ブラック・パンサー党

Black Panther Party

☆ ブラックパンサー党(Black Panther Party for Self-Defense)は、1966年10月に大学生のボビー・シールとヒューイ・P・ニュートンによってカリフォルニア州オークランドで設立された マルクス・レーニン主義、ブラックパワーの政治組織である。1966年から1982年にかけてアメリカで活動し、サンフランシスコ、 ニューヨーク、シカゴ、ロサンゼルス、シアトル、フィラデルフィアを含むアメリカの多くの主要都市に支部を持っていた。 また、多くの刑務所でも活動し、イギリスとアルジェリアには国際的な支部があった。結成当初、党の中心的な活動は、オークランド 警察の過剰な力と不正行為に異議を唱えるために計画された、携帯品を公開するパトロール(「警官ウォッチング」)であった。1969年以降、党は子供のた めの無料朝食プログラム、教育プログラム、地域保健クリニックなどの社会プログラムを創設した。ブラックパンサー党は階 級闘争を提唱し、プロレタリアの前衛を代表すると主張した。

| The Black Panther

Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was a

Marxist–Leninist and black power political organization founded by

college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in

Oakland, California.[8][9][10] The party was active in the United

States between 1966 and 1982, with chapters in many major American

cities, including San Francisco, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles,

Seattle, and Philadelphia.[11] They were also active in many prisons

and had international chapters in the United Kingdom and

Algeria.[12][13] Upon its inception, the party's core practice was its

open carry patrols ("copwatching") designed to challenge the excessive

force and misconduct of the Oakland Police Department. From 1969

onward, the party created social programs, including the Free Breakfast

for Children Programs, education programs, and community health

clinics.[14][15][16][17] The Black Panther Party advocated for class

struggle, claiming to represent the proletarian vanguard.[18] In 1969, J. Edgar Hoover, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), described the party as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country."[19][20][21] The FBI sabotaged the party with an illegal and covert counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, and police harassment, all designed to undermine and criminalize the party. The FBI was involved in the 1969 assassinations of Fred Hampton[22][23] and Mark Clark, who were killed in a raid by the Chicago Police Department.[24][25][26][27] Black Panther Party members were involved in many fatal firefights with police. Huey Newton allegedly killed officer John Frey in 1967, and Eldridge Cleaver (Minister of Information) led an ambush in 1968 of Oakland police officers, in which two officers were wounded and Panther treasurer Bobby Hutton was killed. The party suffered many internal conflicts, resulting in the murders of Alex Rackley and Betty Van Patter. Government persecution initially contributed to the party's growth among African Americans and the political left, who both valued the party as a powerful force against de facto segregation and the US military draft during the Vietnam War. Party membership peaked in 1970 and gradually declined over the next decade, due to vilification by the mainstream press and infighting largely fomented by COINTELPRO.[28] Support further declined over reports of the party's alleged criminal activities, such as drug dealing and extortion.[29] The party's history is controversial. Scholars have characterized the Black Panther Party as the most influential black power organization of the late 1960s, and "the strongest link between the domestic Black Liberation Struggle and global opponents of American imperialism".[30] Other scholars have described the party as more criminal than political, characterized by "defiant posturing over substance".[31] |

ブラックパンサー党(Black Panther Party

for

Self-Defense)は、1966年10月に大学生のボビー・シールとヒューイ・P・ニュートンによってカリフォルニア州オークランドで設立された

マルクス・レーニン主義、ブラックパワーの政治組織である[8][9][10]。1966年から1982年にかけてアメリカで活動し、サンフランシスコ、

ニューヨーク、シカゴ、ロサンゼルス、シアトル、フィラデルフィアを含むアメリカの多くの主要都市に支部を持っていた。

[11]また、多くの刑務所でも活動し、イギリスとアルジェリアには国際的な支部があった[12][13]。結成当初、党の中心的な活動は、オークランド

警察の過剰な力と不正行為に異議を唱えるために計画された、携帯品を公開するパトロール(「警官ウォッチング」)であった。1969年以降、党は子供のた

めの無料朝食プログラム、教育プログラム、地域保健クリニックなどの社会プログラムを創設した[14][15][16][17]。ブラックパンサー党は階

級闘争を提唱し、プロレタリアの前衛を代表すると主張した[18]。 1969年、連邦捜査局(FBI)長官であったJ・エドガー・フーバーは、党を「国の内部安全保障に対する最大の脅威」と評した[19][20] [21]。FBIは、監視、潜入、偽証、警察による嫌がらせなど、党を弱体化させ犯罪者にすることを目的とした違法で極秘の防諜プログラム(コインテルプ ロ)で党を妨害した。FBIは1969年のフレッド・ハンプトン[22][23]とマーク・クラークの暗殺に関与した。ヒューイ・ニュートンは1967年 にジョン・フレイ警官を殺害したとされ、エルドリッジ・クリーバー(情報大臣)は1968年にオークランド警官の待ち伏せを指揮し、2人の警官が負傷し、 パンサー会計のボビー・ハットンが殺害された。党は多くの内部対立に苦しみ、アレックス・ラックリーとベティ・ヴァン・パターが殺害された。 政府の迫害は当初、アフリカ系アメリカ人と政治的左派の間で党が成長する一因となった。彼らはともに、事実上の隔離とベトナム戦争中の米軍徴兵に反対する 強力な勢力として党を評価した。党員数は1970年にピークを迎え、その後の10年間で徐々に減少した。主流派メディアによる中傷と、主にコイント・エル プロによって煽られた内紛が原因であった[28]。 党の歴史は議論の余地がある。学者たちはブラックパンサー党を1960年代後半に最も影響力のあったブラックパワー組織であり、「国内の黒人解放闘争とア メリカ帝国主義の世界的な反対勢力との間の最も強い結びつき」[30]であったと評している。 |

