聖書

Bible

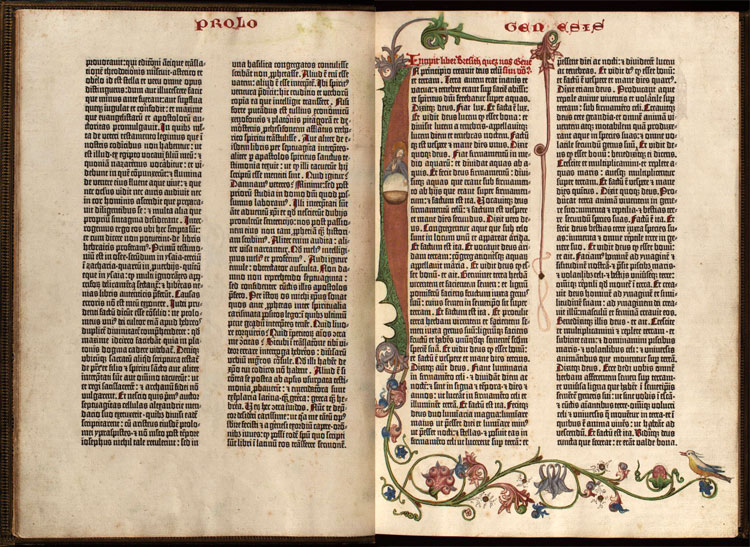

Gutenberg

Bible

☆ 聖書[a]は、キリスト教において神聖視されている宗教的なテキストと聖典のコレクションであり、ユダヤ教、サマリア教、イスラム教、バハーイ教、および その他のアブラハムの宗教の一部でも神聖視されている。聖書は、もともとヘブライ語、アラム語、ギリシャ語で書かれたアンソロジー(さまざまな形式のテキ ストの集成)である。テキストには、指示、物語、詩、預言、その他のジャンルが含まれる。特定の宗教的伝統やコミュニティによって聖書の一部として認めら れている資料の集合は、聖書正典と呼ばれる。信者は一般的に、聖書が神の霊感によるものとみなしているが、その意味するところやテキストの解釈の仕方は様 々である。

| The Bible[a]

is a collection of religious texts and scriptures that are held to be

sacred in Christianity, and partly in Judaism, Samaritanism, Islam, the

Baháʼí Faith, and other Abrahamic religions. The Bible is an anthology

(a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally written in

Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. The texts include instructions,

stories, poetry, prophecies, and other genres. The collection of

materials accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious

tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers generally

consider it to be a product of divine inspiration, but the way they

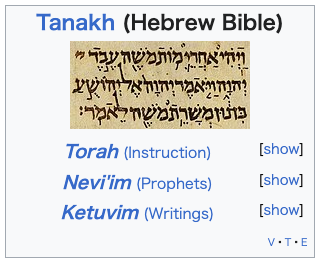

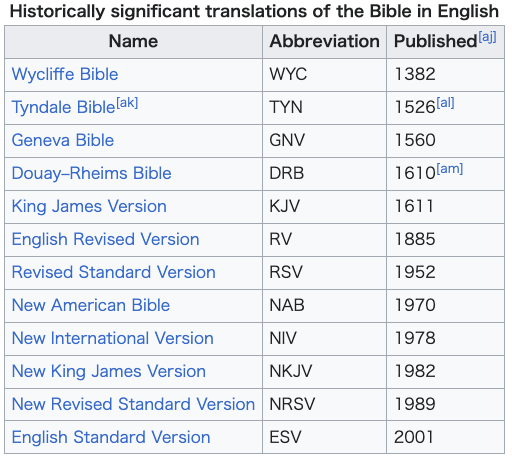

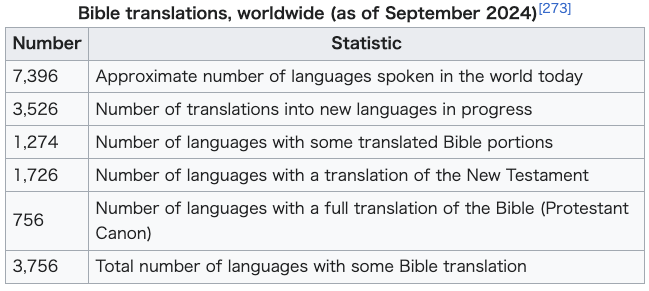

understand what that means and interpret the text varies. The religious texts were compiled by different religious communities into various official collections. The earliest contained the first five books of the Bible, called the Torah in Hebrew and the Pentateuch (meaning "five books") in Greek. The second-oldest part was a collection of narrative histories and prophecies (the Nevi'im). The third collection, the Ketuvim, contains psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories. "Tanakh" (Hebrew: תָּנָ״ךְ, romanized: Tanaḵ) is an alternate term for the Hebrew Bible, which is composed of the first letters of the three components comprising scriptures written originally in Hebrew: the Torah ("Teaching"), the Nevi'im ("Prophets"), and the Ketuvim ("Writings"). The Masoretic Text is the medieval version of the Tanakh—written in Hebrew and Aramaic—that is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible by modern Rabbinic Judaism. The Septuagint is a Koine Greek translation of the Tanakh from the third and second centuries BCE; it largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible. Christianity began as an outgrowth of Second Temple Judaism, using the Septuagint as the basis of the Old Testament. The early Church continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what it saw as inspired, authoritative religious books. The gospels, which are narratives about the life and teachings of Jesus, along with the Pauline epistles, and other texts quickly coalesced into the New Testament. With estimated total sales of over five billion copies, the Bible is the best-selling publication of all time. It has had a profound influence both on Western culture and history and on cultures around the globe. The study of it through biblical criticism has also indirectly impacted culture and history. The Bible is currently translated or is being translated into about half of the world's languages. Some view biblical texts as morally problematic, historically inaccurate, or corrupted by time; others find it a useful historical source for certain peoples and events or a source of ethical teachings. |

聖

書[a]は、キリスト教において神聖視されている宗教的なテキストと聖典のコレクションであり、ユダヤ教、サマリア教、イスラム教、バハーイ教、およびそ

の他のアブラハムの宗教の一部でも神聖視されている。聖書は、もともとヘブライ語、アラム語、ギリシャ語で書かれたアンソロジー(さまざまな形式のテキス

トの集成)である。テキストには、指示、物語、詩、預言、その他のジャンルが含まれる。特定の宗教的伝統やコミュニティによって聖書の一部として認められ

ている資料の集合は、聖書正典と呼ばれる。信者は一般的に、聖書が神の霊感によるものとみなしているが、その意味するところやテキストの解釈の仕方は様々

である。 宗教的なテキストは、異なる宗教的コミュニティによって、さまざまな公式コレクションにまとめられた。最も古いものは、ヘブライ語ではトーラー、ギリシャ 語では「五書」を意味するペンタテュクと呼ばれる、聖書の最初の五書を含んでいる。二番目に古い部分は、物語の歴史と預言のコレクション(ネビーム)であ る。三番目のコレクションであるケトゥビームは、詩篇、箴言、物語の歴史を含んでいる。「タナハ」(ヘブライ語: תָּנָ״ךְ、ローマ字転写: Tanaḵ)は、ヘブライ語聖書の別称であり、ヘブライ語で書かれた聖典を構成する3つの要素の頭文字を取って名付けられた。すなわち、「トーラー」 (「教え」)、「ネヴィイーム」(「預言者」)、「ケトゥービーム」(「文書」)である。マソラ本文は、ヘブライ語とアラム語で書かれた中世版のタナハで あり、現代のラビ・ユダヤ教ではヘブライ語聖書の正典とされている。セプトゥアギンタは、紀元前3世紀から2世紀にかけてのタナハの共通ギリシャ語訳であ り、ヘブライ語聖書と大部分が重複している。 キリスト教は第二神殿ユダヤ教から発展したもので、セプトゥアギンタを旧約聖書の基礎としていた。初期の教会は、霊感を受けた権威ある宗教書として、ユダ ヤ教の伝統を受け継ぎ、執筆と編纂を続けた。イエスの生涯と教えを記した福音書、パウロ書簡、その他のテキストは、急速に新約聖書へとまとめられていっ た。 推定総発行部数は50億部以上であり、聖書は史上最も売れた出版物である。聖書は西洋の文化と歴史、そして世界中の文化に多大な影響を与えてきた。聖書批 評による研究もまた、間接的に文化と歴史に影響を与えている。聖書は現在、世界の言語の約半分に翻訳されているか、翻訳作業が進められている。 聖書のテキストを道徳的に問題があるもの、歴史的に不正確なもの、あるいは時代によって変質したものと見る人もいれば、特定の民族や出来事に関する有益な歴史的資料、あるいは倫理的な教えの源と見る人もいる。 |

| Etymology The term "Bible" can refer to the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Bible, which contains both the Old and New Testaments.[1] The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία, romanized: ta biblia, meaning "the books" (singular βιβλίον, biblion).[2] The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of "scroll" and came to be used as the ordinary word for "book".[3] It is the diminutive of βύβλος byblos, "Egyptian papyrus", possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician seaport Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.[4] The Greek ta biblia ("the books") was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books".[5] The biblical scholar F. F. Bruce notes that John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer (in his Homilies on Matthew, delivered between 386 and 388 CE) to use the Greek phrase ta biblia ("the books") to describe both the Old and New Testaments together.[6] Latin biblia sacra "holy books" translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, "the holy books").[7] Medieval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra "holy book". It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.[8] |

語源 「聖書」という用語は、ヘブライ語聖書またはキリスト教聖書、すなわち旧約聖書と新約聖書の両方を含むものを指すことがある。 英語の「聖書」という語は、ギリシア語の「聖書」τὰ βιβλία(ローマ字表記:ta biblia)に由来し、「書物」(単数形:βιβλίον、biblion)を意味する。 [2] βιβλίονという単語自体は「巻物」という文字通りの意味を持ち、やがて「本」の一般的な言葉として使われるようになった。[3] これは、βύβλος(ビュブロス)「エジプトのパピルス」の縮小形であり、おそらくはフェニキアの海港ビュブロス(ゲバルとも呼ばれる)の名前から名付 けられた。この港からエジプトのパピルスがギリシャに輸出されていた。[4] ギリシャ語の「タ・ビブリア(聖書)」は、「ヘレニズム時代のユダヤ人が彼らの聖典を表現するために用いた表現」である。[5] 聖書学者のF. F. ブルースは、ヨハネス・クリュソストモスが(386年から388年の間に説教された)『マタイによる福音書』の中で、ギリシャ語の「タ・ビブリア(聖 書)」という表現を用いて、旧約聖書と新約聖書をまとめて表現した最初の作家であると指摘している。[6] ラテン語の「聖書」は、ギリシャ語の「神聖な書物」を意味するτὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια(tà biblía tà hágia)を訳したものである。[7] 中世ラテン語の「聖書」は、聖書(聖なる書物)の略である。中世ラテン語では、次第に女性単数形の名詞(biblia、gen. bibliae)として扱われるようになり、そのため、この語は単数形で西ヨーロッパの各国語に借用された。[8] |

