カシキズム/カシキスモ

Caciquism, Caciquismo

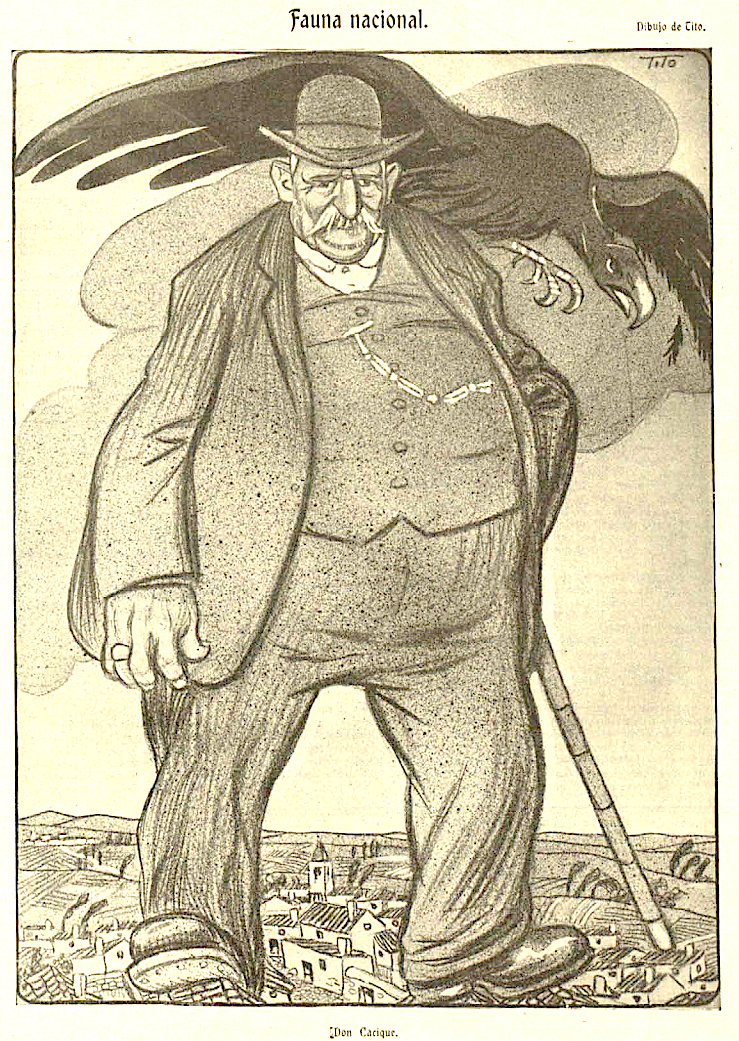

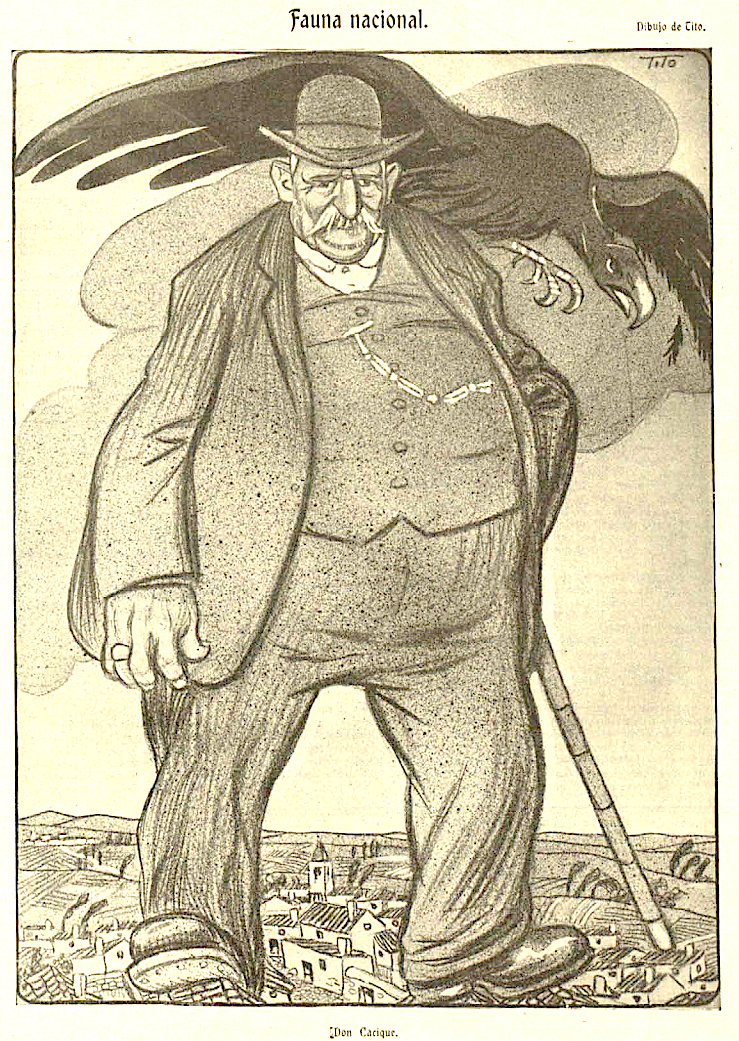

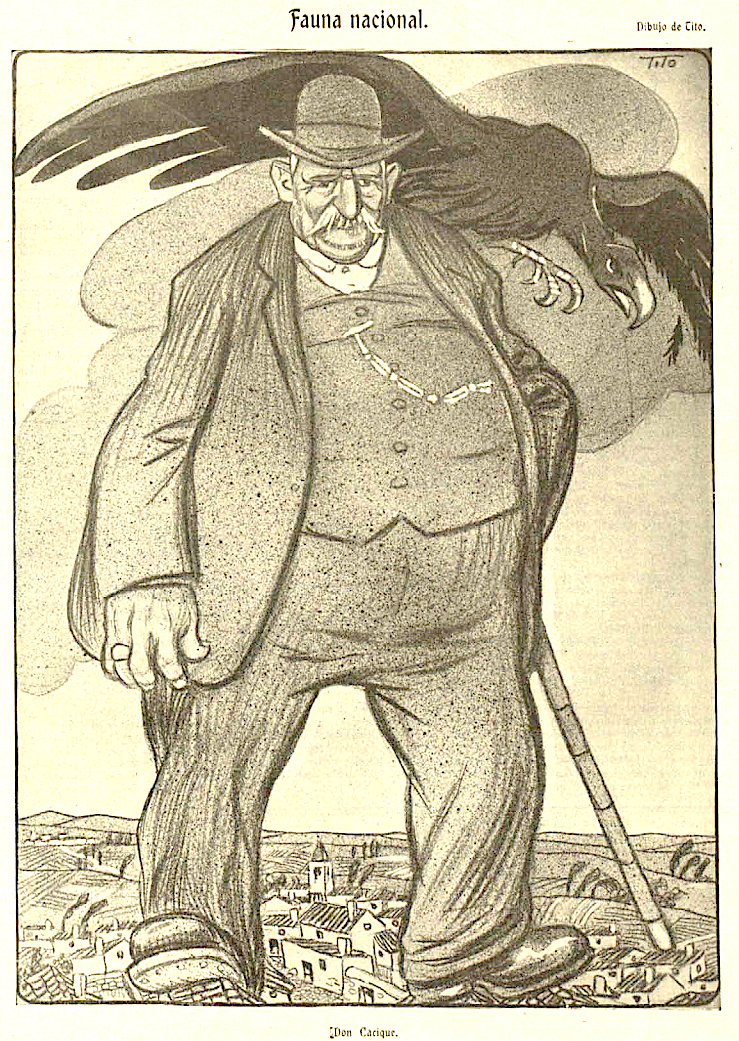

「国民的野生動物:ドン・カシケ」エクソリスト・サルメロン「ティト」作の風刺画, 1912.

☆

カシキズム(Caciquism)とは、地方の指導者である「カシケ」が選挙結果に影響を与えるために用いる政治権力のネットワークである。これは民主化が不完全な現代社会に見

られる特徴だ。

歴史学、ジャーナリズム、当時の知識人層において、この用語はスペインのブルボン復古王政期(1874-1923)の政治体制を指す。ホアキン・コスタが

1901年に発表した影響力ある論文『寡頭政治とカシキズム』(Oligarchie et Caciquisme)がこの用語を普及させた。[3]

とはいえ、カシキズムは同国ではより以前の時代、特にイサベラ2世の治世下でも広く見られた。[4]

また、ポルトガルの立憲君主制時代(1820-1910年)[5] や、同時期のアルゼンチン[6]、メキシコ[7]など、他の体制下でも利用された。

| Caciquism is a

network of political power wielded by local leaders called "caciques",

aimed at influencing electoral outcomes. It is a feature of some

modern-day societies with incomplete democratization.[1][2] In historiography, journalism, and intellectual circles of the era, the term describes the political system of the Bourbon Restoration in Spain (1874-1923). Joaquín Costa's influential essay Oligarchie et Caciquisme [fr] ("Oligarchy and Caciquism") in 1901 popularized the term.[3] Nonetheless, caciquism was also prevalent in earlier periods in the country, particularly during the reign of Isabella II.[4] It was also utilized in other systems, such as in Portugal during the Constitutional Monarchy (1820-1910)[5] as well as in Argentina[6] and Mexico[7] during a similar time period. |

