行動上のモダニティ

Behavioral modernity

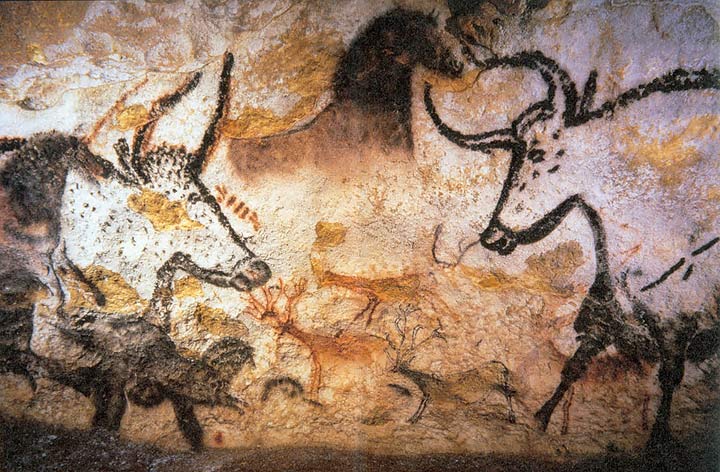

Upper Paleolithic (16,000-year-old) cave painting from Lascaux cave in France

☆

行動上の現代性とは、現在のホモ・サピエンスを解剖学的に現代的なヒト、ヒト属、および霊長類から区別する行動および認知上の特徴の集合であると考えられ

ている。[1]

ほとんどの学者は、現代人の行動は抽象的思考、綿密な計画、象徴的行動(例えば、芸術、装飾)、音楽やダンス、大型動物の狩猟、刃物技術などによって特徴

づけられることに同意している。[2][3]

これらの行動や技術革新の根底には、認知と文化の基盤があり、進化人類学者や文化人類学者によって実験的およびエスノグラフィー的に記録されている。これ

らの人間普遍のパターンには、累積的文化適応、社会規範、言語、そして近親者以外からの広範な支援や協力が含まれる。

進化人類学や関連分野の伝統においては、これらの現代的な行動特性の発達は、最終氷期と最終氷期最盛期の気候条件と相まって人口の減少をもたらし、ネアン

デルタール人やデニソワ人、その他の旧人類と比較してホモ・サピエンスの世界的な進化上の成功に貢献したと主張されている。

解剖学的に現代的な人間が、行動的にも現代的なのかどうかについては、議論が続いている。行動の近代化の進化については、多くの説がある。これらのアプ

ローチは、認知説と漸進説の2つのグループに分かれる傾向がある。後期旧石器時代モデルは、約4万~5万年前のアフリカにおける認知と遺伝子の突然の変化

が、アフリカを出発した一部の現生人類の世界への移動を促し、現生人類の行動を生み出したと理論づけている。

他のモデルでは、現代人の行動が徐々に段階を経て生じた可能性に焦点を当て、そのような行動の考古学的特徴は人口統計学的または生活様式の変化を通じての

み現れるとしている。多くの研究者は、行動の現代性に関する証拠をより早期(少なくとも約15万~7万5千年前、あるいはそれ以前)に、すなわちアフリカ

の中石器時代に見出している。[8][3][9][10][11] 人類学者のサリー・マクブリーティ

とアリソン・S・ブルックスは、ヨーロッパ中心のモデルに異議を唱え、より多くの変化をアフリカの中石器時代に位置づける漸進論の著名な提唱者である。た

だし、このモデルは、時代を遡るほど化石記録が一般的に希薄になるため、立証がより困難である。

| Behavioral modernity

is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits believed to distinguish

current Homo sapiens from other anatomically modern humans, hominins,

and primates.[1] Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be

characterized by abstract thinking, planning depth, symbolic behavior

(e.g., art, ornamentation), music and dance, exploitation of large

game, and blade technology, among others.[2][3] Underlying these behaviors and technological innovations are cognitive and cultural foundations that have been documented experimentally and ethnographically by evolutionary and cultural anthropologists. These human universal patterns include cumulative cultural adaptation, social norms, language, and extensive help and cooperation beyond close kin.[4][5] Within the tradition of evolutionary anthropology and related disciplines, it has been argued that the development of these modern behavioral traits, in combination with the climatic conditions of the Last Glacial Period and Last Glacial Maximum causing population bottlenecks, contributed to the evolutionary success of Homo sapiens worldwide relative to Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other archaic humans.[3][6] Debate continues as to whether anatomically modern humans were behaviorally modern as well. There are many theories on the evolution of behavioral modernity. These approaches tend to fall into two camps: cognitive and gradualist. The Later Upper Paleolithic Model theorizes that modern human behavior arose through cognitive, genetic changes in Africa abruptly around 40,000–50,000 years ago around the time of the Out-of-Africa migration, prompting the movement of some modern humans out of Africa and across the world.[7] Other models focus on how modern human behavior may have arisen through gradual steps, with the archaeological signatures of such behavior appearing only through demographic or subsistence-based changes. Many cite evidence of behavioral modernity earlier (by at least about 150,000–75,000 years ago and possibly earlier) namely in the African Middle Stone Age.[8][3][9][10][11] Anthropologists Sally McBrearty and Alison S. Brooks have been notable proponents of gradualism—challenging Europe-centered models by situating more change in the African Middle Stone Age—though this model is more difficult to substantiate due to the general thinning of the fossil record as one goes further back in time. |

行動上の現代性とは、現在のホモ・サピエンスを解剖学的に現代的なヒ

ト、ヒト属、および霊長類から区別する行動および認知上の特徴の集合であると考えられている。[1]

ほとんどの学者は、現代人の行動は抽象的思考、綿密な計画、象徴的行動(例えば、芸術、装飾)、音楽やダンス、大型動物の狩猟、刃物技術などによって特徴

づけられることに同意している。[2][3] これらの行動や技術革新の根底には、認知と文化の基盤があり、進化人類学者や文化人類学者によって実験的およびエスノグラフィー的に記録されている。これ らの人間普遍のパターンには、累積的文化適応、社会規範、言語、そして近親者以外からの広範な支援や協力が含まれる。 進化人類学や関連分野の伝統においては、これらの現代的な行動特性の発達は、最終氷期と最終氷期最盛期の気候条件と相まって人口の減少をもたらし、ネアン デルタール人やデニソワ人、その他の旧人類と比較してホモ・サピエンスの世界的な進化上の成功に貢献したと主張されている。 解剖学的に現代的な人間が、行動的にも現代的なのかどうかについては、議論が続いている。行動の近代化の進化については、多くの説がある。これらのアプ ローチは、認知説と漸進説の2つのグループに分かれる傾向がある。後期旧石器時代モデルは、約4万~5万年前のアフリカにおける認知と遺伝子の突然の変化 が、アフリカを出発した一部の現生人類の世界への移動を促し、現生人類の行動を生み出したと理論づけている。 他のモデルでは、現代人の行動が徐々に段階を経て生じた可能性に焦点を当て、そのような行動の考古学的特徴は人口統計学的または生活様式の変化を通じての み現れるとしている。多くの研究者は、行動の現代性に関する証拠をより早期(少なくとも約15万~7万5千年前、あるいはそれ以前)に、すなわちアフリカ の中石器時代に見出している。[8][3][9][10][11] 人類学者のサリー・マクブリーティ とアリソン・S・ブルックスは、ヨーロッパ中心のモデルに異議を唱え、より多くの変化をアフリカの中石器時代に位置づける漸進論の著名な提唱者である。た だし、このモデルは、時代を遡るほど化石記録が一般的に希薄になるため、立証がより困難である。 |

Definition A Māori man performing haka, a ceremonial dance. He is displaying several hallmarks of behavioral modernity including the use of jewelry, application of body paint, music and dance, and symbolic behavior. To classify what should be included in modern human behavior, it is necessary to define behaviors that are universal among living human groups. Some examples of these human universals are abstract thought, planning, trade, cooperative labor, body decoration, and the control and use of fire. Along with these traits, humans possess much reliance on social learning.[12][13] This cumulative cultural change or cultural "ratchet" separates human culture from social learning in animals. In addition, a reliance on social learning may be responsible in part for humans' rapid adaptation to many environments outside of Africa. Since cultural universals are found in all cultures, including isolated indigenous groups, these traits must have evolved or have been invented in Africa prior to the exodus.[14][15][16] Archaeologically, a number of empirical traits have been used as indicators of modern human behavior. While these are often debated[17] a few are generally agreed upon. Archaeological evidence of behavioral modernity includes:[3][7] Burial Fishing Figurative art (cave paintings, petroglyphs, dendroglyphs, figurines) Use of pigments (such as ochre) and jewelry for decoration or self-ornamentation Using bone material for tools Transport of resources over long distances Blade technology Diversity, standardization, and regionally distinct artifacts Hearths Composite tools |

定義 儀式の踊りであるハカを踊るマオリ族の男性。彼は、ジュエリーの使用、ボディペイント、音楽と踊り、象徴的な行動など、現代的な行動様式のいくつかの特徴を示している。 現代的な人間の行動に含まれるものを分類するには、生存している人間集団の間で普遍的な行動を定義する必要がある。これらの人間普遍の特徴の例としては、 抽象的思考、計画、交易、共同労働、身体装飾、火の制御と利用などがある。これらの特徴とともに、人間は社会学習に大きく依存している。[12][13] この累積的な文化の変化、あるいは文化の「ラチェット」が、人間の文化を動物の社会学習から隔てている。さらに、社会学習への依存は、アフリカ以外の多く の環境への人間の急速な適応の一因となっている可能性がある。文化の普遍性は孤立した先住民グループを含むあらゆる文化に見られるため、これらの特徴はア フリカから離れる前に進化または発明されたに違いない。 考古学的には、多くの経験的特徴が現代人の行動の指標として用いられてきた。これらはしばしば議論の的となっているが[17]、一般的に認められているものもいくつかある。行動の現代性を示す考古学的証拠には以下のようなものがある: 埋葬 漁撈 象徴的な芸術(洞窟壁画、岩絵、木の年輪に描かれた絵、人形 顔料(黄土など)や装飾用または自己装飾用の宝飾品の使用 道具としての骨材の利用 長距離にわたる資源の輸送 刃物の技術 多様性、標準化、地域的に異なる人工物 囲炉裏 複合的な道具 |

| Critiques [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) Several critiques have been placed against the traditional concept of behavioral modernity, both methodologically and philosophically.[3][17] Anthropologist John Shea outlines a variety of problems with this concept, arguing instead for "behavioral variability", which, according to the author, better describes the archaeological record. The use of trait lists, according to Shea, runs the risk of taphonomic bias, where some sites may yield more artifacts than others despite similar populations; as well, trait lists can be ambiguous in how behaviors may be empirically recognized in the archaeological record.[17] In particular, Shea cautions that population pressure, cultural change, or optimality models, like those in human behavioral ecology, might better predict changes in tool types or subsistence strategies than a change from "archaic" to "modern" behavior.[17] Some researchers argue that a greater emphasis should be placed on identifying only those artifacts which are unquestionably, or purely, symbolic as a metric for modern human behavior.[3] Since 2018, recent dating methods utilized on various cave art sites in Spain and France have shown that Neanderthals performed symbolic artistic expression, consisting of red "lines, dots, and hand stencils" found in caves, prior to contact with anatomically modern humans. This is contrary to previous suggestions that Neanderthals lacked these capabilities.[18][19][20] |

