On De Anima by Aristotles

On De Anima by Aristotles

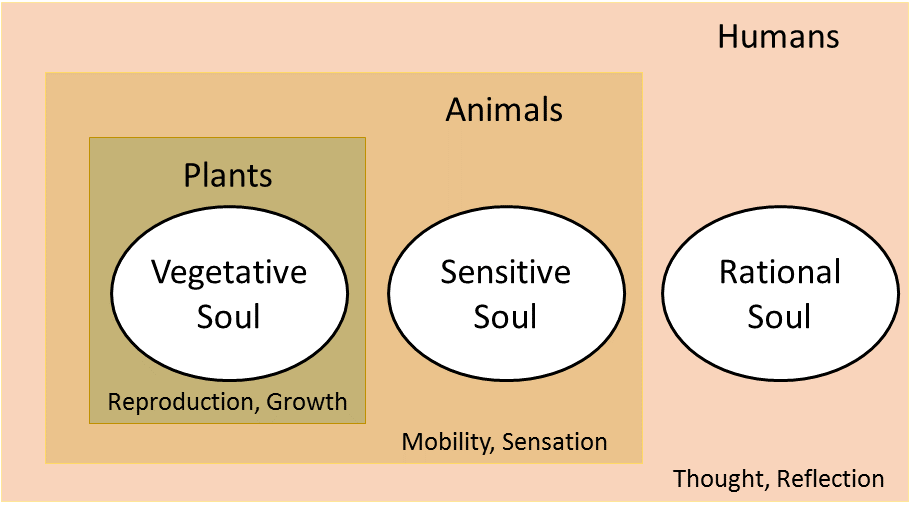

アリストテレスの魂について、と表題を書 いているが、アリストテレスが根性があるとか、ヘタレといった議論とは関係がない。アリストテレスが魂 (プシュケー)をどのように捉えていたのかを検討するのがこのページである。

結論から言うとこうである:「魂は、ある意味で、存在するものすべてであ る、と」中畑正志訳『魂について』431b20(2001:165)。

彼の『魂について』では、魂を次のように 定義している(第2巻第1章)——中畑正志訳。

【定義A】

「可能的に生命をもつ自然的実体の、形相としての実 体」あるいは、

「可能的に生命をもつ自然的実体の、第一次的な現実 態」そして、

「器官をそなえた自然的物体の、第一次的な現実態」

これらは、生命や器官をもつ、つまり、生きていることと、魂があるということが関係していることをさしている。これを、魂は身体の現実態で

ある、と言えよう。ただし、この定義は、心身一元論を言い換えにほかならず、魂は(形相としての)身体であり、(形相としての)身体は魂であると、言って

いる。つまり、トートロジーに他ならない(中畑 2001:248)。これを素材形相論(Hypomorphism)

【定義B】

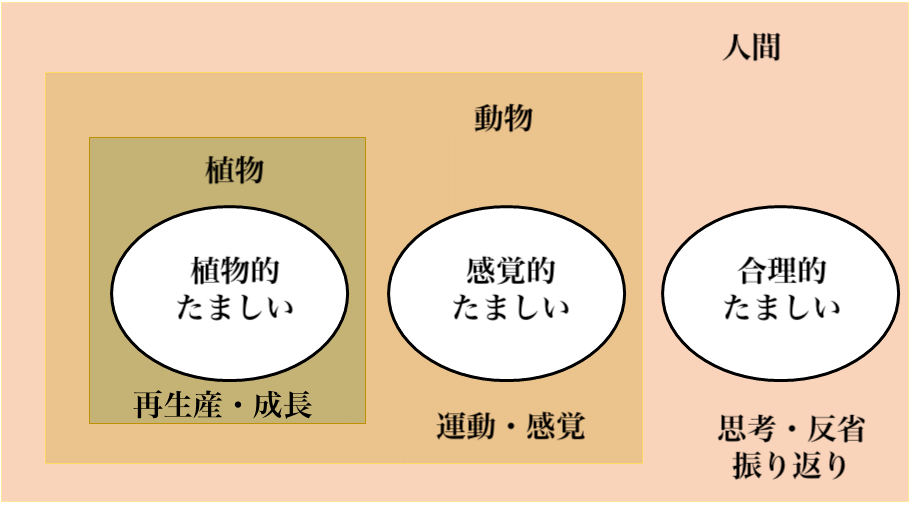

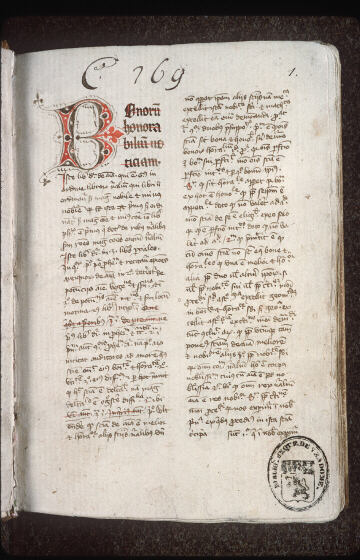

また、第2巻第2章では、「魂は、栄養摂取、感覚、思考、運動などの始原(原理)であり、それらによって、つまり栄養摂取する能力、感覚す る能力、動き(キーネーシス)によって規定される」とも述べている。

すなわち、栄養を摂取する、感覚する、動くということは、すべて、定義Aで示した「生きている」ことを可能にする条件である。したがって、 アリストテレスの魂について考えるということは、これらの「栄養を摂取する、感覚する、動く」という「生きているもの」の具体的な現象から把握しなければ ならないということになる。

