アントニオ・マチャード

Antonio Machado, 1875-1939

☆ アントニオ・シプリアーノ・ホセ・マリア・イ・フランシスコ・デ・サンタ・アナ・マチャド・イ・ルイス(1875年7月26日 - 1939年2月22日)、通称アントニオ・マチャドは、スペインの詩人で、1898年世代として知られるスペイン文学運動の主要人物の一人である。彼の作 品は、当初はモダニズムであったが、ロマン主義的な特徴を持つ親密な象徴主義へと発展した。彼は徐々に、人間性への関与と、存在に対するほぼ道教的な思索 という2つの側面を特徴とするスタイルを確立していった。この統合は、マチャドによれば、最も古い民間伝承の知恵を反映したものだった。ヘラルド・ディエ ゴの言葉を借りれば、マチャドは「詩で語り、詩の中で生きた」のである。

| Antonio Machado Ruiz

(Sevilla, 26 de julio de 1875-Colliure, 22 de febrero de 1939) fue un

poeta español, el más joven representante de la generación del 98. Su

obra inicial, de corte modernista (como la de su hermano Manuel),

evolucionó hacia un intimismo simbolista con rasgos románticos, que

maduró en una poesía de compromiso humano, de una parte, y de

contemplación de la existencia, por otra; una síntesis que en la voz de

Machado se hace eco de la sabiduría popular más ancestral. Dicho en

palabras de Gerardo Diego, «hablaba en verso y vivía en poesía».1 Fue

uno de los alumnos distinguidos de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza,

con cuyos idearios estuvo siempre comprometido. Murió en el exilio

durante la guerra civil española.23 |

アントニオ・マチャド・ルイス(1875年7月26日、セビリア生まれ

-

1939年2月22日、コリウール没)はスペインの詩人で、1898年世代の最年少の代表者であった。初期の作品は、モダニズムのスタイル(彼の兄弟マヌ

エルと同様)で、ロマン主義的な特徴を持つ象徴主義的で内省的な詩へと発展し、一方では人間の献身、他方では

。マチャドの言葉で言えば、それは最も古くから伝わる民衆の知恵を反映した総合的なものだ。ヘラルド・ディエゴの言葉を借りれば、「彼は詩を話し、詩の中

で生きた」1。彼は、インスティトゥシオン・リブレ・デ・エネンサナの優秀な学生の一人であり、その理想に常に献身していた。スペイン内戦中に亡命先で死

去した。2 3 |

| Biografía Infancia en Sevilla  Retrato de Antonio Machado Álvarez y Ana Ruiz, padres de Antonio Antonio Cipriano José María Machado Ruiz nació a las cuatro y media de la madrugada4 del 26 de julio de 1875 (festividad de Santa Ana y por tanto onomástica de su madre), en una de las viviendas de alquiler del llamado palacio de las Dueñas, en Sevilla.b Fue el segundo varón que dio a luz su madre, Ana Ruiz Hernández, de una descendencia de ocho en total.c Once meses antes había nacido Manuel, el primogénito, compañero de muchos pasajes de la vida de Antonio, y con el tiempo también poeta y dramaturgo.  El rincón de la alberca en uno de los patios del Palacio de las Dueñas, en una de cuyas viviendas nació, en 1875, Antonio Machado. La familia materna de Machado tenía una confitería en el barrio de Triana, y el padre, Antonio Machado Álvarez, era abogado, periodista e investigador del folclore, trabajo por el que llegaría a ser reconocido internacionalmente con el seudónimo de «Demófilo».5 En otra vivienda del mismo palacio son vecinos sus abuelos paternos, el médico y naturalista Antonio Machado Núñez, catedrático y rector de la Universidad de Sevilla y convencido institucionista, y su esposa, Cipriana Álvarez Durán, de cuya afición a la pintura quedó como ejemplo un retrato de Antonio Machado a la edad de cuatro años.6d La infancia sevillana de Antonio Machado fue evocada en muchos de sus poemas casi fotográficamente: Mi infancia son recuerdos de un patio de Sevilla y un huerto claro donde madura el limonero... «Retrato», Campos de Castilla (CXVII). Y de nuevo, en un soneto evocando a su padre escribe: Esta luz de Sevilla... Es el palacio donde nací, con su rumor de fuente. Mi padre, en su despacho.—La alta frente, la breve mosca, y el bigote lacio—. Sonetos (IV). En 1883, el abuelo Antonio, con sesenta y ocho años y el apoyo de Giner de los Ríos y otros colegas krausistas, gana una oposición a la cátedra de Zoografía de Articulaciones Vivientes y Fósiles en la Universidad Central de Madrid. La familia acuerda trasladarse a la capital española donde los niños Machado tendrán acceso a los métodos pedagógicos de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza. José Luis Cano, en su biografía de Machado, cuenta que una mañana de primavera, antes de salir para Madrid, «Demófilo» llevó a sus hijos a Huelva a conocer el mar.7 En un estudio más reciente, Gibson anota que el propio Machado le escribía en 1912 a Juan Ramón Jiménez evocando «...sensaciones de mi infancia, cuando yo vivía en esos puertos atlánticos».8 Sea como fuere, quedarían grabadas en la retina del poeta aquellas «estelas en la mar».9 |

経歴 セビリアでの幼少期  アントニオ・マチャド・アルバレスとアナ・ルイスの肖像、アントニオの両親 アントニオ・シプリアーノ・ホセ・マリア・マチャド・ルイスは、1875年7月26日午前4時半(聖アンナの祝日であり、彼の母親の名前の日でもあった) に、セビリアのドゥエニャス宮殿と呼ばれる宮殿の賃貸住宅のひとつで生まれた。b 彼は、母親であるアナ・ルイス・エルナンデスにとって8人目の子供のうちの2番目の息子であった。c 11ヶ月前には、 長男のマヌエルは、アントニオの人生の多くの場面で伴侶となり、後に詩人、劇作家となった。 1875年にアントニオ・マチャドが生まれたパシオ・デ・ラス・ドゥエニャスの中庭にある人工池(Alberca)の角。 マチャドの母方の実家はトリアナ地区で菓子店を営んでいた。父親のアントニオ・マチャド・アルバレスは弁護士、ジャーナリスト、民俗研究家であり、後に 「デモフィロ」というペンネームで国際的に知られるようになる。5 同じ宮殿内の別の家には、父方の祖父母である医師で自然主義者のアントニオ・マチャド・ヌニェス(セビリア大学の教授兼学長であり、確固たる 制度論者であった医師で自然主義者のアントニオ・マチャド・ヌニェスと、妻のシプリアナ・アルバレス・ドゥラン(4歳の頃のアントニオ・マチャドの肖像画 にその絵画への愛が表れている。6d アントニオ・マチャドのセビリアでの子供時代は、彼の詩の多くで写真のように描写されている。 「私の子供時代は、セビリアの中庭の思い出、 そしてレモンの木が熟す明るい果樹園の思い出だ... 」『肖像』、カスティーリャの野原(CXVII)。 また、父親を偲ぶソネットでは次のように書いている。 このセビリアの光... それは私が生まれた宮殿、噴水のせせらぎが聞こえる宮殿だ。 父の執務室、高い額、 短い口ひげ、まっすぐな口ひげ。 ソネット(IV)。 1883年、68歳になった祖父アントニオは、ヒネル・デ・ロス・リオスやその他のクラウシストの同僚の支援を受け、マドリード中央大学の現生および化石 関節動物分類学の教授職をめぐる競争試験に合格した。一家はスペインの首都への移住に同意し、マチャドの子供たちはリブレ・デ・エネサンサ教育機関の教育 方針に触れることができた。ホセ・ルイス・カノは、マチャドの伝記の中で、ある春の朝、マドリードへ発つ前に「デモフィル」が子供たちを連れてウエルバへ 行き、海を見せたことを伝えている。7 最近の研究では、ギブソンは、1912年にマチャド自身がフアン・ラモン・ヒメネスに手紙を書き、「...大西洋の港町に住んでいた幼少期の感覚」を呼び起こしたと指摘している。8 |

| Estudiante en Madrid El 8 de septiembre de 1883, el tren en el que viajaba la familia Machado hizo su entrada en la estación de Atocha. Desde los ocho a los treinta y dos años he vivido en Madrid con excepción del año 1899 y del 1902 que los pasé en París. Me eduqué en la Institución Libre de Enseñanza y conservo gran amor a mis maestros: Giner de los Ríos, el imponderable Cossío, Caso, Sela, Sama (ya muerto), Rubio, Costa (D. Joaquín —a quien no volví a ver desde mis nueve años—). Pasé por el Instituto y la Universidad, pero de estos centros no conservo más huella que una gran aversión a todo lo académico. Antonio Machado, Autobiografía. Diez días después, Manuel (nueve años), Antonio (ocho) y José (cuatro), ingresan en el local provisional de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE). A lo largo de los próximos años, sus profesores serán el propio Giner de los Ríos, Manuel Bartolomé Cossío, Joaquín Costa, José de Caso, Aniceto Sela, Joaquín Sama, Ricardo Rubio, y otros maestros menos conocidos como José Ontañón Arias, Rafael Torres Campos o Germán Flórez. Entre sus compañeros estaban: Julián Besteiro, Juan Uña, José Manuel Pedregal, Pedro Jiménez-Landi, Antonio Vinent y Portuondo o los hermanos Eduardo y Tomás García del Real. La Institución, en coherente armonía con el ambiente familiar de los Machado marcarían su ideario intelectual.10 Con la ILE, descubrió Machado el Guadarrama. En su elegía al maestro Giner, de 1915, Machado concluye: Allí el maestro un día soñaba un nuevo florecer de España. «A Don Francisco Giner de Los Ríos».11 El 16 de mayo de 1889, Machado (al que apenas faltan tres meses para cumplir catorce años) asiste al instituto San Isidro, donde la Institución Libre estaba entonces colegiada, para superar la reválida de ingreso en el bachiller estatal. En junio aprueba Geografía, pero suspende Latín y Castellano, y su expediente es adjudicado al Instituto Cardenal Cisneros para el curso 1889-1890.1213 Entretanto, la economía en casa de los Machado, que llevaba años siendo muy apretada, alcanzó un nivel crítico. Ana Ruiz acababa de tener su noveno y último parto, una niña nacida el 3 de octubre de 1890 que moriría años después. Su marido, un «Demófilo» agotado, desilusionado, cuarentón y con siete hijos, decidió aceptar el puesto de abogado que le ofrecían unos amigos en San Juan de Puerto Rico. Conseguido el permiso del Ministerio de Ultramar, Antonio Machado Álvarez (padre de Antonio Machado) se embarcó rumbo al Nuevo Continente en agosto de 1892. No consiguió fortuna sino el infortunio de una tuberculosis fulminante que acabó con su vida,14 sin llegar a cumplir los cuarenta y siete años. Murió en Sevilla, el 4 de febrero de 1893.15 |

マドリードの学生 1883年9月8日、マチャド一家が乗った列車がアトーチャ駅に到着した。 8歳から32歳までの間、1899年と1902年のパリ滞在を除いて、私はマドリードに住んでいた。私はリブレ・デ・エンセニャンサ学院で教育を受け、恩 師たちへの深い愛情を今も持ち続けている。ヒネル・デ・ロス・リオス、底知れぬコシオ、カソ、セラ、サマ(故人)、ルビオ、コスタ(ドン・ホアキン――私 が9歳を過ぎた後、二度と会うことはなかった)などだ。私は中等教育学校と大学に通ったが、学問に対する嫌悪感以外には、これらの教育機関の面影は何も 残っていない。 アントニオ・マチャド著『自伝』より それから10日後、マヌエル(9歳)、アントニオ(8歳)、ホセ(4歳)の3人は、自由教育機関(ILE)の仮校舎に入学した。それから数年にわたり、彼 らの教師はギネール・デ・ロス・リオス自身、マヌエル・バルトロメ・コッシオ、ホアキン・コスタ、ホセ・デ・カソ、アニセト・セラ、ホアキン・サマ、リカ ルド・ルビオ、そして、ホセ・オンタニョン・アリアス、ラファエル・トーレス・カンポス、ヘルマン・フローレスといったあまり知られていない教師たちで あった。彼の同僚には、フリアン・ベステイロ、フアン・ウニャ、ホセ・マヌエル・ペドレガル、ペドロ・ヒメネス=ランディ、アントニオ・ビニェント・イ・ ポルトゥンド、そしてエドゥアルドとトマス・ガルシア・デル・レアルの兄弟などがいた。 マチャドの家族環境と調和したこの機関は、彼の知的イデオロギーを形成することになる。10 マチャドはILEでグアダラマ山脈を発見した。1915年の教師ヒネルへの挽歌で、マチャドは次のように結んでいる。 ある日、先生は スペインの新たな開花を夢見ていた。 「ドン・フランシスコ・ヒネル・デ・ロス・リオスに」。11 1889年5月16日、14歳の誕生日を3か月後に控えたマチャドは、自由主義機関が登録されていたサン・イシドロ学院で、国家バカロレア入学試験を受験 した。6月には地理の試験に合格したが、ラテン語とスペイン語の試験には落ち、1889-1890年度のカルデナル・シスネロス学院への入学が決定した。 1213 一方、長年非常に苦しい状況が続いていたマチャド家の経済は、危機的なレベルに達していた。アナ・ルイスは1890年10月3日に9人目にして最後の女児 を出産したばかりだったが、その女児は数年後に亡くなった。疲れ果て、幻滅した「デモフィル(愛国者)」であった夫は40代で7人の子供を抱えており、プ エルトリコのサンファンで友人から持ちかけられた弁護士の職を引き受けることを決意した。 アントニオ・マチャド・アルバレス(アントニオ・マチャドの父)は、海外領土省の許可を得て、1892年8月に新大陸に向けて出航した。彼は財産を手に入 れることはできず、むしろ、47歳になる前に、瀕死の結核という不幸に見舞われ、14歳でその生涯を終えた。彼は1893年2月4日にセビリアで亡くなっ た。15 |

| Bohemia madrileña En 1895, Antonio Machado aún no había acabado el bachillerato.e Al año siguiente, dos días antes de su vigesimoprimer cumpleaños, murió su abuelo, el luchador krausista, íntimo amigo de Giner y eminente zoólogo Antonio Machado Núñez. A la pérdida familiar se unió el descalabro económico de una familia de la que Juan Ramón Jiménez dejaría este cruel retrato en su libro El modernismo. Notas de un curso: «[...] Abuela queda viuda y regala casa. Madre inútil. Todos viven pequeña renta abuela. Casa desmantelada. Familia empeña muebles. No trabajan ya hombres. Casa de la picaresca. Venta de libros viejos».16 Ociosos, los jóvenes hermanos Machado, entonces inseparables, se entregaron a la atractiva vida bohemia del Madrid de finales del siglo xix. Cafés de artistas, tablaos, tertulias literarias, el frontón y los toros, todo les interesa. Les deslumbra la rebeldía esperpéntica de un Valle-Inclán y un Sawa o la personalidad de actores como Antonio Vico y Ricardo Calvo Agostí; en lo literario hacen amistad con un Zayas o un Villaespesa y, en general, se dejan estimular por la vida pública de la mayoría de los intelectuales de la época.f En octubre de 1896 Antonio Machado, apasionado del teatro, entró a formar parte como meritorio en la compañía teatral de María Guerrero y Fernando Díaz de Mendoza. El propio poeta recordará con humor su carrera como actor: «[...] yo era uno de los que sujetaban a Manelic, en el final del segundo acto».17 La bohemia oscura y luminosa del Madrid del final del siglo xix se alternaba con la colaboración de ambos hermanos en la redacción de un Diccionario de ideas afines, dirigido por el exministro republicano Eduardo Benot. Era inevitable que los jóvenes Machado sintiesen la atracción de París. |

