バスター

Baster, or the Rehoboth Basters

バスターあるいはレホ ボス・バスター(Rehoboth Basters)は、ナミビアの民族集団。アフリカーナーやドイツを主とするヨーロッパからの移民である白人男性と、先住民であるコイサン人や、18世紀 頃にケープ植民地を経由してナミビアへ移住した奴隷であるマレー人女性の間に生まれた混血人種である。19世紀後半以降に、同国中部のレホボスと、その周 辺にコミュニティを形成する様になった。自国や南アフリカ共和国のアフリカーナーやカラードとは、言語や文化面において、深い歴史的関係を有している。北 ケープ州に居住する南アフリカにおける同様の混血人種も、自ら「バスター」を自称している。バスター」という呼称は、「ろくでなし」「落胤」を意味するオ ランダ語の"bastaard"という単語に由来している。 一部の人々はこの呼び名を蔑称と捉えているものの、バスター達自身は「誇り高き名前」として再解釈して、自身の祖先と歴史を語り、否定的な意味合いにも関 わらず、同称をナミビアにおける文化の一部として扱う事を主張している。

18世紀初頭、バスターは植民地に農場を所有することが多かったが、白人の入植者が増えるに

つれ、次第に土地の所有権をめぐる競争と、人種差別の圧力が強まり、政府と白人の商売敵によって抑圧される様になった。土地を手放した一部の人間は、カ

ラードと同等の使用人になる道を選んだが、白人に屈する事を拒んだ者達は、周辺の土地へ移住し、開拓する様になった。1750年頃から、植民地の北西端に

あるKamiesbergeは、農場主であるバスター達の主要な居住地となり、その一部は多くの使用人や顧客を抱える事に成功した。1780年頃以降、同

地における白人からの弾圧が激化した事に伴い、多くのバスターの世帯が、内陸部の未開拓地へ移住する事を選んだ。彼らは、オレンジ川中部の盆地に定住する

事となり[4]、後にロンドン伝道協会(London

Missionary Society)の宣教師から“グリクア人(Griqua people)”と

改名する様に提案される事となった。

1868年に、バスターはケープ植民地を離れ、北部の内陸部の土地を開拓する意向を発表し、 翌1869年に最初の30世帯が同地を去った。彼等は現在のナミビア中部のナミブ砂漠とカラハリ砂漠の間にある高原にあたるレホボス(英語版)に定住し、 牧畜によって生計を立てる様になった。その後は、1871年から1907年までドイツ礼賢会から派遣された宣教師であるヨハン・クリスチャン・フリードリ ヒ・ハイデマンに仕える事となった[4]。レホボスにおけるバスターの人口は、1872年には333名にまで達した[4]。その後も、ケープ植民地に残っ ていた70世帯のうち、最終的には約60世帯がそれに追従する形でレホボスへ移住し、1876年までにその人口は800名までに増加した。これに伴い、「レホボス自由共和国」の建国を宣言するとともに、現在ではバスターの民族旗とされている、当 時のドイツ国旗をモチーフとした国旗をデザインした。また、独自の憲法(アフリカーンス語: Vaderlike Wette)を制定・採用し、法としての効力が失われた21世紀の現在でも、バスターにとっての行動規範の核として受け継がれている[5]。1870 年代に、レホボスのバスターは一貫して近隣のナマ人とヘレロによる大規模な窃盗団から度々襲撃を受け、家畜を強奪され続けた。1880年に、オーラム人(Oorlam people)の 一部がヘレロに対して蜂起した事を期に、生存の為にバスターは彼等と同盟を結び、損害を被りながらも1884年頃まで抵抗を続けた。

ドイツによる併合の過程で、バスターの部族長であるヘルマナス・ファン・ヴィック(英語版) は、1884年10月11日に同地における原住民としては初めてドイツ帝国との間に、外交をはじめとする行政権におけるバスターの権限が大幅に削減される 代償に、ドイツ人とバスターの共存を保証する内容の保護友好条約に署名した[6]。1893年に、ドイツはバスターに対して独自の憲法の適用を認める居留 地を設置し、以降もバスターの代表による領域の拡大を求める交渉が続けられた。ドイツ人の居留地は、バスターの統治区域よりも面積が広く、同区域内におい てはドイツの植民地法が適用されていた。また、その土地の大部分は、ドイツ人入植者が所有する農場として開発された[4]。1895 年には、バスターの兵役義務に関する条約が批准された事に伴い、バスターによる軽歩兵部隊が設置され、ドイツ帝国軍と共に、先住民による反乱の鎮圧にあ たった。特に、1904年~1907年にかけてのヘレロ戦争(Herero Wars)では、先住民であるヘレロとナマ人に対する大規模な虐殺に加担している[7](→ヘレロ・ナマ虐殺[Herero and Namaqua genocide])。

ドイツ側の国勢調査では、レホボスにおけるバスターの人口は、1912年に3,000人にま

で増加している事と、彼等が兼ね備えている高い移動性を指摘している[4]。レホボスとドイツは、第一次世界大戦勃発後の1914年まで、20年以上も緊

密な関係を保っていた。ドイツの植民地防衛隊(Schutztruppe)は、障碍

の無いバスターの男性全員に兵役義務を課そうとしたが、この事はバスター社会から反発を買う結果を招いた[8]。

| The

Basters (also known as Baasters, Rehobothers or Rehoboth Basters) are a

Southern African ethnic group descended from white European men and

black African women, usually of Khoisan origin, but occasionally also

enslaved women from the Cape, who resided in the Dutch Cape Colony in

the 18th century. Since the second half of the 19th century, the

Rehoboth Baster community has been concentrated in central Namibia, in

and around the town of Rehoboth. Basters are closely related to

Afrikaners, Cape Coloured and Griqua peoples of South Africa, with whom

they share a language and culture. Other people of similar ethnic origin, living chiefly in the Northern Cape, also call themselves Basters. The name Baster is derived from "bastaard", the Dutch word for bastard (or "crossbreed"). While some people consider this term demeaning, the Basters reappropriated it as a "proud name", claiming their ancestry and history, treating it as a cultural category in spite of the negative connotation.[3] Their 6th Kaptein is John McNab, elected in 1999; he has no official status under the Namibian constitution. The Chief's Council of Rehoboth was replaced with a local town council under the new government. The current numbers of Basters remain unclear; figures between 35,000[2] and 40,000 are estimated. Survival of the Baster culture and identity were called into question in modern Namibia. Modern Namibia's politics and public life is largely dominated by the ethnic Owambo people, who constitute nearly half of the population, and their culture. Baster politicians and activists have called Owambo policies oppressive towards their community.[4] |

