シャリバリ

Charivari

William

Hogarth's engraving "Hudibras Encounters the Skimmington" (illustration

to Samuel Butler's Hudibras)

☆ シャリバリ(Charivari あるいは、シバリー(shivaree)またはシバリー(chivaree)とも表記され、スキミングトン(skimmington)とも呼 ばれる)と は、共同体の一員を辱めるために考案されたヨーロッパおよび北米の民俗風習であり、 不協和音の模擬セレナーデを伴って集落内を模擬パレードする。群衆は鍋 やフライパンなど、手に入るものを叩いてできるだけ大きな音を出すことを目的としていたため、こうしたパレードはしばしばラフ・ミュージックと呼ばれる。パ レードには3つのタイプがあった。最初の、そして一般的に最も暴力的な形態では、不義を働いた者や不義を働いた者が自宅や職場から引きずり出され、地域社 会を力ずくでパレードすることがあった。その過程で、彼らは群衆の嘲笑を浴び、小石を投げつけられ、最後には被害者が沈められることもあった。より安全な 方法としては、不義を働いた者の隣人が被害者になりすまして通りを練り歩くというものがあった。そのなりすましは、明らかに自分自身は罰せられず、しばし ば泣き叫んだり、悪事を働いた者をあざ笑う下品な詩を歌ったりした。一般的な形式では、代わりに肖像画が使われ、虐待され、しばしば手続きの終わりに焼か れた。 コミュニティは「荒っぽい音楽」を使って、コミュニティ規範に対するさまざまな種類の違反に対する不承認を表現した。例えば、年上の男やもめとずっと若い 女性との結婚や、未亡人や男やもめの早すぎる再婚など、自分たちが不服とする結婚を対象とすることがあった。村では、不倫関係や、妻を殴る人、未婚の母な どに対しても、シャリバリを使った。また、妻に殴られたにもかかわらず立ちあがらない夫を辱める意味でも使われた。シャリバリはフランス語の原語であり、カナダでは英語圏とフランス語圏の両方で使われている。カナダのオンタリオ州ではChivareeが一般的な変化形となった。アメリカではシヴァリーという言葉が一般的である。 民衆的な正義の儀式の一種であるシャリバリ行事は入念に計画され、伝統的な祝祭の時期に上演されることが多く、それによって正義の実現と祝祭が融合された。

| Charivari

(/ˌʃɪvəˈriː, ˈʃɪvəriː/, UK also /ˌʃɑːrɪˈvɑːri/, US also

/ʃəˌrɪvəˈriː/,[2][3] alternatively spelled shivaree or chivaree and

also called a skimmington) was a European and North American folk

custom designed to shame a member of the community, in which a mock

parade was staged through the settlement accompanied by a discordant

mock serenade. Since the crowd aimed to make as much noise as possible

by beating on pots and pans or anything that came to hand these parades

are often referred to as rough music. Parades were of three types. In the first, and generally most violent form, a wrongdoer or wrongdoers might be dragged from their home or place of work and paraded by force through a community. In the process they were subject to the derision of the crowd, they might be pelted and frequently a victim or victims were dunked at the end of the proceedings. A safer form involved a neighbour of the wrongdoer impersonating the victim whilst being carried through the streets. The impersonator was obviously not themselves punished and often cried out or sang ribald verses mocking the wrongdoer. In the common form, an effigy was employed instead, abused and often burnt at the end of the proceedings.[4] Communities used "rough music" to express their disapproval of different types of violation of community norms. For example, they might target marriages of which they disapproved such as a union between an older widower and much younger woman, or the premature remarriage by a widow or widower. Villages also used charivari in cases of adulterous relationships, against wife beaters, and unmarried mothers. It was also used as a form of shaming upon husbands who were beaten by their wives and had not stood up for themselves.[5] In some cases, the community disapproved of any remarriage by older widows or widowers. Charivari is the original French word, and in Canada it is used by both English and French speakers. Chivaree became the common variant in Ontario, Canada. In the United States, the term shivaree is more common.[6] As species of popular justice rituals Charivaric events were carefully planned and they were often staged at times of traditional festivity thereby blending delivering justice and celebration.[7] |

シャリバリ(Charivariシバリー

(shivaree)またはチバリー(chivaree)とも表記され、スキミングトン(skimmington)とも呼ばれる)と

は、共同体の一員を辱めるために考案されたヨーロッパおよび北米の民俗風習であり、不協和音の模擬セレナーデを伴って集落内を模擬パレードする。群衆は鍋

やフライパンなど、手に入るものを叩いてできるだけ大きな音を出すことを目的としていたため、こうしたパレードはしばしばラフ・ミュージックと呼ばれる。 パレードには3つのタイプがあった。最初の、そして一般的に最も暴力的な形態では、不義を働いた者や不義を働いた者が自宅や職場から引きずり出され、地域 社会を力ずくでパレードすることがあった。その過程で、彼らは群衆の嘲笑を浴び、小石を投げつけられ、最後には被害者が沈められることもあった。より安全 な方法としては、不義を働いた者の隣人が被害者になりすまして通りを練り歩くというものがあった。そのなりすましは、明らかに自分自身は罰せられず、しば しば泣き叫んだり、悪事を働いた者をあざ笑う下品な詩を歌ったりした。一般的な形式では、代わりに肖像画が使われ、虐待され、しばしば手続きの終わりに焼 かれた[4]。 コミュニティは「荒っぽい音楽」を使って、コミュニティ規範に対するさまざまな種類の違反に対する不承認を表現した。例えば、年上の男やもめとずっと若い 女性との結婚や、未亡人や男やもめの早すぎる再婚など、自分たちが不服とする結婚を対象とすることがあった。村では、不倫関係や、妻を殴る人、未婚の母な どに対しても、シャリバリを使った。また、妻に殴られたにもかかわらず立ちあがらない夫を辱める意味でも使われた。シャリバリはフランス語の原語であり、 カナダでは英語圏とフランス語圏の両方で使われている。カナダのオンタリオ州ではChivareeが一般的な変化形となった。アメリカではシヴァリーとい う言葉が一般的である[6]。 民衆的な正義の儀式の一種であるシャリバリ行事は入念に計画され、伝統的な祝祭の時期に上演されることが多く、それによって正義の実現と祝祭が融合さ れた[7]。 |

