米国中央情報局

Central Intelligence Agency

☆ 中央情報局(Central Intelligence Agency、CIA /ˌ.aː.ɪ/)は、アメリカ連邦政府の民間対外情報機関であり、世界中から情報を収集・分析し、秘密工作を行うことで国家安全保障を推進することを任 務としている。本部はバージニア州ラングレーのジョージ・ブッシュ・センター・フォー・インテリジェンスにあり、「ラングレー」という愛称で呼ばれること もある。米国情報コミュニティ(IC)の主要メンバーであるCIAは、2004年以降、国民情報長官の直属となり、大統領と内閣への情報提供に注力してい る。 CIAは長官を長とし、分析局や作戦局などさまざまな部局に分かれている。連邦捜査局(FBI)とは異なり、CIAは法執行機能を持たず、海外での情報収 集に重点を置いており、国内での情報収集は限られている[6]。多くの国で情報サービスの確立に貢献し、多くの外国組織に支援を提供してきた。CIAは、 特別活動センターを含む準軍事作戦ユニットを通じて、外国の政治的影響力を行使している。また、拷問の計画、調整、訓練、実行、技術支援など、いくつかの 外国の政治団体や政府に支援を提供してきた。多くの政権交代に関与し、テロ攻撃や外国指導者の暗殺を計画した。 第二次世界大戦中、アメリカの諜報活動と秘密工作は戦略サービス局(OSS)によって行われていた。OSSは1945年にハリー・S・トルーマン大統領に よって廃止され、トルーマン大統領は1946年に中央情報部(Central Intelligence Group)を創設した。冷戦が激化する中、1947年の国民安全保障法により、中央情報長官(DCI)を長とするCIAが設立された。1949年に制定 された中央情報局法によって、CIAは議会の監視のほとんどを免除され、1950年代にはアメリカの外交政策の主要な手段となった。CIAは共産主義政権 に対する心理作戦を採用し、アメリカの利益を促進するためにクーデターを支援した。CIAが支援した主な作戦には、1953年のイランでのクーデター、 1954年のグアテマラでのクーデター、1961年のキューバへのピッグス湾侵攻、1973年のチリでのクーデターなどがある。1975年、米上院の チャーチ委員会がMKUltraやCHAOSなどの違法な作戦を暴露し、その後、監視が強化された。1980年代、CIAはアフガニスタンのムジャヒディ ンとニカラグアのコントラを支援し、2001年の9.11テロ以来、世界対テロ戦争の一翼を担ってきた。 CIAは、政治的暗殺、拷問、国内盗聴、プロパガンダ、マインドコントロール技術、麻薬密売など、数多くの論争の的となってきた。

| The Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA /ˌsiː.aɪˈeɪ/) is a civilian foreign

intelligence service of the federal government of the United States

tasked with advancing national security through collecting and

analyzing intelligence from around the world and conducting covert

operations. The agency is headquartered in the George Bush Center for

Intelligence in Langley, Virginia, and is sometimes metonymously called

"Langley". A major member of the United States Intelligence Community

(IC), the CIA has reported to the director of national intelligence

since 2004, and is focused on providing intelligence for the president

and the Cabinet. The CIA is headed by a director and is divided into various directorates, including a Directorate of Analysis and Directorate of Operations. Unlike the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the CIA has no law enforcement function and focuses on intelligence gathering overseas, with only limited domestic intelligence collection.[6] The CIA is responsible for coordinating all human intelligence (HUMINT) activities in the IC. It has been instrumental in establishing intelligence services in many countries, and has provided support to many foreign organizations. The CIA exerts foreign political influence through its paramilitary operations units, including its Special Activities Center. It has also provided support to several foreign political groups and governments, including planning, coordinating, training and carrying out torture, and technical support. It was involved in many regime changes and carrying out terrorist attacks and planned assassinations of foreign leaders. During World War II, U.S. intelligence and covert operations had been undertaken by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The office was abolished in 1945 by President Harry S. Truman, who created the Central Intelligence Group in 1946. Amid the intensifying Cold War, the National Security Act of 1947 established the CIA, headed by a director of central intelligence (DCI). The Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949 exempted the agency from most Congressional oversight, and during the 1950s, it became a major instrument of U.S. foreign policy. The CIA employed psychological operations against communist regimes, and backed coups to advance American interests. Major CIA-backed operations include the 1953 coup in Iran, the 1954 coup in Guatemala, the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, and the 1973 coup in Chile. In 1975, the Church Committee of the U.S. Senate revealed illegal operations such as MKUltra and CHAOS, after which greater oversight was imposed. In the 1980s, the CIA supported the Afghan mujahideen and Nicaraguan Contras, and since the September 11 attacks in 2001 has played a role in the Global War on Terrorism. The agency has been the subject of numerous controversies, including its use of political assassinations, torture, domestic wiretapping, propaganda, mind control techniques, and drug trafficking, among others.  |

中央情報局(Central Intelligence

Agency、CIA

/ˌ.aː.ɪ/)は、アメリカ連邦政府の民間対外情報機関であり、世界中から情報を収集・分析し、秘密工作を行うことで国家安全保障を推進することを任

務としている。本部はバージニア州ラングレーのジョージ・ブッシュ・センター・フォー・インテリジェンスにあり、「ラングレー」という愛称で呼ばれること

もある。米国情報コミュニティ(IC)の主要メンバーであるCIAは、2004年以降、国民情報長官の直属となり、大統領と内閣への情報提供に注力してい

る。 CIAは長官を長とし、分析局や作戦局などさまざまな部局に分かれている。連邦捜査局(FBI)とは異なり、CIAは法執行機能を持たず、海外での情報収 集に重点を置いており、国内での情報収集は限られている[6]。多くの国で情報サービスの確立に貢献し、多くの外国組織に支援を提供してきた。CIAは、 特別活動センターを含む準軍事作戦ユニットを通じて、外国の政治的影響力を行使している。また、拷問の計画、調整、訓練、実行、技術支援など、いくつかの 外国の政治団体や政府に支援を提供してきた。多くの政権交代に関与し、テロ攻撃や外国指導者の暗殺を計画した。 第二次世界大戦中、アメリカの諜報活動と秘密工作は戦略サービス局(OSS)によって行われていた。OSSは1945年にハリー・S・トルーマン大統領に よって廃止され、トルーマン大統領は1946年に中央情報部(Central Intelligence Group)を創設した。冷戦が激化する中、1947年の国民安全保障法により、中央情報長官(DCI)を長とするCIAが設立された。1949年に制定 された中央情報局法によって、CIAは議会の監視のほとんどを免除され、1950年代にはアメリカの外交政策の主要な手段となった。CIAは共産主義政権 に対する心理作戦を採用し、アメリカの利益を促進するためにクーデターを支援した。CIAが支援した主な作戦には、1953年のイランでのクーデター、 1954年のグアテマラでのクーデター、1961年のキューバへのピッグス湾侵攻、1973年のチリでのクーデターなどがある。1975年、米上院の チャーチ委員会がMKUltraやCHAOSなどの違法な作戦を暴露し、その後、監視が強化された。1980年代、CIAはアフガニスタンのムジャヒディ ンとニカラグアのコントラを支援し、2001年の9.11テロ以来、世界対テロ戦争の一翼を担ってきた。 CIAは、政治的暗殺、拷問、国内盗聴、プロパガンダ、マインドコントロール技術、麻薬密売など、数多くの論争の的となってきた。 |

| Purpose When the CIA was created, its purpose was to create a clearinghouse for foreign policy intelligence and analysis, collecting, analyzing, evaluating, and disseminating foreign intelligence, and carrying out covert operations.[7] As of 2013, the CIA had five priorities:[3] Counterterrorism Nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction Indications and warnings for senior policymakers Counterintelligence Cyber intelligence |

