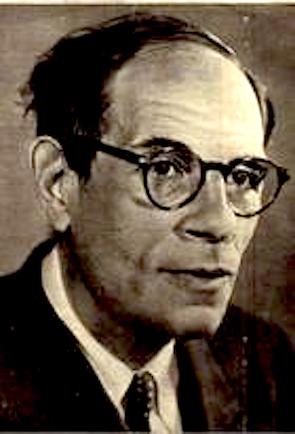

オーレル・コルナイ

Aurel Thomas Kolnai,

1900-1973

☆オー

レル[アウレル]・トマス・コルナイ(* 1900年12月5日、ブダペストにてオーレル・スタイン、†

1973年6月28日[1]、ロンドン)はオーストリア系イギリス人の哲学者で、とりわけ道徳と感情に関する理論で知られるようになった。

| Aurel Thomas Kolnai

(* 5. Dezember 1900 in Budapest als Aurel Stein; † 28. Juni 1973[1] in

London) war ein österreichisch-britischer Philosoph, der vor allem mit

Theorien zur Moral und zu den Emotionen bekannt geworden ist. |

オーレル・トマス・コルナイ(*

1900年12月5日、ブダペストにてオーレル・スタイン、†

1973年6月28日[1]、ロンドン)はオーストリア系イギリス人の哲学者で、とりわけ道徳と感情に関する理論で知られるようになった。 |

| Leben Aurél Stein stammt aus einer jüdischen Familie. Als Gymnasiast war er im linksintellektuellen Galilei-Kreis aktiv. 1918 nahm er den Namen Kolnai an, den er einer Erzählung Ferenc Molnárs entnommen hatte ("A Pál utcai fiúk" – Die Jungen von der Paulstraße). In den Jahren von 1919 bis 1937 lebte Kolnai in Wien, wo er zunächst studierte und promovierte und auch die österreichische Staatsbürgerschaft annahm. Nachdem er bis in seine Studienzeit hinein Agnostiker gewesen war, konvertierte er, beeinflusst von den Schriften Gilbert Keith Chestertons, 1926 (am Tag seiner Graduierung in Wien) zum Katholizismus. Kolnai arbeitete bis 1937 als Journalist für Der Österreichische Volkswirt, Schönere Zukunft, und später auch für „Der christliche Ständestaat“, eine Zeitschrift, die von Dietrich von Hildebrand herausgegeben wurde. Unter dem Druck der politischen Situation verteidigte Kolnai die Regierung Kurt Schuschniggs, die er als Rettungsanker vor dem Nationalsozialismus sah. Nach dem Anschluss Österreichs an das Deutsche Reich ging Kolnai 1940 mit seiner Frau Elisabeth über verschiedene Stationen ins Exil nach New York, wurde aber, wie er in seinen Memoiren schrieb, in den Vereinigten Staaten nicht heimisch. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg lehrte er zunächst an der Université Laval in Québec, Kanada. In den 1950er Jahren kehrte er nach Europa zurück und arbeitete zeitweise am Bedford College in London sowie in Birmingham. Er war während der Regierung von Francisco Franco mehrmals als Vortragender in Spanien und schätzte die dortigen Verhältnisse. Seine letzte Lehrtätigkeit übte Kolnai seit 1968 bis zu seinem Tod an der Marquette University in Wisconsin aus. |

アウレル・シュタインの生涯 アウレル・シュタインはユダヤ人の家庭に生まれた。文法学校の生徒として、左翼知識人ガリレイ・サークルで活動した。1918年、フェレンツ・モルナール (Ferenc Molnár)の物語(「A Pál utcai fiúk」 - The Boys from Paul Street)からコルナイ(Kolnai)と名乗る。 1919年から1937年まで、コルナイはウィーンで暮らし、そこで学び、博士号を取得し、オーストリア国籍を取得した。学生時代まで不可知論者であった 彼は、ギルバート・キース・チェスタートンの著作に影響を受け、1926年(ウィーンでの卒業式の日)にカトリックに改宗した。コルナイは、1937年ま で『Der Österreichische Volkswirt』、『Schönere Zukunft』のジャーナリストとして労働し、その後、ディートリッヒ・フォン・ヒルデブランドが発行する雑誌『Der christliche Ständestaat』でも働いた。政治情勢の重圧の中で、コルナイはクルト・シュシュニッヒ政権を擁護し、国家社会主義からの命綱と見なした。 オーストリアがドイツ帝国に併合された後、コルナイは妻のエリザベートとともに1940年にニューヨークに亡命したが、回顧録にあるように、アメリカでは くつろげなかった。第二次世界大戦後、当初はカナダのケベックにあるラヴァル大学で教鞭をとっていた。1950年代にヨーロッパに戻り、ロンドンのベッド フォード・カレッジとバーミンガムで一時期労働した。フランシスコ・フランコ政権時代に講師として何度かスペインを訪れ、現地の状況を高く評価した。コル ナイの最後の教職は、1968年から亡くなるまでウィスコンシン州のマーケット大学であった。 |

