カール・リネウス

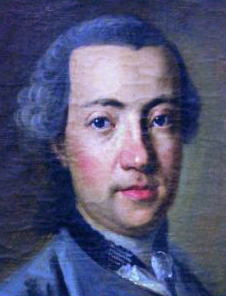

Carl Linnaeus, 1707-1778

Carl

von Linné, 1707-1778, botanist, professor (Alexander Roslin)

☆

カール・フォン・リンネ(Carl Linnaeus、1707年5月23日[注釈 1] -

1778年1月10日)は、1761年に貴族化されてからはカール・フォン・リンネ(Carl von

Linné)とも呼ばれ、生物の命名法である二名法を体系化したスウェーデンの生物学者、医師である。彼は「近代分類学の父」として知られている。

彼の著作の多くはラテン語で書かれており、ラテン語表記ではCarolus Linnæus、1761年の貴族化後はCarolus a

Linnéとなる。

リンネは牧師の息子としてスウェーデン南部のスモーランド地方の田舎にあるラシュフトで生まれた。高等教育のほとんどをウプサラ大学で受け、1730年に

は同大学で植物学の講義を始めた。1735年から1738年にかけては海外で暮らし、オランダで研究を行い、また『Systema

Naturae』の初版を出版した。その後、スウェーデンに戻った彼はウプサラ大学の医学および植物学の教授となった。1740年代には、スウェーデン国

内を何度も旅して、植物や動物を発見し分類した。1750年代と1760年代には、動植物や鉱物の収集と分類を続けながら、複数の著作を出版した。

1778年に亡くなるまでに、彼はヨーロッパで最も高く評価された科学者の一人となった。

哲学者ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは彼に「地上にこれほど偉大な人物はいないと彼に伝えてほしい」というメッセージを送った。

ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテは「シェイクスピアとスピノザを除いて、今は亡き人物の中で、これほどまでに強く私に影響を与えた人物は他にいな

い」と書いた。 スウェーデンの作家アウグスト・ストリンドベリは「リンネは

実際には、たまたま博物学者になった詩人だった」と述べている。リンネは「植物学者の第一人者(Princeps

botanicorum)」、「北方のプリニウス」と呼ばれている。また、近代生態学の創始者の一人とも考えられている。植物学や動物学では、種の名称の

権威としてリンネを示すためにL.という略称が用いられる。 古い出版物では「Linn.」という略称も見られる。リンネの遺体は、国際動物命名規約に従って、現生人類ホモ・サピエンスのタイプ標本となっている。なぜなら、彼が調べたと知られている唯一の標本が彼自身だからである。

| Carl Linnaeus[a] (23

May 1707[note 1] – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in

1761 as Carl von Linné,[3][b] was a Swedish biologist and physician who

formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming

organisms. He is known as the "father of modern taxonomy".[4] Many of

his writings were in Latin; his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus

Linnæus and, after his 1761 ennoblement, as Carolus a Linné. Linnaeus was the son of a curate[5] and was born in Råshult, in the countryside of Småland, southern Sweden. He received most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes. By the time of his death in 1778, he was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe. Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message: "Tell him I know no greater man on Earth."[6] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote: "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly."[6] Swedish author August Strindberg wrote: "Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist."[7] Linnaeus has been called Princeps botanicorum (Prince of Botanists) and "The Pliny of the North".[8] He is also considered one of the founders of modern ecology.[9] In botany and zoology, the abbreviation L. is used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for a species' name.[10] In older publications, the abbreviation "Linn." is found. Linnaeus's remains constitute the type specimen for the species Homo sapiens[11] following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, since the sole specimen that he is known to have examined was himself.[note 2] |

カール・フォン・リンネ[a](Carl

Linnaeus、1707年5月23日[注釈 1] -

1778年1月10日)は、1761年に貴族化されてからはカール・フォン・リンネ(Carl von

Linné)[3][b]とも呼ばれ、生物の命名法である二名法を体系化したスウェーデンの生物学者、医師である。彼は「近代分類学の父」として知られて

いる。[4] 彼の著作の多くはラテン語で書かれており、ラテン語表記ではCarolus Linnæus、1761年の貴族化後はCarolus a

Linnéとなる。 リンネは牧師の息子として[5]スウェーデン南部のスモーランド地方の田舎にあるラシュフトで生まれた。高等教育のほとんどをウプサラ大学で受け、 1730年には同大学で植物学の講義を始めた。1735年から1738年にかけては海外で暮らし、オランダで研究を行い、また『Systema Naturae』の初版を出版した。その後、スウェーデンに戻った彼はウプサラ大学の医学および植物学の教授となった。1740年代には、スウェーデン国 内を何度も旅して、植物や動物を発見し分類した。1750年代と1760年代には、動植物や鉱物の収集と分類を続けながら、複数の著作を出版した。 1778年に亡くなるまでに、彼はヨーロッパで最も高く評価された科学者の一人となった。 哲学者ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは彼に「地上にこれほど偉大な人物はいないと彼に伝えてほしい」というメッセージを送った。[6] ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテは「シェイクスピアとスピノザを除いて、今は亡き人物の中で、これほどまでに強く私に影響を与えた人物は他にいな い」と書いた。[6] スウェーデンの作家アウグスト・ストリンドベリは「リンネは 実際には、たまたま博物学者になった詩人だった」と述べている。[7] リンネは「植物学者の第一人者(Princeps botanicorum)」、「北方のプリニウス」と呼ばれている。[8] また、近代生態学の創始者の一人とも考えられている。[9] 植物学や動物学では、種の名称の権威としてリンネを示すためにL.という略称が用いられる。[10] 古い出版物では「Linn.」という略称も見られる。リンネの遺体は、国際動物命名規約に従って、現生人類ホモ・サピエンスのタイプ標本となっている。 [11] なぜなら、彼が調べたと知られている唯一の標本が彼自身だからである。[注釈 2] |

| Early life Childhood See also: Linné family  Birthplace at Råshult Linnaeus was born in the village of Råshult in Småland, Sweden, on 23 May 1707. He was the first child of Nicolaus (Nils) Ingemarsson (who later adopted the family name Linnaeus) and Christina Brodersonia. His siblings were Anna Maria Linnæa, Sofia Juliana Linnæa, Samuel Linnæus (who would eventually succeed their father as rector of Stenbrohult and write a manual on beekeeping),[12][13][14] and Emerentia Linnæa.[15] His father taught him Latin as a small child.[16] One of a long line of peasants and priests, Nils was an amateur botanist, a Lutheran minister, and the curate of the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland. Christina was the daughter of the rector of Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius.[17] A year after Linnaeus's birth, his grandfather Samuel Brodersonius died, and his father Nils became the rector of Stenbrohult. The family moved into the rectory from the curate's house.[18][19] Even in his early years, Linnaeus seemed to have a liking for plants, flowers in particular. Whenever he was upset, he was given a flower, which immediately calmed him. Nils spent much time in his garden and often showed flowers to Linnaeus and told him their names. Soon Linnaeus was given his own patch of earth where he could grow plants.[20] Carl's father was the first in his ancestry to adopt a permanent surname. Before that, ancestors had used the patronymic naming system of Scandinavian countries: his father was named Ingemarsson after his father Ingemar Bengtsson. When Nils was admitted to the University of Lund, he had to take on a family name. He adopted the Latinate name Linnæus after a giant linden tree (or lime tree), lind in Swedish, that grew on the family homestead.[12] This name was spelled with the æ ligature. When Carl was born, he was named Carl Linnæus, with his father's family name. The son also always spelled it with the æ ligature, both in handwritten documents and in publications.[18] Carl's patronymic would have been Nilsson, as in Carl Nilsson Linnæus.[21] Early education Linnaeus's father began teaching him basic Latin, religion, and geography at an early age.[22] When Linnaeus was seven, Nils decided to hire a tutor for him. The parents picked Johan Telander, a son of a local yeoman. Linnaeus did not like him, writing in his autobiography that Telander "was better calculated to extinguish a child's talents than develop them".[23] Two years after his tutoring had begun, he was sent to the Lower Grammar School at Växjö in 1717.[24] Linnaeus rarely studied, often going to the countryside to look for plants. At some point, his father went to visit him and, after hearing critical assessments by his preceptors, he decided to put the youth as an apprentice to some honest cobbler.[25] He reached the last year of the Lower School when he was fifteen, which was taught by the headmaster, Daniel Lannerus, who was interested in botany. Lannerus noticed Linnaeus's interest in botany and gave him the run of his garden. He also introduced him to Johan Rothman, the state doctor of Småland and a teacher at Katedralskolan (a gymnasium) in Växjö. Also a botanist, Rothman broadened Linnaeus's interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine.[26][27] By the age of 17, Linnaeus had become well acquainted with the existing botanical literature. He remarks in his journal that he "read day and night, knowing like the back of my hand, Arvidh Månsson's Rydaholm Book of Herbs, Tillandz's Flora Åboensis, Palmberg's Serta Florea Suecana, Bromelii's Chloros Gothica and Rudbeckii's Hortus Upsaliensis".[28] Linnaeus entered the Växjö Katedralskola in 1724, where he studied mainly Greek, Hebrew, theology and mathematics, a curriculum designed for boys preparing for the priesthood.[29][30] In the last year at the gymnasium, Linnaeus's father visited to ask the professors how his son's studies were progressing; to his dismay, most said that the boy would never become a scholar. Rothman believed otherwise, suggesting Linnaeus could have a future in medicine. The doctor offered to have Linnaeus live with his family in Växjö and to teach him physiology and botany. Nils accepted this offer.[31][32] |

幼少期 子供時代 関連項目:リンネ家  生誕地:ローシュルト リンネは1707年5月23日、スウェーデンのスモーランド地方にあるローシュルト村で生まれた。父ニコラウス(ニルス)・インゲマールソン(後にリンネ という姓を名乗る)と母クリスティーナ・ブロデションニアの最初の子供であった。彼の兄弟姉妹には、アンナ・マリア・リンネア、ソフィア・ジュリアナ・リ ンネア、サミュエル・リンネウス(後に父の後を継いでステンブロホルトの学長となり、養蜂のマニュアルを執筆した)[12][13][14]、エメレン ティア・リンネアがいる。父親は幼い頃から彼にラテン語を教えた。 農民と牧師の家系の出身であるニルスは、アマチュアの植物学者であり、ルーテル派の牧師であり、スモーランド地方の小さな村ステンブロホルトの牧師補であった。クリスティーナは、ステンブロホルトの牧師であったサミュエル・ブロデロンシウスの娘であった。 リンネが生まれた翌年、祖父のサミュエル・ブロデリウスが死去し、父のニルスがステンブロホルトの牧師となった。一家は牧師館に引っ越した。 幼少期から、リンネは植物、特に花を好んでいたようである。 彼は動揺するとすぐに花を与えられ、落ち着きを取り戻した。 ニルスは庭で多くの時間を過ごし、しばしばリンネに花を見せ、その名前を教えた。 やがてリンネは、植物を育てるための自分の土地を与えられた。[20] カール・フォン・リンネの父親は、先祖の中で初めて永続的な姓を名乗った人物である。それ以前は、先祖はスカンジナビア諸国で用いられていた父称に基づく 名前の命名法を使用しており、父親のイングマール・ベングトソンにちなんでイングマールソンと名付けられていた。ニルスがルンド大学に入学した際には、家 族の姓を名乗らなければならなかった。彼は、家族の屋敷に生えていた大きなシナノキ(またはライムの木)にちなんで、ラテン語風の名前リンネウスを名乗っ た。この名前は、æの合字を用いて綴られていた。カールが生まれたとき、父親の姓を継いでカール・リンネと名付けられた。息子もまた、手書きの文書でも出 版物でも、常にæの合字を用いていた。[18] カールの父称はニルソンとなり、カール・ニルソン・リンネとなるはずであった。[21] 初期の教育 リンネの父親は、幼い頃から彼にラテン語、宗教、地理の基礎を教え始めた。[22] リンネが7歳の時、ニルスは彼のために家庭教師を雇うことを決めた。両親は地元の農夫の息子であるヨハン・テランダーを選んだ。リンネは彼を好きになれ ず、自伝の中でテランダーは「子供の才能を伸ばすよりも、むしろそれを消し去るのに長けていた」と書いている。[23] 家庭教師がつけられてから2年後、1717年に彼はヴェクショーの下級文法学校に入学した。[24] リンネはほとんど勉強せず、しばしば田舎へ植物を探しに出かけた。ある時、父親が彼のもとを訪れ、師の批判的な評価を聞いた後、父親は息子を誠実な靴屋の 見習いとして働かせることにした。[25] 彼は15歳で下級学校の最終学年となり、校長で植物学に興味を持っていたダニエル・ランネラスが教鞭をとっていた。ランネラスはリンネの植物学への興味に 気づき、彼に庭を自由に使えるようにした。 また、スモーランドの州医であり、ヴェクショーのカテドラル・スコーラン(ギムナジウム)の教師でもあったヨハン・ロスマンにも紹介した。同じく植物学者 であったロスマンは、リンネの植物学への興味を広げ、医学への興味を育む手助けをした。[26][27] 17歳までに、リンネは当時の植物学の文献に精通していた。彼は日記に「昼夜を問わず、アルヴィド・マンスソンの『リュダホルムの薬草誌』、ティランツの 『フローラ・オボエンシス』、パルムベリの『スウェーデンの薬草誌』、ブロメリーの『クロロス・ゴティカ』、ルドベッキの『ウプサラ植物園』を、手のひら に書かれた文字を読むように熟知した」と記している。 リンネは1724年にヴェクショーのカテドラル・スクールに入学し、主にギリシャ語、ヘブライ語、神学、数学を学んだ。これは聖職者となるための男子生徒 向けのカリキュラムであった。[29][30] リンネがこの学校の最終学年に在籍していたとき、父親が教授たちを訪ねて息子の学業の進捗状況を尋ねた。教授たちのほとんどは、その少年が学者になること は決してないだろうと答えた。ロスマンはそうは思わず、リンネには医学の道があるのではないかと提案した。その医師は、リンネをヴェクショーの自分の家族 と一緒に住まわせ、生理学と植物学を教えることを申し出た。ニルスはこの申し出を受け入れた。[31][32] |