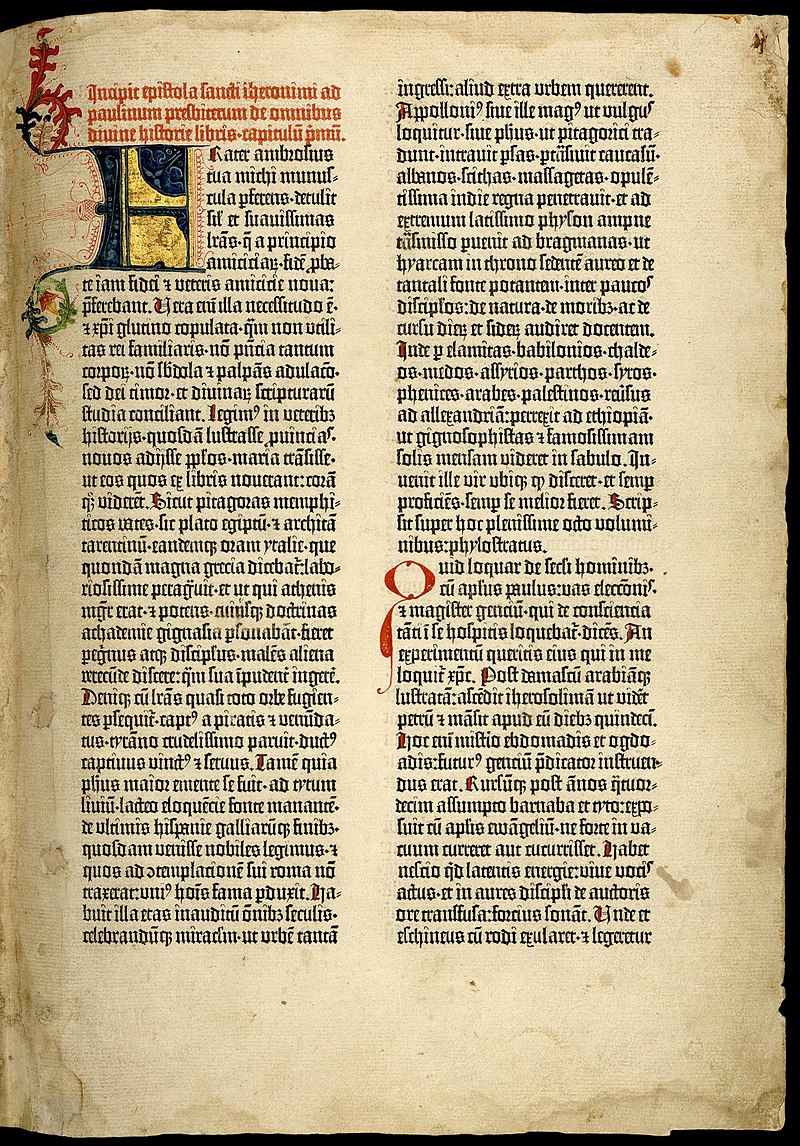

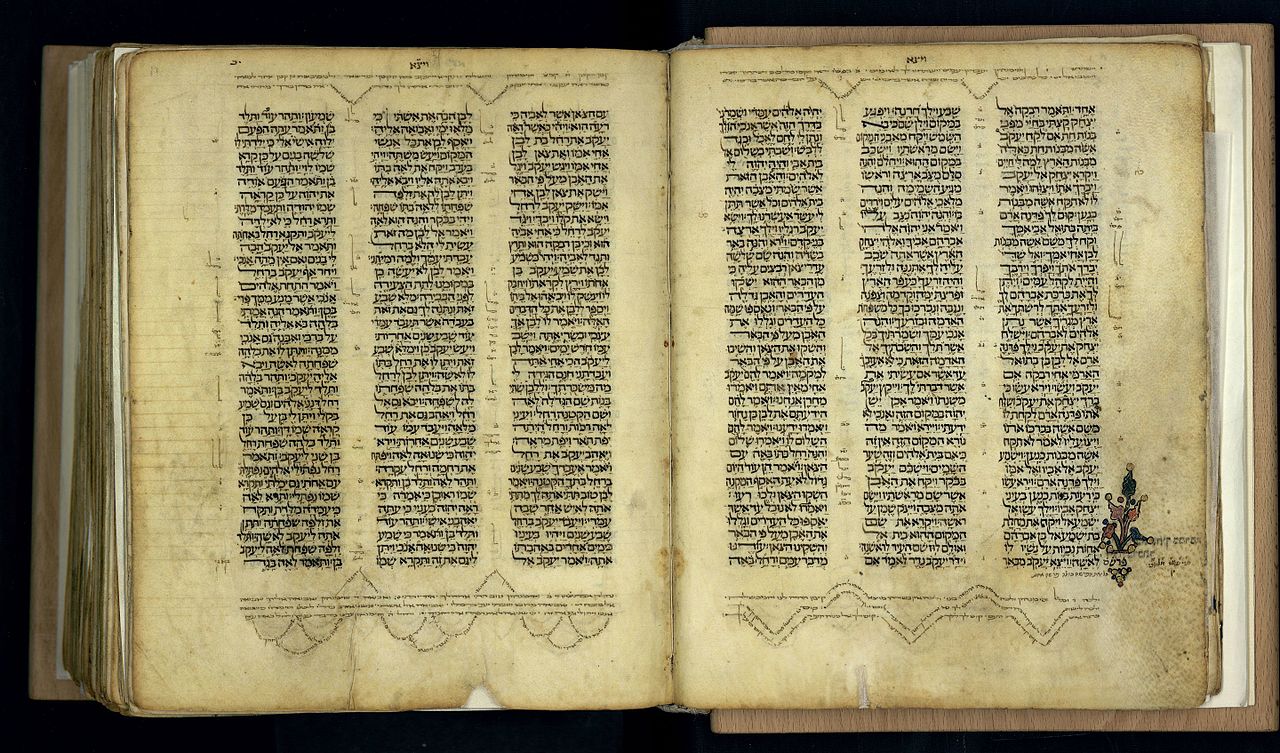

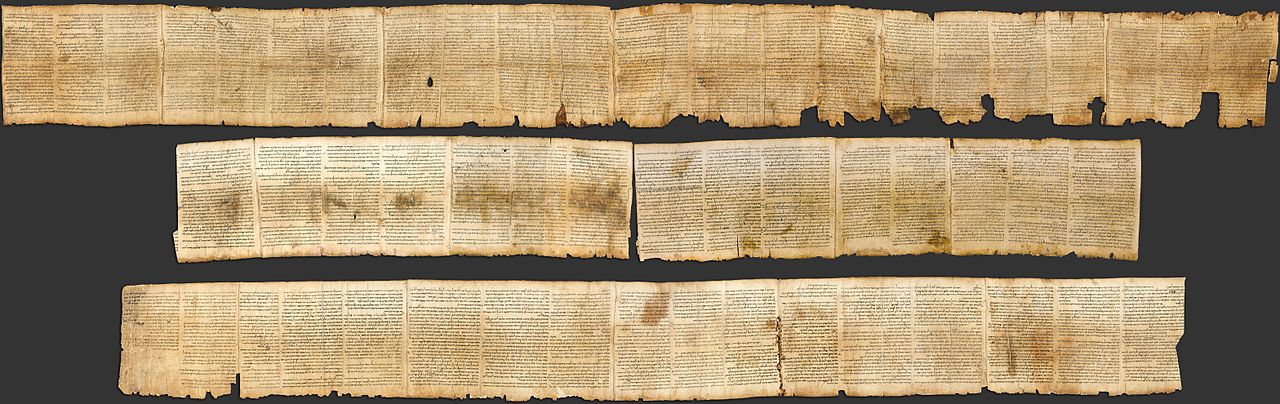

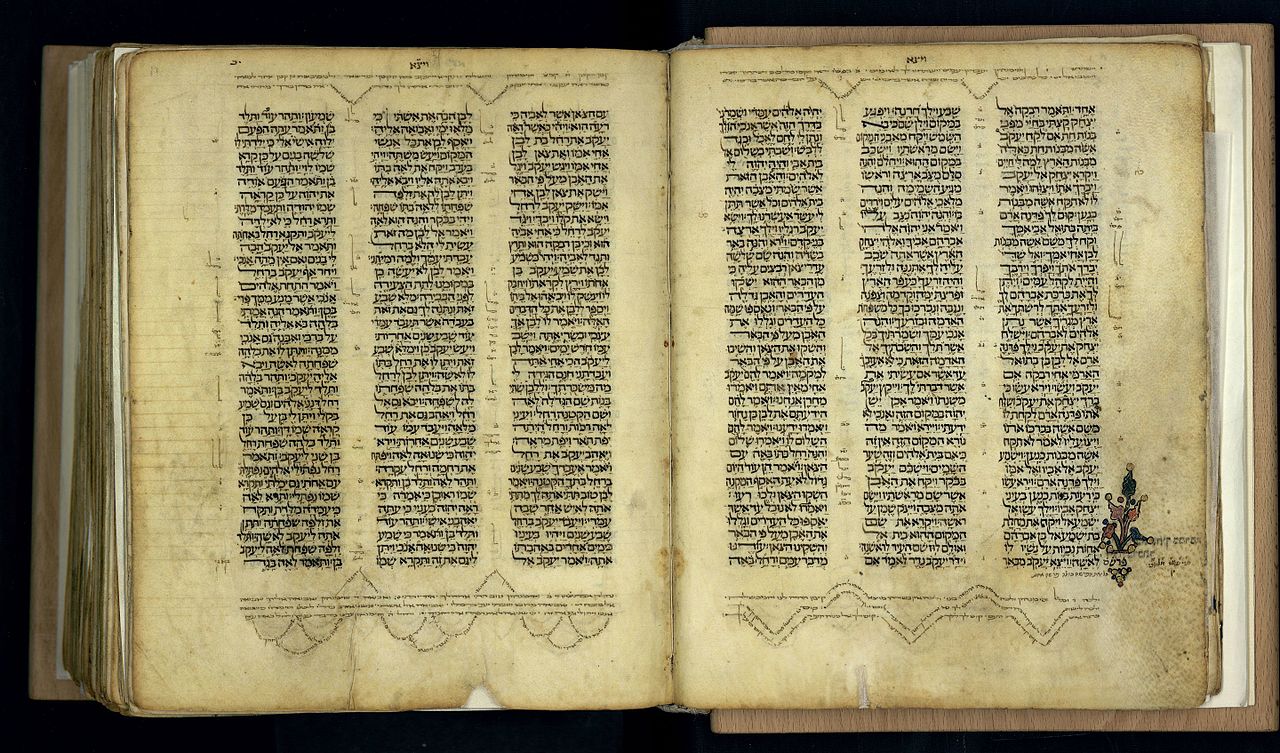

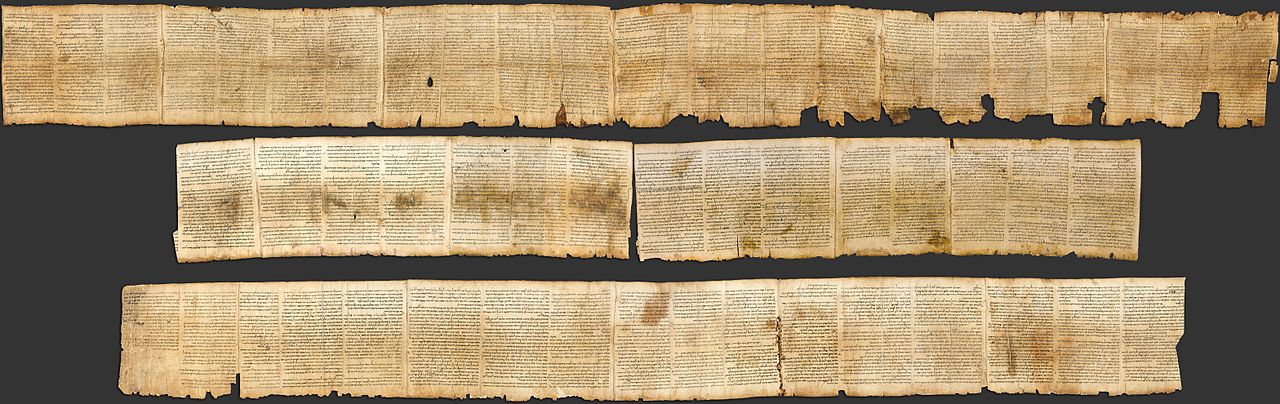

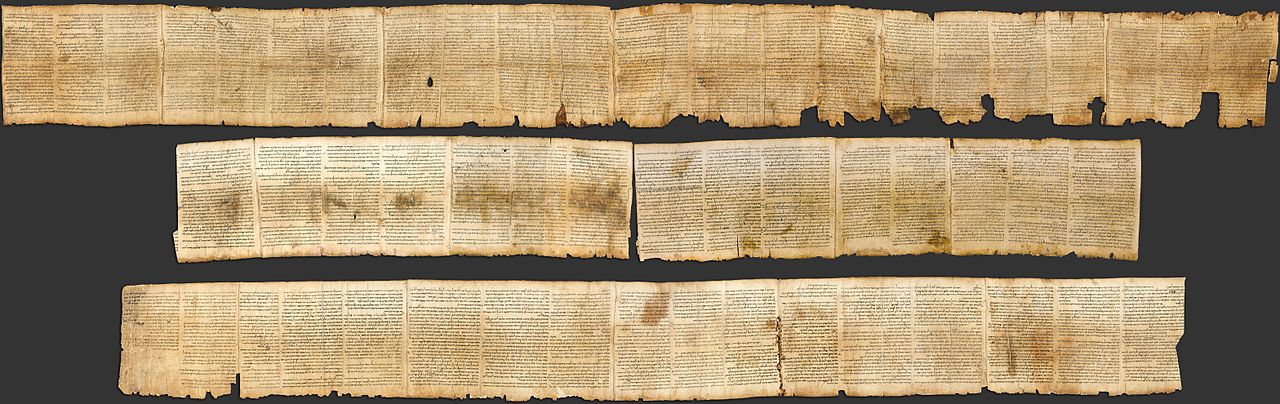

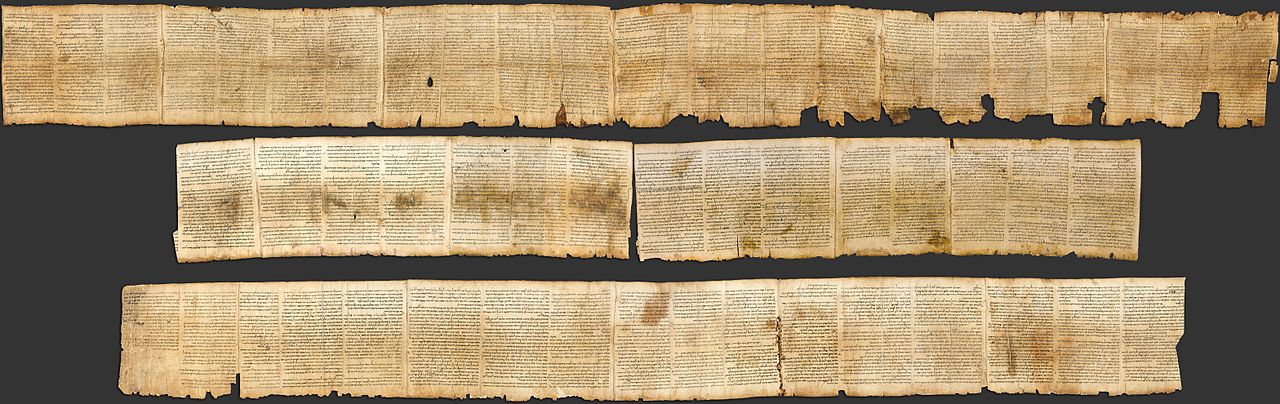

| Development and history See also: Biblical manuscript, Textual criticism, and Samaritan Pentateuch  Hebrew Bible from 1300. Genesis. The Book of Genesis in a c. 1300 Hebrew Bible  The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, is the oldest complete copy of the Book of Isaiah. The Bible is not a single book; it is a collection of books whose complex development is not completely understood. The oldest books began as songs and stories orally transmitted from generation to generation. Scholars of the twenty-first century are only in the beginning stages of exploring "the interface between writing, performance, memorization, and the aural dimension" of the texts. Current indications are that writing and orality were not separate as much as ancient writing was learned in communal oral performance.[9] The Bible was written and compiled by many people, who many scholars say are mostly unknown, from a variety of disparate cultures and backgrounds.[10] British biblical scholar John K. Riches wrote:[11] [T]he biblical texts were produced over a period in which the living conditions of the writers – political, cultural, economic, and ecological – varied enormously. There are texts which reflect a nomadic existence, texts from people with an established monarchy and Temple cult, texts from exile, texts born out of fierce oppression by foreign rulers, courtly texts, texts from wandering charismatic preachers, texts from those who give themselves the airs of sophisticated Hellenistic writers. It is a time-span which encompasses the compositions of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Sophocles, Caesar, Cicero, and Catullus. It is a period which sees the rise and fall of the Assyrian empire (twelfth to seventh century) and of the Persian empire (sixth to fourth century), Alexander's campaigns (336–326), the rise of Rome and its domination of the Mediterranean (fourth century to the founding of the Principate, 27 BCE), the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (70 CE), and the extension of Roman rule to parts of Scotland (84 CE). The books of the Bible were initially written and copied by hand on papyrus scrolls.[12] No originals have survived. The age of the original composition of the texts is, therefore, difficult to determine and heavily debated. Using a combined linguistic and historiographical approach, Hendel and Joosten date the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible (the Song of Deborah in Judges 5 and the Samson story of Judges 16 and 1 Samuel) to having been composed in the premonarchial early Iron Age (c. 1200 BCE).[13] The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in the caves of Qumran in 1947, are copies that can be dated to between 250 BCE and 100 CE. They are the oldest existing copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible of any length that are not fragments.[14] The earliest manuscripts were probably written in paleo-Hebrew, a kind of cuneiform pictograph similar to other pictographs of the same period.[15] The exile to Babylon most likely prompted the shift to square script (Aramaic) in the fifth to third centuries BCE.[16] From the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Hebrew Bible was written with spaces between words to aid reading.[17] By the eighth century CE, the Masoretes added vowel signs.[18] Levites or scribes maintained the texts, and some texts were always treated as more authoritative than others.[19] Scribes preserved and changed the texts by changing the script, updating archaic forms, and making corrections. These Hebrew texts were copied with great care.[20] Considered to be scriptures (sacred, authoritative religious texts), the books were compiled by different religious communities into various biblical canons (official collections of scriptures).[21] The earliest compilation, containing the first five books of the Bible and called the Torah (meaning "law", "instruction", or "teaching") or Pentateuch ("five books"), was accepted as Jewish canon by the fifth century BCE. A second collection of narrative histories and prophesies, called the Nevi'im ("prophets"), was canonized in the third century BCE. A third collection called the Ketuvim ("writings"), containing psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories, was canonized sometime between the second century BCE and the second century CE.[22] These three collections were written mostly in Biblical Hebrew, with some parts in Aramaic, which together form the Hebrew Bible or "TaNaKh" (an abbreviation of "Torah", "Nevi'im", and "Ketuvim").[23] |

発展と歴史 関連項目:聖書写本、本文批評、サマリア五書  1300年頃のヘブライ語聖書。創世記。 1300年頃のヘブライ語聖書における創世記  死海写本の一つである「イザヤ書大写本」(1QIsaa)は、イザヤ書の最古の完全な写本である。 聖書は単一の書物ではなく、複雑な発展過程を持つ複数の書物の集合体であり、その全容は完全に解明されていない。最古の書物は、歌や物語として口頭で世代 から世代へと伝えられていた。21世紀の学者たちは、テキストの「文字、パフォーマンス、暗記、聴覚の次元のインターフェース」を解明する研究の初期段階 にすぎない。現在の知見では、古代の文字は共同体の口頭によるパフォーマンスを通じて学ばれていたことから、文字と口承はそれほど別個のものではなかった ことが示唆されている。[9] 聖書は多くの人々によって書かれ、編纂されたが、その人々の多くは、さまざまな異質な文化や背景を持つ、ほとんど知られていない人々であると多くの学者が 指摘している。[10] 英国の聖書学者ジョン・K・リッチーズは次のように書いている。[11] 聖書のテキストは、著者の政治、文化、経済、生態系などの生活環境が著しく変化した時代に書かれた。遊牧民の生活を反映したテキスト、確立された君主制と 神殿崇拝の民によるテキスト、亡命者のテキスト、外国の支配者による激しい弾圧から生まれたテキスト、宮廷のテキスト、放浪のカリスマ的説教師によるテキ スト、洗練されたヘレニズムの作家を気取る人々によるテキストなどがある。これは、ホメロス、プラトン、アリストテレス、トゥキュディデス、ソフォクレ ス、カエサル、キケロ、カトゥルスなどの作品が生まれた時代である。また、アッシリア帝国(12世紀から7世紀)とペルシア帝国(6世紀から4世紀)の興 亡、 アレクサンダーの遠征(336年~326年)、ローマの勃興と地中海の支配(4世紀から元首制の創設、紀元前27年まで)、エルサレム神殿の破壊(西暦 70年)、ローマの支配がスコットランドの一部にまで及んだこと(西暦84年)などである。 聖書の書籍は、当初はパピルスの巻物に手書きで書かれ、写本された。[12] 現存する原本はない。したがって、テキストの原典の年代を確定することは難しく、激しい論争の的となっている。ヘンデルとヨーステンは、言語学と歴史学の 複合的なアプローチを用いて、ヘブライ語聖書の最古の部分(士師記5章のデボラの歌と士師記16章およびサムエル記上1章のサムソン物語)を、君主制以前 の初期鉄器時代(紀元前1200年頃)に書かれたものと推定している。 [13] 1947年にクムランの洞窟で発見された死海写本は、紀元前250年から西暦100年の間に書かれた写本である。 断片ではないヘブライ語聖書の現存する最古の写本である。[14] 最古の写本は、おそらく、同じ時代の他の絵文字と類似した楔形文字の一種であるパレオヘブライ語で書かれていたと考えられている。[15] バビロンへの追放は、紀元前5世紀から3世紀にかけて、正方形の文字(アラム文字)への移行を促した可能性が高い。[16] 死海写本の時代から、ヘブライ語聖書は読みやすくするために単語と単語の間にスペースを空けて書かれていた。 [17] 西暦8世紀には、マソラ学者たちが母音記号を加えた。[18]レビ人や書記がテキストを管理し、一部のテキストは常に他のテキストよりも権威あるものとし て扱われた。[19]書記たちはテキストを保存し、文字を変え、古風な表現を更新し、修正を加えることでテキストを変更した。これらのヘブライ語のテキス トは、細心の注意を払って複写された。[20] 聖典(神聖で権威ある宗教的テキスト)とみなされたこれらの書籍は、異なる宗教共同体によってさまざまな聖典の正典(聖典の公式コレクション)に編纂され た。[21] 聖書の最初の5冊の書籍を含み、トーラー(「律法」、「教え」、「教訓」の意)または五書(「5冊の書籍」の意)と呼ばれる最も初期の編纂物は、紀元前5 世紀までにユダヤ教の正典として認められた。物語の歴史と預言をまとめた第二のコレクションは「預言者たち」を意味する「ネビーム(Nevi'im)」と 呼ばれ、紀元前3世紀に正典とされた。詩篇、箴言、物語の歴史をまとめた第三のコレクションは「文筆」を意味する「ケトゥビーム(Ketuvim)」と呼 ばれ、紀元前2世紀から紀元後2世紀の間のいつかに正典とされた。 [22] これら3つのコレクションは、大部分が聖書ヘブライ語で書かれ、一部がアラム語で書かれている。これらを合わせてヘブライ語聖書、または「タナハ」 (「トーラー」、「ネヴィーム」、「ケトゥービーム」の略)と呼ばれる。[23] |