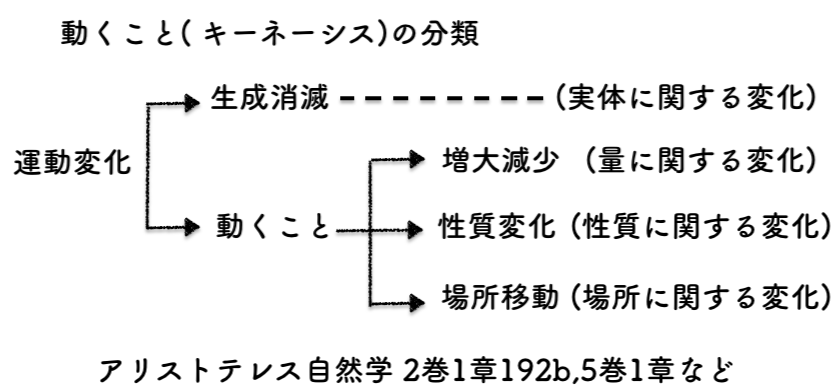

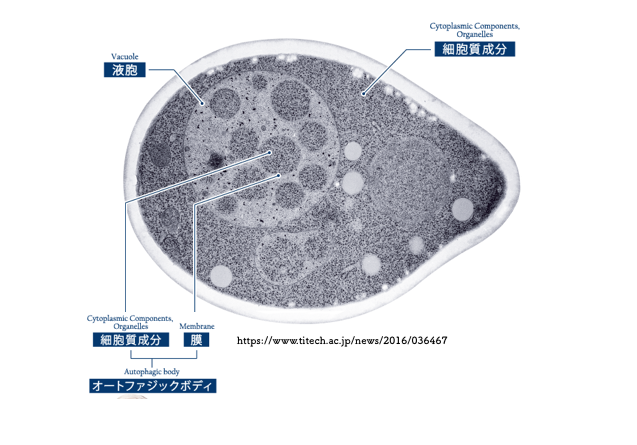

その意味で、大隅良典教授のオートファジーもまた、自己の一部の消化を通して、〈生きるということの動態〉に関する現実態であると言える。

●ニコマコス倫理学

魂(たましい)には、理性的な2つの部分 がある;『ニコマコス倫理学』(1139a*)

(1)エピステーモニコン(知識的部分) と(2)ロギスティコン(理知的部分)である。前者のエピステーモニコンは、他の仕方でもありうるもの である。また後者のロギスティコンとは、熟慮することに関係し(学問的知識は)他の仕方ではありえない、ものである。ここで後者の、熟慮することとは、ギ リシャ語でブーレウエスタイのことである。

◎On the Soul

On the Soul (Greek:

Περὶ Ψυχῆς, Peri Psychēs; Latin: De Anima) is a major treatise written

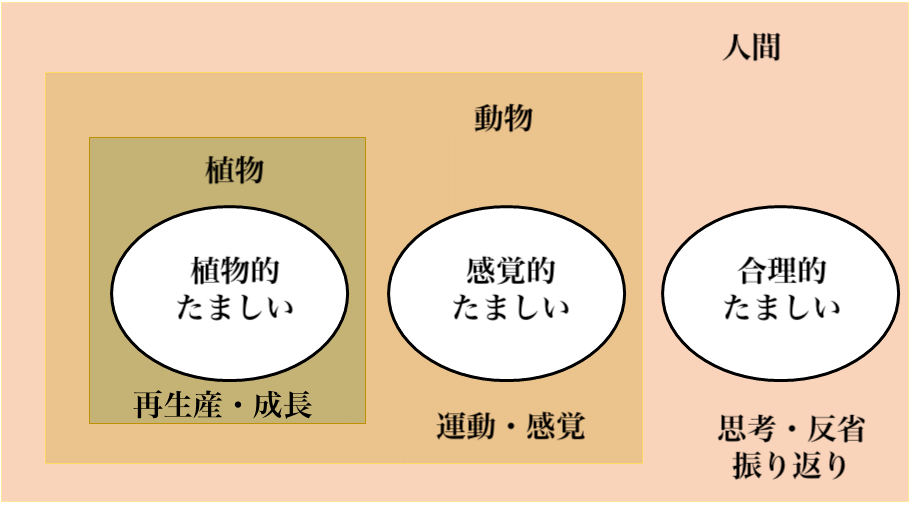

by Aristotle c. 350 BC.[1] His discussion centres on the kinds of souls

possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their

different operations. Thus plants have the capacity for nourishment and

reproduction, the minimum that must be possessed by any kind of living

organism. Lower animals have, in addition, the powers of

sense-perception and self-motion (action). Humans have all these as

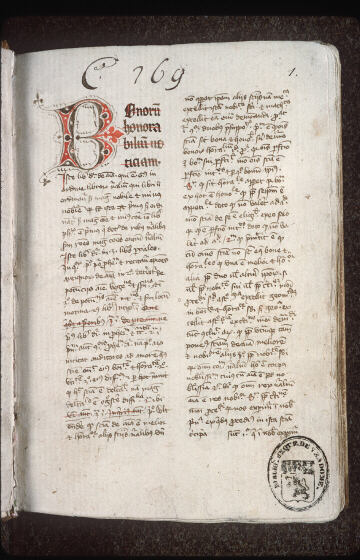

well as intellect. "Expositio et quaestiones" in Aristoteles De Anima (Jean Buridan, c. 1362) Aristotle holds that the soul (psyche, ψυχή) is the form, or essence of any living thing; it is not a distinct substance from the body that it is in. It is the possession of a soul (of a specific kind) that makes an organism an organism at all, and thus that the notion of a body without a soul, or of a soul in the wrong kind of body, is simply unintelligible. (He argues that some parts of the soul — the intellect — can exist without the body, but most cannot.) In 1855, Charles Collier published a translation titled On the Vital Principle. George Henry Lewes, however, found this description also wanting.[2] |

