Schreibstube, Deutschland, Julius Bernhard von Rohr (1719)

解説:池田光穂

官僚制

Bureaucracy

Schreibstube, Deutschland, Julius Bernhard von Rohr (1719)

解説:池田光穂

☆官僚制(/bjʊəˈrɒkrəsi/

ⓘ ビューロークレシー)とは、法律や規制権限が公務員や非選出の役人によって実施される組織体系である。[1]

歴史的に、官僚制とは非選出の役人で構成される部門によって管理される政府行政を指した。[2]

今日では、官僚制とは公的機関であれ私的機関であれ、あらゆる大規模組織を統治する行政システムである。[3]

多くの管轄区域における公共行政は官僚制の一例であり、企業、団体、非営利組織、クラブを含むあらゆる組織の中央集権的な階層構造も同様である。

官僚機構には 2 つの重要なジレンマがある。1

つ目は、官僚は自律的であるべきか、それとも政治的支配者に直接説明責任を果たすべきかという問題である。2

つ目は、官僚が予め定められた規則に従う責任と、事前に予測できない状況に対して適切な解決策を決定するための裁量の程度に関する問題である。

様々な評論家が、現代社会における官僚機構の必要性を主張している。ドイツの社会学者マックス・ヴェーバーは、官僚機構は人間の活動を組織化する上で最も

効率的かつ合理的な方法であり、秩序を維持し、効率を最大化し、偏見を排除するには、体系的なプロセスと組織化された階層構造が必要であると主張した。一

方、ヴェーバーは、無制限の官僚機構は個人の自由に対する脅威であり、規則に基づく合理的な統制という非人格的な「鉄の檻」に個人を閉じ込める可能性があ

ると見なした。

| Bureaucracy

(/bjʊəˈrɒkrəsi/ ⓘ bure-OK-rə-see) is a system of organization where

laws or regulatory authority are implemented by civil servants or

non-elected officials.[1] Historically, a bureaucracy was a government

administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected

officials.[2] Today, bureaucracy is the administrative system governing

any large institution, whether publicly owned or privately owned.[3]

The public administration in many jurisdictions is an example of

bureaucracy, as is any centralized hierarchical structure of an

institution, including corporations, societies, nonprofit

organizations, and clubs. There are two key dilemmas in bureaucracy. The first dilemma relates to whether bureaucrats should be autonomous or directly accountable to their political masters.[4] The second dilemma relates to bureaucrats' responsibility to follow preset rules, and what degree of latitude they may have to determine appropriate solutions for circumstances that are unaccounted for in advance.[4] Various commentators have argued for the necessity of bureaucracies in modern society. The German sociologist Max Weber argued that bureaucracy constitutes the most efficient and rational way in which human activity can be organized and that systematic processes and organized hierarchies are necessary to maintain order, maximize efficiency, and eliminate favoritism. On the other hand, Weber also saw unfettered bureaucracy as a threat to individual freedom, with the potential of trapping individuals in an impersonal "iron cage" of rule-based, rational control.[5][6] |

官僚制(/bjʊəˈrɒkrəsi/ ⓘ

ビューロークレシー)とは、法律や規制権限が公務員や非選出の役人によって実施される組織体系である。[1]

歴史的に、官僚制とは非選出の役人で構成される部門によって管理される政府行政を指した。[2]

今日では、官僚制とは公的機関であれ私的機関であれ、あらゆる大規模組織を統治する行政システムである。[3]

多くの管轄区域における公共行政は官僚制の一例であり、企業、団体、非営利組織、クラブを含むあらゆる組織の中央集権的な階層構造も同様である。 官僚機構には 2 つの重要なジレンマがある。1 つ目は、官僚は自律的であるべきか、それとも政治的支配者に直接説明責任を果たすべきかという問題である。2 つ目は、官僚が予め定められた規則に従う責任と、事前に予測できない状況に対して適切な解決策を決定するための裁量の程度に関する問題である。 様々な評論家が、現代社会における官僚機構の必要性を主張している。ドイツの社会学者マックス・ヴェーバーは、官僚機構は人間の活動を組織化する上で最も 効率的かつ合理的な方法であり、秩序を維持し、効率を最大化し、偏見を排除するには、体系的なプロセスと組織化された階層構造が必要であると主張した。一 方、ヴェーバーは、無制限の官僚機構は個人の自由に対する脅威であり、規則に基づく合理的な統制という非人格的な「鉄の檻」に個人を閉じ込める可能性があ ると見なした。 |

| Etymology and usage The term bureaucracy originated in the French language: it combines the French word bureau – 'desk' or 'office' – with the Greek word κράτος (kratos) – 'rule' or 'political power'.[7] The French economist Jacques Claude Marie Vincent de Gournay coined the word in the mid-18th century.[8] Gournay never wrote the term down but a letter from a contemporary later quoted him: The late M. de Gournay... sometimes used to say: "We have an illness in France which bids fair to play havoc with us; this illness is called bureaumania." Sometimes he used to invent a fourth or fifth form of government under the heading of "bureaucracy." — Baron von Grimm (1723–1807)[9] The first known English-language use dates to 1818[7] with Irish novelist Lady Morgan referring to the apparatus used by the British government to subjugate Ireland as "the Bureaucratie, or office tyranny, by which Ireland has so long been governed".[10] By the mid-19th century the word appeared in a more neutral sense, referring to a system of public administration in which offices were held by unelected career officials. In this context bureaucracy was seen as a distinct form of management, often subservient to a monarchy.[11] In the 1920s the German sociologist Max Weber expanded the definition to include any system of administration conducted by trained professionals according to fixed rules.[11] Weber saw bureaucracy as a relatively positive development; however, by 1944 the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises opined in the context of his experience in the Nazi regime that the term bureaucracy was "always applied with an opprobrious connotation",[12] and by 1957 the American sociologist Robert Merton suggested that the term bureaucrat had become an "epithet, a Schimpfwort" in some circumstances.[13] The word bureaucracy is also used in politics and government with a disapproving tone to disparage official rules that appear to make it difficult—by insistence on procedure and compliance to rule, regulation, and law—to get things done. In workplaces, the word is used very often to blame complicated rules, processes, and written work that are interpreted as obstacles rather than safeguards and accountability assurances.[14] Socio-bureaucracy would then refer to certain social influences that may affect the function of a society.[15] In modern usage, modern bureaucracy has been defined as comprising four features:[16] 1. hierarchy (clearly defined spheres of competence and divisions of labor) 2. continuity (a structure where administrators have a full-time salary and advance within the structure) 3. impersonality (prescribed rules and operating rules rather than arbitrary actions) 4. expertise (officials are chosen according to merit, have been trained, and hold access to knowledge) |

