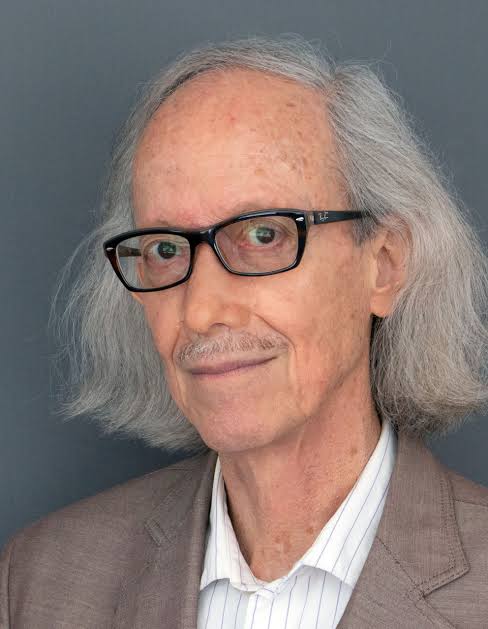

アルトゥーロ・エスコバル

Arturo Escobar, b.1951

☆ アルトゥーロ・エスコバル(1951年11月20日生まれ)は、コロンビア系アメリカ人の人類学者であり、米国ノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校の名誉 教授である。彼の学術研究の関心は、政治生態学、開発人類学、社会運動、反グローバリゼーション運動、政治的存在論、ポスト開発論などである。 エスコバルはポスト開発学派の主要人物であり、「注目すべきポスト開発思想家」と評されている。[4] 彼は、西洋の工業化社会が推奨する開発手法を批判し、代替的な開発ビジョンの可能性を探求する影響力のある著作を執筆している。その中には 『Encountering Development』(1995年)や『Designs for the Pluriverse』(2018年)などがある。

| Arturo

Escobar (born

November 20, 1951) is a Colombian-American anthropologist and professor

emeritus of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill, USA. His academic research interests include political ecology,

anthropology of development, social movements, anti-globalization

movements, political ontology,[2] and postdevelopment theory.[3] Escobar is a major figure in the post-development academic discourse and has been described as a "post-development thinker to be reckoned with".[4] He has authored influential books criticizing development practices championed by western industrialized societies and exploring possibilities for alternative visions of development, including Encountering Development (1995) and Designs for the Pluriverse (2018). |

アルトゥーロ・エスコバル(1951年11月20日生まれ)は、コロン

ビア系アメリカ人の人類学者であり、米国ノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校の名誉教授である。彼の学術研究の関心は、政治生態学、開発人類学、社会運

動、反グローバリゼーション運動、政治的存在論、ポスト開発論などである。 エスコバルはポスト開発学派の主要人物であり、「注目すべきポスト開発思想家」と評されている。[4] 彼は、西洋の工業化社会が推奨する開発手法を批判し、代替的な開発ビジョンの可能性を探求する影響力のある著作を執筆している。その中には 『Encountering Development』(1995年)や『Designs for the Pluriverse』(2018年)などがある。 |

| Education and career Escobar was born in Manizales, Colombia.[1] He currently holds Colombian and American citizenship and publishes in both English and Spanish. He received a Bachelor of Science in chemical engineering in 1975 from the University of Valle in Cali, Colombia, and completed one year of studies in a biochemistry graduate program at the Universidad del Valle Medical School. He subsequently traveled to the United States to earn a master's degree in food science and international nutrition at Cornell University in 1978. After a brief stint in government working in Colombia's Department of National Planning, in Bogota, from 1981 to 1982,[5] in 1987 he received an interdisciplinary Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, in Development Philosophy, Policy and Planning.[5] He has taught mainly at U.S. universities, including the University of Massachusetts Amherst, but also abroad at institutions in Colombia, Finland, Spain, and England. He retired[when?] as professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he taught courses in development theory and social change, often co-teaching with long-time mentee Dr. Michal Osterweil of UNC's Department of Global Studies. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of the Design Research Journal Designabilities.[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arturo_Escobar_(anthropologist) ++++++++++++++++ Biografía y pensamiento Escobar empezó estudiando inicialmente ingeniería en la Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia) y desde esa época (1969) empezó a confrontarse con los problemas relativos al hambre y a la pobreza de vastos sectores de la población colombiana. Pero sus intereses se dirigían cada vez más hacia el área de las ciencias sociales y la antropología del desarrollo, por lo que viajó a Berkeley para realizar un doctorado en "Filosofía, Política y Planificación del Desarrollo" en la Universidad de California. Allí asistió a los últimos cursos ofrecidos por el filósofo francés Michel Foucault, que tendrían una influencia permanente en su pensamiento. Su tesis de doctorado, finalizada en el año de 1987, llevó como título Power and Visibility: The Invention and Management of Development in the Third World. Allí defendió el argumento de que el "Tercer Mundo" no es un fenómeno realmente existente, dotado de una realidad objetiva, sino un campo de intervención creado a partir de intereses geopolíticos de poder, sobre el que se aplican unas determinadas tecnologías de gobierno. El "Tercer Mundo" fue "inventado" después de la segunda guerra mundial, en el marco de la guerra fría y de los intereses norteamericanos en América Latina y las recién independizadas naciones de África y Asia. Después de haber obtenido su doctorado, Escobar enseñó en varias universidades de los Estados Unidos y empezó a interesarse por temas relativos a la Ecología y a las teorías de la complejidad. Realizó varios trabajos de campo en el Pacífico colombiano, junto con comunidades negras, y apoyó sus luchas por el territorio y la identidad. Ha sido profesor invitado en universidades de Colombia, Dinamarca, Ecuador, Brasil, Mali, México e Inglaterra. Actualmente es profesor en el departamento de Antropología de la Universidad de Carolina del Norte (Chapel Hill), donde recibió el título de "Kenan Distinguished Teaching Professor of Anthropology" Formó parte activa del Grupo modernidad/colonialidad, junto con otros académicos latinoamericanos como Enrique Dussel, Walter Mignolo, Aníbal Quijano, Santiago Castro-Gómez y Edgardo Lander. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arturo_Escobar_(antrop%C3%B3logo) |