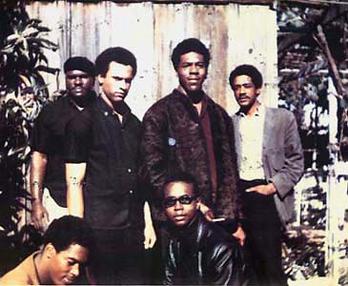

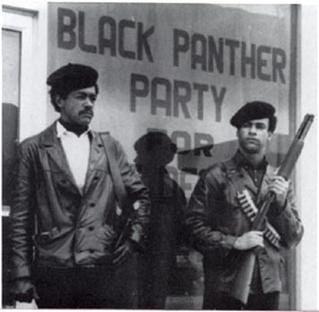

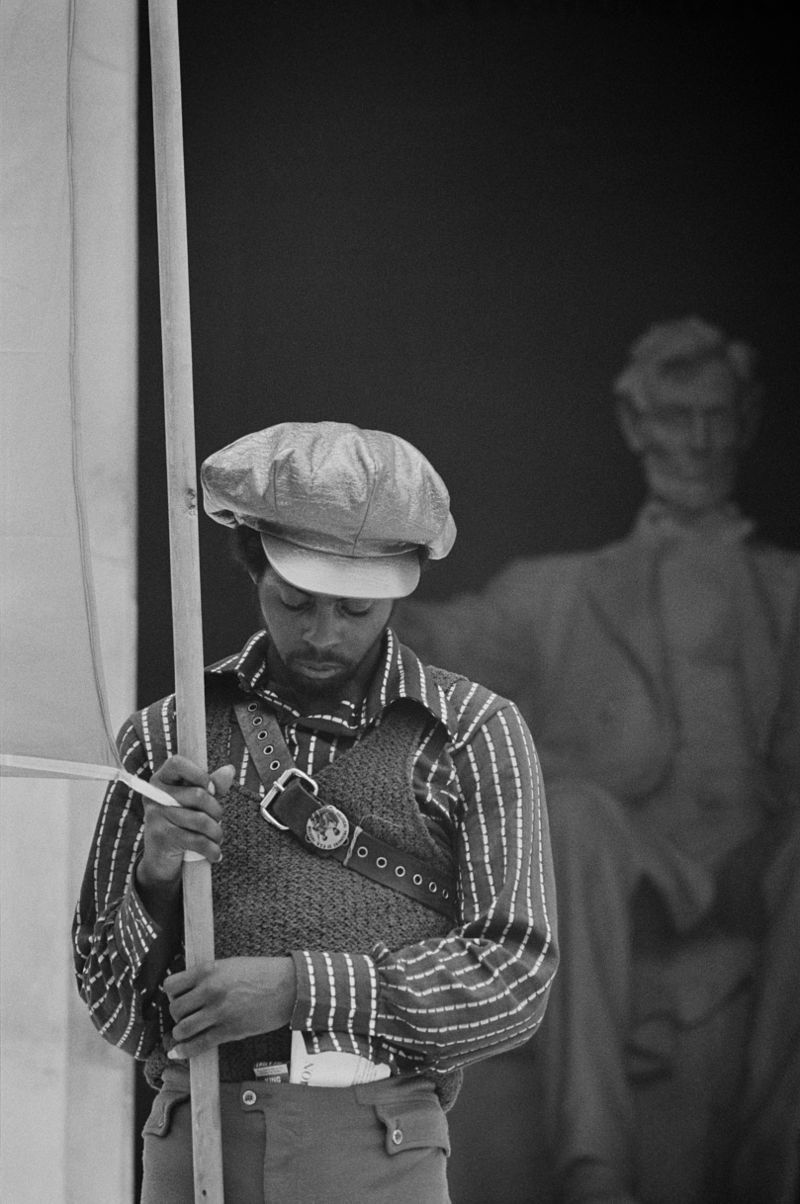

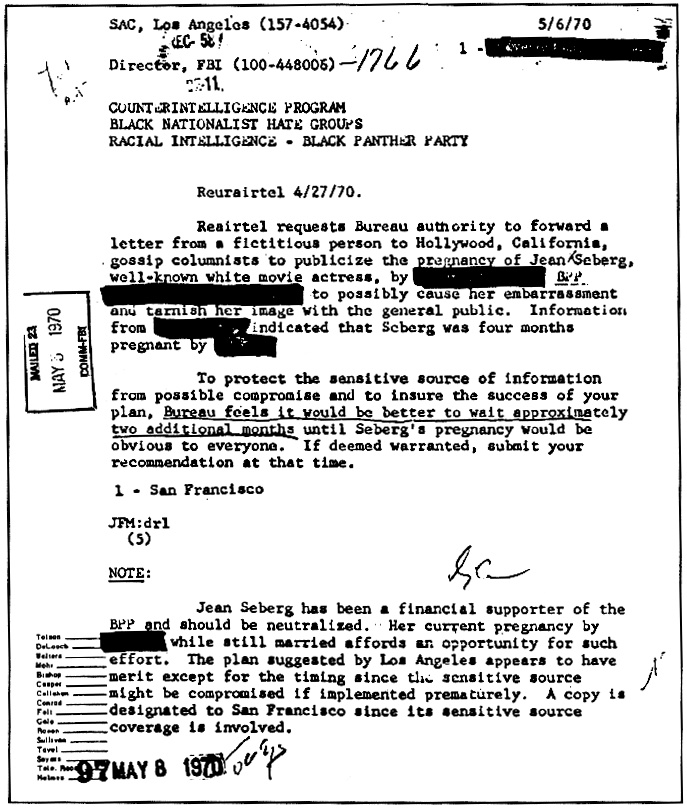

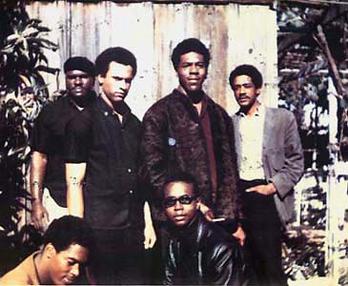

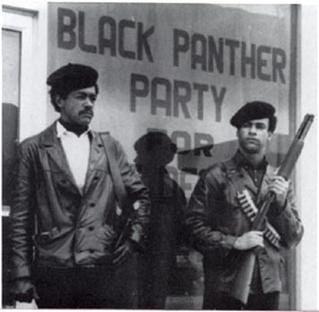

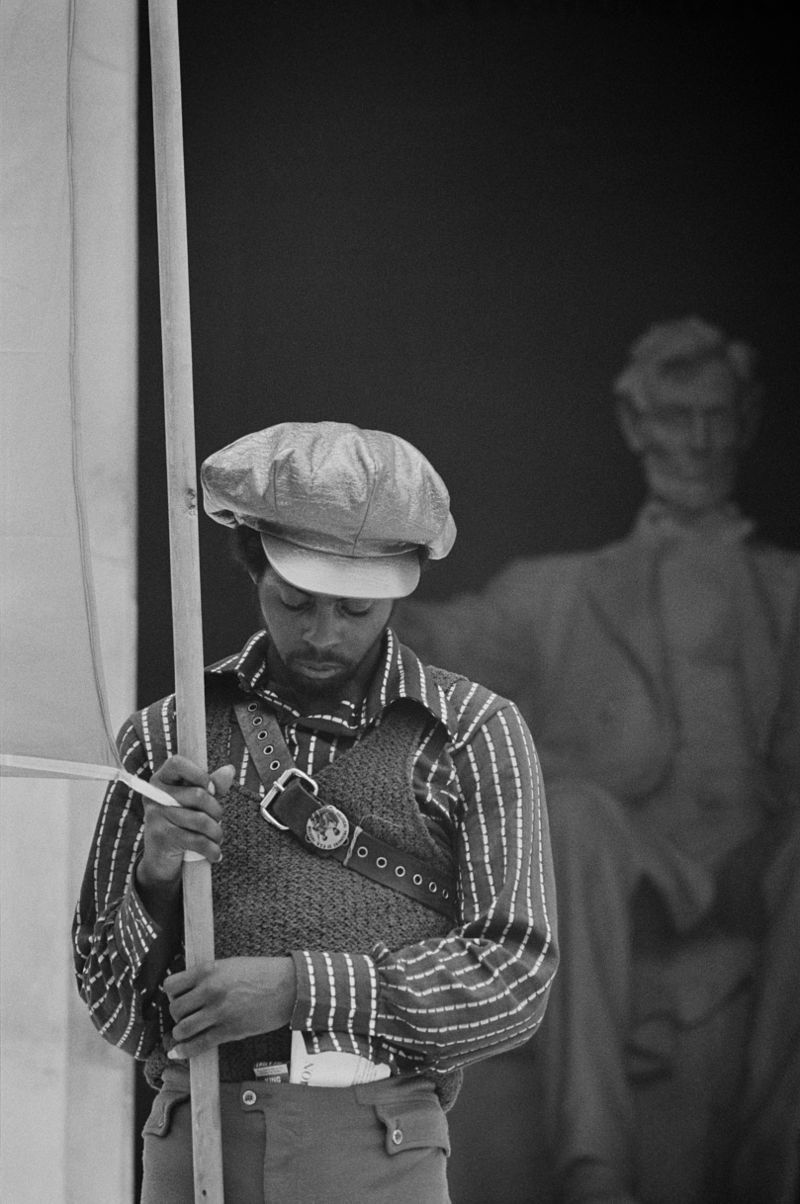

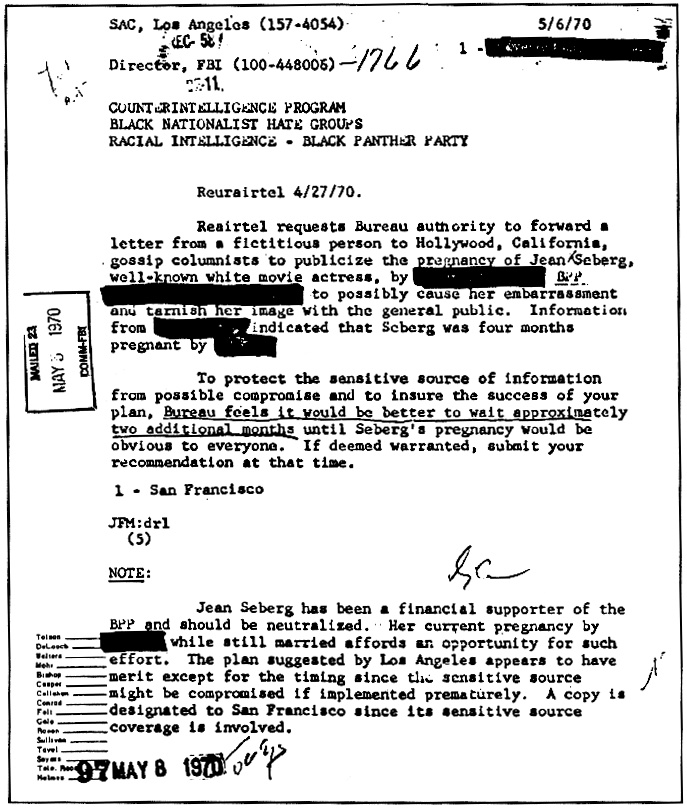

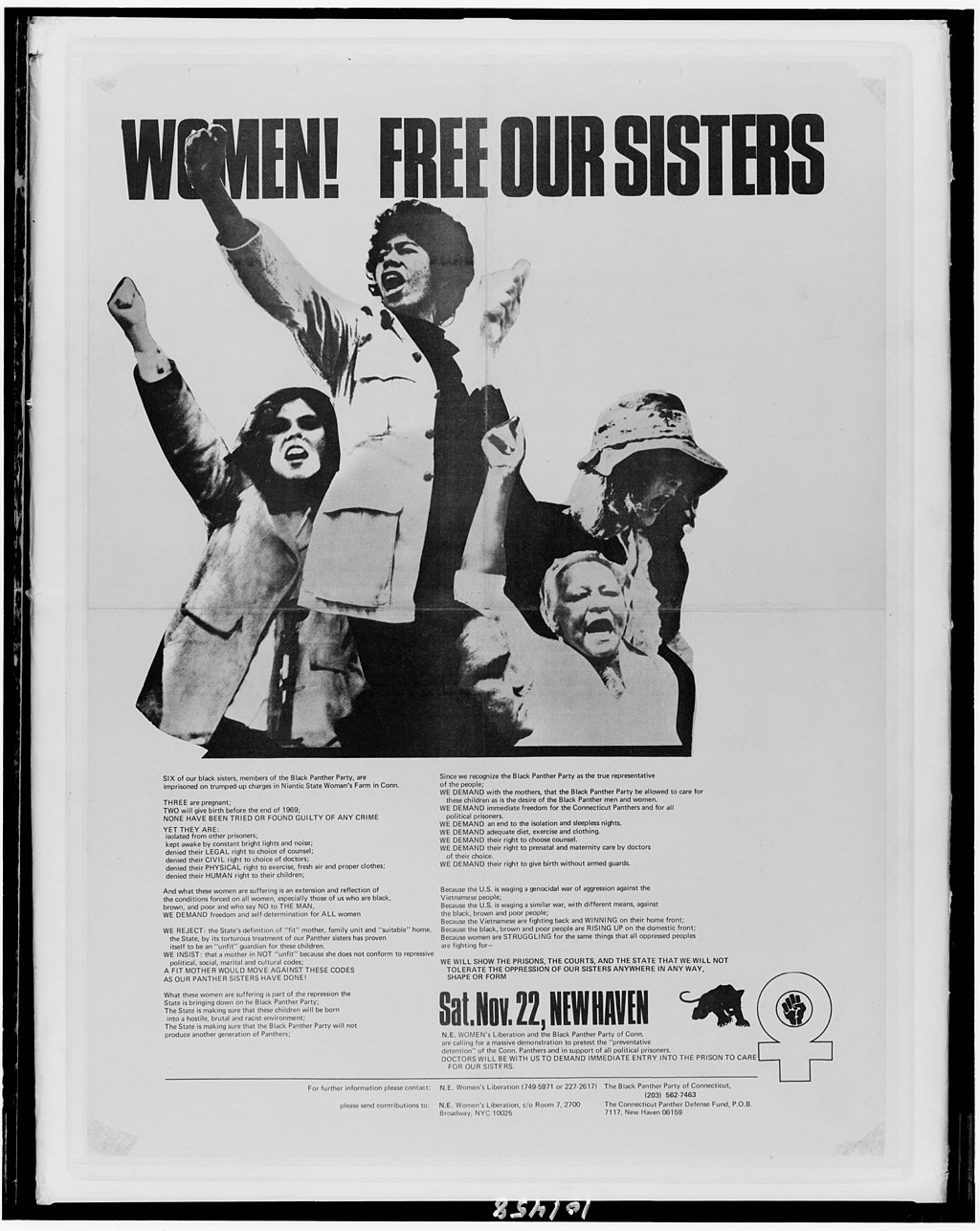

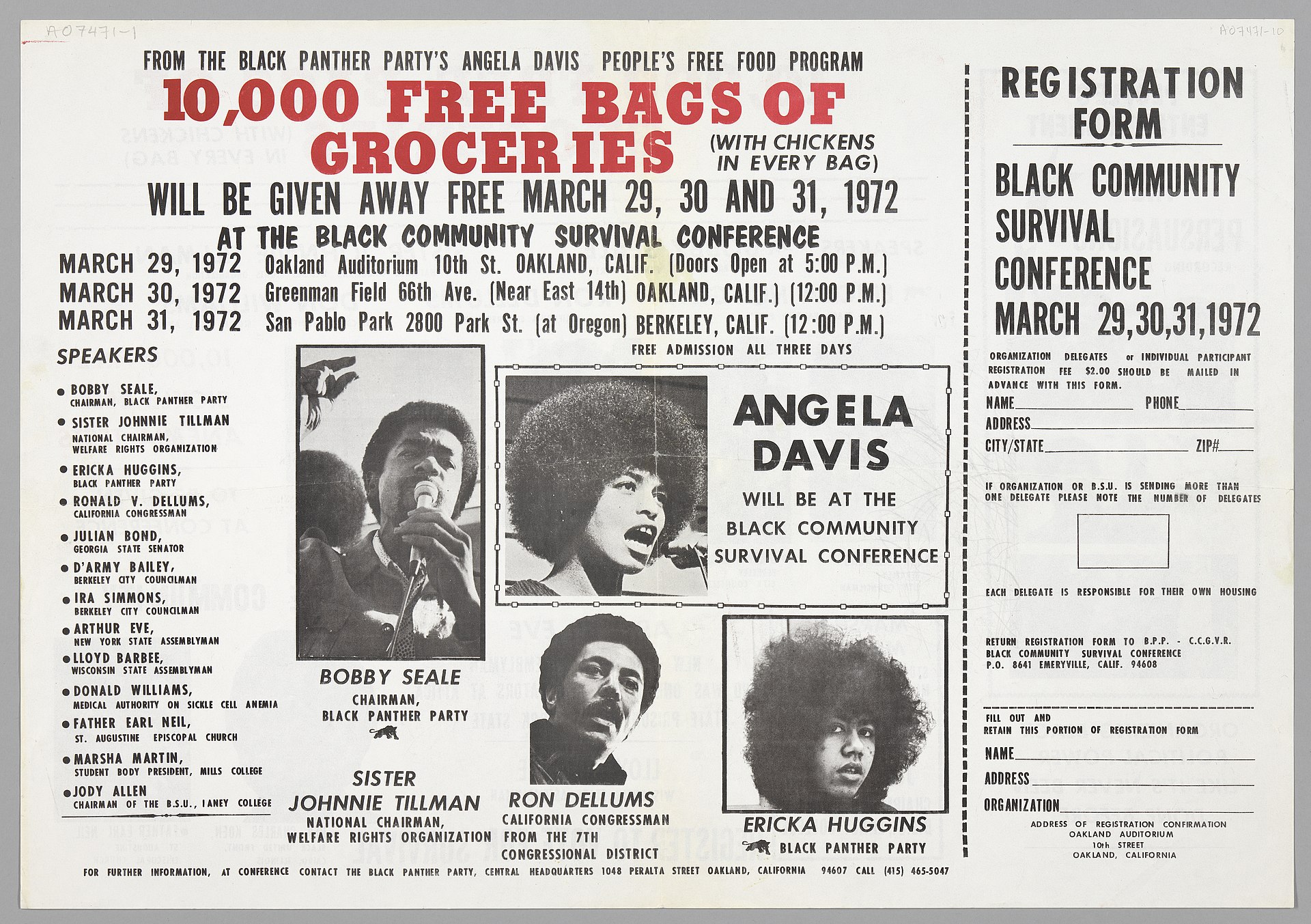

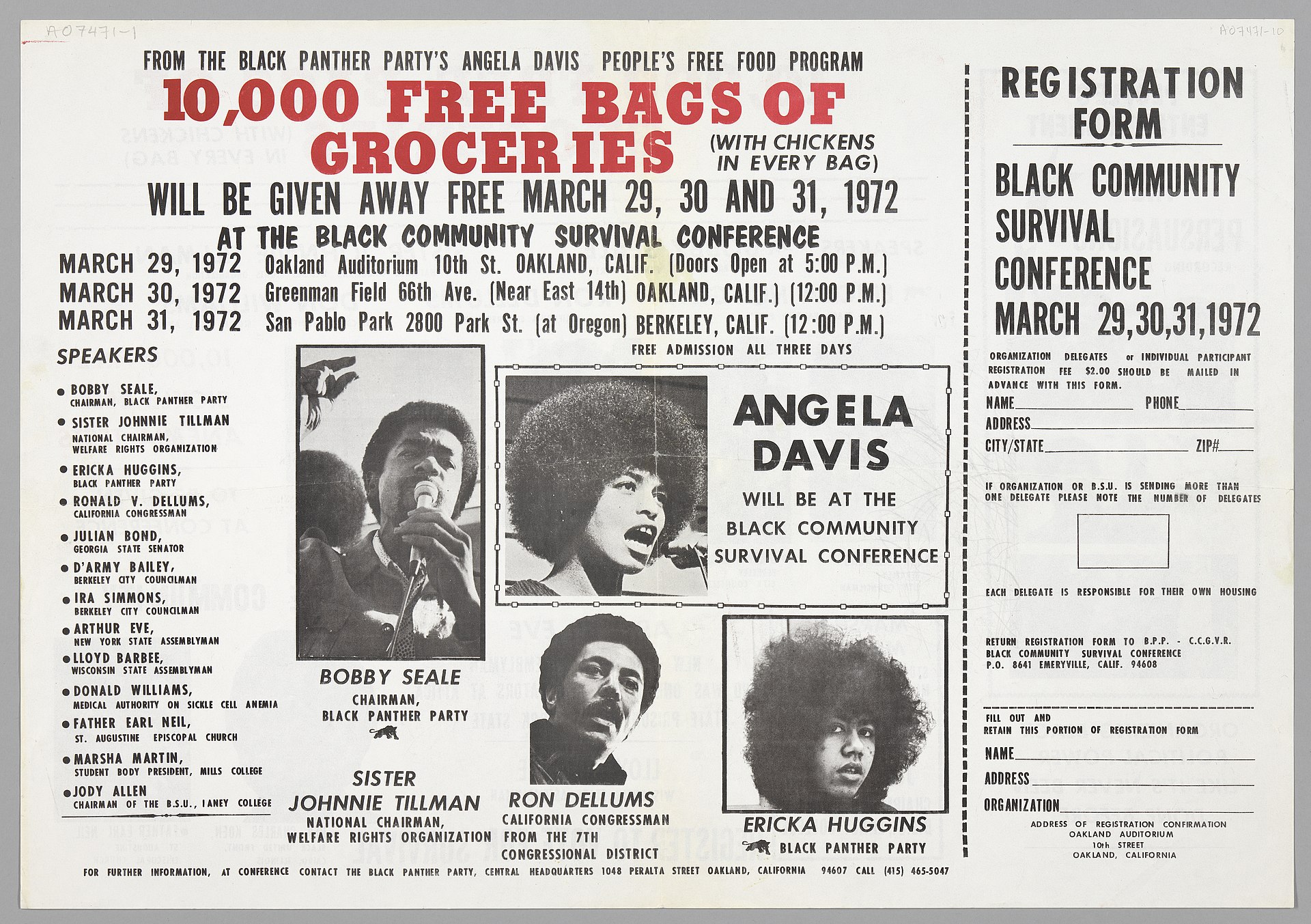

| History Origins  Original six members of the Black Panther Party (1966): Top left to right: Elbert "Big Man" Howard, Huey P. Newton (Defense Minister), Sherwin Forte, Bobby Seale (Chairman); Bottom: Reggie Forte and Little Bobby Hutton (Treasurer). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Panther_Party Newsreel in which Kathleen Cleaver spoke at Hutton Memorial Park in Alameda County, California. The footage also shows a student protest demonstration at Alameda County Courthouse, Oakland, California. Black Panther Party leaders Huey P. Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and Bobby Seale spoke on a 10-point program they wanted from the administration which was to include full employment, decent housing and education, an end to police brutality, and black people to be exempt from the military. Black Panther Party members are shown as they marched in uniform. Students at the rally marched, sang, clapped hands, and carried protest signs. Police in riot gear controlled marchers. During World War II, tens of thousands of black people left the Southern states during the Second Great Migration, moving to Oakland and other cities in the Bay Area to find work in the war industries such as Kaiser Shipyards. The sweeping migration transformed the Bay Area as well as cities throughout the West and North, altering the once white-dominated demographics.[32] A new generation of young black people growing up in these cities faced new forms of poverty and racism unfamiliar to their parents, and they sought to develop new forms of politics to address them.[33] Black Panther Party membership "consisted of recent migrants whose families traveled north and west to escape the southern racial regime, only to be confronted with new forms of segregation and repression".[34] In the early 1960s, the Civil rights movement had dismantled the Jim Crow system of racial subordination in the South with tactics of non-violent civil disobedience, and demanding full citizenship rights for black people.[35] However, not much changed in the cities of the North and West. As the wartime and post-war jobs which drew much of the black migration "fled to the suburbs along with white residents", the black population was concentrated in poor "urban ghettos" with high unemployment and substandard housing and was mostly excluded from political representation, top universities, and the middle class.[36] Northern and Western police departments were almost all white.[37] In 1966, only 16 of Oakland's 661 police officers were African American (less than 2.5%).[38] Civil rights tactics proved incapable of redressing these conditions, and the organizations that had "led much of the nonviolent civil disobedience", such as SNCC and CORE, went into decline.[35] By 1966 a "Black Power ferment" emerged, consisting largely of young urban black people, posing a question the Civil Rights Movement could not answer: "How would black people in America win not only formal citizenship rights, but actual economic and political power?"[37] Young black people in Oakland and other cities developed study groups and political organizations, and from this ferment the Black Panther Party emerged.[39] Founding the Black Panther Party In late October 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense).[10] In formulating a new politics, they drew on their work with a variety of Black Power organizations.[40] Newton and Seale first met in 1962 when they were both students at Merritt College.[41] They joined Donald Warden's Afro-American Association, where they read widely, debated, and organized in an emergent black nationalist tradition inspired by Malcolm X and others.[42] Eventually dissatisfied with Warden's accommodationism, they developed a revolutionary anti-imperialist perspective working with more active and militant groups like the Soul Students Advisory Council and the Revolutionary Action Movement.[43][44] Their paid jobs running youth service programs at the North Oakland Neighborhood Anti-Poverty Center allowed them to develop a revolutionary nationalist approach to community service, later a key element in the Black Panther Party's "community survival programs."[45] Dissatisfied with the failure of these organizations to directly challenge police brutality and appeal to the "brothers on the block", Huey and Bobby took matters into their own hands. After the police killed Matthew Johnson, an unarmed young black man in San Francisco, Newton observed the violent insurrection that followed. He had an epiphany that would distinguish the Black Panther Party from the multitude of Black Power organizations. Newton saw the explosive rebellious anger of the ghetto as a social force and believed that if he could stand up to the police, he could organize that force into political power. Inspired by Robert F. Williams' armed resistance to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and Williams' book Negroes with Guns,[46] Newton studied gun laws in California extensively. Like the Community Alert Patrol in Los Angeles after the Watts Rebellion, he decided to organize patrols to follow the police around to monitor for incidents of brutality. But with a crucial difference: his patrols would carry loaded guns.[47] Huey and Bobby raised enough money to buy two shotguns by buying bulk quantities of the recently publicized Mao's Little Red Book and reselling them to leftists and liberals on the Berkeley campus at three times the price. According to Bobby Seale, they would "sell the books, make the money, buy the guns, and go on the streets with the guns. We'll protect a mother, protect a brother, and protect the community from the racist cops."[48] On October 29, 1966, Stokely Carmichael – a leader of SNCC – championed the call for "Black Power" and came to Berkeley to keynote a Black Power conference. At the time, he was promoting the armed organizing efforts of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in Alabama and their use of the Black Panther symbol. Newton and Seale decided to adopt the Black Panther logo and form their own organization called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.[49] Newton and Seale decided on a uniform of blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, black berets,[50] the latter adopted as an homage to Che Guevara.[51]: 123 Sixteen-year-old Bobby Hutton was their first recruit.[52] By January 1967, the BPP opened its first official headquarters in an Oakland storefront and published the first issue of The Black Panther: Black Community News Service.  Black Panther Party founders Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton standing in the street, armed with a Colt .45 and a shotgun Late 1966 to early 1967 Oakland patrols of police The initial tactic of the party used contemporary open-carry gun laws to protect Party members when policing the police. This act was done to record incidents of police brutality by distantly following police cars around neighborhoods.[53] When confronted by a police officer, Party members cited laws proving they had done nothing wrong and threatened to take to court any officer that violated their constitutional rights.[54] Between the end of 1966 to the start of 1967, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense's armed police patrols in Oakland black communities attracted a small handful of members.[55] Numbers grew slightly starting in February 1967, when the party provided an armed escort at the San Francisco airport for Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow and keynote speaker for a conference held in his honor.[56] The Black Panther Party's focus on militancy was often construed as open hostility,[57][58] feeding a reputation of violence even though early efforts by the Panthers focused primarily on promoting social issues and the exercise of their legal right to carry arms. The Panthers employed a California law that permitted carrying a loaded rifle or shotgun as long as it was publicly displayed and pointed at no one.[50] Generally this was done while monitoring and observing police behavior in their neighborhoods, with the Panthers arguing that this emphasis on active militancy and openly carrying their weapons was necessary to protect individuals from police violence. For example, chants like "The Revolution has come, it's time to pick up the gun. Off the pigs!",[59] helped create the Panthers' reputation as a violent organization. Rallies in Richmond, California The black community of Richmond, California, wanted protection against police brutality.[60] With only three main streets for entering and exiting the neighborhood, it was easy for police to control, contain, and suppress the population.[61] On April 1, 1967, a black unarmed twenty-two-year-old construction worker named Denzil Dowell was shot dead by police in North Richmond.[62] Dowell's family contacted the Black Panther Party for assistance after county officials refused to investigate the case.[63] The Party held rallies in North Richmond that educated the community on armed self-defense and the Denzil Dowell incident.[64] Police seldom interfered at these rallies because every Panther was armed and no laws were broken.[65] The Party's ideals resonated with several community members, who then brought their own guns to the next rallies.[66] Protest at the Statehouse  Black Panther Party armed demonstration on May 2, 1967 Awareness of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense grew rapidly after their May 2, 1967, protest at the California State Capitol. On May 2, 1967, the California State Assembly Committee on Criminal Procedure was scheduled to convene to discuss what was known as the "Mulford Act", which would make the public carrying of loaded firearms illegal. Newton, with Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver, put together a plan to send a group of 26 armed Panthers led by Seale from Oakland to Sacramento to protest the bill. The group entered the assembly carrying their weapons, an incident which was widely publicized, and which prompted police to arrest Seale and five others. The group pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges of disrupting a legislative session.[67] At the time of the protest, the Party had fewer than 100 members in total.[68]  Black Panther convention, Lincoln Memorial, June 19, 1970 In May 1967, the Panthers invaded the State Assembly Chamber in Sacramento, guns in hand, in what appears to have been a publicity stunt. Still, they scared a lot of important people that day. At the time, the Panthers had almost no following. Now, (a year later) however, their leaders speak on invitation almost anywhere radicals gather, and many whites wear "Honkeys for Huey" buttons, supporting the fight to free Newton, who has been in jail since last Oct. 28 (1967) on the charge that he killed a policeman ...[69] In 1967, the Mulford Act was passed by the California legislature and signed by governor Ronald Reagan. The bill was crafted in response to members of the Black Panther Party who were copwatching. The bill repealed a law that allowed the public carrying of loaded firearms. Ten-point program Main article: Ten-Point Program (Black Panther Party) The Black Panther Party first publicized its original "What We Want Now!" Ten-Point program on May 15, 1967, following the Sacramento action, in the second issue of The Black Panther newspaper.[56] We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community. We want full employment for our people. We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community. We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings. We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society. We want all Black men to be exempt from military service. We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people. We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails. We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace. Late 1967 to early 1968 COINTELPRO Further information: COINTELPRO  COINTELPRO document outlining the FBI's plans to 'neutralize' Jean Seberg for her support for the Black Panther Party, by attempting to publicly "cause her embarrassment" and "tarnish her image" In August 1967, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) instructed its program "COINTELPRO" to "neutralize ... black nationalist hate groups" and other dissident groups. In September 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover described the Black Panthers as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country".