アオテアロア

Aotearoa

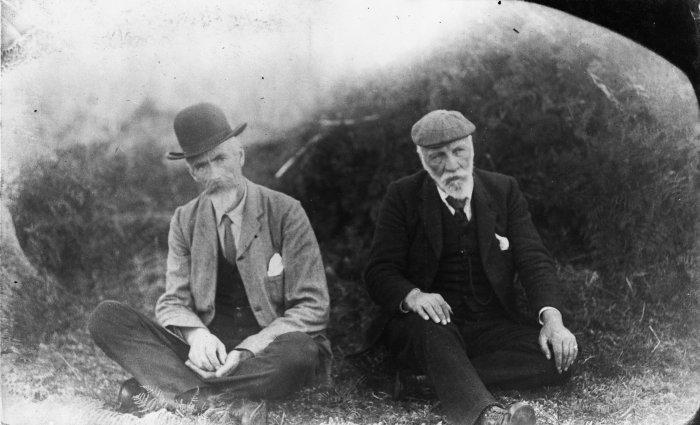

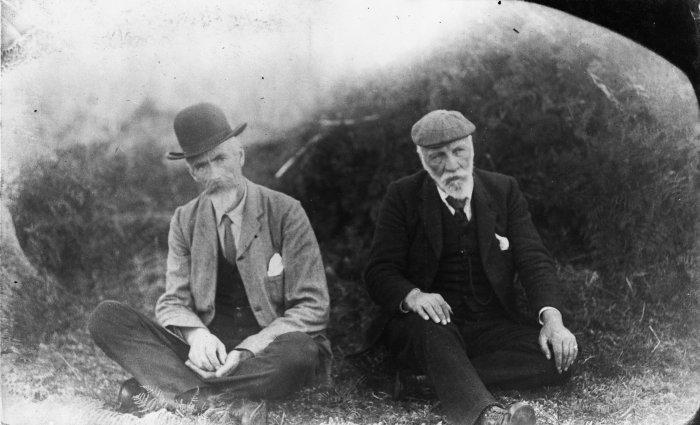

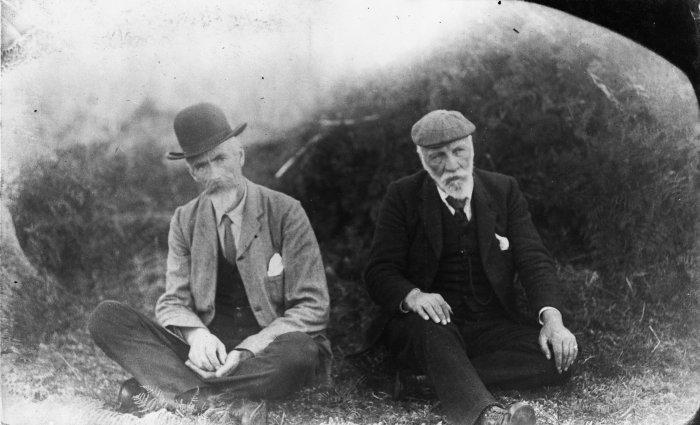

Elsdon Best and Stephenson Percy Smith of the Polynesian Society, who did much to popularise the use of Aotearoa in Edwardian school books, pictured in 1908

A

bilingual sign outside the National Library of New Zealand headquarters

uses Aotearoa alongside New Zealand.

☆アオテアロア[Aotearoa]

(マオリ語発音: [aɔˈtɛaɾɔa]

ⓘ)[1]は、ニュージーランドのマオリ語名である。この名称は元々、マオリ族が北島のみを指す際に使用していた。国全体を指す場合、特に南島では「アオ

テアロア・メ・テ・ワイポウナム」と呼ばれることがあった。[2]

ヨーロッパ人が到来する以前、マオリ族は二つの島を総称する名称を持っていなかった。[3]

アオテアロアにはいくつかの意味が提案されている。最も一般的な訳は「長い白い雲の土地」[4]、あるいはその変形である。これはマオリの口承伝承におい

て、初期のポリネシア人航海士がこの国を見つける手助けをしたとされる雲の形状を指す。[5]