目的 CIAが創設された当時、その目的は外交政策に関する情報と分析のためのクリアリングハウスを創設し、対外情報を収集、分析、評価、発信し、諜報活動を行うことであった[7]。 2013年現在、CIAには次の5つの優先事項がある[3]。 テロ対策 大量破壊兵器の不拡散 上級政策立案者への示唆と警告 防諜活動 サイバー情報 |

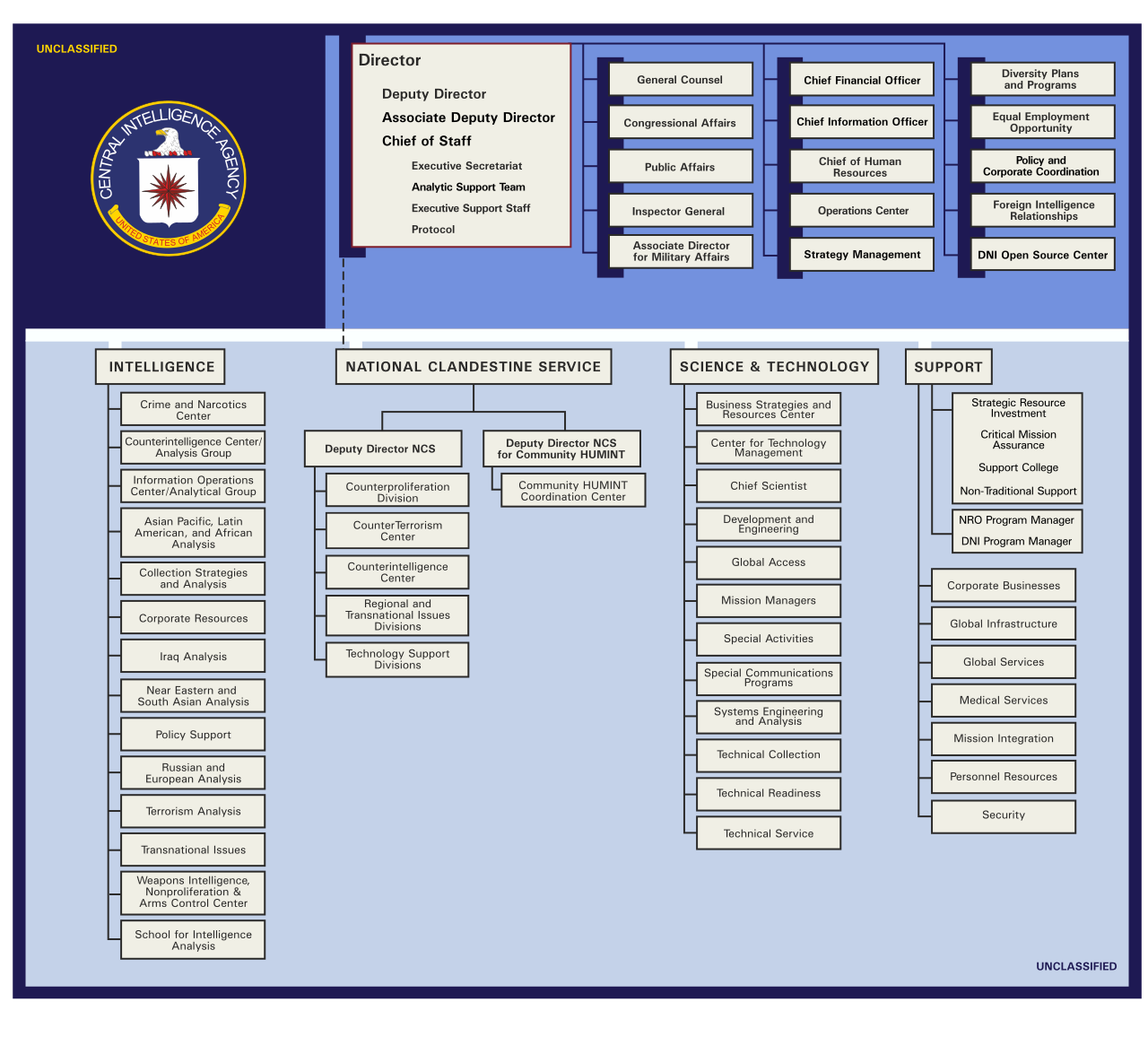

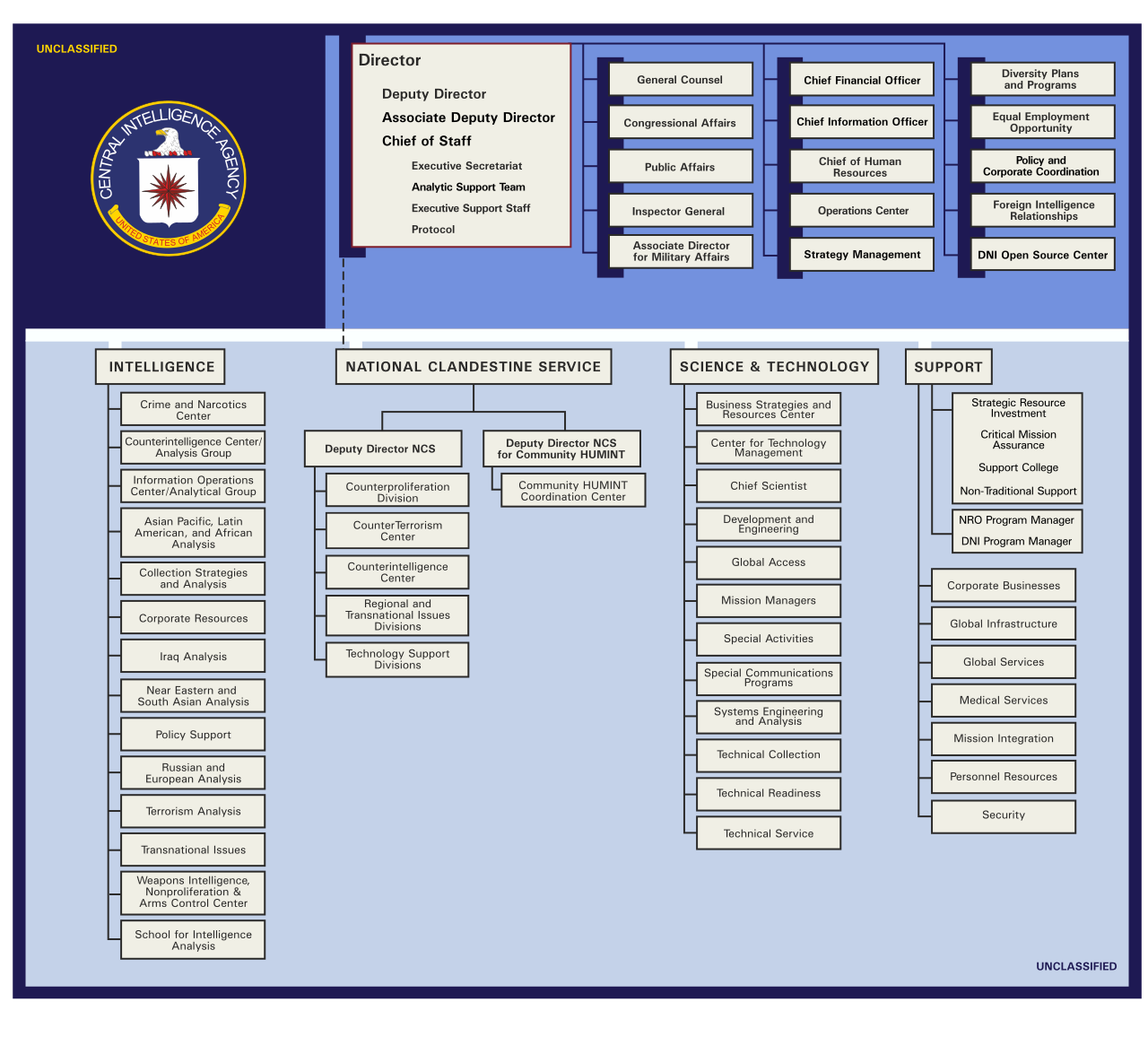

| Organizational structure Main article: Organizational structure of the Central Intelligence Agency  The organization of the Central Intelligence Agency The CIA has an executive office and five major directorates: The Directorate of Digital Innovation The Directorate of Analysis The Directorate of Operations The Directorate of Support The Directorate of Science and Technology Executive Office Further information: Director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency The director of the Central Intelligence Agency (D/CIA) is appointed by the president with Senate confirmation and reports directly to the director of national intelligence (DNI); in practice, the CIA director interfaces with the DNI, Congress, and the White House, while the deputy director (DD/CIA) is the internal executive of the CIA and the chief operating officer (COO/CIA), known as executive director until 2017, leads the day-to-day work[8] as the third-highest post of the CIA.[9] The deputy director is formally appointed by the director without Senate confirmation,[9][10] but as the president's opinion plays a great role in the decision,[10] the deputy director is generally considered a political position, making the chief operating officer the most senior non-political position for CIA career officers.[11] The Executive Office also supports the U.S. military, including the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command, by providing it with information it gathers, receiving information from military intelligence organizations, and cooperating with field activities. The associate deputy director of the CIA is in charge of the day-to-day operations of the agency. Each branch of the agency has its own director.[8] The Office of Military Affairs (OMA), subordinate to the associate deputy director, manages the relationship between the CIA and the Unified Combatant Commands, who produce and deliver regional and operational intelligence and consume national intelligence produced by the CIA.[12] |

組織構造 主な記事 中央情報局の組織構造  CIAの組織 CIAには執行部と5つの主要な部局がある: デジタル・イノベーション本部 分析局 作戦本部 支援総局 科学技術総局 エグゼクティブ・オフィス さらに詳しい情報 中央情報局長官および中央情報局副長官 中央情報局(CIA)長官(Director of the Central Intelligence Agency: D/CIA)は上院の承認を得て大統領によって任命され、国家情報長官(Director of National Intelligence: DNI)に直属する。実際には、CIA長官はDNI、議会、ホワイトハウスとのインターフェイスを担当し、副長官(Deputy Director: DD/CIA)はCIAの内部幹部であり、最高執行責任者(Chief Operating Officer: COO/CIA)は2017年までエグゼクティブ・ディレクターとして知られ、CIAの3番目に高いポストとして日々の業務を指揮する[8]。[9]副長 官は上院の承認なしに長官によって正式に任命されるが[9][10]、大統領の意見が決定に大きな役割を果たすため[10]、副長官は一般的に政治的な役 職とみなされ、最高執行責任者はCIAのキャリアオフィサーにとって最も上級の非政治的な役職となっている[11]。 執行部はまた、米陸軍情報保安司令部を含む米軍に、収集した情報を提供したり、軍の情報組織から情報を受け取ったり、現場の活動に協力したりすることで、 米軍を支援している。CIAの日常業務は副長官が担当している。副長官の部下である軍務局(OMA)は、CIAと、地域情報および作戦情報を作成・提供 し、CIAが作成したナショナリズムを消費する統合戦闘司令部との関係を管理している[12]。 |