バ

スター族(バスターズ、レホボサーズ、レホボス・バスターズとも呼ばれる)は、18世紀にオランダ領ケープ植民地に居住した白人ヨーロッパ人男性と、通常

はコイサン系の黒人アフリカ人女性、時にはケープ地方の奴隷女性との間に生まれた子孫である。19世紀後半以降、レホボスのバスターコミュニティはナミビ

ア中部のレホボス町とその周辺に集中している。バスターは南アフリカのアフリカーナー、ケープ・カラーード、グリクアの人々と密接な関係にあり、言語と文

化を共有している。 主に北ケープ州に住む、同様の民族的起源を持つ他の人々も、自らをバスターと呼んでいる。 「バスター」という名称は、オランダ語で「混血児」を意味する「bastaard」に由来する。この用語を侮蔑的と考える人民もいるが、バスター族は否定 的な意味合いにもかかわらず、自らの祖先と歴史を主張する「誇り高き名称」として再定義し、文化的カテゴリーとして扱っている。[3] 彼らの第6代カプトゥーン(首長)は1999年に選出されたジョン・マクナブである。彼はナミビア憲法上、公式な地位を持たない。レホボトの首長評議会は 新政府下で地方自治体に置き換えられた。 現在のバスターの人口は不明確であり、35,000[2]人から40,000人との推定がある。現代ナミビアにおいて、バスターの文化とアイデンティティ の存続は疑問視されている。現代ナミビアの政治と公共生活は、人口のほぼ半分を占めるオワンボ族とその文化によって大きく支配されている。バスターの政治 家や活動家は、オワンボ族の政策が自らのコミュニティに対して抑圧的だと主張している[4]。 |

| Basters

were mainly persons of mixed-race descent who at one time would have

been absorbed in the white community. This term came to refer to an

economic and cultural group, and it included the most economically

advanced non-white population at the Cape, who had higher status than

the natives. Some of the Basters acted as supervisors of other servants

and were the confidential employees of their white masters. Sometimes,

these were treated almost as members of the white family. Many were

descended from white men, if not directly from men in the families for

whom they worked. The group also included Khoi, free blacks, and persons of mixed-race descent who had succeeded in acquiring property and establishing themselves as farmers in their own right. The term Orlam (Oorlam) was sometimes applied to persons who could also be known as Baster. Orlams were the Khoi and Coloured (mixed-race) people who spoke Dutch and practiced a largely European way of life. Some Basters distinguished themselves from the Coloured, whom they described as descendants of Europeans and Malay or Indonesian slaves brought to South Africa. In the early 18th century, Basters often owned farms in the colony, but with growing competition for land and the pressure of race discrimination, they were oppressed by their white neighbours and the government. Some became absorbed into the Coloured servant class, but those seeking to maintain independence moved to the fringes of settlement. From about 1750, the Kamiesberge in the extreme north-west of the colony became the main area of settlement of independent Baster farmers, some of whom had substantial followings of servants and clients. After about 1780, increasing competition and oppression from whites in this area resulted in the majority of the Baster families moving to the frontier of the interior. They settled in the middle valley of the Orange River, where they settled near De Tuin.[1] Basters of the middle Orange were subsequently persuaded by London Missionary Society missionaries to adopt the name Griqua.[5] Some sources say they chose the name themselves in honor of an early leader. |

バ

スターズは主に混血の出身者で、かつては白人社会に吸収されていた人格だ。この言葉は経済的・文化的な集団を指すようになり、ケープで最も経済的に進んだ

非白人層を含んでいた。彼らは原住民よりも高い地位にあった。バスターズの中には他の使用人を監督する者や、白人主人の腹心の使用人として働く者もいた。

時には、彼らは白人家族の成員のように扱われることもあった。多くの者は白人の子孫であり、直接は雇い主の家族出身ではないにせよ、白人の血を引いてい

た。 この集団には、コイ族、自由黒人、そして財産を取得し自力で農民としての地位を確立した混血の人格も含まれていた。オルラム(Oorlam)という呼称 は、バスターとも呼ばれる人々に用いられることがあった。オルラムとは、オランダ語を話し、主にヨーロッパ式の生活様式を実践するコイ族やカラード(混血 の)の人々を指す。一部のバスターは、カラードを「南アフリカに連れてこられたヨーロッパ人とマレー人またはインドネシア人奴隷の子孫」と表現し、自らを 区別した。 18世紀初頭、バスター族は植民地内で農場を所有することが多かったが、土地をめぐる競争の激化と人種差別の圧力により、白人の隣人や政府から抑圧される ようになった。一部はカラードの従僕階級に吸収されたが、独立を維持しようとする者たちは入植地の辺縁部へ移った。1750年頃から、植民地の最北西端に あるカミースベルゲが独立したバスター農民の主要な定住地となり、中には多くの従僕や被保護者を従える者もいた。 1780年頃以降、この地域における白人からの競争と圧迫の激化により、バスター族の家族の大半は内陸部の辺境へ移住した。彼らはオレンジ川中流域に定住 し、デ・トゥイン付近に居を構えた[1]。その後、ロンドン宣教会の宣教師によって、オレンジ川中流域のバスター族はグリクアという名称を採用するよう説 得された[5]。一部の資料では、彼らが初期の指導者を称えて自らこの名称を選んだとも記されている。 |

| Move to central Namibia Basters announced their intention to leave the Cape Colony in 1868 to search for land in the interior north. About 90 families of 100 left the region, the first 30 in 1869, with others following. They settled in Rehoboth in what is now central Namibia, on a high plateau between the Namib and Kalahari deserts. There they continued an economy based on managing herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. They were followed by Johann Christian Friedrich Heidmann, a missionary of the Rhenish Mission, who served them from 1871 until his retirement in 1907.[1] By 1872, Basters numbered 333 in Rehoboth.[1] They founded the Free Republic of Rehoboth (Rehoboth Gebiet) and designed a German-influenced national flag. They adopted a constitution known as the Paternal Laws (original title in Afrikaans: Vaderlike Wette). It continues to govern the internal affairs of the Baster community into the 21st century.[6] The original document survived and is stored at the National Archives of Namibia in Windhoek.[7] Basters established a community based on birth. Under these laws, a citizen is a child of a Rehoboth citizen, or a person otherwise accepted as a citizen by its rules.[1] Families continued to join them from the Cape Colony, and the community reached about 800 by 1876, when 80 to 90 families had settled there. The area was also occupied by native Damara people, but Basters did not include them in population reports.[1] While Basters remained predominantly based around Rehoboth, some Basters continued to trek northward, settling in the southern Angolan city of Lubango. There they became known as the Ouivamo. They had a similar culture based on maintaining herds of livestock. Through the 1870s, Basters of Rehoboth suffered frequent losses from their herds, with livestock raided and stolen by the much larger groups of surrounding Nama and Herero peoples, who were themselves in competition. In 1880, Jan Afrikaner gathered 600 men against the Herero, and different Nama groups mustered about 1,000 warriors, with the Herero fielding about the same number. Basters tried to make alliances to survive, as they were outnumbered by both sides.[1] The wars continued until about 1884, and, while suffering losses, Basters continued. Through the 1880s, the community at Rehoboth were joined by other Baster families from Grootfontein (South) (whom missionary Heidmann had earlier tried to recruit), Okahandja, and Otjimbingwe.[1] While based on descent within the families, they also accepted both blacks and whites who applied to join the community. |

