政体

Body politic

The

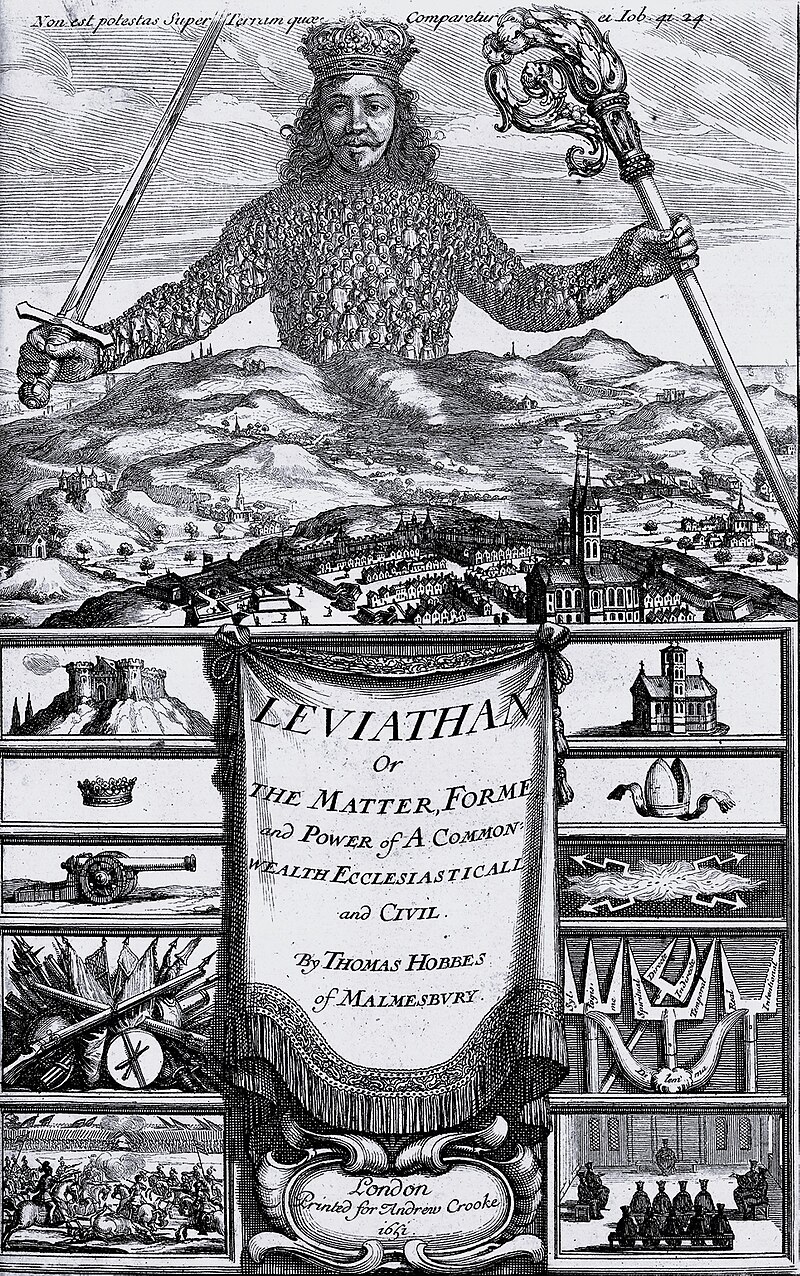

frontispiece of Hobbes's Leviathan shows a body formed of multitudinous

citizens, surmounted by a king's head.[1]

☆

政体(body politic)

は、都市や王国、国家といった政治共同体を隠喩的に肉体と見なした概念である。歴史的に、君主は通常その頭部として描かれ、この比喩はイソップ寓話『腹と

手足』の政治的解釈に見られるように、他の解剖学的部位にも拡張されることがある。この比喩は紀元前6世紀の古代ギリシャ哲学に起源を持ち、後にローマ哲

学で発展した。

中世後期におけるビザンツ法典『コーパス・ユリス・シヴィリス』のラテンヨーロッパでの復興を経て、「政体=国家」は法人論と同一視されることで法学上の

意義を獲得し、13世紀以降、政治思想において重要性を増した。英国法においては、この政体=国家の身体像は「王の二つの身体」理論や「単独法人としての

王冠」という概念へと発展した。

ルネサンス以降、ガレノスに基づく医学知識がウィリアム・ハーヴェイら思想家によって疑問視される中、この隠喩はさらに精緻化された。病気や混乱の想定さ

れる原因と、政治分野におけるそれに対応する要素との類推がなされ、それらは浄化や特効薬で治療可能な疫病や感染と見なされた。[2]

17世紀のトマス・ホッブズの著作は、国家を人工的人格体とする近代国家理論へと、この国家を政体=国家に喩えるイメージを発展させた。ラテン語の

corpus politicumに由来する類似の用語は、他のヨーロッパ言語にも存在する。

| The body politic is

a polity—such as a city, realm, or state—considered metaphorically as a

physical body. Historically, the sovereign is typically portrayed as

the body's head, and the analogy may also be extended to other

anatomical parts, as in political readings of Aesop's fable of "The

Belly and the Members". The image originates in ancient Greek

philosophy, beginning in the 6th century BC, and was later extended in

Roman philosophy. Following the high and late medieval revival of the Byzantine Corpus Juris Civilis in Latin Europe, the "body politic" took on a jurisprudential significance by being identified with the legal theory of the corporation, gaining salience in political thought from the 13th century on. In English law the image of the body politic developed into the theory of the king's two bodies and the Crown as corporation sole. The metaphor was elaborated further from the Renaissance onwards, as medical knowledge based on Galen was challenged by thinkers such as William Harvey. Analogies were drawn between supposed causes of disease and disorder and their equivalents in the political field, viewed as plagues or infections that might be remedied with purges and nostrums.[2] The 17th century writings of Thomas Hobbes developed the image of the body politic into a modern theory of the state as an artificial person. Parallel terms deriving from the Latin corpus politicum exist in other European languages. |