ボヘミアンなマドリード 1895年、アントニオ・マチャドはまだ中等教育を終えていなかった。翌年、21歳の誕生日を2日後に控えた時、彼の祖父であり、クラウシストの闘士であ り、ヒネール(Giner)の親友であり、著名な動物学者であったアントニオ・マチャド・ヌニェスが亡くなった。フアン・ラモン・ヒメネスが著書『モダニ ズム』で残酷なまでに描いたように、一家の経済的破綻が一家の悲しみをさらに深めることとなった。 授業のノート:「...祖母は未亡人となり、家を手放す。役立たずの母親。皆が祖母のわずかな収入で暮らす。家屋は解体される。家族は家具を質入れする。 男たちはもはや働かない。ピカレスクな家。古書の売却」 16 当時、いつも一緒だった若いマチャド兄弟は、19世紀末のマドリードの魅力的なボヘミアン生活に身をゆだねていた。芸術家の集うカフェ、フラメンコクラ ブ、文学の集い、ペロータや闘牛など、彼らは何に対しても興味を示した。彼らは、バジェ=インクランやサワのグロテスクな反逆性や、アントニオ・ビコやリ カルド・カルボ・アゴスティといった俳優の個性に魅了された。文学界では、サヤスやビジャエスペサと親交を結び、一般的に、当時のほとんどの知識人の公生 活から刺激を受けることを許された。 1896年10月、演劇に情熱を傾けていたアントニオ・マチャドは、マリア・ゲレロとフェルナンド・ディアス・デ・メンドーサの劇団に無給の見習いとして 参加した。詩人自身は、俳優としてのキャリアをユーモアを交えて次のように振り返っている。「...私は第2幕の終わりにマヌエルを舞台に残す役目の一人 だった」。17 19世紀末のマドリードの暗くも明るいボヘミアン的な雰囲気は、元共和制大臣エドゥアルド・ベノトが監修した『関連概念辞典』の執筆における2人の兄弟の 協力体制と交互に繰り返された。若き日のマチャドがパリに魅力を感じるのは避けられなかった。 |

| París-Madrid En junio de 1899, Antonio Machado viajó a París, donde ya le esperaba su hermano Manuel. En la capital francesa trabajaron para la Editorial Garnier, se relacionaron con Enrique Gómez Carrillo y Pío Baroja, descubrieron a Paul Verlaine y tuvieron oportunidad de conocer a Oscar Wilde y Jean Moreas.18 Antonio regresó a Madrid en octubre de ese mismo año, incrementando su trato con el «estado mayor» del modernismo, un activo Francisco Villaespesa, un itinerante Rubén Darío y un joven de Moguer, Juan Ramón Jiménez. En abril de 1902, Antonio y Manuel hacen su segundo viaje a París. Allí se reencuentran con otro hermano, Joaquín (El viajero), que regresa de su experiencia americana «enfermo, solitario y pobre», y Antonio se vuelve con él a España el 1 de agosto.19 A finales de ese año, de vuelta en Madrid, el poeta entregó a la imprenta de A. Álvarez Soledades (1899-1902), su primer libro.g Entre 1903 y 1908, el poeta colaboró en diversas revistas literarias: Helios (que publicaba Juan Ramón Jiménez), Blanco y Negro, Alma Española, Renacimiento Latino o La República de las Letras. También firmó el manifiesto de protesta a raíz de la concesión del premio Nobel de Literatura a José Echegaray. En 1906, por consejo de Giner, preparó oposiciones a profesor de francés en Institutos de Segunda Enseñanza, que obtuvo al año siguiente.20 En 1907 publicó en Madrid, con el librero y editor Gregorio Pueyo, su segundo libro de poemas, Soledades. Galerías. Otros poemas (una versión ampliada de Soledades). El poeta tomó posesión de su plaza en el instituto de la capital soriana el 1 de mayo y se incorporó a ella en septiembre. Diferentes versiones han especulado sobre las razones que Machado pudo tener para escoger Soria, en aquel tiempo la capital de provincia más pequeña de España, con poco más de siete mil habitantes.21 Quizá le pareció la plaza más cercana a Madrid a la que su escaso currículo le permitió acceder (de las tres vacantes, Soria, Baeza y Mahón, que quedaban libres de la lista total de siete).22 Ángel Lázaro dejó escrito lo que el propio poeta contestaba, cuando los amigos le preguntaban sobre su decisión: Yo tenía un recuerdo muy bello de Andalucía, donde pasé feliz mis años de infancia. Los hermanos Quintero estrenaron entonces en Madrid El genio alegre, y alguien me dijo: ″Vaya usted a verla. En esa comedia está toda Andalucía″. Y fui a verla, y pensé: ″Si es esto de verdad Andalucía, prefiero Soria.″ Y a Soria me fui. Antonio Machado en González (1986).23h |

パリ-マドリッド 1899年6月、アントニオ・マチャドはパリに旅立ち、すでに兄のマヌエルが彼を待っていた。彼らはパリのガルニエ出版社で働き、エンリケ・ゴメス・カ リージョやピオ・バローハと交流し、ポール・ヴェルレーヌを発見し、オスカー・ワイルドやジャン・モレアスに会う機会を得た。18 アントニオは同年10月にマドリードに戻ったが、モダニズムの「最高幹部」たちとの交流は深まっていた。活動的なフランシスコ・ビジャエスパサ、放浪のル ベン・ダリオ、モゲール出身の若者フアン・ラモン・ヒメネスなどである 。 1902年4月、アントニオとマヌエルは2度目のパリ旅行に出かけた。そこで彼らは、アメリカでの経験から「病み、孤独で、貧しく」なって帰国したもう一 人の兄弟、ホアキン(El viajero)と再会し、アントニオは1902年8月1日に彼とともにスペインに戻った。19 その年の終わりにマドリードに戻った詩人は、A. Álvarez印刷所に最初の著書『Soledades』(1899-1902)を送った。g 1903年から1908年の間、詩人はさまざまな文学雑誌に寄稿した。ヘリオス(フアン・ラモン・ヒメネスが発行)、ブランコ・イ・ネグロ、アルマ・エス パニョーラ、レナシエンシア・ラティーノ、ラ・レプブリカ・デ・ラス・レトラスなどである。また、ホセ・エチェガライのノーベル文学賞受賞に抗議する宣言 文にも署名した。1906年、ヒネールに勧められて中等教育学校のフランス語教師の採用試験の準備を始め、翌年合格した。20 1907年には、詩集『Soledades. Galerías. Otros poemas』(『Soledades』の増補版)をマドリードの書籍販売・出版業者グレゴリオ・プエヨとともに出版した。詩人は5月1日にソリア県の県 庁所在地にある中等学校に赴任し、9月から勤務を開始した。当時スペインで最も人口の少ない州都で、人口7,000人余りのソリアを選んだ理由について は、さまざまな推測がなされている。21 恐らく、彼の限られた学歴でアクセスできるマドリードに最も近い場所だと考えたのだろう(7つのリストから空席となったソリア、バエサ、マオンという3つ の都市)。22 アンヘル・ラサロは 友人たちからその決断について尋ねられた際に、詩人自身が答えた言葉を書き留めた。 「アンダルシアにはとても懐かしい思い出がある。そこで幸せな子供時代を過ごした。キンテーロ兄弟が『陽気な天才』をマドリードで初演したとき、ある人が 私に言った。「それを見に行きなさい。アンダルシアのすべてがその喜劇の中にあるよ」と。そして、私はそれを見に行った。そして思った。「これが本当にア ンダルシアなら、ソリアの方がましだ」と。そして、ソリアに行った。 ゴンサレスの『アントニオ・マチャド』(1986年)23h |

| En Soria El Machado del París simbolista y el Madrid bohemio reflejado en sus Soledades y galerías dio paso en la descarnada realidad soriana a un hombre diferente: «... cinco años en Soria» —escribiría luego en 1917— «orientaron mis ojos y mi corazón hacia lo esencial castellano...» —y añade— «Ya era, además, muy otra mi ideología».24 En lo literario, así quedó reflejado en su siguiente libro, Campos de Castilla; en lo profesional, inició su vida de maestro de pueblo; en lo sentimental, descubrió a Leonor, el gran amor de su vida. |

ソリアにて 象徴主義のパリとボヘミアン的なマドリッドのマチャドは、彼の『孤独』と『ギャラリー』に反映されていたが、ソリアの厳しい現実の中で、彼は別人のように なっていった。「ソリアでの5年間」は、1917年に彼が後に書くように、「私の目と心をカスティーリャの本質に向かわせた... そして、彼はこう付け加えている。「私の思想も今では大きく変わった」。24 文学的な面では、これは次の著書『カスティーリャの大地』に反映されている。職業的な面では、彼は村の教師としての生活を始めた。感傷的な面では、レオ ノールという生涯の伴侶となる女性と出会った。 |

| Leonor Artículo principal: Leonor Izquierdo  Foto de Leonor Izquierdo el día de su boda el 30 de julio de 1909 En diciembre de 1907, al cerrarse la pensión en la que vivía Machado, los huéspedes se trasladaron a un nuevo establecimiento sito en la entonces llamada plaza de Teatinos. En la nueva pensión, regida por Isabel Cuevas y su marido Ceferino Izquierdo, sargento de la Guardia Civil jubilado, quiso el destino que el poeta conociera a Leonor Izquierdo, la hija mayor, y aún apenas una niña de trece años.i El embeleso de Machado fue tan intenso que por primera vez quizá en su vida se mostró impaciente, y cuando tuvo la certeza de que su amor era correspondido acordó el compromiso con la madre de Leonor.j Había pasado poco más de un año, y los novios aún tuvieron que esperar otro hasta que ella alcanzase la edad legal para casarse. Y así, el 30 de julio de 1909 se celebró la ceremonia en la iglesia de Santa María la Mayor de Soria.k Hace un mes que Leonor ha cumplido los quince y el poeta ya tiene treinta y cuatro. Y contra todo pronóstico, el matrimonio fue modelo de entendimiento y felicidad, hasta tal punto que la novia se apasionó por el trabajo del poeta con toda la ilusión de su juventud. Así lo han referido todos los testigos de este episodio de la vida de Antonio Machado.25 En Soria, el espíritu de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza, siempre vivo en el poeta, le llevó a emprender una serie de excursiones por la sierra de Urbión y sus pinares, hasta las fuentes del río Duero y la laguna Negra, escenario trágico de La tierra de Alvargonzález, el más largo poema de Machado. De Soria también fue su amistad con José María Palacio, redactor de Tierra Soriana, el periódico local, y uno de los pocos con los que compartió inquietudes e ideologías en el rudo páramo castellano.26 En diciembre de 1910, Leonor y Antonio viajaron a París, con una beca concedida al poeta por la Junta para la Ampliación de Estudios para perfeccionar sus conocimientos de francés durante un año. Durante los seis primeros meses, la pareja viajó, visitó los museos e intimaron con Rubén Darío y Francisca Sánchez, su compañera.l Machado aprovechó para asistir al curso que Henri Bergson impartía en el Colegio de Francia. El 14 de julio de 1911, cuando el matrimonio iba a partir hacia la Bretaña francesa de vacaciones, Leonor sufrió una hemoptisis y tuvo que ser ingresada. Los médicos, impotentes en aquella época contra la tuberculosis, recomendaron el regreso al aire sano de Soria. Una engañosa mejoría dio paso a un fulminante final, falleciendo el 1 de agosto de 1912. Su última alegría fue tener en sus manos, publicado al fin, el libro que ella había visto crecer ilusionada día a día: la primera edición de Campos de Castilla.27 |

レオノール 詳細は「レオノール・イスキエルド」を参照  1909年7月30日、結婚式当日のレオノール・イスキエルドの写真 1907年12月、マチャドが暮らしていた下宿が閉鎖されたため、ゲストたちは当時テアティノス広場と呼ばれていた場所に新しくできた施設に移った。イサ ベル・クエバスと、退役した治安警備隊の巡査部長セフェリーノ・イスキエルドが経営する新しい下宿で、運命のいたずらか、詩人はまだ13歳の長女レオノー ル・イスキエルドと出会った。i マチャドの熱烈な恋心は、彼にとって初めての経験である焦りを生み、自分の愛が報われたと確信した彼は、 レオノール・カスティージョの母親との婚約に同意した。j それから1年余りが経ち、花嫁と花婿は、彼女が結婚適齢期に達するまで、さらに待たなければならなかった。こうして1909年7月30日、ソリアのサン タ・マリア・ラ・メイオル教会で式が執り行われた。k レオノールは1か月前に15歳になり、詩人はすでに34歳になっていた。しかし、あらゆる予想に反して、この結婚は理解と幸福の模範となり、花嫁は若さの 情熱を傾けて詩人の仕事に情熱を傾けるようになった。これは、アントニオ・マチャドの人生におけるこのエピソードの証人全員が述べていることである。25 ソリアでは、詩人の心に常に息づいていた「自由教育機関(Institución Libre de Enseñanza)」の精神が、ウルビオン山脈と松林を抜け、ドゥエロ川とネグラ湖の水源まで続く一連の遠足へと彼を導いた。この遠足は、マチャドの最 長詩である『アルヴァルゴンセスの地(La tierra de Alvargonzález)』の悲劇的な舞台となった。また、ソリア出身のホセ・マリア・パラシオは、地元紙『ティエラ・ソリアナ』の編集者であり、厳 しいカスティーリャの荒れ野で、彼が唯一、関心事や思想を共有した人物の一人であった。 1910年12月、レオノールとアントニオは、詩人のフランス語の知識を磨くために、学術振興委員会から与えられた奨学金でパリに旅立った。最初の6ヶ月 間、夫妻は旅行をしたり、美術館を訪れたり、ルベン・ダリオと彼のパートナーであるフランシスカ・サンチェスと親交を深めた。マチャドは、この機会を利用 して、アンリ・ベルクソンがコレージュ・ド・フランスで開講していた講座を受講した。 1911年7月14日、夫妻がブルターニュでの休暇に出発しようとしたとき、レオノールが喀血し、入院を余儀なくされた。結核に無力だった当時の医師たち は、空気の澄んだソリアへの帰郷を勧めた。一時的な回復の後、容態は悪化し、1912年8月1日に亡くなった。彼女にとって最後の喜びは、ついに出版され た『カンポス・デ・カスティーリャ』を手にすることだった。27 |

