チャールズ・サンダー・パース

Charles Sanders Peirce, 1839-1914

☆ チャールズ・サンダース・パース(1839年9月10日 - 1914年4月19日)はアメリカの科学者、数学者、論理学者、哲学者で、「プラグマティズムの父」として知られることもある。哲学者のポール・ワイスに よれば、vは「アメリカの哲学者の中で最も独創的で多才であり、アメリカで最も偉大な論理学者」であった。バートランド・ラッセルは「彼は19世紀後半で 最も独創的な頭脳の持ち主であり、アメリカ史上最も偉大な思想家であることは間違いない」と書いている。

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sanders_Peirce からの機械翻訳だが、パースなどの表記が、パイス、ピアースなどになっていることに注意せよ。

| Charles

Sanders Peirce

(/pɜːrs/[8][9] PURSS; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an

American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is

sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism".[10][11] According to

philosopher Paul Weiss, Peirce was "the most original and versatile of

America's philosophers and America's greatest logician".[12] Bertrand

Russell wrote "he was one of the most original minds of the later

nineteenth century and certainly the greatest American thinker ever". Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for thirty years, Peirce meanwhile made major contributions to logic, such as theories of relations and quantification. C. I. Lewis wrote, "The contributions of C.S. Peirce to symbolic logic are more numerous and varied than those of any other writer—at least in the nineteenth century." For Peirce, logic also encompassed much of what is now called epistemology and the philosophy of science. He saw logic as the formal branch of semiotics or study of signs, of which he is a founder, which foreshadowed the debate among logical positivists and proponents of philosophy of language that dominated 20th-century Western philosophy. Peirce's study of signs also included a tripartite theory of predication. Additionally, he defined the concept of abductive reasoning, as well as rigorously formulating mathematical induction and deductive reasoning. He was one of the founders of statistics. As early as 1886, he saw that logical operations could be carried out by electrical switching circuits. The same idea was used decades later to produce digital computers.[13] For metaphysics, Peirce was an "objective idealist" in the tradition of German philosopher Immanuel Kant as well as a scholastic realist about universals. He also held a commitment to the ideas of continuity and chance as real features of the universe, views he labeled synechism and tychism respectively. Peirce believed an epistemic fallibilism and anti-skepticism went along with these views. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sanders_Peirce |

チャー

ルズ・サンダース・パース(1839年9月10日 -

1914年4月19日)はアメリカの科学者、数学者、論理学者、哲学者で、「プラグマティズムの父」として知られることもある。哲学者のポール・ワイスに

よれば、vは「アメリカの哲学者の中で最も独創的で多才であり、アメリカで最も偉大な論理学者」であった。バートランド・ラッセルは「彼は19世紀後半で

最も独創的な頭脳の持ち主であり、アメリカ史上最も偉大な思想家であることは間違いない」と書いている。 化学者としての教育を受け、30年間科学者として働いていたパースは、一方で関係論や数量化など論理学に大きな貢献をした。C.I.ルイスは、「C.S. パースの記号論理学への貢献は、少なくとも19世紀においては、他のどの作家の貢献よりも多く、多岐にわたる」と書いている。パースにとって論理学は、現 在認識論や科学哲学と呼ばれるものの多くも包含していた。論理学は、彼が創始者である記号論の形式的な一分野であり、20世紀の西洋哲学を支配した論理実 証主義者と言語哲学の支持者の論争を予見するものであった。ペイスの記号研究は、述語の三段論法も含んでいた。 さらに、数学的帰納法と演繹法を厳密に定式化するとともに、帰納推論の概念を定義した。彼は統計学の創始者の一人である。1886年には早くも、彼は論理 演算が電気的なスイッチング回路によって実行される可能性があることを見た。同じアイデアは数十年後にデジタル・コンピュータを生み出すために使われた [13]。 形而上学については、パースはドイツの哲学者イマニュエル・カントの伝統にのっとった「客観的観念論者」であり、また普遍についてのスコラ哲学的実在論者 でもあった。また、宇宙の現実的特徴として連続性と偶然性という考え方に傾倒し、それぞれをシネキズムとタイキズムと呼んだ。また、これらの見解には、認 識論的な誤謬主義と反懐疑主義が同居していると考えた。 以下 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sanders_Peirce |

| Biography Early life Peirce's birthplace. Now part of Lesley University's Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences. Peirce was born at 3 Phillips Place in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was the son of Sarah Hunt Mills and Benjamin Peirce, himself a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Harvard University.[a] At age 12, Charles read his older brother's copy of Richard Whately's Elements of Logic, then the leading English-language text on the subject. So began his lifelong fascination with logic and reasoning.[14] He suffered from his late teens onward from a nervous condition then known as "facial neuralgia", which would today be diagnosed as trigeminal neuralgia. His biographer, Joseph Brent, says that when in the throes of its pain "he was, at first, almost stupefied, and then aloof, cold, depressed, extremely suspicious, impatient of the slightest crossing, and subject to violent outbursts of temper".[15] Its consequences may have led to the social isolation of his later life. Education Peirce went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Master of Arts degree (1862) from Harvard. In 1863 the Lawrence Scientific School awarded him a Bachelor of Science degree, Harvard's first summa cum laude chemistry degree.[16] His academic record was otherwise undistinguished.[17] At Harvard, he began lifelong friendships with Francis Ellingwood Abbot, Chauncey Wright, and William James.[18] One of his Harvard instructors, Charles William Eliot, formed an unfavorable opinion of Peirce. This proved fateful, because Eliot, while President of Harvard (1869–1909—a period encompassing nearly all of Peirce's working life), repeatedly vetoed Peirce's employment at the university.[19] United States Coast Survey Peirce in 1859 Between 1859 and 1891, Peirce was intermittently employed in various scientific capacities by the United States Coast Survey, which in 1878 was renamed the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey,[20] where he enjoyed his highly influential father's protection until the latter's death in 1880.[21] At the Survey, he worked mainly in geodesy and gravimetry, refining the use of pendulums to determine small local variations in the Earth's gravity.[20] American Civil War This employment exempted Peirce from having to take part in the American Civil War; it would have been very awkward for him to do so, as the Boston Brahmin Peirces sympathized with the Confederacy.[22] No members of the Peirce family volunteered or enlisted. Peirce grew up in a home where white supremacy was taken for granted, and slavery was considered natural.[23] Peirce's father had described himself as a secessionist until the outbreak of the war, after which he became a Union partisan, providing donations to the Sanitary Commission, the leading Northern war charity. Peirce liked to use the following syllogism to illustrate the unreliability of traditional forms of logic (for the first premise arguably assumes the conclusion):[24] All Men are equal in their political rights. Negroes are Men. Therefore, negroes are equal in political rights to whites. Travels to Europe He was elected a resident fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in January 1867.[25] The Survey sent him to Europe five times,[26] first in 1871 as part of a group sent to observe a solar eclipse. There, he sought out Augustus De Morgan, William Stanley Jevons, and William Kingdon Clifford,[27] British mathematicians and logicians whose turn of mind resembled his own. Harvard observatory From 1869 to 1872, he was employed as an assistant in Harvard's astronomical observatory, doing important work on determining the brightness of stars and the shape of the Milky Way.[28] In 1872 he founded the Metaphysical Club, a conversational philosophical club that Peirce, the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the philosopher and psychologist William James, amongst others, formed in January 1872 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and dissolved in December 1872. Other members of the club included Chauncey Wright, John Fiske, Francis Ellingwood Abbot, Nicholas St. John Green, and Joseph Bangs Warner.[29] The discussions eventually birthed Peirce's notion of pragmatism. National Academy of Sciences "The World on a Quincuncial Projection", 1879.[30] Peirce's projection of a sphere onto a square keeps angles true except at four isolated points on the equator, and has less scale variation than the Mercator projection. It can be tessellated; that is, multiple copies can be joined continuously edge-to-edge. On April 20, 1877, he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences.[31] Also in 1877, he proposed measuring the meter as so many wavelengths of light of a certain frequency,[32] the kind of definition employed from 1960 to 1983. In 1879 Peirce developed Peirce quincuncial projection, having been inspired by H. A. Schwarz's 1869 conformal transformation of a circle onto a polygon of n sides (known as the Schwarz–Christoffel mapping). 1880 to 1891 During the 1880s, Peirce's indifference to bureaucratic detail waxed while his Survey work's quality and timeliness waned. Peirce took years to write reports that he should have completed in months.[according to whom?] Meanwhile, he wrote entries, ultimately thousands, during 1883–1909 on philosophy, logic, science, and other subjects for the encyclopedic Century Dictionary.[33] In 1885, an investigation by the Allison Commission exonerated Peirce, but led to the dismissal of Superintendent Julius Hilgard and several other Coast Survey employees for misuse of public funds.[34] In 1891, Peirce resigned from the Coast Survey at Superintendent Thomas Corwin Mendenhall's request.[35] Johns Hopkins University In 1879, Peirce was appointed lecturer in logic at Johns Hopkins University, which had strong departments in areas that interested him, such as philosophy (Royce and Dewey completed their PhDs at Hopkins), psychology (taught by G. Stanley Hall and studied by Joseph Jastrow, who coauthored a landmark empirical study with Peirce), and mathematics (taught by J. J. Sylvester, who came to admire Peirce's work on mathematics and logic). His Studies in Logic by Members of the Johns Hopkins University (1883) contained works by himself and Allan Marquand, Christine Ladd, Benjamin Ives Gilman, and Oscar Howard Mitchell,[36] several of whom were his graduate students.[7] Peirce's nontenured position at Hopkins was the only academic appointment he ever held. Brent documents something Peirce never suspected, namely that his efforts to obtain academic employment, grants, and scientific respectability were repeatedly frustrated by the covert opposition of a major Canadian-American scientist of the day, Simon Newcomb.[37] Newcomb had been a favourite student of Peirce's father; although "no doubt quite bright", "like Salieri in Peter Shaffer's Amadeus he also had just enough talent to recognize he was not a genius and just enough pettiness to resent someone who was". Additionally "an intensely devout and literal-minded Christian of rigid moral standards", he was appalled by what he considered Peirce's personal shortcomings.[38] Peirce's efforts may also have been hampered by what Brent characterizes as "his difficult personality".[39] In contrast, Keith Devlin believes that Peirce's work was too far ahead of his time to be appreciated by the academic establishment of the day and that this played a large role in his inability to obtain a tenured position.[40] Personal life Juliette and Charles by a well at their home Arisbe in 1907 Peirce's personal life undoubtedly worked against his professional success. After his first wife, Harriet Melusina Fay ("Zina"), left him in 1875,[41] Peirce, while still legally married, became involved with Juliette, whose last name, given variously as Froissy and Pourtalai,[42] and nationality (she spoke French)[43] remains uncertain.[44] When his divorce from Zina became final in 1883, he married Juliette.[45] That year, Newcomb pointed out to a Johns Hopkins trustee that Peirce, while a Hopkins employee, had lived and traveled with a woman to whom he was not married; the ensuing scandal led to his dismissal in January 1884.[46] Over the years Peirce sought academic employment at various universities without success.[47] He had no children by either marriage.[48] Later life and poverty Arisbe in 2011 Charles and Juliette Peirce's grave In 1887, Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy 2,000 acres (8 km2) of rural land near Milford, Pennsylvania, which never yielded an economic return.[49] There he had an 1854 farmhouse remodeled to his design.[50] The Peirces named the property "Arisbe". There they lived with few interruptions for the rest of their lives,[51] Charles writing prolifically, with much of his work remaining unpublished to this day (see Works). Living beyond their means soon led to grave financial and legal difficulties.[52] Charles spent much of his last two decades unable to afford heat in winter and subsisting on old bread donated by the local baker. Unable to afford new stationery, he wrote on the verso side of old manuscripts. An outstanding warrant for assault and unpaid debts led to his being a fugitive in New York City for a while.[53] Several people, including his brother James Mills Peirce[54] and his neighbors, relatives of Gifford Pinchot, settled his debts and paid his property taxes and mortgage.[55] Peirce did some scientific and engineering consulting and wrote much for meager pay, mainly encyclopedic dictionary entries, and reviews for The Nation (with whose editor, Wendell Phillips Garrison, he became friendly). He did translations for the Smithsonian Institution, at its director Samuel Langley's instigation. Peirce also did substantial mathematical calculations for Langley's research on powered flight. Hoping to make money, Peirce tried inventing.[56] He began but did not complete several books.[57] In 1888, President Grover Cleveland appointed him to the Assay Commission.[58] From 1890 on, he had a friend and admirer in Judge Francis C. Russell of Chicago,[59] who introduced Peirce to editor Paul Carus and owner Edward C. Hegeler of the pioneering American philosophy journal The Monist, which eventually published at least 14 articles by Peirce.[60] He wrote many texts in James Mark Baldwin's Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology (1901–1905); half of those credited to him appear to have been written actually by Christine Ladd-Franklin under his supervision.[61] He applied in 1902 to the newly formed Carnegie Institution for a grant to write a systematic book describing his life's work. The application was doomed; his nemesis, Newcomb, served on the Carnegie Institution executive committee, and its president had been president of Johns Hopkins at the time of Peirce's dismissal.[62] The one who did the most to help Peirce in these desperate times was his old friend William James, dedicating his Will to Believe (1897) to Peirce, and arranging for Peirce to be paid to give two series of lectures at or near Harvard (1898 and 1903).[63] Most important, each year from 1907 until James's death in 1910, James wrote to his friends in the Boston intelligentsia to request financial aid for Peirce; the fund continued even after James died. Peirce reciprocated by designating James's eldest son as his heir should Juliette predecease him.[64] It has been believed that this was also why Peirce used "Santiago" ("St. James" in English) as a middle name, but he appeared in print as early as 1890 as Charles Santiago Peirce. (See Charles Santiago Sanders Peirce for discussion and references). |

