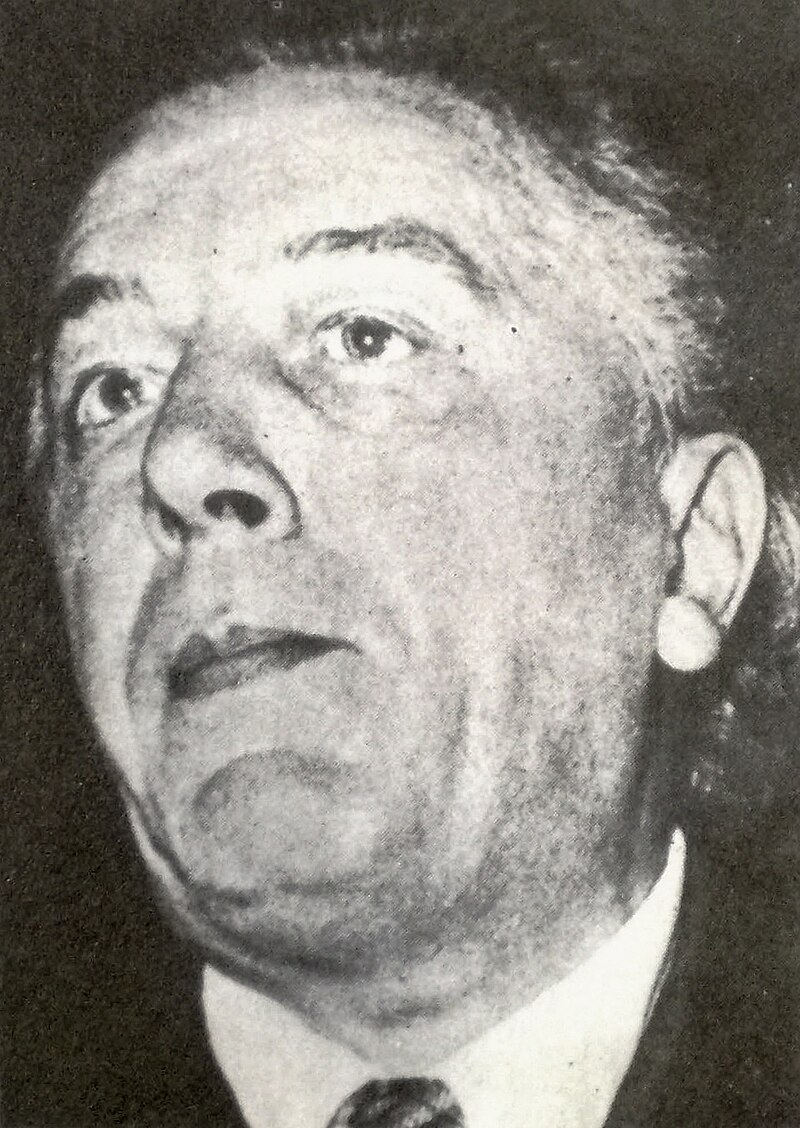

Later life Breton in the 1960s Breton returned to Paris in 1946, where he opposed French colonialism (for example as a signatory of the Manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian War) and continued, until his death, to foster a second group of surrealists in the form of expositions or reviews (La Brèche, 1961–65). In 1959, he organized an exhibit in Paris.[15] Breton consistently supported the francophone Anarchist Federation and he continued to offer his solidarity after the Platformists around founder and Secretary General Georges Fontenis transformed the FA into the Fédération communiste libertaire (FCL).[15] André Breton died at the age of 70 in 1966, and was buried in the Cimetière des Batignolles in Paris.[30] |