語源と用法 官僚制という用語はフランス語に起源を持つ。フランス語の「bureau」(机または事務所)とギリシャ語の「κράτος」(クラトス、支配または政治 的権力)を組み合わせたものである。[7] 18世紀半ば、フランスの経済学者ジャック・クロード・マリー・ヴァンサン・ド・グルネーがこの言葉を造語した。[8] グルネー自身はこの用語を文書に残さなかったが、後世の同時代人の手紙に彼の言葉が引用されている: 故グルネー氏は…時折こう言っていた:「フランスには我々を破滅に追い込む恐れのある病がある。この病は『官僚病』と呼ばれる」。彼は「官僚制」という見出しの下で、第四あるいは第五の政府形態を考案することもあった。 —グリム男爵(1723–1807)[9] 英語での最初の使用例は1818年[7]に遡り、アイルランド人小説家レディ・モーガンが英国政府のアイルランド支配機構を「官僚制、すなわち官庁による 専制。アイルランドはこれによって長らく統治されてきた」と表現している。19世紀半ばまでに、この言葉はより中立的な意味で登場し、選挙で選ばれたでは ないキャリア官僚が職務を遂行する行政制度を指すようになった。この文脈では、官僚機構は、しばしば君主制に従属する、明確な管理形態と見なされていた。 [11] 1920年代、ドイツの社会学者マックス・ヴェーバーは、この定義を、訓練を受けた専門家が固定された規則に従って行うあらゆる行政システムを含むように 拡大した[11]。ヴェーバーは官僚主義を比較的肯定的な発展と捉えていた。しかし、1944年までに、オーストリアの経済学者ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ ミーゼスは、ナチス政権での経験から、官僚主義という用語は「常に蔑称的な意味合いで用いられる」と述べた[12]。また、1957年までに、アメリカの 社会学者ロバート・マートンは、官僚という用語は、ある状況では「蔑称、Schimpfwort」になっていると示唆した。[13] 官僚主義という言葉は、政治や政府においても、手続きや規則、規制、法律の順守を主張することで物事を成し遂げることを困難にしているように見える公式の 規則を軽蔑する、否定的な意味合いで使用される。職場では、複雑な規則やプロセス、文書作業が安全策や説明責任の保証ではなく障害と解釈される場合、この 言葉が頻繁に非難の材料となる[14]。したがって社会官僚制とは、社会の機能に影響を与えうる特定の社会的影響を指す[15]。 現代的な用法では、現代の官僚制は以下の四つの特徴から成ると定義される: [16] 1. 階層性(明確に定義された権限範囲と分業) 2. 継続性(管理者が常勤給与を得て組織内で昇進する構造) 3. 非人格性(恣意的な行動ではなく規定された規則と運用ルール) 4. 専門性(能力に基づいて選抜され、訓練を受け、知識へのアクセス権を持つ職員) |

| History Ancient  Students competed in imperial examinations to receive a position in the bureaucracy of Imperial China. Although the term bureaucracy first originated in the mid-18th century, organized and consistent administrative systems existed much earlier. The development of writing (c. 3500 BC) and the use of documents was a critical component of such systems. The first definitive example of bureaucracy occurred in ancient Sumer, where an emergent class of scribes used clay tablets to document and carry out various administrative functions, such as the management of taxes, workers, and public goods/resources like granaries.[17] Similarly, Ancient Egypt had a hereditary class of scribes that administered a civil-service bureaucracy.[18] Ancient China In China, when the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) unified China under the Legalist system, the emperor assigned administration to dedicated officials rather than nobility, ending feudalism in China, replacing it with a centralized, bureaucratic government. The form of government created by the first emperor and his advisors was used by later dynasties to structure their own government.[19][20] Under this system, the government thrived, as talented individuals could be more easily identified in the transformed society. The Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) established a complicated bureaucracy based on the teachings of Confucius, who emphasized the importance of ritual in family, relationships, and politics.[21] With each subsequent dynasty, the bureaucracy evolved. In 165 BC, Emperor Wen introduced the first method of recruitment to civil service through examinations. Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC) cemented the ideology of Confucius into mainstream governance by installing a system of recommendation and nomination in government service known as xiaolian, and a national academy[22][23][24] where officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of the Confucian classics, from which Emperor Wu would select officials.[25] In the Sui dynasty (581–618) and the subsequent Tang dynasty (618–907) the shi class would begin to present itself by means of the fully standardized civil service examination system, of partial recruitment of those who passed standard exams and earned an official degree. Yet recruitment by recommendations to office was still prominent in both dynasties. It was not until the Song dynasty (960–1279) that the recruitment of those who passed the exams and earned degrees was given greater emphasis and significantly expanded.[26] During the Song dynasty (960–1279) the bureaucracy became meritocratic. Following the Song reforms, competitive examinations took place to determine which candidates qualified to hold given positions.[27] The imperial examination system lasted until 1905, six years before the Qing dynasty collapsed, marking the end of China's traditional bureaucratic system.[28] Ancient Iran In ancient Iran (at least from the time of the legendary Vishtaspa and before the historical Darius, circa the 6th century BCE), there existed an official position ranked below the minister or Vizier (known by titles such as Vuzurg Farmadar or Bozorgmehr) and above the military commanders (spahbods) and provincial governors (satraps).[29][30] This position was called "Iranmarkar" or "Iranmarghar," meaning "the highest-ranking administrator of Iran" or "the highest-ranking official in charge of affairs in Iran." In summary, there was a time when, apart from the king and his minister, there existed a senior-most administrator responsible for the management of the state's affairs—in Achaemenid empire that was a superpower, encompassing at least twenty countries across three continents, with a population amounting to approximately 44 percent of the entire world at the time.[31][32] Therefore, some sorts of bureaucracy techniques (named Diwan or Divan) was one of the significant inventions of the Iranians, holding its own functions, legitimacy, and importance, and continues after it, to be one of the fundamental mechanisms of successor states.[33][34] |

歴史 古代  学生たちは科挙試験で競い合い、中国帝国の官僚機構における地位を得た。 官僚制という用語は18世紀半ばに初めて生まれたが、組織化された一貫した行政システムはそれよりずっと以前から存在していた。文字の発達(紀元前 3500年頃)と文書の使用は、そうしたシステムの重要な要素であった。官僚制の最初の明確な例は古代シュメールに見られる。そこで台頭した書記官階級は 粘土板を用いて、税の管理、労働者の監督、穀倉などの公共財・資源の管理といった様々な行政機能を文書化し遂行した[17]。同様に古代エジプトにも、官 僚制を運営する世襲の書記官階級が存在した。[18] 古代中国 中国では、秦王朝(紀元前221年~206年)が法家思想のもとで中国を統一した際、皇帝は貴族ではなく専門の官吏に行政を委ねた。これにより中国の封建 制は終わり、中央集権的な官僚制政府が代わって成立した。始皇帝とその顧問たちが創り出したこの統治形態は、後の王朝が自らの政府を構築する際に用いられ た。[19][20] この制度下で政府は繁栄した。変革された社会において有能な人材をより容易に発掘できたためである。漢王朝(紀元前202年~紀元220年)は、家族・人 間関係・政治における儀礼の重要性を説いた孔子の教えに基づき、複雑な官僚機構を確立した。[21] その後、各王朝ごとに官僚機構は進化を続けた。紀元前165年、文帝は官吏採用のための最初の試験制度を導入した。武帝(在位:紀元前141年~87年) は、官職における推薦・指名制度(孝廉)と国家学院[22][23][24]を設け、儒教経典の試験に合格した候補者から武帝自らが官吏を選抜する制度を 確立し、儒教思想を主流の統治理念として定着させた。[25] 隋(581-618)と続く唐(618-907)では、完全に標準化された科挙制度によって士階級が台頭し、標準試験に合格して官位を得た者を部分的に登 用するようになった。しかし両王朝とも、推薦による登用は依然として主要な手段であった。試験合格者・学位取得者の登用がより重視され、大幅に拡大された のは、宋王朝(960-1279)になってからである。[26] 宋王朝(960-1279)において、官僚機構は能力主義へと移行した。宋の改革後、特定の官職に就く資格を持つ候補者を決定するため、競争試験が実施さ れた[27]。科挙制度は清王朝が崩壊する6年前の1905年まで続き、中国の伝統的な官僚制度の終焉を告げた。[28] 古代イラン 古代イラン(少なくとも伝説上のヴィシュタスパの時代から歴史上のダレイオス以前の紀元前6世紀頃)には、大臣(ヴィズィール)の下位(ヴズルグ・ファル マダールやボゾルグメフルなどの称号で知られる)でありながら、軍司令官(スパフボド)や地方総督(サトラップ)より上位に位置する官職が存在した。 [29][30] この地位は「イランマルカル」または「イランマルガル」と呼ばれ、「イランの最高位行政官」あるいは「イランの政務を統括する最高位官吏」を意味した。要 するに、王とその宰相以外に、国家の事務管理を担当する最高位の行政官が存在した時代があった。それはアケメネス朝帝国においてであり、この帝国は三大陸 にまたがる少なくとも20カ国を支配する超大国であり、当時世界人口の約44%を占めていた。[31][32] したがって、ある種の官僚制技術(ディワンまたはディヴァンと呼ばれる)は、イラン人による重要な発明の一つであり、独自の機能、正当性、重要性を持ち、 その後も後継国家の基本的な仕組みの一つとして継続している。[33][34] |

| Ancient Rome A hierarchy of regional proconsuls and their deputies administered the Roman Empire.[35] The reforms of Diocletian (Emperor from 284 to 305) doubled the number of administrative districts and led to a large-scale expansion of Roman bureaucracy.[36] The early Christian author Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) claimed that Diocletian's reforms led to widespread economic stagnation, since "the provinces were divided into minute portions, and many presidents and a multitude of inferior officers lay heavy on each territory."[37] After the Empire split, the Byzantine Empire developed a notoriously complicated administrative hierarchy, and in the 20th century the term Byzantine came to refer to any complex bureaucratic structure.[38][39] |

