ボエティウス

Boethius, c.480-524

☆ ボエティウス[Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius](480年頃-524年)は、ローマ元老院議員、領事、司祭、歴史家、中世初期の哲学者。ギリシア古典のラテン語訳の中心人物であり、 スコラ学運動の先駆者であり、カシオドルスとともに6世紀を代表する二人のキリスト教学者の一人であった[9]。パヴィア教区におけるボエティウス信仰 は、1883年に神聖祭儀委員会によって承認され、10月23日に彼を称える教区の慣習が確認された。

| Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius,[6][note

1] commonly known simply as Boethius (/boʊˈiːθiəs/; Latin: Boetius; c.

480–524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, magister officiorum,

historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central

figure in the translation of the Greek classics into Latin, a precursor

to the Scholastic movement, and, along with Cassiodorus, one of the two

leading Christian scholars of the 6th century.[9] The local cult of

Boethius in the Diocese of Pavia was sanctioned by the Sacred

Congregation of Rites in 1883, confirming the diocese's custom of

honouring him on the 23 October.[10] Boethius was born in Rome a few years after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. A member of the Anicii family, he was orphaned following the family's sudden decline and was raised by Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus, a later consul. After mastering both Latin and Greek in his youth, Boethius rose to prominence as a statesman during the Ostrogothic Kingdom, becoming a senator by age 25, a consul by age 33, and later chosen as a personal advisor to Theodoric the Great. In seeking to reconcile the teachings of Plato and Aristotle with Christian theology, Boethius sought to translate the entirety of the Greek classics for Western scholars. He published numerous transcriptions and commentaries of the works of Nicomachus, Porphyry, and Cicero, among others, and wrote extensively on matters concerning music, mathematics, and theology. Though his translations were unfinished following an untimely death, it is largely due to them that the works of Aristotle survived into the Renaissance. Despite his successes as a senior official, Boethius became deeply unpopular among other members of the Ostrogothic court for denouncing the extensive corruption prevalent among other members of government. After publicly defending fellow consul Caecina Albinus from charges of conspiracy, he was imprisoned by Theodoric around the year 523. While jailed Boethius wrote On the Consolation of Philosophy—a philosophical treatise on fortune, death, and other issues—which became one of the most influential and widely reproduced works of the Early Middle Ages. He was tortured and executed in 524,[11] becoming a martyr in the Christian faith by tradition.[note 2][note 3] |

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius、[6]

[注釈 1]、通称ボエティウス(/boʍθiəs/; ラテン語:

Boetius、西暦480年頃-524年)は、ローマ元老院議員、領事、司祭、歴史家、中世初期の哲学者。ギリシア古典のラテン語訳の中心人物であり、

スコラ学運動の先駆者であり、カシオドルスとともに6世紀を代表する二人のキリスト教学者の一人であった[9]。パヴィア教区におけるボエティウス信仰

は、1883年に神聖祭儀委員会によって承認され、10月23日に彼を称える教区の慣習が確認された[10]。 ボエティウスは西ローマ帝国崩壊の数年後にローマで生まれた。アニキイ家の一員であったが、一族の突然の没落により孤児となり、後に執政官となるクィン トゥス・アウレリウス・メミウス・シンマコスに育てられた。若い頃にラテン語とギリシア語の両方を習得したボエティウスは、オストロゴート王国時代に政治 家として頭角を現し、25歳で元老院議員、33歳で領事となり、後にテオドリック大王の個人顧問に選ばれた。 プラトンやアリストテレスの教えをキリスト教神学と調和させようとしたボエティウスは、ギリシア古典のすべてを西洋の学者のために翻訳しようと努めた。ニ コマコス、ポルフィリー、キケロなどの著作の翻刻や注釈を数多く出版し、音楽、数学、神学に関する問題についても幅広く執筆した。彼の翻訳は早すぎる死に よって未完に終わったが、アリストテレスの著作がルネサンス期まで存続したのは、この翻訳によるところが大きい。 上級官僚としての成功にもかかわらず、ボエティウスはオストロゴート朝宮廷の他の議員たちの間に蔓延していた広範な腐敗を糾弾したため、他の議員たちの間 で深い不人気となった。523年、同じ領事であったカエキナ・アルビヌスを陰謀の容疑から公然と擁護した後、テオドリックによって投獄された。獄中でボエ ティウスは『哲学の慰め』を著したが、これは運勢、死、その他の問題に関する哲学的論考であり、中世初期に最も影響力を持ち、広く複製された著作のひとつ となった。彼は拷問を受け、524年に処刑され[11]、伝承ではキリスト教の殉教者となった[注釈 2][注釈 3]。 |

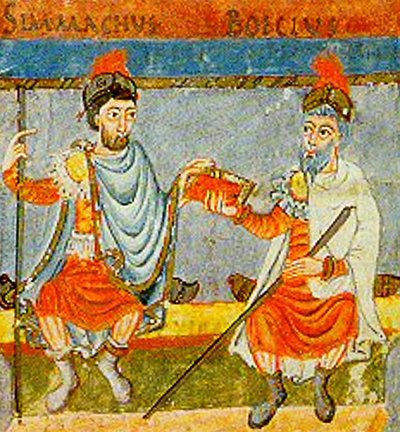

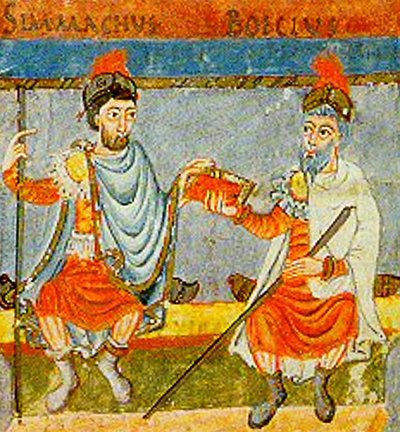

Early life Consular diptych depicting Narius Manlius Boethius, Boethius' birth father Boethius was born in Rome to a patrician family c. 480,[18] but the exact date of his birth is unknown.[8] His birth family, the Anicii, was a notably wealthy and influential gens that included emperors Petronius Maximus and Olybrius, in addition to many consuls.[19] However, in the years prior to Boethius' birth, the family had lost much of its influence. The grandfather of Boethius, a senator by the same name, was appointed as praetorian prefect of Italy but died in 454 during the palace plot against Flavius Aetius.[20][21] Boethius' father, Manlius Boethius, who was appointed consul in 487, died while Boethius was still young.[22] Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus, another patrician, adopted and raised him instead, introducing to him philosophy and literature.[23] As a sign of their good relationship, Boethius would later marry his foster-father's daughter, Rusticiana, with whom he would have two children also named Symmachus and Boethius.[24] Having been adopted into the wealthy Symmachi family, Boethius had access to tutors that would have educated him during his youth.[25] Though Symmachus had some fluency in Greek, Boethius achieved a mastery of the language—an increasingly rare skill in the Western regions of the Empire—and dedicated his early career to translating the entire works of Plato and Aristotle,[26][27] with some of the translations that he produced being the only surviving transcriptions of Greek texts into the Middle Ages.[28][29] The unusual fluency of Boethius in the Greek language has led some scholars to believe that he was educated in the East; a traditional view, first proposed by Edward Gibbon, is that Boethius studied in Athens for eighteen years based on the letters of Cassiodorus, though this was likely to have been a misreading by past historians.[25][note 4] Historian Pierre Courcelle has argued that Boethius studied at Alexandria with the Neoplatonist philosopher Ammonius Hermiae. However, Historian John Moorhead observes that the evidence supporting Boethius having studied in Alexandria is "not as strong as it may appear," adding that he may have been able to acquire his formidable learning without travelling.[31] Whatever the case, Boethius' fluency in Greek proved useful throughout his life in translating the classic works of Greek thinkers, though his interests spanned across a variety of fields including music, mathematics, astrology, and theology.[32] |

生い立ち ボエティウスの生父ナリウス・マンリウス・ボエティウスを描いた領事二枚絵 ボエティウスは480年頃、ローマの貴族家に生まれたが[18]、正確な生年月日は不明である[8]。ボエティウスの生家であるアニキイ家は、皇帝ペトロ ニウス・マクシムスやオリブリウスをはじめ、多くの領事を輩出した裕福で影響力のある家系であった[19]。同名の元老院議員であったボエティウスの祖父 は、イタリアのプラエトリア大将軍に任命されたが、454年にフラウィウス・アエティウスに対する王宮の陰謀の最中に死去した[20][21]。 [22]同じく貴族であったクイントゥス・アウレリウス・メミウス・シンマコウスが代わりにボエティウスを養子に迎えて育て、哲学と文学を教えた [23]。 ボエティウスは裕福なシンマコウス家の養子となったため、青年期に彼を教育する家庭教師を利用することができた[25]。シンマコウスはギリシア語をある 程度流暢に話すことができたが、ボエティウスはギリシア語の熟達を達成し、それは帝国の西部地域ではますます希少なスキルであった。 [エドワード・ギボンが最初に提唱した伝統的な見解では、ボエティウスはカッシオドロスの書簡に基づいて18年間アテネで学んだとされているが、これは過 去の歴史家による誤読であった可能性が高い[25][注釈 4]。 歴史家のピエール・クールセルは、ボエティウスはアレクサンドリアで新プラトン主義の哲学者アモニウス・ヘルミアエに師事していたと主張している。しか し、歴史家ジョン・ムーアヘッドは、ボエティウスがアレクサンドリアで学んだことを裏付ける証拠は「見かけほど強力ではない」とし、ボエティウスは旅をす ることなくその強大な学識を身につけることができたかもしれないと付け加えている[31]。 いずれにせよ、ボエティウスのギリシア語の堪能さは、ギリシアの思想家の古典的著作の翻訳において生涯を通じて役立ったが、彼の関心は音楽、数学、占星 術、神学などさまざまな分野に及んでいた[32]。 |