晩年 1960年代のブルトン 1946年にパリに戻ったブルトンは、フランス植民地主義に反対し(例えば、アルジェリア戦争反対の「121人の宣言」の署名者となった)、死まで、展覧 会や雑誌(『ラ・ブレッシュ』1961年~1965年)を通じて、シュルレアリスムの第二のグループを育成し続けた。1959年には、パリで展覧会を開催 した[15]。 ブルトンは、フランス語圏のアナキスト連盟を一貫して支援し、創設者であり書記長のジョルジュ・フォンテニスを中心としたプラットフォーム派が、FA をフェデレーション・コミューニスト・リベルテール(FCL)に変えた後も、連帯の姿勢を貫いた。 アンドレ・ブルトンは 1966 年に 70 歳で亡くなり、パリのバティニョール墓地に埋葬された。 |

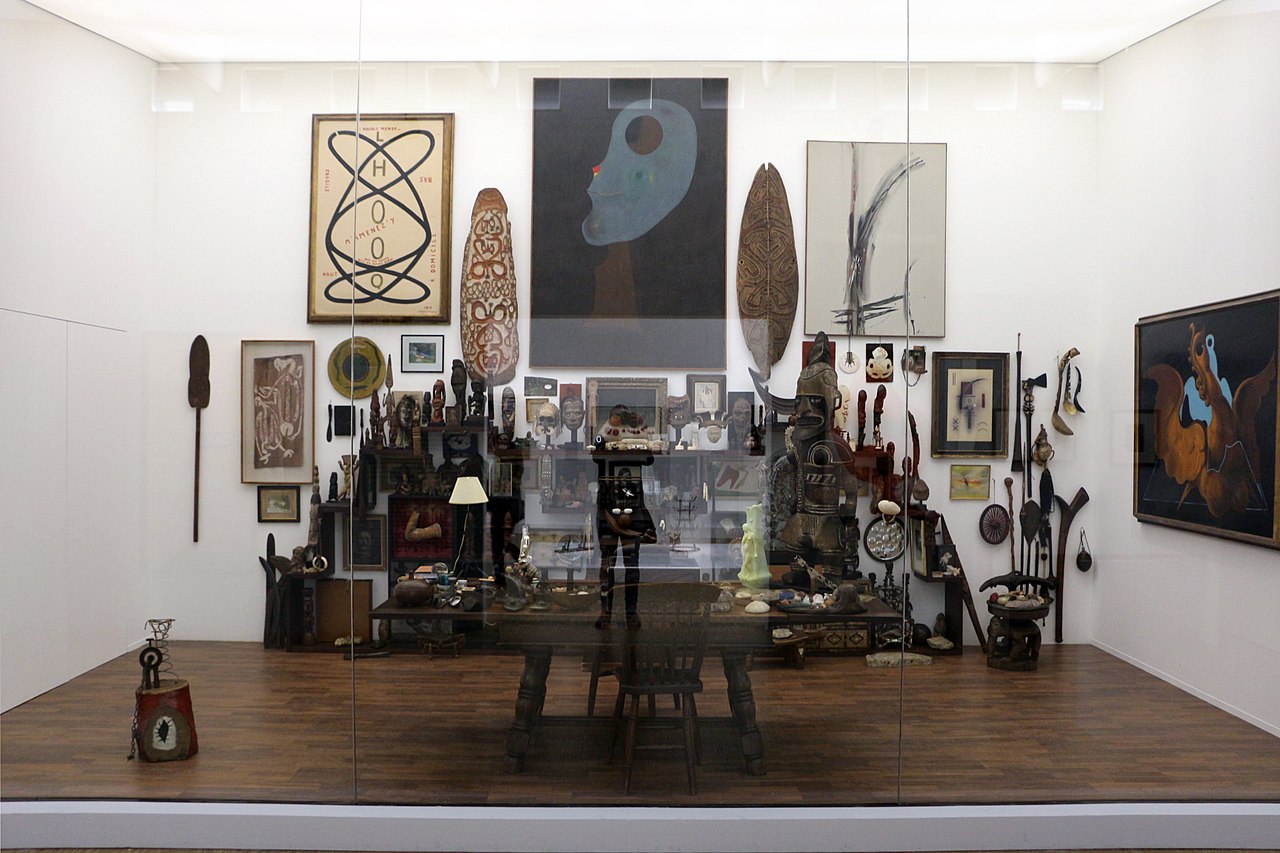

| Legacy Breton as a collector Breton was an avid collector of art, ethnographic material, and unusual trinkets. He was particularly interested in materials from the northwest coast of North America.[31] During a financial crisis he experienced in 1931, most of his collection (along with that of his friend Paul Éluard) was auctioned. He subsequently rebuilt the collection in his studio and home at 42 rue Fontaine. The collection grew to over 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art.[32] French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss endorsed Breton's skill in authentication based on their time together in 1940s New York.[16] After Breton's death on 28 September 1966, his third wife, Elisa, and his daughter, Aube, allowed students and researchers access to his archive and collection. After thirty-six years, when attempts to establish a surrealist foundation to protect the collection were opposed, the collection was auctioned by Calmels Cohen at Drouot-Richelieu. A wall of the apartment is preserved at the Centre Georges Pompidou.