芸術的インスピレーション

Artistic inspiration

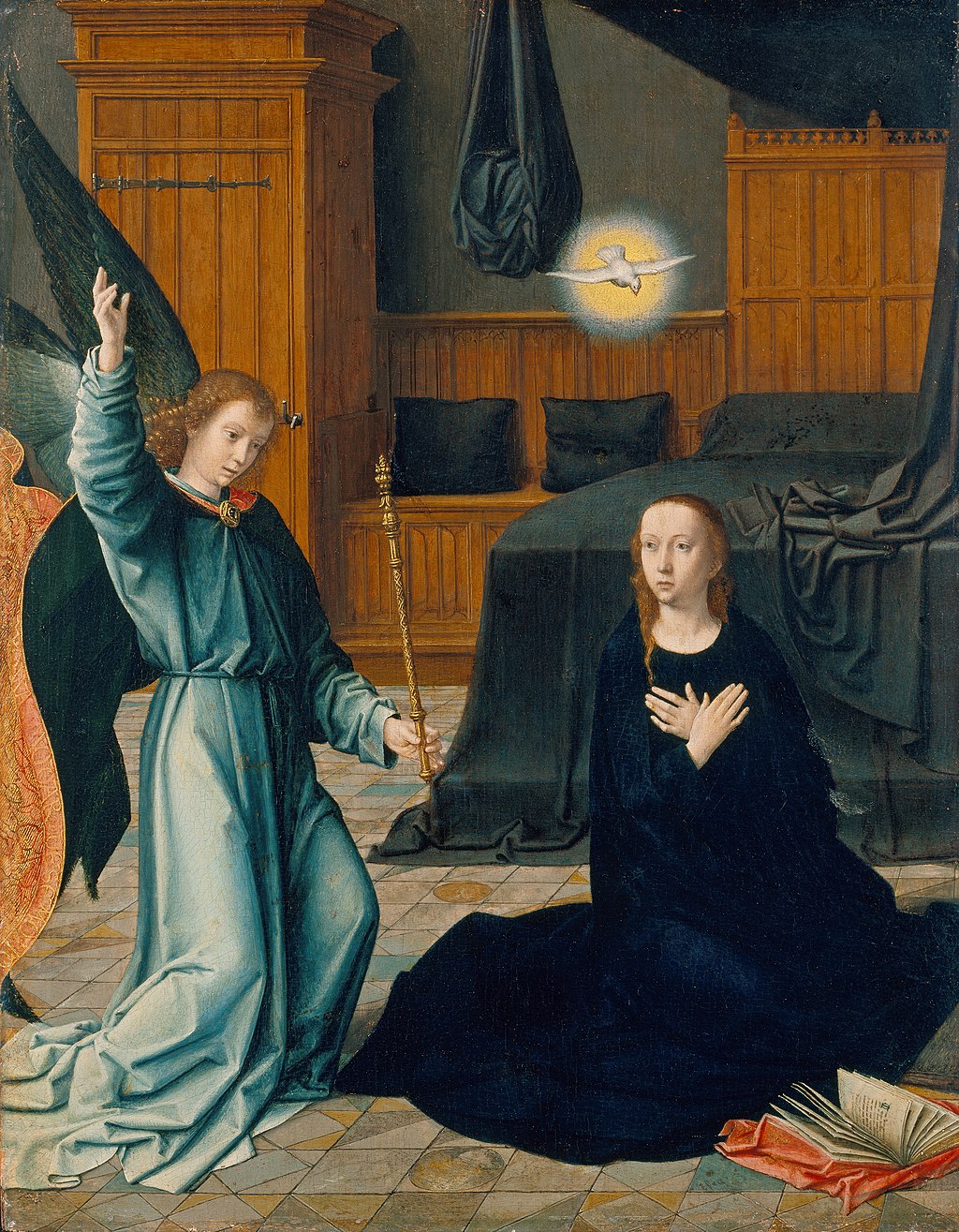

Gerard David の受胎告知

☆ インスピレーション(ラテン語で「息を吹き込む」を意味するinspirareから; inspiration)とは、文学、音楽、視覚芸術、その他の芸術活動において、無意識のう ちに沸き起こる創造性のことである。この概念は、ヘレニズムとヘブライズムの両方に起源を持つ。ギリシャ人は、インスピレーションや "熱意 "は、アポロン神やディオニュソス神と同様に、ミューズからもたらされると信じていた。同様に、古代北欧の宗教では、インスピレーションはオーディンなど の神々からもたらされる。ヘブライ語の詩学においても、霊感は神的なものである。アモス書の中で預言者は、神の声に圧倒され、語らざるを得なかったと語っ ている。キリスト教では、霊感は聖霊の賜物である。

| Inspiration

(from the Latin inspirare, meaning "to breathe into") is an unconscious

burst of creativity in a literary, musical, or visual art and other

artistic endeavours. The concept has origins in both Hellenism and

Hebraism. The Greeks believed that inspiration or "enthusiasm" came

from the muses, as well as the gods Apollo and Dionysus. Similarly, in

the Ancient Norse religions, inspiration derives from the gods, such as

Odin. Inspiration is also a divine matter in Hebrew poetics. In the

Book of Amos the prophet speaks of being overwhelmed by God's voice and

compelled to speak. In Christianity, inspiration is a gift of the Holy

Spirit. In the 18th century philosopher John Locke proposed a model of the human mind in which ideas associate or resonate with one another in the mind. In the 19th century, Romantic poets such as Coleridge and Shelley believed that inspiration came to a poet because the poet was attuned to the (divine or mystical) "winds" and because the soul of the poet was able to receive such visions. In the early 20th century, psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud believed himself to have located inspiration in the inner psyche of the artist. Psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung's theory of inspiration suggests that an artist is one who was attuned to their creative instinct which encoded the archetypes of the human mind. The Marxist theory of art sees it as the expression of the friction between economic base and economic superstructural positions, or as an unaware dialog of competing ideologies, or as an exploitation of a "fissure" in the ruling class's ideology. In modern psychology inspiration is not frequently studied, but it is generally seen as an entirely internal process. |

