考古学

Archaeology

Excavations at Atapuerca, an archaeological site in Spain./ Archaeologists excavating in Rome, Italy

☆ 考古学(Archaeology)または考古学は、物質文化の復元と分析を通じて人間の活動を研究する学問である。考古学的記録は、遺物、建築物、 生物学的遺物または生態学的遺物、遺跡、文化的景観などから構成される。考古学は社会科学であると同時に人文科学の一分野である。通 常、独立した学問分野と考えられているが、人類学(北米では4分野アプローチ)、歴史学、地理学の一部として分類されることもある。

| Archaeology

or archeology[a] is the study of human activity through the recovery

and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of

artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural

landscapes. Archaeology can be considered both a social science and a

branch of the humanities.[1][2][3] It is usually considered an

independent academic discipline, but may also be classified as part of

anthropology (in North America – the four-field approach), history or

geography.[4] Archaeologists study human prehistory and history, from the development of the first stone tools at Lomekwi in East Africa 3.3 million years ago up until recent decades.[5] Archaeology is distinct from palaeontology, which is the study of fossil remains. Archaeology is particularly important for learning about prehistoric societies, for which, by definition, there are no written records. Prehistory includes over 99% of the human past, from the Paleolithic until the advent of literacy in societies around the world.[1] Archaeology has various goals, which range from understanding culture history to reconstructing past lifeways to documenting and explaining changes in human societies through time.[6] Derived from the Greek, the term archaeology means "the study of ancient history".[7] The discipline involves surveying, excavation, and eventually analysis of data collected, to learn more about the past. In broad scope, archaeology relies on cross-disciplinary research. Archaeology developed out of antiquarianism in Europe during the 19th century, and has since become a discipline practiced around the world. Archaeology has been used by nation-states to create particular visions of the past.[8][9] Since its early development, various specific sub-disciplines of archaeology have developed, including maritime archaeology, feminist archaeology, and archaeoastronomy, and numerous different scientific techniques have been developed to aid archaeological investigation. Nonetheless, today, archaeologists face many problems, such as dealing with pseudoarchaeology, the looting of artifacts,[10][11] a lack of public interest, and opposition to the excavation of human remains. |

考古学(Archaeology)

または考古学[a]は、物質文化の復元と分析を通じて人間の活動を研究する学問である。考古学的記録は、遺物、建築物、生物学的遺物または生態学的遺物、

遺跡、文化的景観などから構成される。考古学は社会科学であると同時に人文科学の一分野である[1][2][3]。通常、独立した学問分野と考えられてい

るが、人類学(北米では4分野アプローチ)、歴史学、地理学の一部として分類されることもある[4]。 考古学者は、330万年前に東アフリカのロメクウィで最初の石器が開発されてから最近数十年までの人類の先史時代と歴史を研究している[5]。考古学は、 文字による記録がない先史時代の社会を知る上で特に重要である。先史時代には、旧石器時代から世界中の社会で読み書きができるようになるまでの、人類の過 去の99%以上が含まれる[1]。 考古学には様々な目的があり、文化史の理解から過去の生活様式の復元、時代による人間社会の変化の記録と説明まで多岐にわたる[6]。 この学問分野では、過去についてより深く知るために、調査、発掘、そして最終的には収集したデータの分析が行われる。広い範囲において、考古学は学際的な研究に依存している。 考古学は、19世紀にヨーロッパで古美術主義から発展し、その後、世界中で実践される学問となった。考古学は、過去の特定のヴィジョンを作り出すために国 家によって利用されてきた[8][9]。その初期の発展以来、海洋考古学、フェミニスト考古学、古天文学など、考古学の様々な特定の下位学問分野が発展 し、考古学的調査を助けるために数多くの異なる科学技術が開発されてきた。それにもかかわらず、今日、考古学者は、似非考古学への対応、遺物の略奪、 [10][11]社会的関心の欠如、遺骨発掘への反対など、多くの問題に直面している。 |

