黒い伝説

Black legend

Los murales de Rivera han sido señalados por Powell como una expresión de la leyenda negra en América.

☆ 黒い伝説(スペイン語: Leyenda negra)またはスペイン黒い伝説(スペイン語: Leyenda negra española)は、反スペイン、反カトリックのプロパガンダからなる歴史学的傾向とされるものである。その提唱者は、そのルーツは16世紀に遡り、ス ペインのヨーロッパのライバルたちが政治的・心理的手段によって、スペイン帝国、その国民、その文化を悪者扱いし、スペインの発見や功績を最小化し、世界 情勢におけるスペインの影響力や権力に対抗しようとしていた時代にまで遡ると主張している[1][2][3]。 この説によれば、16世紀のカトリック君主に対するイスパノ=オランダ戦争やイギリス=スペイン戦争の際に発表されたプロテスタントのプロパガンダが、そ の後の歴史家たちの間に反ヒスパニック的なバイアスを醸成した。スペインの歴史とラテンアメリカの歴史に対する歪んだ見方とともに、ポルトガル帝国の他の 地域も、イベリア連合とルソ=オランダ戦争の結果として影響を受けた[1]。この17世紀のプロパガンダは、残虐行為を伴うスペインのアメリカ大陸植民地 化の実際の出来事に基づいていたが、「レイエンダ・ネグラ」の理論によれば、しばしば薄気味悪く誇張された暴力の描写が用いられ、他の列強による同様の行 動が無視されていたことが示唆されている[4]。 16世紀から17世紀にかけてのヨーロッパにおける宗教分裂と新国家形成によって引き起こされた戦争は、カトリック教会の砦であった当時のスペイン帝国に 対するプロパガンダ戦争も引き起こした。そのため、もともとはオランダやイギリスの16世紀のプロパガンダが主流派の歴史に同化したことで、後の歴史家た ちの間にカトリック君主に対する反ヒスパニック的な偏見が醸成され、スペインやラテンアメリカ、その他の地域の歴史に対する歪んだ見方が生まれたと考えら れている[1]。 17世紀と18世紀の反スペインプロパガンダを表現するのにブラックレジェンドという用語が有用であるかもしれないが、この現象が現代にも続いているかど うかについてはコンセンサスが得られていない、というのが多くの学者の意見である。多くの著者が、スペイン帝国の植民地支配に対する無批判なイメージ(い わゆる「白い伝説」)を提示するために、現代において「黒い伝説」という考え方が使用されていることを批判している。

| The Black Legend

(Spanish: Leyenda negra) or the Spanish Black Legend (Spanish: Leyenda

negra española) is a purported historiographical tendency which

consists of anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic propaganda. Its proponents

argue that its roots date back to the 16th century, when Spain's

European rivals were seeking, by political and psychological means, to

demonize the Spanish Empire, its people, and its culture, minimize

Spanish discoveries and achievements, and counter its influence and

power in world affairs.[1][2][3] According to the theory, Protestant propaganda published during the Hispano-Dutch War and the Anglo-Spanish War against the Catholic monarchs of the 16th century fostered an anti-Hispanic bias among subsequent historians. Along with a distorted view of the history of Spain and the history of Latin America, other parts of the world in the Portuguese Empire were also affected as a result of the Iberian Union and the Luso-Dutch Wars.[1] Although this 17th-century propaganda was based in real events from the Spanish colonization of the Americas, which involved atrocities, the theory of the Leyenda Negra suggests that it often employed lurid and exaggerated depictions of violence, and ignored similar behavior by other powers.[4] Wars provoked by the religious schism and the formation of new states in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries also generated a propaganda war against the then Spanish Empire, bastion of the Catholic Church. As such, the assimilation of originally Dutch and English 16th-century propaganda into mainstream history is thought to have fostered an anti-Hispanic bias against the Catholic Monarchs among later historians, along with a distorted view of the history of Spain, Latin America, and other parts of the world.[1] Although most scholars agree that while the term Black Legend might be useful to describe 17th and 18th century anti-Spanish propaganda, there is no consensus on whether the phenomenon persists in the present day. A number of authors have critiqued the use of the "black legend" idea in modern times to present an uncritical image of the Spanish Empire's colonial practices (the so called "white legend"). |

黒い伝説(スペイン語: Leyenda

negra)またはスペイン黒い伝説(スペイン語: Leyenda negra

española)は、反スペイン、反カトリックのプロパガンダからなる歴史学的傾向とされるものである。その提唱者は、そのルーツは16世紀に遡り、ス

ペインのヨーロッパのライバルたちが政治的・心理的手段によって、スペイン帝国、その国民、その文化を悪者扱いし、スペインの発見や功績を最小化し、世界

情勢におけるスペインの影響力や権力に対抗しようとしていた時代にまで遡ると主張している[1][2][3]。 この説によれば、16世紀のカトリック君主に対するイスパノ=オランダ戦争やイギリス=スペイン戦争の際に発表されたプロテスタントのプロパガンダが、そ の後の歴史家たちの間に反ヒスパニック的なバイアスを醸成した。スペインの歴史とラテンアメリカの歴史に対する歪んだ見方とともに、ポルトガル帝国の他の 地域も、イベリア連合とルソ=オランダ戦争の結果として影響を受けた[1]。この17世紀のプロパガンダは、残虐行為を伴うスペインのアメリカ大陸植民地 化の実際の出来事に基づいていたが、「レイエンダ・ネグラ」の理論によれば、しばしば薄気味悪く誇張された暴力の描写が用いられ、他の列強による同様の行 動が無視されていたことが示唆されている[4]。 16世紀から17世紀にかけてのヨーロッパにおける宗教分裂と新国家形成によって引き起こされた戦争は、カトリック教会の砦であった当時のスペイン帝国に 対するプロパガンダ戦争も引き起こした。そのため、もともとはオランダやイギリスの16世紀のプロパガンダが主流派の歴史に同化したことで、後の歴史家た ちの間にカトリック君主に対する反ヒスパニック的な偏見が醸成され、スペインやラテンアメリカ、その他の地域の歴史に対する歪んだ見方が生まれたと考えら れている[1]。 17世紀と18世紀の反スペインプロパガンダを表現するのにブラックレジェンドという用語が有用であるかもしれないが、この現象が現代にも続いているかど うかについてはコンセンサスが得られていない、というのが多くの学者の意見である。多くの著者が、スペイン帝国の植民地支配に対する無批判なイメージ(い わゆる「白い伝説」)を提示するために、現代において「黒い伝説」という考え方が使用されていることを批判している。 |