イ

ンスピレーション(ラテン語で「息を吹き込む」を意味するinspirareから)とは、文学、音楽、視覚芸術、その他の芸術活動において、無意識のうち

に沸き起こる創造性のことである。この概念は、ヘレニズムとヘブライズムの両方に起源を持つ。ギリシャ人は、インスピレーションや "熱意

"は、アポロン神やディオニュソス神と同様に、ミューズからもたらされると信じていた。同様に、古代北欧の宗教では、インスピレーションはオーディンなど

の神々からもたらされる。ヘブライ語の詩学においても、霊感は神的なものである。アモス書の中で預言者は、神の声に圧倒され、語らざるを得なかったと語っ

ている。キリスト教では、霊感は聖霊の賜物である。 18世紀、哲学者ジョン・ロックは、心の中で観念が互いに関連し、共鳴し合うという人間の心のモデルを提唱した。19世紀、コールリッジやシェリーのよう なロマン派の詩人たちは、詩人が(神的または神秘的な)「風」に同調し、詩人の魂がそのようなビジョンを受け取ることができるため、インスピレーションが 詩人にもたらされると信じていた。20世紀初頭には、精神分析学者のジークムント・フロイトが、芸術家の内なる精神にインスピレーションがあると信じてい た。精神科医カール・グスタフ・ユングのインスピレーション理論は、芸術家とは、人間の心の原型をコード化した創造的本能に同調した人であると示唆してい る。 マルクス主義の芸術論は、芸術を経済的基盤と経済的上部構造との間の摩擦の表現として、あるいは競合するイデオロギーの無自覚な対話として、あるいは支配 階級のイデオロギーの「亀裂」の利用としてとらえている。現代心理学では、ひらめきはあまり研究されていないが、一般的には完全に内的なプロセスとみなさ れている。 |

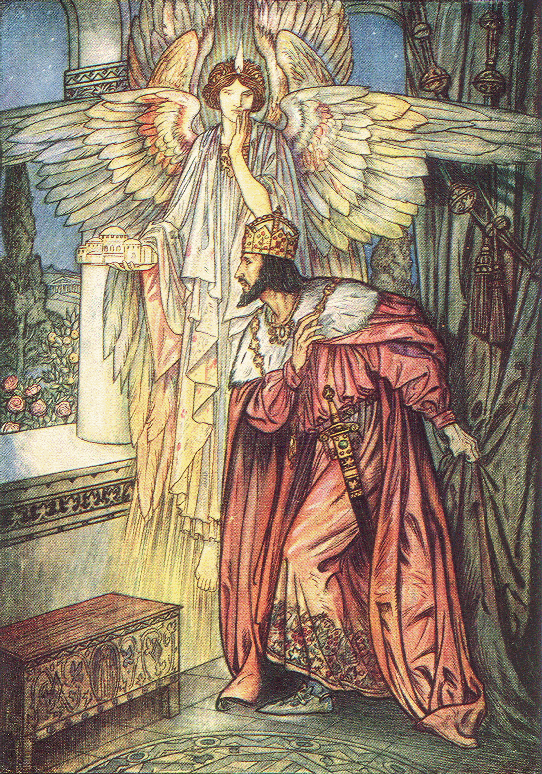

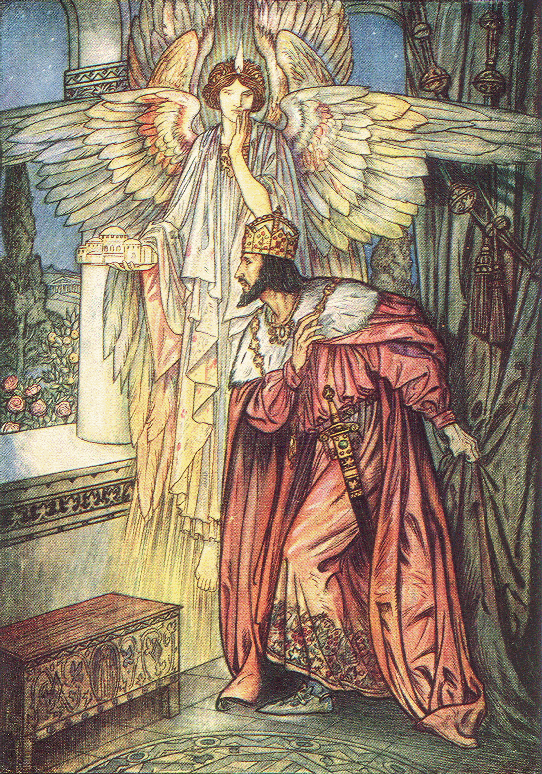

Book

illustration of Byzantine Emperor Justinian's inspiration for Hagia

Sophia. The cathedral had burnt down during a riot; now Justinian would

build an even more beautiful one. Book

illustration of Byzantine Emperor Justinian's inspiration for Hagia

Sophia. The cathedral had burnt down during a riot; now Justinian would

build an even more beautiful one. |

ビザンツ皇帝ユスティニアヌスがアヤソフィアに着想を得た際の挿絵。この大聖堂は暴動で焼失してしまったが、ユスティニアヌスはさらに美しい大聖堂を建設する予定だった。 ビザンツ皇帝ユスティニアヌスがアヤソフィアに着想を得た際の挿絵。この大聖堂は暴動で焼失してしまったが、ユスティニアヌスはさらに美しい大聖堂を建設する予定だった。 |

A webcomic illustrating how inspiration may vary over time A webcomic illustrating how inspiration may vary over time |