Rise to power Boethius (right) and his adoptive father, Symmachus (left); both had been appointed consuls in their own right Taking inspiration from Plato's Republic, Boethius left his scholarly pursuits to enter the service of Theodoric the Great.[33] The two had first met in the year 500 when Theodoric traveled to Rome to stay for six months.[34] Though no record survives detailing the early relationship between Theodoric and Boethius, it is clear that the Ostrogothic king viewed him favorably. In the next few years, Boethius rapidly ascended through the ranks of government, becoming a senator by age 25 and a consul by the year 510.[18][35] His earliest documented acts on behalf of the Ostrogothic ruler were to investigate allegations that the paymaster of Theodoric's bodyguards had debased the coins of their pay, to produce a waterclock for Theodoric to gift to king Gundobad of the Burgundians, and to recruit a lyre-player to perform for Clovis, King of the Franks.[36] Boethius writes in the Consolation that, despite his own successes, he believed that his greatest achievement came when both his sons were selected by Theodoric to be consuls in 522, with each representing the whole of the Roman Empire.[37] The appointment of his sons was an exceptional honor, not only since it made conspicuous Theodoric's favor for Boethius, but also because the Byzantine emperor Justin I had forfeited his own nomination as a sign of goodwill, thus also endorsing Boethius' sons.[38] In the same year as the appointment of his sons, Boethius was elevated to the position of magister officiorum, becoming the head of all government and palace affairs.[38] Recalling the event, he wrote that he was sitting "between the two consuls as if it were a military triumph, [letting my] largesse fulfill the wildest expectations of the people packed in their seats around [me]."[39] Boethius' struggles came within a year of his appointment as magister officiorum: in seeking to mend the rampant corruption present in the Roman Court, he writes of having to thwart the conspiracies of Triguilla, the steward of the royal house; of confronting the Gothic minister, Cunigast, who went to "devour the substance of the poor"; and of having to use the authority of the king to stop a shipment of food from Campania which, if carried, would have exacerbated an ongoing famine in the region.[40] These actions made Boethius an increasingly unpopular figure among court officials, though he remained in Theodoric's favor.[41] |

権力の座へ ボエティウス(右)と養父のシンマコウス(左)。 プラトンの『共和国』からヒントを得たボエティウスは、学問の道を捨て、テオドリック大王に仕えるようになった[33]。2人が初めて出会ったのは、テオ ドリックがローマに6ヶ月滞在した500年のことであった[34]。テオドリックとボエティウスの初期の関係を詳細に記した記録は残っていないが、オスト ロゴート王がボエティウスを好意的に見ていたことは明らかである。その後、ボエティウスは急速に出世し、25歳で元老院議員、510年には領事となった。 [18][35]オストロゴスの支配者のために彼が行った最も初期の文書化された行為は、テオドリックの護衛の給与管理者が彼らの給与のコインを堕落させ たという疑惑を調査すること、テオドリックがブルグント王国のグンドバド王に贈る水時計を製作すること、フランク王国のクローヴィスのために演奏する竪琴 奏者を募集することであった[36]。 ボエティウスは『コンソレイション』の中で、自分自身の成功にもかかわらず、自分の最大の功績は522年にテオドリックによって息子二人がそれぞれローマ 帝国全土を代表する領事に選ばれたことであると信じていたと書いている[37]。息子たちの任命は、ボエティウスに対するテオドリックの好意が目立っただ けでなく、ビザンツ皇帝ユスティヌス1世が親善の証として自らの指名を放棄し、ボエティウスの息子たちを支持したことから、特別な栄誉であった。 [38]息子たちの任命と同じ年、ボエティウスはマイスター・オフィショルムに昇格し、すべての政務と宮廷事務の責任者となった[38]。この出来事を回 想して、彼は「まるで軍事的勝利のように2人の執政官の間に座り、(私の)大盤振る舞いで(私の)周りに詰めかけた民衆の野生の期待を満たしていた」と記 している[39]。 ローマ宮廷に蔓延していた腐敗を修復するために、王家の執事トリギッラの陰謀を阻止しなければならなかったこと、「貧しい人々の物質をむさぼりに」行った ゴート族の大臣クニガストに立ち向かったこと、そして、もし運ばれれば、カンパニア地方で続いていた飢饉を悪化させることになるカンパニアからの食糧の積 荷を、王の権威を行使して止めさせなければならなかったことを記している。 [40]これらの行動により、ボエティウスは宮廷関係者の間でますます不人気な人物となったが、テオドリックの寵愛を受け続けた[41]。 |

| Downfall and death The young philosopher Boethius, a man whose varied accomplishments adorned the middle period of the reign of Theodoric, and whose tragic death was to bring sadness over its close. —Thomas Hodgkin, Theodoric the Goth[42] In 520, Boethius was working to revitalize the relationship between the Roman See and the Constantinopolitan See—though the two were then still a part of the same Church, disagreements had begun to emerge between them. This may have set in place a course of events that would lead to loss of royal favour.[43] Five hundred years later, this continuing disagreement led to the East–West Schism in 1054, in which communion between the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church was broken. In 523, Boethius fell from power. After a period of imprisonment in Pavia for what was deemed a treasonable offence, he was executed in 524.[18][44] The primary sources are in general agreement over the facts of what happened. At a meeting of the Royal Council in Verona, the referendarius Cyprianus accused the ex-consul Caecina Decius Faustus Albinus of treasonous correspondence with Justin I. Boethius leapt to his defense, crying, "The charge of Cyprianus is false, but if Albinus did that, so also have I and the whole senate with one accord done it; it is false, my Lord King."[45]  Manuscript depicting Boethius teaching students (initial) and while imprisoned Cyprianus then also accused Boethius of the same crime and produced three men who claimed they had witnessed the crime. Boethius and Basilius were arrested. First the pair were detained in the baptistery of a church, then Boethius was exiled to the Ager Calventianus, a distant country estate, where he was put to death. Not long afterwards Theodoric had Boethius' father-in-law Symmachus put to death, according to Procopius, on the grounds that he and Boethius together were planning a revolution, and confiscated their property.[46] "The basic facts in the case are not in dispute," writes Jeffrey Richards. "What is disputed about this sequence of events is the interpretation that should be put on them."[47] Boethius claims his crime was seeking "the safety of the Senate". He describes the three witnesses against him as dishonorable: Basilius had been dismissed from Royal service for his debts, while Venantius Opilio and Gaudentius had been exiled for fraud.[48] However, other sources depict these men in a far more positive light. For example, Cassiodorus describes Cyprianus and Opilio as "utterly scrupulous, just and loyal" and mentions they are brothers and grandsons of the consul Opilio.[49] Theodoric was feeling threatened by international events. The Acacian schism had been resolved, and the Nicene Christian aristocrats of his kingdom were seeking to renew their ties with Constantinople. The Catholic Hilderic had become king of the Vandals and had put Theodoric's sister Amalafrida to death,[50] and Arians in the East were being persecuted.[51] Then there was the matter that with his previous ties to Theodahad, Boethius apparently found himself on the wrong side in the succession dispute following the untimely death of Eutharic, Theodoric's announced heir. Boethius, the most learned man of his time, met his death in the hangman's noose...and yet the life of Boethius was a triumph! The West owes this individual, Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, nothing less than its progression toward a culture of reason. —Johannes Fried, The Middle Ages[52] The method of Boethius' execution varies in the sources. He may have been beheaded, clubbed to death, or hanged.[52] It is likely that he was tortured with a rope that was constricted around his head, bludgeoned until his eyes bulged out; then his skull was cracked.[53][54] Following an agonizing death, his remains were entombed in the church of San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro in Pavia, also the resting place of Augustine of Hippo. His wealth was also confiscated, and his wife, Rusticiana, reduced to poverty.[28] Past historians have had a hard time accepting a sincere Christian who was also a serious Hellenist.[28][55] These worries have largely stemmed by the lack of any mention of Jesus in Boethius' Consolation, nor of any other Christian figure.[56] Arnaldo Momigliano argues that "Boethius turned to paganism. His Christianity collapsed—it collapsed so thoroughly that perhaps he did not even notice its disappearance." However, the majority of scholarship has taken a different view,[57] with Arthur Herman writing that Boethius was "unshakably Orthodox Catholic," and Thomas Hodgkin having asserted that uncovered manuscripts "prove beyond a doubt that Boethius was a Christian."[58][56] Furthermore, the community that he was a part of valued equally both classical and Christian culture.[59] |

没落と死 若き哲学者ボエティウスは、その多彩な業績でテオドリック治世の中期を飾ったが、その悲劇的な死は治世の終わりを悲しませた。 -トーマス・ホジキン『ゴート人テオドリック』[42]。 520年、ボエティウスはローマ教皇庁とコンスタンチノープル教皇庁の関係を活性化するために働いていた。500年後の1054年、この継続的な不和がカ トリック教会と東方正教会との交わりを断絶させる東西分裂につながった。523年、ボエティウスは権力を失う。反逆罪とみなされ、パヴィアで投獄された 後、524年に処刑された[18][44]。ヴェローナで開かれた王室会議の席上、レフェンダリウスであったキプリアヌスは、元領事カエキナ・デキウス・ ファウストゥス・アルビヌスがユスティヌス1世と反逆的な書簡を交わしていたことを告発した。ボエティウスは彼を擁護し、「キプリアヌスの告発は虚偽であ るが、もしアルビヌスがそのようなことをしたのであれば、私や元老院全体も一致してそのようなことをしたのであり、それは虚偽であります、国王陛下」 [45]と叫んだ。  ボエティウスが学生を指導する様子(初期)と投獄中の様子を描いた写本 キプリアヌスもまたボエティウスを同じ罪で告発し、犯行を目撃したという3人の男を出した。ボエティウスとバシリウスは逮捕された。まず二人は教会の洗礼 堂に拘留され、その後ボエティウスは遠方のアガー・カルヴェンティアヌス(Ager Calventianus)に追放され、そこで死刑となった。それから間もなく、テオドリックはボエティウスの義父シンマコスを、彼とボエティウスが一緒 に革命を計画していたという理由で、プロコピウスによれば死刑に処し、彼らの財産を没収した[46]。「この一連の出来事について争われているのは、それ らに付すべき解釈である」[47] ボエティウスは、自分の罪は「元老院の安全」を求めたことだと主張している。彼は自分に不利な3人の証人を不名誉な人物だと述べている: バシリウスは借金のために王室から解雇され、ヴェナンティウス・オピリオとガウデンティウスは詐欺のために追放されていた。例えば、カッシオドルスはキプ リアヌスとオピリオを「まったく几帳面で、公正で忠実な人物」と評し、彼らが領事オピリオの兄弟であり孫であると述べている[49]。 テオドリックは国際的な出来事に脅威を感じていた。アカキアの分裂は解決し、彼の王国のニカイア派キリスト教貴族たちはコンスタンティノープルとの結びつ きを強めようとしていた。カトリックのヒルデリックはヴァンダル族の王となり、テオドリックの妹アマラフリダを死に追いやり[50]、東方ではアリウス派 が迫害されていた[51]。さらに、テオダハドと以前からつながりがあったボエティウスは、テオドリックの後継者と公表されていたエウタリックの早すぎる 死後、後継者争いで不利な立場に立たされることになる。 当時最も学識のあったボエティウスは、絞首刑の縄で死を迎えた......しかし、ボエティウスの人生は勝利であった!西洋は、このアニキウス・マンリウス・セヴェリヌス・ボエティウスという人物に、理性文化への前進という何ものにも劣らない借りがある。 -ヨハネス・フリード『中世』[52]。 ボエティウスの処刑方法は資料によって異なる。首をはねられたか、棍棒で撲殺されたか、あるいは絞首刑に処されたかもしれない[52]。頭を縄で締め上げ られ、眼球が膨れ上がるまで殴打された後、頭蓋骨にヒビが入れられたと思われる[53][54]。苦しい死の後、彼の遺骸はヒッポのアウグスティヌスも眠 るパヴィアのサン・ピエトロ・イン・シエル・ドーロ教会に埋葬された。彼の財産も没収され、妻のルスティシアーナは貧困に貶められた[28]。 過去の歴史家たちは、真面目なヘレニストでもあった誠実なキリスト教徒を受け入れるのに苦労してきた[28][55]。これらの心配は、ボエティウスの 『慰め』にはイエスについての言及がなく、また他のキリスト教の人物についても言及がないことに大きく起因している[56]。アルナルド・モミリアーノ は、「ボエティウスは異教に傾倒した。彼のキリスト教は崩壊し、おそらく彼はその消滅にさえ気づかなかったほど、徹底的に崩壊したのである」。しかし、大 半の学者は異なる見解を持っており[57]、アーサー・ハーマンはボエティウスは「揺るぎない正統カトリック教徒」であったと書いており、トマス・ホジキ ンは発掘された写本が「ボエティウスがキリスト教徒であったことを疑う余地なく証明している」と主張している[58][56]。さらに、彼が属していた共 同体は古典文化とキリスト教文化の両方を等しく尊重していた[59]。 |