| En Baeza Artículo principal: Antonio Machado en Baeza  Claustro de profesores del Instituto de Baeza en el patio de columnas. 1918. Fotografía de Francisco Baras. Machado, desesperado, solicitó su traslado a Madrid, pero el único destino vacante era Baeza, donde durante los siete próximos años penó más que vivió, dedicado a la enseñanza como profesor de Gramática Francesa en el instituto de Bachillerato instalado en la antigua Universidad baezana. Esta Baeza, que llaman la Salamanca andaluza, tiene un Instituto, un Seminario, una Escuela de Artes, varios colegios de Segunda Enseñanza, y apenas sabe leer un treinta por ciento de la población. No hay más que una librería donde se venden tarjetas postales, devocionarios y periódicos clericales y pornográficos. Es la comarca más rica de Jaén, y la ciudad está poblada de mendigos y de señoritos arruinados en la ruleta.28 Antonio Machado (de una carta a Unamuno en 1913) El poeta no está dispuesto a contemporizar y su mirada se radicaliza; tan solo le sacan de su indignación y su aburrimiento las excursiones que hace a pie y solitario, por los cerros que le separan de Úbeda, o con los escasos amigos que le visitan, por las sierras de Cazorla y de Segura, en las fuentes del Guadalquivir. También tuvo oportunidad de acercarse con más atención a las voces y ritmos del tesoro popular (no en vano llevaba en su herencia la pasión de su padre por el folclore, que a su vez lo había heredado de la abuela de Machado, Cipriana Álvarez Durán). Fruto en gran parte de esa mirada será su siguiente libro, Nuevas canciones.29 Escapar del «poblachón manchego»30 no fue fácil; para conseguirlo, Machado se vio obligado a estudiar por libre, entre 1915 y 1918, la carrera de Filosofía y Letras. Con ese nuevo título en su menguado currículo, solicitó el traslado al Instituto de Segovia, que en esta ocasión sí se le concedió. Machado abandonó Baeza en el otoño de 1919. A partir de 1912 y durante los siete años de su estancia en Baeza, Antonio Machado viaja con frecuencia a Madrid, donde reside su familia, cuenta con amigos del mundo de las letras y colabora con importantes publicaciones periódicas, entre otras actividades como su participación en la nombrada Liga de Educación Política Española o su presencia en sonadas conferencias de Miguel de Unamuno, además de por tener que examinarse en la Universidad de Madrid como alumno libre de estudios de la licenciatura en Filosofía y Letras y, posteriormente, del doctorado, lo que ocurre entre 1915 y 1919, meses antes de producirse su traslado al Instituto de Segovia [...]31 Antonio Chicharro Poco antes, el 8 de junio de 1916, Machado había conocido a un joven poeta, con el que desde entonces mantuvo amistad, que se llamaba Federico García Lorca.32 |

ベーサにて 詳細は「ベーサのアントニオ・マチャド」を参照  柱廊のある中庭のベサ研究所のスタッフ。1918年。フランシスコ・バラスの撮影。 絶望したマチャドはマドリードへの異動を願い出たが、唯一の空席はベサにあった。彼はその後7年間、ベサ大学跡地の中等教育学校でフランス文法を教えながら、生きているというよりも苦しみ抜いた。 このバエサはアンダルシアのサラマンカと呼ばれているが、そこには中学校、神学校、芸術大学、いくつかの中学校があるだけで、人口の30パーセントしか文 字を読むことができない。本屋は一軒しかなく、そこでは絵葉書、祈祷書、聖職者向けの新聞やポルノ新聞が売られている。ここはハエン州で最も裕福な地域で あり、街には乞食やルーレットで財産を失った紳士たちが住んでいる。28 アントニオ・マチャド(1913年のウナムノ宛ての手紙より) 妥協を許さない詩人の視線はより先鋭的になり、ウベダを隔てる丘陵地帯を一人で散歩したり、グアダルキビール川の源流にあるカソルラ山脈やセグラ山脈を訪 ねてくる数人の友人と過ごすことで、憤りと退屈からようやく解放されるのだった。彼はまた、民衆の宝である声やリズムにもより注意深く耳を傾ける機会を得 た(父親の民俗学への情熱を継承したことは無駄ではなかった。その父親は、マチャドの祖母であるシプリアナ・アルバレス・ドゥランから継承したのだ)。彼 の次の著書『Nuevas canciones(新しい歌)』は、その視線の結果として生まれたものである。29 「poblachón manchego(ラ・マンチャの庶民)」から逃れることは容易ではなかった。これを達成するために、マチャドは1915年から1918年の間、哲学と芸 術の学位取得を目指して独学を余儀なくされた。履歴書に記載できる資格が減る中、彼はセゴビアの学院への転校を申請し、今回はそれが認められた。マチャド は1919年の秋にベアサを離れた。 1912年から7年間にわたってベーサに滞在していた間、アントニオ・マチャドは家族が住むマドリードに頻繁に足を運んでいた。マドリードには文学界の友 人たちがおり、重要な定期刊行物に協力していた。その他にも、前述のスペイン政治教育連盟への参加や、ミゲル・デ・ウナムノの有名な講演への出席など、さ まざまな活動を行っていた。また、マドリード大学で独学で哲学と芸術の学位を取得し、 1915年から1919年の間、セゴビアの研究所に移る数ヶ月前に、哲学と芸術の学位、そして後に博士号を取得するためにマドリード大学で試験を受ける必 要があった。 アントニオ・チチャロ その直前、1916年6月8日に、マチャドは若い詩人、フェデリコ・ガルシア・ロルカと出会った。32 |

| Segovia-Madrid Machado llegó a Segovia el 26 de noviembre de 1919 y acabó instalándose por el modestísimo precio de 3,50 pesetas al día en una aún más modesta pensión.33 Era el mes de noviembre de 1919 y el poeta llegó a tiempo para participar en la fundación de la Universidad Popular Segoviana junto con otros personajes como el marqués de Lozoya, Blas Zambrano, Ignacio Carral, Mariano Quintanilla, Alfredo Marqueríe o el arquitecto Francisco Javier Cabello Dodero, que se encargó de restaurar y adaptar el viejo templo románico de San Quirce, uno de los espacios en los que la innovadora institución se había propuesto como objetivo la instrucción gratuita del pueblo segoviano.34 Ocupó la Cátedra de Francés del Instituto General y Técnico de la ciudad. En este centro impartirá clases hasta 1932, ejerciendo como vicedirector durante varios años.35 Retratado por Leandro Oroz (1925) Machado, que ahora contaba con la ventaja de la cercanía de Madrid, visitaba cada fin de semana la capital participando de nuevo en la vida cultural del país con tanta dedicación que a menudo «perdió el tren de regreso a Segovia muchos lunes, y bastantes martes».36 Este nuevo estatus de perfil bohemio le permitiría recuperar la actividad teatral junto a su hermano Manuel. En Segovia, por su parte, fue asiduo de la tertulia de San Gregorio que —entre 1921 y 1927— se reunía cada tarde en el alfar del ceramista Fernando Arranz, instalado en las ruinas de una iglesia románica, en la que participaban también amigos como Blas Zambrano (catedrático de la Escuela Normal y padre de María Zambrano), Manuel Cardenal Iracheta, el escultor Emiliano Barral y algunos otros tipos pintorescos (como Carranza, cadete de la academia de Artillería, o el padre Villalba, que puso música a un texto de Machado).37 También colaboró en la recién nacida revista literaria Manantial y frecuentó el ambiente del Café Castilla, en la plaza mayor de Segovia.m En 1927, Antonio Machado fue elegido miembro de la Real Academia Española, si bien nunca llegó a tomar posesión de su sillón.n En una carta a Unamuno, el poeta le comenta la noticia con sana ironía: «Es un honor al cual no aspiré nunca; casi me atreveré a decir que aspiré a no tenerlo nunca. Pero Dios da pañuelo a quien no tiene narices...».3839 |

セゴビア-マドリード 1919年11月26日にセゴビアに到着したマチャドは、1日3.50ペセタという非常に手頃な価格の、さらに質素な下宿に落ち着くことになった。33 1919年11月、詩人はロソヤ侯爵、ブラス・サンブラノ、イグナシオ・カラル、マリアーノ・キンテ・ 、アルフレド・マルケリー、建築家のフランシスコ・ハビエル・カベロ・ドデロが参加した。カベロ・ドデロは、古いロマネスク様式のサン・クエルセ教会の修 復と改築を担当し、この革新的な教育機関はセゴビアの人々に無償で教育を提供することを目標としていた。34 彼は市の総合技術学院でフランス語の教授を務めた。 彼はセゴビア市の総合技術学院でフランス語の教授を務めていた。1932年まで同校で教鞭をとり、数年間は副校長も務めた。35 レアンドロ・オロスによる肖像画(1925年) マドリードに近いという利点を得たマチャドは、週末ごとに首都を訪れ、スペインの文化活動に再び熱心に参加するようになった。そのため、「セゴビアに戻る 列車に月曜日に何度も乗り遅れ、火曜日も何度か乗り遅れた」こともあったという。36 この新しい自由人としての地位により、彼は兄マヌエルとともに演劇活動を再開することができた。 一方、セゴビアでは、1921年から1927年の間、彼はサン・グレゴリオの集まりに定期的に参加していた。この集まりは、ロマネスク様式の教会跡に建て られた陶芸家フェルナンド・アランスの工房で、毎日午後に開催されていた。この集まりには、ブラス・サンブラノ(ノルマル学校の教授で、マリア・サンブラ ノの父親)、マヌエル・カルデナル・イラチェタ、彫刻家の エミリアーノ・バラル、その他にも風変わりな人物(例えば、砲兵学校の士官候補生であったカランサや、マチャドの詩に曲をつけたビジャルバ神父など)が参 加していた。37 また、彼は新しく創刊された文芸誌『マナンシア』にも寄稿し、セゴビアの中心広場にあるカフェ・カスティーリャの雰囲気にも親しんでいた。 1927年、アントニオ・マチャドはスペイン王立アカデミーの会員に選出されたが、実際に席に就くことはなかった。n ウナムノに宛てた手紙の中で、詩人はこのニュースを健全な皮肉を込めて次のように評している。「それは私が決して望まなかった名誉だ。あえて言うなら、私 は決してそれを望まなかったと。しかし、神は鼻のない者に鼻をかませるのだ...」38 39 |

| Guiomar Artículo principal: Pilar de Valderrama  Pilar de Valderrama En junio de 1928 aparece en su vida Pilar de Valderrama, dama de la alta burguesía madrileña, casada y madre de tres hijos, autora de varios libros de poesía y obras de teatro y cofundadora del Lyceum Club Femenino.40 Había viajado sola a Segovia buscando serenidad tras una grave crisis conyugal.41 Tiene en Segovia amistades de visitas anteriores42 y esta vez llevaba además una carta de presentación de la hermana del actor Ricardo Calvo para su amigo Antonio Machado a quien ella admiraba. Se hospedó en el incómodo Hotel Comercio, el mejor de la ciudad, y en su sala de recibo la visitó Machado iniciándose así su amistad, que en el poeta enseguida se convierte en un enamoramiento tan intenso que, cuando ella le indica que al estar casada sólo le puede ofrecer una inocente amistad, él acepta esa limitación: "Con tal de verte, lo que sea", aunque en sus cartas se lamenta una y otra vez de esa castidad impuesta. Durante casi nueve años hizo las funciones de musa y «oscuro objeto del deseo» ("la sed que nunca se apaga / del agua que no se bebe") de un rejuvenecido Machado que inmortalizó aquel espejismo poético con el nombre de Guiomar.o43 Desde la publicación en 1950 del libro De Antonio Machado a su grande y secreto amor, escrito por Concha Espina y haciendo pública una colección de cartas entre Machado y una misteriosa pero real Guiomar, varios y variopintos han sido los estudios dedicados al fenómeno Guiomar.44 Todo parece indicar que Pilar de Valderrama nunca estuvo enamorada de Machado (aunque como buena cortesana fue diestra en el arte de «marear la perdiz»),45 como parece deducirse de lo escrito en su libro de memorias Sí, soy Guiomar, libro escrito en su vejez y publicado de manera póstuma, para insistir en el carácter platónico de su relación con el poeta, pero sin explicar por qué de ser así se mantuvo en secreto con tanto celo. Tampoco explicó la inspiradora de Guiomar por qué quemó la mayoría de las cartas que recibió de Machado, cuando —quizá advertida por sus contactos entre la clase acomodada— abandonó Madrid, rumbo a Estoril, en junio de 1936, un mes antes del golpe de Estado.46 |

ギオマール 詳細は「ピラール・デ・バルデラマ」を参照  ピラール・デ・バルデラマ 1928年6月、ピラール・デ・バルデラマが彼の人生に登場した。彼女はマドリードの上流中流階級の女性で、既婚者であり3人の子供の母親であった。ま た、詩や劇の著書も複数あり、女性のためのリセウム・クラブの共同創設者でもあった。40 深刻な夫婦間の危機の後、平穏を求めてセゴビアに一人旅をしていた。41 彼女は以前にもセゴビアを訪れたことがあり、セゴビアには友人もいた。42 そして、今回は 彼女は、尊敬する詩人アントニオ・マチャドの友人である俳優リカルド・カルボの妹から紹介状も持っていた。彼女は市内で一番良いホテル・コメルシオに滞在 し、マチャドは応接室を訪ねた。こうして二人の友情が始まったが、詩人にとってはすぐに激しい恋心へと変わった。彼女が既婚者であるため、無垢な友情しか 提供できないと告げると、彼は「君に会うためには何だってする。何だって」と、その制限を受け入れた。しかし、彼女の手紙には、 禁欲を強いられていることを嘆いていた。 ほぼ9年間、彼女は詩人のミューズであり、「欲望の対象として目立たない存在」(「決して消えることのない渇き/飲まれることのない水への」)として、若 返ったマチャドを支え続けた。そして、その詩的な幻影を「Guiomar.o43」という名前で永遠のものとした。1950年にコンチャ・エスピナが著し た『De Antonio Machado a su grande y secreto amor』が出版され、マチャドと 謎に包まれた実在の女性ギオマールとの書簡集を公表して以来、ギオマール現象に関するさまざまな研究が数多く発表されている。44 ピラール・デ・バルデラマがマチャドと恋愛関係にあったことは一度もなかったことを示す証拠は数多くある(ただし、優れた娼婦として「遠回しな言い方」の 術に長けていたことは確かである)。45 彼女が晩年に書き、死後に出版された回想録『そう、私はギオマール』に書かれていることから、そのように推測できる。詩人との関係がプラトニックなもので あったことを主張しているが、もしそうであったなら、なぜそれほどまでに熱心に秘密にしていたのかについては説明していない。また、クーデターの1か月前 の1936年6月にマドリードからエストリルへ引っ越した際、富裕層に属するマチャドの知人から警告を受けたのか、彼女がマチャドから受け取った手紙のほ とんどを燃やした理由についても、彼女のミューズは説明していない。46 |

| 14 de abril en Segovia El último gran acontecimiento de los años segovianos de Machado ocurrió el 14 de abril de 1931, fecha de la proclamación de la Segunda República española. El poeta, que vive la noticia en Segovia, fue requerido para ser uno de los encargados de izar la bandera tricolor en el balcón del Ayuntamiento. Un momento emotivo que Machado recordaría con estas palabras:47 ¡Aquellas horas, Dios mío, tejidas todas ellas con el más puro lino de la esperanza, cuando unos pocos viejos republicanos izamos la bandera tricolor en el Ayuntamiento de Segovia! (...) Con las primeras hojas de los chopos y las últimas flores de los almendros, la primavera traía a nuestra república de la mano. Antonio Machado |