| Philosophische Ausrichtung Kolnai war zunächst ein Anhänger Sigmund Freuds und wandte sich in der zweiten Hälfte der 1920er Jahre der phänomenologischen Strömung zu. Die Philosophie Edmund Husserls sowie die Wertethik Max Schelers wurden für Kolnai richtungsweisend, wobei er der realistischen Richtung der Phänomenologie zugerechnet werden kann. Einflussreich wurde Kolnais Phänomenologie der Emotionen, insbesondere die Studie "Der Ekel", die José Ortega y Gasset im Erscheinungsjahr 1929 ins Spanische übersetzte und die großen Eindruck auf Salvador Dalí machte.[2] Manche Denker, wie z. B. Karl Popper, zählten Kolnai zu den originellsten, aber auch herausforderndsten Philosophen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Kolnais 1938 erschienenes (und in Wien in englischer Sprache geschriebenes) Buch The War Against the West ist eine der frühesten philosophischen Analysen des Nationalsozialismus und gilt nun als Meisterwerk der Ideologiekritik. Seit seiner Lehrtätigkeit an der Universität Laval, die damals zu den führenden Zentren des Neuthomismus zählte, zeigte sich Kolnai auch von der scholastischen Methode beeinflusst. Während seiner Zeit am Bedford College nahm er auch die analytische Philosophie auf und wurde von den führenden Vertretern der "ordinary language philosophy" auch geschätzt. Sein Werk galt in dieser Phase besonders der sprachanalytischen Diskussion psychologischer und moralischer Erscheinungen, wobei Kolnai nie bei der Analyse stehenblieb und durchaus moralische Wertungen vornahm. Kolnai war als Philosoph dem Realismus verpflichtet und als politischer Denker einem konservativen Weltbild. Scharf wandte er sich gegen alle Utopien von linken und rechten Richtungen. Er kritisierte auch die Demokratie, v. a. den amerikanischen utopischen Egalitarismus, den er als "totalitas sine tyrannide" (Totalitarismus ohne Tyrannei) bezeichnete. In Fragen der Ethik (und vor allem der Sexualmoral) blieb Kolnai einer naturrechtlichen und vom Katholizismus geprägten Auffassung verpflichtet. Neben der phänomenologischen Methode prägte ihn seit seiner englischen Zeit auch die Linguistik. Kolnai gilt als einer derjenigen Philosophen, die früh den "Graben" zwischen der sogenannten kontinentalen Philosophie und der angelsächsischen Philosophie analytischer Prägung überwunden haben. Sein Denken wurde erst seit den 90er Jahren in den Vereinigten Staaten, meist von konservativen und katholischen Denkern, neu entdeckt. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurel_Kolnai |

哲学的志向 コルナイは当初ジークムント・フロイトの信奉者だったが、1920年代後半に現象学運動に傾倒した。エドムント・フッサールの哲学とマックス・シェラーの 価値倫理学がコルナイにとっての潮流となり、現象学のリアリズム学派に属することになった。コルナイの感情の現象学、特にホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットが 1929年にスペイン語に翻訳し、サルバドール・ダリに大きな印象を与えた『嫌悪』という研究は影響力を持った[2]。カール・ポパーのような一部の思想 家は、コルナイを20世紀で最も独創的でありながら、最も挑戦的な哲学者の一人として数えた。1938年に出版されたコルナイの著書『The War Against the West』(ウィーンで英語で書かれた)は、国家社会主義に関する最も初期の哲学的分析のひとつであり、現在ではイデオロギー批判の傑作とみなされてい る。当時ネオ・ホミズムの中心地のひとつであったラヴァル大学で教鞭をとっていたコルナイは、スコラ学的手法の影響も受けていた。ベッドフォード・カレッ ジ時代には分析哲学にも取り組み、「普通の言語哲学」の代表者たちからも高く評価された。この時期、コルナイは特に心理学的・道徳的現象の言語分析的考察 に力を注いだが、決して分析に止まらず、道徳的判断を下すこともあった。哲学者としてのコルナイは現実主義に傾倒し、政治思想家としては保守的な世界観に 傾倒した。左翼的、右翼的傾向のあらゆるユートピアに激しく反対した。また、民主主義、特にアメリカのユートピア的平等主義を批判し、それを「専制なき全 体主義(totalitas sine tyrannide)」と表現した。倫理の問題(とりわけ性道徳)では、コルナイはカトリシズムに特徴づけられる自然法観にこだわり続けた。現象学的手法 に加え、イギリス時代の言語学の影響も受けた。コルナイは、いわゆる大陸哲学と分析的な性格を持つアングロサクソン哲学との「溝」を早い段階で克服した哲 学者の一人とみなされている。彼の思想がアメリカで再発見されたのは1990年代以降のことで、その多くは保守的でカトリック的な思想家たちによるもので ある。 |

| "Der Ekel" (Aufsatz von 1929) Aurel Kolnai 1929 schrieb Aurel Kolnai einen ausführlichen Aufsatz mit dem Titel Der Ekel, der im Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung erschien. Für ihn handelt es sich dabei um eine Abwehrreaktion, die sich vor allem gegen Organisches richtet, aber auch eine moralische Dimension hat. Kolnai bezeichnet Ekel als ambivalente Gefühlsregung, da die auslösenden Objekte nicht nur abstoßend wirkten, sondern zugleich die Aufmerksamkeit fesselten. „Ekel“, so Kolnai, „ist mehr als gesteigertes Mißfallen, aber weniger und anders als Haß; Ekel […] ist körpernäher als alle anderen Formen der Abwehr und Abkehr; Ekel ist deshalb auch etwas anderes als moralische Verachtung und geradezu ein Gegenbegriff zu Angst. […] Im Ekel ist keine Bedrohung spürbar, nur eine unerträgliche Belästigung […].“[12] Der Speiseekel spielt bei Kolnai eine untergeordnete Rolle. Er spricht Geruchs-, Gesichts- und Tastsinn eine wesentlich größere Bedeutung zu als dem Geschmack. Kolnai verwendet den Begriff „Überdrußekel“ für die Reaktion auf übermäßiges Essen und Trinken, aber auch für Müßiggang. Als Urobjekt des Ekels sieht Kolnai alle Formen von Fäulnis und Verwesung an, und daher seien auch Exkremente ekelhaft. Ekelreaktionen auf Insekten erklärt er mit dem optischen Eindruck des Gewimmels und negativen Assoziationen wie Heimtücke und Boshaftigkeit. Außerdem sei auch wild wuchernde Vegetation ekelauslösend. Kolnai führt auch eine Reihe von als unmoralisch empfundenen Verhaltensweisen auf, die er mit Ekel in Verbindung bringt.[13] Kolnais Ausführungen sind nicht wertneutral und nicht wissenschaftlich objektiv. Penning weist darauf hin, dass er aus der Perspektive eines konservativen Katholiken um 1930 schreibt. Salvador Dalí war beeindruckt von Kolnais Der Ekel. In einem 1932 veröffentlichten Essay für die Zeitschrift This Quarter empfahl der Maler den Text nachdrücklich den anderen Surrealisten und hob sein analytisches Verfahren als nachahmenswert hervor.[14] „Spuren der Bilder, Beispiele und Beobachtungen“ Kolnais fänden sich „in vielen Gemälden Dalís wieder, auch in dem Film Un chien andalou.“[14] In ihrer Rezension zu Kolnais seit 2007 in dem Band Ekel, Haß, Hochmut. Zur Phänomenologie feindlicher Gefühle wieder auf Deutsch zugänglichem Essay weist Susanne Mack darauf hin, dass „Der Ekel seiner Auffassung nach durch eine grundsätzliche Aversion, sprich: Angst verursacht (wird), der Angst des Menschen vor dem Sterben, vor Fäulnis- und Verwesungsprozessen, im Grunde vor dem zukünftigen Verwesen des eigenen Körpers.“[15] |