ナミビア中部への移住 バスター族は1868年、ケープ植民地を離れ内陸北部で土地を探す意向を表明した。約100世帯のうち90世帯がこの地域を離れ、最初の30世帯は 1869年に、その後続いた。彼らは現在のナミビア中部に位置するレホボトに定住した。そこはナミブ砂漠とカラハリ砂漠に挟まれた高台である。彼らはそこ で牛・羊・山羊の群畜を管理する経済活動を続けた。その後、ライン川伝道会の宣教師ヨハン・クリスティアン・フリードリヒ・ハイドマンが1871年から 1907年の引退まで彼らに奉仕した。[1] 1872年までに、レホボトのバスターズ人口は333人に達した。[1] 彼らはレホボト自由共和国(レホボト・ゲビート)を建国し、ドイツの影響を受けた国旗をデザインした。父権法(アフリカーンス語原題:Vaderlike Wette)として知られる憲法を採択した。この憲法は21世紀に至るまでバスター共同体の内政を統治し続けている。[6] 原文は現存し、ウィントフックのナミビア国立公文書館に保管されている。[7] バスター族は出生に基づく共同体を形成した。この法律では、市民とはレホボト市民の子孫、もしくは規則により市民として認められた人格を指す。[1] ケープ植民地から家族単位での移住が続き、1876年までに約800人(80~90家族)が定住した。この地域には先住民ダマラの人民も居住していたが、 バスター族は彼らを人口統計に含めなかった。[1] バスター族の大半はレホボト周辺に留まったが、一部は北進を続け、アンゴラ南部の都市ルバンゴに定住した。彼らはそこでウイバモ族として知られるようになった。群畜を維持する点で、バスター族と類似した文化を持っていた。 1870年代を通じて、レホボスのバスター族は頻繁に群畜の損失を被った。周囲のナマ族やヘレロ族といった、より大規模な集団に家畜を襲撃され盗まれたの である。彼ら自身もまた、互いに競合関係にあった。1880年、ヤン・アフリカーナーはヘレロ族に対抗して600人の男を集め、異なるナマ族集団も約 1000人の戦士を動員した。ヘレロ族もほぼ同数の兵力を展開した。バスター族は両陣営に数で劣っていたため、生き残るために同盟を結ぼうとした[1]。 戦争は1884年頃まで続き、苦悩しながらもバスター族は持ちこたえた。 1880年代を通じて、レホボトのコミュニティには、グルートフォンテイン(南)から(宣教師ハイドマンが以前勧誘を試みた者たち)、オカハンジャ、オチ ンビンゲから他のバスター家族が加わった[1]。家族内の血統に基づく一方で、コミュニティへの加入を申請した黒人と白人の双方を受け入れた。 |