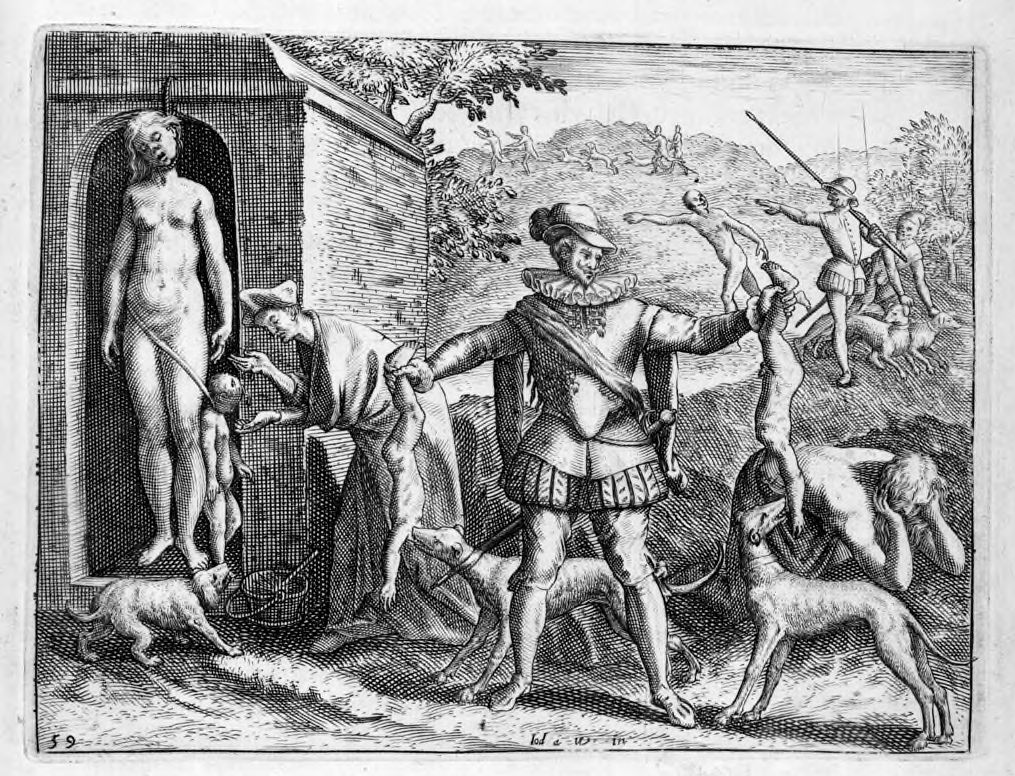

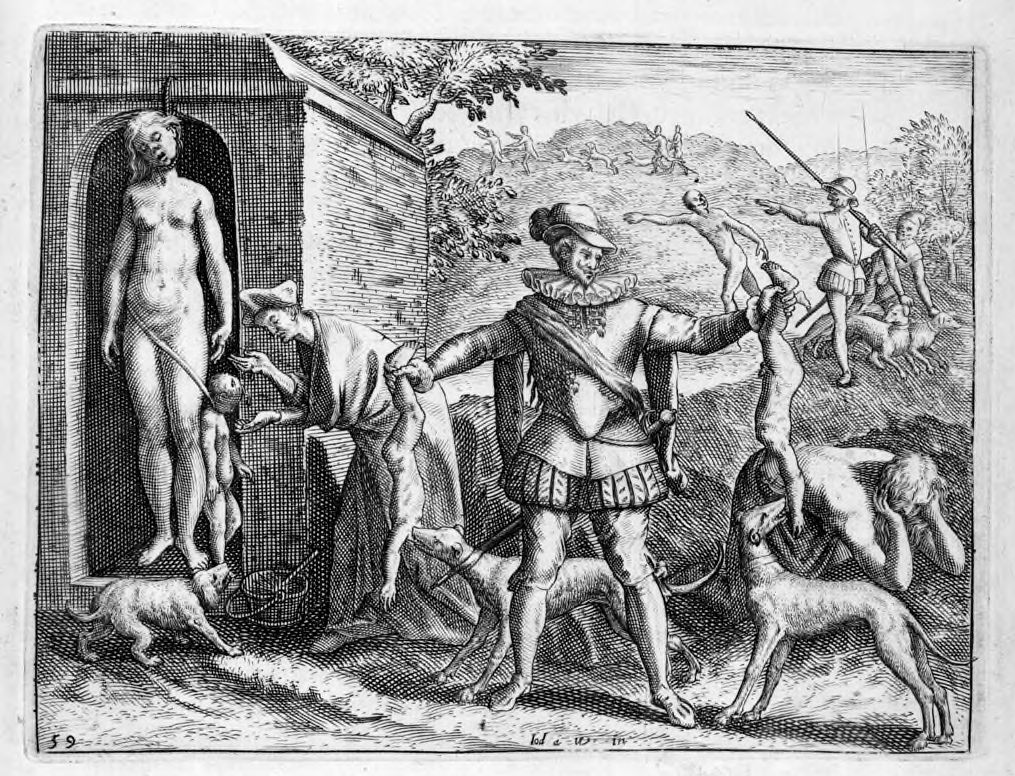

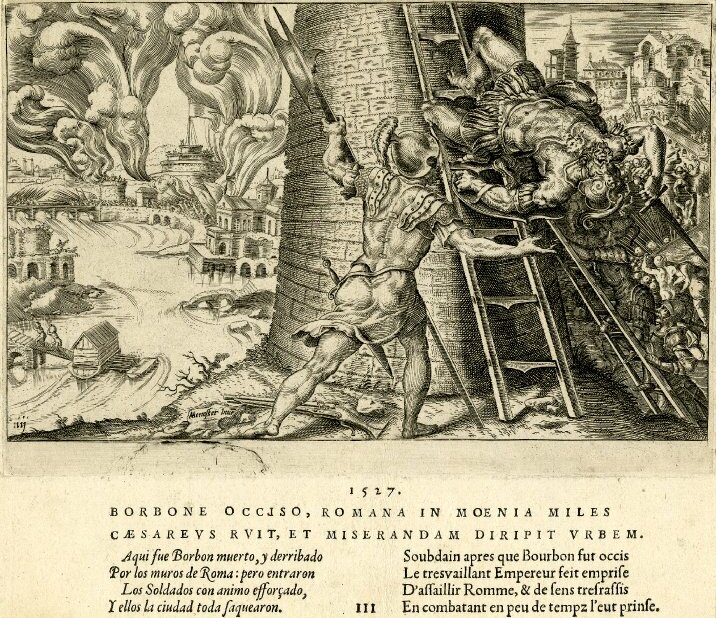

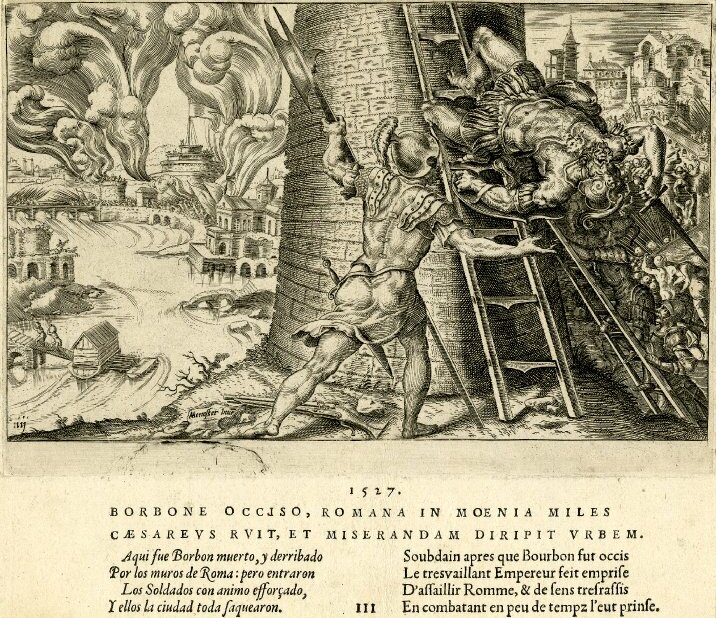

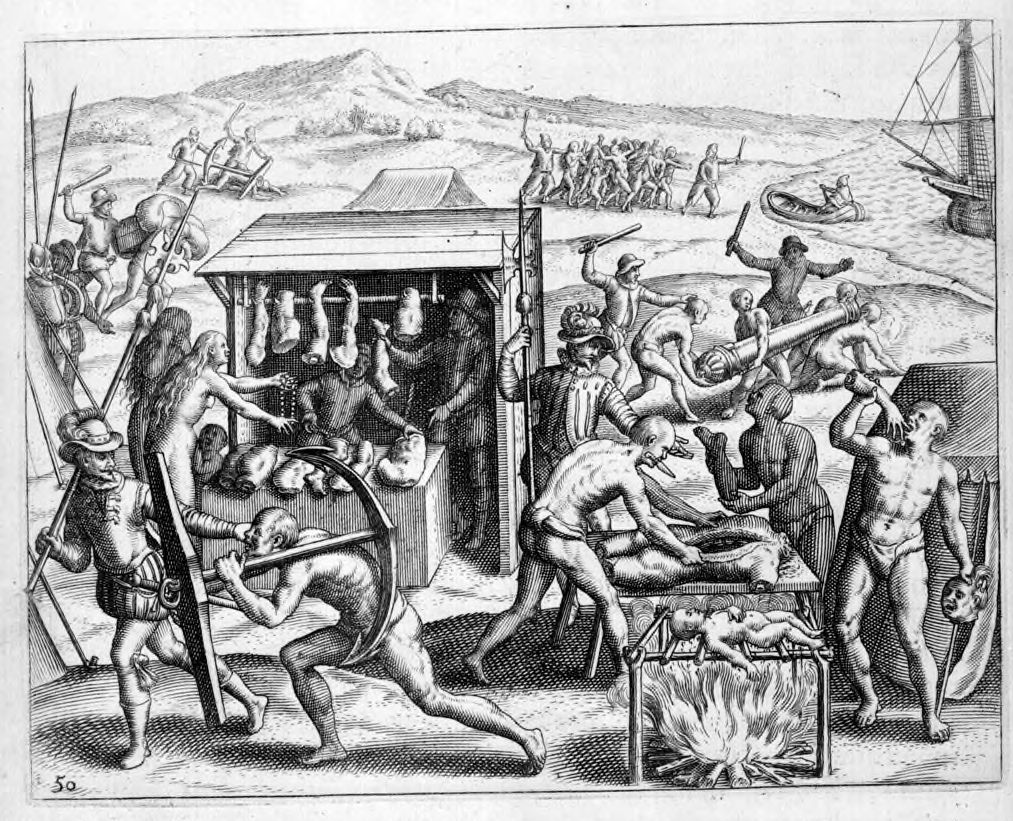

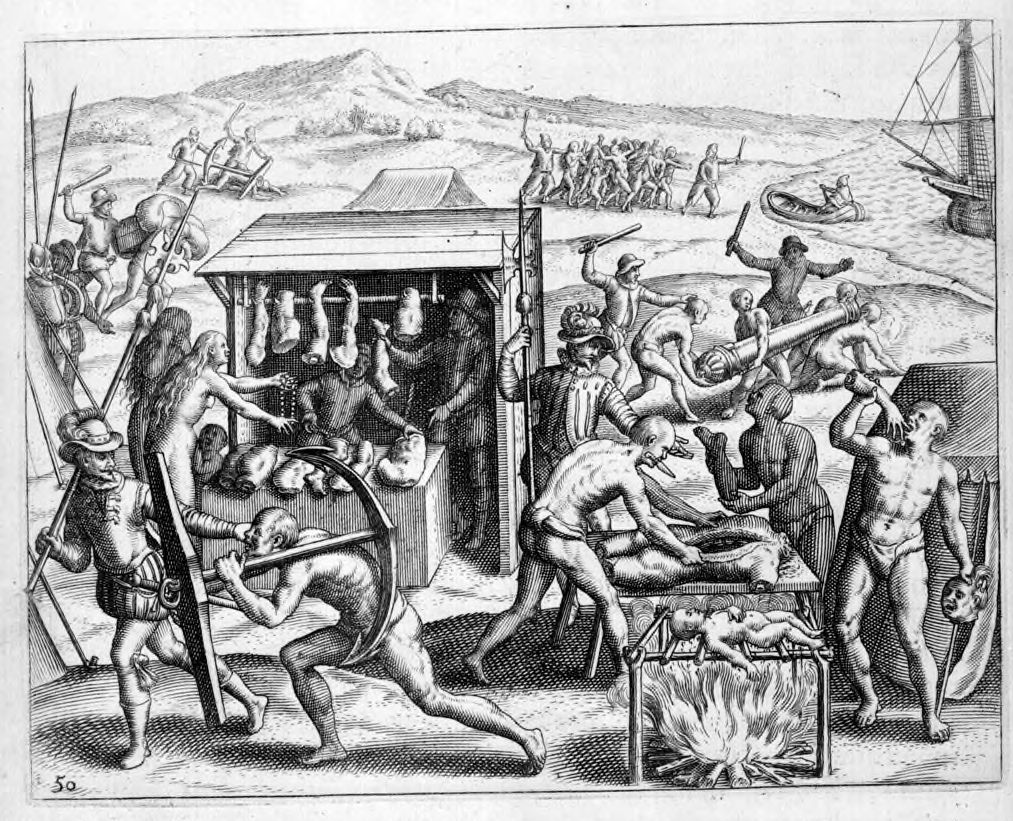

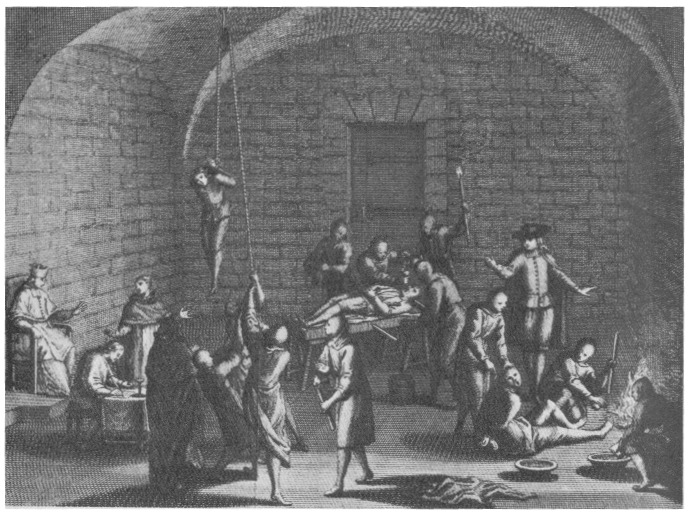

A 1598 engraving by Theodor de Bry depicting a Spaniard feeding slain Indigenous American women and children to his dogs. De Bry's works are characteristic of anti-Spanish propaganda which resulted from the Eighty Years' War. |

テオドール・デ・ブライによる1598年の版画で、スペイン人が殺されたアメリカ先住民の女性や子供を犬に食べさせている様子が描かれている。デ・ブライの作品は、八十年戦争がもたらした反スペイン・プロパガンダの特徴である。 |

| Historiography and definitions of the Spanish Black Legend The term "black legend" was first used by Arthur Lévy in reference to biographies of Napoleon, and he primarily used it in the context of two opposing legends, a "golden legend" and a "black legend": two extreme, simplistic, one-dimensional approaches to a character which portrayed him as a god or a demon. "Golden" and "black legends" had been used by Spanish historians and intellectuals with the same meaning in reference to aspects of Spanish history; Antonio Soler used both terms about the portrayal of Castilian and Aragonese monarchs.[citation needed] The use of the term leyenda negra to refer specifically to a biased, anti-Spanish depiction of history gained currency in the first two decades of the 20th century, and is most associated with Julián Juderías. Throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, scholars have offered divergent interpretations of the Black Legend and debated its usefulness as a historical concept. Origins of the concept of a Spanish Black Legend At an 18 April 1899 Paris conference, Emilia Pardo Bazán used the term "Black Legend" for the first time to refer to a general view of modern Spanish history: Abroad, our miseries are known and often exaggerated without balance; take as an example the book by M. Yves Guyot, which we can consider as the perfect model of a black legend, the opposite of a golden legend. The Spanish black legend is a strawman for those who seek convenient examples to support certain political theses ... The black legend replaces our contemporary history with a novel in the Ponson du Terrail style, with mines and countermines, which doesn't even deserve the honor of analysis.[5] The conference had a great impact in Spain, particularly on Julián Juderías. Juderías, who worked at the Spanish Embassy in Russia, had noticed (and denounced) the spread of anti-Russian propaganda in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom and was interested in its possible long-term consequences. Juderías was the first historian to describe the "black legend" phenomenon, although he did not yet name it as such, in a book regarding the construction of an anti-Russian black legend. His work, initially concerned with the intentional deformation of Russia's image in Europe, led him to identify the same patterns of narration he detected in the construction of anti-Russian discourse in the dominant historical narrative regarding Spain. Juderías investigated the original sources supporting centuries old claims of Spanish atrocities and other misdeeds, tracing the origin or propagation of the majority to rival emerging powers. In his 1914 book, La leyenda negra y la verdad histórica (The Black Legend and Historical Truth), deconstructs aspects of Spain's image (including those in Foxe's Book of Martyrs). According to Juderías, this biased historiography was marked by acceptance of propagandistic and politically motivated historical sources and has consistently presented Spanish history in a negative light, purposefully ignoring Spanish achievements and advances. In La leyenda Negra, he defines the Spanish black legend as: ... the environment created by the fantastic stories about our homeland that have seen the light of publicity in all countries, the grotesque descriptions that have always been made of the character of Spaniards as individuals and collectively, the denial or at least the systematic ignorance of all that is favorable and beautiful in the various manifestations of culture and art, the accusations that in every era have been flung against Spain."[2] [full citation needed] Historiographic development of the term Later writers supported and developed Juderías's critique. In Tree of Hate (1971),[6] Historian Charles Gibson described it as "the accumulated tradition of propaganda and hispanophobia according to which the Spanish Empire is considered cruel, intolerant, degenerate, exploitative and sanctimonious above reality."[1] Historian Philip Wayne Powell argued that the Black Legend was still active in modern history, and plays an active role in shaping Latin America–United States relations. His book provides examples of what he viewed as divergent treatment of Spain and other powers, and illustrates how this allows for a double narrative that taints Americans' view of Hispanic America as a whole: Spaniards who came to the New World seeking opportunities beyond the prospects of their European environment, are contemptuously called cruel and greedy "goldseekers," or other opprobrious epithets virtually synonymous with "Devils"; but Englishmen who sought New World opportunities are more respectfully called "colonists," or "homebuilders," or "seekers after liberty." ... When Spaniards expelled or punished religious dissidents, this came to be known as "bigotry," "intolerance," "fanaticism," and a cause of their decline. When Englishmen, Dutchmen, or Frenchmen did the same thing, it is known as "unifying the nation," or safeguarding it against treason or foreign conspiracy. — Tree of Hate (2008 edition), page 11 In his book Inquisition, Edward Peters wrote: An image of Spain circulated through late sixteenth-century Europe, borne by means of political and religious propaganda that blackened the characters of Spaniards and their ruler to such an extent that Spain became the symbol of all forces of repression, brutality, religious and political intolerance, and intellectual and artistic backwardness for the next four centuries. Spaniards and Hispanophiles have termed this process and the image that resulted from it as "The Black Legend," la leyenda negra. — Inquisition (1989 edition), p.131 In his 2002 book Spain in America: The Origins of Hispanism in the United States, American historian Richard Kagan defined the Spanish black legend: Compounding this perception of Spain as an inferior 'other' was the Black Legend, the centuries-old cluster of Protestant beliefs that the United States inherited from the British and, to a certain extent, from the Dutch. The Black Legend equated Spain with the Inquisition, religious bigotry, and the bloody persecution of Protestants and Jews. It also conjured up images of despotic monarchs who denied their subjects access to any semblance of economic and political freedom and who had consequently set Spain onto the road of economic weakness and political decline. Such a reading of Spanish history was overly simplistic but promoters of American exceptionalism found it useful to see Spain as an example of what would happen to a country whose fundamental values were antithetical to those of the United States." According to Julián Marías, the creation of the Spanish black legend was not an exceptional phenomenon -similar disinformation and fabrication campaigns have affected most global powers of the past, such as Ottoman Turkey or Russia- but its persistence and integration into mainstream historiography is. For Marías the causes of its durability are: Overlap of the Spanish Empire with the introduction of the printing press in England and Germany, which enabled the printing of hundreds of pamphlets daily Religious factors and identification Substitution of the Spanish intellectual class by another favorable to its former rival (France) after the War of the Spanish Succession, which established a French narrative in Spain The unique characteristics of the early modern era's colonial wars and the need for new colonial powers to legitimize claims in now-independent Spanish colonies and the unique, new characteristics of the succeeding empire: the British Empire.[7] Walter Mignolo and Margaret Greer view the Black Legend as a development of Spain's racialisation of Jewishness in the 15th century. The accusations of mixed blood and loose religiosity of the 15th century, first levelled at Jewish and Moorish conversos both inside Spain and abroad, developed into 16th century hispanophobic views of Spaniards as religious fanatics tainted by association with Judaism. The only stable element they see in this hispanophobia is an element of "otherness" marked by interaction with the Eastern and African worlds, of "complete others", cruelty and lack of moral character, in which the same narratives are re-imagined and reshaped.[8] Antonio Espino López suggests that the prominence of the Black Legend in Spanish historiography has meant that the real atrocities and brutal violence of the Spanish conquest of the Americas have not received the attention they deserve within Spain.[9] He believes that some Hispanicists: ...make an effort to justify the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the best way possible, as they were very conscious of the excesses committed by the "Black Legend", a set of ideas that are characterised by their intellectual coarseness.[10] According to historian Elvira Roca Barea, the formation of a black legend and its assimilation by a nation is a phenomenon observed in all multicultural empires (not just the Spanish Empire). For Roca Barea, a black legend about an empire is the cumulative result of the propaganda attacks launched by different groups: smaller rivals, allies within its political sphere and defeated rivals, and propaganda created by rival factions inside the imperial system; alongside self-criticism by the intellectual elite, and the needs of new powers consolidated during (or after) the empire's existence.[11] In response to Roca Barea, José Luis Villacañas states that the "black legend" was primarily a factor related to the geopolitical situation of the 16th and 17th centuries. He argues that: After 1648 [the Black Legend] was not particularly current in European intellectual circles. To the contrary, [Spain's] old enemies, England and Holland, became the greatest defenders of the Spanish Empire at the end of the 17th century, in order to avoid it falling into the hands of [the French]."[12] The conceptual validity of a Spanish black legend is widely but not universally accepted by academics. Benjamin Keen expressed doubt about its usefulness as a historical concept,[13] while Ricardo García Cárcel and Lourdes Mateo Bretos denied its existence in their 1991 book, The Black Legend: It is neither a legend, insofar as the negative opinions of Spain have genuine historical foundations, nor is it black, as the tone was never consistent nor uniform. Gray abounds, but the color of these opinions was always viewed in contrast [to what] we have called the white legend.[14] |

スペインの黒い伝説の歴史学と定義 「黒い伝説」という言葉は、アルチュール・レヴィがナポレオンの伝記に関連して初めて使ったもので、彼は主に「黄金伝説」と「黒い伝説」という2つの対立 する伝説の文脈で使った。つまり、ある人物に対する2つの極端で単純で一面的なアプローチで、彼を神か悪魔のように描いたものである。「黄金伝説 」と 「黒い伝説」は、スペインの歴史家や知識人によって、スペインの歴史の側面について同じ意味で使われていた。アントニオ・ソレールは、カスティーリャとア ラゴンの君主の描写について、この2つの言葉を使った。20世紀から21世紀にかけて、学者たちは黒い伝説についてさまざまな解釈を提示し、歴史的概念と しての有用性を議論してきた。 スペイン黒い伝説概念の起源 1899年4月18日のパリの会議で、エミリア・パルド・バザンは初めて「黒い伝説」という言葉をスペインの近代史全般を指す言葉として使った: イヴ・ギュイヨの著書を例にとれば、黄金伝説の対極にある黒い伝説の完璧なモデルと考えることができる。スペインの黒い伝説は、ある政治的主張を支持する ために都合のいい例を求める人々にとって、藁人形である。黒い伝説は、私たちの現代史を、地雷と反論のある、ポンソン・デュ・テライユ流の小説に置き換え ているのであり、分析の栄誉にすら値しない[5]。 この会議はスペイン、特にフリアン・ジュデリアスに大きな影響を与えた。在ロシア・スペイン大使館に勤務していたジュデリアスは、ドイツ、フランス、イギ リスで反ロシアのプロパガンダが広がっていることに気づいており(そしてそれを非難していた)、その長期的な影響に関心を持っていた。ジュデリアスは、反 ロシアの黒い伝説の構築に関する本の中で、「黒い伝説」現象について、そのような名前はまだなかったが、記述した最初の歴史家であった。当初はヨーロッパ におけるロシアの意図的なイメージの歪曲に関心を抱いていた彼は、スペインに関する支配的な歴史叙述における反ロシア的言説の構築と同じパターンの叙述を 発見した。ジュデリアスは、スペインの残虐行為やその他の悪行に関する何世紀も前の主張を裏付ける原典を調査し、その大多数がライバル関係にある新興大国 に由来するものであることを突き止めた。1914年に発表した著書『黒い伝説と歴史の真実』(La leyenda negra y la verdad histórica)では、(フォクセの『殉教者の書』に書かれたものを含む)スペインのイメージの側面を解体している。ジュデリアスによれば、この偏っ た歴史学は、プロパガンダ的で政治的動機に基づく史料を受け入れ、スペインの功績や進歩を意図的に無視し、スペインの歴史を一貫して否定的に表現してきた という。彼は『黒い伝説』の中で、スペインの黒い伝説を次のように定義している: あらゆる国で宣伝の光を浴びてきた祖国についての幻想的な物語、個人として、また集団としてのスペイン人の性格について常になされてきたグロテスクな描 写、文化や芸術のさまざまな表現における好ましいもの、美しいもののすべてを否定するか、少なくとも組織的に無視すること、あらゆる時代においてスペイン に対して投げかけられてきた非難、これらによって生み出された環境」[2]と定義している。 [完全な引用が必要である]。 この用語の歴史学的発展 後の作家たちはジュデリアスの批評を支持し、発展させた。歴史家のチャールズ・ギブソンは『憎しみの木』(1971年)の中で、この言葉を「スペイン帝国 が現実よりも残酷で、不寛容で、退廃的で、搾取的で、尊大であると考えられているプロパガンダとヒスパノフォビアの蓄積された伝統」と表現している [1]。 歴史家のフィリップ・ウェイン・パウエルは、黒い伝説は現代史においてもなお現役であり、ラテンアメリカとアメリカの関係を形成する上で積極的な役割を果 たしていると主張した。彼の著書は、スペインと他の列強の扱いが異なっていると彼がみなした例を示し、このことがアメリカ人のヒスパニック・アメリカ全体 に対する見方を汚す二重の物語を可能にしていることを説明している: ヨーロッパの環境では得られない機会を求めて新大陸にやってきたスペイン人は、残酷で貪欲な 「ゴールドシーカー 」や、事実上 「デビル 」と同義のその他の忌まわしい蔑称で軽蔑的に呼ばれるが、新大陸に機会を求めたイギリス人は、「入植者」、「ホームビルダー」、「自由を求める者 」と、より敬意を持って呼ばれる。... スペイン人が宗教的な反体制派を追放したり処罰したりすると、それは「偏狭」、「不寛容」、「狂信」として知られるようになり、彼らの衰退の原因となっ た。イギリス人、オランダ人、フランス人が同じことをした場合、それは「国民を統一すること」、あるいは反逆や外国の陰謀から国民を守ることとして知られ ている。 - 憎しみの木』(2008年版)11ページ エドワード・ピーターズはその著書『異端審問』の中でこう書いている: スペインのイメージは16世紀末のヨーロッパを駆け巡り、政治的・宗教的プロパガンダによってスペイン人とその支配者の人格を貶め、スペインはその後4世 紀にわたって、抑圧、残虐性、宗教的・政治的不寛容、知的・芸術的後進性のあらゆる勢力の象徴となった。スペイン人とイスパノフィルは、この過程とそこか ら生まれたイメージを「黒い伝説」la leyenda negraと呼んでいる。 - 異端審問(1989年版), p.131 2002年の著書『アメリカの中のスペイン』では The Origins of Hispanism in the United States)で、アメリカの歴史家リチャード・ケーガンはスペインの黒い伝説を定義した: スペインを劣った 「他者 」として認識することに拍車をかけたのが、黒い伝説であった。黒い伝説とは、アメリカがイギリスから、そしてある程度はオランダから受け継いだ、何世紀に もわたるプロテスタントの信仰である。黒い伝説は、スペインを異端審問、宗教的偏見、プロテスタントやユダヤ人に対する血なまぐさい迫害と同一視してい た。また、経済的・政治的自由のかけらもなく、スペインを経済的弱体化と政治的衰退の道へと導いた専制君主のイメージを想起させた。このようなスペインの 歴史の読み方は単純化されすぎていたが、アメリカ例外主義の推進者たちは、基本的な価値観がアメリカの価値観と相反する国に何が起こるかを示す例としてス ペインを見ることは有益だと考えた。 フリアン・マリアスによれば、スペインの黒い伝説の創作は例外的な現象ではなく、オスマントルコやロシアなど、過去のほとんどの世界的大国が同様の偽情報や捏造キャンペーンに影響を受けてきた。マリアスにとって、その根強さの原因は次のようなものである: スペイン帝国とイギリスやドイツにおける印刷機の導入が重なり、毎日何百というパンフレットを印刷することが可能になった。 宗教的要因と同一化 スペイン継承戦争後、スペインの知識階級がかつてのライバル(フランス)に有利な別の階級に取って代わられ、スペインにフランスの物語が確立された。 近世の植民地戦争の独特な特徴と、今や独立したスペインの植民地における主張を正当化するための新たな植民地大国の必要性、そして後継帝国である大英帝国の独特で新たな特徴[7]。 ウォルター・ミニョーロとマーガレット・グリアは、黒い伝説を15世紀におけるスペインのユダヤ人に対する人種差別の発展として捉えている。15世紀の混 血とゆるやかな宗教性への非難は、まずスペイン内外のユダヤ人とムーア人の信徒に向けられ、16世紀にはスペイン人をユダヤ教との結びつきによって汚染さ れた宗教的狂信者とするヒスパノフォビックな見方へと発展した。彼らがこのヒスパノフォビアに見出す唯一の安定した要素は、東洋やアフリカの世界との交流 によって特徴づけられる「他者性」、「完全な他者」、残酷さ、道徳性の欠如といった要素であり、そこでは同じ物語が再想像され、再構築されている[8]。 アントニオ・エスピノ・ロペスは、スペインの歴史学における黒い伝説の隆盛が、スペインのアメリカ大陸征服における実際の残虐行為や残忍な暴力がスペイン国内で相応の注目を浴びていないことを意味していると指摘する[9]: 彼らは「黒い伝説」、つまり知的な粗雑さによって特徴づけられる一連の思想によって行われた過剰な行為を強く意識していたため、スペインのアメリカ大陸征服を可能な限り最善の方法で正当化しようと努力していた[10]。 歴史家エルヴィラ・ロカ・バレアによれば、黒い伝説の形成と国民によるその同化は、(スペイン帝国だけでなく)すべての多文化帝国において観察される現象 である。ロカ・バレアにとって、帝国に関する黒い伝説とは、帝国システム内部の対立派閥が作り出したプロパガンダ、知的エリートによる自己批判、帝国の存 続中(あるいは存続後)に強化された新たな勢力のニーズと並んで、より小さなライバル、政治圏内の同盟国、敗北したライバルなど、さまざまな集団が仕掛け たプロパガンダ攻撃の累積的な結果である[11]。 ロカ・バレアに対する反論として、ホセ・ルイス・ビジャカニャスは、「黒い伝説」は主として16世紀と17世紀の地政学的状況に関連した要因であったと述べている。彼は次のように主張する: 1648年以降、[黒い伝説は]ヨーロッパの知識人の間では特に流行していなかった。それどころか、[スペインの]古くからの敵であるイングランドとオラ ンダは、17世紀末にはスペイン帝国が[フランスの]手に落ちるのを避けるために、スペイン帝国の最大の擁護者となった」[12]。 スペインの黒い伝説の概念的妥当性は、広く認められてはいるが、学問的に普遍的なものではない。ベンジャミン・キーンは歴史的概念としての有用性に疑念を 表明し[13]、リカルド・ガルシア・カルセルとルルデス・マテオ・ブレトスは1991年の著書『黒い伝説』の中でその存在を否定している: スペインに対する否定的な意見が正真正銘の歴史的基盤を持っている限り、黒い伝説は伝説ではない。灰色は多いが、これらの意見の色は常に、私たちが白の伝説と呼んでいるものとの対比の中で見られていた[14]」。 |