古代ローマ 地方総督とその代理人による階層制がローマ帝国を統治していた。[35] ディオクレティアヌス帝(在位284年~305年)の改革により行政区画が倍増し、ローマ官僚機構が大規模に拡大した。[36] 初期キリスト教の著者ラクタンティウス(約250年 - 約325年)は、ディオクレティアヌスの改革が広範な経済停滞をもたらしたと主張した。その理由は「属州が細分化され、多くの総督と無数の下級官吏が各地 域に重くのしかかった」からである。[37] 帝国分裂後、ビザンツ帝国は悪名高いほど複雑な行政階層を発展させた。20世紀には「ビザンチン的」という用語が、あらゆる複雑な官僚機構を指すように なった。[38][39] |

| Modern Persia This section should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. See why. (July 2024) Uzun Hasan's conquest of most of mainland Iran shifted the seat of power to the east, where the Aq Qoyunlu adopted Iranian customs for administration and culture. In the Iranian areas, Uzun Hasan preserved the previous bureaucratic structure along with its secretaries, who belonged to families that had in a number of instances served under different dynasties for several generations. The four top civil posts of the Aq Qoyunlu were all occupied by Iranians, which under Uzun Hasan included: the vizier, who led the great council (divan); the mostawfi al-mamalek, high-ranking financial accountants; the mohrdar, who affixed the state seal; and the marakur 'stable master', who supervised the royal court. Through the use of his increasing revenue, Uzun Hasan was able to buy the approval of the ulama (clergy) and the mainly Iranian urban elite, while also taking care of the impoverished rural inhabitants.[40] The Safavid state was one of checks and balance, both within the government and on a local level. At the apex of this system was the Shah, with total power over the state, legitimized by his bloodline as a sayyid, or descendant of Muhammad. To ensure transparency and avoid decisions being made that circumvented the Shah, a complex system of bureaucracy and departmental procedures had been put in place that prevented fraud. Every office had a deputy or superintendent, whose job was to keep records of all actions of the state officials and report directly to the Shah. The Shah himself exercised his own measures for keeping his ministers under control by fostering an atmosphere of rivalry and competitive surveillance. And since the Safavid society was meritocratic, and successions seldom were made on the basis of heritage, this meant that government offices constantly felt the pressure of being under surveillance and had to make sure they governed in the best interest of their leader, and not merely their own. The Ottomans adopted Persian bureaucratic traditions and culture. |

近代 ペルシア この節では、英語以外の内容の言語を{{lang}}または{{langx}}で指定すべきである。音訳言語には{{transliteration}} を、音声表記には{{IPA}}を使用し、適切なISO 639コードを付記する。ウィキペディアの多言語サポートテンプレートも使用可能である。詳細は[理由]を参照のこと。(2024年7月) ウズン・ハサンによるイラン本土の大部分の征服は、権力の座を東へ移した。そこでアク・コユンルは行政と文化においてイランの慣習を採用した。イラン地域 では、ウズン・ハサンは以前の官僚機構と、その書記官たちをそのまま維持した。書記官たちは、多くの場合、数世代にわたり異なる王朝に仕えてきた家系の出 身者であった。アク・ギュンル朝の四つの最高官職は全てイラン人が占めていた。ウズン・ハサン治世下では、大評議会(ディヴァン)を率いる宰相、高位の財 務会計官であるモスタウフィ・アル=ママーレク、国璽を押すモフルダル、そして宮廷を監督する厩舎長(マラクル)がそれに当たる。ウズン・ハサンは増大す る歳入を活用し、ウラマー(聖職者)や主にイラン系の都市エリートの支持を買収すると同時に、貧困化した農村住民の生活も配慮したのである。[40] サファヴィー朝国家は、政府内部と地方レベルの両方で権力均衡が機能する体制であった。この制度の頂点に立つのはシャーであり、国家に対する絶対的な権力 を有していた。その権威は、預言者ムハンマドの血筋を引くサイイドとしての血統によって正当化されていた。透明性を確保し、シャーを迂回する決定がなされ るのを防ぐため、複雑な官僚機構と部門別手続きが整備され、不正を防止していた。各官庁には副官または監督官が配置され、その職務は国家公務員のあらゆる 行動を記録し、直接シャーに報告することだった。シャー自身も、競争と相互監視の雰囲気を醸成することで、大臣たちを統制する独自の手段を行使した。サ ファヴィー朝社会は実力主義であり、世襲による継承は稀であったため、政府機関は常に監視下に置かれているという圧力を感じ、自らの利益だけでなく、指導 者の最善の利益のために統治することを確実にする必要があった。 オスマン帝国はペルシャの官僚的伝統と文化を採用した。 |

| Russia The Russian autocracy survived the Time of Troubles and the rule of weak or corrupt tsars because of the strength of the government's central bureaucracy. Government functionaries continued to serve, regardless of the ruler's legitimacy or the boyar faction controlling the throne. In the 17th century, the bureaucracy expanded dramatically. The number of government departments (prikazy; sing., prikaz ) increased from twenty-two in 1613 to eighty by mid-century. Although the departments often had overlapping and conflicting jurisdictions, the central government, through provincial governors, was able to control and regulate all social groups, as well as trade, manufacturing, and even the Eastern Orthodox Church. The tsarist bureaucracy, alongside the military, the judiciary and the Russian Orthodox Church, played a major role in solidifying and maintaining the rule of the Tsars in the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721) and in the Russian Empire (1721–1917). In the 19th century, the forces of change brought on by the Industrial Revolution propelled many countries, especially in Europe, to significant social changes. However, due to the conservative nature of the Tsarist regime and its desire to maintain power and control, social change in Russia lagged behind that of Europe.[41] Russian-speakers referred to bureaucrats as chinovniki (чиновники) because of the rank or chin (чин) which they held.[42] Ashanti Empire The government of the Ashanti Empire was built upon a sophisticated bureaucracy in Kumasi, with separate ministries which saw to the handling of state affairs. Ashanti's Foreign Office was based in Kumasi. Despite the small size of the office, it allowed the state to pursue complex negotiations with foreign powers. The Office was divided into departments that handled Ashanti relations separately with the British, French, Dutch, and Arabs. Scholars of Ashanti history, such as Larry Yarak and Ivor Wilkes, disagree over the power of this sophisticated bureaucracy in comparison to the Asantehene. However, both scholars agree that it was a sign of a highly developed government with a complex system of checks and balances.[43] |