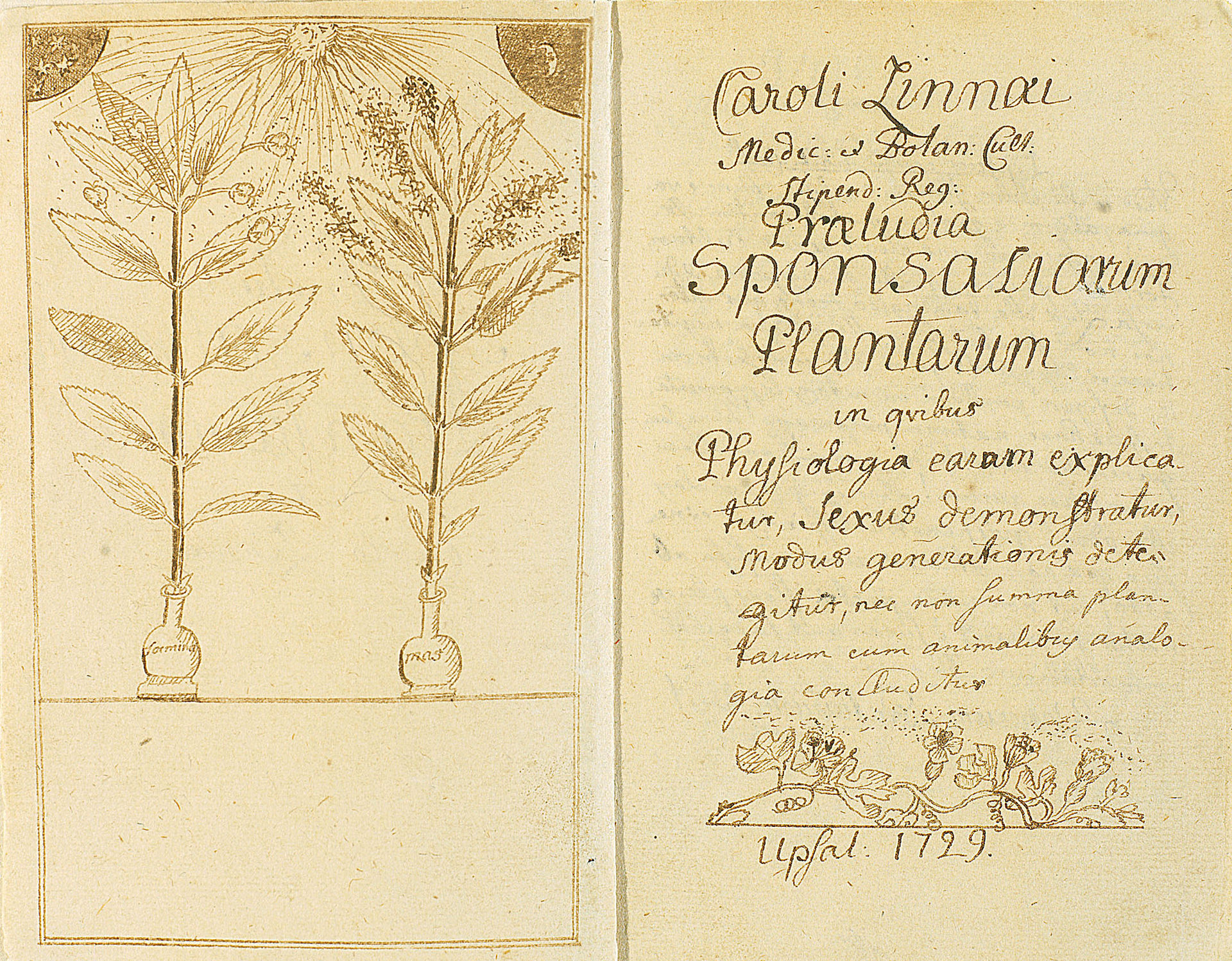

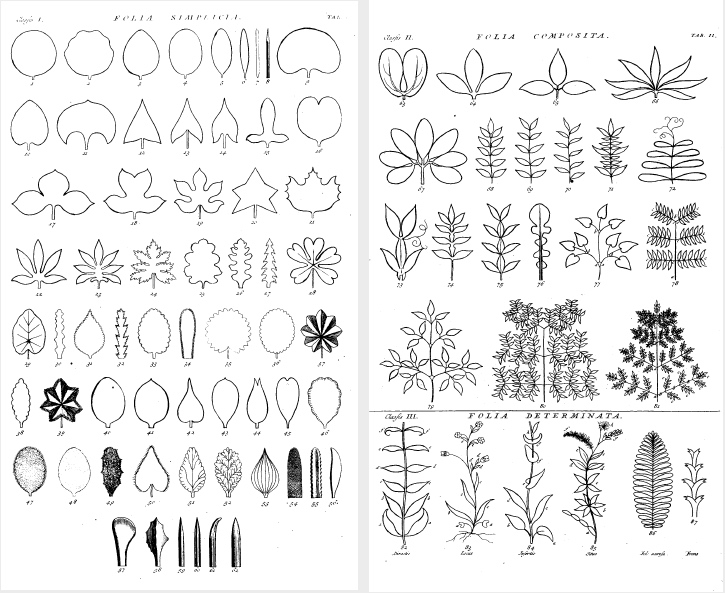

| University studies Lund  Statue as a university student in Lund, by Ansgar Almquist Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject. He taught Linnaeus to classify plants according to Tournefort's system. Linnaeus was also taught about the sexual reproduction of plants, according to Sébastien Vaillant.[31] In 1727, Linnaeus, age 21, enrolled in Lund University in Skåne.[33][34] He was registered as Carolus Linnæus, the Latin form of his full name, which he also used later for his Latin publications.[3] Professor Kilian Stobæus, natural scientist, physician and historian, offered Linnaeus tutoring and lodging, as well as the use of his library, which included many books about botany. He also gave the student free admission to his lectures.[35][36] In his spare time, Linnaeus explored the flora of Skåne, together with students sharing the same interests.[37] Uppsala  Pollination depicted in Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum (1729) In August 1728, Linnaeus decided to attend Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman, who believed it would be a better choice if Linnaeus wanted to study both medicine and botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at the medical faculty at Uppsala: Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg. Although Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good professors, by then they were older and not so interested in teaching. Rudbeck no longer gave public lectures, and had others stand in for him. The botany, zoology, pharmacology and anatomy lectures were not in their best state.[38] In Uppsala, Linnaeus met a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, who was a professor of theology and an amateur botanist.[39] He received Linnaeus into his home and allowed him use of his library, which was one of the richest botanical libraries in Sweden.[40] In 1729, Linnaeus wrote a thesis, Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum on plant sexual reproduction. This attracted the attention of Rudbeck; in May 1730, he selected Linnaeus to give lectures at the University although the young man was only a second-year student. His lectures were popular, and Linnaeus often addressed an audience of 300 people.[41] In June, Linnaeus moved from Celsius's house to Rudbeck's to become the tutor of the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not wane and they continued their botanical expeditions.[42] Over that winter, Linnaeus began to doubt Tournefort's system of classification and decided to create one of his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils. He began writing several books, which would later result in, for example, Genera Plantarum and Critica Botanica. He also produced a book on the plants grown in the Uppsala Botanical Garden, Adonis Uplandicus.[43] Rudbeck's former assistant, Nils Rosén, returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in medicine. Rosén started giving anatomy lectures and tried to take over Linnaeus's botany lectures, but Rudbeck prevented that. Until December, Rosén gave Linnaeus private tutoring in medicine. In December, Linnaeus had a "disagreement" with Rudbeck's wife and had to move out of his mentor's house; his relationship with Rudbeck did not appear to suffer. That Christmas, Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother had disapproved of his failing to become a priest, but she was pleased to learn he was teaching at the University.[43][44] |

大学での研究 ルンド  ルンド大学の学生時代の像、アンシュガー・アルムクヴィスト作 ロスマンはリンネに、植物学は真剣に取り組むべき学問であることを示した。彼はリンネに、トゥルネフォール体系に従って植物を分類する方法を教えた。ま た、セバスチャン・ヴァイヤン(Sébastien Vaillant)から植物の有性生殖についても教わった。1727年、21歳になったリンネはスコーネ地方のルンド大学に入学した。 自然科学者、医師、歴史家であったキリアン・ストゥーベウス教授は、リンネに家庭教師と住居を提供し、さらに植物学に関する多くの書籍を所蔵する自身の図 書館の利用も許可した。また、ストゥーベウス教授はリンネに自身の講義への無料聴講も認めた。[35][36] リンネは余暇には、同じ関心を持つ学生たちとともにスコーネ地方の植物相を探索した。[37] ウプサラ  Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum (1729年)に描かれた受粉 1728年8月、リンネは医学と植物学の両方を学びたいのであれば、ウプサラ大学への進学が望ましいとロスマンに勧められ、その助言に従うことにした。ロ スマンは、ウプサラの医学部で教鞭をとっていた2人の教授、オロフ・ルドベック・ヤングとラース・ロベリを推薦した。 ルドベックとロベリは確かに優れた教授であったが、当時すでに高齢で、教育にはあまり熱心ではなかった。 ルドベックはもはや公開講義を行っておらず、代理に任せていた。植物学、動物学、薬理学、解剖学の講義は最善の状態ではなかった。[38] ウプサラで、リンネは神学の教授でありアマチュア植物学者でもあった新しい後援者、オロフ・セルシウスと出会った。[39] 彼はリンネを自宅に迎え入れ、スウェーデンで最も充実した植物学の図書館の一つである自身の図書館の利用を許可した。[40] 1729年、リンネは植物の有性生殖に関する論文『Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum』を執筆した。これに目を留めたルドベックは、1730年5月、まだ2年生にすぎなかったリンネを大学の講師に抜擢した。彼の講義は人 気を博し、リンネはしばしば300人の聴衆を前に講義を行った。6月、リンネはセルシウスの家からルドベックの家へと移り、ルドベックの24人の子供のう ち最も年下の3人の家庭教師となった。セルシウスとの友情は衰えることなく、彼らは植物学探検を続けた。[42] その冬の間、リンネはトルネフォールの分類体系に疑問を抱くようになり、独自の体系を構築することを決意した。彼の計画は、雄しべと雌しべの数によって植 物を分類するというものだった。彼はいくつかの本を書き始め、そのうちの1冊は後に『植物属』や『植物学評論』として出版された。また、ウプサラ植物園で 栽培されている植物に関する本『Adonis Uplandicus』も執筆した。 ルドベックの元助手であったニルス・ローゼンは、1731年3月に医学の学位を取得して大学に戻った。ローゼンは解剖学の講義を始め、リンネの植物学の講 義を引き継ごうとしたが、ルドベックがそれを妨害した。12月まで、ローゼンはリンネに医学の個人指導を行っていた。12月、リンネはルドベックの妻と 「意見の相違」があり、師の家を出なければならなかった。しかし、リンネとルドベックの関係は悪化しなかったようである。その年のクリスマス、リンネは約 3年ぶりに両親を訪ねて故郷のステンブロフーントに戻った。母親は息子が聖職者にならなかったことを快く思っていなかったが、彼が大学で教鞭をとっている ことを知って喜んだ。[43][44] |

| Expedition to Lapland Main articles: Expedition to Lapland and Flora Lapponica  Carl Linnaeus in Laponian costume (1737) During a visit with his parents, Linnaeus told them about his plan to travel to Lapland; Rudbeck had made the journey in 1695, but the detailed results of his exploration were lost in a fire seven years afterwards. Linnaeus's hope was to find new plants, animals and possibly valuable minerals. He was also curious about the customs of the native Sami people, reindeer-herding nomads who wandered Scandinavia's vast tundras. In April 1732, Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for his journey.[45][46]  Wearing the traditional dress of the Sami people of Lapland, holding the twinflower, later known as Linnaea borealis, that became his personal emblem. Martin Hoffman, 1737. Linnaeus began his expedition from Uppsala on 12 May 1732, just before he turned 25.[47] He travelled on foot and horse, bringing with him his journal, botanical and ornithological manuscripts and sheets of paper for pressing plants. Near Gävle he found great quantities of Campanula serpyllifolia, later known as Linnaea borealis, the twinflower that would become his favourite.[48] He sometimes dismounted on the way to examine a flower or rock[49] and was particularly interested in mosses and lichens, the latter a main part of the diet of the reindeer, a common and economically important animal in Lapland.[50] Linnaeus travelled clockwise around the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, making major inland incursions from Umeå, Luleå and Tornio. He returned from his six-month-long, over 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) expedition in October, having gathered and observed many plants, birds and rocks.[51][52][53] Although Lapland was a region with limited biodiversity, Linnaeus described about 100 previously unidentified plants. These became the basis of his book Flora Lapponica.[54][55] However, on the expedition to Lapland, Linnaeus used Latin names to describe organisms because he had not yet developed the binomial system.[47] In Flora Lapponica Linnaeus's ideas about nomenclature and classification were first used in a practical way, making this the first proto-modern Flora.[56] The account covered 534 species, used the Linnaean classification system and included, for the described species, geographical distribution and taxonomic notes. It was Augustin Pyramus de Candolle who attributed Linnaeus with Flora Lapponica as the first example in the botanical genre of Flora writing. Botanical historian E. L. Greene described Flora Lapponica as "the most classic and delightful" of Linnaeus's works.[56] It was during this expedition that Linnaeus had a flash of insight regarding the classification of mammals. Upon observing the lower jawbone of a horse at the side of a road he was travelling, Linnaeus remarked: "If I only knew how many teeth and of what kind every animal had, how many teats and where they were placed, I should perhaps be able to work out a perfectly natural system for the arrangement of all quadrupeds."[57] In 1734, Linnaeus led a small group of students to Dalarna. Funded by the Governor of Dalarna, the expedition was to catalogue known natural resources and discover new ones, but also to gather intelligence on Norwegian mining activities at Røros.[53] |

