バーナード・マンデヴィル

Bernard Mandeville, 1670-1733

バーナード・マンデヴィル

Bernard Mandeville, 1670-1733

バーナード・マンデヴィル、あるいはマンデビル(Bernard Mandeville,

/ˈmændəvɪ, 1670年11月15日 -

1733年1月21日)は、イギリス系オランダ人の哲学者、政治経済学者、風刺家であった。オランダのロッテルダムに生まれ、生涯のほとんどをイギリスで

過ごし、出版物のほとんどを英語で書いた。『ミツバチの寓話(蜂の寓話)』で有名になった。

| Bernard

Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville (/ˈmændəvɪl/; 15 November 1670 –

21 January 1733), was an Anglo-Dutch philosopher, political economist

and satirist. Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, he lived most of his life

in England and used English for most of his published works. He became

famous for The Fable of the Bees. |

バーナード・マンデヴィル、あるいはマンデビル(Bernard Mandeville, /ˈmændəvɪ, 1670年11月15日 - 1733年1月21日)は、イギリス系オランダ人の哲学者、政治経済学者、風刺家であった。オランダのロッテルダムに生まれ、生涯のほとんどをイギリスで 過ごし、出版物のほとんどを英語で書いた。『ミツバチの寓話(蜂の寓話)』で有名になった。 |

| Mandeville

was born on 15 November 1670, at Rotterdam in the Netherlands, where

his father was a prominent physician of Huguenot origin.[2][3] On

leaving the Erasmus school at Rotterdam he showed his ability by an

Oratio scholastica de medicina (1685), and at Leiden University in 1689

he produced the thesis De brutorum operationibus, in which he advocated

the Cartesian theory of automatism among animals. In 1691 he took his

medical degree, pronouncing an inaugural disputation, De chylosi

vitiata. He moved to England to learn the language,[4] and succeeded so

remarkably that many refused to believe he was a foreigner. His father

had been banished from Rotterdam in 1693 for involvement in the

Costerman tax riots on 5 October 1690; Bernard himself may well have

been involved.[5] As a physician Mandeville was well respected and his literary works were successful as well. His conversational abilities won him the friendship of Lord Macclesfield (chief justice 1710–1718), who introduced him to Joseph Addison, described by Mandeville as "a parson in a tye-wig." He died of influenza on 21 January 1733 at Hackney, aged 62.[6] There is a surviving image of Mandeville but many details of his life still have to be researched. Although the name Mandeville attests a French Huguenot origin, his ancestors had lived in the Netherlands since at least the 16th century.[5] |

ロッ

テルダムのエラスムス学校を出ると、Oratio scholastica de medicina

(1685)でその能力を示し、1689年にライデン大学でDe brutorum

operationibusという論文を発表し、カルテスの動物における自動症説を唱えた。1691年には医学の学位を取得し、「De chylosi

vitiata」という創設時の論争を発表している。彼はイギリスへ渡り、言葉を学び[4]、多くの人が彼が外国人であることを信じないほど、目覚しい成

功を収めた。彼の父親は1690年10月5日のコスターマン税暴動に関与したため、1693年にロッテルダムから追放されており、バーナード自身も関与し

ていた可能性が高い[5]。 医師としてのマンデヴィルは尊敬を集め、彼の文学作品も成功を収めた。彼の会話能力はマクルズフィールド卿(1710-1718)の友好を得、彼はマンデ ヴィルが「タイウィッグを着た牧師」と表現したジョセフ・アディソンに彼を引き合わせた。1733年1月21日にインフルエンザのためハックニーで62歳 で死去した[6]。 マンデヴィルの画像は残っているが、彼の生涯についてはまだ多くの研究が必要である。マンデヴィルという名前はフランスのユグノーに由来することを証明しているが、彼の祖先は少なくとも16世紀以来オランダに住んでいた[5]。 |

| In

1705 he published a poem under the title The Grumbling Hive, or Knaves

Turn'd Honest (two hundred doggerel couplets). In The Grumbling Hive

Mandeville describes a bee community thriving until the bees are

suddenly made honest and virtuous. Without their desire for personal

gain their economy collapses and the remaining bees go to live simple

lives in a hollow tree, thus implying that without private vices there

exists no public benefit.[7] In 1714 the poem was republished as an integral part of the Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits, consisting of a prose commentary, called Remarks, and an essay, An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue. The book was primarily written as a political satire on the state of England in 1705, when the Tories were accusing John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, and the ministry of advocating the War of the Spanish Succession for personal reasons.[6] In 1723 a later edition appeared, including An Essay on Charity and Charity Schools, and A Search into the Nature of Society. The former essay criticised the charity schools, designed to educate the poor and, in doing so, instil virtue in them. Mandeville disagreed with the idea that education adds virtue because he did not believe that evil desires existed only in the poor, but rather he saw the educated and wealthy as much more crafty.[7] Mandeville also believed that educating the poor increased their desires for material things, defeating the purpose of the school and making it more difficult to provide for them.[8] It was vigorously combatted by, among others, Bishop Berkeley and William Law, author of The Serious Call, and in 1729 was made the subject of a prosecution for its immoral tendency. |

1705

年には『The Grumbling Hive, or Knaves Turn'd

Honest』(200のドージェレル連句)というタイトルの詩を発表している。この詩の中でマンデヴィルは、蜜蜂が突然、正直で高潔な性格に変わるま

で、蜜蜂のコミュニティが繁栄していたことを描写している。個人的な利益に対する欲求がなければ、彼らの経済は崩壊し、残った蜂は空洞の木の中で簡素な生

活を送るようになり、したがって、私的な悪徳がなければ公共の利益は存在しないことを暗示している[7]。 1714年、この詩は『蜜蜂の寓話:あるいは私的悪徳、公的利益』の一部として再出版され、『備考』という散文の解説と『道徳的美徳の起源に関する探究』 というエッセイから構成されている。この本は主に、1705年のイギリスの状態を風刺するために書かれたもので、当時、トーリー派は、個人的な理由でスペ イン継承戦争を提唱したジョン・チャーチル(第1代マールボロ公)と省を非難していた[6]。 1723年には、『慈善事業と慈善学校に関するエッセイ』と『社会の本質を探る』を含む後期版が出版された。前者は、貧しい人々を教育し、それによって美 徳を身につけさせることを目的とした慈善学校を批判している。マンデヴィルは、教育が徳をつけるという考えに反対であった。彼は、悪しき欲望が貧しい人々 にのみ存在するとは考えず、むしろ教育を受けた裕福な人々の方がずっと狡猾であると考えたからである[7]。 [7] またマンデヴィルは、貧者を教育すると物質的な欲望が高まり、学校の目的が失われ、彼らを養うことが難しくなると考えた[8]。 バークレー司教や『真剣勝負』の著者ウィリアム・ローらによって精力的に闘われ、1729年にはその不道徳な傾向から訴追対象とされた。 |

