割れ窓理論

Broken windows theory

☆ 犯罪学において、「割れ窓理論(The Broken Windows Theory)」は、目に見える犯罪の兆候、反社会的行動、市民的無秩序が、重大犯罪を含むさらなる犯罪や無秩序を助長する都市環境を作り 出すと主張するものだ。この理論は、破壊行為、徘徊、公共の場での飲酒、料金逃れなどの軽犯罪を対象とした取り締まり方法が、秩序と合法的な雰囲気を作 り出すのに役立つことを示唆している。

★い

くつかの研究は、(1990年代のニューヨークのような)割れ窓取り締まりの見かけ上の成功の多くは、他の要因の結果であると主張している[40]。彼

らは、「割れ窓理論」は相関関係と因果関係を密接に関連付けるものであり、誤りやすい推論であると主張している。ミシガン大学で公共政策と都市計画の助教

授を務めるデビッド・サッハー(David

Thacher)は、2004年の論文で次のように述べている;「社会科学は割れ窓理論に優しくない。多くの学者が、この理論を支持すると思われた初期の

研究を再分析した。また、無秩序と犯罪の関係について、より洗練

された新しい研究を進める学者もいた。その中で最も著名な研究者たちは、無秩序と重大犯罪の関係は緩やかであり、その関係さえも、より根本的な社会的力に

よる捏造(アーティファクト)であると結論づけた」

| The Broken Windows Theory In criminology, the Broken Windows Theory states that visible signs of crime, antisocial behavior and civil disorder create an urban environment that encourages further crime and disorder, including serious crimes.[1] The theory suggests that policing methods that target minor crimes, such as vandalism, loitering, public drinking and fare evasion, help to create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness. The theory was introduced in a 1982 article by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling.[1] It was popularized in the 1990s by New York City police commissioner William Bratton and mayor Rudy Giuliani, whose policing policies were influenced by the theory. The theory became subject to debate both within the social sciences and the public sphere. Broken windows policing has been enforced with controversial police practices, such as the high use of stop-and-frisk in New York City in the decade up to 2013. |

割れ窓理論 犯 罪学において、「割れ窓理論」は、目に見える犯罪の兆候、反社会的行動、市民的無秩序が、重大犯罪を含むさらなる犯罪や無秩序を助長する都市環境を作り出 すと述べている[1]。この理論は、破壊行為、徘徊、公共の場での飲酒、料金逃れなどの軽犯罪を対象とした取り締まり方法が、秩序と合法的な雰囲気を作り 出すのに役立つことを示唆している。 この理論は、社会科学者のジェームズ・Q・ウィルソンとジョージ・L・ケリングが1982年に発表した論文で紹介された[1]。1990年代には、ニュー ヨーク市警察本部長のウィリアム・ブラットンと市長のルディ・ジュリアーニによって広まり、その警察政策はこの理論に影響を受けた。 この理論は、社会科学と公共圏の両方で議論の対象となった。ブロークン・ウィンドウズ・ポリシングは、2013年までの10年間、ニューヨーク市におけるストップ・アンド・フリスクの多用など、物議を醸す警察慣行とともに実施されてきた。 |

| Article and crime prevention James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling first introduced the broken windows theory in an article titled "Broken Windows", in the March 1982 issue of The Atlantic Monthly: Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken. This is as true in nice neighborhoods as in rundown ones. Window-breaking does not necessarily occur on a large scale because some areas are inhabited by determined window-breakers whereas others are populated by window-lovers; rather, one un-repaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing. (It has always been fun.)[1] The article received a great deal of attention and was very widely cited. A 1996 criminology and urban sociology book, Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities by George L. Kelling and Catharine Coles, is based on the article but develops the argument in greater detail. It discusses the theory in relation to crime and strategies to contain or eliminate crime from urban neighborhoods.[2] A successful strategy for preventing vandalism, according to the book's authors, is to address the problems when they are small. Repair the broken windows within a short time, say, a day or a week, and the tendency is that vandals are much less likely to break more windows or do further damage. Clean up the sidewalk every day, and the tendency is for litter not to accumulate (or for the rate of littering to be much less). Problems are less likely to escalate and thus respectable residents do not flee the neighborhood. Oscar Newman introduced defensible space theory in his 1972 book Defensible Space. He argued that although police work is crucial to crime prevention, police authority is not enough to maintain a safe and crime-free city. People in the community help with crime prevention. Newman proposed that people care for and protect spaces that they feel invested in, arguing that an area is eventually safer if the people feel a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the area. Broken windows and vandalism are still prevalent because communities simply do not care about the damage. Regardless of how many times the windows are repaired, the community still must invest some of their time to keep it safe. Residents' negligence of broken window-type decay signifies a lack of concern for the community. Newman says this is a clear sign that the society has accepted this disorder—allowing the unrepaired windows to display vulnerability and lack of defense.[3] Malcolm Gladwell also relates this theory to the reality of New York City in his book, The Tipping Point.[4] Thus, the theory makes a few major claims: that improving the quality of the neighborhood environment reduces petty crime, anti-social behavior, and low-level disorder, and that major crime is also prevented as a result. Criticism of the theory has tended to focus on the latter claim.[5] |

記事と犯罪防止 ジェームズ・Q・ウィルソンとジョージ・L・ケリングは、『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌の1982年3月号に掲載された「割れた窓(Broken Windows)」という記事で、割れた窓理論を初めて紹介した: 社会心理学者と警察官は、建物の窓ガラスが割れて修理されずに放置されると、残りの窓ガラスもすぐに割れてしまうという意見で一致する傾向がある。これ は、良い地域でも、荒れ果てた地域でも同じである。窓割りが必ずしも大規模に行われるわけではないのは、ある地域には決然と窓を割る人が住んでおり、別の 地域には窓を愛する人が住んでいるからである。むしろ、割られた窓が1つ修理されていないことは、誰も気にしていないというシグナルであり、そのため窓を 割ることにコストはかからない。(それは常に楽しいことなのだ)[1]。 この論文は大きな注目を集め、非常に広く引用された。1996年に出版された犯罪学と都市社会学の本『Fixing Broken Windows: Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities』(ジョージ・L・ケリングとキャサリン・コールズ著)は、この論文をベースにしているが、より詳細に議論を展開している。同書 は、犯罪と、都市近隣から犯罪を抑制または排除するための戦略との関連で理論を論じている[2]。 本書の著者によれば、破壊行為を防ぐための成功戦略は、問題が小さいうちに対処することである。割れた窓ガラスを1日や1週間といった短期間で修理すれ ば、破壊者がさらに窓ガラスを割ったり、さらなる被害を与えたりする可能性は低くなる。歩道を毎日清掃すれば、ゴミが溜まらない(あるいはポイ捨ての割合 が大幅に減る)傾向がある。問題がエスカレートしにくいので、立派な住民が近隣から逃げ出すこともない。 オスカー・ニューマンは、1972年に出版した『Defensible Space』という本の中で、防衛可能空間理論を紹介した。彼は、犯罪防止には警察の活動が不可欠だが、犯罪のない安全な都市を維持するには警察の権限だ けでは不十分だと主張した。犯罪防止に貢献するのは、地域社会の人々である。ニューマンは、人々が自分たちが投資していると感じる空間を大切にし、守るこ とを提案し、人々がその地域に対して所有意識と責任感を持つことで、その地域は最終的に安全になると主張した。壊された窓や破壊行為がいまだに蔓延してい るのは、コミュニティが単に被害に無関心だからだ。窓ガラスが何度修理されようとも、地域社会は安全を維持するためにある程度の時間を投資しなければなら ない。住民が割れた窓のような腐敗を放置するのは、地域社会に対する関心の欠如を意味する。ニューマンは、これは社会がこの障害を受け入れている明確な兆 候であり、修理されていない窓が脆弱性と防御の欠如を示すことを許しているのだと言う[3]。 マルコム・グラッドウェルもまた、著書『ティッピング・ポイント』[4]の中で、この理論をニューヨークの現実と関連づけている。 つまり、近隣環境の質を向上させることで、軽犯罪、反社会的行動、低レベルの無秩序が減少し、その結果として重大犯罪も防止されるというものである。この理論に対する批判は後者の主張に集中する傾向がある[5]。 |