魂について』(ギリシア語: Περὶ Ψυχῆς, Peri

Psychēs; ラテン語: De Anima)は、紀元前350年頃にアリストテレスによって書かれた主要な論考である[1]

。植物は栄養と生殖の能力を持っているが、これはあらゆる種類の生物に最低限備わっていなければならないものである。下等動物はそれに加えて、感覚知覚と

自己運動(行動)の能力を持っている。人間はこれらすべてと知性を持っている。 アリストテレス『アニマ論』の "Expositio et quaestiones" (Jean Buridan, c. 1362) アリストテレスは、魂(psyche, ψυχή)は生きとし生けるものの形、あるいは本質であり、魂が宿っている肉体とは別個の物質ではないとする。ある生物を生物たらしめているのは、(特定 の種類の)魂の所有であり、したがって、魂のない身体や、間違った種類の身体に宿った魂という概念は、単に理解できないだけである。(彼は、魂の一部(知 性)は肉体なしでも存在できるが、大部分は存在できないと主張している)。 1855年、チャールズ・コリアーは『生命原理について』と題する翻訳を出版した。しかし、ジョージ・ヘンリー・ルイスはこの記述も不十分であるとした [2]。 |

| Division of chapters The treatise is divided into three books, and each of the books is divided into chapters (five, twelve, and thirteen, respectively). The treatise is near-universally abbreviated "DA", for "De anima", and books and chapters generally referred to by Roman and Arabic numerals, respectively, along with corresponding Bekker numbers. (Thus, "DA I.1, 402a1" means "De anima, book I, chapter 1, Bekker page 402, Bekker column a [the column on the left side of the page], line number 1.) Book I DA I.1 introduces the theme of the treatise; DA I.2–5 provide a survey of Aristotle’s predecessors’ views about the soul Book II DA II.1–3 gives Aristotle's definition of soul and outlines his own study of it,[3] which is then pursued as follows: DA II.4 discusses nutrition and reproduction; DA II.5–6 discuss sensation in general; DA II.7–11 discuss each of the five senses (in the following order: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—one chapter for each); DA II.12 again takes up the general question of sensation; Book III DA III.1 argues there are no other senses than the five already mentioned; DA III.2 discusses the problem of what it means to "sense sensing" (i.e., to "be aware" of sensation); DA III.3 investigates the nature of imagination; DA III.4–7 discuss thinking and the intellect, or mind; DA III.8 articulates the definition and nature of soul; DA III.9–10 discuss the movement of animals possessing all the senses; DA III.11 discusses the movement of animals possessing only touch; DA III.12–13 take up the question of what are the minimal constituents of having a soul and being alive. Summary Book I contains a summary of Aristotle's method of investigation and a dialectical determination of the nature of the soul. He begins by conceding that attempting to define the soul is one of the most difficult questions in the world. But he proposes an ingenious method to tackle the question: Just as we can come to know the properties and operations of something through scientific demonstration, i.e. a geometrical proof that a triangle has its interior angles equal to two right angles, since the principle of all scientific demonstration is the essence of the object, so too we can come to know the nature of a thing if we already know its properties and operations. It is like finding the middle term to a syllogism with a known conclusion. Therefore, we must seek out such operations of the soul to determine what kind of nature it has. From a consideration of the opinions of his predecessors, a soul, he concludes, will be that in virtue of which living things have life. Book II contains his scientific determination of the nature of the soul, an element of his biology. By dividing substance into its three meanings (matter, form, and what is composed of both), he shows that the soul must be the first actuality of a natural, organized body. This is its form or essence. It cannot be matter because the soul is that in virtue of which things have life, and matter is only being in potency. The rest of the book is divided into a determination of the nature of the nutritive and sensitive souls. (1) All species of living things, plant or animal, must be able to nourish themselves, and reproduce others of the same kind. (2) All animals have, in addition to the nutritive power, sense-perception, and thus they all have at least the sense of touch, which he argues is presupposed by all other senses, and the ability to feel pleasure and pain, which is the simplest kind of perception. If they can feel pleasure and pain they also have desire. Some animals in addition have other senses (sight, hearing, taste), and some have more subtle versions of each (the ability to distinguish objects in a complex way, beyond mere pleasure and pain.) He discusses how these function. Some animals have in addition the powers of memory, imagination, and self-motion.  Aristotle describes the structure of the souls of plants, animals, and humans in Books II and III. Book III discusses the mind or rational soul, which belongs to humans alone. He argues that thinking is different from both sense-perception and imagination because the senses can never lie and imagination is a power to make something sensed appear again, while thinking can sometimes be false. And since the mind is able to think when it wishes, it must be divided into two faculties: One which contains all the mind's ideas which are able to be considered, and another which brings them into action, i.e. to be actually thinking about them. These are called the possible and agent intellect. The possible intellect is an "unscribed tablet" and the store-house of all concepts, i.e. universal ideas like "triangle", "tree", "man", "red", etc. When the mind wishes to think, the agent intellect recalls these ideas from the possible intellect and combines them to form thoughts. The agent intellect is also the faculty which abstracts the "whatness" or intelligibility of all sensed objects and stores them in the possible intellect. For example, when a student learns a proof for the Pythagorean theorem, his agent intellect abstracts the intelligibility of all the images his eye senses (and that are a result of the translation by imagination of sense perceptions into immaterial phantasmata), i.e. the triangles and squares in the diagrams, and stores the concepts that make up the proof in his possible intellect. When he wishes to recall the proof, say, for demonstration in class the next day, his agent intellect recalls the concepts and their relations from the possible intellect and formulates the statements that make up the arguments in the proof. The argument for the existence of the agent intellect in Chapter V perhaps due to its concision has been interpreted in a variety of ways. One standard scholastic interpretation is given in the Commentary on De anima begun by Thomas Aquinas.[a] Aquinas' commentary is based on the new translation of the text from the Greek completed by Aquinas' Dominican associate William of Moerbeke at Viterbo in 1267.[4] The argument, as interpreted by Thomas Aquinas, runs something like this: In every nature which is sometimes in potency and act, it is necessary to posit an agent or cause within that genus that, just like art in relation to its suffering matter, brings the object into act. But the soul is sometimes in potency and act. Therefore, the soul must have this difference. In other words, since the mind can move from not understanding to understanding and from knowing to thinking, there must be something to cause the mind to go from knowing nothing to knowing something, and from knowing something but not thinking about it to actually thinking about it. Aristotle also argues that the mind (only the agent intellect) is immaterial, able to exist without the body, and immortal. His arguments are notoriously concise. This has caused much confusion over the centuries, causing a rivalry between different schools of interpretation, most notably, between the Arabian commentator Averroes and Thomas Aquinas.[citation needed] One argument for its immaterial existence runs like this: if the mind were material, then it would have to possess a corresponding thinking-organ. And since all the senses have their corresponding sense-organs, thinking would then be like sensing. But sensing can never be false, and therefore thinking could never be false. And this is of course untrue. Therefore, Aristotle concludes, the mind is immaterial. Perhaps the most important but obscure argument in the whole book is Aristotle's demonstration of the immortality of the thinking part of the human soul, also in Chapter V. Taking a premise from his Physics, that as a thing acts, so it is, he argues that since the active principle in our mind acts with no bodily organ, it can exist without the body. And if it exists apart from matter, it therefore cannot be corrupted. And therefore there exists a mind which is immortal. As to what mind Aristotle is referring to in Chapter V (i.e. divine, human, or a kind of world soul), has represented a hot topic of discussion for centuries. The most likely is probably the interpretation of Alexander of Aphrodisias, likening Aristotle's immortal mind to an impersonal activity, ultimately represented by God. |

