カンタベリーのアンセルムス

Anselm of Canterbury,

1033-1109

☆カンタベリーのアンセルムス OSB [Anselm of Canterbury]

(/ˈænsɛlm/; 1033/4–1109)は、アオスタのアンセルムス(フランス語: Anselme d'Aoste、イタリア語:

アンセルモ・ダオスタ)とも呼ばれ、修道院の地名からベックのアンセルムス(仏語:

アンセルム・デュ・ベック)とも称される。イタリア出身のベネディクト会修道士、修道院長、哲学者、神学者であり、1093年から1109年までカンタベ

リー大司教を務めた。

カンタベリー大司教として、叙任権争いの中でイングランドにおける教会の権益を守った。イングランド王ウィリアム2世とヘンリー1世への抵抗により、二度

追放された。一度目は1097年から1100年まで、二度目は1105年から1107年までである。追放中、南イタリアのギリシャ・カトリック司教たちが

ローマ典礼を採用するよう、バーリ公会議で指導した。彼はカンタベリーがヨーク大司教やウェールズの司教たちに対して優越権を持つよう働きかけ、死の時点

では成功したように見えた。しかし後に教皇パスカリウス2世がこの件に関する教皇の決定を覆し、ヨークの以前の地位を回復させた。

ベック修道院で、アンセルムススは合理的かつ哲学的なアプローチによる対話篇や論文を執筆した。この業績から、彼はスコラ哲学の創始者と称されることもあ

る。当時この分野で評価されなかったにもかかわらず、アンセルムスは現在、神の存在を証明する存在論的論証と贖罪の満足説の創始者として有名である。

死後、アンセルムスは聖人として列聖され、その記念日は4月21日である。1720年、教皇クレメンス11世の教皇勅書により教会の博士に宣言された。

| Anselm of Canterbury

OSB (/ˈænsɛlm/; 1033/4–1109), also known as Anselm of Aosta (French:

Anselme d'Aoste, Italian: Anselmo d'Aosta) after his birthplace and

Anselm of Bec (French: Anselme du Bec) after his monastery, was an

Italian[4] Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian of the

Catholic Church, who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to

1109. As Archbishop of Canterbury, he defended the church's interests in England amid the Investiture Controversy. For his resistance to the English kings William II and Henry I, he was exiled twice: once from 1097 to 1100 and then from 1105 to 1107. While in exile, he helped guide the Greek Catholic bishops of southern Italy to adopt Roman Rites at the Council of Bari. He worked for the primacy of Canterbury over the Archbishop of York and over the bishops of Wales, and at his death he appeared to have been successful; however, Pope Paschal II later reversed the papal decisions on the matter and restored York's earlier status. Beginning at Bec, Anselm composed dialogues and treatises with a rational and philosophical approach, which have sometimes caused him to be credited as the founder of Scholasticism. Despite his lack of recognition in this field in his own time, Anselm is now famous as the originator of the ontological argument for the existence of God and of the satisfaction theory of atonement. After his death, Anselm was canonized as a saint; his feast day is 21 April. He was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by a papal bull of Pope Clement XI in 1720. |

カンタベリーのアンセルムス OSB(/ˈænsɛlm/;

1033/4–1109)は、アオスタのアンセルムス(フランス語: Anselme d'Aoste、イタリア語:

アンセルモ・ダオスタ)とも呼ばれ、修道院の地名からベックのアンセルムス(仏語:

アンセルム・デュ・ベック)とも称される。イタリア出身のベネディクト会修道士、修道院長、哲学者、神学者であり、1093年から1109年までカンタベ

リー大司教を務めた。 カンタベリー大司教として、叙任権争いの中でイングランドにおける教会の権益を守った。イングランド王ウィリアム2世とヘンリー1世への抵抗により、二度 追放された。一度目は1097年から1100年まで、二度目は1105年から1107年までである。追放中、南イタリアのギリシャ・カトリック司教たちが ローマ典礼を採用するよう、バーリ公会議で指導した。彼はカンタベリーがヨーク大司教やウェールズの司教たちに対して優越権を持つよう働きかけ、死の時点 では成功したように見えた。しかし後に教皇パスカリウス2世がこの件に関する教皇の決定を覆し、ヨークの以前の地位を回復させた。 ベック修道院で、アンセルムススは合理的かつ哲学的なアプローチによる対話篇や論文を執筆した。この業績から、彼はスコラ哲学の創始者と称されることもあ る。当時この分野で評価されなかったにもかかわらず、アンセルムスは現在、神の存在を証明する存在論的論証と贖罪の満足説の創始者として有名である。 死後、アンセルムスは聖人として列聖され、その記念日は4月21日である。1720年、教皇クレメンス11世の教皇勅書により教会の博士に宣言された。 |

Biography A plaque commemorating the supposed birthplace of Anselm in Anselm street, Aosta, Italy (The identification may be spurious.)[5] Family Anselm was born in or around Aosta in Upper Burgundy sometime between April 1033 and April 1034.[6] The area now forms part of the Republic of Italy, but Aosta had been part of the post-Carolingian Kingdom of Burgundy until the death of the childless Rudolph III in 1032.[7] The Emperor Conrad II and Odo II, Count of Blois then went to war over the succession. Humbert the White-Handed, Count of Maurienne, so distinguished himself that he was granted a new county carved out of the secular holdings of the bishop of Aosta. Humbert's son Otto was subsequently permitted to inherit the extensive March of Susa through his wife Adelaide[8] in preference to her uncle's families, who had supported the effort to establish an independent Kingdom of Italy under William V, Duke of Aquitaine. Otto and Adelaide's unified lands[9] then controlled the most important passes in the Western Alps and formed the county of Savoy whose dynasty would later rule the kingdoms of Sardinia and Italy.[10][11] Records during this period are scanty, but both sides of Anselm's immediate family appear to have been dispossessed by these decisions[12] in favour of their extended relations.[13] His father Gundulph[14] or Gundulf[15] or Gondulphe[16] was a Lombard noble,[17] probably one of Adelaide's Arduinici uncles or cousins;[18] his mother Ermenberge[16] was almost certainly the granddaughter of Conrad the Peaceful, related both to the Anselmid bishops of Aosta and to the heirs of Henry II who had been passed over in favour of Conrad.[18] The marriage was thus probably arranged for political reasons but proved ineffective in opposing Conrad after his successful annexation of Burgundy on 1 August 1034.[19] (Bishop Burchard subsequently revolted against imperial control but was defeated and was ultimately translated to the diocese of Lyon.) Ermenberge appears to have been the wealthier partner in the marriage. Gundulph moved to his wife's town,[7] where she held a palace, most likely near the cathedral, along with a villa in the valley.[20] Anselm's father is sometimes described as having a harsh and violent temper[14] but contemporary accounts merely portray him as having been overgenerous or careless with his wealth;[21] Meanwhile, Anselm's mother Ermenberge, patient and devoutly religious,[14] made up for her husband's faults by her prudent management of the family estates.[21] In later life, there are records of three relations who visited Bec: Folceraldus, Haimo, and Rainaldus. The first repeatedly attempted to exploit Anselm's renown, but was rebuffed since he already had his ties to another monastery, whereas Anselm's attempts to persuade the other two to join the Bec community were unsuccessful.[22] |

伝記 イタリア、アオスタのアンセルムス通りにある、アンセルムスの推定出生地を記念する銘板(この特定は誤りである可能性がある)[5] 家族 アンセルムスは1033年4月から1034年4月の間に、上ブルゴーニュ地方のアオスタまたはその周辺で生まれた。[6] この地域は現在イタリア共和国の一部だが、アオスタは1032年に子孫のいないルドルフ3世が死去するまで、カロリング朝後のブルゴーニュ王国の一部で あった。[7] その後、皇帝コンラート2世とブロワ伯オド2世が後継者をめぐる戦争を起こした。モーリエンヌ伯ウーベルト・ル・ブラン(白手)は戦功を顕著に立て、アオ スタ司教の世俗領地から切り離された新たな伯領を授けられた。その後、ウーベルトの息子オットーは、妻アデライデ[8]を通じて広大なスーザ辺境伯領を継 承することを認められた。これは、アキテーヌ公ウィリアム5世の下で独立したイタリア王国樹立を支持した妻の叔父の家族を差し置いての決定であった。オッ トーとアデライデが統合した領地は、西アルプスの最重要峠を掌握し、後にサルデーニャ王国とイタリア王国を統治するサヴォイア家(王家)の基盤となった。 この時代の記録は乏しいが、アンセルムスの直系家族双方は、これらの決定[12]によって遠縁の親族[13]に財産を奪われたようだ。父グンドルフ [14]あるいはグンドルフ[15]あるいはゴンドゥルフ[16]はロンバルド貴族[17]で、おそらくアデライデのアルドゥイーニ家の叔父もしくは従兄 弟の一人だった。[18] 母エルメンベルゲ[16]はほぼ間違いなくコンラート平和公の孫娘であり、アオスタのアンセルムス系司教家と、コンラートに優先権を奪われたヘンリー2世 の相続人双方の血筋を引いていた[18]。この結婚はおそらく政治的理由で取り決められたが、1034年8月1日にコンラートがブルゴーニュ併合に成功し た後、彼に対抗する手段としては無効であった。[19] (後に司教ブルハルトは皇帝支配に反旗を翻したが敗北し、最終的にリヨン教区へ転任させられた。)エルメンベルクは婚姻においてより裕福な側であったよう だ。グンドルフは妻の町へ移り住み[7]、彼女は大聖堂近くの宮殿と谷間の別荘を所有していた。[20] アンセルムスの父は時に苛烈で暴力的な気性だったと言われる[14]が、当時の記録では単に財産を浪費し過ぎるか無頓着だったとしか描かれていない [21]。一方、母エルメンベルクは忍耐強く敬虔な信仰心を持つ[14]人物で、家督の管理を慎重に行い、夫の欠点を補っていた。[21] 後年、ベック修道院を訪れた三人の親族の記録が残っている。フォルケラルドゥス、ハイモ、ライナルドゥスである。最初の者はアンセルムスの名声を利用しよ うと繰り返し試みたが、既に別の修道院との繋がりがあったため拒絶された。一方、アンセルムスが他の二人をベック共同体へ誘う試みは成功しなかった。 [22] |

| Early life Monument to St Anselm in Aosta, Xavier de Maistre street At the age of fifteen, Anselm felt the call to enter a monastery but, failing to obtain his father's consent, he was refused by the abbot.[23] The illness he then suffered has been considered by some a psychosomatic effect of his disappointment,[14] but upon his recovery he gave up his studies and for a time lived a carefree life.[14] Following the death of his mother, probably at the birth of his sister Richera,[24] Anselm's father repented his own earlier lifestyle but professed his new faith with a severity that the boy found likewise unbearable.[25] When Gundulph entered a monastery,[26] Anselm, at age 23,[27] left home with a single attendant,[14] crossed the Alps, and wandered through Burgundy and France for three years.[23][a] His countryman Lanfranc of Pavia was then prior of the Benedictine abbey of Bec in Normandy. Attracted by Lanfranc's reputation, Anselm reached Normandy in 1059.[14] After spending some time in Avranches, he returned the next year. His father having died, he consulted with Lanfranc as to whether to return to his estates and employ their income in providing alms for the poor or to renounce them, becoming a hermit or a monk at Bec or Cluny.[28] Given what he saw as his own conflict of interest, Lanfranc sent Anselm to Maurilius, the archbishop of Rouen, who convinced him to enter Bec as a novice at the age of 27.[23] Probably in his first year, he wrote his first work on philosophy, a treatment of Latin paradoxes called the Grammarian.[29] Over the next decade, the Rule of Saint Benedict reshaped his thought.[30] |

幼少期 アオスタ、ザビエル・ド・メストル通りにある聖アンセルムス記念碑 15歳の時、アンセルムスは修道院に入るよう呼びかけを感じたが、父親の同意を得られなかったため、修道院長に拒否された。[23] その後彼が苦悩した病気は、失望による心因性の影響だと考える者もいる[14]。しかし回復後、彼は学業を放棄し、しばらく気ままな生活を送った [14]。 母親の死後(おそらく妹リケラの出産時[24])、アンセルムスの父は自らの過去の生き方を悔い改めたが、新たに抱いた信仰を厳格に貫く姿勢は、少年に とって同様に耐えがたいものだった。[25] グンドゥルフが修道院に入ったとき[26]、23歳のアンセルムス[27]は、付き人1人を連れて家を出て[14]、アルプスを越え、3年間ブルゴーニュ とフランスを放浪した[23][a]。彼の同郷人であるパヴィアのランフランクは、当時ノルマンディーのベックにあるベネディクト会修道院の修道院長で あった。ランフランの評判に惹かれたアンセルムスは、1059年にノルマンディーに到着した。アヴァンシュでしばらく過ごした後、翌年、彼は帰郷した。父 親が亡くなったため、彼は、自分の領地に戻ってその収入を貧しい人々に施しとして使うべきか、それともそれを放棄して、ベックやクリュニーで隠者または修 道士になるべきかを、ランフランに相談した。ランフランクは、アンセルムスが抱える利害の対立を考慮し、彼をルーアン大司教モーリリウスに送った。モーリ リウスは、27歳のアンセルムスにベック修道院の修練生になるよう説得した[23]。おそらく修練生としての最初の年に、彼は最初の哲学著作、ラテン語の パラドックスを扱った『文法家』を著した[29]。その後10年間で、聖ベネディクトの規則が彼の思想を再構築した。[30] |

| Abbot of Bec Early years Bec Abbey in Normandy Three years later, in 1063, Duke William II summoned Lanfranc to serve as the abbot of his new abbey of St Stephen at Caen[14] and the monks of Bec, despite the initial hesitation of some on account of his youth,[23] elected Anselm prior.[31] A notable opponent was a young monk named Osborne. Anselm overcame his hostility first by praising, indulging, and privileging him in all things despite his hostility and then, when his affection and trust were gained, gradually withdrawing all preference until he upheld the strictest obedience.[32] Along similar lines, he remonstrated with a neighbouring abbot who complained that his charges were incorrigible despite being beaten "night and day".[33] After fifteen years, in 1078, Anselm was unanimously elected as Bec's abbot following the death of its founder,[34] the warrior-monk Herluin.[14] He was blessed as abbot by Gilbert d'Arques, Bishop of Évreux, on 22 February 1079.[35] Under Anselm's direction, Bec became the foremost seat of learning in Europe,[14] attracting students from France, Italy, and elsewhere.[36] During this time, he wrote the Monologion and Proslogion.[14] He then composed a series of dialogues on the nature of truth, free will,[14] and the fall of Satan.[29] When the nominalist Roscelin attempted to appeal to the authority of Lanfranc and Anselm at his trial for the heresy of tritheism at Soissons in 1092,[37] Anselm composed the first draft of De Fide Trinitatis as a rebuttal and as a defence of Trinitarianism and universals.[38] The fame of the monastery grew not only from his intellectual achievements, however, but also from his good example[28] and his loving, kindly method of discipline,[14] particularly with the younger monks.[23] There was also admiration for his spirited defence of the abbey's independence from lay and archiepiscopal control, especially in the face of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester and the new Archbishop of Rouen, William Bona Anima.[39] In England A cross at Bec Abbey commemorating the connection between it and Canterbury. Lanfranc, Anselm, and Theobald were all priors at Bec before serving as primates in England. Following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, devoted lords had given the abbey extensive lands across the Channel.[14] Anselm occasionally visited to oversee the monastery's property, to wait upon his sovereign William I of England (formerly Duke William II of Normandy),[40] and to visit Lanfranc, who had been installed as archbishop of Canterbury in 1070.[41] He was respected by William I[42] and the good impression he made while in Canterbury made him the favourite of its cathedral chapter as a future successor to Lanfranc.[14] Instead, upon the archbishop's death in 1089, King William II—William Rufus or William the Red—refused the appointment of any successor and appropriated the see's lands and revenues for himself.[14] Fearing the difficulties that would attend being named to the position in opposition to the king, Anselm avoided journeying to England during this time.[14] The gravely ill Hugh, Earl of Chester, finally lured him over with three pressing messages in 1092,[43] seeking advice on how best to handle the establishment of the new monastery of St Werburgh at Chester.[23] Hugh had recovered by the time of Anselm's arrival,[23] and Anselm was occupied four[14] or five months organizing the new community.[23] He then travelled to his former pupil Gilbert Crispin, abbot of Westminster, and waited, apparently delayed by the need to assemble the donors of Bec's new lands in order to obtain royal approval of the grants.[44] |