| Theoretical explanation The reason the state of the urban environment may affect crime consists of three factors: social norms and conformity; the presence or lack of routine monitoring; and social signaling and signal crime. In an anonymous urban environment, with few or no other people around, social norms and monitoring are not clearly known. Thus, individuals look for signals within the environment as to the social norms in the setting and the risk of getting caught violating those norms; one of the signals is the area's general appearance. Under the broken windows theory, an ordered and clean environment, one that is maintained, sends the signal that the area is monitored and that criminal behavior is not tolerated. Conversely, a disordered environment, one that is not maintained (broken windows, graffiti, excessive litter), sends the signal that the area is not monitored and that criminal behavior has little risk of detection. The theory assumes that the landscape "communicates" to people. A broken window transmits to criminals the message that a community displays a lack of informal social control and so is unable or unwilling to defend itself against a criminal invasion. It is not so much the actual broken window that is important, but the message the broken window sends to people. It symbolizes the community's defenselessness and vulnerability and represents the lack of cohesiveness of the people within. Neighborhoods with a strong sense of cohesion fix broken windows and assert social responsibility on themselves, effectively giving themselves control over their space. The theory emphasizes the built environment, but must also consider human behavior.[6] Under the impression that a broken window left unfixed leads to more serious problems, residents begin to change the way they see their community. In an attempt to stay safe, a cohesive community starts to fall apart, as individuals start to spend less time in communal space to avoid potential violent attacks by strangers.[1] The slow deterioration of a community, as a result of broken windows, modifies the way people behave when it comes to their communal space, which, in turn, breaks down community control. As rowdy teenagers, panhandlers, addicts, and prostitutes slowly make their way into a community, it signifies that the community cannot assert informal social control, and citizens become afraid that worse things will happen. As a result, they spend less time in the streets to avoid these subjects and feel less and less connected from their community, if the problems persist. At times, residents tolerate "broken windows" because they feel they belong in the community and "know their place". Problems, however, arise when outsiders begin to disrupt the community's cultural fabric. That is the difference between "regulars" and "strangers" in a community. The way that "regulars" act represents the culture within, but strangers are "outsiders" who do not belong.[6] Consequently, daily activities considered "normal" for residents now become uncomfortable, as the culture of the community carries a different feel from the way that it was once. With regard to social geography, the broken windows theory is a way of explaining people and their interactions with space. The culture of a community can deteriorate and change over time, with the influence of unwanted people and behaviors changing the landscape. The theory can be seen as people shaping space, as the civility and attitude of the community create spaces used for specific purposes by residents. On the other hand, it can also be seen as space shaping people, with elements of the environment influencing and restricting day-to-day decision making. However, with policing efforts to remove unwanted disorderly people that put fear in the public's eyes, the argument would seem to be in favor of "people shaping space", as public policies are enacted and help to determine how one is supposed to behave. All spaces have their own codes of conduct, and what is considered to be right and normal will vary from place to place. The concept also takes into consideration spatial exclusion and social division, as certain people behaving in a given way are considered disruptive and therefore, unwanted. It excludes people from certain spaces because their behavior does not fit the class level of the community and its surroundings. A community has its own standards and communicates a strong message to criminals, by social control, that their neighborhood does not tolerate their behavior. If, however, a community is unable to ward off would-be criminals on their own, policing efforts help. By removing unwanted people from the streets, the residents feel safer and have a higher regard for those that protect them. People of less civility who try to make a mark in the community are removed, according to the theory.[6] |

理論的説明 都市環境の状態が犯罪に影響を与える理由は、社会規範と適合性、日常的な監視の有無、社会的シグナルとシグナル犯罪という3つの要因からなる。 匿名性が高く、周囲に人がほとんどいない都市環境では、社会規範や監視が明確にはわからない。そのため個人は、その環境における社会規範と、その規範に違反して捕まる危険性についてのシグナルを環境内で探す。シグナルのひとつは、その地域の一般的な外観である。 割れ窓理論では、秩序が保たれた清潔な環境は、その地域が監視されており、犯罪行為は許されないというシグナルを送る。逆に、乱れた環境、整備されていな い環境(割れた窓、落書き、過剰なゴミ)は、その地域が監視されておらず、犯罪行為が発見される危険性が低いというシグナルを送る。 この理論は、景観が人々に「伝える」ことを前提としている。窓ガラスが割れていると、その地域社会は非公式な社会統制が欠如しているため、犯罪者の侵入か ら身を守ることができない、あるいは守ろうとしないというメッセージが犯罪者に伝わる。重要なのは、実際に割れた窓ではなく、割れた窓が人々に送るメッ セージである。窓ガラスはコミュニティの無防備さと脆弱性を象徴し、そこに住む人々の結束力の欠如を表している。強い結束力を持つ地域社会は、割れた窓を 修理し、社会的責任を自ら主張することで、効果的に自分たちの空間を自分たちでコントロールできるようになる。 この理論は建築環境を重視するが、人間の行動も考慮しなければならない[6]。 割れた窓を直さずに放置すると、より深刻な問題につながるという印象のもと、住民は自分たちのコミュニティに対する見方を変え始める。安全であり続けよう とするあまり、見知らぬ人からの暴力的な攻撃を避けるために、共同スペースで過ごす時間が減り始め、結束の固いコミュニティが崩壊し始める。乱暴なティー ンエイジャー、パンパン売り、中毒者、売春婦が徐々にコミュニティに入り込むようになると、コミュニティが非公式の社会的統制を主張できなくなることを意 味し、市民はもっと悪いことが起こるのではないかと恐れるようになる。その結果、こうした対象を避けるために街で過ごす時間が減り、問題が続くと地域社会 とのつながりが希薄になると感じるようになる。 時に、住民が「割れた窓」を容認するのは、自分たちが地域に属し、「自分の居場所を知っている」と感じているからである。しかし問題は、部外者がコミュニ ティの文化的構造を乱し始めたときに生じる。それが、コミュニティにおける「常連」と「よそ者」の違いである。常連」の行動様式は内部の文化を表している が、よそ者は所属しない「部外者」である[6]。 その結果、住民にとって「普通」だと思われていた日常的な活動が、コミュニティの文化がかつてとは異なる感覚を持つようになり、居心地の悪いものになる。 社会地理学に関して、割れ窓理論は、人々と空間との相互作用を説明する方法である。地域社会の文化は、不要な人々や行動の影響によって景観が変化し、時間 の経過とともに悪化したり変化したりする。この理論は、コミュニティの礼節や態度が、住民による特定の目的のために使われる空間を作り出すように、人々が 空間を形成していると見ることができる。一方、環境の要素が日々の意思決定に影響を与えたり、制限したりすることから、空間が人を形成しているとも見るこ とができる。 しかし、公衆の目に恐怖を与えるような無秩序な人々を排除するための取り締まり活動では、公的な政策が制定され、人がどのように振る舞うべきかを決定する のに役立っているため、「人々が空間を形成している」という議論に賛成しているように思われる。すべての空間にはそれぞれの行動規範があり、何が正しく、 何が普通とされるかは場所によって異なる。 この概念は、空間的な排除や社会的分断も考慮に入れている。ある特定の行動をとる人々は、破壊的であり、それゆえ不要な存在とみなされるからだ。ある特定 の空間から人々を排除するのは、彼らの振る舞いがコミュニティやその周囲の階級水準に合わないからである。地域社会は独自の基準を持ち、社会的統制によっ て、犯罪者に対し、近隣は彼らの行動を容認しないという強いメッセージを伝える。しかし、地域社会が自分たちだけでは犯罪者になりそうな人々を追い払うこ とができない場合、取り締まり活動が役立つ。 通りから不要な人間を排除することで、住民はより安全だと感じ、自分たちを守ってくれる人々に対してより高い敬意を抱くようになる。この理論によれば、地域社会で目立とうとする礼節のない人々は排除される[6]。 |

| Concepts Informal social controls Many claim that informal social control can be an effective strategy to reduce unruly behavior. Garland (2001) expresses that "community policing measures in the realization that informal social control exercised through everyday relationships and institutions is more effective than legal sanctions."[7] Informal social control methods have demonstrated a "get tough" attitude by proactive citizens, and express a sense that disorderly conduct is not tolerated. According to Wilson and Kelling, there are two types of groups involved in maintaining order, 'community watchmen' and 'vigilantes'.[1] The United States has adopted in many ways policing strategies of old European times, and at that time, informal social control was the norm, which gave rise to contemporary formal policing. Though, in earlier times, because there were no legal sanctions to follow, informal policing was primarily 'objective' driven, as stated by Wilson and Kelling (1982). Wilcox et al. 2004 argue that improper land use can cause disorder, and the larger the public land is, the more susceptible to criminal deviance.[8] Therefore, nonresidential spaces, such as businesses, may assume to the responsibility of informal social control "in the form of surveillance, communication, supervision, and intervention".[9] It is expected that more strangers occupying the public land creates a higher chance for disorder. Jane Jacobs can be considered one of the original pioneers of this perspective of broken windows. Much of her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, focuses on residents' and nonresidents' contributions to maintaining order on the street, and explains how local businesses, institutions, and convenience stores provide a sense of having "eyes on the street".[10] On the contrary, many residents feel that regulating disorder is not their responsibility. Wilson and Kelling found that studies done by psychologists suggest people often refuse to go to the aid of someone seeking help, not due to a lack of concern or selfishness "but the absence of some plausible grounds for feeling that one must personally accept responsibility".[1] On the other hand, others plainly refuse to put themselves in harm's way, depending on how grave they perceive the nuisance to be; a 2004 study observed that "most research on disorder is based on individual level perceptions decoupled from a systematic concern with the disorder-generating environment."[11] Essentially, everyone perceives disorder differently, and can contemplate seriousness of a crime based on those perceptions. However, Wilson and Kelling feel that although community involvement can make a difference, "the police are plainly the key to order maintenance."[1] Role of fear Ranasinghe argues that the concept of fear is a crucial element of broken windows theory, because it is the foundation of the theory.[12] She also adds that public disorder is "... unequivocally constructed as problematic because it is a source of fear".[13] Fear is elevated as perception of disorder rises; creating a social pattern that tears the social fabric of a community and leaves the residents feeling hopeless and disconnected. Wilson and Kelling hint at the idea, but do not focus on its central importance. They indicate that fear was a product of incivility, not crime, and that people avoid one another in response to fear, weakening controls.[1] Hinkle and Weisburd found that police interventions to combat minor offenses, as per the broken windows model, "significantly increased the probability of feeling unsafe," suggesting that such interventions might offset any benefits of broken windows policing in terms of fear reduction.[14] Comparison to "zero tolerance" Broken windows policing is sometimes described as a "zero tolerance" policing style,[15] including in some academic studies.[16] Bratton and Kelling have said that broken windows policing and zero tolerance are different, and that minor offenders should receive lenient punishment.[17] |