20世紀後半から、アオテアロアは国家機関や組織の二言語表記で広く使われるようになった。1990年代以降、特定の団体がニュージーランド国歌「神よ

ニュージーランドを守り給え」(または「アオテアロア」)をマオリ語と英語の両方で歌うのが慣例となり、この名称がより広い層に知られるようになった。

ニュージーランドの英語話者は、この単語を元のマオリ語発音に様々な程度で近づけて発音する。一端には/ˌɑːəteɪəˈrɔːə/

[ˌɐːɘtæeɘˈɹoːɘ](ネイティビスト的発音)があり、他端には/ˌeɪətiːəˈroʊə/ [ˌæeɘtiːɘˈɹɐʉɘ]

まで様々である。[1] 英語辞書に記載されている発音には、/ˌeɪəteɪəˈroʊə/、[7] /aʊˌteɪəˈroʊə/、[8] および

/ˌɑːoʊtiːəˈroʊə/ がある。[9]

| Aotearoa (Māori

pronunciation: [aɔˈtɛaɾɔa] ⓘ)[1] is the Māori name for New Zealand. The

name was originally used by Māori in reference only to the North

Island, with the whole country sometimes referred to as Aotearoa me Te

Waipounamu, especially in the South Island.[2] In the pre-European era,

Māori did not have a collective name for the two islands.[3] Several meanings for Aotearoa have been proposed; the most popular translation usually given is "land of the long white cloud",[4] or variations thereof. This refers to the cloud formations which are believed to have helped early Polynesian navigators find the country in Māori oral tradition.[5] Beginning in the late 20th century, Aotearoa has become widespread in the bilingual naming of national organisations and institutions. Since the 1990s, it has been customary for particular parties to sing the New Zealand national anthem, "God Defend New Zealand" (or "Aotearoa"), in both Māori and English,[6] which further exposed the name to a wider audience. New Zealand English speakers pronounce the word with various degrees of approximation to the original Māori pronunciation, from /ˌɑːəteɪəˈrɔːə/ [ˌɐːɘtæeɘˈɹoːɘ] at one end of the spectrum (nativist) to /ˌeɪətiːəˈroʊə/ [ˌæeɘtiːɘˈɹɐʉɘ] at the other.[1] Pronunciations documented in dictionaries of English include /ˌeɪəteɪəˈroʊə/,[7] /aʊˌteɪəˈroʊə/,[8] and /ˌɑːoʊtiːəˈroʊə/.[9] |

アオテアロア[Aotearoa](マオリ語発音: [aɔˈtɛaɾɔa]

ⓘ)[1]は、ニュージーランドのマオリ語名である。この名称は元々、マオリ族が北島のみを指す際に使用していた。国全体を指す場合、特に南島では「アオ

テアロア・メ・テ・ワイポウナム」と呼ばれることがあった。[2]

ヨーロッパ人が到来する以前、マオリ族は二つの島を総称する名称を持っていなかった。[3] アオテアロアにはいくつかの意味が提案されている。最も一般的な訳は「長い白い雲の土地」[4]、あるいはその変形である。これはマオリの口承伝承におい て、初期のポリネシア人航海士がこの国を見つける手助けをしたとされる雲の形状を指す。[5] 20世紀後半から、アオテアロアは国家機関や組織の二言語表記で広く使われるようになった。1990年代以降、特定の団体がニュージーランド国歌「神よ ニュージーランドを守り給え」(または「アオテアロア」)をマオリ語と英語の両方で歌うのが慣例となり、この名称がより広い層に知られるようになった。 ニュージーランドの英語話者は、この単語を元のマオリ語発音に様々な程度で近づけて発音する。一端には/ˌɑːəteɪəˈrɔːə/ [ˌɐːɘtæeɘˈɹoːɘ](ネイティビスト的発音)があり、他端には/ˌeɪətiːəˈroʊə/ [ˌæeɘtiːɘˈɹɐʉɘ] まで様々である。[1] 英語辞書に記載されている発音には、/ˌeɪəteɪəˈroʊə/、[7] /aʊˌteɪəˈroʊə/、[8] および /ˌɑːoʊtiːəˈroʊə/ がある。[9] |