ロシア ロシアの専制政治は、混乱の時代や弱体・腐敗した皇帝の統治を乗り切れたのは、政府の中央官僚機構の強さゆえであった。政府役人は、統治者の正当性や王座 を掌握するボヤール派閥に関わらず、職務を継続した。17世紀には官僚機構が劇的に拡大した。政府部門(プリカズ、単数形プリカズ)の数は、1613年の 22から世紀半ばまでに80に増加した。部門間の管轄権が重複し対立することも多かったが、中央政府は地方総督を通じて、あらゆる社会集団、貿易、製造 業、さらには東方正教会までも統制・規制することができた。 ツァーリ官僚機構は、軍隊、司法、ロシア正教会と並んで、ロシア大公国(1547年~1721年)およびロシア帝国(1721年~1917年)における ツァーリの支配を固め維持する上で主要な役割を果たした。19世紀、産業革命がもたらした変革の波は、特にヨーロッパ諸国において大きな社会変化を推進し た。しかし、ツァーリ体制の保守的な性質と権力維持への執着ゆえに、ロシアの社会変化はヨーロッパに遅れをとった。[41] ロシア語話者は、官僚を「チノヴニキ(чиновники)」と呼んだ。これは彼らが持つ階級、すなわち「チン(чин)」に由来する。[42] アシャンティ帝国 アシャンティ帝国の政府はクマシに高度な官僚機構を基盤として構築され、国家事務を処理する別々の省庁が存在した。アシャンティの外務省はクマシに置かれ ていた。その規模は小さいものの、国家が外国勢力との複雑な交渉を進めることを可能にした。同省は英国、フランス、オランダ、アラブ諸国とのアシャンティ 関係をそれぞれ担当する部門に分かれていた。ラリー・ヤラックやアイヴァー・ウィルクスといったアシャンティ史研究者は、この高度な官僚機構の権力がアサ ンテヘネ(アシャンティ王)と比べてどれほど強大だったかについて意見が分かれている。しかし両者とも、これは複雑な権力分立と抑制の仕組みを備えた高度 に発達した政府の証であった点では一致している。[43] |

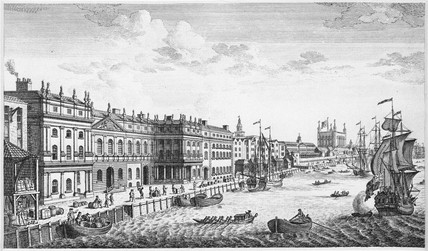

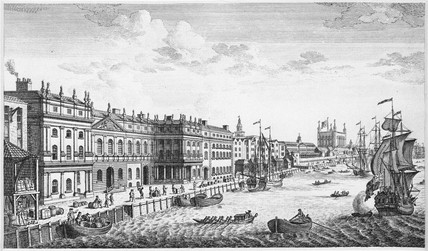

United Kingdom The 18th century Department of Excise developed a sophisticated bureaucracy. Pictured, the Custom House in the City of London. Instead of the inefficient and often corrupt system of tax farming that prevailed in absolutist states such as France, the Exchequer was able to exert control over the entire system of tax revenue and government expenditure.[44] By the late 18th century, the ratio of fiscal bureaucracy to population in Britain was approximately 1 in 1300, almost four times larger than the second most heavily bureaucratized nation, France.[45] Thomas Taylor Meadows, Britain's consul in Guangzhou, argued in his Desultory Notes on the Government and People of China (1847) that "the long duration of the Chinese empire is solely and altogether owing to the good government which consists in the advancement of men of talent and merit only", and that the British must reform their civil service by making the institution meritocratic.[46] Influenced by the ancient Chinese imperial examination, the Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1854 recommended that recruitment should be on the basis of merit determined through competitive examination, candidates should have a solid general education to enable inter-departmental transfers, and promotion should be through achievement rather than "preferment, patronage, or purchase".[47][46] This led to implementation of His Majesty's Civil Service as a systematic, meritocratic civil service bureaucracy.[48] In the British civil service, just as it was in China, entrance to the civil service was usually based on a general education in ancient classics, which similarly gave bureaucrats greater prestige. The Cambridge-Oxford ideal of the civil service was identical to the Confucian ideal of a general education in world affairs through humanism.[49] Well into the 20th century, classics, literature, history and language remained heavily favoured in British civil service examinations.[50] In the period of 1925–1935, 67 percent of British civil service entrants consisted of such graduates.[51] Like the Chinese model's consideration of personal values, the British model also took personal physique and character into account.[52] |

イギリス 18世紀の歳入庁は洗練された官僚機構を発展させた。写真はロンドン市内の税関庁舎である。 フランスなどの絶対主義国家で主流だった非効率で腐敗の多い租税請負制度とは異なり、大蔵省は税収と政府支出の全システムを統制できた[44]。18世紀 後半までに、英国の財政官僚と人口の比率は約1300人に1人となり、官僚制が2番目に発達したフランスよりもほぼ4倍大きかった。[45] 広州駐在の英国領事トーマス・テイラー・メドウズは、著書『中国政府と国民に関する断片的な覚書』(1847年)で「中国帝国の長き存続は、才能と功績あ る者のみを進用する良政にのみ帰する」と論じ、英国も功績主義制度による官僚改革が必要だと主張した。[46] 古代中国の科挙制度に影響を受けた1854年のノースコート=トレヴェリアン報告書は、採用は競争試験による実力主義に基づき、候補者は省庁間異動を可能 にする確固たる教養教育を修め、昇進は「恩顧、庇護、または買官」ではなく実績によって行うべきだと提言した。[47] [46] これにより、体系化された能力主義の官僚機構として「陛下の公務員制度」が実施された。[48] 英国の公務員制度では、中国と同様に、官僚への道は通常、古代の古典を学ぶ一般教養に基づいており、これも同様に官僚に高い威信を与えた。ケンブリッジ・ オックスフォード流の公務員像は、儒教が理想とした人文主義を通じた世界情勢の一般教養と同一であった。[49] 20世紀に入ってもなお、英国の官僚試験では古典・文学・歴史・言語が強く重視された。[50] 1925年から1935年の期間、英国官僚採用者の67%がこうした卒業生で占められた。[51] 中国モデルが個人の資質を考慮したように、英国モデルも個人の体格や性格を勘案した。[52] |

| France Like the British, the development of French bureaucracy was influenced by the Chinese system.[53] Under Louis XIV of France, the old nobility had neither power nor political influence, their only privilege being exemption from taxes. The dissatisfied noblemen complained about this "unnatural" state of affairs, and discovered similarities between absolute monarchy and bureaucratic despotism.[54] With the translation of Confucian texts during the Enlightenment, the concept of a meritocracy reached intellectuals in the West, who saw it as an alternative to the traditional ancien regime of Europe.[55] Western perception of China even in the 18th century admired the Chinese bureaucratic system as favourable over European governments for its seeming meritocracy; Voltaire claimed that the Chinese had "perfected moral science" and François Quesnay advocated an economic and political system modeled after that of the Chinese.[56] The governments of China, Egypt, Peru and Empress Catherine II were regarded as models of Enlightened Despotism, admired by such figures as Diderot, D'Alembert and Voltaire.[54] Napoleonic France adopted this meritocracy system [55] and soon saw a rapid and dramatic expansion of government, accompanied by the rise of the French civil service and its complex systems of bureaucracy. This phenomenon became known as "bureaumania". In the early 19th century, Napoleon attempted to reform the bureaucracies of France and other territories under his control by the imposition of the standardized Napoleonic Code. But paradoxically, that led to even further growth of the bureaucracy.[57] French civil service examinations adopted in the late 19th century were also heavily based on general cultural studies. These features have been likened to the earlier Chinese model.[52] |

フランス 英国と同様、フランス官僚制の発展は中国の制度に影響を受けた。[53] フランス王ルイ14世の治世下では、旧貴族は権力も政治的影響力も持たず、唯一の特権は免税であった。不満を抱いた貴族たちはこの「不自然な」状況を嘆 き、絶対君主制と官僚的専制主義の類似点を見出した。[54] 啓蒙時代における儒教文献の翻訳により、能力主義の概念は西洋の知識人に伝わり、彼らはこれをヨーロッパの伝統的なアンシャン・レジームに代わる選択肢と 見なした。[55] 18世紀の西洋における中国観でさえ、その能力主義的な様相から、中国の官僚制度をヨーロッパの政府体制よりも優れていると賞賛していた。ヴォルテールは 中国人が「道徳科学を完成させた」と主張し、フランソワ・ケネーは中国をモデルとした経済・政治体制を提唱した。[56] 中国、エジプト、ペルー、そしてエカテリーナ2世の統治は啓蒙専制主義の模範と見なされ、ディドロ、ダルランベール、ヴォルテールらに称賛された。 [54] ナポレオン時代のフランスはこの能力主義制度を採用した[55]。その結果、政府は急速かつ劇的に拡大し、フランス官僚機構とその複雑な官僚システムが台 頭した。この現象は「官僚主義の蔓延」として知られるようになった。19世紀初頭、ナポレオンは標準化されたナポレオン法典を施行することで、フランス及 び支配下の諸地域の官僚機構を改革しようとした。しかし逆説的に、それは官僚機構のさらなる肥大化を招いた。[57] 19世紀後半に導入されたフランスの公務員試験も、一般教養科目を大きく重視していた。これらの特徴は、以前の中国モデルに類似していると評されている。[52] |