4月14日、セゴビアにて セゴビアでのマチャドの最後の大きな出来事は、1931年4月14日、スペイン第二共和制の宣言の日であった。 セゴビアに滞在していた詩人は、そのニュースを聞いた後、市庁舎のバルコニーで三色旗を掲揚する責任者の一人に指名された。 それは感動的な瞬間であり、マチャドは次のように語っている。 あの数時間、なんと希望という純粋なリネンで織り上げられたことか!セゴビアの市庁舎で、数人の共和党員がトリコロールの旗を掲げたのだ!ポプラの木々の最初の葉とアーモンドの木々の最後の花とともに、春が共和国を連れてやってきたのだ。 アントニオ・マチャド |

| Madrid republicano En octubre de 1931 la República le concedió a Machado, por fin, una cátedra de francés en Madrid, donde a partir de 1932 pudo vivir de nuevo en compañía de su familia (su madre, su hermano José, mujer e hijas). En la capital, el poeta continuó viéndose en secreto con la inspiradora de Guiomar y estrenando las comedias escritas con Manuel. En una Orden gubernamental de 19 de marzo de 1932, a petición del secretario del Patronato de las Misiones Pedagógicas, se autoriza a Machado a residir en Madrid «para la organización del Teatro popular».48 Durante los siguientes años, Machado escribió menos poesía pero aumentó su producción en prosa, publicando con frecuencia en el Diario de Madrid y El Sol y perfilando definitivamente a sus dos apócrifos, los pensadores (y cómo Machado, poetas y maestros) Juan de Mairena y Abel Martín.p En 1935, Machado se trasladó del Instituto Calderón de la Barca al Cervantes. Días antes, el 1 de septiembre había muerto su maestro Cossío, poco después de haberse reunido con él en su retiro de la sierra de Guadarrama y en compañía de otros institucionistas, Ángel Llorca y Luis Álvarez Santullano. Las pérdidas se acumulan: el 5 de enero muere Valle-Inclán y el 9 de abril un olvidado Francisco Villaespesa... el desfile de la muerte se había adelantado.49 |

マドリードの共和国 1931年10月、共和国はついにマドリードのフランス人向け教育ポストをマチャドに与えた。1932年から彼は再び家族(母親、弟のホセ、妻、娘たち) と暮らすことができた。首都で、詩人はインスピレーションの源であるギオマールとひそかに会い続け、マヌエルとともに書いた戯曲を上演し続けた。 1932年3月19日付の政府命令により、教育宣教委員会の理事の要請により、マチャドは「人民演劇の組織化」のためにマドリードに居住することが許可された。48 その後数年間に、マチャドは詩の執筆は減らしたが、散文の執筆は増やし、ディアリオ・デ・マドリッド紙やエル・ソル紙に頻繁に寄稿し、2人の架空の思想家(マチャドと同様に詩人であり教師でもあった)フアン・デ・マイレーナとアベル・マルティンを明確に描き出した。 1935年、マチャドはカルデロン・デ・ラ・バルカ協会からセルバンテス協会へと移った。その数日前の9月1日には、彼の師であるコッシオが亡くなってい た。グアダラマ山脈の隠れ家で、協会の他のメンバーであるアンヘル・ジョルカとルイス・アルバレス・サントゥラーノとともに彼と会った直後のことだった。 蓄積された損失:1月5日にバジェ=インクランが亡くなり、4月9日には忘れられたフランシスコ・ビジャエスペーサが亡くなった。葬列は前倒しになった。 49 |

| La Guerra Civil Casi desde los primeros días de la guerra, Madrid, ya convulsionada desde los últimos estertores del segundo bienio, se convirtió en un campo abonado para las privaciones y la muerte. La Alianza de Intelectuales decidió, entre otras muchas medidas de emergencia, evacuar a zonas más seguras a una serie de escritores y artistas, Machado entre ellos (por su edad avanzada y por su significación). La oferta, un día de noviembre de 1936, la presentan en el domicilio del poeta, otros dos ilustres colegas: Rafael Alberti y León Felipe. Machado, «concentrado y triste» –según evocaría luego Alberti– se resistía a marchar. Fue necesaria una segunda visita con mayor insistencia y a condición de que sus hermanos Joaquín y José, con sus familias, le acompañasen junto con su madre.50 |

スペイン内戦 戦争の初期から、すでに2度目の2年間の末期から動揺していたマドリードは、略奪と死の温床となった。知識人同盟は、緊急対策のひとつとして、マチャド (高齢であることと、その重要性から)を含む多くの作家や芸術家を安全な地域へ避難させることを決定した。1936年11月のある日、この申し出は、詩人 の自宅で、ラファエル・アルバルティとレオン・フェリペという2人の著名な同僚によって伝えられた。アルバルティが後に回想するように、「集中し、悲し げ」だったマチャドは、立ち去ることに抵抗した。2度目の訪問が必要となり、より強く強く説得し、彼の兄弟であるホアキンとホセが家族とともに同行し、母 親も同行するという条件で、ようやく承諾を得た。50 |

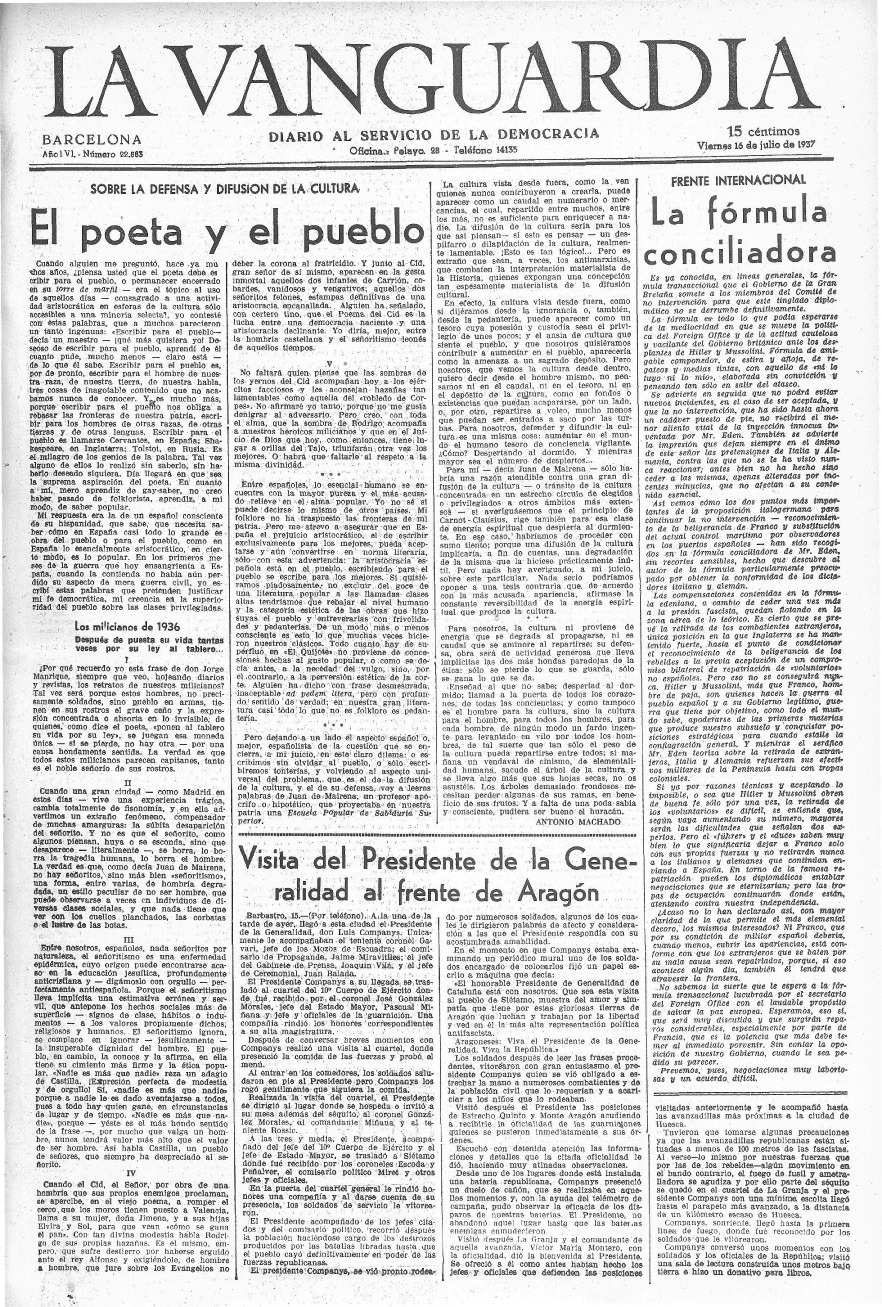

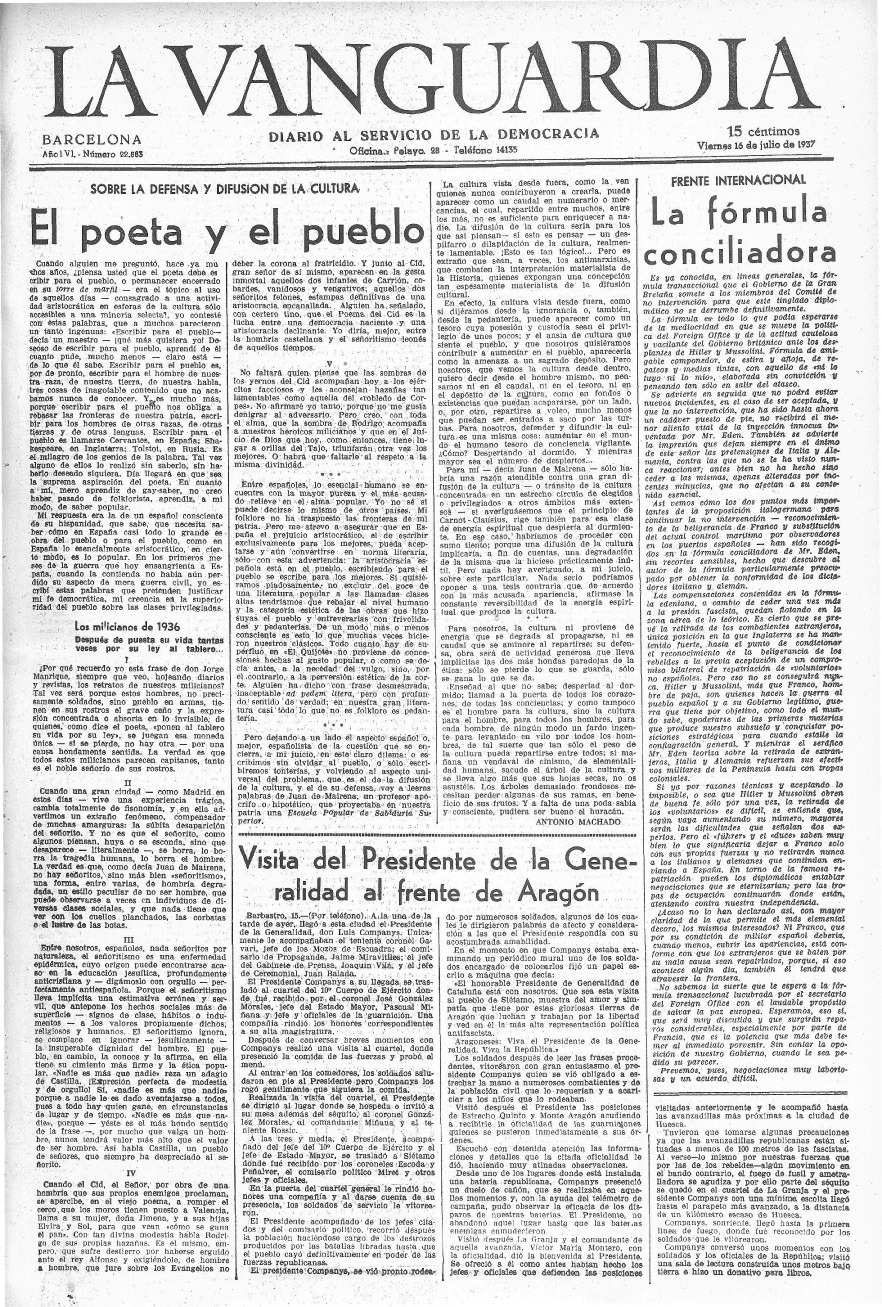

En Rocafort Publicación en portada del diario La Vanguardia del viernes 16 de julio de 1937: «El poeta y el pueblo», discurso de Antonio Machado para el II Congreso Internacional de Escritores para la Defensa de la Cultura organizado por la Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas y celebrado en Valencia. Machado y su familia, tras ser acogidos provisionalmente en la Casa de la Cultura de Valencia, se instalaron en Villa Amparo, un chalet en la localidad de Rocafort, desde finales de noviembre de 1936 hasta abril de 1938, fecha en que fueron evacuados a Barcelona.q Durante su estancia valenciana, el poeta, a pesar del progresivo deterioro de su salud, escribió sin descanso comentarios, artículos, análisis, poemas y discursos (como el que pronunció para las Juventudes Socialistas Unificadas, en una plaza pública de Valencia ante una audiencia multitudinaria), y asistió al II Congreso Internacional de Escritores para la Defensa de la Cultura organizado por la Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas y celebrado en la capital valenciana, donde leyó su reflexión titulada «El poeta y el pueblo».51 Durante los últimos días del Congreso, se realizó la segunda conferencia nacional de la Asociación de Amigos de la Unión Soviética durante la cual se renovaron sus cargos y se eligió a Antonio Machado como miembro de su comité nacional.52 En 1937 publicó La guerra, con ilustraciones de su hermano menor José Machado Ruiz. De entre sus últimos escritos, obra de compromiso histórico y testimonial, destacan textos de hondura estremecedora, como la elegía dedicada a Federico García Lorca: El crimen fue en Granada.r53 |

ロカフォルトにて 1937年7月16日(金)の新聞『ラ・バングアルディア』の第一面掲載記事:「詩人と人民」反ファシスト知識人同盟が主催し、バレンシアで開催された文化擁護作家第二回国際会議におけるアントニオ・マチャドのスピーチ。 マチャドとその家族は、バレンシアの文化会館に仮住まいした後、1936年11月末から1938年4月にバルセロナに避難するまで、ロカフォルトの町にあ る別荘地ビラ・アンパロに落ち着いた。バレンシア滞在中、詩人の健康状態は徐々に悪化していったが、彼は精力的に執筆を続けた。論評、記事、分析、詩を また、演説(バレンシアの広場で大勢の聴衆を前に統一社会主義青年団で行ったものなど)も行い、反ファシスト知識人同盟が主催しバレンシアの首都で開催さ れた文化擁護のための作家第2回国際会議にも出席し、「詩人と人民」と題する論文を読んだ。51 会議の最終日には、スペインのソ連友好協会の第2回全国会議が開催され その役員が再選され、アントニオ・マチャドが全国委員会のメンバーに選出された。52 1937年には、弟のホセ・マチャド・ルイスの挿絵を添えた『La guerra』を出版した。彼の最後の著作の中でも、歴史的な関与と証言をテーマにした作品、とりわけ、フェデリコ・ガルシア・ロルカに捧げられた哀歌 『El crimen fue en Granada』のような、身震いするほど深い文章が際立っている。53 |

| Escala en Barcelona Ante el peligro de que Valencia quede aislada, los Machado se trasladaron a Barcelona, donde tras un hospedaje provisional en el Hotel Majestic, ocuparon la finca de Torre Castañer. El lujo del lugar contrasta con las miserias de la guerra: no hay carbón para las estufas, ni su imprescindible tabaco, ni apenas alimentos. Allí permanecieron desde finales de mayo de 1938 hasta los primeros días del siguiente año.54 |