| Origin The original meaning of Aotearoa is not known.[10] The word can be broken up as: ao ('cloud', 'dawn', 'daytime' or 'world'), tea ('white', 'clear' or 'bright') and roa ('long'). It can also be broken up as Aotea, the name of one of the migratory canoes that travelled to New Zealand, and roa ('long'). The most common literal translation is 'long white cloud',[4] commonly lengthened to 'the land of the long white cloud'.[11] Alternative translations include 'long bright world' or 'land of abiding day', possibly referring to New Zealand having longer summer days in comparison to those further north in the Pacific Ocean.[12] Mythology In some traditional stories, Aotearoa was the name of the canoe (waka) of the explorer Kupe, and he named the land after it.[13] Kupe's wife Kūrāmarotini (in some versions, his daughter) was watching the horizon and called "He ao! He ao!" ('a cloud! a cloud!').[14] Other versions say the canoe was guided by a long white cloud in the course of the day and by a long bright cloud at night. On arrival, the sign of land to Kupe's crew was the long cloud hanging over it. The cloud caught Kupe's attention and he said "Surely is a point of land". Due to the cloud which greeted them, Kupe named the land Aotearoa.[4] |

起源 アオテアロアの元の意味は不明である。[10] この言葉は次のように分解できる:ao(「雲」「夜明け」「昼間」または「世界」)、tea(「白」「澄んだ」「明るい」)、roa(「長い」)。また、 ニュージーランドに渡った移住カヌーの一つであるアオテアの名とroa(「長い」)に分解することもできる。最も一般的な直訳は「長い白い雲」[4]であ り、通常「長い白い雲の国」[11]と拡張される。他の解釈には「長い明るい世界」や「永遠の昼の国」があり、太平洋のより北に位置する地域と比べて ニュージーランドの夏の日照時間が長いことに由来する可能性がある。[12] 神話 伝統的な物語では、アオテアロアは探検家クペのカヌー(ワカ)の名であり、彼はその名に因んでこの地を名付けたとされる。[13] クペの妻クラーマロティニ(一部の説では娘)が地平線を見つめ「ヘ・アオ!ヘ・アオ!」(「雲だ!雲だ!」)と叫んだ。[14] 別の説では、カヌーは昼は長い白い雲に、夜は長い明るい雲に導かれたという。到着時、クペの乗組員が陸地と認識した兆候は、その上に垂れ下がる長い雲だっ た。クペはその雲に気づき「確かに陸地だ」と言った。彼らを迎えた雲にちなみ、クペはこの地をアオテアロアと名付けた。[4] |

| Usage It is not known when Māori began incorporating the name into their oral lore. Beginning in 1845, George Grey, Governor of New Zealand, spent some years amassing information from Māori regarding their legends and histories. He translated it into English, and in 1855 published a book called Polynesian Mythology and Ancient Traditional History of the New Zealand Race. In a reference to Māui, the culture hero, Grey's translation from the Māori reads as follows: Thus died this Maui we have spoken of; but before he died he had children, and sons were born to him; some of his descendants yet live in Hawaiki, some in Aotearoa (or in these islands); the greater part of his descendants remained in Hawaiki, but a few of them came here to Aotearoa.[15]  Elsdon Best and Stephenson Percy Smith of the Polynesian Society, who did much to popularise the use of Aotearoa in Edwardian school books, pictured in 1908 The use of Aotearoa to refer to the whole country is a post-colonial custom.[16] Before the period of contact with Europeans, Māori did not have a commonly used name for the entire New Zealand archipelago. As late as the 1890s the name was used in reference to the North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui) only; an example of this usage appeared in the first issue of Huia Tangata Kotahi, a Māori-language newspaper published on 8 February 1893. It contained the dedication on the front page, "He perehi tenei mo nga iwi Maori, katoa, o Aotearoa, mete Waipounamu",[17] meaning "This is a publication for the Māori tribes of the North Island and the South Island". After the adoption of the name New Zealand (anglicised from Nova Zeelandia[18]) by Europeans, one name used by Māori to denote the country as a whole was Niu Tīreni,[19][note 1] a respelling of New Zealand derived from an approximate pronunciation. The expanded meaning of Aotearoa among Pākehā became commonplace in the late 19th century. Aotearoa was used for the name of New Zealand in the 1878 translation of "God Defend New Zealand", by Judge Thomas Henry Smith of the Native Land Court[20]—this translation is widely used today when the anthem is sung in Māori.[6] Additionally, William Pember Reeves used Aotearoa to mean New Zealand in his history of the country published in 1898, The Long White Cloud: Ao Tea Roa.  A bilingual sign outside the National Library of New Zealand headquarters uses Aotearoa alongside New Zealand. Since the late 20th century Aotearoa is becoming widespread also in the bilingual names of national organisations, such as the National Library of New Zealand / Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.[21] The New Zealand province of the Anglican Church is divided into three cultural streams or tikanga (Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia), with the Aotearoa tikanga covering Māori-speaking congregations within New Zealand.[22] In 2015, to celebrate Te Wiki o te Reo Māori (Māori Language Week), the Black Caps (the New Zealand national cricket team) played under the name Aotearoa for their first match against Zimbabwe.[23] Music Aotearoa is an overture composed in 1940 by Douglas Lilburn.[24] The Land of the Long White Cloud, subtitled Aotearoa, is a piece composed in 1979 by Philip Sparke for brass band or wind band.[25] "Aotearoa" is the Māori version of "God Defend New Zealand", a national anthem of New Zealand.[26] Split Enz refers to Aotearoa in its 1982 song "Six Months in a Leaky Boat". |