政体は、都市や王国、国家といった政治共同体を隠喩的に肉体と見なした

概念である。歴史的に、君主は通常その頭部として描かれ、この比喩はイソップ寓話『腹と手足』の政治的解釈に見られるように、他の解剖学的部位にも拡張さ

れることがある。この比喩は紀元前6世紀の古代ギリシャ哲学に起源を持ち、後にローマ哲学で発展した。 中世後期におけるビザンツ法典『コーパス・ユリス・シヴィリス』のラテンヨーロッパでの復興を経て、「政体=国家」は法人論と同一視されることで法学上の 意義を獲得し、13世紀以降、政治思想において重要性を増した。英国法においては、この政体=国家の身体像は「王の二つの身体」理論や「単独法人としての 王冠」という概念へと発展した。 ルネサンス以降、ガレノスに基づく医学知識がウィリアム・ハーヴェイら思想家によって疑問視される中、この隠喩はさらに精緻化された。病気や混乱の想定さ れる原因と、政治分野におけるそれに対応する要素との類推がなされ、それらは浄化や特効薬で治療可能な疫病や感染と見なされた。[2] 17世紀のトマス・ホッブズの著作は、国家を人工的人格体とする近代国家理論へと、この国家を政体=国家に喩えるイメージを発展させた。ラテン語の corpus politicumに由来する類似の用語は、他のヨーロッパ言語にも存在する。 |

| Etymology The term body politic derives from Medieval Latin corpus politicum, which itself developed from corpus mysticum, originally designating the Catholic Church as the mystical body of Christ but extended to politics from the 11th century on in the form corpus reipublicae (mysticum), "(mystical) body of the commonwealth".[3][4] Parallel terms exist in other European languages, such as Italian corpo politico, Polish ciało polityczne, and German Staatskörper ("state body").[3] An equivalent early modern French term is corps-état;[5] contemporary French uses corps politique.[3] |

語源 「政体=国家」という用語は中世ラテン語のcorpus politicumに由来する。これはcorpus mysticumから発展したもので、元々はカトリック教会をキリストの神秘的身体として指していたが、11世紀以降「(神秘的な)共和国の身体」を意味 するcorpus reipublicae (mysticum)という形で政治分野に拡張された。[3][4] 他のヨーロッパ言語にも類似語が存在する。例えばイタリア語の「corpo politico」、ポーランド語の「ciało polityczne」、ドイツ語の「Staatskörper」(国家の体)などである。[3] 近代初期フランス語における同義語は「corps-état」であった。[5] 現代フランス語では「corps politique」を用いる。[3] |

The frontispiece of Hobbes's Leviathan shows a body formed of multitudinous citizens, surmounted by a king's head.[1] |

ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』の扉絵には、無数の市民から成る身体が描かれ、その頂点に王の頭部が置かれている。[1] |