[70] By 1969, the Black Panthers and their allies had become primary COINTELPRO targets, singled out in 233 of the 295 authorized "Black Nationalist" COINTELPRO actions.[71] The goals of the program were to prevent the unification of militant black nationalist groups and to weaken their leadership, as well as to discredit them to reduce their support and growth. The initial targets included the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Revolutionary Action Movement and the Nation of Islam, as well as leaders including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Maxwell Stanford and Elijah Muhammad. As assistant FBI Director William Sullivan later testified in front of the Church Committee, the Bureau "did not differentiate" between Soviet spies and suspected Communists in black nationalist movements when deploying surveillance and neutralization tactics.[72] COINTELPRO attempted to create rivalries between black nationalist factions and to exploit existing ones. One such attempt was to "intensify the degree of animosity" between the Black Panthers and the Blackstone Rangers, a Chicago street gang. The FBI sent an anonymous letter to the Rangers' gang leader claiming that the Panthers were threatening his life, a letter whose intent was to provoke "preemptive" violence against Panther leadership. In Southern California, the FBI made similar efforts to exacerbate a "gang war" between the Black Panther Party and a black nationalist group called the US Organization, allegedly sending a provocative letter to the US Organization to increase existing antagonism.[73] COINTELPRO also aimed to dismantle the Black Panther Party by targeting their social/community programs, including its Free Breakfast for Children program, whose success had served to "shed light on the government's failure to address child poverty and hunger—pointing to the limits of the nation's War on Poverty".[74] According to Bloom & Martin, the FBI denounced the Party's efforts as a means of indoctrination because the Party taught and provided for children more effectively than the government. "Police and Federal Agents regularly harassed and intimidated program participants, supporters, and Party workers and sought to scare away donors and organizations that housed the programs like churches and community centers".[74][75] Black Panther Party members were involved in many fatal firefights with police. Newton declared: Malcolm, implacable to the ultimate degree, held out to the Black masses ... liberation from the chains of the oppressor and the treacherous embrace of the endorsed [Black] spokesmen. Only with the gun were the black masses denied this victory. But they learned from Malcolm that with the gun, they can recapture their dreams and bring them into reality.[76] Huey Newton charged with murdering John Frey On October 28, 1967, Oakland police officer John Frey was shot to death in an altercation with Huey P. Newton during a traffic stop in which Newton and backup officer Herbert Heanes also sustained gunshot wounds. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter at trial, but the conviction was later overturned. In his book Shadow of the Panther, writer Hugh Pearson alleges that Newton was intoxicated in the hours before the incident, and claimed to have willfully killed John Frey.[77] Free Huey! campaign At the time, Newton claimed that he had been falsely accused, leading to the Party's "Free Huey!" campaign. The police killing gained the party even wider recognition by the radical American left[78] and it stimulated the growth of the Party nationwide.[68] Newton was released after three years, when his conviction was reversed on appeal.[79] As Newton awaited trial, the "Free Huey" campaign developed alliances with numerous students and anti-war activists, "advancing an anti-imperialist political ideology that linked the oppression of antiwar protestors to the oppression of blacks and Vietnamese".[80] The "Free Huey" campaign attracted black power organizations, New Left groups, and other activist groups such as the Progressive Labor Party, Bob Avakian of the Community for New Politics, and the Red Guard.[81] For example, the Black Panther Party collaborated with the Peace and Freedom Party, which sought to promote a strong antiwar and antiracist politics in opposition to the establishment Democratic Party.[82] The Black Panther Party provided needed legitimacy to the Peace and Freedom Party's racial politics and in return received invaluable support for the "Free Huey" campaign.[83] Founding of the L. A. Chapter In 1968 the southern California chapter was founded by Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter in Los Angeles. Carter was the leader of the Slauson Street gang, and many of the L.A. chapter's early recruits were Slausons.[84] Killing of Bobby Hutton Bobby James Hutton was born April 21, 1950, in Jefferson County Arkansas. At the age of three, he and his family moved to Oakland, California after being harassed by racist vigilante groups associated with the Ku Klux Klan. In December 1966, he became the first treasurer and recruit of the Black Panther Party at the age of just 16 years old. On April 6, 1968, two days after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and with riots raging across cities in the United States, the 17-year-old Hutton was traveling with Eldridge Cleaver and other BPP members in a car. The group confronted Oakland Police officers, then fled to an apartment building where they engaged in a 90-minute gun battle with the police. The standoff ended with Cleaver wounded and Hutton voluntarily surrendering. According to Cleaver, although Hutton had stripped down to his underwear and had his hands raised in the air to prove that he was unarmed, Oakland Police shot Hutton more than 12 times, killing him. Two police officers were also shot. He became the first member of the party to be killed by police. Although at the time the BPP claimed that the police had ambushed them, several party members later admitted that Cleaver had led the Panther group on a deliberate ambush of the police officers, provoking the shoot-out.[85][86][87][88][89] Seven other Panthers, including Chief of Staff David Hilliard, were also arrested. Hutton's death became a rallying issue for Panther supporters.[90][91][92] Late 1968 Chronology Early Spring 1968: Eldridge Cleaver's Soul on Ice published. April 6, 1968: Death of Bobby James Hutton, killed in a gunfight with Oakland police.[90] April 17, 1968: Funeral for Bobby James Hutton in Berkeley, followed by a rally at the Alameda County Courthouse.[90] April to mid-June 1968: Cleaver in jail. Mid-July 1968: Huey Newton's murder trial commences. Panthers hold daily "Free Huey" rallies outside the courthouse. August 5, 1968: Three Panthers killed in a gun battle with police at a Los Angeles gas station.[93] Early September 1968: Newton convicted of manslaughter. Late September 1968: Days before he is due to return to prison to serve out a rape conviction, Cleaver flees to Cuba and later Algeria. October 5, 1968: A Panther is killed in a gunfight with police in Los Angeles.[93] November 1968: The BPP finds numerous supporters, establishing relationships with the Peace and Freedom Party and SNCC. Money contributions flow in, and BPP leadership begins embezzlement.[94] November 6, 1968: Lauren Watson, head of the Denver chapter, is arrested by Denver Police for fleeing a police officer and resisting arrest. His trial will be filmed and televised in 1970 as "Trial: The City and County of Denver vs. Lauren R. Watson." November 20, 1968: William Lee Brent and two accomplices in a van marked "Black Panther Black Community News Service" allegedly rob a gas station in San Francisco's Bayview district of $80, resulting in a shootout with police.[95] In 1968, the group shortened its name to the Black Panther Party and sought to focus directly on political action. Members were encouraged to carry guns and to defend themselves against violence. An influx of college students joined the group, which had consisted chiefly of "brothers off the block". This created some tension in the group. Some members were more interested in supporting the Panthers' social programs, while others wanted to maintain their "street mentality".[96] By 1968, the Party had expanded into many U.S. cities,[68] including Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Newark, New Orleans, New York City, Omaha, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, Toledo, and Washington, D.C. Peak membership was near 5,000 by 1969, and their newspaper, under the editorial leadership of Eldridge Cleaver, had a circulation of 250,000.[97] The group created a Ten-Point Program, a document that called for "Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice and Peace", as well as exemption from conscription for black men, among other demands.[98] With the Ten-Point program, "What We Want, What We Believe", the Black Panther Party expressed its economic and political grievances.[99] Curtis Austin states that by late 1968, Black Panther ideology had evolved from black nationalism to become more a "revolutionary internationalist movement": [The Party] dropped its wholesale attacks against whites and began to emphasize more of a class analysis of society. Its emphasis on Marxist–Leninist doctrine and its repeated espousal of Maoist statements signaled the group's transition from a revolutionary nationalist to a revolutionary internationalist movement. Every Party member had to study Mao Tse-tung's "Little Red Book" to advance his or her knowledge of peoples' struggle and the revolutionary process.[4] Panther slogans and iconography spread. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two American medalists, gave the black power salute during the American national anthem. The International Olympic Committee banned them from all future Olympic Games. Film star Jane Fonda publicly supported Huey Newton and the Black Panthers during the early 1970s. She actually ended up informally adopting the daughter of two Black Panther members, Mary Luana Williams. Fonda and other Hollywood celebrities became involved in the Panthers' leftist programs. The Panthers attracted a wide variety of left-wing revolutionaries and political activists, including writer Jean Genet, former Ramparts magazine editor David Horowitz (who later became a major critic of what he describes as Panther criminality)[citation needed] and left-wing lawyer Charles R. Garry, who acted as counsel in the Panthers' many legal battles. The BPP adopted a "Serve the People" program, which at first involved a free breakfast program for children. By the end of 1968, the BPP had established 38 chapters and branches, claiming more than five thousand members. Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver left the country days before Cleaver was to turn himself in to serve the remainder of a thirteen-year sentence for a 1958 rape conviction. They settled in Algeria.[100] By the end of the year, party membership peaked at around 2,000.[101] Party members engaged in criminal activities such as extortion, stealing, violent discipline of BPP members, and robberies. The BPP leadership took one-third of the proceeds from robberies committed by BPP members.[102] Survival programs No kid should be running around hungry in school. Bobby Seale[103] The Black Panther Party's free breakfast program is "the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for." FBI director J. Edgar Hoover[103] Inspired by Mao Zedong's advice to revolutionaries in The Little Red Book, Newton called on the Panthers to "serve the people" and to make "survival programs" a priority within its branches. The most famous of their programs was the Free Breakfast for Children Program, initially run out of an Oakland church. The Free Breakfast For Children program was especially significant because it served as a space for educating youth about the current condition of the Black community, and the actions that the Party was taking to address that condition. "While the children ate their meal[s], members [of the Party] taught them liberation lessons consisting of Party messages and Black history."