批評 [アイコン] この節は拡張が必要である。 あなたはそれを追加することで手助けできる。 (2023年8月) 行動的近代性(行動上のモダニティ)という伝統的な概念に対しては、方法論的にも哲学的にも、いくつかの批判が寄せられている。[3][17] 人類学者ジョン・シーアは、この概念に関するさまざまな問題を概説し、代わりに「行動の多様性」を主張している。シーによれば、形質リストの使用にはタ フォノミック・バイアスのリスクがある。すなわち、同様の人口にもかかわらず、ある遺跡では他の遺跡よりも多くの人工物が出土する可能性がある。また、形 質リストは、行動がどのようにして考古学的記録で経験的に認識されるかについて曖昧である可能性がある。[17] 特に、シーは、人口圧力、文化の変化、または最適性 人間行動生態学におけるような、人口圧力、文化変化、最適性モデルは、「旧石器時代」から「現代」の行動への変化よりも、道具の種類や生活戦略の変化をよ り正確に予測できる可能性があると、シェイは警告している。[17] 一部の研究者は、現代人の行動の指標として、疑いなく、または純粋に象徴的なものだけを特定することに、より重点を置くべきだと主張している。[3] 2018年以降、スペインやフランスのさまざまな洞窟壁画の遺跡で用いられている最新の年代測定法により、ネアンデルタール人は解剖学的に現代人と接触す る以前から、洞窟で見つかった赤色の「線、点、手の型」からなる象徴的な芸術表現を行っていたことが明らかになっている。これは、ネアンデルタール人はこ のような能力を持っていなかったとするこれまでの説に反するものである。[18][19][20] |

| Late Upper Paleolithic Model or "Upper Paleolithic Revolution" The Late Upper Paleolithic Model, or Upper Paleolithic Revolution, refers to the idea that, though anatomically modern humans first appear around 150,000 years ago (as was once believed), they were not cognitively or behaviorally "modern" until around 50,000 years ago, leading to their expansion out of Africa and into Europe and Asia.[7][21][22] These authors note that traits used as a metric for behavioral modernity do not appear as a package until around 40–50,000 years ago. Anthropologist Richard Klein specifically describes that evidence of fishing, tools made from bone, hearths, significant artifact diversity, and elaborate graves are all absent before this point.[7][21] According to both Shea and Klein, art only becomes common beyond this switching point, signifying a change from archaic to modern humans.[7] Most researchers argue that a neurological or genetic change, perhaps one enabling complex language, such as FOXP2, caused this revolutionary change in humans.[7][22] The role of FOXP2 as a driver of evolutionary selection has been called into question following recent research results.[clarification needed][23] Building on the FOXP2 gene hypothesis, cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman has argued that proto-language behaviour existed prior to 50,000 BP, albeit in a more primitive form. Lieberman has advanced fossil evidence, such as neck and throat dimensions, to demonstrate that so-called “anatomically modern” humans from 100,000 BP continued to evolve their SVT (supralaryngeal vocal tract), which already possessed a horizontal portion (SVTh) capable of producing many phonemes which were mostly consonants. According to his theory, Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens would have been able to communicate using sounds and gestures.[24] From 100,000 BP, Homo sapiens necks continued to lengthen to a point, by around 50,000 BP, where Homo sapiens necks were long enough to accommodate a vertical portion to their SVT (SVTv), which is now a universal trait among humans. This SVTv enabled the enunciation of quantal vowels: [i]; [u]; and [a]. These quantal vowels could then be immediately put to use by the already sophisticated neuro-motor-control features of the FOXP2 gene to generate more nuanced sounds and in effect increase by orders of magnitude the number of distinct sounds that can be produced, allowing for fully symbolic language.[25] Goody (1986) draws an analogy between the development of spoken language and that of writing: the shift from pictographic or ideographic symbols into a fully abstract logographic writing system (such as hieroglyphics), or from a logoprahic system into an abjad or alphabet, led to dramatic changes in human civilization.[26] |

後期旧石器時代モデルまたは「旧石器革命」 後期旧石器時代モデルまたは旧石器革命とは、解剖学的に現生人類が15万年前頃に初めて出現したという考え(かつては信じられていた)を指し、彼らは認知 面でも行動面でも5万年前頃までは「現代的」ではなく、 5万年前頃までは、認知能力や行動様式が「現代的な」ものではなかったため、アフリカからヨーロッパやアジアへと拡散していった。[7][21][22] これらの著者は、行動様式の現代性を測る基準として用いられる特徴が、4万~5万年前頃まではまとまって現れていないことを指摘している。人類学者のリ チャード・クラインは、漁業の証拠、骨製の道具、炉、多様な人工物、精巧な墓などは、この時点以前には存在していないと具体的に述べている。[7] [21] シーとクラインの両氏によると、芸術が一般的になるのはこの転換点を超えてからであり、これは旧人から新人への変化を意味する 。ほとんどの研究者は、FOXP2のような複雑な言語を可能にする神経学的あるいは遺伝的変化が、人類にこの革命的な変化をもたらしたと主張している。 認知科学者のフィリップ・リーバーマンは、FOXP2遺伝子仮説を基に、原始言語行動は5万年前よりも以前に存在していたと主張している。ただし、より原 始的な形態ではあったが。リバーマンは、首や喉の寸法などの化石の証拠を提示し、10万年前のいわゆる「解剖学的に現代的な」人類は、SVT(声門上声 路)を進化させ続けており、すでに多くの音素(そのほとんどが子音)を発声できる水平部分(SVTh)を備えていたことを証明した。彼の説によると、ネア ンデルタール人と初期のホモ・サピエンスは音と身振りを使ってコミュニケーションを取ることができたはずである。 10万年前からホモ・サピエンスの首は長くなり続け、約5万年前には、SVTに垂直部分(SVTv)を加えるのに十分な長さになった。SVTvは現在、人 間に共通する特徴である。この SVTv によって、量子母音 [i]、[u]、[a] の発声が可能になった。 これらの量子母音は、FOXP2 遺伝子によるすでに洗練された神経運動制御機能によって、より微妙な音を発生させるために直ちに利用され、事実上、発生可能な明確な音の数を桁違いに増や し、完全な象徴言語を可能にした。 Goody(1986)は、音声言語の発達と文字の発達を比較し、絵文字や表意文字から完全な抽象文字である表語文字(象形文字など)への移行、あるいは表語文字からアブジャドやアルファベットへの移行が、人類文明に劇的な変化をもたらしたと述べている。[26] |

| Alternative models Contrasted with this view of a spontaneous leap in cognition among ancient humans, some anthropologists like Alison S. Brooks, primarily working in African archaeology, point to the gradual accumulation of "modern" behaviors, starting well before the 50,000-year benchmark of the Upper Paleolithic Revolution models.[8][3][27] Howiesons Poort, Blombos, and other South African archaeological sites, for example, show evidence of marine resource acquisition, trade, the making of bone tools, blade and microlithic technology, and abstract ornamentation at least by 80,000 years ago.[8][9] Given evidence from Africa and the Middle East, a variety of hypotheses have been put forth to describe an earlier, gradual transition from simple to more complex human behavior. Some authors have pushed back the appearance of fully modern behavior to around 80,000 years ago or earlier in order to incorporate the South African data.[27] Others focus on the slow accumulation of different technologies and behaviors across time. These researchers describe how anatomically modern humans could have been cognitively the same, and what we define as behavioral modernity is just the result of thousands of years of cultural adaptation and learning.[8][3] Archaeologist Francesco d'Errico, and others, have looked at Neanderthal culture, rather than early human behavior exclusively, for clues into behavioral modernity.[6] Noting that Neanderthal assemblages often portray traits similar to those listed for modern human behavior, researchers stress that the foundations for behavioral modernity may in fact, lie deeper in our hominin ancestors.[28] If both modern humans and Neanderthals express abstract art and complex tools then "modern human behavior" cannot be a derived trait for our species. They argue that the original "human revolution" theory reflects a profound Eurocentric bias. Recent archaeological evidence, they argue, proves that humans evolving in Africa some 300,000 or even 400,000 years ago were already becoming cognitively and behaviourally "modern". These features include blade and microlithic technology, bone tools, increased geographic range, specialized hunting, the use of aquatic resources, long-distance trade, systematic processing and use of pigment, and art and decoration. These items do not occur suddenly together as predicted by the "human revolution" model, but at sites that are widely separated in space and time. This suggests a gradual assembling of the package of modern human behaviours in Africa, and its later export to other regions of the Old World. Between these extremes is the view—currently supported by archaeologists Chris Henshilwood,[29] Curtis Marean,[3] Ian Watts[30] and others—that there was indeed some kind of "human revolution" but that it occurred in Africa and spanned tens of thousands of years. The term "revolution," in this context, would mean not a sudden mutation but a historical development along the lines of the industrial revolution or the Neolithic revolution.[31] In other words, it was a relatively accelerated process, too rapid for ordinary Darwinian "descent with modification" yet too gradual to be attributed to a single genetic or other sudden event. These archaeologists point in particular to the relatively explosive emergence of ochre crayons and shell necklaces, apparently used for cosmetic purposes. These archaeologists see symbolic organisation of human social life as the key transition in modern human evolution. Recently discovered at sites such as Blombos Cave and Pinnacle Point, South Africa, pierced shells, pigments and other striking signs of personal ornamentation have been dated within a time-window of 70,000–160,000 years ago in the African Middle Stone Age, suggesting that the emergence of Homo sapiens coincided, after all, with the transition to modern cognition and behaviour.[32] While viewing the emergence of language as a "revolutionary" development, this school of thought generally attributes it to cumulative social, cognitive and cultural evolutionary processes as opposed to a single genetic mutation.[33] A further view, taken by archaeologists such as Francesco d'Errico[28] and João Zilhão,[34] is a multi-species perspective arguing that evidence for symbolic culture, in the form of utilised pigments and pierced shells, are also found in Neanderthal sites, independently of any "modern" human influence. Cultural evolutionary models may also shed light on why although evidence of behavioral modernity exists before 50,000 years ago, it is not expressed consistently until that point. With small population sizes, human groups would have been affected by demographic and cultural evolutionary forces that may not have allowed for complex cultural traits.[10][11][12][13] According to some authors,[10] until population density became significantly high, complex traits could not have been maintained effectively. Some genetic evidence supports a dramatic increase in population size before human migration out of Africa.[22] High local extinction rates within a population also can significantly decrease the amount of diversity in neutral cultural traits, regardless of cognitive ability.[11] |

