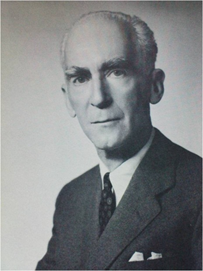

アーノルド・ウォルファーズ

Arnold Oscar Wolfers,

1892-1968

☆

アーノルド・オスカー・ヴォルファース(1892年6月14日 -

1968年7月16日)は、スイス系アメリカ人の弁護士、経済学者、歴史家、国際関係論学者である。イェール大学での業績と、古典的国際関係論リアリズム

の先駆者として最もよく知られている。

母国スイスとドイツで教育を受けたウォルファーズは、1920年代後半にベルリンのドイツ政治大学で講師を務め、1930年代初頭には同大学の学長となっ

た。当初はナチス・ドイツの思想に一定の共感を示していたが、1933年に同国を離れイェール大学の客員教授となり、その後も同大学に留まり、1939年

にアメリカ市民権を取得した。1935年には、影響力のあるイェール大学国際研究所の共同創設者となった。イェール大学ピアソン・カレッジの学部長とし

て、第二次世界大戦中は戦略情報局の人材募集において重要な役割を果たした。1957年にイェール大学を離れ、ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学ワシントン外交政

策研究センターの所長に就任し、1965年に引退するまでその職を務めた。

ウォルファーズの最も有名な2つの著作は、戦間期の2つの外交政策を研究した『二つの戦争の間のイギリスとフランス』(1940年)と、国際関係論に関す

る論文集『不和と協調:国際政治に関するエッセイ』(1962年)である。

| Arnold Oscar

Wolfers

(June 14, 1892 – July 16, 1968) was a Swiss-American lawyer, economist,

historian, and international relations scholar, most known for his work

at Yale University and for being a pioneer of classical international

relations realism. Educated in his native Switzerland and in Germany, Wolfers was a lecturer at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik in Berlin in the late 1920s and then became its director in the early 1930s. Initially having some sympathies with the ideas of Nazi Germany, he left that country to become a visiting professor at Yale in 1933, stayed there, and became a U.S. citizen in 1939. In 1935 he was co-founder of the influential Yale Institute of International Studies. As master of Pierson College at Yale, he played a significant role during World War II by recruiting for the Office of Strategic Services. In 1957 he left Yale and became director of the Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research at Johns Hopkins University, where he served in that role until his retirement in 1965. Wolfers' two most known works are Britain and France Between Two Wars (1940), a study of two foreign policies during the interwar period, and Discord and Collaboration: Essays on International Politics (1962), a collection of papers on international relations theory. |

アーノルド・オスカー・ヴォルファース(1892年6月14日 -

1968年7月16日)は、スイス系アメリカ人の弁護士、経済学者、歴史家、国際関係論学者である。イェール大学での業績と、古典的国際関係論リアリズム

の先駆者として最もよく知られている。 母国スイスとドイツで教育を受けたウォルファーズは、1920年代後半にベルリンのドイツ政治大学で講師を務め、1930年代初頭には同大学の学長となっ た。当初はナチス・ドイツの思想に一定の共感を示していたが、1933年に同国を離れイェール大学の客員教授となり、その後も同大学に留まり、1939年 にアメリカ市民権を取得した。1935年には、影響力のあるイェール大学国際研究所の共同創設者となった。イェール大学ピアソン・カレッジの学部長とし て、第二次世界大戦中は戦略情報局の人材募集において重要な役割を果たした。1957年にイェール大学を離れ、ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学ワシントン外交政 策研究センターの所長に就任し、1965年に引退するまでその職を務めた。 ウォルファーズの最も有名な2つの著作は、戦間期の2つの外交政策を研究した『二つの戦争の間のイギリスとフランス』(1940年)と、国際関係論に関す る論文集『不和と協調:国際政治に関するエッセイ』(1962年)である。 |

| Early life and education Arnold Oskar Wolfers (the spelling of the middle name later changed to Oscar) was born on June 14, 1892,[1] in St. Gallen, Switzerland, to parents Otto Gustav Wolfers (1860–1945) and the former Clara Eugenie Hirschfeld (1869–1950).[2][3] His father was a New York merchant[4] who emigrated and became a naturalized Swiss citizen in 1905,[1] while his mother was from a Jewish family in St. Gallen.[3] Arnold grew up in St. Gallen[5] and attended the gymnasium secondary school there, gaining his Abitur qualification.[1] Wolfers studied law at the University of Lausanne, University of Munich, and University of Berlin beginning in 1912,[2] gaining a certificate (Zeugnis) from the last of these.[1] He served as a first lieutenant in the infantry of the Swiss Army,[2] with some of the service taking place from May 1914 to March 1915,[1] part of which included Switzerland's maintaining a state of armed neutrality during World War I. He first began studying at the University of Zurich in the summer of 1915.[1] He graduated summa cum laude from there with a J.U.D. degree, in both civil and church law,[2] in April 1917.[1] Admitted to the bar in Switzerland in 1917, Wolfers practiced law in St. Gallen from 1917 to 1919.[2][5] His observing of the war, and of the difficulties the Geneva-based League of Nations faced in the aftermath of the war, enhanced his natural Swiss skepticism and led him towards a conservative view regarding the ability of countries to avoid armed conflict.[6] On the other hand, his Swiss background did provide to him an example of how a multi-lingual federation of cantons could prosper.[7] In 1918, Wolfers married Doris Emmy Forrer.[2][5] She was the daughter of the Swiss politician Robert Forrer,[8][9] who as a member of the Free Democratic Party of Switzerland from St. Gallen had been elected to the National Council in the 1908 Swiss federal election, retaining that seat until 1924 and chairing the radical-democratic group (1918–1924).[10] She studied art, attending the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva as well as the University of Geneva,[11] and spent a year at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich during the early stages of World War I.[12] Wolfers studied economics and political science at the Universities of Zurich and Berlin from 1920 to 1924,[2] with his study at the University of Zurich concluding with a certificate in April 1920.[1] He received a Ph.D. from the University of Giessen in Germany in 1924.[2] During this time, Wolfers' abilities with languages allowed him to act as an interpreter in some situations.[13] He first traveled to the United States in 1924 and delivered lectures to various audiences.[13] |

幼少期と教育 アーノルド・オスカー・ヴォルファース(ミドルネームの綴りは後にオスカーに変更された)は、1892年6月14日[1]、スイス・ザンクトガレンで、父 オットー・グスタフ・ヴォルファース(1860–1945)と母クララ・ユージニー・ヒルシュフェルト(旧姓、1869–1950)の間に生まれた。 [2][3] 父はニューヨークの商人[4]で、1905年に移住してスイス国籍を取得した[1]。母はザンクトガレンのユダヤ人家庭の出身だった[3]。アーノルドは ザンクトガレンで育ち[5]、現地のギムナジウム(中等教育学校)に通い、アビトゥア資格を取得した。[1] ヴォルファースは1912年からローザンヌ大学、ミュンヘン大学、ベルリン大学で法律を学び[2]、最後の大学で修了証書(ツェウグニス)を取得した。 [1] 彼はスイス陸軍歩兵部隊で少尉を務めた[2]。その兵役の一部は1914年5月から1915年3月にかけて行われ[1]、第一次世界大戦中にスイスが武装 中立を維持していた時期も含まれていた。彼は1915年の夏にチューリッヒ大学での学業を開始した。[1] 1917年4月、同大学を最優等で卒業し、民法と教会法の両分野でJ.U.D.学位を取得した。[1] 1917年にスイスで弁護士資格を取得したヴォルファースは、1917年から1919年までザンクト・ガレンで弁護士として活動した[2][5]。戦争の 観察と、戦後ジュネーブに拠点を置く国際連盟が直面した困難は、彼の生来のスイス的懐疑心を強め、国家が武力紛争を回避できる能力について保守的な見解へ と導いた。[6] 一方で、彼のスイス人としての背景は、多言語の州連邦が繁栄する実例を彼に提供した。[7] 1918年、ヴォルファースはドリス・エミー・フォラーと結婚した。[2][5] 彼女はスイス政治家ロベルト・フォレールの娘であった。[8][9] 父はザンクト・ガレン州選出の自由民主党員として1908年連邦議会選挙で国民院議員に当選し、1924年までその議席を維持、急進民主党グループ議長 (1918-1924)を務めた。[10] 彼女は美術を学び、ジュネーブのエコール・デ・ボザールとジュネーブ大学に通った[11]。第一次世界大戦初期にはミュンヘン美術アカデミーで1年間過ご した。[12] ヴォルファースは1920年から1924年にかけてチューリッヒ大学とベルリン大学で経済学と政治学を学んだ[2]。チューリッヒ大学での研究は1920 年4月に修了証書を取得して終了した。[1] 1924年にはドイツのギーセン大学で博士号を取得した。[2] この時期、ヴォルファースは語学力を活かして通訳を務めることもあった。[13] 1924年に初めてアメリカを訪れ、様々な聴衆に向けて講演を行った。[13] |