用法 マオリ族がいつからこの名前を口承伝承に取り入れ始めたかは不明だ。1845年から、ニュージーランド総督ジョージ・グレイは数年にわたり、マオリ族の伝 説や歴史に関する情報を収集した。彼はそれを英語に翻訳し、1855年に『ポリネシア神話とニュージーランド人種の古代伝承史』という本を出版した。文化 の英雄マウイに関する記述において、グレイのマオリ語からの翻訳は次の通りである: かくして我らが語るマウイは死んだ。だが死ぬ前に子らをもうけ、息子たちが生まれた。その子孫の幾人かは今もハワイキに生き、幾人かはアオテアロア(すな わちこの諸島)に生きている。子孫の大半はハワイキに残ったが、ごく一部がここアオテアロアへ渡ってきたのである。[15]  ポリネシア協会のエルズドン・ベストとスティーブンソン・パーシー・スミスは、エドワード朝時代の教科書でアオテアロアの普及に大きく貢献した。1908年の写真 アオテアロアを国全体を指す名称として用いるのは、植民地時代以降の習慣である[16]。ヨーロッパ人との接触期以前、マオリ族はニュージーランド諸島全 体を指す共通の名称を持っていなかった。1890年代になっても、この名称は北島(テ・イカ・ア・マウイ)のみを指すのに使われていた。この用法の一例 は、1893年2月8日に発行されたマオリ語新聞『フイア・タンガタ・コタヒ』の創刊号に見られる。その1面には「He perehi tenei mo nga iwi Maori, katoa, o Aotearoa, mete Waipounamu」[17]という献辞が掲載されていた。これは「本出版物は北島と南島のすべてのマオリ部族のためにある」という意味である。 ヨーロッパ人が「ノヴァ・ゼーランディア」[18]を英語化した「ニュージーランド」という名称を採用した後、マオリ族が国全体を指すために用いた名称の一つが「ニウ・ティレニ」[19][注1]であった。これはニュージーランドの近似発音に基づく再綴りである。 19世紀後半には、パケハの間でアオテアロアの意味が拡大して一般的になった。1878年、先住民土地裁判所のトーマス・ヘンリー・スミス判事が「神よ、 ニュージーランドを守りたまえ」を翻訳した際に、ニュージーランドの名称としてアオテアロアが使用された[20]。この翻訳は、今日、マオリ語で国歌が歌 われる際に広く使用されている。[6] さらに、ウィリアム・ペンバー・リーブスは、1898年に出版した自国の歴史書『The Long White Cloud: Ao Tea Roa』の中で、ニュージーランドを意味する言葉としてアオテアロアを使用している。  ニュージーランド国立図書館本部の外にある二か国語表記の看板には、ニュージーランドと並んでアオテアロアが使用されている。 20 世紀後半以降、アオテアロアは、ニュージーランド国立図書館(National Library of New Zealand / Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa)などの国家機関の二か国語名称でも広く使用されるようになった。[21] ニュージーランドの英国国教会管区は、3つの文化的流れ(ティカンガ)に分かれている(アオテアロア、ニュージーランド、ポリネシア)。アオテアロア・ティカンガは、ニュージーランド国内のマオリ語を話す教会を管轄している。[22] 2015年、テ・ウィキ・オ・テ・レオ・マオリ(マオリ語週間)を祝うため、ブラックキャップス(ニュージーランド代表クリケットチーム)はジンバブエとの初戦において「アオテアロア」の名で試合を行った。[23] 音楽 『アオテアロア』は1940年にダグラス・リルバーンが作曲した序曲である。[24] 『長い白い雲の国』(副題:アオテアロア)は、フィリップ・スパークが1979年にブラスバンドまたはウィンドバンドのために作曲した作品である。[25] 「アオテアロア」はニュージーランドの国歌「神よニュージーランドを守り給え」のマオリ語版である。[26] スプリット・エンズは1982年の楽曲「漏れるボートでの6ヶ月」でアオテアロアに言及している。 |