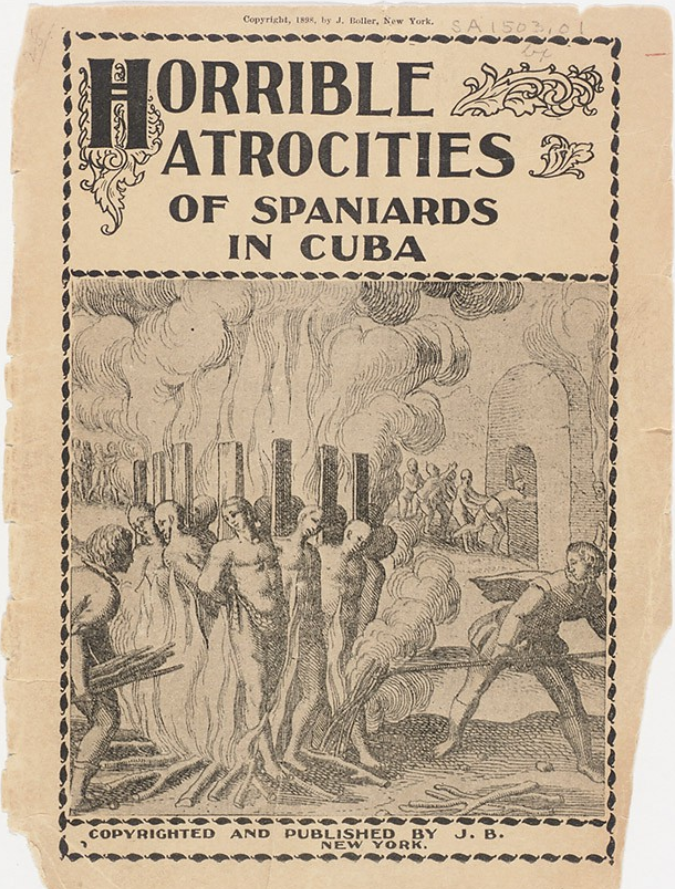

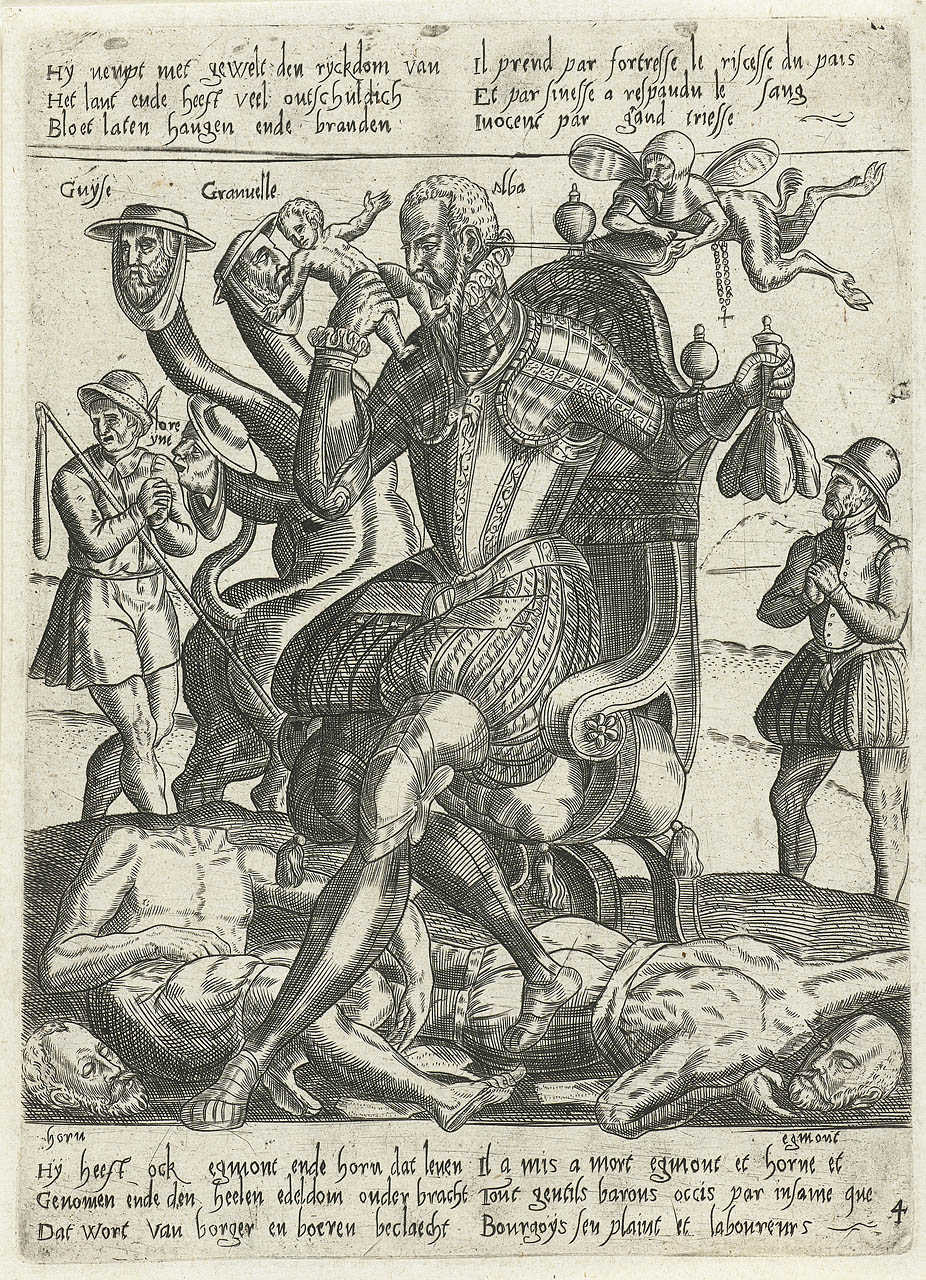

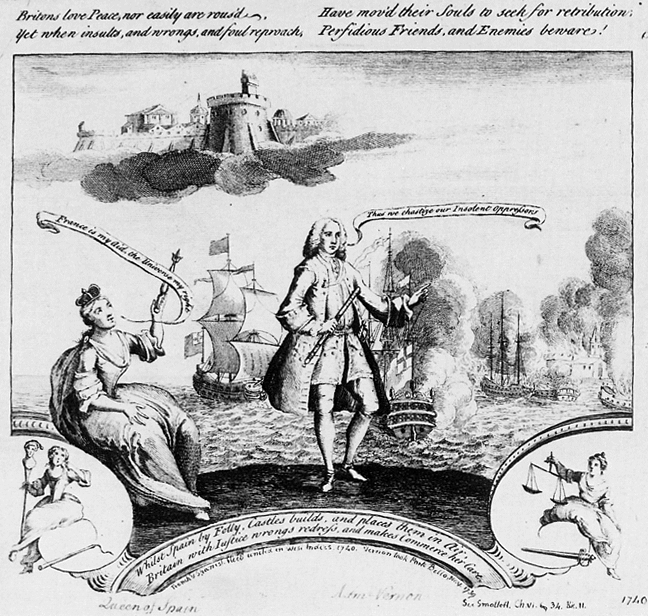

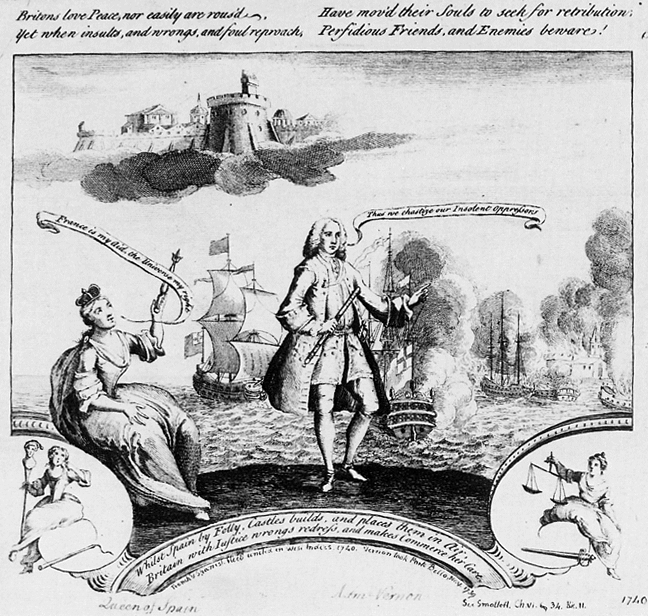

| Historical basis Despite having a vast empire stretching from Mexico to Peru across the Pacific to the Philippines and beyond, which required many Spaniards to travel overseas and deal with foreigners, eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote, "The Spaniard's bad side is that he does not learn from foreigners; that he does not travel in order to get acquainted with other nations; that he is centuries behind in the sciences. He resists any reform; he is proud of not having to work; he is of a romantic quality of spirit, as the bullfight shows; he is cruel, as the former auto-da-fé shows; and he displays in his taste an origin that is partly non-European."[15] Thus, semiotician Walter Mignolo argues that the Spanish black legend was closely tied to race in using Spain's Moorish history to portray Spaniards as racially tainted and its treatment of Africans and Native Americans during Spanish colonization to symbolize the country's moral character. That notwithstanding, there is general agreement that the wave of anti-Spanish propaganda of the 16th and 17th centuries was linked to undisputed events and phenomena which occurred at the apogee of Spanish power between 1492 and 1648.[1][16][3][12] Conquest of the Americas During the three-century European colonization of the Americas, atrocities and crimes were committed by all European nations according to both contemporary opinion and modern moral standards. Spain's colonization involved genocide, massacres, murders, slavery, sexual slavery, torture, rape, forced religious conversion, cultural genocide and other atrocities, especially in the early years, following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean.[12][3] However, Spain was the first in recorded history to pass laws for the protection of indigenous peoples. As early as 1512, the Laws of Burgos attempted to regulate the behavior of Europeans in the New World forbidding the ill-treatment of indigenous people and limiting the power of encomenderos—landowners who received royal grants to indigenous communities and their labor. In return, the laws established a regulated regime of work, provisioning, living quarters, hygiene, and care for the natives. The regulation prohibited the use of any form of punishment by the landowners and required that the huts and cabins of the Indians be built together with those of the Spanish. The laws also ordered that the natives be taught the Christian religion and outlawed bigamy.[1] In July 1513, four more laws were added in what is known as Leyes Complementarias de Valladolid 1513, three related to Indian women and Indian children and another more related to Indian males. In 1542 the New Laws expanded, amended and corrected the previous body of laws in order to ensure their application. These New Laws represented an effort to prevent abuse and de facto enslavement of natives that was not enough to dissuade rebellions by the encomenderos, like that of Gonzalo Pizarro in Perú. However, this body of legislation represents one of the earliest examples of humanitarian laws of modern history.[17]  An illustration of Spanish atrocities by Theodor de Bry. Theodor de Bry's work is characteristic of the anti-Spanish propaganda that emerged in Protestant countries such as the United Provinces and England at the end of the 16th century as a result of the strong commercial and military rivalry with the Spanish Empire. Although these laws were not always followed, they reflect the conscience of the 16th century Spanish monarchy about native rights and well-being, and its will to protect the inhabitants of Spain's territories. These laws came about in the early period of colonization, following abuses reported by Spaniards themselves traveling with Columbus. Spanish colonization methods included the forceful conversion of indigenous populations to Christianity. The "Orders to the Twelve" Franciscan friars in 1523, urged that the natives be converted using military force if necessary.[18] On par with this sentiment, Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda argued that the Indian's inferiority justified using war to civilize and Christianize them. He encouraged enslavement and violence in order to end the barbarism of the natives. Bartolomé de las Casas, on the other hand, was strictly opposed to this viewpoint—claiming that the natives could be peacefully converted.[19] Such reports of Spanish abuses led to an institutional debate in Spain about the colonization process and the rights and protection of indigenous peoples of the Americas. Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas published Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies), a 1542 account of the alleged atrocities committed by landowners and officials during the early period of colonization of New Spain (particularly on Hispaniola).[20] In his Short Account, de las Casas underscores the innocence of the indigenous peoples while comparing the Spanish conquistadors to "ravening wild beasts, wolves, tigers, or lions that had been starved for many days."[21] De las Casas, son of the merchant Pedro de las Casas (who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage), described Columbus's treatment of the natives in his History of the Indies.[22] His description of Spanish actions was used as a basis for attacks on Spain, including in Flanders during the Eighty Years' War. The accuracy of de las Casas's descriptions of Spanish colonization is still debated by some scholars due to supposed exaggerations. Although historian Lewis Hanke thought that de las Casas exaggerated atrocities in his accounts,[23] Benjamin Keen found them more or less accurate.[24] Charles Gibson's 1964 monograph The Aztecs under Spanish Rule (the first comprehensive study of sources about relations between Indians and Spaniards in New Spain[citation needed]), concludes that the demonization of Spain "builds upon the record of deliberate sadism. It flourishes in an atmosphere of indignation which removes the issue from the category of objective understanding. It is insufficient in its understanding of institutions of colonial history."[25] However this view has been broadly criticised by other scholars such as Keen, who view Gibson's focus on legal codes rather than the copious documentary evidence of Spanish atrocities and abuses as problematic.[3] In 1550, Charles I tried to end this debate by halting forceful conquest. Philip II tried to follow in his footsteps with the Philippine Islands, but previous violent conquest had shaped colonial relations irreversibly. This was one of the lasting consequences that led to the dissemination of the Black legend by Spain's enemies.[19] The treatment of indigenous peoples during Spanish colonization was used in propaganda works of rival European powers in order to foster animosity towards the Spanish Empire. De las Casas' work was first cited in English in the 1583 work The Spanish Colonie, or Brief Chronicle of the Actes and Gestes of the Spaniards in the West Indies, at a time when England was preparing to join the Dutch Revolt on the side of the anti-Spanish rebels.[26] Historians have noted that the mistreatment and exploitation of indigenous peoples was committed by all European powers which colonized the Americas, and such acts were never exclusive to the Spanish Empire. The revaluation of the Black Legend on contemporary historiography has led to a reassessment of non-Spanish European colonial records in recent years as the historiographical evaluation of the Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation continues to evolve. According to scholar William B. Maltby, "At least three generations of scholarship have produced a more balanced appreciation of Spanish conduct in both the Old World and the New, while the dismal records of other imperial powers have received a more objective appraisal."[26] War with the Netherlands Spain's war with the United Provinces and, in particular, the victories and atrocities of the Castilian nobleman Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, contributed to anti-Spanish sentiment. Sent in August 1567 to counter political unrest in a part of Europe where printing presses encouraged a variety of opinions (especially against the Catholic Church), Alba seized control of the publishing industry; several printers were banished, and at least one was executed. Booksellers and printers were prosecuted and arrested for publishing banned books, many of which were part of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. After years of unrest in the Low Countries, the summer of 1567 saw renewed violence in which Dutch Calvinists defaced statues and decorations in Catholic monasteries and churches. The March 1567 Battle of Oosterweel was the first Spanish military response to the unrest, and the beginning of the Eighty Years' War. In 1568 Alba had prominent Dutch nobles executed in Brussels' central square, sparking anti-Spanish sentiment. In October 1572, after Orange forces captured the city of Mechelen, its lieutenant attempted to surrender when he heard that a larger Spanish army was approaching. Despite efforts to placate the troops, Fadrique Álvarez de Toledo (son of the governor of the Netherlands and commander of the duke's troops) allowed his men three days to pillage the city; Alba reported to King Philip II that "not a nail was left in the wall". A year later, magistrates were still attempting to retrieve church artifacts which Spanish soldiers had sold elsewhere.[27][28] This sack of Mechelen was the first of a series of events known as the Spanish Fury;[29][30][31][32] several others occurred over the next several years.[33] In November and December 1572, with the duke's permission, Fadrique had residents of Zutphen and Naarden locked in churches and burnt to death.[28][34] In July 1573, after a six-month siege, the city of Haarlem surrendered. The garrison's men (except for the German soldiers) were drowned or had their throats cut by the duke's troops, and eminent citizens were executed.[28] More than 10,000 Haarlemers were killed on the ramparts, nearly 2,000 burned or tortured, and double that number drowned in the river.[35] After numerous complaints to the Spanish court, Philip II decided to change policy and relieve the Duke of Alba. Alba boasted that he had burned or executed 18,600 persons in the Netherlands,[36] in addition to the far greater number he massacred during the war, many of them women and children; 8,000 persons were burned or hanged in one year, and the total number of Alba's Flemish victims can not have fallen short of 50,000.[37]  Contemporary, anonymous painting of the 4 November 1576 Spanish Fury in Antwerp  The Spanish Fury at Maastricht in 1579 The Dutch Revolt spread to the south in the mid-1570s after the Army of Flanders mutinied for lack of pay and went on the rampage in several cities, most notably Antwerp in 1576. Soldiers rampaged through the city, killing, looting, extorting money from residents and burning the homes of those who did not pay. Christophe Plantin's printing establishment was threatened with destruction three times, but was spared each time with payment of a ransom. Antwerp was economically devastated by the attack; 1,000 buildings were torched, and as many as 17,000 civilians were raped, tortured and murdered.[38][39] Parents were tortured in their children's presence, infants were slain in their mother's arms, wives were flogged to death before their husbands' eyes.[40] Maastricht was besieged, sacked and destroyed twice by the Tercios de Flandes (in 1576 and 1579), and the 1579 siege ended with a Spanish Fury which killed 10,000 men, women and children.[41]: 247 Spanish troops who breached the city walls first raped the women, then massacred the population, reputedly tearing people limb from limb.[42] The soldiers drowned hundreds of civilians by throwing them off the bridge over the river Maas in an episode similar to earlier events in Zutphen. Military terror defeated the Flemish movement, and restored Spanish rule in Belgium.[43] The propaganda created by the Dutch Revolt during the struggle against the Spanish Crown can also be seen as part of the Black Legend. The depredations against the Indians that De las Casas had described were compared to the depredations of Alba and his successors in the Netherlands. The Brevissima relación was reprinted no less than 33 times between 1578 and 1648 in the Netherlands (more than in all other European countries combined).[44] The Articles and Resolutions of the Spanish Inquisition to Invade and Impede the Netherlands accused the Holy Office of a conspiracy to starve the Dutch population and exterminate its leading nobles, "as the Spanish had done in the Indies."[45] Marnix of Sint-Aldegonde, a prominent propagandist for the cause of the rebels, regularly used references to alleged intentions on the part of Spain to "colonize" the Netherlands, for instance in his 1578 address to the German Diet. In recent years, Prof. dr. Maarten Larmuseau of KU Leuven has used genetic testing to examine a prevalent belief regarding the Spanish occupation[46] War atrocities committed by the Spanish army in the Low Countries during the 16th century are so ingrained in the collective memory of Belgian and Dutch societies that they generally assume a signature of this history to be present in their genetic ancestry. Historians claim this assumption is a consequence of the so‐called "Black Legend" and negative propaganda portraying and remembering Spanish soldiers as extreme sexual aggressors. — Prof. dr. Maarten Larmuseau, The black legend on the Spanish presence in the low countries: Verifying shared beliefs on genetic ancestry The memory of the large scale rape of local women by Spanish soldiers lives on to such extent that it is popularly believed that their genetic imprint can be seen today, and that most men and women with dark hair in the area descend from children conceived during those rapes. The study found no greater Iberian genetic component in the areas occupied by the Spanish army than in surrounding areas of northern France, and concluded that the genetic impact of the Spanish occupation, if any, must have been too small to survive until the present era. However, the study makes it clear that the absence of a Spanish genetic imprint in modern populations was not incompatible with the occurrence of mass sexual violence. The frequent murder of Flemish rape victims by Spanish soldiers, the fact rape does not always lead to fertilisation, and the reduced survival possibilities of the illegitimate offspring of rape victims would all militate against significant Iberian genetic contribution to modern populations. Larmuseau considers the persistence of the belief in a Spanish genetic contribution in Flanders to be the fruit of the use of Black Legend tropes in the construction of Dutch and Flemish national identities in the 16th–19th century, giving prominence to the idea of the Spanish armies' cruelty in collective memory. In an interview with a local newspaper, Larmuseau compared the persistence in popular memory of the actions of the Spanish with the lesser attention given to the Austrians, the French and the Germans who also occupied the Low Countries and participated in violence against their inhabitants.[47] |