略歴 生い立ち ペアーズの生家。現在はレズリー大学大学院の一部となっている。 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジのフィリップス・プレイス3番地で生まれる。サラ・ハント・ミルズとハーバード大学の数学・天文学教授であったベンジャミ ン・パースの息子であった[a]。12歳の時、チャールズは兄が持っていたリチャード・ホワットリーの『論理学の素』を読んだ。こうして、彼の論理と推 論に対する生涯の魅力が始まった[14]。 彼は10代後半から、当時「顔面神経痛」と呼ばれていた神経症に悩まされ、今日では三叉神経痛と診断されている。彼の伝記作者であるジョセフ・ブレント は、その痛みに苦しんでいたとき、「最初はほとんど茫然自失のようであったが、やがて飄々として、冷淡で、憂鬱で、極度に疑い深く、わずかな交差にもせっ かちで、気性が激しく爆発するようになった」と述べている[15]。 教育 1862年、ハーバード大学で学士号と修士号を取得。ハーバード大学では、フランシス・エリングウッド・アボット、チャウンシー・ライト、ウィリアム・ ジェイムズらと生涯の友誼を結ぶ。エリオットはハーバード大学学長時代(1869年~1909年、つまりペイスの現役時代のほぼすべてを含む)、ペイスの 大学での雇用に何度も拒否権を行使したからである[19]。 米国沿岸調査 1859年のペアーズ 1859年から1891年にかけて、ペアースは合衆国沿岸測量局に断続的に様々な科学的職務に就いていた。この測量局は1878年に合衆国沿岸測地測量局 と改称され[20]、1880年に父親が亡くなるまで、影響力の大きい父親の庇護を受けていた。 アメリカ南北戦争 ボストンのバラモン教徒であったペアーズは南部連合に同調していたため、そうすることは彼にとって非常に気まずいことであっただろう。ペイスの父親は、戦 争が始まるまでは分離独立論者であったが、戦争が始まると北軍の党員となり、北軍を代表する慈善団体である衛生委員会に寄付をした。 パースは次のような三段論法を好んで使い、伝統的な論理形式の信頼性の低さ(第一前提が結論を間違いなく仮定しているため)を説明した[24]。 すべての人間は政治的権利において平等である。 黒人は人間である。 したがって、黒人は白人と政治的権利において平等である。 ヨーロッパ旅行 1867年1月、彼はアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのレジデント・フェローに選出された[25]。同調査は彼を5度ヨーロッパに派遣し[26]、最初は 1871年に日食観測のために派遣されたグループの一員としてヨーロッパを訪れた。そこで彼は、オーガスタス・デ・モーガン、ウィリアム・スタンリー・ ジェヴォンズ、ウィリアム・キングドン・クリフォード[27]といったイギリスの数学者や論理学者を探し求めた。 ハーバード天文台 1869年から1872年まで、ハーバードの天文台で助手として働き、星の明るさや天の川の形状を決定する重要な仕事をした[28]。1872年、彼は形 而上学クラブを設立。このクラブは、ペイス、後の最高裁判事オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア、哲学者で心理学者のウィリアム・ジェームズらが 1872年1月にマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで結成し、1872年12月に解散した。このクラブの他のメンバーには、チャウンシー・ライト、ジョン・ フィスク、フランシス・エリングウッド・アボット、ニコラス・セントジョン・グリーン、ジョセフ・バングス・ワーナーなどがいた[29]。 全米科学アカデミー 「球面を正方形に投影したもので、赤道上の4つの孤立した点を除いて角度を真に保ち、メルカトル図法よりも縮尺の変化が少ない。テッセレーション(四角形 分割)が可能であり、複数の球面を端から端まで連続的に連結することができる。 1877年4月20日、彼は全米科学アカデミーの会員に選出された[31]。また1877年には、1960年から1983年まで採用された定義である [32]、ある周波数の光の波長数としてメートルを測定することを提案した。 1879年、H.A.シュワルツが1869年に発表したn辺の多角形への円のコンフォーマル変換(シュワルツ-クリストッフェルの写像として知られる)に 触発され、ペイスは四角形投影法を開発。 1880年から1891年 1880年代、ペイスは官僚的な細部に無関心になる一方で、サーベイの仕事の質と適時性は低下していった。その一方で、1883年から1909年にかけ て、百科事典『Century Dictionary』のために哲学、論理学、科学、その他のテーマについて、最終的には数千もの項目を執筆した[33]。 [33]1885年、アリソン委員会の調査により、ペイスの容疑は晴れたが、公金の不正使用により、ジュリアス・ヒルガルド監督官をはじめとする沿岸調査 の職員数名が解任された[34]。1891年、トーマス・コーウィン・メンデンホール監督官の要請により、ペイスは沿岸調査を辞職した[35]。 ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学 この大学には、哲学(ロイスとデューイはホプキンスで博士号を取得)、心理学(G.スタンレー・ホールが教え、ジョセフ・ジャストローが研究し、彼はペイ スと画期的な実証的研究を共著した)、数学(J.J.シルヴェスターが教え、彼は数学と論理学に関するペイスの研究を賞賛するようになった)など、彼が興 味を持った分野の強力な学部があった。彼の『ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学のメンバーによる論理学研究』(1883年)には、彼自身とアラン・マーカンド、ク リスティン・ラッド、ベンジャミン・アイブス・ギルマン、オスカー・ハワード・ミッチェル[36]の著作が収められており、そのうちの何人かは彼の大学院 生であった[7]。 つまり、学術的な雇用、助成金、科学的な尊敬を得ようとする彼の努力が、当時のカナダ系アメリカ人の主要な科学者であったサイモン・ニューコムの密かな反 対によって何度も挫折させられたということである。さらに「厳格な道徳基準を持つ、強烈に敬虔で字義を重んじるキリスト教徒」であったブレントは、ペアー ズの個人的な欠点と思われるものに愕然とした[38]。 私生活 1907年、自宅アリスベの井戸のそばで。 ペイスの私生活が彼の仕事上の成功に不利に働いたことは間違いない。最初の妻ハリエット・メルシーナ・フェイ(「ジーナ」)が1875年に彼のもとを去っ た後[41]、法的にはまだ結婚していたペイスはジュリエットと関係を持つようになった。 [その年、ニューコムはジョンズ・ホプキンスの評議員に、ホプキンスの職員でありながら、結婚していない女性と同棲し、旅行していたことを指摘した [45]。 その後の生活と貧困 2011年のアリスベ チャールズとジュリエットの墓 1887年、ペアーズは両親から相続した財産の一部を使い、ペンシルベニア州ミルフォード近郊に2,000エーカー(8km2)の田園地帯の土地を購入し たが、経済的な利益を得ることはなかった[49]。そこで二人は残りの人生をほとんど中断することなく暮らし、[51]チャールズは多作で、彼の作品の多 くは今日まで未発表のままである(「作品」を参照)。身の丈を超えた生活は、やがて深刻な経済的・法的問題に発展し[52]、チャールズは晩年の20年の 大半を、冬に暖房を買う余裕もなく、地元のパン屋から寄付された古いパンで糊口をしのいでいた。新しい文房具を買う余裕もなく、古い原稿の裏面に字を書い ていた。弟のジェイムズ・ミルズ・パース[54]やギフォード・ピンチョットの親戚である隣人など、何人かの人々が彼の借金を整理し、固定資産税と住宅 ローンを支払った[55]。 ペイスは科学と工学のコンサルティングを行い、主に百科事典の辞書項目や『ネイション』誌(その編集者ウェンデル・フィリップス・ギャリソンと親交を深め た)の書評など、わずかな報酬で多くの執筆を行った。スミソニアン協会のサミュエル・ラングレー館長の勧めで、スミソニアン協会の翻訳も手がけた。また、 動力飛行に関するラングレーの研究のために数学的な計算も行った。1888年、グローヴァー・クリーヴランド大統領は彼を検定委員に任命した[58]。 1890年以降、彼はシカゴの判事フランシス・C・ラッセル[59]に友人と崇拝者を持ち、彼はパイオニア的なアメリカの哲学雑誌『The Monist』の編集者ポール・カラスとオーナーであるエドワード・C・ヘゲラーにペアースを紹介し、最終的にペアースの少なくとも14の記事を掲載し た。 [60]彼はジェームズ・マーク・ボールドウィンの『哲学と心理学の辞典』(1901-1905年)に多くの文章を書いたが、彼とクレジットされている文 章の半分は、実際には彼の監督の下、クリスティン・ラッド=フランクリンによって書かれたようである。彼の宿敵であるニューカムはカーネギー研究所の執行 委員会のメンバーであり、その会長はペイスが解任された当時ジョンズ・ホプキンスの会長であった[62]。 最も重要なことは、1907年から1910年にジェームズが亡くなるまで、毎年ジェームズはボストンの知識人の友人たちに手紙を書き、ペアーズのための資 金援助を要請したことである。ペイスは、ジュリエットに先立たれた場合、ジェームズの長男を相続人に指定することで恩返しをした[64]。ペイスがミドル ネームに「サンティアゴ」(英語では「セント・ジェームス」)を使ったのもこのためだと考えられているが、1890年には早くもチャールズ・サンティア ゴ・ペイスとして活字に登場している。(考察と参考文献はチャールズ・サンティアゴ・サンダース・パイアースを参照)。 |