教育と経歴 エスコバルは、コロンビアのマニサレスで生まれた。[1] 現在はコロンビアと米国の国籍を持ち、英語とスペイン語の両方で執筆活動を行っている。 1975年にコロンビアのカリにあるバジェ大学で化学工学の理学士号を取得し、バジェ大学医学部の生化学大学院課程で1年間の研究を修了した。その後、米 国に渡り、1978年にコーネル大学で食品科学および国際栄養学の修士号を取得した。1981年から1982年にかけてはコロンビアの国家計画省で短期間 政府勤務を経験し、1987年にはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で開発哲学、政策、計画学の学際的な博士号を取得した。 マサチューセッツ大学アマースト校をはじめとする主に米国の大学で教鞭をとったが、コロンビア、フィンランド、スペイン、イギリスの教育機関でも教えた。 ノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校で人類学の教授として教鞭をとっていたが、いつ頃かは不明である。同校では開発理論と社会変革のコースを担当し、長年 の教え子であるUNCのグローバル研究科のミハエル・オスターウェイル博士と共同で教えることも多かった。彼は『Design Research Journal Designabilities』の編集諮問委員会のメンバーである。[6] ++++++++++++++ 経歴と思想 エスコバルは当初、バジェ大学(コロンビア、カリ市)で工学を学び始めたが、その頃(1969年)からコロンビア国民の大多数が抱える飢餓と貧困の問題に 直面するようになった。しかし、彼の興味はますます社会科学と開発の人類学に向かい、カリフォルニア大学で「哲学、政治学、開発計画」の博士号を取得する ためにバークレーに向かった。そこでフランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーの最終講義を受け、彼の思考に永続的な影響を与えた。1987年に完成した博士論 文のタイトルは『Power and Visibility: The Invention and Management of Development in the Third World(権力と可視性:第三世界における開発の発明と管理)』であった。そこでは、「第三世界」は客観的な現実を持つ真に存在する現象ではなく、地政 学的な権力利益によって作り出された介入の場であり、そこに特定の統治技術が適用されていると主張した。「第三世界」は第二次世界大戦後、冷戦とラテンアメ リカやアフリカ、アジアの新興独立国に対するアメリカの利害の中で「発明」された。 博士号取得後、エスコバルはアメリカのいくつかの大学で教鞭をとり、生態学や複雑性理論(→オートポイエーシス)に関連する問題に関心を持つようになった。コロンビアの太平洋地域 で黒人コミュニティとフィールドワークを行い、彼らの領土とアイデンティティをめぐる闘いを支援した。コロンビア、デンマーク、エクアドル、ブラジル、マ リ、メキシコ、イギリスの大学で客員教授を務める。現在、ノースカロライナ大学(チャペルヒル校)人類学部教授で、「ケナン人類学特別教授」の称号を授与 されている。 エンリケ・デュッセル[ドゥッセル]、ウォルター・ミニョーロ、アニバル・キハノ、サンティアゴ・カストロ=ゴメス、エドガルド・ランダーといったラテンアメリカの学者 とともに、モダニティ/コロニアリティ・グループのメンバーとして活躍した。 |

| Scholarship Anthropological approach Escobar's approach to anthropology is largely informed by the poststructuralist and postcolonialist traditions and centered around two recent developments: subaltern studies and the idea of a World Anthropologies Network (WAN). His research interests are related to political ecology; the anthropology of development, social movements; Latin American development and politics. Escobar's research uses critical techniques in his provocative analysis of development discourse and practice in general. He also explores possibilities for alternative visions for a postdevelopment era. Criticism of development Escobar contends in his 1995 book, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, that international development became a mechanism of control comparable to colonialism or "cultural imperialism that poor countries had little means of declining politely".[3] The book, which won the 1996 Best Book Prize of the New England Council of Latin American Studies,[7] traced the rise and fall of development through Michel Foucault's discourse analysis, which regards development as ontologically cultural (i.e., by examining linguistic structure and meaning). This led him to conclude that "development planning was not only a problem to the extent that it failed; it was a problem even when it succeeded, because it so strongly set the terms for how people in poor countries could live".[3] Citing Foucault marked a shift in the study of development from realism to interpretivist or post-structuralist approaches, which offered much more than an analysis of mainstream development economics or the sprawling array of development actors and institutions it spawned, giving rise to a coordinated and coherent set of interventions that Escobar calls the "development apparatus". Escobar theorizes that the development era was produced by a discursive construction contained in Harry S. Truman's official representation of his administration's foreign policy. By referring to the three continents of South America, Africa, and Asia as "underdeveloped" and in need of significant change to achieve progress, Truman set in motion a reorganization of bureaucracy around thinking and acting to systematically change the "third world". In addition, he argues that Truman's discursive construction was infused with the imperatives of American social reproduction and imperial pretensions. As a result, the development apparatus functioned to support the consolidation of American hegemony. Escobar encourages scholars to use ethnographic methods to further the post-development era by advancing the deconstructive creations initiated by contemporary social movements (without claiming universal applicability). Indeed, the Colombia case study in Encountering Development demonstrates that development economists' "economization of food" resulted in ambitious plans but not necessarily less hunger. A new 2011 edition of the book begins with a substantial new introduction, in which he argues that "postdevelopment" needs to be redefined and that a field of "pluriversal studies" would be helpful.[8] He further explored the concept of a plurivrse in his 2018 book Designs for the Pluriverse. Political ecology Escobar received a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1997 to study "Cultural and Biological Diversity in the Late Twentieth Century".[7] This project culminated in the publication of his book Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes by Duke University Press in 2008, which "analyzes the politics of difference enacted by specific place-based ethnic and environmental movements in the context of neoliberal globalization".[9] It was written after years of fieldwork in Colombia with a group of Afro-Colombian activists of Colombia's Pacific rainforest region called the Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN).[10] |

研究費取得と学術業績 人類学的なアプローチ エスコバルの人類学へのアプローチは、ポスト構造主義とポストコロニアリズムの伝統から多くを学び、また、従属論と世界人類学ネットワーク(WAN)の理 念という2つの最近の展開を中心としている。彼の研究関心は、政治生態学、開発人類学、社会運動、ラテンアメリカの開発と政治に関連している。エスコバル の研究は、開発に関する言説と実践全般に対する挑発的な分析に批判的な手法を用いている。また、脱開発時代の代替ビジョンについても可能性を探っている。 開発への批判 エスコバルは1995年の著書『開発との遭遇:第三世界の創造と破壊』の中で、国際開発は植民地主義や「貧しい国々が丁重に断る手段をほとんど持たない文 化帝国主義」に匹敵する支配のメカニズムとなっていると主張している。ニューイングランドラテンアメリカ研究協議会の最優秀書籍賞を受賞したこの本は、ミ シェル・フーコーの言説分析を通じて開発の盛衰をたどっている。フーコーの言説分析は、開発を存在論的に文化的(すなわち、言語構造と意味を調査すること によって)とみなすものである。この研究により、彼は「開発計画は失敗したという程度の問題にとどまらず、成功した場合でも問題である。なぜなら、開発計 画は貧しい国々における人々の生活のあり方を強く規定するからだ」という結論に達した。[3] フーコーを引用することは、 開発研究をリアリズムから解釈主義的またはポスト構造主義的なアプローチへと転換させた。それは、主流派開発経済学の分析や、開発によって生み出された広 範な開発関係者や制度の分析をはるかに超えるものであり、エスコバルが「開発装置」と呼ぶ、協調的かつ首尾一貫した一連の介入を生み出した。 エスコバルは、開発時代はハリー・S・トルーマン大統領が自らの政権の外交政策を公式に表現した談話的構築によって生み出されたと理論化している。南米、 アフリカ、アジアの3つの大陸を「発展途上」であり、進歩を達成するには大幅な変化が必要であると表現したトルーマン大統領は、官僚機構の再編成に着手 し、「第三世界」を体系的に変えるための思考と行動を始めた。さらに、トルーマン大統領の言説的構築には、アメリカの社会再生産と帝国主義的野望の必要性 も織り込まれていたとエスコバル氏は主張する。その結果、開発装置はアメリカの覇権の強化を支えるために機能した。 エスコバルは、現代の社会運動によって始められた脱構築的な創造をさらに推し進めることで、ポスト開発時代をさらに進展させるために、民族誌的な手法を学 者たちが用いることを奨励している(ただし、その手法が普遍的に適用できると主張しているわけではない)。実際、『開発との遭遇』のコロンビアのケースス タディでは、開発経済学者による「食糧の経済化」が野心的な計画につながったものの、必ずしも飢餓の減少にはつながらなかったことが示されている。 2011年の新版では、大幅に書き加えられた序文で、著者は「ポスト開発」の概念を再定義する必要があり、「プルーヴァース研究」という分野が役立つだろ うと主張している。[8] さらに、2018年の著書『プルーヴァースのデザイン』では、プルーヴァースの概念を掘り下げている。 政治生態学 エスコバルは1997年に「20世紀後半における文化と生物の多様性」の研究のため、ジョン・シモン・グッゲンハイム記念財団からフェローシップを受け た。[7] このプロジェクトは、2008年にデューク大学出版から出版された著書『差異の領土: 2008年にデューク大学出版から出版されたこの著書は、「新自由主義グローバリゼーションの文脈において、特定の地域に根ざした民族運動や環境保護運動 が実践する差異の政治を分析」したものである。[9] この著書は、コロンビアの太平洋岸熱帯雨林地域に住むアフリカ系コロンビア人の活動家グループ、プロセソ・デ・コミュニダデス・ネグラス(PCN)ととも に、コロンビアで長年フィールドワークを行った後に執筆された。[10] |