カシキズムとは、地方の指導者である「カシケ」が選挙結果に影響を与え

るために用いる政治権力のネットワークである。これは民主化が不完全な現代社会に見られる特徴だ。 歴史学、ジャーナリズム、当時の知識人層において、この用語はスペインのブルボン復古王政期(1874-1923)の政治体制を指す。ホアキン・コスタが 1901年に発表した影響力ある論文『寡頭政治とカシキズム』(Oligarchie et Caciquisme)がこの用語を普及させた。[3] とはいえ、カシキズムは同国ではより以前の時代、特にイサベラ2世の治世下でも広く見られた。[4] また、ポルトガルの立憲君主制時代(1820-1910年)[5] や、同時期のアルゼンチン[6]、メキシコ[7]など、他の体制下でも利用された。 |

| Concept of "cacique" The term "cacique" in Spanish, as well as other Western languages like French, stems from the Arawak term kassequa. It referred specifically to the individuals who had the highest ranking within the Taíno tribes of the West Indies and thus held the title of chief. This linguistic borrowing highlights the historical and cultural connections between these various groups.[6] Brought back by Christopher Columbus upon his return from his first voyage to America [es] in 1492,[8][9] the conquistadors utilized the term and expanded its usage to include the Central American setting and other indigenous groups they encountered,[6][7] even up to the absolute rulers of the pre-Columbian empires.[10] The concept of "cacique" differs from "seigneur" or "señor," which originated from feudalism, in its hierarchical inferiority. Caciques serve as privileged intermediaries and main interlocutors between the authority of the "masters" or "seigneurs" (conquistadors) and the populations they aim to control. A distinction was drawn between the "good caciques" who cooperated obediently with colonial and ecclesiastical authorities - the encomenderos, and the "bad caciques" who needed to be subdued or dismissed.[11] The term remained in use to "indicate the contrast between the conqueror's authority and the authorities of the defeated".[12] Certainly, "the role of the cacique was to bridge the gap between the Indian population and colonial administration." At the same time, his power in the community was based on his positive relations with the central administration. This allowed him to provide service not only for himself but also for the local administration.[13] At least since the eighteenth century, the term has had a broader meaning of "a dominating individual who instills fear and holds influence in a locality," with a negative connotation within the peninsular context. The term "cacique" appears in the 1729 Diccionario de Autoridades [es], where it is defined as the "Lord of the vassals, or the Superior in the Province or Pueblos de Indios". Additionally, the definition explains that the term is used metaphorically to refer to the first leader of a Pueblo or Republic who wields more power and commands more respect by being feared and obeyed by those beneath them. As a result, the term came to be applied to individuals who have an overly influential and powerful role in a community.[11][14] In the 1884 edition of the Royal Spanish Academy's Diccionario de la lengua española, the term appears with its current meaning, which encompasses both: The domination or influence of the cacique of a town or comarca. The abusive interference of a person or authority in certain matters, using his power or influence. The influence of the cacique extends beyond the political sphere and encompasses all human interactions. Consequently, the term "cacique" has evolved into a timeless and universal concept, applicable to any societal group and context in reference to power dynamics that involve patronage, clientelism, paternalism, dependence, favors, punishments, thanks, and curses among unequal individuals.[11] The "good cacique" serves as a protective figure, dispensing favors, and contrasts with the "bad cacique" who represses, excludes, or deprives.[15] |

「カシケ」の概念 スペイン語における「カシケ」という用語は、フランス語などの他の西洋言語と同様に、アラワク語のkassequaに由来する。これは特に西インド諸島の タイノ族部族内で最高位の地位にあり、首長の称号を持つ個人を指した。この言語的借用は、これらの様々な集団間の歴史的・文化的つながりを浮き彫りにして いる。[6] 1492年にクリストファー・コロンブスがアメリカ大陸への初航海から帰国した際[es]に持ち帰ったこの用語は[8][9]、征服者たちによって使用さ れ、その用法は中央アメリカの状況や遭遇した他の先住民族集団[6][7]、さらにはコロンブス以前の帝国における絶対的支配者たちにまで拡大された。 [10] 「カシケ」の概念は、封建制度に由来する「領主(seigneur)」や「主人(señor)」とは、その階層的な下位性において異なる。カシケは「支配 者」あるいは「領主」(征服者)の権威と、彼らが支配しようとする民衆との間の特権的な仲介者かつ主要な対話者として機能した。植民地当局や教会当局(エ ンコメンデロ)に従順に協力する「良きカシケ」と、服従させるか解任すべき「悪しきカシケ」との区別がなされた。[11] この用語は「征服者の権威と敗北した者の権威との対比を示す」ために使用され続けた。[12] 確かに「カシケの役割は、先住民集団と植民地行政の間の隔たりを埋めることだった」。同時に、彼の共同体における権力は中央行政との良好な関係に基づいて いた。これにより彼は自身のためだけでなく、地方行政のためにも奉仕することが可能となった。[13] 少なくとも18世紀以降、この用語は「地域で恐怖を植え付け影響力を持つ支配的な個人」というより広い意味を持ち、半島(スペイン本土)の文脈では否定的 なニュアンスを帯びた。「カシケ」という用語は1729年の『権威辞典』に登場し、「家臣の領主、あるいは州やインディオ集落における上位者」と定義され ている。さらにこの定義では、隠喩的に、下位者から恐れられ服従されることでより大きな権力と尊敬を集める、プエブロや共和国の最初の指導者を指す言葉と して用いられると説明されている。結果として、この用語はコミュニティ内で過度に影響力と権力を振るう個人を指すようになった。[11][14] 1884年版のスペイン王立アカデミー『スペイン語辞典』では、この用語は現在の意味、すなわち以下の両方を包含する形で登場する: 町や郡の首長(カシケ)による支配または影響力。 権力や影響力を用いて特定の問題に不当に干渉する人格や権威の行為。 カシケの影響力は政治領域を超え、あらゆる人間関係に及ぶ。したがって「カシケ」という用語は、不平等な個人間の庇護・クライアント主義・パターナリズ ム・依存・恩恵・罰・感謝・呪いといった力関係を示す普遍的かつ時代を超えた概念へと発展した。[11] 「善きカシケ」は保護者の役割を果たし恩恵を与える存在であるのに対し、「悪しきカシケ」は抑圧し、排除し、剥奪する存在である。[15] |

| Related terms During the time, the Spanish press utilized the term "caudillismo" (caudillismo or caudillaje) interchangeably with "caciquism" to describe the rule of the caciques, who were then referred to as "caudillos".[6] The term "cacicada", meaning "injustice, arbitrary action [by a cacique]", is also derived from "cacique".[16][17]  Iselín Santos Ovejero, Argentine footballer nicknamed el cacique del área. Contemporary uses In soccer circles, Argentine defender Iselín Santos Ovejero was nicknamed el cacique del área ("the cacique of the penalty area") in Spanish.[15] |

関連用語 当時、スペインの報道機関は「カウディージモ」(caudillismo または caudillaje)という用語を「カシキズム」と交替して使用し、カシケ(caciques)の支配を説明した。彼らは当時「カウディージョ」 (caudillos)と呼ばれていた。[6] 「カシカダ(cacicada)」という用語は「不正、恣意的な行為(カシケによる)」を意味し、これも「カシケ」に由来する。[16][17]  イセリン・サントス・オベヘロ。アルゼンチン人サッカー選手で「エリアのカシケ(el cacique del área)」の異名を持つ。 現代的な用法 サッカー界では、アルゼンチン人ディフェンダーのイセリン・サントス・オベヘロがスペイン語で「エリアの首長(el cacique del área)」という愛称で呼ばれた。[15] |