代替モデル 古代の人類の認知能力が自然に飛躍したという見解とは対照的に、アフリカ考古学を専門とするアリソン・S・ブルックスのような一部の人類学者は、旧石器革 命モデルの5万年前という基準値よりもはるか以前から、「現代的な」行動が徐々に蓄積されてきたと指摘している。[8][3][27] 例えば、ハウイソンズ・ポルト、ブロムボス、その他の 例えば、ハウイソン・ポルト、ブロムボス、その他の南アフリカの遺跡からは、少なくとも8万年前には、海洋資源の入手、交易、骨製の道具や刃物、細石器技 術、抽象的な装飾の証拠が発見されている。[8][9] アフリカと中東からの証拠を踏まえ、単純な行動からより複雑な行動への、より早い段階での段階的な移行を説明するさまざまな仮説が提示されている。南アフ リカのデータを組み入れるために、完全に現代的な行動の出現を8万年前かそれ以前にまでさかのぼる研究者もいる。 また、異なる技術や行動が時間をかけてゆっくりと蓄積されてきたことに注目する研究者もいる。こうした研究者たちは、解剖学的に現代的な人間が認知能力に おいても同様であった可能性について述べ、また、我々が行動の現代性と定義するものは、単に数千年にわたる文化への適応と学習の結果に過ぎないとしてい る。[8][3] 考古学者のフランチェスコ・デリコ(Francesco d'Errico)をはじめとする一部の研究者は、行動の現代性に関する手がかりを求めて、初期の人類の行動ではなく、ネアンデルタール人の文化に注目し ている。[ 6] ネアンデルタール人の文化には、現代人の行動として挙げられている特徴と類似したものがしばしば見られることを指摘し、研究者たちは、行動の現代性の基盤 は、実際には私たちのヒト属の祖先のさらに深い部分にある可能性があると強調している。[28] もし現生人類とネアンデルタール人の両方が抽象芸術や複雑な道具を表現しているのなら、「現生人類の行動」は私たちの種に由来する特徴ではない。彼らは、 当初の「人間革命」理論は、深刻なヨーロッパ中心主義の偏見を反映していると主張している。彼らは、最近の考古学的証拠は、30万年前、あるいは40万年 前のアフリカで進化していた人類はすでに認知面でも行動面でも「現代人」的であったことを証明していると主張する。その特徴には、刃物や細石器技術、骨製 の道具、行動範囲の拡大、狩猟の専門化、水産資源の利用、長距離貿易、顔料の組織的な加工と利用、芸術や装飾などが含まれる。これらの特徴は、「人類革 命」モデルが予測するように突然同時に起こったのではなく、空間的にも時間的にも離れた場所で起こった。このことは、アフリカで現生人類の行動様式が徐々 に形成され、それが後に旧世界の他の地域に輸出されたことを示唆している。 この両極端の間に位置するのが、現在、クリス・ヘンシルウッド(Chris Henshilwood)氏[29]、カーティス・マリアン(Curtis Marean)氏[3]、イアン・ワッツ(Ian Watts)氏[30]をはじめとする考古学者が支持している見解であり、確かに何らかの「人類革命」はあったが、それはアフリカで起こり、数万年間にわ たって続いたというものである。この文脈における「革命」という用語は、突然変異ではなく、産業革命や新石器革命のような歴史的発展を意味する。[31] つまり、それは比較的加速されたプロセスであり、通常のダーウィン主義の「変化を伴う進化」としてはあまりにも急速であり、一方で単一の遺伝子やその他の 突発的な出来事によるものとしてはあまりにも緩慢であった。これらの考古学者は、特に化粧用として使用されたと思われる黄土色クレヨンや貝殻ネックレスの 比較的爆発的な出現を指摘している。これらの考古学者は、人間の社会生活の象徴的な組織化こそが、現生人類の進化における重要な転換点であると見ている。 最近、南アフリカのブロムボス洞窟やピンナクル・ポイントなどの遺跡から発見された穴の開いた貝殻や顔料、その他の目を見張るような装飾品は、7万~16 万年前のアフリカ中石器時代のものと推定され、 ホモ・サピエンスの出現は、結局のところ、現代的な認知と行動への移行と一致していたことを示唆している。[32] 言語の出現を「革命的」な発展と捉える一方で、この学派は一般的に、それを単一の遺伝子変異とは対照的な、累積的な社会的、認知的、文化的な進化プロセス に帰する。[33] フランチェスコ・デリコ(Francesco d'Errico)[28]やジョアン・ジルアオ(João Zilhão)[34]などの考古学者が唱える見解は、多種的視点であり、顔料や穴の開いた貝殻といった象徴的文化の証拠は、現生人類の影響とは無関係 に、ネアンデルタール人の遺跡からも発見されているというものである。 文化進化モデルは、5万年前以前にも行動の現代的傾向の証拠が存在していたにもかかわらず、その時点までは一貫して表現されていなかった理由についても、 新たな光を投げかける可能性がある。人口が少なかったため、人類集団は人口統計学的および文化進化上の要因の影響を受け、複雑な文化特性を許容できなかっ た可能性がある。[10][11][12][13] 一部の著述家によると、[10]人口密度が著しく高くなるまでは、複雑な特性は効果的に維持できなかった可能性がある。一部の遺伝学的証拠は、人類がアフ リカから移住する前の人口規模の劇的な増加を裏付けている。[22] また、集団内の高い局地的絶滅率は、認知能力に関係なく、中立的な文化特性の多様性を大幅に減少させる可能性がある。[11]s |

| Archaeological evidence Africa See also: Early expansions of hominins out of Africa, Early human migrations, and Recent African origin of modern humans Research from 2017 indicates that Homo sapiens originated in Africa between around 350,000 and 260,000 years ago.[35][36][37][38] There is some evidence for the beginning of modern behavior among early African H. sapiens around that period.[39][40][41][42] Before the Out of Africa theory was generally accepted, there was no consensus on where the human species evolved and, consequently, where modern human behavior arose. Now, however, African archaeology has become extremely important in discovering the origins of humanity. The first Cro-Magnon expansion into Europe around 48,000 years ago is generally accepted as already "modern",[21] and it is now generally believed that behavioral modernity appeared in Africa before 50,000 years ago, either significantly earlier, or possibly as a late Upper Paleolithic "revolution" soon before which prompted migration out of Africa. A variety of evidence of abstract imagery, widened subsistence strategies, and other "modern" behaviors have been discovered in Africa, especially South, North, and East Africa. The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with geometric designs. Using multiple dating techniques, the site was dated to be around 77,000 and 100,000 to 75,000 years old.[29][43] Ostrich egg shell containers engraved with geometric designs dating to 60,000 years ago were found at Diepkloof, South Africa.[44] Beads and other personal ornamentation have been found from Morocco which might be as much as 130,000 years old; as well, the Cave of Hearths in South Africa has yielded a number of beads dating from significantly prior to 50,000 years ago,[8] and shell beads dating to about 75,000 years ago have been found at Blombos Cave, South Africa.[45][46][47] Specialized projectile weapons as well have been found at various sites in Middle Stone Age Africa, including bone and stone arrowheads at South African sites such as Sibudu Cave (along with an early bone needle also found at Sibudu) dating approximately 72,000–60,000 years ago[48][49][50][51][52] on some of which poisons may have been used,[53] and bone harpoons at the Central African site of Katanda dating to about 90,000 years ago.[54] Evidence also exists for the systematic heat treating of silcrete stone to increase its flake-ability for the purpose of toolmaking, beginning approximately 164,000 years ago at the South African site of Pinnacle Point and becoming common there for the creation of microlithic tools at about 72,000 years ago.[55][56] In 2008, an ochre processing workshop likely for the production of paints was uncovered dating to c. 100,000 years ago at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the two abalone shells, and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones, and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits. Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use.[57][58][59] Modern behaviors, such as the making of shell beads, bone tools and arrows, and the use of ochre pigment, are evident at a Kenyan site by 78,000–67,000 years ago.[60] Evidence of early stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, and date to around 279,000 years ago.[39] Expanding subsistence strategies beyond big-game hunting and the consequential diversity in tool types has been noted as signs of behavioral modernity. A number of South African sites have shown an early reliance on aquatic resources from fish to shellfish. Pinnacle Point, in particular, shows exploitation of marine resources as early as 120,000 years ago, perhaps in response to more arid conditions inland.[9] Establishing a reliance on predictable shellfish deposits, for example, could reduce mobility and facilitate complex social systems and symbolic behavior. Blombos Cave and Site 440 in Sudan both show evidence of fishing as well. Taphonomic change in fish skeletons from Blombos Cave have been interpreted as capture of live fish, clearly an intentional human behavior.[8] Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha, Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ≈100,000 years ago, for the construction of stone tools.[61][62] Evidence was found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago, at the Kenyan site of Olorgesailie, of the early emergence of modern behaviors including: long-distance trade networks (involving goods such as obsidian), the use of pigments, and the possible making of projectile points. It is observed by the authors of three 2018 studies on the site that the evidence of these behaviors is approximately contemporary to the earliest known Homo sapiens fossil remains from Africa (such as at Jebel Irhoud and Florisbad), and they suggest that complex and modern behaviors had already begun in Africa around the time of the emergence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens.[40][41][42] In 2019, further evidence of early complex projectile weapons in Africa was found at Aduma, Ethiopia, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[63] Olduvai Hominid 1 wore facial piercings.[64] |