ラップランド遠征 詳細は「ラップランド遠征」および「ラップランド植物誌」を参照  ラップ人の衣装をまとったカール・フォン・リンネ(1737年) 両親を訪ねた際、リンネはラップランドへの旅の計画を両親に話した。ルドベックは1695年にその旅に出たが、その詳細な探検結果は7年後の火災で失われ ていた。リンネの希望は、新しい植物や動物、そして価値のある鉱物を見つけることだった。また、スカンジナビアの広大なツンドラを放浪するトナカイ遊牧民 である先住民族サーミ人の風習にも興味を持っていた。1732年4月、リンネはウプサラ王立科学協会から旅費の助成金を受けた。  ラップランドのサーメ人の民族衣装を身にまとい、後に「リンネア・ボレアリス」と呼ばれるようになる双頭の花を手にしている。マーティン・ホフマン、1737年。 リンネは25歳になる直前の1732年5月12日に、ウプサラから探検を開始した。[47] 彼は徒歩と馬で旅をし、日記や植物学、鳥類学の原稿、植物を押し葉するための紙を持参した。イェヴレ近郊で、後にリンネア・ボレアリスと呼ばれることにな るツルキンバイ(ツルキンバイソウ)を大量に見つけた。ツルキンバイは、後に彼の最もお気に入りの植物となる。[48] 彼は、花や岩を調べるために、時には馬から降りた。[49] 特にコケや地衣類に興味を示し、後者はトナカイの主な食料であり、ラップランドでは一般的な経済的に重要な動物である。[50] リンネはボスニア湾沿岸を時計回りに旅し、ウメオ、ルレオ、トルニオから内陸に大きく入り込んだ。彼は6か月間にわたる2,000キロメートル (1,200マイル)以上の遠征から10月に戻り、多くの植物、鳥類、岩石を収集し観察した。[51][52][53] ラップランドは生物多様性が限られた地域であったが、リンネはそれまでに未確認であった約100種の植物について記述した。これらは彼の著書『ラップラン ド植物誌』の基礎となった。[54][55] しかし、ラップランドへの遠征では、リンネはまだ二名法を開発していなかったため、生物を記述するのにラテン語名を使用した。[47] 『ラップランド植物誌』において、リンネの命名法と分類法に関する考え方は初めて実用的な形で用いられ、これが最初の近代的な植物誌となった。[56] この著書では534種の植物が取り上げられ、リンネの分類体系が用いられ、記述された種について地理的分布と分類学的注釈が含まれていた。リンネが『ラッ プランド植物誌』を植物誌の最初の例として挙げたのは、オーギュスト・ピラーム・ド・カンドルであった。植物学者のE. L. Greeneは、フローラ・ラッポニカを「最も古典的で素晴らしい」リンネの作品と評した。[56] この探検中に、リンネは哺乳類の分類について閃きを得た。旅の途中で道路脇にあった馬の下顎骨を観察したリンネは、「もし私が、すべての動物が何本の歯を どんな種類持っているか、乳首がいくつあってどこについているかを知ることができれば、四足動物の分類について完璧に自然な体系を構築できるかもしれな い」と述べた。 1734年、リンネは少数の学生たちを率いてダーラナ地方に向かった。ダーラナ総督の資金援助を受けたこの遠征の目的は、既知の天然資源の目録を作成し、新たな資源を発見すること、そしてローロスにおけるノルウェーの採掘活動に関する情報を収集することであった。[53] |