| German South West Africa In the process of the German annexation of South West Africa, Baster Kaptein Hermanus van Wyk signed a 'Treaty of Protection and Friendship' with the German Empire on 11 October 1884. It was the first of its kind between any native-descended peoples in the territory and the Germans (Basters were considered native because of their partial African descent).[8] Other sources date this treaty 15 September 1885,[9] Under this, "the independent executive powers of the Kaptein and Baster Council, especially for "foreign policy", were significantly curtailed."[10] In 1893, the Germans established the territory of the Basters, known as the Rehoboth Gebiet, which the settlers tried to expand through negotiation. In this area, the Paternal Laws were recognized. In addition, the German colony had an administrative district known as Rehoboth, which was larger than the Baster-governed area, with the outside areas under German (white) colonial law. Most of the land was developed as farms owned by European, especially German whites.[1] A second Treaty concerning National Service of the Rehoboth Basters of 1895 established a small armed contingent among the Basters, which fought alongside German colonists and forces in a number of battles and skirmishes against indigenous peoples. When the German colonists encountered a new wave of conflicts with native peoples, Basters fought with them in quelling the uprisings of the OvaHerero (1896), the Swartbooi Nama (1897), and the Bondelswarts (1903). They also participated in the German colonial war and widespread genocide against the OvaHerero and Nama in the Herero Wars of 1904–1907.[9] German census reporting on Basters noted their high mobility. The numbers they recorded for the people changed as the Germans changed their racial classifications. Rather than using people's citizenship (as in the community of Basters), they began to classify people according to appearance, as was done in South Africa. A comparison of records suggests that, in 1912, there were about 3,000 Basters in the Rehoboth District. Most Basters were concentrated in the Rehoboth Gebiet, where they lived under their own law.[1] Relations between Rehoboth and Germany remained close for more than 20 years until 1914, following the outbreak of World War I. The German Schutztruppe ordered all Baster able-bodied men into military service, which they resisted.[10] Believing that the German Schutztruppe had little chance against the superior South African forces (allied with the British), Basters tried to maintain neutrality towards both, but feared losing their limited autonomy. Baster Council believed they reached agreement with Governor Theodor Seitz of South-West Africa that their men would only be used behind the lines. They did not want to participate in a war between whites.[10] They disapproved of their men being issued German uniforms, fearing they would be considered regular soldiers. Despite their protests, Baster soldiers were assigned to duties far from the Gebiet. When Basters were assigned to guard South African prisoners of war in February 1915 at a camp at Uitdraii, they protested because nearly 50 of their men were connected to the people through historic kinship and language. Some aided escape by prisoners, and the Germans limited the number of bullets they issued to the Basters. The South Africans in turn protested being guarded by men they considered as Coloured (according to their racial classifications).[10] General Louis Botha had earlier written to Lieutenant Colonel Franke against using armed non-whites in service, as he was aware of both Cameroons and Basters serving under arms. Botha said he was ensuring that non-whites were not armed; Franke said that he was using the Cameroon and Baster companies only to police non-white communities.[10] Cornelius van Wyk, second Kaptein of the Rehoboth Basters, arranged to secretly meet with South African General Louis Botha on April 1 in Walvis Bay to assure him of the Basters' neutrality. No record was made of the meeting so it is unclear exactly what was promised. Van Wyk was hoping for assurances to have Baster territory and rights acknowledged if South Africa took over the German colony. Botha advised him to stay out of the war.[10] Due to South African successes, the German officers advised the Baster Council that they were moving the prisoners of war and Baster guards to the north. At a meeting, they said Basters had three days to decide whether to comply; the latter feared that having their men in the north would mean they would be considered true combatants against South Africa, endangering their own position. Learning of the planned deployment, the Baster guards advised the Council they would not go. Although negotiations were in process, they learned the trains were due to leave the next day, and the night of April 18, numerous Basters defected from German service, taking arms with them that they intended to turn in at Rehoboth. About 300 men set up defenses in two laagers. Learning of this, the Germans disarmed other Baster soldiers in other posts; in the process, one unarmed Baster was killed. Rehoboth was in an uproar, although leaders tried to meet with the Germans to resolve the issues.[10] In the meantime, Basters and Nama policemen worked to disarm German officers within the Rehoboth Gebiet, but wounded one fatally and killed another outright. An armed contingent including Nama policemen killed several German citizens, including all of the Karl Bauer family. With that, negotiations were over.[10] On 22 April 1915, Lieutenant Colonel Bethe informed the Basters in writing that they had violated the protection treaty and their acts were considered hostile by the Germans. Governor Theodor Seitz cancelled the protection treaty with the Basters, intending to attack Rehoboth. Van Wyk informed General Botha, who advised him to try to get the Basters out of the area.[10] They started moving by wagons and taking large herds of livestock, with many Basters trying to reach the mountains. German attacks against Basters took place around the region. According to Baster history, a 14-year-old Baster girl, who worked for the Germans in a camp, overheard a drunken conversation about their planned attack against the Basters. She took the word to the Kaptein, and around 700 Basters retreated to Sam Khubis 80 kilometres (50 mi) south-east of Rehoboth in the mountains, to prepare for German attack. This group included women and children. Van Wyk had hidden his wife and children at farm Garies, along with the wives and children of Stoffel and Willem van Wyk. Stoffel's wife, two children, an adult daughter of Cornelius van Wyk, and his 18-year-old son, were all killed there. The others, including van Wyk's wife Sara, were taken to Leutwein station and released on May 13.[10] On 8 May 1915, the Germans attacked in the Battle of Sam Khubis, where the stronghold was defended by 700 to 800 Basters. Despite repeated attacks and the use of two cannons and three Maxim machine-guns, the Germans were unable to destroy the Basters' position.[10] They ended the attack at sunset. At the end of the day, Basters had all but run out of ammunition and expected defeat. That night they appealed to God, pledging to commemorate the day forever should they be spared. Their prayer is engraved on a memorial plaque they later installed at Sam Khubis and reads:[9] God van ons vaderen / sterke en machtige God / heilig is Uw naam op die ganse aarde / Uw die de hemelen geschapen heft / neigt Uw oor tot ons / luister na die smekingen van Uwe kinderen / de dood staart ons in het gesicht / die kinderen der bose zoeken onze levens / Red ons uit die hand van onze vijanden / en beskermt onze vrouen en kinderen / En dit zult vier ons en onze nacheschlacht zijn een dag als een Zondag / waarop wij Uw naam prijzen en Uw goedertierenheid tot in euwigheid niet vergeten "God our father / strong and powerful / holy be Thy name all over the earth / Thou that made heaven / bow Thou down to us / listen to the cries of Thy children / death stares us in the face / the children of evil seek our lives / Save us from the hand of our enemies / and protect our wives and children / and this shall be for us and our kin a day like a Sunday / on which we shall praise Thy name / and Thy gratitude shall not be forgotten in eternity." The Germans had received orders to retreat, which they did the next morning. Rehoboth's Baster community survived.[11] This day is celebrated annually by Basters as integral to their history and fortitude. Both units of the Germans were ordered to retreat in order to mobilize against advancing South African troops which reached Rehoboth.[10][9] As Basters returned to Rehoboth, some killed Germans on their farms. The Germans posted some forces for protection, but withdrew them on May 23 as the South Africans approached. Basters took German livestock and plundered their farms, also attacking the two missionaries' houses. The bloodshed on both sides left long resentment after the war.[10] |