ベック修道院長 初期 ノルマンディーのベック修道院 3年後の1063年、ウィリアム2世公は、カーンに新しく設立した聖ステファン修道院の修道院長としてランフランクを招いた[14]。ベック修道院の修道 士たちは、彼の若さを理由に当初は躊躇した者もいたが[23]、アンセルムスを修道院長に選出した[31]。注目すべき反対者は、オズボーンという名の若 い修道士だった。アンセルムススは、彼の敵意にもかかわらず、まずあらゆる面で彼を称賛し、甘やかして、優遇することでその敵意を克服し、彼の愛情と信頼 を得た後、最も厳格な服従を貫くまで、徐々にすべての優遇を取り消していった[32]。同様に、彼は、「昼夜を問わず」殴打されているにもかかわらず、自 分の担当する者たちが改心しないことを不満に思う隣人の修道院長に抗議した。[33] 15年後、1078年に創設者である修道士戦士エルルアン[14]が死去すると、アンセルムスは満場一致でベック修道院の院長に選出された[34]。 1079年2月22日、エヴルー司教ジルベール・ダルクによって院長として祝福を受けた. [35] アンセルムスの指導のもと、ベックはヨーロッパ随一の学問の中心地となり[14]、フランスやイタリアなど各地から学生が集まった[36]。この時期に彼 は『モノロギオン』と『プロスロギオン』を著した[14]。その後、真理の本質、自由意志[14]、サタンの堕落に関する一連の対話篇を執筆した。 [29] 1092年ソワソンで三神論の異端審問を受けた名目論者ロスケランが、ランフランクとアンセルムの権威に訴えようとした時[37]、アンセルムスは反論と して、また三位一体論と普遍概念の擁護として『三位一体の信仰について』の初稿を執筆した。[38] しかし修道院の名声は、彼の知的業績だけでなく、その模範的な行動[28]と、特に若い修道士たちに対する慈愛に満ちた温和な規律の方法[14]によって も高まった。[23] また、世俗勢力や大司教の支配から修道院の独立を力強く守った姿勢も称賛された。特にレスター伯ロベール・ド・ボーモンやルーアンの新大司教ウィリアム・ ボナ・アニマに対して示した抵抗が顕著であった[39]。 イングランドでは ベック修道院とカンタベリーとのつながりを記念する十字架。ランフラン、アンセルムス、テオバルドは、イングランドで最高司教を務める前に、ベックで修道院長を務めていた。 1066年のノーマンによるイングランド征服後、献身的な領主たちは、海峡を越えた広大な土地を修道院に与えた[14]。アンセルムスは、修道院の所有地 を監督し、イングランドの君主ウィリアム1世(元ノルマンディー公ウィリアム2世)に仕え[40]、1070年にカンタベリー大司教に就任したランフラン を訪ねるために、時折この地を訪れた。[41] 彼はウィリアム1世から尊敬され[42]、カンタベリー滞在中に良い印象を与えたため、ランフランの後継者として大聖堂参事会のお気に入りとなった。 [14] しかし、1089年に大司教が死去すると、ウィリアム2世(ウィリアム・ルフス、あるいは赤毛のウィリアム)は後継者の任命を拒否し、司教の領地と収入を 自らに流用した。[14] 王に逆らって大司教に任命される困難を恐れたアンセルムスは、この時期にイングランドへ渡ることを避けた。[14] 重病のチェスター伯ヒューは、1092年に三度の緊急の使者を送り[43]、チェスターに新設される聖ウェルバーガ修道院の運営に関する助言を求めて、つ いに彼を呼び寄せた。[23] アンセルムスが到着した頃にはヒューは回復していた。[23] アンセルムスは四か月[14]か五か月を費やして新たな共同体の組織化に当たった。[23] その後、かつての教え子であるウェストミンスター修道院長のギルバート・クリスピンを訪ねたが、ベック修道院の新領地寄進者たちを召集し、寄進の王室認可 を得る必要に迫られたため、明らかに足止めを食らった。[44] |

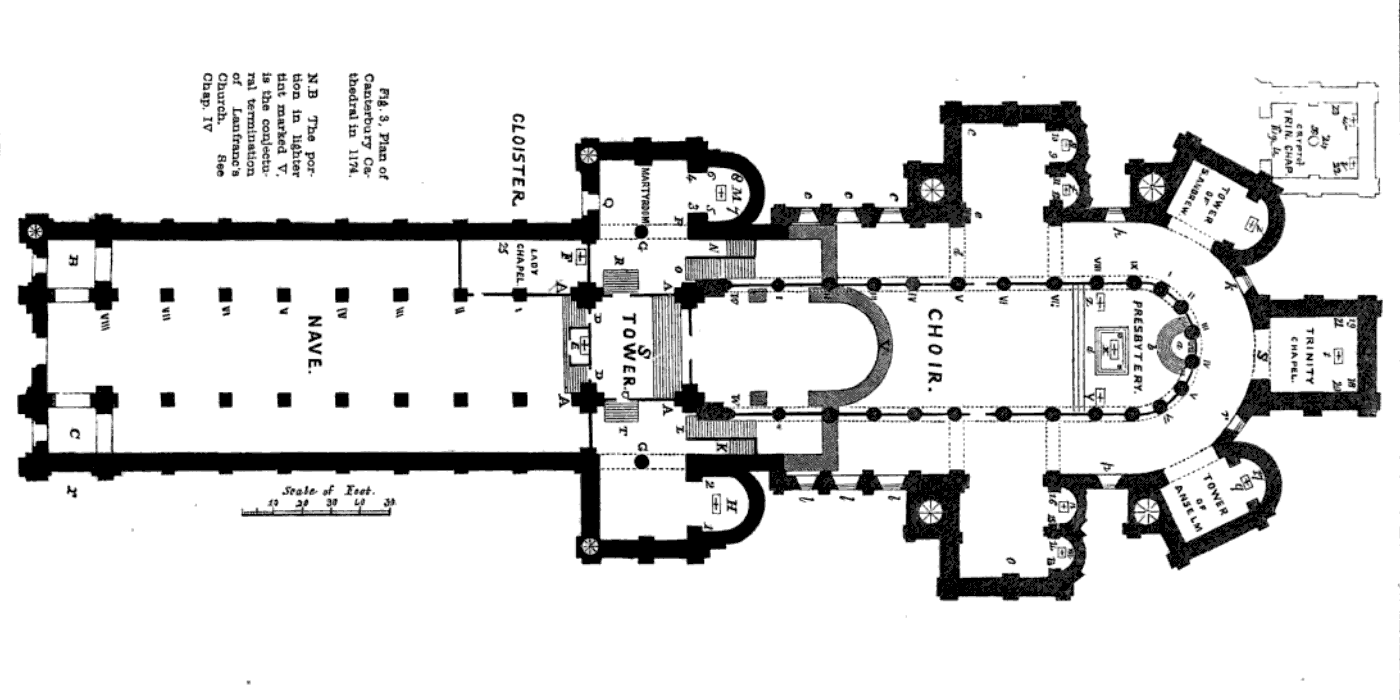

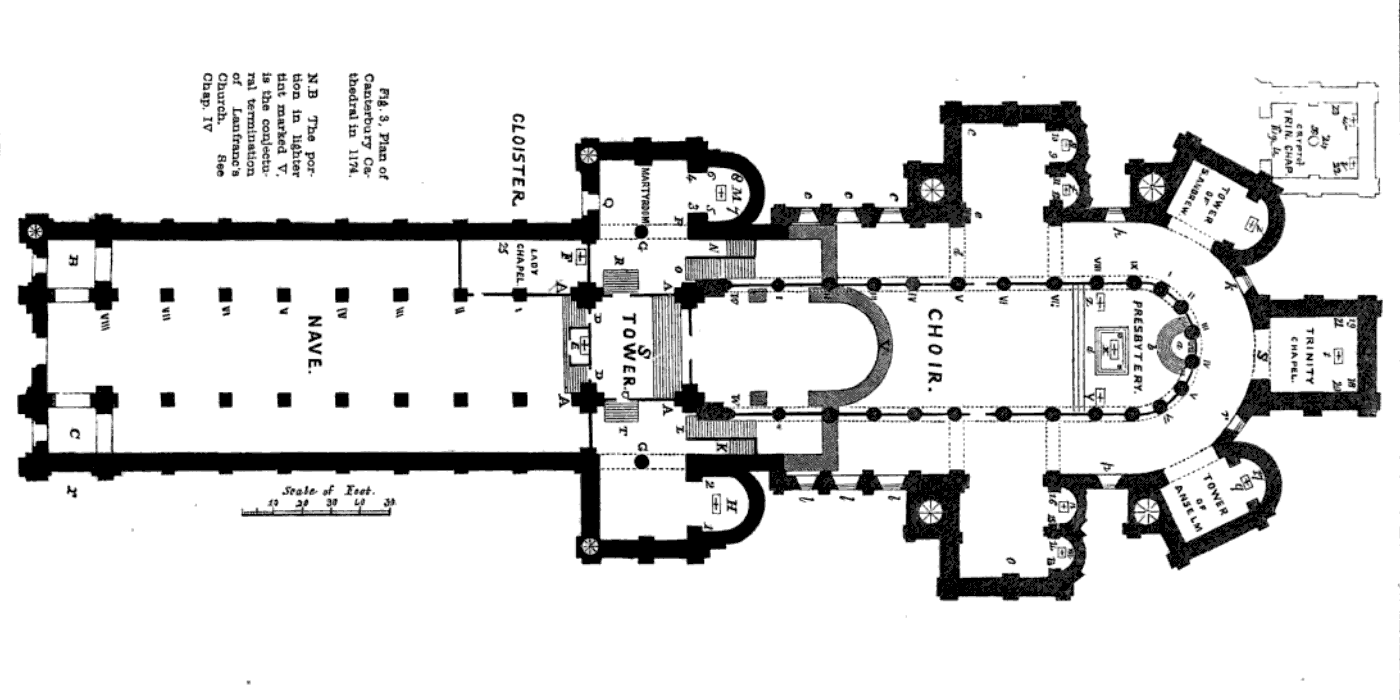

| At

Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither

Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived[45] but in

March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his sinful behavior

was responsible,[46] he summoned Anselm to hear his confession and

administer last rites.[44] He published a proclamation releasing his

captives, discharging his debts, and promising to henceforth govern

according to the law.[23] On 6 March 1093, he further nominated Anselm

to fill the vacancy at Canterbury; the clerics gathered at court

acclaiming him, forcing the crozier into his hands, and bodily carrying

him to a nearby church amid a Te Deum.[47] Anselm tried to refuse on

the grounds of age and ill-health for months[41] and the monks of Bec

refused to give him permission to leave them.[48] Negotiations were

handled by the recently restored Bishop William of Durham and Robert,

count of Meulan.[49] On 24 August, Anselm gave King William the

conditions under which he would accept the position, which amounted to

the agenda of the Gregorian Reform: the king would have to return the

Catholic Church lands which had been seized, accept his spiritual

counsel, and forswear Antipope Clement III in favour of Urban II.[50]

William Rufus was exceedingly reluctant to accept these conditions: he

consented only to the first[51] and, a few days afterwards, reneged on

that, suspending preparations for Anselm's investiture.[citation

needed] Public pressure forced William to return to Anselm and in the

end they settled on a partial return of Canterbury's lands as his own

concession.[52] Anselm received dispensation from his duties in

Normandy,[14] did homage to William, and—on 25 September 1093—was

enthroned at Canterbury Cathedral.[53] The same day, William II finally

returned the lands of the see.[51] From the mid-8th century, it had become the custom that metropolitan bishops could not be consecrated without a woollen pallium given or sent by the pope himself.[54] Anselm insisted that he journey to Rome for this purpose but William would not permit it. Amid the Investiture Controversy, Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV had deposed each other twice; bishops loyal to Henry finally elected Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as a second pope. In France, Philip I had recognized Gregory and his successors Victor III and Urban II, but Guibert (as "Clement III") held Rome after 1084.[55] William had not chosen a side and maintained his right to prevent the acknowledgement of either pope by an English subject prior to his choice.[56] In the end, a ceremony was held to consecrate Anselm as archbishop on 4 December, without the pallium.[51] Archbishop of Canterbury As archbishop, Anselm maintained his monastic ideals, including stewardship, prudence, and proper instruction, prayer and contemplation.[57] Anselm advocated for reform and interests of Canterbury.[58] As such, he repeatedly pressed the English monarchy for support of the reform agenda.[59] His principled opposition to royal prerogatives over the Catholic Church, meanwhile, twice led to his exile from England.[60] The traditional view of historians has been to see Anselm as aligned with the papacy against lay authority and Anselm's term in office as the English theatre of the Investiture Controversy begun by Pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV.[60] By the end of his life, he had proven successful, having freed Canterbury from submission to the English king,[61] received papal recognition of the submission of wayward York[62] and the Welsh bishops, and gained strong authority over the Irish bishops.[63] He died before the Canterbury–York dispute was definitively settled, however, and Pope Honorius II finally found in favour of York instead.[64]  Canterbury Cathedral following Ernulf and Conrad's expansions[65] Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of Canterbury Cathedral from Lanfranc's initial plans.[66] The eastern end was demolished and an expanded choir placed over a large and well-decorated crypt, doubling the cathedral's length.[67] The new choir formed a church unto itself with its own transepts and a semicircular ambulatory opening into three chapels.[68] |

クリスマスにウィリアム二世はルッカの聖顔にかけて誓っ

た。自分が生きている限り、アンセルムスも他の誰もカンタベリー大主教の座につかせないと[45]。だが3月、彼はアルベストンで重病に倒れた。自らの罪

深い行いが原因だと信じて[46]、アンセルムスを呼び寄せ、懺悔を聞き終末の秘蹟を施させた[44]。捕虜を解放し、債務を免除し、今後は法に従って統

治することを約束する布告を公布した[23]。1093年3月6日、彼はさらにアンセルムスをカンタベリー空位の後継者に指名した。宮廷に集まった聖職者

たちは彼を称賛し、司教杖を彼の手に押し付け、テ・デウムの賛美歌が響く中、彼を近くの教会まで物理的に運んだ[47]。アンセルムスは数か月間、年齢と

健康を理由に辞退を試みた[41]。ベックの修道僧たちも彼の離脱を許可しなかった。[48]