| Mandeville's

philosophy gave great offence at the time, and has always been

stigmatised as false, cynical and degrading. His main thesis is that

the actions of men cannot be divided into lower and higher. The higher

life of man is a mere fiction introduced by philosophers and rulers to

simplify government and the relations of society. In fact, virtue

(which he defined as "every performance by which man, contrary to the

impulse of nature, should endeavour the benefit of others, or the

conquest of his own passions, out of a rational ambition of being

good") is actually detrimental to the state in its commercial and

intellectual progress. This is because it is the vices (i.e., the

self-regarding actions of men) which alone, by means of inventions and

the circulation of capital (economics) in connection with luxurious

living, stimulate society into action and progress.[6] Private vice, public benefit Mandeville concluded that vice, at variance with the "Christian virtues" of his time, was a necessary condition for economic prosperity. His viewpoint is more severe when juxtaposed to Adam Smith's. Both Smith and Mandeville believed that individuals' collective actions bring about a public benefit.[9] However, what sets his philosophy apart from Smith's is his catalyst to that public benefit. Smith believed in a virtuous self-interest which results in invisible co-operation. For the most part, Smith saw no need for a guide to garner that public benefit. On the other hand, Mandeville believed it was vicious greed which led to invisible co-operation if properly channelled. Mandeville's qualification of proper channelling further parts his philosophy from Smith's laissez-faire attitude. Essentially, Mandeville called for politicians to ensure that the passions of man would result in a public benefit. It was his stated belief in the Fable of the Bees that "Private Vices by the dextrous Management of a skilful Politician may be turned into Publick Benefits".[10] In the Fable he shows a society possessed of all the virtues "blest with content and honesty," falling into apathy and utterly paralysed. The absence of self-love (cf. Hobbes) is the death of progress. The so-called higher virtues are mere hypocrisy, and arise from the selfish desire to be superior to the brutes. "The moral virtues are the political offspring which flattery begot upon pride." Similarly he arrives at the great paradox that "private vices are public benefits".[6] Among other things, Mandeville argues that the basest and vilest behaviours produce positive economic effects. A libertine, for example, is a vicious character, and yet his spending will employ tailors, servants, perfumers, cooks, prostitutes. These persons, in turn, will employ bakers, carpenters, and the like. Therefore, the rapaciousness and violence of the base passions of the libertine benefit society in general. Similar satirical arguments were made by the Restoration and Augustan satirists. A famous example is Mandeville's Modest Defence of Publick Stews, which argued for the introduction of public, state-controlled brothels. The 1726 paper acknowledges women's interests and mentions e.g. the clitoris as the centre of female sexual pleasure.[11] Jonathan Swift's 1729 satire A Modest Proposal is probably an allusion to Mandeville's title.[11][12] Mandeville was an early describer of the division of labour, and Adam Smith makes use of some of his examples. Mandeville says: But if one will wholly apply himself to the making of Bows and Arrows, whilst another provides Food, a third builds Huts, a fourth makes Garments, and a fifth Utensils, they not only become useful to one another, but the Callings and Employments themselves will in the same Number of Years receive much greater Improvements, than if all had been promiscuously follow'd by every one of the Five... In Watch-making, which is come to a higher degree of Perfection, than it would have been arrived at yet, if the whole had always remain'd the Employment of one Person; and I am persuaded, that even the Plenty we have of Clocks and Watches, as well as the Exactness and Beauty they may be made of, are chiefly owing to the Division that has been made of that Art into many Branches. (The Fable of the Bees, Volume two) — Adam Smith.[13] |

マ

ンデヴィルの哲学は、当時、大きな衝撃を与え、常に虚偽、皮肉、下劣の汚名を着せられ続けてきた。彼の主な主張は、人間の行動は低次と高次に分けられない

というものである。人間の高尚な生活というのは、哲学者や支配者が政治や社会の関係を単純化するために導入した単なる虚構に過ぎない。実際、徳(彼は「人

間が自然の衝動に反して、善良であろうとする合理的な野心から、他人の利益や自分の情熱の克服に努めるべきあらゆる行為」と定義した)は、実は国家の商業

や知的進歩に有害なものである。なぜなら、発明と贅沢な生活と結びついた資本の循環(経済学)によって、社会を行動と進歩に刺激するのは、悪徳(すなわ

ち、人間の自己中心的な行動)だけだからである[6]。 私的な悪徳、公的な利益 マンデヴィルは、当時の「キリスト教の美徳」とは相容れない悪徳が、経済的繁栄の必要条件であると結論づけた。アダム・スミスと比較すると、彼の視点はよ りシビアである。スミスもマンデヴィルも個人の集団行動が公共の利益をもたらすと考えた[9] が、彼の思想がスミスと異なるのは、その公共の利益への触媒としてである。スミスは目に見えない協力をもたらす高潔な利己主義を信じた。ほとんどの場合、 スミスはその公益を集めるための指針は必要ないと考えていた。一方、マンデヴィルは、悪しき貪欲さこそ、適切に導かれれば、目に見えない協力につながると 考えた。マンデヴィルは、この「適切な道しるべ」という点で、スミスの自由放任主義とは一線を画している。マンデヴィルは、人間の情熱が公共の利益につな がるようにすることを政治家に求めていた。それは「巧みな政治家の巧みな管理によって、私的な悪徳は公的な利益に変わるかもしれない」という『蜜蜂の寓 話』の中で彼が述べた信念であった[10]。 寓話の中で彼は、「満足と誠実さに恵まれた」すべての美徳を持つ社会が、無気力に陥り、完全に麻痺している様子を示している。自己愛の欠如(ホッブズ参 照)は、進歩の死である。いわゆる高尚な美徳は単なる偽善であり、獣より優位に立ちたいという利己的な欲求から生じるものである。"徳はお世辞が高慢に産 んだ政治的な子孫である" 同様に彼は「私的な悪徳は公的な利益である」という大きなパラドックスに到達する[6]。 とりわけ、マンデヴィルは最も卑劣で下劣な行動がプラスの経済効果を生むと主張している。例えば、放蕩者は悪徳な人物であるが、彼の支出は仕立て屋、使用 人、調香師、料理人、娼婦を雇うことになる。これらの人々は、今度はパン職人や大工などを雇うことになる。したがって、自由主義者の卑しい情熱の奔放さと 暴力は、社会一般に利益をもたらすのである。このような風刺的な主張は、王政復古期やアウグストゥス期の風刺家たちによってもなされた。有名なのはマンデ ヴィルの『Modest Defence of Publick Stews』で、国が管理する公的な売春宿の導入を主張したものである。1726年の論文では女性の利益を認め、女性の性的快楽の中心としてのクリトリス などに言及している[11]。ジョナサン・スウィフトの1729年の風刺『ささやかな提案』はおそらくマンデヴィルのタイトルへの言及である[11] [12]。 マンデヴィルは分業の初期の記述者であり、アダム・スミスは彼の例のいくつかを利用している。 マンデヴィルは言う。 しかし、ある者が弓矢の製作に専心する一方、別の者が食糧を供給し、3人目が小屋を建て、4人目が衣服を作り、5人目が道具を作れば、互いに役立つだけでなく、同じ年数の間に職業や仕事自体が、5人全員が乱暴に従った場合よりもはるかに大きく改善されるだろう...」と。 また、時計や腕時計がたくさんあるのも、正確で美しいものができるのも、この技術が多くの部門に分かれていることが主な原因であると私は確信している。(ミツバチの寓話、第2巻)。 - アダム・スミス[13]。 |

| While

the author probably had no intention of subverting morality, his views

of human nature were seen by his critics as cynical and degraded.