[33]  Reconstructed wall of Breton's studio at the Centre Pompidou Nine previously partly unpublished manuscripts, including the Manifeste du surréalisme, were auctioned by Sotheby's in May 2008.[34] |

遺産 コレクターとしてのブルトン ブルトンは、美術品、民族誌資料、珍しい小物を熱心に収集していた。彼は、北アメリカ北西海岸の資料に特に興味を持っていた[31]。1931年に経験し た経済危機の間、彼のコレクションのほとんどは(友人のポール・エリュアールのコレクションとともに)オークションにかけられた。その後、彼はフォンテー ヌ通り42番地にある自分のアトリエと自宅でコレクションを再構築した。そのコレクションは、現代絵画、素描、彫刻、写真、書籍、美術カタログ、雑誌、原 稿、大衆芸術やオセアニアの芸術作品など、5,300 点以上にまで膨れ上がった。 フランスの人類学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは、1940年代にニューヨークで過ごした時間から、ブルトンの鑑定の腕前を高く評価していた。 1966年9月28日にブルトンが死去した後、3番目の妻エリザと娘オーブは、学生や研究者に彼のアーカイブとコレクションへのアクセスを許可した。36 年後、コレクションを保護するためのシュルレアリスム財団の設立が反対されたため、コレクションはドロワ・リシュリューのカルメル・コーエン社によって競 売にかけられた。アパートの一部の壁は、ポンピドゥー・センターに保存されている。  ポンピドゥー・センターに再現されたブルトンのアトリエの壁 2008年5月、サザビーズで、「シュルレアリスム宣言」を含む、これまで一部未公開だった9点の原稿がオークションにかけられた。 |

| Personal life Breton married three times:[15] from 1921 to 1931, to Simone Collinet, née Kahn (1897–1980); from 1934 to 1943, to Jacqueline Lamba, with whom he had his only child, a daughter, Aube Elléouët Breton [fr]; from 1945 to 1966 (his death), to Elisa Bindhoff Enet. |

私生活 ブルトンは 3 回結婚した[15]。 1921 年から 1931 年まで、シモーヌ・コリーネット(旧姓カーン、1897 年 - 1980 年)と。 1934 年から 1943 年まで、ジャクリーン・ランバと。この結婚で唯一の子供である娘、オーブ・エウエット・ブルトン [fr] が生まれた。 1945年から1966年(彼の死)まで、エリザ・ビンホフ・エネトと結婚した。 |