考古学的証拠 アフリカ 関連情報:アフリカからの初期の人類拡散、初期の人類の移住、現代人の最近の起源 2017年の研究では、ホモ・サピエンスは約35万年前から26万年前の間にアフリカで誕生したことが示されている。[35][36][37][38] その頃、初期のホモ・サピエンスの間で現代的な行動の始まりを示すいくつかの証拠がある。[39][40][41][42] アフリカ単一起源説が一般的に受け入れられる前は、人類がどこで進化し、その結果、現代的な人間の行動がどこで生まれたかについて、コンセンサスは得られ ていなかった。しかし現在では、アフリカの考古学は人類の起源を発見する上で極めて重要となっている。約4万8千年前にクロマニョン人がヨーロッパに初め て進出したことは、すでに「現代的な」行動であったと一般的に受け入れられている[21]。そして、行動の現代性は5万年前より前にアフリカで現れたと現 在では一般的に考えられている。 抽象的なイメージ、多様化した生活戦略、その他の「現代的な」行動を示すさまざまな証拠が、アフリカ、特に南アフリカ、北アフリカ、東アフリカで発見され ている。例えば、南アフリカのブロムボス洞窟遺跡は、幾何学模様が刻まれた黄土色の長方形の板で有名である。複数の年代測定法により、この遺跡は約7万 7000年から10万~7万5000年前のものであると推定されている。[29][43] 6万年前の幾何学模様が刻まれたダチョウの卵の殻の容器が、南アフリカのディープクルーフで発見されている。[44] モロッコからは、 モロッコからは13万年前のものとされるビーズやその他の装飾品が発見されている。また、南アフリカのハース洞窟からは5万年前よりもかなり前の年代の ビーズが多数出土しており[8]、南アフリカのブロムボス洞窟からは約7万5千年前の貝殻ビーズが発見されている[45][46][47]。 また、中石器時代のさまざまな遺跡から、専門化された投擲武器も発見されている。南アフリカのシブドゥ洞窟(シブドゥでは初期の骨針も発見されている)な どの遺跡からは、約7万2000年~6万年前の骨や石の矢じりが出土している[ 48][49][50][51][52] そのうちのいくつかには毒が使用されていた可能性がある[53]。また、中央アフリカのカタンダ遺跡から出土した約9万年前の骨製の銛もある。石器製作の ために剥離性を高めるために、約16万4千年前に南アフリカのピナクルポイントで始まり、約7万2千年前にはマイクロリシックな道具の製作に一般的に行わ れるようになった。 2008年には、南アフリカのブロムボス洞窟で、おそらく絵具の生産に使用された黄土加工の作業場が約10万年前のものであることが発見された。分析の結 果、顔料を豊富に含む混合物を液化し、2枚のアワビの貝殻に貯蔵していたことが判明した。また、黄土、骨、木炭、磨き石、ハンマーストーンも道具一式の一 部を形成していた。作業の複雑さを示す証拠としては、さまざまな供給源から原材料を調達し組み合わせたこと(彼らがその後の工程を頭の中で組み立てていた ことを暗示している)、骨から脂肪を抽出する際に火薬技術を使用した可能性、化合物を生成するためのレシピを使用した可能性、混合と保存用の貝殻容器を使 用した可能性などが挙げられる。[57][58][59] 貝殻ビーズや骨製の道具や矢じりを作ったり、黄土顔料を使用したりするといった現代的な行動は、 ケニアの遺跡では、78,000年から67,000年前の貝殻ビーズや骨製の道具や矢じり、黄土顔料の使用などの痕跡が発見されている。[60] 初期の石槍(ホモ・サピエンスの特徴的な道具)の証拠となる、槍や投げ槍の石の穂先が、2013年にエチオピアのガデモッタ遺跡で発見され、約27万 9000年前のものであることが判明した。[39] 大型動物の狩猟や、それに伴う道具の種類の多様性といった範囲を超えた生存戦略の拡大は、行動の現代性を示す兆候として注目されている。南アフリカの多く の遺跡では、魚介類などの水産資源への初期の依存が示されている。特にピナクルポイントでは、おそらく内陸部の乾燥化に対応したものと考えられるが、12 万年前にはすでに海洋資源が利用されていたことが示されている。[9] 例えば、予測可能な貝類の堆積物に依存するようになると、移動性が低下し、複雑な社会システムや象徴的行動が促進される可能性がある。スーダンのブロムボ ス洞窟とサイト440では、いずれも漁の痕跡が発見されている。ブロムボス洞窟の魚の骨格に見られるタフォノミック変化は、明らかに意図的な人間の行動で あり、生きた魚を捕獲したものと解釈されている。 北アフリカ(エジプトのナズレト・サバーハ)の人々は、約10万年前にはすでに、石器の製造のために珪岩の採掘を行っていたことが知られている。 2018年には、ケニアのオルゲライエ遺跡で約32万年前の証拠が発見された。その中には、長距離貿易ネットワーク(黒曜石などの物品を含む)、顔料の使 用、および尖頭器の可能性があるものなど、現代的な行動の初期出現が含まれていた。この遺跡に関する2018年の3つの研究の著者らは、これらの行動の証 拠は、アフリカで知られている最古のホモ・サピエンスの化石(ジェベル・イルホードやフローリスバッドなど)とほぼ同時代のものであることを指摘してお り、解剖学的に現代的なホモ・サピエンスが出現した時期に、アフリカではすでに複雑で現代的な行動が始まっていた可能性を示唆している。[40][41] [42] 2019年には、エチオピアのアドゥマで、10万~8万年前のものとされる、初期の複雑な投射武器のさらなる証拠が発見された。これは、槍投げ人が投げたダーツに属する可能性が高いと考えられる先端の形をしている。 オルドヴァイ原人の1号は顔にピアスをしていた。 |

| Europe While traditionally described as evidence for the later Upper Paleolithic Model,[7] European archaeology has shown that the issue is more complex. A variety of stone tool technologies are present at the time of human expansion into Europe and show evidence of modern behavior. Despite the problems of conflating specific tools with cultural groups, the Aurignacian tool complex, for example, is generally taken as a purely modern human signature.[65][66] The discovery of "transitional" complexes, like "proto-Aurignacian", have been taken as evidence of human groups progressing through "steps of innovation".[65] If, as this might suggest, human groups were already migrating into eastern Europe around 40,000 years and only afterward show evidence of behavioral modernity, then either the cognitive change must have diffused back into Africa or was already present before migration. In light of a growing body of evidence of Neanderthal culture and tool complexes some researchers have put forth a "multiple species model" for behavioral modernity.[6][28][67] Neanderthals were often cited as being an evolutionary dead-end, apish cousins who were less advanced than their human contemporaries. Personal ornaments were relegated as trinkets or poor imitations compared to the cave art produced by H. sapiens. Despite this, European evidence has shown a variety of personal ornaments and artistic artifacts produced by Neanderthals; for example, the Neanderthal site of Grotte du Renne has produced grooved bear, wolf, and fox incisors, ochre and other symbolic artifacts.[67] Although few and controversial, circumstantial evidence of Neanderthal ritual burials has been uncovered.[28] There are two options to describe this symbolic behavior among Neanderthals: they copied cultural traits from arriving modern humans or they had their own cultural traditions comparative with behavioral modernity. If they just copied cultural traditions, which is debated by several authors,[6][28] they still possessed the capacity for complex culture described by behavioral modernity. As discussed above, if Neanderthals also were "behaviorally modern" then it cannot be a species-specific derived trait. |

ヨーロッパ 従来、後期旧石器時代モデルの証拠とされてきたが、ヨーロッパの考古学では、この問題はより複雑であることが示されている。ヨーロッパへの人類の拡散の時 期には、さまざまな石器技術が存在し、現代的な行動の証拠を示している。特定の道具と文化集団を混同する問題はあるものの、例えばオーリニャック文化の道 具群は一般的に純粋に現生人類の証拠とみなされている。[65][66] 「原オーリニャック文化」のような「移行期」の道具群の発見は、 「技術革新の段階」を経て進歩した人類集団の証拠とみなされている。[65] この説が正しいとすると、人類集団はすでに4万年前頃には東ヨーロッパに移住しており、その後にのみ行動様式の現代性の証拠が現れたことになる。そうだと すれば、認知の変化はアフリカに逆流して広がったか、あるいは移住以前からすでに存在していたはずである。 ネアンデルタール人の文化や道具の複合体の証拠が増えていることを踏まえ、一部の研究者は行動の近代性について「複数の種モデル」を提示している。[6] [28][67] ネアンデルタール人は進化の行き止まりであり、類人猿の近縁種で、同時代のヒトよりも進歩が遅れていたとよく言及されていた。 装身具は、ホモ・サピエンスが制作した洞窟壁画と比較すると、安っぽい模造品や安物のアクセサリーに過ぎなかった。しかし、ヨーロッパでは、ネアンデル タール人が制作した様々な装飾品や芸術品が発見されている。例えば、ネアンデルタール人の遺跡であるグロット・デュ・レンヌからは、クマ、オオカミ、キツ ネの門歯に溝を入れたものや、黄土色やその他の象徴的な人工物が出土している。 。 数は少なく、論争の的となっているが、ネアンデルタール人の儀式的埋葬の状況証拠も発見されている。[28] ネアンデルタール人のこの象徴的な行動を説明するには、2つの選択肢がある。すなわち、彼らは到着した新人類から文化的な特徴を模倣したか、あるいは彼ら 自身の文化伝統が比較的新しい行動様式と一致していたかのいずれかである。もし彼らが文化伝統を模倣しただけだとしたら、これは複数の著者によって議論さ れているが[6][28]、彼らは行動の現代性によって説明される複雑な文化の能力を依然として有していたことになる。上述の通り、ネアンデルタール人も 「行動の面で現代性」を持っていたとすれば、それは種特異的な派生形質であるはずがない。 |

| Asia Most debates surrounding behavioral modernity have been focused on Africa or Europe but an increasing amount of focus has been placed on East Asia. This region offers a unique opportunity to test hypotheses of multi-regionalism, replacement, and demographic effects.[68] Unlike Europe, where initial migration occurred around 50,000 years ago, human remains have been dated in China to around 100,000 years ago.[69] This early evidence of human expansion calls into question behavioral modernity as an impetus for migration. Stone tool technology is particularly of interest in East Asia. Following Homo erectus migrations out of Africa, Acheulean technology never seems to appear beyond present-day India and into China. Analogously, Mode 3, or Levallois technology, is not apparent in China following later hominin dispersals.[70] This lack of more advanced technology has been explained by serial founder effects and low population densities out of Africa.[71] Although tool complexes comparative to Europe are missing or fragmentary, other archaeological evidence shows behavioral modernity. For example, the peopling of the Japanese archipelago offers an opportunity to investigate the early use of watercraft. Although one site, Kanedori in Honshu, does suggest the use of watercraft as early as 84,000 years ago, there is no other evidence of hominins in Japan until 50,000 years ago.[68] The Zhoukoudian cave system near Beijing has been excavated since the 1930s and has yielded precious data on early human behavior in East Asia. Although disputed, there is evidence of possible human burials and interred remains in the cave dated to around 34–20,000 years ago.[68] These remains have associated personal ornaments in the form of beads and worked shell, suggesting symbolic behavior. Along with possible burials, numerous other symbolic objects like punctured animal teeth and beads, some dyed in red ochre, have all been found at Zhoukoudian.[68] Although fragmentary, the archaeological record of eastern Asia shows evidence of behavioral modernity before 50,000 years ago but, like the African record, it is not fully apparent until that time. |