章立て 本書は3巻に分かれ、各巻はそれぞれ5章、12章、13章に分かれている。本書はほぼ一般的に "De anima "の頭文字をとって "DA "と略され、書と章はそれぞれローマ数字とアラビア数字、それに対応するベッカー番号で表記される。(したがって、"DA I.1, 402a1 "は、"De anima, book I, chapter 1, Bekker page 402, Bekker column a [the column on the left side of the page], line number 1 "を意味する)。 第一書 DA I.1は、この論文のテーマを紹介している; DA I.2-5では、アリストテレスの先人たちの魂についての見解が述べられている。 第II巻 DA II.1-3はアリストテレスの魂の定義を示し、彼自身の魂の研究を概説する[3]: DA II.4は栄養と生殖について論じている; DA II.5-6は感覚一般について論じている; DA II.7-11では、五感のそれぞれについて論じている(視覚、聴覚、嗅覚、味覚、触覚の順に、それぞれ1章ずつ); DA II.12では、再び感覚全般について論じている; 第III巻 DA III.1では、すでに述べた5つの感覚以外に感覚は存在しないと論じている; DA III.2は、「感覚を感じる」(すなわち、感覚を「自覚する」)とはどういうことかという問題について論じている; DA III.3は、想像力の本質を探究する; DA III.4-7は、思考と知性(心)について論じる; DA III.8は魂の定義と性質を明確にする; DA III.9-10 五感を持つ動物の動きについて論じる; DA III.11は触覚のみを持つ動物の動きについて論じる; DA III.12-13では、魂を持ち、生きていることの最小構成要素は何かという問題を取り上げる。 要約 第1巻は、アリストテレスの究明方法の要約と、魂の性質についての弁証法的判断を含んでいる。アリストテレスはまず、魂を定義することはこの世で最も困難 な問題のひとつであることを認める。しかし彼は、この問題に取り組むための独創的な方法を提案する: 科学的実証、つまり三角形の内角が2つの直角に等しいという幾何学的証明によって、私たちが何かの性質や動作を知ることができるように、すべての科学的実 証の原理は対象の本質である。それは、結論がわかっている五段論法の中間項を見つけるようなものである。 したがって、魂がどのような性質を持っているかを判断するためには、魂のそのような操作を探し出さなければならない。先人たちの意見を考慮すると、魂とは 生き物が生命を持つためのものである、と彼は結論づける。 第2巻には、彼の生物学の要素である魂の性質についての科学的な判断が書かれている。物質を3つの意味(物質、形態、その両方で構成されるもの)に分ける ことによって、彼は魂が自然で組織化された肉体の最初の実在でなければならないことを示す。これがその形、あるいは本質である。なぜなら、魂とは物事が生 命を持つためのものであり、物質とは潜在的な存在に過ぎないからである。本書の残りの部分は、栄養的な魂と感受性の魂の性質の決定に分かれている。 (1) 植物であれ動物であれ、生きとし生けるものはすべて、自らを養い、同種のものを繁殖させることができなければならない。 (2)すべての動物は、栄養を与える力に加えて、感覚的知覚を持っている。したがって、すべての動物は少なくとも触覚を持っており、それは他のすべての感 覚によって前提されていると彼は主張する。喜びや痛みを感じることができれば、欲望を持つこともできる。 さらに、他の感覚(視覚、聴覚、味覚)を持っている動物もいるし、それぞれの微妙なバージョン(単なる快楽や苦痛を超えた、複雑な方法で対象を区別する能 力)を持っている動物もいる。彼はこれらがどのように機能するかについて論じている。さらに、記憶力、想像力、自己運動能力を持つ動物もいる。  アリストテレスは植物、動物、人間の魂の構造について第II巻と第III巻で述べている。 第III巻では、人間だけに属する心あるいは理性的な魂について論じている。なぜなら、感覚は決して嘘をつくことができず、想像力は感覚したものを再び出 現させる力だからである。そして、心は望めば考えることができるのだから、2つの能力に分けられなければならない: ひとつは、考えることのできる心の考えをすべて含む能力であり、もうひとつは、それらを行動に移す、つまり実際に考える能力である。 これらは可能知性と行為知性と呼ばれる。可能知性は「無記名の石版」であり、すべての概念、すなわち「三角形」、「木」、「人間」、「赤」などの普遍的な 概念の貯蔵庫である。心が考えようとするとき、代理知性は可能知性からこれらの観念を呼び出し、それらを組み合わせて思考を形成する。エージェント知性は また、知覚されたすべての対象の「何であるか」、つまり理解可能性を抽象化し、可能知性に保存する能力でもある。 例えば、生徒がピタゴラスの定理の証明を学ぶとき、彼の代理知性は、彼の眼が感知したすべてのイメージ(そしてそれは、感覚知覚が想像力によって非物質的 なファンタスマタに変換された結果である)、すなわち、図の中の三角形や四角形の了解可能性を抽象化し、証明を構成する概念を彼の可能知性に格納する。そ の証明を、たとえば翌日の授業で実演するために思い出したいとき、彼の代理知性は可能知性から概念とその関係を呼び出し、証明の論証を構成する文を定式化 する。 第V章における代理知性の存在に関する議論は、その簡潔さゆえか、さまざまに解釈されてきた。一つの標準的なスコラ学的解釈は、トマス・アクィナスによっ て始められた『アニマ論』の注解に示されている[a]。アクィナスの注解は、1267年にアクィナスのドミニコ会の同僚であったモエルベケのウィリアムが ヴィテルボで完成させたギリシャ語からのテキストの新訳に基づいている[4]。 トマス・アクィナスが解釈した議論は次のようなものである: 時に効力を持ち、時に作用するすべての性質において、その属の中に、ちょうどその苦悩する物質との関係における芸術のように、対象を作用させる代理人また は原因を仮定することが必要である。しかし、魂は時に潜在力を持ち、時に作用する。したがって、魂はこの差異を持たなければならない。言い換えれば、心は 理解しない状態から理解する状態へ、そして知っている状態から考える状態へと移行することができるのだから、心を何も知らない状態から何かを知る状態へ、 そして何かを知っているがそれについて考えていない状態から実際にそれについて考える状態へと移行させる何かがなければならない。 アリストテレスはまた、心(知性という主体のみ)は非物質的であり、肉体なしに存在することができ、不滅であるとも論じている。彼の議論は簡潔であること で有名である。もし心が物質的であるならば、それに対応する思考器官を持たなければならない。もし心が物質的であるならば、それに対応する思考器官を持た なければならない。そして、すべての感覚はそれに対応する感覚器官を持っているので、思考は感覚と同じである。しかし、感覚は決して偽ることができず、し たがって思考も偽ることができない。そして、これはもちろん真実ではない。したがって、アリストテレスは、心は非物質であると結論づける。 おそらく本書で最も重要でありながら不明瞭な論証は、同じく第五章にある、人間の魂の思考部分の不滅性を示すアリストテレスの論証であろう。物事が作用す るように、それはそうであるという『物理学』の前提に立ち、彼は、私たちの心の中の活動原理は肉体の器官を伴わずに作用するので、肉体なしに存在しうると 論じる。そして、もしそれが物質から離れて存在するならば、それゆえに堕落することはありえない。それゆえ、不滅の心が存在するのである。アリストテレス が第五章で、どのような心(神的な心、人間的な心、あるいは一種の世界的な心)を指しているのかについては、何世紀にもわたって議論されてきた。最も有力 なのはアフロディジアスのアレクサンダーの解釈で、アリストテレスの不滅の心を、究極的には神に代表される非人格的な活動になぞらえたものであろう。 |