ドイツ領南西アフリカ ドイツによる南西アフリカ併合の過程で、バスター族のカプテイン・ヘルマヌス・ファン・ヴィークは1884年10月11日、ドイツ帝国と「保護と友好の条 約」を締結した。これは同地域における先住民系民族とドイツ人との間で結ばれた初の条約であった(バスター族は部分的なアフリカ系血統ゆえに先住民と見な されていた)。[8] 他の資料ではこの条約の締結日を1885年9月15日としている[9]。これにより「カプトインとバスター評議会の独立した行政権、特に『外交政策』に関 する権限は大幅に制限された」[10]。 1893年、ドイツ人はバスター族の居住地域としてレホボト地域を設立した。入植者たちは交渉を通じてこの地域の拡大を試みた。この地域では父系法が認め られた。加えて、ドイツ植民地にはレーホボートと呼ばれる行政区があり、バスター族が統治する地域よりも広大で、外部地域はドイツ(白人)植民地法の下に あった。土地の大部分は、ヨーロッパ人、特にドイツ系白人が所有する農場として開発された。[1] 1895年の「レホボト・バスター族の国民兵役に関する第二条約」により、バスター族の中に小規模な武装部隊が編成された。この部隊は、先住民に対する数 々の戦闘や小競り合いで、ドイツ人入植者や軍隊と共に戦った。ドイツ人入植者が先住民の人民との新たな衝突に直面した際、バスター族は彼らと共に戦い、オ ヴァヘレロ人民(1896年)、スワルトボイ・ナマ人民(1897年)、ボンデルスワーツ人民(1903年)の反乱を鎮圧した。彼らはまた、1904年か ら1907年にかけてのヘレロ戦争において、ドイツ植民地戦争とオヴァヘレロ族およびナマ族に対する大規模な虐殺にも参加した。[9] ドイツ国勢調査はバスター族の高い移動性を記録している。ドイツが人種分類を変更するにつれ、彼らの記録人数も変動した。市民権に基づく分類(バスター族 コミュニティのように)から、南アフリカと同様の外見に基づく分類へと移行したのだ。記録の比較によれば、1912年時点でレホボト地区には約3,000 人のバスター族が居住していた。バスター族の大半はレホボト地域に集中し、独自の法体系のもとで生活していた[1]。 第一次世界大戦勃発後の1914年まで、レホボトとドイツの関係は20年以上緊密な状態が続いた。ドイツ保護軍は全ての健康なバスター族の男性に兵役を命 じたが、彼らはこれに抵抗した[10]。ドイツ保護軍が(英国と同盟した)優勢な南アフリカ軍に勝つ見込みは薄いと考えたバスター族は、双方に対して中立 を保とうとしたが、限られた自治権を失うことを恐れた。 バスター評議会は、南西アフリカのテオドール・ザイツ総督と、自民族の男性は後方支援任務にのみ従事させることで合意したと確信していた。彼らは白人同士 の戦争には参加したくなかったのだ[10]。自民族の男性にドイツ軍服が支給されることにも反対した。正規兵と見なされることを恐れたのである。抗議にも かかわらず、バスター兵士たちはゲビートから遠く離れた任務に配属された。1915年2月、バスター族がウイトドライの捕虜収容所で南アフリカ人捕虜の監 視任務に就いた際、彼らは抗議した。約50名のバスター族兵士が、歴史的な血縁関係と言語を通じて人民と繋がりを持っていたためだ。一部の兵士は捕虜の脱 走を助けたため、ドイツ軍はバスター族への弾薬支給数を制限した。これに対し南アフリカ人捕虜は、自らが「カラード」(当時の人種分類に基づく呼称)と見 なす者たちによる監視に抗議した。[10] ルイ・ボータ将軍は以前、フランケ中佐に対し、武装した非白人の使用に反対する書簡を送っていた。彼はカメルーン人とバスターズが武装して従軍しているこ とを認識していたからだ。ボータは非白人に武器を持たせないよう確保すると述べた。フランケはカメルーン人部隊とバスターズ部隊を非白人コミュニティの警 備にのみ使用していると答えた。[10] レホボト・バスター族の第二隊長コーネリアス・ファン・ウィックは、4月1日にウォルビスベイで南アフリカのルイ・ボータ将軍と密会し、バスター族の中立 を保証した。会談記録は残っておらず、具体的に何が約束されたかは不明である。ファン・ウィックは、南アフリカがドイツ植民地を接収した場合にバスター族 の領土と権利が認められる保証を求めていた。ボータは戦争への不介入を助言した。[10] 南アフリカの戦況優位を受け、ドイツ軍将校はバスター評議会に対し、捕虜とバスター警備兵を北部に移送すると通告した。会議で彼らはバスター側に3日間の 猶予を与え、従うか否かを決断するよう迫った。バスター側は、兵士を北部に配置すれば南アフリカに対する正真正銘の戦闘員と見なされ、自らの立場が危うく なることを懸念した。この計画を知ったバスター人警備隊は評議会に同行拒否を伝えた。交渉は続いていたが、列車が翌日出発すると知り、4月18日の夜、多 数のバスター人がドイツ軍から離反し、武器を持ち去った。彼らはレホボトで武器を返還するつもりだった。約300人の男たちが二つのラガー(野営地)に防 御陣を敷いた。これを察知したドイツ軍は他拠点のバスター兵士から武装を解除したが、その過程で非武装のバスター兵士1名が死亡した。レホボトは騒然と なったが、指導者たちはドイツ側と会談し問題解決を図ろうとした。[10] その間、バスター族とナマ族警察官はレホボト地区内のドイツ軍将校の武装解除を試みたが、1名を致命傷で負傷させ、もう1名を即死させた。ナマ警察官を含む武装部隊が数名のドイツ市民を殺害し、カール・バウアー一家全員が犠牲となった。これにより交渉は決裂した。[10] 1915年4月22日、ベテ中佐はバスター族に対し、保護条約違反でありその行為はドイツ側にとって敵対的とみなされると文書で通告した。テオドール・ザ イツ総督はバスター族との保護条約を破棄し、レホボト攻撃を計画した。ファン・ヴィークはボータ将軍に報告し、将軍はバスター族を地域から退去させるよう 助言した[10]。彼らは荷車で移動を始め、大量の群畜を連れて山地を目指した。ドイツ軍によるバスター族への攻撃が地域一帯で発生した。 バスターの歴史によれば、ドイツ軍の収容所で働いていた14歳のバスター人少女が、酔ったドイツ兵たちのバスター人襲撃計画を耳にした。彼女はこの情報を 隊長(カプトゥイン)に伝え、約700人のバスター人(女性や子供を含む)はドイツ軍の攻撃に備え、レホボトの南東80キロメートル(50マイル)の山岳 地帯にあるサム・クビスへ退避した。ファン・ウィックは妻と子供をガリーズ農場に隠していた。そこにはストッフェルとウィレム・ファン・ウィックの妻と子 供たちもいた。ストッフェルの妻と二人の子供、コーネリウス・ファン・ウィックの成人した娘、そして18歳の息子が全員そこで殺害された。ファン・ウィッ クの妻サラを含む他の者たちはロイトヴァイン駅へ連行され、5月13日に解放された[10]。 1915年5月8日、ドイツ軍はサム・クビスの戦いで攻撃を開始した。この要塞は700~800人のバスター族によって守られていた。ドイツ軍は繰り返し 攻撃を仕掛け、2門の大砲と3挺の格律機関銃を使用したにもかかわらず、バスター族の陣地を破壊できなかった[10]。日没とともに攻撃は終了した。その 日、バスター族は弾薬がほぼ尽き、敗北を覚悟していた。その夜、彼らは神に祈りを捧げ、もし助かるならばこの日を永遠に記念すると誓った。 彼らの祈りは後にサム・クビスに設置された記念碑に刻まれており、その内容は次の通りである。[9] 我ら祖先の神よ/強き全能の神よ/御名は全地に聖なるものなり/天を創造せし御方よ/我らに御耳を傾け給え/御子らの嘆きに耳を澄ませ給え/死が我らを直視する/悪の子供らが我らの命を狙う/ 我らを敵の手から救い出せ/我らの妻と子を守り給え/ そして我らと子孫の代に/主の日を祝う日を賜え/ その日我らは御名を讃え/御慈悲を永遠に忘れん "我らの父なる神よ/強き力ある神よ/ 御名は全地に聖なるものなり/ 天を造りし御方よ/我らに御顔を垂れ/御子の叫びに耳を傾け給え/死が我らの顔を睨み/邪悪なる者の子らが我らの命を求め/敵の手から我らを救い/妻と子 らを守り給え/これこそ我らと子孫にとって/主の日にも等しき日となる/我ら御名を讃え/御慈愛を永遠に忘れん」 ドイツ軍は撤退命令を受け、翌朝実行した。レホボスのバスター族は生き延びた[11]。この日はバスター族の歴史と不屈の精神を象徴する日として毎年祝われる。ドイツ軍両部隊はレホボスに到達した南アフリカ軍に対抗するため、撤退命令を受けていた[10][9]。 バスター族がレホボトに戻ると、農場でドイツ人を殺害する者も現れた。ドイツ軍は防衛部隊を配置したが、南アフリカ軍の接近に伴い5月23日に撤退した。 バスター族はドイツ軍の家畜を奪い農場を略奪し、二人の宣教師の家屋も襲撃した。双方の流血は戦後も長く続く怨恨を残した[10]。 |