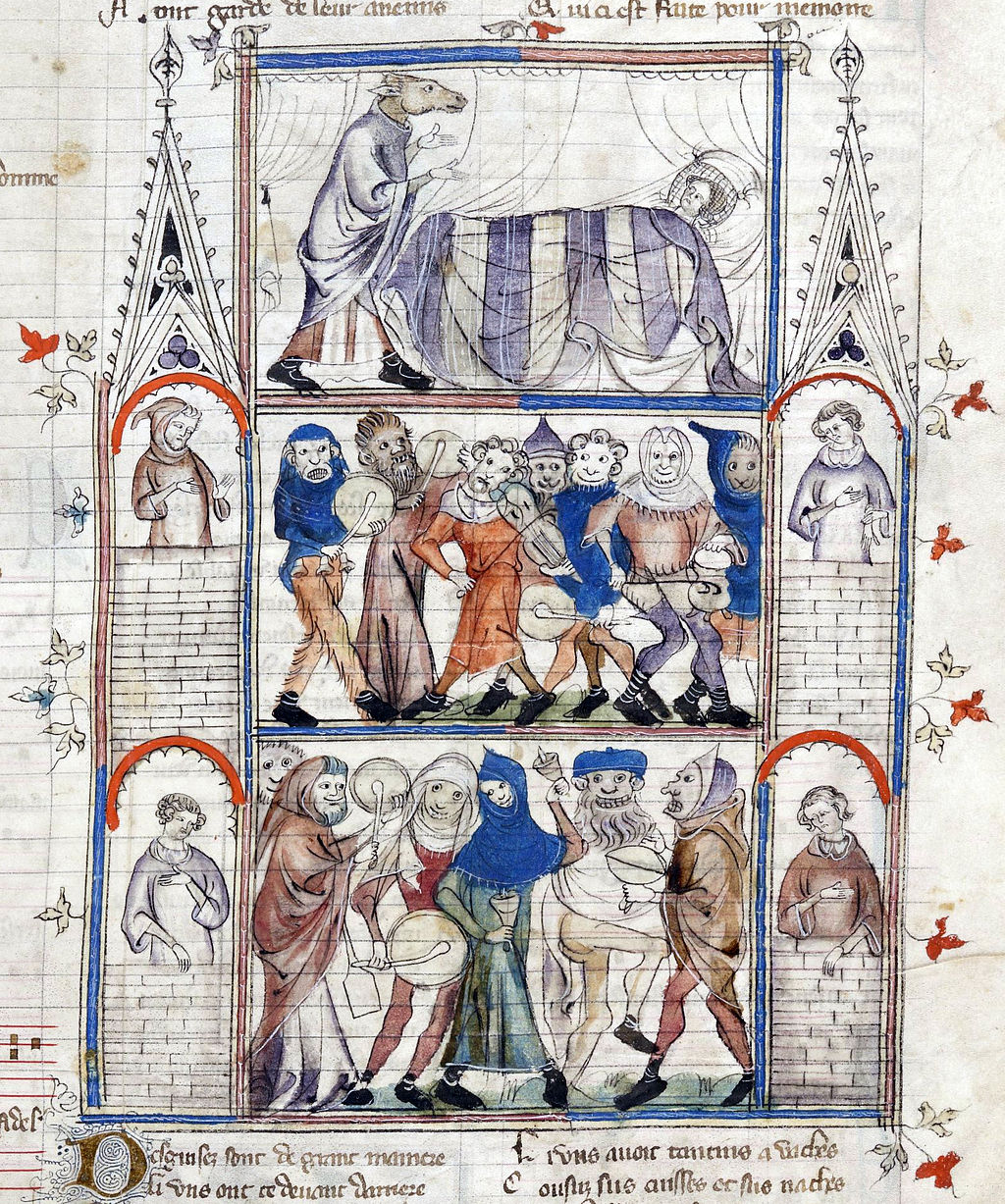

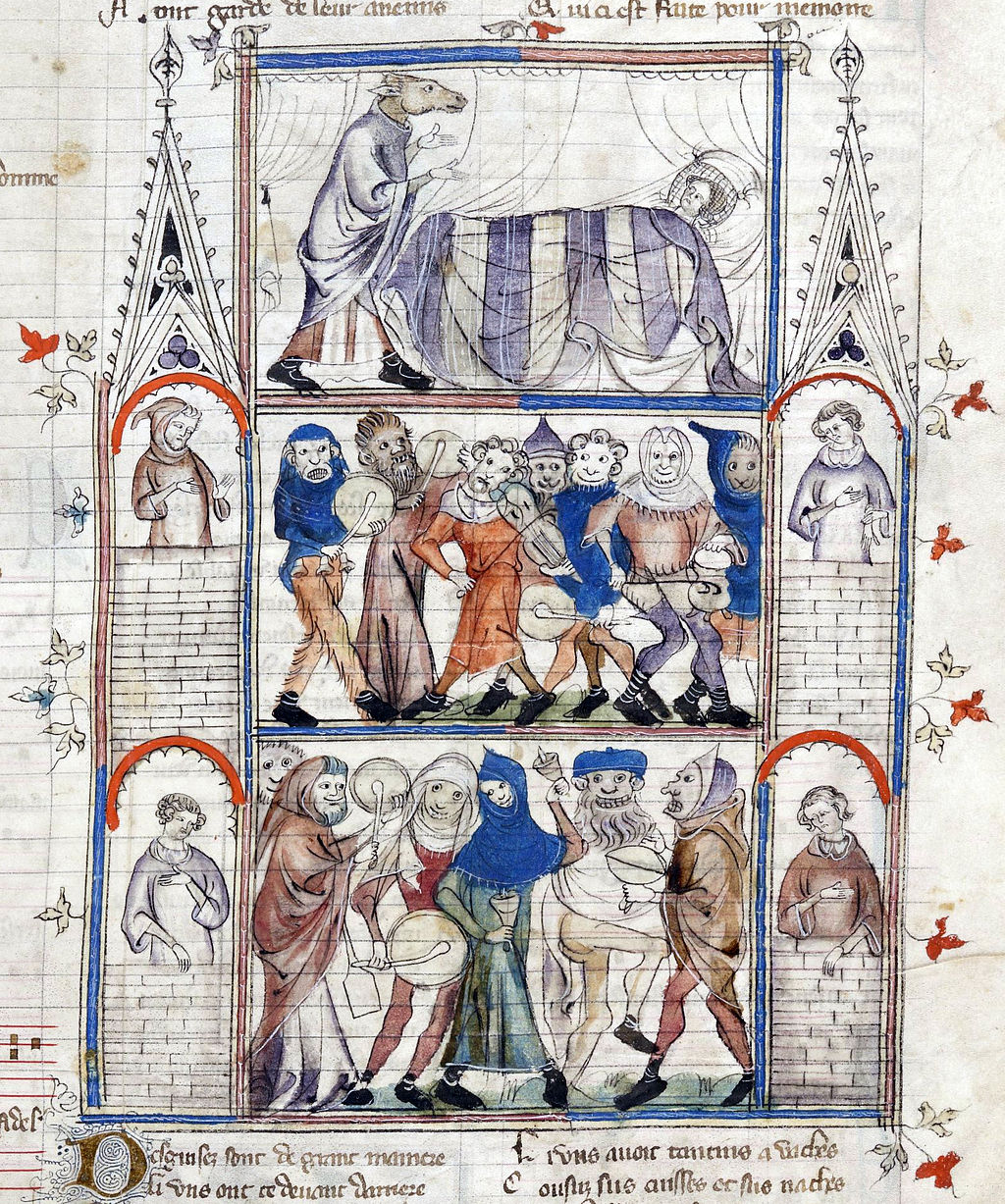

| Etymology Medieval charivari  Depiction of charivari, early 14th century (from the Roman de Fauvel) The origin of the word charivari is likely from the Vulgar Latin caribaria, plural of caribarium, already referring to the custom of rattling kitchenware with an iron rod,[8] itself probably from the Greek καρηβαρία (karēbaría), literally "heaviness in the head" but also used to mean "headache", from κάρα "head" and βαρύς "heavy". In any case, the tradition has been practised for at least 700 years. An engraving in the early 14th-century French manuscript, Roman de Fauvel, shows a charivari underway. |