交渉は、復職したばかりのダラム司教ウィリアムとムラン伯ロベールが担当した[49]。8月24日、アンセルムスはウィリアム王に対し、職を受け入れる条

件を提示した。これはグレゴリオ改革の要求事項に相当するもので、王は没収したカトリック教会の土地を返還し、彼の精神的助言を受け入れ、対立教皇クレメ

ンス3世を排斥してウルバヌス2世を支持することを誓約しなければならなかった。[50]

ウィリアム・ルフスはこれらの条件を受け入れることに非常に消極的だった。彼は最初の条件[51]

にのみ同意したが、その数日後、その約束を破り、アンセルムスの叙任の準備を中断した。[要出典]

世論の圧力により、ウィリアムはアンセルムスと再交渉せざるを得なくなり、結局、カンタベリー大司教の領地の一部返還を彼の譲歩として合意した。[52]

アンセルムスはノルマンディーでの職務を免除され[14]、ウィリアムに忠誠を誓い、1093年9月25日にカンタベリー大聖堂で戴冠した[53]。その

同じ日、ウィリアム2世はついに司教座の領地を返還した。[51] 8世紀半ばから、大司教は教皇自身が授けた、あるいは送った羊毛のパリオなしでは叙階されないという慣習が定着していた。[54] アンセルムスはこの目的のためにローマへ旅立つことを主張したが、ウィリアムはそれを許可しなかった. 叙任権論争の最中、教皇グレゴリウス7世と皇帝ハインリヒ4世は互いに二度ずつ廃位した。ハインリヒに忠実な司教たちは最終的にラヴェンナ大司教ギベール を第二の教皇として選出。フランスではフィリップ1世がグレゴリウスとその後継者ヴィクトル3世、ウルバヌス2世を承認したが、ギベール(「クレメンス3 世」として)は1084年以降ローマを掌握した。[55] ウィリアムはどちらの側にも付かず、自らの選択以前にイングランドの臣民がどちらの教皇も承認することを阻止する権利を保持していた。[56] 結局、12月4日にアンセルムスを大司教に叙任する式典が、パリオ(教皇の象徴)なしで執り行われた。[51] カンタベリー大司教 大主教としてアンセルムスは、管理責任、慎重さ、適切な指導、祈りと瞑想といった修道院の理想を堅持した。[57] アンセルムスはカンタベリーの改革と利益を擁護した。[58] そのため、彼は改革計画への支援をイングランド王室に繰り返し迫った。[59] 一方、カトリック教会に対する王権の特権への原則的な反対は、二度も彼をイングランドからの追放へと導いた。[60] 歴史家たちの従来の見解は、アンセルムスを教皇庁と結託して世俗権力に対抗した人物と位置づけ、彼の在任期間を教皇グレゴリウス7世と皇帝ハインリヒ4世 によって始まった叙任権争いのイングランドにおける舞台と見なしてきた. [60] 生涯の終わりまでに、彼はカンタベリーをイングランド王の支配から解放し[61]、反抗的なヨーク[62]とウェールズの司教たちの服従を教皇に認めさ せ、アイルランドの司教たちに対する強い権威を獲得するなど、成功を収めた。しかしカンタベリーとヨークの争いが最終的に決着する前に死去し、教皇ホノリ ウス2世は結局ヨークを支持する判断を下した。[64]  エルヌルフとコンラートの拡張後のカンタベリー大聖堂[65] 工事の大部分はクライストチャーチの修道院長エルヌルフ(1096–1107)とコンラート(1108–1126)によって進められたが、アンセルムス司 教在任中には、ランフランクの当初の計画からカンタベリー大聖堂が拡張された。[66] 東端は解体され、広大で装飾豊かな地下聖堂の上に拡張された聖歌隊席が設けられ、大聖堂の長さは倍増した。[67] 新たな聖歌隊席は独立した教会を形成し、独自の翼廊と三つの礼拝堂に通じる半円形の回廊を備えていた。[68] |

| Conflicts with William Rufus Anselm's vision was of a Catholic Church with its own internal authority, which clashed with William II's desire for royal control over both church and State.[59] One of Anselm's first conflicts with William came in the month he was consecrated. William II was preparing to wrest Normandy from his elder brother, Robert II, and needed funds.[69] Anselm was among those expected to pay him. He offered £500 but William refused, encouraged by his courtiers to insist on £1000 as a kind of annates for Anselm's elevation to archbishop. Anselm not only refused, he further pressed the king to fill England's other vacant positions, permit bishops to meet freely in councils, and to allow Anselm to resume enforcement of canon law, particularly against incestuous marriages,[23] until he was ordered to silence.[70] When a group of bishops subsequently suggested that William might now settle for the original sum, Anselm replied that he had already given the money to the poor and "that he disdained to purchase his master's favour as he would a horse or ass".[37] The king being told this, he replied Anselm's blessing for his invasion would not be needed as "I hated him before, I hate him now, and shall hate him still more hereafter".[70] Withdrawing to Canterbury, Anselm began work on the Cur Deus Homo.[37] "Anselm Assuming the Pallium in Canterbury Cathedral" from E. M. Wilmot-Buxton's 1915 Anselm[71] Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office.[37] On 25 February 1095, the Lords Spiritual and Temporal of England met in a council at Rockingham to discuss the issue. The next day, William ordered the bishops not to treat Anselm as their primate or as Canterbury's archbishop, as he openly adhered to Urban. The bishops sided with the king, the Bishop of Durham presenting his case[72] and even advising William to depose and exile Anselm.[73] The nobles siding with Anselm, the conference ended in deadlock and the matter was postponed. Immediately following this, William secretly sent William Warelwast and Gerard to Italy,[58] prevailing on Urban to send a legate bearing Canterbury's pallium.[74] Walter, bishop of Albano, was chosen and negotiated in secret with William's representative, the Bishop of Durham.[75] The king agreed to publicly support Urban's cause in exchange for acknowledgement of his rights to accept no legates without invitation and to block clerics from receiving or obeying papal letters without his approval. William's greatest desire was for Anselm to be removed from office. Walter said that "there was good reason to expect a successful issue in accordance with the king's wishes" but, upon William's open acknowledgement of Urban as pope, Walter refused to depose the archbishop.[76] William then tried to sell the pallium to others, failed,[77] tried to extract a payment from Anselm for the pallium, but was again refused. William then tried to personally bestow the pallium to Anselm, an act connoting the church's subservience to the throne, and was again refused.[78] In the end, the pallium was laid on the altar at Canterbury, whence Anselm took it on 10 June 1095.[78] The First Crusade was declared at the Council of Clermont in November.[b] Despite his service for the king which earned him rough treatment from Anselm's biographer Eadmer,[80][81] upon the grave illness of the Bishop of Durham in December, Anselm journeyed to console and bless him on his deathbed.[82] Over the next two years, William opposed several of Anselm's efforts at reform—including his right to convene a council[42]—but no overt dispute is known. However, in 1094, the Welsh had begun to recover their lands from the Marcher Lords and William's 1095 invasion had accomplished little; two larger forays were made in 1097 against Cadwgan in Powys and Gruffudd in Gwynedd. These were also unsuccessful and William was compelled to erect a series of border fortresses.[83] He charged Anselm with having given him insufficient knights for the campaign and tried to fine him.[84] In the face of William's refusal to fulfill his promise of church reform, Anselm resolved to proceed to Rome—where an army of French crusaders had finally installed Urban—in order to seek the counsel of the pope.[59] William again denied him permission. The negotiations ended with Anselm being "given the choice of exile or total submission": if he left, William declared he would seize Canterbury and never again receive Anselm as archbishop; if he were to stay, William would impose his fine and force him to swear never again to appeal to the papacy.[85] |

ウィリアム・ルフスとの対立 アンセルムスは、カトリック教会が独自の内部権威を持つべきだという考えを持っていたが、それは教会と国家の両方を王が支配したいというウィリアム2世の 考えと衝突した。[59] アンセルムスがウィリアムと初めて対立したのは、彼が聖職に就いたその月だった。ウィリアム2世は兄のロベール2世からノルマンディーを奪う準備を進めて おり、資金が必要だった。アンセルムスも彼に資金を提供する者たちの一人だった。アンセルムスは500ポンドを提示したが、ウィリアムはそれを拒否し、廷 臣たちに促されて、アンセルムスの大司教就任に対する一種の献金として1000ポンドを要求した。アンセルムスはこれを拒否しただけでなく、イングランド の他の空席を埋めること、司教たちが自由に評議会で会合することを許可すること、そして、沈黙を命じられるまで、特に近親相姦の結婚に対して、カノン法の 施行を再開することをアンセルムスに許可するよう、さらに王に圧力をかけた。[70] その後、司教団がウィリアムが当初の金額で妥協する可能性を示唆すると、アンセルムスは「その金は既に貧者に与えた」と返答し、「主君の寵愛を馬や驢馬の ように買うような真似はしない」と述べた。[37] 王はこの返答を聞くと、アンセルムスの祝福など不要だと述べた。「以前も彼を憎んでいたし、今も憎んでいる。今後さらに憎むことになるだろう」と。 [70] カンタベリーに戻ったアンセルムスは『神はなぜ人となったか』の執筆を始めた。[37] E. M. ウィルモット=バクストン著『アンセルムス』(1915年)所収「カンタベリー大聖堂におけるパッリウム授与を受けるアンセルムス」[71] ウィリアムが帰国すると、アンセルムスは自身の職位を正当化するパリュウムを授かるため、ウルバヌス2世の宮廷へ赴くよう主張した[37]。1095年2 月25日、イングランドの世俗・教会両院はロッキンガムで会議を開きこの問題を審議した。翌日、ウィリアムは主教たちに命じた。アンセルムススを首座主教 として、あるいはカンタベリー大主教として扱ってはならないと。彼は公然とウルバヌスに帰依していたからだ。司教たちは王に味方し、ダラム司教は自らの主 張を述べ[72]、ウィリアムにアンセルムスを罷免し追放するよう助言さえした[73]。貴族たちはアンセルムスを支持したため、会議は膠着状態に終わ り、問題は先送りとなった。直後にウィリアムは密かにウィリアム・ワレルワストとジェラルドをイタリアへ派遣し[58]、ウルバヌスにカンタベリー大司教 のパッリウムを携えた使節を送るよう働きかけた。[74] アルバノ司教ウォルターが選ばれ、ウィリアムの代理人であるダラム司教と密かに交渉した。[75] 王は、招請なしに教皇使節を受け入れない権利と、自身の承認なしに聖職者が教皇書簡を受け取ったり従ったりすることを阻止する権利を認められる代わりに、 ウルバヌスの主張を公に支持することに同意した。ウィリアムの最大の望みはアンセルムスを職から追放することだった。ウォルターは「国王の意向に沿った成 功が期待できる」と述べたが、ウィリアムがウルバヌスを公然と教皇と認めた後、ウォルターは大司教の罷免を拒否した。[76] ウィリアムは次にパリュウムを他者に売却しようとしたが失敗し、[77] アンセルムスからパリュウム代金を徴収しようとしたが、再び拒否された。ウィリアムは次に、教会が王座に従属することを示す行為として、アンセルムスに個 人的なパリオを授けようとしたが、これも拒否された[78]。結局、パリオはカンタベリー大聖堂の祭壇に置かれ、アンセルムスは1095年6月10日にそ れを取り上げた。[78] 第一次十字軍は11月のクレルモン公会議で宣言された。[b] ウィリアムは国王に仕えた功績からアンセルムの伝記作者エアドマーに酷評されたが[80][81]、12月にダラム司教が重病に陥ると、アンセルムスは彼 の死の床を慰め祝福するために旅立った。[82] その後2年間、ウィリアムはアンセルムスの改革努力の幾つか―公会議召集権を含む[42]―に反対したが、公然たる対立は知られていない. しかし1094年、ウェールズ人は辺境領主から領地を奪還し始め、1095年のウィリアム侵攻もほとんど成果を上げられなかった。1097年にはポウィス のカドグワンとグウィネズのグリフィズに対して大規模な遠征が二度行われたが、これも失敗に終わり、ウィリアムは国境沿いに一連の要塞を築くことを余儀な くされた。[83] ウィリアムはアンセルムスに対し、遠征に十分な騎士を提供しなかったと非難し、罰金を科そうとした[84]。教会改革の約束を果たさないウィリアムに対 し、アンセルムスはローマへ赴く決意を固めた。そこではフランス人十字軍が遂にウルバヌスを教皇に擁立しており、教皇の助言を求めようとしたのである [59]。ウィリアムは再びこれを許可しなかった。交渉はアンセルムスに「亡命か完全服従かの選択」を迫る形で決着した。もし去れば、ウィリアムはカンタ ベリーを接収し、二度とアンセルムスを大司教として認めないと宣言した。もし留まれば、ウィリアムは罰金を科し、二度と教皇庁に訴え出ないことを誓わせる とした。[85] |