Another of his works, A Search into the Nature of Society (1723),

appended to the later versions of the Fable, also startled the public

mind, which his last works, Free Thoughts on Religion (1720) and An

Enquiry into the Origin of Honour and the Usefulness of Christianity

(1732) did little to reassure. The work in which he approximates most

nearly to modern views is his account of the origin of society. His a

priori theories should be compared with the jurist Henry Maine's

historical inquiries (Ancient Law). He endeavours to show that all

social laws are the crystallised results of selfish aggrandizement and

protective alliances among the weak. Denying any form of moral sense or

conscience, he regards all the social virtues as evolved from the

instinct for self-preservation, the give-and-take arrangements between

the partners in a defensive and offensive alliance, and the feelings of

pride and vanity artificially fed by politicians, as an antidote to

dissension and chaos. Mandeville's ironic paradoxes are a criticism of the "amiable" idealism of Shaftesbury; their irony contrasts with the serious egoistic systems of Hobbes and Helvétius. Mandeville's ideas about society and politics were praised by Friedrich Hayek, a proponent of Austrian economics, in his book Law, Legislation and Liberty.[14] But it was above all Keynes who put it back in the spotlight in his Essay on Malthus and in the General Theory. Keynes considers Mandeville as a precursor of the foundation of his own theory of insufficient effective demand. Karl Marx, in his seminal work Capital, praised Mandeville as "an honest man with a clear mind" for his conclusion that the wealth of society depended on the relative poverty of workers. |

作

者には道徳を破壊する意図はなかったのだろうが、彼の人間観は批評家からはシニカルで劣化したものとみなされた。また、『寓話』の後期版に付された『社会

の本質を探る』(1723年)も大衆を驚かせ、彼の最後の作品『宗教に関する自由な考察』(1720年)と『名誉の起源とキリスト教の有用性に関する探

究』(1732年)はほとんど安心させるに足るものではなかった。彼が最も現代的な見解に近い著作は、社会の起源についての説明である。彼の先験的な理論

は、法学者ヘンリー・メインの歴史的探求(Ancient

Law)と比較されるべきものである。彼は、すべての社会法は、利己的な拡張と弱者の保護同盟の結晶であることを示そうと努めている。道徳的な感覚や良心

を否定し、社会的な美徳はすべて自己保存の本能から生まれたものであり、防衛的・攻撃的同盟のパートナー間のギブ・アンド・テイクの取り決めや、政治家に

よって人工的に与えられたプライドと虚栄の感情は、不和と混沌に対する解毒剤であるとする。 マンデヴィルの皮肉な逆説は、シャフツベリの「愛想のいい」理想主義への批判であり、その皮肉はホッブズやヘルヴェティウスの真面目なエゴイズムとは対照的である。 マンデヴィルの社会と政治に関する思想は、オーストリア経済学の提唱者であるハイエクが『法・立法・自由』で賞賛した[14]が、『マルサス論』や『一般 理論』で再び脚光を浴びたのは何と言ってもケインズであった。ケインズはマンデヴィルを自らの有効需要不足説の基礎となる先駆者とみなしている。 カール・マルクスは、その代表作『資本論』の中で、社会の豊かさは労働者の相対的貧困に依存するというマンデヴィルの結論を、「明晰な頭脳を持つ正直者」と賞賛している。 |

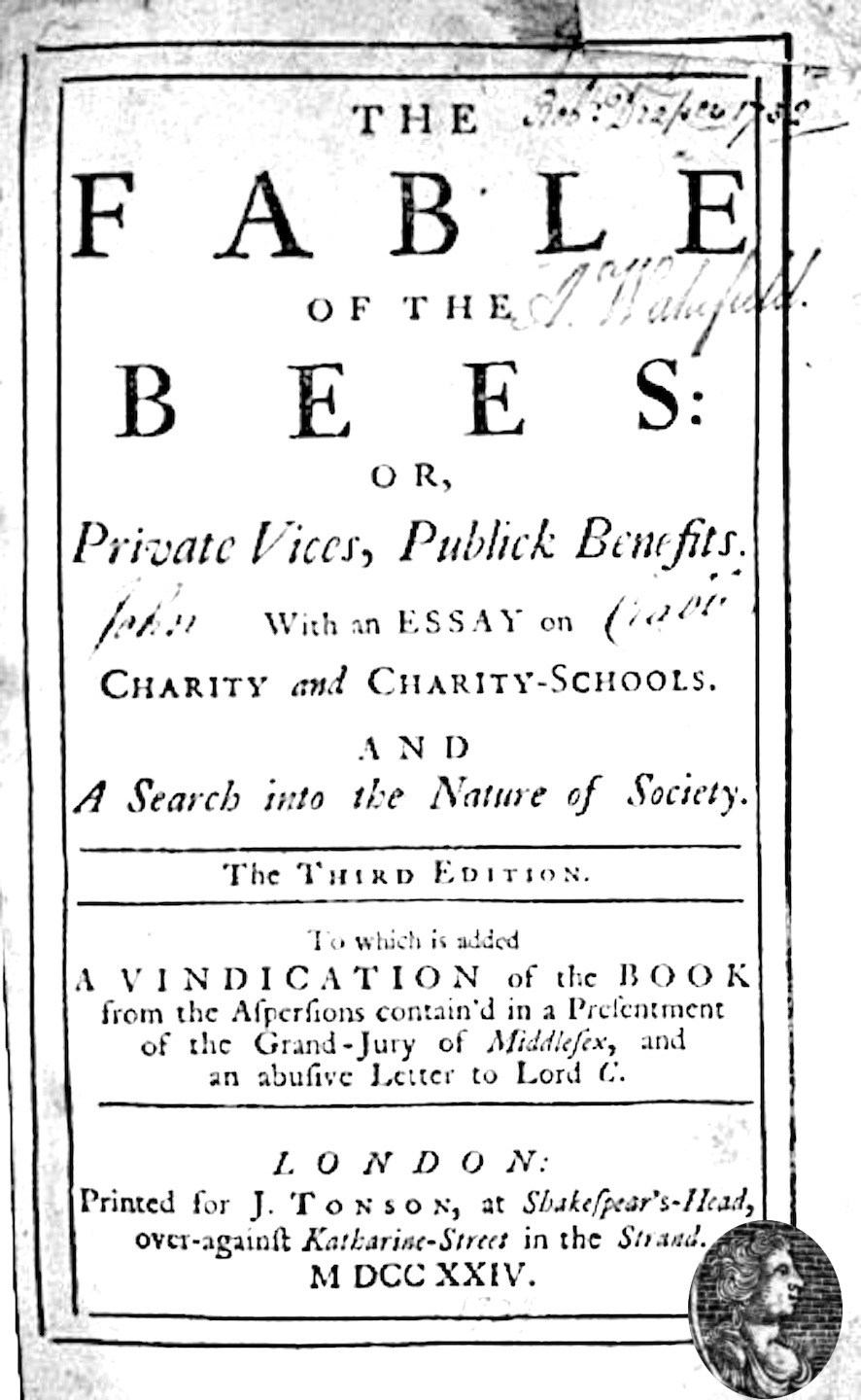

| The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits

(1714) is a book by the Anglo-Dutch social philosopher Bernard

Mandeville. It consists of the satirical poem The Grumbling Hive: or,

Knaves turn'd Honest, which was first published anonymously in 1705; a

prose discussion of the poem, called "Remarks"; and an essay, An

Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue. In 1723, a second edition was