語源 中世のシャリバリ  14世紀初頭のシャリバリの描写(Roman de Fauvelより) charivariの語源は、鉄の棒で台所用品をガチャガチャ鳴らす風習を意味する[8]ヴァルガー・ラテン語のcaribaria (caribariumの複数形)であり、ギリシャ語のκρηβαρία(karēbaría)、文字通り「頭が重い」に由来すると思われるが、κάρα 「頭」とβαρύς「重い」から「頭痛」の意味にも使われる。いずれにせよ、この伝統は少なくとも700年前から行われてきた。14世紀初頭のフランスの 写本『Roman de Fauvel』には、シャリバリの様子が描かれている。 |

| Regional variations England So-called "Rough Music" practices in England were known by many regional or local designations. In the North the most commonly employed term was "stang riding", a stang being a long pole carried on the shoulders of two men between which an object or a person could be mounted. In the South, the term skimmington, or skimmington ride, was most commonly employed, a skimmington being a type of large wooden ladle with which an unruly wife might beat her husband. Other terms include "lewbelling", "tin-panning", "ran tanning", a "nominey" or "wooset".[9] Where effigies of the "wrongdoers" were made they were frequently burned as the climax of the event (as the inscription on the Rampton photograph indicates[10]) or "ritually drowned" (thrown into a pond or river). The very essence of the practice was public humiliation of the victim under the eyes of their neighbours [11] Rough music practices were irregularly scattered throughout English communities in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth they declined but endured in a few places, such as Rampton, Nottinghamshire (1909),[10] Middleton Cheney (1909) and Blisworth (1920s and 1936), Northamptonshire.[12] There were in fact some examples after the Second World War in Sussex, at West Hoathly in 1947 and Copthorne around 1951, and an attempt at traditional rough music practice was last documented by the folklorist Theo Brown in a Devonshire village around 1973.[13] A lewbelling in Warwickshire, 1909. The caption[14] stated that the custom, although dying out, was still occasionally observed. Here it was applied to an immoral couple. In Warwickshire, the custom was known as "loo-belling" or "lewbelling",[15] and in northern England as "riding the stang".[16] Other names given to this or similar customs were "rough-musicking" and "hussitting" (said to be a reference to the Hussites or followers of John Huss).[17] Noisy, masked processions were held outside the home of the accused wrongdoer, involving the cacophonous rattling of bones and cleavers, the ringing of bells, hooting, blowing bull's horns, the banging of frying pans, saucepans, kettles, or other kitchen or barn implements with the intention of creating long-lasting embarrassment to the alleged perpetrator.[18] During a rough music performance, the victim could be displayed upon a pole or donkey (in person or as an effigy), their "crimes" becoming the subject of mime, theatrical performances or recitatives, along with a litany of obscenities and insults.[18] Alternatively, one of the participants would "ride the stang" (a pole carried between the shoulders of two or more men or youths) while banging an old kettle or pan with a stick and reciting a rhyme (called a "nominy") such as the following: With a ran, tan, tan, On my old tin can, Mrs. _______ and her good man. She bang'd him, she bang'd him, For spending a penny when he stood in need. She up with a three-footed stool; She struck him so hard, and she cut so deep, Till the blood run down like a new stuck sheep![19] Rough music processions are well attested in the medieval period as punishments for violations of the assumed gender norms. Men who had allowed themselves to be dominated by their shrewish wives were liable to be targeted and a frieze from Montecute House, an Elizabethan Manor in Somerset depicts just such an occurrence. However, in the nineteenth century the practice seems to have been somewhat refocused; whilst in the early period rough music was often used against men who had failed to assert their authority over their wives, by the end of the nineteenth century it was mostly targeted against men who had exceeded their authority by beating them.[20] Thus, in contrast to the verses above referring to a shrewish wife there were also songs referring to the use of rough music as a protection for wives. Rough music song originating from South Stoke, Oxfordshire:[21] There is a man in our town Who often beats his wife, So if he does it any more, We'll put his nose right out before. Holler boys, holler boys, Make the bells ring, Holler boys, holler boys. God save the King. The participants were generally young men temporarily bestowed with the power of rule over the everyday affairs of the community.[18] As above, issues of sexuality and domestic hierarchy most often formed the pretexts for rough music,[18] including acts of domestic violence or child abuse. However, rough music was also used as a sanction against those who committed certain species of economic crimes such as blocking footpaths, preventing traditional gleaning, or profiteering at times of poor harvests. Occupational groups, such as butchers, employed rough music against others in the same trade who refused to abide by the commonly agreed labour customs.[22] Rough music practices would often be repeated for three or up to seven nights in a row.[12] Many victims fled their communities and cases of suicide are not unknown.[23] As forms of vigilantism that were likely to lead to public disorder, ran-tanning and similar activities were banned under the Highways Act of 1882.[10] Origins, history and form Skimmingtons are recorded in England in early medieval times and they are recorded in colonial America from around the 1730s.[24][25] The term is particularly associated with the West Country region of England and, although the etymology is not certain, it has been suggested that it derived from the ladle used in that region for cheesemaking, which was perceived as a weapon used by a woman to beat a weak or henpecked husband. The rationale for a skimmington varied, but one major theme was disapproval of a man for weakness in his relationship with his wife. A description of the custom in 1856 cites three main targets: a man who is worsted by his wife in a quarrel; a cuckolded man who accepts his wife's adultery; and any married person who engages in licentious conduct.[26] To "ride such a person skimmington" involved exposing them or their effigy to ridicule on a cart, or on the back of a horse or donkey. Some accounts describe the participants as carrying ladles and spoons with which to beat each other, at least in the case of skimmingtons prompted by marital discord. The noisy parade passed through the neighbourhood, and served as a punishment to the offender and a warning to others to abide by community norms; Roberts suggests that the homes of other potential victims were visited in a pointed manner during a skimmington.[26] According to one citation, a skimmington was broken up by the police in a village in Dorset as late as 1917;[16] and incidents have been reported from the 1930s, the 1950s and perhaps even the 1970s.[17] The antiquary and lexicographer Francis Grose described a skimmington as: "Saucepans, frying-pans, poker and tongs, marrow-bones and cleavers, bulls horns, etc. beaten upon and sounded in ludicrous processions" (A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1796). Western Rising During the Western Rising of 1628–1631, which was a rebellion in south-west England against the enclosure of royal forest lands, the name "Lady Skimmington" was adopted by the leader of the protest movement.[27] According to some sources the name was used by a number of men involved with the Western Rising, who dressed in women's clothes not only as a method of disguise, but also in order to symbolise their protest against a breach of the established order.[28] Similar customs Many folk customs around the world have involved making loud noises to scare away evil spirits.[29] Tuneless, cacophonous "rough music", played on horns, bugles, whistles, tin trays and frying pans, was a feature of the custom known as Teddy Rowe's Band. This had taken place annually, possibly for several centuries, in the early hours of the morning, to herald the start of Pack Monday Fair at Sherborne, Dorset, until it was banned by the police in 1964 because of hooliganism the previous year.[30] The fair is still held, on the first Monday after Old Michaelmas Day (10 October)[31] – St Michael's Day in the Old Style calendar. The Tin Can Band at Broughton, Northamptonshire, a seasonal custom, takes place at midnight on the third Sunday in December. The participants march around the village for about an hour, rattling pans, dustbin lids, kettles and anything else that will make a noise.[32][33] The council once attempted to stop the tin-canning; participants were summoned and fined, but a dance was organised to raise money to pay the fines and the custom continues.[12][33] The village is sufficiently proud of its custom for it to feature on the village sign.[34] Mainland Europe Four drunken male Parisians sing a bawdy serenade Paris men sing a drunken serenade in Honoré Daumier's series of humorous cartoons, The Musicians of Paris. Equivalents include the German: haberfeldtreiben and German: katzenmusik, Italian: scampanate, Spanish cacerolada, (also cacerolazo or cacerolada) and French: charivari.[18] The custom has been documented back to the Middle Ages but it is likely that it was traditional before that. It was first recorded in France, as a regular wedding activity to celebrate the nuptials at some point after the vows had been taken. But charivari achieved its greatest importance as it became transformed into a form of community censure against socially unacceptable marriages; for example, the marriage of widows before the end of the customary social period of formal mourning. In the early 17th century at the Council of Tours, the Catholic Church forbade the ritual of charivari and threatened its practitioners with excommunication.[35] It did not want the community taking on the judgment and punishment of parishioners. But the custom continued in rural areas. The charivari as celebration was a custom initially practised by the upper classes, but as time went on, the lower classes also participated and often looked forward to the next opportunity to join in.[36] The two main purposes of the charivari in Europe were to facilitate change in the current social structure and to act as a form of censure within the community. The goal was to enforce social standards and to rid the community of socially unacceptable relationships that threatened the stability of the whole.[37] In Europe various types of charivari took place that differed from similar practices in other parts of the world. For example, the community might conduct a stag hunt against adulterers by creating a mock chase of human "stags" by human "hounds". The hounds would pursue the stags (that is, those who were committing the adulterous relationship) and dispense animal blood on their doorsteps. European charivaris were highly provocative, leading to overt public humiliation. The people used them to acknowledge and correct misbehaviour. In other parts of the world, similar public rituals around nuptials were practised mostly for celebration.[38] Humiliation was the most common consequence of the European charivari. The acts which victims endured were forms of social ostracism often so embarrassing that they would leave the community for places where they were not known.[39] Sometimes the charivari resulted in murder or suicide. Examples from the south of France include five cases of a charivari victim's firing on his accusers: these incidents resulted in two people being blinded and three killed. Some victims committed suicide, unable to recover from the public humiliation and social exclusion.[40] Norman Lewis recorded the survival of the custom in 1950s Ibiza "in spite of the energetic disapproval of the Guardia Civil". It was called cencerrada, consisted of raucous nocturnal music, and was aimed at widows or widowers who remarried prematurely.[41] It is possible that the blowing of car horns after weddings in France (and indeed in many European countries) today is a holdover from the charivari of the past.[42] North America Charivari has been practiced in much of the United States, but it was most frequent on the frontier, where communities were small and more formal enforcement was lacking. It was documented into the early 20th century, but was thought to have mostly died out by mid century. In Canada, charivaris have occurred in Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces, but not always as an expression of disapproval. The early French colonists took the custom of charivari (or shivaree in the United States) to their settlements in Quebec. Some historians believe the custom spread to English-speaking areas of Lower Canada and eventually into the American South, but it was independently common in English society, so was likely to be part of Anglo-American customs. Charivari is well documented in the Hudson Valley from the earliest days of English settlers through the early 1900s.[43] The earliest documented examples of Canadian charivari were in Quebec in the mid-17th century. One of the most notable was on June 28, 1683. After the widow of François Vézier dit Laverdure remarried only three weeks after her husband’s death, people of Quebec City conducted a loud and strident charivari against the newlyweds at their home.[44] As practised in North America, the charivari tended to be less extreme and punitive than the traditional European custom. Each was unique and heavily influenced by the standing of the family involved, as well as who was participating. While embellished with some European traditions, in a North American charivari participants might throw the culprits into horse tanks or force them to buy candy bars for the crowd. All in fun – it was just a shiveree, you know, and nobody got mad about it. At least not very mad. — Johnson (1990), p. 382. This account from an American charivari in Kansas exemplifies the North American attitude. In contrast to punitive charivari in small villages in Europe, meant to ostracize and isolate the evildoers, North American charivaris were used as "unifying rituals", in which those in the wrong were brought back into the community after what might amount to a minor hazing.[45] In some communities the ritual served as a gentle spoof of the newlyweds, intended to disrupt for a while any sexual activities that might be under way. In parts of the midwest US, such as Kansas, in the mid 1960-1970s, shivaree customs continued as good natured wedding humour along the lines of the musical Oklahoma!. Rituals included wheeling the bride about in a wheelbarrow or tying cowbells under a wedding bed. This ritual may be the base of the fastening of tin cans to the newlyweds car.[46] In Tampa, Florida in September 1885, a large chivaree was held on the occasion of local official James T. Magbee's wedding. According to historian Kyle S. Vanlandingham, the party was "the wildest and noisiest of all the chivaree parties in Tampa's history," attended by "several hundred" men and lasting "until near daylight". The music produced during the chivaree was reportedly "hideous and unearthly beyond description".[47] Charivari is believed to have inspired the development of the Acadian tradition of Tintamarre. |