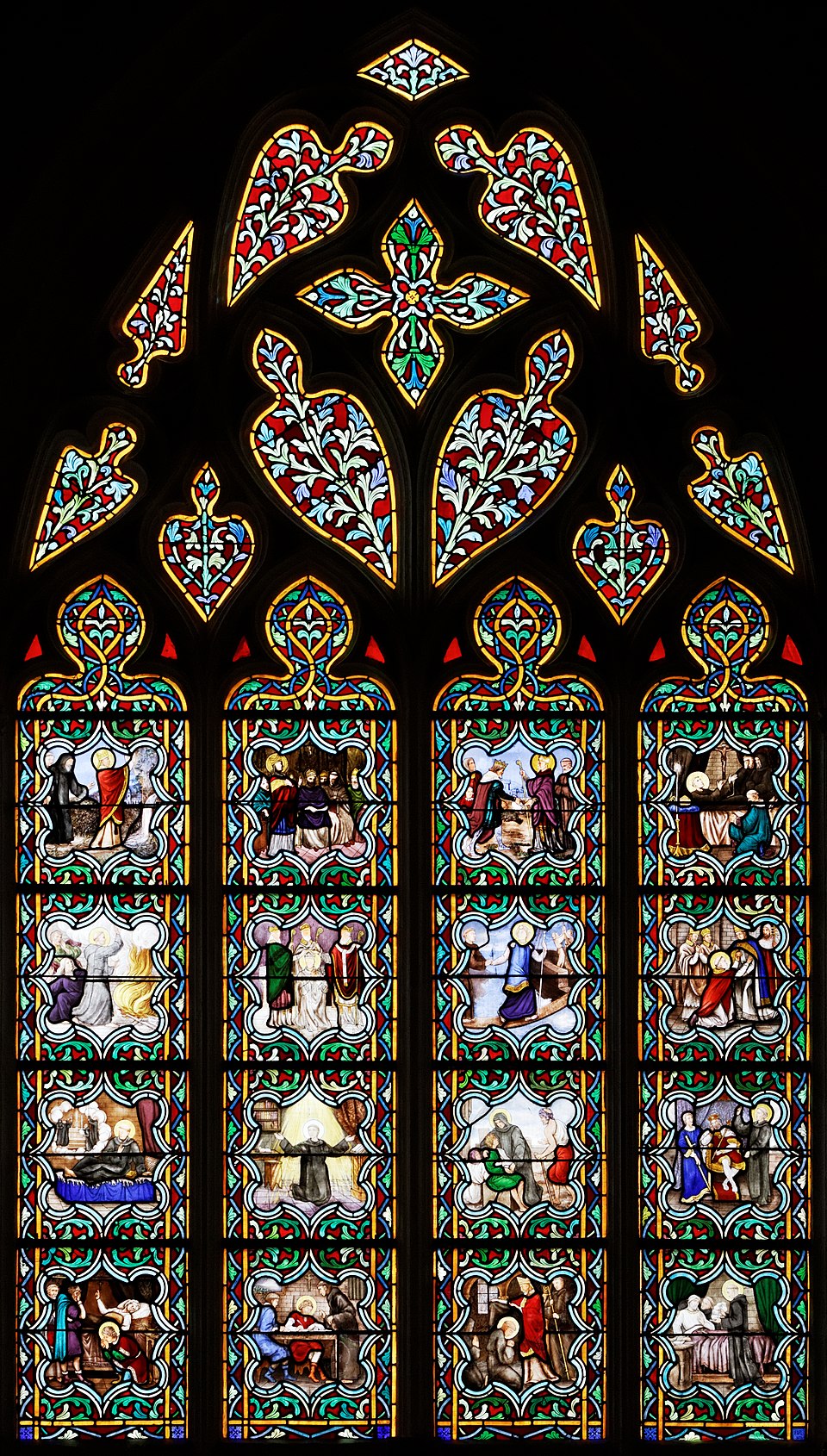

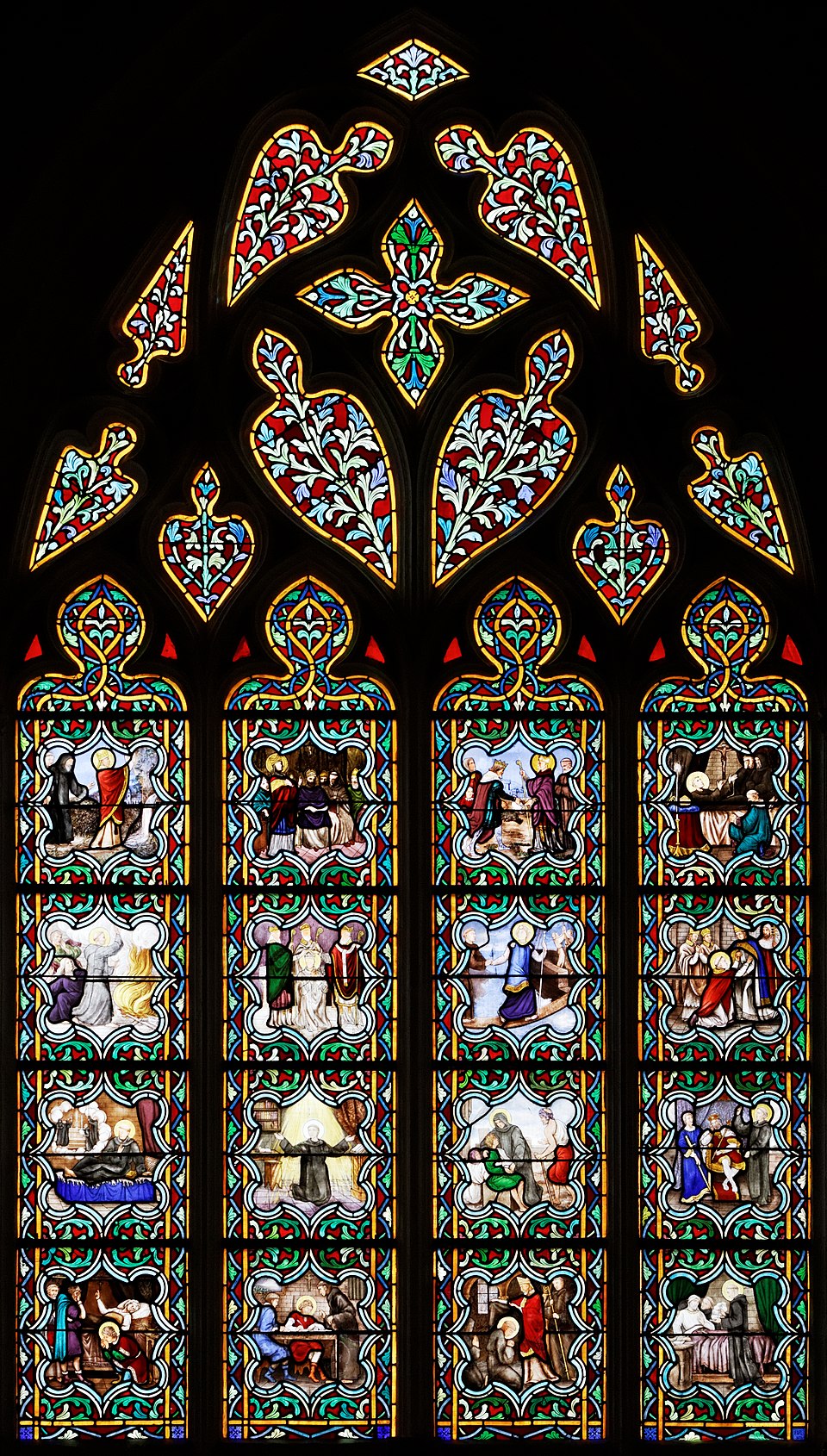

| First exile Romanelli's c. 1640 Meeting of Countess Matilda and Anselm of Canterbury in the Presence of Pope Urban II Anselm chose to depart in October 1097.[59] Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death.[86] From Lyon, Anselm wrote to Urban, requesting that he be permitted to resign his office. Urban refused but commissioned him to prepare a defence of the Western doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit against representatives from the Greek Church.[87] Anselm arrived in Rome by April[87] and, according to his biographer Eadmer, lived beside the pope during the Siege of Capua in May.[88] Count Roger's Saracen troops supposedly offered him food and other gifts but the count actively resisted the clerics' attempts to convert them to Catholicism.[88] At the Council of Bari in October, Anselm delivered his defence of the Filioque and the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist before 185 bishops.[89] Although this is sometimes portrayed as a failed ecumenical dialogue, it is more likely that the "Greeks" present were the local bishops of Southern Italy,[90] some of whom had been ruled by Constantinople as recently as 1071.[89] The formal acts of the council have been lost and Eadmer's account of Anselm's speech principally consists of descriptions of the bishops' vestments, but Anselm later collected his arguments on the topic as De Processione Spiritus Sancti.[90] Under pressure from their Norman lords, the Italian Greeks seem to have accepted papal supremacy and Anselm's theology.[90] The council also condemned William II. Eadmer credited Anselm with restraining the pope from excommunicating him,[87] although others attribute Urban's politic nature.[91] Anselm was present in a seat of honour at the Easter Council at St Peter's in Rome the next year.[92] There, amid an outcry to address Anselm's situation, Urban renewed bans on lay investiture and on clerics doing homage.[93] Anselm departed the next day, first for Schiavi—where he completed his work Cur Deus Homo—and then for Lyon.[91][94] Conflicts with Henry I  The life of St Anselm told in 16 medallions in a stained-glass window in Quimper Cathedral, Brittany, in France William Rufus was killed hunting in the New Forest on 2 August 1100. His brother Henry was present and moved quickly to secure the throne before the return of his elder brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, from the First Crusade. Henry invited Anselm to return, pledging in his letter to submit himself to the archbishop's counsel.[95] The cleric's support of Robert would have caused great trouble but Anselm returned before establishing any other terms than those offered by Henry.[96] Once in England, Anselm was ordered by Henry to do homage for his Canterbury estates[97] and to receive his investiture by ring and crozier anew.[98] Despite having done so under William, the bishop now refused to violate canon law. Henry for his part refused to relinquish a right possessed by his predecessors and even sent an embassy to Pope Paschal II to present his case.[91] Paschal reaffirmed Urban's bans to that mission and the one that followed it.[91] Meanwhile, Anselm publicly supported Henry against the claims and threatened invasion of his brother Robert Curthose. Anselm wooed wavering barons to the king's cause, emphasizing the religious nature of their oaths and duty of loyalty;[99] he supported the deposition of Ranulf Flambard, the disloyal new bishop of Durham;[100] and he threatened Robert with excommunication.[101] The lack of popular support greeting his invasion near Portsmouth compelled Robert to accept the Treaty of Alton instead, renouncing his claims for an annual payment of 3000 marks. Anselm held a council at Lambeth Palace which found that Henry's beloved Matilda had not technically become a nun and was thus eligible to wed and become queen.[102] On Michaelmas in 1102, Anselm was finally able to convene a general church council at London, establishing the Gregorian Reform within England. The council prohibited marriage, concubinage, and drunkenness to all those in holy orders,[103] condemned sodomy[104] and simony,[101] and regulated clerical dress.[101] Anselm also obtained a resolution against the British slave trade.[105] Henry supported Anselm's reforms and his authority over the English Church but continued to assert his own authority over Anselm. Upon their return, the three bishops he had dispatched on his second delegation to the pope claimed—in defiance of Paschal's sealed letter to Anselm, his public acts, and the testimony of the two monks who had accompanied them—that the pontiff had been receptive to Henry's counsel and secretly approved of Anselm's submission to the crown.[106] In 1103, then, Anselm consented to journey himself to Rome, along with the king's envoy William Warelwast.[107] Anselm supposedly travelled in order to argue the king's case for a dispensation[108] but, in response to this third mission, Paschal fully excommunicated the bishops who had accepted investment from Henry, though sparing the king himself.[91] Second exile After this ruling, Anselm received a letter forbidding his return and withdrew to Lyon to await Paschal's response.[91] On 26 March 1105, Paschal again excommunicated prelates who had accepted investment from Henry and the advisors responsible, this time including Robert de Beaumont, Henry's chief advisor.[109] He further finally threatened Henry with the same;[110] in April, Anselm sent messages to the king directly[111] and through his sister Adela expressing his own willingness to excommunicate Henry.[91] This was probably a negotiation tactic[112] but it came at a critical period in Henry's reign[91] and it worked: a meeting was arranged and a compromise concluded at L'Aigle on 22 July 1105. Henry would forsake lay investiture if Anselm obtained Paschal's permission for clerics to do homage for their lands;[113][114] Henry's bishops'[91] and counsellors' excommunications were to be lifted provided they advise him to obey the papacy (Anselm performed this act on his own authority and later had to answer for it to Paschal);[113] the revenues of Canterbury would be returned to the archbishop; and priests would no longer be permitted to marry.[114] Anselm insisted on the agreement's ratification by the pope before he would consent to return to England, but wrote to Paschal in favour of the deal, arguing that Henry's forsaking of lay investiture was a greater victory than the matter of homage.[115] On 23 March 1106, Paschal wrote Anselm accepting the terms established at L'Aigle, although both clerics saw this as a temporary compromise and intended to continue pressing for reforms,[116] including the ending of homage to lay authorities.[117] Even after this, Anselm refused to return to England.[118] Henry travelled to Bec and met with him on 15 August 1106. Henry was forced to make further concessions. He restored to Canterbury all the churches that had been seized by William or during Anselm's exile, promising that nothing more would be taken from them and even providing Anselm with a security payment.[citation needed] Henry had initially taxed married clergy and, when their situation had been outlawed, had made up the lost revenue by controversially extending the tax over all Churchmen.[119] He now agreed that any prelate who had paid this would be exempt from taxation for three years.[citation needed] These compromises on Henry's part strengthened the rights of the church against the king. Anselm returned to England before the new year.[91] |

最初の追放 ロマーネッリ作 1640年頃 教皇ウルバヌス2世の面前におけるマティルダ伯爵夫人とカンタベリー大司教アンセルムスの会見 アンセルムスは1097年10月に去ることを選んだ。[59] アンセルムスは名目上の称号を保持していたが、ウィリアムは直ちに彼の司教区の収入を没収し、死まで保持した。[86] リヨンからアンセルムスはウルバヌスに書簡を送り、職を辞する許可を求めた。ウルバヌスはこれを拒否したが、ギリシャ教会の代表者たちに対する聖霊の流出 に関する西洋教義の弁明を準備するよう彼に命じた。[87] アンセルムスは4月までにローマに到着した[87]。伝記作家エアドマーによれば、5月のカプア包囲戦の間、教皇の傍らで暮らしたという[88]。ロジェ 伯のサラセン人部隊は食糧や贈り物を差し出したとされるが、伯は彼らをカトリックに改宗させようとする聖職者たちの試みを積極的に拒んだ[88]。 10月のバーリ公会議において、アンセルムスは185人の司教の前でフィリオクエ説と聖体拝領における無酵パンの使用を擁護した[89]。これは時に失敗 したエキュメニカル対話として描かれるが、出席した「ギリシャ人」は南イタリアの現地司教たち[90]であり、その一部は1071年までコンスタンティ ノープルの支配下にあった可能性が高い。[89] 公会議の正式な議事録は失われており、エドマーによるアンセルムス演説の記述は主に司教たちの祭服の説明で構成されているが、アンセルムスは後にこの主題 に関する自分の主張を『聖霊の過程について』としてまとめた。[90] ノーマン人の領主からの圧力を受けて、イタリアのギリシャ人たちは教皇の至上権とアンセルムスの神学を受け入れたようである。[90] この公会議はウィリアム2世も非難した。エドマーは、教皇が彼を破門することをアンセルムス(=アンセルムス)が阻止したと評価しているが[87]、他の 者たちはウルバヌスの政治的な性質によるものと見なしている[91]。 アンセルムスは翌年、ローマにある聖ペテロ大聖堂で開催された復活祭公会議に、名誉席で出席した[92]。そこで、アンセルムの状況に対処するよう抗議の 声が上がる中、ウルバヌスは、世俗の叙任権と聖職者の忠誠の誓いに関する禁止令を改めて発した[93]。アンセルムスは翌日、まずスキアヴィに向けて出発 し、そこで『なぜ神は人となったのか』を完成させた後、リヨンへと向かった[91]。[94] ヘンリー1世との対立  フランスのブルターニュ地方、カンペール大聖堂のステンドグラス窓に描かれた、16枚のメダリオンで語られる聖アンセルムススの生涯 ウィリアム・ルフスは、1100年8月2日、ニューフォレストでの狩猟中に殺害された。兄のヘンリーは現場に居合わせ、ノルマンディー公ロベールが第一次 十字軍から帰国する前に、素早く王位を確保した。ヘンリーはアンセルムスに帰国を要請し、大司教の助言に従うことを手紙で約束した[95]。聖職者がロ バートを支持したことは大きな問題となったが、アンセルムスはヘンリーが提示した条件以外の条件を設定することなく帰国した[96]。イングランドに戻っ たアンセルムスは、ヘンリーからカンタベリーの大地に対する忠誠を誓うよう命じられ、指輪と司教杖による叙任を改めて受けた。[98] ウィリアム王の治世下ではこれに従っていたにもかかわらず、司教は今や教会法を犯すことを拒んだ。ヘンリー王は一方、先代王たちが有していた権利を放棄す ることを拒み、自らの主張を述べるために使節団を教皇パスクアーレ2世のもとへさえ派遣した。[91] パスクアーレはウルバヌス2世の使節団に対する破門宣告を、その使節団とそれに続く使節団に対して再確認した。[91] 一方、アンセルムスは公にヘンリーを支持し、兄ロバート・カーソースの主張と侵攻の脅威に反対した。アンセルムスは揺れる貴族たちを王の側に引き寄せよう と、彼らの誓いと忠誠の義務が宗教的性質を持つことを強調した[99]。彼は不忠な新ダラム司教ラヌルフ・フランバードの罷免を支持し[100]、ロバー トを破門すると脅した。[101] ポーツマス近郊での侵攻に民衆の支持が得られなかったため、ロバートは代わりにアルトン条約を受け入れ、年3000マルクの支払いを条件に王位継承権を放 棄した。 アンセルムスはランベス宮殿で教会会議を開き、ヘンリーが寵愛するマティルダは厳密には修道女になっておらず、結婚して王妃となる資格があると認定した [102]。1102年のミカエル祭に、アンセルムスはついにロンドンで総教会会議を招集し、イングランドにおけるグレゴリオ改革を確立した。この公会議 は聖職者全員に対し、婚姻・妾の保持・酩酊を禁じ[103]、同性愛[104]と聖職売買[101]を非難し、聖職者の服装を規制した[101]。アンセ ルムスはまた、ブリトン人奴隷貿易に対する決議も獲得した[105]。ヘンリーはアンセルムスの改革とイングランド教会に対する権威を支持したが、アンセ ルムスに対する自身の権威を主張し続けた。帰国後、教皇への第二使節団として派遣された三人の司教は、パスカルがアンセルムスに送った封印書簡、公的行 為、同行した二人の修道士の証言に反して、教皇がヘンリーの助言を受け入れ、密かにアンセルムスの王権への服従を承認したと主張した。[106] こうして1103年、アンセルムスは王の使節ウィリアム・ワレルワストと共に自らローマへ赴くことに同意した。[107] アンセルムスは王の免除許可[108]を求める主張を行うため旅立ったとされるが、この第三の使節団に対し、パスカルはヘンリーから叙任を受けた司教たち を完全に破門した。ただし王自身は免除した。[91] 二度目の追放 この判決後、アンセルムスは帰国を禁じる書簡を受け取り、パスカルの返答を待つためリヨンへ退いた。[91] 1105年3月26日、パスカルは再びヘンリーから叙任権の授与を受けた高位聖職者及び責任ある顧問たちを破門した。今回はヘンリーの首席顧問ロベール・ ド・ボーモンも含まれていた[109]。さらに彼はついにヘンリーに対しても同様の破門を宣告すると脅した[110]。4月、アンセルムスは王に直接 [111]、また妹アデラの仲介を通じて、自らヘンリーを破門する意思があることを伝えた。[91] これはおそらく交渉戦術であった[112]が、ヘンリー治世の重大な時期に発せられた[91]ため効果を発揮した。1105年7月22日、ラ・ゼーユで会 談が設定され妥協が成立した。アンセルムスが司祭の土地に対する忠誠宣誓をパスカルが許可すれば、ヘンリーは世俗叙任権を放棄する。[113][114] ヘンリーの司教たち[91]と顧問たちの破門は、教皇庁に従うよう彼に助言することを条件に解除されることになった(アンセルムスはこの行為を自らの権限 で行い、後にパスカル教皇に説明を求められた);[113] カンタベリー大司教区の収入は返還されることになった;そして司祭の結婚は今後認められなくなった。[114] アンセルムスは、この合意が教皇によって批准されることを、イングランドへの帰還に同意する条件として主張した。しかし彼はパスカルに書簡を送り、この合 意を支持する立場を示した。ヘンリーが世俗による叙任権を放棄したことは、忠誠の誓いの問題よりも大きな勝利だと論じたのである。[115] 1106年3月23日、パスカルはアンセルムスに書簡を送り、ラ・イーグルで定められた条件を受け入れた。ただし両聖職者はこれを一時的な妥協と見なし、 改革の継続を迫る意図を持っていた[116]。これには世俗権力への忠誠の廃止も含まれていた[117]。 それでもアンセルムスはイングランドへの帰国を拒み続けた[118]。ヘンリーはベックへ赴き、1106年8月15日に彼と会談した。ヘンリーはさらなる 譲歩を迫られた。ウィリアムやアンセルムスの亡命中に没収された全ての教会をカンタベリー大司教区に返還し、今後一切の没収を行わないことを約束。さらに アンセルムスに保証金を支払うことまでした[出典必要]。ヘンリーは当初、既婚聖職者に課税していたが、その状況が違法とされた後、失われた歳入を補うた め、物議を醸す形で全聖職者に課税を拡大していた[119]。彼は今回、この税を支払った聖職者は3年間課税免除とすることを認めた[出典必要]。ヘン リー側のこうした妥協は、国王に対する教会の権利を強化した。アンセルムスは新年前にイングランドへ帰還した[91]。 |