published with two new essays. In The Grumbling Hive, Mandeville describes a bee community that thrives until the bees decide to live by honesty and virtue. As they abandon their desire for personal gain, the economy of their hive collapses, and they go on to live simple, "virtuous" lives in a hollow tree. Mandeville's implication—that private vices create social benefits—caused a scandal when public attention turned to the work, especially after its 1723 edition. Mandeville's social theory and the thesis of the book, according to E. J. Hundert, is that "contemporary society is an aggregation of self-interested individuals necessarily bound to one another neither by their shared civic commitments nor their moral rectitude, but, paradoxically, by the tenuous bonds of envy, competition and exploitation".[1] Mandeville implied that people were hypocrites for espousing rigorous ideas about virtue and vice while they failed to act according to those beliefs in their private lives. He observed that those preaching against vice had no qualms about benefiting from it in the form of their society's overall wealth, which Mandeville saw as the cumulative result of individual vices (such as luxury, gambling, and crime, which benefited lawyers and the justice system). Mandeville's challenge to the popular idea of virtue—in which only unselfish, Christian behaviour was virtuous—caused a controversy that lasted through the eighteenth century and influenced thinkers in moral philosophy and economics. The Fable influenced ideas about the division of labour and the free market (laissez-faire), and the philosophy of utilitarianism was advanced as Mandeville's critics, in defending their views of virtue, also altered them.[2] His work influenced Scottish Enlightenment thinkers such as Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and Adam Smith.[3] |

The

Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits

(1714)は、英蘭の社会哲学者バーナード・マンデヴィルによる著作である。1705年に匿名で出版された風刺詩『The Grumbling

Hive: or, Knaves turn'd Honest』、その散文的考察『Remarks』、小論『An Enquiry into the

Origin of Moral Virtue』で構成されている。1723年には、新たに2つのエッセイを加えた第2版が出版された。 マンデヴィルは『不平不満の巣』の中で、ミツバチが誠実さと美徳によって生きようと決心するまで繁栄しているミツバチのコミュニティを描写している。ミツ バチが私利私欲を捨てると、巣の経済は崩壊し、彼らは空洞の木の中で質素で「徳の高い」生活を送るようになる。私的な悪が社会的利益を生むというマンデ ヴィルの示唆は、特に1723年の版以降、この作品に世間の注目が集まるとスキャンダルとなった。 E. J. Hundertによれば、マンデヴィルの社会理論とこの本のテーゼは、「現代社会は、利己的な個人の集合体であり、市民的コミットメントの共有や道徳的正しさによってではなく、逆説的に、嫉妬、競争、搾取の弱い絆によって互いに結びついている」[1]。 マンデヴィルは、人々が美徳と悪についての厳しい考えを支持しながら、私生活ではその信念に従わないのは偽善者であるとほのめかしたのだ。彼は、悪を否定 する人々は、社会全体の富という形で悪から利益を得ることに何のためらいもないことを観察し、マンデヴィルは、個人の悪(贅沢、賭博、犯罪など、弁護士や 司法制度に利益をもたらすもの)の積み重ねの結果であると見なした。 マンデヴィルは、利己的でないキリスト教的な行動のみが美徳とされる一般的な考え方に疑問を呈し、18世紀を通じて論争を引き起こし、道徳哲学や経済学の 思想家たちに影響を与えた。寓話』は分業や自由市場(レッセフェール)に関する考え方に影響を与え、功利主義の哲学は、マンデヴィルの批評家が徳について の見解を守るために、それらをも変化させることで進歩した[2]。 彼の作品はフランシスコ・ハッチソン、デヴィッド・ヒューム、アダム・スミスといったスコットランドの啓蒙思想家たちに影響を及ぼした[3]。 |

| The

genesis of The Fable of the Bees was Mandeville's anonymous publication

of the poem The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves Turn'd Honest on 2 April

1705 as a sixpenny quarto, which was also pirated at a half-penny. In

1714, the poem was included in The Fable of the Bees: or, Private

Vices, Publick Benefits, also published anonymously. This book included

a commentary, An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue, and twenty

"Remarks". The second edition in 1723 sold at five shillings and

included two new parts: An Essay on Charity and Charity-Schools and A

Search into the Nature of Society. This edition attracted the most

interest and notoriety. Beginning with the 1724 edition Mandeville

included a "Vindication", first published in the London Journal, as a

response to his critics.[4] Between 1724 and 1732, further editions

were published, with changes limited to matters of style, slight

alterations of wording, and a few new pages of preface. During this

period, Mandeville worked on a "Part II", which consisted of six

dialogs and was published in 1729 as The Fable of the Bees. Part II. By

the Author of the First.[5] A French translation was published in 1740. The translation, by Émilie du Châtelet, was not particularly faithful to the original; according to Kaye, it was "a free one, in which the Rabelaisian element in Mandeville was toned down".[6] By this time, French literati were familiar with Mandeville from the 1722 translation by Justus van Effen of his Free Thoughts on Religion, the Church and National Happiness. They had also followed the Fable's scandal in England. The book was especially popular in France between 1740 and 1770. It influenced Jean-François Melon and Voltaire, who had been exposed to the work in England between 1726 and 1729 and reflected on some of its ideas in his 1736 poem Le Mondain.[7] A German translation first appeared in 1761.[5] F. B. Kaye's 1924 edition, based on his Yale dissertation and published by Oxford University's Clarendon Press, included extensive commentary and textual criticism. It renewed interest in the Fable, whose popularity had faded through the 19th century. Kaye's edition, a "model of what a fully annotated edition ought to be"[8] and still important to Mandeville studies,[9] was reprinted in 1988 by the American Liberty Fund. |