| Proposals for official use A 2019 petition initiated by Danny Tahau Jobe for a referendum on whether the official name of New Zealand should change to include Aotearoa[27] received 6,310 signatures.[28] In September 2021, Te Pāti Māori started a petition to change the name of New Zealand to Aotearoa.[29] The petition received 50,000 signatures in two days,[30] and over 70,000 by early June 2022. On 2 June, the petition was submitted to Parliament's Petitions Committee. Party co-leader Rawiri Waititi argued that the proposed name change would recognise New Zealand's indigenous heritage and strengthen its identity as a Pacific country. Waititi objected to the idea of a referendum, claiming it would entrench the "tyranny of the majority". National Party leader Christopher Luxon stated that renaming New Zealand was a constitutional issue that would require a referendum. Māori Development Minister Willie Jackson expressed concerns that a potential name change would create branding issues for the country's tourism industry.[31] A 1News–Colmar Brunton poll in September 2021 found that 58% of respondents wanted to keep the name New Zealand, 9% wanted to change the name to Aotearoa, and 31% wanted the joint name of Aotearoa New Zealand.[32] A January 2023 Newshub-Reid Research poll showed a slight increase in support for the name Aotearoa, with 36.2% wanting Aotearoa New Zealand, 9.6% Aotearoa only, and 52% wanting to keep New Zealand only.[33] |

公的使用に関する提案 2019年、ダニー・タハウ・ジョベが主導した、ニュージーランドの正式名称をアオテアロアを含むものに変更すべきか否かの国民投票を求める請願書には、6,310の署名が集まった。 2021年9月、テ・パティ・マオリはニュージーランドの名称をアオテアロアに変更する請願を開始した。[29] この請願は2日間で5万の署名を集め[30]、2022年6月初旬までに7万を超えた。6月2日、請願は議会の請願委員会に提出された。党共同代表ラウィ リ・ワイティティは、提案された名称変更がニュージーランドの先住民の遺産を認め、太平洋国家としてのアイデンティティを強化すると主張した。ワイティ ティは国民投票案に反対し、「多数派の専制」を固定化すると主張した。国民党党首クリストファー・ラクソンは、国名変更は国民投票を必要とする憲法上の問 題だと述べた。マオリ開発大臣ウィリー・ジャクソンは、国名変更が観光産業のブランディング問題を引き起こす懸念を表明した。[31] 2021年9月の1ニュース・コルマー・ブラントン世論調査では、回答者の58%が「ニュージーランド」の名称維持を望み、9%が「アオテアロア」への変 更を支持、31%が「アオテアロア・ニュージーランド」の併記名称を支持した。[32] 2023年1月のニューズハブ・リードリサーチ世論調査では、アオテアロア支持がわずかに増加し、36.2%が「アオテアロア・ニュージーランド」を、 9.6%が「アオテアロアのみ」を、52%が「ニュージーランドのみ」の維持を希望した。[33] |

| List of New Zealand place name etymologies New Zealand place names |

ニュージーランドの地名語源一覧 ニュージーランドの地名 |

| Explanatory notes a. The spelling varies, for example, the variant Nu Tirani appears in the Māori version of the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand and the Treaty of Waitangi. Whatever the spelling, this name is now rarely used as Māori no longer favour the use of transliterations from English. |