| Other industrialized nations By the mid-19th century, bureaucratic forms of administration were firmly in place across the industrialized world. Thinkers like John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx began to theorize about the economic functions and power-structures of bureaucracy in contemporary life. Max Weber was the first to endorse bureaucracy as a necessary feature of modernity, and by the late 19th century bureaucratic forms had begun their spread from government to other large-scale institutions.[11] Within capitalist systems, informal bureaucratic structures began to appear in the form of corporate power hierarchies, as detailed in mid-century works like The Organization Man and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc nations, a powerful class of bureaucratic administrators termed nomenklatura governed nearly all aspects of public life.[58] The 1980s brought a backlash against perceptions of "big government" and the associated bureaucracy. Politicians like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan gained power by promising to eliminate government regulatory bureaucracies, which they saw as overbearing, and return economic production to a more purely capitalistic mode, which they saw as more efficient.[59][60] In the business world, managers like Jack Welch gained fortune and renown by eliminating bureaucratic structures inside corporations.[61] Still, in the modern world, most organized institutions rely on bureaucratic systems to manage information, process records, and administer complex systems, although the decline of paperwork and the widespread use of electronic databases is transforming the way bureaucracies function.[62] |

その他の先進工業国 19世紀半ばまでに、官僚的な行政形態は先進工業国全体にしっかりと定着していた。ジョン・スチュワート・ミルやカール・マルクスなどの思想家は、現代生 活における官僚機構の経済的機能と権力構造について理論化し始めた。マックス・ヴェーバーは、官僚機構を近代化に必要な要素として初めて支持し、19世紀 後半までに、官僚的な形態は政府から他の大規模な機関へと広がり始めた。[11] 資本主義システムでは、企業内の権力階層という形で非公式の官僚機構が出現し始めた。これは、1950年代半ばの『組織人間』や『灰色のフランネルのスー ツを着た男』といった作品で詳しく述べられている。一方、ソ連や東側諸国では、ノメンクラトゥーラと呼ばれる強力な官僚階級が、公共生活のほぼすべての側 面を支配していた。[58] 1980年代には「大きな政府」とその官僚機構に対する反発が起きた。マーガレット・サッチャーやロナルド・レーガンといった政治家は、政府の規制官僚機 構を「横暴」と断じて排除し、経済生産を「より効率的」と見なした純粋な資本主義様式へ回帰させることを公約に掲げて権力を掌握した。[59] [60] ビジネス界では、ジャック・ウェルチのような経営者が企業内の官僚的構造を排除することで富と名声を得た。[61] それでも現代社会では、ほとんどの組織的機関が情報管理、記録処理、複雑なシステムの運営に官僚的システムに依存している。ただし書類作業の減少と電子 データベースの普及が官僚機構の機能様式を変容させつつある。[62] |

| Theories Karl Marx Karl Marx theorized about the role and function of bureaucracy in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, published in 1843. In Philosophy of Right, Hegel had supported the role of specialized officials in public administration, although he never used the term bureaucracy himself. By contrast, Marx was opposed to bureaucracy. Marx posited that while corporate and government bureaucracy seem to operate in opposition, in actuality they mutually rely on one another to exist. He wrote that "The Corporation is civil society's attempt to become state; but the bureaucracy is the state which has really made itself into civil society."[63] Leon Trotsky Leon Trotsky developed a critical theory of the emerging Soviet bureaucracy during the early years of the Soviet Union. According to political scientist Thomas M. Twiss, Trotsky associated bureaucratism with authoritarianism, excessive centralism and conservatism. Social theorist Martin Krygier had noted the impact of Trotsky's post-1923 writings in shaping receptive views of bureaucracy among later Marxists and many non-Marxists. Twiss argued that Trotsky's theory of Soviet bureaucracy was essential for a study of Soviet history and understanding the process of capitalist restoration in Russia and Eastern Europe. Political scientist, Baruch Knei-Paz argued Trotsky had, above all others, written "to show the historical and social roots of Stalinism" as a bureaucratic system.[64] One of the predictions made by Trotsky in his 1936 work, The Revolution Betrayed, was that the USSR would come before a disjuncture: either the toppling of the ruling bureaucracy by means of a political revolution, or capitalist restoration led by the bureaucracy: The fall of the present bureaucratic dictatorship, if it were not replaced by a new socialist power, would thus mean a return to capitalist relations with a catastrophic decline of industry and culture.[65] John Stuart Mill Writing in the early 1860s, political scientist John Stuart Mill theorized that successful monarchies were essentially bureaucracies, and found evidence of their existence in Imperial China, the Russian Empire, and the regimes of Europe. Mill referred to bureaucracy as a distinct form of government, separate from representative democracy. He believed bureaucracies had certain advantages, most importantly the accumulation of experience in those who actually conduct the affairs. Nevertheless, he believed this form of governance compared poorly to representative government, as it relied on appointment rather than direct election. Mill wrote that ultimately the bureaucracy stifles the mind, and that "a bureaucracy always tends to become a pedantocracy."[66] |

理論 カール・マルクス カール・マルクスは1843年に出版された『ヘーゲルの法哲学批判』において、官僚制の役割と機能について理論化した。ヘーゲルは『法哲学』の中で、自ら 「官僚制」という用語を用いることはなかったものの、行政における専門官僚の役割を支持していた。これに対し、マルクスは官僚制に反対した。マルクスは、 企業と政府の官僚機構は対立して機能しているように見えるが、実際には互いに依存し合って存在していると主張した。彼は「企業は市民社会が国家になろうと する試みである。しかし官僚機構は、実際に自らを市民社会へと変貌させた国家である」と記した[63]。 レオン・トロツキー レオン・トロツキーは、ソビエト連邦の初期に、台頭しつつあったソビエトの官僚機構について批判的な理論を展開した。政治学者のトーマス・M・トゥイスに よれば、トロツキーは官僚主義を権威主義、過度な中央集権主義、保守主義と結びつけていた。社会理論家のマーティン・クリギエは、1923年以降のトロツ キーの著作が、後のマルクス主義者や多くの非マルクス主義者たちの官僚機構に対する受容的な見解の形成に与えた影響に注目していた。トウィスは、トロツ キーのソビエト官僚機構に関する理論は、ソビエトの歴史を研究し、ロシアおよび東ヨーロッパにおける資本主義復活の過程を理解するために不可欠であると主 張した。政治学者バルーク・クネイ=パスは、トロツキーは、とりわけ、官僚機構としての「スターリン主義の歴史的・社会的根源を示す」ために著作を書いた と主張した。[64] トロツキーが 1936 年の著作『裏切られた革命』で予測したことの一つは、ソ連は、政治革命によって支配層である官僚機構が打倒されるか、あるいは官僚機構が主導する資本主義の復活という、二つの選択肢の分岐点に立つだろうということだった。 現在の官僚的独裁体制が崩壊し、それに代わる新しい社会主義的権力が誕生しなければ、産業と文化の壊滅的な衰退を伴う資本主義的関係への回帰を意味するだろう。[65] ジョン・スチュワート・ミル 1860年代初頭に、政治学者ジョン・スチュワート・ミルは、成功した君主制は本質的に官僚制であると理論化し、その存在の証拠を中国帝国、ロシア帝国、 そしてヨーロッパの政権に見出した。ミルは、官僚主義を、代表民主制とは別の、明確な政府の形態として言及した。彼は、官僚機構には、実際に事務を遂行す る者たちの経験の蓄積という、最も重要な利点があると考えていた。それにもかかわらず、彼は、この形態の統治は、直接選挙ではなく任命に依存しているた め、代表政府に比べて見劣りすると考えていた。ミルは、結局のところ、官僚機構は精神を窒息させ、「官僚機構は常に衒学主義の傾向がある」と記している。 |