インスピレーションが時間とともにどのように変化するかを描いたウェブコミック インスピレーションが時間とともにどのように変化するかを描いたウェブコミック |

| History of the concepts Ancient models of inspiration In Greek thought, inspiration meant that the poet or artist would go into ecstasy or furor poeticus, the divine frenzy or poetic madness. The artist would be transported beyond their own mind and given the gods' or goddesses own thoughts to embody. Inspiration is prior to consciousness and outside of skill (ingenium in Latin). Technique and performance are independent of inspiration, and therefore it is possible for the non-poet to be inspired and for a poet or painter's skill to be insufficient to the inspiration. In Hebrew poetics, inspiration is similarly a divine matter. In the Book of Amos, 3:8 the prophet speaks of being overwhelmed by God's voice and compelled to speak. However, inspiration is also a matter of revelation for the prophets, and the two concepts are intermixed to some degree. Revelation is a conscious process, where the writer or painter is aware and interactive with the vision, while inspiration is involuntary and received without any complete understanding. In Christianity, inspiration is a gift of the Holy Spirit. Saint Paul said that all scripture is given by inspiration of God (2 Timothy) and the account of Pentecost records the Holy Spirit descending with the sound of a mighty wind. This understanding of "inspiration" is vital for those who maintain Biblical literalism, for the authors of the scriptures would, if possessed by the voice of God, not "filter" or interpose their personal visions onto the text. For church fathers like Saint Jerome, David was the perfect poet, for he best negotiated between the divine impulse and the human consciousness. In northern societies, such as Old Norse, inspiration was likewise associated with a gift of the gods. As with the Greek, Latin, and Romance literatures, Norse skalds were inspired by a magical and divine state and then shaped the words with their conscious minds. Their training was an attempt to learn to shape forces beyond the human. In the Venerable Bede's account of Cædmon, the Christian and later Germanic traditions combine. Cædmon was a herder with no training or skill at verse. One night, he had a dream where Jesus asked him to sing. He then composed "Cædmon's Hymn", and from then on was a great poet. Inspiration in the story is the product of grace: it is unsought (though desired), uncontrolled, and irresistible, and the poet's performance involves his whole mind and body, but it is fundamentally a gift. Renaissance revival of furor poeticus The Greco-Latin doctrine of the divine origin of poetry was available to medieval authors through the writings of Horace (on Orpheus) and others, but it was the Latin translations and commentaries by the neo-platonic author Marsilio Ficino of Plato's dialogues Ion and (especially) Phaedrus at the end of the 15th century that led to a significant return of the conception of furor poeticus.[1] Ficino's commentaries explained how gods inspired the poets, and how this frenzy was subsequently transmitted to the poet's auditors through his rhapsodic poetry, allowing the listener to come into contact with the divine through a chain of inspiration. Ficino himself sought to experience ecstatic rapture in rhapsodic performances of Orphic-Platonic hymns accompanied by a lyre.[2] The doctrine was also an important part of the poetic program of the French Renaissance poets collectively referred to as La Pléiade (Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay, etc.); a full theory of divine fury / enthusiasm was elaborated by Pontus de Tyard in his Solitaire Premier, ou Prose des Muses, et de la fureur poétique (Tyard classified four kinds of divine inspiration: (1) poetic fury, gift of the Muses; (2) knowledge of religious mysteries, through Bacchus; (3) prophecy and divination through Apollo; (4) inspiration brought on by Venus/Eros.)[1] Enlightenment and Romantic models In the 18th century in England, nascent psychology competed with a renascent celebration of the mystical nature of inspiration. John Locke's model of the human mind suggested that ideas associate with one another and that a string in the mind can be struck by a resonant idea. Therefore, inspiration was a somewhat random but wholly natural association of ideas and sudden unison of thought. Additionally, Lockean psychology suggested that a natural sense or quality of mind allowed persons to see unity in perceptions and to discern differences in groups. This "fancy" and "wit," as they were later called, were both natural and developed faculties that could account for greater or lesser insight and inspiration in poets and painters. Imagination, the Romantics argued, is a tool to see things that the intelligence is blind to.[3] The musical model was satirized, along with the afflatus, and "fancy" models of inspiration, by Jonathan Swift in A Tale of a Tub. Swift's narrator suggests that madness is contagious because it is a ringing note that strikes "chords" in the minds of followers and that the difference between an inmate of Bedlam and an emperor was what pitch the insane idea was. At the same time, he satirized "inspired" radical Protestant ministers who preached through "direct inspiration." In his prefatory materials, he describes the ideal dissenter's pulpit as a barrel with a tube running from the minister's posterior to a set of bellows at the bottom, whereby the minister could be inflated to such an extent that he could shout out his inspiration to the congregation. Furthermore, Swift saw fancy as an antirational, mad quality, where, "once a man's fancy gets astride his reason, common sense is kick't out of doors." The divergent theories of inspiration that Swift satirized would continue, side by side, through the 18th and 19th centuries. Edward Young's Conjectures on Original Composition was pivotal in the formulation of Romantic notions of inspiration. He said that genius is "the god within" the poet who provides the inspiration. Thus, Young agreed with psychologists who were locating inspiration within the personal mind (and significantly away from the realm either of the divine or demonic) and yet still positing a supernatural quality. Genius was an inexplicable, possibly spiritual and possibly external, font of inspiration. In Young's scheme, the genius was still somewhat external in its origin, but Romantic poets would soon locate its origin wholly within the poet. Romantic writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson (The Poet), and Percy Bysshe Shelley saw inspiration in terms similar to the Greeks: it was a matter of madness and irrationality. Inspiration came because the poet tuned himself to the (divine or mystical) "winds" and because he was made in such a way as to receive such visions. Samuel Taylor Coleridge's accounts of inspiration were the most dramatic, and his The Eolian Harp was only the best of the many poems Romantics would write comparing poetry to a passive reception and natural channelling of the divine winds. The story he told about the composition of Kubla Khan has the poet reduced to the level of scribe. William Butler Yeats would later experiment and value automatic writing. Inspiration was evidence of genius, and genius was a thing that the poet could take pride in, even though he could not claim to have created it himself. Modernist and modern concepts Sigmund Freud and other later psychologists located inspiration in the inner psyche of the artist. The artist's inspiration came out of unresolved psychological conflict or childhood trauma. Further, inspiration could come directly from the unconscious. Like the Romantic genius theory and the revived notion of "poetic phrenzy," Freud saw artists as fundamentally special, and fundamentally wounded. Because Freud situated inspiration in the unconscious mind, Surrealist artists sought out this form of inspiration by turning to dream diaries and automatic writing, the use of Ouija boards and found poetry to try to tap into what they saw as the true source of art. Carl Gustav Jung's theory of inspiration reiterated the other side of the Romantic notion of inspiration indirectly by suggesting that an artist is one who was attuned to something impersonal, something outside of the individual experience: racial memory, or a 'Psychopoetry' experience.[4] Materialist theories of inspiration again diverge between purely internal and purely external sources. Karl Marx did not treat the subject directly, but the Marxist theory of art sees it as the expression of the friction between economic base and economic superstructural positions, or as an unaware dialog of competing ideologies, or as an exploitation of a "fissure" in the ruling class's ideology. Therefore, where there have been fully Marxist schools of art, such as Soviet Realism, the "inspired" painter or poet was also the most class-conscious painter or poet, and "formalism" was explicitly rejected as decadent (e.g. Sergei Eisenstein's late films condemned as "formalist error"). Outside of state-sponsored Marxist schools, Marxism has retained its emphasis on the class consciousness of the inspired painter or poet, but it has made room for what Frederic Jameson called a "political unconscious" that might be present in the artwork. However, in each of these cases, inspiration comes from the artist being particularly attuned to receive the signals from an external crisis. In modern psychology, inspiration is not frequently studied, but it is generally seen as an entirely internal process. In each view, however, whether empiricist or mystical, inspiration is, by its nature, beyond control. An example of a modern study on inspiration is one that was conducted by Takeshi Okada and Kentaro Ishibashi, published in 2016 in the multidisciplinary journal, Cognitive Science.[5] In this three-part study, groups of Japanese undergraduate art students were observed to determine whether copying or simply musing upon example artworks that served as their inspiration would increase their creative output. The results of the first and second experiment revealed that copying artwork enabled the students to produce creative drawings that were qualitatively different, but only when the example—the inspiration—featured a style that was unfamiliar to the students. The third experiment revealed that only musing upon the unfamiliar inspiration produced the same effect as copying it. Okada and Ishibashi suggest that these unfamiliar examples were able to facilitate the creativity of the students because they challenged the students' perspectives on drawing. They admit, however, that it is unclear whether their results can be generalized to professional artists as well, but they cite examples of artists, namely Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh, who extensively imitated the work of other artists, which might suggest that "imitation is an effective driver of creativity, even for experts."[5] |