| Directorate of Analysis The Directorate of Analysis, through much of its history known as the Directorate of Intelligence (DI), is tasked with helping "the President and other policymakers make informed decisions about our country's national security" by looking "at all the available information on an issue and organiz[ing] it for policymakers".[13] The directorate has four regional analytic groups, six groups for transnational issues, and three that focus on policy, collection, and staff support.[14] There are regional analytical offices covering the Near East and South Asia, Russia, and Europe; and the Asia–Pacific, Latin America, and Africa. Directorate of Operations Main article: Directorate of Operations (CIA) The Directorate of Operations is responsible for collecting foreign intelligence (mainly from clandestine HUMINT sources), and for covert action. The name reflects its role as the coordinator of human intelligence activities between other elements of the wider U.S. intelligence community with their HUMINT operations. This directorate was created in an attempt to end years of rivalry over influence, philosophy, and budget between the United States Department of Defense (DOD) and the CIA. In spite of this, the Department of Defense announced in 2012 its intention to organize its own global clandestine intelligence service, the Defense Clandestine Service (DCS),[15] under the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Contrary to some public and media misunderstanding, DCS is not a "new" intelligence agency but rather a consolidation, expansion and realignment of existing Defense HUMINT activities, which have been carried out by DIA for decades under various names, most recently as the Defense Human Intelligence Service.[16] This Directorate is known to be organized by geographic regions and issues, but its precise organization is classified.[17] Directorate of Science & Technology Main article: Directorate of Science & Technology The Directorate of Science & Technology was established to research, create, and manage technical collection disciplines and equipment. Many of its innovations were transferred to other intelligence organizations, or, as they became more overt, to the military services. The development of the U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, for instance, was done in cooperation with the United States Air Force. The U-2's original mission was clandestine imagery intelligence over denied areas such as the Soviet Union.[18] |