オーレル・コルナイの「嫌悪」概念 1929年、アウレル・コルナイは『Der Ekel』という詳細なエッセイを書き、『Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung』に掲載された。彼にとって嫌悪とは、主に有機物に対して向けられる防衛反応であるが、道徳的な側面も持っている。コルナイは嫌悪感を 両義的な感情反応と表現している。嫌悪感を引き起こす対象は嫌悪感を抱かせるだけでなく、注目も集めるからだ。コルナイによれば、「嫌悪」とは「不快感を 高めた以上のものであるが、憎悪よりは少なく、異なるものである。[...)嫌悪には知覚できる脅威はなく、耐えがたい煩わしさだけがある[...]」 [12]。 コルナイの作品において、食物の嫌悪感は従属的な役割を果たしている。彼は味覚よりも嗅覚、視覚、触覚を重要視している。コルナイは過度の飲食に対する反 応として「耽溺」という言葉を使うが、怠惰に対しても使う。コルナイは、腐敗や腐敗のあらゆる形態を嫌悪の主な対象とみなしており、したがって排泄物も嫌 悪の対象である。彼は昆虫に対する嫌悪反応を、その群れの視覚的印象と、悪意や悪意といった否定的な連想で説明している。さらに、野生の植物も嫌悪感を抱 かせる。コルナイはまた、不道徳と認識され、嫌悪と結びつけられる行動をいくつか挙げている[13]。コルナイの説明は価値中立的ではなく、科学的に客観 的でもない。ペニングは、彼が1930年頃の保守的なカトリック教徒の視点から書いていることを指摘している。 サルバドール・ダリはコルナイの『嫌悪』に感銘を受けた。1932年に雑誌『This Quarter』に掲載されたエッセイの中で、画家はこのテキストを他のシュルレアリストに強く推薦し、その分析的手法が模倣に値すると強調した [14]。「コルナイのイメージ、例、観察の痕跡」は、映画『Un chien andalou』を含む「ダリの絵画の多くに見出すことができる」[14]。 2007年以降の『Ekel, Haß, Hochmut. Zur Phänomenologie feindlicher Gefühle』(2007年から再びドイツ語で読めるようになった)の中で、Susanne Mackは、「彼の見解では、嫌悪は根源的な嫌悪、すなわち恐怖、死ぬことに対する人間の恐怖、腐敗や腐敗の過程に対する恐怖、基本的には自分自身の身体 が将来腐敗することに対する恐怖によって引き起こされる」と指摘している[15]。 |

| Werke (Auswahl) Psychoanalyse und Soziologie. Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, Wien 1920. Die geistesgeschichtliche Bedeutung der Psychoanalyse. In: Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse. Bd. 9 (1923), S. 345–356. Max Schelers Kritik und Würdigung der Freudschen Libidolehre. In: Imago. Zeitschrift für Anwendung der Psychoanalyse auf die Geisteswissenschaften. Bd. 11 (1925), Heft 1/2, S. 135–146. Der ethische Wert und die Wirklichkeit. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1927. Der Ekel. In: Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung. Bd. 10 (1929), S. 515–569. On disgust. Ed. and with an introd. by Barry Smith and Carolyn Korsmeyer. Open Court, Chicago 2004. Die Machtideen der Klassen. Zur Lage der Landwirtschaft in Pommern. Exkursionsbericht des Instituts für Sozial- und Staatswissenschaften an der Universität Heidelberg. In: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. Bd. 62 (1929), S. 67–110. Sexualethik. Schöningh, Paderborn 1930. Gegenrevolution. In: Kölner Vierteljahrshefte für Soziologie. Bd. 10 (1932), S. 171–199 und 295–319. The War Against the West. With preface by Wickham Steed. Gollancz, London / Viking Press, New York 1938, https://archive.org/details/TheWarAgainstTheWest Konservatives und revolutionäres Ethos. In: Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner (Hg.): Rekonstruktion des Konservatismus. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1972, S. 95–136. Ethics, Value, and Reality. Selected Papers. Athlone, London 1977. The Utopian Mind and Other Papers. A Critical Study in Moral and Political Philosophy. Edited by Francis Dunlop. Athlone, London 1995. Political Memoirs. Lexington, Lanham 1999. Early Ethical Writings of Aurel Kolnai. Translated and introduced by Francis Dunlop. Ashgate, Aldershot 2002, ISBN 0-7546-0648-1. Sexual Ethics: The Meaning and Foundations of Sexual Morality. Translated and edited by Francis Dunlop. Ashgate, Aldershot 2005, ISBN 0-7546-5312-9. Ekel, Haß, Hochmut. Zur Phänomenologie feindlicher Gefühle. Mit einem Nachwort von Axel Honneth. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-518-29445-1 (Aufsätze).[3] Der Krieg gegen den Westen. Hrsg. von Wolfgang Bialas, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2015, 763 S., ISBN 9783525310311. |

著作(抜粋) 精神分析と社会学。国際精神分析出版社、ウィーン 1920年 思想史における精神分析の意義. 国際精神分析ジャーナル。第9巻(1923年)、345-356頁。 フロイトのリビドー理論に対するマックス・シェラーの批判と評価。Imago. 精神分析の人文科学への応用のための雑誌。第11巻(1925年)第1/2号、135-146頁。 倫理的価値と現実。Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1927. 嫌悪。哲学・現象学研究年鑑. 第10巻(1929年)、515-569頁。 嫌悪について。バリー・スミス、キャロリン・コースマイヤー編著。Open Court, Chicago 2004. 階級の権力思想 ポメラニアの農業事情について。ハイデルベルク大学社会政治科学研究所の現地調査報告書。In: Archive for Social Science and Social Policy. 第62巻(1929年)、67-110頁。 性倫理。Schöningh, Paderborn 1930. 反革命。In: Kölner Vierteljahrshefte für Soziologie. 第10巻(1932年)、171-199頁および295-319頁。 西側諸国との戦争。ウィッカム・スティードによる序文付き。Gollancz, London / Viking Press, New York 1938, https://archive.org/details/TheWarAgainstTheWest 保守と革命のエートス。In: Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner (ed.): Reconstruction of Conservatism. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1972, pp.95-136. 倫理、価値、現実。Selected Papers. Athlone, London 1977. ユートピアマインドとその他の論文。道徳・政治哲学の批判的研究。フランシス・ダンロップ編。Athlone, London 1995. 政治回顧録。レキシントン、ランハム 1999年 オーレル・コルナイの初期倫理著作集。フランシス・ダンロップ訳・紹介。Ashgate, Aldershot 2002, ISBN 0-7546-0648-1. 性倫理学:性道徳の意味と基礎。フランシス・ダンロップ著。Ashgate, Aldershot 2005, |

