動物の意識

Animal consciousness

According

to the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, "near human-like levels

of consciousness" have been observed in the grey parrot.

☆ 動 物意識(どうぶついしき、英: animal awareness)とは、動物の自己認識の質または状態のことであり、外部の物体や動物自身の中にある何かを認識している状態のことである。人間の場 合、意識とは、感覚、認識、主観性、クオリア、経験する能力、感じる能力、覚醒、自我の感覚を持つこと、心の実行制御システムなどと定義 されている。動物の意識というテーマは、多くの困難を抱えている。動物には人間の言葉を使う能力がないため、自分たちの経験について語ることができないからである。ま た、動物に意識があることを否定することは、動物には感情がなく、その生命には価値がなく、動物に危害を加えることは道徳的に間違っていないということを 意味するように受け取られがちであるため、この問題を客観的に推論することは難しい。観的な経験こそが意識の本質であると考える哲学者は、一般的に、相関関係として、動物の意識の存在と本質を厳密に知ることはできないと考える。アメリカの 哲学者トーマス・ナーゲルは、『コウモリになるとはどういうことか』と題した影響力のあるエッセイの中で、このような見解を述べている。そして、動物の脳 や行動についてどれだけ知っていたとしても、動物の心の中に入り込み、彼らが自分自身と同じように彼らの世界を体験することはできないと主張した。2012年、神経科学者のグループは、「意識を生成する神経学的基質を持っているという点で、ヒトが唯一無二の存在ではない」と「明白に」主張する「意識 に関するケンブリッジ宣言」に署名した。すべての哺乳類と鳥類を含む人間以外の動物、そしてタコを含む他の多くの生物もまた、これらの神経基質を持ってい る」。

| Animal consciousness, or animal awareness,

is the quality or state of self-awareness within an animal, or of being

aware of an external object or something within itself.[2][3] In

humans, consciousness has been defined as: sentience, awareness,

subjectivity, qualia, the ability to experience or to feel,

wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control

system of the mind.[4] Despite the difficulty in definition, many

philosophers believe there is a broadly shared underlying intuition

about what consciousness is.[5] The topic of animal consciousness is beset with a number of difficulties. It poses the problem of other minds in an especially severe form because animals, lacking the ability to use human language, cannot tell us about their experiences.[6] Also, it is difficult to reason objectively about the question, because a denial that an animal is conscious is often taken to imply that they do not feel, their life has no value, and that harming them is not morally wrong.[7] The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes, for example, has sometimes been criticised for providing a rationale for the mistreatment of animals because he argued that only humans are conscious.[8] Philosophers who consider subjective experience the essence of consciousness also generally believe, as a correlate, that the existence and nature of animal consciousness can never rigorously be known. The American philosopher Thomas Nagel spelled out this point of view in an influential essay titled What Is it Like to Be a Bat?. He said that an organism is conscious "if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism—something it is like for the organism"; and he argued that no matter how much we know about an animal's brain and behavior, we can never really put ourselves into the mind of the animal and experience their world in the way they do themself.[9] Other thinkers, such as the cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter, dismiss this argument as incoherent.[10] Several psychologists and ethologists have argued for the existence of animal consciousness by describing a range of behaviors that appear to show animals holding beliefs about things they cannot directly perceive—Walter Veit's 2023 book A Philosophy for the Science of Animal Consciousness reviews a substantial portion of the evidence.[3] Animal consciousness has been actively researched for over one hundred years.[11] In 1927, the American functional psychologist Harvey Carr argued that any valid measure or understanding of awareness in animals depends on "an accurate and complete knowledge of its essential conditions in man".[12] A more recent review concluded in 1985 that "the best approach is to use experiment (especially psychophysics) and observation to trace the dawning and ontogeny of self-consciousness, perception, communication, intention, beliefs, and reflection in normal human fetuses, infants, and children".[11] In 2012, a group of neuroscientists signed the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, which "unequivocally" asserted that "humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neural substrates."[13] |

動

物意識(どうぶついしき、英: animal

awareness)とは、動物の自己認識の質または状態のことであり、外部の物体や動物自身の中にある何かを認識している状態のことである[2]

[3]。人間の場合、意識とは、感覚、認識、主観性、クオリア、経験する能力、感じる能力、覚醒、自我の感覚を持つこと、心の実行制御システムなどと定義

されている[4]。 動物の意識というテーマは、多くの困難を抱えている。動物には人間の言葉を使う能力がないため、自分たちの経験について語ることができないからである。ま た、動物に意識があることを否定することは、動物には感情がなく、その生命には価値がなく、動物に危害を加えることは道徳的に間違っていないということを 意味するように受け取られがちであるため、この問題を客観的に推論することは難しい。 [例えば、17世紀のフランスの哲学者ルネ・デカルトは、人間だけが意識を持つと主張したため、動物を虐待する根拠を与えたと批判されることがある [8]。 主観的な経験こそが意識の本質であると考える哲学者は、一般的に、相関関係として、動物の意識の存在と本質を厳密に知ることはできないと考える。アメリカ の哲学者トーマス・ナーゲルは、『コウモリになるとはどういうことか』と題した影響力のあるエッセイの中で、このような見解を述べている。そして、動物の 脳や行動についてどれだけ知っていたとしても、動物の心の中に入り込み、彼らが自分自身と同じように彼らの世界を体験することはできないと主張した。 [認知科学者ダグラス・ホフスタッターのような他の思想家は、この議論を支離滅裂なものとして退けている[10]。何人かの心理学者や倫理学者は、動物が 直接知覚できないものについての信念を抱いていることを示すと思われる様々な行動について説明することによって、動物の意識の存在を主張してきた。 1927年、アメリカの機能心理学者ハーヴェイ・カーは、動物における意識の有効な測定や理解は、「人間における意識の本質的条件についての正確で完全な 知識」にかかっていると主張した。 [12]より最近のレビューでは、1985年に「最良のアプローチは、実験(特に心理物理学)と観察を用いて、正常なヒトの胎児、乳児、子どもにおける自 己意識、知覚、コミュニケーション、意図、信念、内省の黎明期と先天性を追跡することである」と結論づけている[11]。2012年、神経科学者のグルー プは、「意識を生成する神経学的基質を持っているという点で、ヒトが唯一無二の存在ではない」と「明白に」主張する「意識に関するケンブリッジ宣言」に署 名した。すべての哺乳類と鳥類を含む人間以外の動物、そしてタコを含む他の多くの生物もまた、これらの神経基質を持っている」[13]。 |

Philosophical background René Descartes argued that only humans are conscious, and not other animals. The mind–body problem in philosophy examines the relationship between mind and matter, and in particular the relationship between consciousness and the brain. A variety of approaches have been proposed. Most are either dualist or monist. Dualism maintains a rigid distinction between the realms of mind and matter. Monism maintains that there is only one kind of stuff, and that mind and matter are both aspects of it. The problem was addressed by pre-Aristotelian philosophers,[14][15] and was famously addressed by René Descartes in the 17th century, resulting in Cartesian dualism. Descartes believed that humans only, and not other animals have this non-physical mind. The rejection of the mind–body dichotomy is found in French Structuralism, and is a position that generally characterized post-war French philosophy.[16] The absence of an empirically identifiable meeting point between the non-physical mind and its physical extension has proven problematic to dualism and many modern philosophers of mind maintain that the mind is not something separate from the body.[17] These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology, and the neurosciences.[18][19][20][21] Epiphenomenalism Main article: Epiphenomenalism Epiphenomenalism is the theory in philosophy of mind that mental phenomena are caused by physical processes in the brain or that both are effects of a common cause, as opposed to mental phenomena driving the physical mechanics of the brain. The impression that thoughts, feelings, or sensations cause physical effects, is therefore to be understood as illusory to some extent. For example, it is not the feeling of fear that produces an increase in heart beat, both are symptomatic of a common physiological origin, possibly in response to a legitimate external threat.[22] The history of epiphenomenalism goes back to the post-Cartesian attempt to solve the riddle of Cartesian dualism, i.e., of how mind and body could interact. La Mettrie, Leibniz and Spinoza all in their own way began this way of thinking. The idea that even if the animal were conscious nothing would be added to the production of behavior, even in animals of the human type, was first voiced by La Mettrie (1745), and then by Cabanis (1802), and was further explicated by Hodgson (1870) and Huxley (1874).[23][24] Huxley (1874) likened mental phenomena to the whistle on a steam locomotive. However, epiphenomenalism flourished primarily as it found a niche among methodological or scientific behaviorism. In the early 1900s scientific behaviorists such as Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and B. F. Skinner began the attempt to uncover laws describing the relationship between stimuli and responses, without reference to inner mental phenomena. Instead of adopting a form of eliminativism or mental fictionalism, positions that deny that inner mental phenomena exist, a behaviorist was able to adopt epiphenomenalism in order to allow for the existence of mind. However, by the 1960s, scientific behaviourism met substantial difficulties and eventually gave way to the cognitive revolution. Participants in that revolution, such as Jerry Fodor, reject epiphenomenalism and insist upon the efficacy of the mind. Fodor even speaks of "epiphobia"—fear that one is becoming an epiphenomenalist. Thomas Henry Huxley defends in an essay titled On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History an epiphenomenalist theory of consciousness according to which consciousness is a causally inert effect of neural activity—"as the steam-whistle which accompanies the work of a locomotive engine is without influence upon its machinery".[25] To this William James objects in his essay Are We Automata? by stating an evolutionary argument for mind-brain interaction implying that if the preservation and development of consciousness in the biological evolution is a result of natural selection, it is plausible that consciousness has not only been influenced by neural processes, but has had a survival value itself; and it could only have had this if it had been efficacious.[26][27] Karl Popper develops in the book The Self and Its Brain a similar evolutionary argument.[28] Animal ethics Bernard Rollin of Colorado State University, the principal author of two U.S. federal laws regulating pain relief for animals, writes that researchers remained unsure into the 1980s as to whether animals experience pain, and veterinarians trained in the U.S. before 1989 were simply taught to ignore animal pain.[29] In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, Rollin asserts that he was regularly asked to prove animals are conscious and provide scientifically acceptable grounds for claiming they feel pain.[29] The denial of animal consciousness by scientists has been described as mentophobia by Donald Griffin.[30] Academic reviews of the topic are equivocal, noting that the argument that animals have at least simple conscious thoughts and feelings has strong support,[31] but some critics continue to question how reliably animal mental states can be determined.[32][33] A refereed journal Animal Sentience[34] launched in 2015 by the Institute of Science and Policy of The Humane Society of the United States is devoted to research on this and related topics. |

哲学的背景 ルネ・デカルトは、意識があるのは人間だけで、他の動物にはないと主張した。 哲学における心身問題とは、心と物質の関係、特に意識と脳の関係を考察するものである。様々なアプローチが提案されている。多くは二元論か一元論である。 二元論は心と物質の領域を厳密に区別する。一元論は、物質は一種類しか存在せず、心と物質はその両方の側面であると主張する。この問題はアリストテレス以 前の哲学者たちによって扱われ[14][15]、17世紀にルネ・デカルトによって扱われたことで有名であり、その結果デカルトの二元論が生まれた。デカ ルトは、この非物理的な心を持っているのは人間だけで、他の動物は持っていないと考えた。 非物理的な心とその物理的な延長との間に経験的に識別可能な会合点が存在しないことは二元論にとって問題であることが証明されており、現代の多くの心の哲 学者は心は身体から切り離されたものではないと主張している[17]。 [17]このようなアプローチは科学、特に社会生物学、コンピュータ科学、進化心理学、神経科学の分野で特に大きな影響力を持っている[18][19] [20][21]。 エピフェノメナリズム 主な記事 エピフェノメナリズム エピフェノメナリズム(Epiphenomenalism)とは、心の哲学における理論であり、精神現象が脳の物理的力学を駆動するのとは対照的に、精神 現象は脳の物理的プロセスによって引き起こされる、あるいは両者は共通の原因の結果であるとする。したがって、思考や感情、感覚が物理的効果を引き起こす という印象は、ある程度幻想的なものと理解される。例えば、心拍の増加をもたらすのは恐怖の感情ではなく、どちらも共通の生理学的起源を示す症状であり、 おそらくは正当な外部からの脅威に対する反応である[22]。 エピフェノメナリズムの歴史は、デカルトの二元論の謎、すなわち心と身体がどのように相互作用しうるのかという謎を解こうとしたカルト以後の試みにまで遡 る。ラ・メトリ、ライプニッツ、スピノザはみな、それぞれのやり方でこの考え方を始めた。動物に意識があったとしても、人間型の動物であっても、行動の生 成には何も付加されないという考えは、ラ・メトリ(1745年)によって最初に表明され、次いでカバニス(1802年)によって表明され、さらにホジソン (1870年)とハクスリー(1874年)によって説明された[23][24]。ハクスリー(1874年)は精神現象を蒸気機関車の汽笛になぞらえた。し かし、エピフェノメナリズムは主に方法論的行動主義や科学的行動主義の中にニッチを見出すことで繁栄した。1900年代初頭、イワン・パブロフ、ジョン・ B・ワトソン、B・F・スキナーといった科学的行動主義者たちは、内面的な心的現象に言及することなく、刺激と反応の関係を記述する法則を明らかにする試 みを始めた。内的な心的現象の存在を否定する立場である排除主義や心的虚構主義を採用する代わりに、行動主義者は心の存在を認めるためにエピフェノメナリ ズムを採用することができた。しかし1960年代になると、科学的行動主義は大きな困難に直面し、やがて認知革命に道を譲ることになる。ジェリー・フォ ドーのようなその革命の参加者は、エピフェノメナリズムを否定し、心の有効性を主張する。フォドーは「エピフォビア」(自分がエピフェノメナリストになり つつあるのではないかという恐れ)さえ口にする。 トマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリーは『動物はオートマタであるという仮説とその歴史について』と題するエッセイの中で、意識は神経活動の因果的に不活性な効果 であるとするエピフェノメナリズムの意識理論を擁護している。もし生物学的進化における意識の保存と発展が自然淘汰の結果であるならば、意識は神経プロセ スの影響を受けてきただけでなく、それ自体に生存価値があったというのはもっともなことである。 動物倫理学 コロラド州立大学のバーナード・ロリンは、動物の苦痛緩和を規制する2つの米国連邦法の主執筆者であるが、研究者は1980年代になっても動物が痛みを感 じるかどうか確信が持てないままであり、1989年以前に米国で訓練された獣医師は単に動物の痛みを無視するように教えられていたと書いている[29]。 科学者や他の獣医師との交流の中で、ロリンは動物に意識があることを証明し、動物が痛みを感じると主張する科学的に許容できる根拠を示すよう定期的に求め られたと主張している。 [29]科学者による動物の意識の否定は、ドナルド・グリフィンによって精神恐怖症と表現されている[30]。このトピックに関する学術的な論評は、動物 が少なくとも単純な意識的思考や感情を持っているという主張が強い支持を得ている[31]としながらも、動物の精神状態をどの程度確実に決定することがで きるかを疑問視し続ける批評家もいる[32][33]。 米国動物愛護協会の科学政策研究所によって2015年に創刊された査読付き学術誌「Animal Sentience」[34]は、このトピックと関連するトピックに関する研究に専念している。 |