分析総局 分析局(Directorate of Analysis)は、その歴史の大半を情報局(Directorate of Intelligence:DI)として知られ、「大統領をはじめとする政策立案者が、ある問題について入手可能な情報をすべて検討し、政策立案者のため に整理する」ことによって、「国民安全保障について十分な情報に基づいた意思決定を行う」のを支援することを任務としている[13]。[同本部には、4つ の地域分析グループ、国境を越えた問題を扱う6つのグループ、政策、収集、スタッフ支援に重点を置く3つのグループがある[14]。近東・南アジア、ロシ ア、ヨーロッパ、アジア太平洋、ラテンアメリカ、アフリカを担当する地域分析事務所がある。 作戦本部 主な記事 作戦本部(CIA) 作戦本部は、対外情報(主に秘密情報源であるHUMINT)の収集と諜報活動を担当している。その名称は、より広い米国情報コミュニティの他の要素と HUMINT作戦との間の人的情報活動の調整役としての役割を反映している。この部局は、米国国防総省(DOD)とCIAの間の影響力、理念、予算をめぐ る長年の対立に終止符を打つために創設された。にもかかわらず、国防総省は2012年、国防情報局(DIA)の下に独自の世界的な秘密情報機関である国防 秘密情報局(DCS)を組織する意図主義を発表した[15]。一部の国民やメディアの誤解に反して、DCSは「新しい」情報機関ではなく、むしろ既存の国 防HUMINT活動の統合、拡大、再編成であり、DIAは数十年にわたってさまざまな名称で、最近では国防ヒューマン・インテリジェンス・サービスとして 実施してきた[16]。 この部局は地理的な地域や問題によって組織されていることが知られているが、その正確な組織は機密扱いになっている[17]。 科学技術総局 主な記事 科学技術総局 科学技術総局は、技術的な収集分野や設備の研究、創造、管理を行うために設立された。その技術革新の多くは、他の諜報組織や、より露骨になるにつれて軍に移管された。 たとえば、高高度偵察機U-2の開発は、アメリカ空軍と協力して行われた。U-2の当初の任務は、ソビエト連邦のような拒否された地域の上空での秘密の画像情報であった[18]。 |

| Directorate of Support Main article: Directorate of Support The Directorate of Support has organizational and administrative functions to significant units including: The Office of Security The Office of Communications The Office of Information Technology Directorate of Digital Innovation The Directorate of Digital Innovation (DDI) focuses on accelerating innovation across the Agency's mission activities. It is the Agency's newest directorate. The Langley, Virginia-based office's mission is to streamline and integrate digital and cybersecurity capabilities into the CIA's espionage, counterintelligence, all-source analysis, open-source intelligence collection, and covert action operations.[19] It provides operations personnel with tools and techniques to use in cyber operations. It works with information technology infrastructure and practices cyber tradecraft.[20] This means retrofitting the CIA for cyberwarfare. DDI officers help accelerate the integration of innovative methods and tools to enhance the CIA's cyber and digital capabilities on a global scale and ultimately help safeguard the United States. They also apply technical expertise to exploit clandestine and publicly available information (also known as open-source data) using specialized methodologies and digital tools to plan, initiate and support the technical and human-based operations of the CIA.[21] Before the establishment of the new digital directorate, offensive cyber operations were undertaken by the CIA's Information Operations Center.[22] Little is known about how the office specifically functions or if it deploys offensive cyber capabilities.[19] The directorate had been covertly operating since approximately March 2015 but formally began operations on October 1, 2015.[23] According to classified budget documents, the CIA's computer network operations budget for fiscal year 2013 was $685.4 million. The NSA's budget was roughly $1 billion at the time.[24] Rep. Adam Schiff, the California Democrat who served as the ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, endorsed the reorganization. "The director has challenged his workforce, the rest of the intelligence community, and the nation to consider how we conduct the business of intelligence in a world that is profoundly different from 1947 when the CIA was founded," Schiff said.[25] Office of Congressional Affairs For more information, see CIA's relationship with the United States Congress. The Office of Congressional Affairs (OCA) serves as the liaison between the CIA and the US Congress. The OCA states that it aims to ensure that Congress is fully and currently informed of intelligence activities.[26] The office is the CIA's primary interface with Congressional oversight committees, leadership, and members. It is responsible for all matters pertaining to congressional interaction and oversight of US intelligence activities. It claims that it aims to:[27] ensure that Congress is kept informed of intelligence issues and activities by providing timely briefings and notifications facilitate prompt and complete responses to congressional requests for information and inquiries maintain a record of the Agency's interaction with Congress track legislation that could affect the Agency educate Agency personnel about their responsibility to keep Congress fully and currently informed |

サポート総局 主な記事 サポート総局 支援総局は、以下のような重要な部門に対する組織的・管理的機能を持つ: 安全保障局 コミュニケーション部 情報技術部 デジタル・イノベーション総局 デジタル・イノベーション総局(DDI)は、CIAのミッション活動全体のイノベーションを加速することに重点を置いている。同局で最も新しい部局であ る。バージニア州ラングレーを拠点とするこの部局の使命は、CIAのスパイ活動、防諜活動、全情報源分析、オープンソース情報収集、諜報活動において、デ ジタルおよびサイバーセキュリティ能力を合理化し、統合することである[19]。これはCIAをサイバー戦争用に改造することを意味する[20]。DDI 職員は、革新的な方法とツールの統合を加速させ、CIAのサイバーとデジタルの能力を世界規模で強化し、最終的に米国の安全を守ることに貢献する。また、 専門的な方法論とデジタルツールを使用して、秘密情報および一般に入手可能な情報(オープンソースデータとしても知られている)を利用するために技術的な 専門知識を適用し、CIAの技術的および人的な作戦を計画、開始、支援する[21]。新しいデジタル部局が設立される前は、攻撃的なサイバー作戦はCIA の情報作戦センターによって実施されていた[22]。 この部局は2015年3月頃から秘密裏に活動していたが、2015年10月1日に正式に活動を開始した[23]。 機密扱いの予算文書によると、2013会計年度のCIAのコンピュータネットワーク運用予算は6億8540万ドルだった。NSAの予算は当時およそ10億 ドルだった[24]。 下院情報委員会の委員長を務めたカリフォルニア州選出の民主党議員、アダム・シフ氏は、この再編成を支持した。「局長は、CIAが創設された1947年と は大きく異なる世界で、どのように諜報活動を行うかを検討するために、彼の従業員、他の諜報コミュニティ、そして国民に挑戦した」とシフ氏は述べた [25]。 議会事務局 詳細は、CIAと米国議会の関係を参照のこと。 議会事務局(OCA)は、CIAと米国議会との連絡窓口となっている。OCAは、議会が情報活動について十分かつ最新の情報を得られるようにすることを目的としているとしている[26]。 OCAはCIAと議会の監視委員会、指導部、議員との主要な窓口である。OCAは、米国情報活動に対する議会との対話と監視に関するすべての事項を担当する。その目的は次のとおりであるとしている[27]。 タイムリーなブリーフィングと通告を行うことにより、議会が情報問題や活動を常に把握できるようにする。 議会からの情報提供要請や問い合わせに対し、迅速かつ完全な回答を行う。 諜報機関と議会とのやりとりの記録を管理する。 諜報機関に影響を及ぼす可能性のある法案を追跡する。 議会に十分かつ最新の情報を提供し続ける責任について、諜報機関の職員を教育する。 |