| Final years The Altar of St Anselm in his chapel at Canterbury Cathedral. It was constructed by English sculptor Stephen Cox from Aosta marble donated by its regional government[120] and consecrated on 21 April 2006 at a ceremony including the Bishop of Aosta and the Abbot of Bec.[121] The location of Anselm's relics, however, remains uncertain. In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop,[61] Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church.[91] The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric.[91] He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the archbishop of York to Canterbury so that future archbishops-elect would have to profess obedience before receiving it.[62] The incumbent archbishop Thomas II had received his own pallium directly and insisted on York's independence. From his deathbed, Anselm anathematized all who failed to recognize Canterbury's primacy over all the English Church. This ultimately forced Henry to order Thomas to confess his obedience to Anselm's successor.[63] On his deathbed, he announced himself content, except that he had a treatise in mind on the origin of the soul and did not know, once he was gone, if another was likely to compose it.[122] He died on Holy Wednesday, 21 April 1109.[108] His remains were translated to Canterbury Cathedral[123] and laid at the head of Lanfranc at his initial resting place to the south of the Altar of the Holy Trinity (now St Thomas's Chapel).[126] During the church's reconstruction after the disastrous fire of the 1170s, his remains were relocated,[126] although it is now uncertain where. On 23 December 1752, Archbishop Herring was contacted by Count Perron, the Sardinian ambassador, on behalf of King Charles Emmanuel, who requested permission to translate Anselm's relics to Italy.[127] (Charles had been duke of Aosta during his minority.) Herring ordered his dean to look into the matter, saying that while "the parting with the rotten Remains of a Rebel to his King, a Slave to the Popedom, and an Enemy to the married Clergy (all this Anselm was)" would be no great matter, he likewise "should make no Conscience of palming on the Simpletons any other old Bishop with the Name of Anselm".[129] The ambassador insisted on witnessing the excavation, however,[131] and resistance on the part of the prebendaries seems to have quieted the matter.[124] They considered the state of the cathedral's crypts would have offended the sensibilities of a Catholic and that it was probable that Anselm had been removed to near the altar of SS Peter and Paul, whose side chapel to the right (i.e., south) of the high altar took Anselm's name following his canonization. At that time, his relics would presumably have been placed in a shrine and its contents "disposed of" during the Reformation.[126] The ambassador's own investigation was of the opinion that Anselm's body had been confused with Archbishop Theobald's and likely remained entombed near the altar of the Virgin Mary,[133] but in the uncertainty nothing further seems to have been done then or when inquiries were renewed in 1841.[135] |

晩年 カンタベリー大聖堂内の礼拝堂にある聖アンセルムス祭壇。これはイングランドの彫刻家スティーブン・コックスが、アオスタ地方政府から寄贈されたアオスタ 産大理石を用いて制作したものである[120]。2006年4月21日、アオスタ司教とベック修道院長らが出席した式典で奉献された[121]。しかしア ンセルムスの遺骨の所在は依然として不明である。 1107年、ロンドン協約により国王と大司教の間の合意が正式に成立した[61]。ヘンリーはイングランド国王が教会の司教を任命する権利を正式に放棄し た[91]。アンセルムスの残りの2年間は、大司教としての職務に費やされた。[91] 彼はパスカルに働きかけ、ヨーク大主教のパッリウムをカンタベリーへ送らせた。これにより、将来の大主教候補者はパッリウムを受ける前に服従を誓わねばな らなくなった。[62] 当時のトマス2世大主教は自身のパッリウムを直接受け取っており、ヨークの独立を主張していた。アンセルムスは死の床で、カンタベリーが全イングランド教 会における首位権を持つことを認めない者をすべて破門した。これによりヘンリーは最終的に、トマスにアンセルムス後継者への服従を告白するよう命じること を余儀なくされた。[63] 死の床で彼は、魂の起源に関する論文を構想していたが、自分が死んだ後、誰かがそれを執筆するかどうか分からなかったこと以外は満足だと述べた。 [122] 彼は1109年4月21日、聖水曜日に死去した。[108] 遺骸はカンタベリー大聖堂に移され[123]、聖三位一体祭壇(現・聖トマス礼拝堂)南側の最初の安置場所であるランフランクの頭部に安置された [126]。1170年代の大火災後の教会再建時に遺骸は移されたが[126]、現在の所在は不明である。 1752年12月23日、ハーリング大司教はサルデーニャ大使ペロン伯爵から、カルロ・エマヌエーレ王の名においてアンセルムスの遺骨をイタリアへ移す許 可を求める連絡を受けた[127](カルロは未成年時代にアオスタ公であった)。ヘリングは教区長に調査を命じ、「王に背いた反逆者、教皇庁の奴隷、既婚 聖職者の敵(アンセルムスはこの全てであった)の腐った遺骸を手放すこと」は大した問題ではないとしつつも、同様に「アンセルムスの名を持つ他の古い司教 を愚かな者たちに押し付けることに良心の呵責を感じるべきではない」と述べた。[129] しかし大使は遺骸発掘に立ち会うことを強く要求した[131]。聖職者たちの抵抗により、この件はおさまったようだ。[124] 彼らは大聖堂の地下聖堂の状態がカトリック信徒の感性を傷つけると考え、アンセルムスは聖ペテロと聖パウロの祭壇近くに移された可能性が高いと推測した。 その祭壇の右側(すなわち南側)にある側礼拝堂は、アンセルムの列聖後に彼の名を冠している。当時、彼の聖遺物は聖堂に収められていたが、宗教改革の際に その中身は「処分」されたと思われる。[126] 大使自身の調査では、アンセルムスの遺体はテオバルド大司教のものと混同され、おそらく聖母マリアの祭壇付近に埋葬されたままであるとの見解を示した [133]。しかし不確実性から、当時も、1841年に調査が再開された際にも[135]、それ以上の措置は取られなかったようだ。 |

| Writings A late 16th-century engraving of Anselm Anselm has been called "the most luminous and penetrating intellect between St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas"[108] and "the father of scholasticism",[38] Scotus Erigena having employed more mysticism in his arguments.[91] Anselm's works are considered philosophical as well as theological since they endeavour to render Christian tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational system.[136] Anselm also studiously analyzed the language used in his subjects, carefully distinguishing the meaning of the terms employed from the verbal forms, which he found at times wholly inadequate.[137] His worldview was broadly Neoplatonic, as it was reconciled with Christianity in the works of St Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius,[3][c] with his understanding of Aristotelian logic gathered from the works of Boethius.[139][140][38] He or the thinkers in northern France who shortly followed him—including Abelard, William of Conches, and Gilbert of Poitiers—inaugurated "one of the most brilliant periods of Western philosophy", innovating logic, semantics, ethics, metaphysics, and other areas of philosophical theology.[141] Anselm held that faith necessarily precedes reason, but that reason can expand upon faith:[142] "And I do not seek to understand that I may believe but believe that I might understand. For this too I believe since, unless I first believe, I shall not understand."[d][143] This is possibly drawn from Tractate XXIX of St Augustine's Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John: regarding John 7:14–18, Augustine counseled "Do not seek to understand in order to believe but believe that thou may understand".[144] Anselm rephrased the idea repeatedly[e] and Thomas Williams (SEP 2007) considered that his aptest motto was the original title of the Proslogion, "faith seeking understanding", which intended "an active love of God seeking a deeper knowledge of God."[145] Once the faith is held fast, however, he argued an attempt must be made to demonstrate its truth by means of reason: "To me, it seems to be negligence if, after confirmation in the faith, we do not study to understand that which we believe."[f][143] Merely rational proofs are always, however, to be tested by scripture[146][147] and he employs Biblical passages and "what we believe" (quod credimus) at times to raise problems or to present erroneous understandings, whose inconsistencies are then resolved by reason.[148] Stylistically, Anselm's treatises take two basic forms, dialogues and sustained meditations.[148] In both, he strove to state the rational grounds for central aspects of Christian doctrines as a pedagogical exercise for his initial audience of fellow monks and correspondents.[148] The subjects of Anselm's works were sometimes dictated by contemporary events, such as his speech at the Council of Bari or the need to refute his association with the thinking of Roscelin, but he intended for his books to form a unity, with his letters and latter works advising the reader to consult his other books for the arguments supporting various points in his reasoning.[149] It seems to have been a recurring problem that early drafts of his works were copied and circulated without his permission.[148] A mid-17th century engraving of Anselm While at Bec, Anselm composed:[29] De Grammatico Monologion Proslogion De Veritate De Libertate Arbitrii De Casu Diaboli De Fide Trinitatis, also known as De Incarnatione Verbi[38] While archbishop of Canterbury, he composed:[29] Cur Deus Homo De Conceptu Virginali De Processione Spiritus Sancti De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati De Sacramentis Ecclesiae De Concordia |

著作 16世紀後半のアンセルムス アンセルムスは「聖アウグスティヌスと聖トマス・アクィナスとの間で最も輝かしく鋭い知性」[108]、「スコラ哲学の父」[38]と呼ばれてきた。スコ トゥス・エリゲナは議論においてより神秘主義を多用していた。[91] アンセルムスの著作は、伝統的に啓示された真理とされてきたキリスト教の信仰教義を合理的な体系として提示しようとする点で、神学的であると同時に哲学的 でもあると見なされている。[136] アンセルムスはまた、研究対象となる言語を精緻に分析し、使用される用語の意味を言語形式から慎重に区別した。彼は言語形式が時に全く不十分であることに 気づいていたのである。[137] 彼の世界観は、聖アウグスティヌスや偽ディオニュシオス[3][c]の著作においてキリスト教と調和された形で、広義の新プラトン主義的であった。また、 ボエティウスの著作から得たアリストテレス的論理学の理解も含まれていた。[139][140][38] 彼、あるいは彼に続いて現れた北フランスの思想家たち―アベラール、コンシュのウィリアム、ポワティエのジルベールら―は「西洋哲学の最も輝かしい時代の 一つ」を開幕させ、論理学、意味論、倫理学、形而上学、その他の哲学的神学の分野で革新をもたらした。[141] アンセルムスは、信仰は必然的に理性に先行するが、理性は信仰を拡張し得ると主張した[142]:「私は理解するために信じるのではない。理解するために 信じるのだ。この点についても、私は信じる。なぜなら、まず信じなければ、理解することはできないからである。」[d][143] この主張はおそらく、聖アウグスティヌスの『ヨハネの第一の手紙に関する十の説教』第29講から引用されたものである。ヨハネによる福音書7章14-18 節について、アウグスティヌスは「信じるために理解しようとせず、理解するために信じよ」と助言している。[144] アンセルムスはこの考えを繰り返し言い換えた[e]。トマス・ウィリアムズ(SEP 2007)は、彼の最も適切なモットーは『プロスロギオン』の原題「理解を求める信仰」であり、これは「神への深い知識を求める積極的な神への愛」を意図 していたと考えた。[145] しかし信仰が確固として保持された後は、理性を用いてその真実性を証明しようとする努力がなされねばならないと彼は主張した。「信仰が確証された後、我々 が信じるものを理解しようと努めないのは怠慢に思える」 [f][143] ただし、純粋に理性的証明は常に聖書によって検証されねばならない[146][147]。彼は聖句や「我々が信じるもの」(quod credimus)を時折用いて問題を提起したり、誤った理解を示したりする。それらの矛盾はその後、理性によって解決されるのである。[148] 文体的には、アンセルムスの論文は基本的に二つの形式を取る。対話形式と持続的な思索形式である[148]。いずれにおいても、彼はキリスト教教義の中心 的な側面に対する理性的根拠を、当初の聴衆である修道士の仲間や文通相手に対する教育的訓練として述べようと努めた. [148] アンセルムスの著作の主題は、バリーの公会議での演説やロスケリンの思想との関連性を否定する必要性など、当時の出来事に左右されることもあった。しかし 彼は著作群を統一的な体系と意図しており、書簡や後期の著作では、論理展開における各論点の根拠については他の著作を参照するよう読者に促している。 [149] 彼の著作の草稿が許可なく写され流通するという問題は繰り返し発生していたようだ。[148] 17世紀中頃のアンセルムスの版画 ベック修道院在任中にアンセルムスは以下を著した:[29] 『文法論』 『独白』 『対話』 『真理について』 『自由意志について』 悪魔の堕落について 三位一体の信仰について(別名『御言葉の受肉について』)[38] カンタベリー大主教在任中に著した作品:[29] 神はなぜ人となったのか 処女の懐胎について 聖霊の進みについて 無酵母と発酵の犠牲について 教会の秘跡について 一致について |