| Death and legacy Peirce died destitute in Milford, Pennsylvania, twenty years before his widow. Juliette Peirce kept the urn with Peirce's ashes at Arisbe. In 1934, Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot arranged for Juliette's burial in Milford Cemetery. The urn with Peirce's ashes was interred with Juliette.[65] Bertrand Russell (1959) wrote "Beyond doubt [...] he was one of the most original minds of the later nineteenth century and certainly the greatest American thinker ever".[66] Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica, published from 1910 to 1913, does not mention Peirce (Peirce's work was not widely known until later).[67] A. N. Whitehead, while reading some of Peirce's unpublished manuscripts soon after arriving at Harvard in 1924, was struck by how Peirce had anticipated his own "process" thinking. (On Peirce and process metaphysics, see Lowe 1964.[28]) Karl Popper viewed Peirce as "one of the greatest philosophers of all times".[68] Yet Peirce's achievements were not immediately recognized. His imposing contemporaries William James and Josiah Royce[69] admired him and Cassius Jackson Keyser, at Columbia and C. K. Ogden, wrote about Peirce with respect but to no immediate effect. The first scholar to give Peirce his considered professional attention was Royce's student Morris Raphael Cohen, the editor of an anthology of Peirce's writings entitled Chance, Love, and Logic (1923), and the author of the first bibliography of Peirce's scattered writings.[70] John Dewey studied under Peirce at Johns Hopkins.[7] From 1916 onward, Dewey's writings repeatedly mention Peirce with deference. His 1938 Logic: The Theory of Inquiry is much influenced by Peirce.[71] The publication of the first six volumes of Collected Papers (1931–1935) was the most important event to date in Peirce studies and one that Cohen made possible by raising the needed funds;[72] however it did not prompt an outpouring of secondary studies. The editors of those volumes, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, did not become Peirce specialists. Early landmarks of the secondary literature include the monographs by Buchler (1939), Feibleman (1946), and Goudge (1950), the 1941 PhD thesis by Arthur W. Burks (who went on to edit volumes 7 and 8), and the studies edited by Wiener and Young (1952). The Charles S. Peirce Society was founded in 1946. Its Transactions, an academic quarterly specializing in Peirce's pragmatism and American philosophy has appeared since 1965.[73] (See Phillips 2014, 62 for discussion of Peirce and Dewey relative to transactionalism.) By 1943 such was Peirce's reputation, in the US at least, that Webster's Biographical Dictionary said that Peirce was "now regarded as the most original thinker and greatest logician of his time".[74] In 1949, while doing unrelated archival work, the historian of mathematics Carolyn Eisele (1902–2000) chanced on an autograph letter by Peirce. So began her forty years of research on Peirce, “the mathematician and scientist,” culminating in Eisele (1976, 1979, 1985). Beginning around 1960, the philosopher and historian of ideas Max Fisch (1900–1995) emerged as an authority on Peirce (Fisch, 1986).[75] He includes many of his relevant articles in a survey (Fisch 1986: 422–448) of the impact of Peirce's thought through 1983. Peirce has gained an international following, marked by university research centers devoted to Peirce studies and pragmatism in Brazil (CeneP/CIEP), Finland (HPRC and Commens), Germany (Wirth's group, Hoffman's and Otte's group, and Deuser's and Härle's group[76]), France (L'I.R.S.C.E.), Spain (GEP), and Italy (CSP). His writings have been translated into several languages, including German, French, Finnish, Spanish, and Swedish. Since 1950, there have been French, Italian, Spanish, British, and Brazilian Peirce scholars of note. For many years, the North American philosophy department most devoted to Peirce was the University of Toronto, thanks in part to the leadership of Thomas Goudge and David Savan. In recent years, U.S. Peirce scholars have clustered at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis, home of the Peirce Edition Project (PEP) –, and Pennsylvania State University. Currently, considerable interest is being taken in Peirce's ideas by researchers wholly outside the arena of academic philosophy. The interest comes from industry, business, technology, intelligence organizations, and the military; and it has resulted in the existence of a substantial number of agencies, institutes, businesses, and laboratories in which ongoing research into and development of Peircean concepts are being vigorously undertaken. — Robert Burch, 2001, updated 2010[20] In recent years, Peirce's trichotomy of signs is exploited by a growing number of practitioners for marketing and design tasks. John Deely writes that Peirce was the last of the "moderns" and "first of the postmoderns". He lauds Peirce's doctrine of signs as a contribution to the dawn of the Postmodern epoch. Deely additionally comments that "Peirce stands...in a position analogous to the position occupied by Augustine as last of the Western Fathers and first of the medievals".[77] |

死と遺産 ペアーズは未亡人に先立つこと20年、ペンシルベニア州ミルフォードで貧困のうちに亡くなった。ジュリエット・ペイスはペイスの遺灰を納めた骨壷をアリス ベに保管していた。1934年、ペンシルバニア州知事ギフォード・ピンチョットは、ジュリエットのミルフォード墓地への埋葬を手配した。ピースの遺灰の 入った骨壷はジュリエットと一緒に埋葬された[65]。 1910年から1913年にかけて出版されたラッセルとホワイトヘッドの『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』にはペイスについての記述はない(ペイスの仕事が 広く知られるようになったのはそれ以後のことである)。 [67]A.N.ホワイトヘッドは、1924年にハーバード大学に着任して間もなく、ペイスの未発表原稿のいくつかを読みながら、ペイスがいかに彼自身の 「過程」思考を先取りしていたかに衝撃を受けた。(ペイスとプロセス形而上学についてはLowe 1964[28]を参照)カール・ポパーはペイスを「あらゆる時代の最も偉大な哲学者の一人」と見なしていた[68]。彼の堂々たる同時代人であるウィリ アム・ジェイムズとジョサイア・ロイス[69]は彼を賞賛し、コロンビア大学のカシアス・ジャクソン・キーサーとC.K.オグデンは尊敬の念を込めてペ アーズについて書いたが、即効性はなかった。 ジョン・デューイはジョンズ・ホプキンス大学でペアースに師事していた[7]。1916年以降、デューイの著作は繰り返しペアースに敬意を持って言及して いる。1938年の『論理学 Collected Papers』(1931年~1935年)の最初の6巻の出版はペアーズ研究において今日までで最も重要な出来事であり、コーエンが必要な資金を調達する ことで可能となったものであった[72]。これらの巻の編集者であるチャールズ・ハーツホーンとポール・ワイスは、パースの専門家にはならなかった。二次 文献の初期の画期的なものとしては、ブフラー(Buchler)(1939年)、フェイブルマン(Feibleman)(1946年)、グッジ (Goudge)(1950年)によるモノグラフ、アーサー・W・バークス(Arthur W. Burks)による1941年の博士論文(彼はその後、第7巻と第8巻を編集した)、ウィーナーとヤング(Wiener and Young)(1952年)によって編集された研究などがある。チャールズ・S・パース協会は1946年に設立された。その『トランザクションズ』はペイ スのプラグマティズムとアメリカ哲学を専門とする学術季刊誌で、1965年から刊行されている[73](トランザクショナリズムに関するペイスとデューイ の議論についてはPhillips 2014, 62を参照)。 1943年までには、少なくともアメリカでは、ウェブスターの人名辞典によれば、パースは「現在では彼の時代の最も独創的な思想家であり、最も偉大な論理 学者とみなされている」と言われるほど、パースの評判は高かった[74]。 1949年、数学史家のキャロライン・アイゼル(Carolyn Eisele, 1902-2000)は、無関係なアーカイブ作業をしていたときに、偶然にもペイスの直筆の手紙を見つけた。そこから40年にわたる「数学者であり科学 者」であるパースに関する研究が始まり、Eisele (1976, 1979, 1985)に結実した。1960年頃から、哲学者であり思想史家でもあるマックス・フィッシュ(Max Fisch, 1900-1995)がペイスに関する権威として頭角を現してきた(Fisch, 1986)[75]。彼は1983年までのペイスの思想の影響に関するサーベイ(Fisch 1986: 422-448)の中に、彼の関連論文を多数含んでいる。 ブラジル(CeneP/CIEP)、フィンランド(HPRCとCommens)、ドイツ(Wirthのグループ、HoffmanとOtteのグループ、 DeuserとHärleのグループ[76])、フランス(L'I.R.S.C.E.)、スペイン(GEP)、イタリア(CSP)において、ペイス研究と プラグマティズムに特化した大学研究センターが設立され、ペイスは国際的な支持を得ている。彼の著作は、ドイツ語、フランス語、フィンランド語、スペイン 語、スウェーデン語など、いくつかの言語に翻訳されている。1950年以降、フランス、イタリア、スペイン、イギリス、ブラジルの著名なパース研究者が誕 生した。トーマス・グッジとデイヴィッド・サヴァンのリーダーシップもあり、長年、北米で最も熱心な哲学科はトロント大学であった。近年、米国のペアーズ 研究者は、インディアナ大学、パデュー大学インディアナポリス、ペンシルバニア州立大学、そしてペアーズ・エディション・プロジェクト(PEP)の本拠地 に集まっている。 現在、学術的な哲学の分野以外の研究者たちも、ペアーズの思想に大きな関心を寄せている。その関心は、産業、ビジネス、技術、情報機関、軍から寄せられ、 その結果、かなりの数の機関、研究所、企業、研究所が存在し、そこでは現在進行形でペアーズの概念の研究と開発が精力的に行われている。 - ロバート・バーチ、2001年、2010年更新[20]。 近年、マーケティングやデザインに携わる実務家の間で、パイアスの標識の三分法が活用される機会が増えている。 ジョン・ディーリーは、ペアーズは「近代」の最後であり、「ポストモダンの最初」であったと書いている。彼は、ポストモダンの黎明期への貢献として、ペイ スの標識の教義を称賛している。さらにディーリーは「パースは...アウグスティヌスが西洋教父の最後であり、中世人の最初として占めた立場に類似した立 場に立っている」とコメントしている[77]。 |

| Works See also: Charles Sanders Peirce bibliography Peirce's reputation rests largely on academic papers published in American scientific and scholarly journals such as Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, The Monist, Popular Science Monthly, the American Journal of Mathematics, Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, The Nation, and others. See Articles by Peirce, published in his lifetime for an extensive list with links to them online. The only full-length book (neither extract nor pamphlet) that Peirce authored and saw published in his lifetime[78] was Photometric Researches (1878), a 181-page monograph on the applications of spectrographic methods to astronomy. While at Johns Hopkins, he edited Studies in Logic (1883), containing chapters by himself and his graduate students. Besides lectures during his years (1879–1884) as lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins, he gave at least nine series of lectures, many now published; see Lectures by Peirce. After Peirce's death, Harvard University obtained from Peirce's widow the papers found in his study, but did not microfilm them until 1964. Only after Richard Robin (1967)[79] catalogued this Nachlass did it become clear that Peirce had left approximately 1,650 unpublished manuscripts, totaling over 100,000 pages,[80] mostly still unpublished except on microfilm. On the vicissitudes of Peirce's papers, see Houser (1989).[81] Reportedly the papers remain in unsatisfactory condition.[82] The first published anthology of Peirce's articles was the one-volume Chance, Love and Logic: Philosophical Essays, edited by Morris Raphael Cohen, 1923, still in print. Other one-volume anthologies were published in 1940, 1957, 1958, 1972, 1994, and 2009, most still in print. The main posthumous editions[83] of Peirce's works in their long trek to light, often multi-volume, and some still in print, have included: 1931–1958: Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (CP), 8 volumes, includes many published works, along with a selection of previously unpublished work and a smattering of his correspondence. This long-time standard edition drawn from Peirce's work from the 1860s to 1913 remains the most comprehensive survey of his prolific output from 1893 to 1913. It is organized thematically, but texts (including lecture series) are often split up across volumes, while texts from various stages in Peirce's development are often combined, requiring frequent visits to editors' notes.[84] Edited (1–6) by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss and (7–8) by Arthur Burks, in print and online. 1975–1987: Charles Sanders Peirce: Contributions to The Nation, 4 volumes, includes Peirce's more than 300 reviews and articles published 1869–1908 in The Nation. Edited by Kenneth Laine Ketner and James Edward Cook, online. 1976: The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce, 4 volumes in 5, included many previously unpublished Peirce manuscripts on mathematical subjects, along with Peirce's important published mathematical articles. Edited by Carolyn Eisele, back in print. 1977: Semiotic and Significs: The Correspondence between C. S. Peirce and Victoria Lady Welby (2nd edition 2001), included Peirce's entire correspondence (1903–1912) with Victoria, Lady Welby. Peirce's other published correspondence is largely limited to the 14 letters included in volume 8 of the Collected Papers, and the 20-odd pre-1890 items included so far in the Writings. Edited by Charles S. Hardwick with James Cook, out of print. 1982–now: Writings of Charles S. Peirce, A Chronological Edition (W), Volumes 1–6 & 8, of a projected 30. The limited coverage, and defective editing and organization, of the Collected Papers led Max Fisch and others in the 1970s to found the Peirce Edition Project (PEP), whose mission is to prepare a more complete critical chronological edition. Only seven volumes have appeared to date, but they cover the period from 1859 to 1892, when Peirce carried out much of his best-known work. Writings of Charles S. Peirce, 8 was published in November 2010; and work continues on Writings of Charles S. Peirce, 7, 9, and 11. In print and online. 1985: Historical Perspectives on Peirce's Logic of Science: A History of Science, 2 volumes. Auspitz has said,[85] "The extent of Peirce's immersion in the science of his day is evident in his reviews in the Nation [...] and in his papers, grant applications, and publishers' prospectuses in the history and practice of science", referring latterly to Historical Perspectives. Edited by Carolyn Eisele, back in print. 1992: Reasoning and the Logic of Things collects in one place Peirce's 1898 series of lectures invited by William James. Edited by Kenneth Laine Ketner, with commentary by Hilary Putnam, in print. 1992–1998: The Essential Peirce (EP), 2 volumes, is an important recent sampler of Peirce's philosophical writings. Edited (1) by Nathan Hauser and Christian Kloesel and (2) by Peirce Edition Project editors, in print. 1997: Pragmatism as a Principle and Method of Right Thinking collects Peirce's 1903 Harvard "Lectures on Pragmatism" in a study edition, including drafts, of Peirce's lecture manuscripts, which had been previously published in abridged form; the lectures now also appear in The Essential Peirce, 2. Edited by Patricia Ann Turisi, in print. 2010: Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Writings collects important writings by Peirce on the subject, many not previously in print. Edited by Matthew E. Moore, in print. |