| Training Further information: CIA University, National Intelligence University, and Warrenton Training Center The CIA established its first training facility, the Office of Training and Education, in 1950. Following the end of the Cold War, the CIA's training budget was slashed, which had a negative effect on employee retention.[28][29] In response, Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet established CIA University in 2002.[28][13] CIA University holds between 200 and 300 courses each year, training both new hires and experienced intelligence officers, as well as CIA support staff.[28][29] The facility works in partnership with the National Intelligence University, and includes the Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis, the Directorate of Analysis' component of the university.[13][30][31] For later stage training of student operations officers, there is at least one classified training area at Camp Peary, near Williamsburg, Virginia. Students are selected, and their progress evaluated, in ways derived from the OSS, published as the book Assessment of Men, Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services.[32] Additional mission training is conducted at Harvey Point, North Carolina.[33] The primary training facility for the Office of Communications is Warrenton Training Center, located near Warrenton, Virginia. The facility was established in 1951 and has been used by the CIA since at least 1955.[34][35] |

トレーニング さらに詳しい情報 CIA大学、ナショナリズム大学、ウォレントン・トレーニング・センター CIAは1950年に最初の訓練施設である訓練教育局を設立した。冷戦終結後、CIAの訓練予算は削減され、従業員の定着に悪影響を及ぼした[28][29]。 これに対し、ジョージ・テネット中央情報局長は2002年にCIAユニバーシティを設立した[28][13]。CIAユニバーシティでは毎年200から 300のコースが開講され、新入社員と経験豊富な情報将校、CIAのサポートスタッフの両方が訓練を受けている[28][29]。 学生作戦将校の後期訓練については、バージニア州ウィリアムズバーグ近郊のキャンプ・ピアリーに少なくとも1つの機密訓練場がある。学生はOSSに由来す る方法で選抜され、その進歩が評価され、『Assessment of Men, Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services』という本として出版されている[32]。追加の任務訓練はノースカロライナ州のハービー・ポイントで行われている[33]。 通信局の主要訓練施設は、バージニア州ウォレントンの近くにあるウォレントン・トレーニング・センターである。この施設は1951年に設立され、少なくとも1955年以降はCIAによって使用されている[34][35]。 |

| Budget Main article: United States intelligence budget Details of the overall United States intelligence budget are classified.[3] Under the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949, the Director of Central Intelligence is the only federal government employee who can spend "un-vouchered" government money.[36] The government showed its 1997 budget was $26.6 billion for the fiscal year.[37] The government has disclosed a total figure for all non-military intelligence spending since 2007; the fiscal 2013 figure is $52.6 billion. According to the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures, the CIA's fiscal 2013 budget is $14.7 billion, 28% of the total and almost 50% more than the budget of the National Security Agency. CIA's HUMINT budget is $2.3 billion, the SIGINT budget is $1.7 billion, and spending for security and logistics of CIA missions is $2.5 billion. "Covert action programs," including a variety of activities such as the CIA's drone fleet and anti-Iranian nuclear program activities, accounts for $2.6 billion.[3] There were numerous previous attempts to obtain general information about the budget.[38] As a result, reports revealed that CIA's annual budget in Fiscal Year 1963 was $550 million (inflation-adjusted US$ 5.6 billion in 2025),[39] and the overall intelligence budget in FY 1997 was US$26.6 billion (inflation-adjusted US$ 52.1 billion in 2025).[40] There have been accidental disclosures; for instance, Mary Margaret Graham, a former CIA official and deputy director of national intelligence for collection in 2005, said that the annual intelligence budget was $44 billion,[41] and in 1994 Congress accidentally published a budget of $43.4 billion (in 2012 dollars) in 1994 for the non-military National Intelligence Program, including $4.8 billion for the CIA.[3] After the Marshall Plan was approved, appropriating $13.7 billion over five years, 5% of those funds or $685 million were secretly made available to the CIA. A portion of the enormous M-fund, established by the U.S. government during the post-war period for reconstruction of Japan, was secretly steered to the CIA.[42] |

予算 主な記事 米国の情報予算 1949年に制定された中央情報局法に基づき、中央情報局長は連邦政府職員の中で唯一「賄賂を受け取っていない」政府資金を使用することができる [36]。政府は1997年度の予算が266億ドルであったことを明らかにしている[37]。政府は2007年以降、軍事費以外の情報支出を合計した数字 を開示しており、2013年度の数字は526億ドルである。2013年の大量監視の開示によると、CIAの2013年度予算は147億ドルで、全体の 28%、ナショナリズムの予算よりも50%近く多い。CIAのHUMINT予算は23億ドル、SIGINT予算は17億ドル、CIAミッションのセキュリ ティとロジスティクスのための支出は25億ドルである。CIAの無人機群や対イラン核計画活動など様々な活動を含む「秘密行動プログラム」は26億ドルで ある[3]。 予算に関する一般的な情報を得ようとする試みは過去にも何度もあった[38]。 その結果、1963会計年度のCIAの年間予算は5億5,000万米ドル(2025年のインフレ調整後では56億米ドル)であったことが報告され [39]、1997会計年度の情報予算全体は266億米ドル(2025年のインフレ調整後では521億米ドル)であったことが明らかになった[40]。 [40] 偶発的な公表もある。例えば、2005年にCIAの元職員で収集担当の国民情報副長官であったメアリー・マーガレット・グラハムは、年間情報予算は440 億ドルであったと発言しており[41]、1994年には議会が誤って、CIAの48億ドルを含む非軍事の国家情報プログラム予算として434億ドル (2012年ドル)を公表している[3]。 マーシャル・プランが承認され、5年間で137億ドルが計上された後、その5%にあたる6億8500万ドルが密かにCIAに提供された。戦後、日本復興のためにアメリカ政府が設立した莫大なM資金の一部は、密かにCIAに使われた[42]。 |

| Relationship with other intelligence agencies Foreign intelligence services The role and functions of the CIA are roughly equivalent to those of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) in Germany, MI6 in the United Kingdom, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) in Australia, the Directorate-General for External Security (DGSE) in France, the Foreign Intelligence Service in Russia, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) in China, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) in India, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in Pakistan, the General Intelligence Service in Egypt, Mossad in Israel, and the National Intelligence Service (NIS) in South Korea. The CIA was instrumental in the establishment of intelligence services in several U.S. allied countries, including Germany's BND and Greece's EYP (then known as KYP).[43][citation needed] The closest links of the U.S. intelligence community to other foreign intelligence agencies are to Anglophone countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Special communications signals that intelligence-related messages can be shared with these four countries.[44] An indication of the United States' close operational cooperation is the creation of a new message distribution label within the main U.S. military communications network. Previously, the marking of NOFORN (i.e., No Foreign Nationals) required the originator to specify which, if any, non-U.S. countries could receive the information. A new handling caveat, USA/AUS/CAN/GBR/NZL Five Eyes, used primarily on intelligence messages, indicates that the material can be shared with Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and New Zealand. The task of the division called "Verbindungsstelle 61" of the German Bundesnachrichtendienst is keeping contact to the CIA office in Wiesbaden.[45] |