| Arabic paraphrase In Late Antiquity, Aristotelian texts became re-interpreted in terms of Neoplatonism. There is a paraphrase of De Anima which survives in the Arabic tradition which reflects such a Neoplatonic synthesis. The text was translated into Persian in the 13th century. It is likely based on a Greek original which is no longer extant, and which was further syncretised in the heterogeneous process of adoption into early Arabic literature.[5] A later Arabic translation of De Anima into Arabic is due to Ishaq ibn Hunayn (d. 910). Ibn Zura (d. 1008) made a translation into Arabic from Syriac. The Arabic versions show a complicated history of mutual influence. Avicenna (d. 1037) wrote a commentary on De Anima, which was translated into Latin by Michael Scotus. Averroes (d. 1198) used two Arabic translations, mostly relying on the one by Ishaq ibn Hunayn, but occasionally quoting the older one as an alternative. Zerahiah ben Shealtiel Ḥen translated Aristotle's De anima from Arabic into Hebrew in 1284. Both Averroes and Zerahiah used the translation by Ibn Zura.[6] |

アラビア語の言い換え 古代末期、アリストテレスのテキストは新プラトン主義の観点から再解釈されるようになった。新プラトン主義的統合を反映した『アニマ論』のアラビア語パラ フレーズが残っている。このテキストは13世紀にペルシア語に翻訳された。このテキストは、おそらく現存しないギリシア語の原文に基づいており、初期アラ ビア文学への異種混交の過程でさらにシンクレタイズされたものである[5]。 De Anima』の後世のアラビア語訳はIshaq ibn Hunayn(910年)による。イブン・ズーラ(1008年)はシリア語からアラビア語に翻訳した。アラビア語版は、相互に影響しあった複雑な歴史を示 している。アヴィセンナ(1037年没)は『De Anima』の注釈書を書き、それをミヒャエル・スコトゥスがラテン語に翻訳した。アヴェロエス(1198年没)は2つのアラビア語訳を用い、その大部分 はイシャク・イブン・フナインの訳に依存していたが、時折古い方の訳を引用することもあった。ゼラヒア・ベン・シェールティエル・Ḥenは1284年、ア リストテレスの『De anima』をアラビア語からヘブライ語に翻訳した。アヴェロエスもゼラヒアもイブン・ズーラの翻訳を使用した[6]。 |