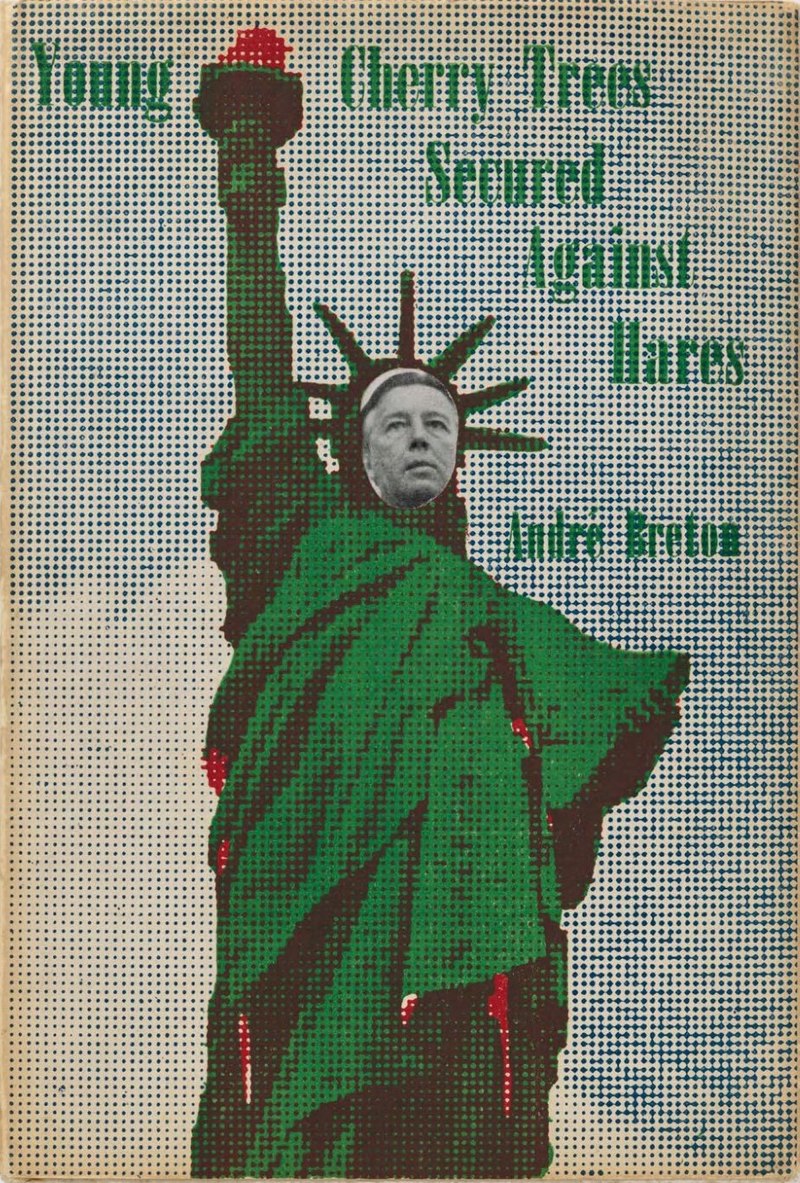

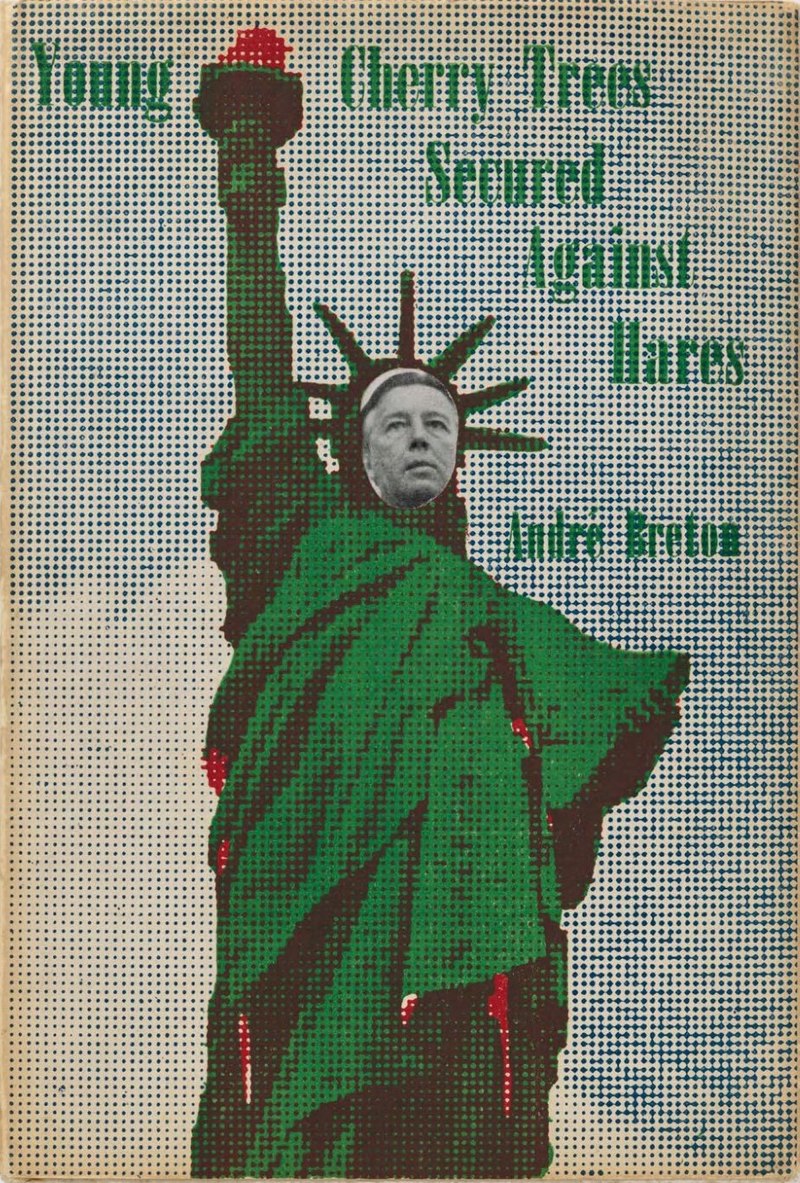

| Works 1919: Mont de piété ["Mount of piety"] 1920: S'il vous plaît – Published in English as: If You Please 1920: Les Champs magnétiques (with Philippe Soupault) – Published in English as: The Magnetic Fields 1923: Clair de terre – Published in English as: Earthlight 1924: Les Pas perdus – Published in English as: The Lost Steps 1924: Manifeste du surréalisme – Published in English as: Surrealist Manifesto 1924: Poisson soluble ["Soluble fish"] 1924: Un cadavre ["A corpse"] 1926: Légitime défense ["Legitimate defense"] 1928: Le Surréalisme et la peinture (expanded editions in 1945 and 1965) – Published in English as: Surrealism and Painting 1928: Nadja (expanded edition 1963) – Published in English as: Nadja 1930: Ralentir travaux ["Slow down, men at work"] (with René Char and Paul Éluard) 1930: Deuxième Manifeste du surréalisme – Published in English as: The Second Manifesto of Surrealism 1930: L'Immaculée Conception (with Paul Éluard) – Published in English as: Immaculate Conception 1931: L'Union libre ["Free union"] 1932: Misère de la poésie ["Poetry's misery"] 1932: Le Revolver à cheveux blancs ["The white-haired revolver"] 1932: Les Vases communicants (expanded edition 1955) – Published in English as: Communicating Vessels 1933: Le Message automatique – Published in English as: The Automatic Message 1934: Qu'est-ce que le surréalisme? – Published in English as: What Is Surrealism? 