アジア 行動的近代性に関する議論のほとんどは、アフリカまたはヨーロッパに焦点を当ててきたが、近年は東アジアに注目が集まることが多くなっている。この地域 は、多地域主義、代替、人口動態効果に関する仮説を検証するユニークな機会を提供している。[68] 5万年前に最初の移住が発生したヨーロッパとは異なり、中国では人骨が約10万年前のものであることが判明している。[69] 人類の拡大を示すこの初期の証拠は、移住の推進力としての行動的近代性に疑問を投げかける。 東アジアでは、特に石器技術が注目に値する。ホモ・エレクトゥスがアフリカから移住した後、アシュール技術は現在のインドを越えて中国にまで広がった形跡 はない。同様に、モード3、またはレヴァロワ技術は、それ以降の人類の拡散の後、中国では見られない。[70] このより高度な技術の欠如は、連続創始者効果とアフリカ国外での人口密度の低さによって説明されている。[71] ヨーロッパと比較できるほどの複雑な道具は見つかっていないか、断片的なものしかないが、他の考古学的証拠は行動の近代性を示している。例えば、日本列島 への人類の移住は、初期の船舶利用を調査する機会を提供する。本州の金通遺跡では、8万4千年前にはすでに船舶が使われていたことを示す証拠があるが、日 本におけるヒト属の他の証拠は、5万年前まで存在していない。 北京近郊にある周口店洞窟群は1930年代から発掘調査が行われており、東アジアにおける初期の人類の行動に関する貴重なデータが得られている。議論の余 地はあるものの、この洞窟では約3万4000年から2万年前の人間の埋葬と埋葬された遺跡の可能性を示す証拠が発見されている。[68] これらの遺跡には、ビーズや加工された貝殻などの装飾品が伴っており、象徴的な行動を示唆している。周口店では、穴の開いた動物の歯やビーズなど、多数の 他の象徴的な物品も、穴を掘って埋葬された可能性のあるものと共に発見されている。その中には、赤色黄土で染色されたものもある。[68] 断片的ではあるが、東アジアの考古学的記録には、5万年前より前の行動の現代的傾向を示す証拠が認められる。しかし、アフリカの記録と同様に、その時点ま では完全に明白ではない。 |

| Anatomically modern human Archaic Homo sapiens Blombos Cave Cultural universal Dawn of Humanity (film) Evolution of human intelligence Female cosmetic coalitions FOXP2 and human evolution Human evolution List of Stone Age art Origin of language Origins of society Prehistoric art Prehistoric music Paleolithic religion Recent African origin Sibudu Cave Sociocultural evolution Symbolism (disambiguation) Symbolic culture Timeline of evolution |

解剖学的現生人類 旧人類ホモ・サピエンス ブロムボス洞窟 文化の普遍性 人類の夜明け(映画) 人類の知性の進化 女性化粧連合 FOXP2と人類の進化 人類の進化 石器時代の芸術の一覧 言語の起源 社会の起源 先史時代の芸術 先史時代の音楽 旧石器時代の宗教 最近のアフリカ起源 シブドゥ洞窟 社会文化進化 象徴(曖昧さ回避) 象徴文化 進化のタイムライン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavioral_modernity |

***

| Forkhead box protein

P2 (FOXP2) is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the FOXP2 gene.

FOXP2 is a member of the forkhead box family of transcription factors,

proteins that regulate gene expression by binding to DNA. It is

expressed in the brain, heart, lungs and digestive system.[5][6] FOXP2 is found in many vertebrates, where it plays an important role in mimicry in birds (such as birdsong) and echolocation in bats. FOXP2 is also required for the proper development of speech and language in humans.[7] In humans, mutations in FOXP2 cause the severe speech and language disorder developmental verbal dyspraxia.[7][8] Studies of the gene in mice and songbirds indicate that it is necessary for vocal imitation and the related motor learning.[9][10][11] Outside the brain, FOXP2 has also been implicated in development of other tissues such as the lung and digestive system.[12] Initially identified in 1998 as the genetic cause of a speech disorder in a British family designated the KE family, FOXP2 was the first gene discovered to be associated with speech and language[13] and was subsequently dubbed "the language gene".[14] However, other genes are necessary for human language development, and a 2018 analysis confirmed that there was no evidence of recent positive evolutionary selection of FOXP2 in humans.[15][16] |

フォークヘッドボックスタンパク質P2(FOXP2)は、ヒトでは

FOXP2遺伝子によってコードされるタンパク質である。FOXP2は、DNAに結合することで遺伝子発現を調節するタンパク質である転写因子フォーク

ヘッドボックスファミリーの一員である。FOXP2は、脳、心臓、肺、消化器系で発現している。[5][6] FOXP2は多くの脊椎動物に存在し、鳥類では模倣(さえずりなど)に、コウモリでは反響定位に重要な役割を果たしている。FOXP2はまた、ヒトの言語 および音声の正常な発達にも必要である。[7]ヒトでは、FOXP2の突然変異が重度の言語障害である発達性言語性協調運動障害を引き起こす。[7] [8]マウスと鳴禽類の遺伝子研究により、 鳴禽類の研究では、この遺伝子は声帯模倣と関連する運動学習に必要であることが示されている。[9][10][11] 脳以外では、FOXP2は肺や消化器系などの他の組織の成長にも関与していることが示唆されている。[12] 1998年にイギリスのKE家と呼ばれる家族における言語障害の遺伝的原因として最初に特定されたFOXP2は、言語と関連があることが発見された最初の 遺伝子であり[13]、その後「言語遺伝子」と呼ばれるようになった[14]。言語遺伝子」と呼ばれるようになった。[14] しかし、人間の言語発達には他の遺伝子も必要であり、2018年の分析では、FOXP2が人間において最近ポジティブな進化選択を受けたという証拠は見つ からなかったことが確認された。[15][16] |

Structure and function Foxp2 is expressed in the developing cerebellum and the hindbrain of the embryonic day 13.5 mouse. Allen Brain Atlases As a FOX protein, FOXP2 contains a forkhead-box domain. In addition, it contains a polyglutamine tract, a zinc finger and a leucine zipper. The protein attaches to the DNA of other proteins and controls their activity through the forkhead-box domain. Only a few targeted genes have been identified, however researchers believe that there could be up to hundreds of other genes targeted by the FOXP2 gene. The forkhead box P2 protein is active in the brain and other tissues before and after birth, and many studies show that it is paramount for the growth of nerve cells and transmission between them. The FOXP2 gene is also involved in synaptic plasticity, making it imperative for learning and memory.[17] FOXP2 is required for proper brain and lung development. Knockout mice with only one functional copy of the FOXP2 gene have significantly reduced vocalizations as pups.[18] Knockout mice with no functional copies of FOXP2 are runted, display abnormalities in brain regions such as the Purkinje layer, and die an average of 21 days after birth from inadequate lung development.[12] FOXP2 is expressed in many areas of the brain,[19] including the basal ganglia and inferior frontal cortex, where it is essential for brain maturation and speech and language development.[20] In mice, the gene was found to be twice as highly expressed in male pups than female pups, which correlated with an almost double increase in the number of vocalisations the male pups made when separated from mothers. Conversely, in human children aged 4–5, the gene was found to be 30% more expressed in the Broca's areas of female children. The researchers suggested that the gene is more active in "the more communicative sex".[21][22] The expression of FOXP2 is subject to post-transcriptional regulation, particularly microRNA (miRNA), causing the repression of the FOXP2 3' untranslated region.[23] Three amino acid substitutions distinguish the human FOXP2 protein from that found in mice, while two amino acid substitutions distinguish the human FOXP2 protein from that found in chimpanzees,[19] but only one of these changes is unique to humans.[12] Evidence from genetically manipulated mice[24] and human neuronal cell models[25] suggests that these changes affect the neural functions of FOXP2. |

構造と機能 FOXP2は、発生中の小脳および胎生13.5日目のマウスの後脳で発現している。 アレン脳アトラス FOXタンパク質として、FOXP2はフォークヘッドボックスドメインを含む。 さらに、ポリグルタミン・トラクト、ジンクフィンガー、およびロイシンジッパーも含む。 このタンパク質は他のタンパク質のDNAに結合し、フォークヘッドボックスドメインを介してそれらの活性を制御する。標的となる遺伝子はまだわずかしか特 定されていないが、FOXP2遺伝子によって標的となる遺伝子は数百に上る可能性があると研究者らは考えている。フォークヘッドボックスP2タンパク質 は、出生前および出生後の脳やその他の組織で活性化しており、神経細胞の成長と神経細胞間の伝達に極めて重要であることを示す研究結果が数多く発表されて いる。FOXP2遺伝子はシナプス可塑性にも関与しており、学習と記憶に不可欠である。 FOXP2は、脳と肺の正常な発達に必要である。FOXP2遺伝子の機能コピーが1つしかないノックアウトマウスは、仔マウスとして発声が著しく減少して いる。[18]FOXP2の機能コピーが全くないノックアウトマウスは、低身長で、プルキンエ層などの脳領域に異常が見られ、肺の発育不全により出生後平 均21日で死亡する。[12] FOXP2は脳の多くの領域で発現しており、大脳基底核や下前頭皮質など、脳の成熟や言語発達に不可欠な部位も含まれる。[20] マウスでは、この遺伝子はメスの子マウスよりもオスの子マウスで2倍も多く発現していることが判明しており、これは母親から引き離されたオスの子マウスが 発する鳴き声の数がほぼ2倍に増加することと相関している。逆に、4~5歳の人間の子供の場合、この遺伝子は女性のブローカ領域で30%多く発現している ことが分かった。研究者らは、この遺伝子は「よりコミュニケーション能力の高い性別」でより活発であると示唆している。[21][22] FOXP2の発現は、特にマイクロRNA(miRNA)による転写後調節の影響を受け、FOXP2の3'非翻訳領域の抑制を引き起こす。 ヒトのFOXP2タンパク質は、3つのアミノ酸置換によりマウスで見られるものとは区別されるが、2つのアミノ酸置換によりチンパンジーで見られるものと も区別される。[19] しかし、これらの変化のうちヒトに特有なものは1つだけである。[12] 遺伝子操作されたマウス[24] およびヒト神経細胞モデル[25] からの証拠は、これらの変化がFOXP2の神経機能に影響を及ぼすことを示唆している。 |

| Clinical significance The FOXP2 gene has been implicated in several cognitive functions including; general brain development, language, and synaptic plasticity. The FOXP2 gene region acts as a transcription factor for the forkhead box P2 protein. Transcription factors affect other regions, and the forkhead box P2 protein has been suggested to also act as a transcription factor for hundreds of genes. This prolific involvement opens the possibility that the FOXP2 gene is much more extensive than originally thought.[17] Other targets of transcription have been researched without correlation to FOXP2. Specifically, FOXP2 has been investigated in correlation with autism and dyslexia, however with no mutation was discovered as the cause.[26][8] One well identified target is language.[27] Although some research disagrees with this correlation,[28] the majority of research shows that a mutated FOXP2 causes the observed production deficiency.[17][27][29][26][30][31] There is some evidence that the linguistic impairments associated with a mutation of the FOXP2 gene are not simply the result of a fundamental deficit in motor control. Brain imaging of affected individuals indicates functional abnormalities in language-related cortical and basal ganglia regions, demonstrating that the problems extend beyond the motor system.[32] Mutations in FOXP2 are among several (26 genes plus 2 intergenic) loci which correlate to ADHD diagnosis in adults – clinical ADHD is an umbrella label for a heterogeneous group of genetic and neurological phenomena which may result from FOXP2 mutations or other causes.[33] A 2020 genome-wide association study (GWAS) implicates single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of FOXP2 in susceptibility to cannabis use disorder.[34] |