1705年4月2日にマ

ンデヴィルが『The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves Turn'd

Honest』という詩を6ペニー四つ切で匿名で出版し、これも半ペニーで海賊版が出たのが『蜜蜂物語(蜂の寓話)』の始まりであった。1714年、この

詩は『The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick

Benefits』に収録され、これも匿名で出版された。この本には、解説書『道徳的美徳の起源に関する探究』と20の「備考」が含まれていた。1723

年の第2版は5シリングで販売され、新たに2部が加えられた。1723年の第2版は5シリングで販売され、「慈善事業と慈善学校についての試論」と「社会

の本性についての探求」の2部が新たに加えられた。この版には、「慈善事業と慈善学校に関する論考」と「社会の本質に関する考察」という2つの新しい部分

が含まれており、この版が最も関心を集め、有名になった。1724年版からは、批評家への反論として『ロンドン・ジャーナル』誌に掲載された「怨嗟の声」

を収録した[4]。1724年から1732年にかけて、文体や表現のわずかな変更、序文の数ページを新たに加える程度の変更で、さらなる版が出版された。

この間、マンデヴィルは6つの対話からなる「第二部」に取り組み、1729年に『蜜蜂の寓話』として出版された。第II部。By the Author

of the First』として出版された[5]。 1740年にフランス語訳が出版された。この頃、フランスの文人たちは、1722年にユストゥス・ヴァン・エフェンが翻訳した『宗教、教会、国民の幸福に ついての自由な考察』によってマンデヴィルに親しんでいた[6]。また、イギリスでの『寓話』のスキャンダルも追っていた。この本は、1740年から 1770年にかけてフランスで特に人気を博した。ジャン=フランソワ・メロンや、1726年から1729年にかけてイギリスでこの作品に触れたヴォルテー ルが影響を受け、1736年の詩『ル・モンダン』でその思想の一部を反映している[7]。 1761年にドイツ語の翻訳が初めて登場した[5]。 F. 1924年、F. B. Kayeがイェール大学の学位論文に基づき、オックスフォード大学のクラレンドン出版社から出版した版には、膨大な解説と本文の批評が含まれている。19 世紀を通じて人気が低迷していた『寓話』への関心を再び呼び起こした。ケイ版は「完全注釈版のあるべき姿のモデル」[8]であり、現在もマンデヴィル研究 において重要な位置を占めている[9]が、1988年にアメリカ自由基金によって再版された。 |

| Poem The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves turn'd Honest (1705) is in doggerel couplets of eight syllables over 433 lines. It was a commentary on contemporary English society as Mandeville saw it.[10] Economist John Maynard Keynes described the poem as setting forth "the appalling plight of a prosperous community in which all the citizens suddenly take it into their heads to abandon luxurious living, and the State to cut down armaments, in the interests of Saving".[11] It begins: A Spacious Hive well stock'd with Bees, That lived in Luxury and Ease; And yet as fam'd for Laws and Arms, As yielding large and early Swarms; Was counted the great Nursery 5 Of Sciences and Industry. No Bees had better Government, More Fickleness, or less Content. They were not Slaves to Tyranny, Nor ruled by wild Democracy; 10 But Kings, that could not wrong, because Their Power was circumscrib'd by Laws. The "hive" is corrupt but prosperous, yet it grumbles about lack of virtue. A higher power decides to give them what they ask for: But Jove, with Indignation moved, At last in Anger swore, he'd rid 230 The bawling Hive of Fraud, and did. The very Moment it departs, And Honesty fills all their Hearts; This results in a rapid loss of prosperity, though the newly virtuous hive does not mind: For many Thousand Bees were lost. Hard'ned with Toils, and Exercise They counted Ease it self a Vice; Which so improved their Temperance; 405 That, to avoid Extravagance, They flew into a hollow Tree, Blest with Content and Honesty. The poem ends in a famous phrase: Bare Virtue can't make Nations live In Splendor; they, that would revive A Golden Age, must be as free, For Acorns, as for Honesty. |

詩 The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves turn'd Honest (1705) は、8音節のドージェレル連句で433行に渡って書かれている。経済学者のジョン・メイナード・ケインズは、この詩を「豊かな社会の中で、市民が突然贅沢 な生活を捨て、国は節約のために軍備を縮小するという恐ろしい状況」を描写していると評している[11]。 広々とした巣箱にはミツバチがよく飼われている。 贅沢と安楽の中に住んでいた。 しかし、法律と武器には目がない。 大群と早期の群れを生み出すように。 科学と産業の偉大な苗床とされた。 科学と工業の。 どんな蜂も優れた政府を持っていない。 より気まぐれで、より少ない満足。 彼らは専制政治の奴隷ではなかった。 野生の民主主義に支配されたわけでもなく、10 しかし、王は間違うことができなかった、なぜなら 彼らの権力は法律によって制限されていたからだ。 蜂の巣」は腐敗しているが繁栄している、しかし徳の欠如を不平に思っている。上位の権力者は、彼らが求めるものを与えることを決定する。 しかし、ジョーブは憤慨して動き出しました。 ついに怒りに駆られたジョーブは、230人を排除すると誓いました。 泣きわめく不正の巣を追い払うと誓い、実行した。 まさにその瞬間、それは去りました。 正直者がすべての心を満たす。 この結果、繁栄は急速に失われたが、新しく徳の高い蜂の巣は気にしていない。 何千匹もの蜂が失われたからだ。 労苦と運動で大変なことになった。 彼らは安楽そのものを悪とみなした。 それが彼らの節制を向上させ、405 それは浪費を避けるために 彼らは空洞の木に飛び込んだ。 満足と誠実さに恵まれた。 この詩は有名なフレーズで終わっている。 裸の美徳では、国を繁栄させることはできない。 輝きを取り戻そうとする者たちは 黄金時代をよみがえらせるためには、自由でなければならない。 どんぐりにも、正直にも。 |

| Charity schools In the 1723 edition, Mandeville added An Essay on Charity and Charity-Schools. He criticised charity schools, which were designed to educate the poor and, in doing so, instill virtue in them. Mandeville disagreed with the idea that education encourages virtue because he did not believe that evil desires existed only in the poor; rather he saw the educated and wealthy as much more crafty. Mandeville believed that educating the poor increased their desires for material things, defeating the purpose of the school and making it more difficult to provide for them.[12] |