概念 インフォーマルな社会的統制 多くの人が、インフォーマルな社会的統制は手に負えない行動を減らすための効果的な戦略になりうると主張している。Garland(2001)は、「日常 的な人間関係や制度を通じて行使されるインフォーマルな社会的統制は、法的制裁よりも効果的であるという認識のもとで、コミュニティ・ポリシングが実施さ れている」と表現している[7]。インフォーマルな社会的統制の方法は、積極的な市民による「厳しい」態度を示し、無秩序な行為は許されないという感覚を 表現している。ウィルソンとケリングによれば、秩序維持に関与する集団には、「地域社会の番人」と「自警団」の2種類がある[1]。米国は、古いヨーロッ パ時代の取り締まり戦略を多くの点で採用しており、当時はインフォーマルな社会統制が主流であったため、現代のフォーマルな取り締まりが生まれた。しか し、それ以前の時代には、従うべき法的制裁がなかったため、インフォーマルな取り締まりは、Wilson and Kelling (1982)が述べているように、主に「目的」主導であった。 ウィルコックスら(2004)は、不適切な土地利用は無秩序を引き起こす可能性があり、公有地が広ければ広いほど、犯罪的逸脱の影響を受けやすくなると論 じている。ジェーン・ジェイコブズは、この「割れ窓」の視点の元祖の一人といえる。彼女の著書『The Death and Life of Great American Cities(アメリカ大都市の死と生)』の大部分は、通りの秩序を維持するための住民と非住民の貢献に焦点を当て、地元の企業、施設、コンビニエンスス トアがいかに「通りに目がある」という感覚を提供しているかを説明している[10]。 逆に、多くの住民は、無秩序を規制することは自分たちの責任ではないと感じる。ウィルソンとケリングは、心理学者の研究によると、人々はしばしば助けを求 めている人の助けに行くことを拒否する。 [2004年の研究では、「無秩序に関する研究のほとんどは、無秩序を発生させる環境に対する体系的な関心から切り離された個人レベルの認識に基づいてい る」と観察されている。しかし、ウィルソンとケリングは、地域社会の関与は変化をもたらすが、「秩序維持の鍵は明らかに警察である」と感じている[1]。 恐怖の役割 ラナシンゲは、恐怖の概念は「割れ窓理論」の重要な要素であると主張する。ウィルソンとケリングはこの考えを示唆しているが、その中心的な重要性には焦点 を当てていない。彼らは、恐怖は犯罪ではなく不公正さの産物であり、人々は恐怖に反応して互いを避け、統制を弱めるのだと示している[1]。ヒンケルとワ イスバードは、割れ窓モデルによる軽微な犯罪に対抗するための警察の介入は、「治安が悪いと感じる確率を有意に増加させる」ことを発見し、そのような介入 は、恐怖の軽減という点で、割れ窓取り締まりの利点を相殺するかもしれないことを示唆している[14]。 ゼロ・トレランス」との比較 ブラットンとケリングは、割れ窓の取り締まりとゼロ・トレランスは異なるものであり、軽微な犯罪者は寛大な処罰を受けるべきだと述べている[17]。 |

| Critical developments In an earlier publication of The Atlantic released March, 1982, Wilson wrote an article indicating that police efforts had gradually shifted from maintaining order to fighting crime.[1] This indicated that order maintenance was something of the past, and soon it would seem as it has been put on the back burner. The shift was attributed to the rise of the social urban riots of the 1960s, and "social scientists began to explore carefully the order maintenance function of the police, and to suggest ways of improving it—not to make streets safer (its original function) but to reduce the incidence of mass violence".[1] Other criminologists argue between similar disconnections, for example, Garland argues that throughout the early and mid 20th century, police in American cities strived to keep away from the neighborhoods under their jurisdiction.[7] This is a possible indicator of the out-of-control social riots that were prevalent at that time.[citation needed] Still many would agree that reducing crime and violence begins with maintaining social control/order.[18] Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities is discussed in detail by Ranasinghe, and its importance to the early workings of broken windows, and claims that Kelling's original interest in "minor offences and disorderly behaviour and conditions" was inspired by Jacobs' work.[19] Ranasinghe includes that Jacobs' approach toward social disorganization was centralized on the "streets and their sidewalks, the main public places of a city" and that they "are its most vital organs, because they provide the principal visual scenes".[20] Wilson and Kelling, as well as Jacobs, argue on the concept of civility (or the lack thereof) and how it creates lasting distortions between crime and disorder. Ranasinghe explains that the common framework of both set of authors is to narrate the problem facing urban public places. Jacobs, according to Ranasinghe, maintains that "Civility functions as a means of informal social control, subject little to institutionalized norms and processes, such as the law" 'but rather maintained through an' "intricate, almost unconscious, network of voluntary controls and standards among people... and enforced by the people themselves".[21] |

批判的な展開 1982年3月に発表された『アトランティック』誌の以前の記事で、ウィルソンは、警察の取り組みが徐々に秩序維持から犯罪撲滅へとシフトしていることを 指摘している。このシフトは1960年代の社会的都市暴動の台頭に起因しており、「社会科学者たちは警察の秩序維持機能を注意深く探求し、それを改善する 方法を提案し始めた。 [例えば、ガーランドは、20世紀初頭から半ばにかけて、アメリカの都市では警察が管轄する地域から遠ざかろうと努力していたと論じている[7]。これ は、当時流行していた制御不能な社会暴動の指標となりうるものである[要出典]。それでもなお、犯罪や暴力を減らすには、社会的な統制/秩序を維持するこ とから始まるという点には多くの人が同意するだろう[18]。 ジェーン・ジェイコブズの『The Death and Life of Great American Cities(アメリカ大都市の死と生)』についてラナシンゲは詳細に論じており、割れ窓の初期の働きに対するその重要性について、またケリングの「軽微 な犯罪や無秩序な行動や状況」に対する当初の関心はジェイコブズの著作に触発されたものであると主張している。 [19]ラナシンハは、社会的無秩序に対するジェイコブズのアプローチが「街路とその歩道、都市の主要な公共の場」に集中しており、「主要な視覚的場面を 提供するため、最も重要な器官である」と述べている[20]。ウィルソンとケリング、そしてジェイコブズは、礼節(またはその欠如)の概念と、それが犯罪 と無秩序の間にどのような持続的な歪みを生み出すかについて論じている。ラナシンハは、両著者に共通する枠組みは、都市の公共の場が直面する問題を叙述す ることだと説明する。ラナシンハによれば、ジェイコブズは「礼節は非公式な社会統制の手段として機能し、法律のような制度化された規範やプロセスにはほと んど左右されない」「むしろ、人々の間の自主的な統制や基準の複雑な、ほとんど無意識的なネットワークを通じて維持され......人々自身によって強制 される」と主張している[21]。 |

