アンチフェミニズム

Antifeminism

☆

反フェミニズム[anti-feminism]とは、フェミニズムへの反対運動を目指す態度や思考法である。19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、反フェミニストたちは女性の権利に関する特定の政策提案、例えば

選挙権、教育機会、財産権、避妊手段へのアクセスなどに反対した[1][2]。20世紀中盤から後半にかけては、反フェミニストたちはしばしば中絶の権利

を求める運動に反対した。

21世紀初頭、一部の反フェミニストは自らのイデオロギーを、男性嫌悪への反応と見なしている。彼らはフェミニズムが、若年男性の大学進学率・卒業率の低

下、自殺におけるジェンダー差、男性性の衰退といった社会問題の原因だと主張する。[3][4][5]

21世紀の反フェミニズムは、時に暴力的な極右過激主義行為の一要素となっている。[6][7][8]

反フェミニズムはしばしば、男性に対する差別を問題視する社会運動である男性権利運動と結びつけられる。[9][10]

| Antifeminism or

anti-feminism is opposition to feminism. In the late 19th century and

early 20th century, antifeminists opposed particular policy proposals

for women's rights, such as the right to vote, educational

opportunities, property rights, and access to birth control.[1][2] In

the mid and late 20th century, antifeminists often opposed the

abortion-rights movement. In the early 21st century, some antifeminists see their ideology as a response to perceived misandry, holding feminism responsible for several social problems, including lower college entrance and graduate rates of young men, gender differences in suicide and a perceived decline in masculinity.[3][4][5] 21st century antifeminism has sometimes been an element of violent, far-right extremist acts.[6][7][8] Antifeminism is often linked to the men's rights movement, a social movement concerned with discrimination against men.[9][10] |

反フェミニズムとは、フェミニズムへの反対を指す。19世紀末から20

世紀初頭にかけて、反フェミニストたちは女性の権利に関する特定の政策提案、例えば選挙権、教育機会、財産権、避妊手段へのアクセスなどに反対した[1]

[2]。20世紀中盤から後半にかけては、反フェミニストたちはしばしば中絶の権利を求める運動に反対した。 21世紀初頭、一部の反フェミニストは自らのイデオロギーを、男性嫌悪への反応と見なしている。彼らはフェミニズムが、若年男性の大学進学率・卒業率の低 下、自殺におけるジェンダー差、男性性の衰退といった社会問題の原因だと主張する。[3][4][5] 21世紀の反フェミニズムは、時に暴力的な極右過激主義行為の一要素となっている。[6][7][8] 反フェミニズムはしばしば、男性に対する差別を問題視する社会運動である男性権利運動と結びつけられる。[9][10] |

| Definition Canadian sociologists Melissa Blais and Francis Dupuis-Déri write that antifeminist thought has primarily taken the form of masculinism, in which "men are in crisis because of the feminization of society".[11] The term antifeminist is also used to describe public female figures, some of whom, such as Naomi Wolf, Camille Paglia, and Katie Roiphe, define themselves as feminists, based on their opposition to some or all elements of feminist movements.[12] Other feminists[who?] label writers such as Roiphe, Christina Hoff Sommers, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese as antifeminist[13][14] because of their positions regarding oppression and lines of thought within feminism.[15] The meaning of antifeminism has varied across time and cultures, and antifeminism attracts both men and women. Some women, like those in the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League, campaigned against women's suffrage.[16] Men's studies scholar Michael Kimmel defines antifeminism as "the opposition to women's equality". He says that antifeminists oppose "women's entry into the public sphere, the re-organization of the private sphere, women's control of their bodies, and women's rights generally." Kimmel further writes that antifeminist argumentation relies on "religious and cultural norms" while proponents of antifeminism advance their cause as a means of "'saving' masculinity from pollution and invasion". He argues that antifeminists consider the "traditional gender division of labor as natural and inevitable, perhaps also divinely sanctioned."[17] |

定義 カナダの社会学者メリッサ・ブレとフランシス・デュピュイ=デリは、反フェミニズム思想は主に男性優位主義の形で現れており、そこでは「社会の女性化によって男性が危機に陥っている」と述べている。[11] 反フェミニストという用語は、公的な女性人物を指す場合にも用いられる。ナオミ・ウルフ、カミーユ・パリア、ケイティ・ロイフェなど、フェミニスト運動の 一部または全要素への反対を理由に自らをフェミニストと定義する人物も含まれる。[12] 一方、他のフェミニスト[誰?]は、ロイフェ、クリスティーナ・ホフ・ソマーズ、ジーン・ベスケ・エルシュタイン、エリザベス・フォックス=ジェノヴェー ゼといった作家たちを、抑圧に関する立場やフェミニズム内部の思想的傾向を理由に反フェミニスト[13][14]とレッテル貼りしている。[15] 反フェミニズムの意味は時代や文化によって異なり、男性と女性の双方を惹きつける。女性国家反参政権連盟のような一部の女性は、女性参政権に反対する運動を行った。[16] 男性学研究者マイケル・キンメルは、反フェミニズムを「女性の平等に対する反対」と定義する。彼は、反フェミニストが「女性の公共圏への進出、私的領域の 再編成、女性の身体に対する自己決定権、そして女性の権利全般」に反対すると述べている。キンメルはさらに、反フェミニズムの論拠は「宗教的・文化的規 範」に依拠していると記し、反フェミニズム支持者は自らの主張を「男性性を汚染や侵略から『救う』手段」として推進すると述べる。彼は反フェミニストが 「伝統的なジェンダー分業を自然かつ不可避なもの、おそらく神聖な承認を得たものと見なしている」と論じている。[17] |

| Ideology Antifeminist ideology rejects at least one of the following general principles of feminism:[18] 1. That social arrangements among men and women are neither natural nor divinely determined. 2. That social arrangements among men and women favor men. 3. That there are collective actions that can and should be taken to transform these arrangements into more just and equitable arrangements Some antifeminists argue that feminism, despite claiming to advocate for equality, ignores rights issues unique to men. They believe that the feminist movement has achieved its aims and now seeks higher status for women than for men via special rights and exemptions, such as female-only scholarships, affirmative action, and gender quotas.[19][20][21] Antifeminism might be motivated by the belief that feminist theories of patriarchy and disadvantages suffered by women in society are incorrect or exaggerated;[18][22] that feminism as a movement encourages misandry and results in harm or oppression of men; or driven by general opposition towards women's rights.[17][23][24][25] Furthermore, antifeminists view feminism as a denial of innate psychological sex differences and an attempt to reprogram people against their biological tendencies.[26] They have argued that feminism has resulted in changes to society's previous norms relating to sexuality, which they see as detrimental to traditional values or conservative religious beliefs.[27][28][29] For example, the ubiquity of casual sex and the decline of marriage are mentioned as negative consequences of feminism.[30][31] In a report from anti-extremism charity HOPE not Hate, half of young men from UK believe that feminism has "gone too far and makes it harder for men to succeed".[32][33] Moreover, other antifeminists oppose women's entry into the workforce, political office, or the voting process, as well as the lessening of male authority in families.[34] They argue that a change of women's roles is a destructive force that endangers the family, or is contrary to religious morals. For example, Paul Gottfried maintains that the change of women's roles "has been a social disaster that continues to take its toll on the family" and contributed to a "descent by increasingly disconnected individuals into social chaos".[35] |

イデオロギー 反フェミニズムのイデオロギーは、フェミニズムの以下の一般的な原則のうち少なくとも一つを拒否する[18]: 1. 男性と女性の間の社会的取り決めは、自然のものでも神によって定められたものでもない。 2. 男性と女性の間の社会的取り決めは男性に有利である。 3. これらの関係を、より公正で平等なものに変えるために、集団で取るべき行動があるということ 一部の反フェミニストは、フェミニズムが平等を主張しながらも、男性特有の権利問題を無視していると主張する。彼らは、フェミニスト運動は目的を達成し、 今では女性限定奨学金、アファーマティブ・アクション、ジェンダークォータといった特別な権利や免除を通じて、男性よりも高い地位を女性に求めようとして いると考えている。[19][20] [21] 反フェミニズムの動機は、フェミニズムの父権制理論や女性が社会で受けた苦悩が誤りか誇張されているという信念[18][22]、フェミニズム運動が男性 嫌悪を助長し男性への危害や抑圧をもたらすという主張、あるいは女性の権利に対する一般的な反対感情にある[17][23][24][25]。 さらに、反フェミニストはフェミニズムを、生来の心理的性差の否定であり、生物学的傾向に反して人々を再プログラムしようとする試みと見なしている。 [26] 彼らは、フェミニズムが性に関する社会の従来の規範に変化をもたらし、それが伝統的価値観や保守的な宗教的信念に有害であると主張している。[27] [28][29] 例えば、カジュアルな性関係の蔓延や結婚の衰退は、フェミニズムの負の結果として挙げられている。[30][31] 反過激主義慈善団体HOPE not Hateの報告書によれば、英国の若年男性の半数が「フェミニズムは行き過ぎで男性の成功を妨げている」と信じている。[32][33] さらに他の反フェミニストは、女性の労働市場参入・公職就任・投票権獲得、および家庭内での男性権威の低下に反対する。[34] 彼らは女性の役割変化が家族を危険に晒す破壊的力である、あるいは宗教的道徳に反すると主張する。例えばポール・ゴットフリードは、女性の役割変化が「家 族に代償を払い続けている社会的災厄」であり、「ますます孤立する個人による社会的混乱への転落」に寄与したと論じている。[35] |