歴史的根拠 18世紀の哲学者イマヌエル・カントは、「スペイン人の悪い面は、外国人から学ばないこと、他の国民と知り合いになるために旅をしないこと、科学において 何世紀も遅れていることである。彼はどんな改革にも抵抗し、働かなくてもよいことに誇りを持ち、闘牛が示すようにロマンチックな精神の質を持ち、かつての オート・ダ・フェが示すように残酷であり、その嗜好には部分的に非ヨーロッパ的な起源を示す。 「15] このように、記号論者のウォルター・ミニョーロは、スペインの黒い伝説は人種と密接に結びついており、スペインのムーア人の歴史を利用してスペイン人を人 種的に汚染されたものとして描き、スペインの植民地化におけるアフリカ人やアメリカ先住民の扱いを利用して、この国の道徳的性格を象徴していると主張す る。とはいえ、16世紀から17世紀にかけての反スペイン・プロパガンダの波は、1492年から1648年にかけてのスペイン権力の絶頂期に起こった、議 論の余地のない出来事や現象に関連していたという点では、一般的な合意が得られている[1][16][3][12]。 アメリカ大陸の征服 3世紀にわたるヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化において、現代の世論と現代の道徳基準に照らせば、残虐行為と犯罪はすべてのヨーロッパ国民によっ て行われた。スペインの植民地化は、特にクリストファー・コロンブスがカリブ海に到着した後の初期において、大量虐殺、虐殺、殺人、奴隷制、性奴隷制、拷 問、レイプ、宗教的改宗の強制、文化的虐殺、その他の残虐行為を含んでいた。1512年には早くもブルゴス法が制定され、新大陸におけるヨーロッパ人の行 動を規制し、先住民の虐待を禁じるとともに、先住民社会とその労働力に対する勅許を受けた土地所有者であるエンコメンデロの権力を制限しようとした。その 見返りとして、法律は先住民の労働、糧食、居住、衛生、介護に関する規制体制を確立した。その規制は、地主によるいかなる処罰も禁止し、先住民の小屋や キャビンをスペイン人の小屋と一緒に建てることを義務付けた。この法律はまた、原住民にキリスト教を教えることを命じ、重婚を違法とした[1]。 1513年7月、さらに4つの法律が追加され、Leyes Complementarias de Valladolid 1513として知られる。3つはインディオの女性とインディオの子供に関するもので、もう1つはインディオの男性に関するものであった。1542年、新法 はその適用を確実にするため、それまでの法律群を拡大、修正、訂正した。これらの新法は、先住民の虐待や事実上の奴隷化を防ぐための努力であったが、ペ ルーのゴンサロ・ピサロのようなエンコメンデロによる反乱を阻止するには十分ではなかった。しかし、この一連の法律は、近代史における人道法の最も初期の 例の一つである[17]。  テオドール・デ・ブライによるスペインの残虐行為のイラスト。テオドール・デ・ブライの作品は、スペイン帝国との強い商業的・軍事的対立の結果、16世紀末に連合州やイングランドなどのプロテスタント諸国で生まれた反スペインプロパガンダの特徴である。 これらの法律は必ずしも遵守されたわけではないが、先住民の権利と幸福に対する16世紀スペイン君主国の良心と、スペイン領土の住民を保護しようとする意 志を反映している。これらの法律は植民地化の初期に、コロンブスとともに旅したスペイン人自身から報告された虐待を受けて生まれた。スペインの植民地化の 方法には、先住民をキリスト教に強制的に改宗させることも含まれていた。1523年のフランシスコ会修道士「12人への命令」は、必要であれば武力を用い て原住民を改宗させるよう促した[18]。この感情と同様に、フアン・ジネス・デ・セプルベダは、インディアンの劣等性が、彼らを文明化しキリスト教化す るために戦争を用いることを正当化すると主張した。彼は原住民の野蛮さをなくすために奴隷化と暴力を奨励した。一方、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、原 住民を平和的に改宗させることができると主張し、この視点に厳しく反対した[19]。 このようなスペインの虐待の報告は、植民地化の過程とアメリカ大陸の先住民の権利と保護についてスペインで組織的な議論を引き起こすことになった。ドミニ コ会修道士バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスは、ニュー・スペイン(特にイスパニョーラ)の植民地化初期に地主や役人が行ったとされる残虐行為について記した 『インディアスの破壊に関する短い記述』(Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias)を1542年に出版した。 [20] デ・ラス・カサスはその短い記述の中で、スペインの征服者たちを「何日も飢えさせた猛獣、狼、虎、ライオン」に例える一方で、先住民の無邪気さを強調して いる。 商人ペドロ・デ・ラス・カサス(コロンブスの2回目の航海に同行)の息子であるデ・ラス・カサスは、『インド史』の中でコロンブスの原住民に対する扱いを 記述している[22]。スペインの行動に関する彼の記述は、80年戦争のフランドル地方を含むスペインへの攻撃の根拠として使われた。スペインの植民地化 に関するデ・ラス・カサスの記述の正確さについては、誇張があったとされるため、一部の学者によっていまだに議論がある。歴史家ルイス・ハンケは、デ・ラ ス・カサスの記述は残虐行為を誇張していると考えていたが[23]、ベンジャミン・キーンは多少なりとも正確であると考えていた[24]。 チャールズ・ギブソンの1964年の単行本『スペイン統治下のアステカ人』(ニュー・スペインにおけるインディアンとスペイン人の関係に関する資料の最初 の包括的研究[要出典])は、スペインの悪魔化は「意図的なサディズムの記録の上に成り立っている」と結論付けている。それは、客観的な理解の範疇から問 題を排除する憤怒の雰囲気の中で花開く。それは植民地史の制度に対する理解において不十分である」[25]。しかしこの見解は、キーンなど他の学者によっ て広く批判されており、彼らはギブソンがスペインの残虐行為や虐待に関する大量の文書的証拠よりもむしろ法規範に焦点を当てていることを問題視している [3]。 1550年、シャルル1世はこの論争に終止符を打つため、強制的な征服を中止しようとした。フィリップ2世はフィリピン諸島で彼の足跡をたどろうとした が、以前の暴力的な征服は植民地関係を不可逆的に形成していた。これは、スペインの敵による黒い伝説の流布につながる永続的な結果のひとつであった [19]。 スペインの植民地化における先住民の扱いは、スペイン帝国に対する反感を醸成するために、敵対するヨーロッパ列強のプロパガンダに利用された。デ・ラス・ カサスの著作が初めて英語で引用されたのは、1583年に出版された『The Spanish Colonie, or Brief Chronicle of the Actes and Gestes of the Spaniards in the West Indies(西インド諸島におけるスペインの植民地、またはスペイン人の行為と行動についての簡潔な年代記)』であった。 歴史家たちは、先住民の虐待と搾取はアメリカ大陸を植民地化したすべてのヨーロッパ列強が行ったことであり、そのような行為は決してスペイン帝国だけのも のではなかったと指摘している。現代の歴史学における黒い伝説の再評価は、西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の影響に対する歴史学的評価が進化を続けている近 年、スペイン以外のヨーロッパの植民地記録の再評価につながっている。学者ウィリアム・B・マルトビーによれば、「少なくとも3世代にわたる研究によっ て、旧世界と新世界の両方におけるスペインの行為について、よりバランスのとれた評価がなされるようになった一方で、他の帝国列強の悲惨な記録はより客観 的な評価を受けるようになった」[26]。 オランダとの戦争 スペインの連合王国との戦争、特にカスティーリャの貴族アルバ公フェルナンド・アルバレス・デ・トレドの勝利と残虐行為は、反スペイン感情に拍車をかけ た。1567年8月、印刷機がさまざまな意見(特にカトリック教会に反対する意見)を助長していたヨーロッパの政治不安に対抗するために派遣されたアルバ は、出版業界を掌握し、何人かの印刷業者を追放し、少なくとも1人は処刑された。何人かの印刷業者は追放され、少なくとも1人は処刑された。書店や印刷業 者は、禁書を出版したことで訴追・逮捕され、その多くは禁書目録の一部となった。 1567年夏、オランダのカルヴァン派がカトリックの修道院や教会の彫像や装飾を破壊するという暴力事件が再び起こった。1567年3月のオーステル ウィールの戦いは、この騒乱に対するスペインの最初の軍事的対応であり、八十年戦争の始まりとなった。1568年、アルバはオランダの著名な貴族たちをブ リュッセルの中央広場で処刑させ、反スペイン感情に火をつけた。1572年10月、オレンジ軍がメヘレン市を占領した後、スペインの大軍が近づいているこ とを聞いたメヘレン中尉は降伏しようとした。軍をなだめる努力にもかかわらず、ファドリケ・アルバレス・デ・トレド(オランダ総督の息子で公爵軍の司令 官)は部下に3日間の略奪を許し、アルバはフィリップ2世に「城壁には釘一本残っていなかった」と報告した。アルバは「城壁に釘は残されていなかった」と フィリップ2世に報告している[27][28]。1年後、判事たちはスペイン兵が他の場所に売却した教会の美術品を取り戻そうとしていた。 1572年11月と12月、公爵の許可を得て、ファドリケはズートフェンとナーデンの住民を教会に閉じ込めて焼き殺させた[28][34]。1573年7 月、6ヶ月の包囲の後、ハーレム市は降伏した。守備隊の兵士(ドイツ兵を除く)は公爵軍によって溺死させられたり喉を切られたりし、著名な市民は処刑され た[28]。 10,000人以上のハールレム市民が城壁で殺され、2,000人近くが焼かれたり拷問を受けたりし、その2倍の数が川で溺死した[35]。アルバ公はオ ランダで18,600人を焼き殺すか処刑したと自慢していたが[36]、それに加えて戦争中に虐殺した人数ははるかに多く、その多くは女性や子供であっ た。  1576年11月4日にアントワープで起こったスペインの大虐殺を描いた現代の匿名の絵  1579年、マーストリヒトでのスペインの怒り オランダの反乱は、1570年代半ばにフランドル軍が給与不足を理由に反乱を起こし、1576年のアントワープを筆頭にいくつかの都市で大暴れした後、南 部に広がった。兵士たちは街を暴れまわり、殺し、略奪し、住民から金を脅し取り、金を払わない者の家を焼き払った。クリストフ・プランタンの印刷所は3度 破壊の危機にさらされたが、身代金を支払うことでその都度免れた。1,000棟の建物が放火され、17,000人もの市民が強姦され、拷問され、殺害され た[38][39]。親は子供の目の前で拷問され、幼児は母親の腕の中で殺され、妻は夫の目の前で鞭打たれて殺された。 [40] マーストリヒトはテルシオス・デ・フランドルによって2度(1576年と1579年)包囲され、略奪され、破壊され、1579年の包囲戦は1万人の男、 女、子供を殺したスペインの怒りで終わった。 [41]: 城壁を突破した247人のスペイン軍は、まず女性を強姦し、その後住民を虐殺し、手足を引き裂いたと言われている[42]。兵士たちは数百人の市民をマー ス川にかかる橋から投げ落として溺死させたが、これは以前ズットフェンで起こった出来事と似たエピソードである。軍事的恐怖がフランドル運動を敗北させ、 ベルギーにおけるスペインの支配を回復させた[43]。 スペイン王室との闘争中にオランダの反乱によって生み出されたプロパガンダもまた、黒い伝説の一部として見ることができる。デ・ラス・カサスが描写したイ ンディオに対する略奪は、オランダにおけるアルバとその後継者たちの略奪と比較された。Brevissima relación』は1578年から1648年の間にオランダで33回以上も再版された(他のヨーロッパ諸国を合わせたよりも多い)[44]。 オランダを侵略し妨害するスペイン異端審問所の条文と決議は、「スペイン人がインドで行ったように」オランダの住民を飢餓に陥れ、その有力貴族を絶滅させ ようとする陰謀であると聖庁を非難した。 「シント・アルデゴンデのマルニックスは、反乱軍の著名な宣伝者であったが、1578年のドイツ議会での演説のように、スペインがオランダを「植民地化」 しようとしているとの疑惑に定期的に言及していた。 近年、ルーヴェン工科大学のマールテン・ラルムソー教授は、遺伝子検査を用いて、スペイン占領に関する通説を検証している[46]。 16世紀にスペイン軍が低地諸国で行った戦争による残虐行為は、ベルギーとオランダの社会の集合的記憶に深く刻み込まれており、彼らは一般的に、この歴史 の署名が遺伝的祖先に存在すると思い込んでいる。歴史家たちは、この思い込みはいわゆる「黒い伝説」や、スペイン兵を極端な性的侵略者として描き、記憶さ せる否定的なプロパガンダの結果だと主張している。 - Dr. Maarten Larmuseau教授、「低地諸国におけるスペイン人の存在に関する黒い伝説」: 遺伝的祖先に関する共通の信念を検証する スペイン兵による地元女性への大規模なレイプの記憶は、今日でもその遺伝的痕跡を見ることができ、この地域の黒髪の男女のほとんどは、そのレイプの際に妊 娠した子供の子孫であると一般に信じられているほど、生き続けている。この研究では、スペイン軍が占領した地域には、フランス北部の周辺地域よりも大きな イベリアの遺伝的要素は見いだされず、スペイン軍の占領による遺伝的影響は、あったとしても、現代まで生き残るには小さすぎたに違いないと結論づけられ た。しかし、この研究は、現代の集団にスペインの遺伝的刻印がないことと、集団的性暴力の発生とは矛盾しないことを明らかにしている。スペイン兵によるフ ランドル人のレイプ被害者の頻繁な殺害、レイプが常に受精につながるとは限らないという事実、レイプ被害者の非嫡出子の生存可能性の減少などはすべて、現 代の集団にイベリア人の遺伝子が大きく寄与していることを否定するものである。ラルムソーは、フランドル地方でスペイン人の遺伝的貢献に対する信仰が根強 く残っているのは、16世紀から19世紀にかけて、オランダとフランドルの国民アイデンティティの構築において黒い伝説が使われ、集団の記憶の中でスペイ ン軍の残虐性が際立ったからだと考えている。 地元紙とのインタビューの中で、ラルムソーは、スペイン軍の行為が民衆の記憶に根強く残っていることと、同じく低地地方を占領し、住民に対する暴力に加担したオーストリア軍、フランス軍、ドイツ軍があまり注目されていないこととを比較した[47]。 |