| Bibliography 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2016. Territorios de diferencia. Lugar, movimientos, vida, redes Popayán. Editorial Universidad del Cauca. Colombia, 2016. 2016. Autonomía y diseño. La realización de lo comunal Popayán. Editorial Universidad del Cauca. Colombia, 2016. 2014. Feel-thinking with the Earth (in Spanish: Sentipensar con la tierra). Medellin, Colombia: Ediciones Unaula, 2014. 2012. La invención del desarrollo Popayán. Editorial Universidad del Cauca. Colombia, 2012. co-edited with Walter Mignolo. 2010. Globalization and the Decolonial Option London: Routledge. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Co-edited with Gustavo Lins Ribeiro. 2006. World Anthropologies: Disciplinary Transformations in Contexts of Power. Oxford: Berg. Escobar, A. and Harcourt, W. (eds) 2005 Women and the Politics of Place. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press. Co-edited with Jai Sen, Anita Anand, and Peter Waterman. 2004. The World Social Forum: Challenging Empires. Delhi: Viveka. German edition: Eine andere Welt Das Weltsozialfoum. Berlin: Karl Dietz Verlag, 2004. Co-edited with Sonia Alvarez and Evelina Dagnino 2000. Cultures of Politics/Politics of Cultures: Revisioning Latin American Social Movements. Boulder: Westview Press. (Also published in Portuguese and Spanish). Portuguese edition: Cultura e Política nos Movimentos Sociais Latino-Americanos. Belo Horizonte: Editoria UFMG, 2000. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (1995). Princeton: Princeton University Press. Best Book Award, New England Council of Latin American Studies, 1996. (In Spanish)1998. La invención del tercer mundo: Construcción y Deconstrucción del Desarrollo. Bogotá [Colombia]: Norma. Co-edited with Sonia Alvarez. 1992. The Making of Social Movements in Latin America: Identity, Strategy, and Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press. |

参考文献 2020年 『多元的ポリティクス:現実と可能性』 ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版 2018年 『多元宇宙のデザイン:ラディカルな相互依存、自律性、世界の創造』 ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版 2016. 差異の領土。場所、運動、生命、ネットワーク。ポパヤン。カウカ大学出版。コロンビア、2016年。 2016. 自治とデザイン。共同体の実現。ポパヤン。カウカ大学出版。コロンビア、2016年。 2014年 『地球とともに感じる(スペイン語:Sentipensar con la tierra)』コロンビア、メデジン:Ediciones Unaula、2014年 2012年 『開発の発明(スペイン語:La invención del desarrollo)』コロンビア、ポパヤン:Editorial Universidad del Cauca、2012年 ウォルター・ミグノロとの共編著。2010年 『グローバリゼーションと脱植民地化の選択(英語:Globalization and the Decolonial Option)』ロンドン:Routledge。 2008. 『差異の領土:場所、運動、生命、ネットワーク』。ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版。 グスタボ・リンス・リベイロとの共編。2006. 『世界のアンソロポロジー:権力の文脈における学問分野の変容』。オックスフォード:Berg。 エスコバル、A.、ハーコート、W.(編)2005. 『女性と場所の政治』。コネチカット州ブルームフィールド:クマリアン・プレス。 ジャイ・セン、アニタ・アナンド、ピーター・ウォーターマンとの共編著。2004年。『世界社会フォーラム:帝国への挑戦』。デリー:ヴィヴェカ。ドイツ 語版:『もう一つの世界 世界社会フォーラム』。ベルリン:カール・ディーツ出版社、2004年。 ソニア・アルバレス、エベリナ・ダニーノとの共編著。2000年。『政治の文化/文化の政治:ラテンアメリカ社会運動の再考』。Boulder: Westview Press。(ポルトガル語とスペイン語でも出版)。ポルトガル語版:『ラテンアメリカ社会運動における文化と政治』。Belo Horizonte: Editoria UFMG、2000年。 1995. 『開発との遭遇:第三世界の形成と崩壊』(1995年)。プリンストン大学出版。1996年、ニューイングランド・ラテンアメリカ研究協議会最優秀書籍賞 受賞。(スペイン語)1998. 『第三世界の発明:開発の構築と脱構築』。ボゴタ(コロンビア):ノルマ。 ソニア・アルバレスとの共編著。1992年。『ラテンアメリカにおける社会運動の形成:アイデンティティ、戦略、民主主義』。Boulder: Westview Press. |

| Alter-globalization Decoloniality Degrowth New materialisms Development anthropology Development criticism (Postdevelopment theory) Postdevelopment theory |

オルターグローバリゼーション 脱植民地性 脱成長 新唯物論 開発人類学 開発批判 ポスト開発論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arturo_Escobar_(anthropologist) |

|

Designs for the pluriverse :

radical interdependence, autonomy,

and the making of worlds / Arturo Escobar, Durham : Duke University

Press , 2018, c2017. - (New ecologies for the twenty-first century) 世界は一つではない。持続可能な世界へのトランジションに向けて、「デ ザイン」の再定義 |

多元世界に向けたデザイン :