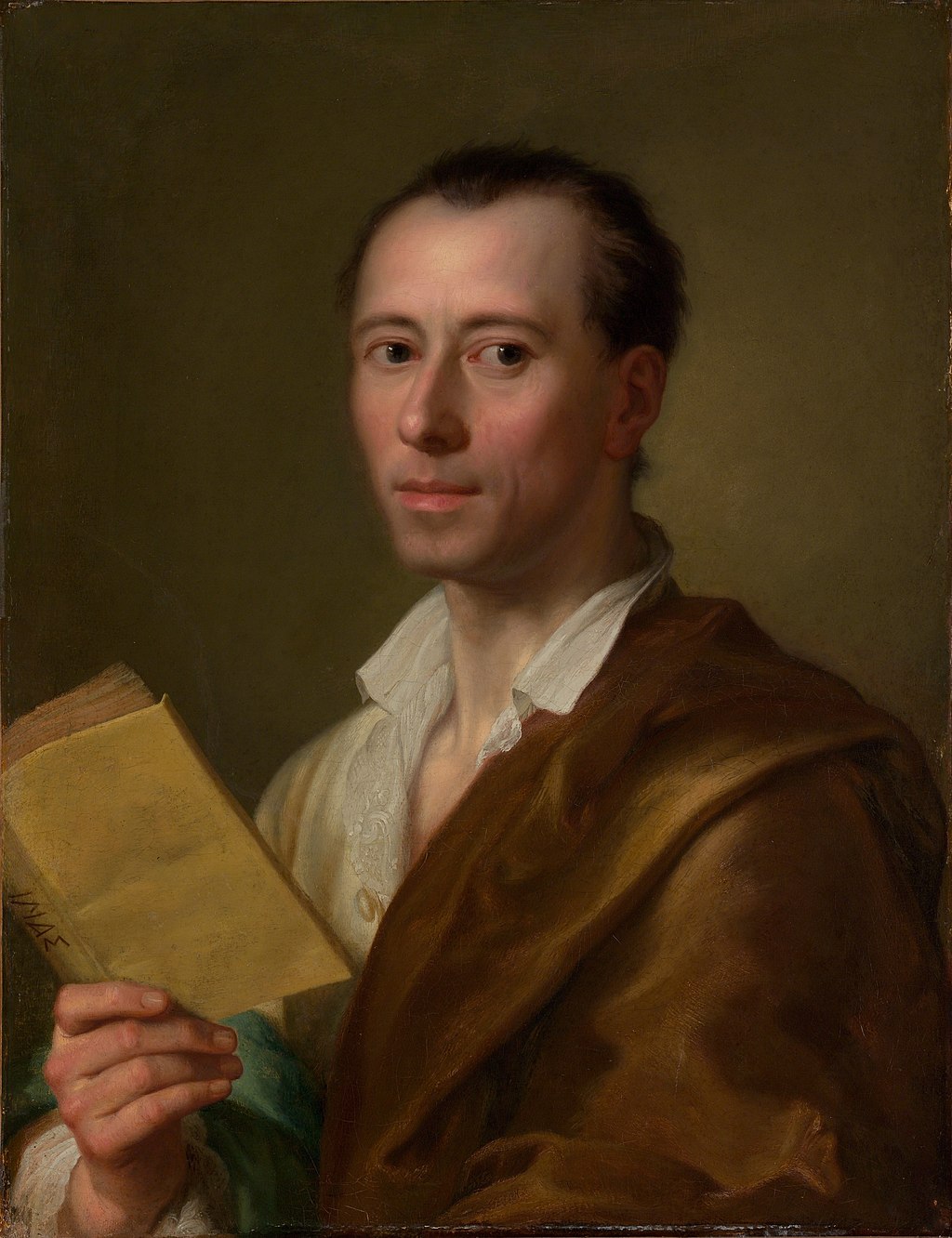

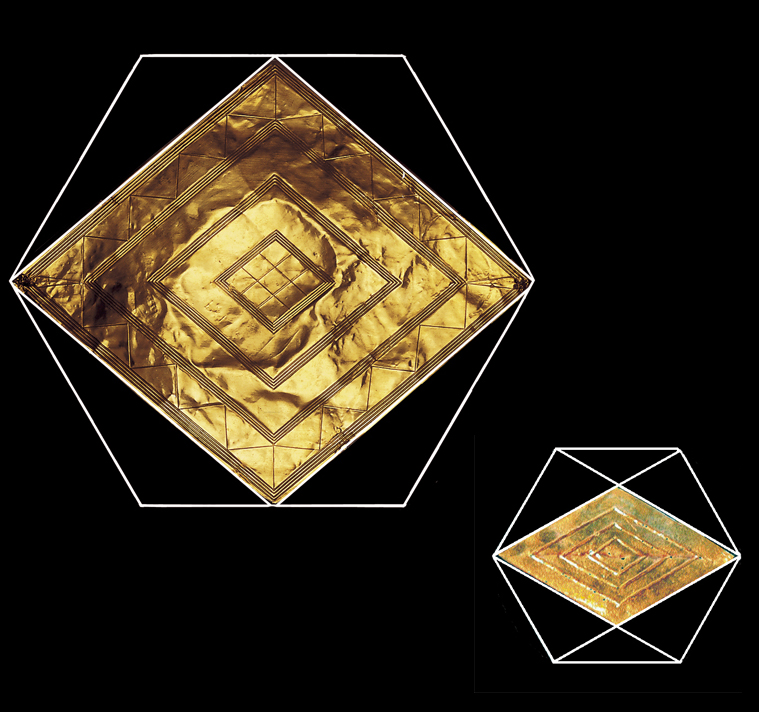

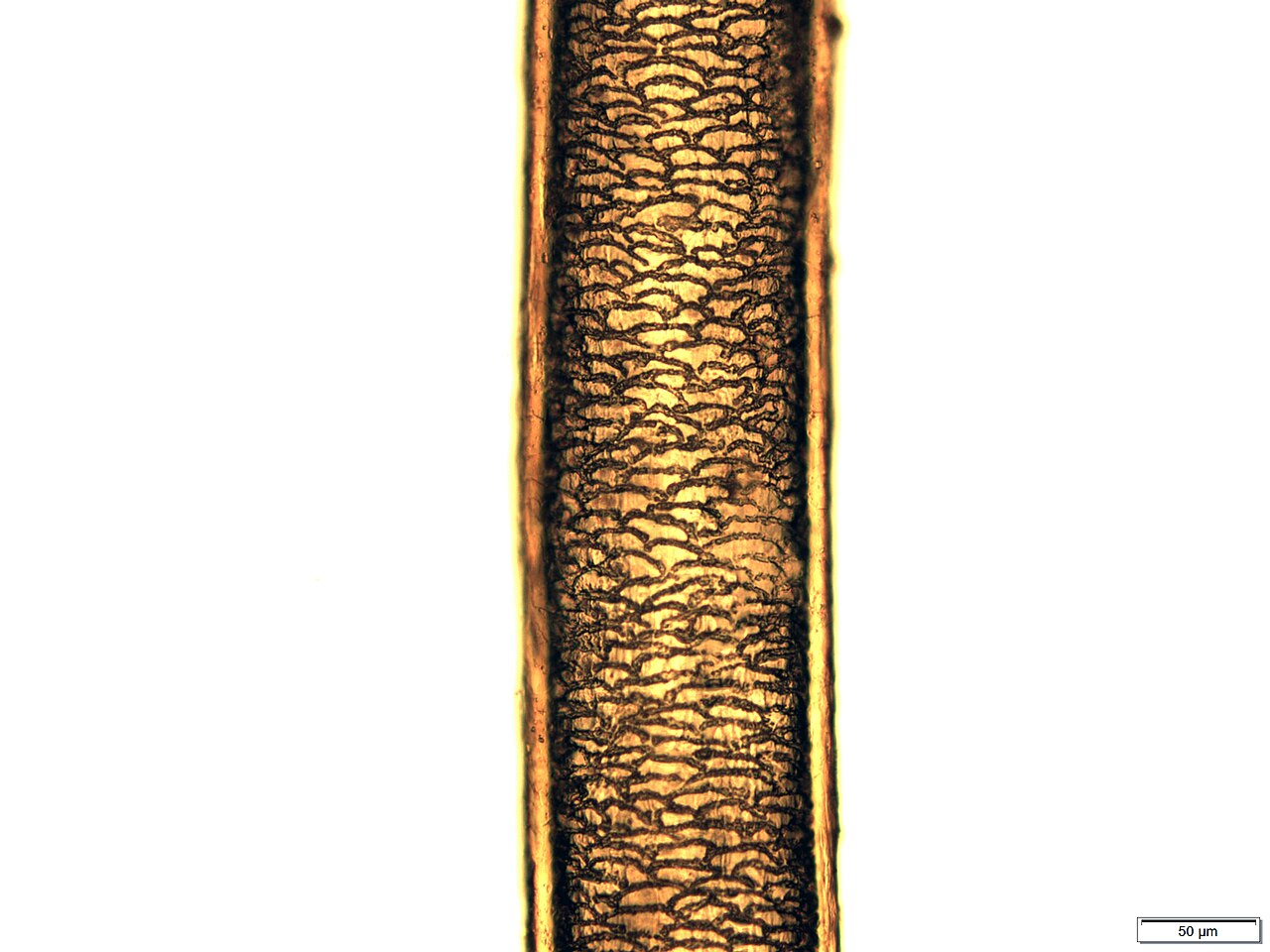

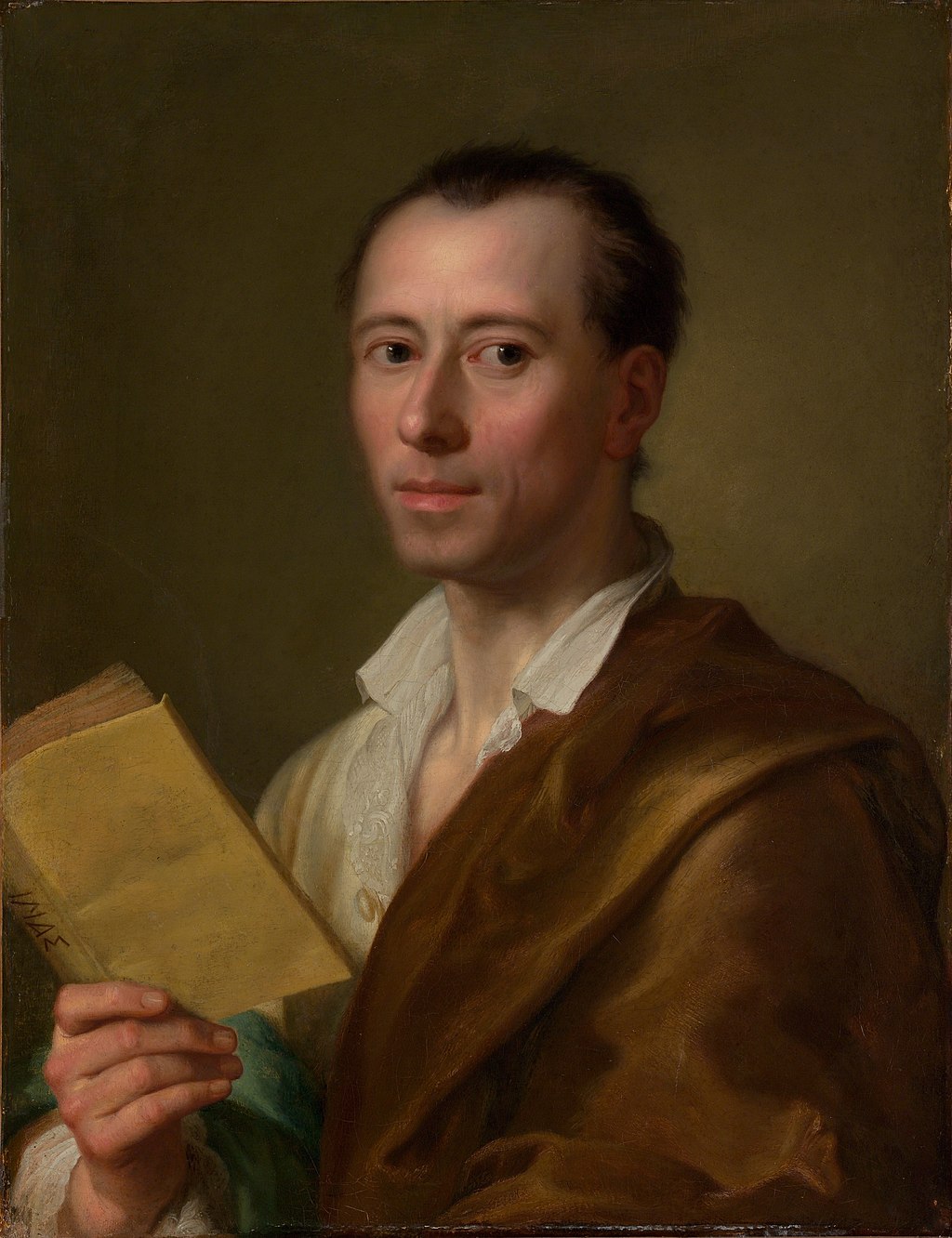

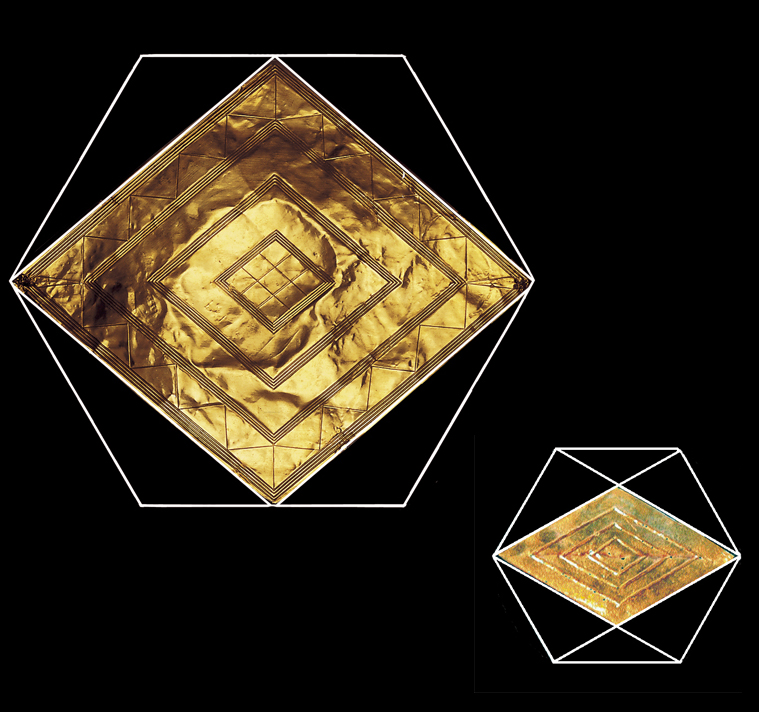

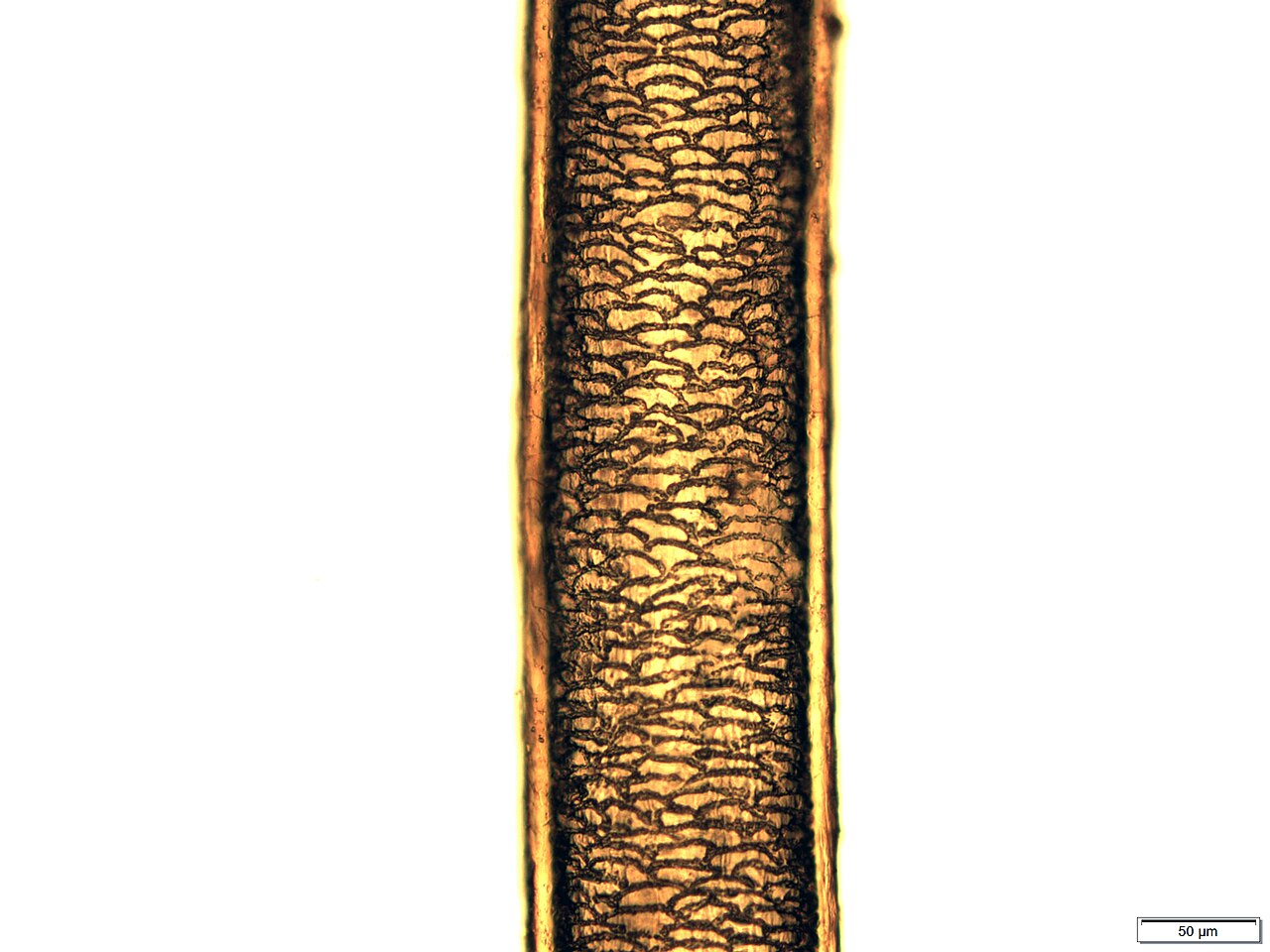

| History Main article: History of archaeology First instances of archaeology Excavations of Nabonidus (c. 550 BCE)  Nabonidus cylinder from Sippar Extract describing the excavation Cuneiform account of the excavation of a foundation deposit belonging to Naram-Sin of Akkad (ruled c. 2200 BCE), by king Nabonidus (ruled c. 550 BCE).[12][13] In Ancient Mesopotamia, a foundation deposit of the Akkadian Empire ruler Naram-Sin (ruled c. 2200 BCE) was discovered and analysed by king Nabonidus, c. 550 BCE, who is thus known as the first archaeologist.[12][13][14] Not only did he lead the first excavations which were to find the foundation deposits of the temples of Šamaš the sun god, the warrior goddess Anunitu (both located in Sippar), and the sanctuary that Naram-Sin built to the moon god, located in Harran, but he also had them restored to their former glory.[12] He was also the first to date an archaeological artifact in his attempt to date Naram-Sin's temple during his search for it.[15] Even though his estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years, it was still a very good one considering the lack of accurate dating technology at the time.[12][15][13] Antiquarians Main article: Antiquarian Further information: History of Chinese archaeology  Archaeologists excavating in Rome, Italy  Cyriacus of Ancona (fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli) The science of archaeology (from Greek ἀρχαιολογία, archaiologia from ἀρχαῖος, arkhaios, "ancient" and -λογία, -logia, "-logy")[16] grew out of the older multi-disciplinary study known as antiquarianism. Antiquarians studied history with particular attention to ancient artifacts and manuscripts, as well as historical sites. Antiquarianism focused on the empirical evidence that existed for the understanding of the past, encapsulated in the motto of the 18th century antiquary, Sir Richard Colt Hoare: "We speak from facts not theory". Tentative steps towards the systematization of archaeology as a science took place during the Enlightenment period in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.[17] In Imperial China during the Song dynasty (960–1279), figures such as Ouyang Xiu[18] and Zhao Mingcheng established the tradition of Chinese epigraphy by investigating, preserving, and analyzing ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions from the Shang and Zhou periods.[19][20](p74)[21](p95) In his book published in 1088, Shen Kuo criticized contemporary Chinese scholars for attributing ancient bronze vessels as creations of famous sages rather than artisan commoners, and for attempting to revive them for ritual use without discerning their original functionality and purpose of manufacture.[22] Such antiquarian pursuits waned after the Song period, were revived in the 17th century during the Qing dynasty, but were always considered a branch of Chinese historiography rather than a separate discipline of archaeology.[20](pp74–76)[21](p97) In Renaissance Europe, philosophical interest in the remains of Greco-Roman civilization and the rediscovery of classical culture began in the late Middle Ages, with humanism. Cyriacus of Ancona was a restlessly itinerant Italian humanist and antiquarian who came from a prominent family of merchants in Ancona, a maritime republic on the Adriatic. He was called by his contemporaries pater antiquitatis ('father of antiquity') and today "father of classical archaeology": "Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific recorder of Greek and Roman antiquities, particularly inscriptions, in the fifteenth century, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding father of modern classical archeology."[23] He traveled throughout Greece and all around the Eastern Mediterranean, to record his findings on ancient buildings, statues and inscriptions, including archaeological remains still unknown to his time: the Parthenon, Delphi, the Egyptian pyramids, the hieroglyphics.[24] He noted down his archaeological discoveries in his diary, Commentaria (in six volumes). Flavio Biondo, an Italian Renaissance humanist historian, created a systematic guide to the ruins and topography of ancient Rome in the early 15th century, for which he has been called an early founder of archaeology.[25] Antiquarians of the 16th century, including John Leland and William Camden, conducted surveys of the English countryside, drawing, describing and interpreting the monuments that they encountered.[26][27] The OED first cites "archaeologist" from 1824; this soon took over as the usual term for one major branch of antiquarian activity. "Archaeology", from 1607 onward, initially meant what we would call "ancient history" generally, with the narrower modern sense first seen in 1837. However, it was Jacob Spon who, in 1685, offered one of the earliest definitions of "archaeologia" to describe the study of antiquities in which he was engaged, in the preface of a collection of transcriptions of Roman inscriptions whiche he had gleaned over the years of his travels, entitled Miscellanea eruditae antiquitatis. Twelfth-century Indian scholar Kalhana's writings involved recording of local traditions, examining manuscripts, inscriptions, coins and architectures, which is described as one of the earliest traces of archaeology. One of his notable work is called Rajatarangini which was completed in c. 1150 and is described as one of the first history books of India.[28][29][30] First excavations old photograph of stonehenge with toppled stones  An early photograph of Stonehenge taken July 1877  Johann Joachim Winckelmann (Raphael Mengs after 1755) One of the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation was Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments in England. John Aubrey (1626–1697) was a pioneer archaeologist who recorded numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England. He was also ahead of his time in the analysis of his findings. He attempted to chart the chronological stylistic evolution of handwriting, medieval architecture, costume, and shield-shapes.[31] Excavations were also carried out by the Spanish military engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre in the ancient towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, both of which had been covered by ash during the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. These excavations began in 1748 in Pompeii, while in Herculaneum they began in 1738. The discovery of entire towns, complete with utensils and even human shapes, as well the unearthing of frescos, had a big impact throughout Europe. However, prior to the development of modern techniques, excavations tended to be haphazard; the importance of concepts such as stratification and context were overlooked.[32] In the mid-18th century, the German Johann Joachim Winckelmann lived in Rome and devoted himself to the study of Roma antiquities and gradually acquired an unrivalled knowledge of ancient art.[33] Then, he visited the archaeological excavations being conducted at Pompeii and Herculaneum.[34] He was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art[35] He was one of the first to separate Greek art into periods and time classifications.[36] Winckelmann has been called both "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology"[37] and the father of the discipline of art history.[38] Development of archaeological method  Artifacts discovered at the 1808 Bush Barrow excavation by Sir Richard Colt Hoare and William Cunnington. The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in Wiltshire from around 1798,[39] funded by Sir Richard Colt Hoare. Cunnington made meticulous recordings of Neolithic and Bronze Age barrows, and the terms he used to categorize and describe them are still used by archaeologists today.[40] However, it is to be recorded that future U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, also proceeded to do his own excavations in 1784, using the trench method, on several Native American burial mounds in Virginia. His excavations were prompted by the "Moundbuilders" question, however his careful methods allowed him enough insight to admitting that he saw no reason why the ancestors of the present-day Native Americans themselves could not have raised those mounds.