地域差 イングランド イングランドにおけるいわゆる "ラフ・ミュージック "は、多くの地域的または地方的な呼称で知られていた。北部では「スタング・ライディング」という呼称が最も一般的で、スタングとは2人の男が肩に担ぐ長 い棒のことで、その間に物や人を乗せることができる。南部では、スキミングトン(スキミングトン・ライド)という言葉が最もよく使われた。スキミングトン とは、手に負えない妻が夫を殴るための大きな木製の柄杓の一種である。他の用語としては、「lewbelling」、「tin-panning」、 「ran tanning」、「nominey」、「wooset」などがある[9]。「不義を働いた者」の肖像が作られた場合、それらはイベントのクライマックス として(Ramptonの写真に刻まれた碑文が示すように[10])しばしば燃やされるか、「儀式的に溺死させられる」(池や川に投げ込まれる)。 この慣習の本質は、近隣住民の目の前で犠牲者を公衆の面前で辱めることであった[11]。荒楽は19世紀にはイギリスのコミュニティ全体に不定期に散在し ていた。20世紀には衰退したが、ノッティンガムシャーのランプトン(1909年)、[10]ミドルトン・チェイニー(1909年)、ノーザンプトン シャーのブリスワース(1920年代と1936年)など、いくつかの場所では存続していた[12]。サセックスでは第二次世界大戦後、1947年にウェス ト・ホースリーで、1951年頃にコプソーンで、実際にいくつかの事例があり、伝統的な荒楽の試みが1973年頃にデヴォンシャーの村で民俗学者のテオ・ ブラウンによって記録されたのが最後である[13]。 1909年、ウォリックシャーのレウベリング。キャプション[14]には、この風習は廃れつつあるものの、今でも時折行われていると記されている。ここで は不道徳なカップルに適用された。 ウォリックシャーでは、この風習は「loo-belling」または「lewbelling」として知られ[15]、イングランド北部では「riding the stang」として知られていた[16]。この風習または類似の風習に付けられた他の名称は、「rough-musicking」や 「hussitting」(フス派またはヨハネ・フスの信者を指すと言われている)であった[17]。 騒々しい、仮面をつけた行列が告発された悪人の家の外で行われ、骨や薙刀の不協和音、鐘の音、雄叫び、雄牛の角笛、フライパン、鍋、やかん、その他の台所 や納屋の道具を叩き、告発された加害者に長く続く恥をかかせることを意図していた。 [18]荒っぽい音楽の演奏の間、被害者は(本人または肖像として)棒やロバの上に飾られ、その「罪」はパントマイム、芝居、朗読の題材となり、卑猥な言 葉や侮辱の数々とともに語られる。 [18] あるいは、参加者の一人が古いやかんや鍋を棒で叩きながら、次のような韻文(「ノミニー」と呼ばれる)を唱えながら「スタング」(二人以上の男や若者の肩 の間に担ぐ棒)に乗ることもあった: ラン、タン、タン、 私の古いブリキ缶に 夫人といい男。 彼女は彼を叩いた、彼女は彼を叩いた、 彼が困っているときに1ペニーを使ったから。 彼女は3本足のスツールで立ち上がった; 彼女は彼を強く打ち,深く切った. 血が流れ落ちるまで。 中世の時代には、想定されたジェンダー規範に違反した者に対する罰として、荒々しい音楽の行進がよく証明されている。狡猾な妻に支配されることを許した男 性は標的にされやすく、サマセットにあるエリザベス朝時代の荘園、モンテキュート・ハウスのフリーズには、まさにそのような出来事が描かれている。しか し、19世紀になると、この習慣はいくぶん焦点が絞られたようである。初期の時代には、荒っぽい音楽は妻に対する権威を主張できなかった男性に対して使わ れることが多かったが、19世紀の終わりには、妻を殴ることによって権威を超えた男性に対して使われることがほとんどだった[20]。したがって、上記の 抜け目のない妻に言及した詩とは対照的に、妻を守るために荒っぽい音楽を使うことに言及した歌もあった。 オックスフォードシャーのサウス・ストークで生まれた荒っぽい音楽の歌[21]。 わが町に一人の男がいる よく妻を殴る男がいる、 それ以上やったら 鼻をへし折るぞ。 ホラー・ボーイ、ホラー・ボーイ、 鐘を鳴らせ ホラー・ボーイ、ホラー・ボーイ 神よ、王を救いたまえ。 上記のように、性的な問題や家庭内のヒエラルキーの問題がラフミュージックの口実となることが最も多く[18]、その中には家庭内暴力や児童虐待の行為も 含まれていた。しかしながら、粗暴な音楽は、あぜ道を塞いだり、伝統的な収穫を妨げたり、不作の時に利益を得たりするような、ある種の経済的犯罪を犯した 者に対する制裁としても使用されていた。肉屋などの職業集団は、一般的に合意された労働慣習を守ることを拒否する同業者に対して荒楽を用いた[22]。 乱暴な音楽はしばしば3晩から最大7晩連続で繰り返された[12]。多くの犠牲者が地域社会から逃げ出し、自殺のケースも珍しくない[23]。 公衆の混乱につながる可能性の高い自警の形態として、1882年のハイウェイ法の下でランタンなめしや同様の活動は禁止された[10]。 起源、歴史、形態 スキミングトンはイングランドでは中世初期に記録されており、植民地時代のアメリカでは1730年代頃から記録されている[24][25]。この用語は特 にイングランドのウェスト・カントリー地方に関連しており、語源は定かではないが、この地方でチーズ作りに使用されていた柄杓に由来すると考えられてい る。スキミングトンの根拠はさまざまだが、大きなテーマのひとつは、妻との関係において弱さを見せる男性への非難だった。1856年の風習に関する記述で は、3つの主な対象が挙げられている。喧嘩で妻にひどい目に遭わされた男、妻の不倫を受け入れた寝取られ男、そして淫らな行為に及んだ既婚者である [26]。そのような者をスキミングトンに乗せる」とは、荷車に乗せたり、馬やロバの背に乗せたりして、その者やその肖像を嘲笑にさらすことであった。少 なくとも夫婦間の不和によるスキミングトンの場合、参加者は互いに殴り合うための柄杓やスプーンを持っていたという記述もある。ロバーツは、スキミングト ンの間、他の潜在的な犠牲者の家も指図される形で訪問されたことを示唆している[26]。ある引用によれば、1917年末にはドーセットの村でスキミング トンが警察によって解散させられており[16]、1930年代、1950年代、そしておそらく1970年代にも事件が報告されている[17]。 古文書学者で辞書編纂者のフランシス・グロースはスキミングトンを次のように説明している: 「ソーセパン、フライパン、火かき棒、トング、骨付き肉、肉切り包丁、雄牛の角などを打ち鳴らし、おかしな行列を作ること」(A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1796)。 西部の蜂起 1628年から1631年にかけてイングランド南西部で起こった、王家の森林地帯の囲い込みに反対する反乱である西部の蜂起の際、「レディ・スキミングト ン」という名前が抗議運動のリーダーによって採用された[27]。いくつかの資料によれば、この名前は西部の蜂起に関わった多くの男性によって使用され、 彼らは変装の方法としてだけでなく、既成の秩序の破壊に対する抗議を象徴するために女装した[28]。 類似の風習 世界中の多くの民間風習では、悪霊を追い払うために大きな音を立てることが行われてきた[29]。 