臨床的意義 FOXP2遺伝子は、一般的な脳の発達、言語、シナプス可塑性など、いくつかの認知機能に関与している。FOXP2遺伝子領域は、フォークヘッドボックス P2タンパク質の転写因子として作用する。転写因子は他の領域に影響を及ぼし、フォークヘッドボックスP2タンパク質は数百の遺伝子の転写因子としても作 用することが示唆されている。この多岐にわたる関与により、FOXP2遺伝子が当初考えられていたよりもはるかに広範囲にわたる可能性がある。[17] 転写の他の標的は、FOXP2との関連性なしに研究されている。特に、FOXP2は自閉症や失読症との関連で調査されてきたが、原因となる突然変異は発見 されていない。[26][8] よく知られている標的のひとつは言語である。[27] 一部の研究ではこの関連性に異論を唱えているが、[28] ほとんどの研究では、突然変異したFOXP2が観察された産生不足の原因であることを示している。[17][27][29][26][30][31] FOXP2遺伝子の変異に関連する言語障害は、単に運動制御の根本的な欠陥の結果ではないことを示すいくつかの証拠がある。障害を持つ患者の脳画像では、 言語に関連する大脳皮質および大脳基底核の領域に機能異常が認められ、問題が運動系を超えて広がっていることが示されている。 FOXP2の突然変異は、成人におけるADHD診断と相関するいくつかの遺伝子座(26の遺伝子と2つの遺伝子間領域)の1つである。臨床的なADHD は、FOXP2の突然変異やその他の原因によって生じる可能性がある、遺伝的および神経学的現象の多様なグループに対する包括的なラベルである。 2020年のゲノムワイド関連解析(GWAS)では、FOXP2の単一ヌクレオチド多型(SNP)が大麻使用障害の感受性に関与していることが示唆されている。[34] |

| Language disorder It is theorized that the translocation of the 7q31.2 region of the FOXP2 gene causes a severe language impairment called developmental verbal dyspraxia (DVD)[27] or childhood apraxia of speech (CAS)[35] So far this type of mutation has only been discovered in three families across the world including the original KE family.[31] A missense mutation causing an arginine-to-histidine substitution (R553H) in the DNA-binding domain is thought to be the abnormality in KE.[36] This would cause a normally basic residue to be fairly acidic and highly reactive at the body's pH. A heterozygous nonsense mutation, R328X variant, produces a truncated protein involved in speech and language difficulties in one KE individual and two of their close family members. R553H and R328X mutations also affected nuclear localization, DNA-binding, and the transactivation (increased gene expression) properties of FOXP2.[8] These individuals present with deletions, translocations, and missense mutations. When tasked with repetition and verb generation, these individuals with DVD/CAS had decreased activation in the putamen and Broca's area in fMRI studies. These areas are commonly known as areas of language function.[37] This is one of the primary reasons that FOXP2 is known as a language gene. They have delayed onset of speech, difficulty with articulation including slurred speech, stuttering, and poor pronunciation, as well as dyspraxia.[31] It is believed that a major part of this speech deficit comes from an inability to coordinate the movements necessary to produce normal speech including mouth and tongue shaping.[27] Additionally, there are more general impairments with the processing of the grammatical and linguistic aspects of speech.[8] These findings suggest that the effects of FOXP2 are not limited to motor control, as they include comprehension among other cognitive language functions. General mild motor and cognitive deficits are noted across the board.[29] Clinically these patients can also have difficulty coughing, sneezing, or clearing their throats.[27] While FOXP2 has been proposed to play a critical role in the development of speech and language, this view has been challenged by the fact that the gene is also expressed in other mammals as well as birds and fish that do not speak.[38] It has also been proposed that the FOXP2 transcription-factor is not so much a hypothetical 'language gene' but rather part of a regulatory machinery related to externalization of speech.[39] |

言語障害 FOXP2遺伝子の7q31.2領域の転座が、発達性言語性ジストニア(DVD)[27]または小児失語症(CAS)[35]と呼ばれる重度の言語障害を 引き起こすという説がある。これまでに、このタイプの突然変異は、 。DNA結合ドメインにおけるアルギニンからヒスチジンへの置換(R553H)を引き起こすミスセンス変異が、KEの異常であると考えられている。 [36] これにより、通常は塩基性の残基がかなり酸性となり、体内のpHで非常に反応性が高くなる。ヘテロ接合性ナンセンス変異であるR328X変異は、1人の KE患者と2人の近親者の言語障害に関与する短縮タンパク質を生成する。R553HとR328Xの変異は、FOXP2の核局在、DNA結合、および転写活 性化(遺伝子発現の増加)特性にも影響を及ぼす。 これらの人々は、欠失、転座、ミスセンス変異を呈する。DVD/CASを持つ人々に対して反復や動詞生成を課題とした場合、fMRI研究において、これら の人々は被殻およびブローカ領域の活性化が低下していた。これらの領域は一般的に言語機能領域として知られている。[37] これがFOXP2が言語遺伝子として知られている主な理由のひとつである。彼らは言語発達の遅れ、不明瞭な発音、吃音、発音障害、および協調運動障害を示 す。[31] この言語障害の主な原因は、正常な言語発声に必要な口や舌の動きを調整できないことにあると考えられている。。さらに、言語の文法および言語学的な側面の 処理にも、より一般的な障害がある。[8] これらの知見は、FOXP2の影響が運動制御に限られたものではないことを示唆している。なぜなら、他の認知言語機能の中には理解力も含まれるからだ。全 般的な軽度の運動および認知障害は、全般的に認められる。[29] 臨床的には、これらの患者は咳やくしゃみ、または喉のつまりを解消することが困難である。[27] FOXP2は言語および音声の発達に重要な役割を果たしていると提唱されているが、この見解は、この遺伝子が、言葉を話さない鳥類や魚類だけでなく、他の 哺乳類にも発現しているという事実によって疑問視されている。[38] また、FOXP2転写因子は、仮説上の「言語遺伝子」というよりも、むしろ音声の外部化に関連する制御機構の一部であるという見解も示されている。 [39] |

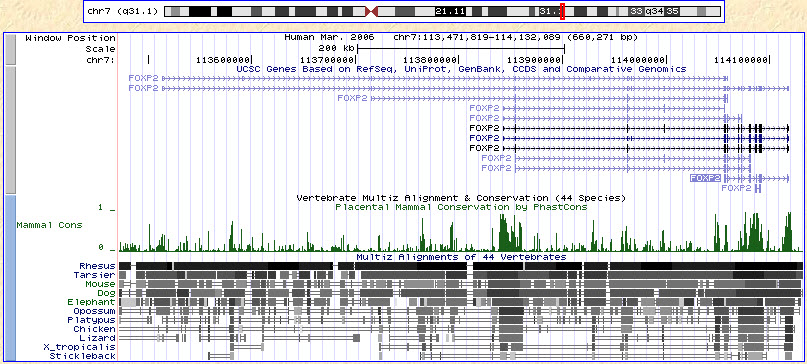

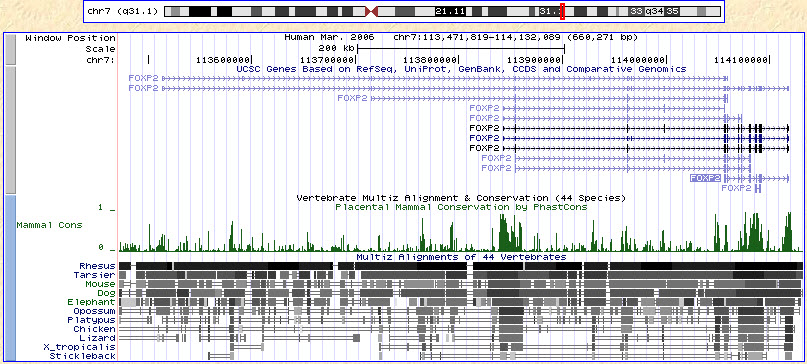

Evolution Human FOXP2 gene and evolutionary conservation is shown in a multiple alignment (at bottom of figure) in this image from the UCSC Genome Browser. Note that conservation tends to cluster around coding regions (exons). The FOXP2 gene is highly conserved in mammals.[19] The human gene differs from that in non-human primates by the substitution of two amino acids, a threonine to asparagine substitution at position 303 (T303N) and an asparagine to serine substitution at position 325 (N325S).[36] In mice it differs from that of humans by three substitutions, and in zebra finch by seven amino acids.[19][40][41] One of the two amino acid differences between human and chimps also arose independently in carnivores and bats.[12][42] Similar FOXP2 proteins can be found in songbirds, fish, and reptiles such as alligators.[43][44] DNA sampling from Homo neanderthalensis bones indicates that their FOXP2 gene is a little different though largely similar to those of Homo sapiens (i.e. humans).[45][46] Previous genetic analysis had suggested that the H. sapiens FOXP2 gene became fixed in the population around 125,000 years ago.[47] Some researchers consider the Neanderthal findings to indicate that the gene instead swept through the population over 260,000 years ago, before our most recent common ancestor with the Neanderthals.[47] Other researchers offer alternative explanations for how the H. sapiens version would have appeared in Neanderthals living 43,000 years ago.[47] According to a 2002 study, the FOXP2 gene showed indications of recent positive selection.[19][48] Some researchers have speculated that positive selection is crucial for the evolution of language in humans.[19] Others, however, were unable to find a clear association between species with learned vocalizations and similar mutations in FOXP2.[43][44] A 2018 analysis of a large sample of globally distributed genomes confirmed there was no evidence of positive selection, suggesting that the original signal of positive selection may be driven by sample composition.[15][16] Insertion of both human mutations into mice, whose version of FOXP2 otherwise differs from the human and chimpanzee versions in only one additional base pair, causes changes in vocalizations as well as other behavioral changes, such as a reduction in exploratory tendencies, and a decrease in maze learning time. A reduction in dopamine levels and changes in the morphology of certain nerve cells are also observed.[24] |