[41] One of the major achievements of 19th-century archaeology was the development of stratigraphy. The idea of overlapping strata tracing back to successive periods was borrowed from the new geological and paleontological work of scholars like William Smith, James Hutton and Charles Lyell. The systematic application of stratigraphy to archaeology first took place with the excavations of prehistorical and Bronze Age sites. In the third and fourth decades of the 19th century, archaeologists like Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen began to put the artifacts they had found in chronological order.  This photo is made of a single goat hair from a textile found on the 14th century ship in Tallinn, Estonia. Photo was done in archaeology department (University of Tartu) by microscope Olympus BX51, magnification 200x A major figure in the development of archaeology into a rigorous science was the army officer and ethnologist, Augustus Pitt Rivers,[42] who began excavations on his land in England in the 1880s. His approach was highly methodical by the standards of the time, and he is widely regarded as the first scientific archaeologist. He arranged his artifacts by type or "typologically, and within types by date or "chronologically". This style of arrangement, designed to highlight the evolutionary trends in human artifacts, was of enormous significance for the accurate dating of the objects. His most important methodological innovation was his insistence that all artifacts, not just beautiful or unique ones, be collected and catalogued.[43]  Archaeological excavation of a Stone Age settlement at Glamilders in Långbergsöda village, Saltvik, Åland, in 1906. William Flinders Petrie is another man who may legitimately be called the Father of Archaeology. His painstaking recording and study of artifacts, both in Egypt and later in Palestine, laid down many of the ideas behind modern archaeological recording; he remarked that "I believe the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details." Petrie developed the system of dating layers based on pottery and ceramic findings, which revolutionized the chronological basis of Egyptology. Petrie was the first to scientifically investigate the Great Pyramid in Egypt during the 1880s.[44] He was also responsible for mentoring and training a whole generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter who went on to achieve fame with the discovery of the tomb of 14th-century BC pharaoh Tutankhamun. earthern fort with many walls  Mortimer Wheeler pioneered systematic excavation in the early 20th century. Pictured, are his excavations at Maiden Castle, Dorset, in October 1937. The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with public was that of Hissarlik, on the site of ancient Troy, carried out by Heinrich Schliemann, Frank Calvert and Wilhelm Dörpfeld in the 1870s. These scholars individuated nine different cities that had overlapped with one another, from prehistory to the Hellenistic period.[45] Meanwhile, the work of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos in Crete revealed the ancient existence of an equally advanced Minoan civilization.[46] The next major figure in the development of archaeology was Sir Mortimer Wheeler, whose highly disciplined approach to excavation and systematic coverage in the 1920s and 1930s brought the science on swiftly. Wheeler developed the grid system of excavation,[47] which was further improved by his student Kathleen Kenyon. Archaeology became a professional activity in the first half of the 20th century, and it became possible to study archaeology as a subject in universities and even schools. By the end of the 20th century nearly all professional archaeologists, at least in developed countries, were graduates. Further adaptation and innovation in archaeology continued in this period, when maritime archaeology and urban archaeology became more prevalent and rescue archaeology was developed as a result of increasing commercial development.[48] |

沿革 主な記事 考古学の歴史 考古学の最初の事例 ナボニドゥスの発掘(前550年頃)  シッパール出土のナボニドゥス円筒 発掘に関する記述の抜粋 ナボニドゥス王(紀元前550年頃統治)による、アッカドのナラム=シン(紀元前2200年頃統治)の礎石堆積物の発掘に関する楔形文字の記述[12][13]。 古代メソポタミアでは、アッカド帝国の支配者ナラム=シン(紀元前2200年頃を統治)の礎石が発見され、紀元前550年頃のナボニドゥス王によって分析 された。 [12][13][14]彼は最初の発掘調査を指揮し、太陽神シャマシュ神殿、戦士の女神アヌニトゥ神殿(いずれもシッパルにある)、ハランにあるナラム =シンが月神のために建てた聖域の礎石を発見しただけでなく、それらをかつての栄光を取り戻させた。 [12]彼はまた、ナラム=シンの神殿を捜索していた際に、考古学的遺物の年代測定を試みた最初の人物でもある[15]。彼の推定は1500年ほど不正確 であったとはいえ、当時の正確な年代測定技術の欠如を考えれば、非常に優れたものであった[12][15][13]。 アンティクリアン 主な記事 アンティクリアン さらに詳しい情報 中国考古学の歴史  イタリア、ローマで発掘する考古学者  アンコーナのキュリアコス(ベノッツォ・ゴッツォーリによるフレスコ画) 考古学(ギリシア語 ἀρχαιολογία, archaiologia ἀχραǶος, -λογία, -logia, "古代")[16]は、古美術学として知られる古い学際的研究から発展した。アンティクリアンは、古代の遺物や写本、史跡に特に注目して歴史を研究してい た。18世紀の古文書学者、リチャード・コルト・ホーア卿のモットーに要約されるように、古文書学は過去を理解するために存在する経験的証拠に焦点を当て ていた: 「我々は理論ではなく事実から語る」。科学としての考古学の体系化に向けた試みは、17~18世紀のヨーロッパにおける啓蒙主義時代に行われた[17]。 宋代(960年~1279年)の帝国中国では、欧陽詢[18]や趙明誠といった人物が、殷周時代の古代中国の青銅器の碑文を調査、保存、分析することに よって、中国の碑文の伝統を確立した。 神郭は1088年に出版した著書の中で、現代の中国の学者たちが古代の青銅器を職人である庶民の作品ではなく、有名な賢人の作品であるとし、本来の機能性 や製造目的を見極めることなく、儀式用に復活させようとしていることを批判した[19][20](p74)[21](p95)。 [22]このような古美術の探求は宋の時代以降衰退し、17世紀の清の時代に復活したが、考古学という独立した学問分野というよりは、中国の歴史学の一分 野であると常に考えられていた[20](pp74-76)[21](p97)。 ルネサンス期のヨーロッパでは、ギリシャ・ローマ文明の遺跡に対する哲学的関心と古典文化の再発見は、中世後期の人文主義から始まった。 アンコーナのキリアコスは、アドリア海に面した海洋共和国アンコーナの商人の名家の出身で、落ち着きなく遍歴を続けたイタリアの人文主義者であり、古美術 研究家であった。彼は同時代の人々からpater antiquitatis(「古代の父」)と呼ばれ、今日では「古典考古学の父」と呼ばれている: アンコーナのキュリアックは、15世紀におけるギリシア・ローマ時代の古代遺物、特に碑文の最も精力的で多産な記録者であり、その記録の一般的な正確さか ら、近代古典考古学の創始者と呼ばれるにふさわしい人物であった」[23]。 「パルテノン神殿、デルフィ、エジプトのピラミッド、ヒエログリフなど、彼の時代にはまだ知られていなかった考古学的遺跡を含む、古代の建造物、彫像、碑 文に関する発見を記録するために、ギリシャ全土、東地中海全域を旅した[24]。 イタリアのルネサンス期の人文主義的歴史家フラヴィオ・ビオンドは、15世紀初頭に古代ローマの遺跡と地形に関する体系的なガイドを作成し、このことから考古学の初期の創始者と呼ばれている[25]。 ジョン・リーランドやウィリアム・カムデンを含む16世紀の考古学者たちは、イギリスの田園地帯を調査し、遭遇した遺跡を描き、記述し、解釈した[26][27]。 OEDが初めて "archaeologist "を引用したのは1824年のことである。1607年以降の "Archaeology "は、当初は一般的に "古代史 "と呼ばれるものを意味し、1837年に初めて現代的な狭い意味で使われるようになった。しかし、1685年にヤコブ・スポンが、長年にわたる旅行で得た ローマ時代の碑文の書き写し集『Miscellanea eruditae antiquitatis』の序文で、彼が従事していた古代学研究を表す "archaeologia "の最も古い定義のひとつを提示した。 12世紀のインド人学者カルハナの著作は、現地の伝統を記録し、写本、碑文、コイン、建築物を調査したもので、考古学の最初期の痕跡のひとつと評されてい る。1150年頃に完成した『ラジャタランギニ』と呼ばれる彼の著作は、インド初の歴史書のひとつとされている[28][29][30]。 最初の発掘 石が倒されたストーンヘンジの古い写真  1877年7月に撮影されたストーンヘンジの初期の写真  ヨハン・ヨアヒム・ヴィンケルマン(1755年以降のラファエル・メングス) 考古学的発掘が最初に行われた場所のひとつが、ストーンヘンジをはじめとするイギリスの巨石遺跡である。ジョン・オーブリー(1626-1697)は、イ ングランド南部で数多くの巨石遺跡やその他の野外遺跡を記録した先駆的な考古学者である。彼はまた、調査結果の分析においても時代を先取りしていた。彼 は、手書き文字、中世の建築、衣装、盾の形などの年代的な様式の変遷を描き出そうとした[31]。 スペインの軍事技術者ロケ・ホアキン・デ・アルクビエレによって、ポンペイとヘルクラネウムの古代の町でも発掘調査が行われた。ポンペイでは1748年 に、ヘルクラネウムでは1738年に発掘が始まった。食器や人型まで揃った町全体の発見やフレスコ画の発掘は、ヨーロッパ全土に大きな衝撃を与えた。 しかし、近代的な技術が開発される以前は、発掘は行き当たりばったりになりがちであり、地層や文脈といった概念の重要性は見過ごされていた[32]。 18世紀半ば、ドイツ人のヨハン・ヨアヒム・ヴィンケルマンはローマに住み、ローマ古美術の研究に没頭し、次第に古代美術に関する比類ない知識を身につけ た[33]。 [34]彼は科学的考古学の創始者の一人であり、様式のカテゴリーを大規模かつ体系的に美術史に初めて適用した[35]。 考古学的手法の発展  サー・リチャード・コルト・ホアとウィリアム・カニントンによる1808年のブッシュ・バロー発掘で発見された遺物。 考古学的発掘の父はウィリアム・カニントン(1754-1810)である。彼は1798年頃からウィルトシャーで発掘調査を行い[39]、サー・リチャー ド・コルト・ホアの資金援助を受けた。カニントンは新石器時代と青銅器時代の墳墓を丹念に記録し、それらを分類・記述するために彼が使用した用語は、今日 でも考古学者によって使用されている[40]。しかし、後にアメリカ大統領となるトーマス・ジェファーソンもまた、1784年にヴァージニア州のいくつか のネイティブ・アメリカンの墳墓で、トレンチ法を用いた独自の発掘調査を進めたことを記録しておかなければならない。彼の発掘は、「マウンドビルダー」問 題に端を発していたが、彼の慎重な方法は、現在のネイティブ・アメリカンの祖先自身がそれらの塚を築いた可能性がない理由がないと認めるに十分な洞察力を 与えていた[41]。 19世紀の考古学の大きな成果の一つは、層序学の発展であった。ウィリアム・スミス、ジェームズ・ハットン、チャールズ・ライエルといった学者たちの新し い地質学的・古生物学的研究から借用したものである。層序学の考古学への体系的な応用は、先史時代や青銅器時代の遺跡の発掘から始まった。19世紀の3、 40年代には、ジャック・ブーシェ・ド・ペルテスやクリスチャン・ユルゲンセン・トムセンのような考古学者が、発見した遺物を年代順に並べ始めた。  この写真は、エストニアのタリンで14世紀の船から発見された織物のヤギの毛1本。写真はタルトゥ大学考古学学部にて、顕微鏡Olympus BX51、倍率200倍で撮影。 考古学を厳密な科学へと発展させた中心人物は、陸軍士官であり民族学者でもあったオーガスタス・ピット・リヴァース[42]であり、彼は1880年代にイ ギリスの自分の土地で発掘調査を始めた。彼のアプローチは当時の基準からすると非常に理路整然としており、最初の科学的考古学者として広く知られている。 彼は遺物を種類ごとに、あるいは「類型的に」、そして種類の中では年代ごとに、あるいは「年代順に」並べた。人類の遺物の進化的傾向を強調するために考案 されたこの配列スタイルは、遺物の正確な年代測定に大きな意味を持った。彼の方法論上の最も重要な革新は、美しいものやユニークなものだけでなく、すべて の遺物を収集し、目録化するという彼の主張であった[43]。  1906年、オーランド、ソルトヴィーク、ローングベルグセーダ村のグラミルデルスにおける石器時代の集落の考古学的発掘。 ウィリアム・フリンダース・ペトリもまた、考古学の父と呼ばれるにふさわしい人物である。エジプトと後のパレスチナにおける彼の丹念な遺物の記録と研究 は、現代の考古学的記録の背後にある多くの考え方を築いた。ペトリーは、土器や陶器の出土品に基づく年代測定システムを開発し、エジプト学の年代学的基礎 に革命をもたらした。ペトリーは、1880年代にエジプトの大ピラミッドを科学的に調査した最初の人物である[44]。彼はまた、紀元前14世紀のファラ オ、ツタンカーメンの墓を発見して有名になったハワード・カーターを含む、全世代のエジプト学者を指導・育成した責任者でもある。 土の砦  モーティマー・ウィーラーは、20世紀初頭に体系的な発掘を行った先駆者である。写真は1937年10月、ドーセット州メイデン・キャッスルでの彼の発掘。 一般に広く知られるようになった最初の層序学的発掘は、1870年代にハインリッヒ・シュリーマン、フランク・カルバート、ヴィルヘルム・デルプフェルド によって行われた古代トロイ遺跡のヒサーリクの発掘である。一方、クレタ島のクノッソスにおけるアーサー・エヴァンス卿の研究は、同様に高度なミノア文明 の古代の存在を明らかにした[46]。 考古学の発展における次の主要人物は、モーティマー・ウィーラー卿であった。1920年代から1930年代にかけて、彼の非常に規律正しい発掘へのアプ ローチと体系的な取材は、この科学を急速に発展させた。ウィーラーは発掘のグリッド・システムを開発し[47]、それは彼の弟子であるキャスリーン・ケニ オンによってさらに改良された。 考古学は20世紀前半には専門的な活動となり、大学や学校でも考古学を科目として学ぶことができるようになった。20世紀末には、少なくとも先進国では、 プロの考古学者のほぼ全員が卒業生となった。考古学のさらなる適応と革新はこの時期にも続き、海洋考古学と都市考古学がより普及し、商業的な開発が進んだ 結果レスキュー考古学が発展した[48]。 |