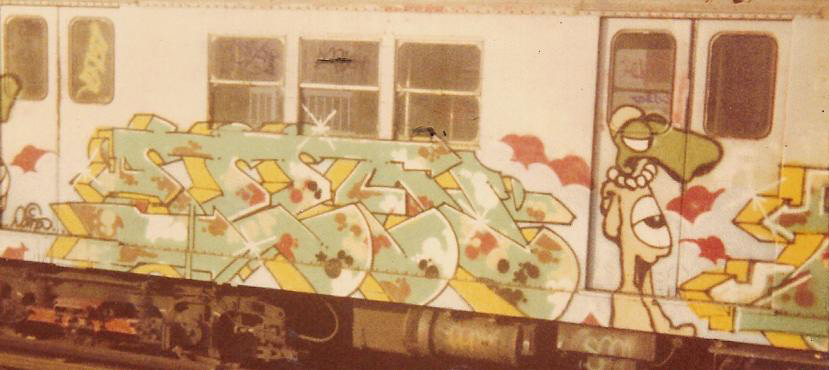

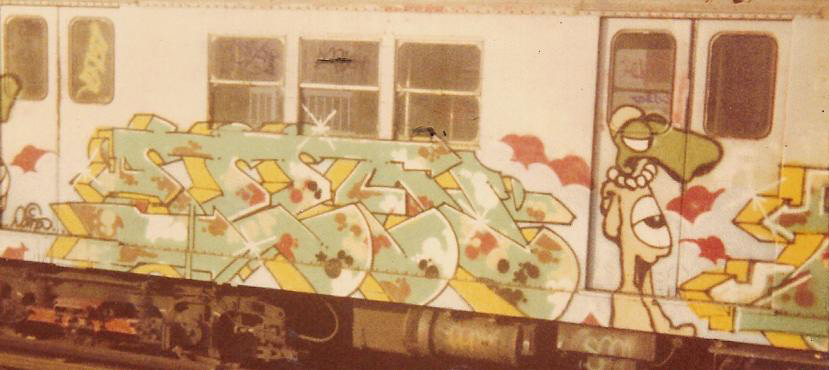

| Case studies See also: Government response to graffiti Precursor experiments Before the introduction of this theory by Wilson and Kelling, Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford psychologist, arranged an experiment testing the broken-window theory in 1969. Zimbardo arranged for an automobile with no license plates and the hood up to be parked idle in a Bronx neighbourhood and a second automobile, in the same condition, to be set up in Palo Alto, California. The car in the Bronx was attacked within minutes of its abandonment. Zimbardo noted that the first "vandals" to arrive were a family—a father, mother, and a young son—who removed the radiator and battery. Within twenty-four hours of its abandonment, everything of value had been stripped from the vehicle. After that, the car's windows were smashed in, parts torn, upholstery ripped, and children were using the car as a playground. At the same time, the vehicle sitting idle in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week until Zimbardo himself went up to the vehicle and deliberately smashed it with a sledgehammer. Soon after, people joined in for the destruction, although criticism has been levelled at this claim as the destruction occurred after the car was moved to the campus of Stanford university and Zimbardo's own students were the first to join him. Zimbardo observed that a majority of the adult "vandals" in both cases were primarily well dressed, Caucasian, clean-cut and seemingly respectable individuals. It is believed that, in a neighborhood such as the Bronx where the history of abandoned property and theft is more prevalent, vandalism occurs much more quickly, as the community generally seems apathetic. Similar events can occur in any civilized community when communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that suggest apathy.[1][22] New York City See also: Crime in New York City  Graffiti in the New York City Subway system in the early 1980s In 1985, the New York City Transit Authority hired George L. Kelling, the author of Broken Windows, as a consultant.[23] Kelling was later hired as a consultant to the Boston and the Los Angeles police departments. One of Kelling's adherents, David L. Gunn, implemented policies and procedures based on the Broken Windows Theory, during his tenure as President of the New York City Transit Authority. One of his major efforts was to lead a campaign from 1984 to 1990 to rid graffiti from New York's subway system. In 1990, William J. Bratton became head of the New York City Transit Police. Bratton was influenced by Kelling, describing him as his "intellectual mentor". In his role, he implemented a tougher stance on fare evasion, faster arrestee processing methods, and background checks on all those arrested. After being elected Mayor of New York City in 1993, as a Republican, Rudy Giuliani hired Bratton as his police commissioner to implement similar policies and practices throughout the city. Giuliani heavily subscribed to Kelling and Wilson's theories. Such policies emphasized addressing crimes that negatively affect quality of life. In particular, Bratton directed the police to more strictly enforce laws against subway fare evasion, public drinking, public urination, and graffiti. Bratton also revived the New York City Cabaret Law, a previously dormant Prohibition era ban on dancing in unlicensed establishments. Throughout the late 1990s, NYPD shut down many of the city's acclaimed night spots for illegal dancing.  New York City Police Department officers c. 2005 According to a 2001 study of crime trends in New York City by Kelling and William Sousa, rates of both petty and serious crime fell significantly after the aforementioned policies were implemented. Furthermore, crime continued to decline for the following ten years. Such declines suggested that policies based on the Broken Windows Theory were effective.[24] Later, in 2016, Brian Jordan Jefferson used the precedent of Kelling and Sousa's study to conduct fieldwork in the 70th precinct of New York City, which it was corroborated that crime mitigation in the area were concerning "quality of life" issues, which included noise complaints and loitering.[25] The falling crime rates throughout New York City had built a mutual relationship between residents and law enforcement in vigilance of disorderly conduct.[citation needed] However, other studies do not find a cause and effect relationship between the adoption of such policies and decreases in crime.[5][26] The decrease may have been part of a broader trend across the United States. The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, made consecutive declines from their peak in 1990, under Giuliani's predecessor, David Dinkins. Other cities also experienced less crime, even though they had different police policies. Other factors, such as the 39% drop in New York City's unemployment rate between 1992 and 1999,[27] could also explain the decrease reported by Kelling and Sousa.[27] A 2017 study found that when the New York Police Department (NYPD) stopped aggressively enforcing minor legal statutes in late 2014 and early 2015 that civilian complaints of three major crimes (burglary, felony assault, and grand larceny) decreased (slightly with large error bars) during and shortly after sharp reductions in proactive policing. There was no statistically significant effect on other major crimes such as murder, rape, robbery, or grand theft auto. These results are touted as challenging prevailing scholarship as well as conventional wisdom on authority and legal compliance by implying that aggressively enforcing minor legal statutes incites more severe criminal acts.[28] Albuquerque Albuquerque, New Mexico, instituted the Safe Streets Program in the late 1990s based on the Broken Windows Theory. The Safe Streets Program sought to deter and reduce unsafe driving and incidence of crime by saturating areas where high crime and crash rates were prevalent with law enforcement officers. Operating under the theory that American Westerners use roadways much in the same way that American Easterners use subways, the developers of the program reasoned that lawlessness on the roadways had much the same effect as it did on the New York City Subway. Effects of the program were reviewed by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and were published in a case study.[29] The methodology behind the program demonstrates the use of deterrence theory in preventing crime.[30] Lowell, Massachusetts In 2005, Harvard University and Suffolk University researchers worked with local police to identify 34 "crime hot spots" in Lowell, Massachusetts. In half of the spots, authorities cleared trash, fixed streetlights, enforced building codes, discouraged loiterers, made more misdemeanor arrests, and expanded mental health services and aid for the homeless. In the other half of the identified locations, there was no change to routine police service. The areas that received additional attention experienced a 20% reduction in calls to the police. The study concluded that cleaning up the physical environment was more effective than misdemeanor arrests.[31][32] Netherlands In 2007 and 2008, Kees Keizer and colleagues from the University of Groningen conducted a series of controlled experiments to determine if the effect of existing visible disorder (such as litter or graffiti) increased other crime such as theft, littering, or other antisocial behavior. They selected several urban locations, which they arranged in two different ways, at different times. In each experiment, there was a "disorder" condition in which violations of social norms as prescribed by signage or national custom, such as graffiti and littering, were clearly visible as well as a control condition where no violations of norms had taken place. The researchers then secretly monitored the locations to observe if people behaved differently when the environment was "disordered". Their observations supported the theory. The conclusion was published in the journal Science: "One example of disorder, like graffiti or littering, can indeed encourage another, like stealing."[33][34] Mexico City An 18-month study by Carlos Vilalta in Mexico City showed that framework of Broken Windows Theory on homicide in suburban neighborhoods was not a direct correlation, but a "concentrated disadvantage" in the perception of fear and modes of crime prevention.[35] In areas with more social disorder (such as public intoxication), an increased perception of law-abiding citizens to feel unsafe amplified the impact of homicide occurring in the neighborhood. It was also found that it was more effective in preventing instances of violent crime among people living in areas with less physical structural decay (such as graffiti), lending credence to the Broken Windows Theory basis that law enforcement is trusted more among those in areas with less disorder. Furthering this data, a 2023 study conducted by Ricardo Massa on residency near clandestine dumpsites associated economic disenfranchisement with high physical disorder.[36] The neighborhoods that had high concentrations of landfill waste were correlated with crimes (such as vehicle theft and robbery), and most significantly crimes related to property. In a space where property damage and neglect is normalized, a person's response to this type of environment can also greatly be affected by their perception of their surroundings. It was also concluded that non-residents of these high-concentration areas tended to fear and avoid these locations, seeing as there was typically less surveillance and lack of community efficacy surrounding clandestine dumpsites. However, despite this fear, Massa also notes that, in this case, individual targets for crime (such as homicide or rape) were unlikely compared to the vandalism of public and private property. |