1934: Point du jour – Published in English as: Break of Day 1934: L'Air de l'eau ["The air of the water"] 1935: Position politique du surréalisme ["Political position of surrealism"] 1936: Au lavoir noir ["At the black washtub"] 1936: Notes sur la poésie ["Notes on poetry"] (with Paul Éluard) 1937: Le Château étoilé ["The starry castle"] 1937: L'Amour fou – Published in English as: Mad Love 1938: Trajectoire du rêve ["Trajectory of dream"] 1938: Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme ["Abridged dictionary of surrealism"] (with Paul Éluard) 1938: Pour un art révolutionnaire indépendant ["For an independent revolutionary art"] (with Diego Rivera) 1940: Anthologie de l'humour noir (expanded edition 1966) – Published in English as: Anthology of Black Humor 1941: "Fata morgana" (A long poem included in subsequent anthologies) 1943: Pleine marge ["Full margin"] 1944: Arcane 17 – Published in English as: Arcanum 17 1945: Situation du surréalisme entre les deux guerres ["Situation of surrealism between the two wars"]  Cover of Young Cherry Trees Secured Against Hares with a photomontage by Marcel Duchamp, 1946 1946: Yves Tanguy (monograph on Yves Tanguy) 1946: Les Manifestes du surréalisme (Expanded editions 1955 and 1962) – Published in English as: Manifestoes of Surrealism 1946: Young Cherry