[74] Through this program, the Party was able to influence young minds, and strengthen their ties to communities as well as gain widespread support for their ideologies. The breakfast program became so popular that the Panthers Party claimed to have fed twenty thousand children in the 1968–69 school year.[104] Other survival programs[105] were free services such as clothing distribution, classes on politics and economics, free medical clinics, lessons on self-defense and first aid, transportation to upstate prisons for family members of inmates, an emergency-response ambulance program, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, and testing for sickle-cell disease.[106] The free medical clinics were very significant because they modeled an idea of how the world might work with free medical care, eventually being established in 13 places across the country. These clinics were involved in community-based health care that had roots connected to the Civil Rights Movement, which made it possible to establish the Medical Committee for Human Rights.[107] Political activities In 1968, BPP Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver ran for presidential office on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket.[108] They were a big influence on the White Panther Party, tied to the Detroit/Ann Arbor band MC5 and their manager John Sinclair (author of the book Guitar Army), which also promulgated a ten-point program. 1969 Chronology Early 1969: In late 1968 and January 1969, the BPP began to purge members due to fears about law enforcement infiltration and various petty disagreements. January 14, 1969: The Los Angeles chapter was involved in a shootout with members of the black nationalist US Organization, and two Panthers are killed. January 1969: The Oakland BPP begins the first free breakfast program for children. March 1969: There is a second purge of BPP members. April 1969: Members of the New York chapter, known as the Panther 21 are indicted and jailed for a bombing conspiracy. All would eventually be acquitted. May 1969: Two more southern California Panthers are killed in violent disputes with US Organization members.[93] May 1969: Members of the New Haven chapter torture and murder Alex Rackley, who they suspected of being an informant. July 1969 the BPP organized the United Front Against Fascism conference in Oakland, which was attended by around 5,000 people representing a number of groups.[109][110] July 17, 1969: Two policemen are shot, and a Panther is killed in a gun battle in Chicago.[93] Late July 1969: The BPP ideology undergoes a shift, with a turn toward self-discipline and anti-racism. August 1969: Bobby Seale is indicted and imprisoned in relation to the Rackley murder. October 18, 1969: A Panther is killed in a gunfight with police outside a Los Angeles restaurant.[93] Mid-to-late 1969: COINTELPRO activity increases. November 13, 1969: A Panther is killed in a gunfight with police in Chicago.[93] December 4, 1969: Fred Hampton and Mark Clark are killed by law enforcement in Chicago.[11] Late 1969: David Hilliard, current BPP head, advocates violent revolution. Panther membership is down significantly from the late 1968 peak. Shoot-out with the US Organization Violent conflict between the Panther chapter in LA and the US Organization, a black nationalist group, resulted in shootings and beatings and led to the murders of at least four Black Panther Party members. On January 17, 1969, Los Angeles Panther Captain Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins were killed in Campbell Hall on the UCLA campus, in a gun battle with members of the US Organization. Another shootout between the two groups on March 17 led to further injuries. Two more Panthers died. Black Panther Party Liberation Schools Paramount to their beliefs regarding the need for individual agency to catalyze community change, the Black Panther Party (BPP) strongly supported the education of the masses. As part of their Ten-Point Program which set forth the ideals and goals of the party, they demanded an equitable education for all black people. Number 5 of the "What We Want Now!" section of the program reads: "We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society." To ensure that this occurred, the Black Panther Party took the education of their youth into their own hands by first establishing after-school programs and then opening up Liberation Schools in a variety of locations throughout the country which focused their curriculum on Black history, writing skills, and political science.[111] Intercommunal Youth Institute The first Liberation School was opened by the Richmond Black Panthers in July 1969 with brunch served and snacks provided to students. Another school was opened in Mt. Vernon New York on July 17 of the subsequent year.[111] These schools were informal in nature and more closely resembled after-school or summer programs.[112] While these campuses were the first to open, the first full-time and longest-running Liberation school was opened in January 1971 in Oakland in response to the inequitable conditions in the Oakland Unified School District which was ranked one of the lowest-scoring districts in California.[113] Named the Intercommunal Youth Institute (IYI), this school, under the directorship of Brenda Bay, and later, Ericka Huggins, enrolled twenty-eight students in its first year, with the majority being the children of Black Panther parents. This number grew to fifty by the 1973–1974 school year. To provide full support for Black Panther parents whose time was spent organizing, some of the students and faculty members lived together year around. The school itself was dissimilar to traditional schools in a variety of ways including the fact that students were separated by academic performance rather than age and students were often provided one on one support as the faculty to student ratio was 1:10.[113] The Panther's goal in opening Liberation Schools, and specifically the Intercommunal Youth Institute, was to provide students with an education that was not being provided in the "white" schools,[114] as the public schools in the district employed a eurocentric assimilationist curriculum with little to no attention to black history and culture. While students were provided with traditional courses such as English, Math, and Science, they were also exposed to activities focused on class structure and the prevalence of institutional racism.[115] The overall goal of the school was to instill a sense of revolutionary consciousness in the students.[112] With a strong belief in experiential learning, students had the opportunity to participate in community service projects as well as practice their writing skills by drafting letters to political prisoners associated with the Black Panther Party.[115] Huggins is noted as saying, "I think that the school's principles came from the socialist principles we tried to live in the Black Panther Party. One of them being critical thinking—that children should learn not what to think but how to think ... the school was an expression of the collective wisdom of the people who envisioned it. And it was ... a living thing [that] changed every year.[112] Joan Kelley oversaw funding for the Intercommunal Youth Institute which was provided through a combination of Black Panther fundraising and community support.[113] Oakland Community School In 1974, due to increased interest in enrolling in the school, school officials decided to move to a larger facility and subsequently changed the school's name to Oakland Community School. During this year, the school graduated its first class.[114] Although the student population continued to grow ranging between 50 and 150 between 1974 and 1977, the original core values of individualized instruction remained.[113] In September 1977, the school received a special award from Governor Edmund Brown Jr. and the California Legislature for "having set the standard for the highest level of elementary education in the state.[114] The school eventually closed in 1982 due to governmental pressure on party leadership which caused insufficient membership and funds to continue running the school.[113] Killing of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark In Chicago, on December 4, 1969, two Panthers were killed when the Chicago Police raided the home of Panther leader Fred Hampton. The raid had been orchestrated by the police in conjunction with the FBI. Hampton was shot and killed, as was Panther guard Mark Clark. A federal investigation reported that only one shot was fired by the Panthers, and police fired at least 80 shots.[116] The only shot fired by the Panthers was from Mark Clark, who appeared to fire a single round determined to be the result of a reflexive death convulsion after he was immediately struck in the chest by shots from the police at the start of the raid. Hampton was sleeping next to his pregnant fiancée and was subsequently shot twice in the head at point-blank range while unconscious. Coroner reports show that Hampton was drugged with a powerful barbiturate that night and would have been unable to have been awoken by the sounds of the police raid.[117] His body was then dragged into the hallway. He was 21 years old and unarmed at the time of his death. Seven other Panthers sleeping at the house at the time of the raid were then beaten and seriously wounded, then arrested under charges of aggravated assault and attempted murder of the officers involved in the raid. These charges would later be dropped. Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan announced to the media later that the Panthers were first to shoot in the interaction and that they showed a "refusal to cease firing... when urged to do so several times." New York Times reporting would later demonstrate that this was not in fact the case and found a great deal of fake evidence being used by Chicago Police to assert their claims.[118] Former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen asserts that the Bureau was guilty of a "plot to murder" the Panthers.[119] Hampton had been slipped the barbiturates which had left him unconscious by William O'Neal, who had been working as an FBI informant. Hanrahan, his assistant and eight Chicago police officers were indicted by a federal grand jury over the raid, but the charges were later dismissed.[97][120] In 1979 civil action, Hampton's family won $1.85 million from the city of Chicago in a wrongful death settlement.[121] Torture-murder of Alex Rackley In May 1969, three members of the New Haven chapter tortured and murdered Alex Rackley, a 19-year-old member of the New York chapter, because they suspected him of being a police informant. Three party officers—Warren Kimbro, George Sams, Jr., and Lonnie McLucas—later admitted taking part. Sams, who gave the order to shoot Rackley at the murder scene, turned state's evidence and testified that he had received orders personally from Bobby Seale to carry out the execution. Party supporters responded that Sams was himself the informant and an agent provocateur employed by the FBI.[122] The case resulted in the New Haven Black Panther trials of 1970. Kimbro, Sams and McLucas were convicted of the murder, but the trials of Seale and Ericka Huggins ended with a hung jury, and the prosecution chose not to seek another trial. International ties Activists from many countries around the globe supported the Panthers and their cause. In Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Finland, for example, left-wing activists organized a tour for Bobby Seale and Masai Hewitt in 1969. At each destination along the tour, the Panthers talked about their goals and the "Free Huey!" campaign. Seale and Hewitt made a stop in Germany as well, gaining support for the "Free Huey!" campaign.[123] 1970 Chronology January 1970: Leonard Bernstein holds a fundraiser for the BPP, which was notoriously mocked by Tom Wolfe in Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers. Spring 1970: The Oakland BPP engages in another ambush of police officers with guns and fragmentation bombs. Two officers are wounded.