| Literatur Carolyn Korsmeyer and Barry Smith, Visceral Values: Aurel Kolnai on Disgust, introduction to Aurel Kolnai, On Disgust, Chicago and La Salle: Open Court Publishing Company, 2004, 4–25. Lee Congdon: Exile and Social Thought: Hungarian Intellectuals in Germany and Austria, 1919–1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991. Francis Dunlop: The Life and Thought of Aurel Kolnai. Aldershot: Ashgate 2002, ISBN 0-7546-1662-2. John P. Hittinger: Aurel Kolnai and the Metaphysics of Political Conservatism (1998; PDF; 204 kB), in: Ders.: Liberty, Wisdom, and Grace. Thomism and Democratic Political Theory, Lanham Md.: Lexington Books, 2002, S. 163–185. Zoltán Balázs & Francis Dunlop: Exploring the world of human practice. Readings in and about the Philosophy of Aurel Kolnai. Central European University Press (CEU Press) 2004. ISBN 963-9241-97-0. Wolfgang Grassl: KOLNAI, Aurél Thomas. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Band 30, Bautz, Nordhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-88309-478-6, Sp. 801–803. |

文献 キャロリン・コースマイヤーとバリー・スミス『内臓的価値:オーレル・コルナイの嫌悪論』オーレル・コルナイ『嫌悪について』序文、シカゴとラ・サール:オープンコート出版、2004年、4–25頁。 リー・コングドン『亡命と社会思想:1919-1933年のドイツ・オーストリアにおけるハンガリー知識人』プリンストン大学出版局、1991年。 フランシス・ダンロップ『オーレル・コルナイの生涯と思想』アッシュゲート出版、2002年、ISBN 0-7546-1662-2。 ジョン・P・ヒッティンガー:オーレル・コルナイと政治的保守主義の形而上学(1998年;PDF;204キロバイト)、同著『自由、知恵、そして恩寵。トミス主義と民主的政治理論』(メリーランド州ラナム:レキシントン・ブックス、2002年)所収、163–185頁。 ゾルターン・バラズ&フランシス・ダンロップ:人間実践の世界を探る。オーレル・コルナイの哲学に関する読本。中央ヨーロッパ大学出版局(CEU Press)2004年。ISBN 963-9241-97-0。 ヴォルフガング・グラースル:コルナイ、オーレル・トマス。収録:『教会人物事典』(BBKL)。第30巻、バウツ社、ノルトハウゼン、2009年、ISBN 978-3-88309-478-6、801–803頁。 |

| 1.

Die Lebensdaten nach Stuart C. Brown, Diané Collinson, Robert Wilkinson

(Hg.): Biographical dictionary of twentieth-century philosophers,

London 1996, S. 410 2. Andreas Dorschel: Genaue Imagination. in: Süddeutsche Zeitung Nr. 106 (7. Mai 2008), S. 14. 3. DLF: „Schlimme Gefühle“, Rezension zu Ekel, Haß, Hochmut, 17. Januar 2008 |

1 スチュアート・C・ブラウン、ディアネ・コリンソン、ロバート・ウィルキンソン編:20世紀哲学者人名辞典、ロンドン、1996年、410頁による。 2 Andreas Dorschel: Precise Imagination. in: Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 106 (7 May 2008), p. 14. 3 DLF: 「Schlimme Gefühle」、『Ekel, Haß, Hochmut』の書評、2008年1月17日。 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurel_Kolnai | |

☆英語版ウィキペディアのオーレル・コルナイ(伝記と哲学の部分)

| Life Kolnai was born Aurel Stein in Budapest, Hungary to Jewish parents but moved to Vienna before his twentieth birthday to enter Vienna University, where he studied under Heinrich Gomperz, Moritz Schlick, Felix Kaufmann, Karl Bühler, and Ludwig von Mises. It was also at this time that he became attracted to the thinking of Franz Brentano and the phenomenological thought of Brentano's student Edmund Husserl. Kolnai studied under Husserl briefly in 1928 in Freiburg.[2] During the early 1920s, Kolnai wrote as an independent scholar with little success. He graduated summa cum laude in 1926, publishing his dissertation on Der Ethische Wert und die Wirklichkeit, which was received favorably in Germany. In 1926, he also converted to Catholicism, largely influenced by G. K. Chesterton, whom Kolnai viewed as "a brilliant, if unsystematic phenomenologist of common experience."[3] He then began a career of political journalism, writing for Der Österreichische Volkswirt and Die Schöne Zukunft. Acutely aware of the real threat posed by the Nazi Party in Austria, he began writing for Der christliche Ständestaat, a periodical founded to combat Nazism and edited by Dietrich von Hildebrand. During this time, he also published some of his own philosophical writings including his Sexualethik, Der Ekel, Der Inhalt der Politik, and Der Versuch über den Haß. Kolnai's philosophical writings, though producing little profit for the author, were well received and generated excellent reviews. Salvador Dalí was impressed by Der Ekel; in a 1932 essay for the journal This Quarter, the painter recommended Kolnai's text strongly to other surrealists, praising its analytical power.[4] During the 1930s, the encroachment of the Nazi Party in Austria remained a major concern. In 1938, Kolnai published his critique of National Socialism titled The War Against the West. The Nazi threat compelled Kolnai to leave Austria in 1937, where he was then a citizen, and depart for France where he married Elisabeth Gemes in 1940, also a Catholic convert. The Vichy threat prevented the newly-wed Kolnai from remaining in France, and after a brief stay in England, Kolnai and his wife moved to Quebec where he accepted a teaching position at the University of Laval. Frustrated by what he saw as the oppressive parochial Catholicism and the rigid neo-Thomism, Kolnai left Quebec in 1955 and returned to England on a Nuffield Foundation Travel Grant. Though he had quite an extensive list of publications in five different languages, Kolnai had little luck finding a permanent professorship in Britain, and fraught with financial worries, his health began to rapidly decline. Due largely to the influence of Harry Acton, Bernard Williams, and David Wiggins, Kolnai was able to secure a part-time "Visiting Lectureship" at Bedford College at London University. In England at this time, Kolnai became very influenced by the English common-sense philosophy of G.E. Moore and other British intuitionists such as H.A. Prichard, E.F. Carritt, and W.D. Ross.[5] In 1961, he received a one-year research fellowship at Birmingham. In 1968, he accepted a visiting professor position at Marquette University in Wisconsin which he maintained until 1973 when he died of a heart attack. Kolnai's wife Elisabeth worked on compiling, translating, and publishing his work until her death in 1982. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurel_Kolnai |