注釈 a. 綴りは様々である。例えば、ニュージーランド独立宣言およびワイタンギ条約のマオリ語版には「ヌ・ティラニ」という異形が現れる。いずれの綴りであれ、この名称は現在ほとんど使われていない。マオリ族はもはや英語からの音訳の使用を好まないからである。 |

| References 1. Bauer, Laurie; Warren, Paul (2004). "New Zealand English: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 580–602. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-038. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5. S2CID 242118647. 2. Marshall, Andrew (2 October 2021). "Ngāi Tahu leader: Let's not rush name change". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 17 October 2025. 3. King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin. p. 41. ISBN 0-14-301867-1. In fact, in the pre-European era, Maori had no name for the country as a whole. 4. McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966). "Aotearoa". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020 – via Te Ara. 5. Morrison, Stacey; Morrison, Scotty (15 November 2021). "Why Referring to New Zealand as Aotearoa Is a Meaningful Step for Travelers". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved 29 June 2023. 6. "God Defend New Zealand/Aotearoa". mch.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017. 7. "Aotearoa". ABC Pronounce. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2021. pron. as per Macq. Dict. 8. "Aotearoa". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. 9. Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0. 10. Orsman, Harry (1998). "Aotearoa". In Robinson, Roger; Nelson, Wattie (eds.). The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195583489.001.0001. ISBN 9780195583489. 11. "Swirling cloud captured above New Zealand — 'The Land of the Long White Cloud'". The Daily Telegraph. 22 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2017. 12. Jock Philips (ed.). "Light -Experiencing New Zealand light". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012. 13 Percy Smith, Stephenson (1910). History and traditions of the Maoris of the West Coast, North Island of New Zealand, prior to 1840 (First ed.). Polynesian Society, New Plymouth. p. 77. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021. The first we hear of this Uenuku in Maori story is, that he was living at a place named Aotea-roa (the same name as New Zealand—a point worth noting) which, from what follows was Tahiti, where indeed his grandfather and great-grandfather held lands, until the former was expelled by Tu-tapu at the point of the spear; but even then the great-grandfather, Kau-ngaki (Kahu-ngaki in Maori), remained there and no doubt kept "the fire burning" on their ancestral lands. 14. Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal. "First peoples in Māori tradition – Kupe". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. 15. Grey, Sir George. "Polynesian Mythology and Ancient Traditional History of the New Zealand Race". New Zealand Texts Collection, Victoria University of Wellington. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2013. 16. Holmes, Paul (10 October 2003). "Michael King talks moa, flightless geese and the name Aotearoa – 1ZB Interview with Michael King – co-recipient of the inaugural Prime Minister's Awards for literary achievement". The Big Idea. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021. The other thing you talk about in your book is the word, the name "Aotearoa" and you say that in fact pre European, Maori did not actually call this place Aotearoa? King: There were some Maori tribes that had a tradition that the North Island had been called Aotea and Aotearoa but the two writers who popularised the Aotearoa name and the story of Kupe associated with it, were a man called Stephenson Percy-Smith and William Pember-Reeves and in a school journal in particular, it went into every school in the country in the early 20th century, they used Percy-Smith's material and the story about Kupe and Aotearoa said this is a wonderful name and its a wonderful story, wouldn't it be great if everybody called New Zealand, Aotearoa. And the result was that Maori children went to school.. We had a pretty extensive education system both in general schools and in the native school system.. And they learnt at school that the Maori name of New Zealand was Aotearoa and that's how it became the Maori name. 17. "Huia Tangata Kotahi". New Zealand Digital Library, University of Waikato. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2019. 18. McKinnon, Malcolm (November 2009). "Place names – Naming the country and the main islands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2011. 19. Robinson, Roger; Nelson, Wattie, eds. (1998). "Niu Tirani". The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195583489.001.0001. ISBN 9780195583489. 20. "History of God Defend New Zealand". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012. 21. "National Library of New Zealand (Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa) Act 2003". legislation.govt.n. Parliamentary Counsel Office. 5 May 2003. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018. 22. "Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and Polynesia". World Council of Churches. January 1948. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022. 23. "New Zealand to play as Aotearoa". ESPNCricinfo. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015. 24. "Overture: Aotearoa". SOUNZ. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2016. 25. "Land of the Long White Cloud". C. Alan Publications. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020. 26. Swarbrick, Nancy (June 2012). "National anthems – New Zealand's anthems". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017. 27. "Petition for referendum to include Aotearoa in official name of New Zealand". Stuff. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019. 28. "Petition of Danny Tahau Jobe – Referendum to include Aotearoa in the official name of New Zealand". New Zealand Parliament. 23 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019. 29. "New Zealand Māori party launches petition to change country's name to Aotearoa". The Guardian. 14 September 2021. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021. 30. "Numbers top 50,000 for petition on name change to Aotearoa". Radio New Zealand. 17 September 2021. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021. 31. McConnell, Glenn (2 June 2022). "Māori Party petition to officially call the country Aotearoa gets 70,000 supporters". Stuff. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022. 32. "1News poll reveals what Kiwis think about changing NZ's name to Aotearoa". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021. 33. Lynch, Jenna (5 February 2023). "Newshub-Reid Research poll: What should country's official name be?". Newshub. Retrieved 18 October 2025 – via Stuff. |