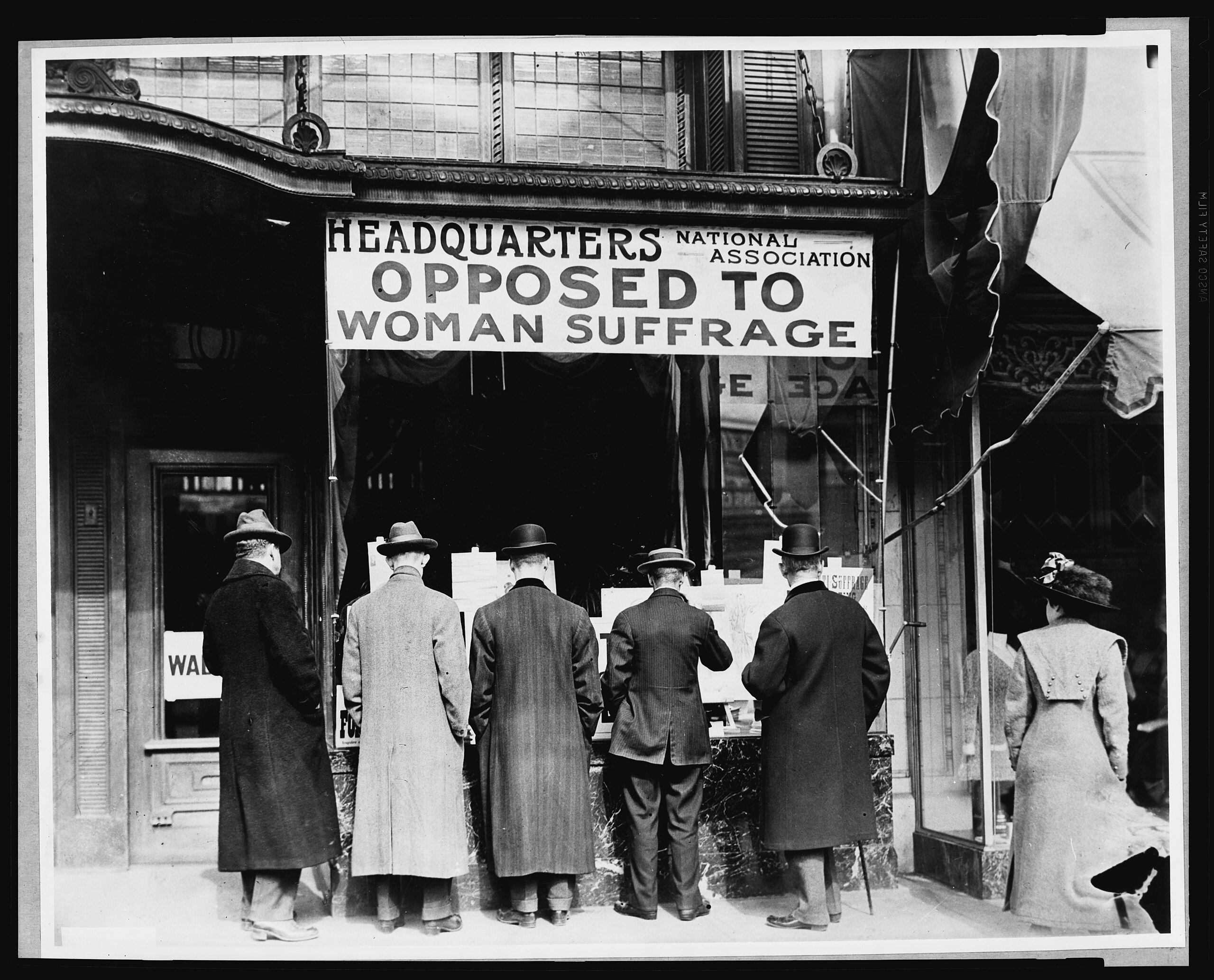

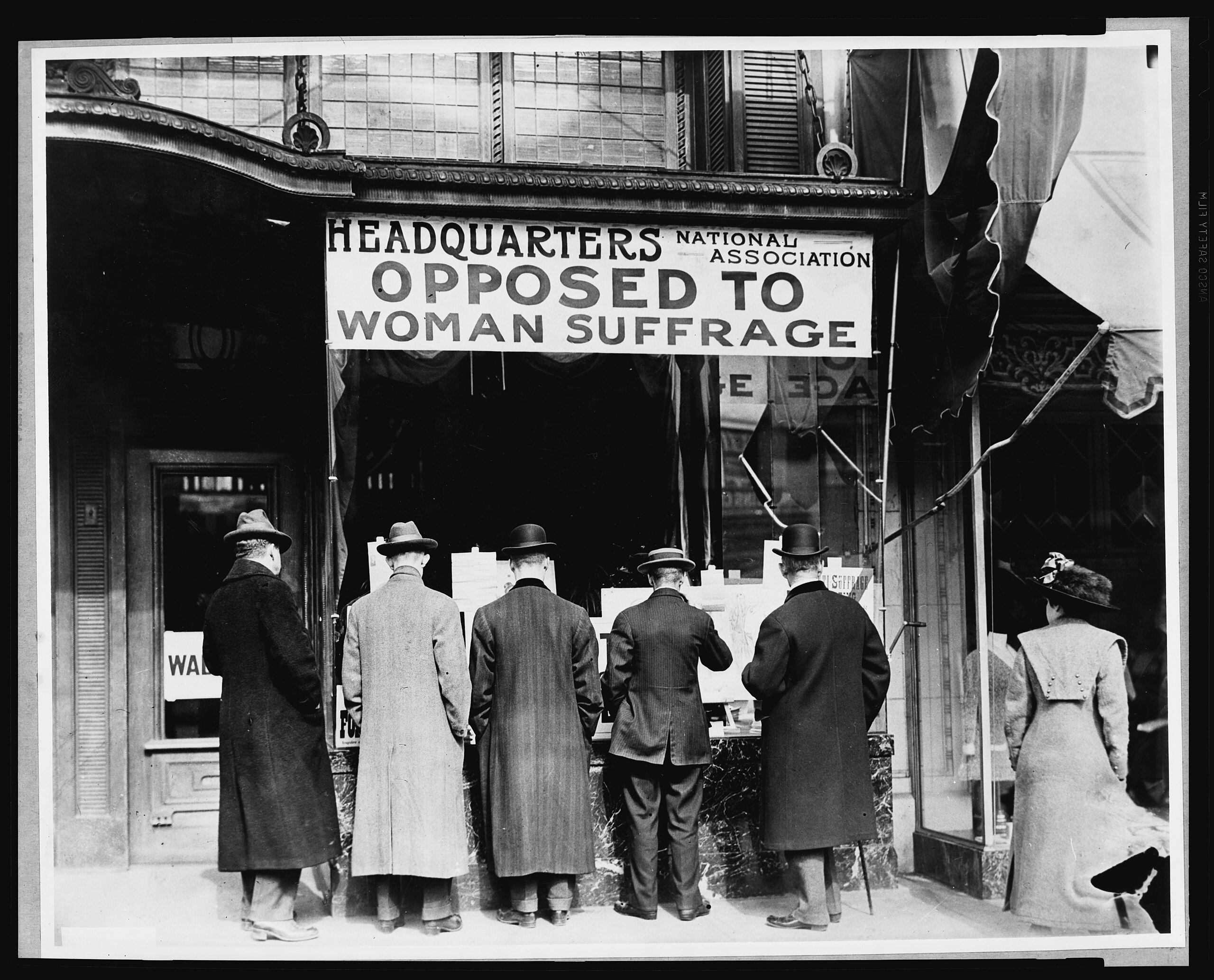

| History United States  American antisuffragists in the early 20th century 19th century The "women's movement" began in 1848, most famously articulated by Elizabeth Cady Stanton demanding voting rights, joined by Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony and others who also pushed for other rights such as education, job freedom, marital and property rights, and the right to choose when or whether to become a mother.[36] By the end of the century, a cultural counter movement had begun. Janet Chafetz identified in a study 32 first-wave antifeminist movements, including those in the 19th century and early 20th century movements.[37] These countermovements were in response to some women's growing demands, which were perceived as threatening to the standard way of life. Though men were not the only antifeminists, men experienced what some have called a "crisis of masculinity"[38] in response to traditional gender roles being challenged. Men's responses to increased feminism varied. Some men subscribed to feminist ideals, and others became decidedly antifeminist. Antifeminist men cited religious models and natural law to emphasize women's need to return to the private sphere, in order to preserve the current social order.[38] In the 19th century, one of the major focal points of antifeminism was opposition to women's suffrage, which began as a grassroots movement in 1848 and spanned for 72 years.[39][2] Opponents of women's entry into institutions of higher learning argued that education was too great a physical burden on women. In Sex in Education: or, a Fair Chance for the Girls (1873), Harvard professor Edward Clarke predicted that if women went to college, their brains would grow bigger and heavier, and their wombs would atrophy.[40] Other antifeminists opposed women's entry into the labor force, their right to join unions, to sit on juries, or to obtain birth control and control of their sexuality.[17] The pro-family movement appeared in the late 19th century, by about 1870.[41] This movement was intended to halt the rising divorce rate and reinforce traditional family values. The National League for the Protection of the Family, formerly known as the Divorce Reform League, took over the movement in 1881.[41][42] Samuel Dike was one of the founders of the League, and was considered an early expert on divorce. Through his efforts, the League garnered attention from pro-family advocates. It underwent a shift from fighting against divorce to promoting marriage and traditional family.[41] Speaking on behalf of the League in an 1887 address to the Evangelical Alliance Conference, Samuel Dike described the ideal family as having "one man and one woman, united in wedlock, together with their children".[41] This movement built the foundation for many pro-family arguments in contemporary antifeminism. |

歴史 アメリカ  20世紀初頭のアメリカの反参政権運動家たち 19世紀 「女性運動」は1848年に始まった。最も有名なのは、エリザベス・キャディ・スタントンが投票権を要求し、ルーシー・ストーン、スーザン・B・アンソ ニーなどがそれに加わり、教育、職業の自由、婚姻権、財産権、母親になる時期や母親になるかどうかを選択する権利など、他の権利も求めたことだ。[36] 世紀の終わりまでに、文化的な反動運動が始まった。ジャネット・チャフェッツは、19世紀および20世紀初頭の運動を含む、32の第一波反フェミニズム運 動を研究で特定した。[37] これらの反動運動は、一部の女性たちの要求の高まりに対する反応であり、それは従来の生活様式を脅かすものと認識されていた。反フェミニストは男性だけで はないが、男性は伝統的なジェンダー役割への挑戦に対し、いわゆる「男らしさの危機」[38]を経験した。フェミニズムの高まりへの男性の反応は様々だっ た。フェミニストの理想を支持する男性もいれば、断固として反フェミニストになる男性もいた。反フェミニストの男性は、現行の社会秩序を維持するため、女 性が私的領域に戻る必要性を強調するために、宗教的規範や自然法を引用した。[38] 19世紀における反フェミニズムの主要な焦点の一つは、女性参政権への反対であった。