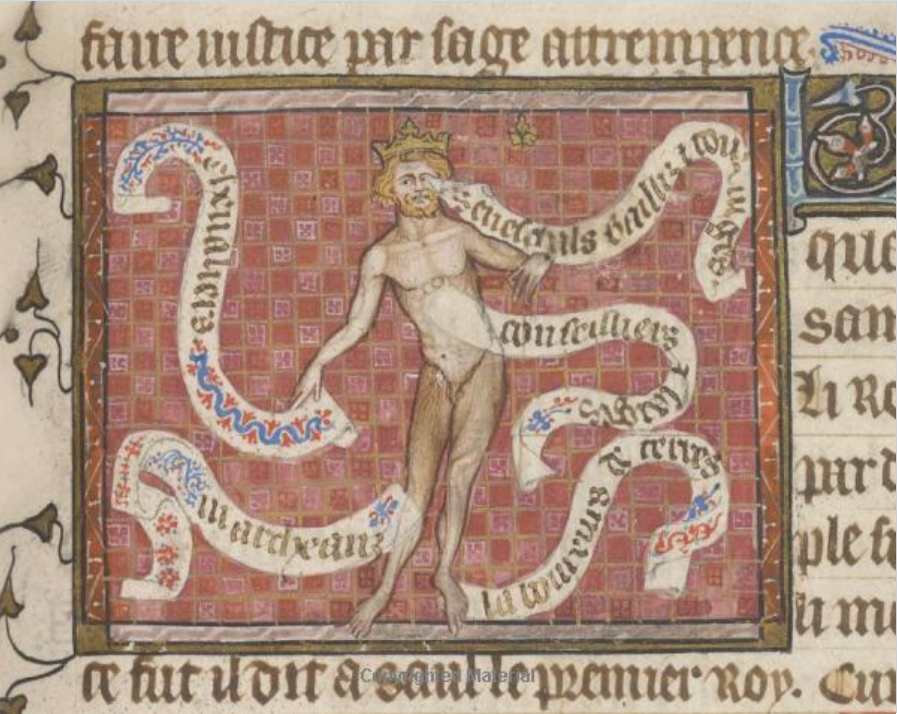

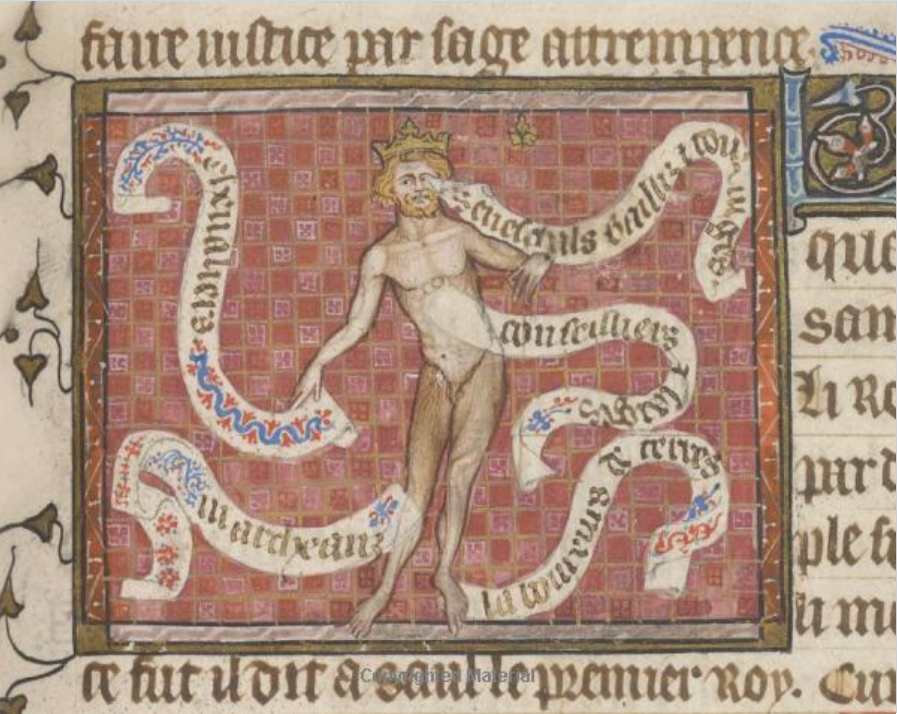

History A visualization of the body politic metaphor in a 14th-century French manuscript. The king is head. Next, the seneschals, bailiffs, and provosts and other judges are compared to eyes and ears. The counsellors and wise men are linked to the heart. As defenders of the commonwealth, the knights are the hands. Because of their constant voyages, the merchants are associated with the legs. Finally, laborers, who work close to the earth and support the body, are its feet. Classical philosophy The Western concept of the "body politic", originally meaning a human society considered as a collective body, originated in classical Greek and Roman philosophy.[6] The general metaphor emerged in the 6th century BC, with the Athenian statesman Solon and the poet Theognis describing cities (poleis) in biological terms as "pregnant" or "wounded".[7] Plato's Republic provided one of its most influential formulations.[8] The term itself, however—in Ancient Greek, τῆς πόλεως σῶμα, tēs poleōs sōma, "the body of the state"—appears as such for the first time in the late 4th century Athenian orators Dinarch and Hypereides at the beginning of the Hellenistic era.[9] In these early formulations, the anatomical detail of the body politic was relatively limited: Greek thinkers typically confined themselves to distinguishing the ruler as head of the body, and comparing political stasis, that is, crises of the state, to biological disease.[10] The image of the body politic occupied a central place in the political thought of the Roman Republic, and the Romans were the first to develop the anatomy of the "body" in full detail, endowing it with nerves, "blood, breath, limbs, and organs".[11] In its origins, the concept was particularly connected to a politicised version of Aesop's fable of "The Belly and the Members", told in relation to the first secessio plebis, the temporary departure of the plebeian order from Rome in 495–93 BC.[12][13] On the account of the Roman historian Livy, a senator explained the situation to the plebeians by a metaphor: the various members of the Roman body had become angry that the "stomach", the patricians, consumed their labours while providing nothing in return. However, upon their secession, they became feeble and realised that the stomach's digestion had provided them vital energy. Convinced by this story, the plebeians returned to Rome, and the Roman body was made whole and functional. This legend formed a paradigm for "nearly all surviving republican discourse of the body politic".[12] Late republican orators developed the image further, comparing attacks on Roman institutions to mutilations of the republic's body. During the First Triumvirate in 59 BC, Cicero described the Roman state as "dying of a new sort of disease".[14] Lucan's Pharsalia, written in the early imperial era in the 60s AD, abounded in this kind of imagery. Depicting the dictator Sulla as a surgeon out of control who had butchered the Roman body politic in the process of cutting out its putrefied limbs, Lucan used vivid organic language to portray the decline of the Roman Republic as a literal process of decay, its seas and rivers becoming choked with blood and gore.[15] |

歴史 14世紀フランス写本における政体=国家を人体に隠喩した比喩の図解。 王は頭にあたる。次に、執事長、代官、警視長その他の裁判官は目と耳に例えられる。顧問や賢者は心臓と結びつく。共同体の守護者たる騎士は手である。絶え 間ない航海ゆえに商人は足と関連づけられる。最後に、大地に近く働き体を支える労働者は足にあたる。 古典哲学 西洋における「政体=国家」という概念は、もともと人間社会を集団的身体と見なしたもので、古典ギリシャ・ローマ哲学に起源を持つ。[6] この隠喩は紀元前6世紀に現れ、アテネの政治家ソロンの詩人テオグニスは都市(ポリス)を生物学的用語で「妊娠した」あるいは「傷ついた」と表現した。 [7] プラトンの『国家』はこの概念の最も影響力ある定式化の一つを提供した。[8] しかしこの用語自体―古代ギリシャ語で「テース・ポレイオス・ソーマ(国家の身体)」―が初めて登場するのは、ヘレニズム時代初期の紀元前4世紀末、アテ ネの弁論家ディナルコスとヒュペレイドスの著作においてである。[9] こうした初期の概念では、政体=国家に関する解剖学的詳細は比較的限定されていた。ギリシャの思想家たちは通常、統治者を頭部として区別し、政治的不安定 (すなわち国家の危機)を生物学的疾患に例えることに留まっていた。[10] 政体=国家という比喩は、ローマ共和政期の政治思想において中心的な位置を占めた。ローマ人は初めて「国家」の解剖学的構造を詳細に展開し、神経や「血 液、呼吸、四肢、器官」といった要素を付与した。[11] この概念の起源は、特にイソップ寓話「腹と手足」の政治化された解釈と結びついていた。この寓話は、紀元前495年から493年にかけての最初のセッセシ オ・プレビス(平民階級のローマ一時離脱)に関連して語られたものである。[12] [13] ローマの歴史家リウィウスの記述によれば、ある元老院議員は平民たちに隠喩を用いて状況を説明した。ローマという身体の各部位が怒り狂ったのだ。貴族であ る「胃袋」が彼らの労働を消費しながら、何の見返りも与えないことに。しかし離脱後、彼らは衰弱し、胃袋の消化作用が生命力を与えていたことに気づいた。 この説得に納得した平民はローマに戻り、政体=国家は完全かつ機能的な状態を取り戻した。この伝説は「共和政期の政体=国家に関する現存するほぼ全ての言 説」の規範となった。[12] 共和政後期のアゴリテスは、この比喩をさらに発展させ、ローマ制度への攻撃を共和政の身体の切断に例えた。紀元前59年の第一次三頭政治時代、キケロは ローマ国家を「新たな病に死にかけている」と表現した。[14] 紀元60年代の帝政初期に書かれたルカヌスの『ファルサリア』には、この種の比喩が溢れている。ルカンは独裁者スッラを制御不能な外科医に喩え、腐敗した 四肢を切除する過程でローマの政体=国家を切り刻んだと描写した。鮮烈な有機的言語を用いて共和政ローマの衰退を文字通りの腐敗過程として描き、その海や 川が血と内臓で詰まる様を表現したのである。[15] |