ラディカルな相互依存性、自治と自律、そして複数の世界をつくること / アルトゥーロ・エスコバル著 ;

増井エドワード [ほか] 訳, 東京 : ビー・エヌ・エヌ , 2024.2 序論 第1部 現実世界のためのデザイン―しかし、どの「世界」の、何を「デザイン」するのか?それは何の「現実」なのか?(スタジオを出て、自然 社会的生活の流れの中へ;デザインのカルチュラル・スタディーズのための要素) 第2部 デザインの存在論的再定位(我々の文化の背景にあるもの:合理主義、存在論的二元論、関係性;存在論的デザインの概要) 第3部 多元世界に向けたデザイン(トランジションのためのデザイン;自治=自律的デザインと、関係性の政治と共同的なもの) 結論 |

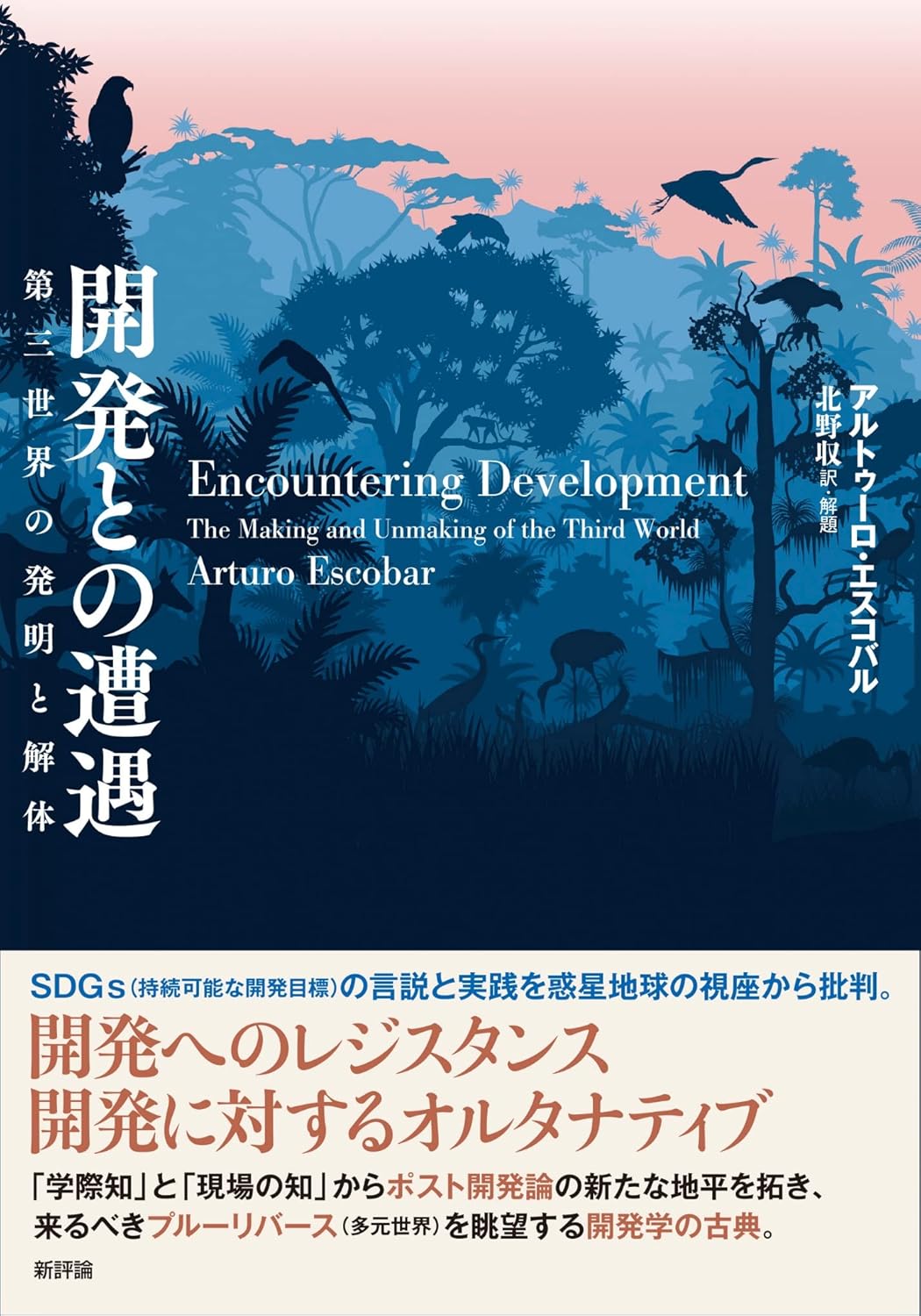

Encountering development : the

making and unmaking of the third

world / Arturo Escobar,Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press ,

2012 (持続可能な開発目標)の言説と実践を惑星地球の視座から批判。開発へのレジスタンス、開発に対するオルタナティブ。「学際知」と「現場の知」からポスト 開発論の新たな地平を拓き、来るべきプルーリバース(多元世界)を眺望する開発学の古典。 |

開発との遭遇 : 第三世界の発明と解体 /

アルトゥーロ・エスコバル[著] ; 北野収訳・解題, 東京 : 新評論 ,

2022.4 第1章 序論—開発とモダニティの人類学 第2章 貧困の問題化—三つの世界と開発をめぐる物語 第3章 経済学と開発の空間—成長と資本をめぐる物語 第4章 権力の拡散—食料と飢えをめぐる物語 第5章 権力と可視性—小農民と女性と環境をめぐる物語 第6章 結論—ポスト開発の時代を構想する 第7章 二〇一二年版への追補 https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC13751514 |

| Encountering Development THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF THE THIRD WORLDBy Arturo Escobar PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1995 Princeton University Press All right reserved. ISBN: 978-0-691-15045-1 Contents Preface....vii Chapter 1 Introduction: Development and the Anthropology of Modernity.....3 Chapter 2 The Problematization of Poverty: The Tale of Three Worlds and Development...21 Chapter 3 Economics and the Space of Development: Tales of Growth and Capital.......55 Chapter 4 The Dispersion of Power: Tales of Food and Hunger....102 Chapter 5 Power and Visibility: Tales of Peasants, Women, and the Environment....154 Notes.........227 References.....249 Index................275  |