チャリティ・スクール 1723年版では、「慈善事業と慈善学校に関する論考」が追加された。彼は、貧しい人々を教育し、それによって美徳を身につけさせることを目的とした慈善 学校を批判した。マンデヴィルは、教育が徳を高めるという考えには反対だった。彼は、悪しき欲望が貧しい人々にのみ存在するとは考えず、むしろ教育を受け た裕福な人々の方がずっと狡猾だと考えていたからだ。マンデヴィルは、貧乏人に教育を施すと、彼らの物欲が高まり、学校の目的が達成されず、彼らを養うこ とが難しくなると考えていた[12]。 |

| At

the time, the book was considered scandalous, being understood as an

attack on Christian virtues. The 1723 edition gained a notoriety that

previous editions had not, and caused debate among men of letters

throughout the eighteenth century. The popularity of the second edition

in 1723 in particular has been attributed to the collapse of the South

Sea Bubble a few years earlier. For those investors who had lost money

in the collapse and related fraud, Mandeville's pronouncements about

private vice leading to public benefit would have been infuriating.[13] The book was vigorously combatted by, among others, the philosopher George Berkeley and the priest William Law. Berkeley attacked it in the second dialogue of his Alciphron (1732). The 1723 edition was presented as a nuisance by the Grand Jury of Middlesex, who proclaimed that the purpose of the Fable was to "run down Religion and Virtue as prejudicial to Society, and detrimental to the State; and to recommend Luxury, Avarice, Pride, and all vices, as being necessary to Public Welfare, and not tending to the Destruction of the Constitution".[14] In the rhetoric of the presentment, Mandeville saw the influence of the Society for the Reformation of Manners.[14] The book was also denounced in the London Journal. Other writers attacked the Fable, notably Archibald Campbell (1691–1756) in his Aretelogia. Francis Hutcheson also denounced Mandeville, initially declaring the Fable to be "unanswerable"―that is, too absurd for comment. Hutcheson argued that pleasure consisted in "affection to fellow creatures", and not the hedonistic pursuit of bodily pleasures. He also disagreed with Mandeville's notion of luxury, which he believed depended on too austere a notion of virtue.[15][16] The modern economist John Maynard Keynes noted that "only one man is recorded as having spoken a good word for it, namely Dr. Johnson, who declared that it did not puzzle him, but 'opened his eyes into real life very much'."[17] Adam Smith expressed his disapproval of The Fable of the Bees in Part VII, Section II of his The Theory of Moral Sentiments. The reason that Adam Smith heavily criticizes Mandeville is that Mandeville mistakes greed as a part of self-interest. Smith claims that, in reality, greed and the self-interest he comments on in the Wealth of Nations are separate concepts that affect the market very differently. |

当

時、この本はキリスト教の美徳を攻撃するものとして理解され、スキャンダラスな本とみなされていた。1723年版は、それまでの版にはなかった悪評を呼

び、18世紀を通じて文人たちの間で議論を巻き起こした。特に1723年の第2版の人気は、その数年前に起きた南海バブルの崩壊に起因すると言われてい

る。この崩壊とそれに関連する詐欺で損をした投資家にとって、マンデヴィルの私的な悪徳が公共の利益につながるという宣言は腹立たしいものであったろう

[13]。 この本は、哲学者のジョージ・バークレーや司祭のウィリアム・ローらによって激しく非難された。バークレーは『アルキフロン』(1732年)の第二対話で この本を攻撃している。1723年版はミドルセックス大陪審によって迷惑行為とされ、寓話の目的は「宗教と美徳を社会に害を与え、国家に害を与えるものと して貶め、贅沢、欲望、高慢、あらゆる悪徳を公共の福祉に必要であり、憲法の破壊につながらないものとして推奨する」ことであると宣言された[14]。 [また、『ロンドン・ジャーナル』誌でも糾弾される。 他の作家も『寓話』を攻撃しており、特にアーチボルド・キャンベル(1691-1756)は『Aretelogia』の中で、『寓話』を攻撃している。フ ランシス・ハッチソンもマンデヴィルを非難し、当初はこの寓話を「答えのないもの」、つまりあまりに不合理で論評に値しないと断じた。ハッチソンは、快楽 とは「同胞への愛情」であり、快楽主義的な肉体的快楽の追求ではないと主張した。彼はまたマンデヴィルの贅沢の概念に同意せず、それは美徳のあまりにも厳 格な概念に依存していると考えた。 15][16] 近代経済学者のジョン・メイナード・ケインズは、「それについて良い言葉を述べた人物としてただ一人、すなわちジョンソン博士が記録されており、彼はそれ が彼を困惑させず、「実生活への彼の目を非常に開いた」ことを宣言している」[17]ことに留意している。 アダム・スミスは『道徳感情論』の第7部第2節で『ミツバチの寓話』に対する不支持を表明している。アダム・スミスがマンデヴィルを激しく批判する理由 は、マンデヴィルが欲を自己利益の一部であると誤解しているからである。スミスは、『国富論』の中でコメントしている「強欲」と「利己心」は実際には別の 概念であり、市場に与える影響は全く異なるものであると主張している。 |

| The book reached Denmark by

1748, where a major Scandinavian writer of the period, Ludvig Holberg

(1684–1754), offered a new critique of the Fable—one that did not

centre on "ethical considerations or Christian dogma".[18] Instead,

Holberg questioned Mandeville's assumptions about the constitution of a

good or flourishing society: "the question is whether or not a society

can be called luxurious in which citizens amass great wealth which is

theirs to use while others live in the deepest poverty. Such is the

general condition in all the so-called flourishing cities which are

reputed to be the crown jewels of the earth."[19] Holberg rejected

Mandeville's ideas about human nature—that such unequal states are

inevitable because humans have an animal-like or corrupt nature—by

offering the example of Sparta, the Ancient Greek city-state. The

people of Sparta were said to have rigorous, immaterialistic ideals,

and Holberg wrote that Sparta was strong because of this system of

virtue: "She was free from internal unrest because there was no

material wealth to give rise to quarrels. She was respected and honored

for her impartiality and justice. She achieved dominion over the other

Greeks simply because she rejected dominion."[20] Jean-Jacques Rousseau commented on the Fable in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1754): Mandeville sensed very well that even with all their morality men would never have been anything but monsters if nature had not given them pity in support of reason; but he did not see that from this quality alone flow all the social virtues he wants to question in men. In fact, what are generosity, clemency, humanity, if not pity applied to the weak, to the guilty, to the human species in general? Mandeville sees greed as “beneficial to the public”[21] and he denies men of all social virtues. It is on this latter point that Rousseau counters Mandeville.[22] Despite some overlap between Rousseau's work on self-reliance and Mandeville’s ideas, Rousseau identifies that virtues are applications of natural pity: “for is desiring that someone not suffer anything other than desiring to be happy?”[22] Rousseau attacked Mandeville in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men primarily because Mandeville denies man of possessing social virtues.[22] Rousseau counters Mandeville using an admission of Mandeville’s as the basis of his argument. Mandeville admitted that nature provided man with pity.[22] Rousseau uses this admission to point out how clemency, generosity, and humanity are applications of human pity applied. Hence, since Mandeville admits to the existence of pity within humanity he must admit to the existence of, in the least, these virtues of clemency, generosity, and humanity. Rousseau seals the point when he furthers it saying: “Benevolence and friendship are, properly understood, products of a constant pity focused on a particular object: For is desiring that someone not suffer anything other than desiring that he be happy?”[22] Rousseau identifies that Mandeville’s admittance of pity within humanity must also be an admittance to man possessing altruism. In the 19th century, Leslie Stephen, writing for the Dictionary of National Biography reported that "Mandeville gave great offense by this book, in which a cynical system of morality was made attractive by ingenious paradoxes. ... His doctrine that prosperity was increased by expenditure rather than by saving fell in with many current economic fallacies not yet extinct.[23] Assuming with the ascetics that human desires were essentially evil and therefore produced 'private vices' and assuming with the common view that wealth was a 'public benefit', he easily showed that all civilization implied the development of vicious propensities.[24] |