コンセプトの歴史 インスピレーションの古代モデル ギリシャの思想では、インスピレーションとは、詩人や芸術家が恍惚状態に陥ること、あるいはfuror poeticus(神の狂乱、詩的狂気)を意味した。芸術家は自分の心を超えて、神々や女神の思考を具現化するために与えられる。 インスピレーションは意識に先行し、技術の外にある(ラテン語でingenium)。したがって、詩人でない者が霊感を受けることは可能であり、詩人や画 家の技量が霊感に対して不十分であることもありうる。ヘブライ語の詩学においても、霊感は同様に神によるものである。アモス書3章8節で、預言者は神の声 に圧倒され、語らざるを得なかったと語っている。しかし、霊感は預言者にとっては啓示の問題でもあり、この2つの概念はある程度混在している。啓示は意識 的なプロセスであり、作家や画家が意識してビジョンと対話するのに対し、霊感は不随意的なものであり、完全に理解することなく受け取るものである。 キリスト教では、霊感は聖霊の賜物である。聖パウロは、すべての聖典は神の霊感によって与えられると述べており(テモテへの手紙二)、聖霊降臨の記録に は、大風の音とともに聖霊が降臨したことが記されている。聖典の著者は、もし神の声に取り憑かれているのであれば、聖書に "フィルター "をかけたり、個人的なヴィジョンを挿入したりはしないからである。聖ジェロームのような教父にとって、ダビデは完璧な詩人であった。 古ノルド語のような北方社会では、インスピレーションも同様に神々の贈り物と関連づけられていた。ギリシア、ラテン、ロマンス文学と同様、北欧の蜥蜴人は 魔術的で神聖な状態から霊感を受け、意識で言葉を形作った。彼らの訓練は、人間を超えた力を形作ることを学ぶ試みであった。崇敬者ベデのケードモンに関す る記述では、キリスト教と後期ゲルマンの伝統が融合している。ケードモンは牧夫で、詩の訓練も技術もなかった。ある夜、彼はイエスに歌うように言われる夢 を見た。そして彼は「ケードモンの賛歌」を作曲し、それ以来偉大な詩人となった。この物語における霊感は恵みの産物である。それは(望まれてはいるが)望 まれることなく、制御されることなく、抗いがたいものであり、詩人の演奏は彼の全身全霊に関わるが、基本的には賜物なのである。 ルネサンスにおける詩的熱狂の復興 詩の神的起源に関するグレコ・ラテン語の教義は、(オルフェウスに関する)ホラーチェの著作などを通じて中世の作家たちにも利用可能であったが、 furor poeticusの概念の重要な復活につながったのは、15世紀末に新プラトン主義の作家マルシリオ・フィチーノがプラトンの対話篇『イオン』と(特に) 『パイドロス』をラテン語に翻訳し、注釈を加えたことであった。 [1]フィチーノの注釈書は、神々が詩人をどのように霊感し、この熱狂がその後どのように詩人の狂詩を通して詩人の聴衆に伝わり、聴衆が霊感の連鎖によっ て神と接触できるようになったかを説明した。フィチーノ自身、竪琴を伴奏にしたオルフィック=プラトニック賛歌の狂詩曲的演奏において、恍惚とした歓喜を 体験しようとした[2]。 この教義はまた、ラ・プレイヤードと総称されるフランス・ルネサンス期の詩人たち(ピエール・ド・ロンサール、ヨアキム・デュ・ベレーなど)の詩的プログ ラムの重要な一部でもあった。 神の激情/熱狂の完全な理論は、ポントゥス・ド・タイアールによって『ソリテール・プルミエ』(Solitaire Premier, ou Prose des Muses, et de la fureur poétique)の中で詳述された(タイアールは神の霊感を4種類に分類した:(1)詩的激情、ミューズの贈り物、(2)バッカスによる宗教的神秘の知 識、(3)アポロンによる予言と占い、(4)ヴィーナス/エロスによる霊感)[1]。 啓蒙主義とロマン主義のモデル 18世紀のイギリスでは、新興の心理学が霊感の神秘的な性質を讃える新興の祝祭と競合していた。ジョン・ロックの人間の心のモデルは、アイデアは互いに関 連し合い、共鳴するアイデアによって心の糸が打たれることを示唆していた。したがって、ひらめきとは、ややランダムだが、まったく自然なアイデアの連想で あり、突然の思考の一致であった。さらに、ロックの心理学は、心の自然な感覚や資質が、知覚の統一性を見抜き、集団の差異を識別することを可能にすること を示唆した。この「空想」と「機知」は、後にそう呼ばれるように、詩人や画家の洞察力やひらめきの大小を説明できる、自然で発達した能力であった。ロマン 派は、想像力は知性では見えないものを見るための道具であると主張した[3]。 この音楽モデルは、ジョナサン・スウィフトによって『ある桶の物語』の中で、アフラトゥスや「空想」のインスピレーションモデルとともに風刺された。ス ウィフトの語り手は、狂気が伝染するのは、それが信奉者の心に「和音」を打つ鳴り物だからであり、ベドラムの収容者と皇帝の違いは、狂気のアイデアがどの ような音程であったかにあると示唆している。同時に彼は、"直接の霊感 "によって説教する "霊感を受けた "急進的なプロテスタントの牧師たちを風刺した。彼は序文の中で、理想的な反体制派の説教壇を、牧師の後頭部から底部のふいごまで管が通っている樽のよう なものと表現している。さらにスウィフトは、空想は「ひとたび空想が理性にまたがれば、常識は門外不出となる」、反動的な狂気の性質であると考えた。 スウィフトが風刺したインスピレーションの多様な理論は、18世紀から19世紀にかけて、並存しながら続くことになる。エドワード・ヤングの『原作に関す る仮説』は、ロマン派のインスピレーションに関する概念を形成する上で極めて重要なものだった。彼は、天才とはインスピレーションを与える詩人の「内なる 神」であると述べた。このようにヤングは、インスピレーションを個人の心の中に位置づけ(神や悪魔の領域から大きく離れ)、なおかつ超自然的な性質を仮定 していた心理学者たちに同意した。天才とは、不可解な、おそらくは霊的な、そしておそらくは外的な、ひらめきの源泉であった。ヤングの構想では、天才はま だその起源においていくらか外的なものであったが、ロマン派の詩人たちはやがてその起源を完全に詩人の内に見出すようになる。ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマー ソン(『詩人』)やパーシー・ビッシェ・シェリーのようなロマン派の作家たちは、インスピレーションをギリシャ人と同じような言葉で捉えていた。 インスピレーションは、詩人が自らを(神的あるいは神秘的な)「風」に 同調させ、そのようなヴィジョンを受け取るようにできているからこそもたらされるのである。サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジのインスピレーションに関 する記述は最も劇的であり、彼の『エオリアン・ハープ』は、詩を神の風の受動的な受信と自然な伝達と比較するロマン派が書いた数多くの詩の中でも最高のも のに過ぎなかった。彼が『クビラ・ハーン』の作曲について語った物語では、詩人は書記に格下げされている。ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツは後に自動書記 を試み、その価値を認めている。インスピレーションは天才の証拠であり、天才は詩人にとって誇れるものであった。 モダニズムと現代の概念 ジークムント・フロイトをはじめとする後世の心理学者は、インスピレーションを芸術家の内面に位置づけた。芸術家のインスピレーションは、未解決の心理的 葛藤や幼少期のトラウマから生まれた。さらに、インスピレーションは無意識から直接もたらされることもあった。ロマン派の天才論や「詩的狂気」の概念の復 活のように、フロイトは芸術家を根本的に特別な存在、そして根本的に傷ついた存在とみなした。フロイトはインスピレーションを無意識の中に位置づけたた め、シュルレアリスムの芸術家たちは、夢日記や自動書記、占いボードの使用、発見された詩などに目を向けることで、このインスピレーションを探し求め、彼 らが芸術の真の源と見なしたものに触れようとした。カール・グスタフ・ユングのインスピレーション論は、芸術家とは非人間的なもの、個人の経験の外にある もの、すなわち人種的記憶や「サイコポエトリー」の経験に同調するものであると示唆することで、間接的にロマン主義的なインスピレーションの概念の反対側 を繰り返した[4]。 インスピレーションの唯物論的理論もまた、純粋に内的な源と純粋に外的な源との間で分岐している。カール・マルクスはこの主題を直接には扱わなかったが、 マルクス主義の芸術論は、芸術を経済的基盤と経済的上部構造との摩擦の表現として、あるいは競合するイデオロギーの無自覚な対話として、あるいは支配階級 のイデオロギーの「亀裂」の利用としてとらえている。したがって、ソビエト・リアリズムのような完全にマルクス主義的な芸術の流派が存在する場合、「触発 された」画家や詩人は、最も階級を意識した画家や詩人でもあり、「形式主義」は退廃的なものとして明確に否定された(例えば、セルゲイ・エイゼンシュテイ ンの晩年の映画は「形式主義の誤り」として非難された)。国家が後援するマルクス主義学校以外では、マルクス主義は触発された画家や詩人の階級意識を重視 する姿勢を保ってきたが、フレデリック・ジェイムソンが「政治的無意識」と呼ぶ、作品に存在するかもしれないものを受け入れる余地はあった。しかし、いず れの場合も、インスピレーションは、芸術家が外的危機からのシグナルを受け取るために特別に同調していることから生まれる。 現代心理学では、インスピレーションはあまり研究されていないが、一般的には完全に内的なプロセスとみなされている。しかし、経験主義的であろうと神秘主義的であろうと、いずれの見方においても、インスピレーションはその性質上、コントロールできないものである。 ひらめきに関する現代的な研究の一例として、岡田武史と石橋健太郎が行った研究があり、2016年に学際的学術誌『Cognitive Science』に発表された[5]。この3部構成の研究では、日本の美術学部生のグループを観察し、ひらめきとなる模範的な作品を模写するか、あるいは 単につぶやくかによって、創造的なアウトプットが増加するかどうかを調べた。1回目と2回目の実験の結果、模写をすることで質的に異なる創造的な絵を描く ことができたが、それは模写が学生にとって馴染みのないスタイルであった場合のみであった。第3の実験では、見慣れないひらめきに思いを馳せるだけで、模 写と同じ効果が得られることが明らかになった。岡田と石橋は、このような見慣れない例が生徒の創造性を促進できたのは、生徒の絵に対する考え方に挑戦した からだと指摘している。しかし彼らは、この結果がプロの芸術家にも一般化できるかどうかは不明であると認めているが、パブロ・ピカソやフィンセント・ファ ン・ゴッホといった芸術家が他の芸術家の作品を広く模倣した例を挙げており、「模倣は専門家にとっても創造性の効果的な原動力である」ことを示唆している のかもしれない[5]。 |