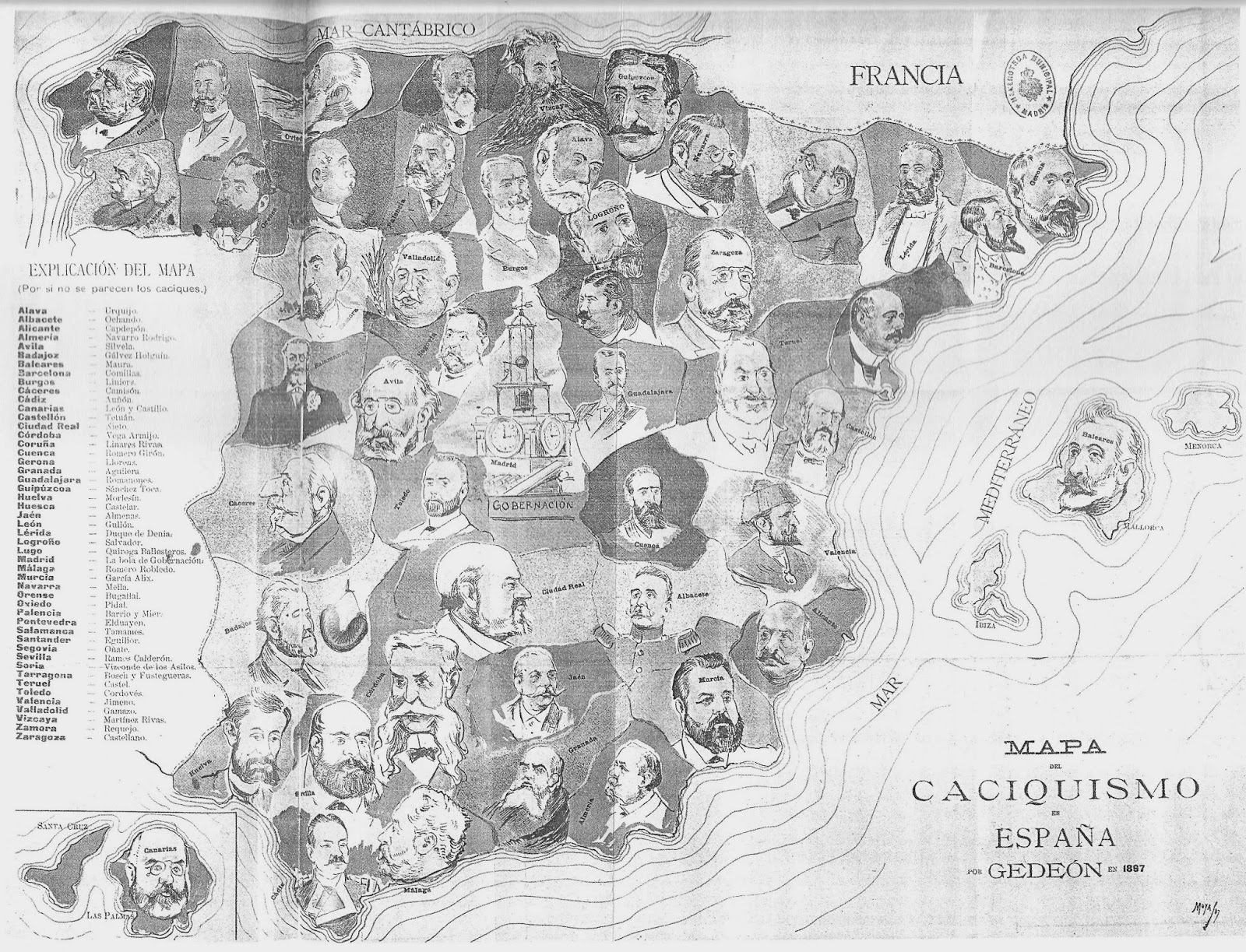

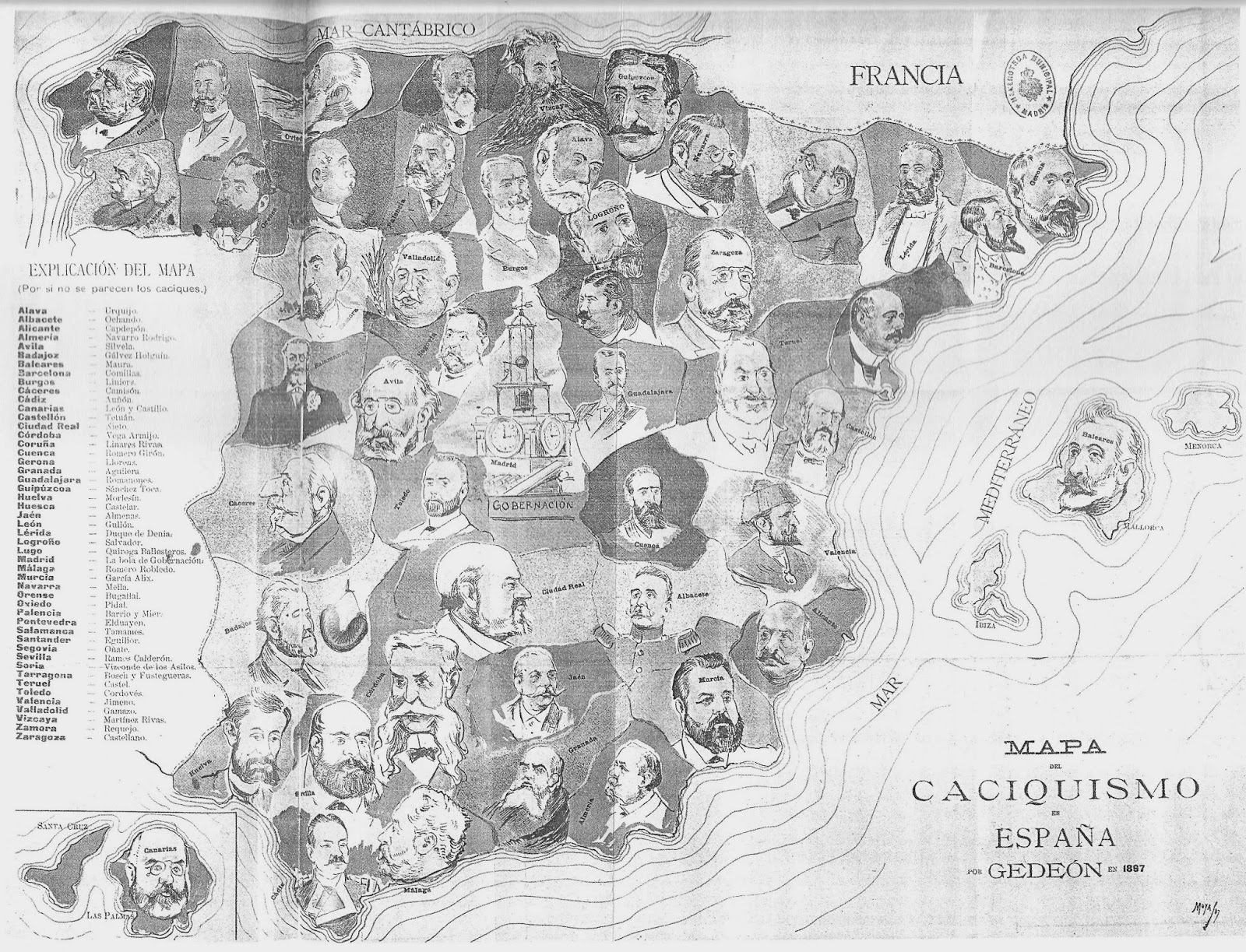

| In Spain "Caciquism" in Spain refers to the clientelist network that shaped the political regime of the Restoration, enabling fraud in all general elections. However, this system had also existed during Isabel II's liberal period and the democratic sexennium.[18] They were able to "manufacture" elections at the central power's whim to ensure political alternation between the conservative and liberal parties, known as the "dynastic parties." This made them a crucial link during the era.[19][20] During the Bourbon Restoration, the term "cacique" referred to influential figures in specific areas. "Nothing was accomplished without his agreement, and never any actions against him. The power of the cacique was immense in spite of his unofficial role. In cases of conflict with the civil governor - the representative of central authority - the cacique held the final say."[21] With the local population under his control and votes not taking place via secret ballot -a phenomenon not unique to Spain- the cacique could easily determine the outcome of elections.[22] In the boss/customer relationship, Manuel Suárez Cortina [fr] points out that an individual in a superior position (boss) provides protection or benefits to a person in an inferior position (customer) by leveraging their resources and influence. In exchange, the customer reciprocates by offering general support, assistance, and sometimes even personal services.[23] On the other hand, clienteles generally remain indifferent to ideologies, programs, or political affiliations in regards to their collective projection. "And this tendency, of course, reduced the ideological aspects of politics," observes José Varela Ortega [fr]. Furthermore, clients anticipated receiving personal favors.[24] Alongside "oligarchy," the term "caciquism" commonly depicted the political regime during the Restoration era. José Varela Ortega positions the beginning of the caciquist system near 1845, prior to which the administration held less sway compared to after that time. Caciquism dominated the dispute between local and central administration, specifically local notables versus caciques and landowners versus civil servants. The Caciquist era of interference by administration and party officials against local notables began after 1845 due to centralization and single-member districts. In 1850, the Count of San Luis established the "Family Assemblies [Cortes]," which ushered in the era of administrative or royal elections. The government actively intervened in the elections. In other words, the government exerted "leadership" rather than "legitimate influence," as the 1930s notables were labeled.[25] With this in mind, Varela Ortega states that Cánovas did not invent caciquism.[26] Rather, it was already present and was distributed more systematically during the Restoration. However, starting in 1850 and particularly in the 1860s and 1870s, the government interfered in elections, taking the place of a non-existent electorate. Similarly, party organizations exploited the administration for their own partisan goals, just as they did during the Restoration.[25] Some scholars argue that the political system during Isabella II's reign was an extreme example of oligarchy, as evidenced by censal suffrage laws that restricted the vote only to large and, occasionally, medium-sized landowners. The political system in Isabelline Spain was largely controlled by caciques, as evidenced by the fact that the party that called the majority of the twenty-two elections held during this period was consistently victorious.[27] Furthermore, clientelist political relationships had become well-established in the mid-nineteenth century and persisted throughout the democratic sexennium without being eliminated, as no government during this time was voted out of power. "When the political system of the Restoration was established, clientelism had already been present in Spain for a significant period of time."[28]  "Map of caciquism in Spain", by Moya (1897). The main deputies rooted in each province, those whose seats were not negotiated in the encasillado and who were the great caciques of the Restoration political regime.[29] |

スペインでは スペインにおける「カシキズム」とは、復古王政期の政治体制を形成した顧客主義的ネットワークを指し、あらゆる総選挙における不正を可能にした。しかしこ の制度は、イサベル2世の自由主義期や民主的六年間にも存在していた。[18] 彼らは中央権力の意向に従い選挙を「操作」し、保守党と自由党という「王朝政党」間の政権交代を保証できた。これにより彼らはこの時代の重要な仲介役と なった。[19][20] ブルボン復古期において、「カシケ」とは特定地域で影響力を持つ人物を指した。「彼の同意なしに何も成し遂げられず、彼に逆らう行動は決して取られなかっ た。非公式な立場にもかかわらず、カシケの権力は絶大であった。中央権力の代表者である地方総督との対立が生じた場合、最終決定権はカシケが握ってい た。」[21] 地元住民を掌握し、投票が秘密投票で行われなかった(スペイン特有の現象ではない)ため、カシケは選挙結果を容易に決定できたのである。[22] ボス/顧客関係において、マヌエル・スアレス・コルティナ[fr]は、上位者(ボス)が資源と影響力を活用して下位者(顧客)に保護や利益を提供すると指 摘する。見返りとして顧客は、一般的な支援や援助、時には個人的な奉仕さえも提供することで応じる。[23] 一方で、クライアント層は自らの集団的利益に関して、イデオロギーや政策綱領、政治的所属には概して無関心である。「この傾向は当然、政治のイデオロギー 的側面を弱めた」とホセ・バレラ・オルテガは指摘する。さらにクライアントは個人的な恩恵を受けることを期待していた。[24] 「寡頭政治」と並んで、「カシキズム」という用語は復古王政期の政治体制を一般的に描写した。ホセ・バレラ・オルテガは、カシキズム体制の始まりを 1845年頃と位置づけている。この時期以前、行政の影響力はその後よりも弱かった。カシキズムは、地方と中央の行政、特に地方の有力者とカシケ、地主と 公務員との対立を支配した。中央集権化と小選挙区制により、1845年以降、行政や政党幹部が地方の有力者に対して干渉するカシキズム時代が始まった。 1850年、サン・ルイス伯爵が「家族議会(コルテス)」を設立し、行政的あるいは王室主導の選挙時代が幕を開けた。政府は選挙に積極的に介入した。つま り政府は、1930年代の有力者たちがそう呼ばれたような「正当な影響力」ではなく、「指導力」を行使したのである。[25] この観点から、バレラ・オルテガはカノバスがカシキズムを発明したわけではないと述べる[26]。むしろそれは既に存在し、復古期に体系的に拡大された。 しかし1850年以降、特に1860~70年代には、政府が存在しない有権者に代わって選挙に干渉した。同様に、政党組織も復古王政期と同様に、自らの党 派的目標のために行政機構を利用したのである。[25] 一部の学者は、イサベル2世治世下の政治体制は寡頭政治の極端な例であったと主張する。その証拠として、選挙権を大規模な、時に中規模の土地所有者にのみ 制限した資産選挙法が挙げられる。イサベル朝スペインの政治体制は、主に地方有力者(カシケ)によって支配されていた。この事実を裏付けるように、この期 間に行われた22回の選挙の大半を主催した政党は、常に勝利を収めていた[27]。さらに、19世紀半ばには顧客主義的な政治関係が確立され、民主的な6 年間(セクセニオ)を通じて存続した。この期間、選挙で政権が交代することはなかったため、顧客主義は消去法による排除が行われず、存続したのである。 「復古王政の政治体制が確立された時点で、スペインには既に長期間にわたってクライアント主義が存在していた」[28]  モヤ作「スペインのカシキズム分布図」(1897年)。各州に根差した主要な代議士たち。彼らの議席はエンカシジャード(議席配分交渉)の対象外であり、復古王政体制における大カシケであった[29]。 |