この本は1748年までにデンマークに届き、この時代のスカンジナビア

の主要な作家であるルドヴィク・ホルベリ(1684-1754)は、「倫理的考察やキリスト教の教義」を中心としない寓話の新しい批判を提供した[18]

その代わりにホルベリは、良い社会あるいは繁栄する社会の構成に関するマンデヴィルの前提に疑問を投げかけている。問題は、市民が大きな富を蓄積し、それ

を自分たちが使うことができる一方で、他の人々が最も深い貧困の中で生きているような社会を贅沢と呼ぶことができるかどうかである」。ホルバーグは、マン

デヴィルの人間性についての考え、つまり人間が動物のような、あるいは腐敗した性質を持っているので、このような不平等な状態は避けられないという考え

を、古代ギリシャの都市国家スパルタの例を挙げて否定している[19]。スパルタの人々は、厳格で非物質的な理想を抱いていたといわれ、ホルバーグは、ス

パルタが強かったのはこの徳の体系があったからだと書いている。「争いを生む物質的な富がなかったから、内乱もなかった。スパルタは、その公平さと正義の

ために尊敬され、栄誉を受けた。彼女は支配を拒否しただけで他のギリシア人に対する支配を達成した」[20]。 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは『人間の間の不平等の起源と基礎に関する論考』(1754年)の中で、この寓話についてコメントしている。 マンデヴィルは、自然が理性の支えとなる憐憫を与えなかったならば、たとえすべての道徳性をもってしても人間は怪物以外の何者でもなかったであろうことを 非常によく感じていた;しかし彼はこの性質だけから、彼が人間の中に問いたいすべての社会的美徳が生まれることに気づかなかったのだ。実際、寛大さ、寛容 さ、人間性とは、弱者、罪人、人類一般に適用される憐憫でなくて何だろうか。 マンデヴィルは強欲を「公衆にとって有益なもの」[21]と見なし、人間のあらゆる社会的美徳を否定しているのである。ルソーがマンデヴィルに対抗するの はこの後者の点である[22]。 自立に関するルソーの仕事とマンデヴィルの考えの間にいくつかの重複があるものの、ルソーは美徳が自然の憐憫の応用であると識別し、「誰かが苦しまないこ とを望むことは、幸せになることを望むこと以外にないのではないか」[22] 。 ルソーは『人間の不平等の起源と基礎に関する論考』でマンデヴィルを攻撃したが、それはマンデヴィルが人間が社会的な美徳を持つことを否定しているからで ある[22] ルソーはマンデヴィルの告白を論拠にして反論している。マンデヴィルは自然が人間に憐憫を与えたことを認めている[22]。 ルソーはこの認めを利用して、慈悲、寛大さ、人間性がいかに人間の憐憫を応用したものであるかを指摘する。したがってマンデヴィルは人間の中に憐れみが存 在することを認めているので、少なくともこれらの礼節、寛大さ、人間性という美徳の存在を認めなければならないのである。ルソーは、この点をさらに強調し てこう言っている。 「博愛と友情は、正しく理解すれば、特定の対象に焦点を当てた絶えざる憐憫の産物である。 なぜなら、誰かが苦しまないようにと願うことは、その人が幸せになるようにと願うこと以外の何物でもないだろうか」[22]。 ルソーは、マンデヴィルが人間の中に憐れみを認めることは、人間が利他主義を持つことを認めることでもあるはずだ、と指摘する。 19世紀、『人名辞典』に寄稿したレスリー・ステファンは、「マンデヴィルはこの本によって大きな不快感を与え、その中で、道徳のシニカルな体系が独創的 な逆説によって魅力的にされている。繁栄は貯蓄よりもむしろ支出によって増加するという彼の教義は、まだ消滅していない現在の多くの経済的誤謬と一致した [23]。 人間の欲望は本質的に悪であり、したがって「私的悪徳」を生み出すと禁欲主義者と仮定し、富は「公的利益」であるという一般の見解と仮定して、彼はすべて の文明が悪質な性向の発展を意味していることを簡単に示してみせた[24]。 |

| As a satire, the poem and

commentary point out the hypocrisy of men who promulgate ideas about

virtue while their private acts are vices.[25] The degree to which

Mandeville's "rigoristic"[26] definitions of virtue and vice followed

those of English society as a whole has been debated by scholars. Kaye

suggests that two related concepts of vice are at play in Mandeville's

formulation. Christianity taught that a virtuous act was unselfish, and

the philosophy of Deism suggested that the use of reason was virtuous

because it would naturally reveal theological truth. Mandeville looked

for acts of public virtue and could not find them, yet observed that

some actions (which must then be vices) led to beneficial outcomes in

society, such as a prosperous state. This was Mandeville's paradox, as

embedded in the book's subtitle: "Private Vices, Publick Benefits". Mandeville was interested in human nature, and his conclusions about it were extreme and scandalous to 18th-century Europeans. He saw humans and animals as fundamentally the same: in a state of nature, both behave according to their passions or basic desires. Man was different, though, in that he could learn to see himself through others' eyes, and thus modify his behaviour if there were a social reward for doing so. In this light Mandeville wrote of the method by which the selfish instincts of "savage man" had been subdued by the political organization of society. It was in the interest of those who had selfish motives, he argued, to preach virtuous behavior to others: It being the Interest then of the very worst of them, more than any, to preach up Publick-spiritedness, that they might reap the Fruits of the Labour and Self-denial of others, and at the same time indulge their own Appetites with less disturbance, they agreed with the rest, to call every thing, which, without Regard to the Publick, Man should commit to gratify any of his Appetites, VICE; if in that Action there cou'd be observed the least prospect, that it might either be injurious to any of the Society, or ever render himself less serviceable to others: And to give the Name of VIRTUE to every Performance, by which Man, contrary to the impulse of Nature, should endeavour the Benefit of others, or the Conquest of his own Passions out of a Rational Ambition of being good.[27] To critics it appeared that Mandeville was promoting vice, but this was not his intention.[3] He said that he wanted to "pull off the disguises of artful men" and expose "the hidden strings" that guided human behaviour.[28] Nevertheless he was seen as a "modern defender of licentiousness", and talk of "private vices" and "public benefits" was common among the educated public in England.[29] |

風刺として、詩と解説は、美徳についての考えを広める一方で、私的な行

為は悪徳である人間の偽善を指摘している[25]