| Defining consciousness About forty meanings attributed to the term consciousness can be identified and categorized based on functions and experiences. The prospects for reaching any single, agreed-upon, theory-independent definition of consciousness appear remote.[35] Consciousness is an elusive concept that presents many difficulties when attempts are made to define it.[36][37] Its study has progressively become an interdisciplinary challenge for numerous researchers, including ethologists, neurologists, cognitive neuroscientists, philosophers, psychologists and psychiatrists.[38][39] In 1976 Richard Dawkins wrote, "The evolution of the capacity to simulate seems to have culminated in subjective consciousness. Why this should have happened is, to me, the most profound mystery facing modern biology".[40] In 2004, eight neuroscientists felt it was still too soon for a definition. They wrote an apology in "Human Brain Function":[41] "We have no idea how consciousness emerges from the physical activity of the brain and we do not know whether consciousness can emerge from non-biological systems, such as computers... At this point the reader will expect to find a careful and precise definition of consciousness. You will be disappointed. Consciousness has not yet become a scientific term that can be defined in this way. Currently we all use the term consciousness in many different and often ambiguous ways. Precise definitions of different aspects of consciousness will emerge ... but to make precise definitions at this stage is premature." Consciousness is sometimes defined as the quality or state of being aware of an external object or something within oneself.[42][43] It has been defined somewhat vaguely as: subjectivity, awareness, sentience, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind.[4] Despite the difficulty in definition, many philosophers believe that there is a broadly shared underlying intuition about what consciousness is.[5] Max Velmans and Susan Schneider wrote in The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness: "Anything that we are aware of at a given moment forms part of our consciousness, making conscious experience at once the most familiar and most mysterious aspect of our lives."[44] Related terms, also often used in vague or ambiguous ways, are: Awareness: the state or ability to perceive, to feel, or to be conscious of events, objects, or sensory patterns. In this level of consciousness, sense data can be confirmed by an observer without necessarily implying understanding. More broadly, it is the state or quality of being aware of something. In biological psychology, awareness is defined as a human's or an animal's perception and cognitive reaction to a condition or event. Self-awareness: the capacity for introspection and the ability to reconcile oneself as an individual separate from the environment and other individuals. Self-consciousness: an acute sense of self-awareness. It is a preoccupation with oneself, as opposed to the philosophical state of self-awareness, which is the awareness that one exists as an individual being; although some writers use both terms interchangeably or synonymously.[45] Sentience: the ability to be aware (feel, perceive, or be conscious) of one's surroundings or to have subjective experiences. Sentience is a minimalistic way of defining consciousness, which is otherwise commonly used to collectively describe sentience plus other characteristics of the mind. Sapience: often defined as wisdom, or the ability of an organism or entity to act with appropriate judgment, a mental faculty which is a component of intelligence or alternatively may be considered an additional faculty, apart from intelligence, with its own properties. Qualia: individual instances of subjective, conscious experience. Sentience (the ability to feel, perceive, or to experience subjectivity) is not the same as self-awareness (being aware of oneself as an individual). The mirror test is sometimes considered to be an operational test for self-awareness, and the handful of animals that have passed it are often considered to be self-aware.[46][47] It remains debatable whether recognition of one's mirror image can be properly construed to imply full self-awareness,[48] particularly given that robots are being constructed which appear to pass the test.[49][50] Much has been learned in neuroscience about correlations between brain activity and subjective, conscious experiences, and many suggest that neuroscience will ultimately explain consciousness; "...consciousness is a biological process that will eventually be explained in terms of molecular signaling pathways used by interacting populations of nerve cells...".[51] However, this view has been criticized because consciousness has yet to be shown to be a process,[52] and the so-called "hard problem" of relating consciousness directly to brain activity remains elusive.[53] |

意識の定義 意識という言葉には、機能や経験に基づいて約40の意味があり、分類することができる。意識について、単一の、合意された、理論に依存しない定義に到達する見込みは遠いようである[35]。 意識はとらえどころのない概念であり、それを定義しようとすると多くの困難が生じる[36][37]。その研究は、倫理学者、神経学者、認知神経科学者、哲学者、心理学者、精神科医など、多くの研究者にとって学際的な課題となっている[38][39]。 1976年、リチャード・ドーキンスは「シミュレーション能力の進化は、主観的意識に結実したようだ。2004年、8人の神経科学者は定義するにはまだ早すぎると感じていた。彼らは『ヒトの脳機能』に次のような謝罪文を書いた[41]。 「脳の物理的活動から意識がどのように出現するのか、またコンピュータのような非生物学的システムから意識が出現するのかどうか、私たちにはわからない。 この時点で読者は、意識の慎重かつ正確な定義を期待するだろう。がっかりするだろう。意識はまだ、このように定義できる科学用語にはなっていない。現在、 私たちは皆、意識という言葉をさまざまに、そしてしばしば曖昧に使っている。意識のさまざまな側面について、正確な定義が出てくるだろう......しか し、現段階で正確な定義をするのは時期尚早だ」。 意識とは、外的な対象や自分自身の中にある何かを認識している性質や状態であると定義されることがある[42][43]。主観性、意識、感覚、経験する能 力や感じる能力、覚醒、自我の感覚を持つこと、心の実行制御システムなど、やや曖昧に定義されている: 「私たちがある瞬間に意識しているものはすべて私たちの意識の一部を形成しており、意識的な経験は私たちの人生において最も身近であると同時に最も神秘的 な側面となっている」[44]。 また、関連する用語として、漠然とした、あるいは曖昧な使われ方をすることが多いのは、以下のようなものである: 意識:出来事や物体、感覚パターンを知覚したり、感じたり、意識したりする状態や能力。この意識レベルでは、必ずしも理解を意味することなく、感覚データ を観察者が確認することができる。より広義には、何かに気づいている状態や質である。生物学的心理学では、意識とはある状態や出来事に対する人間や動物の 知覚や認知的反応と定義される。 自己認識:内観の能力であり、環境や他の個人から切り離された個人として自己を調整する能力。 自己意識:自己認識の鋭い感覚。哲学的な自己認識の状態とは対照的に、自己意識は自分自身に夢中になることであり、自分が個々の存在として存在していることを認識することである。 感覚:自分の周囲の環境を認識する(感じる、知覚する、意識する)能力、または主観的な経験をする能力。感覚は意識を定義するための最小限の方法であり、それ以外は一般に、感覚と心の他の特性を総称して表すのに用いられる。 サピエンス:しばしば知恵、または適切な判断力をもって行動する生物や実体の能力と定義され、知能の構成要素である精神的能力、あるいは知能とは別に、独自の特性をもつ付加的な能力とみなされることもある。 クオリア:主観的で意識的な経験の個々の事例。 感覚(主観を感じたり、知覚したり、経験したりする能力)は自己認識(自分自身を個人として認識すること)とは異なる。鏡テストは自己認識のための実用的 なテストであると考えられていることがあり、これに合格した一握りの動物はしばしば自己認識していると考えられている[46][47]。自分の鏡像を認識 することが、完全な自己認識を意味すると適切に解釈できるかどうかは議論の余地がある[48]。 脳活動と主観的で意識的な経験との間の相関関係については神経科学において多くのことが学ばれており、神経科学が最終的に意識を説明することになるだろうと多くの人が示唆している。 |