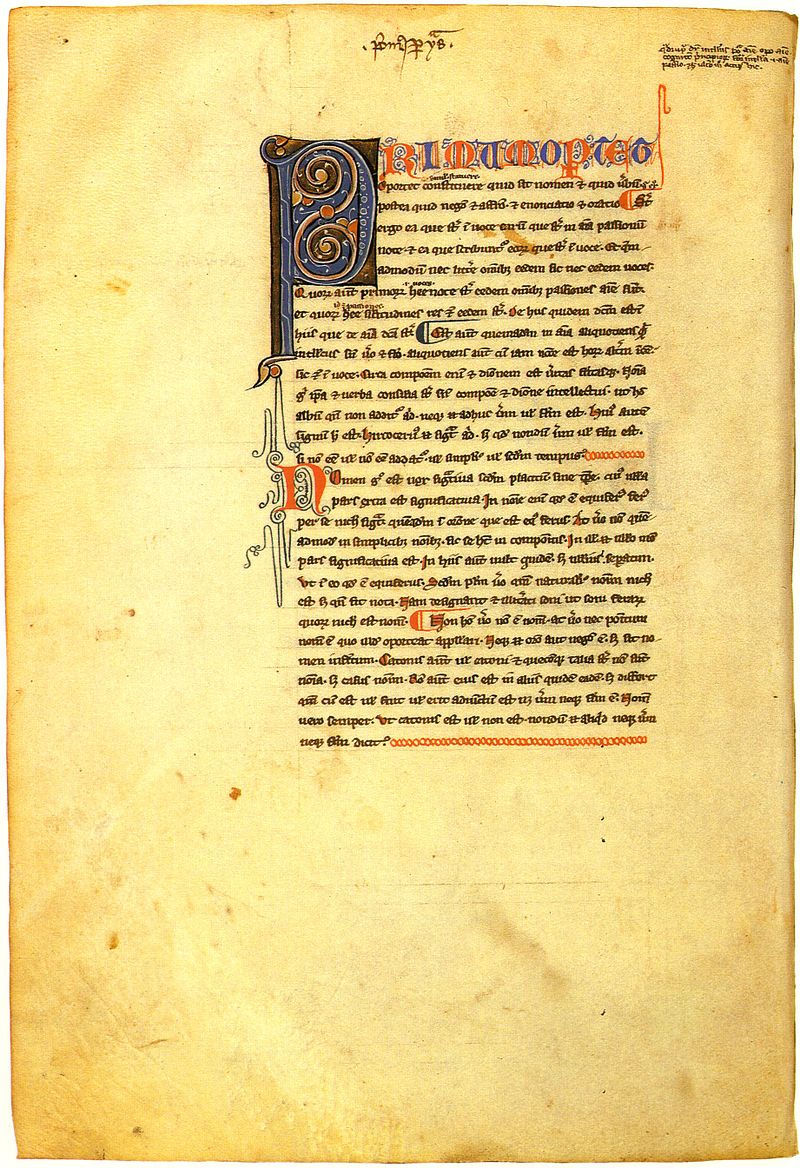

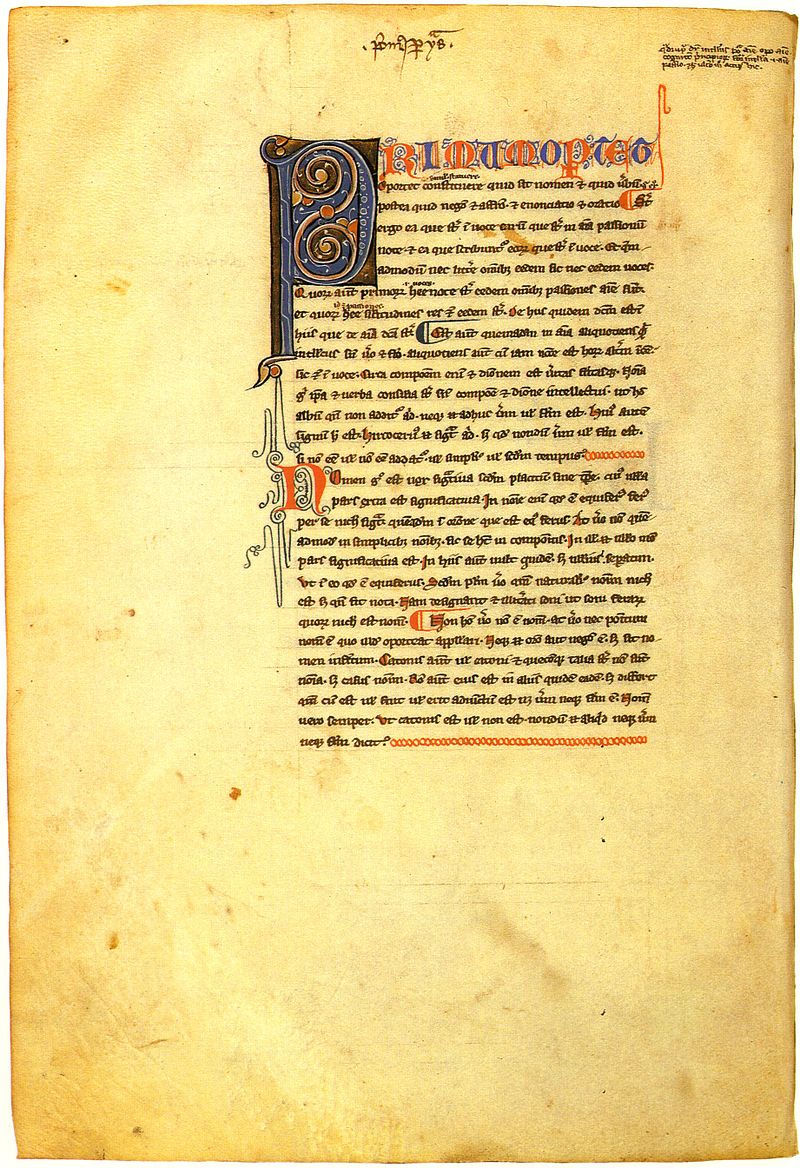

| De consolatione philosophiae Main article: The Consolation of Philosophy Boethius's best known work is the Consolation of Philosophy (De consolatione philosophiae), which he wrote at the very end of his career, awaiting his execution in prison. This work represented an imaginary dialogue between himself and philosophy, with philosophy personified as a woman, arguing that despite the apparent inequality of the world, there is, in Platonic fashion, a higher power and everything else is secondary to that divine Providence.[60] Several manuscripts survived and these were widely edited, translated and printed throughout the late 15th century and later in Europe.[61] Beyond Consolation of Philosophy, his lifelong project was a deliberate attempt to preserve ancient classical knowledge, particularly philosophy. Boethius intended to translate all the works of Aristotle and Plato from the original Greek into Latin.[62][63][64] De topicis differentiis His completed translations of Aristotle's works on logic were the only significant portions of Aristotle available in Latin Christendom from the sixth century until the rediscovery of Aristotle in the 12th century. However, some of his translations (such as his treatment of the topoi in The Topics) were mixed with his own commentary, which reflected both Aristotelian and Platonic concepts.[65] The commentaries themselves have been lost.[66] In addition to his commentary on the Topics, Boethius composed two treatises on Topical argumentation, In Ciceronis Topica and De topicis differentiis. The first work has six books, and is largely a response to Cicero's Topica.[67] The first book of In Ciceronis Topica begins with a dedication to Patricius. It includes distinctions and assertions important to Boethius's overall philosophy, such as his view of the role of philosophy as "establish[ing] our judgment concerning the governing of life",[68] and definitions of logic from Plato, Aristotle and Cicero. He breaks logic into three parts: that which defines, that which divides, and that which deduces.[68] He asserts that there are three types of arguments: those of necessity, of ready believability, and sophistry.[69] He follows Aristotle in defining one sort of Topic as the maximal proposition, a proposition which is somehow shown to be universal or readily believable.[70] The other sort of Topic, the differentiae, are "Topics that contain and include the maximal propositions"; means of categorizing the Topics which Boethius credits to Cicero.[71] Book II covers two kinds of topics: those from related things and those from extrinsic topics. Book III discusses the relationship among things studied through Topics, Topics themselves, and the nature of definition. Book IV analyzes partition, designation and relationships between things (such as pairing, numbering, genus, and species, etc.). After a review of his terms, Boethius spends Book V discussing Stoic logic and Aristotelian causation. Book VI relates the nature of the Topic to causes. In Topicis Differentiis has four books; Book I discusses the nature of rhetorical and dialectical Topics together, Boethius's overall purpose being "to show what the Topics are, what their differentiae are, and which are suited for what syllogisms."[72] He distinguishes between argument (that which constitutes belief) and argumentation (that which demonstrates belief). Propositions are divided into three parts: those that are universal, those that are particular, and those that are somewhere in between.[73] These distinctions, and others, are applicable to both types of Topical argument, rhetorical and dialectical. Books II and III are primarily focused on Topics of dialectic (syllogisms), while Book IV concentrates on the unit of the rhetorical Topic, the enthymeme. Topical argumentation is at the core of Boethius's conception of dialectic, which "have categorical rather than conditional conclusions, and he conceives of the discovery of an argument as the discovery of a middle term capable of linking the two terms of the desired conclusion."[74] Not only are these texts of paramount importance to the study of Boethius, they are also crucial to the history of topical lore. It is largely due to Boethius that the Topics of Aristotle and Cicero were revived, and the Boethian tradition of topical argumentation spans its influence throughout the Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance: "In the works of Ockham, Buridan, Albert of Saxony, and the Pseudo-Scotus, for instance, many of the rules of consequence bear a strong resemblance to or are simply identical with certain Boethian Topics ... Boethius's influence, direct and indirect, on this tradition is enormous."[75] It was also in De Topicis Differentiis that Boethius made a unique contribution to the discourse on dialectic and rhetoric. Topical argumentation for Boethius is dependent upon a new category for the topics discussed by Aristotle and Cicero, and "[u]nlike Aristotle, Boethius recognizes two different types of Topics. First, he says, a Topic is a maximal proposition (maxima propositio), or principle; but there is a second kind of Topic, which he calls the differentia of a maximal proposition.[76] Maximal propositions are "propositions [that are] known per se, and no proof can be found for these."[77] This is the basis for the idea that demonstration (or the construction of arguments) is dependent ultimately upon ideas or proofs that are known so well and are so fundamental to human understanding of logic that no other proofs come before it. They must hold true in and of themselves. According to Stump, "the role of maximal propositions in argumentation is to ensure the truth of a conclusion by ensuring the truth of its premises either directly or indirectly."