| Academic career in Germany By one later account, Wolfers emigrated to Germany following the conclusion of World War I,[14] while another had him living in Germany starting in 1921.[15] Contemporary newspaper stories published in the United States portray Wolfers as a Swiss citizen through at least 1926.[16][13] In 1933, stories describe him as Swiss-German[15] or a native Swiss and naturalized German.[17] But in 1940 he is described as having been a Swiss before being naturalized as an American,[18] something that a later historical account also states.[19] From 1924 to 1930, Wolfers was a lecturer in political science at the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik (Institute of Politics) in Berlin.[2][20] Headed by Ernst Jaeckh, it was considered Berlin's best school for the study of political behavior.[14] In 1927, he took on the additional duties of being studies supervisor.[21] Wolfers was one of the early people in the circle around Lutheran theologian Paul Tillich,[22] with he and Doris giving much-needed economic support to Tillich in Berlin during the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic period.[12] As such Wolfers might have been considered a religious socialist.[22] The Hochschule attracted many religious socialists, who were interested in combining spiritual development with social reform in an effort to provide an attractive alternative to Marxism.[22] Wolfers became the director of the Hochschule für Politik from 1930 until 1933, with Jaeckh as president and chair.[2][21] Wolfers and Jaeckh both gave lecture tours in America, made contacts there, and secured funding for the Hochschule's library and publications from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Rockefeller Foundation.[21] Two endowed visiting lectureships were sponsored by Carnegie, one of which would be held by Hajo Holborn.[21] In a period where there was considerable student unrest, Wolfers led popular classroom discussion sessions regarding the state of world affairs.[23] Between 1929 and 1933, Wolfers was a privatdozent (roughly, assistant professor) in economics at the University of Berlin.[2][20] He was active in the International Student Service and presided over their annual conference in 1931, held in the midst of the Great Depression, at Mount Holyoke College in the United States.[24] In his address before them, Wolfers urged more financial help from Great Britain and the United States to Continental Europe: "What Europe needs is not general declarations for peace and cooperation – people are getting sick of them. We need proposals to help overcome concrete pressing difficulties."[25] Wolfers, like other German academics, witnessed first-hand the demise of the Weimar Republic and the rise to power of the Nazi Party.[26][27] While some of the academics perceived immediately the reality of the Nazis, Wolfers, along with Jaeckh, did not.[26] Wolfers had a belief in the great man theory, extended to the role of great nations, and was drawn to the notion of spectacular actions in international relations; as such he found some Nazi rhetoric appealing.[28] In this manner Wolfers tended to be in agreement with some of the foreign policy objectives of the Nazi regime, especially in the East, thinking that those objectives could play a part in restoring the European balance of power.[29] As for other aspects of the Nazis, Wolfers failed to comprehend the amount of racism and authoritarianism essential to Nazi ideology.[26] In a November 1932 article in the journal International Affairs, Wolfers prophesied that "Hitler, with all his anti-democratic tendencies, is caught by the fact that he leads a mass movement... He may therefore become, against his own original programme, a force making for democracy. ... The further we go, the more this character of his movement as a safeguard against social reaction is likely to come to the fore."[30] Hitler seized control in the Machtergreifung in January 1933. At some point, Wolfers, a "half-Jew" (Halbjude) in the language of the Third Reich, was classified as "undesirable" (unerwünscht) by the new regime.[19] In late April 1933, Wolfers was offered a position as a visiting professor of international relations at Yale University,[19] and in late May, the appointment was publicly announced by Yale, with Wolfers being assigned to Yale's graduate school,[31] where he was to lecture on world economics and European governments.[32] Also in May, Wolfers served as general rapporteur to that year's International Studies Conference in London.[2][33] |

ドイツにおける学問的経歴 ある後の記述によれば、ヴォルファースは第一次世界大戦終結後にドイツへ移住した[14]。別の記述では1921年からドイツ在住とされている[15]。 アメリカで発表された当時の新聞記事は、少なくとも1926年までヴォルファースをスイス市民として描いている。[16][13] 1933年の記事では、彼はスイス・ドイツ人[15] あるいはスイス生まれでドイツ国籍を取得した人物[17] と記述されている。しかし1940年には、アメリカ国籍を取得する前はスイス人であった[18] と記されており、これは後の歴史的記述でも確認されている[19]。 1924年から1930年まで、ヴォルファースはベルリンのドイツ政治大学(Deutsche Hochschule für Politik)で政治学講師を務めた[2][20]。エルンスト・イェックが率いるこの大学は、ベルリンで最も優れた政治行動研究機関と評されていた。 [14] 1927年には研究指導責任者を兼任した。[21] ヴォルファースはルーテル派神学者ポール・ティリッヒの初期の知人であり、[22] ワイマール共和国時代のハイパーインフレ期に、彼とドリスはベルリンでティリッヒに経済的支援を提供した。[12] この点でヴォルファースは宗教的社会主義者と見なされたかもしれない。[22] 同校には多くの宗教的社会主義者が集い、精神的な発展と社会改革を結びつけ、マルクス主義に代わる魅力的な選択肢を提供しようと試みていた。[22] ヴォルファースは1930年から1933年まで政治高等学院の院長を務め、ヤークが学長兼議長を務めた。[2][21] ヴォルファースとヤークは共にアメリカで講演旅行を行い、現地で人脈を築き、カーネギー国際平和財団とロックフェラー財団から学院の図書館と出版物への資 金援助を確保した。[21] カーネギー財団は2つの寄付講座を後援し、その一つはハヨ・ホルボルンが担当することになった。[21] 学生運動が活発化した時期に、ヴォルファースは国際情勢に関する人気のある教室討論会を主導した。[23] 1929年から1933年にかけて、ヴォルファースはベルリン大学で経済学の私講師(助教授に相当)を務めた。[2][20] 彼は国際学生サービス(ISS)で活動し、1931年には大恐慌の最中にアメリカのマウント・ホリヨーク大学で開催された年次会議の議長を務めた。 [24] ウォルファースは演説で、英国と米国に対し大陸ヨーロッパへの財政支援拡大を訴えた。「欧州に必要なのは平和と協力の一般宣言ではない。人民はそれらにう んざりしている。我々が求めるのは、差し迫った具体的な困難を克服する提案だ」[25] ウォルファースは他のドイツ人学者同様、ワイマール共和国の崩壊とナチ党の台頭を直接目撃した。[26][27] 一部の学者がナチスの実態を即座に認識した一方で、ヴォルファースはイェックと共にそうではなかった。[26] ヴォルファースは偉人理論を国民の役割にまで拡張して信じ、国際関係における劇的な行動の概念に惹かれていた。そのため彼はナチスのレトリックの一部に魅 力を感じたのである。[28] このようにヴォルファースは、特に東方におけるナチ政権の外交政策目標の一部には同意する傾向があった。それらの目標がヨーロッパの勢力均衡回復に寄与し 得ると考えていたのである。[29] ナチスの他の側面については、ヴォルファースはナチス思想の本質である人種主義と権威主義の程度を理解できなかった。[26] 1932年11月の『国際問題』誌記事で、ヴォルファースはこう予言した。「ヒトラーは反民主的傾向の全てを持ちながらも、大衆運動を率いるという事実に とらわれている…したがって彼は、自らの当初の計画に反して、民主主義を推進する勢力となり得る。…事態が進展すればするほど、彼の運動が社会的反動に対 する防護壁としての性格を前面に出す可能性が高まるだろう」[30] ヒトラーは1933年1月の権力掌握(マハトグライフング)で支配権を掌握した。第三帝国の用語で「半ユダヤ人」(ハルプユデ)であったヴォルファース は、新体制によって「望ましくない人物」(ウンデルヴィュンシュト)と分類された。[19] 1933年4月下旬、ウォルファースはイェール大学国際関係学の客員教授職を打診された[19]。5月下旬にはイェール大学が公にこの任命を発表し、ウォ ルファースは大学院に配属された[31]。そこで世界経済と欧州諸政府に関する講義を担当することになっていた[32]。また同年5月、ウォルファースは ロンドンで開催された国際研究会議の総合報告者を務めた。[2][33] |