開発との遭遇 第三世界の形成と解体アルトゥーロ・エスコバル著 プリンストン大学出版局 Copyright © 1995 Princeton University Press 無断複写・転載を禁じる ISBN: 978-0-691-15045-1 目次 序文....vii 第1章 序論:開発と近代性の人類学.....3 第2章 貧困の問題化:三つの世界と開発の物語...21 第3章 経済学と開発の空間:成長と資本の物語.......55 第4章 力の分散:食糧と飢餓の物語....102 第5章 権力と可視性:農民、女性、環境の物語....154 注釈.........227 参考文献.....249 索引................275  |

| Chapter One INTRODUCTION: DEVELOPMENT AND THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF MODERNITY There is a sense in which rapid economic progress is impossible without painful adjustments. Ancient philosophies have to be scrapped; old social institutions have to disintegrate; bonds of caste, creed and race have to burst; and large numbers of persons who cannot keep up with progress have to have their expectations of a comfortable life frustrated. Very few communities are willing to pay the full price of economic progress. —United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs, Measures for the Economic Development of Underdeveloped Countries, 1951 In his inaugural address as president of the United States on January 20, 1949, Harry Truman announced his concept of a "fair deal" for the entire world. An essential component of this concept was his appeal to the United States and the world to solve the problems of the "underdeveloped areas" of the globe. More than half the people of the world are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate, they are victims of disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas. For the first time in history humanity possesses the knowledge and the skill to relieve the suffering of these people. ... I believe that we should make available to peace-loving peoples the benefits of our store of technical knowledge in order to help them realize their aspirations for a better life.... What we envisage is a program of development based on the concepts of democractic fair dealing.... Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace. And the key to greater production is a wider and more vigorous application of modern scientific and technical knowledge. (Truman [1949] 1964) The Truman doctrine initiated a new era in the understanding and management of world affairs, particularly those concerning the less economically accomplished countries of the world. The intent was quite ambitious: to bring about the conditions necessary to replicating the world over the features that characterized the "advanced" societies of the time—high levels of industrialization and urbanization, technicalization of agriculture, rapid growth of material production and living standards, and the widespread adoption of modern education and cultural values. In Truman's vision, capital, science, and technology were the main ingredients that would make this massive revolution possible. Only in this way could the American dream of peace and abundance be extended to all the peoples of the planet. This dream was not solely the creation of the United States but the result of the specific historical conjuncture at the end of the Second World War. Within a few years, the dream was universally embraced by those in power. The dream was not seen as an easy process, however; predictably perhaps, the obstacles perceived ahead contributed to consolidating the mission. One of the most influential documents of the period, prepared by a group of experts convened by the United Nations with the objective of designing concrete policies and measures "for the economic development of underdeveloped countries," put it thus: There is a sense in which rapid economic progress is impossible without painful adjustments. Ancient philosophies have to be scrapped; old social institutions have to disintegrate; bonds of cast, creed and race have to burst; and large numbers of persons who cannot keep up with progress have to have their expectations of a comfortable life frustrated. Very few communities are willing to pay the full price of economic progress. (United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs [1951], 15) The report suggested no less than a total restructuring of "underdeveloped" societies. The statement quoted earlier might seem to us today amazingly ethnocentric and arrogant, at best naive; yet what has to be explained is precisely the fact that it was uttered and that it made perfect sense. The statement exemplified a growing will to transform drastically two-thirds of the world in the pursuit of the goal of material prosperity and economic progress. By the early 1950s, such a will had become hegemonic at the level of the circles of power. This book tells the story of this dream and how it progressively turned into a nightmare. For instead of the kingdom of abundance promised by theorists and politicians in the 1950s, the discourse and strategy of development produced its opposite: massive underdevelopment and impoverishment, untold exploitation and oppression. The debt crisis, the Sahelian famine, increasing poverty, malnutrition, and violence are only the most pathetic signs of the failure of forty years of development. In this way, this book can be read as the history of the loss of an illusion, in which many genuinely believed. Above all, however, it is about how the "ThirdWorld" has been produced by the discourses and practices of development since their inception in the early post–World War II period. |

第一章 序論:発展と近代性の人類学 ある意味で、急速な経済的進歩は痛みを伴う調整なしには不可能だ。古代の哲学は廃棄されねばならず、古い社会制度は崩壊せねばならず、カーストや信条、人 種による絆は断ち切られねばならず、進歩についていけぬ大勢の人々は安楽な生活への期待を裏切られる。経済的進歩の代償を全額支払うことをいとわない共同 体はほとんどない。―国連社会経済局『後進国経済開発のための措置』1951年 1949 年1月20日、ハリー・トルーマンはアメリカ合衆国大統領就任演説において、全世界に向けた「公正な取引」という構想を表明した。この構想の核心は、地球上の「未開発地域」の問題解決に向け、アメリカと世界が取り組むよう訴えた点にあった。 世界人口の半数以上が、悲惨に近い状況で生きている。食糧は不足し、疾病に苦しむ。経済生活は原始的で停滞している。その貧困は彼ら自身とより豊かな地域 双方にとって障害であり脅威だ。人類は史上初めて、こうした人々の苦悩を取り除く知識と技術を手にした。...我々は平和を愛する人々に、技術知識の蓄積 による恩恵を提供し、より良い生活への願望を実現させるべきだと信じる。我々が構想するのは、民主的で公正な取引の概念に基づく開発計画である。…生産拡 大こそが繁栄と平和の鍵だ。そして生産拡大の鍵は、現代の科学的・技術的知識をより広く、より力強く応用することにある。(トルーマン[1949 年]1964) トルーマン・ドクトリンは、世界情勢、特に経済的に発展途上の国々に関する理解と管理において新たな時代を切り開いた。その意図は非常に野心的であった。 当時の「先進」社会を特徴づける要素―高度な工業化と都市化、農業の技術化、物質生産と生活水準の急速な向上、そして近代的教育と文化的価値観の広範な普 及―を世界中に再現するために必要な条件を整えることだった。トルーマンの構想では、資本と科学技術こそがこの大規模な変革を可能にする主要な要素であっ た。この方法によってのみ、平和と豊かさを追求するアメリカの夢を地球上の全ての人々に広げられると考えたのである。 この夢は米国単独の産物ではなく、第二次世界大戦終結時の特異な歴史的状況が生み出した結果であった。わずか数年で、この夢は権力者たちの間で普遍的に受 け入れられるようになった。しかしこの夢は容易な過程とは見なされなかった。おそらく予想通り、先に見据えられた障害こそが使命を固める一因となった。当 時の最も影響力ある文書の一つは、国連が招集した専門家グループによって作成された。「発展途上国の経済発展」に向けた具体的政策・措置を設計する目的で 作成されたこの文書は、次のように述べている: ある意味で、苦痛を伴う調整なしに急速な経済的進歩は不可能である。古い哲学は廃棄されねばならない。古い社会制度は崩壊せねばならない。カースト、信 条、人種による絆は断ち切られねばならない。そして進歩についていけない大勢の人々は、快適な生活への期待を挫かれねばならない。経済的進歩の代償を全額 支払うことをいとわない共同体はほとんどない。(国連社会経済局[1951]、15頁) この報告書は「未開発」社会全体の再構築を提言した。先に引用した記述は、現代の我々には驚くほど自民族中心的で傲慢、少なくとも素朴に映るかもしれな い。しかし説明すべきは、この主張が実際に発せられ、当時完全に理にかなっていたという事実そのものだ。この記述は、物質的繁栄と経済的進歩という目標追 求のため、世界の3分の2を根本的に変革しようとする意思の高まりを象徴していた。1950年代初頭までに、この意志は権力中枢において支配的となった。 本書は、この夢が次第に悪夢へと変貌していく過程を描く。1950年代の理論家や政治家が約束した豊穣の王国とは裏腹に、開発の言説と戦略は正反対の結果 を生んだ。すなわち、大規模な未発達と貧困化、計り知れない搾取と抑圧である。債務危機、サヘル地域の飢饉、増大する貧困、栄養失調、暴力は、四十年にも 及ぶ開発の失敗がもたらした最も痛ましい兆候に過ぎない。この意味で、本書は多くの者が真に信じていた幻想の喪失の歴史として読まれるだろう。しかし何よ りも、第二次世界大戦直後の時期に始まった開発の言説と実践が、いかに「第三世界」を生産してきたかについての書物である。 |