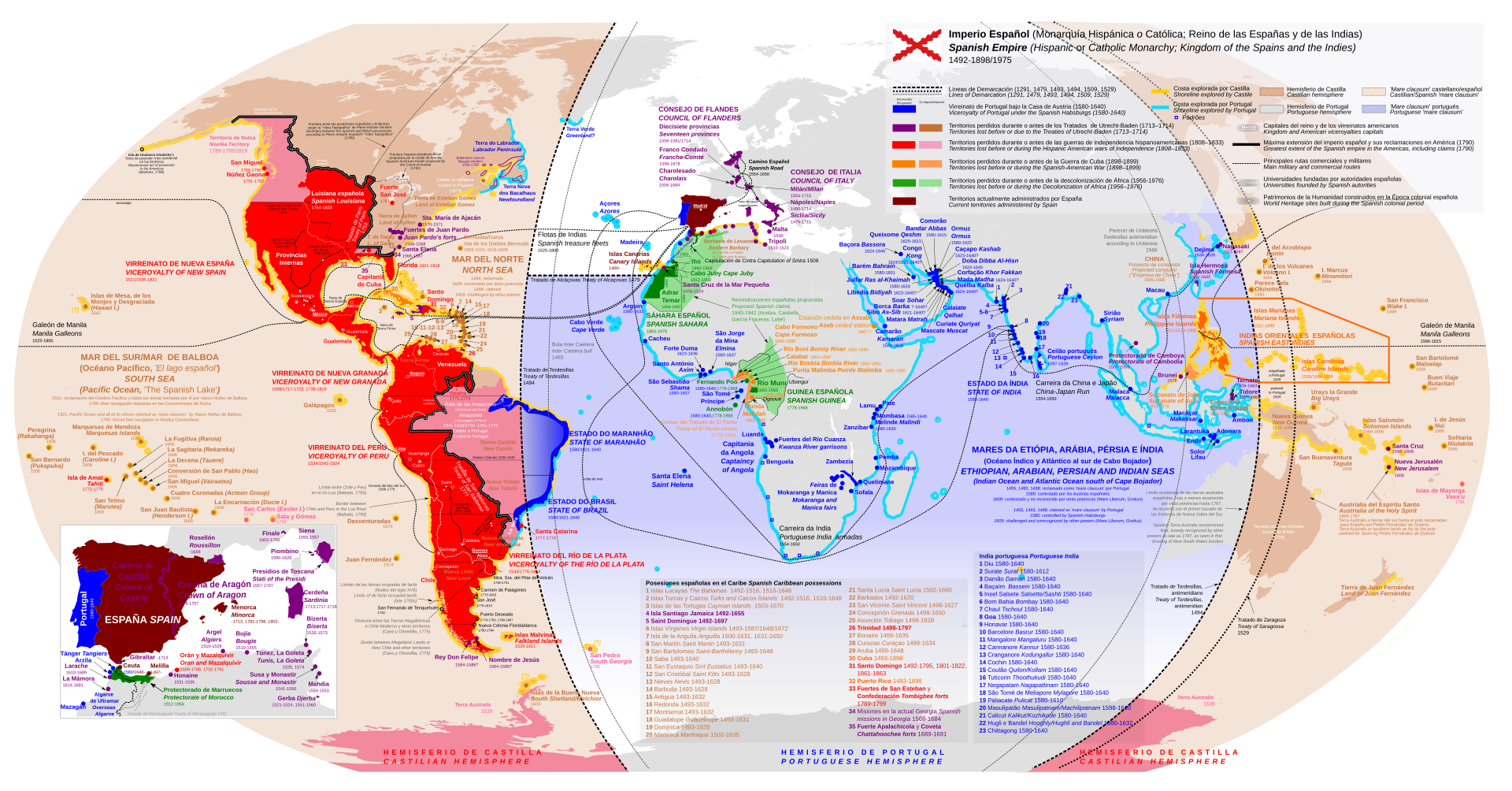

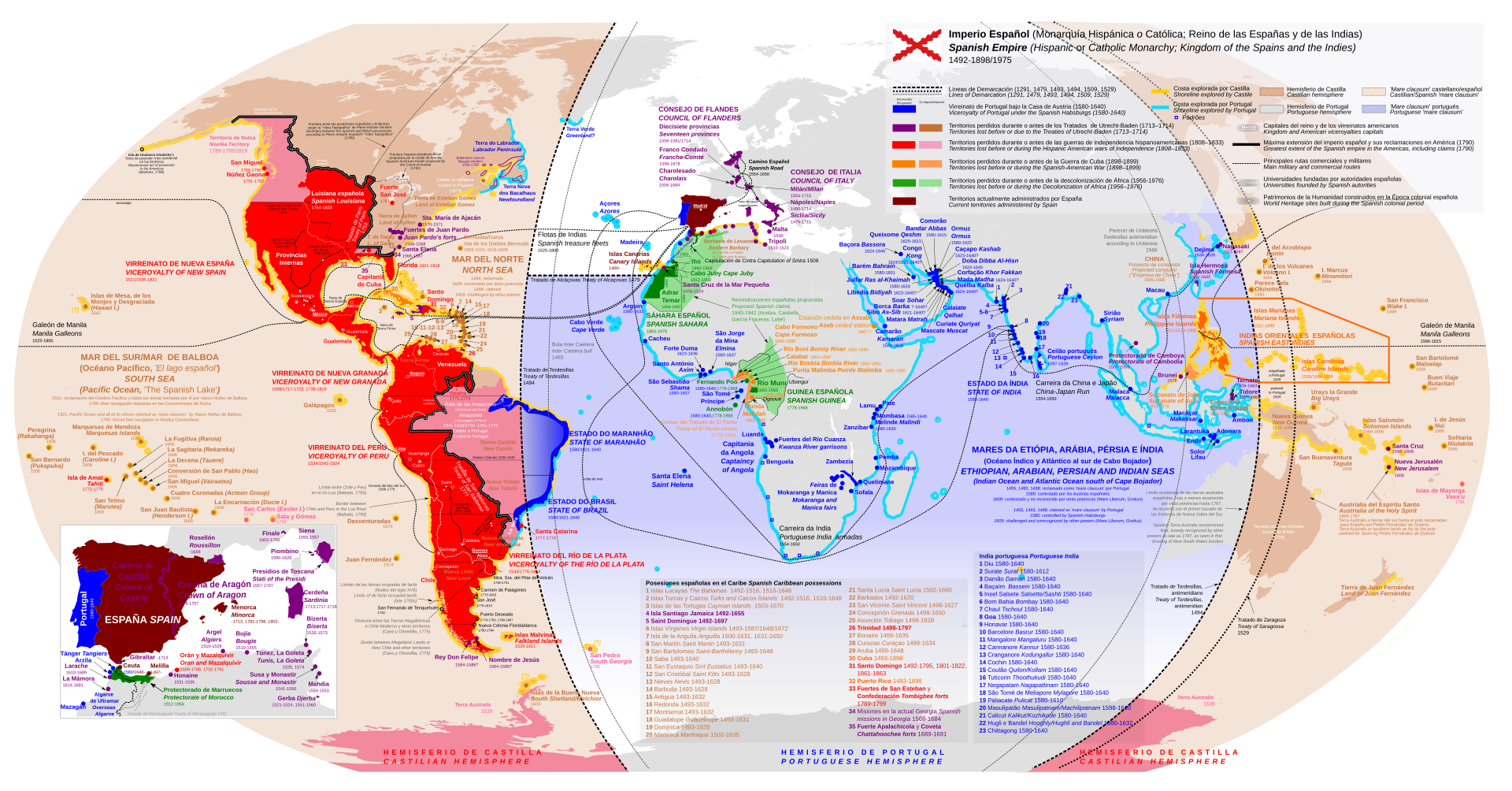

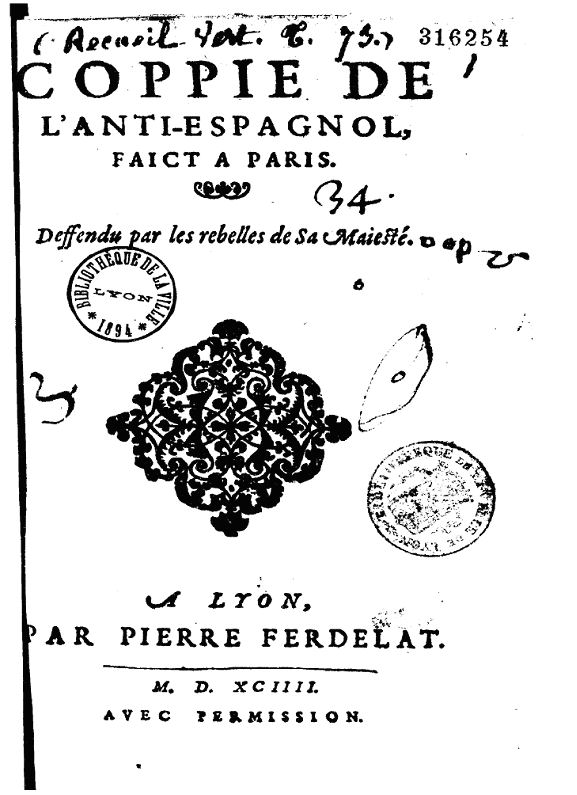

Regional perspectives Anachronous map of the Spanish Empire, including territorial claims Italy Sverker Arnoldsson of the University of Gothenburg supports Juderías' hypothesis of a Spanish black legend in European historiography and identifies its origins in medieval Italy, unlike previous authors (who date it to the 16th century). In his book The Black Legend: A Study of its Origins, Arnoldsson cites studies by Benedetto Croce and Arturo Farinelli to assert that Italy was hostile to Spain during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries when the Crown of Aragon occupied most of Italy and texts produced and distributed there were later used as a base by Protestant nations.[full citation needed] Liberal historians such as Benedetto Croce see in the Il Risorgimento process the conclusion of the unifying trend that began with the Italian Renaissance, which suffered a long interruption between the middle of the 16th century and the beginning of the 18th century that coincided with direct domination by the Hispanic Monarchy over half of Italy and indirectly over part of the other half. Croce's statements about the Italian aristocracy and their responsibility for the decline of Italy, published in 1917, when the country was in the middle of the world war, aroused reactions, accusations and even indignation on the part of historians, writers, intellectuals and politicians and "...the controversy..." writes a well-known contemporary Spanish historian "...it has not yet died out, but there are many historians who today accept, at least in part, Croce's arguments."[48] The vision of some Italian historians continues to identify the Spanish domination of Italy with a period of decadence for the country, due, in part, to the action of the Inquisition (the traditional religious court, not to be confused with the Spanish institution, which operated with different criteria). Authors such as Campanella or Giordano Bruno suffered persecution for religious reasons, as had also happened at the end of the fifteenth century and in the Florence of Savonarola. The identification of the occupier with oppression was part of the widely spread anti-Spanish propaganda known as the black legend, whose artistic products include Manzoni's "The Betrothed" (set in 17th-century Milan) or Verdi's "Don Carlos". According to one interpretation of the Risorgimento, the historical period of Spanish misrule in Milan had been chosen by Manzoni with the intention of alluding to the same oppressive rule of Austrian rule over northern Italy. Other literary critics believe instead that what Manzoni wanted to describe was the Italian society of all times, with all its defects that have remained over time.[49] Arnoldsson's theory on the origins of Spain's black legend has been criticized as conflating the process of black-legend generation with a negative view (or critique) of a foreign power. The following objections have been raised:[50] The Italian origin of the earliest writings against Spain is an insufficient reason to identify Italy as the origin of the black legend; it is a normal reaction in any society dominated by a foreign power. The phrase "black legend" suggests a tradition (non-existent in Italian writings) based on a reaction to the recent presence of Spanish troops (which quickly faded).[citation needed] In 15th- and 16th-century Italy, critics and Italian intellectual admirers of Spain (particularly Ferdinand II of Aragon) coexisted. Edward Peters states in his work "Inquisition": In Italian anti-Spanish invective, the very Christian self-consciousness that had inspired much of the drive to purify the Spanish kingdoms, including the distinctive institution of the Spanish Inquisition, was regarded outside of Spain as a necessary cleansing, since all Spaniards were accused of having Moorish and Jewish ancestry. ... First condemned for the impurity of their Christian faith, the Spaniards then came under fire for excess of zeal in defending Catholicism. Influenced by the political and religious policies of Spain, a common kind of ethnic invective became an eloquent and vicious form of description by character assassination. Thus when Bartolomé de las Casas wrote his criticism of certain governmental policies in the New World, his limited, specific rhetorical purpose was ignored. — Edward Peters, Inquisition According to William S. Maltby, Italian writings lack a "conducting theme": a common narrative which would form the Spanish black legend in the Netherlands and England.[51] Roca Barea agrees; although she does not deny that Italian writings may have been used by German rivals, the original Italian writings "lack the viciousness and blind deformation of black-legend writings" and are merely reactions to occupation.[This quote needs a citation] Germany Arnoldsson offered an alternative to the Italian-origin theory in its polar opposite: the German Renaissance.[52] German humanism, deeply nationalistic, wanted to create a German identity in opposition to that of the Roman invaders. Ulrich of Hutten and Martin Luther, the main authors of the movement, used "Roman" in the broader concept "Latin". The Latin world, which included Spain, Portugal, France, and Italy, was perceived as "foreign, immoral, chaotic and fake, in opposition to the moral, ordered and German."[53] In addition to the identification of Spaniards with Jews, heretics, and "Africans", there was an increase in anti-Spanish propaganda by detractors of Emperor Charles V. The propaganda against Charles was nationalistic, identifying him with Spain and Rome although he was born in Flanders, spoke Dutch but little Spanish and no Italian at the time, and was often at odds with the pope. To further the appeal of their cause, rulers opposed to Charles focused on identifying him with the pope (a view Charles had encouraged to force Spanish troops to accept involvement in his German wars, which they had resisted). The fact that troops and supporters of Charles included German and Protestant princes and soldiers was an extra reason to reject the Spanish elements attached to them. It was necessary to instill fear of Spanish rule, and a certain image had to be created. Among published points most often highlighted were the identification of Spaniards with Moors and Jews (due to the frequency of intermarriage), the number of conversos (Jews or Muslims who converted to Christianity) in their society, and the "natural cruelty of those two."[54] England/ Britain Spanish statesman Antonio Pérez del Hierro, who served as the secretary to Philip II of Spain before fleeing to France and then England after being arrested, wrote Pedacos de Historia o Relaciones, which was published in London by English printer Richard Field in 1594. The work, which was read widely in England, heavily denounced the Spanish monarchy and further contributed to pre-existing anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiments among the English. A violently hispanophobic preacher and pamphleteer, Thomas Scott, would echo this sort of epithet a generation later, in the 1620s, when he urged England to go to war against "those wolvish Antichristians" instead of accepting the Spanish match.[55] William S. Maltby, regarding Spain in the Netherlands, said that: As part of an Elizabethan campaign against Spain and the Catholic Church ...Literally hundreds of anti-Spanish publications appeared in English, Dutch, French, and German in the sixteenth century. New editions, and new works restating old accusations, would appear in the Thirty Years War and in other occasions when it seemed useful to excite anti-Spanish sentiment. Given the pervasiveness of such material, it is not surprising that the authors of scholarly histories absorbed anti-hispanism and transmitted it to later generations. — William S. Maltby, The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Empire Sephardic Jews See also: Jewish pirates According to Philip Wayne Powell, the criticism which was spread by the Jews who were expelled by Spain's Catholic monarchs was an important factor in the spread of anti-Spanish sentiment (particularly religious stereotypes). Powell places the beginning of the criticism of the Jewish populations against Spain in 1480, with the creation of the Spanish Inquisition, which was directed mainly against crypto-Jews and false converts. But it was from the expulsion of 1492 that this opinion became general. Despite the fact that they had previously been expelled from almost all European countries, in no other had they had such deep roots during the Middle Ages, coming to live what has been called a Golden Age, giving special relevance to this expulsion.[56] The persecution of Jews, crypto-Jews, Muslims and converts was viewed favorably in the rest of Europe and even applauded in the case of "a country so mixed with Jews and Moors" like Spain.[57] Studies by Kaplan, Yerushalmi, Mechoulan and Jaime Contreras show that many expelled Jewish intellectuals collaborated in spreading the negative image of Spain. The largest Sephardic community was in Amsterdam, in the Netherlands, with two synagogues. His activity, "little affected to the service of his Majesty", came to provoke the protest of the Spanish ambassadors before the archduke in Brussels. Especially hated was the Inquisition, considered the "fourth beast spoken of by the prophet Daniel", a denatured justification, an accumulation of evil, which had corrupted society. Criticism spread to Flanders and Venice, where Sephardim had also settled. Thus, the communities publicized the executions of the Inquisition, such as the one that occurred in 1655 in Córdoba.[58] The Sephardim were grateful to their new homeland during the Eighty Years' War: just as Spain was a "land of idolatry" and slavery, like Egypt, whose rulers suffer the curse of Yahweh; The Netherlands, on the other hand, is the land of freedom, on which the God of Israel will bring down all the blessings, as Daniel Levi de Barrios or Menasseh Ben Israel (previously called Manoel Soeiro) wrote.[59] They also used their power within the publishing industry, both to support the Dutch in their struggle and to spread criticism of Spain.[56] Islamophobia and antisemitism Outside Spain the Inquisition was regarded as a necessary cleansing which needed to be performed in Spain, since all Spaniards were accused of having Moorish and Jewish ancestry ... First condemned by the impurity of their beliefs, the Spanish then came under fire for their excess of zeal in defending Catholicism. Influenced by the political and religious policies of Spain, a common type of ethnic inventive became an eloquent form of description by character assassination. So, when Bartolomé de las Casas wrote his criticism of certain governmental policies in the New World, his limited, persuasive, specific purpose was ignored. — Edward Peters, Inquisition (1985)[full citation needed] According to Elvira Roca Barea, the Spanish Black Legend is a variant of the antisemitic narratives which had already been circulated in medieval-era Northern, Central and Southern European nations since the 13th century, critical of the perceived tolerance of Jews and heretics in Spain.[11] In 1555, after the expulsion of the Spanish Jews, Pope Paul IV described Spaniards as "heretics, schismatics, accursed of God, the offspring of Jews and Moors, the very scum of the earth".[60] This climate would facilitate the transfer of antisemitic and anti-Muslim stereotypes to Spaniards.[61] This case has three main sources of proof, the texts of German Renascence Intellectuals, the existence of the black legend narrative in Europe prior to the conquest of America, and the similarity of the stereotypes to other stereotypes which were attributed to Judaism by anti-Semitic Europeans and the stereotypes which the Black Legend attributed to the Spanish.[62] Martin Luther correlated "the Jew" (who was detested in Germany at the time) with "the Spanish", whose power was increasing in the region. According to Sverker Arnoldsson, Luther: Identified Italy and Spain with the papacy, even though the Pontifical States and Spain were enemies at the time Ignored the coexistence (including intermarriage) of Christians and Jews in Spain Conflated Spain and Turkey out of fear of an invasion by either power.[63] In 1566, Luther's conversations were published. Among many other similar affirmations, he is quoted as saying: ... Spaniern ..., die essen gern weiss Brot vnd küssen gern weisse Meidlein, vnd sind sie stiffelbraun vnd pechschwartz wie König Balthasar mit seinem Affen. The Spanish eat white bread with pleasure and kiss white women with pleasure, but they are as dirt-brown and tar-black as King Balthasar and his monkeys". —Johann Fischart, Geschichtklitterung (1575). Ideo prophetatum est Hispanos velle subigere Germaniam aut per se aut per alios, scilicet Turcam ... Et ita Germania vexabitur et viribus ac bonis suis exhausta Hispanico regno subiugabitur. Eo tendit Sathan, quod Germaniam liberam perturbare tentat Thus, it is prophesied that the Spaniards want to subjugate Germany, by itself or through others, such as the Turks. And so Germany will be humiliated and stripped of its men and property, will be submitted to the kingdom of Spain. Satan tries this because he tries to prevent a free Germany —Luther[62] |