| Hebrew Bible There are three major historical versions of the Hebrew Bible: the Septuagint, the Masoretic Text, and the Samaritan Pentateuch (which contains only the first five books). They are related but do not share the same paths of development. The Septuagint, or the LXX, is a translation of the Hebrew scriptures and some related texts into Koine Greek and is believed to have been carried out by approximately seventy or seventy-two scribes and elders who were Hellenic Jews,[24] begun in Alexandria in the late third century BCE and completed by 132 BCE.[25][26][b] Probably commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, King of Egypt, it addressed the need of the primarily Greek-speaking Jews of the Graeco-Roman diaspora.[25][27] Existing complete copies of the Septuagint date from the third to the fifth centuries CE, with fragments dating back to the second century BCE.[28] Revision of its text began as far back as the first century BCE.[29] Fragments of the Septuagint were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls; portions of its text are also found on existing papyrus from Egypt dating to the second and first centuries BCE and to the first century CE.[29]: 5 The Masoretes began developing what would become the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible in Rabbinic Judaism near the end of the Talmudic period (c. 300–c. 500 CE), but the actual date is difficult to determine.[30][31][32] In the sixth and seventh centuries, three Jewish communities contributed systems for writing the precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora (from which we derive the term "masoretic").[30] These early Masoretic scholars were based primarily in the Galilean cities of Tiberias and Jerusalem and in Babylonia (modern Iraq). Those living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee (c. 750–950) made scribal copies of the Hebrew Bible texts without a standard text, such as the Babylonian tradition had, to work from. The canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (called Tiberian Hebrew) that they developed, and many of the notes they made, therefore, differed from the Babylonian.[33] These differences were resolved into a standard text called the Masoretic text in the ninth century.[34] The oldest complete copy still in existence is the Leningrad Codex dating to c. 1000 CE.[35] The Samaritan Pentateuch is a version of the Torah maintained by the Samaritan community since antiquity, which European scholars rediscovered in the 17th century; its oldest existing copies date to c. 1100 CE.[36] Samaritans include only the Pentateuch (Torah) in their biblical canon.[37] They do not recognize divine authorship or inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh.[c] A Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.[38] The first codex form of the Hebrew Bible was produced in the seventh century. The codex is the forerunner of the modern book. Popularized by early Christians, it was made by folding a single sheet of papyrus in half, forming "pages". Assembling multiples of these folded pages together created a "book" that was more easily accessible and more portable than scrolls. In 1488, the first complete printed press version of the Hebrew Bible was produced.[39] |

ヘブライ語聖書 ヘブライ語聖書には、大きく分けて3つの歴史的版がある。セプトゥアギンタ、マソラ本文、サマリア五書(最初の5冊の書のみを含む)である。これらは関連 しているが、同じ発展の過程をたどったものではない。セプトゥアギンタ(またはLXX)は、ヘブライ語聖書と関連するいくつかのテキストをコイネー・ギリ シャ語に翻訳したもので、ヘレニズム期のユダヤ人である約70人または72人の書記と長老たちによって行われたと考えられている。作業は紀元前3世紀後半 にアレクサンドリアで開始され、紀元前132年に完了した。 [25][26][b] これは、おそらくエジプト王プトレマイオス2世フィラデルフォスが命じたもので、ギリシャ語を話すユダヤ人が主に住んでいたギリシャ・ローマのディアスポ ラのニーズに応えるものであった。[25][27] 現存するセプトゥアギンタの完全な写本は、西暦3世紀から5世紀のもので、断片は紀元前2世紀まで遡る。[28] そのテキストの改訂は、紀元前1世紀にまで遡る。 [29] セプトゥアギンタの断片は死海写本の中から発見されており、そのテキストの一部は紀元前2世紀から1世紀、および紀元1世紀のエジプトのパピルスにも存在 している。[29]:5 マソラ学者たちは、タルムード時代の終わり頃(西暦300年頃から500年頃)にラビ・ユダヤ教において、ヘブライ語聖書の24の書籍のヘブライ語および アラム語の権威あるテキストとなるものを開発し始めたが、実際の年代は特定が難しい。 [30][31][32] 6世紀と7世紀には、3つのユダヤ人共同体が正確な文字テキストを記述するシステムを考案し、その発音とアクセントはマスーラ(mas'sora)として 知られるようになった(そこから「マソラ」という用語が派生した)。[30] 初期のマソラ学者たちは主にガリラヤ地方のティベリアとエルサレム、およびバビロニア(現在のイラク)に拠点を置いていた。古代ガリラヤのティベリアのユ ダヤ人コミュニティに居住していた人々(750年頃~950年頃)は、バビロニアの伝統のように、作業の基盤となる標準的なテキストを持たずに、ヘブライ 語聖書の写本を書き写していた。彼らが発展させたヘブライ語聖書の正典の標準的な発音(ティベリアン・ヘブライ語と呼ばれる)や、彼らが作成した注釈の多 くは、バビロニアのものと異なっていた。[33] これらの相違は、9世紀にマソラ本文と呼ばれる標準的なテキストにまとめられた。[34] 現存する最古の完全な写本は、西暦1000年頃のレニングラード写本である。[35] サマリア五書は、古代以来サマリア人社会で維持されてきたトーラーの版であり、17世紀にヨーロッパの学者によって再発見された。現存する最古の写本は西 暦1100年頃のものである。[36] サマリア人は聖書正典に五書(トーラー)のみを含める。 [37] 彼らはユダヤ教の聖典タナハの他のどの書物についても、神聖な著作や霊感によるものとは認めない。[c] タナハのヨシュア記を部分的に基にしたサマリア人のヨシュア記も存在するが、サマリア人はそれを正典ではない世俗的な歴史年代記とみなしている。[38] ヘブライ語聖書の最初の写本は7世紀に作成された。この写本は、現代の書籍の先駆けである。初期のキリスト教徒によって普及したこの写本は、パピルスの紙 を半分に折り、「ページ」を形成する。この折りたたんだページを複数集めることで、巻物よりも持ち運びが容易な「書籍」が作成された。1488年には、ヘ ブライ語聖書の最初の完全な印刷版が作成された。[39] |

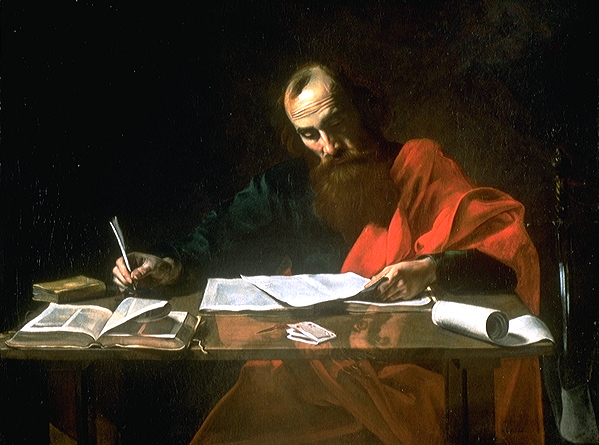

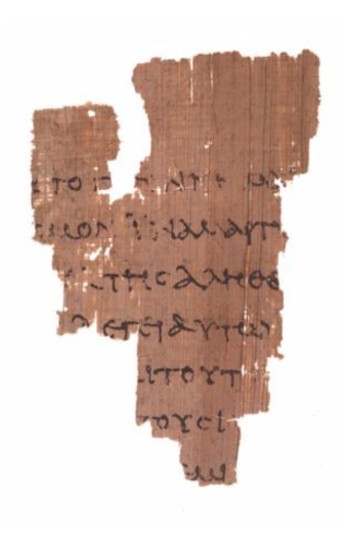

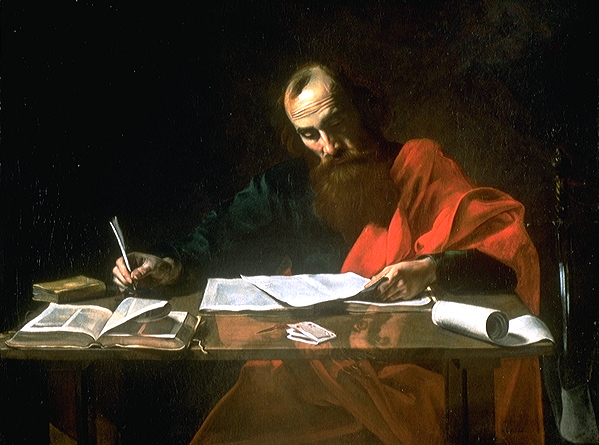

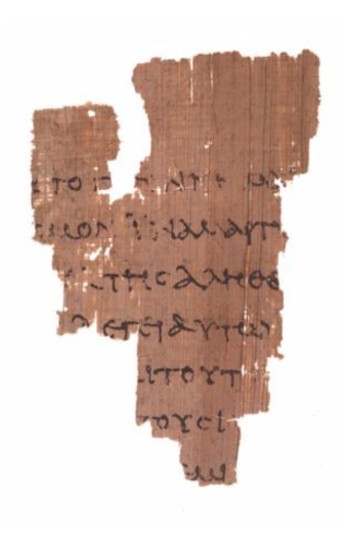

New Testament Paul the Apostle depicted in Saint Paul Writing His Epistles, a c. 1619 portrait by Valentin de Boulogne  photo of a fragment of papyrus with writing on it The Rylands fragment P52 verso is the oldest existing fragment of New Testament papyrus, including phrases from the 18th chapter of the Gospel of John.[40] During the rise of Christianity in the first century CE, new scriptures were written in Koine Greek. Christians eventually called these new scriptures the "New Testament" and began referring to the Septuagint as the "Old Testament".[41] The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work.[42][43] Most early Christian copyists were not trained scribes.[44] Many copies of the gospels and Paul's letters were made by individual Christians over a relatively short period of time, very soon after the originals were written.[45] There is evidence in the Synoptic Gospels, in the writings of the early church fathers, from Marcion, and in the Didache that Christian documents were in circulation before the end of the first century.[46][47] Paul's letters were circulated during his lifetime, and his death is thought to have occurred before 68 during Nero's reign.[48][49] Early Christians transported these writings around the Empire, translating them into Old Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Latin, and other languages.[50] Bart Ehrman explains how these multiple texts later became grouped by scholars into categories: During the early centuries of the church, Christian texts were copied in whatever location they were written or taken to. Since texts were copied locally, it is no surprise that different localities developed different kinds of textual tradition. That is to say, the manuscripts in Rome had many of the same errors, because they were for the most part "in-house" documents, copied from one another; they were not influenced much by manuscripts being copied in Palestine; and those in Palestine took on their own characteristics, which were not the same as those found in a place like Alexandria, Egypt. Moreover, in the early centuries of the church, some locales had better scribes than others. Modern scholars have come to recognize that the scribes in Alexandria – which was a major intellectual center in the ancient world – were particularly scrupulous, even in these early centuries, and that there, in Alexandria, a very pure form of the text of the early Christian writings was preserved, decade after decade, by dedicated and relatively skilled Christian scribes.[51] These differing histories produced what modern scholars refer to as recognizable "text types". The four most commonly recognized are Alexandrian, Western, Caesarean, and Byzantine.[52] The list of books included in the Catholic Bible was established as canon by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397. Between 385 and 405 CE, the early Christian church translated its canon into Vulgar Latin (the common Latin spoken by ordinary people), a translation known as the Vulgate.[53] Since then, Catholic Christians have held ecumenical councils to standardize their biblical canon. The Council of Trent (1545–63), held by the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, authorized the Vulgate as its official Latin translation of the Bible.[54] A number of biblical canons have since evolved. Christian biblical canons range from the 73 books of the Catholic Church canon and the 66-book canon of most Protestant denominations to the 81 books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon, among others.[55] Judaism has long accepted a single authoritative text, whereas Christianity has never had an official version, instead having many different manuscript traditions.[56] |

新約聖書 使徒パウロを描いた『パウロ書簡執筆中』、ヴァランタン・ド・ブローニュによる1619年頃の肖像画  パピルスに書かれた文章の断片の写真 ライランズ写本P52の裏面は、現存する新約聖書のパピルス断片としては最古のもので、ヨハネによる福音書第18章の文章が含まれている。 西暦1世紀のキリスト教勃興期には、新しい聖句はコイネー・ギリシア語で書かれた。キリスト教徒は最終的にこれらの新しい聖句を「新約聖書」と呼ぶように なり、セプトゥアギンタを「旧約聖書」と呼ぶようになった。[41] 新約聖書は、古代の作品の中で最も多くの写本が保存されている。[42][43] 初期のキリスト教の写本のほとんどは、訓練を受けた書記によるものではなかった。 [44] 福音書やパウロの手紙の写本の多くは、オリジナルが書かれた直後から比較的短期間のうちに、個々のキリスト教徒の手によって作成された。[45] 共観福音書、初期の教会の父祖たちの著作、マルキオン、そして『ディダケー』には、キリスト教の文書が1世紀の終わりまでに流通していたことを示す証拠が ある。 [46][47] パウロの手紙は彼の存命中に流通しており、彼の死はネロの治世下の68年以前に起こったと考えられている。[48][49] 初期のキリスト教徒たちは、これらの文書を帝国各地に運び、シリア語(古シリア語)、コプト語、エチオピア語、ラテン語、その他の言語に翻訳した。 バート・エーマンは、これらの複数のテキストが後に学者たちによってカテゴリーに分類された経緯について、次のように説明している。 初期の教会の時代には、キリスト教のテキストは、それが書かれた場所や持ち運ばれた場所で写本化されていた。テキストは各地で写本化されていたため、異な る地域で異なる種類のテキストの伝統が発展したとしても不思議ではない。つまり、ローマの写本には多くの同じ誤りが見られるが、それはそれらの写本のほと んどが「社内」文書であり、互いに写し合われたものだったからである。それらはパレスチナで写された写本からあまり影響を受けておらず、パレスチナの写本 はエジプトのアレキサンドリアで見られるものとは異なる独自の特性を持っていた。さらに、初期の教会では、地域によって優れた書記がいた。現代の学者たち は、古代世界の主要な知的中心地であったアレクサンドリアの写本作成者たちが、初期の数世紀の間でさえも特に厳密であったこと、そして、献身的で比較的熟 練したキリスト教徒の写本作成者たちによって、初期キリスト教のテキストの非常に純粋な形が何十年にもわたってアレクサンドリアで保存されていたことを認 識するに至っている。 これらの異なる歴史が、現代の学者が「テキストの種類」として認識しているものを生み出した。最も一般的に認識されているのは、アレクサンドリア、西方、カイザリオン、ビザンチウムの4つである。 カトリックの聖書に含まれる書籍のリストは、382年のローマ公会議で正典として制定され、393年のヒッポ公会議、397年のカルタゴ公会議でも続い た。西暦385年から405年の間、初期キリスト教会は、その正典を俗ラテン語(一般の人々が話すラテン語)に翻訳した。この翻訳はウルガタとして知られ ている。[53] それ以来、カトリックのキリスト教徒は、聖書の正典を標準化するために、エキュメニカル評議会を開催してきた。プロテスタントの宗教改革を受けてカトリッ ク教会が開催したトレント公会議(1545年~1563年)では、ウルガタをラテン語訳聖書の公式訳として承認した。キリスト教の聖書正典は、カトリック 教会の73冊の正典から、ほとんどのプロテスタント宗派の66冊の正典、エチオピア正教会の81冊の正典など、さまざまなものがある。[55] ユダヤ教では長い間、単一の権威あるテキストが受け入れられてきたが、キリスト教には公式版が存在したことはなく、代わりに多くの異なる写本の伝統があ る。[56] |

| Variants All biblical texts were treated with reverence and care by those who copied them, yet there are transmission errors, called variants, in all biblical manuscripts.[57][58] A variant is any deviation between two texts. Textual critic Daniel B. Wallace explains, "Each deviation counts as one variant, regardless of how many MSS [manuscripts] attest to it."[59] Hebrew scholar Emanuel Tov says the term is not evaluative; it is a recognition that the paths of development of different texts have separated.[60] Medieval handwritten manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were considered extremely precise: the most authoritative documents from which to copy other texts.[61] Even so, David Carr asserts that Hebrew texts still contain some variants.[62] The majority of all variants are accidental, such as spelling errors, but some changes were intentional.[63] In the Hebrew text, "memory variants" are generally accidental differences evidenced by such things as the shift in word order found in 1 Chronicles 17:24 and 2 Samuel 10:9 and 13. Variants also include the substitution of lexical equivalents, semantic and grammar differences, and larger scale shifts in order, with some major revisions of the Masoretic texts that must have been intentional.[64] Intentional changes in New Testament texts were made to improve grammar, eliminate discrepancies, harmonize parallel passages, combine and simplify multiple variant readings into one, and for theological reasons.[63][65] Bruce K. Waltke observes that one variant for every ten words was noted in the recent critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, leaving 90% of the Hebrew text without variation. The fourth edition of the United Bible Society's Greek New Testament notes variants affecting about 500 out of 6900 words, or about 7% of the text.[66] Further information: Textual variants in the Hebrew Bible and Textual variants in the New Testament |