| Afflatus, the Romantic concept of inspiration Aristic Parfums, an exclusive perfume house Automatic writing Divine spark Epiphany (feeling) Genius (literature), the development of the concept of the genius from daemon to innate gift Glossolalia (or speaking in tongues) Muses, the classical sources of inspiration |

Afflatus、インスピレーションというロマンティックなコンセプト アリスティック・パルファン、高級香水メゾン 自動書記 神の閃き エピファニー(感情) 天才(文学)、デーモンから天賦の才能への天才概念の発展 グロッソラリア(異言で話すこと) ミューズ、古典的なインスピレーションの源 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_inspiration |

|

| An epiphany

(from the ancient Greek ἐπιφάνεια, epiphanea, "manifestation, striking

appearance") is an experience of a sudden and striking realization.

Generally the term is used to describe a scientific breakthrough or a

religious or philosophical discovery, but it can apply in any situation

in which an enlightening realization allows a problem or situation to

be understood from a new and deeper perspective. Epiphanies are studied

by psychologists[1][2] and other scholars, particularly those

attempting to study the process of innovation.[3][4][5] Epiphanies are relatively rare occurrences and generally follow a process of significant thought about a problem. Often they are triggered by a new and key piece of information, but importantly, a depth of prior knowledge is required to allow the leap of understanding.[3][4][6][7] Famous epiphanies include Archimedes's discovery of a method to determine the volume of an irregular object ("Eureka!") and Isaac Newton's realization that a falling apple and the orbiting moon are both pulled by the same force.[6][7][8] |

エ

ピファニー(古代ギリシア語 ἐπιφάνεια,

epiphanea「顕現、印象的な出現」から)とは、突然の印象的な気づきの体験である。一般的にこの言葉は、科学的な飛躍的進歩や宗教的・哲学的な発

見を表すのに使われるが、悟りを開くような気づきによって、問題や状況が新たな深い視点から理解されるような状況であれば、どのような状況にも当てはめる

ことができる。エピファニーは心理学者[1][2]やその他の学者、特にイノベーションのプロセスを研究しようとする学者によって研究されている[3]

[4][5]。 エピファニーは比較的稀な出来事であり、一般的には、ある問題に対して重要な思考を重ねる過程を経て起こる。多くの場合、エピファニーは新しい重要な情報 によって引き起こされるが、重要なことは、理解の飛躍を可能にするためには、深い予備知識が必要であるということである。 有名なエピファニーとしては、アルキメデスが不規則な物体の体積を決定する方法を発見したこと(「ユーレカ!」)や、アイザック・ニュートンが落下するリ ンゴと公転する月がどちらも同じ力で引っ張られていることに気づいたことなどが挙げられる[6][7][8]。 |