地域的視点 領土主張を含むスペイン帝国の時代錯誤(時代を区別しない)の地図 イタリア ヨーテボリ大学のスヴェルケル・アーノルドソンは、ヨーロッパの歴史学におけるスペインの黒い伝説というユデリアスの仮説を支持し、その起源を中世イタリ アに特定した。彼の著書『黒い伝説』では、その起源について考察している: アーノルドソンは、ベネデット・クローチェとアルトゥーロ・ファリネッリの研究を引用し、アラゴン王家がイタリアの大部分を占領していた14世紀から15 世紀、16世紀にかけて、イタリアはスペインと敵対関係にあり、そこで制作・配布されたテキストは後にプロテスタント国民によって拠点として利用されたと 主張している[要出典]。 ベネデット・クローチェのような自由主義的な歴史家は、イタリア・ルネサンスから始まった統一的な流れが、16世紀半ばから18世紀初頭にかけて、ヒスパ ニック王政がイタリアの半分を直接支配し、残りの半分の一部を間接的に支配することによって、長い中断を余儀なくされたイタリア・ルネサンスの過程で終結 したと考えている。イタリアが世界大戦の真っ只中にあった1917年に発表された、イタリア貴族とそのイタリアの衰退に対する責任についてのクローチェの 発言は、歴史家、作家、知識人、政治家たちの反感、非難、さらには憤慨を呼び起こし、「...論争は...」と現代の有名なスペインの歴史家は書いてい る。 イタリアの歴史家の中には、スペインのイタリア支配を、異端審問(伝統的な宗教裁判所。) カンパネラやジョルダーノ・ブルーノのような作家は、15世紀末やサヴォナローラのフィレンツェでも起こったように、宗教的理由から迫害を受けた。占領者 を抑圧と同一視することは、黒い伝説として広く知られる反スペイン・プロパガンダの一部であり、マンゾーニの『婚約者』(17世紀のミラノが舞台)やヴェ ルディの『ドン・カルロス』などがその芸術的産物である。リソルジメントに関するある解釈によれば、ミラノにおけるスペインの圧政という歴史的時代は、北 イタリアを支配するオーストリアの圧政を暗示する意図でマンゾーニによって選ばれたという。他の文芸批評家たちは、マンゾーニが描きたかったのは、時を経 ても残る欠点だらけのあらゆる時代のイタリア社会であったと考えている[49]。 スペインの黒い伝説の起源に関するアルノルドソンの説は、黒い伝説の生成過程を外国勢力に対する否定的な見方(批判)と混同していると批判されている。以下のような反論がなされている[50]。 スペインに対する最古の著作の起源がイタリアであることは、黒い伝説の起源がイタリアであると特定するには不十分な理由である。 黒い伝説」という表現は、スペイン軍の最近の駐留に対する反応に基づく伝統(イタリアの著作には存在しない)を示唆している(すぐに風化した)[要出典]。 15~16世紀のイタリアでは、スペイン(特にアラゴンのフェルディナンド2世)を賞賛する批評家とイタリアの知識人が共存していた。 エドワード・ピーターズは著書『異端審問』の中で次のように述べている: イタリアの反スペイン的誹謗中傷では、スペイン異端審問という特徴的な制度を含め、スペイン王国を浄化しようとする動きの多くを鼓舞したキリスト教的自意 識そのものが、スペイン国外では、すべてのスペイン人がムーア人やユダヤ人の祖先を持っていると非難されたことから、必要な浄化とみなされた。... スペイン人はまず、自分たちのキリスト教信仰が不純であると非難され、次にカトリックを擁護する熱意が過剰であると非難されるようになった。スペインの政 治的・宗教的政策に影響され、一般的な民族的悪口は、雄弁で悪質な人格攻撃という形になっていった。こうして、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが新大陸の特 定の政府政策に対する批判を書いたとき、彼の限定された特定の修辞的目的は無視された。 - エドワード・ピーターズ『異端審問 ウィリアム・S・マルトビーによれば、イタリアの著作には「伝導テーマ」、すなわちオランダやイギリスにおけるスペインの黒い伝説を形成することになる共 通の物語が欠如している[51]。ロカ・バレアもこれに同意している。彼女はイタリアの著作がドイツのライバルによって利用された可能性を否定はしない が、オリジナルのイタリアの著作には「黒い伝説の著作のような悪意や盲目的なデフォルメがなく」、占領に対する反応に過ぎない。 ドイツ アーノルドソンは、イタリア起源説の対極にあるもの、すなわちドイツ・ルネサンスに代替案を提示した[52]。 ドイツの人文主義は深い民族主義的なものであり、ローマ帝国の侵略に対抗するドイツのアイデンティティを創造しようとした。この運動の主著者であるウル リッヒ・オブ・ハッテンとマルティン・ルターは、「ローマ」をより広い概念である「ラテン」の中で用いていた。スペイン、ポルトガル、フランス、イタリア を含むラテン世界は、「外国、不道徳、混沌、偽物であり、道徳的で秩序あるドイツと対立するもの」と認識されていた[53]。 スペイン人がユダヤ人、異端者、「アフリカ人」と同一視されたことに加え、皇帝シャルル5世を非難する人々による反スペインプロパガンダが増加した。シャ ルルに対するプロパガンダは、フランドル生まれでオランダ語を話すがスペイン語はほとんど話せず、当時イタリア語も話せず、しばしばローマ教皇と対立して いたにもかかわらず、シャルルをスペインとローマと同一視する民族主義的なものであった。 自分たちの大義名分をさらにアピールするために、シャルルに反対する支配者たちはシャルルをローマ教皇と同一視することに力を注いだ(シャルルは、スペイ ン軍が抵抗していたドイツ戦争への参加を受け入れさせるために、この見方を奨励した)。シャルルの軍隊や支持者にドイツやプロテスタントの王子や兵士が含 まれていたことは、彼らに付随するスペイン的要素を拒絶する余計な理由となった。スペインの支配に対する恐怖心を植え付け、一定のイメージを植え付ける必 要があった。最もよく取り上げられたのは、スペイン人がムーア人やユダヤ人と同一視されていること(婚姻の頻度による)、彼らの社会におけるコンヴォーソ (キリスト教に改宗したユダヤ人やイスラム教徒)の数、そして「この2人の自然な残酷さ」であった[54]。 イギリス/英国 スペインの政治家アントニオ・ペレス・デル・ヒエロは、スペインのフィリップ2世の秘書を務めた後、逮捕されてフランス、そしてイギリスに逃れたが、 『Pedacos de Historia o Relaciones』を書き、1594年にイギリスの印刷業者リチャード・フィールドによってロンドンで出版された。イギリスで広く読まれたこの著作 は、スペイン王政を激しく非難し、イギリス人の間に以前からあった反スペイン、反カトリック感情をさらに助長した。激しくスペイン嫌いの説教者でありパン フレット作成者であったトーマス・スコットは、1世代後の1620年代に、スペインとの結婚を受け入れる代わりに「狼のような反キリスト教徒たち」と戦争 するようイングランドに促し、このような蔑称を繰り返すことになる[55]。 ウィリアム・S・マルトビーは、オランダのスペインに関して次のように述べている: スペインとカトリック教会に対するエリザベス朝のキャンペーンの一環として......16世紀には文字通り何百もの反スペイン出版物が英語、オランダ 語、フランス語、ドイツ語で出版された。三十年戦争や、反スペイン感情を煽るのに有効と思われるその他の機会にも、新しい版や、古い非難を再掲した新しい 作品が登場した。このような資料が蔓延していたことを考えれば、学問的な歴史書の著者が反イスパニア主義を吸収し、後世に伝えたとしても驚くには当たらな い。 - ウィリアム・S・マルトビー『スペイン帝国の興亡 セファルディック・ユダヤ人 以下も参照のこと: ユダヤ人海賊 フィリップ・ウェイン・パウエルによれば、スペインのカトリック君主によって追放されたユダヤ人たちが広めた批判は、反スペイン感情(特に宗教的ステレオ タイプ)を広める重要な要因となった。パウエルは、スペインに対するユダヤ人の批判が始まったのは、1480年にスペイン異端審問所が設立されたときであ り、それは主に隠遁ユダヤ人や偽改宗者に向けられたものであったとする。しかし、この意見が一般的になったのは1492年の追放からである。ユダヤ人、偽 ユダヤ人、イスラム教徒、改宗者に対する迫害は、ヨーロッパの他の国々では好意的に受け止められ、スペインのような「ユダヤ人とムーア人が混在する国」に 対しては喝采さえ送られた[57]。 カプラン、イェルシャルミ、メクーラン、ハイメ・コントレラスの研究によれば、追放されたユダヤ人知識人の多くがスペインの否定的なイメージを広めること に協力していた。最大のセファルディコミュニティはオランダのアムステルダムにあり、2つのシナゴーグがあった。その活動は「国王陛下への奉仕にほとんど 影響を与えなかった」ため、ブリュッセルの大公の前でスペイン大使たちの抗議を招くことになった。特に嫌われたのは異端審問で、「預言者ダニエルが語った 第4の獣」、社会を腐敗させた悪の集積であり、変性した正当化であるとみなされた。批判は、セファルディムが定住していたフランドルやヴェネツィアにも広 がった。こうして共同体は、1655年にコルドバで起こったような異端審問の処刑を公にした[58]。 セファルディムは80年戦争の間、新しい祖国に感謝していた。スペインがエジプトのような「偶像崇拝」と奴隷の国であり、その支配者はヤハウェの呪いに苦 しんでいたように、一方オランダは自由の国であり、イスラエルの神がすべての祝福を下してくださるとダニエル・レヴィ・デ・バリオスやメナセ・ベン・イス ラエル(以前はマノエル・ソエイロと呼ばれていた)は書いていた。 [彼らはまた、オランダの闘争を支援し、スペインに対する批判を広めるために、出版業界における権力を利用した[56]。 イスラム恐怖症と反ユダヤ主義 スペイン国外では、異端審問はスペインで行われる必要がある浄化とみなされていた。スペイン人はまず、その信仰の不純さによって非難され、次にカトリック を擁護するための過剰な熱意によって非難を浴びるようになった。スペインの政治的・宗教的政策に影響され、よくあるタイプの民族的創作は、人格攻撃による 雄弁な描写となった。そのため、バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスが新大陸の特定の政府政策に対する批判を書いたとき、彼の限定的で説得力のある特定の目的は 無視された。 - エドワード・ピーターズ『異端審問』(1985年)[完全な引用が必要]。 エルヴィラ・ロカ・バレアによれば、スペイン黒い伝説は、13世紀以来、中世時代の北欧、中欧、南欧の国民にすでに流布していた反ユダヤ主義的な物語の変 形であり、スペインにおけるユダヤ人や異端者に対する寛容さを批判するものであった[11]。 1555年、スペインのユダヤ人が追放された後、教皇パウロ4世はスペイン人を「異端者、分裂主義者、神から呪われた者、ユダヤ人とムーア人の子孫、まさ に地のカス」と評した。 [このような風潮は、反ユダヤ的で反イスラム的なステレオタイプのスペイン人への移入を促進することになる[60]。 この事例には3つの主な証拠資料がある。ドイツのルナサンス知識人のテキスト、アメリカ征服以前のヨーロッパにおける黒い伝説の物語の存在、そして反ユダ ヤ主義的なヨーロッパ人によってユダヤ教に帰属させられた他のステレオタイプと黒い伝説がスペイン人に帰属させたステレオタイプとの類似性である [62]。 マルティン・ルターは、「ユダヤ人」(当時ドイツで嫌悪されていた)と、この地域で勢力を拡大していた「スペイン人」を関連づけた。スヴェルカー・アーノルドソンによれば、ルターは次のように述べている: イタリアとスペインをローマ教皇庁と同一視した(教皇庁とスペインは当時敵対関係にあったにもかかわらず)。 スペインにおけるキリスト教徒とユダヤ人の共存(婚姻を含む)を無視した。 どちらかの国による侵略を恐れ、スペインとトルコを混同した[63]。 1566年、ルターの会話が出版された。その中で、ルターは次のように語っている: ... スペイン人は......、白いパンをおいしそうに食べ、白いパンをおいしそうに食べる。 スペイン人は喜んで白いパンを食べ、喜んで白い女とキスをするが、彼らはバルタザール王と彼の猿のように汚れた茶色でタールのように黒い」。 -ヨハン・フィシャール『ドイツ史』(1575年)。 予言者は、イスパノスがドイツを征服するのは自分たちだけでなく、他国、たとえばトルコのようなものであると考えた。そしてそれはゲルマニアを混乱させ、彼のウイルスと善良な兵士は、ヒスパニックの政権を征服する。こうしてサタンは、ゲルマニアが解放されることを企てた。 このように、スペイン人は、自ら、あるいはトルコ人などの他者を介して、ドイツを従属させたいと考えていると予言されている。こうしてドイツは屈辱を受 け、人員と財産を奪われ、スペイン王国に服従することになる。サタンがこれを試みるのは、自由なドイツを阻止しようとするからである。 -ルター[62] |