人生 コルナイは、ハンガリーのブダペストでユダヤ人の両親の間にオーレル・スタインとして生まれたが、20歳の誕生日を迎える前にウィーンに移住し、ウィーン 大学に入学した。そこで、ハインリッヒ・ゴンペルツ、モーリッツ・シュリック、フェリックス・カウフマン、カール・ビューラー、ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ ミーゼスに師事した。また、この時期に、フランツ・ブレントノの思想と、ブレントノの弟子であるエドムント・フッサールの現象学的思想に惹かれるように なった。コルナイは、1928年にフライブルクでフッサールに短期間師事した[2]。1920年代初頭、コルナイは独立した学者として執筆活動を行った が、あまり成功しなかった。1926年に最優等で卒業し、博士論文『倫理的価値と現 実』を発表した。この論文はドイツで好評を博した。同年、主にG・K・チェスタートンの影響を受けてカトリックに改宗した。コルナイはチェスタートンを 「体系化されていないとはいえ、日常経験の卓越した現象学者」と見なしていた。[3] その後、政治ジャーナリストとしてのキャリアを始め、『オーストリア経済新聞』や『美しい未来』に寄稿した。オーストリアにおけるナチ党の現実的な脅威を 強く認識していた彼は、ナチズムに対抗するために創刊され、ディートリヒ・フォン・ヒルデブランドが編集する『キリスト教的階級国家』誌への執筆を開始し た。この時期、彼は自身の哲学的著作も発表している。代表作に『性倫理』『嫌悪』『政治の本質』『憎悪に関する試論』などがある。コルナイの哲学著作は著 者にとって利益をもたらさなかったが、高い評価を得て優れた書評を生んだ。サルバドール・ダリは『嫌悪』に感銘を受けた。1932年に雑誌『ディス・ クォーター』に寄稿したエッセイで、この画家は他のシュルレアリストたちにコルナイの著作を強く推奨し、その分析力を称賛している[4]。 1930年代を通じて、オーストリアにおけるナチ党の進出は重大な懸念事項であり続けた。1938年、コルナイは『西洋に対する戦争』と題した国家社会主 義批判書を出版した。ナチスの脅威により、当時オーストリア市民であったコルナイは1937年に同国を離れ、フランスへ渡った。1940年には同じくカト リックに改宗したエリザベート・ゲメスと結婚する。ヴィシー政権の脅威により新婚のコルナイはフランスに留まることができず、イギリスに短期間滞在した 後、夫妻はケベックへ移住。ラヴァル大学で教職に就いた。抑圧的なカトリックの偏狭さと硬直した新トマス主義に失望したコルナイは、1955年にケベック を離れ、ナフィールド財団の旅行助成金でイギリスに戻った。5カ国語で膨大な著作リストを持っていたにもかかわらず、イギリスで常勤教授職を得ることはほ とんど叶わず、経済的不安に苛まれながら、彼の健康は急速に悪化し始めた。ハリー・アクトン、バーナード・ウィリアムズ、デイヴィッド・ウィギンズらの影 響が大きく、コルナイはロンドン大学ベッドフォード・カレッジで非常勤の「客員講師職」を得ることができた。この頃のイギリスで、コルナイはG.E.ムー アの英国の常識哲学や、H.A.プリチャード、E.F.カリット、W.D.ロスといった他の英国直観主義者たちに強く影響を受けた。[5] 1961年にはバーミンガム大学で1年間の研究フェローシップを得た。1968年にはウィスコンシン州のマルケット大学で客員教授職を受け入れ、1973 年に心臓発作で亡くなるまでその職を維持した。コルナイの妻エリザベスは、1982年に亡くなるまで彼の著作の編纂、翻訳、出版に取り組んだ。 |

| The War Against the West is a critical study of German National Socialism

written by Aurel Kolnai and published in 1938.[1] It describes German

National Socialism as diametrically opposed to the [classical] liberal,

democratic, Constitutional, and free-enterprise "Western" tendencies

found mainly within Britain and the United States. During the twenties and thirties, Kolnai, who converted to Catholicism under the influence of G.K. Chesterton, read extensively in the German language fascist and national socialist literature. The book compiles and critiques the anti-Enlightenment works of national socialist writers themselves. Kolnai's study was the first comprehensive survey in English of German national socialist ideology as a counter-revolution against what German thinkers saw as the materialistic, rootless civilizations dominated by comfort-addicted, money-and-security-centered, liberal bourgeois and rootless cosmopolitan Jews; the antithesis of the heroic model of more vital civilizations, prepared to risk their lives, to die for ostensibly "higher" ideals. Kolnai argues that national socialist ideology is not only alien to the West, but profoundly disturbing and dangerous. Kolnai described the German national socialists' war against the West as, in essence, a war of paganism against Christian civilization. In citations from Hitler, Goebbels, and others, Kolnai sought to expose what he saw as "the obsessive German national socialist effort to replace Christianity with a crude and barbaric form of pagan religion, to twist the cross of Christ into a swastika." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_War_Against_the_West |