ケーススタディ こちらもご覧ください: 落書きに対する政府の対応 先行実験 ウィルソンとケリングがこの理論を発表する以前の1969年、スタンフォード大学の心理学者フィリップ・ジンバルドが、割れ窓理論を検証する実験を行っ た。ジンバルドーは、ナンバープレートがなくボンネットを上げた自動車をブロンクスの近所にアイドリング状態で駐車させ、同じ状態の2台目の自動車をカリ フォルニア州パロアルトに設置するよう手配した。ブロンクスの車は捨てられてから数分で襲われた。ジンバルドーは、最初にやってきた 「破壊者 」は父親、母親、幼い息子の家族で、彼らはラジエーターとバッテリーを取り外したと述べている。放置されてから24時間以内に、価値のあるものはすべて車 から剥ぎ取られた。その後、車の窓ガラスは割られ、部品は破かれ、内装は裂かれ、子供たちが車を遊び場にしていた。同時に、パロアルトで眠っていた車は、 ジンバルドー自身が車に近づき、ハンマーでわざと叩き割るまで、1週間以上手つかずのまま放置されていた。この破壊は、車がスタンフォード大学のキャンパ スに移され、ジンバルドーの学生たちが最初に彼に加わった後に起こったため、この主張には批判がある。ジンバルドーは、両事件における成人の 「破壊者 」の大半は、主に身なりがよく、白人で、清潔で、一見立派な人物であったと観察している。ブロンクスのように、遺棄物や窃盗の歴史が多い地域では、地域社 会が一般的に無関心に見えるため、破壊行為がより迅速に発生すると考えられている。無関心を示唆するような行為によって共同体の障壁、つまり相互の配慮や 礼節の義務感が低下すると、文明化された地域社会であればどこでも同様の出来事が起こりうる[1][22]。 ニューヨーク 関連項目 ニューヨークの犯罪  1980年代初頭のニューヨーク市地下鉄の落書き 1985年、ニューヨーク市交通局は『ブロークン・ウィンドウズ』の著者であるジョージ・L・ケリングをコンサルタントとして雇った[23]。 ケリングの信奉者の一人であるデビッド・L・ガンは、ニューヨーク市交通局の社長在任中に、「壊れた窓理論」に基づく政策と手続きを実施した。彼の主な努 力のひとつは、1984年から1990年にかけて、ニューヨークの地下鉄から落書きをなくすキャンペーンを指揮したことである。 1990年、ウィリアム・J・ブラットンがニューヨーク市交通警察のトップに就任した。ブラットンはケリングから影響を受け、彼を「知的な師」と評した。ブラットンは、運賃逃れの取り締まりを強化し、逮捕者の処理方法を迅速化し、逮捕者全員の身元調査を実施した。 1993年に共和党からニューヨーク市長に選出されたルディ・ジュリアーニは、ブラットンを警察本部長として採用し、同様の政策と慣行をニューヨーク市全 体に導入した。ジュリアーニはケリングとウィルソンの理論を重んじた。このような政策は、生活の質に悪影響を及ぼす犯罪に対処することに重点を置いてい た。特にブラットンは、地下鉄の運賃逃れ、公共の場での飲酒、放尿、落書きに対する法律をより厳しく取り締まるよう警察に指示した。ブラットンはまた、 ニューヨーク市のキャバレー法(禁酒法時代に制定された、無許可の店でのダンスを禁止する法律)を復活させた。1990年代後半を通じて、NYPDは違法 ダンスで評判の高い市内のナイトスポットの多くを閉鎖した。  2005年頃、ニューヨーク市警の警官たち ケリングとウィリアム・スーザによるニューヨーク市の犯罪動向に関する2001年の研究によると、前述の政策が実施された後、軽犯罪と重大犯罪の両方の割 合が大幅に減少した。さらに、その後の10年間、犯罪は減少し続けた。このような減少は、ブロークン・ウィンドウズ理論に基づく政策が効果的であることを 示唆していた[24]。その後、2016年にブライアン・ジョーダン・ジェファーソンは、ケリングとスーザの研究の先例を用いてニューヨーク市第70管区 でフィールドワークを実施し、その地域における犯罪の軽減が騒音苦情やうろつきなどの「生活の質」の問題に関するものであったことが裏付けられた [25]。 しかし、他の研究では、このような政策の採用と犯罪の減少との間に因果関係は見つかっていない[5][26]。ジュリアーニの前任者であるデイヴィッド・ ディンキンズの時代には、すべてのカテゴリーの暴力犯罪を含むほとんどの犯罪の発生率が1990年のピークから連続して減少していた。他の都市でも、警察 の方針は違えど犯罪は減少している。1992年から1999年の間にニューヨーク市の失業率が39%低下した[27]といった他の要因も、ケリングとスー ザが報告した減少を説明する可能性がある[27]。 2017年の研究では、ニューヨーク市警察(NYPD)が2014年末から2015年初めにかけて、軽微な法律法規の積極的な取り締まりを停止したとこ ろ、3つの重大犯罪(強盗、重罪暴行、大窃盗)の市民からの苦情が、積極的な取り締まりの急激な減少中とその直後に(大きなエラーバーでわずかに)減少し たことがわかった。殺人、強姦、強盗、自動車窃盗など、その他の重大犯罪には統計的に有意な影響は見られなかった。これらの結果は、軽微な法律法規を積極 的に執行することが、より深刻な犯罪行為を誘発することを示唆するもので、権威と法の遵守に関する一般的な学問や従来の常識に挑戦するものとして注目され ている[28]。 アルバカーキ ニューメキシコ州アルバカーキは、1990年代後半にブロークン・ウィンドウズ理論に基づくセーフ・ストリート・プログラムを制定した。セーフ・ストリー ト・プログラムは、犯罪率や事故率が高い地域に警察官を常駐させることで、危険な運転や犯罪の発生を抑止・減少させようとするものであった。アメリカ東部 人が地下鉄を利用するのと同じように、アメリカ西部人も車道を利用するという理論に基づき、このプログラムの開発者たちは、車道での無法はニューヨークの 地下鉄と同じ効果があると考えた。このプログラムの効果は、米国道路交通安全局(NHTSA)によって検証され、事例研究として発表された[29]。この プログラムの背後にある方法論は、犯罪防止における抑止理論の利用を示している[30]。 マサチューセッツ州ローウェル 2005年、ハーバード大学とサフォーク大学の研究者は、地元警察と協力して、マサチューセッツ州ローウェルの34の「犯罪多発地点」を特定した。その半 数では、当局がゴミの撤去、街灯の整備、建築基準法の施行、徘徊者の抑制、軽犯罪の検挙数増加、精神衛生サービスとホームレス支援の拡充を行った。残りの 半分の地域では、日常的な警察活動に変化はなかった。 さらに注意を払った地域では、警察への通報が20%減少した。この研究では、軽犯罪による逮捕よりも、物理的な環境の浄化の方が効果的であると結論づけている[31][32]。 オランダ 2007年と2008年、フローニンゲン大学のKees Keizerと同僚は、既存の目に見える無秩序(ゴミや落書きなど)の影響が、窃盗、ポイ捨て、その他の反社会的行動などの他の犯罪を増加させるかどうか を調べるために、一連の対照実験を行った。彼らはいくつかの都市の場所を選び、異なる時間に2つの異なる方法で配置した。それぞれの実験では、落書きやゴ ミのポイ捨てなど、標識や国の慣習で定められた社会規範の違反がはっきりと目につく「無秩序」条件と、規範違反が起きていない対照条件が設定された。研究 者たちはその場所を密かに監視し、環境が「無秩序」になったときに人々の行動が異なるかどうかを観察した。その結果、理論が裏付けられた。結論は『サイエ ンス』誌に掲載された: 「落書きやゴミのポイ捨てのような無秩序の一例は、盗みのような別の行動を実際に助長する」[33][34]。 メキシコシティ メキシコシティにおけるカルロス・ビラルタによる18ヶ月の研究は、郊外の近隣における殺人に対するブロークン・ウィンドウズ理論の枠組みが直接的な相関 関係ではなく、恐怖の認識と犯罪予防の様式における「集中的な不利」であることを示した[35]。 社会的無秩序(公共の場での酩酊など)がより多い地域では、法を遵守する市民が危険を感じるという認識の増加が、近隣で発生する殺人の影響を増幅させた。 また、物理的な構造的腐敗(落書きなど)が少ない地域に住む人々の間では、暴力犯罪の発生を防止する上でより効果的であることも判明しており、無秩序が少 ない地域の人々の間では法執行機関がより信頼されているという「割れ窓理論」の根拠の信憑性を高めている。 このデータをさらに裏付けるように、リカルド・マッサが2023年に行った、秘密のゴミ捨て場付近の居住に関する研究では、経済的権利の剥奪と物理的無秩 序の多さが関連していた[36]。ゴミ捨て場の廃棄物が集中している地域は、犯罪(車両の窃盗や強盗など)と相関しており、最も顕著なのは財産に関する犯 罪であった。器物損壊や放置が常態化している空間では、このような環境に対する人の反応も、周囲の環境に対する認知に大きく影響される可能性がある。ま た、このようなゴミの集中する地域の住民以外は、このような場所を恐れ、避ける傾向があると結論づけられた。しかし、このような恐怖心にもかかわらず、マ サは、この場合、公共物や私有地の破壊行為に比べれば、(殺人やレイプのような)犯罪のターゲットになる可能性は低いとも指摘している。 |