異文 聖書のテキストは、それを写した人々によってすべて敬意と注意を払って扱われたが、聖書の写本にはすべて、異文と呼ばれる伝達エラーが存在する。[57] [58] 異文とは、2つのテキスト間のあらゆる相違を指す。本文批評家のダニエル・B・ウォレスは、「それぞれの相違は、それが何種類の写本によって証明されてい るかに関わらず、1つの異文として数えられる」と説明している。[59] ヘブライ語学者エマニュエル・トヴは、この用語は評価的なものではなく、異なるテキストの展開の道筋が分かれてきたことを認識するものであると述べてい る。[60] 中世に書かれたヘブライ語聖書の写本は、非常に正確であると考えられていた。他のテキストを複写する際の最も権威ある文書である。[61] それでも、デビッド・カーはヘブライ語のテキストには依然としていくつかの異本が存在すると主張している。[62] 異本の大部分は、スペルミスなどの偶然によるものであるが、意図的な変更もいくつかある。 [63] ヘブライ語のテキストでは、「記憶の相違」は一般的に偶然の差異であり、1歴代誌17:24と2サムエル10:9および13に見られる語順の変化などがそ の例である。相違には、語彙の同等語の置き換え、意味や文法の違い、より大規模な順序の変更も含まれ、マソラ本文の大幅な修正の中には意図的なものもあっ たと考えられる。 新約聖書のテキストにおける意図的な変更は、文法の改善、矛盾の解消、並行箇所の調和、複数の異なった読み方を1つにまとめること、神学上の理由などで行 われた。[63][65] ブルース・K・ウォルツケは、最近のヘブライ語聖書の批判版である『Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia』では、10語につき1語の割合で異同が指摘されているが、ヘブライ語のテキストの90%は異同なしのままであると指摘して いる。ユナイテッド・バイブル・ソサエティによるギリシャ語新約聖書の第4版では、6900語のうち約500語、すなわちテキストの約7%に影響する異文 が注記されている。[66] さらに詳しい情報については、ヘブライ語聖書におけるテキストの異文および新約聖書におけるテキストの異文を参照のこと。 |

| Content and themes Themes Further information: Ethics in the Bible, Jewish ethics, and Christian ethics  Creation of Light by Gustave Doré. The narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, parables, and unique genres of the Bible provide opportunity for discussion on most topics of concern to human beings: The role of women,[67]: 203 sex,[68] children, marriage,[69] neighbours,[70]: 24 friends, the nature of authority and the sharing of power,[71]: 45–48 animals, trees and nature,[72]: xi money and economics,[73]: 77 work, relationships,[74] sorrow and despair and the nature of joy, among others.[75] Philosopher and ethicist Jaco Gericke adds: "The meaning of good and evil, the nature of right and wrong, criteria for moral discernment, valid sources of morality, the origin and acquisition of moral beliefs, the ontological status of moral norms, moral authority, cultural pluralism, [as well as] axiological and aesthetic assumptions about the nature of value and beauty. These are all implicit in the texts."[76] However, discerning the themes of some biblical texts can be problematic.[77] Much of the Bible is in narrative form and in general, biblical narrative refrains from any kind of direct instruction, and in some texts the author's intent is not easy to decipher.[78] It is left to the reader to determine good and bad, right and wrong, and the path to understanding and practice is rarely straightforward.[79] God is sometimes portrayed as having a role in the plot, but more often there is little about God's reaction to events, and no mention at all of approval or disapproval of what the characters have done or failed to do.[80] The writer makes no comment, and the reader is left to infer what they will.[80] Jewish philosophers Shalom Carmy and David Schatz explain that the Bible "often juxtaposes contradictory ideas, without explanation or apology".[81] The Hebrew Bible contains assumptions about the nature of knowledge, belief, truth, interpretation, understanding and cognitive processes.[82] Ethicist Michael V. Fox writes that the primary axiom of the book of Proverbs is that "the exercise of the human mind is the necessary and sufficient condition of right and successful behavior in all reaches of life".[83] The Bible teaches the nature of valid arguments, the nature and power of language, and its relation to reality.[76] According to Mittleman, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character.[84][85] In the biblical metaphysic, humans have free will, but it is a relative and restricted freedom.[86] Beach says that Christian voluntarism points to the will as the core of the self, and that within human nature, "the core of who we are is defined by what we love".[87] Natural law is in the Wisdom literature, the Prophets, Romans 1, Acts 17, and the book of Amos (Amos 1:3–2:5), where nations other than Israel are held accountable for their ethical decisions even though they do not know the Hebrew god.[88] Political theorist Michael Walzer finds politics in the Hebrew Bible in covenant, law, and prophecy, which constitute an early form of almost democratic political ethics.[89] Key elements in biblical criminal justice begin with the belief in God as the source of justice and the judge of all, including those administering justice on earth.[90] Carmy and Schatz say the Bible "depicts the character of God, presents an account of creation, posits a metaphysics of divine providence and divine intervention, suggests a basis for morality, discusses many features of human nature, and frequently poses the notorious conundrum of how God can allow evil."[91] |

内容とテーマ テーマ さらに詳しい情報:聖書の倫理、ユダヤ教の倫理、キリスト教の倫理  ギュスターヴ・ドレによる「光の創造」。 聖書の物語、律法、知恵の言葉、たとえ話、独特なジャンルは、人間が関心を寄せるほとんどのテーマについて議論する機会を提供している。女性の役割 [67]: 203、性[68]、子供、結婚[69]、隣人[70]: 24、友人、権威の性質と権力の共有[71]: 45–48 動物、樹木、自然、[72]: xi お金と経済、[73]: 77 仕事、人間関係、[74] 悲しみと絶望、喜びの本質、その他。[75] 哲学者で倫理学者のヤコ・ゲリケは次のように付け加えている。「善と悪の意味、正義と悪の性質、道徳的識別の基準、道徳の妥当な源泉、道徳的信念の起源と 獲得、道徳的規範の存在論的地位、道徳的権威、文化的多元主義、価値と美の本質に関する価値論的および審美的前提。これらはすべて本文に暗黙的に含まれて いる」[76] しかし、聖書のテキストのテーマを識別することは問題となる可能性がある。[77] 聖書の大部分は物語形式であり、一般的に聖書の物語はあらゆる種類の直接的な指示を避けている。また、テキストによっては著者の意図を読み解くことが容易 ではない。[78] 善悪や正誤を判断するのは読者に委ねられており、理解と実践への道筋はまっすぐなものではない。 [79] 神は時折、筋書きの中で役割を持つように描かれるが、神が事象に対してどのような反応を示すかについてはほとんど描かれず、登場人物が何をしたか、あるい は何をしなかったかについて、神がそれを承認または非承認したという記述は一切ない。[80] 著者は何のコメントもせず、読者は各自で推測するほかない。 [80] ユダヤ人の哲学者であるシャロム・カーミーとデビッド・シャッツは、聖書は「説明や弁明なしに、しばしば矛盾する考えを並置する」と説明している。 [81] ヘブライ語聖書には、知識、信念、真理、解釈、理解、認識プロセスに関する前提が含まれている。[82] 倫理学者のマイケル・V・ フォックスは、箴言の主要な公理は「人間の精神の鍛錬は、人生のあらゆる局面において、正しい行動と成功を収めるための必要かつ十分な条件である」という ものであると書いている。[83] 聖書は、有効な論証の性質、言語の性質と力、そして現実との関係について教えている。[76] ミットルマンによると、聖書は行動と性格に焦点を当てた道徳的推論のパターンを提供している。[84][85] 聖書の形而上学では、人間には自由意志があるが、それは相対的で制限された自由である。[86] ビーチは、キリスト教の意志論は意志を自己の核心としており、人間の本性において、「私たちが何者であるかの核心は、私たちが何を愛するかによって定義さ れる」と述べている。 [87] 自然法は、知恵文学、預言者、ローマ人への手紙1章、使徒行伝17章、アモス書(アモス1:3-2:5)に登場する。そこでは、イスラエル以外の国民も、 ヘブライの神を知らなくとも、倫理的な決定に対して責任を負うものとされている。 [88] 政治理論家のマイケル・ウォルツアーは、ヘブライ語聖書における政治は、契約、法、預言に見られるものであり、これらはほぼ民主的な政治倫理の初期の形態 を構成していると主張している。[89] 聖書の刑事司法の主要な要素は、神が正義の源であり、地上で正義を執行する者も含めたすべてを裁く存在であるという信念から始まっている。[90] カーミーとシャッツは、聖書は「神の性格を描き、天地創造の物語を提示し、神の摂理と神の介入という形而上学を仮定し、道徳の基礎を示唆し、人間の本性の多くの特徴を論じ、そして、神が悪を許容できるのかという悪名高い難問を頻繁に提起している」と述べている。[91] |

Hebrew Bible The authoritative Hebrew Bible is taken from the masoretic text (called the Leningrad Codex) which dates from 1008. The Hebrew Bible can therefore sometimes be referred to as the Masoretic Text.[92] The Hebrew Bible is also known by the name Tanakh (Hebrew: תנ"ך). This reflects the threefold division of the Hebrew scriptures, Torah ("Teaching"), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings") by using the first letters of each word.[93] It is not until the Babylonian Talmud (c. 550 BCE) that a listing of the contents of these three divisions of scripture are found.[94] The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some small portions (Ezra 4:8–6:18 and 7:12–26, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4–7:28)[95] written in Biblical Aramaic, a language which had become the lingua franca for much of the Semitic world.[96] |

ヘブライ語聖書 権威あるヘブライ語聖書は、1008年にさかのぼるマソラ本文(レニングラード写本と呼ばれる)から採られている。そのため、ヘブライ語聖書はマソラ本文と呼ばれることもある。[92] ヘブライ語聖書は、タナハ(ヘブライ語: תנ"ך)という名称でも知られている。これはヘブライ語聖書の3つの区分、トーラー(「教え」)、ネヴィーム(「預言者」)、ケトゥヴィーム(「文 書」)を、各単語の最初の文字を用いて表したものである。[93] これらの3つの区分の聖書の内容の一覧は、バビロニア・タルムード(紀元前550年頃)まで見られない。[94] 聖書は主に聖書ヘブライ語で書かれており、一部の小部分(エズラ記4:8-6:18、7:12-26、エレミヤ書10:11、ダニエル書2:4-7:28)は聖書アラム語で書かれている。聖書アラム語は、セム語族世界の多くの地域で共通語となっていた言語である。 |