ホルン、ラッパ、口笛、ブリキのトレイ、フライパンなどで演奏される、音色のない不協和音の「荒々しい音楽」は、テディ・ロウズ・バンドとして知られる風 習の特徴であった。これは、おそらく数世紀にわたって毎年、ドーセット州シャーボーンでパック・マンデー・フェアの開始を告げるために早朝に行われていた が、1964年に前年のフーリガン行為を理由に警察によって禁止された[30]。 ノーサンプトンシャー州ブロートンのブリキ缶バンドは、季節の風物詩であり、12月の第3日曜日の真夜中に行われる。参加者は、フライパン、ごみ箱のふ た、やかん、その他音の出るものなら何でも鳴らしながら、村の中を約1時間行進する[32][33]。議会はかつてブリキ缶を止めようとし、参加者は召喚 され罰金を科されたが、罰金を支払うための資金集めのためにダンスが企画され、習慣は続いている[12][33]。 ヨーロッパ本土 泥酔した4人のパリジェンヌが歌う下品なセレナーデ オノレ・ドーミエの一連のユーモラスな漫画『パリの音楽隊』で、パリの男たちが酔っぱらってセレナーデを歌う。 同義語として、ドイツ語:haberfeldtreiben、ドイツ語:katzenmusik、イタリア語:scampanate、スペイン語: cacerolada(cacerolazoまたはcaceroladaとも)、フランス語:charivariがある[18]。 この風習は中世までさかのぼる記録があるが、それ以前から伝統的なものであった可能性が高い。フランスで最初に記録されたのは、誓いを立てた後のある時点 で結婚を祝うための定期的な婚礼行事としてであった。しかし、チャリヴァリは、社会的に容認されない結婚、例えば、社会的な慣習である正式な喪の期間が終 わる前の未亡人との結婚に対して、地域社会が非難する形に変化していく中で、最大の重要性を持つようになった。17世紀初頭のトゥール公会議において、カ トリック教会はシャリバリの儀式を禁止し、その実践者を破門で脅した[35]。しかし、農村部ではこの習慣は続いていた。 祝典としてのシャリバリは、当初は上流階級によって行われていた習慣であったが、時代が下るにつれて下層階級も参加するようになり、しばしば次の機会を楽 しみにして参加するようになった[36]。ヨーロッパにおけるシャリバリの2つの主な目的は、現在の社会構造の変化を促進することと、共同体内部の非難の 一形態として機能することであった。その目的は、社会基準を強制し、全体の安定を脅かす社会的に受け入れがたい関係をコミュニティから排除することであっ た[37]。 ヨーロッパでは、世界の他の地域における同様の慣習とは異なる様々なタイプのシャリバリが行われていた。例えば、共同体は人間の「猟犬」による人間の「雄 鹿」の模擬追跡を作り出すことによって、姦通者に対する雄鹿狩りを行うことがあった。猟犬は雄鹿(つまり不倫関係を結んだ者)を追いかけ、玄関先で動物の 血を流すのだ。ヨーロッパのシャリバリは非常に挑発的で、あからさまな公衆の面前での屈辱につながった。人々は、不品行を認め、正すためにそれを利用し た。世界の他の地域では、婚礼にまつわる同様の公的儀式は、主に祝賀のために行われていた[38]。 屈辱はヨーロッパのシャリバリの最も一般的な結果であった。被害者が耐え忍ぶ行為は、社会的追放の一形態であり、しばしば非常に恥ずかしいものであったた め、被害者はそのコミュニティを離れ、自分たちが知られていない場所へと移動した[39]。南フランスの例では、チャリヴァリの被害者が告発者に発砲した 5つの事件があり、その結果、2人が失明し、3人が死亡した。犠牲者の中には、公衆の面前での屈辱と社会的排除から立ち直れずに自殺した者もいた [40]。 ノーマン・ルイスは、1950年代のイビサで、「ガーディア・シビルの熱心な反対にもかかわらず」この風習が残っていたことを記録している。それは cencerradaと呼ばれ、夜間の騒々しい音楽で構成され、早々に再婚した未亡人や男やもめに向けられたものだった[41]。 今日、フランス(そして多くのヨーロッパ諸国)で結婚式の後に車のクラクションを鳴らすのは、かつてのシャリバリの名残である可能性がある[42]。 北米 シャリバリはアメリカ全土で行われていたが、コミュニティが小さく、より正式な取締りが行われていなかった辺境で最も頻繁に行われていた。20世紀初頭ま で記録されていたが、世紀半ばにはほとんど消滅したと考えられている。カナダでは、オンタリオ州、ケベック州、大西洋岸諸州でチャリヴァリが行われている が、必ずしも不服の表明として行われているわけではない。 初期のフランス人入植者たちは、チャリヴァリ(アメリカではシヴァリー)の習慣をケベック州の入植地に持ち込んだ。歴史家の中には、この習慣がカナダ南部 の英語圏に広まり、やがてアメリカ南部にも広まったと考える者もいるが、イギリス社会では独自に一般的なものであったため、英米の習慣の一部であった可能 性が高い。ハドソン・バレーでは、イギリス人入植者の初期から1900年代初期まで、シャリバリの記録がよく残っている[43]。カナダのシャリバリの最 も古い記録例は、17世紀半ばのケベック州である。最も有名なのは1683年6月28日である。フランソワ・ヴェジエの未亡人が夫の死後わずか3週間後に 再婚した後、ケベック・シティの人々は新婚夫婦の家で大声で激しいシャリバリを行った[44]。 北米で行われていたシャリバリは、伝統的なヨーロッパの風習よりも過激で懲罰的ではない傾向があった。それぞれが独特で、関係する家族の地位や誰が参加す るかに大きく影響された。ヨーロッパの伝統もあるが、北米のシャリバリでは、参加者が犯人を馬の水槽に投げ込んだり、観客にキャンディバーを買わせたりす ることもある。 すべては楽しみのためである。少なくともあまり怒らなかった - Johnson (1990), p. 382. カンザスで行われたアメリカのシャリバリでのこの証言は、北米の態度を例証している。ヨーロッパの小さな村での懲罰的なシャリバリが、悪人を追放し孤立さ せることを目的としていたのとは対照的に、北米のシャリバリは「団結の儀式」として使われ、悪いことをした者は、ちょっとしたしごきの後、コミュニティに 戻された[45]。いくつかのコミュニティでは、儀式は新婚夫婦に対する穏やかなしごきとして機能し、しばらくの間、進行中の性行為を中断させることを目 的としていた。1960年代半ばから1970年代にかけて、カンザス州のようなアメリカ中西部の一部では、シバリーの習慣はミュージカル『オクラホマ!』 のような、気さくな結婚式のユーモアとして続いていた。手押し車で花嫁を移動させたり、カウベルを結婚式のベッドの下にくくりつけたりする儀式もあった。 この儀式が、新婚夫婦の車にブリキ缶を固定するベースになっているのかもしれない[46]。 1885年9月、フロリダ州タンパでは、地元の役人であるジェームズ・T・マグビーの結婚式に際して、大規模なチバリーが開催された。歴史家のカイル・ S・ヴァンランディンガムによると、このパーティーは「タンパの歴史上、最も荒々しく騒々しい」もので、「数百人」の男たちが参加し、「日没近くまで」続 いたという。シヴァリー中に生み出された音楽は「筆舌に尽くしがたいほど醜悪で、得体の知れないもの」だったと伝えられている[47]。 シャリバリは、アカディア人の伝統であるティンタマーレの発展に影響を与えたと考えられている。 |