[124] May 1970: Huey Newton's conviction is overturned, but he remains incarcerated. July 1970: Newton tells The New York Times that "we've never advocated violence". August 1970: Newton is released from prison. International travels In 1970, a group of Panthers including Eldridge Cleaver and Elaine Brown traveled to Asia and they were welcomed as guests of the governments of China,[125]: 39 North Vietnam, and North Korea. The group's first stop was in North Korea, where the Panthers met with local officials to discuss ways in which they could help each other fight against American imperialism. Cleaver traveled to Pyongyang twice in 1969 and 1970 and following these trips he made an effort to publicize the writings and works of North Korean leader Kim Il Sung in the United States.[126] After leaving North Korea, the group traveled to North Vietnam with the same agenda in mind: finding ways to put an end to American imperialism. Eldridge Cleaver was invited to speak to Black GIs by the North Vietnamese government. He encouraged them to join the Black Liberation Struggle by arguing that the United States government was only using them for its own purposes. Instead of risking their lives on the battlefield for a country that continued to oppress them, Cleaver believed that the black GIs should risk their lives in support of their own liberation. After leaving Vietnam, Cleaver met with the Chinese ambassador to Algeria to express their mutual animosity towards the American government.[127] When Algeria held its first Pan-African Cultural Festival, they invited many important figures from the United States. Among the important figures invited to the festival were Bobby Seale and Cleaver. The cultural festival allowed Black Panthers to network with representatives of various international anti-imperialist movements. This was a significant time, which led to the formation of the International Section of the Party.[128] It is at this festival that Cleaver met with the ambassador of North Korea, who later invited him to an International Conference of Revolutionary Journalists in Pyongyang. Eldridge also met with Yasser Arafat and gave a speech supporting the Palestinians and their goal of achieving liberation.[129] In fall 1971, a larger group of Panthers visited China.[125]: 39 1971–1974 Newton focused the BPP on the Party's Oakland school and various other social service programs. In early 1971, the BPP founded the "Intercommunal Youth Institute" in January 1971,[130] with the intent of demonstrating how black youth ought to be educated. Ericka Huggins was the director of the school and Regina Davis was an administrator.[131] The school was unique in that it did not have grade levels but instead had different skill levels so an 11-year-old could be in second-level English and fifth-level science.[131] Elaine Brown taught reading and writing to a group of 10- to 11-year-olds deemed "uneducable" by the system.[132] The school children were given free busing; breakfast, lunch, and dinner; books and school supplies; children were taken to have medical checkups; many children were given free clothes.[133] Split Significant disagreements among the Party's leaders over how to confront ideological differences led to a split within the party. Certain members felt that the Black Panthers should participate in local government and social services, while others encouraged constant conflict with the police. For some of the Party's supporters, the separations among political action, criminal activity, social services, access to power, and grass-roots identity became confusing and contradictory as the Panthers' political momentum was bogged down in the criminal justice system. These (and other) disagreements led to a split. In January 1971, Newton expelled Geronimo Pratt who, since 1970, had been in jail facing a pending murder charge. Newton also expelled two of the New York 21 and his own secretary, Connie Matthews, who fled the country. Some Panther leaders, such as Huey P. Newton and David Hilliard, favored a focus on community service coupled with self-defense; others, such as Eldridge Cleaver, embraced a more confrontational strategy. In February 1971, Eldridge Cleaver deepened the schism in the party when he publicly criticized the Party for adopting a "reformist" rather than "revolutionary" agenda and called for Hilliard's removal. Cleaver was expelled from the Central Committee but went on to lead a splinter group, the Black Liberation Army, which had previously existed as an underground paramilitary wing of the Party.[134] The split turned violent, as the Newton and Cleaver factions carried out retaliatory assassinations of each other's members, resulting in the deaths of four people.[135] From mid-to-late 1971, hundreds of members throughout the country quit the Black Panther Party.[136] In May 1971, Bobby Seale was acquitted of ordering the Rackley murder, and returned to Oakland. Delegation to China In late September 1971, Huey P. Newton led a delegation to China and stayed for 10 days.[137] At every airport in China, Huey was greeted by thousands of people waving copies of the Little Red Book and displaying signs that said "we support the Black Panther Party, down with US imperialism" or "we support the American people but the Nixon imperialist regime must be overthrown". During the trip, the Chinese arranged for him to meet and have dinner with a DPRK ambassador, a Tanzanian ambassador, and delegations from both North Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam.[138] Huey was under the impression he was going to meet Mao Zedong, but instead had two meetings with the first Premier of the People's Republic of China Zhou Enlai. One of these meetings also included Mao Zedong's wife Jiang Qing. Huey described China as "a free and liberated territory with a socialist government".[139] Newton solidifies control and centralizes power in Oakland In early 1972, the party began closing down dozens of chapters and branches all over the country and bringing members and operations to Oakland.[140] The political arm of the southern California chapter was shut down and its members moved to Oakland, although the underground military arm remained for a time.[141] The underground remnants of the LA chapter, which had emerged from the Slausons street gang, eventually re-emerged as the Crips, a street gang who at first advocated social reform before devolving into racketeering.[142] Minister of Education Ray "Masai" Hewitt created the Buddha Samurai, the party's underground security cadre in Oakland. Newton expelled Hewitt from the party later in 1972, but the security cadre remained in operation under the leadership of Flores Forbes. One of the cadre's main functions was to extort and rob drug dealers and after-hours clubs.[141] The party developed a five-year plan to take over the city of Oakland politically and focused nearly all of its resources on winning political power in the Oakland city government. Bobby Seale ran for mayor, Elaine Brown ran for city council, and other Panthers ran for minor offices. Neither Seale nor Brown were elected, and many Party members resigned after the losses,[140] although a few Panthers won seats on local government commissions. Following the electoral defeat, Newton embarked on a major purge of the party in early 1974, expelling Bobby and John Seale, David and June Hilliard, Robert Bay, and numerous other top party leaders. Dozens of other Panthers loyal to Seale resigned or deserted. Newton indicted for violent crimes In 1974, Huey Newton and eight other Panthers were arrested and charged with assault on police officers. In August 1974, Newton went into exile in Cuba to avoid prosecution for the murder of Kathleen Smith, an eighteen-year-old prostitute. Newton was also indicted for pistol-whipping his tailor, Preston Callins. Although Newton confided to friends that Kathleen Smith was his "first nonpolitical murder", he was ultimately acquitted, after one witness's testimony was impeached by her admission that she had been smoking marijuana on the night of the murder, and another prostitute witness recanted her testimony.[143][144] Newton was also acquitted of assaulting Preston Callins after Callins refused to press charges.[145][clarification needed] 1974–1977 The Panthers under Elaine Brown In 1974, as Huey Newton prepared to go into exile in Cuba, he appointed Elaine Brown as the first Chairwoman of the Party.[146] Under Brown's leadership, the Party became involved in organizing for more radical electoral campaigns, including Brown's 1975 unsuccessful run for Oakland City Council.[147] The Party supported Lionel Wilson in his successful election as the first black mayor of Oakland, in exchange for Wilson's assistance in having criminal charges dropped against Party member Flores Forbes, leader of the Buddha Samurai cadre.[141] In addition to changing the Party's direction towards more involvement in the electoral arena, Brown also increased the influence of women Panthers by placing them in more visible roles within the previously male-dominated organization. Death of Betty van Patter Panther leader Elaine Brown hired Betty Van Patter in 1974 as a bookkeeper. Van Patter had previously served as a bookkeeper for Ramparts magazine and was introduced to the Panther leadership by David Horowitz, who had been the editor of Ramparts and a major fundraiser and board member for the Panther school.[148] Later that year, after a dispute with Brown over financial irregularities,[149] Van Patter went missing on December 13, 1974. Some weeks later, her severely beaten corpse was found on a San Francisco Bay beach. There was insufficient evidence for police to charge anyone with van Patter's murder, but the Black Panther Party leadership was "almost universally believed to be responsible".[150][151] Huey Newton later allegedly confessed to a friend that he had ordered Van Patter's murder, and that Van Patter had been tortured and raped before being killed.[144][152] FBI files investigating Van Patter were destroyed in 2009 for reasons the FBI has declined to provide.[153] 1977–1982 Return of Huey Newton and the demise of the party In 1977, Newton returned from exile in Cuba, and received complaints from male members about the excessive power of women in the organization, who now outnumbered men. According to Elaine Brown, Newton authorized the physical punishment of school administrator Regina Davis for scolding a male coworker. Davis was hospitalized with a broken jaw.[154] Brown said, "The beating of Regina would be taken as a clear signal that the words 'Panther' and 'comrade' had taken a gender-on-gender connotation, denoting an inferiority in the female half of us."[155][156][157] Brown resigned from the party and fled to LA.[158] Although many scholars and activists date the Party's downfall to the period before Brown's leadership, a shrinking cadre of Panthers struggled through the 1970s. By 1980, Panther membership had dwindled to 27, and the Panther-sponsored Oakland Community School closed in 1982 amid a scandal over Newton embezzling funds for his drug addiction,[147][159] which marked the formal end of the Black Panther Party.[146] Panthers attempt to assassinate a witness against Newton In October 1977, Flores Forbes, the party's assistant chief of staff, led a botched attempt to assassinate Crystal Gray, a key prosecution witness in Newton's upcoming trial, who had been present the day of Kathleen Smith's murder. When three Panthers attacked the wrong house by mistake, the occupant returned fire and killed one of the Panthers, Louis Johnson, while the other two assailants escaped.[160] One of them, Flores Forbes, fled to Las Vegas, Nevada, with the help of Panther paramedic Nelson Malloy. Fearing that Malloy would discover the truth behind the botched assassination attempt, Newton allegedly ordered a "house cleaning", and Malloy was shot and buried alive in the desert. Although permanently paralyzed from the waist down, Malloy escaped and told police that fellow Panthers Rollin Reid and Allen Lewis were behind his attempted murder.[161] Newton denied any involvement or knowledge and said the events "might have been the result of overzealous party members".[162] Newton was ultimately acquitted of the murder of Kathleen Smith, after Crystal Gray's testimony was impeached by her admission that she had smoked marijuana on the night of the murder, and he was acquitted of assaulting Preston Callins after Callins refused to press charges. |