| South African mandate rule

(1915–1966) South Africa defeated the Germans, concluding the Peace of Khorab on July 9, 1915. It formally took over administration of South-West Africa and established martial law. Colonel H. Mentz advised the Baster leaders to avoid all confrontation with the Germans, in an effort to defuse tensions, and to report livestock losses or other problems to his administration at Windhoek. He also said that South African patrols would regularly be sent to the Rehoboth area to keep the peace.[10] After the conclusion of the Great War, Basters applied to have their native land become a British Protectorate like Basutoland, but were turned down by South Africa. All special rights as granted to Basters by the Germans were revoked under the South African mandate to govern South-West Africa.[9] South Africa conducted regular censuses of the Basters from 1921 to 1991; the records reflect their ideas about racial classifications.[1] Some Basters continued to push for the legitimacy of the 'Free Republic of Rehoboth.' Claiming that the republic had been recognised by the League of Nations, they said international law supported their desire for self-determination, which the League used as a principle in the organization of new nations after the Great War. They asserted that the Republic should have the status of a sovereign nation. In 1952, Basters presented a petition to the United Nations (the successor to the League of Nations) to this effect, with no result. But they had some practical autonomy under South Africa. During this period, some Baster leaders founded new political parties and were active in various movements in South-West Africa, also known as Namibia. By the early 1960s, they were among the first to petition the United Nations for international intervention to end the South African control of Namibia.[12] The Owambo and other indigenous peoples also agitated for an end to South African colonialism, especially as that state had established apartheid with severe legal racial discrimination against the African peoples. South Africa passed the ‘Rehoboth Self-government Act’ of 1976, providing a kind of autonomy for the Basters. They settled for a semi-autonomous Baster Homeland (known as Baster Gebiet) based around Rehoboth, similar in status to the South African bantustans. This was established in 1976, and an election was held for Kaptein. In 1979, Johannes "Hans" Diergaardt won a court challenge to the disputed election, in which incumbent Dr. Ben Africa had placed first. Diergaardt was installed as the 5th Kaptein of the Basters in accordance with the regulations of the 1976 Rehoboth Self-Determination Act and the Basters' Paternal Laws. In 1981, South West Africa had a population of one million, divided into more than a dozen ethnic and tribal groups, and 39 political parties. With not more than 35,000 people at the time, Basters had become one of the smaller minority groups in the country of over one million.[13] In the 1980s, Basters still controlled about 1.4 million hectares of farmland in this territory. In earlier times, requirements for farms were thought to be about 7,000 ha, but Basters claimed they could also survive with farms of 4,000 ha. Nonetheless, even by the 1930s they were having to find alternative forms of employment to support their population. In 1981, the Baster population was estimated to at about 25,181 by Hartmut Lang, according to his 1998 article on the Baster group. Requirements for viable farms suggest that Namibia could not achieve self-sufficiency for its expanding population through farming; land redistribution could not yield enough area for viable farms.[1] |

南アフリカの委任統治(1915年–1966年) 南アフリカはドイツ軍を破り、1915年7月9日にホラブの平和条約を締結した。南西アフリカの統治権を正式に引き継ぎ、戒厳令を敷いた。H・メンツ大佐 は、緊張緩和のためバスター族の指導者に対し、ドイツ人との一切の対立を避け、家畜の損失やその他の問題はウィントフックの行政機関に報告するよう助言し た。また、平和維持のため南アフリカの巡回部隊が定期的にレホボス地域に派遣されると述べた[10]。 第一次世界大戦終結後、バスター族は自領をバソトランドのような英国保護領とするよう申請したが、南アフリカに拒否された。南西アフリカ統治委任統治下に おいて、ドイツがバスター族に与えた全ての特権は撤回された[9]。南アフリカは1921年から1991年までバスター族の定期的な国勢調査を実施し、そ の記録は彼らの人種分類に関する考え方を反映している。[1] 一部のバスター族は『レホボト自由共和国』の正当性を主張し続けた。同共和国が国際連盟に承認されたと主張し、国際法が彼らの自決権を支持していると述べ た。国際連盟は第一次世界大戦後の新国家組織においてこの原則を用いたのである。彼らは共和国が主権国民の地位を持つべきだと主張した。1952年、バス ター族はこの趣旨の請願書を国連(国際連盟の後継機関)に提出したが、結果は得られなかった。しかし彼らは南アフリカ統治下で一定の自治権を保持してい た。 この時期、一部のバスター族指導者は新たな政党を結成し、南西アフリカ(ナミビア)における様々な運動に積極的に関与した。1960年代初頭までに、彼ら はナミビアにおける南アフリカの支配を終わらせるための国際的介入を国連に要請した最初の集団の一つとなった[12]。オワンボ族や他の先住民も、特に南 アフリカがアフリカ系住民に対する厳しい法的差別を伴うアパルトヘイトを確立していたことから、南アフリカの植民地支配の終結を求めて活動した。 南アフリカは1976年、「レホボト自治法」を制定し、バスター族に一種の自治権を与えた。彼らはレホボトを中心とする半自治のバスター・ホームランド(バスター・ゲビートとして知られる)を受け入れた。その地位は南アフリカのバンツースタンと類似していた。 これは1976年に設立され、カプテイン(首長)の選挙が実施された。1979年、ヨハネス・「ハンス」・ディールガートは、現職のベン・アフリカ博士が 首位となった争議選挙に対する法廷闘争に勝利した。ディールガートは1976年レホボト自治法とバスター族の父系法に基づく規定に従い、第5代バスター族 長に就任した。 1981年、南西アフリカの人口は100万人に達し、十数以上の民族・部族集団と39の政党に分かれていた。当時3万5千人以下だったバスターズは、100万人超のこの国において少数派集団の中でも小規模な存在となっていた。[13] 1980年代においても、バスター族はこの地域で約140万ヘクタールの農地を支配していた。かつて農場に必要な面積は約7,000ヘクタールと考えられ ていたが、バスター族は4,000ヘクタールの農場でも生存可能だと主張した。しかしながら、1930年代までに彼らは人口を支えるための代替的な雇用形 態を模索せざるを得なくなっていた。1981年、バスター族の人口はハートムート・ラングによる1998年の論文で、約25,181人と推定された。持続 可能な農場に必要な面積を考慮すると、ナミビアは農業によって増加する人口の自給自足を達成できず、土地再分配でも持続可能な農場を確保できる面積を確保 できなかった。[1] |