Purpose Cast of the skull of the Taung child, uncovered in South Africa. The Child was an infant of the Australopithecus africanus species, an early form of hominin The purpose of archaeology is to learn more about past societies and the development of the human race. Over 99% of the development of humanity has occurred within prehistoric cultures, who did not make use of writing, thereby no written records exist for study purposes. Without such written sources, the only way to understand prehistoric societies is through archaeology. Because archaeology is the study of past human activity, it stretches back to about 2.5 million years ago when the first stone tools are found – The Oldowan Industry. Many important developments in human history occurred during prehistory, such as the evolution of humanity during the Paleolithic period, when the hominins developed from the australopithecines in Africa and eventually into modern Homo sapiens. Archaeology also sheds light on many of humanity's technological advances, for instance the ability to use fire, the development of stone tools, the discovery of metallurgy, the beginnings of religion and the creation of agriculture. Without archaeology, little or nothing would be known about the use of material culture by humanity that pre-dates writing.[49] However, it is not only prehistoric, pre-literate cultures that can be studied using archaeology but historic, literate cultures as well, through the sub-discipline of historical archaeology. For many literate cultures, such as Ancient Greece and Mesopotamia, their surviving records are often incomplete and biased to some extent. In many societies, literacy was restricted to the elite classes, such as the clergy, or the bureaucracy of court or temple. The literacy of aristocrats has sometimes been restricted to deeds and contracts. The interests and world-view of elites are often quite different from the lives and interests of the populace. Writings that were produced by people more representative of the general population were unlikely to find their way into libraries and be preserved there for posterity. Thus, written records tend to reflect the biases, assumptions, cultural values and possibly deceptions of a limited range of individuals, usually a small fraction of the larger population. Hence, written records cannot be trusted as a sole source. The material record may be closer to a fair representation of society, though it is subject to its own biases, such as sampling bias and differential preservation.[50] Often, archaeology provides the only means to learn of the existence and behaviors of people of the past. Across the millennia many thousands of cultures and societies and billions of people have come and gone of which there is little or no written record or existing records are misrepresentative or incomplete. Writing as it is known today did not exist in human civilization until the 4th millennium BCE, in a relatively small number of technologically advanced civilizations. In contrast, Homo sapiens has existed for at least 200,000 years, and other species of Homo for millions of years (see Human evolution). These civilizations are, not coincidentally, the best-known; they are open to the inquiry of historians for centuries, while the study of pre-historic cultures has arisen only recently. Within a literate civilization many events and important human practices may not be officially recorded. Any knowledge of the early years of human civilization – the development of agriculture, cult practices of folk religion, the rise of the first cities – must come from archaeology. In addition to their scientific importance, archaeological remains sometimes have political or cultural significance to descendants of the people who produced them, monetary value to collectors, or strong aesthetic appeal. Many people identify archaeology with the recovery of such aesthetic, religious, political, or economic treasures rather than with the reconstruction of past societies. This view is often espoused in works of popular fiction, such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Mummy, and King Solomon's Mines. When unrealistic subjects are treated more seriously, accusations of pseudoscience are invariably levelled at their proponents (see Pseudoarchaeology). However, these endeavours, real and fictional, are not representative of modern archaeology. Theory Main article: Archaeological theory There is no one approach to archaeological theory that has been adhered to by all archaeologists. When archaeology developed in the late 19th century, the first approach to archaeological theory to be practised was that of cultural-history archaeology, which held the goal of explaining why cultures changed and adapted rather than just highlighting the fact that they did, therefore emphasizing historical particularism.[51] In the early 20th century, many archaeologists who studied past societies with direct continuing links to existing ones (such as those of Native Americans, Siberians, Mesoamericans etc.) followed the direct historical approach, compared the continuity between the past and contemporary ethnic and cultural groups.[51] In the 1960s, an archaeological movement largely led by American archaeologists like Lewis Binford and Kent Flannery arose that rebelled against the established cultural-history archaeology.[52][53] They proposed a "New Archaeology", which would be more "scientific" and "anthropological", with hypothesis testing and the scientific method very important parts of what became known as processual archaeology.[51] In the 1980s, a new postmodern movement arose led by the British archaeologists Michael Shanks,[54][55][56][57] Christopher Tilley,[58] Daniel Miller,[59][60] and Ian Hodder,[61][62][63][64][65][66] which has become known as post-processual archaeology. It questioned processualism's appeals to scientific positivism and impartiality, and emphasized the importance of a more self-critical theoretical reflexivity.[citation needed] However, this approach has been criticized by processualists as lacking scientific rigor, and the validity of both processualism and post-processualism is still under debate. Meanwhile, another theory, known as historical processualism, has emerged seeking to incorporate a focus on process and post-processual archaeology's emphasis of reflexivity and history.[67] Archaeological theory now borrows from a wide range of influences, including neo-evolutionary thought,[68][35] phenomenology, postmodernism, agency theory, cognitive science, structural functionalism, gender-based and feminist archaeology, and systems theory. |

目的 南アフリカで発見されたタウンの子供の頭蓋骨の鋳型。アウストラロピテクス・アフリカヌス種の幼児で、ヒト科の初期型である。 考古学の目的は、過去の社会や人類の発展について知ることである。人類の発展の99%以上は、文字を使わなかった先史時代の文化の中で起こった。そのよう な文字資料がなければ、先史時代の社会を理解する唯一の方法は考古学である。考古学は過去の人類の活動を研究する学問であるため、最初の石器が発見された 約250万年前までさかのぼる。例えば、旧石器時代に人類が進化し、アフリカのアウストラピテクスから現代のホモ・サピエンスへと発展した。考古学はま た、例えば火を使う能力、石器の開発、冶金の発見、宗教の始まり、農業の創造など、人類の技術的進歩の多くに光を当てている。考古学がなければ、文字が書 かれる以前の人類の物質文化の使用についてはほとんど何も知られていなかっただろう[49]。 しかし、考古学を使って研究できるのは、先史時代の文字以前の文化だけでなく、歴史考古学という下位分野を通じて、歴史的な文字文化も研究することができ る。古代ギリシャやメソポタミアのような識字文化の多くは、現存する記録が不完全で、ある程度偏っていることが多い。多くの社会では、識字は聖職者や宮 廷・神殿の官僚といったエリート階級に限られていた。貴族の識字は、証書や契約に限定されることもあった。エリートの関心や世界観は、民衆の生活や関心と はまったく異なることが多い。一般民衆を代表するような人々によって書かれた文書が図書館に収蔵され、後世に残ることはまずなかった。このように、書かれ た記録は、限られた範囲の個人(通常は、より多くの人口のごく一部)の偏見、思い込み、文化的価値観、そしておそらくは欺瞞を反映する傾向がある。した がって、文字による記録は唯一の情報源として信頼することはできない。物質的な記録は、サンプリング・バイアスや保存状態の違いといった独自のバイアスに 左右されるものの、社会の公正な表現に近いかもしれない[50]。 多くの場合、考古学は過去の人々の存在や行動を知るための唯一の手段を提供する。何千年もの間、何千という文化や社会、何十億という人々が生まれては消え ていったが、その記録はほとんど、あるいはまったく残っていないか、あるいは既存の記録が誤っていたり不完全であったりする。今日知られているような文字 が人類の文明に存在したのは、比較的少数の技術的に進んだ文明において、紀元前4千年紀までであった。対照的に、ホモ・サピエンスは少なくとも20万年、 他のホモの種は数百万年前から存在している(人類の進化を参照)。これらの文明が最もよく知られているのは偶然ではなく、何世紀にもわたって歴史家の探究 の対象になっているのに対し、有史以前の文化の研究が始まったのはごく最近のことである。識字文明の中では、多くの出来事や重要な人間の習慣が公式には記 録されていないかもしれない。農耕の発展、民間宗教のカルト的実践、最初の都市の勃興など、人類文明の初期に関するあらゆる知識は、考古学から得なければ ならない。 科学的な重要性に加えて、考古学的な遺物は、それを生み出した人々の子孫にとって政治的・文化的な意味を持つこともあれば、収集家にとって金銭的な価値を 持つこともあれば、強い美的魅力を持つこともある。多くの人々は、考古学を過去の社会の復元ではなく、そのような美的、宗教的、政治的、経済的な宝物の復 元と認識している。 このような見方は、『レイダース 失われたアーク』、『ミイラ』、『ソロモン王の鉱山』といった大衆小説の中でしばしば唱えられている。非現実的な題材がより真剣に扱われるようになると、 必ずと言っていいほど疑似科学という非難がその支持者に浴びせられる(「疑似考古学」を参照)。しかし、これらの試みは、現実であれフィクションであれ、 現代考古学を代表するものではない。 理論 主な記事 考古学理論 すべての考古学者に支持されている考古学理論というものは存在しない。19世紀後半に考古学が発展した際、最初に実践された考古学理論のアプローチは文化 史考古学であり、文化が変化・適応したという事実を強調するのではなく、なぜ変化・適応したのかを説明することを目的としていたため、歴史的特殊性が強調 された[51]。 1960年代には、ルイス・ビンフォードやケント・フラナリーといったアメリカの考古学者が中心となって、既存の文化史考古学に反旗を翻す考古学運動が起 こった[52][53]。 1980年代には、イギリスの考古学者マイケル・シャンクス[54][55][56][57]、クリストファー・ティリー[58]、ダニエル・ミラー [59][60]、イアン・ホッダー[61][62][63][64][65][66]らによって新たなポストモダンの運動が起こり、それはポスト・プロ セッショナル考古学として知られるようになった。しかし、このアプローチはプロセス主義者からは科学的厳密性に欠けるとして批判されており、プロセス主義 とポスト・プロセッシアリズムの妥当性については現在も議論が続いている。一方、歴史的プロセス主義として知られる別の理論が登場し、プロセス重視とポス ト・プロセッシュアル考古学が強調する反射性と歴史性を取り入れようとしている[67]。 考古学理論は現在、新進化思想、[68][35]現象学、ポストモダニズム、エージェンシー理論、認知科学、構造機能主義、ジェンダーに基づくフェミニスト考古学、システム理論など、幅広い影響力を借りている。 |