沿革 起源  ブラックパンサー党のオリジナルメンバー6人(1966年): 左上から右へ エルバート・"ビッグマン"・ハワード、ヒューイ・P・ニュートン(国防相)、シャーウィン・フォルテ、ボビー・シール(議長); 下: 下:レジー・フォルテ、リトル・ボビー・ハットン(会計)。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Panther_Party キャスリーン・クリーバーがカリフォルニア州アラメダ郡のハットン記念公園で演説したニュースリール。この映像には、カリフォルニア州オークランドのアラ メダ郡裁判所での学生による抗議デモの様子も映っている。ブラックパンサー党のリーダー、ヒューイ・P・ニュートン、エルドリッジ・クリーバー、ボビー・ シールが、完全雇用、まともな住宅と教育、警察の横暴の廃止、黒人の兵役免除など、政権に求める10項目のプログラムについて演説。制服を着て行進するブ ラックパンサー党員たち。集会に参加した学生たちは、行進し、歌い、手を叩き、抗議のサインを掲げた。暴動鎮圧服に身を包んだ警察がデモ行進を取り締まっ た。 第二次世界大戦中、何万人もの黒人が、カイザー造船所などの戦争産業で働くために、南部の州を離れ、オークランドやベイエリアの他の都市に移り住んだ。こ の大移動は、ベイエリアだけでなく西部や北部の都市を変貌させ、かつては白人が支配していた人口構成に変化をもたらした[32]。これらの都市で育った新 しい世代の若い黒人は、親にはなじみのない新しい形の貧困や人種差別に直面し、それらに対処するために新しい形の政治を展開しようとした。 [33]ブラック・パンサー党の党員は、「南部の人種体制から逃れるために家族が北部や西部を旅行し、新たな形態の隔離と抑圧に直面することになった最近 の移民で構成されていた」[34]。1960年代初頭、公民権運動は、非暴力的な市民的不服従の戦術によって、南部の人種的従属のジム・クロウ体制を解体 し、黒人の完全な市民権を要求していた。戦時中と戦後、黒人の移住の多くを引き寄せていた仕事が「白人住民とともに郊外に逃げていった」ため、黒人人口は 高い失業率と標準以下の住宅を擁する貧しい「都市ゲットー」に集中し、政治的代表権、一流大学、中流階級からほとんど排除されていた[36]。北部と西部 の警察はほとんど白人ばかりだった[37]。1966年には、オークランドの警察官661人のうちアフリカ系アメリカ人はわずか16人(2.5%未満) だった[38]。 公民権戦術はこうした状況を是正することができないことが判明し、SNCCやCOREといった「非暴力的市民的不服従の多くを主導してきた」組織は衰退し ていった[35]。1966年までに、主に都市部の若い黒人からなる「ブラックパワー発酵」が出現し、公民権運動が答えることができなかった問題を提起し た: 「アメリカの黒人はどのようにして、形式的な市民権だけでなく、実際の経済的、政治的権力を獲得するのだろうか? ブラックパンサー党の設立 1966年10月下旬、ヒューイ・P・ニュートンとボビー・シールはブラック・パンサー党(当初は自衛のためのブラック・パンサー党)を創設した [10]。新しい政治を策定するにあたり、彼らはさまざまなブラック・パワー組織での活動を活用した[40]。 ニュートンとシールが初めて出会ったのは、ともにメリット・カレッジの学生だった1962年のことであった[41]。彼らはドナルド・ウォーデンのアフ ロ・アメリカン・アソシエーションに参加し、そこでマルコムXなどに触発された新興のブラック・ナショナリストの伝統に基づき、幅広く本を読み、討論し、 組織化した。 [やがて彼らは、ウォーデンの融和主義に不満を抱き、ソウル・スチューデント・アドバイザリー・カウンシルや革命的行動運動といった、より活動的で戦闘的 なグループと協力しながら、革命的な反帝国主義の視点を発展させていった[43][44]。 ノース・オークランド近隣反貧困センターで青少年奉仕プログラムを運営する有給の仕事によって、彼らは、後にブラックパンサー党の「コミュニティ・サバイ バル・プログラム」[45]の重要な要素となる、コミュニティ奉仕に対する革命的ナショナリストのアプローチを発展させることができた。] これらの組織が警察の横暴に直接異議を唱え、「ブロックの兄弟」に訴えかけることができなかったことに不満を抱いたヒューイとボビーは、自分たちの手で問 題を解決した。警察がサンフランシスコで丸腰の黒人青年マシュー・ジョンソンを殺害した後、ニュートンはその後に起こった暴力的な反乱を観察した。彼は、 ブラック・パンサー党を多数のブラック・パワー組織から区別することになる啓示を受けた。ニュートンはゲットーの爆発的な反抗的怒りを社会的な力としてと らえ、警察に立ち向かうことができれば、その力を政治的な力に組織化できると信じた。クー・クラックス・クラン(KKK)に対するロバート・F・ウィリア ムズの武力抵抗とウィリアムズの著書『Negroes with Guns』[46]に触発されたニュートンは、カリフォルニアの銃規制を幅広く研究した。ワッツの反乱後のロサンゼルスの地域警戒パトロールのように、彼 はパトロール隊を組織して警察を尾行し、蛮行がないかを監視することにした。ヒューイとボビーは、最近出版された『毛沢東の小さな赤い本』を大量に購入 し、それをバークレー・キャンパスの左翼やリベラル派に3倍の値段で転売することで、ショットガンを2丁購入するのに十分な資金を調達した[47]。ボ ビー・シール曰く、彼らは「本を売り、金を稼ぎ、銃を買い、銃を持って街に出る。俺たちは母親を守り、兄弟を守り、人種差別主義者の警官から地域を守る」 [48]。 1966年10月29日、SNCCのリーダーであったストークリー・カーマイケルは、「ブラック・パワー」の呼びかけを支持し、ブラック・パワー会議の基 調講演のためにバークレーを訪れた。当時、彼はアラバマ州のLowndes County Freedom Organization(LCFO)の武装組織化とブラック・パンサー・シンボルの使用を推進していた。ニュートンとシールは、ブラック・パンサー・ロ ゴを採用し、ブラック・パンサー自衛党と呼ばれる自分たちの組織を結成することを決めた[49]。ニュートンとシールは、青いシャツ、黒いズボン、黒いレ ザージャケット、黒いベレー帽[50]というユニフォームを決め、後者はチェ・ゲバラへのオマージュとして採用された[51]: 123 16歳のボビー・ハットンが最初の新兵だった[52]。 1967年1月までに、BPPは最初の公式本部をオークランドの店先に開設し、『ブラックパンサー』を創刊した: Black Community News Service)』を創刊した。  コルト45口径とショットガンで武装し、路上に立つブラックパンサー党創設者のボビー・シールとヒューイ・P・ニュートン 1966年後半から1967年前半 オークランド警察のパトロール 党の初期の戦術は、警察を取り締まる際に党員を守るために現代の携帯銃刀法を利用した。この行為は、近隣のパトカーを遠巻きに尾行することで、警察の蛮行 を記録するために行われた[53]。警察官と対峙したとき、党員たちは自分たちが何も悪いことをしていないことを証明する法律を引用し、自分たちの憲法上 の権利を侵害した警察官を法廷に訴えると脅した。 [54]1966年の終わりから1967年の初めにかけて、ブラック・パンサー党によるオークランドの黒人コミュニティでの武装した警察のパトロールは、 ほんの一握りのメンバーを惹きつけた[55]。1967年2月、マルコムXの未亡人であり、マルコムXの名誉のために開催された会議の基調講演者であった ベティ・シャバズのためにサンフランシスコ空港で武装した護衛を提供したときから、党員数はわずかに増加した[56]。 ブラックパンサー党の過激さへの焦点は、しばしば公然の敵意と解釈され[57][58]、パンサーによる初期の取り組みが主に社会問題の推進と武器携帯の 法的権利の行使に焦点を当てていたにもかかわらず、暴力の評判を与えていた。パンサーズは、装填されたライフルやショットガンを公然と陳列し、誰にも向け ない限り携帯することを許可するカリフォルニア州法を採用した[50]。一般的にこれは、近隣での警察の行動を監視し観察しながら行われ、パンサーズは、 このように積極的な戦闘性と公然と武器を携帯することに重点を置くことが、警察の暴力から個人を守るために必要であると主張した。例えば、「革命が来た、 銃を手に取る時だ。豚どもを殺せ!」[59]といった唱和は、パンサーズが暴力的な組織であるという評判を高めるのに役立った。 カリフォルニア州リッチモンドでの集会 カリフォルニア州リッチモンドの黒人コミュニティは、警察の蛮行からの保護を望んでいた[60]。 この地域に出入りするための大通りは3本しかなく、警察が住民を統制し、封じ込め、抑圧することは容易であった[61]。 1967年4月1日、ノース・リッチモンドで、デンジル・ダウエルという22歳の非武装の黒人建設労働者が警察に射殺された。 [パンサーは全員武装しており、法律に違反することはなかったため、これらの集会で警察が介入することはほとんどなかった[64]。 州議会での抗議  1967年5月2日のブラックパンサー党武装デモ 1967年5月2日のカリフォルニア州議会議事堂での抗議行動後、ブラックパンサー党の認知度は急速に高まった。1967年5月2日、カリフォルニア州議 会の刑事訴訟委員会が招集され、弾を込めた銃器の公衆携帯を違法とする「マルフォード法」と呼ばれる法案が審議される予定だった。ニュートンは、情報大臣 のエルドリッジ・クリーバーとともに、この法案に抗議するため、シールが率いる26人の武装したパンサーズのグループをオークランドからサクラメントに送 る計画をまとめた。この事件は広く報道され、警察はシールら5人を逮捕した。抗議当時、党員は100人に満たなかった[68]。  ブラック・パンサー大会、リンカーン・メモリアル、1970年6月19日 1967年5月、パンサーは銃を手にサクラメントの州議会議事堂に侵入し、売名行為のように見えた。その日、彼らは多くの重要人物を恐怖に陥れた。当時、 パンサーズにはほとんど支持者がいなかった。しかし、今(1年後)、彼らの指導者たちは、急進派が集まるところならほとんどどこでも招待を受けて演説し、 多くの白人が「Honkeys for Huey」のボタンをつけ、昨年(1967年)10月28日に警察官を殺害した容疑で刑務所に収監されているニュートンを釈放するための闘いを支持してい る...[69]。 1967年、マルフォード法がカリフォルニア州議会で可決され、ロナルド・レーガン州知事が署名した。この法案は、警官を監視していたブラックパンサー党 員に対抗して作られたものだった。この法案は、装填した銃器の公然携帯を許可していた法律を廃止した。 10項目のプログラム 主な記事 テン・ポイント・プログラム(ブラックパンサー党) ブラック・パンサー党は、5月15日、オリジナルの "What We Want Now!"を初めて公表した。1967年5月15日、サクラメントでの行動の後、ブラック・パンサー新聞の第2号でテン・ポイント・プログラムを公表した [56]。 我々は自由が欲しい。黒人社会の運命を決定する力が欲しい。 われわれは黒人の完全雇用を望む。 われわれは、われわれの黒人コミュニティに対する資本家たちによる強奪に終止符を打ちたい。 私たちは、人間の住居にふさわしい、まともな住宅が欲しい。 私たちは、この退廃したアメリカ社会の本質を暴く教育を、私たちの人々に求めます。私たちは、私たちの真の歴史と現代社会における私たちの役割を教える教 育が欲しい。 私たちは、すべての黒人男性に兵役を免除してほしい。 私たちは、黒人の警察による残虐行為と殺人を直ちに止めさせたい。 私たちは、連邦、州、郡、市の刑務所や拘置所に収容されているすべての黒人に自由を求めます。 私たちは、すべての黒人が裁判にかけられた時、合衆国憲法によって定義されたように、彼らの仲間や黒人コミュニティの人々からなる陪審員によって法廷で裁 かれることを望みます。 私たちは土地、パン、住居、教育、衣服、正義、そして平和を求める。 1967年後半から1968年前半 コインテルプロ さらなる情報 コインテルプロ  ブラックパンサー党を支持するジーン・セバーグを「無力化」するために、公に「恥をかかせ」、「イメージを悪化させる」ことを試みたFBIの計画を概説す るコイントエルプロの文書。 1967年8月、連邦捜査局(FBI)はそのプログラム "COINTELPRO "に、「......黒人民族主義者のヘイト・グループ」やその他の反体制派グループを無力化するよう指示した。1968年9月、FBI長官J.エド ガー・フーバーは、ブラック・パンサーを「国内安全保障に対する最大の脅威」と評した[70]。1969年までに、ブラック・パンサーとその同盟勢力は主 要なコイントテルプロの標的となり、認可された295の「ブラック・ナショナリスト」コイントテルプロ活動のうち233で特別視された[71]。 このプログラムの目標は、過激なブラック・ナショナリスト・グループの結束を阻止し、その指導力を弱めることであり、また彼らの信用を失墜させ、彼らの支 持と成長を抑えることであった。初期の標的には、南部キリスト教指導者会議、学生非暴力調整委員会、革命行動運動、イスラム国、そしてマーティン・ルー サー・キング・ジュニア牧師、ストークリー・カーマイケル、H・ラップ・ブラウン、マクスウェル・スタンフォード、イライジャ・ムハンマドなどの指導者が 含まれていた。ウィリアム・サリバンFBI長官補が後に教会委員会の前で証言したように、FBIは監視と無力化の戦術を展開する際、ソ連のスパイと黒人民 族主義運動の共産主義者と疑われる人物を「区別しなかった」[72]。 コイントテルプロは黒人民族主義者の派閥間の対立を作り出し、既存の対立を利用しようとした。そのような試みの一つは、ブラック・パンサーとシカゴのスト リート・ギャングであるブラックストーン・レンジャーズとの間の「敵意の度合いを強める」ことであった。FBIはレンジャーズのギャング・リーダーに匿名 の手紙を送り、パンサーズが彼の命を脅かしていると主張した。南カリフォルニアでは、FBIはブラックパンサー党とUSオーガニゼーションと呼ばれる黒人 民族主義グループの間の「ギャングの抗争」を悪化させるために同様の努力をし、既存の敵対関係を強めるためにUSオーガニゼーションに挑発的な手紙を送っ たとされている[73]。 コインテルプロはまた、ブラックパンサー党の社会/コミュニティ・プログラムを標的にすることで、ブラックパンサー党の解体を目指した。その中には、「貧 困戦争」の限界を指し示す「子どもの貧困と飢餓に対処する政府の失敗に光を当てる」ための「子どものための無料朝食」プログラムも含まれていた。「警察と 連邦捜査官は定期的にプログラム参加者、支持者、党員に対して嫌がらせや脅迫を行い、寄付者や教会やコミュニティセンターのようなプログラムを収容する組 織を追い払おうとした」[74][75]。 ブラックパンサー党員は、警察との多くの致命的な銃撃戦に巻き込まれた。ニュートンはこう宣言した: マルコムは、究極的なまでに冷酷であり、黒人大衆に......抑圧者の鎖からの解放と、支持された(黒人の)代弁者の裏切りの抱擁を突きつけた。黒人大 衆は銃によってのみ、この勝利を否定された。しかし彼らはマルコムから、銃があれば自分たちの夢を取り戻し、現実にすることができることを学んだ [76]。 ヒューイ・ニュートン、ジョン・フレイ殺害で起訴 1967年10月28日、オークランド警察の警官ジョン・フレイは、交通取り締まり中にヒューイ・P・ニュートンと口論になり射殺され、ニュートンと予備 の警官ハーバート・ヒーンズも銃創を負った。ニュートンは裁判で過失致死罪で有罪判決を受けたが、後に有罪判決は覆された。作家のヒュー・ピアソンはその 著書『Shadow of the Panther』の中で、ニュートンは事件の数時間前に酒に酔っており、故意にジョン・フレイを殺したと主張している[77]。 フリー・ヒューイ!キャンペーン 当時、ニュートンは自分が冤罪であると主張し、党の「フリー・ヒューイ!」キャンペーンにつながった。