他の諜報機関との関係 外国の諜報機関 CIAの役割と機能は、ドイツの連邦情報局(BND)、イギリスのMI6、オーストラリアのオーストラリア秘密情報局(ASIS)、フランスの対外安全保 障総局(DGSE)、ロシアの対外情報部、中国の国家安全部(MSS)、インドの調査分析局(RAW)、パキスタンの国家間情報部(ISI)、エジプトの 総合情報部、イスラエルのモサド、韓国の国民情報院(NIS)とほぼ同等である。 CIAはドイツのBNDやギリシャのEYP(当時はKYPとして知られていた)など、米国の同盟国数カ国における諜報機関の設立に尽力した[43][要出典]。 米国の諜報機関が他の外国の諜報機関と最も密接な関係にあるのは、英語圏の国々である: オーストラリア、カナダ、ニュージーランド、イギリスである。特別な通信信号は、諜報関連のメッセージをこれら4カ国と共有することができる[44]。米 国の緊密な作戦協力の表れは、米軍の主要な通信ネットワーク内に新しいメッセージ配信ラベルを作成したことである。以前は、NOFORN(すなわち、ナ ショナリズム禁止)のマークを付けるには、発信者が、米国以外のどの国が情報を受信できるかを指定する必要があった。 USA/AUS/CAN/GBR/NZLファイブ・アイズという新しい取り扱い上の注意は、主に情報メッセージに使用され、オーストラリア、カナダ、イギ リス、ニュージーランドと情報を共有できることを示している。 ドイツ連邦情報局(Bundesnachrichtendienst)の 「Verbindungsstelle 61 」と呼ばれる部門の任務は、ヴィースバーデンのCIA事務所との連絡を保つことである[45]。 |

| History of the CIA |

CIAの歴史(→別項に移動) |

| Open-source intelligence Further information: Foreign Broadcast Information Service and Open Source Center Until the 2004 reorganization of the intelligence community, one of the "services of common concern" that the CIA provided was open-source intelligence from the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS).[257] FBIS, which had absorbed the Joint Publication Research Service, a military organization that translated documents,[258] moved into the National Open Source Enterprise under the Director of National Intelligence. During the Reagan administration, Michael Sekora (assigned to the DIA), worked with agencies across the intelligence community, including the CIA, to develop and deploy a technology-based competitive strategy system called Project Socrates. Project Socrates was designed to utilize open-source intelligence gathering almost exclusively. The technology-focused Socrates system supported such programs as the Strategic Defense Initiative in addition to private sector projects.[259][260] Increasingly, the CIA is a major consumer of social media intelligence.[261] CIA launched a Twitter account in June 2014.[262] CIA also launched its own .onion website to collect anonymous feedback.[263] |

オープンソースインテリジェンス さらに詳しい情報 外国放送情報局とオープンソース・センター 2004年の情報コミュニティの再編成まで、CIAが提供していた「共通の関心事であるサービス」のひとつが、外国放送情報サービス(FBIS)からの オープンソースインテリジェンスであった[257]。FBISは、文書を翻訳する軍事組織である統合出版調査サービス(Joint Publication Research Service)を吸収し[258]、国家情報長官(Director of National Intelligence)傘下のナショナリズム(National Open Source Enterprise)に移った。 レーガン政権時代、マイケル・セコラ(DIAに配属)は、CIAを含む情報機関全体と協力して、プロジェクト・ソクラテスと呼ばれるテクノロジーベースの 競争戦略システムを開発・展開した。プロジェクト・ソクラテスは、オープンソースの情報収集をほぼ独占的に活用するように設計されていた。テクノロジーに 特化したソクラテス・システムは、民間セクターのプロジェクトに加えて、戦略防衛構想などのプログラムもサポートした[259][260]。 261]CIAは2014年6月にTwitterアカウントを開設した[262]。またCIAは匿名のフィードバックを収集するために独自の.onionウェブサイトを開設した[263]。 |

| Outsourcing and privatization See also: Intelligence outsourcing Many of the duties and functions of Intelligence Community activities, not the CIA alone, are being outsourced and privatized. Mike McConnell, former Director of National Intelligence, was about to publicize an investigation report of outsourcing by U.S. intelligence agencies, as required by Congress.[264] However, this report was then classified.[265][266] Hillhouse speculates that this report includes requirements for the CIA to report:[265][267] different standards for government employees and contractors; contractors providing similar services to government workers; analysis of costs of contractors vs. employees; an assessment of the appropriateness of outsourced activities; an estimate of the number of contracts and contractors; comparison of compensation for contractors and government employees; attrition analysis of government employees; descriptions of positions to be converted back to the employee model; an evaluation of accountability mechanisms; an evaluation of procedures for "conducting oversight of contractors to ensure identification and prosecution of criminal violations, financial waste, fraud, or other abuses committed by contractors or contract personnel"; and an "identification of best practices of accountability mechanisms within service contracts." According to investigative journalist Tim Shorrock: ...what we have today with the intelligence business is something far more systemic: senior officials leaving their national security and counterterrorism jobs for positions where they essentially perform the same jobs they once held at the CIA, the NSA, and other agencies – but for double or triple the salary and profit. It's a privatization of the highest order, in which our collective memory and experience in intelligence – our crown jewels of spying, so to speak – are owned by corporate America. There is essentially no government oversight of this private sector at the heart of our intelligence empire. And the lines between public and private have become so blurred as to be nonexistent.[268][269] Congress had required an outsourcing report by March 30, 2008:[267] The Director of National Intelligence has been granted the authority to increase the number of positions (FTEs) on elements in the Intelligence Community by up to 10% should there be a determination that activities performed by a contractor should be done by a U.S. government employee."[267] Part of the problem, according to author Tim Weiner, is that political appointees designated by recent presidential administrations have sometimes been under-qualified or over-zealous politically. Large purges have taken place in the upper echelons of the CIA, and when those talented individuals are pushed out the door, they have frequently gone on to found new independent intelligence companies which can suck up CIA talent.[117] Another part of the contracting problem comes from Congressional restrictions on the number of employees within the IC. According to Hillhouse, this resulted in 70% of the de facto workforce of the CIA's National Clandestine Service being made up of contractors. "After years of contributing to the increasing reliance upon contractors, Congress is now providing a framework for the conversion of contractors into federal government employees – more or less."[267] The number of independent contractors hired by the Federal government across the intelligence community has skyrocketed. So, not only does the CIA have trouble hiring, but those hires will frequently leave their permanent employ for shorter term contract gigs which have much higher pay and allow for more career mobility.[117] As with most government agencies, building equipment often is contracted. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), responsible for the development and operation of airborne and spaceborne sensors, long was a joint operation of the CIA and the United States Department of Defense. The NRO, then under DCI authority, contracted more of the design that had been their tradition, and to a contractor without extensive reconnaissance experience, Boeing. The next-generation satellite Future Imagery Architecture project "how does heaven look," which missed objectives after $4 billion in cost overruns, was the result of this contract.[270][271] Some of the cost problems associated with intelligence come from one agency, or even a group within an agency, not accepting the compartmented security practices for individual projects, requiring expensive duplication.[272] |