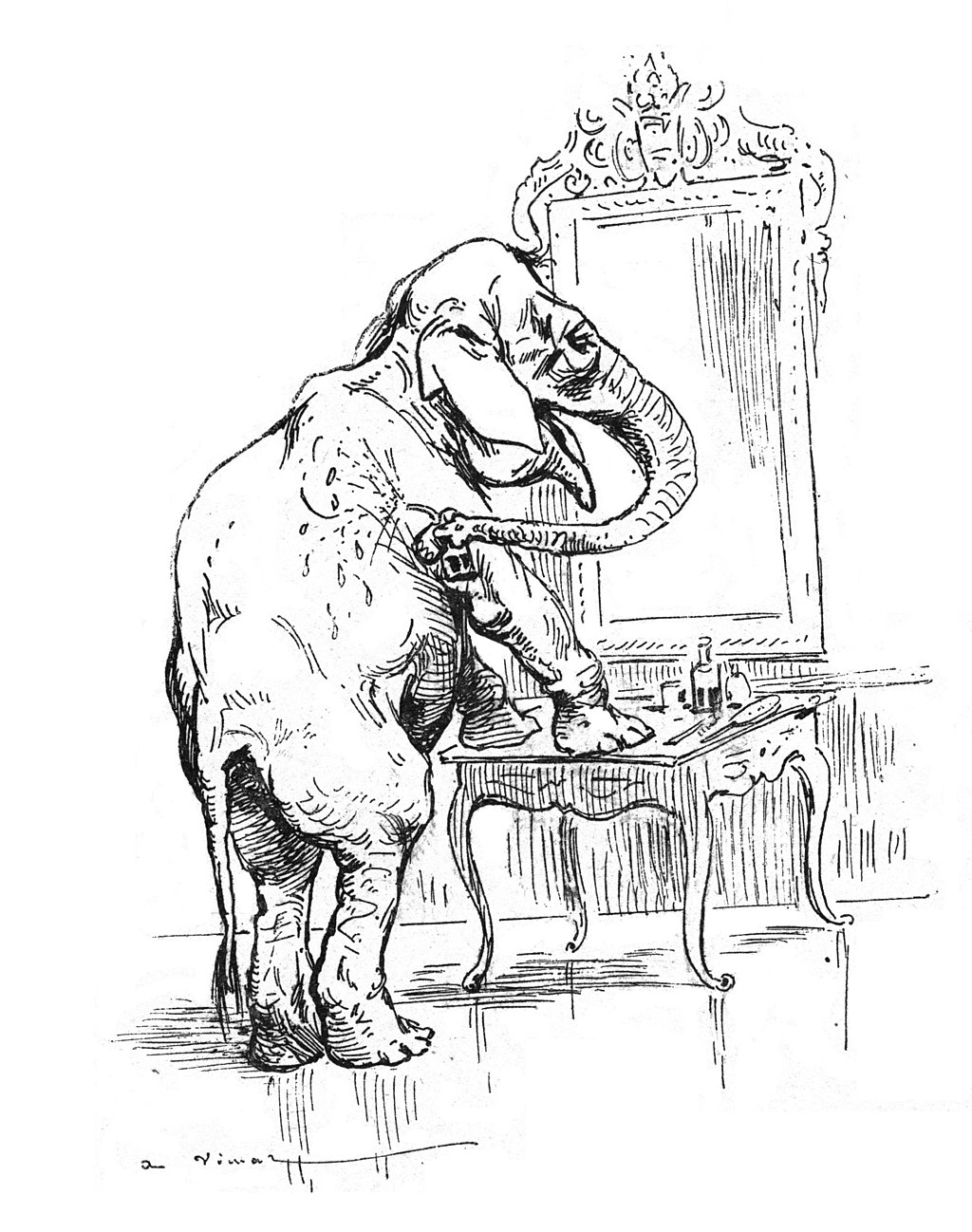

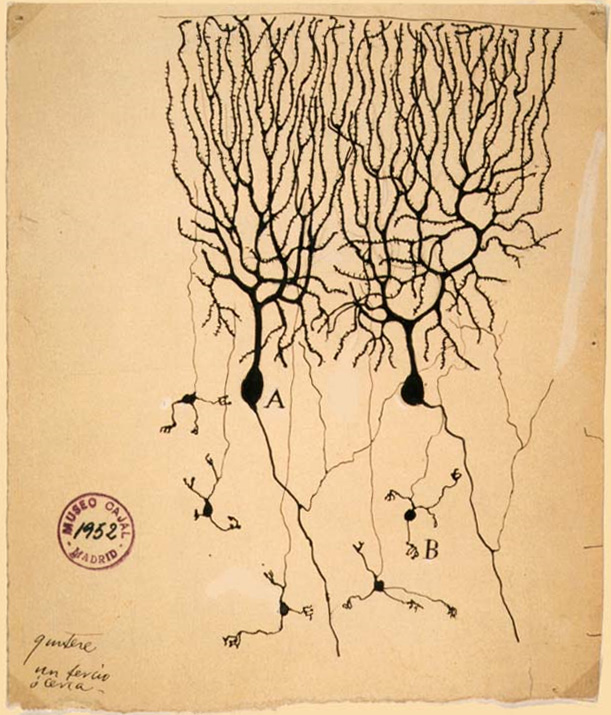

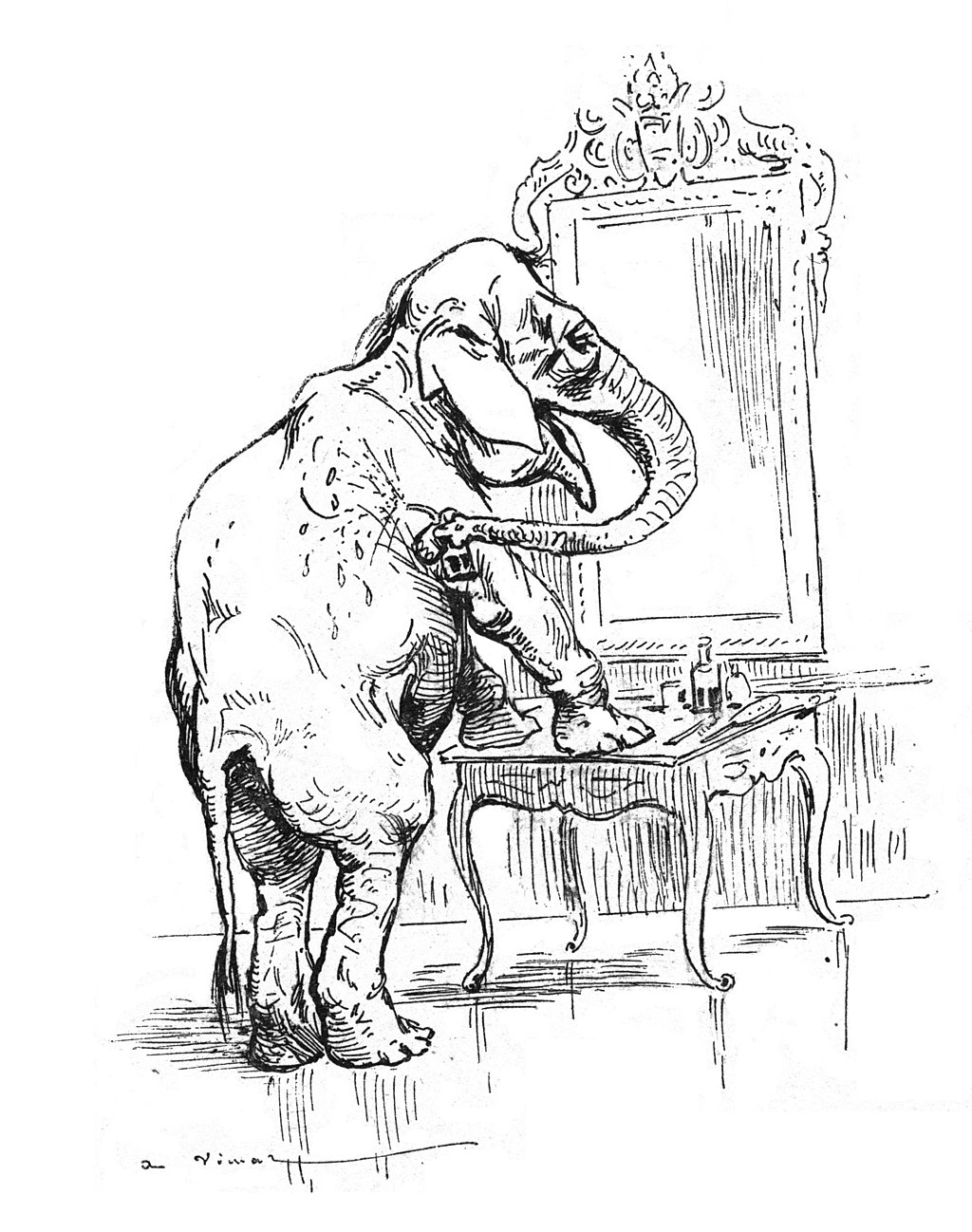

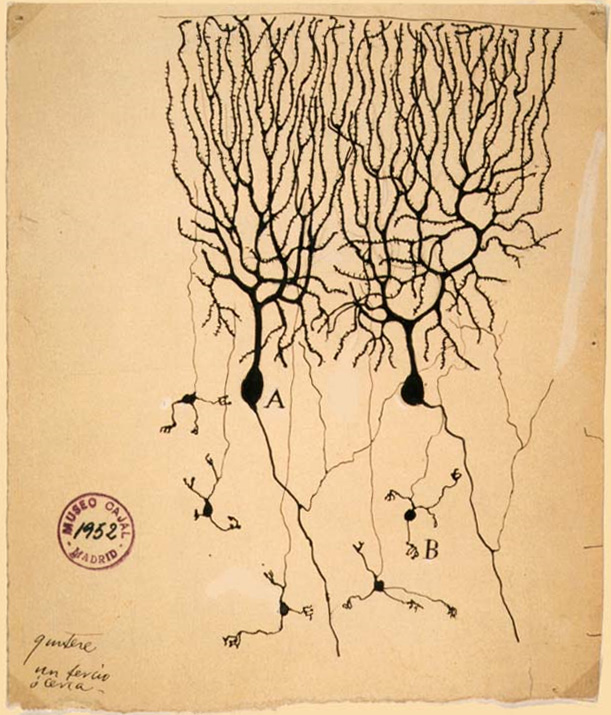

| Scientific approaches Since Descartes's proposal of dualism, it became a general consensus that the mind had become a matter of philosophy and that science was not able to penetrate the issue of consciousness – that consciousness was outside of space and time. However, in recent decades many scholars have begun to move toward a science of consciousness. Antonio Damasio and Gerald Edelman are two neuroscientists who have led the move to neural correlates of the self and of consciousness. Damasio has demonstrated that emotions and their biological foundation play a critical role in high level cognition,[54][55] and Edelman has created a framework for analyzing consciousness through a scientific outlook. The current problem consciousness researchers face involves explaining how and why consciousness arises from neural computation.[56][57] In his research on this problem, Edelman has developed a theory of consciousness, in which he has coined the terms primary consciousness and secondary consciousness.[58][59] Eugene Linden, author of The Parrot's Lament suggests there are many examples of animal behavior and intelligence that surpass what people would suppose to be the boundary of animal consciousness. Linden contends that in many of these documented examples, a variety of animal species exhibit behavior that can only be attributed to emotion, and to a level of consciousness that we would normally ascribe only to our own species.[60] Philosopher Daniel Dennett counters that: Consciousness requires a certain kind of informational organization that does not seem to be 'hard-wired' in humans, but is instilled by human culture. Moreover, consciousness is not a black-or-white, all-or-nothing type of phenomenon, as is often assumed. The differences between humans and other species are so great that speculations about animal consciousness seem ungrounded. Many authors simply assume that an animal like a bat has a point of view, but there seems to be little interest in exploring the details involved.[61] Consciousness in mammals (including humans) is an aspect of the mind generally thought to comprise qualities such as subjectivity, sentience, and the ability to perceive the relationship between oneself and one's environment. It is a subject of much research in philosophy of mind, psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science. Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is subjective experience itself, and access consciousness, which refers to the global availability of information to processing systems in the brain.[62] Phenomenal consciousness has many different experienced qualities, often referred to as qualia. Phenomenal consciousness is usually consciousness of something or about something, a property known as intentionality in philosophy of mind.[62] In humans, there are three common methods of studying consciousness: verbal reporting, behavioural demonstrations, and neural correlation with conscious activity, though these can only be generalized to non-human taxa with varying degrees of difficulty.[63] In a new study conducted in rhesus monkeys, Ben-Haim and his team used a process dissociation approach that predicted opposite behavioral outcomes for the two modes of perception. They found that monkeys displayed exactly the same opposite behavioral outcomes as humans when they were aware or unaware of the stimuli presented.[64] Mirror test  Elephants can recognize themselves in a mirror.[65] External videos video icon Self-recognition in apes – National Geographic Main article: Mirror test The sense in which animals (or human infants) can be said to have consciousness or a self-concept has been hotly debated; it is often referred to as the debate over animal minds. The best known research technique in this area is the mirror test devised by Gordon G. Gallup, in which the skin of an animal (or human infant) is marked, while they are asleep or sedated, with a mark that cannot be seen directly but is visible in a mirror. The animal is then allowed to see their reflection in a mirror; if the animal spontaneously directs grooming behaviour towards the mark, that is taken as an indication that they are aware of themself.[66][67] Over the past 30 years, many studies have found evidence that animals recognise themselves in mirrors. Self-awareness by this criterion has been reported for: Land mammals: apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans and gorillas)[68][69][70] and elephants.[65] Cetaceans: bottlenose dolphins,[71][72] killer whales and possibly false killer whales.[73] Birds: magpies and[67][74] pigeons (can pass the mirror test after training in the prerequisite behaviors).[75] Until recently, it was thought that self-recognition was absent in animals without a neocortex, and was restricted to mammals with large brains and well-developed social cognition. However, in 2008, a study of self-recognition in corvids reported significant results for magpies. Mammals and birds inherited the same brain components from their last common ancestor nearly 300 million years ago, and have since independently evolved and formed significantly different brain types. The results of the mirror and mark tests showed that neocortex-less magpies are capable of understanding that a mirror image belongs to their own body. The findings show that magpies respond in the mirror and mark tests in a manner similar to apes, dolphins and elephants. The magpies were chosen to study based on their empathy and lifestyle, a possible precursor to their ability to develop self-awareness.[67] For chimpanzees, the occurrence is about 75% in young adults and considerably less in young and old individuals.[76] For monkeys, non-primate mammals, and a number of bird species, exploration of the mirror and social displays were observed. Hints at mirror-induced self-directed behavior have been obtained.[77] According to a 2019 study, cleaner wrasses have become the first fish ever observed to pass the mirror test.[78] However, the test's inventor Gordon Gallup has said that the fish were most likely trying to scrape off a perceived parasite on another fish and that they did not demonstrate self-recognition. The authors of the study retorted that because the fish checked themselves in the mirror before and after the scraping, this meant that the fish had self-awareness and recognized that their reflections belonged to their own bodies.[79][80][81] The mirror test has attracted controversy among some researchers because it is entirely focused on vision, the primary sense in humans, while other species rely more heavily on other senses such as the olfactory sense in dogs.[82][83][84] A study in 2015 showed that the "sniff test of self-recognition (STSR)" provides evidence of self-awareness in dogs.[84] Language External videos video icon Whale song – Oceania Project video icon This is Einstein! – Knoxville Zoo See also: Animal language, Origin of language, Evolutionary linguistics, Talking bird, and FOXP2 Another approach to determine whether a non-human animal is conscious derives from passive speech research with a macaw (see Arielle). Some researchers propose that by passively listening to an animal's voluntary speech, it is possible to learn about the thoughts of another creature and to determine that the speaker is conscious. This type of research was originally used to investigate a child's crib speech by Weir (1962) and in investigations of early speech in children by Greenfield and others (1976). Zipf's law might be able to be used to indicate if a given dataset of animal communication indicate an intelligent natural language. Some researchers have used this algorithm to study bottlenose dolphin language.[85] Pain or suffering This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarize the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (February 2020) See also: Pain in animals and Animal cruelty Further arguments revolve around the ability of animals to feel pain or suffering. Suffering implies consciousness. If animals can be shown to suffer in a way similar or identical to humans, many of the arguments against human suffering could then, presumably, be extended to animals. Others have argued that pain can be demonstrated by adverse reactions to negative stimuli that are non-purposeful or even maladaptive.[86] One such reaction is transmarginal inhibition, a phenomenon observed in humans and some animals akin to mental breakdown. Carl Sagan, the American cosmologist, points to reasons why humans have had a tendency to deny animals can suffer: Humans – who enslave, castrate, experiment on, and fillet other animals – have had an understandable penchant for pretending animals do not feel pain. A sharp distinction between humans and 'animals' is essential if we are to bend them to our will, make them work for us, wear them, eat them – without any disquieting tinges of guilt or regret. It is unseemly of us, who often behave so unfeelingly toward other animals, to contend that only humans can suffer. The behavior of other animals renders such pretensions specious. They are just too much like us.[87] John Webster, a professor of animal husbandry at Bristol, argues: People have assumed that intelligence is linked to the ability to suffer and that because animals have smaller brains they suffer less than humans. That is a pathetic piece of logic, sentient animals have the capacity to experience pleasure and are motivated to seek it, you only have to watch how cows and lambs both seek and enjoy pleasure when they lie with their heads raised to the sun on a perfect English summer's day. Just like humans.[88] However, there is no agreement where the line should be drawn between organisms that can feel pain and those that cannot. Justin Leiber, a philosophy professor at Oxford University writes that: Montaigne is ecumenical in this respect, claiming consciousness for spiders and ants, and even writing of our duties to trees and plants. Singer and Clarke agree in denying consciousness to sponges. Singer locates the distinction somewhere between the shrimp and the oyster. He, with rather considerable convenience for one who is thundering hard accusations at others, slides by the case of insects and spiders and bacteria, they pace Montaigne, apparently and rather conveniently do not feel pain. The intrepid Midgley, on the other hand, seems willing to speculate about the subjective experience of tapeworms ...Nagel ... appears to draw the line at flounders and wasps, though more recently he speaks of the inner life of cockroaches.[89] There are also some who reject the argument entirely, arguing that although suffering animals feel anguish, a suffering plant also struggles to stay alive (albeit in a less visible way). In fact, no living organism 'wants' to die for another organism's sustenance. In an article written for The New York Times, Carol Kaesuk Yoon argues that: When a plant is wounded, its body immediately kicks into protection mode. It releases a bouquet of volatile chemicals, which in some cases have been shown to induce neighboring plants to pre-emptively step up their own chemical defenses and in other cases to lure in predators of the beasts that may be causing the damage to the plants. Inside the plant, repair systems are engaged and defenses are mounted, the molecular details of which scientists are still working out, but which involve signaling molecules coursing through the body to rally the cellular troops, even the enlisting of the genome itself, which begins churning out defense-related proteins ... If you think about it, though, why would we expect any organism to lie down and die for our dinner? Organisms have evolved to do everything in their power to avoid being extinguished. How long would any lineage be likely to last if its members effectively didn't care if you killed them?[90] Cognitive bias and emotion  Is the glass half empty or half full? See also: Cognitive bias in animals and Emotion in animals Cognitive bias in animals is a pattern of deviation in judgment, whereby inferences about other animals and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion.[91] Individuals create their own "subjective social reality" from their perception of the input.[92] It refers to the question "Is the glass half empty or half full?", used as an indicator of optimism or pessimism. Cognitive biases have been shown in a wide range of species including rats, dogs, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings and honeybees.[93][94][95] The neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux advocates avoiding terms derived from human subjective experience when discussing brain functions in animals.[96] For example, the common practice of calling brain circuits that detect and respond to threats "fear circuits" implies that these circuits are responsible for feelings of fear. LeDoux argues that Pavlovian fear conditioning should be renamed Pavlovian threat conditioning to avoid the implication that "fear" is being acquired in rats or humans.[97] Key to his theoretical change is the notion of survival functions mediated by survival circuits, the purpose of which is to keep organisms alive rather than to make emotions. For example, defensive survival circuits exist to detect and respond to threats. While all organisms can do this, only organisms that can be conscious of their own brain's activities can feel fear. Fear is a conscious experience and occurs the same way as any other kind of conscious experience: via cortical circuits that allow attention to certain forms of brain activity. LeDoux argues the only differences between an emotional and non-emotion state of consciousness are the underlying neural ingredients that contribute to the state.[98][99] Neuroscience  Drawing by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1899) of neurons in the pigeon cerebellum Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system.[100] It is a highly active interdisciplinary science that collaborates with many other fields. The scope of neuroscience has broadened recently to include molecular, cellular, developmental, structural, functional, evolutionary, computational, and medical aspects of the nervous system. Theoretical studies of neural networks are being complemented with techniques for imaging sensory and motor tasks in the brain. According to a 2008 paper, neuroscience explanations of psychological phenomena currently have a "seductive allure", and "seem to generate more public interest" than explanations which do not contain neuroscientific information.[101] They found that subjects who were not neuroscience experts "judged that explanations with logically irrelevant neuroscience information were more satisfying than explanations without.[101] Neural correlates See also: Neural correlates of consciousness The neural correlates of consciousness constitute the minimal set of neuronal events and mechanisms sufficient for a specific conscious percept.[102] Neuroscientists use empirical approaches to discover neural correlates of subjective phenomena.[103] The set should be minimal because, if the brain is sufficient to give rise to any given conscious experience, the question is which of its components is necessary to produce it. Visual sense and representation was reviewed in 1998 by Francis Crick and Christof Koch. They concluded sensory neuroscience can be used as a bottom-up approach to studying consciousness, and suggested experiments to test various hypotheses in this research stream.[104] A feature that distinguishes humans from most animals is that we are not born with an extensive repertoire of behavioral programs that would enable us to survive on our own ("physiological prematurity"). To compensate for this, we have an unmatched ability to learn, i.e., to consciously acquire such programs by imitation or exploration. Once consciously acquired and sufficiently exercised, these programs can become automated to the extent that their execution happens beyond the realms of our awareness. Take, as an example, the incredible fine motor skills exerted in playing a Beethoven piano sonata or the sensorimotor coordination required to ride a motorcycle along a curvy mountain road. Such complex behaviors are possible only because a sufficient number of the subprograms involved can be executed with minimal or even suspended conscious control. In fact, the conscious system may actually interfere somewhat with these automated programs.