これは1848年に草の根運動として始まり、72年間にわたって続い た[39][2]。高等教育機関への女性の参入に反対する者たちは、教育が女性にとって身体的負担が大きすぎると主張した。『教育における性:あるいは少 女たちに公平な機会を』(1873年)でハーバード大学のエドワード・クラーク教授は、女性が大学に通えば脳が大きくなり重くなり、子宮が萎縮すると予測 した[40]。他の反フェミニストたちは、女性の労働力参加、組合加入権、陪審員としての参加権、避妊手段の取得や性に対する自己決定権に反対した。 [17] 家族擁護運動は19世紀後半、1870年頃に現れた[41]。この運動は離婚率の上昇を食い止め、伝統的な家族価値観を強化することを目的としていた。国 民家族保護連盟(旧称:離婚改革連盟)は1881年にこの運動を引き継いだ。[41][42] サミュエル・ダイクは連盟の創設者の一人であり、離婚問題の初期の専門家と見なされていた。彼の尽力により、連盟は家族擁護派の注目を集めた。活動は離婚 反対から結婚と伝統的家族の促進へと移行した。[41] 1887年の福音同盟会議における同連盟代表としての演説で、サミュエル・ダイクは理想的な家族を「一人の男性と一人の女性が婚姻関係で結ばれ、その子供 たちと共に暮らす状態」と定義した。[41] この運動は、現代の反フェミニズムにおける多くの家族擁護論の基盤を築いた。 |

| Early 20th century Women's suffrage was achieved in the US in 1920, and early 20th-century antifeminism was primarily focused on fighting this. Suffragists scoffed at antisuffragists. Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) from 1904 to 1915, presumed that the antisuffragists were merely working under the influence of male forces.[43] Later historians tended to dismiss antisuffragists as subscribing to the model of domestic idealism, that a woman's place is in the home. This undermines and belittles the true power and numbers behind the antisuffrage movement, which was primarily led by women themselves.[43] Arguments employed by antisuffragists at the turn of the century had less to do with a woman's place in the home as much as it had to do with a woman's proper place in the public realm. Leaders of the movement often encouraged other women to leave the home and participate in society.[43] What they opposed was women participating in the political sphere. There were two reasons antisuffragists opposed women participating in the political realm. Some argued that women were already overburdened. The majority of them, however, argued that a woman's participation in the political realm would hinder her participation in social and civic duties. If they won the right to vote, women would have to align with a particular party, which would destroy their ability to be politically neutral. Antisuffragists feared this would hinder their influence with legislative authorities.[43] |

20世紀初頭 アメリカでは1920年に女性参政権が実現したが、20世紀初頭の反フェミニズム運動は主にこれに反対することを主眼としていた。参政権運動家たちは反参 政権運動家たちを嘲笑した。1904年から1915年まで全米女性参政権協会(NAWSA)の会長を務めたアンナ・ハワード・ショーは、反参政権運動家た ちは単に男性勢力の影響下で活動しているに過ぎないと見なしていた。[43] 後世の歴史家たちは、反参政権派を「女性の居場所は家庭にある」という家庭的理想主義のモデルを信奉する者と軽視する傾向があった。これは反参政権運動の 真の力と規模を過小評価するものであり、同運動は主に女性自身によって主導されていたのである。[43] 世紀の変わり目に反参政権派が用いた論点は、女性の家庭内での立場というより、むしろ公共領域における女性の適切な立場に関わるものだった。運動の指導者 たちはしばしば他の女性たちに家庭を離れ社会参加するよう促した。[43] 彼らが反対したのは、女性が政治的領域に参加することだった。 反参政権派が女性の政治的領域参加に反対した理由は二つあった。一部は、女性は既に負担が重いと主張した。しかし大多数は、女性が政治に参加すれば、社会 や市民としての義務を果たせなくなるという主張だった。もし投票権を獲得すれば、女性は特定の政党に属さざるを得なくなり、政治的中立性を失うことにな る。反参政権派は、これが立法機関への影響力を損なうことを恐れていたのだ。[43] |

| Mid 20th century In 1951, two journalists published Washington Confidential. The novel claimed that Communist leaders used their men and women to recruit a variety of minorities in the nation's capital, such as females, colored males, and homosexual males. The popularity of the book led the Civil Service Commission to create a "publicity campaign to improve the image of federal employees"[44] in hopes to save their federal employees from losing their jobs. This ploy failed once the journalists linked feminism to communism in their novel, and ultimately reinforced antifeminism by implying that defending the "white, Christian, heterosexual, patriarchal family" was the only way to oppose communism.[44] |