警察による殺害は、アメリカの急進左派によって党が さらに広く認知されるようになり[78]、党の全国的な成長を刺激した[68]。ニュートンは3年後、控訴審で有罪判決が覆り、釈放された[79]。 ニュートンが裁判を待つ間、「フリー・ヒューイ」キャンペーンは多くの学生や反戦活動家と同盟関係を築き、「反戦抗議者への抑圧を黒人やベトナム人への抑 圧と結びつける反帝国主義的な政治イデオロギーを提唱した」[80]。 [例えば、ブラックパンサー党は、既成の民主党に対抗して強力な反戦・反人種主義政治を推進しようとする平和自由党と協力した[82]。ブラックパンサー 党は平和自由党の人種政治に必要な正当性を提供し、その見返りとして「フリー・ヒューイ」キャンペーンに貴重な支援を受けた[83]。 LA支部の設立 1968年、南カリフォルニア支部がアルプレンティス "バンチー "カーターによってロサンゼルスに設立された。カーターはスラウソン・ストリートのギャングのリーダーであり、L.A.支部の初期の新人の多くはスラウソ ンだった[84]。 ボビー・ハットンの殺害 ボビー・ジェームス・ハットンは1950年4月21日、アーカンソー州ジェファーソン郡で生まれた。3歳のとき、クー・クラックス・クランに関連する人種 差別自警団から嫌がらせを受け、家族とともにカリフォルニア州オークランドに移住。1966年12月、わずか16歳でブラック・パンサー党の初代会計兼新 兵となる。 1968年4月6日、マーティン・ルーサー・キング牧師暗殺の2日後、全米各都市で暴動が激化する中、17歳のハットンはエルドリッジ・クリーバーや他の BPPメンバーと車で移動していた。一行はオークランド市警の警官に立ち向かい、アパートに逃げ込んで警察と90分間の銃撃戦を繰り広げた。にらみ合いの 末、クリーバーは負傷し、ハットンは自発的に投降した。クリーバーによると、ハットンは丸腰であることを証明するために下着姿になり、両手を上げていた が、オークランド警察はハットンを12発以上撃ち、死亡させた。警官2人も撃たれた。彼は警察に殺された最初の党員となった。 当時、BPPは警察に待ち伏せされたと主張していたが、後に数人の党員が、クリーバーがパンサー・グループを率いて警察官を意図的に待ち伏せし、銃撃戦を 引き起こしたと認めた[85][86][87][88][89]。 デヴィッド・ヒリアード参謀長を含む他の7人のパンサーも逮捕された。ハットンの死はパンサー支持者の結集問題となった[90][91][92]。 1968年後半 年表 1968年初春: エルドリッジ・クリーヴァーの『ソウル・オン・アイス』出版。 1968年4月6日 ボビー・ジェームス・ハットン、オークランド警察との銃撃戦で死亡[90]。 1968年4月17日 バークレーでボビー・ジェイムズ・ハットンの葬儀、その後アラメダ郡裁判所にて集会[90]。 1968年4月から6月中旬: クリーバーは刑務所に収監。 1968年7月中旬: ヒューイ・ニュートンの殺人裁判が始まる。パンサーたちは毎日、裁判所の外で「ヒューイを解放せよ」という集会を開く。 1968年8月5日 ロサンゼルスのガソリンスタンドで警察との銃撃戦で3人のパンサーが死亡[93]。 1968年9月初旬: ニュートンに過失致死罪で有罪判決。 1968年9月下旬 レイプの有罪判決を受け服役するため刑務所に戻る数日前、クリーバーはキューバ、後にアルジェリアに逃亡。 1968年10月5日 ロサンゼルスの警察との銃撃戦でパンサーが殺害される[93]。 1968年11月 BPPは多くの支持者を見つけ、平和自由党やSNCCと関係を築く。資金提供が殺到し、BPP指導部は横領を始める[94]。 1968年11月6日: デンバー支部長のローレン・ワトソンが警官から逃走し、逮捕に抵抗したとしてデンバー警察に逮捕される。彼の裁判は1970年に「裁判」として撮影されテ レビ放映される: "裁判:デンバー市郡対ローレン・R・ワトソン "として1970年にテレビ放映される。 1968年11月20日 ブラック・パンサー・ブラック・コミュニティ・ニュース・サービス」と書かれたバンに乗ったウィリアム・リー・ブレントと共犯者2人がサンフランシスコの ベイビュー地区のガソリンスタンドから80ドルを強奪したとされ、警察と銃撃戦になる[95]。 1968年、グループはその名前をブラックパンサー党に短縮し、政治的行動に直接焦点を当てようとした。メンバーは銃を携帯し、暴力から身を守ることを奨 励された。それまでは主に「ブロック外の兄弟」で構成されていたグループに、大学生が流入してきた。このことがグループ内に緊張をもたらした。パンサーズ の社会的プログラムを支援することに関心を持つメンバーもいれば、「ストリートの精神性」を維持したいと考えるメンバーもいた[96]。 1968年までに、党はアトランタ、ボルチモア、ボストン、シカゴ、クリーブランド、ダラス、デンバー、デトロイト、カンザスシティ、ロサンゼルス、 ニューアーク、ニューオーリンズ、ニューヨークシティ、オマハ、フィラデルフィア、ピッツバーグ、サンディエゴ、サンフランシスコ、シアトル、トレド、ワ シントンD.C.など、アメリカの多くの都市に拡大し[68]、1969年までにピーク時の党員数は5,000人近くに達し、エルドリッジ・クリーバーの 編集指導の下、彼らの新聞は250,000部を発行していた。 [97]グループは、「土地、パン、住宅、教育、衣服、正義、平和」、そして黒人男性の徴兵免除、その他の要求と同様に呼びかけた文書である「10項目プ ログラム」を作成した[98]。10項目プログラム「私たちが望むもの、私たちが信じるもの」によって、ブラックパンサー党はその経済的、政治的不満を表 明した[99]。 カーティス・オースティンは、1968年後半までにブラック・パンサー党のイデオロギーは黒人ナショナリズムから進化し、より「革命的な国際主義運動」に なったと述べている: [党は)白人に対する全面的な攻撃をやめ、社会の階級分析をより強調し始めた。マルクス・レーニン主義の教義を重視し、毛沢東主義の声明を繰り返し支持し たことは、グループが革命的ナショナリストから革命的国際主義運動へと移行したことを示していた。すべての党員は、人民の闘争と革命プロセスに関する知識 を深めるために、毛沢東の「小赤書」を勉強しなければならなかった[4]。 パンサーのスローガンと図像は広まっていった。1968年の夏季オリンピックでは、アメリカのメダリストであるトーミー・スミスとジョン・カルロスが、ア メリカ国歌斉唱の際にブラックパワー敬礼を行った。国際オリンピック委員会は、今後のすべてのオリンピック大会から彼らを追放した。映画スター、ジェー ン・フォンダは、1970年代初頭、ヒューイ・ニュートンとブラック・パンサーを公に支持した。彼女は実際に、2人のブラック・パンサー・メンバーの娘、 メアリー・ルアナ・ウィリアムズを非公式に養子に迎えることになった。フォンダをはじめとするハリウッドの有名人たちは、パンサーズの左翼プログラムに参 加するようになった。パンサーズは、作家のジャン・ジュネ、『ランパート』誌の元編集者デイヴィッド・ホロヴィッツ(彼は後にパンサーズの犯罪性を批判す るようになる)[要出典]、左翼弁護士のチャールズ・R・ギャリーなど、さまざまな左翼革命家や政治活動家を惹きつけた。 BPPは "Serve the People "プログラムを採用し、当初は子供たちのための無料朝食プログラムを行っていた。1968年末までに、BPPは38の支部と支部を設立し、5,000人以 上のメンバーを擁した。エルドリッジとキャスリーン・クリーバーは、1958年のレイプ事件で有罪判決を受けたクリーバーが13年の刑期の残りを服役する ために出頭する数日前に出国した。彼らはアルジェリアに定住した[100]。 党員は恐喝、窃盗、BPP党員への暴力的懲罰、強盗などの犯罪活動に従事した。BPP指導部はBPP党員による強盗の収益の3分の1を受け取っていた [102]。 サバイバル・プログラム 学校で空腹のまま走り回る子供はいないはずだ。 ボビー・シール[103] ブラックパンサー党の無料朝食プログラムは、"BPPを無力化し、その象徴するものを破壊しようとする当局の努力に対する最大の脅威 "である。 FBI長官J・エドガー・フーバー[103]。 毛沢東が『小赤書』の中で革命家たちにアドバイスしたことに触発されたニュートンは、パンサーズに「人々に奉仕する」よう呼びかけ、支部内で「生存プログ ラム」を優先させた。彼らのプログラムの中で最も有名なものは、当初オークランドの教会で実施された「子供のための無料朝食プログラム」であった。 子どもたちのための無料朝食プログラムは、黒人社会の現状と、その現状に対処するために党がとっている行動について、若者たちに教育する場として機能した ため、特に重要な意味をもっていた。「このプログラムを通じて、党は若者の心に影響を与え、地域社会との結びつきを強め、彼らのイデオロギーに対する広範 な支持を得ることができた。朝食プログラムは大人気となり、パンサーズ党は1968年から69年の学年で2万人の子どもたちに食事を提供したと主張した [104]。 その他の生存プログラム[105]は、衣服の配布、政治や経済に関する授業、無料診療所、護身術や応急手当の授業、受刑者の家族のための北部刑務所への移 送、緊急対応救急車プログラム、薬物やアルコールのリハビリテーション、鎌状赤血球症の検査などの無料サービスであった[106]。無料診療所は、無料医 療によって世界がどのように機能するかのアイデアをモデル化した点で非常に重要であり、最終的に全国13か所に設立された。これらの診療所は、公民権運動 と結びついた地域に根ざした医療に携わっており、それが人権医療委員会の設立を可能にした[107]。 政治活動 1968年、BPPの情報大臣エルドリッジ・クリーヴァーは、平和自由党のチケットで大統領選に出馬した[108]。彼らはホワイトパンサー党に大きな影 響を与え、デトロイト/アナーバーのバンドMC5とそのマネージャー、ジョン・シンクレア(著書『ギター・アーミー』の著者)と結びつき、10項目のプロ グラムも公布した。 1969 年表 1969年初頭:1968年末から1969年1月にかけて、BPPは法執行機関の侵入や様々な些細な意見の相違を恐れ、メンバーの粛清を始めた。 1969年1月14日:ロサンゼルス支部が黒人民族主義組織USオーガニゼーションのメンバーとの銃撃戦に巻き込まれ、2人のパンサーが殺害される。 1969年1月: オークランドBPPが子供たちのために初の無料朝食プログラムを開始。 1969年3月: BPPメンバーの2度目の粛清が行われる。 1969年4月 パンサー21として知られるニューヨーク支部のメンバーが爆破陰謀で起訴され、投獄される。最終的に全員が無罪となる。 1969年5月: さらに2人の南カリフォルニアのパンサーがUS組織のメンバーとの暴力的な争いで殺害される[93]。 1969年5月 ニューヘイブン支部のメンバーが、情報提供者であると疑っていたアレックス・ラックリーを拷問し殺害。 1969年7月 BPPはオークランドで「ファシズムに反対する統一戦線(United Front Against Fascism)」会議を開催し、多くのグループを代表する約5000人が参加する[109][110]。 1969年7月17日:シカゴでの銃撃戦で警官2人が撃たれ、パンサー1人が死亡[93]。 1969年7月下旬:BPPのイデオロギーが転換し、自己規律と反人種主義に向かう。 1969年8月: ボビー・シール、ラックリー殺害事件で起訴され、投獄される。 1969年10月18日 パンサーがロサンゼルスのレストランの外で警察との銃撃戦で死亡する[93]。 1969年半ばから後半: コインテルプロ活動が活発化。 1969年11月13日 シカゴで警察との銃撃戦でパンサーが殺される[93]。 1969年12月4日 フレッド・ハンプトンとマーク・クラークがシカゴで警察によって殺害される[11]。 1969年後半 現BPP代表のデビッド・ヒリアードが暴力革命を提唱。パンサー会員数は1968年後半のピークから大幅に減少。 米国組織との銃撃戦 ロサンゼルスのパンサー支部と黒人民族主義グループのUS組織との間で暴力的な対立が起こり、銃撃や殴打が行われ、少なくとも4人のブラックパンサー党員 が殺害された。1969年1月17日、ロサンゼルスのパンサー隊長バンチー・カーターと副大臣ジョン・ハギンズがUCLAキャンパスのキャンベル・ホール で、USオーガニゼーションのメンバーとの銃撃戦で殺された。月17日にも2つのグループの間で銃撃戦があり、さらに負傷者が出た。さらに2人のパンサー が死亡した。 ブラックパンサー党の解放学校 コミュニティの変革を触媒する個人の主体性の必要性に関する彼らの信念の中で、ブラックパンサー党(BPP)は大衆の教育を強く支持した。党の理想と目標 を定めた10項目のプログラムの一環として、彼らはすべての黒人に公平な教育を要求した。綱領の「今、私たちが望むもの!」の第5項にはこうある: 「この退廃的なアメリカ社会の本質を暴くような教育が欲しい。われわれは、われわれの真の歴史と現代社会におけるわれわれの役割を教える教育を望む。" これを確実にするために、ブラック・パンサー党は、まず放課後プログラムを設立し、その後、黒人の歴史、文章力、政治学に焦点を当てたカリキュラムを提供 する解放学校を全米のさまざまな場所に開設することによって、若者たちの教育を自分たちの手に委ねた[111]。 インターコミュニナル・ユース・インスティテュート 最初の解放学校は、1969年7月にリッチモンド・ブラック・パンサーズによって開校され、生徒たちにブランチと軽食が提供された。これらの学校は非公式 なものであり、放課後や夏のプログラムに近いものであった[112]。これらのキャンパスが最初に開校された一方で、最初のフルタイムの解放学校が 1971年1月にオークランドに開校され、最も長い間運営された。 [113] インターコミュナル・ユース・インスティテュート(IYI)と名付けられたこの学校は、ブレンダ・ベイ、後にエリッカ・ハギンズの指導の下、初年度に28 人の生徒が入学したが、その大半はブラック・パンサーを両親に持つ子どもたちだった。この数は、1973-1974年度には50人にまで増えた。組織作り に時間を費やすブラック・パンサー保護者たちを全面的にサポートするため、生徒と教員の何人かは一年中同居していた。学校自体は、生徒が年齢ではなく学業 成績によって分けられ、生徒に対する教員の比率が1対10であったため、生徒がしばしばマンツーマンでサポートされるなど、様々な点で従来の学校とは異 なっていた[113]。 パンサーが解放学校、特にインターコミュニナル・ユース・インスティテュートを開設した目的は、「白人」の学校では提供されていない教育を生徒に提供する ことであった[114]。生徒たちは英語、数学、科学といった伝統的な授業を受ける一方で、階級構造や制度的な人種差別の蔓延に焦点を当てた活動にも触れ ていた[115]。この学校の全体的な目標は、生徒たちに革命意識の感覚を植え付けることだった。 [ハギンズは、「この学校の原則は、私たちがブラックパンサー党で生きようとした社会主義の原則から来ていると思います。そのひとつは批判的思考であり、 子どもたちは何を考えるかではなく、どう考えるかを学ぶべきだということだった。そしてそれは......毎年変化する生きたものであった[112]。 ジョーン・ケリーは、ブラック・パンサーからの資金調達とコミュニティからの支援の組み合わせによって提供されたインターコミュニナル・ユース・インス ティテュートの資金調達を監督していた[113]。 オークランド・コミュニティ・スクール 1974年、同校への入学希望者が増加したため、学校関係者はより大きな施設に移転することを決定し、その後校名をオークランド・コミュニティ・スクール に変更した。この年、同校は最初のクラスを卒業した[114]。1974年から1977年の間に生徒数は50人から150人の間で増え続けたが、個別指導 という当初の中心的価値観は維持された[113]。1977年9月、同校は「州内の最高レベルの初等教育の基準を打ち立てた」として、エドマンド・ブラウ ン・ジュニア州知事とカリフォルニア州議会から特別賞を受賞した[114]。 