『西洋に対する戦争』は、オーレル・コルナイが1938年に発表したド

イツ国民国家社会主義の批判的研究である[1]。本書はドイツ国民国家社会主義を、主に英国と米国に見られる[古典的]自由主義、民主主義、立憲主義、自

由企業といった「西洋的」傾向と正反対のものとして描いている。 1920年代から30年代にかけて、G・K・チェスタートンの影響でカトリックに改宗したコルナイは、ドイツ語のファシスト・ナショナリズム文献を広く読 破した。本書はナショナリズム者たち自身による啓蒙主義批判の著作を収集し、批判している。コルナイの研究は、ドイツの思想家たちが物質主義的で根無し草 の文明と見なした、快適さに溺れ金と安全中心のリベラルなブルジョワや根無し草のコスモポリタン的ユダヤ人に支配された文明に対する反革命として、ドイツ 国民社会主義イデオロギーを英語で初めて包括的に調査したものである。それは、より活力ある文明の英雄的モデル、すなわち表向き「高尚」な理想のために命 を危険に晒し、死をも厭わない姿勢の対極に位置する。コルナイは、国民社会主義イデオロギーが西洋にとって異質であるだけでなく、深く不安を煽り危険であ ると主張する。 コルナイは、ドイツ国家社会主義者による西洋への戦争を、本質的には異教主義によるキリスト教文明への戦争だと描写した。ヒトラーやゲッベルスらの引用を 通じて、コルナイは「キリスト教を粗野で野蛮な異教宗教に置き換え、キリストの十字架を卍(スワスティカ)に歪めようとする、ドイツ国家社会主義者の強迫 的な試み」と彼が捉えたものを暴こうとしたのである。 |

| Philosophical writings and major themes Kolnai was an eclectic, well-read thinker in the fields of philosophy, economics, and politics. His major philosophical influences were the phenomenological school of Husserl and British analytic philosophy. A major theme in his writings is the effort to recover the givenness of reality and the sovereignty of the object in order to develop a common-sense approach to philosophy. Kolnai drew on the philosophical realism of Thomas Aquinas and believed that Aquinas could provide a valuable contribution to the recovery of broad dialectical objectivism, but he was opposed to the rigidity of 20th century neo-Thomistic orthodoxy and the dogmatic claims of Thomistic ideology.[6] Kolnai's objectivism rests on four claims: 1. The importance of ordinary experience to provide access to the real 2. The importance of secular experience and common sense in the standards of 'tradition' 3. The importance of philosophical teachers and Authorities to 'guide, instruct, and inform' 4. The importance of receptivity to the 'multiplicity of objects and modes of cognition' to overcome subjectivity[7] Kolnai was critical of Martin Heidegger's and Sartre's existentialism, claiming that "they have nothing to offer but doom-consciousness spiced with a high-sounding idealistic demand—or worse: a new version of the aesthete's surrender to active barbarism, an espousal of totalitarian tyranny as the next best substitute for the impossible pursuit of total freedom."[8] Because the world was fallen and tension-ridden, Kolnai thought that Christianity should make its concern the secular world, in order to instill in it practical reason and morality, as expressed in a revealing passage in The War Against the West: Personally I am inclined to think that in spite of its Christian polish, Luther's pessimism is more pagan than Hegel's pagan optimism, the latter being not entirely foreign to nineteenth-century progressive and constitutionalist views. For black despair is the very core of overweening arrogance. It is true that with Luther this is wrapped in the thread-bare guise of reckless belief in God's grace independent of man's conduct. Hegel, on the other hand, preserves some elements of actual morality.[9] Another major theme in Kolnai's writings is his anti-utopianism. Daniel Mahoney contextualizes Kolnai's anti-utopianism among such thinkers as Alain Besançon and Václav Havel as well as Solzhenitsyn who viewed utopian thinking as the ideological underpinning of totalitarianism. Kolnai explores what he calls the "utopian mind" phenomenologically, which he links with what he calls the "perfectionist illusion", which is marked by the view that human goods existing in a state of tension can somehow be reconciled. The reconciliation of value and reality, according to Kolnai "suggests the idea of a rupture between the given reality of the world and the counter-reality 'set apart.'"[10] Kolnai thought that the identification of utopianism with a search for justice was misguided, led to the "forced negation of ineliminable tensions."[11] The quest for a utopia was, in its essence, a quest for a world no longer fraught with tension or human alienation—a quest which Kolnai saw as doomed to inevitable failure. Kolnai's political thought arises from both his phenomenological method and his belief in the importance of philosophy for human life. His emphasis on common sense and his practical point of view frames his political discussions in which he expresses himself as a genuine conservative, praising such concepts as social privilege and hierarchy. However, though Kolnai was sympathetic to what he called "the conservative ethos", he was not a partisan thinker but rather a self-proclaimed centrist opposed to all forms of totalitarianism. Kolnai had an ongoing concern that unrestrained liberalism would inevitably end in totalitarianism, and his critiques of liberalism as he saw it manifest in the United States and Europe center on preventing such consequences. While supporting the cause of the liberal West and affirming pluralism, Kolnai also aptly stated that "to love democracy well, it is necessary to love it moderately."[12] Kolnai's ethical thought is characterized by strong loves and hates and expressed in terms of values and universal meanings. Broadly, his ethical thought can be described as Christian imperfectionism opposed to the elevation of morality beyond the everyday life. The negative character of moral duties was key for Kolnai, as expressed in his treatise on "Morality and Practice II:" When we speak of 'respecting' alien property (as also life or rights) we use that word in its weak sense of 'leaving alone,' 'not touching,' 'not interfering with,' much as it is used in French medical language (the rash of typhus fever 'respects' the face, i.e. in the soberer style of English textbooks, the face 'escapes'), not in its strong sense of positive appreciation for something distinctively noble and respectable . . .[13] Kolnai was strongly influenced by Max Scheler's value ethics, and he thought that if all things were viewed axiologically, assessed first for value, as opposed to the language of 'ought' or 'must,' then one was provided with "a realm of approbative or disapprobative insights . . . without stressing the unbridgeable gulf between Is and Ought." Thus, "value ethics precludes the classic pitfalls in Ethics: Hedonism or Eudemonism; Utilitarianism and Consequentialism of any kind, i.e. the interpretation of moral in terms of allegedly more evident primary, natural cognitive experiences; and various kinds of Imperativism: 'duty' cut off from Good and Bad, and its interpretation in terms either of a concrete (social, monarchical, fashionable . . . ) authority, or the 'rational ego,' or of 'Conscience. . . . Axiological ethic directs our attention not only to the plurality of moral values and disvalues, but to the falseness of every monism in regard to the object of moral valuation: be it action, intention, maxim or motive, virtue and vice, character, and all the more of course wisdom or again ontological perfection."[14] Kolnai currently remains relatively unknown, but especially in the light of the dialectical return to classical political theory in the writings of Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, as well as the recent debates concerning neo-Conservative philosophy, it is likely that Kolnai will receive increasingly more attention in the near future. Kolnai has been praised by influential figures such as Dietrich von Hildebrand, H.B. Acton, Bernard Williams, and Pierre Manent. |