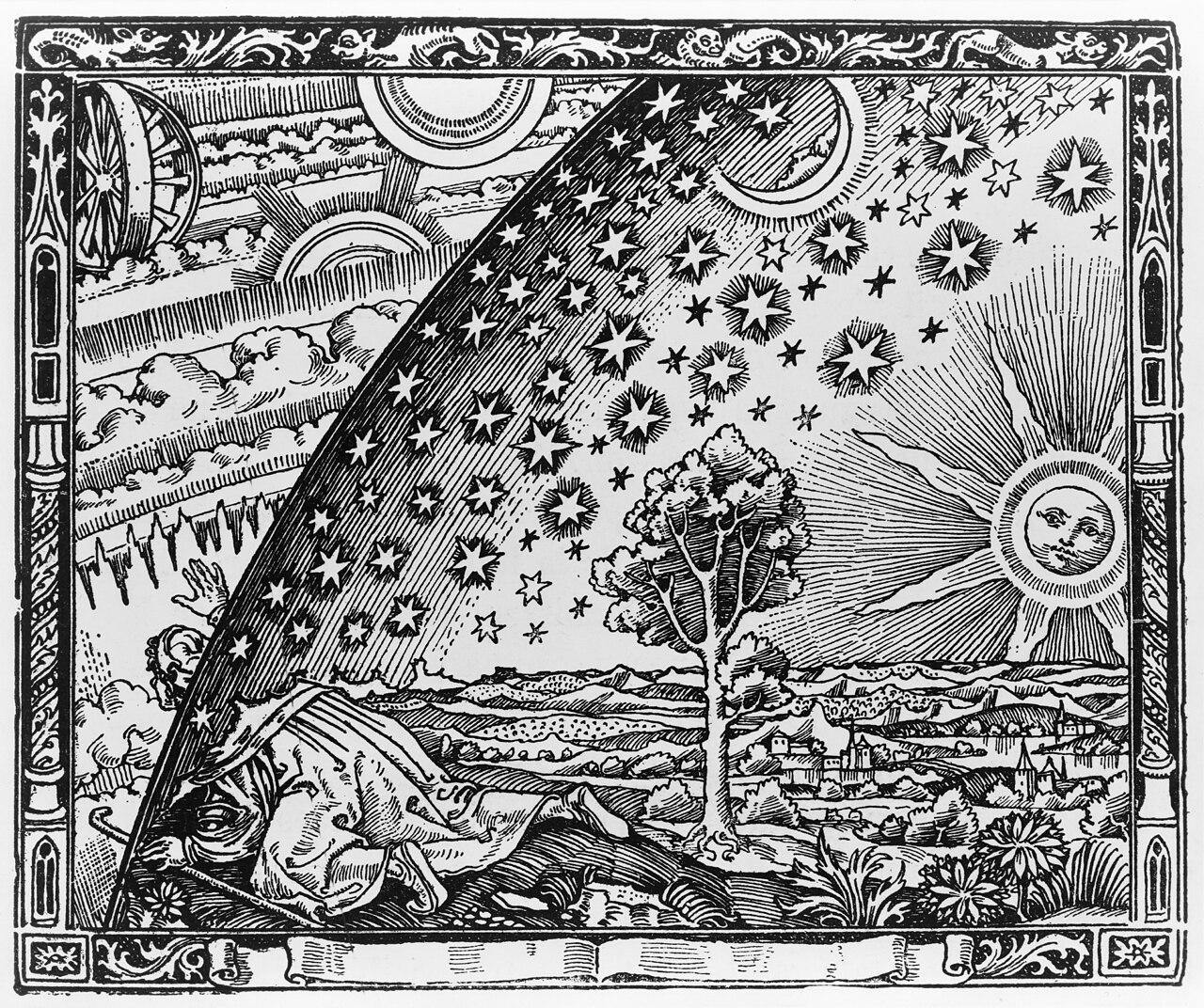

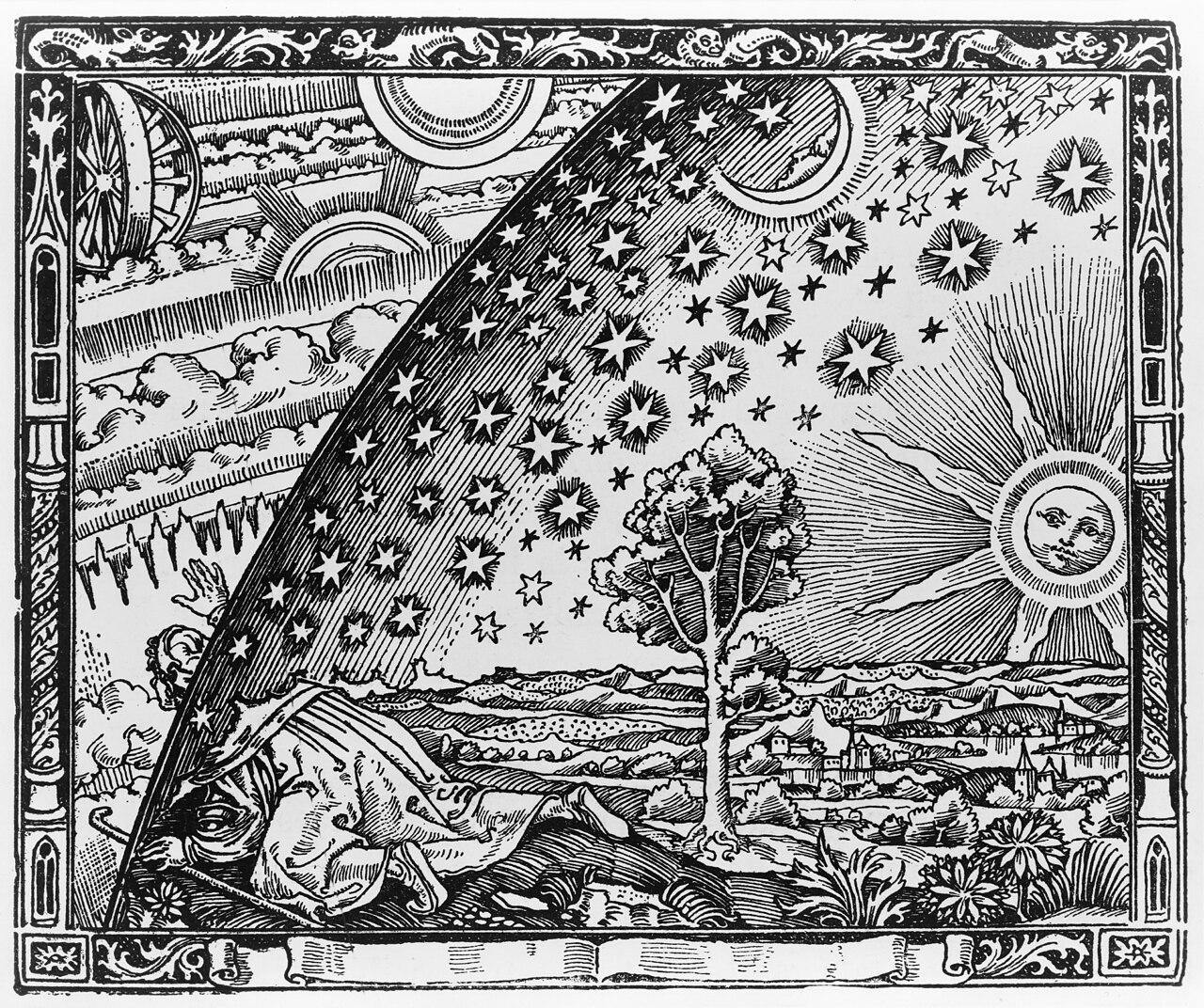

| History The word epiphany originally referred to insight through the divine.[9][10] Today, this concept is more often used without such connotations, but a popular implication remains that the epiphany is supernatural, as the discovery seems to come suddenly from the outside.[9] The word's secular usage may owe much of its popularity to Irish novelist James Joyce. The Joycean epiphany has been defined as "a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether from some object, scene, event, or memorable phase of the mind – the manifestation being out of proportion to the significance or strictly logical relevance of whatever produces it".[11] The author used epiphany as a literary device within each entry of his short story collection Dubliners (1914); his protagonists came to sudden recognitions that changed their view of themselves and/or their social conditions. Joyce had first expounded on epiphany's meaning in the fragment Stephen Hero (published posthumously in 1944). For the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, epiphany or a manifestation of the divine is seen in another's face (see face-to-face).  Flammarion engraving. From "L'atmosphère", book of 1888. In traditional and pre-modern cultures, initiation rites and mystery religions have served as vehicles of epiphany, as well as the arts. The Greek dramatists and poets would, in the ideal, induct the audience into states of catharsis or kenosis, respectively. In modern times an epiphany lies behind the title of William Burroughs' Naked Lunch, a drug-influenced state, as Burroughs explained, "a frozen moment when everyone sees what is at the end of the fork." Both the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp and the Pop Artist Andy Warhol would invert expectations by presenting commonplace objects or graphics as works of fine art (for example a urinal as a fountain), simply by presenting them in a way no one had thought to do before; the result was intended to induce an epiphany of "what art is" or is not. |

歴史 エピファニー(epiphany)という言葉は、もともとは神による洞察のことを指していた[9][10]。今日、この概念はそのような意味合いを含まず に使われることが多くなっているが、発見が突然外からやってくるように見えることから、エピファニーとは超自然的なものであるという一般的な意味合いが 残っている[9]。 この言葉の世俗的な用法は、アイルランドの小説家ジェイムズ・ジョイスにその人気の多くを負っているかもしれない。ジョイスのエピファニー (epiphany)は、「ある物体、場面、出来事、あるいは心の記憶に残る局面からであれ、突然の精神的な顕現-その顕現は、それを生み出すものの重要 性や厳密に論理的な関連性とは比例しない」[11]と定義されている。ジョイスは、短編集『ダブリナーズ』(1914年)の各エントリーの中で、エピファ ニーを文学的な装置として用いており、彼の主人公たちは、自分自身や社会状況に対する見方を変えるような突然の認識に至る。ジョイスは『スティーヴン・ ヒーロー』(1944年、死後出版)の断片の中で、エピファニーについて初めてその意味を説明している。哲学者エマニュエル・レヴィナスにとって、エピ ファニー、あるいは神の顕現は、他者の顔の中に見られる(「face-to-face」を参照)。  Flammarionのエングレーヴィング。1888年刊『L'atmosphère』より。 伝統文化や前近代文化では、入信儀礼や神秘宗教は、芸術と同様に、啓示の手段として機能してきた。ギリシアの劇作家や詩人は、理想においては、観客をそれ ぞれカタルシスやケノーシスの状態に導く。現代では、ウィリアム・バロウズの『裸のランチ』のタイトルの背後にあるエピファニー(啓示)は、バロウズの説 明によれば、"フォークの先にあるものを誰もが見る凍りついた瞬間 "であり、ドラッグに影響された状態である。ダダイストのマルセル・デュシャンも、ポップ・アーティストのアンディ・ウォーホルも、ありふれた物やグラ フィックを美術作品として(例えば、小便器を噴水として)見せることで、それまで誰も思いつかなかったような期待を裏切る。 |

| Process Epiphanies can come in many different forms, and are often generated by a complex combination of experience, memory, knowledge, predisposition and context. A contemporary example of an epiphany in education might involve the process by which a student arrives at some form of new insight or clarifying thought.[12] Despite this popular image, epiphany is the result of significant work on the part of the discoverer, and is only the satisfying result of a long process.[13] The surprising and fulfilling feeling of epiphany is so surprising because one cannot predict when one's labor will bear fruit, and our subconscious can play a significant part in delivering the solution; and is fulfilling because it is a reward for a long period of effort.[4][13] |