作品 こちらもご覧ください: チャールズ・サンダース・ペアース書誌 ペイスの名声は、『Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences』、『Journal of Speculative Philosophy』、『The Monist』、『Popular Science Monthly』、『American Journal of Mathematics』、『Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences』、『The Nation』など、アメリカの科学・学術雑誌に掲載された学術論文によるところが大きい。生前に発表されたペイスの論文リストとオンラインへのリンク は、Articles by Peirce, published in his lifetimeを参照。ペイスが生前に執筆し、出版された唯一の長編本(抄録でもパンフレットでもない)はPhotometric Researches (1878)で、天文学への分光法の応用に関する181ページのモノグラフである[78]。ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学在学中には、彼自身と彼の大学院生に よる章を含む『論理学研究』(Studies in Logic、1883年)を編集した。1879年から1884年までジョンズ・ホプキンス大学で論理学の講師を務めた時期には、講義のほかに少なくとも9 つの連続講義を行い、その多くは現在出版されている。 ペイスの死後、ハーバード大学はペイス未亡人から彼の書斎で発見された論文を入手したが、1964年までマイクロフィルム化されなかった。リチャード・ロ ビン(Richard Robin)(1967)[79]がこのナクラス(Nachlass)の目録を作成して初めて、パースが約1,650点、合計10万ページを超える未発表 の原稿を残していたことが明らかになった[80]。ペイスの論文の変遷については、Houser(1989)を参照のこと[81]。 ペイスの論文を集めた最初のアンソロジーは『偶然と愛と論理』(Chance, Love and Logic)である: 1923年、モリス・ラファエル・コーエン編集。その他にも1940年、1957年、1958年、1972年、1994年、2009年に1巻のアンソロ ジーが出版され、そのほとんどが現在も出版されている。ペイスの著作の主な遺稿集[83]は、その長い光への旅路の中で、しばしば複数巻に及び、一部は現 在も印刷中である: 1931-1958: Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (CP)』全8巻には、未発表の著作や書簡の一部とともに、多くの出版物が収められている。1860年代から1913年までのペイスの著作から抜粋された この長年の標準版は、1893年から1913年までの彼の多作を最も包括的に調査したものである。テーマ別に構成されているが、テキスト(講義シリーズを 含む)は巻をまたいで分割されていることが多く、また、ペイスの発展における様々な段階のテキストが組み合わされていることが多いため、編集者の注を頻繁 に参照する必要がある[84] Charles HartshorneとPaul WeissとArthur Burksによって編集された(1-6)。 1975-1987: チャールズ・サンダース・パース 1869年から1908年にかけて『ネイション』誌に掲載された300以上の評論や記事を収録。ケネス・レイン・ケトナー、ジェイムズ・エドワード・クッ ク編集、オンライン。 1976: The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce, 4 volumes in 5, 数学的テーマに関する未発表のPeirceの原稿を多数収録。キャロライン・アイゼル編、復刊。 1977: 記号論と意義 The Correspondence between C. S. Peirce and Victoria Lady Welby (2nd edition 2001), Peirceとヴィクトリア・ウェルビー夫人との書簡全文(1903-1912年)を収録。ペイスのその他の書簡は、『論文集』第8巻に収録された14通 の書簡と、『著作集』に収録された1890年以前の20数通に限られている。チャールズ・S・ハードウィックとジェームズ・クック編、絶版。 1982-現在 Writings of Charles S. Peirce, A Chronological Edition (W)、第1巻から第6巻、第8巻、全30巻の予定。Collected Papersは収録範囲が狭く、編集や構成に欠陥があったため、1970年代にMax FischらによってPeirce Edition Project (PEP)が設立された。現在までに出版されたのは7巻のみであるが、それらは1859年から1892年までの、ペイスが最もよく知られた仕事の多くを 行った時期を網羅している。2010年11月にWritings of Charles S. Peirce, 8が出版され、Writings of Charles S. Peirce, 7, 9, 11の制作が続けられている。印刷版とオンライン版があります。 1985: 歴史的視点からのパースの科学論理: 科学史』全2巻。アウスピッツは、[85]「ペイスが当時の科学にどれほど没頭していたかは、『ネイション』誌の書評や、科学史や科学実践に関する論文、 助成金申請書、出版社の目論見書からも明らかである」と述べており、後者については『歴史的展望』(Historical Perspectives)に言及している。キャロライン・アイゼル編、復刊。 1992: Reasoning and the Logic of Things(推論と事物の論理)』は、1898年にウィリアム・ジェームズに招かれたペイスの一連の講義を一冊にまとめたもの。ケネス・レイン・ケト ナー編集、ヒラリー・パットナム解説。 1992-1998: The Essential Peirce (EP)全2巻は、ペイスの哲学的著作の最近の重要なサンプラーである。Nathan HauserとChristian Kloesel、Peirce Edition Project編集部編。 1997: Peirce's 1903 Harvard "Lectures on Pragmatism "を収録した、Peirceの講義原稿の草稿を含む研究版。 2010: 数学の哲学: Peirce の数学に関する重要な著作を集めたもの。マシュー・E・ムーア編、印刷中。 |

| Mathematics Peirce's most important work in pure mathematics was in logical and foundational areas. He also worked on linear algebra, matrices, various geometries, topology and Listing numbers, Bell numbers, graphs, the four-color problem, and the nature of continuity. He worked on applied mathematics in economics, engineering, and map projections, and was especially active in probability and statistics.[86] Discoveries ↓ The Peirce arrow, symbol for "(neither) ... nor ...", also called the Quine dagger Peirce made a number of striking discoveries in formal logic and foundational mathematics, nearly all of which came to be appreciated only long after he died: In 1860[87] he suggested a cardinal arithmetic for infinite numbers, years before any work by Georg Cantor (who completed his dissertation in 1867) and without access to Bernard Bolzano's 1851 (posthumous) Paradoxien des Unendlichen. In 1880–1881[88] he showed how Boolean algebra could be done via a repeated sufficient single binary operation (logical NOR), anticipating Henry M. Sheffer by 33 years. (See also De Morgan's Laws.) In 1881[89] he set out the axiomatization of natural number arithmetic, a few years before Richard Dedekind and Giuseppe Peano. In the same paper Peirce gave, years before Dedekind, the first purely cardinal definition of a finite set in the sense now known as "Dedekind-finite", and implied by the same stroke an important formal definition of an infinite set (Dedekind-infinite), as a set that can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with one of its proper subsets. In 1885[90] he distinguished between first-order and second-order quantification.[91][92] In the same paper he set out what can be read as the first (primitive) axiomatic set theory, anticipating Zermelo by about two decades (Brady 2000,[93] pp. 132–133). Existential graphs: Alpha graphs In 1886, he saw that Boolean calculations could be carried out via electrical switches,[13] anticipating Claude Shannon by more than 50 years. By the later 1890s[94] he was devising existential graphs, a diagrammatic notation for the predicate calculus. Based on them are John F. Sowa's conceptual graphs and Sun-Joo Shin's diagrammatic reasoning. The New Elements of Mathematics Peirce wrote drafts for an introductory textbook, with the working title The New Elements of Mathematics, that presented mathematics from an original standpoint. Those drafts and many other of his previously unpublished mathematical manuscripts finally appeared[86] in The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce (1976), edited by mathematician Carolyn Eisele. Nature of mathematics Peirce agreed with Auguste Comte in regarding mathematics as more basic than philosophy and the special sciences (of nature and mind). Peirce classified mathematics into three subareas: (1) mathematics of logic, (2) discrete series, and (3) pseudo-continua (as he called them, including the real numbers) and continua. Influenced by his father Benjamin, Peirce argued that mathematics studies purely hypothetical objects and is not just the science of quantity but is more broadly the science which draws necessary conclusions; that mathematics aids logic, not vice versa; and that logic itself is part of philosophy and is the science about drawing conclusions necessary and otherwise.[95] Mathematics of logic Mathematical logic and foundations, some noted articles "On an Improvement in Boole's Calculus of Logic" (1867) "Description of a Notation for the Logic of Relatives" (1870) "On the Algebra of Logic" (1880) "A Boolian [sic] Algebra with One Constant" (1880 MS) "On the Logic of Number" (1881) "Note B: The Logic of Relatives" (1883) "On the Algebra of Logic: A Contribution to the Philosophy of Notation" (1884/1885) "The Logic of Relatives" (1897) "The Simplest Mathematics" (1902 MS) "Prolegomena to an Apology for Pragmaticism" (1906, on existential graphs) Probability and statistics Peirce held that science achieves statistical probabilities, not certainties, and that spontaneity (absolute chance) is real (see Tychism on his view). Most of his statistical writings promote the frequency interpretation of probability (objective ratios of cases), and many of his writings express skepticism about (and criticize the use of) probability when such models are not based on objective randomization.[96] Though Peirce was largely a frequentist, his possible world semantics introduced the "propensity" theory of probability before Karl Popper.[97][98] Peirce (sometimes with Joseph Jastrow) investigated the probability judgments of experimental subjects, "perhaps the very first" elicitation and estimation of subjective probabilities in experimental psychology and (what came to be called) Bayesian statistics.[2] Peirce was one of the founders of statistics. He formulated modern statistics in "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" (1877–1878) and "A Theory of Probable Inference" (1883). With a repeated measures design, Charles Sanders Peirce and Joseph Jastrow introduced blinded, controlled randomized experiments in 1884[99] (Hacking 1990:205)[1] (before Ronald A. Fisher).[2] He invented optimal design for experiments on gravity, in which he "corrected the means". He used correlation and smoothing. Peirce extended the work on outliers by Benjamin Peirce, his father.[2] He introduced terms "confidence" and "likelihood" (before Jerzy Neyman and Fisher). (See Stephen Stigler's historical books and Ian Hacking 1990.[1]) As a philosopher Peirce was a working scientist for 30 years, and arguably was a professional philosopher only during the five years he lectured at Johns Hopkins. He learned philosophy mainly by reading, each day, a few pages of Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, in the original German, while a Harvard undergraduate. His writings bear on a wide array of disciplines, including mathematics, logic, philosophy, statistics, astronomy,[28] metrology,[3] geodesy, experimental psychology,[4] economics,[5] linguistics,[6] and the history and philosophy of science. This work has enjoyed renewed interest and approval, a revival inspired not only by his anticipations of recent scientific developments but also by his demonstration of how philosophy can be applied effectively to human problems. Peirce's philosophy includes a pervasive three-category system: belief that truth is immutable and is both independent from actual opinion (fallibilism) and discoverable (no radical skepticism), logic as formal semiotic on signs, on arguments, and on inquiry's ways—including philosophical pragmatism (which he founded), critical common-sensism, and scientific method—and, in metaphysics: Scholastic realism, e.g. John Duns Scotus, belief in God, freedom, and at least an attenuated immortality, objective idealism, and belief in the reality of continuity and of absolute chance, mechanical necessity, and creative love. In his work, fallibilism and pragmatism may seem to work somewhat like skepticism and positivism, respectively, in others' work. However, for Peirce, fallibilism is balanced by an anti-skepticism and is a basis for belief in the reality of absolute chance and of continuity,[100] and pragmatism commits one to anti-nominalist belief in the reality of the general (CP 5.453–457). For Peirce, First Philosophy, which he also called cenoscopy, is less basic than mathematics and more basic than the special sciences (of nature and mind). It studies positive phenomena in general, phenomena available to any person at any waking moment, and does not settle questions by resorting to special experiences.[101] He divided such philosophy into (1) phenomenology (which he also called phaneroscopy or categorics), (2) normative sciences (esthetics, ethics, and logic), and (3) metaphysics; his views on them are discussed in order below. Peirce did not write extensively in aesthetics and ethics,[102] but came by 1902 to hold that aesthetics, ethics, and logic, in that order, comprise the normative sciences.[103] He characterized aesthetics as the study of the good (grasped as the admirable), and thus of the ends governing all conduct and thought.[104] Influence and legacy Umberto Eco described Peirce as "undoubtedly the greatest unpublished writer of our generation"[105] and by Karl Popper as "one of the greatest philosophers of all time".[106] The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy says of Peirce that although "long considered an eccentric figure whose contribution to pragmatism was to provide its name and whose importance was as an influence upon James and Dewey, Peirce's significance in his own right is now largely accepted."[107] |