| Methods An archaeological investigation usually involves several distinct phases, each of which employs its own variety of methods. Before any practical work can begin, however, a clear objective as to what the archaeologists are looking to achieve must be agreed upon. This done, a site is surveyed to find out as much as possible about it and the surrounding area. Second, an excavation may take place to uncover any archaeological features buried under the ground. And, third, the information collected during the excavation is studied and evaluated in an attempt to achieve the original research objectives of the archaeologists. It is then considered good practice for the information to be published so that it is available to other archaeologists and historians, although this is sometimes neglected.[30] Remote sensing Before actually starting to dig in a location, remote sensing can be used to look where sites are located within a large area or provide more information about sites or regions. There are two types of remote sensing instruments—passive and active. Passive instruments detect natural energy that is reflected or emitted from the observed scene. Passive instruments sense only radiation emitted by the object being viewed or reflected by the object from a source other than the instrument. Active instruments emit energy and record what is reflected. Satellite imagery is an example of passive remote sensing. Here are two active remote sensing instruments: Lidar: Lidar (light detection and ranging) uses a laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) to transmit a light pulse and a receiver with sensitive detectors to measure the backscattered or reflected light. Distance to the object is determined by recording the time between the transmitted and backscattered pulses and using the speed of light to calculate the distance travelled. Lidars can determine atmospheric profiles of aerosols, clouds, and other constituents of the atmosphere. Laser altimeter: A laser altimeter uses a lidar (see above) to measure the height of the instrument platform above the surface. By independently knowing the height of the platform with respect to the mean Earth's surface, the topography of the underlying surface can be determined.[69] Field survey Main article: Archaeological survey  Monte Albán archaeological site The archaeological project then continues (or alternatively, begins) with a field survey. Regional survey is the attempt to systematically locate previously unknown sites in a region. Site survey is the attempt to systematically locate features of interest, such as houses and middens, within a site. Each of these two goals may be accomplished with largely the same methods. Survey was not widely practised in the early days of archaeology. Cultural historians and prior researchers were usually content with discovering the locations of monumental sites from the local populace, and excavating only the plainly visible features there. Gordon Willey pioneered the technique of regional settlement pattern survey in 1949 in the Viru Valley of coastal Peru,[70][71] and survey of all levels became prominent with the rise of processual archaeology some years later.[72] Survey work has many benefits if performed as a preliminary exercise to, or even in place of, excavation. It requires relatively little time and expense, because it does not require processing large volumes of soil to search out artifacts. (Nevertheless, surveying a large region or site can be expensive, so archaeologists often employ sampling methods.)[73] As with other forms of non-destructive archaeology, survey avoids ethical issues (of particular concern to descendant peoples) associated with destroying a site through excavation. It is the only way to gather some forms of information, such as settlement patterns and settlement structure. Survey data are commonly assembled into maps, which may show surface features and/or artifact distribution.  Inverted kite aerial photo of an excavation of a Roman building at Nesley near Tetbury in Gloucestershire. The simplest survey technique is surface survey. It involves combing an area, usually on foot but sometimes with the use of mechanized transport, to search for features or artifacts visible on the surface. Surface survey cannot detect sites or features that are completely buried under earth, or overgrown with vegetation. Surface survey may also include mini-excavation techniques such as augers, corers, and shovel test pits. If no materials are found, the area surveyed is deemed sterile. Aerial survey is conducted using cameras attached to airplanes, balloons, UAVs, or even Kites.[74] A bird's-eye view is useful for quick mapping of large or complex sites. Aerial photographs are used to document the status of the archaeological dig. Aerial imaging can also detect many things not visible from the surface. Plants growing above a buried human-made structure, such as a stone wall, will develop more slowly, while those above other types of features (such as middens) may develop more rapidly. Photographs of ripening grain, which changes colour rapidly at maturation, have revealed buried structures with great precision. Aerial photographs taken at different times of day will help show the outlines of structures by changes in shadows. Aerial survey also employs ultraviolet, infrared, ground-penetrating radar wavelengths, Lidar and thermography.[75] Geophysical survey can be the most effective way to see beneath the ground. Magnetometers detect minute deviations in the Earth's magnetic field caused by iron artifacts, kilns, some types of stone structures, and even ditches and middens. Devices that measure the electrical resistivity of the soil are also widely used. Archaeological features whose electrical resistivity contrasts with that of surrounding soils can be detected and mapped. Some archaeological features (such as those composed of stone or brick) have higher resistivity than typical soils, while others (such as organic deposits or unfired clay) tend to have lower resistivity. Although some archaeologists consider the use of metal detectors to be tantamount to treasure hunting, others deem them an effective tool in archaeological surveying.[76] Examples of formal archaeological use of metal detectors include musketball distribution analysis on English Civil War battlefields, metal distribution analysis prior to excavation of a 19th-century ship wreck, and service cable location during evaluation. Metal detectorists have also contributed to archaeology where they have made detailed records of their results and refrained from raising artifacts from their archaeological context. In the UK, metal detectorists have been solicited for involvement in the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Regional survey in underwater archaeology uses geophysical or remote sensing devices such as marine magnetometer, side-scan sonar, or sub-bottom sonar.[77] Excavation Main article: Archaeological excavation  Excavations at the 3800-year-old Edgewater Park Site, Iowa  Archaeological excavation that discovered prehistoric caves in Vill (Innsbruck), Austria  An archaeologist sifting for POW remains on Wake Island. Archaeological excavation existed even when the field was still the domain of amateurs, and it remains the source of the majority of data recovered in most field projects. It can reveal several types of information usually not accessible to survey, such as stratigraphy, three-dimensional structure, and verifiably primary context. Modern excavation techniques require that the precise locations of objects and features, known as their provenance or provenience, be recorded. This always involves determining their horizontal locations, and sometimes vertical position as well (also see Primary Laws of Archaeology). Likewise, their association, or relationship with nearby objects and features, needs to be recorded for later analysis. This allows the archaeologist to deduce which artifacts and features were likely used together and which may be from different phases of activity. For example, excavation of a site reveals its stratigraphy; if a site was occupied by a succession of distinct cultures, artifacts from more recent cultures will lie above those from more ancient cultures. Excavation is the most expensive phase of archaeological research, in relative terms. Also, as a destructive process, it carries ethical concerns. As a result, very few sites are excavated in their entirety. Again the percentage of a site excavated depends greatly on the country and "method statement" issued. Sampling is even more important in excavation than in survey. Sometimes large mechanical equipment, such as backhoes (JCBs), is used in excavation, especially to remove the topsoil (overburden), though this method is increasingly used with great caution. Following this rather dramatic step, the exposed area is usually hand-cleaned with trowels or hoes to ensure that all features are apparent. The next task is to form a site plan and then use it to help decide the method of excavation. Features dug into the natural subsoil are normally excavated in portions to produce a visible archaeological section for recording. A feature, for example a pit or a ditch, consists of two parts: the cut and the fill. The cut describes the edge of the feature, where the feature meets the natural soil. It is the feature's boundary. The fill is what the feature is filled with, and will often appear quite distinct from the natural soil. The cut and fill are given consecutive numbers for recording purposes. Scaled plans and sections of individual features are all drawn on site, black and white and colour photographs of them are taken, and recording sheets are filled in describing the context of each. All this information serves as a permanent record of the now-destroyed archaeology and is used in describing and interpreting the site. Analysis Main article: Post-excavation analysis  Five of the seven known fossil teeth of Homo luzonensis found in Callao Cave, the Philippines. Once artifacts and structures have been excavated, or collected from surface surveys, it is necessary to properly study them. This process is known as post-excavation analysis, and is usually the most time-consuming part of an archaeological investigation. It is not uncommon for final excavation reports for major sites to take years to be published. At a basic level of analysis, artifacts found are cleaned, catalogued and compared to published collections. This comparison process often involves classifying them typologically and identifying other sites with similar artifact assemblages. However, a much more comprehensive range of analytical techniques are available through archaeological science, meaning that artifacts can be dated and their compositions examined. Bones, plants, and pollen collected from a site can all be analyzed using the methods of zooarchaeology, paleoethnobotany, palynology and stable isotopes[78] while any texts can usually be deciphered. These techniques frequently provide information that would not otherwise be known, and therefore they contribute greatly to the understanding of a site. Computational and virtual archaeology Main articles: Computational archaeology and Virtual archaeology Computer graphics are now used to build virtual 3D models of sites, such as the throne room of an Assyrian palace or ancient Rome.[79] Photogrammetry is also used as an analytical tool, and digital topographical models have been combined with astronomical calculations to verify whether or not certain structures (such as pillars) were aligned with astronomical events such as the sun's position at a solstice.[79] Agent-based modelling and simulation can be used to better understand past social dynamics and outcomes. Data mining can be applied to large bodies of archaeological 'grey literature'. Drones Archaeologists around the world use drones to speed up survey work and protect sites from squatters, builders and miners. In Peru, small drones helped researchers produce three-dimensional models of Peruvian sites instead of the usual flat maps – and in days and weeks instead of months and years.[80] Drones costing as little as £650 have proven useful. In 2013, drones have flown over at least six Peruvian archaeological sites, including the colonial Andean town Machu Llacta 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) above sea level. The drones continue to have altitude problems in the Andes, leading to plans to make a drone blimp, employing open source software.[80] Jeffrey Quilter, an archaeologist with Harvard University said, "You can go up three metres and photograph a room, 300 metres and photograph a site, or you can go up 3,000 metres and photograph the entire valley."[80] In September 2014 drones weighing about 5 kg (11 lb) were used for 3D mapping of the above-ground ruins of the Greek city of Aphrodisias. The data are being analysed by the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna.[81] |