| Some manuscripts Codex Vaticanus 253 Codex Vaticanus 253 is one of the most important manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol L. Paleographically it has been assigned to the 13th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript is not complete; it contains only Book III. It belongs to the textual family λ, together with the manuscripts E, Fc, Lc, Kd, and P. The manuscript was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. Currently it is housed at the Vatican Library (gr. 253) in Rome. Codex Vaticanus 260 Codex Vaticanus 260 is one of the most important manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol U. Paleographically it has been assigned to the 11th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains the complete text of the treatise. It belongs to the textual family ν, together with the manuscripts X, v, Ud, Ad, and Q. The manuscript was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. Currently it is housed at the Vatican Library (Vat. gr. 260) in Rome. Codex Vaticanus 266 Codex Vaticanus 266 is one of the most important manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol V. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 14th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. It belongs to the textual family κ, but only to Chapter 8. of II book. Another member of the family κ: Gc W Hc Nc Jd Oc Zc Vc Wc f Nd Td. The manuscript was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, and Apelt in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. David Ross did not use the manuscript in his own edition. Currently it is housed at the Vatican Library (gr. 266) in Rome. Codex Vaticanus 1026 Codex Vaticanus 1026 is a manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by symbol W. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 13th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The Greek text of the manuscript is eclectic. It belongs to the textual family μ[7] to II book, 7 chapter, 419 a 27. Since 419 a 27 it is a representative of the family κ.[8] The manuscript was not cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. It means the manuscript has not high value. Currently it is housed at the Vatican Library (gr. 1026) at Rome. Codex Vaticanus 1339 Codex Vaticanus 1339 is a manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by symbol P. Paleographically it has been assigned to the 14th or 15th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The text of the manuscript is eclectic. It represents the textual family σ in book II of the treatise, from II, 2, 314b11, to II, 8, 420a2.[9] After book II, chapter 9, 429b16, it belongs to the family λ.[10] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in rheir critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. This means the manuscript is not of high value. Currently it is housed at the Vatican Library (gr. 1339) at Rome. Codex Ambrosianus 435 Codex Ambrosianus 435 is one of the most important manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol X. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 12th or 13th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains the complete text of the treatise. It belongs to the textual family ν, together with the manuscripts v Ud Ad U Q. The manuscript is one of nine manuscripts that was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and one of five cited by Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. Currently it is housed at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana (435 (H. 50)) in Milan. Codex Ambrosianus 837 Codex Ambrosianus 837 is a manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol Dc. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 13th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The text of the manuscript is eclectic. It represents to the textual family σ, in I-II books of the treatise.[11] In III book of the treatise it belongs to the family τ.[12] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, or Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. Currently it is housed at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana (837 (B 7 Inf.)) in Milan. Codex Coislinianus 386 Codex Coislinianus 386 is one of the important manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by the symbol C. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 11th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains the complete text of the treatise. It belongs to the textual family ξ, together with the manuscripts T Ec Xd Pd Hd. The manuscript was cited by David Ross in his critical edition of the treatise On the Soul. Currently it is housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Coislin 386) in Paris. Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 2 Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 2 is a manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by symbol Td. Dated by a Colophon to the year 1496. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The text of the manuscript represents the textual family κ.[13] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. It means the manuscript has not high value. Currently it is housed at the Austrian National Library (Philos. 2) at Vienna. Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 75 Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 75 is a manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by symbol Sd. Dated by a Colophon to the year 1446. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The text of the manuscript represents to the textual family ρ.[14] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. It means the manuscript has not high value. Currently it is housed at the Austrian National Library (Philos. 75) at Vienna. Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 157 Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 157 is a manuscripts of the treatise. It is designated by symbol Rd. Paleographically it had been assigned to the 15th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains a complete text of the treatise. The text of the manuscript represents the textual family π.[15] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. It means the manuscript has not high value. Currently it is housed at the Austrian National Library (Philos. 157) at Vienna. Codex Marcianus CCXXVIII (406) Codex Marcianus GR. Z. 228 (=406) contains a partial manuscript of the treatise. It is designated by symbol Oc. Paleographically, it has been assigned to the 14th century. It is written in Greek minuscule letters. The manuscript contains the incomplete text of the treatise. The text of Book II ends at 419 a 27. It has not Book III of the treatise. The codex includes commentary on the treatise by Simplicius of Cilicia and Sophonias and paraphrases by Themistius (fourteenth century). The text of the manuscript represents the textual family κ.[16] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul. It means the manuscript does not have high value. The codex also has commentary by Pseudo-Diadochus on Plato's Timaeus, commentary by Simplicius of Cilicia on Aristotle's On the Heavens, commentary by Ammonius Hermiae’s on Plato's Phaedrus, and commentary by Proclus on Plato's Parmenides. Currently, it is housed at the Biblioteca Marciana (BNM Gr. Z. 228 (=406)) in Venice. |