| Master at Yale Wolfers traveled to the United States on the SS Albert Ballin, arriving on August 11, 1933.[32] He commented that Europeans generally felt threatened by U.S. monetary policy, but that people in Germany were sympathetic to U.S. leadership in trying to overcome the Depression.[32] In a November 1933 address at Yale, Wolfers described Hitler as saying that Germany would return to the League of Nations if reparations-based discrimination against her ended and that France and Germany could be allied against the Bolshevik threat from the east. Wolfers added, "Hitler's policy is not only an outgrowth of dire necessity. His party's emphasis is on domestic affairs. The 'militant' energies of Germany's soldier-like citizens are at last finding a field of action at home that satisfies all needs."[34] In a February 1934 speech before the Foreign Policy Association in New York, Wolfers said, "The cause of present unrest is France's extravagant demands. ... Germany has lost her territorial cohesion; she has been forced to live in conflict with her Eastern neighbors, and is deprived of the most meager of self-defense."[35] In 1934 the German embassy in Washington expressed satisfaction with the contents of Wolfers' lectures in the United States.[29] The contradictions inherent in the Nazi government's classification of Wolfers, compared to the Nazis' and Wolfers' somewhat complimentary views of each other at this time, have been noted by the German political scientist Rainer Eisfeld.[19] Wolfers destroyed his personal and work files several times over the course of his career and thus it is difficult to know if his leaving Germany was for academic or political reasons or exactly what his thinking was at the time.[19] Intellectually, Wolfers' early work on international politics and economics was influenced by European conflicts and their effect upon the world and revealed something of a Realpolitik point of view.[36][6] However he was not as heavily devoted to this perspective as was his colleague Nicholas J. Spykman.[37] In terms of economics, Wolfers spoke somewhat favorably of New Deal initiatives such as the National Recovery Administration that sought to manage some competitive forces.[38] In 1935, Wolfers was named as professor of international relations at Yale.[5] In taking the position, Wolfers was essentially proclaiming his lack of desire to return to Germany under Nazi rule.[39] As part of gaining the position, Wolfers received an honorary A.M. from Yale in 1935,[2] a standard practice at Yale when granting full professorships to scholars who did not previously have a Yale degree.[40] Also in 1935, Wolfers was appointed master of Pierson College at Yale, succeeding Alan Valentine.[20] The college system had just been created at Yale two years earlier and masterships were sought after by faculty for the extra stipend and larger living environment they allotted.[41] A master was expected to provide a civilizing influence to the resident students and much of that role was filled by Doris Wolfers.[42] She decorated with eighteenth century Swiss furniture, played the host with enthusiasm, and together the couple made the Master's House at Pierson a center for entertaining on the campus second only to the house of the president of the university.[9] When diplomats visited the campus, it was the Wolferses who provided the entertainment.[9] The couple collected art and in 1936 loaned some of their modern art to an exhibit at the Yale Gallery of the Fine Arts.[43] Doris Wolfers became a frequent attendee or patroness at tea dances and other events to celebrate debutantes.[44] He would accompany her to some university dances.[45] One former Yale undergraduate later said that he had lived in Pierson and that as head of the hall, Wolfers had been wiser and more useful regarding the practical issues of foreign policy than any of the faculty in political science.[46] Veterans returning after the war would express how much they had missed Doris.[42] Another development in 1935 was that the Yale Institute of International Studies was created, with Wolfers as one of three founding members along with Frederick S. Dunn and Nicholas J. Spykman with Spykman as the first director.[14] The new entity sought to use a "realistic" perspective to produce scholarly but useful research that would be useful to government decision makers.[47] Wolfers was one of the senior academics who gave both the institute and Yale as a whole gravitas in the area and the nickname of the "Power School".[47] The members of the institute launched a weekly seminar called "Where Is the World Going?" at which various current issues would be discussed, and from this Wolfers developed small study groups to address problems sent from the U.S. Department of State.[48] Wolfers traveled to the State Department in Washington frequently and also discussed these matters with his friend and Yale alumnus Dean Acheson.[48] Wolfers gained campus renown for his lectures on global interests and strategy.[49] Politically, Wolfers styled himself a "Tory-Liberal",[9] perhaps making reference to the Tory Liberal coalition in Britain of that time. Wolfers had a distinctive image on campus: tall and well-dressed with an aristocratic demeanor and a crisp voice that rotated between people in conversation "rather like a searchlight" in the words of one observer.[9] Whatever appeal the Nazis had held for Wolfers had ended by the conclusion of the 1930s,[50] and in 1939, Wolfers was naturalized as an American citizen.[5] His 1940 book Britain and France Between Two Wars, a study of the foreign policies of the two countries in the interwar period, became influential.[51] An assessment in The New York Times Book Review by Edgar Packard Dean said that the book was a "substantial piece of work" and that Wolfers handled his descriptions with "extraordinary impartiality" but that his analysis of French policy was stronger than of British policy.[52] Another review in the same publication referred to Britain and France Between Two Wars as "a most excellent and carefully documented study" by an "eminent Swiss scholar".[53] |

イェール大学で修士号を取得した ヴォルファースはSSアルベルト・バリン号でアメリカに渡り、1933年8月11日に到着した[32]。彼は、ヨーロッパ人は概してアメリカの金融政策に 脅威を感じているが、ドイツの人民は不況克服に向けたアメリカの指導力に共感していると述べた[32]。 1933年11月のイェール大学での講演で、ヴォルファースはヒトラーが「賠償金に基づくドイツへの差別が終結すれば、ドイツは国際連盟に復帰する」と述 べたと説明した。さらに「フランスとドイツは東方のボルシェビキ脅威に対して同盟を結べる」とも語った。ヴォルファースは付け加えた。「ヒトラーの政策 は、単に差し迫った必要性から生まれたものではない。彼の政党は国内問題に重点を置いている。」 ドイツの兵士のような市民の『好戦的』エネルギーは、ついに国内で全ての欲求を満たす行動の場を見出したのだ」と述べた。[34] 1934年2月、ニューヨークの外交政策協会での演説でウォルファーズはこう語った。「現在の不安の原因はフランスの過剰な要求にある。... ドイツは領土の一体性を失い、東隣国との対立を強いられ、最低限の自衛手段すら奪われている」と述べた[35]。1934年、ワシントン駐在ドイツ大使館 は、ウォルファースの米国講演内容に満足を表明している[29]。 ナチス政権によるヴォルファースの分類に内在する矛盾は、当時のナチスとヴォルファースの相互にやや称賛し合う見解と比較され、ドイツの政治学者ライ ナー・アイスフェルトによって指摘されている[19]。ヴォルファースはキャリアの過程で数度にわたり人格ファイルと業務ファイルを破棄したため、彼のド イツ離脱が学術的理由か政治的理由か、あるいは当時の正確な考え方は不明である[19]。 知的側面では、ヴォルファースの国際政治・経済に関する初期の研究は、欧州の紛争とそれが世界に及ぼす影響に影響を受け、ある種の現実政治(レアルポリ ティーク)的視点が窺える[36][6]。しかし同僚のニコラス・J・スパイクマンほどこの視点に傾倒していたわけではない[37]。経済面では、競争原 理の一部を管理しようとする国家復興局(NRA)などのニューディール政策について、ヴォルファースは比較的肯定的に言及している。[38] 1935年、ウォルファーズはイェール大学国際関係学教授に任命された。[5] この職を受け入れることは、ナチス支配下のドイツへの帰国を望まない意思表明に等しかった。[39] 教授職獲得の一環として、ウォルファーズは1935年にイェール大学から名誉文学修士号を授与された。[2] これはイェール大学において、同大学学位を持たない学者に正教授職を与える際の標準的な慣行であった。[40] 同じく1935年、ウォルファーズはアラン・バレンタインの後任としてイェール大学ピアソン・カレッジのマスターに任命された。[20] カレッジ制度はわずか2年前にイェールで創設されたばかりで、追加手当と広い居住環境が与えられるため、教職員の間でマスター職は人気が高かった。 [41] マスターは寮生に教養ある影響を与えることが期待され、その役割の大半はドリス・ウォルファーズが担った[42]。彼女は18世紀のスイス製家具で装飾を 施し、熱意を持って主人役を務めた。夫妻は協力してピアソン・カレッジのマスターズ・ハウスを、学長邸に次ぐ学内随一の社交の場とした。[9] 外交官がキャンパスを訪問する際、接待を担当したのはウォルファーズ夫妻であった。[9] 夫妻は美術品を収集し、1936年には所蔵する現代美術作品をイェール大学美術館の展覧会へ貸し出した。[43] ドリス・ウォルファーズは、社交界デビューを祝うティーパーティーや舞踏会に頻繁に出席し、後援者となった。[44] 夫は彼女に付き添い、大学の舞踏会にも参加した。[45] 後にイェール大学を卒業したある人物は、ピアソン寮に住んでいた頃、寮長だったウォルファーズが外交政策の実務問題に関して、政治学部のどの教授よりも賢 明で有用だったと語っている。[46] 戦後帰還した退役軍人たちは、ドリスがいかに恋しかったかを口にした。[42] 1935年のもう一つの進展は、イェール国際研究所の創設であった。ウォルファーズはフレデリック・S・ダン、ニコラス・J・スパイクマンと共に三人の創 設メンバーの一人となり、初代所長はスパイクマンが務めた。[14] この新組織は「現実主義的」視点を用い、学術的でありながら政府の意思決定者に役立つ研究を生み出すことを目指した。[47] ウォルファーズは、同研究所とイェール大学全体にこの分野での権威と「パワースクール」という異名をもたらした上級学者の一人であった。[47] 研究所のメンバーは「世界はどこへ向かうのか?」と題した週次セミナーを開始し、様々な時事問題を議論した。ウォルファーズはこの活動から、米国務省から 送られてくる問題に取り組む小規模な研究グループを発展させた。[48] ウォルファーズはワシントンの国務省へ頻繁に赴き、友人でありイェール卒業生でもあるディーン・アチソンともこれらの問題を議論した。[48] ウォルファーズは国際的な利益と戦略に関する講義で学内でも有名になった。[49] 政治的には、ウォルファーズは自らを「トーリー・リベラル」と称した。[9] おそらく当時の英国におけるトーリー党と自由党の連立政権に言及したものだろう。ウォルファーズは学内で独特の印象を残していた。背が高く、身なりも良 く、貴族的な風貌に、会話する人々を「まるでサーチライトのように」次々と照らすような明瞭な声を持っていたと、ある観察者は述べている。[9] ナチスに対するウォルファーズの関心は1930年代の終わりまでに完全に失われていた。[50] そして1939年、ウォルファーズはアメリカ市民権を取得した。[5] 1940年に出版された彼の著書『二つの戦争の間の英国とフランス』は、戦間期の両国の外交政策を研究したもので、影響力を持つようになった。[51] 『ニューヨーク・タイムズ・ブック・レビュー』誌のエドガー・パッカード・ディーンによる書評は、この本を「実質的な研究」と評し、ウォルファーズが記述 を「並外れた公平さ」で扱ったと述べたが、フランス政策の分析は英国政策のそれよりも優れていると指摘した。[52] 同誌の別の書評では、『二つの戦争の間のイギリスとフランス』を「卓越した、入念に資料を収集した研究」であり、「著名なスイス人学者」によるものと評し た。[53] |