| Independence The Baster Gebiet operated until 29 July 1989 and the imminent independence of Namibia. Upon assuming power in 1990, Namibia's new ruling party, the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) announced it would not recognise any special legal status for the Baster community. Many Basters felt that while SWAPO claimed it spoke for the whole country, it too strongly promoted the interests of its own political base in Ovamboland.[13] The Kaptein's Council sought compensation for Rehoboth lands that it claimed had been confiscated by the government, with much sold to non-Basters. The Council was given locus standi (the right of a party to appear and be heard before a court), but "in 1995, a High Court verdict declared that Rehoboth lands were voluntarily handed over by the Rehoboth Baster community to the then new Namibian government."[14][9] In 1998, Kaptein Hans Diergaardt, elected in 1979 when Rehoboth had autonomous status under South Africa, filed an official complaint with the United Nations Human Rights Committee, charging Namibia with violations of minority rights of Basters. In Diergaardt v. Namibia (2000) the committee ruled that there was evidence of linguistic discrimination, as Namibia refused to use Afrikaans in dealing with Basters.[15] In 1999, following the death of Diergaardt, Basters elected John McNab as the 6th Kaptein of their community. He has no official status under the Namibian government. He has protested against the government's management of former Baster land and says his farmers were forced to buy it back at high prices. Much of it has been sold to others since independence.[14] As preparations were underway for Sam Khubis Day in 2006, a respected social worker, Hettie Rose-Junius, asked the organising committee to "consider inviting a delegation from the Nama-speaking people to this year’s festivities and in future." The chairperson rejected the suggestion by saying that historically the Nama had a separate fight with the Germans and were not involved with the Basters. Activities on this day include a re-enactment of the attack on the Basters in 1915, a flag raising, wreath laying and a church service.[16] In February 2007, the Kapteins Council has represented the Basters at the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO),[14] an international pro-democracy organization founded in 1991. Operating in The Hague, it works to "facilitate the voices of unrepresented and marginalised nations and peoples worldwide, helping minorities to gain self-determination." Since November 2012, the UNPO has called on the Namibian government to recognize Basters as a 'traditional authority' in their historic territory,[14] as it has for some other ethnic groups in the country. |

独立 バスター地域は1989年7月29日、ナミビアの独立直前まで存続した。1990年に政権を掌握したナミビアの新与党、南西アフリカ人民機構 (SWAPO)は、バスター共同体に対する特別な法的地位を一切認めないと宣言した。多くのバスターは、SWAPOが全国を代表すると主張しながらも、実 際にはオバンボランドにある自らの政治基盤の利益を強く優先していると感じていた。[13] カプトゥイン評議会は、政府によって没収され、その多くが非バスターに売却されたと主張するレホボトの土地に対する補償を求めた。評議会は訴訟参加資格 (裁判所に出頭し意見を述べる権利)を認められたが、「1995年、高等裁判所の判決はレホボトの土地が当時の新ナミビア政府にレホボト・バスター共同体 によって自発的に引き渡されたと宣言した」[14][9]。 1998年、南アフリカ統治下の自治権を有していた1979年に選出されたカプトイン・ハンス・ディエルガルトは、ナミビアがバスター族の少数派権利を侵 害していると告発し、国連人権委員会に正式な苦情を申し立てた。ディエルガルト対ナミビア事件(2000年)において、委員会はナミビアがバスター族との 対応においてアフリカーンス語の使用を拒否したことから、言語的差別の証拠があると判断した。[15] 1999年、ディールガルトの死後、バスター族はジョン・マクナブを第6代カプトインに選出した。彼はナミビア政府の下で公式な地位を持たない。彼は政府 による旧バスター族の土地管理に抗議し、農民たちが高値で買い戻すことを強制されたと述べている。独立後、その土地の多くは他者に売却された。[14] 2006年のサム・クビス・デー準備中、尊敬される社会福祉士ヘッティ・ローズ=ユニウスは実行委員会に対し「今年の祭典及び今後、ナマ語を話す人民の代 表団を招待することを検討してほしい」と要請した。委員長は「歴史的にナマ族はドイツ人との別個の闘争を経験しており、バスターズとは関わりがない」とし てこの提案を拒否した。この日の行事には、1915年のバスター族襲撃再現劇、国旗掲揚、献花、教会礼拝が含まれる。[16] 2007年2月、キャプテン評議会はバスター族を代表し、非代表民族・人民機構(UNPO)[14]に参加した。UNPOは1991年設立の国際民主主義 推進組織である。ハーグを拠点とする同組織は、「世界中の未代表かつ周縁化された国民・人民の声を促進し、少数民族が自己決定権を獲得するのを支援する」 ことを目的としている。2012年11月以降、UNPOはナミビア政府に対し、国内の他の民族グループと同様に、バスター族を歴史的領土における「伝統的 権威」として承認するよう要請している。 |