一部の写本 ヴァチカン写本253 ヴァチカン写本253は、この論文の最も重要な写本の一つである。 記号Lで指定されている。 古筆学的に13世紀に書かれたものとされている。 ギリシャ語の小文字で書かれている。この写本は完全ではなく、第3巻のみが含まれている。この写本は、E、Fc、Lc、Kd、Pの写本とともに、λという テキスト系列に属する。 この写本は、トレンドレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版で引用されている。現在、この写本はローマのヴァチカン図書館(gr. 253)に所蔵されている。 ヴァチカン写本260 ヴァチカン写本260は、本論文の最も重要な写本の一つである。 記号Uで指定されている。 古筆学的には11世紀に書かれたものとされている。 ギリシャ語の小文字で書かれている。 この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 テキストファミリーνに属し、写本X、v、Ud、Ad、Qと並ぶ。 この写本は、トレンドレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版で引用されている。現在、この写本はローマのヴァチカン図書館(Vat. gr. 260)に所蔵されている。 ヴァチカン写本 266 ヴァチカン写本266は、この論文の最も重要な写本の一つである。 記号Vで指定されている。 古筆学的に14世紀に書かれたものとされている。 ギリシャ語の小文学体で書かれている。 この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 テキストのファミリーはκであるが、第2巻の第8章のみである。 κのファミリーに属する別の写本:Gc W Hc Nc Jd Oc Zc Vc Wc f Nd Td。 この写本は、トレンドレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルトが『魂について』の批判的版で引用している。デビッド・ロスは自身の版ではこの写本を使用していない。現在、この写本はローマのヴァチカン図書館(gr. 266)に所蔵されている。 ヴァチカン写本1026 ヴァチカン写本1026は、論文の写本である。記号Wで指定されている。古筆学上は13世紀に属する。ギリシャ語小文学で書かれている。この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 この写本のギリシャ語テキストは折衷的である。テキストのファミリーとしてはμ[7]に属し、第2巻、第7章、419 a 27に該当する。419 a 27以降は、ファミリーκの代表例である。[8] この写本は、トレンドレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーリ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版では引用されていない。つまり、この写本は価値 が高いものではないということである。現在、この写本はローマのヴァチカン図書館(gr. 1026)に保管されている。 ヴァチカン写本 1339 Codex Vaticanus 1339は、論文の写本である。 記号Pで指定されている。 古筆学的に14世紀または15世紀に書かれたものとされている。 ギリシャ語の小文字で書かれている。 この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 写本の本文は折衷的である。論文の第2巻では、第2巻第2章第314b11節から第2巻第8章第420a2節まで、本文系統σに属する。[9] 第2巻第9章第429b16節以降は本文系統λに属する。[10] ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的注釈版では、この写本は引用されていない。これは、この写本 がそれほど価値の高いものではないことを意味する。現在、この写本はローマのヴァチカン図書館(gr. 1339)に所蔵されている。 アンブロシウス写本435 アンブロシウス写本435は、この論文の最も重要な写本の一つである。 記号Xで指定されている。 古筆学上は12世紀または13世紀に属する。 ギリシャ語の小文学体で書かれている。 この写本には論文の完全なテキストが収められている。 テキストのファミリーνに属し、写本v Ud Ad U Q.と並ぶ。 この写本は、トレンドレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルトが引用した9つの写本のうちの1つであり、またロスが『魂について』の批判的版で引用 した5つの写本のうちの1つでもある。現在、ミラノのアンブロジアーナ図書館(435 (H. 50))に所蔵されている。 アンブロシウス写本837 アンブロシウス写本837は、論文の写本である。Dcという記号で指定されている。古筆学上は13世紀に書かれたものとされている。ギリシャ語の小文学で書かれている。この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 この写本のテキストは折衷的である。論文のI-II巻では、テキストファミリーσに属する。[11]論文のIII巻では、テキストファミリーτに属する。[12] ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版では、この写本は引用されていない。現在、この写本はミラノのアンブロジアーナ図書館(837 (B 7 Inf.))に所蔵されている。 コイズリン写本386 コイズリン写本386は、この論文の重要な写本の一つである。 記号Cで指定されている。 古筆学的に11世紀に書かれたものとされている。 ギリシャ語の小文学体で書かれている。 この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 テキストファミリーξに属し、T、Ec、Xd、Pd、Hdの写本とともに分類されている。 この写本は、デビッド・ロス(David Ross)が『魂について』の批判版で引用している。現在、この写本はパリのフランス国立図書館(Coislin 386)に所蔵されている。 ウィーンの写本『哲学』2 ウィーンの写本『哲学』2は、論文の写本である。記号Tdで指定されている。コロフォンにより1496年のものと特定されている。ギリシャ語の小文字で書かれている。この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 この写本のテキストはテキストファミリーκに属する。 ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる論文『魂について』の批判的版では、この写本は引用されていない。つまり、この写本 は高い価値を持たないということである。現在、ウィーンのオーストリア国立図書館(Philos. 2)に所蔵されている。 ウィーン・ボドム写本 Philos. 75 ウィーン・ボドム写本 Philos. 75は、論文の写本である。記号Sdで指定されている。コロフォンにより1446年のものとされる。ギリシャ語の小文学体で書かれている。この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 写本の本文は、テキストファミリーρに属する。[14] ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版では、この写本は引用されていない。つまり、この写本は価 値が高いものではないということである。現在、この写本はウィーンのオーストリア国立図書館(Philos. 75)に所蔵されている。 ウィーン写本 Philos. 157 Codex Vindobonensis Philos. 157は論文の写本である。Rdという記号で指定されている。古筆学的に15世紀に書かれたものとされている。ギリシャ語の小文学で書かれている。この写本には論文の完全なテキストが含まれている。 この写本のテキストはテキストファミリーπを表している。[15] ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーリ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版では、この写本は引用されていない。つまり、この写本はそ れほど価値のあるものではないということである。現在、この写本はウィーンのオーストリア国立図書館(Philos. 157)に所蔵されている。 マルキアヌス写本CCXXVIII(406) Codex Marcianus GR. Z. 228 (=406) は、論文の断片的な写本を含んでいる。古筆学上は14世紀に属する。ギリシャ語の小文学体で書かれている。この写本には論文の不完全なテキストが含まれて いる。第2巻のテキストは419 a 27で終わっている。第3巻は含まれていない。この写本には、キリキアのシンプリキオスとソフォニアスの論文に関する注釈、およびテミスティオス(14世 紀)によるパラフレーズが含まれている。 この写本のテキストは、テキストファミリーκに属する。 ティエンデレンブルク、トルストリック、ビーレ、アペルト、ロスによる『魂について』の批判的版では、この写本は引用されていない。つまり、この写本は高い価値を持たないということである。 また、この写本には、偽ディアドコスのプラトン著『ティマイオス』注釈、キリキアのシンプリチウスのアリストテレス著『天について』注釈、アンモニオス・ヘルミエのプラトン著『パイドロス』注釈、プロクルスのプラトン著『パルメニデス』注釈も含まれている。 現在、それはヴェネツィアのマルチャーナ図書館(BNM Gr. Z. 228 (=406))に所蔵されている。 |