方法 考古学的調査には通常、いくつかの段階があり、それぞれの段階において様々な手法が用いられます。しかし、実際の作業を開始する前に、考古学者たちが何を 達成しようとしているのか、明確な目的が合意されなければなりません。そうして、遺跡とその周辺地域について可能な限り多くのことを調べるための調査が行 われる。次に、地中に埋もれている考古学的特徴を発見するために発掘調査が行われる。そして第三に、発掘調査中に収集された情報は、考古学者の当初の調査 目的を達成するために調査・評価される。そして、他の考古学者や歴史学者が利用できるように、その情報を公表するのが良い方法とされているが、これは時に 軽視されることもある[30]。 リモートセンシング 実際にその場所で発掘を始める前に、リモートセンシングを利用して、広い地域のどこに遺跡があるのかを調べたり、遺跡や地域に関する詳細な情報を得ること ができる。リモートセンシング機器には、パッシブ型とアクティブ型の2種類がある。パッシブ型は、観測対象から反射または放射される自然エネルギーを検出 する。パッシブ型観測機器は、観測対象物から放射される放射線、または観測機器以外から反射される放射線のみを感知する。能動的観測機器はエネルギーを放 出し、反射されたものを記録する。衛星画像はパッシブ・リモート・センシングの一例である。以下に2つの能動的リモートセンシング機器を挙げる: ライダー: ライダー(光検出と測距)は、レーザー(放射の誘導放出による光増幅)を使って光パルスを送信し、高感度検出器を備えた受信機で後方散乱光または反射光を 測定する。物体までの距離は、送信パルスと後方散乱パルスの間の時間を記録し、光速を使用して移動距離を計算することによって決定される。ライダーは、エ アロゾル、雲、その他の大気成分の大気プロファイルを測定することができる。 レーザー高度計: レーザー高度計は、ライダー(上記参照)を使用して、地表から機器プラットフォームの高さを測定します。平均地表面に対するプラットフォームの高さを独自に知ることで、その下にある地表の地形を決定することができる[69]。 現地調査 主な記事 考古学的調査  モンテ・アルバン遺跡 考古学プロジェクトは、その後、現地調査によって継続される(あるいは開始される)。地域調査とは、これまで知られていなかった地域の遺跡を体系的に探し 出す試みである。遺跡調査とは、遺跡の中にある住居や土坑など、興味のある特徴を系統的に見つける試みである。この2つの目的は、ほぼ同じ方法で達成でき る。 考古学の黎明期には、調査はあまり行われていなかった。文化史家やそれ以前の研究者たちは、地元の人々から遺跡の場所を聞き出し、そこで目に見える特徴だ けを発掘することで満足していた。ゴードン・ウィリーは1949年にペルー沿岸部のヴィル渓谷で地域的な集落パターン調査の技法を開拓し[70] [71]、その数年後にプロセス考古学の台頭とともにあらゆるレベルの調査が目立つようになった[72]。 調査作業は、発掘の予備作業として、あるいは発掘の代わりとして行われれば、多くの利点がある。遺物を探し出すために大量の土を処理する必要がないため、 時間も費用も比較的少なくて済む。(とはいえ、広い地域や遺跡を調査するには費用がかかるため、考古学者はサンプリング法を採用することが多い) [73]。他の非破壊考古学と同様、調査は、発掘によって遺跡を破壊することに伴う倫理的な問題(特に子孫の人々にとって懸念される)を回避することがで きる。集落パターンや集落構造など、いくつかの情報を収集する唯一の方法である。調査データは一般的に地図にまとめられ、地表の特徴や遺物の分布が示され ることもある。  グロスターシャーのテトベリー近郊ネスリーで発掘されたローマ時代の建物の倒立凧航空写真。 最も単純な調査技法は地表調査である。これは、通常は徒歩で、時には機械化された移動手段を使って、ある地域をくまなく調査し、地表に見える特徴や遺物を 探すものである。地表調査では、完全に土に埋もれていたり、植物が生い茂っていたりする遺跡や遺物は発見できない。地表調査には、オーガー、コアラー、 ショベル・テスト・ピットなどのミニ発掘技術も含まれる。物質が発見されない場合、調査された地域は無菌とみなされる。 航空調査は、飛行機、気球、UAV、あるいは凧に取り付けられたカメラを使って実施される[74]。航空写真は、考古学的発掘の状況を記録するために使用 される。航空写真は、地上からは見えない多くのものを発見することもできる。石垣のような埋もれた人工構造物の上に生えている植物はゆっくりと成長する が、他の種類の構造物(土坑など)の上に生えている植物は急速に成長する。成熟すると急速に色が変化する穀物の写真は、埋もれた構造物を非常に正確に明ら かにしている。異なる時間帯に撮影された航空写真は、影の変化によって構造物の輪郭を示すのに役立つ。航空調査には、紫外線、赤外線、地中レーダー波長、 ライダー、サーモグラフィも用いられる[75]。 物理探査は、地面の下を見る最も効果的な方法である。磁力計は、鉄製品、窯、ある種の石造構造物、さらには溝や土坑によって引き起こされる地球の磁場の微 小な偏差を検出する。土壌の電気抵抗率を測定する装置も広く使われている。電気抵抗率が周囲の土壌の電気抵抗率と対照的な考古学的特徴を検出し、マッピン グすることができる。石やレンガでできた遺跡のように、一般的な土壌よりも電気抵抗率が高い遺跡もあれば、有機堆積物や未焼成の粘土のように、電気抵抗率 が低い遺跡もある。 金属探知機の使用を宝探しに等しいと考える考古学者もいるが、考古学的調査における効果的なツールとみなす考古学者もいる[76]。金属探知機の考古学的 な正式な使用例としては、イギリス南北戦争の戦場におけるマスケット銃の弾丸の分布分析、19世紀の難破船の発掘前の金属分布分析、鑑定中のサービスケー ブルの位置特定などがある。また、金属探知機は、その結果を詳細に記録し、考古学的背景から遺物を持ち出すことを控えることで、考古学に貢献してきまし た。英国では、金属探知機使用者は携帯古物調査制度に参加するよう要請されている。 水中考古学における地域調査では、海洋磁力計、サイドスキャンソナー、サブボトムソナーなどの物理学的装置やリモートセンシング装置を使用する[77]。 発掘調査 主な記事 考古学的発掘  アイオワ州、3800年前のエッジウォーターパーク遺跡の発掘調査  オーストリア、ヴィル(インスブルック)で先史時代の洞窟を発見した考古学的発掘調査  ウェーク島で捕虜の遺骨を探す考古学者。 考古学的発掘調査は、その分野がまだアマチュアの領域であった時代から存在し、現在でもほとんどのフィールド・プロジェクトで回収されるデータの大半の源 となっている。発掘調査によって、層序、三次元構造、検証可能な一次的文脈など、通常調査にはアクセスできない数種類の情報を明らかにすることができる。 現代の発掘技術では、出土品や遺物の正確な位置を記録する必要がある。これには、常に水平方向の位置、時には垂直方向の位置も決定する必要がある(考古学 の基本法則も参照)。同様に、近隣の遺物や遺構との関連性も、後の分析のために記録しておく必要がある。これによって考古学者は、どの遺物や遺構が一緒に 使われた可能性が高いか、またどの遺物が異なる活動段階のものかを推測することができる。例えば、遺跡の発掘調査によって、その遺跡の地層が明らかにな る。ある遺跡が異なる文化によって次々と占拠されていた場合、より新しい文化の遺物は、より古い文化の遺物の上に位置することになる。 発掘調査は、相対的に見れば、考古学的調査の中で最も費用のかかる段階である。また、破壊的なプロセスであるため、倫理的な問題もある。そのため、遺跡全 体が発掘されることはほとんどない。この場合も、発掘される遺跡の割合は、国や「方法書」によって大きく異なる。発掘調査においては、サンプリングが調査 以上に重要である。発掘では、特に表土(残土)を取り除くために、バックホー(JCB)のような大型機械が使われることもあるが、この方法は非常に慎重に 行われるようになってきている。このかなり大げさなステップに続いて、すべての特徴が明らかになるように、露出した部分は通常、こてや鍬を使って手作業で 清掃される。 次の作業は、遺跡の平面図を作成し、それをもとに発掘方法を決めることである。自然の下層土に掘られた特徴物は通常、記録のために目に見える考古学的断面 を作るために部分的に掘られる。ピットや溝などのフィーチャは、切り口と盛り土の2つの部分から構成される。切り口は、その特徴が自然土と接する辺を示 す。これは特徴物の境界である。盛り土は、そのフィーチャが満たされている部分であり、多くの場合、自然の土とは全く異なって見える。切土と盛土には、記 録のために連続した番号が付けられる。個々の遺構の縮尺された平面図や断面図はすべて現場で描かれ、白黒写真やカラー写真が撮影され、それぞれの遺構の背 景を記した記録用紙に記入される。これらの情報はすべて、今は破壊されてしまった考古学の永久的な記録となり、遺跡の説明や解釈に使われる。 分析 主な記事 発掘後の分析  フィリピンのカラオ洞窟で発見されたホモ・ルゾネンシスの7本の歯の化石のうち5本。 遺物や構造物が発掘されたり、地表調査で採集されたりしたら、それらを適切に調査する必要がある。このプロセスは発掘後分析と呼ばれ、通常、考古学調査の 中で最も時間のかかる部分である。主要な遺跡の最終的な発掘調査報告書が出版されるまでに何年もかかることも珍しくない。 基本的な分析レベルでは、発見された遺物は洗浄され、カタログ化され、公表されているコレクションと比較される。この比較作業では、遺物を類型的に分類 し、似たような遺物群を持つ他の遺跡を特定することが多い。しかし、考古学ではより包括的な分析技術が利用できるため、遺物の年代を測定したり、その組成 を調べたりすることができる。遺跡から採集された骨、植物、花粉はすべて、動物考古学、古脊椎動物学、植物学、安定同位体学[78]などの手法で分析する ことができ、テキストは通常解読することができる。 これらの技術は、他の方法では知り得なかった情報を提供することが多いため、遺跡の理解に大きく貢献する。 計算考古学とバーチャル考古学 主な記事 計算考古学とバーチャル考古学 また、デジタル地形モデルと天文計算を組み合わせることで、特定の構造物(柱など)が夏至の太陽の位置などの天文現象と一致していたかどうかを検証するこ ともできる[79]。エージェントベースのモデリングやシミュレーションを利用することで、過去の社会力学や結果をより深く理解することができる。データ マイニングは、大量の考古学的「灰色文献」に適用することができる。 ドローン 世界中の考古学者がドローンを使って調査作業を迅速化し、不法占拠者や建設業者、採掘業者から遺跡を保護している。ペルーでは、小型ドローンのおかげで、 研究者たちはペルーの遺跡の3次元モデルを、通常の平面地図ではなく、数カ月から数年ではなく、数日から数週間で作成することができた[80]。 わずか650ポンドのドローンが有用であることが証明されている。2013年には、海抜4,000メートルの植民地時代のアンデスの町マチュ・ラクタを含 む、少なくとも6つのペルーの遺跡上空をドローンが飛行した。ドローンはアンデス山脈で高度の問題を抱え続けており、オープンソースソフトウェアを採用し たドローン飛行船を作る計画につながっている[80]。 ハーバード大学の考古学者であるジェフリー・キルターは、「3メートル上昇して部屋を撮影することも、300メートル上昇して遺跡を撮影することも、3,000メートル上昇して谷全体を撮影することもできる」と述べている[80]。 2014年9月、重さ約5kg(11ポンド)のドローンが、ギリシャの都市アフロディシアスの地上遺跡の3Dマッピングに使用された。データはウィーンのオーストリア考古学研究所によって分析されている[81]。 |

| Academic sub-disciplines Main article: Subfields of archaeology As with most academic disciplines, there are a very large number of archaeological sub-disciplines characterized by a specific method or type of material (e.g., lithic analysis, music, archaeobotany), geographical or chronological focus (e.g. Near Eastern archaeology, Islamic archaeology, Medieval archaeology), other thematic concern (e.g. maritime archaeology, landscape archaeology, battlefield archaeology), or a specific archaeological culture or civilization (e.g. Egyptology, Indology, Sinology).[82] Historical archaeology Main article: Historical archaeology Historical archaeology is the study of cultures with some form of writing and deals with objects and issues from the past. In medieval Europe, archaeologists have explored the illicit burial of unbaptized children in medieval texts and cemeteries.[83] In downtown New York City, archaeologists have exhumed the 18th century remains of the African Burial Ground. When remnants of the WWII Siegfried Line were being destroyed, emergency archaeological digs took place whenever any part of the line was removed, to further scientific knowledge and reveal details of the line's construction. Ethnoarchaeology Main article: Ethnoarchaeology Ethnoarchaeology is the ethnographic study of living people, designed to aid in our interpretation of the archaeological record.[84][85][86][87][88][89] The approach first gained prominence during the processual movement of the 1960s, and continues to be a vibrant component of post-processual and other current archaeological approaches.[68][90][91][92][93] Early ethnoarchaeological research focused on hunter-gatherer or foraging societies; today ethnoarchaeological research encompasses a much wider range of human behaviour. Experimental archaeology Main article: Experimental archaeology Experimental archaeology represents the application of the experimental method to develop more highly controlled observations of processes that create and impact the archaeological record.[94][95][96][97][98] In the context of the logical positivism of processualism with its goals of improving the scientific rigor of archaeological epistemologies, the experimental method gained importance. Experimental techniques remain a crucial component to improving the inferential frameworks for interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeometry Main article: Archaeological science Archaeometry aims to systematize archaeological measurement. It emphasizes the application of analytical techniques from physics, chemistry, and engineering. It is a field of research that frequently focuses on the definition of the chemical composition of archaeological remains for source analysis.[99] Archaeometry also investigates different spatial characteristics of features, employing methods such as space syntax techniques and geodesy as well as computer-based tools such as geographic information system technology.[100] Rare earth elements patterns may also be used.[101] A relatively nascent subfield is that of archaeological materials, designed to enhance understanding of prehistoric and non-industrial culture through scientific analysis of the structure and properties of materials associated with human activity.[102] Cultural resources management Main article: Cultural resources management This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (March 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Archaeology can be a subsidiary activity within Cultural resources management (CRM), also called Cultural heritage management (CHM) in the United Kingdom.[103] CRM archaeologists frequently examine archaeological sites that are threatened by development. Today, CRM accounts for most of the archaeological research done in the United States and much of that in western Europe as well. In the US, CRM archaeology has been a growing concern since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966, and most taxpayers, scholars, and politicians believe that CRM has helped preserve much of that nation's history and prehistory that would have otherwise been lost in the expansion of cities, dams, and highways. Along with other statutes, the NHPA mandates that projects on federal land or involving federal funds or permits consider the effects of the project on each archaeological site. The application of CRM in the United Kingdom is not limited to government-funded projects. Since 1990, PPG 16[104] has required planners to consider archaeology as a material consideration in determining applications for new development. As a result, numerous archaeological organizations undertake mitigation work in advance of (or during) construction work in archaeologically sensitive areas, at the developer's expense. In England, ultimate responsibility of care for the historic environment rests with the Department for Culture, Media and Sport[105] in association with English Heritage.[106] In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the same responsibilities lie with Historic Scotland,[107] Cadw[108] and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency[109] respectively. In France, the Institut national du patrimoine (The National Institute of Cultural Heritage) trains curators specialized in archaeology. Their mission is to enhance the objects discovered. The curator is the link between scientific knowledge, administrative regulations, heritage objects and the public. Among the goals of CRM are the identification, preservation, and maintenance of cultural sites on public and private lands, and the removal of culturally valuable materials from areas where they would otherwise be destroyed by human activity, such as proposed construction. This study involves at least a cursory examination to determine whether or not any significant archaeological sites are present in the area affected by the proposed construction. If these do exist, time and money must be allotted for their excavation. If initial survey and/or test excavations indicate the presence of an extraordinarily valuable site, the construction may be prohibited entirely. Cultural resources management has, however, been criticized. CRM is conducted by private companies that bid for projects by submitting proposals outlining the work to be done and an expected budget. It is not unheard of for the agency responsible for the construction to choose the proposal that asks for the least funding. CRM archaeologists face considerable time pressure, often being forced to complete their work in a fraction of the time that might be allotted for a purely scholarly endeavour. Compounding the time pressure is the vetting process of site reports that are required (in the US) to be submitted by CRM firms to the appropriate State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). From the SHPO's perspective there is to be no difference between a report submitted by a CRM firm operating under a deadline, and a multi-year academic project. The result is that for a Cultural Resource Management archaeologist to be successful, they must be able to produce academic quality documents at a corporate world pace. The annual ratio of open academic archaeology positions (inclusive of post-doc, temporary, and non- tenure track appointments) to the annual number of archaeology MA/MSc and PhD students is disproportionate. Cultural Resource Management, once considered an intellectual backwater for individuals with "strong backs and weak minds",[110] has attracted these graduates, and CRM offices are thus increasingly staffed by advance degreed individuals with a track record of producing scholarly articles but who also have extensive CRM field experience. |