同校は結局、党指導部に対する政府の圧力により、学校運営を継続するための会員数と資金が不足したため、1982年に閉鎖された[113]。 フレッド・ハンプトンとマーク・クラークの殺害 シカゴでは、1969年12月4日、シカゴ警察がパンサー・リーダー、フレッド・ハンプトンの家を襲撃し、2人のパンサーが殺害された。この襲撃は、警察 がFBIと連携して画策したものだった。ハンプトンは射殺され、パンサー・ガードのマーク・クラークも射殺された。連邦政府の調査によると、パンサーが発 砲したのは1発だけで、警察が発砲したのは少なくとも80発であった[116]。 ハンプトンは妊娠中の婚約者の隣で寝ており、その後、意識を失った状態で至近距離から頭を2発撃たれた。検視官の報告によると、ハンプトンはその夜、強力 なバルビツール酸系薬物を投与されており、警察の突入音で目を覚ますことはできなかっただろう[117]。死亡時、彼は21歳で、丸腰だった。その後、家 宅捜索時にその家で寝ていた他の7人のパンサーが殴打され重傷を負い、家宅捜索に関与した警官に対する加重暴行と殺人未遂の容疑で逮捕された。これらの容 疑は後に取り下げられた。 クック郡の州検事エドワード・ハンラハンは、パンサーズが最初に発砲し、"何度か発砲をやめるよう促されても......発砲をやめようとしなかった "と後にメディアに発表した。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の報道は、これが事実ではなかったことを後に証明することになり、シカゴ警察が自分たちの主張を主 張するために使用している大量の偽の証拠を発見した[118]。 元FBI捜査官のウェズリー・スウェアリンジェンは、FBIはパンサーズの「殺害計画」の罪を犯していたと主張している[119]。1979年の民事訴訟 で、ハンプトンの遺族はシカゴ市から不当死の和解金として185万ドルを勝ち取った[121]。 アレックス・ラックリー拷問殺人事件 1969年5月、ニューヘイブン支部の3人のメンバーが、ニューヨーク支部の19歳のメンバー、アレックス・ラックリーを警察の情報提供者と疑って拷問し 殺害した。3人の党役員(ウォーレン・キンブロ、ジョージ・サムス・ジュニア、ロニー・マクルーカス)は、後に参加したことを認めた。殺人現場でラック リー射殺の命令を下したサムスは、州側証拠に転じ、ボビー・シールから個人的に処刑実行の命令を受けたと証言した。党支持者たちは、サムス自身が情報提供 者であり、FBIに雇われた挑発工作員であったと反論した[122]。この事件は1970年のニューヘイブン・ブラックパンサー裁判に発展した。キンブ ロ、サムス、マクルーカスは殺人罪で有罪判決を受けたが、シールとエリカ・ハギンズの裁判は評決不一致で終わり、検察側は再裁判を求めないことを選択し た。 国際的なつながり 世界中の多くの国の活動家がパンサーズとその大義を支持した。例えば、ノルウェーやフィンランドなどのスカンジナビア諸国では、左翼活動家たちが1969 年にボビー・シールとマサイ・ヒューイットのためのツアーを企画した。ツアーの各目的地で、パンサーズは自分たちの目標と「ヒューイを自由に!」キャン ペーンについて語った。シールとヒューイットはドイツにも立ち寄り、「フリー・ヒューイ!」キャンペーンへの支持を得た[123]。 1970 年表 1970年1月: レナード・バーンスタインがBPPのための資金調達パーティーを開催。これは、トム・ウルフが『Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers』で嘲笑したことで有名である。 1970年春: オークランドBPPが銃と破片爆弾で警官を待ち伏せ。警官2人が負傷[124]。 1970年5月 ヒューイ・ニュートンの有罪判決が覆るが、彼は投獄されたまま。 1970年7月 ニュートン、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に「我々は暴力を提唱したことはない」と語る。 1970年8月 ニュートンが釈放される。 国際的な旅 1970年、エルドリッジ・クリーバーとエレイン・ブラウンを含むパンサーズの一団がアジアを訪れ、中国、[125]、北ベトナム、北朝鮮政府の賓客とし て迎えられる: 39 北ベトナム、北朝鮮の政府から賓客として迎えられた。一行が最初に訪れたのは北朝鮮で、パンサーたちは現地の高官と会談し、アメリカ帝国主義に対抗して闘 うために互いに助け合う方法について話し合った。クリーヴァーは1969年と1970年に2度平壌を訪れ、これらの旅行後、彼は北朝鮮の指導者である金日 成の著作や作品を米国で広める努力をした[126]。北朝鮮を離れた後、一行は同じ議題、すなわちアメリカの帝国主義に終止符を打つ方法を見つけることを 念頭に置いて北ベトナムを旅行した。エルドリッジ・クリーバーは、北ベトナム政府から黒人GIたちに講演するよう招かれた。彼は、アメリカ政府は自分たち の目的のために彼らを利用しているだけだと主張し、黒人解放闘争に参加するよう促した。クリーバーは、自分たちを抑圧し続ける国のために戦場で命を賭ける のではなく、黒人GIは自分たちの解放のために命を賭けるべきだと考えた。ベトナムを去った後、クリーヴァーはアルジェリアの中国大使と会談し、アメリカ 政府に対する互いの反感を表明した[127]。 アルジェリアが最初の汎アフリカ文化祭を開催したとき、彼らはアメリカから多くの重要人物を招待した。文化祭に招待された重要人物の中には、ボビー・シー ルとクリーヴァーも含まれていた。この文化祭によって、ブラック・パンサーはさまざまな国際的な反帝国主義運動の代表者たちとネットワークを築くことがで きた。クリーバーはこの文化祭で北朝鮮の大使と会い、後に平壌で開かれた革命ジャーナリスト国際会議に招待された。エルドリッジはまたヤセル・アラファト とも会い、パレスチナ人と彼らの解放達成という目標を支持するスピーチを行った[129]。 1971年秋、パンサーズの大規模なグループが中国を訪問した[125]: 39 1971-1974 ニュートンはBPPを党のオークランド校と他の様々な社会奉仕プログラムに集中させた。1971年初頭、BPPは1971年1月に 「Intercommunal Youth Institute」を設立し[130]、黒人の若者がどのように教育されるべきかを示すことを意図した。エリカ・ハギンズがこの学校のディレクターであ り、レジーナ・デイヴィスが管理者であった[131]。この学校のユニークな点は、学年を設けず、その代わりに異なるスキルレベルを設けていたことであ り、11歳の子供が2レベルの英語と5レベルの科学に触れることができた。 [131]エレイン・ブラウンは、制度上「教育不可能」とみなされた10歳から11歳の子どもたちに読み書きを教えた[132]。子どもたちには無料のバ ス、朝食、昼食、夕食、本、学用品が与えられ、子どもたちは健康診断に連れて行かれ、多くの子どもたちには無料の衣服が与えられた[133]。 分裂 イデオロギーの違いにどう立ち向かうかについて、党の指導者たちの間で大きな意見の相違があり、党内の分裂につながった。あるメンバーは、ブラック・パン サーは地方政府や社会サービスに参加すべきだと考え、他のメンバーは警察との絶え間ない対立を奨励した。党の支持者の一部にとって、政治活動、犯罪活動、 社会サービス、権力へのアクセス、草の根のアイデンティティの間の分離は、パンサーズの政治的勢いが刑事司法制度の中で泥沼化するにつれて、混乱し矛盾す るようになった。こうした(そしてその他の)意見の相違が分裂につながった。1971年1月、ニュートンはジェロニモ・プラットを除名した。彼は1970 年以来、未決の殺人容疑に直面して刑務所にいた。ニュートンはまた、ニューヨーク21の2人と、国外に逃亡した自身の秘書コニー・マシューズを追放した。 ヒュー・P・ニュートンやデビッド・ヒリアードのようなパンサー指導者の中には、自己防衛と結びついた社会奉仕活動に重点を置くことを支持する者もいれ ば、エルドリッジ・クリーバーのような、より対決的な戦略を採用する者もいた。1971年2月、エルドリッジ・クリーバーは、党が「革命的」アジェンダで はなく「改革主義的」アジェンダを採用していると公に批判し、ヒリアードの解任を要求したことで、党内の分裂を深めた。クリーヴァーは中央委員会から追放 されたが、党の地下準軍事組織として存在していた分派グループ、ブラック解放軍を率いるようになった[134]。ニュートン派とクリーヴァー派が互いのメ ンバーの報復暗殺を行い、4人の死者を出したため、分裂は暴力的になった[135]。 1971年5月、ボビー・シールはラックリー殺害を命じた罪で無罪となり、オークランドに戻った。 中国への代表団 1971年9月下旬、ヒューイ・P・ニュートンは代表団を率いて中国を訪れ、10日間滞在した[137]。 中国のどの空港でも、ヒューイは『小さな赤い本』のコピーを振り、「我々はブラック・パンサー党を支持し、アメリカ帝国主義を打倒する」あるいは「我々は アメリカ国民を支持するが、ニクソン帝国主義政権は打倒されなければならない」と書かれた看板を掲げた何千人もの人々に迎えられた。フエは毛沢東に会うと 思われていたが、その代わりに中華人民共和国の初代首相周恩来と2回会談した。そのうちの1回には、毛沢東の妻の江青も含まれていた。ヒューイは中国を 「社会主義政府を持つ自由で解放された領土」と表現した[139]。 ニュートンはオークランドで支配を固め、権力を集中させる 南カリフォルニア支部の政治部門は閉鎖され、そのメンバーはオークランドに移ったが、地下の軍事部門は一時的に残っていた[141]。 [141]ストリート・ギャングのスラウソンズから生まれたLA支部の地下残党は、最終的にクリップスとして再登場し、最初は社会改革を提唱していたスト リート・ギャングであったが、恐喝に堕落した。[142]教育大臣のレイ・"マサイ"・ヒューイットは、オークランドの党の地下警備幹部であるブッダ・サ ムライを創設した。ニュートンは1972年の後半にヒューイットを党から追放したが、警備部隊はフローレス・フォーブスの指導の下で活動を続けた。幹部の 主な任務のひとつは、麻薬の売人やアフターアワーのクラブを恐喝し、強奪することだった[141]。 党はオークランド市を政治的に乗っ取るための5カ年計画を策定し、その資源のほぼすべてをオークランド市政における政治権力の獲得に集中させた。ボビー・ シールは市長選に、エレイン・ブラウンは市議選に、その他のパンサーたちはマイナーな役職に立候補した。シールもブラウンも落選し、多くの党員は敗戦後に 辞職した[140]が、数人のパンサーが地方自治体の委員会の議席を獲得した。選挙での敗北を受けて、ニュートンは1974年初めに党の大粛清に着手し、 ボビー・シールとジョン・シール、デヴィッド・ヒリアードとジューン・ヒリアード、ロバート・ベイ、その他多数の党幹部たちを追放した。シールに忠誠を 誓った他の数十人のパンサーも辞職または脱走した。 ニュートンが暴力犯罪で起訴される 1974年、ヒューイ・ニュートンと他の8人のパンサーが逮捕され、警察官に対する暴行罪で起訴された。1974年8月、ニュートンは18歳の売春婦キャ スリーン・スミス殺害事件の起訴を避けるためキューバに亡命。ニュートンは、仕立屋のプレストン・カリンズをピストルで殴打した罪でも起訴された。ニュー トンはキャスリーン・スミスが彼にとって「初めての非政治的な殺人」であったことを友人に打ち明けたが、目撃者の1人が殺人の夜にマリファナを吸っていた ことを認めたことで証言が弾劾され、別の売春婦の目撃者が証言を撤回したため、最終的に無罪となった[143][144]。 キャリンズが告訴を拒否したため、ニュートンはプレストン・キャリンズへの暴行についても無罪となった[145][要解説]。 1974-1977 エレイン・ブラウン率いるパンサーズ 1974年、ヒューイ・ニュートンはキューバに亡命する準備をし、エレイン・ブラウンを党の初代議長に任命した[146]。ブラウンのリーダーシップの 下、党はより急進的な選挙運動の組織化に関与するようになり、ブラウンの1975年のオークランド市議会議員選挙への出馬は落選した[147]。 [147]党は、オークランド初の黒人市長に当選したライオネル・ウィルソンを支援し、ブッダ・サムライ幹部のリーダーであった党員のフローレス・フォー ブスに対する刑事告発を取り下げさせるためにウィルソンの支援を得た[141]。 ブラウンは、党の方向性を選挙の場への関与を強める方向に変えただけでなく、それまで男性中心の組織であった女性パンサーをより目立つ役割に就かせること で、女性パンサーたちの影響力を高めた。 ベティ・ヴァン・パターの死 パンサー・リーダーのエレイン・ブラウンは、1974年にベティ・ヴァン・パターを簿記係として雇った。ヴァン・パターは以前ランパーツ誌の簿記係をして おり、ランパーツ誌の編集者であり、パンサー学校の主要な資金調達者であり理事であったデイヴィッド・ホロヴィッツによってパンサー指導部に紹介された [148]。その年の後半、不正な会計処理についてブラウンと争った後[149]、ヴァン・パターは1974年12月13日に行方不明になった。数週間 後、彼女のひどく殴られた死体がサンフランシスコ湾の浜辺で発見された。 警察がヴァン・パター殺害で誰かを告発するには証拠が不十分であったが、ブラックパンサー党の指導部は「ほとんど誰もが責任があると信じていた」 [150][151]。 ヒューイ・ニュートンは後に、自分がヴァン・パター殺害を命じたこと、ヴァン・パターは殺される前に拷問されレイプされたことを友人に告白したとされる [144][152]。 ヴァン・パッターを捜査していたFBIのファイルは、FBIが提供を拒否した理由により2009年に破棄された[153]。 1977-1982 ヒューイ・ニュートンの復帰と党の終焉 1977年、キューバでの亡命生活から戻ったニュートンは、男性メンバーから、組織内の女性の権力が強すぎることについての苦情を受けた。エレイン・ブラ ウンによると、ニュートンは、同僚の男性を叱った学校管理者のレジーナ・デイヴィスへの体罰を許可した。ブラウンによれば、「レジーナへの殴打は、『パン サー』や『同志』という言葉がジェンダー対ジェンダーの意味合いを持つようになり、私たちの女性の半分の劣等性を示すようになったという明確なシグナルと して受け取られるだろう」[155][156][157]。 多くの学者や活動家は、党の没落をブラウンが指導する以前の時期にさかのぼるが、パンサーズの縮小する幹部は1970年代を通して苦闘していた。1980 年までにパンサー党員は27人に減少し、パンサーが後援していたオークランド・コミュニティ・スクールは、ニュートンが薬物中毒のために資金を横領したと いうスキャンダルの中で1982年に閉鎖され[147][159]、ブラックパンサー党の正式な終焉を迎えた[146]。 パンサーによるニュートンの目撃者暗殺未遂事件 1977年10月、党の副参謀長であったフローレス・フォーブスは、ニュートンの来るべき裁判の重要な検察側証人であり、キャスリーン・スミスが殺害され た日にその場にいたクリスタル・グレイを暗殺しようとする失敗を主導した。3人のパンサーが間違えて間違った家を攻撃したとき、住人が応戦してパンサーの 1人ルイス・ジョンソンを殺害し、他の2人の加害者は逃亡した[160]。そのうちの1人フローレス・フォーブスは、パンサー救急隊員ネルソン・マロイの 助けを借りてネバダ州ラスベガスに逃亡した。マロイが暗殺未遂の真相を知ることを恐れたニュートンは「家の掃除」を命じ、マロイは撃たれて砂漠に生き埋め にされたとされる。マロイは腰から下が麻痺したまま逃走し、警察に仲間のパンサーズであるロリン・リードとアレン・ルイスが殺人未遂の背後にいたと話した [161]。 [162]ニュートンは、クリスタル・グレイの証言が殺人の夜にマリファナを吸ったという彼女の告白によって弾劾された後、最終的にキャスリーン・スミス 殺害で無罪となり、カリンズが告発を拒否した後、プレストン・カリンズへの暴行で無罪となった。 |