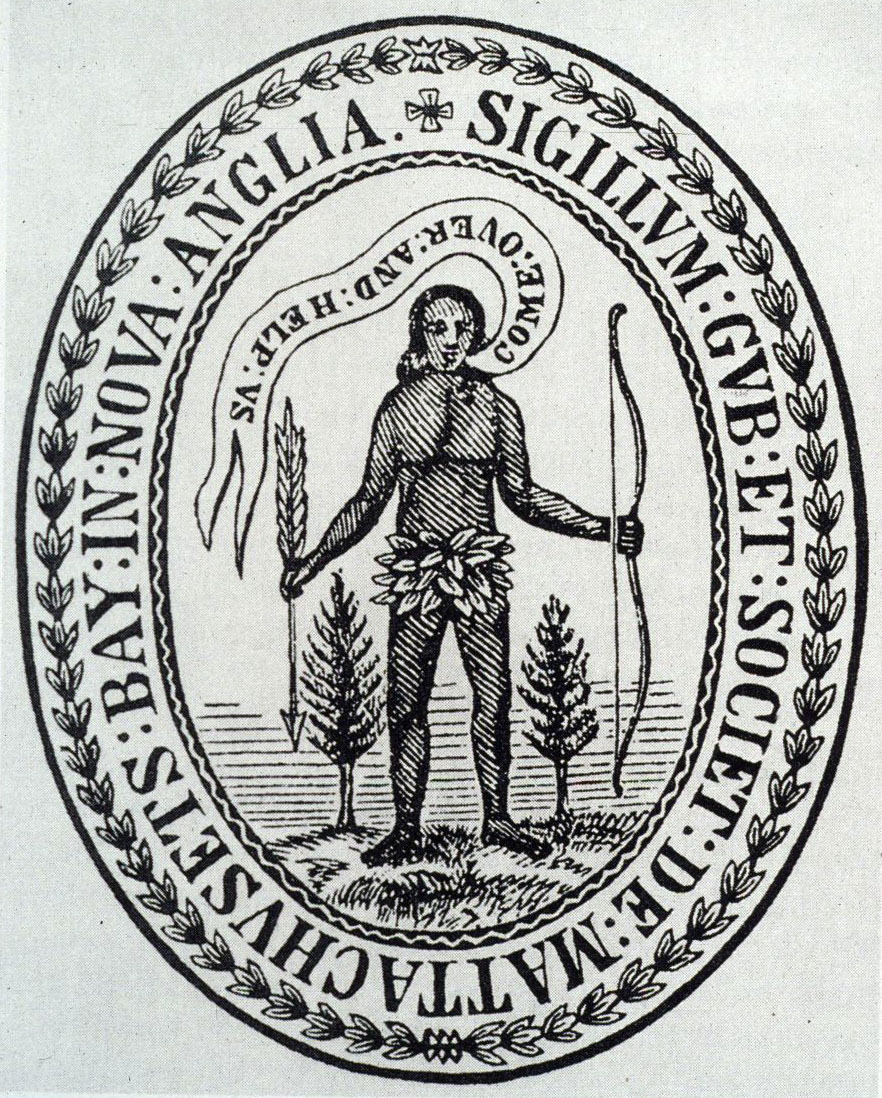

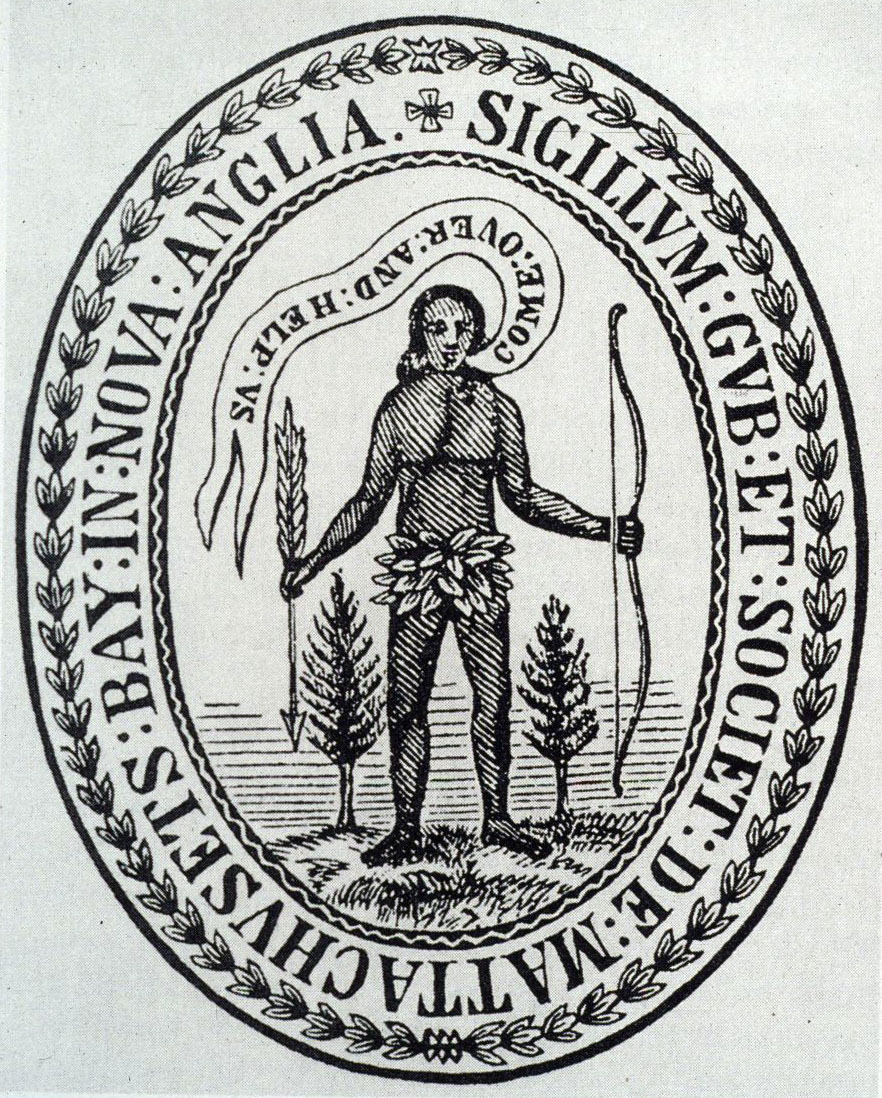

| Distribution Proponents such as Powell,[6] Mignolo[64] and Roca Barea[11] allege that the Spanish Black Legend prevails in most of Europe, especially Protestant nations and France, and the Americas. There is, however, no significant trace of it in the Muslim world or Turkey despite the almost seven centuries of sustained warfare in which Spain and the Islamic world were engaged. Historian Walter Mignolo has argued that the Black Legend was closely tied to ideologies of race, both in the way that it used the Moorish history of Spain to depict Spaniards as racially tainted, and in the way that the treatment of Africans and Native Americans during Spanish colonial projects came to symbolize their moral character.[65] America The first Puritan settlers were deeply hostile to Spain, seeing themselves as the Protestant advance guard that would free the Indians from Spanish oppression and cruelty. Prominent among these Puritan authors was Cotton Mather, who translated the Bible into Spanish for distribution among the Indians of New Spain.[66] After its independence, the United States soon became a territorial rival of Spain in America, both on the border with New Spain, and in Florida, the Mississippi or in New Orleans, a port that the Americans wanted to export their products from. The enlightened and liberal ideas that had entered the United States in the eighteenth century, joined their sympathies for the new republics emerging to the south, increasing anti-Spanish sentiment.[67] This hostility reached its zenith during the Spanish-American War, when the propaganda machine of Hearst and Pulitzer, used by their newspaper empires, had an enormous influence on public opinion in their country. The hispanophobic speeches heard in Congress during the conflict were so insulting that they led to massive protests in Spain.[68] The tensions in Hispanic America between the upper classes of creoles and peninsulares, that is, the Spaniards from the Iberian Peninsula, predate the independence of the Latin American countries. It was a confrontation for the right to control and exploit the riches of the American lands and peoples and that, in general, did not affect the lower classes. Around 1800, the ideas of the Enlightenment, with its anticlericalism, its skepticism to authorities, and its support by Masonic lodges, had been enthusiastically embraced among American intellectuals. According to Powell, these ideas were mixed with the black legend, that is, with the identification of Spain as a "horrible example" of obscurantism and backwardness, as an enemy of modernity.[69] Indeed, he claims that the American wars of independence were to some degree civil wars, with the rebels led by minorities of Creoles. With this background, Powell argues that the rebels were able to use the black legend as a propaganda weapon against the metropolis. Countless manifestos and proclamations were published quoting and praising Las Casas, poems and hymns describing the depraved nature of the "Spaniards", letters and pamphlets designed to advance the patriotic cause.[70] One of the first was the Peruvian Juan Pablo Vizcardo y Guzmán in his Carta dirigida a los españoles americanos por uno de sus compatriotas, accusing the metropolis of the serious exploitation suffered, summarizing the situation as «ingratitude, injustice, servitude and desolation». Another example is one of the great heroes of American independence, Simón Bolívar, an admirer of Las Casas, whose texts he would use profusely, blamed the Spanish for all the sins committed in America (by Creoles and non-Creoles) in the last 200 years, making the Creoles the victims, the "colonized". He would also be one of the first to appeal for the theft of American wealth and claim its return.[71] This anti-Spanish mentality was maintained during the 19th century and part of the 20th among the liberal elites, who considered "de-Hispanization" the solution to national problems.[72] The historian Powell affirms that as a consequence of denigrating Spanish culture, it has been possible to denigrate their own, of which the first is a part, both in their own eyes and in foreign eyes. In addition, the fact would have produced a certain lack of roots among the American peoples, by rejecting part of their own.[73] Europe At the same time, on the beginning of the 19th century, a school of liberal historians appeared in Spain and France who began to speak of the Spanish decline, considering the Inquisition responsible for this economic and cultural decline and for all the ills that afflicted the country. Other European historians would take up the subject later, maintaining this position in some authors until today. The reasoning stated that the expulsion of the Jews and the persecution of the converts would have led to the impoverishment and decline of Spain, in addition to the destruction of the middle class.[74] In 1867 Joaquín Costa had also raised the issue of Spanish decline. Both he and Lucas Mallada wondered if the fact was due to the Spanish character. He was joined by French and Italian sociologists, anthropologists and criminologists, who spoke more of "degeneration" than decadence, and later other Spaniards such as Rafael Salillas or Ángel Pulido. Pompeu Gener blamed Spanish decadence on religious intolerance and Juan Valera on Spanish pride. These ideas passed into literature with the Generation of '98, in texts by Pío Baroja, Azorín and Antonio Machado: «[Castilla...] a piece of the planet crossed by the wandering shadow of Caín»; reaching in some extremes to masochism and the inferiority complex. Joseph Pérez relates this rejection of one part of his own history (the expulsion of the Jews, the Inquisition, the conquest of America) and the idealization of another (Al-Andalus) with similar movements in Portugal and France.[75] Also, after the Unification of Italy, many Italian historians tended to narrate in a negative way the time when part of the Italian peninsula had formed a dynastic union with Spain. In particular, Gabriele Pepe denounced what in his eyes had been the plunder and corruption of southern Italy "under the Spanish".[76] This view only began to change in the last third of the 20th century, thanks to a series of congresses and authors such as Rosario Villari and Elena Fasano Guarini.[77] The works of Alessandro Manzoni[78][79][80][81] and Giuseppe Verdi[82] also propagated anti-Spanish propaganda on Italian literature. East Asia The period of Spanish rule in the Philippines is often presented negatively in the present day.[citation needed] Although the Philippine Islands were occupied by both Spain and the United States and the Empire of Japan, only the Spaniards were considered as the oppressors who kept the society in feudal backwardness, along with the development of a servile mentality and the cause of the ignorance through religious fanaticism, while the Americans were portrayed as liberators of the nation in the process of building a national identity against the interference of other powers (the Spanish Catholics and the Islamic sultanates), who, with their defects, were able to bring Modernization in the Islands with its liberal policies.[citation needed] A lot of investigators mention that United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands has an important role in the construction of anti-Spanish propaganda on Philippines' education.[83] The anti-Spanish propaganda has endured in historiography to this day, since scholars used to copy from the same standard books that have distorted the images of the Philippines with such tropes of the black legend.[84] That being the case, it has been denounced that "official" historiography in the Philippines, from the nationalist and liberal school, has lacked objectivity by assuming long-repeated misconceptions regarding the early modern history of the Philippines.[84] According to Phillip Powell, the leading historians of the United States in the 19th century, Francis Parkman, George Bancroft, William H. Prescott, and John Lothrop Motley, would also write History tinged with the black legend, texts that remain important in later American historiography.[85] An example of this is The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, important source of Philippine history for non-Spanish speakers that has been criticized by modern historians, notably Glòria Cano, for deliberately distorting the original Spanish documents to portray the Captaincy General of the Philippines in a negative light.[86][87] In addition, after the United States Occupation of the Philippines, the Schurman Commission was carried out, with the purpose of preparing the conditions for the government of the Philippine islands, and in which the Philippine upper class of the Principalía and the Ilustrado intellectuals participated. Thus, Jacob Schurman built and shaped a discourse that emphasized a negative view of the Philippine Republic (while declaring that the Filipinos are not ready for independence) and outlined an obscurantist image of the Spanish regime, for which they appealed typical dichotomies between modernity vs. tradition, where the Spanish regime represented an apparent medieval and reactionary backwardness, while the US administration presented itself as liberal and progressive.[citation needed] Thus, the Americans in the Philippines developed a narrative with they belittled Spain, following the traditional lines of the Black Legend, as a feudal, exploitative and oppressive power, while also praising the Hispanic legacy in the Filipino (on a more social than political level), especially their conversion of "savages" to Christianity, but at the cost of underestimating Filipino customs (many of Hispanic origin by Catholic tradition, which the Americans considered a mistake for the Spanish to seek to achieve cultural syncretism with the barbaric and pagan).[88] American works such as The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, by Blair and Robertson, or The Americans in the Philippines, by James LeRoy, have been accused of having presented a caricatural image of Spanish history in the islands, as well as giving an erroneous image of the Catholic Church and its power as opposed to any possibility of social reforms in the Philippines.[89][90] The US administration invoked negative views of Spanish colonialism to legitimize its occupation of the islands during the next decades, as a benevolent, modern and democratic colonization against a tyrannical and backward malevolent colonizer who had not been able to develop a national identity to the Filipinos.[91] |