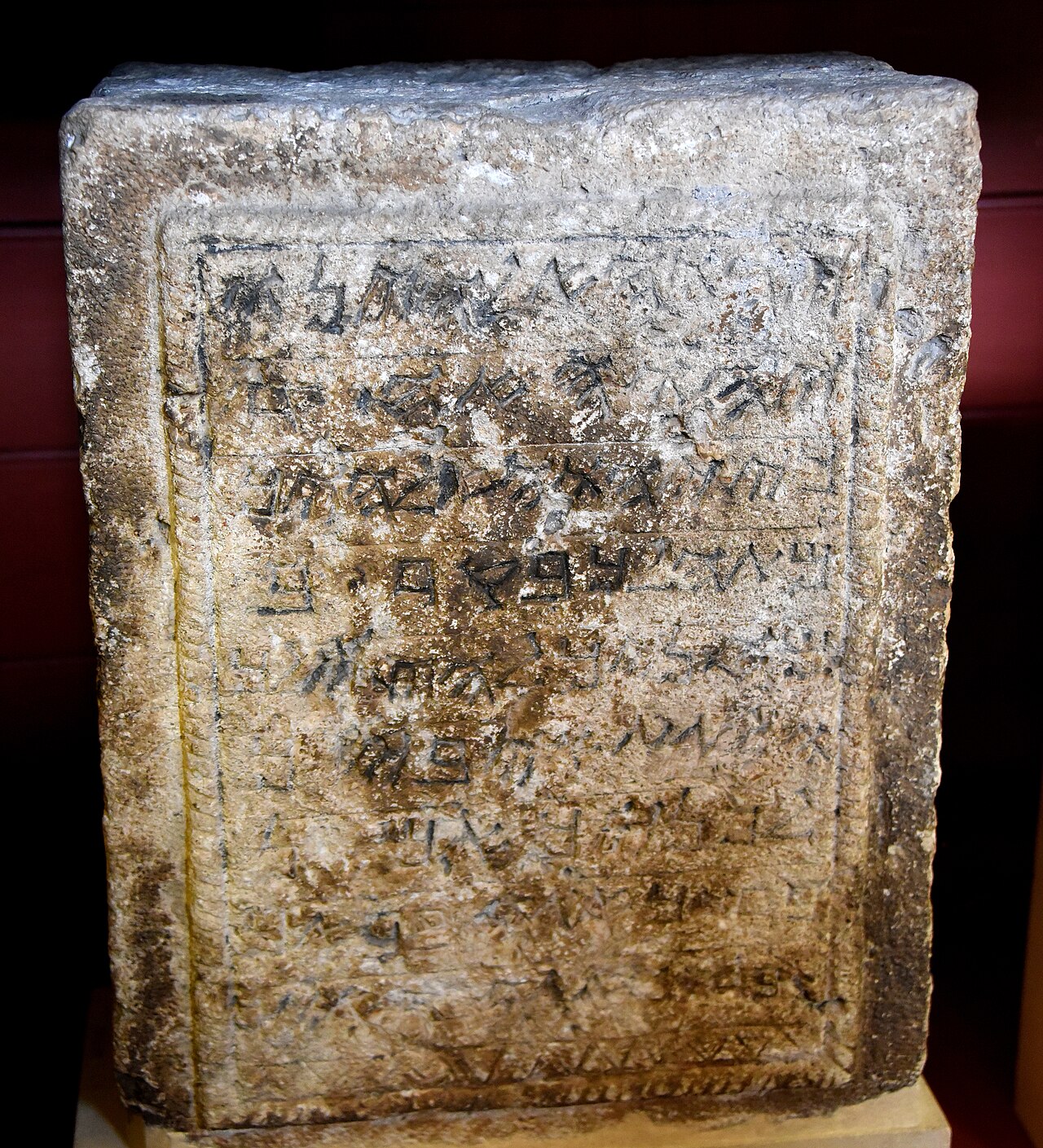

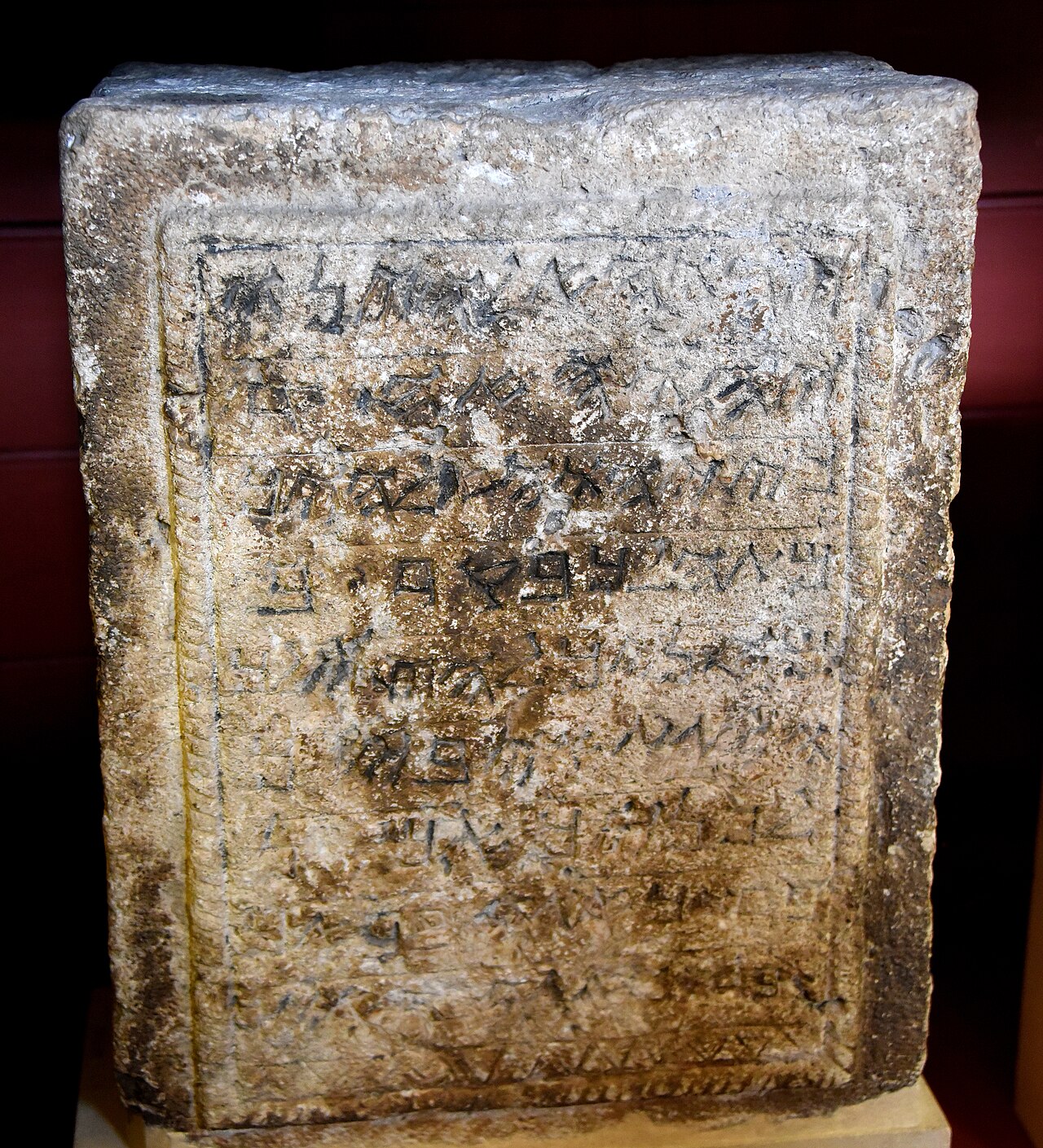

| Torah Main article: Torah See also: Oral Torah  A Torah scroll recovered from Glockengasse Synagogue in Cologne  Samaritan Inscription containing a portion of the Bible in nine lines of Hebrew text, currently housed in the British Museum in London The Torah (תּוֹרָה) is also known as the "Five Books of Moses" or the Pentateuch, meaning "five scroll-cases".[97] Traditionally these books were considered to have been dictated to Moses by God himself.[98][99] Since the 17th century, scholars have viewed the original sources as being the product of multiple anonymous authors while also allowing the possibility that Moses first assembled the separate sources.[100][101] There are a variety of hypotheses regarding when and how the Torah was composed,[102] but there is a general consensus that it took its final form during the reign of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE),[103][104] or perhaps in the early Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).[105] The Hebrew names of the books are derived from the first words in the respective texts. The Torah consists of the following five books: Genesis, Bereshith (בראשית) Exodus, Shemot (שמות) Leviticus, Vayikra (ויקרא) Numbers, Bamidbar (במדבר) Deuteronomy, Devarim (דברים) The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world and the history of God's early relationship with humanity. The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God's covenant with the biblical patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel) and Jacob's children, the "Children of Israel", especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt. The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. He leads the Children of Israel from slavery in ancient Egypt to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation was ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.[106] The commandments in the Torah provide the basis for Jewish religious law. Tradition states that there are 613 commandments (taryag mitzvot). |

トーラー 詳細は「トーラー」を参照 関連項目:口伝律法  ケルンのグロッケンガッセ・シナゴーグから発見されたトーラーの巻物  サマリア碑文は、ヘブライ語のテキストで9行にわたって聖書の一部を記載しており、現在はロンドンの大英博物館に収蔵されている トーラー(תּוֹרָה)は「モーセの五書」または「五書」とも呼ばれ、「五つの巻物」を意味する。[97] 伝統的に、これらの書物は神自身によってモーセに口述されたと考えられてきた。[98][99] 17世紀以降、学者たちは、複数の匿名の著者の作品が元になっていると見なす一方で、モーセが最初に個々の資料をまとめた可能性も認めている。 [100][101] いつ、どのようにしてトーラーが編纂されたかについては、さまざまな仮説があるが[102]、一般的には、アケメネス朝ペルシアの支配下(おそらく紀元前 450年から350年)に最終的な形になったという説[103][104]、あるいはヘレニズム時代初期(紀元前333年から164年)に編纂されたとい う説が有力である[105]。 ヘブライ語の書名は、それぞれのテキストの冒頭の言葉に由来する。トーラーは以下の5つの書から構成される。 創世記(Bereshith、בראשית) 出エジプト記(Shemot、שמות) レビ記(Vayikra、ויקרא) 民数記(Bamidbar、במדבר) 申命記(Devarim、דברים) 創世記の最初の11章では、世界の創造(または秩序)と、神と人類の初期の関係の歴史が描かれている。創世記の残りの39章では、聖書の家長であるアブラ ハム、イサク、ヤコブ(イスラエルとも呼ばれる)とヤコブの子供たち、すなわち「イスラエルの子ら」と神との契約が描かれている。特に、ヨセフに焦点が当 てられている。神がアブラハムに命じ、家族とウル市の家を離れ、最終的にカナンの地に移住するよう命じたこと、そしてイスラエルの子孫が後にエジプトに移 住したことが語られている。 トーラーの残りの4冊の本は、族長たちの何百年も後に生きたモーセの物語を伝えている。彼は古代エジプトでの奴隷生活から、シナイ山での神との契約の更 新、そしてカナンの地に入国する準備のできた新しい世代が現れるまでの間の砂漠での放浪まで、イスラエルの子らを導いた。トーラーはモーセの死をもって終 わる。[106] トーラーの戒律はユダヤ教の宗教法の基礎となっている。伝統によると、戒律は613(taryag mitzvot)あるとされる。 |

| Nevi'im Main article: Nevi'im Nevi'im (Hebrew: נְבִיאִים, romanized: Nəḇī'īm, "Prophets") is the second main division of the Tanakh, between the Torah and Ketuvim. It contains two sub-groups, the Former Prophets (Nevi'im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים, the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Nevi'im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים, the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets). The Nevi'im tell a story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy and its division into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah, focusing on conflicts between the Israelites and other nations, and conflicts among Israelites, specifically, struggles between believers in "the Lord God"[107] (Yahweh) and believers in foreign gods,[d][e] and the criticism of unethical and unjust behaviour of Israelite elites and rulers;[f][g][h] in which prophets played a crucial and leading role. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, followed by the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the neo-Babylonian Empire and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. |

ネヴィイーム 詳細は「ネヴィイーム」を参照 ネヴィイーム(ヘブライ語: נְבִיאִים、ローマ字転写: Nəḇī'īm、「預言者たち」の意)は、トーラーとケトゥビームの間に位置する、タナハの第二の主要部分である。旧約聖書には、2つのサブグループ、す なわち、前預言者(Nevi'im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים、ヨシュア記、士師記、サムエル記、列王記の物語)と、後預言者(Nevi'im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים、イザヤ書、エレミヤ書、エゼキエル書、十二小預言者の書)がある。 ネビームは、ヘブライ人の君主制の勃興と、イスラエル王国とユダ王国の2つの王国への分裂について、イスラエル人と他の国民との対立、およびイスラエル人 同士の対立、特に「主なる神」[107](ヤハウェ)を信奉する者と外国の神々を信奉する者との争い[d][e]、そしてイスラエル人のエリートや支配者 たちの非倫理的かつ不正な行動に対する批判[f][g][h]に焦点を当てて描いている。 (ヤハウェ)と外国の神々を信奉する者たちとの闘争[d][e]、そしてイスラエルのエリートや支配者たちの非倫理的かつ不正な行動に対する批判[f] [g][h]に焦点を当てている。預言者たちが重要な指導的役割を果たした。物語は、新アッシリア帝国によるイスラエル王国の征服で幕を閉じ、その後、新 バビロニア帝国によるユダ王国の征服とエルサレム神殿の破壊が続く。 |

| Former Prophets The Former Prophets are the books Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. They contain narratives that begin immediately after the death of Moses with the divine appointment of Joshua as his successor, who then leads the people of Israel into the Promised Land, and end with the release from imprisonment of the last king of Judah. Treating Samuel and Kings as single books, they cover: Joshua's conquest of the land of Canaan (in the Book of Joshua), the struggle of the people to possess the land (in the Book of Judges), the people's request to God to give them a king so that they can occupy the land in the face of their enemies (in the Books of Samuel) the possession of the land under the divinely appointed kings of the House of David, ending in conquest and foreign exile (Books of Kings) |

旧預言者 旧預言者とは、ヨシュア記、士師記、サムエル記、列王記を指す。 モーセの死後すぐに、神がヨシュアを後継者に任命し、ヨシュアがイスラエルの民を約束の地へと導くという物語から始まり、ユダ王国最後の王の投獄からの解 放で終わる。 サムエル記と列王記をそれぞれ一冊の本として扱う場合、以下が含まれる。 ヨシュアによるカナンの地征服(ヨシュア記)、 その地を所有するための民の苦闘(士師記)、 敵に直面しながらその地を占領するために民が神に王を求めること(サムエル記)、 神に定められたダビデ家の王によるその地の所有、征服と外国への追放で終わる(列王記) |

| Latter Prophets Further information: Major prophet The Latter Prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets, counted as a single book. Hosea, Hoshea (הושע) denounces the worship of gods other than Yahweh (God), comparing Israel to a woman being unfaithful to her husband. Joel, Yo'el (יואל) includes a lament and a promise from God. Amos, Amos (עמוס) speaks of social justice, providing a basis for natural law by applying it to unbelievers and believers alike. Obadiah, Ovadya (עבדיה) addresses the judgment of Edom and restoration of Israel. Jonah, Yona (יונה) tells of a reluctant redemption of Ninevah. Micah, Mikha (מיכה) reproaches unjust leaders, defends the rights of the poor, and looks forward to world peace. Nahum, Nakhum (נחום) speaks of the destruction of Nineveh. Habakkuk, Havakuk (חבקוק) upholds trust in God over Babylon. Zephaniah, Tzefanya (צפניה) pronounces coming of judgment, survival and triumph of remnant. Haggai, Khagay (חגי) rebuild Second Temple. Zechariah, Zekharya (זכריה) God blesses those who repent and are pure. Malachi, Malakhi (מלאכי) corrects lax religious and social behaviour. |

後世の預言者 詳細情報:主要な預言者 後世の預言者とは、イザヤ、エレミヤ、エゼキエル、そして12人の小預言者のことで、1つの書物として数えられる。 ホセア(ホセア書)のホセア(הושע)は、ヤハウェ(神)以外の神々への崇拝を非難し、イスラエルを夫に不誠実な女性に例えている。 ヨエル書(ヨエル書)は、神からの嘆きと約束を含んでいる。 アモス書(アモス書)は、社会正義について語り、自然法を信者と信者でない人々に適用することで、その基礎を提供している。 オバデヤ書(オバデヤ書)は、エドムの裁きとイスラエルの回復について述べている。 ヨナ書(ヨナ、יונה)は、消極的なニネベの救済について述べている。 ミカ書(ミカ、מיכה)は、不正な指導者を非難し、貧者の権利を擁護し、世界平和を待ち望んでいる。 ナホム書(ナホム、נחום)は、ニネベの滅亡について述べている。 ハバクク書(ハバクク、חבקוק)は、バビロンよりも神への信頼を支持している。 ゼパニヤ(ツェファニア)は、裁きが訪れること、生き残ること、そして残党の勝利を宣言する。 ハガイ(ハガイ)は第二神殿を再建する。 ゼカリヤ(ゼカリヤ)は、悔い改め、純粋な人々を神が祝福する。 マラキ(マラキ)は、宗教的および社会的行動の緩みを正す。 |

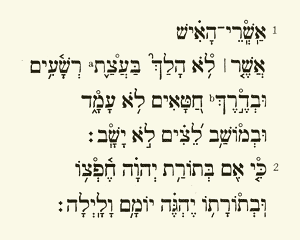

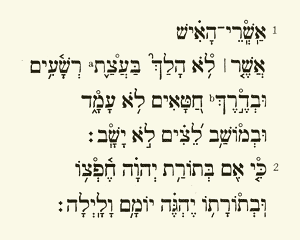

| Ketuvim Main articles: Ketuvim and Poetic Books  Hebrew text of Psalm 1:1–2 Ketuvim (in Biblical Hebrew: כְּתוּבִים, romanized: Kəṯūḇīm "writings") is the third and final section of the Tanakh. The Ketuvim are believed to have been written under the inspiration of Ruach HaKodesh (the Holy Spirit) but with one level less authority than that of prophecy.[108] In Masoretic manuscripts (and some printed editions), Psalms, Proverbs and Job are presented in a special two-column form emphasizing their internal parallelism, which was found early in the study of Hebrew poetry. "Stichs" are the lines that make up a verse "the parts of which lie parallel as to form and content".[109] Collectively, these three books are known as Sifrei Emet (an acronym of the titles in Hebrew, איוב, משלי, תהלים yields Emet אמ"ת, which is also the Hebrew for "truth"). Hebrew cantillation is the manner of chanting ritual readings as they are written and notated in the Masoretic Text of the Bible. Psalms, Job and Proverbs form a group with a "special system" of accenting used only in these three books.[110] |

啓示文学 主な記事:啓示文学と詩篇  詩篇1:1-2のヘブライ語テキスト 啓示文学(聖書ヘブライ語:כְּתוּבִים、ローマ字表記:Kəṯūḇīm「文書」)は、聖書の第三の、そして最後のセクションである。ケトゥビームは、聖霊の霊感を受けて書かれたと信じられているが、預言よりも一段低い権威を持つとされる。 マソラ本文(および一部の印刷版)では、詩篇、箴言、ヨブ記は、ヘブライ語詩の研究の初期に発見された、その内部の平行性を強調する特別な2段組形式で提 示されている。「スティヒ」とは、詩節を構成する行であり、「その形と内容が平行している部分」である。[109] これら3つの書物は、まとめて「シフレ・エメット」(ヘブライ語のタイトル「ヨブ記」、「ミシュリーム」、「テーリーム」の頭文字を並べると「エメット」 となる。「エメット」はヘブライ語で「真実」の意味でもある)として知られている。ヘブライ語のカンティレーションは、マソラ本文に記された聖書の朗読 を、その通りに歌う方法である。詩篇、ヨブ記、箴言は、この3つの書物のみで使用されるアクセントの「特別なシステム」を持つグループを形成している。 [110] |

| The five scrolls Further information: Five Megillot  Song of Songs (Das Hohelied Salomos), No. 11 by Egon Tschirch, published in 1923 The five relatively short books of Song of Songs, Book of Ruth, the Book of Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Book of Esther are collectively known as the Hamesh Megillot. These are the latest books collected and designated as authoritative in the Jewish canon even though they were not complete until the second century CE.[111] |

五巻の巻物 詳細情報:五巻の巻物  『雅歌』(『ソロモンの歌』)第11巻、エゴン・チルヒ著、1923年刊行 比較的短い五つの書物である『雅歌』、『ルツ記』、『哀歌』、『伝道の書』、『エステル記』は、まとめて「五つの巻物」として知られている。これらは、ユ ダヤ教の正典に収集され、権威あるものとして指定された最も新しい書物であるが、完成したのは西暦2世紀になってからであった。[111] |

Other books The Isaiah scroll, part of the Dead Sea Scrolls, contains almost the whole Book of Isaiah and dates from the second century BCE. The books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah[i] and Chronicles share a distinctive style that no other Hebrew literary text, biblical or extra-biblical, shares.[112] They were not written in the normal style of Hebrew of the post-exilic period. The authors of these books must have chosen to write in their own distinctive style for unknown reasons.[113] Their narratives all openly describe relatively late events (i.e., the Babylonian captivity and the subsequent restoration of Zion). The Talmudic tradition ascribes late authorship to all of them. Two of them (Daniel and Ezra) are the only books in the Tanakh with significant portions in Aramaic. |