| Other effects Real estate Other side effects of better monitoring and cleaned up streets may well be desired by governments or housing agencies and the population of a neighborhood: broken windows can count as an indicator of low real estate value and may deter investors. Real estate professionals may benefit from adopting the "Broken Windows Theory", because if the number of minor transgressions is monitored in a specific area, there is likely to be a reduction in major transgressions as well. This may actually increase or decrease value in a house or apartment, depending on the area.[37] Fixing windows is, therefore, also a step of real estate development, which may lead, whether it is desired or not, to gentrification. By reducing the number of broken windows in the community, the inner cities would appear to be attractive to consumers with more capital. Eliminating danger in spaces that are notorious for criminal activity, such as downtown New York City and Chicago, would draw in investment from consumers, increase the city's economic status, and provide a safe and pleasant image for present and future inhabitants.[26] Education In education, the broken windows theory is used to promote order in classrooms and school cultures. The belief is that students are signaled by disorder or rule-breaking and that they in turn imitate the disorder. Several school movements encourage strict paternalistic practices to enforce student discipline. Such practices include language codes (governing slang, curse words, or speaking out of turn), classroom etiquette (sitting up straight, tracking the speaker), personal dress (uniforms, little or no jewelry), and behavioral codes (walking in lines, specified bathroom times). From 2004 to 2006, Stephen B. Plank and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University conducted a correlational study to determine the degree to which the physical appearance of the school and classroom setting influence student behavior, particularly in respect to the variables concerned in their study: fear, social disorder, and collective efficacy.[38] They collected survey data administered to 6th-8th students by 33 public schools in a large mid-Atlantic city. From analyses of the survey data, the researchers determined that the variables in their study are statistically significant to the physical conditions of the school and classroom setting. The conclusion, published in the American Journal of Education, was: ...the findings of the current study suggest that educators and researchers should be vigilant about factors that influence student perceptions of climate and safety. Fixing broken windows and attending to the physical appearance of a school cannot alone guarantee productive teaching and learning, but ignoring them likely greatly increases the chances of a troubling downward spiral.[38] Statistical evidence A 2015 meta-analysis of broken windows policing implementations found that disorder policing strategies, such as "hot spots policing" or problem-oriented policing, result in "consistent crime reduction effects across a variety of violent, property, drug, and disorder outcome measures".[39] As a caveat, the authors noted that "aggressive order maintenance strategies that target individual disorderly behaviors do not generate significant crime reductions," pointing specifically to zero tolerance policing models that target singular behaviors such as public intoxication and remove disorderly individuals from the street via arrest. The authors recommend that police develop "community co-production" policing strategies instead of merely committing to increasing misdemeanor arrests.[39] |

その他の効果 不動産 窓ガラスが割れていることは、不動産価値が低いことを示す指標となり、投資家の足を引っ張る可能性がある。不動産の専門家は、「割れ窓理論」を採用するこ とで利益を得られるかもしれない。というのも、特定の地域で軽微な違反が監視されれば、重大な違反も減る可能性が高いからだ。したがって、窓を修理するこ とは不動産開発の一歩でもあり、望むと望まざるとにかかわらず、ジェントリフィケーション(高級化)につながる可能性がある。コミュニティ内の割れた窓の 数を減らすことで、都心部はより多くの資本を持つ消費者にとって魅力的に見えるだろう。ニューヨークやシカゴのダウンタウンのような、犯罪行為で悪名高い 空間の危険をなくすことは、消費者からの投資を呼び込み、都市の経済的地位を高め、現在および将来の住民に安全で快適なイメージを提供することになる [26]。 教育 教育では、割れ窓理論が教室や学校文化の秩序を促進するために使われている。生徒たちは無秩序や規則違反によって合図を受け、その無秩序を真似るようにな るという信念である。いくつかの学校運動では、生徒の規律を強制するために、厳格な父権主義的実践を奨励している。そのような実践には、言語規範(スラン グ、呪いの言葉、暴言の禁止)、教室でのエチケット(背筋を伸ばして座る、発言者を追跡する)、身だしなみ(制服、アクセサリーはほとんどつけない、つけ ない)、行動規範(列を作って歩く、トイレの時間を指定する)などがある。 2004年から2006年にかけて、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学のスティーブン・B・プランク(Stephen B. Plank)らは、学校と教室の物理的な外観が生徒の行動にどの程度影響するかを調べる相関研究を実施した。調査データの分析から、研究者たちは、研究の 変数は学校や教室の物理的条件と統計的に有意であると判断した。American Journal of Education』誌に発表された結論は次の通りである: ......今回の研究結果は、教育者や研究者が、風土や安全に対する生徒の認識に影響を与える要因について用心深くあるべきことを示唆している。割れた 窓を直したり、学校の物理的な外観に気を配ったりするだけでは、生産的な教育や学習を保証することはできないが、それらを無視することは、厄介な下降スパ イラルに陥る可能性を大きくする可能性が高い[38]。 統計的証拠 2015年に実施された割れ窓取り締まりのメタ分析によると、「ホットスポット取り締まり」や問題志向の取り締まりなどの無秩序取り締まり戦略は、「暴 力、財物、薬物、無秩序のさまざまな結果指標にわたって一貫した犯罪減少効果」をもたらすことがわかった[39]。注意点として、著者らは、「個々の無秩 序な行動を対象とする積極的な秩序維持戦略は、有意な犯罪減少をもたらさない」と指摘し、特に、公然酩酊のような特異な行動を対象とし、逮捕によって無秩 序な人物を路上から排除するゼロ・トレランス取り締まりモデルを指摘している。著者は、警察が単に軽犯罪の検挙数を増やすことにコミットするのではなく、 「コミュニティ共同制作」の取り締まり戦略を開発することを推奨している[39]。 |