| English translations Mark Shiffman, De Anima: On the Soul, (Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Co, 2011). ISBN 978-1585102488 Joe Sachs, Aristotle's On the Soul and On Memory and Recollection (Green Lion Press, 2001). ISBN 1-888009-17-9 Hugh Lawson-Tancred, De Anima (On the Soul) (Penguin Classics, 1986). ISBN 978-0140444711 Hippocrates Apostle, Aristotle's On the Soul, (Grinell, Iowa: Peripatetic Press, 1981). ISBN 0-9602870-8-6 D.W. Hamlyn, Aristotle De Anima, Books II and III (with passages from Book I), translated with Introduction and Notes by D.W. Hamlyn, with a Report on Recent Work and a Revised Bibliography by Christopher Shields (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968). Walter Stanley Hett, On the Soul (Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press "Loeb Classical Library", 1957). John Alexander Smith, On the Soul (1931) MIT Internet Classics Archive Adelaide Google Books Classics in the History of Psychology UVa EText Center Georgetown R. D. Hicks, Aristotle De Anima with Translation, Introduction, and Notes (Cambridge University Press, 1907). Archive.org Free Audiobook (Public Domain) of De Anima at Archive.org Edwin Wallace, Aristotle's Psychology in Greek and English, with Introduction and Notes by Edwin Wallace (Cambridge University Press, 1882). Archive.org Thomas Taylor, On the Soul (Prometheus Trust, 2003, 1808). ISBN 1-898910-23-5 |

英語訳 マーク・シフマン著『デ・アニマ:魂について』(ニューベリーポート、マサチューセッツ州:フォーカス・パブリッシング/R.プルリンズ社、2011年)。ISBN 978-1585102488 ジョー・サックス著『アリストテレス著『魂について』および『記憶と想起について』』(グリーン・ライオン・プレス、2001年)。ISBN 1-888009-17-9 ヒュー・ローソン=タンクレッド著『魂について』(ペンギン・クラシックス、1986年)。ISBN 978-0140444711 ヒポクラテス・アポストル著『アリストテレス『魂について』』(アイオワ州グリーネル:ペリパテティック・プレス、1981年)。ISBN 0-9602870-8-6 D.W. Hamlyn, Aristotle De Anima, Books II and III (with passages from Book I), translated with Introduction and Notes by D.W. Hamlyn, with a Report on Recent Work and a Revised Bibliography by Christopher Shields (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968). Walter Stanley Hett, On the Soul (Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press 「Loeb Classical Library」, 1957). ジョン・アレクサンダー・スミス著『魂について』(1931年) MITインターネット・クラシックス・アーカイブ アデレード Googleブックス 心理学史における古典 バージニア大学電子テキストセンター ジョージタウン R. D. ヒックス著『アリストテレス『魂について』』翻訳、序文、注釈付き(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1907年)。 アーカイブ・ドットコム アーカイブ・ドットコムの『魂について』の無料オーディオブック(パブリックドメイン) エドウィン・ウォレス著『ギリシャ語と英語によるアリストテレスの心理学』、エドウィン・ウォレスによる序文と注釈付き(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1882年)。 Archive.org トマス・テイラー著『魂について』(プロメテウス・トラスト、2003年、1808年)。ISBN 1-898910-23-5 |

| Rüdiger Arnzen, Aristoteles' De

anima : eine verlorene spätantike Paraphrase in arabischer und

persischer Überlieferung, Leiden, Brill, 1998 ISBN 90-04-10699-5. J. Barnes, M. Schofield, & R. Sorabji, Articles on Aristotle, vol. 4, 'Psychology and Aesthetics'. London, 1979. M. Durrant, Aristotle's De Anima in Focus. London, 1993. M. Nussbaum & A. O. Rorty, Essays on Aristotle's De Anima. Oxford, 1992. F. Nuyens, L'évolution de la psychologie d'Aristote. Louvain, 1973. Paweł Siwek, Aristotelis tractatus De anima graece et latine, Desclée, Romae 1965. |

ルディガー・アルツェン著『アリストテレス『魂について』:失われた後期古代の注釈のペルシャ語とアラビア語による伝承』、ライデン、ブリル、1998年、ISBN 90-04-10699-5。 J. バーンズ、M. スコフィールド、R. ソラブジ共著『アリストテレスに関する論文集』第4巻「心理学と美学」。ロンドン、1979年。 M. ダラント著『アリストテレス『魂について』の焦点』。ロンドン、1993年。 M. ヌスバウム、A. O. ローティ共著『アリストテレス『魂について』に関する論文集』。オックスフォード、1992年。 F. Nuyens, L'évolution de la psychologie d'Aristote. Louvain, 1973. Paweł Siwek, Aristotelis tractatus De anima graece et latine, Desclée, Romae 1965. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Soul |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