| World War II involvements Wolfers actively assisted the U.S. war effort during World War II.[50] From 1942 to 1944 he served as a special advisor and lecturer at the School of Military Government in Charlottesville, Virginia, where he conveyed his knowledge of Germany's society and government to those taking training courses to become part of a future occupying force.[2][54][55] He served as an expert consultant to the Office of Provost Marshal General, also from 1942 to 1944.[2] He was also a consultant to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1944 and 1945.[2] The masters at Yale served as contact points for recruiting appropriate students into the intelligence services, and according to the historian Robin Winks, none did so more than Wolfers, who made excellent use of his connections in Washington through the Yale Institute of International Studies.[56] Overall a disproportionate number of intelligence workers came from Pierson College; in addition to Wolfers, other Pierson fellows who did recruiting included Wallace Notestein and C. Bradford Welles.[49] Pierson College residents who later became intelligence figures included James Jesus Angleton, who often spent time in Wolfers' living room listening to poets such as Robert Frost that Wolfers brought in to read.[57] Other attendees to these sessions included a future U.S. Poet Laureate, Reed Whittemore.[57] Wolfers liked the young Angleton and kept in touch with him in subsequent years.[57] Another protégé of Wolfers was Robert I. Blum, who became one of the early core members of the X-2 Counter Espionage Branch of the OSS, which provided liaison with the British in the exploitation of Ultra signals intelligence.[58] Wolfers had worked on a study of American diplomatic communications, including telecommunications and codes and ciphers.[51] He thus became one of the few people to have a professional-level interest in intelligence matters before the war.[58] In addition, Anita Forrer, Doris's sister, became an OSS agent and conducted secret and dangerous operations in Switzerland on behalf of Allen Dulles.[9] Before that, she had been a correspondent of poet Rainer Maria Rilke.[59] In June 1944, Wolfers was among a group of ten prominent Protestant clergy and laymen organized by the Commission on a Just and Durable Peace who issued a signed statement advocating a way of dealing with Germany after war. The statement said that Germany should not be left economically destitute or subjected to excessive reparations, as "an impoverished Germany will continue to be a menace to the peace of the world," and that punishment for German extermination campaigns against Jews and war crimes against those in occupied territories should be limited to those responsible and not extended to those just carrying out orders.[60] A month after V-E Day, Wolfers had a letter published wherein he remarked upon "the shocking revelations" of Nazi concentration camps but still recommended "stern but humane rules" for directing the future of the German people.[5] |

第二次世界大戦への関与 ヴォルファーズは第二次世界大戦中、米国の戦争遂行に積極的に協力した。[50] 1942年から1944年にかけて、バージニア州シャーロッツビルにある軍事統治学校で特別顧問兼講師を務め、将来の占領軍となる訓練課程受講者に対し、 ドイツの社会と政府に関する知識を伝えた。[2][54] [55] 同期に、1942年から1944年まで陸軍憲兵総監部(Office of Provost Marshal General)の専門顧問を務めた。[2] また1944年と1945年には戦略情報局(Office of Strategic Services, OSS)の顧問も担当した。[2] イェール大学の教授陣は、諜報機関に適した学生を募集する窓口として機能した。歴史家ロビン・ウィンクスによれば、ウォルファーズほど積極的に活動した者 はいなかった。彼はイェール国際研究所を通じてワシントンでの人脈を巧みに活用したのである。[56] 全体として、ピアソン・カレッジ出身者が諜報機関職員に占める割合は異常に高かった。ウォルファーズに加え、ウォレス・ノットスタインやC・ブラッド フォード・ウェルズといったピアソン・フェローたちも募集活動に関与した。[49] ピアソン・カレッジの居住者で後に諜報機関の要職に就いた人物には、ジェームズ・ジーザス・アングルトンがいる。彼はよくウォルファーズの居間に訪れ、 ウォルファーズが招いたロバート・フロストなどの詩人の朗読を聴いていた。[57] これらの朗読会には、後に米国桂冠詩人となるリード・ウィットモアも参加していた。[57] ウォルファーズは若きアングルトンを気に入り、その後も交流を続けた。[57] ウォルファーズのもう一人の後援対象はロバート・I・ブルームで、彼はOSSのX-2対諜報部門の初期中核メンバーの一人となり、ウルトラ暗号の解析にお ける英国との連絡役を担った。[58] ウォルファーズは、通信や暗号を含むアメリカ外交通信の研究に携わっていた。[51] そのため、彼は戦前に諜報問題に専門的な関心を持つ数少ない専門の人民の一人となった。[58] さらに、ドリス・フォーラーの姉であるアニタ・フォーラーはOSSの工作員となり、アレン・ダレスの指示でスイスにおいて秘密かつ危険な作戦を遂行した。 [9] それ以前には、詩人ライナー・マリア・リルケの文通相手でもあった。[59] 1944年6月、ウォルファーズは「公正かつ永続的な平和のための委員会」が組織した10名の著名なプロテスタント聖職者・信徒グループの一員として、戦 後のドイツへの対応方針を提唱する署名声明を発表した。声明は「貧困化したドイツは世界の平和に対する脅威であり続ける」として、ドイツを経済的に困窮状 態に置いたり過大な賠償を課したりすべきでないと主張。また、ユダヤ人絶滅作戦や占領地における戦争犯罪に対する処罰は責任者に限定し、命令を実行しただ けの者には拡大すべきでないと述べた。[60] ヨーロッパ戦勝記念日から一ヶ月後、ヴォルファースは書簡を発表した。その中で彼はナチス強制収容所の「衝撃的な暴露」に言及しつつも、ドイツの人民の将 来を導くには「厳格だが人道的な規則」を推奨したのである。[5] |