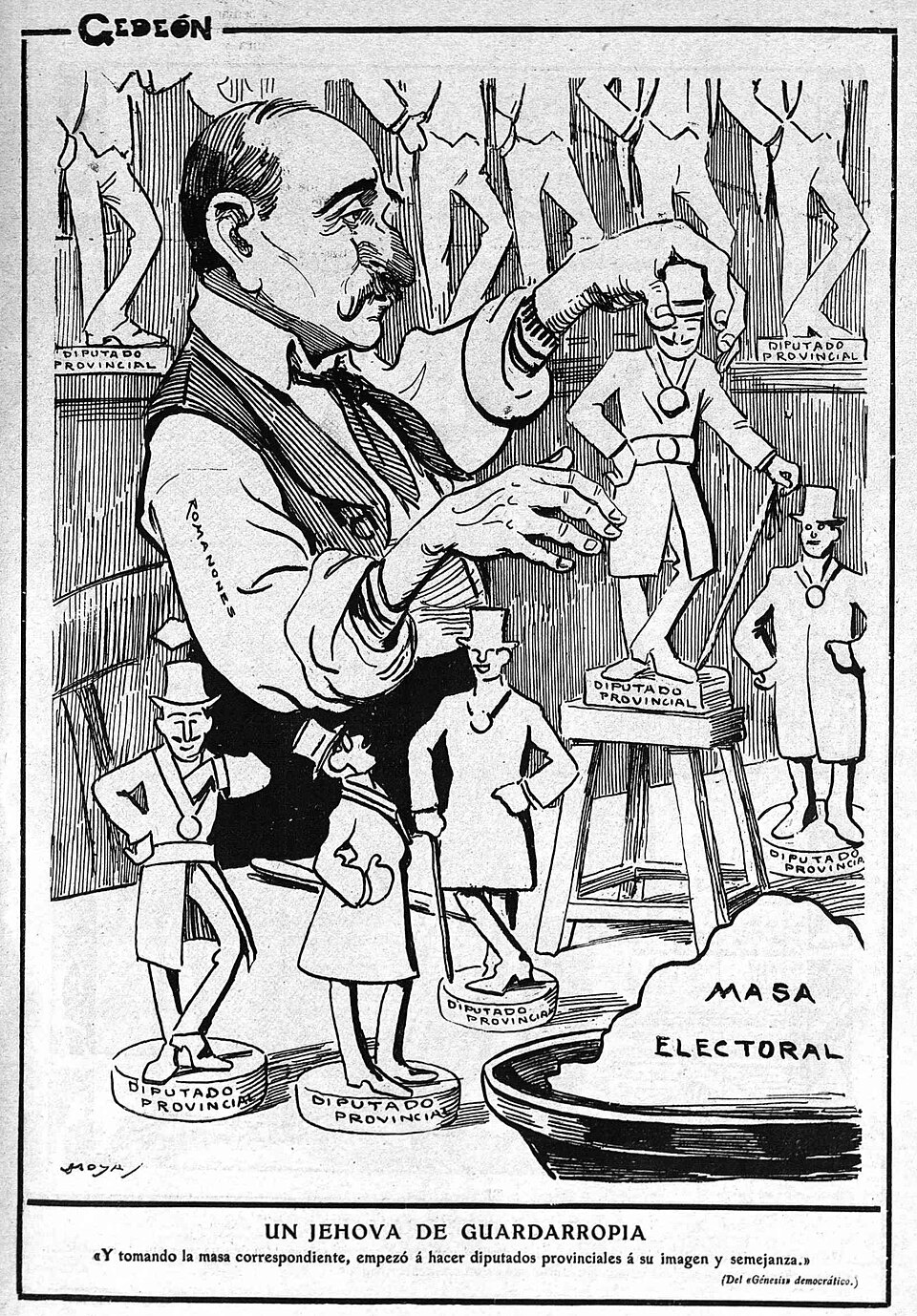

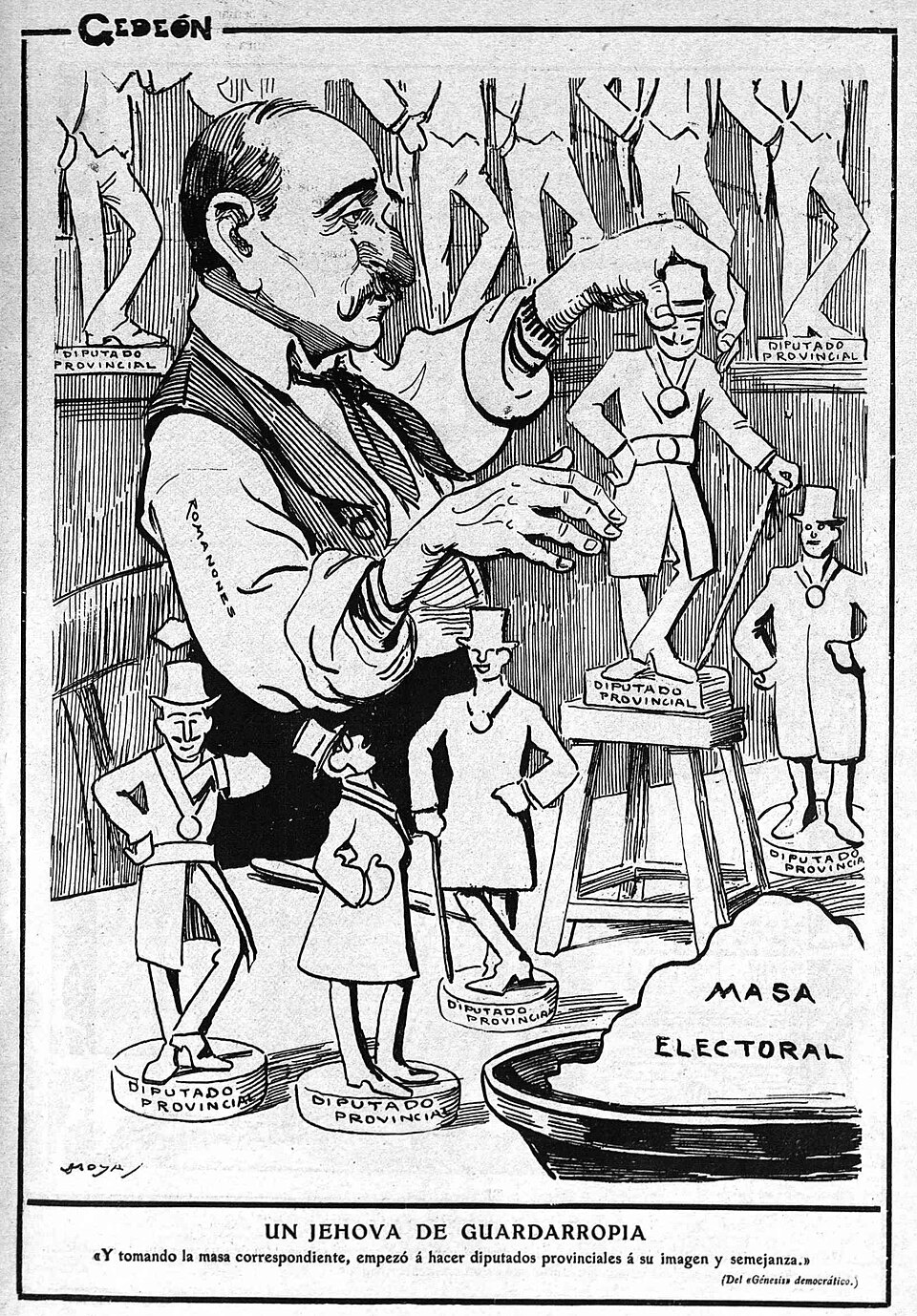

| Caciquism and Restoration Main article: Turno Although the term "caciquism" was used early to refer to the political regime of the Restoration, and people were already criticizing the "disgusting scourge of caciquism" at the 1891 general elections,[30] which were won by the government, it wasn't until the "disaster of [18]98" that the term became widely used. In that same year, liberal Santiago Alba was already attributing the disaster to "unbearable caciquism".[31] Caciquism played a significant role in rural areas, particularly until the end of the regime. Although the caciquist system was criticized by supporters of reformation and disapproved in the big cities and public opinion, such criticisms held minimal impact in most of the country. The local poor even tolerated the system, with few families in one small town that didn't have at least one member involved.[32] In the end, caciquism was enabled by the apathy its actions aroused among the majority, as well as the ineffective mobilization of a significant portion of the voting population.[33] In 1901, the Ateneo de Madrid conducted a survey and debate focused on Spain's socio-political system, with the participation of around sixty politicians and intellectuals. Joaquín Costa, a regenerationist, summarized the discussion in his work titled Oligarchy and Caciquism as Representing the Current Form of Government in Spain [fr]. Urgency and potential solutions. To address this issue, urgent action is required. In his work, Costa argues that Spain's political landscape is dominated by an oligarchy, with no true representation or political parties. This minority's interests solely serve their own, creating an unjust ruling class. The oligarchy's top executives, or "primates", consist of professional politicians based in Madrid, the center of power. This group is supported by a vast network of "caciques" scattered throughout the country, who hold varying degrees of power and influence. The relationship between the dominant "primates" and the regional caciques was established by the civil governors [fr]. In his report, Costa maintained that oligarchy and caciquism were not anomalies in the system, but rather the norm and the governing structure itself. The majority of participants in the survey-debate concurred with this assertion, which remains a widely held perspective today. More than a century later, Carmelo Romero Salvador notes that Costa's two-word description, which has become the title of historical literature and manuals, remains the most commonly used term to depict the Restorationist period.[34] As an illustration, José María Jover, in a university textbook frequently used in the 1960s and 1970s, characterized the Restoration regime in the following manner: "We are, therefore, in the presence of a constitutional reality that is certainly not foreseen in the written text of the Constitution. This reality is based on two de facto institutions. On the one hand, on the existence of an oligarchy or ruling political minority, made up of men from both parties (ministers, senators, deputies, civil governors, owners of press titles...) and closely connected both by its social extraction and by its family and social relations with the dominant social groups (landowners, blood nobility, business bourgeoisie, etc.). On the other hand, in a kind of seigneurial survival in rural milieus, by virtue of which certain figures in the town or locality, distinguished by their economic power, administrative function, prestige or "influence" with the oligarchy, directly control large groups of people; this seigneurial survival will be called caciquism. The "politician" in Madrid; the "cacique" in each comarca; the civil governor in the capital of each province as a link between the one and the other, constitute the three key pieces in the actual functioning of the system."  Satirical caricature of the Count of Romanones, "making provincial deputies in his own image and likeness" from "electoral paste", by Moya (Gedeón, 1911). Manuel Suárez Cortina notes that Costa and other critics of the Restoration system, like Gumersindo de Azcárate, viewed the political operations of the era as a new form of feudalism, wherein the political will of the citizens was hijacked for the profit of the elite: an oligarchy that abused the nation's true will through election fraud and corruption. The "interpretative line" was reinforced in Marxist and liberal Spanish historiography.[35] A comparable interpretation of Costa's analysis is shared by Joaquín Romero Maura, cited by Feliciano Montero [fr], who also agrees that it was the most commonly used explanation for the phenomenon of caciquism during the Restoration era in Spain. According to Romero Maura, Costa and those who share his interpretation view caciquismo as a political manifestation of the economic dominance of landed and financial elites. This phenomenon is facilitated by a disengaged electorate, which is a result of the low level of economic development and social integration in various regions of the country, including factors such as poor communication, a closed economy, and high illiteracy rates.[36] In the early 1970s, a new perspective on caciquism emerged among historians, including Joaquín Romero Maura, José Varela Ortega, and Javier Tusell. This perspective, which is now the dominant one, focuses exclusively on political factors and views caciquism as the outcome of patron-client relationships.[37] According to Suárez Cortina, the interpretation's most distinctive components emphasize the non-economic aspect of the patron-client relationship, the electorate's widespread demobilization, the predominance of rural components vis-à-vis urban components, and the varied nature of relations and exchanges between patrons and clients across different times and places - altogether constituting the key features that characterize patronage relations.[38]  "National Wildlife: Don Cacique", caricature by Exoristo Salmerón « Tito » [es] published in El Gran Bufón magazine in 1912. |