[78]These propositions would be used in constructing arguments through the Differentia, which is the second part of Boethius' theory. This is "the genus of the intermediate in the argument."[79] So maximal propositions allow room for an argument to be founded in some sense of logic while differentia are critical for the demonstration and construction of arguments. Boethius' definition of "differentiae" is that they are "the Topics of arguments ... The Topics which are the Differentiae of [maximal] propositions are more universal than those propositions, just as rationality is more universal than man."[80] This is the second part of Boethius' unique contribution to the field of rhetoric. Differentia operate under maximal propositions to "be of use in finding maximal propositions as well as intermediate terms," or the premises that follow maximal propositions.[81] Though Boethius is drawing from Aristotle's Topics, Differentiae are not the same as Topics in some ways. Boethius arranges differentiae through statements, instead of generalized groups as Aristotle does. Stump articulates the difference. They are "expressed as words or phrases whose expansion into appropriate propositions is neither intended nor readily conceivable", unlike Aristotle's clearly defined four groups of Topics. Aristotle had hundreds of topics organized into those four groups, whereas Boethius has twenty-eight "Topics" that are "highly ordered among themselves."[82] This distinction is necessary to understand Boethius as separate from past rhetorical theories. Maximal propositions and Differentiae belong not only to rhetoric, but also to dialectic. Boethius defines dialectic through an analysis of "thesis" and hypothetical propositions. He claims that "[t]here are two kinds of questions. One is that called, 'thesis' by the [Greek] dialecticians. This is the kind of question which asks about and discusses things stripped of relation to other circumstances; it is the sort of question dialecticians most frequently dispute about—for example, 'Is pleasure the greatest good?' [or] 'Should one marry?'.[83]" Dialectic has "dialectical topics" as well as "dialectical-rhetorical topics", all of which are still discussed in De Topicis Differentiis.[76] Dialectic, especially in Book I, comprises a major component of Boethius' discussion on Topics. Boethius planned to completely translate Plato's Dialogues, but there is no known surviving translation, if it was actually ever begun.[84] |

哲学の慰め 主な記事 哲学の慰め ボエティウスの最も有名な著作は『哲学の慰め』(De consolatione philosophiae)である。この著作は、哲学を女性に擬人化した彼と哲学の架空の対話であり、世界の明白な不平等にもかかわらず、プラトン流に言 えば、より高次の力が存在し、他のすべてはその神の摂理にとって二次的なものであると主張している[60]。 哲学の慰め』以外にも、彼の生涯をかけたプロジェクトは、古代の古典的知識、特に哲学を保存するための意図的な試みであった。ボエティウスはアリストテレスとプラトンの全著作を原典のギリシア語からラテン語に翻訳することを意図していた[62][63][64]。 デ・トピキス・ディファレンティス 彼が完成させたアリストテレスの論理学に関する著作の翻訳は、6世紀から12世紀にアリストテレスが再発見されるまで、ラテン・キリスト教圏で利用可能な アリストテレスの唯一の重要な部分であった。しかし、彼の翻訳の一部(『トピックス』におけるトポイの扱いなど)は、アリストテレス的概念とプラトン的概 念の両方を反映した彼自身の注釈と混在していた[65]。 ボエティウスは『トピックス』の注釈に加えて、『In Ciceronis Topica』と『De topicis differentiis』というトポイ論に関する2つの論考を著した。In Ciceronis Topica』の第1巻はパトリキウスへの献辞で始まる。この本には、哲学の役割を「生活の統治に関する我々の判断を確立すること」とする彼の見解 [68]や、プラトン、アリストテレス、キケロからの論理学の定義など、ボエティウスの哲学全体にとって重要な区別や主張が含まれている。彼は論理学を 「定義するもの」「分割するもの」「演繹するもの」の3つの部分に分けている[68]。 アリストテレスに従って、トピックの一種を最大命題と定義しており、普遍的または容易に信じられることが何らかの形で示される命題である[70]。 トピックのもう一種であるディファレンシアエは「最大命題を含み、それを含むトピック」であり、ボエティウスがキケロ[71]の功績としているトピックを 分類する手段である。 第II巻は、関連する事物からのトピックと外在的なトピックからのトピックの2種類を扱っている。第III巻は、トピックを通じて研究される事物間の関 係、トピックそれ自体、および定義の性質について論じている。第IV巻は、分割、呼称、事物間の関係(対、数、属、種など)を分析する。用語の復習の後、 ボエティウスは第5巻でストア派の論理学とアリストテレス派の因果関係について述べている。第VI巻はトピックの本質と原因との関係である。 In Topicis Differentiis』には4冊の本があり、第1巻では修辞学的トピックと弁証法的トピックの性質について論じ、ボエティウスの全体的な目的は「ト ピックとは何か、その差異とは何か、どのトピックがどのようなシロジズムに適しているかを示すこと」[72]である。命題は、普遍的なもの、特殊なもの、 その中間のものという3つの部分に分けられる[73]。これらの区別やその他の区別は、修辞的論証と弁証法的論証の両方のタイプのトピカル・アロギュー ションに当てはまる。第II巻と第III巻は主に弁証法的トピック(シロギス)に焦点を当てており、第IV巻は修辞的トピックの単位であるエンシメメに焦 点を当てている。トピック論証はボエティウスの弁証法概念の中核をなすものであり、それは「条件的な結論よりもむしろ定言的な結論を持ち、彼は論証の発見 を、望ましい結論の二つの項を結びつけることのできる中間項の発見として考えている」[74]。 これらのテキストはボエティウスの研究にとって最も重要であるだけでなく、話題の伝承の歴史にとっても極めて重要である。アリストテレスとキケロの論題が 復活したのはボエティウスによるところが大きく、ボエティウスによる論題の伝統は、中世からルネサンス初期に至るまでその影響力を広げている: 「例えば、オッカム、ブリダン、アルベルト・オブ・ザクセン、偽スコトゥスの作品では、結果法則の多くがボエティウスのトピックに酷似しているか、まった く同じである。この伝統に対するボエティウスの影響は、直接的にも間接的にも甚大である」[75]。 ボエティウスが弁証法と修辞学に関する言説にユニークな貢献をしたのは、『トピック差論』(De Topicis Differentiis)においてもであった。アリストテレスとキケロによって論じられたトピックに対して、ボエティウスにとってのトピック論法は新し いカテゴリーに依存しており、「アリストテレスとは異なり、ボエティウスは2つの異なるタイプのトピックを認めている。第一に、トピックとは最大命題 (maxima propositio)、すなわち原理であるが、トピックには第二の種類があり、彼はこれを最大命題のdifferentiaと呼んでいる[76]。最大 命題とは「それ自体既知の命題であり、これらについて証明を見つけることはできない」[77]。 これは、実証(あるいは論証の構築)は、最終的には、非常によく知られており、論理学の人間的理解にとって非常に基本的で、他のいかなる証明もその前に出 てこないような考えや証明に依存するという考え方の基礎である。それ自体が真でなければならない。スタンプによれば、「論証における最大命題の役割は、そ の前提の真理を直接的または間接的に保証することによって、結論の真理を保証することである」[78]。これらの命題は、ボエティウスの理論の第二部分で あるディファレンシアを通じて論証を構築する際に使用される。これは「論証における中間的なものの属格」[79]であり、最大命題は論証がある意味論理的 に成立する余地を与える一方で、ディファレンシアは論証の実証と構築にとって重要である。 ボエティウスによる「ディファレンシア」の定義は、「論証のトピック」である。最大]命題のディファレンシアであるトピックは、合理性が人間よりも普遍的 であるように、それらの命題よりも普遍的である」[80]。ディファレンシアは最大命題の下で「最大命題と中間項、すなわち最大命題に続く前提を見出すの に役立つ」ように作用する[81]。 ボエティウスはアリストテレスのトピックスを参考にしているが、ディファレンシアエはトピックスとは異なる点もある。ボエティウスはアリストテレスのよう に一般化されたグループではなく、陳述を通してディファレンシアエを配置している。スタンプはその違いを次のように述べている。ディファレンシアエは、ア リストテレスが明確に定義した4つのトピックのグループとは異なり、「適切な命題への展開が意図されておらず、容易に思いつくこともできない言葉や句とし て表現されている」。アリストテレスが何百ものトピックをこの4つのグループに編成していたのに対し、ボエティウスは28の「トピック」を持っており、そ れらは「それ自身の間で高度に秩序づけられている」[82]。この区別は、ボエティウスを過去の修辞理論とは別のものとして理解するために必要である。 最大命題と差延命題は修辞学のみならず弁証法にも属する。ボエティウスは「テーゼ」と仮言命題の分析を通じて弁証法を定義している。彼は次のように主張す る。ひとつは、(ギリシアの)弁証法家たちが『テーゼ』と呼ぶものである。これは他の状況との関係を取り除いた物事について問い、議論する種類の問いであ り、弁証法家たちが最も頻繁に論争する種類の問いである-たとえば『快楽は最大の善か』[あるいは]『結婚すべきか』[83]」。弁証法には「弁証法的ト ピック」と「弁証法的・修辞学的トピック」があり、これらはすべて『トピックの差延論』(De Topicis Differentiis)でも論じられている[76]。 ボエティウスはプラトンの『対話篇』を完全に翻訳することを計画していたが、実際に翻訳が開始されたとしても、現存する翻訳は知られていない[84]。 |