その他の書籍 死海写本の一つであるイザヤ書巻は、ほぼイザヤ書の全文を含み、紀元前2世紀に遡る。 エステル記、ダニエル書、エズラ記・ネヘミヤ記[i]、歴代誌は、聖書に登場する他のヘブライ語文学作品には見られない独特の文体を持っている。 [112] これらは、バビロン捕囚後のヘブライ語の通常の文体で書かれたものではない。これらの書籍の著者は、不明な理由から、独特の文体を選択したに違いない。 これらの物語はすべて、比較的最近の出来事(すなわち、バビロン捕囚とそれに続くシオンの復興)を率直に描写している。 タルムードの伝統では、それらのすべてが後世の著作であるとしている。 そのうちの2つ(ダニエルとエズラ)は、聖書全書の中で唯一、かなりの部分がアラム語で書かれている。 |

| Book order The following list presents the books of Ketuvim in the order they appear in most current printed editions. Tehillim (Psalms) תְהִלִּים is an anthology of individual Hebrew religious hymns. Mishlei (Book of Proverbs) מִשְלֵי is a "collection of collections" on values, moral behaviour, the meaning of life and right conduct, and its basis in faith. Iyov (Book of Job) אִיּוֹב is about faith, without understanding or justifying suffering. Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs) or (Song of Solomon) שִׁיר הַשִׁירִים (Passover) is poetry about love and sex. Ruth (Book of Ruth) רוּת (Shavuot) tells of the Moabite woman Ruth, who decides to follow the God of the Israelites, and remains loyal to her mother-in-law, who is then rewarded. Eikha (Lamentations) איכה (Ninth of Av) [Also called Kinnot in Hebrew.] is a collection of poetic laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes) קהלת (Sukkot) contains wisdom sayings disagreed over by scholars. Is it positive and life-affirming, or deeply pessimistic? Ester (Book of Esther) אֶסְתֵר (Purim) tells of a Hebrew woman in Persia who becomes queen and thwarts a genocide of her people. Dani’el (Book of Daniel) דָּנִיֵּאל combines prophecy and eschatology (end times) in story of God saving Daniel just as He will save Israel. ‘Ezra (Book of Ezra–Book of Nehemiah) עזרא tells of rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile. Divrei ha-Yamim (Chronicles) דברי הימים contains genealogy. The Jewish textual tradition never finalized the order of the books in Ketuvim. The Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14b–15a) gives their order as Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations of Jeremiah, Daniel, Scroll of Esther, Ezra, Chronicles.[114] One of the large scale differences between the Babylonian and the Tiberian biblical traditions is the order of the books. Isaiah is placed after Ezekiel in the Babylonian, while Chronicles opens the Ketuvim in the Tiberian, and closes it in the Babylonian.[115] The Ketuvim is the last of the three portions of the Tanakh to have been accepted as canonical. While the Torah may have been considered canon by Israel as early as the fifth century BCE and the Former and Latter Prophets were canonized by the second century BCE, the Ketuvim was not a fixed canon until the second century CE.[111] Evidence suggests, however, that the people of Israel were adding what would become the Ketuvim to their holy literature shortly after the canonization of the prophets. As early as 132 BCE references suggest that the Ketuvim was starting to take shape, although it lacked a formal title.[116] Against Apion, the writing of Josephus in 95 CE, treated the text of the Hebrew Bible as a closed canon to which "... no one has ventured either to add, or to remove, or to alter a syllable..."[117] For an extended period after 95CE, the divine inspiration of Esther, the Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes was often under scrutiny.[118] |

書籍の順序 以下のリストは、現行の印刷版で表示されている順序で、Ketuvimの書籍を提示している。 Tehillim(詩篇)תְהִלִּיםは、個々のヘブライ語の宗教的賛美歌のアンソロジーである。 Mishlei(箴言)מִשְלֵיは、価値観、道徳的行動、人生の意味と正しい行動、そして信仰の基礎に関する「コレクションのコレクション」である。 ヨブ記(ヨブの書)אִיּוֹבは、苦しみに対する理解や正当化を伴わない信仰についてである。 雅歌(ソロモンの歌)שִׁיר הַשִׁירִים(過ぎ越しの祭り)は、愛と性に関する詩である。 ルツ記(ルツ記) רוּת(五旬節)は、イスラエル人の神に従うことを決意し、義理の母に忠実であり続けたモアブ人の女性ルツの物語である。 哀歌(エレミヤ書) איכה(アヴの第九の日)は、紀元前586年のエルサレムの破壊を詩的に嘆く詩の集まりである。 コヘレトの言葉(伝道の書) קהלת(スコーット)は、学者の間で意見が分かれる知恵の言葉を含んでいる。それは前向きで人生を肯定するものなのか、それとも深く悲観的なものなのか? エステル記(エステル記)אֶסְתֵּר(プリム祭)は、ペルシャのヘブライ人女性が王妃となり、自民族の大量虐殺を阻止する物語である。 ダニエル書(ダニエル書)דָּנִיֵּאלは、神がダニエルを救い、イスラエルを救うという物語で、預言と終末論(終末)を組み合わせている。 『エズラ記』(エズラ記–ネヘミヤ記)は、バビロン捕囚後のエルサレムの城壁再建について述べている。 『歴代誌』(歴代誌)は系図を含んでいる。 ユダヤ教のテキストの伝統では、ケトゥビームの書籍の順序は最終的に確定されることはなかった。バビロニア・タルムード(バヴァ・バトラ14b-15a) では、その順序はルツ記、詩篇、ヨブ記、箴言、伝道の書、雅歌、エレミヤの哀歌、ダニエル書、エステル記、エズラ記、歴代誌となっている。 バビロニアとティベリアの聖書伝承の間に存在する大きな相違点のひとつは、書籍の順序である。バビロニアではイザヤ書はエゼキエル書の後に置かれているが、ティベリアでは歴代志が Ketuvim の冒頭に置かれ、バビロニアではその書籍の最後に置かれている。 ケトゥビームは、正典として認められた3つの部分からなるタナハの最後の部分である。トーラーは紀元前5世紀にはすでにイスラエルで正典とみなされていた 可能性があり、前・後代預言書は紀元前2世紀には正典化されていたが、ケトゥビームは西暦2世紀まで正典として確定されていなかった。 しかし、証拠によると、イスラエルの民は預言者の正典化の直後に、聖なる文学にケトゥビームとなるものを追加していたことが示唆されている。早くも紀元前 132年には、ケトゥビームが形になり始めていたことを示す参照があるが、正式なタイトルはまだなかった。 [116] ヨセフスが紀元95年に著した『アピオンに対するユダヤ人の反論』では、ヘブライ語聖書の本文は「... 誰一人として、一音節たりとも加えたり、削除したり、変更したりしようとはしなかった」という、閉じた正典として扱われている。[117] 95年以降、長い期間にわたって、エステル記、雅歌、伝道の書の神の啓示はしばしば精査された。[118] |

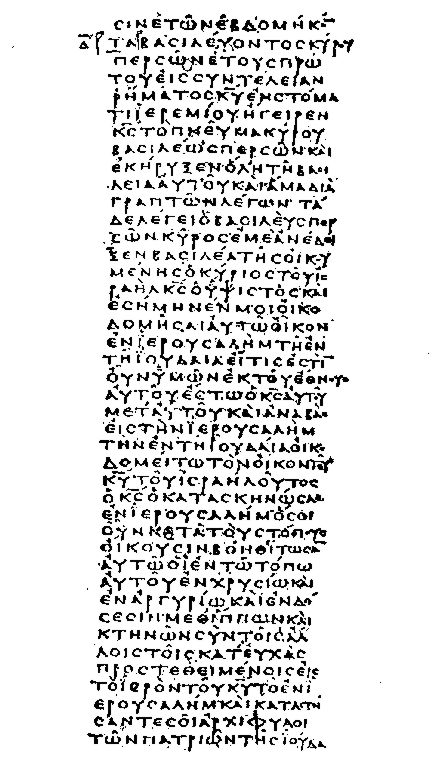

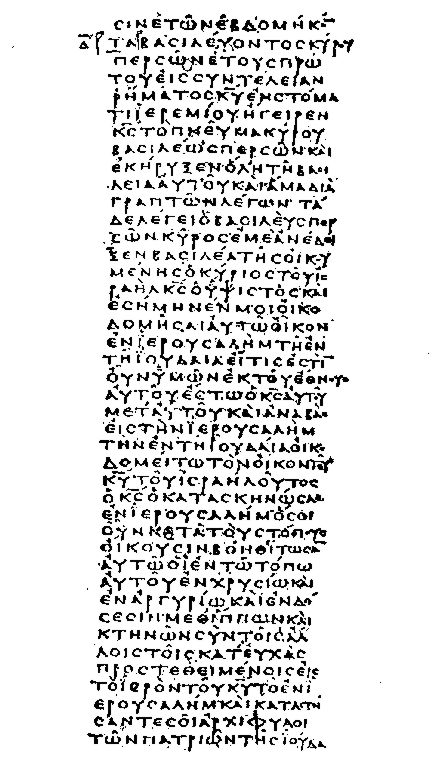

| Septuagint Main articles: Septuagint and Jewish apocrypha See also: Deuterocanonical books and Biblical apocrypha  A fragment of a Septuagint: A column of uncial book from 1 Esdras in the Codex Vaticanus c. 325–350 CE, the basis of Sir Lancelot Charles Lee Brenton's Greek edition and English translation  The contents page in a complete 80 book King James Bible, listing "The Books of the Old Testament", "The Books called Apocrypha", and "The Books of the New Testament". The Septuagint ("the Translation of the Seventy", also called "the LXX"), is a Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible begun in the late third century BCE. As the work of translation progressed, the Septuagint expanded: the collection of prophetic writings had various hagiographical works incorporated into it. In addition, some newer books such as the Books of the Maccabees and the Wisdom of Sirach were added. These are among the "apocryphal" books, (books whose authenticity is doubted). The inclusion of these texts, and the claim of some mistranslations, contributed to the Septuagint being seen as a "careless" translation and its eventual rejection as a valid Jewish scriptural text.[119][120][j] The apocrypha are Jewish literature, mostly of the Second Temple period (c. 550 BCE – 70 CE); they originated in Israel, Syria, Egypt or Persia; were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, and attempt to tell of biblical characters and themes.[122] Their provenance is obscure. One older theory of where they came from asserted that an "Alexandrian" canon had been accepted among the Greek-speaking Jews living there, but that theory has since been abandoned.[123] Indications are that they were not accepted when the rest of the Hebrew canon was.[123] It is clear the Apocrypha were used in New Testament times, but "they are never quoted as Scripture."[124] In modern Judaism, none of the apocryphal books are accepted as authentic and are therefore excluded from the canon. However, "the Ethiopian Jews, who are sometimes called Falashas, have an expanded canon, which includes some Apocryphal books".[125] The rabbis also wanted to distinguish their tradition from the newly emerging tradition of Christianity.[b][k] Finally, the rabbis claimed a divine authority for the Hebrew language, in contrast to Aramaic or Greek – even though these languages were the lingua franca of Jews during this period (and Aramaic would eventually be given the status of a sacred language comparable to Hebrew).[l] |

セプトゥアギンタ 詳細は「セプトゥアギンタとユダヤ教外典」を参照 関連項目:「第二正典」と「聖書外典」も参照  セプトゥアギンタの断片:325年から350年頃のヴァチカン写本に収められた『第一エズラ記』のアンシャル体本の1コラム。サー・ランスロット・チャールズ・リー・ブレントンによるギリシャ語版と英語訳の基となった  80巻からなる完全版の欽定訳聖書(King James Bible)の目次ページ。「旧約聖書」、「外典」、「新約聖書」が記載されている。 セプトゥアギンタ(「七十人の翻訳」、または「LXX」とも呼ばれる)は、紀元前3世紀後半に開始されたヘブライ語聖書のギリシャ語訳である。 翻訳作業が進むにつれ、セプトゥアギンタは拡大していった。預言者の著作のコレクションには、さまざまな聖人伝が組み込まれた。さらに、マカバイ記やシラ の知恵書などの新しい書籍も追加された。これらは「外典」(真正性が疑われる書物)に分類される。これらのテキストが含まれたこと、および一部に誤訳があ るという主張により、セプトゥアギンタは「いい加減な」翻訳と見なされ、最終的にはユダヤ教の正典としての地位を失うこととなった。[119][120] [j] 外典はユダヤ教の文学であり、そのほとんどは第二神殿時代(紀元前550年頃 - 70年)のものである。それらはイスラエル、シリア、エジプト、あるいはペルシアで生まれ、もともとはヘブライ語、アラム語、あるいはギリシャ語で書かれ たもので、聖書の登場人物やテーマについて述べようとするものである。それらがどこから来たかに関する古い説のひとつでは、アレクサンドリアの規範が、そ こに住むギリシャ語を話すユダヤ人の間で受け入れられていたと主張しているが、その説はその後放棄されている。[123] ヘブライ語聖書の他の規範が受け入れられなかった時期に、それらも受け入れられなかったことを示す兆候がある。[123] 外典が新約聖書の時代に使用されていたことは明らかであるが、「それらは決して聖典として引用されることはなかった」のである。 [124] 現代のユダヤ教では、外典はどれも正典として認められていないため、正典から除外されている。しかし、「ファラシャと呼ばれることもあるエチオピア系ユダ ヤ人は、いくつかの外典を含む拡大された正典を持っている」[125]。 ラビたちはまた、新たに台頭しつつあったキリスト教の伝統と自分たちの伝統を区別しようとした。最後に、ラビたちは、この時代にはユダヤ人の共通語として アラム語やギリシャ語が使われていたにもかかわらず(そして、アラム語は最終的にヘブライ語に匹敵する神聖な言語としての地位を獲得することになる)、ヘ ブライ語に神聖な権威を主張した。 |

| Incorporations from Theodotion The Book of Daniel is preserved in the 12-chapter Masoretic Text and in two longer Greek versions, the original Septuagint version, c. 100 BCE, and the later Theodotion version from c. second century CE. Both Greek texts contain three additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children; the story of Susannah and the Elders; and the story of Bel and the Dragon. Theodotion's translation was so widely copied in the Early Christian church that its version of the Book of Daniel virtually superseded the Septuagint's. The priest Jerome, in his preface to Daniel (407 CE), records the rejection of the Septuagint version of that book in Christian usage: "I ... wish to emphasize to the reader the fact that it was not according to the Septuagint version but according to the version of Theodotion himself that the churches publicly read Daniel."[126] Jerome's preface also mentions that the Hexapla had notations in it, indicating several major differences in content between the Theodotion Daniel and the earlier versions in Greek and Hebrew. Theodotion's Daniel is closer to the surviving Hebrew Masoretic Text version, the text which is the basis for most modern translations. Theodotion's Daniel is also the one embodied in the authorized edition of the Septuagint published by Sixtus V in 1587.[127] |

テオドシオンによるダニエル書からの編纂は ダニエル書は、12章からなるマソラ本文と、より長い2つのギリシャ語訳、紀元前100年頃のセプトゥアギンタ(七十人訳聖書)の原典、および紀元後2世 紀頃のテオドシオスの訳の2つに保存されている。 両方のギリシャ語訳には、ダニエル書に3つの追加部分が含まれている。アザリアの祈りと三人の聖なる子供たちの歌、スザンナと長老たちの物語、ベルとドラ ゴンの物語である。テオドシオスの翻訳は初期キリスト教会で広く模倣されたため、事実上、セプトゥアギンタの『ダニエル書』はテオドシオスの翻訳に取って 代わられた。 407年の『ダニエル書』の序文で、聖職者ヒエロニムスは、キリスト教界でセプトゥアギンタの『ダニエル書』が拒絶されたことを記録している。「私 は...読者の方々に、教会が公にダニエル書を朗読していたのはセプトゥアギンタ版ではなく、テオドシオスの版に従っていたという事実を強調したいと思い ます。」[126] ジェロームの前書きには、ヘクサプラに注釈が記載されており、テオドシオスのダニエルとギリシャ語やヘブライ語の初期の版との間に、内容にいくつかの大き な相違点があることが示されている。 テオドシウスのダニエル書は、現存するヘブライ語マソラ本文版に近く、このテキストはほとんどの現代の翻訳の基盤となっている。テオドシウスのダニエル書は、1587年にシクストゥス5世が出版したセプトゥアギンタの公認版にも採用されている。[127] |

| Final form Further information: Deuterocanonical books and Biblical apocrypha Textual critics are now debating how to reconcile the earlier view of the Septuagint as 'careless' with content from the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, scrolls discovered at Wadi Murabba'at, Nahal Hever, and those discovered at Masada. These scrolls are 1000–1300 years older than the Leningrad text, dated to 1008 CE, which forms the basis of the Masoretic text.[128] The scrolls have confirmed much of the Masoretic text, but they have also differed from it, and many of those differences agree with the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch or the Greek Old Testament instead.[119] Copies of some texts later declared apocryphal are also among the Qumran texts.[123] Ancient manuscripts of the book of Sirach, the "Psalms of Joshua", Tobit, and the Epistle of Jeremiah are now known to have existed in a Hebrew version.[129] The Septuagint version of some biblical books, such as the Book of Daniel and Book of Esther, are longer than those in the Jewish canon. In the Septuagint, Jeremiah is shorter than in the Masoretic text, but a shortened Hebrew Jeremiah has been found at Qumran in cave 4.[119] The scrolls of Isaiah, Exodus, Jeremiah, Daniel and Samuel exhibit striking and important textual variants from the Masoretic text.[119] The Septuagint is now seen as a careful translation of a different Hebrew form or recension (revised addition of the text) of certain books, but debate on how best to characterize these varied texts is ongoing.[119] |