カシキズムと復古 主な記事: ターン 「カシキズム」という用語は、復古王政の政治体制を指すために早くから使われていた。1891年の総選挙では、政府が勝利したにもかかわらず、人々はすで に「カシキズムという忌まわしい災い」を批判していた[30]。しかし、この用語が広く使われるようになったのは、「[18]98年の惨事」以降のことで ある。同年、自由主義者のサンティアゴ・アルバは既にこの惨事を「耐え難いカシキズム」のせいだと指摘していた。[31] カシキズムは特に政権末期まで、地方で重要な役割を果たした。改革派から批判され、大都市や世論からも非難されたものの、こうした批判は国内の大部分では ほとんど影響を持たなかった。地方の貧しい層でさえこの制度を容認しており、小さな町では少なくとも一人は関与していない家族はほとんどなかった。 [32] 結局、地方支配者制度は、その行動が大多数に無関心を呼び起こしたこと、そして有権者の相当部分が効果的に動員されなかったことによって可能となったので ある。[33] 1901年、マドリード・アテネオはスペインの社会政治制度に焦点を当てた調査と討論会を実施し、約60名の政治家や知識人が参加した。再生主義者ホアキ ン・コスタは、その議論を『スペインの現行政府形態としての寡頭政治と地方支配層』[fr]と題した著作にまとめた。緊急性と潜在的な解決策。この問題に 対処するには緊急の行動が必要だ。コスタは著作で、スペインの政治情勢は寡頭政治に支配されており、真の代表制も政党も存在しないと論じている。この少数 派の利益は彼ら自身のもののみに奉仕し、不正な支配階級を生み出している。寡頭制の最高幹部、いわゆる「首脳」は、権力の中心地マドリードに拠点を置く職 業政治家から成る。この集団は、全国各地に散在し、様々な程度の権力と影響力を持つ「地方支配者」の広範なネットワークによって支えられている。支配的な 「首脳」と地方の支配者との関係は、地方行政官によって確立された。コスタは報告書で、寡頭政治と地方支配者制度は制度の異常ではなく、むしろ規範であり 統治構造そのものだと主張した。調査討論会参加者の大多数はこの見解に同意し、これは今日でも広く共有される視点である。一世紀以上を経た現在、カルメ ロ・ロメロ・サルバドールは、コスタの二語による記述が歴史文献や教科書の見出しとなり、復古王政期を描く最も一般的な用語として残っていると指摘する。 [34] 一例として、1960~70年代に広く用いられた大学教科書でホセ・マリア・ホベルは復古王政体制を次のように特徴づけている: 「したがって我々は、憲法の条文には確かに規定されていない憲法上の現実を目の当たりにしている。この現実は二つの事実上の制度に基づいている。一方で は、両党(大臣、上院議員、下院議員、地方行政官、新聞発行者など)の出身者で構成され、その社会的出自と支配的社会的集団(地主、世襲貴族、実業家ブル ジョワジーなど)との家族的・社会的関係によって緊密に結びついた寡頭制、すなわち支配的政治的少数派の存在である。他方では、農村地域における一種の領 主制の残滓が存在する。これにより、町や地域において、経済力、行政機能、威信、あるいは寡頭政治層に対する「影響力」によって際立つ特定の人物が、直接 的に大勢の人々を支配している。この領主制の残滓は、カシキズムと呼ばれる。マドリードの「政治家」、各地方の「カシケ」、そして両者を結ぶ各州都の行政 長官が、この制度の実質的な機能における三つの要となる。  モヤ作「選挙用粘土」による、ローマノネス伯爵の風刺画。「自らの姿に似せて地方代議士を作り上げる」場面(ゲデオン、1911年)。 マヌエル・スアレス・コルティナは、コスタやグメルシンド・デ・アスカラテら復古王政体制批判者たちが、当時の政治運営を新たな封建制と見なしていたと指 摘する。すなわち、市民の政治的意思がエリート層の利益のために乗っ取られた形態であり、選挙不正と腐敗を通じて国民の真の意思を乱用する寡頭政治であっ た。この「解釈の系譜」はマルクス主義及び自由主義的なスペイン史学において強化された[35]。コスタの分析に対する同種の解釈は、フェリシアーノ・モ ンテロ[fr]が引用するホアキン・ロメロ・マウラも共有しており、彼もまた、この解釈がスペイン復古王政期におけるカシキズム現象に対する最も一般的な 説明であったことに同意している。ロメロ・マウラによれば、コスタ及び同解釈を支持する者らは、カシキズムを土地所有者・金融エリートの経済的支配が政治 的に顕在化したものと見なす。この現象は、国内諸地域における経済発展の遅れや社会統合の低さ(通信網の不備、閉鎖的な経済、高い非識字率などの要因を含 む)がもたらした有権者の無関心が助長している。[36] 1970年代初頭、ホアキン・ロメロ・マウラ、ホセ・バレラ・オルテガ、ハビエル・トゥセルら歴史家たちの間で、カシキズムに関する新たな視点が生まれ た。現在主流となっているこの視点は、政治的要因のみに焦点を当て、カシキズムをパトロン・クライアント関係の帰結と見なすものである。[37] スアレス・コルティナによれば、この解釈の最も特徴的な要素は、パトロン・クライアント関係の非経済的側面、有権者の広範な動員不足、都市部に対する農村 部の優位性、そして時代や場所によって異なるパトロンとクライアント間の関係や交換の多様性である。これら全体が、パトロネージ関係を特徴づける主要な要 素を構成している。[38]  「国民的野生動物:ドン・カシケ」エクソリスト・サルメロン「ティト」作の風刺画[スペイン語]。1912年『エル・グラン・ブフォン』誌掲載。 |