アカデミックなサブディシプリン 主な記事 考古学の下位分野 ほとんどの学問分野がそうであるように、特定の方法や資料の種類(例:石器分析、音楽、考古学的植物学など)、地理的または年代的な焦点(例:近東考古 学、イスラム考古学、考古学的植物学など)によって特徴付けられる非常に多くの考古学の下位分野が存在する、 石器分析、音楽、考古植物学など)、地理的または年代的な焦点(近東考古学、イスラム考古学、中世考古学など)、その他のテーマ的関心(海洋考古学、景観 考古学、戦場考古学など)、あるいは特定の考古学的文化や文明(エジプト学、インド学、中国学など)を特徴とする非常に多くの考古学的下位分野がある [82]。 歴史考古学 主な記事 歴史考古学 歴史考古学とは、何らかの形で文字が残っている文化を研究し、過去の物や問題を扱う学問である。 中世ヨーロッパでは、考古学者が中世の書物や墓地における洗礼を受けていない子供の不法埋葬について調査している[83]。第二次世界大戦時のジークフ リートラインの残骸が破壊されていたとき、科学的知識を深め、ラインの建設の詳細を明らかにするために、ラインの一部が撤去されるたびに緊急考古学調査が 行われた。 民族考古学 主な記事 民族考古学 エスノアルケオロジー(Ethnoarchaeology)とは、考古学的記録の解釈を助けるために考案された、生きている人々の民族誌的研究のことであ る[84][85][86][87][88][89]。このアプローチは、1960年代のプロセス的運動で初めて脚光を浴び、ポスト・プロセッショナルや その他の現在の考古学的アプローチの活気ある構成要素であり続けている。 [初期のエスノアコオロギー研究は狩猟採集社会や採食社会に焦点を当てたものであったが、今日ではエスノアコオロギー研究はより広範な人間行動を対象とし ている。 実験考古学 主な記事 実験考古学 実験考古学は、考古学的記録を作成し、それに影響を与えるプロセスをより高度に制御された形で観察するための実験的手法の応用である[94][95] [96][97][98]。考古学的認識論の科学的厳密性を向上させるという目標を掲げた過程主義の論理実証主義の文脈において、実験的手法は重要性を増 した。実験的手法は、考古学的記録を解釈するための推論的枠組みを改善する上で、依然として重要な要素である。 考古学 主な記事 考古学 計量考古学は、考古学的な測定を体系化することを目的としている。物理学、化学、工学の分析技術の応用に重点を置いている。また、空間合成技術や測地学な どの手法や、地理情報システム技術などのコンピュータベースのツールを用いて、特徴のさまざまな空間的特徴を調査する[99]。 [100] 希土類元素のパターンも使用されることがある[101]。比較的新しい下位分野として、考古学的材料学があり、人間の活動に関連する材料の構造や特性の科 学的分析を通じて、先史時代や非工業文化の理解を深めることを目的としている[102]。 文化資源管理 主な記事 文化資源管理 このセクションには独自の研究が含まれている可能性があります。主張を検証し、インライン引用を追加することで改善してください。独自研究のみからなる記述は削除してください。(2014年3月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 考古学は、イギリスでは文化遺産管理(Cultural Heritage Management: CHM)とも呼ばれる文化資源管理(Cultural Resource Management: CRM)の補助的な活動であることもある[103]。今日、CRMは米国で行われる考古学調査のほとんどを占め、西ヨーロッパでもその多くを占めている。 アメリカでは、1966年に国家歴史保存法(National Historic Preservation Act:NHPA)が制定されて以来、考古学的調査に対する関心が高まっており、納税者、学者、政治家の多くは、CRMによって、都市、ダム、高速道路の 拡張によって失われるはずだった国の歴史や先史時代の多くが保存されるようになったと信じている。他の法令とともに、NHPAは、連邦の土地でのプロジェ クトや、連邦の資金や許可を伴うプロジェクトは、各考古学的遺跡への影響を考慮することを義務づけている。 イギリスにおけるCRMの適用は、政府資金によるプロジェクトに限定されるものではない。1990年以降、PPG16[104]は、新規開発の申請を決定 する際に、考古学を重要な考慮事項として考慮することを計画者に義務づけている。その結果、多くの考古学団体が、考古学的に影響を受けやすい場所での建設 工 事の前(あるいは工事中)に、開発者の費用負担で、影響緩和のための作業を行うようになっ ている。 イングランドでは、歴史的環境の管理に関する最終的な責任は、文化・メディア・スポーツ省[105]がイングリッシュ・ヘリテージと共同で負っている [106]。 スコットランド、ウェールズ、北アイルランドでは、同様の責任はそれぞれヒストリック・スコットランド[107]、Cadw[108]、北アイルランド環 境庁[109]にある。 フランスでは、国立文化遺産研究所(Institut national du patrimoine)が考古学専門の学芸員を養成している。彼らの使命は、発見された対象物をより良いものにすることである。学芸員は、科学的知識、行 政規則、遺産、一般市民をつなぐ役割を担っている。 CRMの目標のひとつは、公有地や私有地における文化遺跡の特定、保存、維持管理、そして、建設予定地などの人間活動によって破壊される可能性のある地域 から、文化的に価値のある物質を取り除くことである。この調査では、建設予定地の影響を受ける地域に、重要な遺跡が存在するかどうかを少なくともざっと調 査する。遺跡が存在する場合は、その発掘調査のために時間と費用を割かなければならない。最初の調査や試掘で、極めて貴重な遺跡の存在が判明した場合、工 事は全面的に禁止されることもある。 しかし、文化資源管理には批判もある。文化資源管理は民間企業によって行われ、プロポーザルを提出し、作業内容と予想される予算を提示して入札する。工事 を担当する機関が、最も資金を必要としない提案を選ぶことも珍しくない。CRMの考古学者は、かなりの時間的プレッシャーに直面し、純粋に学術的な取り組 みに割り当てられる時間のほんの一部で仕事を完了することを余儀なくされることが多い。このような時間的プレッシャーにさらに追い打ちをかけるのが、(米 国では)遺跡調査報告書の審査プロセスである。SHPOの立場からすれば、期限に追われるCRM会社から提出される報告書と、数年にわたる学術プロジェク トに違いはないはずだ。その結果、文化資源管理の考古学者が成功するためには、アカデミックな品質の文書を企業並みのペースで作成できなければならないと いうことになる。 ポスドク、臨時職員、テニュアトラックでない職員も含めた考古学の学術職の年間公募数と、考古学の修士課程・博士課程の年間学生数の比率は不釣り合いであ る。文化資源管理は、かつては「腰は強いが頭脳は弱い」人たちの知的僻地と考えられていたが[110]、このような卒業生を惹きつけ、その結果、CRMの オフィスには、学術論文を発表した実績を持ち、CRMのフィールドでの経験も豊富な上級学位を持つ人材がますます多く配置されるようになっている。 |

Protection Karl von Habsburg, on a Blue Shield International fact-finding mission in Libya The protection of archaeological finds for the public from catastrophes, wars and armed conflicts is increasingly being implemented internationally. This happens on the one hand through international agreements and on the other hand through organizations that monitor or enforce protection. United Nations, UNESCO and Blue Shield International deal with the protection of cultural heritage and thus also archaeological sites. This also applies to the integration of United Nations peacekeeping. Blue Shield International has undertaken various fact-finding missions in recent years to protect archaeological sites during the wars in Libya, Syria, Egypt and Lebanon. The importance of archaeological finds for identity, tourism and sustainable economic growth is repeatedly emphasized internationally.[111][112][113][114][115][116] The President of Blue Shield International, Karl von Habsburg, said during a cultural property protection mission in Lebanon in April 2019 with the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon: "Cultural assets are part of the identity of the people who live in a certain place. If you destroy their culture, you also destroy their identity. Many people are uprooted, often have no prospects anymore and subsequently flee from their homeland."[117] |

保護 カール・フォン・ハプスブルク、リビアでのブルーシールド・インターナショナルの実態調査ミッションにて 大災害や戦争、武力紛争から考古学的発見物を保護することは、国際的にますます重要になってきている。これは一方では国際的な協定を通じて、他方では保護 を監視または実施する組織を通じて行われている。国際連合、ユネスコ、ブルー・シールド・インターナショナルは、文化遺産の保護、つまり遺跡の保護に取り 組んでいる。これは国連平和維持活動の統合にも当てはまる。ブルー・シールド・インターナショナルは近年、リビア、シリア、エジプト、レバノンでの戦争中 に、遺跡を保護するためにさまざまな実態調査任務を遂行した。アイデンティティ、観光、持続可能な経済成長にとっての考古学的発見の重要性は、国際的に繰 り返し強調されている[111][112][113][114][115][116]。 ブルー・シールド・インターナショナルの社長であるカール・フォン・ハプスブルクは、2019年4月に国連レバノン暫定軍とともにレバノンで行われた文化 財保護ミッションにおいて、「文化財はある場所に住む人々のアイデンティティの一部です。彼らの文化を破壊すれば、彼らのアイデンティティも破壊すること になります。多くの人々が根こそぎ奪われ、多くの場合、展望がなくなり、その後、祖国から逃げ出すのです」[117]。 |

Popular views of archaeology Extensive excavations at Beit She'an, Israel  Permanent exhibition in a German multi-storey car park, explaining the archaeological discoveries made during the construction of this building Early archaeology was largely an attempt to uncover spectacular artifacts and features, or to explore vast and mysterious abandoned cities and was mostly done by upper class, scholarly men. This general tendency laid the foundation for the modern popular view of archaeology and archaeologists. Many of the public view archaeology as something only available to a narrow demographic. The job of archaeologist is depicted as a "romantic adventurist occupation".[118] and as a hobby more than a job in the scientific community. Cinema audiences form a notion of "who archaeologists are, why they do what they do, and how relationships to the past are constituted",[118] and is often under the impression that all archaeology takes place in a distant and foreign land, only to collect monetarily or spiritually priceless artifacts. The modern depiction of archaeology has incorrectly formed the public's perception of what archaeology is. Much thorough and productive research has indeed been conducted in dramatic locales such as Copán and the Valley of the Kings, but the bulk of activities and finds of modern archaeology are not so sensational. Archaeological adventure stories tend to ignore the painstaking work involved in carrying out modern surveys, excavations, and data processing. Some archaeologists refer to such off-the-mark portrayals as "pseudoarchaeology".[119] Archaeologists are also very much reliant on public support; the question of for whom they are working is often discussed.[120] |