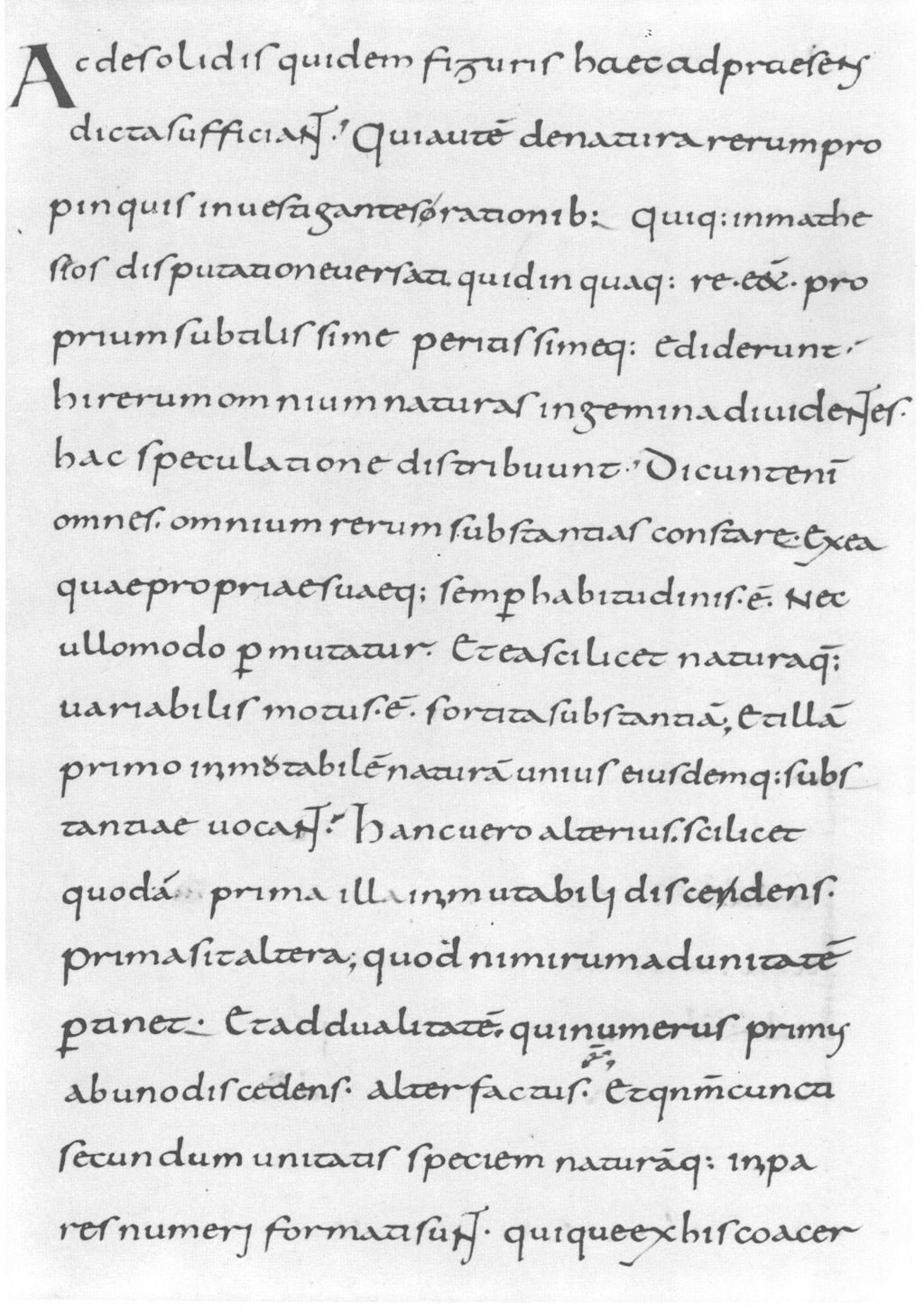

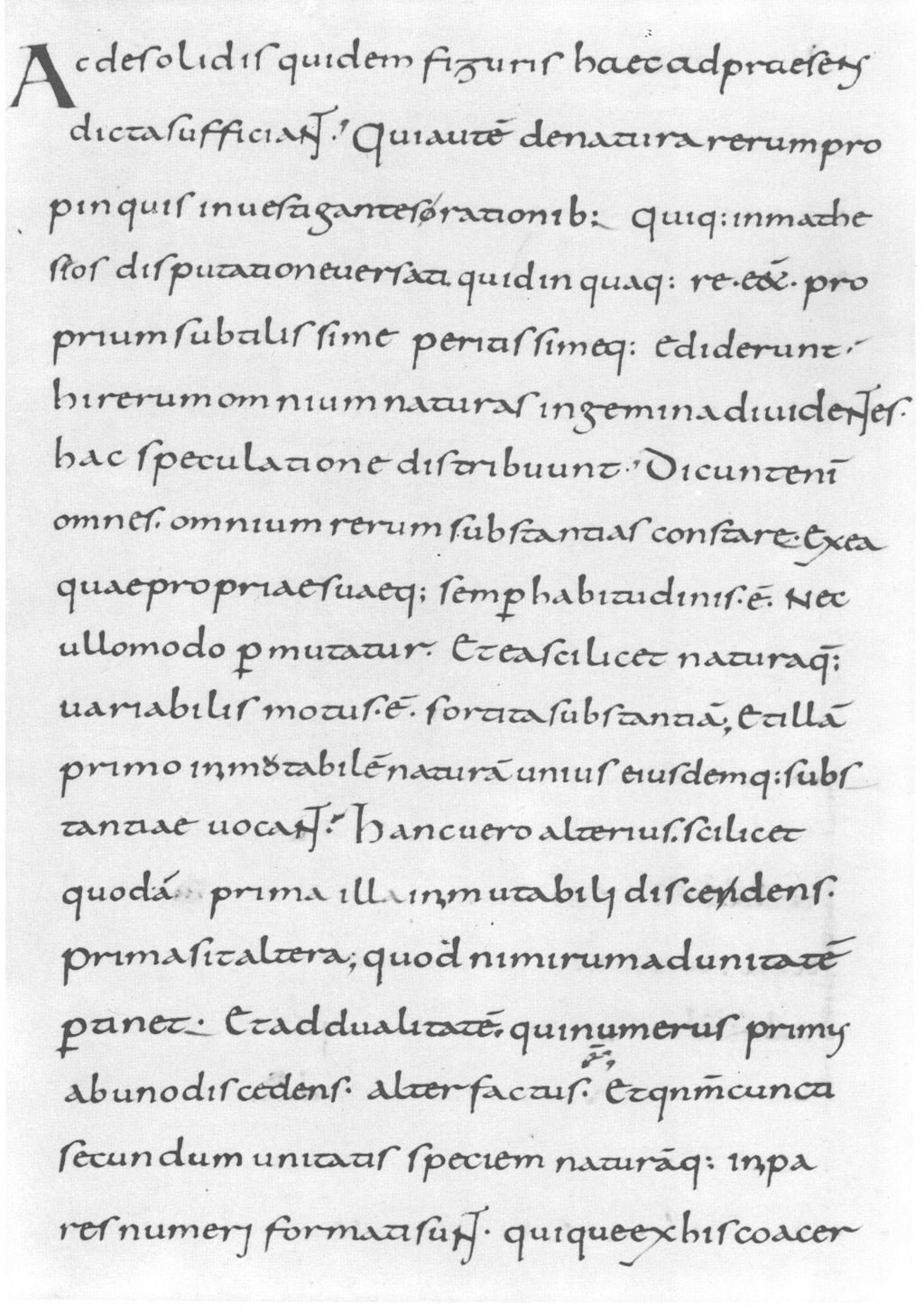

The beginning of Aristotle's De interpretatione in Boethius' Latin translation |

ボエティウスのラテン語訳によるアリストテレスの『解釈の法』の冒頭部分 |

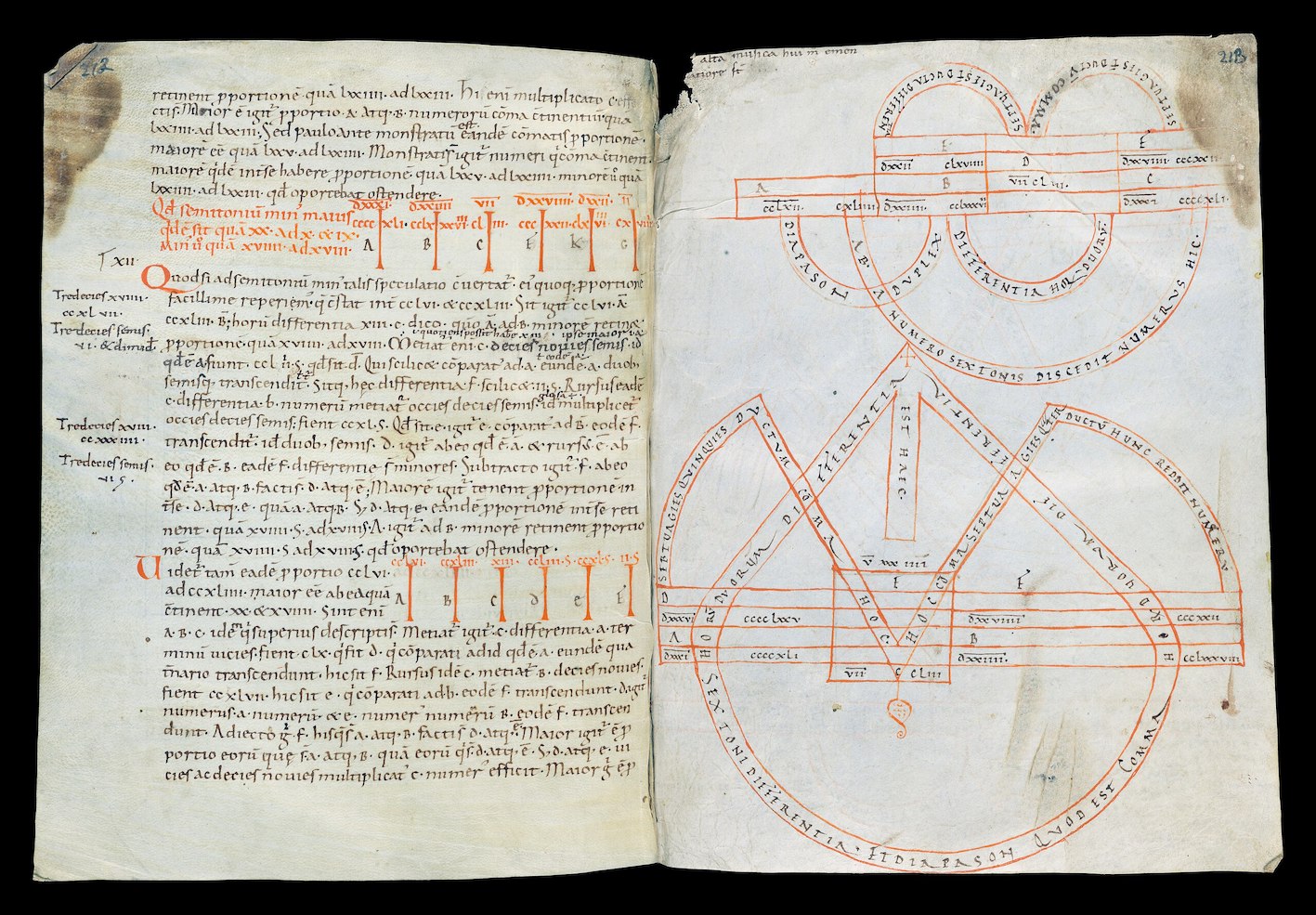

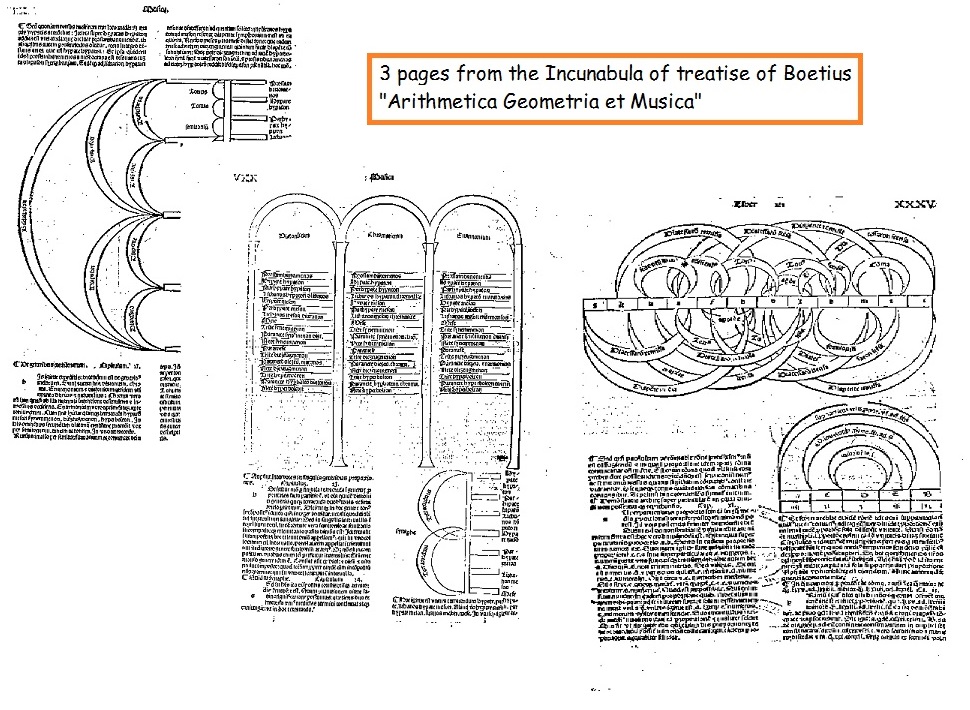

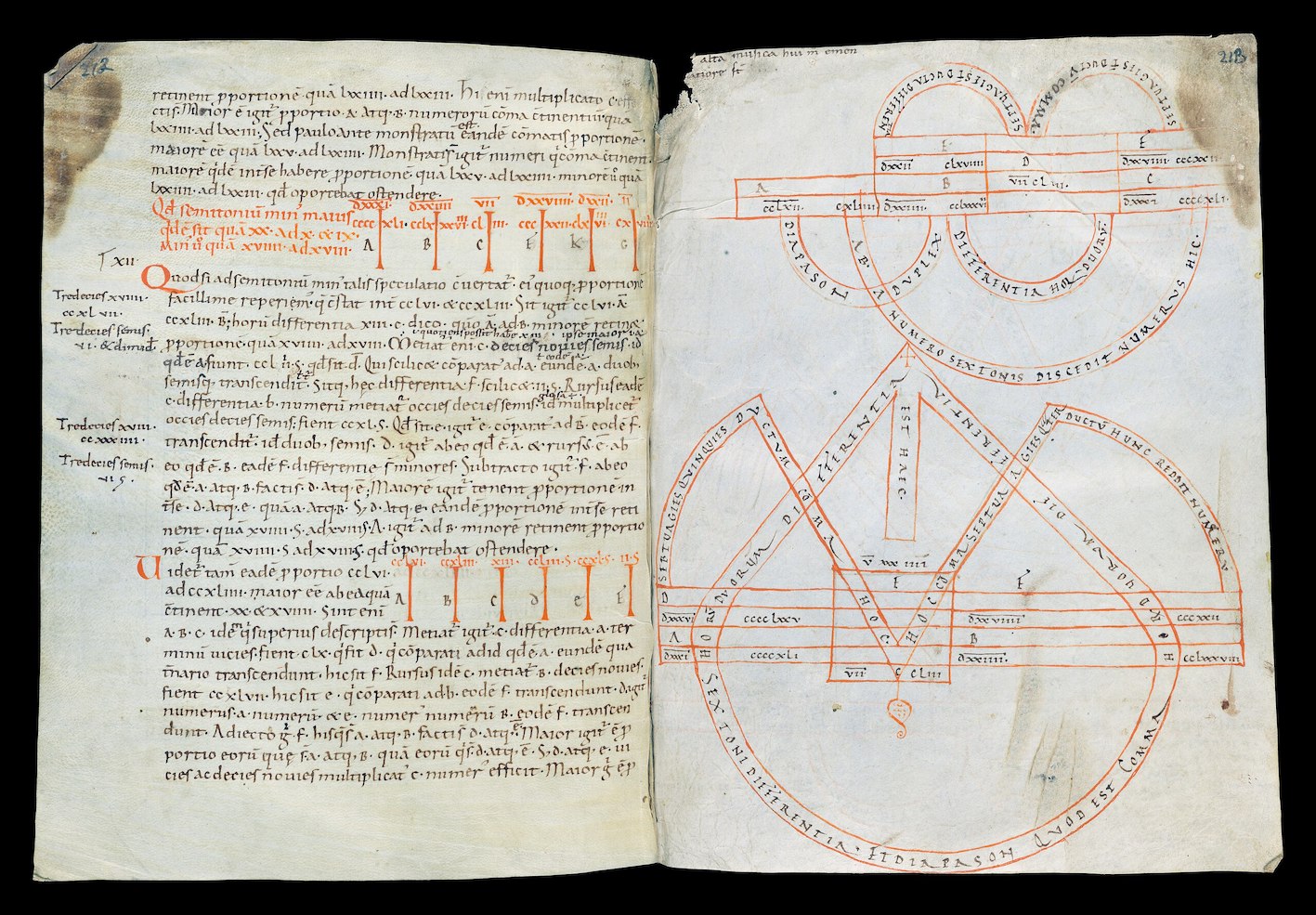

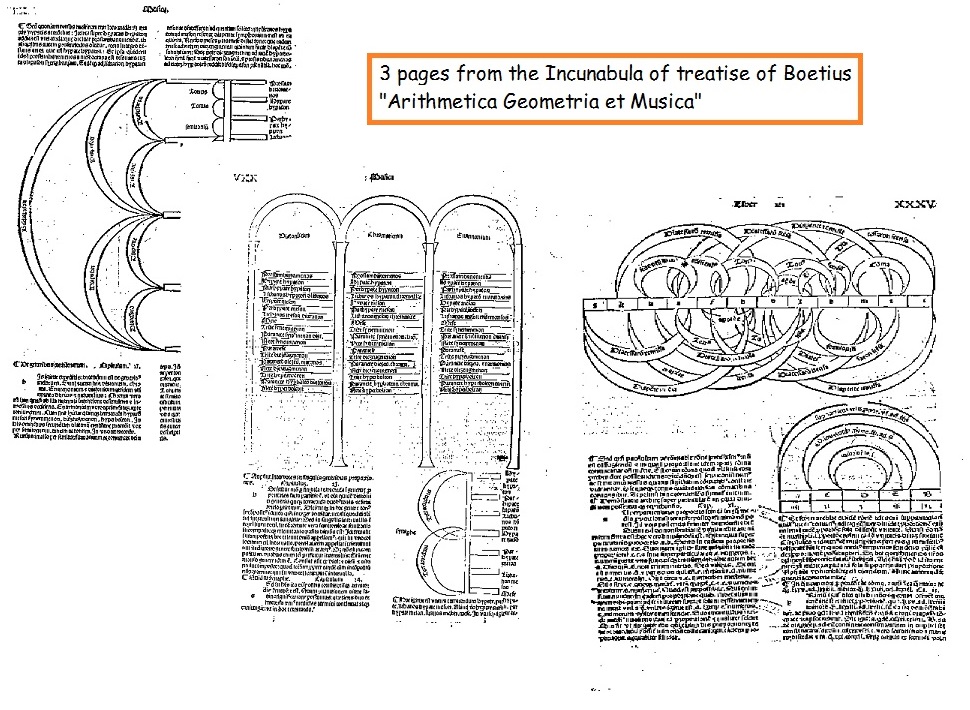

De arithmetica Boethius' De arithmetica in a manuscript written for Charles the Bald Boethius chose to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music, astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.[85] Several of Boethius' writings, which were hugely influential during the Middle Ages, drew on the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus.[86] Boethius wrote a commentary on the Isagoge by Porphyry,[87] which highlighted the existence of the problem of universals: whether these concepts are subsistent entities which would exist whether anyone thought of them, or whether they only exist as ideas. This topic concerning the ontological nature of universal ideas was one of the most vocal controversies in medieval philosophy. Besides these advanced philosophical works, Boethius is also reported to have translated important Greek texts on the topics of the quadrivium[84] His loose translation of Nicomachus's treatise on arithmetic (De institutione arithmetica libri duo) and his textbook on music (De institutione musica libri quinque, unfinished) contributed to medieval education.[87] De arithmetica begins with modular arithmetic, such as even and odd, evenly even, evenly odd, and oddly even. He then turns to unpredicted complexity by categorizing numbers and parts of numbers.[88] His translations of Euclid on geometry and Ptolemy on astronomy,[89] if they were completed, no longer survive. Boethius made Latin translations of Aristotle's De interpretatione and Categories with commentaries.[43] In his article The Ancient Classics in the Mediaeval Libraries, James Stuart Beddie cites Boethius as the reason Aristotle's works were popular in the Middle Ages, as Boethius preserved many of the philosopher's works.[90] De institutione musica  Boethius' De institutione musica was one of the first musical texts to be printed in Venice between the years of 1491 and 1492. It was written toward the beginning of the sixth century and helped medieval theorists during the ninth century and onwards understand ancient Greek music.[91] Like his Greek predecessors, Boethius believed that arithmetic and music were intertwined, and helped to mutually reinforce the understanding of each, and together exemplified the fundamental principles of order and harmony in the understanding of the universe as it was known during his time.[92] In De Musica, Boethius introduced the threefold classification of music:[93] Musica mundana – music of the spheres/world; this "music" was not actually audible and was to be understood rather than heard Musica humana – harmony of human body and spiritual harmony Musica instrumentalis – instrumental music  Boethius, Arithmetica Geometrica Musica (1492 first printed edition, from Hans Adler Collection) In De musica I.2, Boethius describes 'musica instrumentis' as music produced by something under tension (e.g., strings), by wind (e.g., aulos), by water, or by percussion (e.g., cymbals). Boethius himself does not use the term 'instrumentalis', which was used by Adalbold II of Utrecht (975–1026) in his Epistola cum tractatu.[full citation needed] The term is much more common in the 13th century and later.[citation needed] It is also in these later texts that musica instrumentalis is firmly associated with audible music in general, including vocal music. Scholars have traditionally assumed that Boethius also made this connection, possibly under the header of wind instruments ("administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis"[note 5][94]), but Boethius himself never writes about "instrumentalis" as separate from "instrumentis" explicitly in his very brief description. In one of his works within De institutione musica, Boethius said that "music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired."[95] During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts.[89] The historian R. W. Southern called Boethius "the schoolmaster of medieval Europe."[96] An 1872 German translation of "De Musica" was the magnum opus of Oscar Paul.[97][non-primary source needed] Opuscula sacra Boethius also wrote Christian theological treatises, which supported Catholicism and condemned Arianism and other heterodox forms of Christianity.[98] Five theological works are known:[99] De Trinitate – "The Trinity", where he defends the Council of Chalcedon Trinitarian position, that God is in three persons who have no differences in nature. He argues against the Arian view of the nature of God, which put him at odds with the faith of the Arian King of Italy. Utrum Pater et filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur – "Whether Father, Son and Holy Spirit are Substantially Predicated of the Divinity", a short work where he uses reason and Aristotelian epistemology to argue that the Catholic views of the nature of God are correct.[100] Quomodo substantiae, Boethius' claim that all substances are good.[101] De fide catholica – "On the Catholic Faith" Contra Eutychen et Nestorium – "Against Eutyches and Nestorius," from c. 513, which dates it as the earliest of his theological works. Eutyches and Nestorius were contemporaries in the early to mid-5th century who held divergent Christological theologies. Boethius argues for a middle ground in conformity with Roman Catholic faith. His theological works played an important part during the Middle Ages in philosophical thought, including the fields of logic, ontology, and metaphysics.[102] Dates of works  Gravestone of Boethius in the Pavia Civic Museum Dates of composition:[103] Mathematical works De arithmetica (On Arithmetic, c. 500) adapted translation of the Introductio Arithmeticae by Nicomachus of Gerasa (c. 160 – c. 220). De musica (On Music, c. 510), based on a lost work by Nicomachus of Gerasa and on Ptolemy's Harmonica. Possibly a treatise on geometry, extant only in fragments.[104] Logical Works A) Translations Porphyry's Isagoge In Categorias Aristotelis: Aristotle's Categories De interpretatione vel periermenias: Aristotle's De Interpretatione Interpretatio priorum Analyticorum (two versions): Aristotle's Prior Analytics Interpretatio Topicorum Aristotelis: Aristotle's Topics Interpretatio Elenchorum Sophisticorum Aristotelis: Aristotle's Sophistical Refutations B) Commentaries In Isagogen Porphyrii commenta (two commentaries, the first based on a translation by Marius Victorinus, (c. 504–05); the second based on Boethius' own translation (507–509) ). In Categorias Aristotelis (c. 509–11) In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria minora (not before 513) In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria majora (c. 515–16) In Aristotelis Analytica Priora (c. 520–523) Commentaria in Topica Ciceronis (incomplete: the end the sixth book and the seventh are missing) Original Treatises De divisione (515–520?) De syllogismo cathegorico (505–506) Introductio ad syllogismos cathegoricos (c. 523) De hypotheticis syllogismis (516–522) De topicis differentiis (c. 522–23) Opuscula Sacra (Theological Treatises) De Trinitate (c. 520–21) Utrum Pater et Filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur (Whether Father and Son and Holy Spirit are Substantially Predicated of the Divinity) Quomodo substantiae in eo quod sint bonae sint cum non sint substantialia bona [also known as De hebdomadibus] (How Substances are Good in that they Exist, when They are not Substantially Good) De fide Catholica Contra Eutychen et Nestorium (Against Eutyches and Nestorius) De consolatione Philosophiae (524–525). |