[105] The growing ability of neuroscientists to manipulate neurons using methods from molecular biology in combination with optical tools depends on the simultaneous development of appropriate behavioural assays and model organisms amenable to large-scale genomic analysis and manipulation.[106] A combination of such fine-grained neuronal analysis in animals with ever more sensitive psychophysical and brain imaging techniques in humans, complemented by the development of a robust theoretical predictive framework, will hopefully lead to a rational understanding of consciousness. Neocortex and equivalents  Previously researchers had thought that patterns of neural sleep exhibited by zebra finches needed a mammalian neocortex.[1] The neocortex is a part of the brain of mammals. It consists of the grey matter, or neuronal cell bodies and unmyelinated fibers, surrounding the deeper white matter (myelinated axons) in the cerebrum. The neocortex is smooth in rodents and other small mammals, whereas in primates and other larger mammals it has deep grooves and wrinkles. These folds increase the surface area of the neocortex considerably without taking up too much more volume. Also, neurons within the same wrinkle have more opportunity for connectivity, while neurons in different wrinkles have less opportunity for connectivity, leading to compartmentalization of the cortex. The neocortex is divided into frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes, which perform different functions. For example, the occipital lobe contains the primary visual cortex, and the temporal lobe contains the primary auditory cortex. Further subdivisions or areas of neocortex are responsible for more specific cognitive processes. The neocortex is the newest part of the cerebral cortex to evolve (hence the prefix "neo"); the other parts of the cerebral cortex are the paleocortex and archicortex, collectively known as the allocortex. In humans, 90% of the cerebral cortex is neocortex. Researchers have argued that consciousness in mammals arises in the neocortex, and therefore by extension used to argue that consciousness cannot arise in animals which lack a neocortex. For example, Rose argued in 2002 that the "fishes have nervous systems that mediate effective escape and avoidance responses to noxious stimuli, but, these responses must occur without a concurrent, human-like awareness of pain, suffering or distress, which depend on separately evolved neocortex."[107] Recently that view has been challenged, and many researchers now believe that animal consciousness can arise from homologous subcortical brain networks.[1] For instance, evidence suggests the pallium in bird brains to be functionally equivalent to the mammalian cerebral cortex as a basis of consciousness.[108][109] Attention Attention is the cognitive process of selectively concentrating on one aspect of the environment while ignoring other things. Attention has also been referred to as the allocation of processing resources.[110] Attention also has variations amongst cultures. Voluntary attention develops in specific cultural and institutional contexts through engagement in cultural activities with more competent community members.[111] Most experiments show that one neural correlate of attention is enhanced firing. If a neuron has a certain response to a stimulus when the animal is not attending to the stimulus, then when the animal does attend to the stimulus, the neuron's response will be enhanced even if the physical characteristics of the stimulus remain the same. In many cases attention produces changes in the EEG. Many animals, including humans, produce gamma waves (40–60 Hz) when focusing attention on a particular object or activity.[112] Extended consciousness Extended consciousness is an animal's autobiographical self-perception. It is thought to arise in the brains of animals which have a substantial capacity for memory and reason. It does not necessarily require language. The perception of a historic and future self arises from a stream of information from the immediate environment and from neural structures related to memory. The concept was popularised by Antonio Damasio and is used in biological psychology. Extended consciousness is said to arise in structures in the human brain described as image spaces and dispositional spaces. Image spaces imply areas where sensory impressions of all types are processed, including the focused awareness of the core consciousness. Dispositional spaces include convergence zones, which are networks in the brain where memories are processed and recalled, and where knowledge is merged with immediate experience.[113][114] Metacognition Metacognition is defined as "cognition about cognition", or "knowing about knowing."[115] It can take many forms; it includes knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving.[115] It has been suggested that metacognition in some animals provides evidence for cognitive self-awareness.[116] There are generally two components of metacognition: knowledge about cognition, and regulation of cognition.[117] Writings on metacognition can be traced back at least as far as De Anima and the Parva Naturalia of the Greek philosopher Aristotle.[118] Metacognologists believe that the ability to consciously think about thinking is unique to sapient species and indeed is one of the definitions of sapience.[citation needed] There is evidence that rhesus monkeys and apes can make accurate judgments about the strengths of their memories of fact and monitor their own uncertainty,[119] while attempts to demonstrate metacognition in birds have been inconclusive.[120] A 2007 study provided some evidence for metacognition in rats,[121][122][123] but further analysis suggested that they may have been following simple operant conditioning principles,[124] or a behavioral economic model.[125] Mirror neurons Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when an animal acts and when the animal observes the same action performed by another.[126][127][128] Thus, the neuron "mirrors" the behavior of the other, as though the observer were themselves acting. Such neurons have been directly observed in primate and other species including birds. The function of the mirror system is a subject of much speculation. Many researchers in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive psychology consider that this system provides the physiological mechanism for the perception action coupling (see the common coding theory).[128] They argue that mirror neurons may be important for understanding the actions of other people, and for learning new skills by imitation. Some researchers also speculate that mirror systems may simulate observed actions, and thus contribute to theory of mind skills,[129][130] while others relate mirror neurons to language abilities.[131] Neuroscientists such as Marco Iacoboni (UCLA) have argued that mirror neuron systems in the human brain help us understand the actions and intentions of other people. In a study published in March 2005, Iacoboni and his colleagues reported that mirror neurons could discern if another person who was picking up a cup of tea planned to drink from it or clear it from the table. In addition, Iacoboni and a number of other researchers have argued that mirror neurons are the neural basis of the human capacity for emotions such as empathy.[128][132] Vilayanur S. Ramachandran has speculated that mirror neurons may provide the neurological basis of self-awareness.[133][134] Evolutionary psychology See also: Evolutionary psychology Consciousness is likely an evolved adaptation since it meets George Williams' criteria of species universality, complexity,[135] and functionality, and it is a trait that apparently increases fitness.[136] Opinions are divided as to where in biological evolution consciousness emerged and about whether or not consciousness has survival value. It has been argued that consciousness emerged (i) exclusively with the first humans, (ii) exclusively with the first mammals, (iii) independently in mammals and birds, or (iv) with the first reptiles.[137] Donald Griffin suggests in his book Animal Minds a gradual evolution of consciousness.[138] Each of these scenarios raises the question of the possible survival value of consciousness. In his paper "Evolution of consciousness," John Eccles argues that special anatomical and physical adaptations of the mammalian cerebral cortex gave rise to consciousness.[139] In contrast, others have argued that the recursive circuitry underwriting consciousness is much more primitive, having evolved initially in pre-mammalian species because it improves the capacity for interaction with both social and natural environments by providing an energy-saving "neutral" gear in an otherwise energy-expensive motor output machine.[140] Once in place, this recursive circuitry may well have provided a basis for the subsequent development of many of the functions that consciousness facilitates in higher organisms, as outlined by Bernard J. Baars.[141] Richard Dawkins suggested that humans evolved consciousness in order to make themselves the subjects of thought.[142] Daniel Povinelli suggests that large, tree-climbing apes evolved consciousness to take into account one's own mass when moving safely among tree branches.[142] Consistent with this hypothesis, Gordon Gallup found that chimpanzees and orangutans, but not little monkeys or terrestrial gorillas, demonstrated self-awareness in mirror tests.[142] The concept of consciousness can refer to voluntary action, awareness, or wakefulness. However, even voluntary behaviour involves unconscious mechanisms. Many cognitive processes take place in the cognitive unconscious, unavailable to conscious awareness. Some behaviours are conscious when learned but then become unconscious, seemingly automatic. Learning, especially implicitly learning a skill, can take place outside of consciousness. For example, plenty of people know how to turn right when they ride a bike, but very few can accurately explain how they actually do so.[142] Neural Darwinism Main article: Neural Darwinism Neural Darwinism is a large scale theory of brain function initially proposed in 1978 by the American biologist Gerald Edelman.[143] Edelman distinguishes between what he calls primary and secondary consciousness: Primary consciousness: is the ability, found in humans and some animals, to integrate observed events with memory to create an awareness of the present and immediate past of the world around them. This form of consciousness is also sometimes called "sensory consciousness". Put another way, primary consciousness is the presence of various subjective sensory contents of consciousness such as sensations, perceptions, and mental images. For example, primary consciousness includes a person's experience of the blueness of the ocean, a bird's song, and the feeling of pain. Thus, primary consciousness refers to being mentally aware of things in the world in the present without any sense of past and future; it is composed of mental images bound to a time around the measurable present.[144] Secondary consciousness: is an individual's accessibility to their history and plans. The concept is also loosely and commonly associated with having awareness of one's own consciousness. The ability allows its possessors to go beyond the limits of the remembered present of primary consciousness.[58] Primary consciousness can be defined as simple awareness that includes perception and emotion. As such, it is ascribed to most animals. By contrast, secondary consciousness depends on and includes such features as self-reflective awareness, abstract thinking, volition and metacognition.[58][145] Edelman's theory focuses on two nervous system organizations: the brainstem and limbic systems on one side and the thalamus and cerebral cortex on the other side. The brain stem and limbic system take care of essential body functioning and survival, while the thalamocortical system receives signals from sensory receptors and sends out signals to voluntary muscles such as those of the arms and legs. The theory asserts that the connection of these two systems during evolution helped animals learn adaptive behaviors.[144] Other scientists have argued against Edelman's theory, instead suggesting that primary consciousness might have emerged with the basic vegetative systems of the brain. That is, the evolutionary origin might have come from sensations and primal emotions arising from sensors and receptors, both internal and surface, signaling that the well-being of the creature was immediately threatened—for example, hunger for air, thirst, hunger, pain, and extreme temperature change. This is based on neurological data showing the thalamic, hippocampal, orbitofrontal, insula, and midbrain sites are the key to consciousness of thirst.[146] These scientists also point out that the cortex might not be as important to primary consciousness as some neuroscientists have believed.[146] Evidence of this lies in the fact that studies show that systematically disabling parts of the cortex in animals does not remove consciousness. Another study found that children born without a cortex are conscious. Instead of cortical mechanisms, these scientists emphasize brainstem mechanisms as essential to consciousness.[146] Still, these scientists concede that higher order consciousness does involve the cortex and complex communication between different areas of the brain. While animals with primary consciousness have long-term memory, they lack explicit narrative, and, at best, can only deal with the immediate scene in the remembered present. While they still have an advantage over animals lacking such ability, evolution has brought forth a growing complexity in consciousness, particularly in mammals. Animals with this complexity are said to have secondary consciousness. Secondary consciousness is seen in animals with semantic capabilities, such as the four great apes. It is present in its richest form in the human species, which is unique in possessing complex language made up of syntax and semantics. In considering how the neural mechanisms underlying primary consciousness arose and were maintained during evolution, it is proposed that at some time around the divergence of reptiles into mammals and then into birds, the embryological development of large numbers of new reciprocal connections allowed rich re-entrant activity to take place between the more posterior brain systems carrying out perceptual categorization and the more frontally located systems responsible for value-category memory.[58] The ability of an animal to relate a present complex scene to their own previous history of learning conferred an adaptive evolutionary advantage. At much later evolutionary epochs, further re-entrant circuits appeared that linked semantic and linguistic performance to categorical and conceptual memory systems. This development enabled the emergence of secondary consciousness.[147][148] Ursula Voss of the Universität Bonn believes that the theory of protoconsciousness[149] may serve as adequate explanation for self-recognition found in birds, as they would develop secondary consciousness during REM sleep.[150] She added that many types of birds have very sophisticated language systems. Don Kuiken of the University of Alberta finds such research interesting as well as if we continue to study consciousness with animal models (with differing types of consciousness), we would be able to separate the different forms of reflectiveness found in today's world.[151] For the advocates of the idea of a secondary consciousness, self-recognition serves as a critical component and a key defining measure. What is most interesting then, is the evolutionary appeal that arises with the concept of self-recognition. In non-human species and in children, the mirror test (see above) has been used as an indicator of self-awareness. |