| Criticism Other factors Several studies have argued that many of the apparent successes of broken windows policing (such as New York City in the 1990s) were the result of other factors.[40] They claim that the "broken windows theory" closely relates correlation with causality: a reasoning prone to fallacy. David Thacher, assistant professor of public policy and urban planning at the University of Michigan, stated in a 2004 paper:[40] [S]ocial science has not been kind to the broken windows theory. A number of scholars reanalyzed the initial studies that appeared to support it.... Others pressed forward with new, more sophisticated studies of the relationship between disorder and crime. The most prominent among them concluded that the relationship between disorder and serious crime is modest, and even that relationship is largely an artifact of more fundamental social forces. C. R. Sridhar, in his article in the Economic and Political Weekly, also challenges the theory behind broken windows policing and the idea that the policies of William Bratton and the New York Police Department was the cause of the decrease of crime rates in New York City.[16] The policy targeted people in areas with a significant amount of physical disorder and there appeared to be a causal relationship between the adoption of broken windows policing and the decrease in crime rate. Sridhar, however, discusses other trends (such as New York City's economic boom in the late 1990s) that created a "perfect storm" that contributed to the decrease of crime rate much more significantly than the application of the broken windows policy. Sridhar also compares this decrease of crime rate with other major cities that adopted other various policies and determined that the broken windows policy is not as effective. In a 2007 study called "Reefer Madness" in the journal Criminology and Public Policy, Harcourt and Ludwig found further evidence confirming that mean reversion fully explained the changes in crime rates in the different precincts in New York in the 1990s.[41] Further alternative explanations that have been put forward include the waning of the crack epidemic,[42] unrelated growth in the prison population by the Rockefeller drug laws,[42] and that the number of males from 16 to 24 was dropping regardless of the shape of the US population pyramid.[43] It has also been argued that rates of major crimes also dropped in many other US cities during the 1990s, both those that had adopted broken windows policing and those that had not.[44] It is thought that this is due to the exposure of children to environmental lead, which leads to loss of impulse control, and when they reach young adulthood, criminal acts. There appears to be a correlation with a 25-year lag with the addition and removal of lead from paint and gasoline and rises and falls in murder arrests.[45][46] Baltimore criminologist Ralph B. Taylor argues in his book that fixing windows is only a partial and short-term solution. His data supports a materialist view: changes in levels of physical decay, superficial social disorder, and racial composition do not lead to higher crime, but economic decline does. He contends that the example shows that real, long-term reductions in crime require that urban politicians, businesses, and community leaders work together to improve the economic fortunes of residents in high-crime areas.[47] In 2015, Northeastern University assistant professor Daniel T. O'Brien criticised the broken theory model. Using his Big Data based research model, he argues that the broken window model fails to capture the origins of crime in a neighbourhood. He concludes that crime comes from the social dynamics of communities and private spaces and spills out into public spaces [48] Relationship between crime and disorder According to a study by Robert J. Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush, the premise on which the theory operates, that social disorder and crime are connected as part of a causal chain, is faulty. They argue that a third factor, collective efficacy, "defined as cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space," is the actual cause of varying crime rates that are observed in an altered neighborhood environment. They also argue that the relationship between public disorder and crime rate is weak.[49] In the winter 2006 edition of the University of Chicago Law Review, Bernard Harcourt and Jens Ludwig looked at the later Department of Housing and Urban Development program that rehoused inner-city project tenants in New York into more-orderly neighborhoods.[26] The broken windows theory would suggest that these tenants would commit less crime once moved because of the more stable conditions on the streets. However, Harcourt and Ludwig found that the tenants continued to commit crime at the same rate. Another tack was taken by a 2010 study questioning the legitimacy of the theory concerning the subjectivity of disorder as perceived by persons living in neighborhoods. It concentrated on whether citizens view disorder as a separate issue from crime or as identical to it. The study noted that crime cannot be the result of disorder if the two are identical, agreed that disorder provided evidence of "convergent validity" and concluded that broken windows theory misinterprets the relationship between disorder and crime.[50] Racial bias  Man getting arrested Broken windows policing has sometimes become associated with zealotry, which has led to critics suggesting that it encourages discriminatory behaviour. Some campaigns such as Black Lives Matter have called for an end to broken windows policing.[51] In 2016, a Department of Justice report argued that it had led the Baltimore Police Department to discriminate against and alienate minority groups.[52] A central argument is that the concept of disorder is vague, and giving the police broad discretion to decide what disorder is will lead to discrimination. In Dorothy Roberts's article, "Foreword: Race, Vagueness, and the Social Meaning of Order Maintenance and Policing", she says that the broken windows theory in practice leads to the criminalization of communities of color, who are typically disfranchised.[53] She underscores the dangers of vaguely written ordinances that allow for law enforcers to determine who engages in disorderly acts, which, in turn, produces a racially skewed outcome in crime statistics.[54] Similarly, Gary Stewart wrote, "The central drawback of the approaches advanced by Wilson, Kelling, and Kennedy rests in their shared blindness to the potentially harmful impact of broad police discretion on minority communities."[55] According to Stewart, arguments for low-level police intervention, including the broken windows hypothesis, often act "as cover for racist behavior".[55] The theory has also been criticized for its unsound methodology and its manipulation of racialized tropes. Specifically, Bench Ansfield has shown that in their 1982 article, Wilson and Kelling cited only one source to prove their central contention that disorder leads to crime: the Philip Zimbardo vandalism study (see Precursor Experiments above).[56] But Wilson and Kelling misrepresented Zimbardo's procedure and conclusions, dispensing with Zimbardo's critique of inequality and community anonymity in favor of the oversimplified claim that one broken window gives rise to "a thousand broken windows". Ansfield argues that Wilson and Kelling used the image of the crisis-ridden 1970s Bronx to stoke fears that "all cities would go the way of the Bronx if they didn't embrace their new regime of policing."[57] Wilson and Kelling manipulated the Zimbardo experiment to avail themselves of the racialized symbolism found in the broken windows of the Bronx.[56] Robert J. Sampson argues that based on common misconceptions by the masses, it is clearly implied that those who commit disorder and crime have a clear tie to groups suffering from financial instability and may be of minority status: "The use of racial context to encode disorder does not necessarily mean that people are racially prejudiced in the sense of personal hostility." He notes that residents make a clear implication of who they believe is causing the disruption, which has been termed as implicit bias.[58] He further states that research conducted on implicit bias and stereotyping of cultures suggests that community members hold unrelenting beliefs of African Americans and other disadvantaged minority groups, associating them with crime, violence, disorder, welfare, and undesirability as neighbors.[58] A later study indicated that this contradicted Wilson and Kelling's proposition that disorder is an exogenous construct that has independent effects on how people feel about their neighborhoods.[50] In response, Kelling and Bratton have argued that broken windows policing does not discriminate against law-abiding communities of minority groups if implemented properly.[17] They cited Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods,[59] a study by Wesley Skogan at Northwestern University. The study, which surveyed 13,000 residents of large cities, concluded that different ethnic groups have similar ideas as to what they would consider to be "disorder". Minority groups have tended to be targeted at higher rates by the Broken Windows style of policing. Broken Windows policies have been utilized more heavily in minority neighborhoods where low-income, poor infrastructure, and social disorder were widespread, causing minority groups to perceive that they were being racially profiled under Broken Windows policing.[23][60] Class bias  Homeless man talking with a police officer A common criticism of broken windows policing is the argument that it criminalizes the poor and homeless. That is because the physical signs that characterize a neighborhood with the "disorder" that broken windows policing targets correlate with the socio-economic conditions of its inhabitants. Many of the acts that are considered legal but "disorderly" are often targeted in public settings and are not targeted when they are conducted in private. Therefore, those without access to a private space are often criminalized. Critics, such as Robert J. Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush of Harvard University, see the application of the broken windows theory in policing as a war against the poor, as opposed to a war against more serious crimes.[61] Since minority groups in most cities are more likely to be poorer than the rest of the population, a bias against the poor would be linked to a racial bias.[53] According to Bruce D. Johnson, Andrew Golub, and James McCabe, the application of the broken windows theory in policing and policymaking can result in development projects that decrease physical disorder but promote undesired gentrification. Often, when a city is so "improved" in this way, the development of an area can cause the cost of living to rise higher than residents can afford, which forces low-income people out of the area. As the space changes, the middle and upper classes, often white, begin to move into the area, resulting in the gentrification of urban, poor areas. The local residents are affected negatively by such an application of the broken windows theory and end up evicted from their homes as if their presence indirectly contributed to the area's problem of "physical disorder".[53] Popular press In More Guns, Less Crime (2000), economist John Lott, Jr. examined the use of the broken windows approach as well as community- and problem-oriented policing programs in cities over 10,000 in population, over two decades. He found that the impacts of these policing policies were not very consistent across different types of crime. Lott's book has been subject to criticism, while other groups support Lott's conclusions. In the 2005 book Freakonomics, coauthors Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner confirm and question the notion that the broken windows theory was responsible for New York's drop in crime, saying "the pool of potential criminals had dramatically shrunk". Levitt had in the Quarterly Journal of Economics attributed that possibility to the legalization of abortion with Roe v. Wade, which correlated with a decrease, one generation later, in the number of delinquents in the population at large.[62] In his 2012 book Uncontrolled: The Surprising Payoff of Trial-and-Error for Business, Politics, and Society, Jim Manzi writes that of the randomized field trials conducted in criminology, only nuisance abatement per broken windows theory has been successfully replicated.[63][64] |