哲学的著作と主要テーマ コルナイは哲学、経済学、政治学の分野において博識で折衷的な思想家であった。彼の哲学的思索に大きな影響を与えたのはフッサールの現象学派と英国分析哲 学である。著作における主要テーマは、現実の与えられし性と対象の主権を回復し、哲学に対する常識的アプローチを展開しようとする試みである。コルナイは トマス・アクィナスの哲学的現実主義を援用し、アクィナスが広範な弁証法的客観主義の回復に貴重な貢献をもたらし得ると考えた。しかし彼は、20世紀の新 トマス主義正統派の硬直性とトマス主義イデオロギーの教条的主張には反対した[6]。コルナイの客観主義は四つの主張に立脚する: 1. 現実へのアクセスを提供する上で、日常的な経験の重要性 2. 「伝統」の基準における世俗的な経験と常識の重要性 3. 「指導、教育、情報提供」を行う哲学教師や権威者の重要性 4. 主体性を克服するための「多様な対象と認識様式」に対する受容性の重要性 コルナイは、マーティン・ハイデガーとサルトルの実存主義を批判し、「彼らには、高尚な理想主義的な要求を添えた破滅意識、あるいはさらに悪いことに、美 意識を持つ者が積極的な野蛮性に屈服する新たな形態、完全な自由の追求が不可能であることに次ぐ最善の代替手段としての全体主義的専制政治の支持しか提供 できない」と主張した。[8] 世界は堕落し、緊張に満ちていたため、コルナイは、キリスト教は世俗の世界に関心を向け、そこに実践的理性と道徳を植え付けるべきだと考えた。これは『西 洋との戦争』の次の明快な一節に表れている。 人格的には、キリスト教的な装いにもかかわらず、ルターの悲観主義はヘーゲルの異教的楽観主義よりもむしろ異教的であると思う。後者は19世紀の進歩主義 的・立憲主義的見解に全く無縁ではない。なぜなら、深い絶望こそが傲慢の核心だからだ。確かにルターにおいては、これは人間の行いとは無関係な神の恩寵へ の無謀な信仰という、擦り切れた衣で包まれている。一方ヘーゲルは、実際の道徳性の一端を保持している。[9] コルナイの著作におけるもう一つの主要テーマは、彼の反ユートピア主義である。ダニエル・マホーニーは、コルナイの反ユートピア主義を、アラン・ベサンソ ンやヴァーツラフ・ハヴェル、そしてユートピア的思考を全体主義のイデオロギー的基盤と見なしたソルジェニーツィンといった思想家たちとの文脈に位置づけ ている。コルナイは現象学的に「ユートピア的思考」を考察し、これを「完璧主義的幻想」と結びつける。この幻想は、緊張状態にある人間の善が如何なる形で あれ調和し得るとの見解によって特徴づけられる。コルナイによれば、価値と現実の調和は「与えられた世界の現実と『分離された』対抗現実との断絶という観 念を暗示する」のである。[10] コルナイは、ユートピア主義を正義の探求と同一視する考えは誤りであり、「排除不可能な緊張の強制的な否定」につながると考えた。[11] ユートピアの追求は、本質的に、もはや緊張や人間の疎外に満ちていない世界への探求であり、コルナイはこれを必然的な失敗に終わるものと見なした。 コルナイの政治思想は、現象学的方法論と、人間の生活における哲学の重要性への信念の両方から生じている。彼の常識への重視と実践的視点は、政治論議の枠 組みを形成し、そこでは彼は社会特権や階層といった概念を称賛する真の保守主義者として自己を表明する。しかしコルナイは、自らが「保守的エートス」と呼 ぶものには共感しつつも、党派的な思想家ではなく、あらゆる形態の全体主義に反対する自称中道主義者であった。彼は、抑制されない自由主義が必然的に全体 主義に陥ることを常に懸念し、米国や欧州に見られる自由主義への批判は、そうした帰結を防ぐことに焦点を当てていた。リベラルな西側諸国の理念を支持し多 元主義を肯定しつつも、コルナイは「民主主義を正しく愛するには、節度をもって愛さねばならない」とも適切に述べている[12]。 コルナイの倫理思想は、強い愛憎によって特徴づけられ、価値や普遍的意味の観点から表現される。大まかに言えば、彼の倫理思想は日常生活を超越した道徳観 の崇高化に反対する、キリスト教的不完全主義と形容できる。コルナイにとって道徳的義務の否定的性格は重要であり、その著書『道徳と実践II』で次のよう に述べている: 他者の財産(生命や権利も同様)を「尊重する」と言う場合、この言葉は「放っておく」「触れない」「干渉しない」という弱い意味で使われる。『干渉しな い』という意味で用いている。これはフランス医学用語における用法(チフス熱の発疹は顔を『尊重』する、すなわち英語教科書でより抑制的に表現されるな ら、顔は『免れる』)に近く、何か特に高貴で尊敬に値するものに対する積極的な評価という意味での強い用法ではない…… [13] コルナイはマックス・シェラーの価値倫理学に強い影響を受けていた。彼は、万物を「あるべき」や「しなければならない」という言語ではなく、まず価値を評 価する「価値論的」視点で捉えるならば、「あるべき」と「ある」の間の埋めがたい隔たりを強調することなく、「賛否の洞察の領域」が得られると考えてい た。したがって、 「価値倫理学は倫理学における古典的な落とし穴を回避する。快楽主義や幸福主義、 あらゆる種類の功利主義や帰結主義、すなわち道徳を、より明白とされる一次的な自然的認知経験に還元する解釈、そして様々な命令主義——善悪から切り離さ れた『義務』を、具体的権威(社会的・君主的・流行的な権威など)、あるいは『合理的自我』や『良心』に還元する解釈——を回避する。価値論的倫理学は、 道徳的価値と非価値の多様性だけでなく、道徳的評価の対象に関するあらゆる一元論の虚偽性にも注意を向ける。その対象が行動であれ、意図であれ、格律や動 機であれ、美徳と悪徳であれ、性格であれ、ましてや知恵や存在論的完全性であれ、当然のことながら。[14] コルナイは現在、比較的知られていないが、レオ・シュトラウスやエリック・ヴォーゲリンの著作に見られる古典的政治理論への弁証法的回帰、そして新保守主 義哲学に関する最近の議論を踏まえると、近い将来、コルナイへの注目はますます高まるだろう。コルナイはディートリヒ・フォン・ヒルデブランド、H・B・ アクトン、バーナード・ウィリアムズ、ピエール・マナンといった影響力のある人物たちから称賛されている。 |