アウトソーシングと民営化 こちらも参照のこと: インテリジェンスのアウトソーシング CIAだけでなく、情報コミュニティ活動の任務や機能の多くがアウトソーシングされ、民営化されている。マイク・マコネル前国家情報長官は、議会の要求に 従い、米国の情報機関によるアウトソーシングに関する調査報告書を公表しようとしていた[264]が、この報告書はその後機密扱いとなった[265] [266]。 ヒルハウスは、この報告書にはCIAが報告すべき以下の要件が含まれていると推測している[265][267]。 政府職員と請負業者に対する異なる基準; 政府職員と同様のサービスを提供する請負業者 請負業者と職員のコストの比較分析; 外部委託活動の妥当性の評価; 契約および請負業者の数の推定; 請負業者と政府職員の報酬の比較; 政府職員の減少分析 職員モデルに戻すべき役職の説明; 説明責任メカニズムの評価 請負業者または契約職員による犯罪違反、財政的浪費、詐欺、またはその他の不正行為を確実に特定し、起訴するための請負業者監視の実施」手順の評価、および サービス契約におけるアカウンタビリティ・メカニズムのベストプラクティスの特定」である。 調査ジャーナリストのティム・ショーロックは言う: 国家安全保障や対テロリズムの仕事を辞めた高官たちが、CIAやNSA、その他の機関でかつて就いていたのと同じ仕事を、2倍、3倍の給料と利益でこなす ようになったのだ。これは最高レベルの民営化であり、われわれの諜報活動の記憶と経験、いわばスパイの至宝がアメリカ企業に所有されているのだ。情報帝国 の中心であるこの民間部門には、基本的に政府の監視はない。そして公私の境界線は、存在しないかのように曖昧になっている[268][269]。 議会は2008年3月30日までにアウトソーシングの報告書を要求していた[267]。 国民情報長官は、請負業者が行っている活動を米国政府職員が行うべきだと判断した場合、情報コミュニティ内の要素のポジション(FTE)の数を最大10%増やす権限を与えられている」[267]。 著者のティム・ワイナーによれば、問題の一部は、最近の大統領政権によって指名された政治任用者が、政治的に不適格であったり、過剰であったりすることが あることである。CIAの上層部では大規模な粛清が行われており、そのような有能な人材が門前払いされると、CIAの人材を吸い上げることができる新しい 独立情報会社を設立することが多い[117]。契約問題のもう一つの原因は、IC内の職員数に対する議会の制限にある。ヒルハウスによれば、この結果、 CIAのナショナリズム・サービスの事実上の労働力の70%が請負業者によって構成されている。「長年にわたって請負業者への依存度を高める一因となって きた請負業者を、連邦議会は現在、多かれ少なかれ連邦政府職員に転換する枠組みを提供している」[267] 情報機関全体で連邦政府が雇用する独立請負業者の数は急増している。そのため、CIAは採用に苦労しているだけでなく、採用された社員は、給与がはるかに 高く、キャリアの流動性が高い短期契約の仕事を求めて、正社員を辞めることが多い[117]。 ほとんどの政府機関と同様に、設備の建設はしばしば請負である。国民偵察局(NRO)は、空中センサーと宇宙センサーの開発と運用を担当し、長い間CIA と米国国防総省の共同運営であった。当時DCIの権限下にあったNROは、彼らの伝統であった設計の多くを、豊富な偵察経験を持たない請負業者ボーイング 社に委託した。次世代衛星フューチャー・イメージ・アーキテクチャー・プロジェクト「天国はどのように見えるか」は、40億ドルのコスト超過の末に目標を 逃したが、この契約の結果であった[270][271]。 インテリジェンスに関連するコスト問題の中には、ある機関、あるいは機関内のグループが、個々のプロジェクトのための区画されたセキュリティ慣行を受け入れず、高価な重複を必要とすることに起因するものもある[272]。 |

| Controversies Main article: List of CIA controversies See also: Human rights violations by the CIA, Allegations of CIA drug trafficking, CIA influence on public opinion, Project Mockingbird, Extraordinary rendition, Assassination of Orlando Letelier, Cubana de Aviación Flight 455, and Operation Condor The CIA has been the subject of numerous controversies. The agency ran an operation code-named "Chaos" that ran from 1967 to 1974 where they routinely performed surveillance on Americans who were a part of various peace groups protesting the Vietnam War. The operation was authorized by order of President Lyndon B. Johnson in October 1967 as the CIA gathered the information of 300,000 American people and organizations and extensive files on 7,200 citizens. The program was exposed by the Church Committee in 1975 as a part of the investigation into the Watergate scandal.[221][273] The CIA also conducted a secret program called MKUltra, which ran from the early 1950s to the 1970s and involved illegal human experimentation to develop mind-control techniques. Subjects were often unaware they were part of the experiments, which included the administration of psychoactive drugs like LSD and other methods of psychological manipulation.[274][275] The program, exposed in the 1970s, led to widespread public outrage and calls for greater oversight of intelligence agencies.[276] The CIA was also linked to the Iran-Contra Affair wherein missiles were sold to the Iranian government as an exchange for the release of hostages and the profits the agency made from selling the weapons at a marked-up price went towards assisting the contras in Nicaragua. Another source of controversy has been the CIA's role in Operation Condor, which was a United States-backed campaign of repression and state terrorism involving intelligence operations, CIA-backed coup d'états and assassinations against leaders in South America from 1968 to 1989. By the Operation's end in 1989, up to 80,000 people had been killed.[277] Similarly, the CIA was complicit in the actions of death squads in El Salvador and Honduras.[278][279] An additional controversy surrounds the Bush Administration's claim that Iraq had "weapons of mass destruction" in 2002, and again in 2003 as justification for invading the Middle Eastern country. The CIA went along with the claim despite contradicting the president in testimony to the Senate Intelligence Committee in 2002. They produced a national intelligence estimate claiming that if the Iraqi government was able to acquire "sufficient fissile material from abroad, it could make nuclear weapons within a year".[280] |