Trees Secured Against Hares – Jeunes cerisiers garantis contre les lièvres [Bilingual edition of poems translated by Edouard Roditi] 1947: Ode à Charles Fourier – Published in English as: Ode to Charles Fourier 1948: Martinique, charmeuse de serpents (with André Masson) – Published in English as: Martinique: Snake Charmer 1948: La Lampe dans l'horloge ["The lamp in the clock"] 1948: Poèmes 1919–48 ["Poems 1919–48"] 1949: Flagrant délit ["Red-handed"] 1952: Entretiens – Published in English as: Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism 1953: La Clé des champs – Published in English as: Free Rein 1954: Farouche à quatre feuilles ["Four-leaf feral"] (with Lise Deharme, Julien Gracq, Jean Tardieu) 1957: L'Art magique – Published in English as: Magical Art 1959: Constellations (with Joan Miró) – Published in English as: Constellations 1961: Le la ["The A"] 1966: Clair de terre (Anthology of poems 1919–1936) – Published in English as: Earthlight 1968: Signe ascendant (Anthology of poems 1935–1961) ["Ascendant sign"] 1970: Perspective cavalière – [Literally: Cavalier perspective] 1988: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 1 ["Breton: The Complete Works, tome 1"] 1992: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 2 ["Breton: The Complete Works, tome 2"] 1999: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 3 ["Breton: The Complete Works, tome 3"] |