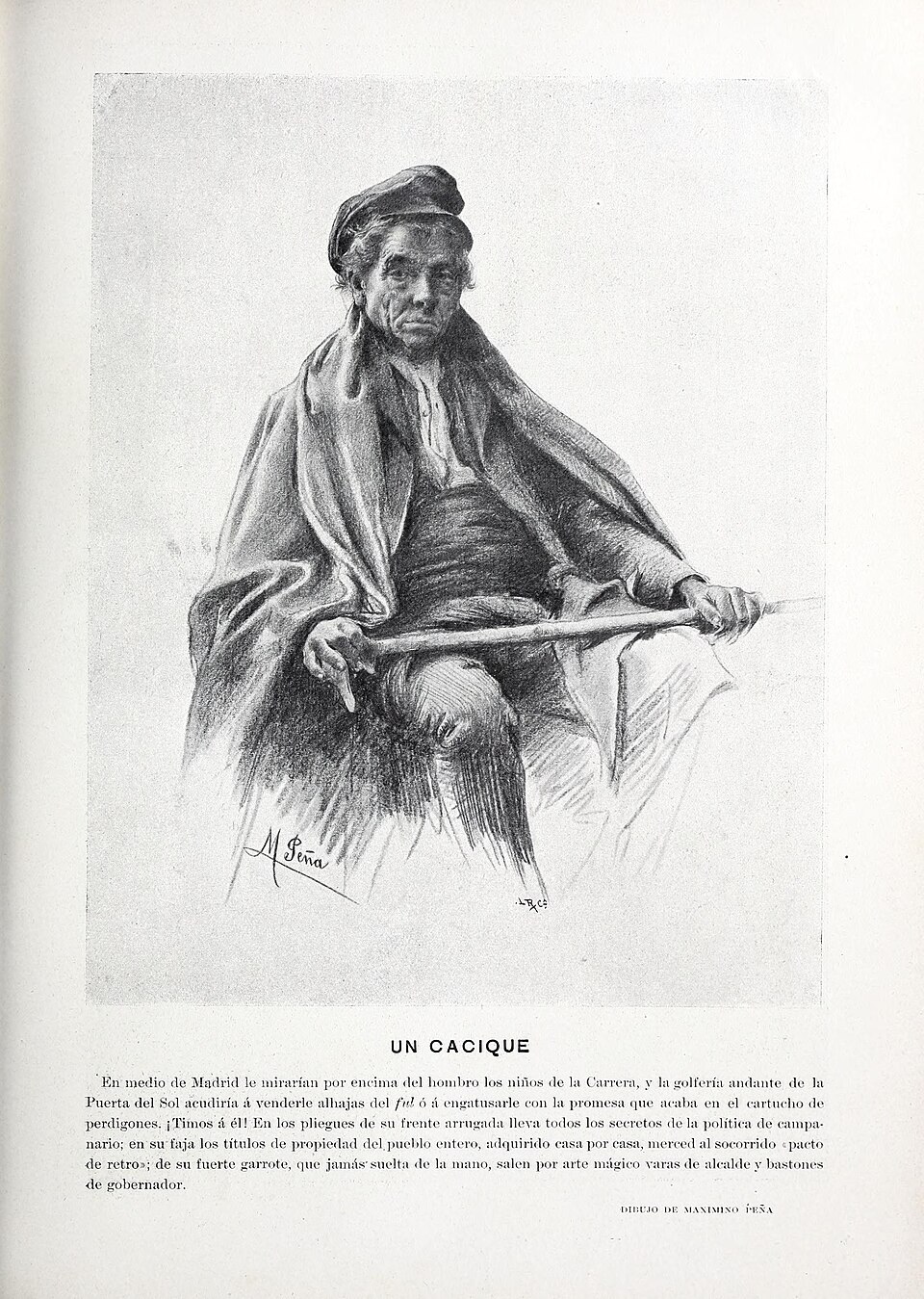

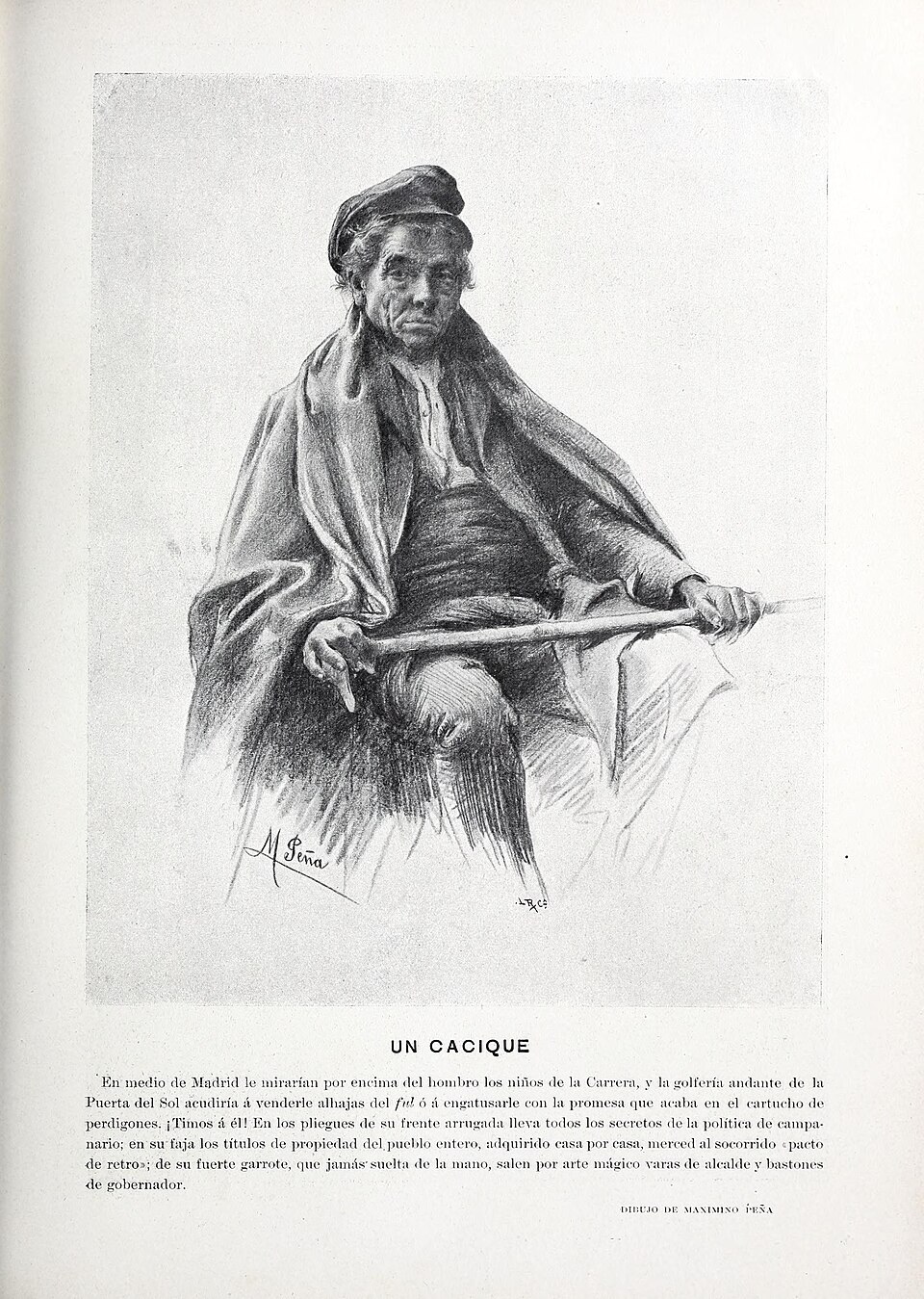

| Functioning Caciques, like politicians of their time, are seldom personally corrupt. They typically do not seek personal gain through corruption. Rather, corruption resides in the structures of the system, where the state and its resources serve an oligarchy, of which the cacique is a vital component.[39] The central role of a cacique, who typically lacks an official position and may not be a powerful figure, is to act as an intermediary between the Administration and their extensive clientele from all social strata. They consistently pursue fulfilling the interests of their clients through illicit measures, as "caciquism feeds on illegality". The caciques serve as intermediaries, serving as the missing links between a deficient state and its constituents who are physically and symbolically distant.[21][40] Within the individual beneficiaries or recipients of favors, there are those who obtain an exemption from military service and those who receive a lower assessment of taxable wealth. On the other hand, certain benefits are accrued either to the public at large (such as a highway, railroad crossing, or educational institutions) or to the well-being of a specific socio-economic group, with a cacique positioned at its helm to cement their position.[41] To illustrate, Asturias boasted a truly deluxe network of roads during the early 20th century thanks to cacique Alejandro Pidal y Mon and his son Pedro.[39] Similarly, Juan de la Cierva y Peñafiel established the University of Murcia in 1914.[39] Electoral fraud, such as ballot box stuffing, replacement, and the use of deceased individuals' votes,[42] is typically orchestrated by the cacique (pucherazo).[1] The cacique's influence, derived from an array of resources including economic, administrative, fiscal, academic, and medical, is the foundation of their client base. The cacique operates through arrangements for those who serve him and coercion, including pressure, threats, and blackmail for others. He can create or eliminate jobs, open or close businesses, manipulate local justice and administration,[43] obtain exemptions from military obligations, misappropriate taxes to benefit local politicians, allow discreet purchases of essential goods without payment of consumos,[44] assist with administrative procedures, facilitate the creation of new infrastructure like roads or schools,[40] and lend his own money. He provides loans without interest, either personally or on behalf of the State. He is not in a rush to be reimbursed as his benevolence gains him the appreciation of the common folk who seek his guidance and, naturally, follow his lead at the polls.[21] The local political leader, whether aligned with the liberal or conservative party, wields influence over administrative decisions. This influence extends to the use of illegal means to control the administration.[45][46] The leader's immunity from government intervention is derived from their status as the head of their local political party: "the law is applied for the benefit of the leader's supporters and to the disadvantage of their opponents."[47][48] "The cacique distributes things that belong to the jurisdiction of the state, the provinces and the municipality, and he is distributed according to his whim. Positions in these administrations, permits to build or open businesses or exercise professions, reductions or exemptions from legal obligations of all kinds, added to the fact that, if he has the power to do all this, he also has the power to harm his enemies, and free his friends. In some cases, the cacique with a personal fortune may make concessions e his own nest egg, but normally what the cacique does is channel administrative favors. Caciquism, therefore, feeds on illegality [...]. The cacique must ensure that a whole range of administrative and judicial decisions important to the life or people of the locality are taken according to anti-legal criteria that convince him." — Joaquín Romero Maura Feliciano Montero characterizes the cacique as the intermediary between the central administration and the citizens, indicating that the entity yields influence beyond the electoral period, despite this being the most scandalous time. Montero posits that the cacique's impact maintains consistency within the political life of the country. Caciquism primarily represents the manifestation and logical expression of a social and political structure that persistently displays in the daily interpersonal interactions through patron-client relationships and political-administrative connections.[49] During the Restoration era, a judge described caciquism as "the personal regime exercised in the villages [pueblos] by twisting or corrupting the proper functions of the State through political influence, in order to subordinate them to the selfish interests of certain individuals or groups."[50] Consequently, the administration controlled the core of the caciquil system.[51] The liberal José Canalejas, in 1910, referred to a powerful cacique in Osuna, stating in a letter to the conservative Antonio Maura that the cacique had nothing aside from influence with various senior officials who disobeyed the government and gossiped abuses of all sorts.[52] In other words, the cacique is the local party leader who manipulates the administrative apparatus for his own benefit and that of his clients.[53]  "Un cacique" (Blanco y Negro, 1900). Illustration by Maximino Peña. Under the Restoration, political and electoral practices deviated from the legal standards. Reports frequently surfaced regarding the preparation of elections, which included the "encasillado" process. This entailed the Ministry of the Interior filling in constituencies' "boxes" with the names of government-preferred candidates who would receive protection. These candidates could be from either the ruling party, which obtained the decree to dissolve the Cortes and organized the elections to win a majority, or from the opposition. The encasillado was not solely a government directive but rather the outcome of bitter negotiations between multiple political factions. Indeed, within the same political party that controlled the Council of Ministers, various factions routinely coexisted, each represented by leaders of different clienteles who claimed a certain number of parliamentary seats based on their influence. The dissolution of the two dynastic parties under the reign of Alfonso XIII further multiplied the number of power brokers, thereby complicating the practice of "encasillado." The caciques were part of a large informal hierarchical network. The local cacique answered to the district cacique, who then received instructions from the civil governor of the province.[1][54] Following the encasillado event in Madrid, discussions continued on a local level through the designated representative of central power in each province, the civil governor. The governor aimed to reach an understanding with the caciques in their respective zones to enable the adjustment of results based on the ministry's wishes. The powerful local political figures, known as caciques, exerted significant influence over key positions such as town halls and courts. In many cases, they imposed their will on government representatives. Municipal councils and opposition judges frequently resigned in support of ministerial supporters, but those who refused to do so could have their functions suspended by the authorities. As carrying out these falsifications became more challenging, some political bosses went so far as to include deceased individuals from local cemeteries in their electoral rolls. Occasionally, individuals nominated by established political parties would change parties between consecutive elections.[19] In the late 19th century, the cacique of Motril (Granada) made a statement at the local casino after learning the election results. This anecdote depicts the workings of caciquism and the seizure of power by the two dynastic parties.[55] "We Liberals were convinced we would win the election. But God didn't want us to. - Long pause - From the looks of it, we Conservatives won the election." The implementation of universal suffrage in 1890 did not democratize the system, instead it significantly increased Caciquist practices.[30][56] The dynastic parties perpetuated this institutionalized corruption, refraining from comprehensive reform of the municipal system. Even though they criticized the system, they did not take action to amend it, despite the submission of 20 local government reform proposals between 1882 and 1923. The political groups excluded from the turno had the genuine political intention to stop the abuses of the networks of influence.[57] Nevertheless, while they succeeded in some districts, the effect on a national scale was too marginal. The groups excluded from the turno were first the conservatives, republicans and socialists of Silvela,[32] and then the Regionalist League of Catalonia.[58] |