科学的アプローチ デカルトが二元論を提唱して以来、心は哲学の問題であり、科学は意識の問題(意識は空間と時間の外にある)に踏み込むことはできないというのが一般的なコ ンセンサスとなった。しかし、ここ数十年、多くの学者が意識の科学に向けて動き始めた。アントニオ・ダマシオとジェラルド・エーデルマンは、自己と意識の 神経相関への動きをリードしてきた2人の神経科学者である。ダマシオは情動とその生物学的基盤が高度な認知において重要な役割を果たしていることを実証し [54][55]、エーデルマンは科学的展望を通して意識を分析する枠組みを作り上げた。意識の研究者が直面している現在の問題は、意識が神経計算からど のように、そしてなぜ生じるのかを説明することである[56][57]。この問題についての研究において、エーデルマンは意識の理論を開発し、その中で彼 は一次意識と二次意識という用語を作り出した[58][59]。 オウムの嘆き』の著者であるユージン・リンデンは、動物の行動や知性には、人々が動物意識の境界線と考えるものを凌駕するような例が数多くあることを示唆 している。リンデンは、文書化されたこれらの例の多くにおいて、様々な動物種が、感情や、通常であれば私たち自身の種にのみ帰属する意識のレベルにのみ帰 することができる行動を示していると主張している[60]。 哲学者のダニエル・デネットはこう反論する: 意識にはある種の情報組織が必要であり、それは人間に『遺伝的』には備わっていないようだが、人間の文化によって植え付けられたものである。さらに、意識 は、しばしば想定されるように、白か黒か、オール・オア・ナッシングのタイプの現象ではない。人間と他の種との違いは非常に大きいので、動物の意識につい ての推測は根拠がないように思われる。多くの著者は、コウモリのような動物が視点を持っていると単純に仮定しているが、その詳細を探求することにはあまり 関心がないようである[61]。 哺乳類(ヒトを含む)における意識とは、主観性、感覚、自分と環境との関係を認識する能力などの性質を含むと一般的に考えられている心の側面である。心の 哲学、心理学、神経科学、認知科学の分野で多くの研究対象になっている。一部の哲学者は意識を、主観的な経験そのものである現象的意識と、脳の処理システ ムに対する情報のグローバルな利用可能性を指すアクセス意識に分ける[62]。現象意識は通常、何かについての意識であり、心の哲学では意図性として知ら れている性質である[62]。 ヒトでは、意識を研究する一般的な方法として、言語による報告、行動による実証、意識活動との神経相関の3つがあるが、これらをヒト以外の分類群に一般化 することは、程度の差こそあれ困難である[63]。アカゲザルで行われた新しい研究で、ベン=ハイムと彼のチームは、2つの知覚様式について正反対の行動 結果を予測するプロセス解離アプローチを用いた。その結果、サルは提示された刺激に気づいているときと気づいていないときに、ヒトとまったく同じ正反対の 行動結果を示すことがわかった[64]。 ミラーテスト  ゾウは鏡の中の自分を認識することができる[65]。 外部動画 ビデオアイコン類人猿の自己認識 - ナショナルジオグラフィック 主な記事 ミラーテスト 動物(あるいは人間の幼児)に意識や自己概念があると言えるかどうかについては、熱い議論が交わされてきた。この分野で最もよく知られている研究手法は、 ゴードン・G・ギャラップが考案したミラーテストである。動物(または人間の幼児)の皮膚に、眠った状態か鎮静剤をかけた状態で、直接見ることはできない が鏡に映る印をつける。その後、動物に鏡に映った自分の姿を見せ、動物が自発的にその印に向かって毛づくろいをする行動をとれば、それは動物が自分自身を 認識している証拠とみなされる[66][67]。過去30年以上にわたり、多くの研究が動物が鏡の中の自分を認識している証拠を発見してきた。この基準に よる自己認識は以下の動物で報告されている: 陸生哺乳類:類人猿(チンパンジー、ボノボ、オランウータン、ゴリラ)[68][69][70]、ゾウ[65]。 鯨類:バンドウイルカ[71][72]、シャチ、おそらくニセシャチ[73]。 鳥類:カササギ、[67][74]ハト(前提行動を訓練するとミラーテストに合格できる)[75]。 最近まで、自己認識は大脳新皮質を持たない動物には存在せず、大きな脳を持ち、社会的認知が発達した哺乳類に限られると考えられていた。しかし2008 年、哺乳類の自己認識に関する研究で、カササギに有意な結果が報告された。哺乳類と鳥類は、約3億年前の最後の共通祖先から同じ脳の構成要素を受け継ぎ、 その後独自に進化して大きく異なる脳タイプを形成してきた。鏡テストとマークテストの結果、大脳新皮質を持たないカササギは鏡像が自分の体のものであるこ とを理解できることがわかった。その結果、カササギは類人猿、イルカ、ゾウと同様の方法で鏡像テストやマークテストに反応することがわかった。カササギ は、自己認識を発達させる能力の前兆である可能性のある共感性と生活様式に基づいて研究対象として選ばれた[67]。チンパンジーについては、その出現率 は若年成体で約75%であり、若年および老齢個体ではかなり少ない[76]。サル、霊長類以外の哺乳類、および多くの鳥類については、鏡の探索と社会的表 示が観察された。鏡によって誘発される自己指示行動のヒントが得られている[77]。 2019年の研究によると、クリーナー・ベラはミラー・テストに合格することが観察された初めての魚となった[78]。 しかしながら、このテストの考案者であるゴードン・ギャラップは、この魚は他の魚に寄生していると認識された寄生虫を掻き取ろうとしていた可能性が高く、 自己認識は示していないと述べている。この研究の著者は、魚は削り取る前と後に鏡で自分の姿を確認したので、これは魚に自己認識があり、自分の反射が自分 の体のものであることを認識していたことを意味する、と反論している[79][80][81]。 鏡テストは、ヒトの主要な感覚である視覚に完全に焦点を当てている一方で、他の種では犬の嗅覚など他の感覚に大きく依存しているため、一部の研究者の間で 論争を呼んでいる[82][83][84]。2015年の研究では、「自己認識の嗅覚テスト(STSR)」が犬の自己認識の証拠を提供することが示された [84]。 言語 外部動画 video icon クジラの歌 - オセアニアプロジェクト ビデオアイコン This is Einstein!- ノックスヴィル動物園 こちらもご覧ください: 動物言語、言語の起源、進化言語学、話す鳥、FOXP2 人間以外の動物に意識があるかどうかを判断するもうひとつのアプローチは、コンゴウインコの受動的発話研究から派生したものである(アリエルを参照)。動 物の自発的な発話を受動的に聞くことで、他の生物の思考を知ることができ、その発話者に意識があるかどうかを判断することができると提唱する研究者もい る。この種の研究はもともと、Weir(1962年)による子どものベビーベッドでの発話調査や、Greenfieldら(1976年)による子どもの初 期発話調査に用いられていた。 Zipfの法則は、与えられた動物のコミュニケーションのデータセットが、知的な自然言語を示しているかどうかを示すのに使えるかもしれない。このアルゴリズムを使ってバンドウイルカの言語を研究した研究者もいる[85]。 痛みや苦しみ このセクションは引用が多すぎたり、長すぎたりしています。引用の要約にご協力ください。直接の引用はウィキクォートに、抜粋はウィキソースに移すことを検討してください。(2020年2月) 関連項目 動物の痛みと動物虐待 さらなる議論は、動物が痛みや苦しみを感じることができるかどうかで展開される。苦しみは意識を意味する。もし動物が人間と同じような苦しみを感じること ができれば、人間の苦しみに反対する議論の多くが、動物にも適用されることになるだろう。そのような反応のひとつが、ヒトや一部の動物で観察される、精神 衰弱に似た現象である「トランスマージナル・インヒビション」である[86]。 アメリカの宇宙学者カール・セーガンは、人間が動物が苦しむことを否定する傾向がある理由を指摘している: 他の動物を奴隷にしたり、去勢したり、実験したり、切り身にしたりする人間には、動物が痛みを感じないふりをする傾向がある。私たちが動物を意のままに操 り、自分のために働かせ、身につけさせ、食べようとするならば、罪悪感や後悔の念を抱くことなく、人間と「動物」を峻別することが不可欠である。人間だけ が苦しむことができると主張するのは、他の動物に対して無感情に振る舞うことの多い私たちにとって見苦しいことだ。他の動物たちの振る舞いを見れば、その ような見栄は疑わしい。彼らはあまりにも私たちと似ているのだ[87]。 ブリストルの畜産学教授であるジョン・ウェブスターはこう主張する: 人々は、知能は苦しむ能力と関係があり、動物は脳が小さいので人間よりも苦しむことが少ないと思い込んでいる。感覚を持つ動物には快楽を経験する能力があ り、快楽を求める動機がある。牛や子羊が完璧なイギリスの夏の日に太陽に向かって頭を上げて横たわり、どのように快楽を求め、楽しんでいるかを見ればわか る。人間と同じように。 しかし、痛みを感じることができる生物とそうでない生物の間に、どこで線を引くべきかという点については、意見が一致していない。オックスフォード大学の哲学教授であるジャスティン・ライバーは次のように書いている: モンテーニュはこの点では寛容であり、クモやアリに意識があると主張し、樹木や植物に対する義務についてさえ書いている。シンガーとクラークは、海綿動物 に対する意識の否定で一致している。シンガーは、その区別をエビとカキの間に置いている。昆虫やクモやバクテリアは、モンテーニュと同じように痛みを感じ ないらしい。一方、勇敢なミッドグレイは、サナダ虫の主観的経験について喜んで推測しているようである......ネーゲルは......ヒラメとスズメ バチで一線を引いているように見えるが、最近ではゴキブリの内的生活について語っている[89]。 また、苦しんでいる動物は苦悩を感じるが、苦しんでいる植物も(目に見えない形ではあるが)生き続けようともがくのだと主張し、この議論を完全に否定する 者もいる。実際、他の生物の糧のために「死にたい」と思う生物はいない。キャロル・ケーソク・ユンは『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙に寄稿した記事の中で、 次のように論じている: 植物が傷つくと、その体はすぐに保護モードに入る。揮発性の化学物質を放出し、近隣の植物に化学的防御を先制的に強化させる場合もあれば、植物にダメージ を与えている可能性のある獣の捕食者をおびき寄せる場合もある。植物の内部では、修復システムが働き、防御が開始される。その分子的な詳細については、科 学者たちはまだ解明中だが、細胞部隊を結集させるために体内を駆け巡るシグナル伝達分子や、防御に関連するタンパク質を作り出し始めるゲノムそのものさえ も関与している...。考えてみれば、なぜ私たちは、どんな生物であれ、私たちの夕食のために横になって死んでくれると期待するのだろうか?生物は絶滅を 避けるために、あらゆる手段を講じるように進化してきた。もしそのメンバーが事実上殺されても気にしないのであれば、どのような系統がどれほどの期間存続 する可能性があるのだろうか[90]。 認知バイアスと感情  グラスは半分空なのか、それとも半分満たされているのか? こちらも参照: 動物の認知バイアス、動物の感情 動物における認知バイアスとは、他の動物や状況についての推論が非論理的な方法で引き出される可能性のある、判断における逸脱のパターンである[91]。 個体は入力の知覚から自分自身の「主観的な社会的現実」を作り出す[92]。認知バイアスはラット、イヌ、アカゲザル、ヒツジ、ヒヨコ、ムクドリ、ミツバ チなど幅広い種で示されている[93][94][95]。 神経科学者のジョセフ・ルドゥーは、動物の脳機能を論じる際に人間の主観的経験に由来する用語を避けることを提唱している[96]。例えば、脅威を検知し 反応する脳回路を「恐怖回路」と呼ぶ一般的な慣習は、これらの回路が恐怖の感情を担っていることを暗示している。ルドゥーは、ラットやヒトにおいて「恐 怖」が獲得されるという含意を避けるために、パブロフの恐怖条件付けはパブロフの脅威条件付けと改名されるべきであると主張している[97]。彼の理論的 変化の鍵は、生存回路によって媒介される生存機能という概念であり、その目的は感情を作ることよりもむしろ生物を生かすことにある。例えば、防御的生存回 路は脅威を検知し、それに対応するために存在する。これはすべての生物にできることだが、恐怖を感じることができるのは、自分の脳の活動を意識できる生物 だけである。恐怖は意識的な体験であり、他の種類の意識的な体験と同じように、ある種の脳活動に注意を向けることができる皮質回路を介して起こる。ル ドゥーは、感情的な意識状態と非感情的な意識状態の違いは、その状態に寄与する根底にある神経成分だけであると主張している[98][99]。 神経科学  サンティアゴ・ラモン・イ・カハールによるハトの小脳のニューロンの図面(1899年) 神経科学は、神経系の科学的研究であり[100]、他の多くの分野と連携する非常に活発な学際的科学である。神経科学の範囲は近年拡大しており、神経系の 分子的、細胞的、発生的、構造的、機能的、進化的、計算的、医学的側面を含んでいる。神経ネットワークの理論的研究は、脳の感覚や運動タスクを画像化する 技術によって補完されつつある。2008年の論文によると、心理学的現象に関する神経科学的説明は現在「魅惑的な魅力」を持っており、神経科学的情報を含 まない説明よりも「より多くの人々の関心を引き出している」ようである[101]。神経科学の専門家ではない被験者は、「論理的に無関係な神経科学的情報 を含む説明は、含まない説明よりも満足度が高いと判断する」ことがわかった[101]。 神経相関 こちらも参照: 意識の神経相関 意識の神経相関は、特定の意識的知覚に十分なニューロン事象とメカニズムの最小集合を構成する[102]。神経科学者は主観的現象の神経相関を発見するために経験的アプローチを用いる[103]。 1998年、フランシス・クリックとクリストフ・コッホによって、視覚の感覚と表現が見直された。彼らは、感覚神経科学は意識を研究するためのボトムアッ プ・アプローチとして使用することができると結論付け、この研究の流れにおける様々な仮説を検証するための実験を提案した[104]。 ヒトが多くの動物と異なる特徴は、自力で生存できるような行動プログラムの豊富なレパートリー(「生理的未熟児」)を持って生まれてこないことである。こ れを補うために、ヒトは学習能力、つまり模倣や探索によってそのようなプログラムを意識的に獲得する能力を持っている。いったん意識的に獲得され、十分に 訓練されると、これらのプログラムは、私たちの意識の領域を超えて実行されるまでに自動化される。例えば、ベートーヴェンのピアノソナタを演奏する際に発 揮される驚異的な微細運動技能や、カーブの多い山道をオートバイで走行する際に必要とされる感覚運動協調性である。このような複雑な行動が可能なのは、関 係するサブプログラムの十分な数が、意識的な制御を最小限に、あるいは停止したままでも実行できるからにほかならない。実際には、意識システムはこれらの 自動化されたプログラムを多少妨害しているのかもしれない[105]。 神経科学者が、分子生物学的手法と光学的手法を組み合わせてニューロンを操作する能力を高めていくには、適切な行動アッセイと、大規模なゲノム解析と操作 が可能なモデル生物の同時開発が不可欠である[106]。動物におけるこのようなきめ細かなニューロン解析と、ヒトにおけるこれまで以上に高感度な心理物 理学的手法や脳イメージング手法の組み合わせが、強固な理論的予測枠組みの開発によって補完されることで、意識の合理的理解につながることが期待される。 大脳新皮質とそれに相当するもの  これまで研究者たちは、zebra finches が示す神経睡眠のパターンには哺乳類の大脳新皮質が必要だと考えていた[1]。 大脳新皮質は哺乳類の脳の一部である。大脳新皮質は、大脳深部の白質(有髄軸索)を取り囲む灰白質、すなわち神経細胞体と無髄線維からなる。大脳新皮質 は、げっ歯類やその他の小型哺乳類では滑らかであるが、霊長類やその他の大型哺乳類では深い溝やしわがある。これらのしわは、体積をそれほど大きくするこ となく、大脳新皮質の表面積をかなり増大させる。また、同じ皺の中にあるニューロンはより多くの結合の機会を持つが、異なる皺の中にあるニューロンはより 少ない結合の機会しか持たず、大脳皮質のコンパートメント化につながる。大脳新皮質は前頭葉、頭頂葉、後頭葉、側頭葉に分けられ、それぞれ異なる機能を果 たす。例えば、後頭葉には一次視覚野があり、側頭葉には一次聴覚野がある。大脳新皮質のさらに細分化された領域は、より特殊な認知過程を担当する。大脳新 皮質は大脳皮質の中で最も新しく進化した部分であり(そのため接頭辞に "neo "がついている)、大脳皮質の他の部分には古皮質と大脳弓状皮質があり、これらを総称して大脳皮質連合(allocortex)と呼ぶ。ヒトの場合、大脳 皮質の90%が新皮質である。 研究者たちは、哺乳類における意識は大脳新皮質で生じると主張し、ひいては大脳新皮質を持たない動物に意識は生じないと主張してきた。例えば、ローズは 2002年に、「魚類は有害な刺激に対する効果的な逃避・回避反応を媒介する神経系を持っているが、これらの反応は、別に進化した大脳新皮質に依存する、 痛み、苦しみ、苦痛に対する人間のような意識を同時に持たずに起こるに違いない」と主張した[107]。 「107]。最近ではこの見解が覆され、多くの研究者が、動物の意識は同種の皮質下脳ネットワークから生じ得ると考えるようになっている。 注意 注意とは、環境のある側面に選択的に集中する一方で、他の事柄を無視する認知プロセスである。注意はまた処理資源の配分とも呼ばれている。自発的注意は特定の文化的・制度的文脈の中で、より有能な共同体メンバーとの文化的活動への参加を通じて発達する[111]。 ほとんどの実験では、注意の神経相関の一つは発火の亢進である。動物が刺激に注意を向けていないときに、ある刺激に対す るニューロンの応答がある場合、動物が刺激に注意を向けると、 刺激の物理的特性が同じであってもニューロンの応答が増強 される。多くの場合、注意は脳波に変化をもたらす。ヒトを含む多くの動物は、特定の物体や活動に注意を向けるとガンマ波(40~60Hz)を発生する [112]。 拡張意識 拡張意識は動物の自伝的自己認識である。これは、記憶と理性に相当な能力を持つ動物の脳に生じると考えられている。必ずしも言語を必要としない。歴史的で 未来的な自己の知覚は、身近な環境からの情報の流れと、記憶に関連する神経構造から生じる。この概念はアントニオ・ダマシオによって広められたもので、生 物学的心理学で用いられている。拡張された意識は、イメージ空間と気質空間と呼ばれる人間の脳の構造で生じると言われている。イメージ空間は、中核意識の 集中した意識を含め、あらゆる種類の感覚的印象が処理される領域を意味する。処分空間には、記憶が処理され想起される脳のネットワークであり、知識が即時 的な経験と融合されるコンバージェンス・ゾーンが含まれる[113][114]。 メタ認知 メタ認知は「認知に関する認知」、または「知っていること に関する認知」と定義される[115]。メタ認知は様々な形 態をとることができ、学習や問題解決のために特定の方略をいつ、ど のように使うかに関する知識も含まれる[115]。 [116] 一般的にメタ認知には、認知に関する知識と認知の調節という2つの要素がある[117]。 [メタ認知学者は、思考について意識的に考える能力はサピエンス種に特有のものであり、実際にサピエンスの定義の1つであると信じている。 [しかし、2007年の研究では、ラットが単純なオペラント条件付けの原理[124]、あるいは行動経済モデルに従っている可能性が示唆されている [125]。 ミラーニューロン ミラー・ニューロンは、ある動物が行動するときと、その動物が他者によって行われる同じ行動を観察するときの両方で発火するニューロンである[126] [127][128]。したがって、このニューロンは、観察者自身が行動しているかのように、他者の行動を「ミラー」する。このようなニューロンは、霊長 類や鳥類を含む他の種で直接観察されている。ミラーシステムの機能は、多くの推測の対象となっている。認知神経科学や認知心理学の研究者の多くは、この系 が知覚作用連関の生理学的メカニズムを提供していると考えている(共通符号化理論参照)[128]。彼らは、ミラーニューロンは他者の行動を理解し、模倣 によって新しい技能を学習するために重要であると主張している。マルコ・イアコボーニ(UCLA)のような神経科学者は、ヒトの脳のミラーニューロン系が 他者の行動や意図を理解するのに役立っていると主張している[131]。2005年3月に発表された研究で、イアコボーニと彼の同僚たちは、ミラーニュー ロンが、お茶を手に取っている他の人が、そのお茶を飲むつもりなのか、テーブルから片付けるつもりなのかを見分けることができると報告した。さらに、イア コボーニと他の多くの研究者は、ミラーニューロンが、共感などの感情を持つ人間の能力の神経基盤であると主張している[128][132]。ヴィラヤヌー ル・S・ラマチャンドランは、ミラーニューロンが自己認識の神経基盤を提供するかもしれないと推測している[133][134]。 進化心理学 以下も参照: 進化心理学 意識は種の普遍性、複雑性[135]、機能性というジョージ・ウィリアムズの基準を満たし、明らかに適性を高める形質であることから、進化した適応である 可能性が高い[136]。意識が生物進化のどこで出現したのか、また意識が生存価値を持つのかどうかについては意見が分かれている。意識は(i)最初の人 間だけに出現した、(ii)最初の哺乳類だけに出現した、(iii)哺乳類と鳥類に独立して出現した、(iv)最初の爬虫類だけに出現した、と主張されて いる[137]。ドナルド・グリフィンは著書『Animal Minds』の中で、意識の漸進的進化を示唆している[138]。 ジョン・エクルズはその論文「意識の進化」の中で、哺乳類の大脳皮質の特殊な解剖学的・物理的適応が意識を生み出したと主張している。 [バーナード・J・バースが概説しているように、この再帰的な回路は、意識が高等生物において促進する機能の多くを、その後発達させるための基礎となった 可能性が高い[141]。 [ダニエル・ポヴィネリは、木に登る大型の類人猿は、木の枝の間を安全に移動する際に自分の質量を考慮するために意識を進化させたと示唆している。 意識という概念は、自発的な行動、意識、覚醒を指すことがある。しかし、自発的な行動でさえも、無意識的なメカニズムを含んでいる。多くの認知過程は認知 的無意識の中で行われ、意識的な意識は利用できない。いくつかの行動は、学習時には意識的であるが、その後無意識になり、一見自動的である。学習、特に暗 黙のうちに技術を習得することは、意識の外で行われることがある。例えば、自転車に乗るときに右折する方法を知っている人はたくさんいるが、実際にどのよ うに右折するのかを正確に説明できる人はほとんどいない[142]。 神経ダーウィニズム 主な記事 神経ダーウィニズム 神経ダーウィニズムとは、アメリカの生物学者ジェラルド・エデルマンが1978年に提唱した脳機能に関する大規模な理論である[143]: 一次意識:人間や一部の動物に見られる能力で、観察された出来事を記憶と統合し、現在と直近の過去という周囲の世界の認識を作り出す。この形の意識は「感 覚意識」とも呼ばれることがある。別の言い方をすれば、一次意識とは、感覚、知覚、心的イメージなど、さまざまな主観的な感覚的意識内容の存在である。例 えば、海の青さ、鳥のさえずり、痛みの感覚などが一次意識に含まれる。このように、第一次意識とは、過去や未来の感覚なしに、現在の世界の物事を精神的に 認識していることを指し、それは測定可能な現在を中心とした時間に束縛された心的イメージで構成されている[144]。 二次意識:個人が自分の歴史や計画にアクセスできること。この概念はまた、緩く一般的に自分自身の意識を意識することと関連している。この能力によって、その所有者は一次意識の記憶された現在の限界を超えることができる[58]。 一次意識は知覚と感情を含む単純な意識として定義することができる。そのため、ほとんどの動物に備わっている。対照的に、二次意識は自己反省的な意識、抽象的思考、意志、メタ認知などの特徴に依存し、それらを含む[58][145]。 エーデルマンの理論では、片側の脳幹と大脳辺縁系、もう片側の視床と大脳皮質という2つの神経系組織に焦点を当てている。脳幹と大脳辺縁系は身体に不可欠 な機能と生存を司り、視床皮質系は感覚受容器からの信号を受け取り、腕や脚などの随意筋に信号を送る。この理論では、進化の過程でこれら2つのシステムが 結びついたことで、動物が適応行動を学習することができたと主張している[144]。 他の科学者たちはエーデルマンの理論に反論しており、その代わりに、第一次意識は脳の基本的な植物システムとともに出現した可能性を示唆している。つま り、進化的な起源は、生き物の幸福が直ちに脅かされていることを知らせる、内部と表面の両方のセンサーとレセプターから生じる感覚と原始的な感情、例え ば、空気に対する飢え、喉の渇き、空腹感、痛み、極端な温度変化から生じたのかもしれない。これは、視床、海馬、眼窩前頭、島皮質、中脳の部位が喉の渇き を意識する鍵であることを示す神経学的データに基づいている[146]。これらの科学者はまた、一部の神経科学者が考えているほど、大脳皮質は一次意識に とって重要ではないかもしれないと指摘している[146]。その証拠に、動物の大脳皮質の一部を系統的に無効にしても意識はなくならないという研究結果が ある。別の研究では、大脳皮質を持たずに生まれた子どもにも意識があることがわかった。これらの科学者は、大脳皮質のメカニズムの代わりに、脳幹のメカニ ズムが意識に不可欠であることを強調している。 一次意識を持つ動物は長期記憶を持っているが、明示的な物語を持たず、せいぜい記憶された現在の目の前の光景にしか対処できない。そのような能力を欠く動 物よりもまだ有利ではあるが、進化は特に哺乳類において、意識の複雑化をもたらした。このような複雑さを持つ動物は、二次意識を持つと言われている。二次 意識は、四大猿のような意味能力を持つ動物に見られる。二次意識は、構文と意味論からなる複雑な言語を持つユニークな種であるヒトにおいて、最も豊かな形 で存在する。第一次意識の基礎となる神経メカニズムが進化の過程でどのように発生し、維持されたかを考察すると、爬虫類から哺乳類へ、そして鳥類へと分岐 した頃のある時期に、胚発生学的に新しい相互結合が大量に発達したことで、知覚的分類を行うより後方に位置する脳システムと、価値範疇記憶を行うより前方 に位置する脳システムとの間で、豊かな再入可能な活動が行われるようになったと提唱されている。さらに後の進化的エポックでは、意味的・言語的パフォーマ ンスとカテゴリー的・概念的記憶システムとを結びつける、さらなる再入可能な回路が出現した。この発達が、二次的意識の出現を可能にした[147] [148]。 ボン大学のウルスラ・ヴォスは、鳥類がレム睡眠中に二次意識を発達させることから、原始意識[149]の理論が鳥類に見られる自己認識の適切な説明になる と考えている[150]。アルバータ大学のドン・クイケンは、(意識のタイプが異なる)動物モデルを使って意識を研究し続ければ、今日の世界で見られるさ まざまな反射性の形態を分けることができるだろうとして、このような研究を興味深いと考えている[151]。 第二の意識という考え方の提唱者にとって、自己認識は重要な構成要素であり、重要な定義尺度となる。そこで最も興味深いのは、自己認識という概念から生じる進化論的な魅力である。人間以外の種や子供では、自己認識の指標として鏡テスト(上記参照)が用いられてきた。 |