20世紀半ば 1951年、二人のジャーナリストが『ワシントン・コンフィデンシャル』を出版した。この小説は、共産主義の指導者たちが国民の首都ワシントンで、女性や 有色人種の男性、同性愛者の男性など、様々な少数派を勧誘するために自らの部下を利用していると主張した。この本の大ヒットを受け、公務員委員会は「連邦 職員のイメージ向上キャンペーン」[44]を立ち上げた。連邦職員の職を失う事態を防ごうとしたのだ。しかしこの策略は失敗に終わった。ジャーナリストた ちが小説の中でフェミニズムと共産主義を結びつけたためだ。結局、共産主義に対抗する唯一の方法は「白人・キリスト教徒・異性愛者・家父長制の家族」を守 ることだとほのめかすことで、反フェミニズムを強化する結果となった。[44] |

| Late 20th century Equal Rights Amendment The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a perennially proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that would grant equal rights and opportunities to every citizen of the United States, regardless of their sex. In 1950 and 1953, ERA was passed by the Senate with a provision known as "the Hayden rider", making it unacceptable to ERA supporters.[45][46] The Hayden rider was included to keep special protections for women. A new section to the ERA was added, stating: "The provisions of this article shall not be construed to impair any rights, benefits, or exemptions now or hereafter conferred by law upon persons of the female sex." That is, women could keep their existing and future special protections that men did not have.[47] By 1972, the amendment was supported by both major parties and was immensely popular. However, it was defeated in Congress when it failed to get the vote of 38 legislatures by 1982.[47] Supporters of an unaltered ERA rejected the Hayden rider, believing an ERA containing the rider did not provide for equality.[48] In 1986, Jerome Himmelstein identified two main theories about the appeal of antifeminism and its role in opposition to the ERA. One theory is that it was a clash between upper-class liberal voters and the older, more conservative lower-class rural voters, who often serve as the center for right-wing movements. This theory identifies particular social classes as more inherently friendly to antifeminism. Another theory holds that women who feel vulnerable and dependent upon men, are likely to oppose anything that threatens that tenuous stability. Under this view, while educated, independent career women may support feminism, housewives who lack such resources are more drawn to antifeminism. Himmelstein says both views are at least partially wrong, arguing that the primary dividing line between feminists and antifeminists is cultural, rather than stemming from differences in economic and social status.[49] There are similarities between income between activists on both sides of the ERA debate. The most indicative factors when predicting ERA position, especially among women, were race, marital status, age, and education.[50] ERA opposition was much higher among white, married, older, and less educated citizens.[50] Women who opposed the ERA tended to fit characteristics consistent with the Religious Right.[51] In 1983, Val Burris said that high-income men opposed the amendment, because they would gain the least with it being passed; that those men had the most to lose, since the ratification of the ERA would mean more competition for their jobs and possibly a lowered self-esteem.[47] Because of the support of antifeminism from conservatives and the constant "conservative reactions to liberal social politics", such as the New Deal attacks, the attack on the ERA has been called a "right-wing backlash".[47] In a 2012 study, their methods include actions such as "insults proffered in emails or on the telephone, systematic denigration of feminism in the media, Internet disclosure of confidential information (e.g. addresses) on resources for battered women"[11] and more. |

20世紀後半 平等権修正条項 平等権修正条項(ERA)は、性別に関わらず全ての米国市民に平等な権利と機会を保障する、米国憲法への恒久的な修正案である。1950年と1953年、 ERAは「ヘイデン付帯条項」と呼ばれる規定を伴って上院を通過したが、この条項がERA支持者にとって受け入れがたいものとなった。[45][46] ヘイデン付帯条項は、女性に対する特別な保護を維持するために盛り込まれた。ERAに新たな条項が追加され、次のように定められた。「本条の規定は、法律 によって女性に対して現在または将来付与される権利、利益、または免除を損なうものと解釈してはならない」。つまり、女性は男性が持たない既存および将来 の特別な保護を維持できるというわけだ。[47] 1972年までに、この修正条項は両主要政党の支持を得て、非常に高い人気を博した。しかし、1982年までに38州の議会の承認を得られなかったため、 議会で否決された。[47] 修正条項を一切変更しないことを求める支持者たちは、ヘイデン付帯条項を拒否した。付帯条項を含む修正条項は平等を保障しないと考えたからだ。[48] 1986年、ジェローム・ヒメルスタインは、反フェミニズムの支持基盤とそのERA反対運動における役割について、主に二つの理論を指摘した。一つは、上 流階級のリベラルな有権者と、保守的な下層階級の農村部有権者(右派運動の中心となることが多い)との対立という理論だ。この理論は、特定の社会階級が本 質的に反フェミニズムに親和性が高いと位置づける。もう一つの理論は、男性に依存し脆弱な立場にあると感じる女性は、その不安定な安定を脅かすあらゆるも のに反対しがちだというものだ。この見解によれば、教育を受けた自立したキャリアウーマンはフェミニズムを支持する可能性があるが、そうした資源を持たな い主婦は反フェミニズムに惹かれやすい。ヒメルシュタインは、フェミニストと反フェミニストの主な分断線は文化的要因によるものであり、経済的・社会的地 位の違いに起因するものではないと主張し、両方の見解は少なくとも部分的に誤っていると述べている。[49] ERA論争における活動家の所得には共通点が見られる。ERA支持の立場を予測する上で最も示唆的な要因、特に女性においては、人種、婚姻状況、年齢、教 育水準であった。[50] ERA反対は、白人、既婚者、高齢者、低学歴の市民層で著しく高かった。[50] ERAに反対した女性は、宗教的右派と一致する特徴を持つ傾向があった. [51] 1983年、ヴァル・バリスは、高所得の男性が修正条項に反対したのは、それが可決されても彼らが得るものが最も少なく、ERAの批准が彼らの仕事への競 争激化と自尊心の低下を意味するため、失うものが最も大きかったからだと述べた。[47] 保守派による反フェミニズム支持と、ニューディール批判のような「リベラルな社会政策への保守的反発」が常態化したため、ERAへの攻撃は「右翼の反動」 と呼ばれている。[47] 2012年の研究によれば、彼らの手法には「電子メールや電話による侮辱、メディアにおけるフェミニズムの体系的な貶め、虐待被害女性向け支援機関の機密 情報(住所など)のインターネット上での公開」[11]などが含まれる。 |

| Abortion Anti abortion rhetoric largely has religious underpinnings, influence, and is often promoted by activists of strong religious faith.[52] The anti-abortion movement protests in the form of educational outreach, political mobilisation, street protests (largely at abortion clinics), and is often aimed at convincing pregnant women to carry their pregnancies to term.[52] Abortion remains one of the most controversial topics in the United States. Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, and abortion was utilized by many antifeminists to rally supporters. Antiabortion views helped further several right-wing movements, including explicit antifeminism, and helped right-wing politicians rise to power.[53][54] |

中絶 中絶反対の主張は、主に宗教的背景と影響力に支えられており、強い信仰を持つ活動家によって推進されることが多い。[52] 中絶反対運動は、啓発活動、政治的動員、街頭抗議(主に中絶クリニック前)という形で抗議を行い、妊娠した女性に妊娠を継続させるよう説得することを目的 としている。[52] 中絶はアメリカにおいて最も議論の多いテーマの一つであり続けている。1973年にロー対ウェイド判決が下され、中絶は多くの反フェミニストが支持者を集 めるために利用された。反中絶の立場は、露骨な反フェミニズムを含むいくつかの右翼運動をさらに推進し、右翼政治家の台頭を助けた。[53][54] |

21st century A group of Polish ultranationalists protest an International Women's Day march in Warsaw, 2010 Some current antifeminist practices can be traced back to the rise of the Christian right in the late 1970s.[12] Antifeminist internet communities and hashtags include men's rights activists, incels ("involuntary celibates"), pickup artists, "meninism", "Red Pill", #YourSlipisShowing, #gamergate, and Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW). These communities overlap with various white supremacist, authoritarian, and populist movements.[55] In 2014, users of the social media hashtag #WomenAgainstFeminism argued that feminism demonizes men (See Misandry) and that women are not oppressed in 21st century Western countries.[22][56][57][58] A meta-analysis in 2023 published in the journal Psychology of Women Quarterly investigated the stereotype of feminists' attitudes to men and concluded that feminist views of men were no different to that of non-feminists or men towards men and titled the phenomenon the misandry myth – "We term the focal stereotype the misandry myth in light of the evidence that it is false and widespread, and discuss its implications for the movement."[59] Many scholars consider the men's rights movement a backlash[9] or countermovement[10] to feminism. The men's rights movement generally incorporates points of view that reject feminist and profeminist ideas.[60][61] Men's rights activists say feminism has radicalized its objective and harmed men.[61][62][63][64] Men's rights activists believe that men are victims of feminism and "feminizing" influences in society,[65] and that entities such as public institutions now discriminate against men.[66][62] The website Jezebel has also reported on an increasing number of women and female celebrities rejecting feminism and instead subscribing to humanism.[67] In response to the social media trend, modern day feminists also began to upload similar pictures to websites such as Twitter and Tumblr. Most used the same hashtag, "womenagainstfeminism", but instead made satirical and bluntly parodic comments.[68] In November 2014, Time magazine included "feminist" on its annual list of proposed banished words. After initially receiving the majority of votes (51%), a Time editor apologized for including the word in the poll and removed it from the results.[69][70] |