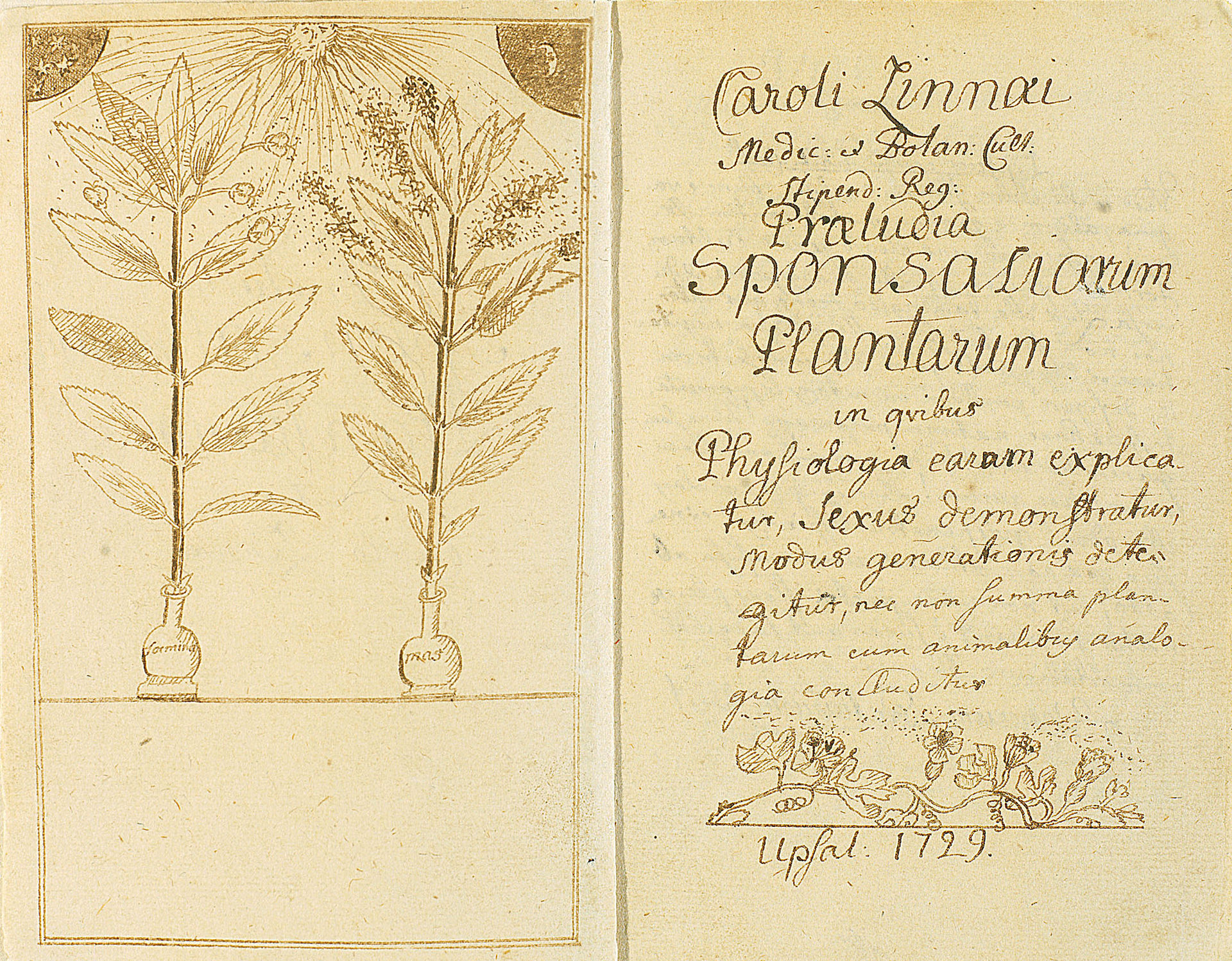

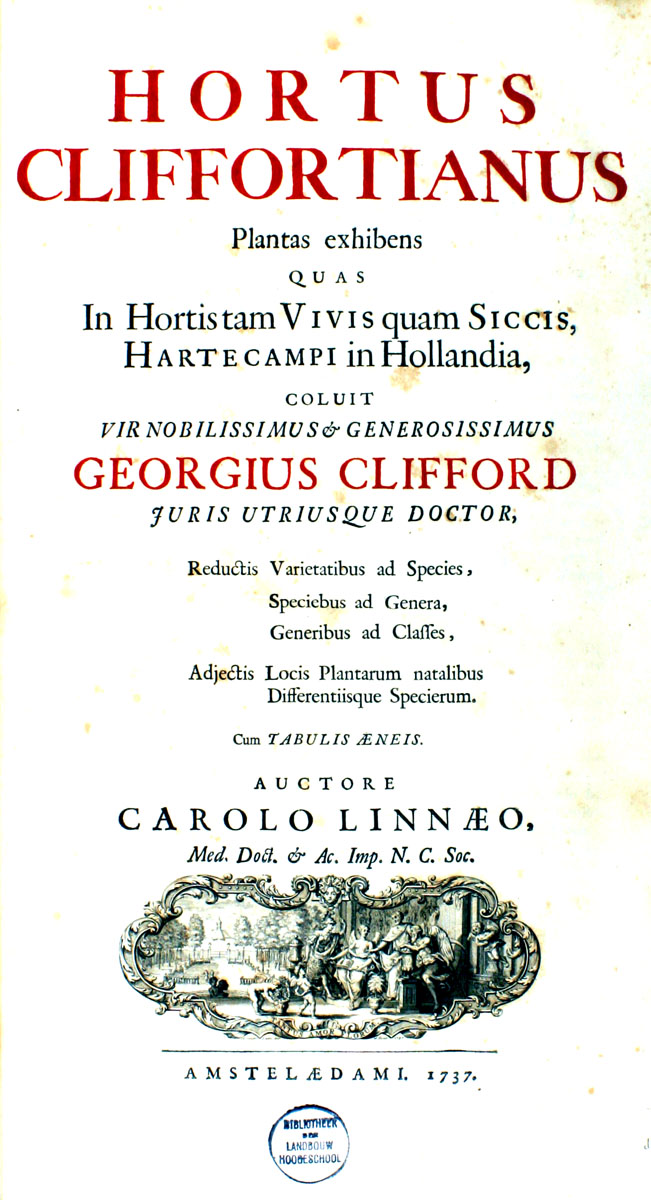

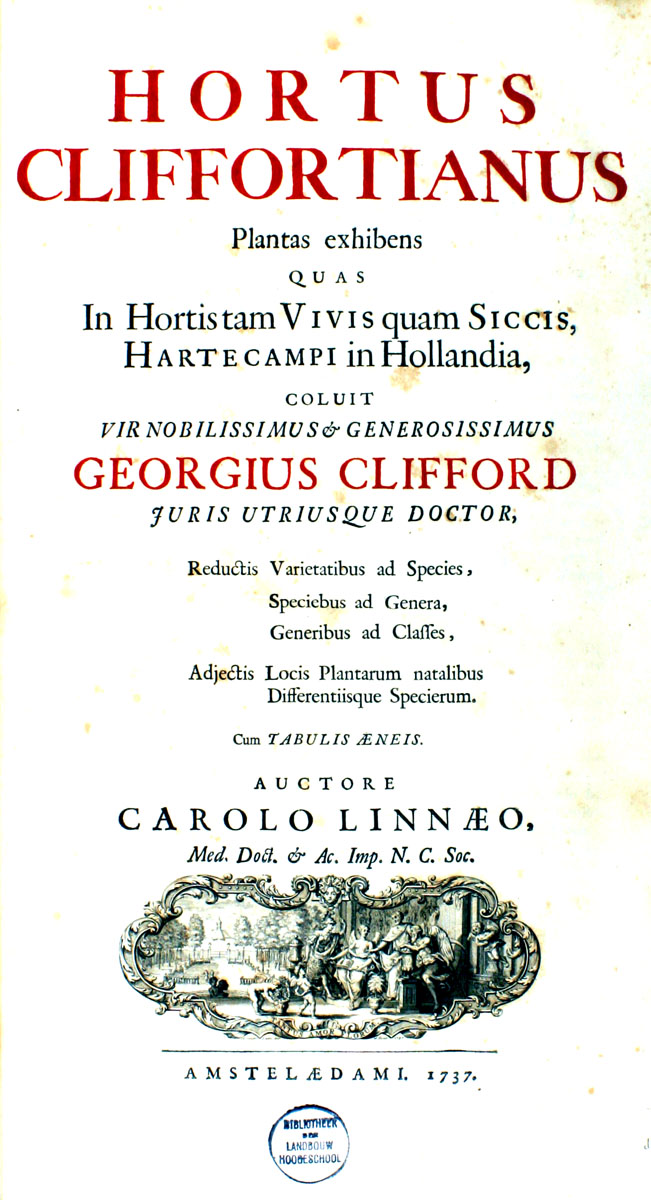

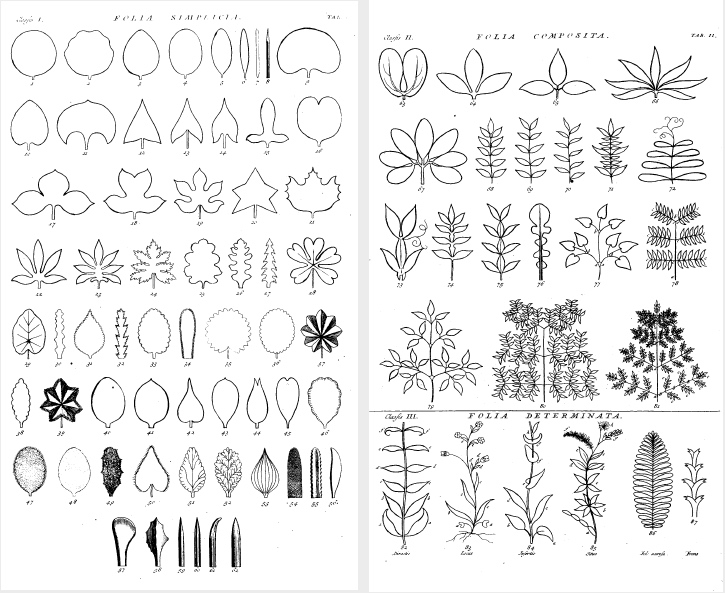

Years in the Dutch Republic (1735–38) The Hamburg Hydra, from the Thesaurus (1734) of Albertus Seba. Linnaeus identified the hydra specimen as a fake in 1735.  View of Hartekamp, where Carl von Linné lived and studied for three years, from 1735 until 1738  Title page of Musa Cliffortiana (1736), Linnaeus's first botanical monograph  Title page of Hortus Cliffortianus (1737). The work was a collaboration between Linnaeus and Georg Dionysius Ehret, financed by George Clifford III, one of the directors of the VOC.  Doctorate  Cities where he worked; those outside Sweden were only visited during 1735–1738 His relations with Nils Rosén having worsened, Linnaeus accepted an invitation from Claes Sohlberg, son of a mining inspector, to spend the Christmas holiday in Falun, where Linnaeus was permitted to visit the mines.[58] In April 1735, at the suggestion of Sohlberg's father, Linnaeus and Sohlberg set out for the Dutch Republic, where Linnaeus intended to study medicine at the University of Harderwijk[59] while tutoring Sohlberg in exchange for an annual salary. At the time, it was common for Swedes to pursue doctoral degrees in the Netherlands, then a highly revered place to study natural history.[60] On the way, the pair stopped in Hamburg, where they met the mayor, who proudly showed them a supposed wonder of nature in his possession: the taxidermied remains of a seven-headed hydra. Linnaeus quickly discovered the specimen was a fake, cobbled together from the jaws and paws of weasels and the skins of snakes. The provenance of the hydra suggested to Linnaeus that it had been manufactured by monks to represent the Beast of Revelation. Even at the risk of incurring the mayor's wrath, Linnaeus made his observations public, dashing the mayor's dreams of selling the hydra for an enormous sum. Linnaeus and Sohlberg were forced to flee from Hamburg.[61][62] Linnaeus began working towards his degree as soon as he reached Harderwijk, a university known for awarding degrees in as little as a week.[63] He submitted a dissertation, written back in Sweden, entitled Dissertatio medica inauguralis in qua exhibetur hypothesis nova de febrium intermittentium causa,[note 3] in which he laid out his hypothesis that malaria arose only in areas with clay-rich soils.[64] Although he failed to identify the true source of disease transmission, (i.e., the Anopheles mosquito),[65] he did correctly predict that Artemisia annua (wormwood) would become a source of antimalarial medications.[64] Within two weeks he had completed his oral and practical examinations and was awarded a doctoral degree.[61][63] That summer Linnaeus reunited with Peter Artedi, a friend from Uppsala with whom he had once made a pact that should either of the two predecease the other, the survivor would finish the decedent's work. Ten weeks later, Artedi drowned in the canals of Amsterdam, leaving behind an unfinished manuscript on the classification of fish.[66][67] Publishing of Systema Naturae One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Johan Frederik Gronovius, to whom Linnaeus showed one of the several manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system for classifying plants. When Gronovius saw it, he was very impressed, and offered to help pay for the printing. With an additional monetary contribution by the Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson, the manuscript was published as Systema Naturae (1735).[68][69] Linnaeus became acquainted with one of the most respected physicians and botanists in the Netherlands, Herman Boerhaave, who tried to convince Linnaeus to make a career there. Boerhaave offered him a journey to South Africa and America, but Linnaeus declined, stating he would not stand the heat. Instead, Boerhaave convinced Linnaeus that he should visit the botanist Johannes Burman. After his visit, Burman, impressed with his guest's knowledge, decided Linnaeus should stay with him during the winter. During his stay, Linnaeus helped Burman with his Thesaurus Zeylanicus. Burman also helped Linnaeus with the books on which he was working: Fundamenta Botanica and Bibliotheca Botanica.[70] George Clifford, Philip Miller, and Johann Jacob Dillenius Folia Simplicia Folia Composita et Folia Determinata Leaf forms from Hortus Cliffortianus In August 1735, during Linnaeus's stay with Burman, he met George Clifford III, a director of the Dutch East India Company and the owner of a rich botanical garden at the estate of Hartekamp in Heemstede. Clifford was very impressed with Linnaeus's ability to classify plants, and invited him to become his physician and superintendent of his garden. Linnaeus had already agreed to stay with Burman over the winter, and could thus not accept immediately. However, Clifford offered to compensate Burman by offering him a copy of Sir Hans Sloane's Natural History of Jamaica, a rare book, if he let Linnaeus stay with him, and Burman accepted.[71][72] On 24 September 1735, Linnaeus moved to Hartekamp to become personal physician to Clifford, and curator of Clifford's herbarium. He was paid 1,000 florins a year, with free board and lodging. Though the agreement was only for a winter of that year, Linnaeus practically stayed there until 1738.[73] It was here that he wrote a book Hortus Cliffortianus, in the preface of which he described his experience as "the happiest time of my life". (A portion of Hartekamp was declared as public garden in April 1956 by the Heemstede local authority, and was named "Linnaeushof".[74] It eventually became, as it is claimed, the biggest playground in Europe.[75]) In July 1736, Linnaeus travelled to England, at Clifford's expense.[76] He went to London to visit Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of natural history, and to see his cabinet,[77] as well as to visit the Chelsea Physic Garden and its keeper, Philip Miller. He taught Miller about his new system of subdividing plants, as described in Systema Naturae. Miller was in fact reluctant to use the new binomial nomenclature, preferring the classifications of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and John Ray at first. Linnaeus, nevertheless, applauded Miller's Gardeners Dictionary,[78] the conservative Scot actually retained in his dictionary a number of pre-Linnaean binomial signifiers discarded by Linnaeus but which have been retained by modern botanists. He only fully changed to the Linnaean system in the edition of The Gardeners Dictionary of 1768. Miller ultimately was impressed, and from then on started to arrange the garden according to Linnaeus's system.[79] Linnaeus also travelled to Oxford University to visit the botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius. He failed to make Dillenius publicly fully accept his new classification system, though the two men remained in correspondence for many years afterwards. Linnaeus dedicated his Critica Botanica to him, as "opus botanicum quo absolutius mundus non-vidit". Linnaeus would later name a genus of tropical tree Dillenia in his honour. He then returned to Hartekamp, bringing with him many specimens of rare plants.[80] The next year, 1737, he published Genera Plantarum, in which he described 935 genera of plants, and shortly thereafter he supplemented it with Corollarium Generum Plantarum, with another sixty (sexaginta) genera.[81] His work at Hartekamp led to another book, Hortus Cliffortianus, a catalogue of the botanical holdings in the herbarium and botanical garden of Hartekamp. He wrote it in nine months (completed in July 1737), but it was not published until 1738.[70] It contains the first use of the name Nepenthes, which Linnaeus used to describe a genus of pitcher plants.[82][note 4] Linnaeus stayed with Clifford at Hartekamp until 18 October 1737 (new style), when he left the house to return to Sweden. Illness and the kindness of Dutch friends obliged him to stay some months longer in Holland. In May 1738, he set out for Sweden again. On the way home, he stayed in Paris for about a month, visiting botanists such as Antoine de Jussieu. After his return, Linnaeus never again left Sweden.[83][84] |

オランダ共和国での年数(1735年~1738年) アルバートゥス・セバの『テサロス』(1734年)より、ハンブルク・ヒドラ。 リンネは1735年にヒドラ標本を偽物と特定した。  カール・フォン・リンネが3年間住み、研究を行ったハルテカンプの眺め(1735年~1738年)  リンネの最初の植物学の専門書『Musa Cliffortiana』(1736年)のタイトルページ  『Hortus Cliffortianus』(1737年)のタイトルページ。この作品は、VOCの取締役の一人であったジョージ・クリフォード3世の資金提供を受け、リンネとゲオルク・ディオニュシオス・エーレトとの共同作業であった。  博士号  彼が働いた都市。スウェーデン国外の都市は、1735年から1738年の間に訪問しただけである ニルス・ローゼンとの関係が悪化したため、リンネは鉱山検査官の息子であるクレス・ソールベリからの招待を受け入れ、クリスマス休暇をファールンで過ごすことになった。ファールンでは、リンネは鉱山の見学を許可された。 1735年4月、ソールベリの実父の勧めにより、リンネとソールベリはオランダ共和国に向かった。リンネはハーレウェイク大学で医学を学ぶつもりでいたが [59]、ソールベリに家庭教師として教える代わりに、年俸を受け取っていた。当時、スウェーデン人がオランダで博士号を取得することは一般的であった。 当時、オランダは自然史を研究する上で非常に尊敬されていた場所であった。 途中ハンブルクに立ち寄った際、市長に会い、市長が所有する自然界の驚異とされるものを見せてもらった。それは剥製にした7つの頭を持つヒュドラの死骸 だった。リンネはすぐに、その標本がイタチの前足と後足、そして蛇の皮を縫い合わせた偽物であることに気づいた。そのヒュドラの由来から、リンネは修道士 たちが黙示録の獣を象徴するために作ったものだと考えた。市長の怒りを買う危険を冒してでも、リンネは自分の観察結果を公表し、市長がヒュドラを巨額で売 り飛ばそうという夢を打ち砕いた。リンネとソールベリはハンブルクから逃げることを余儀なくされた。 リンネはハーレウィクに到着するとすぐに学位取得に向けての研究を始めた。ハーレウィク大学は最短1週間で学位を授与することで知られていた。[63] スウェーデンに戻ってから書いた論文『間歇熱の新しい仮説に関する医学的序論』を提出した。[注釈 3] その論文で、 彼は、マラリアは粘土質の土壌を持つ地域のみで発生するという仮説を提示した。[64] 彼は、病気の感染の真の原因(すなわち、ハマダラカ)を特定することはできなかったが、[65] アルテミシア・アニュア(ヨモギ)が抗マラリア薬の原料となることを正しく予測した。[64] 2週間以内に口頭試問と実技試験を終え、博士号を取得した。 その夏、リンネはウプサラ時代の友人であるピーター・アルテディと再会した。アルテディとは、どちらかが先に他界した場合は、生存者が他方の仕事を完成さ せるという約束を交わしていた。その10週間後、アルテディはアムステルダム運河で溺死し、魚類分類の未完成の原稿を残した。 『動物誌』の出版 オランダでリンネが最初に会った科学者の一人にヨハン・フリードリヒ・グロノビウスがおり、リンネはスウェーデンから持参したいくつかの原稿のうちの1つ を彼に見せた。その原稿は植物の分類に関する新しい体系を説明したものだった。グロンオービウスはこれを見て非常に感銘を受け、印刷費用の一部を負担する ことを申し出た。スコットランド人医師アイザック・ローソンからの追加の資金援助もあり、この原稿は『Systema Naturae』(1735年)として出版された。[68][69] リンネはオランダで最も尊敬されていた医師であり植物学者であったヘルマン・ブールハーフェと知り合い、ブールハーフェはリンネにオランダでキャリアを築 くよう説得しようとした。ブールハーフェはリンネに南アフリカとアメリカへの旅を提案したが、リンネは暑さに耐えられないと断った。代わりにブールハー フェは、リンネが植物学者のヨハネス・ブルマンを訪問すべきだと説得した。訪問後、ブルマンは客の博識ぶりに感銘を受け、冬の間はリンネを自分の家に滞在 させることにした。滞在中、リンネはブルマンの『セイランシス・ゼイラニクス』の作成を手伝った。また、ブルマンはリンネが執筆中の『植物学の基礎』と 『植物学図書館』の作成も手伝った。 ジョージ・クリフォード、フィリップ・ミラー、ヨハン・ヤコブ・ディリニュス Folia Simplicia Folia Composita et Folia Determinata Hortus Cliffortianusの葉の形 1735年8月、リンネがブルマン宅に滞在している間、オランダ東インド会社の取締役であり、ヘームステーデのハーテカンプの敷地内に豊かな植物園を所有 するジョージ・クリフォード3世と出会った。Cliffordは、リンネの植物分類能力に非常に感銘を受け、自分の医師兼庭園の監督になるよう彼を招待し た。リンネはすでに冬の間はBurmanの家に滞在することに同意していたため、すぐに承諾することはできなかった。しかし、クリフォードは、リンネを自 分のもとに置くことを許可するなら、ハンズ・スローン卿の著書『ジャマイカの自然史』という稀覯本をバーマンに提供すると申し出た。バーマンはこれを受け 入れ、リンネは1735年9月24日にハーテカンプに移り住み、クリフォードの個人医師となり、クリフォードの植物標本庫の管理者となった。リンネは年間 1,000フローリンの報酬を受け取り、食事と宿泊は無料で提供された。その年の冬だけの契約であったが、リンネは事実上1738年までそこに滞在した。 [73] ここでリンネは『Hortus Cliffortianus』を執筆し、その序文で「人生で最も幸せな時期」と自身の経験を記述した。(ハルテカンプの一部は、1956年4月にヘームス テーデの地方自治体によって公共庭園として宣言され、「リンネスホフ」と名付けられた。[74] 最終的には、主張されているように、ヨーロッパ最大の遊び場となった。[75]) 1736年7月、リンネはクリフォードの費用負担でイングランドに渡った。[76] 彼はロンドンで博物学者のハンス・スローン卿を訪問し、彼のキャビネットを見学した。[77] また、チェルシー薬草園と園長のフィリップ・ミラーも訪問した。リンネはミラーに、Systema Naturaeで説明されている植物の新しい分類体系について教えた。ミラーは実際には新しい二名法の使用に消極的で、当初はジョセフ・ピトン・ド・トゥ ルヌフォールとジョン・レイの分類法を好んでいた。しかし、リンネはミラーの『園芸家辞典』を称賛し[78]、保守的なスコットランド人であるミラーは、 リンネが破棄したものの、現代の植物学者たちによって保持されているリンネ以前の二名法の記号を自身の辞典に多数残した。彼は1768年版の『園芸家辞 典』で初めて完全にリンネ式に変更した。ミラーは最終的に感銘を受け、それ以降はリンネの体系に従って庭を整理し始めた。 リンネはオックスフォード大学にも足を運び、植物学者ヨハン・ヤコブ・ディリニュスを訪問した。しかし、リンネはディリニュスに自身の新しい分類体系を完 全に受け入れさせることはできなかった。リンネはディリニュスに『植物誌』を献呈し、「opus botanicum quo absolutius mundus non-vidit(これほどまでに世界を完全に理解した植物学)」と記した。リンネは後に、ディリニュスの名誉を称えて熱帯樹の一種に「ディリニア」と いう学名をつけた。その後、彼はハーテカンプに戻り、多くの珍しい植物の標本を持ち帰った。[80] 翌年、1737年に彼は『植物の属』を出版し、その中で935の植物の属を記述し、その後まもなく『植物の属の補遺』でさらに60の属を追加した。 [81] ハルテカンプでの彼の仕事は、もう1冊の著書『Hortus Cliffortianus』につながった。これは、ハルテカンプの植物園とハーバリウムの植物目録である。彼は9か月で書き上げ(1737年7月に完 成)、1738年になってようやく出版された。[70] そこには、ネペンテス属の植物を説明する際にリンネが初めて用いた「ネペンテス」という名称が含まれている。[82][注釈 4] リンネは1737年10月18日(新暦)までクリフォードのハルテカンプに滞在し、その後スウェーデンに戻るために家を出た。病気とオランダ人の友人たち の親切心により、彼はオランダに数か月長く滞在せざるを得なかった。1738年5月、彼は再びスウェーデンに向けて出発した。帰路、彼はパリに約1か月滞 在し、アントワーヌ・ド・ジュシーなどの植物学者を訪問した。帰国後、リンネは二度とスウェーデンを離れることはなかった。[83][84] |