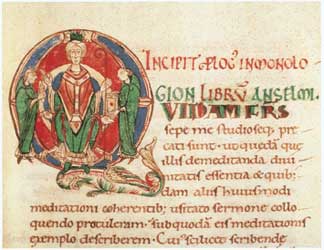

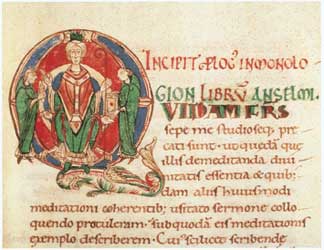

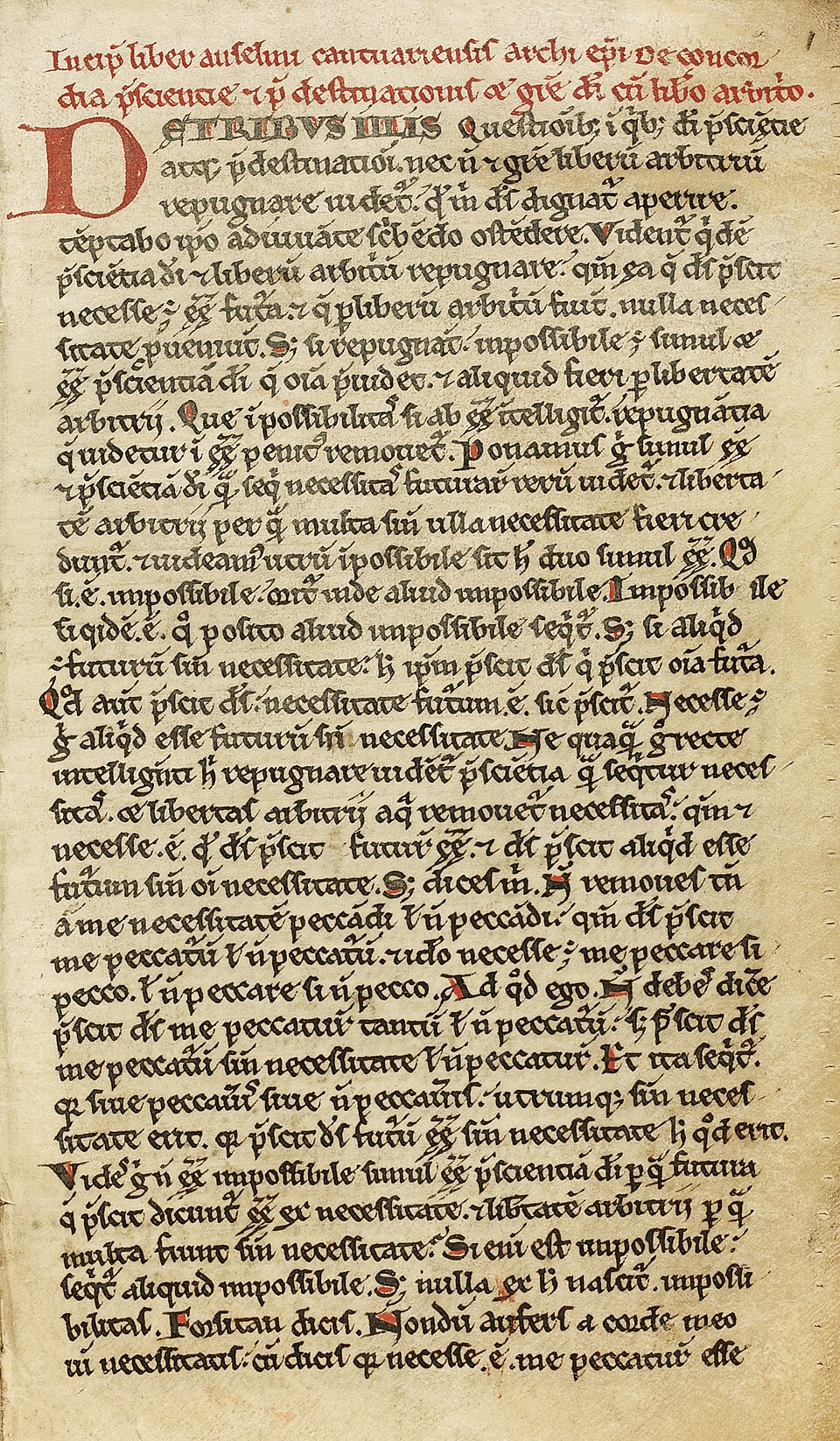

The illuminated beginning of an 11th-century manuscript of the Monologion Monologion The Monologion (Latin: Monologium, "Monologue"), originally entitled A Monologue on the Reason for Faith (Monoloquium de Ratione Fidei)[150][g] and sometimes also known as An Example of Meditation on the Reason for Faith (Exemplum Meditandi de Ratione Fidei),[152][h] was written in 1075 and 1076.[29] It follows St Augustine to such an extent that Gibson argues neither Boethius nor Anselm state anything which was not already dealt with in greater detail by Augustine's De Trinitate;[154] Anselm even acknowledges his debt to that work in the Monologion's prologue.[155] However, he takes pains to present his reasons for belief in God without appeal to scriptural or patristic authority,[156] using new and bold arguments.[157] He attributes this style—and the book's existence—to the requests of his fellow monks that "nothing whatsoever in these matters should be made convincing by the authority of Scripture, but whatsoever... the necessity of reason would concisely prove".[158] In the first chapter, Anselm begins with a statement that anyone should be able to convince themselves of the existence of God through reason alone "if he is even moderately intelligent".[159] He argues that many different things are known as "good", in many varying kinds and degrees. These must be understood as being judged relative to a single attribute of goodness.[160] He then argues that goodness is itself very good and, further, is good through itself. As such, it must be the highest good and, further, "that which is supremely good is also supremely great. There is, therefore, some one thing that is supremely good and supremely great—in other words, supreme among all existing things."[161] Chapter 2 follows a similar argument, while Chapter 3 argues that the "best and greatest and supreme among all existing things" must be responsible for the existence of all other things.[161] Chapter 4 argues that there must be the highest level of dignity among existing things and that the highest level must have a single member. "Therefore, there is a certain nature or substance or essence who through himself is good and great and through himself is what he is; through whom exists whatever truly is good or great or anything at all; and who is the supreme good, the supreme great thing, the supreme being or subsistent, that is, supreme among all existing things."[161] The remaining chapters of the book are devoted to consideration of the attributes necessary to such a being.[161] The Euthyphro dilemma, although not addressed by that name, is dealt with as a false dichotomy.[162] God is taken to neither conform to nor invent the moral order but to embody it:[162] in each case of his attributes, "God having that attribute is precisely that attribute itself".[163] A letter survives of Anselm responding to Lanfranc's criticism of the work. The elder cleric took exception to its lack of appeals to scripture and authority.[155] The preface of the Proslogion records his own dissatisfaction with the Monologion's arguments, since they are rooted in a posteriori evidence and inductive reasoning.[157] |

11世紀写本『モノローギオン』の装飾された冒頭部 モノローギオン 『モノローギオン』(ラテン語: モノローギウム、独白)は、1075年から1076年に書かれた。[29] この著作は聖アウグスティヌスに極めて忠実であり、ギブソンによれば、ボエティウスもアンセルムスも、アウグスティヌスの『三位一体論』で既に詳細に論じ られた内容を超えて何も述べていない[154]。アンセルムス自身も『独白』の序文で、同著作への負債を認めている。[155] しかし彼は、聖書や教父の権威に訴えることなく、新たな大胆な論証を用いて神への信仰の根拠を示すことに努めている。[156][157] この文体と著作そのものは、同僚修道士たちの「これらの事柄において、聖書の権威によって何一つ説得力を与えるべきではなく、理性の必然性が簡潔に証明す るあらゆる事柄によってのみ」という要求に由来すると彼は述べている。[158] 第一章でアンセルムスは、「たとえ中程度の知性を持つ者であっても」理性のみによって神の存在を自ら確信できるはずだと述べる。[159] 彼は、様々な種類の「善」が、多様な種類と程度で知られていると論じる。これらは単一の善の属性に対して相対的に判断されるものと理解されねばならない。 [160] 次に彼は、善そのものが極めて善であり、さらにそれ自体によって善であることを論じる。ゆえにそれは最高の善でなければならない。さらに「最も善なるもの は同時に最も偉大である。したがって、ある一つのものが最も善であり最も偉大である——言い換えれば、あらゆる存在物の中で至高である」と結論づける。 [161] 第2章は同様の論証を続ける。第3章では「あらゆる存在物の中で最も優れ、最も偉大で、至高なるもの」が他の全ての存在物の存在の根拠でなければならない と論じる。[161] 第4章は、存在するものの中で最高の尊厳のレベルが存在しなければならず、その最高レベルは単一の成員を持たねばならないと論じる。「したがって、ある種 の性質、実体、あるいは本質が存在する。それはそれ自体によって善であり偉大であり、それ自体によってそのものである。それを通じて、真に善であるもの、 偉大であるもの、あるいはあらゆるものが存在する。そしてそれは至高の善、至高の偉大なるもの、至高の存在、あるいは実体、すなわちあらゆる存在するもの の中で至高のものである。」[161] 本書の残りの章は、そのような存在に必要な属性についての考察に充てられている。[161] ユティフロのジレンマは、その名称では扱われていないが、偽の二分法として論じられている。[162] 神は道徳秩序に適合するものでも、それを発明するものでもなく、それを体現するものとして捉えられる。[162] 神の属性の各事例において、「神がその属性を持つことは、まさにその属性そのものである」。[163] アンセルムスがランフランクの批判に応答した書簡が現存する。年長の聖職者は、聖書や権威への言及が欠如している点を問題視した。[155] 『独白』の序文には、ア・ポステリオリな証拠と帰納的推論に根ざしているとして、彼自身が『独語』の論証に不満を抱いていたことが記されている。 [157] |

| Proslogion Main articles: Proslogion and Ontological argument The Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, "Discourse"), originally entitled Faith Seeking Understanding (Fides Quaerens Intellectum) and then An Address on God's Existence (Alloquium de Dei Existentia),[150][164][i] was written over the next two years (1077–1078).[29] It is written in the form of an extended direct address to God.[148] It grew out of his dissatisfaction with the Monologion's interlinking and contingent arguments.[148] His "single argument that needed nothing but itself alone for proof, that would by itself be enough to show that God really exists"[165] is commonly[j] taken to be merely the second chapter of the work. In it, Anselm reasoned that even atheists can imagine the greatest being, having such attributes that nothing greater could exist (id quo nihil maius cogitari possit).[108] However, if such a being's attributes did not include existence, a still greater being could be imagined: one with all of the attributes of the first and existence. Therefore, the truly greatest possible being must necessarily exist. Further, this necessarily-existing greatest being must be God, who therefore necessarily exists.[157] This reasoning was known to the Scholastics as "Anselm's argument" (ratio Anselmi) but it became known as the ontological argument for the existence of God following Kant's treatment of it.[165][k]  A 12th-century illumination from the Meditations of St. Anselm More probably, Anselm intended his "single argument" to include most of the rest of the work as well,[148] wherein he establishes the attributes of God and their compatibility with one another. Continuing to construct a being greater than which nothing else can be conceived, Anselm proposes such a being must be "just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be".[168] Chapter 6 specifically enumerates the additional qualities of awareness, omnipotence, mercifulness, impassibility (inability to suffer),[167] and immateriality;[169] Chapter 11, self-existent,[169] wisdom, goodness, happiness, and permanence; and Chapter 18, unity.[167] Anselm addresses the question-begging nature of "greatness" in this formula partially by appeal to intuition and partially by independent consideration of the attributes being examined.[169] The incompatibility of, e.g., omnipotence, justness, and mercifulness are addressed in the abstract by reason, although Anselm concedes that specific acts of God are a matter of revelation beyond the scope of reasoning.[170] At one point during the 15th chapter, he reaches the conclusion that God is "not only that than which nothing greater can be thought but something greater than can be thought".[148] In any case, God's unity is such that all of his attributes are to be understood as facets of a single nature: "all of them are one and each of them is entirely what [God is] and what the other[s] are".[171] This is then used to argue for the triune nature of the God, Jesus, and "the one love common to [God] and [his] Son, that is, the Holy Spirit who proceeds from both".[172] The last three chapters are a digression on what God's goodness might entail.[148] Extracts from the work were later compiled under the name Meditations or The Manual of St Austin.[23] |