作品 1919年:モン・ド・ピエテ(「慈悲の山」) 1920年:S'il vous plaît(英語版タイトル:If You Please 1920年:Les Champs magnétiques(フィリップ・スーポーと共著)(英語版タイトル:The Magnetic Fields 1923年:Clair de terre(英語版タイトル:Earthlight 1924年:『失われた歩み』 – 英語版タイトル:『The Lost Steps』 1924年:『シュルレアリスム宣言』 – 英語版タイトル:『Surrealist Manifesto』 1924年:『溶ける魚』 1924年:『死体』 1926年:『正当防衛』 1928: Le Surréalisme et la peinture(1945年と1965年に増補版発行) – 英語版タイトル: Surrealism and Painting 1928: Nadja(1963年に増補版発行) – 英語版タイトル: Nadja 1930: Ralentir travaux [「作業員、作業を遅らせろ」](ルネ・シャルとポール・エリュアールとの共著) 1930年:『シュルレアリスムの第二宣言』 – 英語版タイトル:『The Second Manifesto of Surrealism』 1930年:『無原罪の受胎』(ポール・エリュアールと共著) – 英語版タイトル:『Immaculate Conception』 1931年:『自由連合』 1932年:『詩の悲惨』 1932年:『白い髪の拳銃』 1932年:『連通する壺』(1955年増補版) – 英語版タイトル:『Communicating Vessels』 1933年:『自動メッセージ』 – 英語版タイトル:『The Automatic Message』 1934年:『シュルレアリスムとは何か?』 – 英語版タイトル:『What Is Surrealism?』 1934: Point du jour – 英語版タイトル: Break of Day 1934: L『Air de l』eau [「水の空気」] 1935: Position politique du surréalisme [「シュルレアリスムの政治的立場」] 1936: Au lavoir noir [「黒い洗濯桶で」] 1936: 詩に関するノート [「Notes on poetry」](ポール・エリュアールと共著) 1937: 星の城 [「The starry castle」] 1937: 狂愛 – 英語版タイトル: Mad Love 1938: 夢の軌跡 [「Trajectory of dream」] 1938年:『シュルレアリスムの略語辞典』 (ポール・エリュアールとの共著) 1938年:『独立した革命芸術のために』 (ディエゴ・リベラとの共著) 1940年:『ブラック・ユーモアのアンソロジー』 (1966年に増補版発行) – 英語版タイトル:『Anthology of Black Humor』 1941年:「ファタ・モルガナ」(後のアンソロジーに収録された長編詩 1943年:『プレイン・マルジュ』 [「完全な余白」 1944年:『アルカネ 17』 – 英語版は『アルカヌム 17』として出版 1945年:『2つの戦争間のシュルレアリスムの状況』  マルセル・デュシャンのフォトモンタージュを表紙に採用した『ウサギから守る若い桜の木』の表紙、1946年 1946: イヴ・タンギー(イヴ・タンギーのモノグラフ) 1946: 『シュルレアリスムの宣言』(1955年と1962年に拡大版発行) – 英語版タイトル:『シュルレアリスムの宣言』 1946年:『若桜を野ウサギから守る』 – Jeunes cerisiers garantis contre les lièvres [エドゥアール・ロディティ訳の詩の二言語版] 1947年:『シャルル・フーリエへのオード』 – 英語版タイトル:『Ode to Charles Fourier』 1948年:『マルティニーク、蛇使い』(アンドレ・マッソンとの共作) – 英語版タイトル:『Martinique: Snake Charmer』 1948年:『時計の中のランプ』 1948年:『1919年から1948年の詩』 1949年:『現行犯』 1952年:『対話』 – 英語版は『Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism』として出版 1953年:『La Clé des champs』 – 英語版『Free Rein』 1954年:『Farouche à quatre feuilles』 [「四つ葉の野獣」] (リズ・デアルム、ジュリアン・グラック、ジャン・タルデューとの共著) 1957年:『L'Art magique』 – 英語版『Magical Art』 1959年:『Constellations』 (ジョアン・ミロとの共著) – 英語版『Constellations』 1961年:『レ・ラ』 [「The A」] 1966年:『クレール・ド・テール』(1919年~1936年の詩集) – 英語版タイトル:『アースライト』 1968年:『シグネ・アサンダン』(1935年~1961年の詩集) [「アセンダント・サイン」] 1970年:『パースペクティブ・キャバリエール』 – [直訳:騎士の視点] 1988年:ブルトン:全作品、第1巻 [「ブルトン:全作品、第1巻」] 1992年:ブルトン:全作品、第2巻 [「ブルトン:全作品、第2巻」] 1999年:ブルトン:全作品、第3巻 [「ブルトン:全作品、第3巻」] |

| Anti-art Hector Hyppolite |

反芸術 ヘクター・イポリット |

| André Breton: Surrealism and Painting – edited and with an introduction by Mark Polizzotti. Manifestoes of Surrealism by André Breton, translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. ISBN 0-472-06182-8 |

アンドレ・ブルトン:シュルレアリスムと絵画 – マーク・ポリゾッティ編集、序文。 シュルレアリスム宣言、アンドレ・ブルトン著、リチャード・シーバー、ヘレン・R・レーン訳。ISBN 0-472-06182-8 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9_Breton |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