プロセス エピファニーには様々な形があり、経験、記憶、知識、素質、文脈が複雑に組み合わさって生み出されることが多い。このような一般的なイメージとは裏腹に、 エピファニーとは、発見者の側での多大な努力の結果であり、長いプロセスの満足のいく結果にすぎない。 [13]エピファニーという驚きと充足感に満ちた感覚は、自分の労働がいつ実を結ぶかを予測することができず、私たちの潜在意識が解決策を提供する上で重 要な役割を果たすことがあるため、とても驚くべきものであり、長い期間の努力に対する報酬であるため、充足感のあるものである[4][13]。 |

| Myth A common myth predicts that most, if not all, innovations occur through epiphanies.[6] Not all innovations occur through epiphanies; Scott Berkun notes that "the most useful way to think of an epiphany is as an occasional bonus of working on tough problems."[7] Most innovations occur without epiphany, and epiphanies often contribute little towards finding the next one.[7] Crucially, epiphany cannot be predicted, or controlled.[7] Although epiphanies are only a rare occurrence, crowning a process of significant labor, there is a common myth that epiphanies of sudden comprehension are commonly responsible for leaps in technology and the sciences.[6][7] Famous epiphanies include Archimedes' realization of how to estimate the volume of a given mass, which inspired him to shout "Eureka!" ("I have found it!").[3] The biographies of many mathematicians and scientists include an epiphanic episode early in the career, the ramifications of which were worked out in detail over the following years. For example, allegedly Albert Einstein was struck as a young child by being given a compass, and realizing some unseen force in space was making it move. Another, perhaps better, example from Einstein's life occurred in 1905 after he had spent an evening unsuccessfully trying to reconcile Newtonian physics and Maxwell's equations. While taking a streetcar home, he looked behind him at the receding clocktower in Bern and realized that if the car sped up (close to the speed of light) he would see the clock slow down; with this thought, he later remarked, "a storm broke loose in my mind," which would allow him to understand special relativity. Einstein had a second epiphany two years later in 1907 which he called "the happiest thought of my life" when he imagined an elevator falling, and realized that a passenger would not be able to tell the difference between the weightlessness of falling, and the weightlessness of space – a thought which allowed him to generalize his theory of relativity to include gravity as a curvature in spacetime. A similar flash of holistic understanding in a prepared mind was said to give Charles Darwin his "hunch" (about natural selection), and Darwin later said he always remembered the spot in the road where his carriage was when the epiphany struck. Another famous epiphany myth is associated with Isaac Newton's apple story,[4] and yet another with Nikola Tesla's discovery of a workable alternating current induction motor. Though such epiphanies might have occurred, they were almost certainly the result of long and intensive periods of study those individuals had undertaken, rather than an out-of-the-blue flash of inspiration about an issue they had not thought about previously.[6][7] Another myth is that epiphany is simply another word for (usually spiritual) vision. Actually, realism and psychology make epiphany a different mode as distinguished from vision, even though both vision and epiphany are often triggered by (sometimes seemingly) irrelevant incidents or objects.[8][14] |