21世紀 2010年、ワルシャワで国際女性デーの行進に抗議するポーランドの超国家主義者グループ 現在の反フェミニズム運動のいくつかは、1970年代後半のキリスト教右派の台頭に遡ることができる。[12] 反フェミニストのインターネットコミュニティやハッシュタグには、男性権利活動家、インセル(「非自発的独身者」)、ナンパ師、「メニニズム」、「レッド ピル」、#YourSlipisShowing、#gamergate、そしてMen Going Their Own Way(MGTOW)が含まれる。これらのコミュニティは、様々な白人至上主義、権威主義、ポピュリスト運動と重なっている。[55] 2014年、ソーシャルメディアのハッシュタグ#WomenAgainstFeminism(フェミニズムに反対する女性たち)のユーザーは、フェミニズ ムが男性を悪魔化している(ミサンドリー参照)と主張し、21世紀の西洋諸国では女性は抑圧されていないと論じた。[22][56][57][58] 2023年に『Psychology of Women Quarterly』誌に掲載されたメタ分析は、フェミニストの男性に対する態度に関する固定観念を調査し、フェミニストの男性観は非フェミニストや男性 自身の男性観と異なることはない、と結論づけた。この現象を「男性嫌悪神話」と命名し、「我々は、この焦点となる固定観念が虚偽であり広範に存在するとい う証拠を踏まえ、これを男性嫌悪神話と呼称し、運動への影響について論じる」と記した。[59] 多くの学者は、男性権利運動をフェミニズムへの反動[9]または対抗運動[10]と見なしている。男性権利運動は一般的に、フェミニストおよびプロフェミ ニストの思想を拒否する見解を取り入れている。[60][61] 男性権利活動家は、フェミニズムがその目的を過激化し、男性に害を及ぼしたと主張する。[61][62][63] [64] 男性権利活動家は、男性がフェミニズムや社会における「女性化」の影響の犠牲者だと信じている[65]。また、公的機関などの組織が現在、男性を差別して いると主張する[66][62]。 ウェブサイト「ジェゼベル」は、フェミニズムを拒否し代わりにヒューマニズムを支持する女性や女性有名人が増加していることも報じている。[67] このソーシャルメディアの流行を受けて、現代のフェミニストたちもTwitterやTumblrなどのサイトに同様の画像を投稿し始めた。大半は同じハッ シュタグ「womenagainstfeminism」を使用したが、代わりに風刺的で露骨なパロディ的コメントを添えた。[68] 2014年11月、タイム誌は「フェミニスト」をその年の「廃止すべき言葉」候補リストに選出した。当初は投票の過半数(51%)を獲得したが、タイム誌 の編集者はこの語を投票対象に含めたことを謝罪し、結果から削除した。[69][70] |

| Germany In March 2019, the Verein Deutsche Sprache [de] ("German Language Association"), an advocacy group for German language purism, organized a petition proclaiming that billions of Euros are being wasted in Germany on "gender gaga" (gender-neutral language and gender studies). This is money the organization believes can be better used to fund hospitals, natural science faculties and virus research institutes.[71] Serbia In April 2022, far-right political party Leviathan, with a significant public profile of almost 300,000 Facebook followers, missed out on a seat in parliament in Serbia's 2022 election. The Leviathan party portrays migrants as criminals, and themselves as the defenders of Serbian women. The group has been praised by some in Serbia for defending 'traditional family values' and hierarchical gender roles, while opposing the empowerment of women and feminist ideologies.[72] South Korea Disgruntled young men have become vocal critics of feminism and feminist women who speak out in public in the recent years. Yoon Suk-yeol narrowly won South Korea's 2022 presidential election. During his run for presidency, he called for the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family to be abolished, and accused its officials of treating men like "potential sex criminals."[73] Yoon also said that he doesn't think systemic structural discrimination based on gender exists in South Korea. Due to the various methods of calculating and measuring gender inequality, South Korea's gender inequality rankings vary across different reports. In 2023, South Korea ranked 30th out of 177 countries on the Women, Peace and Security Index, which is based on 13 indicators of inclusion, justice, and security.[74] In 2023, South Korea has ranked 20th out of 193 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI). In 2025, it ranked 12th out of 172 countries on Gender Inequality Index(GII), making the country the 2nd least gender unequal state in Asia.[75][76] On the other hand, South Korea ranked low on Global Gender Gap Report, placing 99th out of 146 in 2022, leading to criticism of having deep gender inequalities.[77][78][full citation needed] Hwang argued that despite decades of anti-discriminatory gender policies and better education for women, there is persistent discrimination of gender in workplaces in South Korea. He explained that the reasons for this is due to the lack of legal and inefficient enforcement of the gender-based policies. He described the punishment for gender-based crimes to be weak, and argued that the culture of South Korea typically favors male dominance which influences the organizational structure of workplaces and boosts societal pressures for women. Hwang claimed that driven by public anger and media coverage, South Korea has seen a boost in actions against sex crimes since the mid 2000's. South Korean K-WomenLink has advocated for systems to support the survivors of sexual violence whilst highlighting the deficiencies in the system. Hwang also argued that Cases with high influence of victim-blaming, flawed procedures, moreover cases involving individuals (perpetrators) in high social positions were challenged by the organization.[79] There has been a hashtag, that was popular on Twitter in South Korea "#iamafeminist" which normalized the term "feminism", in a society where it was once unacceptable. This hashtag facilitated feminist activism and played a role against misogyny, where identification as a feminist is often stigmatized.[80] The expression of feminist identity was utilized through this hashtag, and people started to discuss their personal experiences that were related to gender inequality.[80] The hashtag was used for a variety of issues, where not only feminists and activists, but also ordinary individuals shared their hardships on housework, equal pay, sexual harassment, etc.[80] |

ドイツ 2019年3月、ドイツ語の純粋主義を主張する団体「ドイツ語協会」は、ドイツで「ジェンダー・ガガ」(ジェンダーニュートラルな言語とジェンダー研究) に何十億ユーロもの資金が浪費されていると訴える請願を組織した。同団体は、この資金は病院、自然科学学部、ウイルス研究所への資金援助に充てるべきだと 主張している。[71] セルビア 2022年4月、極右政党「リヴァイアサン」は、フェイスブックで30万人近いフォロワーを持つ高い知名度を持ちながらも、セルビアの2022年総選挙で 議席を獲得できなかった。リヴァイアサン党は移民を犯罪者と描き、自らはセルビア人女性の守護者と称する。同党は「伝統的な家族価値観」と階層的なジェン ダー役割を擁護し、女性のエンパワーメントやフェミニストイデオロギーに反対する姿勢から、セルビア国内の一部から称賛されている。[72] 韓国 近年、不満を抱える若い男性たちが、フェミニズムや公の場で発言するフェミニスト女性たちに対する批判を声高に主張するようになった。尹錫悦(ユン・ソン ニョル)は2022年の韓国大統領選挙で辛勝した。大統領選の選挙運動中、彼はジェンダー平等家族部の廃止を要求し、同部の職員が男性を「潜在的な性犯罪 者」のように扱っていると非難した。[73] 尹氏はまた、韓国にジェンダーに基づく体系的な構造的差別は存在しないとの見解を示した。ジェンダー不平等を算出・測定する手法が多様であるため、韓国の ジェンダー不平等ランキングは報告書によって異なる。2023年、韓国は「女性・平和・安全保障指数」において177カ国中30位であった。同指数は包摂 性、公正性、安全保障の13指標に基づく。[74] 2023年、韓国は人間開発指数(HDI)で193カ国中20位となった。2025年にはジェンダー不平等指数(GII)で172カ国中12位となり、ア ジアで2番目にジェンダー不平等が少ない国となった。[75] [76] 一方、韓国は世界ジェンダーギャップ報告書では低位に位置し、2022年には146カ国中99位となり、深刻なジェンダー不平等が存在するとの批判を招い た。[77][78][出典明記が必要] ファンは、数十年にわたる反差別的ジェンダー政策と女性の教育水準向上にもかかわらず、韓国の職場では根強いジェンダー差別が存在すると主張した。その理 由として、法的基盤の欠如とジェンダー政策の非効率的な施行を挙げた。彼はジェンダーに基づく犯罪への罰則が弱いと説明し、韓国の文化が一般的に男性優位 を是認する傾向にあるため、職場の組織構造に影響を与え、女性に対する社会的圧力を増幅させていると論じた。黄氏は、世論の怒りとメディア報道に後押しさ れ、2000年代半ば以降、韓国では性犯罪対策が強化されたと主張した。韓国のK-WomenLinkは、性暴力被害者を支援する制度の構築を提唱すると 同時に、制度の欠陥を指摘してきた。黄氏はさらに、被害者非難が強く影響した事件、手続き上の欠陥のある事件、加えて社会的地位の高い個人(加害者)が関 与した事件に対して、同団体が異議を申し立てたと述べた。[79] 韓国では「#iamafeminist」というハッシュタグがTwitterで流行した。かつて受け入れられなかった「フェミニズム」という言葉を社会に 定着させた。このハッシュタグはフェミニスト活動に拍車をかけ、フェミニストであることを表明することがしばしば烙印を押されるような女性嫌悪に対抗する 役割を果たした。[80] このハッシュタグを通じてフェミニストとしてのアイデンティティが表明され、人々はジェンダー不平等に関連する個人的体験を語り始めた。[80] このハッシュタグは多様な問題に用いられ、フェミニストや活動家だけでなく一般市民も家事労働、同一賃金、セクハラなどに関する苦境を共有した。[80] |