| Importance of noise The use of excessive noise was a universal practice in association with variations in the custom. Loud singing and chanting were common in Europe, including England, and throughout North America. For an 1860 English charivari against a wife-beater, someone wrote an original chant which the crowd was happy to adopt: Has beat his wife! Has beat his wife! It is a very great shame and disgrace To all who live in this place It is indeed, upon my life![48] In Europe the noise, songs, and chants had special meanings for the crowd. When directed against adulterers, the songs represented the community’s disgust. For a too-early remarriage of a widow or widower, the noises symbolized the scream of the late husband or wife in the night.[49] |

騒音の重要性 過度な騒音の使用は、習慣のバリエーションと関連して普遍的な慣習であった。大声で歌ったり詠唱したりすることは、イギリスを含むヨーロッパ、そして北米 で一般的だった。1860年に英国で行われた、妻を殴る男に対するシャリバリでは、誰かがオリジナルのチャントを書き、観客はそれを喜んで採用した: 妻を殴った! 妻を殴った! それは非常に大きな恥と不名誉である この地に住むすべての者にとって まさに私の命にかかわることだ![48]」。 ヨーロッパでは、騒音、歌、聖歌は群衆にとって特別な意味を持っていた。姦淫者に向けられた場合、歌は共同体の嫌悪を表していた。未亡人や寡婦の早すぎる 再婚に対しては、騒音は夜中の亡き夫や妻の悲鳴を象徴していた[49]。 |

| Other usages Perhaps the most common usage of the word today is in relation to circus performances, where a 'charivari' is a type of show opening that sees a raucous tumble of clowns and other performers into the playing space. This is the most common form of entrance used in today's classical circus, whereas the two and three-ring circuses of the last century usually preferred a parade, or a 'spec'. Charivari was sometimes called "riding the 'stang", when the target was a man who had been subject to scolding, beating, or other abuse from his wife. The man was made to "ride the 'stang", which meant that he was placed backwards on a horse, mule or ladder and paraded through town to be mocked, while people banged pots and pans.[50][51][52][53] The charivari was used to belittle those who could not or would not consummate their marriage. In the mid-16th century, historic records attest to a charivari against Martin Guerre in the small village of Artigat in the French Pyrenees for that reason. After he married at the age of 14, his wife did not get pregnant for eight years, so villagers ridiculed him. Later in his life, another man took over Guerre's identity and life. The trial against the impostor was what captured the events for history. In the 20th century, the events formed the basis of a French film, Le Retour de Martin Guerre (1982) and the history, The Return of Martin Guerre, by the American history professor Natalie Zemon Davis.[54] With the charivari widely practised among rural villagers across Europe,[55] the term and practice were part of common culture. Over time, the word was applied to other items. In Bavaria, charivari was adopted as the name for the silver ornaments worn with Lederhosen; the items consist of small trophies from game, like teeth from wild boar, or deer, jaws and fangs from foxes and various marters, feathers and claws from jaybirds and birds of prey. A Bavarian Charivari resembles the so-called "chatelaine", a women's ornament consisting of a silver chain with numerous pendants like a mini silver box of needles, a small pair of scissors, a tiny bottle of perfume, etc.. In the Philippines, the term "Charivari" is used by the Revised Penal Code for a type of criminalised public disorder. Defined in Article 155 as a medley of discordant voices, it is classed under alarm and scandal and is punishable by a fine. |