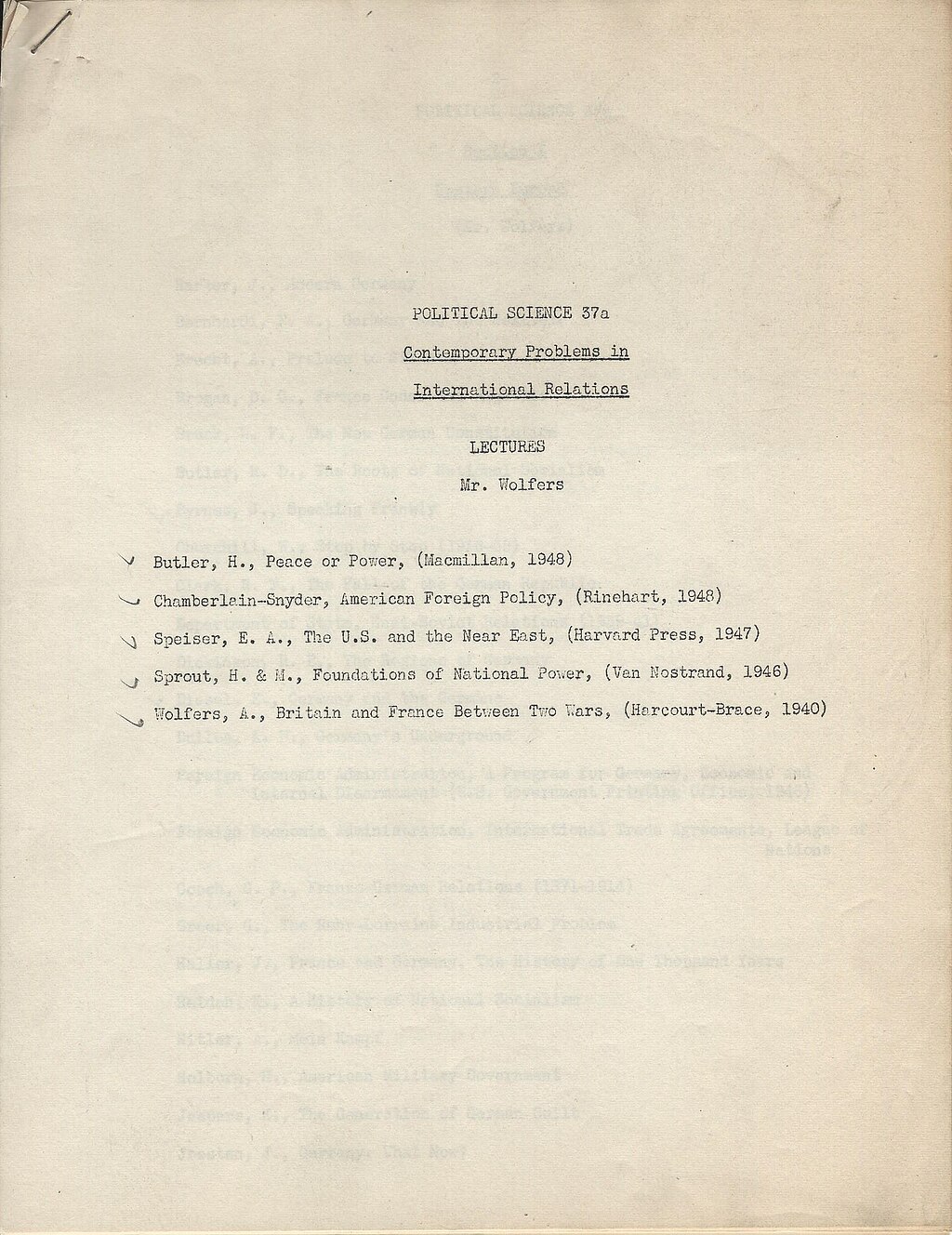

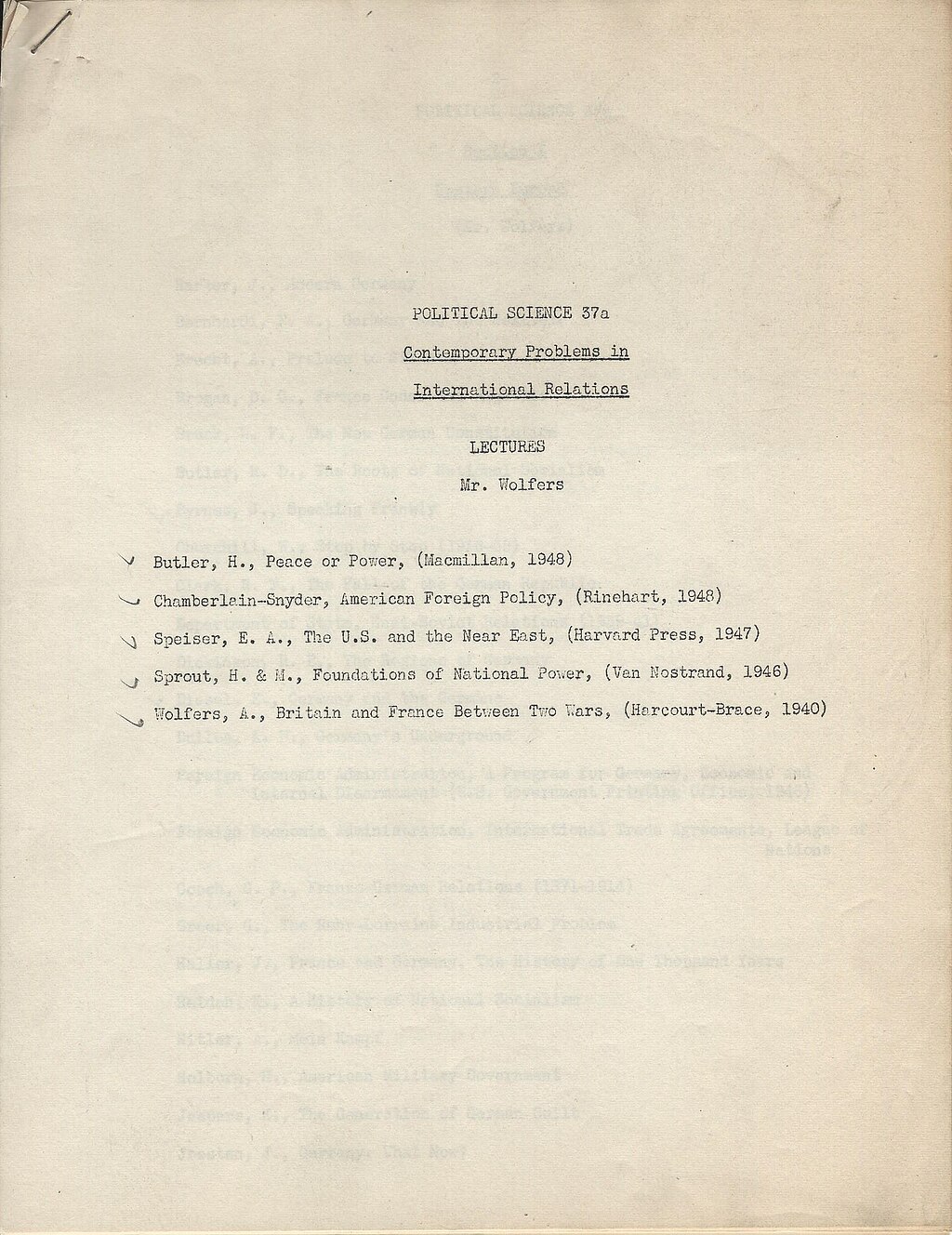

Later Yale years Reading list for Wolfers' "Contemporary Problems in International Relations" political science course, Fall 1948 Wolfers was one of the contributors to Bernard Brodie's landmark 1946 volume The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order, which focused on the effect of the new atomic bomb on U.S.-Soviet relations.[61] He worked with Basil Duke Henning, the master of Saybrook College, on a study of what Soviet leaders would judge American foreign policy options to be if they used the European press for their information.[62] Wolfers continued to serve as a recruiter for the Central Intelligence Agency when it was formed after the war.[47] He was a strong influence on John A. McCone, who later became Director of Central Intelligence (1961–65).[63] A distinguishing feature of Wolfers' career was his familiarity with power and his policy-oriented focus, which assumed that academia should try to shape the policies of government.[64] A noted American international relations academic, Kenneth W. Thompson, subsequently wrote that Wolfers, as the most policy-oriented of the Yale institute's scholars, "had an insatiable yearning for the corridors of power" and because of that may have compromised his scholarly detachment and independence.[47] Wolfers was a member of the resident faculty of the National War College in 1947 and a member of its board of consultants from 1947 to 1951.[2][65] He was a consultant to the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs during 1951[2] and served as President of the World Peace Foundation during 1953.[2] In 1953 he was named a member of the board of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation.[66] The Wolferses, who had spent summers in Switzerland in the prewar years, considered moving back to Switzerland after the war, but decided to stay in the United States.[12] In 1947 the couple commissioned a summer home on a Naskeag Point bluff in Brooklin, Maine.[67] Designed by Walter Gropius and The Architect's Collective, the innovative Bauhaus-influenced design incorporated a gull-wing roof and large overhangs; the adventuresome design reflected the couple's artistic nature and cosmopolitan outlook.[67] The home was featured in House & Garden magazine in 1948 (and would be featured again in Portland Monthly Magazine in 2013).[67] Wolfers was named a Sterling professor of international relations in 1949,[2] which remains Yale's highest level of academic rank.[68] He was, as one author later stated, "a revered doyen in the field of international relations".[27] He was also named to direct two new entities at Yale, the Division of Social Sciences and the Social Science Planning Center.[5] He stepped down as master of Pierson College at that time;[2] President of Yale Charles Seymour said, "I regret exceedingly that we must take from Pierson College a master who has conducted its affairs with wisdom and understanding for fourteen years."[5] The Wolferses continued to reside in New Haven.[11] In 1950 and 1951, the Yale Institute of International Studies ran into conflict with a new President of Yale University, A. Whitney Griswold, who felt that scholars should conduct research as individuals rather than in cooperative groups[69] and that the institute should do more historical, detached analysis rather than focus on current issues and recommendations on policy. Most of the institute's scholars left Yale, with many of them going to Princeton University and founding the Center of International Studies there in 1951, but Wolfers remained at Yale for several more years.[69] In May 1954, Wolfers attended the Conference on International Politics, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and convened in Washington, D.C., which brought together Hans Morgenthau, Reinhold Niebuhr, Walter Lippmann, Paul Nitze, Kenneth W. Thompson, Kenneth Waltz, Dean Rusk, and others. The conference has since been seen as an attempt to define an international relations theory through modern realism.[70] |

イェール大学時代後期 1948年秋学期、ウォルファーズの政治学講座「国際関係における現代的問題」の読書リスト ウォルファーズは、1946年に刊行されたバーナード・ブロディの画期的な著作『絶対兵器:原子力と世界秩序』に寄稿した一人である。同書は新たな原子爆 弾が米ソ関係に与える影響に焦点を当てていた。[61] 彼はセイブルック・カレッジの学部長であるバジル・デューク・ヘニングと共に、ソ連指導者が欧州の報道機関を情報源として利用した場合、米国の外交政策選 択肢をどのように判断するかを研究した。[62] ウォルファーズは戦後設立された中央情報局(CIA)の採用担当者としての職務を継続した。[47] 彼は後に中央情報局長官(1961–65)となるジョン・A・マコーンに強い影響を与えた。[63] ウォルファーズの経歴の特徴は、権力への精通と政策志向の姿勢にあった。彼は学界が政府の政策形成に関与すべきだと考えていた。[64]著名なアメリカ国 際関係学者ケネス・W・トンプソンは後に、ウォルファーズがイェール研究所の学者の中で最も政策志向が強く、「権力の廊下への飽くなき憧れ」を抱いていた ため、学問的客観性と独立性を損なった可能性があると記している。[47] ウォルファーズは、1947年に国民戦争大学(National War College)の常勤教員となり、1947年から1951年まで同大学の諮問委員会の委員を務めた。[2][65] 1951年には教育文化局(Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs)の顧問を務め[2]、1953年には世界平和財団(World Peace Foundation)の会長を務めた。[2] 1953年には、ウッドロウ・ウィルソン財団の理事に任命された。[66] 戦前にスイスで夏を過ごしていたウルファーズ夫妻は、戦後スイスに戻ることを考えたが、米国に留まることを決めた。[12] 1947年、夫妻はメイン州ブルックリンのナスキアグ岬の崖の上に夏の別荘を建てた。[67] ウォルター・グロピウスと建築家集団によって設計された、バウハウスに影響を受けた革新的なデザインは、ガルウィングの屋根と大きな張り出しを特徴として いた。この冒険的なデザインは、夫妻の芸術的性質と国際的な世界観を反映していた。[67] この家は、1948年に『House & Garden』誌で紹介された(そして2013年には『Portland Monthly Magazine』誌でも再び紹介されることになる)。[67] ウォルファーズは1949 年に国際関係学のスターリング教授に任命された[2]。これは現在もイェール大学における最高位の学術職である[68]。ある著者が後に述べたように、彼 は「国際関係学分野で尊敬される重鎮」であった。[27] また彼はイェール大学内に新設された二つの組織、社会科学部門と社会科学計画センターの責任者に任命された。[5] 同時にピアソン・カレッジの学部長職を退いた。[2] イェール大学学長チャールズ・シーモアは「14年にわたり英知と理解をもってピアソン・カレッジを運営してきた学部長を同カレッジから引き離さねばならな いことを深く遺憾に思う」と述べた。[5] ウォルファーズ夫妻はその後もニューヘイブンに居住を続けた。[11] 1950年から1951年にかけ、イェール国際研究所は新学長A・ホイットニー・グリスウォルドと対立した。グリスウォルドは、研究は協力グループではな く個人で行うべきだと考え[69]、研究所は時事問題や政策提言に注力するより、歴史的・客観的分析を強化すべきだと主張した。研究所の学者たちの大半は イェールを去り、その多くはプリンストン大学に移り、1951年に同大学に国際研究センターを設立したが、ウォルファーズはその後数年間イェールに残留し た。 1954年5月、ウォルファーズはロックフェラー財団主催でワシントンD.C.で開催された国際政治会議に出席した。この会議にはハンス・モーゲンソー、 ラインホールド・ニーバー、ウォルター・リップマン、ポール・ニッツェ、ケネス・W・トンプソン、ケネス・ウォルツ、ディーン・ラスクらが集結した。この 会議は現代現実主義を通じて国際関係理論を定義しようとする試みと見なされてきた[70]。 |