Organizations Symbol used for signs and buttons by ERA opponents Founded in the U.S. by Phyllis Schlafly in 1972, Stop ERA, now known as "Eagle Forum", lobbied successfully to block the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment in the U.S.[81] It was also Schlafly who forged links between Stop ERA and other conservative organizations, as well as single-issue groups against abortion, pornography, gun control, and unions. By integrating Stop ERA with the thus-dubbed "New Right", she was able to leverage a wider range of technological, organizational and political resources, successfully targeting pro-feminist candidates for defeat.[81] In India, the Save Indian Family Foundation is an antifeminist organization[82] opposed to a number of laws that they claim to have been used against men.[83] The Concerned Women of America (CWA) are also an antifeminist organization. Like other conservative women's groups, they oppose abortion and same-sex marriage and make appeals for maternalism and biological differences between women and men.[84][85] The Independent Women's Forum (IWF) is another antifeminist, conservative, women-oriented group. It's younger and less established than the CWA, though the two organizations are often discussed in relation to each other. It was founded to take on the "old feminist establishment".[85] Both of these organizations pride themselves on rallying women who do not identify with feminist rhetoric together. These organizations frame themselves as being by women, for women, in order to fight the idea that feminism is the only women-oriented ideology. These organizations chastise feminists for presuming to universally speak for all women. The IWF claims to be "the voice of reasonable women with important ideas who embrace common sense over divisive ideology".[85] Another antifeminist merger, which is not yet an acknowledged organization but became a large movement, is the "incel" movement, an internet-culture, which is increasingly widespread via online forums, especially in the US. After the term came up the first time by a woman in the 1990s to define feelings of social awkwardness, in began that the term was used in other contexts.[23] Lately, the term incel is composed of the words "involuntarily" and "celibate" (sexual abstinence) and it is mostly young men in their mid-twenties, identifying with the incel movement, whose overall themes consist of failure and frustration[13] what for they accuse woman and society's structure changes of experiencing a shortage of sexual activity and romantic success, how the Anti-Defamation League defined that movement. The movement can be classified as misogynist, violent and extremist. Some incels are considered as a danger to the public as well as to individuals, especially women. Their ideology consists of antifeminist ideologies, according to which a hierarchy, based on appearance determines access to sexual relationships and recognition in society, as well as the belief in "hypergamy", that woman use their sexuality for social advancement, which would make them sexually selective and ultimately leads to the third ideology of the rejection of feminism. According to the German Federal Agency for Civic Education, their hierarchy is composed by three classes of men, the attractive men at the top, as "chads" or "alphas", followed by the so called "normies", the normal men and finally the incels as the loser of the system. With their allegations, they claim to have a fundamental right to sex, which they are denied. In addition to the accusations towards women, their beliefs are anti-immigrant, as their hatred is also directed against migrants, who would take away their sexual partners.[39] |

組織 ERA反対派が標識やボタンに使用したシンボル 1972年にフィリス・シュラフリーによって米国で設立されたストップ・ERA(現イーグル・フォーラム)は、米国における平等権修正条項(ERA)の成 立阻止に成功したロビー活動を行った。[81] またシュラフリーは、ストップERAと他の保守団体、ならびに中絶・ポルノ・銃規制・労働組合に反対する単一課題団体との連携を構築した。ストップERA をこうして「新右派」と称される勢力と統合することで、彼女はより広範な技術的・組織的・政治的資源を活用し、フェミニスト支持候補の落選を成功裏に狙い 撃つことができた。[81] インドでは、セーブ・インディアン・ファミリー財団が反フェミニスト団体として活動している[82]。彼らは、男性に対して悪用されてきたと主張する数々の法律に反対している[83]。 アメリカ懸念女性会(CWA)もまた反フェミニスト団体である。他の保守系女性団体と同様、彼らは中絶や同性婚に反対し、母性主義や男女の生物学的差異を訴えている[84]。[85] 独立女性フォーラム(IWF)は、別の反フェミニスト的・保守的・女性志向の団体である。CWAより歴史が浅く確立度は低いものの、両組織はしばしば相互 に関連して論じられる。設立目的は「旧来のフェミニスト体制」に対抗するためであった[85]。これらの団体はいずれも、フェミニストのレトリックに共感 しない女性を結束させることを自負している。これらの組織は、フェミニズムが唯一の女性志向イデオロギーだという考えと戦うため、自らを「女性による、女 性のための」組織と位置づけている。フェミニストが全ての女性を代表すると決めつける姿勢を非難するのだ。IWFは「分断的なイデオロギーより常識を重ん じる、重要な考えを持つ理性的な女性の声」を標榜している。[85] もう一つの反フェミニズム的統合は、まだ公認組織ではないが大きな運動となった「インセル」運動である。これはインターネット文化であり、特に米国でオン ラインフォーラムを通じて急速に広まっている。この用語は1990年代に女性が社会的居心地の悪さを定義するために初めて用いた後、他の文脈でも使われる ようになった。[23] 近年では「インセル」は「involuntarily(非自発的)」と「celibate(禁欲)」を組み合わせた造語であり、主に20代半ばの若年男性 が同運動に帰属意識を持つ。その全体的なテーマは失敗と挫折[13]であり、彼らは性的活動や恋愛的成功の不足を経験している原因として女性や社会構造の 変化を非難する。反誹謗同盟はこの運動をそのように定義した。 この運動は女性嫌悪的、暴力的、過激主義的と分類できる。一部のインセルは、個人(特に女性)だけでなく公共の安全に対する脅威と見なされている。彼らの イデオロギーは反フェミニズムイデオロギーから成り、外見に基づく階層が性的関係へのアクセスや社会的承認を決定すると主張する。さらに「ハイパーガ ミー」の信念、すなわち女性が社会的上昇のために性を利用し、結果として性的選択性を高め、最終的にフェミニズム拒絶という第三のイデオロギーに至るとい う考え方だ。 ドイツ連邦市民教育庁によれば、彼らの階層は三つの男性階級で構成される。頂点に立つ魅力的な男性(「チャド」や「アルファ」と呼ばれる)、次に「ノーマ ル」と呼ばれる普通の男性、そして最後にシステムの敗者であるインセルである。彼らは自らの主張において、否定されている性行為への基本的権利を主張して いる。女性への非難に加え、彼らの思想は反移民的でもある。なぜなら、彼らの憎悪は移民にも向けられており、移民が彼らの性的パートナーを奪うと信じてい るからだ。[39] |

| Explanatory theories According to Amherst College sociology professor Jerome L. Himmelstein, antifeminism is rooted in social stigmas against feminism and is thus a purely reactionary movement. Himmelstein identifies two prevailing theories that seek to explain the origins of antifeminism: the first theory, proposed by Himmelstein, is that conservative opposition in the abortion and Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) debates has created a climate of hostility toward the entire feminist movement.[49] The second theory Himmelstein identifies states that the female antifeminists who lead the movement are largely married, low education, and low personal income women who embody the "insecure housewife scenario" and seek to perpetuate their own situation in which women depend on men for fiscal support. However, numerous studies have failed to correlate the aforementioned demographic factors with support for antifeminism, and only religiosity correlates positively with antifeminist alignment.[49] Authors Janet Saltzman Chafetz and Anthony Gary Dworkin, writing for Gender and Society, argue that the organizations most likely to formally organize against feminism are religious. This is because women's movements may demand access to male-dominated positions within the religious sector, like the clergy, and women's movements threaten male-oriented values of some religions.[37] The more successful a feminist movement is in challenging the authority of male-dominated groups, the more these groups will organize a countermovement.[37] |