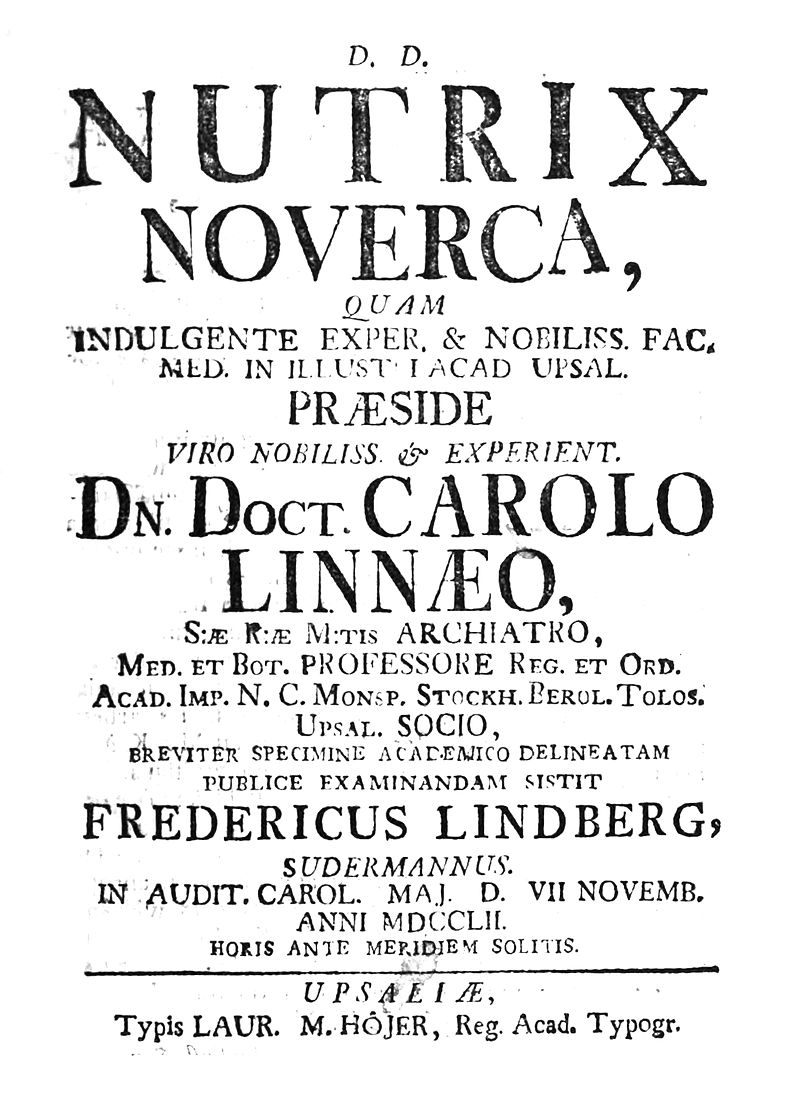

Return to Sweden Wedding portrait When Linnaeus returned to Sweden on 28 June 1738, he went to Falun, where he entered into an engagement to Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Three months later, he moved to Stockholm to find employment as a physician, and thus to make it possible to support a family.[85][86] Once again, Linnaeus found a patron; he became acquainted with Count Carl Gustav Tessin, who helped him get work as a physician at the Admiralty.[87][88] During this time in Stockholm, Linnaeus helped found the Royal Swedish Academy of Science; he became the first Praeses of the academy by drawing of lots.[89] Because his finances had improved and were now sufficient to support a family, he received permission to marry his fiancée, Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Their wedding was held 26 June 1739. Seventeen months later, Sara gave birth to their first son, Carl. Two years later, a daughter, Elisabeth Christina, was born, and the subsequent year Sara gave birth to Sara Magdalena, who died when 15 days old. Sara and Linnaeus would later have four other children: Lovisa, Sara Christina, Johannes and Sophia.[85][90]  House in Uppsala In May 1741, Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University, first with responsibility for medicine-related matters. Soon, he changed place with the other Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosén, and thus was responsible for the Botanical Garden (which he would thoroughly reconstruct and expand), botany and natural history, instead. In October that same year, his wife and nine-month-old son followed him to live in Uppsala.[91] Öland and Gotland Ten days after he was appointed Professor, he undertook an expedition to the island provinces of Öland and Gotland with six students from the university to look for plants useful in medicine. First, they travelled to Öland and stayed there until 21 June, when they sailed to Visby in Gotland. Linnaeus and the students stayed on Gotland for about a month, and then returned to Uppsala. During this expedition, they found 100 previously unrecorded plants. The observations from the expedition were later published in Öländska och Gothländska Resa, written in Swedish. Like Flora Lapponica, it contained both zoological and botanical observations, as well as observations concerning the culture in Öland and Gotland.[92][93] During the summer of 1745, Linnaeus published two more books: Flora Suecica and Fauna Suecica. Flora Suecica was a strictly botanical book, while Fauna Suecica was zoological.[85][94] Anders Celsius had created the temperature scale named after him in 1742. Celsius's scale was inverted compared to today, the boiling point at 0 °C and freezing point at 100 °C. In 1745, Linnaeus inverted the scale to its present standard.[95] Västergötland In the summer of 1746, Linnaeus was once again commissioned by the Government to carry out an expedition, this time to the Swedish province of Västergötland. He set out from Uppsala on 12 June and returned on 11 August. On the expedition his primary companion was Erik Gustaf Lidbeck, a student who had accompanied him on his previous journey. Linnaeus described his findings from the expedition in the book Wästgöta-Resa, published the next year.[92][96] After he returned from the journey, the Government decided Linnaeus should take on another expedition to the southernmost province Scania. This journey was postponed, as Linnaeus felt too busy.[85] In 1747, Linnaeus was given the title archiater, or chief physician, by the Swedish king Adolf Frederick—a mark of great respect.[97] The same year he was elected member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin.[98] Scania In the spring of 1749, Linnaeus could finally journey to Scania, again commissioned by the Government. With him he brought his student, Olof Söderberg. On the way to Scania, he made his last visit to his brothers and sisters in Stenbrohult since his father had died the previous year. The expedition was similar to the previous journeys in most aspects, but this time he was also ordered to find the best place to grow walnut and Swedish whitebeam trees; these trees were used by the military to make rifles. While there, they also visited the Ramlösa mineral spa, where he remarked on the quality of its ferruginous water.[99] The journey was successful, and Linnaeus's observations were published the next year in Skånska Resa.[100][101] Rector of Uppsala University  Summer home at his Hammarby estate  The Linnaean Garden in Uppsala In 1750, Linnaeus became rector of Uppsala University, starting a period where natural sciences were esteemed.[85] Perhaps the most important contribution he made during his time at Uppsala was to teach; many of his students travelled to various places in the world to collect botanical samples. Linnaeus called the best of these students his "apostles".[102] His lectures were normally very popular and were often held in the Botanical Garden. He tried to teach the students to think for themselves and not trust anybody, not even him. Even more popular than the lectures were the botanical excursions made every Saturday during summer, where Linnaeus and his students explored the flora and fauna in the vicinity of Uppsala.[103] Philosophia Botanica Linnaeus published Philosophia Botanica in 1751.[104] The book contained a complete survey of the taxonomy system he had been using in his earlier works. It also contained information of how to keep a journal on travels and how to maintain a botanical garden.[105] Nutrix Noverca  Cover of Nutrix Noverca (1752) During Linnaeus's time it was normal for upper class women to have wet nurses for their babies. Linnaeus joined an ongoing campaign to end this practice in Sweden and promote breast-feeding by mothers. In 1752 Linnaeus published a thesis along with Frederick Lindberg, a physician student,[106] based on their experiences.[107] In the tradition of the period, this dissertation was essentially an idea of the presiding reviewer (prases) expounded upon by the student. Linnaeus's dissertation was translated into French by J. E. Gilibert in 1770 as La Nourrice marâtre, ou Dissertation sur les suites funestes du nourrisage mercénaire. Linnaeus suggested that children might absorb the personality of their wet nurse through the milk. He admired the child care practices of the Lapps[108] and pointed out how healthy their babies were compared to those of Europeans who employed wet nurses. He compared the behaviour of wild animals and pointed out how none of them denied their newborns their breastmilk.[108] It is thought that his activism played a role in his choice of the term Mammalia for the class of organisms.[109] Species Plantarum Main article: Species Plantarum Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, the work which is now internationally accepted as the starting point of modern botanical nomenclature, in 1753.[110] The first volume was issued on 24 May, the second volume followed on 16 August of the same year.[note 5][112] The book contained 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes; it described over 7,300 species.[113][114] The same year the king dubbed him knight of the Order of the Polar Star, the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight in this order. He was then seldom seen not wearing the order's insignia.[115] Ennoblement  His coat of arms Linnaeus felt Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy, so he bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The next year, he bought a neighbouring farm, Edeby. He spent the summers with his family at Hammarby; initially it only had a small one-storey house, but in 1762 a new, larger main building was added.[101][116] In Hammarby, Linnaeus made a garden where he could grow plants that could not be grown in the Botanical Garden in Uppsala. He began constructing a museum on a hill behind Hammarby in 1766, where he moved his library and collection of plants. A fire that destroyed about one third of Uppsala and had threatened his residence there necessitated the move.[117] Since the initial release of Systema Naturae in 1735, the book had been expanded and reprinted several times; the tenth edition was released in 1758. This edition established itself as the starting point for zoological nomenclature, the equivalent of Species Plantarum.[113][118] The Swedish King Adolf Frederick granted Linnaeus nobility in 1757, but he was not ennobled until 1761. With his ennoblement, he took the name Carl von Linné (Latinised as Carolus a Linné), 'Linné' being a shortened and gallicised version of 'Linnæus', and the German nobiliary particle 'von' signifying his ennoblement.[3] The noble family's coat of arms prominently features a twinflower, one of Linnaeus's favourite plants; it was given the scientific name Linnaea borealis in his honour by Gronovius. The shield in the coat of arms is divided into thirds: red, black and green for the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral and vegetable) in Linnaean classification; in the centre is an egg "to denote Nature, which is continued and perpetuated in ovo." At the bottom is a phrase in Latin, borrowed from the Aeneid, which reads "Famam extendere factis": we extend our fame by our deeds.[119][120][121] Linnaeus inscribed this personal motto in books that were given to him by friends.[122] After his ennoblement, Linnaeus continued teaching and writing. His reputation had spread over the world, and he corresponded with many different people. For example, Catherine II of Russia sent him seeds from her country.[123] He also corresponded with Giovanni Antonio Scopoli, "the Linnaeus of the Austrian Empire", who was a doctor and a botanist in Idrija, Duchy of Carniola (nowadays Slovenia).[124] Scopoli communicated all of his research, findings, and descriptions (for example of the olm and the dormouse, two little animals hitherto unknown to Linnaeus). Linnaeus greatly respected Scopoli and showed great interest in his work. He named a solanaceous genus, Scopolia, the source of scopolamine, after him, but because of the great distance between them, they never met.[125][126] |

スウェーデンに戻る 結婚式の肖像画 1738年6月28日にスウェーデンに戻ったリンネはファールンに行き、そこでサラ・エリザベス・モーラと婚約した。3か月後、医師として就職し、家族を 養うためにストックホルムに移った。[85][86] リンネは再びパトロンを見つけ、カール・グスタフ・テッシン伯爵と知り合った。海軍省で医師として働く機会を得るのに一役買ってくれた。[87][88] ストックホルムに滞在していたこの時期、リンネはスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの創設に尽力し、くじ引きでアカデミーの初代会長に選ばれた。[89] 経済状況が改善し、家族を養うのに十分な余裕ができたため、婚約者サラ・エリザベス・モーラと結婚する許可を得た。ふたりの結婚式は1739年6月26日 に行われた。17か月後、サラはふたりの最初の息子カールを出産した。さらに2年後には娘のエリザベス・クリスティーナが生まれ、翌年サラはサラ・マグダ レーナを出産したが、生後15日で死亡した。サラとリンネにはその後、ロヴィーサ、サラ・クリスティーナ、ヨハネス、ソフィアの4人の子供が生まれた。  ウプサラの家 1741年5月、リンネはウプサラ大学の医学教授に任命され、医学関連の責任を負うことになった。まもなく、彼は他の医学教授であるニルス・ローゼンと交 代し、代わりに植物園(彼はそれを徹底的に再建し拡張した)、植物学、自然史の責任を負うことになった。同年10月には、妻と生後9か月の息子もウプサラ に移り住んだ。[91] エーランド島とゴットランド島 教授に任命されてから10日後、彼は医学に役立つ植物を探すため、大学の学生6名とともにエーランド島とゴットランド島への遠征に出発した。まず一行は エーランド島に向かい、6月21日まで滞在した後、ゴットランド島のヴィスビューに向けて出帆した。リンネと学生たちはゴットランドに約1か月滞在し、そ の後ウプサラに戻った。この遠征中、彼らはそれまで記録されていなかった100種類の植物を発見した。遠征の観察結果は後にスウェーデン語で書かれた 『Öländska och Gothländska Resa』として出版された。『Flora Lapponica』と同様に、動物学と植物学の両方の観察結果、およびエーランド島とゴットランド島の文化に関する観察結果が含まれている。[92] [93] 1745年の夏、リンネはさらに2冊の本を出版した。『フローラ・スエシカ』と『ファウナ・スエシカ』である。Flora Suecicaは厳密な植物学の書物であり、Fauna Suecicaは動物学の書物であった。[85][94] アンデシュ・セルシウスは1742年に自身の名を冠した温度目盛を考案していた。セルシウスの目盛は現在とは逆転しており、沸点は0℃、氷点は100℃で あった。1745年、リンネは目盛を現在の標準的なものに変更した。[95] ヴェストイェートランド 1746年の夏、リンネは政府から再び遠征の依頼を受け、今度はスウェーデンのヴェストイェートランド地方に向かった。彼は6月12日にウプサラを出発 し、8月11日に帰還した。この遠征の主な同行者は、以前の旅にも同行したことのある学生エリック・グスタフ・リドベックであった。リンネは翌年に出版さ れた著書『ヴェストイェータ旅行記』の中で、この遠征での発見について記述している。[92][96] 旅から戻ると、政府はリンネにスカニア地方という最南端の州への新たな遠征を命じた。しかし、リンネが多忙であると感じたため、この旅は延期された。 [85] 1747年、リンネはスウェーデン王アドルフ・フレドリックから最高医師(archiater)の称号を与えられ、これは彼への大きな敬意の表れであった。[97] 同年、彼はベルリン科学アカデミーの会員に選出された。[98] スコーネ 1749年の春、リンネはついに政府の依頼でスコーネへの旅に出た。彼とともに、弟子のオロフ・セーデルベリも同行した。スコーネに向かう途中、前年に父 が亡くなっていたため、ステンブロフルトの兄弟姉妹のもとを最後に訪れた。この探検は、ほとんどの面でこれまでの旅と似ていたが、今回はクルミとスウェー デンギンバイカの最適な生育地を見つけることも命じられていた。これらの樹木は軍隊がライフル銃を作るのに使用していた。また、一行はラームローサの鉱泉 にも立ち寄り、彼はその鉄分を含む水の質について言及した。[99] この旅は成功を収め、翌年にはリンネの観察結果が『Skånska Resa』で発表された。[100][101] ウプサラ大学学長  ハンマルビーの屋敷の夏の別荘  ウプサラのリンネ庭園 1750年、リンネはウプサラ大学の学長となり、自然科学が尊重される時代が始まった。[85] ウプサラに在籍していた期間に彼が成し遂げた最も重要な貢献は、おそらく教育であった。彼の教え子の多くは、植物標本を収集するために世界中のさまざまな 場所へと旅立った。リンネは、これらの学生の中でも特に優秀な者を「使徒」と呼んだ。[102] 彼の講義は通常、非常に人気があり、植物園で開かれることも多かった。彼は学生たちに、自分自身で考え、誰の言うことも信用しないように教えようとした。 講義よりもさらに人気があったのは、夏の間、毎週土曜日に開催された植物観察遠足で、リンネと学生たちはウプサラ近郊の動植物を探索した。[103] 『植物哲学』 リンネは1751年に『植物哲学』を出版した。[104] この本には、それ以前の著作で彼が使用していた分類体系の完全な調査が含まれていた。また、旅行日記のつけ方や植物園の管理方法についても記されていた。[105] 『Nutrix Noverca(乳母)』  『Nutrix Noverca』の表紙(1752年 リンネの時代には、上流階級の女性が乳母に赤ちゃんを預けることは一般的であった。リンネは、スウェーデンでこの慣習を廃止し、母親による母乳育児を推進 する運動に加わった。1752年、リンネは医師の学生であるフレデリック・リンドバーグ(Frederick Lindberg)とともに、自分たちの経験に基づく論文を発表した。[107] 当時の慣習では、この論文は本質的には審査委員長(prases)の考えを学生が説明したものだった。リンネの論文は、1770年にJ. E. Gilibertによってフランス語に翻訳され、『La Nourrice marâtre, ou Dissertation sur les suites funestes du nourrisage mercénaire』と題された。リンネは、乳児は母乳を通じて乳母の人格を吸収する可能性があると示唆した。彼はラップ人の育児方法を賞賛し [108]、乳母を使うヨーロッパ人の乳児と比較して、彼らの乳児がいかに健康であるかを指摘した。彼は野生動物の行動を比較し、そのどれもが新生児に母 乳を与えないことを指摘した。[108] 彼の活動主義が、生物の分類に哺乳類という用語を選んだ理由のひとつであると考えられている。[109] 『植物種誌 詳細は「植物種誌」を参照 リンネは1753年に『植物種誌』(Species Plantarum)を出版した。この著作は現在では、近代植物命名法の原点として国際的に認められている。第1巻は5月24日に発行され、第2巻は同年 8月16日に発行された。 12] この本は2巻構成で1,200ページあり、7,300種以上が記載されていた。[113][114] 同年、国王は彼をポーラスター勲章の騎士に叙任し、スウェーデンで初めてこの勲章を受けた民間人となった。それ以来、彼はこの勲章を身につけていないとこ ろをほとんど見られなくなった。[115] 貴族化  彼の紋章 リンネはウプサラがうるさく不健康だと感じていたため、1758年にハンマルビーとセーヴィアの2つの農場を購入した。翌年には隣接する農場エーデビーも 購入した。彼は家族とともに夏をハンマルビーで過ごした。当初は小さな平屋しかなかったが、1762年に新しい大きな主屋が増築された。[101] [116] ハンマルビーでリンネは、ウプサラの植物園では栽培できない植物を育てるための庭を作った。1766年にはハンマルビーの裏山に博物館の建設を開始し、自 身の蔵書と植物コレクションを移した。ウプサラの3分の1を焼失させた火災が彼の住居を脅かし、移転が必要となったのである。 1735年に『Systema Naturae』が最初に出版されて以来、この本は何度か増補され、再版された。10版は1758年に出版された。この版は、動物命名法の出発点として確立され、『Species Plantarum』に相当するものとなった。 スウェーデンの国王アドルフ・フレドリックは1757年にリンネに貴族の称号を与えたが、彼が実際に貴族となったのは1761年になってからだった。貴族 となったリンネは、カール・フォン・リンネ(ラテン語表記ではカロルス・ア・リンネ)と名乗り、「リンネ」は「リンネウス」を短縮し、フランス風に変えた ものである。また、ドイツの貴族を示す接尾語「フォン」は 貴族であることを意味する。[3] 貴族の家紋には、リンネの愛した植物であるツル植物が大きく描かれている。これは、リンネの栄誉を称えて、グロノヴィウスによって学名Linnaea borealisと名付けられた。紋章の盾は3等分されており、赤、黒、緑はリンネの分類における自然界の3つの王国(動物、鉱物、植物)を表している。 中央には卵があり、「卵の中で絶えることなく永遠に続く自然を象徴する」という意味が込められている。下には『アエネーイス』から引用したラテン語のフ レーズ「Famam extendere factis」が記されている。「我々は自らの行いによって名声を広げていく」という意味である。[119][120][121] リンネは友人から贈られた本にこの個人的なモットーを書き記した。[122] 貴族に列せられた後も、リンネは教育と執筆活動を続けた。彼の名声は世界中に広まり、多くの人々と文通した。例えば、ロシアの女帝エカチェリーナ2世は、 自国からリンネに種子を送った。[123] また、イドリヤ(カルニオラ公国、現スロベニア)の医師であり植物学者であった「オーストリア帝国のリンネ」ことジョヴァンニ・アントニオ・スコポリとも 文通した (現スロベニア)の医師であり植物学者であった。スコポリは、自身の研究、発見、記述(例えば、ニレウスがそれまで知らなかった2匹の小動物、オームとヤ マネ)をすべて伝えた。リンネはスコポリを非常に尊敬し、彼の研究に強い関心を示した。スコポリの名にちなんで、スコポラミンという名称のナス科の植物が 命名されたが、2人の間には大きな隔たりがあったため、2人は会うことはなかった。[125][126] |