| Declarations on animal consciousness Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.[152] In 2012, a group of neuroscientists attending a conference on "Consciousness in Human and non-Human Animals" at the University of Cambridge in the UK, signed the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness (see box on the right).[1][153] In the accompanying text they "unequivocally" asserted:[1] "The field of Consciousness research is rapidly evolving. Abundant new techniques and strategies for human and non-human animal research have been developed. Consequently, more data is becoming readily available, and this calls for a periodic reevaluation of previously held preconceptions in this field. Studies of non-human animals have shown that homologous brain circuits correlated with conscious experience and perception can be selectively facilitated and disrupted to assess whether they are in fact necessary for those experiences. Moreover, in humans, new non-invasive techniques are readily available to survey the correlates of consciousness."[1] "The neural substrates of emotions do not appear to be confined to cortical structures. In fact, subcortical neural networks aroused during affective states in humans are also critically important for generating emotional behaviors in animals. Artificial arousal of the same brain regions generates corresponding behavior and feeling states in both humans and non-human animals. Wherever in the brain one evokes instinctual emotional behaviors in non-human animals, many of the ensuing behaviors are consistent with experienced feeling states, including those internal states that are rewarding and punishing. Deep brain stimulation of these systems in humans can also generate similar affective states. Systems associated with affect are concentrated in subcortical regions where neural homologies abound. Young human and non-human animals without neocortices retain these brain-mind functions. Furthermore, neural circuits supporting behavioral/electrophysiological states of attentiveness, sleep and decision making appear to have arisen in evolution as early as the invertebrate radiation, being evident in insects and cephalopod mollusks (e.g., octopus)."[1] "Birds appear to offer, in their behavior, neurophysiology, and neuroanatomy a striking case of parallel evolution of consciousness. Evidence of near human-like levels of consciousness has been most dramatically observed in grey parrots. Mammalian and avian emotional networks and cognitive microcircuitries appear to be far more homologous than previously thought. Moreover, certain species of birds have been found to exhibit neural sleep patterns similar to those of mammals, including REM sleep and, as was demonstrated in zebra finches, neurophysiological patterns previously thought to require a mammalian neocortex. Magpies in particular have been shown to exhibit striking similarities to humans, great apes, dolphins, and elephants in studies of mirror self-recognition."[1] "In humans, the effect of certain hallucinogens appears to be associated with a disruption in cortical feedforward and feedback processing. Pharmacological interventions in non-human animals with compounds known to affect conscious behavior in humans can lead to similar perturbations in behavior in non-human animals. In humans, there is evidence to suggest that awareness is correlated with cortical activity, which does not exclude possible contributions by subcortical or early cortical processing, as in visual awareness. Evidence that human and non-human animal emotional feelings arise from homologous subcortical brain networks provide compelling evidence for evolutionarily shared primal affective qualia."[1] New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness In 2024, a conference on "The Emerging Science of Animal Consciousness" at New York University[154] produced The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness.[155] This brief declaration, signed by a number of academics, asserts that, as well as "strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds", there is additional empirical evidence which "indicates at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates (including reptiles, amphibians, and fishes) and many invertebrates (including, at minimum, cephalopod mollusks, decapod crustaceans, and insects)."[155][156] The declaration further asserts that "when there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal".[155] |