数学 ペアーズの純粋数学における最も重要な仕事は、論理的で基礎的な分野であった。彼はまた、線形代数、行列、様々な幾何学、トポロジーとリスティング数、ベ ル数、グラフ、4色問題、および連続性の性質に取り組んだ。 彼は経済学、工学、地図投影における応用数学に取り組み、特に確率と統計に積極的であった[86]。 発見 ↓ ペアーズの矢印、 クワインの短剣とも呼ばれる。 ペアーズは形式論理学と数学の基礎となる数多くの顕著な発見を行ったが、そのほとんどすべてが評価されるようになったのは、彼が亡くなってからずっと後の ことであった: 1860年[87]、彼は無限数のための基数演算を提案したが、これはゲオルク・カントール(彼は1867年に学位論文を完成させた)によるどの研究より も何年も前のことであり、またバーナード・ボルツァーノによる1851年の(遺著となった)Paradoxien des Unendlichenにアクセスすることもできなかった。 1880年から1881年にかけて[88]、彼はヘンリー・M・シェファーを33年先取りして、ブール代数が繰り返される十分な単一の二項演算(論理 NOR)を介してどのように行われるかを示した。(ド・モルガンの法則も参照)。 1881年[89]には、リチャード・デデキントやジュゼッペ・ペアノよりも数年早く、自然数算術の公理化を打ち出した。同じ論文でペアースは、デデキン トよりも何年も前に、現在「デデキント有限」として知られている意味での有限集合の最初の純粋に基数的な定義を与え、同じストロークで無限集合(デデキン ト無限)の重要な形式的定義を暗示した。 1885年[90],彼は一階量化と二階量化を区別した[91][92]。同じ論文の中で,彼は最初の(原始的な)公理的集合論と読めるものを打ち出し, ツェルメロを約20年先取りした(Brady 2000,[93] pp.132-133)。 実存グラフ アルファグラフ 1886年、クロード・シャノンを50年以上先取りして、電気スイッチによってブール計算ができることを発見した[13]。1890年代後半には [94]、述語微積分の図式的表記法である実存グラフを考案していた。それを基にしたのが、ジョン・F・ソーワの概念グラフであり、スン・ジュ・シンの図 式推論である。 数学の新要素 数学の新要素』というタイトルで、独自の立場から数学を紹介する入門教科書の草稿を執筆。これらの草稿と他の多くの未発表の数学原稿は、数学者キャロライ ン・アイゼルが編集した『The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce』(1976年)に最終的に掲載された[86]。 数学の本質 数学は哲学や特殊科学(自然科学や精神科学)よりも基礎的なものであるという点で、パースはオーギュスト・コントに同意していた。数学は、(1)論理数 学、(2)離散級数、(3)擬似連続体(実数を含む)と連続体の3つに分類された。父ベンジャミンの影響を受け、数学は純粋に仮説的な対象を研究し、単な る量の科学ではなく、より広く必要な結論を導き出す科学であること、数学は論理学を助けるものであり、その逆ではないこと、論理学自体は哲学の一部であ り、必要な結論とそうでない結論を導き出す科学であることを主張した[95]。 論理学の数学 数理論理学とその基礎、いくつかの著名な論文 「ブールの論理微積分の改良について」(1867年) 「親族の論理のための記法の説明" (1870) 「論理の代数について」(1880年) 「一つの定数を持つブーリアン代数」 (1880 MS) 「数の論理について」 (1881) 「ノートB:親族の論理」 (1883) 論理の代数について" (1883 MS) 記法の哲学への貢献" (1884/1885) 「親族の論理」(1897年) 「最も簡単な数学" (1902 MS) 「プラグマティシズムの弁明へのプロレゴメナ" (1906, 実存グラフについて) 確率と統計 ペアーズは、科学が達成するのは確実性ではなく統計的確率であり、自発性(絶対的偶然性)は実在すると考えていた(彼の見解についてはタイキズムを参 照)。彼の統計的な著作のほとんどは確率の頻度解釈(ケースの客観的な比率)を促進し、そのようなモデルが客観的なランダム化に基づかない場合、彼の著作 の多くは確率に対する懐疑主義を表明している(そして確率の使用を批判している)[96] ペアースは主に頻度論者であったが、彼の可能世界意味論はカール・ポパーよりも前に確率の「傾向性」理論を導入していた。 [97][98]ペイスは(時にはジョセフ・ジャストローとともに)実験被験者の確率判断を調査し、実験心理学や(後にベイズ統計学と呼ばれるようになっ た)主観的確率の「おそらく最初の」抽出と推定を行った[2]。 ペアーズは統計学の創始者の一人である。彼は "Illustrations of the Logic of Science"(1877-1878)と "A Theory of Probable Inference"(1883)で近代統計学を定式化した。反復測定計画によって,チャールズ・サンダーズ・パースとジョセフ・ジャストローは 1884年に盲検化された対照ランダム化実験を導入した[99](Hacking 1990:205)[1](ロナルド・A・フィッシャーより前)[2]。 重力に関する実験では「平均を補正」する最適計画を考案した。彼は相関と平滑化を用いた。ペイスは父であるベンジャミン・ペイスによる外れ値に関する研究 を拡張した[2]。 彼は「信頼」と「尤度」という用語を導入した(イエジー・ネイマンやフィッシャーより前)。(スティーブン・スティグラーの歴史的著書やイアン・ハッキン グ1990を参照[1])。 哲学者として ペアーズは30年間現役の科学者であり、プロの哲学者であったのは間違いなくジョンズ・ホプキンスで講義をしていた5年間だけである。彼はハーバード大学 在学中、主にイマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』を毎日数ページずつドイツ語の原書で読み、哲学を学んだ。彼の著作は、数学、論理学、哲学、統計学、天 文学、[28]計量学、[3]測地学、実験心理学、[4]経済学、[5]言語学、[6]科学史、科学哲学など、幅広い分野に及んでいる。この著作は、近年 の科学的発展に対する彼の先見性だけでなく、哲学を人間の問題にいかに効果的に応用できるかを示したことに触発され、再び関心と支持を集めている。 すなわち、真理は不変であり、実際の意見から独立していると同時に発見可能であるという信念(fallibilism)、標識、論証、探求の方法に関する 形式的記号論としての論理学(彼が創設した哲学的プラグマティズム、批判的コモン・センシズム、科学的方法を含む)、そして形而上学である: 形而上学では、スコラ哲学的実在論、例えばジョン・ドゥンス・スコトゥス、神、自由、少なくとも減弱した不死への信仰、客観的観念論、連続性の実在と絶対 的偶然性、機械的必然性、創造的愛への信仰。彼の作品において、可謬主義とプラグマティズムは、それぞれ他の人の作品における懐疑主義と実証主義のよう に、いくらか機能しているように見えるかもしれない。しかし、ペイスにとって、可謬主義は反懐疑主義によって均衡が保たれており、絶対的な偶然の実在と連 続性の実在を信じる根拠となっており[100]、プラグマティズムは一般的なものの実在を信じる反名辞主義にコミットしている(CP 5.453-457)。 ペアースにとって、第一哲学はセノスコピーとも呼ばれ、数学よりも基礎的ではなく、(自然と心の)特殊科学よりも基礎的である。彼はこのような哲学を (1)現象学(ファネロスコピーまたはカテゴリー論とも呼んだ)、(2)規範科学(美学、倫理学、論理学)、(3)形而上学に分けた。 彼は美学を(立派なものとして把握される)善の研究、したがってすべての行為と思考を支配する目的の研究として特徴づけていた[104]。 影響と遺産 ウンベルト・エーコはペアースを「間違いなく我々の世代で最も偉大な未発表の作家」[105]と評し、カール・ポパーは「史上最も偉大な哲学者の一人」 [106]と評している。 Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophyはペアースについて、「プラグマティズムへの貢献はその名前を提供することであり、その重要性はジェイムズとデューイへの影響として であったが、彼自身におけるペアースの重要性は現在ではほぼ受け入れられている」と述べている[107]。 |