進化 ヒトFOXP2遺伝子と進化上の保存は、UCSC Genome Browserのこの画像のマルチプルアラインメント(図の下部)に示されている。保存はコード領域(エクソン)の周辺に集まる傾向があることに注目。 FOXP2遺伝子は哺乳類において高度に保存されている。[19]ヒトの遺伝子は、303番目の位置のアミノ酸がスレオニンからアスパラギンに置換 (T303N)し、325番目の位置のアミノ酸がアスパラギンからセリンに置換(N325S)している点で、非ヒト霊長類の遺伝子と異なる。[36]マウ スでは、 ヒトとは3つのアミノ酸置換で異なり、キンカチョウでは7つのアミノ酸で異なる。[19][40][41] ヒトとチンパンジーの2つのアミノ酸の差延のうちの1つは、肉食動物やコウモリでも独立して生じている。[12][42] 同様のFOXP2タンパク質は、鳴禽類、魚類、ワニなどの爬虫類にも見られる。[43][44] ホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスの骨から採取したDNAサンプルから、FOXP2遺伝子はホモ・サピエンス(すなわちヒト)のものとほぼ同じだが、若干異な ることが示されている。[45][46] 以前の遺伝子解析では、ホモ・サピエンスのFOXP2遺伝子が集団に定着したのは12万5000年前頃であるとされていた。[47] 一部の ネアンデルタール人の発見は、その遺伝子がネアンデルタール人との最も近い共通祖先よりも前の26万年以上前に集団に広まったことを示すと考える研究者も いる。[47] 他の研究者たちは、4万3千年前に生きていたネアンデルタール人の中に現れたはずのヒト属版FOXP2遺伝子について、別の説明を提示している。[47] 2002年の研究によると、FOXP2遺伝子は最近のポジティブ選択の兆候を示していた。[19][48] ポジティブ選択は、ヒトの言語進化に不可欠であると推測する研究者もいる。[19] しかし、学習した発声とFOXP2の類似した変異との間に明確な関連性を見いだせない研究者もいる。[43][44] 2018年の分析では、世界中に分布する多数のゲノムサンプルを分析した結果、 ゲノムの大規模サンプルの分析により、ポジティブ選択の証拠は見つからなかったことが確認され、ポジティブ選択の最初の兆候はサンプル構成によって引き起 こされた可能性があることが示唆された。[15][16] ヒトの変異を両方ともマウスに挿入すると、FOXP2のバージョンはヒトやチンパンジーのバージョンとは1つの追加塩基対のみで異なるが、発声の変化だけ でなく、探索傾向の減少や迷路学習時間の減少などの他の行動変化も引き起こされる。ドーパミンレベルの低下と特定の神経細胞の形態の変化も観察されてい る。[24] |

| Interactions FOXP2 is known to regulate CNTNAP2, CTBP1,[49] SRPX2 and SCN3A.[50][20][51] FOXP2 downregulates CNTNAP2, a member of the neurexin family found in neurons. CNTNAP2 is associated with common forms of language impairment.[52] FOXP2 also downregulates SRPX2, the 'Sushi Repeat-containing Protein X-linked 2'.[53][54] It directly reduces its expression, by binding to its gene's promoter. SRPX2 is involved in glutamatergic synapse formation in the cerebral cortex and is more highly expressed in childhood. SRPX2 appears to specifically increase the number of glutamatergic synapses in the brain, while leaving inhibitory GABAergic synapses unchanged and not affecting dendritic spine length or shape. On the other hand, FOXP2's activity does reduce dendritic spine length and shape, in addition to number, indicating it has other regulatory roles in dendritic morphology.[53] |

相互作用 FOXP2はCNTNAP2、CTBP1、[49] SRPX2、SCN3Aを調節することが知られている。[50][20][51] FOXP2はニューロンに存在するニューレキシンファミリーの一員であるCNTNAP2をダウンレギュレートする。CNTNAP2は一般的な言語障害と関連している。[52] FOXP2はまた、SRPX2(「Sushi Repeat-containing Protein X-linked 2」)もダウンレギュレートする。[53][54] SRPX2は、大脳皮質におけるグルタミン酸作動性シナプスの形成に関与しており、小児期により多く発現する。SRPX2は、脳内のグルタミン酸作動性シ ナプスの数を特に増加させるようだが、抑制性のGABA作動性シナプスには変化はなく、樹状突起の棘の長さや形状にも影響しない。一方、FOXP2の活性 は、数に加えて樹状突起の棘の長さや形状も減少させることから、樹状突起の形態に他の調節作用があることが示唆される。[53] |

| In other animals Chimpanzees In chimpanzees, FOXP2 differs from the human version by two amino acids.[55] A study in Germany sequenced FOXP2's complementary DNA in chimps and other species to compare it with human complementary DNA in order to find the specific changes in the sequence.[19] FOXP2 was found to be functionally different in humans compared to chimps. Since FOXP2 was also found to have an effect on other genes, its effects on other genes is also being studied.[56] Researchers deduced that there could also be further clinical applications in the direction of these studies in regards to illnesses that show effects on human language ability.[25] Mice In a mouse FOXP2 gene knockouts, loss of both copies of the gene causes severe motor impairment related to cerebellar abnormalities and lack of ultrasonic vocalisations normally elicited when pups are removed from their mothers.[18] These vocalizations have important communicative roles in mother–offspring interactions. Loss of one copy was associated with impairment of ultrasonic vocalisations and a modest developmental delay. Male mice on encountering female mice produce complex ultrasonic vocalisations that have characteristics of song.[57] Mice that have the R552H point mutation carried by the KE family show cerebellar reduction and abnormal synaptic plasticity in striatal and cerebellar circuits.[9] Humanized FOXP2 mice display altered cortico-basal ganglia circuits. The human allele of the FOXP2 gene was transferred into the mouse embryos through homologous recombination to create humanized FOXP2 mice. The human variant of FOXP2 also had an effect on the exploratory behavior of the mice. In comparison to knockout mice with one non-functional copy of FOXP2, the humanized mouse model showed opposite effects when testing its effect on the levels of dopamine, plasticity of synapses, patterns of expression in the striatum and behavior that was exploratory in nature.[24] When FOXP2 expression was altered in mice, it affected many different processes including the learning motor skills and the plasticity of synapses. Additionally, FOXP2 is found more in the sixth layer of the cortex than in the fifth, and this is consistent with it having greater roles in sensory integration. FOXP2 was also found in the medial geniculate nucleus of the mouse brain, which is the processing area that auditory inputs must go through in the thalamus. It was found that its mutations play a role in delaying the development of language learning. It was also found to be highly expressed in the Purkinje cells and cerebellar nuclei of the cortico-cerebellar circuits. High FOXP2 expression has also been shown in the spiny neurons that express type 1 dopamine receptors in the striatum, substantia nigra, subthalamic nucleus and ventral tegmental area. The negative effects of the mutations of FOXP2 in these brain regions on motor abilities were shown in mice through tasks in lab studies. When analyzing the brain circuitry in these cases, scientists found greater levels of dopamine and decreased lengths of dendrites, which caused defects in long-term depression, which is implicated in motor function learning and maintenance. Through EEG studies, it was also found that these mice had increased levels of activity in their striatum, which contributed to these results. There is further evidence for mutations of targets of the FOXP2 gene shown to have roles in schizophrenia, epilepsy, autism, bipolar disorder and intellectual disabilities.[58] |

他の動物では チンパンジー チンパンジーでは、FOXP2はヒトのバージョンと2つのアミノ酸が異なる。[55] ドイツでの研究では、チンパンジーと他の種におけるFOXP2の相補的DNAの塩基配列を決定し、ヒトの相補的DNAと比較することで、塩基配列における 特定の変化を特定した。[19] FOXP2はヒトとチンパンジーで機能的に異なることが判明した。FOXP2は他の遺伝子にも影響を及ぼすことが分かっているため、他の遺伝子への影響に ついても研究が進められている。[56] 研究者らは、人間の言語能力に影響を及ぼす疾患に関する研究の方向性として、さらに臨床応用が可能であると推測している。[25] マウス マウスのFOXP2遺伝子ノックアウトでは、遺伝子の両コピーが失われることで、小脳の異常に関連する重度の運動障害や、通常、子マウスが母親から引き離 された際に発せられる超音波発声の欠如が引き起こされる。[18] これらの発声は、母子間のコミュニケーションにおいて重要な役割を果たしている。コピーの喪失は、超音波発声の障害と軽度の発達遅延と関連していた。雄の マウスが雌のマウスと遭遇すると、歌の特徴を持つ複雑な超音波発声を行う。[57] KEファミリーによって運ばれるR552H点突然変異を持つマウスは、小脳の縮小と線条体および小脳回路における異常なシナプス可塑性を示す。[9] ヒト化FOXP2マウスでは、大脳皮質と線条体の回路に変化が見られる。FOXP2遺伝子のヒト対立遺伝子を相同組み換えによりマウスの胚に導入すること で、ヒト化FOXP2マウスが作られた。また、FOXP2のヒト変異体はマウスの探索行動にも影響を与えた。FOXP2の機能していないコピーを1つ持つ ノックアウトマウスと比較すると、ヒト化マウスモデルでは、ドーパミンレベル、シナプスの可塑性、線条体の発現パターン、探索行動に逆の効果が現れた。 FOXP2の発現がマウスで変化すると、学習運動技能やシナプスの可塑性など、多くの異なるプロセスに影響が及んだ。さらに、FOXP2は大脳皮質第5層 よりも第6層に多く存在しており、感覚統合においてより大きな役割を果たしていることを裏付けている。FOXP2はまた、マウスの脳の側方膝状体に存在し ており、これは聴覚入力が視床を通過する際に通過する処理領域である。その変異は、言語学習の発達を遅らせる役割を果たしていることが分かっている。ま た、大脳皮質小脳回路のプルキンエ細胞や小脳核で高度に発現していることも分かっている。FOXP2は、線条体、黒質、視床下核、腹側被蓋野のドーパミン 受容体1型を発現する有棘ニューロンでも高発現している。FOXP2の突然変異がこれらの脳領域の運動能力に及ぼす悪影響は、研究室での研究課題を通じて マウスで示された。これらのケースにおける脳回路を分析したところ、科学者たちはドーパミンのレベルが高く、樹状突起の長さが減少していることを発見し た。これは長期抑圧の欠陥を引き起こし、運動機能の学習と維持に関与している。また、脳波研究により、これらのマウスでは線条体の活動レベルが高く、これ が結果に寄与していることも分かった。統合失調症、てんかん、自閉症、双極性障害、知的障害に関与することが示されているFOXP2遺伝子の標的の突然変 異に関するさらなる証拠がある。[58] |