その他の用法 シャリバリ」とは、ショーのオープニングの一種で、ピエロやその他のパフォーマーたちが騒々しく舞台空間に転げ落ちる様を見るものである。前世紀の2リン グ・サーカスや3リング・サーカスでは通常、パレードや「スペック」が好まれていた。 シャリバリは、妻から叱られたり、殴られたり、その他の虐待を受けている男性をターゲットにした場合、「スタングに乗る」と呼ばれることもあった。その男 は「スタングに乗る」ように仕向けられ、馬やラバやはしごに後ろ向きに乗せられ、人々が鍋やフライパンを叩く中、嘲笑されるために町を練り歩いた[50] [51][52][53]。 シャリバリは、結婚を完遂できない、あるいは完遂しようとしない人々を侮蔑するために用いられた。16世紀半ば、フランスのピレネー山脈にあるアルティガ という小さな村で、マルタン・ゲールに対してそのような理由でシャリバリが行われたという歴史的記録が残っている。彼が14歳で結婚した後、妻は8年間妊 娠しなかったため、村人たちは彼を嘲笑した。その後、別の男がゲールの身元と人生を乗っ取った。この偽者に対する裁判が、歴史に残る出来事となった。20 世紀には、この出来事はフランス映画『Le Retour de Martin Guerre』(1982年)や、アメリカの歴史教授ナタリー・ゼモン・デイヴィスによる歴史書『The Return of Martin Guerre』の基礎となった[54]。 シャリバリはヨーロッパ中の農村で広く行われており[55]、この言葉と習慣は一般的な文化の一部であった。時が経つにつれ、この言葉は他の項目にも適用 されるようになった。バイエルンでは、チャリヴァリはレーダーホーゼンと一緒に着用する銀製の装飾品の名称として採用された。その品々は、イノシシやシカ の歯、キツネの顎や牙、様々なマーター、カケスや猛禽類の羽や爪など、狩猟で得た小さな戦利品で構成されている。バイエルンのシャリバリは、いわゆる "シャトレーヌ "と呼ばれる女性用の装飾品に似ている。シャトレーヌとは、銀のチェーンに、銀のミニ針箱、小さなハサミ、香水の小瓶など、多数のペンダントが付いたもの である。 フィリピンでは、「シャリバリ」という用語は、改正刑法で犯罪化された公然わいせつの一種として使われている。155条で不協和音の混声と定義され、警報 とスキャンダルに分類され、罰金刑に処される。 |

| In music Charivari would later be taken up by composers of the French Baroque tradition as a 'rustic' or 'pastoral' character piece. Notable examples are those of the renowned viola da gamba virtuoso Marin Marais in his five collections of pieces for the basse de viole and continuo. Some are quite advanced and difficult and subsequently evoke the title's origins. The British period instrument/early music ensemble, Charivari Agréable (founded in 1993), states that their name translates as, "'pleasant tumult' (from Saint-Lambert’s 1707 treatise on accompaniment)".[56] |

音楽では シャリバリは、後にフランス・バロックの伝統的な作曲家たちによって、「素朴な」あるいは「牧歌的な」性格の曲として取り上げられるようになる。著名な ヴィオラ・ダ・ガンバの名手、マリン・マレによるヴィオラ・バスと通奏低音のための5つの作品集がその顕著な例である。かなり高度で難解なものもあり、タ イトルの由来を想起させる。 イギリスのピリオド楽器/early musicアンサンブルであるCharivari Agréable(1993年設立)は、自分たちの名前を「『心地よい騒ぎ』(サン=ランベールの1707年の伴奏論から)」と訳している[56]。 |

Marin Marais (1656-1728) - Pieces de viole, Livre 1-5 (Jordi Savall) |

|

| In art and literature In the 14th-century political satire Roman de Fauvel, the evil half-man, half-horse central character Fauvel marries the allegorical figure of Vainglory, and the townspeople hold a charivari in the street as he goes to his marriage bed. In Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose, shortly after new bride Susan Burling Ward arrives in 1876 in the California mining town New Almaden, her husband learns with alarm that "[t]here was some talk about a charivari" among the miners, some of whom throw snickering glances at Susan. The Late Lancashire Witches, a play by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, features a horseback skimmington ride prompted by a woman who seeks greater independence In Samuel Butler's Hudibras, the central character encounters a skimmington in a scene notably illustrated by William Hogarth A skimmington is depicted in a plaster frieze in Montacute House, which dates from the Elizabethan era, and shows a man mounted on a pole, carried on the shoulders of others[57] A skimmington forms a well-known scene in Thomas Hardy's 1884 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge.[12] Effigies of the mayor and Lucetta, a former lover, are paraded through the streets on a donkey by a noisy crowd when rumours of their prior relationship surface. Lucetta, now respectably married to Henchard's rival Farfrae, collapses in distress and humiliation, miscarries her baby and dies. "They are coming up Corn Street after all! They sit back to back!" "What—two of 'em—are there two figures?" "Yes. Two images on a donkey, back to back, their elbows tied to one another's! She's facing the head, and he's facing the tail." "Is it meant for anybody in particular?" "Well--it mid be. The man has got on a blue coat and kerseymere leggings; he has black whiskers, and a reddish face. 'Tis a stuffed figure, with a falseface." (...) The numerous lights round the two effigies threw them up into lurid distinctness; it was impossible to mistake the pair for other than the intended victims. "Come in, come in," implored Elizabeth; "and let me shut the window!" "She's me—she's me—even to the parasol—my green parasol!" cried Lucetta with a wild laugh as she stepped in. She stood motionless for one second—then fell heavily to the floor. — Thomas Hardy, The Mayor of Casterbridge The Skimmity Hitchers are a Scrumpy & Western band from the West Country of England. They took their name from the Skimmington (known as Skimmity in Dorset) to reflect their music and stage show which is a mix of rough music, parody, drunkenness and audience humiliation. |

芸術と文学 14世紀の政治風刺小説『ロマン・ド・フォーベル』では、邪悪な半人半馬の中心人物フォーベルが寓意的な人物ヴェイングローリーと結婚し、彼が結婚のベッ ドに向かうとき、町の人々は通りでシャリバリを行う。 ウォレス・ステグナーのピューリッツァー賞受賞作『安息の角』では、1876年に新婚のスーザン・バーリング・ウォードがカリフォルニアの炭鉱町ニューア ルマデンに到着した直後、彼女の夫は、炭鉱労働者たちの間で「チャリヴァリの話が持ち上がっている」ことを憂慮して知る。 トーマス・ヘイウッドとリチャード・ブロームの戯曲『ランカシャーの魔女たち』(The Late Lancashire Witches)には、より自立を求める女性によって促された馬に乗ってのスキミングトンが登場する。 サミュエル・バトラーの『ハディブラス』では、ウィリアム・ホガースが特に描いた場面で、主人公がスキミングトンに遭遇する。 スキミングトンは、エリザベス朝時代のモンタキュート・ハウスにある石膏のフリーズに描かれており、棒に乗った男が他の人の肩に担がれている様子が描かれ ている[57]。 スキミングトンは、トマス・ハーディの1884年の小説『キャスターブリッジの市長』でよく知られた場面を形成している[12]。市長とかつての恋人ル セッタのエフィギギーが、二人の以前の関係の噂が浮上すると、騒然とした群衆によってロバに乗せられて通りを練り歩く。ルチェッタは現在、ヘンチャードの ライバルであるファーフレイと立派に結婚していたが、苦悩と屈辱のあまり倒れ、赤ん坊を流産して死んでしまう。 "結局、彼らはコーン・ストリートにやってくる!二人は背中合わせに座っている。 "何、2体も......2つの像があるのか?" 「ロバに乗った2人の像が背中合わせになり、互いに肘を結んでいる!彼女は頭の方を向いていて、彼は尻尾の方を向いている。 "誰か特定の人のためのものですか?" 「そうだ。男は青いコートを着て、カージーミアのレギンスをはき、黒いひげを生やし、赤みがかった顔をしている。偽の顔をした、剥製のような人物です」。 (...) 二人の肖像画を囲む多数の照明が、二人を薄気味悪いほど鮮明に浮かび上がらせていた。 「入って、入って」とエリザベスは懇願した。 「ルセッタは一歩中に入ると、荒々しく笑いながら叫んだ。彼女は1秒間動かずに立っていたが、床に大きく倒れ込んだ。 - トマス・ハーディ『キャスターブリッジ市長 スキミティ・ヒッチャーズは、イングランド西部のスクランピー&ウェスタン・バンド。彼らの名前はスキミングトン(ドーセット州ではスキミティと呼ばれ る)から取ったもので、ラフな音楽、パロディ、泥酔、観客の屈辱をミックスした彼らの音楽とステージを反映している。 |