神話 一般的な神話では、すべてではないにせよ、ほとんどのイノベー ションは啓示によって起こるとされている[6]。すべてのイノベー ションが啓示によって起こるわけではなく、スコット・バークン は「啓示を考える最も有用な方法は、困難な問題に取り組む際の時折 のボーナスとして考えることである」と述べている[7]。 エピファニーは、重要な労働のプロセスの頂点に立つ稀な出来事でしかないが、突然の理解によるエピファニーが、技術や科学における飛躍の一般的な原因であ るという俗説がある。 [6][7]有名なエピファニーは、アルキメデスが与えられた質量の体積を推定する方法に気づき、「ユリイカ!」(「私はそれを見つけた!」)と叫んだこ とである。例えば、アルベルト・アインシュタインは幼い頃、羅針盤を与えられ、空間の見えない力が羅針盤を動かしていることに気づき、衝撃を受けたと言わ れている。アインシュタインの人生におけるもうひとつの、おそらくより良い例は、1905年、ニュートン物理学とマクスウェルの方程式を調和させようとし て失敗した夜を過ごした後に起こった。アインシュタインは、市電に乗って家に帰る途中、ベルンの時計塔が遠ざかっていくのを背後から眺め、車速を上げれば (光速に近づけば)時計が遅くなることに気がついた。アインシュタインは、その2年後の1907年、エレベーターの落下を想像して、乗客が落下の無重力と 宇宙の無重力との違いを見分けられないことに気づいたとき、「私の人生で最も幸せな考え」と呼ぶ2度目の啓示を受けた。チャールズ・ダーウィンが(自然淘 汰について)「直感」を得たのは、準備された頭脳の中で同じような全体論的理解が閃いたからだと言われている。ダーウィンは後に、啓示を受けたときに馬車 がいた道路の場所をいつも覚えていたと語っている。もうひとつの有名な天啓神話は、アイザック・ニュートンのリンゴの話と関連しており[4]、さらにもう ひとつは、ニコラ・テスラが実用的な交流誘導電動機を発見したことに関連している。このような天啓は起こったかもしれないが、それまで考えてもみなかった 問題について突然ひらめいたというよりは、ほぼ間違いなく、そのような人たちが取り組んだ長期にわたる集中的な研究の結果であった[6][7]。 もう一つの神話は、エピファニーとは単に(通常は霊的な)ビジョンの別の言葉であるというものである。実際には、現実主義と心理学は、ヴィジョンとエピ ファニーをヴィジョンとは異なるモードとして区別しているが、ヴィジョンもエピファニーも(時には一見)無関係な出来事や対象によって引き起こされること が多い。 |

| In religion Further information: Epiphany (holiday), theophany, and hierophany In Christianity, the Epiphany refers to a realization that Christ is the Son of God. Western churches generally celebrate the Visit of the Magi as the revelation of the Incarnation of the infant Christ, and commemorate the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6. Traditionally, Eastern churches, following the Julian rather than the Gregorian calendar, have celebrated Epiphany (or Theophany) in conjunction with Christ's baptism by John the Baptist and celebrated it on January 19; however, other Eastern churches have adopted the Western Calendar and celebrate it on January 6.[15] Some Protestant churches often celebrate Epiphany as a season, extending from the last day of Christmas until either Ash Wednesday, or the Feast of the Presentation on February 2. In more general terms, the phrase "religious epiphany" is used when a person realizes their faith, or when they are convinced an event or happening was really caused by a deity or being of their faith. In Hinduism, for example, epiphany might refer to Arjuna's realization that Krishna (incarnation of God serving as his charioteer in the "Bhagavad Gita") is indeed representing the Universe. The Hindu term for epiphany would be bodhodaya, from Sanskrit bodha "wisdom" and udaya "rising". Or in Buddhism, the term might refer to the Buddha obtaining enlightenment under the bodhi tree, finally realizing the nature of the universe, and thus attaining Nirvana. The Zen term kensho also describes this moment, referring to the feeling attendant on realizing the answer to a koan. |

宗教 さらに詳しい情報 エピファニー(祝日)、テオファニー、ヒエロファニー キリスト教では、公現祭はキリストが神の子であることを悟ることを意味する。西方教会では一般的に、幼子キリストの受肉の啓示としてマギの訪問を祝い、1 月6日の公現祭を記念する。伝統的に、グレゴリオ暦ではなくユリウス暦に従う東方諸教会は、洗礼者ヨハネによるキリストの洗礼とともにエピファニー(また はテオファニー)を祝い、1月19日に祝ってきたが、他の東方諸教会は西暦を採用し、1月6日に祝っている[15]。一部のプロテスタント教会では、エピ ファニーをクリスマスの最終日から灰の水曜日、または2月2日の公現祭まで続く季節として祝うことが多い。 より一般的な用語として、「宗教的啓示」という言葉は、人が自分の信仰に気づいたり、ある出来事や出来事が本当に自分の信仰する神や存在によって引き起こ されたと確信したりするときに使われる。例えば、ヒンドゥー教では、クリシュナ(「バガヴァッド・ギーター」で戦車手として奉仕する神の化身)が本当に宇 宙を代表していることをアルジュナが悟ることをエピファニーと呼ぶかもしれない。ヒンズー教では、サンスクリット語のbodha「知恵」とudaya「上 昇」を語源とするbodhodayaと呼ばれる。仏教では、釈迦が菩提樹の下で悟りを開き、宇宙の本質を悟り、涅槃に達することを指す。また、禅の「解脱 (けんじょう)」という言葉もこの瞬間を表しており、公案の答えを悟ったときの感覚を指している。 |

| Anagnorisis Apophenia Eureka effect Hierophany Kenshō Lateral thinking Peripeteia Revelation Satori Samadhi Theophany |

アナグノリシス アポフェニア ユーレカ効果 ヒエログリフ 剣聖 ラテラル・シンキング ペリペテイア 啓示 サトリ サマディ 神智 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epiphany_(feeling) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