考古学に対する一般的な見方 イスラエルのベイト・シェアンでの大規模な発掘調査  ドイツの立体駐車場に常設展示され、この建物の建設中に発見された考古学的発見について説明している。 初期の考古学は、目を見張るような遺物や遺跡を発見したり、広大で神秘的な廃墟となった都市を探検したりすることが主な目的であった。この一般的な傾向 が、考古学や考古学者に対する現代の一般的な見方の基礎を築いた。一般大衆の多くは、考古学は狭い層だけが利用できるものと考えている。考古学者という職 業は「ロマンティックな冒険主義者の職業」として描かれ[118]、科学界では仕事というよりも趣味として描かれる。映画の観客は「考古学者とは誰か、な ぜそのような仕事をするのか、過去との関係はどのように構成されるのか」という概念を形成し[118]、すべての考古学は遠く離れた異国の地で行われ、金 銭的あるいは精神的に貴重な遺物を収集するためだけに行われるという印象を持たれがちである。現代における考古学の描写は、考古学とは何かという一般大衆 の認識を誤って形成してきた。 コパンや王家の谷のようなドラマチックな場所では、確かに多くの徹底的で生産的な調査が行われてきたが、現代の考古学の活動や発見の大部分は、それほどセ ンセーショナルなものではない。考古学の冒険物語は、現代の調査や発掘、データ処理に関わる骨の折れる作業を無視しがちだ。考古学者の中には、このような 的外れな描写を「似非考古学」と呼ぶ者もいる[119]。また考古学者は公的支援に大きく依存しており、誰のために仕事をしているのかという疑問がしばし ば議論される[120]。 |

| Current issues and controversy Public archaeology Motivated by a desire to halt looting, curb pseudoarchaeology, and to help preserve archaeological sites through education and fostering public appreciation for the importance of archaeological heritage, archaeologists are mounting public-outreach campaigns.[121] They seek to stop looting by combatting people who illegally take artifacts from protected sites, and by alerting people who live near archaeological sites of the threat of looting. Common methods of public outreach include press releases, the encouragement of school field trips to sites under excavation by professional archaeologists, and making reports and publications accessible outside of academia.[122][123] Public appreciation of the significance of archaeology and archaeological sites often leads to improved protection from encroaching development or other threats. One audience for archaeologists' work is the public. Archaeologists increasingly realize that their work can benefit non-academic and non-archaeological audiences, and that they have a responsibility to educate and inform the public about archaeology. Local heritage awareness is aimed at increasing civic and individual pride through projects such as community excavation projects, and better public presentations of archaeological sites and knowledge.[citation needed] The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service (USFS) operates a volunteer archaeology and historic preservation program called the Passport in Time (PIT). Volunteers work with professional USFS archaeologists and historians on national forests throughout the U.S. Volunteers are involved in all aspects of professional archaeology under expert supervision.[124] Television programs, web videos and social media can also bring an understanding of underwater archaeology to a broad audience. The Mardi Gras Shipwreck Project[125] integrated a one-hour HD documentary,[126] short videos for public viewing and video updates during the expedition as part of the educational outreach. Webcasting is also another tool for educational outreach. For one week in 2000 and 2001, live underwater video of the Queen Anne's Revenge Shipwreck Project was webcast to the Internet as a part of the QAR DiveLive[127] educational program that reached thousands of children around the world.Southerly, C.; Gillman-Bryan, J. (19 February 2009). Diving on the Queen Anne's Revenge. The American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Created and co-produced by Nautilus Productions and Marine Grafics, this project enabled students to talk to scientists and learn about methods and technologies used by the underwater archaeology team.[128][129] In the UK, popular archaeology programs such as Time Team and Meet the Ancestors have resulted in a huge upsurge in public interest.[citation needed] Where possible, archaeologists now make more provisions for public involvement and outreach in larger projects than they once did,[130] and many local archaeological organizations operate within the Community archaeology framework[131] to expand public involvement in smaller-scale, more local projects. Archaeological excavation, however, is best undertaken by well-trained staff that can work quickly and accurately. Often this requires observing the necessary health and safety and indemnity insurance issues involved in working on a modern building site with tight deadlines. Certain charities and local government bodies sometimes offer places on research projects either as part of academic work or as a defined community project.[citation needed] There is also a flourishing industry selling places on commercial training excavations and archaeological holiday tours.[citation needed] Archaeologists prize local knowledge and often liaise with local historical and archaeological societies, which is one reason why Community archaeology projects are starting to become more common. Often archaeologists are assisted by the public in the locating of archaeological sites, which professional archaeologists have neither the funding, nor the time to do. Archaeological Legacy Institute (ALI), is a registered 501[c] [3] non-profit, media and education corporation registered in Oregon in 1999. ALI founded a website, The Archaeology Channel to support the organization's mission "to nurturing and bringing attention to the human cultural heritage, by using media in the most efficient and effective ways possible."[132] There is a considerable international body of research focused on archaeology and public value and tangible benefits of archaeology include[133] helping to counteract racism, documenting accomplishments of ignored communities, providing time-depth as a response to short-termism of the modern age, and contributing to human ecology, independent evidence base, historic context development and tourism[134] The delivery of public benefits through archaeology can be summarised as follows: through making a contribution to a shared history,[135] artistic and cultural treasures, local values, place-making and social cohesion, educational benefits, contribution to science and innovation, health and wellbeing, and added economic value to developers.[136][130] Pseudoarchaeology Main article: Pseudoarchaeology Pseudoarchaeology is an umbrella term for all activities that falsely claim to be archaeological but in fact violate commonly accepted and scientific archaeological practices. It includes much fictional archaeological work (discussed above), as well as some actual activity. Many non-fiction authors have ignored the scientific methods of processual archaeology, or the specific critiques of it contained in post-processualism.[citation needed] An example of this type is the writing of Erich von Däniken. His 1968 book, Chariots of the Gods?, together with many subsequent lesser-known works, expounds a theory of ancient contacts between human civilization on Earth and more technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations. This theory, known as palaeocontact theory, or Ancient astronaut theory, is not exclusively Däniken's, nor did the idea originate with him. Works of this nature are usually marked by the renunciation of well-established theories on the basis of limited evidence, and the interpretation of evidence with a preconceived theory in mind.[citation needed] Looting A looter's pit on the morning following its excavation, taken at Rontoy, Huaura Valley, Peru in June 2007. Several small holes left by looters' prospecting probes can be seen, as well as their footprints. Looting of archaeological sites is an ancient problem. For instance, many of the tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs were looted during antiquity.[137] Archaeology stimulates interest in ancient objects, and people in search of artifacts or treasure cause damage to archaeological sites. The commercial and academic demand for artifacts contributes directly to the illicit antiquities trade. Smuggling of antiquities abroad to private collectors has caused great cultural and economic damage in many countries whose governments lack the resources and or the will to deter it. Looters damage and destroy archaeological sites, denying future generations information about their ethnic and cultural heritage. Indigenous peoples especially lose access to and control over their 'cultural resources', ultimately denying them the opportunity to know their past.[138] In 1937, W. F. Hodge the Director of the Southwest Museum released a statement that the museum would no longer purchase or accept collections from looted contexts.[139] The first conviction of the transport of artifacts illegally removed from private property under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act was in 1992 in the State of Indiana.[140] Archaeologists trying to protect artifacts may be placed in danger by looters or locals trying to protect the artifacts from archaeologists who are viewed as looters by the locals.[141] Some historical archaeology sites are subjected to looting by metal detector hobbyists who search for artifacts using increasingly advanced technology. Efforts are underway among all major Archaeological organizations to increase education and legitimate cooperation between amateurs and professionals in the metal detecting community.[142] While most looting is deliberate, accidental looting can occur when amateurs, who are unaware of the importance of Archaeological rigor, collect artifacts from sites and place them into private collections. Descendant peoples In the United States, examples such as the case of Kennewick Man have illustrated the tensions between Native Americans and archaeologists, which can be summarized as a conflict between a need to remain respectful toward sacred burial sites and the academic benefit from studying them. For years, American archaeologists dug on Indian burial grounds and other places considered sacred, removing artifacts and human remains to storage facilities for further study. In some cases human remains were not even thoroughly studied but instead archived rather than reburied. Furthermore, Western archaeologists' views of the past often differ from those of tribal peoples. The West views time as linear; for many natives, it is cyclic. From a Western perspective, the past is long-gone; from a native perspective, disturbing the past can have dire consequences in the present. As a consequence of this, American Indians attempted to prevent archaeological excavation of sites inhabited by their ancestors, while American archaeologists believed that the advancement of scientific knowledge was a valid reason to continue their studies. This contradictory situation was addressed by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA, 1990), which sought to reach a compromise by limiting the right of research institutions to possess human remains. Due in part to the spirit of postprocessualism, some archaeologists have begun to actively enlist the assistance of indigenous peoples likely to be descended from those under study. Archaeologists have also been obliged to re-examine what constitutes an archaeological site in view of what native peoples believe to constitute sacred space. To many native peoples, natural features such as lakes, mountains or even individual trees have cultural significance. Australian archaeologists especially have explored this issue and attempted to survey these sites to give them some protection from being developed. Such work requires close links and trust between archaeologists and the people they are trying to help and at the same time study. While this cooperation presents a new set of challenges and hurdles to fieldwork, it has benefits for all parties involved. Tribal elders cooperating with archaeologists can prevent the excavation of areas of sites that they consider sacred, while the archaeologists gain the elders' aid in interpreting their finds. There have also been active efforts to recruit aboriginal peoples directly into the archaeological profession. Repatriation See Repatriation and reburial of human remains A new trend in the heated controversy between First Nations groups and scientists is the repatriation of native artifacts to the original descendants.[clarification needed] An example of this occurred on 21 June 2005, when community members and elders from a number of the 10 Algonquian nations in the Ottawa area convened on the Kitigan Zibi reservation near Maniwaki, Quebec, to inter ancestral human remains and burial goods—some dating back 6,000 years. It was not determined, however, if the remains were directly related to the Algonquin people who now inhabit the region. The remains may be of Iroquoian ancestry, since Iroquoian people inhabited the area before the Algonquin. Moreover, the oldest of these remains might have no relation at all to the Algonquin or Iroquois, and belong to an earlier culture who previously inhabited the area.[citation needed] The remains and artifacts, including jewelry, tools and weapons, were originally excavated from various sites in the Ottawa Valley, including Morrison and the Allumette Islands. They had been part of the Canadian Museum of Civilization's research collection for decades, some since the late 19th century. Elders from various Algonquin communities conferred on an appropriate reburial, eventually deciding on traditional red cedar and birch bark boxes lined with red cedar chips, muskrat and beaver pelts.[citation needed] An inconspicuous rock mound marks the reburial site where close to 80 boxes of various sizes are buried. Because of this reburial, no further scientific study is possible. Although negotiations were at times tense between the Kitigan Zibi community and museum, they were able to reach agreement.[143] African diaspora archaeology Main article: African diaspora archaeology African Diaspora Archaeology is an area of study within the subfield of historical archaeology that studies those that have been forcibly transported through the Atlantic Slave Trade, the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade, and the Indian Ocean Slave Trade, as well as their descendants. Although of global relevance, most research has been conducted in the Americas and Africa.[144][145] In the United States, Similar to the experience of Native Americans, the history of African diaspora archaeology is one of controversies over Whiteness in archaeology and anthropology, a lack of inclusion of the African descendant community,[146] and possession of human remains in the collections of universities and museums.[147] In the 1990s, anthropologist Michael Blakey was the director of research during the New York African Burial Ground Project where he initiated a protocol for collaborating with the African descendant community. In 2011, the Society of Black Archaeologists was created in the United States.[148] Co-founders Ayana Omilade Flewellen, archaeologist at the University of California, Riverside and Justin Dunnavant, archaeologist and assistant professor of anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles intend to build a restorative justice-based structure in archaeology. They suggest to define descendants not only in genealogical terms, but also to welcome input of African Americans whose ancestors had a shared historical experience in enslavement.[149] The United States Senate unanimously passed a bill[150] in December 2020 that centers African American cemeteries at risk in South Carolina. The bill is made to better protect historic African burial grounds and can lead to the creation of an African American Burial Grounds Network.[151] Barbados, eight days after becoming a republic on November 30, 2021, announced plans for the construction of the Newton Enslaved Burial Ground Memorial as well as a museum dedicated to the history of the Atlantic slave trade.[152] The Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye is to lead the project that is to commemorate an estimated 570 West Africans buried in unmarked graves at the site of the former Newton sugar plantation.[152][153] Barbados can be seen as a good example of respectful preservation of an African burial ground. Throughout the Americas however the burial grounds are in danger of being destroyed or human remains are being excavated without the descendant community being involved.[154][155][156][157][158] In 2022, residents on Sint Eustatius, Dutch Caribbean spoke out strongly against what they found were unethical excavations of their ancestors on the Godet African Burial Ground and the Golden Rock African Burial Ground.[159] Climate change and archaeology As anthropogenic climate change affects our environment, projections show that there will be changes in rainfall with increased drought and desertification, increases in intensity and frequency of rainfall, increases in temperature (winter and summer), increases in both the temperature and frequency of heatwaves, rising sea levels, and warmer seas, ocean acidification and changes in oceanic currents. These climate drivers will result in changes to flora and fauna, and changes in ground conditions (both on and below the surface) and so will also affect archaeological deposits and structures, while human responses to the climate crisis will also impact archaeological sites. The archaeologist's knowledge and skills are relevant to supporting society in adapting to a changing climate and a low carbon future.[160][161] Another effect of higher temperatures has been melting of glaciers and ice patches. This has led to the discovery of artifacts and bodies long buried in the ice, fostering the new field of glacial archaeology.[162][163] Archaeological sites can be seen as habitats that support ecosystems and fulfil biodiversity goals.[164] |