機能 カシークは、当時の政治家と同様、個人的な腐敗に満ちていることは稀だ。彼らは通常、汚職を通じて私利を図ることはない。むしろ、腐敗はシステムの構造に内在しており、国家とその資源は寡頭政治層に奉仕する。カシークはその重要な構成要素である。[39] 通常、公的な地位を持たず、権力者でもないカシークの中心的な役割は、行政とあらゆる社会階層に広がる広範な顧客層との仲介者となることだ。彼らは「カ シーク主義は違法行為によって成り立つ」ため、顧客の利益を違法な手段で満たすことを一貫して追求する。カシークは仲介者として、機能不全の国家と物理 的・象徴的に隔絶された構成員との間の欠落した環として機能する。[21][40] 個別恩恵の受益者には、兵役免除を得る者や課税対象資産の評価額を引き下げられる者がいる。一方、特定の社会経済集団の福祉や、一般大衆(幹線道路、鉄道 踏切、教育機関など)に向けられた利益もあり、その頂点に立つカシケが自らの地位を固める役割を担う。[41] 具体例として、アストゥリアス地方は20世紀初頭、カシケのアレハンドロ・ピダル・イ・モンとその息子ペドロの尽力により、実に豪華な道路網を誇った [39]。同様に、フアン・デ・ラ・シエルバ・イ・ペニャフィエルは1914年にムルシア大学を設立した。[39] 投票箱への不正な票の詰め込み、票のすり替え、死亡者の投票権の悪用といった選挙不正[42]は、通常、カシケによって仕組まれる(プチェラソ)。[1] カシケの影響力は、経済的・行政的・財政的・学術的・医療的資源など多岐にわたる基盤から成り立つ。カシケは、自身に仕える者への取り決めと、圧力・脅 迫・恐喝を含む強制手段によって他者を支配する。彼は職を創出・消滅させ、事業を許可・閉鎖し、地方司法や行政を操作し[43]、兵役義務の免除を得さ せ、地方政治家の利益のために税金を横領し、消費税(consumos)を支払わずに必需品を密かに購入させ[44]、行政手続きを支援し、道路や学校な どの新たなインフラ整備を促進し[40]、自身の資金を貸し出す。彼は無利子で融資を行う。個人的名義でも国家名義でも構わない。返済を急がせることもな い。その寛大さが庶民の感謝を買い、彼に助言を求める民衆は当然ながら選挙でも彼に従うからだ。[21] 地方の政治指導者は、自由党派であれ保守党派であれ、行政決定に影響力を行使する。この影響力は、行政を支配するための違法な手段の使用にまで及ぶ。 [45][46] 指導者が政府の介入から免れるのは、彼らが地元政党のトップであるという地位に由来する。「法律は指導者の支持者の利益のために適用され、反対派には不利 に働く」のである。[47] [48] 「カシークは国家・州・自治体の管轄に属するものを分配する。そして彼は気まぐれに従って分配するのだ。これらの行政機関における地位、建設や事業開設、 職業遂行の許可、あらゆる法的義務の減免や免除。さらに、これら全てを行う権限を持つと同時に、敵を害し、友を救う力も握っているという事実が加わる。」 個人的資産を持つカシケは自らの蓄えから譲歩することもあるが、通常は行政上の便宜を仲介する。故にカシキズムは違法性に依存する[…]。カシケは地域住 民の生活に関わる行政・司法判断の全範囲を、自らの納得する反法的基準で決定させねばならない。」 —ホアキン・ロメロ・マウラ フェリシアーノ・モンテロは、カシケを中央行政と市民の間の仲介者と位置づけ、選挙期間が最もスキャンダラスな時期であるにもかかわらず、その影響力が選 挙期間を超えて及ぶことを指摘している。モンテロは、カシケの影響力が国の政治生活において一貫性を保っていると主張する。カシキズムは主に、日常的な人 間関係においてパトロン・クライアント関係や政治的・行政的繋がりを通じて持続的に現れる社会政治構造の顕現であり、論理的表現である。[49] 復古期において、ある判事はカシキズムを「政治的影響力によって国家の正当な機能を歪め、腐敗させ、特定の個人や集団の私利私欲に従属させるために、村々 (プエブロス)で行使される個人的体制」と記述した。[50] その結果、行政はカシキ体制の中核を掌握した。[51] 自由主義者のホセ・カナレハスは1910年、オスナ地方の有力なカシケについて言及し、保守派のアントニオ・マウラへの書簡で「このカシケが持つのは、政 府に逆らいあらゆる不正を囁く高官たちへの影響力だけだ」と記した[52]。つまりカシケとは、行政機構を自らの利益とクライアントの利益のために操る地 方政党の指導者である。[53]  「地方の有力者」(『ブランコ・イ・ニグロ』誌、1900年)。マキシミノ・ペーニャ作。 復古王政期には、政治・選挙慣行が法的基準から逸脱した。選挙準備に関する報告が頻繁に浮上し、その中には「エンカシジャード」と呼ばれる過程が含まれて いた。これは内務省が選挙区の「枠」に、政府が保護を与えることを望む候補者名を記入することを意味した。これらの候補者は、議会解散令を獲得し選挙を組 織して多数派を確保した与党出身者でも、野党出身者でもありえた。エンカシジャードは単なる政府指令ではなく、複数の政治派閥間の激しい交渉の結果であっ た。実際、閣僚評議会を掌握する同一政党内でも、様々な派閥が日常的に共存していた。各派閥は異なる支持基盤の指導者によって代表され、その影響力に応じ て一定数の議席を要求した。アルフォンソ13世治世下での二大王朝政党の解体は、権力仲介者の数をさらに増大させ、「エンカシジャード」の実践を複雑化し た。 地方の権力者(カシケ)は、広範な非公式な階層的ネットワークの一部であった。地方のカシケは地区のカシケに服従し、地区のカシケは州の民政長官から指示を受けていた。[1][54] マドリードでのエンカシジャード事件後、各州に配置された中央権力の代表者である民政長官を通じて、地方レベルでの協議が続けられた。長官は、各地域のカ シケと合意を形成し、省庁の意向に沿った結果の調整を可能にしようとした。地方の有力政治家であるカシケは、市庁舎や裁判所といった要職に多大な影響力を 行使した。多くの場合、彼らは政府代表者に自らの意思を押し付けた。市議会や反対派の裁判官は、大臣支持派を支持して頻繁に辞任したが、これを拒否した者 は当局によって職務停止処分を受ける可能性があった。こうした不正行為の実施が困難になるにつれ、一部の政治ボスたちは、地元の墓地から死亡者を選挙人名 簿に追加するといった手段にまで及んだ。 確立された政党から指名された人物が、連続する選挙の間に政党を変えることもあった[19]。19世紀末、モトリル(グラナダ)の地方政治指導者は選挙結 果を知ると、地元のカジノで声明を発表した。この逸話は、地方政治指導者による支配と二大政党による権力掌握の実態を描いている。[55] 「我々自由党は選挙に勝つと確信していた。だが神はそれを望まなかった。―長い間―どうやら保守党が選挙に勝ったようだ」 1890年の普通選挙導入は制度を民主化せず、むしろカシキズム的慣行を著しく増大させた。[30][56] 王朝政党はこの制度化された腐敗を永続させ、自治体制度の包括的改革を回避した。1882年から1923年にかけて20件の地方自治改革案が提出されたに もかかわらず、彼らは制度を批判しながらも改正行動を起こさなかった。ターンオから排除された政治グループは、影響力ネットワークの乱用を阻止するという 真摯な政治的意図を持っていた[57]。しかし、一部の地区では成功したものの、国民規模での影響はごくわずかだった。ターンオから排除されたグループ は、まずシルヴェラの保守派、共和派、社会主義者たち[32]であり、次にカタルーニャ地域主義連盟であった[58]。 |

| The end of caciquism: the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the Second Republic From the 20th century onward, the system became increasingly fragile and relied exclusively on economically underdeveloped rural regions. In such areas, voter turnout is exceptionally high, implying significant vote manipulation. In contrast, major urban centers usually experienced low turnout and saw a marked decline of dynastic parties. These parties disappeared from the political landscape in Barcelona early in the century and later in Valencia.[59][60] At times, there was a possibility that public opinion could shatter the oligarchic political circle, such as the instances when universal male suffrage was implemented in 1890, during the colonial crisis in 1898, or towards the end of the Restoration when the turno parties were disbanding. However, this did not come to fruition. The public's acceptance of Primo de Rivera's coup d'état in 1923 can be partially attributed to the sense of powerlessness felt by those seeking significant political change. The dictatorship's program emphasized the termination of "old politics" and the rejuvenation of the country as top priorities. The replacement of the "tiny politics" of the previous caciquil stage, which served only clientele, with "authentic politics" was among the declared aims of the regime. The dictator's actions were believed to be those of a messiah, expected to magically lift the state out of its lethargy. However, the measures taken against caciquism by the new regime were temporary. Municipal councils and deputations were suspended and given over to military authorities in each province, and later to government delegates appointed specifically for this purpose. In many cases, these delegates ended up replacing the caciques or facing opposition from them, making their regenerative efforts impossible. The proclamation of the Republic in 1931 resulted in comprehensive participation of political currents previously excluded, including the Republican and Socialist parties. Additionally, fairer and more participatory electoral laws were introduced. In certain regions, the caciquist system faced an irreversible crisis. However, in other regions, this system remained resilient due to the enduring bonds of personal influence that underpinned its domination. Meanwhile, powerful traditional entities in the agrarian sphere started organizing themselves into political parties capable of competing under the new circumstances, in order to defend their interests. The emergence of new conservative political forces, exemplified by the agrarians, was a direct result of these changes. Other groups, such as radicalism, underwent significant processes of moderation. Additionally, the formation of important mass parties, such as the CEDA, marked a pivotal moment in political history. |