| Medieval usage The metaphor of the body politic remained in use after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[8] The Neoplatonist Islamic philosopher al-Farabi, known in the West as Alpharabius, discussed the image in his work The Perfect State (c. 940), stating, "The excellent city resembles the perfect and healthy body, all of whose limbs cooperate to make the life of the animal perfect".[16] John of Salisbury gave it a definitive Latin high medieval form in his Policraticus around 1159: the king was the body's head; the priest was the soul; the councillors were the heart; the eyes, ears, and tongue were the magistrates of the law; one hand, the army, held a weapon; the other, without a weapon, was the realm's justice. The body's feet were the common people. Each member of the body had its vocation, and each was beholden to work in harmony for the benefit of the whole body.[17] In the Late Middle Ages, the concept of the corporation, a legal person made up of a group of real individuals, gave the idea of a body politic judicial significance.[18] The corporation had emerged in imperial Roman law under the name universitas, and a formulation of the concept attributed to Ulpian was collected in the 6th century Digest of Justinian I during the early Byzantine era.[19] The Digest, along with the other parts of Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis, became the bedrock of medieval civil law upon its recovery and annotation by the glossators beginning in the 11th century.[20] It remained for the glossators' 13th century successors, the commentators—especially Baldus de Ubaldis—to develop the idea of the corporation as a persona ficta, a fictive person, and apply the concept to human societies as a whole.[18]  The imperial eagle in Dante's Paradiso, depicted by Giovanni di Paolo in the 1440s Where his jurist predecessor Bartolus of Saxoferrato conceived the corporation in essentially legal terms, Baldus expressly connected the corporation theory to the ancient, biological and political concept of the body politic. For Baldus, not only was man, in Aristotelian terms, a "political animal", but the whole populus, the body of the people, formed a type of political animal in itself: a populus "has government as part of [its] existence, just as every animal is ruled by its own spirit and soul".[21] Baldus equated the body politic with the respublica, the state or realm, stating that it "cannot die, and for this reason it is said that it has no heir, because it always lives on in itself".[22] From here, the image of the body politic became prominent in the medieval imagination. In Canto XVIII of his Paradiso, for instance, Dante, writing in the early 14th century, presents the Roman Empire as a corporate body in the form of an imperial eagle, its body made of souls.[23] The French court writer Christine de Pizan discussed the concept at length in her Book of the Body Politic (1407).[24] The idea of the body politic, rendered in legal terms through corporation theory, also drew natural comparison to the theological concept of the church as a corpus mysticum, the mystical body of Christ. The concept of the people as a corpus mysticum also featured in Baldus,[25] and the idea that the realm of France was a corpus mysticum formed an important part of late medieval French jurisprudence. Jean de Terrevermeille (fr), around 1418–19, described the French laws of succession as established by the "whole civic or mystical body of the realm", and the Parlement of Paris in 1489 proclaimed itself a "mystical body" composed of both ecclesiastics and laymen, representing the "body of the king".[26] From at least the 14th century, the doctrine developed that the French kings were mystically married to the body politic; at the coronation of Henry II in 1547, he was said to have "solemnly married his realm".[27] The English jurist John Fortescue also invoked the "mystical body" in his De Laudibus Legum Angliae (c. 1470): just as a physical body is "held together by the nerves", the mystical body of the realm is held together by the law, and Just as the physical body grows out of the embryo, regulated by one head, so does there issue from the people the kingdom, which exists as a corpus mysticum governed by one man as head.[28] |

中世における用法 政体=国家を身体に喩える隠喩は、西ローマ帝国崩壊後も用いられ続けた[8]。新プラトン主義のイスラム哲学者アル=ファラービー(西洋ではアルファラビ ウスとして知られる)は、著書『理想国家』の約940年頃の記述でこの比喩を論じ、「優れた都市は完全で健全な身体に似ている。その身体の全ての肢は、動 物の生命を完全なものとするために協力し合う」と述べている。[16] ジョン・オブ・ソールズベリーは1159年頃の『ポリクラティクス』において、この比喩を中世ラテン語で決定的な形にまとめた。王は身体の頭、司祭は魂、 参謀は心臓、目・耳・舌は法の執行官、片方の手(軍隊)は武器を握り、もう片方の手(武器を持たない)は王国の正義を表す。身体の足は庶民である。身体の 各部分はそれぞれの役割を持ち、全体のために調和して働く義務を負っていた。[17] 中世後期には、実在する個人の集団で構成される法人という概念が、政体=国家という思想に司法上の意義を与えた。[18] この法人概念は、ローマ帝国法においてユニヴェルシタス(universitas)の名で現れ、ウルピアンに帰せられる概念の定式化は、6世紀のユスティ ニアヌス1世の『ディジェスト』に収められた。この『ディジェスト』は、ユスティニアヌスの『コーパス・ユリス・シヴィリス』の他の部分と共に、11世紀 以降にグロサトゥールたちによって復元・注釈されることで、中世市民法の基盤となった。法人を「擬制人格(persona ficta)」として発展させ、人間社会全体にこの概念を適用したのは、13世紀の注釈者たちの後継者である解説者たち、特にバルドゥス・デ・ウバルディ スであった。[18]  ダンテの『神曲・天国篇』に登場する帝国の鷲。ジョヴァンニ・ディ・パオロによる1440年代の描写 彼の法学者としての先駆者であるザクソフェラートのバルトルスが法人を本質的に法的な観点から捉えたのに対し、バルドゥスは法人理論を古代の生物学的・政 治的概念である「政体=国家」と明示的に結びつけた。バルドゥスにとって、人間はアリストテレスの言う「政治的動物」であるだけでなく、民衆全体(ポピュ ラス)そのものが一種の政治的動物を構成していた。すなわちポピュラスは「あらゆる動物が自らの精神と魂に支配されるのと同様に、その存在の一部として統 治を有する」のである。[21] バルドゥスは政体=国家をレプブリカ(共和国・国家)と同一視し、「それは死なず、このゆえに後継者を持たないとされる。常に自己の中に存続するからであ る」と述べた。[22] ここから政体=国家のイメージは中世の想像力において顕著な位置を占めるようになった。例えば14世紀初頭に書かれたダンテの『神曲』第十八歌では、ロー マ帝国が帝国の鷲という形態の法人格として描かれ、その体は魂で構成されている[23]。フランス宮廷作家クリスティン・ド・ピザンは『政体=国家』 (1407年)でこの概念を詳細に論じた。[24] 法人理論を通じて法的に表現された政体=国家という身体の概念は、キリストの神秘的身体(corpus mysticum)としての教会という神学的概念とも当然のように比較された。民衆を神秘的身体と捉える概念はバルドゥス[25]にも見られ、フランス王 国が神秘的身体であるという考えは中世後期フランス法学の重要な部分を形成した。ジャン・ド・テルヴェルメイユ(fr)は1418年から1419年頃、フ ランス王位継承法を「王国の市民的かつ神秘的な身体全体」によって確立されたものと記述した。また1489年のパリ議会は、聖職者と世俗の者から成る「神 秘的な身体」であり、「王の身体」を代表するものと自らを宣言した[26]。少なくとも14世紀から、フランス王は政体=国家と神秘的に結婚しているとい う教義が発展した。1547年のアンリ2世の戴冠式では、彼は「厳かに自らの王国と結婚した」と伝えられている[27]。英国の法学者ジョン・フォートス キューも『イングランド法の称賛』(1470年頃)において「神秘的身体」を引用している: 肉体的な身体が「神経によって結びつけられる」のと同様に、王国の神秘的身体は法によって結びつけられる。 肉体的な身体が胚から成長し、一つの頭によって統制されるのと同様に、国民から王国が生まれ出る。それは一つの頭である一人の人間によって統治される神秘 的身体として存在するのだ。[28] |