マンデヴィルの「厳格な」[26]美徳と悪徳の定義が、イギリス社会全体のそれにどの程度従っていたか、研究者によって議論されてきた。ケイは、マンデ

ヴィルの定式化には2つの関連した悪徳の概念が作用していることを示唆している。キリスト教では、徳のある行為は無欲であると教え、神学では、理性を働か

せることは神学的真理を自然に明らかにするので徳があるとした。マンデヴィルは、公徳の行為を探しても見つからないのに、ある行為(それなら悪徳に違いな

い)が国家の繁栄など社会の有益な結果につながっていることを観察した。これがマンデヴィルのパラドックスであり、この本の副題に込められている。「私的

な悪徳、公的な利益」。 マンデヴィルは人間の本性に関心を持ち、それに関する彼の結論は、18世紀のヨーロッパの人々にとっては極端でスキャンダラスなものであった。マンデヴィ ルは、人間と動物とは基本的に同じものだと考えていた。しかし、人間は、他人の目を通して自分を見ることを学び、社会的な報酬があれば、自分の行動を修正 することができるという点で、異なっていた。このような観点から、マンデヴィルは「野蛮な人間」の利己的な本能が、社会の政治的組織によって抑制された方 法について書いている。利己的な動機を持つ者にとって、他者に高潔な振る舞いを説くことは利益となる、と彼は主張した。 そして、他人の労苦と自己犠牲の果実を得ると同時に、より少ない妨害で自分の食欲を満足させるために、公共の精神を説くことは、誰よりも最悪の人々の関心 事であるとして、彼らは他の人々と同意し、公共のことを気にせずに、人間が自分の食欲を満たすために行うあらゆることを「ヴァイス」と呼ぶことにした。そ の行為において、社会の誰かを傷つけ、あるいは自分自身の有用性を低下させる可能性が少しでも観察されるならば。そして、人間が自然の衝動に反して、善で あるという合理的な野心から他人の利益や自分の情熱の征服に努力すべきあらゆる行為に、真実という名前を与えることである[27]。 批評家にはマンデヴィルが悪徳を助長しているように見えたが、これは彼の意図ではなかった[3]。 彼は「巧妙な人間の偽装を取り除き」、人間の行動を導く「隠れた糸」を暴露したかったと言った[28]。 それでも彼は「現代の放縦の擁護者」として見られ、「個人の悪」と「公共の利益」についての話はイギリスの教育を受けた人々の間でよく見られたものであっ た[29]。 |

| As literature Less attention has been paid to the literary qualities of Mandeville's book than to his argument. Kaye called the book "possessed of such extraordinary literary merit"[30] but focused his commentary on its implications for moral philosophy, economics, and utilitarianism. Harry L. Jones wrote in 1960 that the Fable "is a work having little or no merit as literature; it is a doggerel, pure and simple, and it deserves no discussion of those aspects of form by which art can be classified as art".[31] |

文学として マンデヴィルの本の文学的特質については、彼の議論よりもあまり注目されてこなかった。ケイはこの本を「並外れた文学的な価値を有している」[30]とし ながらも、道徳哲学、経済学、功利主義への示唆を中心に論評を行った。ハリー・L・ジョーンズは1960年にこの寓話を「文学としての利点がほとんどない 作品であり、純粋で単純なドーガレル(doggerel=韻律の揃わない不揃いなヘボ詩)であり、芸術を芸術として分類できるような形式の側面についての 議論に値しない」と書いている[31]。 |

| Mandeville is today generally

regarded as a serious economist and philosopher.[3] His second volume

of The Fable of the Bees in 1729 was a set of six dialogs that

elaborated on his socio-economic views. His ideas about the division of

labor draw on those of William Petty, and are similar to those of Adam

Smith.[32] Mandeville says: When once Men come to be govern’d by written Laws, all the rest comes on a-pace. Now Property, and Safety of Life and Limb, may be secured: This naturally will forward the Love of Peace, and make it spread. No number of Men, when once they enjoy Quiet, and no Man needs to fear his Neighbour, will be long without learning to divide and subdivide their Labour... Man, as I have hinted before, naturally loves to imitate what he sees others do, which is the reason that savage People all do the same thing: This hinders them from meliorating their Condition, though they are always wishing for it: But if one will wholly apply himself to the making of Bows and Arrows, whilst another provides Food, a third builds Huts, a fourth makes Garments, and a fifth Utensils, they not only become useful to one another, but the Callings and Employments themselves will in the same Number of Years receive much greater Improvements, than if all had been promiscuously follow’d by every one of the Five... The truth of what you say is in nothing so conspicuous, as it is in Watch-making, which is come to a higher degree of Perfection, than it would have been arrived at yet, if the whole had always remain'd the Employment of one Person; and I am persuaded, that even the Plenty we have of Clocks and Watches, as well as the Exactness and Beauty they may be made of, are chiefly owing to the Division that has been made of that Art into many Branches.[33] The poem suggests many key principles of economic thought, including division of labor and the "invisible hand", seventy years before these concepts were more thoroughly elucidated by Adam Smith.[34] Two centuries later, John Maynard Keynes cited Mandeville to show that it was "no new thing ... to ascribe the evils of unemployment to ... the insufficiency of the propensity to consume",[35] a condition also known as the paradox of thrift, which was central to his own theory of effective demand. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fable_of_the_Bees |

マンデヴィルは今日、一般に真面目な経済学者、哲学者とみなされている

[3]。

1729年の『蜜蜂の寓話』第2巻は、彼の社会経済的見解を詳しく説明した6つの対話のセットであった。分業に関する彼の考えは、ウィリアム・ペティのそ

れを参考にしており、アダム・スミスのそれと類似している[32] マンデヴィルは言う。 人間は一度文書化された法律によって支配されるようになると、他のすべてが急速に進歩するようになる。今、財産、生命と手足の安全が確保されるかもしれな い。このことは当然、平和を愛する心を前進させ、それを広めることになる。一旦、静寂を享受し、隣人を恐れる必要がなくなれば、労働を分割し細分化するこ とを学ばずにいられる人間はいないでしょう。 前にもほのめかしたように、人間はもともと他人のすることを真似るのが好きで、それが野蛮な人々がみな同じことをする理由である。しかし、もし一人が弓矢 の製作に専念し、別の一人が食物を提供し、三人が小屋を建て、四人が衣服を作り、五人が道具を作れば、互いに役立つようになるだけでなく、同じ年数の間に 職業や仕事自体が、五人全員が乱暴に従った場合よりもはるかに大きく改善されるでしょう...。 そのため、このような些細なことでも: このため、彼らは常にそれを望んでいるにもかかわらず、自分たちの状態を改善することを妨げています。しかし、もし一人が弓矢の製作に専念し、別の一人が 食物を供給し、三人が小屋を建て、四人が衣服を作り、五人が道具を作ると、互いに役立つようになるだけでなく、同じ年数の間に職業や仕事自体が、五人全員 が乱暴に従った場合よりもはるかに大きく改善されるだろう…… この詩では、経済学的な観点から、経済学的な観点から、莫大な量の莫大な量の時計が、或いは、その製造が、或る程度まで正確に、或いは、莫大な量に達するまで製造できることを指摘している[33] 。 2世紀後、ジョン・メイナード・ケインズはマンデヴィルを引用して、「失業の弊害を...消費性向の不足に帰することは...新しいことではない」ことを示し、また彼自身の有効需要の理論の中心となった倹約のパラドックスとして知られる状態[35]を示していた。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Mandeville |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報