| Max Weber The fully developed bureaucratic apparatus compares with other organisations exactly as does the machine with the non-mechanical modes of production. –Max Weber[67] The German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) was the first to study bureaucracy formally, and his works led to the popularization of this term.[68] In his essay Bureaucracy,[69] published in his magnum opus, Economy and Society in 1921, Weber described many ideal-typical forms of public administration, government, and business. His ideal-typical bureaucracy, whether public or private, is characterized by: hierarchical organization formal lines of authority (chain of command) a fixed area of activity rigid division of labor regular and continuous execution of assigned tasks all decisions and powers specified and restricted by regulations officials with expert training in their fields career advancement dependent on technical qualifications qualifications evaluated by organizational rules, not by individuals[5][70][71] Weber listed several preconditions for the emergence of bureaucracy, including an increase in the amount of space and population being administered, an increase in the complexity of the administrative tasks being carried out, and the existence of a monetary economy requiring a more efficient administrative system.[70] Development of communication and transportation technologies make more efficient administration possible, and democratization and rationalization of culture results in demands for equal treatment.[70] Although he was not necessarily an admirer of bureaucracy, Weber saw bureaucratization as the most efficient and rational way of organizing human activity and therefore as the key to rational-legal authority, indispensable to the modern world.[72] Furthermore, he saw it as the key process in the ongoing rationalization of Western society.[5][73] Weber also saw bureaucracy, however, as a threat to individual freedoms, and ongoing bureaucratization as leading to a "polar night of icy darkness", in which increasing rationalization of human life traps individuals in a soulless "iron cage" of bureaucratic, rule-based, rational control.[5][6] Weber's critical study of the bureaucratization of society became one of the most enduring parts of his work.[5][73] Many aspects of modern public administration are based on his work, and a classic, hierarchically organized civil service of the Continental type is called a "Weberian civil service" or a "Weberian bureaucracy".[74] Social scientists debate whether Weberian bureaucracy contributes to economic growth.[75] Political scientist Jan Vogler challenges Max Weber's characterization of modern bureaucracies.[76] Whereas Weber describes bureaucracies as entailing strict merit recruitment, clearly delineated career-paths for bureaucrats, the full separation of bureaucratic operations from politics, and mutually exclusive spheres of competence for government agencies, Vogler argues that the overwhelming majority of existing public administrative systems are not like this. Instead, modern bureaucracies require only "minimal competence" from candidates for bureaucratic offices, leaving space for biases in recruitment processes that give preferential treatment to members of specific social, economic, or ethnic groups, which are observed in many real-world bureaucratic systems. Bureaucracies are also not strictly separated from politics. |

マックス・ヴェーバー 完全に発達した官僚機構は、他の組織と、機械が非機械的な生産様式とまったく同じように比較される。 –マックス・ヴェーバー[67] ドイツの社会学者マックス・ヴェーバー(1864-1920)は、官僚機構を正式に研究した最初の人物であり、彼の著作によってこの用語が普及した。 [68] 1921年に発表した大著『経済と社会』に収められた論文「官僚制」[69]の中で、ヴェーバーは行政、政府、企業における多くの理想的な典型形態につい て論じている。彼の理想的な典型的な官僚制は、公的か私的かを問わず、以下の特徴を持つ。 階層的な組織 正式な権限系統(指揮系統) 固定された活動領域 厳格な分業 割り当てられた任務の定期的かつ継続的な遂行 すべての決定と権限が規則によって規定され制限されている 各分野の専門的訓練を受けた職員 技術的資格に依存する昇進 個人ではなく組織の規則によって評価される資格[5][70] [71] ヴェーバーは、官僚制が出現するためのいくつかの前提条件を挙げている。それには、管理される空間と人口の増加、遂行される行政業務の複雑化の増加、より 効率的な行政システムを必要とする貨幣経済の存在などが含まれる。[70] 通信および交通技術の発展は、より効率的な行政を可能にし、文化の民主化と合理化は、平等な扱いを求める要求をもたらす。[70] ヴェーバーは必ずしも官僚主義を称賛していたわけではないが、官僚化は人間活動を組織化する上で最も効率的かつ合理的な方法であり、したがって、現代社会 に欠かせない合理的・法的権威の鍵であると見なしていた。[72] さらに、彼はそれを西洋社会の継続的な合理化における重要なプロセスと見なしていた。[5][73] しかし、ヴェーバーは、官僚主義は個人の自由に対する脅威であり、官僚化の進行は、人間の生活が合理化されるにつれて、個人が官僚的で規則に基づく合理的 な統制という魂のない「鉄の檻」に閉じ込められる「極寒の夜の氷のような暗闇」へとつながるとも考えていた。[5][6] ヴェーバーによる社会の官僚化に関する批判的研究は、彼の著作の中で最も永続的な部分の一つとなった。[5][73] 現代の行政の多くの側面は彼の研究に基づいており、大陸型という階層的に組織された古典的な公務員制度は、「ヴェーバー的公務員制度」または「ヴェーバー 的官僚機構」と呼ばれる。[74] 社会科学者は、ヴェーバー的官僚機構が経済成長に貢献するかどうかについて議論している。[75] 政治学者のヤン・フォグラーは、マックス・ヴェーバーによる近代官僚機構の特徴付けに異議を唱えている。[76] ヴェーバーは、官僚機構とは、厳格な能力主義による採用、官僚のキャリアパスの明確な規定、政治からの官僚機構の完全な分離、政府機関間の相互に排他的な 権限範囲などを伴うものと説明しているが、フォグラーは、既存の行政システムの大半はそうではないと主張している。その代わりに、現代の官僚機構は、官僚 職の候補者に「最低限の能力」しか要求せず、現実の多くの官僚制度で見られるように、特定の社会的、経済的、あるいは民族的グループのメンバーを優遇する 採用プロセスにおける偏見の余地を残している。また、官僚機構は政治から厳密に分離されているわけではない。 |

| Woodrow Wilson Writing as an academic while a professor at Bryn Mawr College, Woodrow Wilson's essay The Study of Administration[77] argued for bureaucracy as a professional cadre, devoid of allegiance to fleeting politics. Wilson advocated a bureaucracy that: ...is a part of political life only as the methods of the counting house are a part of the life of society; only as machinery is part of the manufactured product. But it is, at the same time, raised very far above the dull level of mere technical detail by the fact that through its greater principles it is directly connected with the lasting maxims of political wisdom, the permanent truths of political progress. Wilson did not advocate a replacement of rule by the governed, he simply advised that, "Administrative questions are not political questions. Although politics sets the tasks for administration, it should not be suffered to manipulate its offices". This essay became a foundation for the study of public administration in America.[78] |

ウッドロウ・ウィルソン ブリンマー大学教授として学術的な文章を書いたウッドロウ・ウィルソンの論文『行政学の研究』[77] は、官僚機構を、つかの間の政治への忠誠心のない、専門的な幹部として論じた。ウィルソンは、次のような官僚機構を提唱した。 ...それは、会計事務所の方法が社会生活の一部であるのと同じように、政治生活の一部である。それは、機械が製造製品の一部であるのと同じである。しか し同時に、そのより大きな原則を通じて、政治の英知の永続的な格言、政治の進歩の恒久的な真理と直接結びついているという事実によって、単なる技術的な細 部の退屈なレベルからはるかに高いレベルに引き上げられている。 ウィルソンは、統治される者による統治の代替を提唱したわけではない。彼は単に、「行政上の問題は政治上の問題ではない。政治は行政の任務を設定するが、 その職務を操作することは許されるべきではない」と助言しただけである。この論文は、アメリカの行政学の研究の基礎となった。 |