| Washington Center of Foreign

Policy Research Wolfers left Yale in 1957, at the age of 65, but retained an emeritus title there.[2] He was appointed director of the Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research at Johns Hopkins University.[5] This was a new institute founded by Paul Nitze, who wanted to create a center within the School of Advanced International Studies that would join academics and policymakers.[71] Unsettled by some feuding going on at Yale regarding the future of international relations study there, Wolfers was willing to leave Yale and move to Washington to take on the new position.[72] At the Washington Center, Wolfers brought academics and government officials together to discuss national security policy.[73] Nitze would later say that Wolfers had been an asset in running discussions wherein members were encouraged to bring forth their ideas and defend them while others kept an open mind.[74] Wolfers was willing to question prevailing academic opinions and ideologies and, in Nitze's words, "brought a wind of fresh air to what had been a fairly stodgy and opinionated group. He was a joy to work with."[74] Wolfers' own thoughts at the time still revolved around classical balance of power relationships.[71] Overall, the directorship of Wolfers added an academic prestige to the center that it had previously not had.[73] Wolfers consulted for the Institute for Defense Analyses in 1960 and 1961 and was a consultant to the State Department from 1960 on.[2] He also consulted for the U.S. Department of the Army.[47] A 1962 book from Wolfers, Discord and Collaboration: Essays on International Politics, presented sixteen essays on international relations theory, most of which had already been published in some form but some of which were completely new. Many of the essays had been influential when first published, and the book came to be viewed as a classic.[75] In a foreword, Reinhold Niebuhr said that Wolfers was more of political philosopher than a political scientist who nonetheless sought empirical verification of his theories and suppositions.[76] Wolfers belonged to a number of academic organizations and clubs, including the International Institute for Strategic Studies (for which he was a member of the international advisory council), the American Political Science Association, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Century Association, and the Cosmos Club.[2] |

ワシントン外交政策研究センター ウォルファーズは1957年、65歳でイェール大学を去ったが、同大学の名誉教授の称号は保持した[2]。彼はジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学のワシントン外交 政策研究センターの所長に任命された[5]。これは、ポール・ニッツェが設立した新しい研究所であり、高等国際問題研究大学院内に、学者と政策立案者を結 集するセンターを作りたいと考えていた。[71] イエール大学で国際関係学の研究の将来について争いが続いており、不安を感じていたウォルファーズは、イエール大学を離れてワシントンに移り、新しい職に 就くことを決意した。[72] ワシントンセンターでは、ウォルファーズは学者と政府高官を集め、国家安全保障政策について議論した。[73] ニッツェは後に、ウォルファーズは、メンバーが自分の考えを提示し、それを擁護することを奨励し、他のメンバーはオープンマインドを保つという議論の運営 において、貴重な存在であったと述べている。[74] ウォルファーズは、主流の学術的見解やイデオロギーに疑問を投げかけることを厭わず、ニッツェの言葉によれば、「かなり堅苦しく、独断的なグループに新鮮 な風を吹き込んだ。彼と仕事をするのは楽しいことだった」という。[74] 当時のウォルファーズ自身の考えは、依然として古典的な勢力均衡関係を中心に回っていた。[71] 全体として、ウォルファーズの所長就任は、同センターにそれまでなかった学術的威信をもたらした。[73] ウォルファーズは1960年と1961年に国防分析研究所の顧問を務め、1960年以降は国務省の顧問でもあった。[2] 彼はまた米国陸軍省の顧問も務めた。[47] 1962年に出版されたウォルファーズの著書『不和と協調:国際政治論集』は、国際関係論に関する16編の論文を収録している。その大半は既に何らかの形 で発表済みだったが、完全に新規の論文も含まれていた。多くの論文は初出時に影響力を持っており、本書は古典として評価されるようになった。[75] 序文でラインホールド・ニーバーは、ウォルファーズは政治学者というより政治哲学者でありながら、自らの理論や仮説に対して実証的検証を求めた人物だと述 べている。[76] ウォルファーズは複数の学術団体やクラブに所属していた。国際戦略研究所(国際諮問委員会のメンバーを務めた)、アメリカ政治学会、外交問題評議会、セン チュリー協会、コスモスクラブなどである。[2] |

| Final years Wolfers retired from the Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research in 1965[5] but remained affiliated to it with the status of special adviser.[2] Wolfers destroyed his files on three occasions when undergoing changes of position, in 1949, 1957, and 1966.[77] Beginning in 1958, the Wolferses spent more time at their Maine house,[67] even though he officially still lived in Washington.[5] They entertained in Maine often, bringing in guests of all different political persuasions and artistic endeavors.[67] Encouraged by the Wolferses' acquaintance Carl Jung, who thought that Doris had a greater creative instinct than her role as Arnold's secretary and amanuensis made use of, she had resumed her career as an artist in the early-to-mid 1950s.[12] She specialized in embroidery-based textual montages.[11][12] Beginning in 1960, she had her work exhibited at galleries in Washington, New York, Rhode Island, and Maine.[11] Wolfers died on July 16, 1968, in a hospital in Blue Hill, Maine.[5] Doris focused even more on her artistic endeavors after he was gone[12] and would live until 1987.[67] |

晩年 ウォルファーズは1965年にワシントン外交政策研究センターを退職したが[5]、特別顧問の地位で引き続き関与した[2]。ウォルファーズは1949 年、1957年、1966年の三度にわたり、職位の変更に伴い自身のファイルを破棄した。[77] 1958年以降、ウォルファーズ夫妻はメイン州の自宅での時間を増やした[67]。公式にはワシントン在住のままだったが[5]、メイン州では頻繁に接待 を行い、異なる政治的立場や芸術的活動に携わる客人を招いた. [67] ウォルファーズ夫妻の知人カール・ユングの勧めで、ドリスは1950年代前半から中盤にかけて芸術家としての活動を再開した。ユングは、ドリスがアーノル ドの秘書兼代筆者としての役割では発揮しきれていない創造的本能を秘めていると考えていたのだ。[12] 彼女は刺繍を基にしたテキスト・モンタージュを専門とした。[11][12] 1960年以降、ワシントン、ニューヨーク、ロードアイランド、メインの各州の画廊で作品を発表した。[11] ウルフャーズは1968年7月16日、メイン州ブルーヒルの病院で死去した。[5] 彼の死後、ドリスは芸術活動にさらに専念し[12]、1987年まで生き続けた。[67] |

| Awards and honors Wolfers received an honorary Litt.D. from Mount Holyoke College in 1934.[78] He had a long relationship with that school, including giving the Founder's Day address in 1933,[78] conducting public assemblies in 1941,[79] and delivering a commencement address in 1948.[80] Wolfers was also granted an honorary LL.D. from the University of Rochester in 1945.[2] An endowed chair, the Arnold Wolfers Professor of Political Science, was created at Yale following Wolfers' death, funded by a $600,000 gift from Arthur K. Watson of IBM.[81] Watson's gift was subsequently increased to $1 million.[82] |