| In popular culture Le Charivari was the name given to a French satirical magazine first published in 1832. Its British counterpart, established in 1841, was entitled Punch, or The London Charivari. In the film The Purchase Price, members of a North Dakota farming community celebrate the marriage of Barbara Stanwyck's and George Brent's characters by holding a noisy, drunken shivaree a couple days after their nuptials. In the television show The Waltons, the episode titled "The Shivaree" focused around a wedding between a city boy and a country girl. The groom almost calls off the marriage after being humiliated by a shivaree thrown by his wife's family and friends. In the television show The Rifleman, in episode titled "Shivaree", two travelers are forced to get married when it is discovered that they are actually a young unmarried couple in disguise. The Midsomer Murders television episode "Four Funerals and a Wedding" prominently features a Skimmington ride. In the fantasy novel series Discworld, Terry Pratchett refers to the 'dissonant piping and war-drums of vengeance' sounds of rough music in a scene where a rural town finds out that a local man beat his daughter, causing her miscarriage, and a drunken mob come to kill him for the crime. In the television show Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, the episode titled "Return Engagement, Part 1" references a shivaree after an ex-prostitute marries the telegraph operator. In the musical Oklahoma!, Laurey and Curly are given a shivaree on their wedding night by a group of rowdy cowboys near the end of Act II. In the British drama series Jamestown, Season 2, Episode 8, the Widow Castell is made to walk a Skimmington in order to shame her for not remarrying soon enough. The men in power want her under the control of a husband to stymie her meddling in colony politics. In the 1950 film Never A Dull Moment, newlyweds Chris and Kay are given a shivaree by local ranchers on Kay’s first night at her husband’s ranch. In the American animated sitcom Archer, Season 5, Episode 12, titled "Filibuster", Cyril proposes that the servants conduct a shivaree while he and Julia Calderon consummate their marriage. She declines. In the 1966 film El Dorado, Cole Thorton (John Wayne) tells Mississippi (James Caan) that they were unable to re-enter the saloon they just left because the "shivaree" (i.e., the fight they had with other bar patrons) "wore out our welcome". In the television show Death Valley Days, Season 1, Episode 8, "The Chivaree", the couple getting married discuss the expected "chivareeing" to follow their upcoming wedding. The groom opposes, after having already been chided in the town previously, but the scorned ex-lover of the bride insists. The bride and groom sit quietly in the window and endure the ruckus for two days before inviting the crowd in for food and drink. |

大衆文化において ル・シャリヴァリは、1832年に創刊されたフランスの風刺雑誌に与えられた名称である。1841年に創刊されたイギリスの同種の雑誌は、パンチ、または ロンドン・シャリヴァリと名付けられた。 映画『The Purchase Price』では、ノースダコタの農村社会の住人たちが、バーバラ・スタンウィックとジョージ・ブレント演じるキャラクターの結婚を祝って、結婚式の数日 後に騒々しく酔っ払ったシバリーを開催する。 テレビ番組『ザ・ウォルトンズ』の「シバリー」というタイトルのエピソードでは、都会の青年と田舎の少女の結婚式が描かれている。花嫁の家族や友人たちが 開いたシバリーで屈辱的な思いをした新郎は、結婚を白紙に戻そうとする。 テレビ番組『ザ・ライフルマン』の「シバリー」というタイトルのエピソードでは、2人の旅人が、実は若い未婚のカップルが変装していることがばれてしま い、結婚を余儀なくされる。 テレビドラマ『ミッドサマー・マーダー』のエピソード「Four Funerals and a Wedding」では、スキミングトン・ライドが大きく取り上げられている。 ファンタジー小説シリーズ『ディスクワールド』の中で、テリー・プラチェットは、田舎町で地元の男が娘を殴り、流産させたことが発覚し、酔っ払った暴徒た ちがその罪で彼を殺しに来るという場面で、荒々しい音楽の「不協和音の笛と復讐の太鼓」の音を引用している。 テレビ番組『ドクタークイン 〜女医物語〜』の「Return Engagement, Part 1」というエピソードでは、元娼婦が電信技手と結婚した後にシバーリーが行われる。 ミュージカル『オクラホマ!』では、第2幕の終わり近くで、ローリーとカーリーが結婚式の夜に乱暴なカウボーイの一団からシバーリーを受ける。 英国のドラマシリーズ『ジェームズタウン』シーズン2、第8話では、未亡人キャステルが、すぐに再婚しないことを恥じるためにスキミングトンを歩かされ る。権力を持つ男たちは、彼女が植民地の政治に干渉するのを阻止するために、彼女を夫の管理下に置きたいと考えていた。 1950年の映画『Never A Dull Moment』では、新婚のクリスとケイが、ケイが夫の牧場に初めて来た夜に、地元の牧場主たちからシバリーを授けられる。 アメリカのアニメシットコム『Archer』シーズン5、第12話「Filibuster」では、シリルが、彼とジュリア・カルデロンが結婚生活を始める 間、使用人たちにシバリーを行うことを提案する。彼女はそれを断る。 1966年の映画『エルドラド』では、コール・ソーントン(ジョン・ウェイン)がミシシッピ(ジェームズ・カーン)に、自分たちが先ほどまでいた酒場に再 び入ることができなかったのは、「シバリー」(すなわち、他の客たちとの喧嘩)で「歓迎されなくなった」からだと話す。 テレビ番組『デスバレー・デイズ』シーズン1、第8話「The Chivaree」では、結婚を控えたカップルが、結婚式後に予想される「チバレ」について話し合っている。新郎は、すでに町で叱責された経験があったた め反対するが、花嫁の軽蔑した元恋人は主張する。花嫁と花婿は窓際に静かに座り、群衆を招いて食べ物や飲み物を振る舞うまでの2日間、騒動に耐える。 |

| Cacerolazo Dorset Ooser Escrache Extrajudicial punishment Mobbing Riding a rail Tarring and feathering The Rogue's March Vigilantism |

カセロラソ ドーセット・ウーセル エスクラチェ 超法規的処罰 モッビング レールに乗る 羽交い締め ならず者の行進 私刑 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charivari |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