| Ludwig von Mises This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Bureaucracy" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In his 1944 work Bureaucracy, the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises compared bureaucratic management to profit management. Profit management, he argued, is the most effective method of organization when the services rendered may be checked by economic calculation of profit and loss. When, however, the service in question cannot be subjected to economic calculation, bureaucratic management is necessary. He did not oppose universally bureaucratic management; on the contrary, he argued that bureaucracy is an indispensable method for social organization, for it is the only method by which the law can be made supreme, and is the protector of the individual against despotic arbitrariness. Using the example of the Catholic Church, he pointed out that bureaucracy is only appropriate for an organization whose code of conduct is not subject to change. He then went on to argue that complaints about bureaucratization usually refer not to the criticism of the bureaucratic methods themselves, but to "the intrusion of bureaucracy into all spheres of human life." Mises saw bureaucratic processes at work in both the private and public spheres; however, he believed that bureaucratization in the private sphere could only occur as a consequence of government interference. According to him, "What must be realized is only that the strait jacket of bureaucratic organization paralyzes the individual's initiative, while within the capitalist market society an innovator still has a chance to succeed. The former makes for stagnation and preservation of inveterate methods, the latter makes for progress and improvement."[12] Robert K. Merton American sociologist Robert K. Merton expanded on Weber's theories of bureaucracy in his work Social Theory and Social Structure, published in 1957. While Merton agreed with certain aspects of Weber's analysis, he also noted the dysfunctional aspects of bureaucracy, which he attributed to a "trained incapacity" resulting from "over conformity". He believed that bureaucrats are more likely to defend their own entrenched interests than to act to benefit the organization as a whole but that pride in their craft makes them resistant to changes in established routines. Merton stated that bureaucrats emphasize formality over interpersonal relationships, and have been trained to ignore the special circumstances of particular cases, causing them to come across as "arrogant" and "haughty".[13] |

ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼス この節は検証可能な情報源を必要としている。信頼できる情報源をこの節に追加し、記事の改善に協力してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。 出典を探す: 「官僚制」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学術文献 · JSTOR (2019年1月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 1944年の著作『官僚制』において、オーストリアの経済学者ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼスは官僚的管理と利益管理を比較した。利益管理は、提供される サービスが損益の経済計算によって検証可能な場合に最も効果的な組織方法だと彼は主張した。しかし、当該サービスが経済計算の対象とならない場合、官僚的 管理が必要となる。彼は官僚的管理を全面的に否定したわけではない。むしろ、官僚制は社会組織にとって不可欠な方法だと主張した。なぜなら、官僚制こそが 法を至高のものとし、個人の専制的恣意から守る唯一の方法だからだ。カトリック教会を例に挙げ、行動規範が変更されない組織にのみ官僚制が適していると指 摘した。さらに彼は、官僚化への不満は通常、官僚的手法そのものへの批判ではなく、「官僚主義が人間の生活のあらゆる領域に侵入すること」への批判である と論じた。ミーゼスは官僚的プロセスが民間と公共の両領域で機能していると見なしたが、民間領域における官僚化は政府の干渉の結果としてのみ起こり得ると 考えていた。ミゼスは、「認識すべきは、官僚組織という拘束衣が個人のイニシアチブを麻痺させる一方で、資本主義市場社会では革新者が成功するチャンスが まだ残されているということだ。前者は停滞と旧態依然とした方法の維持をもたらし、後者は進歩と改善をもたらす」と述べている。 ロバート・K・マートン アメリカの社会学者ロバート・K・マートンは、1957年に出版された著書『社会理論と社会構造』の中で、ヴェーバーの官僚制理論をさらに発展させた。 マートンはヴェーバーの分析の特定の側面には同意したが、官僚制の機能不全の側面にも注目し、それを「過度な順応」に起因する「訓練された無能」とみなし た。彼は、官僚は組織全体のために活動するよりも、自らの既得権益を守る傾向が強いが、その職務に対する誇りが、確立された慣例の変化に抵抗する要因と なっていると信じていた。マートンは、官僚は対人関係よりも形式を重視し、特定の事例の特別な状況を無視するように訓練されているため、「傲慢」で「高 慢」な印象を与えると述べた。[13] |

| Elliott Jaques In his book A General Theory of Bureaucracy, first published in 1976, Elliott Jaques describes the discovery of a universal and uniform underlying structure of managerial or work levels in the bureaucratic hierarchy for any type of employment systems.[79] Jaques argues and presents evidence that for the bureaucracy to provide a valuable contribution to the open society some of the following conditions must be met: The number of levels in the hierarchy of a bureaucracy must match the complexity level of the employment system for which the bureaucratic hierarchy is created. (Jaques identified a maximum of eight levels of complexity for bureaucratic hierarchies.) Roles within a bureaucratic hierarchy differ in the level of work complexity. The level of work complexity in the roles must be matched by the level of human capability of the role holders. (Jaques identified maximum of eight levels of human capability.) The level of work complexity in any managerial role within a bureaucratic hierarchy must be one level higher than the level of work complexity of the subordinate roles. Any managerial role in a bureaucratic hierarchy must have full managerial accountabilities and authorities (veto selection to the team, decide task types and specific task assignments, decide personal effectiveness and recognition, decide initiation of removal from the team within due process). Lateral working accountabilities[clarification needed] and authorities must be defined for all the roles in the hierarchy (seven types of lateral working accountabilities and authorities: collateral, advisory, service-getting and -giving, coordinative, monitoring, auditing, prescribing).[80][81][82] |

エリオット・ジャックス 1976年に初版が刊行された著書『官僚制の一般理論』の中で、エリオット・ジャックスは、あらゆるタイプの雇用システムにおける官僚的階層構造の根底にある、普遍的かつ均一な管理レベルまたは業務レベルの構造を発見したと述べている[79]。 ジャックスは、官僚機構が開放社会に貴重な貢献をするためには、以下の条件の一部が満たされなければならないと主張し、その証拠を提示している。 官僚機構の階層におけるレベル数は、その官僚機構が構築された雇用システムの複雑さのレベルと一致していなければならない。(ジャックスは、官僚機構の階層における複雑さのレベルは最大 8 つであると特定した。 官僚機構の階層における役割は、仕事の複雑さのレベルが異なる。 役割における仕事の複雑さのレベルは、その役割を担う者の能力のレベルと一致していなければならない。(ジャークスは人間の能力レベルを最大8段階と特定した。) 官僚的階層内の管理職役割における業務複雑性のレベルは、下位役割の業務複雑性レベルより1段階高くなければならない。 官僚的階層内の管理職役割は、完全な管理責任と権限(チームのメンバー選定に対する拒否権、タスクの種類と具体的な割り当ての決定、個人の効果性と評価の決定、適正手続きに基づくチームからの解任の決定)を有していなければならない。 階層内の全役割に対して、横方向の業務責任[注釈が必要]と権限を定義しなければならない(横方向の業務責任と権限には7種類がある:付随的、助言的、サービス提供・受領、調整的、監視的、監査的、指示的)。[80][81][82] |

| Bureaucracy and democracy See also: Bureaucratic drift, Bureaucratic inertia, and Representative bureaucracy Constitutional values including democracy are arguments for opposition to democratic backsliding by bureaucracies.[83] Democracies tend to be bureaucratic, with numerous civil servants and regulatory agencies with devolved power. On occasion a group might seize control of a bureaucratic state, as the Nazis did in Germany in the 1930s.[84] Although numerous ideals associated with democracy, such as equality, participation, and individuality, are in stark contrast to those associated with modern bureaucracy, specifically hierarchy, specialization, and impersonality, political theorists did not recognize bureaucracy as a threat to democracy. Yet, democratic theorists still have not developed an adequate response to the challenge[further explanation needed] posed by bureaucratic power within democratic governance.[85] One approach to addressing this issue rejects the idea that bureaucracy has any role at all in a true democracy. Theorists who adopt this perspective typically understand that they must demonstrate that bureaucracy does not necessarily occur in every contemporary society; only in those they perceive to be non-democratic. Thus, 19th century British writers frequently referred to bureaucracy as the "Continental nuisance," because their democracy was resistant to it, in their point of view.[85] According to Marx and other socialist thinkers, the most advanced bureaucracies were those in France and Germany. However, they argued that bureaucracy was a symptom of the bourgeois state and would vanish along with capitalism, which gave rise to the bourgeois state. Though clearly not the democracies Marx had in mind, socialist societies ended up being more bureaucratic than the governments they replaced. Similarly, after capitalist economies developed the administrative systems required to support their extensive welfare states, the idea that bureaucracy exclusively exists in socialist governments could scarcely be maintained.[85] |