Final years Headstone of him and his son Carl Linnaeus the Younger Linnaeus was relieved of his duties in the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in 1763, but continued his work there as usual for more than ten years after.[85] In 1769 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society for his work.[127] He stepped down as rector at Uppsala University in December 1772, mostly due to his declining health.[84][128] Linnaeus's last years were troubled by illness. He had had a disease called the Uppsala fever in 1764, but survived due to the care of Rosén. He developed sciatica in 1773, and the next year, he had a stroke which partially paralysed him.[129] He had a second stroke in 1776, losing the use of his right side and leaving him bereft of his memory; while still able to admire his own writings, he could not recognise himself as their author.[130][131] In December 1777, he had another stroke which greatly weakened him, and eventually led to his death on 10 January 1778 in Hammarby.[132][128] Despite his desire to be buried in Hammarby, he was buried in Uppsala Cathedral on 22 January.[133][134] His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children. Joseph Banks, an eminent botanist, wished to purchase the collection, but his son Carl refused the offer and instead moved the collection to Uppsala. In 1783 Carl died and Sara inherited the collection, having outlived both her husband and son. She tried to sell it to Banks, but he was no longer interested; instead an acquaintance of his agreed to buy the collection. The acquaintance was a 24-year-old medical student, James Edward Smith, who bought the whole collection: 14,000 plants, 3,198 insects, 1,564 shells, about 3,000 letters and 1,600 books. Smith founded the Linnean Society of London five years later.[134][135] The von Linné name ended with his son Carl, who never married.[7] His other son, Johannes, had died aged 3.[136] There are over two hundred descendants of Linnaeus through two of his daughters.[7] |

晩年 彼と息子のカール・フォン・リンネの墓碑 リンネは1763年にスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの職を解かれたが、その後も10年以上は通常通り仕事を続けた。[85] 1769年には、その業績によりアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された。[127] リンネは1772年12月にウプサラ大学の学長を辞任したが、その主な理由は健康状態の悪化であった。[84][128] リンネの晩年は病に悩まされた。1764年にはウプサラ熱と呼ばれる病にかかったが、ローゼンの手当てにより一命を取り留めた。1773年には坐骨神経痛 を発症し、翌年には脳卒中で半身不随となった。[129] 1776年には二度目の脳卒中を起こし、右半身の麻痺と記憶喪失に見舞われた。自分の書いた文章を鑑賞することはできても、その作者が自分であるとは認識 できなかった。[130][131] 1777年12月、彼は再び脳卒中に見舞われ、体力が著しく衰え、最終的に1778年1月10日にハマルビーで死去した。[132][128] ハマルビーに埋葬されることを望んでいたにもかかわらず、1月22日にウプサラ大聖堂に埋葬された。[133][134] 彼の蔵書とコレクションは未亡人のサラと子供たちに遺贈された。著名な植物学者ジョセフ・バンクスはコレクションの購入を希望したが、息子のカールは申し 出を断り、代わりにコレクションをウプサラに移した。1783年にカールが亡くなり、サラがコレクションを相続した。サラはコレクションをバンクスに売却 しようとしたが、彼はもはや興味を示さなかった。代わりに、彼の知人がコレクションの購入に同意した。その人物は24歳の医学生ジェームズ・エドワード・ スミスで、彼はコレクション全体、すなわち14,000種の植物、3,198種の昆虫、1,564種の貝、およそ3,000通の手紙、1,600冊の本を 買い取った。スミスは5年後にロンドン・リンネ協会を設立した。[134][135] フォン・リンネの名は、結婚しなかった彼の息子カールで途絶えた。[7] もう一人の息子ヨハネスは3歳で亡くなった。[136] リンネには2人の娘がおり、その2人の娘を通じて200人以上の子孫がいる。[7] |

| Apostles Main article: Apostles of Linnaeus  Carl Peter Thunberg was a VOC physician and an apostle of Linnaeus.  Peter Forsskål was among the apostles who met a tragic fate abroad. During Linnaeus's time as Professor and Rector of Uppsala University, he taught many devoted students, 17 of whom he called "apostles". They were the most promising, most committed students, and all of them made botanical expeditions to various places in the world, often with his help. The amount of this help varied; sometimes he used his influence as Rector to grant his apostles a scholarship or a place on an expedition.[137] To most of the apostles he gave instructions of what to look for on their journeys. Abroad, the apostles collected and organised new plants, animals and minerals according to Linnaeus's system. Most of them also gave some of their collection to Linnaeus when their journey was finished.[138] Thanks to these students, the Linnaean system of taxonomy spread through the world without Linnaeus ever having to travel outside Sweden after his return from Holland.[139] The British botanist William T. Stearn notes, without Linnaeus's new system, it would not have been possible for the apostles to collect and organise so many new specimens.[140] Many of the apostles died during their expeditions. Early expeditions Christopher Tärnström, the first apostle and a 43-year-old pastor with a wife and children, made his journey in 1746. He boarded a Swedish East India Company ship headed for China. Tärnström never reached his destination, dying of a tropical fever on Côn Sơn Island the same year. Tärnström's widow blamed Linnaeus for making her children fatherless, causing Linnaeus to prefer sending out younger, unmarried students after Tärnström.[141] Six other apostles later died on their expeditions, including Pehr Forsskål and Pehr Löfling.[140] Two years after Tärnström's expedition, Finnish-born Pehr Kalm set out as the second apostle to North America. There he spent two-and-a-half years studying the flora and fauna of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Canada. Linnaeus was overjoyed when Kalm returned, bringing back with him many pressed flowers and seeds. At least 90 of the 700 North American species described in Species Plantarum had been brought back by Kalm.[142] Cook expeditions and Japan  Apostle Daniel Solander (far left) with Joseph Banks (left, sitting) accompanied James Cook (centre) on his journey to Australia. Daniel Solander was living in Linnaeus's house during his time as a student in Uppsala. Linnaeus was very fond of him, promising Solander his eldest daughter's hand in marriage. On Linnaeus's recommendation, Solander travelled to England in 1760, where he met the English botanist Joseph Banks. With Banks, Solander joined James Cook on his expedition to Oceania on the Endeavour in 1768–71.[143][144] Solander was not the only apostle to journey with James Cook; Anders Sparrman followed on the Resolution in 1772–75 bound for, among other places, Oceania and South America. Sparrman made many other expeditions, one of them to South Africa.[145] Perhaps the most famous and successful apostle was Carl Peter Thunberg, who embarked on a nine-year expedition in 1770. He stayed in South Africa for three years, then travelled to Japan. All foreigners in Japan were forced to stay on the island of Dejima outside Nagasaki, so it was thus hard for Thunberg to study the flora. He did, however, manage to persuade some of the translators to bring him different plants, and he also found plants in the gardens of Dejima. He returned to Sweden in 1779, one year after Linnaeus's death.[146] |

使徒 詳細は「リンネの使徒」を参照  カール・ペッテション・トゥンベリ(カール・ペータ・ソーンバーグ)はオランダ東インド会社の医師であり、リンネの使徒であった。  ピーター・フォシュクオールは、海外で悲劇的な最期を遂げた使徒の一人であった。 リンネがウプサラ大学の教授および学長を務めていた時代、彼は多くの献身的な学生たちに教鞭を執り、そのうちの17人を「使徒」と呼んだ。彼らは最も有望 で、最も熱心な学生であり、全員がしばしば彼の助力を得て、世界各地で植物学の探検を行った。この助力の程度は様々であり、時には学長としての影響力を利 用して、使徒たちに奨学金や探検への参加の機会を与えた。[137] ほとんどの使徒たちに対して、彼は旅の間に何を探すかを指示した。弟子たちは各地で、リンネの体系に従って新しい植物、動物、鉱物を収集し、整理した。 また、ほとんどの弟子たちは、旅を終えると収集したものの一部をリンネに贈った。[138] 弟子たちのおかげで、リンネの分類体系は、リンネがオランダから帰国後、スウェーデン国外に出ることなく世界中に広がった。[ 139] 英国の植物学者ウィリアム・T・スターンは、リンネの新しい分類体系がなければ、使徒たちがこれほど多くの新しい標本を収集し、整理することは不可能だっ ただろうと指摘している。 初期の探検 最初の使徒であり、43歳で妻と子供を持つ牧師であったクリストファー・ターンストルムは、1746年に旅に出た。彼はスウェーデン東インド会社の船に乗 り込み、中国に向かった。ターンストルムは目的地に到達することなく、同年、コンソン島で熱帯熱マラリアにより死亡した。ターンストルムの未亡人は、リン ネウスが自分の子供たちから父親を奪ったと非難し、リンネウスはターンストルムの後に若い未婚の学生を派遣することを好むようになった。[141] ペール・フォルスコーとペール・ローフリングを含む6人の使徒が後に遠征中に死亡した。[140] ターンスストロームの遠征から2年後、フィンランド生まれのペール・カルムが2人目の宣教師として北米に旅立った。 彼はそこで2年半を過ごし、ペンシルベニア、ニューヨーク、ニュージャージー、カナダの動植物相を研究した。カールが帰国し、多くの押し花や種子を持ち 帰ったとき、リンネは大喜びした。 カールは『植物種』で述べられた北米の700種の植物のうち、少なくとも90種を持ち帰っていたのである。 クック探検と日本  使徒ダニエル・ソランダー(左端)とジョセフ・バンクス(左、座っている)は、ジェームズ・クック(中央)のオーストラリアへの旅に同行した。 ダニエル・ソランダーは、ウプサラで学生だった時代にリンネの家に住んでいた。リンネは彼を大変可愛がり、長女との結婚を約束した。リンネの推薦で、ソラ ンダーは1760年にイギリスに渡り、そこでイギリスの植物学者ジョセフ・バンクスと出会った。ソランダーはバンクスの推薦で、1768年から1771年 にかけてエンデバー号でオセアニアへ遠征したジェームズ・クックの航海に参加した。[143][144] ソランダーはジェームズ・クックの航海に参加した唯一の使節ではなかった。1772年から1775年にかけて、オセアニアや南アメリカなどに向かったレゾ リューション号には、アンダース・スパーマンが同行した。スパーマンは他にも多くの探検を行い、そのうちの1つは南アフリカであった。[145] おそらく最も有名で成功した宣教師は、1770年に9年間の探検に出発したカール・ペッテル・ツンベリであろう。彼は3年間南アフリカに滞在した後、日本 へと旅立った。当時、日本に滞在する外国人はすべて長崎の外にある出島に滞在することを余儀なくされていたため、ツンベリーが植物を研究することは困難で あった。しかし、彼は通訳者の何人かを説得してさまざまな植物を持ってくるようにし、出島の庭園でも植物を見つけた。彼はリンネの死から1年後の1779 年にスウェーデンに戻った。[146] |