論争 主な記事 CIAの論争のリスト 以下も参照のこと: CIAによる人権侵害、CIAの麻薬密売疑惑、CIAの世論への影響力、モッキンバード計画、異例な強制連行、オーランド・レトリエ暗殺、キューバ航空455便、コンドル作戦 CIAは数々の論争の的となってきた。CIAは1967年から1974年まで、「カオス」というコードネームの作戦を実行し、ベトナム戦争に抗議するさま ざまな平和団体の一員であるアメリカ人を日常的に監視していた。この作戦は1967年10月、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領の命令によって認可され、 CIAは30万人のアメリカ人民と団体の情報を集め、7200人の市民に関する広範なファイルを作成した。このプログラムは、ウォーターゲート事件に関す る調査の一環として、1975年にチャーチ委員会によって暴露された[221][273]。 CIAはまた、1950年代初頭から1970年代にかけて、マインドコントロール技術を開発するための違法な人体実験を伴う、MKUltraと呼ばれる秘 密プログラムも実施していた。被験者は自分が実験の一部であることに気づかないことが多く、LSDのような精神作用のある薬物の投与や、その他の心理操作 の方法が含まれていた。[274][275] 1970年代に暴露されたこのプログラムは、広く国民の怒りを買い、情報機関に対する監視の強化を求める声につながった[276]。 CIAはイラン・コントラ事件にも関連しており、人質解放の交換条件としてイラン政府にミサイルが売られ、武器を高値で売って得た利益はニカラグアのコントラ支援に使われた。 コンドル作戦は、1968年から1989年にかけて、南米の指導者たちに対する諜報活動、CIAの支援によるクーデター、暗殺を含む弾圧と国家テロリズム のキャンペーンであった。同様に、CIAはエルサルバドルとホンジュラスの決死隊の行動に加担していた[278][279]。 さらなる論争は、ブッシュ政権が2002年にイラクが「大量破壊兵器」を保有していると主張し、2003年にも中東の国への侵攻を正当化するものとして主 張したことにまつわるものである。CIAは2002年の上院情報委員会での証言で大統領に反論したにもかかわらず、この主張に従った。彼らは、イラク政府 が「海外から十分な核分裂性物質を入手できれば、1年以内に核兵器を製造できる」と主張するナショナリズムの見積もりを作成した[280]。 |

| Abu Omar case Blue sky memo Church Committee CIA's relationship with the United States Military Classified information in the United States Enhanced interrogation techniques Freedom of Information Act (United States) Intellipedia Kryptos National Intelligence Board Operation Peter Pan Reagan Doctrine Title 32 of the Code of Federal Regulations U.S. Army and CIA interrogation manuals United States Department of Homeland Security United States Intelligence Community Vault 7 The World Factbook, published by the CIA |

アブ・オマル事件 青空メモ 教会委員会 CIAと米軍の関係 米国の機密情報 尋問技術の強化 情報公開法 インテリペディア クリプトス 国民情報委員会 ピーターパン作戦 レーガン・ドクトリン 連邦規則集タイトル32 米陸軍とCIAの尋問マニュアル 米国国土安全保障省 米国情報コミュニティ 保管庫7 CIA発行「ワールド・ファクトブック |

| References Anderson, Scott (2020). The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-54046-9. Brysk, Alison; Meade, Everard; Shafir, Gershon (2016). "Constructing National and Global Insecurity". In Aceves, William; Meade, Everard; Shafir, Gershon (eds.). Lessons and Legacies of the War on Terror. London/New York: Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-63841-8. Gordon, Rebecca (2014). Mainstreaming Torture: Ethical Approaches in the Post-9/11 United States. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780199336432. Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2022). A Question of Standing: The History of the CIA. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284796-6. Kuzmarov, Jeremy (April 2009). "Modernizing Repression: Police Training, Political Violence, and Nation-Building in the 'American Century'". Diplomatic History. 33 (2). Oxford University Press: 191–221. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2008.00760.x. McCoy, Alfred W. (2007). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. London: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 63–71. ISBN 9780805082487. Reid, Stuart A. (2023). The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5247-4881-4. Schwab, Stephen Irving Max (June 2014). "Once a Jedburgh Always a Jedburgh". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 27 (2). Taylor & Francis: 405–412. doi:10.1080/08850607.2014.872540. Simpson, Christopher (2003). "U.S. Mass Communication Research, Counterinsurgency, and Scientific 'Reality'". In Braman, Sandra (ed.). Communication Researchers and Policy-making. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 253–292. ISBN 9780262523400. Valcourt, Richard R. (January 1989). "Tossing Wins Away: Lost Victory: A Firsthand Account of America's Sixteen-Year Involvement in Vietnam". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 3 (4). Taylor & Francis: 567–605. doi:10.1080/08850608908435122. Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3. OCLC 82367780. Wilford, Hugh (2024). The CIA: An Imperial History. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-541-64591-2. |

参考文献 アンダーソン、スコット (2020). クワイエット・アメリカンズ 冷戦黎明期の4人のCIAスパイ。Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-54046-9. Brysk, Alison; Meade, Everard; Shafir, Gershon (2016). 「Constructing National and Global Insecurity". Aceves, William; Meade, Everard; Shafir, Gershon (eds.). Lessons and Legacies of the War on Terror. London/New York: p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-63841-8. Gordon, Rebecca (2014). Mainstreaming Torture: 9/11後の米国における倫理的アプローチ。Oxford/New York: ISBN 9780199336432. Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. テキサス大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2022). A Question of Standing: The History of the CIA. オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-284796-6. Kuzmarov, Jeremy (April 2009). 「Modernizing Repression: Modernizing Repression: Police Training, Political Violence, and Nation-Building in the 『American Century』". Diplomatic History. 33 (2). Oxford University Press: 191–221. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2008.00760.x. McCoy, Alfred W. (2007). 拷問を問う: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. ロンドン: マクミラン・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 9780805082487. Reid, Stuart A. (2023). The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5247-4881-4. Schwab, Stephen Irving Max (June 2014). 「Once a Jedburgh Always a Jedburgh」. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 27 (2). doi:10.1080/08850607.2014.872540. Simpson, Christopher (2003). 「U.S. Mass Communication Research, Counterinsurgency, and Scientific 『Reality』". In Braman, Sandra (ed.). Communication Researchers and Policy-making. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262523400. Valcourt, Richard R. (January 1989). 「勝利を捨てる: 失われた勝利: A Firsthand Account of America's Sixteen Year Involvement in Vietnam". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 3 (4). Taylor & Francis: 567-605. doi:10.1080/08850608908435122. Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3. OCLC 82367780. Wilford, Hugh (2024). CIA: An Imperial History. ベーシック・ブックス。ISBN 978-1-541-64591-2. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Intelligence_Agency |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