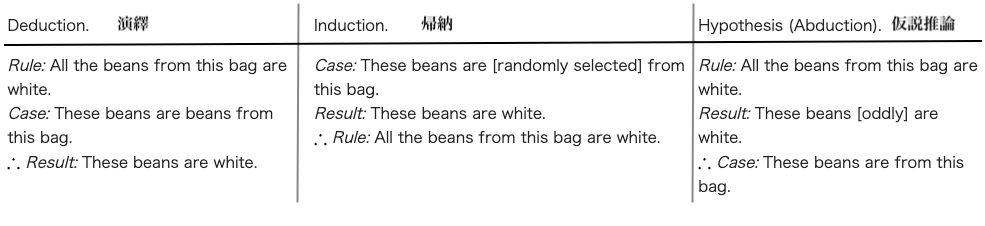

| Pragmatism Main articles: Pragmaticism, Pragmatic maxim, and Pragmatic theory of truth § Peirce Some noted articles and lectures Illustrations of the Logic of Science (1877–1878): inquiry, pragmatism, statistics, inference The Fixation of Belief (1877) How to Make Our Ideas Clear (1878) The Doctrine of Chances (1878) The Probability of Induction (1878) The Order of Nature (1878) Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis (1878) The Harvard lectures on pragmatism (1903) What Pragmatism Is (1905) Issues of Pragmaticism (1905) Pragmatism (1907 MS in The Essential Peirce, 2) Peirce's recipe for pragmatic thinking, which he called pragmatism and, later, pragmaticism, is recapitulated in several versions of the so-called pragmatic maxim. Here is one of his more emphatic reiterations of it: Consider what effects that might conceivably have practical bearings you conceive the objects of your conception to have. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object. As a movement, pragmatism began in the early 1870s in discussions among Peirce, William James, and others in the Metaphysical Club. James among others regarded some articles by Peirce such as "The Fixation of Belief" (1877) and especially "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878) as foundational to pragmatism.[108] Peirce (CP 5.11–12), like James (Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 1907), saw pragmatism as embodying familiar attitudes, in philosophy and elsewhere, elaborated into a new deliberate method for fruitful thinking about problems. Peirce differed from James and the early John Dewey, in some of their tangential enthusiasms, in being decidedly more rationalistic and realistic, in several senses of those terms, throughout the preponderance of his own philosophical moods. In 1905 Peirce coined the new name pragmaticism "for the precise purpose of expressing the original definition", saying that "all went happily" with James's and F.C.S. Schiller's variant uses of the old name "pragmatism" and that he coined the new name because of the old name's growing use in "literary journals, where it gets abused". Yet he cited as causes, in a 1906 manuscript, his differences with James and Schiller and, in a 1908 publication, his differences with James as well as literary author Giovanni Papini's declaration of pragmatism's indefinability. Peirce in any case regarded his views that truth is immutable and infinity is real, as being opposed by the other pragmatists, but he remained allied with them on other issues.[109][circular reference] Pragmatism begins with the idea that belief is that on which one is prepared to act. Peirce's pragmatism is a method of clarification of conceptions of objects. It equates any conception of an object to a conception of that object's effects to a general extent of the effects' conceivable implications for informed practice. It is a method of sorting out conceptual confusions occasioned, for example, by distinctions that make (sometimes needed) formal yet not practical differences. He formulated both pragmatism and statistical principles as aspects of scientific logic, in his "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series of articles. In the second one, "How to Make Our Ideas Clear", Peirce discussed three grades of clearness of conception: Clearness of a conception familiar and readily used, even if unanalyzed and undeveloped. Clearness of a conception in virtue of clearness of its parts, in virtue of which logicians called an idea "distinct", that is, clarified by analysis of just what makes it applicable. Elsewhere, echoing Kant, Peirce called a likewise distinct definition "nominal" (CP 5.553). Clearness in virtue of clearness of conceivable practical implications of the object's conceived effects, such that fosters fruitful reasoning, especially on difficult problems. Here he introduced that which he later called the pragmatic maxim. By way of example of how to clarify conceptions, he addressed conceptions about truth and the real as questions of the presuppositions of reasoning in general. In clearness's second grade (the "nominal" grade), he defined truth as a sign's correspondence to its object, and the real as the object of such correspondence, such that truth and the real are independent of that which you or I or any actual, definite community of inquirers think. After that needful but confined step, next in clearness's third grade (the pragmatic, practice-oriented grade) he defined truth as that opinion which would be reached, sooner or later but still inevitably, by research taken far enough, such that the real does depend on that ideal final opinion—a dependence to which he appeals in theoretical arguments elsewhere, for instance for the long-run validity of the rule of induction.[110] Peirce argued that even to argue against the independence and discoverability of truth and the real is to presuppose that there is, about that very question under argument, a truth with just such independence and discoverability. Peirce said that a conception's meaning consists in "all general modes of rational conduct" implied by "acceptance" of the conception—that is, if one were to accept, first of all, the conception as true, then what could one conceive to be consequent general modes of rational conduct by all who accept the conception as true?—the whole of such consequent general modes is the whole meaning. His pragmatism does not equate a conception's meaning, its intellectual purport, with the conceived benefit or cost of the conception itself, like a meme (or, say, propaganda), outside the perspective of its being true, nor, since a conception is general, is its meaning equated with any definite set of actual consequences or upshots corroborating or undermining the conception or its worth. His pragmatism also bears no resemblance to "vulgar" pragmatism, which misleadingly connotes a ruthless and Machiavellian search for mercenary or political advantage. Instead the pragmatic maxim is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection[111] arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the formation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the use and improvement of verification.[112] Peirce's pragmatism, as method and theory of definitions and conceptual clearness, is part of his theory of inquiry,[113] which he variously called speculative, general, formal or universal rhetoric or simply methodeutic.[114] He applied his pragmatism as a method throughout his work. Theory of inquiry See also: Inquiry In "The Fixation of Belief" (1877), Peirce gives his take on the psychological origin and aim of inquiry. On his view, individuals are motivated to inquiry by desire to escape the feelings of anxiety and unease which Peirce takes to be characteristic of the state of doubt. Doubt is described by Peirce as an "uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief." Peirce uses words like "irritation" to describe the experience of being in doubt and to explain why he thinks we find such experiences to be motivating. The irritating feeling of doubt is appeased, Peirce says, through our efforts to achieve a settled state of satisfaction with what we land on as our answer to the question which led to that doubt in the first place. This settled state, namely, belief, is described by Peirce as "a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid." Our efforts to achieve the satisfaction of belief, by whichever methods we may pursue, are what Peirce calls "inquiry". Four methods which Peirce describes as having been actually pursued throughout the history of thought are summarized below in the section after next. Critical common-sensism Critical common-sensism,[115] treated by Peirce as a consequence of his pragmatism, is his combination of Thomas Reid's common-sense philosophy with a fallibilism that recognizes that propositions of our more or less vague common sense now indubitable may later come into question, for example because of transformations of our world through science. It includes efforts to work up in tests genuine doubts for a core group of common indubitables that vary slowly if at all. Rival methods of inquiry In "The Fixation of Belief" (1877), Peirce described inquiry in general not as the pursuit of truth per se but as the struggle to move from irritating, inhibitory doubt born of surprise, disagreement, and the like, and to reach a secure belief, belief being that on which one is prepared to act. That let Peirce frame scientific inquiry as part of a broader spectrum and as spurred, like inquiry generally, by actual doubt, not mere verbal, quarrelsome, or hyperbolic doubt, which he held to be fruitless. Peirce sketched four methods of settling opinion, ordered from least to most successful: The method of tenacity (policy of sticking to initial belief) – which brings comforts and decisiveness but leads to trying to ignore contrary information and others' views as if truth were intrinsically private, not public. The method goes against the social impulse and easily falters since one may well notice when another's opinion seems as good as one's own initial opinion. Its successes can be brilliant but tend to be transitory. The method of authority – which overcomes disagreements but sometimes brutally. Its successes can be majestic and long-lasting, but it cannot regulate people thoroughly enough to withstand doubts indefinitely, especially when people learn about other societies present and past. The method of the a priori – which promotes conformity less brutally but fosters opinions as something like tastes, arising in conversation and comparisons of perspectives in terms of "what is agreeable to reason". Thereby it depends on fashion in paradigms and goes in circles over time. It is more intellectual and respectable but, like the first two methods, sustains accidental and capricious beliefs, destining some minds to doubt it. The method of science – wherein inquiry supposes that the real is discoverable but independent of particular opinion, such that, unlike in the other methods, inquiry can, by its own account, go wrong (fallibilism), not only right, and thus purposely tests itself and criticizes, corrects, and improves itself. Peirce held that, in practical affairs, slow and stumbling ratiocination is often dangerously inferior to instinct and traditional sentiment, and that the scientific method is best suited to theoretical research,[116] which in turn should not be trammeled by the other methods and practical ends; reason's "first rule"[117] is that, in order to learn, one must desire to learn and, as a corollary, must not block the way of inquiry. Scientific method excels over the others finally by being deliberately designed to arrive—eventually—at the most secure beliefs, upon which the most successful practices can be based. Starting from the idea that people seek not truth per se but instead to subdue irritating, inhibitory doubt, Peirce showed how, through the struggle, some can come to submit to truth for the sake of belief's integrity, seek as truth the guidance of potential conduct correctly to its given goal, and wed themselves to the scientific method. Scientific method Insofar as clarification by pragmatic reflection suits explanatory hypotheses and fosters predictions and testing, pragmatism points beyond the usual duo of foundational alternatives: deduction from self-evident truths, or rationalism; and induction from experiential phenomena, or empiricism. Based on his critique of three modes of argument and different from either foundationalism or coherentism, Peirce's approach seeks to justify claims by a three-phase dynamic of inquiry: Active, abductive genesis of theory, with no prior assurance of truth; Deductive application of the contingent theory so as to clarify its practical implications; Inductive testing and evaluation of the utility of the provisional theory in anticipation of future experience, in both senses: prediction and control. Thereby, Peirce devised an approach to inquiry far more solid than the flatter image of inductive generalization simpliciter, which is a mere re-labeling of phenomenological patterns. Peirce's pragmatism was the first time the scientific method was proposed as an epistemology for philosophical questions. A theory that succeeds better than its rivals in predicting and controlling our world is said to be nearer the truth. This is an operational notion of truth used by scientists. Peirce extracted the pragmatic model or theory of inquiry from its raw materials in classical logic and refined it in parallel with the early development of symbolic logic to address problems about the nature of scientific reasoning. Abduction, deduction, and induction make incomplete sense in isolation from one another but comprise a cycle understandable as a whole insofar as they collaborate toward the common end of inquiry. In the pragmatic way of thinking about conceivable practical implications, every thing has a purpose, and, as possible, its purpose should first be denoted. Abduction hypothesizes an explanation for deduction to clarify into implications to be tested so that induction can evaluate the hypothesis, in the struggle to move from troublesome uncertainty to more secure belief. No matter how traditional and needful it is to study the modes of inference in abstraction from one another, the integrity of inquiry strongly limits the effective modularity of its principal components. Peirce's outline of the scientific method in §III–IV of "A Neglected Argument"[118] is summarized below (except as otherwise noted). There he also reviewed plausibility and inductive precision (issues of critique of arguments). Abductive (or retroductive) phase. Guessing, inference to explanatory hypotheses for selection of those best worth trying. From abduction, Peirce distinguishes induction as inferring, on the basis of tests, the proportion of truth in the hypothesis. Every inquiry, whether into ideas, brute facts, or norms and laws, arises from surprising observations in one or more of those realms (and for example at any stage of an inquiry already underway). All explanatory content of theories comes from abduction, which guesses a new or outside idea so as to account in a simple, economical way for a surprising or complicated phenomenon. The modicum of success in our guesses far exceeds that of random luck, and seems born of attunement to nature by developed or inherent instincts, especially insofar as best guesses are optimally plausible and simple in the sense of the "facile and natural", as by Galileo's natural light of reason and as distinct from "logical simplicity".[119] Abduction is the most fertile but least secure mode of inference. Its general rationale is inductive: it succeeds often enough and it has no substitute in expediting us toward new truths.[120] In 1903, Peirce called pragmatism "the logic of abduction".[121] Coordinative method leads from abducting a plausible hypothesis to judging it for its testability[122] and for how its trial would economize inquiry itself.[123] The hypothesis, being insecure, needs to have practical implications leading at least to mental tests and, in science, lending themselves to scientific tests. A simple but unlikely guess, if not costly to test for falsity, may belong first in line for testing. A guess is intrinsically worth testing if it has plausibility or reasoned objective probability, while subjective likelihood, though reasoned, can be misleadingly seductive. Guesses can be selected for trial strategically, for their caution (for which Peirce gave as example the game of Twenty Questions), breadth, or incomplexity.[124] One can discover only that which would be revealed through their sufficient experience anyway, and so the point is to expedite it; economy of research demands the leap, so to speak, of abduction and governs its art.[123] Deductive phase. Two stages: i. Explication. Not clearly premised, but a deductive analysis of the hypothesis so as to render its parts as clear as possible. ii. Demonstration: Deductive Argumentation, Euclidean in procedure. Explicit deduction of consequences of the hypothesis as predictions about evidence to be found. Corollarial or, if needed, Theorematic. Inductive phase. Evaluation of the hypothesis, inferring from observational or experimental tests of its deduced consequences. The long-run validity of the rule of induction is deducible from the principle (presuppositional to reasoning in general) that the real "is only the object of the final opinion to which sufficient investigation would lead";[110] in other words, anything excluding such a process would never be real. Induction involving the ongoing accumulation of evidence follows "a method which, sufficiently persisted in", will "diminish the error below any predesignate degree". Three stages: i. Classification. Not clearly premised, but an inductive classing of objects of experience under general ideas. ii. Probation: direct Inductive Argumentation. Crude or Gradual in procedure. Crude Induction, founded on experience in one mass (CP 2.759), presumes that future experience on a question will not differ utterly from all past experience (CP 2.756). Gradual Induction makes a new estimate of the proportion of truth in the hypothesis after each test, and is Qualitative or Quantitative. Qualitative Gradual Induction depends on estimating the relative evident weights of the various qualities of the subject class under investigation (CP 2.759; see also Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, 7.114–120). Quantitative Gradual Induction depends on how often, in a fair sample of instances of S, S is found actually accompanied by P that was predicted for S (CP 2.758). It depends on measurements, or statistics, or counting. iii. Sentential Induction. "...which, by Inductive reasonings, appraises the different Probations singly, then their combinations, then makes self-appraisal of these very appraisals themselves, and passes final judgment on the whole result". Against Cartesianism Peirce drew on the methodological implications of the four incapacities—no genuine introspection, no intuition in the sense of non-inferential cognition, no thought but in signs, and no conception of the absolutely incognizable—to attack philosophical Cartesianism, of which he said that:[125] "It teaches that philosophy must begin in universal doubt" – when, instead, we start with preconceptions, "prejudices [...] which it does not occur to us can be questioned", though we may find reason to question them later. "Let us not pretend to doubt in philosophy what we do not doubt in our hearts." "It teaches that the ultimate test of certainty is...in the individual consciousness" – when, instead, in science a theory stays on probation till agreement is reached, then it has no actual doubters left. No lone individual can reasonably hope to fulfill philosophy's multi-generational dream. When "candid and disciplined minds" continue to disagree on a theoretical issue, even the theory's author should feel doubts about it. It trusts to "a single thread of inference depending often upon inconspicuous premisses" – when, instead, philosophy should, "like the successful sciences", proceed only from tangible, scrutinizable premisses and trust not to any one argument but instead to "the multitude and variety of its arguments" as forming, not a chain at least as weak as its weakest link, but "a cable whose fibers", soever "slender, are sufficiently numerous and intimately connected". It renders many facts "absolutely inexplicable, unless to say that 'God makes them so' is to be regarded as an explanation"[126] – when, instead, philosophy should avoid being "unidealistic",[127] misbelieving that something real can defy or evade all possible ideas, and supposing, inevitably, "some absolutely inexplicable, unanalyzable ultimate", which explanatory surmise explains nothing and so is inadmissible. |