| Bats FOXP2 has implications in the development of bat echolocation.[36][42][59] Contrary to apes and mice, FOXP2 is extremely diverse in echolocating bats.[42] Twenty-two sequences of non-bat eutherian mammals revealed a total number of 20 nonsynonymous mutations in contrast to half that number of bat sequences, which showed 44 nonsynonymous mutations.[42] All cetaceans share three amino acid substitutions, but no differences were found between echolocating toothed whales and non-echolocating baleen cetaceans.[42] Within bats, however, amino acid variation correlated with different echolocating types.[42] Birds In songbirds, FOXP2 most likely regulates genes involved in neuroplasticity.[10][60] Gene knockdown of FOXP2 in area X of the basal ganglia in songbirds results in incomplete and inaccurate song imitation.[10] Overexpression of FOXP2 was accomplished through injection of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 (AAV1) into area X of the brain. This overexpression produced similar effects to that of knockdown; juvenile zebra finch birds were unable to accurately imitate their tutors.[61] Similarly, in adult canaries, higher FOXP2 levels also correlate with song changes.[41] Levels of FOXP2 in adult zebra finches are significantly higher when males direct their song to females than when they sing song in other contexts.[60] "Directed" singing refers to when a male is singing to a female usually for a courtship display. "Undirected" singing occurs when for example, a male sings when other males are present or is alone.[62] Studies have found that FoxP2 levels vary depending on the social context. When the birds were singing undirected song, there was a decrease of FoxP2 expression in Area X. This downregulation was not observed and FoxP2 levels remained stable in birds singing directed song.[60] Differences between song-learning and non-song-learning birds have been shown to be caused by differences in FOXP2 gene expression, rather than differences in the amino acid sequence of the FOXP2 protein. Zebrafish In zebrafish, FOXP2 is expressed in the ventral and dorsal thalamus, telencephalon, diencephalon where it likely plays a role in nervous system development. The zebrafish FOXP2 gene has an 85% similarity to the human FOX2P ortholog.[63] |

コウモリ FOXP2は、コウモリのエコーロケーション能力の発達に影響を与えている可能性がある。[36][42][59] エコーロケーション能力を持つコウモリでは、FOXP2は類人猿やマウスとは対照的に、きわめて多様である。[42] コウモリ以外の真獣類の22の配列では、20の非同義突然変異が確認されたが、 一方、コウモリの配列では、非同義置換は44個であった。[42] すべてのクジラ類は3つのアミノ酸置換を共有しているが、エコーロケーションを行う歯クジラ類と、エコーロケーションを行わないヒゲクジラ類との間には差 異は認められなかった。[42] しかし、コウモリ類内では、アミノ酸の変異は異なるエコーロケーションの種類と相関していた。[42] 鳥類 鳴禽類では、FOXP2は神経可塑性に関与する遺伝子を制御している可能性が高い。[10][60] 鳴禽類の基底核のX領域におけるFOXP2遺伝子のノックダウンにより、不完全で不正確な歌の模倣が生じる。[10] FOXP2の過剰発現は、脳のX領域へのアデノ随伴ウイルス1型(AAV1)の注入により達成された。この過剰発現はノックダウンの場合と同様の影響をも たらし、幼いキンカチョウは正確に模倣することができなかった。[61] 同様に、成鳥のカナリアでもFOXP2のレベルが高いとさえずりに変化が現れる。[41] オスのセイキインコがメスに向けて歌う場合、他の状況で歌う場合よりも、成鳥のFOXP2レベルが著しく高くなる。[60] 「指示された」歌とは、通常、求愛行動としてオスがメスに向けて歌うことを指す。「指示されていない」歌は、例えば他のオスがいる場合や、オスが単独で歌 う場合などに発生する。[62] 研究により、FoxP2レベルは社会的文脈によって異なることが分かっている。鳥が非指向性歌を歌っているときは、X領域におけるFOXP2の発現が減少 する。この発現低下は観察されず、指向性歌を歌っている鳥ではFOXP2レベルは安定している。 歌を学習する鳥と歌を学習しない鳥との差異は、FOXP2タンパクのアミノ酸配列の差異よりも、FOXP2遺伝子の発現の差異によって生じていることが示されている。 ゼブラフィッシュ ゼブラフィッシュでは、FOXP2は腹側および背側視床、終脳、間脳で発現しており、神経系の発達に何らかの役割を果たしていると考えられる。ゼブラフィッシュのFOXP2遺伝子は、ヒトのFOX2Pオルソログと85%の類似性がある。[63] |

| History FOXP2 and its gene were discovered as a result of investigations on an English family known as the KE family, half of whom (15 individuals across three generations) had a speech and language disorder called developmental verbal dyspraxia. Their case was studied at the Institute of Child Health of University College London.[64] In 1990, Myrna Gopnik, Professor of Linguistics at McGill University, reported that the disorder-affected KE family had severe speech impediment with incomprehensible talk, largely characterized by grammatical deficits.[65] She hypothesized that the basis was not of learning or cognitive disability, but due to genetic factors affecting mainly grammatical ability.[66] (Her hypothesis led to a popularised existence of "grammar gene" and a controversial notion of grammar-specific disorder.[67][68]) In 1995, the University of Oxford and the Institute of Child Health researchers found that the disorder was purely genetic.[69] Remarkably, the inheritance of the disorder from one generation to the next was consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance, i.e., mutation of only a single gene on an autosome (non-sex chromosome) acting in a dominant fashion. This is one of the few known examples of Mendelian (monogenic) inheritance for a disorder affecting speech and language skills, which typically have a complex basis involving multiple genetic risk factors.[70] The FOXP2 gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 7, at position 31. In 1998, Oxford University geneticists Simon Fisher, Anthony Monaco, Cecilia S. L. Lai, Jane A. Hurst, and Faraneh Vargha-Khadem identified an autosomal dominant monogenic inheritance that is localized on a small region of chromosome 7 from DNA samples taken from the affected and unaffected members.[5] The chromosomal region (locus) contained 70 genes.[71] The locus was given the official name "SPCH1" (for speech-and-language-disorder-1) by the Human Genome Nomenclature committee. Mapping and sequencing of the chromosomal region was performed with the aid of bacterial artificial chromosome clones.[6] Around this time, the researchers identified an individual who was unrelated to the KE family but had a similar type of speech and language disorder. In this case, the child, known as CS, carried a chromosomal rearrangement (a translocation) in which part of chromosome 7 had become exchanged with part of chromosome 5. The site of breakage of chromosome 7 was located within the SPCH1 region.[6] In 2001, the team identified in CS that the mutation is in the middle of a protein-coding gene.[7] Using a combination of bioinformatics and RNA analyses, they discovered that the gene codes for a novel protein belonging to the forkhead-box (FOX) group of transcription factors. As such, it was assigned with the official name of FOXP2. When the researchers sequenced the FOXP2 gene in the KE family, they found a heterozygous point mutation shared by all the affected individuals, but not in unaffected members of the family and other people.[7] This mutation is due to an amino-acid substitution that inhibits the DNA-binding domain of the FOXP2 protein.[72] Further screening of the gene identified multiple additional cases of FOXP2 disruption, including different point mutations[8] and chromosomal rearrangements,[73] providing evidence that damage to one copy of this gene is sufficient to derail speech and language development. |

歴史 FOXP2とその遺伝子は、発達性言語性ジストニアと呼ばれる言語障害を持つイギリス人家族(KE家族)の半数が(3世代15人)が調査の結果発見され た。彼らの症例は、ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジの小児保健研究所で研究された。[64] 1990年、マギル大学言語学教授のマーナ・ゴプニックは、この障害を持つKE家の人々は、文法的な欠陥を主とする、理解不能な深刻な言語障害を抱えてい ると報告した。[6 5] 彼女は、その原因は学習や認知障害ではなく、主に文法能力に影響を与える遺伝的要因によるものだと仮説を立てた。[66](彼女の仮説は、「文法遺伝子」 という概念を一般に広め、文法特異的障害に関する論争的な概念を生み出した。[67][68] 1995年、 オックスフォード大学と小児保健研究所の研究者が、この障害が純粋に遺伝によるものであることを発見した。[69] 驚くべきことに、この障害の世代から世代への遺伝は、常染色体優性遺伝、すなわち、優性遺伝様式で作用する常染色体(性染色体以外の染色体)上の単一遺伝 子の突然変異と一致していた。これは、言語および言語能力に影響を与える障害のメンデル(単一遺伝子)遺伝の数少ない既知の例のひとつであり、通常、複数 の遺伝的リスク要因が複雑に関与している。[70] FOXP2遺伝子は、第7染色体長腕(q)の31番の位置にある。 1998年、オックスフォード大学の遺伝学者であるサイモン・フィッシャー、アンソニー・モナコ、セシリア・S・L・ライ、ジェーン・A・ハース、ファラ ネ・ヴァルガ・ハデムは、 。[5] この染色体領域(遺伝子座)には70の遺伝子が含まれていた。[71] この遺伝子座はヒトゲノム命名委員会により「SPCH1」(言語障害1型)という正式名称が与えられた。この染色体領域のマッピングと配列決定は、バクテ リア人工染色体クローンの助けを借りて行われた。[6] この頃、研究チームはKE家とは無関係だが、同様の言語障害を持つ人物を特定した。このケースでは、CSと呼ばれる子供が、7番染色体の一部が5番染色体 の一部と入れ替わる染色体再編成(転座)を有していた。染色体7の切断部位は、SPCH1領域内に位置していた。[6] 2001年、研究チームはCSにおいて、突然変異がタンパク質をコードする遺伝子の中央に存在することを突き止めた。[7] バイオインフォマティクスとRNA分析を組み合わせた手法により、この遺伝子が転写因子フォークヘッドボックス(FOX)群に属する新規タンパク質をコー ドしていることが発見された。そのため、FOXP2という正式名称が割り当てられた。研究者がKE家のFOXP2遺伝子を配列決定したところ、影響を受け たすべての個体に共通するヘテロ接合型点突然変異が発見されたが、影響を受けていない家族のメンバーや他の人々には見られなかった。[7] この突然変異は、FOXP2タンパク質のDNA結合ドメインを阻害するアミノ酸置換によるものである。FOXP2タンパク質のDNA結合ドメインを阻害す る。[72] さらに遺伝子をスクリーニングしたところ、異なる点変異[8]や染色体再編成[73]を含むFOXP2の破壊の複数の追加例が特定され、この遺伝子のコ ピーが1つ損傷するだけでも、言語および言語発達に支障をきたすのに十分であるという証拠が得られた。 |

| Chimpanzee genome project Evolutionary linguistics FOX proteins Olduvai domain Origin of language Vocal learning |

チンパンジーゲノムプロジェクト 進化言語学 FOXタンパク質 オルドヴァイ領域 言語の起源 声楽学習 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FOXP2 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