動物の意識に関する宣言 意識に関するケンブリッジ宣言 意識に関するケンブリッジ宣言 大脳新皮質がないからといって、生物が情動状態を経験できないわけではない。収束した証拠は、ヒト以外の動物が、意図的な行動を示す能力とともに、意識状 態の神経解剖学的、神経化学的、神経生理学的基盤を持っていることを示している。その結果、意識を生み出す神経学的基質を持っているのはヒトだけではない ことが、証拠の重みによって示されている。すべての哺乳類と鳥類を含むヒト以外の動物、そしてタコを含む他の多くの生物もまた、これらの神経学的基質を 持っている[152]。 2012年、イギリスのケンブリッジ大学で開催された「ヒトとヒト以外の動物における意識」に関する会議に出席した神経科学者のグループが、「意識に関するケンブリッジ宣言」(右のボックス参照)に署名した[1][153]。 添付された文章の中で、彼らは「明確に」次のように主張している[1]。 「意識研究の分野は急速に発展している。ヒトやヒト以外の動物研究のための新しい技術や戦略が豊富に開発されている。その結果、より多くのデータが容易に 入手できるようになり、この分野で以前から抱いていた先入観を定期的に再評価することが求められている。ヒト以外の動物を用いた研究では、意識経験や知覚 に関連する相同な脳回路を選択的に促進したり破壊したりすることで、それらの経験が実際に必要かどうかを評価できることが示されている。さらに、ヒトにお いては、新しい非侵襲的手法が、意識の相関を調査するために容易に利用できるようになった」[1]。 「感情の神経基盤は皮質構造に限定されているわけではない。実際、ヒトが情動状態にあるときに喚起される皮質下神経回路網は、動物が情動行動を起こすとき にも決定的に重要である。同じ脳領域を人工的に覚醒させることで、ヒトでもヒト以外の動物でも、対応する行動や感情の状態が生成される。ヒト以外の動物で は、脳のどこで本能的な情動行動を喚起しても、その結果生じる行動の多くは、報酬や罰を与える内的状態を含め、経験した情動状態と一致している。人間にお いても、これらのシステムを脳深部から刺激することで、同様の情動状態を生み出すことができる。情動に関連するシステムは、神経の相同性が多い皮質下領域 に集中している。大脳新皮質を持たない若いヒトやヒト以外の動物は、これらの脳心機能を保持している。さらに、注意深さ、睡眠、意思決定などの行動的/電 気生理学的状態を支える神経回路は、進化の過程で無脊椎動物の放射の初期に生じたようであり、昆虫や頭足類の軟体動物(タコなど)に顕著である」[1]。 「鳥類は、その行動、神経生理学、神経解剖学において、意識の並行進化の顕著な事例を提供しているように見える。ヒトに近いレベルの意識の証拠は、オウム で最も劇的に観察されている。哺乳類と鳥類の情動ネットワークや認知微小回路は、これまで考えられていたよりもはるかに相同性が高いようだ。さらに、ある 種の鳥類は、レム睡眠を含む哺乳類に類似した神経睡眠パターンを示すことが分かっており、ゼブラフィンチで実証されたように、以前は哺乳類の大脳新皮質を 必要とすると考えられていた神経生理学的パターンも見られる。特にカササギは、鏡による自己認識の研究において、ヒト、類人猿、イルカ、ゾウとの顕著な類 似性を示すことが示されている」[1]。 「ヒトでは、ある種の幻覚剤の効果は、皮質のフィードフォワードとフィードバック処理の混乱と関連しているようである。ヒトの意識行動に影響を与えること が知られている化合物をヒト以外の動物に薬理学的に介入させると、ヒト以外の動物でも同様の行動障害を引き起こす可能性がある。ヒトでは、意識は皮質活動 と相関していることを示唆する証拠があるが、これは視覚的意識におけるように、皮質下あるいは皮質初期の処理による寄与の可能性を排除するものではない。 ヒトとヒト以外の動物の情動が、相同な皮質下脳ネットワークから生じているという証拠は、進化的に共有された原始的情動クオリアの説得力のある証拠とな る」[1]。 動物の意識に関するニューヨーク宣言 2024年、ニューヨーク大学[154]で「動物意識の新たな科学」に関する会議が開かれ、「動物意識に関するニューヨーク宣言」が発表された [155]。 [155]多くの学者が署名したこの簡潔な宣言は、「他の哺乳類や鳥類に意識的経験が帰属することを科学的に強く支持する」だけでなく、「すべての脊椎動 物(爬虫類、両生類、魚類を含む)と多くの無脊椎動物(最低でも頭足類の軟体動物、十脚類の甲殻類、昆虫を含む)に意識的経験が存在する現実的な可能性を 少なくとも示す」経験的証拠が存在すると主張している。 「155][156]宣言はさらに、「ある動物に意識経験の現実的な可能性がある場合、その動物に影響を与える決定においてその可能性を無視することは無 責任である」と主張している[155]。 |