バルセロナへの移転 バレンシアが孤立する危険に直面したマチャド夫妻はバルセロナへ移り、ホテル・マジェスティックに一時滞在した後、トーレ・カスタニェール邸宅に入居し た。この邸宅の贅沢さは戦争の悲惨さと対照的であった。ストーブ用の石炭も、必需品のタバコも、食料もほとんどない。彼らは1938年5月末から翌年頭ま でそこに留まった。54 |

| Exilio y muerte El 22 de enero de 1939, y ante la inminente ocupación de la ciudad por las fuerzas del bando sublevado, el poeta y su familia salieron de Barcelona en un vehículo de la Dirección de Sanidad conseguido por el doctor José Puche Álvarez; les acompañan, entre otros amigos, el filósofo Joaquín Xirau, el filólogo Tomás Navarro Tomás, el humanista catalán Carlos Riba, el novelista Corpus Barga y una interminable caravana de cientos de miles de españoles anónimos huyendo de su patria.55s56 Tras una última noche en suelo español, en Viladasens, las cuarenta personas que componían el grupo cubrió el último tramo hacia el exilio. Apenas a medio kilómetro de la frontera con Francia, tuvieron que abandonar los coches de Sanidad, embotellados en el colapso de la huida. Allí quedaron también sus maletas, al pie de la larga cuesta que hubo que recorrer bajo la lluvia y el frío del atardecer hasta la aduana francesa, que solo gracias a las gestiones de Corpus Barga (que disponía de un permiso de residencia en Francia) pudieron superar. Unos coches les llevaron hasta la estación ferroviaria de Cerbère, donde gracias a las influencias de Xirau se les permitió pasar la noche en un vagón estacionado en vía muerta. A la mañana siguiente, con la ayuda de Navarro Tomás y Corpus Barga, se trasladaron en tren hasta Colliure (Francia), donde el grupo encontró albergue en la tarde del día 28 de enero, en el Hotel Bougnol-Quintana. Allí quedaron a la espera de una ayuda que no llegaría a tiempo.t  Tumba de Antonio Machado y su madre, Ana Ruiz, en el cementerio de Colliure (Francia) Antonio Machado murió a las tres y media de la tarde del 22 de febrero de 1939, Miércoles de Ceniza.u25758v José Machado relataría luego que su madre, saliendo por unos instantes del estado de semiinconsciencia en el que la habían sumido las penalidades del viaje, y al ver vacía la cama de su hijo junto a la suya, preguntó por él con ansiedad. No creyó las piadosas mentiras que le dijeron y comenzó a llorar. Murió el 25 de febrero, justo el día en que cumplía ochenta y cinco años de edad,w59 haciendo efectiva la promesa que formuló en voz alta en Rocafort: «Estoy dispuesta a vivir tanto como mi hijo Antonio».6061 Ana Ruiz fue enterrada junto a su hijo en el nicho cedido por una vecina de Colliure, en el pequeño cementerio de la localidad francesa donde reposan sus restos desde entonces. Late, corazón... No todo se lo ha tragado la tierra. Antonio Machado en Gibson (2006).62 |

亡命と死 1939年1月22日、反乱軍の部隊によるバルセロナ占領が迫る中、詩人とその家族は、ホセ・プチェ・アルバレス医師が手に入れた保健局の車両でバルセロ ナを後にした。彼らは、友人である哲学者のホアキン・シラウ、言語学者のトマス・ナバーロ・トマス、カタロニア人ヒューマニストのカルロス・リバ、小説家 のコーパス・バルガ、そして 故郷を後にした何十万人ものスペイン人の無名の群れが延々と続いた。55秒56秒 スペイン領内での最後の夜をビラダセンで過ごした後、一行40人は亡命への最後の道のりを歩いた。フランス国境まであとわずか半キロの地点で、彼らは崩壊 した脱出ルートで立ち往生した衛生局の車を放棄せざるを得なかった。そこには、彼らのスーツケースも置かれており、彼らは雨と夜の寒さの中、長い坂を下 り、フランス税関まで移動しなければならなかった。彼らは、コーパス・バルガ(フランス在住許可証を所持)の尽力により、ようやく税関に到着することがで きた。一部の車は彼らをセルベール駅まで送り、そこではシラウの尽力により、彼らは側線に停車中の車両で夜を過ごすことを許された。 翌朝、ナバーロ・トマスとバルガの協力により、一行は列車でコリウール(フランス)へ向かった。一行は1月28日の午後、ホテル・ブニョル・キンターナに宿泊した。そこで彼らは、間に合わなかった支援を待った。  コリウール(フランス)の墓地にあるアントニオ・マチャドと母親アナ・ルイスの墓 アントニオ・マチャドは1939年2月22日、灰の水曜日の午後3時半に亡くなった。u25758v ホセ・マチャドは後に、旅の苦難により半意識状態に陥っていた母親が、一瞬意識を取り戻し、隣のベッドが空になっているのを見て、不安になり、息子のこと を尋ねた、と語っている。母親は、告げられた敬虔な嘘を信じることができず、泣き始めた。彼女は85歳になるはずだった2月25日に亡くなった。ロカフォ ルトで声に出して誓った「息子のアントニオと同じだけ生きるつもりだ」という約束を果たしたのだ。6061アナ・ルイスは、コリウールの隣人が用意した ニッチに息子の隣に埋葬された。フランスのこの町の小さな墓地には、それ以来、彼の遺骨が安置されている それ以来、彼女の遺体はそこに眠っている。 心臓の鼓動、鼓動... すべてが土に飲み込まれたわけではない。 アントニオ・マチャド作『ギブソン』(2006年)62 |

| Depuración post mortem y rehabilitación Como todos los profesores de Segunda Enseñanza, fue sometido por las autoridades franquistas a un expediente de depuración. La Comisión de Depuración C de Madrid pidió un informe al Instituto Cervantes de Madrid donde tenía su plaza de catedrático y la dirección del centro le comunicó a la Comisión que había fallecido «según referencias de los periódicos». Así que, sin solicitar más informes, se procedió a la separación definitiva del cuerpo de catedráticos de Instituto decretada el 7 de julio de 1941, dos años después de haber muerto en el exilio.63 Mucho tiempo antes, al comienzo de la guerra civil española, los compañeros de Machado del Instituto de Segovia donde también había estado le habían declarado indeseable junto con otros profesores defensores de la legalidad republicana y remitieron una nota al diario local El Adelantado de Segovia que la publicó el 27 de noviembre de 1936.64 En ella se decía:65 Publicadas recientemente y por distintos medios de difusión diferentes actuaciones, imputadas a los ex catedráticos de este instituto Antonio Machado Ruiz, Rubén Landa Vaz y Jaén Morente, indiscutiblemente censurables, por antipatrióticas y contrarias al Movimiento Nacional, el claustro de este centro no podía mostrarse ajeno... en sesión celebrada el 11 de noviembre, declaró indeseables a tales señores y estimando a la vez como depresiva la presencia de sus nombres en el mismo escalafón al que nos honramos pertenecer. Hubo que esperar hasta 1981 para que fuera rehabilitado (con la misma fórmula) como profesor del Instituto Cervantes de Madrid, por orden ministerial de un gobierno democrático.x Varios autores han estudiado si Machado era masón o en qué grado lo fue.68 Según António Apolinário Lourenço sería «prácticamente unánime» la aceptación de este hecho, aunque destaca la nula actividad del poeta en actividades de la orden.69 Para el hispanista Paul Aubert, si bien este no descarta la posibilidad, no existen pruebas de su vinculación con ninguna logia, aunque señala sus contactos con miembros de la masonería.70 |

死後の粛清と名誉回復 他の中等教育教師と同様、フランコ政権当局による粛清の対象となった。マドリードの粛清委員会は、彼の教授職があったマドリードのセルバンテス学院に報告 を求めたが、学院の経営陣は委員会に対し、彼が「新聞報道によると」死亡したと伝えた。そのため、それ以上の報告を求めることなく、亡命先の死から2年後 の1941年7月7日、彼はセゴビアのセルバンテス協会の教授リストから正式に削除された。63 それよりずっと以前、スペイン内戦の勃発当初、マドリードのセルバンテス協会の同僚たちは、彼もかつて所属していたセゴビアの協会で、共和制の正統性を擁 護する他の教授たちとともにマドリードを不適格であると宣言し、 地元紙「セゴビア・アドランタード」に送った。同紙は1936年11月27日にこれを掲載した。64 その内容は以下の通りである。65 最近発表され、さまざまなメディアを通じて伝えられた、この学院の元教授であるアントニオ・マチャド・ルイス、ルベン・ランダ・バス、ハエン・モレンテの 3名による、紛れもなく非難されるべき、非愛国的で国家運動に反するさまざまな行動について、この学院の教授陣が知らぬ存ぜぬではいられない。11月11 日に開催された会議において、同会議は、この3名を望ましくない人物と宣言し、同時に、 我々が名誉ある一員として所属しているのと同じヒエラルキーに彼らの名前があることは、是正が必要であると判断した。 マドリードのセルバンテス協会の教授職に復帰(同じ方式で)したのは、民主政府の閣僚命令によるもので、1981年まで待たねばならなかった。x 複数の著述家が、マチャドがフリーメイソンであったかどうか、またどの程度であったかについて研究している。68 アントニオ・アポリナリオ・ロレンソによると、この事実を受け入れることは「実質的に全会一致」であるが、彼は詩人が同団体の活動にほとんど参加していな かったことを強調している。 69 スペイン文学者のポール・オーベールは、可能性を否定はしないものの、彼がどのロッジと関係を持っていたという証拠はないと指摘している。しかし、彼は彼 がフリーメイソンのメンバーと接触していたことを指摘している。70 |

| Autorretrato En una breve autobiografía casi improvisada por Machado en 1913, dejó escritas algunas claves personales que dibujan mejor que ningún estudio crítico su perfil humano: Tengo un gran amor a España y una idea de España completamente negativa. Todo lo español me encanta y me indigna al mismo tiempo. Mi vida está hecha más de resignación que de rebeldía; pero de cuando en cuando siento impulsos batalladores que coinciden con optimismos momentáneos de los cuales me arrepiento y sonrojo a poco indefectiblemente. Soy más autoinspectivo que observador y comprendo la injusticia de señalar en el vecino lo que noto en mí mismo. Mi pensamiento está generalmente ocupado por lo que llama Kant conflictos de las ideas trascendentales y busco en la poesía un alivio a esta ingrata faena. En el fondo soy creyente en una realidad espiritual opuesta al mundo sensible.y Antonio Machado, Autobiografía. |

自画像 1913年にマチャドが書いた即興に近い短い自伝には、彼の人間像をあらゆる批評的研究よりもよく描いた個人的な手がかりがいくつか残されている。 私はスペインを心から愛しているが、スペインに対しては完全に否定的な考えを持っている。私はスペインのすべてを愛しているが、同時に憤りも感じている。 私の人生は反抗よりも諦観に満ちているが、時折、闘争的な衝動に駆られることがある。それは一瞬の楽観主義と一致するもので、私は必ず少しずつ後悔し、赤 面する。私は観察よりも自己批判的であり、自分自身で気づいたことを他人に指摘することの不当性を理解している。私の思考は概して、カントが「超越論的観 念の葛藤」と呼ぶものに占められており、私はこの報われない作業から詩によって救済を求めている。心の奥底では、感覚的な世界とは対極にある精神的な現実 を信じている。アントニオ・マチャド、自伝より。 |

| Ideología Creo que la mujer española alcanza una virtud insuperable y que la decadencia de España depende del predominio de la mujer y de su enorme superioridad sobre el varón. Me repugna la política donde veo el encanallamiento del campo por el influjo de la ciudad. Detesto al clero mundano que me parece otra degradación campesina. En general me agrada más lo popular que lo aristocrático social y más el campo que la ciudad. El problema nacional me parece irresoluble por falta de virilidad espiritual; pero creo que se debe luchar por el porvenir y crear una fe que no tenemos. Creo más útil la verdad que condena el presente, que la prudencia que salva lo actual a costa siempre de lo venidero. La fe en la vida y el dogma de la utilidad me parecen peligrosos y absurdos. Estimo oportuno combatir a la Iglesia católica y proclamar el derecho del pueblo a la conciencia y estoy convencido de que España morirá por asfixia espiritual si no rompe ese lazo de hierro. Para ello no hay más obstáculos que la hipocresía y la timidez. Ésta no es una cuestión de cultura —se puede ser muy culto y respetar lo ficticio y lo inmoral— sino de conciencia. La conciencia es anterior al alfabeto y al pan. Antonio Machado, Autobiografía. |

イデオロギー 私はスペインの女性が比類なき美徳を体現していると信じており、スペインの衰退は女性の優位性と男性に対する圧倒的な優位性に起因していると考えている。 私は、都会の影響によって田舎が退廃していくのを目の当たりにする政治に嫌悪感を抱いている。また、農民のさらなる退廃であるかのように見える俗世の聖職 者たちを嫌悪している。一般的に、私は貴族社会よりも庶民社会を、都市よりも田舎を好む。国家の問題は、精神的な強さの欠如により、私には解決不可能に思 える。しかし、私たちは未来のために戦い、自分たちにない信念を創り出さなければならないと信じている。私は、未来を犠牲にして現在を維持しようとする慎 重さよりも、現在を断罪する真実の方が有益だと信じている。生命への信仰や功利主義の教義は、私には危険で馬鹿げているように思える。私はカトリック教会 と戦い、民衆の良心の権利を宣言することが適切だと考えている。そして、スペインがその鉄の絆を断ち切らなければ、精神的な窒息によって死んでしまうと確 信している。これを行うために唯一の障害は偽善と臆病である。これは文化の問題ではない。高度な教養を持ち、虚構や不道徳を尊重することも可能だ。しか し、これは良心の問題である。良心は、読み書きや食事よりも優先されるべきものなのだ。 アントニオ・マチャド、『自伝』より。 |

| Iconografía De entre la numerosa galería de retratos literarios, pictóricos y fotográficos compuestos y conservados de Antonio Machado, hay que destacar algunos que en diferentes ocasiones han merecido el calificativo de magistrales y que conforman su iconografía universal. Documentos de indudable valor histórico-artístico son los diversos retratos y dibujos que su hermano José le dedicó a lo largo de su vida, tomados del natural o a partir de fotografías del poeta.71 De mayor valor artístico son el retrato al óleo que Sorolla pintó de Machado en diciembre de 1917; el lápiz hecho por Leandro Oroz en 1925, y el óleo casi vanguardista de Cristóbal Ruiz, en 1927.72 Quizá el capítulo más popular de la iconografía del poeta lo constituyan los retratos fotográficos que los dos Alfonsos (Alfonso Sánchez García y su hijo Alfonso Sánchez Portela) hicieron de Machado entre 1910 y 1936.73 En especial el Retrato de perfil de 1927, y el Retrato del café de Las Salesas.74z75 |