分布 パウエル[6]、ミニョーロ[64]、ロカ・バレア[11]などの支持者は、スペインの黒い伝説はヨーロッパの大部分、特にプロテスタント諸国とフラン ス、そしてアメリカ大陸に広まっていると主張している。しかし、スペインとイスラム世界がほぼ7世紀にわたって持続的な戦争を繰り広げていたにもかかわら ず、イスラム世界やトルコにはその痕跡がほとんどない。歴史家のウォルター・ミニョーロは、黒い伝説はスペインのムーア人の歴史を利用してスペイン人を人 種的に汚染されたものとして描いた点でも、スペインの植民地事業におけるアフリカ人やアメリカ先住民の扱いが彼らの道徳的性格を象徴するようになった点で も、人種に関するイデオロギーと密接に結びついていたと論じている[65]。 アメリカ 最初のピューリタン入植者たちはスペインを深く敵視し、自分たちはスペインの抑圧と残酷さからインディアンを解放するプロテスタントの先兵だと考えてい た。これらのピューリタンの著者の中で著名なのはコットン・メイザーで、彼は聖書をスペイン語に翻訳し、ニュー・スペインのインディアンの間で配布した [66]。独立後、アメリカはすぐに、ニュー・スペインとの国境、フロリダ、ミシシッピ、またはアメリカ人が製品の輸出を望んだ港であるニューオーリンズ の両方において、アメリカにおけるスペインの領土的ライバルとなった。18世紀にアメリカに流入した啓蒙的で自由主義的な思想は、南部に台頭した新しい共 和国への共感と結びついて、反スペイン感情を増大させた[67]。この敵意は米西戦争中に頂点に達し、ハーストとピューリッツァーの新聞帝国によるプロパ ガンダ・マシンが自国の世論に多大な影響を及ぼした。紛争中に議会で聞かれたヒスパノフォビア(スペイン人嫌悪)的な演説は、スペインで大規模な抗議を引 き起こすほど侮辱的なものだった[68]。 ヒスパニック・アメリカにおけるクレオール人とペニンシュラ人、つまりイベリア半島出身のスペイン人の上流階級間の緊張は、ラテンアメリカ諸国の独立より も前にあった。それは、アメリカの土地と民族の富を支配し搾取する権利をめぐる対立であり、一般的に下層階級には影響を与えなかった。1800年頃、反教 権主義、権威への懐疑主義、メーソンロッジによる支持といった啓蒙思想が、アメリカの知識人の間で熱狂的に受け入れられていた。パウエルによれば、こうし た思想は黒い伝説、すなわちスペインを蒙昧主義と後進性の「恐ろしい見本」として、近代性の敵として同一視することと混ざり合っていた[69]。実際、ア メリカの独立戦争は、少数派のクレオール人が率いた反乱軍による、ある程度内戦的なものであったと彼は主張する。 こうした背景からパウエルは、反乱軍は大都市に対するプロパガンダの武器として黒い伝説を利用することができたと主張する。ラス・カサスを引用し賞賛する 無数のマニフェストや宣言文、「スペイン人」の堕落した性質を描写する詩や賛美歌、愛国的大義を推進するための手紙やパンフレットが出版された。 [70] その最初の一人がペルー人のフアン・パブロ・ビスカルド・イ・グスマンで、『Carta dirigida a los españoles americanos por uno de sus compatriotas』の中で、「恩義、不正義、隷属、荒廃」と要約し、大都市が受けた深刻な搾取を非難した。もう一つの例は、アメリカ独立の偉大な 英雄の一人、シモン・ボリーバルである。彼はラス・カサスを敬愛し、そのテキストを多用し、過去200年間にアメリカで(クレオールと非クレオールによっ て)犯したすべての罪をスペイン人になすりつけ、クレオールを被害者、「植民地化」された者とした。彼はまた、アメリカの富の窃盗を訴え、その返還を要求 する最初の人物の一人でもあった[71]。 このような反スペイン的なメンタリティは、19世紀から20世紀の一部にかけて、「脱ヒスパニゼーション」を国民的問題の解決策と考えるリベラルなエリー トたちの間で維持された[72]。歴史家パウエルは、スペイン文化を否定した結果として、スペイン文化がその一部である自国の文化を、自国の目にも外国の 目にも否定することが可能になったと断言する。加えて、この事実は、自国の文化の一部を否定することによって、アメリカ国民の間にある種のルーツの欠如を 生み出すことになった[73]。 ヨーロッパ 同じ頃、19世紀初頭にスペインとフランスで自由主義的な歴史家の一派が現れ、スペインの衰退について語り始め、異端審問がこの経済的・文化的衰退の原因 であり、スペインを苦しめたあらゆる悪の原因であると考えた。他のヨーロッパの歴史家たちも後にこのテーマを取り上げ、今日までこの立場を維持している著 者もいる。その理由は、ユダヤ人の追放と改宗者の迫害は、中産階級の破壊に加えて、スペインの貧困化と衰退につながったというものであった[74]。 1867年、ホアキン・コスタもスペインの衰退の問題を提起していた。彼とルーカス・マジャダはともに、その事実がスペインの性格によるものなのかどうか 疑問に思っていた。彼にフランスやイタリアの社会学者、人類学者、犯罪学者が加わり、彼らは退廃というよりも「退化」について語り、後にはラファエル・サ リリャスやアンヘル・プリドといった他のスペイン人も加わった。ポンペウ・ジェネルはスペインの退廃を宗教的不寛容のせいにし、フアン・バレラはスペイン のプライドのせいにした。このような考えは、ピオ・バロハ、アゾリン、アントニオ・マチャドらによって書かれた98年のジェネレーションとともに、文学へ と受け継がれた: 「カスティーリャは...カインの彷徨う影が横切る地球の一部」、極端な言い方をすればマゾヒズムと劣等コンプレックスに達する。ジョセフ・ペレスは、自 国の歴史の一部(ユダヤ人の追放、異端審問、アメリカの征服)を拒絶し、別の歴史(アル=アンダルス)を理想化するこの動きを、ポルトガルとフランスにお ける同様の動きと関連付けている[75]。 また、イタリア統一後、多くのイタリアの歴史家は、イタリア半島の一部がスペインと王朝連合を形成していた時代を否定的に叙述する傾向があった。特にガブ リエーレ・ペペは、彼の目には「スペインの下」での南イタリアの略奪と腐敗と映ったことを非難した[76]。このような見方が変わり始めたのは、20世紀 の最後の3分の1において、一連の会議やロザリオ・ヴィッラーリやエレナ・ファザーノ・グアリーニといった作家のおかげである[77]。 アレッサンドロ・マンゾーニ[78][79][80][81]やジュゼッペ・ヴェルディ[82]の作品もまた、イタリア文学における反スペインのプロパガ ンダを広めた。 東アジア フィリピンにおけるスペイン統治時代は、現代では否定的に語られることが多い。 [フィリピン諸島はスペインとアメリカ、そして大日本帝国によって占領されたが、スペイン人だけが、隷属的なメンタリティの発達とともに封建的な後進社会 を維持し、宗教的狂信によって無知をもたらした抑圧者とみなされた、 一方、アメリカ人は、他の勢力(スペインのカトリックとイスラムのスルタン)の干渉に対抗して国民的アイデンティティを構築する過程における国民の解放者 として描かれ、彼らはその欠陥によって、その自由主義的な政策で島に近代化をもたらすことができた。 [反スペイン・プロパガンダは歴史学において今日まで存続しており、学者たちはフィリピンのイメージをそのような黒い伝説で歪めた標準的な書物からコピー していた。 [84]そうなると、フィリピンの「公式」歴史学は、ナショナリストやリベラル派のものであり、フィリピンの近世史に関して長年繰り返されてきた誤解を前 提とすることで客観性を欠いてきたと非難されてきた[84]。 フィリップ・パウエルによれば、19世紀のアメリカを代表する歴史家たち、フランシス・パークマン、ジョージ・バンクロフト、ウィリアム・H・プレスコッ ト、ジョン・ロスロップ・モトリーもまた、黒い伝説に彩られた『歴史』を書いており、それらは後のアメリカの歴史学においても重要な位置を占めている。 [その一例が『フィリピン諸島、1493-1898』であり、非スペイン語話者のためのフィリピン史の重要な資料であるが、グロリア・カノを筆頭とする現 代の歴史家からは、フィリピン総督府を否定的に描くためにスペイン語の原文書を意図的に歪曲しているとの批判を受けている。 [86][87]さらに、アメリカによるフィリピン占領後、フィリピン諸島の統治条件を整えることを目的としたシュルマン委員会が実施され、フィリピンの 上流階級であるプリンシパリアとイルストラードの知識人が参加した。こうしてジェイコブ・シュルマンは、フィリピン共和国に対する否定的な見方を強調し (フィリピン人は独立の準備ができていないと宣言しながら)、スペイン政権に対する不明瞭なイメージを概説する言説を構築し、そのためにスペイン政権が明 らかに中世的で反動的な後進性を表すのに対し、アメリカ政権は自らを自由主義的で進歩的であるとする、近代対伝統の典型的な二項対立に訴えた[要出典]。 こうしてフィリピンのアメリカ人たちは、黒い伝説の伝統的な路線に従って、スペインを封建的で搾取的で抑圧的な大国として侮蔑する一方で、フィリピン人に おけるヒスパニックの遺産を(政治的なレベルよりも社会的なレベルで)賞賛するという物語を展開した、 特に「未開人」をキリスト教に改宗させたが、その代償としてフィリピン人の風習(カトリックの伝統によってヒスパニック系に由来するものが多く、アメリカ 人はスペイン人が野蛮で異教徒との文化的シンクレティズムを達成しようとしたのは間違いであったと考えた)を過小評価していた。 [88]ブレアとロバートソンによる『フィリピン諸島、1493-1898』やジェイムズ・ルロイによる『フィリピンのアメリカ人』といったアメリカの著 作は、フィリピン諸島におけるスペインの歴史を戯画的に表現し、フィリピンにおける社会改革の可能性と対立するカトリック教会とその権力について誤ったイ メージを与えたとして非難されている。 [89][90]アメリカ政権は、その後数十年の間、フィリピン人に国民的アイデンティティを育むことができなかった専制的で後進的な悪意ある植民者に対 抗する善意ある近代的で民主的な植民地化として、スペイン植民地主義に対する否定的な見解を持ち出し、島々の占領を正当化した[91]。 |

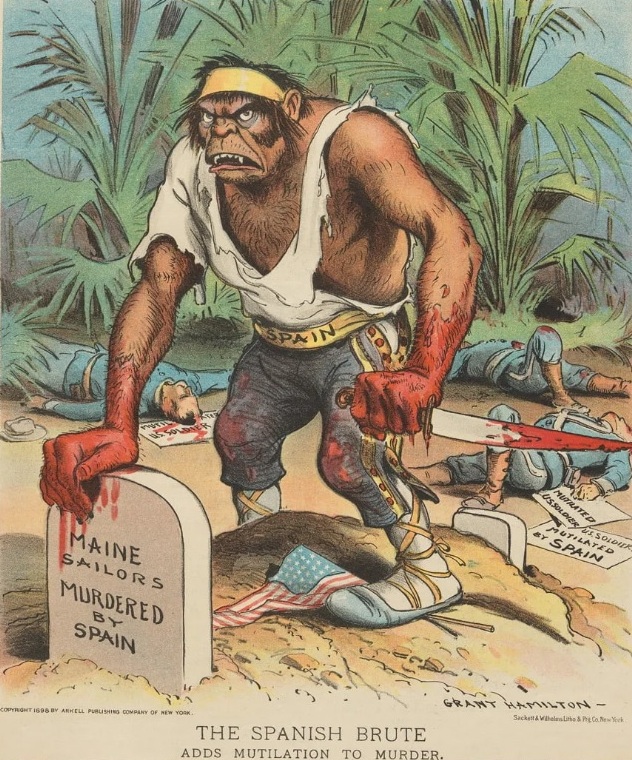

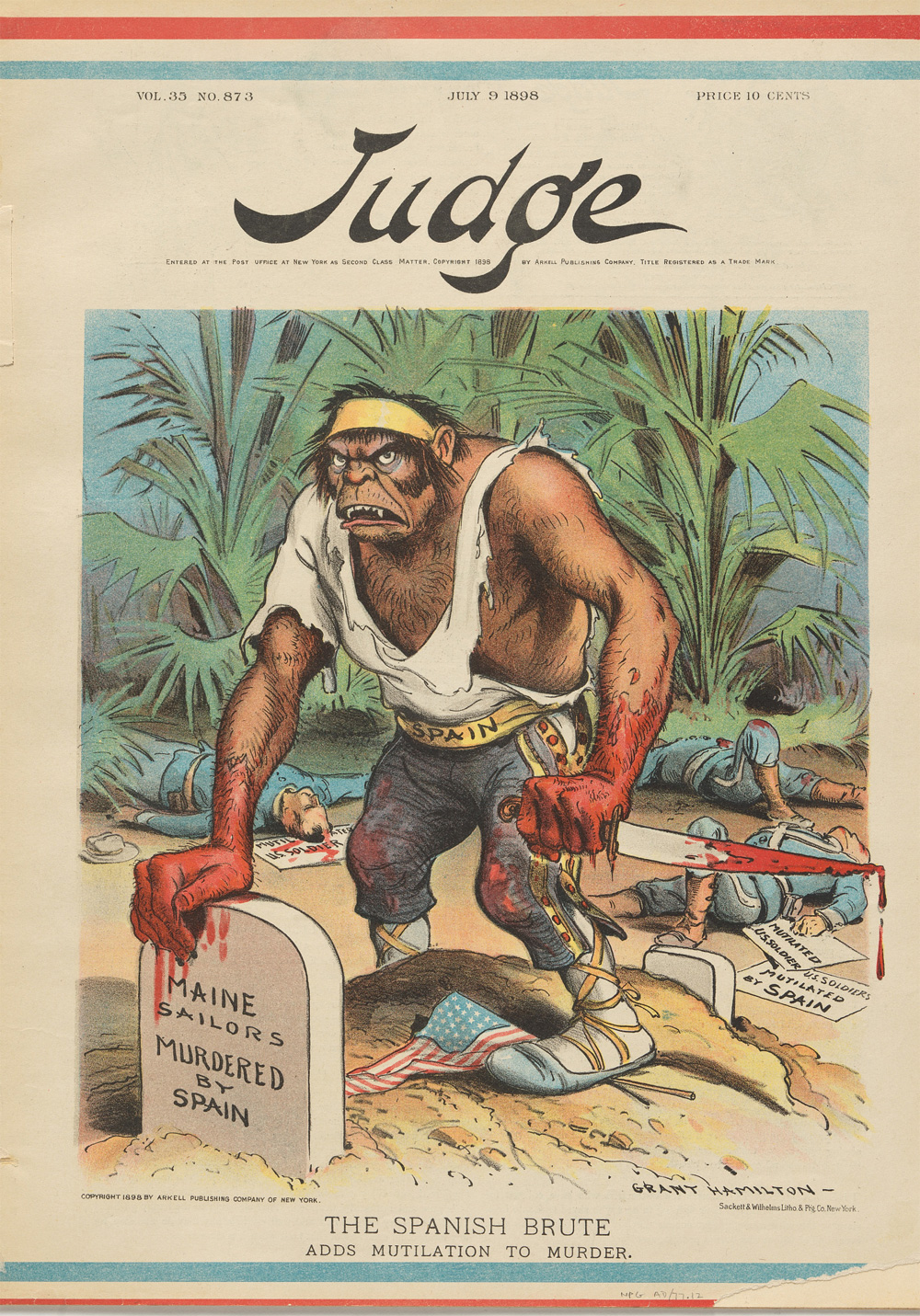

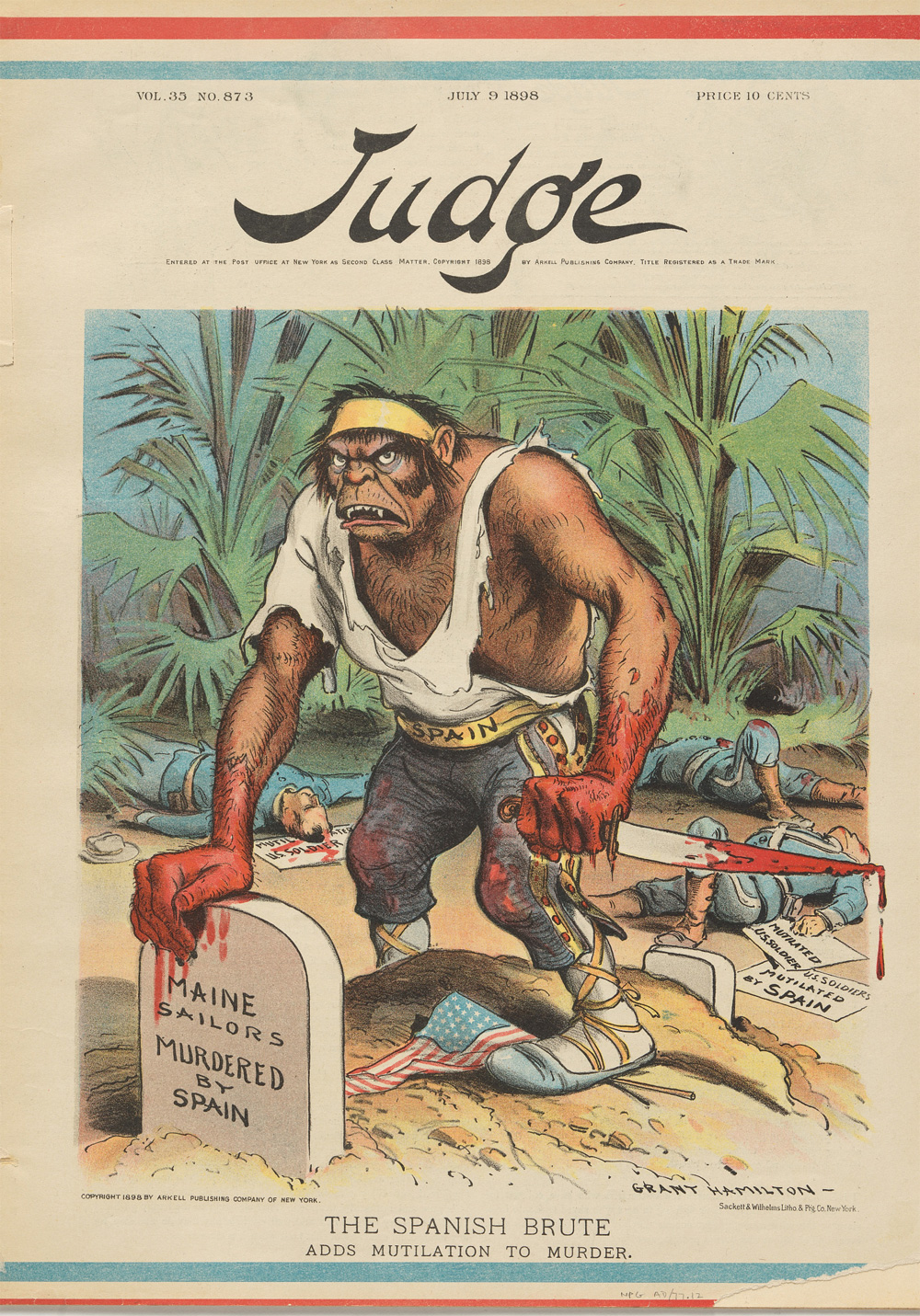

| Modern era This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. Please help clarify the section. There might be a discussion about this on the talk page. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  The Spanish Brute, US cartoon, 1898 Historians disagree on whether the Black Legend exists as a genuine factor in current discourse around Spain and its history.In recent years a group of historians including Alfredo Alvar, Ricardo García Cárcel and Lourdes Mateo Bretos have argued that the Black Legend does not currently exist beyond Spanish society's own perception of how the world views Spain's legacy.[92] According to Carmen Iglesias, the Black Legend consists of negative traits which the Spanish people see in themselves and is shaped by political propaganda.[93] The view of the group around García Cárcel is echoed by Benjamin Keen, writing in 1969. He argues that the concept of the Black Legend cannot be considered valid, given that the negative depiction of Spanish behavior in the Americas was largely accurate. He further claims that whether a concerted campaign of anti-Spanish propaganda based on imperial rivalry ever existed is at least open to question.[94] Henry Kamen argues that the Black Legend existed during the 16th century but has disappeared in contemporary perceptions of Spain. However, other authors, like Elvira Roca Barea, Tony Horowitz and Philip Wayne Powell, have argued that it still affects the manner in which Spain is perceived, and that it is brought up strategically during diplomatic conflicts of interest as well as in popular culture to draw attention away from the negative actions of other nations. Historian John Tate Lanning argued that the most detrimental impact of the Black Legend was to reduce the Spanish colonization of the Americas (and the resulting culture that emerged) to "three centuries of theocracy, obscurantism, and barbarism."[95] In 2006, Tony Horowitz argued in The New York Times that the Spanish Black Legend affected current U.S. immigration policy.[96] The Venezuelan case has been studied by Gilberto Ramón Quintero Lugo in his book «La Leyenda Negra y su influjo en la historiografía venezolana de la Independencia» (April 2004).[97] In her 2016 book exploring “empire-phobia” as a recurring sociopolitical phenomenon in human history, Elvira Roca Barea argues that the unique persistence of the Spanish Black Legend beyond the end of the Spanish Empire is tied to a continued anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiment in traditionally Protestant European countries: If we deprive Europe of its hispanophobia and anti-Catholicism, its modern history becomes incomprehensible.[98] José Luis Villacañas, in his 2019 response to Roca Barea, labels her work as "populist national-Catholic propaganda" and accuses her of minimising Spanish atrocities in the Americas along with those of the Inquisition. He argues that, for all intents and purposes, the Black Legend has no meaning outside the context of 17th century propaganda, although he recognises that certain negative stereotypes of Spain may have persisted during the Franco regime.[12] García Cárcel criticises Roca Barea's position as adding to a long tradition of Spanish society's insecurities about how other countries perceive it. On the other hand, he also criticizes Villacañas's discourse as being heavily ideological in the opposite direction and systematically indulging in presentism. García Cárcel calls for an analysis of Spain's history that renounces both “narcissism and masochism” in favor of nuanced awareness of its “lights and shadows”.[99] Other proponents of the continuity theory include musicologist Judith Etzion[100] and Roberto Fernandez Retamar,[101] and Samuel Amago who, in his essay "Why Spaniards Make Good Bad Guys" analyzes the persistence of the legend in contemporary European cinema.[102] |