プロスロギオン 主な記事: プロスロギオンと存在論的論証 『プロスロギオン』(ラテン語: Proslogium、「言説」)は、当初『理解を求める信仰』(Fides Quaerens Intellectum)と題され、後に『神の存在に関する談話』(Alloquium de Dei Existentia)と改題された。 [150][164][i] はその後2年間(1077–1078年)に執筆された[29]。これは神への長大な直接的呼びかけの形式で書かれている[148]。この著作は『モノロー ギオン』の相互連関的で条件付きの議論に対する彼の不満から生まれたものである。[148] 彼の「それ自体だけで証明を必要とせず、それだけで神の実在を十分に示し得る唯一の論証」[165]は、一般に[j]この著作の第2章のみを指すと解釈さ れる。その中でアンセルムスは、無神論者でさえ想像し得る「より偉大なものは存在し得ない属性(id quo nihil maius cogitari possit)を備えた至高の存在」を論じた。[108] しかし、もしそのような存在の属性に「存在」が含まれていないならば、さらに偉大な存在を想像できる。すなわち、最初の存在の全ての属性に加え「存在」を 持つ存在である。したがって、真に可能な限り偉大な存在は必然的に存在しなければならない。さらに、この必然的に存在する最も偉大な存在は神でなければな らない。ゆえに神は必然的に存在する。[157] この推論はスコラ学派において「アンセルムスの論証」(ラティオ・アンセルミ)として知られていたが、カントによる考察を経て、神の存在に関する存在論的 論証として知られるようになった。[165][k]  聖アンセルムスの『神の存在に関する思索』の12世紀の装飾写本 おそらくアンセルムスは、この「単一の論証」に著作の大部分を含める意図があった[148]。そこでは神の属性とその相互の調和が確立されている。さらに 「それより優れたものは考えられない存在」を構築する過程で、アンセルムスは「正義に満ち、真実であり、幸福であり、存在しない状態よりも優れたあらゆる 性質を備えた存在」が必然的に存在すると主張する。[168] 第6章では特に、意識、全能、慈悲深さ、無感情性(苦悩を受けない性質)[167]、非物質性[169]といった追加の特質を列挙している。第11章では 自己存在性[169]、知恵、善性、幸福、永続性を、第18章では単一性を挙げている。[167] アンセルムスはこの定式における「偉大さ」の循環論法的問題を、部分的には直観への訴え、部分的には検討対象の属性に対する独立した考察によって対処して いる。[169] 全能性、正義、慈悲深さといった属性の両立不可能性は、抽象的には理性によって論じられるが、アンセルムスは神の具体的な行為は理性の範囲を超えた啓示の 問題であると認めている。[170] 第15章のある時点で、彼は神は「単にそれより偉大なものは考えられない存在であるだけでなく、考え得るものよりも偉大な存在である」という結論に達す る。[148] いずれにせよ、神の単一性は、その全ての属性が単一の本性の側面として理解されるべきものである:「それらは全て一つであり、それぞれが完全に[神が]何 であるか、そして他の[属性]が何であるかを表している」。[171] この考えは、神、イエス、そして「神とその子に共通する唯一の愛、すなわち両者から発する聖霊」という三位一体の性質を論じるために用いられる。 [172] 最後の三章は、神の善性が何を意味しうるかについての余談である。[148] この著作からの抜粋は後に『黙想録』または『聖アウグスティヌスの手引書』としてまとめられた。[23] |

| Responsio The argument presented in the Proslogion has rarely seemed satisfactory[157][l] and was swiftly opposed by Gaunilo, a monk from the abbey of Marmoutier in Tours.[176] His book "for the fool" (Liber pro Insipiente)[m] argues that we cannot arbitrarily pass from idea to reality[157] (de posse ad esse not fit illatio).[38] The most famous of Gaunilo's objections is a parody of Anselm's argument involving an island greater than which nothing can be conceived.[165] Since we can conceive of such an island, it exists in our understanding and so must exist in reality. This is, however, absurd, since its shore might arbitrarily be increased and in any case varies with the tide. Anselm's reply (Responsio) or apology (Liber Apologeticus)[157] does not address this argument directly, which has led Klima,[179] Grzesik,[38] and others to construct replies for him and led Wolterstorff[180] and others to conclude that Gaunilo's attack is definitive.[165] Anselm, however, considered that Gaunilo had misunderstood his argument.[165][176] In each of Gaunilo's four arguments, he takes Anselm's description of "that than which nothing greater can be thought" to be equivalent to "that which is greater than everything else that can be thought".[176] Anselm countered that anything which does not actually exist is necessarily excluded from his reasoning and anything which might or probably does not exist is likewise aside the point. The Proslogion had already stated "anything else whatsoever other than [God] can be thought not to exist".[181] The Proslogion's argument concerns and can only concern the single greatest entity out of all existing things. That entity both must exist and must be God.[165] |

レスポンシオ 『プロスロギオン』で提示された議論は、ほとんど満足のいくものとは見なされなかった[157][l]。そしてトゥールのマルムティエ修道院の修道士ガウ ニロによって即座に反論された[176]。彼の著書『愚者への書』(Liber pro Insipiente)[m]は、我々が恣意的に観念から現実へ移行することはできないと主張する[157](de posse ad esse not fit illatio)。[38] ガウニロの反論で最も有名なのは、アンセルムスの「考え得る限り最大の島」論をパロディ化したものだ[165]。我々はそのような島を想像できる以上、そ れは我々の理解の中に存在し、したがって現実にも存在しなければならない。しかしこれは荒唐無稽である。なぜならその岸辺は恣意的に拡大されうる上、いず れにせよ潮の満ち干によって変化するからだ。 アンセルムスの反論(レスポンシオ)あるいは弁明書(リベル・アポロゲティクス)[157]はこの議論に直接触れていない。このためクリマ[179]、グ ジェシク[38]らは彼に代わって反論を構築し、ウォルターストルフ[180]らはガウニロの攻撃が決定的だと結論づけた。[165] しかしアンセルムススは、ガウニロが自身の論証を誤解していると考えた。[165][176] ガウニロの四つの論証において、彼はアンセルムスが「それより偉大なものは考えられないもの」と表現したものを、「考え得るあらゆるものより偉大なもの」 と同等と見なしている。[176] アンセルムスは反論した。実際に存在しないものは必然的に彼の推論から除外され、存在する可能性が低いものや存在しない可能性が高いものも同様に論点外で あると。『プロスロギオン』は既に「神以外のあらゆるものは存在しないと考え得る」と述べている。[181] 『プロスロギオン』の論証が関わるのは、存在する全てのものの中で唯一最大の存在のみである。その存在は存在せねばならず、かつ神でなければならない。 [165] |

Dialogues MS Auct. D2. 6 An illuminated archbishop—presumably Anselm—from a 12th-century edition of his Meditations All of Anselm's dialogues take the form of a lesson between a gifted and inquisitive student and a knowledgeable teacher. Except for in Cur Deus Homo, the student is not identified but the teacher is always recognizably Anselm himself.[148] Anselm's De Grammatico ("On the Grammarian"), of uncertain date,[n] deals with eliminating various paradoxes arising from the grammar of Latin nouns and adjectives[152] by examining the syllogisms involved to ensure the terms in the premises agree in meaning and not merely expression.[183] The treatment shows a clear debt to Boethius's treatment of Aristotle.[139] Between 1080 and 1086, while still at Bec, Anselm composed the dialogues De Veritate ("On Truth"), De Libertate Arbitrii ("On the Freedom of Choice"), and De Casu Diaboli ("On the Devil's Fall").[29] De Veritate is concerned not merely with the truth of statements but with correctness in will, action, and essence as well.[184] Correctness in such matters is understood as doing what a thing ought or was designed to do.[184] Anselm employs Aristotelian logic to affirm the existence of an absolute truth of which all other truth forms separate kinds. He identifies this absolute truth with God, who therefore forms the fundamental principle both in the existence of things and the correctness of thought.[157] As a corollary, he affirms that "everything that is, is rightly".[186] De Libertate Arbitrii elaborates Anselm's reasoning on correctness with regard to free will. He does not consider this a capacity to sin but a capacity to do good for its own sake (as opposed to owing to coercion or for self-interest).[184] God and the good angels therefore have free will despite being incapable of sinning; similarly, the non-coercive aspect of free will enabled man and the rebel angels to sin, despite this not being a necessary element of free will itself.[187] In De Casu Diaboli, Anselm further considers the case of the fallen angels, which serves to discuss the case of rational agents in general.[188] The teacher argues that there are two forms of good—justice (justicia) and benefit (commodum)—and two forms of evil: injustice and harm (incommodum). All rational beings seek benefit and shun harm on their own account but independent choice permits them to abandon bounds imposed by justice.[188] Some angels chose their own happiness in preference to justice and were punished by God for their injustice with less happiness. The angels who upheld justice were rewarded with such happiness that they are now incapable of sin, there being no happiness left for them to seek in opposition to the bounds of justice.[187] Humans, meanwhile, retain the theoretical capacity to will justly but, owing to the Fall, they are incapable |

対話集 MS Auct. D2. 6 12世紀版『瞑想録』に描かれた装飾された大司教——おそらくアンセルムス—— アンセルムスの対話集は全て、才能ある探究心豊かな生徒と博識な教師との授業形式を取っている。『神はなぜ人となったのか』を除き、生徒の正体は明かされないが、教師は常にアンセルムス本人と認識できる。[148] アンセルムスの『文法家について』(De Grammatico)は、作成時期が不明[n]であるが、ラテン語の名詞と形容詞の文法から生じる様々な逆説[152]を排除することを扱っている。こ れは、前提における用語が単に表現上ではなく、意味においても一致していることを確認するために、関連する三段論法を検証することによって行われる [183]。この論考はボエティウスのアリストテレス解釈への明らかな影響を示している[139]。 1080年から1086年の間、ベック修道院に在職中、アンセルムスは対話篇『真実について』『自由意志について』『悪魔の堕落について』を著した。 [29] 『真実について』は、単なる命題の真偽だけでなく、意志・行為・本質における正しさをも扱う。[184] こうした事柄における正しさとは、あるものがなすべきこと、あるいはそのために設計されたことを行うこととして理解される。[184] アンセルムスはアリストテレスの論理を用いて、他のあらゆる真実が派生する絶対的真実の存在を主張する。彼はこの絶対的真実を神と同一視し、神はそれゆえ に万物の存在と思考の正しさの両方における根本原理を形成する。[157] その帰結として、彼は「存在するものはすべて正しく存在する」と断言する。[186]『自由意志について』は、自由意志に関するアンセルムス (Anselm)の正しさの論理を展開する。彼はこれを罪を犯す能力とは見なさず、強制や自己利益によるものではなく、それ自体のために善を行う能力と見 なす。[184] したがって神と善なる天使は、罪を犯す能力を持たないにもかかわらず自由意志を有する。同様に、自由意志の非強制的側面は、人間と反逆天使に罪を犯すこと を可能にしたが、これは自由意志そのものの必須要素ではない。[187] 『悪魔の堕落について』においてアンセルムスはさらに堕天使の事例を検討し、これは理性ある行為者全般の事例を論じるために役立っている。[188] 教師は、善には二つの形態——正義(justicia)と利益(commodum)——があり、悪にも二つの形態——不正義と害(incommodum) ——があると論じる。全ての理性ある存在は自らのために利益を求め害を避けるが、独立した選択により正義が課す境界を放棄することが可能である。 [188] ある天使たちは正義よりも自らの幸福を優先して選択し、その不正義ゆえに神から幸福の減少という罰を受けた。正義を守った天使たちは、今や罪を犯すことす らできないほどの幸福を授けられた。正義の境界に反して求めるべき幸福が、もはや彼らには残されていないからだ。[187] 一方、人間は理論的には正義を志す能力を保持しているが、堕落のため、実際にはそれができない。 |

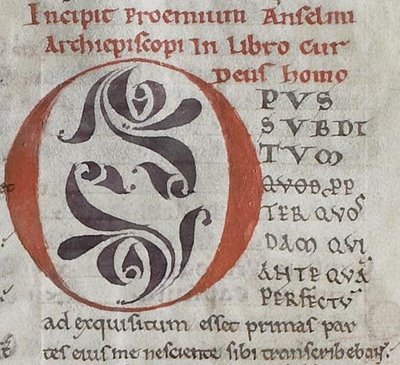

The beginning of the Cur Deus Homo's prologue, from a 12th-century manuscript held at Lambeth Palace Cur Deus Homo Main articles: Cur Deus Homo and Satisfaction theory of atonement Cur Deus Homo ("Why God was a Man") was written from 1095 to 1098 once Anselm was already archbishop of Canterbury[29] as a response for requests to discuss the Incarnation.[190] It takes the form of a dialogue between Anselm and Boso, one of his students.[191] Its core is a purely rational argument for the necessity of the Christian mystery of atonement, the belief that Jesus's crucifixion was necessary to atone for mankind's sin. Anselm argues that, owing to the Fall and mankind's fallen nature ever since, humanity has offended God. Divine justice demands restitution for sin but human beings are incapable of providing it, as all the actions of men are already obligated to the furtherance of God's glory.[192] Further, God's infinite justice demands infinite restitution for the impairment of his infinite dignity.[189] The enormity of the offence led Anselm to reject personal acts of atonement, even Peter Damian's flagellation, as inadequate[193] and ultimately vain.[194] Instead, full recompense could only be made by God, which His infinite mercy inclines Him to provide. Atonement for humanity, however, could only be made through the figure of Jesus, as a sinless being both fully divine and fully human.[190] Taking it upon himself to offer his own life on our behalf, his crucifixion accrues infinite worth, more than redeeming mankind and permitting it to enjoy a just will in accord with its intended nature.[189] This interpretation is notable for permitting divine justice and mercy to be entirely compatible[160] and has exercised immense influence over church doctrine,[157][195] largely supplanting the earlier theory developed by Origen and Gregory of Nyssa[108] that had focused primarily on Satan's power over fallen man.[157] Cur Deus Homo is often accounted Anselm's greatest work,[108] but the legalist and amoral nature of the argument, along with its neglect of the individuals actually being redeemed, has been criticized both by comparison with the treatment by Abelard[157] and for its subsequent development in Protestant theology.[196] |

『なぜ神は人となったのか』の序文の冒頭部分。ランベス宮殿所蔵の12世紀写本より なぜ神は人となったのか 関連項目: なぜ神は人となったのか、償いの理論 『なぜ神は人となったか』(Cur Deus Homo)は、アンセルムスがカンタベリー大司教に就任した後の1095年から1098年にかけて執筆された[29]。受肉論に関する議論を求める要請に 応える形で書かれたものである[190]。この著作は、アンセルムスとその弟子ボソとの対話形式を取っている[191]。その核心は、キリスト教の贖罪の 神秘、すなわち人類の罪を償うためにイエスの磔刑が必要であったという信念の必然性を、純粋に理性的に論証するものである。アンセルムスは、原罪とそれ以 来の人類の堕落した性質により、人類は神を冒涜したと論じる。神の正義は罪に対する償いを要求するが、人間のあらゆる行為は既に神の栄光を増すことに義務 付けられているため、人間はそれを提供することができない。[192] さらに、神の無限の正義は、その無限の尊厳を損なったことに対する無限の償いを要求する。[189] この冒涜の甚大さゆえに、アンセルムスはペトロ・ダミアノの鞭打ちすら含む個人的な贖罪行為を不十分[193] かつ究極的には無益[194] として退けた。代わりに、完全な償いは神のみが為し得、神の無限の慈悲がそれを提供するように導くのである。しかし人類のための贖罪は、完全なる神性かつ 完全なる人間性を持つ罪なき存在であるイエスの姿を通してのみ成し得た[190]。自らを犠牲にして我々のために命を捧げた彼の磔刑は、人類を贖い、本来 の性質にかなった正義の意志を享受させる以上の、無限の価値を生み出すのである。[189] この解釈は、神の正義と慈悲が完全に両立し得ることを認める点で注目に値する[160]。そして教会教義に多大な影響を及ぼし[157][195]、主に 堕落した人間に対するサタンの力に焦点を当てたオリゲネスやニッサのグレゴリウスが展開した以前の理論[108]をほぼ置き換えたのである。[157] 『神はなぜ人となられたか』はアンセルムス最高傑作とされることが多い[108]が、その議論の法制度主義的・非道徳的性質、そして実際に救われる個人へ の配慮の欠如は、アベラールの扱い[157]との比較において、またプロテスタント神学におけるその後の展開[196]においても批判されてきた。 |