図像学 アントニオ・マチャドが作成し保存していた文学、絵画、写真による数多くの肖像画ギャラリーの中から、さまざまな場面で「素晴らしい」と評されたもの、そして彼の普遍的な図像学を構成するものをいくつか取り上げてみる価値はあるだろう。 疑う余地のない歴史的・芸術的価値を持つ資料としては、生涯を通じて彼の兄ホセがマチャドに捧げた様々な肖像画やデッサンがある。これらは詩人の実物や写 真をもとに描かれたものである。71 芸術的価値がより高いのは、1917年12月にソロージャがマチャドを描いた油彩画、1925年にレアンドロ・オロスが描いた鉛筆画、そして 1927年のクリストバル・ルイスの前衛的な油絵である。72 おそらく、詩人の肖像画の中で最も人気のある章は、1910年から1936年の間に2人のアルフォンソ(アルフォンソ・サンチェス・ガルシアと彼の息子ア ルフォンソ・サンチェス・ポルテラ)が撮影したマチャドの肖像写真で構成されている。73 特に、1927年の横顔の肖像画と、ラス・サリーサス・カフェの肖像画である。74z75 |

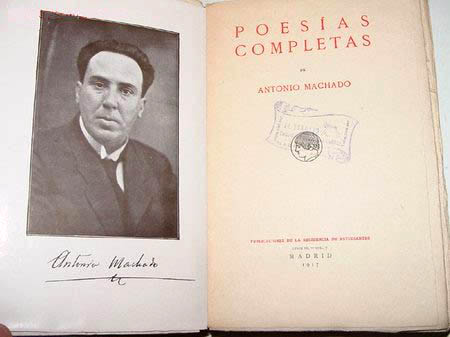

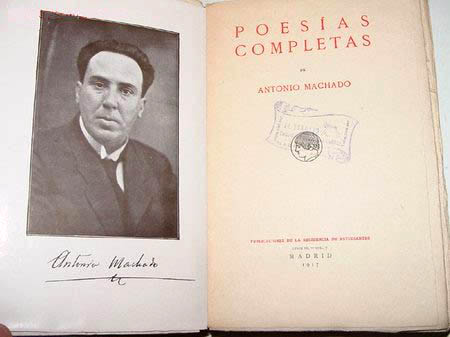

Obra Dibujo de Antonio Machado. Exposición temporal Por la defensa de la Cultura en el Centro del Carmen de Valencia. Como análisis literario elemental, Max Aub recogió en su Manual de Historia de la Literatura Española el conocido silogismo que plantea que si Unamuno representó «un modo de sentir» y Ortega «un modo de pensar» Machado representa «un modo de ser». Max Aub completó el retrato, matizando en ese modo de ser: «la estirpe romántica, la sencilla bondad, el vigor intelectual y la sincera melancolía».76 Su obra poética se abrió con Soledades, escrito entre 1901 y 1902, y casi reescrito en Soledades. Galerías. Otros poemas, que publicó en octubre de 1907.77 Durante su estancia en Soria, Machado escribió su libro más noventayochista, Campos de Castilla, publicado por la editorial Renacimiento en 1912. Sus protagonistas son las tierras castellanas y los hombres que las habitan. Le siguió la primera edición de sus Poesías completas (1917), en la que se incrementan los libros anteriores con nuevos poemas y se añaden los poemas escritos en Baeza tras la muerte de Leonor, los populares «Proverbios y cantares» —«poemas breves, de carácter reflexivo y sentencioso»—, y una colección de textos de crítica social, dibujando la España de aquel momento. En 1924 publicó las Nuevas canciones, recuperando materiales escritos en Baeza y aún en Soria, y mezclando ejemplos de sentenciosa poesía gnómica y análisis en torno al hecho de la creación poética, con paisajes soñados, algunas galerías y los primeros sonetos que se le conocen.78 Las ediciones de Poesías completas de 1928 y 1933 incluyeron algunos de los textos adjudicados a sus dos apócrifos, «Juan de Mairena» y «Abel Martín» –maestro de Mairena—, y en la edición de 1933 las primeras Canciones a Guiomar. En 1936, en vísperas de la guerra civil española, publicó: Juan de Mairena. Sentencias, donaires, apuntes y recuerdos de un profesor apócrifo. El estallido de la rebelión militar impidió la difusión del volumen que durante años permaneció en el limbo de lo desconocido.79 |

アントニオ・マチャドによる 作品。バレンシアのカルメンセンターにて、文化擁護のための特別展。 マックス・オーブは、文学の初歩的分析として、ウナムノを「感じ方」、オルテガを「考え方」と表現したならば、マチャドは「存在の仕方」を表現していると いう、よく知られた三段論法を『スペイン文学史マニュアル』に盛り込んだ。マックス・オーブは、その在り方を「ロマン主義の血統、純粋な善良さ、知的な活 力、そして誠実な憂鬱」と表現して、その肖像を完成させた。76 彼の詩作は、1901年から1902年にかけて書かれた『孤独』から始まり、ほぼ『孤独』の改訂版ともいえる『ギャラリー。その他の詩』を1907年10月に発表した。77 ソリア滞在中にマチャドが書いた最も重要な著書『カスティーリャの野原』は、1912年にレナシメント社から出版された。この作品の主人公はカスティー リャの土地とそこに住む人々である。続いて1917年に出版された『Poesías completas(詩集)』の初版では、レオノール死去後にベアサで書かれた詩や、広く知られた『Proverbios y cantares(諺と歌)』、「思索的で簡潔な性質を持つ短い詩」の詩集、当時のスペイン社会を描写した社会批判の文章集などが、それ以前の著作に新た な詩を加えて収録された。1924年には『Nuevas canciones(新しい歌)』を出版し、ベアサやソリアで書いた作品を復活させ、簡潔なグノーシス主義詩の例と詩作行為の分析を、夢のような風景や ギャラリー、そして私たちに知られている最初のソネットと混ぜ合わせた。78 1928年と1933年の『Poesías completas(詩集)』には、彼の2人の偽作家「フアン・デ・マイレーナ」と「アベル・マルティン」に帰せられる作品の一部が含まれている。 1928年と1933年の『Poesías completas』には、彼の2人の架空の人物、「フアン・デ・マイレーナ」と「アベル・マルティン(マイレーナの師)」に帰せられたテキストの一部が 含まれており、1933年版には「グイオマルへの歌」の最初のものが収録されている。 1936年、スペイン内戦の直前、彼は『フアン・デ・マイレーナ』を出版した。 架空の教師の文章、冗談、メモ、思い出。 軍事反乱の勃発により、この本の普及は妨げられ、何年もの間、この本は無名のまま宙に浮いた状態となった。79 |

bel Martín y Juan de Mairena Estatua de Machado ante el Teatro Juan Bravo en la plaza Mayor de Segovia Juan de Mairena y Abel Martín, heterónimos de Machado (él mismo llegó a reconocer que Mairena era su «yo filosófico»),aa desplazaron al poeta modernista y simbolista, sustituyéndolo por un pensador original, hondo y precursor de un género mixto que luego sería imitado por muchos otros autores.80 Originalmente concebidos como poetas, Martín y Mairena se presentan como filósofos populares, herederos de la «lengua hecha» (que el poeta citaba siempre a propósito de Cervantes y el Quijote) y en defensa de la «lengua hablada», dicho con palabras de Machado: «Rehabilitemos la palabra en su valor integral. Con la palabra se hace música, pintura y mil cosas más; pero sobre todo, se habla».80 Gran parte del Juan de Mairena, publicado por Espasa-Calpe en 1936, reúne la colección de ensayos que Machado había publicado en la prensa madrileña desde 1934. A través de sus páginas, un imaginario profesor y sus alumnos analizan la sociedad, la cultura, el arte, la literatura, la política, la filosofía, planteados con una caprichosa variedad de tonos, desde la aparente frivolidad hasta la gravedad máxima, pasando por la sentencia, la paradoja, el adagio, la erudición, la introspección, la retórica como arte, la cuchufleta o el más fino y sutil humor celtibérico.8182 |

ベル・マルティンとフアン・デ・マイレーナ セゴビアのマヨール広場にあるフアン・ブラボー劇場の前にあるマチャドの銅像 フアン・デ・マイレーナとアベル・マルティンは、マチャードの異名であり(マチャード自身、マイレーナを「哲学的自己」と認識していた)、モダニズムと象 徴主義の詩人を追いやり、独創的で深遠な思想家、そして後に多くの作家に模倣されることになる混合ジャンルの先駆者へと置き換えた。 当初は詩人として構想されたマルティンとマイレーナは、大衆の哲学者として自らを表現し、「作られた言語」(詩人は常にセルバンテスとドン・キホーテを引 き合いに出してこれを引用していた)の継承者であり、「話し言葉」の擁護者として、マチャードの言葉で言えば、「話し言葉を復権させよう」と主張した。 彼らは「作られた言語」(詩人は常にセルバンテスとドン・キホーテを引き合いに出してこの言葉を引用していた)の継承者であり、マチャドの言葉によれば 「話し言葉を擁護する」存在であった。「言葉の持つ価値を回復しよう。言葉によって音楽や絵画、その他さまざまなものが生まれる。しかし何よりも、人は言 葉によって語るのだ」80 1936年にエスパサ・カルペ社から出版された『フアン・デ・マイレーナの大部分』は、1934年からマドリードの新聞に発表されたマチャドのエッセイ集 をまとめたものである。そのページ全体を通して、架空の教師と生徒たちが、社会、文化、芸術、文学、政治、哲学を分析している。そのトーンは、一見したと ころ軽薄なものから極めて深刻なものまで、実にさまざまに変化に富んでいる。文章、逆説、格言、博識、内省、芸術としての修辞、いたずら、あるいは最高に 繊細なケルトイベリアのユーモアなどを通して表現されている。ケルトイベリア語。8182 |

| Teatro Durante la década de 1920 y los primeros años de la década del treinta, Machado escribió teatro en colaboración con su hermano Manuel. Se llegaron a estrenar en Madrid las siguientes obras: Desdichas de la fortuna o Julianillo Valcárcel (1926), Juan de Mañara (1927), Las adelfas (1928), La Lola se va a los puertos (1929), La prima Fernanda (1931) y La duquesa de Benamejí (1932).83 |

演劇 1920年代から1930年代初頭にかけて、マチャードは弟のマヌエルと共同で戯曲を執筆した。マドリードで初演された作品には、Desdichas de la fortuna o Julianillo Valcárcel(1926年)、Juan de Mañara(1927年)、Las adelfas(1928年)、La Lola se va a los puertos(1929年)、La prima Fernanda(1931年)、La duquesa de Benamejí(1932年)がある。83 |

Auto-poética Página de título de la primera edición de las Poesías completas de Antonio Machado, con autógrafo y foto del autor (tomada hacia 1917, en su etapa de profesor en Baeza). Fondos de la Biblioteca del Ateneo de Madrid. El verbo El adjetivo y el nombre remansos del agua limpia son accidentes del verbo en la gramática lírica del hoy que será mañana del ayer que es todavía. Los complementarios, 1914 y Nuevas canciones, "De mi cartera" 1917-1930 |

オートポエティックス アントニオ・マチャードの詩全集の初版のタイトルページ。著者の自筆署名と写真(1917年頃、ベアサで教師をしていた頃に撮影)付き。アテネオ・デ・マドリード図書館所蔵。 動詞 形容詞と名詞 きれいな水の支流 は、動詞の派生形 であり、 今日であり、明日となる 昨日の ——補足的なもの、1914年と新曲、1917年から1930年の「私の財布から」 |

| Tiempo poético La poesía es —decía Mairena— el diálogo del hombre, de un hombre con su tiempo. Eso es lo que el poeta pretende eternizar, sacándolo fuera del tiempo, labor difícil y que requiere mucho tiempo, casi todo el tiempo de que el poeta dispone. El poeta es un pescador, no de peces, sino de pescados vivos; entendámonos: de peces que puedan vivir después de pescados. Juan de Mairena (IX), 1936. |

詩的な時間 詩とは、マイレーナが言ったように、人間と、人間と時の対話である。 詩人は、それを永遠のものにすることを目指す。それは、時間を超越したものにするという、困難で時間のかかる作業であり、詩人が使える時間のほとんどすべ てを費やす作業である。 詩人は漁師であり、魚ではなく生きている魚を捕まえる。はっきりさせておこう。捕まえても生き延びることができる魚を捕まえるのだ。 フアン・デ・マイレーナ(IX)、1936年。 |

| Tiempo mundano Poeta ayer, hoy triste y pobre filósofo trasnochado tengo en monedas de cobre el oro de ayer cambiado. Galerías (XCV. «Coplas mundanas»), 1907. Dice la monotonía del agua clara al caer: un día es como otro día; hoy es lo mismo que ayer Soledades, 1889-1907. |

世俗の時間 昨日は詩人、今日は悲しく貧しい 時代遅れの哲学者 昨日の黄金を銅貨に変えてしまった。 Galerías (XCV. 「Coplas mundanas」), 1907. 澄んだ水が落ちる時の 単調さを語る。 一日は他の日と同じ。 今日も昨日と同じ。 Soledades, 1889-1907. |

| Tiempo filosófico Nuestras horas son minutos cuando esperamos saber, y siglos cuando sabemos lo que se puede aprender. Campos de Castilla, "CXXXVI. Proverbios y cantares", 1912 |

哲学的な時間 私たちの時間は、 知ろうとするときは分単位で あり、 学べることは何でも学ぼうというときは 世紀単位である。 カンポス・デ・カスティーリャ、「CXXXVI. Proverbios y cantares」、1912年 |

| Diálogo Ayer soñé que veía a Dios y que a Dios hablaba; y soñé que Dios me oía... Después soñé que soñaba. Campos de Castilla, "CXXXVI.Proverbios y cantares", 1912 |

対話 昨日、私は夢の中で 神を見、神と話をした。 そして、神が私の話を聞いた夢を見た... それから、夢を見ている夢を見た。 カンポス・デ・カスティーリャ、「CXXXVI. 諺と歌」、1912年 |

| Los símbolos Mucha literatura se ha escrito sobre «símbolos machadianos». Cualquier lector de su poesía, tras un simple y breve vistazo a una de las muchas antologías poéticas de Antonio Machado, podrá enumerar: camino, fuente, sueño, ciprés, agua, noche, mar, jardín, alma, tarde, primavera, muerte, soledades... O que yo pueda asesinar un día en mi alma, al despertar, esa persona que me hizo el mundo mientras yo dormía.84 |