| ORIENTALISM, AFRICANISM, AND DEVELOPMENTALISM Until the late 1970s, the central stake in discussions on Asia, Africa, and Latin America was the nature of development. As we will see, from the economic development theories of the 1950s to the "basic human needs approach" of the 1970s—which emphasized not only economic growth per se as in earlier decades but also the distribution of the benefits of growth—the main preoccupation of theorists and politicians was the kinds of development that needed to be pursued to solve the social and economic problems of these parts of the world. Even those who opposed the prevailing capitalist strategies were obliged to couch their critique in terms of the need for development, through concepts such as "another development," "participatory development," "socialist development," and the like. In short, one could criticize a given approach and propose modifications or improvements accordingly, but the fact of development itself, and the need for it, could not be doubted. Development had achieved the status of a certainty in the social imaginary. Indeed, it seemed impossible to conceptualize social reality in other terms. Wherever one looked, one found the repetitive and omnipresent reality of development: governments designing and implementing ambitious development plans, institutions carrying out development programs in city and countryside alike, experts of all kinds studying underdevelopment and producing theories ad nauseam. The fact that most people's conditions not only did not improve but deteriorated with the passing of time did not seem to bother most experts. Reality, in sum, had been colonized by the development discourse, and those who were dissatisfied with this state of affairs had to struggle for bits and pieces of freedom within it, in the hope that in the process a different reality could be constructed. More recently, however, the development of new tools of analysis, in gestation since the late 1960s but the application of which became widespread only during the 1980s, has made possible analyses of this type of "colonization of reality" which seek to account for this very fact: how certain representations become dominant and shape indelibly the ways in which reality is imagined and acted upon. Foucault's work on the dynamics of discourse and power in the representation of social reality, in particular, has been instrumental in unveiling the mechanisms by which a certain order of discourse produces permissible modes of being and thinking while disqualifying and even making others impossible. Extensions of Foucault's insights to colonial and postcolonial situations by authors such as Edward Said, V. Y. Mudimbe, Chandra Mohanty, and Homi Bhabha, among others, have opened up new ways of thinking about representations of the Third World. Anthropology's self-critique and renewal during the 1980s have also been important in this regard. Thinking of development in terms of discourse makes it possible to maintain the focus on domination—as earlier Marxist analyses, for instance, did—and at the same time to explore more fruitfully the conditions of possibility and the most pervasive effects of development. Discourse analysis creates the possibility of "stand[ing] detached from [the development discourse], bracketing its familiarity, in order to analyze the theoretical and practical context with which it has been associated" (Foucault 1986, 3). It gives us the possibility of singling out "development" as an encompassing cultural space and at the same time of separating ourselves from it by perceiving it in a totally new form. This is the task the present book sets out to accomplish. To see development as a historically produced discourse entails an examination of why so many countries started to see themselves as underdeveloped in the early post–World War II period, how "to develop" became a fundamental problem for them, and how, finally, they embarked upon the task of "un-underdeveloping" themselves by subjecting their societies to increasingly systematic, detailed, and comprehensive interventions. As Western experts and politicians started to see certain conditions in Asia, Africa, and Latin America as a problem—mostly what was perceived as poverty and backwardness—a new domain of thought and experience, namely, development, came into being, resulting in a new strategy for dealing with the alleged problems. Initiated in the United States and Western Europe, this strategy became in a few years a powerful force in the Third World. The study of development as discourse is akin to Said's study of the discourses on the Orient. "Orientalism," writes Said, can be discussed and analyzed as the corporate institution for dealing with the Orient—dealing with it by making statements about it, authorizing views of it, describing it, by teaching it, settling it, ruling over it: in short, Orientalism as a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient. ... My contention is that without examining Orientalism as a discourse we cannot possibly understand the enormously systematic discipline by which European culture was able to manage—and even produce—the Orient politically, sociologically, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period. (1979, 3) Since its publication, Orientalism has sparked a number of creative studies and inquiries about representations of the Third World in various contexts, although few have dealt explicitly with the question of development. Nevertheless, the general questions some of these works raised serve as markers for the analysis of development as a regime of representation. In his excellent book The Invention of Africa, the African philosopher V. Y. Mudimbe, for example, states his objective thus: "To study the theme of the foundations of discourse about Africa ... [how] African worlds have been established as realities for knowledge" (1988, xi) in Western discourse. His concern, moreover, goes beyond "the `invention' of Africanism as a scientific discipline" (9), particularly in anthropology and philosophy, in order to investigate the "amplification" by African scholars of the work of critical European thinkers, particularly Foucault and Lévi-Strauss. Although Mudimbe finds that even in the most Afrocentric perspectives the Western epistemological order continues to be both context and referent, he nevertheless finds some works in which critical European insights are being carried even further than those works themselves anticipated. What is at stake for these latter works, Mudimbe explains, is a critical reinterpretation of African history as it has been seen from Africa's (epistemological, historical, and geographical) exteriority, indeed, a weakening of the very notion of Africa. This, for Mudimbe, implies a radical break in African anthropology, history, and ideology. Critical work of this kind, Mudimbe believes, may open the way for "the process of refounding and reassuming an interrupted historicity within representations" (183), in other words, the process by which Africans can have greater autonomy over how they are represented and how they can construct their own social and cultural models in ways not so mediated by a Western episteme and historicity—albeit in an increasingly transnational context. This notion can be extended to the Third World as a whole, for what is at stake is the process by which, in the history of the modern West, non- European areas have been systematically organized into, and transformed according to, European constructs. Representations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America as Third World and underdeveloped are the heirs of an illustrious genealogy of Western conceptions about those parts of the world. Timothy Mitchell unveils another important mechanism at work in European representations of other societies. Like Mudimbe, Mitchell's goal is to explore "the peculiar methods of order and truth that characterise the modern West" (1988, ix) and their impact on nineteenth-century Egypt. The setting up of the world as a picture, in the model of the world exhibitions of the last century, Mitchell suggests, is at the core of these methods and their political expediency. For the modern (European) subject, this entailed that s/he would experience life as if s/he were set apart from the physical world, as if s/he were a visitor at an exhibition. The observer inevitably "enframed" external reality in order to make sense of it; this enframing took place according to European categories. What emerged was a regime of objectivism in which Europeans were subjected to a double demand: to be detached and objective, and yet to immerse themselves in local life. This experience as participant observer was made possible by a curious trick, that of eliminating from the picture the presence of the European observer (see also Clifford 1988, 145); in more concrete terms, observing the (colonial) world as object "from a position that is invisible and set apart" (Mitchell 1988, 28). The West had come to live "as though the world were divided in this way into two: into a realm of mere representations and a realm of the `real'; into exhibitions and an external reality; into an order of mere models, descriptions or copies, and an order of the original" (32). This regime of order and truth is a quintessential aspect of modernity and has been deepened by economics and development. It is reflected in an objectivist and empiricist stand that dictates that the Third World and its peoples exist "out there," to be known through theories and intervened upon from the outside. The consequences of this feature of modernity have been enormous. Chandra Mohanty, for example, refers to the same feature when raising the questions of who produces knowledge about Third World women and from what spaces; she discovered that women in the ThirdWorld are represented in most feminist literature on development as having "needs" and "problems" but few choices and no freedom to act. What emerges from such modes of analysis is the image of an average Third World woman, constructed through the use of statistics and certain categories: This average third world woman leads an essentially truncated life based on her feminine gender (read: sexually constrained) and her being "third world" (read: ignorant, poor, uneducated, tradition-bound, domestic, family-oriented, victimized, etc.). This, I suggest, is in contrast to the (implicit) self-representation of Western women as educated, as modern, as having control over their own bodies and sexualities, and the freedom to make their own decisions. (1991b, 56) These representations implicitly assume Western standards as the benchmark against which to measure the situation of Third World women. The result, Mohanty believes, is a paternalistic attitude on the part of Western women toward their Third World counterparts and, more generally, the perpetuation of the hegemonic idea of the West's superiority. Within this discursive regime, works about Third World women develop a certain coherence of effects that reinforces that hegemony. "It is in this process of discursive homogenization and systematization of the oppression of women in the third world," Mohanty concludes, "that power is exercised in much of recent Western feminist discourse, and this power needs to be defined and named" (54). (Continues...) |