算術書 シャルル禿頭王のために書かれたボエティウスの『算術書』(De arithmetica) ボエティウスは、音楽、天文学、幾何学、算術に関するマニュアルを書くことで、偉大なグレコ・ローマ文化を後世に伝えることを選んだ[85]。 中世において大きな影響力を持ったボエティウスの著作のいくつかは、ポルフィリーやイアンブリヒコスの考え方を参考にしていた[86]。ボエティウスはポ ルフィリーの『イサゴゲ』の注釈書を書いており[87]、普遍の問題の存在を強調していた。普遍的観念の存在論的性質に関するこのテーマは、中世哲学にお ける最も声高な論争のひとつであった。 このような高度な哲学的著作のほかに、ボエティウスは四分学のトピックに関するギリシア語の重要なテキストを翻訳したとも伝えられている[84]。ニコマ コスの算術論(De institutione arithmetica libri duo)の緩やかな翻訳と、彼の音楽の教科書(De institutione musica libri quinque、未完)は中世の教育に貢献した[87]。幾何学に関するユークリッドと天文学に関するプトレマイオスの翻訳[89]は、完成していたとし ても、もはや残っていない。ボエティウスはアリストテレスの『解釈学』と『カテゴリーズ』のラテン語訳に注釈をつけている[43]。 James Stuart Beddieは彼の論文『The Ancient Classics in the Mediaeval Libraries』の中で、アリストテレスの著作が中世に人気があった理由として、ボエティウスが哲学者の著作の多くを保存していたことを挙げている [90]。 音楽制度論  ボエティウスの『De institutione musica』は、1491年から1492年にかけてヴェネツィアで印刷された最初の音楽テキストのひとつである。それは6世紀の初め頃に書かれ、9世紀 以降の中世の理論家たちが古代ギリシア音楽を理解するのに役立った[91]。ギリシアの先人たちと同様に、ボエティウスは算術と音楽は絡み合っており、そ れぞれの理解を相互に強化するのに役立っており、彼の時代に知られていた宇宙の理解における秩序と調和の基本原理を共に例証していると考えていた [92]。 De Musica』においてボエティウスは音楽の3つの分類を紹介している[93]。 ムジカ・ムンダナ(Musica mundana)-球体/世界の音楽。この「音楽」は実際には聴くことができず、聴くよりも理解するものであった。 ムジカ・ヒューマナ(Musica humana)-人体の調和と精神の調和 Musica instrumentalis - 器楽  Boethius, Arithmetica Geometrica Musica (1492年初版、ハンス・アドラー・コレクションより) De musica I.2の中で、ボエティウスは「musica instrumentis」を、張力のあるもの(例えば弦楽器)、風(例えばアウロス)、水、打楽器(例えばシンバル)によって生み出される音楽と説明し ている。ボエティウス自身は「インストゥルメンタリス」という用語を使っていないが、これはユトレヒトのアダルボルト2世(975-1026)が『エピス トラクトラ(Epistola cum tractatu)』の中で使ったものである。学者たちは伝統的に、ボエティウスもおそらく管楽器(「administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis」[注釈 5][94])のヘッダーの下でこの関連付けを行ったと仮定してきたが、ボエティウス自身は非常に短い記述の中で、「instrumentalis」を 「instrumentis」と明確に分けて書くことはなかった。 ボエティウスは彼の著作の一つである『De institutione musica』の中で、「音楽はわれわれと自然に結びついているので、われわれが望んだとしても、そこから自由になることはできない」と述べている [95]。ボエティウスはトリヴィアムの主題を扱わなかったが、修辞学、文法、論理学の原理を説明する多くの論文を書いた。中世の間、3つの初等芸術を学 ぶ際には、これらの学問に関する彼の著作がよく用いられた[89]。歴史家R.W.サザンはボエティウスを「中世ヨーロッパの校長」と呼んだ[96]。 『デ・ムジカ』の1872年のドイツ語訳はオスカー・パウルの大著であった[97][要出典]。 オプスキュラ・サクラ ボエティウスはまた、カトリックを支持し、アリウス主義や他の異端的なキリスト教を非難するキリスト教神学書を書いた[98]。 神学的著作は以下の5つが知られている[99]。 De Trinitate - 『三位一体』では、カルケドン公会議の三位一体の立場を擁護している。神の性質に関するアリウス派の見解に反論しており、イタリアのアリウス王の信仰と対立した。 Utrum Pater et filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur - "Whether Father, Son and Holy Spirit are Substantially Predicated of the Divinity"』は、理性とアリストテレス的認識論を用いて、カトリックの神性観が正しいことを論じた短い著作である[100]。 Quomodo substantiae』:すべての物質は善であるというボエティウスの主張[101]。 De fide catholica - "カトリックの信仰について" Contra Eutychen et Nestorium - "Against Eutyches and Nestorius" 513年頃のもので、彼の神学著作の中では最も古い。エウティケスとネストリウスは、5世紀初頭から半ばにかけて同時代に活躍したキリスト論神学者であ る。ボエティウスは、ローマ・カトリックの信仰に合致する中間的な立場を主張している。 彼の神学的著作は中世において、論理学、存在論、形而上学の分野を含む哲学思想において重要な役割を果たした[102]。 著作の年代  パヴィア市民博物館にあるボエティウスの墓碑 作曲年代:[103] 数学作品 De arithmetica (On Arithmetic, c. 500) ジェラサのニコマコス(160頃-220頃)によるIntroductio Arithmeticaeの翻案。 ゲラサのニコマコスの失われた著作とプトレマイオスの『ハーモニカ』に基づく。 現存するのは断片のみだが、幾何学に関する論考の可能性もある[104]。 論理的著作 A) 翻訳 ポルフィリーの『イサゴーゲ アリストテレスのカテゴリー アリストテレスのカテゴリー アリストテレスの『解釈の法』(De interpretatione vel periermenias) アリストテレスの『解釈論』(De Interpretatione Interpretatio priorum Analyticorum(2つのバージョン): アリストテレスの先行分析学 Interpretatio Topicorum Aristotelis: アリストテレスのトピックの解釈: アリストテレスのトピック Interpretatio Elenchorum Sophisticorum Aristotelis: アリストテレスの詭弁的解釈: アリストテレスの詭弁的反論 B) 注釈書 Isagogen Porphyrii commenta』(2つの注釈書、1つ目はマリウス・ヴィクトリヌスの翻訳に基づく(504-05年頃)、2つ目はボエティウス自身の翻訳に基づく(507-509年頃))。 アリストテレスのカテゴリー』(509-11年) In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria minora(アリストテレス解釈小注釈書)(513年以前 In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria majora (c. 515-16) アリストテレス・アナリティカ・プリオラ』所収(520-523年頃) トピカ・キケロニスの注釈書(不完全:第6巻の終わりと第7巻が欠落している) 原論 分割論(515-520?) 三段論法(505-506年) カテゴリコス論理学入門(523年頃) 仮説的シロギズム(516-522) 差異のトピック論(522-23年) 神学書(Opuscula Sacra) 三位一体論(520-21年) 父と子と聖霊とが実質的に神性であるかどうか(Utrum Pater et Filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur) Quomodo substantiae in eo quod sint bonae sint cum non sint substantialia bona [De hebdomadibusとしても知られる](物質が実体的に善でないとき、物質が存在することがいかに善であるか) カトリックの信条 Contra Eutychen et Nestorium(エウティケスとネストリウスに反対して) 哲学者の慰め』(524-525年) |