象徴 「マチャードの象徴」については、すでに多くのことが書かれている。アントニオ・マチャードの詩のアンソロジーのひとつを簡単にざっと目を通しただけで も、彼の詩を読んだことのある人なら、次のような言葉を挙げることができるだろう。道、泉、夢、糸杉、水、夜、海、庭、魂、夕暮れ、春、死、孤独... あるいは、私はいつか 目覚めたときに、自分の魂の中で、 私が眠っている間に世界を作ってくれたその人を、目覚めたときに殺してしまうかもしれない。84 |

| La rima Recordemos hoy a Gustavo Adolfo, el de las rimas pobres, la asonancia indefinida y los cuatro verbos por cada adjetivo definidor. Alguien ha dicho con indudable acierto: «Bécquer, un acordeón tocado por un ángel». Conforme: el ángel de la verdadera poesía. Juan de Mairena —XLIII. Sobre Bécquer—, 1936.ab |

韻を踏む 今日、私たちは貧弱な韻を踏む、不確定な母音韻、そして形容詞を定義する4つの動詞を駆使した詩人、グスタボ・アドルフォを偲ぶ。 ある人が疑いようのない正確さでこう言った。「ベッケルは天使が奏でるアコーディオンだ」。 同意する。真の詩の天使。 フアン・デ・マイレーナ —XLIII. ベッケルについて—, 1936.ab |

| Imágenes De los suprarrealistas hubiera dicho Juan de Mairena: Todavía no han comprendido esas mulas de noria que no hay noria sin agua Juan de Mairena XLIX, 1936)ac |

イメージ 作品について、フアン・デ・マイレーナはこう言っただろう。「あの愚かなロバたちは、水がなければ水車は回らないということをまだ理解していないのだ。」 フアン・デ・マイレーナ XLIX、1936年)ac |

| Poética «Antes de escribir un poema —decía Mairena a sus alumnos— conviene imaginar el poeta capaz de escribirlo. Terminada nuestra labor, podemos conservar el poeta con su poema, o prescindir del poeta —como suele hacerse— y publicar el poema; o bien tirar el poema al cesto de los papeles y quedarnos con el poeta, o por último, quedarnos sin ninguno de los dos, conservando siempre al hombre imaginativo para nuevas experiencias poéticas». (Juan de Mairena —XXII—, 1936) |

詩学 「詩を書く前に」とマイレーナは生徒たちに言った。「それを書くことのできる詩人を想像してみるのがいい。作品が完成したら、詩人と詩を一緒に残すことも できるし、あるいは詩人を省いて詩だけを出版することもできる。あるいは、詩をゴミ箱に捨てて詩人を残すこともできるし、最終的にはどちらも残さず、常に 想像力豊かな人間を新しい詩的体験のために残しておくこともできる。(フアン・デ・マイレーナ -XXII-、1936年) |

| Cronología de publicaciones A modo de guía, y según su fecha de publicación:8586 Poesía 1903 - Soledades: poesías 1907 - Soledades. Galerías. Otros poemas 1912 - Campos de Castilla 1917 - Páginas escogidas 1917 - Poesías completas 1917 - Poemas 1918 - Soledades y otras poesías 1919 - Soledades, galerías y otros poemas 1924 - Nuevas canciones 1928 - Poesías completas (1899-1925) 1933 - Poesías completas (1899-1930) 1933 - La tierra de Alvargonzález 1936 - Poesías completas 1937 - La guerra (1936-1937) Prosa 1936 - Juan de Mairena (sentencias, donaires, apuntes y recuerdos de un profesor apócrifo) 1957 - Los complementarios (recopilación póstuma a cargo de Guillermo de Torre publicada en Buenos Aires por Editorial Losada). 1994 - Cartas a Pilar (edición de G. C. Depretis, en Madrid con Anaya-Mario Muchnik). 2004 - El fondo machadiano de Burgos. Los papeles de AM (edición de A. B. Ibáñez Pérez, en Burgos por la Institución Fernán González). Teatro (con Manuel Machado) 1926 - Desdichas de la fortuna o Julianillo Valcárcel 1927 - Juan de Mañara 1928 - Las adelfas 1930 - La Lola se va a los puertos 1930 - La prima Fernanda 1932 - La duquesa de Benamejí 1932 - Teatro completo, I, Madrid, Renacimiento. 1947 - El hombre que murió en la guerra (homenaje en Buenos Aires) (adaptaciones de clásicos, en colaboración) 1924 - El condenado por desconfiado, de Tirso de Molina (con José López Hernández), estrenada el 2 de enero de 1924, en el Teatro Español de Madrid, con Ricardo Calvo como protagonista principal. 1924 - Hernani, de Victor Hugo (con Francisco Villaespesa), estrenada el 1 de enero de 1925, en el Teatro Español de Madrid, por la compañía de María Guerrero y Fernando Díaz de Mendoza.87 1926 - La niña de plata, de Lope de Vega (con José López Hernández). |

出版物の年表 参考までに、出版年順に記載する。85 86 詩 1903年 - 『孤独:詩集 1907年 - 『孤独。ギャラリー。その他の詩 1912年 - 『カスティーリャの野原 1917年 - 『抜粋 1917年 - 『詩集 1917年 - 『詩集 1918年 - 孤独とその他の詩 1919年 - 孤独、ギャラリー、その他の詩 1924年 - 新しい歌 1928年 - 詩集(1899年~1925年 1933年 - 詩集(1899年~1930年 1933年 - アルバルゴンサレスの地 1936年 - 詩集 1937年 - 戦争(1936年-1937年) 散文 1936年 - フアン・デ・マイレーナ(架空の教師の格言、冗談、覚え書き、思い出 1957年 - 補遺(ギジェルモ・デ・トーレによる死後編集、ブエノスアイレスのロサーダ出版社より出版)。 1994年 - Cartas a Pilar(G. C. Depretis編集、マドリードのAnaya-Mario Muchnik出版)。 2004年 - El fondo machadiano de Burgos. Los papeles de AM(A. B. Ibáñez Pérez編集、ブルゴスのInstitución Fernán González出版)。 戯曲 (マヌエル・マチャドとの共作) 1926年 - 『Desdichas de la fortuna』または『Julianillo Valcárcel』 1927年 - 『Juan de Mañara 1928年 - 『Las adelfas 1930年 - 『La Lola se va a los puertos 1930年 - 『La prima Fernanda 1932年 - 『La duquesa de Benamejí 1932年 - 『Teatro completo, I, Madrid, Renacimiento. 1947年 - 『戦争で死んだ男』(ブエノスアイレスでのトリビュート) (古典の翻案、共同制作) 1924年 - ティルソ・デ・モリーナ作『疑い深い男』(ホセ・ロペス・エルナンデスとの共演)、1924年1月2日、マドリードのテアトロ・エスパニョールにて初演、主役はリカルド・カルボ。 1924年 - ビクトル・ユーゴー作『エルナニ』(フランシスコ・ビジャエスペーサ出演)が、マドリードのテアトロ・エスパニョールで1925年1月1日に初演された。マリア・ゲレロとフェルナンド・ディアス・デ・メンドーサの劇団による。87 1926年 - ロペ・デ・ベガ作『銀の娘』(ホセ・ロペス・エルナンデス出演)。 |

| En la escultura Las cabezas de Pablo Serrano El 19 de junio de 2007 se instaló en los jardines de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, sobre un pedestal del diseñador Alberto Corazón, la última «cabeza» de Antonio Machado de la casi legendaria serie realizada por el escultor Pablo Serrano desde años sesenta. Antes, en 1981, otra «cabeza» de don Antonio había sido regalada por Serrano y expuesta en el museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, y una más en Soria en 1982, frente al colegio donde el poeta impartió sus clases de francés. La supuesta «cabeza original» de toda la serie pudo colocarse finalmente en Baeza en 1983.88 En 1985 una nueva cabeza decoró el monumento titulado "El Pueblo de Madrid al poeta Antonio Machado", en el barrio madrileño Ciudad de los poetas y junto a la estación de metro que también lleva su nombre.ad Fuera de España, pueden verse "cabezas" de Machado en el Centre Georges Pompidou de París (obra de Serrano de 1962, adquirida por la institución francesa en 1971), otra en el MOMA de Nueva York, al parecer comprada en 1967, y una tercera en la Universidad Brown, en Providence (Rhode Island) (Estados Unidos).89 |

彫刻において パブロ・セラーノによるパブロ・セラノの頭部 2007年6月19日、彫刻家パブロ・セラーノが1960年代から制作してきた伝説的なシリーズの最後の「頭部」が、アルベルト・コラソンのデザインによ る台座に設置され、マドリード国立図書館の庭園に展示された。それ以前の1981年には、セラーノがもう一体の「頭部」を寄贈し、王立サン・フェルナンド 美術アカデミーの美術館に展示された。また、1982年にはソリアに、詩人がフランス語を教えた学校の前に、もう一体が設置された。この一連の「頭部」の 「オリジナル」とされるものは、1983年に最終的にバエサに設置された。 1985年には、マドリードの「詩人アントニオ・マチャドを称えるマドリードの人々」と題されたモニュメントに、新たな「頭部」が飾られた。このモニュメントは、マドリードの「詩人の町」と呼ばれる地区にあり、同じ名前の地下鉄駅の隣にある。 1985年には、マドリードの「詩人アントニオ・マチャドを称えるマドリードの人々」と題されたモニュメントに新たな頭部が飾られた。このモニュメントは、マドリードの「詩人の町」地区にあり、同じ名前の地下鉄駅の隣にある。 スペイン国外では、マドリードの詩人アントニオ・マチャドの「頭部」がパリのポンピドゥー・センター(1962年のセラーノの作品で、1971年にフラン ス機関が取得)とニューヨークのMOMA(1967年に購入されたものと思われる)とロードアイランド州プロビデンスのブラウン大学(米国)の3か所で見 ることができる。89 |

| Esculturas callejeras No podían faltar representaciones del poeta "ligero de equipaje",90 abundando en la moda de las esculturas callejeras. Pueden verse Machados de bronce, paseando, sentado leyendo o pensando, ausente de la silla que sujeta su amada Leonor, con la maleta a mano... El paseante se encontrará con ellas en las ciudades machadianas: Soria, Segovia, Baeza.91  Antonio Machado por Barral (hacia 1920-22) En 1922, Emiliano Barral concluyó y regaló a Machado un busto blanco del poeta. Una copia hecha por Pedro Barral recuerda desde un rincón del jardín que da acceso a la Casa-Museo de Machado en Segovia aquellos versos que unieron a los dos artistas en la eternidad:92 ... y, so el arco de mi cejo, dos ojos de un ver lejano, que yo quisiera tener como están en tu escultura: cavados en piedra dura, ::en piedra, para no ver. |

ストリート彫刻 「軽い荷物」の詩人マチャドスの表現は、ストリート彫刻の流行に欠かすことのできないものであった。マチャドスはブロンズ像となっており、歩いたり、座っ て読書や思索にふけったり、愛するレオノールに支えられた椅子に座ったり、手にはスーツケースを持っている。マチャドの詩を詠んだ通りを歩いていると、ソ リア、セゴビア、ベーサといったマチャドゆかりの都市で彼らに出会うことができる。91  アントニオ・マチャドの肖像(1920年~1922年頃、バラル作) 1922年、エミリアーノ・バラルがマチャドの白い胸像を完成させ、彼に贈った。セゴビアのマチャドの家博物館に通じる庭の一角には、ペドロ・バラルが作った複製があり、2人の芸術家を永遠に結びつけた詩が刻まれている。 ...そして、私の眉のアーチの下に、 遠くを見通す二つの目、 それを あなたの彫刻のようにしてほしい。 硬い石に刻まれた、 ::石のように、見えないように。 |

| Reconocimientos Además de las variopintas esculturas dedicadas al poeta, entre los numerosos reconocimientos dedicados a Antonio Machado, su obra y su memoria, pueden mencionarse de modo aleatorio:  Placa en honor a Antonio Machado en la antigua universidad de Baeza. Siendo Instituto de Bachillerato, el poeta impartió aquí clases de Gramática Francesa desde 1912 hasta 1919. Aún en vida del poeta, Machado fue homenajeado en Soria y declarado Hijo Adoptivo de la ciudad, el 5 de octubre de 1932.93 El homenaje que desde el Instituto Hispánico, en Estados Unidos, le tributaron en el décimo aniversario de su muerte, amigos en el exilio, con un comité formado por: Tomás Navarro Tomás, Jorge Guillén, Rafael Heliodoro Valle, Federico de Onís, Arturo Torres Rioseco, Andrés Iduarte, Eugenio Florit y Gabriel Pradal. La exposición homenaje de los artistas españoles en París, inmortalizada por el cartel autógrafo que realizó Pablo Picasso, con fecha de 3 de enero de 1955. El cartel de Joan Miró realizado en 1966 para el frustrado homenaje a Machado en Baeza.94 El álbum Dedicado a Antonio Machado, poeta (1969), del cantautor Joan Manuel Serrat, que contribuyó a la recuperación y popularización del poeta. Ángel González, uno de los más aplicados biógrafos y estudiosos de la figura y la obra de Antonio Machado, le dedicó también algunos de sus poemas más personales, como la elegía que incluyó en su tercer libro Grado Elemental (1962), titulada "Camposanto en Colliure". El historiador Manuel Tuñón de Lara dedicó su libro Antonio Machado, poeta del pueblo (1967), además de numerosos artículos, a quien fuera su poeta predilecto. En el titulado "Los grandes temas de la cultura española en la hora presente"(Cuadernos Americanos, N.º 6, 1964), situó a Machado como «el prototipo del intelectual por su ejemplo y su obra humanista».95 Como en el caso de otros miembros de la generación del 98, su nombre ha sido reflejado en numerosos callejeros de ciudades españolas; así, por ejemplo en Madrid en una avenida entre los barrios de Valdezarza y Ciudad Universitaria, en el distrito Moncloa-Aravaca,96 coincidiendo con la apertura de una de las estaciones de la línea 7 del Metro de Madrid. En el nuevo edificio de la School of Foreign Studies de la Universidad de Osaka (Japón) hay un gran mural con citas de muchos idiomas. Como representante del español se escogieron los versos de Antonio Machado "Caminante no hay camino, se hace camino al andar". |