最終版 さらに詳しい情報: デューテロカノニカル書籍と聖書外典 テキスト批評家たちは現在、セプトゥアギンタを「不注意」とみなす以前の見解と、クムランの死海写本、ワディ・ムルアバト、ナハル・ヘヴェルで発見された 写本、マサダで発見された写本の内容をどのように調和させるかについて議論している。これらの写本は、マソラ本文の基礎となっている西暦1008年とされ るレニングラード写本よりも1000年から1300年も古いものである。[128] これらの写本はマソラ本文の多くを裏付けているが、異なる部分もあり、その違いの多くはセプトゥアギンタ、サマリア五書、あるいはギリシャ語の旧約聖書と 一致している。[119] 後に偽書とされたテキストの写本もクムランの文書の中にはある。[123] シラ書、ヨシュアの詩篇、トビト、エレミヤ書などの古代写本は、ヘブライ語版が存在していたことが現在では知られている。[129] ダニエル書やエステル記などの聖書書籍のセプトゥアギンタ版は、ユダヤ教正典のものよりも長い。セプトゥアギンタでは、エレミヤの文章はマソラ本文よりも 短いが、短縮されたヘブライ語のエレミヤはクムランの洞窟4で発見されている。[119] イザヤ書、出エジプト記、エレミヤ書、ダニエル書、サムエル記の巻物は、マソラ本文とは著しく異なる重要なテキストの変種を示している。 [119] セプトゥアギンタは、特定の書籍については、異なるヘブライ語の形または校訂本(テキストの改訂版)を慎重に翻訳したものと現在では考えられているが、こ れらのさまざまなテキストをどのように特徴づけるのが最善かについては、現在も議論が続いている。[119] |

| Pseudepigraphal books Main articles: Jewish apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha See also: Authorship of the Bible Pseudepigrapha are works whose authorship is wrongly attributed. A written work can be pseudepigraphical and not be a forgery, as forgeries are intentionally deceptive. With pseudepigrapha, authorship has been mistransmitted for any one of a number of reasons.[130] For example, the Gospel of Barnabas claims to be written by Barnabas the companion of the Apostle Paul, but both its manuscripts date from the Middle Ages. Apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works are not the same. Apocrypha includes all the writings claiming to be sacred that are outside the canon because they are not accepted as authentically being what they claim to be. Pseudepigrapha is a literary category of all writings whether they are canonical or apocryphal. They may or may not be authentic in every sense except a misunderstood authorship.[130] The term "pseudepigrapha" is commonly used to describe numerous works of Jewish religious literature written from about 300 BCE to 300 CE. Not all of these works are actually pseudepigraphical. (It also refers to books of the New Testament canon whose authorship is questioned.) The Old Testament pseudepigraphal works include the following:[131] 3 Maccabees 4 Maccabees Assumption of Moses Ethiopic Book of Enoch (1 Enoch) Slavonic Book of Enoch (2 Enoch) Hebrew Book of Enoch (3 Enoch) (also known as "The Revelation of Metatron" or "The Book of Rabbi Ishmael the High Priest") Book of Jubilees Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (2 Baruch) Letter of Aristeas (Letter to Philocrates regarding the translating of the Hebrew scriptures into Greek) Life of Adam and Eve Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah Psalms of Solomon Sibylline Oracles Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (3 Baruch) Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs |

偽典 詳細は「ユダヤ教外典」および「偽典」を参照 聖書の著者の項も参照 偽典は、誤って著者が帰属された著作である。文書作品は偽典である場合もあるが、偽造ではない。偽造は意図的に人を欺くものであるためである。偽典の場 合、著者の帰属が誤って伝えられた理由はいくつかある。例えば、『バルナバの手紙』は使徒パウロの仲間であるバルナバが著したと主張しているが、その写本 はどちらも中世のものである。 外典と偽典は同じものではない。外典は、正典として認められていないため、聖典であると主張しているにもかかわらず、正典として認められていないすべての 著作物を含む。偽典は、正典であるか外典であるかに関わらず、すべての著作物の文学的カテゴリーである。それらは、誤解された著述を除いて、あらゆる意味 で真正である場合もそうでない場合もある。 「偽典」という用語は、紀元前300年頃から西暦300年頃にかけて書かれたユダヤ教の宗教文学の数々を指すために一般的に使用されている。これらの作品 のすべてが実際に偽典であるわけではない。(また、著者が疑問視されている新約聖書の正典の書物も指す。)旧約聖書の偽典には以下のものがある。 [131] 3マカバイ記 4マカバイ記 モーセの昇天 エチオピア語版エノク書(1エノク書) スラヴ語版エノク書(2エノク書) ヘブライ語版エノク書(3エノク書)(「メタトロンの啓示」または「大祭司イシュマエルラビの書」とも呼ばれる) ユビレイスの書 シリア語版バルクの黙示録(2バルク) アリストテレスの手紙(ヘブライ語聖書のギリシャ語訳に関するフィロクラテスへの手紙) アダムとイブの生涯 イザヤの殉教と昇天 ソロモンの詩篇 シビュラの託宣 ギリシャ語のバルクの黙示録(3バルク 十二族の遺言 |

| Book of Enoch Notable pseudepigraphal works include the Books of Enoch such as 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, which survives only in Old Slavonic, and 3 Enoch, surviving in Hebrew of the c. fifth century – c. sixth century CE. These are ancient Jewish religious works, traditionally ascribed to the prophet Enoch, the great-grandfather of the patriarch Noah. The fragment of Enoch found among the Qumran scrolls attest to it being an ancient work.[132] The older sections (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) are estimated to date from about 300 BCE, and the latest part (Book of Parables) was probably composed at the end of the first century BCE.[133] Enoch is not part of the biblical canon used by most Jews, apart from Beta Israel. Most Christian denominations and traditions may accept the Books of Enoch as having some historical or theological interest or significance. Part of the Book of Enoch is quoted in the Epistle of Jude and the Book of Hebrews (parts of the New Testament), but Christian denominations generally regard the Books of Enoch as non-canonical.[134] The exceptions to this view are the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[132] The Ethiopian Bible is not based on the Greek Bible, and the Ethiopian Church has a slightly different understanding of canon than other Christian traditions.[135] In Ethiopia, canon does not have the same degree of fixedness, (yet neither is it completely open).[135] Enoch has long been seen there as inspired scripture, but being scriptural and being canon are not always seen the same. The official Ethiopian canon has 81 books, but that number is reached in different ways with various lists of different books, and the book of Enoch is sometimes included and sometimes not.[135] Current evidence confirms Enoch as canonical in both Ethiopia and in Eritrea.[132] |

エノク書 著名な偽典としては、1エノク、2エノクなど、現存するのは古スラヴ語のみであるエノク書や、5世紀頃から6世紀頃のヘブライ語で現存する3エノクなどが ある。これらは古代のユダヤ教の宗教的な作品であり、伝統的に預言者エノク、すなわち家長ノアの曽祖父に帰せられている。クムランの巻物群から発見された エノクの断片は、それが古代の作品であることを証明している。[132] 古い部分(主に「監視者たちの書」)は紀元前300年頃のものと推定され、最も新しい部分(「たとえ話の書」)は紀元前1世紀の終わり頃に書かれたと考え られている。[133] エノク書は、ベタ・イスラエルを除いて、ほとんどのユダヤ人が用いる聖書正典には含まれていない。ほとんどのキリスト教の宗派や伝統では、エノク書は歴史 的または神学的な関心や重要性を持つものとして受け入れられている。エノク書の一部はユダの手紙やヘブライ人への手紙(新約聖書の一部)にも引用されてい るが、キリスト教の宗派は一般的にエノク書を正典とは見なしていない。[134] この見解の例外はエチオピア正教会とエリトリア正教会である。[132] エチオピア語聖書はギリシャ語聖書を基にしておらず、エチオピア教会は正典に対する理解が他のキリスト教の伝統とは若干異なっている。[135] エチオピアでは、正典は同じ程度の固定性を有しているわけではない(とはいえ、完全に開かれているわけでもない)。[135] エノクは長い間、霊感を受けた聖典として見なされてきたが、聖典であることと正典であることは必ずしも同じではない。エチオピア正教会の正典は81冊であ るが、この数字は異なる書籍のさまざまなリストから異なる方法で導き出されたものであり、エノク書は時として含まれ、また含まれないこともある。 [135] 現在の証拠では、エチオピアとエリトリアの両方で、エノク書が正典であることが確認されている。[132] |

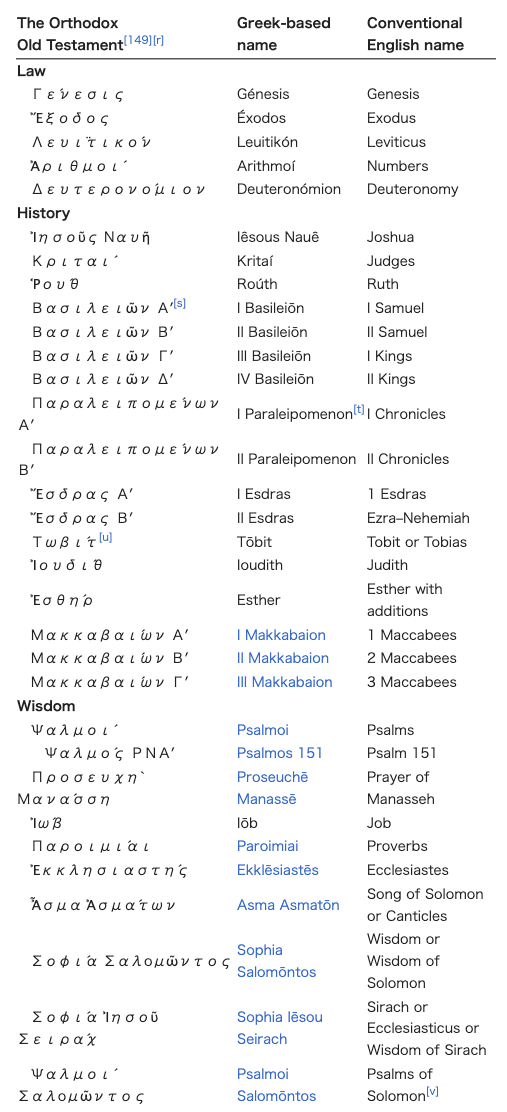

| Christian Bible A Christian Bible is a set of books divided into the Old and New Testament that a Christian denomination has, at some point in their past or present, regarded as divinely inspired scripture by the Holy Spirit.[136] The Early Church primarily used the Septuagint, as it was written in Greek, the common tongue of the day, or they used the Targums among Aramaic speakers. Modern English translations of the Old Testament section of the Christian Bible are based on the Masoretic Text.[35] The Pauline epistles and the gospels were soon added, along with other writings, as the New Testament.[137] Old Testament Main article: Old Testament Further information: Development of the Old Testament canon The Old Testament has been important to the life of the Christian church from its earliest days. Bible scholar N. T. Wright says "Jesus himself was profoundly shaped by the scriptures."[138] Wright adds that the earliest Christians searched those same Hebrew scriptures in their effort to understand the earthly life of Jesus. They regarded the "holy writings" of the Israelites as necessary and instructive for the Christian, as seen from Paul's words to Timothy (2 Timothy 3:15), as pointing to the Messiah, and as having reached a climactic fulfilment in Jesus generating the "new covenant" prophesied by Jeremiah.[139] The Protestant Old Testament of the 21st century has a 39-book canon. The number of books (although not the content) varies from the Jewish Tanakh only because of a different method of division. The term "Hebrew scriptures" is often used as being synonymous with the Protestant Old Testament, since the surviving scriptures in Hebrew include only those books. However, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes 46 books as its Old Testament (45 if Jeremiah and Lamentations are counted as one),[140] and the Eastern Orthodox Churches recognize six additional books. These additions are also included in the Syriac versions of the Bible called the Peshitta and the Ethiopian Bible.[m][n][o] Because the canon of Scripture is distinct for Jews, Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Western Protestants, the contents of each community's Apocrypha are unique, as is its usage of the term. For Jews, none of the apocryphal books are considered canonical. Catholics refer to this collection as "Deuterocanonical books" (second canon) and the Orthodox Church refers to them as "Anagignoskomena" (that which is read).[141][p] Books included in the Catholic, Orthodox, Greek, and Slavonic Bibles are: Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah (also called the Baruch Chapter 6), 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, the Greek Additions to Esther and the Greek Additions to Daniel.[142] The Greek Orthodox Church, and the Slavonic churches (Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia) also add:[143] 3 Maccabees 1 Esdras Prayer of Manasseh Psalm 151 2 Esdras (4 Esdras), which is not included in the Septuagint, does not exist in Greek, though it does exist in Latin. There is also 4 Maccabees which is only accepted as canonical in the Georgian Church. It is in an appendix to the Greek Orthodox Bible, and it is therefore sometimes included in collections of the Apocrypha.[144] The Syriac Orthodox Church also includes: Psalms 151–155 The Apocalypse of Baruch The Letter of Baruch[145] The Ethiopian Old Testament Canon uses Enoch and Jubilees (that only survived in Ge'ez), 1–3 Meqabyan, Greek Ezra, 2 Esdras, and Psalm 151.[o][m] The Revised Common Lectionary of the Lutheran Church, Moravian Church, Reformed Churches, Anglican Church and Methodist Church uses the apocryphal books liturgically, with alternative Old Testament readings available.[q] Therefore, editions of the Bible intended for use in the Lutheran Church and Anglican Church include the fourteen books of the Apocrypha, many of which are the deuterocanonical books accepted by the Catholic Church, plus 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh, which were in the Vulgate appendix.[147] The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches use most of the books of the Septuagint, while Protestant churches usually do not. After the Protestant Reformation, many Protestant Bibles began to follow the Jewish canon and exclude the additional texts, which came to be called apocryphal. The Apocrypha are included under a separate heading in the King James Version of the Bible, the basis for the Revised Standard Version.[148] |