Legacy Depiction of Boethius in the Nuremberg Chronicle Edward Kennard Rand dubbed Boethius the "last of the Roman philosophers and the first of the scholastic theologians".[105] Despite the use of his mathematical texts in the early universities, it is his final work, the Consolation of Philosophy, that assured his legacy in the Middle Ages and beyond. This work is cast as a dialogue between Boethius himself, at first bitter and despairing over his imprisonment, and the spirit of philosophy, depicted as a woman of wisdom and compassion. "Alternately composed in prose and verse,[86] the Consolation teaches acceptance of hardship in a spirit of philosophical detachment from misfortune".[106] Parts of the work are reminiscent of the Socratic method of Plato's dialogues, as the spirit of philosophy questions Boethius and challenges his emotional reactions to adversity. The work was translated into Old English by King Alfred and later into English by Chaucer and Queen Elizabeth.[98] Many manuscripts survive and it was extensively edited, translated and printed throughout Europe from the 14th century onwards.[107] "The Boethian Wheel" is a model for Boethius' belief that history is a wheel,[108] a metaphor that Boethius uses frequently in the Consolation; it remained very popular throughout the Middle Ages, and is still often seen today. As the wheel turns, those who have power and wealth will turn to dust; men may rise from poverty and hunger to greatness, while those who are great may fall with the turn of the wheel. It was represented in the Middle Ages in many relics of art depicting the rise and fall of man. Descriptions of "The Boethian Wheel" can be found in the literature of the Middle Ages from the Romance of the Rose to Chaucer.[109] De topicis differentiis was the basis for one of the first works of logic in a western European vernacular, a selection of excerpts translated into Old French by John of Antioch in 1282.[110] |

遺産 ニュルンベルク年代記におけるボエティウスの描写 エドワード・ケナード・ランドは、ボエティウスを「ローマ最後の哲学者であり、スコラ神学者の最初の人物」と呼んだ[105]。初期の大学では彼の数学的 テキストが使用されていたにもかかわらず、中世以降における彼の遺産を確実なものにしたのは、彼の最後の著作である『哲学の慰め』である。この作品は、ボ エティウス自身と哲学の精神との対話として描かれており、ボエティウスは最初、投獄されたことを苦々しく思い、絶望していた。散文と詩で交互に構成された [86]『慰め』は、哲学的に不幸を切り離す精神で苦難を受け入れることを教えている」[106]。 哲学の精神がボエティウスに問いかけ、逆境に対する彼の感情的な反応に挑戦しているため、作品の一部はプラトンの対話におけるソクラテスの手法を彷彿とさ せる。この作品はアルフレッド王によって古英語に翻訳され、後にチョーサーとエリザベス女王によって英語に翻訳された[98]。多くの写本が残っており、 14世紀以降、ヨーロッパ全土で広く編集、翻訳、印刷された[107]。 ボエティウスの車輪」は、歴史は車輪であるというボエティウスの信念のモデルであり[108]、ボエティウスは『慰め』の中でこの比喩を頻繁に用いてい る。車輪が回るにつれて、権力や富を持つ者は塵と化す。人は貧困や飢餓から偉大な存在へと昇華することもあれば、偉大な存在であっても車輪の回転とともに 没落することもある。中世には、人間の栄華と没落を描いた多くの芸術遺物で表現された。薔薇のロマンス』からチョーサーに至るまで、中世の文学には「ボエ スの車輪」の記述が見られる[109]。 De topicis differentiis』は、1282年にアンティオキアのジョンによって古フランス語に翻訳された、西ヨーロッパの方言による最初の論理学の著作のひとつである抜粋の基礎となった[110]。 |

Veneration The Tomb of Boethius in San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro Boethius was regarded as a Christian martyr by those who lived in succeeding centuries after his death.[17][9] Currently, he is recognized as a saint and martyr for the Catholic faith.[53] He is included within the Roman Martyrology, though to Watkins "his status as martyr is dubious".[111] His cult is held in Pavia, where Boethius' status as a saint was confirmed in 1883, and in the Church of Santa Maria in Portico in Rome. His feast day is 23 October, provided by some as a date for his death.[9][112][111][113] In the current Martyrologium Romanum, his feast is still restricted to that diocese.[114] Pope Benedict XVI explained the relevance of Boethius to modern day Christians by linking his teachings to an understanding of Providence.[85] He is also venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[115] |

崇敬 サン・ピエトロ・イン・チエル・ドーロにあるボエティウスの墓 ボエティウスは、死後数世紀を経た人々からキリスト教の殉教者として見なされていた[17][9]。 現在、カトリックの聖人、殉教者として認められている[53]。ローマ殉教録に含まれているが、ワトキンスによれば「殉教者としての地位は疑わしい」 [111]。教皇ベネディクト16世は、ボエティウスの教えを摂理の理解と結びつけることによって、現代のキリスト教徒とボエティウスとの関連性を説明し ている[85]。 |

In popular culture Boethius' Farewell To His Family by Jean-Victor Schnetz In Dante's Divine Comedy, the spirit of Boethius is pointed out by Saint Thomas Aquinas and is mentioned further in the poem. In the novel A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole, Boethius is the favorite philosopher of the main character, Ignatius J. Reilly. The "Boethian Wheel" is a theme throughout the book, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981.[116] C.S. Lewis references Boethius in chapter 27 of the Screwtape Letters.[117] Boethius also appears in the 2002 film 24 Hour Party People where he is played by Christopher Eccleston. In 1976, a lunar crater was named in honor of Boethius. The title of Alain de Botton's book, The Consolations of Philosophy, is derived from Boethius' Consolation. A codex of Boethius' The Consolation of Philosophy is the focus of The Late Scholar, a Lord Peter Wimsey novel by Jill Paton Walsh. |

大衆文化の中で ジャン=ヴィクトール・シュネッツ著『ボエティウスの家族への別れ』 ダンテの『神曲』の中で、ボエティウスの精神は聖トマス・アクィナスによって指摘され、詩の中でさらに言及されている。 ジョン・ケネディ・トゥールの小説『A Confederacy of Dunces』では、ボエティウスは主人公イグナティウス・J・ライリーのお気に入りの哲学者である。ボエティウスの車輪」は、1981年にピューリッ ツァー賞フィクション部門を受賞したこの本全体のテーマである[116]。 C.S.ルイスは『ねじまき鳥の手紙』の第27章でボエティウスに言及している[117]。 ボエティウスは2002年の映画『24 Hour Party People』にも登場し、クリストファー・エクルストンが演じている。 1976年、月のクレーターがボエティウスにちなんで命名された。 アラン・ド・ボットンの著書『哲学の慰め』のタイトルは、ボエティウスの『慰め』に由来する。 ボエティウスの『哲学の慰め』の写本は、ジル・パトン・ウォルシュによるロード・ピーター・ウィムジーの小説『The Late Scholar』の焦点となっている。 |

| De Fide Catolica The Consolations of Philosophy (by Alain de Botton) Prison literature Elpis (wife of Boethius) |

デ・フィデ・カトリカ 哲学の慰め(アラン・ド・ボットン著) 獄中文学 エルピス(ボエティウスの妻) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boethius |

★ボエティウス:『算術論』、『音楽論』 1350年頃 写本(V. A. 14) ヴィットリオ・エマヌエーレ3世国立図書館、ナポリ

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