謝辞 詩人に捧げられたカラフルな彫刻に加え、アントニオ・マチャドの作品や思い出に捧げられた数多くのトリビュートの中から、以下をランダムに挙げてみよう。  ベサの旧大学にあるアントニオ・マチャドを称える銘板。この高校で、詩人は1912年から1919年までフランス語の文法を教えた。 詩人が存命中、1932年10月5日にはソリア市でマチャドを称え、同市の「養子」と宣言した。93 米国のヒスパニック研究所が彼の死後10周年を記念して彼に捧げた賛辞は、亡命中の友人たちによって捧げられた。トマス・ナバーロ・トマス、ホルヘ・ギ ジェン、ラファエル・ヘリオドロ・バジェ、フェデリコ・デ・オニス、アルトゥロ・トーレス・リオセコ、アンドレス・イダルテ、エウヘニオ・フロリト、ガブ リエル・プラダル。 1955年1月3日付けのパブロ・ピカソのサイン入りポスターによって永遠のものとなった、パリにおけるスペイン人芸術家たちによる追悼展。 1966年にマチャドへの不満を込めてベアサで制作されたジョアン・ミロのポスター。 詩人アントニオ・マチャドに捧ぐアルバム(1969年)は、シンガーソングライターのジョアン・マヌエル・セラによるもので、彼は詩人の再評価と普及に貢献した。 アントニオ・マチャドの生涯と作品について最も熱心に研究した伝記作家の一人であるアンヘル・ゴンサレスも、彼に捧げた最も個人的な詩をいくつか残してい る。例えば、彼の3冊目の詩集『Grado Elemental』(1962年)に収録された挽歌「カンパントゥン・エン・コリウール」などである。 歴史家のマヌエル・トゥニョン・デ・ララは、お気に入りの詩人であるマチャドに、著書『アントニオ・マチャド、人民の詩人』(1967年)と多数の論文を 捧げた。「スペイン文化の主要テーマ」(『アメリカ研究ノート』第6号、1964年)と題された論文で、彼はマチャドを「その模範とヒューマニズムの仕事 により、知識人の原型」と表現した。 98年世代の他のメンバーと同様に、彼の名はスペインの都市の数多くの通りの名称に反映されている。例えば、マドリードでは、モンクロア=アラバカ地区の バルデサルサ地区とシウダ・ウニベルシタリア地区の間の大通りに、マドリードメトロ7号線の駅の一つが開通したことに合わせて、彼の名が付けられた。 大阪大学外国語学部の新校舎には、多くの言語で書かれた引用句が描かれた大きな壁画がある。スペインを代表する句として選ばれたのは、アントニオ・マチャドの「旅人よ、道はない。道とは歩むことによって作られるものだ」という詩である。 |

| Documental y cómic Ambos tienen el título "Antonio Machado. Los días azules" que es el último verso que escribió: <<Estos días azules y este sol de la infancia>>. El documental recupera la memoria y la obra de Antonio Machado, en el 80 aniversario de su muerte. La vida del poeta como símbolo de la España que se perdió: un canto a la importancia de la cultura para la vida, para el progreso y para crear una sociedad mejor. El cómic es obra de Cecília Hill y Josep Salvia.9798 |

ドキュメンタリーと漫画 どちらもタイトルは「アントニオ・マチャド。ロス・ディアス・アスーレス(青の日々)」で、これは彼が最後に書いた詩である。「青の日々、この子供時代の 太陽」。ドキュメンタリーは、彼の死から80年を経て、アントニオ・マチャドの思い出と業績を振り返る。失われたスペインの象徴としての詩人の生涯:生 活、進歩、より良い社会の創造にとって文化が持つ重要性への賛歌。このコミックは、セシリア・ヒルとジョセップ・サルビアの作品である。9798 |

| Machado rechazaba el tópico

andaluz, la falsa Andalucía de vendedores como los hermanos Quintero; y

dejó su opinión en boca de Abel Infanzón, uno de los doce poetas que

pudieron existir: Sevilla y su verde orilla sin toreros ni gitanos, Sevilla sin sevillanos, ¡oh maravilla¡ |

マチャドは、キンテロ兄弟のようなセールスマンの作り話のアンダルシアを拒絶し、実在したかもしれない12人の詩人のうちの1人であるアベル・インファンソンの口に自らの意見を語らせた。 セビリアと緑の岸辺 闘牛士もジプシーもいない セビリア、セビリア人がいないセビリア、 なんと素晴らしいことか! |

| Alonso, Monique (1985). Antonio Machado poeta en el exilio. Barcelona: Anthropos. Aub, Max (1966). Manual de historia de la literatura española. Madrid, Akal Editor. ISBN 847339030-X. Aubert, Paul (1994). Antonio Machado hoy, 1939-1989: coloquio internacional. Casa de Velázquez. ISBN 84-86839-48-3. Baltanás, Enrique (2006). Los Machado. Sevilla: Fundación José Manuel Lara. ISBN 8496556255. Barjau, Eustaquio (1975). Antonio Machado: teoría y práctica del apócrifo. Barcelona: Ariel. ISBN 9788434483187. Cano, José Luis (1986). Antonio Machado. Barcelona: Salvat Editores. ISBN 8434581868. Gibson, Ian (2006). Ligero de equipaje. Madrid: Santillana Editores G. ISBN 8403096860. González, Ángel (1986). Antonio Machado. Madrid: Ediciones Jucar. ISBN 8433430181. Gullón, Ricardo; Anderson Imbert, Enrique (1973). El pícaro Juan de Mairena (1939). Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. —; Diego, Gerardo (1973). «Tempo» lento en Antonio Machado. Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. —; Lida, Raimundo (1973). Elogio de Mairena (1948). Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. Lourenço, António Apolinário (1997). Identidad y alteridad en Fernando Pessoa y Antonio Machado. Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 84-7481-855-9. Machado, Antonio (2009). Doménech, Jordi, ed. Epistolario. Barcelona: Octadedro. ISBN 978-84-8063-976-7. — (2009). Doménech, Jordi, ed. Escritos dispersos (1893-1936). Barcelona: Octadedro. ISBN 978-84-8063-976-7. — (1994). Depretis, Giancarlo, ed. Cartas a Pilar. Madrid: Anaya y Mario Muchnik. ISBN 84-7979-105-5. Mora, José Luis (2011). Cajasegovia - Univ. Autónoma de Madrid, ed. De ley y de corazón. Cartas (1957-1976). Madrid. ISBN 9788483441954. Sanmartín, Rosa (2010). Ediciones Mágina, ed. La labor dramática de Manuel y Antonio Machado. Granada: Octaedro. ISBN 9788495345-74-5. Xirau, Joaquim (1998). Joaquím Xirau y Ramón Xirau, ed. Escritos fundamentales, Volumen 1. Anthropos Editorial. ISBN 9788476585436. Consultado el 23 de noviembre de 2017. |

Alonso, Monique (1985). Antonio Machado poeta en el exilio. Barcelona: Anthropos. Aub, Max (1966). Manual de historia de la literatura española. Madrid, Akal Editor. ISBN 847339030-X. ポール・オーベール(1994年)『アントニオ・マチャド、今日、1939年から1989年:国際会議』。カサ・デ・ヴェラスケス。ISBN 84-86839-48-3。 エンリケ・バルタナス(2006年)『マチャド家の人々』。セビリア:ホセ・マヌエル・ララ財団。ISBN 8496556255。 バルハオ、エウスタキオ(1975年)アントニオ・マチャド:偽書の理論と実践。バルセロナ:アリエル。ISBN 9788434483187。 カノ、ホセ・ルイス(1986年)アントニオ・マチャド。バルセロナ:サルバト・エディトーレス。ISBN 8434581868。 ギブソン、イアン(2006年)。『軽量』。マドリード:サンティリャーナ・エディトレス G. ISBN 8403096860. ゴンサレス、アンヘル(1986年)。『アントニオ・マチャド』。マドリード:エディシオネス・フカル。ISBN 8433430181. Gullón, Ricardo; Anderson Imbert, Enrique (1973). El pícaro Juan de Mairena (1939). Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. —; Diego, Gerardo (1973). 「Tempo」 lento en Antonio Machado. Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. —; Lida, Raimundo (1973). Elogio de Mairena (1948). Madrid: Ediciones Taurus. ISBN 843062063X. Lourenço, António Apolinário (1997). Identidad y alteridad en Fernando Pessoa y Antonio Machado. University of Salamanca. ISBN 84-7481-855-9. マチャド、アントニオ(2009年)。ドメネク、ジョルディ編。書簡集。バルセロナ:オクタベドロ。ISBN 978-84-8063-976-7。 —(2009年)。ドメネク、ジョルディ編。散逸した著作(1893-1936)。バルセロナ:オクタベドロ。ISBN 978-84-8063-976-7. — (1994). ジャンカルロ・デプレティス編。ピラールへの手紙。マドリード:アナヤ・イ・マリオ・ムチニック。ISBN 84-7979-105-5. モラ、ホセ・ルイス(2011年)。カハセゴビア - マドリード自治大学出版。法律と心。手紙(1957-1976)。マドリード。ISBN 9788483441954。 サンマルティン、ロサ(2010年)。エディシオネス・マハナ出版。マヌエル・マチャドとアントニオ・マチャドの劇作品。グラナダ:Octaedro. ISBN 9788495345-74-5. Xirau, Joaquim (1998). Joaquím Xirau and Ramón Xirau, eds. Escritos fundamentales, Volume 1. Anthropos Editorial. ISBN 9788476585436. 2017年11月23日アクセス。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Machado |

Antonio Machado, por Joaquín Sorolla

★英語版

| Antonio Cipriano José María y Francisco de Santa Ana Machado y Ruiz

(26 July 1875 – 22 February 1939), known as Antonio Machado, was a

Spanish poet and one of the leading figures of the Spanish literary

movement known as the Generation of '98. His work, initially modernist,

evolved towards an intimate form of symbolism with romantic traits. He

gradually developed a style characterised by both an engagement with

humanity on one side and an almost Taoist contemplation of existence on

the other, a synthesis that, according to Machado, echoed the most

ancient popular wisdom. In Gerardo Diego's words, Machado "spoke in

verse and lived in poetry."[1] |

ア

ントニオ・シプリアーノ・ホセ・マリア・イ・フランシスコ・デ・サンタ・アナ・マチャド・イ・ルイス(1875年7月26日 -

1939年2月22日)、通称アントニオ・マチャドは、スペインの詩人で、1898年世代として知られるスペイン文学運動の主要人物の一人である。彼の作

品は、当初はモダニズムであったが、ロマン主義的な特徴を持つ親密な象徴主義へと発展した。彼は徐々に、人間性への関与と、存在に対するほぼ道教的な思索

という2つの側面を特徴とするスタイルを確立していった。この統合は、マチャドによれば、最も古い民間伝承の知恵を反映したものだった。ヘラルド・ディエ

ゴの言葉を借りれば、マチャドは「詩で語り、詩の中で生きた」のである。 |

| Biography Machado was born in Seville, Spain, one year after his brother Manuel. He was a grandson to the noted Spanish folklorist, Cipriana Álvarez Durán.[2] The family moved to Madrid in 1883 and both brothers enrolled in the Institución Libre de Enseñanza. During these years—with the encouragement of his teachers—Antonio discovered his passion for literature. While completing his Bachillerato in Madrid, economic difficulties forced him to take several jobs, including working as an actor. In 1899, he and his brother traveled to Paris to work as translators for a French publisher. During these months in Paris, he came into contact with the great French Symbolist poets Jean Moréas, Paul Fort and Paul Verlaine, and also with other contemporary literary figures, including Rubén Darío and Oscar Wilde. These encounters cemented Machado's decision to dedicate himself to poetry.  Statue of Antonio Machado on Calle San Pablo in Baeza, Jaén, Spain  Machado's grave at Collioure cemetery In 1901, he had his first poems published in the literary journal 'Electra'. His first book of poetry was published in 1903, titled Soledades. Over the next few years, he gradually amended the collection, removing some and adding many more. In 1907, the definitive collection was published with the title Soledades and Galerías. Otros Poemas. In the same year, Machado was offered the job of Professor of French at the school in Soria. Here, he met Leonor Izquierdo, daughter of the owners of the boarding house Machado was staying in. They were married in 1909, he was 34 and Leonor was 15. Early in 1911, the couple went to live in Paris where Machado read more French literature and studied philosophy. In the summer however, Leonor was diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis and they returned to Spain. On 1 August 1912, Leonor died, just a few weeks after the publication of Campos de Castilla. Machado was devastated and left Soria, the city that had inspired the poetry of Campos, never to return. He went to live in Baeza, Andalusia, where he stayed until 1919. Here, he wrote a series of poems dealing with the death of Leonor which were added to a new (and now definitive) edition of Campos de Castilla published in 1916 along with the first edition of Nuevas canciones. While his earlier poems are in an ornate, Modernist style, with the publication of "Campos de Castilla" he showed an evolution toward greater simplicity, a characteristic that was to distinguish his poetry from then on. |

経歴 マチャドは、兄マヌエルより1年遅れてスペインのセビリアで生まれた。著名なスペインの民俗学者シプリアーナ・アルバレス・ドゥランの孫であった。[2] 1883年に一家はマドリードに移り、兄弟はともにインスティトゥシオン・リブレ・デ・エンセニャンサに入学した。この時期、教師たちの勧めもあって、ア ントニオは文学への情熱を見出した。マドリードでバカロレア(大学入学資格)を取得する間、経済的な困難から、俳優などいくつかの仕事を掛け持ちせざるを 得なかった。1899年、彼は弟とともにフランス人出版社の翻訳者として働くためにパリに渡った。パリに滞在していた数ヶ月間、彼はフランスの象徴派の詩 人ジャン・モレアス、ポール・フォール、ポール・ヴェルレーヌ、そしてルベン・ダリオやオスカー・ワイルドといった同時代の文学者たちと交流した。これら の出会いは、マチャドが詩作に専念するという決意を固めることとなった。  スペイン、ハエン、ベーサのサン・パブロ通りにあるアントニオ・マチャドの像  コリウール墓地にあるマチャドの墓 1901年、彼は文学雑誌『エレクトラ』に最初の詩を発表した。最初の詩集は1903年に出版され、『孤独』と題された。その後数年間で、彼は徐々に詩集 を修正し、いくつかの詩を削除し、さらに多くの詩を追加した。1907年には、最終的な詩集が『孤独と回廊』というタイトルで出版された。同年、マチャド はソリアの学校でフランス語の教授職のオファーを受ける。ここで、マチャドが滞在していた下宿のオーナーの娘レオノール・イスキエルドと出会う。1909 年、34歳だったマチャドと15歳だったレオノールは結婚した。1911年初頭、夫妻はパリに移り住み、マチャドはフランス文学をさらに学び、哲学を研究 した。しかし夏になるとレオノールは進行した結核と診断され、ふたりはスペインに戻った。1912年8月1日、レオノールが亡くなった。カンポス・デ・カ スティーリャの出版からわずか数週間後のことだった。マチャドは打ちのめされ、カンポスの詩のインスピレーションとなったソリアを去り、二度と戻ることは なかった。彼はアンダルシアのベーサに移り住み、1919年までそこに滞在した。ここで彼はレオノール夫人の死を扱った一連の詩を書き、それらは1916 年に出版された『カンポス・デ・カスティーリャ』の新装版(そして最終版)に『ヌエバス・カンシオネス』の初版とともに追加された。初期の詩は装飾的でモ ダニズム的なスタイルであったが、『カンポス・デ・カスティーリャ』の出版により、よりシンプルなスタイルへと進化を遂げた。この特徴は、それ以降の彼の 詩を際立たせるものとなった。 |

| Between

1919 and 1931, Machado was Professor of French at the Instituto de

Segovia, in Segovia. He moved there to be nearer to Madrid, where

Manuel lived. The brothers would meet at weekends to work together on a

number of plays, the performances of which earned them great

popularity. It was here also that Antonio had a secret affair with

Pilar de Valderrama, a married woman with three children, to whom he

would refer in his work by the name Guiomar. In 1932, he was given the

post of professor at the "Instituto Calderón de la Barca" in Madrid. He

collaborated with Rafael Alberti and published articles in his