プラグマティズム 主な記事 語用論、語用論的格言、語用論的真理論 § ペアース 著名な論文と講義 科学論理学の図解』(1877-1878年): 探究、プラグマティズム、統計、推論 信念の固定化 (1877) 考えを明確にする方法(1878年) 偶然の理論(1878年) 帰納の確率(1878年) 自然の秩序 (1878) 演繹、帰納、仮説 (1878) プラグマティズムに関するハーバード講義 (1903) プラグマティズムとは何か(1905年) プラグマティシズムの問題点 (1905) プラグマティズム (1907 MS 『エッセンシャル・ペアーズ』2) プラグマティズム、のちにプラグマティシズムと呼ばれるようになったペイスのプラグマティズム的思考のレシピは、いわゆるプラグマティック・マキシマムの いくつかのバージョンに要約されている。以下は、彼がより強調的に繰り返した格言のひとつである: 自分の観念の対象がどのような効果を持つと考えるか。そして、それらの効果についてのあなたの観念が、その対象についてのあなたの観念のすべてである。 運動としてのプラグマティズムは、1870年代初頭、形而上学クラブにおけるペイス、ウィリアム・ジェイムズらの議論から始まった。ジェイムズらは「信念 の固定化」(1877年)、特に「我々の考えを明確にする方法」(1878年)といったペイスのいくつかの論文をプラグマティズムの基礎となるものとみな していた[108]。ペイス(CP 5.11-12)はジェイムズ(Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 1907年)と同様に、プラグマティズムを、哲学やその他の分野で慣れ親しんだ態度を、問題について実りある思考をするための新しい熟慮的な方法として具 体化したものとみなしていた。ペイスは、ジェイムズや初期のジョン・デューイとは異なり、哲学的な気分の大部分を通じて、より合理的で現実的であった。 1905年、ペイスはプラグマティシズムという新しい名称を「元の定義を表現する正確な目的のために」作り、ジェイムズやF.C.S.シラーが「プラグマ ティズム」という古い名称をさまざまに使い分けることで「すべてがうまくいった」と述べ、古い名称が「濫用される文芸誌」で使われるようになったために新 しい名称を作ったと語った。しかし彼は、1906年の原稿ではジェイムズやシラーとの相違を、1908年の出版物ではジェイムズとの相違を、また文学者 ジョヴァンニ・パピーニがプラグマティズムの定義不可能性を宣言したことを原因として挙げている。ペイスはいずれにせよ、真理は不変であり、無限は実在す るという彼の見解を他のプラグマティストたちから反対されているとみなしていたが、他の問題に関しては彼らと同盟を結んでいた[109][回文参照]。 プラグマティズムは、信念とは人が行動する用意のあるものであるという考えから始まる。ペイスのプラグマティズムは対象の概念を明確にする方法である。あ る対象に関するあらゆる概念を、その対象がもたらす影響に関する概念と、その影響 が情報に基づいた実践に対して考えうる一般的な意味合いに関する概念と同一視する。それは、例えば、形式的な違いはあっても実践的な違いはない(時に必要 とされる)区別によって引き起こされる概念の混乱を整理する方法である。プラグマティズムと統計原理の両方を科学的論理学の一側面として定式化したのが、 彼の「科学論理学の図解」シリーズである。その第2回「我々の考えを明瞭にする方法」で、パースは概念の明瞭さについて3つの等級を論じた: たとえ未分析で未発達であったとしても、身近で容易に使用できる概念の明瞭さ。 論理学者が思想を「明瞭」と呼ぶ、つまり、何がそれを適用可能にしているのかを分析することによって明瞭化される。また、カントの言葉を借りて、パースは 同様に明確な定義を「名辞」と呼んだ(CP 5.553)。 明瞭さとは、対象が思い描く効果の考えられる実際的な含意が明瞭であることによって、特に困難な問題について実りある推論を促進するようなものである。こ こで彼は、後に語用論的格言と呼ばれるものを導入した。 どのように概念を明確にするかという例として、彼は真理と実在に関する概念を、推論全般の前提の問題として取り上げた。明晰さの第二段階(「名目的」段 階)において、彼は真理を記号とその対象との対応として定義し、実在をそのような対応の対象として定義した。このような必要ではあるが限定されたステップ を経て、次に明晰性の第三段階(実用主義的、実践指向的な段階)において、彼は真理を、十分な距離をとった研究によって遅かれ早かれ、しかしやはり必然的 に到達するであろう意見として定義した。 [真理と実在の独立性と発見可能性に反論することは、まさにそのような独立性と発見可能性を持つ真理が存在することを前提とすることである。 つまり、まず第一に、その概念を真であると受け入れるとすれば、その概念を真であると受け入れるすべての人による、結果として生じる理性的な行動の一般的 な様式とは何であると考えられるか。彼のプラグマティズムは、ミーム(あるいはプロパガンダ)のように、観念の意味、つまりその知的な趣旨を、その観念が 真であるという観点の外にある、その観念それ自体の考え出された利益やコストと同一視しない。また、観念は一般的なものであるから、その意味は、その観念 やその価値を裏付けたり損なったりする、実際の結果やアップショットの明確な集合と同一視されることもない。彼のプラグマティズムはまた、傭兵的あるいは 政治的な利点を求める冷酷でマキャベリ的な探求を誤解を招くような「低俗な」プラグマティズムとは似ても似つかない。その代わりにプラグマティックな格言 は、考えられる確証的状況と否認的状況の観点から概念に到達する実験的な精神的反省[111]の方法としての彼のプラグマティズムの核心であり、説明的仮 説の形成に適した方法であり、検証の使用と改善に資する方法である[112]。 ペイスのプラグマティズムは定義と概念の明確化の方法と理論として、彼の探求の理論の一部であり[113]、彼は様々に思弁的、一般的、形式的、普遍的な 修辞学、あるいは単にメトデューティックと呼んでいた[114]。 探究理論 参照 探究 The Fixation of Belief」(1877年)の中で、パースは探求の心理的起源と目的について彼の見解を述べている。彼の見解によれば、個人が探究に駆り立てられるの は、疑念の状態に特徴的とされる不安や焦燥の感情から逃れたいという欲求によるものである。疑いとは、「不安で不満な状態であり、そこから解放され、信念 の状態に移行しようともがく状態」であるとパースは述べている。パースは「苛立ち」といった言葉を使って、疑心暗鬼に陥る経験を説明し、なぜそのよう な経験が動機づけになると考えるのかを説明している。疑念という苛立たしい感情は、疑念を抱くに至ったそもそもの疑問に対する答えとして着地したものに満 足するという定まった状態に到達するための努力によって鎮められる、とパースは言う。この落ち着いた状態、すなわち信念を、パースは "避けたいとは思わない、穏やかで満足できる状態 "と表現している。どのような方法であれ、信念の満足を達成しようとする私たちの努力を、パースは「探究」と呼んでいる。思想の歴史を通じて実際に追求 されてきたとパースが述べている4つの方法を、次節以降に要約する。 批判的共通感覚主義 ピースがプラグマティズムの帰結として扱った批判的コモンセンス主義[115]は、トマス・リードのコモンセンス哲学と、科学による我々の世界の変容など によって、現在では確証可能である我々の多かれ少なかれ曖昧なコモンセンスの命題が後に疑問視される可能性があることを認識する可謬主義を組み合わせたも のである。このような哲学には、たとえ変化があったとしても緩やかなものである共通の不可疑事項の中核的なグループに対して、真正な疑念を試験的に作り上 げていく努力も含まれる。 対立する探究方法 信念の固定化」(1877年)の中で、パースは一般的な探究を、真理の追求そのものではなく、驚きや意見の不一致などから生まれる刺激的で抑制的な疑念 から脱し、確実な信念に到達するための闘いであると述べている。科学的探究をより広範なスペクトルの一部としてとらえ、一般的な探究と同様に、言葉によ る、喧嘩腰の、あるいは大げさな疑念ではなく、実際の疑念によって駆り立てられるものとしてとらえたのである。ペアーズは、意見をまとめるための4つの方 法を、最も成功率の低いものから順に並べた: 粘り強さ(最初の信念に固執する方針)の方法-これは快適さと決断力をもたらすが、あたかも真実が本質的に公的なものではなく私的なものであるかのよう に、反対情報や他人の意見を無視しようとすることにつながる。この方法は社会的衝動に反し、簡単に挫折してしまう。なぜなら、他の人の意見が自分の最初の 意見と同じくらい良いと思われるとき、人はよく気づくからである。その成功は輝かしいものだが、一過性のものになりがちだ。 権威の方法 - 意見の相違を克服するが、時に残酷である。その成功は荘厳で長く続くが、人々を徹底的に統制することはできず、特に人々が現在と過去の他の社会について学 んだときには、疑念にいつまでも耐えることはできない。 先験的な方法-それは、より残酷に適合性を促進するものではないが、「理性にかなうもの」という観点から、会話や観点の比較の中で生じる、嗜好のようなも のとして意見を育てるものである。そのため、パラダイムの流行に左右され、時間の経過とともに堂々巡りになる。より知的で立派な方法だが、最初の2つの方 法と同様、偶発的で気まぐれな信念を維持し、それを疑う心を持つ人もいる。 科学の方法 - 真理は発見可能であるが、特定の意見とは無関係であると仮定し、他の方法とは異なり、探求は、それ自身の説明によって、正しいだけでなく、間違って(可謬 主義)行くことができ、したがって、意図的に自分自身をテストし、批判し、修正し、改善する。 理性の「第一の規則」[117]は、学ぶためには、人は学びたいと願わなければならず、その副次的なものとして、探究の道を妨げてはならないというもので ある。科学的方法は、最終的に最も確実な信念に到達するように意図的に設計されており、その信念に基づいて最も成功する実践を行うことができるという点 で、最終的に他の方法よりも優れている。人は真理そのものを求めるのではなく、刺激的で抑制的な疑念を鎮めるために真理を求めるのだという考えから出発し たパースは、闘争を通じて、信念の完全性のために真理に服従し、与えられた目標に正しく向かう潜在的な行動の指針を真理として求め、科学的方法に身を委 ねるようになる人々を示した。 科学的方法 プラグマティズムは、プラグマティックな反省による解明が説明仮説に適し、予測と検証を促進する限りにおいて、通常の基礎的選択肢の二者択一を超えたもの を指し示す:自明の真理からの演繹、すなわち合理主義、経験的現象からの帰納、すなわち経験主義。 3つの論証様式に対する批判に基づき、基礎主義とも首尾一貫主義とも異なるペアーズのアプローチは、3段階の探求のダイナミズムによって主張を正当化しよ うとするものである: 能動的、帰納的な理論の創出; 偶発的な理論を演繹的に適用し、その実践的意味を明らかにする; 帰納的なテストと、将来の経験を予期した暫定理論の有用性の評価。 これによってパースは、現象学的パターンの単なる再ラベリングである単純な帰納的一般化という平板なイメージよりも、はるかに堅実な探究へのアプローチ を考案したのである。ペイスのプラグマティズムは、科学的方法が哲学的問題の認識論として初めて提案されたものであった。 私たちの世界を予測し制御する上で、ライバルよりも優れた成功を収める理論は、真理に近いと言われる。これは、科学者が用いる真理の運用上の概念である。 パースは、古典論理学の原料からプラグマティック・モデルや探究理論を抽出し、記号論理学の初期の発展と並行して、科学的推論の本質に関する問題に対処す るためにそれを改良した。 帰納法、演繹法、帰納法は、それぞれ単独では不完全な意味を持つが、探究という共通の目的に向かって協力する限り、全体として理解可能なサイクルを構成す る。考えられる実際的な意味合いについて考えるプラグマティックな方法では、すべての物事には目的があり、可能な限り、まずその目的が示されるべきであ る。アブダクションは、厄介な不確実性からより確実な信念へと移行するための闘いにおいて、帰納法が仮説を評価できるように、演繹法が検証すべき含意へと 解明するための説明を仮説として提起する。推論の様式を互いに抽象化して研究することがいかに伝統的で必要なことであっても、探究の完全性は、その主要な 構成要素の効果的なモジュール性を強く制限する。 無視された議論』[118]の§III-IVにおける科学的方法に関するペイスの概説を以下に要約する(特に断りのない限り)。そこでは、もっともらしさ と帰納的正確さ(論証の批判の問題)についても検討されている。 帰納的(あるいは遡及的)段階。推測、説明仮説への推論、試してみる価値が最もあるものを選択するため。パースは帰納法を、テストに基づいて仮説の真実の 割合を推論することとして、アブダクションと区別している。あらゆる探究は、それが観念であれ、厳然たる事実であれ、規範や法則であれ、それらの領域の1 つ以上における驚くべき観察から生じる(例えば、すでに進行中の探究のどの段階においても)。理論の説明内容はすべてアブダクションに由来する。アブダク ションとは、驚くべき、あるいは複雑な現象を単純で経済的な方法で説明するために、新しい、あるいは外部にある考えを推測することである。私たちの推測に おけるわずかな成功は、偶然の幸運をはるかに凌ぐものであり、特に最良の推測が、ガリレオの理性の自然光によるような、また「論理的単純さ」とは異なるよ うな、「容易で自然な」という意味において、最適にもっともらしく単純である限りにおいて、発達した、あるいは固有の本能による自然への同調から生まれる ように思われる[119]。1903年、パースはプラグマティズムを「アブダクションの論理」と呼んだ[121]。協調的方法は、もっともらしい仮説を アブダクションすることから、その検証可能性[122]や、その試みがいかに探究そのものを節約するかを判断することにつながる。単純だがありそうもない 推測は、虚偽を検証するコストがかからないのであれば、検証の第一候補に属するかもしれない。主観的な可能性は、理性的ではあっても、誤解を招くような魅 惑的なものである可能性がある。推測は、その注意深さ(その例としてパースは「20の質問」ゲームを挙げている)、広さ、あるいは複雑さのために、戦略 的に試行のために選択することができる[124]。人はいずれにせよ、十分な経験を通じて明らかになるであろうことだけを発見することができるのであり、 したがってポイントはそれを促進することである。 演繹的段階。二つの段階: i. 説明。明確な前提はないが、仮説を演繹的に分析し、その部分を可能な限り明確にする。 ii. 実証: 演繹的論証、ユークリッド的手順。発見される証拠に関する予測として、仮説の結果を明示的に演繹する。帰納的、または必要であれば定理的。 帰納的段階。仮説の評価、推論された結果の観察的または実験的テストからの推論。帰納法のルールの長期的な妥当性は、実在とは「十分な調査が導く最終的な 意見の対象のみである」という原則(一般的な推論の前提)から導かれる[110]。証拠の継続的な蓄積を含む帰納法は、「十分に継続する」ことによって 「誤りをあらかじめ指定された程度以下に減少させる」方法に従う。3つの段階 i. 分類。明確な前提はないが、一般的な考えの下に経験対象を帰納的に分類する。 ii. 検証:直接的な帰納的論証。手順が粗野か漸進的か。粗雑な帰納法は、一塊の経験に基礎を置き(CP 2.759)、ある問題についての将来の経験が、過去のすべての経験とまったく異ならないことを前提とする(CP 2.756)。漸進的帰納法(Gradual Induction)は、検証のたびに仮説の真実の割合を新たに推定するもので、質的帰納法(Qualitative Induction)と量的帰納法(Quantitative Induction)がある。質的漸進的帰納法は、調査対象のクラスのさまざまな性質の相対的な明白さの重みを推定することに依存する(CP 2.759;『チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集』7.114-120も参照)。量的漸進的帰納法は、Sの事例の公正なサンプルにおいて、SがSにつ いて予測されたPを実際に伴っていることがどれくらいの頻度で発見されるかに依存する(CP 2.758)。それは、測定、統計、または計数に依存する。 iii. 文の帰納。「帰納的推論によって、さまざまな推定を単独で評価し、次にそれらの組み合わせを評価し、次にこれらの評価そのものを自己評価し、全体の結果に ついて最終的な判断を下す」。 デカルト主義への反論 パースは、4つの無能力の方法論的意味合い-真の内観がないこと、非推論的認識の意味での直観がないこと、記号においてのみ思考することがないこと、絶 対的に認識不可能なものの概念がないこと-を利用して、哲学的デカルト主義を攻撃し、それについて彼は次のように述べている[125]。 「哲学は普遍的な疑いから始めなければならないと教えている。「心の中で疑っていないことを、哲学の中で疑うふりをしないようにしよう」。 「科学の世界では、理論が合意に達するまで執行猶予がつくと、実際に疑う者はいなくなる。哲学の何世代にもわたる夢を実現するためには、一個人では無理な のだ。理論的な問題に関して「率直で訓練された頭脳」が意見を異にし続ければ、その理論の著者でさえも疑念を感じるはずである。 哲学は、「成功した諸科学と同様に」、目に見える、精査可能な前提からのみ推論を進め、一つの論証ではなく、「その論証の多数性と多様性」を信頼すべきな のに、それは「目立たない前提」に依存する「一本の推論の糸」を信頼することになる。 それは多くの事実を「絶対的に説明不可能なもの」[126]にしてしまうが、「神がそうさせている」と言うことが説明とみなされるのでなければ」 [127]、そうではなく、哲学は「非理想的」であることを避けるべきであり[128]、現実の何かがあらゆる可能な考えを無視したり回避したりすること ができると誤信し、必然的に「絶対的に説明不可能な、分析不可能な究極的なもの」を仮定する。 |