受賞と栄誉 ウォルファーズは、1934年にマウント・ホリヨーク大学から名誉文学博士号を授与された[78]。彼はこの大学と長年の関係があり、1933年には創立 記念日の演説を行い[78]、1941年には公開集会を開催し[79]、1948年には卒業式で祝辞を述べた。[80] ウルファーズは1945年にロチェスター大学から名誉法学博士号も授与された。[2] ウルファーズの死後、IBMのアーサー・K・ワトソンによる60万ドルの寄付により、イェール大学にアーノルド・ウルファーズ政治学教授という寄付講座が 創設された。[81] ワトソンの寄付はその後100万ドルに増額された。[82] |

| Legacy Two Festschrift volumes were published in tribute to Wolfers. The first, Foreign Policy in the Sixties: The Issues and the Instruments: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers, edited by Roger Hilsman and Robert C. Good, came out in 1965 during Wolfers' lifetime. It largely featured contributions from his former students, including ones from Raymond L. Garthoff, Laurence W. Martin, Lucian W. Pye, W. Howard Wriggins, Ernest W. Lefever, and the editors. The second, Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers, edited by Douglas T. Stuart and Stephen F. Szabo, came out in 1994 based on a 1992 conference at Dickinson College. It featured contributions from Martin again, Catherine McArdle Kelleher, Vojtech Mastny, and others, as well as the editors. In terms of international relations theory, the editors of the second Festschrift characterize Wolfers as "the reluctant realist".[83] Wolfers could be categorized as belonging to "progressive realists", figures who often shared legal training, left-leaning traits in their thinking, and institutionally reformist goals.[84] Wolfers' focus on morality and ethics in international relations, which he viewed as something that could transcend demands for security depending upon circumstances, is also unusual for a realist.[85] Martin believes Wolfers "swam against the tide" within the realist school, taking "a middle line that makes him seem in retrospect a pioneer revisionist of realism."[86] But Wolfers did not subscribe to alternative explanations for international relations, such as behaviorism or quantification, instead preferring to rely upon, as he said, "history, personal experience, introspection, common sense and the gift of logical reason".[87] The progressive, democratic reputation that the Deutsche Hochschule für Politik enjoyed for decades became diminished as a result of scholarly research performed in the latter part of the twentieth century which showed that the Hochschule's relationship with the Nazi Party was not the one of pure opposition that had been portrayed.[88] With those findings, Wolfers' reputation in connection to his role there suffered somewhat as well.[89] By one account, it took six decades for any of Wolfers' former students in the United States to concede that Wolfers, even after having left Germany and finding a secure position at Yale, had still during the 1930s shown some ideological sympathies with the Nazi regime.[26] Two of Wolfers' formulations have often been repeated. The first provides a metaphor for one model of who the participants are in international relations: states-as-actors behaving as billiard balls that collide with one another.[90] The second provides two components for the notion of national security; Wolfers wrote that "security, in an objective sense, measures the absence of threats to acquired values, in a subjective sense, the absence of fear that such values will be attacked."[91] Wolfers found composition difficult and his written output was small, with Britain and France Between Two Wars and Discord and Collaboration being his two major works.[92][93] Much of his influence lay in how he brought people and discussions together in productive ways and bridged gaps between theory and practice.[93] But what Wolfers did write found an audience; by 1994, Discord and Collaboration was in its eighth printing, twenty-five years after his death.[94] In the introduction to the second Festschrift, Douglas T. Stuart wrote, "The book stands the test of time for two reasons. First, the author addresses enduring aspects of international relations and offers insightful recommendations about the formulation and execution of foreign policy. Second, Wolfers's writings are anchored in a sophisticated theory of situational ethics that is valid for any historical period, but that is arguably more relevant today than it was when Wolfers was writing."[94] Nevertheless, Wolfers' name is often not remembered as well as it might. In a 2008 interview, Robert Jervis, the Adlai E. Stevenson Professor of International Politics at Columbia University, listed international relations scholars who had influenced him, and he concluded by saying, "then there is one scholar who's not as well known as he should be: Arnold Wolfers, who was I think the most sophisticated, subtle, and well-grounded of the early generation of Realists."[95] In his 2011 book, political theorist William E. Scheuerman posits three "towering figures" of mid-twentieth century classical realism – E. H. Carr, Hans J. Morgenthau, Reinhold Niebuhr – and next includes Wolfers, along with John H. Herz and Frederick L. Schuman, in a group of "prominent postwar US political scientists, relatively neglected today but widely respected at mid century".[75] On the other hand, in a 2011 remark the British international relations scholar Michael Cox mentioned Wolfers as one of the "giants" of international relations theory, along with Hans Morgenthau, Paul Nitze, William T. R. Fox, and Reinhold Niebuhr.[96] In the 2011 Encyclopedia of Power, Douglas T. Stuart wrote that "More than 40 years after his death, Arnold Wolfers remains one of the most influential experts in the field of international relations."[97] |

遺産 ウルファーズに敬意を表して、2冊の記念論文集が刊行された。1冊目は、ロジャー・ヒルズマンとロバート・C・グッドが編集した『1960年代の外交政 策:課題と手段:アーノルド・ウルファーズに捧げる論文集』で、ウルファーズの存命中の1965年に刊行された。この本には、レイモンド・L・ガートホ フ、ローレンス・W・マーティン、ルシアン・W・パイ、W・ハワード・リギンズ、アーネスト・W・レフィーバー、そして編集者たちなど、彼の元学生たちに よる寄稿が数多く掲載されている。2冊目は、ダグラス・T・スチュワートとスティーブン・F・サボが編集した『新しいヨーロッパにおける不和と協力:アー ノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ集』で、1992年にディキンソン大学で開催された会議に基づいて1994年に出版された。この本には、マーティ ン、キャサリン・マッカーダル・ケレハー、ヴォイテック・マストニー、その他、編集者たちによる寄稿が掲載されている。 国際関係論の観点から、2冊目の記念論文集の編集者たちは、ウォルファーズを「不本意な現実主義者」と評している[83]。ウォルファーズは「進歩的現実 主義者」に分類されるだろう。この人たちは、多くの場合、法律の訓練を受け、左寄りの考え方を持ち、制度的な改革を目標としていた。[84] ウォルファーズが国際関係における道徳や倫理に焦点を当てたことも、現実主義者としては珍しい。[85] マーティンは、ウォルファーズが現実主義学派の中で「逆流に泳いだ」と評価し、「振り返ってみると、現実主義の先駆的な修正主義者と思われるような中道的 な立場」を取ったと述べている。[86] しかし、ウォルファーズは、行動主義や定量化など、国際関係に関する他の説明には賛同せず、代わりに、彼が言うところの「歴史、個人的経験、内省、常識、 そして論理的推論の才能」に頼ることを好んだ。[87] ドイツ政治大学が数十年にわたって享受してきた進歩的で民主的な評判は、20 世紀後半に行われた学術研究の結果、同大学とナチ党との関係は、これまで描かれてきたような純粋な対立関係ではなかったことが明らかになったことで、低下 した。[88] こうした発見により、ウルファースの同大学での役割に関する評判も、ある程度苦悩した。[89] ある説によれば、ヴォルファースの元教え子たちが、彼がドイツを離れてイェール大学で安定した地位を得た後も、1930年代にナチス政権への思想的共感を 示していたことを認めるまでに、アメリカでは60年を要したという。[26] ヴォルファースの提唱した二つの概念は繰り返し引用されてきた。一つは国際関係における主体像の隠喩として用いられる:国家をビリヤードの球に喩え、互い に衝突する行為主体として描くものだ。[90] もう一つは国民安全保障概念の二要素を提示するもので、ウォルファーズは「安全保障とは客観的には獲得した価値への脅威の不在を、主観的にはそうした価値 が攻撃される恐れのない状態を測る尺度である」と記した。[91] ウォルファーズは執筆が苦手で著作は少なく、『二つの戦争の間の英国とフランス』と『不和と協調』が主要な二作品である[92][93]。彼の影響力の多 くは、人々や議論を生産的に結びつけ、理論と実践の隔たりを埋めた点にあった。[93] しかし、ウォルファーズが書いたものは読者を獲得した。1994年までに、『不和と協調』は、彼の死から25年を経て、8回目の増刷となった。[94] 2冊目の記念論文集の序文で、ダグラス・T・スチュワートは、「この本は、2つの理由から時の試練に耐えている。第一に、著者は国際関係の永続的な側面を 取り上げ、外交政策の策定と実行について洞察に満ちた提言を行っている。第二に、ウォルファーズの著作は、あらゆる歴史的時代において有効である、洗練さ れた状況倫理の理論に根ざしている。しかし、その理論は、ウォルファーズが執筆していた当時よりも、今日の方がより関連性が高いといえるだろう」と述べ た。[94] それにもかかわらず、ウォルファーズの名前は、本来あるべきほどよく記憶されていないことが多い。2008年のインタビューで、コロンビア大学の国際政治 学教授であるロバート・ジャーヴィスは、彼に影響を与えた国際関係学者を挙げ、次のように結論づけた。「そして、その中には、本来あるべきほど有名ではな い学者が一人いる。アーノルド・ウォルファーズだ。彼は、初期のリアリスト世代の中で最も洗練され、繊細で、確固たる基盤を持つ人物だったと思う」 [95]。政治理論家ウィリアム・E・シェウアーマンは2011年の著書で、20世紀中葉の古典的現実主義における三人の「傑出した人物」を提示している ——E・H・カー、ハンス・J・モーゲンソー、ラインホルト・ニーバー——を挙げ、続いてウルファーズをジョン・H・ハーツ、フレデリック・L・シューマ ンと共に「戦後米国の著名な政治学者たち。今日では比較的軽視されているが、20世紀半ばには広く尊敬されていた」グループに含めている。[75] 一方、2011年の発言で、英国の国際関係学者マイケル・コックスは、ハンス・モーゲンソー、ポール・ニッツェ、ウィリアム・T・R・フォックス、ライン ホールド・ニーバーとともに、国際関係理論の「巨人」の一人としてウォルファーズの名を挙げている。[96] 2011年の『権力の百科事典』の中で、ダグラス・T・スチュワートは「死後40年以上経った今でも、アーノルド・ウォルファーズは国際関係学分野で最も 影響力のある専門家の一人である」と記している。[97] |

| Published works Die Verwaltungsorgane der Aktiengesellschaft nach schweizerischem Recht unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Verhältnisses von Verwaltungsrat und Direktion (Sauerländer, 1917) (Zürcher Beiträge zur Rechtswissenschaft 66). Die Aufrichtung der Kapitalherrschaft in der abendländischen Geschichte (1924, thesis). "Über monopolistische und nichtmonopolistische Wirtschaftsverbände", Archiv für Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik 59 (1928), 291–321. "Ueberproduktion, fixe Kosten und Kartellierung", Archiv für Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik 60 (1928), 382–395. Amerikanische und deutsche Löhne: eine Untersuchung über die Ursachen des hohen Lohnstandes in den Vereinigten Staaten (Julius Springer, 1930). Das Kartellproblem im Licht der deutschen Kartellliteratur (Duncker & Humblot, 1931). "Germany and Europe", Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs 9 (1930), 23–50. "The Crisis of the Democratic Régime in Germany", International Affairs 11 (1932), 757–783. Britain and France Between Two Wars: Conflicting Strategies of Peace Since Versailles (Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1940); revised edition (W. W. Norton, 1966) The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order (Harcourt Brace, 1946) [co-author with Bernard Brodie, Frederick Sherwood Dunn, William T. R. Fox, Percy Ellwood Corbett] The Anglo-American Tradition in Foreign Affairs (Yale University Press, 1956) [co-editor with Laurence W. Martin] Alliance Policy in the Cold War (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1959) [editor] Developments in Military Technology and Their Impact on United States Strategy and Foreign Policy (Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research for U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 1959) [co-author with Paul Nitze and James E. King] Discord and Collaboration: Essays on International Politics (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1962) |