官僚制と民主主義 関連項目:官僚的流転、官僚的惰性、代表的官僚制 民主主義を含む憲法上の価値は、官僚機構による民主主義の後退に反対する根拠となる。[83] 民主主義は官僚的になりがちで、多数の公務員と権限が委譲された規制機関が存在する。時折、ある集団が官僚国家の支配権を掌握することがある。1930年 代のドイツでナチスがそうしたように。[84] 平等、参加、個性といった民主主義に関連する多くの理想は、現代の官僚制に関連する理想、特に階層制、専門分化、非人格性とは対照的である。しかし政治理 論家たちは、官僚制が民主主義に対する脅威であると認識しなかった。それでもなお、民主主義理論家たちは、民主的統治における官僚的権力がもたらす課題 [詳細な説明が必要]に対して、十分な対応策を未だに確立していない。[85] この問題への一つのアプローチは、真の民主主義において官僚制が一切の役割を持たないという考えを否定するものである。この視点を採用する理論家たちは通 常、官僚制が必ずしも全ての現代社会で発生するわけではなく、彼らが非民主的と認識する社会でのみ発生することを示さねばならないと理解している。した がって、19世紀の英国人著述家たちは、自らの民主主義が官僚制に抵抗力を持つと考える観点から、官僚制を「大陸の厄介者」と呼ぶことが多かった。 [85] マルクスや他の社会主義思想家によれば、最も進んだ官僚制はフランスとドイツに存在した。しかし彼らは、官僚制はブルジョア国家の症状であり、ブルジョア 国家を生み出した資本主義と共に消滅すると主張した。明らかにマルクスが想定した民主主義ではなかったが、社会主義社会は結局、それらが取って代わった政 府よりも官僚的になった。同様に、資本主義経済が広範な福祉国家を支えるための行政システムを発展させた後では、官僚制が社会主義政府にのみ存在するとの 見解は、もはや維持し難くなったのである。[85] |

| Adhocracy Anarchy Authority Civil servant Hierarchical organization Franz Kafka Machinery of government Michel Crozier Outline of organizational theory Power (social and political) Public administration Red tape Requisite organization State (polity) Technocracy |

アドホクラシー 無政府状態 権威 公務員 階層的組織 フランツ・カフカ 政府機構 ミシェル・クロジエ 組織論の概説 権力(社会的・政治的) 公共行政 官僚主義 必要最小限の組織 国家(政治共同体) テクノクラシー |

| Albrow, Martin. Bureaucracy. (London: Macmillan, 1970). Cheng, Tun-Jen, Stephan Haggard, and David Kang. "Institutions and growth in Korea and Taiwan: the bureaucracy". in East Asian Development: New Perspectives (Routledge, 2020) pp. 87–111. online Cornell, Agnes, Carl Henrik Knutsen, and Jan Teorell. "Bureaucracy and Growth". Comparative Political Studies 53.14 (2020): 2246–2282. online Crooks, Peter, and Timothy H. Parsons, eds. Empires and bureaucracy in world history: from late antiquity to the twentieth century (Cambridge University Press, 2016) online. Kingston, Ralph. Bureaucrats and Bourgeois Society: Office Politics and Individual Credit, 1789–1848. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Neil Garston (ed.), Bureaucracy: Three Paradigms. Boston: Kluwer, 1993. On Karl Marx: Hal Draper, Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, Volume 1: State and Bureaucracy. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979. Marx comments on the state bureaucracy in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right and Engels discusses the origins of the state in Origins of the Family, marxists.org Ludwig von Mises, Bureaucracy, Yale University Press, 1962. Liberty Fund (2007), ISBN 978-0-86597-663-4 Schwarz, Bill. (1996). The expansion of England: race, ethnicity and cultural history. Psychology Pres; ISBN 0-415-06025-7. Watson, Tony J. (1980). Sociology, Work and Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32165-5. On Weber Weber, Max. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. Translated by A.M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons. London: Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1947. Wilson, James Q. (1989). Bureaucracy. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00785-1. Weber, Max, "Bureaucracy" in Weber, Max. Weber's Rationalism and Modern Society: New translations on Politics, Bureaucracy, and Social Stratification. Edited and Translated by Tony Waters and Dagmar Waters, 2015. ISBN 1137373539. English translation of "Bureaucracy" by Max Weber. |

アルブロー、マーティン。『官僚機構』 (ロンドン:マクミラン、1970年)。 チェン、トゥンジェン、ステファン・ハガード、デビッド・カン。「韓国と台湾の制度と成長:官僚機構」 『東アジアの発展:新しい視点』 (ラウトリッジ、2020年) 87-111 ページ。オンライン コーネル、アグネス、カール・ヘンリック・クヌッセン、ヤン・テオレル。「官僚機構と成長」。比較政治学研究 53.14 (2020): 2246–2282。オンライン クルックス、ピーター、ティモシー・H・パーソンズ編『世界史における帝国と官僚制:古代末期から20世紀まで』(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2016年)オンライン キングストン、ラルフ『官僚とブルジョワ社会:官庁政治と個人の信用、1789–1848年』(パルグレイブ・マクミラン、2011年) ニール・ガーストン編『官僚制:三つのパラダイム』ボストン:クルワー、1993年。 カール・マルクスについて:ハル・ドレイパー『カール・マルクスの革命理論 第1巻:国家と官僚制』ニューヨーク:マンスリー・レビュー・プレス、1979年。 マルクスは『ヘーゲル法哲学批判』で国家官僚制について論じ、エンゲルスは『家族・私有財産・国家の起源』で国家の起源について論じている。marxists.org ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼス『官僚制』イェール大学出版局、1962年。リバティ・ファンド(2007年)、ISBN 978-0-86597-663-4 シュワルツ、ビル。(1996)。イングランドの拡大:人種、民族、文化史。心理学出版; ISBN 0-415-06025-7。 ワトソン、トニー J. (1980)。社会学、仕事、産業。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-0-415-32165-5。ヴェーバーについて ヴェーバー、マックス。『社会経済組織論』。A.M. ヘンダーソン、タルコット・パーソンズ訳。ロンドン:コリア・マクミラン出版社、1947年。 ウィルソン、ジェームズ・Q. (1989). 『官僚制』。ベーシック・ブックス。ISBN 978-0-465-00785-1。 ヴェーバー、マックス、「官僚制」ヴェーバー、マックス著。ヴェーバーの合理主義と現代社会:政治、官僚制、社会階層に関する新訳。トニー・ウォーター ズ、ダグマー・ウォーターズ編、翻訳、2015年。ISBN 1137373539。マックス・ヴェーバー著「官僚制」の英訳。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bureaucracy |

|

☆M.ウェーバーの概念を、R.ベン ディッ クスがまとめているので、下記に引用しよう(ただし、論文などに引用する際には必ず図書館で原典を チェックしよう)。

「官僚制という用語は……価値中立な用語 であって文書による権利—義務の規制、契約にもとづく任命等々といった属性の存在を指示するのに用いら れてい る。ウェーバーは、この概念を、たえず家産的な行政の形態と対比しながら設定した。彼は、官僚制 が「愛、憎しみ、その他いっさいの純個人的感情を、公務の遂行から」排除するかぎり、近代の統治にはこのような特質がそなわるであろうと主 張した。だからわれわれは、西ヨーロッパ諸社会における近代の行政は、以前の中世的統治形態と対比して没 主観的(インパーソナル)である、ということができるのである。しかし、近代の社会内部の諸団体が、行政にたいして、どの方向に、どの程度の圧力をかける かに応じて、近代の行政は、それ自体としてはきわめて多様な形態をとりうる」(ベンディクス 1988:510)。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099