| The king's body politic In England In Tudor and Stuart England, the concept of the body politic was given a peculiar additional significance through the idea of the king's two bodies, the doctrine discussed by the German-American medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz in his eponymous work. This legal doctrine held that the monarch had two bodies: the physical "king body natural" and the immortal "King body politic". Upon the "demise" of an individual king, his body natural fell away, but the body politic lived on.[29] This was an indigenous development of English law without a precise equivalent in the rest of Europe.[30] Extending the identification of the body politic as a corporation, English jurists argued that the Crown was a "corporation sole": a corporation made up of one body politic that was at the same time the body of the realm and its parliamentary estates, and also the body of the royal dignity itself—two concepts of the body politic that were conflated and fused.[31]  Elizabethan jurists held that the immaturity of Edward VI's body natural was expunged by his body politic. The development of the doctrine of the king's two bodies can be traced in the Reports of Edmund Plowden. In the 1561 Case of the Duchy of Lancaster, which concerned whether an earlier gift of land made by Edward VI could be voided on account of his "nonage", that is, his immaturity, the judges held that it could not: the king's "Body politic, which is annexed to his Body natural, takes away the Imbecility of his Body natural".[32] The king's body politic, then, "that cannot be seen or handled", annexes the body natural and "wipes away" all its defects.[33] What was more, the body politic rendered the king immortal as an individual: as the judges in the case Hill v. Grange argued in 1556, once the king had made an act, "he as King never dies, but the King, in which Name it has Relation to him, does ever continue"—thus, they held, Henry VIII was still "alive", a decade after his physical death.[29] The doctrine of the two bodies could serve to limit the powers of the real king. When Edward Coke, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas at the time, reported the way in which judges had differentiated the bodies in 1608, he noted that it was the "natural body" of the king that was created by God—the "politic body", by contrast, was "framed by the policy of man".[34] In the Case of Prohibitions of the same year, Coke denied the king "in his own person" any right to administer justice or order arrests.[35] Finally, in its declaration of 27 May 1642 shortly before the start of the English Civil War, Parliament drew on the theory to invoke the powers of the body politic of Charles I against his body natural,[36] stating: What they [Parliament] do herein, hath the Stamp of Royal Authority, although His Majesty seduced by evil Counsel, do in His own Person, oppose, or interrupt the same. For the King's Supreme Power, and Royal Pleasure, is exercised and declared in this High Court of Law, and Council, after a more eminent and obligatory manner, than it can be by any personal Act or Resolution of His Own.[37] The 18th century jurist William Blackstone, in Book I of his Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), summarised the doctrine of the king's body politic as it subsequently developed after the Restoration: the king "in his political capacity" manifests "absolute perfection"; he can "do no wrong", nor even is he capable of "thinking wrong"; he can have no defect, and is never in law "a minor or under age". Indeed, Blackstone says, if an heir to the throne should accede while "attainted of treason or felony", his assumption of the crown "would purge the attainder ipso facto". The king manifests "absolute immortality": "Henry, Edward, or George may die; but the king survives them all".[38] Soon after the appearance of the Commentaries, however, Jeremy Bentham mounted an extensive attack on Blackstone which the historian Quentin Skinner describes as "almost lethal" to the theory: legal fictions like the body politic, Bentham argued, were conducive to royal absolutism and should be entirely avoided in law. Bentham's position dominated later British legal thinking, and though aspects of the theory of the body politic would survive in subsequent jurisprudence, the idea of the Crown as a corporation sole was widely critiqued.[39] In the late 19th century, Frederic William Maitland revived the legal discourse of the king's two bodies, arguing that the concept of the Crown as corporation sole had originated from the amalgamation of medieval civil law with the law of church property.[40] He proposed, in contrast, to view the Crown as an ordinary corporation aggregate, that is, a corporation of many people, with a view to describing the legal personhood of the state.[41] In France A related but contrasting concept in France was the doctrine termed by Sarah Hanley the king's one body, summarised by Jean Bodin in his own 1576 pronouncement that "the king never dies".[42] Rather than distinguishing the immortal body politic from the mortal body natural of the king, as in the English theory, the French doctrine conflated the two, arguing that the Salic law had established a single king body politic and natural that constantly regenerated through the biological reproduction of the royal line.[43] The body politic, on this account, was biological and necessarily male, and 15th century French jurists such as Jean Juvénal des Ursins argued on this basis for the exclusion of female heirs to the crown—since, they argued, the king of France was a "virile office".[44] In the ancien régime, the king's heir was held to assimilate the body politic of the old king in a physical "transfer of corporeality" upon his accession.[45] In the United States James I in the second charter for Virginia, as well as both the Plymouth and Massachusetts Charter, grant body politic.[46][47][48] |