| Major publications Main article: Carl Linnaeus bibliography Systema Naturae  Title page of the 10th edition of Systema Naturæ (1758) Main article: Systema Naturae The first edition of Systema Naturae was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve-page work.[147] By the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People from all over the world sent their specimens to Linnaeus to be included. By the time he started work on the 12th edition, Linnaeus needed a new invention—the index card—to track classifications.[148] In Systema Naturae, the unwieldy names mostly used at the time, such as "Physalis annua ramosissima, ramis angulosis glabris, foliis dentato-serratis", were supplemented with concise and now familiar "binomials", composed of the generic name, followed by a specific epithet—in the case given, Physalis angulata. These binomials could serve as a label to refer to the species. Higher taxa were constructed and arranged in a simple and orderly manner. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature, was partially developed by the Bauhin brothers (see Gaspard Bauhin and Johann Bauhin) almost 200 years earlier,[149] Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently throughout the work, including in monospecific genera, and may be said to have popularised it within the scientific community. After the decline in Linnaeus's health in the early 1770s, publication of editions of Systema Naturae went in two different directions. Another Swedish scientist, Johan Andreas Murray, issued the Regnum Vegetabile section separately in 1774 as the Systema Vegetabilium, rather confusingly labelled the 13th edition.[150] Meanwhile, a 13th edition of the entire Systema appeared in parts between 1788 and 1793 under the editorship of Johann Friedrich Gmelin. It was through the Systema Vegetabilium that Linnaeus's work became widely known in England, following its translation from the Latin by the Lichfield Botanical Society as A System of Vegetables (1783–1785).[151] Orbis eruditi judicium de Caroli Linnaei MD scriptis ('Opinion of the learned world on the writings of Carl Linnaeus, Doctor') Published in 1740, this small octavo-sized pamphlet was presented to the State Library of New South Wales by the Linnean Society of NSW in 2018. This is considered among the rarest of all the writings of Linnaeus, and crucial to his career, securing him his appointment to a professorship of medicine at Uppsala University. From this position he laid the groundwork for his radical new theory of classifying and naming organisms for which he was considered the founder of modern taxonomy. Species Plantarum Main article: Species Plantarum Species Plantarum (or, more fully, Species Plantarum, exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas) was first published in 1753, as a two-volume work. Its prime importance is perhaps that it is the primary starting point of plant nomenclature as it exists today.[110] Genera Plantarum Main article: Genera Plantarum Genera plantarum: eorumque characteres naturales secundum numerum, figuram, situm, et proportionem omnium fructificationis partium was first published in 1737, delineating plant genera. Around 10 editions were published, not all of them by Linnaeus himself; the most important is the 1754 fifth edition.[152] In it Linnaeus divided the plant Kingdom into 24 classes. One, Cryptogamia, included all the plants with concealed reproductive parts (algae, fungi, mosses and liverworts and ferns).[153] Philosophia Botanica Main article: Philosophia Botanica Philosophia Botanica (1751)[104] was a summary of Linnaeus's thinking on plant classification and nomenclature, and an elaboration of the work he had previously published in Fundamenta Botanica (1736) and Critica Botanica (1737). Other publications forming part of his plan to reform the foundations of botany include his Classes Plantarum and Bibliotheca Botanica: all were printed in Holland (as were Genera Plantarum (1737) and Systema Naturae (1735)), the Philosophia being simultaneously released in Stockholm.[154] |

主要な出版物 詳細は「カール・フォン・リンネの著作一覧」を参照 『動物誌』  『動物誌』第10版(1758年)のタイトルページ 詳細は「『動物誌』」を参照 『Systema Naturae』の初版は1735年にオランダで印刷された。12ページの著作であった。[147] 1758年に第10版が刊行されるまでに、動物4,400種、植物7,700種を分類した。世界中の人々が、分類に含めるために標本をリンネに送った。リ ンネが第12版の作業に取り掛かったときには、分類を追跡するためにインデックスカードという新たな発明が必要になっていた。 『動物誌』では、当時主に使用されていた扱いにくい名称、例えば「Physalis annua ramosissima, ramis angulosis glabris, foliis dentato-serratis」のようなものは、簡潔で現在ではおなじみの「二名法」で補足された。二名法は、属名に特定の形容詞を続けたもので、こ の例では「Physalis angulata」となる。この二名法は、種を参照するラベルとして使用できる。より上位の分類群は、単純かつ整然とした方法で構築され、整理された。現 在二名法として知られるこの体系は、約200年前にバウヒン兄弟(Gaspard BauhinとJohann Bauhinを参照)によって部分的に開発されていたが[149]、リンネは単一種属を含むすべての著作において一貫してこの体系を使用した最初の人物で あり、科学界に普及させた人物であると言える。 1770年代初頭にリンネの健康状態が悪化すると、『動物誌』の版の出版は2つの異なる方向に向かった。スウェーデンの科学者ヨハン・アンドレアス・マ リーは、1774年に『植物界』を『植物体系』として別個に発行したが、これは13版という紛らわしいラベルが貼られていた。[150] 一方、ヨハン・フリードリヒ・グメリンの編集により、1788年から1793年の間に『植物体系』の13版が部分的に発行された。Systema Vegetabiliumを通じて、リネアスの業績は、リッチフィールド植物学会によるラテン語からの翻訳『野菜の体系』(1783年~1785年)によ り、イギリスで広く知られるようになった。[151] Orbis eruditi judicium de Caroli Linnaei MD scriptis (「カール・フォン・リンネ博士の著作に対する学識者たちの評価」) 1740年に出版されたこの小型の八つ折り判パンフレットは、2018年にニューサウスウェールズ州のリンネ学会によってニューサウスウェールズ州立図書 館に寄贈された。これは、リンネの著作の中でも最も貴重なもののひとつと考えられており、彼にとってウプサラ大学の医学教授職を得ることはキャリア上極め て重要であった。この地位から、彼は生物の分類と命名に関する急進的な新理論の基礎を築き、現代分類学の創始者とみなされるようになった。 『植物種誌 詳細は「植物種誌」を参照 Species Plantarum (または、より完全には、Species Plantarum, exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas) は、1753年に2巻本として初めて出版された。その最も重要な点は、今日存在する植物命名法の原点であるということである。[110] 植物属 詳細は「植物属」を参照 Genera plantarum: eorumque characteres naturales secundum numerum, figuram, situm, et proportionem omnium fructificationis partium(植物属:それらの自然の特徴を数、図、位置、およびすべての果実形成部分の比率に従って)は、1737年に初めて出版され、植物の属を定 義した。およそ10版が出版されたが、そのすべてがリンネ自身によるものではない。最も重要なのは1754年の第5版である。[152] リンネは、この中で植物界を24の綱に分類した。そのうちの1つである隠花植物綱には、生殖器官が隠れている植物(藻類、菌類、蘚類、苔類、シダ類)がす べて含まれていた。[153] 『植物哲学』 詳細は「植物哲学」を参照 『植物哲学』(1751年)は、リンネの植物分類と命名法に関する考えをまとめたものであり、彼が以前に『植物学の基礎』(1736年)と『植物学の批 判』(1737年)で発表した研究をさらに発展させたものだった。植物学の基礎を改革するという彼の計画の一部を成すその他の出版物には、彼の著書『植物 分類誌』や『植物学図書館』などがある。これらはすべてオランダで印刷された(『植物属』(1737年)や『自然体系』(1735年)も同様)。『哲学』 は同時にストックホルムでも出版された。[154] |

Collections Linnaeus marble by Léon-Joseph Chavalliaud (1899), outside the Palm House at Sefton Park, Liverpool At the end of his lifetime the Linnean collection in Uppsala was considered one of the finest collections of natural history objects in Sweden. Next to his own collection he had also built up a museum for the university of Uppsala, which was supplied by material donated by Carl Gyllenborg (in 1744–1745), crown-prince Adolf Fredrik (in 1745), Erik Petreus (in 1746), Claes Grill (in 1746), Magnus Lagerström (in 1748 and 1750) and Jonas Alströmer (in 1749). The relation between the museum and the private collection was not formalised and the steady flow of material from Linnean pupils were incorporated to the private collection rather than to the museum.[155] Linnaeus felt his work was reflecting the harmony of nature and he said in 1754 "the earth is then nothing else but a museum of the all-wise creator's masterpieces, divided into three chambers". He had turned his own estate into a microcosm of that 'world museum'.[156] In April 1766 parts of the town were destroyed by a fire and the Linnean private collection was subsequently moved to a barn outside the town, and shortly afterwards to a single-room stone building close to his country house at Hammarby near Uppsala. This resulted in a physical separation between the two collections; the museum collection remained in the botanical garden of the university. Some material which needed special care (alcohol specimens) or ample storage space was moved from the private collection to the museum. In Hammarby the Linnean private collections suffered seriously from damp and the depredations by mice and insects. Carl von Linné's son (Carl Linnaeus) inherited the collections in 1778 and retained them until his own death in 1783. Shortly after Carl von Linné's death his son confirmed that mice had caused "horrible damage" to the plants and that also moths and mould had caused considerable damage.[157] He tried to rescue them from the neglect they had suffered during his father's later years, and also added further specimens. This last activity however reduced rather than augmented the scientific value of the original material. In 1784 the young medical student James Edward Smith purchased the entire specimen collection, library, manuscripts, and correspondence of Carl Linnaeus from his widow and daughter and transferred the collections to London.[158][159] Not all material in Linné's private collection was transported to England. Thirty-three fish specimens preserved in alcohol were not sent and were later lost.[160] In London Smith tended to neglect the zoological parts of the collection; he added some specimens and also gave some specimens away.[161] Over the following centuries the Linnean collection in London suffered enormously at the hands of scientists who studied the collection, and in the process disturbed the original arrangement and labels, added specimens that did not belong to the original series and withdrew precious original type material.[157] Much material which had been intensively studied by Linné in his scientific career belonged to the collection of Queen Lovisa Ulrika (1720–1782) (in the Linnean publications referred to as "Museum Ludovicae Ulricae" or "M. L. U."). This collection was donated by her grandson King Gustav IV Adolf (1778–1837) to the museum in Uppsala in 1804. Another important collection in this respect was that of her husband King Adolf Fredrik (1710–1771) (in the Linnean sources known as "Museum Adolphi Friderici" or "Mus. Ad. Fr."), the wet parts (alcohol collection) of which were later donated to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and is today housed in the Swedish Museum of Natural History at Stockholm. The dry material was transferred to Uppsala.[155] |

コレクション レオン=ジョゼフ・シャヴァリオー作のリンネウス大理石(1899年)、リバプール、セフトン・パークのパーム・ハウスの外 生涯の終わりには、ウプサラのリンネコレクションはスウェーデンで最も優れた自然史コレクションのひとつと考えられていた。自身のコレクションの他に、 カール・ギレンボルグ(1744年~1745年)、皇太子アドルフ・フレドリック(1745年)、エリック・ペトレウス(1746年)、クレス・グリル (1746年)、マグヌス・ラーゲストロム(1748年および1750年)、ヨナス・アルストロマー(1749年)から寄贈された資料を展示するウプサラ 大学の博物館も設立した。 45年)、エリック・ペトレウス(1746年)、クレス・グリル(1746年)、マグヌス・ラーゲルストレム(1748年と1750年)、ヨナス・アルス トロマー(1749年)から寄贈された資料によって充実した。博物館と個人コレクションの関係は正式なものではなく、リンネの弟子たちから寄せられた資料 は、博物館ではなく個人コレクションに組み込まれた。[155] リンネは、自らの研究が自然界の調和を反映していると感じており、1754年には「地球は、全知の創造主の傑作を集めた博物館であり、3つの部屋に分けら れている」と述べている。彼は自身の土地を、その「世界博物館」の縮図に変えたのである。[156] 1766年4月、街の一部が火災で焼失し、リンネの個人コレクションは街外れの納屋に移され、その後まもなくウプサラ近郊のハマービーにあるカントリーハ ウスの近くにある石造りの一室に移された。これにより、2つのコレクションは物理的に分離されることとなった。博物館のコレクションは大学の植物園に残さ れた。特別な注意(アルコール標本)や十分な保管スペースを必要とする一部の資料は、個人コレクションから博物館に移された。 ハマービーでは、リンネの個人コレクションは湿気やネズミや昆虫による被害に深刻な打撃を受けていた。カール・フォン・リンネの息子(カール・フォン・リ ンネ)は1778年にコレクションを相続し、1783年に死去するまでコレクションを保管した。カール・フォン・リンネの死後まもなく、息子が植物に「ひ どい被害」を与えたのはネズミの仕業であり、ガやカビもかなりの被害をもたらしたことを確認した。[157] 彼は、父親の晩年に放置されていた植物を救い出し、さらに標本を追加した。しかし、この最後の活動は、元の材料の科学的価値を増大させるというよりも、む しろ減少させるものだった。 1784年、若い医学生ジェームズ・エドワード・スミスが、未亡人と娘からカール・フォン・リンネの標本コレクション、図書館、原稿、書簡のすべてを購入 し、コレクションをロンドンに移した。[158][159] リンネの個人コレクションのすべてがイギリスに運ばれたわけではない。アルコール漬けにされた33点の魚類標本は送られず、後に紛失した。[160] ロンドンでスミスは、コレクションの動物学的な部分をないがしろにする傾向があった。彼はいくつかの標本を追加し、またいくつかの標本を譲渡した。 [161] その後の数世紀にわたって、ロンドンのリンネコレクションは、コレクションを研究する科学者たちによって甚大な被害を受け、その過程で元の配置やラベルが 乱され、元のシリーズに属さない標本が追加され、貴重な元のタイプ標本が撤去された。[157] リンネが科学者として精力的に研究した多くの資料は、ルイーザ・ウルリカ女王(1720年 - 1782年)のコレクションに属していた(リンネ協会の出版物では「Museum Ludovicae Ulricae」または「M. L. U.」と表記されている)。このコレクションは、彼女の孫であるグスタフ4世アドルフ王(1778年 - 1837年)によって1804年にウプサラの博物館に寄贈された。この点で、もうひとつ重要なコレクションは、彼女の夫であるアドルフ・フレドリク王 (1710年 - 1771年)のコレクション(リンネの資料では「アドルフィ・フリデリイ博物館」または「Mus. Ad. Fr.」として知られている)である。そのうちの湿った部分(アルコールコレクション)は後にスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーに寄贈され、現在はストック ホルムの自然史博物館に収蔵されている。乾燥した標本はウプサラに移された。[155] |