オリエンタリズム、アフリカニズム、そして開発主義 1970年代後半まで、アジア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカに関する議論の中心的な争点は、開発の性質であった。これから見ていくように、1950年代の経 済発展理論から、1970年代の「人間の基本的ニーズへのアプローチ」に至るまで―これは、それ以前の数十年のように経済成長そのものだけでなく、成長の 恩恵の分配も強調したものだ―理論家や政治家の主な関心事は、これらの地域が抱える社会経済的問題を解決するために追求すべき発展の種類であった。支配的 な資本主義的戦略に反対する者でさえ、「別の開発」「参加型開発」「社会主義的開発」といった概念を通じて、批判を「開発の必要性」という枠組みで表現せ ざるを得なかった。要するに、特定のアプローチを批判し、それに応じた修正や改善を提案することはできたが、開発そのものの事実と必要性は疑う余地がな かったのだ。開発は社会的な想像の中で、確固たる地位を確立していたのだ。 実際、社会現実を他の概念で捉えることなど不可能に思えた。どこを見渡しても、開発という反復的で遍在する現実が目に飛び込んだ。政府が野心的な開発計画 を立案・実行し、機関が都市でも農村でも開発プログラムを実施し、あらゆる専門家が未開発を研究し、飽きるほど理論を生み出していた。大多数の人々の生活 状況が改善されるどころか、時が経つにつれて悪化しているという事実は、ほとんどの専門家を悩ませるようには見えなかった。要するに、現実は開発言説に よって占領され、この状況に不満を持つ者たちは、その中でのわずかな自由を求めて闘わねばならなかった。その過程で異なる現実が構築されることを期待しな がら。 しかし近年、1960年代後半から醸成されつつあった新たな分析手法が、1980年代になって広く応用されるようになった。これにより、現実の「占領」と いう現象――特定の表象が支配的となり、現実の想像や実践の仕方を不可逆的に形作る過程――を解明する分析が可能となったのである。特にフーコーの、社会 的現実の表象における言説と権力の力学に関する研究は、ある種の言説秩序が許容される存在や思考の様式を生み出す一方で、他の様式を排除し、さらには不可 能にさえするメカニズムを明らかにする上で決定的に役立った。エドワード・サイード、V・Y・ムディンベ、チャンドラ・モハンティ、ホーミ・バーバらによ る、フーコーの洞察を植民地・ポストコロニアル状況へ拡張した研究は、第三世界の表象について考える新たな道を開いた。1980年代における人類学の自己 批判と刷新も、この点で重要であった。 開発を言説の観点から考えることで、支配への焦点を維持しつつ(例えば初期のマルクス主義分析がそうであったように)、開発の可能性条件と最も広範な影響 をより実りある形で探求することが可能となる。言説分析は「(開発言説から)距離を置き、その慣れ親しみを括弧に入れ、それが関連付けられてきた理論的・ 実践的文脈を分析する」可能性を生み出す(フーコー 1986, 3)。それは「開発」を包括的な文化的空間として抽出しつつ、同時に全く新しい形でそれを認識することで、そこから自らを分離する可能性を我々に与える。 本書が成し遂げようとする課題はこれである。 開発を歴史的に生成された言説と捉えることは、なぜ第二次世界大戦直後の時期にこれほど多くの国々が自らを未発達と見なすようになったのか、いかにして 「開発する」ことがそれらの国々にとって根本的問題となったのか、そして最終的に、いかにして社会をますます体系的・詳細・包括的な介入に晒すことで「未 発達状態からの脱却」という課題に着手したのかを検証することを意味する。西洋の専門家や政治家がアジア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカにおける特定の状況― 主に貧困と後進性として認識されたもの―を問題視し始めた時、新たな思考と経験の領域、すなわち「開発」が誕生した。これにより、問題とされる事象に対処 する新たな戦略が生まれたのである。米国と西欧で始まったこの戦略は、わずか数年で第三世界において強力な力となった。 開発を言説として研究することは、サイードがオリエントに関する言説を研究したことに似ている。サイードはこう書いている。 オリエンタリズムは、オリエントに対処するための組織的制度として議論・分析できる。つまり、オリエントについて発言し、見解を認可し、描写し、教え、開 拓し、支配する——要するに、オリエンタリズムとは西洋がオリエントを支配し、再構築し、権威を振るう様式である。... 私の主張は、オリエンタリズムを言説として検証しなければ、啓蒙主義以後の時代にヨーロッパ文化が政治的・社会学的・イデオロギー的・科学的・想像的にオ リエントを管理し、さらには生産し得た、この極めて体系的な規律を理解することは不可能だということである。(1979, 3) 『オリエンタリズム』の出版以来、様々な文脈における第三世界の表象に関する創造的な研究や探求が数多く生み出されてきたが、開発の問題を明示的に扱った ものはほとんどない。とはいえ、こうした研究が提起した一般的な問いは、表象の体制としての開発分析における指標となり得る。例えばアフリカ人哲学者 V.Y.ムディンベは優れた著作『アフリカの発明』において、その目的を次のように述べている。「アフリカに関する言説の基盤という主題を研究するこ と……西洋言説においてアフリカ世界が如何にして知識の現実として確立されてきたかを考察すること」(1988年、xi頁)。さらに彼の関心は、「科学的 な学問分野としてのアフリカ主義の『発明』」(9頁)——特に人類学や哲学における——を超え、アフリカ人学者による批判的なヨーロッパ思想家(特にフー コーやレヴィ=ストロース)の著作の「拡大解釈」を調査することにある。ムディンベは、最もアフリカ中心主義的な視点においても、西洋の認識論的秩序が依 然として文脈かつ参照対象であり続けていると指摘する。しかしながら、批判的なヨーロッパ的洞察が、それらの著作自体が想定していた以上にさらに推し進め られている事例もいくつか見出している。ムディンベによれば、こうした後者の著作が問うのは、アフリカの(認識論的・歴史的・地理的)外部性から見てきた アフリカ史の批判的再解釈、つまりアフリカという概念そのものの弱体化である。これはムディンベにとって、アフリカ人類学・歴史学・イデオロギーにおける 根本的な断絶を意味する。 ムディンベは、こうした批判的作業が「表象における中断された歴史性の再構築と再獲得のプロセス」(183頁)への道を開くと考えている。つまり、アフリ カ人が自らの表象方法や、西洋の認識論と歴史性による媒介を比較的受けずに自らの社会的・文化的モデルを構築する方法について、より大きな自律性を獲得す るプロセスである。ただし、それはますます国際的な文脈の中で行われることになる。この考え方は、第三世界全体にも拡大することができる。なぜなら、問題 となっているのは、近代西洋の歴史において、非ヨーロッパ地域が体系的に組織化され、ヨーロッパの概念に従って変容してきたプロセスであるからだ。アジ ア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカを第三世界や発展途上国として表現することは、これらの地域に関する西洋の概念の輝かしい系譜の継承者である。ティモシー・ ミッチェルは、ヨーロッパによる他社会表現の背後で働くもうひとつの重要なメカニズムを明らかにしている。ムディンベと同様、ミッチェルの目的は「近代西 洋を特徴づける秩序と真実の特異な方法」(1988年、ix)と、それが19世紀のエジプトに与えた影響を探求することである。ミッチェルは、前世紀の世 界博覧会をモデルとした、世界を絵画のように設定することが、これらの方法とその政治的便宜性の中核を成していると示唆している。現代(ヨーロッパ)の主 体にとって、これは、あたかも自分が物理的な世界から切り離された、あたかも自分が博覧会の訪問者のように、人生を体験することを意味した。観察者は、必 然的に、外部現実を理解するためにそれを「枠組み」に収めた。この枠組みは、ヨーロッパのカテゴリーに従って行われた。その結果、客観主義の体制が生ま れ、ヨーロッパ人は、客観的かつ客観的であることと、現地の生活に没頭することという、二重の要求にさらされることになった。 この参与観察としての経験は、ヨーロッパ人観察者の存在を絵から消去するという奇妙なトリックによって可能になった(Clifford 1988, 145 も参照)。より具体的に言えば、「見えない、隔離された立場」から(植民地)世界を客観として観察することである(Mitchell 1988, 28)。西洋は、「世界がこのように二つに分割されているかのように」生きることになった。つまり、単なる表現の領域と「現実」の領域、展示と外部の現 実、単なるモデル、記述、複製の秩序とオリジナルの秩序に分割されているかのように(32)。この秩序と真実の体制は、近代性の本質的な側面であり、経済 学と開発によってさらに深まっている。これは、第三世界とその人々は「外」に存在し、理論によって知られ、外部から介入されるべきであるとする客観主義 的・経験主義的立場に反映されている。 この近代性の特徴がもたらした結果は甚大である。例えばチャンドラ・モハンティは、第三世界の女性に関する知識を誰が、どの空間から生み出すのかという問 題を提起する際、この特徴に言及している。彼女は、開発に関するフェミニスト文献の大半において、第三世界の女性が「ニーズ」や「問題」を抱えつつも、選 択肢は少なく行動の自由もない存在として描かれていることを発見した。こうした分析手法から浮かび上がるのは、統計と特定のカテゴリーを用いて構築された 「平均的な第三世界の女性」像である: この平均的な第三世界の女性は、ジェンダー(つまり性的に制約された存在)と「第三世界」であること(つまり無知、貧困、無学、伝統に縛られ、家庭的、家 族中心、被害者など)に基づいて、本質的に断片化された人生を送っている。これは、西洋の女性が自らを教育を受け、近代的で、自らの身体と性に対する支配 権を持ち、自らの決断を下す自由を持つと(暗黙のうちに)自己表現していることとは対照的だと言える。(1991b, 56) これらの表象は、第三世界の女性の状況を測る基準として西洋の規範を暗黙のうちに前提としている。その結果、モハンティは、西洋の女性が第三世界の女性に 対して見せるパターナリスティックな態度、そしてより広くは西洋の優越性というヘゲモニックな思想の永続化をもたらすと考える。この言説体制の中で、第三 世界の女性に関する著作は、そのヘゲモニーを強化する特定の効果の一貫性を発展させる。「第三世界の女性に対する抑圧を言説的に均質化し体系化するこの過 程において」とモハンティは結論づける、「近年の西洋フェミニスト言説の大部分で権力が行使されており、この権力は定義され、名指しされる必要がある」 (54)。 (続く...) |