批判 その他の要因 いくつかの研究は、(1990年代のニューヨークのような)割れ窓取り締まりの見かけ上の成功の多くは、他の要因の結果であると主張している[40]。彼 らは、「割れ窓理論」は相関関係と因果関係を密接に関連付けるものであり、誤りやすい推論であると主張している。ミシガン大学で公共政策と都市計画の助教 授を務めるデビッド・サッハー(David Thacher)は、2004年の論文で次のように述べている[40]。 「社会科学は割れ窓理論に優しくない。多くの学者が、この理論を支持すると思われた初期の研究を再分析した。また、無秩序と犯罪の関係について、より洗練 された新しい研究を進める学者もいた。その中で最も著名な研究者たちは、無秩序と重大犯罪の関係は緩やかであり、その関係さえも、より根本的な社会的力に よる捏造(アーティファクト)であると結論づけた」 C. R. Sridharもまた、『Economic and Political Weekly』誌の論文の中で、割れ窓取り締まりの背後にある理論や、ウィリアム・ブラットンとニューヨーク市警の政策がニューヨーク市の犯罪率減少の原 因であるという考えに異議を唱えている[16]。この政策は、物理的な無秩序がかなり多い地域の人々を対象としており、割れ窓取り締まりの採用と犯罪率減 少の間には因果関係があるように見える。しかし、スリダールは、割れ窓ポリシーの適用よりもはるかに大きく犯罪率の減少に貢献した「パーフェクト・ストー ム」を生み出した他の傾向(1990年代後半のニューヨークの好景気など)について論じている。スリダールはまた、この犯罪率の減少を、他のさまざまな政 策を採用した他の大都市と比較し、割れ窓政策はそれほど効果的ではないと判断している。 2007年の『Criminology and Public Policy』誌に掲載された「Reefer Madness」と呼ばれる研究において、ハーコートとルートヴィヒは、平均回帰が1990年代のニューヨークの異なる管区における犯罪率の変化を完全に 説明していることを確認するさらなる証拠を発見した[41]。さらに別の説明として、クラック流行の衰退、[42]ロックフェラー薬物法による刑務所人口 の無関係な増加、[42]アメリカの人口ピラミッドの形状に関係なく16歳から24歳の男性の数が減少していることなどが提唱されている[43]。 また、ブロークン・ウィンドウ・ポリシングを採用している都市とそうでない都市の両方において、1990年代に他の多くのアメリカの都市でも重大犯罪の発 生率が低下したと論じられている[44]。これは、子どもたちが環境中の鉛にさらされることによって衝動制御ができなくなり、若年成人期に達したときに犯 罪行為に至るためだと考えられている。ペンキやガソリンからの鉛の添加と除去には25年のタイムラグがあり、殺人検挙数の増減には相関関係があるようだ [45][46]。 ボルティモアの犯罪学者ラルフ・B・テイラーは、その著書の中で、窓の修理は部分的かつ短期的な解決策に過ぎないと主張している。彼のデータは唯物論的な 見方を支持している:物理的な腐敗、表面的な社会的無秩序、人種構成のレベルの変化は犯罪の増加につながらないが、経済的衰退は犯罪の増加につながる。彼 は、この例は、犯罪の真の長期的な減少には、都市の政治家、企業、コミュニティのリーダーが協力して、犯罪の多い地域の住民の経済的な運命を改善する必要 があることを示していると主張する[47]。 2015年、ノースイースタン大学のダニエル・T・オブライエン助教授は破たん理論モデルを批判した。彼はビッグデータに基づいた研究モデルを用いて、割 れ窓モデルは近隣における犯罪の起源を捉えることに失敗していると主張している。彼は、犯罪はコミュニティと私的空間の社会的力学から生まれ、公共空間に 波及すると結論付けている[48]。 犯罪と無秩序の関係 ロバート・J・サンプソンとスティーヴン・ローデンブッシュの研究によれば、社会的無秩序と犯罪が因果の連鎖の一部としてつながっているという、この理論 の前提には誤りがある。彼らは、第三の要因である集団的効力(「公共空間の社会的統制に対する期待の共有と結びついた住民間の結束と定義される」)が、変 化した近隣環境で観察されるさまざまな犯罪率の実際の原因であると主張している。彼らはまた、公共の無秩序と犯罪率の関係は弱いと主張している[49]。 シカゴ大学ロー・レビューの2006年冬号において、バーナード・ハーコートとイェンス・ルートヴィヒは、ニューヨークの都心部のプロジェクト入居者をよ り秩序のある地域に再入居させるという、後の住宅都市開発省のプログラムについて考察している。しかし、ハーコートとルートヴィヒは、入居者が同じ割合で 犯罪を犯し続けていることを発見した。2010年に行われた別の研究では、近隣に住む人々が認識する無秩序の主観性に関する理論の正当性に疑問が呈され た。この研究では、市民が無秩序を犯罪とは別の問題としてとらえているのか、それとも犯罪と同一のものとしてとらえているのかに焦点が当てられている。こ の研究では、両者が同一である場合、犯罪が無秩序の結果であることはあり得ないと指摘し、無秩序が「収束的妥当性」の証拠を提供することに同意し、割れ窓 理論が無秩序と犯罪の関係を誤って解釈していると結論づけた[50]。 人種的偏見  逮捕される男性 割れ窓の取り締まりは時に狂信的なものと結びつき、それが差別的な行動を助長しているという批判につながっている。Black Lives Matterのような一部のキャンペーンは、割れ窓取り締まりの廃止を求めている[51]。2016年、司法省の報告書は、それがボルチモア警察をマイノ リティグループに対する差別と疎外に導いたと主張した[52]。 中心的な議論は、無秩序の概念が曖昧であり、無秩序とは何かを決定する幅広い裁量を警察に与えることは差別につながるというものである。ドロシー・ロバー ツの論文「まえがき: ドロシー・ロバーツの論文「序文:人種、曖昧さ、秩序維持と取り締まりの社会的意味」において、彼女は「割れ窓理論」が実際には、一般的に権利を剥奪され ている有色人種のコミュニティを犯罪化することにつながると述べている[53]。 [同様に、ゲーリー・スチュワートは、「ウィルソン、ケリング、ケネディが提唱したアプローチの中心的な欠点は、マイノリティのコミュニティに対する警察 の広範な裁量権の潜在的な有害な影響に対する共通の盲目にある」と書いている[55]。スチュワートによれば、割れ窓仮説を含む低レベルの警察介入の議論 は、しばしば「人種差別的行動の隠れ蓑として」機能する。 この理論はまた、その不健全な方法論や人種差別的な主題の操作についても批判されている。具体的には、ベンチ・アンスフィールドは、1982年の論文にお いて、ウィルソンとケリングが、無秩序が犯罪を引き起こすという彼らの中心的な主張を証明するために、フィリップ・ジンバルドーの破壊行為研究(上記の前 兆実験を参照)というたった一つの情報源しか引用していないことを示した[56]。しかし、ウィルソンとケリングは、ジンバルドーの手順と結論を誤って伝 えており、不平等とコミュニティの匿名性に対するジンバルドーの批判を無視して、1つの割れた窓が「1000の割れた窓」を生み出すという単純化されすぎ た主張を支持している。アンズフィールドは、ウィルソンとケリングが危機的状況に陥った1970年代のブロンクスのイメージを利用して、「自分たちの新し い取り締まり体制を受け入れなければ、すべての都市がブロンクスのようになってしまう」という恐怖を煽ったと論じている[57]。ウィルソンとケリング は、ブロンクスの割れた窓に見られる人種的象徴性を利用するためにジンバルドー実験を操作した[56]。 ロバート・J・サンプソンは、大衆の一般的な誤解に基づけば、無秩序や犯罪を犯す人々は、経済的な不安定さに苦しんでいる集団と明らかに結びついており、 マイノリティである可能性があることが暗示されていると論じている: 「無秩序を符号化するために人種的文脈を用いることは、必ずしも人々が個人的敵意という意味で人種的偏見を持っていることを意味しない」。彼はさらに、暗 黙のバイアスと文化のステレオタイプについて行われた研究によると、地域住民はアフリカ系アメリカ人やその他の不利な立場にあるマイノリティ・グループに 対して、犯罪、暴力、無秩序、生活保護、隣人として好ましくないといった容赦ない信念を抱いていることが示唆されていると述べている[58]。 [58] 後の研究では、このことは、無秩序は外生的な構成要素であり、人々が自分の近隣についてどう感じるかに独立した影響を及ぼすというウィルソンとケリングの 命題と矛盾することが示された[50]。 これに対して、ケリングとブラットンは、適切に実施されれば、割れ窓の取り締まりはマイノリティ集団の法を遵守するコミュニティを差別するものではないと 主張している[17]: ノースウェスタン大学のWesley Skoganによる研究[59]であるDisorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoodsを引用している。大都市の住民1万3,000人を調査したこの研究では、異なる民族集団が何を「無秩序」と考えるかについて、 似たような考えを持っていると結論づけている。 マイノリティ・グループは、ブロークン・ウィンドウズ流の取り締まりによって高い確率で標的にされる傾向がある。ブロークン・ウィンドウズ政策は、低所 得、貧弱なインフラ、社会的無秩序が蔓延しているマイノリティの居住区でより多く利用されており、マイノリティのグループはブロークン・ウィンドウズポリ シングのもとで人種差別的プロファイリングを受けていると認識する原因となっている[23][60]。 階級的偏見  警察官と話すホームレスの男性 割れ窓取り締まりに対する一般的な批判は、それが貧困層やホームレスを犯罪者扱いしているという議論である。なぜなら、割れ窓取り締まりが対象とする「無 秩序」な地域を特徴づける物理的な兆候は、そこに住む人々の社会経済的状況と相関しているからだ。合法だが「無秩序」とみなされる行為の多くは、公共の場 で行われることが多く、私的な場で行われる場合は対象とされない。そのため、私的な空間を利用できない者は、しばしば犯罪化される。ハーバード大学のロ バート・J・サンプソンやスティーブン・ラウデンブッシュなどの批評家は、警察における割れ窓理論の適用は、より重大な犯罪に対する戦争とは対照的に、貧 困層に対する戦争であると見ている[61]。ほとんどの都市では、マイノリティ・グループは他の人口よりも貧困である可能性が高いため、貧困層に対する偏 見は人種的偏見に結びつくことになる[53]。 ブルース・D・ジョンソン、アンドリュー・ゴルブ、ジェームズ・マッケイブによれば、「割れ窓」理論を取り締まりや政策立案に適用すると、物理的な無秩序 は減少するものの、望ましくない高級化を促進するような開発プロジェクトが行われる可能性がある。このように都市が「改善」されると、その地域の開発に よって生活費が住民の許容範囲を超えて上昇し、低所得者層がその地域から追い出されてしまうことがよくある。空間が変わると、中流階級や上流階級(多くの 場合白人)がその地域に移り住み始め、その結果、都市部の貧しい地域がジェントリフィケーション(高級化)する。地域住民は、割れ窓理論のこのような適用 によって否定的な影響を受け、あたかも彼らの存在が「物理的な無秩序」という地域の問題に間接的に貢献したかのように、家を追い出される羽目になる [53]。 大衆紙 経済学者のJohn Lott, Jr.は、『More Guns, Less Crime』(2000年)の中で、人口1万人以上の都市における、割れ窓のアプローチと、地域社会や問題志向の取り締まりプログラムの20年間にわたる 利用を調査した。彼は、こうした取り締まり政策の影響は、犯罪の種類によってあまり一貫していないことを発見した。ロットの著書は批判にさらされている が、一方でロットの結論を支持するグループもある。 共著者のスティーブン・D・レビットとスティーブン・J・ダブナーは、2005年に出版された『フリーコノミクス』の中で、「潜在的な犯罪者のプールは劇 的に縮小した」として、割れ窓理論がニューヨークの犯罪減少の原因であるという考え方を肯定し、疑問を呈している。レヴィットは『Quarterly Journal of Economics』において、その可能性をロー対ウェイド事件による中絶の合法化に起因するとしており、それは一世代後、人口全体における非行少年の数 の減少と相関していた[62]。 2012年の著書『Uncontrolled: ジム・マンジは、犯罪学で実施されたランダム化実地試験のうち、割れ窓理論による迷惑行為の軽減だけが再現に成功していると書いている[63][64]。 |

| Anti-social behaviour order Consent search Crime in New York City Crime prevention through environmental design Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution Graffiti abatement Legalized abortion and crime effect Bastiat's Parable of the broken window and the law of unintended consequences Pygmalion effect Racial profiling Safer Cities Initiative Social proof – Psychological phenomenon regarding conformity Stigmergy Stop-and-frisk in New York City Terry stop Tragedy of the commons William Wilberforce#Moral reform |

反社会的行動命令 同意捜査 ニューヨーク市の犯罪 環境デザインによる犯罪防止 合衆国憲法修正第4条 落書きの軽減 妊娠中絶の合法化と犯罪への影響 バスティアの「割れ窓のたとえ」と意図せざる結果の法則 ピグマリオン効果 人種プロファイリング 安全都市構想 社会的証明-適合に関する心理現象 スティグマージー ニューヨーク市におけるストップ・アンド・フリスク テリー・ストップ コモンズの悲劇 ウィリアム・ウィルバーフォース#道徳改革 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broken_windows_theory |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