地方支配体制の終焉:プリモ・デ・リベラの独裁政権と第二共和国 20世紀に入ると、この体制は次第に脆弱化し、経済的に未発達な農村地域にのみ依存するようになった。こうした地域では投票率が異常に高く、大規模な票操 作が行われていたことを示唆している。一方、主要都市部では投票率が低く、王朝政党の衰退が顕著だった。これらの政党は世紀初頭にバルセロナの政治舞台か ら姿を消し、後にバレンシアでも消滅した[59][60]。 時折、世論が寡頭政治の輪を打ち砕く可能性も存在した。例えば1890年の男子普通選挙導入時、1898年の植民地危機時、あるいは復古王政末期にターン 党が解体されつつあった時期などがそれにあたる。しかし、それは実現しなかった。1923年のプリモ・デ・リベラのクーデターが公衆に受け入れられた背景 には、大きな政治的変革を求める者たちの無力感があった。独裁政権の政策は「旧来の政治」の終焉と国家の刷新を最優先課題として強調した。旧来のカシキズ ム段階における、単なる利権集団に奉仕する「小さな政治」を「真の政治」に置き換えることが、政権の公言された目的の一つであった。独裁者の行動は救世主 のそれと見なされ、国家を呪術的に停滞から救い出すと期待された。しかし新政権によるカシキズム対策は一時的なものに過ぎなかった。各州の市議会と代議員 会は停止され、軍当局、後にこの目的のために特別に任命された政府代表者に引き継がれた。多くの場合、これらの代表者はカシケに取って代わるか、彼らから の抵抗に直面し、再生の努力は不可能となった。 1931年の共和国宣言は、共和党や社会党を含む、これまで排除されてきた政治勢力の包括的な参加をもたらした。さらに、より公平で参加型の選挙法が導入 された。特定の地域では、カシキズム体制は取り返しのつかない危機に直面した。しかし他の地域では、支配の基盤となっていた個人的影響力の持続的な絆によ り、この体制は依然として強靭さを保っていた。一方、農業分野の有力な伝統的勢力は、自らの利益を守るため、新たな状況下で競争可能な政党として組織化を 始めた。農業派に代表される新たな保守的政治勢力の出現は、こうした変化の直接的な結果であった。急進主義などの他のグループは、著しい穏健化プロセスを 経た。さらに、CEDA(民主社会統一戦線)のような重要な大衆政党の形成は、政治史における転換点となった。 |

| Interpretations According to British historian Raymond Carr, caciquism is a result of formally democratic institutions being imposed on an underdeveloped economy, an "anemic society" as described by José Ortega y Gasset. This was enabled by centralization of the Restoration system, where local administrations, municipal and provincial, were fully manipulated by the central power, as well as by politicization of the judiciary.[61] To maintain the functionality of this system, electoral conflicts were typically preceded by significant turnovers in local mayors and judges.[62] As per the analysis by historian Pamela Radcliff, caciquism emerged as a modern mechanism of the liberal revolution that articulated the new state within the specific local/central dynamics of nineteenth-century Spain. Like pronunciamientos and military intervention, caciquism was another channel through which the liberal state functioned, not the main evidence of its failure.[63] |

解釈 英国の歴史家レイモンド・カーによれば、カシキズムは未発達な経済、すなわちホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットが「貧血的な社会」と表現した社会に、形式的な 民主主義制度が押し付けられた結果である。これは復古王政体制による中央集権化によって可能となった。この体制下では、地方行政機関(市町村及び州レベ ル)が中央権力によって完全に操られ、司法も政治化されたのである。[61] この制度の機能を維持するため、選挙紛争の前には通常、地方の市長や裁判官の大幅な交代が行われた。[62] 歴史家パメラ・ラドクリフの分析によれば、カシキズムは19世紀スペイン特有の地方/中央の力学の中で新たな国家を構築した自由主義革命の近代的メカニズ ムとして出現した。クーデターや軍事介入と同様に、カシキズムは自由主義国家が機能するための別の経路であり、その失敗の主要な証拠ではない。[63] |

| Cacique democracy – Term coined for the feudal political system of the Philippines Encasillado Political System of the Restoration (Spain) |

カシケ民主主義 – フィリピンの封建的政治体制を指す造語 エンカシジャード 復古王政期の政治体制(スペイン) |

| References |

脚注省略 |

| Related articles Clientelism Turno Paternalism Power (social and political) Symbolic power Opinion leadership Banana republic Social network |

関連記事 恩顧主義/ 縁故主義(Clientelism;クライアンテリズム) ターン(トゥルノ=順番) パターナリズム 権力(社会的・政治的) 象徴的権力 世論指導 バナナ共和国 ソーシャルネットワーク |

| Bibliography (es) Raymond Carr (trans. from English), España: de la Restauración a la democracia: 1875~1980 ["Modern Spain 1875-1980"], Barcelone, Ariel, coll. "Ariel Historia", 2001, 7th ed., 266 p. ISBN 9-788434-465428. (es) Raymond Carr (trans. from English), España: 1808-1975, Barcelone, Ariel, coll. "Ariel Historia", 2003, 12th ed., 826 p. ISBN 84-344-6615-5. (es) Joaquín Costa, Oligarquía y caciquismo como la forma actual de gobierno en España: Urgencia y modo de cambiarla, 1901 (read online archive) (ca) Alfons Cucó, Sobre la ideologia blasquista: Un assaig d'aproximació, Valence, 3i4, July 1979, 111 p. ISBN 84-7502-001-1. (es) Carlos Dardé, La Restauración, 1875-1902: Alfonso XII y la regencia de María Cristina, Madrid, Historia 16, coll. "Temas de Hoy", 1996 ISBN 84-7679-317-0. (es) María D. Elizalde Pérez-Grueso and Blanca Buldain Jaca (dir.), Historia contemporánea de España: 1808-1923, Madrid, Akal, 2011 ISBN 978-84-460-3104-8, part IV, "La Restauración, 1875-1902", p. 371-521. (es) Miguel Martorell Linares and Santos Juliá, Manual de historia política y social de España (1808-2011), RBA, 2019, 544 p. ISBN 9788490562840. (es) Feliciano Montero, La Restauración. De la Regencia a Alfonso XIII, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1997, 1-188 p. ISBN 84-239-8959-3, "La Restauración (1875-1885)". (fr) Joseph Pérez, Histoire de l’Espagne, Paris, Fayard, 1996, 921 p. ISBN 978-2-213-03156-9. (es) Pamela Radcliff (trans. from English by Francisco García Lorenzana), La España contemporánea: Desde 1808 hasta nuestros días, Barcelone, Ariel, 2018, 1221 p. (ASIN B07FPVCYMS). Romero Salvador, Carmelo (2021). Caciques y caciquismo en España (1834-2020) (in Spanish). Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata. ISBN 978-8413522128. (es) Manuel Suárez Cortina, La España Liberal (1868-1917): Política y sociedad, Madrid, Síntesis, 2006 ISBN 84-9756-415-4. (pt) Pedro Tavares de Almeida, Eleições e caciquismo no Portugal oitocentista (1868-1890), Difel, 1991 ISBN 972-29-0248-2, read online archive). (es) José Varela Ortega (préf. Raymond Carr), Los amigos políticos: Partidos, elecciones y caciquismo en la restauración (1875-1900), Madrid, Marcial Pons / Junta de Castilla-León, coll. "Historia Estudios", 2001, 557 p. ISBN 84-7846-993-1. |

参考文献 (es) レイモンド・カー(英訳)、『スペイン:復古王政から民主主義へ:1875~1980年』[原題:Modern Spain 1875-1980]、バルセロナ、アリエル社、「アリエル歴史叢書」シリーズ、2001年、第7版、266ページ。ISBN 9-788434-465428. (es) レイモンド・カー(英訳)、『スペイン:1808-1975』、バルセロナ、アリエル社、「アリエル・ヒストリア」叢書、2003年、第12版、826頁。ISBN 84-344-6615-5。 (es) ホアキン・コスタ『スペインにおける現在の統治形態としての寡頭政治と地方支配:その緊急性と変革の方法』1901年(オンラインアーカイブで閲覧可能) (ca) アルフォンス・クコー『ブラスク主義のイデオロギーについて:接近の試み』バレンシア、3i4、1979年7月、111ページ。ISBN 84-7502-001-1. (es) カルロス・ダルデ著『復古王政期 1875-1902:アルフォンソ12世とマリア・クリスティーナ摂政時代』マドリード、ヒストリア16社、「現代の課題」叢書、1996年 ISBN 84-7679-317-0. (es) マリア・D・エリサルデ・ペレス=グルエソとブランカ・ブルダイン・ハカ(編)、『スペイン現代史:1808-1923』、マドリード、アカル、2011 年 ISBN 978-84-460-3104-8、第IV部「復古王政期、1875-1902」、 p. 371-521. (es) ミゲル・マルトレル・リナレスとサントス・フリア著、『スペイン政治社会史ハンドブック(1808-2011)』、RBA、2019年、544頁。ISBN 9788490562840。 (es) フェリシアーノ・モンテロ著、『復古王政。摂政時代からアルフォンソ13世まで、マドリード、エスパサ・カルペ、1997年、1-188頁。ISBN 84-239-8959-3、「復古王政期(1875-1885年)」。 (fr) ジョゼフ・ペレス、『スペイン史』、パリ、ファヤール、1996年、921頁。ISBN 978-2-213-03156-9。 (es) パメラ・ラドクリフ(スペイン語訳:フランシスコ・ガルシア・ロレンサーナ)、『現代スペイン:1808年から今日まで』、バルセロナ、アリエル、2018年、1221頁。(ASIN B07FPVCYMS)。 ロメロ・サルバドール・カルメロ(2021年)。『スペインの地方支配者と地方支配(1834-2020)』(スペイン語)。マドリード:ロス・リブロス・デ・ラ・カタラータ。ISBN 978-8413522128。 (es) マヌエル・スアレス・コルティナ、『自由主義的スペイン(1868-1917): 政治と社会、マドリード、シンテシス、2006年 ISBN 84-9756-415-4。 (ポルトガル語) ペドロ・タヴァレス・デ・アルメイダ、『19世紀ポルトガルの選挙と地方支配者(1868-1890)』、ディフェル、1991年 ISBN 972-29-0248-2、オンラインアーカイブで閲覧可能。 (es) ホセ・バレラ・オルテガ(レイモンド・カー序文)、『政治的友人たち:復古王政期(1875-1900)の政党、選挙、地方支配者層』、マドリード、マル シャル・ポンス/カスティーリャ・イ・レオン州政府、シリーズ「歴史研究」、2001年、557ページ ISBN 84-7846-993-1。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caciquism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099