| Excerpted from Encountering Development by Arturo Escobar Copyright © 1995 by Princeton University Press. Excerpted by permission of PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. |

『開発との遭遇』より抜粋 著者 アルトゥーロ・エスコバル 著作権 © 1995 プリンストン大学出版局。プリンストン大学出版局の許可を得て抜粋。無断複写・転載を禁ず。出版社の書面による許可なく、本書の一部または全部を複製または転載することはできない。 抜粋はDial-A-Book Inc.が、本ウェブサイト訪問者の個人的利用のみを目的として提供している。 |

★Designs for the pluriverse : radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds / Arturo Escobar, Durham : Duke University Press , 2018, c2017. - (New ecologies for the twenty-first century)/ 多元世界に向けたデザイン : ラディカルな相互依存性、自治と自律、そして複数の世界をつくること / アルトゥーロ・エスコバル著 ; 増井エドワード [ほか] 訳, 東京 : ビー・エヌ・エヌ , 2024.2[pdf]

1. 現実世界のためのデザイン

1.1 (1章) スタジオを出て自然社会的生活の中へ

1.2 (2章) デザインのカルチュラル・スタディーズのための要素

2. デザインの存在論的再定位

2.1(3章)我々の文化の背景にあるもの:合理性、存在論的二元論、関係性

2.2(4章)存在論的デザインの概要

3. 多元世界に向けたデザイン

3.1(5章)トランジションのためのデザイン

3.2(6章)自治=自律的デザインと関係性の政治と共同的なもの

4. 結論

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