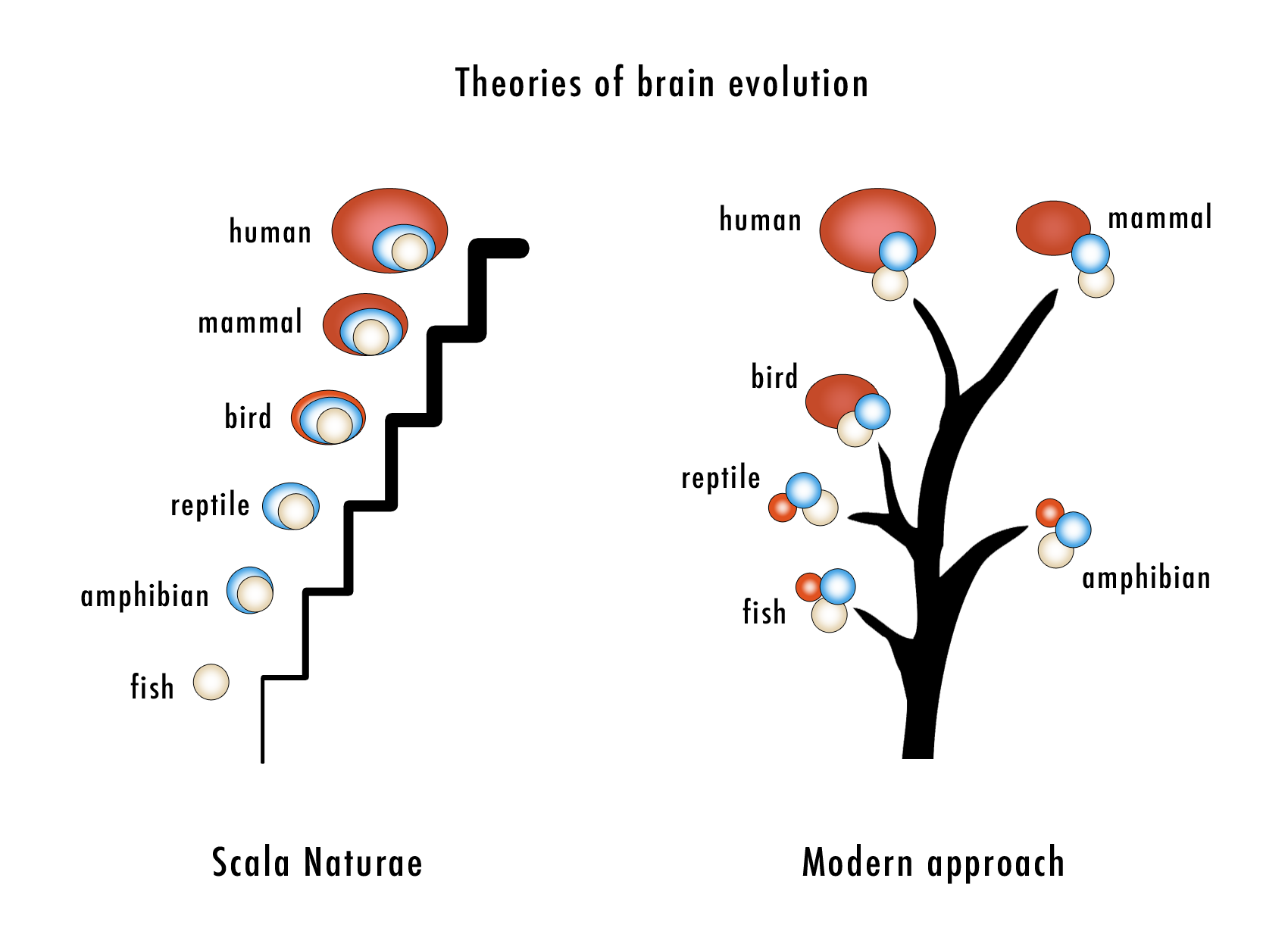

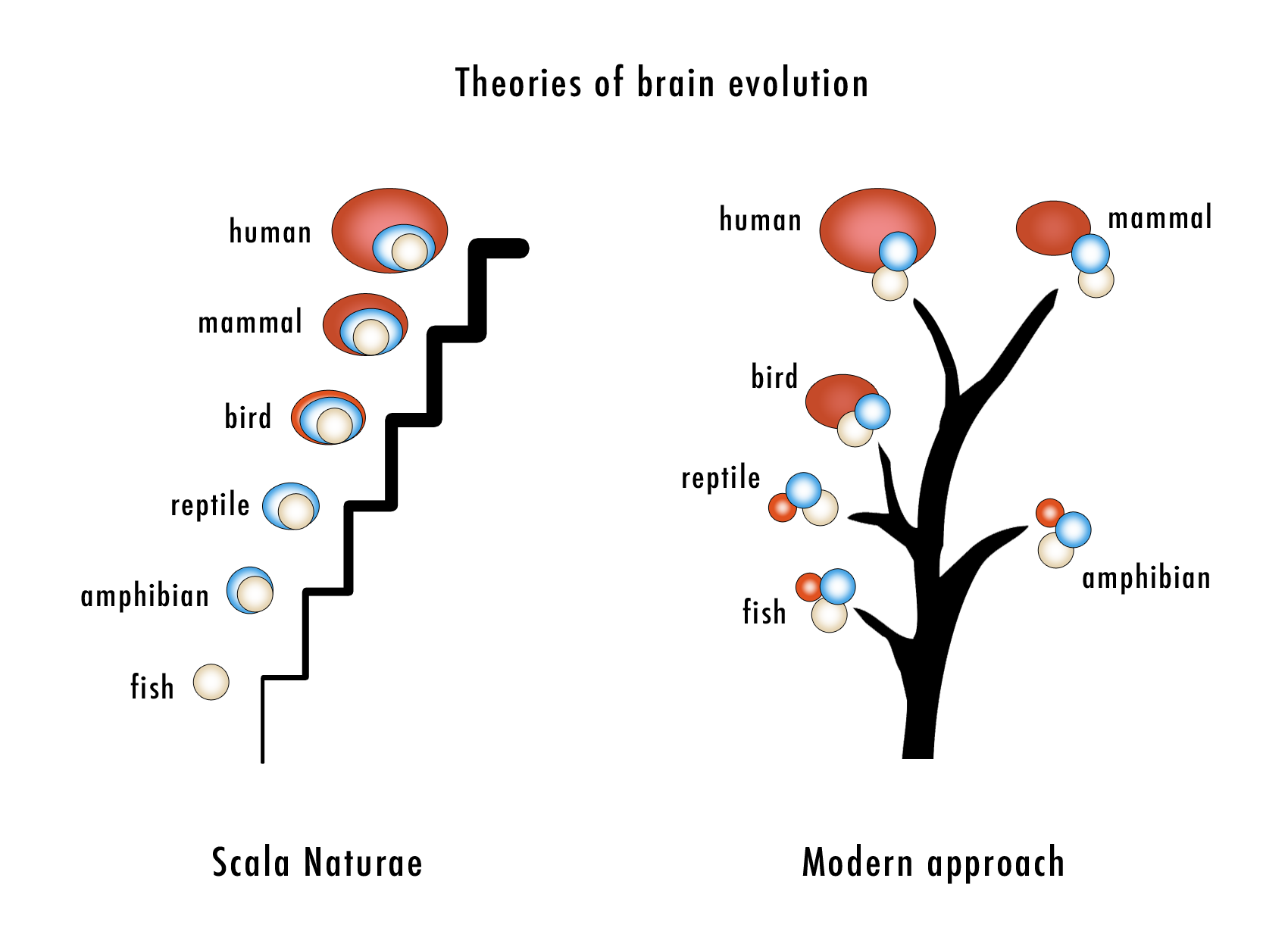

Examples Theories of brain evolution in animals. The old scala naturae model versus the modern approach. A common image is the scala naturae, the ladder of nature on which animals of different species occupy successively higher rungs, with humans typically at the top.[157] A more useful approach has been to recognize that different animals may have different kinds of cognitive processes, which are better understood in terms of the ways in which they are cognitively adapted to their different ecological niches, than by positing any kind of hierarchy.[158][159] Mammals See also: Elephant cognition, Primate cognition, and Cetacean intelligence § Self-awareness Dogs See also: Dog intelligence Dogs were previously listed as non-self-aware animals. Traditionally, self-consciousness was evaluated via the mirror test. But dogs, and many other animals, are not (as) visually oriented.[160][161] A 2015 study claims that the "sniff test of self-recognition" (STSR) provides significant evidence of self-awareness in dogs, and could play a crucial role in showing that this capacity is not a specific feature of only great apes, humans and a few other animals, but it depends on the way in which researchers try to verify it. According to the biologist Roberto Cazzolla Gatti (who published the study), "the innovative approach to test the self-awareness with a smell test highlights the need to shift the paradigm of the anthropocentric idea of consciousness to a species-specific perspective".[84][162] This study has been confirmed by another study.[163] Birds See also: Bird intelligence Grey parrots Research with captive grey parrots, especially Irene Pepperberg's work with an individual named Alex, has demonstrated they possess the ability to associate simple human words with meanings, and to intelligently apply the abstract concepts of shape, colour, number, zero-sense, etc. According to Pepperberg and other scientists, they perform many cognitive tasks at the level of dolphins, chimpanzees, and even human toddlers.[164] Another notable African grey is N'kisi, which in 2004 was said to have a vocabulary of over 950 words which she used in creative ways.[165] For example, when Jane Goodall visited N'kisi in his New York home, he greeted her with "Got a chimp?" because he had seen pictures of her with chimpanzees in Africa.[166] In 2011, research led by Dalila Bovet of Paris West University Nanterre La Défense, demonstrated grey parrots were able to coordinate and collaborate with each other to an extent. They were able to solve problems such as two birds having to pull strings at the same time to obtain food. In another example, one bird stood on a perch to release a food-laden tray, while the other pulled the tray out from the test apparatus. Both would then feed. The birds were observed waiting for their partners to perform the necessary actions so their behaviour could be synchronized. The parrots appeared to express individual preferences as to which of the other test birds they would work with.[167] Corvids  The Eurasian magpie passes the mirror test. It was thought that self-recognition was restricted to mammals with large brains and highly evolved social cognition, but absent from animals without a neocortex. However, in 2008, an investigation of self-recognition in corvids was conducted to determine the ability of self-recognition in the magpie. Mammals and birds inherited the same brain components from their last common ancestor nearly 300 million years ago, and have since independently evolved and formed significantly different brain types. The results of the mirror test showed that although magpies do not have a neocortex, they are capable of understanding that a mirror image belongs to their own body. The findings show that magpies respond to the mirror test in a manner similar to that of apes, dolphins, killer whales, pigs and elephants.[67] A 2020 study found that carrion crows show a neuronal response that correlates with their perception of a stimulus, which they argue to be an empirical marker of (avian) sensory consciousness – the conscious perception of sensory input – in the crows which do not have a cerebral cortex. The study thereby substantiates the theory that conscious perception does not require a cerebral cortex and that the basic foundations for it – and possibly for human-type consciousness – may have evolved before the last common ancestor >320 Mya or independently in birds.[168][169] A related study showed that the birds' pallium's neuroarchitecture is reminiscent of the mammalian cortex.[170] Invertebrates  Octopus travelling with shells collected for protection See also: Cephalopod intelligence and Pain in invertebrates Octopuses are highly intelligent, possibly more so than any other order of invertebrates. The level of their intelligence and learning capability are debated,[171][172][173][174] but maze and problem-solving studies show they have both short- and long-term memory. Octopus have a highly complex nervous system, only part of which is localized in their brain. Two-thirds of an octopus's neurons are found in the nerve cords of their arms. Octopus arms show a variety of complex reflex actions that persist even when they have no input from the brain.[175] Unlike vertebrates, the complex motor skills of octopuses are not organized in their brain using an internal somatotopic map of their body, instead using a non-somatotopic system unique to large-brained invertebrates.[176] Some octopuses, such as the mimic octopus, move their arms in ways that emulate the shape and movements of other sea creatures. In laboratory studies, octopuses can easily be trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns. They reportedly use observational learning,[177] although the validity of these findings is contested.[171][172] Octopuses have also been observed to play: repeatedly releasing bottles or toys into a circular current in their aquariums and then catching them.[178] Octopuses often escape from their aquarium and sometimes enter others. They have boarded fishing boats and opened holds to eat crabs.[173] At least four specimens of the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) have been witnessed retrieving discarded coconut shells, manipulating them, and then reassembling them to use as shelter.[179][180] |