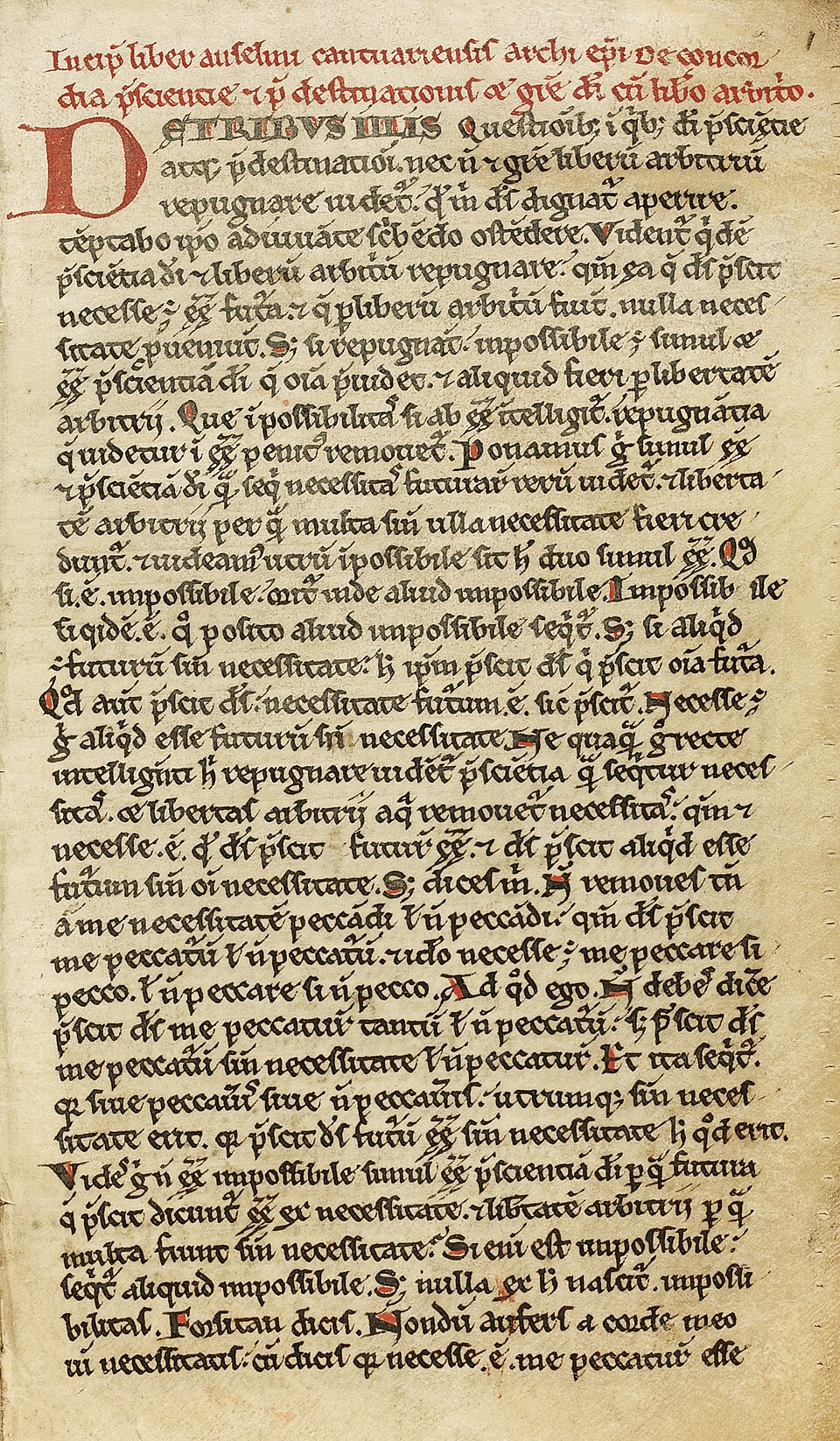

The first page of a 12th-century manuscript of the De Concordia Other works Anselm's De Fide Trinitatis et de Incarnatione Verbi Contra Blasphemias Ruzelini ("On Faith in the Trinity and on the Incarnation of the Word Against the Blasphemies of Roscelin"),[38] also known as Epistolae de Incarnatione Verbi ("Letters on the Incarnation of the Word"),[29] was written in two drafts in 1092 and 1094.[38] It defended Lanfranc and Anselm from association with the supposedly tritheist heresy espoused by Roscelin of Compiègne, as well as arguing in favour of Trinitarianism and universals. De Conceptu Virginali et de Originali Peccato ("On the Virgin Conception and Original Sin") was written in 1099.[29] He claimed to have written it out of a desire to expand on an aspect of Cur Deus Homo for his student and friend Boso and takes the form of Anselm's half of a conversation with him.[148] Although Anselm denied belief in Mary's Immaculate Conception,[197] his thinking laid two principles which formed the groundwork for that dogma's development. The first is that it was proper that Mary should be so pure that—apart from God—no purer being could be imagined. The second was his treatment of original sin. Earlier theologians had held that it was transmitted from generation to generation by the sinful nature of sex. As in his earlier works, Anselm instead held that Adam's sin was borne by his descendants through the change in human nature which occurred during the Fall. Parents were unable to establish a just nature in their children which they had never had themselves.[198] This would subsequently be addressed in Mary's case by dogma surrounding the circumstances of her own birth. De Processione Spiritus Sancti Contra Graecos ("On the Procession of the Holy Spirit Against the Greeks"),[164] written in 1102,[29] is a recapitulation of Anselm's treatment of the subject at the Council of Bari.[90] He discussed the Trinity first by stating that human beings could not know God from Himself but only from analogy. The analogy that he used was the self-consciousness of man. The peculiar double nature of consciousness, memory, and intelligence represents the relation of the Father to the Son. The mutual love of these two (memory and intelligence), proceeding from the relation they hold to one another, symbolizes the Holy Spirit.[157] De Concordia Praescientiae et Praedestinationis et Gratiae Dei cum Libero Arbitrio ("On the Harmony of Foreknowledge and Predestination and the Grace of God with Free Choice") was written from 1107 to 1108.[29] Like the De Conceptu Virginali, it takes the form of a single narrator in a dialogue, offering presumable objections from the other side.[148] Its treatment of free will relies on Anselm's earlier works, but goes into greater detail as to the ways in which there is no actual incompatibility or paradox created by the divine attributes.[149] In its 5th chapter, Anselm reprises his consideration of eternity from the Monologion. "Although nothing is there except what is present, it is not the temporal present, like ours, but rather the eternal, within which all times altogether are contained. If in a certain way, the present time contains every place and all the things that are in any place, likewise, every time is encompassed in the eternal present, and everything that is in any time."[200] It is an overarching present, all beheld at once by God, thus permitting both his "foreknowledge" and genuine free choice on the part of mankind.[201] Fragments survive of the work Anselm left unfinished at his death, which would have been a dialogue concerning certain pairs of opposites, including ability/inability, possibility/impossibility, and necessity/freedom.[202] It is thus sometimes cited under the name De Potestate et Impotentia, Possibilitate et Impossibilitate, Necessitate et Libertate.[38] Another work, probably left unfinished by Anselm and subsequently revised and expanded, was De Humanis Moribus per Similitudines ("On Mankind's Morals, Told Through Likenesses") or De Similitudinibus ("On Likenesses").[203] A collection of his sayings (Dicta Anselmi) was compiled, probably by the monk Alexander.[204] He also composed prayers to various saints.[17] Anselm wrote nearly 500 surviving letters (Epistolae) to clerics, monks, relatives, and others,[205] the earliest being those written to the Norman monks who followed Lanfranc to England in 1070.[17] Southern asserts that all of Anselm's letters "even the most intimate" are statements of his religious beliefs, consciously composed so as to be read by many others.[206] His long letters to Waltram, bishop of Naumberg in Germany (Epistolae ad Walerannum) De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati ("On Unleavened and Leavened Sacrifice") and De Sacramentis Ecclesiae ("On the Church's Sacraments") were both written between 1106 and 1107 and are sometimes bound as separate books.[29] Although he seldom asked others to pray for him, two of his letters to hermits do so, "evidence of his belief in their spiritual prowess".[207] His letters of guidance—one to Hugh, a hermit near Caen, and two to a community of lay nuns—endorse their lives as a refuge from the difficulties of the political world with which Anselm had to contend.[207] Many of Anselm's letters contain passionate expressions of attachment and affection, often addressed "to the beloved lover" (dilecto dilectori). While there is wide agreement that Anselm was personally committed to the monastic ideal of celibacy, some academics such as McGuire[208] and Boswell[209] have characterized these writings as expressions of a homosexual inclination.[210] The general view, expressed by Olsen[211] and Southern, sees the expressions as representing a "wholly spiritual" affection "nourished by an incorporeal ideal".[212] |

『一致について』の12世紀写本の最初のページ その他の著作 アンセルムスの『三位一体の信仰と聖言の受肉について、ルゼリヌスの冒涜に対する論駁』 (『三位一体の信仰と御言葉の受肉について、ルゼリーニの冒涜に対する論駁』)[38]、別名『御言葉の受肉に関する書簡集』(Epistolae de Incarnatione Verbi)[29]は、1092年と1094年の二度にわたり草稿が作成された。[38] この書簡は、ランフランクとアンセルムスを、コンピエーニュのロズェランが主張したとされる三神論的異端との関連から擁護するとともに、三位一体論と普遍 概念を支持する論拠を提示した。 『処女の受胎と原罪について』(De Conceptu Virginali et de Originali Peccato)は1099年に書かれた[29]。彼は、教え子であり友人であるボソのために『神はなぜ人となったのか』の一側面を補足したいという思い からこれを書いたと主張し、アンセルムスがボソとの対話の半分を担う形式を取っている。[148] アンセルムススはマリアの無原罪の御宿りへの信仰を否定した[197]が、彼の思想はその教義発展の基盤となる二つの原理を打ち立てた。第一に、マリアは 神を除けば想像しうる最も純粋な存在であるべきだという点だ。第二に、原罪の扱い方である。以前の神学者たちは、原罪が性行為の罪深い性質によって世代か ら世代へ伝播されると主張していた。アンセルムスは、以前の著作と同様に、アダムの罪は堕落の際に生じた人間性の変化を通じて子孫に受け継がれたと主張し た。親は、自分たちが一度も持ったことのない正義の性質を子供に確立することはできなかったのだ[198]。この問題は後に、マリア自身の誕生を取り巻く 教義によって、マリアの場合において扱われることになる。 『聖霊の流出について、ギリシア人に対する』(De Processione Spiritus Sancti Contra Graecos)[164]は1102年に書かれた[29]。これはバーリ公会議におけるアンセルムスによる主題論の要約である[90]。彼はまず、人間 は神そのものからではなく類推によってのみ神を知ることができると述べ、三位一体論を論じた。彼が用いた類推は人間の自己意識である。意識、記憶、知性と いう特異な二重性が父と子の関係を象徴する。これら二者(記憶と知性)の相互愛は、両者の関係から生じるものであり、聖霊を象徴するのだ[157]。 『予知と予定と神の恩寵と自由意志の調和について』(De Concordia Praescientiae et Praedestinationis et Gratiae Dei cum Libero Arbitrio)は1107年から1108年にかけて執筆された[29]。『処女の懐胎について』(De Conceptu Virginali)と同様、対話形式で単一の語り手が、反対側の立場から想定される異議を提示する形式を取っている[148]。自由意志に関する論述は アンセルムススの先行著作に依拠しつつ、神の属性によって生じる実際の矛盾やパラドックスが存在しない点についてより詳細に論じている。[149] 第5章では『独白』における永遠性の考察を再展開する。「そこには現在に存在するもの以外は何もないが、それは我々の時間的な現在ではなく、あらゆる時間 を包含する永遠の現在である。ある意味で、現在という時があらゆる場所とあらゆる場所にある全てのものを包含するように、同様に、あらゆる時は永遠の現在 の中に包含され、あらゆる時に存在する全てのものが含まれるのだ。」[200] これは包括的な現在であり、神によって同時に全てが把握される。それゆえ、神の「予知」と人類の真の自由選択の両方が可能となるのである。[201] アンセルムススが死の床で未完のまま残した著作の断片が現在も残っている。これは能力/無能力、可能性/不可能性、必然性/自由といった対立概念のペアに ついて論じた対話形式の著作であったと考えられる。[202] そのため、この著作は『能力と無能力、可能性と不可能性、必然性と自由について』(De Potestate et Impotentia, Possibilitate et Impossibilitate, Necessitate et Libertate)という名称で引用されることもある。[38] もう一つの著作は、おそらくアンセルムスによって未完のまま残され、その後改訂・拡大された『De Humanis Moribus per Similitudines』(「類推を通して語られる人類の道徳について」)あるいは『De Similitudinibus』(「類推について」)である。[203] 彼の格言集(Dicta Anselmi)は、おそらく修道士アレクサンダーによって編集された。[204] また、彼はさまざまな聖人への祈りも作成した。[17] アンセルムスは、聖職者、修道士、親族などに対して、500通近くの現存する手紙(Epistolae)を書いた。[205] 最も古いものは、1070年にランフランクに従ってイングランドに渡ったノーマンの修道士たち宛てに書かれたものである。[17] サザンは、アンセルムスの手紙は「最も親密な」ものさえも、彼の宗教的信念の表明であり、多くの人々に読まれることを意識して書かれたものであると主張し ている。[206] ドイツのナウムベルク司教ヴァルトラムへの長い手紙(Epistolae ad Walerannum)『De Sacrificio Azymi et Fermentati(無酵の犠牲と発酵の犠牲について)』と『De Sacramentis Ecclesiae(教会の秘跡について)』は、いずれも 1106 年から 1107 年の間に書かれ、時には別々の本として綴じられることもある。[29] 彼は他人に祈りを求めることは稀だったが、隠者への二通の手紙ではそうしており、「彼らの霊的力への信頼の証」である[207]。指導の手紙―カーン近郊 の隠者ヒューへの一通と、修道女共同体への二通―は、アンセルムスが直面した政治世界の困難から逃れる避難所としての彼らの生活を支持している。 [207] アンセルムススの書簡の多くは、情熱的な愛着と愛情の表現を含み、しばしば「最愛の恋人へ」(dilecto dilectori)と宛てられている。アンセルムスが修道院の独身主義という理想に個人的な献身を示していた点については広く合意があるが、マクガイア [208]やボスウェル[209]といった一部の学者は、これらの文章を同性愛的傾向の表現と特徴づけている。[210] オルセン[211]やサザンが示す一般的な見解では、これらの表現は「非物質的な理想によって育まれた」「完全に霊的な」愛情を表しているとされている。 [212] |

Legacy A 12th-century illumination of Eadmer composing Anselm's biography Two biographies of Anselm were written shortly after his death by his chaplain and secretary Eadmer (Vita et Conversatione Anselmi Cantuariensis) and the monk Alexander (Ex Dictis Beati Anselmi).[28] Eadmer also detailed Anselm's struggles with the English monarchs in his history (Historia Novorum). Another was compiled about fifty years later by John of Salisbury at the behest of Thomas Becket.[205] The historians William of Malmesbury, Orderic Vitalis, and Matthew Paris all left full accounts of his struggles against the second and third Norman kings.[205] Anselm's students included Eadmer, Alexander, Gilbert Crispin, Honorius Augustodunensis, and Anselm of Laon. His works were copied and disseminated in his lifetime and exercised an influence on the Scholastics, including Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham.[140] His thoughts have guided much subsequent discussion on the procession of the Holy Spirit and the atonement. His work also anticipates much of the later controversies over free will and predestination.[56] An extensive debate occurred—primarily among French scholars—in the early 1930s about "nature and possibility" of Christian philosophy, which drew strongly on Anselm's work.[140] Modern scholarship remains sharply divided over the nature of Anselm's episcopal leadership. Some, including Fröhlich[213] and Schmitt,[214] argue for Anselm's attempts to manage his reputation as a devout scholar and cleric, minimizing the worldly conflicts he found himself forced into.[214] Vaughn[215] and others argue that the "carefully nurtured image of simple holiness and profound thinking" was precisely employed as a tool by an adept, disingenuous political operator,[214] while the traditional view of the pious and reluctant church leader recorded by Eadmer—one who genuinely "nursed a deep-seated horror of worldly advancement"—is upheld by Southern[216] among others.[207][214] |