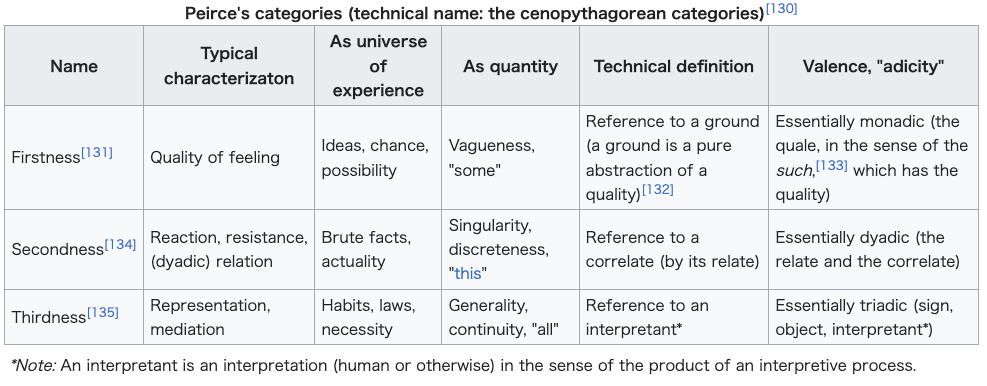

| Theory of categories Main article: Categories (Peirce) On May 14, 1867, the 27-year-old Peirce presented a paper entitled "On a New List of Categories" to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, which published it the following year. The paper outlined a theory of predication, involving three universal categories that Peirce developed in response to reading Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, and G. W. F. Hegel, categories that Peirce applied throughout his work for the rest of his life.[20] Peirce scholars generally regard the "New List" as foundational or breaking the ground for Peirce's "architectonic", his blueprint for a pragmatic philosophy. In the categories one will discern, concentrated, the pattern that one finds formed by the three grades of clearness in "How To Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878 paper foundational to pragmatism), and in numerous other trichotomies in his work. "On a New List of Categories" is cast as a Kantian deduction; it is short but dense and difficult to summarize. The following table is compiled from that and later works.[128] In 1893, Peirce restated most of it for a less advanced audience.[129]  |

カテゴリー論 主な記事 カテゴリー(ペアーズ) 1867年5月14日、27歳のパースはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミー(American Academy of Arts and Sciences)に「カテゴリーの新しいリストについて」と題する論文を提出した。この論文は、アリストテレス、イマヌエル・カント、G.W.F.ヘー ゲルを読んで開発した3つの普遍的なカテゴリーを含む述語の理論を概説したものであり、このカテゴリーはペアーズが生涯を通じて彼の仕事を通して適用した ものであった[20]。このカテゴリーには、「How To Make Our Ideas Clear」(プラグマティズムの基礎となった1878年の論文)における明晰さの3つの等級によって形成されるパターンや、彼の著作における他の数多く の三分法によって形成されるパターンが凝縮されている。 「範疇の新しい一覧表について」はカント的な演繹として投げかけられており、短いが濃密で要約が難しい。以下の表はその著作とそれ以降の著作から編集され たものである[128]。1893年、パースはその大部分をより高度でない聴衆のために再編集した[129]。 |