| 1. Wiggins, David; Dunlop,

Francis (23 September 2004). "Aurel Kolnai". Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68904. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or

UK public library membership required.) 2. Carolyn Korsmeyer and Barry Smith. "Visceral Values: Aurel Kolnai on Disgust." On Disgust Open Court Publishing Company, a division of Carus Publishing Company: Peru, Illinois. 2004. Page 4. 3. Mahoney, Daniel J. "The Recovery of the Common World: An Introduction to the Moral and Political Reflection of Aurel Kolnai." Privilege and Liberty and Other Essays in Political Philosophy. Lexington Books: Lanham, Maryland. 1999. Page 2. 4. Andreas Dorschel, 'Genaue Imagination', in: Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 106 (7 May 2008), p. 14 5. David Wiggins and Bernard Williams. "Aurel Thomas Kolnai." Ethics, Value, and Reality: Selected Papers of Aurel Kolnai. University of London Athlone Press: 1977. 6. Mahoney, Daniel J. "The Recovery of the Common World: An Introduction to the Moral and Political Reflection of Aurel Kolnai." Privilege and Liberty and Other Essays in Political Philosophy. Lexington Books: Lanham, Maryland. 1999. Page 5. 7. Kolnai. Ethics, Value, and Reality: Selected Papers of Aurel Kolnai. University of London Athlone Press: 1977. Pages 27-29. 8. Kolnai. Ethics, Value, and Reality: Selected Papers of Aurel Kolnai. University of London Athlone Press: 1977. Page 136. Quoted in Mahoney, "The Recovery of the Common World." Page 6. 9. Kolnai, The War Against the West. Page 127. 10. Kolnai, The Utopian Mind. Page 157. Quoted in Mahoney "The Recovery of the Common World." Page 9. 11. Kolnai, The Utopian Mind. Page 158, 185-95. Quoted in Mahoney, Ibid, Page 9. 12. Manent, Pierre. Tocqueville and the Nature of Democracy. Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD. 1996. Page 32. Quoted in Mahoney "The Recovery of the Common World." Page 15. 13. Kolnai, "Morality and Practice II."" Page 105-106. 14. Kolnai, Ethics, Value, and Reality: Selected Papers of Aurel Kolnai. University of London Athlone Press: 1977. Page xx-xxi. |

1.

ウィギンズ、デイヴィッド;ダンロップ、フランシス(2004年9月23日)。「オーレル・コルナイ」。『オックスフォード国民人物事典』(オンライン

版)。オックスフォード大学出版局。doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68904。(購読、ウィキペディア図書館アクセス、または英国公共図書

館の会員資格が必要である。) 2. キャロリン・コースマイヤー、バリー・スミス「内臓的価値:嫌悪感に関するオーレル・コルナイ」『嫌悪感について』オープンコート出版(カラス出版会社の一部門)、イリノイ州ペルー。2004年。4ページ。 3. ダニエル・J・マホーニー「共通世界の回復:オーレル・コルナイの道徳的・政治的考察への序説」 特権と自由、その他の政治哲学論考。レキシントン・ブックス:メリーランド州ラナム。1999年。2ページ。 4. アンドレアス・ドルシェル、「正確な想像力」、『南ドイツ新聞』第106号(2008年5月7日)、14ページ 5. デイヴィッド・ウィギンズ、バーナード・ウィリアムズ「オーレル・トーマス・コルナイ」『倫理、価値、現実:オーレル・コルナイ選集』ロンドン大学アスローン出版:1977年。 6. マホーニー、ダニエル・J.「共通世界の回復:オーレル・コルナイの道徳的・政治的考察への序説」『特権と自由、その他の政治哲学論考』 レキシントン・ブックス:メリーランド州ラナム。1999年。5ページ。 7. コルナイ。『倫理、価値、現実:オーレル・コルナイ選集』。ロンドン大学アスローン・プレス:1977年。27-29ページ。 8. コルナイ。『倫理、価値、現実:オーレル・コルナイ選集』。ロンドン大学アスローン・プレス:1977年。136ページ。マホーニー『共通世界の回復』6ページで引用。 9. コルナイ『西洋に対する戦争』127ページ。 10. コルナイ『ユートピア的思考』157ページ。マホーニー『共通世界の回復』9ページで引用。 11. コルナイ『ユートピア的思考』158頁、185-195頁。マホーニー『同上』9頁で引用。 12. マネ、ピエール『トクヴィルと民主主義の本質』ローマン・アンド・リトルフィールド社:メリーランド州ラナム、1996年。32頁。マホーニー「共通世界の回復」15頁で引用。 13. コルナイ「道徳と実践 II」105-106頁。 14. コルナイ『倫理、価値、現実:オーレル・コルナイ論文集』ロンドン大学アスローン出版:1977年。xx-xxi頁。 |

| Further reading Balazs, Zoltan; Dunlop, Francis (2005). Exploring the world of human practice : readings in and about the philosophy of Aurel Kolnai. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9786611376567. |

参考文献 Balazs, Zoltan; Dunlop, Francis (2005). 『人間実践の世界を探る:オーレル・コルナイの哲学に関する読本』. ブダペスト: 中央ヨーロッパ大学出版局. ISBN 9786611376567. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurel_Kolnai |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099