参考文献 1. バーラー, ローリー; ウォーレン, ポール (2004). 「ニュージーランド英語: 音韻論」. シュナイダー, エドガー・W.; バリッジ, ケイト; コルトマン, ベルント; メストリー, ラジェンド; アップトン, クライヴ (編). 『英語の変種ハンドブック』. 第1巻: 音韻論. ベルリン: ムートン・デ・グリュイター. pp. 580–602. doi:10.1515/9783110197181-038. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5. S2CID 242118647. 2. Marshall, Andrew (2021年10月2日). 「Ngāi Tahu リーダー: 名前の変更を急ぐべきではない」。オタゴ・デイリー・タイムズ。2025年10月17日取得。 3. キング、マイケル (2003)。『ペンギン・ニュージーランド史』。ペンギン社。41ページ。ISBN 0-14-301867-1。実際、ヨーロッパ人が到来する以前、マオリ族は国全体を指す名称を持っていなかった。 4. マクリントック、A. H. 編(1966年)。「アオテアロア」。『ニュージーランド百科事典』。2020年5月3日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年7月19日閲覧 – Te Ara経由。 5. モリソン、ステイシー;モリソン、スコッティ(2021年11月15日)。「ニュージーランドをアオテアロアと呼ぶことが旅行者にとって意味ある一歩である理由」. コンデナスト・トラベラー. 2023年6月29日閲覧. 6. 「神よニュージーランド/アオテアロアを守り給え」. mch.govt.nz. 文化遺産省. 2017年5月7日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年4月29日閲覧. 7. 「アオテアロア」. ABC発音. オーストラリア放送協会. 2007年12月21日. 2019年2月19日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年10月7日閲覧. 発音はマック辞書による. 8. 「アオテアロア」. レキシコ英国英語辞典. オックスフォード大学出版局. 2021年10月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 9. Wells, John C. (2008). 『ロングマン発音辞典』(第3版). ロングマン. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0. 10. Orsman, Harry (1998). 「アオテアロア」. In Robinson, Roger; Nelson, Wattie (eds.). 『オックスフォード・ニュージーランド文学事典』. オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/acref/9780195583489.001.0001。ISBN 9780195583489。 11. 「ニュージーランド上空で捉えられた渦巻く雲 — 『長い白い雲の国』」。デイリー・テレグラフ。2009年1月22日。2018年4月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2017年4月29日に取得。 12. ジョック・フィリップス(編)。「光 - ニュージーランドの光を体験する」。テ・アラ:ニュージーランド百科事典。2012年10月26日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2012年5月19日に取得。 13 パーシー・スミス、スティーブンソン (1910). 『1840年以前のニュージーランド北島西海岸マオリ族の歴史と伝統』(初版). ポリネシア協会、ニュープリマス. p. 77. 2021年12月10日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年3月14日閲覧。このウエヌクについてマオリの物語で最初に聞くのは、彼がアオテアロア(ニュージーランドと同じ名前である点は注目に値する) という場所に住んでいたという話である。後の記述から、この場所はタヒチであったことがわかる。実際、彼の祖父と曾祖父はそこで土地を所有していたが、祖 父はトゥ・タプに槍で追放された。それでも曾祖父のカウ・ンガキ(マオリ語でカフ・ンガキ)はそこに残り、祖先の土地で「火を絶やさなかった」に違いな い。 14. テ・アフカラム・チャールズ・ロイヤル。「マオリの伝統における最初の民 – クペ」。テ・アラ – ニュージーランド百科事典。2019年8月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 15. グレー卿、ジョージ。「ポリネシア神話とニュージーランド人種の古代伝統史」。ニュージーランド文献コレクション、ウェリントン・ビクトリア大学。2012年11月11日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年4月27日取得。 16. ホームズ、ポール (2003年10月10日). 「マイケル・キングが語るモア、飛べないガチョウ、そしてアオテアロアの名 – 1ZB インタビュー:初代首相文学賞共同受賞者マイケル・キング」. The Big Idea. 2021年3月13日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年3月14日閲覧。君の著書で言及しているもう一つの事柄は、「アオテアロア」という名称についてだ。実際にはヨーロッパ人が来る前、マオリはこ の地をアオテアロアとは呼んでいなかったと述べているな?キング:北島はアオテアとアオテアロアと呼ばれていたという伝統を持つマオリ族も一部存在した が、アオテアロアという名称とそれに関連するクペの物語を普及させたのは、スティーブンソン・パーシー・スミスとウィリアム・ペンバー・リーブスという二 人の作家だった。