説明理論 アマースト大学社会学教授ジェローム・L・ヒメルシュタインによれば、反フェミニズムはフェミニズムに対する社会的偏見に根ざしており、したがって純粋に 反動的な運動である。ヒメルシュタインは反フェミニズムの起源を説明しようとする二つの主流理論を特定している。第一の理論はヒメルシュタイン自身が提唱 したもので、中絶問題や平等権修正条項(ERA)論争における保守派の反対が、フェミニズム運動全体に対する敵意の雰囲気を生み出したというものだ。 [49] ヒメルシュタインが指摘する第二の理論は、この運動を主導する女性反フェミニストの大半が既婚で、低学歴かつ低個人的所得の女性であり、「不安定な主婦シ ナリオ」を体現し、女性が経済的支援を男性に依存する現状の永続化を望んでいると主張する。しかし、数多くの研究が前述の人口統計学的要因と反フェミニズ ム支持の相関関係を確認できず、宗教的傾向のみが反フェミニズム的立場と正の相関を示している。[49] 『ジェンダーと社会』誌に寄稿したジャネット・ソルツマン・チャフェッツとアンソニー・ゲイリー・ドワーキンは、フェミニズムに正式に対抗する組織化を行 う可能性が最も高いのは宗教団体だと論じている。その理由は、女性運動が聖職者など宗教分野における男性優位の地位へのアクセスを要求する可能性があり、 また女性運動が一部の宗教における男性中心の価値観を脅かすからである。[37] フェミニスト運動が男性優位の集団の権威に挑戦するほど、これらの集団は反動的な運動を組織化する傾向が強まる。[37] |

| Implicit feminism University of Illinois at Chicago sociology professor Danielle Giffort argues that the stigma against feminism created by antifeminists has resulted in organizations that practice "implicit feminism", which she defines as the "strategy practiced by feminist activists within organizations that are operating in an anti- and post-feminist environment in which they conceal feminist identities and ideas while emphasizing the more socially acceptable angles of their efforts".[86] Due to the stigma against feminism, some activists, such as those involved with Girls Rock, may take the principles of feminism as a foundation of thought and teach girls and women independence and self-reliance without explicitly labeling it with the stigmatized brand of feminism. Thus, most women continue to practice feminism in terms of seeking equality and independence for women, yet avoid the label.[86] |

暗黙のフェミニズム イリノイ大学シカゴ校社会学教授ダニエル・ギフォートは、反フェミニストによって生み出されたフェミニズムへの偏見が、「暗黙のフェミニズム」を実践する 組織を生み出したと主張する。彼女はこれを「反フェミニズム的・ポストフェミニズム的環境下で活動する組織内において、フェミニスト活動家が実践する戦 略」と定義し、「フェミニストとしてのアイデンティティや思想を隠しつつ、自らの取り組みの中でより社会的に受け入れられやすい側面を強調する」と説明し ている。[86] フェミニズムへの偏見ゆえに、ガールズ・ロック運動などに関わる活動家の中には、フェミニズムの原理を思想の基盤としつつ、偏見の烙印を押された「フェミ ニズム」というラベルを明示せずに、少女や女性に自立と自力更生を教える者もいる。こうして大半の女性は、女性の平等と自立を求めるという点でフェミニズ ムを実践し続けるが、そのラベルは避けるのである。[86] |

| Connections to far-right extremism Antifeminism has been identified as an underlying motivation for far-right extremism.[6][7][8] For example, the perpetrators of the Christchurch massacre and the El Paso shooting appear to have been motivated by the conspiracy theory that white people are being replaced by non-whites largely as a result of feminist stances in Western societies.[87] Many who affiliate with the white nationalist alt-right movement are antifeminist,[88][89] with antifeminism and resentment of women being a common recruitment gateway into the movement.[90][91] Media researcher Michele White argues that contemporary antifeminism often supports antisemitism and white supremacy, citing the example of the Neo-Nazi websites Stormfront and The Daily Stormer, which often claim that feminism represents a Jewish plot to destroy Western civilization.[92] According to Helen Lewis, the far-right ideology considers it vital to control female reproduction and sexuality: "Misogyny is used predominantly as the first outreach mechanism", where "You were owed something, or your life should have been X, but because of the ridiculous things feminists are doing, you can't access them."[87] Similar strands of thought are found in the incel subculture, which centers around misogynist fantasies about punishing women for not having sex with them.[93] |

極右過激主義との関連性 反フェミニズムは、極右過激主義の根底にある動機として特定されている。[6][7][8] 例えば、クライストチャーチ虐殺事件やエルパソ銃乱射事件の犯人は、西洋社会におけるフェミニストの姿勢が主な原因で白人が非白人に置き換えられていると いう陰謀論に動機づけられていたようだ。[87] 白人至上主義のオルタナ右翼運動に連なる者の多くは反フェミニストであり、[88][89] 反フェミニズムと女性への怨恨が、この運動への一般的な勧誘の入り口となっている。[90] [91] メディア研究者ミシェル・ホワイトは、現代の反フェミニズムがしばしば反ユダヤ主義や白人至上主義を支持すると主張する。ネオナチ系ウェブサイト「ストー ムフロント」や「ザ・デイリー・ストーマー」を例に挙げ、これらのサイトがフェミニズムを西洋文明を破壊するユダヤ人の陰謀だと主張することが多いと指摘 している。[92] ヘレン・ルイスによれば、極右イデオロギーは女性の生殖と性欲を制御することが不可欠だと考えている: 「女性嫌悪は主に最初の接触手段として利用される」。そこでは「お前には何かが与えられるべきだった、あるいはお前の人生はこうあるべきだった。だがフェ ミニストたちの馬鹿げた行動のせいで、それらが得られない」という理屈が展開される。[87] 同様の思想はインセル(性的関係を持たない男性)サブカルチャーにも見られ、女性と性交できないことへの報復を夢想する女性嫌悪的幻想が中心となってい る。[93] |

| Antifeminist politics The rise of the radical right since the 1980s[94] is, if one focuses on Europe is also accompanied by antifeminist approaches,[95] since the political approach of right-wing extremist parties is mostly based on a "patriarchal constitution".[96] Hostile narratives are seen in feminism, in addition to immigration and Judaism, which are reacted primarily with xenophobia.[97] As the current european governments clarify, a conservative, sexist environment does not oppose the participation of woman in these contexts.[96] Anti-feminist conservative family and migration policies are pursued by woman-led governments themselves, together with right-wing populist ones. For example through the narrative of a mother, used by Giorgia Meloni, the Italian prime minister,[98] or by Marine Le Pen, former leader of the national Rally party, who presents herself as the "modern mother of the nation". But this by no means has a feminist approach, because along with right-wing populist approaches, Le Pen also pursues a pro-natalist policy in the National Front party, that does not aim at equality, but rather grants women primarily reproductive functions.[96] However, women with anti-feminism attitudes can take advantage of the fact that a "feminine image" leads to their being perceived as less radical and far-right. Taking advantage of gender-specific attributions would be therefore an important contribution to the normalization and demonization strategy of anti-feminist and far-right approaches.[96] |

反フェミニズム政治 1980年代以降の急進的右派の台頭[94]は、欧州に焦点を当てれば反フェミニズム的アプローチを伴う[95]。右派過激政党の政治的アプローチは主に 「家父長制憲法」に基づくからだ[96]。移民やユダヤ教に加え、フェミニズムに対しても敵対的言説が見られ、これらは主に外国人排斥主義で反応される。 [97] 現在の欧州諸政府が示すように、保守的で性差別的な環境は、こうした文脈における女性の参加を妨げない。[96] 反フェミニズム的な保守的な家族政策や移民政策は、女性主導の政府自身や、右派ポピュリスト政党によって推進されている。例えば、イタリアの首相ジョルジ ア・メローニ[98] や、国民連合党の元党首マリーヌ・ル・ペンが「現代の国民の母」として自らをアピールする、母親という物語を通じてである。しかし、これは決してフェミニ スト的アプローチではない。なぜなら、ル・ペンは、右翼ポピュリスト的アプローチとともに、国民戦線党において、平等を目指すのではなく、主に女性に生殖 機能を認める、出産奨励政策も追求しているからだ[96]。しかし、反フェミニズム的態度を持つ女性は、「女性的なイメージ」によって、過激で極右的では ないと認識されるという事実を利用することができる。したがって、ジェンダーに基づく属性を利用することは、反フェミニズム的・極右的アプローチの正常化 と悪魔化戦略にとって重要な貢献となるのである。[96] |

| Backlash (sociology) École Polytechnique massacre Feminazi Incel The Manipulated Man Manosphere Men's rights movement Sexism Social justice warrior |