王の政体 イングランドでは チューダー朝およびスチュワート朝のイングランドでは、政体の概念は、ドイツ系アメリカ人の中世史家エルンスト・カントロヴィッツが同名の著作で論じた 「王の二つの体」という思想によって、独特の追加的意味合いを与えられた。この法理論は、君主には二つの体、すなわち肉体である「王の自然体」と不滅の 「王の政治体」があると主張した。個々の王が「死去」すると、その肉体は消滅したが、政体は生き続けた[29] これは、ヨーロッパの他の地域には正確な対応物がない、英国法固有の発展であった[30]。政体を法人として認識することをさらに拡大し、英国の法学者 は、王冠は「単独法人」であると主張した。つまり、王冠は、同時に、王国の体であり、その議会財産であり、また、王室の威厳そのものの体でもある、一つの 政体で構成される法人である、という二つの政治体の概念が融合されたものである。[31]  エリザベス朝の法学者たちは、エドワード6世の自然的身体(個人としての未成熟)は、その政体=国家によって解消されたと主張した。 国王の二つの身体という学説の発展は、エドマンド・プラウデンの判例集に辿ることができる。1561年のランカスター公領事件では、エドワード6世が未成 年であるという理由で以前に贈与した土地を無効にできるかが争点となったが、裁判官らは無効にできないと判示した。王の「自然体に付随する政体は、自然体 の未熟さを消し去る」からである。[32] つまり、王の「政体=国家」は「目に見えず、触れることもできない」ものであり、自然的身体に付随してその欠陥を「消し去る」のである。[33] さらに、政体=国家は個人としての王を不死たらしめた。1556年のヒル対グランジ事件で判事らが論じたように、王が一度行為を行えば「王としての彼は決 して死なず、その名において彼に関連する王は永遠に存続する」——したがって彼らは、ヘンリー8世が肉体の死から十年経った後もなお「生存している」と主 張したのである。[29] 二つの身体の教義は、実在する王の権力を制限する役割を果たし得た。当時の普通法裁判所長官エドワード・コークが1608年に判事たちが両身体を区別した 方法を報告した際、彼は「自然的身体」こそが神によって創造されたものであり、対照的に「政治的身体」は「人間の策略によって構築された」ものであると指 摘した。[34] 同年の禁止令事件において、コークは国王が「その個人的人格として」司法を執行したり逮捕を命じる権利を一切認めなかった。[35] 最後に、イングランド内戦勃発直前の1642年5月27日の宣言で、議会はこの理論を援用し、チャールズ1世の自然的身体に対してその政体=国家の権力を 発動した。[36] 宣言はこう述べている: 彼らが[議会]ここで行うことは、王権の印章を有する。たとえ陛下が悪しき助言に惑わされ、ご自身の人格においてこれに反対し、あるいは妨害しようとも。 王の至高の権力と王の御意は、この高等法廷と評議会において、より顕著かつ義務的な方法で、行使され宣言される。それは、陛下ご自身の個人的な行為や決議 によってなされるよりも、はるかに優れた方法である。[37] 18世紀の法学者ウィリアム・ブラックストーンは、著書『イングランド法解説』(1765年)第1巻において、王政復古後に発展した「国王の政体=国家」 の法理を要約している。国王は「政治的立場において」絶対的完全性を示す。国王は「過ちを犯す」ことも「過ちを考える」ことすらできず、 欠陥を持つこともなく、法的には決して「未成年者」ではない。実際、ブラックストーンによれば、王位継承者が「反逆罪または重罪で有罪判決を受けた状態」 で即位した場合、その戴冠は「その事実によって有罪判決を無効にする」という。王は「絶対的不死性」を示す:「ヘンリーも、エドワードも、ジョージも死ぬ かもしれない。だが王は彼ら全員を生き延びる」。[38] しかし『論評』発表後まもなく、ジェレミー・ベンサムがブラックストーン理論に対し「ほぼ致命的」と歴史家クエンティン・スキナーが評する大規模な批判を 展開した。ベンサムは「政体=国家」のような法的虚構は王権絶対主義を助長するため、法において完全に排除すべきだと主張した。ベンサムの立場は後の英国 法思想を支配し、政体=国家という理論の一部は後世の法学にも残ったものの、王冠を単独法人とする考え方は広く批判された。 19世紀末、フレデリック・ウィリアム・メイトランドは「王の二つの身体」という法的言説を復活させ、王冠を単独法人とする概念は中世の市民法と教会財産 法の融合に起源を持つと主張した[40]。彼は対照的に、国家の法人格を説明するため、王冠を通常の集合法人、すなわち多数の人々からなる法人と見ること を提案した。[41] フランスでは フランスにおける関連するが対照的な概念は、サラ・ハンリーが「王の一つの身体」と呼んだ学説であり、ジャン・ボダンが1576年の自身の宣言で「王は決 して死なない」と要約したものである。[42] イングランドの理論のように不死の政体=国家と王の死すべき自然体を区別するのではなく、フランス学説は両者を同一視し、サリカ法が王家の血統による生物 学的再生産を通じて絶えず再生する単一の王としての政体=国家かつ自然体を確立したと主張した。[43] この見解によれば、政体=国家は生物学的であり必然的に男性である。ジャン・ジュヴナル・デ・ウルザンのような15世紀のフランス法学者たちは、この根拠 に基づき王位継承権から女性を排除することを主張した。彼らは、フランス国王は「男性的な職務」であると論じたのである。[44] 旧体制下では、国王の後継者は即位時に、身体的な「肉体の移転」によって前王の政体=国家を同化すると考えられていた。[45] アメリカ合衆国において ジェームズ1世は、バージニアへの第二憲章ならびにプリマス及びマサチューセッツの憲章において、政体=国家を付与している。[46][47][48] |