キリスト教聖書 キリスト教の聖書は、キリスト教の宗派が過去または現在のある時点で、神聖な霊感を受けた聖典としてみなした、旧約聖書と新約聖書に分けられた一連の書物 である。[136] 初期の教会は、当時共通語であったギリシャ語に訳されたセプトゥアギンタを主に使用していたが、アラム語話者の間ではタルグムも使用されていた。キリスト 教聖書の旧約聖書の現代英語訳はマソラ本文に基づいている。[35] その後、パウロ書簡や福音書が他の文書とともに新約聖書として加えられた。[137] 旧約聖書 詳細は「旧約聖書」を参照 さらに詳しい情報:「旧約聖書の正典の変遷 旧約聖書は、初期のキリスト教会の歴史において重要な役割を果たしてきた。聖書学者のN. T. ライトは、「イエス自身が聖書から深い影響を受けていた」と述べている。[138] ライトはさらに、初期のキリスト教徒たちは、イエスの地上での生涯を理解しようと努める中で、同じヘブライ語の聖書を調べた、と付け加えている。彼らは、 イスラエル人の「聖典」をキリスト教徒にとって必要かつ有益なものとみなしていた。それは、パウロがテモテに宛てた言葉(2テモテ3:15)から見て、救 世主を指し示しており、エレミヤが予言した「新しい契約」を生み出したイエスにおいて最高潮に達する成就を遂げたものだったからである。 21世紀のプロテスタントの旧約聖書は39冊の正典から成る。 書籍の数(内容ではない)がユダヤ教のタナハと異なるのは、区分の方法が異なるためである。 ヘブライ語聖書という用語は、現存するヘブライ語の聖書がこれらの書籍のみを含んでいるため、プロテスタントの旧約聖書と同義語として使用されることが多 い。 しかし、ローマ・カトリック教会は46冊を自らの旧約聖書としており(エレミヤ書と哀歌を1冊として数える場合は45冊)[140]、東方正教会はさらに 6冊を認めている。これらの追加された書物は、ペシッタと呼ばれるシリア語版聖書やエチオピア聖書にも含まれている。[m][n][o] ユダヤ教、東方正教会、ローマ・カトリック、西方プロテスタントでは聖典の正典が異なるため、それぞれのコミュニティにおける外典の内容も、その用語の用 法も独特である。ユダヤ教では、外典はどれも正典とはみなされていない。カトリック教会では、このコレクションを「第二正典」と呼び、正教会では「アナギ ノスコメナ」(読まれるもの)と呼んでいる。[141][p] カトリック、正教会、ギリシャ語聖書、スラヴ語聖書に含まれる書籍は、トビト記、ユディト記、ソロモンの知恵、シラ書(または『教会憲章』)、バルク、エ レミヤの手紙(バルク書第6章とも呼ばれる)、第1マカバイ記、第2マカバイ記、ギリシャ語版エステル記、ギリシャ語版ダニエル書である。 ギリシャ正教会、およびスラヴ教会(ベラルーシ、ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ、ブルガリア、マケドニア共和国、モンテネグロ、ポーランド、ウクライナ、ロシア、セルビア、チェコ共和国、スロバキア、スロベニア、クロアチア)は、さらに以下のものを加えている。[143] 3マカバイ記 1エズラ記 マナセの祈り 詩篇151 セプトゥアギンタには含まれていないが、ギリシャ語には存在しない2エズラ(4エズラ)は、ラテン語では存在する。また、4マカバイアは、グルジア教会で のみ正典として認められている。これはギリシャ正教聖書の付録に含まれているため、外典のコレクションに含まれることもある。 シリア正教会では、以下のものも含まれる。 詩篇151-155 バルクの黙示録 バルクの手紙[145] エチオピアの旧約聖書正典では、エノク書とユビレイ(ゲエズ語でしか現存していない)1-3メカビアン、ギリシャ語版エズラ記、2エスドラ、詩篇151を使用している。[o][m] ルーテル教会、モラヴィア教会、改革派教会、聖公会、メソジスト教会の改訂共通典礼暦では、外典を典礼で使用しており、旧約聖書の代替の朗読も用意されて いる。 [q] そのため、ルーテル教会や聖公会で使用される聖書の版には、カトリック教会で認められている外典の多くであるアポクリファの14冊の書物が含まれている。 さらに、ウルガタ聖書の付録に含まれていた1エズラ、2エズラ、マナセの祈りも含まれている。 ローマ・カトリック教会と東方正教会はセプトゥアギンタのほとんどの書籍を使用しているが、プロテスタント教会では通常使用しない。プロテスタントの宗教 改革後、多くのプロテスタントの聖書はユダヤ教の正典に従うようになり、追加のテキストを除外するようになった。追加のテキストは偽典と呼ばれるように なった。偽典は、改訂標準版聖書の基となった欽定訳聖書では、別の見出しで記載されている。[148] |

|

|

| New Testament Main article: New Testament See also: Development of the New Testament canon, New Testament apocrypha, Antilegomena, and Language of the New Testament Further information: Category:New Testament content St. Jerome in His Study, published in 1541 by Marinus van Reymerswaele. Jerome produced a fourth-century Latin edition of the Bible, known as the Vulgate, that became the Catholic Church's official translation. The New Testament is the name given to the second portion of the Christian Bible. While some scholars assert that Aramaic was the original language of the New Testament,[151] the majority view says it was written in the vernacular form of Koine Greek. Still, there is reason to assert that it is a heavily Semitized Greek: its syntax is like conversational Greek, but its style is largely Semitic.[152][y][z] Koine Greek was the common language of the western Roman Empire from the Conquests of Alexander the Great (335–323 BCE) until the evolution of Byzantine Greek (c. 600) while Aramaic was the language of Jesus, the Apostles and the ancient Near East.[151][aa][ab][ac] The term "New Testament" came into use in the second century during a controversy over whether the Hebrew Bible should be included with the Christian writings as sacred scripture.[153] It is generally accepted that the New Testament writers were Jews who took the inspiration of the Old Testament for granted. This is probably stated earliest in 2 Timothy 3:16: "All scripture is given by inspiration of God". Scholarship on how and why ancient Jewish–Christians came to create and accept new texts as equal to the established Hebrew texts has taken three forms. First, John Barton writes that ancient Christians probably just continued the Jewish tradition of writing and incorporating what they believed were inspired, authoritative religious books.[154] The second approach separates those various inspired writings based on a concept of "canon" which developed in the second century.[155] The third involves formalizing canon.[156] According to Barton, these differences are only differences in terminology; the ideas are reconciled if they are seen as three stages in the formation of the New Testament.[157] The first stage was completed remarkably early if one accepts Albert C. Sundberg [de]'s view that "canon" and "scripture" are separate things, with "scripture" having been recognized by ancient Christians long before "canon" was.[158] Barton says Theodor Zahn concluded "there was already a Christian canon by the end of the first century", but this is not the canon of later centuries.[159] Accordingly, Sundberg asserts that in the first centuries, there was no criterion for inclusion in the "sacred writings" beyond inspiration, and that no one in the first century had the idea of a closed canon.[160] The gospels were accepted by early believers as handed down from those Apostles who had known Jesus and been taught by him.[161] Later biblical criticism has questioned the authorship and dating of the gospels. At the end of the second century, it is widely recognized that a Christian canon similar to its modern version was asserted by the church fathers in response to the plethora of writings claiming inspiration that contradicted orthodoxy: (heresy).[162] The third stage of development as the final canon occurred in the fourth century with a series of synods that produced a list of texts of the canon of the Old Testament and the New Testament that are still used today. Most notably the Synod of Hippo in 393 CE and that of c. 400. Jerome produced a definitive Latin edition of the Bible (the Vulgate), the canon of which, at the insistence of the Pope, was in accord with the earlier Synods. This process effectively set the New Testament canon. New Testament books already had considerable authority in the late first and early second centuries.[163] Even in its formative period, most of the books of the NT that were seen as scripture were already agreed upon. Linguistics scholar Stanley E. Porter says "evidence from the apocryphal non-Gospel literature is the same as that for the apocryphal Gospels – in other words, that the text of the Greek New Testament was relatively well established and fixed by the time of the second and third centuries".[164] By the time the fourth century Fathers were approving the "canon", they were doing little more than codifying what was already universally accepted.[165] The New Testament is a collection of 27 books[166] of 4 different genres of Christian literature (Gospels, one account of the Acts of the Apostles, Epistles and an Apocalypse). These books can be grouped into: The Gospels are narratives of Jesus's last three years of life, his death and resurrection. Synoptic Gospels Gospel of Matthew Gospel of Mark Gospel of Luke Gospel of John The narrative literature provides an account and history of the very early Apostolic age. Acts of the Apostles The Pauline epistles are written to individual church groups to address problems, provide encouragement and give instruction. Epistle to the Romans First Epistle to the Corinthians Second Epistle to the Corinthians Epistle to the Galatians Epistle to the Ephesians Epistle to the Philippians Epistle to the Colossians First Epistle to the Thessalonians Second Epistle to the Thessalonians The pastoral epistles discuss the pastoral oversight of churches, Christian living, doctrine and leadership. First Epistle to Timothy Second Epistle to Timothy Epistle to Titus Epistle to Philemon Epistle to the Hebrews The Catholic epistles, also called the general epistles or lesser epistles. Epistle of James encourages a lifestyle consistent with faith. First Epistle of Peter addresses trial and suffering. Second Epistle of Peter more on suffering's purposes, Christology, ethics and eschatology. First Epistle of John covers how to discern true Christians: by their ethics, their proclamation of Jesus in the flesh, and by their love. Second Epistle of John warns against docetism. Third Epistle of John encourage, strengthen and warn. Epistle of Jude condemns opponents. The apocalyptic literature (prophetical) Book of Revelation, or the Apocalypse, predicts end time events. Catholicism, Protestantism, and Eastern Orthodox currently have the same 27-book New Testament Canon. They are ordered differently in the Slavonic tradition, the Syriac tradition and the Ethiopian tradition.[167] |

新約聖書 詳細は「新約聖書」を参照 関連項目:新約聖書の正典の歴史、新約聖書の外典、アンティレゴメナ、新約聖書の言語 さらに詳しい情報:カテゴリー:新約聖書の内容 マリヌス・ファン・レイマースウェイクが1541年に出版した『書斎の聖ヒエロニムス』。ヒエロニムスは、ウルガタ訳として知られる4世紀のラテン語訳聖書を作成し、それはカトリック教会の公式訳となった。 新約聖書は、キリスト教聖書の第2部に対して与えられた名称である。一部の学者は、新約聖書の原語はアラム語であったと主張しているが[151]、大多数 の見解では、新約聖書はコイネー・ギリシャ語の口語体で書かれたとしている。しかし、新約聖書はヘブライ語の影響を強く受けたギリシャ語であると主張する 理由もある。その構文は会話体ギリシャ語に似ているが、その文体は主にヘブライ語である。 [152][y][z] コイネー・ギリシャ語は、アレクサンドロス大王の征服(紀元前335年~323年)からビザンチン・ギリシャ語が発展するまで(600年頃)のローマ帝国 西部の共通語であった。一方、イエス、使徒、古代中近東の言語はアラム語であった。 [151][aa][ab][ac] 「新約聖書」という用語は、ヘブライ語聖書をキリスト教の聖典に含めるべきか否かという論争が起こった2世紀に用いられるようになった。 新約聖書の著者は、旧約聖書から着想を得たユダヤ人であったというのが一般的な見方である。このことは、おそらく2テモテ3:16の「聖書はすべて、神の 霊感によるもので、教えと戒めと矯正と義の訓練とのために有益です」という一節が最も早い時期に述べられている。古代のユダヤ人キリスト教徒が、なぜ、そ してどのようにして、確立されたヘブライ語のテキストと同等に新しいテキストを作成し、受け入れるようになったかという研究は、3つの形態をとっている。 まず、ジョン・バートンは、古代のキリスト教徒はおそらく、霊感を受けた、権威ある宗教書であると信じたものを書き、取り入れるというユダヤ教の伝統をそ のまま引き継いだだけだと述べている。[154] 2つ目のアプローチは、2世紀に発展した「正典」という概念に基づいて、さまざまな霊感を受けた文書を区別するものである。[155] 3つ目は、正典を公式化することである。 [156] バートンによると、これらの相違は用語上の相違にすぎず、新約聖書の形成における3つの段階として見れば、その考え方は一致する。 もし「正典」と「聖書」は別物であり、「聖書」は「正典」よりもずっと以前に古代キリスト教徒たちによって認められていたというアルバート・C・サンド バーグ(Albert C. Sundberg)の見解を受け入れるのであれば、最初の段階は驚くほど早く完了していたことになる。[158] バートンはテオドール・ツァーンが「1世紀の終わりにはすでにキリスト教の正典が存在していた」と結論づけたと述べているが、これは後の世紀の正典ではな い。 [159] それゆえ、Sundbergは、初期の数世紀の間は、霊感以上の「聖典」に含めるための基準はなく、初期の数世紀には、閉じた正典という考えは存在しな かったと主張している。[160] 福音書は、イエスを知り、彼から教えを受けた使徒たちから伝えられたものとして、初期の信者たちに受け入れられた。[161] 後の聖書批評では、福音書の著述と年代が疑問視されている。 2世紀の終わり頃には、正統派の教義に反する霊感を受けたとする膨大な数の文書(異端)に対して、教会の父祖たちが現代版に類似したキリスト教の正典を主 張したことが広く認識されるようになった。[162] 最終的な正典としての発展の第3段階は、4世紀に開催された一連の会議で、現在も使用されている旧約聖書と新約聖書の正典のテキストの一覧が作成された。 特に重要なのは、393年のヒッポス公会議と400年頃の公会議である。 ヒエロニムスは、ラテン語聖書(ウルガタ)の決定版を制作したが、その正典は、教皇の主張により、それ以前の公会議と一致していた。 このプロセスは、事実上、新約聖書の正典を確定した。 新約聖書の書籍は、1世紀後半から2世紀初頭にはすでに大きな権威を持っていた。[163] 形成期においても、聖典と見なされていた新約聖書の書籍のほとんどはすでに合意されていた。言語学者のスタンリー・E・ 「外典の非福音文学からの証拠は、外典の福音書からの証拠と同じである。つまり、ギリシャ語の新約聖書のテキストは、2世紀と3世紀の頃には、比較的よく 確立され、固定されていた」と述べている。[164] 4世紀の教父たちが「正典」を承認する頃には、彼らはすでに広く受け入れられていたものを体系化する以上のことはほとんどしていなかった。[165] 新約聖書は、キリスト教文学の4つの異なるジャンル(福音書、使徒行伝の一説、書簡、黙示録)から成る27冊の書物である。[166] これらの書物は、以下のように分類することができる。 福音書は、イエスの最後の3年間の生涯、死、復活についての物語である。 共観福音書 マタイによる福音書 マルコによる福音書 ルカによる福音書 ヨハネによる福音書 物語文学は、使徒の時代のごく初期の出来事や歴史を伝えている。 使徒行伝 パウロ書簡は、個々の教会グループに宛てて書かれたもので、問題への対処、励まし、指導を目的としている。 ローマ人への手紙 コリント人への第一の手紙 コリント人への第二の手紙 ガラテヤ人への手紙 エフェソ人への手紙 ピリピ人への手紙 コロサイ人への手紙 テサロニケ人への第一の手紙 テサロニケ人への第二の手紙 牧会書簡は、教会の牧会的監督、キリスト教徒の生活、教義、指導について論じている。 テモテへの第一の手紙 テモテへの第二の手紙 テトスへの手紙 フィレモンへの手紙 ヘブライ人への手紙 カトリック書簡は、一般書簡または小書簡とも呼ばれる。 ヤコブの手紙は、信仰にふさわしい生活を奨励している。 ペトロの手紙一は、試練と苦難について述べている。 ペトロの手紙二は、苦難の目的、キリスト論、倫理、終末論についてより詳しく述べている。 ヨハネの手紙一は、真のキリスト教徒を見分ける方法を扱っている。すなわち、彼らの倫理観、肉体を持ったイエスを宣べ伝えること、そして彼らの愛によってである。 ヨハネの手紙二は、ドクエティスム(キリストの受肉説)を警告している。 ヨハネの手紙三は、奨励、強化、警告を行っている。 ユダの手紙は反対者を非難している。 終末論の文献(予言) ヨハネの黙示録、またはヨハネの黙示録は、終末の出来事を予言している。 カトリック、プロテスタント、東方正教会は現在、同じ27冊の書物からなる新約聖書正典を有している。スラヴ語派の伝統、シリア語派の伝統、エチオピア語派の伝統では、異なる順序になっている。[167] |

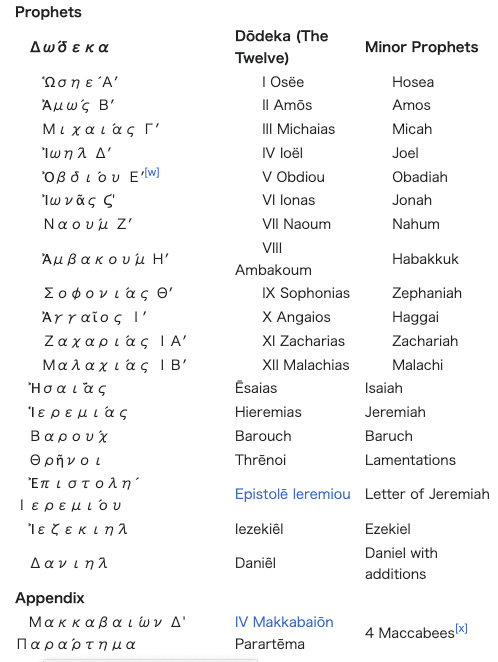

| Canon variations Peshitta Main article: Peshitta The Peshitta (Classical Syriac: ܦܫܺܝܛܬܳܐ or ܦܫܝܼܛܬܵܐ pšīṭtā) is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition. The consensus within biblical scholarship, although not universal, is that the Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated into Syriac from biblical Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century CE, and that the New Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Greek.[ad] This New Testament, originally excluding certain disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, Revelation), had become a standard by the early 5th century. The five excluded books were added in the Harklean Version (616 CE) of Thomas of Harqel.[ae][151] Catholic Church canon The canon of the Catholic Church was affirmed by the Council of Rome (382), the Synod of Hippo (393), the Council of Carthage (397), the Council of Carthage (419), the Council of Florence (1431–1449) and finally, as an article of faith, by the Council of Trent (1545–1563) establishing the canon consisting of 46 books in the Old Testament and 27 books in the New Testament for a total of 73 books in the Catholic Bible.[168][169][af] Ethiopian Orthodox canon Main article: Orthodox Tewahedo biblical canon The canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is wider than the canons used by most other Christian churches. There are 81 books in the Ethiopian Orthodox Bible.[171] In addition to the books found in the Septuagint accepted by other Orthodox Christians, the Ethiopian Old Testament Canon uses Enoch and Jubilees (ancient Jewish books that only survived in Ge'ez, but are quoted in the New Testament),[142] Greek Ezra and the Apocalypse of Ezra, 3 books of Meqabyan, and Psalm 151 at the end of the Psalter.[o][m] The three books of Meqabyan are not to be confused with the books of Maccabees. The order of the books is somewhat different in that the Ethiopian Old Testament follows the Septuagint order for the Minor Prophets rather than the Jewish order.[171] |