特に学校誌では、 20世紀初頭、国内のすべての学校に配布された学校雑誌で、パーシー=スミスの資料とクペとアオテアロアの物語が紹介され、これは素晴らしい名前であり、 素晴らしい物語だ、皆がニュージーランドをアオテアロアと呼べば素晴らしいだろう、と書かれた。その結果、マオリの子供たちは学校に通い... 私たちは、一般学校と先住民学校の両方で、かなり広範な教育制度を持っていた... そして学校で、ニュージーランドのマオリ名はアオテアロアだと教わった。こうしてそれがマオリ名となったのだ。 17. 「Huia Tangata Kotahi」. ニュージーランドデジタル図書館、ワイカト大学. 2017年11月7日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2019年4月7日閲覧. 18. マッキノン, マルコム (2009年11月). 「地名 – 国と主要諸島の命名」. Te Ara: ニュージーランド百科事典. 2018年6月13日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2011年1月24日閲覧. 19. ロビンソン, ロジャー; ネルソン, ワティ, 編 (1998). 「ニュイ・ティラニ」. 『オックスフォード・ニュージーランド文学事典』. オックスフォード大学出版局. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195583489.001.0001. ISBN 9780195583489. 20. 「神よニュージーランドを守り給えの歴史」. 文化遺産省. 2011年10月27日. 2012年10月20日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2012年9月26日に取得。 21. 「2003年ニュージーランド国立図書館(テ・プナ・マタウランガ・オ・アオテアロア)法」. legislation.govt.nz. 議会顧問局. 2003年5月5日. 2018年12月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2018年12月5日に取得. 22. 「アオテアロア、ニュージーランド、ポリネシアの英国国教会」. 世界教会協議会. 1948年1月. 2022年8月20日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2022年6月9日に閲覧. 23. 「ニュージーランドはアオテアロアとしてプレーする」. ESPNCricinfo. 2015年7月30日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2015年7月27日に閲覧。 24. 「序曲:アオテアロア」SOUNZ。2017年4月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年10月13日に閲覧。 25. 「長い白い雲の国」C. Alan Publications。2020年7月20日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年7月19日に閲覧。 26. スワーブリック、ナンシー(2012年6月)。「国歌 – ニュージーランドの国歌」。テ・アラ:ニュージーランド百科事典。2017年10月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年10月18日に閲覧。 27. 「ニュージーランドの正式名称にアオテアロアを含める国民投票を求める請願」。Stuff。2019年2月1日。2019年5月5日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年5月5日に取得。 28. 「ダニー・タハウ・ジョベの請願 – ニュージーランドの正式名称にアオテアロアを含める国民投票」。ニュージーランド議会。2018年5月23日。2019年4月19日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年4月20日に取得。 29. 「ニュージーランド・マオリ党、国名をアオテアロアに変更する請願を開始」。ガーディアン。2021年9月14日。2021年9月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年9月15日閲覧。 30. 「国名をアオテアロアに変更する請願の署名数が5万人を突破」。ラジオ・ニュージーランド。2021年9月17日。2021年9月17日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年9月17日閲覧。 31. マコーネル、グレン(2022年6月2日)。「国名をアオテアロアと正式に呼ぶよう求めるマオリ党の請願、7万人の支持を得る」。スタッフ。2022年6月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年6月3日に取得。 32. 「1ニュース世論調査、ニュージーランドの名称をアオテアロアに変更することに対するニュージーランド人の考えを明らかに」。TVNZ。2021年9月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年9月28日に取得。 33. リンチ、ジェナ(2023年2月5日)。「ニューズハブ・リード調査:国の正式名称はどうあるべきか?」。ニューズハブ。2025年10月18日に取得 – Stuff経由。 |

| The dictionary definition of Aotearoa at Wiktionary |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aotearoa |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099