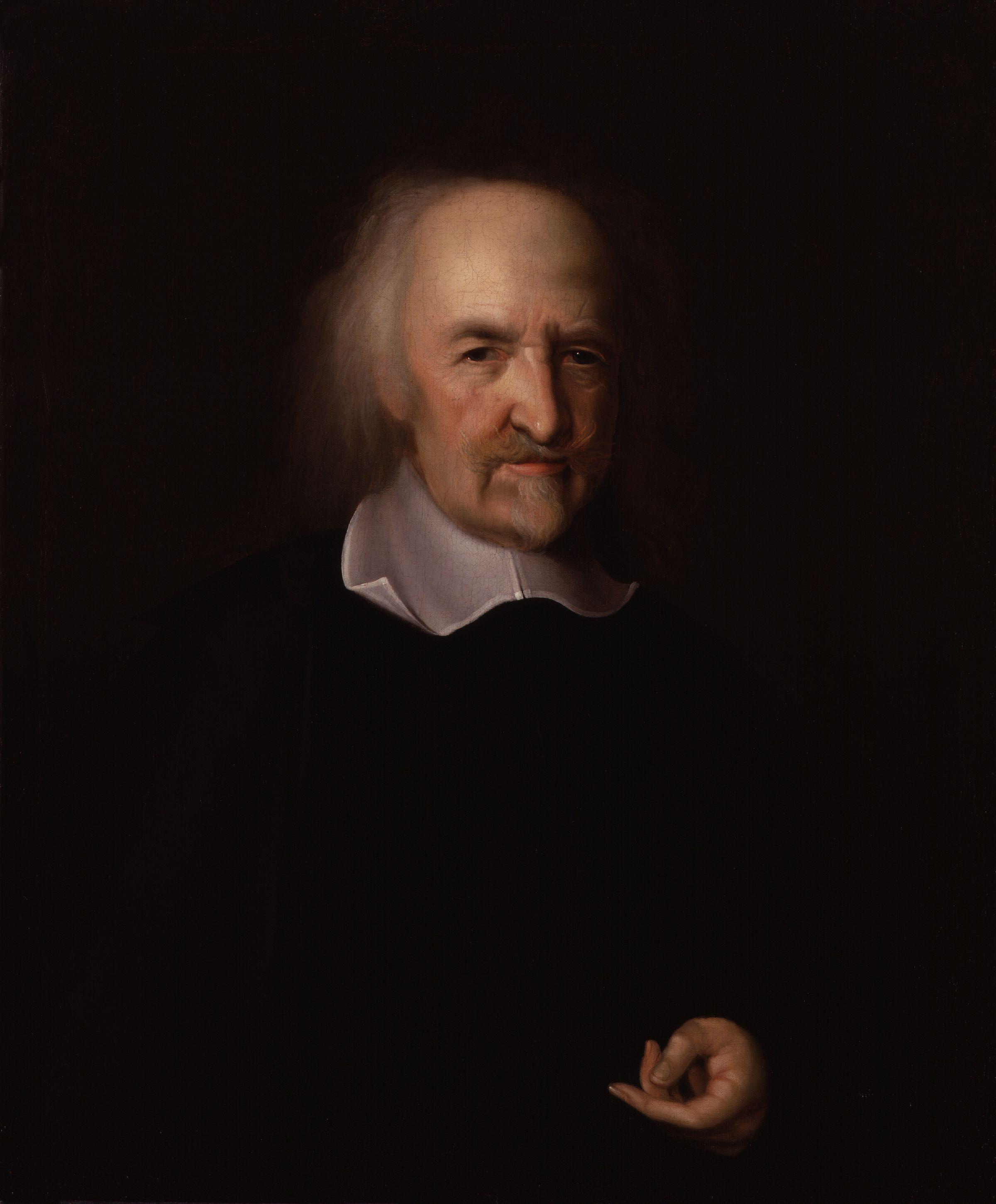

Hobbesian state theory Thomas Hobbes, c. 1669–70 Aside from the doctrine of the king's two bodies, the conventional image of the whole of the realm as a body politic had also remained in use in Stuart England: James I compared the office of the king to "the office of the head towards the body".[49] Upon the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, however, parliamentarians such as William Bridge put forward the argument that the "ruling power" belonged originally to "the whole people or body politicke", who could revoke it from the monarch.[50] The execution of Charles I in 1649 made necessary a radical revision of the whole concept.[51] In 1651, Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan made a decisive contribution to this effect, reviving the concept while endowing it with new features. Against the parliamentarians, Hobbes maintained that sovereignty was absolute and the head could certainly not be "of lesse power" than the body of the people; against the royal absolutists, however, he developed the idea of a social contract, emphasising that the body politic—Leviathan, the "mortal god"—was fictional and artificial rather than natural, derived from an original decision by the people to constitute a sovereign.[52][53] Hobbes's theory of the body politic exercised an important influence on subsequent political thinkers, who both repeated and modified it. Republican partisans of the Commonwealth presented alternative figurations of the metaphor in defence of the parliamentarian model. James Harrington, in his 1656 Commonwealth of Oceana, argued that "the delivery of a Model Government ... is no less than political Anatomy"; it must "imbrace all those Muscles, Nerves, Arterys and Bones, which are necessary to any Function of a well order'd Commonwealth". Invoking William Harvey's recent discovery of the circulatory system, Harrington presented the body politic as a dynamic system of political circulation, comparing his ideal bicameral legislature, for example, to the ventricles of the human heart. In contrast to Hobbes, the "head" was once more dependent on the people: the execution of the law must follow the law itself, so that "Leviathan may see, that the hand or sword that executeth the Law is in it, and not above it".[54] In Germany, Samuel von Pufendorf recapitulated Hobbes's explanation of the origin of the state as a social contract, but extended his notion of personhood to argue that the state must be a specifically moral person with a rational nature, and not simply coercive power.[55] In the 18th century, Hobbes's theory of the state as an artificial body politic gained wide acceptance both in Britain and continental Europe.[56] Thomas Pownall, later the British governor of Massachusetts and a proponent of American liberty, drew on Hobbes's theory in his 1752 Principles of Polity to argue that "the whole Body politic" should be conceived as "one Person"; states were "distinct Persons and independent".[57] At around the same time, the Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel pronounced that "states are bodies politic", "moral persons" with their own "understanding and ... will", a statement that would become accepted international law.[58] The tension between organic understandings of the body politic and theories emphasizing its artificial character formed a theme in English political debates in this period. Writing in 1780, during the American Revolutionary War, the British reformist John Cartwright emphasised the artificial and immortal character of the body politic in order to refute the use of biological analogies in conservative rhetoric. Arguing that it was better conceived as a machine operating by the "due action and re-action of the ... springs of the constitution" than a human body, he termed "the body politic" a "careless figurative expression": "It is not corporeal ... not formed from the dust of the earth. It is purely intellectual; and its life-spring is truth."[59] |