バックラッシュ(社会学) エコール・ポリテクニーク虐殺事件 フェミニスト過激派 インセル 操作された男 マノスフィア 男性の権利運動 性差別 社会正義戦士 |

| References |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antifeminism |

| Further reading Faraut, Martine (2003). "Women resisting the vote: a case of anti-feminism?". Women's History Review. 12 (4): 605–621. doi:10.1080/09612020300200376. S2CID 145708717. Howard, Angela; Adams Tarrant, Sasha Ranaé, eds. (1997). Opposition to the Women's Movement in the United States, 1848-1929. Antifeminism in America: A Collection of Readings From the Literature of the Opponents to U.S. Feminism, 1848 to the Present. Vol. 1. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-2713-4. Howard, Angela; Adams Tarrant, Sasha Ranaé, eds. (1997). Reaction to the Modern Women's Movement, 1963 to the Present. Antifeminism in America: A Collection of Readings From the Literature of the Opponents to U.S Feminism, 1848 to the Present. Vol. 3. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-2715-8. Howard, Angela; Adams Tarrant, Sasha Ranaé, eds. (1997). Redefining the New Woman, 1920–1963. Antifeminism in America: A Collection of Readings From the Literature of the Opponents to U.S. Feminism, 1848 to the Present. Vol. 2. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-2714-1. Kampwirth, Karen (2006). "Resisting the feminist threat: antifeminist politics in post-Sandinista Nicaragua". NWSA Journal. 18 (2): 73–100. doi:10.2979/NWS.2006.18.2.73 (inactive 11 July 2025). JSTOR 4317208. S2CID 145487146. Kampwirth, Karen (2003). "Arnoldo Alemán takes on the NGOs: antifeminism and the new populism in Nicaragua". Latin American Politics and Society. 45 (2): 133–158. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2003.tb00243.x. JSTOR 3176982. S2CID 153608755. Kampwirth, Karen (1998). "Feminism, antifeminism, and electoral politics in post-war Nicaragua and El Salvador". Political Science Quarterly. 113 (2): 259–279. doi:10.2307/2657856. JSTOR 2657856. Kinnard, Cynthia D. (1986). Antifeminism in American thought: an annotated bibliography. Boston, Mass.: G.K. Hall & Co. ISBN 978-0-8161-8122-3. Mansbridge, Jane (1986). Why we lost the ERA. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50357-8. Nielsen, Kim E. (2001). Un-American womanhood : antiradicalism, antifeminism, and the first Red Scare. Columbus: Ohio State University Press 978-0-8142-0882-3. ISBN 978-0-8142-0882-3. Price-Robertson, Rhys (Spring 2012). "Anti-feminist men's groups in Australia (An interview with Michael Flood)" (PDF). DVRCV Quarterly (3 ed.). Collingwood, Vic.: Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria. pp. 10–13. ISSN 1838-7926 – via Xyonline.net. Schreiber, Ronnee (2008). Righting feminism: conservative women and American politics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533181-3. Swanson, Gillian (2013) [first published 1999]. Antifeminism in America: A Historical Reader (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315051970. ISBN 978-1-3150-5197-0. |

追加文献(さらに読む) Faraut, Martine (2003). 「投票に抵抗する女性たち:反フェミニズムの事例か?」。『女性史レビュー』 12 (4): 605–621. doi:10.1080/09612020300200376. S2CID 145708717. ハワード、アンジェラ、アダムス・タラント、サーシャ・ラナエ編 (1997). 『1848年から1929年までの米国における女性運動への反対運動』 『アメリカにおける反フェミニズム:1848年から現代までの米国フェミニズム反対派文献選集』第1巻。ニューヨーク:ガーランド出版。ISBN 978-0-8153-2713-4。 ハワード、アンジェラ;アダムス・タラント、サーシャ・ラナエ編(1997)。『現代女性運動への反動、1963年から現在まで』アメリカにおける反フェ ミニズム:米国フェミニズム反対派の文献からの読本集、1848年から現在まで。第3巻。ニューヨーク:ガーランド出版。ISBN 978-0-8153-2715-8。 ハワード、アンジェラ;アダムズ・タラント、サーシャ・ラネー編(1997)。『新女性再定義、1920–1963年』。アメリカにおける反フェミニズ ム:米国フェミニズム反対派文献選集、1848年から現在まで。第2巻。ニューヨーク:ガーランド出版。ISBN 978-0-8153-2714-1。 カンプワース、カレン(2006)。「フェミニストの脅威への抵抗:サンディニスタ政権崩壊後のニカラグアにおける反フェミニズム政治」。NWSAジャー ナル。18(2): 73–100。doi:10.2979/NWS.2006.18.2.73 (2025年7月11日現在無効)。JSTOR 4317208。S2CID 145487146。 カンプワース、カレン(2003)。「アルノルド・アレマンがNGOと対決:ニカラグアにおける反フェミニズムと新たなポピュリズム」『ラテンアメリカ政 治と社会』45巻2号:133–158頁。doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2003.tb00243.x。JSTOR 3176982。S2CID 153608755. カンプワース、カレン(1998)。「戦後ニカラグアとエルサルバドルにおけるフェミニズム、反フェミニズム、選挙政治」。『政治学季刊』。113巻2号:259–279頁。doi:10.2307/2657856。JSTOR 2657856. キナード、シンシア・D.(1986年)。『アメリカ思想における反フェミニズム:注釈付き書誌』ボストン、マサチューセッツ州:G.K.ホール社。ISBN 978-0-8161-8122-3。 マンスブリッジ、ジェーン(1986年)。『なぜ我々はERAを失ったのか』シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-50357-8。 Nielsen, Kim E. (2001). Un-American womanhood : antiradicalism, antifeminism, and the first Red Scare. Columbus: Ohio State University Press 978-0-8142-0882-3. ISBN 978-0-8142-0882-3。 プライス=ロバートソン、リース(2012年春)。「オーストラリアの反フェミニスト男性団体(マイケル・フラッドへのインタビュー)」(PDF)。 DVRCV Quarterly(第3版)。コリングウッド、ビクトリア州:家庭内暴力リソースセンター・ビクトリア。pp. 10–13. ISSN 1838-7926 – via Xyonline.net. シュライバー、ロニー (2008). フェミニズムの是正:保守的な女性とアメリカの政治. ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-533181-3. スワンソン、ジリアン(2013年)[初版1999年]。『アメリカの反フェミニズム:歴史的読本』(第1版)。ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ。doi:10.4324/9781315051970。ISBN 978-1-3150-5197-0。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antifeminism |

★

| Nathan Schlueter, Why Antifeminism Isn’t Enough. March 24, 2024, Public Discourse | |

| Alongside the fierce debate

happening within modern feminism between so-called “trans-exclusionary”

gender-critical feminists and “trans-inclusive” radical feminists over

whether to embrace or repudiate transgenderism (the so-called “TERF

Wars”), there is an emerging “FemWar” within American conservatism. All the parties to this conservative debate agree that modern feminism, with its denial of natural differences between men and women, its cultural, political, and economic pressure on women to delay or abandon both marriage and motherhood for professional careers, its celebration of the sexual revolution and commitment to abortion on demand, and its denigration of men, or at least “manly” men who express typical masculine virtue, is a false ideology that has deeply damaged both our social fabric and countless individual women, men, and children, born and unborn. |

現代フェミニズム内部で、いわゆる「トランス排除的」ジェンダー批判的

フェミニストと「トランス包摂的」急進的フェミニストの間で、トランスジェンダー主義を受け入れるか否かをめぐる激しい論争(いわゆる「TERF戦争」)

が繰り広げられる一方で、アメリカ保守主義内部では新たな「フェム戦争」が勃発しつつある。 この保守的な議論のすべての当事者は、現代フェミニズムが以下の点において誤ったイデオロギーであり、社会の基盤と無数の女性、男性、そして生まれたばか りの子どもや胎児に深刻な損害を与えていることに同意している。すなわち、男女の自然な差異を否定し、女性が結婚と母性を遅らせたり放棄したりして専門職 のキャリアを追求するよう文化的・政治的・経済的圧力をかけ、性的革命を称賛し要求に応じた中絶を支持し、男性、少なくとも典型的な男性的徳を表現する 「男らしい」男性を貶める点である。男性、そして生まれた子どもも、生まれていない子どもも、無数の個人に深刻な損害を与えた偽りのイデオロギーであると いう点で一致している。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099