System of taxonomy Table of the Animal Kingdom (Regnum Animale) from the 1st edition of Systema Naturæ (1735) Main article: Linnaean taxonomy The establishment of universally accepted conventions for the naming of organisms was Linnaeus's main contribution to taxonomy—his work marks the starting point of consistent use of binomial nomenclature.[162] During the 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, Linnaeus also developed what became known as the Linnaean taxonomy; the system of scientific classification now widely used in the biological sciences. A previous zoologist Rumphius (1627–1702) had more or less approximated the Linnaean system and his material contributed to the later development of the binomial scientific classification by Linnaeus.[163] The Linnaean system classified nature within a nested hierarchy, starting with three kingdoms. Kingdoms were divided into classes and they, in turn, into orders, and thence into genera (singular: genus), which were divided into species (singular: species).[164] Below the rank of species he sometimes recognised taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank; these have since acquired standardised names such as variety in botany and subspecies in zoology. Modern taxonomy includes a rank of family between order and genus and a rank of phylum between kingdom and class that were not present in Linnaeus's original system.[165] Linnaeus's groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics, and not based upon differences.[165] Of his higher groupings, only those for animals are still in use, and the groupings themselves have been significantly changed since their conception, as have the principles behind them. Nevertheless, Linnaeus is credited with establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification which is based upon observable characteristics and intended to reflect natural relationships.[162][166] While the underlying details concerning what are considered to be scientifically valid "observable characteristics" have changed with expanding knowledge (for example, DNA sequencing, unavailable in Linnaeus's time, has proven to be a tool of considerable utility for classifying living organisms and establishing their evolutionary relationships), the fundamental principle remains sound. Human taxonomy Main article: Human taxonomy § History Linnaeus's system of taxonomy was especially noted as the first to include humans (Homo) taxonomically grouped with apes (Simia), under the header of Anthropomorpha. German biologist Ernst Haeckel speaking in 1907 noted this as the "most important sign of Linnaeus's genius".[167] Linnaeus classified humans among the primates beginning with the first edition of Systema Naturae.[168] During his time at Hartekamp, he had the opportunity to examine several monkeys and noted similarities between them and man.[169] He pointed out both species basically have the same anatomy; except for speech, he found no other differences.[170][note 6] Thus he placed man and monkeys under the same category, Anthropomorpha, meaning "manlike".[171] This classification received criticism from other biologists such as Johan Gottschalk Wallerius, Jacob Theodor Klein and Johann Georg Gmelin on the ground that it is illogical to describe man as human-like.[172] In a letter to Gmelin from 1747, Linnaeus replied:[173][note 7] It does not please [you] that I've placed Man among the Anthropomorpha, perhaps because of the term 'with human form',[note 8] but man learns to know himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name we apply. But I seek from you and from the whole world a generic difference between man and simian that [follows] from the principles of Natural History.[note 9] I absolutely know of none. If only someone might tell me a single one! If I would have called man a simian or vice versa, I would have brought together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to have by virtue of the law of the discipline.  Detail from the sixth edition of Systema Naturae (1748) describing Ant[h]ropomorpha with a division between Homo and Simia The theological concerns were twofold: first, putting man at the same level as monkeys or apes would lower the spiritually higher position that man was assumed to have in the great chain of being, and second, because the Bible says man was created in the image of God[174] (theomorphism), if monkeys/apes and humans were not distinctly and separately designed, that would mean monkeys and apes were created in the image of God as well. This was something many could not accept.[175] The conflict between world views that was caused by asserting man was a type of animal would simmer for a century until the much greater, and still ongoing, creation–evolution controversy began in earnest with the publication of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin in 1859. After such criticism, Linnaeus felt he needed to explain himself more clearly. The 10th edition of Systema Naturae introduced new terms, including Mammalia and Primates, the latter of which would replace Anthropomorpha[176] as well as giving humans the full binomial Homo sapiens.[177] The new classification received less criticism, but many natural historians still believed he had demoted humans from their former place of ruling over nature and not being a part of it. Linnaeus believed that man biologically belongs to the animal kingdom and had to be included in it.[178] In his book Dieta Naturalis, he said, "One should not vent one's wrath on animals, Theology decree that man has a soul and that the animals are mere 'automata mechanica,' but I believe they would be better advised that animals have a soul and that the difference is of nobility."[179]  Anthropomorpha, from the 1760 dissertation by C. E. Hoppius[180] 1. Troglodyta Bontii, 2. Lucifer Aldrovandi, 3. Satyrus Tulpii, 4. Pygmaeus Edwardi Linnaeus added a second species to the genus Homo in Systema Naturae based on a figure and description by Jacobus Bontius from a 1658 publication: Homo troglodytes ("caveman")[181][182] and published a third in 1771: Homo lar.[183] Swedish historian Gunnar Broberg states that the new human species Linnaeus described were actually simians or native people clad in skins to frighten colonial settlers, whose appearance had been exaggerated in accounts to Linnaeus.[184] For Homo troglodytes Linnaeus asked the Swedish East India Company to search for one, but they did not find any signs of its existence.[185] Homo lar has since been reclassified as Hylobates lar, the lar gibbon.[186] See also: Race (human categorization) In the first edition of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus subdivided the human species into four varieties: "Europæus albesc[ens]" (whitish European), "Americanus rubesc[ens]" (reddish American), "Asiaticus fuscus" (tawny Asian) and "Africanus nigr[iculus]" (blackish African).[187][188] In the tenth edition of Systema Naturae he further detailed phenotypical characteristics for each variety, based on the concept of the four temperaments from classical antiquity,[189][dubious – discuss] and changed the description of Asians' skin tone to "luridus" (yellow).[190] While Linnaeus believed that these varieties resulted from environmental differences between the four known continents,[191] the Linnean Society acknowledges that his categorization's focus on skin color and later inclusion of cultural and behavioral traits cemented colonial stereotypes and provided the foundations for scientific racism.[192] Additionally, Linnaeus created a wastebasket taxon "monstrosus" for "wild and monstrous humans, unknown groups, and more or less abnormal people".[193] In 1959, W. T. Stearn designated Linnaeus to be the lectotype of H. sapiens.[194][195][196] Influences and economic beliefs  Statue on University of Chicago campus Linnaeus's applied science was inspired not only by the instrumental utilitarianism general to the early Enlightenment, but also by his adherence to the older economic doctrine of Cameralism.[197] Additionally, Linnaeus was a state interventionist. He supported tariffs, levies, export bounties, quotas, embargoes, navigation acts, subsidised investment capital, ceilings on wages, cash grants, state-licensed producer monopolies, and cartels.[198] |

分類体系 『動物界(Regnum Animale)』の表(『自然体系(Systema Naturæ)』第1版(1735年)より 詳細は「リンネの分類学」を参照 生物の命名に関する世界的に受け入れられた規約の確立は、分類学におけるリンネの主な功績であり、彼の業績は二名法の一貫した使用の出発点となった。 [162] 18世紀の自然史の知識の拡大に伴い、リンネは後にリンネ分類学として知られるようになった分類体系を開発した。この体系は現在、生物学の分野で広く使用 されている科学的な分類体系である。以前の動物学者ルンピウス(1627年-1702年)は、リンネの体系にほぼ近似した分類体系を構築しており、彼の資 料は後にリンネによる二名法に基づく科学的分類の発展に貢献した。 リンネの体系では、自然界は3つの界から始まる入れ子状の階層構造で分類された。界はさらにクラスに分けられ、クラスはさらにオーダに分けられ、オーダは さらに属(単数形:属)に分けられ、属はさらに種(単数形:種)に分けられた。[164] 種のランクより下位には、時にはより下位の(名称のない)ランクの分類群が認められた。これらは、植物学では変種、動物学では亜種など、標準化された名称 が与えられている。現代の分類学では、リンネの原体系には存在しなかった、目(order)と属(genus)の間に科(family)の階級、界 (phylum)と門(class)の間に門(phylum)の階級が含まれている。 リンネの分類は、共通の物理的特性に基づいており、相違点に基づいていたわけではない。[165] 彼の分類体系のうち、動物に関するもののみが現在も使用されているが、その分類体系自体は、その概念が生まれた当初から大幅に変更されており、その背景に ある原則も変更されている。それでもなお、リンネは、観察可能な特徴に基づいて自然界の関係を反映することを目的とした分類の階層構造という考え方を確立 した功績を認められている。[162][166] 科学的に有効な「 知識の拡大に伴って変化してきたが(例えば、リンネの時代には存在しなかったDNA配列は、生物の分類や進化上の関係を明らかにする上で非常に有用な手段 であることが証明されている)、基本的な原則は依然として健全である。 ヒトの分類 詳細は「ヒトの分類 § 歴史」を参照 リンネの分類体系は、特にヒト(ホモ)が類人猿(シミア)とともに「人型」という見出しのもとに分類された最初の例として注目された。1907年にドイツの生物学者エルンスト・ヘッケルは、これを「リンネの天才の最も重要な兆候」であると述べた。[167] リンネは『動物誌』の初版から、人間を霊長類に分類していた。[168] ハルテカンプに滞在していた間、彼はいくつかの猿を観察する機会があり、それらと人間との類似点に気づいた。[169] 彼は、両種は基本的に同じ解剖学的構造を持っていると指摘した。言語を除いて、それ以外の違いは見出せなかった。[170][注釈 6] したがって、彼は人間と猿を同じ 「人間のような」という意味の「Anthropomorpha」という同じカテゴリーに置いた。[171] この分類は、ヨハン・ゴットシャルク・ワレリウス、ヤコブ・テオドール・クライン、ヨハン・ゲオルク・ゲムリンといった他の生物学者から、人間を人間のよ うなものとして表現するのは非論理的であるという理由で批判を受けた。[172] 1747年のゲムリン宛ての手紙で、リンネは次のように答えている。[173][注釈 7] 私が人間を人型類に分類したことがお気に召さないようだが、それはおそらく「人型」という表現が原因だろう。[注釈 8] しかし、人間は自分自身を知ることを学ぶ。言葉の定義についてあれこれ言うのはやめよう。どのような名称を適用しようと、私にとっては同じことだ。しか し、私はあなたや全世界から、自然史の原則から導かれる人間と類人猿の一般的な違いを求めている。[注9] 私はまったく知らない。誰か教えてくれたらいいのに!もし私が人間を類人猿と呼んだり、その逆のことをしたら、すべての神学者を敵に回すことになるだろ う。おそらく、規律の法則に従うべきだっただろう。  Systema Naturae(1748年)第6版の「ヒト上科」の図。ヒトとサルを区別している 神学上の懸念は2つあった。まず、人間を猿や類人猿と同じレベルに置くことは、人間が「存在の連鎖」の中で持つと想定されていた精神的に高い地位を低下さ せることになる。次に、聖書は人間が神の像に創造されたと述べているため(174)(神の像としての人間説)、猿や類人猿と人間が明確に区別されて別々に 設計されていないのであれば、猿や類人猿も神の像に創造されたことになる。これは多くの人々には受け入れがたいことだった。[175] 人間が動物の一種であると主張することによって生じた世界観の対立は、1859年にチャールズ・ダーウィンが『種の起源』を出版し、現在も続く創造論と進 化論の論争が本格的に始まるまで、1世紀にわたってくすぶり続けた。 このような批判を受けて、リンネはより明確に説明する必要があると感じた。『動物誌』第10版では、新たに「哺乳類」や「霊長類」などの用語が導入され、 後者は「人型類」に代わるものとなった。また、人間には「ホモ・サピエンス」という完全な二名法が与えられた。[177] この新しい分類法はそれほど批判を受けなかったが、多くの博物学者は、リンネが人間を自然界を支配する存在から、自然界の一部ではない存在へと格下げした と考えた。リンネは、人間は生物学的に動物界に属し、動物界に含められるべきだと考えていた。[178] 著書『Dieta Naturalis』の中で、彼は「動物に対して怒りをぶつけるべきではない。神学では、人間には魂があり、動物は単なる『機械仕掛けの人形』であると定 めているが、私は動物にも魂があり、その違いは尊厳性にあると考える」と述べている。[179]  1760年のC. E. Hoppiusによる論文に登場するAnthropomorpha(ヒト形類)[180] 1. Troglodyta Bontii、2. Lucifer Aldrovandi、3. Satyrus Tulpii、4. Pygmaeus Edwardi リンネは、1658年に出版されたヤコブス・ボンティウスの著書に記載された図と説明に基づいて、『動物誌』の中でホモ属に2番目の種を追加した。ホモ・ トログローデス(「穴居人」)[181][182]、そして1771年に3番目の種を発表した。スウェーデンの歴史家グンナー・ブロバーグは、リンネが記 述した新しいヒトの種は、実際にはサルか、植民地開拓者を怖がらせるために毛皮をまとった先住民であり、その外見は リンネに伝えられた話が誇張されたものだったと述べている。[184] ホモ・トロゴディテスについて、リンネはスウェーデン東インド会社にその探索を依頼したが、トロゴディテスの存在を示す痕跡は発見されなかった。 [185] ホモ・ラルは、それ以来、テナガザルの一種であるヒロバテス・ラル(lar gibbon)として再分類されている。[186] 参照:人種(人間の分類) 『動物誌』の初版において、リンネは人間の種を4つの品種に細分した。「Europæus albesc[ens]」(白っぽいヨーロッパ人)、「Americanus rubesc[ens]」(赤っぽいアメリカ人)、「Asiaticus fuscus」(黄褐色のアジア人)、「Africanus nigr[iculus]」(黒っぽいアフリカ人)である。[187][188] 『動物誌』の第10版では、 古典古代の4つの気質の概念に基づいて、各品種について表現型の特徴をさらに詳細に説明し[189][疑わしいので議論が必要]、アジア人の肌の色調の説 明を「luridus」(黄色)に変更した。[190] リンネは、これらの品種は4つの既知の大陸間の環境の違いから生じたと考えていたが、[191] リンネ学会は、彼の分類が肌の色に焦点を当て、後に文化的および行動的特徴を含めたことで、植民地主義的な固定観念が固まり、科学的人種差別の基礎が築か れたことを認めている。[192] さらに、リンネは「野生で怪物のような人間、未知の集団、および多かれ少なかれ異常な人々」のために「monstrosus」というごみ箱分類群を作っ た。[193] 1959年、W. T. Stearnは、H. sapiensのレクトタイプとしてリンネを指定した。[194][195][196] 影響と経済観  シカゴ大学構内の像 リンネの応用科学は、初期の啓蒙主義に共通する道具的功利主義だけでなく、カムパニスムという古い経済学説への固執からも影響を受けている。[197] さらに、リンネは国家介入主義者でもあった。彼は関税、課徴金、輸出奨励金、割当、禁輸、航海法、助成金付き投資資金、賃金上限、現金給付、国が認可した 生産者の独占、およびカルテルを支持した。[198] |