出版作品 スイス法に基づく株式会社の管理機関、特に取締役会と経営陣の関係について(Sauerländer、1917年)(チューリッヒ法学論文集 66)。 西洋史における資本支配の確立(1924年、論文)。 「独占的および非独占的経済団体について」、社会科学および社会政策アーカイブ 59 (1928)、291–321。 「過剰生産、固定費およびカルテル化」、社会科学および社会政策アーカイブ 60 (1928)、382–395。 アメリカとドイツの賃金:米国における高賃金の原因に関する調査(Julius Springer、1930年)。 ドイツのカルテル文献に照らしたカルテル問題(Duncker & Humblot、1931年)。 「ドイツとヨーロッパ」、王立国際問題研究所ジャーナル 9 (1930)、23–50。 「ドイツにおける民主主義体制の危機」、International Affairs 11 (1932)、757–783。 二つの戦争の間の英国とフランス:ヴェルサイユ以来の相反する平和戦略(Harcourt, Brace and Co.、1940年)、改訂版(W. W. Norton、1966年) 絶対兵器: 原子力と世界秩序(Harcourt Brace、1946年) [バーナード・ブロディ、フレデリック・シャーウッド・ダン、ウィリアム・T・R・フォックス、パーシー・エルウッド・コーベットとの共著] 外交における英米の伝統(イェール大学出版、1956年) [ローレンス・W・マーティンとの共編] 冷戦における同盟政策 (ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版、1959年)[編集] 軍事技術の発展とそれが米国の戦略および外交政策に与える影響(米国上院外交委員会ワシントン外交政策研究センター、1959年)[ポール・ニッツェ、 ジェームズ・E・キングとの共著] 不和と協力:国際政治に関するエッセイ(ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版、1962年) |

| Bibliography Eisfeld, Rainer (2014). "From the Berlin Political Studies Institute to Columbia and Yale: Ernest Jaeckh and Arnold Wolfers". In Rösch, Felix (ed.). Émigré Scholars and the Genesis of International Relations: A European Discipline in America?. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 113–131. Guilhot, Nicolas (2011). "The Realist Gambit: Postwar American Political Science and the Birth of IR Theory". In Guilhot, Nicolas (ed.). The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 128–161. Haslam, Jonathan (2002). No Virtue Like Necessity: Realist Thought in International Relations Since Machiavelli. New Haven: Yale University Press. Hilsman, Roger; Good, Robert C. (1965). "Introduction". In Hilsman, Roger; Good, Robert C. (eds.). Foreign Policy in the Sixties: The Issues and the Instruments: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. pp. ix–xii. Kaplan, Fred (1983). The Wizards of Armageddon. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Korenblat, Steven D. (September 2006). "A School for the Republic? Cosmopolitans and Their Enemies at the Deutsche Hochschule Für Politik, 1920–1933". Central European History. 39 (3): 394–430. doi:10.1017/S0008938906000148. S2CID 144221659. Martin, Laurence (1994). "Arnold Wolfers and the Anglo-American Tradition". In Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.). Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Policy Institute, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. pp. 11–16. Nitze, Paul H. (1994). "Foreword". In Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.). Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Policy Institute, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. pp. v–vi. Parmar, Inderjeet (2011). "American Hegemony, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of Academic International Relations in the United States". In Guilhot, Nicolas (ed.). The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 182–209. Scheuerman, William E. (2011). The Realist Case for Global Reform. Cambridge: Polity Press. Stuart, Douglas T. (1994). "Discord and Collaboration: Enduring Insights of Arnold Wolfers". In Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.). Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Policy Institute, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. pp. 3–10. Szabo, Stephen F. (1994). "Conclusion: Wolfers and Europe Today". In Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.). Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe: Essays in Honor of Arnold Wolfers. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Policy Institute, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. pp. 239–250. Who's Who in America 1966–1967 (34th ed.). Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1966. Williams, Robert E. Jr. (Summer 2012). "Review: The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on Theory, Nicolas Guilhot, ed". Ethics & International Affairs. 26 (2): 284–286. doi:10.1017/S0892679412000366. S2CID 145419172. Winks, Robin W. (1987). Cloak & Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939–1961. New York: William Morrow and Company. |

参考文献 アイスフェルト、ライナー(2014)。「ベルリン政治研究所からコロンビア大学とイェール大学へ:エルネスト・イェックとアーノルド・ヴォルファー ス」。フェリックス・レッシュ編『亡命学者と国際関係論の創生:アメリカにおけるヨーロッパの学問分野か?』所収。ハンプシャー州ベージングストーク:パ ルグレイブ・マクミラン。113–131頁。 ギヨ, ニコラ (2011). 「現実主義の駆け引き:戦後アメリカ政治学と国際関係理論の誕生」. ギヨ, ニコラ (編). 『国際関係理論の発明:現実主義、ロックフェラー財団、そして1954年理論会議』. ニューヨーク: コロンビア大学出版局. pp. 128–161. ハスラム、ジョナサン(2002)。『必要ほど美徳はない:マキャヴェッリ以来の国際関係における現実主義的思考』。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版 局。 ヒルズマン、ロジャー;グッド、ロバート C.(1965)。「序文」。ヒルズマン、ロジャー;グッド、ロバート C.(編)。60年代の外交政策:問題と手段:アーノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ。ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンズ出版。ix–xii ページ。 カプラン、フレッド(1983)。アルマゲドンの魔法使いたち。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版。 コーレンブラット、スティーブン D.(2006年9月)。「共和国のための学校?1920年から1933年のドイツ政治大学におけるコスモポリタンとその敵たち」。中央ヨーロッパの歴 史。39 (3): 394–430. doi:10.1017/S0008938906000148. S2CID 144221659. マーティン、ローレンス (1994). 「アーノルド・ウォルファーズと英米の伝統」 スチュワート、ダグラス T.; サーボ、スティーブン F. (編). 『新しいヨーロッパにおける不和と協力:アーノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ』 ワシントン D.C.: 外交政策研究所、ポール H. ニッツェ高等国際問題研究大学院、ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学. pp. 11–16. ニッツェ、ポール H. (1994). 「序文」. スチュワート、ダグラス T.、サボ、スティーブン F. (編). 『新しいヨーロッパにおける不和と協力:アーノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ』. ワシントン D.C.: ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学ポール・H・ニッツェ高等国際問題研究大学院外交政策研究所. pp. v–vi. Parmar, Inderjeet (2011). 「アメリカのヘゲモニー、ロックフェラー財団、そして米国における国際関係学の台頭」. Guilhot, Nicolas (編). 『国際関係理論の発明:リアリズム、ロックフェラー財団、そして 1954 年の理論会議』. ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局. pp. 182–209. pp. 182–209. Scheuerman, William E. (2011). The Realist Case for Global Reform. Cambridge: Polity Press. Stuart, Douglas T. (1994). 「不和と協力:アーノルド・ウォルファーズの永続的な洞察」. In Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.). 新しいヨーロッパにおける不和と協力:アーノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ。ワシントン D.C.:外交政策研究所、ポール・H・ニッツェ高等国際問題研究大学院、ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学。3-10 ページ。 Szabo, Stephen F. (1994). 「結論:ウォルファーズと今日のヨーロッパ」。Stuart, Douglas T.; Szabo, Stephen F. (eds.) 編。新しいヨーロッパにおける不和と協力:アーノルド・ウォルファーズを称えるエッセイ。ワシントン D.C.:外交政策研究所、ポール・H・ニッツェ高等国際研究大学院、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学。239-250 ページ。 Who『s Who in America 1966–1967 (第 34 版)。シカゴ:Marquis Who』s Who。1966 年。 ウィリアムズ、ロバート・E・ジュニア(2012年夏)。「レビュー:国際関係理論の発明:現実主義、ロックフェラー財団、そして1954年の理論に関す る会議、ニコラス・ギロ、編」。倫理と国際問題。26 (2): 284–286。doi:10.1017/S0892679412000366. S2CID 145419172. ウィンクス、ロビン・W. (1987). 『ローブとガウン:秘密戦争の学者たち、1939–1961』. ニューヨーク: ウィリアム・モロー・アンド・カンパニー. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_Wolfers |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099