ホッブズ国家論 トーマス・ホッブズ、1669年~1670年頃 王の二つの身体という教義とは別に、王国全体を政体=国家として捉えるという従来の考え方も、スチュワート朝のイングランドでは引き続き用いられていた。 ジェームズ1世は、王の職務を「身体に対する頭部の職務」に例えた。[49] しかし、1642年にイングランド内戦が勃発すると、ウィリアム・ブリッジなどの議会派は、「支配権」はもともと「国民全体、つまり政治体」に属してお り、国民は君主からその権力を剥奪することができるという主張を展開した。[50] 1649年のチャールズ1世の処刑により、この概念全体の抜本的な見直しが必要となった。[51] 1651年、トマス・ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』は、この概念を復活させ、新たな特徴を付与することで、この見直しに決定的な貢献をした。ホッブズは議 会派に対して、主権は絶対的であり、首長が人民の身体よりも「権力が劣る」ことはあり得ないと主張した。しかし王権絶対主義者に対しては、社会契約の概念 を発展させ、政体=国家―「死すべき神」リヴァイアサン―が自然的なものではなく、人民が主権者を作るという原初的な決定から派生した虚構的人工物である ことを強調した。[52] [53] ホッブズの政体=国家理論は、後世の政治思想家に重要な影響を与え、彼らはこれを繰り返しつつ修正を加えた。イングランド共和国の支持者たちは、議会制モ デルを擁護するため、この隠喩の代替的な形象を提示した。ジェームズ・ハリントンは1656年の『オセアナ共和国』において、「模範政府の提示は…政治解 剖学に他ならない」と論じ、 それは「秩序ある共和国のあらゆる機能に必要な筋肉、神経、動脈、骨格を包含せねばならない」 ホッブズとは対照的に、この「頭」は再び民衆に依存する。法の執行は法そのものに従わねばならず、それによって「リヴァイアサンは、法を執行する手、すな わち剣が、自らの内にあり、自らの上にないことを認識できる」のである。[54] ドイツでは、サミュエル・フォン・プフェンドルフが国家の起源を社会契約として説明するホッブズの理論を再構成したが、人格概念を拡張し、国家は単なる強 制力ではなく、理性的な性質を持つ特異な道徳的人格でなければならないと主張した。[55] 18世紀には、国家を人工的な政体=国家とするホッブズの理論が、英国と大陸ヨーロッパの両方で広く受け入れられた. [56] 後にマサチューセッツ総督となりアメリカの自由を提唱したトーマス・ポウノールは、1752年の『政治原理』においてホッブズの理論を援用し、「政体全 体」は「一つの人格」として捉えるべきだと論じた。国家は「独立した人格」であり「互いに独立している」と述べた。[57] ほぼ同時期に、スイスの法学者エメール・ド・ヴァテルは「国家は政体=国家である」「独自の『理解力と意志』を持つ道徳的人格である」と宣言した。この主 張は後に国際法として受け入れられることになる。[58] この時代、政体を有機体として捉える見方と、その人工的性格を強調する理論との間の緊張関係は、英国の政治論争における主題となった。アメリカ独立戦争中 の1780年、英国の改革派ジョン・カートライトは、保守派のレトリックにおける生物学的比喩の使用を反駁するため、政体=国家の人工的かつ不滅の性格を 強調した。彼は、政体を人間の身体ではなく、「憲法のバネによる適切な作用と反作用」によって作動する機械として捉える方が適切だと主張し、「政体=国 家」という表現を「不用意な比喩的表現」と呼んだ。「それは物質的ではない…大地の塵から形成されたものではない。純粋に知的なものであり、その生命の源 は真実である」[59]。 |

| Modern law The English term "body politic" is sometimes used in modern legal contexts to describe a type of legal person, typically the state itself or an entity connected to it. A body politic is a type of taxable legal person in British law, for example,[60] and likewise a class of legal person in Indian law.[61][62] In the United States, a municipal corporation is considered a body politic, as opposed to a private body corporate.[63] The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the theory of the state as an artificial body politic in the 1851 case Cotton v. United States, declaring that "every sovereign State is of necessity a body politic, or artificial person, and as such capable of making contracts and holding property, both real and personal", and differentiated the United States' powers as a sovereign from its rights as a body politic.[64] |

現代法 現代の法的文脈では、英語の「body politic」という用語が、ある種の法人格、典型的には国家自体またはそれに結びついた実体を指すために用いられることがある。例えば英国法では、 body politicは課税対象となる法人格の一種である[60]。同様に、インド法においても法人格の一類型である[61][62]。米国では、地方自治体は 私法上の法人格とは対照的に、政体=国家と見なされる。[63] 米国最高裁は1851年のコットン対合衆国事件において、政体を人工的なボディ・ポリティックとする理論を支持し、「あらゆる主権国家は必然的に政体、す なわち人工的人格体であり、それゆえ契約を締結し、不動産及び個人的を所有する能力を有する」と宣言した。また、主権としての合衆国の権限と、政体として の権利とを区別した。[64] |

| Social organism, the concept in

sociology Volkskörper, the German "national body" Lex animata, the king as the "living law" Kokutai, a related Japanese concept Royal we |

社会有機体、社会学における概念 フォルクスコーペル、ドイツの「国民体」 レックス・アニマータ、王を「生ける法」とする思想 国体、関連する日本の概念 王室我(われ) |

| References |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Body_politic |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099