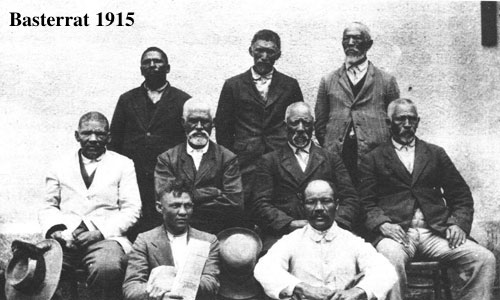

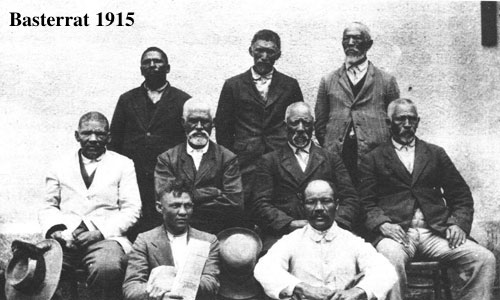

| Paternal Laws The first Kaptein's Council established the Vaderlike Wette (Paternal Laws), established as a constitution of Baster people in the Free Republic of Rehoboth. These have influenced the actions of the Baster community into the 21st century, although they no longer have the force of law.[6] Basters have a long democratic tradition of electing their leadership. According to the Paternal Laws of 1872, a Kaptein is elected for life. This Kaptein was granted the powers to appoint members of a Council, and together they formed the Executive government of Rehoboth. The Paternal Laws also provided for a Peoples Council (Volksraad) which was elected every five years; it formed the Legislature of the Rehoboth government. The Basters have had seven Kapteins since the Paternal Laws were enacted: 1872–1905: Hermanus van Wyk[17] 1905–1914: Germans suspended the Kapteinship position and instead established a Basterrat (English: Council of Basters)[17] 1914–1924: Cornelius van Wyk[17] 1924–1925: Albert Mouton[18] 1925–1975: The South African administration transferred all power from the Raad and the Kaptein to the Rehoboth Magistrate[19] 1977–1979: Ben Africa[19] 1979–1998: Hans Diergaardt[20] 1999–2020: John McNab since 2021: Jacky Britz[21] Every male burger (citizen) of Rehoboth had the right to apply for a free piece of land at the age of 18. Although the size of this erf was decreased from 1,300 square metres (0.32 acres) to about 300 square metres (0.074 acres), due to land shortage and servicing costs, Basters continued to honor this provision until 21 March 1990, when the new socialist government took over the lands.[22] The newly independent Namibian government passed legislation about land use and title that took precedence over Baster traditions. Basters can no longer allocate land to their young men. The land is controlled by the local town council, which replaced the Chief's Council. |

父権法 初代カプテイン評議会は、レホボト自由共和国のバスター人憲法として「ヴェーデルライク・ヴェッテ(父権法)」を制定した。これらはもはや法的効力を有しないものの、21世紀に至るまでバスター共同体の行動に影響を与え続けている。[6] バスター族は指導者を選挙で選ぶ長い民主的伝統を持つ。1872年の父権法によれば、キャプテンは終身で選出される。このキャプテンには評議会のメンバー を任命する権限が与えられ、彼らは共にレホボトの行政政府を形成した。父権法はまた、5年ごとに選出される人民評議会(フォルクスラード)を規定してお り、これがレホボト政府の立法府を形成した。 父権法制定以降、バスター族は7人のカプテインを擁してきた: 1872–1905: ヘルマヌス・ファン・ウィック[17] 1905–1914: ドイツ人によるカプテイン職停止。代わりにバスターラート(英語:バスター族評議会)を設置[17] 1914–1924: コーネリウス・ファン・ウィック[17] 1924–1925: アルバート・ムートン[18] 1925–1975: 南アフリカ政府は評議会とカプトインの全権限をレホボト治安判事に移管した[19] 1977–1979: ベン・アフリカ[19] 1979–1998: ハンス・ディールガルト[20] 1999–2020: ジョン・マクナブ 2021年以降: ジャッキー・ブリッツ[21] レホボスの男性市民(ブルガー)は全員、18歳で無料の土地を申請する権利を持っていた。土地不足と整備費用のため、この土地の面積は1,300平方メー トル(0.32エーカー)から約300平方メートル(0.074エーカー)に縮小されたが、バスター族はこの規定を1990年3月21日に新社会主義政府 が土地を接収するまで守り続けた。[22] 新たに独立したナミビア政府は、土地利用と所有権に関する法律を制定し、バスターの伝統に優先させた。バスターはもはや若者たちに土地を分配できなくなっ た。土地は首長評議会に代わって設置された地方自治体の町議会によって管理されている。 |

| Religion Basters from Mainline churches are mostly Calvinist. They sing traditional hymns almost identical to those of the 17th-century Netherlands; these songs were preserved in the colony and their group during a period when the Netherlands churches were absorbing new music. |

宗教 主流派教会の信徒はほとんどがカルヴァン主義者だ。彼らが歌う伝統的な賛美歌は、17世紀オランダのものとほぼ同じである。これらの歌は、オランダの教会が新しい音楽を取り入れていた時期に、植民地とその集団の中で守られてきたのだ。 |

| The

first Kaptein was Hermanus van Wyk, the 'Moses' of the Baster nation,

who led the community to Rehoboth from South Africa. He served as

Kaptein until his death in 1905.[6] After his death, the German

colonial government established a separate council. The Rehoboth

Basters did not elect another Kaptein until the United Kingdom took

over the territory as a British Protectorate in 1914 during World War

I. Basters elected Cornelius van Wyk as Kaptein. He was not officially

recognised by the South African authorities, which administered the

territory from 1915 to Namibian independence in 1990. |

初

代カプトインはヘルマヌス・ファン・ウィックであった。彼はバスター国民の「モーゼ」と呼ばれ、南アフリカからレホボトへ共同体を導いた。彼は1905年

に死去するまでカプトインを務めた[6]。彼の死後、ドイツ植民地政府は別の評議会を設置した。レホボスのバスター族が新たなカプトインを選出したのは、

第一次世界大戦中の1914年にイギリスがこの地域を保護領として接収してからである。バスター族はコーネリウス・ファン・ワイクをカプトインに選出し

た。しかし1915年から1990年のナミビア独立までこの地域を統治した南アフリカ当局は、彼を正式に承認しなかった。 |

| Other Baster communities Similar terms are used for unrelated mixed-race Dutch and native communities in South Africa and elsewhere. For instance, a mixed-race community in the Richtersveld in South Africa are known as the 'Boslys Basters.' In Indonesia, the people of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent are called Blaster(an). |

その他のバスターコミュニティ 南アフリカやその他の地域では、無関係な混血のオランダ人と先住民コミュニティに対して同様の用語が使われる。例えば、南アフリカのリヒタースフェルトにある混血コミュニティは「ボスリー・バスターズ」として知られている。 インドネシアでは、オランダ人とインドネシア人の混血の子孫はブラスター(an)と呼ばれる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baster |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099